Thick Description:Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture (by C. Geertz)

クリフォード・ ギアーツの論文「厚い記述」ノート

解説:池田光穂

"In her book, Philosophy in a New Key, Susanne Langer remarks that certain ideas burst upon the intelectual landscape with a tremendous force."

"In her book, Philosophy in a New Key, Susanne Langer remarks that certain ideas burst upon the intellectual landscape with a tremendous force. They resolve so many fundamental problems at once that they seem also to promise that they will resolve all fundamental problems, clarify all obscure issues. Everyone snaps them up as the open sesame of some new positive science, the conceptual center-point around which a comprehensive system of analysis can be built. The sudden vogue of such a grande idee, crowding out almost everything else for a while, is due, she says, "to the fact that all sensitive and active minds turn at once to exploiting it. We try it in every connection, for every purpose, experiment with possible stretches of its strict meaning, with generalizetions and derivatives." "

●ギアツ「厚い記述」ノート:クリフォード・ギアツ(ギアーツ;1926-2006)

(「人類学は著述、論文、講義、博物館の展 示、‥‥フィルムの 中にも存在する 」p.27)

"anthropology exists in the book, the article, the lecture, the museum display, or, sometimes nowadays, the film (p.16)"

【厚い記述】のミニマムな説明

「「厚い記述」(thick

description):厚い記述あるいは分厚い記述とは、米国の文化人類学者クリフォード・ギアーツ(1926

-2006)が同名の論文で提唱したも

のであるが、元々は英国の哲学者ギルバート・ライルによる。人類学者はフィールドワークをするときに、現地の人と仲良くなり、情報を提供してもらう人を探

し、関連文書を写し、系譜関係をとり、付近の地図をつくり、活動の日記などを書く。これらの一連の行為を厚い記述と呼ぶ。そして反対に、薄い記述とは、

「少年が瞬きした」というようにそれ以外に情報のないシンプルな記述をいう。瞬きは、付近にいる誰かに合図したのか、それとも目にゴミが入ったのか、ある

いは以前に読んだ小説の感動的な部分を思い出して涙ぐんだのか、などの情報の収集、などの記録の積み重ねにより、少年の瞬きを描いてゆくことを厚い記述と

呼ぶ。フィールドワークではそれだけ記述を重ねることの重要なのだが、事情はそれほど簡単ではない。レヴィ=ストロースは『悲しき熱帯』(1955)で何

日もかけて奥地の住民を探し出したが、必要とする情報が手に入らず、系譜関係の収集などわずか数十分で終わることがあり、そんな徒労の積み重ねがフィール

ドワークだという。つまりフィールドワークと厚い記述とは直接の関係性がない。他方で、多くの人類学者は、文化人類学の方法論を知らない時代や人が書いた

旅行記や事件記録などに触れて、自分が積み重ねてきた厚い記述が一瞬にして瓦解するぐらいインパクトがある(=より厚い)ことを感じる。厚い記述は単に自

分のフィールドノートの記録を厚くしてゆくことではない。だからと言って、厚い記述はフィールドワーカーの精神性が可能にするものでもない。逆に厚い記述

をフィールドワークの精神論としてのみ理解するだけでは、決してそのような記述(=厚い記述)が常に可能になるわけではない。」100%の出典)

I.

◆文化の概念をせばめることが、この概念の重要性を保証する

「人類学という学問全体が文化の概念をめぐって生まれてきたのであり、この概念の広い適用を人類学はますますせばめ、特定のものに限定し、 その中心を定め、これを抑制するようになっている。」(p.5)

"[C]ertainly this pattern fits the concept of culture, around which the whole discipline of anthropology arose, and whose domination that discipline has been increasingly concerned to limit, specify, focus, and contain."

E・B・タイラー(1832-1917)の文化の概念(総合としての文化, 1871)は混乱を生んだのであるから、それらを「よりせばめた、限定し、理論上いっそう強力な文化の概念を用いること」を提唱する。(p.5)

"[S]o I imagine, theoretically more powerful concept of culture to replace E. B. Tylor's famous “ most complex whole," which, its originative power not denied, seems to me to have reached the point where it obscures a good deal more than it reveals"(p.4).

◆折衷主義に関する戒め

「折衷主義が自滅するのは、歩むべき有効な方向が一つしかないからではなく、それがたくさんあるからである。どうしても選択する必要なので ある」(p.6)

"Eclecticism is self-defeating not because there is only one direction in which it is useful to move, but because there are so many: it is necessary to choose"(p.5).

◆記号論的な文化の概念

「私の採用する文化の概念は‥‥本質的に記号論的なものである。‥‥。人間は自分自身がはりめぐらした意味の網の中にかかっている動物であ ると考え、文化をこの網として捉える。したがって文化の研究はどうしても法則を探求する実験科学の一つにはならないのであって、それは意味を探求する解釈 学的な学問に入ると考える」(p.6)

"The concept of culture I espouse, and whose utility the essays below attempt to demonstrate, is essentially a semiotic one. Belie'ving, with Max Weber, that man is an animal suspended in webs of significance hehimself has spun, I take culture to be those webs, and the analysis of it to be therefore not an experimental science in search of law but an interpretive one in search of meaning"(p.5).

II.

◆民族誌を行うこと=厚い記述

「‥‥民族誌をおこなうとは何かを理解するためには、どんな人類学的研究が知識のひとつになるかを捉えることから出発することができ る。‥‥。ひとつの観点つまり教科書の視点からすれば、民族誌をおこなうと言うことは、研究対象の社会の人びとと親しくなり、インフォーマントを選び、文 書を写し、系譜関係をとり、調査地の地図を作り、日記を書くなどのことを指す。しかし、研究計画を決めるのは、こういう技術とか手続きではない。それを決 めるのはまさに一種の知的な作業なのであって、ギルバート・ライルの語を借りるなら「厚い記述」における念入りな試みである。」(pp.7-8)

"In anthropology, or anyway social anthropology, what the practioners do is ethnography. And it is in understanding what ethnography is, or more exactly what doing ethnography is, that a start can be made to / ward grasping what anthropological analysis amounts to as a form of knowledge. This, it must immediately be said, is not a matter of methods. From one point of view, that of the textbook, doing ethnography is establishing rapport, selecting informants, transcribing texts, taking genealogies, mapping fields, keeping a diary, and so on. But it is not these things, techniques and received procedures, that define the enterprise. What defines it is the kind of intellectual effort it is: an elaborate venture in, to borrow a notion from Gilbert Ryle,“thick description""(pp.5-6).

