シュルレアリスム

Surrealism

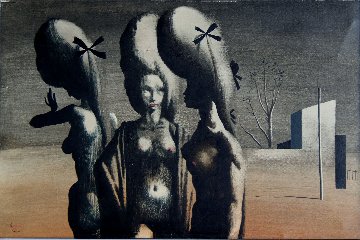

☆ シュルレアリスム(Surrealism)は、第一次世界大戦後のヨーロッパで発展した文化運動であり、芸術家たちは人びとを狼狽させるような非論理的な情景を描き、無意識が自ら を表現するための技法を開発した。その目的は、指導者のアンドレ・ブルトンによれば、「夢と現実というこれまで矛盾していた条件を、絶対的な現実、 超現実へと解決すること」すなわち超現実の実現であった。

★Surrealism, シュールレアリスム[日本語ウィキ]、シュルリアリズム

Surrealism

is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of

World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and

developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express

itself.[1] Its aim was, according to leader André Breton, to "resolve

the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an

absolute reality, a super-reality", or surreality.[2][3][4] It produced

works of painting, writing, theatre, filmmaking, photography, and other

media. Surrealism

is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of

World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and

developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express

itself.[1] Its aim was, according to leader André Breton, to "resolve

the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an

absolute reality, a super-reality", or surreality.[2][3][4] It produced

works of painting, writing, theatre, filmmaking, photography, and other

media.Works of Surrealism feature the element of surprise, unexpected juxtapositions and non sequitur. However, many Surrealist artists and writers regard their work as an expression of the philosophical movement first and foremost (for instance, of the "pure psychic automatism" Breton speaks of in the first Surrealist Manifesto), with the works themselves being secondary, i.e., artifacts of surrealist experimentation.[5] Leader Breton was explicit in his assertion that Surrealism was, above all, a revolutionary movement. At the time, the movement was associated with political causes such as communism and anarchism. It was influenced by the Dada movement of the 1910s.[6] The term "Surrealism" originated with Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917.[7][8] However, the Surrealist movement was not officially established until after October 1924, when the Surrealist Manifesto published by French poet and critic André Breton succeeded in claiming the term for his group over a rival faction led by Yvan Goll, who had published his own surrealist manifesto two weeks prior.[9] The most important center of the movement was Paris, France. From the 1920s onward, the movement spread around the globe, impacting the visual arts, literature, film, and music of many countries and languages, as well as political thought and practice, philosophy, and social theory. |

シュ

ルレアリスム(Surrealism)は、第一次世界大戦後のヨーロッパで発展した文化運動であり、芸術家たちは人びとを狼狽させるような非論理的な情景を描き、無意識が自らを表

現するための技法を開発した[1]。その目的は、指導者のアンドレ・ブルトンによれば、「夢と現実というこれまで矛盾していた条件を、絶対的な現実、超現

実へと解決すること」、すなわち超現実であった[2][3][4]。 シュ

ルレアリスム(Surrealism)は、第一次世界大戦後のヨーロッパで発展した文化運動であり、芸術家たちは人びとを狼狽させるような非論理的な情景を描き、無意識が自らを表

現するための技法を開発した[1]。その目的は、指導者のアンドレ・ブルトンによれば、「夢と現実というこれまで矛盾していた条件を、絶対的な現実、超現

実へと解決すること」、すなわち超現実であった[2][3][4]。シュルレアリスムの作品は、驚き、予期せぬ並置、非連続性といった要素を特徴としている。しかし、シュルレアリスムの芸術家や作家の多くは、自分たちの作 品を、何よりもまず哲学的な運動の表現(例えば、第一次シュルレアリスム宣言でブルトンが語っている「純粋な精神的オートマティスム」)とみなしており、 作品そのものは二次的なもの、つまりシュルレアリスムの実験の成果物である[5]。当時、この運動は共産主義やアナキズムといった政治的大義と結びついて いた。1910年代のダダ運動の影響を受けていた[6]。 シュルレアリスム」という言葉は、1917年にギヨーム・アポリネールによって生まれた[7][8]。しかし、シュルレアリスム運動が正式に確立されたの は1924年10月以降であり、フランスの詩人であり批評家であったアンドレ・ブルトンによって発表されたシュルレアリスム宣言が、その2週間前に自身の シュルレアリスム宣言を発表していたイヴァン・ゴルによって率いられた対立派閥を抑えて、自身のグループのためにこの言葉を主張することに成功した時で あった[9]。1920年代以降、この運動は世界中に広がり、多くの国や言語の視覚芸術、文学、映画、音楽、さらには政治思想や実践、哲学、社会理論にも 影響を与えた。 |

