マニラ・ガレオン船貿易

Manila galleon

☆

マニラ・ガレオン(スペイン語: Galeón de Manila、タガログ語: Galeon ng

Maynila)とは、スペイン領東インド(フィリピン)とメキシコ(ニュー・スペイン)を太平洋を越えて結んだスペインの貿易船を指す。16世紀後半か

ら19世紀初頭にかけて、マニラ港とアカプルコ港の間を年間1~2往復した。[2]

「マニラ・ガレオン」という用語は、1565年から1815年まで運用されたマニラとアカプルコ間の貿易ルートそのものを指す場合もある。[1]

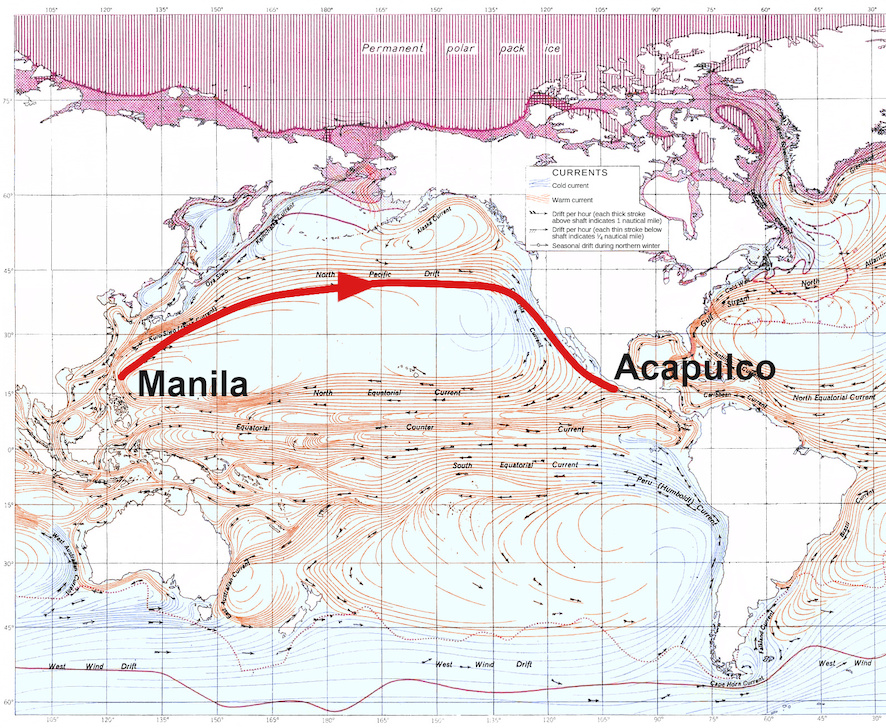

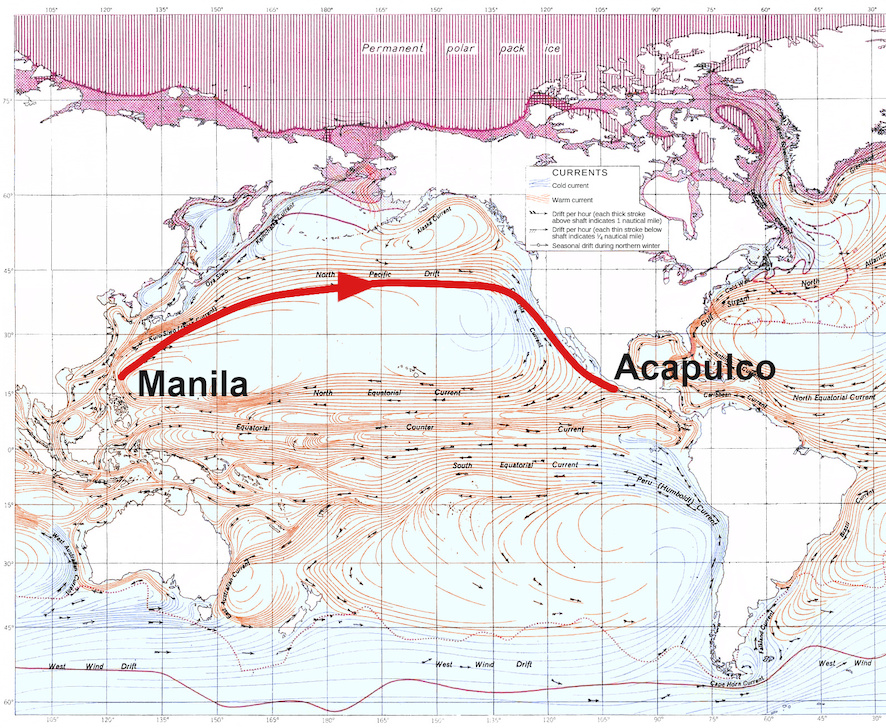

マニラ・ガレオン貿易ルートは、1565年にアウグスチノ会の修道士であり航海士でもあるアンドレス・デ・ウルダネタがフィリピンからメキシコへの帰路

(トルナビアヘ)を開拓した後に開設された。ウルダネタとアロンソ・デ・アレジャノは同年、黒潮を利用することで初の往復航海に成功した。ガレオン船は6

月末か7月初旬にマニラ湾のカビテを出航し、北太平洋を航行して翌年3月から4月にかけてアカプルコに到着した。アカプルコからの帰路は赤道に近い低緯度

海域を通過し、マリアナ諸島で停泊後、サマール島エスプリトゥサント岬沖のサンベルナルディーノ海峡を経てマニラ湾へ。6月か7月までに再びカビテ沖に停

泊した[1][3]。「ウルダネタ航路」を用いた貿易は、メキシコ独立戦争が勃発した1815年まで続いた。これらのガレオン船の大半はカビテの造船所で

建造・積載された。フィリピン産チークなどの現地産広葉樹が用いられ、帆はイロコス地方で生産され、索具やロープは耐塩性のマニラ麻で作られた。乗組員の

大部分はフィリピン人原住民で、農民や路上の子供、浮浪者などが船員として強制徴用された者も多かった。士官やその他の熟練乗組員は通常スペイン人(その

多くはバスク系)であった。ガレオン船は国家の船舶であったため、建造費と維持費はスペイン王室が負担した。[3][4]

| The Manila galleon

(Spanish: Galeón de Manila; Tagalog: Galeon ng Maynila) refers to the

Spanish trading ships that linked the Philippines in the Spanish East

Indies to Mexico (New Spain), across the Pacific Ocean. The ships made

one or two round-trip voyages per year between the ports of Manila and

Acapulco from the late 16th to early 19th century.[2] The term "Manila

galleon" can also refer to the trade route itself between Manila and

Acapulco that was operational from 1565 to 1815.[1] The Manila galleon trade route was inaugurated in 1565 after the Augustinian friar and navigator Andrés de Urdaneta pioneered the tornaviaje or return route from the Philippines to Mexico. Urdaneta and Alonso de Arellano made the first successful round trips that year, by taking advantage of the Kuroshio Current. The galleons set sail from Cavite, in Manila Bay, at the end of June or the first week of July, sailing through the northern Pacific and reaching Acapulco in March to April of the next calendar year. The return route from Acapulco passes through lower latitudes closer to the equator, stopping over in the Marianas, then sailing onwards through the San Bernardino Strait off Cape Espiritu Santo in Samar and then to Manila Bay and anchoring again off Cavite by June or July.[1][3] The trade using "Urdaneta's route" lasted until 1815, when the Mexican War of Independence broke out. The majority of these galleons were built and loaded in shipyards in Cavite, utilizing native hardwoods like the Philippine teak, with sails produced in Ilocos, and with the rigging and cordage made from salt-resistant Manila hemp. The vast majority of the galleon's crew consisted of Filipino natives; many of whom were farmers, street children, or vagrants press-ganged into service as sailors. The officers and other skilled crew were usually Spaniards (a high percentage of whom were of Basque descent). The galleons were state vessels and thus the cost of their construction and upkeep was borne by the Spanish Crown.[3][4] The galleons mostly carried cargoes of Chinese and other Asian luxury goods in exchange for New World silver. Silver prices in Asia were substantially higher than in America, leading to an arbitrage opportunity for the Manila galleon. Every space of the galleons was packed tightly with cargo, even spaces outside the holds like the decks, cabins, and magazines. In extreme cases, they towed barges filled with more goods. While this resulted in slow passage (which sometimes resulted in shipwrecks or turning back), the profit margins were so high that it was commonly practiced.[3] These goods included Indian ivory and precious stones, Chinese silk and porcelain, cloves from the Moluccas islands, cinnamon, ginger, lacquers, tapestries and perfumes from all over Asia. In addition, slaves (collectively known as "chinos") from various parts of Asia (mainly slaves bought from the Portuguese slave markets and Muslim captives from the Spanish–Moro conflict) were also transported from the Manila slave markets to Mexico.[5] Free indigenous Filipinos also migrated to Mexico via the galleons (including galleon crew that jumped ship), comprising the majority of free Asian settlers ("chinos libres") in Mexico, particularly in regions near the terminal ports of the Manila galleons.[5][6] The route also fostered cultural exchanges that shaped the identities and the culture of the countries involved.[1] The Manila galleons were also known colloquially in New Spain as La Nao de China ("The China Ship") because they carried mostly Chinese goods shipped from Manila.[3][7][8][9] The Manila Galleon route was an early instance of globalization, representing a trade route from Asia that crossed to the Americas, thereby connecting all the world's continents in global silver trade.[10] In 2015, the Philippines and Mexico began preparations for the nomination of the Manila–Acapulco Galleon Trade Route in the UNESCO World Heritage List with backing from Spain, which has also suggested the tri-national nomination of the archives on the Manila–Acapulco Galleons in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. |

マニラ・ガレオン(スペイン語: Galeón de

Manila、タガログ語: Galeon ng

Maynila)とは、スペイン領東インド(フィリピン)とメキシコ(ニュー・スペイン)を太平洋を越えて結んだスペインの貿易船を指す。16世紀後半か

ら19世紀初頭にかけて、マニラ港とアカプルコ港の間を年間1~2往復した。[2]

「マニラ・ガレオン」という用語は、1565年から1815年まで運用されたマニラとアカプルコ間の貿易ルートそのものを指す場合もある。[1] マニラ・ガレオン貿易ルートは、1565年にアウグスチノ会の修道士であり航海士でもあるアンドレス・デ・ウルダネタがフィリピンからメキシコへの帰路 (トルナビアヘ)を開拓した後に開設された。ウルダネタとアロンソ・デ・アレジャノは同年、黒潮を利用することで初の往復航海に成功した。ガレオン船は6 月末か7月初旬にマニラ湾のカビテを出航し、北太平洋を航行して翌年3月から4月にかけてアカプルコに到着した。アカプルコからの帰路は赤道に近い低緯度 海域を通過し、マリアナ諸島で停泊後、サマール島エスプリトゥサント岬沖のサンベルナルディーノ海峡を経てマニラ湾へ。6月か7月までに再びカビテ沖に停 泊した[1][3]。「ウルダネタ航路」を用いた貿易は、メキシコ独立戦争が勃発した1815年まで続いた。これらのガレオン船の大半はカビテの造船所で 建造・積載された。フィリピン産チークなどの現地産広葉樹が用いられ、帆はイロコス地方で生産され、索具やロープは耐塩性のマニラ麻で作られた。乗組員の 大部分はフィリピン人原住民で、農民や路上の子供、浮浪者などが船員として強制徴用された者も多かった。士官やその他の熟練乗組員は通常スペイン人(その 多くはバスク系)であった。ガレオン船は国家の船舶であったため、建造費と維持費はスペイン王室が負担した。[3][4] ガレオン船は主に、新大陸の銀と引き換えに中国やその他のアジアの奢侈品を積んでいた。アジアにおける銀の価格はアメリカ大陸よりも大幅に高かったため、 マニラ・ガレオン船には裁定取引の機会が生まれたのである。ガレオン船のあらゆる空間は貨物でぎっしり詰まっていた。甲板や船室、弾薬庫といった貨物倉以 外の場所さえも例外ではなかった。極端な場合には、さらに貨物を積んだはしけを曳航することさえあった。これにより航海は遅くなり(難破や帰還を招くこと もあった)、しかし利益率は非常に高かったため、この手法は広く行われていた。[3] これらの貨物には、インディアン産の象牙や宝石、中国の絹や磁器、モルッカ諸島産のクローブ、シナモン、ショウガ、漆器、タペストリー、アジア各地の香料 が含まれていた。さらに、アジア各地(主にポルトガル人奴隷市場で購入した奴隷や、スペインとモロ人の紛争で捕らえられたイスラム教徒の捕虜)から集めら れた奴隷(総称して「チノス」と呼ばれた)も、マニラの奴隷市場からメキシコへ輸送された。自由な先住民フィリピン人もガレオン船でメキシコへ移住した (船を降りた乗組員を含む)。彼らはメキシコにおける自由なアジア系移民(「自由なチノス」)の大半を占め、特にマニラガレオン船の終着港周辺地域に集中 した。この航路は文化交流も促進し、関係諸国のアイデンティティと文化形成に寄与した。 マニラガレオン船は、主にマニラから出荷された中国製品を運んでいたため、ニュー・スペインでは俗に「ラ・ナオ・デ・チナ(中国船)」とも呼ばれていた。 [3][7][8][9] マニラガレオン航路は、アジアからアメリカ大陸へ至る交易路として、世界の全大陸を銀貿易で結んだグローバル化の初期事例であった。[10] 2015年、フィリピンとメキシコはスペインの後押しを得て、マニラ・アカプルコ・ガレオン貿易航路をユネスコ世界遺産リストへの登録に向けた準備を開始 した。スペインはさらに、マニラ・アカプルコ・ガレオンに関する記録をユネスコ記憶遺産に登録する三国共同提案も提唱している。 |