(ライルの2つの論文とは「思考と内省」「思考の思考」『ライル論文集』Vol.2に所収)

◆民族誌の目的

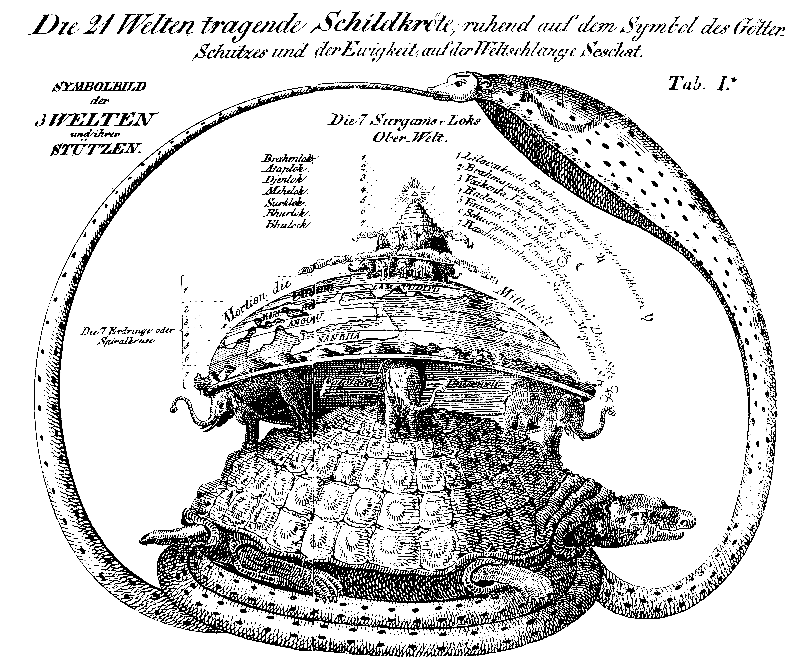

まず民族誌の目的は(a)「厚い記述」と「薄い記述」のあいだにある。

「しかし、ライルが「薄い記述」と呼んだもの、つまり目くばせを練習する者(真似をする者、目くばせをする者、自然にまばたく者‥‥(マ マ))が行っている(「右目をまたたく」)という記述と、彼がやっている(「秘密のたくらみがあるかのように、人をだますために友だちがまばたくのを真似 る」)という「厚い記述」との間に民族誌の目的があるということが重要なのである。」(p.10)

また民族誌の目的は(b)意味の構造のヒエラルヒーにある。

「つまり民族誌の目的は、無意識的なまばたき、目くばせ、にせの目くばせ、目くばせの真似、目くばせの真似の練習などが生まれ、知覚され、 解釈される意味の構造のヒエラルヒーにあり、このヒエラルヒーがなければ、まばたき、目くばせなどのものは、誰かがまばたきで何を意味しても、あるいは何 も意味しないとしても、事実存在しないのである。」(p.10)

"But the point is that between what Ryle calls the “ thin description" of what the rehearser (parodist, winker, twitcher .. .) is doing (“rapidly contracting his right eyelids") and the “ thick description" of what he is doing (“practicing a burlesque of a friend faking a wink to deceive an innocent into thinking a conspiracy is in motion") 1ies the object of ethnography: a stratified hierarchy of meaningful structures in terms of which twitches, winks, fake-winks, parodies, rehearsals of parodies are produced, perceived, and interpreted, and without which they would not (not even the zero-form twitches, which, as a cultural category, are as much nonwinks as winks are nontwitches) in fact exist, no matter what anyone did or didn't do with his eyelids"(p.7).

◆モロッコでの「事件」の記述=解釈について解釈すること

民族誌的なノートそのものは「厚い」ものである。人類学の著作では「彼ら自らの解釈に関するわれわれ自身の解釈」ということがはっきりしな い。その理由は「ある出来事、儀礼、習慣、考えその他のどんなものでも、それを理解するために必要なものの多くは、それ自体を直接扱う前に、背景をなす資 料として暗に含まれてしまっているからである。」そして、これは避けられないことである(それ自体は悪いことではない)。「‥‥われわれはすでに解釈して いるのであり、さらに、解釈について解釈しているのである。それはいわば、目くばせに対する目くばせへの目くばせである。」(p.15)

***

"In finished anthropological writings, including those collected here, this fact--that what we call our data are really our own constructions of other people's constructions of what they and their compatriots are up to--is obscured because most of what we need to comprehend a particular event, ritual, custom, idea, or whatever is insinuated as background information before the thing itself is directly examined. (Even to reveal that this little drama took place in the highlands of central Morocco in 1912--and was recounted there in 1968--is to determine much of our understanding of it. There is nothing particularly wrong with this, and it is in any case inevitable. But it does lead to a view of anthropological research as rather more of an observational and rather less of an interpretive activity than it really is."

◆分析するとはどういうことか

まず、分析は(a)意味の構造をえりわけること(「意味の構造」はライルが「コード」と呼んだもの。)。また、分析は(b)「意味構造の社 会の基盤」と「意味内容」をさぐること。

【エピソード】

"The French (the informant said) had only just arrived. They set up twenty or so small forts between here, the town, and the Marmusha area up in the middle of the mountains, placing them on promontories so they could survey the countryside. But for all this they couldn't guarantee safety, especially at night, so although the mezrag (trade-pact-system) was supposed to be legally abolished it in fact continued as before.

One night, when Cohen (who speaks fluent Berber) was up there (at Marmusha) two other Jews who were traders to a neighboring tribe came by to purchase some goods from him. Some Berbers--from yet another neighboring tribe--tried to break into Cohen`s place, but he fired his rifle in the air. (Traditionally, Jews were not allowed to carry weapons; but at this period things were so unsettled many did so anyway.) This attracted the attention of the French and the marauders fled. The next night, however, they came back, and one of them disguised as a woman who knocked on the door with some sort of a story. Cohen was suspicious and didn't want to let "her" in, but the other Jews said: "oh, it's all right, it's only a woman." So they opened the door and the whole lot came pouring in. They killed the two visiting Jews, but Cohen managed to barricade himself in an adjoining room. He heard the robbers planning to burn him alive in the shop after they removed his goods, and so he opened the door and--laying about him wildly with a club--managed to escape through a window.