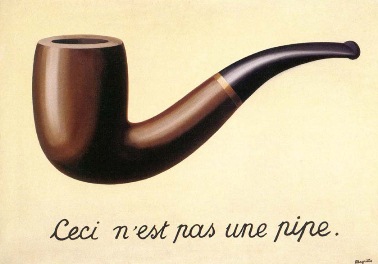

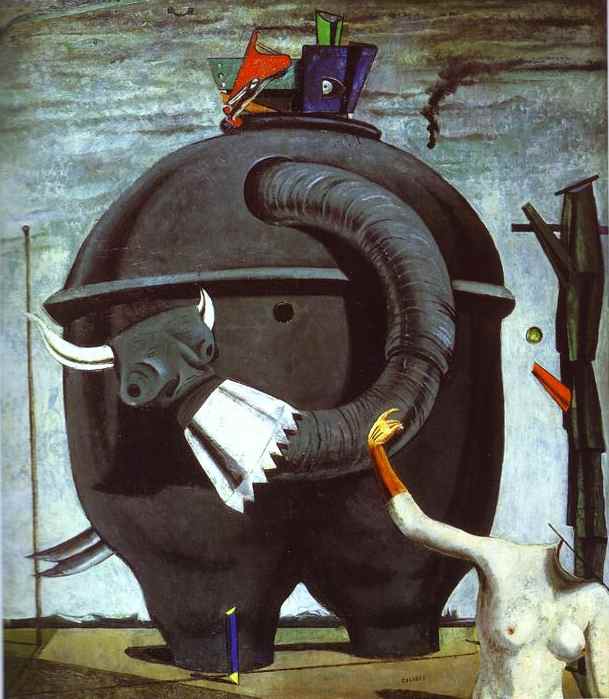

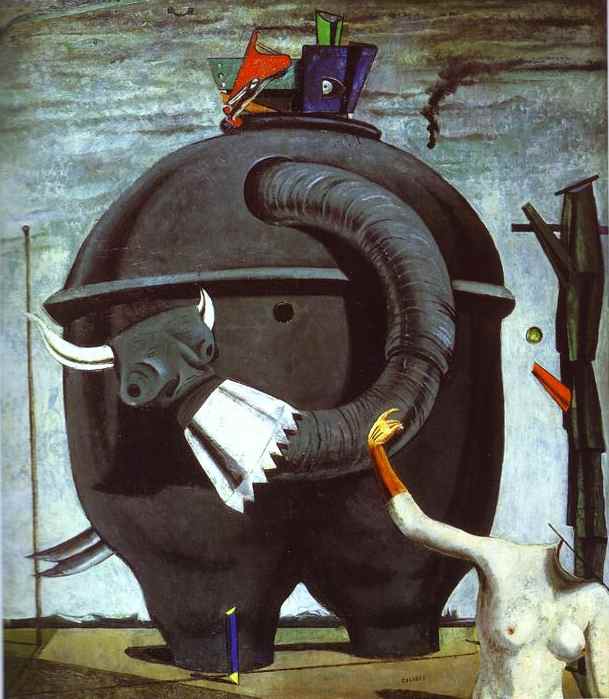

Founding of the movement Max Ernst, The Elephant Celebes, 1921 The word surrealism was first coined in March 1917 by Guillaume Apollinaire.[10] He wrote in a letter to Paul Dermée: "All things considered, I think in fact it is better to adopt surrealism than supernaturalism, which I first used" [Tout bien examiné, je crois en effet qu'il vaut mieux adopter surréalisme que surnaturalisme que j'avais d'abord employé].[11] Apollinaire used the term in his program notes for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, Parade, which premiered 18 May 1917. Parade had a one-act scenario by Jean Cocteau and was performed with music by Erik Satie. Cocteau described the ballet as "realistic". Apollinaire went further, describing Parade as "surrealistic":[12] This new alliance—I say new, because until now scenery and costumes were linked only by factitious bonds—has given rise, in Parade, to a kind of surrealism, which I consider to be the point of departure for a whole series of manifestations of the New Spirit that is making itself felt today and that will certainly appeal to our best minds. We may expect it to bring about profound changes in our arts and manners through universal joyfulness, for it is only natural, after all, that they keep pace with scientific and industrial progress. (Apollinaire, 1917)[13] The term was taken up again by Apollinaire, both as subtitle and in the preface to his play Les Mamelles de Tirésias: Drame surréaliste,[14] which was written in 1903 and first performed in 1917.[15] World War I scattered the writers and artists who had been based in Paris, and in the interim, many became involved with Dada, believing that excessive rational thought and bourgeois values had brought the conflict of the war upon the world. The Dadaists protested with anti-art gatherings, performances, writings and art works. After the war, when they returned to Paris, the Dada activities continued. During the war, André Breton, who had trained in medicine and psychiatry, served in a neurological hospital where he used Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic methods with soldiers suffering from shell-shock. Meeting the young writer Jacques Vaché, Breton felt that Vaché was the spiritual son of writer and pataphysics founder Alfred Jarry. He admired the young writer's anti-social attitude and disdain for established artistic tradition. Later Breton wrote, "In literature, I was successively taken with Rimbaud, with Jarry, with Apollinaire, with Nouveau, with Lautréamont, but it is Jacques Vaché to whom I owe the most."[16] Back in Paris, Breton joined in Dada activities and started the literary journal Littérature along with Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault. They began experimenting with automatic writing—spontaneously writing without censoring their thoughts—and published the writings, as well as accounts of dreams, in the magazine. Breton and Soupault continued writing evolving their techniques of automatism and published The Magnetic Fields (1920). By October 1924 two rival Surrealist groups had formed to publish a Surrealist Manifesto. Each claimed to be successors of a revolution launched by Appolinaire. One group, led by Yvan Goll consisted of Pierre Albert-Birot, Paul Dermée, Céline Arnauld, Francis Picabia, Tristan Tzara, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Pierre Reverdy, Marcel Arland, Joseph Delteil, Jean Painlevé and Robert Delaunay, among others.[17] The group led by André Breton claimed that automatism was a better tactic for societal change than those of Dada, as led by Tzara, who was now among their rivals. Breton's group grew to include writers and artists from various media such as Paul Éluard, Benjamin Péret, René Crevel, Robert Desnos, Jacques Baron, Max Morise,[18] Pierre Naville, Roger Vitrac, Gala Éluard, Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Luis Buñuel, Man Ray, Hans Arp, Georges Malkine, Michel Leiris, Georges Limbour, Antonin Artaud, Raymond Queneau, André Masson, Joan Miró, Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Prévert, and Yves Tanguy.