Wittgenstein's office...

火掻き棒事件をめぐる〈熱い〉記述

On Thick description of Wittgenstein's poker

Wittgenstein's office...

【事の発端】5W1Hふうに書くと…… (これは薄い記述である←→厚い記述)

When: 1946年10月25日

Where: 英国のケンブリッジ大学キングスカレッジ・ギブス棟H階段3号室(H3号室)、モラルサイエンスクラブという研究会の席上で

Who: ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン(LW)とカール・ ポパー(KP)

What: 「哲学の諸問題はあるか」というテーマをめぐって両者が口論をした

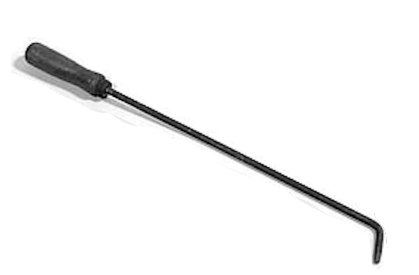

How: LWが火掻き棒をいじった後、部屋を出ていった

Why: ——〈議論したい我々の疑問〉——

【KPによる記述】

「自分(KP—引用者)は、ほんとうの哲学の問題だと信じる問題をいくつか提起した。だがウィトゲンシュタインはあっさりとしりぞけた。そ して『自分の主張を強調したいとき、指揮者がタクトをふるような感じで』いらいらと火かき棒をふりまわしていたという。論争の途中で、道徳の地位がテーマ になった。ウィトゲンシュタインは、道徳的な規則の実例をあげよとポパーにせまった。『わたしはこうこたえた——ゲストの講師を火かき棒でおどさないこ と。するとウィトゲンシュタインは激怒して火かき棒をなげすて、たたきつけるようにドアをしめてでていってしまった』」(エドモンズとエーディナウ 2003:7)——1974年『果てしなき探求』。

Wittgenstein's office...

【ピーター・ギーチ(アンスコムさんの夫)教授の証言】

(KPの言明は)「はじめからおわりまで」嘘である。——当日現場に居合わせたLW派の哲学者

彼の「記憶によれば、ウィトゲンシュタインは火かき棒を手にとり、それを哲学上の例についてふれるなかで使っていた。使いながらポパーに 『この火かき棒について考えてみたまえ』といった。たしかに二人のあいだでは激しい議論のやりとりがおこなわれていた。ウィトゲンシュタインはゲストを黙 らせようとしたわけではなく(そこはいつもとちがう)、ゲストのほうもウィトゲンシュタインを黙らせようとしたわけではなく(このことも異例である)。/ ウィトゲンシュタインはポパーの主張につぎつぎと異論をとなえたが、ついにあきらめた。とにかく議論のさなか、ウィトゲンシュタインはいったん席から立ち 上がったようである。席にもどってきて、腰掛けたのをギーチが目撃しているはからである。そのときは、まだ火かき棒を手にもっていた。とても憔悴した表情 で、椅子の背に大きくよりかかり、暖炉のほうに手をのばした。火かき棒は炉の床のタイルのうえに、かたんとちいさな音をたてて落ちた」(エドモンズとエー ディナウ 2003:27)。

【ピーター・ミュンツ(Peter Munz, 1921-2006)の証言】——KP派 の従者?*

彼は「ウィトゲンシュタインが暖炉の火のなかから、赤く灼熱した火かき棒をとつぜんとりだしたのを憶えている。そしてポパーの目のまえで 怒ったようにそれをふりかざした。それまでずっと沈黙していたラッセルが。口からパイプを離してきっぱりといった。『ウィトゲンシュタイン、その火かき棒 をいますぐ床におきたまえ』。ラッセルの声は高く、しわがれたような響きだった。ウィトゲンシュタインはいわれたとおりにした。そのあとわずかな間をおい て、かれは部屋から歩き去った。たたきつけるようにドアがしまった」(エドモンズとエーディナウ 2003:28)。

