ゲイル・ルービン

Gayle S. Rubin, b.1949

Rubin

speaking at the GLBT History Museum in San Francisco, June 7, 2012

☆ ゲイル・S・ルービン(1949年1月1日生まれ)は、アメリカの文化人類学者、理論家、活動家であり、フェミニズム理論やクィア・スタディーズの先駆的 な業績で知られる。 彼女のエッセイ 「The Traffic in Women」(1975年)は、ジェンダー抑圧は家父長制に関するマルクス主義的概念では十分に説明できないと主張し、第二波フェミニズムと初期のジェン ダー研究に永続的な影響を与えた。1984年に発表したエッセイ『Thinking Sex』は、ゲイ&レズビアン研究、セクシュアリティ研究、クィア理論の創始的テキストとして広く知られている。セクシュアリティの政治学、ジェンダー抑 圧、サドマゾヒズム、ポルノグラフィ、レズビアン文学、都市のセクシュアル・サブカルチャーの人類学的研究など、さまざまなテーマについて執筆しており、 ミシガン大学で人類学と女性学の准教授を務めている。

★ルー ビンは自著『女性の交通:セックスの政治経済学ノート』において、レヴィ=ストロースによる親族関係理論、フロイトによる精神分析理論、そしてラカンによ る構造主義批判を組み合わせて、女性が交換される瞬間(主に結婚行為を通じて)に身体が生成され、女性となるのだと主張した。

| Gayle S. Rubin (born

January 1, 1949) is an American cultural anthropologist, theorist and

activist, best known for her pioneering work in feminist theory and

queer studies. Her essay "The Traffic in Women" (1975) had a lasting influence in second-wave feminism and early gender studies, by arguing that gender oppression could not be adequately explained by Marxist conceptions of the patriarchy.[3][4][5] Her 1984 essay "Thinking Sex" is widely regarded as a founding text of gay and lesbian studies, sexuality studies, and queer theory.[6][7][8] She has written on a range of subjects including the politics of sexuality, gender oppression, sadomasochism, pornography and lesbian literature, as well as anthropological studies of urban sexual subcultures,[8] and is an associate professor of Anthropology and Women's Studies at the University of Michigan.[9] |

ゲイル・S・ルービン(1949年1月1日生まれ)は、アメリカの文化

人類学者、理論家、活動家であり、フェミニズム理論やクィア・スタディーズの先駆的な業績で知られる。 彼女のエッセイ 「The Traffic in Women」(1975年)は、ジェンダー抑圧は家父長制に関するマルクス主義的概念では十分に説明できないと主張し、第二波フェミニズムと初期のジェン ダー研究に永続的な影響を与えた。1984年に発表したエッセイ『Thinking Sex』は、ゲイ&レズビアン研究、セクシュアリティ研究、クィア理論の創始的テキストとして広く知られている。セクシュアリティの政治学、ジェンダー抑 圧、サドマゾヒズム、ポルノグラフィ、レズビアン文学、都市のセクシュアル・サブカルチャーの人類学的研究など、さまざまなテーマについて執筆しており、 ミシガン大学で人類学と女性学の准教授を務めている。 |

| Biography Early life Rubin was raised in a white middle-class Jewish home in then-segregated South Carolina. She attended segregated public schools, her classes only being desegregated when she was a senior. Rubin has written that her experiences growing up in the segregated South has given her "an abiding hatred of racism in all its forms and a healthy respect for its tenacity." As one of the few Jews in her Southern city, she resented the dominance of white Protestants over African-Americans, Catholics, and Jews. The only Jewish child in her elementary school, she claims she was punished for refusing to recite the Lord's Prayer.[10] College, early activism, and early writing In 1968 Rubin was part of an early feminist consciousness raising group active on the campus of the University of Michigan and also wrote on feminist topics for women's movement papers and the Ann Arbor Argus.[11] In 1970 she helped found Ann Arbor Radicalesbians, an early lesbian feminist group.[11] She was also a graduate worker in 1975, when the Graduate Employees' Organization 3550 was formed at the University of Michigan. At the time, she and Anne Bobroff, a fellow graduate student, wrote and distributed a leaflet titled "The Fetishization of Bargaining",[12] which argued that bargaining alone is not enough to convince management. Rubin first rose to recognition through her 1975 essay "The Traffic in Women: Notes on the 'Political Economy' of Sex",[13] which had a galvanizing effect on feminist theory.[14] San Francisco In 1978 Rubin moved to San Francisco to begin studies of the gay male leather subculture, seeking to examine a minority sexual practice neither from a clinical perspective nor through the lens of individual psychology but rather as an anthropologist studying a contemporary community.[15] Rubin was a member of Cardea, a women's discussion group within a San Francisco BDSM organization called the Society of Janus; Cardea existed from 1977 to 1978 before discontinuing. A core of lesbian members of Cardea, including Rubin, Pat Califia (who identified as a lesbian at the time), and sixteen others, were inspired to start Samois on June 13, 1978, as an exclusively lesbian BDSM group.[16][17] Samois was a lesbian-feminist BDSM organization based in San Francisco that existed from 1978 to 1983, and was the first lesbian BDSM group in the United States.[18] In 1984 Rubin cofounded The Outcasts, a social and educational organization for women interested in BDSM with other women, also based in San Francisco.[19][20][21] That organization was disbanded in the mid-1990s; its successor organization The Exiles is still active.[22] In 2012, The Exiles in San Francisco received the Small Club of the Year award as part of the Pantheon of Leather Awards.[23] In the field of public history, Rubin was a member of the San Francisco Lesbian and Gay History Project, a private study group founded in 1978 whose members included Allan Berube, Estelle Freedman and Amber Hollibaugh.[24] Rubin also is a founding member of the GLBT Historical Society (originally known as the San Francisco Bay Area Gay and Lesbian Historical Society), established in 1985.[24][25] Arguing the need for well-maintained historical archives for sexual minorities, Rubin has written that "queer life is full of examples of fabulous explosions that left little or no detectable trace.... Those who fail to secure the transmission of their histories are doomed to forget them".[26] She became the first woman to judge a major national gay male leather title contest in 1991, when she judged the Mr. Drummer contest.[27] This contest was associated with Drummer magazine, which was based in San Francisco.[28] The San Francisco South of Market Leather History Alley consists of four works of art along Ringold Alley honoring the leather subculture; it opened in 2017.[29][30] One of the works of art is a black granite stone etched with, among other things, a narrative by Rubin.[30][31][32] Rubin was an important member of the community advisory group that was consulted to develop the designs of the works of art.[30] Academic career In 1994, Rubin completed her Ph.D. in anthropology at the University of Michigan with a dissertation entitled The valley of kings: Leathermen in San Francisco, 1960–1990.[33] In addition to her appointment at the University of Michigan, she was the 2014 F. O. Matthiessen Visiting Professor of Gender and Sexuality at Harvard University.[34][35] Rubin serves on the editorial board of the journal Feminist Encounters[36] and on the international advisory board of the feminist journal Signs.[37] Other Rubin is a sex-positive feminist.[38] The 1982 Barnard Conference on Sexuality is often credited as the moment that signaled the beginning of the feminist sex wars;[39] Rubin gave a version of her work "Thinking Sex" (see below) as a workshop there.[40] "Thinking Sex" then had its first publication in 1984, in Carole Vance's book Pleasure and Danger, which was an anthology of papers from that conference.[40] "Thinking Sex" is a sex-positive piece[38] which is widely regarded as a founding text of gay and lesbian studies, sexuality studies, and queer theory.[6][7] Rubin served on the board of directors of the Leather Archives and Museum from 1992 to 2000.[27] Rubin is on the Board of Governors for the Leather Hall of Fame.[41][42] |

