Moore's Paradox

ムーアのパラドクス

Moore's Paradox

かいせつ:池田光穂

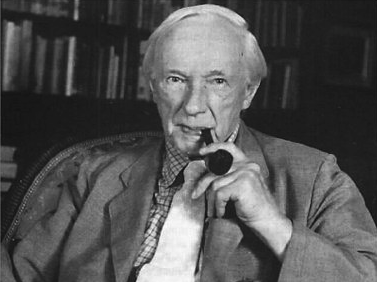

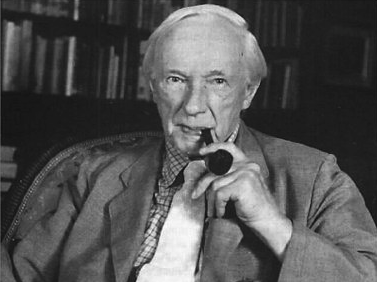

1944年のケンブリッジ大学のウィトゲ ンシュタインが主宰していたモラル・サイエンス・クラブで、ジョージ・エドワー ド・ムーア(1873- 1958)が講演で提案し、1945年10月25日にウィトゲンシュタインが命名した日常言語上のパラドクス。

ムーアのパラドクスは、彼自身が講演した タイトルのように「Pである、しかしわたくしはPであるとは思わない」 という形であらわされる言語表現 である。

このパラドクスの具体例には次のようなも のがある。スミスは部屋を出ていったけど、わたくしはそうは思わない。この部屋には暖炉があるが、私は そうは思わない。

これは「スミスは部屋を出ていった。しか し、スミスは部屋に残っている」というような、論理矛盾をきたしているものではない。

ムーアのパラドクスは、論理矛盾はしてい ないが、受け入れ難いものである。したがって、ウィトゲンシュタインによると、それは言語の論理に挑戦 するものである。なぜなら、論理矛盾をおこさずとも、言語には使えないものがあるということである*。

これは、ウィトゲンシュタインをして、言 語による厳密な論理よりも、日常の言語の使い方についての関心をもたらすことになったという。

さて、医療の現場ではムーアのパラドクス に出会う事例が多くある。「私はがん患者だが、自分はがんとは思わない」というものである。

また医療人類学では、パラドクスというよ りも論理的な矛盾としてそのまま書名[著者本人は、論理的な命題と矛盾することについての実践的様態を 明らかにしたが、このような矛盾を認める患者のサブカルチャーの論理について考察を十分には行っていない]『病気だけど病気でない』という論文もある。

*[脚注]2つの文章からなりたつような 無矛盾ではないが使えない言明は他にもあります。最も有名なのが、ノー ム・チョムスキーの『統語構造 Syntactic Structures』1957に出てくる、Colourless green ideas sleep furiously. (色のない緑色の考えたちは、荒れ狂ったように眠る)というのがあります。これは、文法上は間違いがない[=構文は正しい]にもかかわらず、あり得ない文 [=意味論的にはナンセンス]です。ただし、この文章そのものは一文だけでナンセ ンスですが、ムーアのパラドクスは、ナンセンスではない2つの構文が、矛 盾をおこさないにも関わらず、完全におかしいという点で、チョムスキーの例文と全くおなじという意味ではありません。

[文全体に対する註釈]

ムーアは、カント流の倫理学、すなわち人間存在において「なになにである(be)」という事実から、「なにな にすべきである(ought)」を 導くようなやり方を、自然主義的誤謬であると批判したその人です。ムー アのカント批判はこのページの引用者にとってはまったく妥当な主張であり、また、こ のページで指摘されているパラドックスに気づいたことも、さすが自然主義的誤謬を指摘した哲学者ならでは指摘であると思いました。(→自然主義的論法について)

