フォークサイコロジー

Folk psychology

☆フォークサイコロジー(Folk psychology)、

コモンセンスサイコロジー、ナイーブサイコロジーとは、人々の行動や精神状態に関する、専門家ではない普通の、直感的な、あるいは非専門的な理解、説明、

合理化のことである[1]。心の哲学や認知科学では、この概念の学術的研究を指すこともある。痛み、喜び、興奮、不安など日常生活で遭遇する過程や項目に

は、専門用語や科学用語とは対照的に、一般的な言語用語が使用される。フォークサイコロジーは社会的相互作用やコミュニケーションに対する洞察を可能にす

るため、つながりの重要性やそれがどのように経験されるかを引き伸ばしている。

伝統的にフォークサイコロジーの研究は、日常的な人々、つまり科学の様々な学術分野で正式な訓練を受けていない人々が、どのように精神状態を帰属させるか

に焦点を当ててきた。この領域は主に、個人の信念と欲求を反映する意図主義的な状態に中心が置かれてきた。それぞれは日常的な言葉や、「信念」、「欲

求」、「恐れ」、「希望」といった概念で説明される[3]。

信念と欲望はどちらも私たちの精神状態を示唆するものとして、フォークサイコロジーの主要な考え方となっている。信念は、私たちが世界をどのように受け止

めているかという考え方から来るものであり、欲望は、私たちが世界をどのように望んでいるかという考え方から来るものである。この両方の考え方から、他人

の精神状態を予測する私たちの強さは、異なる結果をもたらす可能性がある[要出典]。

フォークサイコロジーは多くの心理学者によって、意図主義的立場と調整主義的立場の2つの視点から捉えられている。フォークサイコロジーの調整的な見方

は、人格の行動は社会的規範に向かって行動することに向けられていると主張するのに対して、意図主義的な見方は、人がどのように行動すべきかという状況に

基づいて行動すると主張する[4]。

| Folk psychology,

commonsense psychology, or naïve psychology is the ordinary, intuitive,

or non-expert understanding, explanation, and rationalization of

people's behaviors and mental states.[1] In philosophy of mind and

cognitive science, it can also refer to the academic study of this

concept. Processes and items encountered in daily life such as pain,

pleasure, excitement, and anxiety use common linguistic terms as

opposed to technical or scientific jargon.[2] Folk psychology allows

for an insight into social interactions and communication, thus

stretching the importance of connection and how it is experienced. Traditionally, the study of folk psychology has focused on how everyday people—those without formal training in the various academic fields of science—go about attributing mental states. This domain has primarily been centered on intentional states reflective of an individual's beliefs and desires; each described in terms of everyday language and concepts such as "beliefs", "desires", "fear", and "hope".[3] Belief and desire have been the main idea of folk psychology as both suggest the mental states we partake in. Belief comes from the mindset of how we take the world to be while desire comes from how we want the world to be. From both of these mindsets, our intensity of predicting others mental states can have different results.[citation needed] Folk psychology is seen by many psychologists from two perspectives: the intentional stance or the regulative view. The regulative view of folk psychology insists that a person's behavior is more geared to acting towards the societal norms whereas the intentional stance makes a person behave based on the circumstances of how they are supposed to behave.[4] |

