Private Language

私的言語

Private Language

解説:池田光穂

私的言語(Private

Language)とは「話し手だけが知ることのできるもの、つまり彼の直接的な私

的感

覚に言及するものであり、他の人はこの言語を理解することはできない」という感覚経験のことである(ウィトゲンシュタイン『哲学探究』§243)。ウィトゲンシュタインは、そのようなものは「言語」としては、存在しないと主張する。

この主張は、一般に、社会学者や人類学者にとっては、哲学上の思考実験というよりも、《社会的トークンとしての言語》あるいは《言語が持つ社会性》として

考えることができる。

●ウィトゲンシュタインと痛み(あるいは 「私的言語」批判)——「痛み」という実在にどのように向き合うの か?

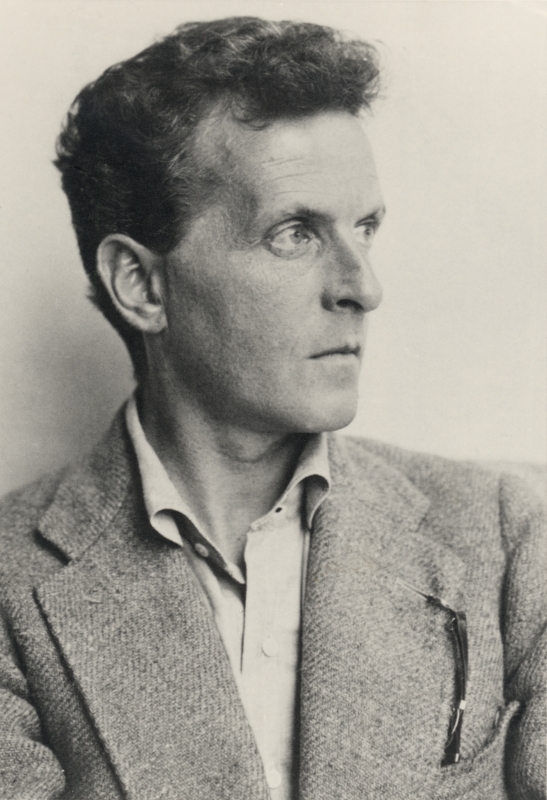

| Private Language The idea of a private language was made famous in philosophy by Ludwig Wittgenstein, who in §243 of his book Philosophical Investigations explained it thus: “The words of this language are to refer to what only the speaker can know — to his immediate private sensations. So another person cannot understand the language.” This is not intended to cover (easily imaginable) cases of recording one’s experiences in a personal code, for such a code, however obscure in fact, could in principle be deciphered. What Wittgenstein had in mind is a language conceived as necessarily comprehensible only to its single originator because the things which define its vocabulary are necessarily inaccessible to others. Immediately after introducing the idea, Wittgenstein goes on to argue that there cannot be such a language. The importance of drawing philosophers’ attention to a largely unheard-of notion and then arguing that it is unrealizable lies in the fact that an unformulated reliance on the possibility of a private language is arguably essential to mainstream epistemology, philosophy of mind and metaphysics from Descartes to versions of the representational theory of mind which became prominent in late twentieth century cognitive science. |

私的言語 私的言語という考え方は、哲学の世界ではルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインがその著書『哲学的考察』の§243でこう説明して有名になったものである。 「この言語の言葉は、話し手だけが知ることのできるもの、つまり彼の直接的な私的感 覚に言及するものである。だから、他の人はこの言語を理解することはできない」。 これは、自分の経験を個人的なコードに記録する(容易に想像できる)場合を対象としたものではなく、そのようなコードは、たとえ事実が不明瞭であっても、 原理的には解読することが可能だからである。ウィトゲンシュタインが考えていたのは、その語彙を規定するものが必然的に他者にはアクセスできないため、必 然的にその一人の発案者にしか理解できない言語というものであった。 ウィトゲンシュタインは、この考えを紹介した直後に、そのような言語は 存在し得ないと主張する。 哲学者の注意をほとんど耳にしたことのない概念に引きつけ、それが実現不可能であると主張することの重要性は、私的言語の可能性に対する形のない信頼が、 デカルトから20世紀後半の認知科学で顕著となった心の表象理論のバージョンに至るまでの主流の認識論、心の哲学、形而上学に間違いなく不可欠であるとい う事実の下にある。 |

