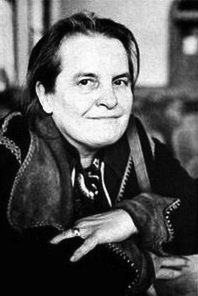

G.E.M.アンスコム

Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe,

1919-2001

☆ ガートルード・エリザベス・マーガレット・アンスコム(1919-2001)、オックスフォードの哲学者の中の最大級の変人、ウィトゲンシュタインの弟子,カソリック教徒、「ローマ教皇よりもより篤信なカソリック」と言われた。

| Gertrude

Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe FBA (/ˈænskəm/; 18 March 1919 – 5 January

2001), usually cited as G. E. M. Anscombe or Elizabeth Anscombe, was a

British[1] analytic philosopher. She wrote on the philosophy of mind,

philosophy of action, philosophical logic, philosophy of language, and

ethics. She was a prominent figure of analytical Thomism, a Fellow of

Somerville College, Oxford, and a professor of philosophy at the

University of Cambridge. Anscombe was a student of Ludwig Wittgenstein and became an authority on his work and edited and translated many books drawn from his writings, above all his Philosophical Investigations. Anscombe's 1958 article "Modern Moral Philosophy" introduced the term consequentialism into the language of analytic philosophy, and had a seminal influence on contemporary virtue ethics.[2] Her monograph Intention (1957) was described by Donald Davidson as "the most important treatment of action since Aristotle".[3][4] It is "widely considered a foundational text in contemporary philosophy of action" and has also had influence in the philosophy of practical reason."[5] |

ガー

トルード・エリザベス・マーガレット・アンスコム(Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe FBA / 発音例:

ˈænskəm /、1919年3月18日 - 2001年1月5日)は、通常G. E. M.

アンスコムまたはエリザベス・アンスコムと表記され、イギリスの分析哲学者である。彼女は心の哲学、行動の哲学、哲学論理学、言語哲学、倫理学について執

筆した。彼女は分析的トミズムの著名な人物であり、オックスフォード大学ソマーヴィル・カレッジのフェロー、ケンブリッジ大学哲学科の教授であった。 彼女はルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの弟子であり、彼の研究の権威となり、彼の著作から多くの書籍を編集・翻訳した。特に『哲学探究』は有名であ る。1958年に発表された論文「現代道徳哲学」では、分析哲学の用語に帰結主義という概念を導入し、現代の徳倫理学に多大な影響を与えた。彼女の単行本 『意図』(1957年)は、 ドナルド・デヴィッドソンによって「アリストテレス以来の行動に関する最も重要な研究」と評された。[3][4] これは「現代の行動哲学の基礎となるテキストとして広く考えられている」ものであり、実践理性の哲学にも影響を与えている。[5] |

| Life Anscombe was born to Gertrude Elizabeth (née Thomas) and Captain Allen Wells Anscombe, on 18 March 1919, in Limerick, Ireland, where her father had been stationed with the Royal Welch Fusiliers during the Irish War of Independence.[6] Both her mother and father were involved with education. Her mother was a headmistress and her father went on to head the science and engineering side at Dulwich College.[7] Anscombe attended Sydenham High School and then, in 1937, went on to read literae humaniores ('Greats') at St Hugh's College, Oxford. She was awarded a Second Class in her honour moderations in 1939 and (albeit it with reservations on the part of her Ancient History examiners[8]) a First in her degree finals in 1941.[7] While still at Sydenham High School, Anscombe converted to Catholicism. During her first year at St Hugh's, she was received into the church, and was a practising Catholic thereafter.[7] In 1941 she married Peter Geach. Like her, Geach was a Catholic convert who became a student of Wittgenstein and a distinguished academic philosopher. Together they had three sons and four daughters.[7] After graduating from Oxford, Anscombe was awarded a research fellowship for postgraduate study at Newnham College, Cambridge, from 1942 to 1945.[7] Her purpose was to attend Ludwig Wittgenstein's lectures. Her interest in Wittgenstein's philosophy arose from reading the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus as an undergraduate. She claimed to have conceived the idea of studying with Wittgenstein as soon as she opened the book in Blackwell's and read section 5.53, "Identity of object I express by identity of sign, and not by using a sign for identity. Difference of objects I express by difference of signs." She became an enthusiastic student, feeling that Wittgenstein's therapeutic method helped to free her from philosophical difficulties in ways that her training in traditional systematic philosophy could not. As she wrote: For years, I would spend time, in cafés, for example, staring at objects saying to myself: 'I see a packet. But what do I really see? How can I say that I see here anything more than a yellow expanse?' ... I always hated phenomenalism and felt trapped by it. I couldn't see my way out of it but I didn't believe it. It was no good pointing to difficulties about it, things which Russell found wrong with it, for example. The strength, the central nerve of it remained alive and raged achingly. It was only in Wittgenstein's classes in 1944 that I saw the nerve being extracted, the central thought "I have got this, and I define 'yellow' (say) as this" being effectively attacked. — Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind: The Collected Philosophical Papers of G.E.M. Anscombe, Volume 2 (1981) pp. vii–x. After her fellowship at Cambridge ended, she was awarded a research fellowship at Somerville College, Oxford,[7] but during the academic year of 1946/47, she continued to travel to Cambridge once a week to attend tutorials with Wittgenstein that were devoted mainly to the philosophy of religion.[9] She became one of Wittgenstein's favourite students and one of his closest friends.[10][11] Wittgenstein affectionately addressed her by the pet name "old man" – she being (according to Ray Monk) "an exception to his general dislike of academic women".[10][11] His confidence in Anscombe's understanding of his perspective is shown by his choice of her as the translator of his Philosophical Investigations (for which purpose he arranged for her to spend some time in Vienna to improve her German[12][6]). Wittgenstein appointed Anscombe as one of his three literary executors and so she played a major role in translating and spreading his works.[13] Anscombe visited Wittgenstein many times after he left Cambridge in 1947, and Wittgenstein stayed at her house in Oxford for a period in 1950. She travelled to Cambridge in April 1951 to visit him on his deathbed. Wittgenstein named her, along with Rush Rhees and Georg Henrik von Wright, as his literary executor.[6][14] After his death in 1951 she was responsible for editing, translating, and publishing many of Wittgenstein's manuscripts and notebooks.[6][11] Anscombe did not avoid controversy. As an undergraduate in 1939 she had publicly criticised Britain's entry into the Second World War.[15] And, in 1956, while a research fellow, she unsuccessfully protested against Oxford granting an honorary degree to Harry S. Truman, whom she denounced as a mass murderer for his use of atomic bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[16][17][18] She would further publicise her position in a (sometimes erroneously dated[19]) pamphlet privately printed soon after Truman's nomination for the degree was approved. In the same she said she "should fear to go" to the Encaenia (the degree conferral ceremony) "in case God's patience suddenly ends."[20] She would also court controversy with some of her colleagues by defending the Catholic Church's opposition to contraception.[11] Later in life, she would be arrested protesting outside an abortion clinic, after abortion had been legalised in Great Britain.[17][21] Having remained at Somerville College since 1946, Anscombe was elected Professor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge in 1970, where she served until her retirement in 1986. She was elected a fellow of the British Academy in 1967, and a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1979.[22] In her later years, Anscombe suffered from heart disease, and was nearly killed in a car crash in 1996. She never fully recovered and she spent her last years in the care of her family in Cambridge.[7] On 5 January 2001, she died from kidney failure at Addenbrooke's Hospital at the age of 81, with her husband and four of their seven children at her bedside, just after praying the Sorrowful Mysteries of the rosary.[7][6][23] Anscombe's "last intentional act was kissing Peter Geach", her husband of sixty years.[24] Anscombe was buried adjacent to Wittgenstein in the St Giles' graveyard, Huntingdon Road, (now the Ascension Parish burial ground). her husband joined her there in 2013.[7][25] Debate with C. S. Lewis As a young philosophy don, Anscombe acquired a reputation as a formidable debater. In 1948, she presented a paper at a meeting of Oxford's Socratic Club in which she disputed C. S. Lewis's argument that naturalism was self-refuting (found in the third chapter of the original publication of his book Miracles). Some associates of Lewis, primarily George Sayer and Derek Brewer, have remarked that Lewis lost the subsequent debate on her paper and that this loss was so humiliating that he abandoned theological argument and turned entirely to devotional writing and children's literature.[26] This is a claim disputed by Walter Hooper[27] and Anscombe's impression of the effect upon Lewis was somewhat different: The fact that Lewis rewrote that chapter, and rewrote it so that it now has those qualities [to address Anscombe's objections], shows his honesty and seriousness. The meeting of the Socratic Club at which I read my paper has been described by several of his friends as a horrible and shocking experience which upset him very much. Neither Dr Havard (who had Lewis and me to dinner a few weeks later) nor Professor Jack Bennet remembered any such feelings on Lewis' part ... My own recollection is that it was an occasion of sober discussion of certain quite definite criticisms, which Lewis' rethinking and rewriting showed he thought was accurate. I am inclined to construe the odd accounts of the matter by some of his friends – who seem not to have been interested in the actual arguments or the subject matter – as an interesting example of the phenomenon called "projection". — Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind: The Collected Philosophical Papers of G.E.M. Anscombe, Volume 2 (1981) p.x. As a result of the debate, Lewis substantially rewrote chapter 3 of Miracles for the 1960 paperback edition.[28] |

