リアリズム文学

realism in literature

リアリズム文学

realism in literature

文学的リアリズムとは、文学のジャンルの一つで、芸術における広義のリ アリズムの一部であり、推理小説や超自然的要素を避け、主題を忠実に表現しようとするものである。19世紀半ばのフランス文学(スタンダール)やロシア文 学(アレクサンドル・プーシキン)に始まるリアリズム芸術運動に端を発する[1]。文学的リアリズムは、身近なものをありのままに表現しようとする。リア リズムの作家は、日常的で平凡な活動や経験を描くことを選択した。

| Literary realism

is

a literary genre, part of the broader realism in arts, that attempts to

represent subject-matter truthfully, avoiding speculative fiction and

supernatural elements. It originated with the realist art movement that

began with mid-nineteenth-century French literature (Stendhal) and

Russian literature (Alexander Pushkin).[1] Literary realism attempts to

represent familiar things as they are. Realist authors chose to depict

everyday and banal activities and experiences. |

文学的リアリズムとは、文学のジャンルの一つで、芸術における広義のリ

アリズムの一部であり、推理小説や超自然的要素を避け、主題を忠実に表現しようとするものである。19世紀半ばのフランス文学(スタンダール)やロシア文

学(アレクサンドル・プーシキン)に始まるリアリズム芸術運動に端を発する[1]。文学的リアリズムは、身近なものをありのままに表現しようとする。リア

リズムの作家は、日常的で平凡な活動や経験を描くことを選択した。 |

| Broadly defined as "the

representation of reality",[2] realism in the arts is the attempt to

represent subject matter truthfully, without artificiality and avoiding

artistic conventions, as well as implausible, exotic and supernatural

elements. Realism has been prevalent in the arts at many periods, and

is in large part a matter of technique and training, and the avoidance

of stylization. In the visual arts, illusionistic realism is the

accurate depiction of lifeforms, perspective, and the details of light

and colour. Realist works of art may emphasize the ugly or sordid, such

as works of social realism, regionalism, or kitchen sink realism.[3][4]

There have been various realism movements in the arts, such as the

opera style of verismo, literary realism, theatrical realism and

Italian neorealist cinema. The realism art movement in painting began

in France in the 1850s, after the 1848 Revolution.[5] The realist

painters rejected Romanticism, which had come to dominate French

literature and art, with roots in the late 18th century. |

広義には「現実の表現」と定義され[2]、芸術におけるリアリズムと

は、人為的なものを排除し、芸術上の慣習や、ありえない、エキゾチック、超自然的な要素を避け、対象を真実に表現しようとすることである。リアリズムは多

くの時代で芸術の世界に浸透しており、技術や訓練、様式化の回避が大きな要因である。視覚芸術において、幻想的なリアリズムとは、生命体、遠近法、光と色

の細部を正確に描写することである。リアリズムの芸術作品は、社会的リアリズム、地域主義、キッチンシンクのリアリズムの作品など、醜いものや不潔なもの

を強調することがある[3][4]

芸術におけるリアリズム運動は、オペラ様式のベリスモ、文学的リアリズム、演劇的リアリズム、イタリアのネオリアリズム映画など様々であった。絵画におけ

るリアリズム芸術運動は、1848年の革命後の1850年代にフランスで始まった[5]。

リアリズムの画家たちは、18世紀後半にルーツを持ち、フランスの文学や芸術を支配するようになったロマン主義を否定した。 |

| Realism as a movement in

literature was a post-1848 phenomenon, according to its first theorist

Jules-Français Champfleury. It aims to reproduce "objective reality",

and focused on showing everyday, quotidian activities and life,

primarily among the middle or lower class society, without romantic

idealization or dramatization.[6] It may be regarded as the general

attempt to depict subjects as they are considered to exist in third

person objective reality, without embellishment or interpretation and

"in accordance with secular, empirical rules."[7] As such, the approach

inherently implies a belief that such reality is ontologically

independent of man's conceptual schemes, linguistic practices and

beliefs, and thus can be known (or knowable) to the artist, who can in

turn represent this 'reality' faithfully. As literary critic Ian Watt

states in The Rise of the Novel, modern realism "begins from the

position that truth can be discovered by the individual through the

senses" and as such "it has its origins in Descartes and Locke, and

received its first full formulation by Thomas Reid in the middle of the

eighteenth century."[8] |

文学における運動としてのリアリズムは、その最初の理論家であるジュー

ル=フランセ・シャンプフルーリーによれば、1848年以降の現象である。それは「客観的現実」を再現することを目的とし、ロマンチックな理想化やドラマ

化をせずに、主に中・下層社会の日常的でありふれた活動や生活を示すことに焦点を当てた[6]。それは、装飾や解釈なしに、「世俗的で経験則に従って」、

三人称的客観現実に存在するとみなされる対象をそのまま描くという一般的試みと見なすことができる[7]。

そのため、このアプローチは本質的に、そのような現実は人間の概念的スキーム、言語的慣習、信念から存在論的に独立しており、したがって芸術家が知ること

ができる(または知ることができる)、その結果芸術家はこの「現実」を忠実に表現できるという信念を含意している[7].

文芸評論家のイアン・ワットが『小説の台頭』の中で述べているように、近代リアリズムは「真実は感覚を通して個人によって発見できるという立場から始ま

り」、それゆえに「デカルトとロックに起源を持ち、18世紀半ばにトマス・リードによって最初の完全な定式化を受けた」[8]。 |

| In the Introduction to The Human

Comedy (1842) Balzac "claims that poetic creation and scientific

creation are closely related activities, manifesting the tendency of

realists towards taking over scientific methods".[9] The artists of

realism used the achievements of contemporary science, the strictness

and precision of the scientific method, in order to understand reality.

The positivist spirit in science presupposes feeling contempt towards

metaphysics, the cult of the fact, experiment and proof, confidence in

science and the progress that it brings, as well as striving to give a

scientific form to studying social and moral phenomena."[10] |

バルザックは『人間喜劇』(1842年)の序文で「詩的創造と科学的創

造は密接に関連した活動であり、科学的方法を引き継ぐというリアリストの傾向が現れていると主張している」[9]

リアリズムの芸術家は現実を理解するために現代科学の成果、科学方法の厳密さと正確さを利用したのである。科学における実証主義の精神は、形而上学に対す

る侮蔑、事実・実験・証明の崇拝、科学とそれがもたらす進歩に対する信頼、そして社会的・道徳的現象の研究に科学的形式を与えようとする努力を前提として

いる」[10]。 |

| In the late 18th century

Romanticism was a revolt against the aristocratic social and political

norms of the previous Age of Reason and a reaction against the

scientific rationalization of nature found in the dominant philosophy

of the 18th century,[11] as well as a reaction to the Industrial

Revolution.[12] It was embodied most strongly in the visual arts,

music, and literature, but had a major impact on historiography,[13]

education[14] and the natural sciences.[15] |

18世紀後半、ロマン主義はそれまでの理性の時代の貴族的な社会的・政

治的規範に対する反乱であり、18世紀の支配的な哲学に見られる自然の科学的合理化に対する反発であり[11]、また産業革命に対する反発でもあった

[12]。 視覚芸術、音楽、文学において最も強く体現され、歴史学、教育、自然科学に大きな影響を与えた[13] [14] [15]。 |

| 19th-century realism was in its

turn a reaction to Romanticism, and for this reason it is also commonly

derogatorily referred as traditional or "bourgeois realism".[16]

However, not all writers of Victorian literature produced works of

realism.[17] The rigidities, conventions, and other limitations of

Victorian realism prompted in their turn the revolt of modernism.

