フリーダ・カーロ

Magdalena Frida Carmen Kahlo y Calderón,

1907-1954

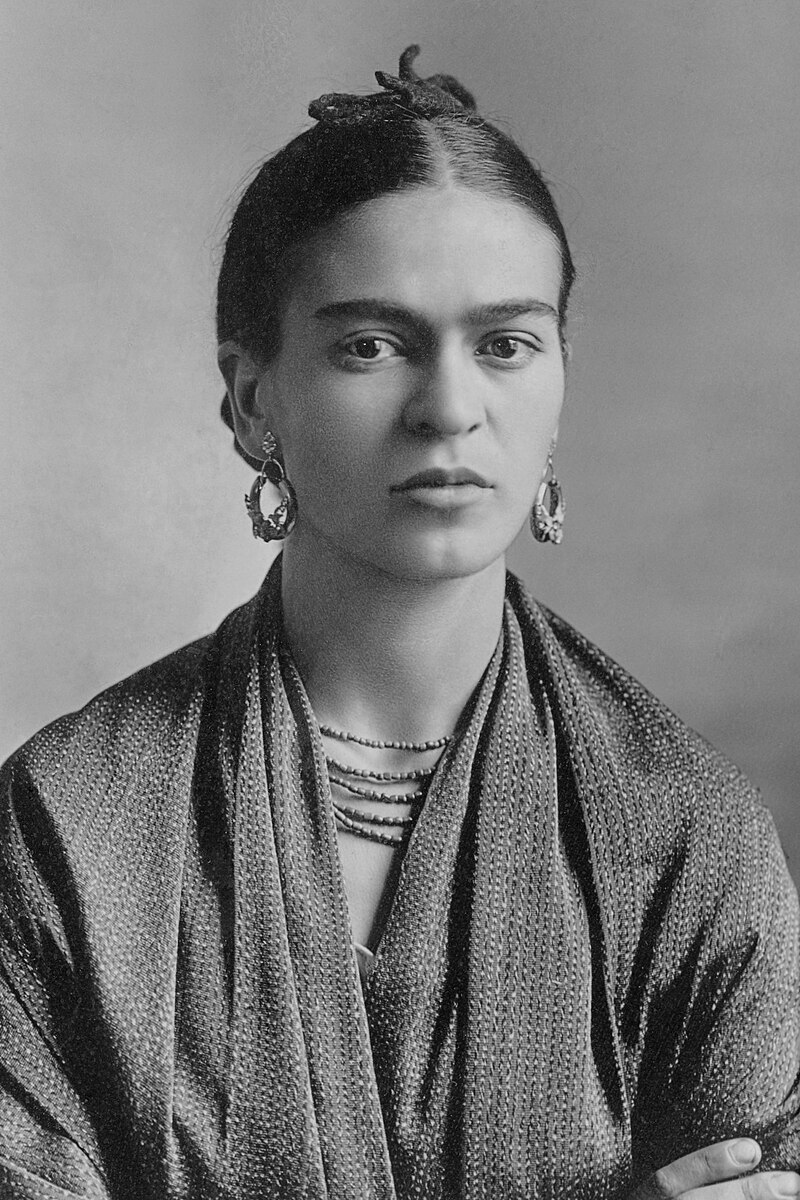

☆ フリーダ・カーロとして知られるマグダレナ・フリーダ・カルメン・カーロ・イ・カルデロン(1907年7月6日メキシコシティ、コヨアカン-1954年7 月13日メキシコシティ、コヨアカン)はメキシコの画家である。フリーダ・カーロとして知られるメキシコの画家である。自画像を中心に150点もの作品を 制作し、そこには生きることへの葛藤が投影されている。また、メキシコ文化のポップ・アイコンとしても知られている。 若い頃にバス事故で寝たきりになり、32回もの手術を受けるなど、型破りな人生を送った。 フリーダの作品と夫で画家のディエゴ・リベラの作品は互いに影響を与え合っている。両者とも、土着に根ざしたメキシコの民俗芸術を好み、革命後のメキシコ の画家たちにインスピレーションを与えた。 1939年、アンドレ・ブルトンから招待を受けたフリーダは、フランスで絵画展を開催し、「シュルレアリスム」であると説得した。しかし、フリーダは自分 の芸術がこのような風潮に反映されたものだとは考えていなかった。この展覧会に出品された作品のひとつ(『自画像-額縁』、現在はポンピドゥー・センター に展示)は、メキシコ人画家として初めてルーヴル美術館に収蔵された。彼の作品は、パブロ・ピカソ、ワシリ・カンディンスキー、アンドレ・ブルトン、マル セル・デュシャン、ティナ・モドッティ、コンチャ・ミシェルなど、当時を代表する画家や知識人に賞賛された。1954年7月13日、47歳で死去。遺体は 火葬され、遺灰は現在フリーダ・カーロ美術館として知られるカサ・アズールに運ばれた(→「フリーダ・カーロと痛みの芸術」)。

| Magdalena Frida

Carmen Kahlo y Calderón (Coyoacán, Ciudad de México, 6 de julio de

1907-Coyoacán, Ciudad de México, 13 de julio de 1954), conocida como

Frida Kahlo, fue una pintora mexicana. Su obra gira temáticamente en

torno a las vivencias de su vida personal. Realizó un total de 150

obras, principalmente autorretratos, en los que proyectó sus

dificultades por sobrevivir. También es considerada como un icono pop

de la cultura de México. Su vida estuvo marcada por un grave accidente de autobús en su juventud que la mantuvo postrada en cama durante largos periodos, llegando a someterse hasta a 32 operaciones quirúrgicas. Llevó una vida poco convencional. La obra de Frida y la de su marido, el pintor Diego Rivera, se influyeron mutuamente. Ambos compartieron el gusto por el arte popular mexicano de raíces indígenas, inspirando a otros pintores mexicanos del periodo posrevolucionario. En 1939, sus pinturas fueron expuestas en Francia tras haber recibido una invitación de André Breton, quien intentó convencerla de que eran «surrealistas». Sin embargo, Frida no veía su arte reflejado en esta tendencia ya que ella consideraba que no pintaba sueños, sino su propia vida. Una de las obras de esta exposición (Autorretrato-El marco, que actualmente se encuentra en el Centro Pompidou) se convirtió en el primer cuadro de un artista mexicano adquirido por el Museo del Louvre. Su obra gozó de la admiración de destacados pintores e intelectuales de la época como Pablo Picasso, Vasili Kandinski, André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Tina Modotti y Concha Michel. Falleció el 13 de julio de 1954, a los 47 años. Su cuerpo fue cremado y sus cenizas fueron llevadas a la Casa Azul, hoy conocida como museo Frida Kahlo. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frida_Kahlo |

フリーダ・カーロとして知られるマグダレナ・フリーダ・カルメン・カー

ロ・イ・カルデロン(1907年7月6日メキシコシティ、コヨアカン-1954年7月13日メキシコシティ、コヨアカン)はメキシコの画家である。フリー

ダ・カーロとして知られるメキシコの画家である。自画像を中心に150点もの作品を制作し、そこには生きることへの葛藤が投影されている。また、メキシコ

文化のポップ・アイコンとしても知られている。 若い頃にバス事故で寝たきりになり、32回もの手術を受けるなど、型破りな人生を送った。 フリーダの作品と夫で画家のディエゴ・リベラの作品は互いに影響を与え合っている。両者とも、土着に根ざしたメキシコの民俗芸術を好み、革命後のメキシコ の画家たちにインスピレーションを与えた。 1939年、アンドレ・ブルトンから招待を受けたフリーダは、フランスで絵画展を開催し、「シュルレアリスム」であると説得した。しかし、フリーダは自分 の芸術がこのような風潮に反映されたものだとは考えていなかった。この展覧会に出品された作品のひとつ(『自画像-額縁』、現在はポンピドゥー・センター に展示)は、メキシコ人画家として初めてルーヴル美術館に収蔵された。彼の作品は、パブロ・ピカソ、ワシリ・カンディンスキー、アンドレ・ブルトン、マル セル・デュシャン、ティナ・モドッティ、コンチャ・ミシェルなど、当時を代表する画家や知識人に賞賛された。1954年7月13日、47歳で死去。遺体は 火葬され、遺灰は現在フリーダ・カーロ美術館として知られるカサ・アズールに運ばれた。 |

| Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón[a]

(Spanish pronunciation: [ˈfɾiða ˈkalo]; 6 July 1907 – 13 July 1954[1])

was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and

works inspired by the nature and artifacts of Mexico. Inspired by the

country's popular culture, she employed a naïve folk art style to

explore questions of identity, postcolonialism, gender, class, and race

in Mexican society.[2] Her paintings often had strong autobiographical

elements and mixed realism with fantasy. In addition to belonging to

the post-revolutionary Mexicayotl movement, which sought to define a

Mexican identity, Kahlo has been described as a surrealist or magical

realist.[3] She is also known for painting about her experience of

chronic pain.[4] Born to a German father and a mestiza mother (of Purépecha[5] descent), Kahlo spent most of her childhood and adult life at La Casa Azul, her family home in Coyoacán – now publicly accessible as the Frida Kahlo Museum. Although she was disabled by polio as a child, Kahlo had been a promising student headed for medical school until being injured in a bus accident at the age of 18, which caused her lifelong pain and medical problems. During her recovery, she returned to her childhood interest in art with the idea of becoming an artist. Kahlo's interests in politics and art led her to join the Mexican Communist Party in 1927,[1] through which she met fellow Mexican artist Diego Rivera. The couple married in 1929[1][6] and spent the late 1920s and early 1930s travelling in Mexico and the United States together. During this time, she developed her artistic style, drawing her main inspiration from Mexican folk culture, and painted mostly small self-portraits that mixed elements from pre-Columbian and Catholic beliefs. Her paintings raised the interest of surrealist artist André Breton, who arranged for Kahlo's first solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in 1938; the exhibition was a success and was followed by another in Paris in 1939. While the French exhibition was less successful, the Louvre purchased a painting from Kahlo, The Frame, making her the first Mexican artist to be featured in their collection.[1] Throughout the 1940s, Kahlo participated in exhibitions in Mexico and the United States and worked as an art teacher. She taught at the Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado ("La Esmeralda") and was a founding member of the Seminario de Cultura Mexicana. Kahlo's always-fragile health began to decline in the same decade. While she had had solo exhibitions elsewhere, she had her first solo exhibition in Mexico in 1953, shortly before her death in 1954 at the age of 47. Kahlo's work as an artist remained relatively unknown until the late 1970s, when her work was rediscovered by art historians and political activists. By the early 1990s, not only had she become a recognized figure in art history, but she was also regarded as an icon for Chicanos, the feminism movement, and the LGBTQ+ community. Kahlo's work has been celebrated internationally as emblematic of Mexican national and Indigenous traditions and by feminists for what is seen as its uncompromising depiction of the female experience and form.[7] |

マ

グダレナ・カルメン・フリーダ・カーロ・イ・カルデロン[a](スペイン語発音:[ˈf'ˈkalo]、1907年7月6日 -

1954年7月13日[1])はメキシコの画家で、多くの肖像画、自画像、メキシコの自然や工芸品に触発された作品で知られる。メキシコの大衆文化に触発

された彼女は、ナイーブなフォークアートのスタイルを用いて、メキシコ社会におけるアイデンティティ、ポストコロニアリズム、ジェンダー、階級、人種に関

する問題を探求した[2]。メキシコのアイデンティティを定義しようとした革命後のメキシカヨトル運動に属していたことに加え、カーロはシュルレアリスト

または魔術的リアリストと評されている[3]。 ドイツ人の父とメスチザ(プレペチャ[5]系)の母の間に生まれたカーロは、幼少期と成人期のほとんどをコヨアカンの実家ラ・カサ・アズールで過ごした。 幼少時にポリオに罹患したカーロは、18歳の時にバス事故で負傷するまでは、医学部を目指す有望な学生であった。回復の過程で、彼女は芸術家になることを 考え、幼少期に興味を持っていた芸術に戻った。 カーロは政治と芸術への関心から、1927年にメキシコ共産党に入党し[1]、その中で同じメキシコの芸術家ディエゴ・リベラと出会う。二人は1929年 に結婚し[1][6]、1920年代後半から1930年代前半にかけてメキシコとアメリカを共に旅した。この時期、彼女はメキシコの民俗文化から主なイン スピレーションを得ながら芸術的なスタイルを確立し、先コロンブスやカトリックの信仰の要素をミヘした小さな自画像を主に描いた。彼女の絵はシュルレアリ スムのアーティスト、アンドレ・ブルトンの興味を引き、彼は1938年にニューヨークのジュリアン・レヴィ・ギャラリーでカーロの初個展を企画した。フラ ンスの展覧会はあまり成功しなかったが、ルーヴル美術館はカーロの絵画『額縁』を購入し、カーロは同美術館に収蔵された最初のメキシコ人画家となった [1]。1940年代を通して、カーロはメキシコとアメリカの展覧会に参加し、美術教師としても働いた。ラ・エスメラルダ美術学校で教鞭をとり、メキシコ 文化セミナーの創立メンバーでもあった。常に不安定だったカーロの健康は、同じ10年間に衰え始めた。他の場所では個展を開いていたが、1954年に47 歳で亡くなる直前、1953年にメキシコで初めての個展を開いた。 芸術家としてのカーロの作品は、1970年代後半に美術史家や政治活動家によって再発見されるまで、比較的無名のままだった。1990年代初頭までに、彼 女は美術史において認知された人物となっただけでなく、チカーノ、フェミニズム運動、LGBTQ+コミュニティのアイコンとしても見なされるようになっ た。カーロの作品は、メキシコの国民と先住民の伝統を象徴するものとして、また、女性の経験と形を妥協することなく描いていると見なされることから、フェ ミニストたちによって国際的に称賛されている[7]。 |