生涯 アンスコムは、1919年3月18日にアイルランドのリムリックで、ゲートルード・エリザベス(旧姓トーマス)とアレン・ウェルズ・アンスコム大尉の間に 生まれた。父親はアイルランド独立戦争中にロイヤル・ウェールズ・フュージリアーズに所属していた。[6] 母親も父親も教育関係の仕事に携わっていた。母親は校長を務め、父親はダルウィッチ・カレッジの科学・工学部門の責任者となった。[7] アンスコムはシドナム・ハイスクールに通い、1937年にオックスフォード大学セント・ヒューズ・カレッジの「リテラエ・ヒューニオル(グレート)」課程に進学した。1939年に優等で卒業し、1941年には学位取得のための最終試験で首席の成績を収めた。 シドナム・ハイスクール在学中に、アンスコムはカトリックに改宗した。セント・ヒューズ・カレッジに入学した最初の年に彼女は教会に受け入れられ、それ以降はカトリックの信者となった。 1941年、彼女はピーター・ギーチと結婚した。ギーチも彼女と同じくカトリックに改宗し、ウィトゲンシュタインの弟子となり、著名な学術哲学者となった。二人には3人の息子と4人の娘が生まれた。 オックスフォード大学を卒業後、アンスコムは1942年から1945年まで、ケンブリッジ大学ニューナム・カレッジの大学院研究員として研究奨学金を授与 された。[7] 彼女の目的はルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの講義に出席することであった。ウィトゲンシュタインの哲学への関心は、学部生時代に『論理哲学論考』を 読んだことから生じた。ブラックウェルズでその本を開き、第5.53項「対象の同一性は記号の同一性によって表現され、記号の同一性によって表現されるの ではない。対象の差異は記号の差異によって表現される」を読んだ瞬間、ウィトゲンシュタインのもとで学ぶという考えが浮かんだと彼女は主張している。ウィ トゲンシュタインの治療的な方法は、従来の体系的な哲学の訓練では不可能だった方法で、彼女を哲学上の困難から解放してくれたと感じた彼女は、熱心な学生 となった。彼女は次のように書いている。 何年もの間、私はカフェなどで時間を費やし、物を見つめながらこう自問していた。『私は包み紙を見ている。しかし、私は本当に何を見ているのか? ここで黄色い広がり以上の何かを見ていると言えるのか?』...私は現象論を嫌い、それに囚われていると感じていた。そこから抜け出す方法が見つからな かったが、それを信じてはいなかった。例えばラッセルが間違っていると指摘したような、そのことに関する困難を指摘しても意味がなかった。その強さ、その 中心的な神経は生き続け、痛烈に猛威を振るっていた。1944年のウィトゲンシュタインの授業で、その神経が引き抜かれ、中心的な考えである「私はこれを 持っている。そして、『黄色』を(例えば)このように定義する」という考えが効果的に攻撃されているのを目にした。 —『形而上学と心の哲学:G.E.M. アンスコムの哲学論文集 第2巻』(1981年)pp. vii–x. ケンブリッジでの研究員としての任期が終了した後、彼女はオックスフォード大学ソマーヴィル・カレッジの研究員に任命されたが[7]、1946年から 1947年の学年度の間は、ウィトゲンシュタインの宗教哲学を主題とするチュートリアルに出席するために、週に一度ケンブリッジを訪れ続けた[9]。彼女 はウィトゲンシュタインのお気に入りの学生の一人となり、最も親しい友人の一人となった[10][11]。ウィトゲンシュタインは 彼女を「オールドマン」という愛称で親しみを込めて呼んでいた。彼女は(レイ・モンクによると)「学究肌の女性に対する彼の一般的な嫌悪感の例外」であっ た。[10][11] 彼の視点に対するアンスコムの理解に対する信頼は、彼の著書『哲学探究』の翻訳者に彼女を選んだことからも明らかである(その目的のために、彼は彼女がド イツ語を上達させるためにウィーンでしばらく過ごすよう手配した[12][6])。 ウィトゲンシュタインはアンスコムを3人の遺稿整理人のうちの1人に指名し、彼女は彼の作品の翻訳と普及において重要な役割を果たした。 アンスコムは1947年にウィトゲンシュタインがケンブリッジを去った後も何度も彼を訪問し、1950年にはウィトゲンシュタインがオックスフォードの彼 女の家に滞在した時期もあった。彼女は1951年4月にケンブリッジを訪れ、彼の臨終に立ち会った。ウィトゲンシュタインは、ラッシュ・リースとゲオル ク・ヘンリク・フォン・ライトとともに、彼女を文学上の遺言執行者として指名した。[6][14] 1951年の彼の死後、彼女はウィトゲンシュタインの原稿やノートブックの多くを編集、翻訳、出版する責任を担った。[6][11] アンスコムは論争を避けなかった。1939年、学部生だった彼女はイギリスの第二次世界大戦参戦を公に批判していた。また、1956年には研究員として、 オックスフォード大学がトルーマンに名誉学位を授与することに抗議したが、これは失敗に終わった。トルーマンを 広島と長崎への原爆投下を理由に大量殺人者と非難した。[16][17][18] トルーマンが学位授与候補として承認された直後に、彼女は個人的に印刷したパンフレット(日付が誤っている場合もある[19])で、自らの立場をさらに公 表した。その中で彼女は、「神の忍耐が突然尽きるようなことがあれば、エンケイニア(学位授与式)に出席するのは恐ろしい」と述べた。[20] また、彼女は避妊に対するカトリック教会の反対を擁護することで、一部の同僚と論争を繰り広げることにもなった。[11] その後、英国で中絶が合法化された後、彼女は中絶クリニックの外で抗議活動を行い、逮捕された。[17][21] 1946年よりソマーヴィル・カレッジに在籍していたアンスコムは、1970年にケンブリッジ大学の哲学教授に選出され、1986年に引退するまでその職 に就いた。1967年には英国学士院のフェローに、1979年にはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーの外国人名誉会員に選出された。 晩年、アンスコムは心臓病を患い、1996年には交通事故で死にかけた。その後、彼女は完全に回復することはなく、ケンブリッジの家族の世話になりながら 晩年を過ごした。2001年1月5日、彼女は81歳で腎不全によりアデンブルーク病院で死去した。7人の子供のうち4人が枕元に付き添う中、ロザリオの悲 しみの神秘を祈った直後に亡くなった。[7][6][23] アンカムの「最後の意図的な行為は、60年間連れ添った夫のピーター・ギーチにキスをしたこと」だった。[24] アンスコムは、ハンティンドン・ロードの聖ジャイルズ墓地(現アセンション教区墓地)でウィトゲンシュタインの隣に埋葬された。2013年には夫もそこに合葬された。 C. S. ルイスとの論争 若い哲学講師であった頃、アンスコムは優れた論客として評判を得ていた。1948年、彼女はオックスフォードのソクラテス・クラブの会合で、C. S. ルイスの著書『奇蹟』の原著の第3章で展開された自然主義は自己矛盾であるという主張に異議を唱える論文を発表した。ルイスの友人であったジョージ・セイ ヤーやデレク・ブリューワーらは、ルイスは彼女の論文に関するその後の討論で敗北し、その屈辱が原因で神学上の議論を放棄し、信仰に関する執筆や児童文学 に専念するようになったと述べている。[26] しかし、ウォルター・フーパーはこれを否定しており[27]、ルイスに対するアンスコムの印象は多少異なっていた。 ルイスがその章を書き直し、書き直した結果、今ではそれらの性質を備えるようになったという事実は、彼の誠実さと真剣さを示している。私が論文を読んだソ クラテス・クラブの会合は、彼の友人たちの何人かによって、彼をひどく動揺させた恐ろしく衝撃的な経験であったと描写されている。ハーバード博士(数週間 後、博士はルイスと私を夕食に招待した)もジャック・ベネット教授も、ルイスがそのような感情を抱いていたとはまったく覚えていない... 私の記憶では、それはある明確な批判について冷静に議論した機会であり、ルイスの再考と書き直しは、その批判が的を射たものだったことを示していた。私 は、実際の議論や主題には興味がなかったと思われる彼の友人たちの奇妙な証言を、「投影」と呼ばれる現象の興味深い例と解釈したい。 —『形而上学と心の哲学:G.E.M. アンスコムの哲学論文集 第2巻』(1981年)p.x. この論争の結果、ルイスは1960年のペーパーバック版のために『奇跡』の第3章を大幅に書き直した。[28] |

