メキシコに渡ったフィリピン移民

Filipino immigration to Mexico

☆フィ

リピン系メキシコ人(スペイン語: Mexicanos Filipinos)とは、フィリピン人の祖先を持つメキシコ市民を指す。[1]

メキシコには約1,200人のフィリピン国民が居住している。[2]

さらに遺伝学的研究によれば、ゲレーロ州で調査対象となった人々の中で、約3分の1がアジア系の祖先を持ち、その遺伝子マーカーはフィリピン人集団のもの

と一致している。[3]

| Filipino Mexicans

(Spanish: Mexicanos Filipinos) are Mexican citizens who are descendants

of Filipino ancestry.[1] There are approximately 1,200 Filipino

nationals residing in Mexico.[2] In addition, genetic studies indicate

that about a third of people sampled from Guerrero have Asian ancestry

with genetic markers matching those of the populations of the

Philippines.[3] |

フィ

リピン系メキシコ人(スペイン語: Mexicanos Filipinos)とは、フィリピン人の祖先を持つメキシコ市民を指す。[1]

メキシコには約1,200人のフィリピン国民が居住している。[2]

さらに遺伝学的研究によれば、ゲレーロ州で調査対象となった人々の中で、約3分の1がアジア系の祖先を持ち、その遺伝子マーカーはフィリピン人集団のもの

と一致している。[3] |

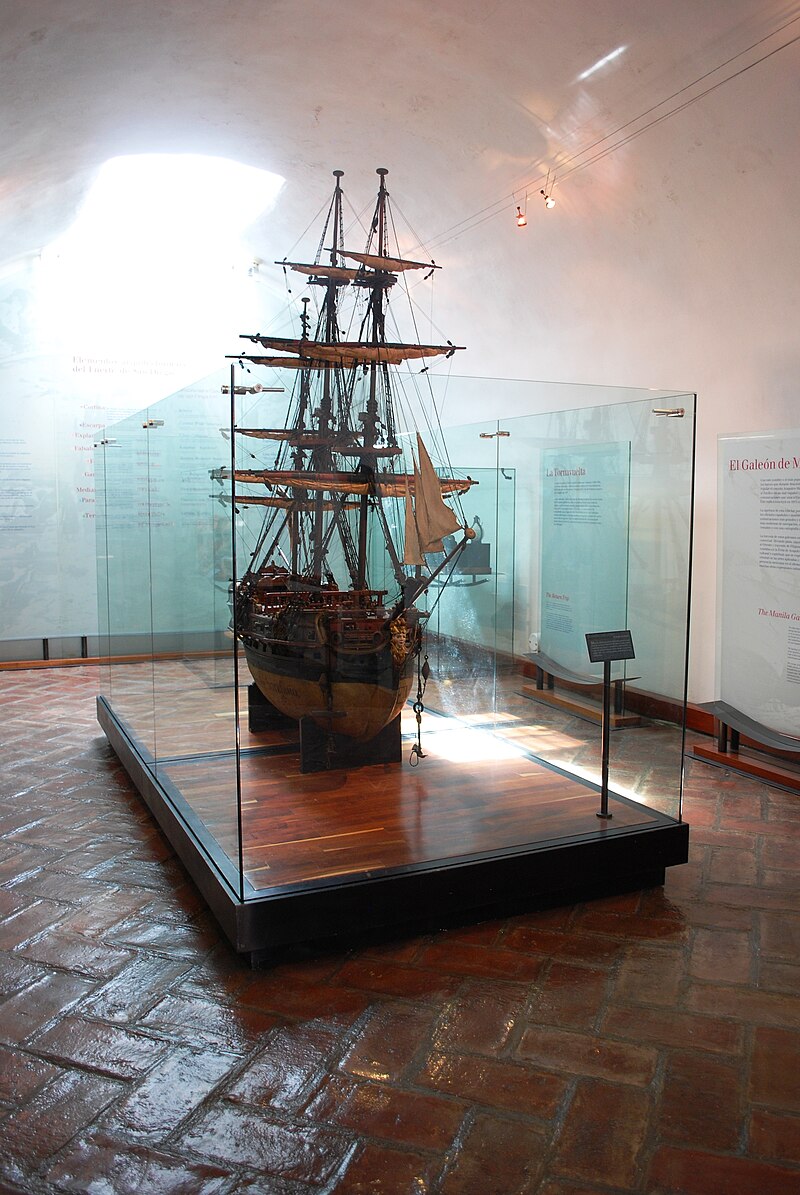

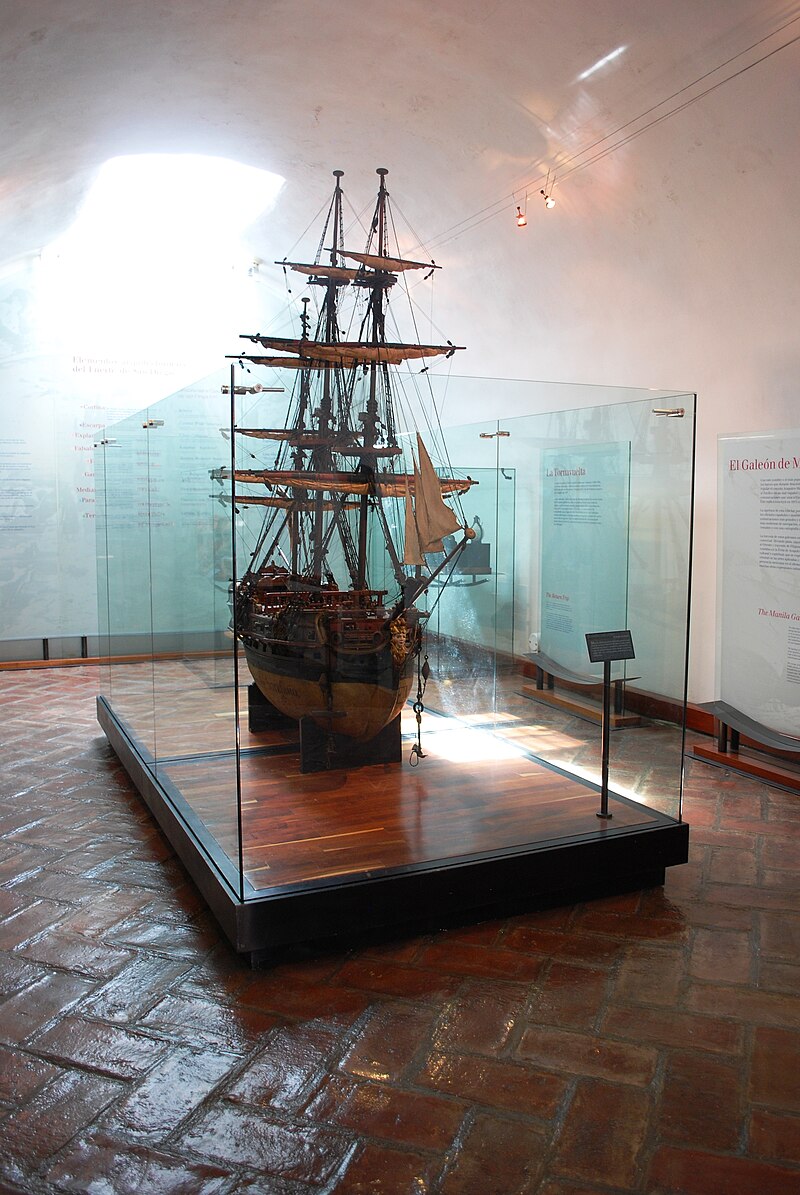

Model of the ship San Pedro de Cerdeña on display at the San Diego Fort in Acapulco |