Starting around 1900, the driving motive of modernist literature was

the criticism of the 19th-century bourgeois social order and world

view, which was countered with an antirationalist, antirealist and

antibourgeois program.[16][18][19] |

19世紀リアリズムはロマン主義への反動であり、そのため一般に伝統的

リアリズム、ブルジョアリアリズムと揶揄される[16]が、ヴィクトリア文学の作家すべてがリアリズム作品を制作したわけではない[17]。1900年頃

からモダニズム文学の原動力は、19世紀のブルジョア社会秩序・世界観への批判であり、それに対抗して、反理想主義、反理念主義、反ブルジョア主義的なプ

ログラムが展開された[16][18][19]。 |

| Social Realism Social Realism is an international art movement that includes the work of painters, printmakers, photographers and filmmakers who draw attention to the everyday conditions of the working classes and the poor, and who are critical of the social structures that maintain these conditions. While the movement's artistic styles vary from nation to nation, it almost always uses a form of descriptive or critical realism.[20] Kitchen sink realism (or kitchen sink drama) is a term coined to describe a British cultural movement that developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s in theatre, art, novels, film and television plays, which used a style of social realism. Its protagonists usually could be described as angry young men, and it often depicted the domestic situations of working-class Britons living in cramped rented accommodation and spending their off-hours drinking in grimy pubs, to explore social issues and political controversies. The films, plays and novels employing this style are set frequently in poorer industrial areas in the North of England, and use the rough-hewn speaking accents and slang heard in those regions. The film It Always Rains on Sunday (1947) is a precursor of the genre, and the John Osborne play Look Back in Anger (1956) is thought of as the first of the genre. The gritty love-triangle of Look Back in Anger, for example, takes place in a cramped, one-room flat in the English Midlands. The conventions of the genre have continued into the 2000s, finding expression in such television shows as Coronation Street and EastEnders.[21] In art, "Kitchen Sink School" was a term used by critic David Sylvester to describe painters who depicted social realist–type scenes of domestic life.[22] |

社会的リアリズム 社会的リアリズムは、労働者階級や貧困層の日常的な状況に注目し、これらの状況を維持する社会構造に批判的な画家、版画家、写真家、映画制作者の作品を含 む国際的な芸術運動である[20]。この運動の芸術的スタイルは国によって異なるが、ほとんどの場合、描写的リアリズムまたは批判的リアリズムの形式を用 いる[20]。 キッチンシンク・リアリズム(またはキッチンシンク・ドラマ)は、1950年代後半から1960年代前半にかけて演劇、美術、小説、映画、テレビ劇で展開 されたイギリスの文化運動を表す造語で、社会的リアリズムの様式を用いたものであった。主人公は通常、怒れる若者と表現され、狭い賃貸住宅に住み、休みの 日には薄汚れたパブで酒を飲んで過ごす労働者階級のイギリス人の家庭の状況を描き、社会問題や政治的論争を探ったことが多い。 このスタイルを採用した映画、演劇、小説は、イングランド北部の貧しい工業地帯を舞台とすることが多く、その地域で聞かれる荒っぽい話し方のアクセントや スラングが使われている。映画『日曜日はいつも雨』(1947)はこのジャンルの先駆けであり、ジョン・オズボーンの戯曲『怒りのルックバック』 (1956)はこのジャンルの最初の作品と考えられている。例えば、『Look Back in Anger』の骨太のラブ・トライアングルは、英国ミッドランド地方の狭いワンルーム・アパートで繰り広げられる。このジャンルの定石は2000年代に 入っても続き、『コロネーション・ストリート』や『イーストエンダーズ』といったテレビ番組で表現されている[21]。 美術の分野では、「キッチン・シンク・スクール」は、社会的現実主義的な家庭生活の場面を描いた画家を表現するために、評論家のデヴィッド・シルヴェス ターによって使われた言葉である[22]。 |

| Socialist Realism Socialist realism is the official Soviet art form that was institutionalized by Joseph Stalin in 1934 and was later adopted by allied Communist parties worldwide.[20] This form of realism held that successful art depicts and glorifies the proletariat's struggle toward socialist progress. The Statute of the Union of Soviet Writers in 1934 stated that socialist realism "is the basic method of Soviet literature and literary criticism. It demands of the artist the truthful, historically concrete representation of reality in its revolutionary development. Moreover, the truthfulness and historical concreteness of the artistic representation of reality must be linked with the task of ideological transformation and education of workers in the spirit of socialism."[23] The strict adherence to the above tenets, however, began to crumble after the death of Stalin when writers started expanding the limits of what is possible. However, the changes were gradual since the social realism tradition was so ingrained into the psyche of the Soviet literati that even dissidents followed the habits of this type of composition, rarely straying from its formal and ideological mold.[24] The Soviet socialist realism did not exactly emerge on the very day it was promulgated in the Soviet Union in 1932 by way of a decree that abolished independent writers' organizations. This movement has been existing for at least fifteen years and was first seen during the Bolshevik Revolution. The 1934 declaration only formalized its canonical formulation through the speeches of the Andrei Zhdanov, the representative of the Party's Central Committee. The official definition of social realism has been criticized for its conflicting framework. While the concept itself is simple, discerning scholars struggle in reconciling its elements. According to Peter Kenez, "it was impossible to reconcile the teleological requirement with realistic presentation," further stressing that "the world could either be depicted as it was or as it should be according to theory, but the two are obviously not the same."[25] |

社会主義リアリズム 社会主義リアリズムは、1934年にヨシフ・スターリンによって制度化され、後に世界中の同盟共産党によって採用されたソ連の公式の芸術形式である [20]。 このリアリズムの形式は、成功した芸術が社会主義の進歩に向けたプロレタリアートの闘いを描き、美化するとした。1934年のソビエト作家同盟の規約は、 社会主義リアリズムが「ソビエト文学と文学批評の基本的な方法である」と述べていた。それは、革命的発展における現実を、真実かつ歴史的に具体的に表現す ることを芸術家に要求する。さらに、現実の芸術的表現の真実性と歴史的具体性は、社会主義の精神における思想的変革および労働者の教育の任務と結びつかな ければならない[23]」。 しかしながら、上記の教義への厳格な遵守は、スターリンの死後、作家が可能なことの限界を広げ始めると崩れ始めた。しかし、社会的リアリズムの伝統がソビ エトの文学者の精神に深く根付いていたため、反体制派でさえこのタイプの構成の習慣に従い、その形式的・思想的型から外れることはほとんどなかったため、 変化は緩やかだった[24] ソ連の社会主義リアリズムは、独立作家の組織を廃止した法令によって1932年にソ連で発布されたその日に出現したわけでは必ずしもなかった。この運動 は、少なくとも15年前から存在し、ボルシェビキ革命のときに初めて見られた。1934年の宣言は、党中央委員会の代表者であるアンドレイ・ジュダーノフ の演説によって、その正典が正式に示されたに過ぎない。 社会的現実主義の公式な定義は、その矛盾した枠組みから批判を浴びている。概念自体は単純だが、目の肥えた学者たちは、その要素を調整するのに苦労してい る。ピーター・ケネスによれば、「目的論的な要求と現実的な表現とを調和させることは不可能であった」とし、さらに「世界はあるがままに描かれるか、理論 に従ってそうあるべきかのいずれかであり、この二つは明らかに同じではない」と強調している[25]。 |

