ジョージ・エドワード・ムーア

George Edward Moore, 1873-1958

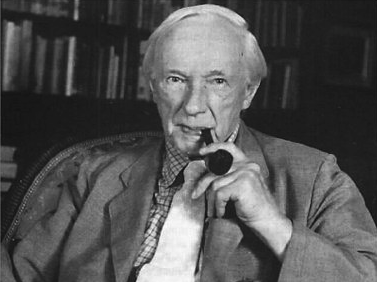

☆ ジョージ・エドワード・ムーア(George Edward Moore OM FBA、1873年11月4日 - 1958年10月24日)はイギリスの哲学者で、バートランド・ラッセル、ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン、それ以前のゴットローブ・フレーゲととも に分析哲学の創始者の一人である。ラッセルとともに、当時イギリスの哲学者の間で流行していた観念論を軽視し始め、常識的な概念を提唱して倫理学、認識 論、形而上学に貢献したことで知られるようになった。彼は「類まれな人格と道徳的性格」を持っていたと言われている[6]。後にレイ・モンクは彼を「同時 代で最も尊敬された哲学者」と呼んだ[7]。 ケンブリッジ大学の哲学教授として、知識人の非公式グループであるブルームズベリー・グループに影響を与えたが、棄権した。雑誌『マインド』を編集した。 1894年から1901年までケンブリッジの使徒のメンバーであり[8]、1918年からは英国アカデミーのフェローであり、1912年から1944年ま でケンブリッジ大学道徳科学クラブの会長であった[9][10]。ヒューマニストとして、1935年から1936年まで英国倫理同盟(現在のヒューマニス トUK)を主宰した[11]。

| George Edward Moore

OM FBA (4 November 1873 – 24 October 1958) was an English philosopher,

who with Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein and earlier Gottlob

Frege was among the initiators of analytic philosophy. He and Russell

began deemphasizing the idealism which was then prevalent among British

philosophers and became known for advocating common-sense concepts and

contributing to ethics, epistemology and metaphysics. He was said to

have an "exceptional personality and moral character".[6] Ray Monk

later dubbed him "the most revered philosopher of his era".[7] As Professor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge, he influenced but abstained from the Bloomsbury Group, an informal set of intellectuals. He edited the journal Mind. He was a member of the Cambridge Apostles from 1894 to 1901,[8] a fellow of the British Academy from 1918, and was chairman of the Cambridge University Moral Sciences Club in 1912–1944.[9][10] As a humanist, he presided over the British Ethical Union (now Humanists UK) in 1935–1936.[11] |

ジョージ・エドワード・ムーア(George Edward

Moore OM FBA、1873年11月4日 -

1958年10月24日)はイギリスの哲学者で、バートランド・ラッセル、ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン、それ以前のゴットローブ・フレーゲととも

に分析哲学の創始者の一人である。ラッセルとともに、当時イギリスの哲学者の間で流行していた観念論を軽視し始め、常識的な概念を提唱して倫理学、認識

論、形而上学に貢献したことで知られるようになった。彼は「類まれな人格と道徳的性格」を持っていたと言われている[6]。後にレイ・モンクは彼を「同時

代で最も尊敬された哲学者」と呼んだ[7]。 ケンブリッジ大学の哲学教授として、知識人の非公式グループであるブルームズベリー・グループに影響を与えたが、棄権した。雑誌『マインド』を編集した。 1894年から1901年までケンブリッジの使徒のメンバーであり[8]、1918年からは英国アカデミーのフェローであり、1912年から1944年ま でケンブリッジ大学道徳科学クラブの会長であった[9][10]。ヒューマニストとして、1935年から1936年まで英国倫理同盟(現在のヒューマニス トUK)を主宰した[11]。 |

| Life George Edward Moore was born in Upper Norwood, in south-east London, on 4 November 1873, the middle child of seven of Daniel Moore, a medical doctor, and Henrietta Sturge.[12][13][14] His grandfather was the author George Moore. His eldest brother was Thomas Sturge Moore, a poet, writer and engraver.[12][15][16] He was educated at Dulwich College[17] and, in 1892, began attending Trinity College, Cambridge, to learn classics and moral sciences.[18] He became a Fellow of Trinity in 1898 and was later University of Cambridge Professor of Mental Philosophy and Logic from 1925 to 1939. Moore is known best now for defending ethical non-naturalism, his emphasis on common sense for philosophical method, and the paradox that bears his name. He was admired by and influenced other philosophers and some of the Bloomsbury Group. But unlike his colleague and admirer Bertrand Russell, who for some years thought Moore fulfilled his "ideal of genius",[19] he is mostly unknown presently except among academic philosophers. Moore's essays are known for their clarity and circumspection of writing style and methodical and patient treatment of philosophical problems. He was critical of modern philosophy for lack of progress, which he saw as a stark contrast to the dramatic advances in the natural sciences since the Renaissance. Among Moore's most famous works are his Principia Ethica,[20] and his essays, "The Refutation of Idealism", "A Defence of Common Sense", and "A Proof of the External World". Moore was an important and admired member of the secretive Cambridge Apostles, a discussion group drawn from the British intellectual elite. At the time another member, 22-year-old Bertrand Russell, wrote "I almost worship him as if he were a god. I have never felt such an extravagant admiration for anybody",[7] and would later write that "for some years he fulfilled my ideal of genius. He was in those days beautiful and slim, with a look almost of inspiration as deeply passionate as Spinoza's".[21] From 1918 to 1919, Moore was chairman of the Aristotelian Society, a group committed to systematic study of philosophy, its historical development and its methods and problems.[22] He was appointed to the Order of Merit in 1951.[23] Moore died in England in the Evelyn Nursing Home on 24 October 1958.[24] He was cremated at Cambridge Crematorium on 28 October 1958 and his ashes interred at the Parish of the Ascension Burial Ground in the city. His wife, Dorothy Ely (1892–1977), was buried there. Together, they had two sons, the poet Nicholas Moore and the composer Timothy Moore.[25][26] |

生涯 ジョージ・エドワード・ムーアは1873年11月4日、ロンドン南東部のアッパー・ノーウッドで、医師ダニエル・ムーアとヘンリエッタ・スタージの7人兄 弟の真ん中として生まれた[12][13][14]。 祖父は作家のジョージ・ムーア。長兄は詩人、作家、彫刻家のトーマス・スタージ・ムーアである[12][15][16]。 1898年にトリニティ・カレッジのフェローとなり、その後1925年から1939年までケンブリッジ大学の精神哲学・論理学の教授を務めた。 ムーアは現在、倫理的非自然主義の擁護、哲学的方法における常識の重視、そして彼の名を冠したパラドックスでよく知られている。彼は他の哲学者やブルーム ズベリー・グループの何人かに賞賛され、影響を与えた。しかし、彼の同僚であり崇拝者であったバートランド・ラッセルが、ムーアは「天才の理想」を満たし ていると数年間考えていたのとは異なり[19]、現在ではアカデミックな哲学者の間以外ではほとんど知られていない。ムーアのエッセイは、その明晰で控え めな文体と、哲学的問題の理路整然とした忍耐強い扱いによって知られている。ルネサンス以降の自然科学の飛躍的な進歩とは対照的で、進歩のない近代哲学を 批判した。ムーアの最も有名な著作に、『プリンキピア・エチカ』[20]、エッセイ『観念論の反駁』、『常識の擁護』、『外界の証明』がある。 ムーアは、イギリスの知的エリートから選ばれた秘密の討論グループ「ケンブリッジの使徒たち」の重要なメンバーであり、賞賛されていた。当時、もう一人の メンバーであった22歳のバートランド・ラッセルは、「私はほとんど彼を神のように崇拝している。これほど贅沢な憧れを誰かに抱いたことはない」[7]と 書き、後に「何年かの間、彼は私の理想とする天才像を満たしてくれた。当時の彼は美しくスリムで、スピノザと同じように深く情熱的で、ほとんど霊感のよう な表情をしていた」[21]。 1918年から1919年まで、ムーアはアリストテレス協会の会長であった。アリストテレス協会は哲学の体系的な研究、その歴史的発展、その方法と問題に 取り組んでいるグループであった[22]。 1958年10月28日にケンブリッジ火葬場で荼毘に付され、遺灰はケンブリッジのアセンション教区墓地に埋葬された[24]。妻のドロシー・エリー (1892-1977)もそこに埋葬された。ふたりの間には、詩人のニコラス・ムーアと作曲家のティモシー・ムーアというふたりの息子がいた[25] [26]。 |