| 1. Overview: Wittgenstein’s

Argument and its Interpretations Wittgenstein’s main attack on the idea of a private language is contained in §§244–271 of Philosophical Investigations (though the ramifications of the matter are recognizably pursued until §315). These passages, especially those from §256 onwards, are now commonly known as ‘the private language argument’, despite the fact that he brings further considerations to bear on the topic in other places in his writings; and despite the fact that the broader context, of §§243–315, does not contain a singular critique of just one idea, namely, a private language—rather, the passages address many issues, such as privacy, identity, inner/outer relations, sensations as objects, and sensations as justification for sensation talk, amongst others. Nevertheless, the main argument of §§244–271 is, apparently, readily summarized. The conclusion is that a language in principle unintelligible to anyone but its originating user is impossible. The reason for this is that such a so-called language would, necessarily, be unintelligible to its supposed originator too, for he would be unable to establish meanings for its putative signs. We should, however, note that Wittgenstein himself never employs the phrase ‘private language argument’. And a few commentators (e.g., Baker 1998, Canfield 2001 pp. 377–9, Stroud 2000 p. 69) have questioned the very existence in the relevant passages of a unified structure properly identifiable as a sustained argument. This suggestion, however, depends for its plausibility on a tendentiously narrow notion of argument—roughly, as a kind of proof, with identifiable premisses and a firm conclusion, rather than the more general sense which would include the exposure of a confusion through a variety of reasoned twists and turns, of qualifications, weighings-up and re-thinkings—and is a reaction against some drastic and artificial reconstructions of the text by earlier writers. Nevertheless, there is a point to be made, and the summary above conceals, as we shall see, a very intricate discussion. Even among those who accept that there is a reasonably self-contained and straightforward private language argument to be discussed, there has been fundamental and widespread disagreement over its details, its significance and even its intended conclusion, let alone over its soundness. The result is that every reading of the argument (including that which follows) is controversial. Some of this disagreement has arisen because of the notorious difficulty and occasional elusiveness of Wittgenstein’s own text (sometimes augmented by problems of translation). But much derives from the tendency of philosophers to read into the text their own preconceptions without making them explicit and asking themselves whether its author shared them. Some commentators, for instance, supposing it obvious that sensations are private, have interpreted the argument as intended to show they cannot be talked about; some, supposing the argument to be an obvious but unsustainable attempt to wrest special advantage from scepticism about memory, have maintained it to be unsound because it self-defeatingly implies the impossibility of public discourse as well as private; some have assumed it to be a direct attack on the problem of other minds; some have claimed it to commit Wittgenstein to behaviourism or verificationism; some have thought it to imply that language is, of necessity, not merely potentially but actually social (this has come to be called the ‘community view’ of the argument). The early history of the secondary literature is largely one of disputation over these matters. Yet what these earlier commentators have in common is significant enough to outweigh their differences and make it possible to speak of them as largely sharing an Orthodox understanding of the argument. After the publication in 1982 of Saul Kripke’s definitely unorthodox book, however, in which he suggested that the argument poses a sceptical problem about the whole notion of meaning, public or private, disputation conducted by Orthodox rules of engagement was largely displaced by a debate on the issues arising from Kripke’s interpretation. (However, there is overlap: Kripke himself adheres to the community view of the argument’s implications, with the result that renewed attention has been paid to that issue, dispute over which began in 1954.) Both debates, though, show a tendency to proceed with only the most cursory attention to the original argument which started them off. This rush to judgment about what is at stake, compounded by a widespread willingness to discuss commentators’ more accessible accounts of the text rather than confront its difficulties directly, has made it hard to recover the original from the accretion of more or less tendentious interpretation which has grown up around it. Such a recovery is one of the tasks attempted in this article. The criterion of success in this task which is employed here is one of coherence: a good account should accommodate all of Wittgenstein’s remarks in §§244–271, their (not necessarily linear) ordering as well as their content, and should make clear how these remarks fit with the context provided by the rest of the book. (One of the problems with many of the commentaries on this matter, especially the earlier ones, is that their writers have quarried the text for individual remarks which have then been re-woven into a set of views said to be Wittgenstein’s but whose relation to the original is tenuous. A striking example of this approach is Norman Malcolm’s famous and influential 1954 review of Philosophical Investigations, which was commonly taken as an accurate representation of Wittgenstein’s own thinking and formed the target of many “refutations”.) |