[19][20]  Cover of the first issue of La Révolution surréaliste, December 1924 As they developed their philosophy, they believed that Surrealism would advocate the idea that ordinary and depictive expressions are vital and important, but that the sense of their arrangement must be open to the full range of imagination according to the Hegelian Dialectic. They also looked to the Marxist dialectic and the work of such theorists as Walter Benjamin and Herbert Marcuse.[citation needed] Freud's work with free association, dream analysis, and the unconscious was of utmost importance to the Surrealists in developing methods to liberate imagination. They embraced idiosyncrasy, while rejecting the idea of an underlying madness. As Dalí later proclaimed, "There is only one difference between a madman and me. I am not mad."[18] Beside the use of dream analysis, they emphasized that "one could combine inside the same frame, elements not normally found together to produce illogical and startling effects."[21] Breton included the idea of the startling juxtapositions in his 1924 manifesto, taking it in turn from a 1918 essay by poet Pierre Reverdy, which said: "a juxtaposition of two more or less distant realities. The more the relationship between the two juxtaposed realities is distant and true, the stronger the image will be−the greater its emotional power and poetic reality."[22] The group aimed to revolutionize human experience, in its personal, cultural, social, and political aspects. They wanted to free people from false rationality, and restrictive customs and structures. Breton proclaimed that the true aim of Surrealism was "long live the social revolution, and it alone!" To this goal, at various times Surrealists aligned with communism and anarchism. In 1924 two Surrealist factions declared their philosophy in two separate Surrealist Manifestos. That same year the Bureau of Surrealist Research was established and began publishing the journal La Révolution surréaliste. Surrealist Manifestos  Yvan Goll, Surréalisme, Manifeste du surréalisme,[23] Volume 1, Number 1, October 1, 1924, cover by Robert Delaunay Main article: Surrealist Manifesto Leading up to 1924, two rival surrealist groups had formed. Each group claimed to be successors of a revolution launched by Apollinaire. One group, led by Yvan Goll, consisted of Pierre Albert-Birot, Paul Dermée, Céline Arnauld, Francis Picabia, Tristan Tzara, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Pierre Reverdy, Marcel Arland, Joseph Delteil, Jean Painlevé and Robert Delaunay, among others.[24] The other group, led by Breton, included Aragon, Desnos, Éluard, Baron, Crevel, Malkine, Jacques-André Boiffard and Jean Carrive, among others.[25] Yvan Goll published the Manifeste du surréalisme, 1 October 1924, in his first and only issue of Surréalisme[23] two weeks prior to the release of Breton's Manifeste du surréalisme, published by Éditions du Sagittaire, 15 October 1924. Goll and Breton clashed openly, at one point literally fighting, at the Comédie des Champs-Élysées,[24] over the rights to the term Surrealism. In the end, Breton won the battle through tactical and numerical superiority.[26][27] Though the quarrel over the anteriority of Surrealism concluded with the victory of Breton, the history of surrealism from that moment would remain marked by fractures, resignations, and resounding excommunications, with each surrealist having their own view of the issue and goals, and accepting more or less the definitions laid out by André Breton.[28][29] Breton's 1924 Surrealist Manifesto defines the purposes of Surrealism. He included citations of the influences on Surrealism, examples of Surrealist works, and discussion of Surrealist automatism. He provided the following definitions: Dictionary: Surrealism, n. Pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought. Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation. Encyclopedia: Surrealism. Philosophy. Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life.[4] |