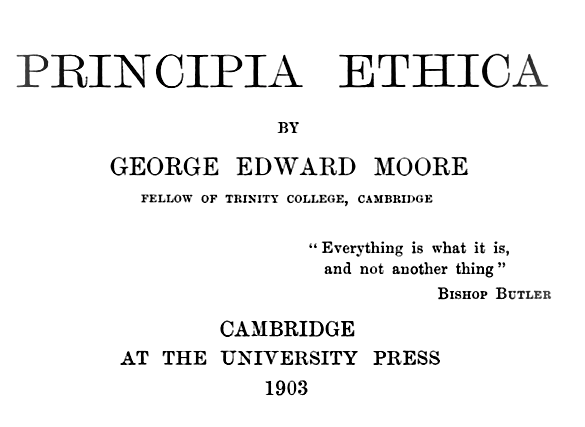

| Philosophy Ethics  The title page of Principia Ethica. His influential work Principia Ethica is one of the main inspirations of the reaction against ethical naturalism (see ethical non-naturalism) and is partly responsible for the twentieth-century concern with meta-ethics.[27] The naturalistic fallacy Main article: Naturalistic fallacy Moore asserted that philosophical arguments can suffer from a confusion between the use of a term in a particular argument and the definition of that term (in all arguments). He named this confusion the naturalistic fallacy. For example, an ethical argument may claim that if an item has certain properties, then that item is 'good.' A hedonist may argue that 'pleasant' items are 'good' items. Other theorists may argue that 'complex' things are 'good' things. Moore contends that, even if such arguments are correct, they do not provide definitions for the term 'good'. The property of 'goodness' cannot be defined. It can only be shown and grasped. Any attempt to define it (X is good if it has property Y) will simply shift the problem (Why is Y-ness good in the first place?). Open-question argument Main article: Open-question argument Moore's argument for the indefinability of 'good' (and thus for the fallaciousness in the "naturalistic fallacy") is often termed the open-question argument; it is presented in §13 of Principia Ethica. The argument concerns the nature of statements such as "Anything that is pleasant is also good" and the possibility of asking questions such as "Is it good that x is pleasant?". According to Moore, these questions are open and these statements are significant; and they will remain so no matter what is substituted for "pleasure". Moore concludes from this that any analysis of value is bound to fail. In other words, if value could be analysed, then such questions and statements would be trivial and obvious. Since they are anything but trivial and obvious, value must be indefinable. Critics of Moore's arguments sometimes claim that he is appealing to general puzzles concerning analysis (cf. the paradox of analysis), rather than revealing anything special about value. The argument clearly depends on the assumption that if 'good' were definable, it would be an analytic truth about 'good', an assumption that many contemporary moral realists like Richard Boyd and Peter Railton reject. Other responses appeal to the Fregean distinction between sense and reference, allowing that value concepts are special and sui generis, but insisting that value properties are nothing but natural properties (this strategy is similar to that taken by non-reductive materialists in philosophy of mind). Good as indefinable Moore contended that goodness cannot be analysed in terms of any other property. In Principia Ethica, he writes: It may be true that all things which are good are also something else, just as it is true that all things which are yellow produce a certain kind of vibration in the light. And it is a fact, that Ethics aims at discovering what are those other properties belonging to all things which are good. But far too many philosophers have thought that when they named those other properties they were actually defining good; that these properties, in fact, were simply not "other," but absolutely and entirely the same with goodness. (Principia, § 10 ¶ 3) Therefore, we cannot define 'good' by explaining it in other words. We can only indicate a thing or an action and say "That is good." Similarly, we cannot describe to a person born totally blind exactly what yellow is. We can only show a sighted person a piece of yellow paper or a yellow scrap of cloth and say "That is yellow." Good as a non-natural property In addition to categorising 'good' as indefinable, Moore also emphasized that it is a non-natural property. This means that it cannot be empirically or scientifically tested or verified—it is not analyzable by "natural science". Moral knowledge Moore argued that, once arguments based on the naturalistic fallacy had been discarded, questions of intrinsic goodness could be settled only by appeal to what he (following Sidgwick) termed "moral intuitions": self-evident propositions which recommend themselves to moral thought, but which are not susceptible to either direct proof or disproof (Principia, § 45). As a result of his opinion, he has often been described by later writers as an advocate of ethical intuitionism. Moore, however, wished to distinguish his opinions from the opinions usually described as "Intuitionist" when Principia Ethica was written: In order to express the fact that ethical propositions of my first class [propositions about what is good as an end in itself] are incapable of proof or disproof, I have sometimes followed Sidgwick's usage in calling them 'Intuitions.' But I beg that it may be noticed that I am not an 'Intuitionist,' in the ordinary sense of the term. Sidgwick himself seems never to have been clearly aware of the immense importance of the difference which distinguishes his Intuitionism from the common doctrine, which has generally been called by that name. The Intuitionist proper is distinguished by maintaining that propositions of my second class—propositions which assert that a certain action is right or a duty—are incapable of proof or disproof by any enquiry into the results of such actions. I, on the contrary, am no less anxious to maintain that propositions of this kind are not 'Intuitions,' than to maintain that propositions of my first class are Intuitions. — G. E. Moore, Principia Ethica, Preface ¶ 5 Moore distinguished his view from the opinion of deontological intuitionists, who claimed that "intuitions" could determine questions about what actions are right or required by duty. Moore, as a consequentialist, argued that "duties" and moral rules could be determined by investigating the effects of particular actions or kinds of actions (Principia, § 89), and so were matters for empirical investigation rather than direct objects of intuition (Principia, § 90). According to Moore, "intuitions" revealed not the rightness or wrongness of specific actions, but only what items were good in themselves, as ends to be pursued. Right action, duty and virtue Moore holds that right actions are those producing the most good.[28] The difficulty with this is that the consequences of most actions are too complex for us to properly take into account, especially the long-term consequences. Because of this, Moore suggests that the definition of duty is limited to what generally produces better results than probable alternatives in a comparatively near future.[29]: §109 Whether a given rule of action is also a duty depends to some extent on the conditions of the corresponding society but duties agree mostly with what common-sense recommends.[29]: §95 Virtues, like honesty, can in turn be defined as permanent dispositions to perform duties.[29]: §109 Proof of an external world Main article: Here is one hand One of the most important parts of Moore's philosophical development was his differing with the idealism that dominated British philosophy (as represented by the works of his former teachers F. H. Bradley and John McTaggart), and his defence of what he regarded as a "common sense" type of realism. In his 1925 essay "A Defence of Common Sense", he argued against idealism and scepticism toward the external world, on the grounds that they could not give reasons to accept that their metaphysical premises were more plausible than the reasons we have for accepting the common sense claims about our knowledge of the world, which sceptics and idealists must deny. He famously put the point into dramatic relief with his 1939 essay "Proof of an External World", in which he gave a common sense argument against scepticism by raising his right hand and saying "Here is one hand" and then raising his left and saying "And here is another", then concluding that there are at least two external objects in the world, and therefore that he knows (by this argument) that an external world exists. Not surprisingly, not everyone preferring sceptical doubts found Moore's method of argument entirely convincing; Moore, however, defends his argument on the grounds that sceptical arguments seem invariably to require an appeal to "philosophical intuitions" that we have considerably less reason to accept than we have for the common sense claims that they supposedly refute. The "Here is one hand" argument also influenced Ludwig Wittgenstein, who spent his last years working out a new method for Moore's argument in the remarks that were published posthumously as On Certainty.) Moore's paradox Moore is also remembered for drawing attention to the peculiar inconsistency involved in uttering a sentence such as "It is raining, but I do not believe it is raining", a puzzle now commonly termed "Moore's paradox". The puzzle is that it seems inconsistent for anyone to assert such a sentence; but there doesn't seem to be any logical contradiction between "It is raining" and "I don't believe that it is raining", because the former is a statement about the weather and the latter a statement about a person's belief about the weather, and it is perfectly logically possible that it may rain whilst a person does not believe that it is raining. In addition to Moore's own work on the paradox, the puzzle also inspired a great deal of work by Ludwig Wittgenstein, who described the paradox as the most impressive philosophical insight that Moore had ever introduced. It is said[by whom?] that when Wittgenstein first heard this paradox one evening (which Moore had earlier stated in a lecture), he rushed round to Moore's lodgings, got him out of bed and insisted that Moore repeat the entire lecture to him. Organic wholes Moore's description of the principle of the organic whole is extremely straightforward, nonetheless, and a variant on a pattern that began with Aristotle: The value of a whole must not be assumed to be the same as the sum of the values of its parts (Principia, § 18). According to Moore, a moral actor cannot survey the 'goodness' inherent in the various parts of a situation, assign a value to each of them, and then generate a sum in order to get an idea of its total value. A moral scenario is a complex assembly of parts, and its total value is often created by the relations between those parts, and not by their individual value. The organic metaphor is thus very appropriate: biological organisms seem to have emergent properties which cannot be found anywhere in their individual parts. For example, a human brain seems to exhibit a capacity for thought when none of its neurons exhibit any such capacity. In the same way, a moral scenario can have a value different than the sum of its component parts. To understand the application of the organic principle to questions of value, it is perhaps best to consider Moore's primary example, that of a consciousness experiencing a beautiful object. To see how the principle works, a thinker engages in "reflective isolation", the act of isolating a given concept in a kind of null-context and determining its intrinsic value. In our example, we can easily see that, of themselves, beautiful objects and consciousnesses are not particularly valuable things. They might have some value, but when we consider the total value of a consciousness experiencing a beautiful object, it seems to exceed the simple sum of these values. Hence the value of a whole must not be assumed to be the same as the sum of the values of its parts. |

哲学 倫理学  『プリンキピア・エシカ』(倫理学原理と邦訳されている)のタイトルページ。 彼の影響力のある著作『プリンキピア・エチカ』は、倫理的自然主義(倫理的非自然主義を参照)に対する反動の主なインスピレーションの一つであり、メタ倫 理学に対する20世紀の関心の一因となっている[27]。 自然主義的誤謬 主な記事 自然主義的誤謬 ムーアは、哲学的議論は、特定の議論における用語の使用と、(すべての議論における)その用語の定義との間の混乱に悩まされることがあると主張した。彼は この混乱を自然主義的誤謬と名付けた。例えば、倫理的な議論では、ある品物がある性質を持つならば、その品物は「善」であると主張することがある。快楽主 義者は、「快い」アイテムは「良い」アイテムであると主張するかもしれない。他の理論家は、「複雑な」ものが「良い」ものであると主張するかもしれない。 ムーアは、そのような主張が正しいとしても、「良い」という用語の定義にはならないと主張する。善』という性質は定義できない。それは示され、把握される だけである。それを定義しようとしても(Xは性質Yを持っていれば善である)、単に問題(そもそもY-nessはなぜ善なのか)をずらすだけである。 公開質問状論法 主な記事 公開質問状論証 ムーアの「善」の定義不可能性(ひいては「自然主義的誤謬」の誤謬性)についての議論は、しばしば公開質問型議論と呼ばれる。この議論は、「快いものはす べて善でもある」というような言明の性質と、「xが快いことは善であるか」というような問いの可能性に関するものである。ムーアによれば、これらの問いは 開かれたものであり、これらの記述は重要である。ムーアはこのことから、価値の分析は失敗に終わると結論づけている。言い換えれば、もし価値が分析できる のであれば、このような質問や発言は些細なことであり、自明なことである。それらは些細で自明なものではないのだから、価値は定義できないものに違いな い。 ムーアの議論を批判する人々は、ムーアは価値について何か特別なことを明らかにしているのではなく、分析に関する一般的なパズル(分析のパラドックスを参 照)に訴えているのだと主張することがある。この議論は明らかに、「善」が定義可能であれば「善」についての分析的真理になるという仮定に依存している が、この仮定はリチャード・ボイドやピーター・レイルトンのような現代の道徳的実在論者の多くが否定している。また、価値概念が特殊で特殊なものであるこ とは認めつつも、価値の性質は自然的な性質にすぎないと主張する(この戦略は、心の哲学における非還元的唯物論者がとる戦略に似ている)。 定義不可能な善 ムーアは、善は他のいかなる特性からも分析できないと主張した。プリンキピア・エチカ』の中で、彼はこう書いている: 黄色であるものはすべて、光にある種の振動を生じさせるということが真実であるように、善であるものはすべて、何か他のものでもあるということが真実であ るかもしれない。そして、倫理学は、善であるすべてのものに属する他の性質が何であるかを発見することを目的としている。しかし、あまりにも多くの哲学者 が、それらの他の性質を名づけるとき、実際に善を定義しているのだと考えてきた。これらの性質は、実際には、単に「他の」ものではなく、善と絶対的かつ完 全に同じものなのだと。(プリンキピア』第10章第3節)。 したがって、他の言葉で説明することによって「善」を定義することはできない。私たちができるのは、物事や行為を示して、"それは善である "と言うことだけである。同様に、生まれつき全盲の人に、黄色とは何かを正確に説明することはできない。目の見える人に、黄色い紙切れや黄色い布切れを見 せて、"それは黄色だ "と言うしかない。 非自然的性質としての善 ムーアは、「善」を定義不可能なものとして分類することに加えて、それが非自然的な性質であることも強調した。つまり、経験的、科学的にテストしたり検証 したりすることができない、「自然科学」では分析できない、ということである。 道徳的知識 ムーアは、自然主義的誤謬に基づく議論が捨て去られた後は、本質的な善の問題は、(シドウィックに倣って)彼が「道徳的直観」と呼ぶもの、すなわち道徳的 思考に自らを推薦するが、直接的な証明も反証もできない自明の命題に訴えることによってのみ解決できると主張した(『プリンキピア』第45章)。彼の意見 の結果、後の作家はしばしば倫理的直観主義の提唱者と評した。しかし、ムーアは、『プリンキピア・エチカ』が書かれた当時、通常「直観主義」と表現されて いた意見と自分の意見を区別したかったのである: 私の第一級の倫理的命題[それ自体として何が善であるかについての命題]は、証明も反証もできないという事実を表現するために、私はシドウィックの用法に 従って、それらを『直観』と呼ぶことがある。しかし、私は普通の意味での「直観主義者」ではないことに注意していただきたい。シドウィック自身は、彼の直 観主義と一般にその名で呼ばれている教義とを区別する違いの重要性を、はっきりと認識していなかったようである。直観主義者は、私の第二分類の命題、すな わちある行為が正しいとか義務であると主張する命題は、そのような行為の結果についてのいかなる調査によっても証明することも反証することもできないと主 張することによって区別される。私は逆に、この種の命題は「直観」ではないと主張することは、私の第一分類の命題が「直観」であると主張することに勝ると も劣らない。 - G・E・ムーア『プリンキピア・エチカ』序文¶5 ムーアは、「直観」によって、どのような行為が正しいか、あるいは義務によって要求されるかについての疑問を決定できると主張する脱自律論的直観主義者の 意見と自分の見解を区別した。ムーアは結果論者として、「義務」や道徳的規則は、特定の行為や行為の種類の影響を調査することによって決定することができ (『プリンキピア』第89条)、したがって、直観の直接的な対象ではなく、経験的調査のための問題であると主張した(『プリンキピア』第90条)。ムーア によれば、「直観」は特定の行為の正しさや不正確さを明らかにするのではなく、追求すべき目的として、どのような項目がそれ自体として善であるかを明らか にするだけであった。 正しい行為、義務、徳 ムーアは、正しい行為とは最も善を生み出す行為であるとする[28]。このことの難しさは、ほとんどの行為の結果が複雑すぎて、特に長期的な結果を適切に 考慮することができないことである。このため、ムーアは義務の定義を、比較的近い将来に起こりうる代替案よりも一般的に良い結果をもたらすものに限定する ことを提案している[29]: §109 ある行動規則が義務であるかどうかは、対応する社会の状況にある程度依存するが、義務は、常識が推奨するものとほとんど一致する[29]: §95 誠実さのような徳は、ひいては義務を遂行するための永続的な気質として定義されうる[29]: §109 外界の証明 主な記事 ここに一つの手がある ムーアの哲学的発展における最も重要な部分の一つは、(彼のかつての教師であったF・H・ブラッドリーやジョン・マクタガートの著作に代表されるような) イギリス哲学を支配していた観念論との対立であり、彼が「常識」的な実在論とみなしたものを擁護したことであった。1925年のエッセイ "A Defence of Common Sense "では、外界に対する観念論や懐疑論に対して、形而上学的な前提が、懐疑論者や観念論者が否定しなければならない、世界についての知識についての常識的な 主張を受け入れる理由よりももっともらしいと受け入れる理由を与えることができないという理由で反論した。彼は1939年のエッセイ『外界の証明』で、こ の点をドラマチックに浮き彫りにした。このエッセイでは、懐疑論に対する常識的な反論として、右手を挙げて「ここに一つの手がある」と言い、左手を挙げて 「そしてここにもう一つの手がある」と言う。しかしムーアは、懐疑的な議論には必ず「哲学的直観」に訴える必要があるように思われるが、その理由は、懐疑 的な議論が反駁するとされる常識的な主張に対して私たちが抱く理由よりも、私たちが受け入れる理由の方がかなり少ないからである。ここに片手がある」論法 はルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインにも影響を与え、彼は晩年、『確実性について』として死後に出版された論考の中で、ムーアの論法に対する新たな方法 を模索していた)。 ムーアのパラドックス ムーアは、「雨が降っているが、私は雨が降っているとは思わない」というような文章を口にする際に生じる独特の矛盾に注目したことでも知られている。しか し、「雨が降っている」と「雨が降っているとは思わない」の間には論理的矛盾はないように思われる。前者は天気に関する記述であり、後者は天気に関する人 の信念に関する記述である。 ムーア自身のパラドックスに関する研究に加え、このパズルはルートヴィヒ・ヴィトゲンシュタインにも多大なインスピレーションを与え、ヴィトゲンシュタイ ンはこのパラドックスをムーアが紹介した中で最も印象的な哲学的洞察であると評した。ある晩、ウィトゲンシュタインがこのパラドックス(ムーアが以前に講 義で述べたもの)を初めて耳にしたとき、彼はムーアの下宿に駆けつけ、彼をベッドから叩き起こし、ムーアに講義の全文を繰り返し聞かせたと言われている。 有機ホール 有機的全体の原理に関するムーアの説明は、アリストテレスから始まったパターンを変形したもので、極めて単純なものである: 全体の価値は、その部分の価値の合計と同じであると仮定してはならない(『プリンキピア』第18章)。 ムーアによれば、道徳的行為者は、ある状況のさまざまな部分に内在する「善」を調査し、それぞれに価値を割り当て、その合計の価値を知るために合計を出す ことはできない。道徳的なシナリオは複雑な部分の集合体であり、その総合的な価値は、個々の価値によってではなく、それらの部分間の関係によって生み出さ れることが多い。生物は、個々の部分には見いだせない創発的な特性を持っているように見える。例えば、人間の脳は、どのニューロンもそのような能力を示さ ないのに、思考能力を示しているように見える。同じように、道徳的なシナリオは、その構成要素の総和とは異なる価値を持つことができる。 価値の問題への有機的原理の適用を理解するためには、ムーアの主要な例である、美しい物体を体験する意識の例を考えるのがおそらく最善であろう。この原理 がどのように働くかを知るために、思想家は「反省的孤立」、つまりある概念をある種の空文脈の中に孤立させ、その本質的価値を決定する行為に取り組む。こ の例では、それ自体としては、美しい物や意識は特に価値のあるものではないことが容易にわかる。それらは何らかの価値を持つかもしれないが、美しい物体を 経験する意識の価値を総合的に考えると、それはこれらの価値の単純な合計を超えるように思われる。したがって、全体の価値は部分の価値の合計と同じである と仮定してはならない。 |