1. 概要 ウィトゲンシュタインの主張とその解釈 ウィトゲンシュタインの私的言語の思想に対する主な攻撃は、『哲学的考察』の§244-271に収められている(ただし、この問題の影響が認められるのは §315までである)。これらの文章、特に§256以降の文章は、現在では一般に「私的言語論」として知られているが、彼は著作の他の箇所でもこのテーマ についてさらなる考察を加えており、§243-315という広い文脈では、私的言語というただ一つの思想に対する批判ではなく、プライバシー、アイデン ティティ、内外の関係、対象としての感覚、感覚話の正当性としての感覚など、多くの問題について述べているにもかかわらず、この文章は、「私的言語論」で ある。 とはいえ、§244-271の主要な論点は、見かけ上、容易に要約される。結論は、その起点となる使用者以外には原理的に理解不能な言語は不可能である、 というものである。その理由は、そのようないわゆる言語は、必然的にその発案者にとっても意味不明となるからである。なぜなら、彼はその想定される記号に 意味を設定することができないからである。 しかし、ウィトゲンシュタイン自身は「私的言語論」という言葉を決して使っていないことに注意しなければならない。また、少数の論者(例えば、Baker 1998, Canfield 2001 pp.377-9, Stroud 2000 p.69)は、関連箇所において、持続的議論として適切に識別できる統一構造の存在そのものに疑問を呈している。しかし、この提案は、論証の概念、つま り、識別可能な前提条件と確固たる結論を持つ一種の証明としてではなく、より一般的な意味で、様々な理性的なねじれや転回、修飾、計量、再考を通して混乱 を露呈することを含む、傾向的に狭い概念にその妥当性を依存しており、初期の作家によるテキストの思い切った、人工的な再構成に対する反発であった。とは いえ、指摘すべき点はあり、上記の要約には、これから見るように、非常に入り組んだ議論が隠されている。 議論すべき合理的に自己完結した分かりやすい私的言語論が存在することを認める人々の間でさえ、その健全性はおろか、その詳細や意義、意図する結論さえも 根本的かつ広範囲に渡って意見が分かれている。その結果、この議論のあらゆる読み方が(以下に述べるものも含めて)論議を呼んでいるのである。この不一致 の一部は、ウィトゲンシュタイン自身のテキストの悪名高い難しさと、時には難解さ(時には翻訳の問題によって増強された)から生じています。しかし、その 多くは、哲学者たちが自分たちの先入観を明示することなくテキストに読み込ませ、その著者がそれを共有していたかどうかを自問する傾向に由来している。例 えば、ある論者は、感覚は私的なものであることは自明だとして、この議論を、感覚について語ることができないことを示すためのものだと解釈した。ある論者 は、この議論を、記憶に関する懐疑論から特別な利点を引き出そうとする自明だが維持できない試みだと考え、この議論は自滅的に公的言説と同様に私的言説の 不可能性を意味するとして不健全だと断言した。また、ウィトゲンシュタインが行動主義や検証主義に傾倒していると主張する者もいる。さらに、言語は必然的 に、単に潜在的にではなく、実際に社会的であることを暗示していると考える者もいる(これは、この議論の「コミュニティ観」と呼ばれるようになった)。 二次文献の初期の歴史は、こうした事柄をめぐる論争の歴史であった。しかし、これらの初期の論者たちに共通していることは、その違いを凌駕するほど重要で あり、彼らがこの議論に対する正統派の理解をほぼ共有していると語ることが可能である。しかし、1982年にソール・クリプキが、この論考は公的あるいは 私的な意味の概念全体に対して懐疑的な問題を提起していると示唆する、明らかに異端な本を出版した後、正統派の規則に従って行われた論争は、クリプキの解 釈から生じる問題についての論争に大きく取って代わられることになる。(ただし、重なる部分もある。クリプキ自身はこの議論の意味するところについて共同 体観に固執しており、その結果、1954年に始まった論争であるこの問題に再び注目が集まっている)。しかし、いずれの議論も、その発端となった原論に は、ほとんど注意を払わないまま進行する傾向が見られる。 このように、何が問題であるかの判断を急ぐあまり、テキストの難点に直接立ち向かうよりも、注釈者たちのよりわかりやすい説明を議論しようとする姿勢が広 まった結果、オリジナルを、その周りに形成された多かれ少なかれ傾向的な解釈の付加から回復することが困難になってしまったのである。このような回復が、 この論文で試みられている課題の一つである。良い説明とは、§244-271におけるウィトゲンシュタインのすべての発言を、その内容だけでなく(必ずし も直線的ではない)順序も含めて受け入れ、これらの発言がこの本の残りの部分によって提供される文脈にどのように適合するかを明確にすることである。(こ の問題に関する多くの解説、特に初期の解説の問題点の一つは、執筆者がテキストから個々の発言を切り出し、それをウィトゲンシュタインのものとされる一連 の見解に編み直したものの、オリジナルとの関係が希薄であることである)。このアプローチの顕著な例は、ノーマン・マルコムの有名で影響力のある1954 年の『哲学的考察』の書評で、これは一般にウィトゲンシュタイン自身の考えを正確に表現したものとされ、多くの「反駁」の標的になった)。 |