*ピーター・ミュンツは、エドモンズとエーディナウの著書の後に、『ウィトゲンシュタインのポーカーを超えて』という本を出している。

【記憶の対立】

・火かき棒は灼熱していた/冷たかった

・LWは怒りふりかざした/ただ「使っていた」(指揮棒/道具/実例/もてあそぶ)

・部屋を出たのはラッセルとの会話の後/ポパーの火かき棒原則を口にした後

・静かに出た/ドアをたたきつけるように出た

・ラッセルは金切り声をあげた/「吠えた」

【ポパーの自負】

・哲学における本当の問題は帰納にまつわることだった(=ウィーン学団のいう検証可能性の原則を攻撃するために帰納の問題を取り上げる。 ウィーン学団の検証可能性は帰納により推論する)。

・ポパーによると、意味のあるもの/ないものの区分、科学と疑似科学の区分は、〈反証可能性〉にあり、〈帰納による検証可能性〉にあるので はない。

【いくつかの哲学問題】

・確率の問題:KPはハイゼンベルグの不確定性の原理、コペンハーゲン解釈における量子力学の主観主義(=世界にはどうしても知り得ないも のがある)と闘っているつもりでいた(cf. 神は骰子遊びはしない——アインシュタイン)。KPは確率というものは認めても、自然には傾向性があり、そ れゆえに確率には確実性があると主張。

・[カントール]無限の概念をどのように理解するかという問題。アリストテレスの潜在的無限と現実的無限の区分。アリストテレスは潜在的無 限を理解可能なものとしてとらえることで、ゼノンのパラドクスは生き残った。カントールはさらに現実的無限の可能性を示唆した。しかしラッセル(BR)に よるとトリストラム・シャンディのパラドクスを招来することになるという、H3教室でも議論された可能性がある。

・トリストラム・シャンディのパラドクスとは、ローレンス・スターンの小説『トリストラム・シャンディ氏の生活と意見』に出てくるエピソー ドで、自伝を書こうとしたシャンディ氏は、遅筆なために完璧に丸一日のことを書くのに1年間かかってしまった。もしシャンディ氏がこのペースで永遠に書き 続けると、彼は自伝を書き上げることができるだろうか、というものである。もし彼に永遠に時間を与えることができれば、永遠の時間を使って一日一日を書き 続けることで最期にはできてしまうように思える。他方で、実際に計算してみると書けないようにも思える。1日分を1年かけて書くとすると、残り364日分 を書くためには、364年かかる。その366年目の最初の1日が書き上がるのが367年目で.... でも心配ご無用、自伝を書くための時間は永遠にある のだから。

【ポパーのメティス】メティスとは「狡 知」(=ずる賢い)のこと

セミナーにおいて、LWを挑発して「哲学には本当の問題など存在せず、あるのは言語的パズルだけである」というLWの主張を彼じしんに言わ せ——それはPKが最も嫌うものであった——LWと論戦を闘わせる。

【2人の地位】

LW——ケンブリッジ大学教授、当代きっての花形哲学者

KP——LSEで論理学と科学方法論の上級講師(准教授相当)

【論敵に対する事前情報】

LW——「ポパー、知らないなあ」ピーター・ミュンツの証言(エドモンズとエーディナウ 2003:334)

KP——自著『開かれた社会とその敵』の公刊(1945年)に自信。同じウィーン出身の改宗ユダヤ人ではあるが、育った社会階層・性格・人 生観においてLWと共通点は少ない。著書のなかでLWの秘密主義を批判。他方、LWを評価しケンブリッジに招聘した、バートランド・ラッセルに深く傾倒。

【開戦時より激しい応酬】秘書ワスフィ・ ヒジャブのメモ

「ポパー ウィトゲンシュタインとその一派は、予備的なことがらをとらえて、それが哲学だといいはっている。その予備的な考察の外にでて、 もっと重要な哲学の問題を考察しようとしない。/(ポパー、問題の実例をいくつかあげる。言語的表面より深くもくらなければ解決できない問題の例)」