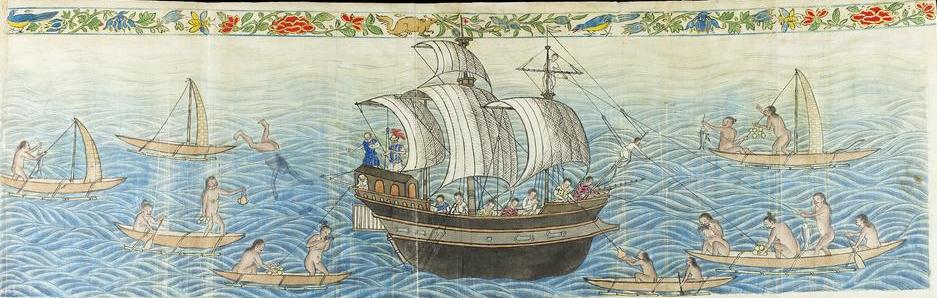

"Reception of the Manila Galleon by the Chamorro in the Ladrones Islands, ca. 1590" English Translated Caption from the book "The Boxer Codex: Transcription and Translation of an Illustrated Late Sixteenth-Century Spanish Manuscript Concerning the Geography, History and Ethnography of the Pacific, South-east and East Asia" by George Bryan Souza and Jeffrey Scott Turley, with comments from Professor Charles Ralph Boxer, the manuscript's namesake. The scene depicts early encounters of the Spanish Manila Galleon with the Chamorro inhabitants of the Marianas Islands, called by the Spaniards as "Ladrones" meaning thieves, circa 1590 AD within the Boxer Codex, as its first illustration in the first few pages. It is a foldout (24 in. by 8 in. or 61 cm. by 20 cm.), the only one in the Codex which depicts a trading encounter between a Manila Galleon and "Ladrones" (Chamorro) in outrigger canoes. |

「ラドロネス諸島におけるチャモロ族によるマニラ・ガレオン船の受入れ、約1590年」 ジョージ・ブライアン・ソウザとジェフリー・スコット・ターリーによる書籍『ボクサー・コーデックス:太平洋・東南アジア・東アジアの地理・歴史・民族誌 に関する16世紀末スペイン写本の写本と翻訳』より、英語キャプションを翻訳したもの。チャールズ・ラルフ・ボクサー教授(写本の命名者)による注釈付 き。この場面は、1590年頃のボクサー写本初頁に描かれた最初の挿絵で、スペインのマニラ・ガレオン船がマリアナ諸島のチャモロ人(スペイン人により 「ラドロネス」=盗賊と呼ばれた)と初めて遭遇した情景を描いている。これは折り込み図版(縦24インチ×横8インチ/縦61cm×横20cm)であり、 マニラ・ガレオン船とアウトリガーカヌーに乗った「ラドロネス」(チャモロ人)との交易場面を描いた、この写本で唯一の図版である。 |

