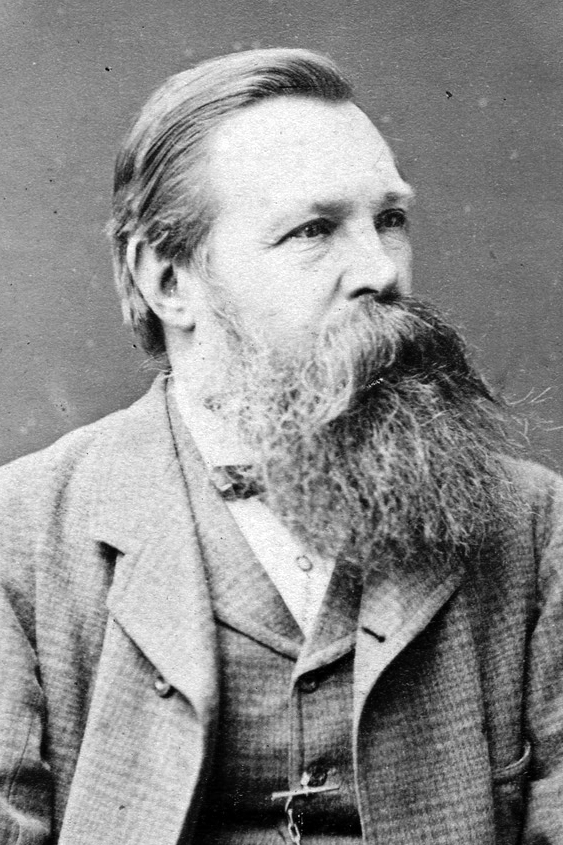

Friedrich

Engels (/ˈɛŋɡəlz/ ENG-gəlz;[2][3][4] German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈʔɛŋl̩s];

28

November 1820 – 5 August 1895) was a German philosopher, political

theorist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He was

also a businessman and Karl Marx's lifelong friend and closest

collaborator, serving as a leading authority on Marxism. Friedrich

Engels (/ˈɛŋɡəlz/ ENG-gəlz;[2][3][4] German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈʔɛŋl̩s];

28

November 1820 – 5 August 1895) was a German philosopher, political

theorist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He was

also a businessman and Karl Marx's lifelong friend and closest

collaborator, serving as a leading authority on Marxism.

Engels, the son of a wealthy textile manufacturer, met Marx in 1844.

They jointly authored works including The Holy Family (1844), The

German Ideology (written 1846), and The Communist Manifesto (1848), and

worked as political organisers and activists in the Communist League

and First International. Engels also supported Marx financially for

much of his life, enabling him to continue writing after he moved to

London in 1849. After Marx's death in 1883, Engels compiled Volumes II

and III of his Das Kapital (1885 and 1894).

Engels wrote eclectic works of his own, including The Condition of the

Working Class in England (1845), Anti-Dühring (1878), Dialectics of

Nature (1878–1882), The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the

State (1884), and Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German

Philosophy (1886). His writings on materialism, idealism, and

dialectics supplied Marxism with an ontological and metaphysical

foundation.[citation needed]

|

フ

リードリヒ・エンゲルス(/ˈɛŋɡəlz/ ENG-gəlz;[2][3][4] ドイツ語: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈʔɛŋl̩s];

1820年11月28日 -

1895年8月5日)は、ドイツの哲学者、政治理論家、歴史家、ジャーナリスト、革命的社会主義者である。実業家でもあり、カール・マルクスの生涯の友人

であり、最も親しい協力者であり、マルクス主義の第一人者でもあった。 フ

リードリヒ・エンゲルス(/ˈɛŋɡəlz/ ENG-gəlz;[2][3][4] ドイツ語: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈʔɛŋl̩s];

1820年11月28日 -

1895年8月5日)は、ドイツの哲学者、政治理論家、歴史家、ジャーナリスト、革命的社会主義者である。実業家でもあり、カール・マルクスの生涯の友人

であり、最も親しい協力者であり、マルクス主義の第一人者でもあった。

裕福な織物製造業者の息子であったエンゲルスは、1844年にマルクスと出会った。彼らは『聖家族』(1844年)、『ドイツ・イデオロギー』(1846

年)、『共産党宣言』(1848年)などの著作を共同執筆し、共産主義者同盟および第一インターナショナルで政治的組織者および活動家として働いた。ま

た、エンゲルスは生涯の大半にわたって経済的にマルクスを支援し、1849年にロンドンに移住したマルクスが執筆を続けることを可能にした。1883年に

マルクスが死去した後、エンゲルスは『資本論』第2巻と第3巻(1885年と1894年)を編集した。

エンゲルスは、独自の折衷的な著作を執筆した。『イギリスにおける労働者階級の状況』(1845年)、『反デューリング』(1878年)、『自然の弁証

法』(1878年~1882年)、『家族・私有財産・国家の起源』(1884年)、『ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハと古典的ドイツ哲学の終焉』

(1886年)などである。唯物論、観念論、弁証法に関する彼の著作は、マルクス主義に存在論的および形而上学的基盤をもたらした。[要出典]

|

Early life

Friedrich Engels was born on 28 November 1820 in Barmen,

Jülich-Cleves-Berg, Prussia (now Wuppertal, Germany), as eldest son of

Friedrich Engels Sr. (1796–1860) and of Elisabeth "Elise" Franziska

Mauritia von Haar (1797–1873).[10] The wealthy Engels family owned

large cotton-textile mills in Barmen and Salford, both expanding

industrial metropoles. Friedrich's parents were devout Pietist

Protestants[5] and they raised their children accordingly.

At the age of 13, Engels attended grammar school (Gymnasium) in the

adjacent city of Elberfeld but had to leave at 17, due to pressure from

his father, who wanted him to become a businessman and start work as a

mercantile apprentice in the family firm.[11] After a year in Barmen,

the young Engels was in 1838 sent by his father to undertake an

apprenticeship at a trading house in Bremen.[12][13] His parents

expected that he would follow his father into a career in the family

business. Their son's revolutionary activities disappointed them. It

would be some years before he joined the family firm.

Whilst at Bremen, Engels began reading the philosophy of Georg Wilhelm

Friedrich Hegel, whose teachings dominated German philosophy at that

time. In September 1838 he published his first work, a poem entitled

"The Bedouin", in the Bremisches Conversationsblatt No. 40. He also

engaged in other literary work and began writing newspaper articles

critiquing the societal ills of industrialisation.[14][15] He wrote

under the pseudonym "Friedrich Oswald" to avoid connecting his family

with his provocative writings.

In 1841, Engels performed his military service in the Prussian Army as

a member of the Household Artillery (German: Garde-Artillerie-Brigade).

Assigned to Berlin, he attended university lectures at the University

of Berlin and began to associate with groups of Young Hegelians. He

anonymously published articles in the Rheinische Zeitung, exposing the

poor employment- and living-conditions endured by factory workers.[13]

The editor of the Rheinische Zeitung was Karl Marx, but Engels would

not meet Marx until late November 1842.[16] Engels acknowledged the

influence of German philosophy on his intellectual development

throughout his career.[12] In 1840, he also wrote: "To get the most out

of life you must be active, you must live and you must have the courage

to taste the thrill of being young."[17]

Engels developed atheistic beliefs and his relationship with his

parents became strained.[18]

|

幼少期

フリードリヒ・エンゲルスは、1820年11月28日、プロイセン領ユーリッヒ・クレヴェス・ベルクのバルメン(現在のドイツ・ブッパータール)で、フ

リードリヒ・エンゲルス・シニア(1796-1860)とエリザベス・フランツィスカ・マウリティア・フォン・ハール(1797-1873)の長男として

生まれた。 10]

富豪エンゲルス家は工業都市に発展したバルメンとサルフォードで大きな綿繊維工場を保有していた。両親は敬虔なプロテスタント信徒であり[5]、それに

従って子供たちを育てた。

13歳のとき、エンゲルスは隣接するエルバーフェルトの文法学校(ギムナジウム)に通ったが、実業家になって家業の商人見習いになることを望む父親の圧力

により、17歳で退学せざるを得なかった[11]。バルメンでの1年の後、1838年に若きエンゲルスは父親に送られて、ブレーメンの商社で見習いをする

ことになった[12][13]。

両親は彼が父親に従って家業のキャリアに入るものと期待していた。息子の革命的な活動は両親を失望させた。彼が家業に加わるのは数年後のことであった。

ブレーメンにいたとき、エンゲルスはゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルの哲学を読み始め、その教えは当時のドイツ哲学を支配していた。

1838年9月、彼は最初の作品である詩「ベドウィン」を『ブレーメンの会話誌』第40号に発表した。また、他の文学活動にも従事し、工業化の社会悪を批

判する新聞記事を書き始めた[14][15]。

彼は家族と自分の挑発的な文章とのつながりを避けるため、「フリードリヒ・オズワルド」というペンネームで執筆していた。

1841年、エンゲルスはプロイセン陸軍の家庭砲兵隊(ドイツ語:Garde-Artillerie-Brigade)の一員として兵役に就いた。ベルリ

ンに配属された彼は、ベルリン大学で講義を受け、青年ヘーゲル主義者のグループと付き合うようになる。彼は匿名で『ライン・ツァイトゥング』に記事を掲載

し、工場労働者が耐えている劣悪な雇用と生活条件を暴露した[13]。ライン・ツァイトゥングの編集者はカール・マルクスだったが、エンゲルスがマルクス

に会うのは1842年11月末だった[16]。

エンゲルスは無神論的な信念を持ち、両親との関係もぎくしゃくしたものになった[18]。

|

Manchester and Salford

In 1842, his parents sent the 22-year-old Engels to Manchester,

England, a manufacturing centre where industrialisation was on the

rise. He was to work in Weaste, Salford,[19] in the offices of Ermen

and Engels's Victoria Mill, which made sewing threads.[20][21][22]

Engels's father thought that working at the Manchester firm might make

his son reconsider some of his radical opinions.[12][21] On his way to

Manchester, Engels visited the office of the Rheinische Zeitung in

Cologne and met Karl Marx for the first time. Initially they were not

impressed with each other.[23] Marx mistakenly thought that Engels was

still associated with the Berliner Young Hegelians, with whom Marx had

just broken off ties.[24]

In Manchester, Engels met Mary Burns, a fierce young Irish woman with

radical opinions who worked in the Engels factory.[25][26] They began a

relationship that lasted 20 years until her death in 1863.[27][28] The

two never married, as both were against the institution of marriage.

