The funeral usually includes a ritual through which the corpse receives a final disposition.[2] Depending on culture and religion, these can involve either the destruction of the body (for example, by cremation, sky burial, decomposition, disintegration or dissolution) or its preservation (for example, by mummification). Differing beliefs about cleanliness and the relationship between body and soul are reflected in funerary practices. A memorial service (or celebration of life) is a funerary ceremony that is performed without the remains of the deceased person.[3]

The word funeral comes from the Latin funus, which had a variety of meanings, including the corpse and the funerary rites themselves. Funerary art is art produced in connection with burials, including many kinds of tombs, and objects specially made for burial like flowers with a corpse.

葬儀には通常、死体が最後の処分を受ける儀式が含まれる[2]。文化や宗教によって、遺体を破壊する(火葬、空葬、分解、崩壊、溶解など)か、保存する (ミイラ化など)かのいずれかが含まれる。清潔さや肉体と魂の関係についての考え方の違いは、葬儀の慣習に反映されている。追悼式(または生前祭)は、亡 くなった人の遺骨なしで行われる葬儀の儀式である[3]。

葬儀という言葉はラテン語のfunusに由来し、死体や葬儀そのものなど様々な意味を持つ。葬送美術とは、埋葬に関連して制作された美術品のことで、多く の種類の墓や、遺体とともに飾る花のような埋葬のために特別に作られた品々を含む。

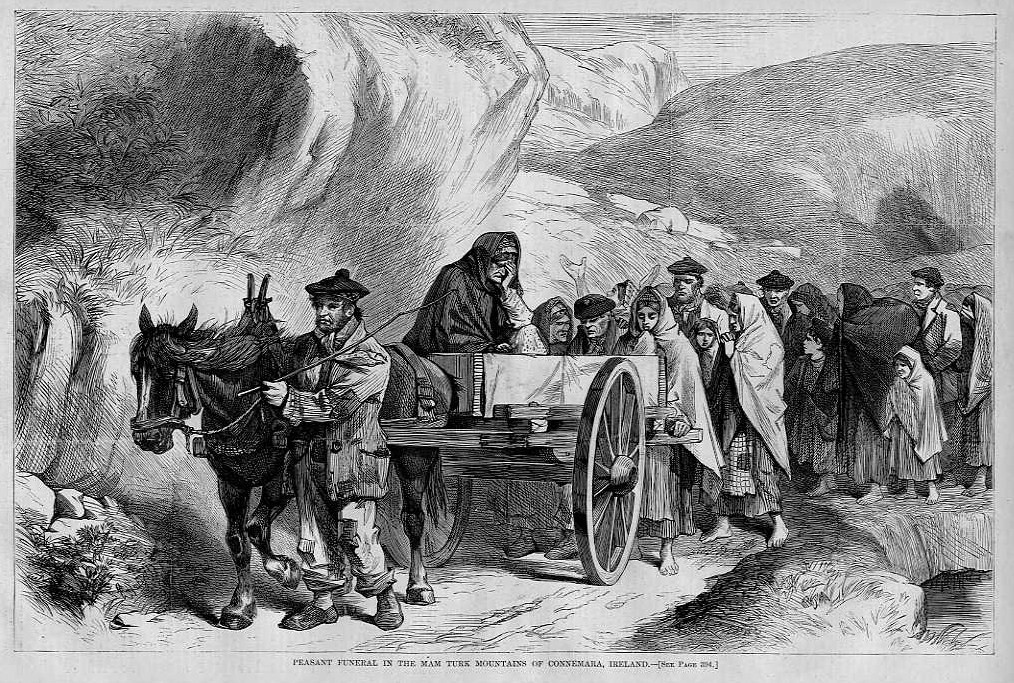

Peasant funeral in the Mam Turk mountains of Connemara, Ireland, 1870

Funeral rites are as old as human culture itself, pre-dating modern Homo sapiens and dated to at least 300,000 years ago.[4] For example, in the Shanidar Cave in Iraq, in Pontnewydd Cave in Wales and at other sites across Europe and the Near East,[4] archaeologists have discovered Neanderthal skeletons with a characteristic layer of flower pollen. This deliberate burial and reverence given to the dead has been interpreted as suggesting that Neanderthals had religious beliefs,[4] although the evidence is not unequivocal – while the dead were apparently buried deliberately, burrowing rodents could have introduced the flowers.[5]

Substantial cross-cultural and historical research document funeral customs as a highly predictable, stable force in communities.[6][7] Funeral customs tend to be characterized by five "anchors": significant symbols, gathered community, ritual action, cultural heritage, and transition of the dead body (corpse).[2]

1870年、アイルランド、コネマラのマム・ターク山地での農民葬。

例えば、イラクのシャニダール洞窟、ウェールズのポントネウィド洞窟、ヨーロッパと近東の他の遺跡[4]では、考古学者が特徴的な花粉の層を持つネアンデ ルタール人の骸骨を発見している。このような意図的な埋葬と死者への畏敬の念は、ネアンデルタール人が宗教的信念を持っていたことを示唆していると解釈さ れているが[4]、証拠は明確ではない。

葬儀の習慣は、重要なシンボル、集まったコミュニティ、儀式的行為、文化的遺産、死体(死体)の変遷という5つの「アンカー」によって特徴づけられる傾向 がある[2]。

Bahá'í Faith

Funerals in the Bahá'í Faith are characterized by not embalming, a prohibition against cremation, using a chrysolite or hardwood casket, wrapping the body in silk or cotton, burial not farther than an hour (including flights) from the place of death, and placing a ring on the deceased's finger stating, "I came forth from God, and return unto Him, detached from all save Him, holding fast to His Name, the Merciful, the Compassionate." The Bahá'í funeral service also contains the only prayer that is permitted to be read as a group – congregational prayer, although most of the prayer is read by one person in the gathering. The Bahá'í decedent often controls some aspects of the Bahá'í funeral service, since leaving a will and testament is a requirement for Bahá'ís. Since there are no Bahá'í clergy, services are usually conducted under the guise, or with the assistance of, a Local Spiritual Assembly.[8]

Buddhist

Main article: Funeral (Buddhism)

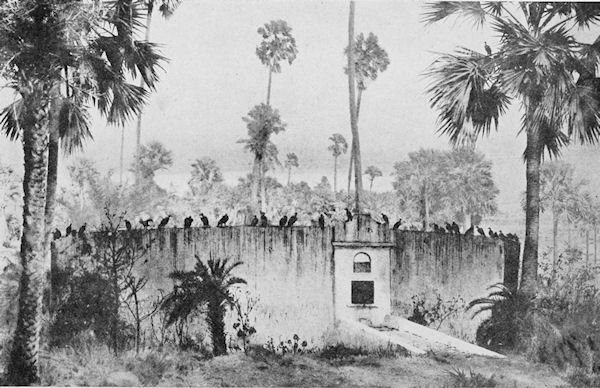

Vultures feeding on a human corpse in a sky burial

A Buddhist funeral marks the transition from one life to the next for the deceased. It also reminds the living of their own mortality. Cremation is the preferred choice,[9] although burial is also allowed. Buddhists in Tibet perform sky burials where the body is exposed to be eaten by vultures. The body is dissected with a blade on the mountain top before the exposure. Crying and wailing is discouraged and the rogyapas (body breakers who perform the ritual) laugh as if they are doing farm work. Tibetan Buddhists believe that a light-hearted atmosphere during the funeral helps the soul of the dead to get a better afterlife. After the vultures consume all the flesh the rogpyas smash the bones into pieces and mix them with tsampa to feed to the vultures.[10]

Christian

See also: Christian burial and Cremation in the Christian World

Funeral of Indian Syro-Malabar Catholic, Venerable Varghese Payyappilly Palakkappilly on 6 October 1929

Congregations of varied denominations perform different funeral ceremonies, but most involve offering prayers, scripture reading from the Bible, a sermon, homily, or eulogy, and music.[2][11] One issue of concern as the 21st century began was with the use of secular music at Christian funerals, a custom generally forbidden by the Catholic Church.[12]

Christian burials have traditionally occurred on consecrated ground such as in churchyards. There are many funeral norms like in Christianity to follow.[13] Burial, rather than a destructive process such as cremation, was the traditional practice amongst Christians, because of the belief in the resurrection of the body. Cremations later came into widespread use, although some denominations forbid them. The US Conference of Catholic Bishops said "The Church earnestly recommends that the pious custom of burying the bodies of the deceased be observed; nevertheless, the Church does not prohibit cremation unless it was chosen for reasons contrary to Christian doctrine" (canon 1176.3).[14]

Hindu

Main article: Antyesti

A Hindu cremation rite in Nepal. The samskara above shows the body wrapped in saffron red on a pyre.

Antyesti, literally 'last rites' or 'last sacrifice', refers to the rite-of-passage rituals associated with a funeral in Hinduism.[15] It is sometimes referred to as Antima Samskaram, Antya-kriya, Anvarohanyya, or Vahni Sanskara.

A dead adult Hindu is cremated, while a dead child is typically buried.[16][17] The rite of passage is said to be performed in harmony with the sacred premise that the microcosm of all living beings is a reflection of a macrocosm of the universe.[18] The soul (Atman, Brahman) is believed to be the immortal essence that is released at the Antyeshti ritual, but both the body and the universe are vehicles and transitory in various schools of Hinduism. They consist of five elements: air, water, fire, earth and space.[18] The last rite of passage returns the body to the five elements and origins.[16][18] The roots of this belief are found in the Vedas, for example in the hymns of Rigveda in section 10.16, as follows:

Burn him not up, nor quite consume him, Agni: let not his body or his skin be scattered,

O all possessing Fire, when thou hast matured him, then send him on his way unto the Fathers.

When thou hast made him ready, all possessing Fire, then do thou give him over to the Fathers,

When he attains unto the life that waits him, he shall become subject to the will of gods.

The Sun receive thine eye, the Wind thy Prana (life-principle, breathe); go, as thy merit is, to earth or heaven.

Go, if it be thy lot, unto the waters; go, make thine home in plants with all thy members.

— Rigveda 10.16[19]

The final rites of a burial, in case of untimely death of a child, is rooted in Rigveda's section 10.18, where the hymns mourn the death of the child, praying to deity Mrityu to "neither harm our girls nor our boys", and pleads the earth to cover, protect the deceased child as a soft wool.[20][21]

Among Hindus, the dead body is usually cremated within a day of death. The body is washed, wrapped in white cloth for a man or a widow, red for a married woman,[17] the two toes tied together with a string, a Tilak (red mark) placed on the forehead.[16] The dead adult's body is carried to the cremation ground near a river or water, by family and friends, and placed on a pyre with feet facing south.[17] The eldest son, or a male mourner, or a priest then bathes before leading the cremation ceremonial function.[16][22] He circumambulates the dry wood pyre with the body, says a eulogy or recites a hymn in some cases, places sesame seed in the dead person's mouth, sprinkles the body and the pyre with ghee (clarified butter), then draws three lines signifying Yama (deity of the dead), Kala (time, deity of cremation) and the dead.[16] The pyre is then set ablaze, while the mourners mourn. The ash from the cremation is consecrated to the nearest river or sea.[22] After the cremation, a period of mourning is observed for 10 to 12 days after which the immediate male relatives or the sons of the deceased shave their head, trim their nails, recites prayers with the help of priest or Brahmin and invite all relatives, kins, friends and neighbours to eat a simple meal together in remembrance of the deceased. This day, in some communities, also marks a day when the poor and needy are offered food in memory of the dead.[23]

Zoroastrianism

Parsi Tower of Silence, Bombay

The belief that bodies are infested by Nasu upon death greatly influenced Zoroastrian burial ceremonies and funeral rites. Burial and cremation of corpses was prohibited, as such acts would defile the sacred creations of earth and fire respectively.[24] Burial of corpses was so looked down upon that the exhumation of "buried corpses was regarded as meritorious." For these reasons, "Towers of Silence" were developed—open air, amphitheater like structures in which corpses were placed so carrion-eating birds could feed on them.

Sagdīd, meaning 'seen by a dog,' is a ritual that must be performed as promptly after death as possible. The dog is able to calculate the degree of evil within the corpse, and entraps the contamination so it may not spread further, expelling Nasu from the body.[25] Nasu remains within the corpse until it has been seen by a dog, or until it has been consumed by a dog or a carrion-eating bird.[26] According to chapter 31 of the Denkard, the reasoning for the required consumption of corpses is that the evil influences of Nasu are contained within the corpse until, upon being digested, the body is changed from the form of nasa into nourishment for animals. The corpse is thereby delivered over to the animals, changing from the state of corrupted nasa to that of hixr, which is "dry dead matter," considered to be less polluting.

A path through which a funeral procession has traveled must not be passed again, as Nasu haunts the area thereafter, until the proper rites of banishment are performed.[27] Nasu is expelled from the area only after "a yellow dog with four eyes, or a white dog with yellow ears" is walked through the path three times.[28] If the dog goes unwillingly down the path, it must be walked back and forth up to nine times to ensure that Nasu has been driven off.[29]

Zoroastrian ritual exposure of the dead is first known of from the writings of the mid-5th century BCE Herodotus, who observed the custom amongst Iranian expatriates in Asia Minor. In Herodotus' account (Histories i.140), the rites are said to have been "secret", but were first performed after the body had been dragged around by a bird or dog. The corpse was then embalmed with wax and laid in a trench.

While the discovery of ossuaries in both eastern and western Iran dating to the 5th and 4th centuries BCE indicates that bones were isolated, that this separation occurred through ritual exposure cannot be assumed: burial mounds,[30] where the bodies were wrapped in wax, have also been discovered. The tombs of the Achaemenid emperors at Naqsh-e Rustam and Pasargadae likewise suggest non-exposure, at least until the bones could be collected. According to legend (incorporated by Ferdowsi into his Shahnameh), Zoroaster is himself interred in a tomb at Balkh (in present-day Afghanistan).

Writing on the culture of the Persians, Herodotus reports on the Persian burial customs performed by the Magi, which are kept secret. However, he writes that he knows they expose the body of male dead to dogs and birds of prey, then they cover the corpse in wax, and then it is buried.[31] The Achaemenid custom is recorded for the dead in the regions of Bactria, Sogdia, and Hyrcania, but not in Western Iran.

The Byzantine historian Agathias has described the burial of the Sasanian general Mihr-Mihroe: "the attendants of Mermeroes took up his body and removed it to a place outside the city and laid it there as it was, alone and uncovered according to their traditional custom, as refuse for dogs and horrible carrion".