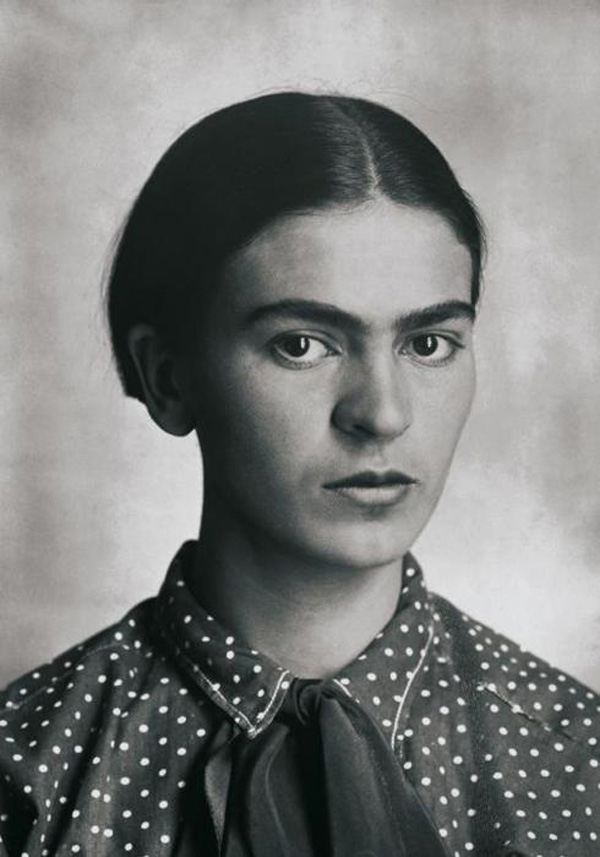

| Artistic career Early career  Kahlo on 15 June 1919, aged 11 Kahlo enjoyed art from an early age, receiving drawing instruction from printmaker Fernando Fernández (who was her father's friend)[8] and filling notebooks with sketches.[9] In 1925, she began to work outside of school to help her family.[10] After briefly working as a stenographer, she became a paid engraving apprentice for Fernández.[11] He was impressed by her talent,[12] although she did not consider art as a career at this time.[9] A severe bus accident at the age of 18 left Kahlo in lifelong pain. Confined to bed for three months following the accident, Kahlo began to paint.[13] She started to consider a career as a medical illustrator, as well, which would combine her interests in science and art. Her mother provided her with a specially-made easel, which enabled her to paint in bed, and her father lent her some of his oil paints. She had a mirror placed above the easel, so that she could see herself.[14][13] Painting became a way for Kahlo to explore questions of identity and existence.[15] She explained, "I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best."[13] She later stated that the accident and the isolating recovery period made her desire "to begin again, painting things just as [she] saw them with [her] own eyes and nothing more."[16] Most of the paintings Kahlo made during this time were portraits of herself, her sisters, and her schoolfriends.[17] Her early paintings and correspondence show that she drew inspiration especially from European artists, in particular Renaissance masters such as Sandro Botticelli and Bronzino[18] and from avant-garde movements such as Neue Sachlichkeit and Cubism.[19] On moving to Morelos in 1929 with her husband Diego Rivera, Kahlo was inspired by the city of Cuernavaca where they lived.[20] She changed her artistic style and increasingly drew inspiration from Mexican folk art.[21] Art historian Andrea Kettenmann states that she may have been influenced by Adolfo Best Maugard's treatise on the subject, for she incorporated many of the characteristics that he outlined – for example, the lack of perspective and the combining of elements from pre-Columbian and colonial periods of Mexican art.[22] Her identification with La Raza, the people of Mexico, and her profound interest in its culture remained important facets of her art throughout the rest of her life.[23] |

アーティストとしてのキャリア 初期のキャリア  1919年6月15日、11歳のカーロ カーロは幼い頃から美術に親しみ、版画家のフェルナンド・フェルナンデス(父の友人)からデッサンの指導を受け、ノートにスケッチを描き続けた。速記者と して短期間働いた後、フェルナンデスのもとで有給の版画見習いとなった。速記者として短期間働いた後、フェルナンデスのもとで有給の彫刻見習いとなった が、フェルナンデスは彼女の才能に感銘を受けた。 118歳の時のバス事故が原因で、カーロは生涯痛みを抱えたままだった。事故後3ヶ月間寝たきりになったカーロは、絵を描き始めた。カーロは、科学と芸術 への興味を結びつける医療イラストレーターとしてのキャリアも考え始めた。母親は、ベッドで絵を描けるように特製のイーゼルを用意し、父親も油絵の具を貸 してくれた。イーゼルの上には鏡が置かれ、自分の姿が見えるようになっていた。絵を描くことは、カーロにとってアイデンティティと存在についての疑問を探 求する方法となった。カーロは、「私が自分自身を描くのは、私がしばしば孤独であり、私が一番よく知っている対象が私だからです」と説明した。後に彼女 は、事故と孤独な回復期間によって、「もう一度始めたい、自分の目で見たとおりに描きたい、それ以上のことはしたくない」と思うようになったと述べてい る。 この時期にカーロが描いた絵のほとんどは、自分自身や姉妹、学友の肖像画だった。初期の絵画や書簡から、彼女が特にヨーロッパの芸術家、とりわけサンド ロ・ボッティチェリやブロンヅィーノといったルネサンスの巨匠たち、そしてノイエ・ザッハリッヒカイトやキュビスムといった前衛運動からインスピレーショ ンを得ていたことがわかる。1929年、夫のディエゴ・リベラとモレロスに移り住んだカーロは、二人が暮らしたクエルナバカの街からインスピレーションを 得た。彼女は画風を変え、メキシコの民芸品からインスピレーションを得ることが多くなった。美術史家のアンドレア・ケッテンマンは、彼女はアドルフォ・ベ スト・モーガードの論考に影響を受けたのではないかと述べている。彼女は、彼が概説した特徴の多く、例えば遠近法の欠如や、メキシコ美術の先コロンビア時 代と植民地時代の要素の組み合わせなどを取り入れていたからだ。ラサ、メキシコの人々との同一性、メキシコ文化への深い関心は、生涯を通じて彼女の芸術の 重要な側面であり続けた。 |

Work in the United States Kahlo in 1926 When Kahlo and Rivera moved to San Francisco in 1930, Kahlo was introduced to American artists such as Edward Weston, Ralph Stackpole, Timothy L. Pflueger, and Nickolas Muray.[24] The six months spent in San Francisco were a productive period for Kahlo,[25] who further developed the folk art style she had adopted in Cuernavaca.[26] In addition to painting portraits of several new acquaintances,[27] she made Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931), a double portrait based on their wedding photograph,[28] and The Portrait of Luther Burbank (1931), which depicted the eponymous horticulturist as a hybrid between a human and a plant.[29] Although she still publicly presented herself as simply Rivera's spouse rather than as an artist,[30] she participated for the first time in an exhibition, when Frieda and Diego Rivera was included in the Sixth Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists in the Palace of the Legion of Honor.[31][32] On moving to Detroit with Rivera, Kahlo experienced numerous health problems related to a failed pregnancy.[33] Despite these health problems, as well as her dislike for the capitalist culture of the United States,[34] Kahlo's time in the city was beneficial for her artistic expression. She experimented with different techniques, such as etching and frescos,[35] and her paintings began to show a stronger narrative style.[36] She also began placing emphasis on the themes of "terror, suffering, wounds, and pain".[35] Despite the popularity of the mural in Mexican art at the time, she adopted a diametrically opposed medium, votive images or retablos, religious paintings made on small metal sheets by amateur artists to thank saints for their blessings during a calamity.[37] Amongst the works she made in the retablo manner in Detroit are Henry Ford Hospital (1932), My Birth (1932), and Self-Portrait on the Border of Mexico and the United States (1932).[35] While none of Kahlo's works were featured in exhibitions in Detroit, she gave an interview to the Detroit News on her art; the article was condescendingly titled "Wife of the Master Mural Painter Gleefully Dabbles in Works of Art".[38] |

米国での仕事 Kahlo in 1926 1930年に2人がサンフランシスコに移住すると、カーロはエドワード・ウェストン、ラルフ・スタックポール、ティモシー・L・プルーガー、ニコラス・ム レイといったアメリカの芸術家たちと知り合った。[24] サンフランシスコでの6か月間はカーロにとって実りの多い期間となり、[25] 彼女はクエルナバカで取り入れたフォークアートスタイルをさらに発展させた 。さらに、彼女はフリーダとディエゴ・リベラ(1931年)という、二人の結婚写真を題材にした二重肖像画を描き、また、ルサー・バーバンクの肖像画 (1931年)では、同名の園芸学者を人間と植物のハイブリッドとして描いた 人間と植物のハイブリッドとして描いた。[29] 彼女は依然として、芸術家としてではなく、単にリベラの配偶者として公に自己紹介していたが、[30] フリーダ・カーロとディエゴ・リベラが、サンフランシスコ女性芸術家協会の第6回展覧会に、リージェンシー・オブ・オナー宮殿で展示されたのを機に、初め て展覧会に参加した。[31][32] リベラとともにデトロイトに移住したカーロは、妊娠の失敗に関連した数々の健康問題を経験した。[33] これらの健康問題や、アメリカ合衆国の資本主義的文化に対する嫌悪感にもかかわらず、[34] カーロはデトロイトでの生活を芸術表現に有益なものとした。彼女はエッチングやフレスコ画など、異なる技法を試み[35]、彼女の絵画はより強い物語性を 見せ始めた[36]。また、「恐怖、苦悩、傷、痛み」をテーマとする作品にも重点を置くようになった[35]。当時メキシコ美術では壁画が人気を博してい たが、彼女はそれとは対極にある メディウム、奉納画またはレターボ、災厄から救われたことを聖人に感謝するためにアマチュアの芸術家が小さな金属板に描いた宗教画を採用した。[37] デトロイトでレターボの手法で描いた作品には、ヘンリー・フォード病院(1932年)、私の誕生(1932年)、メキシコとアメリカの国境での自画像 (1932年)などがある。[35] デトロイトでは、カーロの作品はどれも展覧会で展示されることはなかったが、彼女はデトロイト・ニュース紙のインタビューに答え、その記事は「壁画画家の 妻が芸術作品に楽しげに手を出す」という見下したようなタイトルが付けられた。[38] |

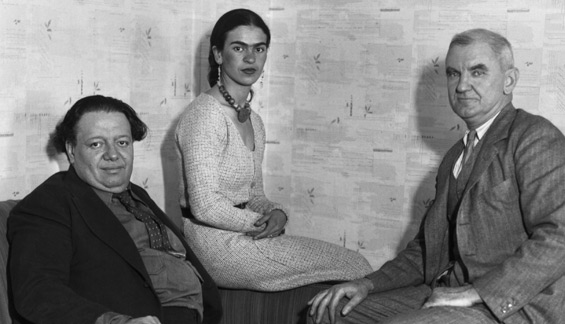

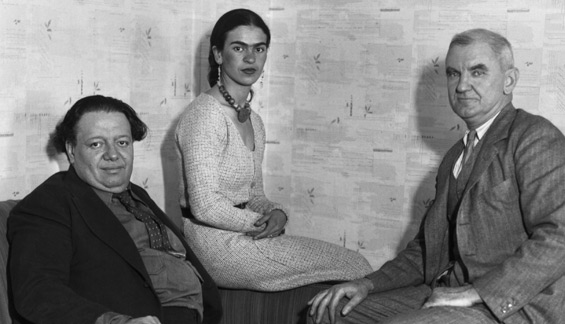

| Return to Mexico City and international recognition Upon returning to Mexico City in 1934 Kahlo made no new paintings, and only two in the following year, due to health complications.[39] In 1937 and 1938, however, Kahlo's artistic career was extremely productive, following her divorce and then reconciliation with Rivera. She painted more "than she had done in all her eight previous years of marriage", creating such works as My Nurse and I (1937), Memory, the Heart (1937), Four Inhabitants of Mexico (1938), and What the Water Gave Me (1938).[40] Although she was still unsure about her work, the National Autonomous University of Mexico exhibited some of her paintings in early 1938.[41] She made her first significant sale in the summer of 1938 when film star and art collector Edward G. Robinson purchased four paintings at $200 each.[41] Even greater recognition followed when French Surrealist André Breton visited Rivera in April 1938. He was impressed by Kahlo, immediately claiming her as a surrealist and describing her work as "a ribbon around a bomb".[42] He not only promised to arrange for her paintings to be exhibited in Paris but also wrote to his friend and art dealer, Julien Levy, who invited her to hold her first solo exhibition at his gallery on the East 57th Street in Manhattan.[43]  Rivera, Kahlo, and Anson Goodyear In October, Kahlo traveled alone to New York, where her colorful Mexican dress "caused a sensation" and made her seen as "the height of exotica".[42] The exhibition opening in November was attended by famous figures such as Georgia O'Keeffe and Clare Boothe Luce and received much positive attention in the press, although many critics adopted a condescending tone in their reviews.[44] For example, Time wrote that "Little Frida's pictures ... had the daintiness of miniatures, the vivid reds, and yellows of Mexican tradition and the playfully bloody fancy of an unsentimental child".[45] Despite the Great Depression, Kahlo sold half of the 25 paintings presented in the exhibition.[46] She also received commissions from A. Conger Goodyear, then the president of the MoMA, and Clare Boothe Luce, for whom she painted a portrait of Luce's friend, socialite Dorothy Hale, who had committed suicide by jumping from her apartment building.[47] During the three months she spent in New York, Kahlo painted very little, instead focusing on enjoying the city to the extent that her fragile health allowed.[48] She also had several affairs, continuing the one with Nickolas Muray and engaging in ones with Levy and Edgar Kaufmann, Jr.[49] In January 1939, Kahlo sailed to Paris to follow up on André Breton's invitation to stage an exhibition of her work.[50] When she arrived, she found that he had not cleared her paintings from the customs and no longer even owned a gallery.[51] With the aid of Marcel Duchamp, she was able to arrange for an exhibition at the Renou et Colle Gallery.[51] Further problems arose when the gallery refused to show all but two of Kahlo's paintings, considering them too shocking for audiences,[52] and Breton insisted that they be shown alongside photographs by Manuel Alvarez Bravo, pre-Columbian sculptures, 18th- and 19th-century Mexican portraits, and what she considered "junk": sugar skulls, toys, and other items he had bought from Mexican markets.[53] The exhibition opened in March, but received much less attention than she had received in the United States, partly due to the looming Second World War, and made a loss financially, which led Kahlo to cancel a planned exhibition in London.[54] Regardless, the Louvre purchased The Frame, making her the first Mexican artist to be featured in their collection.[55] She was also warmly received by other Parisian artists, such as Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró,[53] as well as the fashion world, with designer Elsa Schiaparelli designing a dress inspired by her and Vogue Paris featuring her on its pages.[54] However, her overall opinion of Paris and the Surrealists remained negative; in a letter to Muray, she called them "this bunch of coocoo lunatics and very stupid surrealists"[53] who "are so crazy 'intellectual' and rotten that I can't even stand them anymore".[56] In the United States, Kahlo's paintings continued to raise interest. In 1941, her works were featured at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, and, in the following year, she participated in two high-profile exhibitions in New York, the Twentieth-Century Portraits exhibition at the MoMA and the Surrealists' First Papers of Surrealism exhibition.[57] In 1943, she was included in the Mexican Art Today exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Women Artists at Peggy Guggenheim's The Art of This Century gallery in New York.[58]  A portrait of Kahlo by Magda Pach, wife of Walter Pach, in the Smithsonian American Art Museum (1933) Kahlo gained more appreciation for her art in Mexico as well. She became a founding member of the Seminario de Cultura Mexicana, a group of twenty-five artists commissioned by the Ministry of Public Education in 1942 to spread public knowledge of Mexican culture.[59] As a member, she took part in planning exhibitions and attended a conference on art.[60] In Mexico City, her paintings were featured in two exhibitions on Mexican art that were staged at the English-language Benjamin Franklin Library in 1943 and 1944. She was invited to participate in "Salon de la Flor", an exhibition presented at the annual flower exposition.[61] An article by Rivera on Kahlo's art was also published in the journal published by the Seminario de Cultura Mexicana.[62] In 1943, Kahlo accepted a teaching position at the recently reformed, nationalistic Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado "La Esmeralda".[63] She encouraged her students to treat her in an informal and non-hierarchical way and taught them to appreciate Mexican popular culture and folk art and to derive their subjects from the street.[64] When her health problems made it difficult for her to commute to the school in Mexico City, she began to hold her lessons at La Casa Azul.[65] Four of her students – Fanny Rabel, Arturo García Bustos, Guillermo Monroy, and Arturo Estrada – became devotees, and were referred to as "Los Fridos" for their enthusiasm.[66] Kahlo secured three mural commissions for herself and her students.[67] Kahlo struggled to make a living from her art until the mid to late 1940s, as she refused to adapt her style to suit her clients' wishes.[68] She received two commissions from the Mexican government in the early 1940s. She did not complete the first one, possibly due to her dislike of the subject, and the second commission was rejected by the commissioning body.[68] Nevertheless, she had regular private clients, such as engineer Eduardo Morillo Safa, who ordered more than thirty portraits of family members over the decade.[68] Her financial situation improved when she received a 5000-peso national prize for her painting Moses (1945) in 1946 and when The Two Fridas was purchased by the Museo de Arte Moderno in 1947.[69] According to art historian Andrea Kettenmann, by the mid-1940s, her paintings were "featured in the majority of group exhibitions in Mexico". Further, Martha Zamora wrote that she could "sell whatever she was currently painting; sometimes incomplete pictures were purchased right off the easel".[70] |