これと類似しますが、全く異なった学問上 の意義をもつ、ナンセンスな構文に, "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously"(無色の緑の考えは荒れ狂いながら眠る)というのがあります。これは、ノーム・チョムスキーのものですが、ナンセンスだが文法的には なんらおかしいものではないという事例にしばしば登場するものです。

| Moore's paradox

concerns the apparent absurdity involved in asserting a first-person

present-tense sentence such as "It is raining, but I do not believe

that it is raining" or "It is raining, but I believe that it is not

raining." The first author to note this apparent absurdity was George

E. Moore.[1] These 'Moorean' sentences, as they have become known, are

paradoxical in that while they appear absurd, they nevertheless Can be true; Are (logically) consistent; and Are not (obviously) contradictions. The term 'Moore's paradox' is attributed to Ludwig Wittgenstein,[2] who considered the paradox Moore's most important contribution to philosophy.[3] Wittgenstein wrote about the paradox extensively in his later writings,[a] which brought Moore's paradox the attention it would not have otherwise received.[4] Moore's paradox has been associated with many other well-known logical paradoxes, including, though not limited to, the liar paradox, the knower paradox, the unexpected hanging paradox, and the preface paradox.[5] There is currently not any generally accepted explanation of Moore's paradox in the philosophical literature. However, while Moore's paradox remains a philosophical curiosity, Moorean-type sentences are used by logicians, computer scientists, and those working with artificial intelligence as examples of cases in which a knowledge, belief, or information system is not modified in response to new data.[6] |

ムーアのパラドックスは、"It is raining, but

I don't believe that it is raining "や "It is raining, but I believe

that it is not raining

"のような一人称の現在形の文を主張する際の明らかな不条理に関するものである。この明らかな不条理を最初に指摘したのは、ジョージ・E・ムーアである

[1]。これらの「ムーア的」文は、不条理に見えるが、それにもかかわらず次のような逆説的な文として知られるようになった。 真である可能性がある; 論理的に)一貫している 明らかに)矛盾していない。 ムーアのパラドックス」という用語はルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインに起因しており[2]、彼はこのパラドックスをムーアの哲学に対する最も重要な貢 献であると考えていた[3]。ウィトゲンシュタインは後年の著作でこのパラドックスについて幅広く書いており[a]、その結果ムーアのパラドックスは他の 方法では注目されることはなかったであろう[4]。 ムーアのパラドックスは、嘘つきのパラドックス、知識人のパラドックス、予期せぬ首吊りのパラドックス、序文のパラドックスなど、これらに限定されない が、他の多くのよく知られた論理的なパラドックスと関連している[5]。 ムーアのパラドックスに関する一般的な説明は、現在のところ哲学の文献にはない。しかし、ムーアのパラドックスが哲学的好奇心のままである一方で、ムーア 型の文は、知識、信念、情報システムが新しいデータに対応して修正されない場合の例として、論理学者、コンピュータ科学者、人工知能に携わる人々によって 使用されている[6]。 |

| The problem Since Jaakko Hintikka's seminal treatment of the problem,[7] it has become standard to present Moore's paradox by explaining why it is absurd to assert sentences that have the logical form: "P and NOT(I believe that P)" or "P and I believe that NOT-P." Philosophers refer to these, respectively, as the omissive and commissive versions of Moore's paradox. Moore himself presented the problem in two versions.[1][8] The more fundamental manner of stating the problem starts from the three premises following: It can be true at a particular time both that P, and that I do not believe that P. I can assert or believe one of the two at a particular time. It is absurd to assert or believe both of them at the same time. I can assert that it is raining at a particular time. I can assert that I don't believe that it is raining at a particular time. If I say both at the same time, I am saying or doing something absurd. But the content of what I say—the proposition the sentence expresses—is perfectly consistent: it may well be raining, and I may not believe it. So why can I not assert that it is so?[citation needed] Moore presents the problem in a second, distinct, way: It is not absurd to assert the past-tense counterpart; e.g., "It was raining, but I did not believe that it was raining." It is not absurd to assert the second- or third-person counterparts to Moore's sentences; e.g., "It is raining, but you do not believe that it is raining," or "Michael is dead, but they do not believe that he is." It is absurd to assert the present-tense "It is raining, and I don't believe that it is raining."[citation needed] I can assert that I was a certain way—e.g., believing it was raining when it wasn't—and that you, he, or they are that way but not that I am that way.[citation needed] Subsequent philosophers have said that there is an apparent absurdity in asserting a first-person future-tense sentence such as "It will be raining, and I will believe that it is not raining."[9] |

