Western philosophy

See also: Free will in antiquity

The underlying questions are whether we have control over our actions,

and if so, what sort of control, and to what extent. These questions

predate the early Greek stoics (for example, Chrysippus), and some

modern philosophers lament the lack of progress over all these

centuries.[11][12]

On one hand, humans have a strong sense of freedom, which leads them to

believe that they have free will.[13][14] On the other hand, an

intuitive feeling of free will could be mistaken.[15][16]

It is difficult to reconcile the intuitive evidence that conscious

decisions are causally effective with the view that the physical world

can be explained entirely by physical law.[17] The conflict between

intuitively felt freedom and natural law arises when either causal

closure or physical determinism (nomological determinism) is asserted.

With causal closure, no physical event has a cause outside the physical

domain, and with physical determinism, the future is determined

entirely by preceding events (cause and effect).

The puzzle of reconciling 'free will' with a deterministic universe is

known as the problem of free will or sometimes referred to as the

dilemma of determinism.[18] This dilemma leads to a moral dilemma as

well: the question of how to assign responsibility for actions if they

are caused entirely by past events.[19][20]

Compatibilists maintain that mental reality is not of itself causally

effective.[21][22] Classical compatibilists have addressed the dilemma

of free will by arguing that free will holds as long as humans are not

externally constrained or coerced.[23] Modern compatibilists make a

distinction between freedom of will and freedom of action, that is,

separating freedom of choice from the freedom to enact it.[24] Given

that humans all experience a sense of free will, some modern

compatibilists think it is necessary to accommodate this

intuition.[25][26] Compatibilists often associate freedom of will with

the ability to make rational decisions.

A different approach to the dilemma is that of incompatibilists,

namely, that if the world is deterministic, then our feeling that we

are free to choose an action is simply an illusion. Metaphysical

libertarianism is the form of incompatibilism which posits that

determinism is false and free will is possible (at least some people

have free will).[27] This view is associated with non-materialist

constructions,[15] including both traditional dualism, as well as

models supporting more minimal criteria; such as the ability to

consciously veto an action or competing desire.[28][29] Yet even with

physical indeterminism, arguments have been made against libertarianism

in that it is difficult to assign Origination (responsibility for

"free" indeterministic choices).

Free will here is predominantly treated with respect to physical

determinism in the strict sense of nomological determinism, although

other forms of determinism are also relevant to free will.[30] For

example, logical and theological determinism challenge metaphysical

libertarianism with ideas of destiny and fate, and biological, cultural

and psychological determinism feed the development of compatibilist

models. Separate classes of compatibilism and incompatibilism may even

be formed to represent these.[31]

Below are the classic arguments bearing upon the dilemma and its underpinnings.

Incompatibilism

Main article: Incompatibilism

Incompatibilism is the position that free will and determinism are

logically incompatible, and that the major question regarding whether

or not people have free will is thus whether or not their actions are

determined. "Hard determinists", such as d'Holbach, are those

incompatibilists who accept determinism and reject free will. In

contrast, "metaphysical libertarians", such as Thomas Reid, Peter van

Inwagen, and Robert Kane, are those incompatibilists who accept free

will and deny determinism, holding the view that some form of

indeterminism is true.[32] Another view is that of hard

incompatibilists, which state that free will is incompatible with both

determinism and indeterminism.[33]

Traditional arguments for incompatibilism are based on an "intuition

pump": if a person is like other mechanical things that are determined

in their behavior such as a wind-up toy, a billiard ball, a puppet, or

a robot, then people must not have free will.[32][34] This argument has

been rejected by compatibilists such as Daniel Dennett on the grounds

that, even if humans have something in common with these things, it

remains possible and plausible that we are different from such objects

in important ways.[35]

Another argument for incompatibilism is that of the "causal chain".

Incompatibilism is key to the idealist theory of free will. Most

incompatibilists reject the idea that freedom of action consists simply

in "voluntary" behavior. They insist, rather, that free will means that

someone must be the "ultimate" or "originating" cause of his actions.

They must be causa sui, in the traditional phrase. Being responsible

for one's choices is the first cause of those choices, where first

cause means that there is no antecedent cause of that cause. The

argument, then, is that if a person has free will, then they are the

ultimate cause of their actions. If determinism is true, then all of a

person's choices are caused by events and facts outside their control.

So, if everything someone does is caused by events and facts outside

their control, then they cannot be the ultimate cause of their actions.

Therefore, they cannot have free will.[36][37][38] This argument has

also been challenged by various compatibilist philosophers.[39][40]

A third argument for incompatibilism was formulated by Carl Ginet in

the 1960s and has received much attention in the modern literature. The

simplified argument runs along these lines: if determinism is true,

then we have no control over the events of the past that determined our

present state and no control over the laws of nature. Since we can have

no control over these matters, we also can have no control over the

consequences of them. Since our present choices and acts, under

determinism, are the necessary consequences of the past and the laws of

nature, then we have no control over them and, hence, no free will.

This is called the consequence argument.[41][42] Peter van Inwagen

remarks that C.D. Broad had a version of the consequence argument as

early as the 1930s.[43]

The difficulty of this argument for some compatibilists lies in the

fact that it entails the impossibility that one could have chosen other

than one has. For example, if Jane is a compatibilist and she has just

sat down on the sofa, then she is committed to the claim that she could

have remained standing, if she had so desired. But it follows from the

consequence argument that, if Jane had remained standing, she would

have either generated a contradiction, violated the laws of nature or

changed the past. Hence, compatibilists are committed to the existence

of "incredible abilities", according to Ginet and van Inwagen. One

response to this argument is that it equivocates on the notions of

abilities and necessities, or that the free will evoked to make any

given choice is really an illusion and the choice had been made all

along, oblivious to its "decider".[42] David Lewis suggests that

compatibilists are only committed to the ability to do something

otherwise if different circumstances had actually obtained in the

past.[44]

Using T, F for "true" and "false" and ? for undecided, there are

exactly nine positions regarding determinism/free will that consist of

any two of these three possibilities:[45]

ncompatibilism may occupy any of the nine positions except (5), (8) or

(3), which last corresponds to soft determinism. Position (1) is hard

determinism, and position (2) is libertarianism. The position (1) of

hard determinism adds to the table the contention that D implies FW is

untrue, and the position (2) of libertarianism adds the contention that

FW implies D is untrue. Position (9) may be called hard incompatibilism

if one interprets ? as meaning both concepts are of dubious value.

Compatibilism itself may occupy any of the nine positions, that is,

there is no logical contradiction between determinism and free will,

and either or both may be true or false in principle. However, the most

common meaning attached to compatibilism is that some form of

determinism is true and yet we have some form of free will, position

(3).[46]

A domino's movement is determined completely by laws of physics.

Alex Rosenberg makes an extrapolation of physical determinism as

inferred on the macroscopic scale by the behaviour of a set of dominoes

to neural activity in the brain where; "If the brain is nothing but a

complex physical object whose states are as much governed by physical

laws as any other physical object, then what goes on in our heads is as

fixed and determined by prior events as what goes on when one domino

topples another in a long row of them."[47] Physical determinism is

currently disputed by prominent interpretations of quantum mechanics,

and while not necessarily representative of intrinsic indeterminism in

nature, fundamental limits of precision in measurement are inherent in

the uncertainty principle.[48] The relevance of such prospective

indeterminate activity to free will is, however, contested,[49] even

when chaos theory is introduced to magnify the effects of such

microscopic events.[29][50]

Below these positions are examined in more detail.[45]

Hard determinism

Main article: Hard determinism

A simplified taxonomy of philosophical positions regarding free will and determinism.

Determinism can be divided into causal, logical and theological

determinism.[51] Corresponding to each of these different meanings,

there arises a different problem for free will.[52] Hard determinism is

the claim that determinism is true, and that it is incompatible with

free will, so free will does not exist. Although hard determinism

generally refers to nomological determinism (see causal determinism

below), it can include all forms of determinism that necessitate the

future in its entirety.[53] Relevant forms of determinism include:

Causal determinism

The idea that everything is caused by prior conditions, making it

impossible for anything else to happen.[54] In its most common form,

nomological (or scientific) determinism, future events are necessitated

by past and present events combined with the laws of nature. Such

determinism is sometimes illustrated by the thought experiment of

Laplace's demon. Imagine an entity that knows all facts about the past

and the present, and knows all natural laws that govern the universe.

If the laws of nature were determinate, then such an entity would be

able to use this knowledge to foresee the future, down to the smallest

detail.[55][56]

Logical determinism

The notion that all propositions, whether about the past, present or

future, are either true or false. The problem of free will, in this

context, is the problem of how choices can be free, given that what one

does in the future is already determined as true or false in the

present.[52]

Theological determinism

The idea that the future is already determined, either by a creator

deity decreeing or knowing its outcome in advance.[57][58] The problem

of free will, in this context, is the problem of how our actions can be

free if there is a being who has determined them for us in advance, or

if they are already set in time.

Other forms of determinism are more relevant to compatibilism, such as

biological determinism, the idea that all behaviors, beliefs, and

desires are fixed by our genetic endowment and our biochemical makeup,

the latter of which is affected by both genes and environment, cultural

determinism and psychological determinism.[52] Combinations and

syntheses of determinist theses, such as bio-environmental determinism,

are even more common.

Suggestions have been made that hard determinism need not maintain

strict determinism, where something near to, like that informally known

as adequate determinism, is perhaps more relevant.[30] Despite this,

hard determinism has grown less popular in present times, given

scientific suggestions that determinism is false – yet the intention of

their position is sustained by hard incompatibilism.[27]

Metaphysical libertarianism

Main article: Libertarianism (metaphysics)