| Naturalism Naturalism was a literary movement or tendency from the 1880s to 1930s that used detailed realism to suggest that social conditions, heredity, and environment had inescapable force in shaping human character. It was a mainly unorganized literary movement that sought to depict believable everyday reality, as opposed to such movements as Romanticism or Surrealism, in which subjects may receive highly symbolic, idealistic or even supernatural treatment. Naturalism was an outgrowth of literary realism, influenced by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.[26] Whereas realism seeks only to describe subjects as they really are, naturalism also attempts to determine "scientifically" the underlying forces (e.g., the environment or heredity) influencing the actions of its subjects.[27] Naturalistic works often include supposed sordid subject matter, for example, Émile Zola's frank treatment of sexuality, as well as a pervasive pessimism. Naturalistic works tend to focus on the darker aspects of life, including poverty, racism, violence, prejudice, disease, corruption, prostitution, and filth. As a result, naturalistic writers were frequently criticized for focusing too much on human vice and misery.[28] |

自然主義 自然主義とは、1880年代から1930年代にかけての文学運動またはその傾向のことで、社会的条件、遺伝、環境などが人間の人格形成に不可避の力をもっ ているとする詳細なリアリズムを用いたものである。ロマン主義やシュルレアリスムなど、象徴的、観念的、あるいは超自然的に扱われることがある運動とは対 照的に、信じられる日常の現実を描こうとする、主に非組織的な文学運動であった。 自然主義は、チャールズ・ダーウィンの進化論の影響を受けた文学的リアリズムの発展である[26]。リアリズムが対象をありのままに描写しようとするのに 対し、自然主義は対象の行動に影響を与える根本的な力(例えば環境や遺伝)を「科学的に」決定しようとする[27]。自然主義的な作品は、貧困、人種差 別、暴力、偏見、病気、腐敗、売春、汚物など、人生の暗い側面に焦点を当てる傾向がある。そのため、自然主義的な作家は人間の悪徳や悲惨さに焦点を当てす ぎているとしばしば批判された[28]。 |

| Australia In the early nineteenth century, there was growing impetus to establish an Australian culture that was separate from its English Colonial beginnings.[29] Common artistic motifs and characters that were represented in Australian realism were the Australian Outback, known simply as "the bush", in its harsh and volatile beauty, the British settlers, the Indigenous Australian, the squatter and the digger–although some of these bordered into a more mythic territory in much of Australia's art scene. A significant portion of Australia's early realism was a rejection of, according to what the Sydney Bulletin called in 1881 a "romantic identity" of the country.[30] Most of the earliest writing in the colony was not literature in the most recent international sense, but rather journals and documentations of expeditions and environments, although literary style and preconceptions entered into the journal writing. Oftentimes in early Australian literature, romanticism and realism co-existed,[30] as exemplified by Joseph Furphy's Such Is Life (1897)–a fictional account of the life of rural dwellers, including bullock drivers, squatters and itinerant travellers, in southern New South Wales and Victoria, during the 1880s. Catherine Helen Spence's Clara Morison (1854), which detailed a Scottish woman's immigration to Adelaide, South Australia, in a time when many people were leaving the freely settled state of South Australia to claim fortunes in the gold rushes of Victoria and New South Wales. The burgeoning literary concept that Australia was an extension of another, more distant country, was beginning to infiltrate into writing: "[those] who have at last understood the significance of Australian history as a transplanting of stocks and the sending down of roots in a new soil". Henry Handel Richardson, author of post-Federation novels such as Maurice Guest (1908) and The Getting of Wisdom (1910), was said to have been heavily influenced by French and Scandinavian realism. In the twentieth century, as the working-class community of Sydney proliferated, the focus was shifted from the bush archetype to a more urban, inner-city setting: William Lane's The Working Man's Paradise (1892), Christina Stead's Seven Poor Men of Sydney (1934) and Ruth Park's The Harp in the South (1948) all depicted the harsh, gritty reality of working class Sydney.[31] Patrick White's novels Tree of Man (1955) and Voss (1957) fared particularly well and in 1973 White was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.[32][33] A new kind of literary realism emerged in the late twentieth century, helmed by Helen Garner's Monkey Grip (1977) which revolutionised contemporary fiction in Australia, though it has since emerged that the novel was diaristic and based on Garner's own experiences. Monkey Grip concerns itself with a single-mother living in a succession of Melbourne share-houses, as she navigates her increasingly obsessive relationship with a drug addict who drifts in and out of her life. A sub-set of realism emerged in Australia's literary scene known as "dirty realism", typically written by "new, young authors"[34] who examined "gritty, dirty, real existences",[34] of lower-income young people, whose lives revolve around a nihilistic pursuit of casual sex, recreational drug use and alcohol, which are used to escape boredom. Examples of dirty-realism include Andrew McGahan's Praise (1992), Christos Tsiolkas's Loaded (1995), Justine Ettler's The River Ophelia (1995) and Brendan Cowell's How It Feels (2010), although many of these, including their predecessor Monkey Grip, are now labelled with a genre coined in 1995 as "grunge lit".[35] |