While Engels regarded stable monogamy as a virtue, he considered the

current state and church-regulated marriage as a form of class

oppression.[29][30] Burns guided Engels through Manchester and Salford,

showing him the worst districts for his research.

Engels was often described as a man with a very strong libido and not

much restraint. He had numerous affairs with a string of lovers and

despite his condemnation of prostitution as "exploitation of the

proletariat by the bourgeoisie" he also occasionally paid for sex. In

1846 he wrote to Marx: "If I had an income of 5000 francs I would do

nothing but work and amuse myself with women until I went to pieces. If

there were no Frenchwomen, life wouldn't be worth living. But so long

as there are grisettes, well and good!" His most controversial

relationship was with the wife of his rival Moses Hess, Sibylle, who

later accused him of rape.[5]

While in Manchester between October and November 1843, Engels wrote his

first critique of political economy, entitled "Outlines of a Critique

of Political Economy".[31] Engels sent the article to Paris, where Marx

published it in the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher in 1844.[20]

While observing the slums of Manchester in close detail, Engels took

notes of its horrors, notably child labour, the despoiled environment,

and overworked and impoverished labourers.[32] He sent a trilogy of

articles to Marx. These were published in the Rheinische Zeitung and

then in the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher, chronicling the conditions

among the working class in Manchester. He later collected these

articles for his influential first book, The Condition of the Working

Class in England (1845).[33] Written between September 1844 and March

1845, the book was published in German in 1845. In the book, Engels

described the "grim future of capitalism and the industrial age",[32]

noting the details of the squalor in which the working people

lived.[34] The book was published in English in 1887. Archival

resources contemporary to Engels's stay in Manchester shed light on

some of the conditions he describes, including a manuscript (MMM/10/1)

held by special collections at the University of Manchester. This

recounts cases seen in the Manchester Royal Infirmary, where industrial

accidents dominated and which resonate with Engels's comments on the

disfigured persons seen walking round Manchester as a result of such

accidents.

Engels continued his involvement with radical journalism and politics.

He frequented areas popular among members of the English labour and

Chartist movements, whom he met. He also wrote for several journals,

including The Northern Star, Robert Owen's New Moral World, and the

Democratic Review newspaper.[27][35][36]

|

マンチェスターとサルフォード

1842年、両親は22歳のエンゲルスを工業化が進んでいた製造業の中心地であるイギリスのマンチェスターに送り出す。エンゲルスの父親は、マンチェス

ターの会社で働くことで、息子が彼の過激な意見のいくつかを考え直すかもしれないと考えていた[12][21]。

マンチェスターに向かう途中、エンゲルスはケルンのRheinische

Zeitungのオフィスを訪れ、カール・マルクスに初めて会った。当初、彼らは互いに印象が悪かった[23]。マルクスは、エンゲルスが、マルクスが関

係を絶ったばかりのベルリンの青年ヘーゲル派とまだ関係があると誤解していた[24]。

エンゲルスはマンチェスターで、エンゲルスの工場で働いていた過激な意見を持つ若いアイルランド人女性メアリー・バーンズと出会った[25][26]。

彼らは1863年に彼女が死ぬまで20年間続く関係を始めた[27][28]。2人とも結婚制度に反対だったため、結婚することはなかった。エンゲルスは

安定した一夫一婦制を美徳とする一方で、現在の国家や教会が規制する結婚を階級的抑圧の一形態と考えていた[29][30]。

バーンズはマンチェスターとサルフォードを案内し、エンゲルスの調査に最悪の地区を案内している。

エンゲルスはしばしば、非常に強い性欲を持ち、あまり自制心のない男であると言われていた。彼は多くの恋人と関係を持ち、売春を「ブルジョアジーによるプ

ロレタリアートの搾取」と非難していたにもかかわらず、時折、お金を払ってセックスをすることもあった。1846年、彼はマルクスにこう書いている。「も

し私に5000フランの収入があったら、私は何もせずに働き、ボロボロになるまで女と遊んだだろう。もしフランス女性がいなかったら、生きる価値はないだ

ろう。でも、グリゼットがいる限りはいいんだ!」。最も物議を醸したのは、ライバルであったモーゼ・ヘスの妻シビレとの関係であり、彼女は後に彼をレイプ

で訴えた[5]。

1843年10月から11月にかけてマンチェスターに滞在していたとき、エンゲルスは「Outlines of a Critique of

Political Economy」と題する彼の最初の政治経済批判を書いた[31]。

エンゲルスはその論文をパリに送り、マルクスはそれを1844年の『Deutsch-Französische

Jahrbücher』に掲載した[20]。

エンゲルスは、マンチェスターのスラム街を詳細に観察しながら、その恐怖、特に児童労働、荒廃した環境、過労と貧困にあえぐ労働者についてメモをとってい

た[32]。これらは、『Rheinische Zeitung』に掲載され、その後、『Deutsch-Französische

Jahrbücher』で、マンチェスターの労働者階級の状況を記録したものであった。彼は後に影響力のある彼の最初の本であるThe

Condition of the Working Class in England (1845)のためにこれらの記事を収集した[33]

1844年9月から1845年3月の間に書かれ、この本は1845年にドイツ語で出版された。この本の中で、エンゲルスは「資本主義と産業時代の厳しい未

来」を描写し[32]、労働者たちが住んでいる汚部屋の詳細に言及した[34]。この本は、1887年に英語で出版された。エンゲルスのマンチェスター滞

在と同時期の資料には、マンチェスター大学の特別コレクションが所蔵する原稿(MMM/10/1)など、彼が記述した状況の一部を明らかにするものがあ

る。この原稿には、産業事故が多発したマンチェスター王立診療所での事例が記されており、このような事故の結果、マンチェスター周辺を歩く醜い人たちを見

たエンゲルスのコメントと共鳴する。

エンゲルスは、急進的なジャーナリズムや政治との関わりを持ち続けた。彼は、イギリスの労働運動やチャーティスト運動のメンバーに人気のある地域に頻繁に

出向き、彼らと知り合った。また、『ノーザン・スター』、ロバート・オーウェンの『新道徳世界』、『民主主義評論』などの雑誌に執筆した[27][35]

[36]。

|

Paris

Engels decided to return to Germany in 1844. On the way, he stopped in

Paris to meet Karl Marx, with whom he had an earlier correspondence.

Marx had been living in Paris since late October 1843, after the

Rheinische Zeitung was banned in March 1843 by Prussian governmental

authorities.[40] Prior to meeting Marx, Engels had become established

as a fully developed materialist and scientific socialist, independent

of Marx's philosophical development.[41]

In Paris, Marx was publishing the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher.

Engels met Marx for a second time at the Café de la Régence on the

Place du Palais, 28 August 1844. The two quickly became close friends

and remained so their entire lives. Marx had read and was impressed by

Engels's articles on The Condition of the Working Class in England in

which he had written that "[a] class which bears all the disadvantages

of the social order without enjoying its advantages, [...] Who can

demand that such a class respect this social order?"[42] Marx adopted

Engels's idea that the working class would lead the revolution against

the bourgeoisie as society advanced toward socialism, and incorporated

this as part of his own philosophy.[43]

Engels stayed in Paris to help Marx write The Holy Family.[44] It was

an attack on the Young Hegelians and the Bauer brothers, and was

published in late February 1845. Engels's earliest contribution to

Marx's work was writing for the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher, edited

by both Marx and Arnold Ruge, in Paris in 1844. During this time in

Paris, both Marx and Engels began their association with and then

joined the secret revolutionary society called the League of the

Just.[45] The League of the Just had been formed in 1837 in France to

promote an egalitarian society through the overthrow of the existing

governments. In 1839, the League of the Just participated in the 1839

rebellion fomented by the French utopian revolutionary socialist, Louis

Auguste Blanqui; however, as Ruge remained a Young Hegelian in his

belief, Marx and Ruge soon split and Ruge left the Deutsch–Französische

Jahrbücher.[46] Nonetheless, following the split, Marx remained

friendly enough with Ruge that he sent Ruge a warning on 15 January

1845 that the Paris police were going to execute orders against him,

Marx and others at the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher requiring all to

leave Paris within 24 hours.[47] Marx himself was expelled from Paris

by French authorities on 3 February 1845 and settled in Brussels with

his wife and one daughter.[48] Having left Paris on 6 September 1844,

Engels returned to his home in Barmen, Germany, to work on his The

Condition of the Working Class in England, which was published in late

May 1845.[49] Even before the publication of his book, Engels moved to

Brussels in late April 1845, to collaborate with Marx on another book,

German Ideology.[50] While living in Barmen, Engels began making

contact with Socialists in the Rhineland to raise money for Marx's

publication efforts in Brussels; however, these contacts became more

important as both Marx and Engels began political organizing for the

Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany.[51]

|

パリ

1844年、エンゲルスはドイツへの帰国を決意する。その途中、パリに立ち寄り、以前から文通をしていたカール・マルクスに会うことになる。マルクスは、

1843年3月にプロイセン政府当局によって『ライン新聞』が発禁処分を受けた後、1843年10月末からパリに住んでいた[40]。マルクスに会う前

に、エンゲルスはマルクスの哲学的発展とは別に、完全に発展した唯物論的・科学的社会主義者として確立されていた[41]。

パリでは、マルクスは『Deutsch-Französische

Jahrbücher』を出版していた。エンゲルスは、1844年8月28日、パレ広場のカフェ・ド・ラ・レジャンスでマルクスと2度目の出会いを果た

す。二人はすぐに親しい友人となり、生涯にわたってその関係を続けた。マルクスはエンゲルスの『イギリスにおける労働者階級の状態』に関する論文を読んで

感銘を受け、その中で「社会秩序の利益を享受せずにそのすべての不利益を負担する階級、[...]そのような階級にこの社会秩序を尊重せよと誰が要求でき

るだろうか」と書いていた[42]