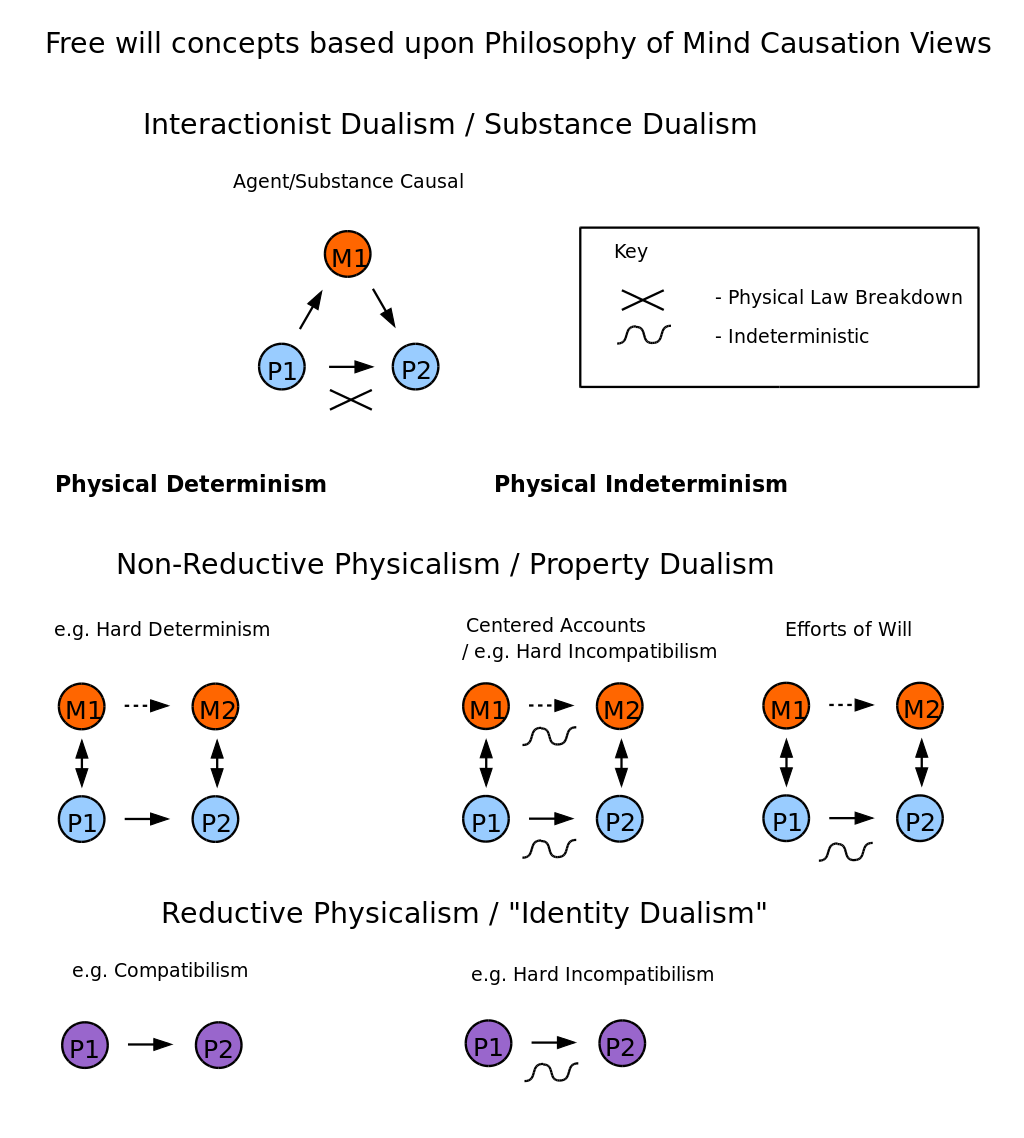

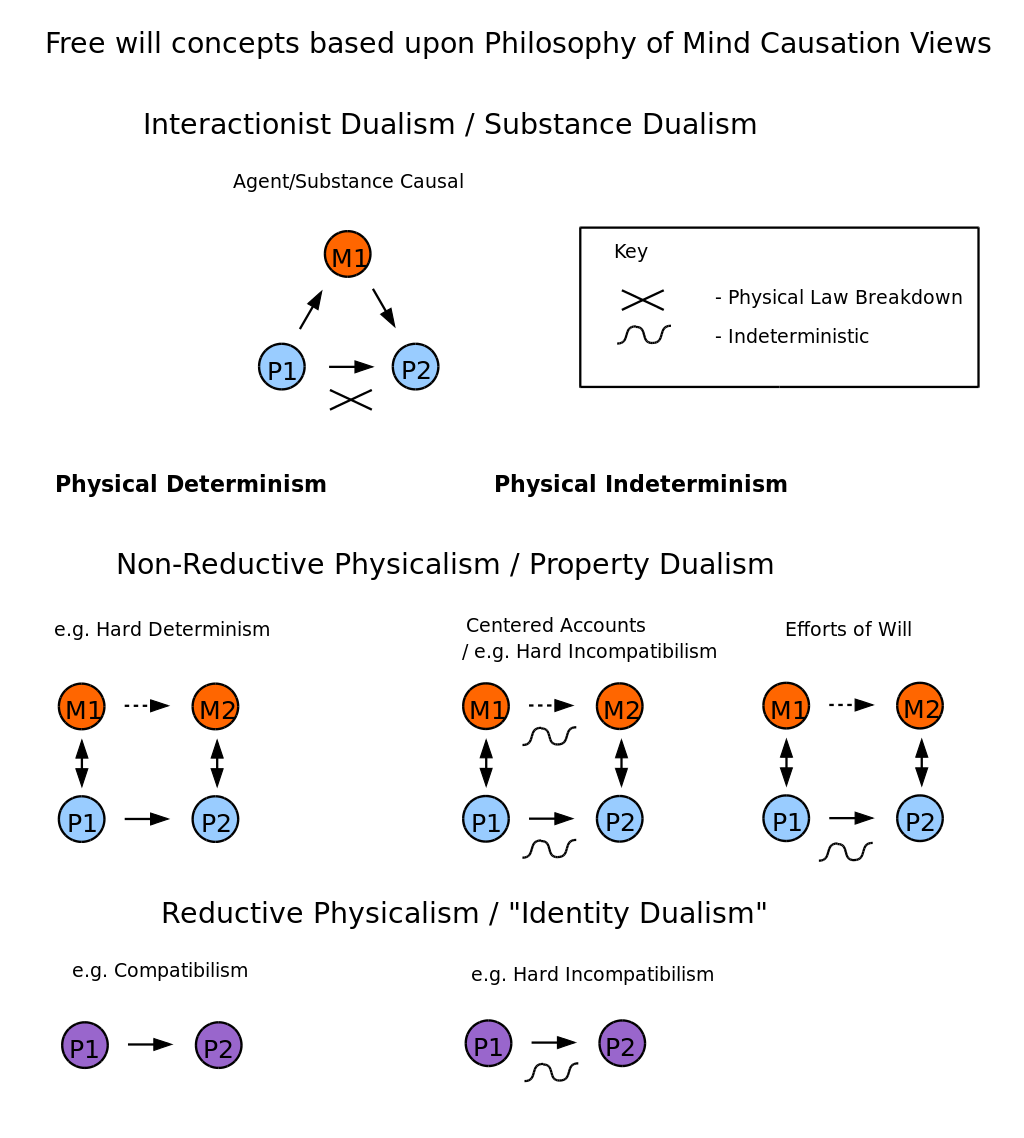

Various definitions of free will that have been proposed for

Metaphysical Libertarianism (agent/substance causal,[59] centered

accounts,[60] and efforts of will theory[29]), along with examples of

other common free will positions (Compatibilism,[17] Hard

Determinism,[61] and Hard Incompatibilism[33]). Red circles represent

mental states; blue circles represent physical states; arrows describe

causal interaction.

Metaphysical libertarianism is one philosophical view point under that

of incompatibilism. Libertarianism holds onto a concept of free will

that requires that the agent be able to take more than one possible

course of action under a given set of circumstances.[62]

Accounts of libertarianism subdivide into non-physical theories and

physical or naturalistic theories. Non-physical theories hold that the

events in the brain that lead to the performance of actions do not have

an entirely physical explanation, which requires that the world is not

closed under physics. This includes interactionist dualism, which

claims that some non-physical mind, will, or soul overrides physical

causality. Physical determinism implies there is only one possible

future and is therefore not compatible with libertarian free will. As

consequent of incompatibilism, metaphysical libertarian explanations

that do not involve dispensing with physicalism require physical

indeterminism, such as probabilistic subatomic particle behavior –

theory unknown to many of the early writers on free will.

Incompatibilist theories can be categorised based on the type of

indeterminism they require; uncaused events, non-deterministically

caused events, and agent/substance-caused events.[59]

Non-causal theories

Non-causal accounts of incompatibilist free will do not require a free

action to be caused by either an agent or a physical event. They either

rely upon a world that is not causally closed, or physical

indeterminism. Non-causal accounts often claim that each intentional

action requires a choice or volition – a willing, trying, or

endeavoring on behalf of the agent (such as the cognitive component of

lifting one's arm).[63][64] Such intentional actions are interpreted as

free actions. It has been suggested, however, that such acting cannot

be said to exercise control over anything in particular. According to

non-causal accounts, the causation by the agent cannot be analysed in

terms of causation by mental states or events, including desire,

belief, intention of something in particular, but rather is considered

a matter of spontaneity and creativity. The exercise of intent in such

intentional actions is not that which determines their freedom –

intentional actions are rather self-generating. The "actish feel" of

some intentional actions do not "constitute that event's activeness, or

the agent's exercise of active control", rather they "might be brought

about by direct stimulation of someone's brain, in the absence of any

relevant desire or intention on the part of that person".[59] Another

question raised by such non-causal theory, is how an agent acts upon

reason, if the said intentional actions are spontaneous.

Some non-causal explanations involve invoking panpsychism, the theory

that a quality of mind is associated with all particles, and pervades

the entire universe, in both animate and inanimate entities.

Event-causal theories

Event-causal accounts of incompatibilist free will typically rely upon

physicalist models of mind (like those of the compatibilist), yet they

presuppose physical indeterminism, in which certain indeterministic

events are said to be caused by the agent. A number of event-causal

accounts of free will have been created, referenced here as

deliberative indeterminism, centred accounts, and efforts of will

theory.[59] The first two accounts do not require free will to be a

fundamental constituent of the universe. Ordinary randomness is

appealed to as supplying the "elbow room" that libertarians believe

necessary. A first common objection to event-causal accounts is that

the indeterminism could be destructive and could therefore diminish

control by the agent rather than provide it (related to the problem of

origination). A second common objection to these models is that it is

questionable whether such indeterminism could add any value to

deliberation over that which is already present in a deterministic

world.

Deliberative indeterminism asserts that the indeterminism is confined

to an earlier stage in the decision process.[65][66] This is intended

to provide an indeterminate set of possibilities to choose from, while

not risking the introduction of luck (random decision making). The

selection process is deterministic, although it may be based on earlier

preferences established by the same process. Deliberative indeterminism

has been referenced by Daniel Dennett[67] and John Martin Fischer.[68]

An obvious objection to such a view is that an agent cannot be assigned

ownership over their decisions (or preferences used to make those

decisions) to any greater degree than that of a compatibilist model.

Centred accounts propose that for any given decision between two

possibilities, the strength of reason will be considered for each

option, yet there is still a probability the weaker candidate will be

chosen.[60][69][70][71][72][73][74] An obvious objection to such a view

is that decisions are explicitly left up to chance, and origination or

responsibility cannot be assigned for any given decision.

Efforts of will theory is related to the role of will power in decision

making. It suggests that the indeterminacy of agent volition processes

could map to the indeterminacy of certain physical events – and the

outcomes of these events could therefore be considered caused by the

agent. Models of volition have been constructed in which it is seen as

a particular kind of complex, high-level process with an element of

physical indeterminism. An example of this approach is that of Robert

Kane, where he hypothesizes that "in each case, the indeterminism is

functioning as a hindrance or obstacle to her realizing one of her

purposes – a hindrance or obstacle in the form of resistance within her

will which must be overcome by effort."[29] According to Robert Kane

such "ultimate responsibility" is a required condition for free

will.[75] An important factor in such a theory is that the agent cannot

be reduced to physical neuronal events, but rather mental processes are

said to provide an equally valid account of the determination of

outcome as their physical processes (see non-reductive physicalism).

Although at the time quantum mechanics (and physical indeterminism) was

only in the initial stages of acceptance, in his book Miracles: A

preliminary study C.S. Lewis stated the logical possibility that if the

physical world were proved indeterministic this would provide an entry

point to describe an action of a non-physical entity on physical

reality.[76] Indeterministic physical models (particularly those

involving quantum indeterminacy) introduce random occurrences at an

atomic or subatomic level. These events might affect brain activity,

and could seemingly allow incompatibilist free will if the apparent

indeterminacy of some mental processes (for instance, subjective

perceptions of control in conscious volition) map to the underlying

indeterminacy of the physical construct. This relationship, however,

requires a causative role over probabilities that is questionable,[77]

and it is far from established that brain activity responsible for

human action can be affected by such events. Secondarily, these

incompatibilist models are dependent upon the relationship between

action and conscious volition, as studied in the neuroscience of free

will. It is evident that observation may disturb the outcome of the

observation itself, rendering limited our ability to identify

causality.[48] Niels Bohr, one of the main architects of quantum

theory, suggested, however, that no connection could be made between

indeterminism of nature and freedom of will.[49]

Agent/substance-causal theories

Agent/substance-causal accounts of incompatibilist free will rely upon

substance dualism in their description of mind. The agent is assumed

power to intervene in the physical

world.[78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85] Agent (substance)-causal

accounts have been suggested by both George Berkeley[86] and Thomas

Reid.[87] It is required that what the agent causes is not causally

determined by prior events. It is also required that the agent's

causing of that event is not causally determined by prior events. A

number of problems have been identified with this view. Firstly, it is

difficult to establish the reason for any given choice by the agent,

which suggests they may be random or determined by luck (without an

underlying basis for the free will decision). Secondly, it has been

questioned whether physical events can be caused by an external

substance or mind – a common problem associated with interactionalist

dualism.