| Work On Wittgenstein Some of Anscombe's most frequently cited works are translations, editions, and expositions of the work of her teacher Ludwig Wittgenstein, including an influential exegesis[29] of Wittgenstein's 1921 book, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. This brought to the fore the importance of Gottlob Frege for Wittgenstein's thought and, partly on that basis, attacked "positivist" interpretations of the work. She co-edited his posthumous second book, Philosophische Untersuchungen/Philosophical Investigations (1953) with Rush Rhees. Her English translation of the book appeared simultaneously and remains standard. She went on to edit or co-edit several volumes of selections from his notebooks, (co-)translating many important works like Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics (1956) and Wittgenstein's "sustained treatment" of G. E. Moore's epistemology, On Certainty (1969).[30] In 1978, Anscombe was awarded the Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, 1st class for her work on Wittgenstein.[31] Intention Her most important work is the monograph Intention (1957). Three volumes of collected papers were published in 1981: From Parmenides to Wittgenstein; Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind; and Ethics, Religion and Politics. Another collection, Human Life, Action and Ethics appeared posthumously in 2005.[12] The aim of Intention (1957) was to make plain the character of human action and will. Anscombe approaches the matter through the concept of intention, which, as she notes, has three modes of appearance in the English language:  She suggests that a true account must somehow connect these three uses of the concept, though later students of intention have sometimes denied this, and disputed some of the things she presupposes under the first and third headings. It is clear though that it is the second that is crucial to her main purpose, which is to comprehend the way in which human thought and understanding and conceptualisation relate to the "events in a man's history", or the goings on to which he is subject. Rather than attempt to define intentions in abstraction from actions, thus taking the third heading first, Anscombe begins with the concept of an intentional action. This soon connected with the second heading. She says that what is up with a human being is an intentional action if the question "Why", taken in a certain sense (and evidently conceived as addressed to him), has application.[32] An agent can answer the "why" question by giving a reason or purpose for her action. "To do Y" or "because I want to do Y" would be typical answers to this sort of "why?"; though they are not the only ones, they are crucial to the constitution of the phenomenon as a typical phenomenon of human life.[33] The agent's answer helps supply the descriptions under which the action is intentional. Anscombe was the first to clearly spell out that actions are intentional under some descriptions and not others. In her famous example, a man's action (which we might observe as consisting of moving an arm up and down while holding a handle) may be intentional under the description "pumping water" but not under other descriptions such as "contracting these muscles", "tapping out this rhythm", and so on. This approach to action influenced Donald Davidson's theory, despite the fact that Davidson went on to argue for a causal theory of action that Anscombe never accepted.[34][35] Intention (1957) is also the classic source for the idea that there is a difference in "direction of fit" between cognitive states like beliefs and conative states like desire. (This theme was later taken up and discussed by John Searle.)[36] Cognitive states describe the world and are causally derived from the facts or objects they depict. Conative states do not describe the world, but aim to bring something about in the world. Anscombe used the example of a shopping list to illustrate the difference.[37] The list can be a straightforward observational report of what is actually bought (thereby acting like a cognitive state), or it can function as a conative state such as a command or desire, dictating what the agent should buy. If the agent fails to buy what is listed, we do not say that the list is untrue or incorrect; we say that the mistake is in the action, not the desire. According to Anscombe, this difference in direction of fit is a major difference between speculative knowledge (theoretical, empirical knowledge) and practical knowledge (knowledge of actions and morals). Whereas "speculative knowledge" is "derived from the objects known", practical knowledge is – in a phrase Anscombe lifts from Aquinas – "the cause of what it understands".[38] |

ウィトゲンシュタインに関する研究 アンスコムの最もよく引用される研究のいくつかは、彼女の師であるルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの著作の翻訳、版、解説であり、その中には、ウィト ゲンシュタインの1921年の著書『論理哲学論考』に関する影響力のある注釈[29]も含まれる。これにより、ウィトゲンシュタインの思想におけるゴット ロープ・フレーゲの重要性が浮き彫りになり、そのことを根拠に、この作品の「実証主義的」解釈を攻撃した。彼女は、彼の死後に出版された2冊目の著書『哲 学探究』(1953年)をラッシュ・リースと共同編集した。彼女によるこの本の英訳は同時に出版され、現在でも標準的なものとなっている。彼女はその後 も、彼のノートからの抜粋を編集または共同編集し、また『数学の基礎について』(1956年)や、ウィトゲンシュタインによるG. E. ムーアの認識論に関する「持続的考察」『確実性について』(1969年)など、多くの重要な著作の翻訳を共同で行った。[30] 1978年、ウィトゲンシュタインに関する研究により、アンスコムはオーストリア科学・芸術名誉大十字章を授与された。 意図 彼女の最も重要な著作は、単行本『意図』(1957年)である。論文集3巻は1981年に出版された。『パルメニデスからウィトゲンシュタインへ』、『形 而上学と心の哲学』、『倫理・宗教・政治』である。もう一つの論文集『人間の生活、行動、倫理』は、2005年に死後出版された。 『意図(intenstion)』(1957年)の目的は、人間の行動と意志の性質を明らかにすることだった。 アンスコムは、意図という概念を通じてこの問題に取り組んでいる。彼女が指摘しているように、英語では意図には3つの用法がある。  彼 女は、真の説明はこれらの3つの概念の使用法を何らかの形で結びつけなければならないと主張しているが、後の志向性の研究者はこれを否定し、彼女が最初の 見出しと3番目の見出しで前提としているいくつかの事柄を論争することがある。しかし、彼女の主な目的にとって重要なのは2番目の見出しであることは明ら かである。それは、人間の思考や理解、概念化が「人間の歴史における出来事」、つまり人間が従属する出来事とどのように関係しているかを理解することであ る。 行動から抽象的に意図を定義しようとするのではなく、つまり第3のテーマを最初に扱うのではなく、アンスコムは意図的な行動の概念から始める。これはすぐ に第2のテーマと関連する。彼女は、ある意味で「なぜ」という問い(明らかに自分自身に向けられたものとして考えられている)が当てはまる場合、人間が意 図的な行動を取る、と述べている。[32] 行為者は、理由や目的を挙げることで「なぜ」という問いに答えることができる。「Yをすること」や「Yをしたいから」は、この種の「なぜ?」に対する典型 的な答えである。ただし、これらが唯一の答えというわけではないが、人間の生活における典型的な現象として、この現象を構成する上で不可欠である。 [33] 行為者の答えは、その行為が意図的なものであることを説明するのに役立つ。アンソムは、ある記述においては行動が意図的であり、別の記述においては意図的 ではないことを明確に説明した最初の人物である。彼女の有名な例では、ある男性の行動(私たちは、その行動を、柄を握りながら腕を上下に動かすものとして 観察するかもしれない)は、「水を汲む」という記述においては意図的であるかもしれないが、「この筋肉を収縮させる」、「このリズムを刻む」など、他の記 述においては意図的ではないかもしれない。この行動に対するアプローチは、ドナルド・デヴィッドソンの理論に影響を与えたが、デヴィッドソンは、アンスコ ムが決して受け入れなかった因果行動理論を主張し続けた。[34][35] また、1957年の著書『意図』は、信念のような認知的状態と欲求のような志向的状態の間には「適合の方向」に違いがあるという考え方の古典的な出典でも ある。(このテーマは後にジョン・サールによって取り上げられ、議論された。)[36] 認知的状態は世界を描写し、描写する事実や対象から因果的に導かれる。志向的状態は世界を描写するのではなく、世界の何らかの事柄を実現することを目的と する。アンスコムは、この違いを説明するために買い物リストの例を挙げている。[37] 買い物リストは、実際に購入したものを単に観察した報告(つまり認識状態)である場合もあれば、購入すべきものを指示する命令や欲求といった志向状態とし て機能する場合もある。もし購入者がリストに書かれたものを購入し損ねたとしても、私たちはそのリストが真実ではないとか間違っているとは言わない。アン スコムによると、この適合の方向性の違いは、思弁的知識(理論的、経験的知識)と実践的知識(行動や道徳に関する知識)の間の大きな違いである。思弁的知 識」が「既知の対象から派生する」ものであるのに対し、実践的知識は、アンスコムがアクィナスから引用した表現を用いれば、「理解するものの原因」であ る。[38] |

