Teaching you to pass from a piece of disguised nonsense to something that is patent nonsense

判然としたナンセンスへの誘い

Teaching you to pass from a piece of disguised nonsense to something that is patent nonsense

池田光穂

アンスコム翻訳の『哲学探究』(464)には、My aim is: to teach you to pass from a piece of disguised nonsense to something that is patent nonsense. とあるのに、日本の(ウィトゲンシュタイン)全集(8巻267頁)の藤本隆志訳には、貴方を教え導く(to teach you to pass)という文言がない。これでは、まるで、後者(=藤本隆志)はモノローグ哲学者の自分の意図や意思の開陳になってしまっており、前者(=ウィトゲ ンシュタイン)がもつ《哲学とは判然とする ナンセンス》ないしは《哲学はナンセンスなのだが、そのナンセンスは判然としないものなのではなく、判然としたナンセンスなのだ》というニュアンスが伝わ らない。そして彼=ウィトゲンシュタインは、それを教えたいと言っている。丘沢静也訳では、「私が教えようとしているのは、明白ではないナンセンスから明 白なナンセンスに移ること」となっている。

464. Was ich lehren will, ist: von einem

nicht offenkundigen

Unsinn zu einem offenkundigen übergehen.

255「哲学者が問いを処置することは、ちょうど病気(病い)への処置と似ている」The philosopher's treatment of a question is like the treatment of an illness. ドイツ語から翻訳した丘沢静也訳では「哲学者は問いをあつかう。病気を治療するように」となっている(岩波書店、175頁、2013年)。255. Der Philosoph behandelt eine Frage; wie eine Krankheit.