メキシコシティに戻り、国際的な評価を得る 1934年にメキシコシティに戻った後、カーロは新たな絵画を描かず、翌年には2点しか描かなかった。これは、健康上の問題によるものだった。[39] しかし、1937年と1938年には、リベラとの離婚と和解を経て、カーロの芸術家としてのキャリアは非常に生産的なものとなった。彼女は「結婚前の8年 間で描いた以上の」作品を描き、『私の看護婦と私』(1937年)、『記憶、心』(1937年)、『メキシコの4人の住人』(1938年)、『水が私にく れたもの』(1938年)などの作品を制作した。[40] 彼女はまだ自分の作品について確信を持てていなかったが、 1938年初頭には、メキシコ国立自治大学が彼女の絵画をいくつか展示した。[41] 1938年夏には、映画スターで美術品の収集家でもあったエドワード・G・ロビンソンが4枚の絵画を1枚200ドルで購入し、彼女にとって初めての大きな 売り上げとなった。[41] さらに大きな評価が得られたのは、1938年4月にフランスのシュールレアリスト、アンドレ・ブルトンがリベラを訪れたときだった。彼はカーロに感銘を受 け、すぐに彼女をシュールレアリストと称し、彼女の作品を「爆弾に巻かれたリボン」と表現した。[42] 彼は、彼女の絵画をパリで展示するよう取り計らうことを約束しただけでなく、友人の美術商ジュリアン・レヴィに手紙を書き、カーロをマンハッタンのイース ト57丁目の彼のギャラリーで初めての個展を開催するよう招待した。[43]  Rivera, Kahlo, and Anson Goodyear 10月、カーロは単身ニューヨークへ渡り、そこで彼女のカラフルなメキシコのドレスは「センセーションを巻き起こし」、彼女は「エキゾチックの極み」と見 なされた。[42] 11月に開かれた展覧会には、ジョージア・オキーフやクレア・ブース・ルースといった著名人が出席し、マスコミでも好意的に取り上げられたが、多くの批評 家は見下したような論調で評した。[44] たとえば、タイム誌は「 リトル・フリーダの絵画は... ミニチュアの繊細さ、メキシコの伝統の鮮やかな赤や黄色、そして感情を表に出さない子供らしい遊び心のある血なまぐさい空想を表現している」と評した。 [45] 大恐慌にもかかわらず、フリーダは展覧会に出展した25点の絵画のうち半分の絵画を売り上げた。[46] また、当時ニューヨーク近代美術館(MoMA)の館長であったA. コンジャー・グッドイヤーとクレア・ブース・ルースから依頼を受け、 彼女は、ルースの友人で、自殺した社交界の女性ドロシー・ヘイルの肖像画を描いた。ヘイルは、自宅のマンションから飛び降り自殺をしていた。[47] ニューヨークに3か月間滞在した間、カーロはほとんど絵を描かず、その代わり、自身の脆弱な健康状態が許す限り、この都市を満喫することに専念した。 [48] 彼女はまた、数人の男性と関係を持ち、ニコラス・ムレイとの関係を継続し、レヴィやエドガー・カウフマン・ジュニアとも関係を持った。[49] 1939年1月、カーロはアンドレ・ブルトンの招待を受けて、自身の作品の展覧会を開くためにパリへと向かった。[50] 彼女が到着すると、ブルトンは彼女の絵画を税関から通関しておらず、ギャラリーさえも所有していなかった。[51] マルセル・デュシャンの助力により、彼女はルヌー・エ・コール・ギャラリーでの展覧会を準備することができた。[51] さらに問題が発生したのは、 ギャラリー側が、カーロの絵画のうち2点以外は展示しないと拒否した。ギャラリー側は、それらの絵画は観客にとって衝撃的すぎると考えたのだ。[52] さらに、ブルトンは、マニュエル・アルバレス・ブラボーの写真、コロンブス到来以前の彫刻、18世紀と19世紀のメキシコの肖像画、そしてカーロが「ガラ クタ」と呼ぶもの、すなわち、頭蓋骨の砂糖細工、おもちゃ、その他メキシコの市場で彼が購入した品々を、カーロの絵画と一緒に展示するよう主張した。 [53] この展覧会は3月に開幕したが、アメリカ国内で彼女が受けたほどの注目は集めず、その理由の一つには第二次世界大戦が迫っていたことが挙げられる。また、 経済的にも損失を出し、カーロはロンドンでの展覧会を中止せざるを得なかった。[54] それでもルーヴル美術館は『フレーム』を購入し、彼女は同美術館のコレクションに展示された最初のメキシコ人アーティストとなった 。彼女はまた、パブロ・ピカソやジョアン・ミロといった他のパリの芸術家たちからも温かく迎え入れられ、ファッション界でもデザイナーのエルザ・スキャパ レリが彼女にインスパイアされたドレスをデザインし、ヴォーグ・パリが彼女を特集した。しかし、 パリとシュールレアリストたちに対する彼女の全体的な評価は否定的なままであり、彼女はマレー宛ての手紙で彼らを「この気違いじみた狂気じみた集団と、と ても愚かなシュールレアリストたち」と呼び、「彼らはとても狂気じみた『インテリ』で腐りきっていて、私はもう彼らに耐えられない」と述べている。 アメリカでは、カーロの絵画への関心が衰えることはなかった。1941年にはボストン現代美術館で作品が展示され、翌年にはニューヨークで注目度の高い2 つの展覧会に参加した。1つはニューヨーク近代美術館(MoMA)の「20世紀の肖像画」展、もう1つは「シュルレアリスムの第一宣言書」展である 。1943年には、フィラデルフィア美術館で開催された「メキシコ現代美術展」と、ニューヨークのペギー・グッゲンハイム・ギャラリーで開催された「女性 アーティスト展」に出展した。[58]  A portrait of Kahlo by Magda Pach, wife of Walter Pach, in the Smithsonian American Art Museum (1933) メキシコでも、彼女の芸術に対する評価は高まっていった。彼女は、メキシコ文化の普及を目的として1942年に文部省から委託された25人の芸術家グルー プ「メキシコ文化セミナー」の創設メンバーとなった。[59] メンバーとして、彼女は 展覧会の企画に参加し、美術に関する会議にも出席した。[60] メキシコシティでは、1943年と1944年に英語話者向けのベンジャミン・フランクリン図書館で開催されたメキシコ美術に関する2つの展覧会で、彼女の 絵画が展示された。彼女は「サロン・デ・ラ・フロー(Salon de la Flor)」という、毎年開催される花の博覧会での展示会への参加を依頼された。[61] リベラによるカーロの芸術に関する記事も、メキシコ文化セミナー(Seminario de Cultura Mexicana)が発行する雑誌に掲載された。[62] 1943年、カーロは最近になって改革されたばかりの民族主義的な国立美術学校「ラ・エスメラルダ」で教職に就いた。[63] 彼女は生徒たちに、彼女に対しては非公式で上下関係のない態度で接するよう勧め、メキシコのポピュラー文化や民芸品を鑑賞し、題材を街から得ることを教え た。[64] 彼女の健康問題により メキシコシティの学校に通うのが困難になったため、彼女はラ・カサ・アスルで授業を行うようになった。[65] 彼女の生徒のうち、ファニー・ラベル、アルトゥーロ・ガルシア・ブストス、ギジェルモ・モンロイ、アルトゥーロ・エストラダの4人は熱心な信奉者となり、 「ロス・フリドス」と呼ばれた。[66] カロは、自分と生徒たちのために3つの壁画制作の依頼を確保した。[67] 1940年代半ばから後半にかけて、彼女は顧客の希望に合わせてスタイルを変えることを拒んだため、芸術で生計を立てるのに苦労した。[68] 1940年代初頭には、メキシコ政府から2つの依頼を受けた。最初の依頼は、おそらく主題を好まなかったためか、完成させることはなかった。2つ目の依頼 は、依頼元に拒否された。[68] それでも、彼女には定期的に依頼する顧客がおり、エンジニアのエドゥアルド・モリロ・サファは、10年以上にわたって家族の肖像画を30点以上も注文し た。[68] 彼女の経済状況は、1946年に『モーゼス』(1945年)で5000ペソの国家賞を受賞したことと、 1946年に『モーゼス』(1945年)で5000ペソの国民賞を受賞し、1947年には『二人のフリーダ』がメキシコ近代美術館に購入されたことで、彼 女の経済状況は改善した。[69] 美術史家のアンドレア・ケッテンマンによると、1940年代半ばには、彼女の絵画は「メキシコで開催されるグループ展の大半で展示される」ようになってい た。さらに、マーサ・サモラは「彼女が現在描いているものは何でも売れる。時には未完成の絵画がイーゼルからすぐに購入されることもあった」と書いてい る。[70] |