略歴 生い立ち ルービンは、当時人種隔離されていたサウスカロライナ州のユダヤ系白人中流階級の家庭で育った。隔離された公立学校に通い、クラスが人種差別撤廃されたの は彼女が4年生の時だった。ルービンは、隔離された南部で育った経験から、「あらゆる形態の人種差別を憎み、その粘り強さを健全に尊重するようになった」 と書いている。南部の街で数少ないユダヤ人の一人として、彼女は白人プロテスタントがアフリカ系アメリカ人、カトリック、ユダヤ人を支配していることに憤 慨した。小学校で唯一のユダヤ人の子供だった彼女は、主の祈りを暗唱することを拒否したために罰を受けたと主張している[10]。 大学、初期の活動、初期の執筆活動 1968年、ルービンはミシガン大学のキャンパスで活動する初期のフェミニスト意識改革グループの一員であり、また女性運動紙やアナーバー・アーガス紙に フェミニストのトピックについて執筆していた[11]。1970年、彼女は初期のレズビアン・フェミニスト・グループであるアナーバー・ラディカルズビア ンズの設立に協力した[11]。1975年、ミシガン大学で大学院職員組織3550が結成されたとき、彼女は大学院職員でもあった。当時、彼女は同じ大学 院生であったアン・ボブロフとともに、交渉だけでは経営陣を納得させることはできないと主張する「交渉のフェティシズム化」と題するリーフレットを作成 し、配布した[12]。 ルービンは1975年に発表したエッセイ『女性の交通』によって初めてその名を知られるようになった: この論文はフェミニズム理論に大きな影響を与えた[14]。 サンフランシスコ 1978年、ルービンはサンフランシスコに移り住み、ゲイ男性のレザー・サブカルチャーの研究を始めた。マイノリティの性実践を、臨床的な視点や個人心理学のレンズを通してではなく、むしろ現代のコミュニティを研究する人類学者として検証しようとしたのである[15]。 ルービンは、ヤヌスの会と呼ばれるサンフランシスコのBDSM組織内の女性ディスカッショングループであるカルデアのメンバーであった。ルービン、パッ ト・カリフィア(当時レズビアンであることを自認していた)、その他16名を含むカルデアのレズビアンの中心メンバーは、1978年6月13日、レズビア ンのみのBDSMグループとしてサモイスを立ち上げるきっかけとなった[16][17]。サモイスはサンフランシスコを拠点とするレズビアン・フェミニス トのBDSM組織で、1978年から1983年まで存在し、アメリカ初のレズビアンのBDSMグループであった[18]。 [18]1984年、ルービンは同じくサンフランシスコを拠点とする、BDSMに興味を持つ女性のための社会的・教育的組織である「アウトキャスツ」を他 の女性と共同で設立した[19][20][21]。この組織は1990年代半ばに解散したが、その後継組織である「エグザイルズ」は現在も活動している [22]。2012年、サンフランシスコの「エグザイルズ」はパンテオン・オブ・レザー・アワードの一環としてスモール・クラブ・オブ・ザ・イヤー賞を受 賞した[23]。 公的な歴史の分野では、ルービンは1978年に設立されたアラン・ベルーベ、エステル・フリードマン、アンバー・ホリボーらをメンバーとする私的研究グ ループ「サンフランシスコ・レズビアン&ゲイ・ヒストリー・プロジェクト」のメンバーであった。 [24]また、ルービンは1985年に設立されたGLBT歴史協会(当初はサンフランシスコ・ベイエリア・ゲイ・レズビアン歴史協会として知られていた) の創設メンバーでもある[24][25]。セクシュアル・マイノリティのために整備された歴史的アーカイブの必要性を主張するルービンは、「クィアな生活 は、ほとんどあるいは全く検出可能な痕跡を残さなかった素晴らしい爆発の例に満ちている......」と書いている。自分たちの歴史の伝達を確保できない 者は、それを忘れてしまう運命にある」[26]。 1991年、彼女はミスター・ドラマー・コンテストの審査員を務め、女性として初めて全米ゲイ男性レザー・タイトル・コンテストの審査員となった[27]。 このコンテストはサンフランシスコを拠点とするドラマー誌に関連していた[28]。 サンフランシスコ・サウス・オブ・マーケット・レザー・ヒストリー・アレイは、レザー・サブカルチャーを称えるリングールド・アレイ沿いの4つのアート作 品から構成されており、2017年にオープンした[29][30]。アート作品のひとつは、ルービンによる物語などがエッチングされた黒御影石の石である [30][31][32]。ルービンは、アート作品のデザインを開発するために協議されたコミュニティ諮問グループの重要なメンバーであった[30]。 学術的キャリア 1994年、ルービンはミシガン大学で人類学の博士号を取得した: The valley of kings: Leathermen in San Francisco, 1960-1990』と題する論文でミシガン大学の人類学博士号を取得した[33]。 ミシガン大学での任用に加え、2014年にはハーバード大学でジェンダーとセクシュアリティのF・O・マティッセン客員教授を務めた[34][35]。 雑誌『Feminist Encounters』の編集委員[36]、フェミニスト雑誌『Signs』の国際諮問委員を務める[37]。 その他 ルービンはセックスに肯定的なフェミニストである[38]。1982年のバーナード・コンファレンス・オン・セクシュアリティは、フェミニストのセックス 戦争の始まりを告げる瞬間としてしばしば信じられている[39]。 [40]「考えるセックス」は1984年、その会議の論文を集めたアンソロジーであるキャロル・ヴァンスの著書『快楽と危険』の中で初めて出版された [40]。「考えるセックス」はセックス・ポジティブな作品であり[38]、ゲイ&レズビアン研究、セクシュアリティ研究、クィア理論の創始的なテキスト として広く評価されている[6][7]。 ルービンは1992年から2000年までLeather Archives and Museumの理事を務めた[27]。 ルービンはレザーの殿堂の理事会のメンバーである[41][42]。 |