| Nonsense

is a form of communication, via speech, writing, or any other symbolic

system, that lacks any coherent meaning. In ordinary usage, nonsense is

sometimes synonymous with absurdity or the ridiculous. Many poets,

novelists and songwriters have used nonsense in their works, often

creating entire works using it for reasons ranging from pure comic

amusement or satire, to illustrating a point about language or

reasoning. In the philosophy of language and philosophy of science,

nonsense is distinguished from sense or meaningfulness, and attempts

have been made to come up with a coherent and consistent method of

distinguishing sense from nonsense. It is also an important field of

study in cryptography regarding separating a signal from noise. |

ナンセンスとは、話し言葉や文章、その他の象徴体系を介した、首尾一貫

した意味を欠くコミュニケーション形態のことである。通常の用法では、ナンセンスは時に不条理や荒唐無稽と同義である。多くの詩人、小説家、作詞家がナン

センスを作品に用いており、純粋なコミカルな娯楽や風刺から、言語や推論に関する論点を説明するためまで、様々な理由で作品全体をナンセンスで構成するこ

ともある。言語哲学や科学哲学では、ナンセンスはセンスや意味性とは区別され、センスとナンセンスを区別する首尾一貫した一貫性のある方法を考え出そうと

試みられてきた。また、暗号学においても、ノイズから信号を分離するための重要な研究分野である。 |

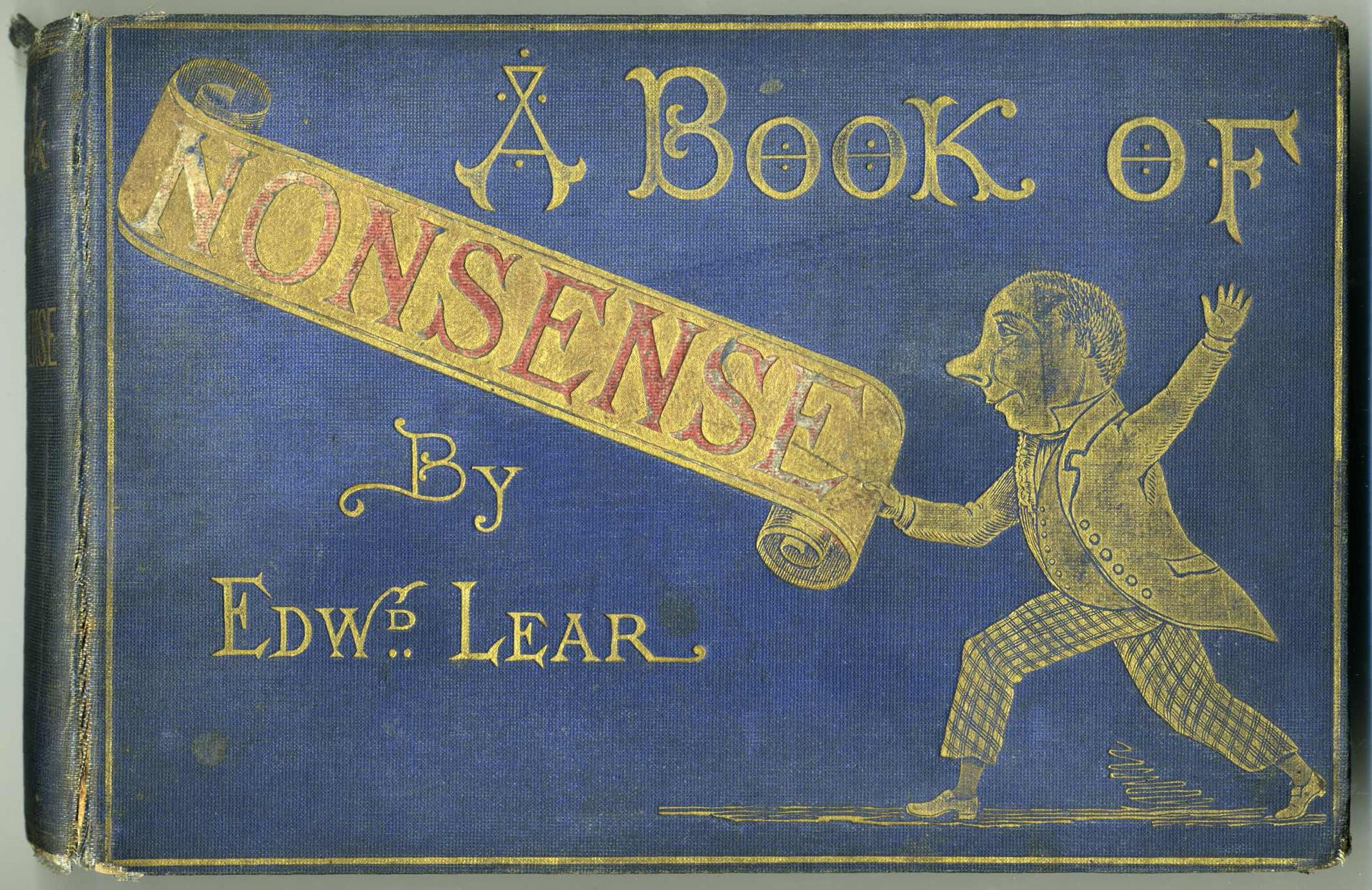

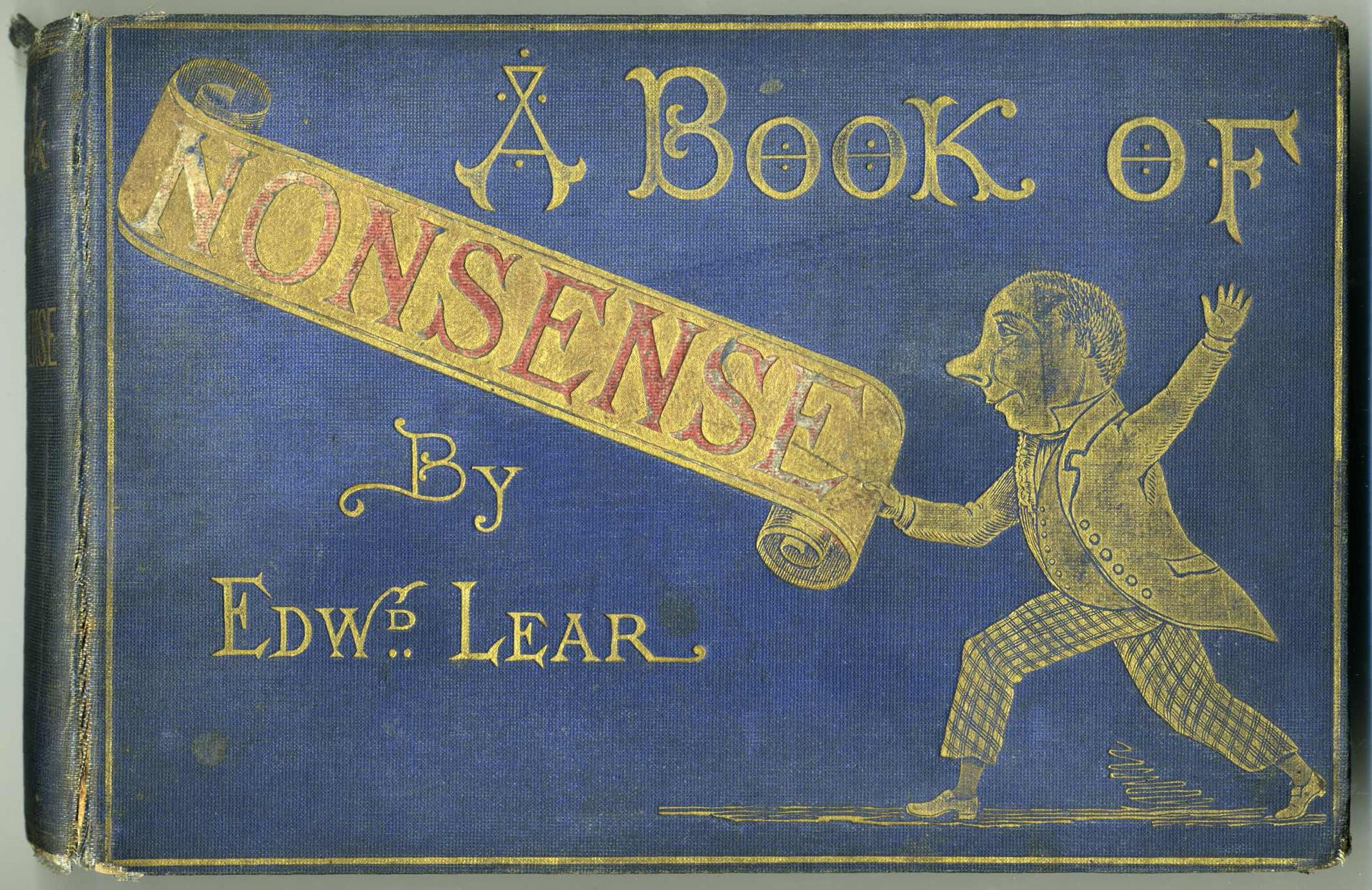

Literary A Book of Nonsense (c. 1875 James Miller edition) by Edward Lear Main article: Literary nonsense The phrase "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously" was coined by Noam Chomsky as an example of nonsense. However, this can easily be confused with poetic symbolism. The individual words make sense and are arranged according to proper grammatical rules, yet the result is nonsense. The inspiration for this attempt at creating verbal nonsense came from the idea of contradiction and seemingly irrelevant and/or incompatible characteristics, which conspire to make the phrase meaningless, but are open to interpretation. The phrase "the square root of Tuesday" operates on the latter principle. This principle is behind the inscrutability of the kōan "What is the sound of one hand clapping?", where one hand would presumably be insufficient for clapping without the intervention of another. [Editor’s note: It is possible to imagine a context where case-sensitive word-strings such as “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously” could be meaningfully used as a passphrase to decrypt a digital file. This one