マルクスは、社会主義への社会の進展とともに労働者階級がブルジョアジーに対する革命を主導するというエンゲルスの考えを取り入れ、自分の哲学の一部とし

てこれを取り入れた[43]。

エンゲルスはパリに滞在し、マルクスの『聖家族』の執筆を手伝った[44]。この作品は、青年ヘーゲル派とバウアー兄弟に対する攻撃であり、1845年2

月末に出版された。エンゲルスのマルクスへの最も早い貢献は、1844年にパリでマルクスとアーノルド・ルーゲの両者が編集した『Deutsch-

Französische

Jahrbücher』に寄稿したことであった。この間、マルクスとエンゲルスは、「正義同盟」という秘密革命結社との交際を始め、それに参加した

[45]。正義同盟は、1837年にフランスで、既存の政府を転覆することによって平等主義的社会を促進するために結成された。1839年、正義同盟はフ

ランスのユートピア革命的社会主義者であるルイ・オーギュスト・ブランキが起こした1839年の反乱に参加したが、ルゲがヤング・ヘーゲル主義者の信念を

持ち続けたため、マルクスとルゲはすぐに分裂しルゲは『ドイツ・フランセーズ・ヤールビュヒャー』を脱退した[46]。

[しかし、分裂後もマルクスはルジェと友好的であり、1845年1月15日にルジェにパリ警察が自分、マルクス、ドイチュ・フランツォシェ・ヤールビュ

ヒャーの他の者に対して24時間以内にパリを離れるようにという命令を出すという警告を送った[47]。

マルクス自身も1845年2月3日にフランス当局によってパリから追放され、妻と娘1人とブリュッセルに住むことになった[48]。

[1844年9月6日にパリを離れたエンゲルスは、ドイツのバルメンの自宅に戻り、1845年5月末に出版された『イギリスにおける労働者階級の状況』の

執筆に取り組んだ[49]。

[エンゲルスはバルメンに住んでいる間、ブリュッセルでのマルクスの出版活動のための資金を調達するためにラインラントの社会主義者と接触し始めたが、マ

ルクスとエンゲルスの両方がドイツ社会民主労働党のための政治的組織化を始めると、これらの接触がより重要になった[51]。

|

Brussels

The nation of Belgium, founded in 1830, was endowed with one of the

most liberal constitutions in Europe and functioned as refuge for

progressives from other countries. From 1845 to 1848, Engels and Marx

lived in Brussels, spending much of their time organising the city's

German workers. Shortly after their arrival, they contacted and joined

the underground German Communist League. The Communist League was the

successor organisation to the old League of the Just which had been

founded in 1837, but had recently disbanded.[53] Influenced by Wilhelm

Weitling, the Communist League was an international society of

proletarian revolutionaries with branches in various European

cities.[54]

The Communist League also had contacts with the underground

conspiratorial organisation of Louis Auguste Blanqui. Many of Marx's

and Engels's current friends became members of the Communist League.

Old friends like Georg Friedrich Herwegh, who had worked with Marx on

the Rheinsche Zeitung, Heinrich Heine, the famous poet, a young

physician by the name of Roland Daniels, Heinrich Bürgers and August

Herman Ewerbeck all maintained their contacts with Marx and Engels in

Brussels. Georg Weerth, who had become a friend of Engels in England in

1843, now settled in Brussels. Carl Wallau and Stephen Born (real name

Simon Buttermilch) were both German immigrant typesetters who settled

in Brussels to help Marx and Engels with their Communist League work.

Marx and Engels made many new important contacts through the Communist

League. One of the first was Wilhelm Wolff, who was soon to become one

of Marx's and Engels's closest collaborators. Others were Joseph

Weydemeyer and Ferdinand Freiligrath, a famous revolutionary poet.

While most of the associates of Marx and Engels were German immigrants

living in Brussels, some of their new associates were Belgians.

Phillipe Gigot, a Belgian philosopher and Victor Tedesco, a lawyer from

Liège, both joined the Communist League. Joachim Lelewel a prominent

Polish historian and participant in the Polish uprising of 1830–1831

was also a frequent associate.[55][56]

The Communist League commissioned Marx and Engels to write a pamphlet

explaining the principles of communism. This became the Manifesto of

the Communist Party, better known as The Communist Manifesto.[57] It

was first published on 21 February 1848 and ends with the world-famous

phrase: "Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution.

The proletariat have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a

world to win. Working Men of All Countries, Unite!"[12]

Engels's mother wrote in a letter to him of her concerns, commenting

that he had "really gone too far" and "begged" him "to proceed no

further".[58] She further stated:

You have paid more heed to other people, to strangers, and have taken

no account of your mother's pleas. God alone knows what I have felt and

suffered of late. I was trembling when I picked up the newspaper and

saw therein that a warrant was out for my son's arrest.[58]

|

ブリュッセル

1830年に建国されたベルギーは、ヨーロッパで最も自由な憲法を持ち、他国からの進歩主義者の避難所として機能していた。1845年から1848年ま

で、エンゲルスとマルクスはブリュッセルに滞在し、この街のドイツ人労働者の組織化に多くの時間を費やした。到着して間もなく、彼らは地下のドイツ共産主

義者同盟に接触し、加入した。共産主義者同盟は、1837年に設立され、最近解散した古い公正連盟の後継組織であった[53]。ヴィルヘルム・ヴァイトリ

ングの影響を受け、共産主義者同盟はヨーロッパの様々な都市に支部を持つプロレタリア革命家の国際社会であった[54]。

共産主義者同盟はまたルイ・オーギュスト・ブランキの地下陰謀組織と接触していた。マルクスとエンゲルスの現在の友人の多くは、共産主義者同盟のメンバー

になった。マルクスとともに『ラインシェ・ツァイトゥング』を書いていたゲオルク・フリードリヒ・ヘルヴェーグ、有名な詩人ハインリッヒ・ハイネ、ローラ

ンド・ダニエルズという名の若い医師、ハインリッヒ・ビュルガー、アウグスト・ヘルマン・エヴェルベックといった古い友人たちは、ブリュッセルでマルクス

とエンゲルスと連絡を取り続けていた。1843年にイギリスでエンゲルスの友人となったゲオルク・ヴェールトは、今度はブリュッセルに居を構えた。カー

ル・ワラウとステファン・ボルン(本名シモン・ブッターミルヒ)は、ドイツから移住した活版工で、ブリュッセルに定住してマルクスとエンゲルスの共産主義

者同盟の活動を助けていた。マルクスとエンゲルスは、共産主義者同盟を通じて、新たに多くの重要な人脈を得た。その一人がヴィルヘルム・ヴォルフで、彼は

やがてマルクスとエンゲルスの最も親しい協力者の一人となる。また、ヨーゼフ・ヴァイデマイヤーや、有名な革命詩人フェルディナンド・フレイリグラートも

そうであった。マルクスとエンゲルスの仲間の多くはブリュッセルに住むドイツ系移民であったが、新たに加わった仲間の中にはベルギー人もいた。ベルギー人

の哲学者フィリップ・ジゴとリエージュの弁護士ヴィクトル・テデスコは、共に共産主義者同盟に参加した。ヨアヒム・レレヴェルの著名なポーランドの歴史

家、1830年から1831年のポーランドの蜂起の参加者もまた頻繁な仲間であった[55][56]。

共産主義者同盟はマルクスとエンゲルスに共産主義の原理を説明する小冊子を書くように依頼した。これは、『共産党宣言』としてよりよく知られる『共産党宣

言』となった[57]。それは、1848年2月21日に最初に出版され、「支配階級は共産主義革命に震え上がろう。プロレタリアートは、失うものは彼らの

鎖以外には何もない。彼らは世界を勝ち取るのだ。万国の労働者よ、団結せよ!」[12]。

エンゲルスの母親は、彼への手紙の中で、彼が「本当に行き過ぎた」、「これ以上進めないように懇願する」とコメントし、彼女の懸念を書き記した[58]。

あなたは他人や見知らぬ人にばかり気を使い、お母さんの嘆願を全く考慮しませんでした。このところ、私が何を感じ、何に苦しんでいるかは、神のみぞ知ると

ころです。私は新聞を手に取り、そこに息子の逮捕状が出ているのを見たとき、震えていました[58]。

|

Return to Prussia

There was a revolution in France in 1848 that soon spread to other

Western European countries. These events caused Engels and Marx to

return to their homeland of the Kingdom of Prussia, specifically to the

city of Cologne. While living in Cologne, they created and served as

editors for a new daily newspaper called the Neue Rheinische

Zeitung.[20] Besides Marx and Engels, other frequent contributors to

the Neue Rheinische Zeitung included Karl Schapper, Wilhelm Wolff,

Ernst Dronke, Peter Nothjung, Heinrich Bürgers, Ferdinand Wolff and

Carl Cramer.[59] Friedrich Engels's mother, herself, gives unwitting

witness to the effect of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung on the

revolutionary uprising in Cologne in 1848. Criticising his involvement

in the uprising she states in a 5 December 1848 letter to Friedrich

that "nobody, ourselves included, doubted that the meetings at which

you and your friends spoke, and also the language of (Neue) Rh.Z. were

largely the cause of these disturbances."[60]

Engels's parents hoped that young Engels would "decide to turn to

activities other than those which you have been pursuing in recent

years and which have caused so much distress".[60] At this point, his

parents felt the only hope for their son was to emigrate to America and

start his life over. They told him that he should do this or he would

"cease to receive money from us"; however, the problem in the

relationship between Engels and his parents was worked out without

Engels having to leave England or being cut off from financial

assistance from his parents.[60] In July 1851, Engels's father arrived

to visit him in Manchester, England. During the visit, his father

arranged for Engels to meet Peter Ermen of the office of Ermen &

Engels, to move to Liverpool and to take over sole management of the

office in Manchester.[61]

In 1849, Engels travelled to the Kingdom of Bavaria for the Baden and

Palatinate revolutionary uprising, an even more dangerous involvement.

Starting with an article called "The Magyar Struggle", written on 8

January 1849, Engels, himself, began a series of reports on the

Revolution and War for Independence of the newly founded Hungarian

Republic.[62] Engels's articles on the Hungarian Republic became a

regular feature in the Neue Rheinische Zeitung under the heading "From

the Theatre of War"; however, the newspaper was suppressed during the

June 1849 Prussian coup d'état. After the coup, Marx lost his Prussian

citizenship, was deported and fled to Paris and then London.[63] Engels

stayed in Prussia and took part in an armed uprising in South Germany

as an aide-de-camp in the volunteer corps of August

Willich.[64][65][66] Engels also brought two cases of rifle cartridges

with him when he went to join the uprising in Elberfeld on 10 May

1849.[67] Later when Prussian troops came to Kaiserslautern to suppress

an uprising there, Engels joined a group of volunteers under the

command of August Willich, who were going to fight the Prussian

troops.[68] When the uprising was crushed, Engels was one of the last

members of Willich's volunteers to escape by crossing the Swiss border.

