ジョージ・エリオット

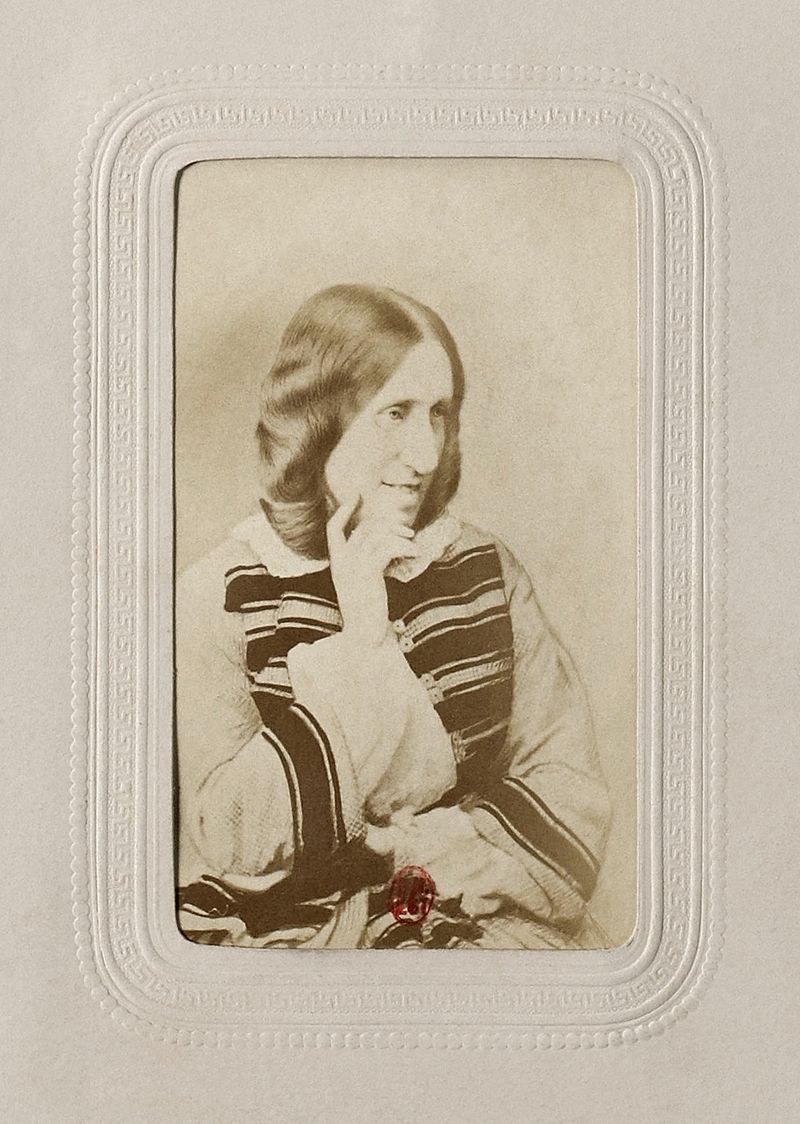

George Eliot, Mary Ann Evans, 1819-1880

☆ジョージ・エリオットのペンネームで知られるメアリー・アン・エヴァン ス(Mary Ann Evans, 1819年11月22日 - 1880年12月22日: アダム・ベデ』(1859年)、『The Mill on the Floss』(1860年)、『Silas Marner』(1861年)、『Romola』(1862-1863年)、『Felix Holt, the Radical』(1866年)、『Middlemarch』(1871-1872年)、『Daniel Deronda』(1876年)。チャールズ・ディケンズやトーマス・ハーディと同様、彼女はイギリスの地方出身であり、ほとんどの作品がイギリスを舞台 にしている。彼女の作品は、リアリズム、心理的洞察、場所の感覚、田園地帯の詳細な描写で知られている。『ミドルマーチ』は、小説家ヴァージニア・ウルフに 「大人のために書かれた数少ないイギリス小説のひとつ」と評され、マーティン・エイミスとジュリアン・バーンズには「英語で最も偉大な 小説」と評された。

| Mary Ann Evans (22

November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or

Marian[1][2]), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English

novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers

of the Victorian era.[3] She wrote seven novels: Adam Bede (1859), The

Mill on the Floss (1860), Silas Marner (1861), Romola (1862–1863),

Felix Holt, the Radical (1866), Middlemarch (1871–1872) and Daniel

Deronda (1876). As with Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy, she emerged

from provincial England; most of her works are set there. Her works are

known for their realism, psychological insight, sense of place and

detailed depiction of the countryside. Middlemarch was described by the

novelist Virginia Woolf as "one of the few English novels written for

grown-up people"[4] and by Martin Amis[5] and Julian Barnes[6] as the

greatest novel in the English language. Scandalously and unconventionally for the era, she lived with George Henry Lewes as his conjugal partner, from 1854–1878, and called him her husband. He remained married to his wife and supported their children, even after she left him to live with another man and have children with him. In May 1880, eighteen months after Lewes's death, George Eliot married her long-time friend, John Cross, a man much younger than she, and she changed her name to Mary Ann Cross. |

ジョージ・エリオットのペンネームで知られるメアリー・アン・エヴァン

ス(Mary Ann Evans, 1819年11月22日 - 1880年12月22日: アダム・ベデ』(1859年)、『The Mill

on the Floss』(1860年)、『Silas Marner』(1861年)、『Romola』(1862-1863年)、『Felix

Holt, the Radical』(1866年)、『Middlemarch』(1871-1872年)、『Daniel

Deronda』(1876年)。チャールズ・ディケンズやトーマス・ハーディと同様、彼女はイギリスの地方出身であり、ほとんどの作品がイギリスを舞台

にしている。彼女の作品は、リアリズム、心理的洞察、場所の感覚、田園地帯の詳細な描写で知られている。ミドルマーチ』は、小説家ヴァージニア・ウルフに

「大人のために書かれた数少ないイギリス小説のひとつ」[4]と評され、マーティン・エイミス[5]とジュリアン・バーンズ[6]には「英語で最も偉大な

小説」と評された。 1854年から1878年まで、当時としてはスキャンダラスで型破りなことに、彼女はジョージ・ヘンリー・ルイスと夫婦同然に暮らし、彼を夫と呼んだ。妻 が別の男性と暮らし、彼との間に子供ができた後も、彼は妻との結婚生活を続け、子供たちを養った。1880年5月、ルイスの死から18ヵ月後、ジョージ・ エリオットは長年の友人であった自分よりずっと年下の男性ジョン・クロスと結婚し、メアリー・アン・クロスと改名した。 |