アカプルコのサンディエゴ要塞に展示されているサン・ペドロ・デ・セルデニャ号の模型 |

| History Main articles: Landing of the first Filipinos and Manila galleon Filipinos first arrived in Mexico during the Spanish colonial period via the Manila-Acapulco Galleon. For two and a half centuries, between 1565 and 1815, many Filipinos and Mexicans sailed to and from Mexico and the Philippines as sailors, crews, slaves, prisoners, adventurers and soldiers in the Manila-Acapulco Galleon assisting Spain in its trade between Asia and the Americas.[4] The majority of the Asian migrants to Mexico during this period were Filipinos, and to a smaller extent, other Asian slaves bought from the Portuguese or captured through war.[5][6][7][8]  Embassy of The Philippines in Colonia Veronica Anzures, Mexico City During the early period of the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, Spaniards took advantage of the indigenous alipin (bonded serf) system in the Philippines to circumvent the Leyes de las Indias and acquire Filipino slaves for the voyage back to New Spain. Though the numbers are unknown, it was so prevalent that slaves brought on ships were restricted to one per person (except persons of rank) in the "Laws Regarding Navigation and Commerce" (1611–1635) to avoid exhausting ship provisions. They were also taxed heavily upon arrival in Acapulco in an effort to reduce slave traffic. Traffic in Filipina women as slaves, servants, and mistresses of government officials, crew, and passengers, also caused scandals in the 17th century. Women comprised around 20 percent of the migrants from the Philippines.[4][5] Filipinos were also pressed into service as sailors, due to the native maritime culture of the Philippine Islands. By 1619, the crew of the Manila galleons were composed almost entirely of native sailors, many of whom died during the voyages due to harsh treatment and dangerous conditions. Many of the galleons were also old, overloaded, and poorly repaired. A law passed in 1608 restricted the gear of Filipino sailors to "ropa necesaria" which consisted of a single pair of breeches, further causing a great number of deaths of Filipino sailors through exposure. These conditions prompted King Philip III to sign a law in 1620 forcing merchants to issue proper clothing to native crews. During this period, many Filipino sailors deserted as soon as they reached Acapulco. Sebastian de Piñeda, the captain of the galleon Espiritu Santo complained to the king in 1619 that of the 75 Filipino crewmen aboard the ship, only 5 remained for the return voyage. The rest had deserted. These sailors settled in Mexico and married locals (even though some may have been previously married in the Philippines), particularly since they were also in high demand by wine-merchants in Colima for their skills in the production of tubâ (palm wine).[5][9] Christianized Filipinos comprised the majority of free Asian immigrants (chino libre) and could own property and have rights that even Native Americans did not have, including the right to carry a sword and dagger for personal protection.[4] They often owned coconut plantations in Colima, an example from 1619 was Andrés Rosales who owned twenty-eight coconut palms. Others were merchants, like Tomás Pangasinan, a native of Pampanga, who was recorded to have paid thirteen pesos in taxes for the purchase of Chinese silks from the Manila galleons in the 17th century. The cities of Mexico, Puebla, and Guadalajara had enough Filipino neighborhoods that they formed segregated markets of Asian goods called Parián (named after similar markets in the Philippines).[4] The descendants of these early migrants mostly settled in the regions near the terminal ports of the Manila galleons. These include Acapulco, Barra de Navidad, and San Blas, Nayarit, as well as numerous smaller intermediate settlements along the way. They also settled the regions of Colima and Jalisco before the 17th century, which were seriously depopulated of Native American settlements during that period due to the Cocoliztli epidemics and Spanish forced labor.[5] They also settled in signiciant numbers in the barrio San Juan of Mexico City, although in modern times, the area has become more associated with later Chinese migrants.[4] A notably large settlement of Filipinos during the colonial era is Coyuca de Benítez along the Costa Grande of Guerrero, which at one point in history was called "Filipino town".[10] |