Works The gravestone of G. E. Moore and his wife Dorothy Moore in the Ascension Parish Burial Ground, Cambridge. G. E. Moore, "The Nature of Judgment" (1899) G. E. Moore (1903). "IV.—Experience and Empiricism". Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 3: 80–95. doi:10.1093/aristotelian/3.1.80. G. E. Moore, Principia Ethica (1903) G. E. Moore, "Review of Franz Brentano's The Origin of the Knowledge of Right and Wrong" (1903) G. E. Moore, "The Refutation of Idealism" (1903) G. E. Moore (1904). "VII.—Kant's Idealism". Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 4: 127–140. doi:10.1093/aristotelian/4.1.127. G. E. Moore, "The Nature and Reality of the Objects of Perception" (1905–6) G. E. Moore (1908). "III.—Professor James' "Pragmatism"". Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 8: 33–77. doi:10.1093/aristotelian/8.1.33. G. E. Moore (1910). "II.—The Subject-Matter of Psychology". Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 10: 36–62. doi:10.1093/aristotelian/10.1.36. G. E. Moore, Ethics (1912) G. E. Moore, "Some Judgments of Perception" (1918) G. E. Moore, Philosophical Studies (1922) [papers published 1903–21] G. E. Moore, "The Conception of Intrinsic Value" G. E. Moore, "The Nature of Moral Philosophy" G. E. Moore, "Are the Characteristics of Things Universal or Particular?" (1923) G. E. Moore, "A Defence of Common Sense" (1925) G. E. Moore and F. P. Ramsey, Facts and Proposition (Symposium) (1927) W. Kneale and G. E. Moore, "Symposium: Is Existence a Predicate?" (1936) G. E. Moore, "An Autobiography," and "A reply to my critics," in: The Philosophy Of G. E. Moore. ed. Schilpp, Paul Arthur (1942). G. E. Moore, Some Main Problems of Philosophy (1953) [lectures delivered 1910–11] G. E. Moore, Ch. 3, "Propositions" G. E. Moore, Philosophical Papers (1959) G. E. Moore, Ch. 7: "Proof of an External World" "Margin Notes by G. E. Moore on The Works of Thomas Reid (1849: With Notes by Sir William Hamilton)". G. E. Moore, The Early Essays, edited by Tom Regan, Temple University Press (1986). G. E. Moore, The Elements of Ethics, edited and with an introduction by Tom Regan, Temple University Press, (1991). G. E. Moore, 'On Defining "Good,'" in Analytic Philosophy: Classic Readings, Stamford, CT: Wadsworth, 2002, pp. 1–10. ISBN 0-534-51277-1. |

作品 ケンブリッジのアセンション教区埋葬地にあるG.E.ムーアと妻ドロシー・ムーアの墓碑。 G.E.ムーア『審判の本質』(1899年) G. E. ムーア (1903). 「IV.-経験と経験主義」. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 3: 80-95. doi:10.1093/aristotelian/3.1.80. G. E. Moore, Principia Ethica (1903). G.E.ムーア「フランツ・ブレンターノ『善悪の知識の起源』の書評」(1903) G.E.ムーア、「観念論の反駁」(1903年) G. E. ムーア (1904). "VII.-カントの観念論". Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 4: 127-140. doi:10.1093/aristotelian/4.1.127. G. E. Moore, "The Nature and Reality of the Objects of Perception" (1905-6). G. E. ムーア (1908). "III.-ジェイムズ教授の「プラグマティズム」". Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 8: 33-77. doi:10.1093/aristotelian/8.1.33. G. E. Moore (1910). "II.-心理学の主題". Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 10: 36-62. doi:10.1093/aristotelian/10.1.36. G・E・ムーア『倫理学』(1912年) G.E.ムーア「知覚のいくつかの判断」(1918年) G. E. Moore, "Philosophical Studies" (1922) [1903-21年発表の論文]. G.E.ムーア、"本質的価値の概念" G.E.ムーア、"道徳哲学の本質" G.E.ムーア、"事物の特性は普遍的か、それとも特殊的か?" (1923) G.E.ムーア「常識の擁護」(1925年) G.E.ムーアとF.P.ラムゼイ、事実と命題(シンポジウム) (1927) W. ニール、G.E.ムーア「シンポジウム: 存在は述語か?(1936) G.E.ムーア、「自伝」、「批評家への返答」、『G.E.ムーアの哲学』(1936年): シルプ、ポール・アーサー編『G. E. ムーアの哲学』(1942年)。 G. E. Moore, Some Main Problems of Philosophy (1953) [1910-11年の講義]. G.E.ムーア、第3章、"命題" G.E.ムーア『哲学論文集』(1959年) G.E.ムーア、第7章:"外部世界の証明" 「G.E.ムーアによるトマス・リードの著作に関する余白注(1849年:サー・ウィリアム・ハミルトンによる注を付す)」。 G. E. Moore, The Early Essays, edited by Tom Regan, Temple University Press (1986). G. E. Moore, The Elements of Ethics, edited and with an introduction by Tom Regan, Temple University Press, (1991). G. E. Moore, 'On Defining "Good'," in Analytic Philosophy: G. E. Moore, 'On Defining "Good'," in Analytic Philosophy: Classic Readings, Stamford, CT: Wadsworth, 2002, pp. ISBN 0-534-51277-1. |

| George Edward Moore First published Fri Mar 26, 2004 G.E. Moore (1873-1958) (who hated his first names, ‘George Edward’ and never used them — his wife called him ‘Bill’) was an important British philosopher of the first half of the twentieth century. He was one of the trinity of philosophers at Trinity College Cambridge (the others were Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein) who made Cambridge one of centres of what we now call ‘analytical philosophy’. But his work embraced themes and concerns that reach well beyond any single philosophical programme. 1. Life and Career 2. The Refutation of Idealism 3. Principia Ethica 4. Philosophical Analysis 5. Perception and Sense-data 6. Common Sense and Certainty 7. Moore's Legacy Bibliography Academic Tools Other Internet Resources Related Entries https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moore/ |