counterfactual suggests that both literary meaning and nonsense are dependent upon the particular “language-game” in which words (or characters) are used or misused. (See Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, §23.][citation needed][1] Verse Jabberwocky, a poem (of nonsense verse) found in Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There by Lewis Carroll (1871), is a nonsense poem written in the English language. The word jabberwocky is also occasionally used as a synonym of nonsense.[2] Nonsense verse is the verse form of literary nonsense, a genre that can manifest in many other ways. Its best-known exponent is Edward Lear, author of The Owl and the Pussycat and hundreds of limericks. Nonsense verse is part of a long line of tradition predating Lear: the nursery rhyme Hey Diddle Diddle could also be termed a nonsense verse. There are also some works which appear to be nonsense verse, but actually are not, such as the popular 1940s song Mairzy Doats. Lewis Carroll, seeking a nonsense riddle, once posed the question How is a raven like a writing desk?. Someone answered him, Because Poe wrote on both. However, there are other possible answers (e.g. both have inky quills). Examples The first verse of Jabberwocky by Lewis Carroll; 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. The first four lines of On the Ning Nang Nong by Spike Milligan;[3] On the Ning Nang Nong Where the cows go Bong! and the monkeys all say BOO! There's a Nong Nang Ning The first verse of Spirk Troll-Derisive by James Whitcomb Riley;[4] The Crankadox leaned o'er the edge of the moon, And wistfully gazed on the sea Where the Gryxabodill madly whistled a tune To the air of "Ti-fol-de-ding-dee." The first four lines of The Mayor of Scuttleton by Mary Mapes Dodge;[4] The Mayor of Scuttleton burned his nose Trying to warm his copper toes; He lost his money and spoiled his will By signing his name with an icicle quill; Oh Freddled Gruntbuggly by Prostetnic Vogon Jeltz; a creation of Douglas Adams Oh freddled gruntbuggly, Thy micturations are to me As plurdled gabbleblotchits on a lurgid bee. Groop I implore thee, my foonting turlingdromes, And hooptiously drangle me with crinkly bindlewurdles, Or I will rend thee in the gobberwarts With my blurglecruncheon, see if I don't! |