| Ethics Main article: Modern Moral Philosophy Anscombe made great contributions to ethics as well as metaphysics. Her 1958 essay "Modern Moral Philosophy" is credited with having coined the term "consequentialism",[39] as well as with reviving interest in and study of virtue ethics in Western academic philosophy.[40][41] The Anscombe Bioethics Centre in Oxford is named after her, and conducts bioethical research in the Catholic tradition.[42] Brute and institutional facts Anscombe also introduced the idea of a set of facts being 'brute relative to' some fact. When a set of facts xyz stands in this relation to a fact A, they are a subset out of a range some subset among which holds if A holds. Thus if A is the fact that I have paid for something, the brute facts might be that I have handed him a cheque for a sum which he has named as the price for the goods, saying that this is the payment, or that I gave him some cash at the time that he gave me the goods. There tends, according to Anscombe, to be an institutional context which gives its point to the description 'A', but of which 'A' is not itself a description: that I have given someone a shilling is not a description of the institution of money or of the currency of the country. According to her, no brute facts xyz can generally be said to entail the fact A relative to which they are 'brute' except with the proviso "under normal circumstances", for "one cannot mention all the things that were not the case, which would have made a difference if they had been."[43] A set of facts xyz ... may be brute relative to a fact A which itself is one of a set of facts ABC ... which is brute relative to some further fact W. Thus Anscombe's account is not of a distinct class of facts, to be distinguished from another class, 'institutional facts': the essential relation is that of a set of facts being 'brute relative to' some fact. Following Anscombe, John Searle derived another conception of 'brute facts' as non-mental facts to play the foundational role and generate similar hierarchies in his philosophical account of speech acts and institutional reality.[44] First person Her paper "The First Person"[34] buttressed remarks by Wittgenstein (in his Lectures on "Private Experience"[45]) arguing for the now-notorious conclusion that the first-person pronoun, "I", does not refer to anything (not, e.g., to the speaker) because of its immunity from reference failure. Having shown by counter-example that 'I' does not refer to the body, Anscombe objected to the implied Cartesianism of its referring at all. Few people accept the conclusion – though the position was later adopted in a more radical form by David Lewis – but the paper was an important contribution to work on indexicals and self-consciousness that has been carried on by philosophers as varied as John Perry, Peter Strawson, David Kaplan, Gareth Evans, John McDowell, and Sebastian Rödl.[46] Causality In her article, "Causality and Determination",[47] Anscombe defends two main ideas: that causal relations are perceivable, and that causation does not require a necessary connection and a universal generalization linking cause and effect. Regarding her idea that causal relations are perceivable, she believes that we perceive the causal relations between objects and events. In defending her idea that causal relations are perceivable, Anscombe poses a question "How did we come by our primary knowledge of causality?".[47] She proposes two answers to this question: By "learning to speak, we learned the linguistic representation and application of a host of causal concepts"[47] By observing that some action(s) caused a certain event In proposing her first answer, that by "learning to speak, we learned the linguistic representation and application of a host of causal concepts", Anscombe thinks that by learning to speak we already have a linguistic representation of certain causal concepts and she gives an example of transitive verbs, such as scrape, push, carry, knock over. Example: I knocked over a vase of flowers. In proposing her second answer, that by observing some actions we can see causation, Anscombe thinks that we cannot ignore the fact that certain actions, which produced a certain event are possible to observe. Example: a cat spilled milk. The second idea that Anscombe defends in the article "Causality and Determination"[47] is that causation requires neither a necessary connection nor a universal generalization linking cause and effect. Anscombe states that it is assumed that causality is some kind of necessary connection.[47] |

倫理学 詳細は「近代道徳哲学」を参照 アンスコムは、形而上学だけでなく倫理学にも多大な貢献をした。彼女の1958年の論文「近代道徳哲学」は、「帰結主義(consequentialism)」という用語を初めて使用した論文 として知られており[39]、また西洋の学術哲学における徳倫理学への関心と研究を復活させたことでも知られている[40][41]。 オックスフォードにあるアンスコム生命倫理センターは彼女の名にちなんで名付けられ、カトリックの伝統に則った生命倫理の研究を行っている。 露骨な事実と制度的事実( Brute and institutional facts) アンスコムはまた、ある事実に対して「相対的な事実」という考え方を導入した。ある事実 A に対して、ある事実 xyz が「~に相対する」という関係にある場合、xyz は A が成り立つ場合に成り立つ範囲の一部集合である。 したがって、A が私が何かに対して支払いを済ませたという事実である場合、その「生々しい事実」は、私が彼に商品の代金を指定した金額の小切手を渡し、「これが支払い だ」と言ったことや、彼が私に商品を手渡した際に現金を渡したことであるかもしれない。アンスコムによれば、Aという記述に意味を与える制度的背景がある 傾向にあるが、A自体は記述ではない。つまり、私が誰かに1シリングを渡したことは、貨幣制度やその国の通貨の記述ではない。彼女によれば、「通常の状況 下」という但し書きを付けた場合を除いて、一般的に、xyzという「粗野な事実」が、それらが「粗野」であるという事実Aを必然的に伴うということはでき ない。なぜなら、「そうではなかったすべての事柄を挙げることはできない。それらがそうであったならば違いが生じていただろうから」[43] 事実の集合xyzは、 事実Aに相対するものであり、事実A自体は事実ABCの集合の1つであり、さらに別の事実Wに相対するものである。したがって、アンソムの説明は、別のク ラスである「制度的事実」と区別されるべき、明確なクラスの事実ではない。本質的な関係は、事実の集合が「ある事実の相対する事実」であるという関係であ る。アンスコムに倣い、ジョン・サールは、言語行為と制度上の現実に関する自身の哲学的な説明において、基礎的な役割を果たし、同様の階層を生み出す非精 神的事実としての「生々しい事実」という別の概念を導き出した。 一人称 彼女の論文「一人称」[34]は、ウィトゲンシュタイン(「私的経験」に関する講義[45])の主張を補強し、一人称代名詞「私」は、参照の失敗から免れ ているため、何にも(話し手などには)言及していないという、今では悪名高い結論を論じている。「I」が身体を指し示さないことを反例によって示したアン スコムは、それが指し示しているということが暗黙のうちにデカルト主義的であることに異議を唱えた。この結論を受け入れる人はほとんどいないが、この立場 は後にデイヴィッド・ルイスによってより急進的な形で採用された。しかし、この論文は、ジョン・ペリー、ピーター・ストロースン、デイヴィッド・カプラ ン、ガレス・エヴァンス、ジョン・マクダウェル、セバスチャン・ロドルなど、さまざまな哲学者たちによって引き継がれてきた、指示詞と自己意識に関する研 究への重要な貢献であった。 因果関係 論文「因果関係と決定」において、[47] アンスコムは主に2つの考え方を擁護している。すなわち、因果関係は知覚可能であること、そして因果関係は、原因と結果を結びつける必要不可欠なつながり と普遍的な一般化を必要としないことである。 因果関係は知覚可能であるという考え方について、彼女は、私たちは物事と出来事の因果関係を認識していると信じている。 因果関係が知覚可能であるという考えを擁護するにあたり、アンスコムは「因果関係に関する我々の基本的知識は、どのようにして得られたのか?」という問いを投げかけている。[47] 彼女はこの問いに対する2つの答えを提案している。 「言葉を習得することで、我々は数多くの因果概念の言語表現と応用を学んだ」[47] ある行動が特定の出来事を引き起こしたことを観察すること 最初の答えとして、「話すことを学ぶことで、私たちは言語による因果概念の表現と応用を学んだ」という考えを提示するにあたり、アンスコムは、話すことを 学ぶことで、私たちはすでに特定の因果概念の言語による表現を習得していると考え、その例として、引っかく、押す、運ぶ、倒すなどの他動詞を挙げている。 例:私は花瓶の花を倒してしまった。 彼女の2つ目の回答として、ある行動を観察することで因果関係を理解できるという考えを提示するにあたり、アンスコムは、ある出来事を引き起こした特定の行動が観察可能であるという事実を無視することはできないと考えている。 例:猫がミルクをこぼした。 アンスコムが論文「因果関係と決定」[47]で擁護する2つ目の考え方は、因果関係には、原因と結果を結びつける必要的なつながりも普遍的な一般化も必要ないというものである。 アンスコムは、因果関係は必要的なつながりであると想定されていると述べている。[47] |

| Views of her work The philosopher Candace Vogler says that Anscombe's "strength" is that "'when she is writing for [a] Catholic audience, she presumes they share certain fundamental beliefs,' but she is equally willing to write for people who do not share her assumptions."[48] In 2010, philosopher Roger Scruton wrote that Anscombe was "perhaps the last great philosopher writing in English".[49] Mary Warnock described her as "the undoubted giant among women philosophers"[50] while John Haldane said she "certainly has a good claim to be the greatest woman philosopher of whom we know".[40] |

彼女の研究に対する見解 哲学者のキャンディス・ヴォグラーは、アンスコムの「強み」は、「『カトリックの読者に向けて書いているときは、彼らも特定の基本的な信念を共有している と仮定する』が、彼女の仮定を共有していない人々にも同じように喜んで書く」ことであると述べている。[48] 2010年には、哲学者のロジャー・スクラットンが 「おそらく英語で執筆する最後の偉大な哲学者」と評した。[49] メアリー・ウォーノックは彼女を「女性哲学者の中で疑いようのない巨人」と評し[50]、ジョン・ハルデーンは「我々が知る限り、最も偉大な女性哲学者で あることは間違いない」と述べた。[40] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G._E._M._Anscombe |