Marx and others became concerned for Engels's life until they finally

heard from him.[69]

Engels travelled through Switzerland as a refugee and eventually made

it to safety in England.[12] On 6 June 1849 Prussian authorities issued

an arrest warrant for Engels which contained a physical description as

"height: 5 feet 6 inches; hair: blond; forehead: smooth; eyebrows:

blond; eyes: blue; nose and mouth: well proportioned; beard: reddish;

chin: oval; face: oval; complexion: healthy; figure: slender. Special

characteristics: speaks very rapidly and is short-sighted".[70] As to

his "short-sightedness", Engels admitted as much in a letter written to

Joseph Weydemeyer on 19 June 1851 in which he says he was not worried

about being selected for the Prussian military because of "my eye

trouble, as I have now found out once and for all which renders me

completely unfit for active service of any sort".[71] Once he was safe

in Switzerland, Engels began to write down all his memories of the

recent military campaign against the Prussians. This writing eventually

became the article published under the name "The Campaign for the

German Imperial Constitution".[72]

|

プロイセンへの帰還

1848年、フランスで革命が起こり、やがて西ヨーロッパ諸国にも波及した。エンゲルスとマルクスは、故郷のプロイセン王国、特にケルン市に戻ることに

なった。ノイエ・ラインニッシェ・ツァイトゥング』には、マルクスとエンゲルスの他に、カール・シャッパー、ヴィルヘルム・ヴォルフ、エルンスト・ドロン

ケ、ペーター・ノートユング、ハインリッヒ・ビュルガース、フェルディナンド・ヴォルフ、カール・クラマーなどが寄稿した[59]...

エンゲルスの母は、1848年のケルンの革命蜂起に『ノイエ・ラインニッシェ・ツァイトゥング』が影響を与えることを知らないうちに見てしまうようにな

る。彼女はフリードリッヒに宛てた1848年12月5日の手紙の中で、彼の蜂起への関与を批判し、「あなたやあなたの友人が話した集会や、(ノイエ)

Rh.Z.の言葉がこれらの騒動の大きな原因であることは、私たちも含めて誰も疑っていませんでした」[60]と述べている。

エンゲルスの両親は、若いエンゲルスが「近年あなたが追求し、多くの苦痛を与えてきた活動以外の活動に転じることを決意する」ことを望んでいた[60]。

この時点で、両親は息子にとって唯一の希望はアメリカに移住して人生をやり直すことであると感じていた。しかし、エンゲルスと両親の間の問題は、エンゲル

スがイギリスを離れ、両親からの経済的援助を絶たれることなく解決された[60]。

1851年7月、エンゲルスの父はイギリスのマンチェスターに彼を訪ねて来た。この訪問の間、父親はエンゲルスがエルメン&エンゲルス事務所のピーター・

エルメンと出会い、リバプールに移り、マンチェスターの事務所の経営を一手に引き受けるよう手配した[61]。

1849 年、エンゲルスはバーデンとプファルツの革命蜂起のためにバイエルン王国に赴き、さらに危険

な関わりを持つことになる。1849年1月8日に書かれた「マジャール闘争」という記事を皮切りに、エンゲルス自身、新しく設立されたハンガリー共和国の

革命と独立戦争に関する一連のレポートを始めた[62]。

エンゲルスのハンガリー共和国に関する記事は、「戦争の舞台から」という見出しで『ノイエラインシュテツング』の定期刊行物となるが、1849年6月にプ

ロイセンのクーデターで新聞は制圧されることになった。エンゲルスはプロイセンに留まり、アウグスト・ウィリッヒの義勇軍の副官として南ドイツでの武装蜂

起に参加した[64][65][66]。また1849年5月10日にエルバーフェルトでの蜂起に参加した際にはライフルカートリッジ2箱を持参していた

[67]。

[その後、プロイセン軍がカイザースラウテルンの蜂起を鎮圧するためにやってきたとき、エンゲルスはプロイセン軍と戦うためにアウグスト・ウィリッヒの指

揮する志願兵の一団に加わった[68]

蜂起が鎮圧されたとき、エンゲルスはウィリッヒの志願兵の最後の一人としてスイス国境を渡って逃亡した。マルクスらはエンゲルスの命を心配し、ようやく彼

から連絡があった[69]。

1849年6月6日、プロイセン当局はエンゲルスの逮捕状を発行し、そこには「身長:5フィート6インチ、髪:ブロンド、額:滑らか、眉:ブロンド、目:

青、鼻と口:整った、髭:赤っぽい、顎:楕円、顔:楕円、顔色:健康、姿:痩身」という身体描写が含まれていた[12]。特別な特徴:非常に早口で、近視

である」[70]

彼の「近視」については、エンゲルスは1851年6月19日にヨセフ・ヴァイデマイヤーに書いた手紙の中でそれを認めており、「私の目の病気、今一度わ

かったように、私はいかなる種類の現役にも全く適さない」のでプロシア軍に選ばれる心配はないとしている[71]

スイスで安全になるとエンゲルスは最近のプロシアに対する軍事行動のすべての記憶を書き留めることを始めた。この文章は最終的に「ドイツ帝国憲法のための

キャンペーン」という名前で発表された論文となった[72]。

|

Back in Britain

To help Marx with Neue Rheinische Zeitung Politisch-ökonomische Revue,

the new publishing effort in London, Engels sought ways to escape the

continent and travel to London. On 5 October 1849, Engels arrived in

the Italian port city of Genoa.[73] There, Engels booked passage on the

English schooner, Cornish Diamond under the command of a Captain

Stevens.[74] The voyage across the western Mediterranean, around the

Iberian Peninsula by sailing schooner took about five weeks. Finally,

the Cornish Diamond sailed up the River Thames to London on 10 November

1849 with Engels on board.[75]

Upon his return to Britain, Engels re-entered the Manchester company in

which his father held shares to support Marx financially as he worked

on Das Kapital.[76][77] Unlike his first period in England (1843),

Engels was now under police surveillance. He had "official" homes and

"unofficial homes" all over Salford, Weaste and other inner-city

Manchester districts where he lived with Mary Burns under false names

to confuse the police.[34] Little more is known, as Engels destroyed

over 1,500 letters between himself and Marx after the latter's death so

as to conceal the details of their secretive lifestyle.[34]

Despite his work at the mill, Engels found time to write a book on

Martin Luther, the Protestant Reformation and the 1525 revolutionary

war of the peasants, entitled The Peasant War in Germany.[78] He also

wrote a number of newspaper articles including "The Campaign for the

German Imperial Constitution" which he finished in February 1850[79]

and "On the Slogan of the Abolition of the State and the German

'Friends of Anarchy'" written in October 1850.[80] In April 1851, he

wrote the pamphlet "Conditions and Prospects of a War of the Holy

Alliance against France".[81]

Marx and Engels denounced Louis Bonaparte when he carried out a coup

against the French government and made himself president for life on 2

December 1851. In condemning this action, Engels wrote to Marx on 3

December 1851, characterising the coup as "comical"[82] and referred to

it as occurring on "the 18th Brumaire", the date of Napoleon I's coup

of 1799 according to the French Republican Calendar.[83] Marx was later

to incorporate this comically ironic characterisation of Louis

Bonaparte's coup into his essay about the coup. Indeed, Marx even

called the essay The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte again using

Engels's suggested characterisation.[84] Marx also borrowed Engels'

characterisation of Hegel's notion of the World Spirit that history

occurred twice, "once as a tragedy and secondly as a farce" in the

first paragraph of his new essay.[85]

Meanwhile, Engels started working at the mill owned by his father in

Manchester as an office clerk, the same position he held in his teens

while in Germany where his father's company was based. Engels worked

his way up to become a partner of the firm in 1864.[citation needed]

Five years later, Engels retired from the business and could focus more

on his studies.[20] At this time, Marx was living in London but they

were able to exchange ideas through daily correspondence. One of the

ideas that Engels and Marx contemplated was the possibility and

character of a potential revolution in the Russias. As early as April

1853, Engels and Marx anticipated an "aristocratic-bourgeois revolution

in Russia which would begin in "St. Petersburg with a resulting civil

war in the interior".[86] The model for this type of

aristocratic-bourgeois revolution in Russia against the autocratic

Tsarist government in favour of a constitutional government had been

provided by the Decembrist Revolt of 1825.[87]

Although an unsuccessful revolt against the Tsarist government in

favour of a constitutional government, both Engels and Marx anticipated

a bourgeois revolution in Russia would occur which would bring about a

bourgeois stage in Russian development to precede a communist stage. By

1881, both Marx and Engels began to contemplate a course of development

in Russia that would lead directly to the communist stage without the

intervening bourgeois stage. This analysis was based on what Marx and

Engels saw as the exceptional characteristics of the Russian village

commune or obshchina.[88] While doubt was cast on this theory by Georgi

Plekhanov, Plekhanov's reasoning was based on the first edition of Das

Kapital (1867) which predated Marx's interest in Russian peasant

communes by two years. Later editions of the text demonstrate Marx's

sympathy for the argument of Nikolay Chernyshevsky, that it should be

possible to establish socialism in Russia without an intermediary

bourgeois stage provided that the peasant commune were used as the

basis for the transition.[89]

In 1870, Engels moved to London where he and Marx lived until Marx's

death in 1883.[12] Engels's London home from 1870 to 1894 was at 122

Regent's Park Road.[90] In October 1894 he moved to 41 Regent's Park

Road, Primrose Hill, NW1, where he died the following year.[citation

needed]

Marx's first London residence was a cramped apartment at 28 Dean

Street, Soho. From 1856, he lived at 9 Grafton Terrace, Kentish Town,

and then in a tenement at 41 Maitland Park Road in Belsize Park from

1875 until his death in March 1883.[91]