Hard incompatibilism

Hard incompatibilism is the idea that free will cannot exist, whether

the world is deterministic or not. Derk Pereboom has defended hard

incompatibilism, identifying a variety of positions where free will is

irrelevant to indeterminism/determinism, among them the following:

Determinism (D) is true, D does not imply we lack free will (F), but in fact we do lack F.

D is true, D does not imply we lack F, but in fact we don't know if we have F.

D is true, and we do have F.

D is true, we have F, and F implies D.

D is unproven, but we have F.

D isn't true, we do have F, and would have F even if D were true.

D isn't true, we don't have F, but F is compatible with D.

Derk Pereboom, Living without Free Will,[33] p. xvi.

Pereboom calls positions 3 and 4 soft determinism, position 1 a form of

hard determinism, position 6 a form of classical libertarianism, and

any position that includes having F as compatibilism.

John Locke denied that the phrase "free will" made any sense (compare

with theological noncognitivism, a similar stance on the existence of

God). He also took the view that the truth of determinism was

irrelevant. He believed that the defining feature of voluntary behavior

was that individuals have the ability to postpone a decision long

enough to reflect or deliberate upon the consequences of a choice:

"...the will in truth, signifies nothing but a power, or ability, to

prefer or choose".[88]

The contemporary philosopher Galen Strawson agrees with Locke that the

truth or falsity of determinism is irrelevant to the problem.[89] He

argues that the notion of free will leads to an infinite regress and is

therefore senseless. According to Strawson, if one is responsible for

what one does in a given situation, then one must be responsible for

the way one is in certain mental respects. But it is impossible for one

to be responsible for the way one is in any respect. This is because to

be responsible in some situation S, one must have been responsible for

the way one was at S−1. To be responsible for the way one was at S−1,

one must have been responsible for the way one was at S−2, and so on.

At some point in the chain, there must have been an act of origination

of a new causal chain. But this is impossible. Man cannot create

himself or his mental states ex nihilo. This argument entails that free

will itself is absurd, but not that it is incompatible with

determinism. Strawson calls his own view "pessimism" but it can be

classified as hard incompatibilism.[89]

Causal determinism

Main article: Determinism

Causal determinism is the concept that events within a given paradigm

are bound by causality in such a way that any state (of an object or

event) is completely determined by prior states. Causal determinism

proposes that there is an unbroken chain of prior occurrences

stretching back to the origin of the universe. Causal determinists

believe that there is nothing uncaused or self-caused. The most common

form of causal determinism is nomological determinism (or scientific

determinism), the notion that the past and the present dictate the

future entirely and necessarily by rigid natural laws, that every

occurrence results inevitably from prior events. Quantum mechanics

poses a serious challenge to this view.

Fundamental debate continues over whether the physical universe is

likely to be deterministic. Although the scientific method cannot be

used to rule out indeterminism with respect to violations of causal

closure, it can be used to identify indeterminism in natural law.

Interpretations of quantum mechanics at present are both deterministic

and indeterministic, and are being constrained by ongoing

experimentation.[90]

Destiny and fate

Main article: Destiny

Destiny or fate is a predetermined course of events. It may be

conceived as a predetermined future, whether in general or of an

individual. It is a concept based on the belief that there is a fixed

natural order to the cosmos.

Although often used interchangeably, the words "fate" and "destiny" have distinct connotations.

Fate generally implies there is a set course that cannot be deviated

from, and over which one has no control. Fate is related to

determinism, but makes no specific claim of physical determinism. Even

with physical indeterminism an event could still be fated externally

(see for instance theological determinism). Destiny likewise is related

to determinism, but makes no specific claim of physical determinism.

Even with physical indeterminism an event could still be destined to

occur.

Destiny implies there is a set course that cannot be deviated from, but

does not of itself make any claim with respect to the setting of that

course (i.e., it does not necessarily conflict with incompatibilist

free will). Free will if existent could be the mechanism by which that

destined outcome is chosen (determined to represent destiny).[91]

Logical determinism

See also: B-theory of time

Discussion regarding destiny does not necessitate the existence of

supernatural powers. Logical determinism or determinateness is the

notion that all propositions, whether about the past, present, or

future, are either true or false. This creates a unique problem for

free will given that propositions about the future already have a truth

value in the present (that is it is already determined as either true

or false), and is referred to as the problem of future contingents.

Omniscience

Main article: Omniscience

Omniscience is the capacity to know everything that there is to know

(included in which are all future events), and is a property often

attributed to a creator deity. Omniscience implies the existence of

destiny. Some authors have claimed that free will cannot coexist with

omniscience. One argument asserts that an omniscient creator not only

implies destiny but a form of high level predeterminism such as hard

theological determinism or predestination – that they have

independently fixed all events and outcomes in the universe in advance.

In such a case, even if an individual could have influence over their

lower level physical system, their choices in regard to this cannot be

their own, as is the case with libertarian free will. Omniscience

features as an incompatible-properties argument for the existence of

God, known as the argument from free will, and is closely related to

other such arguments, for example the incompatibility of omnipotence

with a good creator deity (i.e. if a deity knew what they were going to

choose, then they are responsible for letting them choose it).

Predeterminism

Main article: Predeterminism

See also: Predestination

Predeterminism is the idea that all events are determined in

advance.[92][93] Predeterminism is the philosophy that all events of

history, past, present and future, have been decided or are known (by

God, fate, or some other force), including human actions.

Predeterminism is frequently taken to mean that human actions cannot

interfere with (or have no bearing on) the outcomes of a pre-determined

course of events, and that one's destiny was established externally

(for example, exclusively by a creator deity). The concept of

predeterminism is often argued by invoking causal determinism, implying

that there is an unbroken chain of prior occurrences stretching back to

the origin of the universe. In the case of predeterminism, this chain

of events has been pre-established, and human actions cannot interfere

with the outcomes of this pre-established chain. Predeterminism can be

used to mean such pre-established causal determinism, in which case it

is categorised as a specific type of determinism.[92][94] It can also

be used interchangeably with causal determinism – in the context of its

capacity to determine future events.[92][95] Despite this,

predeterminism is often considered as independent of causal

determinism.[96][97] The term predeterminism is also frequently used in

the context of biology and heredity, in which case it represents a form

of biological determinism.[98]

The term predeterminism suggests not just a determining of all events,

but the prior and deliberately conscious determining of all events

(therefore done, presumably, by a conscious being). While determinism

usually refers to a naturalistically explainable causality of events,

predeterminism seems by definition to suggest a person or a "someone"

who is controlling or planning the causality of events before they

occur and who then perhaps resides beyond the natural, causal universe.

Predestination asserts that a supremely powerful being has indeed fixed

all events and outcomes in the universe in advance, and is a famous

doctrine of the Calvinists in Christian theology. Predestination is

often considered a form of hard theological determinism.

Predeterminism has therefore been compared to fatalism.[99] Fatalism is

the idea that everything is fated to happen, so that humans have no

control over their future.

Theological determinism

Main article: Theological determinism

Theological determinism is a form of determinism stating that all

events that happen are pre-ordained, or predestined to happen, by a

monotheistic deity, or that they are destined to occur given its

omniscience. Two forms of theological determinism exist, here

referenced as strong and weak theological determinism.[100]

The first one, strong theological determinism, is based on the concept

of a creator deity dictating all events in history: "everything that

happens has been predestined to happen by an omniscient, omnipotent

divinity."[101]

The second form, weak theological determinism, is based on the concept

of divine foreknowledge – "because God's omniscience is perfect, what

God knows about the future will inevitably happen, which means,

consequently, that the future is already fixed."[102]

There exist slight variations on the above categorisation. Some claim

that theological determinism requires predestination of all events and

outcomes by the divinity (that is, they do not classify the weaker

version as 'theological determinism' unless libertarian free will is

assumed to be denied as a consequence), or that the weaker version does

not constitute 'theological determinism' at all.[53] Theological

determinism can also be seen as a form of causal determinism, in which

the antecedent conditions are the nature and will of God.[54] With

respect to free will and the classification of theological

compatibilism/incompatibilism below, "theological determinism is the

thesis that God exists and has infallible knowledge of all true

propositions including propositions about our future actions," more

minimal criteria designed to encapsulate all forms of theological

determinism.[30]