フォークサイコロジー、コモンセンスサイコロジー、ナイーブサイコロ

ジーとは、人々の行動や精神状態に関する、専門家ではない普通の、直感的な、あるいは非専門的な理解、説明、合理化のことである[1]。心の哲学や認知科

学では、この概念の学術的研究を指すこともある。痛み、喜び、興奮、不安など日常生活で遭遇する過程や項目には、専門用語や科学用語とは対照的に、一般的

な言語用語が使用される。フォークサイコロジーは社会的相互作用やコミュニケーションに対する洞察を可能にするため、つながりの重要性やそれがどのように

経験されるかを引き伸ばしている。 伝統的にフォークサイコロジーの研究は、日常的な人々、つまり科学の様々な学術分野で正式な訓練を受けていない人々が、どのように精神状態を帰属させるか に焦点を当ててきた。この領域は主に、個人の信念と欲求を反映する意図主義的な状態に中心が置かれてきた。それぞれは日常的な言葉や、「信念」、「欲 求」、「恐れ」、「希望」といった概念で説明される[3]。 信念と欲望はどちらも私たちの精神状態を示唆するものとして、フォークサイコロジーの主要な考え方となっている。信念は、私たちが世界をどのように受け止 めているかという考え方から来るものであり、欲望は、私たちが世界をどのように望んでいるかという考え方から来るものである。この両方の考え方から、他人 の精神状態を予測する私たちの強さは、異なる結果をもたらす可能性がある[要出典]。 フォークサイコロジーは多くの心理学者によって、意図主義的立場と調整主義的立場の2つの視点から捉えられている。フォークサイコロジーの調整的な見方 は、人格の行動は社会的規範に向かって行動することに向けられていると主張するのに対して、意図主義的な見方は、人がどのように行動すべきかという状況に 基づいて行動すると主張する[4]。 |

| Key folk concepts Intentionality When perceiving, explaining, or criticizing human behaviour, people distinguish between intentional and unintentional actions.[5] An evaluation of an action as stemming from purposeful action or accidental circumstances is one of the key determinants in social interaction. Others are the environmental conditions or pre-cognitive matters. For example, a critical remark that is judged to be intentional on the part of the receiver of the message can be viewed as a hurtful insult. Conversely, if considered unintentional, the same remark may be dismissed and forgiven. The folk concept of intentionality is used in the legal system to distinguish between intentional and unintentional behavior.[6] When looking at an individual, there is an unconventional way of explaining behavior in law. By looking at behaviors and expressions, folk psychology is used to predict behaviors that have been acted out in the past. The importance of this concept transcends almost all aspects of everyday life: with empirical studies in social and developmental psychology exploring perceived intentionality's role as a mediator for aggression, relationship conflict, judgements of responsibility blame or punishment.[7][8] Recent empirical literature on folk psychology has shown that people's theories regarding intentional actions involve four distinct factors: beliefs, desires, causal histories, and enabling factors.[5] Here, beliefs and desires represent the central variables responsible for the folk theories of intention. Desires embody outcomes that an individual seeks, including those that are impossible to achieve.[9] The key difference between desires and intentions is that desires can be purely hypothetical, whereas intentions specify an outcome that the individual is actually trying to bring to fruition.[9] In terms of beliefs, there are several types that are relevant to intentions—outcome beliefs and ability beliefs. Outcome beliefs are beliefs as to whether a given action will fulfill an intention, as in "purchasing a new watch will impress my friends".[5] Ability consists of an actor's conviction regarding his or her ability to perform an action, as in "I really can afford the new watch". In light of this, Heider postulated that ability beliefs could be attributed with causing individuals to form goals that would not otherwise have been entertained.[10] |

主要な民間概念 意図主義(志向性) 人間の行動を知覚したり、説明したり、批判したりするとき、人は意図的な行動と意図的でない行動を区別する[5]。ある行動が意図的な行動に由来するもの なのか、偶然の状況に由来するものなのかを評価することは、社会的相互作用における重要な決定要因の1つである。他には、環境条件や認知以前の事柄があ る。例えば、メッセージの受け手側が意図的に行ったと判断される批判的な発言は、傷つけられる侮辱とみなされることがある。逆に、意図的でないと判断され れば、同じ発言は否定され、許されるかもしれない。 意図主義の民間概念は、意図的な行動と意図的でない行動を区別するために法制度で用いられている[6]。個人を見る場合、法における行動を説明する従来と は異なる方法がある。行動や表情を見ることで、フォークサイコロジーは過去に実行された行動を予測するために用いられる。 この概念の重要性は日常生活のほとんどすべての側面に及んでいる。社会心理学および発達心理学における実証的研究では、攻撃性、人間関係の葛藤、責任非難や処罰の判断の媒介者としての知覚された意図主義の役割が探求されている[7][8]。 フォークサイコロジーに関する最近の経験的文献は、意図的行 動に関する人々の理論には4つの異なる要因、すなわち信念、欲求、 因果史、実現可能な要因が関与していることを示している。 欲望と意図の重要な相違点は、欲望が純粋に仮説的なものである可能性があるのに対して、意図は個人が実際に実現しようとしている結果を特定することである[9]。 信念に関しては、意図主義に関連するいくつかの種類がある-結果信念 と能力信念である。結果信念とは、「新しい腕時計を買えば友達に感心してもらえる」[5] のように、ある行動が意図を実現するかどうかについての信念のことである。このことを踏まえて、ハイダーは、能力の信念は、そうでなければ抱くことのな かったような目標を個人に形成させることに帰着しうると仮定した[10]。 |