Towers are a much later invention and are first documented in the early 9th century CE. The ritual customs surrounding that practice appear to date to the Sassanid era (3rd–7th century CE). They are known in detail from the supplement to the Shāyest nē Shāyest, the two Revayats collections, and the two Saddars.

Islamic

Main article: Islamic funeral

1779 Algerian funerals

Equipment for washing and preparing bodies at Afaq khoja Mosque, Kashgar

Funerals in Islam (called Janazah in Arabic) follow fairly specific rites. In all cases, however, sharia (Islamic religious law) calls for burial of the body, preceded by a simple ritual involving bathing and shrouding the body, followed by salat (prayer).

Burial rituals should normally take place as soon as possible and include:

Bathing the dead body with water, camphor and leaves of ziziphus lotus,[32] except in extraordinary circumstances as in battle.[33]

Enshrouding the dead body in a white cotton or linen cloth except extraordinary cases such as battle. In such cases apparel of corpse is not changed.[34]

Reciting the funeral prayer in all cases for a Muslim.

Burial of the dead body in a grave in all cases for a Muslim.

Positioning the deceased so that when the face or body is turned to the right side it faces Mecca.

The mourning period is 40 days long.[35]

Jewish

Main article: Bereavement in Judaism

In Judaism, funerals follow fairly specific rites, though they are subject to variation in custom. Halakha calls for preparatory rituals involving bathing and shrouding the body accompanied by prayers and readings from the Hebrew Bible, and then a funeral service marked by eulogies and brief prayers, and then the lowering of the body into the grave and the filling of the grave. Traditional law and practice forbid cremation of the body; the Reform Jewish movement generally discourages cremation but does not outright forbid it.[36][37]

Burial rites should normally take place as soon as possible and include:

Bathing the dead body.

Enshrouding the dead body. Men are shrouded with a kittel and then (outside the Land of Israel) with a tallit (shawl), while women are shrouded in a plain white cloth.

Keeping watch over the dead body.

Funeral service, including eulogies and brief prayers.

Burial of the dead body in a grave.[36]

Filling of the grave, traditionally done by family members and other participants at the funeral.

In many communities, the deceased is positioned so that the feet face the Temple Mount in Jerusalem (in anticipation that the deceased will be facing the reconstructed Third Temple when the messiah arrives and resurrects the dead).[38]

Sikh

In Sikhism death is not considered a natural process, an event that has absolute certainty and only happens as a direct result of God's Will or Hukam.[clarification needed] In Sikhism, birth and death are closely associated, as they are part of the cycle of human life of "coming and going" (Punjabi: ਆਵਣੁ ਜਾਣਾ, romanized: Aana Jaana) which is seen as a transient stage towards Liberation (ਮੋਖੁ ਦੁਆਰੁ, Mokh Du-aar), understood as completely in unity with God. Sikhs believe in reincarnation.

The soul itself is not subject to the cycle of birth and death;[citation needed] death is only the progression of the soul on its journey from God, through the created universe and back to God again. In life a Sikh is expected to constantly remember death so that they may be sufficiently prayerful, detached and righteous to break the cycle of birth and death and return to God.

The public display of grief by wailing or crying out loud at the funeral (called Antam Sanskar) is discouraged and should be kept to a minimum. Cremation is the preferred method of disposal, burial and burial at sea are also allowed if by necessity or by the will of the person. Markers such as gravestones, monuments, etc. are not allowed, because the body is considered to be just the shell and the person's soul is their real self.[39]

On the day of the cremation, the body is washed and dressed and then taken to the Gurdwara or home where hymns (Shabadads) from Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, the Sikh Scriptures are recited by the congregation. Kirtan may also be performed by Ragis while the relatives of the deceased recite "Waheguru" sitting near the coffin. This service normally takes from 30 to 60 minutes. At the conclusion of the service, an Ardas is said before the coffin is taken to the cremation site.

At the point of cremation, a few more Shabadads may be sung and final speeches are made about the deceased person. The eldest son or a close relative generally lights the fire. This service usually lasts about 30 to 60 minutes. The ashes are later collected and disposed of by immersing them in a river, preferably one of the five rivers in the state of Punjab, India.

The ceremony in which the Sidharan Paath is begun after the cremation ceremony, may be held when convenient, wherever the Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji is present.

Hymns are sung from Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji; the first five and final verses of "Anand Sahib," the "Song of Bliss," are recited or sung. The first five verses of Sikhism's morning prayer, "Japji Sahib", are read aloud to begin the Sidharan paath. A hukam, or random verse, is then read from Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. Ardas, a prayer, is offered, and Prashad, a sacred sweet, is distributed. Langar, a meal, is then served to guests.

While the Sidharan paath is being read, the family may also sing hymns daily. Reading may take as long as needed to complete the paath.

This ceremony is followed by Sahaj Paath Bhog, Kirtan Sohila, night time prayer is recited for one week, and finally Ardas called the "Antim Ardas" ("Final Prayer") is offered the last week.[40]

Celtic

It was custom for an officiant to walk in front of the coffin with a horse's skull; this tradition was still observed by Welsh peasants up until the 19th century.[41]

バハーイー教

バハーイー教における葬儀の特徴は、防腐処理をしないこと、火葬の禁止、クリソライトまたは硬材の棺を使用すること、遺体を絹または綿で包むこと、死亡場 所から1時間以内(飛行機を含む)に埋葬すること、故人の指に指輪をはめることである。バハイの葬儀には、集団で読むことが許されている唯一の祈り、すな わち会衆祈祷も含まれるが、祈祷のほとんどは集会の中の一人によって読まれる。遺言を残すことはバハーの必須条件であるため、バハーの葬儀のある側面は故 人がコントロールすることが多い。バハーの聖職者は存在しないため、サービスは、通常、装いの下で、またはローカルスピリチュアルアセンブリの支援を受け て行われる[8]。

仏教

主な記事 葬儀(仏教)

空葬で人間の死体を捕食するハゲワシ

仏教の葬儀は、故人の生から次の生への移行を示すものである。また、生きている者に自らの死を思い起こさせるものでもある。火葬が好ましいが[9]、土葬 も認められている。チベットの仏教徒は、ハゲワシに食べられるように遺体をさらす天葬を行う。遺体は晒される前に山の頂上で刃物で解剖される。泣き叫ぶこ とは禁じられ、ロギャパ(儀式を執り行う遺体解体者)はまるで農作業をしているかのように笑う。チベット仏教徒は、葬儀中の明るい雰囲気が死者の魂をより 良い死後の世界へと導くと信じている。ハゲワシが肉を食べ尽くした後、ロギャパは骨を粉々に砕き、ツァンパと混ぜてハゲワシの餌にする[10]。

キリスト教

こちらも参照: キリスト教世界における埋葬と火葬

1929年10月6日、インドのシロ・マラバル・カトリック、ヴァルゲーゼ・パヤッピリー・パラッカッピリー師の葬儀。

さまざまな宗派の信徒がさまざまな葬儀を執り行うが、ほとんどの場合、祈り、聖書の朗読、説教、講話、弔辞、音楽を捧げる[2][11]。21世紀に入っ てから懸念された問題のひとつが、キリスト教の葬儀で世俗的な音楽を使用することであった。

キリスト教の葬儀は伝統的に教会の庭のような聖なる場所で行われてきた。火葬のような破壊的な処理ではなく、埋葬がキリスト教徒の間で伝統的に行われてい た。その後、火葬が広く行われるようになったが、宗派によっては火葬を禁じているところもある。米国カトリック司教協議会は、「教会は、故人の遺体を埋葬 するという敬虔な習慣を守ることを切に勧めるが、キリスト教の教義に反する理由で火葬が選ばれたのでない限り、教会は火葬を禁止しない」(カノン 1176.3)と述べている[14]。

ヒンドゥー教

主な記事 ヒンドゥー教

ネパールのヒンドゥー教の火葬儀礼。上のサムスカーラは、サフランの赤に包まれた遺体を火葬する様子を示している。

アンティースティは、文字通り「最後の儀式」または「最後の犠牲」であり、ヒンドゥー教における葬儀に関連する通過儀礼のことを指す[15]。 アンティマ・サムスカラム、アンティヤ・クリヤ、アンヴァロハンヤ、ヴァーニ・サンスカーラと呼ばれることもある。

成人のヒンドゥー教徒の死者は火葬され、子供の死者は埋葬されるのが一般的である[16][17]。この通過儀礼は、すべての生き物の小宇宙は宇宙の大宇 宙の反映であるという神聖な前提に調和して行われると言われている[18]。魂(アートマン、ブラフマン)は、アンティシュティの儀式で解放される不滅の 本質であると信じられているが、ヒンドゥー教の様々な学派では、肉体も宇宙も乗り物であり、儚いものである。この信仰のルーツはヴェーダにあり、例えばリ グヴェーダの讃歌10.16節には次のように書かれている:

アグニよ、彼を焼き尽くさず、完全に焼き尽くさず、彼の体も皮膚も散らさないようにせよ、

火を持つ者よ、汝が彼を成熟させたら、父祖の元へ彼を送りなさい。

全き火の所有者よ、汝が彼を準備させた時、汝は彼を父祖のもとへ渡しなさい、

彼が彼を待つ生命に到達するとき、彼は神々の意志に従うようになる。

太陽は汝の眼を受け、風は汝のプラーナ(生命原理、呼吸)を受けよ。汝の功徳のままに、地へも天へも行け。

もし汝の運命であるならば、水の中に行け。汝は行け、汝の全ての構成員と共に植物に汝の住処を作れ。

- リグヴェーダ10.16[19]。

リグヴェーダの10.18節では、子供が早死にした場合の埋葬の最終的な儀式に根ざしており、讃美歌は子供の死を悼み、ムリティウ神に「私たちの女の子や 男の子を傷つけないように」と祈り、大地が柔らかい羊毛のように亡くなった子供を覆い、守ってくれるよう嘆願している[20][21]。

ヒンズー教では、死体は通常、死後1日以内に火葬される。遺体は洗われ、男性または未亡人は白い布、既婚女性は赤い布で包まれ[17]、両足の指を紐で結 び、額にティラック(赤い印)が付けられる[16]。成人の遺体は家族や友人によって川や水辺の火葬場まで運ばれ、南向きに足を向けて薪の上に置かれる [17]。 [16][22]遺体とともに枯れ木の薪を囲み、弔辞を述べ、場合によっては賛美歌を朗読し、死者の口に胡麻を入れ、遺体と薪にギー(澄ましバター)を振 りかけ、ヤマ(死者の神)、カラ(時間、火葬の神)、死者を意味する3本の線を引く[16]。火葬の灰は最寄りの川や海に奉納される[22]。火葬後、 10~12日間喪に服し、近親者や故人の息子は頭を剃り、爪を切り、僧侶やバラモンの助けを借りて祈りを唱え、故人を偲んで親戚、親族、友人、隣人全員を 招いて簡単な食事を共にする。この日は、地域によっては、貧しい人々や困窮している人々に死者を偲んで食べ物を提供する日でもある[23]。

ゾロアスター教

パールシーの沈黙の塔、ボンベイ

死後、遺体には那須がはびこるという信仰は、ゾロアスター教の埋葬儀式や葬儀に大きな影響を与えた。死体の埋葬と火葬は、それぞれ神聖な創造物である土と 火を汚す行為として禁じられていた[24]。このような理由から、「沈黙の塔」が開発された。野外の円形劇場のような建造物に死体を安置し、腐肉を食べる 鳥がそれを食べることができるようにしたのである。

サグディードとは「犬に見られる」という意味で、死後できるだけ早く行わなければならない儀式である。犬は死体の中にある悪の度合いを計算することがで き、汚染がこれ以上広がらないように封じ込め、那須を死体から追い出す[25]。那須は犬に見られるか、犬か腐肉を食べる鳥に食べられるまで、死体の中に とどまる。 [26]『伝カルド』第31章によると、死体の消費が義務付けられている理由は、那須の邪悪な影響が死体の中に封じ込められており、消化されることで死体 が那須の形から動物の栄養に変わるからである。こうして死体は動物に引き渡され、腐敗したナサの状態から、より汚染が少ないとされる「乾いた死骸」である ヒクスルの状態に変化する。

葬列が通った道は、那須がその後その地域に出没するため、適切な追放の儀式が行われるまで二度と通ってはならない[27]。 那須は、「4つの目を持つ黄色い犬、または黄色い耳を持つ白い犬」がその道を3回歩いた後にのみ、その地域から追放される[28]。 犬が不本意にその道を通った場合は、那須が追い払われたことを確認するために、9回まで往復しなければならない[29]。

ゾロアスター教の死者晒しの儀式が最初に知られるようになったのは、紀元前5世紀半ばのヘロドトスの著作からであり、彼は小アジアのイラン人駐在員の間で この習慣を観察している。ヘロドトスの記述(Histories i.140)では、その儀式は「秘密」であったとされているが、遺体はまず鳥や犬に引きずり回された後に行われた。その後、死体は蝋で防腐処理され、溝に 安置された。

前5世紀と前4世紀のイラン東部と西部で発見された納骨堂は、骨が分離されていたことを示しているが、この分離が儀式的な露出によって行われたとは考えら れない。ナクシュ=エ=ルスタムやパサルガダイにあるアケメネス朝皇帝の墓も同様に、少なくとも骨が収集されるまでは露出されていなかったことを示唆して いる。伝説(フェルドウィーは『シャーフメーヌ』にこの伝説を取り入れた)によれば、ゾロアスターはバルフ(現在のアフガニスタン)の墓に埋葬されてい る。

ヘロドトスはペルシャの文化について書いているが、その中でマギが行ったペルシャの埋葬の習慣について報告している。31]アケメネス朝の風習はバクトリ ア、ソグディア、ヒュルカニアの死者について記録されているが、西イランでは記録されていない。

ビザンティンの歴史家アガティアスは、ササン朝将軍ミール=ミヒロイの埋葬について、「メルメロエスの従者たちは彼の遺体を運び上げ、都市の外の場所に移 し、伝統的な習慣に従って、そのまま、単独で、覆いもせずに、犬やおぞましい腐肉のゴミとして埋葬した」と記述している。

塔はずっと後の発明で、9世紀初頭に初めて記録されている。その習慣にまつわる儀式の風習は、サッサニ朝時代(紀元3~7世紀)にまでさかのぼるようだ。 それらは、『シャーイェスト・ネー・シャーイェスト』の補遺、2つの『レヴァヤト集』、2つの『サッダール集』から詳細に知られている。