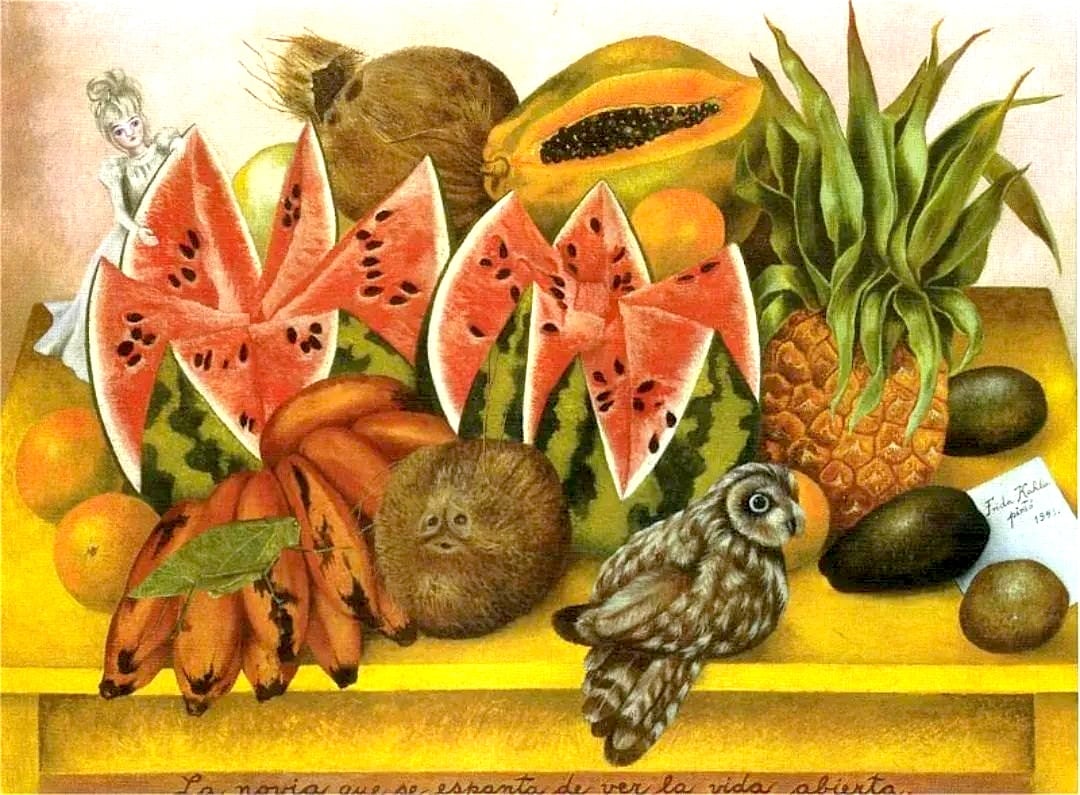

| Later years External images image icon The Broken Column (1944) image icon Moses (1945) image icon Without Hope (1945) image icon Tree of Hope, Stand Fast (1946) Even as Kahlo was gaining recognition in Mexico, her health was declining rapidly, and an attempted surgery to support her spine failed.[71] Her paintings from this period include Broken Column (1944), Without Hope (1945), Tree of Hope, Stand Fast (1946), and The Wounded Deer (1946), reflecting her poor physical state.[71] During her last years, Kahlo was mostly confined to the Casa Azul.[72] She painted mostly still lifes, portraying fruit and flowers with political symbols such as flags or doves.[73] She was concerned about being able to portray her political convictions, stating that "I have a great restlessness about my paintings. Mainly because I want to make it useful to the revolutionary communist movement... until now I have managed simply an honest expression of my own self ... I must struggle with all my strength to ensure that the little positive my health allows me to do also benefits the Revolution, the only real reason to live."[74][75] She also altered her painting style: her brushstrokes, previously delicate and careful, were now hastier, her use of color more brash, and the overall style more intense and feverish.[76] Photographer Lola Alvarez Bravo understood that Kahlo did not have much longer to live, and thus staged her first solo exhibition in Mexico at the Galería Arte Contemporaneo in April 1953.[77] Though Kahlo was initially not due to attend the opening, as her doctors had prescribed bed rest for her, she ordered her four-poster bed to be moved from her home to the gallery. To the surprise of the guests, she arrived in an ambulance and was carried on a stretcher to the bed, where she stayed for the duration of the party.[77] The exhibition was a notable cultural event in Mexico and also received attention in mainstream press around the world.[78] The same year, the Tate Gallery's exhibition on Mexican art in London featured five of her paintings.[79] In 1954, Kahlo was again hospitalized in April and May.[80] That spring, she resumed painting after a one-year interval.[81] Her last paintings include the political Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick (c. 1954) and Frida and Stalin (c. 1954) and the still-life Viva La Vida (1954).[82] |

晩年 外部画像 画像アイコン 折れた柱 (1944年) 画像アイコン モーゼ (1945年) 画像アイコン 希望なき (1945年) 画像アイコン 希望の木、耐え忍べ (1946年) メキシコで名声を得る一方で、彼女の健康状態は急速に悪化し、背骨を支える手術を試みたが失敗した。[71] この時期の彼女の絵画には、『Broken Column』(1944年)、『Without Hope』(1945年)、『Tree of Hope, Stand Fast』(1946年)、『The Wounded Deer』(1946年)などがあり、彼女の 体調不良を反映している。[71] 晩年、カーロはほとんどをカサ・アスルで過ごした。[72] 彼女は主に静物を描き、旗やハトなどの政治的シンボルとともに果物や花を描いた。[73] 彼女は政治的信念を表現できるかどうかを懸念しており、「私は自分の絵画について大きな不安を抱いている。主に、革命的な共産主義運動に役立つものにした いからだ。これまで私は、ただ単に自分自身の正直な表現を管理してきた。私は、私の健康が許すわずかな前向きな活動も革命に役立つよう、全力で努力しなけ ればならない。それが生きる唯一の理由なのだ」[74][75] 彼女はまた、絵画のスタイルも変えた。以前は繊細で慎重だった筆使いはより急ぎ足になり、色使いは大胆になり、全体的なスタイルはより激しく熱狂的なもの になった。 写真家のローラ・アルバレス・ブラボーは、カーロが長くは生きられないことを理解しており、1953年4月にメキシコのギャラリー・アルテ・コントラネオ でカーロの最初の個展を開催した。[77] カーロは当初、医師から安静を命じられていたため、オープニングには出席しない予定だったが、四柱式ベッドを自宅からギャラリーに移動させた。招待客を驚 かせたのは、彼女が救急車で到着し、担架に乗せられてベッドまで運ばれたことだった。彼女はパーティーの間、ベッドで過ごした。[77] この展覧会はメキシコで注目すべき文化イベントとなり、また世界の主要な報道機関でも注目された。[78] 同年、ロンドンのテート・ギャラリーで開催されたメキシコ美術展では、彼女の絵画5点が展示された。[79] 1954年、4月と5月に再び入院した。[80] その春、彼女は1年間の休止期間を経て絵画制作を再開した。[81] 彼女の最後の絵画には、政治的なマルクス主義を題材にした『病める者に保健を』(1954年頃)や『フリーダとスターリン』(1954年頃)、静物画『ビ バ・ラ・ビダ』(1954年)などがある。[82] |

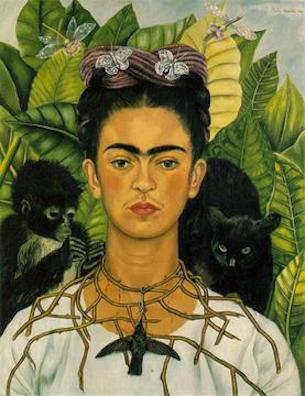

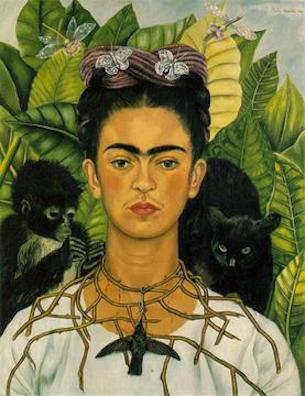

| Self-portraits Self-portraiture Self-portrait on the Border of Mexico and the United States (1932) Henry Ford Hospital (1932) Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky (1937) The Two Fridas (1939) Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940) Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair |

自画像 自画像 メキシコと米国の国境での自画像(1932年 ヘンリー・フォード病院(1932年 レオン・トロツキーに捧げる自画像(1937年 二人のフリーダ(1939年 とげのネックレスとハチドリの自画像(1940年 短く刈った髪の自画像 |

Style and influences Self-portrait in a Velvet Dress, 1926 See also: List of paintings by Frida Kahlo Estimates vary on how many paintings Kahlo made during her life, with figures ranging from fewer than 150[83] to around 200.[84][85] Her earliest paintings, which she made in the mid-1920s, show influence from Renaissance masters and European avant-garde artists such as Amedeo Modigliani.[86] Towards the end of the decade, Kahlo derived more inspiration from Mexican folk art,[87] drawn to its elements of "fantasy, naivety, and fascination with violence and death".[85] The style she developed mixed reality with surrealistic elements and often depicted pain and death.[88] One of Kahlo's earliest champions was Surrealist artist André Breton, who claimed her as part of the movement as an artist who had supposedly developed her style "in total ignorance of the ideas that motivated the activities of my friends and myself".[89] This was echoed by Bertram D. Wolfe, who wrote that Kahlo's was a "sort of 'naïve' Surrealism, which she invented for herself".[90] Although Breton regarded her as mostly a feminine force within the Surrealist movement, Kahlo brought postcolonial questions and themes to the forefront of her brand of Surrealism.[91] Breton also described Kahlo's work as "wonderfully situated at the point of intersection between the political (philosophical) line and the artistic line".[92] While she subsequently participated in Surrealist exhibitions, she stated that she "detest[ed] Surrealism", which to her was "bourgeois art" and not "true art that the people hope from the artist".[93] Some art historians have disagreed whether her work should be classified as belonging to the movement at all. According to Andrea Kettenmann, Kahlo was a symbolist concerned more in portraying her inner experiences.[94] Emma Dexter has argued that, as Kahlo derived her mix of fantasy and reality mainly from Aztec mythology and Mexican culture instead of Surrealism, it is more appropriate to consider her paintings as having more in common with magical realism, also known as New Objectivity. It combined reality and fantasy and employed similar style to Kahlo's, such as flattened perspective, clearly outlined characters and bright colours.[95] |

スタイルとその影響 Self-portrait in a Velvet Dress, 1926 参照:フリーダ・カーロの絵画作品一覧 カーロが生涯に描いた絵画の数は、150点以下という説[83]から200点程度という説[84][85]まで、さまざまな推定がある。彼女が1920年 代半ばに描いた初期の絵画には、ルネサンスの巨匠やアメデオ・モディリアーニなどのヨーロッパの前衛芸術家からの影響が見られる 。1920年代の終わり頃には、カーロはメキシコの民芸品からより多くのインスピレーションを得るようになり、その要素である「ファンタジー、ナイーブ さ、暴力と死への魅力」に惹かれるようになった。彼女が発展させたスタイルは現実と超現実主義的な要素を混ぜ合わせたもので、しばしば痛みや死を描いた。 彼女の初期の支援者の一人は、シュールレアリスムの芸術家アンドレ・ブルトンであり、彼は「友人や私の活動の動機となる考えを全く知らずに」彼女のスタイ ルを開発した芸術家として、運動の一員であると主張した。[89] これは、ベルトラム・D・ウルフによっても繰り返され、彼は「一種の『素朴な 彼女自身のために作り出した『素朴な』シュールレアリスム」であると述べている。[90] しかし、シュールレアリスム運動の中で、彼女は主に女性的な存在として見られていた。カローは、ポストコロニアルの問いやテーマを、彼女のシュールレアリ スムのスタイルの最前線に持ち込んだ。[91] また、ブルトンはカローの作品を「政治(哲学)的な路線と芸術的な路線の交差点に、見事に位置している」と表現している。 。」[92] その後、彼女はシュールレアリスムの展覧会に参加したが、「シュールレアリスムを嫌悪する」と述べた。彼女にとってシュールレアリスムは「ブルジョワの芸 術」であり、「人々が芸術家に期待する真の芸術」ではなかったのだ。[93] 一部の美術史家は、彼女の作品がこの運動に属するものとして分類されるべきかどうかについて異論を唱えている。アンドレア・ケッテンマンによると、カーロ は内面の経験を描写することに重きを置く象徴主義者であったという。[94] エマ・デクスターは、カーロが幻想と現実の混合を主にアステカ神話とメキシコ文化から引き出しており、シュールレアリスムからではなく、彼女の絵画は呪術 的リアリズム、別名「新客観主義」と共通点が多いと考える方がより適切であると主張している。現実と空想を組み合わせ、フラットな遠近法、はっきりと輪郭 が描かれた人物、鮮やかな色彩など、同様のスタイルを採用していた。[95] |

| Mexicanidad Similarly to many other contemporary Mexican artists, Kahlo was heavily influenced by Mexicanidad, a romantic nationalism that had developed in the aftermath of the revolution.[96][85] The Mexicanidad movement claimed to resist the "mindset of cultural inferiority" created by colonialism, and placed special importance on Indigenous cultures.[97] Before the revolution, Mexican folk culture – a mixture of Indigenous and European elements – was disparaged by the elite, who claimed to have purely European ancestry and regarded Europe as the definition of civilization which Mexico should imitate.[98] Kahlo's artistic ambition was to paint for the Mexican people, and she stated that she wished "to be worthy, with my paintings, of the people to whom I belong and to the ideas which strengthen me".[93] To enforce this image, she preferred to conceal the education she had received in art from her father and Ferdinand Fernandez and at the preparatory school. Instead, she cultivated an image of herself as a "self-taught and naive artist".[99] When Kahlo began her career as an artist in the 1920s, muralists dominated the Mexican art scene. They created large public pieces in the vein of Renaissance masters and Russian socialist realists: they usually depicted masses of people, and their political messages were easy to decipher.[100] Although she was close to muralists such as Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siquieros and shared their commitment to socialism and Mexican nationalism, the majority of Kahlo's paintings were self-portraits of relatively small size.[101][85] Particularly in the 1930s, her style was especially indebted to votive paintings or retablos, which were postcard-sized religious images made by amateur artists.[102] Their purpose was to thank saints for their protection during a calamity, and they normally depicted an event, such as an illness or an accident, from which its commissioner had been saved.[103] The focus was on the figures depicted, and they seldom featured a realistic perspective or detailed background, thus distilling the event to its essentials.[104] Kahlo had an extensive collection of approximately 2,000 retablos, which she displayed on the walls of La Casa Azul.[105] According to Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen, the retablo format enabled Kahlo to "develop the limits of the purely iconic and allowed her to use narrative and allegory".[106] Many of Kahlo's self-portraits mimic the classic bust-length portraits that were fashionable during the colonial era, but they subverted the format by depicting their subject as less attractive than in reality.[107] She concentrated more frequently on this format towards the end of the 1930s, thus reflecting changes in Mexican society. Increasingly disillusioned by the legacy of the revolution and struggling to cope with the effects of the Great Depression, Mexicans were abandoning the ethos of socialism for individualism.[108] This was reflected by the "personality cults", which developed around Mexican film stars such as Dolores del Río.[108] According to Schaefer, Kahlo's "mask-like self-portraits echo the contemporaneous fascination with the cinematic close-up of feminine beauty, as well as the mystique of female otherness expressed in film noir."[108] By always repeating the same facial features, Kahlo drew from the depiction of goddesses and saints in Indigenous and Catholic cultures.[109] Out of specific Mexican folk artists, Kahlo was especially influenced by Hermenegildo Bustos, whose works portrayed Mexican culture and peasant life, and José Guadalupe Posada, who depicted accidents and crime in satiric manner.[110] She also derived inspiration from the works of Hieronymus Bosch, whom she called a "man of genius", and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, whose focus on peasant life was similar to her own interest in the Mexican people.[111] Another influence was the poet Rosario Castellanos, whose poems often chronicle a woman's lot in the patriarchal Mexican society, a concern with the female body, and tell stories of immense physical and emotional pain.[87] |