「ウィトゲンシュタイン 純粋数学や社会学にしか、もはや〈問題〉などというものはない。/(聴衆、ポパーの実例に納得していない。雰囲気 に変化。室内、かつてないほどの激しい議論、声高ににはなす者あり)」出典は共に(エドモンズとエーディナウ 2003:341)。

【再現された真相】

——言うまでもなくここでのエドモンズと エーディナウは「素朴実在主義者」たちである。

・ウィトゲンシュタインは、いつも行なっているような反射的しぐさおこない、炉にあった火かき棒を握り、語り始める。彼の言葉の句切りと同 時に、痙攣するように火かき棒をつき始める。(いつもやるようだが、この日はかなり激しく——ゲストから反撃を喰らう機会は少ない)。「火かき棒を床にお きたまえ」との発言は誰かわからない(ラッセルの可能性は高い)。LWは音節毎に、それを突きながら「ポパー、君はまちがっている……まち・がって・い る!」と話す。

・次に聴衆がみたのは、火かき棒を投げ捨てたLWが立ち上がり、同時にラッセルも立ち上がった。LWは(今度は)ラッセルに対して「あなた はいつもぼくを誤解するね、フラッセル[そのように聴衆には聞こえた]」。

・ラッセルはそれに対して「ちがうよ、ウィトゲンシュタイン。ものごとをごっちゃにするのは君のほうだ。いつもごっちゃにするんだ」と返 答。

・たたきつけられたようにドアが閉まる。LWは出て行った。

・LWが出て行った後も議論が続いていた(それはこの回だけでなく、LWは議論を独占したくないことを理由にしばしば途中で会場を後にする 癖があった)

・ホストのブレイスェイトがポパーに[議論の続きである]道徳的原則の実例をあげるように促した。ポパーは「ゲストの講師を火かき棒で脅か さないこと」(エドモンズとエーディナウ 2003:344)と答えた。一瞬の間の後に、誰かが笑った。

・質問は続き誰かが「サー、キャベンディシュの実験ですが、秘密裏におこなわれたものは科学と言えますか?」。ポパー「言えない」。

【再現の信憑性】

・ウィトゲンシュタインは、道徳的原則の実例をポパーに聞くようなことはしない。

・火かき棒の件については、議事録には記されておらず、それ自体が重要視された形跡はない。

・キャベンディシュの実験の質問は、ギーチの罠である。反証可能性を保証するために「秘密裏に」真理が発見されても、それは科学とは言えな いことを、言わせようとした可能性がある。

・ウィトゲンシュタインを諭したのはラッセル以外にはありえない(当時のクラブそのものが、LWの信奉者がほとんどであった)

・LWが会合の途中で退席することは稀ではないが、そのことを知らないKPには、異様に映ったように思われる。

・ポパーが自伝に書いたことに対する非難としてKPが「老人呆け」だったというのがあるが、これは当たらない(同じ著作の他の部分や、他の 著作もはまともに記述しているので)。

・なぜなら、ポパーはこの部分に関しては、何度も書き直しをしている。とくに、ケンブリッジを訪れた理由を「そそのかすため、誘うため、お びきよせるため、挑戦するため」などと書き直し、最終的に最後のフレーズを使った。

・つまりポパーは実質的には確信犯であった可能性が高い(エドモンズとエーディナウ 2003:352)

・精神科医ピーター・フェンウィックの発言:

「知覚のなかでも、記憶はもっとも逆説的なはたらきをする。記憶はとても強力で、ごくとりとめのない印象でも保存している。すっかり忘 れたと思っても、数年後に細部まで克明に思い出すことがある。それでいて、まったく違ったこともおぼえ込ませることができるので、なんとも信頼がおけな い」(エドモンズとエーディナウ 2003:354)。

【ポパーのノート断章】(エドモンズと エーディナウ 2003:359-360)