イスラム

主な記事 イスラム式葬儀

1779年 アルジェリアの葬儀

カシュガル、アファク・コジャ・モスクでの遺体の洗浄と準備のための設備

イスラム教の葬儀(アラビア語ではジャナザ(Janazah)と呼ばれる)は、かなり特殊な儀式に従って行われる。しかし、どのような場合でも、シャリー ア(イスラム教の宗教法)では、遺体を埋葬し、その前に沐浴と遺体の覆いをする簡単な儀式を行い、その後にサラート(礼拝)を行うことになっている。

通常、埋葬の儀式はできるだけ早く行われるべきで、以下のようなものがある:

水、樟脳、ハスの葉で遺体を入浴させる[32]。

戦いのような特別な場合を除き、死体を白い綿または麻の布で包むこと。この場合、死体の服装は変えない[34]。

ムスリムが葬儀に参列する場合、葬儀の祈りを唱えること。

ムスリムが墓に遺体を埋葬すること。

故人の顔や体を右側に向けたとき、メッカを向くようにすること。

喪の期間は40日間である[35]。

ユダヤ教

主な記事 ユダヤ教における死別

ユダヤ教では、葬儀はかなり特定の儀式に従う。ハラハでは、ヘブライ語の聖書からの祈りと朗読を伴う遺体の沐浴と覆いを含む準備儀式を行い、弔辞と短い祈 りを特徴とする葬儀を行い、その後、遺体を墓に納め、墓を埋める。伝統的な法律と慣習では、遺体を火葬することは禁じられている。改革派のユダヤ教運動で は、一般的に火葬を推奨しないが、全面的に禁止はしていない[36][37]。

通常、埋葬の儀式はできるだけ早く行われるべきであり、以下を含む:

遺体を入浴させる。

遺体を包む。男性はキッテル、そして(イスラエル国外では)タリート(ショール)をかぶり、女性は真っ白な布をかぶる。

遺体を見守る。

弔辞と簡単な祈りを含む葬儀。

遺体を墓に埋葬する[36]。

墓を埋める。伝統的に家族や葬儀の他の参加者によって行われる。

多くのコミュニティでは、故人の足がエルサレムの神殿山に向くように配置される(救世主の到来と死者の復活の際に、故人が再建された第三神殿に向かうこと を見越して)[38]。

シク教

シーク教では、死は自然のプロセスではなく、絶対的な確実性を持ち、神の意志またはフカムの直接的な結果としてのみ起こる出来事であると考えられている。 [シーク教では、誕生と死は密接に関連しており、「往生と還生」(パンジャブ語: ਆਵਣ↪Mn_A41E, ローマ字表記: Aana Jaana)という人間の生のサイクルの一部である: アーナー・ジャーナー)は、解脱(ਮੋਖ ੁਦ ੁ, Mokh Du-aar)に向かう一過性の段階と見なされ、完全に神と一体化すると理解される。シーク教徒は輪廻転生を信じている。

死は、神から創造された宇宙を経て再び神に戻るという魂の旅の過程に過ぎない。シーク教徒は、生と死のサイクルを断ち切り、神のもとへ戻るために、十分に 祈り、離れ、義を重んじるようになるため、生前から常に死を思い出すことが期待されている。

葬儀の際に大声で泣き叫んだり(アンタム・サンスカールと呼ばれる)、慟哭したりすることによって悲しみを公に示すことは推奨されず、最小限にとどめるべ きである。火葬が好ましい処分方法だが、必要な場合や本人の意思による場合は土葬や海洋葬も認められる。墓石や記念碑などの目印をつけることは、遺体は単 なる殻であり、その人の魂が本当の自分であると考えられているため、認められていない[39]。

火葬の日、遺体は洗われ、服を着せられ、グルドワラまたは家に運ばれ、シーク教の聖典であるシュリ・グル・グラント・サーヒブ・ジからの賛美歌(シャバ ダッド)が会衆によって朗読される。故人の親族が棺の近くに座って「Waheguru」と唱える間、ラギによってキルタンが行われることもある。この礼拝 は通常30分から60分かかる。礼拝が終わると、棺が火葬場に運ばれる前にアーダスが唱えられます。

火葬の時点では、さらにいくつかのシャバドが歌われ、故人についての最後のスピーチが行われることもある。長男か近親者が火をつけるのが一般的である。こ の儀式は通常30分から60分ほど続く。遺灰は後に回収され、川(できればインドのパンジャーブ州にある5つの川のうちの1つ)に浸して処分される。

火葬の儀式の後、シダラン・パースを始める儀式は、スリ・グル・グラント・サーヒブ・ジがおられる場所であれば、都合の良い時に行うことができる。

讃美歌はシュリ・グル・グラント・サーヒブ・ジから歌われ、「至福の歌」である「アナンド・サーヒブ」の最初の5節と最後の1節が朗読または歌われる。シ ク教の朝の祈りである「ジャプジー・サーヒブ」の最初の5節が音読され、シダラン・パースが始まる。その後、スリ・グル・グラント・サーヒブ・ジからフー カム(無作為の詩)が読まれる。アーダス(祈り)が捧げられ、プラシャード(神聖なお菓子)が配られる。その後、ランガル(食事)が客に振る舞われる。

シダラン・パースが読まれている間、家族は毎日賛美歌を歌うこともある。読経は、パースを終えるのに必要なだけ長くかかることもある。

この儀式に続いて、Sahaj Paath Bhog、Kirtan Sohila、夜の祈りが1週間唱えられ、最後に「Antim Ardas」(「最後の祈り」)と呼ばれるArdasが最後の週に捧げられる[40]。

ケルト

この伝統は19世紀までウェールズの農民によって守られていた[41]。

Classical antiquity

Ancient Greece

The lying in state of a body (prothesis) attended by family members, with the women ritually tearing their hair (Attic, latter 6th century BCE)

Main article: Ancient Greek funerals and burial

The Greek word for funeral – kēdeía (κηδεία) – derives from the verb kēdomai (κήδομαι), that means attend to, take care of someone. Derivative words are also kēdemón (κηδεμών, "guardian") and kēdemonía (κηδεμονία, "guardianship"). From the Cycladic civilization in 3000 BCE until the Hypo-Mycenaean era in 1200–1100 BCE the main practice of burial is interment. The cremation of the dead that appears around the 11th century BCE constitutes a new practice of burial and is probably an influence from the East. Until the Christian era, when interment becomes again the only burial practice, both cremation and interment had been practiced depending on the area.[42]

The ancient Greek funeral since the Homeric era included the próthesis (πρόθεσις), the ekphorá (ἐκφορά), the burial and the perídeipnon (περίδειπνον). In most cases, this process is followed faithfully in Greece until today.[43]

Próthesis is the deposition of the body of the deceased on the funeral bed and the threnody of his relatives. Today the body is placed in the casket, that is always open in Greek funerals. This part takes place in the house where the deceased had lived. An important part of the Greek tradition is the epicedium, the mournful songs that are sung by the family of the deceased along with professional mourners (who are extinct in the modern era). The deceased was watched over by his beloved the entire night before the burial, an obligatory ritual in popular thought, which is maintained still.

Ekphorá is the process of transport of the mortal remains of the deceased from his residence to the church, nowadays, and afterward to the place of burial. The procession in the ancient times, according to the law, should have passed silently through the streets of the city. Usually certain favourite objects of the deceased were placed in the coffin in order to "go along with him". In certain regions, coins to pay Charon, who ferries the dead to the underworld, are also placed inside the casket. A last kiss is given to the beloved dead by the family before the coffin is closed.

Funeral with flowers on marble

The Roman orator Cicero[44] describes the habit of planting flowers around the tomb as an effort to guarantee the repose of the deceased and the purification of the ground, a custom that is maintained until today. After the ceremony, the mourners return to the house of the deceased for the perídeipnon, the dinner after the burial. According to archaeological findings – traces of ash, bones of animals, shards of crockery, dishes and basins – the dinner during the classical era was also organized at the burial spot. Taking into consideration the written sources, however, the dinner could also be served in the houses.[45]

The Necrodeipnon (Νεκρόδειπνον) was the funeral banquet which was given at the house of the nearest relative.[46][47]

Two days after the burial, a ceremony called "the thirds" was held. Eight days after the burial the relatives and the friends of the deceased assembled at the burial spot, where "the ninths" would take place, a custom still kept. In addition to this, in the modern era, memorial services take place 40 days, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 1 year after the death and from then on every year on the anniversary of the death. The relatives of the deceased, for an unspecified length of time that depends on them, are in mourning, during which women wear black clothes and men a black armband.[clarification needed]

Nekysia (Νεκύσια), meaning the day of the dead, and Genesia (Γενέσια), meaning the day of the forefathers (ancestors), were yearly feasts in honour of the dead.[48][49]

Nemesia (Νεμέσια) or Nemeseia (Nεμέσεια) was also a yearly feast in honour of the dead, most probably intended for averting the anger of the dead.[50][51]

Ancient Rome

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Tomb of the Scipios, in use from the 3rd century BCE to the 1st century CE

Main article: Roman funerals and burial

In ancient Rome, the eldest surviving male of the household, the pater familias, was summoned to the death-bed, where he attempted to catch and inhale the last breath of the decedent.

Funerals of the socially prominent usually were undertaken by professional undertakers called libitinarii. No direct description has been passed down of Roman funeral rites. These rites usually included a public procession to the tomb or pyre where the body was to be cremated. The surviving relations bore masks bearing the images of the family's deceased ancestors. The right to carry the masks in public eventually was restricted to families prominent enough to have held curule magistracies. Mimes, dancers, and musicians hired by the undertakers, and professional female mourners, took part in these processions. Less well-to-do Romans could join benevolent funerary societies (collegia funeraticia) that undertook these rites on their behalf.

Nine days after the disposal of the body, by burial or cremation, a feast was given (cena novendialis) and a libation poured over the grave or the ashes. Since most Romans were cremated, the ashes typically were collected in an urn and placed in a niche in a collective tomb called a columbarium (literally, "dovecote"). During this nine-day period, the house was considered to be tainted, funesta, and was hung with Taxus baccata or Mediterranean Cypress branches to warn passersby. At the end of the period, the house was swept out to symbolically purge it of the taint of death.

Several Roman holidays commemorated a family's dead ancestors, including the Parentalia, held February 13 through 21, to honor the family's ancestors; and the Feast of the Lemures, held on May 9, 11, and 13, in which ghosts (larvae) were feared to be active, and the pater familias sought to appease them with offerings of beans.

The Romans prohibited cremation or inhumation within the sacred boundary of the city (pomerium), for both religious and civil reasons, so that the priests might not be contaminated by touching a dead body, and that houses would not be endangered by funeral fires.

Restrictions on the length, ostentation, expense of, and behaviour during funerals and mourning gradually were enacted by a variety of lawmakers. Often the pomp and length of rites could be politically or socially motivated to advertise or aggrandise a particular kin group in Roman society. This was seen as deleterious to society and conditions for grieving were set. For instance, under some laws, women were prohibited from loud wailing or lacerating their faces and limits were introduced for expenditure on tombs and burial clothes.

The Romans commonly built tombs for themselves during their lifetime. Hence these words frequently occur in ancient inscriptions, V.F. Vivus Facit, V.S.P. Vivus Sibi Posuit. The tombs of the rich usually were constructed of marble, the ground enclosed with walls, and planted around with trees. But common sepulchres usually were built below ground, and called hypogea. There were niches cut out of the walls, in which the urns were placed; these, from their resemblance to the niche of a pigeon-house, were called columbaria.

North American funerals

Within the United States and Canada, in most cultural groups and regions, the funeral rituals can be divided into three parts: visitation, funeral, and the burial service. A home funeral (services prepared and conducted by the family, with little or no involvement from professionals) is legal in nearly every part of North America, but in the 21st century, they are uncommon in the US.[52]

A western-style funeral motorcade for a member of a high-ranking military family in South Korea

Visitation

"Open casket" redirects here. For other uses, see Open casket (disambiguation).

At the visitation (also called a "viewing", "wake" or "calling hours"), in Christian or secular Western custom, the body of the deceased person (or decedent) is placed on display in the casket (also called a coffin, however almost all body containers are caskets). The viewing often takes place on one or two evenings before the funeral. In the past, it was common practice to place the casket in the decedent's home or that of a relative for viewing. This practice continues in many areas of Ireland and Scotland. The body is traditionally dressed in the decedent's best clothes. In recent times there has been more variation in what the decedent is dressed in – some people choose to be dressed in clothing more reflective of how they dressed in life. The body will often be adorned with common jewelry, such as watches, necklaces, brooches, etc. The jewelry may be taken off and given to the family of the deceased prior to burial or be buried with the deceased. Jewelry has to be removed before cremation in order to prevent damage to the crematory. The body may or may not be embalmed, depending upon such factors as the amount of time since the death has occurred, religious practices, or requirements of the place of burial.

The most commonly prescribed aspects of this gathering are that the attendees sign a book kept by the deceased's survivors to record who attended. In addition, a family may choose to display photographs taken of the deceased person during his/her life (often, formal portraits with other family members and candid pictures to show "happy times"), prized possessions and other items representing his/her hobbies and/or accomplishments. A more recent trend is to create a DVD with pictures and video of the deceased, accompanied by music, and play this DVD continuously during the visitation.

The viewing is either "open casket", in which the embalmed body of the deceased has been clothed and treated with cosmetics for display; or "closed casket", in which the coffin is closed. The coffin may be closed if the body was too badly damaged because of an accident or fire or other trauma, deformed from illness, if someone in the group is emotionally unable to cope with viewing the corpse, or if the deceased did not wish to be viewed. In cases such as these, a picture of the deceased, usually a formal photo, is placed atop the casket.

The tombstone of Yossele the Holy Miser. According to Jewish bereavement tradition, the dozens of stones on his tombstone mark respect for the Holy Miser.

However, this step is foreign to Judaism; Jewish funerals are held soon after death (preferably within a day or two, unless more time is needed for relatives to come), and the corpse is never displayed. Torah law forbids embalming.[53] Traditionally flowers (and music) are not sent to a grieving Jewish family as it is a reminder of the life that is now lost. The Jewish shiva tradition discourages family members from cooking, so food is brought by friends and neighbors.[35] (See also Jewish bereavement.)