Mary Burns suddenly died of heart disease in 1863, after which Engels

became close with her younger sister Lydia ("Lizzie"). They lived

openly as a couple in London and married on 11 September 1878, hours

before Lizzie's death.[92][93]

|

イギリスへの帰国

ロンドンでの新しい出版活動であるノイエ・ラインシュ・ツァイトゥング・ポリティッシュ・オコノミッシェ・レヴューでマルクスを助けるために、エンゲルス

は大陸を逃れ、ロンドンに行く方法を探していた。1849年10月5日、エンゲルスはイタリアの港町ジェノバに到着し、そこでスティーブンス船長の指揮す

るイギリスのスクーナー船、コーニッシュ・ダイヤモンド号に乗船することを予約した[74]。スクーナー船による地中海西部とイベリア半島周辺の航海は約

5週間かかったという。最終的にコーニッシュ・ダイアモンド号は、1849年11月10日にエンゲルスを乗せたままテムズ川を遡り、ロンドンに向けて出航

した[75]。

エンゲルスはイギリスに戻ると、父親が株を持っていたマンチェスターの会社に再入社し、『資本論』を執筆するマルクスを経済的に支援した[76][77]

イギリスでの最初の期間(1843年)とは異なり、エンゲルスは警察の監視下に置かれるようになった。エンゲルスはサルフォード、ウィーステ、その他のマ

ンチェスターの都心部の至る所に「公式」な家と「非公式な家」を持ち、警察を混乱させるためにメリー・バーンズと偽名で暮らしていた[34]。エンゲルス

がマルクスが死んだ後に、彼らの秘密のライフスタイルの詳細を隠すために彼と彼の間の1500以上の手紙を破棄したので、これ以上はほとんどわかっていな

い[34]。

工場での仕事にもかかわらず、エンゲルスはマルティン・ルター、プロテスタントの宗教改革、1525年の農民の革命戦争に関する本『ドイツにおける農民戦

争』を書く時間を見つけた[78]。

[また、1850年2月に書き上げた「ドイツ帝国憲法のためのキャンペーン」[79]や1850年10月に書いた「国家廃止のスローガンとドイツの『無政

府の友』について」などの新聞記事を書いていた[80]。

1851年4月に「フランスに対する神聖同盟の戦争の条件と展望」というパンフレットを執筆していた[81]。

マルクスとエンゲルスは、1851年12月2日にルイ・ボナパルトがフランス政府に対してクーデターを起こし、終身大統領となったときに非難した。この行

動を非難するために、エンゲルスは1851年12月3日にマルクスに手紙を書き、クーデターを「滑稽」[82]と特徴づけ、フランス共和暦による1799

年のナポレオン1世のクーデターの日、「18日ブルメール」に発生したと言及した[83]。

マルクスは後にルイ・ボナパルトのクーデターをこの滑稽で皮肉った特徴づけで、そのエッセーで取り入れることになる。実際、マルクスはエンゲルスの提案し

た性格付けを用いて再びこのエッセイを「ルイ・ボナパルトの18ブリュメール」と呼んだりもした[84]。またマルクスは新しいエッセイの第1パラグラフ

で、歴史が「一度は悲劇として、二度は茶番として」二度発生するというヘーゲルの世界精神に関する概念のエンゲルスの性格付けも借用した[85]。

一方、エンゲルスはマンチェスターにある父親の所有する工場で事務員として働き始めたが、これは父親の会社の本拠地であるドイツにいた10代の頃と同じ役

職であった。この頃、マルクスはロンドンに住んでいたが、日常的に文通をして意見交換をすることができた[20]。エンゲルスとマルクスが熟考した考えの

1つは、ロシアにおける潜在的な革命の可能性とその特徴であった。1853年4月の時点で、エンゲルスとマルクスは「サンクトペテルブルクで始まるであろ

うロシアにおける貴族ブルジョア革命とそれに伴う内陸部での内戦」を予想していた[86]。ロシアにおけるこの種の貴族ブルジョア革命のモデルは、立憲政

府を支持し、独裁者ツァーリに対抗する1825年のデシャンブリスト反乱によって提供されたものであった[87]。

しかし、エンゲルスとマルクスは、ロシアでブルジョア革命が起こり、共産主義段階に先立ってブルジョア段階が訪れることを予期していた。1881年になる

と、マルクスもエンゲルスも、ブルジョア段階を介さずに共産主義段階に直接つながるロシアの発展過程を考えるようになった。この分析は、マルクスとエンゲ

ルスがロシアの村落コミューンまたはオブシキナの例外的な特徴として見たものに基づいていた[88]。Georgi

Plekhanovによってこの理論に疑いが投げかけられたが、プレハノフの理由は、ロシアの農民コミューンに対するマルクスの関心より2年前の『Das

Kapital』初版(1867)に基づいたものだった。このテキストの後の版は、農民コミューンが移行の基礎として使われるならば、中間的なブルジョア

段階なしにロシアで社会主義を確立することが可能であるというニコライ・チェルニシェフスキーの議論に対するマルクスの共感を示している[89]。

1870年にエンゲルスはロンドンに移り、マルクスと共に1883年にマルクスが亡くなるまで暮らしていた[12]。1870年から1894年までのエン

ゲルスのロンドンの家はリージェンツパークロード122番地だった[90]。1894年10月に彼はNW1、プリムローズヒルのリージェンツパークロード

41番に移り、そこで翌年亡くなった[引用者註:必要]。

マルクスのロンドンでの最初の住居は、ソーホーのディーン・ストリート28番地の狭いアパートであった。1856年からはケンティッシュ・タウンのグラフ

トン・テラス9番地、1875年から1883年3月に亡くなるまではベルサイズ・パークのメイトランド・パーク・ロード41番地の長屋に住んでいた

[91]。

メアリー・バーンズは1863年に心臓病で急死し、その後エンゲルスは彼女の妹リディア(「リジー」)と親しくなった。二人はロンドンで夫婦として公然と

生活し、リジーが亡くなる数時間前の1878年9月11日に結婚した[92][93]。

|

Later years

Later in their life, both Marx and Engels came to argue that in some

countries workers might be able to achieve their aims through peaceful

means.[94] In following this, Engels argued that socialists were

evolutionists, although they remained committed to social

revolution.[95] Similarly, Tristram Hunt argues that Engels was

sceptical of "top-down revolutions" and later in life advocated "a

peaceful, democratic road to socialism".[32] Engels also wrote in his

introduction to the 1891 edition of Marx's The Class Struggles in

France that "[r]ebellion in the old style, street fighting with

barricades, which decided the issue everywhere up to 1848, was to a

considerable extent obsolete",[96][97] although some such as David W.

Lowell empashised their cautionary and tactical meaning, arguing that

"Engels questions only rebellion 'in the old style', that is,

insurrection: he does not renounce revolution. The reason for Engels'

caution is clear: he candidly admits that ultimate victory for any

insurrection is rare, simply on military and tactical grounds".[98]

In his introduction to the 1895 edition of Marx's The Class Struggles

in France, Engels attempted to resolve the division between reformists

and revolutionaries in the Marxist movement by declaring that he was in

favour of short-term tactics of electoral politics that included

gradualist and evolutionary socialist measures while maintaining his

belief that revolutionary seizure of power by the proletariat should

remain a goal. In spite of this attempt by Engels to merge gradualism

and revolution, his effort only diluted the distinction of gradualism

and revolution and had the effect of strengthening the position of the

revisionists.[99] Engels's statements in the French newspaper Le

Figaro, in which he wrote that "revolution" and the "so-called

socialist society" were not fixed concepts, but rather constantly

changing social phenomena, and argued that this made "us socialists all

evolutionists", increased the public perception that Engels was

gravitating towards evolutionary socialism. Engels also argued that it

would be "suicidal" to talk about a revolutionary seizure of power at a

time when the historical circumstances favoured a parliamentary road to

power that he predicted could bring "social democracy into power as

early as 1898". Engels's stance of openly accepting gradualist,

evolutionary and parliamentary tactics while claiming that the

historical circumstances did not favour revolution caused confusion.

Marxist revisionist Eduard Bernstein interpreted this as indicating

that Engels was moving towards accepting parliamentary reformist and

gradualist stances, but he ignored that Engels's stances were tactical

as a response to the particular circumstances and that Engels was still

committed to revolutionary socialism.[100] Engels was deeply distressed

when he discovered that his introduction to a new edition of The Class

Struggles in France had been edited by Bernstein and orthodox Marxist

Karl Kautsky in a manner which left the impression that he had become a

proponent of a peaceful road to socialism.[99] On 1 April 1895, four

months before his death, Engels responded to Kautsky:

I was amazed to see today in the Vorwärts an excerpt from my

'Introduction' that had been printed without my knowledge and tricked

out in such a way as to present me as a peace-loving proponent of

legality [at all costs]. Which is all the more reason why I should like

it to appear in its entirety in the Neue Zeit in order that this

disgraceful impression may be erased. I shall leave Liebknecht in no

doubt as to what I think about it and the same applies to those who,

irrespective of who they may be, gave him this opportunity of

perverting my views and, what's more, without so much as a word to me

about it.[101]

After Marx's death, Engels devoted much of his remaining years to

editing Marx's unfinished volumes of Das Kapital; however, he also

contributed significantly in other areas. Engels made an argument using

anthropological evidence of the time to show that family structures

changed over history, and that the concept of monogamous marriage came

from the necessity within class society for men to control women to

ensure their own children would inherit their property. He argued a

future communist society would allow people to make decisions about

their relationships free of economic constraints. One of the best

examples of Engels's thoughts on these issues are in his work The

Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. On 5 August 1895,

Engels died of throat cancer in London, aged 74.[102][103] Following

cremation at Woking Crematorium, his ashes were scattered off Beachy

Head, near Eastbourne, as he had requested.[103][104] He left a

considerable estate to Eduard Bernstein and Louise Freyberger (wife of

Ludwig Freyberger), valued for probate at £25,265 0s. 11d, equivalent

to £3,104,733 in 2021.[105][106]

|

後年

同様にトリストラム・ハントは、エンゲルスが「トップダウン革命」に懐疑的であり、後年「社会主義への平和的、民主的な道」を提唱したと論じている

[95]。

またエンゲルスは1891年版のマルクスの『フランスにおける階級闘争』の序文で、「1848年までどこでも問題を決定していた古いスタイルでの反乱、バ

リケードを使ったストリートファイトはかなりの程度時代遅れである」と書いているが[96][97]、デヴィッド・W・ローウェルなどはその警告的、戦術

的意味を強調して、「エンゲルスは『古いスタイルの』反乱、つまり反乱だけを問題にしており、彼は革命を放棄していない」と主張している[97][93]