| Regulative The regulative view of folk psychology is not the same of the intentional stance of folk psychology. This point of view is primarily concerned with the norms and patterns that correspond with our behavior and applying them in social situations.[11] Our thoughts and behaviors are often shaped by folk psychology into the normative molds that help others predict and comprehend us.[12] According to the regulative point of view, social roles, cultural norms, generalizations, and stereotypes are grounded on social and developmental psychology's empirical data, which is what normative structures allude to.[13] Based on how someone displays themselves, things like how you treat babies differently from adults and boys differently from girls might foretell how people will behave or react. According to this regulative perspective, folk psychology fulfills a "curiosity state" and a satisfactory answer satisfies the needs of the inquirer.[12] Moral character judgements play a significant role in comprehending folk psychology from a regulative perspective. Three categories of moral character traits are assigned: virtue-labeling, narrative-based moral assessment, as well as gossiping about traits and they use different approaches to social cognition. Although character judgement is a component in folk psychology, it does not take into consideration other processes that we engage in on the daily basis.[12] |

調整的(レギュラティブ) フォークサイコロジーの調整的観点は、フォークサイコロジーの意図主義的観点とは異なる。この視点は主に私たちの行動に対応する規範やパターンに関心があ り、社会的状況においてそれらを適用するものである[11]。私たちの思考や行動はしばしばフォークサイコロジーによって規範的な型にはめられ、他者が私 たちを予測し理解するのに役立っている[12]。 調整的視点によれば、社会的役割、文化的規範、一般化、ステレオタイプは社会心理学や発達心理学の経験的データに基づくものであり、規範的構造とはそれを 示唆するものである。この規制的観点によれば、フォークサイコロジーは「好奇心の状態」を満たし、満足のいく答えは探究者の欲求を満たす[12]。 道徳的性格判断は、調整的観点からフォークサイコロジーを理解する上で重要な役割を果たしている。道徳的性格特性には、徳のラベリング、物語に基づく道徳 的評価、および特性についての噂話という3つのカテゴリーが割り当てられており、これらは社会的認知に対する異なるアプローチを用いている。性格判断は フォークサイコロジーにおける構成要素ではあるが、私たちが日常的に行っている他のプロセスは考慮されていない[12]。 |

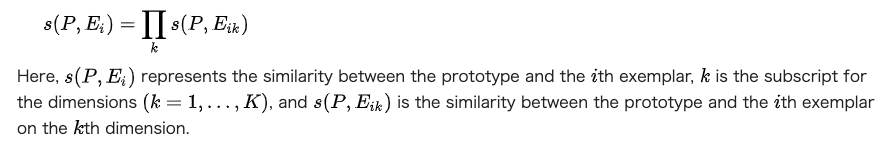

| Comprehension and prediction Context model Folk psychology is crucial to evaluating and ultimately understanding novel concepts and items. Developed by Medin, Altom, and Murphy, the Context Model[14] hypothesizes that as a result of mental models in the form of prototype and exemplar representations, individuals are able to more accurately represent and comprehend the environment around them. According to the model, the overall similarity between the prototype and a given instance of a category is evaluated based on multiple dimensions (e.g., shape, size, color). A multiplicative function modeled after this phenomenon was created.  |