The decedent's closest friends and relatives who are unable to attend frequently send flowers to the viewing, with the exception of a Jewish funeral,[54] where flowers would not be appropriate (donations are often given to a charity instead).

Obituaries sometimes contain a request that attendees do not send flowers (e.g. "In lieu of flowers"). The use of these phrases has been on the rise for the past century. In the US in 1927, only 6% of the obituaries included the directive, with only 2% of those mentioned charitable contributions instead. By the middle of the century, they had grown to 15%, with over 54% of those noting a charitable contribution as the preferred method of expressing sympathy.[55]

Funeral

Funeral for a child, 1920

The deceased is usually transported from the funeral home to a church in a hearse, a specialized vehicle designed to carry casketed remains. The deceased is often transported in a procession (also called a funeral cortège), with the hearse, funeral service vehicles, and private automobiles traveling in a procession to the church or other location where the services will be held. In a number of jurisdictions, special laws cover funeral processions – such as requiring most other vehicles to give right-of-way to a funeral procession. Funeral service vehicles may be equipped with light bars and special flashers to increase their visibility on the roads. They may also all have their headlights on, to identify which vehicles are part of the cortege, although the practice also has roots in ancient Roman customs.[56] After the funeral service, if the deceased is to be buried the funeral procession will proceed to a cemetery if not already there. If the deceased is to be cremated, the funeral procession may then proceed to the crematorium.

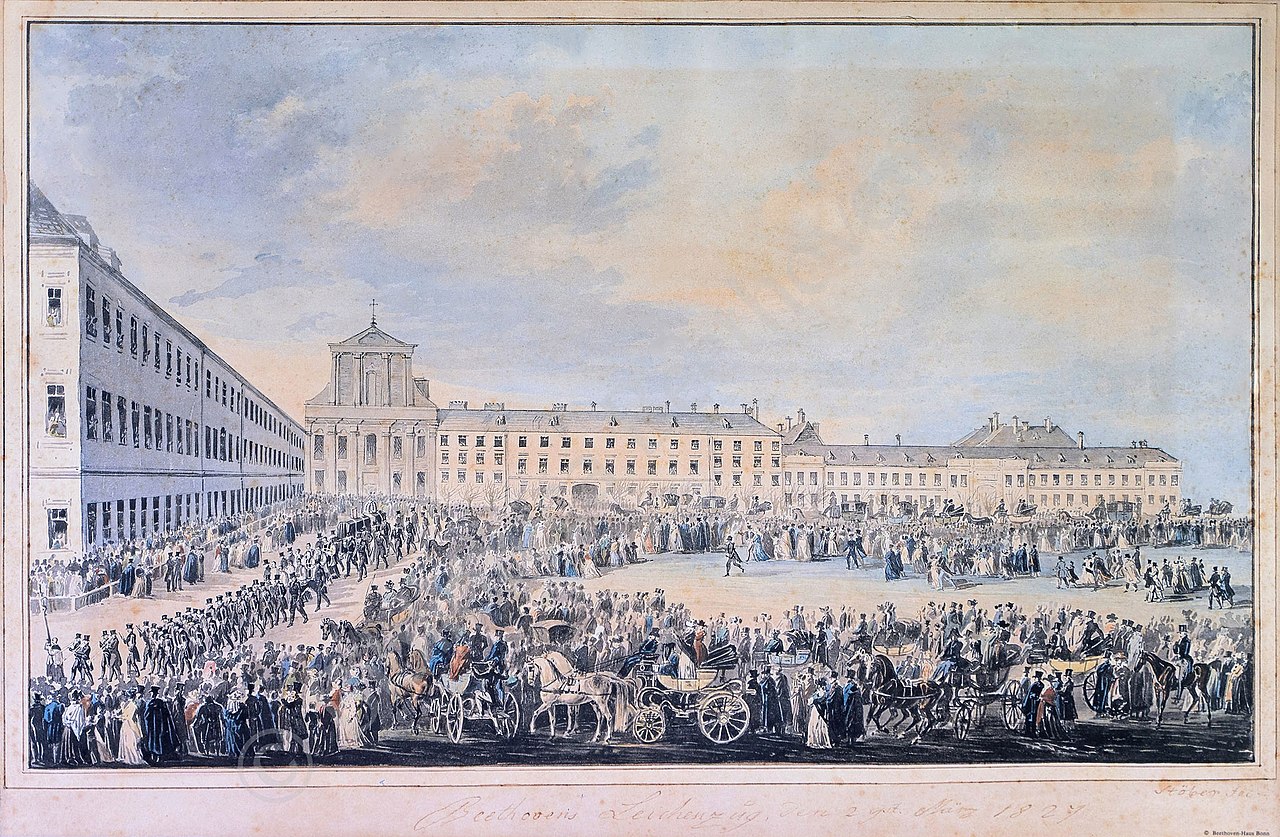

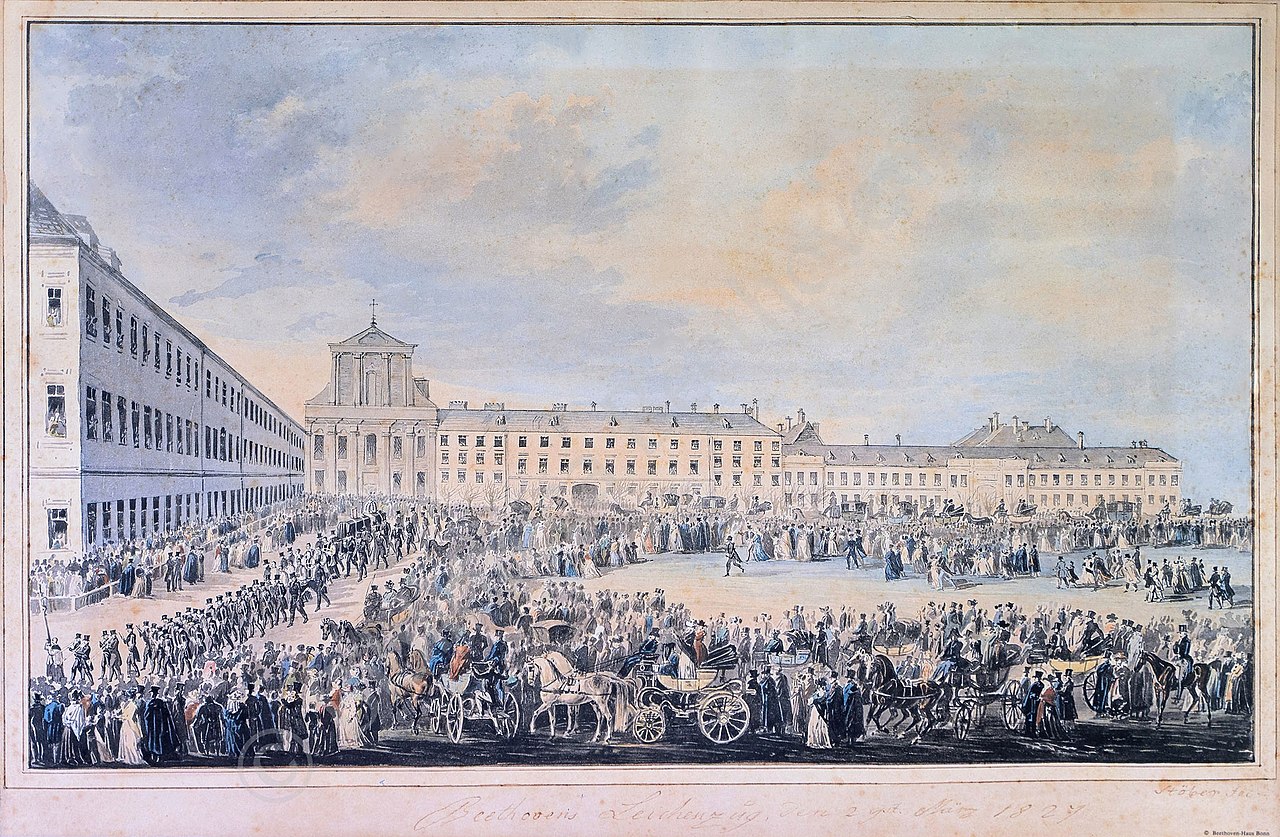

Beethoven's funeral as depicted by Franz Xaver Stöber

Funeral customs vary from country to country. In the United States, any type of noise other than quiet whispering or mourning is considered disrespectful.

A burial tends to cost more than a cremation.[57]

Burial service

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

John Everett Millais – The Vale of Rest

At a religious burial service, conducted at the side of the grave, tomb, mausoleum or cremation, the body of the decedent is buried or cremated at the conclusion.

Sometimes, the burial service will immediately follow the funeral, in which case a funeral procession travels from the site of the funeral to the burial site. In some other cases, the burial service is the funeral, in which case the procession might travel from the cemetery office to the grave site. Other times, the burial service takes place at a later time, when the final resting place is ready, if the death occurred in the middle of winter.

If the decedent served in a branch of the Armed forces, military rites are often accorded at the burial service.[58]

In many religious traditions, pallbearers, usually males who are relatives or friends of the decedent, will carry the casket from the chapel (of a funeral home or church) to the hearse, and from the hearse to the site of the burial service.[59]

Most religions expect coffins to be kept closed during the burial ceremony. In Eastern Orthodox funerals, the coffins are reopened just before burial to allow mourners to look at the deceased one last time and give their final farewells. Greek funerals are an exception as the coffin is open during the whole procedure unless the state of the body does not allow it.

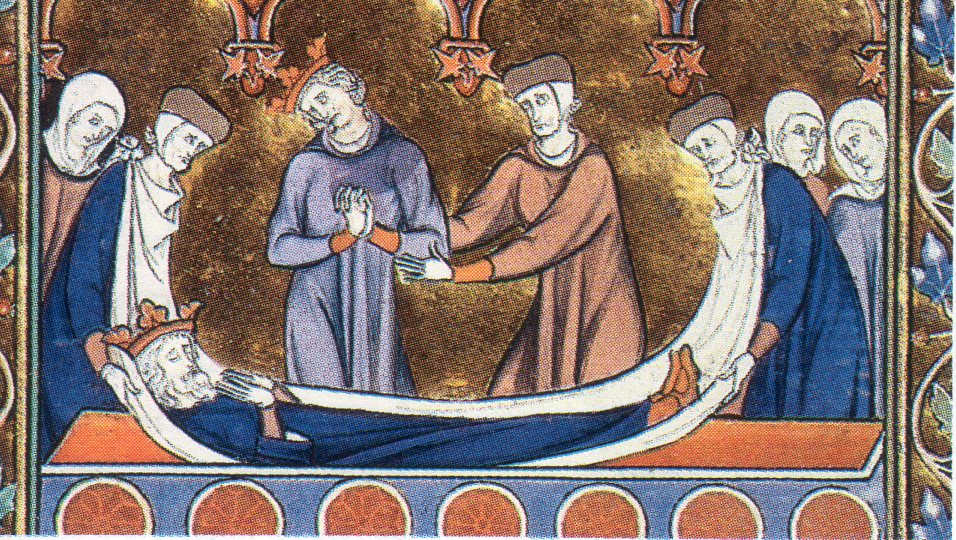

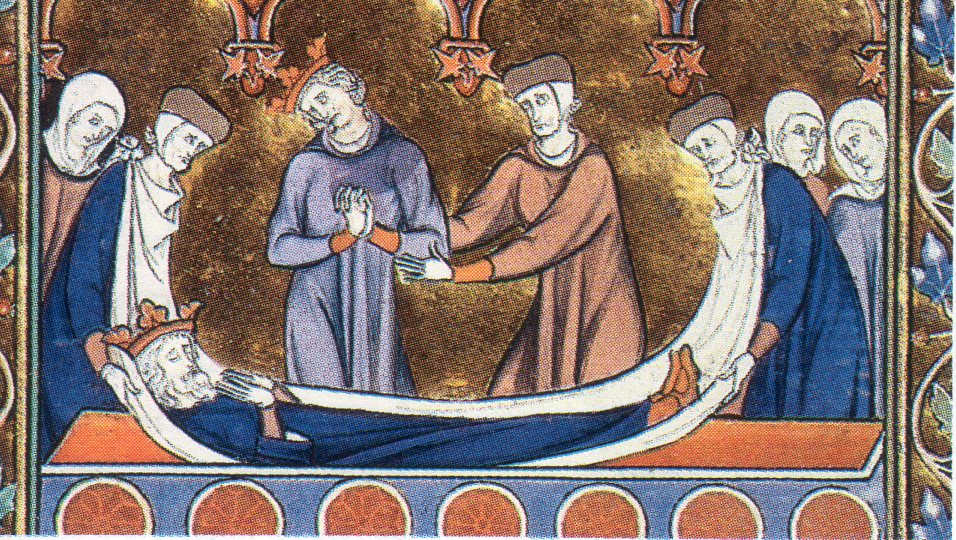

Medieval depiction of a royal body being laid in a coffin

Morticians may ensure that all jewelry, including wristwatch, that were displayed at the wake are in the casket before it is buried or entombed. Custom requires that everything goes into the ground; however this is not true for Jewish services. Jewish tradition stipulates that nothing of value is buried with the deceased.

In the case of cremation such items are usually removed before the body goes into the furnace. Pacemakers are removed prior to cremation – if left in they could explode.

Indigenous Americans

Funerals for indigenous people, like many other cultures, are a method to remember, commemorate and respect the dead through their own cultural practices and traditions.

California

In the past, there has been scrutiny when the topic of indigenous funeral sites was approached. Thus the federal government deemed it necessary to include a series of acts that would protect and accurately affiliate some of these burials with their correct native individuals or groups. This was enacted through the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. Furthermore, in 2001 California created the California Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act that would "require all state agencies and museums that receive state funding and that have possession or control over collections of humans remains or cultural items to provide a process for identification and repatriates of these items to appropriate tribes." In 2020, it was amended to include tribes that were beyond State and Federal knowledge.

Western Yuman region

In the Ipai, Tipai, Paipai, and Kiliwa regions funeral practices are similar in their social and power dynamics. The way that these funeral sites were created was based on previous habitation. Meaning, these were sites were their peoples may have died or if they had been a temporary home for some of these groups.[60] Additionally, these individual burials were characterized by grave markers and/or grave offerings. The markers included inverted metates, fractured pieces of metates as well as cairns. As for offerings, food, shell and stone beads were often found in burial mounds along with portions human remains.