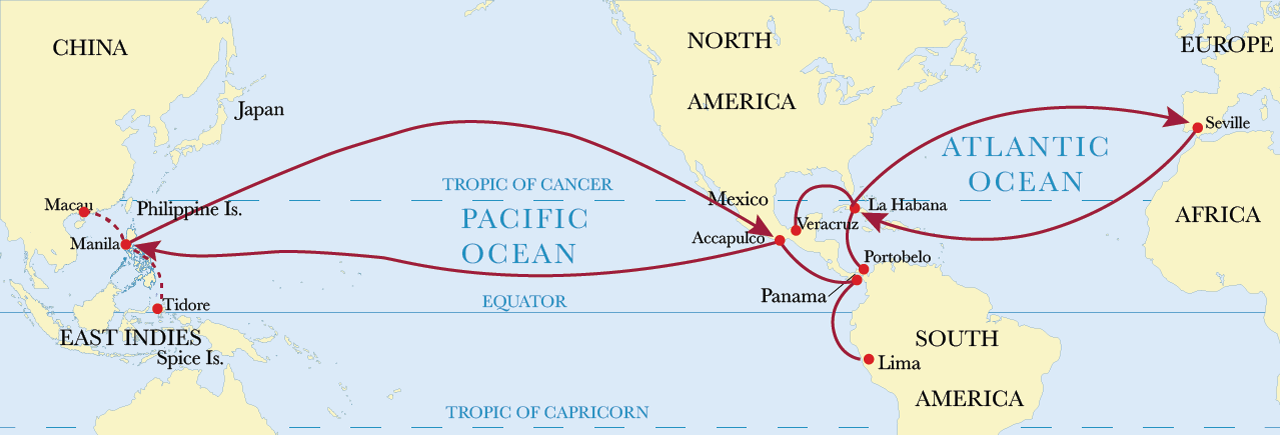

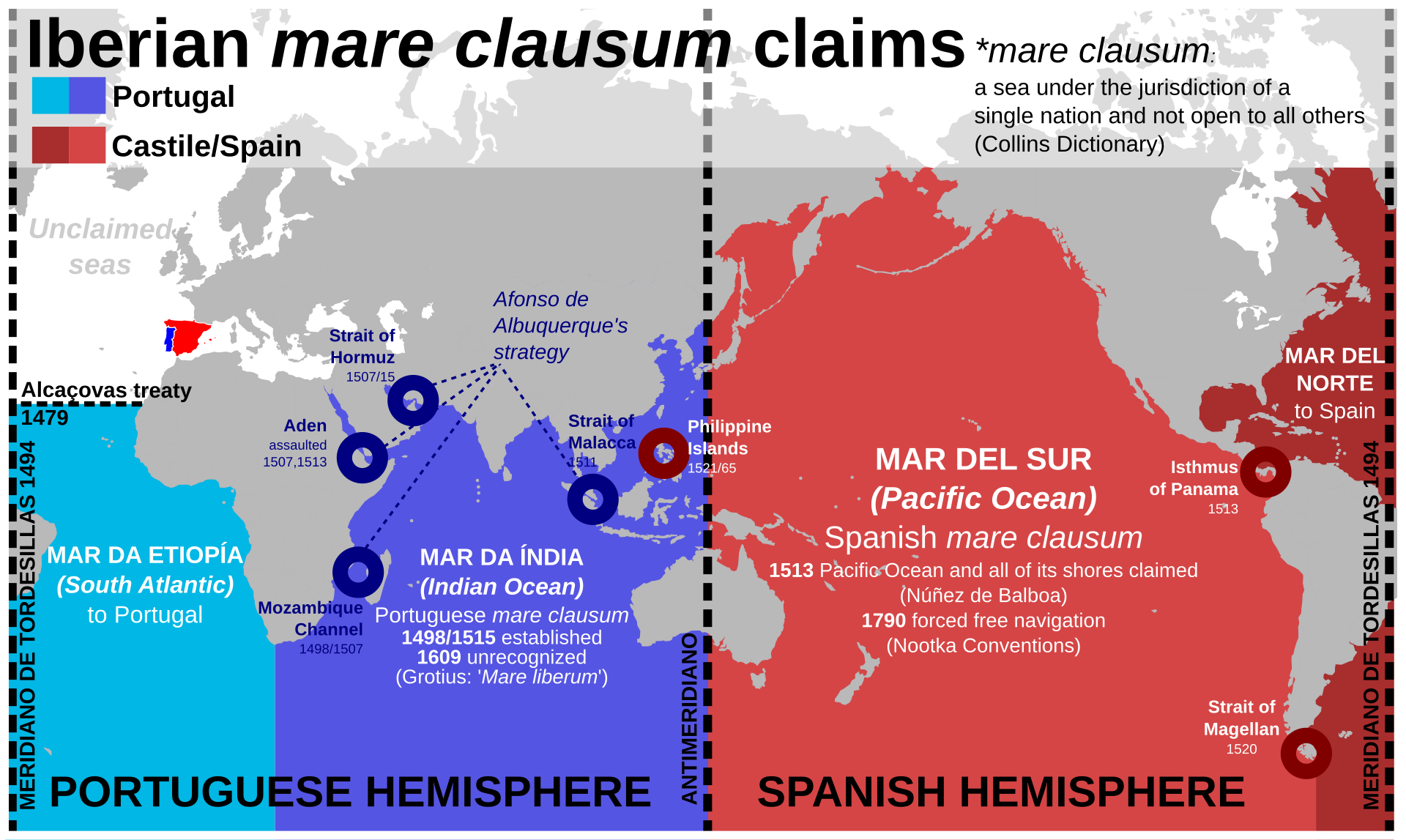

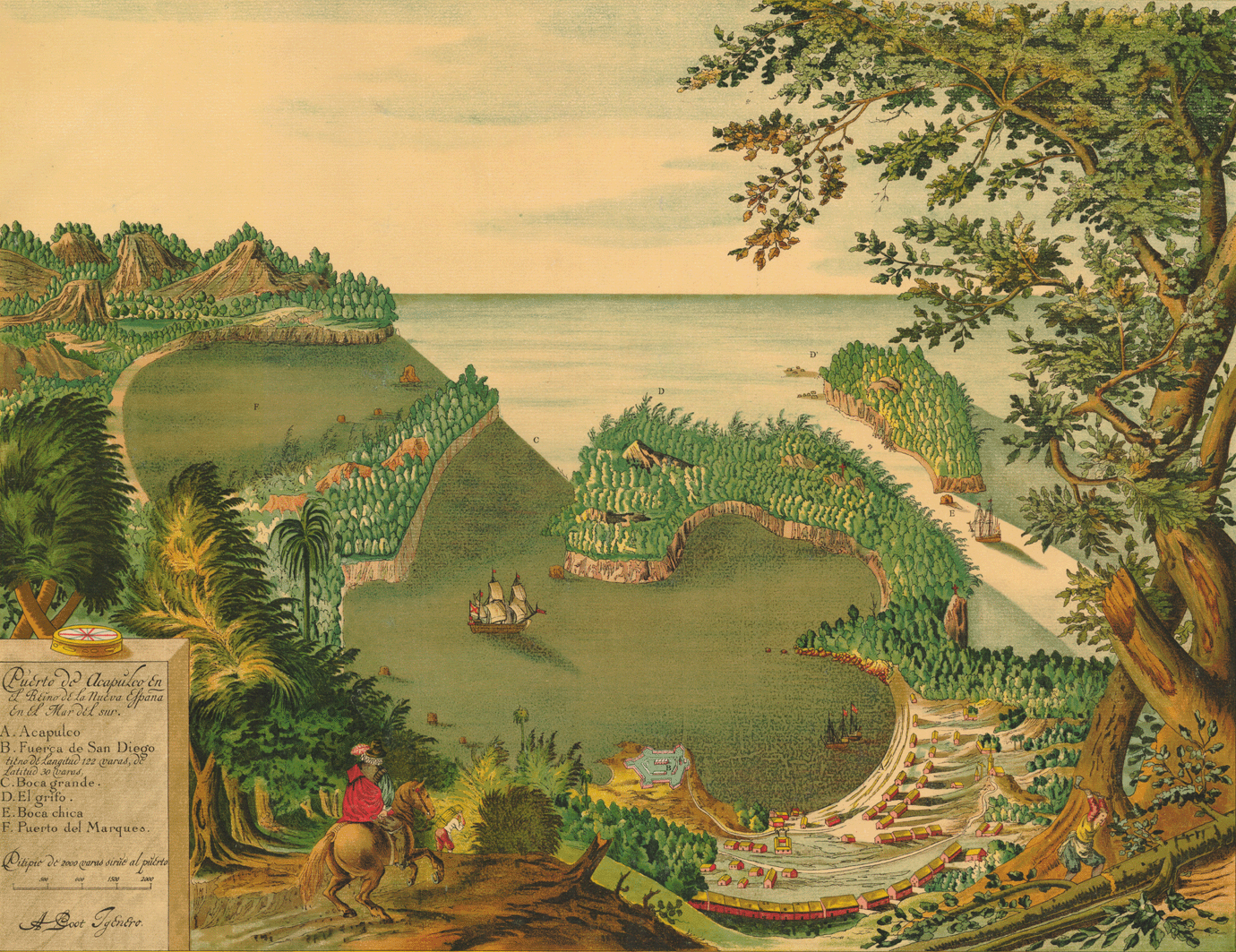

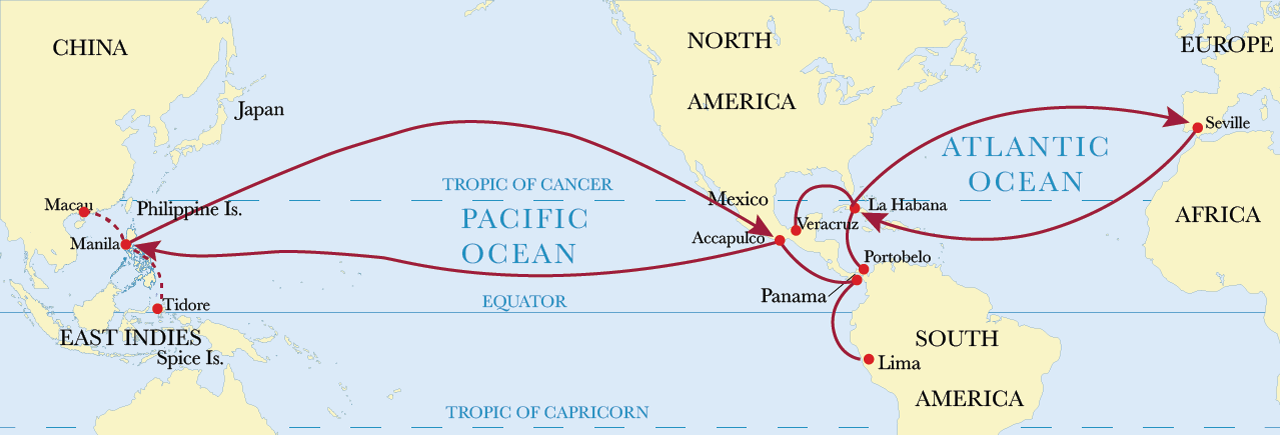

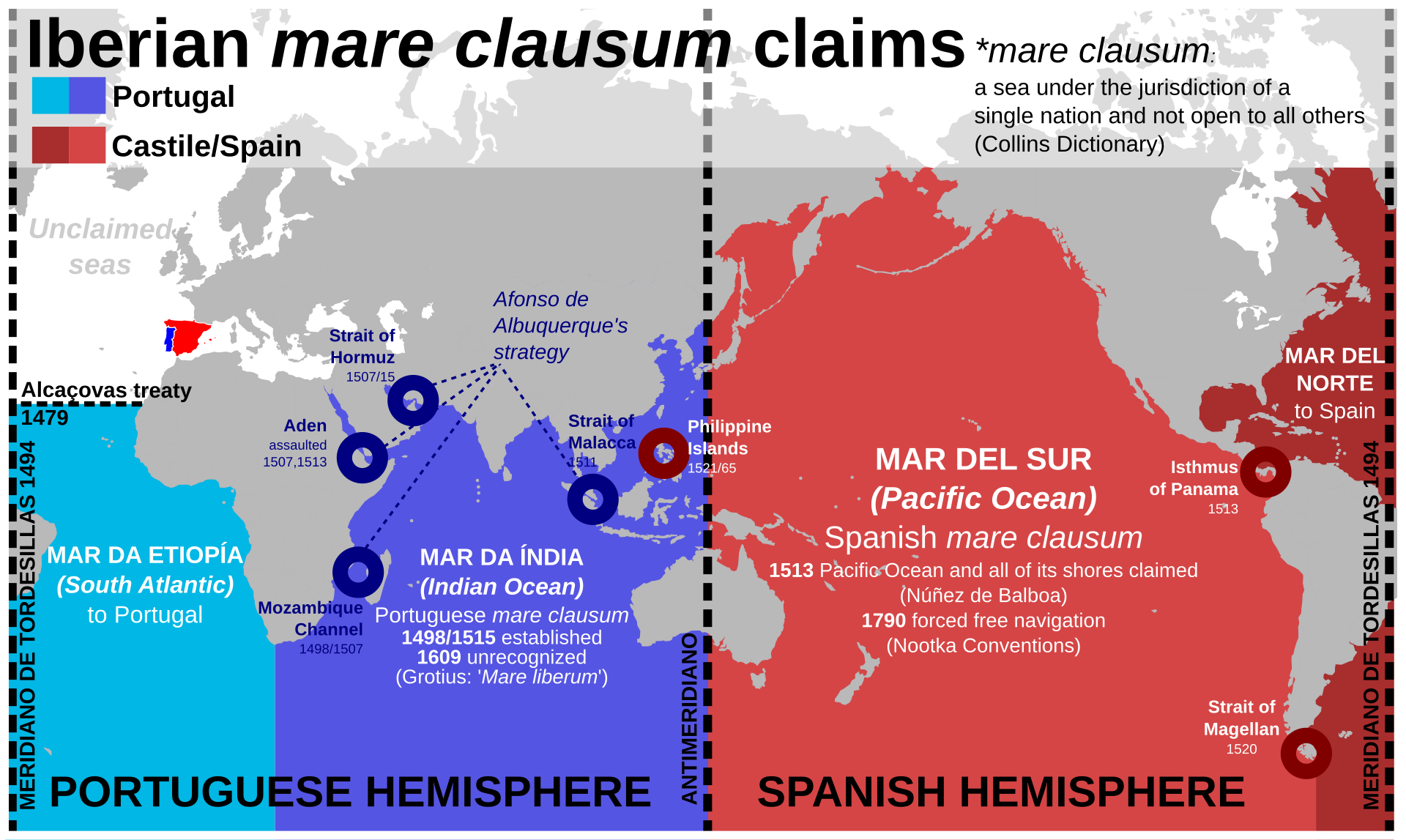

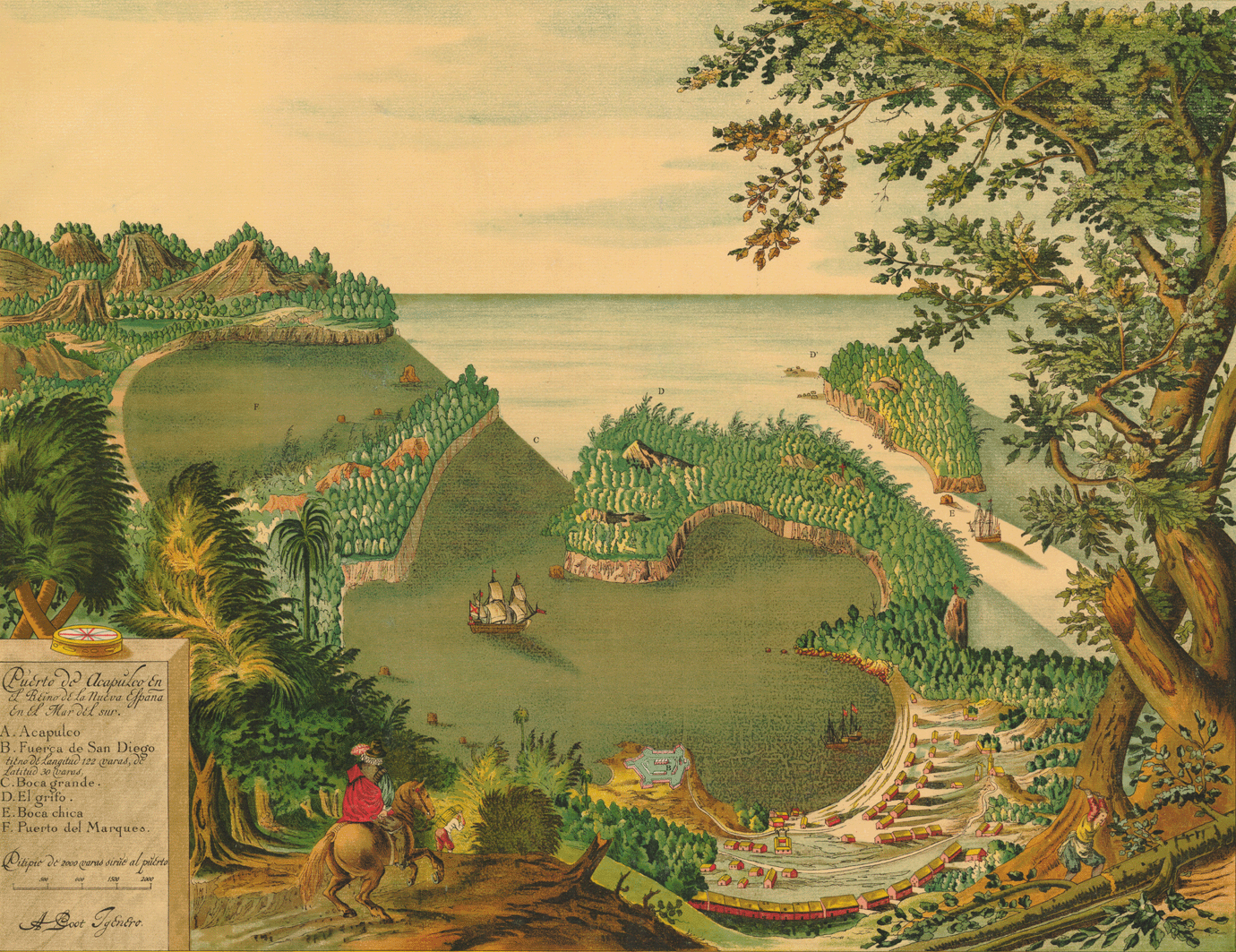

History Manila-Acapulco galleon trade route, showing onward route to Spain Discovery of the route  Iberian mare clausum claims during the Age of Discovery In 1521, a Spanish expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan sailed west across the Pacific using the westward trade winds. The expedition discovered the Mariana Islands and the Philippines and claimed them for Spain. Although Magellan was killed by natives commanded by Lapulapu during the battle of Mactan in the Philippines, one of his ships, the Victoria, made it back to Spain by continuing westward.  Acapulco in 1628, Mexican terminus of the Manila galleon  Northerly trade route as used by eastbound Manila galleons To settle and trade with these islands from the Americas, an eastward maritime return path was necessary. The Trinidad, which tried this a few years later, failed. In 1529, Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón also tried sailing east from the Philippines, but could not find "westerlies" across the Pacific. In 1543, Bernardo de la Torre also failed. In 1542, however, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo helped pave the way by sailing north from Mexico to explore the Pacific coast, reaching just north of the 38th parallel at the Russian River. The frustration of these failures is shown in a letter sent in 1552 from Portuguese Goa by the Spanish missionary Francis Xavier to Simão Rodrigues asking that no more fleets attempt the New Spain–East Asia route, lest they be lost.[11] Despite prior failures navigator Andrés de Urdaneta effectively persuaded Spanish officials in New Spain that a Philippines-Mexico trade route was preferable to other alternatives. He argued against direct trade between Spain and the Philippines through the strait of Magellan on the basis that climate would make passage through the strait possible only during summer and that therefore ships would need to stay the winter in a more northern port. His preference for Mexico rather than for the shorter overland route through Darién is thought to have been due to his links to Pedro de Alvarado.[12] The Manila–Acapulco galleon trade finally began when Spanish navigators Alonso de Arellano and Andrés de Urdaneta discovered the eastward return route in 1565. Sailing as part of the expedition commanded by Miguel López de Legazpi to conquer the Philippines in 1564, Urdaneta was given the task of finding a return route.[13] Reasoning that the trade winds of the Pacific might move in a gyre as the Atlantic winds did, they sailed north, going all the way to the 38th parallel north, off the east coast of Japan, before catching the westerlies that would take them back across the Pacific. He commanded a vessel which completed the eastward voyage in 129 days; this marked the opening of the Manila galleon trade.[14] Reaching the west coast of North America, Urdaneta's ship, the San Pedro, hit the coast near Santa Catalina Island, California, then followed the shoreline south to San Blas and later to Acapulco, arriving on October 8, 1565.[15] Most of his crew died on the long initial voyage, for which they had not sufficiently provisioned. Arellano, who had taken a more southerly route, had already arrived. The English privateer Francis Drake also reached the California coast, in 1579. After capturing a Spanish ship heading for Manila, Drake turned north, hoping to meet another Spanish treasure ship coming south on its return from Manila to Acapulco. He failed in that regard, but staked an English claim somewhere on the northern California coast. Although the ship's log and other records were lost, the officially accepted location is now called Drakes Bay, on Point Reyes south of Cape Mendocino.