ジョージ・エドワード・ムーア 初版 2004年3月26日(金) G.E.ムーア(1873-1958)(彼は「ジョージ・エドワード」というファーストネームを嫌い、決して使用しなかった。彼の妻は彼を「ビル」と呼ん でいた)は、20世紀前半の英国の重要な哲学者である。ケンブリッジ大学トリニティ・カレッジの哲学者3人組(他の2人はバートランド・ラッセルとルート ヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン)の1人であり、彼らの功績により、ケンブリッジは現在「分析哲学」と呼ばれる学問の中心地のひとつとなった。しかし、彼の 研究は、単一の哲学プログラムをはるかに超えるテーマと関心を取り扱っていた。 1. 生涯と経歴 2. 観念論の反駁 3. プリンキピア・エチカ 4. 哲学分析 5. 知覚と感覚資料 6. 常識と確実性 7. ムーアの遺産 参考文献 学術ツール その他のインターネットリソース 関連項目 |

| 1. 生涯とキャリア ムーアは南ロンドンで育った(彼の長兄は詩人のT. Sturge Mooreで、W. B. Yeatsのイラストレーターとして働いていた)。1892年、古典を学ぶためにケンブリッジ大学のトリニティ・カレッジに入学した。そこで、2年先輩の バートランド・ラッセルと、当時トリニティ・カレッジの哲学フェローとしてカリスマ的な存在であったJ. M. E. マクタガートの2人と知り合った。彼らの勧めにより、ムーアは古典学に哲学を加えることを決意し、1896年に哲学の分野で最優秀の成績を収めて卒業し た。この時点で、彼はトリニティ・カレッジの「賞」フェローシップを獲得し、そこで哲学の研究を続けることで、マクタガートとラッセルの足跡をたどろうと 決意した。1898年に彼は成功し、その後6年間で、彼は英国で当時支配的であったマクタガートや他の人々の観念論哲学からラッセルを離れさせるなど、ダ イナミックな若手哲学者として成長した。 1904年にムーアのフェローシップは終了し、ケンブリッジを離れていた時期を経て、1911年にムーアはケンブリッジ大学で教鞭をとるために同大学に戻 り、その後は生涯をそこで過ごした(1940年から1944年にかけて米国に長期滞在した期間を除く)。1921年には英国の主要な哲学誌『Mind』の 編集者となり、1925年にはケンブリッジ大学の教授に就任した。この2つの地位を得たことで、彼は当時最も尊敬を集めていた英国の哲学者としての地位を 確固たるものとした。そして、1929年以降ウィトゲンシュタインがケンブリッジに戻ったことで、ケンブリッジは世界で最も重要な哲学の中心地となった。 ムーアは1939年に教授職を退き(後任はウィトゲンシュタイン)、1944年にはMind誌の編集長も退いた。これらの退任は、ムーアの卓越した地位の 終焉を意味するだけでなく、ケンブリッジ哲学の黄金時代の終焉をも意味した。 ケンブリッジにいた初期の頃、ムーアは後に「ブルームズベリー・グループ」を結成することになる若者たち、例えばリットン・ストラチェイ、レナード・ウル フ、メイナード・ケインズらと友人となった。 これらの交友関係を通じて、ムーアは、より「社会参加」的な哲学者たちと同様に、間接的に20世紀の英国文化に多大な影響を与えた。これらの長年にわたる 交友関係は、ソクラテス的な性格を持つムーアの証であり、彼の著作からは伝わってこない彼の性格の一面を物語っている。ムーアの後継者としてMind誌の 編集長を務め、1945年以降の英国を代表する哲学者となったオックスフォード大学の哲学者ギルバート・ライルは、ムーアのこの人格の一面を強調してい る。 彼は譲歩によってではなく、若さや内気さに対して一切譲歩しないことによって、私たちに勇気を与えた。彼は私たちを矯正可能であり、したがって責任ある思 考家であるとみなした。彼は、哲学の権威者の間違いや混乱に対してそうするのと同じように、また、自身の間違いや混乱に対してそうするのと同じように、温 和な激しさをもって、私たちの間違いや混乱を厳しく非難した。(Ryle 270) |

|

| 2. 理想主義への反論 ムーアはマクタガートとの接触を通じて初めて哲学に惹きつけられ、マクタガートの影響下で、特にF. H. ブラッドリーの著作に影響を受け、一時的にイギリス観念論の虜となった。そのため、1897年にトリニティで初のフェローシップ獲得を試みた際には、「倫 理学の形而上学的基礎」に関する論文を提出し、ブラッドリーへの負い目を認め、観念論的倫理理論を提示した。この理論の要素のひとつは、彼が「善の経験主 義的定義に内在する誤謬」と呼ぶもので、これはすぐに、彼の有名な主張である『プリンキピア・エティカ』における、自然主義的な善の定義には「自然主義的 誤謬」という誤謬があるという主張の先駆けであることが分かる。この点から、以下で見るように、ムーアはブラッドリーとマクタガートの観念論哲学をすぐに 否定するようになったが、J. S. ミルの哲学に代表される経験論に対する彼らの批判は妥当であると主張し、この経験論に対する敵意を成熟した哲学にも持ち越したことがわかる。この点におい て、したがって、彼の初期の観念論への熱狂は、彼の思想に永続的な影響を与えた。 この初期の論文の大部分はカントの道徳哲学の批判的考察に割かれており、ムーアは全体的なアプローチと結論においてブラッドリーが唱えた理想主義を支持し ているにもかかわらず、カントの実践理性の概念に対してすでに批判的な見解を示していることは注目に値する。ムーアは、カントがこの概念を用いることで、 「判断や推論を行う心理的機能」と「真実かつ客観的なもの」との区別が曖昧になっていると論じている。ムーアは、この区別は「取り払うことも、埋め合わせ ることもできない」と主張する。したがって、実践理性のア・プリオリな原理に基づくカントの道徳観は成り立たない、と彼は論じる。この考え方をさらに推し 進めると、カントのア・プリオリな観念一般に対する批判へと発展することは容易に理解できる。そして、ムーアは1898年の論文でまさにこの一般化を試み ている。同時に、彼はブラッドリーの観念論に対する以前の熱狂は根拠のないものだったと気づく(とはいえ、ブラッドリーとマクタガートが時間の実在性に対 する主張に欠陥があることを受け入れるには、まだしばらく時間がかかった)。 このように、1898年の論文でムーアは、カント主義とブラッドリー主義の両方の観念論に明確に反対する立場をとる。 これにはいくつかの側面がある。私が指摘したように、彼はカントのア・プリオリに関する考え方を、主観主義や心理主義の濁った形態として拒絶している。『実践理性批判』(1903年)からの次の引用は、この時期の彼の著作の多くに見られる彼の論争を象徴している。 「真である」意味することは、ある特定の方法で考えられているということである。したがって、それは確実に誤りである。しかし、この主張はカントの「哲学 におけるコペルニクス的転回」において最も中心的な役割を果たしており、この転回によって生み出された、認識論と呼ばれる現代の膨大な文献のすべてを無価 値なものとしている。(『実践理性批判』183) ムーアがここで思考と客観的または現実的なものとの間に引いている区別は、彼の観念論批判全体に貫かれているものである。 彼がそれを詳しく論じた初期の重要な文脈は、彼の有名な論文『判断の本質』(1899年)における意味についての議論であり、その大部分は1898年の論 文『学位論文』から来ている。ムーアはここで、ブラッドリーが判断の全体的内容から抽象化された意味について、準経験論的な見解を持っていると主張するこ とから始める。これは間違いであるが、重要なのはその後の主張である。ムーアは、ブラッドリーのこの見解に反対し、彼が「概念」と呼ぶ意味は、完全に非心 理学的であると主張する。意味は命題に集約され、それは思考の「対象」であり、それゆえ、いかなる心的内容や表象とも明確に区別されるべきである。実際、 真の命題は事実や現実の状態を表したり、対応するものではない。代わりに、それらはただ事実である。彼は、その点を1年後に書いた「真理」という短い文章 で非常に明確に述べている。 真理は、それが単に対応していると想定されている現実とは、いかなる点においても異なるものではないことは明らかであるように思われる。例えば、私が存在 するという真理は、対応する現実である私の存在とは、いかなる点においても異なるものではない。現時点では、実際、真理が現実を参照して定義されるのでは なく、現実が真理を参照してのみ定義される。(『真理』21) ムーアが10年後に気づいたように、この真命題の根本的な形而上学はあまりにも単純すぎる。しかし、この文脈において、この考え方が際立っているのは、そ れ自体が観念論と実在論の狭間をさまよっている点である。命題が判断の内容であると考えられる場合、現実が真命題のみで構成されていると主張することは観 念論的な立場を取ることを意味する。ムーアの立場を現実主義的なものとしているのは、命題と概念に関する彼の妥協のない現実主義である。それらは思考の対 象となり得るが、ムーアは「それらを定義するものではない」と記している。なぜなら、「それらを誰かが考えるかどうかは、それらの本質とは無関係である」 からだ(『判断の本質』4)。 ムーアの理想主義に対する最も有名な批判は、論文『理想主義の反駁』(1903年)にまとめられている。この論文の基本的なテーマは、意味に関連して遭遇 した心と対象との間の強い区別を感覚経験に拡張することである。ムーアはここで「青の感覚」の事例に焦点を当て、この経験は青に関する一種の「透明な」意 識または認識であり、経験の「内容」ではなく、経験に依存することなく存在する実体であると主張する。彼の主張の一部は現象学的なもので、「青の感覚を内 省しようとしても、見えるのは青だけだ」(41)というものだが、それとは逆に「青」が単に経験の内容であると考えることは、それが経験の性質であると考 えることになり、経験は青いビーズが青いこととほぼ同じ意味で青いということになる、と彼は主張している。当然ながら、ムーアの批判者たちはこの比較に満 足しなかったが、1940年代にデュカスが提唱した「副詞的」経験理論が定式化されるまでは、青色の感覚を持つ人は「青く感じる」人であるという考え方 だったため、ムーアの批判に対する妥当な反論は存在しなかった。しかしながら、ムーアの論文の奇妙な点は、彼が有名な「錯覚からの論証」にまったく言及し ていないことである。ムーアは、「私が『青』を経験するとき、それは私の経験の対象であると同時に、私が認識する最も崇高で独立した実体である」と結論づ けている(42)。彼がすぐに気づいたように、実際には青くないものが青く見える場合に対処するには、さらに多くのことが言われる必要がある。 モアの観念論に対する批判的反応の最後の側面は、イギリス観念論の特徴であった一元論を彼が否定したことに関係している。これは、通常の事物は本質的に密 接に関連し合っており、それらが一体となって「有機的統一」を構成しているという全体論的命題である。この命題は、ブラッドリーの観念論に特に特徴的であ り、それによれば、絶対者が唯一の実在である。初期の著作や『Principia Ethica』において、ムーアはこの命題に対して多くの論争的な批判を行っているが、現実主義的多元論の強固な肯定とは対照的に、これに反対する論拠を 見つけるのは難しい。しかし、それより後の論文「外的および内的関係」(1919年執筆)において、ムーアは一元論の命題の核心にある内的関係の観念に焦 点を当てた。ムーアは、すべての関係は内部的なものであるという説に対する反論として、物事の本質は相互に関連しているわけではなく、ある側面におけるあ る物事の変化が他のすべての物事の変化を必然的に引き起こすことはないという我々の常識的な信念と矛盾しているため、その説を支持する側がその証拠を示す べきであるという主張から出発している。ムーアは、この命題の最も有力な理由は論理的な誤謬を含むと主張し、関係がすべて内部的なものであるという命題 が、論争の余地のない原則である「関係が異なるものは同一性も異なる」というライプニッツの法則から、いかにして妥当ではあるが誤って推論される可能性が あるかを示している。少し単純化して、ムーアの含意(下記参照)の概念を用いると、彼の主張は以下のようになる。 ライプニッツの法則は、xRy が (z = x → zRy) を必然的に導くことを示している。ここで「→」は真理関数条件である。 必然性は必然的なつながりであるため、xRy → 必然的に (z = x → zRy) が導かれる。 (2)から、xRy → 必然的に (x = x → xRy) がすぐに導かれる。 x = x はそれ自体が必然的な真実であるため、xRy → 必然的に (xRy) が導かれる。これは、すべての関係は内部的なものであるという命題を表している。 つまり、一見したところ、この命題はライプニッツの法則から導かれている。しかしムーアは、(1)から(2)へのステップは無効であると指摘している。こ のステップは、関係の必然性と結果の必然性を混同している。通常の言語では、この区別は明確に示されないが、適切な形式言語では簡単に区別できる。 ムーアの論証は洗練された非公式の様相論理であるが、ブラッドリーの絶対的観念論の動機の本質を本当に突いているかどうかは疑わしい。私の考えでは、ブ ラッドリーの弁証法は、思考が現実の表現として不十分であるという異なる命題に基づいている。したがって、ブラッドリーの単一論の根拠を明らかにし、その 誤りを示すためには、ブラッドリーの観念論的形而上学をより深く掘り下げる必要がある。 |