オーストラリア 19世紀初頭には、イギリス植民地時代の始まりとは別のオーストラリア文化を確立しようという機運が高まっていた[29]。オーストラリアのリアリズムに 共通する芸術的モチーフやキャラクターは、単に「ブッシュ」として知られるオーストラリアのアウトバック、その過酷で不安定な美しさ、イギリス入植者、 オーストラリア先住民、不法占拠者や掘削者であったが、オーストラリアの多くのアートシーンでは、これらの一部はより神話の領域に近いものとなっている。 オーストラリアの初期のリアリズムのかなりの部分は、1881年にSydney Bulletin紙が「ロマンティックなアイデンティティ」と呼んだものを拒絶するものであった[30]。 植民地時代の初期の文章のほとんどは、国際的な意味での文学ではなく、探検や環境についての日記や記録であったが、日記には文学的なスタイルや先入観が入 り込んでいた。初期のオーストラリア文学では、ロマン主義とリアリズムが共存することがしばしばあった[30]。この例として、ジョセフ・ファーフィ (Joseph Furphy)の『Such Is Life』(1897)は、1880年代のニューサウスウェールズ南部とビクトリア州の牛追い、無断居住、旅人などの農村生活者を描いた架空の物語です。 キャサリン・ヘレン・スペンスのClara Morison(1854年)は、スコットランド人女性が南オーストラリア州のアデレードに移住したときの様子を描いた作品である。この時代、多くの人々 が自由に入植できる南オーストラリア州を離れ、ビクトリア州やニューサウスウェールズ州のゴールドラッシュで財をなしたいと考えていた。 オーストラリアはもっと遠い別の国の延長線上にあるという文学的な概念が、文章に浸透し始めていた。「オーストラリアの歴史が、株の移植であり、新しい土 壌に根を下ろすことであるという意義をようやく理解した人たち」。連邦制後の小説『モーリス・ゲスト』(1908年)や『知恵の獲得』(1910年)の作 者ヘンリー・ヘンデル・リチャードソンは、フランスやスカンジナビアのリアリズムに大きな影響を受けていると言われている。20世紀に入ると、シドニーの 労働者階級のコミュニティが急増し、ブッシュの原型から、より都会的な都心部の設定に焦点が移されました。ウィリアム・レインの『The Working Man's Paradise』(1892年)、クリスティーナ・ステッドの『Seven Poor Men of Sydney』(1934年)、ルース・パークの『The Harp in the South』(1948年)は、シドニーの労働階級の過酷で厳しい現実を描いた[31]。パトリック・ホワイトの小説『人間の木』(1955)と『ボス』 (1957)は特に評判が良く、1973年にホワイトがノーベル文学賞を授与された[32][33]。 20世紀後半には新しい文学的リアリズムが出現し、ヘレン・ガーナーの『モンキーグリップ』(1977年)はオーストラリアの現代小説に革命をもたらした が、その後、この小説はガーナー自身の体験に基づいた日記調であることが明らかにされた。この小説は、メルボルンのシェアハウスに住むシングルマザーを主 人公に、彼女の人生に出入りする薬物中毒者との強迫観念的な関係を描いている。オーストラリアの文学シーンでは、「ダーティ・リアリズム」と呼ばれるリア リズムのサブセットが登場し、典型的には「新しい若い作家」[34]によって書かれ、低所得の若者たちの「硬質で汚れた現実の存在」、退屈から逃れるため に利用するカジュアルセックスや娯楽的薬物の使用、アルコールなどを虚無的に追求する生活を考察したものであった[34]。ダーティ・リアリズムの例とし ては、アンドリュー・マクガハンの『Praise』(1992)、クリストス・ツィオルカスの『Loaded』(1995)、ジャスティン・エトラーの 『The River Ophelia』(1995)、ブレンダン・コーウェルの『How It Feels』(2010)などがあるが、前作の『モンキーグリップ』を含めこれらの多くは現在、「グランジ・リット」として1995年に造られたジャンル でくくられることがある[35]。 |

| United Kingdom Ian Watt in The Rise of the Novel (1957) saw the novel as originating in the early 18th-century and he argued that the novel's 'novelty' was its 'formal realism': the idea 'that the novel is a full and authentic report of human experience'.[36] His examples are novelists Daniel Defoe, Samuel Richardson and Henry Fielding. Watt argued that the novel's concern with realistically described relations between ordinary individuals, ran parallel to the more general development of philosophical realism, middle-class economic individualism and Puritan individualism. He also claims that the form addressed the interests and capacities of the new middle-class reading public and the new book trade evolving in response to them. As tradesmen themselves, Defoe and Richardson had only to 'consult their own standards' to know that their work would appeal to a large audience.[37] Later in the 19th century George Eliot's (1819–1880) Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life (1871–72), described by novelists Martin Amis and Julian Barnes as the greatest novel in the English language, is a work of realism.[38][39] Through the voices and opinions of different characters the reader becomes aware of important issues of the day, including the Reform Bill of 1832, the beginnings of the railways, and the state of contemporary medical science. Middlemarch also shows the deeply reactionary mindset within a settled community facing the prospect of what to many is unwelcome social, political and technological change. While George Gissing (1857–1903), author of New Grub Street (1891), amongst many other works, has traditionally been viewed as a naturalist, mainly influenced by Émile Zola,[40] Jacob Korg has suggested that George Eliot was a greater influence.[41] Other novelists, such as Arnold Bennett (1867–1931) and Anglo-Irishman George Moore (1852–1933), consciously imitated the French realists.[42] Bennett's most famous works are the Clayhanger trilogy (1910–18) and The Old Wives' Tale (1908). These books draw on his experience of life in the Staffordshire Potteries, an industrial area encompassing the six towns that now make up Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England. George Moore, whose most famous work is Esther Waters (1894), was also influenced by the naturalism of Zola.[43] |

イギリス イアン・ワットは『The Rise of the Novel』(1957年)で、小説は18世紀初頭に生まれたとし、小説の「新しさ」はその「形式的リアリズム」、すなわち「小説は人間の経験の完全かつ 本物の報告であるという考え」だと主張した[36]。彼の例は小説家のダニエル・デフォー、サムエル・リチャードソンとヘンリー・フィールディングであ る。ワットは、普通の個人間の関係を現実的に描写する小説の関心は、哲学的リアリズム、中流階級の経済的個人主義、ピューリタンの個人主義のより一般的な 展開と並行していたと主張した。また、この形式は、新しい中産階級の読書家とそれに呼応して発展してきた新しい書籍商の関心と能力に対応するものであった と主張している。商人であるデフォーとリチャードソンは、自分たちの作品が多くの読者にアピールすることを知るために「自分たちの基準を参照」するだけで よかったのである[37]。 19世紀後半には、ジョージ・エリオット George Eliot (1819-1880) の『ミドルマーチ』(Middlemarch: 小説家のMartin AmisとJulian Barnesによって英語圏で最も偉大な小説と評されたGeorge Eliot (1819-1880) Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life (1871-72) はリアリズムの作品であり[38][39]、異なる人物の声と意見を通して、読者は1832年の改革法案、鉄道の始まり、現代医学の状態など当時の重要問 題を認識することになる。ミドルマーチはまた、多くの人にとって歓迎されない社会的、政治的、技術的変化の見通しに直面した定住社会における深い反動的な 考え方を示している。 他の多くの作品の中で『新グラブ街』(1891)の著者であるジョージ・ギッシング(1857-1903)は、伝統的に主にエミール・ゾラの影響を受けた 自然主義者として見られてきたが[40]、ジェイコブ・コルグはジョージ・エリオットがより大きな影響を与えたと示唆している[41]。 アーノルド・ベネット(1867-1931)やアングロ・アイリッシュのジョージ・ムーア(1852-1933)のような他の小説家は、意識的にフランス のリアリストを模倣した[42]。ベネットの代表作は、クレイハンガー三部作(1910-18)と老妻の物語(1908)である。これらの作品は、スタッ フォードシャー・ポタリー(現在、イングランドのスタッフォードシャー州にあるストーク・オン・トレントを構成する6つの町を包括する工業地帯)での彼の 生活体験に基づくものである。エスター・ウォーターズ』(1894年)が代表作のジョージ・ムーアもゾラの自然主義に影響を受けている[43]。 |