運動の創設 マックス・エルンスト《象のセレベス》1921年 シュルレアリスムという言葉は、1917年3月にギヨーム・アポリネールによって初めて作られた[10]。 彼はポール・デルメに宛てた手紙の中で、「あらゆることを考慮すると、私が最初に用いた超自然主義よりも、シュルレアリスムを採用する方が実際には良いと 思う」と書いている[11]。 アポリネールは、1917年5月18日に初演されたセルゲイ・ディアギレフのバレエ・リュス『パレード』のプログラムノートでこの言葉を使用している。パ レード』はジャン・コクトーによる一幕物のシナリオで、エリック・サティの音楽で上演された。コクトーはこのバレエを「写実的」と評した。アポリネールは さらに踏み込んで、『パレード』を「超現実的」と評した[12]。 この新しい同盟は--新しいと言ったのは、これまでは風景と衣装は事実上の結びつきでしかなかったからである--『パレード』において、一種のシュルレア リスムを生み出した。科学や産業の進歩に歩調を合わせるのは、結局のところ当然のことなのだから。(アポリネール、1917年)[13]。 この言葉はアポリネールによって再び取り上げられ、彼の戯曲『ティレジアスの女たち』の副題として、また序文で使われた: この戯曲は1903年に書かれ、1917年に初演された[14]。 第一次世界大戦により、パリを拠点としていた作家や芸術家たちは散り散りになり、その間に多くの人々が、過剰な合理的思考とブルジョワ的価値観が戦争の対 立を世界にもたらしたと考え、ダダと関わるようになる。ダダイストたちは、反芸術の集会、パフォーマンス、著作、芸術作品によって抗議した。戦後、パリに 戻った後もダダの活動は続いた。 戦時中、医学と精神医学の訓練を受けたアンドレ・ブルトンは、神経科病院に勤務し、ジークムント・フロイトの精神分析法を用いて、砲弾ショックに苦しむ兵 士たちを治療した。若き作家ジャック・ヴァシェと出会ったブルトンは、ヴァシェが作家でありパタフィジックス創始者であるアルフレッド・ジャリの精神的な 息子であると感じた。彼はこの若い作家の反社会的な態度と、既成の芸術的伝統を軽んじる姿勢に敬服した。後にブルトンは、「文学において、私はランボー、 ジャリー、アポリネール、ヌーヴォー、ロートレアモンと相次いで魅了されたが、私が最も恩義を感じているのはジャック・ヴァシェである」と書いている [16]。 パリに戻ったブルトンは、ダダの活動に参加し、ルイ・アラゴンやフィリップ・スポーとともに文芸誌『リテラチュア』を創刊。彼らは、自分の思考を検閲する ことなく自発的に書くという自動筆記の実験を始め、その文章や夢の記録を雑誌に掲載した。ブルトンとスーポーは、オートマティズムのテクニックを進化させ ながら執筆を続け、『磁場』(1920年)を出版した。 1924年10月までに、シュルレアリスムの2つのグループが結成され、シュルレアリスム宣言が発表された。それぞれが、アポリネールが起こした革命の後 継者であると主張していた。イヴァン・ゴルが率いるグループは、ピエール・アルベール=ビロ、ポール・デルメ、セリーヌ・アルノルド、フランシス・ピカビ ア、トリスタン・ツァラ、ジュゼッペ・ウンガレッティ、ピエール・ルヴェルディ、マルセル・アーランド、ジョゼフ・デルテイユ、ジャン・パンルヴェ、ロ ベール・ドローネらで構成されていた[17]。 アンドレ・ブルトンが率いるグループは、オートマティスムは、ダダよりも優れた社会変革の戦術であると主張した。ブルトンのグループは、ポール・エリュ アール、ベンジャミン・ペレ、ルネ・クレヴェル、ロベール・デスノ、ジャック・バロン、マックス・モリゼ、[18] ピエール・ナヴィル、ロジェ・ヴィトラック、ガラ・エリュアールなど、様々なメディアの作家やアーティストを含むまでに成長した、 マックス・エルンスト、サルバドール・ダリ、ルイス・ブニュエル、マン・レイ、ハンス・アルプ、ジョルジュ・マルキネ、ミシェル・レイリス、ジョルジュ・ ランブール、アントナン・アルトー、レイモン・ケノー、アンドレ・マッソン、ジョアン・ミロ、マルセル・デュシャン、ジャック・プレヴェール、イヴ・タン ギー。 [19][20]  1924年12月、『La Révolution surréaliste』創刊号の表紙。 彼らは哲学を発展させながら、シュルレアリスムは、平凡で描写的な表現は生命力があり重要であるが、その配置の感覚はヘーゲル弁証法に従って想像力の全範 囲に開かれていなければならないという考えを提唱すると信じていた。