|

| 3. Principia Ethica ムーアの初期の主要な業績は、著書『Principia Ethica』である。この本は1903年に出版されたが、その内容は1897年の論文『倫理学の形而上学的基礎』でムーアが始めた考察の集大成であっ た。しかし、主な推進力となったのは、1898年後半にムーアがロンドンで行った一連の講義「倫理学の諸要素」であった。ムーアはこれらの講義のテキスト を出版することを視野に入れてタイプした。しかし、考えがまとまるにつれ、テキストを書き直し、その成果が『プリンキピア・エティカ』である(講義は最近 『倫理学の諸要素』として出版された)。最初の3章のほとんどは1898年の講義から取られたもので、最後の3章は大部分が新しい内容である。 最初の3章でムーアは「倫理的自然主義」に対する批判を展開している。これらの批判の核心は、ムーアが倫理の根本的価値であると考える「善」を、快楽や欲 望、あるいは進化の過程といった自然主義的な用語で定義できると想定することには誤りがあるという命題、すなわち「自然主義的誤謬」が含まれているという 主張である。こうした主張のすべてに対して、ムーアは善は定義できない、あるいは分析できないと主張し、したがって倫理学は自律的な科学であり、自然科学 や、実際には形而上学にも還元できないと主張する。善の定義の可能性に対するムーアの主な主張は、仮説の定義、例えば「善であることは、望むことを望むこ とである」という定義に直面したとき、その定義が真であるという主張は、定義上、真であるとは言えないと指摘している。なぜなら、その真偽は、単に言葉の 理解を明確にする定義である場合、疑うことは不可能であるが、疑う余地があるという意味で「未解決の問題」のままであるからだ。この議論の妥当性には疑問 がある。多くの場合、定義の真偽を合理的に疑うことができる。特に、定義が通常の理解の範囲外にある発見を利用している場合、つまり自然科学における定義 の場合には、その傾向が強い。しかし、私は、この反論を回避する方法があると考えている。すなわち、倫理的な問いは倫理的な信念の明示的な関与なしには答 えられないという認識論的命題に依拠する方法である。この命題が倫理的価値の自然主義的定義に敵対する理由は、自然科学やその他の分野における定義の重要 な役割は、それによって、そうでなければ不可能な質問に新たな方法で答えられるようになることである。しかし、例えば幹細胞研究におけるヒト胚の利用の可 否に関するような新しい倫理的問題に対して、馴染みのある倫理的「表現型」、すなわち明示的な倫理的観念に頼らずに答えを出せるような倫理的価値の定義を 見つけることで答えを出そうとするような受け入れ方はありえない。 ムーアの議論のこの擁護は、異なる懸念には対応していない。すなわち、この議論は倫理的価値の定義を含む倫理的実在論のバージョンにのみ適用されるため、 倫理的価値は還元不可能な自然の特性であると主張する自然主義の立場は、この議論の影響を受けないという懸念である。この種の立場に対するムーアの反論 は、状況の倫理的価値は、その状況の他の特性から独立した特徴ではないという主張に基づいている。それどころか、それは他の特性に依存している。彼が『プ リンキピア・エチカ』の第2版のために書いた序文で述べているように(しかし実際には出版されなかった)、ある事物の「本質的価値」はその「本質的性質」 に依存しており、彼はこの依存関係を、現在では「随伴性」と呼ばれている関係(ただしムーアは用語を使用していない)の観点から説明している。同じ本質的 性質、つまり自然な性質を持つ事物は、同じ本質的価値を持つに違いない(「本質的価値の概念」286ページを参照)。 。ムーアは、超越論的関係は本質的に還元論的な関係ではないと考え、したがって、善は自然な性質に後天的であるにもかかわらず、善は自然な性質ではないと 主張することは矛盾しないと主張した。しかし、もし善がそれ自体自然な性質であるという見解を取るのであれば、善が他の自然な性質に後天的であるという事 実は、還元論的命題を避けることを不可能にする、と彼は仮定した。したがって、本質的価値の超越論は、彼の倫理的非自然主義の立場に矛盾することなく、非 還元論的自然主義の選択肢を排除する。 その後の議論により、超越論と還元論の関係は複雑な問題であることが示されている。私はムーアの立場は擁護できると考えているが、この問題をさらに掘り下 げるには場違いである。代わりに、ムーアの理論の中心となる本質的価値の概念に目を向けたい。この概念の1つの側面は容易に理解できる。すなわち、状況の 「本質的」価値と「手段的」価値の区別である。これは、状況に内在する価値と、その状況の結果のみに依存する価値の区別である。この区別にもかかわらず、 手段的価値は状況の結果の本質的価値の観点から定義できるため、本質的価値は倫理的価値の基本的タイプであることに変わりはない。しかし、本質的価値は単 に非道具的価値ではない。なぜなら、ムーアが状況の「部分としての価値」と呼ぶもの、すなわち、ある状況が、それが「部分」である複雑な状況の価値に対し て、本質的価値を超えて付加する追加的な貢献とも区別されるべきだからである。これは私たちにとって馴染みのある概念ではないが、ムーアは次の例でその点 を説明している。知識それ自体にはほとんど本質的価値はないが、美しい芸術作品の美的鑑賞の価値(ムーアによれば、それは存在するものの中で最も価値のあ るもののひとつである可能性がある)は、その作品に関する知識によって大幅に高められる。したがって、このような知識は、本質的な価値はほとんどないとし ても、実質的な「部分としての価値」を持つことができる。状況の価値は、その状況が自身の本質的な価値を超える貢献をする複雑な状況の全体的な本質的な価 値という観点で定義されるため、依然として本質的な価値が価値の根本的な概念であることに変わりはない。しかし、この点から、あるものの本質的な価値は、 その帰結とは無関係に単にその価値であるというわけではなく、その文脈とは無関係にその価値でもあることが示唆される。したがって、本質的価値の概念と は、ある状況がすべての文脈において同じ本質的価値を持つようなものである。これが、ムーアが本質的価値は「本質的性質」のみに依存すると主張する理由で ある。 ここには2つの関連した問題がある。1つ目は、複雑な状況の要素として発生した場合、その「部分としての価値」が、単純に本質的価値を考慮した結果ではな い形で、後者の価値に影響を与える可能性があることを受け入れることに関係している。この判断は、ムーアの「有機的統一体の原則」に示されている。この原 則は、複雑な状況のこのような非集約的評価が起こりうることを宣言している。ここで問題となるのは、ムーアの原則が誤っているということではなく、むしろ 道徳的な推論を妨げるため、非合理的であると思われることである。2つ目の問題は、本質的価値はあらゆる状況において同じであるという主張に関するもので ある。この主張は、例えば友情の価値は状況によって異なるという点で、単に間違っているように思われる。ムーアが正しく指摘しているように、友情は通常、 最も価値のあるもののひとつであるが、法廷のように正義の主張が問題となる場では、友情にはまったく価値がない。したがって、ムーアの考えた絶対普遍的な 本質的価値は、特定の文脈における通常の価値を「括弧でくくる」ことを可能にする考え方に置き換えられるべきである。そして、これが実現され、ムーアが提 供するよりも洗練された規範的価値の説明が加われば、ムーアの非合理的な有機的一体性の原理によって捉えられた現象が、より理解しやすい解釈を見出すこと が期待できるだろう。 ムーアの倫理理論が問題となるもう一つの領域は、倫理的知識に関する彼の説明である。倫理的自然主義に対する敵意から、ムーアは倫理的知識は経験的探究の 対象ではないと否定している。しかし、すでに見たように、彼はカントの根本的倫理的真理は理性の真理であるという合理主義的主張にも同様に敵対している。 その代わり、道徳的知識は、根本的な道徳的真理を直観的に把握する能力に依存していると主張する。その理由は、その真理を説明できる理由がないからだ。こ の主張の問題点は、もしそのような知識を裏付ける主張を何もできないのであれば、それに反対する人々はただ反対意見を表明して立ち去るだけである。した がって、道徳的議論は、解決策のない相反する判断の表明に陥りやすい。この観点から見ると、ムーアの倫理理論が道徳の認知上の地位を損なうものとして見な されたとしても驚くにはあたらない。ムーアの影響を受けたA. J. エイヤーやC. L. スティーブンソンといった人々によって、ムーアの倫理理論は直接的に非認知主義へと発展した。しかし、道徳的問題に関するムーアの議論にはもう一つの側面 があり、彼は、快楽こそが唯一の肯定的な本質的価値であるとする快楽主義の論文に反対する議論をしていることに気づいていた。公式には、そのような議論は 成り立たないとしていたにもかかわらずである。このような「間接的な」論証方法を用いる場合、ムーアは真理を確立するよりも同意を得ることを目指している と自覚しているが、一人称の視点から見ると、両者の間にほとんど違いはないことも認めている。この間接的な方法は、彼の倫理探究の公式な方法に統合されて いないため、その前提条件についてはほとんど言及していない。しかし、私には、この方法に、任意の複雑な状況の相対的な本質的価値に関する直観的判断への 彼の公式な訴えよりもはるかに望ましい、倫理に対する「常識的」アプローチの萌芽を見出すことができるように思われる。 これまで私は、ムーアの「超価値論」、すなわち倫理的価値の形而上学と倫理的知識の本質に関する彼の見解について論じてきた。この強調は、ムーアの倫理理 論のこの側面が最も影響力を持っているという事実を反映している。しかし、彼の道徳理論のいくつかの要点についても簡単に触れておく価値はあるだろう。 ムーアは、正しいことと善いことの関係について、単純な結果論的な説明をしている。正しい行動とは、最善の結果をもたらす行動である。実際には、何が最善 の結果であるかを自分自身で判断することは非常に困難であるため、ムーアは、確立された規則に従うことが最善であると主張している。そのため、ムーアは保 守的な帰結主義を推奨することになり、ケインズやラッセルから批判された。W. D. ロスなどの後世の批評家は、ムーアが私たちの個人的責任を最善の結果を生み出すという非人格的なテストに委ねているため、彼の立場は、特定の人々との関係 から生じる私たちの責任のあり方を十分に捉えていないと主張した。最近の批評家は、ムーアの道徳理論は断固として「主体中立」であり、それゆえ不可分に 「主体相対」の価値を含む個人的責任の説明としては不適切であると述べている。 最後に、『プリンキピア・エチカ』の最終章で、ムーアは「理想」を提示している。それは、本質的な善(友情や美の鑑賞など)と本質的な悪(痛みの意識な ど)を意図的に体系化しないリストにしたものである。ムーアの価値観の選択は際立っている。それは、芸術と愛に捧げられた生活という「ブルームズベリー」 の理想とつながり、平等や自由といった社会的価値観を排除している。結果として生じた道徳の個人主義は、ムーアがこれらの本質的価値は共約不可能であり、 したがってそれらの優先順位の評価は個人の判断に委ねられるべき不可避の問題であると主張しているという事実によって強化されている。ケインズが述べたよ うに、ムーアの理想は一種の世俗的な「宗教」であり、公共政策にはあまり役立たないが、詳細な価値判断において異なる意見を持つことに同意できる才能ある 個人にとっては素晴らしいものだった。 |