The state of the human remains found at the site can vary, data suggests[60] that cremations are recent in prehistory compared to just burials. Ranging from the middle Holocene era to the Late Prehistoric Period. Additionally, the position these people were placed in plays a role in how the afterlife was viewed. With recent ethnographic evidence coming from the Yuman people, it is believed that the spirits of the dead could potentially harm the living. so, they would often layer the markers or offerings above the body so that they would be unable to "leave" their graves and enact harm.

Western Yuman Region, California and Baja California

Tongva

In the Los Angeles Basin, researchers discovered communal mourning features at West Bluffs and Landing Hill. These communal mourning rituals were estimated to have taken place during the Intermediate Period (3,000-1,000 B.P.). Archaeologists have found fragmented pieces of a large schist pestle which was deliberately broken in a methodical way. Other fragmented vessels show signs of uneven burning on the interior surface presumed to have been caused by burning combustible material.

In the West Bluffs and Landing Hill assemblages there are many instances of artifacts that were dyed in red ochre pigment after being broken. The tradition of intentionally breaking objects has been a custom in the region for thousands of years for the purpose of releasing the spirit within the object, reducing harm to the community, or as an expression of grief. Pigmentation of grave goods also has many interpretations, the Chumash associate the color red with both earth and fire. While some researchers consider the usage of the red pigment as an important transitional moment in the adult life cycle.[61]

Memorial services

See also: Memorial service in the Eastern Orthodox Church

Order of exercises, local memorial service in Nashua, New Hampshire, for U.S. President William McKinley on September 19, 1901, following his assassination

A memorial service[62] is one given for the deceased, often without the body present. The service takes place after cremation or burial at sea, after donation of the body to an academic or research institution, or after the ashes have been scattered. It is also significant when the person is missing and presumed dead, or known to be deceased though the body is not recoverable. These services often take place at a funeral home;[63] however, they can be held in a home, school, workplace, church or other location of some significance. A memorial service may include speeches (eulogies), prayers, poems, or songs to commemorate the deceased. Pictures of the deceased and flowers are usually placed where the coffin would normally be placed.

After the sudden deaths of important public officials, public memorial services have been held by communities, including those without any specific connection to the deceased. For examples, community memorial services were held after the assassinations of US presidents James A. Garfield and William McKinley.

European funerals

United Kingdom

In the UK, funerals are commonly held at a church, crematorium or cemetery chapel.[64] Historically, it was customary to bury the dead, but since the 1960s, cremation has been more common.[65]

While there is no visitation ceremony like in North America, relatives may view the body beforehand at the funeral home. A room for viewing is usually called a chapel of rest.[66] Funerals typically last about half an hour.[67] They are sometimes split into two ceremonies: a main funeral and a shorter committal ceremony. In the latter, the coffin is either handed over to a crematorium[67] or buried in a cemetery.[68] This allows the funeral to be held at a place without cremation or burial facilities. Alternatively, the entire funeral may be held in the chapel of the crematorium or cemetery. It is not customary to view a cremation; instead, the coffin may be removed from the chapel or hidden with curtains towards the end of the funeral.[67]

After the funeral, it is common for the mourners to gather for refreshments. This is sometimes called a wake, though this is different to how to the term is used in other countries, where a wake is a ceremony before the funeral.[64]

Finland

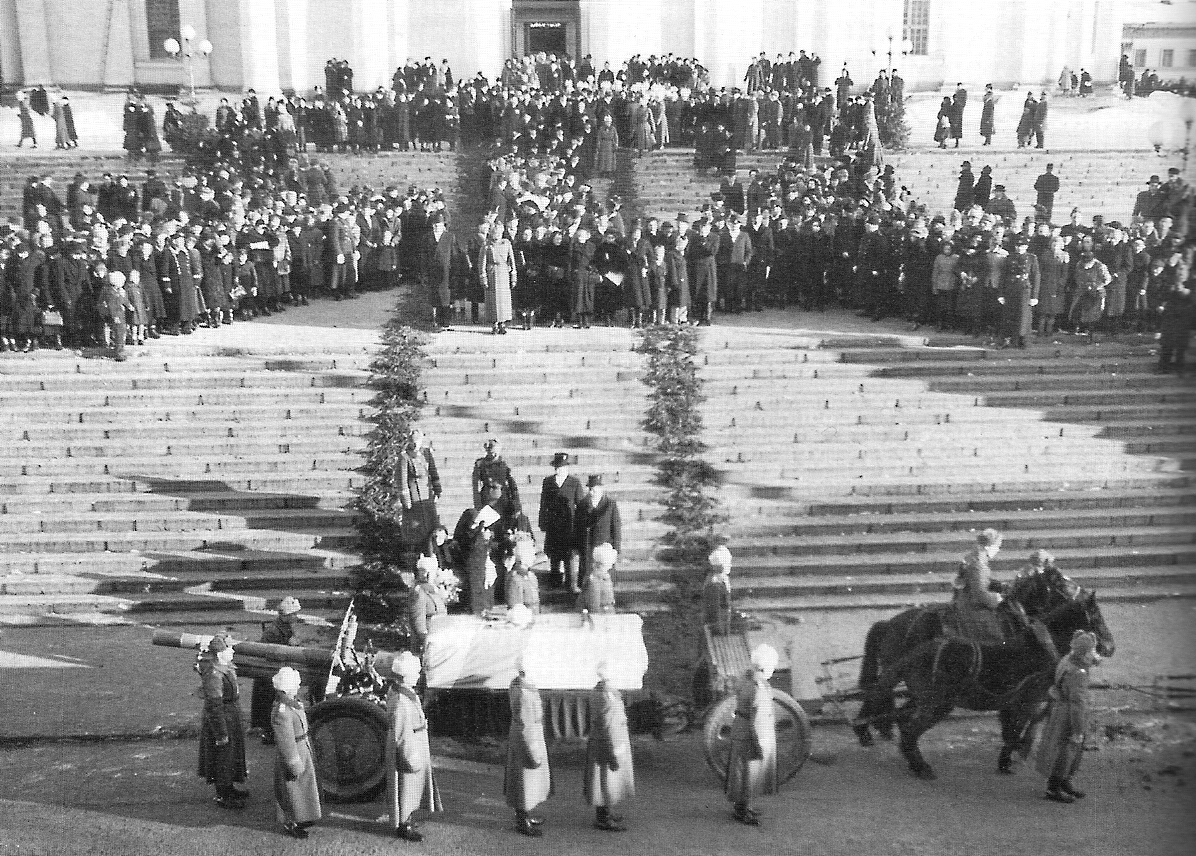

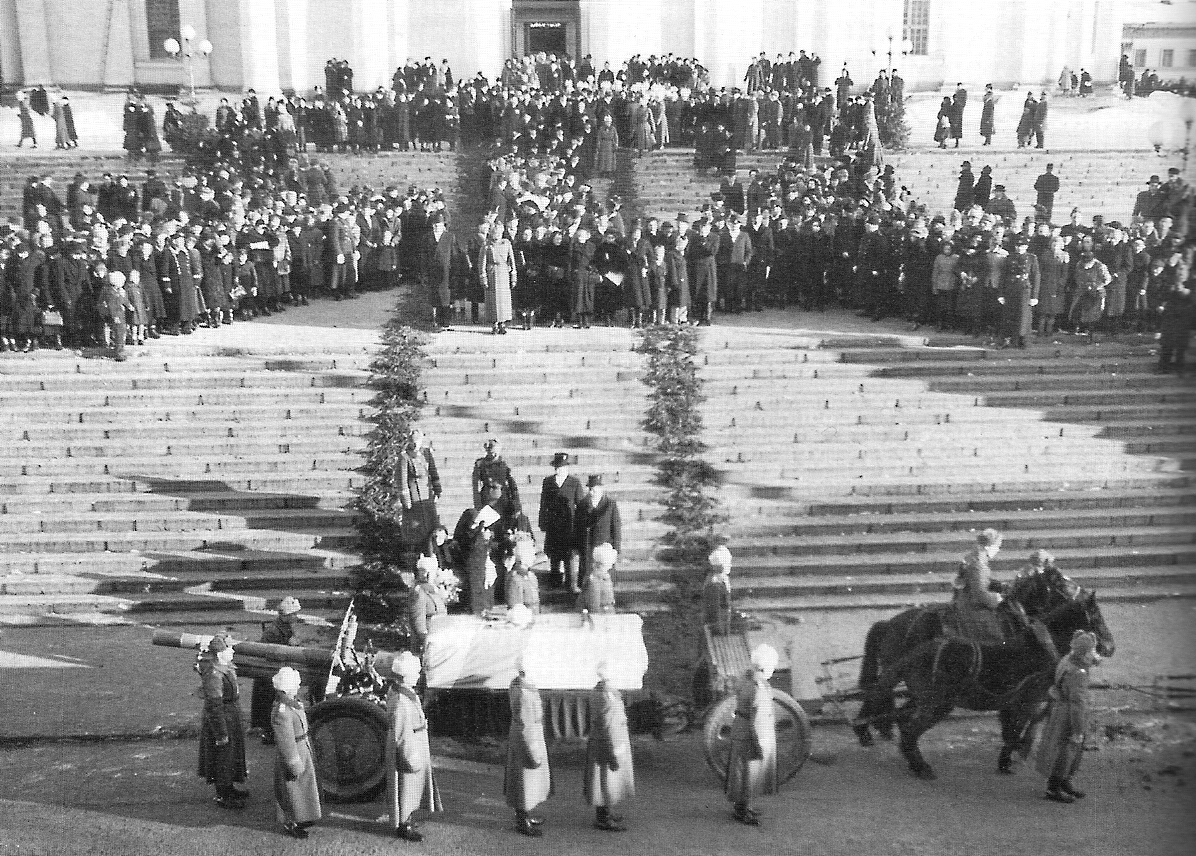

A funeral parade of Marshal Mannerheim in Helsinki, Finland, on February 4, 1951. Helsinki Lutheran Cathedral on the background.

In Finland, religious funerals (hautajaiset) are quite ascetic. The local priest or minister says prayers and blesses the deceased in their house. The mourners (saattoväki) traditionally bring food to the mourners' house. Common current practice has the deceased placed into the coffin in the place where they died. The undertaker will pick up the coffin and place it in the hearse and drive it to the funeral home, while the closest relatives or friends of the deceased will follow the hearse in a funeral procession in their own cars. The coffin will be held at the funeral home until the day of the funeral. The funeral services may be divided into two parts. First is the church service (siunaustilaisuus) in a cemetery chapel or local church, then the burial.

Iceland

Further information: Icelandic funeral

Italy

The majority of Italians are Roman Catholic and follow Catholic funeral traditions. Historically, mourners would walk in a funeral procession to the gravesite; today vehicles are used.

Greece

Greek funerals are generally held in churches, including a Trisagion service. There is usually a 40-day mourning period, and the end of which, a memorial service is held. Every year following, a similar service takes place, to mark the anniversary of the death.[69][70]

Poland

See also: Catholic funeral

In Poland, in urban areas, there are usually two, or just one "stop". The body, brought by a hearse from the mortuary, may be taken to a church or to a cemetery chapel. There is then a funeral mass or service at cemetery chapel. Following the mass or Service the casket is carried in procession (usually on foot) by hearse to the grave. Once at the grave-site, the priest will commence the graveside committal service and the casket is lowered. The mass or service usually takes place at the cemetery.

In some traditional rural areas, the wake (czuwanie) takes place in the house of the deceased or their relatives. The body lies in state for three days in the house. The funeral usually takes place on the third day. Family, neighbors and friends gather and pray during the day and night on those three days and nights. There are usually three stages in the funeral ceremony (ceremonia pogrzebowa, pogrzeb): the wake (czuwanie), then the body is carried by procession (usually on foot) or people drive in their own cars to the church or cemetery chapel for mass, and another procession by foot to the gravesite.

After the funeral, families gather for a post-funeral get-together (stypa). It can be at the family home, or at a function hall. In Poland cremation is less popular because the Catholic Church in Poland prefers traditional burials (though cremation is allowed). Cremation is more popular among non-religious people and Protestants in Poland.

Russia

Further information: Russian traditions and superstitions

Scotland

An old funeral rite from the Scottish Highlands involved burying the deceased with a wooden plate resting on his chest. On the plate were placed a small amount of earth and salt, to represent the future of the deceased. The earth hinted that the body would decay and become one with the earth, while the salt represented the soul, which does not decay. This rite was known as "earth laid upon a corpse". This practice was also carried out in Ireland, as well as in parts of England, particularly in Leicestershire, although in England the salt was intended to prevent air from distending the corpse.[71]

Spain

In Spain, a burial or cremation may occur very soon after a death. Most Spaniards are Roman Catholics and follow Catholic funeral traditions. First, family and friends sit with the deceased during the wake until the burial. Wakes are a social event and a time to laugh and honor the dead. Following the wake comes the funeral mass (Tanatorio) at the church or cemetery chapel. Following the mass is the burial. The coffin is then moved from the church to the local cemetery, often with a procession of locals walking behind the hearse.