歴史 s 主な記事:最初のフィリピン人の上陸とマニラ・ガレオン船 フィリピン人はスペイン植民地時代にマニラ・アカプルコ・ガレオン船を通じて初めてメキシコに到達した。1565年から1815年までの2世紀半にわた り、多くのフィリピン人とメキシコ人が船員、乗組員、奴隷、囚人、冒険者、兵士としてマニラ・アカプルコ・ガレオン船でメキシコとフィリピン間を往復し、 スペインのアジアとアメリカ大陸間の貿易を支援した。[4] この時期にメキシコへ移住したアジア系移民の大半はフィリピン人であり、少数ながらポルトガルから購入された、あるいは戦争で捕らえられた他のアジア人奴 隷も含まれていた。[5][6][7][8]  フィリピン大使館(メキシコシティ、コロニア・ベロニカ・アンズレス) スペインによるフィリピン植民地化の初期段階において、スペイン人は現地のアリピン(債務奴隷)制度を利用し、インド諸島法(Leyes de las Indias)を回避してフィリピン人奴隷を獲得し、新スペインへの帰還航海に供した。その数は不明だが、この慣行は広く普及していたため、「航海及び通 商に関する法令」(1611年~1635年)では、船の食糧を消耗させないよう、船に持ち込める奴隷を一人につき一人(身分のある者を除く)と制限した。 また、奴隷取引を減らすため、アカプルコ到着時には重税が課された。17世紀には、フィリピン人女性を奴隷・使用人・政府高官や乗組員、乗客の愛人として 取引する行為もスキャンダルを引き起こした。フィリピンからの移民の約20%を女性が占めていた[4]。[5] フィリピン諸島の土着的な海洋文化ゆえに、フィリピン人は船員として強制的に徴用された。1619年までにマニラ・ガレオン船の乗組員はほぼ完全に現地人 船員で構成され、その多くは過酷な扱いと危険な状況下で航海中に死亡した。ガレオン船の多くは老朽化・過積載・手入れ不足だった。1608年に制定された 法律はフィリピン人船員の装備を「ロパ・ネサリサ」(必要最低限の衣服)に制限し、これは単一のズボン一着のみを指した。このため多くのフィリピン人船員 が寒さで命を落とした。こうした状況を受け、フェリペ3世は1620年に商人に対し現地船員への適切な衣服支給を義務付ける法律に署名した。この時期、多 くのフィリピン人船員はアカプルコに到着するとすぐに脱走した。ガレオン船エスプリトゥ・サント号の船長セバスティアン・デ・ピニェダは1619年、国王 にこう訴えた。船に乗っていた75人のフィリピン人乗組員のうち、帰路に残ったのはわずか5人だったと。残りは全員脱走した。これらの船員はメキシコに定 住し、現地人と結婚した(フィリピンで既に結婚していた者もいたが)。特にコリマのワイン商人たちが、トゥバ(ヤシ酒)製造の技能を求めて彼らを高く評価 したためである。[5] [9] キリスト教化されたフィリピン人は、自由アジア移民(チノ・リブレ)の大半を占め、財産を所有し、ネイティブアメリカンですら持たない権利、例えば個人的 な自己防衛のための剣や短剣の携帯権さえも有していた。[4] 彼らはしばしばコリマでココナッツ農園を所有しており、1619年の例ではアンドレス・ロサレスが28本のココナッツヤシを所有していた。商人として活動 した者もいた。パンパンガ出身のトマス・パンガシナンは、17世紀にマニラガレオン船から中国絹を購入した際、13ペソの税金を納めた記録が残っている。 メキシコシティ、プエブラ、グアダラハラの各都市にはフィリピン人街が形成され、フィリピンの市場に因んで「パリアン」と呼ばれるアジア商品専門の隔離市 場が生まれた。[4] これらの初期移民の子孫は、主にマニラ・ガレオン船の終着港周辺地域に定住した。アカプルコ、バラ・デ・ナヴィダード、ナヤリット州サン・ブラス、そして 途中の数多くの小規模な中継地が含まれる。また17世紀以前にはコリマ州やハリスコ州にも定住した。これらの地域では当時、ココロイツリ疫病とスペイン人 による強制労働により先住民集落が深刻な人口減少に見舞われていた[5]。さらにメキシコシティのサン・フアン地区にも相当数のフィリピン人が定住した が、現代ではこの地域は後世の中国人移民との関連性が強くなっている。[4] 植民地時代にフィリピン人が特に大規模に定住したのは、ゲレーロ州コスタ・グランデ沿いのコユカ・デ・ベニテスである。この地は歴史上ある時期、「フィリ ピン人町」と呼ばれていた。[10] |