| Thought The Traffic in Women: Notes on the 'Political Economy' of Sex Main article: The Traffic in Women: Notes on the Political Economy of Sex In this essay, Rubin devised the phrase "sex/gender system", which she defines as "the set of arrangements by which a society transforms biological sexuality into products of human activity, and in which these transformed sexual needs are satisfied."[13] She takes as a starting point writers who have previously discussed gender and sexual relations as an economic institution which serves a conventional social function (Claude Lévi-Strauss) and is reproduced in the psychology of children (Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan). She argues that these writers fail to adequately explain women's oppression, and offers a reinterpretation of their ideas. Rubin addresses Marxist thought by identifying women's role within a capitalist society.[43] She argues that the reproduction of labor power depends upon women's housework to transform commodities into sustenance for the worker. The system of capitalism cannot generate surplus without women, yet society does not grant women access to the resulting capital. Rubin argues that historical patterns of female oppression have constructed this role for women in capitalist societies. She attempts to analyze these historical patterns by considering the sex/gender system. According to Rubin, "Gender is a socially imposed division of the sexes."[43] She cites the exchange of women within patriarchal societies as perpetuating the pattern of female oppression, referencing Marcel Mauss' Essay on the Gift[44] and using his idea of the "gift" to establish the notion that gender is created within this exchange of women by men in a kinship system. Women are born biologically female, but only become gendered when the distinction between male giver and female gift is made within this exchange. For men, giving the gift of a daughter or a sister to another man for the purpose of matrimony allows for the formation of kinship ties between two men and the transfer of "sexual access, genealogical statuses, lineage names and ancestors, rights and people"[43] to occur. When using a Marxist analysis of capitalism within this sex/gender system, the exclusion of women from the system of exchange establishes men as the capitalists and women as their commodities fit for exchange. She ultimately argues that, in the current moment, a genderless identity and a polymorphous sexuality with no hierarchies are possible if we break away from the "now functionless" sex/gender system.[45] [43] Thinking Sex In her 1984 essay Thinking Sex, Rubin interrogated the value system that social groups—whether left- or right-wing, feminist or patriarchal—attribute to sexuality which defines some behaviours as good/natural and others (such as homosexuality or BDSM) as bad/unnatural. In this essay she introduced the idea of the "Charmed Circle" of sexuality, that sexuality that was privileged by society was inside of it, while all other sexuality was outside of, and in opposition to it. The binaries of this "charmed circle" include couple/alone or in groups, monogamous/promiscuous, same generation/cross-generational, and bodies only/with manufactured objects. The "Charmed Circle" speaks to the idea that there is a hierarchical valuation of sex acts. In this essay, Rubin also discusses a number of ideological formations that permeate sexual views. The most important is sex negativity, in which Western cultures consider sex to be a dangerous, destructive force. If marriage, reproduction, or love are not involved, almost all sexual behavior is considered bad. Related to sex negativity is the fallacy of the misplaced scale. Rubin explains how sex acts are troubled by an excess of significance. Rubin's discussion of all of these models assumes a domino theory of sexual peril. People feel a need to draw a line between good and bad sex as they see it standing between sexual order and chaos. There is a fear that if certain aspects of "bad" sex are allowed to move across the line, unspeakable acts will move across as well. One of the most prevalent ideas about sex is that there is one proper way to do it. Society lacks a concept of benign sexual variation. People fail to recognize that just because they do not like to do something does not make it repulsive. Rubin points out that we have learned to value other cultures as unique without seeing them as inferior, and we need to adopt a similar understanding of different sexual cultures as well.[46] Legacy of Thinking Sex Rubin's 1984 essay Thinking Sex is widely regarded as a founding text of gay and lesbian studies, sexuality studies, and queer theory.[6][7] The University of Pennsylvania hosted a "state of the field" conference in gender and sexuality studies on March 4 to 6, 2009, titled "Rethinking Sex" and held in recognition of the twenty-fifth anniversary of Thinking Sex.[47][48] Rubin was a featured speaker at the conference, where she presented "Blood under the Bridge: Reflections on 'Thinking Sex,'" to an audience of nearly eight hundred people.[49] In 2011 GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies published a special issue, also titled "Rethinking Sex," featuring work emerging from this conference, and including Rubin's piece "Blood under the Bridge: Reflections on 'Thinking Sex'".[50] In a 2011 reflection on "Rethinking Sex", Rubin clarified that her "comments on sex and children were made in a different context", at a time in the 1980s when moral panics about Satanists and kidnappers were prevalent, and she never imagined people would claim she "supported the rape of pre-pubescents." She stated that her writings had been misconstrued by right-wingers and anti-pornography advocates.[51] |