Wales

Traditionally, a good funeral (as they were called) had one draw the curtains for a period of time; at the wake, when new visitors arrived, they would enter from the front door and leave through the back door. The women stayed at home whilst the men attended the funeral, the village priest would then visit the family at their home to talk about the deceased and to console them.[72]

The first child of William Price, a Welsh Neo-Druidic priest, died in 1884. Believing that it was wrong to bury a corpse, and thereby pollute the earth, Price decided to cremate his son's body, a practice which had been common in Celtic societies. The police arrested him for the illegal disposal of a corpse.[73] Price successfully argued in court that while the law did not state that cremation was legal, it also did not state that it was illegal. The case set a precedent that, together with the activities of the newly founded Cremation Society of Great Britain, led to the Cremation Act 1902.[74] The Act imposed procedural requirements before a cremation could occur and restricted the practice to authorised places.[75]

古典古代

古代ギリシャ

家族が参列する遺体安置(プロテーゼ)、女性は儀礼的に髪を裂く(アッティカ、前6世紀後半)

主な記事 古代ギリシャの葬儀と埋葬

ギリシャ語で葬儀を意味するkēdeía(κηδεία)は、誰かに付き添う、世話をするという意味の動詞kēdomai(κήδομαι)に由来する。 派生語にkēdemón(κηδεμών、「後見人」)、kēdemonía(κηδεμονία、「後見」)がある。前3000年のキクラデス文明から 前1200-1100年のハイポ・ミケーネ時代まで、埋葬の主な習慣は埋葬である。紀元前11世紀頃に見られる死者の火葬は、埋葬の新しい習慣であり、お そらく東方からの影響であろう。埋葬が再び唯一の埋葬習慣となるキリスト教時代までは、地域によって火葬と埋葬の両方が行われていた[42]。

ホメロス時代以降の古代ギリシアの葬儀には、プロテーゼ(πρόθεσις)、エクフォラ(ἐκφορά)、埋葬、ペリデイプノン (περίδειπνον)が含まれる。ほとんどの場合、このプロセスは今日までギリシャで忠実に守られている[43]。

プロテーゼ(Próthesis)とは、故人の遺体を葬儀用のベッドに安置し、親族が弔辞を述べることである。今日、遺体はギリシャの葬儀では常に開かれ ている棺に納められる。この部分は、故人が住んでいた家で行われる。ギリシャの伝統で重要なのはエピセディウムと呼ばれる弔いの歌で、プロの弔問客(現代 では絶滅した)とともに遺族が歌う。故人は埋葬の前夜、最愛の人に見守られる。これは民衆の間では義務的な儀式であり、現在も維持されている。

エクフォラとは、故人の遺骨を住居から教会まで運び、その後埋葬場所まで運ぶことである。古代の行列は、法律に従い、街の通りを静かに通過しなければなら なかった。通常、棺の中には故人の好きだったものが入れられ、「一緒に行く」ようにした。地域によっては、死者を冥界に運ぶカロンに支払うためのコインも 棺の中に入れる。棺を閉じる前に、家族が最愛の死者に最後のキスをする。

大理石に花を飾る葬儀

古代ローマの弁論家キケロ[44]は、墓の周囲に花を植える習慣について、故人の安らかな眠りと地面の浄化を保証するための努力であると述べている。儀式 の後、弔問客はペリデイプノン(埋葬後の夕食)のために故人の家に戻る。考古学的な調査結果(灰、動物の骨、食器の破片、皿、洗面器など)によれば、古典 時代の夕食会も埋葬地で行われていた。しかし、文献資料を考慮すると、夕食は家でも提供された可能性がある[45]。

ネクロダイプノン(Νεκρόδειπνον)は、最も近い親族の家で行われた葬儀の宴であった[46][47]。

埋葬の2日後には「三々九度」と呼ばれる儀式が行われた。埋葬の8日後には、親族と故人の友人たちが埋葬場所に集まり、「九日目」が行われる。これに加え て現代では、死後40日、3カ月、6カ月、9カ月、1年、それ以降は毎年命日に法要が行われる。故人の親族は、その親族によって異なる不特定の期間、喪に 服し、その間、女性は黒い服を、男性は黒い腕章をつける[clarification needed]。

死者の日を意味するネキシア(Νεκύσια)と先祖(祖先)の日を意味するゲネシア(Γενέσια)は、死者を讃える年中行事であった[48] [49]。

ネメシア(Nemesia:Νεμέσια)またはネメシア(Nemeseia:Nεμέσεια)も死者を称える年中行事であり、おそらく死者の怒りを 避けるためのものであった[50][51]。

古代ローマ

このセクションには引用元がありません。信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、このセクションの改善にご協力ください。ソースのないものは異議申し 立てがなされ、削除されることがあります。(2014年2月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)

紀元前3世紀から紀元後1世紀まで使用されたスキピオスの墓

主な記事 ローマの葬儀と埋葬

古代ローマでは、一家の長男であるパテル・ファミリアが死の床に呼ばれ、そこで故人の息を吸い取ろうとした。

社会的に著名な人々の葬儀は通常、リビチナリと呼ばれる専門の葬儀屋が請け負っていた。ローマ時代の葬儀に関する直接的な記述は伝わっていない。これらの 儀式には通常、遺体を火葬する墓や火葬場までの一般参列者が含まれていた。残された親族は、一族の亡くなった先祖の姿が描かれた仮面をつけた。仮面を公の 場に持ち出す権利は、やがてキュルレ司政権を持つほどの名家に限られるようになった。葬儀屋が雇ったパントマイム、踊り子、音楽家、そしてプロの女性弔問 客がこれらの行列に参加した。裕福でないローマ人は、これらの儀式を代行する善意の葬儀社(collegia funeraticia)に加入することができた。

埋葬または火葬による遺体の処理から9日後、祝宴(cena novendialis)が催され、墓や遺灰に酒が注がれた。ほとんどのローマ人は火葬されたので、遺灰は一般的に骨壷に集められ、コロンバリウム(文字 通り「鳩小屋」)と呼ばれる集合墓のニッチに納められた。この9日間は、家は汚染されたフネスタ(funesta)とみなされ、通行人に警告するためにタ クサスバッカータ(Taxus baccata)や地中海サイプレス(Mediterranean Cypress)の枝が吊るされた。この期間が終わると、象徴的に死の穢れを祓うために家が掃き清められた。

2月13日から21日にかけて行われた家族の先祖を祀るParentaliaや、5月9日、11日、13日に行われたLemuresの祭日は、幽霊(幼 虫)が活動していると恐れられ、pater familiasは豆を供えて彼らを鎮めようとした。

ローマ人は、宗教的な理由と民事的な理由の両方から、都市の神聖な境界(ポメリウム)内での火葬や埋葬を禁止した。

葬儀の長さ、派手さ、費用、葬儀や弔いの最中の振る舞いに対する規制は、さまざまな法律家によって徐々に制定されていった。葬儀の華やかさや長さは、ロー マ社会における特定の親族集団の宣伝や誇示を目的とした政治的、社会的な動機によるものであることがしばしばあった。これは社会にとって有害であるとみな され、悲しむための条件が設定された。例えば、いくつかの法律では、女性は大声で泣き叫んだり、顔を裂いたりすることが禁止され、墓や埋葬用の衣服への支 出に制限が設けられた。

ローマ人は生前に自分のために墓を建てるのが一般的だった。それゆえ、古代の碑文には、V.F. Vivus Facit、V.S.P. Vivus Sibi Posuitという言葉が頻繁に登場する。金持ちの墓は通常、大理石で造られ、地面は壁で囲まれ、周囲には樹木が植えられていた。しかし、一般的な墓は地 下に造られ、ハイポゲアと呼ばれた。鳩小屋のニッチに似ていることから、コロンバリアと呼ばれた。

北米の葬儀

米国とカナダでは、ほとんどの文化集団と地域で、葬儀の儀式は、訪問、葬儀、埋葬の3つの部分に分けることができる。自宅葬(専門家がほとんど関与せず、 家族が準備し、執り行う葬儀)は北米のほぼすべての地域で合法であるが、21世紀のアメリカでは珍しい[52]。

韓国の高級軍人家族のための西洋式葬儀の車列

参列

「開棺」はここからリダイレクトされる。他の用法については、開棺 (曖昧さ回避)を参照のこと。

キリスト教または世俗的な西洋の習慣では、面会(「ビューイング」、「ウェイク」、「コーリングアワー」とも呼ばれる)では、故人(または被相続人)の遺 体が棺(棺とも呼ばれるが、ほとんどすべての遺体容器は棺である)に展示される。葬儀の1日か2日前の夜に行われることが多い。かつては、棺を故人の自宅 や親族の家に安置し、それを見るのが一般的だった。この習慣はアイルランドやスコットランドの多くの地域で続いている。遺体は伝統的に、故人が最もよく着 ていた服に身を包む。最近では、生前の服装を反映した服装を選ぶ人もいる。遺体には、時計、ネックレス、ブローチなどの一般的な宝石が飾られていることが 多い。ジュエリーは埋葬前に外して遺族に渡すか、故人と一緒に埋葬する。火葬場への損傷を防ぐため、火葬前に宝石類は外さなければならない。遺体に防腐処 理を施す場合と施さない場合があるが、これは死亡してからの時間、宗教的慣習、埋葬場所の要件などによる。

この集まりで最も一般的に規定されているのは、故人の遺族が保管する参列者記録帳に参列者が署名することである。さらに、故人の生前の写真(多くの場合、 他の家族と一緒に撮ったフォーマルな写真や、「幸せな時」を示す率直な写真)、大切にしていた持ち物、故人の趣味や業績を表す品々を展示することもありま す。最近の傾向としては、故人の写真やビデオを音楽とともにDVDにし、面会中にこのDVDを流し続ける。

面会は、エンバーミングされた故人の遺体に衣服を着せ、化粧品で処理して展示する「開棺」と、棺を閉じて行う「閉棺」の2種類があります。事故や火災など の外傷で遺体の損傷が激しかったり、病気で変形していたり、グループの誰かが精神的に遺体を見ることに耐えられない場合、あるいは故人が遺体を見ることを 望まなかった場合などに、棺を閉じることがある。このような場合、故人の写真(通常はフォーマルな写真)が棺の上に置かれる。

聖なるみじめ者ヨゼレの墓碑。ユダヤ人の死別の伝統によれば、彼の墓碑にある数十個の石は、聖ミゼールへの敬意を示すものである。

ユダヤ教の葬儀は死後すぐに行われ(親族が来るまでに時間が必要な場合を除き、できれば1日か2日以内に)、遺体を飾ることはない。トーラー法は防腐処理 を禁じている[53]。伝統的に、悲嘆に暮れるユダヤ人の家族に花(と音楽)は贈らない。ユダヤ教のシヴァの伝統では、家族が料理をすることを禁じている ため、友人や隣人によって料理が運ばれる[35](ユダヤ教の死別も参照)。

参列できない被相続人の親しい友人や親族は、ユダヤ教の葬儀を除いて[54]、会葬に花を贈ることが多い。

訃報記事には、参列者が花を贈らないようにというお願いが書かれていることがある(「In lieu of flowers」など)。このようなフレーズの使用は、過去1世紀にわたって増加の一途をたどっている。1927年のアメリカでは、訃報記事のわずか6% しかこのような指示はなく、そのうちの2%だけが代わりに慈善寄付について言及していた。しかし、今世紀半ばには15%にまで増加し、そのうちの54%以 上が、弔意を表す方法として慈善寄付を挙げている[55]。

葬儀

子供の葬儀、1920年

故人は通常、葬儀場から教会まで霊柩車(棺に入った遺体を運ぶための特殊車両)で運ばれる。霊柩車、葬儀用車両、自家用車が行列をなして教会や葬儀が行わ れる場所まで移動する。多くの管轄区域では、葬列を対象とする特別な法律が定められており、例えば、他のほとんどの車両は葬列に道を譲る必要がある。葬儀 用の車両には、道路での視認性を高めるためにライトバーや特殊な点滅装置が装備されていることがあります。また、どの車両が葬列の一部であるかを識別する ために、すべての車両がヘッドライトを点灯することもあるが、この習慣は古代ローマの習慣にもルーツがある[56]。葬儀の後、故人が埋葬される場合は、 葬列はまだ墓地になければ墓地まで進む。故人が火葬される場合は、葬列は火葬場へと進む。

フランツ・クサヴァー・シュテーバーが描いたベートーヴェンの葬儀

葬儀の習慣は国によって異なる。アメリカでは、静かにささやくか弔う以外のいかなる騒音も無礼とみなされる。

埋葬は火葬よりも費用がかかる傾向がある[57]。

埋葬サービス

このセクションでは、出典を引用していません。信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、このセクションの改善にご協力ください。ソースのないものは異 議申し立てがなされ、削除されることがあります。(2014年2月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)

ジョン・エヴァレット・ミレイ - 安息の谷

墓、墓、霊廟、火葬場の側で行われる宗教的な埋葬式では、被相続人の遺体は最後に埋葬または火葬される。

葬儀の直後に埋葬式が行われることもあり、その場合は葬列が葬儀会場から埋葬会場まで移動する。また、埋葬式が葬儀の後に行われる場合もあり、その場合は 墓地事務所から墓地まで行列が移動することもある。また、真冬に亡くなった場合は、埋葬の準備が整ってから埋葬することもある。

被相続人が軍隊に所属していた場合は、埋葬式で軍隊の儀式が行われることが多い[58]。

多くの宗教の伝統では、喪主は通常、被相続人の親族または友人である男性で、棺を(葬儀場や教会の)礼拝堂から霊柩車まで運び、霊柩車から埋葬の場所まで 運ぶ[59]。

ほとんどの宗教では、埋葬の儀式の間、棺を閉じておくことが期待されている。東方正教会の葬儀では、棺は埋葬の直前に再び開けられ、弔問客が最後にもう一 度故人を見つめ、最後の別れを告げることができるようにする。ギリシャの葬儀は例外で、遺体の状態がそれを許さない場合を除き、棺は葬儀の間ずっと開いて いる。

中世に描かれた棺に安置される王家の遺体

納棺師は、遺体を埋葬または納棺する前に、通夜で飾られていた腕時計などの宝石類がすべて棺の中に入っていることを確認することがある。しかし、ユダヤ教 の葬儀ではそうではない。ユダヤ教の伝統では、価値のあるものは故人と一緒に埋葬しないと定められている。

火葬の場合、そのようなものは通常、遺体が炉に入る前に取り除かれる。ペースメーカーは火葬の前に取り外される。

アメリカ先住民

先住民の葬儀は、他の多くの文化と同様に、独自の文化的慣習や伝統を通じて死者を記憶し、記念し、尊重する方法である。

カリフォルニア

過去には、先住民の葬儀場に関する話題が持ち上がると、詮索されたこともあった。そのため連邦政府は、これらの埋葬地を保護し、正しい先住民の個人または グループと正確に関連付ける一連の法律を盛り込む必要があると考えた。これは、アメリカ先住民墓地保護・送還法(Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act)によって制定された。さらに2001年、カリフォルニア州は「カリフォルニア州先住民の墓の保護と本国送還法」を制定し、「州からの資金提供を受 け、遺骨や文化財のコレクションを所有または管理しているすべての州機関および博物館に対し、これらの遺骨や文化財を特定し、適切な部族に本国送還するた めのプロセスを提供することを義務づける」とした。2020年には、州や連邦の知識が及ばない部族も含めるよう改正された。

西ユマン地域

イパイ、ティパイ、パイパイ、キリワ地域の葬儀慣習は、その社会的、権力的力学において類似している。これらの葬儀場の作り方は、以前の居住地に基づいて いる。つまり、これらの場所は、その民族が死亡した場所であったり、これらのグループの一部にとって一時的な住居であった場所であったりする。墓標には、 逆メテート、メテートの破片、ケルンなどがあった。供物としては、食料、貝殻、石のビーズなどが、遺骨とともに埋葬塚からしばしば発見された。