| Influence The Filipinos introduced many cultural practices to Mexico, such as the method of making palm wine, called "tubâ",[11][12][13] the mantón de Manila,[14][15][16] the chamoy,[17] and possibly the guayabera (called filipina in Veracruz and the Yucatán Peninsula).[18] Distillation technology used by bootleggers for the production of mezcal was also introduced by Filipino migrants in the late 16th century, via the adaptation of the stills used in the production of Philippine palm liquor (lambanog) which were introduced to Colima with tubâ.[19][20] Filipino words also entered Mexican vernacular, such as the word for palapa (originally meaning "coconut palm leaf petiole" in Tagalog), which became applied to a type of thatching using coconut leaves that resembles the Filipino nipa hut.[4] Various crops were also introduced from the Philippines, including coconuts,[21] the Ataulfo and Manilita mangoes,[22][23] abacá, and bananas. A genetic study in 2018 found that around a third of the population of Guerrero have 10% Filipino ancestry.[3] |

影響 フィリピン人はメキシコに多くの文化慣習をもたらした。例えば「トゥバ」と呼ばれるヤシ酒の醸造法[11][12][13]、マニラのマンタ[14] [15][16]、チャモイ[17]、そしておそらくグアヤベラ(ベラクルス州とユカタン半島ではフィリピナと呼ばれる)などである。[18] メスカル製造に密造業者が用いる蒸留技術も、16世紀後半にフィリピン移民によって導入された。これはフィリピン産ヤシ酒(ランバノグ)の製造に用いられ る蒸留器を改良したもので、トゥバと共にコリマ州に伝来したものである。[19] [20] フィリピン語由来の単語もメキシコ語に浸透した。例えば「パラパ」はタガログ語で「ココナッツヤシの葉柄」を意味したが、フィリピンのニパ小屋に似たココナッツ葉葺きの屋根を指すようになった。[4] フィリピンからは様々な作物も導入された。ココナッツ[21]、アタウルフォ種とマニリタ種のマンゴー[22][23]、アバカ、バナナなどがそれにあたる。 2018年の遺伝子研究によれば、ゲレロ州住民の約3分の1が10%のフィリピン系祖先を持つことが判明している[3]。 |

| Historical records Colonial-era Filipino immigrants to Mexico are difficult to trace in historical records because of several factors. The most significant factor being the use of the terms indio and chino. In the Philippines, natives were known as indios, but they lost that classification when they reached the Americas, since the term in New Spain referred to Native Americans. Instead they were called chinos, leading to the modern confusion of early Filipino immigrants with the much later Chinese immigrants in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Intermarriage and assimilation into Native American communities also buried the true extent of Filipino immigration, as they became indistinguishable from the bulk of the peasantry.[5][24] Another factor is the pre-colonial Filipino (and Southeast Asian) tradition of not having last names. Filipinos and Filipino migrants acquired Spanish surnames, either after conversion to Christianity or enforced by the Catálogo alfabético de apellidos during the mid-19th century. This makes it very difficult to trace Filipino immigrants in colonial records.[5] |

歴史的記録 植民地時代のフィリピン人移民がメキシコに渡った記録は、いくつかの要因から歴史的記録で追跡するのが難しい。最も重要な要因は「インディオ」と「チノ」 という用語の使用だ。フィリピンでは先住民はインディオと呼ばれていたが、アメリカ大陸に渡るとその分類は失われた。新スペインではこの用語がネイティブ アメリカンを指すようになったからだ。代わりに彼らは「チノ」と呼ばれ、これが現代における混乱の原因となっている。すなわち、初期のフィリピン移民と、 はるかに後の1800年代末から1900年代初頭の中国人移民が混同されるのである。異民族間の結婚や先住民コミュニティへの同化もまた、フィリピン移民 の真の規模を埋もれさせた。彼らは農民の大多数と区別がつかなくなったのである。[5][24] もう一つの要因は、植民地化以前のフィリピン人(及び東南アジア人)に姓を持たない伝統があったことだ。フィリピン人とフィリピン人移民は、キリスト教へ の改宗後、あるいは19世紀半ばの『姓アルファベット目録』によって強制的にスペイン系の姓を名乗るようになった。このため植民地時代の記録でフィリピン 人移民を追跡するのは非常に困難である。[5] |

| Notable Mexicans of Filipino descent Ramón Fabié - Lieutenant Colonel commander of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla Luis Pinzón - Military commander of José María Morelos Isidoro Montes de Oca – Mexican General and Lieutenant commander of Vicente Guerrero Romeo Tabuena – painter and printmaker Alejandro Gómez Maganda – Governor of Guerrero (1951–1954) Lili Rosales – Representative of Mexico in the Reina Hispanoamericana 2011 beauty contest Miguel A. Reina - Mexican filmmaker, screenwriter and film producer. |