| Life Early life and education Mary Ann Evans was born in Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England, at South Farm on the Arbury Hall estate.[7] She was the third child of Welshman Robert Evans (1773–1849), manager of the Arbury Hall estate, and Christiana Evans (née Pearson, 1788–1836), daughter of a local mill-owner. Her full siblings were: Christiana, known as Chrissey (1814–59), Isaac (1816–1890), and twin brothers who died a few days after birth in March 1821. She also had a half-brother, Robert Evans (1802–64), and half-sister, Frances "Fanny" Evans Houghton (1805–82), from her father's previous marriage to Harriet Poynton (1780–1809). In early 1820, the family moved to a house named Griff House, between Nuneaton and Bedworth.[8] The young Evans was a voracious reader and obviously intelligent. Because she was not considered physically beautiful, Evans was not thought to have much chance of marriage, and this, coupled with her intelligence, led her father to invest in an education not often afforded to women.[9] From ages five to nine, she boarded with her sister Chrissey at Miss Latham's school in Attleborough, from ages nine to thirteen at Mrs. Wallington's school in Nuneaton, and from ages thirteen to sixteen at Miss Franklin's school in Coventry. At Mrs. Wallington's school, she was taught by the evangelical Maria Lewis—to whom her earliest surviving letters are addressed. In the religious atmosphere of the Misses Franklin's school, Evans was exposed to a quiet, disciplined belief opposed to evangelicalism.[10] After age sixteen, Evans had little formal education.[11] Thanks to her father's important role on the estate, she was allowed access to the library of Arbury Hall, which greatly aided her self-education and breadth of learning. Her classical education left its mark; Christopher Stray has observed that "George Eliot's novels draw heavily on Greek literature (only one of her books can be printed correctly without the use of a Greek typeface), and her themes are often influenced by Greek tragedy".[12] Her frequent visits to the estate also allowed her to contrast the wealth in which the local landowner lived with the lives of the often much poorer people on the estate, and different lives lived in parallel would reappear in many of her works. The other important early influence in her life was religion. She was brought up within a low church Anglican family, but at that time the Midlands was an area with a growing number of religious dissenters. Move to Coventry In 1836, her mother died and Evans (then 16) returned home to act as housekeeper, though she continued to correspond with her tutor Maria Lewis. When she was 21, her brother Isaac married and took over the family home, so Evans and her father moved to Foleshill near Coventry. The closeness to Coventry society brought new influences, most notably those of Charles and Cara Bray. Charles Bray had become rich as a ribbon manufacturer and had used his wealth in the building of schools and in other philanthropic causes. Evans, who had been struggling with religious doubts for some time, became intimate friends with the radical, free-thinking Brays, who had a casual view of marital obligations[13] and the Brays' "Rosehill" home was a haven for people who held and debated radical views. The people whom the young woman met at the Brays' house included Robert Owen, Herbert Spencer, Harriet Martineau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Through this society Evans was introduced to more liberal and agnostic theologies and to writers such as David Strauss and Ludwig Feuerbach, who cast doubt on the literal truth of Biblical texts. In fact, her first major literary work was an English translation of Strauss's Das Leben Jesu kritisch bearbeitet as The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined (1846), which she completed after it had been left incomplete by Elizabeth "Rufa" Brabant, another member of the "Rosehill Circle". The Strauss book had caused a sensation in Germany by arguing that the miracles in the New Testament were mythical additions with little basis in fact.[14][15][16] Evans's translation had a similar effect in England, with the Earl of Shaftesbury calling her translation "the most pestilential book ever vomited out of the jaws of hell."[17][18][19][20] Later she translated Feuerbach's The Essence of Christianity (1854). The ideas in these books would have an effect on her own fiction. As a product of their friendship, Bray published some of Evans's own earliest writing, such as reviews, in his newspaper the Coventry Herald and Observer.[21] As Evans began to question her own religious faith, her father threatened to throw her out of the house, but his threat was not carried out. Instead, she respectfully attended church and continued to keep house for him until his death in 1849, when she was 30. Five days after her father's funeral, she travelled to Switzerland with the Brays. She decided to stay on in Geneva alone, living first on the lake at Plongeon (near the present-day United Nations buildings) and then on the second floor of a house owned by her friends François and Juliet d'Albert Durade on the rue de Chanoines (now the rue de la Pelisserie). She commented happily that "one feels in a downy nest high up in a good old tree". Her stay is commemorated by a plaque on the building. While residing there, she read avidly and took long walks in the beautiful Swiss countryside, which was a great inspiration to her. François Durade painted her portrait there as well.[22] Move to London and editorship of the Westminster Review On her return to England the following year (1850), she moved to London with the intent of becoming a writer, and she began referring to herself as Marian Evans.[23] She stayed at the house of John Chapman, the radical publisher whom she had met earlier at Rosehill and who had published her Strauss translation. She then joined Chapman's ménage-à-trois along with his wife and mistress.[13] Chapman had recently purchased the campaigning, left-wing journal The Westminster Review. Evans became its assistant editor in 1851 after joining just a year earlier. Evans's writings for the paper were comments on her views of society and the Victorian way of thinking.[24] She was sympathetic to the lower classes and criticised organised religion throughout her articles and reviews and commented on contemporary ideas of the time.[25] Much of this was drawn from her own experiences and knowledge and she used this to critique other ideas and organisations. This led to her writing being viewed as authentic and wise but not too obviously opinionated. Evans also focused on the business side of the Review with attempts to change its layout and design.[26] Although Chapman was officially the editor, it was Evans who did most of the work of producing the journal, contributing many essays and reviews beginning with the January 1852 issue and continuing until the end of her employment at the Review in the first half of 1854.[27] Eliot sympathized with the 1848 Revolutions throughout continental Europe, and even hoped that the Italians would chase the "odious Austrians" out of Lombardy and that "decayed monarchs" would be pensioned off, although she believed a gradual reformist approach to social problems was best for England.[28][29] In 1850–51, Evans attended classes in mathematics at the Ladies College in Bedford Square, later known as Bedford College, London.[30] Relationship with George Henry Lewes  Portrait of George Eliot by Samuel Laurence, c. 1860 The philosopher and critic George Henry Lewes (1817–78) met Evans in 1851, and by 1854 they had decided to live together. Lewes was already married to Agnes Jervis, although in an open marriage. In addition to the three children they had together, Agnes also had four children by Thornton Leigh Hunt.[31] In July 1854, Lewes and Evans travelled to Weimar and Berlin together for the purpose of research. Before going to Germany, Evans continued her theological work with a translation of Feuerbach's The Essence of Christianity, and while abroad she wrote essays and worked on her translation of Baruch Spinoza's Ethics, which she completed in 1856, but which was not published in her lifetime because the prospective publisher refused to pay the requested £75.[32] In 1981, Eliot's translation of Spinoza's Ethics was finally published by Thomas Deegan, and was determined to be in the public domain in 2018 and published by the George Eliot Archive.[33] It has been re-published in 2020 by Princeton University Press.[34] The trip to Germany also served as a honeymoon for Evans and Lewes, who subsequently considered themselves married. Evans began to refer to Lewes as her husband and to sign her name as Mary Ann Evans Lewes, legally changing her name to Mary Ann Evans Lewes after his death.[35] The refusal to conceal the relationship was contrary to the social conventions of the time, and attracted considerable disapproval.[citation needed] Career in fiction  Photograph (albumen print) of George Eliot, c. 1865 While continuing to contribute pieces to the Westminster Review, Evans resolved to become a novelist, and set out a pertinent manifesto in one of her last essays for the Review, "Silly Novels by Lady Novelists"[36] (1856). The essay criticised the trivial and ridiculous plots of contemporary fiction written by women. In other essays, she praised the realism of novels that were being written in Europe at the time, an emphasis on realistic storytelling confirmed in her own subsequent fiction. She also adopted a nom-de-plume, George Eliot; as she explained to her biographer J. W. Cross, George was Lewes's forename, and Eliot was "a good mouth-filling, easily pronounced word".[37] Although female authors were published under their own names during her lifetime, she wanted to escape the stereotype of women's writing being limited to lighthearted romances or other lighter fare not to be taken very seriously.[38] She also wanted to have her fiction judged separately from her already extensive and widely known work as a translator, editor, and critic. Another factor in her use of a pen name may have been a desire to shield her private life from public scrutiny, thus avoiding the scandal that would have arisen because of her relationship with Lewes, who was married.[39] In 1857, when she was 37 years of age, "The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton", the first of the three stories included in Scenes of Clerical Life, and the first work of "George Eliot", was published in Blackwood's Magazine.[40] The Scenes (published as a 2-volume book in 1858),[40] was well received, and was widely believed to have been written by a country parson, or perhaps the wife of a parson. Eliot was profoundly influenced by the works of Thomas Carlyle. As early as 1841, she referred to him as "a grand favourite of mine", and references to him abound in her letters from the 1840s and 1850s. According to University of Victoria professor Lisa Surridge, Carlyle "stimulated Eliot's interest in German thought, encouraged her turn from Christian orthodoxy, and shaped her ideas on work, duty, sympathy, and the evolution of the self."[41] These themes made their way into Evans's first complete novel, Adam Bede (1859).[40] It was an instant success, and prompted yet more intense curiosity as to the author's identity: there was even a pretender to the authorship, one Joseph Liggins. This public interest subsequently led to Marian Evans Lewes's acknowledgment that it was she who stood behind the pseudonym George Eliot. Adam Bede is known for embracing a realist aesthetic inspired by Dutch visual art.[42] The revelations about Eliot's private life surprised and shocked many of her admiring readers, but this did not affect her popularity as a novelist. Her relationship with Lewes afforded her the encouragement and stability she needed to write fiction, but it would be some time before the couple were accepted into polite society. Acceptance was finally confirmed in 1877 when they were introduced to Princess Louise, the daughter of Queen Victoria. The queen herself was an avid reader of all of Eliot's novels and was so impressed with Adam Bede that she commissioned the artist Edward Henry Corbould to paint scenes from the book.[43]  Blue plaque, Holly Lodge, 31 Wimbledon Park Road, London When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, Eliot expressed sympathy for the Union cause, something which historians have attributed to her abolitionist sympathies.[28][29] In 1868, she supported philosopher Richard Congreve's protests against governmental policies in Ireland and had a positive view of the growing movement in support of Irish home rule.[28][29] She was influenced by the writings of John Stuart Mill and read all of his major works as they were published.[44] In Mill's The Subjection of Women (1869) she judged the second chapter excoriating the laws which oppress married women "excellent."[29] She was supportive of Mill's parliamentary run, but believed that the electorate was unlikely to vote for a philosopher and was surprised when he won.[28] While Mill served in parliament, she expressed her agreement with his efforts on behalf of female suffrage, being "inclined to hope for much good from the serious presentation of women's claims before Parliament."[45] In a letter to John Morley, she declared her support for plans "which held out reasonable promise of tending to establish as far as possible an equivalence of advantage for the two sexes, as to education and the possibilities of free development", and dismissed appeals to nature in explaining women's lower status.[45][29] In 1870, she responded enthusiastically to Lady Amberley's feminist lecture on the claims of women for education, occupations, equality in marriage, and child custody.[29] However, it would not be correct to assume that the female protagonists of her works can be considered "feminist", with the sole exception perhaps of Romola de' Bardi, who resolutely rejects the State and Church obligations of her time.[46] After the success of Adam Bede, Eliot continued to write popular novels for the next fifteen years. Within a year of completing Adam Bede, she finished The Mill on the Floss, dedicating the manuscript: "To my beloved husband, George Henry Lewes, I give this MS. of my third book, written in the sixth year of our life together, at Holly Lodge, South Field, Wandsworth, and finished 21 March 1860." Silas Marner (1861) and Romola (1863) soon followed, and later Felix Holt, the Radical (1866) and her most acclaimed novel, Middlemarch (1871–1872). Her last novel was Daniel Deronda, published in 1876, after which she and Lewes moved to Witley, Surrey. By this time Lewes's health was failing, and he died two years later, on 30 November 1878. Eliot spent the next six months editing Lewes's final work, Life and Mind, for publication, and found solace and companionship with longtime friend and financial adviser John Walter Cross, a Scottish commission agent[47] 20 years her junior, whose mother had recently died. Marriage to John Cross and death  Eliot's grave in Highgate Cemetery On 16 May 1880, eighteen months after Lewes' death, Eliot married John Walter Cross (1840–1924)[43] and again changed her name, this time to Mary Ann Cross. She was much older than him, likely generating comments, but it pleased her brother Isaac. He had broken off relations with her when she had begun to live with Lewes, and now sent congratulations. While the couple were honeymooning in Venice, Cross, in a suicide attempt, jumped from the hotel balcony into the Grand Canal. He survived, and the newlyweds returned to England. They moved to a new house in Chelsea, but Eliot fell ill with a throat infection. This, coupled with the kidney disease with which she had been afflicted for several years, led to her death on 22 December 1880 at the age of 61.[48][49] Due to her denial of the Christian faith and her relationship with Lewes,[citation needed] Eliot was not buried in Westminster Abbey. She was instead interred in Highgate Cemetery (East), Highgate, London, in the area reserved for political and religious dissenters and agnostics, beside the love of her life, George Henry Lewes.[a] The graves of Karl Marx and her friend Herbert Spencer are nearby.[51] In 1980, on the centenary of her death, a memorial stone was established for her in the Poets' Corner between W. H. Auden and Dylan Thomas, with a quote from Scenes of Clerical Life: "The first condition of human goodness is something to love; the second something to reverence". Personal appearance George Eliot was a physically unattractive woman; she herself knew this and made jokes about her appearance in letters to friends.[52] Yet somehow the force of her personality overcame her ugliness. This was noted by numerous acquaintances.[52] Of his first meeting with her on 9 May 1869, Henry James wrote: ... To begin with she is magnificently ugly — deliciously hideous. She has a low forehead, a dull grey eye, a vast pendulous nose, a huge mouth, full of uneven teeth & a chin & jawbone qui n'en finissent pas ["which never end"] ... Now in this vast ugliness resides a most powerful beauty which, in a very few minutes steals forth & charms the mind, so that you end as I ended, in falling in love with her.[53] Spelling of her name She spelled her name differently at different times. Mary Anne was the spelling used by her father for the baptismal record and she uses this spelling in her earliest letters. Within her family, however, it was spelled Mary Ann. By 1852, she had changed to Marian,[54] but she reverted to Mary Ann in 1880 after she married John Cross.[55] Her memorial stone reads[56] Here lies the body of 'George Eliot' Mary Ann Cross |