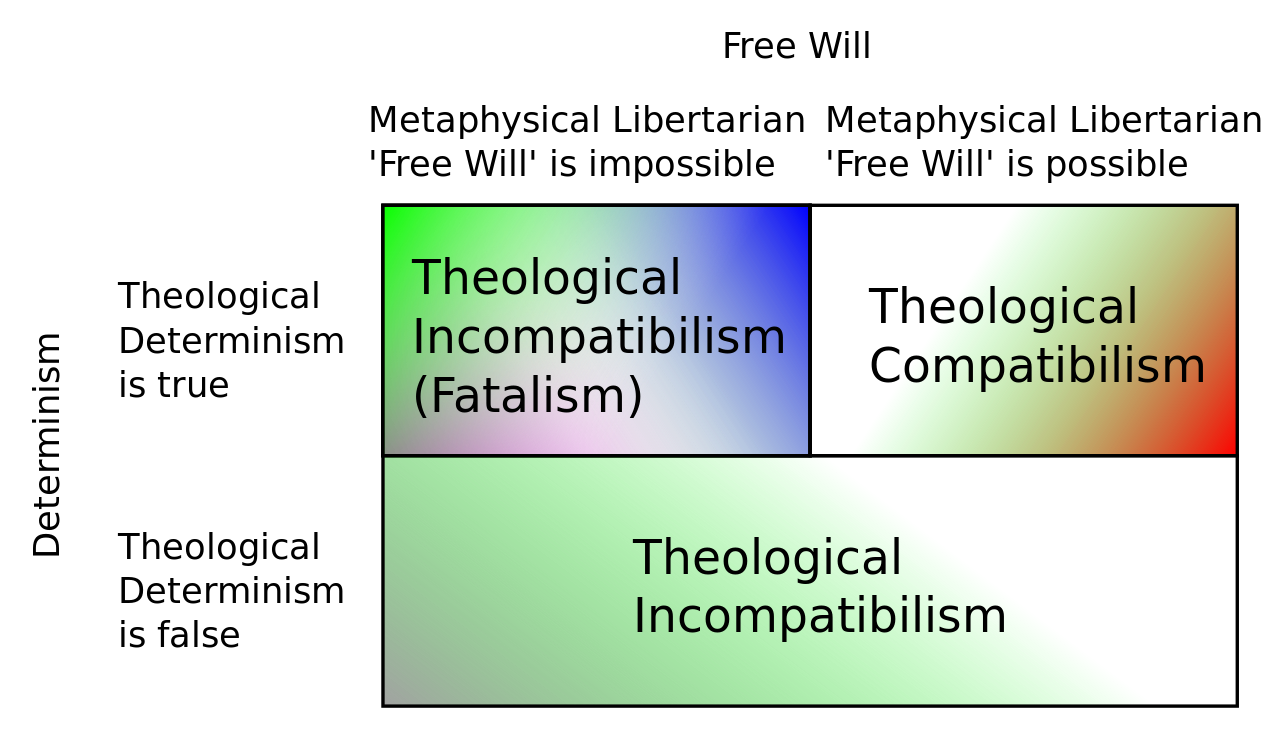

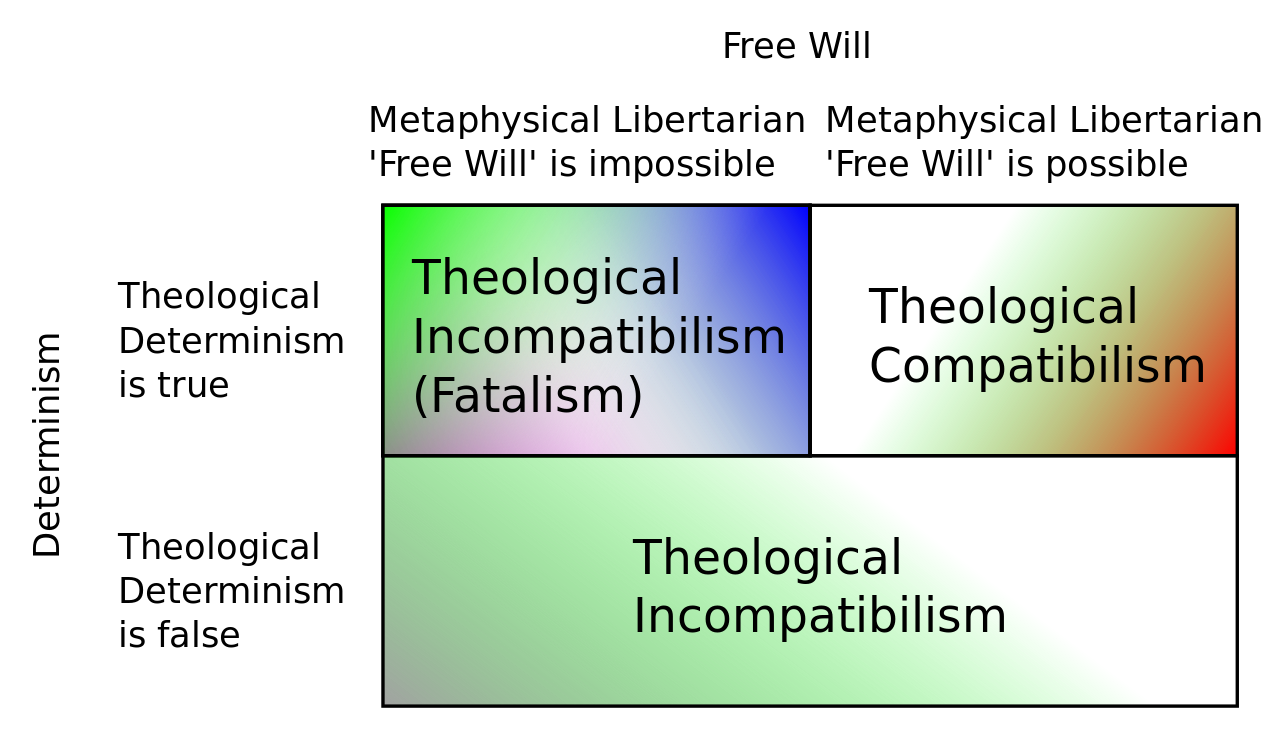

A simplified taxonomy of philosophical positions regarding free will and theological determinism[31]

There are various implications for metaphysical libertarian free will

as consequent of theological determinism and its philosophical

interpretation.

Strong theological determinism is not compatible with metaphysical

libertarian free will, and is a form of hard theological determinism

(equivalent to theological fatalism below). It claims that free will

does not exist, and God has absolute control over a person's actions.

Hard theological determinism is similar in implication to hard

determinism, although it does not invalidate compatibilist free

will.[31] Hard theological determinism is a form of theological

incompatibilism (see figure, top left).

Weak theological determinism is either compatible or incompatible with

metaphysical libertarian free will depending upon one's philosophical

interpretation of omniscience – and as such is interpreted as either a

form of hard theological determinism (known as theological fatalism),

or as soft theological determinism (terminology used for clarity only).

Soft theological determinism claims that humans have free will to

choose their actions, holding that God, while knowing their actions

before they happen, does not affect the outcome. God's providence is

"compatible" with voluntary choice. Soft theological determinism is

known as theological compatibilism (see figure, top right). A rejection

of theological determinism (or divine foreknowledge) is classified as

theological incompatibilism also (see figure, bottom), and is relevant

to a more general discussion of free will.[31]

The basic argument for theological fatalism in the case of weak theological determinism is as follows:

Assume divine foreknowledge or omniscience

Infallible foreknowledge implies destiny (it is known for certain what one will do)

Destiny eliminates alternate possibility (one cannot do otherwise)

Assert incompatibility with metaphysical libertarian free will

This argument is very often accepted as a basis for theological

incompatibilism: denying either libertarian free will or divine

foreknowledge (omniscience) and therefore theological determinism. On

the other hand, theological compatibilism must attempt to find problems

with it. The formal version of the argument rests on a number of

premises, many of which have received some degree of contention.

Theological compatibilist responses have included:

Deny the truth value of future contingents, although this denies foreknowledge and therefore theological determinism.

Assert differences in non-temporal knowledge (space-time independence),

an approach taken for example by Boethius,[103] Thomas Aquinas,[104]

and C.S. Lewis.[105]

Deny the Principle of Alternate Possibilities: "If you cannot do

otherwise when you do an act, you do not act freely." For example, a

human observer could in principle have a machine that could detect what

will happen in the future, but the existence of this machine or their

use of it has no influence on the outcomes of events.[106]

In the definition of compatibilism and incompatibilism, the literature

often fails to distinguish between physical determinism and higher

level forms of determinism (predeterminism, theological determinism,

etc.) As such, hard determinism with respect to theological determinism

(or "Hard Theological Determinism" above) might be classified as hard

incompatibilism with respect to physical determinism (if no claim was

made regarding the internal causality or determinism of the universe),

or even compatibilism (if freedom from the constraint of determinism

was not considered necessary for free will), if not hard determinism

itself. By the same principle, metaphysical libertarianism (a form of

incompatibilism with respect to physical determinism) might be

classified as compatibilism with respect to theological determinism (if

it was assumed such free will events were pre-ordained and therefore

were destined to occur, but of which whose outcomes were not

"predestined" or determined by God). If hard theological determinism is

accepted (if it was assumed instead that such outcomes were predestined

by God), then metaphysical libertarianism is not, however, possible,

and would require reclassification (as hard incompatibilism for

example, given that the universe is still assumed to be indeterministic

– although the classification of hard determinism is technically valid

also).[53]

Mind–body problem

Main article: Mind–body problem

See also: Philosophy of mind, Dualism (philosophy of mind), Monism, and Physicalism

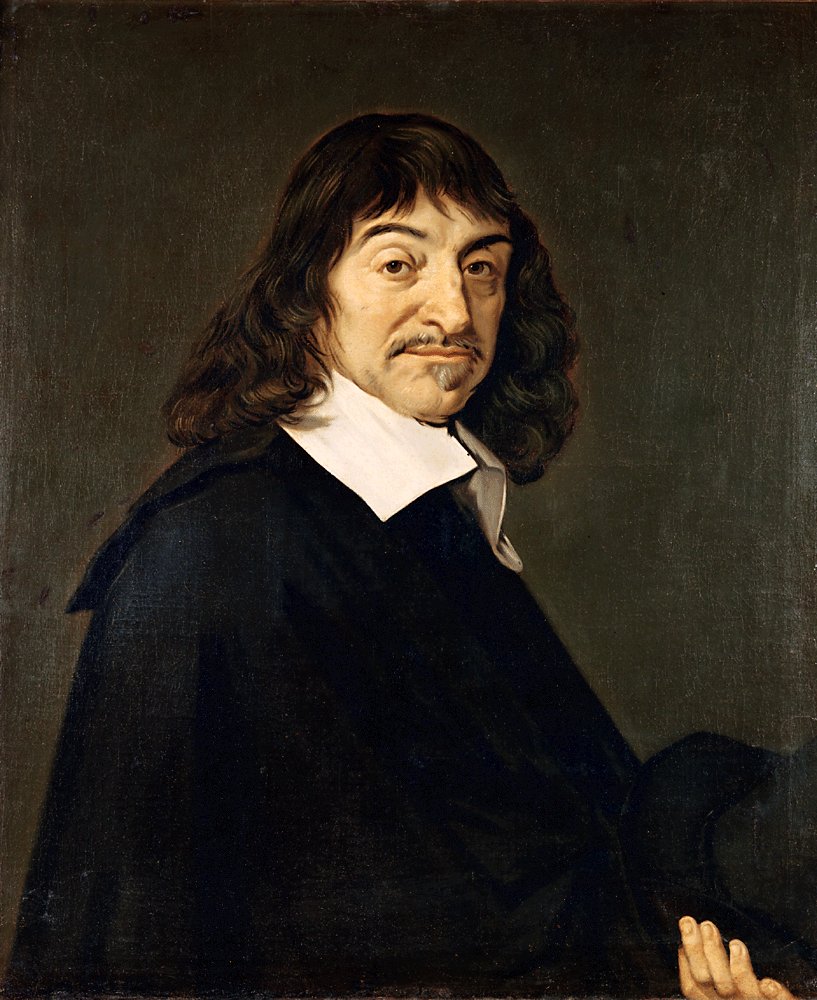

René Descartes

The idea of free will is one aspect of the mind–body problem, that is,

consideration of the relation between mind (for example, consciousness,

memory, and judgment) and body (for example, the human brain and

nervous system). Philosophical models of mind are divided into physical

and non-physical expositions.

Cartesian dualism holds that the mind is a nonphysical substance, the

seat of consciousness and intelligence, and is not identical with

physical states of the brain or body. It is suggested that although the

two worlds do interact, each retains some measure of autonomy. Under

cartesian dualism external mind is responsible for bodily action,

although unconscious brain activity is often caused by external events

(for example, the instantaneous reaction to being burned).[107]

Cartesian dualism implies that the physical world is not deterministic

– and in which external mind controls (at least some) physical events,

providing an interpretation of incompatibilist free will. Stemming from

Cartesian dualism, a formulation sometimes called interactionalist

dualism suggests a two-way interaction, that some physical events cause

some mental acts and some mental acts cause some physical events. One

modern vision of the possible separation of mind and body is the

"three-world" formulation of Popper.[108] Cartesian dualism and

Popper's three worlds are two forms of what is called epistemological

pluralism, that is the notion that different epistemological

methodologies are necessary to attain a full description of the world.

Other forms of epistemological pluralist dualism include psychophysical

parallelism and epiphenomenalism. Epistemological pluralism is one view

in which the mind-body problem is not reducible to the concepts of the

natural sciences.

A contrasting approach is called physicalism. Physicalism is a

philosophical theory holding that everything that exists is no more

extensive than its physical properties; that is, that there are no

non-physical substances (for example physically independent minds).

Physicalism can be reductive or non-reductive. Reductive physicalism is

grounded in the idea that everything in the world can actually be

reduced analytically to its fundamental physical, or material, basis.

Alternatively, non-reductive physicalism asserts that mental properties

form a separate ontological class to physical properties: that mental

states (such as qualia) are not ontologically reducible to physical

states. Although one might suppose that mental states and neurological

states are different in kind, that does not rule out the possibility

that mental states are correlated with neurological states. In one such

construction, anomalous monism, mental events supervene on physical

events, describing the emergence of mental properties correlated with

physical properties – implying causal reducibility. Non-reductive

physicalism is therefore often categorised as property dualism rather

than monism, yet other types of property dualism do not adhere to the

causal reducibility of mental states (see epiphenomenalism).

Incompatibilism requires a distinction between the mental and the

physical, being a commentary on the incompatibility of (determined)

physical reality and one's presumably distinct experience of will.