[a][24] By the 18th century, it was understood that a less northerly track was sufficient when nearing the North American coast, and galleon navigators steered well clear of the rocky and often fogbound northern and central California coast. According to historian William Lytle Schurz, "They generally made their landfall well down the coast, somewhere between Point Conception and Cape San Lucas ... After all, these were preeminently merchant ships, and the business of exploration lay outside their field, though chance discoveries were welcomed".[25] The first motivation for land exploration of present-day California was to scout out possible way stations for the seaworn Manila galleons on the last leg of their journey. Early proposals came to little, but in 1769, the Portola expedition established ports at San Diego and Monterey (which became the administrative center of Alta California), providing safe harbors for returning Manila galleons. |

歴史 マニラ・アカプルコ間ガレオン船貿易航路図(スペインへの航路を示す) 航路の発見  大航海時代におけるイベリア半島の閉ざされた海域の主張(両端がトリデシャス条約[1494]/中央がサラゴサ条約[1529]) 1521年、フェルディナンド・マゼラン率いるスペイン遠征隊は西向きの貿易風を利用し太平洋を西へ航海した。この遠征隊はマリアナ諸島とフィリピン諸島 を発見し、スペイン領と宣言した。マゼランはフィリピン・マクタン島の戦いでラプラプ率いる先住民に殺害されたが、彼の船団の一隻であるビクトリア号は西 進を続けスペインへ帰還した。  1628年のアカプルコ、マニラガレオン船のメキシコ側終着点  東行きのマニラガレオン船が利用した北寄りの交易路 アメリカ大陸からこれらの島々に定住し交易を行うには、東へ向かう海上帰還路が必要だった。数年後にこれを試みたトリニダード号は失敗した。1529年に はアルヴァロ・デ・サアベドラ・セロンもフィリピンから東航を試みたが、太平洋を横断する「西風」を見つけられなかった。1543年にはベルナルド・デ・ ラ・トーレも失敗した。しかし1542年、フアン・ロドリゲス・カブリロがメキシコから北上して太平洋岸を探検し、ロシア川付近の北緯38度線直北まで到 達したことで、道筋が拓かれた。こうした失敗の苛立ちは、1552年にポルトガル領ゴアからスペイン人宣教師フランシスコ・ザビエルがシモン・ロドリゲス に送った書簡に表れている。そこでは、新スペインと東アジアを結ぶ航路への艦隊派遣をこれ以上行わないよう要請し、さもなければ船団が失われる恐れがある と記されている[11]。 先行する失敗にもかかわらず、航海士アンドレス・デ・ウルダネタは新スペインのスペイン当局に対し、フィリピンとメキシコを結ぶ貿易ルートが他の選択肢よ りも優れていることを効果的に説得した。彼はマゼラン海峡経由のスペインとフィリピン間の直接貿易に反対した。その根拠は、気候上海峡通過が可能となるの は夏季のみであり、船はより北の港で越冬する必要があるというものであった。ダリエン経由のより短い陸路ではなくメキシコを優先した理由は、ペドロ・デ・ アルバラードとの繋がりに起因すると考えられている。[12] マニラとアカプルコを結ぶガレオン船による貿易は、1565年にスペイン人航海士アロンソ・デ・アレジャーノとアンドレス・デ・ウルダネタが東帰航路を発 見したことでようやく始まった。ウルダネタは1564年にフィリピン征服を目的としたミゲル・ロペス・デ・レガスピ率いる遠征隊の一員として航海し、帰路 の発見を任されていた。[13] 太平洋の貿易風が大西洋の風と同様に渦を巻いて移動すると推測した彼らは北へ進み、日本の東海岸沖の北緯38度線まで到達した後、太平洋を横断して戻る西 風を捉えた。彼が指揮した船は東行航海を129日で完遂し、これがマニラ・ガレオン貿易の始まりとなった。[14] 北米西岸に到達したウルダネタの船「サン・ペドロ号」は、カリフォルニア州サンタ・カタリナ島付近で座礁した。その後、海岸線に沿って南下しサン・ブラス を経てアカプルコに到達、1565年10月8日に到着した。[15] 十分な食糧を積んでいなかったため、乗組員の大半は長い初航海で死亡した。より南寄りの航路を取ったアレジャーノは既に到着していた。 1579年には、英国の私掠船船長フランシス・ドレイクもカリフォルニア海岸に到達した。マニラ行きのスペイン船を捕獲した後、ドレイクは北へ進路を変 え、マニラからアカプルコへ戻る途中のスペインの宝船と遭遇することを狙った。その目的は達成できなかったが、カリフォルニア北岸のどこかで英国の領有権 を主張した。船の航海日誌やその他の記録は失われたが、公式に認められている場所は現在、メンドシーノ岬の南にあるポイント・レイズのドレイクス湾と呼ば れている。[a][24] 18世紀までに、北米海岸に近づく際にはそれほど北寄りの航路を取る必要はないことが理解されるようになり、ガレオン船の航海士たちは岩が多く霧に覆われ がちなカリフォルニア北部および中部の海岸を大きく避けて航行した。歴史家ウィリアム・ライトル・シュルツによれば、「彼らは概して海岸線からかなり南下 した地点、ポイント・コンセプションとサン・ルカーチ岬の間のどこかに上陸した…何しろこれらは主に商船であり、探検事業は彼らの専門外であった。とはい え偶然の発見は歓迎された」という。[25] 現在のカリフォルニアにおける陸上探検の最初の動機は、航海に疲れたマニラ・ガレオン船の最終航路における中継基地候補地を偵察することだった。初期の提 案はほとんど成果を上げなかったが、1769年にポルトラ遠征隊がサンディエゴとモントレー(後にアルタ・カリフォルニアの行政中心地となる)に港を設立 し、帰還するマニラ・ガレオン船に安全な停泊地を提供した。 |

| The Manila galleon and California This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Monterey, California, was about two months and three weeks out from Manila in the 18th century, and the galleon tended to stop there 40 days before arriving in Acapulco. Galleons stopped in Monterey prior to California's Spanish settlement in 1769; however, visits became regular between 1777 and 1794 because the Crown ordered the galleon to stop in Monterey.[26] |

マニラ・ガレオン船とカリフォルニア この節は検証可能な情報源を必要としている。信頼できる情報源をこの節に追加し、記事の改善に協力してほしい。出典のない記述は削除される可能性がある。(2020年1月)(このメッセージの削除方法と時期について) 18世紀、カリフォルニア州モントレーはマニラから約2か月3週間の航海距離にあり、ガレオン船はアカプルコ到着の40日前に同地に寄港する傾向があっ た。ガレオン船は1769年のカリフォルニア植民地化以前からモントレーに寄港していたが、1777年から1794年にかけては王室命令により定期寄港が 義務付けられた。[26] |