| United States William Dean Howells (1837–1920) was the first American author to bring a realist aesthetic to the literature of the United States.[44] His stories of middle and upper class life set in the 1880s and 1890s are highly regarded among scholars of American fiction.[citation needed] His most popular novel, The Rise of Silas Lapham (1885), depicts a man who, ironically, falls from materialistic fortune by his own mistakes. Other early American realists include Samuel Clemens (1835–1910), better known by his pen name of Mark Twain, author of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884),[45][46] and Stephen Crane (1871–1900). Twain's style, based on vigorous, realistic, colloquial American speech, gave American writers a new appreciation of their national voice. Twain was the first major author to come from the interior of the country, and he captured its distinctive, humorous slang and iconoclasm. For Twain and other American writers of the late 19th century, realism was not merely a literary technique: It was a way of speaking truth and exploding worn-out conventions. Crane was primarily a journalist who also wrote fiction, essays, poetry, and plays. Crane saw life at its rawest, in slums and on battlefields. His haunting Civil War novel, The Red Badge of Courage, was published to great acclaim in 1895, but he barely had time to bask in the attention before he died, at 28, having neglected his health. He has enjoyed continued success ever since—as a champion of the common man, a realist, and a symbolist. Crane's Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (1893), is one of the best, if not the earliest, naturalistic American novel. It is the harrowing story of a poor, sensitive young girl whose uneducated, alcoholic parents utterly fail her. In love, and eager to escape her violent home life, she allows herself to be seduced into living with a young man, who soon deserts her. When her self-righteous mother rejects her, Maggie becomes a prostitute to survive but soon dies. Crane's earthy subject matter and his objective, scientific style, devoid of moralizing, earmark Maggie as a naturalist work.[47] Other later American realists are John Steinbeck, Frank Norris, Theodore Dreiser, Upton Sinclair, Jack London, Edith Wharton and Henry James. |

アメリカ合衆国 1880年代から1890年代にかけての中流・上流階級の生活を描いた彼の物語は、アメリカ小説の研究者の間で高く評価されている[44]。 彼の最も人気のある小説『サイラス・ラパムの出世』(1885)は、皮肉にも、自らの過ちで物質主義の富から転落する男を描いたものである。また、『ハッ クルベリー・フィンの冒険』(1884)の作者で、マーク・トウェインのペンネームで知られるサミュエル・クレメンズ(1835-1910)や、スティー ブン・クレーン(1871-1900)なども初期アメリカのリアリストとして知られています[45][46]。 トウェインの作風は、勢いがあり、現実的で、口語的なアメリカの話し言葉に基づくもので、アメリカの作家たちに、自分たちの国の声に対する新しい認識を与 えた。トウェインは、アメリカ内陸部出身の最初の大作家であり、その独特のユーモラスなスラングと象徴性をとらえた。トウェインをはじめとする19世紀末 のアメリカの作家たちにとって、リアリズムは単なる文学の技法にとどまりません。それは、真実を語り、使い古された慣習を打ち破る方法だったのです。クレ インはジャーナリストでありながら、小説、エッセイ、詩、戯曲を書きました。スラム街や戦場など、最も過酷な現実を目の当たりにした。1895年に出版さ れた南北戦争の小説『勇気の赤いバッジ』は大きな反響を呼んだが、彼はその注目を浴びる間もなく、健康を害し、28歳でこの世を去った。その後、庶民の味 方、現実主義者、象徴主義者として、成功を収め続けている。クレインの「マギー:路上の少女」(1893年)は、自然主義的なアメリカの小説の中で、最も 早いとは言えないまでも、最も優れた作品の一つである。貧しく繊細な少女は、無学でアルコール依存症の両親にすっかり見放されてしまう。恋する少女は、暴 力的な家庭生活から逃れたいと願い、誘惑に負けて若い男と一緒に暮らすが、彼はすぐに彼女を捨ててしまう。独善的な母親に拒絶されたマギーは、生きるため に娼婦になるが、やがて死んでしまう。クレインの土俗的な題材と、道徳的な表現を排除した客観的で科学的な文体は、『マギー』を自然主義的な作品として位 置づけている[47]。 他の後期アメリカのリアリストには、ジョン・スタインベック、フランク・ノリス、セオドア・ドライザー、アプトン・シンクレア、ジャック・ロンドン、エ ディス・ウォートン、ヘンリー・ジェームズがいる。 |

| Europe Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850) is the most prominent representative of 19th-century realism in fiction through the inclusion of specific detail and recurring characters.[48][49][50] His La Comédie humaine, a vast collection of nearly 100 novels, was the most ambitious scheme ever devised by a writer of fiction—nothing less than a complete contemporary history of his countrymen. Realism is also an important aspect of the works of Alexandre Dumas, fils (1824–1895). Many of the novels in this period, including Balzac's, were published in newspapers in serial form, and the immensely popular realist "roman feuilleton" tended to specialize in portraying the hidden side of urban life (crime, police spies, criminal slang), as in the novels of Eugène Sue. Similar tendencies appeared in the theatrical melodramas of the period and, in an even more lurid and gruesome light, in the Grand Guignol at the end of the century. Gustave Flaubert's (1821–1880) acclaimed novels Madame Bovary (1857), which reveals the tragic consequences of romanticism on the wife of a provincial doctor, and Sentimental Education (1869) represent perhaps the highest stages in the development of French realism. Flaubert also wrote other works in an entirely different style and his romanticism is apparent in the fantastic The Temptation of Saint Anthony (final version published 1874) and the baroque and exotic scenes of ancient Carthage in Salammbô (1862). In German literature, 19th-century realism developed under the name of "Poetic Realism" or "Bourgeois Realism," and major figures include Theodor Fontane, Gustav Freytag, Gottfried Keller, Wilhelm Raabe, Adalbert Stifter, and Theodor Storm.[51] In Italian literature, the realism genre developed a detached description of the social and economic conditions of people in their time and environment. Major figures of Italian Verismo include Luigi Capuana, Giovanni Verga, Federico De Roberto, Matilde Serao, Salvatore Di Giacomo, and Grazia Deledda, who in 1926 received the Nobel Prize for Literature. Later realist writers included Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy, Benito Pérez Galdós, Guy de Maupassant, Anton Chekhov, Leopoldo Alas (Clarín), José Maria de Eça de Queiroz, Henryk Sienkiewicz, Bolesław Prus and, in a sense, Émile Zola, whose naturalism is often regarded as an offshoot of realism.[citation needed] |