・「われわれは、理性的方法をつかってさまざまな問題にとりくむ学究の徒である。それはほんとうの〈問題〉ということだ。言語問題や、言語 的謎ではない」。

・「哲学における方法」「1.このテーマを選んだ理由、2.哲学的方法の歴史について、3.哲学における言語学的方法の評価と批判、4.哲 学と方法についてのいくつかのテーゼ」

・「哲学は予備的問題から予備的問題へといきつもどりつしながら、道をみうしなっている。率直なところ、これが哲学ならわたくしは哲学に興 味をもてない」。

・「わたくしは、哲学の〈謎〉についての議論をはじめるようにとのことで招かれました。……疑似問題の言語的分析方法。問題は消滅するか、 ときには、哲学//の性質についてのテーゼと組みあわあされます。学問的問題ではなく、〈謎〉を一掃する活動というわけです。精神分析とも比較できるよう な、ある種の治療だとされるのです。……招待状ではこれらすべてが想定されています。だからこそ、わたしはこの想定をうけいれることはできません。この招 待状には、哲学の性格と哲学の方法について、かなりはっきりした見解がみられるようですが、わたしはこうした見解をもっていないからです。このような見解 が想定されているために、わたしは多かれ少なかれ、この見解そのものを講演のテーマにせざるをえないのです」。

・「ポパーがウィトゲンシュタインを引用するのは、いつも『論考』に論理実証主義の誤謬の根源を見いだし、それを糾弾するためである」——

ドミニック・ルクール『ポパーとウィトゲンシュタイン』野崎次郎訳、p.151、国文社、1992年

【会合後のウィトゲンシュタインのノート 断章】

・「けがらわしいあつまり。ロンドンからきたロバ、ポパー博士が、およそ聞いたこともないような屑ばなしをながながとくりひろげた。わたし は例によってたくさん話した……」(エドモンズとエーディナウ 2003:362)

——にもかかわらずLWのことを憎めないのはなぜか? そして僅かな瑕疵のあるポパーのお茶目な事実の歪 曲を許さない気持ちはどこに由来する? それは私[池田]はLWを贔屓にしているから? しかし、どうもそれだけではないようだ。

・LWのアーカイブの専門家によると、LWが親しんでいたドイツの諺から、驢馬は何も考えないで行動する人間であり、ウィーンの環状道路 (リンクシュトラーセ)の匂いが染みつく嫌な奴という意味もあるかもしれない。もちろん、ビュリダンのロバ[→解説のあるリンク先]は非現実的で哀れな論理主義者の隠喩である。

ビュリダンのロバに関するエッセーと言えば、花田清輝『復興期の精神』のどこかにあったということが 私には想起されますが、内容の詳細については失念しました。

・また事件の三週間後の会合で、KPを意識して「哲学の問いを一般的なかたちでしめすと、こうなる。それは『わたしは泥のなかにはまりこん だ。道がわからない』というものだ」とLWが発言(エドモンズとエーディナウ 2003:363)。

【その後のH3号室】

・書斎は、王立天文台長マーティン・リース爵と、経済史のエマ・ロスチャイルド(アマルティア・センの妻)のオフィスとして利用されてい る。

・その後の哲学者の議論から情熱が消えた理由は?:エドモンズとエーディナウ(2003:367)によると、現在では、寛容性、相対主義、 自分の立場を決めることを拒むポストモダンな姿勢、不確実性の文化の勝利、そして学問の専門分化化だというのだ。はたして本当だろうか?[池田]。

・現在の暖炉の写真(エドモンズとエーディナウ 2003:368)[授業では紹介しました](→ムーアのパラドックス[関連リンク] の事例のなかに「暖炉」が登場)

【課題】

この歴史上著名な?エピソードから、我々が学ぶべきことはなにか?——この両派(LW vs. KP)のコミュニケーションの齟齬について(i)記録すること、(ii)記述を読んで想像すること、(iii)想像したことをもとにその文脈から飛翔した 別種の議論をおこなうこと、の意義について考えなさい。