問題 ヤーッコ・ヒンティッカがこの問題を扱って以来[7]、ムーアのパラドックスを提示する際には、論理的な形式を持つ文を主張することがなぜ不合理なのかを 説明するのが定番となっている: 「PとNOT(私はPを信じている)」あるいは「Pと私はNOT-Pを信じている」という論理形式を持つ文を主張することがなぜ不合理なのかを説明するこ とによって、ムーアのパラドックスを提示することが標準となっている。哲学者たちは、これらをそれぞれムーアのパラドックスの省略版と委託版と呼んでい る。 ムーア自身はこの問題を2つのバージョンで提示している[1][8]。 より基本的な問題の述べ方は、以下の3つの前提から始まる: ある特定の時点において、Pと、Pを信じていないということの両方が真である可能性がある。 私はある時点で、この2つのうちの1つを主張することも信じることもできる。 その両方を同時に主張したり信じたりするのは不合理である。 ある時刻に雨が降っていると断言することができる。ある時刻に雨が降っているとは思わないと断言することもできる。もしその両方を同時に言うなら、私は何 か不合理なことを言ったりやったりしていることになる。雨は降っているかもしれないし、降っていないと信じているかもしれない。では、なぜ私はそうだと断 言できないのだろうか? ムーアはこの問題を2つ目の、明確な方法で提示している: 例えば、"It was raining, but I didn't believe that it was raining."(雨が降っていたが、私は雨が降っているとは信じていなかった)というように、過去形の対格を主張することは不合理ではない。 例えば、"It is raining, but you don't believe that it is raining." や "Michael is dead, but they don't believe that he is." のようにである。 現在形の "It is raining, and I don't believe that it is raining"[要出典]を主張するのは馬鹿げている。 例えば、雨が降っていないのに雨が降っていると信じているなどである。 その後の哲学者たちは、「雨が降るだろう、そして私は雨が降っていないと信じるだろう」というような一人称の未来時制の文を主張することには明らかな不条 理があると述べている[9]。 |

| Proposed explanations Philosophical interest in Moore's paradox, since Moore and Wittgenstein, has experienced a resurgence, starting with, though not limited to, Jaakko Hintikka,[7] continuing with Roy Sorensen,[5] David Rosenthal,[10] Sydney Shoemaker[11] and the first publication, in 2007, of a collection of articles devoted to the problem.[12] There have been several proposed constraints on a satisfactory explanation in the literature, including (though not limited to): It should explain the absurdity of both the omissive and the commissive versions. It should explain the absurdity of both asserting and believing Moore's sentences. It should preserve, and reveal the roots of, the intuition that contradiction (or something contradiction-like) is at the root of the absurdity. The first two conditions have generally been the most challenged, while the third appears to be the least controversial. Some philosophers have claimed that there is, in fact, no problem in believing the content of Moore's sentences (e.g. David Rosenthal). Others (e.g. Sydney Shoemaker) claim that an explanation of the problem at the level of belief will automatically provide us with an explanation of the absurdity at the level of assertion via the linking principle that what can reasonably be asserted is determined by what can reasonably be believed. Some have also denied (e.g. Rosenthal) that a satisfactory explanation to the problem need be uniform in explaining both the omissive and commissive versions. Most of the explanations offered of Moore's paradox are united in claiming that contradiction is the basis of the absurdity. One type of explanation at the level of assertion exploits the opinion that assertion implies or expresses belief in some way, so that if someone asserts that p they imply or express the belief that p. Several versions of this opinion exploit elements of speech act theory, which can be distinguished according to the particular explanation given of the link between assertion and belief. Whatever version of this opinion is preferred, whether cast in terms of the Gricean intentions (see Paul Grice) or in terms of the structure of Searlean illocutionary acts[13] An alternative opinion is that the assertion "I believe that p" often (though not always) functions as an alternative way of asserting "p", so that the semantic content of the assertion "I believe that p" is just p: it functions as a statement about the world and not about anyone's state of mind. Accordingly, what someone asserts when they assert "p and I believe that not-p" is just "p and not-p" Asserting the commissive version of Moore's sentences is again assimilated to the more familiar (putative) impropriety of asserting a contradiction.[14] Another alternative opinion, due to Richard Moran,[15] considering the existence of Moore's paradox as symptomatic of creatures who are capable of self-knowledge, capable of thinking for themselves from a deliberative point of view, as well as about themselves from a theoretical point of view. On this view, anyone who asserted or believed one of Moore's sentences would be subject to a loss of self-knowledge—in particular, would be one who, with respect to a particular 'object', broadly construed, e.g. person, apple, the way of the world, would be in a situation which violates, what Moran calls, the Transparency Condition: if I want to know what I think about X, then I consider/think about nothing but X itself. Moran's opinion seems to be that what makes Moore's paradox so distinctive is not some contradictory-like phenomenon (or at least not in the sense that most commentators on the problem have construed it), whether it be located at the level of belief or that of assertion. Rather, that the very possibility of Moore's paradox is a consequence of our status as agents (albeit finite and resource-limited ones) who are capable of knowing (and changing) their own minds. |