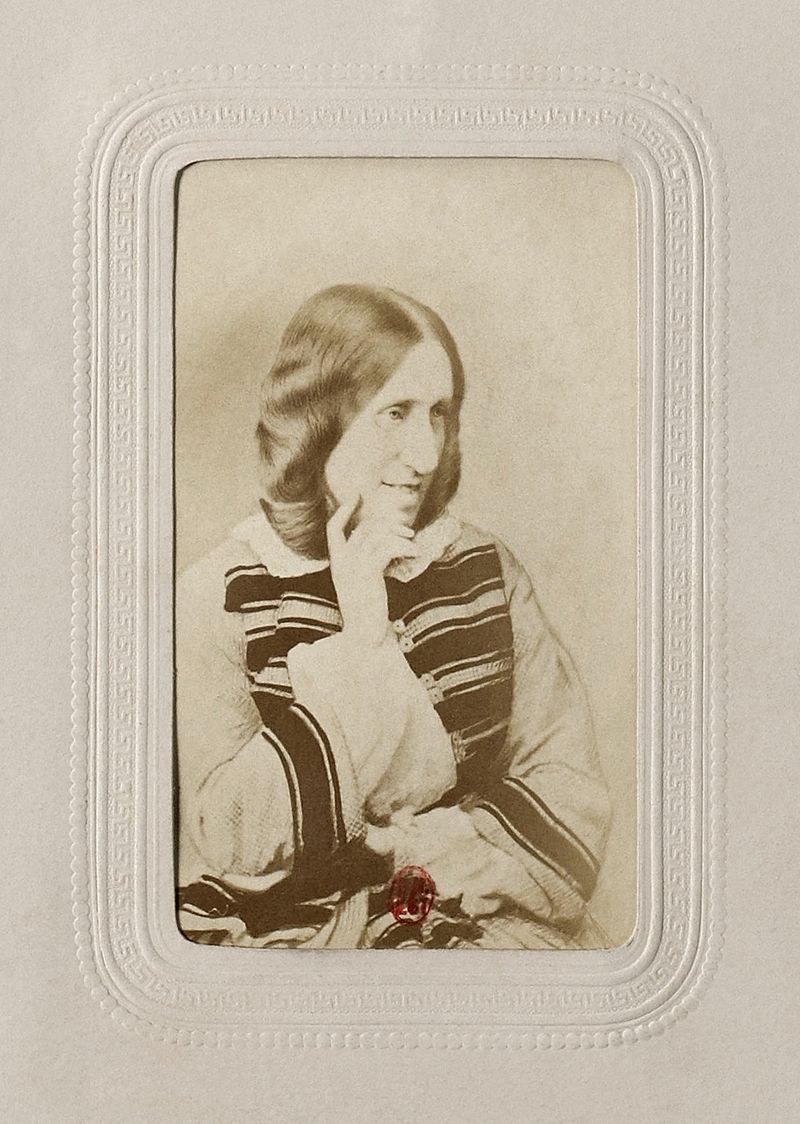

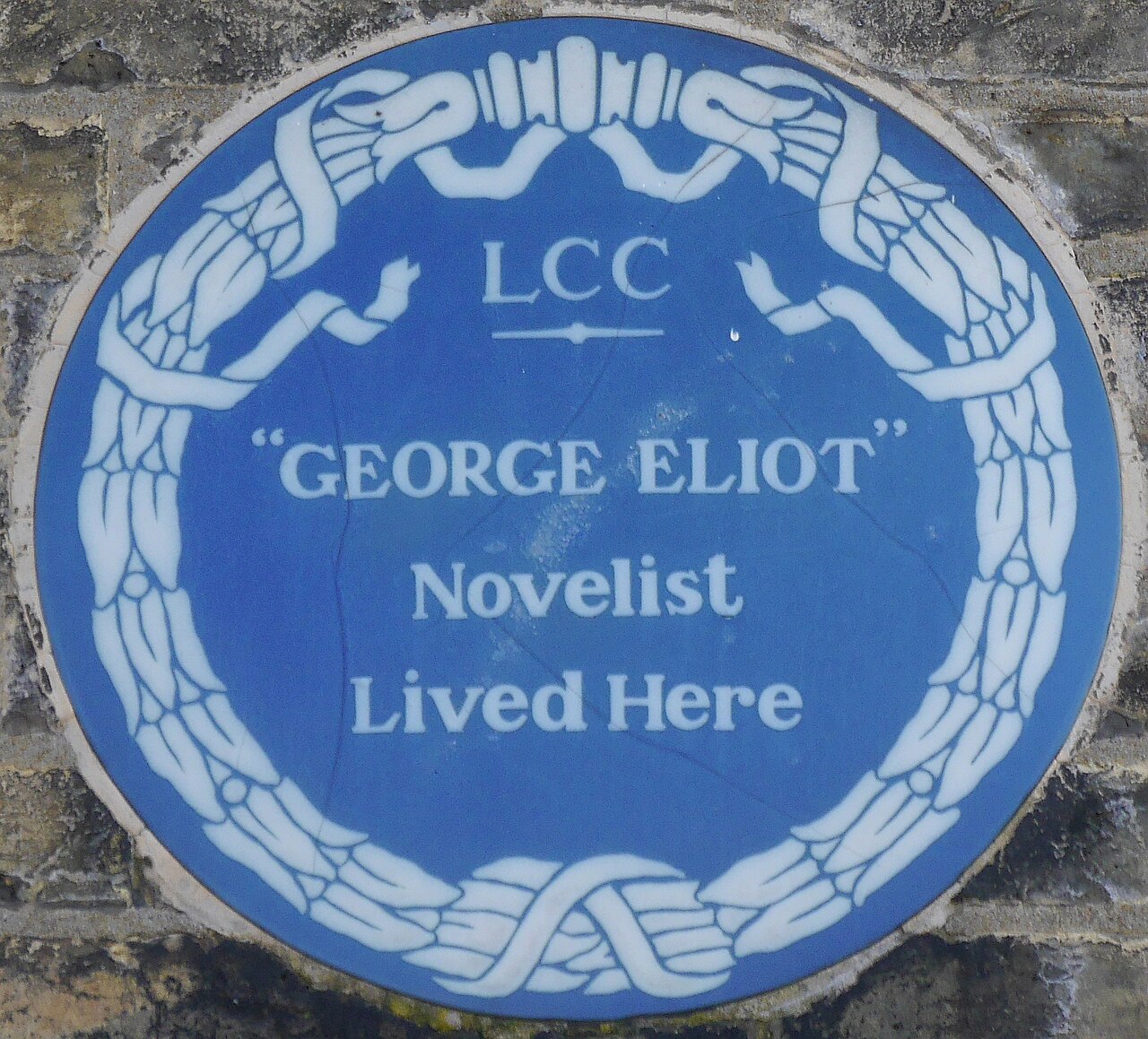

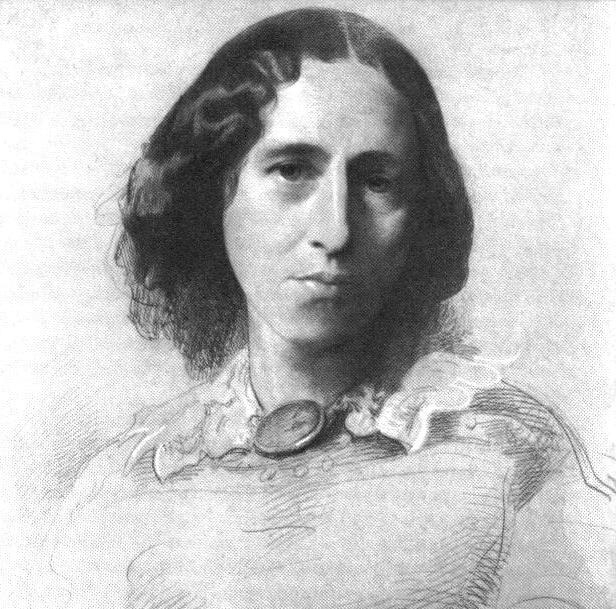

生涯 幼少期と教育 メアリー・アン・エヴァンスはイングランド、ウォリックシャーのヌニートンで、アーベリーホールの地所のサウス・ファームに生まれた[7]。彼女はアーベ リーホールの地所の管理人であったウェールズ人のロバート・エヴァンス(1773-1849)と、地元の工場主の娘クリスティアナ・エヴァンス(旧姓ピア ソン、1788-1836)の3番目の子供であった。彼女の全兄弟は以下の通り: クリスティアナ、通称クリスシー(1814-59)、アイザック(1816-1890)、そして双子の兄弟がいたが、1821年3月に生まれて数日で亡く なった。また、父親の前の結婚相手ハリエット・ポイントン(1780-1809)との間に、腹違いの兄ロバート・エヴァンス(1802-64)と、腹違い の妹フランシス・"ファニー"・エヴァンス・ホートン(1805-82)がいた。1820年初頭、一家はヌニートンとベッドワースの間にあるグリフ・ハウ スという名の家に引っ越した[8]。 若いエヴァンスは読書家で、明らかに知的だった。5歳から9歳までは姉のクリスシーとともにアトルボローのミス・レイサムの学校で、9歳から13歳までは ヌニートンのミセス・ウォリントンの学校で、13歳から16歳まではコヴェントリーのミス・フランクリンの学校で過ごした。ウォリントン夫人の学校では、 福音主義者のマリア・ルイスに教えを受けた。フランクリン女史の学校の宗教的な雰囲気の中で、エヴァンズは福音主義に反対する静かで規律正しい信仰に触れ た[10]。 16歳以降、エヴァンズはほとんど正式な教育を受けなかったが[11]、父親が領地内で重要な役割を担っていたおかげで、彼女はアーベリーホールの図書館 を利用することが許され、それが彼女の独学と幅広い学習に大いに役立った。クリストファー・ストレイは「ジョージ・エリオットの小説はギリシア文学を多用 し(彼女の本の中でギリシア語の書体を使わずに正しく印刷できたのは1冊だけ)、彼女のテーマはしばしばギリシア悲劇の影響を受けている」と述べている。 彼女の人生におけるもうひとつの重要な初期の影響は宗教だった。彼女は低教会の英国国教会の家庭で育ったが、当時のミッドランズは宗教に反対する人々が増 えていた地域だった。 コベントリーへの移住 1836年、母親が亡くなり、エヴァンス(当時16歳)は家政婦として家に戻ったが、家庭教師のマリア・ルイスとは文通を続けていた。彼女が21歳の時、 兄のアイザックが結婚して実家を継いだため、エヴァンズと父親はコベントリー近郊のフォールズヒルに引っ越した。コベントリーの社交界に近づいたことで、 特にチャールズ・ブレイとカーラ・ブレイから新たな影響を受けた。チャールズ・ブレイはリボン製造業で大金持ちになり、その富を学校建設やその他の慈善事 業に使っていた。以前から宗教的な疑念に苦しんでいたエヴァンスは、結婚の義務[13]を軽んじる急進的で自由な考えを持つブレイ夫妻と親しい友人とな り、ブレイ夫妻の「ローズヒル」邸は急進的な考えを持ち、議論する人々の避難所となった。若い女性がブレイズ家で出会った人々には、ロバート・オーウェ ン、ハーバート・スペンサー、ハリエット・マーティノー、ラルフ・ワルド・エマーソンなどがいた。エヴァンスはこの社交界を通じて、よりリベラルで不可知 論的な神学や、聖書のテキストの文字通りの真実に疑問を投げかけるダヴィッド・シュトラウスやルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハといった作家たちに出会っ た。実際、彼女の最初の主要な文学作品は、シュトラウスの『イエスの生涯(Das Leben Jesu kritisch bearbeitet)』を英訳したもので、「ローズヒル・サークル」のもう一人のメンバーであるエリザベス・"ルーファ"・ブラバントによって未完成の まま残された後、彼女が完成させたものだった(1846年)。 シュトラウスの本は、新約聖書における奇跡は神話的な追加であり、事実の根拠はほとんどないと主張し、ドイツでセンセーションを巻き起こしていた[14] [15][16]。エヴァンスの翻訳はイギリスでも同様の影響を与え、シャフツベリー伯爵は彼女の翻訳を「地獄の顎から吐き出された最も疫病的な本」と呼 んだ[17][18][19][20]。これらの本の思想は、彼女自身の小説にも影響を与えることになる。 二人の友情の産物として、ブレイはエヴァンズ自身の初期の執筆物(批評など)のいくつかを彼の新聞『コヴェントリー・ヘラルド・アンド・オブザーヴァー』 に掲載した[21]。エヴァンズが自身の宗教的信仰に疑問を持ち始めると、父親は彼女を家から追い出すと脅したが、その脅しは実行されなかった。その代わ り、彼女は謹んで教会に通い、1849年に父が30歳で亡くなるまで、父のために家を守り続けた。父の葬儀の5日後、彼女はブレイ夫妻とともにスイスに向 かった。彼女はジュネーヴに一人で留まることを決め、最初はプロンジョンの湖畔(現在の国連の建物の近く)に住み、その後、シャノワンヌ通り(現在のペリ セリー通り)にある友人フランソワとジュリエット・ダルベール・デュラード夫妻の家の2階に住んだ。彼女は「古い木の高いところにある羽毛の巣にいるよう な気分」と嬉しそうに語った。彼女の滞在を記念するプレートが建物に掲げられている。滞在中、彼女は熱心に読書をし、スイスの美しい田園地帯を長く散歩し た。フランソワ・デュラードはそこで彼女の肖像画も描いている[22]。 ロンドンへの移住と『ウェストミンスター・レビュー』誌の編集長就任 翌年(1850年)イギリスに戻った彼女は、作家になるつもりでロンドンに移り住み、自分のことをマリアン・エヴァンスと呼ぶようになる[23]。チャッ プマンは最近、運動的で左翼的な雑誌『ウェストミンスター・レビュー』を購入していた[13]。エバンズは、わずか1年前に入社した後、1851年にその 副編集長となった。彼女は下層階級に同情的で、記事や批評を通して組織宗教を批判し、当時の現代的な思想についてコメントした[25]。そのため、彼女の 文章は本物であり、賢明であるが、あまり露骨に意見を述べるものではないと見なされた。エバンスはまた、レイアウトやデザインを変えようとするなど、レ ビュー誌のビジネス面にも力を注いだ[26]。公式にはチャップマンが編集者であったが、雑誌の制作のほとんどを手がけたのはエバンスであり、1852年 1月号から1854年前半にレビュー誌での仕事を終えるまで、多くのエッセイや評論を寄稿した。 [27]エリオットはヨーロッパ大陸の1848年の革命に共感しており、イタリア人が「憎むべきオーストリア人」をロンバルディアから追い出し、「朽ち果 てた君主」が年金をもらえるようになることを望んでいたが、社会問題に対しては緩やかな改革主義的アプローチがイギリスにとって最善であると考えていた [28][29]。 1850年から51年にかけて、エヴァンズはベッドフォード・スクエアのレディース・カレッジ(後にロンドンのベッドフォード・カレッジとして知られる) で数学の授業を受けた[30]。 ジョージ・ヘンリー・ルイスとの関係  サミュエル・ローレンスによるジョージ・エリオットの肖像 1860年頃 哲学者・批評家のジョージ・ヘンリー・ルイス(1817-78)は1851年にエヴァンスと出会い、1854年には一緒に暮らすことを決めていた。ルイス はすでにアグネス・ジャーヴィスと公開結婚していた。1854年7月、ルイスとエヴァンスは調査のためにワイマールとベルリンを一緒に訪れた。ドイツに行 く前、エヴァンスはフォイエルバッハの『キリスト教の本質』の翻訳で神学的研究を続け、外国にいる間にエッセイを書き、バルーク・スピノザの『倫理学』の 翻訳に取り組んだ。 [32]1981年、スピノザの『倫理学』のエリオット訳はトーマス・ディーガンによってようやく出版され、2018年にはパブリックドメインであると判 断され、ジョージ・エリオット・アーカイヴによって出版された。 ドイツへの旅はエヴァンスとルイスの新婚旅行でもあり、彼らはその後結婚したと考えた。エバンスはルイスを夫と呼び、メアリー・アン・エバンス・ルイスと 署名するようになり、彼の死後、法的にメアリー・アン・エバンス・ルイスに改名した[35]。関係を隠すことを拒否したことは当時の社会通念に反し、かな りの不評を買った[要出典]。 