メキシコ性 他の多くの現代メキシコ人アーティストと同様に、カーロは革命後に発展したロマン主義的ナショナリズムであるメキシコ性に強く影響を受けていた。[96] [85] メキシコ性運動は、植民地主義によって生み出された「文化的劣等感」に抵抗することを主張し、先住民文化を特に重要視していた。[97] 革命以前、先住民とヨーロッパの要素が混ざり合ったメキシコの民間文化は、純粋な ヨーロッパの血筋を引くことを主張し、ヨーロッパこそが模倣すべき文明の定義であると考えていた。[98] カーロの芸術的野心はメキシコ国民のために絵を描くことであり、彼女は「自分の絵で、自分が属する国民と自分を強くしてくれる考え方にふさわしい存在にな りたい」と述べた。[93] このイメージを強化するために、彼女は父親やフェルディナンド・フェルナンデス、そして予備校で受けた美術教育を隠すことを好んだ。その代わりに、彼女は 「独学で純朴な芸術家」というイメージを自らに植え付けた。[99] 1920年代に画家としてのキャリアをスタートさせたとき、メキシコの美術界は壁画画家たちによって支配されていた。彼らはルネサンスの巨匠やロシアの社 会主義リアリズムの系譜を継ぐ、大規模な公共作品を制作していた。彼らは通常、大勢の人々を描き、その政治的なメッセージは容易に読み取ることができた。 [100] 彼女はリベラ、ホセ・クレメンテ・オロスコ、ダビド・アルファロ・シケイロスといった壁画画家たちと親交があり、社会主義やメキシコ・ナショナリズムに対 する彼らの献身を共有していたが、彼女の絵画の大半は比較的小さなサイズの自画像であった。[101][85 特に1930年代には、彼女のスタイルは特に、献納画やレタブロに影響を受けていた。レタブロとは、アマチュアの画家が描いたハガキ大の宗教画である。 [102] その目的は、災厄から守ってくれた聖人に感謝することであり、通常は、依頼者が病気や事故から救われた出来事が描かれていた。[103] 焦点は描かれた人物像に当てられ、 現実的な視点や詳細な背景はほとんど描かれず、出来事を本質的なものに凝縮していた。[104] カロは約2,000点ものレタブロのコレクションを所有しており、それらをラ・カサ・アスルの壁に展示していた。[105] ローラ・マルヴィーとピーター・ウォレンによると、レタブロという形式によって、カロは「純粋に象徴的な限界を押し広げ、物語や寓話を使用することが可能 になった」という。[106] カーロの自画像の多くは、植民地時代に流行した上半身の肖像画を模倣しているが、その被写体は現実よりも魅力的に描かれていない。[107] 彼女は1930年代の終わり頃から、この形式にさらに頻繁に集中するようになり、メキシコ社会の変化を反映するようになった。革命の遺産にますます幻滅 し、世界恐慌の影響に対処することに苦慮するメキシコ人は、社会主義の精神を捨てて個人主義へと向かっていた。[108] これは、ドロレス・デル・リオなどのメキシコ人映画スターの周りに生まれた「偶像崇拝」に反映されていた。[108] シェーファーによると、 「仮面のような自画像」は、映画のクローズアップによる女性的な美しさへの同時代の熱狂、そしてフィルム・ノワールに表現された女性の他者性への神秘性を 反映している」と述べている。[108] 常に同じ顔の特徴を繰り返すことで、カーロは先住民やカトリック文化における女神や聖人の描写から着想を得た。[109] メキシコの特定の民芸作家のうち、特にカーロは、メキシコ文化や農民生活を描いたエルメネジルド・ブストスや、風刺的な手法で事故や犯罪を描いたホセ・グ アダルーペ・ポサダから影響を受けた。また、彼女は「天才」と呼んだヒエロニムス・ボスの作品や、 農民生活に焦点を当てたピーテル・ブリューゲル(父)の作品は、メキシコの人々に対する彼女自身の関心と類似していた。[111] もう一人の影響を受けた人物は詩人のロサリオ・カステリャノスで、彼女の詩は家父長制のメキシコ社会における女性の境遇をしばしば記録し、女性の身体への 関心を示し、肉体と精神の大きな苦痛を物語っている。[87] |

Symbolism and iconography Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940), Harry Ransom Center. Kahlo's paintings often feature root imagery, with roots growing out of her body to tie her to the ground. This reflects in a positive sense the theme of personal growth; in a negative sense of being trapped in a particular place, time and situation; and in an ambiguous sense of how memories of the past influence the present for good and/or ill.[112] In My Grandparents and I, Kahlo painted herself as a ten-year old, holding a ribbon that grows from an ancient tree that bears the portraits of her grandparents and other ancestors while her left foot is a tree trunk growing out of the ground, reflecting Kahlo's view of humanity's unity with the earth and her own sense of unity with Mexico.[113] In Kahlo's paintings, trees serve as symbols of hope, of strength and of a continuity that transcends generations.[114] Additionally, hair features as a symbol of growth and of the feminine in Kahlo's paintings and in Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair, Kahlo painted herself wearing a man's suit and shorn of her long hair, which she had just cut off.[115] Kahlo holds the scissors with one hand menacingly close to her genitals, which can be interpreted as a threat to Rivera – whose frequent unfaithfulness infuriated her – and/or a threat to harm her own body like she has attacked her own hair, a sign of the way that women often project their fury against others onto themselves.[116] Moreover, the picture reflects Kahlo's frustration not only with Rivera, but also her unease with the patriarchal values of Mexico as the scissors symbolize a malevolent sense of masculinity that threatens to "cut up" women, both metaphorically and literally.[116] In Mexico, the traditional Spanish values of machismo were widely embraced, but Kahlo was always uncomfortable with machismo.[116] As she suffered for the rest of her life from the bus accident in her youth, Kahlo spent much of her life in hospitals and undergoing surgery, much of it performed by quacks who Kahlo believed could restore her back to where she had been before the accident.[113] Many of Kahlo's paintings are concerned with medical imagery, which is presented in terms of pain and hurt, featuring Kahlo bleeding and displaying her open wounds.[113] Many of Kahlo's medical paintings, especially dealing with childbirth and miscarriage, have a strong sense of guilt, of a sense of living one's life at the expense of another who has died so one might live.[114] Although Kahlo featured herself and events from her life in her paintings, they were often ambiguous in meaning.[117] She did not use them only to show her subjective experience but to raise questions about Mexican society and the construction of identity within it, particularly gender, race, and social class.[118] Historian Liza Bakewell has stated that Kahlo "recognized the conflicts brought on by revolutionary ideology": What was it to be a Mexican? – modern, yet pre-Columbian; young, yet old; anti-Catholic yet Catholic; Western, yet New World; developing, yet underdeveloped; independent, yet colonized; mestizo, yet not Spanish nor Indian.[119] To explore these questions through her art, Kahlo developed a complex iconography, extensively employing pre-Columbian and Christian symbols and mythology in her paintings.[120] In most of her self-portraits, she depicts her face as mask-like, but surrounded by visual cues which allow the viewer to decipher deeper meanings for it. Aztec mythology features heavily in Kahlo's paintings in symbols including monkeys, skeletons, skulls, blood, and hearts; often, these symbols referred to the myths of Coatlicue, Quetzalcoatl, and Xolotl.[121] Other central elements that Kahlo derived from Aztec mythology were hybridity and dualism.[122] Many of her paintings depict opposites: life and death, pre-modernity and modernity, Mexican and European, male and female.[120] In addition to Aztec legends, Kahlo frequently depicted two central female figures from Mexican folklore in her paintings: La Llorona and La Malinche[123] as interlinked to the hard situations, the suffering, misfortune or judgement, as being calamitous, wretched or being "de la chingada".[124] For example, when she painted herself following her miscarriage in Detroit in Henry Ford Hospital (1932), she shows herself as weeping, with dishevelled hair and an exposed heart, which are all considered part of the appearance of La Llorona, a woman who murdered her children.[125] The painting was traditionally interpreted as simply a depiction of Kahlo's grief and pain over her failed pregnancies. But with the interpretation of the symbols in the painting and the information of Kahlo's actual views towards motherhood from her correspondence, the painting has been seen as depicting the unconventional and taboo choice of a woman remaining childless in Mexican society.[citation needed] Kahlo often featured her own body in her paintings, presenting it in varying states and disguises: as wounded, broken, as a child, or clothed in different outfits, such as the Tehuana costume, a man's suit, or a European dress.[126] She used her body as a metaphor to explore questions on societal roles.[127] Her paintings often depicted the female body in an unconventional manner, such as during miscarriages, and childbirth or cross-dressing.[128] In depicting the female body in graphic manner, Kahlo positioned the viewer in the role of the voyeur, "making it virtually impossible for a viewer not to assume a consciously held position in response".[129] According to Nancy Cooey, Kahlo made herself through her paintings into "the main character of her own mythology, as a woman, as a Mexican, and as a suffering person ... She knew how to convert each into a symbol or sign capable of expressing the enormous spiritual resistance of humanity and its splendid sexuality".[130] Similarly, Nancy Deffebach has stated that Kahlo "created herself as a subject who was female, Mexican, modern, and powerful", and who diverged from the usual dichotomy of roles of mother/whore allowed to women in Mexican society.[131] Due to her gender and divergence from the muralist tradition, Kahlo's paintings were treated as less political and more naïve and subjective than those of her male counterparts up until the late 1980s.[132] According to art historian Joan Borsa, the critical reception of her exploration of subjectivity and personal history has all too frequently denied or de-emphasized the politics involved in examining one's own location, inheritances and social conditions ... Critical responses continue to gloss over Kahlo's reworking of the personal, ignoring or minimizing her interrogation of sexuality, sexual difference, marginality, cultural identity, female subjectivity, politics and power.[83] |

シンボリズムとイコノグラフィー Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940), Harry Ransom Center. カーロの絵画には、しばしば根がモチーフとして登場する。根は彼女の体から生えており、彼女を地面に結びつけている。これは、肯定的な意味では個人の成長 というテーマを反映し、否定的な意味では特定の場所、時間、状況に囚われていることを意味し、また曖昧な意味では、過去の記憶が現在に良くも悪くも影響を 及ぼしていることを意味している。[112] 『私と祖父母』では、10歳の頃の彼女自身を描き、祖父母やその他の先祖の肖像画が描かれた古代の木から伸びるリボンを手に持ち、左足は 大地から生える木の幹となっており、これは、人類と地球の一体性に対する彼女の見解と、メキシコとの一体感に対する自身の感覚を反映している。[113] カーロの絵画では、木々は希望、強さ、世代を超えた継続性の象徴となっている。[114] さらに、カーロの絵画や『髪を切った自画像』では、髪は成長と女性の象徴となっている。彼女は男性用のスーツを着て長い髪を切ったばかりの姿で自画像を描 いている。[115] カーロは、片手で脅迫的に自分の性器に近づけたハサミを握っている。これは、彼女を激怒させたリベラに対する脅迫、あるいは彼女が自分の髪を攻撃したよう に、自分の体を傷つけるという脅迫と解釈できる。これは、女性がしばしば他人に対して抱く怒りを自分自身にぶつけるという傾向の表れである。。さらに、こ の絵は、リベラに対するだけでなく、メキシコの家父長的価値観に対する彼女の不安をも反映している。はさみは、女性を「切り刻む」という悪意のある男性的 な感覚を象徴しており、それは比喩的にも文字通りにもとらえられる。[116] メキシコでは、スペインの伝統的価値観であるマッチョイズムが広く受け入れられていたが、カーロはマッチョイズムに常に違和感を抱いていた。[116] 若い頃に遭ったバス事故の後遺症に生涯苦しんだ彼女は、人生の大半を病院で過ごし、手術を受けていた。その多くは、事故前の状態に戻れると彼女が信じてい た、ヤブ医者が執刀したものだった。[113] 彼女の絵画の多くは医療的なイメージを扱っており、 出血や開いた傷口をフィーチャーし、痛みや傷を表現している。[113] 特に出産や流産を扱った医療画の多くには、罪の意識や、自分が生きるために誰かが死ぬという犠牲の上に自分の人生があるという感覚が強く感じられる。 [114] 彼女は自身の絵画に自身の姿や人生の出来事を描いていたが、それらの意味はしばしば曖昧であった。[117] 彼女は自身の主観的な経験を示すためだけに絵画を描いていたのではなく、メキシコ社会やその社会におけるアイデンティティの構築、特にジェンダー、人種、 社会階級について疑問を投げかけるために描いていた。[118] 歴史家のライザ・ベイクウェルは、カーロは「革命的イデオロギーがもたらした葛藤を認識していた」と述べている。 メキシコ人であるとはどういうことなのか? それは、現代でありながらコロンブス到来以前の時代であり、若くありながら老いており、反カトリックでありながらカトリックであり、西洋でありながら新世 界であり、発展しつつありながら発展途上であり、独立しているが植民地化されており、メスティーソでありながらスペイン人でもインディアンでもないという ことである。[119] こうした疑問を芸術作品を通じて探求するため、コルテス到来以前のシンボルやキリスト教のシンボル、神話を自身の絵画に広く取り入れ、複雑な図像学を展開 した。[120] 彼女のほとんどの自画像では、自身の顔を仮面のように描いているが、その周囲には、見る者がより深い意味を読み取れるような視覚的な手がかりが描かれてい る。猿、骸骨、頭蓋骨、血、心臓などのシンボルがアステカ神話を強く意識したものであり、これらのシンボルは、多くの場合、コアトリクエ、ケツァルコアト ル、ショロトルの神話に言及している。 。その他にも、カーロがアステカ神話から取り入れた中心的な要素として、混血と二元論がある。[122] 彼女の絵画の多くは、相反するものを描いている。すなわち、生と死、前近代と近代、メキシコとヨーロッパ、男性と女性である。[120] アステカの伝説に加え、カーロはメキシコの民話に登場する2人の女性像、ラ・ジョローナとラ・マリンチェをしばしば自身の絵画に描いた。[123] 困難な状況、苦しみ、不幸、あるいは判断と関連づけられ、悲惨で、みじめで、「うんざりする」ものとして描かれた。[124] 例えば、デトロイトのヘンリー・フォード病院で流産後に自身を描いた作品( 彼女は泣き崩れ、乱れた髪と露わになった胸をさらけ出している。これらはすべて、子供を殺した女性として知られるラ・ジョローナの外見の一部とされてい る。[125] この絵画は、伝統的には単に、妊娠の失敗に対するカーロの悲しみと苦痛を描いたものと解釈されてきた。しかし、絵画に描かれたシンボルの解釈と、彼女の書 簡から得られた母性に対する実際の考え方に関する情報により、この絵画は、メキシコ社会において子供を持たないという型破りでタブーとされる選択を描いた ものと見なされるようになった。 彼女は自身の身体をしばしば絵画に描き、さまざまな状態や仮装で表現した。傷ついた身体、壊れた身体、子供の身体、あるいはテワナ族の衣装、男性のスー ツ、ヨーロッパのドレスなど、異なる衣装をまとった身体である。[126] 彼女は自身の身体を比喩として用い、社会的な役割に関する疑問を探求した。[127] 彼女の絵画は、流産や出産、女装など、型破りな方法で女性の身体を描くことが多かった。[128] グラフィックな方法で女性の身体を描くことで、カーロは鑑賞者を覗き見する者の役割に位置づけ、「鑑賞者が意識的に反応する立場を仮定しないことは事実上 不可能」にした。[129] ナンシー・クーイによると、カーロは自身の絵画を通して、女性として、メキシコ人として、苦悩する人間として、自身の神話の主人公となった。彼女は、それ ぞれを、人類の持つ巨大な精神的な抵抗と素晴らしい性を表現できる象徴や記号に変える術を知っていた」と述べている。[130] 同様に、ナンシー・デフェバックは、カーロは「女性であり、メキシコ人であり、現代人であり、力強い存在として自らを創造した」と述べ、 。彼女の性別と壁画画家の伝統からの逸脱により、1980年代後半までは、男性画家の作品よりもカローの絵画は政治色が弱く、より素朴で主観的であるとみ なされていた。 彼女の主観性と個人的な歴史の探求に対する批評家の反応は、あまりにも頻繁に、自身の位置、遺産、社会状況を調査する際に伴う政治性を否定したり、軽視し たりしてきた。... 批評家の反応は、彼女の個人的な再解釈を美化し続け、彼女のセクシュアリティ、性的な違い、周縁性、文化的アイデンティティ、女性の主観性、政治、権力に 対する疑問を無視したり、最小限に抑えたりしている。[83] |