ヨーロッパ オノレ・ド・バルザック(1799-1850)は、具体的な細部や繰り返し登場する人物を含めることによって、小説における19世紀のリアリズムの最も顕 著な代表である[48][49][50]。約100編の小説を集めた膨大な『人間喜劇』は、小説家がこれまでに考え出した最も意欲的な構想で、彼の国の人 々に関する完全な現代史に他ならないものであった。アレクサンドル・デュマ(1824-1895)の作品には、リアリズムも重要な要素である。 バルザックをはじめ、この時代の小説の多くは新聞に連載され、絶大な人気を誇ったリアリズム「ロマン・フィユルトン」は、ウジェーヌ・スーの小説のよう に、都市生活の裏側(犯罪、警察スパイ、犯罪スラング)を描くことに特化した傾向がある。同様の傾向は、この時代の演劇のメロドラマや、世紀末のグラン・ ギニョルにも見られるが、より薄気味悪く陰惨なものである。 フロベール(1821~1880)は、ロマン主義が地方医師の妻にもたらした悲劇を描いた『ボヴァリー夫人』(1857)や『感傷的な教育』(1869) で、フランス写実主義の最高峰に位置づけられる作家である。フロベールはこのほかにも、まったく異なる作風の作品を書いており、幻想的な『聖アントニウス の誘惑』(最終版は1874年出版)やバロック的でエキゾチックな古代カルタゴの情景を描いた『サラマンボ』(1862年)には、彼のロマン主義が見て取 れる。 ドイツ文学では、19世紀のリアリズムは「詩的リアリズム」または「ブルジョワ・リアリズム」という名称で発展し、主要な人物としてテオドール・フォン ターネ、グスタフ・フライターク、ゴットフリート・ケラー、ヴィルヘルム・ラーベ、アダルベルト・シュティフター、テオドール・ストームなどが挙げられる [51]。 イタリア文学では、リアリズムというジャンルで、時代や環境に応じた人々の社会的・経済的状況を淡々と描写することが発展した。イタリアのヴェリズモの主 要人物には、ルイジ・カプアーナ、ジョヴァンニ・ヴェルガ、フェデリコ・デ・ロベルト、マティルデ・セラオ、サルヴァトーレ・ディ・ジャコモ、グラツィ ア・デレッダがおり、1926年にノーベル文学賞を受賞している。 後のリアリズム作家には、フョードル・ドストエフスキー、レオ・トルストイ、ベニート・ペレス・ガルドス、ギ・ド・モーパッサン、アントン・チェーホフ、 レオポルド・アラス(クラリン)、ジョゼ・マリア・デ・エサ・デ・ケイロス、ヘンレク・シエンキェヴィッチ、ボレスワフ・プルス、ある意味ではエミール・ ゾラなどがおり、その自然主義はしばしばリアリズムの分派として考えられている[citation needed][quote] 。 |

| Realism in the Theatre Theatrical realism was a general movement in 19th-century theatre from the time period of 1870–1960 that developed a set of dramatic and theatrical conventions with the aim of bringing a greater fidelity of real life to texts and performances. Part of a broader artistic movement, it shared many stylistic choices with naturalism, including a focus on everyday (middle-class) drama, ordinary speech, and dull settings. Realism and naturalism diverge chiefly on the degree of choice that characters have: while naturalism believes in the overall strength of external forces over internal decisions, realism asserts the power of the individual to choose (see A Doll's House). Russia's first professional playwright, Aleksey Pisemsky, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy (The Power of Darkness (1886)), began a tradition of psychological realism in Russia which culminated with the establishment of the Moscow Art Theatre by Constantin Stanislavski and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko.[52] Their ground-breaking productions of the plays of Anton Chekhov in turn influenced Maxim Gorky and Mikhail Bulgakov. Stanislavski went on to develop his 'system', a form of actor training that is particularly suited to psychological realism. 19th-century realism is closely connected to the development of modern drama, which, as Martin Harrison explains, "is usually said to have begun in the early 1870s" with the "middle-period" work of the Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen. Ibsen's realistic drama in prose has been "enormously influential."[53] In opera, verismo refers to a post-Romantic Italian tradition that sought to incorporate the naturalism of Émile Zola and Henrik Ibsen. It included realistic – sometimes sordid or violent – depictions of contemporary everyday life, especially the life of the lower classes. In France in addition to melodramas, popular and bourgeois theater in the mid-century turned to realism in the "well-made" bourgeois farces of Eugène Marin Labiche and the moral dramas of Émile Augier. |

演劇におけるリアリズム 演劇リアリズムは、1870年から1960年までの19世紀の演劇界における一般的な運動であり、テキストやパフォーマンスに現実の生活により忠実である ことを目指し、一連のドラマや演劇の慣習を発展させたものである。より広い芸術運動の一部であり、日常的な(中流階級の)ドラマ、普通の会話、退屈な設定 に焦点を当てるなど、自然主義と多くの文体上の選択を共有した。リアリズムと自然主義の違いは、主に登場人物の選択の度合いにある。自然主義が内的な決定 よりも外的な力の総合力を信じるのに対し、リアリズムは個人の選択の力を主張する(「人形の家」参照)。 ロシア初のプロの劇作家であるアレクセイ・ピセムスキー、フョードル・ドストエフスキー、レオ・トルストイ(『闇の力』1886年)は、ロシアにおける心 理的リアリズムの伝統を始め、コンスタンティン・スタニスラフスキーとウラジミール・ネミロヴィチ=ダンチェンコによるモスクワ芸術劇場の設立で頂点に達 した[52]。アントン・チェーホフの劇における彼らの革新的演出は、マキシム・ゴーリキーとミハイル・ブルガーコフに影響を及ぼした。スタニスラフス キーは、心理的リアリズムに特に適した俳優訓練の形式である「システム」を発展させることになった。 19世紀のリアリズムは、マーティン・ハリソンが説明するように、ノルウェーの劇作家ヘンリック・イプセンの「中期の」作品から「通常1870年代初頭に 始まったとされる」近代劇の発展と密接に結びついている。イプセンの散文による現実的なドラマは「非常に大きな影響力を持っている」[53]。 オペラでは、ヴェリズモはエミール・ゾラやヘンリック・イプセンの自然主義を取り入れようとしたロマン派以降のイタリアの伝統を指している。オペラでは、 エミール・ゾラやヘンリック・イプセンの自然主義を取り入れようとしたロマン派以後のイタリアの伝統を指す。 フランスでは、メロドラマに加えて、ウジェーヌ・マラン・ラビッシュの「よくできた」ブルジョア・ファースやエミール・オージェの道徳劇など、世紀半ばの 大衆・ブルジョア演劇はリアリズムに傾倒していった。 |

| Criticism Critics of realism cite that depicting reality is not often realistic with some observers calling it "imaginary" or "project".[54] This argument is based on the idea that we do not often get what is real correctly. To present reality, we draw on what is "real" according to how we remember it as well as how we experience it. However, remembered or experienced reality does not always correspond to what the truth is. Instead, we often obtain a distorted version of it that is only related to what is out there or how things really are. Realism is criticized for its supposed inability to address this challenge and such failure is seen as tantamount to complicity in a creating a process wherein "the artefactual nature of reality is overlooked or even concealed."[55] According to Catherine Gallagher, realistic fiction invariably undermines, in practice, the ideology it purports to exemplify because if appearances were as self-sufficient, there would probably be no need for novels.[54] This can be demonstrated in the literary naturalism's focus in the United States during the late nineteenth century on the larger forces that determine the lives of its characters as depicted in agricultural machines portrayed as immense and terrible, shredding "entangled" human bodies without compunction.[56] The machines were used as a metaphor but it contributed to the perception that such narratives were more like myth than reality.[56] There are also critics who fault realism in the way it supposedly defines itself as a reaction to the excesses of literary genres such as Romanticism and the Gothic – those that focus on the exotic, sentimental, and sensational narratives.[57] Some scholars began to call this an impulse to contradict so that in the end, the limit that it imposes on itself leads to "either the representation of verifiable and objective truth or the merely relative, some partial, subjective truth, therefore no truth at all."[58] There are also critics who cite the absence of a fixed definition. The argument is that there is no pure form of realism and the position that it is almost impossible to find literature that is not in fact realist, at least to some extent while, and that whenever one searches for pure realism, it vanishes.[59] J.P. Stern countered this position when he maintained that this "looseness" or "untidiness" makes the term indispensable in common and literary discourse alike.[54] Others also dismiss it as obvious and simple-minded while denying realistic aesthetic, branding as pretentious since it is considered mere reportage,[60] not art, and based on naïve metaphysics.[61] |