|

| Books Intention. Oxford: Blackwell. 1957. An Introduction to Wittgenstein's Tractatus. 1959. Three Philosophers. With P. T. Geach. 1961. Causality and Determination: an inaugural lecture. CUP Archive. 1971. ISBN 978-0-521-08304-1. reprinted in Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind. Times, Beginnings and Causes (PDF). Oxford University Press [for the British Academy]. 1975. ISBN 978-0-19-725712-8. From Parmenides to Wittgenstein. The Collected Philosophical Papers of G. E. M. Anscombe. Vol. 1. 1981. ISBN 978-0-631-12922-6. Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind. The Collected Philosophical Papers of G. E. M. Anscombe. Vol. 2. Oxford: Blackwell. 1981. ISBN 978-0-631-12932-5. Ethics, Religion and Politics. The Collected Philosophical Papers of G. E. M. Anscombe. Vol. 3. 1981. ISBN 978-0-631-12942-4. Human Life, Action and Ethics. Edited by Mary Geach; Luke Gormally. St. Andrews Studies in Philosophy and Public Affairs. 4. Exeter, England: Imprint Academic. 2005. ISBN 978-1-84540-013-2 La filosofia analitica y la espiritualidad del hombre (in Spanish). Edited by J. M. Torralba; J. Nubiola. Pamplona, Spain: Ediciones de la Universidad de Navarra S.A. 2005. ISBN 978-84-313-2245-8. Faith in a Hard Ground: Essays on Religion, Philosophy and Ethics. Edited by Mary Geach; Luke Gormally. St. Andrews Studies in Philosophy and Public Affairs. 11. Exeter, England: Imprint Academic. 2008. ISBN 978-1-84540-121-4 From Plato to Wittgenstein. Edited by Mary Geach; Luke Gormally. St. Andrews Studies in Philosophy and Public Affairs. 18. Exeter, England: Imprint Academic. 2011. ISBN 978-1-84540-232-7 Select papers/book chapters Anscombe, G. E. M. (1957). "XIV.—Intention". Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 57: 321–332. doi:10.1093/aristotelian/57.1.321. "On Brute Facts" (PDF). Analysis. 18 (3). Oxford: Oxford University Press: 69–72. 1958. doi:10.2307/3326788. ISSN 0003-2638. JSTOR 3326788. Austin, J. L.; Anscombe, G. E. M. (1958). "Pretending". Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume. 32. Aristotelian Society: 261–294. doi:10.1093/aristoteliansupp/32.1.261. G. E. M. Anscombe; J. Körner (12 July 1964). "Substance". Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume. 38 (1). Aristotelian Society: 69–90. doi:10.1093/aristoteliansupp/38.1.69. XIV.— "Times, Beginnings and Causes" Proceedings of the British Academy 60, 1974 (1975) Anscombe, G.E.M. "Memory, 'Experience' and Causation" in: Lewis, Hywel David (ed.) Contemporary British Philosophy Personal Statements Fourth Series (1976) Anscombe, G.E.M. "'Soft' determinism" in: Gilbert Ryle (ed.), Contemporary aspects of philosophy (1977) Lockwood, Michael; Anscombe, G. E. M. (1983). "Sins of Omission? The Non-Treatment of Controls in Clinical Trials". Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume. 57. Aristotelian Society: 207–227. doi:10.1093/aristoteliansupp/57.1.207. Festschriften Gormally, Luke, ed. (1994). Moral truth and Moral Tradition: Essays in Honour of Peter Geach and Elizabeth Anscombe. Dublin: Four Courts Press. |

書籍 意図主義(インテンション)。オックスフォード:ブラックウェル。1957年。 ウィトゲンシュタインの『論理哲学論考』入門。1959年。 三人の哲学者。P・T・ギアチとの共著。1961年。 因果性と決定:就任講演。CUPアーカイブ。1971年。ISBN 978-0-521-08304-1。再版『形而上学と精神哲学』所収。 『時間、始まり、原因』(PDF)。オックスフォード大学出版局[英国学士院刊]。1975年。ISBN 978-0-19-725712-8。 パルメニデスからウィトゲンシュタインへ。G. E. M. アンスコム哲学論文集。第1巻。1981年。ISBN 978-0-631-12922-6。 形而上学と精神哲学。G. E. M. アンスコム哲学論文集。第2巻。オックスフォード:ブラックウェル。1981年。ISBN 978-0-631-12932-5。 倫理、宗教、政治。G. E. M. アンスコムの哲学論文集。第3巻。1981年。ISBN 978-0-631-12942-4。 人間の生活、行動、倫理。メアリー・ギアチ、ルーク・ゴーマリー編。セント・アンドルー哲学・公共問題研究。4。イングランド、エクセター:インプリント・アカデミック。2005年。ISBN 978-1-84540-013-2 La filosofia analitica y la espiritualidad del hombre(スペイン語)。J. M. Torralba、J. Nubiola 編集。スペイン、パンプローナ:Ediciones de la Universidad de Navarra S.A. 2005年。ISBN 978-84-313-2245-8。 Faith in a Hard Ground: Essays on Religion, Philosophy and Ethics(厳しい状況における信仰:宗教、哲学、倫理に関するエッセイ)。Mary Geach、Luke Gormally 編集。セント・アンドルー哲学・公共問題研究。11。イングランド、エクセター:インプリント・アカデミック。2008年。ISBN 978-1-84540-121-4 プラトンからウィトゲンシュタインまで。メアリー・ギアチ、ルーク・ゴーマリー編。セント・アンドルー哲学・公共問題研究。18。イングランド、エクセター:インプリント・アカデミック。2011年。ISBN 978-1-84540-232-7 論文・書籍の章 アンスコム, G. E. M. (1957). 「XIV.—意図」. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 57: 321–332. doi:10.1093/aristotelian/57.1.321. 「生々しい事実について」(PDF). 『分析』. 18 (3). オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局: 69–72. 1958. doi:10.2307/3326788. ISSN 0003-2638. JSTOR 3326788. オースティン, J. L.; アンスコム, G. E. M. (1958). 「ふり」. アリストテレス学会補遺. 32. アリストテレス学会: 261–294. doi:10.1093/aristoteliansupp/32.1.261. G. E. M. アンスコム; J. ケルナー (1964年7月12日). 「実体」. アリストテレス協会補遺. 38 (1). アリストテレス協会: 69–90. doi:10.1093/aristoteliansupp/38.1.69. XIV.— 「時間、始まり、原因」英国学士院紀要 60, 1974 (1975) アンスコム, G.E.M. 「記憶、『経験』、因果関係」ルイス, ハイウェル・デイヴィッド (編) 現代英国哲学 個人的声明 第四シリーズ (1976) アンスコム, G.E.M. 「『軟弱な』決定論」 in: ギルバート・ライル (編), 現代哲学の諸相 (1977) ロックウッド, マイケル; アンスコム, G. E. M. (1983). 「不作為の罪か? 臨床試験における対照群の非治療」. アリストテレス協会補遺第57巻。アリストテレス協会:207–227頁。doi: 10.1093/aristoteliansupp/57.1.207. 記念論文集 ゴーマリー、ルーク編(1994)。『道徳的真実と道徳的伝統:ピーター・ギアチとエリザベス・アンスコムへの敬意を込めて』ダブリン:フォー・コート・プレス。 |