彼らはまた、マルクス主義の弁証法や、ヴァルター・ベンヤミンやヘルベルト・マルクー ゼのような理論家の仕事にも注目していた[要出典]。 フロイトの自由連想、夢分析、無意識に関する研究は、想像力を解放する方法を開発する上で、シュルレアリスムにとって最も重要なものであった。彼らは、根 底にある狂気という考えを否定しながらも、特異性を受け入れた。後にダリが宣言したように、「狂人と私の違いはただ一つ。私は狂っていない」[18]。 夢分析の使用の他に、彼らは「非論理的で驚くべき効果を生み出すために、通常一緒に見られない要素を同じ枠の中で組み合わせることができる」ことを強調し た[21]: 「多かれ少なかれ離れた二つの現実の並置。並置された2つの現実の間の関係が遠く、真実であればあるほど、イメージはより強くなり、感情的な力と詩的なリ アリティが増す」[22]。 このグループは、個人的、文化的、社会的、政治的な側面において、人間の経験に革命を起こすことを目指していた。彼らは、誤った合理性、制限的な習慣や構 造から人々を解放したかった。ブルトンは、シュルレアリスムの真の目的は「社会革命万歳、そしてそれのみだ!」と宣言した。この目標のために、シュルレア リストたちはさまざまな時期に共産主義やアナキズムと手を組んだ。 1924年、シュルレアリスムの2つの派閥は、2つの別々のシュルレアリスム宣言で自分たちの哲学を宣言した。同年、シュルレアリスム研究局が設立され、雑誌『La Révolution surréaliste』の発行を開始した。 シュルレアリスム宣言  イヴァン・ゴル『シュルレアリスム宣言』[23] 第1巻第1号、1924年10月1日、表紙:ロベール・ドローネー 主な記事 シュルレアリスム宣言 1924年に至るまで、2つの対立するシュルレアリスト・グループが形成されていた。それぞれのグループは、アポリネールが起こした革命の後継者であると 主張していた。イヴァン・ゴルが率いる一方のグループは、ピエール・アルベール=ビロ、ポール・デルメ、セリーヌ・アルノルド、フランシス・ピカビア、ト リスタン・ツァラ、ジュゼッペ・ウンガレッティ、ピエール・ルヴェルディ、マルセル・アーランド、ジョゼフ・デルテイユ、ジャン・パンルヴェ、ロベール・ ドローネなどで構成されていた[24]。 ブルトンが率いるもう一方のグループには、アラゴン、デスノス、エルアール、バロン、クレヴェル、マルキーヌ、ジャック=アンドレ・ボワファール、ジャン・カリヴなどがいた[25]。 イヴァン・ゴルは、1924年10月15日にエディシオン・デュ・サジテールから出版されたブルトンの『シュールレアリスム宣言』(Manifeste du surréalisme)が発表される2週間前、1924年10月1日に『シュールレアリスム宣言』(Manifeste du surréalisme)[23]を、彼の創刊号であり唯一の号である『シュールレアリスム』誌に発表した。 ゴルとブルトンは、シュルレアリスムという言葉の権利をめぐり、シャンゼリゼ劇場で公然と衝突し、一時は文字通り喧嘩をしたこともあった[24]。シュル レアリスムの先行性をめぐる争いはブルトンの勝利で終結したものの、その瞬間からのシュルレアリスムの歴史は、分裂、辞任、そして破門によって特徴づけら れ、それぞれのシュルレアリストが問題と目標について独自の見解を持ち、アンドレ・ブルトンによって示された定義を多かれ少なかれ受け入れていた[28] [29]。 ブルトンの1924年のシュルレアリスム宣言はシュルレアリスムの目的を定義している。彼はシュルレアリスムへの影響の引用、シュルレアリスムの作品の例、シュルレアリスムのオートマティスムについての議論を含んでいた。シュルレアリスムの定義は以下の通り: 辞書 シュルレアリスム、n. 純粋な精神的自動主義、これによって人は、口頭で、文章で、あるいは他のいかなる方法でも、思考の本当の働きを表現することを提案する。理性によるコントロールが一切ない状態で、美的・道徳的なこだわりから外れた思考の指示。 百科事典: シュルレアリスム。哲学。シュルレアリスムは、これまで無視されてきたある種の連想の優れた実在性、夢の全能性、思考の無関心な戯れに対する信念に基づい ている。シュルレアリスムは、他の精神的なメカニズムを一旦、完全に破滅させ、人生のすべての主要な問題を解決する上で、それ自身をそれらに取って代わろ うとする傾向がある[4]。 |