小説家としてのキャリア  ジョージ・エリオットの写真(アルバムプリント)、1865年頃 ウェストミンスター・レビュー』誌への寄稿を続けながら、エヴァンスは小説家になることを決意し、『レビュー』誌への最後のエッセイのひとつである「女性 小説家による愚かな小説」[36](1856)で適切なマニフェストを掲げた。このエッセイは、女性によって書かれた現代小説のくだらなく滑稽なプロット を批判した。他のエッセイでは、当時ヨーロッパで書かれていた小説のリアリズムを賞賛しており、このリアリズム重視の姿勢は、その後の彼女自身の小説でも 確認されている。伝記作家のJ.W.クロスに彼女が説明したように、ジョージはルイスの名字であり、エリオットは「口がふさがり、発音しやすい言葉」で あった。 [37]存命中、女性作家は自分の名前で出版されていたが、彼女は、女性の書くものは軽薄なロマンスや、あまり真剣に受け取られないような軽いものに限ら れるという固定観念から逃れたいと考えていた。ペンネームを使用したもう一つの要因は、私生活を世間の目から守りたかったため、既婚者であったルイスとの 関係から生じるスキャンダルを避けたかったのかもしれない[39]。 1857年、彼女が37歳のとき、『Scenes of Clerical Life』に収録されている3つの物語のうちの最初の物語であり、「ジョージ・エリオット」の最初の作品である「The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton」が『Blackwood's Magazine』に掲載された[40]。この『Scenes』(1858年に2巻本として出版)は好評を博し[40]、田舎の牧師、あるいは牧師の妻に よって書かれたと広く信じられていた。 エリオットはトマス・カーライルの作品に大きな影響を受けていた。1841年の時点で、彼女はカーライルを「私の大のお気に入り」と呼び、1840年代か ら1850年代にかけての彼女の手紙にはカーライルへの言及があふれている。ビクトリア大学のリサ・サリッジ教授によれば、カーライルは「エリオットのド イツ思想への関心を刺激し、キリスト教正統派からの転向を促し、仕事、義務、同情、自己の進化に関する彼女の考えを形成した」[41]。これらのテーマは エヴァンズの最初の完全な小説『アダム・ベッド』(1859年)に反映された[40]。この作品はたちまち成功を収め、作者の正体についてさらに強い好奇 心を引き起こした。このような世間の関心は、後にマリアン・エバンス・ルイスが、ジョージ・エリオットというペンネームの背後にいるのは自分であることを 認めるに至った。アダム・ビードは、オランダの視覚芸術から着想を得たリアリズムの美学を取り入れたことで知られている[42]。 エリオットの私生活についての暴露は、彼女の崇拝する読者の多くを驚かせ、ショックを与えたが、小説家としての彼女の人気には影響しなかった。ルイスとの 関係は、彼女が小説を書くのに必要な励ましと安定を与えてくれたが、夫婦が礼儀正しい社会に受け入れられるまでにはしばらく時間がかかった。1877年、 ヴィクトリア女王の娘であるルイーズ王女に紹介され、ようやく受け入れられた。王妃自身、エリオットの小説の熱心な読者であり、『アダム・ベッド』に感銘 を受け、画家のエドワード・ヘンリー・コーボールドにこの本のシーンを描くよう依頼した[43]。  ロンドン、ウィンブルドン・パーク・ロード31番地のホリー・ロッジの青いプレート 1861年にアメリカ南北戦争が勃発すると、エリオットは北軍の大義に同調する姿勢を示したが、これは歴史家たちが彼女の奴隷制度廃止論へのシンパシーに 起因するものだと考えている[28][29]。 1868年、彼女はアイルランドにおける政府の政策に対する哲学者リチャード・コングリーヴの抗議を支持し、アイルランドの自治を支持する運動の高まりに 対して肯定的な見方をしていた[28][29]。 彼女はジョン・スチュアート・ミルの著作に影響を受け、彼の主要な著作は出版されるたびにすべて読んだ[44]。 ミルの『女性の従属』(1869年)では、既婚女性を抑圧する法律を糾弾する第2章を「素晴らしい」と評価した。 「彼女はミルの議会選挙への出馬を支持していたが、選挙民は哲学者に投票する可能性は低いと信じており、彼が勝利したときには驚いた[28]。ミルが議会 で奉仕している間、彼女は女性参政権のための彼の努力に同意することを表明し、「議会での女性の主張の真剣なプレゼンテーションから多くの良いことを期待 する傾向があった。 「ジョン・モーリーに宛てた手紙の中で、彼女は「教育や自由な発達の可能性に関して、両性の利点の同等性を可能な限り確立する傾向にある合理的な見込みの ある」計画への支持を表明し、女性の地位の低さを説明する上での自然への訴えを退けた[45][29]。 1870年、彼女は教育、職業、結婚における平等、子どもの親権に対する女性の主張に関するアンバーリー夫人のフェミニスト講演に熱心に応じた[29]。 しかし、彼女の作品の女性主人公を「フェミニスト」とみなすことは正しくない。 アダム・ベードの成功後、エリオットはその後15年間大衆小説を書き続けた。アダム・ベデ』の完成から1年も経たないうちに、彼女は『The Mill on the Floss』を完成させ、原稿を捧げた: 「私の最愛の夫、ジョージ・ヘンリー・ルイスに、この私の3冊目の本のMSを捧げる。Silas Marner』(1861年)と『Romola』(1863年)がすぐに続き、その後『Felix Holt, the Radical』(1866年)、そして最も評価の高い小説『Middlemarch』(1871-1872年)が発表された。 最後の小説は1876年に出版された『ダニエル・デロンダ』(Daniel Deronda)。この頃、ルイスの健康状態は悪化しており、2年後の1878年11月30日に亡くなった。エリオットはその後6ヵ月間、ルイスの遺作と なった『人生と心』を出版するための編集作業に没頭し、長年の友人でありファイナンシャル・アドバイザーであったジョン・ウォルター・クロス(20歳年下 のスコットランド人エージェント[47]。 ジョン・クロスとの結婚と死  ハイゲート墓地にあるエリオットの墓 1880年5月16日、ルイスの死から1年半後、エリオットはジョン・ウォルター・クロス(1840-1924)と結婚し[43]、再び名前をメアリー・ アン・クロスに変えた。彼女はエリオットよりずっと年上で、おそらくコメントも年上だったのだろうが、それは彼女の兄アイザックを喜ばせた。彼は、彼女が ルイスと暮らし始めたときに関係を断っていたが、今は祝福を送っている。夫妻がヴェニスで新婚旅行をしていたとき、クロスは自殺未遂でホテルのバルコニー から大運河に飛び込んだ。彼は一命を取り留め、新婚夫婦はイギリスに戻った。二人はチェルシーの新居に移ったが、エリオットは喉の感染症で倒れた。数年前 から患っていた腎臓病と相まって、1880年12月22日に61歳で死去した[48][49]。 キリスト教信仰を否定していたことと、ルイスとの関係から[要出典]、エリオットはウェストミンスター寺院に埋葬されなかった。その代わりに、彼女はロン ドンのハイゲートにあるハイゲート墓地(東)に埋葬され、政治的・宗教的な異端者や無宗教者のために用意されたエリアに、生涯の恋人であったジョージ・ヘ ンリー・ルイスの傍らに埋葬された[a]。 [51] 1980年、彼女の没後100周年を記念して、W.H.オーデンとディラン・トマスの間の詩人コーナーに彼女のための記念石が設置され、『Scenes of Clerical Life』から「人間の善の第一の条件は、愛するものであり、第二の条件は、尊敬するものである」という言葉が引用されている。 外見 ジョージ・エリオットは肉体的に魅力のない女性であった。彼女自身もそのことを知っており、友人に宛てた手紙では自分の容姿についてジョークを飛ばしてい た[52]。1869年5月9日に彼女と初めて会ったときのことを、ヘンリー・ジェイムズはこう書いている[52]: ... まず第一に、彼女は驚くほど醜い。彼女は低い額、つぶらな灰色の目、大きく尖った鼻、不揃いな歯でいっぱいの巨大な口、顎と顎骨のqui n'en finissent pas(「決して終わらない」)...を持っている。この巨大な醜さの中に最も強力な美が存在し、それはほんの数分のうちに心を奪い、魅了する。 名前のスペル 彼女は時代によって名前の綴りを変えていた。メアリー・アンは父親が洗礼記録に使った綴りであり、彼女も初期の手紙ではこの綴りを使っている。しかし、家 族内ではメアリー・アンと表記されていた。1852年までにはマリアンに変わったが[54]、1880年にジョン・クロスと結婚した後、メアリー・アンに 戻った[55]。 ここに眠る ジョージ・エリオット メアリー・アン・クロス |