He went up to the fort (then) to have his wounds dressed, and complained to the local commandant, one Captain Dumari, saying he wanted his "ar-ie", four or five times the value of the merchandise stolen from him. The robbers were from a tribe which had not yet submitted to French authority and were in open rebellion against it, and he wanted authorization to go with his mezrag-holder, the Marmusha tribal sheikh, to collect the indemnity that, under traditional rules, he had coming to him. Captain Dumari couldn`t officially give him permission to do this--because of the French prohibition of the mezrag relationship--but he gave him verbal authorization saying, "If you get killed, it's your problem."

モロッコの事例では、えりわけるとは「ユダヤ人」「ベルベル人」「フランス人」の解釈の枠をえりわけること。続いて、「どのように、(また なぜ)あの場所で、彼らがいっしょにいるということが、ある状況を‥‥生みだしたかを示すこと」。

◆民族誌家は「複雑な概念的構造の多重性」(p.16)に直面する。

「このことは、インフォーマントに面接し、儀礼を観察し、親族名称を聞き出し、所有地の境界をたどり、各世帯の構成を調べ、‥‥日誌をつけ るといった、最も詳細な、原始林でおこなうようなフィールドワークの段階について言える」(p.16)。そして、ここで書物のメタファーがでてくる。「民 族誌をおこなうということは、ある原稿を、「解釈をおこなう」という意味で、読もうとするようなものである。」(p.16)

"And this is true at the most down-to-earth, jungle field work levels of his activity: interviewing informants, observing rituals, eliciting kin terms, tracing property lines, censusing households ... writing his journal"

III.

◆文化についての説明

「文化は理念的なものであるが、人間の頭の中に存在しているものではない。それは非物質的なものだが、超自然的なものでもない。」

文化を「主観的」/「客観的」とするかという論争は不毛である。

"Culture, this acted document, thus is public, like a burlesqued wink or a mock sheep raid. Though ideational it does not exist in someone's head; though unphysical is not an occult entity. The interminable, because unterminable, debate within anthropology as to whether culture is "subjective" or "objective," together with the mutual exchange of intellectual insults ("idealist!"--"materialist!"; "mentalist!"--`'behaviorist!"; "impressionist!"--"positivist!") which accompanies it, is wholly misconceived. "

「人間の行動を象徴的行為としてみると、‥‥、文化がパターンをもった行為なのか、また一つの心の持ち方なのか、あるいは両者の入り交じっ たものであるのかという問いは意味を失う。」(p.17)

"Once human behavior is seen as (most of the time; there are true twitches) symbolic action which, like phonation in speech, pigment in painting, line in writing, or sonance in music, signifies, the question as to whether culture is patterned conduct or a frame of mind, or even the two somehow mixed together, loses sense. "

文化に関しては人類学の内部おいてはふたつの対立がある。ひとつは(a)「文化を具体的なものとみる」立場。もうひとつは(b)文化を(観 察される生の行動などに)還元してみる立場である。しかし、上のように、この2つの見方は「人間の行動を象徴的行為としてみる」立場からは、双方とも誤っ ている(?:不十分?)とみえる。

ギアツによれば論文が書かれた当時の「人類学における理論上の泥沼状態」の原因は文化をめぐる混乱状況に対する反動として発展してきたもの で、その最たるものはWard Goodenough の言うような「文化は人間の精神や心」にあるという見解だ(p.18)。

"The interminable, because unterminable, debate within anthropology as to whether cu1ture is “subjective" or “ objective," together with the mutual exchange of intellectual insults (“idealist! "ー“materialist!" ;“mentalist!"-“behaviorist!"; “impressionist!" -“positivist!") which accompanies it, is wholly misconceived. Once human behavior is seen as (most of the time; there are true twitches) symbolic action-action which, like phonation in speech, pigment in painting, line in writing, or sonance in music, signifies-the question as to whether culture is patterned conduct or a frame of mind, or even the two somehow mixed together, loses sense"(p.12).

◆文化が公的なものであるのは、意味が公的なものであるのと同様:"Culture is public because meaning is".

「文化が公的なものであるのは意味が公的だからである」(p.20)。「文化は心理現象であるとか、誰かの心理の特徴であるとか、パーソナ リティや認知構造などであるとは言えない」(pp.21-22)。

"Culture, this acted document, thus is public, like a burlesqued wink or a mock sheep raid"(p.10).

"Culture is public because meaning is"(p.12).

**

"As Wittgenstein has been invoked, he may as well be quoted:

"We ... say of some people that they are transparent to us. It is, however important as regards this observation, that one human being can be a complete enigma to another. We learn this when we come into a strange country with entirely strange traditions; and. what is more, even given a mastery of the country's language. We do not understand the people. (And not because of not knowing what they are saying to themselves.) We cannot find our feet with them.""

IV.

◆自分自身を彼の中に見いだすこと

「自分自身を彼らの中に見いだすことは、ほとんど成功することのない絶望的な作業であるが、民族誌的調査は個人の経験としては、こういう作 業からなっている。」(邦訳、p.23)

"Finding our feet, an unnerving business which never more than distantly succeeds is what ethnographic research consists of as a personal experience; ....."

我々の足元を見れば、気力をなくさせる仕事であり、成功にはおぼつかないものなのだが、民族誌調査というものは個人的な経験から成り立 つ。

(その道のりは遠いが)人類学を体系化しようとする試みである。

「われわれは、あるいは少なくとも私は、現地人(‥‥)になろうとつとめることはないし、彼らの真似をしようともしない。‥‥。われわれが 求めているのは、ただ話すということよりも広い意味で、未知の人に限らず、彼らと話しあうことであり、これは普通考えられているよりははるかにむずかしい ことである。」(p.23)

"We are not, or at least I am not, seeking either to become natives (a compromised word in any case) or to mimic them. Only romantics or spies would seem to find point in that. We are seeking, in the widened sense of the term in which it encompasses very much more than talk, to converse with them, a matter a great deal more difflcult, and not only with strangers, than is commonly recognized. "If speaking for someone else seems to be a mysterious process," Stanley Cavell has remarked, ''that may be because speaking to someone does not seem mysterious enough""

そして、人類学の目的は人間の対話の拡大にある。むろん人類学はこういう目的を遂行する唯一の学問でもない。

「解釈できる記号の互いに絡みあった体系」(=象徴)として文化は、「力ではなく、社会事象、行動、制度、過程などの原因とされるようなも のではない」(p.24)

「文化はコンテクストであり、その中で社会事象、行動、制度などが理解できるように——つまり厚く——記述されるものなのである。」

"As interworked systems of construable signs (what, ignoring provincial usages, I would call symbols), culture is not a power, something to which social events, behaviors, institutions, or processes can be causally attributed; it is a context, something within which they can be intelligibly--that is, thickly--described."