[93]。エンゲルスの警戒心の理由は明らかであり、彼は単に軍事的、戦術的な理由から、どのような反乱であっても究極の勝利は稀であると率直に認めてい

るのである」[98]。

エンゲルスは、1895年版のマルクスの『フランスにおける階級闘争』の序文で、プロレタリアートによる権力の革命的奪取が目標であり続けるべきであると

いう確信を維持しながら、漸進的で進化的な社会主義の方策を含む選挙政治の短期戦術に賛成であることを宣言して、改革派と革命派の間の分裂を解決しようと

した[99]。エンゲルスがこのように漸進主義と革命を融合させようとしたにもかかわらず、彼の努力は漸進主義と革命の区別を薄め、修正主義者の立場を強

化する効果しかもたらさなかった[99]。フランスの新聞『Le

Figaro』で、「革命」と「いわゆる社会主義社会」は固定した概念ではなく、絶えず変化する社会現象だと書き、そのために「我々社会主義者はみな進化

論者」だと主張したことで、エンゲルスが進化主義社会へと傾斜していると一般大衆は認識したのであった。また、エンゲルスは、歴史的状況が議会による権力

の獲得に有利な時期に、革命的な権力の奪取を語ることは「自殺行為」であると主張し、「早ければ1898年には社会民主主義が政権を握る」と予言した。エ

ンゲルスは、漸進主義、進化主義、議会主義を公然と容認する一方で、歴史的状況は革命に有利ではないと主張し、混乱を招いたのである。マルクス主義の修正

主義者エドゥアルド・バーンスタインは、これをエンゲルスが議会改革主義や漸進主義的な姿勢を受け入れる方向に向かっていることを示していると解釈した

が、彼はエンゲルスの姿勢が特定の状況への対応として戦術的であり、エンゲルスが依然として革命的社会主義に取り組んでいたことを無視している

[100]。

[エンゲルスは、『フランスにおける階級闘争』の新版に対する自分の序文が、バーンスタインと正統派マルクス主義のカール・カウツキーによって、彼が社会

主義への平和的道の提唱者になったかのような印象を与える形で編集されていることを知り、深く心を痛めていた[99]。

1895年4月1日、死の4ヶ月前にエンゲルスはカウツキーに対して返答している。

今日、『フォアベルト』紙で私の『序文』からの抜粋が、私の知らないうちに印刷され、私を平和を愛する合法性の支持者であるかのように装っているのを見

て、私は驚きを隠せませんでした。だからこそ、この不名誉な印象を払拭するために、『ノイエ・ツァイト』に全文を掲載することを望むのです。私はリープク

ネヒトに、私がそれについてどう考えているかを疑わせないようにする。また、誰であろうと、私の見解を曲げるこの機会を彼に与え、しかも、それについて私

に一言も言わない人々にも同じことが当てはまる[101]。

マルクスの死後、エンゲルスはその余生をマルクスの未完の『資本論』の編集に捧げたが、他の分野でも大きく貢献した。エンゲルスは、当時の人類学的証拠を

用いて、家族構造が歴史の中で変化したこと、そして一夫一婦制の結婚の概念は、階級社会の中で男性が自分の子供が確実に財産を相続するために女性を支配す

る必要性から生まれたことを論証していた。彼は、将来の共産主義社会では、人々が経済的制約を受けずに人間関係を決定できるようになると主張した。これら

の問題に対するエンゲルスの考えを最もよく表しているのが、彼の著作『家族・私有財産・国家の起源』である。1895年8月5日、エンゲルスは咽頭癌のた

めロンドンで74歳で死去した[102][103]。ウォーキング斎場での火葬の後、遺灰は彼の希望通りイーストボーン近くのビーチーヘッド沖で撒かれた

[103][104]

彼はかなりの遺産をエドワード・バーンスタインとルイーズ・フレイベルガー(ルードヴィヒ・フレイベルガーの妻)に残し、検認では25,265

0s.11d £とされた。11d、2021年の£3,104,733に相当する[105][106]。

|

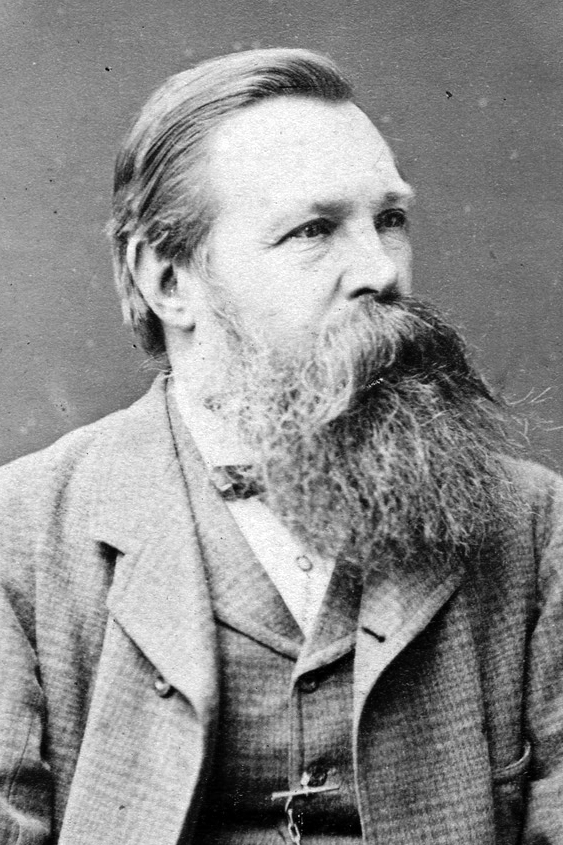

Personality

Engels's interests included poetry, fox hunting and hosting regular

Sunday parties for London's left-wing intelligentsia where, as one

regular put it, "no one left before two or three in the morning". His

stated personal motto was "take it easy" while "jollity" was listed as

his favourite virtue.[108]

Of Engels's personality and appearance, Robert Heilbroner described him

in The Worldly Philosophers as "tall and rather elegant, he had the

figure of a man who liked to fence and to ride to hounds and who had

once swum the Weser River four times without a break" as well as having

been "gifted with a quick wit and facile mind" and of a gay

temperament, being able to "stutter in twenty languages". He had a

great enjoyment of wine and other "bourgeois pleasures". Engels

favoured forming romantic relationships with that of the proletariat

and found a long-term partner in a working-class woman named Mary

Burns, although they never married. After her death, Engels was

romantically involved with her younger sister Lydia Burns.[109]

Historian and former Labour MP Tristram Hunt, author of The

Frock-Coated Communist: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels,[5]

argues that Engels "almost certainly was, in other words, the kind of

man Stalin would have had shot".[32] Hunt sums up the disconnect

between Engels's personality and the Soviet Union which later utilised

his works, stating:

This great lover of the good life, passionate advocate of

individuality, and enthusiastic believer in literature, culture, art

and music as an open forum could never have acceded to the Soviet

Communism of the 20th century, all the Stalinist claims of his

paternity notwithstanding.[5][32]

As to the religious persuasion attributable to Engels, Hunt writes:

In that sense the latent rationality of Christianity comes to permeate

the everyday experience of the modern world—its values are now

variously incarnated in the family, civil society, and the state. What

Engels particularly embraced in all of this was an idea of modern

pantheism, or, rather, pandeism, a merging of divinity with progressing

humanity, a happy dialectical synthesis that freed him from the fixed

oppositions of the pietist ethos of devout longing and estrangement.

'Through Strauss I have now entered on the straight road to

Hegelianism... The Hegelian idea of God has already become mine, and

thus I am joining the ranks of the "modern pantheists",' Engels wrote

in one of his final letters to the soon-to-be-discarded Graebers

[Wilhelm and Friedrich, priest trainees and former classmates of

Engels].[5]

Engels was a polyglot and was able to write and speak in numerous

languages, including Russian, Italian, Portuguese, Irish, Spanish,

Polish, French, English, German and the Milanese dialect.[110]

|

パーソナリティ

エンゲルスの趣味は、詩作、キツネ狩り、ロンドンの左翼知識人のための定期的な日曜パーティの主催などであり、ある常連に言わせると「朝の2時か3時前に

は誰も帰らない」ものだったという。彼の個人的なモットーは「気楽にやる」であり、「陽気さ」は彼の好きな美徳として挙げられていた[108]。

エンゲルスの性格や外見について、ロバート・ハイルブロナーは『世俗の哲学者たち』の中で、「背が高く、かなり優雅で、柵作りと猟犬に乗るのが好きな男の

姿をしており、かつてヴェーザー川を休みなく4回泳いだことがある」、また「機転と頭の回転が速く」、「20か国語でどもる」ことができる、陽気な気質で

あるとして彼を紹介している[108]。ワインをはじめとする「ブルジョワの楽しみ」をこよなく愛した。エンゲルスはプロレタリアートとの恋愛関係を好

み、メアリー・バーンズという労働者階級の女性に長年のパートナーを見つけたが、結婚はしなかった。彼女の死後、エンゲルスは彼女の妹であるリディア・

バーンズと恋愛関係にあった[109]。

歴史学者で元労働党議員のトリストラム・ハント(『The Frock-Coated

Communist』の著者。ハントはエンゲルスの人格と、後に彼の著作を利用したソ連との間の断絶について、次のようにまとめている[32]。

この善良な生活の偉大な恋人、個性の情熱的な擁護者、そして開かれた場としての文学、文化、芸術、音楽への熱狂的な信奉者は、彼の父性についてのスターリ

ン主義の主張にもかかわらず、20世紀のソ連共産主義に決して同意することができなかった[5][32]」。

エンゲルスに起因する宗教的な説得力について、ハントはこう書いている。

その意味で、キリスト教の潜在的な合理性は現代世界の日常的な経験に浸透するようになり、その価値は今や家族、市民社会、国家において様々に具現化されて

いるのである。エンゲルスがこの中で特に受け入れたのは、現代の汎神論、いや、むしろパンデイズムという考え方で、神性と進歩する人間性の融合、幸福な弁

証法的総合が、敬虔な憧れと疎外という敬虔主義の倫理観の固定的対立から彼を解放したのである。シュトラウスを通して、私は今、ヘーゲル主義へのまっすぐ

な道に入った......」。ヘーゲル的な神の思想はすでに私のものとなり、こうして私は「現代の汎神論者」の仲間入りをすることになった」とエンゲルス

は、まもなく捨てられることになるグレーバー(Wilhelm and

Friedrich、エンゲルスの司祭研修生で元クラスメート)宛ての最後の手紙に書いている[5]。

エンゲルスはポリグロットであり、ロシア語、イタリア語、ポルトガル語、アイルランド語、スペイン語、ポーランド語、フランス語、英語、ドイツ語、ミラノ

方言など、数多くの言語で書いたり話したりすることができた[110]。

|

In his biography of Engels,

Vladimir Lenin wrote: "After his friend Karl Marx (who died in 1883),

Engels was the finest scholar and teacher of the modern proletariat in

the whole civilised world. [...] In their scientific works, Marx and

Engels were the first to explain that socialism is not the invention of

dreamers, but the final aim and necessary result of the development of

the productive forces in modern society. All recorded history hitherto

has been a history of class struggle, of the succession of the rule and

victory of certain social classes over others."[111] According to Paul

Kellogg, there is "some considerable controversy" regarding "the place

of Frederick Engels in the canon of 'classical Marxism'". While some

such as Terrell Carver dispute "Engels' claim that Marx agreed with the

views put forward in Engels' major theoretical work, Anti-Dühring",

others such as E. P. Thompson "identified a tendency to make 'old

Engels into a whipping boy, and to impugn him any sign that once

chooses to impugn subsequent Marxsisms'".[96]

Tristram Hunt argues that Engels has become a convenient scapegoat, too

easily blamed for the state crimes of Communist regimes such as China,

the Soviet Union and those in Africa and Southeast Asia, among others.