Secondarily, metaphysical libertarian free will must assert influence

on physical reality, and where mind is responsible for such influence

(as opposed to ordinary system randomness), it must be distinct from

body to accomplish this. Both substance and property dualism offer such

a distinction, and those particular models thereof that are not

causally inert with respect to the physical world provide a basis for

illustrating incompatibilist free will (i.e. interactionalist dualism

and non-reductive physicalism).

It has been noted that the laws of physics have yet to resolve the hard

problem of consciousness:[109] "Solving the hard problem of

consciousness involves determining how physiological processes such as

ions flowing across the nerve membrane cause us to have

experiences."[110] According to some, "Intricately related to the hard

problem of consciousness, the hard problem of free will represents the

core problem of conscious free will: Does conscious volition impact the

material world?"[15] Others however argue that "consciousness plays a

far smaller role in human life than Western culture has tended to

believe."[111]

Compatibilism

Main article: Compatibilism

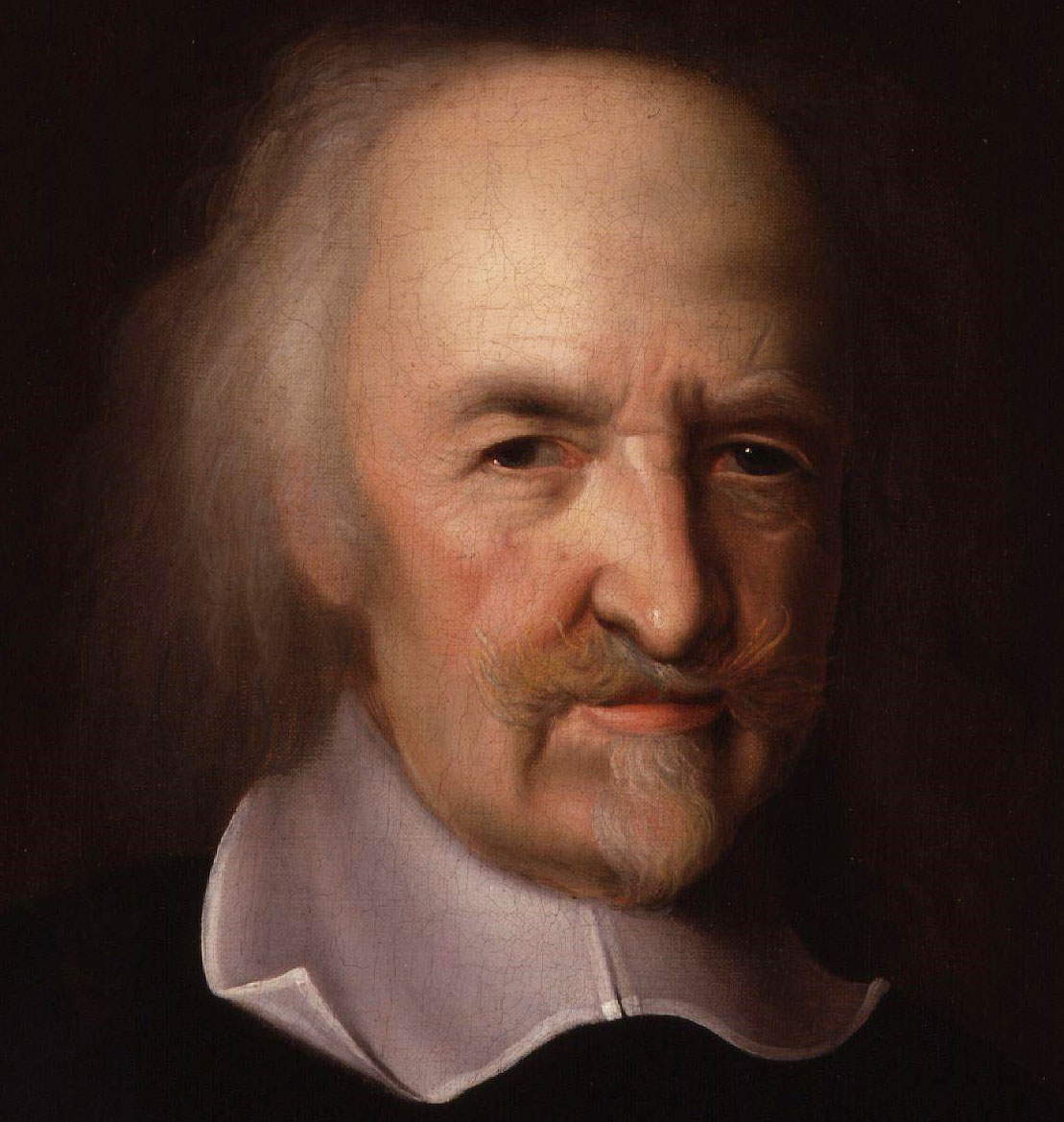

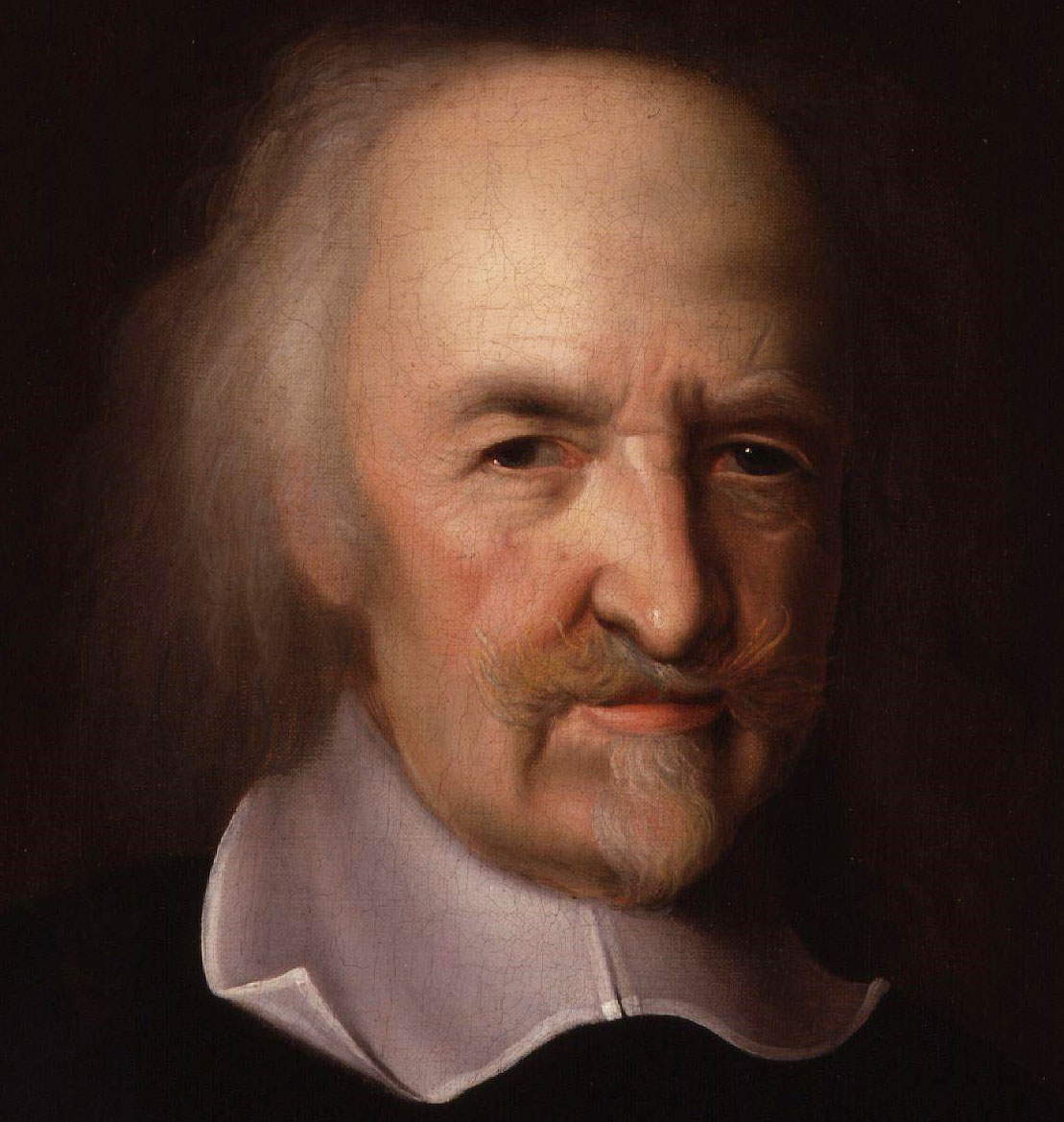

Thomas Hobbes was a classical compatibilist.

Compatibilists maintain that determinism is compatible with free will.

They believe freedom can be present or absent in a situation for

reasons that have nothing to do with metaphysics. For instance, courts

of law make judgments about whether individuals are acting under their

own free will under certain circumstances without bringing in

metaphysics. Similarly, political liberty is a non-metaphysical

concept.[citation needed] Likewise, some compatibilists define free

will as freedom to act according to one's determined motives without

hindrance from other individuals. So for example Aristotle in his

Nicomachean Ethics,[112] and the Stoic Chrysippus.[113] In contrast,

the incompatibilist positions are concerned with a sort of

"metaphysically free will", which compatibilists claim has never been

coherently defined. Compatibilists argue that determinism does not

matter; though they disagree among themselves about what, in turn, does

matter. To be a compatibilist, one need not endorse any particular

conception of free will, but only deny that determinism is at odds with

free will.[114]

Although there are various impediments to exercising one's choices,

free will does not imply freedom of action. Freedom of choice (freedom

to select one's will) is logically separate from freedom to implement

that choice (freedom to enact one's will), although not all writers

observe this distinction.[24] Nonetheless, some philosophers have

defined free will as the absence of various impediments. Some "modern

compatibilists", such as Harry Frankfurt and Daniel Dennett, argue free

will is simply freely choosing to do what constraints allow one to do.

In other words, a coerced agent's choices can still be free if such

coercion coincides with the agent's personal intentions and

desires.[35][115]

Free will as lack of physical restraint

Most "classical compatibilists", such as Thomas Hobbes, claim that a

person is acting on the person's own will only when it is the desire of

that person to do the act, and also possible for the person to be able

to do otherwise, if the person had decided to. Hobbes sometimes

attributes such compatibilist freedom to each individual and not to

some abstract notion of will, asserting, for example, that "no liberty

can be inferred to the will, desire, or inclination, but the liberty of

the man; which consisteth in this, that he finds no stop, in doing what

he has the will, desire, or inclination to doe [sic]."[116] In

articulating this crucial proviso, David Hume writes, "this

hypothetical liberty is universally allowed to belong to every one who

is not a prisoner and in chains."[117] Similarly, Voltaire, in his

Dictionnaire philosophique, claimed that "Liberty then is only and can

be only the power to do what one will." He asked, "would you have

everything at the pleasure of a million blind caprices?" For him, free

will or liberty is "only the power of acting, what is this power? It is

the effect of the constitution and present state of our organs."

Free will as a psychological state

Compatibilism often regards the agent free as virtue of their reason.

Some explanations of free will focus on the internal causality of the

mind with respect to higher-order brain processing – the interaction

between conscious and unconscious brain activity.[118] Likewise, some

modern compatibilists in psychology have tried to revive traditionally

accepted struggles of free will with the formation of character.[119]

Compatibilist free will has also been attributed to our natural sense

of agency, where one must believe they are an agent in order to

function and develop a theory of mind.[120][121]

The notion of levels of decision is presented in a different manner by

Frankfurt.[115] Frankfurt argues for a version of compatibilism called

the "hierarchical mesh". The idea is that an individual can have

conflicting desires at a first-order level and also have a desire about

the various first-order desires (a second-order desire) to the effect

that one of the desires prevails over the others. A person's will is

identified with their effective first-order desire, that is, the one

they act on, and this will is free if it was the desire the person

wanted to act upon, that is, the person's second-order desire was

effective. So, for example, there are "wanton addicts", "unwilling

addicts" and "willing addicts". All three groups may have the

conflicting first-order desires to want to take the drug they are

addicted to and to not want to take it.