理解力と予測 文脈モデル フォークサイコロジーは、新規の概念やアイテムを評価し、最終 的に理解するために極めて重要である。Medin、Altom、Murphyによって開発されたコンテクスト・モ デル[14]は、プロトタイプ表現と模範表現という形のメンタルモ デルの結果として、個人は周囲の環境をより正確に表現し理解する ことができるという仮説を立てている。 このモデルによると、あるカテゴリのプロトタイプと所与のイン スタンスとの間の全体的な類似性は、複数の次元(例えば形状、サイズ、 色)に基づいて評価される。この現象をモデル化した乗法関数が作成された。 |

| Prediction model There are other prediction models when it comes to the different cognitive thoughts an individual might have when trying to predict human behavior or human mental states. From Lewis, one platitude includes individuals casually expressing stimuli and behavior. The other platitude includes assuming a type of mental state another has. [15] |

予測モデル 人間の行動や精神状態を予測しようとするとき、個人が持つかもしれない異なる認知的思考に関しては、他にも予測モデルがある。ルイスによれば、1つのプラ ティチュードには、個人が何気なく刺激や行動を表現することが含まれる。もう1つのプラティチュードは、他の人が持っている精神状態の種類を想定すること である。[15] |

| Consequence of prediction model The prediction model has received some cautions as the idea of folk psychology has been a part of Lewis's ideas. Common statements about mental health have been considered in Lewis's prediction model, therefore there was an assumed lack of quality scientific research. |

予測モデルの結果 ルイスの考えにはフォークサイコロジーの考え方が含まれていたため、予測モデルにはいくつかの注意点があった。ルイスの予測モデルでは、精神保健に関する一般的な記述が考慮されているため、質の高い科学的研究の欠如が想定されていた。 |

| Explanation Conversational Model Given that folk psychology represents causal knowledge associated with the mind's categorization processes,[16] it follows that folk psychology is actively employed in aiding the explanation of everyday actions. Denis Hilton's (1990) Conversational Model was created with this causal explanation in mind, with the model having the ability to generate specific predictions. Hilton coined his model the 'conversational' model because he argued that as a social activity, unlike prediction, explanation requires an audience: to whom the individual explains the event or action.[17] According to the model, causal explanations follow two particular conversational maxims from Grice's (1975) models of conversation—the manner maxim and the quantity maxim. Grice indicated that the content of a conversation should be relevant, informative, and fitting of the audience's gap in knowledge.[18] Cognizant of this, the Conversational Model indicates that the explainer, upon evaluation of his audience, will modify his explanation to cater their needs. In essence, demonstrating the inherent need for mental comparison and in subsequent modification of behaviour in everyday explanations. |

解説 会話モデル フォークサイコロジーが心のカテゴリー化プロセスに関連する因果的知識を表していることを考えると[16]、フォークサイコロジーは日常的な行動の説明を 助けるために積極的に用いられていることになる。デニス・ヒルトン(1990年)の会話モデルは、この因果的説明を念頭に置いて作成されたものであり、モ デルには具体的な予測を生み出す能力が備わっている。ヒルトンは、社会的活動として、予測とは異なり、説明には聴衆が必要である、つまり、個人が出来事や 行動を説明する相手が必要であると主張したため、彼のモデルを「会話」モデルと名付けた[17]。このモデルによれば、原因説明はグライス(1975)の 会話モデルにある2つの個別会話格律(作法の格律と量の格律)に従う。グライスは、会話の内容は関連性があり、有益で、聴衆の知識のギャッ プに合うものであるべきだと指摘している。要するに、日常的な説明において、心的比較とそれに続く行動の修正が本質的に必要であることを示しているのであ る。 |