| References Citations Boxer, Sarah (13 January 2001). "G. E. M. Anscombe, 81, British Philosopher". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 June 2019. "Ninety-four pages & then some: Roger Teichmann interviewed by Richard Marshall". 3:16. Retrieved 14 June 2021. Anscombe's paper was rightly credited with having helped start up the renewed interest in Aristotelian ethics, an interest which produced what is now often called 'virtue ethics'. Wiseman, Rachael (1 January 2015). "Anscombe's Intention". Jurisprudence. 6 (1): 182–193. doi:10.5235/20403313.6.l.182 (inactive 6 July 2025). ISSN 2040-3313. Stoutland, Frederick (2011). "Introduction: Anscombe's Intention in Context". Essays on Anscombe's Intention. Anton Ford, Jennifer Hornsby, Frederick Stoutland. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 1–22. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674060913.intro. ISBN 978-0-674-06091-3. OCLC 754715004. Singh, Keshav (30 December 2020). "Anscombe on Acting for Reasons". In Chang, Ruth; Kurt, Sylvan (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Practical Reason. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-33712-9. Teichman, Jenny (2003). "Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe, 1919–2001" (PDF). In Thompson, F.M.L (ed.). Proceedings of the British Academy, Volume 115 Biographical Memoirs of Fellows, I. British Academy. doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197262788.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-175421-0. Teichman, Jenny (2017). "Anscombe, (Gertrude) Elizabeth Margaret (1919–2001), philosopher | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/75032. Retrieved 17 June 2019. Mac Cumhaill, Clare; Wiseman, Rachael (2022). Metaphysical Animals: How Four Women Brought Philosophy Back to Life. New York: Penguin. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-9848-9898-2. Teichmann, Roger (2008). "Introduction". The Philosophy of Elizabeth Anscombe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-153845-2. OCLC 269285454. The philosophy examiners wanted to give her a First ... but the ancient history examiners would agree to this only on condition that she showed a minimum knowledge of their subject in a viva voce (oral) examination. Anscombe's performance ... was less than spectacular... To the last two questions she answered 'No', these being 'Can you give us the name of a Roman provincial governor?' and (in some desperation) 'Is there any fact about the period you are supposed to have studied which you would like to tell us?' The examiners cannot have been well pleased, but somehow or other ended up being persuaded by the philosophers ... As Michael Dummett writes in his obituary ... 'For the [ancient historians] to have yielded, her philosophy papers must have been astonishing'. Drury, M. O'C. (Maurice O'Connor) (21 September 2017). The selected writings of Maurice O'Connor Drury : on Wittgenstein, philosophy, religion and psychiatry. Hayes, John (Professor of Philosophy). London. pp. 407–409. ISBN 978-1-4742-5636-0. OCLC 946967786. Monk, Ray. (1990). Ludwig Wittgenstein : the duty of genius (1st American ed.). New York: Free Press. pp. 497–498. ISBN 0-02-921670-2. OCLC 21560991. Driver, Julia (2018), "Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2018 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 19 June 2019 The Oxford Handbook of Wittgenstein. Kuusela, Oskari., McGinn, Marie. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2011. pp. 715 (fn.2). ISBN 978-0-19-928750-5. OCLC 764568769. Michael L. Coulter; Richard S. Myers; Joseph A. Varacalli (2012). Encyclopedia of Catholic Social Thought, Social Science, and Social Policy Supplement. Vol. 3. Scarecrow Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780810882751. Malcolm, Norman (1967). Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir. Oxford University Press. p. 97. "Professor G E M Anscombe". The Daily Telegraph. 6 January 2001. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2019. In the autumn of 1939, while still an undergraduate, she and a friend wrote a pamphlet entitled The Justice of the Present War Examined. In this, Elizabeth Anscombe argued that while Britain was certainly fighting against an unjust cause, it was not fighting for a just one. ... Subsequently, the Catholic Archbishop of Birmingham told the two students to withdraw the pamphlet because they had described it as Catholic without getting a Church licence. Meyers, Diana Tietjens (2008). "Anscombe, Elizabeth". In Smith, Bonnie G. (ed.). The Oxford encyclopedia of women in world history. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514890-9. OCLC 167505633. Anscombe ... opposed Britain's entry into World War II on the grounds that fighting the war would certainly involve killing non-combatants. When Oxford decided to award the U.S. president Harry Truman an honorary degree in 1956, Anscombe protested vigorously, arguing that the atomic bombing of innocent civilians at Hiroshima and Nagasaki disqualified him for such an honour. "Elizabeth Anscombe // de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture // University of Notre Dame". ethicscenter.nd.edu. Retrieved 6 May 2019. Anscombe ... was a vigorous opponent of the use of nuclear weapons and led a protest of Oxford's awarding a degree to President Harry Truman on the grounds that a mass-murderer should not be so honoured. She was also a fierce opponent of abortion; on one occasion late in her life, she had to be dragged bodily by police away from a sit-in at an abortion clinic. Wiseman, Rachael (2016). "The Intended and Unintended Consequences of Intention" (PDF). American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly. 90 (2): 207–227. doi:10.5840/acpq201622982. Retrieved 17 June 2019. On 1st May 1956, Oxford University's Convocation ...considered nominations for honorary degrees ... One of the nominations was Harry S. Truman ... Anscombe ..."caused a small stir" ... by arguing that the nomination should be rejected on the grounds that Truman was guilty of mass murder ... Anscombe's speech did not persuade ...The House was asked to indicate its attitude toward the nomination, and showed overwhelming support. ... On 20th June, Truman was awarded his honorary degree Gormally, L. – Kietzmann, C. – Torralba, J. M., Bibliography of Works by G.E.M. Anscombe, Seventh Version – June 2012 The date in CP is "1957" and there is no date in the original pamphlet. However, according to the facts it must have been published in 1956. The Honorary Degree was conferred on June 20th. 1956 and the Bodleian stamp of the pamphlet is "11 July 1956". See Torralba, J. M., Acción intencional y razonamiento práctico según G.E.M. Anscombe, Pamplona: Eunsa, 2005, pp. 58-61. "G. E. M. Anscombe "Mr. Truman's Degree"". 1956. Retrieved 17 June 2019. "Rare Pics Surface of Elizabeth Anscombe Arrested for Blocking Abortion Clinic". ChurchPOP. 18 October 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2019. "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter A" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 19 April 2011. Rutler, George W. (1 September 2004). "Cloud of Witnesses: G.E.M Anscombe". Crisis Magazine. Retrieved 12 September 2024. Dolan, John M. (1 May 2001). "G. E. M. Anscombe: Living the Truth". First Things. Retrieved 30 August 2024. Hayes, John (2020). "G.E.M. ANSCOMBE—Irish-born philosopher". History Ireland. 28 (5): 42–44. ISSN 0791-8224. JSTOR 26934660. "Frequently Asked Questions about C.S. Lewis". Biblical Discernment Ministries. 1999. Archived from the original on 24 October 2005. Retrieved 9 November 2017. "Truth about Anscombe v C S Lewis". The Telegraph. 11 January 2001. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021. when writing my C. S. Lewis: a Companion and Guide (1996). Lewis told me in 1963 that he thought he won the debate with Anscombe at the Socratic Club in 1948. However, he accepted that he had been unclear and revised Chapter III of the book. Ironically, many philosophers disagree with Anscombe's argument, and maintain that the original chapter was philosophically sound, and that Lewis did not need to rewrite it. It is also not true that Lewis "never again wrote straightforward polemics for Christianity". In 1952, he revised his BBC wartime broadcasts as Mere Christianity. That book has probably caused more people to accept the faith than any other philosophical tome of the last century. Lewis was a man of such titanic imagination that he didn't need to go over and over the same ideas. It was not fear of Anscombe or anyone else that caused him to write the seven incomparable Chronicles of Narnia in the 1950s. Three theological works followed them. Smilde, Arend (6 December 2017). "What Lewis really did to Miracles A philosophical layman's attempt to understand the Anscombe affair". Journal of Inklings Studies. 1 (2): 9–24. doi:10.3366/ink.2011.1.2.3. Anscombe, G. E. M. (1959). An Introduction to Wittgenstein's Tractatus. London: Hutchinson. Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1969). On Certainty. Oxford: BasilBlackwell. Zekauskas, Jeffrey (April 1983). "Reviewed Work: Remarks on the Philosophy of Psychology by Ludwig Wittgenstein, G. E. M. Anscombe, G. H. Von Wright". Ethics. 93 (3): 606–8. doi:10.1086/292476. JSTOR 2380641. "Reply to a Parliamentary Question" (PDF) (in German). Vienna. p. 521. Retrieved 21 October 2012. Anscombe 1957, sec. 5–8. Anscombe 1957, sec. 18–21. Anscombe, G. E. M. (1981). Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind (collected papers vol 2). Oxford: Basil Blackwell. pp. 21–36. ISBN 0-631-12932-4. Anscombe 1957. Searle, John R. (1983). Intentionality, an essay in the philosophy of mind. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22895-6. OCLC 9196773. Anscombe 1957, sec. 32. Anscombe 1957, sec. 48. Seidel, Christian (2019). Consequentialism: new directions, new problems. Oxford moral theory. New York (N.Y.): Oxford university press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-19-027011-7. Haldane, John (2000). "In Memoriam: G. E. M. Anscombe (1919–2001)" (PDF). The Review of Metaphysics. 53 (4): 1019–1021. ISSN 0034-6632. Crisp, Roger; Slote, Michael (1997). "Introduction". In Crisp, Roger; Slote, Michael (eds.). Virtue ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-19-875189-3. OCLC 37028589. "Home". bioethics.org.uk. Anscombe, G. E. M. (1958). "On Brute Facts". Analysis. 18 (3): 69–72. doi:10.2307/3326788. JSTOR 3326788. Searle, John (1995). The Construction of Social Reality. London: Allen Lane The Penguin Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 0-14-023590-6. Wittgenstein, Lugwig (1993). "Notes for Lectures on "Private Experience" and "Sense Data"". In Klagge, J.; Nordmann, A. (eds.). Philosophical Occasions. Indianapolis: Hackett. p. 228. "Into the Coast: Sebastian Rödl". 10 January 2019. Anscombe, G.E.M. "Causality and Determination". Metaphysics, edited by Jaegwon Kim, Daniel Z. Korman and Ernest Sosa, Wiley-Blackwell, 2012, pp. 386-396. Oppenheimer, Mark (8 January 2011). "Renaissance for Outspoken Catholic Philosopher". The New York Times. p. A14. Retrieved 9 November 2017. Scruton, Roger (2010). "Wine and Philosophy". Decanter. Vol. 35. pp. 57–59. Retrieved 9 November 2017. Warnock, Mary, ed. (1996). Women Philosophers. London: J.M.Dent & Sons Ltd. p. 203. ISBN 0-460-87738-0. OCLC 34407377. the undoubted giant among women philosophers, a writer of immense breadth, authority and penetration. |