遺跡で発見された人骨の状態は様々で、火葬は埋葬に比べ先史時代では最近のことであるというデータがある[60]。完新世中期から先史時代後期まで。さら に、これらの人々が置かれた位置は、死後の世界がどのように見られていたかに一役買っている。最近のユマン族の民俗学的証拠によると、死者の霊は生者に危 害を加える可能性があると信じられている。そのため、彼らはしばしば遺体の上に目印や供え物を重ね、彼らが墓から「出て」危害を加えられないようにしてい た。

西ユマン地域、カリフォルニア州、バハ・カリフォルニア州

トングバ

ロサンゼルス盆地では、研究者たちがウェスト・ブラフとランディング・ヒルで共同殯葬の特徴を発見した。これらの共同追悼儀式は、中間期 (B.P.3,000-1,000)に行われたと推定されている。考古学者たちは、故意に几帳面に割られた大きな片岩の杵の破片を発見した。他の破片容器 には、可燃物の燃焼によって生じたと推定される、内面に不均一な燃焼の痕跡が見られる。

ウェスト・ブラフとランディング・ヒルの遺物群には、割った後に赤色黄土色の顔料で染めた遺物が多く見られる。意図的に物を壊す習慣は、その物の中にある 魂を解放するため、コミュニティへの害を減らすため、あるいは悲しみの表現として、この地域で何千年も続いてきた。チュマシュ族は赤色を土と火の両方に関 連付ける。研究者の中には、赤い色素の使用を成人のライフサイクルにおける重要な過渡期と考える者もいる[61]。

追悼行事

こちらも参照: 東方正教会における追悼式

1901年9月19日、ニューハンプシャー州ナシュアで行われたウィリアム・マッキンリー米大統領暗殺後の追悼式。

追悼式[62]は、故人のために行われるもので、遺体なしで行われることが多い。火葬や海洋葬の後、学術・研究機関への献体の後、あるいは散骨の後に行わ れる。また、行方不明で死亡が推定される場合や、遺体は回収できないが死亡が判明している場合にも行われる。これらの追悼式は葬儀場で行われることが多い が[63]、自宅、学校、職場、教会、その他何らかの意義のある場所で行われることもある。追悼式では、故人を偲ぶスピーチ(弔辞)、祈り、詩、歌などが 行われる。故人の写真や花は通常、棺が置かれる場所に置かれる。

重要な公務員の突然の死後、故人とは特に関係のない地域社会も含めて、公的な追悼式が行われてきた。例えば、ジェームズ・A・ガーフィールドやウィリア ム・マッキンリーが暗殺された後、地域社会による追悼式が行われた。

ヨーロッパの葬儀

イギリス

イギリスでは、葬儀は教会、火葬場、墓地のチャペルで行われるのが一般的である[64]。歴史的には死者を埋葬する習慣があったが、1960年代以降は火 葬が一般的になっている[65]。

北米のような面会式はないが、親族は葬儀場で事前に遺体を見ることができる。葬儀は通常30分ほどで終わる[67]。本葬と短い告別式に分かれることもあ る。後者の場合、棺は火葬場[67]に引き渡されるか、墓地に埋葬される[68]。あるいは、葬儀全体を火葬場や墓地の礼拝堂で行うこともある。火葬の様 子を見る習慣はなく、葬儀の終盤に棺を礼拝堂から出したり、カーテンで隠したりすることがある[67]。

葬儀の後、弔問客が集まって軽食をとるのが一般的である。これは通夜と呼ばれることもあるが、通夜が葬儀の前の儀式である諸外国での使われ方とは異なる [64]。

フィンランド

1951年2月4日、フィンランドのヘルシンキで行われたマンネルヘイム元帥の葬儀パレード。背景はヘルシンキ・ルーテル大聖堂。

フィンランドでは、宗教的な葬儀(hautajaiset)は非常に禁欲的である。地元の司祭や牧師が故人の家で祈りをささげ、祝福する。喪主 (saattoväki)は伝統的に喪主の家に食べ物を持参する。現在の一般的な慣習では、故人は亡くなった場所で棺に納められる。葬儀屋が棺を引き取 り、霊柩車に乗せて葬儀場まで運び、故人の近親者や友人は自家用車で霊柩車の後を追って葬列を組む。棺は葬儀当日まで斎場で保管される。葬儀は2つに分け られる。まず墓地の礼拝堂や地元の教会で教会式(siunaustilaisuus)を行い、その後埋葬を行う。

アイスランド

さらに詳しい情報 アイスランドの葬儀

イタリア

イタリア人の大半はローマ・カトリック教徒であり、カトリックの葬儀の伝統に従っている。歴史的には、弔問客は墓地まで葬列を組んで歩いていたが、今日で は自動車が使われる。

ギリシャ

ギリシャの葬儀は一般的に教会で行われ、トリサギオンの礼拝も行われる。通常40日間の服喪期間があり、その終わりに追悼礼拝が行われる。その後、毎年命 日に同様の礼拝が行われる[69][70]。

ポーランド

こちらも参照: カトリック葬儀

ポーランドでは、都市部では通常2回、または1回の「停止」が行われる。霊安室から霊柩車で運ばれた遺体は、教会または墓地の礼拝堂に運ばれる。その後、 墓地のチャペルで葬儀のミサや礼拝が行われる。ミサや礼拝の後、棺は霊柩車によって墓場まで行列(通常は徒歩)で運ばれる。墓地に到着すると、司祭が墓前 祭を開始し、棺が降ろされます。ミサや礼拝は通常、墓地で行われる。

伝統的な農村部では、通夜(czuwanie)が故人やその親族の家で行われることもある。遺体はその家で3日間安置される。葬儀は通常3日目に行われ る。その3日間の昼と夜に家族、隣人、友人が集まり、祈りを捧げる。通夜(czuwanie)、遺体を運ぶ行列(通常は徒歩)、または自家用車で教会や墓 地の礼拝堂に向かいミサを行い、さらに徒歩で墓地まで移動する。

葬儀が終わると、家族は葬儀後の懇親会(スタイパ)に集まる。自宅で行うこともあれば、ホールで行うこともある。ポーランドのカトリック教会は伝統的な埋 葬を好むため、ポーランドでは火葬はあまり普及していません(火葬は認められています)。ポーランドでは、無宗教者やプロテスタントの間で火葬が盛んで す。

ロシア

さらに詳しい情報 ロシアの伝統と迷信

スコットランド

スコットランドのハイランド地方に古くから伝わる葬儀の儀式では、故人の胸に木製の皿を載せて埋葬する。皿の上には少量の土と塩が置かれ、これは故人の未 来を表している。土は肉体が朽ちて大地と一体化することを暗示し、塩は朽ちない魂を表していた。この儀式は「死体に土を盛る」として知られていた。この儀 式はアイルランドやイングランドの一部、特にレスターシャーでも行われていたが、イングランドでは塩を入れるのは死体が空気で膨張するのを防ぐためであっ た[71]。

スペイン

スペインでは、死後すぐに埋葬や火葬が行われることがある。ほとんどのスペイン人はローマ・カトリック教徒であり、カトリックの葬儀の伝統に従う。まず、 通夜から埋葬までの間、家族や友人が故人と一緒に座る。通夜は社交の場であり、故人を偲び、笑い合う時間である。通夜に続いて、教会または墓地の礼拝堂で 葬儀ミサ(Tanatorio)が行われる。ミサに続いて埋葬が行われる。棺は教会から地元の墓地に移され、多くの場合、柩の後ろを地元の人々が行列を 作って歩く。

ウェールズ

伝統的に、良い葬儀(と呼ばれていた)は、しばらくの間カーテンを閉める。男性たちが葬儀に参列している間、女性たちは家に留まり、村の司祭が家族の家を 訪れて故人について話し、慰めた[72]。

1884年、ウェールズの新ドルイド教司祭ウィリアム・プライスの最初の子供が亡くなった。プライスは、死体を埋葬し、それによって大地を汚染することは 間違っていると考え、ケルト人の社会では一般的であった息子の遺体を火葬することにした。プライスは法廷で、法律には火葬が合法であるとは書かれていない が、違法であるとも書かれていないと主張し、成功した[73]。この事件は、新しく設立されたグレートブリテン火葬協会の活動とともに、1902年の火葬 法(Cremation Act 1902)につながる先例となった[74]。同法は、火葬を行う前に手続き上の要件を課し、火葬を許可された場所に制限した[75]。

The burial of a bird

Celebration of life

A growing number of families choose to hold a life celebration or celebration of life[76][77] event for the deceased in addition to or instead of a traditional funeral. Unlike funerals, the focus of the ceremony is on the life that was lived.[78] Such ceremonies may be held outside the funeral home or place of worship; restaurants, parks, pubs and sporting facilities are popular choices based on the specific interests of the deceased. Celebrations of life focus on a life that was lived, including the person's best qualities, interests, achievements and impact, rather than mourning a death.[76] Some events are portrayed as joyous parties, instead of a traditional somber funeral. Taking on happy and hopeful tones, celebrations of life discourage wearing black and focus on the deceased's individuality.[76] An extreme example might have "a fully stocked open bar, catered food, and even favors."[77] Notable recent celebrations of life ceremonies include those for René Angélil[79] and Maya Angelou.[80]

Jazz funeral

Main article: Jazz funeral

Originating in New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S., alongside the emergence of jazz music in late 19th and early 20th centuries, the jazz funeral is a traditionally African-American burial ceremony and celebration of life unique to New Orleans that involves a parading funeral procession accompanied by a brass band playing somber hymns followed by upbeat jazz music. Traditional jazz funerals begin with a processional led by the funeral director, family, friends, and the brass band, i.e., the "main line", who march from the funeral service to the burial site while the band plays slow dirges and Christian hymns. After the body is buried, or "cut loose", the band begins to play up-tempo, joyful jazz numbers, as the main line parades through the streets and crowds of "second liners" join in and begin dancing and marching along, transforming the funeral into a street festival.[81]

Green

Main article: Natural burial

A natural burial gravesite with just a stone to mark the grave

The terms "green burial" and "natural burial", used interchangeably, apply to ceremonies that aim to return the body with the earth with little to no use of artificial, non-biodegradable materials. As a concept, the idea of uniting an individual with the natural world after they die appears as old as human death itself, being widespread before the rise of the funeral industry. Holding environmentally-friendly ceremonies as a modern concept first attracted widespread attention in the 1990s. In terms of North America, the opening of the first explicitly "green" burial cemetery in the U.S. took place in the state of South Carolina. However, the Green Burial Council, which came into being in 2005, has based its operations out of California. The institution works to officially certify burial practices for funeral homes and cemeteries, making sure that appropriate materials are used.[82]

Religiously, some adherents of the Roman Catholic Church often have particular interest in "green" funerals given the faith's preference to full burial of the body as well as the theological commitments to care for the environment stated in Catholic social teaching.[82]

Those with concerns about the effects on the environment of traditional burial or cremation may be placed into a natural bio-degradable green burial shroud. That, in turn, sometimes gets placed into a simple coffin made of cardboard or other easily biodegradable material. Furthermore, individuals may choose their final resting place to be in a specially designed park or woodland, sometimes known as an "ecocemetery", and may have a tree or other item of greenery planted over their grave both as a contribution to the environment and a symbol of remembrance.

Humanist and otherwise not religiously affiliated

See also: Humanist celebrant

Humanists UK organises a network of humanist funeral celebrants or officiants across England and Wales, Northern Ireland, and the Channel Islands[83] and a similar network is organised by the Humanist Society Scotland. Humanist officiants are trained and experienced in devising and conducting suitable ceremonies for non-religious individuals.[84] Humanist funerals recognise no "afterlife", but celebrate the life of the person who has died.[83] In the twenty-first century, humanist funerals were held for well-known people including Claire Rayner,[85] Keith Floyd,[86][87] Linda Smith,[88] and Ronnie Barker.[89]

In areas outside of the United Kingdom, Ireland has featured an increasing number of non-religious funeral arrangements according to publications such as Dublin Live. This has occurred in parallel with a trend of increasing numbers of people carefully scripting their own funerals before they die, writing the details of their own ceremonies. The Irish Association of Funeral Directors has reported that funerals without a religious focus occur mainly in more urbanized areas in contrast to rural territories.[90] Notably, humanist funerals have started to become more prominent in other nations such as the Republic of Malta, in which civil rights activist and humanist Ramon Casha had a large scale event at the Radisson Blu Golden Sands resort devoted to laying him to rest. Although such non-religious ceremonies are "a rare scene in Maltese society" due to the large role of the Roman Catholic Church within that country's culture, according to Lovin Malta, "more and more Maltese people want to know about alternative forms of burial... without any religion being involved".[91][92]

Actual events during non-religious funerals vary, but they frequently reflect upon the interests and personality of the deceased. For example, the humanist ceremony for the aforementioned Keith Floyd, a restaurateur and television personality, included a reading of Rudyard Kipling's poetic work If— and a performance by musician Bill Padley.[86] Organizations such as the Irish Institute of Celebrants have stated that more and more regular individuals request training for administering funeral ceremonies, instead of leaving things to other individuals.[90]

More recently, some commercial organisations offer "civil funerals" that can integrate traditionally religious content.[93]

Police/fire services

Traditional "crossed-ladders" for a fire department funeral

Funerals specifically for fallen members of fire or police services are common in United States and Canada. These funerals involve honour guards from police forces and/or fire services from across the country and sometimes from overseas.[94] A parade of officers often precedes or follows the hearse carrying the fallen comrade.[94] A traditional fire department funeral consists of two raised aerial ladders.[95] The firefighters travel under the aerials on their ride, on the fire apparatus, to the cemetery. Once there, the grave service includes the playing of bagpipes. The pipes have come to be a distinguishing feature of a fallen hero's funeral. Also a "Last Alarm Bell" is rung. A portable fire department bell is tolled at the conclusion of the ceremony.

Masonic

A Masonic funeral is held at the request of a departed Mason or family member. The service may be held in any of the usual places or a Lodge room with committal at graveside, or the complete service can be performed at any of the aforementioned places without a separate committal. Freemasonry does not require a Masonic funeral.