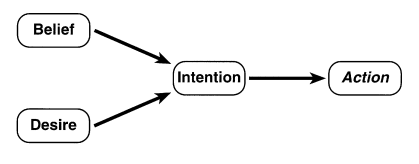

| Application and functioning Belief–desire model The belief–desire model of psychology illustrates one method in which folk psychology is utilized in everyday life. According to this model, people perform an action if they want an outcome and believe that it can be obtained by performing the action. However, beliefs and desires are not responsible for immediate action; intention acts as a mediator of belief/desire and action.[9] In other words, consider a person who wants to achieve a goal, "G", and believes action "A" will aid in attaining "G"; this leads to an intention to perform "A", which is then carried out to produce action "A".  A schematic representation of folk psychology of belief, desire, intention, and action Schank & Abelson (1977) described this inclusion of typical beliefs, desires, and intentions underlying an action as akin to a "script" whereby an individual is merely following an unconscious framework that leads to the ultimate decision of whether an action will be performed.[19] Similarly, Barsalou (1985) described the category of the mind as an "ideal" whereby if a desire, a belief, and an intention were all present, they would "rationally" lead to a given action. They coined this phenomenon the "ideal of rational action".[20] |

応用と機能 信念-欲求モデル 心理学の信念-欲求モデルは、フォークサイコロジーが日常生活で活用されている方法の一つを示している。このモデルによると、人はある結果を望み、その行 動を行うことでそれが得られると信じている場合に行動を行う。しかし、パ フォーマティビティや欲求が即座に行動に結びつくわけではなく、 意図主義が信念・欲求と行動の媒介として作用する[9]。言い換えれば、ある目標 「G」を達成したいと考え、行動「A」が「G」の達成に役立つと信 じている人格を考える。  信念、欲求、意図(志向性)、行動のフォークサイコロジーの概略図 シャンク&アベルソン(1977)は、行動の根底にある典型的な信念、欲求、 意図がこのように含まれることを「台本」のようなものと表現し、それによって個 人は行動を実行するかどうかの最終的な決定につながる無意識の枠組み に従っているに過ぎないと説明した[19] 。彼らはこの現象を「合理的行動の理想」と名付けた[20]。 |

| Goal-intentional action model Existing literature has widely corroborated the fact that social behavior is greatly affected by the causes to which people attribute actions.[10] In particular, it has been shown that an individual's interpretation of the causes of behavior reflects their pre-existing beliefs regarding the actor's mental state and motivation behind his or her actions.[21] It follows that they draw on the assumed intentions of actors to guide their own responses to punish or reward the actor. This concept is extended to cover instances in which behavioral evidence is lacking. Under these circumstances, it has been shown that the individual will again draw on assumed intentions in order to predict the actions of the third party.[10] Although the two components are often used interchangeably in common parlance, there is an important distinction between the goals and intentions. This discrepancy lies in the fact that individuals with an intention to perform an action also foster the belief that it will be achieved, whereas the same person with a goal may not necessarily believe that the action is able to be performed in spite of having a strong desire to do so. Predicting goals and actions, much like the Belief-Desire Model, involves moderating variables that determine whether an action will be performed. In the Goal-Intentional Action Model, the predictors of goals and actions are: the actors' beliefs about his or her abilities and their actual possession of preconditions required to carry out the action.[22] Additionally, preconditions consist of the various conditions necessary in order for realization of intentions. This includes abilities and skills in addition to environmental variables that may come into play. Schank & Abelson raises the example of going to a restaurant, where the preconditions include the ability to afford the bill and get to the correct venue, in addition to the fact that the restaurant must be open for business.[19] Traditionally, people prefer to allude to preconditions to explain actions that have a high probability of being unattainable, whereas goals tend to be described as a wide range of common actions. |