The first group, wanton addicts, have no second-order desire not to

take the drug. The second group, "unwilling addicts", have a

second-order desire not to take the drug, while the third group,

"willing addicts", have a second-order desire to take it. According to

Frankfurt, the members of the first group are devoid of will and

therefore are no longer persons. The members of the second group freely

desire not to take the drug, but their will is overcome by the

addiction. Finally, the members of the third group willingly take the

drug they are addicted to. Frankfurt's theory can ramify to any number

of levels. Critics of the theory point out that there is no certainty

that conflicts will not arise even at the higher-order levels of desire

and preference.[122] Others argue that Frankfurt offers no adequate

explanation of how the various levels in the hierarchy mesh

together.[123]

Free will as unpredictability

In Elbow Room, Dennett presents an argument for a compatibilist theory

of free will, which he further elaborated in the book Freedom

Evolves.[124] The basic reasoning is that, if one excludes God, an

infinitely powerful demon, and other such possibilities, then because

of chaos and epistemic limits on the precision of our knowledge of the

current state of the world, the future is ill-defined for all finite

beings. The only well-defined things are "expectations". The ability to

do "otherwise" only makes sense when dealing with these expectations,

and not with some unknown and unknowable future.

According to Dennett, because individuals have the ability to act

differently from what anyone expects, free will can exist.[124]

Incompatibilists claim the problem with this idea is that we may be

mere "automata responding in predictable ways to stimuli in our

environment". Therefore, all of our actions are controlled by forces

outside ourselves, or by random chance.[125] More sophisticated

analyses of compatibilist free will have been offered, as have other

critiques.[114]

In the philosophy of decision theory, a fundamental question is: From

the standpoint of statistical outcomes, to what extent do the choices

of a conscious being have the ability to influence the future?

Newcomb's paradox and other philosophical problems pose questions about

free will and predictable outcomes of choices.

The physical mind

See also: Neuroscience of free will

Compatibilist models of free will often consider deterministic

relationships as discoverable in the physical world (including the

brain). Cognitive naturalism[126] is a physicalist approach to studying

human cognition and consciousness in which the mind is simply part of

nature, perhaps merely a feature of many very complex self-programming

feedback systems (for example, neural networks and cognitive robots),

and so must be studied by the methods of empirical science, such as the

behavioral and cognitive sciences (i.e. neuroscience and cognitive

psychology).[107][127] Cognitive naturalism stresses the role of

neurological sciences. Overall brain health, substance dependence,

depression, and various personality disorders clearly influence mental

activity, and their impact upon volition is also important.[118] For

example, an addict may experience a conscious desire to escape

addiction, but be unable to do so. The "will" is disconnected from the

freedom to act. This situation is related to an abnormal production and

distribution of dopamine in the brain.[128] The neuroscience of free

will places restrictions on both compatibilist and incompatibilist free

will conceptions.

Compatibilist models adhere to models of mind in which mental activity

(such as deliberation) can be reduced to physical activity without any

change in physical outcome. Although compatibilism is generally aligned

to (or is at least compatible with) physicalism, some compatibilist

models describe the natural occurrences of deterministic deliberation

in the brain in terms of the first person perspective of the conscious

agent performing the deliberation.[15] Such an approach has been

considered a form of identity dualism. A description of "how conscious

experience might affect brains" has been provided in which "the

experience of conscious free will is the first-person perspective of

the neural correlates of choosing."[15]

Recently,[when?] Claudio Costa developed a neocompatibilist theory

based on the causal theory of action that is complementary to classical

compatibilism. According to him, physical, psychological and rational

restrictions can interfere at different levels of the causal chain that

would naturally lead to action. Correspondingly, there can be physical

restrictions to the body, psychological restrictions to the decision,

and rational restrictions to the formation of reasons (desires plus

beliefs) that should lead to what we would call a reasonable action.

The last two are usually called "restrictions of free will". The

restriction at the level of reasons is particularly important since it

can be motivated by external reasons that are insufficiently conscious

to the agent. One example was the collective suicide led by Jim Jones.

The suicidal agents were not conscious that their free will have been

manipulated by external, even if ungrounded, reasons.[129]

Non-naturalism

Not to be confused with Religious naturalism.

Alternatives to strictly naturalist physics, such as mind–body dualism

positing a mind or soul existing apart from one's body while

perceiving, thinking, choosing freely, and as a result acting

independently on the body, include both traditional religious

metaphysics and less common newer compatibilist concepts.[130] Also

consistent with both autonomy and Darwinism,[131] they allow for free

personal agency based on practical reasons within the laws of

physics.[132] While less popular among 21st-century philosophers,

non-naturalist compatibilism is present in most if not almost all

religions.[133]

Other views

Some philosophers' views are difficult to categorize as either

compatibilist or incompatibilist, hard determinist or libertarian. For

example, Ted Honderich holds the view that "determinism is true,

compatibilism and incompatibilism are both false" and the real problem

lies elsewhere. Honderich maintains that determinism is true because

quantum phenomena are not events or things that can be located in space

and time, but are abstract entities. Further, even if they were

micro-level events, they do not seem to have any relevance to how the

world is at the macroscopic level. He maintains that incompatibilism is

false because, even if indeterminism is true, incompatibilists have not

provided, and cannot provide, an adequate account of origination. He

rejects compatibilism because it, like incompatibilism, assumes a

single, fundamental notion of freedom. There are really two notions of

freedom: voluntary action and origination. Both notions are required to

explain freedom of will and responsibility. Both determinism and

indeterminism are threats to such freedom. To abandon these notions of

freedom would be to abandon moral responsibility. On the one side, we

have our intuitions; on the other, the scientific facts. The "new"

problem is how to resolve this conflict.[134]

Free will as an illusion

Baruch Spinoza thought that there is no free will.

"Experience teaches us no less clearly than reason, that men believe

themselves free, simply because they are conscious of their actions,

and unconscious of the causes whereby those actions are determined."

Baruch Spinoza, Ethics[135]

David Hume discussed the possibility that the entire debate about free

will is nothing more than a merely "verbal" issue. He suggested that it

might be accounted for by "a false sensation or seeming experience" (a

velleity), which is associated with many of our actions when we perform

them. On reflection, we realize that they were necessary and determined

all along.[136]

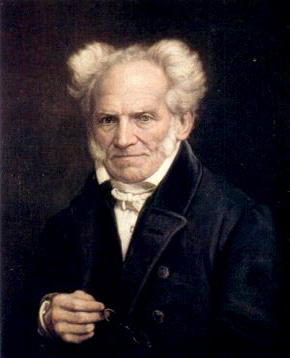

Arthur Schopenhauer claimed that phenomena do not have freedom of the

will, but the will as noumenon is not subordinate to the laws of

necessity (causality) and is thus free.

According to Arthur Schopenhauer, the actions of humans, as phenomena,

are subject to the principle of sufficient reason and thus liable to

necessity. Thus, he argues, humans do not possess free will as

conventionally understood. However, the will [urging, craving,

striving, wanting, and desiring], as the noumenon underlying the

phenomenal world, is in itself groundless: that is, not subject to

time, space, and causality (the forms that governs the world of

appearance). Thus, the will, in itself and outside of appearance, is

free. Schopenhauer discussed the puzzle of free will and moral

responsibility in The World as Will and Representation, Book 2, Sec. 23:

But the fact is overlooked that the individual, the person, is not will

as thing-in-itself, but is phenomenon of the will, is as such

determined, and has entered the form of the phenomenon, the principle

of sufficient reason. Hence we get the strange fact that everyone

considers himself to be a priori quite free, even in his individual

actions, and imagines he can at any moment enter upon a different way

of life... But a posteriori through experience, he finds to his

astonishment that he is not free, but liable to necessity; that

notwithstanding all his resolutions and reflections he does not change

his conduct, and that from the beginning to the end of his life he must

bear the same character that he himself condemns, and, as it were, must

play to the end the part he has taken upon himself.[137]

Schopenhauer elaborated on the topic in Book IV of the same work and in

even greater depth in his later essay On the Freedom of the Will. In

this work, he stated, "You can do what you will, but in any given

moment of your life you can will only one definite thing and absolutely

nothing other than that one thing."[138]

In his book Free Will, philosopher and neuroscientist Sam Harris argues

that free will is an illusion, stating that "thoughts and intentions

emerge from background causes of which we are unaware and over which we

exert no conscious control."[139]

Free will as "moral imagination"

Rudolf Steiner, who collaborated in a complete edition of Arthur

Schopenhauer's work,[140] wrote The Philosophy of Freedom, which

focuses on the problem of free will. Steiner (1861–1925) initially

divides this into the two aspects of freedom: freedom of thought and

freedom of action. The controllable and uncontrollable aspects of

decision making thereby are made logically separable, as pointed out in

the introduction. This separation of will from action has a very long

history, going back at least as far as Stoicism and the teachings of

Chrysippus (279–206 BCE), who separated external antecedent causes from

the internal disposition receiving this cause.[141]

Steiner then argues that inner freedom is achieved when we integrate

our sensory impressions, which reflect the outer appearance of the

world, with our thoughts, which lend coherence to these impressions and

thereby disclose to us an understandable world. Acknowledging the many

influences on our choices, he nevertheless points out that they do not

preclude freedom unless we fail to recognise them. Steiner argues that

outer freedom is attained by permeating our deeds with moral

imagination. "Moral" in this case refers to action that is willed,

while "imagination" refers to the mental capacity to envision

conditions that do not already hold. Both of these functions are

necessarily conditions for freedom. Steiner aims to show that these two

aspects of inner and outer freedom are integral to one another, and

that true freedom is only achieved when they are united.[142]

Free will as a pragmatically useful concept

William James' views were ambivalent. While he believed in free will on

"ethical grounds", he did not believe that there was evidence for it on

scientific grounds, nor did his own introspections support it.[143]

Ultimately he believed that the problem of free will was a metaphysical

issue and, therefore, could not be settled by science. Moreover, he did

not accept incompatibilism as formulated below; he did not believe that

the indeterminism of human actions was a prerequisite of moral

responsibility. In his work Pragmatism, he wrote that "instinct and

utility between them can safely be trusted to carry on the social

business of punishment and praise" regardless of metaphysical

theories.[144] He did believe that indeterminism is important as a

"doctrine of relief" – it allows for the view that, although the world

may be in many respects a bad place, it may, through individuals'

actions, become a better one. Determinism, he argued, undermines

meliorism – the idea that progress is a real concept leading to

improvement in the world.[144]

Free will and views of causality

See also: Principle of sufficient reason

In 1739, David Hume in his A Treatise of Human Nature approached free

will via the notion of causality. It was his position that causality

was a mental construct used to explain the repeated association of

events, and that one must examine more closely the relation between

things regularly succeeding one another (descriptions of regularity in

nature) and things that result in other things (things that cause or

necessitate other things).[145] According to Hume, 'causation' is on

weak grounds: "Once we realise that 'A must bring about B' is

tantamount merely to 'Due to their constant conjunction, we are

psychologically certain that B will follow A,' then we are left with a

very weak notion of necessity."[146]

This empiricist view was often denied by trying to prove the so-called

apriority of causal law (i.e. that it precedes all experience and is

rooted in the construction of the perceivable world):

Kant's proof in Critique of Pure Reason (which referenced time and time ordering of causes and effects)[147]

Schopenhauer's proof from The Fourfold Root of the Principle of

Sufficient Reason (which referenced the so-called intellectuality of

representations, that is, in other words, objects and qualia perceived

with senses)[148]

In the 1780s Immanuel Kant suggested at a minimum our decision

processes with moral implications lie outside the reach of everyday

causality, and lie outside the rules governing material objects.[149]

"There is a sharp difference between moral judgments and judgments of

fact... Moral judgments... must be a priori judgments."[150]

Freeman introduces what he calls "circular causality" to "allow for the

contribution of self-organizing dynamics", the "formation of

macroscopic population dynamics that shapes the patterns of activity of

the contributing individuals", applicable to "interactions between

neurons and neural masses... and between the behaving animal and its

environment".[151] In this view, mind and neurological functions are

tightly coupled in a situation where feedback between collective

actions (mind) and individual subsystems (for example, neurons and

their synapses) jointly decide upon the behaviour of both.