【資料の続編】

【附録】

附録:火かき棒事件追加資料

出典:いしいひさいち「火かき棒事件その後」『現代思想の遭難者たち(増補版)』p.184、東京:講談社、2006年

「火かき棒事件その後」(4コマ漫画)=著作権法の問題がありますので、テキストデータだけを掲載します。

【1】

文献

野家啓一「「ホーリズム」の擁護」(「日本ポパー哲学研究会第8回年次研究大会」講演、1997年6月28日、ウェブで読めます [2008年5月確認])

【2】

【3】

【4】

__________________________

【用語集】

■厚い記述:ウィキペディアの同項目では「哲学者ギルバート・ライル (1900-1976)に由来する。ライル[→当該論文リンク: 引用者]によれば、われわれは誰かから目配せをされても、文脈がわからなければそれがどういう意味か理解できない。愛情のしるしなのかもしれないし、密か に伝えたいことがあるのかもしれない。あなたの話がわかったというしるしなのかもしれないし、他の理由かもしれない。文脈が変われば目配せの意味も変わ る」と説明。本家はライルだが、この用語を最も有名にしたのは、この作業を文化人類学(ないしは解釈学的人類学)の課題にし、かつ同名の論文にしたクリフォード・ギアツ(1926-2006)である。[→さらに興味のあるオタクはこちらへ]。ちなみにウィキの記述(2007年6月13日)には、民族誌は厚い記述であるべ き風に記載してあるが、含蓄——そう含蓄とは相矛盾するが権威ある情報がそれぞれ満載されている——にもとづく曖昧的記述の天才であったギアツは、民族誌 と厚い記述(およびライルのいう薄い記述)の関係については、もうちょっとややこしい書き方をしている。下記を参照。

"[T]he points is that between what call Ryle calls the "thin description" of what the reherser (parodist, winker, twitcher...) is doing ("rapidly contracting his right eyelids") and the "thick description" of what he is doing ("practicing a burlesque of a friend faking a wink to deceive an innocent into thinking a conspiracy is in motion") lies the object of ethnography: a stratified hierarchy of meaningful structures in terms of which twitches, winks, fake-winks, parodies, rehearsals of parodies are produced, perceived, and interpreted, and without which they would not (not even the zero-form twitches, which, as cultural category, are as much nonwinks as winks are nontwitches) in fact exist, no matter what anyone did or didn't do with his eyelid."(Geertz 1973: 7)

■熱い記述:火掻き棒が熱かった(hot) のと、LWとKPの議論は全くすれ違いであれ感情的には深い対立を呈していたため状況は加熱した(excite)ので、それを掛けた池田による冗談。

■反証可能性:カール・ポパー(Karl Raimund Poppr, 1902-1994)の科学論におけるもっとも重要なテーゼ。科学理論の客観性を保証するためには、その仮説が実験や観察によって反証される可能性がなけ ればならないというもの。つまり、ポパーによれば、科学理論は反証される潜在性をもつ仮説のあつまりであり、反証に対して抵抗力のある(=反証に対してき ちんと反論できる)ものが信頼性の高い科学理論である。(→反証可能性)

| In the social

sciences and related fields, a thick

description

is a description of human social action that describes not just

physical behaviors, but their context as interpreted by the actors as

well, so that it can be better understood by an outsider. A thick

description typically adds a record of subjective explanations and

meanings provided by the people engaged in the behaviors, making the

collected data of greater value for studies by other social scientists. The term was first introduced by 20th-century philosopher Gilbert Ryle. However, the predominant sense in which it is used today was developed by anthropologist Clifford Geertz in his book The Interpretation of Cultures (1973) to characterise his own method of doing ethnography.[1] Since then, the term and the methodology it represents has gained widespread currency, not only in the social sciences but also, for example, in the type of literary criticism known as New Historicism. |