意図主義(志向性)行動モデル 既存の文献は、社会的行動は人々が行動を帰属させる原因に大きく影響されるという事実を広く裏付けている[10]。特に、行動の原因に関する個人の解釈 は、行為者の精神状態や行動の背後にある動機に関する彼らの既存の信念を反映することが示されている[21]。この概念は、行動証拠が不足している場合を カバーするために拡張される。このような状況下では、個人は第三者の行動を予測するために再び仮定された意図を利用することが示されている[10]。 この2つの要素は一般的な言い回しではしばしば同じ意味で使われるが、目標と意図の間には重要な違いがある。この相違は、ある行動を実行する意図を持つ個 人は、それが達成されると いう信念も育むという事実にある。一方、目標を持つ同じ人格は、そうしたいと 強く願っているにもかかわらず、その行動が実行できるとは必ずしも 思わないかもしれない。 目標や行動を予測するには、信念-欲求モデルと同様に、行動が実行されるかどうかを決定する調節変数が関与する。目標・意図行動モデルでは、目標や行動の 予測変数は、行為者の能力に関する信念と、行動を実行するために必要な前提条件を実際に所有していることである[22]。さらに、前提条件は、意図を実現 するために必要な様々な条件から構成される。これには、環境変数に加え、能力やスキルも含まれる。シャンク&アベルソンは、レストランに行くことを例に挙 げ、前提条 件には、レストランが営業中であることに加えて、勘定を払う余裕があり、 適切な会場に行くことができることが含まれる[19]。 |

| Model of everyday inferences Models of everyday inferences capture folk psychology of human informal reasoning. Many models of this nature have been developed. They express and refine our folk psychological ways of understanding of how one makes inferences. For example, one model[23] describes human everyday reasoning as combinations of simple, direct rules and similarity-based processes. From the interaction of these simple mechanisms, seemingly complex patterns of reasoning emerge. The model has been used to account for a variety of reasoning data. |

日常推論のモデル 日常的推論のモデルは、人間の非公式推論のフォークサイコロジーを捉えている。この種のモデルは数多く開発されている。これらのモデルは、人がどのように推論を行うかについてのフォークサイコロジー的な理解の仕方を表現し、洗練している。 例えば、1つのモデル[23]は、人間の日常的な推論を、単純で直接的な規則と 類似性に基づくプロセスの組み合わせとして記述している。これらの単純なメカニズムの相互作用から、一見複雑な推論のパターンが出現する。このモデルは様 々な推論データを説明するために使用されてきた。 |

| Controversy Further information: Eliminative materialism Folk psychology remains the subject of much contention in academic circles with respect to its scope, method and the significance of its contributions to the scientific community.[24] A large part of this criticism stems from the prevailing impression that folk psychology is a primitive practice reserved for the uneducated and non-academics in discussing their everyday lives.[25] There is significant debate over whether folk psychology is useful for academic purposes; specifically, whether it can be relevant with regard to the scientific psychology domain. It has been argued that a mechanism used for laypeople's understanding, predicting, and explaining each other's actions is inapplicable with regards to the requirements of the scientific method.[25] Conversely, opponents have called for patience, seeing the mechanism employed by laypeople for understanding each other's actions as important in their formation of bases for future action when encountering similar situations. Malle & Knobe hailed this systematization of people's everyday understanding of the mind as an inevitable progression towards a more comprehensive field of psychology.[5] Medin et al. provide another advantage of conceptualizing folk psychology with their Mixture Model of Categorization:[26] it is advantageous as it helps predict action. |

論争 さらに詳しい情報 排除的唯物論 フォークサイコロジーは、その範囲、方法、および科学的コミュニティに対するその貢献の意義に関して、学界において依然として多くの論争の的となっている [24]。この批判の大部分は、フォークサイコロジーが日常生活について議論する際に無学で非学者だけに許された原始的な実践であるという一般的な印象か ら生じている[25]。 フォークサイコロジーが学術的目的に有用であるかどうか、具体的には科学的心理学の領域と関連しうるかどうかについては、大きな議論がある。素人が互いの 行動を理解し、予測し、説明するために用いられるメカニズムは、科学的方法の要件に関しては適用できないと主張されてきた[25]。逆に、反対派は、素人 が互いの行動を理解するために用いるメカニズムは、同じような状況に遭遇したときに将来の行動の基盤を形成する上で重要であるとみなし、忍耐を要求してき た。MalleとKnobeは、人々の日常的な心の理解を体系化することは、より包括的な心理学の分野へと向かう必然的な進歩であると評価している。 |

| Common sense Intentional stance Popular psychology Theory of mind |

常識 意図主義的スタンス 大衆心理学 心の理論 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Folk_psychology |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099