Free will according to Thomas Aquinas

Thirteenth century philosopher Thomas Aquinas viewed humans as

pre-programmed (by virtue of being human) to seek certain goals, but

able to choose between routes to achieve these goals (our Aristotelian

telos). His view has been associated with both compatibilism and

libertarianism.[152][153]

In facing choices, he argued that humans are governed by intellect,

will, and passions. The will is "the primary mover of all the powers of

the soul... and it is also the efficient cause of motion in the

body."[154] Choice falls into five stages: (i) intellectual

consideration of whether an objective is desirable, (ii) intellectual

consideration of means of attaining the objective, (iii) will arrives

at an intent to pursue the objective, (iv) will and intellect jointly

decide upon choice of means (v) will elects execution.[155] Free will

enters as follows: Free will is an "appetitive power", that is, not a

cognitive power of intellect (the term "appetite" from Aquinas's

definition "includes all forms of internal inclination").[156] He

states that judgment "concludes and terminates counsel. Now counsel is

terminated, first, by the judgment of reason; secondly, by the

acceptation of the appetite [that is, the free-will]."[157]

A compatibilist interpretation of Aquinas's view is defended thus:

"Free-will is the cause of its own movement, because by his free-will

man moves himself to act. But it does not of necessity belong to

liberty that what is free should be the first cause of itself, as

neither for one thing to be cause of another need it be the first

cause. God, therefore, is the first cause, Who moves causes both

natural and voluntary. And just as by moving natural causes He does not

prevent their acts being natural, so by moving voluntary causes He does

not deprive their actions of being voluntary: but rather is He the

cause of this very thing in them; for He operates in each thing

according to its own nature."[158][159]

Free will as a pseudo-problem

Historically, most of the philosophical effort invested in resolving

the dilemma has taken the form of close examination of definitions and

ambiguities in the concepts designated by "free", "freedom", "will",

"choice" and so forth. Defining 'free will' often revolves around the

meaning of phrases like "ability to do otherwise" or "alternative

possibilities". This emphasis upon words has led some philosophers to

claim the problem is merely verbal and thus a pseudo-problem.[160] In

response, others point out the complexity of decision making and the

importance of nuances in the terminology.[citation needed]

|

西洋哲学

こちらもご覧ください: 古代における自由意志

根底にある疑問は、私たちは自分の行動をコントロールできるのか、できるとしたらどのようなコントロールがどの程度可能なのかということである。このよう

な疑問は、初期のギリシアのストア派(例えばクリシッポス)よりも古く、現代の哲学者の中には、何世紀にもわたって進歩がないことを嘆く者もいる[11]

[12]。

一方では人間には自由に対する強い感覚があり、それが自分には自由意志がある と信じることにつながっている[13][14]。

意識的な意思決定が因果的に有効であるという直観的な証拠と、物理的世界はすべて物理法則によって説明できるという見解とを調和させることは難しい

[17]。直観的に感じられる自由と自然法則との間の対立は、因果的閉鎖性または物理的決定論(名目的決定論)のいずれかが主張されるときに生じる。因果

的閉鎖性では、いかなる物理的事象も物理的領域外に原因を持たず、物理的決定論では、未来は先行する事象(原因と結果)によって完全に決定される。

自由意志」と決定論的な宇宙を調和させるというパズルは、自由意志の問題として知られており、決定論のジレンマと呼ばれることもある[18]。

古典的な両立主義者は、人間が外部から制約されたり強制されたりしない限り、自由意志は保持されると主張することによって、自由意志のジレンマに対処して

きた。

[23]現代の両立主義者は意志の自由と行動の自由を区別しており、つまり選択の自由をそれを実行する自由から分離している[24]。人間は誰でも自由意

志の感覚を経験することを考えると、現代の両立主義者の中にはこの直観を受け入れることが必要だと考える者もいる[25][26]。

このジレンマに対する異なるアプローチは非両立論者のものであり、すなわち世界が決定論的であるならば、我々が行動を自由に選択できるという感覚は単なる

幻想であるというものである。形而上学的リバタリアニズムは非物質論的リバタリアニズムの一形態であり、決定論は誤りであり、自由意志は可能である(少な

くとも一部の人は自由意志を持っている)と仮定している[27]。この見解は非物質論的構成と関連しており[15]、伝統的な二元論だけでなく、行動や競

合する欲求を意識的に拒否する能力など、より最小限の基準を支持するモデルも含まれている。

[28][29]しかし、物理的不確定性においてさえも、起源(「自由な」不確定性選択の責任)を割り当てることが難しいという点で、リバタリアニズムに

対して議論がなされてきた。

例えば、論理的決定論と神学的決定論は運命と宿命という考え方で形而上学的自由意志論に挑戦しており、生物学的決定論、文化的決定論、心理学的決定論は両

立主義モデルの発展に寄与している。両立主義と非両立主義の別々のクラスが、これらを表すために形成されることさえある[31]。

以下は、ジレンマとその基礎に関わる古典的な議論である。

非両立論

主な記事 非両立論

インコンパティビリズムとは、自由意志と決定論は論理的に相容れないという立場であり、人に自由意志があるかどうかに関する主要な問題は、その行動が決定

されているかどうかということである。ドルバックのような「ハード決定論者」は、決定論を受け入れ、自由意志を否定する非決定論者である。対照的に、トー

マス・リード、ピーター・ヴァン・インワーゲン、ロバート・ケインなどの「形而上学的自由主義者」は、自由意志を受け入れ、決定論を否定する非可分論者で

あり、ある種の不確定論が真であるという見解を持っている[32]。もう一つの見解は、自由意志は決定論と不確定論の両方と両立しないとするハード非可分

論者の見解である[33]。

非可分主義に対する伝統的な議論は、「直観ポンプ」に基づいている:もし人が、からくり玩具、ビリヤードのボール、人形、ロボットなど、行動が決定される

他の機械的なもののようであるならば、人は自由意志を持ってはならない[32][34]。この議論は、ダニエル・デネットのような両立主義者によって、た

とえ人間がこれらのものと共通する何かを持っているとしても、重要な点で、人間がそのような対象とは異なっていることは可能であり、もっともらしいという

理由で否定されている[35]。

非両立論のもう一つの論拠は「因果の連鎖」である。非両立主義は観念論者の自由意志理論の鍵である。ほとんどの非両立論者は、行動の自由が単に「自発的

な」行動から成り立っているという考えを否定する。彼らはむしろ、自由意志とは誰かが自分の行動の「究極的な」あるいは「起源的な」原因でなければならな

いことを意味すると主張する。伝統的な言い方をすれば、「因果応報」でなければならない。自分の選択に責任があるということは、その選択の第一原因であ

り、第一原因とは、その原因の先行原因が存在しないことを意味する。つまり、もし人が自由意志を持っているならば、その人が自分の行動の究極的な原因なの

だ、という主張である。もし決定論が真実なら、人の選択はすべて、その人のコントロールの及ばない出来事や事実によって引き起こされることになる。だか

ら、もし誰かがすることすべてが自分のコントロールの及ばない出来事や事実によって引き起こされるのであれば、その人は自分の行動の究極的な原因にはなり

えない。したがって、自由意志を持つことはできない。この議論は様々な両立主義の哲学者たちによっても異議を唱えられている[39][40]。

非両立論に対する第三の議論は1960年代にカール・ジーネによって定式化され、現代の文献において多くの注目を集めている。もし決定論が真であるなら

ば、我々は現在の状態を決定した過去の出来事や自然の法則を制御することはできない。もし決定論が真実なら、私たちは現在の状態を決定した過去の出来事や

自然の法則をコントロールすることはできない。決定論のもとでは、私たちの現在の選択と行為は過去と自然法則の必然的な結果であるため、私たちはそれらを

制御できず、したがって自由意志もない。これは結果論と呼ばれる[41][42]。ピーター・ヴァン・インワーゲンは、C.D.ブロードが1930年代に

は早くも結果論のバージョンを持っていたと述べている[43]。

ある種の両立論者にとってこの議論が困難であるのは、自分が持っている以外のものを選択することが不可能であるという事実を含んでいるからである。例え

ば、ジェーンが相利共生論者であり、ソファーに座ったところだとすると、ジェーンは、そう望めば立ったままでいられたという主張にコミットしていることに

なる。しかし、もしジェーンが立ったままであったなら、矛盾を引き起こすか、自然法則に違反するか、過去を変えてしまうことになる。それゆえ、ジネットと

ヴァン・インワーゲンによれば、両立主義者は「信じられないような能力」の存在にコミットしているのである。この議論に対する一つの反論は、能力と必然性

という概念について同値である、あるいは、与えられた選択をするために呼び起こされる自由意志は実際には幻想であり、その選択はその「決定者」に気づかれ

ることなく、最初からなされていたというものである[42]。デイヴィッド・ルイスは、相反希求主義者は、過去に異なる状況が実際に生じていた場合に、そ

うでなければ何かをすることができるという能力にのみコミットしていると示唆している[44]。

Tを「真」、Fを「偽」、「?」を「未定」とすると、決定論/自由意志に関して、これら3つの可能性のうちいずれか2つからなる立場は正確に9つ存在する[45]。

非両立主義は、(5)、(8)、(3)を除く9つのポジションのいずれかを占める可能性があり、最後のポジションはソフト決定論に相当する。(1)の立場

はハード決定論であり、(2)の立場はリバタリアニズムである。ハード決定論の(1)の立場は、DはFWが真でないことを意味するという主張を追加し、リ

バタリアニズムの(2)の立場は、FWはDが真でないことを意味するという主張を追加する。もし(9)の立場を、両概念の価値が疑わしいと解釈するなら

ば、ハード・インコンパティビリズムと呼ぶこともできる。つまり、決定論と自由意志の間には論理的矛盾はなく、原理的にはどちらか一方が真であっても、両

方が偽であってもよいのである。しかしながら、両立主義に付けられる最も一般的な意味は、何らかの形の決定論が真であり、なおかつ何らかの形の自由意志が

あるということであり、(3)の立場である[46]。

ドミノの動きは物理法則によって完全に決定される。

アレックス・ローゼンバーグは、ドミノの集合の振る舞いによって巨視的スケールで推測される物理的決定論を、脳の神経活動に外挿する。

「物理的決定論は現在、量子力学の著名な解釈によって議論されており、必ずしも自然界に内在する不確定性を代表するものではないが、測定における精度の基

本的な限界は不確定性原理に内在している[48]。しかし、そのようなミクロな事象の影響を拡大するためにカオス理論が導入されている場合でさえも、その

ような将来の不確定な活動と自由意志との関連性は議論されている[49]。

以下では、これらの立場についてより詳細に検討する[45]。

ハード決定論

主な記事 ハード決定論

自由意志と決定論に関する哲学的立場の単純化された分類法

決定論は因果的決定論、論理的決定論、神学的決定論に分けられる[51]。これらの異なる意味のそれぞれに対応して、自由意志には異なる問題が生じる

[52]。ハード決定論は一般的に名辞論的決定論(以下の因果的決定論を参照)を指すが、それは未来全体を必要とする決定論のすべての形態を含むことがで

きる[53]:

因果的決定論

その最も一般的な形態である名辞学的(または科学的)決定論では、未来の出来事は過去と現在の出来事と自然の法則との組み合わせによって必然化される。こ

のような決定論は、ラプラスの悪魔の思考実験によって説明されることがある。過去と現在に関するすべての事実を知り、宇宙を支配するすべての自然法則を

知っている存在を想像してみよう。もし自然法則が決定論的であるならば、そのような存在はこの知識を使って未来を細部に至るまで予見することができるだろ

う[55][56]。

論理的決定論

過去、現在、未来を問わず、すべての命題は真か偽のいずれかであるという考え方。この文脈における自由意志の問題とは、未来に何をするかは現在においてす

でに真か偽か決定されていることを前提とした上で、どのように選択を自由にすることができるかという問題である[52]。

神学的決定論

神学的決定論とは、未来は、創造主である神によって事前に決定されるか、その結果を知っているかのいずれかによって、既に決定されているという考え方であ

る[57][58]。この文脈における自由意志の問題とは、私たちのために事前に決定している存在が存在する場合、あるいは、私たちの行動が既に時間的に

設定されている場合、どのようにして自由であり得るかという問題である。

生物学的決定論は、すべての行動、信念、欲望は遺伝的素質と生化学的構成によって固定されるという考え方であり、後者は遺伝子と環境の両方によって影響される。

ハード決定論は厳密な決定論を維持する必要はなく、それに近いもの、非公式に適切な決定論として知られているようなものの方がおそらく適切であるという提

案がなされている[30]。にもかかわらず、ハード決定論は、決定論が誤りであるという科学的な示唆があることから、現代ではあまり人気がなくなってきて

いる。

形而上学的リバタリアニズム

主な記事 形而上学的リバタリアニズム

形而上学的リバタリアニズムのために提案されてきた自由意志の様々な定義(代理人/物質因果論、[59]中心的説明、[60]意志理論の努力[29])

と、他の一般的な自由意志の立場(コンパティビリズム、[17]ハード決定論、[61]ハード非コンパティビリズム[33])の例。赤丸は心的状態、青丸

は物理的状態、矢印は因果的相互作用を表す。

形而上学的リバタリアニズムは非両立主義の下にある一つの哲学的視点である。リバタリアニズムは自由意志の概念を保持しており、その自由意志は、エージェントが与えられた一連の状況下で複数の可能な行動方針を取ることができることを要求している[62]。

リバタリアニズムの説明は、非物理的理論と物理的理論または自然主義的理論に分かれる。非物理的理論では、行動の実行につながる脳内の出来事は完全に物理

的な説明を持っておらず、世界は物理学のもとでは閉じていないとする。これには相互作用論的二元論が含まれ、非物理的な心、意志、魂が物理的因果性を上書

きすると主張する。物理的決定論は可能な未来が一つしかないことを意味し、自由意志とは相容れない。非両立主義の結果として、物理主義を排除しない形而上

学的な自由意志の説明には、確率的な素粒子の振る舞いのような物理的不確定論が必要となる。非因果論的理論は、必要とする不確定性の種類に基づいて分類す

ることができる;非因果的事象、非決定論的に引き起こされる事象、代理人/物質が引き起こす事象である[59]。

非因果論

非因果論的自由意志に関する非因果論的説明では、自由な行動がエージェントや物

理的出来事のいずれかによって引き起こされることを要求しない。それらは因果的に閉じていない世界か、物理的不確定性に依存している。非因果論的な説明で

はしばしば、各意図的行為には選択または意志が必要である、つまり(腕を上げるという認知的要素のような)エージェントに代わって意思を持ち、試み、努力

することが必要であると主張する[63][64]。しかしながら、そのような行為は特定の何ものに対しても支配を行使しているとは言えないことが示唆され

ている。非因果的な説明によれば、行為者による因果関係は、特定の何かに対する欲求、信念、意図を含む心的状態や出来事による因果関係という観点から分析

することはできず、むしろ自発性や創造性の問題と考えられる。このような意図的行為における意図の行使は、その自由を決定するものではなく、意図的行為は

むしろ自己生成的なものである。このような非因果的理論が提起するもう一つの疑問は、意図的行為が自発的なものである場合、行為者はどのように理性に働き

かけるのかということである。

非因果的な説明の中には、汎心論、つまり心の質はすべての粒子と関連しており、生物・無生物を問わず宇宙全体に浸透しているという理論を呼び起こすものもある。

事象原因説

非両立論的自由意志の事象原因論的説明は、典型的には(両 立論者のものと同じように)心の物理主義的モデルに依拠しているが、物理

的不確定性を前提としている。ここでは意図的不確定性論、中心的説明、意志理論の努力として参照される。普通のランダム性は、自由意志論者が必要だと考え

る「余裕」を提供するものとして訴えられる。事象を原因とする説明に対する一般的な反論の第一は、不確定性が破壊的である可能性があり、それゆえ主体によ

る制御を提供するよりもむしろ減少させる可能性があるというものである(起源の問題に関連している)。これらのモデルに対する第二の一般的な反論は、その

ような不確定性が、決定論的世界にすでに存在する熟慮に何らかの価値を付加しうるかどうか疑わしいというものである。

熟慮的決定不能論は、決定不能論は意思決定プロセスの初期段階に限定されると主張する[65][66]。これは、運(ランダムな意思決定)の導入のリスク

を回避しつつ、選択する可能性の不確定な集合を提供することを意図している。選択プロセスは決定論的であるが、同じプロセスによって確立された以前の選好

に基づいている場合もある。このような考え方に対する明らかな反論は、エージェントは自分の意思決定(またはそれらの意思決定を行うために使用される選

好)に対する所有権を、相反希求主義モデルのそれよりも高い程度で割り当てることができないということである[67]。

中心的説明では、2つの可能性の間で与えられた決定について、それぞれの選択肢について理性の強さが考慮されるが、それでもなお弱い方の候補が選択される

確率があると提唱している[60][69][70][71][72][73][74]。このような見解に対する明らかな反論は、決定が明らかに偶然に委ね

られており、与えられた決定について起源や責任を割り当てることができないということである。

意志の努力理論は意思決定における意志の力の役割に関連している。これはエージェントの意志決定過程の不確定性が、ある種の物理的事象の不確定性に対応す

る可能性を示唆するものであり、したがってこれらの事象の結果はエージェントによって引き起こされたと考えることができる。意志のモデルは、物理的な不確

定性の要素を持つ複雑で高度なプロセスとして構築されてきた。このアプローチの例はロバート・ケインのものであり、彼は「それぞれの場合において、不確定

性は彼女の目的の一つを実現するための障害や障害物として機能している-努力によって克服されなければならない彼女の意志の中の抵抗という形の障害や障害

物として。

「ロバート・ケインによれば、このような「究極的な責任」は自由意志の必要条件である[75]。このような理論における重要な要素は、エージェントを物理

的なニューロン事象に還元することはできず、むしろ精神的プロセスがその物理的プロセスと同様に結果の決定について妥当な説明を提供すると言われているこ

とである(非還元的物理主義を参照)。

当時、量子力学(および物理的不確定性)はまだ受け入れられ始めたばかりであったが、C:

C.S.ルイスは、物理的世界が非決定論的であると証明されれば、物理的現実に対する非物理的存在の作用を記述するための入口を提供することになるという

論理的可能性を述べている[76]。非決定論的物理モデル(特に量子的不確定性を伴うもの)は、原子や素粒子レベルでのランダムな事象を導入する。このよ

うな事象は脳の活動に影響を与えるかもしれず、ある精神的プロセスの見かけ上の不確定性(例えば、意識的意志におけるコントロールの主観的知覚)が、物理

的構成要素の根底にある不確定性に対応するのであれば、一見、非決定論的自由意志を許容することができるかもしれない。しかしながら、この関係は確率に対

する因果的な役割を必要とするが、それは疑わしい[77]。第二に、これらの非両立論的モデルは、自由意志の神経科学で研究されているような、行為と意識

的意志との関係に依存している。しかし、量子論の主要な立役者の一人であるニールス・ボーアは、自然

の不確定性と意志の自由との間に関連性を持たせることはできないと示唆し ている[49]。

代理人/物質原因論

非可換主義的自由意志の代理人/物質原因論的説明は、心の記述において物質二元論に依拠している。エージェントは物理的世界に介入する力を持つと仮定され

る[78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85]。エージェント(物質)-因果的説明は、ジョージ・バークレー[86]とトマス・

リード[87]の両方によって提案されている。また、エージェントがその事象を引き起こすことが、先行する事象によって因果的に決定されないことも要求さ

れる。この見解には多くの問題が指摘されている。第一に、エージェントがどのような選択をしたのか、その理由を明らかにすることは困難であり、ランダムで

あったり、運によって決定されたりする可能性がある(自由意志による決定の根本的な根拠がない)。第二に、物理的な出来事が外的な物質や心によって引き起

こされうるかどうかが疑問視されており、これは相互作用論的二元論によく見られる問題である。

ハード非両立論

ハード非両立主義は、世界が決定論的であろうとなかろうと、自由意志は存在しえないという考え方である。デルク・ペレブームはハード非可逆主義を擁護し、自由意志が決定論/不確定論と無関係である様々な立場を特定した:

決定論(D)は真であり、Dは我々に自由意志(F)がないことを意味しないが、実際我々はFを欠いている。

Dは真であり、Dは我々がFを欠いていることを意味しないが、実際には我々はFを持っているかどうかわからない。

Dは真であり、我々はFを持っている。

Dは真で、我々はFを持っており、FはDを暗示する。

Dは証明できないが、我々にはFがある。

Dは真ではなく、Fがあり、Dが真でもFがある。

Dは真ではなく、我々はFを持っていないが、FはDと両立する。

Derk Pereboom, Living without Free Will,[33] p. xvi.

ペレブームは立場3と4をソフト決定論、立場1をハード決定論の一形態、立場6を古典的リバタリアニズムの一形態、そしてFを持つことを含む立場を両立主義と呼んでいる。

ジョン・ロックは「自由意志」という言葉が意味を持つことを否定した(神の存在に関する同様の立場である神学的非認知主義と比較)。彼はまた、決定論の真

偽は関係ないという見解もとった。彼は、自発的な行動の決定的な特徴は、個人が選択の結果について考えたり熟慮したりするのに十分な時間、決定を延期する

能力を持っていることであると信じていた。

現代の哲学者であるゲイレン・ストローソンは、決定論の真偽は問題とは無関係であるというロックに同意している[89]。ストローソンによれば、もし人が

ある状況において何をするかに責任があるのであれば、人はある精神的な点における自分のあり方に責任があるはずである。しかし、どのような点においても自

分のあり方に責任を持つことは不可能である。なぜなら、ある状況Sにおいて責任を負うためには、S-1における自分のあり方に責任を負わなければならない

からである。S-1でのあり方に責任を持つためには、S-2でのあり方に責任を持たなければならない。この連鎖のどこかの時点で、新たな因果の連鎖を生み

出す行為があったに違いない。しかし、これは不可能である。人間は、自分自身や自分の精神状態を虚無的に創造することはできない。この議論は、自由意志自

体が不合理であることを含意しているが、決定論と相容れないことを含意しているわけではない。ストローソンは彼自身の見解を「悲観主義」と呼んでいるが、

ハード・インカティビリズムに分類することができる[89]。

因果決定論

主な記事 決定論