| Memorials and tributes Several landmarks in her birthplace of Nuneaton are named in her honour. These include the George Eliot Academy, Middlemarch Junior School, George Eliot Hospital (formerly Nuneaton Emergency Hospital),[57] and George Eliot Road, in Foleshill, Coventry. Also, The Mary Anne Evans Hospice in Nuneaton.  Nuneaton Museum and Art Gallery, in Riversley Park, home of collection on writer George Eliot A statue of Eliot is in Newdegate Street, Nuneaton, and Nuneaton Museum & Art Gallery has a display of artifacts related to her. A tunnel boring machine constructing the Bromford Tunnel on High Speed 2 was named in honour of her. [58] Literary assessment  Portrait by Frederick William Burton, 1864 Throughout her career, Eliot wrote with a politically astute pen. From Adam Bede to The Mill on the Floss and Silas Marner, Eliot presented the cases of social outsiders and small-town persecution. Felix Holt, the Radical and The Legend of Jubal were overtly political, and political crisis is at the heart of Middlemarch, in which she presents the stories of a number of inhabitants of a small English town on the eve of the Reform Bill of 1832; the novel is notable for its deep psychological insight and sophisticated character portraits. The roots of her realist philosophy can be found in her review of John Ruskin's Modern Painters in Westminster Review in 1856. Eliot also express proto-Zionist ideas in Daniel Deronda.[59] Readers in the Victorian era praised her novels for their depictions of rural society. Much of the material for her prose was drawn from her own experience. She shared with Wordsworth the belief that there was much value and beauty to be found in the mundane details of ordinary country life. Eliot did not, however, confine herself to stories of the English countryside. Romola, an historical novel set in late fifteenth century Florence, was based on the life of the Italian priest Girolamo Savonarola. In The Spanish Gypsy, Eliot made a foray into verse, but her poetry's initial popularity has not endured. Working as a translator, Eliot was exposed to German texts of religious, social, and moral philosophy such as David Friedrich Strauss's Life of Jesus and Feuerbach's The Essence of Christianity; also important was her translation from Latin of Jewish-Dutch philosopher Spinoza's Ethics. Elements from these works show up in her fiction, much of which is written with her trademark sense of agnostic humanism. According to Clare Carlisle, who published a new biography on George Eliot in 2023,[60] the overdue publication of Spinoza's Ethics was a real shame, because it could have provided some illuminating cues for understanding the more mature works of the writer.[34] She had taken particular notice of Feuerbach's conception of Christianity, positing that our understanding of the nature of the divine was to be found ultimately in the nature of humanity projected onto a divine figure. An example of this philosophy appeared in her novel Romola, in which Eliot’s protagonist displayed a "surprisingly modern readiness to interpret religious language in humanist or secular ethical terms."[61] Though Eliot herself was not religious, she had respect for religious tradition and its ability to maintain a sense of social order and morality. The religious elements in her fiction also owe much to her upbringing, with the experiences of Maggie Tulliver from The Mill on the Floss sharing many similarities with the young Mary Ann Evans. Eliot also faced a quandary similar to that of Silas Marner, whose alienation from the church simultaneously meant his alienation from society. Because Eliot retained a vestigial respect for religion, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche excoriated her system of morality for figuring sin as a debt that can be expiated through suffering, which he demeaned as characteristic of "little moralistic females à la Eliot."[62] She was at her most autobiographical in Looking Backwards, part of her final published work Impressions of Theophrastus Such. By the time of Daniel Deronda, Eliot's sales were falling off, and she had faded from public view to some degree. This was not helped by the posthumous biography written by her husband, which portrayed a wonderful, almost saintly, woman totally at odds with the scandalous life people knew she had led. In the 20th century she was championed by a new breed of critics, most notably by Virginia Woolf, who called Middlemarch "one of the few English novels written for grown-up people".[4] In 1994, literary critic Harold Bloom placed Eliot among the most important Western writers of all time.[63] In a 2007 authors' poll by Time, Middlemarch was voted the tenth greatest literary work ever written.[64] In 2015, writers from outside the UK voted it first among all British novels "by a landslide".[65] The various film and television adaptations of Eliot's books have re-introduced her to the wider reading public. |