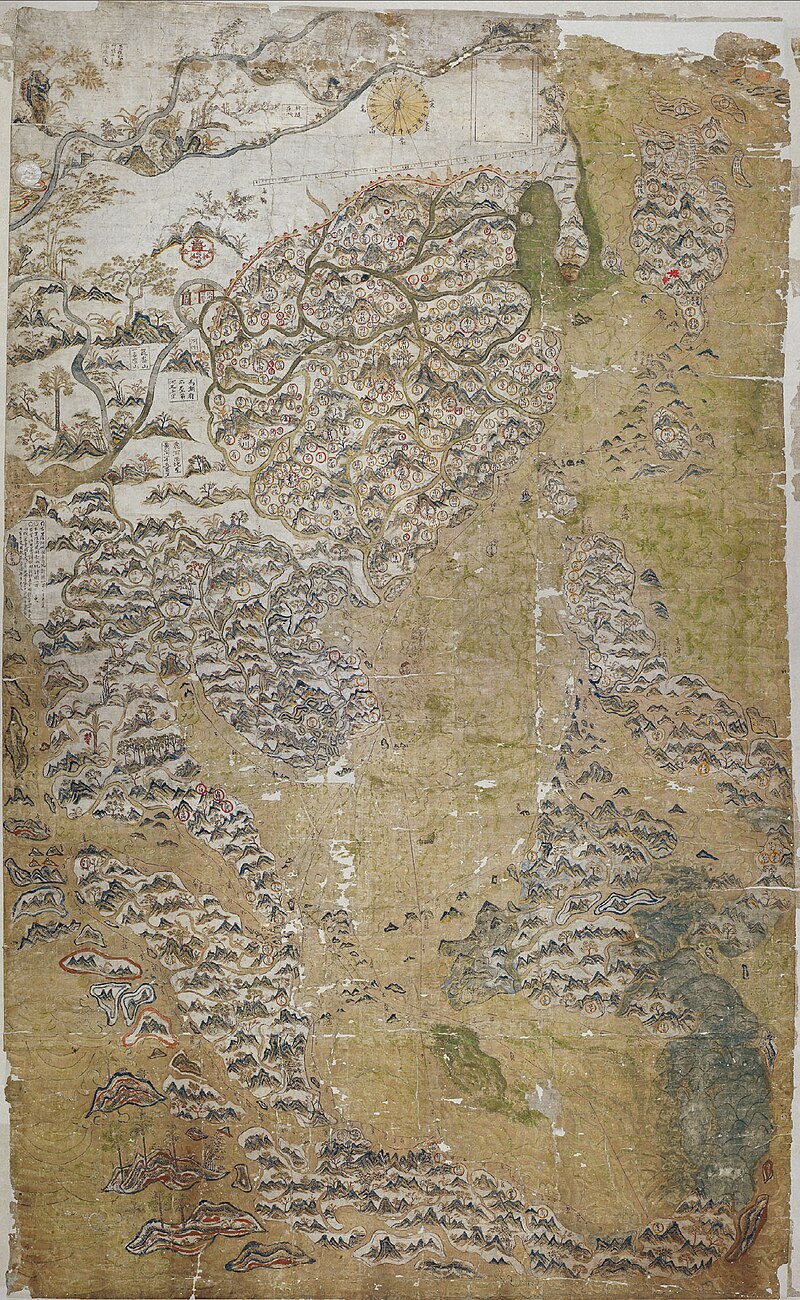

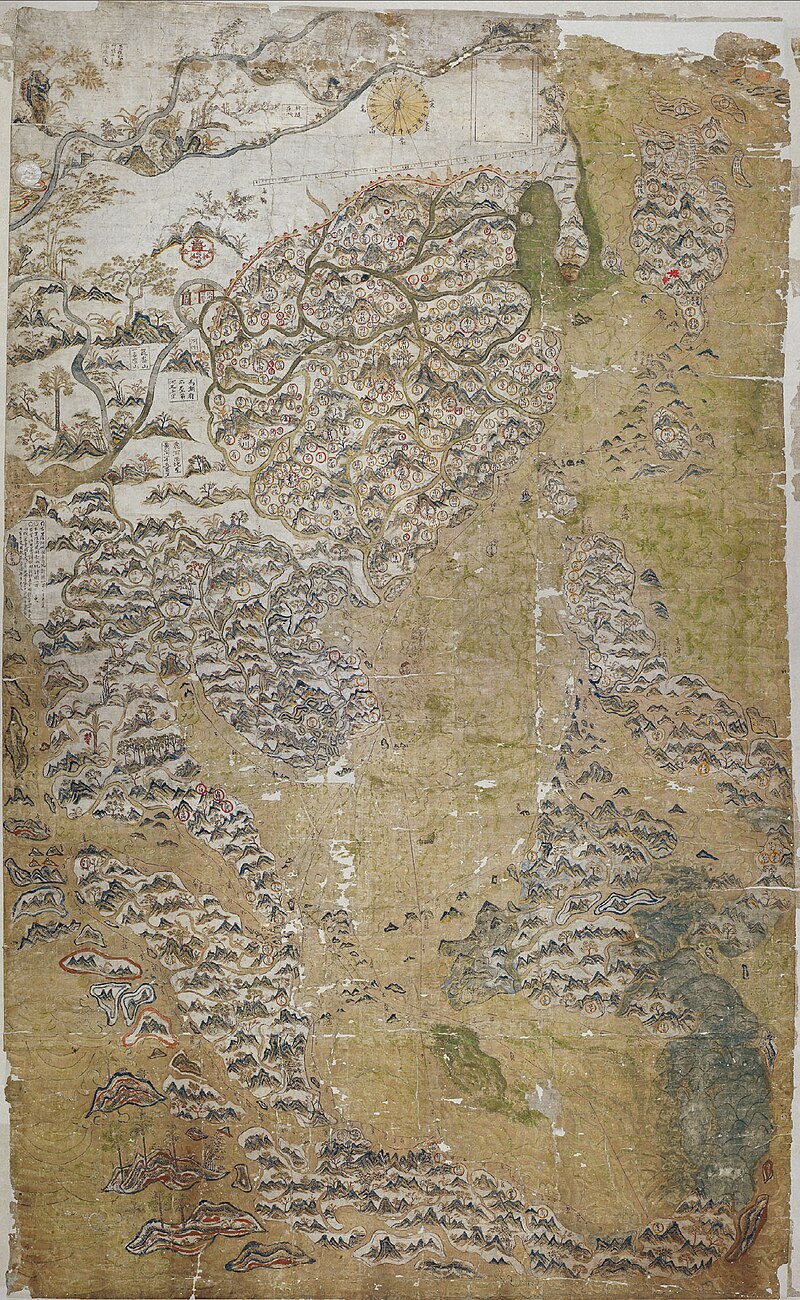

Trade White represents the route of the Manila galleons in the Pacific and the flota in the Atlantic. (Blue represents Portuguese routes). Trade with Ming China via Manila served as a major source of revenue for the Spanish Empire and as a fundamental source of income for Spanish colonists in the Philippine Islands. Galleons used for the trade between East and West were crafted by Filipino artisans.[27] Until 1593, two or more ships would set sail annually from each port.[28] The Manila trade became so lucrative that Seville merchants petitioned king Philip II of Spain to protect the monopoly of the Casa de Contratación based in Seville. This led to the passing of a decree in 1593 that set a limit of two ships sailing each year from either port, with one kept in reserve in Acapulco and one in Manila. An "armada", or armed escort of galleons, was also approved. Due to official attempts to control the galleon trade, contraband and understating of ships' cargoes became widespread.[29]  The Selden Map, a merchant map showing trade routes with its epicenter from Quanzhou to Manila and the Spanish Philippines, then across the Far East The galleon trade was supplied by merchants largely from port areas of Fujian, such as Quanzhou, as depicted in the Selden Map, and Yuegang (the old port of Haicheng in Zhangzhou, Fujian),[30] who traveled to Manila to sell the Spaniards spices, porcelain, ivory, lacquerware, processed silk cloth and other valuable commodities. Cargoes varied from one voyage to another but often included goods from all over Asia: jade, wax, gunpowder and silk from China; amber, cotton and rugs from India; spices from Indonesia and Malaysia; and a variety of goods from Japan, the Spanish part of the so-called Nanban trade, including Japanese fans, chests, screens, porcelain and lacquerware.[31] In addition, slaves of various origins, including East Africa, Portuguese India, the Muslim sultanates of Southeast Asia, and the Spanish Philippines, were transported from Manila and sold in New Spain. African slaves were categorized as negros or cafres while all slaves of Asian origin were called chinos. The lack of detailed records makes it difficult to estimate the total number of slaves transported or the proportions of slaves from each region.[32] Galleons transported goods to be sold in the Americas, namely in New Spain and Peru, as well as in European markets. East Asia trading primarily functioned on a silver standard due to Ming China's use of silver ingots as a medium of exchange. As such, goods were mostly bought with silver mined from New Spain and Potosí.[29] The cargoes arrived in Acapulco and were transported by land across Mexico. Mule trains would carry the goods along the China Road from Acapulco first to the administrative center of Mexico City, then on to the port of Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico, where they were loaded onto the Spanish treasure fleet bound for Spain. The transport of goods overland by porters, the housing of travelers and sailors at inns by innkeepers, and the stocking of long voyages with food and supplies provided by haciendas before departing Acapulco helped to stimulate the economy of New Spain.[33] The trade of goods and exchanges of people were not limited to Mexico and the Philippines, since Guatemala, Panama, Ecuador, and Peru also served as supplementary streams to the main one between Mexico and Philippines.[34] |

貿易 白は太平洋におけるマニラ・ガレオン船の航路と、大西洋におけるフロタの航路を表す(青はポルトガル航路を表す)。 マニラ経由の明中国との貿易は、スペイン帝国にとって主要な収入源であり、フィリピン諸島のスペイン人入植者にとって基本的な収入源であった。東西間の貿 易に使用されたガレオン船は、フィリピンの職人によって建造された[27]。1593年まで、各港から毎年2隻以上の船が出航していた。[28] マニラ貿易は極めて収益性が高かったため、セビリアの商人たちはスペイン王フェリペ2世に対し、セビリアに本拠を置く通商局(カサ・デ・コントラタシオ ン)の独占権保護を請願した。これにより1593年に勅令が発布され、各港からの年間出航船数を2隻に制限し、1隻はアカプルコに、もう1隻はマニラに待 機させることとなった。また、ガレオン船の武装護衛艦隊「アルマダ」の編成も承認された。ガレオン貿易を統制しようとする当局の試みにより、密輸や積荷の 申告不足が蔓延したのである。[29]  セルデン地図は、泉州からマニラ、スペイン領フィリピンを経て極東に至る交易路を示す商人用地図である ガレオン貿易の供給源は、セルデン地図に描かれたように、泉州などの福建省港湾地域や余崗(福建省漳州市海城市の旧港)[30]の商人たちが担った。彼ら はマニラに渡り、スペイン人に対して香辛料、磁器、象牙、漆器、加工絹織物などの貴重品を販売した。積荷は航海ごとに異なるが、アジア各地の品々が含まれ ることが多かった。中国からは翡翠、蜜蝋、火薬、絹。インドからは琥珀、綿、絨毯。インドネシアやマレーシアからは香辛料。そしていわゆる南蛮貿易のスペ イン側、すなわち日本からは扇子、箪笥、屏風、磁器、漆器など多様な品々である。[31] 加えて、東アフリカ、ポルトガル領インド、東南アジアのイスラム教スルタン国、スペイン領フィリピンなど、様々な出身地の奴隷がマニラから輸送され、ヌエ バ・エスパーニャで販売された。アフリカ人奴隷は「ニグロ」または「カフレ」に分類され、アジア出身の奴隷は全て「チノス」と呼ばれた。詳細な記録が不足 しているため、輸送された奴隷の総数や各地域からの奴隷の割合を推定するのは困難である。[32] ガレオン船は、アメリカ大陸(主にニュー・エスパーニャとペルー)およびヨーロッパ市場で販売される商品を輸送した。東アジア貿易は、明朝の中国が銀塊を 交換媒体として使用していたため、主に銀本位制で機能していた。したがって、商品は主にニュー・エスパーニャとポトシで採掘された銀で買われた。[29] 貨物はアカプルコに到着後、陸路でメキシコ全土へ運ばれた。ラバ隊はアカプルコからチャイナ街道を経て、まず行政中心地メキシコシティへ、次にメキシコ湾 岸のベラクルス港へ貨物を運んだ。そこでスペイン本国行きのスペイン宝船隊へ積み替えられた。荷役人による陸路の物資輸送、宿屋経営者による旅行者や船員 の宿泊提供、アカプルコ出港前のアシエンダによる長期航海用の食料・物資の備蓄は、新スペインの経済を活性化させる一助となった。[33] 物資の取引や人々のは、メキシコとフィリピンに限定されなかった。グアテマラ、パナマ、エクアドル、ペルーも、メキシコとフィリピンを結ぶ主要ルートへの補助的な流れとして機能していたのだ。[34] |

Sample of goods brought via Manila galleon in Acapulco Around 80% of the goods shipped back from Acapulco to Manila were from the Americas – silver, cochineal, seeds, sweet potato, corn, tomato, tobacco, chickpeas, chocolate and cocoa, watermelon seeds, vines, and fig trees. The remaining 20% were goods transshipped from Europe and North Africa such as wine and olive oil, and metal goods such as weapons, knobs and spurs.[31] This Pacific route was the alternative to the trip west across the Indian Ocean, and around the Cape of Good Hope, which was reserved to Portugal according to the Treaty of Tordesillas. It also avoided stopping over at ports controlled by competing powers such as Portugal and the Netherlands. From the early days of exploration, the Spanish knew that the American continent was much narrower across the Panamanian isthmus than across Mexico. They tried to establish a regular land crossing there, but the thick jungle and tropical diseases such as yellow fever and malaria made it impractical.[citation needed] It took at least four months to sail across the Pacific Ocean from Manila to Acapulco, and the galleons were the main link between the Philippines and the viceregal capital at Mexico City and thence to Spain itself. Many of the so-called "Kastilas" or Spaniards in the Philippines were actually of Mexican descent, and the Hispanic culture of the Philippines is influenced by Spanish and Mexican culture in particular.[35] Soldiers and settlers recruited from Mexico and Peru also gathered in Acapulco before they were sent to settle at the presidios of the Philippines.[36] Even after the galleon era, and at the time when Mexico finally gained its independence, the two nations still continued to trade, except for a brief lull during the Spanish–American War. In Manila, the safety of ocean crossings was commended to the virgin Nuestra Señora de la Soledad de Porta Vaga in masses held by the Archbishop of Manila. If the expedition was successful the voyagers would go to La Ermita (the church) to pay homage and offer gold, gems or jewelry from Hispanic countries to the image of the virgin. So it came to be that the virgin was named the "Queen of the Galleons". Economic shocks due to the arrival of Spanish-American silver in China were among the factors that led to the end of the Ming dynasty. |