◆エキゾチズムと人類学的理解

人類学がエキゾチックなものに沈潜する理由(?)は「本質的には、鈍くなっている日常的感覚を新鮮なものにするための方策」(p.24)だ から。それによって「行動の意味が生活のパターン‥‥によって異なる程度を明らかにする。ある民族の文化を理解することは、彼らの特殊性を希薄にしてしま うことなく、その通常性を明らかにすることである。(モロッコ人のおこなっていることが分かれば分かるほど、彼らがいっそう論理的に、またいっそう特異に 思われてくる。)このように、彼らが身近に感じられ、彼らを彼ら自身の日常的状況の中においておくことによって彼らの分かりにくさがうすれてくるのであ る。」(p.24)

"The famous anthropological absorption with the (to us) exotic Berber horsemen, Jewish peddlers, French Legionnaires--is, thus, essentially a device for displacing the dulling sense of familiarity with which the mysteriousness of our own ability to relate perceptively to one another is concealed from us. Looking at the ordinary in places where it takes unaccustomed forms brings out not, as has so often been claimed, the arbitrariness of human behavior (there is nothing especially arbitrary about taking sheep theft for insolence in Morocco), but the degree to which its meaning varies according to the pattern of life by, which it is informed. Understanding a people's culture exposes their normalness without reducing their particularity. (The more I manage to follow what the Moroccans are up to, the more logical, and the more singular, they seem.) It renders them accessible: setting them in the frame of their own banalities, it dissolves their opacity."

人類学者の行為。「遠くから冷静にみる」=「人喰い人種の島の不思議な物語を述べる」=「行為者の立場からみる」=「了解的 verstehen アプローチ」=「エミック分析」(pp.24-5)。

"It is this maneuver, usually too casually referred to as "seeing things from the actor's point of view," too bookishly as "the verstehen approach," or too technically as "emic analysis," that so often leads to the notion that anthropology is a variety of either long-distance mind reading or cannibal-isle fantasizing, and which, for someone anxious to navigate past the wrecks of a dozen sunken philosophies, must therefore be executed with a great deal of care."

◆人類学の著作を理解すること

""Not only other peoples": anthropology can be trained on the culture of which it is itself a part, and it increasingly is; a fact of profound importance, but which, as it raises a few tricky and rather special second order problems, I shall put to the side for the moment".

「人類学とは何かを、またそれが解釈である程度を理解するためには、他の人びとの象徴体系に関するわれわれのとらえかたが行為者に志向して いなければならないということが何を意味し、何を意味しないかを正確に理解することが何よりも必要なのである。」(p.25)。その文化に関する記述は 「彼らが現実の世界に用いていると思われる概念構成によってなされなければならない。‥‥。記述は、特定の人びとの経験に対する解釈によってなされなけれ ばならない。というのも、それは彼らが記述していると主張するところのものだからである。記述が人類学的なのは、そのように主張するのは事実人類学者だか らでもある。」(p.25)

"What it does not mean is that such descriptions are themselves Berber, Jewish, or French--that is, part of the reality they are ostensibly describing; they are anthropological --that is, part of a developing system of scientific analysis. They must be cast in terms of the interpretations to which persons of a particular denomination subject their experience, because that is what they profess to be descriptions of; they are anthropological because it is, in fact, anthropologists who profess them. "

「‥‥『フィネガンズ・ウェークへの手引き』は『フィネガンズ・ウェーク』でないことは明白である。しかし、文化の研究では、分析が研究対 象の内部にまで入りこむにつれて、‥‥、(a)自然の事実としてのモロッコ文化と、(b)理論的構成物としてのモロッコ文化との境界線がぼやけてくる傾向 がある。理論構成としてのモロッコの文化が、暴力、名誉、神聖性、正義をはじめ、部族、財産、任命権、首長制などあらゆるもののモロッコ人観念に関する行 為者の観点による記述の様式で示されると、その境界はいっそうあいまいになる。」(p.26)

"Normally, it is not necessary to point out quite so laboriously that the object of study is one thing and the study of it another. It is clear enough that the physical world is not physics and A Skelton Key to Finnegan's Wake is not Finnegan's Wake. But, as, in the study of culture, analysis penetrates into the very body of the object--that is, we begin with our own interpretations of what our informants are up to, or think they are up to, and then systematize those--the line between (Moroccan) culture as a natural fact and (Moroccan) culture as a theoretical entity tends to get blurred. All the more so, as the latter is presented in the form of an actor's-eye description of (Moroccan) conceptions of everything from violence, honor, divinity, and justice, to tribe, property, patronage, and chiefship."

★ここでのギアツは、文化には本質的なものがある(→(a))と主張していることに注意せよ。

◆人類学の著述は解釈=フィクションである

「人類学の著述はそれ自体が解釈であり、さらに二次的、三次的解釈なのである。(本来、現地人のみが一次的解釈をおこなう。それは彼の文化 にほかならない。)人類学の著述はしたがって創作である。それが「作られるもの」、「形作られるもの」であるという意味——fictio‾の本来の意味は そこにある——における創作である、それはまちがっている意味でも、事実に反するということでも、また単なる「架空の」思索という意味もない。」 (p.26)

"[A]nthropological writings are themselves interpretations, and second and third order ones to boot. (By definition, only a "native" makes first order ones: it's his culture.)※ They are, thus, fictions; fictions, in the sense that they are "something made," "something fashioned"--the original meaning of fictio--not that they are false, unfactual, or merely "as if" thought experiments".

※→"The order problem is, again, complex. Anthropological works based on other anthropological works ( Levi-Strauss', for example) may, of course, be fourth order or higher, and informants frequently, even habitually, make second order interpretations--what have come to be known as "native models." In literate cultures, where "native" interpretation can proceed to higher levels--in connection with the Maghreb, one has only to think of Ibn Khaldun; with the United States, Margaret Mead--these matters become intricate indeed."