文学 エドワード・リア著『ナンセンスの本』(1875年ジェームズ・ミラー版 主な記事 文学的ナンセンス ノーム・チョムスキーがナンセンスの例として「無色の緑色のアイデアは猛烈に眠る」という言葉を作った。しかし、これは詩的象徴主義と混同されやすい。個 々の単語は意味を持ち、適切な文法規則に従って並べられているが、結果はナンセンスである。言葉によるナンセンスを創造しようとするこの試みの着想は、矛 盾や、一見無関係に見える、あるいは相容れない特性というアイデアから生まれたもので、これらはフレーズを無意味にするために共謀しているが、解釈は自由 である。火曜日の平方根」というフレーズは、後者の原理に基づいている。この原理は、「片手で拍手する音は何ですか」という公案の不可解さの背後にある。 [編集部注:大文字と小文字を区別する単語列、例えば「Colorless green ideas sleep furiously(色彩のない緑色のアイデアは猛烈に眠る)」が、デジタル・ファイルを復号するためのパスフレーズとして有意義に使用される文脈を想像 することは可能である。この一つの反事実は、文学的な意味もナンセンスも、言葉(あるいは文字)が使われたり誤用されたりする特定の「言語ゲーム」に依存 していることを示唆している。(ウィトゲンシュタインの『哲学探究』第23節参照)[要出典][1]。 詩 ジャバウォッキー(Jabberwocky)は、ルイス・キャロルの『Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There』(1871年)にある詩(ナンセンス詩)で、英語で書かれたナンセンス詩である。ジャバウォッキーという言葉は、ナンセンスの同義語として使 われることもある[2]。 ナンセンス詩は文学的ナンセンスの詩型であり、他にも様々な形で現れるジャンルである。最もよく知られているのはエドワード・リアで、『フクロウと小猫』 や何百もの叙事詩の作者である。 童謡『ヘイ・ディドル・ディドル』もナンセンス詩と呼ぶことができる。また、ナンセンス詩のように見えて実はそうではない作品もあり、1940年代に流行 した歌「メアジー・ドーツ」などがある。 ルイス・キャロルは、ナンセンスな謎かけを探していた。ポーが両方に書いたからだ」と答えた人がいた。しかし、他の答えも考えられる(例えば、両方ともイ ンキ色の羽ペンを持っている)。 例 ルイス・キャロルの『ジャバウォッキー』の最初の詩; 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves 'Twas brillig and slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; ボロゴーブたちは、みんなまねっこだった、 そして、もじゃもじゃのラスは、grabeを飛び出した。 スパイク・ミリガンの『On the Ning Nang Nong』の最初の4行である[3]。 オン・ザ・ニン・ナン・ノン 牛がボンと鳴くところ! そして猿はみんなBOOと言う! ニン・ナン・ニンがいる ジェイムズ・ホイットコム・ライリーの「Spirk Troll-Derisive」の最初の詩、[4]。 クランカドックスは月の縁に寄りかかった、 そして切なく海を見つめていた グリクサボディルが狂ったように口笛を吹く。 "ティ・フォル・ディン・ディ "の歌を口笛で吹きながら。 メアリー・メイプス・ドッジ作『スカットルトン市長』の最初の4行である[4]。 スカットルトン市長は鼻を火傷した 銅のつま先を温めようとして 彼は金を失い、遺書を台無しにした 氷柱の羽ペンで自分の名前に署名した; Oh Freddled Gruntbuggly by Prostetnic Vogon Jeltz; ダグラス・アダムスの創作である。 おお、フレドルド・グラントバグリーよ、 汝の呟きは私にとって ルルギド・ビーについたガブルブロチットのように。 汝に祈る、 汝、汝、汝、汝、汝、汝、 さもなくば、汝をゴキブリスで引き裂くぞ。 この "ブルブルクランチョン "でな! |