社会科学やその関連分野において、厚みのある記述(=厚い記述)と

は、人間の社会的行動を記述するもので、物理的な行動だけでなく、行為者によって解釈されたその文脈も記述することで、外部の人間によりよく理解できるよ

うにするものである。厚みのある記述では通常、行動に関与した人々によって提供された主観的な説明や意味の記録が追加されるため、収集されたデータは他の

社会科学者による研究にとってより価値のあるものとなる。 この用語は、20世紀の哲学者ギルバート・ライルによって初めて紹介された。それ以来、この用語とその方法論は、社会科学のみならず、例えばニュー・ヒス トリカリズムとして知られる文学批評の分野でも広く使われるようになった。 |

| Gilbert Ryle Thick description was first introduced by the British philosopher Gilbert Ryle in 1968 in "The Thinking of Thoughts: What is 'Le Penseur' Doing?" and "Thinking and Reflecting".[2] thin, which includes surface-level observations of behaviour; and thick, which adds context to such behaviour. To explain such context required grasping individuals' motivations for their behaviors and how these behaviors were understood by other observers of the community as well. This method emerged at a time when the ethnographic school was pushing for an ethnographic approach that paid particular attention to everyday events. The school of ethnography thought seemingly arbitrary events could convey important notions of understanding that could be lost at a first glance.[3] Similarly Bronisław Malinowski put forth the concept of a native point of view in his 1922 work, Argonauts of the Western Pacific. Malinowski felt that an anthropologist should try to understand the perspectives of ethnographic subjects in relation to their own world. |

ギルバート・ライル 厚みのある記述は、1968年にイギリスの哲学者ギルバート・ライルが「思考の思考」で初めて紹介した: Le Penseur "は何をしているのか?"と "Thinking and Reflecting "で紹介された[2]。 行動の表面レベルの観察を含むthinと そのような行動に文脈を加える厚いもの。 このような文脈を説明するためには、個人の行動の動機と、その行動がコミュニティの他の観察者にどのように理解されているかを把握する必要があった。 この手法が登場したのは、エスノグラフィ学派が日常的な出来事に特に注意を払うエスノグラフィ的アプローチを推し進めていた時期である。同様に、ブロニス ワフ・マリノフスキーは1922年の著作『西太平洋のアルゴノーツ』において、先住民の視点という概念を提唱した。マリノフスキーは、人類学者は民族誌の 対象者の視点を彼ら自身の世界との関係において理解しようと努めるべきだと考えていた。 |

| Clifford Geertz Following Ryle's work, the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz re-popularized the concept. Known for his symbolic and interpretive anthropological work, Geertz's methods were in response to his critique of existing anthropological methods that searched for universal truths and theories. He was against comprehensive theories of human behavior; rather, he advocated methodologies that highlight culture from the perspective of how people looked at and experienced life. His 1973 article, "Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture", synthesizes his approach.[4] Thick description emphasized a more analytical approach, whereas previously observation alone was the primary approach. To Geertz, analysis separated observation from interpretative methodologies. An analysis is meant to pick out the critical structures and established codes. This analysis begins with distinguishing all individuals present and coming to an integrative synthesis that accounts for the actions produced. The ability of thick descriptions to showcase the totality of a situation to aid in the overall understanding of findings was called mélange of descriptors. As Lincoln & Guba (1985) indicate, findings are not the result of thick description; rather they result from analyzing the materials, concepts, or persons that are "thickly described."[5] Geertz (1973) takes issue with the state of anthropological practices in understanding culture. By highlighting the reductive nature of ethnography, to reduce culture to "menial observations," Geertz hoped to reintroduce ideas of culture as semiotic. By this he intended to add signs and deeper meaning to the collection of observations. These ideas would challenge Edward Burnett Tylor's concepts of culture as a "most complex whole" that is able to be understood; instead culture, to Geertz, could never be fully understood or observed. Because of this, ethnographic observations must rely on the context of the population being studied by understanding how the participants come to recognize actions in relation to one another and to the overall structure of the society in a specific place and time. Today, various disciplines have implemented thick description in their work.[6] Geertz pushes for a search for a "web of meaning". These ideas were incompatible with textbook definitions of ethnography of the times that described ethnography as systematic observations[7] of different populations under the guise of Race categorization and categorizing the "other."[citation needed] To Geertz, culture should be treated as symbolic, allowing for observations to be connected with greater meanings.[8] This approach brings about its own difficulties. Studying communities via large-scale anthropological interpretation will bring about discrepancies in understanding. As cultures are dynamic and changing, Geertz also emphasizes the importance of speaking to rather than speaking for the subjects of ethnographic research and recognizing that cultural analysis is never complete. This method is essential to approach the actual context of a culture. As such, Geertz points out that interpretive works provide ethnographers the ability to have conversations with the people they study.[9] |