アカプルコでマニラガレオン船によって運ばれた商品の例 アカプルコからマニラへ運ばれた商品の約80%はアメリカ大陸産であった。銀、コチニール、種子、サツマイモ、トウモロコシ、トマト、タバコ、ヒヨコ豆、 チョコレートとカカオ、スイカの種、ブドウの蔓、イチジクの樹などが含まれる。残りの20%は、ワインやオリーブオイルといったヨーロッパや北アフリカか らの積み替え品、武器や取っ手、拍車などの金属製品であった。[31] この太平洋航路は、トルデシリャス条約によりポルトガルに独占権が認められていたインド洋を西へ横断し、喜望峰を回る航路に代わるものだった。また、ポルトガルやオランダといった競合国が支配する港での寄港を回避することもできた。 探検の初期段階から、スペイン人はアメリカ大陸がメキシコ横断よりもパナマ地峡横断の方がはるかに狭いことを知っていた。彼らはそこに定期的な陸路の横断路を確立しようとしたが、密林と黄熱病やマラリアなどの熱帯病がそれを非現実的なものにした。 マニラからアカプルコまで太平洋を横断するには少なくとも4か月を要し、ガレオン船はフィリピンとメキシコシティの副王領首都、そしてスペイン本土を結ぶ 主要な連絡手段であった。フィリピンにおけるいわゆる「カスティーリャ人」すなわちスペイン人の多くは実際にはメキシコ系であり、フィリピンのヒスパニッ ク文化は特にスペインとメキシコの文化の影響を受けている。[35] メキシコやペルーから募集された兵士や入植者も、フィリピンの要塞(プレシディオ)に送られる前にアカプルコに集結した。[36] ガレオン船時代が終わった後も、メキシコが最終的に独立を勝ち取った時代でさえ、両国民は貿易を継続した。米西戦争中の短い停滞期を除いては。 マニラでは、大司教が執り行うミサにおいて、航海の安全が聖母ヌエストラ・セニョーラ・デ・ラ・ソレダッド・デ・ポルタ・ヴァーガに祈願された。遠征が成 功すれば、航海者たちはラ・エルミタ(教会)へ赴き、聖母の像に敬意を表し、ヒスパニック諸国産の金や宝石、装飾品を捧げた。こうして聖母は「ガレオンの 女王」と呼ばれるようになったのである。 スペイン・アメリカ銀の中国流入による経済的衝撃は、明王朝の終焉をもたらした要因の一つであった。 |

| End of the galleons In 1740, as part of the administrative changes of the Bourbon Reforms, the Spanish crown began allowing the use of registered ships or navíos de registro in the Pacific. These ships traveled solo, outside the convoy system of the galleons. While these solo voyages would not immediately replace the galleon system, they were more efficient and better able to avoid being captured by the Royal Navy of Great Britain.[37] In 1813, the Cortes of Cádiz decreed the suppression of the route and the following year, with the end of the Peninsular War, Ferdinand VII of Spain ratified the dissolution. The last ship to reach Manila was the San Fernando or Magallanes,[1] which arrived empty, as its cargo had been requisitioned in Mexico.[1] The Manila–Acapulco galleon trade ended in 1815, a few years before Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821. After this, the Spanish Crown took direct control of the Philippines and governed directly from Madrid. Sea transport became easier in the mid-19th century after the invention of steam powered ships and the opening of the Suez Canal, which reduced the travel time from Spain to the Philippines to 40 days. |

ガレオン船の終焉 1740年、ブルボン改革の行政改革の一環として、スペイン王室は太平洋における登録船(ナヴィオス・デ・レジストロ)の使用を許可し始めた。これらの船 はガレオン船の護送船団システムの外で単独航行した。単独航海が直ちにガレオン船制度に取って代わることはなかったが、より効率的で、イギリス王立海軍に よる捕獲を回避しやすかった。[37] 1813年、カディス議会はこの航路の廃止を決定した。翌年、半島戦争の終結とともに、スペイン王フェルナンド7世が廃止を正式に承認した。マニラに到達 した最後の船はサン・フェルナンド号(別名マゼラン号)であった[1]。しかしその船は空っぽで到着した。積荷はメキシコで徴発されていたのである [1]。 マニラ・アカプルコ間のガレオン船貿易は1815年に終焉を迎えた。これはメキシコが1821年にスペインから独立する数年前のことである。その後、スペ イン王室はフィリピンを直接統治し、マドリードから直接支配を行った。19世紀半ばには蒸気船の発明とスエズ運河の開通により海上輸送が容易になり、スペ インからフィリピンまでの航海時間は40日に短縮された。 |

| Galleons Construction Spanish galleon Between 1609 and 1616, nine galleons and six galleys were constructed in Philippine shipyards. The average cost was 78,000 pesos per galleon and at least 2,000 trees. The galleons constructed included the San Juan Bautista, San Marcos, Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe, Angel de la Guardia, San Felipe, Santiago, Salbador, Espiritu Santo, and San Miguel. "From 1729 to 1739, the main purpose of the Cavite shipyard was the construction and outfitting of the galleons for the Manila to Acapulco trade run."[38] Due to the route's high profitability but long voyage time, it was essential to build the largest possible galleons, which were the largest class of European ships known to have been built until then.[39][40] In the 16th century, they averaged from 1,700 to 2,000 tons[which?][citation needed], were built of Philippine hardwoods and could carry 300–500 passengers. The Concepción, wrecked in 1638, was 43 to 49 m (141 ft 1 in to 160 ft 9 in) long and displaced some 2,000 tons. The Santísima Trinidad was 51.5 m (169 ft 0 in) long. Most of the ships were built in the Philippines; only eight were built in Mexico. |

ガレオン船 建造 スペインのガレオン船 1609年から1616年の間に、フィリピンの造船所で9隻のガレオン船と6隻のガレー船が建造された。平均費用は1隻あたり78,000ペソで、少なく とも2,000本の木が必要だった。建造されたガレオン船には、サン・フアン・バウティスタ号、サン・マルコス号、ヌエストラ・セニョーラ・デ・グアダ ルーペ号、アンヘル・デ・ラ・グアルディア号、サン・フェリペ号、サンティアゴ号、サルバドール号、エスプリトゥ・サント号、サン・ミゲル号が含まれた。 「1729年から1739年にかけて、カビテ造船所の主な目的は、マニラからアカプルコへの貿易航路向けのガレオン船の建造と装備であった。」[38] この航路は収益性が高い反面、航海時間が長かったため、可能な限り大型のガレオン船を建造することが不可欠であった。これらは当時建造されたヨーロッパ船 としては最大級のクラスであった。[39] [40] 16世紀のガレオン船は平均1,700~2,000トン[どの資料?][出典必要]で、フィリピン産硬材を用いて建造され、300~500名の乗客を収容 できた。1638年に難破したコンセプシオン号は全長43~49メートル(141フィート1インチ~160フィート9インチ)、排水量約2,000トンで あった。サンティシマ・トリニダード号は全長51.5メートル(169フィート0インチ)であった。ほとんどの船はフィリピンで建造され、メキシコで建造 されたのはわずか8隻であった。 |

| Crews Sailors averaged age 28 or 29 while the oldest were between 40 and 50. Ships' pages were children who entered service mostly at age 8, many orphans or poor taken from the streets of Seville, Mexico and Manila. Apprentices were older than the pages and if successful would be certified as sailor at age 20. Mortality rates were high, with ships arriving in Manila with a majority of their crew often dead from starvation, disease and scurvy, especially in the early years, so Spanish officials in Manila found it difficult to find men to crew their ships to return to Acapulco. Many native Filipinos and others of Southeast Asian origin (also called Indios) made up the majority of the crew. Other crew were made up of deportees and criminals from Spain and other Spanish colonies. Many criminals were sentenced to serve as crew on royal ships. Less than a third of the crew was Spanish, and they usually held key positions aboard the galleon.[41] At port, goods were unloaded by dockworkers, and food was often supplied locally. In Acapulco, the arrival of the galleons provided seasonal work for dockworkers, who were typically free African men highly paid for their backbreaking labor, and for farmers and haciendas across Mexico who helped stock the ships with food before voyages. On land, travelers were often housed at inns or mesones, and had goods transported by muleteers, which provided opportunities for Mexico's native population. By providing for the galleons, colonial Spanish America was tied into the broader global economy.[33] |

乗組員 船員の平均年齢は28歳か29歳であり、最年長は40歳から50歳の間であった。船の少年見習いは主に8歳で入職する子供たちで、多くはセビリア、メキシ コ、マニラの路上で拾われた孤児や貧民であった。見習いは少年見習いより年上で、成功すれば20歳で船員として認定された。死亡率は高く、特に初期の頃 は、飢餓や病気、壊血病で乗組員の大半が死亡した状態でマニラに到着する船が多かった。そのためマニラのスペイン当局は、アカプルコに戻る船の乗組員を確 保するのに苦労した。乗組員の大半は、フィリピン人などの東南アジア出身者(インディオとも呼ばれた)で構成されていた。その他の乗組員は、スペインやそ の他のスペイン植民地からの追放者や犯罪者で構成されていた。多くの犯罪者は王室船の乗組員として服役するよう判決を受けていた。乗組員の3分の1未満が スペイン人で、彼らは通常ガレオン船内の要職に就いていた。[41] 港では荷役労働者が貨物を積み下ろし、食料は現地で調達されることが多かった。アカプルコではガレオン船の到着が季節労働を生み、過酷な労働に見合う高賃 金で雇われる自由黒人労働者や、航海前の食料積み込みを手伝うメキシコ各地の農民・アシエンダに仕事をもたらした。陸路では、旅行者は宿屋やメソネスに宿 泊し、荷物はラバ使いによって運ばれた。これはメキシコの先住民にとっての機会となった。ガレオン船を支えることで、植民地時代のスペイン領アメリカは広 範な世界経済と結びついていたのだ。[33] |

| Shipwrecks The wrecks of the Manila galleons are legends second only to the wrecks of treasure ships in the Caribbean. In 1568, Miguel López de Legazpi's own ship, the San Pablo (300 tons), was the first Manila galleon to be wrecked en route to Mexico. Between the years 1576 when the Espiritu Santo was lost and 1798 when the San Cristobal was lost, twenty Manila galleons[42] wrecked within the Philippine archipelago. In 1596 the San Felipe was wrecked in Japan. At least one galleon, probably the Santo Cristo de Burgos, is believed to have wrecked on the coast of Oregon in 1693. Known as the Beeswax wreck, the event is described in the oral histories of the Tillamook and Clatsop, which suggest that some of the crew survived.[43][44][45] This shipwreck inspired the popular 1985 film The Goonies. |

難破船 マニラ・ガレオン船の難破は、カリブ海の宝船の難破に次ぐ伝説である。1568年、ミゲル・ロペス・デ・レガスピ自身の船サン・パブロ号(300トン) が、メキシコへ向かう途上で難破した最初のマニラ・ガレオン船となった。1576年にエスプリトゥ・サント号が沈没してから1798年にサン・クリストバ ル号が沈没するまでの間に、フィリピン列島内で20隻のマニラ・ガレオン船が沈没した。1596年にはサン・フェリペ号が日本で沈没した。 少なくとも1隻のガレオン船、おそらくサント・クリスト・デ・ブルゴス号は、1693年にオレゴン州沿岸で難破したと考えられている。この事件は「蜜蝋難 破船」として知られ、ティラムック族とクラトープ族の口承史に記述されている。それによると、乗組員の一部は生存したようだ[43][44][45]。こ の難破事件は、1985年の人気映画『グーニーズ』の着想源となった。 |