批判 現実主義の批評家は、現実を描くことはしばしば現実的ではないことを挙げ、それを「想像」や「投影」と呼ぶ観察者もいる[54]。この議論は、我々はしば しば何が現実であるかを正しく理解していないとの考えに基づいている。現実を提示するために、私たちはそれをどのように記憶し、またどのように経験するか に従って「現実」であるものを引き寄せる。しかし、記憶や経験のある現実が、必ずしも真実の姿と一致しているとは限らない。しかし、記憶や経験された現実 は、必ずしも真実とは一致せず、むしろ、そこにあるもの、あるいは物事の本当の姿にのみ関係する、歪んだ現実を手に入れることが多い。キャサリン・ギャラ ガーによれば、現実主義的なフィクションは常に、それが例証しようとするイデオロギーを実践的に損なっており、もし外見が自己充足的であれば、おそらく小 説は必要ないだろうからである[55]。 [これは19世紀後半にアメリカにおいて文学的自然主義が巨大で恐ろしいものとして描かれ、「絡まった」人間の体を平気で細断する農業機械に描かれた登場 人物の人生を決定する大きな力に焦点を当てていたことで実証できる[56]。 機械は比喩として使われたが、そのような物語は現実よりも神話のようだという認識を助長するものであった[56]。 また、ロマン主義やゴシックなどの文学ジャンルの行き過ぎ、つまりエキゾチックで感傷的でセンセーショナルな物語に焦点を当てたものに対する反応として、 リアリズムが自らを定義しているとされる方法で非難する批評家がいる[57]。 一部の学者はこれを矛盾への衝動と呼び始め、最終的にはそれが自らに課す限界は「検証可能で客観的真実の表現か、単に相対的で何らかの部分で、主観的真 実、したがって全く真実ではない」ことにつながっているのである[58]。 また、固定された定義がないことを挙げる批判者もいる。その主張は、リアリズムの純粋な形態は存在せず、少なくともある程度までは実際にリアリズムでない 文学を見つけることはほとんど不可能であり、純粋なリアリズムを探せばいつでもそれは消えてしまうという立場である[59] J.P.スターンはこの立場に反論した。スターンはこの立場に反論し、この「緩さ」や「穢れ」がこの用語を一般的な言説や文学的な言説において同様に不可 欠なものにしていると主張していた[54]。 また、現実主義の美学を否定しながら明白で単純思考であるとし、芸術ではなく単なるルポルタージュであると考えられることから気取ったものである [60]、ナイーブな形而上学に基づいているとの烙印を押して却下した者もいる[61]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Literary_realism |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

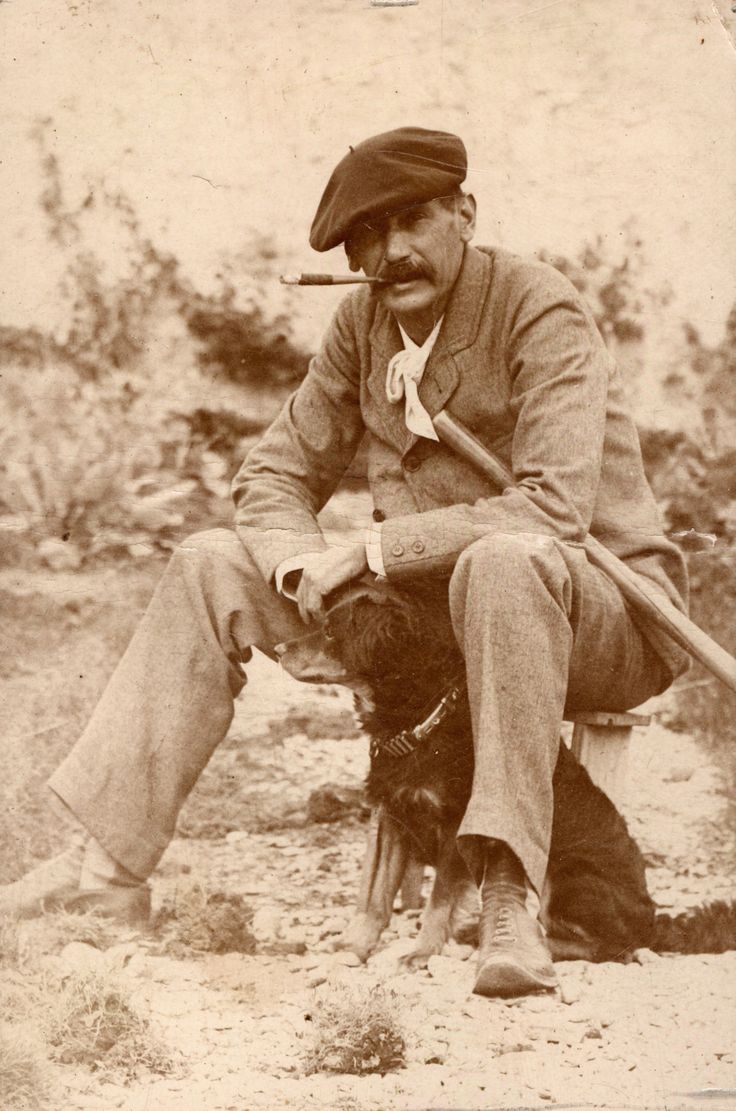

◎ベニート・ペレス・ガルドス

ベニート・ペレス・ガルドス(Benito Perez

Galdos、1843年5月10日-1920年1月4日)は、スペインの写実主義の小説家である。ミゲル・デ・セルバンテスに次ぐ名声を持ち[1]