思想 女性の売買 性の「政治経済学」ノート 主な記事 女性の売買 性の政治経済学ノート このエッセイの中でルービンは「セックス/ジェンダー・システム」 という言葉を考案し、彼女はそれを「社会が生物学的なセクシュアリティを人間活動の産物に変容させ、変容させられた性的欲求が満たされる一連の取り決め」 と定義している[13]。彼女は、ジェンダーと性関係を、従来の社会的機能を果たす経済的制度(クロード・レヴィ=ストロース)として、また子どもの心理 学に再生産されるもの(ジークムント・フロイトとジャック・ラカン)として論じてきた作家たちを出発点としている。彼女は、これらの作家が女性の抑圧を適 切に説明できていないと主張し、彼らの思想の再解釈を提示している。ルービンは、資本主義社会における女性の役割を明らかにすることで、マルクス主義思想 に取り組んでいる[43]。彼女は、労働力の再生産は、商品を労働者の糧に変える女性の家事に依存していると主張する。資本主義のシステムは女性なしには 余剰を生み出せないが、社会はその結果生じる資本へのアクセスを女性に認めていない。 ルービンは、女性抑圧の歴史的パターンが、資本主義社会における女性のこのような役割を構築してきたと主張する。彼女は、性/ジェンダー・システムを考慮することによって、こうした歴史的パターンを分析しようとしている。ルービンによれば、「ジェンダーとは、社会的に課せられた男女の分断である」[43]。 彼女は、家父長制社会における女性の交換が女性抑圧のパターンを永続させているとして、マルセル・モースの『贈与に関するエッセイ』[44]を参照し、彼 の「贈与」という考え方を用いて、ジェンダーは親族制度における男性による女性の交換の中で生み出されるという概念を確立している。女性は生物学的に女性 として生まれてくるが、この交換の中で男性の贈り手と女性の贈り物の区別がなされることによって初めてジェンダー化されるのである。男性にとって、婚姻を 目的として娘や姉妹を他の男性に贈与することは、二人の男性の間に親族関係の結びつきを形成し、「性的アクセス、系譜上の地位、血統名と先祖、権利と人」 [43]の移転を可能にする。この性/ジェンダー・システムの中で資本主義をマルクス主義的に分析すると、交換のシステムから女性が排除されることで、男 性は資本家として、女性は交換に適した商品として確立される。彼女は最終的に、現在の瞬間において、「今や機能しない」性/ジェンダー・システムから脱却 すれば、ジェンダーレスなアイデンティティと、ヒエラルキーのない多形的なセクシュアリティが可能になると主張する[45] [43] 。 セックスを考える ルービンは1984年に発表したエッセイ『考えるセックス』で、左翼であれ右翼であれ、フェミニストであれ家父長主義であれ、社会集団がセクシュアリティ に帰属させる価値観に疑問を投げかけ、ある行動は善/自然であり、他の行動(同性愛やBDSMなど)は悪/不自然であると定義した。このエッセイの中で、 彼女はセクシュアリティの「チャームド・サークル」という考え方を紹介した。つまり、社会によって特権化されたセクシュアリティは社会の内側にあり、それ 以外のセクシュアリティは社会の外側にあり、社会と対立するという考え方である。この「チャームド・サークル」の二項対立には、カップル/単独またはグ ループ、一夫一婦制/プロミスキャス、同世代/異世代、身体のみ/製造されたモノとの関係などがある。魅惑の輪」は、性行為には階層的な評価があるという 考えを物語っている。このエッセイの中でルービンは、性的な見方に浸透している多くのイデオロギー形成についても論じている。最も重要なのはセックス否定 論で、西洋文化ではセックスは危険で破壊的な力であると考えられている。結婚、生殖、愛が関係していない場合、ほとんどすべての性的行動は悪いものとみな される。セックス否定論と関連しているのは、見当違いの尺度の誤りである。ルービンは、性行為がいかに過剰な意義によって悩まされるかを説明している。 これらすべてのモデルに関するルービンの議論は、性的危害のドミノ理論を前提としている。人々は、セックスの良し悪しを線引きする必要性を感じ、それが性 の秩序と混沌の間に立っていると考えるからだ。もし「悪い」セックスのある側面がその一線を越えることが許されるなら、言いようのない行為もまた越えてし まうのではないかという恐れがある。セックスに関する最も一般的な考え方のひとつは、セックスにはひとつの正しいやり方があるというものだ。社会には良性 の性的変化という概念が欠けている。人々は、何かをするのが嫌だからといって、それが嫌悪につながるわけではないということを認識していない。ルービン は、私たちは他の文化を劣ったものと見なすことなく、ユニークなものとして評価することを学んだと指摘し、私たちは異なる性文化に対しても同様の理解を採 用する必要があると述べている[46]。 考えるセックス』の遺産 ルービンの1984年のエッセイ『Thinking Sex』は、ゲイ&レズビアン研究、セクシュアリティ研究、そしてクィア理論の創始的なテキストとして広く評価されている[6][7]。 ペンシルバニア大学は2009年3月4日から6日にかけて、『Thinking Sex』の25周年を記念して「Rethinking Sex」と題されたジェンダー・セクシュアリティ研究における「分野の現状」会議を開催した[47][48]: 2011年、GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studiesは、「Rethinking Sex」と題された特集号を発行し、この会議から生まれた作品を取り上げ、ルービンの作品「Blood under the Bridge: 考えるセックス』についての考察」である[50]。 2011年の『セックス再考』に関する考察の中で、ルービンは「セックスと子どもに関するコメントは、悪魔崇拝者や誘拐犯に対するモラル・パニックが蔓延 していた1980年代に、別の文脈でなされたもの」であり、「思春期前の子どもたちのレイプを支持している」と主張されるとは想像もしていなかったことを 明らかにした。彼女は自分の著作が右翼や反ポルノ擁護派によって誤解されていると述べた[51]。 |

| Awards and honors 2019: Race Bannon Advocacy Award from the National Coalition for Sexual Freedom[52] 2017: The San Francisco South of Market Leather History Alley consists of four works of art along Ringold Alley honoring the leather subculture; it opened in 2017.[29][30] One of the works of art is a black granite stone etched with, among other things, a narrative by Rubin.[30][31][32] Rubin was an important member of the community advisory group that was consulted to develop the designs of the works of art.[30] 2012: Her book Deviations: A Gayle Rubin Reader received the National Leather Association's Geoff Mains Non-fiction book award for 2012.[53] 2012: Ruth Benedict Prize[54] 2003: David R. Kessler Award for LGBTQ Studies, CLAGS: The Center for LGBTQ Studies[55] 2000: Leather Archives and Museum "Centurion"[27] 2000: National Leather Association Lifetime Achievement Award[56] 1992: Pantheon of Leather Forebear Award[57] 1988: National Leather Association Jan Lyon Award for Regional or Local Work[58] Unknown date: Induction into the Society of Janus Hall of Fame[59] |

受賞歴と栄誉 2019年:全米性的自由連合よりレース・バノン擁護賞[52] 2017年:サンフランシスコ・サウス・オブ・マーケット地区のレザー歴史路地は、リングオールド路地に沿って設置された4つの芸術作品で構成され、レ ザーサブカルチャーを称えるものである。2017年に開設された。[29][30] 芸術作品の一つは、ルビンの叙述文などが刻まれた黒い花崗岩の石である。[30][31][32] ルビンは、芸術作品のデザイン開発に助言したコミュニティ諮問グループの重要なメンバーであった。[30] 2012年:著書『Deviations: A Gayle Rubin Reader』が全米レザー協会より2012年度ジェフ・メインズノンフィクション書籍賞を受賞した。[53] 2012年:ルース・ベネディクト賞[54] 2003年:LGBTQ研究分野におけるデイヴィッド・R・ケスラー賞(CLAGS:LGBTQ研究センター)[55] 2000年:レザー・アーカイブズ・アンド・ミュージアム「センチュリオン」賞[27] 2000年:全米レザー協会生涯功労賞[56] 1992年:レザー先駆者殿堂賞[57] 1988年:全米レザー協会地域貢献賞(ジャン・ライオン賞)[58] 不明:ジャナス協会殿堂入り[59] |