Captures George Anson's capture of the Manila galleon on April 20, 1743 Between 1565 and 1815, 108 ships operated as Manila galleons, of which 26 were captured or sunk by the enemy during wartime, including the Santa Ana captured in 1587 by Thomas Cavendish off the coast of Baja California;[1] the San Diego, which was sunk in 1600 in Bahía de Manila by Oliver Van Noort;[1] Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación captured by Woodes Rogers in 1709;[1] Nuestra Senora de la Covadonga captured in 1743 by George Anson;[1] Nuestra Senora de la Santisima Trinidad captured in 1762 by HMS Panther and HMS Argo[38] at the Action of 30 October 1762 in the San Bernardino Strait;[1] San Sebastián and Santa Ana captured in 1753–54 by George Compton;[1][46] and Nuestra Señora de la Santísima Trinidad, in 1762, by Samuel Cornish.[1] |

捕獲 ジョージ・アンソンによるマニラ・ガレオン船の捕獲(1743年4月20日) 1565年から1815年の間に、108隻のマニラ・ガレオン船が運航された。そのうち26隻は戦時中に敵に捕獲または撃沈された。これには以下の船が含 まれる:1587年、トーマス・キャベンディッシュがバハ・カリフォルニア沖で捕獲したサンタ・アナ号;[1]1600年、オリバー・ヴァン・ノールトが マニラ湾で撃沈したサン・ディエゴ号;[1] 1709年にウッズ・ロジャースに捕獲されたヌエストラ・セニョーラ・デ・ラ・エンカルナシオン号;[1] 1743年にジョージ・アンソンに捕獲されたヌエストラ・セニョーラ・デ・ラ・コバドンガ号;[1] 1762年10月30日のサン・ベルナルディーノ海峡海戦でHMSパンサー号とHMSアルゴ号に捕獲されたヌエストラ・セニョーラ・デ・ラ・サンティシ マ・トリニダード号;[38] [1] サン・セバスティアン号とサンタ・アナ号は1753年から1754年にかけてジョージ・コンプトンによって拿捕された;[1][46] またヌエストラ・セニョーラ・デ・ラ・サンティシマ・トリニダード号は1762年にサミュエル・コーニッシュによって拿捕された。[1] |

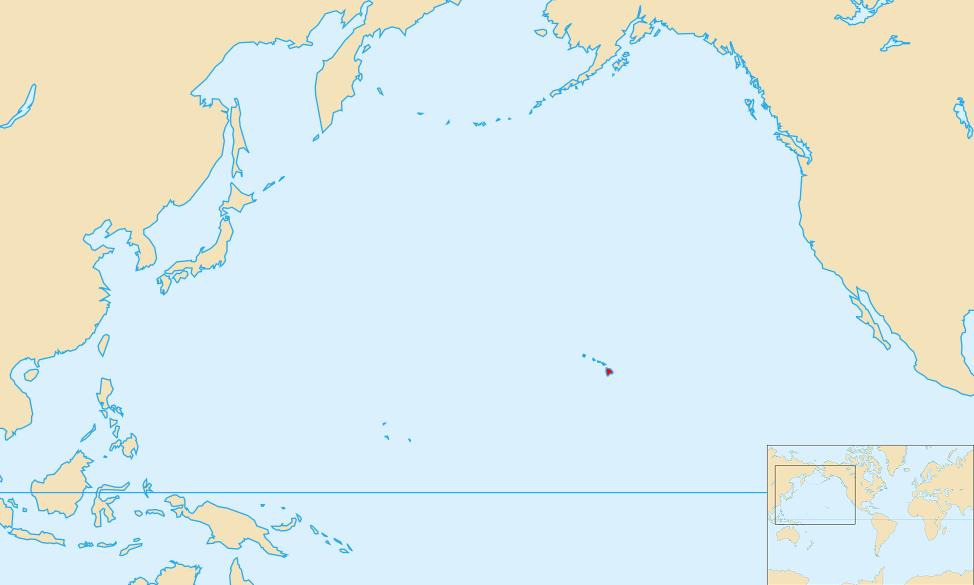

| Possible contact with Hawaii Over 250 years, there were hundreds of Manila galleon crossings of the Pacific Ocean between present-day Mexico and the Philippines, with their route taking them just south of the Hawaiian Islands on the westward leg of their round trip and yet there are no records of contact with the Hawaiians. British historian Henry Kamen maintains that the Spaniards did not have the ability to properly explore the Pacific Ocean and were not capable of finding the islands which lay at a latitude 20° north of the westbound galleon route and its currents.[47] However, Spanish exploration in the Pacific was paramount until the late 18th century. Spanish navigators discovered many islands including Guam, the Marianas, the Carolines and the Philippines in the North Pacific, as well as Tuvalu, the Marquesas, the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, and Easter Island in the South Pacific. Spanish navigators also discovered the Pitcairn and Vanuatu archipelagos during their search for Terra Australis in the 17th century.  Pacific Ocean with Mauna Kea highlighted This navigational activity poses the question as to whether Spanish explorers did arrive in the Hawaiian Islands two centuries before Captain James Cook's first visit in 1778. Ruy López de Villalobos commanded a fleet of six ships that left Acapulco in 1542 with a Spanish sailor named Ivan Gaetan or Juan Gaetano aboard as pilot. Depending on the interpretation, Gaetano's reports seem to describe the discovery of either Hawaii or the Marshall Islands in 1555.[48]  The Manila–Acapulco Galleon Memorial at Plaza Mexico in Intramuros, Manila. The westward route from Mexico passed south of Hawaii, making a short stopover in Guam before heading for Manila. The exact route was kept secret to protect the Spanish trade monopoly against competing powers, and to avoid Dutch and English pirates. Due to this policy of discretion, if the Spaniards did find Hawaii during their voyages, they would not have published their findings and the discovery would have remained unknown. From Gaetano's account, the Hawaiian islands were not known to have any valuable resources, so the Spaniards would not have made an effort to settle them.[48] This happened in the case of the Marianas and the Carolines, which were not effectively settled until the second half of the 17th century. Spanish archives[when?] contain a chart that depicts islands in the latitude of Hawaii but with the longitude ten degrees east of the Islands (reliable methods of determining longitude were not developed until the mid-18th century). In this manuscript, the Island of Maui is named "La Desgraciada" (the unhappy, or unfortunate), and what appears to be the Island of Hawaii is named "La Mesa" (the table). Islands resembling Kahoolawe, Lanai, and Molokai are named "Los Monjes" (the monks).[49] The theory that the first European visitors to Hawaii were Spaniards is reinforced by the findings of William Ellis, a writer and missionary who lived in early 19th century Hawaii; he recorded several folk stories about foreigners who had visited Hawaii prior to first contact with Cook. According to Hawaiian writer Herb Kawainui Kane, one of these stories: concerned seven foreigners who landed eight generations earlier at Kealakekua Bay in a painted boat with an awning or canopy over the stern. They were dressed in clothing of white and yellow, and one wore a sword at his side and a feather in his hat. On landing, they kneeled down in prayer. The Hawaiians, most helpful to those who were most helpless, received them kindly. The strangers ultimately married into the families of chiefs, but their names could not be included in genealogies".[48] Some scholars, particularly American, have dismissed these claims as lacking credibility.[50][51] Debate continues as to whether the Hawaiian Islands were actually visited by the Spanish in the 16th century[52] with researchers like Richard W. Rogers looking for evidence of Spanish shipwrecks.[53][54] |

ハワイとの接触の可能性 250年以上にわたり、現在のメキシコとフィリピン間を数百隻のマニラ・ガレオン船が太平洋を横断した。その航路は往復航路の西行時にハワイ諸島のすぐ南 を通過していたにもかかわらず、ハワイアンとの接触記録は存在しない。英国の歴史家ヘンリー・ケイメンは、スペイン人は太平洋を適切に探検する能力がな く、西行ガレオン船の航路と海流から北緯20度にある島々を発見できなかったと主張している[47]。しかし、18世紀後半までスペインの太平洋探検は極 めて重要であった。スペインの航海者たちは北太平洋ではグアム、マリアナ諸島、カロリン諸島、フィリピン諸島を、南太平洋ではツバル、マルケサス諸島、ソ ロモン諸島、ニューギニア、イースター島を含む多くの島々を発見した。17世紀のテラ・アウストラリス探索中、ピトケアン諸島とバヌアツ諸島も発見してい る。  マウナケア山を強調した太平洋図 この航海活動は、スペインの探検家が1778年にジェームズ・クック船長が初めて訪問する2世紀も前にハワイ諸島に到着したかどうかという疑問を投げかけ る。ルイス・ロペス・デ・ビジャロボスは1542年にアカプルコを出航した6隻の艦隊を指揮し、その船団にはイバン・ガエタンまたはフアン・ガエターノと いう名のスペイン人船員が航海士として乗船していた。解釈次第では、ガエターノの報告は1555年のハワイ諸島またはマーシャル諸島の発見を記述している ように見える。[48]  マニラ・イントラムロス地区のプラザ・メヒコにあるマニラ~アカプルコ航路記念碑。 メキシコからの西進航路はハワイの南を通過し、グアムで短期間寄港した後マニラへ向かった。正確な航路は、スペインの貿易独占を競合勢力から守るため、ま たオランダやイギリスの海賊を避けるために秘密にされていた。この慎重な方針のため、スペイン人が航海中にハワイを発見していたとしても、その発見は公表 されず、知られぬままだっただろう。ガエターノの記述によれば、ハワイ諸島には価値ある資源は存在しなかったため、スペイン人が入植を試みることはなかっ た。[48] マリアナ諸島やカロリン諸島の場合も同様で、これらが実質的に開拓されたのは17世紀後半になってからである。スペインの公文書[時期不明]には、ハワイ の緯度に位置する島々を描いた海図が残されているが、経度は諸島の東10度と記されている(経度を正確に測定する方法は18世紀半ばまで確立されなかっ た)。この写本では、マウイ島は「ラ・デスグラシアダ(不幸な島)」と記され、ハワイ島と思われる島は「ラ・メサ(テーブル島)」と名付けられている。カ ホオラウェ島、ラナイ島、モロカイ島に似た島々は「ロス・モンヘス(修道僧たち)」と呼ばれている。[49] ハワイに最初に訪れたヨーロッパ人がスペイン人だったという説は、19世紀初頭のハワイに暮らした作家兼宣教師ウィリアム・エリスによる発見によって裏付 けられている。彼はクックとの最初の接触以前にハワイを訪れた外国人に関する複数の民間伝承を記録した。ハワイの作家ハーブ・カワイヌイ・ケインによれ ば、その一つはこうだ: 八世代前に、船尾に日除けや天蓋をつけた彩色された船でケアラケクア湾に上陸した七人の外国人に関する話だ。彼らは白と黄色の服を着ており、一人は腰に剣 を帯び、帽子に羽根を挿していた。上陸すると、彼らは跪いて祈りを捧げた。ハワイ人は、最も無力な者ほど親切に接する習わしで、彼らを温かく迎えた。異邦 人たちは最終的に首長の家系に嫁入りしたが、その名は系図に記されることはなかった。[48] 一部の学者、特にアメリカ人学者は、これらの主張を信憑性に欠けるとして退けている。[50][51] ハワイ諸島が16世紀に実際にスペイン人によって訪問されたかどうかについては議論が続いており[52]、リチャード・W・ロジャーズのような研究者がス ペイン船の難破の証拠を探している。[53][54] |

| Preparations for UNESCO nominations In 2010, the Philippines foreign affairs secretary organized a diplomatic reception attended by at least 32 countries, for discussions about the historic galleon trade and the possible establishment of a galleon museum. Various Mexican and Filipino institutions and politicians also made discussions about the importance of the galleon trade in their shared history.[55] In 2013, the Philippines released a documentary regarding the Manila galleon trade route.[56] In 2014, the idea to nominate the Manila–Acapulco Galleon Trade Route as a World Heritage Site was initiated by the Mexican and Filipino ambassadors to UNESCO. Spain has also backed the nomination and suggested that the archives related to the route under the possession of the Philippines, Mexico, and Spain be nominated as part of another UNESCO list, the Memory of the World Register.[57] In 2015, the Unesco National Commission of the Philippines (Unacom) and the Department of Foreign Affairs organized an expert's meeting to discuss the trade route's nomination. Some of the topics presented include the Spanish colonial shipyards in Sorsogon, underwater archaeology in the Philippines, the route's influences on Filipino textile, the galleon's eastward trip from the Philippines to Mexico called tornaviaje, and the historical dimension of the galleon trade focusing on important and rare archival documents.[58] In 2017, the Philippines established the Manila–Acapulco Galleon Museum in Metro Manila, one of the necessary steps in nominating the trade route to UNESCO.[59] In 2018, Mexico reopened its Manila galleon gallery at the Archaeological Museum of Puerto Vallarta, Cuale.[60] In 2020, Mexico released a documentary regarding the Manila galleon trade route.[61] |