|

| 4. 哲学的分析 1911年にムーアがケンブリッジに戻り、同校で教職に就いた頃、ラッセルとホワイトヘッドは、数学の論理的基礎を明らかにするという大規模なプロジェク ト、プリンキピア・マスマティカの仕上げに取り組んでいた。ムーアは数学者でも論理学者でもなかったが、ラッセルの新しい論理理論が哲学にとって不可欠な ツールであり、重要な新しい洞察をもたらすものであることを最初に理解した人物の一人であった。その一例として、思考の「対象」である命題の地位に関する ものがある。前述の通り、初期の著作においてムーアは、命題は思考とはまったく独立したものであると強調し、事実とは真の命題に他ならないとさえ主張して いた。しかし、1910年から1911年にかけての講義『Some Main Problems of Philosophy』で虚偽についてさらに深く考えるようになった彼は、命題の真偽がその存在論的地位に影響を与えるべきではないし、一方で、虚偽の命 題に事実の地位を与えるのは馬鹿げているため、この立場は誤りであることが明らかになった。そこで彼は、事実とは真の命題に他ならないという見解を否定し た。彼の新しい見解では、事実とは依然として、対象とその性質によって構成される。しかし、命題についてはどうだろうか? ムーアによると、哲学者たちが命題について正当に語るのは、思考や言語の側面を特定し、真理や推論の問題に不可欠なものとするためであり、そうすること で、命題を本物の実体としてみなしているように見えるかもしれない。しかし、ムーアは現在、この含意は正当化されないと考えている。ここで犯されている誤 りは、「何かを表す名称であるように見える表現はすべて、実際にもそうであるに違いない」と仮定することである(『哲学の主要問題』266ページ)。ムー アはここでラッセルの不完全記号と論理上の仮説に関する理論を明示的に言及しているわけではないが、彼がこのような立場であることは明らかである。この新 しい論理によって、実在論的形而上学を受け入れずに実在論的な外観を維持することが可能になる。 しかし、ムーアはラッセルの無批判な追随者ではなかった。ラッセルが命題間の含意の論理関係には真理関数的な条件がすべてを表現すると提案した含意の説明 については批判的であり、代わりにこの後者の関係に「含意」という用語を導入した(「外部と内部の関係」90ページ以下)。彼は、含意が論理的な必然性と 密接に関連していることを認識しながら、含意は真理関数条件の必然性の問題だけではないと考え、それにより今日まで続くこの関係についての議論が巻き起 こった。また、ムーアはラッセルの存在の扱い、特に、存在を特定の対象の第一級述語として扱うことに意味があるというラッセルの否定を批判した(ラッセル にとって、存在は存在量化子によって表現されなければならないため、存在は述語の第二級述語である)。ムーアは、ラッセルが存在は単純な第一級述語ではな い(「飼いならされた虎は存在する」と「飼いならされた虎は唸る」では論理形式が異なる)という点に同意しながらも、「これは存在しないかもしれない」と いった主張は十分に理にかなっており、「これは存在する」というより単純な主張が理にかなっているのでなければ、そのような主張は成り立たないはずだと主 張した(『存在は述語か?』145ページ)。 ムーアによるラッセルの論理学の使用は、哲学の方法としての分析の使用というより広範な文脈の中で行われている。ムーアは常に哲学が単なる分析ではないと 否定していたが、彼の哲学において分析が中心的な役割を果たしていることは否定できない。したがって、この役割を動機づけるものが何であるかを明らかにす ることは重要である。この問いは、特にムーアの場合に切迫したものとなる。なぜなら、彼は20世紀の哲学における主要な分析プログラム、すなわちウィトゲ ンシュタインの論理原子論と、ウィーン学団のメンバーや彼らの追随者であるA.J.エイヤーなどの論理経験論を否定したからである。まず第一に、ムーア は、存在するものはすべて必然的に存在するというウィトゲンシュタインの命題を否定した。すべての関係は内部にあるという観念論者の命題と同様に、ムーア は、存在するもののうち、存在しなかったかもしれないという我々の常識的な確信は、その反対を主張する哲学者に対して強い疑いを抱かせるものであり、論理 原子論者の立場は、この疑いを覆す説得力のある理由を提供していないと主張した。さらに、ムーアは、ヴィトゲンシュタインが主張したように、すべての必然 性が論理的必然性であるというわけではないと主張した。初期の著作において、カントに対する敵意にもかかわらず、彼は明白に「必然的総合的真理」の概念を 擁護しており、この点については考えを変えなかった。この論点もまた、論理経験論を拒絶する理由となっている。なぜなら、論理経験論では、すべての必然的 真理は「分析的」であるという命題が有名だからである。しかし、ムーアは、ウィリアム・ジェームズのプラグマティズムに対する初期の批判が論理経験主義の 立場にも適用できることを認識していた。ジェームズとの関連で、ムーアは、命題が過去に関するものである場合、その事柄についてどちらの方向にも証拠がな いため、命題とその否定の両方が検証不可能な状況にある可能性があることを観察していた。しかし、彼は主張した。「排中律のおかげで、命題またはその否定 のどちらかが真であると今断言できないというわけではない。その場合、真実が検証可能性であるということはありえない。それは、ジェームズの実利主義と論 理経験論の両方に反する。 それでは、なぜムーアは命題の分析がそれほど重要だと考えたのだろうか。その動機の一部は、ラッセルが導入した原則を受け入れたことによる。すなわち、 「我々が理解できる命題はすべて、我々が知っている構成要素のみで構成されていなければならない」という原則である(Russell 91)。この原則は、ムーアが多大な関心を寄せた知覚の「感覚データ分析」を動機づけるものであり、この分析については後ほど詳しく述べる。さらに、哲学 的な分析の重要性を説明する際、彼はある議論で何が問題となっているかを明確にすることの重要性を強調したが、彼自身が明確にできていなかった問題は、分 析の含意に関するものであった。初期の著作では、命題の分析がそれを明らかにする限り、その存在論的な含意も明らかにされるという見解をとっていた。した がって、分析が物質的な物体の存在を疑問視することは、物質的な物体に関する命題の現象主義的分析に対する異議申し立てであると彼は考えていた。しかし、 その後、彼は反対の立場に転じ、現象論的分析は、それらの存在が何を意味するのかを説明するに過ぎない、と主張した。この2つの立場の中間にある1925 年の論文「常識の擁護」(以下でさらに詳しく論じる)において、ムーアは、知覚の感覚データ分析が示すのは、感覚データが知覚に関する命題の「主要な、あ るいは究極の主題」であるということであると主張した。この指摘は、ムーアにとっての哲学分析の真の重要性を反映していると思う。彼にとってのその重要性 を考える場合、それは、私たちの日常的な常識的な思考や会話の主題である「究極」の物質を明らかにするという点で、形而上学的である。 |

|

| 5. 知覚と感覚データ ムーアは、『観念論の反駁』で主張した現実主義の立場が「ナイーブ」すぎて維持できないことにすぐに気づいた。彼は「偽りの」外見を何とかして受け入れな ければならない。しかし、ムーアがこの問題に対処するために採用した戦略は、『観念論の反駁』の基本命題に忠実であり、物事の外見は経験の一次対象の性質 によって説明されるべきであり、経験そのものの性質によって説明されるべきではないというものであった。この立場をより詳しく説明するために、ムーアは経 験の一次対象を説明する用語として「感覚データ」という用語を導入した。 さて、私たちはあの封筒を見たとき、それぞれに何が起こったのだろうか。まず、私に起こったことの一部について述べよう。私はある形をした、ある特定の 白っぽい色の領域を見た。この白っぽい色の領域、そしてその大きさや形は、実際に私が目にしたものである。そして、私はこれらを色や大きさ、形と呼ぶこと にする。感覚データ…(Some Main Problems of Philosophy 30) ムーアはここで、色、形、大きさがそれぞれ異なる感覚データであることをほのめかしているが、彼はすぐに用語を修正し、これらは「実際に見た」あるいは彼が通常言うように「直接把握した」視覚の感覚データの性質であるとみなされるようになった。 感覚データの概念がこのように導入されれば、誤った知覚は、我々が知覚する感覚データの性質と、それらの感覚データを生み出す物理的対象の性質とを区別す ることで処理できることが容易に理解できる。しかし、感覚データと物理的対象との関係はどうなっているのだろうか。ムーアは、考慮すべき3つの有力な候補 があると主張した。(i) 間接的実在論的立場、すなわち、感覚データは非物理的だが、物理的対象と私たちの感覚との相互作用によって何らかの形で生み出されるという立場、(ii) 現象論的立場、すなわち、物理的対象に対する私たちの概念は、私たちが把握する感覚データ間の観察された、あるいは予想される均一性を表現するものにすぎ ないという立場、(iii)直接実在論的立場、すなわち、感覚データは物理的対象の一部であり、例えば視覚的感覚データは物理的対象の表面の目に見える部 分であるという立場 。間接的実在論の立場は、彼が当初惹きつけられた立場である。しかし、この立場では、物理的世界に関する我々の信念が懐疑的な疑いにさらされることにな る。なぜなら、これらの信念の証拠となる観察は、非物理的な感覚データの性質のみに関わるものであり、物理的世界の性質と我々の感覚データとの関係に関す る仮説を裏付けるさらなる証拠を我々が得るための明白な方法はないからだ。この議論はロックに対するバークレーの批判を彷彿とさせるものであり、そのため ムーアはバークレーの現象論的代替案を慎重に検討した。ムーアは当初、この立場に対して、暗示されている物理的世界の概念はあまりにも「ピクウィック的」 で信じがたいという反応を示した。これは、バークレーに対するジョンソン博士の有名な異議申し立てのように直感的に過ぎると感じられるかもしれないが、 ムーアは現象論的立場に対する実質的な異議申し立てがあることも理解していた。例えば、感覚データにおける重要な均一性を識別し予測する通常の方法が、物 理的空間における位置や物理的感覚器官の状態に関する信念に依拠しているという事実などである。 ムーアの弁証法はこれまでは馴染みのあるものだった。しかし、感覚データが物理的であるという彼の直接実在論的な立場は馴染みのないものである。この立場 はこれまでに遭遇した問題を回避するが、偽りの外観を許容するために、ムーアは感覚データが我々がそれらに備わっていると認識する性質を欠いている可能性 を認めなければならない。感覚データがオブジェクトである限り、これは不可避であると思われるかもしれない。しかし、ムーアは感覚データの表面的な性質を 説明する必要があり、これらの表面的な性質を我々の経験の性質として解釈することで、感覚データ理論の当初の動機に立ち返らずにこれを説明できるかどうか は明らかではない。しかし、ムーアがこの直接現実主義の立場に反対する理由は、実際には、それが幻覚の扱いに関する問題につながると考えていることにあ る。このような場合、ムーアは、我々が知覚する感覚データは物理的な物体の構成要素ではないと主張する。そのため、直接実在論を適用することはできない が、通常の経験で知覚する感覚データと本質的に異なるという理由はない。この最後の点は、論争の余地があるかもしれない。ムーア自身も、ある時点で「主観 的」と「客観的」の感覚データの区別を考える可能性を考慮している。しかし、感覚データを経験の主要な対象として最初に導入した以上、ムーアが認める以上 の経験について仮定しない限り、ここで区別をつけることは容易ではない。 ムーアは知覚について、他のどのテーマよりも広範にわたって書いている。これらの著作において、彼はここで提示した3つの選択肢の間を行き来しているが、 確固たる結論には至っていない。外から見ると、彼を迷わせたのは感覚データ仮説そのものであり、知覚に関する彼の考察は、この仮説の帰謬法則の延長上にあ るものと考えられる。デュカスによる副詞理論に、センスデータ仮説に代わる真剣な選択肢を見出したのは、彼のキャリアの終盤になってからだった。しかし、 デュカスによる副詞理論は、ムーアが直面した困難を簡単に回避する方法を提供するものではない。ムーアは、感覚領域の構造が副詞的な用語でどのように解釈 できるのかがまったく明らかではないと、デュカスに正しく異議を唱えた。しかし、他にも選択肢はあった。特に、20世紀初頭から現象学運動は、感覚データ 説の落とし穴をいくつか回避する、知覚の本質的な意図主義の認識に基づく知覚の説明を提供していた。ムーアがこの立場に立ち向かわなかったのは残念なこと だが、この距離感は、当時、分析学と現象学の伝統の関係を特徴づけるものだった。 |