| Philosophy of language and of

science Further information: Sense In the philosophy of language and the philosophy of science, nonsense refers to a lack of sense or meaning. Different technical definitions of meaning delineate sense from nonsense. Logical positivism Further information: Logical positivism Wittgenstein Further information: Ludwig Wittgenstein In Ludwig Wittgenstein's writings, the word "nonsense" carries a special technical meaning which differs significantly from the normal use of the word. In this sense, "nonsense" does not refer to meaningless gibberish, but rather to the lack of sense in the context of sense and reference. In this context, logical tautologies, and purely mathematical propositions may be regarded as "nonsense". For example, "1+1=2" is a nonsensical proposition.[5] Wittgenstein wrote in Tractatus Logico Philosophicus that some of the propositions contained in his own book should be regarded as nonsense.[6] Used in this way, "nonsense" does not necessarily carry negative connotations. Disguised Epistemic Nonsense In Ludwig Wittgenstein’s later work, Philosophical Investigations (PI §464), he says that “My aim is: to teach you to pass from a piece of disguised nonsense to something that is patent nonsense.” In his remarks On Certainty (OC), he considers G. E. Moore’s “Proof of an External World” as an example of disguised epistemic nonsense. Moore’s “proof” is essentially an attempt to assert the truth of the sentence ‘Here is one hand’ as a paradigm case of genuine knowledge. He does this during a lecture before The British Academy where the existence of his hand is so obvious as to appear indubitable. If Moore does indeed know that he has a hand, then philosophical skepticism (formerly called idealism) must be false. (cf. Schönbaumsfeld (2020). Wittgenstein however shows that Moore’s attempt fails because his proof tries to solve a pseudo-problem that is patently nonsensical. Moore mistakenly assumes that syntactically correct sentences are meaningful regardless of how one uses them. In Wittgenstein’s view, linguistic meaning for the most part is the way sentences are used in various contexts to accomplish certain goals (PI §43). J. L. Austin likewise notes that "It is, of course, not really correct that a sentence ever is a statement: rather, it is used in making a statement, and the statement itself is a 'logical construction' out of the makings of statements" (Austin 1962, p1, note1). Disguised epistemic nonsense therefore is the misuse of ordinary declarative sentences in philosophical contexts where they seem meaningful but produce little or nothing of significance (cf. Contextualism). Moore’s unintentional misuse of ‘Here is one hand’ thus fails to state anything that his audience could possibly understand in the context of his lecture. According to Wittgenstein, such propositional sentences instead express fundamental beliefs that function as non-cognitive “hinges”. Such hinges establish the rules by which the language-game of doubt and certainty is played. Wittgenstein points out that “If I want the door to turn the hinges must stay put” (OC §341-343).[6] In a 1968 article titled “Pretence”, Robert Caldwell states that: “A general doubt is simply a groundless one, for it fails to respect the conceptual structure of the practice in which doubt is sometimes legitimate” (Caldwell 1968, p49). "If you are not certain of any fact," Wittgenstein notes, "you cannot be certain of the meaning of your words either" (OC §114). Truth-functionally speaking, Moore’s attempted assertion and the skeptic’s denial are epistemically useless. "Neither the question nor the assertion makes sense" (OC §10). In other words, both philosophical realism and its negation, philosophical skepticism, are nonsense (OC §37&58). Both bogus theories violate the rules of the epistemic game that make genuine doubt and certainty meaningful. Caldwell concludes that: “The concepts of certainty and doubt apply to our judgments only when the sense of what we judge is firmly established” (Caldwell, p57). The broader implication is that classical philosophical “problems” may be little more than complicated semantic illusions that are empirically unsolvable (cf. Schönbaumsfeld 2016). They arise when semantically correct sentences are misused in epistemic contexts thus creating the illusion of meaning. With some mental effort however, they can be dissolved in such a way that a rational person can justifiably ignore them. According to Wittgenstein, "It is not our aim to refine or complete the system of rules for the use of our words in unheard-of ways. For the clarity that we are aiming at is indeed complete clarity. But this simply means that the philosophical problems should completely disappear" (PI §133). The net effect is to expose a “A whole cloud of philosophy condensed into a drop of grammar” (PI p222). In contrast to the above Wittgensteinian approach to nonsense, Cornman, Lehrer and Pappas argue in their textbook, Philosophical Problems and Arguments: An Introduction (PP&A) that philosophical skepticism is perfectly meaningful in the semantic sense. It is only in the epistemic sense that it seems nonsensical. For example, the sentence ‘Worms integrate the moon by C# when moralizing to rescind apples’ is neither true nor false and therefore is semantic nonsense. Epistemic nonsense, however, is perfectly grammatical and semantical. It just appears to be preposterously false. When the skeptic boldly asserts the sentence [x]: ‘We know nothing whatsoever’ then: “It is not that the sentence asserts nothing; on the contrary, it is because the sentence asserts something [that seems] patently false…. The sentence uttered is perfectly meaningful; what is nonsensical and meaningless is the fact that the person [a skeptic] has uttered it. To put the matter another way, we can make sense of the sentence [x]; we know what it asserts. But we cannot make sense of the man uttering it; we do not understand why he would utter it. Thus, when we use terms like ‘nonsense’ and ‘meaningless’ in the epistemic sense, the correct use of them requires only that what is uttered seem absurdly false. Of course, to seem preposterously false, the sentence must assert something, and thus be either true or false.” (PP&A, 60). Keith Lehrer makes a similar argument in part VI of his monograph, “Why Not Scepticism?” (WNS 1971). A Wittgensteinian, however, might respond that Lehrer and Moore make the same mistake. Both assume that it is the sentence [x] that is doing the “asserting”, not just the philosopher’s misuse of it in the wrong context. Both Moore’s attempted “assertion” and the skeptic’s “denial” of ‘Here is one hand’ in the context of the British Academy are preposterous. Therefore, both claims are epistemic nonsense disguised in meaningful syntax. “[T]he mistake here” according to Caldwell, “lies in thinking that [epistemic] criteria provide us with certainty when they actually provide sense” (Caldwell p53). No one, including philosophers, has special dispensation from committing this semantic fallacy. “The real discovery,” according to Wittgenstein, “is the one that makes me capable of stopping doing philosophy when I want to.—The one that gives philosophy peace, so that it is no longer tormented by questions which bring itself in question…. There is not a philosophical method, though there are indeed methods, like different therapies” (PI §133). He goes on to say that “The philosopher's treatment of a question is like the treatment of an illness” (PI §255). Leonardo Vittorio Arena Starting from Wittgenstein, but through an original perspective, the Italian philosopher Leonardo Vittorio Arena, in his book Nonsense as the meaning, highlights this positive meaning of nonsense to undermine every philosophical conception which does not take note of the absolute lack of meaning of the world and life. Nonsense implies the destruction of all views or opinions, on the wake of the Indian Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna. In the name of nonsense, it is finally refused the conception of duality and the Aristotelian formal logic. |