| Personal life 1907–1924: Family and childhood  Kahlo (on the right) and her sisters Cristina, Matilde, and Adriana, photographed by their father, 1916 Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón[b] was born on 6 July 1907 in Coyoacán, a village on the outskirts of Mexico City.[134][135] Kahlo stated that she was born at the family home, La Casa Azul (The Blue House), but according to the official birth registry, the birth took place at the nearby home of her maternal grandmother.[136] Kahlo's parents were photographer Guillermo Kahlo (1871–1941) and Matilde Calderón y González (1876–1932), and they were thirty-six and thirty, respectively, when they had her.[137] Originally from Germany, Guillermo had immigrated to Mexico in 1891, after epilepsy caused by an accident ended his university studies.[138] Although Kahlo said her father was Jewish and her paternal grandparents were Jews from the city of Arad,[139] this claim was challenged in 2006 by a pair of German genealogists who found he was instead a Lutheran.[140][141] Matilde was born in Oaxaca to an Indigenous father and a mother of Spanish descent.[142] In addition to Kahlo, the marriage produced daughters Matilde (c. 1898–1951), Adriana (c. 1902–1968), and Cristina (c. 1908–1964).[143] She had two half-sisters from Guillermo's first marriage, María Luisa and Margarita, but they were raised in a convent.[144] Kahlo later described the atmosphere in her childhood home as often "very, very sad".[145] Both parents were often sick,[146] and their marriage was devoid of love.[147] Her relationship with her mother, Matilde, was extremely tense.[148] Kahlo described her mother as "kind, active and intelligent, but also calculating, cruel and fanatically religious".[148] Her father Guillermo's photography business suffered greatly during the Mexican Revolution, as the overthrown government had commissioned works from him, and the long civil war limited the number of private clients.[146] When Kahlo was six years old, she contracted polio, which eventually made her right leg grow shorter and thinner than the left.[149][c] The illness forced her to be isolated from her peers for months, and she was bullied.[152] While the experience made her reclusive,[145] it made her Guillermo's favorite due to their shared experience of living with disability.[153] Kahlo credited him for making her childhood "marvelous ... he was an immense example to me of tenderness, of work (photographer and also painter), and above all in understanding for all my problems." He taught her about literature, nature, and philosophy, and encouraged her to play sports to regain her strength, despite the fact that most physical exercise was seen as unsuitable for girls.[154] He also taught her photography, and she began to help him retouch, develop, and color photographs.[155] Due to polio, Kahlo began school later than her peers.[156] Along with her younger sister Cristina, she attended the local kindergarten and primary school in Coyoacán and was homeschooled for the fifth and sixth grades.[157] While Cristina followed their sisters into a convent school, Kahlo was enrolled in a German school due to their father's wishes.[158] She was soon expelled for disobedience and was sent to a vocational teachers school.[157] Her stay at the school was brief, as she was sexually abused by a female teacher.[157] In 1922, Kahlo was accepted to the elite National Preparatory School, where she focused on natural sciences with the aim of becoming a physician.[159] The institution had only recently begun admitting women, with only 35 girls out of 2,000 students.[160] She performed well academically,[11] was a voracious reader, and became "deeply immersed and seriously committed to Mexican culture, political activism and issues of social justice".[161] The school promoted indigenismo, a new sense of Mexican identity that took pride in the country's Indigenous heritage and sought to rid itself of the colonial mindset of Europe as superior to Mexico.[162] Particularly influential to Kahlo at this time were nine of her schoolmates, with whom she formed an informal group called the "Cachuchas" – many of them would become leading figures of the Mexican intellectual elite.[163] They were rebellious and against everything conservative and pulled pranks, staged plays, and debated philosophy and Russian classics.[163] To mask the fact that she was older and to declare herself a "daughter of the revolution", she began saying that she had been born on 7 July 1910, the year the Mexican Revolution began, which she continued throughout her life.[164] She fell in love with Alejandro Gomez Arias, the leader of the group and her first love. Her parents did not approve of the relationship. Arias and Kahlo were often separated from each other, due to the political instability and violence of the period, so they exchanged passionate love letters.[13][165] |

私的生活(→年譜は「フリーダ・カーロと痛みの芸術」) 1907–1924: Family and childhood  Kahlo (on the right) and her sisters Cristina, Matilde, and Adriana, photographed by their father, 1916 マグダレーナ・カルメン・フリーダ・カーロ・イ・カルデロン[b]は1907年7月6日、メキシコシティ郊外の村であるコヨアカンで生まれた。[134] [135] カーロは、自分が家族の家である「青い家」で生まれたと述べているが、公式の出生登録によると、出産は母親方の祖母の家の近くで行われた。[13 6] カロの父母は写真家のギジェルモ・カロ(1871年 - 1941年)とマティルデ・カルデロン・イ・ゴンサレス(1876年 - 1932年)で、カロが生まれたとき、それぞれ36歳と30歳だった。[137] ドイツ出身のギジェルモは、事故によるてんかんの発作で大学での勉学を断念した後、1891年にメキシコに移住した。[1 38] カロは父親がユダヤ人であり、父方の祖父母はアラド出身のユダヤ人であったと述べているが[139]、2006年にドイツの系図学者2人組が、カロの父親 はむしろルター派であったと主張し、この主張に異議を唱えた。[140][141] マチルデはオアハカで先住民の父親とスペイン系母親の間に生まれた。[142] カロのほかに、 結婚により、娘のマチルデ(1898年頃 - 1951年)、アドリアナ(1902年頃 - 1968年)、クリスティーナ(1908年頃 - 1964年)が生まれた。[143] ギジェルモの最初の結婚から、彼女にはマリア・ルイサとマルガリータという2人の異母姉妹がいたが、彼女たちは修道院で育てられた。[144] カーロは後に、幼少期の家庭の雰囲気を「とてもとても悲しい」と表現している。[145] 両親はともに病気がちで[146]、夫婦の仲は愛のないものだった。[147] 母親のマティルデとの関係は極度に緊張したものだった。[148] カーロは 「優しく、活発で聡明だが、計算高く、残酷で狂信的な宗教家でもあった」と評している。[148] 父親のギジェルモの写真事業は、メキシコ革命の際に打倒された政府から仕事を依頼されていたため、大きな打撃を受けた。また、長期にわたる内戦により、民 間顧客の数が限られていた。[146] 6歳のとき、カローはポリオに感染し、最終的に右足が左足よりも短く細くなってしまった。[149][c] この病気により、彼女は何ヶ月も同年代の子供たちから隔離され、いじめられた。[152] この経験により彼女は内向的になったが、[14 5] しかし、障害を抱えて生きるという共通の経験から、彼女はギジェルモのお気に入りとなった。[153] カーロは、自身の子供時代を「素晴らしいものにしてくれた」と彼に感謝している。「彼は、優しさ、写真家や画家としての仕事、そして何よりも、私の抱える あらゆる問題に対する理解の面で、私にとって計り知れないお手本だった。」 彼は彼女に文学、自然、哲学について教え、また、ほとんどの運動が女の子には不向きとされていたにもかかわらず、体力をつけるためにスポーツをするよう彼 女を励ました。[154] また、彼は彼女に写真を教え、彼女は写真のレタッチ、現像、着色を手伝うようになった。[155] ポリオのため、カーロは同年代の子供たちよりも遅れて学校に入学した。[156] 妹のクリスティーナとともに、コヨアカンにある地元の幼稚園と小学校に通い、5年生と6年生のときは自宅で教育を受けた。[157] クリスティーナが姉妹とともに修道女学校に入学したのに対し、 父親の希望により、カーロはドイツ人学校に入学した。[158] 彼女はすぐに反抗的な態度で退学処分となり、職業教師学校に送られた。[157] 彼女がその学校にいた期間は短かった。なぜなら、彼女は女性教師から性的虐待を受けていたからだ。[157] 1922年、カーロはエリート校である国立予備校への入学を許可され、医師になることを目指して自然科学を専攻した。[159] 当時、この学校では女性を受け入れ始めたばかりで、2,000人の学生のうち女子学生はわずか35人だった。[160] カーロは学業でも優秀な成績を収め、[11] 熱心な読書家であり、「メキシコ文化、政治活動、社会正義の問題に深く没頭し、真剣に取り組んだ」[161]。この学校は、メキシコの固有の伝統に誇りを 持ち、ヨーロッパの植民地主義的な考え方を排除しようとする、メキシコのアイデンティティの新しい感覚である「インディヘニスム」を推進していた [162]。特に この時期、彼女に特に大きな影響を与えたのは、彼女の同級生9人であった。彼女たちは「Cachuchas」という非公式のグループを結成し、そのうちの 多くがメキシコの知識人エリートの指導的人物となった。[163] 彼らは反逆的で、保守的なものすべてに反対し、いたずらをしたり、劇を上演したり、哲学やロシアの古典について討論したりしていた。[163] 年長であることを隠し、「革命の娘」であると宣言するために、彼女はメキシコ革命が始まった1910年7月7日に生まれたと主張し始め、それは生涯続い た。[164] 彼女はグループのリーダーであり初恋の人であるアレハンドロ・ゴメス・アリアスと恋に落ちた。両親は2人の交際に反対した。アリアスとカーロは、当時の政 治的不安定と暴力により、しばしば離ればなれになっていたため、熱烈なラブレターを交換していた。[13][165] |

1925–1930: Bus accident and marriage to Diego Rivera Kahlo photographed by her father in 1926 On 17 September 1925, Kahlo and her boyfriend, Arias, were on their way home from school. They boarded one bus, but they got off the bus to look for an umbrella that Kahlo had left behind. They then boarded a second bus, which was crowded, and they sat in the back. The driver attempted to pass an oncoming electric streetcar. The streetcar crashed into the side of the wooden bus, dragging it a few feet. Several passengers were killed in the accident. While Arias suffered minor injuries, Frida was impaled with an iron handrail that went through her pelvis. She later described the injury as "the way a sword pierces a bull". The handrail was removed by Arias and others, which was incredibly painful for Kahlo.[165][166][167] Kahlo suffered many injuries: her pelvic bone had been fractured, her abdomen and uterus had been punctured by the rail, her spine was broken in three places, her right leg was broken in eleven places, her right foot was crushed and dislocated, her collarbone was broken, and her shoulder was dislocated.[165][168] She spent a month in hospital and two months recovering at home before being able to return to work.[166][167][169] As she continued to experience fatigue and back pain, her doctors ordered X-rays, which revealed that the accident had also displaced three vertebrae.[170] As treatment she had to wear a plaster corset which confined her to bed rest for the better part of three months.[170] The accident ended Kahlo's dreams of becoming a physician and caused her pain and illness for the rest of her life; her friend Andrés Henestrosa stated that Kahlo "lived dying".[171] Kahlo's bed rest was over by late 1927, and she began socializing with her old schoolfriends, who were now at university and involved in student politics. She joined the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) and was introduced to a circle of political activists and artists, including the exiled Cuban communist Julio Antonio Mella and the Italian-American photographer Tina Modotti.[172] At one of Modotti's parties in June 1928, Kahlo was introduced to Diego Rivera.[173] They had met briefly in 1922 when he was painting a mural at her school.[174] Shortly after their introduction in 1928, Kahlo asked him to judge whether her paintings showed enough talent for her to pursue a career as an artist.[175] Rivera recalled being impressed by her works, stating that they showed "an unusual energy of expression, precise delineation of character, and true severity ... They had a fundamental plastic honesty, and an artistic personality of their own ... It was obvious to me that this girl was an authentic artist".[176]  Kahlo with husband Diego Rivera in 1932 Kahlo soon began a relationship with Rivera, who was 21 years her senior and had two common-law wives.[177] Kahlo and Rivera were married in a civil ceremony at the town hall of Coyoacán on 21 August 1929.[178] Her mother opposed the marriage, and both parents referred to it as a "marriage between an elephant and a dove", referring to the couple's differences in size; Rivera was tall and overweight while Kahlo was petite and fragile.[179] Regardless, her father approved of Rivera, who was wealthy and therefore able to support Kahlo, who could not work and had to receive expensive medical treatment.[180] The wedding was reported by the Mexican and international press,[181] and the marriage was subject to constant media attention in Mexico in the following years, with articles referring to the couple as simply "Diego and Frida".[182] Soon after the marriage, in late 1929, Kahlo and Rivera moved to Cuernavaca in the rural state of Morelos, where he had been commissioned to paint murals for the Palace of Cortés.[183] Around the same time, she resigned her membership of the PCM in support of Rivera, who had been expelled shortly before the marriage for his support of the leftist opposition movement within the Third International.[184] During the civil war Morelos had seen some of the heaviest fighting, and life in the Spanish-style city of Cuernavaca sharpened Kahlo's sense of a Mexican identity and history.[20] Similar to many other Mexican women artists and intellectuals at the time,[185] Kahlo began wearing traditional Indigenous Mexican peasant clothing to emphasize her mestiza ancestry: long and colorful skirts, huipils and rebozos, elaborate headdresses and masses of jewelry.[186] She especially favored the dress of women from the allegedly matriarchal society of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, who had come to represent "an authentic and indigenous Mexican cultural heritage" in post-revolutionary Mexico.[187] The Tehuana outfit allowed Kahlo to express her feminist and anti-colonialist ideals.[188] |