★現地人の解釈に特権的な地位を認めている、丸括弧内の記述に注目せよ。

ただし、人類学者とフロベールが制作するものが同じものというのではなく、それが「作られた条件とその重点が異なっている」(p.27)。

◆フィクションと言うことで人類学の知識の客観性が脅かされることはうわべだけである。

より重要なことは次のようなことだ。「民族誌的記述の注意をうながすべきだということは、その著者が遥かかなたの場所で未開人の事実をとら え、それを仮面か彫刻のようにそっくりそのまま持ち帰ってくる能力にむけられているのではなく、著者がそういう遠隔の地で起きていることを明らかにし、見 知らぬ背景から現れてくる、わけの分からぬ行為が生みだす当惑——それは人びとのいったいどのような作法なのだろうかという——を軽減させる程度に向けら れている。」(pp.27-8)

"This is a difference of no mean importance; indeed, precisely the one Madame Bovary had difficulty grasping. But the importance does not lie in the fact that her story was created while Cohen's was only noted. The conditions of their creation, all "the point of it (to say nothing of the manner and the quality) differ. But the one is as much a fictio--a making"--as the other."

「もし、民族誌が厚い記述であり、民族誌学者が厚い記述をおこなっているとすれば、調査日誌の短文であれ、マリノフスキーの長大なモノグラ フであれ、どんな例についても、決定的な問いは、それが目くばせから出発しているかどうかというものである。われわれの解釈力を吟味しなければならないの は、解釈されていない資料、きわめて薄い記述についてではなく、見知らぬ人びとの生活にわれわれを接触させるような科学的想像力についてである。」 (p.28)

" If ethnography is thick description and ethnographers those who are doing the describing, then the determining question for any given example of it, whether a field journal squib or a Malinowski-sized monograph, is whether it sorts winks from twitches and real winks from mimicked ones. It is not against a body of uninterpreted data, radically thinned descriptions, that we must measure the cogency of our explications, but against the power of the scientific imagination to bring us into touch with the lives of strangers. It is not worth it, as Thoreau said, to go round the world to count the cats in Zanzibar. "

V.

◆エスノサイエンス批判

(説明)エスノサイエンス的アプローチによると“文化は純粋に象徴体系として——「それ自体においてper se」——最も有効に取り扱われる‥‥。文化の諸要素間の内的関係を明らかにし、文化の全体系を何らかの方法によって特徴づけることによって、文化をの諸 要素を取り出すことによっておこなわれる”(p.29:訳文は不明瞭。原文を必ず参照せよ)あるいは「文化の特徴づけは、文化を構成している中心的なシン ボルにより、潜在的構造‥‥により、さらに文化が基礎をおいている理念的原理によっておこなわれる」(p.29)

"Now, this proposition, that it is not in our interest to bleach human behavior of the very properties that interest us before we begin to examine it, has sometimes been escalated into a larger claim: namely, that as it is only those properties that interest us, we need not attend, save cursorily, to behavior at all."

"Culture is most effectively treated, the argument goes, purely as a symbolic system (the catch phrase is, "in its own terms"), by isolating its elements, specifying the internal relationships among those elements, and then characterizing the whole system in some general way--according to the core symbols around which it is organized, the underlying structures of which it is a surface expression, or the ideological principles upon which it is based."

(批判)「この研究法は、文化の分析を、その固有の対象、つまり実生活のインフォーマルな論理の外に固定してしまう危険をおかしている‥‥ ように思われる」(p.29)

★*節では、他に「よい解釈‥‥は、解釈の対象の核心にわれわれを導くものである」(p.32)という印象批評まがいの指摘があるが、ここ では検討しない。

"[T]his hermetical approach to things seems to me to run the danger (and increasingly to have been overtaken by it) of locking cultural analysis away from its proper object, the informal logic of actual life. There is little profit in extricating a concept from the defects of psychologism only to plunge it immediately into those of schematicism."

◆吟味可能な社会的対話の記録

「重要なのは、一つの人類学的解釈がどこにあるかを示すことにある。それは社会的対話の流れを追求すること、それを吟味できる形におくこと にある。」「民族誌家は社会的対話を「書き記す」。それを書きとめるのである。こうすることによって、ある時点においてのみ起こった一つのできごとを、記 録のなかで再び見ることのできる記事にするのである。」(p.32)

"If anthropological interpretation is constructing a reading of what happens, then to divorce it from what happens--from what, in this time or that place, specific people say, what they do, what is done to them, from the whole vast business of the world--is to divorce it from its applications and render it vacant. A good interpretation of anything--a poem, a person, a history, a ritual, an institution, a society--takes us into the heart of that of which it is the interpretation. When it does not do that, but leads us instead somewhere else--into an admiration of its own elegance, of its author's cleverness, or of the beauties of Euclidean order--it may have its intrinsic charms; but it is something else than what the task at hand--figuring out what all that rigamarole with the sheep is about--calls for."

◆リクールによる書くこととは何か

「書くことは何を規定するか」=「書くことが規定するのは、話すという事象ではなく、「話された内容」である。「話された内容」というの は、話す目的による意図的な有形化を意味する。‥‥われわれが書くことは、話すことのノエマ(noema:思想内容要点)なのである。」(p.33:ギア ツが引用するリクールの言葉)

""What," Paul Ricoeur, from whom this whole idea of the inscription of action is borrowed and somewhat twisted, asks, "what does writing fix?"

"Not the event of speaking, but the ''said" of speaking, where we understand by the "said" of speaking that intentional exteriorization constitutive of the aim of discourse thanks to which the 'Sagen'--the saying--wants to become the 'Aussage': the enunciated. In short, what we write is the noema ["thought", ''content,'' "gist''] of the speaking. It is the meaning of the speech event, not the event as event. "

***

"This is not itself so very "said"--if Oxford philosophers run to little stories, phenomenological ones run to large sentences; but it brings us anyway to a more precise answer to our generative question, "What does the ethnographer do?"--he writes" ※

※→Or, again, more exactly, "inscribes." Most ethnography is in fact to be found in books and articles, rather than in films, records, museum displays, or whatever; but even in them there are, of course, photographs, drawings, diagrams, tables, and so on. Self-consciousness about modes of representation (not to speak of experiments with them) has been very lacking in anthropology.

◆文化の分析とは...