言語哲学と科学哲学 さらに詳しい情報 センス 言語哲学や科学哲学において、ナンセンスとは意味や意味の欠如を指す。意味の異なる専門的定義が、意味とナンセンスを区別している。 論理実証主義 さらに詳しい情報はこちら: 論理実証主義 ウィトゲンシュタイン さらなる情報 ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの著作において、「ナンセンス」という言葉は、通常の使い方とは大きく異なる特別な技術的意味を持つ。この意味におい て、「ナンセンス」とは無意味な失言のことではなく、むしろ意味と参照の文脈における意味の欠如を指す。この文脈では、論理的な同語反復や純粋に数学的な 命題も「ナンセンス」とみなされる。例えば、"1+1=2 "はナンセンスな命題である[5]。ウィトゲンシュタインは『哲学哲学論考』の中で、自身の著書に含まれる命題のいくつかはナンセンスとみなされるべきで あると書いている[6]。 認識論的ナンセンスの偽装 ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの後期の著作『哲学探究』(PI §464)において、彼は「私の目的は、偽装されたナンセンスから特許のあるナンセンスに通じることを教えることである」と述べている。確実性について』 (OC)の中で、彼はG.E.ムーアの「外界の証明」を偽装された認識論的ナンセンスの例として取り上げている。ムーアの「証明」は本質的に、「ここに一 つの手がある」という文の真理を、真の知識のパラダイムケースとして主張しようとするものである。ムーアは、英国アカデミーの講義の中で、自分の手の存在 が明白であるかのように見せるために、このようなことを行っているのである。もしムーアが本当に自分が手を持っていることを知っているのなら、哲学的懐疑 論(以前は観念論と呼ばれていた)は誤りでなければならない。(シェーンバウムスフェルド(2020)を参照)。 しかしウィトゲンシュタインは、ムーアの証明が明らかに無意味な擬似問題を解こうとしているために、ムーアの試みが失敗することを示している。ムーアは、 構文的に正しい文は、それをどのように使おうとも意味があると誤解している。ウィトゲンシュタインの見解では、言語的意味とは、ほとんどの場合、文が特定 の目的を達成するために様々な文脈で使われる方法である(PI§43)。J.L.オースティンも同様に、「文が文であるというのは、もちろん、実際には正 しくない。むしろ、文は文を作るために使われるのであり、文そのものは文を作るための『論理的構築物』なのである」(オースティン 1962, p1, note1)と述べている。したがって、認識論的ナンセンスの偽装とは、哲学的文脈における通常の宣言文の誤用であり、一見意味があるように見えるが、重 要なことはほとんど何も生み出さない(文脈主義を参照)。ムーアの「ここに片手がある」という意図的でない誤用は、このように彼の聴衆が彼の講義の文脈で 理解できるようなことを述べていない。 ウィトゲンシュタインによれば、このような命題文は、代わりに非認知的な「ヒンジ」として機能する基本的な信念を表現している。このようなヒンジは、疑念 と確信の言語ゲームが行われる際のルールを確立する。ウィトゲンシュタインは、「もし私がドアを回したければ、蝶番はそのままでなければならない」(OC §341-343)と指摘している[6]。ロバート・コールドウェルは1968年の「見せかけ」と題する論文で次のように述べている: 「一般的な疑念は単に無根拠なものであり、疑念が時として正当なものとなる実践の概念構造を尊重していないからである」(Caldwell 1968, p49)。「ウィトゲンシュタインは、「もしあなたがいかなる事実についても確信が持てないのであれば、あなたは自分の言葉の意味についても確信が持てな い」(OC§114)と指摘している。真理-機能的に言えば、ムーアの主張と懐疑論者の否定は、認識論的に役に立たない。「質問も主張も意味をなさない」 (OC§10)。言い換えれば、哲学的実在論もその否定である哲学的懐疑論もナンセンスである(OC§37&58)。どちらのインチキ理論も、本 物の疑いと確信を意味あるものにする認識論的ゲームのルールに違反している。コールドウェルはこう結論づける: 「確かさと疑いという概念は、われわれが判断することの意味が確固として確立されているときにのみ、われわれの判断に適用される」(Caldwell, p57)。 