1925-1930 バス事故とディエゴ・リベラとの結婚 Kahlo photographed by her father in 1926 1925年9月17日、フリーダ・カーロとボーイフレンドのアリアスは学校からの帰途にあった。2人は1台のバスに乗ったが、カーロがバスの中に忘れた傘 を取りに戻ったため、バスを降りた。そして2人は混雑した2台目のバスに乗り込み、後部座席に座った。運転手が対向してくる市電を追い越そうとした。路面 電車は木造バスの側面に衝突し、数フィート引きずった。この事故で数人の乗客が死亡した。アリアスは軽傷で済んだが、フリーダは鉄の手すりが骨盤を貫通し た。彼女は後にこの傷を「剣が雄牛を貫くようなもの」と表現した。手すりはアリアスや他の人々によって取り除かれたが、それはカーロにとって信じられない ほど痛みを伴うものだった。[165][166][167] カウロは多くの怪我を負った。骨盤が骨折し、腹部と子宮が手すりで突き刺され、背骨が3か所で折れ、右足が11か所で折れ、右足が潰れて脱臼し、鎖骨が折 れ、肩が脱臼した。職場復帰するまでに、1か月間入院し、2か月間自宅で療養した。[166][167][169] その後も疲労と背中の痛みに悩まされ続けたため、医師はX線検査を命じ、事故により3つの脊椎がずれていることが判明した。[170] 治療としてギプスコルセットを着用しなければならず、3か月間の大半をベッドで安静に過ごさなければならなかった。[170] この事故により、医師になるという夢は断たれ、生涯にわたって苦痛と病に悩まされることになった。友人のアンドレス・エネストロサは、カーロは「死ぬよう に生きている」と述べた。[171] カーロの安静臥床生活は1927年末には終わり、彼女は大学に進学して学生政治に関わっていた昔の同級生たちと交流を始めた。彼女はメキシコ共産党 (PCM)に入党し、亡命中のキューバ人共産主義者フリオ・アントニオ・メーヤやイタリア系アメリカ人の写真家ティナ・モドッティなど、政治活動家や芸術 家のサークルに紹介された。 1928年6月、モドッティのパーティーで、カーロはディエゴ・リベラと出会った。[173] 2人は1922年に、彼が彼女の学校で壁画を描いていたときに、短時間会っていた。[174] 1928年に2人が出会ってから間もなく、 1928年に紹介された後、カーロは自分の絵画に画家としてのキャリアを追求するに足る才能があるかどうかを判断してもらうよう彼に求めた。[175] リベラは彼女の作品に感銘を受けたことを思い出し、次のように述べた。「表現における並外れたエネルギー、性格の正確な描写、真の厳しさ...。それらは 根本的な造形的な誠実さ、そして独自の芸術的な個性を備えていた...。この少女が本物の芸術家であることは明らかだった」。[176]  Kahlo with husband Diego Rivera in 1932 21歳年上で、内縁の妻が2人いたリベラと、カーロはすぐに交際を始めた。[177] カーロとリベラは1929年8月21日にコヨアカン区役所で民事婚式を行った。[178] 母親は結婚に反対したが、両親は2人の体格の違いを「象とハトの結婚」と表現した。リベラは長身で 一方、カーロは小柄でか弱い女性であった。[179] それでも、父親はリベラを承認した。リベラは裕福で、そのため働くことのできないカーロを経済的に支えることができた。カーロは高額な医療を受けなければ ならなかった。[180] 結婚式はメキシコおよび国際的な報道機関によって報道され、[181] その後の数年間、メキシコではこの結婚は常にメディアの注目を集め、記事では2人を単に「ディエゴとフリーダ」と表記した。[182] 結婚後まもなく、1929年の終わりに、カローとリベラはモレロス州の田舎にあるクエルナバカに移り住んだ。そこには、彼がコルテス宮殿の壁画を描くよう 依頼されていたからである。[183] 同じ頃、彼女はリベラを支援するためにPCMの会員を辞めた。リベラは、結婚の直前に第三インターナショナル内の左派反対運動を支持したとして除名されて いた。[184] モレロス州はメキシコ内戦で最も激しい戦闘のいくつかを目撃しており、スペイン風の都市クエルナバカでの生活は、カーロのメキシコ人としてのアイデンティ ティと歴史に対する感覚を研ぎ澄ませた。[20] カーロは、当時メキシコの多くの女性芸術家や知識人と同様に、[185] メスティーサとしての先祖を強調するために、メキシコ先住民の伝統的な農民の服装を身に着けるようになった。それは、カラフルで長いスカート、ウィピル、 レボゾ、手の込んだ頭飾り、そして大量の宝石類であった。 精巧な頭飾り、そして大量の宝石類を身につけるようになった。[186] 特に、テワンテペック地峡の女性たちが着用していた服装を好んだ。この地峡は、母系社会であるとされる地域であり、革命後のメキシコでは「本物のメキシコ 固有の文化遺産」を象徴する存在となっていた。[187] テワンテペックの服装は、カーロがフェミニストおよび反植民地主義の理想を表現することを可能にした。[188] |

1931–1933: Travels in the United States Frida photographed in 1932 by her father, Guillermo After Rivera had completed the commission in Cuernavaca in late 1930, he and Kahlo moved to San Francisco, where he painted murals for the Luncheon Club of the San Francisco Stock Exchange and the California School of Fine Arts.[189] The couple was "feted, lionized, [and] spoiled" by influential collectors and clients during their stay in the city.[24] Her long love affair with Hungarian-American photographer Nickolas Muray most likely began around this time.[190] Kahlo and Rivera returned to Mexico for the summer of 1931, and in the fall traveled to New York City for the opening of Rivera's retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). In April 1932, they headed to Detroit, where Rivera had been commissioned to paint murals for the Detroit Institute of Arts.[191] By this time, Kahlo had become bolder in her interactions with the press, impressing journalists with her fluency in English and stating on her arrival to the city that she was the greater artist of the two of them.[192] "Of course he [Rivera] does well for a little boy, but it is I who am the big artist" — Frida Kahlo in interview with the Detroit News, 2 February 1933.[193] The year spent in Detroit was a difficult time for Kahlo. Although she had enjoyed visiting San Francisco and New York City, she disliked aspects of American society, which she regarded as colonialist, as well as most Americans, whom she found "boring".[194] She disliked having to socialize with capitalists such as Henry and Edsel Ford, and was angered that many of the hotels in Detroit refused to accept Jewish guests.[195] In a letter to a friend, she wrote that "although I am very interested in all the industrial and mechanical development of the United States", she felt "a bit of a rage against all the rich guys here, since I have seen thousands of people in the most terrible misery without anything to eat and with no place to sleep, that is what has most impressed me here, it is terrifying to see the rich having parties day and night while thousands and thousands of people are dying of hunger."[34] Kahlo's time in Detroit was also complicated by a pregnancy. Her doctor agreed to perform an abortion, but the medication used was ineffective.[196] Kahlo was deeply ambivalent about having a child and had already undergone an abortion earlier in her marriage to Rivera.[196] Following the failed abortion, she reluctantly agreed to continue with the pregnancy, but miscarried in July, which caused a serious hemorrhage that required her being hospitalized for two weeks.[33] Less than three months later, her mother died from complications of surgery in Mexico.[197] External images image icon Henry Ford Hospital (1932) image icon Self-portrait on the Border of Mexico and the United States (1932) image icon My Dress Hangs There (1933) image icon My Birth (1932) Kahlo and Rivera returned to New York in March 1933, for he had been commissioned to paint a mural for the Rockefeller Center.[198] During this time, she only worked on one painting, My Dress Hangs There (1933).[198] She also gave further interviews to the American press.[198] In May, Rivera was fired from the Rockefeller Center project and was instead hired to paint a mural for the New Workers School.[199][198] Although Rivera wished to continue their stay in the United States, Kahlo was homesick, and they returned to Mexico soon after the mural's unveiling in December 1933.[200] |

1931-1933 渡米 Frida photographed in 1932 by her father, Guillermo 1930年後半にリベラがクエルナバカでの任務を終えると、彼はカーロとともにサンフランシスコに移り住み、サンフランシスコ証券取引所の昼食会クラブや カリフォルニア美術学校のために壁画を描いた。この街に滞在していた間、夫妻は有力なコレクターや顧客たちから「もてはやされ、崇拝され、甘やかされた」 [24]。ハンガリー系アメリカ人の写真家ニコラス・ムレイとの長い愛情関係は、おそらくこの頃に始まった。 1931年の夏、カーロとリベラはメキシコに戻り、秋にはニューヨーク近代美術館(MoMA)で開催されたリベラの回顧展のオープニングに出席するために ニューヨークを訪れた。1932年4月、2人はデトロイトに向かった。そこでは、リベラがデトロイト美術館のために壁画を描く依頼を受けていたのだ。 [191] この頃には、カーロは報道陣との交流にも大胆になり、流暢な英語を駆使してジャーナリストたちを感嘆させ、デトロイトに到着した際には、自分の方が2人の うちの優れた芸術家であると述べた。[192] 「もちろん、彼は(リベラは)少年としてはよくやっているが、私が偉大な芸術家だ」 — 1933年2月2日付デトロイト・ニュース紙のインタビューにおけるフリーダ・カーロの発言。[193] デトロイトで過ごした1年は、カーロにとってつらい時期であった。彼女はサンフランシスコやニューヨークを訪れることを楽しんでいたが、アメリカ社会の植 民地主義的な側面や、ほとんどのアメリカ人を「退屈」だと感じて嫌っていた。[194] 彼女はヘンリー・フォードやエドセル・フォードのような資本家たちと付き合わなければならなかったことを嫌い、 デトロイトの多くのホテルがユダヤ人の宿泊客を受け入れないことに憤慨していた。[195] 友人に宛てた手紙の中で、彼女は「私は米国の産業や機械のあらゆる発展に非常に興味を持っているが、」と書き、「 食べ物もなく、寝る場所もない、最もひどい悲惨な状況にある何千人もの人々を目にした。それがここでの最も印象的なことだった。何千、何万もの人々が飢え で死んでいく一方で、金持ちたちが昼夜を問わずパーティーを開いているのを見るのは恐ろしいことだ」[34] デトロイトでのカーロの生活は、妊娠によってさらに複雑なものとなった。担当医は中絶手術に同意したが、使用された薬は効果的ではなかった。[196] カーロは子供を持つことについて深く複雑な思いを抱いており、すでにリベラとの結婚当初に中絶手術を受けていた。[196] 中絶手術の失敗後、彼女は しぶしぶ妊娠継続に同意したが、7月に流産し、大量出血により2週間の入院が必要となった。[33] それから3か月も経たないうちに、メキシコでの手術の合併症により、彼女の母親が死亡した。[197] 外部画像 画像アイコン ヘンリー・フォード病院(1932年) 画像アイコン メキシコと米国の国境での自画像(1932年) 画像アイコン 私のドレスがそこに掛かっている(1933年) 画像アイコン 私の誕生(1932年) 1933年3月、カーロとリベラはニューヨークに戻った。彼はロックフェラー・センターの壁画制作を依頼されていたからだ。[198] この間、彼女は『My Dress Hangs There』(1933年)という1枚の絵画のみを手がけた。[198] また、彼女はアメリカの報道陣にさらにインタビューを行った。[198] 5月、リベラはロックフェラー・センターのプロジェクトから解雇され、代わりにニュー・ワーカーズ・スクール(New Workers School)の壁画を描くために雇われた。[199][198] リベラはアメリカでの滞在を続けたいと考えていたが、カーロはホームシックにかかり、1933年12月に壁画が公開された後、すぐにメキシコに戻った。 [200] |