(禁じ手)「自己発生的な秩序原理とか、人間精神の普遍的属性とか、‥‥先験的な世界観に帰するような」こと(=「不変の意味の世界を見い だすこと」)は科学ではなく、科学を装うことである(pp.34-5)。

"To set forth symmetrical crystals of significance, purified of the material complexity in which they were located, and then attribute their existence to autogenous principles of order, universal properties of the human mind, or vast, a priori weltanschauungen is to pretend a science that does not exist and imagine a reality that cannot be found. "

(文化の分析の範囲)文化の分析は、「意味を推定すること、その推定を評価すること、より優れた推定から説明的な結論を導きだすこと」であ る。

"Cultural analysis is (or should be) guessing at meanings, assessing the guesses, and drawing explanatory conclusions from the better guesses, not discovering the Continent of Meaning and mapping out its bodiless landscape. "

VI.

◆民族誌記述の3(あるいは4)つの特色

(1)「解釈をおこなうこと:it is interpretive」

(2)「解釈する対象は社会的対話の流れ:what it is interpretive of is the flow of social discourse」

(3)「解釈はそういう対話が消滅してしまわないうちにその「言われたこと」を救出することであり、それが読めるようにすること」

"the interpreting involved consists in trying to rescue the "said" of such discourse from its perishing occasions and fix it in perusable terms"

★“クラ(kula)はなくなったり変容したが、「よかれ悪しかれ」 Argonautsは残る”と彼は書く("The kula is gone or altered; but, for better or worse, The Argonauts of the Western Pacific remains")。

**※クラとはマリノフスキー『西太平洋の遠洋航海者』のなかで紹介された広域的な贈与交換システムの現地総称のことであ る。

(4)微視的である:"a fourth characteristic of such description, at least as I practice it: it is microscopic."

◆民族誌と社会のモデルの関係についての考察

(2つのモデルを考える)

(i)ジョンズヴィルはアメリカ合衆国のモデルである(マイクロコズム)

(ii)イースター島はひとつのテストケースである(自然の実験)

*******************

(i)ジョンズヴィルはアメリカ合衆国のモデルである(マイクロコズム)

全体の要約が典型的だと見いだされると考えるのは誤りである。ジョンズヴィルはジョンズヴィルであるし、微視的な研究をする価値が、小 世界の中に大きな世界を見るという前提にたてば、研究調査そのものの意味がなくなる。

「研究の場所は研究の対象ではない。人類学者は村落‥‥を研究するのではく、村落において研究するのである」(p.38)。微視的で具 体的な例から一般化を論じることによってすべてが得られるというのは「叢林のなかにあまりにも長くいた人だけが考えそうな観念」(P.38)である

"The locus of study is not the object of study. Anthropologists don't study villages (tribes, towns, neighborhoods ...); they study in villages. "(→ローカル・ノレッジ)

(ii)イースター島はひとつのテストケースである(自然の実験)

どんな媒介変数も操作できないのに「実験室」とアナロジーすることが誤り。民族誌を実験室的なアナロジーで捉える(マリノフスキーも含 めて)見解に対して次のギアツの言葉は重要である。

「自然の実験室という考え方は、民族誌的調査に基づく資料が、他の社会研究に基づく資料よりもずっと純粋で、いっそう根本的、または確 実で、あまりよそから影響されていない‥‥という観念に達するからである。」(pp.38-9)

"The "natural laboratory" notion has been equally pernicious, not only because the analogy is false--what kind of a laboratory is it where none of the parameters are manipulated?--but because it leads to a notion that the data derived from ethnographic studies are purer, or more fundamental, or more solid, or less conditioned (the most favored word is "elementary") than those derived from other sorts of social inquiry."

「エディプス・コンプレックスがトロブリアンド諸島では逆になっていること、チャンブリでは男女の役割が(西洋社会と)逆になっている こと、またプエブロ・インディアンには攻撃性が欠けていること(これらがすべて否定的な表現であることに特色がある‥‥)などを示そうとした有名な研究は いずれも、経験的に妥当するかどうかはさておいて、「科学的に検証されず、証明されない」仮説である。それらは、他のものと同様に解釈であり、あるいは 誤った解釈である。それらは他のものと同じように到達した解釈であり、他のものと同じように未完のものである。それらの解釈に、自然科学の実験に基づくよ うな権威を与えるのは、単に方法論上のごまかしにすぎない。」(p.39)

"The famous studies purporting to show that the Oedipus complex was backwards in the Trobriands, sex roles were upside down in Tchambuli, and the Pueblo Indians lacked aggression (it is characteristic that they were all negative--"but not in the South"), are, whatever their empirical validity may or may not be, not "scientifically tested and approved" hypotheses. They are interpretations, or misinterpretations, like any others, arrived at in the same way as any others, and as inherently inconclusive as any others, and the attempt to invest them with the authority of physical experimentation is but methodological sleight of hand. Ethnographic findings are not privileged, just particular: another country heard from. To regard them as anything more (or anything less) than that distorts both them and their implications, which are far profounder than mere primitivity, for social theory."

◆民族誌の有用性は素材の提供にある

「人類学者の見いだす事実で重要なのは、その複雑な特殊性と脈絡性というものである」(p.40)

"The important thing about the anthropologist's findings is their complex specificness, their circumstantiality. It is with the kind of material produced by long-term, mainly (though not exclusively) qualitative, highly participative, and almost obsessively fine-comb field study in confined contexts that the mega-concepts with which contemporary social science is afflicted--legitimacy, modernization, integration, conflict, charisma, structure, ... meaning--can be given the sort of sensible actuality that makes it possible to think not only realistically and concretely about them, but, what is more important, creatively and imaginatively with them."

VII.

◆解釈学的研究の欠陥

(a)概念操作をさまたげる傾向がある

(b)体系的な検討をのがれることがある

つまり、解釈が恣意的になり、それに対する外部からの操作に抵抗してしまう。つまり人類学者が道義的非難をするところのエスノセントリズム に陥ってしまう。

(c)理論化を困難にさせてしまう要素=条件がある

(c)−1:文化理論=<理論が抽象的な概念操作よりも経験に近い>。

これは、(経験と理論を中和させるために)ある種のジレンマに陥る。(象徴行為の未知の世界に入る必要性←|→文化理論を発展させること) (理解する必要性←|→分析する必要性)(p.42:原著p.24)

"The besetting sin of interpretive approaches to anything--literature, dreams, symptoms, culture--is that they tend to resist, or to be permitted to resist, conceptual articulation and thus to escape systematic modes of assessment. You either grasp an interpretation or you do not, see the point of it or you do not, accept it or you do not. Imprisoned in the immediacy of its own detail, it is presented as self-validating, or, worse, as validated by the supposedly developed sensitivities of the person who presents it; any attempt to cast what it says in terms other than its own is regarded as a travesty--as, the anthropologist's severest term of moral abuse, ethnocentric."