フィリピン系メキシコ人の著名人 ラモン・ファビエ - ミゲル・イダルゴ・イ・コスティージャの副司令官 ルイス・ピンソン - ホセ・マリア・モレロスの軍事指揮官 イシドロ・モンテス・デ・オカ - メキシコ軍将軍、ビセンテ・ゲレーロの副司令官 ロメオ・タブエナ - 画家、版画家 アレハンドロ・ゴメス・マガンダ - ゲレーロ州知事(1951年~1954年) リリ・ロサレス - 2011年ヒスパノアメリカン女王コンテストにおけるメキシコ代表 ミゲル・A・レイナ - メキシコの映画監督、脚本家、映画プロデューサー |

| Mexico–Philippines relations Manila galleon Mexican settlement in the Philippines Mestizos in Mexico Filipino mestizo |

メキシコとフィリピンの関係 マニラ・ガレオン船 フィリピンにおけるメキシコ人入植 メキシコのメスティーソ フィリピンのメスティーソ |

| References 1. "Filipinos in Mexican history". www.ezilon.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2022. 2. "Welcome to Manila Bulletin Online". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on 2009-02-09. Retrieved 2017-02-15. 3. Wade, Lizzie (12 April 2018). "Latin America's lost histories revealed in modern DNA". Science. Retrieved 14 July 2021. 4. Carrillo, Rubén. "Asia llega a América. Migración e influencia cultural asiática en Nueva España (1565-1815)". raco.cat. Asiadémica. Retrieved 19 December 2016. 5. Guzmán-Rivas, Pablo (1960). "Geographic Influences of the Galleon Trade on New Spain". Revista Geográfica. 27 (53): 5–81. ISSN 0031-0581. JSTOR 41888470. 6. Bethell, Leslie, ed. (1984). The Cambridge History of Latin America. Vol. 2 of The Cambridge History of Latin America: Colonial Latin America. I-II (illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-521-24516-8. 7. López-Calvo, Ignacio (2013). The Affinity of the Eye: Writing Nikkei in Peru. Fernando Iwasaki. University of Arizona Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-8165-9987-5. 8. Hoerder, Dirk (2002). Cultures in Contact: World Migrations in the Second Millennium. Andrew Gordon, Alexander Keyssar, Daniel James. Duke University Press. p. 200. ISBN 0-8223-8407-8. 9. Machuca, Paulina (2019). "To make tuba in Mexico and the Philippines. Four centuries of shared history". EncArtes. 2 (3): 214–225. doi:10.29340/en.v2n3.82. 10. "Cultural exchanges between Mexico and the Philippines". Geo-Mexico. Retrieved 14 August 2022. 11. Astudillo-Melgar, Fernando; Ochoa-Leyva, Adrián; Utrilla, José; Huerta-Beristain, Gerardo (22 March 2019). "Bacterial Diversity and Population Dynamics During the Fermentation of Palm Wine From Guerrero Mexico". Frontiers in Microbiology. 10: 531. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00531. PMC 6440455. PMID 30967846. 12. Veneracion, Jaime (2008). "The Philippine-Mexico Connection". In Poddar, Prem; Patke, Rajeev S.; Jensen, Lars (eds.). Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures – Continental Europe and its Empires. Edinburgh University Press. p. 574. ISBN 978-0-7486-3027-1. 13. Mercene, Floro L. (2007). Manila Men in the New World: Filipino Migration to Mexico and the Americas from the Sixteenth Century. UP Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-971-542-529-2. 14. Arranz, Adolfo (27 May 2018). "The China Ship". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 19 May 2019. 15. Nash, Elizabeth (13 October 2005). Seville, Cordoba, and Granada: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. pp. 136–143. ISBN 978-0-19-518204-0. 16. Maxwell, Robyn (2012). Textiles of Southeast Asia: Trade, Tradition and Transformation. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-0698-7. 17. Tellez, Lesley. "The Spicy, Sour, Ruby-Red Appeal of Chamoy". Taste. Retrieved 1 November 2021. 18. Armario, Christine (30 June 2004). "Guayabera's Origin Remains a Puzzle". Miami Herald. Retrieved 10 April 2015. 19. Zizumbo-Villarreal, Daniel; Colunga-GarcíaMarín, Patricia (June 2008). "Early coconut distillation and the origins of mezcal and tequila spirits in west-central Mexico". Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 55 (4): 493–510. doi:10.1007/s10722-007-9255-0. 20. Bruman, Henry J. (July 1944). "The Asiatic Origin of the Huichol Still". Geographical Review. 34 (3): 418. doi:10.2307/209973. 21. Gunn, Bee F.; Baudouin, Luc; Olsen, Kenneth M. (22 June 2011). "Independent Origins of Cultivated Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) in the Old World Tropics". PLOS ONE. 6 (6) e21143. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021143. hdl:1885/62987. PMC 3120816. 22. Rocha, Franklin H.; Infante, Francisco; Quilantán, Juan; Goldarazena, Arturo; Funderburk, Joe E. (March 2012). "'Ataulfo' Mango Flowers Contain a Diversity of Thrips (Thysanoptera)". Florida Entomologist. 95 (1): 171–178. doi:10.1653/024.095.0126. 23. Adams, Lisa J. (19 June 2005). "Mexico tries to claim 'Manila mango' name as its own". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018. 24. Slack, Edward R. (2009). "The Chinos in New Spain: A Corrective Lens for a Distorted Image". Journal of World History. 20 (1): 35–67. ISSN 1045-6007. JSTOR 40542720. |