より広範な含意は、古典的な哲学的「問題」は、経験的に解決不可能な複雑な意味論的錯覚にすぎないかもしれないということである(cf. Schönbaumsfeld 2016)。意味論的に正しい文章が認識論的文脈で誤用されることで、意味の錯覚が生じるのである。しかし、何らかの精神的努力によって、合理的な人が正 当に無視できるように、錯覚は解消することができる。ウィトゲンシュタインによれば、「われわれの目的は、われわれの言葉を前代未聞の方法で使用するため の規則体系を洗練させたり完成させたりすることではない。われわれが目指している明瞭さとは、実に完全な明瞭さなのである。しかし、これは単に哲学的な問 題が完全に消滅することを意味する」(PI §133)。正味の効果は、「一滴の文法に凝縮された哲学の雲全体」(PI p222)を暴露することである。 上記のウィトゲンシュタイン的なナンセンスへのアプローチとは対照的に、コーンマン、レーラー、パパスは、その教科書『哲学的問題と議論』 (Philosophical Problems and Arguments: An Introduction (PP&A)では、哲学的懐疑論は意味論的には完全に意味があるとしている。哲学的懐疑論が無意味に思えるのは、認識論的な意味においてだけであ る。例えば、「ワームはリンゴを取り消すために道徳を説くとき、C#によって月を統合する」という文章は真でも偽でもないため、意味論的にはナンセンスで ある。しかし、認識論的なナンセンスは、文法的にも意味的にも完全にナンセンスである。ただ、とんでもなく間違っているように見えるだけである。懐疑論者 が[x]という文章を大胆に主張するとき、「私たちは何も知らない」となる: その文が何も主張していないのではなく、それどころか、その文が(明らかに間違っていると思われる)何かを主張しているからなのだ......」。その文 章は完全に意味のあるものであり、無意味で無意味であるのは、その人(懐疑論者)がそれを口にしたという事実なのである。別の言い方をすれば、我々は [x]という文章を理解することができる。しかし、それを口にした人物を理解することはできない。なぜ彼がそれを口にしたのか理解できないのである。この ように、認識論的な意味で「ナンセンス」や「無意味」といった用語を使う場合、正しく使うためには、発せられたものが不条理に虚偽に見えることだけが必要 なのである。もちろん、不条理に虚偽に見えるためには、その文章は何かを主張していなければならず、したがって真か偽のどちらかでなければならない」。 (PP&A、60)。 Keith Lehrerは、彼のモノグラフ "Why Not Scepticism? "の第VI部で同様の議論をしている(WNS 1971)。(WNS 1971)の第VI部でも同様の主張をしている。しかし、ウィトゲンシュタイン論者は、レーラーとムーアは同じ間違いを犯していると答えるかもしれない。 両者とも、「主張」しているのは[x]という文であって、哲学者が誤った文脈で[x]を誤用しているだけではないと仮定している。ムーアが試みた「主張」 も、懐疑論者が英国アカデミーの文脈で「ここに一つの手がある」と「否定」することも、どちらもとんでもないことである。したがって、どちらの主張も意味 のある構文に見せかけた認識論的ナンセンスである。「コールドウェルによれば、「ここでの誤りは、(認識論的)基準が実際には意味を与えてくれるのに、確 実性を与えてくれると考えることにある」(コールドウェルp53)。哲学者を含め、誰もこの意味論的誤謬を犯さない特別な免罪符を持っているわけではな い。 「ウィトゲンシュタインによれば、「本当の発見とは、哲学をやめたいときにやめさせるものである。哲学的方法というものは存在しないが、さまざまな治療法 のような方法は確かに存在する」(PI §133)。さらに彼は、「哲学者の疑問に対する治療は、病気の治療のようなものである」(PI §255)と述べている。 レオナルド・ヴィットリオ・アレーナ ウィトゲンシュタインから出発して、しかし独自の視点を通して、イタリアの哲学者レオナルド・ヴィットリオ・アレーナは、その著書『意味としてのナンセン ス』の中で、世界と人生の絶対的な意味の欠如に留意しないあらゆる哲学的観念を弱体化させるために、このナンセンスの積極的な意味を強調している。ナンセ ンスとは、インドの仏教哲学者ナーガールジュナに倣って、あらゆる見解や意見の破壊を意味する。ナンセンスの名の下に、二元性の概念やアリストテレス的な 形式論理は最終的に否定される。 |