Hunt writes that "Engels is left holding the bag of 20th century

ideological extremism" while Karl Marx "is rebranded as the acceptable,

post–political seer of global capitalism".[32] Hunt largely exonerates

Engels, stating that "[i]n no intelligible sense can Engels or Marx

bear culpability for the crimes of historical actors carried out

generations later, even if the policies were offered up in their

honor".[32] Andrew Lipow describes Marx and Engels as "the founders of

modern revolutionary democratic socialism".[112]

While admitting the distance between Marx and Engels on one hand and

Joseph Stalin on the other, some writers such as Robert Service are

less charitable, noting that the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin predicted

the oppressive potential of their ideas, arguing that "[i]t is a

fallacy that Marxism's flaws were exposed only after it was tried out

in power. [...] [Marx and Engels] were centralisers. While talking

about 'free associations of producers', they advocated discipline and

hierarchy".[113] Paul Thomas, of the University of California,

Berkeley, claims that while Engels had been the most important and

dedicated facilitator and diffuser of Marx's writings, he significantly

altered Marx's intents as he held, edited and released them in a

finished form and commentated on them. Engels attempted to fill gaps in

Marx's system and extend it to other fields. In particular, Engels is

said to have stressed historical materialism, assigning it a character

of scientific discovery and a doctrine, forming Marxism as such. A case

in point is Anti-Dühring which both supporters and detractors of

socialism treated as an encompassing presentation of Marx's thought.

While in his extensive correspondence with German socialists Engels

modestly presented his own secondary place in the couple's intellectual

relationship and always emphasised Marx's outstanding role, Russian

communists such as Lenin raised Engels up with Marx and conflated their

thoughts as if they were necessarily congruous. Soviet Marxists then

developed this tendency to the state doctrine of dialectical

materialism.[114]

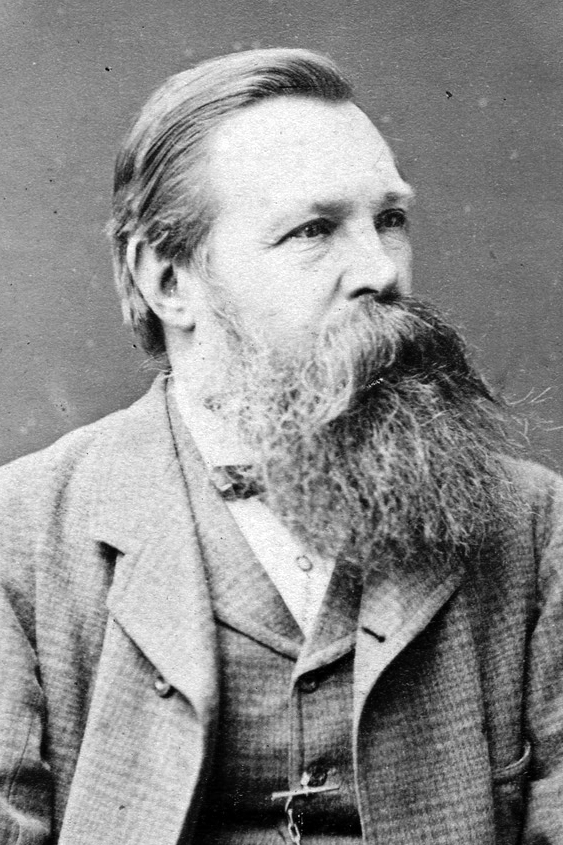

Since 1931, Engels has had a Russian city named after him—Engels,

Saratov Oblast. It served as the capital of the Volga German Republic

within Soviet Russia and as part of Saratov Oblast. A town named Marx

is located 50 kilometres (30 miles) northeast. In 2014, Engels's

"magnificent beard" inspired a climbing wall sculpture in Salford. The

5-metre-high (16 ft) beard statue, described as a "symbol of wisdom and

learning", was planned to stand on the campus of the University of

Salford. Engine, the arts company behind the piece, stated that "the

idea came from a 1980s plan to relocate an Eastern Bloc statue of the

thinker to Manchester".[115]

In the summer of 2017, as part of the Manchester International

Festival, a Soviet-era statue of Engels was installed by sculptor Phil

Collins at Tony Wilson Place in Manchester.[116] It was transported

from the village of Mala Pereshchepina in Eastern Ukraine, after the

statue had been deposed from its central position in the village in the

wake of laws outlawing communist symbols in Ukraine introduced in 2015.

In recognition of the important influence Manchester had on his work,

the 3.5 metre statue now stands in Tony Wilson Place, a prominent

eatery district on Manchester's First Street.[117][118] The

installation of what was originally an instrument of propaganda drew

criticism from Kevin Bolton in The Guardian.[119]

The Friedrich Engels Guards Regiment (also known as NVA Guard Regiment

1) was a special guard unit of the East German National People's Army

(NVA). The guard regiment was established in 1962 from parts of the

Hugo Eberlein Guards Regiment but wasn't given the title "Friedrich

Engels" until 1970.

|

ウラジーミル・レーニンは、エンゲルスの伝記で、「友人カール・マルク

ス(1883年に死去)の後、エンゲルスは、全文明世界で最も優れた学者であり近代プロレタリアートの教師であった。[中略)マルクスとエンゲルスは、そ

の科学的著作において、社会主義が夢想家の発明ではなく、近代社会における生産力の発展の最終目的であり必要な結果であることを、初めて説明したのであ

る。ポール・ケロッグによれば、「『古典的マルクス主義』の正典におけるフレデリック・エンゲルスの位置」に関して「かなりの論争がある」[111]とい

う。テレル・カーヴァーのような一部の者は「マルクスがエンゲルスの主要な理論的著作『反デューリング』で提示された見解に同意したというエンゲルスの主

張」に異議を唱えているが、E・P・トンプソンのような他の者は「『古いエンゲルスを鞭打ち少年とし、一度後続のマルクス主義を非難することを選択した場

合には、いかなる兆候であれ彼を非難する』傾向を確認した」[96]。

トリストラム・ハントは、エンゲルスが便利なスケープゴートとなり、中国、ソ連、アフリカや東南アジアなどの共産主義政権の国家犯罪のためにあまりにも簡

単に非難されるようになったことを論じている[96]。ハントは、カール・マルクスが「グローバル資本主義の許容できる、ポスト政治的な先見者として再ブ

ランディングされる」一方で、「エンゲルスは20世紀のイデオロギー的過激主義の袋を持ったまま」だと書いている[32]。

アンドリュー・リポーはマルクスとエンゲルスを「現代の革命的民主社会主義の創設者」として記述している[112]。

一方ではマルクスとエンゲルスとヨシフ・スターリンとの間の距離を認めながらも、ロバート・サービスのような一部の作家は、アナーキストのミハイル・バ

クーニンが彼らの思想の抑圧的可能性を予言していたと指摘し、「マルクス主義の欠陥は、それが権力を持って試された後にのみ露呈したというのは誤りだ」と

論じている。[マルクスとエンゲルスは)中央集権主義者であった。カリフォルニア大学バークレー校のポール・トーマスは、エンゲルスがマルクスの著作の最

も重要で献身的な促進者であり普及者であった一方で、彼が著作を保有し、編集し、完成した形で発表し、それについてコメントすることによってマルクスの意

図を大幅に変更したと主張する[113]。エンゲルスは、マルクスの体系の空白を埋め、他の分野への拡張を試みた。特にエンゲルスは、史的唯物論を強調

し、科学的発見と教義の性格を付与して、マルクス主義を形成したといわれる。社会主義の支持者も否定者も、マルクスの思想を包括的に提示したものとして

扱った『反デューリング』がその一例である。エンゲルスは、ドイツの社会主義者との広範な書簡のなかで、二人の知的関係のなかで自分の立場を控えめに示

し、常にマルクスの優れた役割を強調したが、レーニンなどのロシアの共産主義者は、エンゲルスをマルクスとともに持ち上げ、あたかも両者の考えが必ずしも

一致しているように混同していたのである。そしてソ連のマルクス主義者はこの傾向を弁証法的唯物論という国家の教義に発展させた[114]。

1931年以来、エンゲルスは彼の名を冠したロシアの都市(サラトフ州エンゲルス)を持っている。ソビエト連邦内のヴォルガ・ドイツ共和国の首都であり、

サラトフ州の一部であった。北東50kmにはマルクスという町がある。2014年、エンゲルスの「立派なひげ」に触発され、サルフォードにクライミング

ウォールの彫刻が作られた。知恵と学びの象徴」とされる高さ5メートル(16フィート)のひげの像は、サルフォード大学のキャンパスに立つ予定だった。こ

の作品の背後にあるアートカンパニーであるエンジンは、「このアイデアは、東欧圏の思想家の像をマンチェスターに移設するという1980年代の計画から来

た」と述べている[115]。

2017年の夏、マンチェスター国際フェスティバルの一環として、彫刻家フィル・コリンズによってソ連時代のエンゲルスの像がマンチェスターのトニー・

ウィルソン・プレイスに設置された[116]。

それは、2015年に導入されたウクライナの共産主義のシンボルを違法とする法律を受けて、村の中心位置から像を退位させた後に東ウクライナのマーラ・ペ

レシュチェピナから輸送されたものであった。マンチェスターが彼の作品に与えた重要な影響を認め、3.5メートルの像は現在マンチェスターのファーストス

トリートの著名な飲食店街であるトニー・ウィルソン・プレイスに立っている[117][118]。

本来プロパガンダの道具であるものの設置は、ガーディアン紙のケビン・ボルトンの批評を呼んだ[119]。

フリードリヒ・エンゲルス警備連隊(NVA警備連隊1としても知られる)は、東ドイツ国家人民軍(NVA)の特別警備隊であった。1962年にフーゴ・

エーベルライン親衛連隊の一部から創設されたが、「フリードリヒ・エンゲルス」の称号が与えられたのは1970年になってからである。

|

Influences

In spite of his criticism of the utopian socialists, Engels's own

beliefs were nonetheless influenced by the French socialist Charles

Fourier. From Fourier, he derives four main points that characterize

the social conditions of a communist state. The first point maintains

that every individual would be able to fully develop their talents by

eliminating the specialization of production. Without specialization,

every individual would be permitted to exercise any vocation of their

choosing for as long or as little as they would like. If talents

permitted it, one could be a baker for a year and an engineer the next.