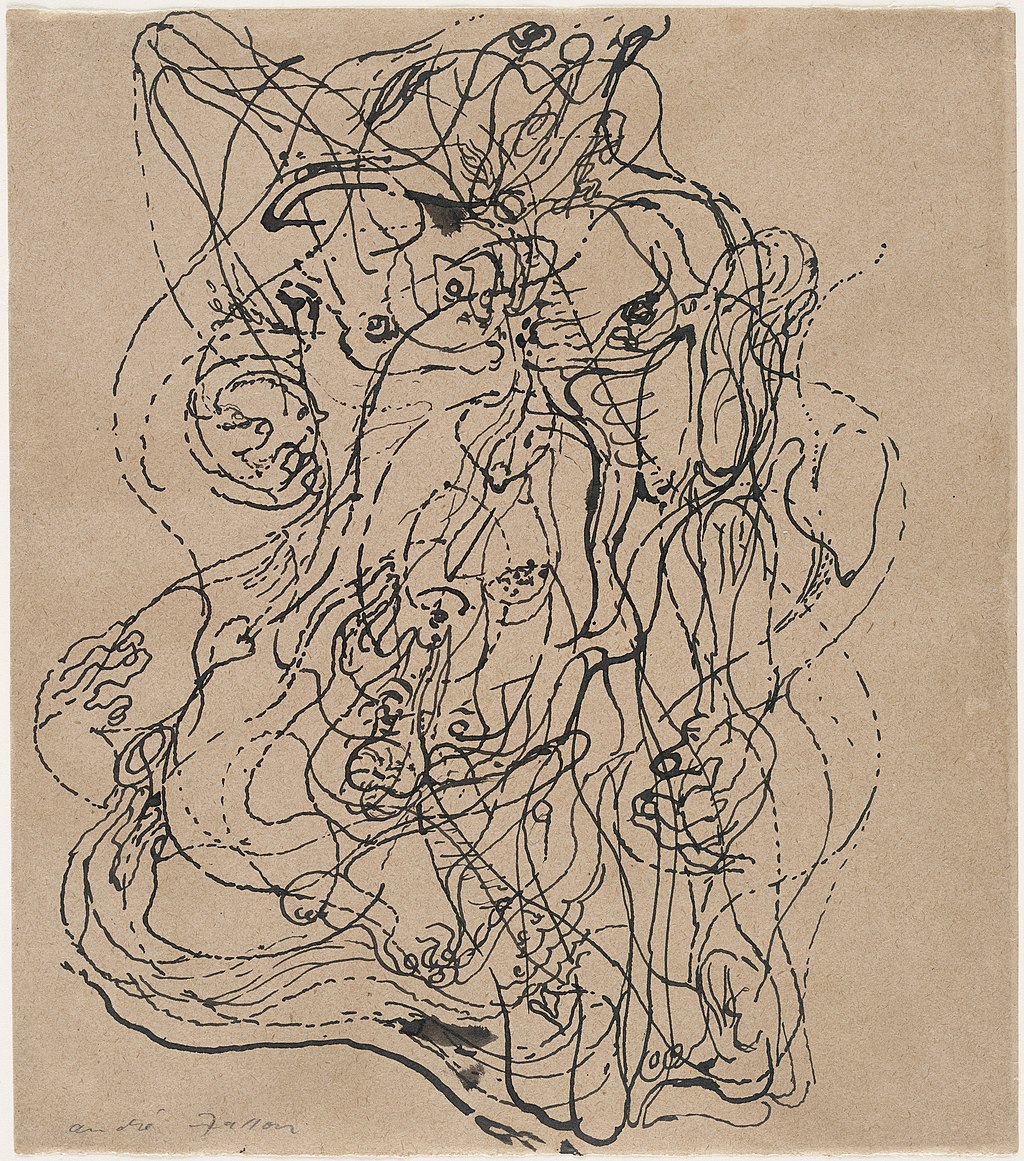