|

| 6. 常識と確実性 ムーアが理想主義を否定する上で重要な点は、彼が「常識」的リアリズムの立場を肯定したことであり、それによれば、我々の日常的な常識的な世界観は概ね正 しいということになる。ムーアは、1910年から1911年にかけての講義『哲学の主要問題』で初めてこの立場を明確に支持したが、1925年に「哲学上 の立場」を説明してほしいという依頼に応えて、これを「常識の擁護」として発表した際に、この立場を自身のものとした。ムーアは論文の冒頭で、「私の体が 生まれる前から地球はずっと存在していた」といった「自明の理」を多数列挙している。これらの自明の理について、彼はまず、自分がそれらを確かに知ってい ること、次に、他の人々も同様に、自分自身に関する同等の自明の理の真実を確かに知っていること、そして第三に、彼がこの第二の一般的な真実を知っている こと(そして、暗黙のうちに、他の人々も知っていること)を主張している。つまり、これらの自明の理の真実性と一般的な知識は、常識の問題であるというこ とだ。これらの自明の理を提示した上で、ムーアは一部の哲学者たちがその真理を否定している、あるいはより一般的には、われわれがそれらを知っていること を否定している(ムーアによれば、彼らもまたそれらを知っているにもかかわらず)ことを認め、これらの否定は矛盾しているか、あるいは正当化されないもの であることを示そうとしている。これらの主張は、急進的な哲学論争にはほとんど余地がないように思われるかもしれない。しかし、論文の最後の部分でムーア は、彼の常識の擁護論は、常識的世界観を構成する真理命題をどのように分析するかという問題を完全に未解決のままにしていると主張している。分析は、分析 される命題の真実性と認識可能性と矛盾しない限り、望む限りラディカルなものであってよい。したがって、例えば、彼は、物理的世界に関する命題の現象論的 分析が正しいことを哲学的な議論が示す可能性を認めることに満足している。 この最後の指摘は、ムーアの常識論の擁護が、当初考えられていたほど哲学理論の制約にはならないことを示している。なぜなら、哲学分析は、真実命題の「主 要な、あるいは究極の主題」に関する事実を明らかにすることができるが、それは決して常識が想定するようなものではないからだ。この含意は、ムーアの最も 有名な論文である「外部世界の証明」を考察する際に重要となる。この論文は、ムーアがケンブリッジ大学の教授職を退く直前の1939年に英国学士院で行っ た講演の原稿である。ムーアはここで、カントが以前に自らに課した課題、すなわち「外部対象」の存在証明を行うという課題を自らに課している。講演の大部 分は、「外部対象」として数えられるものを解明することに費やされ、ムーアは、それらは我々の経験に依存しない存在であると主張する。つまり、そのような ものの存在を証明できれば、「外部世界」の存在を証明できると主張するのだ。ムーアは、自分にはそれができると主張する。 どのようにしてか?両手を挙げ、右手で特定のジェスチャーをしながら「ここに片方の手がある」と言い、左手で特定のジェスチャーをしながら「そしてもう片方もある」と付け加えることによってである(『外部世界の証明』166ページ)。 ムーアは、この手のデモンストレーションは「完全に厳密な」外部の物体の存在証明であると主張する。その前提は確かに結論を必然的に導き、それらは彼が真実であると知っていたことである。 私は、あるジェスチャーを最初の「ここ」という言葉と組み合わせることで示された場所に片方の手があること、そして、あるジェスチャーを2番目の「ここ」 という言葉と組み合わせることで示された異なる場所にもう片方の手があることを知っていた。それを知らず、ただ信じていただけだなどと、そんな馬鹿げたこ とを言うのはどうだろうか。私が今、立って話していることを知らないなどと言うのは、結局のところ、私は立っていないのかもしれないし、私が立っていると いうことも確実ではないのかもしれないと言っているようなものだ。(『外部世界の証明』166ページ) このパフォーマンスの意義については、ムーアが提示して以来、議論が続いている。一般的に、ムーアはここで哲学的懐疑論を論駁しようとしたと考えられてい る。そして、彼のパフォーマンスは興味深いものの、失敗に終わったとされている。しかし、この解釈は正しくない。ムーアの公言した目的は、外部世界の存在 を証明することであり、外部世界の存在に関する知識を証明することではない。ムーア自身、その後の講義の議論の中で、この点を明確に示している。 私は、一部の哲学者によってなされた2つの異なる命題を区別することがある。すなわち、(1)「物質的なものは存在しない」という命題と、(2)「物質的 なものが存在することを誰も確実に知ることはできない」という命題である。そして、私が最近行った英国学士院での講演「外部世界の証明」では、最初の命題 について、次のように暗示した。すなわち、片手を挙げ、「この手は物質的なものである。したがって、少なくとも1つの物質的なものがある」と言うことに よって、このようにして、それが偽であることを証明することができる、と。しかし、2つの命題のうちの2つ目に関しては… それがこのような単純な方法で証明できると私がほのめかしたことは一度もないと思う…(『私の批判者たちへの反論』668ページ) したがって、反懐疑的な意図はさておき、評価が必要なのは、ムーアの証明の形而上学的意義であり、それは「外部世界」の証明である。明らかに、ここで重要 なのは「外部」として数えられるものすべてであり、特に、ムーアが自分の手の存在を証明したことが、経験や思考とはまったく関係のない事物の存在を証明す るものかどうかということである。それは証明できないことは明らかである。なぜなら、その問題は、理想主義に関するより広範な哲学的な疑問に依存するもの であり、そのような方法では解決できないからである。ここで、ムーア自身の真理に関する疑問と分析に関する疑問の区別を導入すべきである。ムーアの「証 明」は、彼の手という単純な自明の理の「経験的」真実を示しているが、この自明の理の分析という問題は完全に放置されている。しかし、手のようなものは経 験や思考から完全に独立しているのかという「超越論的」な問いは、分析のレベルで答えられるべきものである。 私が指摘したように、ムーアは自身の「証明」を懐疑論の反駁として意図したわけではないが、彼は懐疑論的な見解に対しては頻繁に反論していた。初期の著作 では、先ほど引用した箇所があるにもかかわらず、彼は「これは鉛筆であると私は知っている」といった単純な知識の事例を提示するだけで懐疑論を反駁できる と考えているかのような印象を与えることがある。しかし、よく考えてみると、彼のこの戦略はより巧妙であることがわかる。彼は、私たちが知識を理解するの は主にこの種の単純な事例を通してであり、したがって懐疑論の議論は自己矛盾していると主張したいのだ。なぜなら、懐疑論は知識の限界に関する一般的な原 則に依存し、それによって知識の理解がある程度想定されるが、一方で、そのような単純な事例は存在しないとほのめかすことによって、この理解を損なうから である。しかし、この種の議論の説得力は疑わしい。懐疑論者は、知識の可能性を帰謬法として常に自分の主張を提示できるからだ。また、ムーアが懐疑論者の 実用上の矛盾を証明しようとした他の試みにも同じことが当てはまる。 ムーアは、最後の著作である『懐疑論の四形態』と『確実性』の2作において、おそらくそれ以前の議論や自身の「証明」の誤解に不満を抱き、再びこの問題に 戻り、デカルト主義的懐疑論を論駁するという課題に自ら挑んだ。悪名高いことに、『確実性』の終わりには、ムーアは敗北を認めている。自分が夢を見ている のではないと知らないのであれば、自分が立って話していることなど知らないことになる、と同意した上で、夢を見ているのではないと確実に知ることはできな いことを(留保付きで)受け入れている。ほとんどの論者は、ムーアがここで道を見失ったことに同意している。しかし、ムーアには明らかな間違いがないた め、どこで道を見失ったのかは明らかではない。それでも、懐疑論に対する「常識」的な反応の妥当性は、このトピックに関する後世の議論における重要な特徴 として残っている。例えば、ムーアが、ラッセルが懐疑論を頻繁に公言していたにもかかわらず、ラッセルは疑いの余地なく、何千回もの場面で自分が座ってい ることを完全に確信していたと述べたのは明らかである。しかし、ここで難しいのは、ムーアの「常識」による確実性の主張の重要性を示しながら、疑い論法の 主張が知識は疑い論法の主張に直面しても正当化される必要はないという独断的な主張にならないようにすることである。私自身は、ムーアの影響を強く受けた ウィトゲンシュタインの著書『確実性について』が、このことを最もよく示していると考えているが、この場でそれを証明することはできない。 |

|

| 7. ムーアの遺産 ムーアは体系的な哲学者ではなかった。リードの常識哲学とは異なり、ムーアの「常識」は体系ではない。彼が「理論」を提示するのに最も近い倫理学において も、彼は善の体系的な説明を提供しようとするいかなる野望も明確に否定している。したがって、これまでの議論が示しているように、ムーアの遺産は主に、議 論、謎、挑戦の集合体である。すでに述べたものに加えて注目すべきものとしては、「ムーアのパラドックス」がある。もし私が何かについて誤解しているとす れば、それは事実ではないことを私が信じているということである。例えば、雨が降っていないのに、雨が降っていると信じている、などである。しかし、もし 私がこの誤解を自分自身に帰属させ、「雨は降っていないが、私は雨が降っていると信じている」と述べた場合、私の発言は不条理である。なぜそうなるのか? なぜ、自分自身について真実であることを私が言うことが不合理なのか? ムーア自身は、この説明は、一般的に人は自分が言ったことを信じているというだけだと考えた。つまり、「雨は降っていない」と言うとき、私はこれを信じて いるということを暗に意味している。しかし、ウィトゲンシュタインは、この説明は表面的であり、ムーアは、思考者としての自己同一性に関する、より深い現 象を指摘していたと正しく理解していた。 このケースは典型的なものである。ムーアは哲学的な「現象」を特定する類まれな能力を持っていた。彼自身のそれらの重要性の議論は必ずしも満足のいくもの ではないが、彼はまず間違いなく、自身の誤りを認めるだろう。重要なのは、我々が彼と同じ出発点に立つのであれば、我々は自分自身と世界について重要なこ とを教えてくれる何かに取り組んでいると確信できるということだ。 |