There is no single convention for a Masonic funeral service. Some Grand Lodges have a prescribed service (as it is a worldwide organisation). Some of the customs include the presiding officer wearing a hat while doing his part in the service, the Lodge members placing sprigs of evergreen on the casket, and a small white leather apron may being placed in or on the casket. The hat may be worn because it is Masonic custom (in some places in the world) for the presiding officer to have his head covered while officiating. To Masons the sprig of evergreen is a symbol of immortality. A Mason wears a white leather apron, called a "lambskin", on becoming a Mason, and he may continue to wear it even in death.[96][97]

鳥葬

生涯を振り返る祝い(Celebration of life)

伝統的な葬儀に加えて、あるいは葬儀の代わりに、故人を偲ぶ終活[76][77]イベントを行うことを選ぶ家族も増えている。このようなセレモニーは、葬 儀場や礼拝所の外で行われることもある[78]。レストラン、公園、パブ、スポーツ施設などは、故人の特定の関心に基づいた人気のある選択肢である。人生 の祝典は、死を悼むというよりも、その人の最高の資質、興味、業績、影響力など、生きた人生に焦点を当てるものである。幸福で希望に満ちた色調を帯びた生 前祝いは、黒い服を着ることを控え、故人の個性に焦点を当てる[76]。極端な例では、「品揃え豊富なオープンバー、ケータリングされた料理、引き出物ま で用意する」[77]かもしれない。最近の著名な生前祝いの儀式には、ルネ・アンジェリル[79]やマヤ・アンジェロウ[80]のものがある。

ジャズ葬

主な記事 ジャズ葬

ジャズ葬は、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてのジャズ音楽の台頭とともに、アメリカのルイジアナ州ニューオーリンズで生まれた伝統的なアフリカ系ア メリカ人の埋葬儀式であり、ニューオーリンズ特有の生を祝う儀式でもある。伝統的なジャズ葬は、葬儀監督、家族、友人、ブラスバンドが先導する行列、すな わち「メインライン」で始まり、バンドがゆっくりとした挽歌やキリスト教の賛美歌を演奏しながら、葬儀から埋葬地まで行進する。遺体が埋葬された後、つま り「切り離された」後、バンドはアップテンポで陽気なジャズナンバーを演奏し始め、メインラインが通りをパレードし、「セカンドライナー」の群衆も加わっ て踊りながら行進し始め、葬儀はストリートフェスティバルへと変貌する[81]。

グリーン

主な記事 自然葬

墓標に石を置くだけの自然葬墓地

緑葬」と「自然葬」という言葉は、同じ意味で使われるが、人工的で生分解性のない物質をほとんど使用せず、遺体を土に還すことを目的とした儀式に適用され る。コンセプトとしては、死後、個人と自然界を結びつけるという考え方は、人間の死そのものと同じくらい古く、葬儀産業が台頭する以前から広まっていたよ うだ。現代的な概念として環境に配慮したセレモニーが注目されるようになったのは、1990年代に入ってからである。北米でいえば、サウスカロライナ州に 米国初の明確な「グリーン」埋葬墓地がオープンした。しかし、2005年に設立されたグリーン・バリアル・カウンシルは、カリフォルニア州を拠点に活動し ている。この機関は、葬儀社や墓地の埋葬方法を公式に認証し、適切な材料が使用されていることを確認するために活動している[82]。

宗教的には、ローマ・カトリック教会の信者の一部は、カトリックの社会教説に述べられている環境への配慮に対する神学的コミットメントと同様に、遺体を完 全に埋葬することを好むことから、「環境に優しい」葬儀に特別な関心を持つことが多い[82]。

伝統的な埋葬や火葬による環境への影響を懸念する人々は、自然な生物分解性のある緑色の埋葬用シュラウドに納められることがある。また、段ボールなどの生 分解しやすい素材でできたシンプルな棺に納められることもある。さらに、「エコ墓地」として知られることもある、特別に設計された公園や森林地帯を終の棲 家とし、環境への貢献と追悼のシンボルとして、墓の上に樹木やその他の緑を植えることもある。

ヒューマニストなど宗教に関係ない場合

こちらも参照: ヒューマニスト・セレブリスト

Humanists UKは、イングランドとウェールズ、北アイルランド、チャンネル諸島にヒューマニスト葬儀司式者のネットワークを組織しており[83]、同様のネットワー クはHumanist Society Scotlandによって組織されている。ヒューマニストの司式者は、無宗教の人々に適した儀式を考案し、執り行うための訓練を受け、経験を積んでいる [84]。 ヒューマニストの葬儀は「死後の世界」を認めず、亡くなった人の人生を讃えるものである[83]。 21世紀には、クレア・レイナー[85]、キース・フロイド[86][87]、リンダ・スミス[88]、ロニー・バーカー[89]などの著名人のために ヒューマニストの葬儀が執り行われた。

ダブリン・ライブ』などの出版物によれば、イギリス以外の地域では、アイルランドでは無宗教の葬儀が増加している。これは、生前に自分の葬儀を入念に脚本 化し、儀式の詳細を自分で書く人が増えている傾向と並行して起こっている。アイルランドの葬儀業者協会は、宗教にこだわらない葬儀は主に都市部で行われて おり、農村部とは対照的であると報告している[90]。注目すべきは、マルタ共和国など他の国でも人文主義者の葬儀が目立ち始めていることで、公民権運動 家で人文主義者のラモン・カシャは、ラディソン・ブル・ゴールデン・サンズ・リゾートで大規模なイベントを行い、彼の安らかな眠りについた。このような非 宗教的な儀式は、マルタの文化におけるローマ・カトリック教会の大きな役割のため、「マルタ社会では珍しい光景」であるが、Lovin Maltaによれば、「より多くのマルタの人々が、宗教を介さない...代替的な埋葬の形式について知りたがっている」[91][92]。

無宗教の葬儀で実際に行われる行事はさまざまだが、故人の関心や個性を反映することが多い。例えば、前述のレストラン経営者でテレビパーソナリティでも あったキース・フロイドの人文主義的なセレモニーでは、ラドヤード・キプリングの詩集『If-』の朗読や、ミュージシャンのビル・パドリーによる演奏が行 われた[86]。アイルランドのセレブランツ協会(Irish Institute of Celebrants)などの団体は、葬儀を人任せにするのではなく、葬儀を執り行うためのトレーニングを希望する一般人が増えていると述べている [90]。

最近では、伝統的な宗教的内容を統合することができる「市民葬」を提供する営利団体もある[93]。

警察/消防

消防署の葬儀における伝統的な「渡り梯子

アメリカやカナダでは、消防や警察の殉職者のための葬儀が一般的である。これらの葬儀には、全国から、時には海外からも、警察や消防の儀仗隊が参加する [94]。殉職した仲間を乗せた柩の前後に、警官のパレードが続くことが多い[94]。伝統的な消防署の葬儀は、2本の高くなった空中梯子で構成される [95]。消防隊員は、消防車に乗って空中梯子の下をくぐり、墓地まで移動する。墓地に到着すると、墓前祭ではバグパイプが演奏される。このパイプは、殉 職した英雄の葬儀の際立った特徴となっている。また、「最後の警鐘」も鳴らされる。式典の最後には、消防署の携帯ベルが鳴らされる。

メーソン

メーソンの葬儀は、亡くなったメーソンまたは家族の要望で行われる。葬儀は、通常の場所、またはロッジの一室で行われ、墓前で棺に納めることもできるし、 別に棺に納めることなく、前述のいずれかの場所で完全な葬儀を行うこともできる。フリーメーソンはメーソンの葬儀を必要としない。

メーソンの葬儀に単一の慣習はない。いくつかのグランド・ロッジは、(それが世界的な組織であるため)所定のサービスを持っています。いくつかの習慣に は、司式者が自分の役割を果たすときに帽子をかぶること、ロッジのメンバーが棺にエバーグリーンの小枝を置くこと、棺の中や棺の上に小さな白い革のエプロ ンを置くことなどがある。棺の中や棺の上に小さな白い革のエプロンを置くこともある。司式者が司式中に頭を覆うのは(世界のいくつかの地域では)メイソン の習慣であるため、帽子をかぶることがある。メイソンにとって常緑樹の小枝は不死の象徴である。メイソンは、メイソンになるときに「ラムスキン」と呼ばれ る白い革のエプロンを着用し、死んでも着用し続けることができる[96][97]。

See also: Chinese funerary art, Chinese veneration of the dead, Ancestor veneration in China, wu (shaman), shi (personator), joss paper, and Culture of Vietnam § Funeral

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

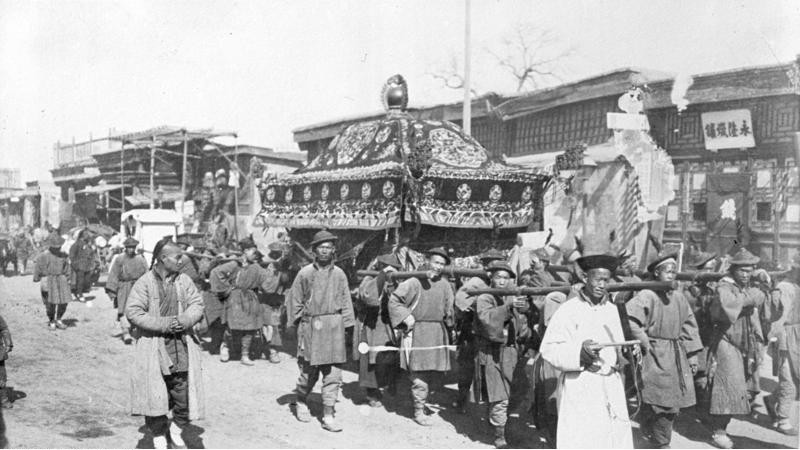

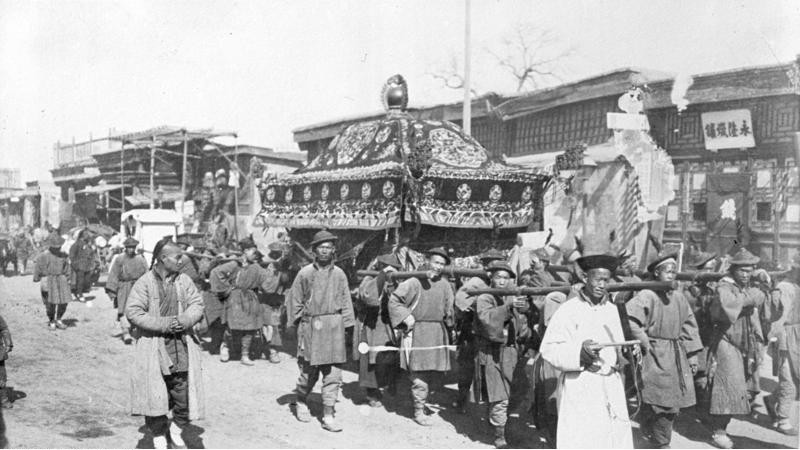

Funeral procession in Beijing, 1900

A traditional armband indicating seniority and lineage in relation to the deceased, a common practice in South Korea

In most East Asian, South Asian and many Southeast Asian cultures, the wearing of white is symbolic of death. In these societies, white or off-white robes are traditionally worn to symbolize that someone has died and can be seen worn among relatives of the deceased during a funeral ceremony. In Chinese culture, red is strictly forbidden as it is a traditionally symbolic color of happiness. Exceptions are sometimes made if the deceased has reached an advanced age such as 85, in which case the funeral is considered a celebration, where wearing white with some red is acceptable. Contemporary Western influence however has meant that dark-colored or black attire is now often also acceptable for mourners to wear (particularly for those outside the family). In such cases, mourners wearing dark colors at times may also wear a white or off-white armband or white robe.

Contemporary South Korean funerals typically mix western culture with traditional Korean culture, largely depending on socio-economic status, region, and religion. In almost all cases, all related males in the family wear woven armbands representing seniority and lineage in relation to the deceased, and must grieve next to the deceased for a period of three days before burying the body. During this period of time, it is customary for the males in the family to personally greet all who come to show respect. While burials have been preferred historically, recent trends show a dramatic increase in cremations due to shortages of proper burial sites and difficulties in maintaining a traditional grave. The ashes of the cremated corpse are commonly stored in columbaria.

In Japan

Main article: Japanese funeral

Sudangee or last offices being performed on a dead person, illustration from 1867

Most Japanese funerals are conducted with Buddhist and/or Shinto rites.[98] Many ritually bestow a new name on the deceased; funerary names typically use obsolete or archaic kanji and words, to avoid the likelihood of the name being used in ordinary speech or writing. The new names are typically chosen by a Buddhist priest, after consulting the family of the deceased.

Religious thought among the Japanese people is generally a blend of Shintō and Buddhist beliefs. In modern practice, specific rites concerning an individual's passage through life are generally ascribed to one of these two faiths. Funerals and follow-up memorial services fall under the purview of Buddhist ritual, and 90% Japanese funerals are conducted in a Buddhist manner. Aside from the religious aspect, a Japanese funeral usually includes a wake, the cremation of the deceased, and inclusion within the family grave. Follow-up services are then performed by a Buddhist priest on specific anniversaries after death.

According to an estimate in 2005, 99% of all deceased Japanese are cremated.[99] In most cases the cremated remains are placed in an urn and then deposited in a family grave. In recent years however, alternative methods of disposal have become more popular, including scattering of the ashes, burial in outer space, and conversion of the cremated remains into a diamond that can be set in jewelry.

In the Philippines

Main article: Funeral practices and burial customs in the Philippines

Funeral practices and burial customs in the Philippines encompass a wide range of personal, cultural, and traditional beliefs and practices which Filipinos observe in relation to death, bereavement, and the proper honoring, interment, and remembrance of the dead. These practices have been vastly shaped by the variety of religions and cultures that entered the Philippines throughout its complex history.

Most if not all present-day Filipinos, like their ancestors, believe in some form of an afterlife and give considerable attention to honouring the dead.[100] Except amongst Filipino Muslims (who are obliged to bury a corpse less than 24 hours after death), a wake is generally held from three days to a week.[101] Wakes in rural areas are usually held in the home, while in urban settings the dead is typically displayed in a funeral home. Friends and neighbors bring food to the family, such as pancit noodles and bibingka cake; any leftovers are never taken home by guests, because of a superstition against it.[35] Apart from spreading the news about someone's death verbally,[101] obituaries are also published in newspapers. Although the majority of the Filipino people are Christians,[102] they have retained some traditional indigenous beliefs concerning death.[103][104]

In Korea

Main article: Korean traditional funeral

Yukgaejang is a spicy soup with a beef and vegetables in it. It is a Korean traditional food and served during funerals.