| 3. The Private Language Argument

Expounded 3.1 Preliminaries As already noted, the private language sections of Philosophical Investigations are usually held to begin at §243 (though we shall see that Wittgenstein relies on points made much earlier in the book). The methodological issues canvassed above arise at the outset, in the interpretation of §243’s crucial second paragraph. On a substantial/non-Pyrrhonian reading, Wittgenstein begins to clarify what kind of philosophically important notion of private language is to be examined, i.e., one that is necessarily private and which refers to one’s immediate private sensations. In the remarks that follow, Wittgenstein argues that the idea of such a private language is nonsensical or incoherent because it is a violation of grammar (i.e., Wittgenstein draws on his substantive views on meaning). On a resolute/Pyrrhonian reading, it is emphasized that the reader is asked in the first sentence of the second paragraph whether one can actually imagine a language for one’s inner experiences, for private use. Wittgenstein at this point reminds the interlocutor that we already use ordinary language for that. But the interlocutor quickly replies in the last three lines of §243 that what he is asking is whether we can imagine a private language that refers to what only the speaker can know. In the following sections, Wittgenstein examines ‘whether there is a way of meaning the words of the penultimate sentence [of §243] that does not simply return us to a banality, whether in fact his interlocutor means anything in particular with those words’ (Mulhall 2007, p. 18). The question is whether the notion of a language ‘which only I myself can understand’ can be given any substantial meaning to begin with. On this latter reading, §§258 and 270, for example, are attempts to give the interlocutor what he says he wants, but which, in the end, amount to nothing (in the case of 258) or bring us back to a publicly understandable language (in the case of 270). As we saw above, in section 1.2, it is not clear that we must choose between these two readings. On either, the point of the private language argument is that the idea is exposed as unintelligible when pressed—we cannot make sense of the circumstances in which we should say that someone is using a private language. So, having introduced the idea of a private language in the way already quoted, Wittgenstein goes on to argue in a preliminary discussion (§§244–255) that there are two senses of ‘private’ which a philosopher might have in mind in suggesting that sensations are private, and that sensations as they are talked about in natural languages (such as English and German) are in fact private in neither of them. He then turns, at §256, to the question whether there could be a private language at all. He continues to talk of sensations, and of pain as an example, but one should remember that these are not our sensations, the everyday facts of human existence, but the supposed exemplars of philosophical accounts of the everyday facts. Thus, for instance, they might be the sensations of something like a Cartesian soul (perhaps one associated with a physical body, as indicated in §§257 and 283), something which has no publicly available mental life and whose “experiences” are accordingly private. (It is worth noting that the earlier Anscombe translation is misleading here: in §243, for example, where the idea of a private language is introduced, it loses the crucial contrast, so evident in the original German, between the ordinary human beings described as solitary speakers in the first paragraph and the second paragraph’s mysterious ‘one’ who is the ‘speaker’ of a private language and whose nature is carefully left unclear. See the recent 4th edition translation of this paragraph, a relevant part is in the first sentence of this article, to find a version closer to the original German.) Consistent with this point is that in §256 Wittgenstein suggests that one cannot arrive at the idea of a private language by considering a natural language: natural languages are not private, for our sensations are expressed. But neither can we arrive at the idea by starting with a natural language and just subtracting from it all expression of sensations (temporary paralysis is clearly not in question), as he considers next, for as he says in §257, even if there could be language in such a situation as this where teaching is impossible, the earlier argument of Philosophical Investigations (§§33–35), concerning ostensive definition, has shown that mere “mental association” of one thing with another is not alone enough to make the one into a name of the other. Naming one’s sensation requires a place for the new word: that is, a notion of sensation. The attempt to name a sensation in a conceptual vacuum merely raises the questions of what this business is supposed to consist in, and what is its point. But, for the sake of getting to the heart of the matter, Wittgenstein puts the first of these questions on one side and pretends that it is sufficient for the second to imagine himself in the position of establishing a private language for the purpose of keeping a diary of his sensations. However, to investigate the possibility of the imagined diary case by exploring it from the inside (the only way, he thinks, really to expose the confusions involved) requires him to use certain words when it is just the right to use these words which is in question. Thus he is forced to mention in §258 examples like ostensive definition, concentrating the attention, speaking, writing, remembering, believing and so on, in the very process of suggesting that none of these can really occur in the situation under consideration (§261). This difficulty has often gone unnoticed by commentators on the argument, with particularly unhappy results for the understanding of the discussion of the diary example. Fogelin [1976], for instance, a paradigm representative of Orthodoxy, treats this as a case where he himself, a living embodied human being, keeps a diary and records the occurrences of a sensation which he finds it impossible to describe to anyone else. But we are not to assume that the description of the keeping of the diary is a description of a possible or even ultimately intelligible case. In particular, we are not to think of such a human being’s keeping a real diary, but of something like the Cartesian internal equivalent. It is thus vital to the argument that the diary case is presented in the first person, without our pressing the question, ‘Who is speaking?’ At this stage we are simply not to worry about whether the diary story ultimately makes sense or not. But the fact that it may not make sense must be remembered in reading what follows, which in strictness should constantly be disfigured with scare quotes. (We shall, as we have already, occasionally supply them as a reminder, reserving double quotes for this purpose.) To summarize the argument’s preliminary stage: In §256 Wittgenstein asked of the “private language”, ‘How do I use words to signify my sensations?’, and reminded us in §257 that we cannot answer ‘As we ordinarily do’. So this question, which is the same question as ‘How do I obtain meaning for the expressions in a “private language”?’ is still open; and the answer must be independent of our actual connections between words and sensations. In the attempt to arrive at an answer, and explore the question in its full depth, he temporarily allows the use of the notions of sensation and diary-keeping (despite the objections of §257), and imagines himself in the position of a private linguist recording his sensations in a diary. The aim is to show that even if this concession is made, meaning for a sensation-word still cannot be secured and maintained by such a linguist. The crucial central part of the argument begins here, at §258. |