ユネスコ登録に向けた準備 2010年、フィリピン外務大臣は少なくとも32カ国が参加する外交レセプションを主催し、歴史的なガレオン船貿易とガレオン船博物館の設立可能性につい て議論した。メキシコとフィリピンの様々な機関や政治家も、両国の共有歴史におけるガレオン船貿易の重要性について議論した。[55] 2013年、フィリピンはマニラ・ガレオン貿易ルートに関するドキュメンタリーを制作した。[56] 2014年、メキシコとフィリピンのユネスコ大使が、マニラ~アカプルコ・ガレオン貿易ルートを世界遺産に推薦する構想を提唱した。スペインもこの推薦を 支持し、フィリピン・メキシコ・スペインが所蔵する航路関連文書を、ユネスコの別リスト「世界の記憶」への登録を提案した。[57] 2015年、フィリピンユネスコ国内委員会(UNACOM)と外務省は、この交易路の登録を議論する専門家会議を開催した。提示された議題には、ソルソゴ ンにあるスペイン植民地時代の造船所、フィリピンにおける水中考古学、同航路がフィリピン織物に与えた影響、フィリピンからメキシコへのガレオン船の東航 (トルナビハジェ)、そして重要かつ希少な公文書に焦点を当てたガレオン貿易の歴史的側面などが含まれた[58]。 2017年、フィリピンはマニラ首都圏にマニラ・アカプルコ・ガレオン博物館を設立した。これは貿易路をユネスコに推薦するための必要条件の一つであった。[59] 2018年、メキシコはプエルト・バジャルタ考古学博物館(クアレ)内のマニラ・ガレオン展示室を再開した。[60] 2020年、メキシコはマニラ・ガレオン貿易ルートに関するドキュメンタリーを制作した。[61] |

| Asian Mexicans – Ethnic group of Asian-descending Mexicans Battles of La Naval de Manila – Naval battle of the Eighty Years' War Bernardo de la Torre – Spanish navigator (died 1545) Chamorro people – Indigenous people of the Mariana Islands Filipino immigration to Mexico – Overview of immigration along the Galleon Route Global silver trade from the 16th to 19th centuries – International trade route carrying silver History of the Philippines (1521–1898) – Spanish colonial period of the Philippines History of the west coast of North America Landing of the first Filipinos – Arrival of Filipinos to the current United States in 1587 María de Lajara Mexican settlement in the Philippines – Mesoamerican peoples in the Southeast Asian country Pedro Cubero Pedro de Unamuno – Spanish soldier and explorer Spanish East Indies – Spanish colony from 1565 to 1901 Spanish Main – Spanish Empire holdings in the Americas Spanish treasure fleet – Convoy system used by the Spanish Empire from 1566 to 1790 |

アジア系メキシコ人 – アジア系祖先を持つメキシコ人の民族集団 マニラの海戦 – 八十年戦争における海戦 ベルナルド・デ・ラ・トーレ – スペインの航海者(1545年没) チャモロ人民 – マリアナ諸島の先住民 フィリピン人によるメキシコ移民 – ガレオン航路に沿った移民の概要 16世紀から19世紀にかけての銀の世界貿易 – 銀を運ぶ国際貿易ルート フィリピンの歴史(1521年–1898年) – フィリピンのスペイン植民地時代 北米西海岸の歴史 最初のフィリピン人の上陸 – 1587年に現在のアメリカ合衆国へフィリピン人が到着した出来事 マリア・デ・ラハラ フィリピンにおけるメキシコ人入植 – 東南アジアの国におけるメソアメリカ系民族 ペドロ・クベロ ペドロ・デ・ウナムノ – スペインの軍人・探検家 スペイン東インド – 1565年から1901年までのスペイン植民地 スペイン本土 – スペイン帝国がアメリカ大陸に保有した領土 スペインの宝船隊 – 1566年から1790年までスペイン帝国が使用した護送船団制度 |

| Notes a. The Drakes Cove site began its review by the National Park Service (NPS) in 1994, thus starting an 18-year study of the suggested Drake sites. The first formal nomination to mark the Nova Albion site at Drake's Cove as a National Historic Landmark was provided to NPS on January 1, 1996. As part of its review, NPS obtained independent, confidential comments from professional historians. The NPS staff concluded that the Drake's Cove site is the "most probable"[16] and "most likely"[17][18][19][20] Drake landing site. The National Park System Advisory Board Landmarks Committee sought public comments on the Port of Nova Albion Historic and Archaeological District Nomination[21] and received more than two dozen letters of support and none in opposition. At the Committee's meeting of November 9, 2011, in Washington, DC, representatives of the government of Spain, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Congresswoman Lynn Wolsey all spoke in favor of the nomination: there was no opposition. Staff and the Drake Navigators Guild's president, Edward Von der Porten, gave the presentation. The Nomination was strongly endorsed by committee member Dr. James M. Allan, Archaeologist, and the Committee as a whole which approved the nomination unanimously. The National Park System Advisory Board sought further public comments on the Nomination,[22] but no additional comments were received. At the Board's meeting on December 1, 2011, in Florida, the nomination was further reviewed: the Board approved the nomination unanimously. On October 16, 2012, Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar signed the nomination and on October 17, 2012, The Drakes Bay Historic and Archaeological District was formally announced as a new National Historic Landmark.[23] |

注記 a. ドレイクス・コーブ遺跡は1994年に国立公園局(NPS)による審査を開始し、これによりドレイク関連遺跡候補地に関する18年にわたる調査が始まっ た。ドレイクス・コーブのノヴァ・アルビオン遺跡を国家歴史的記念物に指定する最初の正式な申請は、1996年1月1日にNPSに提出された。審査の一環 として、NPSは専門の歴史家から独立した機密扱いの意見書を取得した。NPS職員は、ドレイクズ・コーブ遺跡がドレイク上陸地点として「最も可能性が高 い」[16]、「最も有力である」[17][18][19][20]と結論付けた。国立公園システム諮問委員会記念物委員会は「ノヴァ・アルビオン港歴 史・考古学地区指定」[21]に関する公衆意見募集を行い、20通以上の支持書簡を受け取ったが、反対意見は一切なかった。2011年11月9日にワシン トンD.C.で開催された委員会会議では、スペイン政府代表、米国海洋大気庁(NOAA)、リン・ウォルシー下院議員が全員、この指定に賛成の意見を述べ た。反対意見はなかった。職員とドレイク航海者ギルドのエドワード・フォン・デル・ポーテン会長がプレゼンテーションを行った。この指定案は、委員である 考古学者ジェームズ・M・アラン博士と委員会全体から強く支持され、全会一致で承認された。国立公園システム諮問委員会は指定案について追加の公的意見を 求めたが、新たな意見は寄せられなかった。2011年12月1日にフロリダで開催された委員会会議で指定案は再審議され、委員会は全会一致で承認した。 2012年10月16日、ケン・サラザール内務長官が指名書に署名し、翌17日、ドレイクス湾歴史・考古学地区が新たな国家歴史的建造物として正式に発表 された[23]。 |

| References |

References(省略) |

| Sources Osborne, Thomas J. (2013). Pacific Eldorado: A History of Greater California. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-9454-9. |

出典 オズボーン、トーマス・J. (2013). 『太平洋エルドラド:大カリフォルニアの歴史』. ジョン・ワイリー・アンド・サンズ. ISBN 978-1-4051-9454-9. |

| Further reading Bjork, Katharine (1998). "The Link that Kept the Philippines Spanish: Mexican Merchant Interests and the Manila Trade, 1571–1815." Journal of World History vol. 9, no. 1, 25–50. Carrera Stampa, Manuel (1959). "La Nao de la China." Historia Mexicana 9 no. 33, pp. 97-118. Gasch-Tomás, José Luis (2018). The Atlantic World and the Manila Galleon: Circulation, Market, and Consumption of Asian Goods in the Spanish Empires, 1565-1650. Leiden: Brill. Giraldez, Arturo (2015). The Age of Trade: The Manila Galleons and the Dawn of the Global Economy. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield. Luengo, Josemaria Salutan (1996). A History of the Manila-Acapulco Slave Trade, 1565–1815. Tubigon, Bohol: Mater Dei Publications. McCarthy, William J. (1993). "Between Policy and Prerogative: Malfeasance in the Inspection of the Manila Galleons at Acapulco, 1637." Colonial Latin American Historical Review 2, no. 2, pp. 163–83. Oropeza Keresey, Deborah (2007). "Los 'indios chinos' en la Nueva España: la inmigración de la Nao de China, 1565–1700." PhD dissertation, El Colegio de México, Centro de Estudios Históricos. Rogers, R. (1999). Shipwreck of Hawai'i: a maritime history of the Big Island. Haleiwa, Hawaii: Pilialoha Publishing. ISBN 0967346703 Schurz, William Lytle. (1917) "The Manila Galleon and California", Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 107–126 Schurz, William Lytle (1939). The Manila Galleon. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc. |

追加文献(さらに読む) ビョーク、キャサリン(1998)。「フィリピンをスペイン領に留めた絆:メキシコ商人の利害とマニラ貿易、1571–1815年」。『世界史ジャーナル』第9巻第1号、25–50頁。 カレラ・スタンパ、マヌエル(1959)。「中国船」『ヒストリア・メヒカーナ』第9巻第33号、97-118頁。 ガッシュ=トマス、ホセ・ルイス(2018)。『大西洋世界とマニラ・ガレオン船:スペイン帝国におけるアジア商品の流通・市場・消費、1565-1650年』。ライデン:ブリル。 ヒラルデス、アルトゥーロ(2015)。『貿易の時代:マニラ・ガレオン船と世界経済の夜明け』。ランハム、マサチューセッツ州:ローマン&リトルフィールド。 ルエンゴ、ホセマリア・サルタン(1996)。『マニラ-アカプルコ奴隷貿易史、1565–1815』。トゥビゴン、ボホール州:マテル・デイ出版。 マッカーシー、ウィリアム・J.(1993)。「政策と特権の間:アカプルコにおけるマニラ・ガレオン船検査の不正行為、1637年」。『植民地ラテンアメリカ歴史評論』2巻2号、163-183頁。 オロペサ・ケレシー、デボラ(2007)。「ヌエバ・エスパーニャにおける『中国系インディオ』:中国船移民、1565–1700年」。博士論文、エル・コレヒオ・デ・メヒコ、歴史研究センター。 ロジャース、R.(1999)。『ハワイの難破船:ビッグアイランドの海洋史』。ハワイ州ハレイワ:ピリアロハ出版。ISBN 0967346703 シュルツ、ウィリアム・ライトル(1917)『マニラ・ガレオンとカリフォルニア』サウスウェスタン歴史季刊、第21巻第2号、107–126頁 シュルツ、ウィリアム・ライトル(1939)『マニラ・ガレオン』ニューヨーク:E. P. ダットン社 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manila_galleon |

Acapulco in 1628, Mexican terminus of the Manila galleon

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099