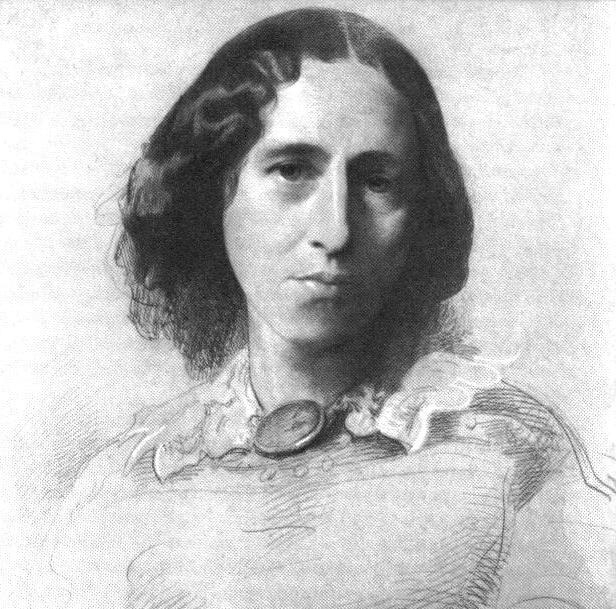

記念碑と賛辞 ジョージ・エリオットの生まれ故郷であるヌニートンには、彼女の名を冠した名所がいくつかある。ジョージ・エリオット・アカデミー、ミドルマーチ中学校、 ジョージ・エリオット病院(旧ヌニートン救急病院)[57]、コヴェントリーのフォールズヒルにあるジョージ・エリオット・ロードなどである。また、ヌ ニートンのメアリー・アン・エヴァンス・ホスピスもある。  作家ジョージ・エリオットに関するコレクションが収蔵されている。 ヌニートンのニューデゲート・ストリートにはエリオットの銅像があり、ヌニートン博物館・美術館にはエリオット関連の品々が展示されている。 高速道路2号線のブロムフォード・トンネルを建設するトンネル掘削機は、エリオットにちなんで名付けられた。[58] 文学的評価  フレデリック・ウィリアム・バートンの肖像画、1864年 エリオットはそのキャリアを通じて、政治的に鋭い筆致で作品を書いた。アダム・ベードから『The Mill on the Floss』や『Silas Marner』まで、エリオットは社会的アウトサイダーや田舎町の迫害の事例を紹介した。急進者フェリックス・ホルト』や『ジュバルの伝説』はあからさま に政治的であり、政治的危機が『ミドルマーチ』の核心である。彼女のリアリズム思想のルーツは、1856年にWestminster Review誌に掲載されたジョン・ラスキンの『Modern Painters』の書評に見出すことができる。また、エリオットは『ダニエル・デロンダ』において原始シオニスト的な思想を表現している[59]。 ヴィクトリア朝時代の読者は、農村社会を描いた彼女の小説を賞賛した。彼女の散文の素材の多くは、彼女自身の経験から引き出された。彼女はワーズワースと 同じように、平凡な田舎暮らしの細部にこそ多くの価値と美があるという信念を持っていた。しかし、エリオットはイギリスの田舎の物語にとどまることはな かった。15世紀末のフィレンツェを舞台にした歴史小説『Romola』は、イタリアの司祭ジローラモ・サヴォナローラの生涯に基づいている。スパニッ シュ・ジプシー』でエリオットは詩の世界に進出したが、彼女の詩の最初の人気は長続きしなかった。 翻訳家として働いていたエリオットは、ダヴィド・フリードリヒ・シュトラウスの『イエスの生涯』やフォイエルバッハの『キリスト教の本質』など、ドイツの 宗教哲学、社会哲学、道徳哲学のテキストに触れた。これらの作品の要素が彼女の小説に現れており、その多くは彼女のトレードマークである不可知論的ヒュー マニズムのセンスで書かれている。2023年にジョージ・エリオットの新しい伝記を出版したクレア・カーライルによれば[60]、スピノザの『倫理学』の 出版が遅れたことは本当に残念なことだった。この哲学の一例は彼女の小説『ロモーラ』に登場し、エリオットの主人公は「宗教的な言葉を人文主義的あるいは 世俗的な倫理用語で解釈しようとする、驚くほど現代的な用意周到さ」を示している[61]。エリオット自身は無宗教であったが、彼女は宗教的な伝統と、社 会秩序と道徳観を維持するその能力に敬意を払っていた。彼女の小説における宗教的要素もまた、彼女の生い立ちに負うところが多く、『The Mill on the Floss』に登場するマギー・タリヴァーの体験は、若き日のメアリー・アン・エヴァンスと多くの類似点を共有している。エリオットはまた、教会からの疎 外が同時に社会からの疎外を意味するサイラス・マーナーのような苦境にも直面した。エリオットは宗教に対するうっすらとした敬意を保っていたため、ドイツ の哲学者フリードリヒ・ニーチェは、彼女の道徳の体系を、罪を苦しみによって償うことのできる負債と見なしているとして非難し、それを「エリオットのよう な小さな道徳主義的な女性」の特徴として貶めた[62]。 テオフラストスの印象』(Impressions of Theophrastus Such)という最終作の一部である『後ろを見て』(Looking Backwards)において、彼女は最も自伝的であった。ダニエル・デロンダ』の頃には、エリオットの売り上げは落ち込んでおり、彼女は世間の目からあ る程度遠ざかっていた。夫によって書かれた死後の伝記は、彼女が歩んできたスキャンダラスな人生とはまったく相反する、ほとんど聖人のような素晴らしい女 性を描いていた。1994年、文芸評論家のハロルド・ブルームは、エリオットを史上最も重要な西洋の作家の一人に挙げた[63]。 [63]2007年にタイム誌が行った作家の投票では、『ミドルマーチ』は史上10番目に偉大な文学作品に選ばれた[64]。2015年には、英国外の作 家が「地滑り的に」全英国小説の中で1位に選出した[65]。エリオットの著書の様々な映画化やテレビ化によって、エリオットはより多くの読者に再紹介さ れた。 |

| Works Novels Adam Bede (1859) The Mill on the Floss (1860) Silas Marner (1861) Romola (1863) Felix Holt, the Radical (1866) Middlemarch (1871–1872) "Quarry for Middlemarch", MS Lowell 13, Houghton Library, Harvard University (A digital facsimile of the manuscript of research notes) Daniel Deronda (1876) Short story collection and novellas Scenes of Clerical Life (1857) The Sad Fortunes of the Rev. Amos Barton Mr Gilfil's Love Story Janet's Repentance The Lifted Veil (1859) Brother Jacob (1864) Impressions of Theophrastus Such (1879) Translations Das Leben Jesu, kritisch bearbeitet (The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined) Volume 2 by David Strauss (1846) Das Wesen des Christentums (The Essence of Christianity) by Ludwig Feuerbach (1854) The Ethics of Benedict de Spinoza by Benedict de Spinoza (1856) Poetry Knowing That I Must Shortly Put Off This Tabernacle (1840) In a London Drawingroom (1865) A Minor Prophet (1865) Two Lovers (1866) The Choir Invisible (1867) The Spanish Gypsy (1868) Agatha (1868) Brother and Sister (1869) How Lisa Loved the King (1869) Armgart (1870) Stradivarius (1873) Arion (1873) The Legend of Jubal (1874) I Grant You Ample Leave (1874) Evenings Come and Go, Love (1878) Self and Life (1879) A College Breakfast Party (1879) The Death of Moses (1879) Non-fiction "Three Months in Weimar" (1855) "Silly Novels by Lady Novelists" (1856) "The Natural History of German Life" (1856) Review of John Ruskin's Modern Painters in Westminster Review, April 1856 "The Influence of Rationalism" (1865) |

作品紹介 小説 アダム・ビード(1859年) フロス上の水車小屋(1860年) サイラス・マーナー(1861年) ロモーラ(1863年) 急進派フェリックス・ホルト(1866年) ミドルマーチ (1871-1872) "Quarry for Middlemarch", MS Lowell 13, Houghton Library, Harvard University (研究ノート原稿のデジタル・ファクシミリ) ダニエル・デロンダ(1876年) 短編小説集 事務生活の情景(1857年) エイモス・バートン牧師の悲運 ギルフィル氏の恋物語 ジャネットの悔い改め ベールを脱いで(1859年) ブラザー・ジェイコブ (1864) テオフラストスの印象 (1879) 翻訳 ダヴィッド・シュトラウス著『イエスの生涯』第2巻 (1846) ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハ著『キリスト教の本質』(1854) ベネディクト・デ・スピノザの倫理学 by ベネディクト・デ・スピノザ (1856) 詩集 まもなくこの幕屋を去らねばならぬことを知りながら (1840) ロンドンの応接間にて(1865年) 小預言者(1865年) ふたりの恋人 (1866) 見えない聖歌隊(1867年) スペインのジプシー(1868年) アガサ(1868年) ブラザーとシスター(1869年) リサは王をいかに愛したか(1869年) アームガート(1870年) ストラディバリウス(1873年) アリオン(1873年) ジュバルの伝説(1874年) 私はあなたに十分な休暇を与える(1874年) 夕べが来たり来たり、愛 (1878) 自己と人生(1879年) 大学の朝食会(1879年) モーゼの死(1879年) ノンフィクション 「ワイマールでの3ヶ月 (1855) 「女性小説家による愚かな小説 (1856) 「ドイツ生活博物誌」(1856年) ジョン・ラスキンの『現代の画家たち』(『ウェストミンスター・レビュー』1856年4月号)の書評 「合理主義の影響」(1865年) |