3. 私的言語論証の展開 3.1 前提条件 すでに述べたように、『哲学的考察』の私的言語の部分は、通常§243から始まるとされている(ただし、ウィトゲンシュタインはこの本のもっと前の段階の 指摘に依拠していることを確認する必要がある)。上記のような方法論的な問題は、§243の重要な第二段落の解釈において、冒頭で発生する。 実質的/非ピルロン的な読み方をすれば、ウィトゲンシュタインは、私的言語という哲学的に重要な概念がどのようなものか、すなわち、必然的に私的であり、 自分の直接的な私的感覚に言及するものであるかを明らかにし始める。そして、そのような私的言語の概念は、文法違反であるため、無意味あるいは支離滅裂で あることを論じる(つまり、ウィトゲンシュタインは、意味に関する実体的な見解を引き出している)。 レゾルート/ピュロン派の読み方では、第2段落の第1文で「自分の内的な経験のための言語、私的な使用のための言語を実際に想像できるか」と読者に問いか けていることが強調される。このときウィトゲンシュタインは、私たちはすでにそのために普通の言葉を使っている、と対談者に念を押している。しかし対談者 は§243の最後の3行で、自分が尋ねているのは、話し手だけが知り得ることに言及する私的な言語を想像できるかどうかだとすぐに答えている。以下、ウィ トゲンシュタインは、「(§243の)最後から二番目の文の言葉を、単に平凡に戻さないような意味の付け方があるのか、実際、対話者がその言葉で特に何か を意味しているのか」(Mulhall 2007, p.18)を検証している。問題は、「私自身だけが理解できる」言語という概念に、そもそも実質的な意味を与えることができるのかどうかである。この後者 の読み方では、例えば§258 と§270 は、対話者が望むと言うものを与えようとする試みであるが、結局は無に帰すか(258 の場合)、公的に理解できる言語に戻すか(270 の場合)である。 1.2 節で見たように、この二つの読みのどちらかを選ばなければなら ないというのは明確ではない。このように、私的言語論のポイントは、その考えを押しつけられると理解不能であることが露呈すること、つまり、誰かが私的言 語を使っていると言うべき状況を理解することができないことである。 そこでウィトゲンシュタインは、既に引用した方法で私的言語の考え方を導入した上で、哲学者が感覚を私的であると示唆する際に念頭に置くであろう「私的」 には二つの意味があり、自然言語(英語、ドイツ語など)で語られる感覚は、実際にはそのいずれにおいても私的ではないことを予備的議論(§244- 255)として論じている。そして、§256で、私的な言語が存在しうるかどうかという問題に目を向ける。彼は感覚について、そして例として痛みについて 話し続けるが、これらは我々の感覚、つまり人間存在の日常的事実ではなく、日常的事実についての哲学的説明の模範とされるものであることを忘れてはならな いだろう。したがって、例えば、デカルトの魂のようなもの(§257 と 283 で示したように、おそらく肉体と結びついたもの)、つまり、公に利用可能な精神生活を持たず、それゆえ「経験」が私的なものであるものの感覚であるかもし れないのです。(例えば§243では、私的言語という考え方が導入されているが、第1段落で孤独な話し手として描かれている普通の人間と、第2段落で私的 言語の「話し手」でありその性質が慎重に明らかにされていない謎の「者」との間の、原語では非常に明白な対比が失われている(以前のアンスコム訳はこの点 で誤解を招きかねない。この段落の原文に近いものを探すには、この記事の冒頭にある、最近の第4版の翻訳を参照されたい)。この指摘と一致するのは、§ 256でウィトゲンシュタインが、自然言語を考えることによって私的言語の考えに到達することはできないと示唆していることである:自然言語は私的ではな い、なぜなら我々の感覚は表現されるからである。しかし、次に考えるように、自然言語から出発して、そこから感覚の表現をすべて差し引くだけでは、その考 えに到達することはできない(一時的な麻痺は明らかに問題ではない)。§257で彼が言うように、このように教えることが不可能な状況において言語があり うるとしても、「哲学的考察」の先の議論(§33-35)では、仰々しい定義に関して、あるものを他のものと単に「心的連想」するだけでは、一方を他のも のの名称とすることは十分ではないことが示されている。自分の感覚に名前をつけるには、新しい言葉のための場所、つまり感覚の概念が必要である。概念的な 空白の中で感覚に名前を付けようとする試みは、このビジネスが何から構成されることになっているのか、そのポイントは何なのかという疑問を投げかけるだけ である。しかし、ウィトゲンシュタインは、問題の核心に迫るために、これらの疑問のうち第一のものを片付け、第二のものは、自分の感覚を日記につけるため に私的言語を確立する立場にある自分を想像すれば十分であるかのように装うのである。 しかし、想像した日記のケースの可能性を内側から探っていくこと(これが本当に混乱を露呈させる唯一の方法だと彼は考えている)は、ある言葉を使う権利が 問題になっているときに、その言葉を使うことを要求している。そのため、彼は§258で仰々しい定義、注意の集中、話す、書く、記憶する、信じるなどの例 に言及せざるを得ないが、まさにその過程で、これらのどれもが検討中の状況では実際には起こり得ないことを示唆している(§261)。 この困難さは、しばしば議論の論者によって気づかれることなく、特に日記の例の議論の理解には不幸な結果をもたらしてきた。例えば正統派のパラダイム代表 であるフォーゲリン[1976]は、生きた身体化された人間である彼自身が日記をつけ、他の誰にも説明できないような感覚の発生を記録する場合としてこれ を扱っている。しかし、この日記をつけるという記述が、可能な、あるいは究極的に理解可能なケースの記述であると仮定してはならない。特に、そのような人 間が本物の日記を付けていると考えるのではなく、デカルトの内的等価物のようなものを考えているのである。したがって、「誰が話しているのか」という問い を私たちに押し付けることなく、日記のケースを一人称で提示することが議論にとって不可欠なのである。この段階では、日記の話が最終的に意味をなすかどう かについては、単に気にしないことである。しかし、意味がない可能性があるという事実は、この後の文章を読む際に覚えておかなければならない。(すでに述 べたように、この目的のために二重引用符を留保し、注意喚起のために時折引用符を供給することにしよう)。 議論の前段階を要約すると、ウィトゲンシュタインは§256で「私的言語」について、「私は自分の感覚を意味するためにどのように言葉を使うのか」と問 い、§257で「通常行うように」とは答えられないことを思い知らされた。だから、この問いは、『「私的言語」の表現に対して、私はどのようにして意味を 得るのか』と同じ問いであり、その答えは、私たちの言葉と感覚の実際の結びつきとは無関係でなければならないのである。その答えに辿り着き、この問いを深 く掘り下げるために、彼は(§257の反対にもかかわらず)感覚と日記をつけるという概念の使用を一時的に認め、自分の感覚を日記に記録する私的言語学者 の立場を想像している。このように譲歩しても、感覚語に対する意味は、そのような言語学者によって確保され維持されることはないことを示すのが目的であ る。この議論の重要な中心部分は、ここ、§258から始まる。 |