クリフォード・ギアーツ ライルの研究に続いて、アメリカの人類学者クリフォード・ギアーツがこの概念を再普及させた。象徴人類学や解釈人類学の研究で知られるギアーツの手法は、 普遍的な真理や理論を探求する既存の人類学的手法への批判に応えるものであった。彼は人間の行動に関する包括的な理論に反対し、むしろ、人々がどのように 人生を見つめ、経験してきたかという視点から文化を浮き彫りにする方法論を提唱した。彼の1973年の論文「厚い記述: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture(厚い記述:文化の解釈理論に向けて)」は彼のアプローチを統合したものである[4]。 以前は観察のみが主要なアプローチであったのに対し、厚みのある記述はより分析的なアプローチを強調していた。ギアーツにとって分析とは、観察から解釈的 方法論を切り離すことであった。分析とは、批判的な構造と確立されたコードを選び出すことである。この分析は、その場にいるすべての個人を区別し、生み出 された行動を説明する統合的な総合に至ることから始まる。所見の全体的な理解を助けるために、状況の全体性を示す厚い記述の能力は、記述子のメランジと呼 ばれる。リンカーン&グーバ(1985)が示すように、所見は厚い記述の結果ではなく、むしろ「厚く記述された」材料、概念、または人物を分析した結果で ある[5]。 Geertz(1973)は文化を理解する上での人類学的実践のあり方を問題視している。文化を「下らない観察」に還元する民族誌の還元的な性質を強調す ることで、ゲアーツは文化を記号論的なものとして捉え直すことを望んだ。これによって彼は、観察の収集に記号と深い意味を加えることを意図したのである。 こうした考え方は、エドワード・バーネット・タイラーが提唱した「最も複雑な全体」としての文化を理解するという概念に挑戦するものである。このため、民 族誌的観察は、特定の場所と時間において、参加者がどのように互いの関係や社会の全体構造との関係において行動を認識するようになったかを理解することに よって、研究対象集団の文脈に依存しなければならない。今日、様々な学問領域において、厚みのある記述が実践されている[6]。 ギアーツは「意味の網」の探求を推し進めている。このような考えは、民族分類や「他者」の分類を装って異なる集団の体系的な観察[7]として民族誌を記述 していた当時の民族誌の教科書的な定義とは相容れないものであった[要出典]。ギアーツにとって、文化は象徴的なものとして扱われるべきであり、観察をよ り大きな意味と結びつけることを可能にするものであった[8]。 このアプローチは独自の困難をもたらす。大規模な人類学的解釈によって共同体を研究することは、理解に食い違いをもたらす。文化はダイナミックに変化する ものであるため、ギアーツはまた、民族誌的調査の対象者のために語るのではなく、対象者に語りかけ、文化分析が決して完全なものではないことを認識するこ との重要性を強調している。この方法は、文化の実際の文脈にアプローチするために不可欠である。このように、ゲアーツは解釈的作品によって、民俗学者に研 究対象である人々と会話する能力を提供すると指摘している[9]。 |