★彼が引く文化解釈の知識の展開のメタファー「‥‥徐々に知識がふえていくといった上昇カーブをたどるのではなく、文化の分析は、いっそう 大胆な突撃を何度もおこなうような、バラバラではあるが一貫した試みに分解される。」(p.43)

"And from this follows a peculiarity in the way, as a simple matter of empirical fact, our knowledge of culture (cultures, a culture) grows: in spurts. Rather than following a rising curve of cumulative findings, cultural analysis breaks up into a disconnected yet coherent sequence of bolder and bolder sorts. "

理論構成は解釈と表裏一体をなしている。そのために理論だけを抽出すればたんなる常識(あるいは空虚)に終わってしまう。「文化解釈の一般 理論」を書くことは不可能である(できてもそれはカスである)。可能なことは、ある民族誌の理論解釈を、別の民族誌の解釈に活用することである。

「理論構成の基本的な課題は、抽象的規則性を取り出すことではなく、厚い記述を可能にすることであり、いくつも事例を通じて一般化すること ではなく、事例の中で一般化することなのである」(p.44)

"[O]ne can, but there appears to be little profit in it, because the essential task of theory building here is not to codify abstract regularities but to make thick description possible, not to generalize across cases but to generalize within them."

(→ここでギアツはclinical inference:臨床推理)を例にあげるが、ここでは省略するが、要するに、理論の効用は隠されたものを暴くということだ。

"To generalize within cases is usually called, at least in medicine and depth psychology, clinical inference. Rather than beginning with a set of observations and attempting to subsume them under a governing law, such inference begins with a set of (presumptive) signifiers and attempts to place them within an intelligible frame. Measures are matched to theoretical predictions, but symptoms (even when they are measured) are scanned for theoretical peculiarities--that is, they are diagnosed. In the study of culture the signifiers are not symptoms or clusters of symptoms, but symbolic acts or clusters of symbolic acts, and the aim is not therapy but the analysis of social discourse. But the way in which theory is used--to ferret out the unapparent import of things--is the same. "

(c)−2:文化理論=<厳密な意味で予測をおこなうものではない>

"The diagnostician doesn't predict measles; he decides that someone has them, or at the very most clincially decides that someone is rather likely shortly to get them."

「理論構成の臨床的な性格において、概念化というものは、まさにすでにえられた資料の解釈をおこなうことに向けられているのであって、実験 操作の結果を生みだすことを目的とするのではなく、また特定の体系の未来の状態を推論しようとするものでもない」(p.46)

"It is true that in the clinical style of theoretical formulation, conceptualization is directed toward the task of generating interpretations of matters already in hand, not toward projecting outcomes of experimental manipulations or deducing future states of a determined system."

「厚い記述」と「診断」のアナロジカルな比較(p.47-)

"Such a view of how theory functions in an interpretive science suggests that the distinction, relative in any case, that appears in the experimental or observational sciences between "description" and "explanation" appears here as one, even more relative, between "inscription" ("thick description") and "specification" ("diagnosis")--between setting down the meaning particular social actions have for the actors whose actions they are, and stating, as explicitly as we can manage, what the knowledge thus attained demonstrates about the society in which it is found and, beyond that, about social life as such. Our double task is to uncover the conceptual structures that inform our subjects' acts, the "said" of social discourse, and to construct a system of analysis in whose terms what is generic to those structures, what belongs to them because they are what they are, will stand out against the other determinants of human behavior. In ethnography, the office of theory is to provide a vocabulary in which what symbolic action has to say about itself--that is, about the role of culture in human life--can be expressed"

◆文化の実体(Society's forms are culture's substance)

「‥‥社会関係のパターンを再編成することは、経験される世界の諸要素を再編することである‥‥。社会の形態は文化の実体なのである。」 (p.48):★エソテリックですな、これでは。

"Our innocent-looking "note in a bottle" is more than a portrayal of the frames of meaning of Jewish peddlers, Berber warriors, and French proconsuls, or even of their mutual interference. It is an argument that to rework the pattern of social relationships is to rearrange the coordinates of the experienced world. Society's forms are culture's substance."

VIII.

◆文化の分析は不完全だ。

「文化の分析は本質的に不完全なものである。さらにそれよりも悪いことには、分析を深めれば深めるほど、いっそう不充分なものになる、これ は奇妙なサイエンスである。」(p.49)。

"Cultural analysis is intrinsically incomplete. And, worse than that, the more deeply it goes the less complete it is. It is a strange science whose most telling assertions are its most tremulously based, in which to get somewhere with the matter at hand is to intensify the suspicion, both your own and that of others, that you are not quite getting it right."

「‥‥解釈人類学は、完全な意見の一致よりも議論にみがきあげることによって進歩が示されるような学問である」(p.50)

"Anthropology, or at least interpretive anthropology, is a science whose progress is marked less by a perfection of consensus than by a refinement of debate. What gets better is the precision with which we vex each other."

◆意味という概念を取り扱うのだ。

意味はかってはまやかしの概念だといわれていたが、今や(その当時においては)学問の中心に戻ってきた、とギアツはいう。

「‥‥私自身の立場は、一方で主観主義と他方で神秘哲学に抵抗し、象徴形態の分析をできるだけ具体的な社会の現象、出来事、日常生活の公的 世界に即した形でおこなおうとし、さらに理論構成と記述的解釈が不明瞭な学問の魅力にくもらされないように研究を進めることである。」(p.51)

"My own position in the midst of all this has been to try to resist subjectivism on the one hand and cabbalism on the other, to try to keep the analysis of symbolic forms as closely tied as I could to concrete social events and occasions, the public world of common life, and to organize it in such a way that the connections between theoretical formulations and descriptive interpretations were unobscured by appeals to dark sciences."