| This is the argument

of §265, which has often been mistakenly given an epistemological

interpretation. Again we cannot assume that there has been an actual

table (even a mental one) of meanings in the case of the private

linguist, a table which is now recalled and about which the linguist

must rely on recall since the original has gone. Rather, as §§260–264

show, there may be nothing determinate other than this “remembering of

the table”. So when we think that a private linguist could remember the

meaning of ‘S’ by remembering a past correlation of the sign ‘S’ with a

sensation, we are supposing what needs to be itself established—that

there was indeed some independent correlation to be remembered.

Fallibility of memory, even of memory of meaning, is neither here nor

there: the point is not that there is doubt now about the

trustworthiness of memory, but that there was doubt then about the

status of what occurred. And this original, non-epistemological, doubt

cannot later be removed by “recollections” of a status inherently

dubious in the first place. That is, if there was no genuine original

correlation in the first place, a “memory” will not create one. But if,

alternatively, we do not suppose that there was something independent

of the memory to be remembered, again ‘what seems right is right’; the

“memory” of the “correlation” is being employed to confirm itself, for

there is no independent access to the “remembered correlation”. (Not

even the independent access that we have as posers of the example,

since the question is, can we pose such an example? The typical mistake

commentators make here is to disguise the problem by thinking of S in

terms of some already established concept, such as pain, which they

bring to the example themselves.) This is why Wittgenstein says in

§265, ‘As if someone were to buy several copies of today’s morning

paper to assure himself that what it said was true’. |

これは、しばしば誤って認識論的な解釈を与えられてきた§265の議論

である。ここでも、私的言語学者の場合、意味の実際の表(精神的なものであっても)があったと仮定することはできない。その表は現在想起されており、オリ

ジナルがなくなってしまった以上、言語学者は想起に頼らざるを得ないのである。むしろ§260-264が示すように、この「テーブルの記憶」以外には確定