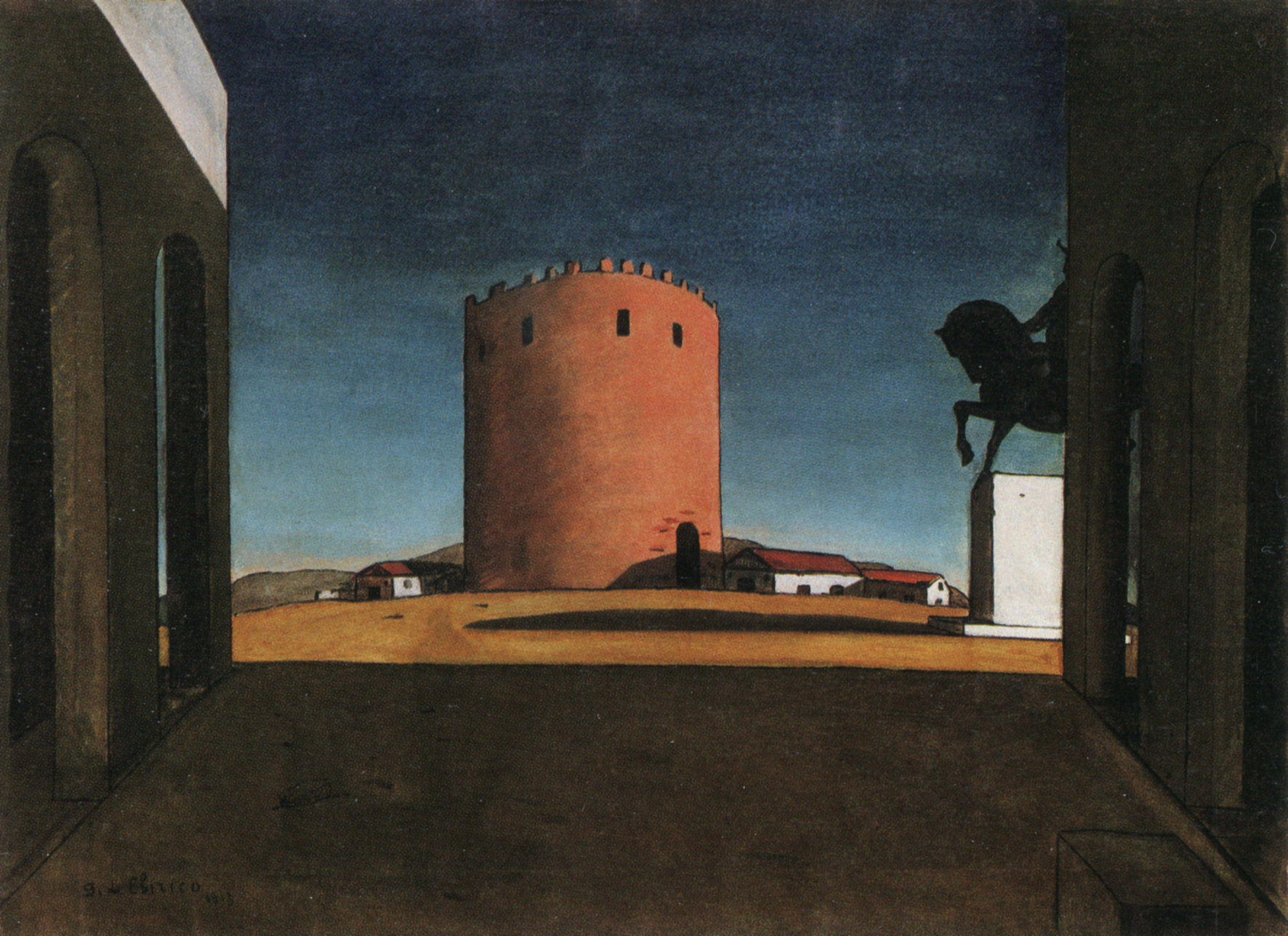