| While

the biographical consensus is that Lewes and Eliot had a perfect

partnership, this view has been somewhat modified by Beverley Park

Rilett, who argued in 2013 and 2017 that Lewes's protective love may

have amounted to coercive control.[50] |

ルイスとエリオットは完璧なパートナーシップを築いていたというのが伝記上のコンセンサスだが、2013年と2017年にルイスの保護的な愛情は強制的な

支配に等しかったかもしれないと主張したビヴァリー・パーク・リレットによって、この見方はいくらか修正されている[50]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Eliot |

|

| 『サイラス・マーナー ―ラヴィロウの織工―』(Silas Marner: The Weaver of Raveloe)は、1861年に出版されたジョージ・エリオットの長編小説。 ★サイラス・マーナーは、小説の構成などの点で完成度の高い作品として評価されている。エリオット作品の特徴である起伏に富む展開や印象的な登場人物といった要素は薄い。そのため、エリオットの作品の中では例外に属するものとみられている。 ◎あらすじ 19世紀初頭が舞台となっている。機織りのサイラス・マーナーは、イングランド北部にあるスラム街のランタンヤードで、小さなカルヴァン主義の集会に参加していた。サイラスは重い病気の執事を看病している間に、会の資金を盗んだとのぬれぎぬを着せられてしまう。 サイラスには2つの証拠がつきつけられていた。現場にサイラスのポケットナイフがあったことと、自宅からお金が入っていたバッグが見つかったことである [2]。サイラスは、直前にポケットナイフを親友であるウィリアム・デーンに貸していたので、デーンが自分に罪を着せたのだと主張した。ラ ンタンヤードの住人は、神が真実を明らかにすると信じており、サイラスもそう思っていた。しかし御神籤の結果は、サイラスは有罪であるというものだった。 やがてサイラスと婚約していた女性は結婚を取りやめ、デーンと結婚する。人生が崩壊し、神への信頼が失われ、心を病んだサイラスは、町を出て行った[3]。 サイラスは南に行き、イングランド中部にあるウォリックシャーのラヴィロー村に移り住んだ。そこでは、機織りの仕事以外に住民と接触することは最小限にとどめることにして、一人孤独に暮らした。サイラスは機織りに専念し、それによって蓄えた金貨を崇拝するようになった[4]。 ある霧の夜、サイラスが大事にしていた2袋の金が盗まれた[5]。犯人は、村の大地主であるスクワイア(郷士)・キャスの放蕩次男ダンスタン(ダンジー)・キャスなのであるが、サイラスも村人も犯人が誰であるかは分かっていなかった。ダンジーは盗難後すぐに姿を消した。しかし過去に何回も姿を消したことがあるので、村人はこの消失をほとんど気にせず、盗難と結びつけることもしなかった[6]。盗難発見後、村人はサイラスをなぐさめたが、サイラスは深く落ち込んだ[7]。 一方、ダンジーの兄であるゴッドフリー・キャスは秘密の過去を抱えていた。彼は別の町に住むアヘン中毒の労働者階級の女性モリー・ファレンと結婚していたのである[8]。 ゴッドフリーは、若い中流階級の女性ナンシー・ラミターと結婚するつもりでいたので、この秘密が明らかにされるわけにはいかなかった[9]。ところがモ リーは大晦日の夜、自分はゴッドフリーの妻であるということを周囲に発表するため、キャス家で開かれているパーティーに2歳になる娘と一緒に乗り込もうと した[10]。しかし、道中、モリーは雪の中で倒れ意識を失い、娘はサイラスの家に迷い込んだ。サイラスは娘を見つけると、雪の中で子供の足跡をたどり、 死んだ女性を発見した[11]。 サイラスは残された子供を自分の手で育てることにして、亡くなった母と妹にちなんでエピーと名付けた[12]。エピーによってサイラスの人生は完全に変わった。サイラスは、失った金貨がエピーに姿を変えて自分のところにやってきたのだと思った[13]。ゴッドフリー・キャスはナンシーと自由に結婚できるようになったが、モリーとの結婚と子供についての事実はナンシーに隠し続けていた。その代わり、ゴッ ドフリーは時折金銭的な援助をすることで、マーナーがエピーの世話をするのを助けていた。マーナーの隣人であるドリー・ウィンスロップは、より実際的な育 児方法についてマーナーに対し親切に教えサポートした。ドリーの助けとアドバイスは、エピーの育児だけでなく、マーナーとエピーが村の社会に溶け込むこと にも役立った。 16年後、エピーは成長し、サイラスと強い絆を持つようになった。一 方、ゴッドフリーとナンシーは、自分たちの子供がいないことを悲しんでいた。やがて、サイラスの金を盗んだダンスタン・キャスの骸骨が、サイラスの家の近 くの採石場の底で、金貨と一緒に発見され、金貨は正式にサイラスに返還された[14]。これをきっかけに、ゴッ ドフリーは、モリーが自分の最初の妻であること、エピーが自分の子であることをナンシーに告白した。そして、ゴッドフリーとナンシーの夫妻はサイラスの家 に行き、エピーを自分たちの娘として屋敷に迎え育て上げることを申し出た[15]。しかし、それはエピーがサイラスとの生活を放棄することを意味してい た。エピーは丁重に断り、「父がいなければ、幸せなど考えられません[16]」と言った。 サイラスはランタンヤードでの窃盗事件について、自分の無実が明らかになったか知りたいと思い、エピーを連れて30年ぶりに再訪した。しかし昔の風景は一 掃されており、大きな工場に変わっていた。ランタンヤードの住民たちがその後どうなったのかについては、誰も知らないようだった。しかし、サ イラスは昔起きた事件の真実を知ることができないことを受け入れ、今ではラヴィロー村で自分の家族や友人とともに幸せな生活を送っている[17]。エピー は、地元で一緒に育ったドリーの息子アーロンと結婚し、彼らはゴッドフリーの好意で新しく改良されたサイラスの家に引っ越した。2人の結婚は周りの人々全 員に祝福された[18]。人々はサイラスの人生を振り返り、サイラスはエピーを実の親のように長年世話をしてきたからこそ、自分も幸せになれたのだと語っ た。エピーはサイラスに、私たちほど幸せな家族は他にいないと言った[19]。 https://x.gd/plOia |