| Writings Deviations: A Gayle Rubin Reader (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012). "Samois", in Marc Stein, ed., Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender History in America (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2003). (PDF download.) "Studying Sexual Subcultures: the Ethnography of Gay Communities in Urban North America", in Ellen Lewin and William Leap, eds., Out in Theory: The Emergence of Lesbian and Gay Anthropology. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002) "Old Guard, New Guard", in Cuir Underground, Issue 4.2, Summer 1998. (Online text.) "Sites, Settlements, and Urban Sex: Archaeology And The Study of Gay Leathermen in San Francisco 1955–1995", in Robert Schmidt and Barbara Voss, eds., Archaeologies of Sexuality (London: Routledge, 2000). "The Miracle Mile: South of Market and Gay Male Leather in San Francisco 1962–1996", in James Brook, Chris Carlsson, and Nancy Peters, eds., Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, Culture (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1998). "From the Past: The Outcasts" from the newsletter of Leather Archives & Museum No. 4, April 1998. "Music from a Bygone Era", in Cuir Underground, Issue 3.4, May 1997. (Online text.) "Elegy for the Valley of the Kings: AIDS and the Leather Community in San Francisco, 1981–1996", in Martin P. Levine, Peter M. Nardi, and John H. Gagnon, eds. In Changing Times: Gay Men and Lesbians Encounter HIV/AIDS (University of Chicago Press, 1997). Rubin, Gayle (1997), "The traffic in women : notes on the "political economy" of sex", in Nicholson, Linda (ed.), The second wave: a reader in feminist theory, New York: Routledge, pp. 27–62, ISBN 9780415917612. The valley of kings: Leathermen in San Francisco, 1960–1990. University of Michigan, 1994. (Doctoral dissertation.) "Of catamites and kings: Reflections on butch, gender, and boundaries", in Joan Nestle (Ed). The Persistent Desire. A Femme-Butch-Reader. Boston: Alyson. 466 (1992). Misguided, Dangerous and Wrong: An Analysis of Anti-Pornography Politics, 1992. (PDF download) "The Catacombs: A temple of the butthole", in Mark Thompson, ed., Leatherfolk — Radical Sex, People, Politics, and Practice, Boston, Alyson Publications, 1991, ISBN 1555831877, pp. 119–141, reprinted in Deviations. A Gayle Rubin Reader, Duke University Press, 2011, ISBN 0822349868, pp. 224–240, pdf, retrieved September 30, 2014. "Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality, in Carole Vance, ed., Pleasure and Danger (Routledge & Kegan, Paul, 1984. Also reprinted in many other collections, including Abelove, H.; Barale, M. A.; Halperin, D. M.), The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader (New York: Routledge, 1994). "The Leather Menace", Body Politic no. 82 (33–35), April 1982. "Sexual Politics, the New Right, and the Sexual Fringe" in The Age Taboo, Alyson, 1981, pp. 108–115. "The Traffic in Women: Notes on the 'Political Economy' of Sex", in Rayna Reiter, ed., Toward an Anthropology of Women, New York, Monthly Review Press (1975); also reprinted in Second Wave: A Feminist Reader and many other collections. (PDF download.) |

著作 『逸脱:ゲイル・ルービン・リーダー』(ノースカロライナ州ダーラム、デューク大学出版、2012年)。 「サモア」、『アメリカにおけるレズビアン、ゲイ、バイセクシュアル、トランスジェンダーの歴史事典』マーク・スタイン編(ニューヨーク、チャールズ・スクリブナーズ・サンズ、2003年)。(PDFダウンロード) 「性的サブカルチャーの研究:北米都市部のゲイコミュニティの民族誌」エレン・ルーウィン、ウィリアム・リープ編『理論におけるアウト:レズビアンおよびゲイ人類学の出現』(アーバナ:イリノイ大学出版、2002年) 「オールドガード、ニューガード」『Cuir Underground』第4.2号、1998年夏(オンラインテキスト) 「場所、居住地、そして都市のセックス:1955年から1995年にかけてのサンフランシスコにおけるゲイのレザーマンに関する考古学と研究」、『セクシュアリティの考古学』(ロバート・シュミット、バーバラ・ヴォス編、ロンドン:ラウトリッジ、2000年)所収。 「ミラクルマイル:1962年から1996年のサンフランシスコ、サウス・オブ・マーケットとゲイの男性用レザー」、『サンフランシスコの奪還:歴史、政 治、文化』(ジェームズ・ブルック、クリス・カールソン、ナンシー・ピーターズ編、サンフランシスコ:シティ・ライツ・ブックス、1998年)。 「過去から:追放者たち」『レザー・アーカイブズ&ミュージアム』ニュースレター第 4 号、1998 年 4 月。 「過ぎ去った時代の音楽」『Cuir Underground』第 3.4 号、1997 年 5 月。(オンラインテキスト) 「王家の谷への哀歌:1981年から1996年のサンフランシスコにおけるエイズとレザーコミュニティ」マーティン・P・レバイン、ピーター・M・ナル ディ、ジョン・H・ギャグノン編『変わりゆく時代:ゲイとレズビアンがHIV/エイズと出会う』(シカゴ大学出版局、1997年)所収。 ルービン、ゲイル(1997)、「女性の取引:セックスの『政治経済学』に関する注記」、ニコルソン、リンダ(編)、『第二の波:フェミニスト理論の読本』、ニューヨーク:ラウトリッジ、27-62 ページ、ISBN 9780415917612。 『王たちの谷:サンフランシスコのレザーメン、1960-1990年』ミシガン大学、1994年。(博士論文) 「娼夫と王たちについて:ブッチ、ジェンダー、境界に関する考察」ジョーン・ネストル編『持続する欲望:ファム・ブッチ・リーダー』ボストン:アリソン、466頁(1992年) 誤った、危険で間違った:反ポルノグラフィー政治の分析、1992年。(PDFダウンロード) 「カタコンベ:肛門の聖堂」マーク・トンプソン編『レザーフォーク―急進的性、人々、政治、実践』ボストン、アリソン出版、1991年、 ISBN 1555831877、119-141 ページ、Deviations. A Gayle Rubin Reader(デューク大学出版、2011 年、ISBN 0822349868、224-240 ページ)に再掲載、pdf、2014 年 9 月 30 日取得。 「セックスを考える:セクシュアリティの政治に関する急進的な理論のためのノート」、キャロル・ヴァンス編、『快楽と危険』(Routledge & Kegan, Paul、1984年)。また、Abelove, H.; Barale, M. A.; ハルペリン、D. M. 編『レズビアンとゲイ研究リーダー』(ニューヨーク:ラウトレッジ、1994年)。 「革の脅威」、『ボディ・ポリティック』第82号(33-35)、1982年4月。 「性的政治、新右翼、そして性的フリンジ」、『年齢のタブー』、アリソン、1981年、 pp. 108–115. 「女性の取引:『性の政治経済学』に関する覚書」レイナ・ライター編『女性人類学へ向けて』ニューヨーク、月刊レビュー出版社(1975年)所収。また『セカンド・ウェーブ:フェミニスト・リーダー』及びその他多数のアンソロジーに再録。(PDFダウンロード可) |