参考文献 引用 Boxer, Sarah (2001年1月13日). 「G. E. M. アンスコム, 81, British Philosopher」. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. 2019年6月17日閲覧。 「94ページとそれ以上:ロジャー・タイクマン、リチャード・マーシャルによるインタビュー」. 3:16. 2021年6月14日閲覧. アンスコムの論文は、アリストテレス倫理学への関心の再燃を促した功績を正しく認められており、この関心は現在「徳倫理学」と呼ばれる学問を生み出した。 ワイズマン、レイチェル(2015年1月1日)。「アンスコムの意図」。『法学』。6巻1号:182–193頁。doi:10.5235/20403313.6.l.182(2025年7月6日現在非アクティブ)。ISSN 2040-3313。 スタウトランド、フレデリック(2011)。「序論:アンスコムの『意図』の文脈」。『アンスコムの『意図』に関する論考』。アントン・フォード、ジェニ ファー・ホーンズビー、フレデリック・スタウトランド編。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。pp. 1–22。doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674060913.intro. ISBN 978-0-674-06091-3. OCLC 754715004. シン、ケシャブ(2020年12月30日)。「理由に基づく行動に関するアンスコムの考察」。チャン、ルース; カート、シルヴァン (編). 『実践的理性のラウトレッジ・ハンドブック』. ラウトレッジ. ISBN 978-1-000-33712-9. タイクマン、ジェニー (2003). 「ガートルード・エリザベス・マーガレット・アンスコム、1919–2001」 (PDF). F.M.L. トンプソン編『英国学士院紀要 第115巻 会員伝記集 I』英国学士院. doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197262788.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-175421-0. テイチマン、ジェニー(2017)。「アンスコム、(ガートルード)エリザベス・マーガレット(1919–2001)、哲学者|オックスフォード国家人物 事典」。オックスフォード国家人物事典(オンライン版)。オックスフォード大学出版局。doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/75032。2019 年6月17日閲覧。 マック・クメール、クレア; ワイズマン、レイチェル (2022). 『形而上学的な動物たち:四人の女性が哲学に命を吹き返した方法』. ニューヨーク: ペンギン. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-9848-9898-2. タイクマン、ロジャー (2008). 「序文」. 『エリザベス・アンスコムの哲学』. オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-153845-2。OCLC 269285454。哲学の試験官は彼女に最高評価を与えようとしたが、古代史の試験官は口頭試験で最低限の知識を示すことを条件とした。アンスコムのパ フォーマンスは…見事とは言い難かった… 最後の二つの質問には「いいえ」と答えた。質問内容は「ローマの属州総督の名前を挙げられますか?」と(やや必死に)「あなたが研究したとされる時代につ いて、何か話したい事実はありますか?」だった。審査員たちは満足していなかったが、どうにかして哲学者の説得に屈した...マイケル・ダメットが追悼文 で書いているように... 「古代史学者たちが折れたということは、彼女の哲学論文は驚くべき内容だったに違いない」 Drury, M. O『C. (Maurice O』Connor) (2017年9月21日). 『モーリス・オコナー・ドリュリーの選集:ウィトゲンシュタイン、哲学、宗教、精神医学について』. ヘイズ, ジョン (哲学教授). ロンドン. pp. 407–409. ISBN 978-1-4742-5636-0. OCLC 946967786. モンク、レイ(1990)。『ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン:天才の義務』(第1版アメリカ版)。ニューヨーク:フリープレス。pp. 497–498. ISBN 0-02-921670-2. OCLC 21560991. ドライバー, ジュリア (2018), 「ガートルード・エリザベス・マーガレット・アンスコム」, ザルタ, エドワード・N. (編), 『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』(2018年春版), メタフィジックス研究ラボ, スタンフォード大学, 2019年6月19日取得 『オックスフォード・ウィトゲンシュタイン手引書』. クースエラ, オスカリ., マクギン, マリー. オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局. 2011. pp. 715 (fn.2). ISBN 978-0-19-928750-5. OCLC 764568769. Michael L. Coulter; Richard S. Myers; Joseph A. Varacalli (2012). 『カトリック社会思想、社会科学、社会政策補遺事典』第 3 巻。スケアクロウ・プレス。6 ページ。ISBN 9780810882751。 マルコム、ノーマン (1967)。『ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン:回顧録』。オックスフォード大学出版局。97 ページ。 「G E M アンスコム教授」。デイリー・テレグラフ。2001年1月6日。ISSN 0307-1235。2011年6月5日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2019年6月19日に取得。1939年の秋、まだ大学生だった彼女と友人は、「現 在の戦争の正当性について」という小冊子を執筆した。この小冊子の中で、エリザベス・アンスコムは、英国は確かに不当な大義のために戦っているが、正当な 大義のために戦っているわけではないと主張した。...その後、バーミンガムのカトリック大司教は、2人の学生に、教会の許可を得ずにカトリックと記述し たとして、小冊子を撤回するよう指示した。 マイヤーズ、ダイアナ・ティエティエンス(2008)。「アンスコム、エリザベス」。スミス、ボニー・G(編)。『世界史における女性オックスフォード百 科事典』。オックスフォード[イングランド]:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-514890-9。OCLC 167505633。アンスコムは...戦争遂行が非戦闘員の殺害を必然的に伴うとして、英国の第二次世界大戦参戦に反対した。1956年にオックス フォード大学がハリー・トルーマン米大統領に名誉学位を授与すると決定した際、アンスコムは激しく抗議した。広島と長崎における無実の民間人への原子爆弾 投下は、彼にそのような栄誉を与える資格を喪失させると主張したのである。 「エリザベス・アンスコム // デ・ニコラ倫理文化センター // ノートルダム大学」. ethicscenter.nd.edu. 2019年5月6日閲覧. アンスコムは核兵器使用の強力な反対者であり、大量殺戮者を称えるべきではないとして、オックスフォード大学がハリー・トルーマン大統領に学位を授与した ことに抗議を主導した。彼女はまた中絶の激しい反対者でもあった。晩年のある時、中絶クリニックでの座り込みから警察に物理的に引きずり出される事態と なった。 ワイズマン、レイチェル(2016)。「意図主義の意図的および非意図的結果」(PDF)。『アメリカン・カトリック哲学季刊』。90(2): 207–227。doi:10.5840/acpq201622982. 2019年6月17日閲覧。1956年5月1日、オックスフォード大学の卒業式典...名誉学位の候補者選考を行った... 候補者の一人にハリー・S・トルーマンが挙がった...アンスコムは...トルーマンが大量殺戮の罪を犯したとして候補者を拒否すべきだと主張し、「小さ な騒ぎ」を引き起こした...アンスコムの演説は説得力を持たなかった...議会は候補者に対する態度を示すよう求められ、圧倒的な支持を示した...6 月20日、トルーマンは名誉学位を授与された ゴーマリー、L. – キートツマン、C. – トラルバ、J. M.、『G.E.M.アンスコム著作目録』第七版 – 2012年6月CP(『パブリケーション・クリティカル』)記載の発行年は「1957年」であり、原パンフレットには発行年が記載されていない。しかし事 実関係から判断すれば、1956年に刊行されたに違いない。名誉学位は1956年6月20日に授与され、パンフレットのボドリアン図書館スタンプは 「1956年7月11日」である。参照:Torralba, J. M., Acción intencional y razonamiento práctico según G.E.M.アンスコム, Pamplona: Eunsa, 2005, pp. 58-61. 「G. E. M. アンスコム『トルーマン氏の学位』」。1956年。2019年6月17日閲覧。 「中絶クリニック封鎖で逮捕されたエリザベス・アンスコムの貴重な写真が公開」. ChurchPOP. 2016年10月18日. 2019年6月13日閲覧. 「会員名簿 1780–2010: A章」 (PDF). アメリカ芸術科学アカデミー. 2011年4月19日閲覧. ラトラー、ジョージ・W. (2004年9月1日). 「証人の群れ:G.E.M.アンスコム」. クライシス・マガジン. 2024年9月12日閲覧. ドーラン、ジョン・M. (2001年5月1日). 「G.E.M.アンスコム:真実を生きる」. ファースト・シングス. 2024年8月30日閲覧. ヘイズ、ジョン(2020年)。「G.E.M.アンスコム―アイルランド生まれの哲学者」。『ヒストリー・アイルランド』28巻5号:42–44頁。ISSN 0791-8224。JSTOR 26934660。 「C.S.ルイスに関するよくある質問」. 聖書的識別ミニストリーズ. 1999年. 2005年10月24日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2017年11月9日に閲覧. 「アンスコム対C.S.ルイス論争の真実」. テレグラフ. 2001年1月11日. 2021年3月24日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2021年3月24日閲覧。私の著書『C・S・ルイス:コンパニオン・アンド・ガイド』(1996年)を執筆中、ルイスは1963年に私にこう語った。 1948年のソクラテス・クラブでのアンスコムとの論争では自分が勝ったと思っている、と。しかし彼は自身の主張が不明確だったことを認め、同書の第 III章を改訂した。皮肉なことに、多くの哲学者はアンスコムの主張に反対し、元の章は哲学的に妥当であり、ルイスが書き直す必要はなかったと主張してい る。また、ルイスが「キリスト教のための率直な論争を二度と書かなかった」というのも事実ではない。1952年、彼はBBCの戦時放送を『キリスト教の真 髄』として改訂した。この本は、おそらく前世紀の他のどの哲学書よりも多くの人々に信仰を受け入れさせた。ルイスは想像力が非常に豊かだったため、同じ考 えを繰り返し述べる必要はなかった。1950年代に七つの比類なき『ナルニア国物語』を執筆したのは、アンスコムや他の誰かを恐れたからではない。その 後、三つの神学著作が続いた。 スミルデ、アレント(2017年12月6日)。「ルイスが『奇跡論』に実際に行ったこと アンスコム論争を理解しようとする哲学的素人の試み」『インクリングス研究ジャーナル』1巻2号:9-24頁。doi:10.3366/ink.2011.1.2.3。 アンスコム、G. E. M.(1959)。『ウィトゲンシュタインの『論理哲学論考』入門』ロンドン:ハッチンソン社。 ウィトゲンシュタイン、ルートヴィヒ(1969年)。『確信について』オックスフォード:バジル・ブラックウェル社。 ゼカウスカス、ジェフリー(1983年4月)。「書評:ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン、G. E. M. アンスコム、G. H. フォン・ライト著『心理学の哲学に関する所見』」『倫理学』 93 (3): 606–8. doi:10.1086/292476. JSTOR 2380641. 「議会質問への回答」 (PDF) (ドイツ語). ウィーン. p. 521. 2012年10月21日閲覧。 アンスコム 1957, 第5–8節。 アンスコム 1957, 第18-21節。 アンスコム, G. E. M. (1981). 『形而上学と精神哲学』(論文集第2巻). オックスフォード: バーゼル・ブラックウェル. pp. 21–36. ISBN 0-631-12932-4. アンスコム 1957. サール, ジョン R. (1983). 『意図主義:精神哲学の試論』. ケンブリッジ[ケンブリッジシャー]: ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 0-521-22895-6. OCLC 9196773. アンスコム 1957, 第32節. アンスコム 1957, 第48節. ザイデル、クリスチャン(2019)。『帰結主義:新たな方向性と新たな問題』。オックスフォード道徳理論。ニューヨーク(ニューヨーク州):オックスフォード大学出版局。pp. 2–3。ISBN 978-0-19-027011-7。 ハルデーン、ジョン(2000)。「追悼:G・E・M・アンスコム(1919–2001)」(PDF)。『形而上学評論』53巻4号:1019–1021頁。ISSN 0034-6632。 クリスプ、ロジャー;スロート、マイケル(1997)。「序論」. クリスプ, ロジャー; スロート, マイケル (編). 『徳倫理学』. オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局. p. 3. ISBN 0-19-875189-3. OCLC 37028589. 「ホーム」. bioethics.org.uk. アンスコム, G. E. M. (1958). 「動物的事実について」『分析』18巻3号: 69–72頁. doi:10.2307/3326788. JSTOR 3326788. サール, John (1995). 『社会的現実の構築』ロンドン: Allen Lane The Penguin Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 0-14-023590-6. ウィトゲンシュタイン、ルートヴィヒ (1993). 「『私的経験』と『感覚データ』に関する講義ノート」. クラッゲ、J.; ノードマン、A. (編). 『哲学的機会』. インディアナポリス: ハケット. p. 228. 「海岸へ:セバスチャン・レードル」. 2019年1月10日. アンスコム, G.E.M. 「因果性と決定」. 『形而上学』, ジェイグウォン・キム, ダニエル・Z・コーマン, アーネスト・ソーサ編, ワイリー・ブラックウェル, 2012年, pp. 386-396. オッペンハイマー、マーク(2011年1月8日)。「率直なカトリック哲学者へのルネサンス」。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙。p. A14。2017年11月9日取得。 スクルートン、ロジャー(2010)。「ワインと哲学」。デカンター誌。第35巻。pp. 57–59。2017年11月9日取得。 ワーノック、メアリー編(1996)。『女性哲学者たち』。ロンドン:J.M.デント&サンズ社。203頁。ISBN 0-460-87738-0。OCLC 34407377。女性哲学者の中で疑いようのない巨人であり、膨大な広さ、権威、洞察力を持つ作家である。 |