| Cryptography The problem of distinguishing sense from nonsense is important in cryptography and other intelligence fields. For example, they need to distinguish signal from noise. Cryptanalysts have devised algorithms to determine whether a given text is in fact nonsense or not. These algorithms typically analyze the presence of repetitions and redundancy in a text; in meaningful texts, certain frequently used words recur, for example, the, is and and in a text in the English language. A random scattering of letters, punctuation marks and spaces do not exhibit these regularities. Zipf's law attempts to state this analysis mathematically. By contrast, cryptographers typically seek to make their cipher texts resemble random distributions, to avoid telltale repetitions and patterns which may give an opening for cryptanalysis.[citation needed] It is harder for cryptographers to deal with the presence or absence of meaning in a text in which the level of redundancy and repetition is higher than found in natural languages (for example, in the mysterious text of the Voynich manuscript).[citation needed] |

暗号技術 センスとナンセンスを区別する問題は、暗号やその他の諜報分野において重要である。例えば、シグナルとノイズを区別する必要がある。暗号解読者は、与えら れたテキストが実際にナンセンスかどうかを判断するアルゴリズムを考案してきた。これらのアルゴリズムは通常、テキスト中の繰り返しや冗長性の有無を分析 する。意味のあるテキストでは、例えば英語のテキストではthe、is、andのように、頻繁に使われる特定の単語が繰り返し使われる。ランダムに散ら ばった文字、句読点、空白はこのような規則性を示さない。ジプフの法則は、この分析を数学的に記述しようとするものである。これとは対照的に、暗号解読者 は通常、暗号テキストをランダムな分布に似せるように努め、暗号解読の隙を与えるようなわかりやすい繰り返しやパターンを避けるようにしている[要出 典]。 冗長性と反復のレベルが自然言語よりも高いテキスト(例えば、ヴォイニッチ手稿の謎めいたテキスト)において、暗号技術者が意味の有無を扱うのは難しい [要出典]。 |

| Teaching machines to talk

nonsense See also: SCIgen Scientists have attempted to teach machines to produce nonsense. The Markov chain technique is one method which has been used to generate texts by algorithm and randomizing techniques that seem meaningful. Another method is sometimes called the Mad Libs method: it involves creating templates for various sentence structures and filling in the blanks with noun phrases or verb phrases; these phrase-generation procedures can be looped to add recursion, giving the output the appearance of greater complexity and sophistication. Racter was a computer program which generated nonsense texts by this method; however, Racter's book, The Policeman’s Beard is Half Constructed, proved to have been the product of heavy human editing of the program's output. |

機械に戯言を教える こちらも参照のこと: SCIgen(サイジェン) 科学者たちは、機械にナンセンスな言葉を教えようと試みてきた。マルコフ連鎖法は、アルゴリズムとランダム化技術によって意味のありそうな文章を生成する ために使われてきた手法のひとつである。様々な文構造のテンプレートを作成し、空白を名詞句や動詞句で埋めていく。このような文節生成手順をループさせて 再帰性を持たせることで、出力がより複雑で洗練されたように見せることができる。ラクターは、この方法でナンセンス文章を生成するコンピューター・プログ ラムであったが、ラクターの著書『警察官の髭は半分生えている』は、プログラムの出力を人間が大幅に編集した産物であることが証明された。 |

| Absurdity Asemic writing Bullshit Dada, nonsense as art Gibberish Gobbledygook Language game Literary nonsense Logorrhoea, an excessively wordy style of abstract prose lacking concrete meaning, i.e. nonsense Metasemantic poetry Mojibake, random nonsense characters generated by foreign text Nonce word Non-lexical vocables in music Nonsense word Scat singing SCIgen, a program that generates nonsense research papers Sokal affair Spoetry and Spam Lit, nonsense text derived from e-mail spam Word salad Broken English Simlish Moonshine Mark V. Shaney |

不条理 意味不明な文章 でたらめ ダダ、芸術としてのナンセンス ちんぷんかんぷん ちんぷんかんぷん 言語ゲーム 文学的ナンセンス 具体的な意味を欠いた抽象的な散文、すなわちナンセンスである。 メタ意味詩 もじばけ、外国語テキストからランダムに生成されるナンセンス文字 ノンスワード 音楽における非レクシス語彙 ナンセンス語 スキャット歌唱 SCIgen、ナンセンス研究論文を生成するプログラム ソーカル事件 SpoetryとSpam Lit、電子メールのスパムから派生したナンセンステキスト ワードサラダ ブロークンイングリッシュ シムリッシュ ムーンシャイン マーク・V・シェイニー |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nonsense |

☆

★意味の論理学 / G・ドゥルーズ著 ; 小泉義之訳, 上,下. - 東京 : 河出書房新社 , 2007.1. - (河出文庫)

『意味の論理学』は、形而上学、認識論、文法、そして最終的には精神分析を通じて、意味と無意味、あるいは「常識」と「ナンセンス」を探求する著作である。

巻:純粋生成のパラドックス︎▶︎ 表面効果のパラドックス▶︎ 命題▶︎ 二元性▶︎ 意味▶︎ セリー化▶︎ 秘教的な語▶︎ 構造▶︎ 問題性▶︎ 理念的なゲーム▶︎ 無−意味▶︎ パラドックス▶︎ 分裂病者と少女▶︎ 二重の原因性▶︎ 特異性▶︎ 存在論的な静的発生▶︎ 論理学的な静的発生▶︎ 哲学者の三つのイマージュ▶︎ ユーモア▶︎ ストア派のモラル問題▶︎ 出来事▶︎ 磁器と火山▶︎ アイオーン▶︎ 出来事の交流★

下巻:一義性︎▶︎言葉▶︎ 口唇性▶︎ 性▶︎ 善意は当然にも罰せられる▶︎ 幻影▶︎ 思考▶︎ セリーの種類▶︎ アリスの冒険▶︎ 第一次秩序と第二次組織▶︎ 付録(シミュラクルと古代哲学;幻影と現代文学)☆リ ンク

文 献

そ

の他の情報

Do not copy and paste, but you might [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