The second point builds upon the first as with the ability of workers

to cycle through different jobs of their choosing, the fundamental

basis of the social division of labour is destroyed and the social

division of labour will disappear as a result. If anyone can employ

himself at any job that he wishes, then there are clearly no longer any

divisions or barriers to entry for labour, otherwise such fluidity

between entirely different jobs would not exist. The third point

continues from the second as once the social division of labour is

gone, the division of social classes based on property ownership will

fade with it. If labour division puts a man in charge of a farm, that

farmer owns the productive resources of that farm. The same applies to

the ownership of a factory or a bank. Without labour division, no

single social class may claim exclusive rights to a particular means of

production since the absence of labour division allows all to use it.

Finally, the fourth point concludes that the elimination of social

classes destroys the sole purpose of the state and it will cease to

exist. As Engels stated in his own writing, the only purpose of the

state is to abate the effects of class antagonisms. With the

elimination of social classes based on property, the state becomes

obsolete and a communist society, at least in the eyes of Engels, is

achieved.[120]

|

影響

ユートピア社会主義者を批判しながらも、エンゲルス自身の信念は、フランスの社会主義者シャルル・フーリエの影響を受けている。フーリエからは、共産主義

国家の社会的条件を特徴づける4つの主要なポイントを導き出している。第一は、生産の専門化を排除することによって、各人がその才能を十分に発揮できるよ

うになることである。専門化がなければ、一人ひとりが自分の好きな職業を、好きなだけ、好きなだけ行うことが許される。才能があれば、1年間はパン屋さん

で、次の年はエンジニアになることもできる。第二の点は、労働者が自分の好きな仕事を転々とすることができるようになれば、社会的分業の基本的基礎が破壊

され、その結果、社会的分業が消滅することになる、という第一の点を基礎としている。誰でも好きな仕事に就けるのであれば、もはや労働の分業や参入障壁は

明らかに存在しない。そうでなければ、まったく異なる仕事間の流動性は存在しないことになる。第三の点は、第二の点から続くもので、社会的分業がなくなれ

ば、財産所有に基づく社会階級の区分もそれとともに薄れることになる。分業によって、ある人が農場を管理するようになれば、その農場の生産資源はその農家

に所有される。工場や銀行の所有権も同じである。分業がなければ、特定の生産手段に対して、どの社会階級も排他的権利を主張することはできない。なぜな

ら、分業がなければ、すべての人がその生産手段を使うことができるからである。最後に、第四点は、社会階級の排除は、国家の唯一の目的を破壊し、国家は消

滅すると結論づけている。エンゲルスが自著で述べているように、国家の唯一の目的は、階級的対立の影響を緩和することである。財産に基づく社会階級の排除

によって、国家は時代遅れとなり、少なくともエンゲルスの目には共産主義社会が達成される[120]。

|

Major works

The Holy Family (1844)

This book was written by Marx and Engels in November 1844. It is a

critique on the Young Hegelians and their trend of thought which was

very popular in academic circles at the time. The title was suggested

by the publisher and is meant as a sarcastic reference to the Bauer

Brothers and their supporters.[121]

The book created a controversy with much of the press and caused Bruno

Bauer to attempt to refute the book in an article published in Wigand's

[de] Vierteljahrsschrift in 1845. Bauer claimed that Marx and Engels

misunderstood what he was trying to say. Marx later replied to his

response with his own article published in the journal

Gesellschaftsspiegel [de] in January 1846. Marx also discussed the

argument in chapter 2 of The German Ideology.[121]

The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845)

Main article: The Condition of the Working Class in England

A study of the deprived conditions of the working class in Manchester

and Salford, based on Engels's personal observations. The work also

contains seminal thoughts on the state of socialism and its

development. Originally published in German and only translated into

English in 1887, the work initially had little impact in England;

however, it was very influential with historians of British

industrialisation throughout the twentieth century.[122]

The Peasant War in Germany (1850)

Main article: The Peasant War in Germany

An account of the early 16th-century uprising known as the German

Peasants' War, with a comparison with the recent revolutionary

uprisings of 1848–1849 across Europe.[123]

Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science (1878)

Main article: Anti-Dühring

Popularly known as Anti-Dühring, this book is a detailed critique of

the philosophical positions of Eugen Dühring, a German philosopher and

critic of Marxism. In the course of replying to Dühring, Engels reviews

recent advances in science and mathematics seeking to demonstrate the

way in which the concepts of dialectics apply to natural phenomena.

Many of these ideas were later developed in the unfinished work,

Dialectics of Nature. Three chapters of Anti-Dühring were later edited

and published under the separate title, Socialism: Utopian and

Scientific.

Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (1880)

Main article: Socialism: Utopian and Scientific

One of the best selling socialist books of the era.[124] In this work,

Engels briefly described and analyzed the ideas of notable utopian

socialists such as Charles Fourier and Robert Owen, pointed out their

strongpoints and shortcomings, and provides an explanation of the

scientific socialist framework for understanding of capitalism, and an

outline of the progression of social and economic development from the

perspective of historical materialism.

Dialectics of Nature (1883)

Main article: Dialectics of Nature

Dialectics of Nature (German: "Dialektik der Natur") is an unfinished

1883 work by Engels that applies Marxist ideas, particularly those of

dialectical materialism, to science. It was first published in the

Soviet Union in 1925.[125]

The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884)

Main article: The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State

In this work, Engels argues that the family is an ever-changing

institution that has been shaped by capitalism. It contains a

historical view of the family in relation to issues of class, female

subjugation and private property.

|

主な作品

聖家族 (1844年)

1844年11月、マルクスとエンゲルスによって書かれた本。この本は、当時、学界で非常に人気があった青年ヘーゲル派とその思想傾向に対する批判であ

る。タイトルは出版社が提案したもので、バウアー兄弟とその支持者に対する皮肉な言及という意味である[121]。

この本は多くのマスコミと論争を起こし、ブルーノ・バウアーは1845年にヴィーガンドの[de]

Vierteljahrsschriftに掲載された記事の中でこの本に反論しようとした。バウアーは、マルクスとエンゲルスが彼の言おうとしていること

を誤解していると主張した。マルクスはその後、1846年1月に雑誌『ゲゼルシャフトシュピーゲル』[de]に掲載された自らの論文でその反論に答えてい

る。またマルクスは『ドイツ・イデオロギー』の第2章でもこの議論を展開している[121]。

『イギリスにおける労働者階級の状況』(1845年)

主な記事 イングランドにおける労働者階級の状況

エンゲルスの個人的な観察に基づいて、マンチェスターとサルフォードの労働者階級の困窮した状況を研究したものである。社会主義のあり方とその発展に関す

る画期的な思想も含まれている。ドイツ語で出版され、1887年に初めて英語に翻訳されたこの作品は、当初イギリスではほとんど影響を与えなかったが、

20世紀を通じてイギリスの工業化の歴史家に非常に大きな影響を与えた[122]。

ドイツにおける農民戦争(1850年)

主な記事 ドイツの農民戦争

ドイツの農民戦争として知られる16世紀初頭の反乱について、1848年から1849年にかけてヨーロッパ各地で起こった最近の革命的な反乱と比較しなが

ら説明したもの[123]。

オイゲン・デューリング博士の科学革命(1878年)

主な記事 アンチ・デューリング

本書は、ドイツの哲学者でありマルクス主義を批判したオイゲン・デューリングの哲学的立場を詳細に批判したもので、「反デュールリンク」として親しまれて

いる。エンゲルスは、デューリングに反論する過程で、最近の科学や数学の進歩を検討し、弁証法の概念が自然現象に適用できることを証明しようとした。これ

らの思想の多くは、後に未完の著作『自然の弁証法』で展開されることになる。反デューリング』の3章は、後に『社会主義』という別の題名で編集され出版さ

れた。ユートピア的、科学的

社会主義。ユートピア的で科学的な社会主義 (1880年)

主な記事 社会主義 ユートピア的・科学的

エンゲルスは、シャルル・フーリエやロバート・オーウェンなど著名なユートピア社会主義者の思想を簡潔に記述・分析し、その長所と短所を指摘するととも

に、資本主義を理解する科学的社会主義の枠組みの説明と、社会・経済の発展過程を史的唯物論の立場から概説した著作[124]である。

自然の弁証法 (1883年)

主な記事 自然弁証法

マルクス主義、特に弁証法的唯物論の考え方を科学に応用した、エンゲルスの1883年の未完の著作。1925年にソビエト連邦で初めて出版された

[125]。

家族・私有財産・国家の起源』(1884年)(原題:The Origin of the Family, Private Property and

the State

主な記事 家族、私有財産、国家の起源』(1884年

この著作でエンゲルスは、家族は資本主義によって形成された常に変化する制度であると論じている。この著作には、階級、女性の隷属、私有財産の問題との関

連で、家族の歴史的見解が含まれている。

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_Engels

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|