| Sources Anscombe (1957). Intention. Oxford: Blackwell. 1957. Further reading Anscombe, G. E. M. (1975). "The First Person". In Guttenplan, Samuel (ed.). Mind and Language. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2017. ——— (1981). "On Transubstantiation". Ethics, Religion and Politics. The Collected Philosophical Papers of G. E. M. Anscombe. Vol. 3. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 107–112. ISBN 978-0-631-12942-4 – via Second Spring. ——— (1993) [rev. ed. first published 1975]. "Contraception and Chastity [rev. ed.]" (PDF). In Smith, Janet E. (ed.). Why Humanae Vitae Was Right: A Reader. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017. Doyle, Bob. "G. E. M. Anscombe". The Information Philosopher. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Retrieved 10 November 2017. Driver, Julia (2014). "Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford, California: Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054. Retrieved 9 November 2017. Gormally, Luke (2011). "G E M Anscombe (1919–2001)" (PDF). Oxford: Anscombe Bioethics Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2017. O'Grady, Jane (11 January 2011). "Elizabeth Anscombe". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 9 November 2017. "Portrait of a Catholic Philosopher". Oxford: Anscombe Bioethics Centre. Archived from the original on 21 January 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017. Mac Cumhaill, Clare; Wiseman, Rachael (2022). Metaphysical animals : how four women brought philosophy back to life. London. ISBN 978-0-385-54570-9. OCLC 1289274891. "Professor G E M Anscombe". The Telegraph. London. 22 November 2001. Archived from the original on 7 April 2008. Retrieved 9 November 2017. Richter, Duncan. "G. E. M. Anscombe (1919–2001)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002. Retrieved 9 November 2017. Rutler, George W. (2004). "G. E. M. Anscombe". Cloud of Witnesses. Crisis. Vol. 22, no. 8. Washington: Morley Publishing Group. Archived from the original on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2017. Teichman, Jenny (2003). "Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe, 1919–2001". In Thompson, F. M. L. (ed.). Biographical Memoirs of Fellows. Volume 1. Proceedings of the British Academy. Vol. 115. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197262788.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-726278-8. Torralba, José M. (2014). "G.E.M. Anscombe Bibliography". Pamplona, Spain: University of Navarra. Retrieved 10 November 2017. Wallgren, Thomas H., ed. (2024). The Creation of Wittgenstein: Understanding the Roles of Rush Rhees, Elizabeth Anscombe and Georg Henrik von Wright. Bloomsbury Publishing. |

出典 アンスコム(1957)。『意図』。オックスフォード:ブラックウェル。1957年。[1-18節原文 pdf] 追加文献(さらに読む) アンスコム、G. E. M.(1975)。「第一人称」。サミュエル・ガッテンプラン編『心と言語』。オックスフォード:クラレンドン・プレス。2007年6月13日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。2017年11月9日に取得。 ——— (1981). 「変質説について」. 『倫理、宗教、政治』. G. E. M. アンスコム哲学論文集. 第3巻. オックスフォード: ブラックウェル. pp. 107–112. ISBN 978-0-631-12942-4 – セカンド・スプリング経由。 ——— (1993) [改訂版、初版1975年]. 「避妊と貞操 [改訂版]」 (PDF). スミス、ジャネット・E.(編)『なぜ「人間の生命」は正しかったのか:読本』サンフランシスコ:イグナティウス・プレス。2017年11月9日時点のオ リジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ。2017年11月9日閲覧。 ドイル、ボブ。「G. E. M. アンスコム」『情報哲学者』マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ。2017年11月10日閲覧。 ドライバー、ジュリア(2014)。「ガートルード・エリザベス・マーガレット・アンスコム」。ザルタ、エドワード・N(編)。『スタンフォード哲学百科 事典』。カリフォルニア州スタンフォード:スタンフォード大学。ISSN 1095-5054。2017年11月9日に閲覧。 ゴーマリー、ルーク (2011). 「G・E・M・アンスコム (1919–2001)」 (PDF). オックスフォード: アンスコム生命倫理センター. 2021年7月25日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ. 2017年11月9日取得. オグレイディ、ジェーン (2011年1月11日). 「エリザベス・アンスコム」. ガーディアン. ロンドン. 2017年11月9日取得. 「カトリック哲学者の肖像」. オックスフォード: アンスコム生命倫理センター. 2017年1月21日オリジナルからアーカイブ. 2017年11月9日取得. マク・クメール, クレア; ワイズマン, レイチェル (2022). 形而上学の動物たち:四人の女性が哲学に命を吹き返した方法。ロンドン。ISBN 978-0-385-54570-9。OCLC 1289274891。 「G・E・M・アンスコム教授」。『テレグラフ』。ロンドン。2001年11月22日。2008年4月7日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2017年11月9日に取得。 リヒター、ダンカン。「G. E. M. アンスコム(1919–2001)」。インターネット哲学百科事典。ISSN 2161-0002。2017年11月9日取得。 ラトラー、ジョージ・W. (2004)。「G. E. M. アンスコム」。『証人の群れ』。危機。第22巻第8号。ワシントン:モーリー出版グループ。2007年8月14日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2017年11月9日に取得。 テイチマン、ジェニー(2003)。「ガートルード・エリザベス・マーガレット・アンスコム、1919–2001」。トンプソン、F. M. L.(編)。フェロー伝記回顧録。第1巻。英国学士院紀要。第115巻。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。doi: 10.5871/bacad/9780197262788.001.0001。ISBN 978-0-19-726278-8。 トラルバ、ホセ・M。 (2014). 「G.E.M. アンスコム書誌」. スペイン、パンプローナ: ナバラ大学. 2017年11月10日取得. ウォールグレン, トーマス・H., 編 (2024). 『ウィトゲンシュタインの創造: ラッシュ・リース、エリザベス・アンスコム、ゲオルグ・ヘンリク・フォン・ライトの役割を理解する』. ブルームズベリー出版. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G._E._M._Anscombe |

☆意図的なものには、3つの相がある:1)意図的な行動、2)意図をもって行動している、3)今は意図をもっているが行動に未着手なもの(=純粋意図)

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