参考文献 1. 「メキシコ史におけるフィリピン人」. www.ezilon.com. 2007年9月27日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2022年1月13日閲覧. 2. 「マニラ・ブレティン・オンラインへようこそ」. マニラ・ブレティン. 2009年2月9日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2017年2月15日閲覧. 3. ウェイド、リジー (2018年4月12日). 「現代DNAが明らかにしたラテンアメリカの失われた歴史」. サイエンス. 2021年7月14日に閲覧. 4. カリージョ、ルベン. 「アジアがアメリカに到達する。ヌエバ・エスパーニャにおけるアジアの移民と文化的影響 (1565-1815)」. raco.cat. アシアデミカ. 2016年12月19日閲覧。 5. グスマン=リバス、パブロ (1960). 「ガレオン貿易が新スペインに与えた地理的影響」. 『地理学雑誌』. 27 (53): 5–81. ISSN 0031-0581. JSTOR 41888470. 6. ベセル、レスリー編(1984)。『ケンブリッジ・ラテンアメリカ史』第2巻『植民地時代のラテンアメリカ』I-II(図版付き、復刻版)。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。p. 21。ISBN 0-521-24516-8。 7. ロペス=カルボ、イグナシオ(2013)。目の親和性:ペルーにおける日系人の記述。フェルナンド・イワサキ。アリゾナ大学出版。134 ページ。ISBN 978-0-8165-9987-5。 8. ホーダー、ダーク (2002)。接触する文化:第二千年紀における世界的な移住。アンドルー・ゴードン、アレクサンダー・ケイサー、ダニエル・ジェームズ。デューク大学出版。200 ページ。ISBN 0-8223-8407-8。 9. マチュカ、パウリーナ (2019)。「メキシコとフィリピンにおけるチューバの製作。4世紀にわたる共有の歴史」。EncArtes。2 (3): 214–225. doi:10.29340/en.v2n3.82。 10. 「メキシコとフィリピンの文化交流」. Geo-Mexico. 2022年8月14日閲覧. 11. アストゥディージョ=メルガル, フェルナンド; オチョア=レイバ, アドリアン; ウトリージャ, ホセ; ウエルタ=ベリスタイン, ヘラルド (2019年3月22日). 「メキシコ・ゲレロ州産パームワイン発酵過程における細菌多様性と個体群動態」. Frontiers in Microbiology. 10: 531. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00531. PMC 6440455. PMID 30967846. 12. ベネラシオン、ハイメ(2008)。「フィリピンとメキシコのつながり」。ポッダー、プレム;パトケ、ラジーブ・S.;ジェンセン、ラース(編)。『ポス トコロニアル文学の歴史的コンパニオン-大陸ヨーロッパとその帝国』エディンバラ大学出版局。574頁。ISBN 978-0-7486-3027-1。 13. メルセン、フローロ・L.(2007)。『新世界のマニラ人:16世紀からのフィリピン人メキシコ・アメリカ大陸移住史』。UPプレス。125頁。ISBN 978-971-542-529-2。 14. アランツ、アドルフォ(2018年5月27日)。「チャイナシップ」. サウスチャイナ・モーニング・ポスト. 2019年5月19日閲覧. 15. ナッシュ, エリザベス (2005年10月13日). 『セビリア、コルドバ、グラナダ:文化史』. オックスフォード大学出版局. pp. 136–143. ISBN 978-0-19-518204-0. 