|

| 『ミドルマーチ(Middlemarch, A Study of Provincial Life)』 ★ ミドルマーチは、1829年から1832年改革法までの架空のミッドランドの町、ミドルマーチの住民の生活に焦点を当てている[3]。物語は、力点の置き 方の違う四つの筋書きから成り立っている[3]、すなわち、ドロシア・ブルックの生涯、テルティウス・リドゲイトのキャリア、フレッド・ヴィンシーによる メアリー・ガースへの求愛、ニコラス・ブルストロードの不名誉である。2つの主要な筋書きは、ドロテアとリドゲイトのそれである[4]。それぞれの筋書き は同時進行で進んでいくが、ブルストロードの物語は後の章に集中している[5]。 ドロシア・ブルックは両親を早く失くした19歳の孤児で、妹のセリアと共に大地主の伯父ブルックの庇護を受けて暮らしている。ドロシアは美貌で、特に敬虔な若い女性で、叔父は好ましく思っていないが、趣味は小作農の建物の改修である。 ドロシアは、自分と同年代の若い地主、ジェームス・チェタム卿から求愛されるが、彼女は彼のことが良くわからない。彼女は代わりに、自分よりも27歳も年 上の中年エドワード・カソーボン牧師に惹かれている。ドロシアは、妹の懸念にもかかわらず、カソーボンからの結婚の申し出を受諾する。チェタムは、彼に興 味を持ったセリアに関心を向けるようになる。 フレッドとロザモンド・ヴィンシーは、ミドルマーチの町長の長男と長女である。大学を卒業したことがないフレッドは、大学を卒業していないので、失敗者で 怠け者と思われているが、金持ちだが不快な印象を与える叔父フェザーストーンの相続人と目されているため、ダラダラと暮らしていくことが許されている。 フェザーストーンは、結婚しにより彼の姪になったメアリー・ガースを住み込みの使用人(companion)として置いている。メアリー・ガースは地味だ と見られているが、フレッドは彼女に恋をしていて、彼女と結婚したいと思っている。 ドロシアとカソーボンは、ローマでの新婚旅行で結婚の最初の緊張を経験する。ドロシアは、夫が彼女を知的な探究の道連れとするのに興味がなく、結婚の主な 理由であった大量のメモを公開するつもりのないのに気づいてしまった。 彼女は、カソーボンのはるかに若く相続権のない従弟のウィル・ラディスロウに出会う。ウィルをカソーボン金銭的に面倒を見てやっている。ラディスロウはド ロシアに惹かれ始めていく。彼女は気づかないままだが、2人は友好的になる。 フレッドは多額の借金を抱え、借金を返すことができないことに悩む。メアリーの父親であるガースに借金の保証人に頼んでいるので、彼はガースにそれを放棄 しなければならないと告げる。その結果、ガース夫人の4年間の収入からの貯蓄は、メアリーの貯蓄と同様に、彼女の最年少の息子の教育のために留保されてい た。その結果、ガースはメアリーにフレッドと結婚しないように警告する。 フレッドは病気にかかり、ミドルマーチに新しく到着した医師であるテルティウス・リドゲート博士の治療を受ける。リドゲイトは医学と衛生について現代的な 考えを持っており、医師は処方するべきであるが、自分で薬を調剤するべきではないという信念を持っている。これは、町の多くの人々の怒りと批判を巻き起こ す。彼は、リドゲートの友人であるフェアブラザーがブルストロードの誠実さについて懸念を持つにもかかわらず、リドゲートの医学的信念に従う病院と診療所 を建設したいと考えている、裕福で教会に通う地主であり開発者であるブルストロードと同盟を結んでいる。 リドゲイトはまた、ロザモンド・ヴィンシーとも知り合うようになる。彼の美しさと教養は、浅薄で自己陶酔的である。良い出会いを求めていた彼女は裕福な家 族の出身であるリドゲイトと結婚することを決心し、フレッドの病気を医者に近づく機会として利用しようとする。 リドゲートは当初、彼らの関係を純粋な浮気と見なし、世間が彼らが実際に婚約者同士と見ているのを知り、ロザモンドから離れようとする。しかし、彼女に最 後に会ったとき、彼は決意を破り、2人は婚約する。 カソーボンはそれと同じ時期にローマから戻ってきたが、心臓発作を起こした。彼に付き添うために連れてこられたリドゲイトは、ドロシアに、カソーボンの病 気の性質と回復の可能性について断言は難しいと語る。 彼が勉強をやめれば、のんびりと暮せば、実際に約15年生きれるかもしれないが、病気は急速に進行する可能性があり、その場合は突然死ぬこともある。フ レッドが回復すると、フェザーストーン氏は病気になる。 フェザーストーンは死の床で、2つの心残りを打ち明け、メアリーに1つを片付けるのに手を貸してほしいと頼む。 彼女はビジネスに巻き込まれるのを望まず、協力を拒んで拒否し、フェザーストーンは心残りをそのままに亡くなる。フェザーストーンの計画では、 10,000ポンドがフレッド・ヴィンシーに渡される予定だったが、彼の財産と財産は代わりに、彼の非嫡出子であるジョシュア・レグに渡される。 カソーボンは、健康状態も悪く、ドロシアのラディスロウへの善意に疑心暗鬼になっていく。彼はドロシアに、彼が死んだら永遠に「私が嫌うことを避け、私が 望むことをするように心がける」ことを約束させようとする。彼女は同意を躊躇し、彼女が答える前に彼は死んでしまう。カソーボンの遺言には、ドロシアがラ ディスロウと結婚した場合、相続財産を失うという条項が含まれるのが判明する。この状態の特異な本質は、世間が、ラディスロウとドロシアが愛し合っている と疑っていて、それが2人の間にぎこちなさを生み出しているということだ。ラディスロウはドロシアに恋をしているが、この秘密を抱えていて、彼女がスキャ ンダルに巻き込まれたり、相続財産を失ったりするのを望んでいない。 彼女はそうした間に、自分が彼に恋愛観所を持っいるのに気づくが、それは秘めておかねばならない。彼はミドルマーチに残り、ブルックの新聞社で編集者とし て働いている。ブルックは議会の改革路線へ向けてキャンペーンをはろうとしている。 ロザモンドを喜ばせようとするリドゲートの努力は、すぐに彼に大きな借金を残し、彼はブルストロードに助けを求めることを余儀なくされた。彼は、カムデ ン・フェアブラザーとの友情によって部分的に支えられている。 一方、フレッド・ヴィンシーは、カレブ・ガースの経済的挫折の責任者であるという屈辱にショックを受け、自分の人生を再評価することを余儀なくされる。彼 は寛容なカレブの下で土地管理人として仕事を学ぶことを決意する。 フレッドは、フェアブラザーがメアリー・ガースにも恋をしていることに気づかずに、フェアブラザーに彼の事件をメアリー・ガースに弁護するように頼みこ む。フェアブラザーはそれに応じるが、それはメアリーのために自分の欲望を犠牲にすることだった。 メアリーはフレッドを本当に愛していることに気づき、彼が世界で自分の居場所を見つけるのを待つことにする。 ジョン・ラッフルズというう、ブルストロードの怪しげな過去を知っている謎の男がミドルマーチに現れ、彼を脅迫するしようと企む。教会に通うバルストロー ドは、若い頃、疑わしい金融取引に従事していたことがある。彼の財産は、裕福ではるかに年上の未亡人との結婚によるものである。 母の遺産を相続したはずの未亡人の娘が家出をした。ブルストロードは彼女を見つけたが、これを未亡人に開示しなかったため、彼は彼女の娘の代わりに財産を 相続した。 未亡人の娘には息子がいたが、その息子はラディスロウであることが判明した。彼らのつながりを把握すると、ブルストロードは罪悪感に襲われ、ラディスロウ に多額の金を提供するが、ラディスロウはそれを汚れた金として拒否する。ブルストロードは、公の場で偽善者として暴露されるのを恐れにより、致命的な病気 のラッフルズの死を早め、自分が以前に借金の救済を拒否したリドゲートに多額の融資を行った。しかし、ブルストロードの不名誉な話は、拡散してしまってお り、リドゲイトもそれに巻き込まれ、遺産の話が尾ひれをつけて、リドゲートもブルストロードに加担しているかのように語られてしまう。 ドロシアとフェアブラザーだけがリドゲイトを信頼し続けているが、リドゲートとロザモンドは依然として一般的な非難によってミドルマーチを去るように周囲 から言われている。 屈辱を与えられ、ののしられたブルストロードの唯一の慰めは、彼も亡命に直面しているときに妻がそばに立っていることであった。 ブルックの選挙運動が崩壊したとき、ラディスロウは町を離れることを決心し、ドロシアを訪ねて別れを告げるが、ドロシアは彼に恋をしている。彼女はカソー ボンの財産を放棄し、ラディスロウと結婚することを発表して家族に衝撃を与えた。同時に、新しいキャリアで成功したフレッドは、メアリーと結婚することに なる。 終幕では、主人公たちのその後の運命が語られる。フレッドとメアリーは結婚し、3人の息子と幸せに暮らしている。リドゲイトはミドルマーチの外で開業医と して成功を収め、良い収入を得たが、充実感を見つけることができず、50歳で亡くなり、ロザモンドと4人の子供を残した。 彼の死後、ロザモンドは裕福な医師と結婚する。ラディスロウは公共改革に取り組み、ドロシアは妻と2人の子供の母親として満足している。彼らの息子は最終 的にアーサー・ブルックの財産を相続することになる。 https://x.gd/ToMXq |

★登場人物 ドロシア・ブルック: 大きな野心を持つ知的な裕福な女性であるドロシアは、自分の富を見せびらかすことを避け、叔父のテナントのためにコテージを再設計するなどのプロジェクト に着手する。彼女は年配のエドワード・カソーボン牧師と結婚し、彼の研究「すべての神話の鍵」で彼を助けるという理想主義的な考えを抱いていた。しかし、 カソーボンは彼女を真剣に受け止めず、彼女の若さ、熱意、エネルギーに共感を持てないため、彼女はこの結婚は間違いだったと悟る。彼を助けたいというドロ シアの要求は、彼が自分の研究が何年も前のものであることを隠すことを難しくしていく。新婚旅行でカサウボンの冷たさに直面したドロシアは、親戚のウィ ル・ラディスロウと友達になる。カソーボンの死から数年後、彼女はウィルと恋に落ち、彼と結婚する。 テルティウス・リドゲイト: 理想主義的で才能のある、しかし素朴な若い医師で、比較的貧しいが、生まれは良い。彼は研究を通じて医学を大きく進歩させることを望んでいるが、ロザモン ド・ヴィンシーとの不幸な結婚に終わる。彼が誰に対しても責任を負わないことを示そうとする彼の試みは失敗し、最終的に彼は町を離れなければならず、妻を 喜ばせるために彼の高い理想を犠牲にした。 牧師エドワード・カソーボン: 知ったかぶりで利己的な年配の聖職者で、学問的研究に夢中になりすぎて、ドロシアとの結婚は愛のないものになった。彼の未完の著書「すべての神秘学への 鍵」は、キリスト教シンクレティズムの記念碑として意図されているが、ドイツ語が読めないため、彼の研究は時代遅れである。彼はこれを認識しているが、誰 にも認めていない。 メアリー・ガース: カレブとスーザン・ガースの娘で、素朴で親切な子。フェザーストーン氏の看護師を務めている。彼女とフレッド・ヴィンシーは子供時代の恋人だったが、彼が真剣に、実際に、誠実に生きる意思と能力を示すまで、彼に口説かれることはない。 アーサー・ブルック:ドロシア・ブルックとセリア・ブルックの叔父。しばしば頭を悩ませるは羽目になり、あまり利口ではない。地元では最悪の領主という評判を得ているが、議会では改革派に属している。 セリア・ブルックス:ドロシアの妹で美人。彼女はドロシアよりも官能的で、姉のような理想主義と禁欲主義は待ち合わせていない。ドロシアがジェームズ・チェタム卿を拒否したとき、彼女が彼と一緒になって幸せになる。 ジェームス・チェタム卿: 近所の地主で、ドロシアに恋をしており、土地の借り手の条件を改善しようとする彼女の計画を手伝っている。彼女がカソーボンと結婚すると、彼は彼女の妹セリアと結婚する。 ロザモンド・ヴィンシー: 美しいが、虚栄心が強く、浅薄なロザモンドは、自分の魅力を過大評価し、ミドルマーチ社会を見下している。彼女は、テルティウス・リドゲイトと結婚すれ ば、自分の社会的地位が高まり、いい暮らしができると思って結婚する。しかし、夫が経済的困難に陥ると、節約しようとする夫を邪魔し、そのような犠牲を払 うのは自分に対する侮辱ととる。彼女はその社会的地位を失うという考えに耐えられそうにない。 フレッド・ヴィンシー: ロザモンドの兄は幼い頃からメアリー・ガースを愛していた。 彼の家族は、彼が聖職者になることで社会的に進歩することを望んでいますが、メアリーが結婚しても結婚しないことを彼は知っている。 叔父のフェザーストーンからの相続を期待して育てられた彼は、浪費家だが、後にメアリーへの愛情を通じて変化し、メアリーの父親の下で勉強することで、メ アリーの尊敬を集める職業を見つける。 ウィル・ラディスロウ: カソーボンのこの若いいとこには財産がない。彼の祖母は貧しいポーランドの音楽家と結婚し、相続を放棄したためである。彼は元気で理想主義で才能のある男 だが、決まった職業を持たない。彼はドロシアに恋をしているが、カソーボン氏の財産を失うことなく彼女と結婚することはできない。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