| Feminist anthropology Feminist sex wars Feminist sexology |

フェミニスト人類学 フェミニストの性戦争 フェミニスト性科学 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gayle_Rubin |

|

| The

Traffic in Women: Notes on the "Political Economy" of Sex is an article

regarding theories of the oppression of women originally published in

1975 by feminist anthropologist Gayle Rubin.[1] In the article, Rubin

argued against the Marxist conceptions of women's

oppression—specifically the concept of "patriarchy"—in favor of her own

concept of the "sex/gender" system.[2][3] It was by arguing that

women's oppression could not be explained by capitalism alone as well

as being an early article to stress the distinction between biological

sex and gender that Rubin's work helped to develop women's and gender

studies as independent fields.[4] The framework of the article was also

important in that it opened up the possibility of researching the

change in meaning of this categories over historical time.[5] Rubin

used a combination of kinship theories from Lévi-Strauss,

psycho-analytic theory from Freud, and critiques of structuralism by

Lacan to make her case that it was at moments where women were

exchanged (principally through marriage acts) that bodies were

engendered and became women. Rubin's article has been

republished numerous times since its debut in 1975, and it has remained

a key piece of feminist anthropological theory and a foundational work

in gender studies.[6][7] |

『女

性の売買(あるいは交通):

セックスの「政治経済」に関するノート』は、フェミニスト人類学者ゲイル・ルービンが1975年に発表した女性抑圧論に関する論文である。この論文でルー

ビンは、女性の抑圧に関するマルクス主義的概念、特に「家父長制」の概念に反対し、彼女自身の「セックス/ジェンダー」システムの概念を支持している。女

性の抑圧は資本主義だけでは説明できないと主張し、また生物学的なセックスとジェンダーの区別を強調した初期の論文であったことで、ルービンの研究は女性

学とジェンダー研究を独立した分野として発展させる一助となった。この論文の枠組みは、歴史的な時間の経過によるこのカテゴリーの意味の変化を研究する可

能性を開いたという点でも重要であった。ルービンは、レヴィ=ストロースによる親族関係理論、フロイトによる精神分析理論、そしてラカンによる構造主義批判を組み合わせて、女性が交換される瞬間(主に結婚行為を通じて)に身体が生成され、女性となるのだと主張した。ルービンの論文は1975年の発表以来、何度も再刊され、フェミニズム人類学理論の重要な部分であり、ジェンダー研究の基礎となる著作であり続けている。 |

| Origins and Publication Rubin began work on the article when she was an undergraduate at the University of Michigan, based on her wide readings in social science and humanities theory under her advisor Marshall Sahlins.[8][9] At the time, Rubin wished to be a Women's Studies major, but no such program existed. Rubin therefore declared one as an independent field and became the first Women's Studies graduate from the university in 1972.[10] At the university, Rubin took part in reading groups organized by members of the New Left, and she was enmeshed in Marxist theory and critiques.[11] She became a reader of publications like the New Left Review, which exposed her also to the critiques and analyses of Marxism by Lacan and Althusser that informed her writing.[10] She was struck at the time in by how Marxists failed to adequately explain the roots of female oppression in the global world, and how it was also subsumed as a problem for analysis by Marxists for the problems of capitalism more generally.[10] Encouraged by Sahlins, it was also during this time that she first read Claude Lévi-Strauss' book The Elementary Structures of Kinship. As Rubin would say in a later interview with Judith Butler: "It [Lévi-Strauss] completely blew my mind."[10] In addition, Rubin was then reading the newly emergent strands of post-structuralist theory from French intellectuals.[10] The paper arose from several drafts of a term paper for a course she was taking with Sahlins. Parts of this term paper were reworked by Rubin to become a section of her undergraduate thesis, and it was this section that Rayna Reiter later excised and published in 1975 in the feminist anthology Toward an Anthropology of Women.[10] Though the article was also published in a lesser known feminist studies journal at around the same time, it was from the anthology by Reiter that it gained a wide audience.[10] |

起源と出版 ルービンはミシガン大学の学部生であったとき、指導教官であったマーシャル・サーリンズのもとで社会科学と人文科学の理論を幅広く読んだことをもとに、こ の論文の執筆を始めた[8][9]。当時、ルービンは女性学を専攻することを希望していたが、そのようなプログラムは存在しなかった。ルービンは大学で、 新左翼のメンバーによって組織された読書会に参加し、マルクス主義の理論と批評にのめり込んでいった[11]。 [彼女は当時、マルクス主義者がいかにグローバル世界における女性抑圧の根源を適切に説明できなかったか、またそれがいかにマルクス主義者によってより一 般的な資本主義の問題を分析するための問題として包摂されていたかに衝撃を受けた。ルービンは後にジュディス・バトラーとのインタヴューで「それ(レヴィ =ストロース)は私の心を完全に揺さぶった」と語っている[10]。さらにルービンは当時、フランスの知識人から新たに生まれたポスト構造主義理論の流れ を読んでいた[10]。 この論文は、彼女がサーリンズとともに受講していたコースのタームペーパーのいくつかの草稿から生まれた。このターム・ペーパーの一部はルービンによって 手直しされ、彼女の学士論文の一部となり、後にレイナ・ライターがこの部分を抜粋し、1975年にフェミニスト・アンソロジー『女性の人類学に向けて』に 発表した[10]。この論文は同時期にあまり知られていないフェミニスト研究誌にも発表されたが、幅広い読者を獲得したのはライターのアンソロジーからで あった[10]。 |