16. マクスウェル、ロビン(2012年)。『東南アジアの織物:貿易、伝統、変容』。タトル出版。ISBN 978-1-4629-0698-7。 17. テレズ、レスリー。「チャモイの辛くて酸っぱくてルビー色の魅力」。テイスト。2021年11月1日取得。 18. アルマリオ、クリスティン(2004年6月30日)。「グアヤベラの起源は謎のままである」。『マイアミ・ヘラルド』。2015年4月10日取得。 19. ジズンボ=ビジャレアル、ダニエル;コロンガ=ガルシアマリン、パトリシア(2008年6月)。「メキシコ中西部の初期ココナッツ蒸留とメスカル・テキー ラ酒の起源」『遺伝資源と作物進化』55巻4号: 493–510頁. doi:10.1007/s10722-007-9255-0. 20. ブルマン、ヘンリー・J.(1944年7月)。「ウィチョル蒸留器のアジア起源」。『地理学評論』。34巻3号:418頁。doi:10.2307/209973。 21.ガン、ビー・F.;ボードワン、リュック;オルセン、ケネス・M.(2011年6月22日)。「旧世界熱帯地域における栽培ココナッツ(Cocos nucifera L.)の独立した起源」。PLOS ONE。6 (6) e21143。doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021143。hdl:1885/62987。PMC 3120816。 22. Rocha, Franklin H.; Infante, Francisco; Quilantán, Juan; Goldarazena, Arturo; Funderburk, Joe E. (2012年3月). 「『アタウルフォ』マンゴーの花には多様なアザミウマ(Thysanoptera)が生息している」. Florida Entomologist. 95 (1): 171–178. doi:10.1653/024.095.0126. 23. Adams, Lisa J. (2005年6月19日). 「メキシコは『マニラマンゴー』の名称を自国のものであると主張しようとしている」. The San Diego Union-Tribune. 2018年10月11日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2018年10月11日に取得。 24. スラック、エドワード・R. (2009). 「ニュースペインのチノス:歪んだイメージを正すレンズ」. 『世界史ジャーナル』. 20 (1): 35–67. ISSN 1045-6007. JSTOR 40542720. |

| External links Color Q World: Asian-Latino Intermarriage in the Americas Filipinos in Mexican History Afro-Filipino Mongoys (Photo of General Francisco Mongoy's descendants in the State of Guerrero) Insurgent Leaders during Mexican War of Independence against Spain |

外部リンク カラーQワールド:アメリカ大陸におけるアジア系とラテン系の異民族間結婚 メキシコ史におけるフィリピン人 アフロ・フィリピン人モンゴイ族(ゲレロ州におけるフランシスコ・モンゴイ将軍の子孫の写真) スペインに対するメキシコ独立戦争時の反乱指導者たち |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filipino_immigration_to_Mexico |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099