的なものはないのかもしれない。だから、私的な言語学者が「S」という記号と感覚との過去の相関関係を記憶することによって「S」の意味を記憶できると考

えるとき、私たちは、記憶すべき何らかの独立した相関関係が実際にあったという、それ自体が立証されなければならないことを仮定しているのである。記憶の

誤りは、たとえ意味の記憶であっても、ここでもそこでもない。重要なのは、記憶の信頼性に関して今疑問があるのではなく、起こったことの状態に関して当時

疑問があったということである。そして、この元来の、認識論的でない疑念は、そもそも本質的に疑わしい状態の「回想」によって後で取り除かれることはあり

えない。つまり、そもそも本物の元の相関関係がなければ、「記憶」によって相関関係が生まれることはないのです。しかし、逆に、記憶されるべき記憶から独

立したものがあったと仮定しなければ、やはり「正しいと思われることは正しい」のです。「相関」の「記憶」は自分自身を確認するために用いられているので

あって、「記憶された相関」への独立したアクセスは存在しないのだから。(というのも、「記憶された相関関係」への独立したアクセスはないからです(例の

提起者としての独立したアクセスすらないが、問題は、そのような例を提起できるかどうかということであるから)。ここで解説者が犯す典型的な間違いは、S

を既に確立された概念、例えば痛みなどの観点から考え、それを自ら例に持ち込むことで問題を誤魔化すことである)。ウィトゲンシュタインが§265で「あ

たかも誰かが今日の朝刊を何部も買って、そこに書いてあることが真実であることを確信するように」と述べているのはこのためである。 |

| https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/private-language/ |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

★

●私

的言語(private

language)

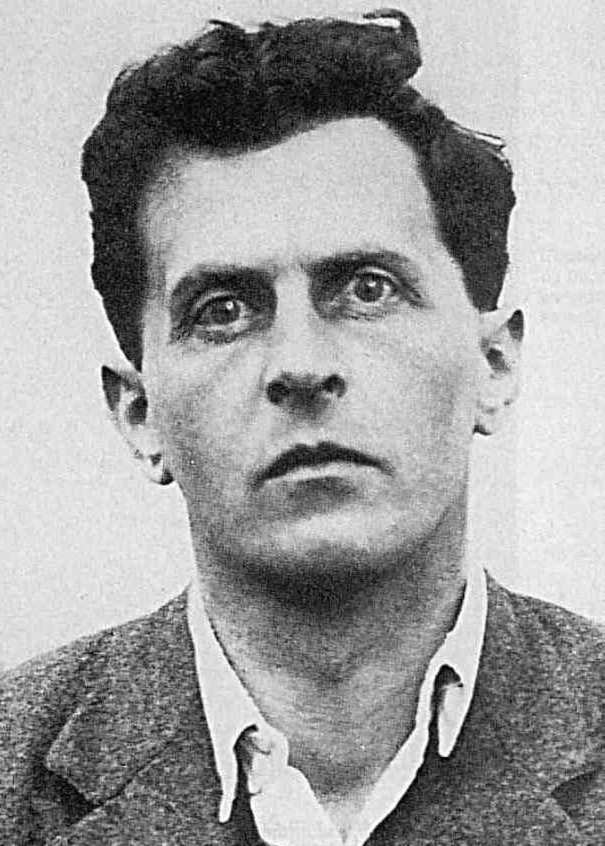

私的言語(してきげんご、private

language)はルートヴィヒ・ヴィトゲンシュタインの後期の著作、特に『哲学探究』で紹介された哲学的主張。[1]私的言語論は20世紀後

半に哲学

的議論の中心となり、その後も関心を惹いている。私的言語論では、ただ一人の人だけ

が理解できる言語は意味をなさないと

示すことになっている。

『哲学探究』では、ヴィトゲンシュタインは彼の主張を簡潔・直接的な形では提出しなかった。ただ、彼は特殊な言語の使用について記述し、読者がそういった

言語の使用の意味を熟考するように仕向けている。結果として、この主張の特徴とその意味について大きな論争が生じることになる。実際に、私的言語「論」に

ついて話すことが一般的になってきた。

哲学史家は様々な史料、特にゴットロープ・フレーゲとジョン・ロックの著作に私的言語論の先駆けを見出している[2]。ロックもこの主張に目標を定められ

た観点の提唱者である。というのは彼は『人間悟性論』において、言葉の指示する物はそれの意味する「表象」であると述べているからである。私的言語論は、

言語の本性についての議論において最も重要である。言語についての、ひとつの説得力のある理論は「言語は語を(各人の心の中の)観念・概念・表象へと写像

する」というものである。この説明では、わたしの概念はあなたのそれとは区別される(異なる)。けれども、わたしはわたしの概念を、我々の共通言語におけ

る語に結びつけることができる。そして、わたしはその語を話す。それを聞いたあなたは、いま聞いた語をあなたの概念へと結びつける。このように、我々の概

念とはつまり(それ自体は各人において異なり、また心の中に匿されているという意味で)私的言語であるが、それは共通言語との翻訳を介して共有されてもい

る、というわけである。こうした説明は、たとえば(ジョン・ロックの)『人間悟性論』、近年ではジェリー・フォーダーの思考の言語論に見られるものであ

る。

後期ヴィトゲンシュタインは、私的言語のこうした説明は矛盾すると主張する。私的言語という考えに矛盾がある(成り立たない)として、その論理的な帰結の

ひとつは、すべての言語はある社会的な機能の召使いにすぎない、とい

うことである。このことは哲学と心理学の他の領域に重大な影響を与えることとなった。たとえば、もし人が私的言語を持つことができないのであれば、私的な

経験や私的な心的状態について語ることは、まったく意味をなさないことになる。

この主張は『哲学探究』第一部で述べられている。『哲学探究』第一部は順次番号づけられた「意見」の羅列よりなる。主張が中心的に述べられているのは第

256章及びその先だと一般的には考えられているが、最初に紹介されるのは第243章である。もし誰かが、かれ以外の誰にも理解できない言語を、理解するかのように振る舞うことがあったと