[2]、スペインの写実主義を代表する小説家である。彼はグラン・カナリア島のラス・パルマス・デ・グラン・カナリアで生まれたが、19歳の時にマドリー

ドに引っ越して生涯の大半を過ごした。スペイン国内で彼の最も人気のある作品は、46巻からなる『国民挿話』Episodios

nacionalesや『フォルトゥナータとハシンタ』Fortunata y Jacintaであるが、国外ではNovelas espanolas

contemporaneasの方がよく知られている。

初期には、文献調査を行って歴史上の人物と架空の人物が登場する作品を書いた。オノレ・ド・バルザックの小説のように、何人かの登場人物は別の小説にも登

場する。1805年から19世紀末までを描いており、ガルドスの急進的で反聖職者的な視点が垣間見える。1876年のDona

Perfectaは、急進派の若者が抑圧的な反聖職者の街を訪れる話である。1878年のMarianelaは、盲目の若い男が視力を取り戻し、親友のマ

リアネラの容姿の醜さを知って拒絶する話である。1888年のMiauは、政権交代によって公務員の父が失業して見栄張りの家族が生計を失い、結局は彼を

殺害する話である。

1886年から1887年に書かれたガルドスの傑作が『フォルトゥナータとハシンタ』である。レフ・トルストイの『戦争と平和』とほぼ同じ長さで、若い遊

び人とその妻、その下級生の女主人とその夫という4人の登場人物の運命を描いている。1891年のAngel

Guerraは、敬虔で手が届かない女性をものにしようとする男が、その過程で不可知論からカトリシズムに変節する物語である。

● ファトワー(=イスラームに おいてイスラム法学に基づいて発令される勧告、布告、見解、裁断)問題とリアリズム

したがって、サルマン・ラシュディに対するファトワー(=イスラームにおいてイスラム法学に基づ

いて発令される勧告、布告、見解、裁断)は、ラシュディのフィクションを「現実のムスリムやその神学概念」に対する「冒涜」と有責責任であると、倫理的に

判断する決定のことである。

サルマン・ラシュディ『悪魔の詩』梗概

・ジャンル:マジックリアリズム

・梗概

現代の2人のインド人

映画俳優ジブリール・ファリシュタ

ボンベイの裕福な家の息子サラディン・チャムチャ(ラシュディの境遇が投影されている)

2人がロンドン行きの飛行機に乗り合わせたのだが空中爆発し、ヒマラヤの空中からドーバー 海峡に投げ出され、結果的にロンドンのインド移民のたまり場に着く。やがて、ヨーロッパの大都会でさまざまなドタバタを演じる。

・ムスリムにとって冒涜

(1)ファリシュタ:

ウルドゥー語で天使。ジブリールはガブリエルで大天使。孤児であった彼の養父役になった のが実業家マハウンド(これはムハンマドのヨーロッパでのかつての蔑称)。ジブリー ルの夢想のなかで、マハウンドは商人ムハンマドの化身となって、予言者 の生涯のパロディーを演ずる。

天使(神の言葉を伝える)/予言者ムハンマド

孤児(ジブリール)=夢想の中の予言者/後見人(マハウンド)

(2)「悪魔の詩」のエピソード

ムハンマドが天使ガブリエルの伝える神の言葉を読誦するとき、悪魔がガブリエルの姿を もってイス ラーム以前の3人の女神をたたえる言葉を紛れこませたというエピソードがある。聖典 になく、エピソードとして流布しているが、この話がジブリールの妄想の なかにそのまま登場する。このエピソードは、アッラーの唯一絶対神信仰の権威を否定する。

(3)ジャーヒリーヤ町の娼婦

イスラーム以前における無明の時代を意味する「ジャーヒリーヤ」の町の綱紀粛正をマハ ウンドがおこないハーレムが閉鎖されようとするが、町の人びとは娼婦たちにマハウンド12人の名を名乗らせ、役割に見合ったサービスをさせてハーレムの晩 を興じる。

●テクストの外で?

サルマン・ラシュディ(Sir Salman Rushdie, b.1947)1947年生まれ。インドのムスリム出身で、英国の大学を卒業し、そ のまま英 国籍を取得し、英語作家となる。『悪魔の詩』1988年出版。クルアーンやムハンマドを冒涜するものとしてイスラーム社会で抗議行動を引き起こす。イス ラーム各国で発禁処分。インド、パキスタンでは死者もでる。1989年2月シーア派のホメイニから懸賞金つきでの死刑の宣告(=ファトゥワ/勅諭)が発せ られる。同年6月「神の名の下で、何人もこの判断を覆すことはできない」と宣言。作者ばかりでなく、出版社や翻訳者も同罪ということで襲撃される。

●オリエンタリズムの構図の中で

「いかなる信仰といえども、疑義をはさまれることは避けられず、いかなる著作者もその信ずる ことを表現することを禁じられるべきではありません。『悪魔の詩』は世界的に著名な作家の重要な作品であり、日本の方々に是非とも読まれるべきです。」イ ギリス・ペン・センター

・「子供じみた無罪宣言にとどまるまいとするなら、このラシュディの振る舞いには身の毛のよ だつものがあり、まさしくそれこそが文学とその恍惚の可能性の条件なのだということが見てとれる。」(pp.18-19)

●フェティ・ベンスラマ『物騒なフィクション』

・

涜神行為……神の絶対性

文字の神聖性……想像力の絶対性

・〜の名において語ること=より高次なものに価値をおくという前提が必要

〜:神、人間、人、神聖、人間の尊厳

・テクストを創出し、それを確立し操作する主体を認めること→内在の超越化

・イスラムにおける<書物>の二重性

1)アル・キターブ:クルアーンに書かれたこと→ウム・アル・キターブ(書物の母体)

2)アル・ムシフ:具体的著作として

・ヨーロッパ人にとって<読むこと>

技術の本質/暴くことをテクストにまでおよぼす。書き手(モンタージュする主体)の本性を 暴く。書く=暴くということの本質の絶対性。『ドン・キホーテ』。つまり、近代精神の発露とは<剥ぐ>ことである。

・機嫌を分有しないことを当たり前とみなし、あたかもそれを当然のように受け入れる。

・自らがたどったテクストを主体のあり方の古いタイプのものを忘却してしまう。

・

・近代に対する4つの類型。保守主義;過去を再現する。原理主義;過去に回帰する。近代主 義;過去を清算する(→ラシュディ)。現代派;過去との関係を新しく創造する。

・ヨーロッパでは、文学と社会に関する関係が忘れられたものとなっていた。

・フィクションだからこそ、社会的影響力を持ちうるという近代の逆説。

・文学は無垢ではなく有罪だ(バタイユ)

・ラシュディはその意味で確信犯なのである。そして、そのやり方はヨーロッパ的なテクスト実 験であった。

・ムスリムにとっての<父>なるテキストの冒涜。

・文脈的に冒涜を犯すことが明らかな場合、それをフィクションとして特権化することには限界 あり。

・言語行為こそが冒涜なのだ。

・ラシュディ事件の社会的意味を明らかにすることが我々の責務。

・:精神分析編

・分有の企ての実践

・小説は神話のない(失った)共同体においてのみ成立する。

・<父>のテクスト

・ディアスポラ小説//ベンスラマの臨床経験における<移民>のディアスポラ経験

・

・ヨーロッパ文明:起源から人びとを解放し、歴史的な時間への通路を開く。

・イスラームは、その解放への過程にある。普遍的なものへテキストを従属させる=起源に死を 宣告する。

・イスラームの国民解放の二重性

1)イスラームの名において:イスラームの起源:土着のものを押しつける//死刑宣告

2)普遍的なものの名において:かつて宗主国が押しつけてきたもの//ダブルスタンダード な政治的虚構にしがみつく//断罪

・イスラム改革運動派=モダニスト

・テクストの権威を守り切れず、死をもって償わせるものだとしたら、すでにその権威はゆらい でいるということなのか?。だから死=恐怖という装置を動員させようとしているのか?

++++++++++

◎ク

レジット:旧クレジット「ジンの嘆き,

物議をかもすフィクション」

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