| Interpretive turn Geertz is revered for his pioneering field methods and clear, accessible prose writing style (cf. Robinson's critique, 1983). He was considered "for three decades...the single most influential cultural anthropologist in the United States."[10] Interpretive methodologies were needed to understand culture as a system of meaning. Because of this, Geertz's influence is connected with "a massive cultural shift" in the social sciences referred to as the interpretive turn. The interpretive turn in the social sciences had strong foundations in cultural anthropological methodology. In doing so, there was a shift from structural approaches as an interpretive lens, towards meaning. With the interpretive turn, contextual and textual information took the lead in understanding reality, language, and culture. This was all under the assumption that a better anthropology included understanding the particular behaviors of the communities being studied.[11][12] Geertz's thick description approach, along with the theories of Claude Lévi-Strauss, has become increasingly recognized as a method of symbolic anthropology,[7][3] enlisted as a working antidote to overly technocratic, mechanistic means of understanding cultures, organizations, and historical settings. Influenced by Gilbert Ryle, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Max Weber, Paul Ricoeur, and Alfred Schütz, the method of descriptive ethnography that came to be associated with Geertz is credited with resuscitating field research from an endeavor of ongoing objectification—the focus of research being "out there"—to a more immediate undertaking, where participant observation embeds the researcher in the enactment of the settings being reported. However, despite its dissemination among the disciplines, some theorists[13] pushed back on thick description, skeptical about its ability to somehow interpret meaning by compiling large amounts of data. They also questioned how this data was supposed to provide the totality of a society naturally.[7] |

解釈的転回 ギアーツはその先駆的なフィールドメソッドと明快でわかりやすい散文の文体で尊敬されている(ロビンソンの批評、1983年参照)。彼は「30年間... 米国で最も影響力のある唯一の文化人類学者」とみなされていた[10]。 文化を意味の体系として理解するためには、解釈的方法論が必要であった。このため、ギアーツの影響は、解釈的転回と呼ばれる社会科学における「大規模な文 化的転換」と結びついている。社会科学における解釈的転回は、文化人類学の方法論に強い基盤があった。その際、解釈的レンズとしての構造的アプローチか ら、意味へとシフトした。解釈的転回により、現実、言語、文化を理解する上で、文脈やテキスト情報が主導権を握るようになった。これはすべて、より良い人 類学には研究対象であるコミュニティの特定の行動を理解することが含まれるという仮定のもとであった[11][12]。 ギアーツの厚みのある記述のアプローチはクロード・レヴィ=ストロースの理論とともに象徴人類学の方法としてますます認識されるようになり、文化、組織、 歴史的設定を理解するための過度に技術主義的で機械的な手段に対する有効な解毒剤として列挙されている[7][3]。ギルバート・ライル、ルートヴィヒ・ ヴィトゲンシュタイン、マックス・ウェーバー、ポール・リクール、アルフレッド・シュッツの影響を受け、ゲルツと結びつくようになった記述的エスノグラ フィーの方法は、フィールド調査を継続的な客観化の努力から、つまり研究の焦点が「そこにある」ことから、参加者観察によって報告される設定の実践に研究 者を組み込む、より直接的な事業へと蘇らせたと評価されている。しかし、厚い記述(thick description)が学問分野に広まったにもかかわらず、一部の理論家[13]は、大量のデータをまとめることで意味を解釈する能力に懐疑的で、厚 い記述に反発した。彼らはまた、このデータがどのようにして社会の全体性を自然に提供することになるのかに疑問を呈していた[7]。 |

| Contextualism Cultural studies Indexicality Claude Lévi-Strauss Symbolic anthropology |

文脈主義 カルチュラル・スタディーズ 指標性 クロード・レヴィ=ストロース 象徴人類学 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thick_description |

【文献】

【関連リンク】

【クレジット】

このページのオリジナルは「事件:過去の予言・未来の想起」で 2007年6月に発表されたものですが、このことに関する継続的な議論はこちらを中心にしておこなっています。

Peter Geach with his wife and fellow philosopher, Margaret Anscombe