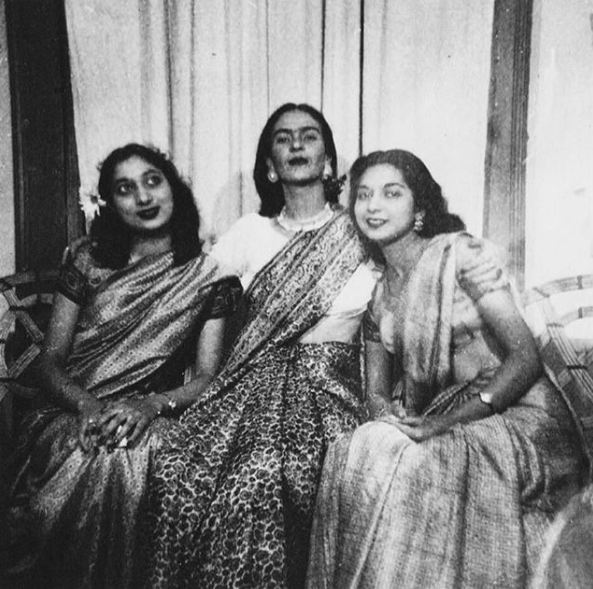

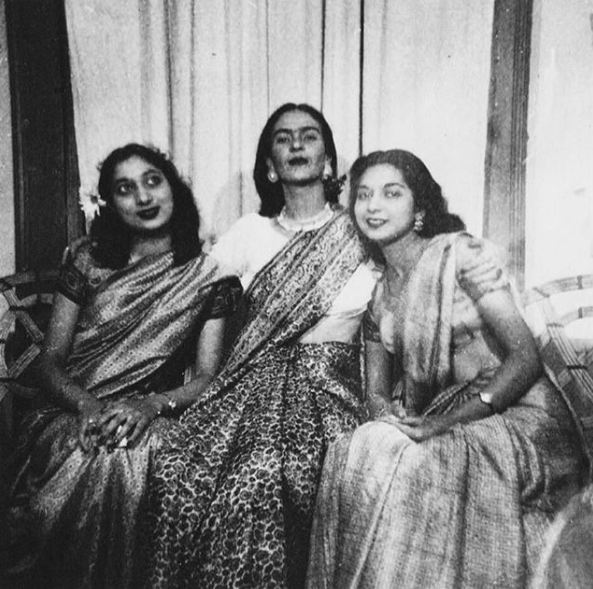

1934–1949: La Casa Azul and declining health Kahlo and Rivera's houses in San Ángel. They lived there from 1934 until their divorce in 1939, after which it became his studio. Back in Mexico City, Kahlo and Rivera moved into a new house in the wealthy neighborhood of San Ángel.[201] Commissioned from Le Corbusier's student Juan O'Gorman, it consisted of two sections joined by a bridge; Kahlo's was painted blue and Rivera's pink and white.[202] The bohemian residence became an important meeting place for artists and political activists from Mexico and abroad.[203] Kahlo once again experienced health problems – undergoing an appendectomy, two abortions, and the amputation of gangrenous toes[204][151] – and her marriage to Rivera had become strained. He was not happy to be back in Mexico and blamed Kahlo for their return.[205] While he had been unfaithful to her before, he now embarked on an affair with her younger sister Cristina, which deeply hurt Kahlo's feelings.[206] After discovering the affair in early 1935, she moved to an apartment in central Mexico City and considered divorcing him.[207] She also had an affair of her own with American artist Isamu Noguchi.[208] Kahlo was reconciled with Rivera and Cristina later in 1935 and moved back to San Ángel.[209] She became a loving aunt to Cristina's children, Isolda and Antonio.[210] Despite the reconciliation, both Rivera and Kahlo continued their infidelities.[211] She also resumed her political activities in 1936, joining the Fourth International and becoming a founding member of a solidarity committee to provide aid to the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War.[212] She and Rivera successfully petitioned the Mexican government to grant asylum to former Soviet leader Leon Trotsky and offered La Casa Azul for him and his wife Natalia Sedova as a residence.[213] The couple lived there from January 1937 until April 1939, with Kahlo and Trotsky not only becoming good friends but also having a brief affair.[214] Kahlo painted Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky in 1937 during their time together in Mexico City, including a written inscription to Trotsky in the painting on a letter that Kahlo's figure holds.[215] External images image icon A Few Small Nips (1935) image icon My Nurse and I (1937) image icon Four Inhabitants of Mexico (1938)  1937 photograph by Toni Frissell, from a fashion shoot for Vogue After opening an exhibition in Paris, Kahlo sailed back to New York.[216] She was eager to be reunited with Muray, but he decided to end their affair, as he had met another woman whom he was planning to marry.[217] Kahlo traveled back to Mexico City, where Rivera requested a divorce from her. The exact reasons for his decision are unknown, but he stated publicly that it was merely a "matter of legal convenience in the style of modern times ... there are no sentimental, artistic, or economic reasons".[218] According to their friends, the divorce was mainly caused by their mutual infidelities.[219] He and Kahlo were granted a divorce in November 1939, but remained friendly; she continued to manage his finances and correspondence.[220]  La Casa Azul, Kahlo's childhood home and residence from 1939 until her death in 1954  The garden at La Casa Azul Following her separation from Rivera, Kahlo moved back to La Casa Azul and, determined to earn her own living, began another productive period as an artist, inspired by her experiences abroad.[221] Encouraged by the recognition she was gaining, she moved from using the small and more intimate tin sheets she had used since 1932 to large canvases, as they were easier to exhibit.[222] She also adopted a more sophisticated technique, limited the graphic details, and began to produce more quarter-length portraits, which were easier to sell.[223] She painted several of her most famous pieces during this period, such as The Two Fridas (1939), Self-portrait with Cropped Hair (1940), The Wounded Table (1940), and Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940). Three exhibitions featured her works in 1940: the fourth International Surrealist Exhibition in Mexico City, the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco, and Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art in MoMA in New York.[224][225] On 21 August 1940, Trotsky was assassinated in Coyoacán, where he had continued to live after leaving La Casa Azul.[226] Kahlo was briefly suspected of being involved, as she knew the murderer, and was arrested and held for two days with her sister Cristina.[227] The following month, Kahlo traveled to San Francisco for medical treatment for back pain and a fungal infection on her hand.[228] Her continuously fragile health had increasingly declined since her divorce and was exacerbated by her heavy consumption of alcohol.[229] Rivera was also in San Francisco after he fled Mexico City following Trotsky's murder and accepted a commission.[230] Although Kahlo had a relationship with art dealer Heinz Berggruen during her visit to San Francisco,[231] she and Rivera were reconciled.[232] They remarried in a simple civil ceremony on 8 December 1940.[233] Kahlo and Rivera returned to Mexico soon after their wedding. The union was less turbulent than before for its first five years.[234] Both were more independent,[235] and while La Casa Azul was their primary residence, Rivera retained the San Ángel house for use as his studio and second apartment.[236] Both continued having extramarital affairs; Kahlo, being bisexual, had affairs with both men and women, with evidence suggesting her male lovers were more important to Kahlo than her female lovers.[235][237]  Kahlo (centre), Nayantara Sahgal (right) and Rita Dar at Casa Azul in 1947 Despite the medical treatment she had received in San Francisco, Kahlo's health problems continued throughout the 1940s. Due to her spinal problems, she wore twenty-eight separate supportive corsets, varying from steel and leather to plaster, between 1940 and 1954.[238] She experienced pain in her legs, the infection on her hand had become chronic, and she was also treated for syphilis.[239] The death of her father in April 1941 plunged her into a depression.[234] Her ill health made her increasingly confined to La Casa Azul, which became the center of her world. She enjoyed taking care of the house and its garden, and was kept company by friends, servants, and various pets, including spider monkeys, Xoloitzcuintlis, and parrots.[240] While Kahlo was gaining recognition in her home country, her health continued to decline. By the mid-1940s, her back had worsened to the point that she could no longer sit or stand continuously.[241] In June 1945, she traveled to New York for an operation which fused a bone graft and a steel support to her spine to straighten it.[242] The difficult operation was a failure.[71] According to biographer Hayden Herrera, Kahlo also sabotaged her recovery by not resting as required and by once physically re-opening her wounds in a fit of anger.[71] Her paintings from this period, such as The Broken Column (1944), Without Hope (1945), Tree of Hope, Stand Fast (1946), and The Wounded Deer (1946), reflect her declining health.[71] |

1934-1949 青い家と健康状態の悪化 Kahlo and Rivera's houses in San Ángel. They lived there from 1934 until their divorce in 1939, after which it became his studio. メキシコシティに戻ったカーロとリベラは、サン・アンヘルの富裕層が住む地区に新居を購入した。[201] ル・コルビュジエの弟子であるファン・オゴルマンに依頼したもので、2つのセクションが橋でつながれた構造になっており、カーロの部屋は青、リベラの部屋 はピンクと白で塗られていた。[202] この自由奔放な住まいは、メキシコ国内および国外の芸術家や政治活動家にとって重要な集いの場となった。[203] カーロは再び健康問題に悩まされ、虫垂切除術、2度の人工妊娠中絶、壊疽した足指の切断手術を受けた[204][151]。リベラとの結婚生活はぎくしゃ くしていた。彼はメキシコに戻ってきたことを喜んではおらず、ふたりの帰国をカーロのせいだと非難した。[205] 以前にも彼女に対して不誠実な態度を取っていたが、今度は妹のクリスティーナと浮気し、カーロの心を深く傷つけた。[2 06] 1935年初頭に不倫関係を知った彼女はメキシコシティ中心部のアパートに引っ越し、離婚を検討した。[207] 彼女はまた、アメリカ人芸術家イサム・ノグチとも不倫関係にあった。[208] 1935年後半に、カーロはリベラとクリスティーナと和解し、サン・アンヘルに戻った。[209] 彼女はクリスティーナの子供たち、イゾルダとアントニオにとって愛情深い叔母となった。[210] 和解後も、リベラとカーロは不貞を続けた。[211] 彼女は1936年に政治活動も再開し、第四インターナショナルに参加 国際に参加し、スペイン内戦における共和党への支援を行う連帯委員会の創設メンバーとなった。[212] 彼女とリベラは、元ソビエト連邦指導者レオン・トロツキーに亡命を認めるようメキシコ政府に請願し、トロツキー夫妻の住居としてラ・カサ・アスルを提供し た。[213] 夫妻は1937年1月から1939年4月までそこに住み、 。2人は親しい友人となっただけでなく、短い間、情事を交わす仲にもなった。[214] 1937年、2人がメキシコシティで一緒に暮らしていた間に、彼女は「レオン・トロツキーに捧げる自画像」を描いた。この絵には、彼女の描いた手紙にトロ ツキーへの献辞が書かれている。[215] 外部画像 画像アイコン A Few Small Nips (1935) 画像アイコン My Nurse and I (1937) 画像アイコン Four Inhabitants of Mexico (1938)  1937 photograph by Toni Frissell, from a fashion shoot for Vogue パリでの展覧会を終えた後、カーロはニューヨークに戻った。[216] 彼女はムレーと再会することを切望していたが、彼は結婚を考えていた別の女性と出会っていたため、2人の関係を終わらせることを決意した。[217] カーロはメキシコシティに戻ったが、そこでリベラから離婚を求められた。その決断の正確な理由は不明であるが、彼は公に「単に現代的な法律上の都合の問題 であり、感傷的な理由でも芸術的な理由でも経済的な理由でもない」と述べた。[218] 友人たちの話によると、 、離婚の主な原因は2人の不貞関係であったとされている。[219] 1939年11月に2人は離婚が認められたが、友好的な関係は続いた。彼女は引き続き彼の財務管理と文通の管理を続けた。[220]  La Casa Azul, Kahlo's childhood home and residence from 1939 until her death in 1954  The garden at La Casa Azul リベラと別れた後、カーロはラ・カサ・アスールに戻り、自活を決意して、海外での経験からインスピレーションを得て、芸術家として新たな生産的な時期を始 めた。[221] 彼女が獲得しつつあった評価に後押しされ、1932年から使用していた小さく親密なブリキ板から、展示しやすい大きなキャンバスへと移行した。[222] また、より洗練された技法を取り入れ グラフィックな細部を控え、より販売しやすい半身像の肖像画を描くようになった。この時期に彼女は、最も有名な作品のいくつか、例えば『二人のフリーダ』 (1939年)、『髪を切った自画像』(1940年)、『傷ついたテーブル』(1940年)、『とげのネックレスとハチドリの自画像』(1940年)など を描いた。1940年には、彼女の作品が3つの展覧会で展示された。メキシコシティで開催された第4回国際シュルレアリスム展、サンフランシスコで開催さ れたゴールデンゲート国際博覧会、ニューヨーク近代美術館で開催された「メキシコ芸術20世紀」展である。 1940年8月21日、トロツキーはラ・カサ・アスルを去った後も住み続けていたコヨアカンで暗殺された。[226] 殺人犯と面識があったため、カーロは一時的に容疑者とみなされ、逮捕され、妹のクリスティーナとともに2日間勾留された 妹のクリスティーナとともに2日間勾留された。[227] 翌月、カホーは背中の痛みと手の真菌感染症の治療のためサンフランシスコに旅立った。[228] 離婚以来、彼女の健康状態は常に不安定で、アルコールの過剰摂取によりさらに悪化した。[229] リベラもトロツキー暗殺後にメキシコシティを脱出し、委任を受け入れた後、サンフランシスコに滞在していた。[230] サンフランシスコ滞在中に画商ハインツ・ベルググレンと関係を持ったものの、[231] カーロとリベラは和解した。[232] 1940年12月8日、2人は簡素な民事式で再婚した。[233] カーロとリベラは結婚式後すぐにメキシコに戻った。最初の5年間は、以前よりも平穏な結婚生活を送った。[234] 2人ともより自立し、[235] ラ・カサ・アスールを主な住居としながらも、リベラはサン・アンヘルにある家をアトリエ兼2軒目のアパートとして維持した。[2 36] 2人とも婚外恋愛を続けていた。カフカは両性愛者であり、男女両方と関係を持っていた。証拠によると、カフカにとって女性よりも男性の恋人のほうが重要で あったようである。[235][237]  Kahlo (centre), Nayantara Sahgal (right) and Rita Dar at Casa Azul in 1947 サンフランシスコで受けた医療にもかかわらず、1940年代を通して、カーロの健康問題は続いた。脊椎の問題により、1940年から1954年の間、彼女 は28着の異なるコルセットを着用した。コルセットは、スチールや革製のものから石膏製のものまで様々であった。[238] 彼女は足に痛みを感じ、手の感染症は慢性化し、 また、梅毒の治療も受けていた。[239] 1941年4月に父が亡くなったことで、彼女は深い悲しみに暮れた。[234] 彼女の健康状態が悪化したことで、ラ・カサ・アスールにますます閉じこもるようになり、そこが彼女の世界の中心となった。彼女は家の庭の手入れを楽しみ、 友人や使用人、蜘蛛ザル、ショロイツクイントゥリ、オウムなどのさまざまなペットに囲まれていた。 メキシコ国内で徐々に知名度を上げていく一方で、彼女の健康状態は悪化の一途をたどった。1940年代半ばには、背中の痛みがひどくなり、座ったり立った りすることができなくなった。[241] 1945年6月、彼女は背骨をまっすぐにするために、骨移植とスチール製の支柱を融合させる手術を受けるためにニューヨークへ旅立った。[242] この難しい手術は失敗に終わった。[71] 伝記作家ヘイデン・ヘレラによると、 カーロは、必要な安静を保たず、また、怒りに任せて一度は肉体的につけた傷を再び開いてしまったことで、回復を妨害した。伝記作家ヘイデン・ヘレラによる と、この時期の彼女の絵画、『折れた柱』(1944年)、『希望なし』(1945年)、『希望の木、耐え忍べ』(1946年)、『傷ついた鹿』(1946 年)などは、彼女の健康状態の悪化を反映している。 |