|

| Bibliography Primary Sources [* indicates the edition used for page references in this entry] ‘The Nature of Judgment’ Mind 8 (1899) 176-93. Reprinted in *G. E. Moore: Selected Writings1-19. ‘Truth’ in J. Baldwin (ed.) Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology Macmillan, London: 1901-2. Reprinted in *G. E. Moore: Selected Writings 20-2. ‘The Refutation of Idealism’ Mind 12 (1903) 433-53. Reprinted in Philosophical Studies and in *G. E. Moore: Selected Writings23-44. Principia Ethica Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1903. *Revised edition with ‘Preface to the second edition’ and other papers, ed. T. Baldwin, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1993. Ethics Williams & Norgate, London: 1912. ‘External and Internal Relations’ Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society20 (1919-20) 40-62. Reprinted in Philosophical Studies and in *G. E. Moore: Selected Writings 79-105. ‘The Conception of Intrinsic Value’ in Philosophical Studies. Reprinted in *Revised edition of Principia Ethica, 280-98. Philosophical Studies K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co, London: 1922. ‘A Defence of Common Sense’ in J. H. Muirhead (ed.) Contemporary British Philosophy (2nd series), Allen and Unwin, London: 1925, 193-223. Reprinted in Philosophical Papers and in *G. E. Moore: Selected Writings106-33. ‘Is Existence a Predicate?’ Aristotelian Society Supplementary volume 15 (1936) 154-88. Reprinted in Philosophical Papers and in *G. E. Moore: Selected Writings 134-46. ‘Proof of an External World’ Proceedings of the British Academy 25 (1939) 273-300. Reprinted in Philosophical Papers and in *G. E. Moore: Selected Writings 147-70. ‘A Reply to My Critics’ in P. A. Schilpp (ed.) The Philosophy of G. E. Moore Northwestern University Press, Evanston ILL: 1942, 535-677. Some Main Problems of Philosophy George, Allen and Unwin, London: 1953. ‘Certainty’ in Philosophical Papers 226-251. Reprinted in *G. E. Moore: Selected Writings 171-96. Philosophical Papers George, Allen and Unwin, London: 1959. The Elements of Ethics, T. Regan (ed.), Temple University Press, Philadelphia PA: 1991. G. E. Moore: Selected Writings, T. Baldwin (ed.), Routledge, London: 1993. For a complete bibliography of Moore's published writings up to 1966, see P. A. Schilpp (ed.) The Philosophy of G. E. Moore Northwestern University Press, Evanston ILL: 1942, 691-701. Secondary Sources General P. A. Schilpp (ed.) The Philosophy of G. E. Moore Northwestern University Press, Evanston ILL: 1942. A. Ambrose and M. Lazerowitz (eds.) G. E. Moore: Essays in Retrospect Allen and Unwin, London: 1970. T. Baldwin G. E. Moore Routledge, London: 1990. Section 1. Life and Career J. M. Keynes ‘My Early Beliefs’ in Two Memoirs Hart-Davis, London: 1949. G. Ryle ‘G. E. Moore’ in Collected Papers I, Hutchinson, London: 1971. Section 2. The Refutation of Idealism C. Ducasse ‘Moore's Refutation of Idealism’ in P. A. Schilpp (ed.) The Philosophy of G. E. Moore. P. Hylton Russell, Idealism and the Emergence of Analytic Philosophy Oxford University Press, Oxford: 1990. Section 3. Principia Ethica C. D. Broad ‘Certain Features in Moore's Ethical Doctrines’ in P. A. Schilpp (ed.) The Philosophy of G. E. Moore. W. J. Frankena ‘Obligation and Value in the Ethics of G. E. Moore’ in P. A. Schilpp (ed.) The Philosophy of G. E. Moore. W. J. Frankena ‘The Naturalistic Fallacy’ Mind 48 (1939). N. M. Lemos Intrinsic Value. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1994. W. D. Ross The Right and the Good Oxford University Press, Oxford: 1930. N. Sturgeon ‘Ethical Intuitionism and Ethical Naturalism’ in P. Stratton-Lake (ed.) Ethical Intuitionism Oxford University Press, Oxford: 2002. Ethics 113 (2003) — special edition for centenary of Principia Ethica The Journal of Value Inquiry 37 (2003) — special edition for centenary of Principia Ethica. Section 4. Philosophical Analysis B. Russell The Problems of Philosophy, Williams and Norgate, London: 1912. N. Malcolm ‘Moore and Ordinary Language’ in P. A. Schilpp (ed.) The Philosophy of G. E. Moore. J. Wisdom ‘Moore's Technique’ in P. A. Schilpp (ed.) The Philosophy of G. E. Moore. Section 5. Perception and Sense-data O. K. Bowsma ‘Moore's Theory of Sense-data’ in P. A. Schilpp (ed.) The Philosophy of G. E. Moore. R. Chisholm ‘The Theory of Appearing’ in R. Swarz (ed.) Perceiving, Sensing and Knowing Doubleday & Co., Garden City NY: 1965, 168-86. G. A. Paul ‘Is There a Problem about Sense-Data?’ in R. Swarz (ed.) Perceiving, Sensing and Knowing Doubleday & Co., Garden City NY: 1965, 271-87. Section 6. Common Sense and Certainty T. Clarke ‘The Legacy of Skepticism’ Journal of Philosophy (1972). N. Malcolm ‘Defending Common Sense’ Philosophical Review (1949). N. Malcolm ‘Moore and Wittgenstein on the sense of “I Know”’ in Thought and Language, Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY: 1977. M. McGinn Sense and Certainty Blackwell, Oxford: 1989. A. Stroll Moore and Wittgenstein Oxford University Press, New York: 1994. B. Stroud The Significance of Philosophical SkepticismOxford University Press, Oxford: 1984. L. Wittgenstein On Certainty Blackwell, Oxford: 1969. C. J. Wright ‘Facts and Certainty’ Proceedings of the British Academylxxi (1985) 429-72. Section 7. Moore's Legacy L. Wittgenstein Philosophical Investigations Blackwell, Oxford: 1953 (see part II section x for ‘Moore's paradox’). Academic Tools sep man icon How to cite this entry. sep man icon Preview the PDF version of this entry at the Friends of the SEP Society. inpho icon Look up topics and thinkers related to this entry at the Internet Philosophy Ontology Project (InPhO). phil papers icon Enhanced bibliography for this entry at PhilPapers, with links to its database. Other Internet Resources G.E. Moore (maintained by Garth Kemerling) Related Entries analysis | Ayer, Alfred Jules | Bradley, Francis Herbert | consequentialism | Kant, Immanuel | metaethics | Moore, George Edward: moral philosophy | moral non-naturalism | naturalism: moral | perception: epistemological problems of | perception: the problem of | propositions | reasons for action: justification, motivation, explanation | Reid, Thomas | Russell, Bertrand | sense data | skepticism | supervenience | truth: identity theory of | value: intrinsic vs. extrinsic | Wittgenstein, Ludwig |

参考文献 一次資料 [*印は、本項目でページを参照する際に使用した版を示す] 「判断の本質」Mind 8 (1899) 176-93。*G. E. Moore: Selected Writings1-19 に再掲。 「真理」J. ボールドウィン編『哲学・心理学辞典』マクミラン、ロンドン:1901-2年。再版:*G. E. ムーア著『セレクテッド・ライティングス』20-2ページ。 「観念論の反駁」Mind 12(1903年)433-53ページ。再版:Philosophical Studies』および*G. E. ムーア著『セレクテッド・ライティングス』23-44ページ。 プリンキピア・エティカ ケンブリッジ大学出版局、ケンブリッジ:1903年。*「第2版への序文」およびその他の論文を追加した改訂版、編者T. ボールドウィン、ケンブリッジ大学出版局、ケンブリッジ:1993年。 倫理学 ウィリアムズ・アンド・ノーゲート、ロンドン:1912年。 「外部と内部の関係」Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society20 (1919-20) 40-62. Philosophical Studiesおよび*G. E. Moore: Selected Writings 79-105に再掲。 「本質的価値の概念」Philosophical Studies。*Principia Ethicaの改訂版、280-98に再掲。 Philosophical Studies K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co, London: 1922. 『常識の擁護』J. H. Muirhead (編) Contemporary British Philosophy (第2シリーズ), Allen and Unwin, London: 1925, 193-223. 『哲学的論文集』および*『G. E. Moore: Selected Writings』106-33にも再録。 「存在は述語か?」アリストテレス協会補巻15(1936年)154-88頁。哲学論文集および*G. E. Moore: Selected Writings 134-46頁にも再録。 「外部世界の証明」英国学士院紀要25(1939年)273-300頁。Philosophical Papers および*G. E. Moore: Selected Writings 147-70 に再録。 P. A. Schilpp (ed.) The Philosophy of G. E. Moore Northwestern University Press, Evanston ILL: 1942, 535-677. Some Main Problems of Philosophy George, Allen and Unwin, London: 1953. 「哲学論文」における「確実性」226-251ページ。*G. E. Moore: Selected Writings 171-96に再掲。 哲学論文 George, Allen and Unwin, London: 1959. The Elements of Ethics, T. Regan (ed.), Temple University Press, Philadelphia PA: 1991. G. E. Moore: Selected Writings, T. Baldwin (ed.), Routledge, London: 1993. 1966年までのムーアの出版物の完全な書誌については、P. A. Schilpp (ed.) The Philosophy of G. E. Moore Northwestern University Press, Evanston ILL: 1942, 691-701を参照のこと。 二次資料 一般 P. A. Schilpp (編) 『G. E. ムーアの哲学』 Northwestern University Press, Evanston ILL: 1942. A. Ambrose and M. Lazerowitz (編) 『G. E. ムーア:回顧録』 Allen and Unwin, London: 1970. T. Baldwin 『G. E. ムーア』 Routledge, London: 1990. 第1節 生涯と経歴 J. M. ケインズ『私の初期の信念』Two Memoirs(2つの回想録)ハート・デイヴィス、ロンドン:1949 年。 G. Ryle『G. E. Moore』Collected Papers I(論文集 I)ハッチンソン、ロンドン:1971 年。 第2節 観念論の反駁 C. デュカス「ムーアの観念論に対する反駁」P. A. シルップ編『G. E. ムーアの哲学』 P. ヒルトン・ラッセル著『観念論と分析哲学の誕生』オックスフォード大学出版局、オックスフォード、1990年 第3章『プリンキピア・エティカ C. D. Broad「ムーアの倫理学における特徴」P. A. Schilpp(編)『G. E. ムーアの哲学』 W. J. Frankena「G. E. ムーアの倫理学における義務と価値」P. A. Schilpp(編)『G. E. ムーアの哲学』 W. J. Frankena『自然主義的誤謬』Mind 48 (1939)。 N. M. Lemos『本質的価値』ケンブリッジ大学出版局、ケンブリッジ:1994年。 W. D. Ross『正義と善』オックスフォード大学出版局、オックスフォード:1930年。 N. スタージョン「倫理的直観論と倫理的自然主義」P. ストラットン=レイク編『倫理的直観論』オックスフォード大学出版局、オックスフォード、2002年。 倫理学 113(2003年)—『プリンキピア・エティカ』出版100周年記念特別号 価値探究ジャーナル 37(2003年)—『プリンキピア・エティカ』出版100周年記念特別号。 第4節。哲学的分析 B. ラッセル著『哲学の問題』ウィリアムズ・アンド・ノーゲート、ロンドン、1912年。 N. マルコム著「ムーアと日常言語」P. A. シルップ編『G. E. ムーアの哲学。 J. ウィズダム著「ムーアのテクニック」P. A. シルップ編『G. E. ムーアの哲学。 第5章 知覚と感覚データ O. K. Bowsma「ムーアの感覚データ理論」P. A. Schilpp(編)『G. E. ムーアの哲学』 R. Chisholm「出現の理論」R. Swarz(編)『知覚、感覚、認識』Doubleday & Co., Garden City NY: 1965, 168-86. G. A. ポール「感覚データに問題があるか?」R. Swarz (編)『知覚、感覚、認識』Doubleday & Co., Garden City NY: 1965, 271-87. 第6節. 常識と確実性 T. クラーク「懐疑論の遺産」『哲学ジャーナル』(1972年)。 N. マルコム『常識の擁護』Philosophical Review(1949 年)。 N. マルコム「“I Know”の意味におけるムーアとウィトゲンシュタイン」Thought and Language(コーネル大学出版、ニューヨーク州イサカ:1977 年)。 M. マギン『Sense and Certainty』(ブラックウェル、オックスフォード:1989 年)。 A. Stroll Moore and Wittgenstein Oxford University Press, New York: 1994. B. Stroud The Significance of Philosophical SkepticismOxford University Press, Oxford: 1984. L. Wittgenstein On Certainty Blackwell, Oxford: 1969. C. J. Wright 「事実と確実性」Proceedings of the British Academylxxi (1985) 429-72. 第7節 ムーアの遺産 L. ウィトゲンシュタイン『哲学探究』Blackwell, Oxford: 1953(「ムーアのパラドックス」については第II部第10章を参照)。 学術ツール この項目の引用方法 この項目のPDF版をFriends of the SEP Societyでプレビューする。 この項目に関連するトピックや思想家をInternet Philosophy Ontology Project (InPhO)で調べる。 この項目に関する詳細な文献目録(PhilPapers、データベースへのリンク付き) その他のインターネット情報源 G.E. Moore (Garth Kemerling によるメンテナンス) 関連項目 分析 | エイヤー、アルフレッド・ジュール | ブラッドリー、フランシス・ハーバート | 帰結主義 | カント、イマニュエル | メタ倫理学 | ムーア、ジョージ・エドワード:道徳哲学 | 道徳的非自然主義 | 自然主義:道徳 | 知覚:認識論上の問題 | 知覚:問題 | 命題 | 行動の理由:正当化、動機づけ、説明 | リード、トマス | ラッセル、バートランド | 感覚データ | 懐疑論 | 超越論的現象学 | 真理:同一性理論の | 価値:本質的 vs. 非本質的 内在的 vs. 外在的 | ウィトゲンシュタイン、ルートヴィヒ |

| https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moore/ |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