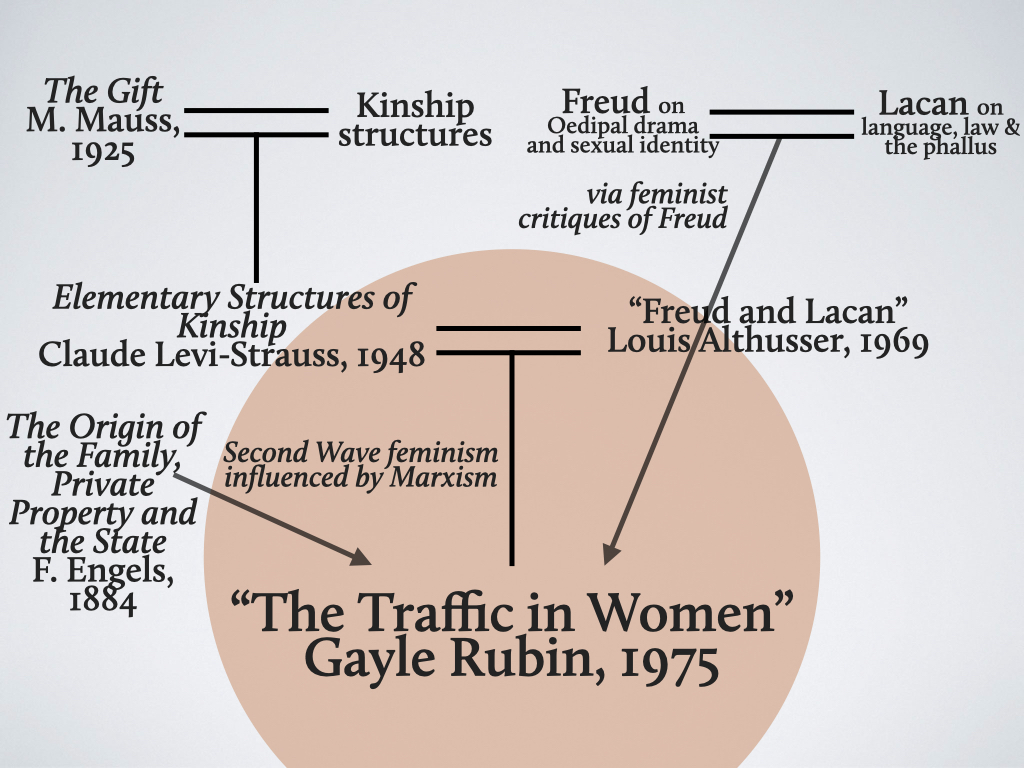

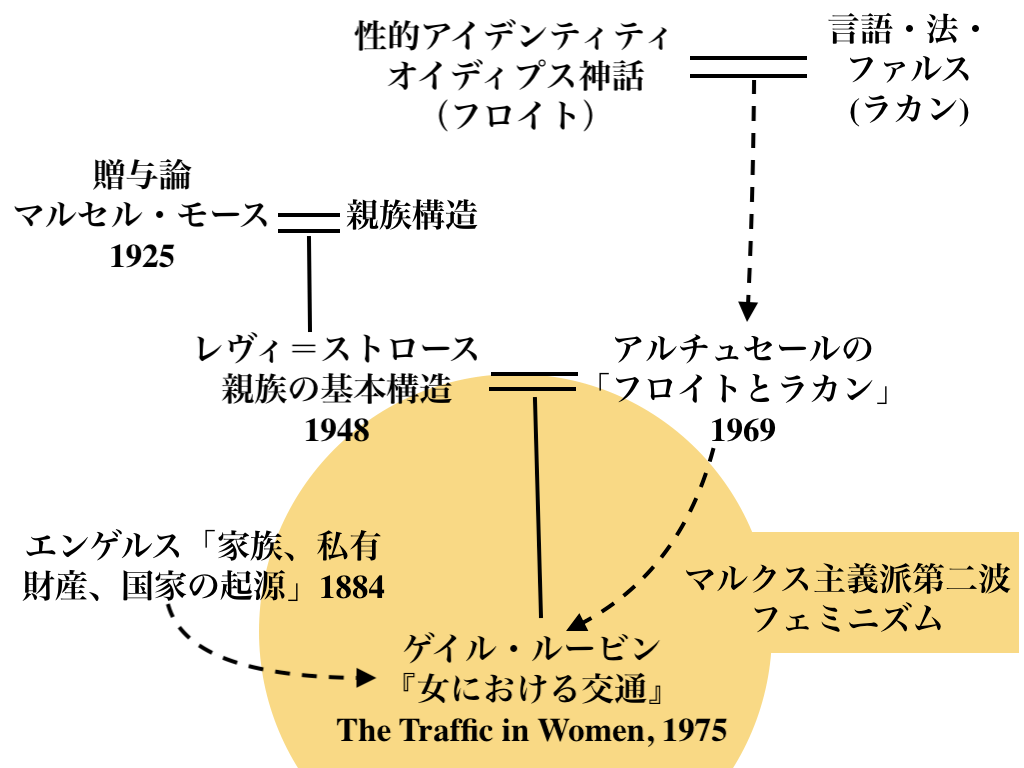

Summary A kinship diagram of theoretical influences on Gayle Rubin's landmark article "The Traffic in Women" Rubin's article is about fully understanding and accounting for the generalized oppression of women in the world—in both industrial capitalist and other kinds of societies. Rubin refers to this part of the social as the "sex/gender system." In making this analysis, she combines elements of various theoretical frameworks. She first attacks Marxism, arguing that it is unable to "fully express or conceptualize sex oppression."[12] Marx offers a very useful account of women's role only in the industrial capitalist context. Men work for wage labor jobs—their surplus value being converted into profits for the ruling class or bourgeoisie—while women work at home to sustain and reproduce this labor. The problem with this analysis lies not in explaining the usefulness of this kind of reproductive labor to capitalism, as this is very apparent to Rubin. Rather, as Rubin puts it: "But to explain women's usefulness to capitalism is one thing. To argue that this usefulness explains the genesis of the oppression of women is quite another."[13] Classical Marxism therefore fails to explain why it is the women should be so oppressed merely because they perform this reproductive labor. Just as it cannot account for the oppression of women within capitalist societies, Marxism also cannot explain why it exists outside of them. Rubin provides several examples, such as in the New Guinea highlands and in the Amazon river valley, where the oppression of women thrives and yet capitalist conditions are not present. She also points out that the pre-capitalist European world was also not free of women's oppression. Rather than being inherent to it, the oppression of women therefore exists independently of capitalism as a system.[13] Rubin then turns to the work of Friedrich Engels. She uses Engels' method in The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, wherein he argues that women's oppression has been inherited from the social systems prior to capitalism (such as feudal and slave economies). Rubin argues that "We need to pursue the project that Engels abandoned" and recognize that women's oppression is tied to the means of production in all social forms, not just capitalism. As a method of studying this oppression in all social forms, Rubin examines kinship structures as they were theorized in The Elementary Structures of Kinship by Claude Lévi-Strauss. In particular, Rubin focuses on 1) the "gift exchange" of women and 2) Strauss' idea of incest as the ultimate human taboo. For Strauss, the marriage of women (in pre-capitalist forms of society) was always a form of gift exchange. The incest taboo functioned to promote these exchanges of women between families. By forbidding certain kinds of marriage between kin, it ensured that other forms of marriage would take place. Strauss showed that men were principally in control of the exchange and reception of women, or a kind of kinship exchange, rather than simply a gift exchange based on principles of reciprocity (as Marcel Mauss argued in his essay, The Gift). Rubin considers this "exchange of women" to be an "initial step toward building an arsenal of concepts with which sexual systems can be described."[14] Rather than describing it merely in kinship terms as Strauss did, Rubin wants to also highlight the economic implications of this exchange. She holds that the Lévi-Straussian anthropological analysis based on terms of kinship cannot explain how gender arises and is connected to certain human bodies. This is because the incest taboo is not so universal as Strauss would have us think. There are certain groups of people where incest is normal and "such a marital future is taken for granted."[15] Therefore, it cannot be the universal basis for why gender exists and why certain rights are reserved solely for men. Rubin investigates the incest taboo further by bringing in the Oedipus Complex theory of Sigmund Freud. Rubin focuses on how Freudian theories of sexual repression (wherein young girls repress their sexual desires for their mothers) lead to a world where "language and...cultural meanings" are "imposed upon anatomy."[16] Drawing upon Lacan's analysis of the symbolic exchange of the phallus, Rubin complicates Freud's Oedipal analysis. Rubin stresses the point that girls and women cannot give the phallus—they can only receive it "but only as a gift from a man."[17] It is ultimately only by coming to terms with this lack of the ability to give the phallus that girls/women recognize themselves as such. In other words, they are to be exchanged and "trafficked," and this is the idea that defines their gender identity as it relates to their sexual, bodily or biological being. In her conclusion, Rubin argues for a feminist analysis of the problem of the sex/gender system. She argues that it is only by seeing the system in total—in its symbolic, cultural, and economic implications—can we ask the appropriate questions of it: "there are other questions to ask of a marriage system than whether or not it exchanges women."[18] Rubin calls for new research on the sex/gender system in different contexts, arguing that scholars should ask for what purpose this exchange transpires in different societies. |