したら、それこそが私的言語だということができよう[3]。とはいえ、その言語が単に孤立した言語である、つまりかつて翻訳されたことがな

いというだけでは、十分ではない。ある言語がヴィトゲンシュタインのいう私的言語で

あるためには、原理的に(通用する言語に)翻訳できない言語でなければならない。

たとえば、他人には窺い知ることができないような内的経験を記述する言語である[4]。ここでいう私的言語とは、単に「事実として」ただひとりが理解する

言語のことではなく、「原理的に」ただひとりにしか理解できない言語のことである。絶滅寸前の言語を話す最後のひとりは私的言語を話しているわけではな

い。その言語はなお原理的に習得可能だからである。私的言語は習得不可能かつ翻訳不可能でなければならない。そして、にもかかわらず話者はその意味を理解

するかのようでなければならない(→「言語の翻訳不可論は論理的に破綻」→「言語とみなされるものは必ず翻訳可能性を獲得する」)。

ヴィトゲンシュタインは、感覚が起きたときにカレンダーに書いてある「S」という字と再帰的に起こってくる感覚を結びつけて考えている人を想像する思考実

験を行っている。[5]

この場合はヴィトゲンシュタインの考えるような私的言語になっている。さらに、「S」が他の言葉で、例えば「マノメーターが上がったときに私が受けた感

覚」というように定義できないばあいを推定する。すると、公共的言語の中に「S」が位置づけられ、その場合「S」が私的言語であらわせないことになる。

[6]

感覚と象徴に注目して、「ある種の直示的定義」を「S」に適用する場合が想定される。『哲学探究』の最初のほうでヴィトゲンシュタインは直示的定義の有効

性を攻撃している[7]。彼は、二つの木の実を指さして「これは『2』だと言える」と言う人物の場合を想定する。これを聞いた人がこれを木の実の種類や

数、あるいはコンパスの指す向きなどではなく物品の数と結びつけて考えるということはどのように起こるのだろうか?一つの結論としては、これは、関係する

ためには直示的定義が「生活形式」に必然的に伴う過程や文脈を理解していることが前提とされるということだとされる[8]。もう一つの結論としては、「直

示的定義は『あらゆる』場合に異なった意味で解釈され得る」ということがある[9]。

「S」の感覚の事例を出して、ヴィトゲンシュタインは、正しい「ように見える」ことは正しい「ことである」(し、このことは「正しさ」について語ることは

できないことを端的に示している)ので、以上のような直示的定義の正しさの基準は存在しないと主張した[5]。私的言語を否定する正確な根拠に関しては議

論がなされてきた。一つの主張として「記憶懐疑論」と呼ばれるものがあるが、それは、ある人が感覚を間違って「記憶」すれば、その人は結果として「S」と

言う言葉を間違って使うことになるというものである。「意味懐疑論」というもう一つの立場では、こういうやり方で定義される言葉の「意味」を人は決して知

ることはないというものである。

一方の一般的な解釈は、人が感覚を間違って覚える可能性があり、それゆえに人はそれぞれの場合に「S」を使う確かな「基準」を持ちえないというものである

[10]

。だから、例えば、私はある日「あの」感覚に注目し、それを「S」という象徴に結び付けたかもしれない。しかしその次の日、私は「今」持っている感覚が昨

日のものと同じであるかを知る基準を記憶の他に持たない。そして私は記憶を欠落しているかもしれないので、私には今持っている感覚が実際に「S」であるか

を知る確かな基準が何もない。

しかしながら、記憶懐疑論は公共的言語にも適用できるので、私的言語だけに対する攻撃たりえないとして批判されてきた。一人の人が間違って記憶しうるなら

ば、複数の人が記憶を間違えるということも完全に可能である。だから、記憶懐疑論は公共的言語に与えられう直示的言語にも同じ効果を及ぼすことができる。

例えば、ジムとジェニーがある日どこか独特な木を「T」と呼ぶことに決めたかもしれない。しかし次の日に「二人とも」自分たちがどの木に名づけたか記憶違

いをする。彼らが完全に記憶に頼っており、木の位置を書き記したり誰かほかの人に教えたりしていなかったならば、一人の人が「S」を直示的に定義した場合

と同様の困難が現れるであろう。そのため、こういった場合であれば私的言語に対して提出された主張が公共的言語にも同じく適用されるであろう。

リンク

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