提案されている説明 ムーアとウィトゲンシュタイン以来、ムーアのパラドックスに対する哲学的関心は、ヤーッコ・ヒンティッカに始まり[7]、ロイ・ソレンセン[5]、デイ ヴィッド・ローゼンタール[10]、シドニー・シューメーカー[11]、そして2007年に初めて出版されたこの問題に特化した論文集[12]など、限定 はされないが復活を遂げている。 文献の中では、満足のいく説明に関するいくつかの制約が提案されている: 省略型と受託型の両方の不合理を説明しなければならない。 ムーアの文を主張することと信じることの両方の不合理を説明すべきである。 矛盾(あるいは矛盾に似たもの)が不条理の根源にあるという直観を維持し、その根源を明らかにすること。 最初の2つの条件は一般的に最も議論の的となっているが、3番目の条件は最も議論の余地が少ないように思われる。哲学者の中には、ムーアの文の内容を信じ ることに問題はないと主張する者もいる(デイヴィッド・ローゼンタールなど)。また、合理的に主張できるものは合理的に信じられるものによって決まるとい う連結原理によって、信念のレベルでの問題の説明が、主張のレベルでの不条理の説明を自動的に与えてくれると主張する者もいる(シドニー・シューメイカー など)。また、この問題に対する満足のいく説明は、省略型とコミッシブ型の両方を一様に説明する必要があることを否定する人もいる(ローゼンタールな ど)。ムーアのパラドックスに関する説明のほとんどは、矛盾が不条理の根底にあると主張することで一致している。 この意見のいくつかのバージョンは、発話行為理論の要素を利用したものであり、主張と信念の間の関連性についてどのような説明がなされるかによって区別さ れる。この意見のどのバージョンが好まれるにせよ、グライス的意図(ポール・グライス参照)の観点から投げかけられるにせよ、シアーリアン的発話行為の構 造の観点から投げかけられるにせよ[13]。 別の意見としては、「私はpだと思う」という主張は、(常にではないが)しばしば「p」を主張する別の方法として機能し、「私はpだと思う」という主張の 意味内容は単に「p」である。したがって、誰かが「pであり、pでないと信じている」と主張するときに主張していることは、「pであり、pでない」だけで ある。ムーアの文のコミッシブ・バージョンを主張することは、矛盾を主張するのにより馴染みのある(仮定上の)不適切さと再び同化する[14]。 リチャード・モランによる別の代替的な意見[15]は、ムーアのパラドックスの存在を、理論的な観点から自分自身について考えるだけでなく、熟慮的な観点 から自分自身について考えることのできる、自己認識のできる生き物の徴候であると考えている。この考え方によれば、ムーアの文章を主張したり信じた人は、 自己認識の喪失に陥ることになる-特に、広義に解釈される特定の「対象」、例えば、人、リンゴ、世界のあり方に関して、モランが「透明性の条件」と呼ぶも のに違反する状況に陥ることになる。モランの意見は、ムーアのパラドックスを際立たせているのは、信念のレベルであれ主張のレベルであれ、矛盾のような現 象ではない(少なくとも、この問題を論じる多くの論者が解釈してきたような意味ではない)ということのようだ。むしろ、ムーアのパラドックスの可能性その ものが、私たちが(有限で資源が限られているとはいえ)自分の考えを知る(そして変える)ことのできる主体であるということの帰結なのである。 |

| Belief Consistency Doublethink Doubt Doxastic logic Epistemology Contradiction Irrationality List of paradoxes Philosophy of mind Rationality Self-knowledge (psychology) Self-deception |

信念 一貫性 二重思考 疑念 ドクサスティック・ロジック 認識論 矛盾 非合理性 パラドックスのリスト 心の哲学 合理性 自己認識(心理学) 自己欺瞞 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moore%27s_paradox |

|

リンク

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099