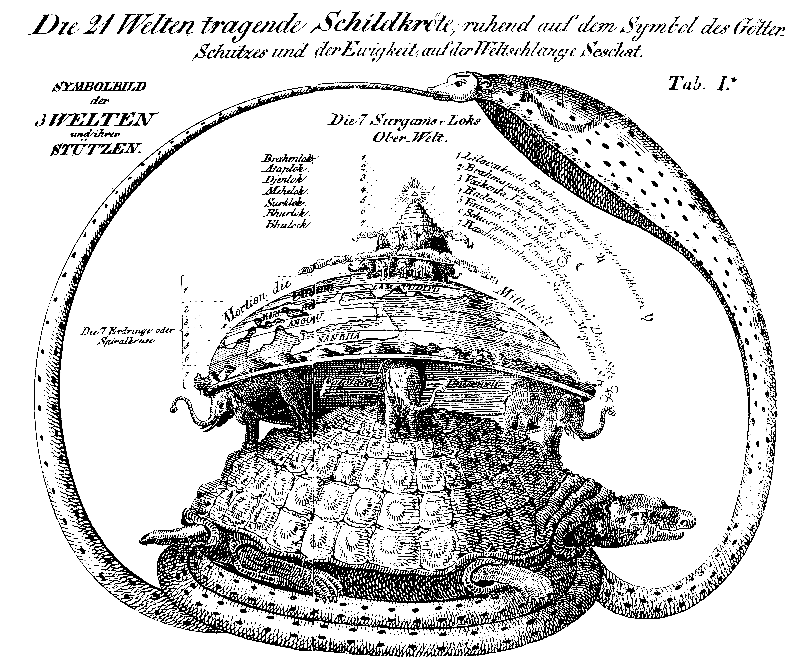

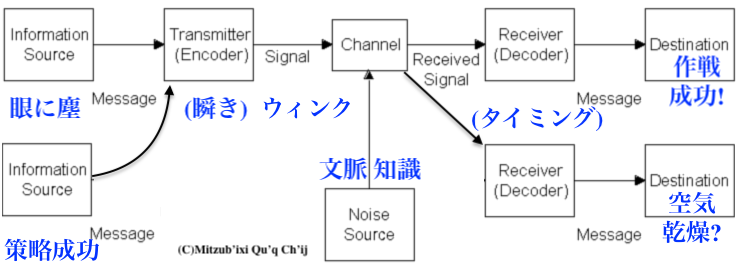

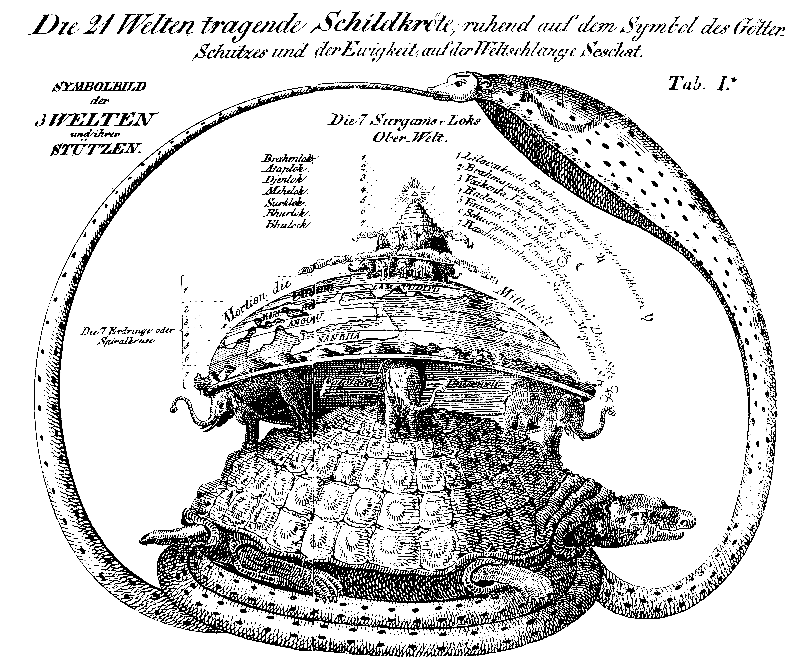

◆文化の分析とは、...

「亀ののっている下を次から次に探っていく文化の分析は、政治・経済・階層的現実‥‥などの生活のきびしい側面とか、この側面の依存してい る生物学的生理学的欲求などとの接触を失うのではないかという危険は常に存在する。このようにならないための、また文化の分析を一種の社会学的耽美主義に 陥らせないためには、文化の分析を、政治・経済・階層的現実や生物・生理的欲求についておこなうことにある」(pp.51-2)

"The danger that cultural analysis, in search of all-too-deep-lying turtles, will lose touch with the hard surfaces of life--with the political, economic, stratificatory realities within which men are everywhere contained--and with the biological and physical necessities on which those surfaces rest, is an ever-present one. "

「社会行為の象徴的領域——芸術、宗教、理念、学問、法、道徳、常識——をみることは、‥‥、その苦しみ(the existental dilemmas of life)のまっただ中に突入することにほかならない。解釈的人類学の本質的使命は、もっとも深遠な問いに答えることにあるのではなく、人間が言ったこと に関する参照できる記録のなかにそれをふくませることにある。」(p.52)

"To look at the symbolic dimensions of social action--art,

religion,

ideology, science, law, morality, common sense--is not to turn away

from

the existential dilemmas of life for some empyrean realm of

deemotionalized

forms; it is to plunge into the midst of them. The essential vocation

of

interpretive anthropology is not to answer our deepest questions, but

to

make available to us answers that others, guarding other sheep in other

valleys, have given, and thus to include them in the consultable record

of what man has said. " - Thick

Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture .

この宇宙論の亀の無限後退のジョークは、もともとはウィリアム・ジェームズ()によるものらしい。"In July 1882 philosopher William James

published an essay in “The Princeton Review”,

and he mentioned iterated rocks not iterated turtles:- William James

(Harvard College), Start Page 58, Quote Page 82, New York. Like

the old woman in the story who described the world as resting on a

rock, and then explained that rock to be supported by another rock, and

finally when pushed with questions said it was “rocks all the way

down,” he who believes this to be a radically moral universe must hold

the moral order to rest either on an absolute and ultimate should or on

a series of shoulds “all the way down.”

| ★「厚い記述」の英文と翻訳のテクストはこちらです. |

【出典】

C・ギアツ「厚い記述——文化の解釈学的理論をめざして」『文化の解 釈学I』(吉田禎吾ほか訳)岩波書店、1987年(Geertz, Clifford.,1973, Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture, in "The Interpretation of Culture", New York: Basic Books.,pp.3-30.)

英文(全文サイト)の引用は以下のところ からおこなった(最終確認日 2010年11月7日)

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099