概要 ゲイル・ルービンの画期的な論文 「The Traffic in Women 」に影響を与えた理論的な系譜図である。 ルービンの論文は、産業資本主義社会と他の種類の社会の両方において、世界における女性への一般化された抑圧を完全に理解し、説明することを目的としてい る。ルービンは社会のこの部分を 「性/ジェンダー・システム 」と呼んでいる。この分析を行うにあたり、彼女は様々な理論的枠組みの要素を組み合わせている。 彼女はまずマルクス主義を攻撃し、マルクス主義は「性の抑圧を完全に表現することも概念化することもできない」と主張する。男性は賃金労働に従事し、その 剰余価値は支配階級またはブルジョアジーの利益に転換される。一方、女性はこの労働を維持し再生産するために家庭で働く。この分析の問題点は、この種の再 生産労働が資本主義にとって有用であることを説明することにあるのではない。むしろ、ルービンはこう言う: 「しかし、資本主義にとっての女性の有用性を説明することは一つのことである。それゆえ、古典的マルクス主義は、なぜ女性がこのような生殖労働を行うとい うだけで、これほどまでに抑圧されなければならないのかを説明することができない。 資本主義社会における女性の抑圧を説明できないように、マルクス主義もまた、資本主義社会の外になぜそれが存在するのかを説明できない。ルービンは、 ニューギニア高地やアマゾン川流域など、女性の抑圧が盛んでありながら資本主義的条件が存在しないいくつかの例を示している。彼女はまた、資本主義以前の ヨーロッパ世界にも女性の抑圧がなかったわけではないと指摘する。それゆえ、女性の抑圧は資本主義に内在しているというよりも、システムとして資本主義と は無関係に存在しているのである[13]。 ルービンは次にフリードリヒ・エンゲルスの著作に目を向ける。彼女はエンゲルスの『家族・私有財産・国家の起源』の手法を用い、女性の抑圧は資本主義以前 の社会システム(封建経済や奴隷経済など)から受け継がれてきたものだと主張する。ルービンは、「エンゲルスが放棄したプロジェクトを追求する必要があ る」と主張し、女性の抑圧が資本主義だけでなく、あらゆる社会形態における生産手段と結びついていることを認識している。 あらゆる社会形態におけるこの抑圧を研究する方法として、ルービンはクロード・レヴィ=ストロースの『親族関係の初歩的構造』で理論化された親族関係を検 証する。特にルービンは、1)女性の「贈与交換」と、2)人間の究極のタブーとしての近親相姦というシュトラウスの考えに焦点を当てている。シュトラウス にとって、(資本主義以前の社会形態における)女性の結婚は常に贈与交換の一形態であった。近親相姦のタブーは、このような家族間の女性の交換を促進する ために機能した。親族間のある種の結婚を禁じることで、他の形の結婚が行われるようにしたのである。マルセル・モースがそのエッセイ『贈与』で主張したよ うに)単に互酬性の原則に基づく贈与交換ではなく、女性の交換と受容、すなわち一種の親族交換を支配していたのは主として男性であったことを、シュトラウ スは示したのである。ルービンはこの「女性の交換」を「性的システムを記述できる概念の武器庫を構築するための最初の一歩」であると考えている[14]。 ストロースのように単に親族関係の用語で説明するのではなく、ルービンはこの交換の経済的意味合いも強調したいと考えている。彼女は、親族関係の用語に基 づくレヴィ=シュトラウス的人類学的分析では、ジェンダーがどのように発生し、特定の人間の身体と結びついているのかを説明できないと主張する。というの も、近親相姦のタブーはシュトラウスが考えさせるほど普遍的ではないからだ。近親相姦が普通であり、「そのような夫婦の未来が当然とされている」[15] ようなある種の集団が存在するのだから、ジェンダーが存在する理由や、ある権利が男性だけに留保されている理由の普遍的な根拠にはなりえない。 ルービンは、ジークムント・フロイトのエディプス・コンプレックス理論を持ち込むことで、近親相姦のタブーをさらに調査している。ルービンは、フロイトの 性的抑圧理論(幼い少女が母親への性的欲望を抑圧する)が、「言語と...文化的意味」が「解剖学に押し付けられる」世界をどのように導くかに焦点を当て ている。ルービンは、少女や女性はファルスを与えることができないという点を強調している-彼女たちは「男性からの贈り物としてのみ」ファルスを受け取る ことができるのである[17]。少女/女性が自分自身をそのようなものとして認識するのは、結局のところ、ファルスを与える能力の欠如と折り合いをつける ことによってのみなのである。言い換えれば、彼女たちは交換され、「人身売買」されるのであり、これこそが、性的、身体的、あるいは生物学的存在に関連す る彼女たちのジェンダー・アイデンティティを定義する考え方なのである。 結論としてルービンは、セックス/ジェンダー・システムの問題に対するフェミニズム的分析を主張する。その象徴的、文化的、経済的な意味合いにおいて、こ のシステムを総合的に見ることによってのみ、私たちはこのシステムに適切な問いを投げかけることができる、と彼女は主張する: 「ルービンは、異なる文脈における性/ジェンダー・システムに関する新たな研究を求め、学者たちはこの交換が異なる社会でどのような目的で行われているの かを問うべきだと主張している。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