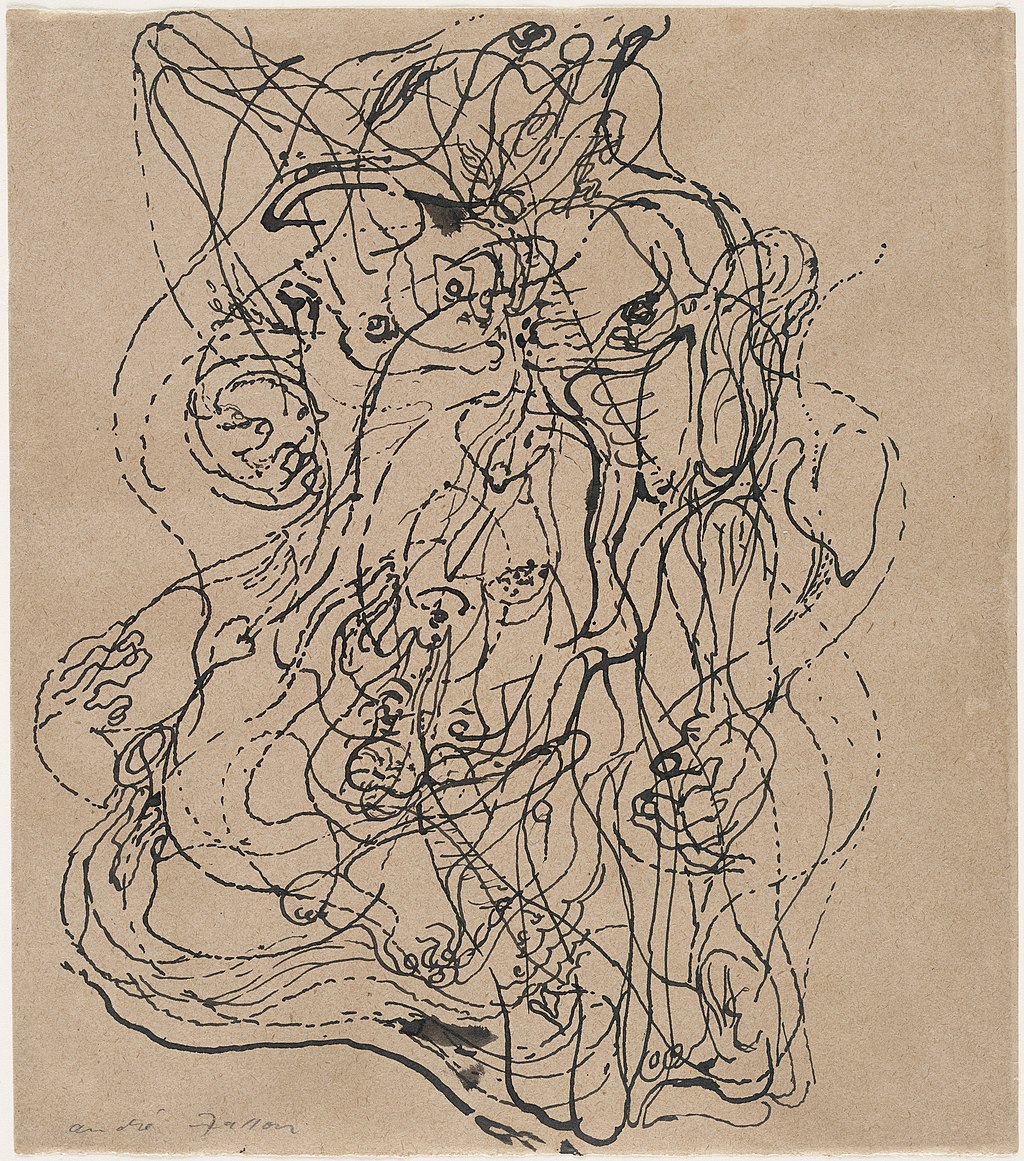

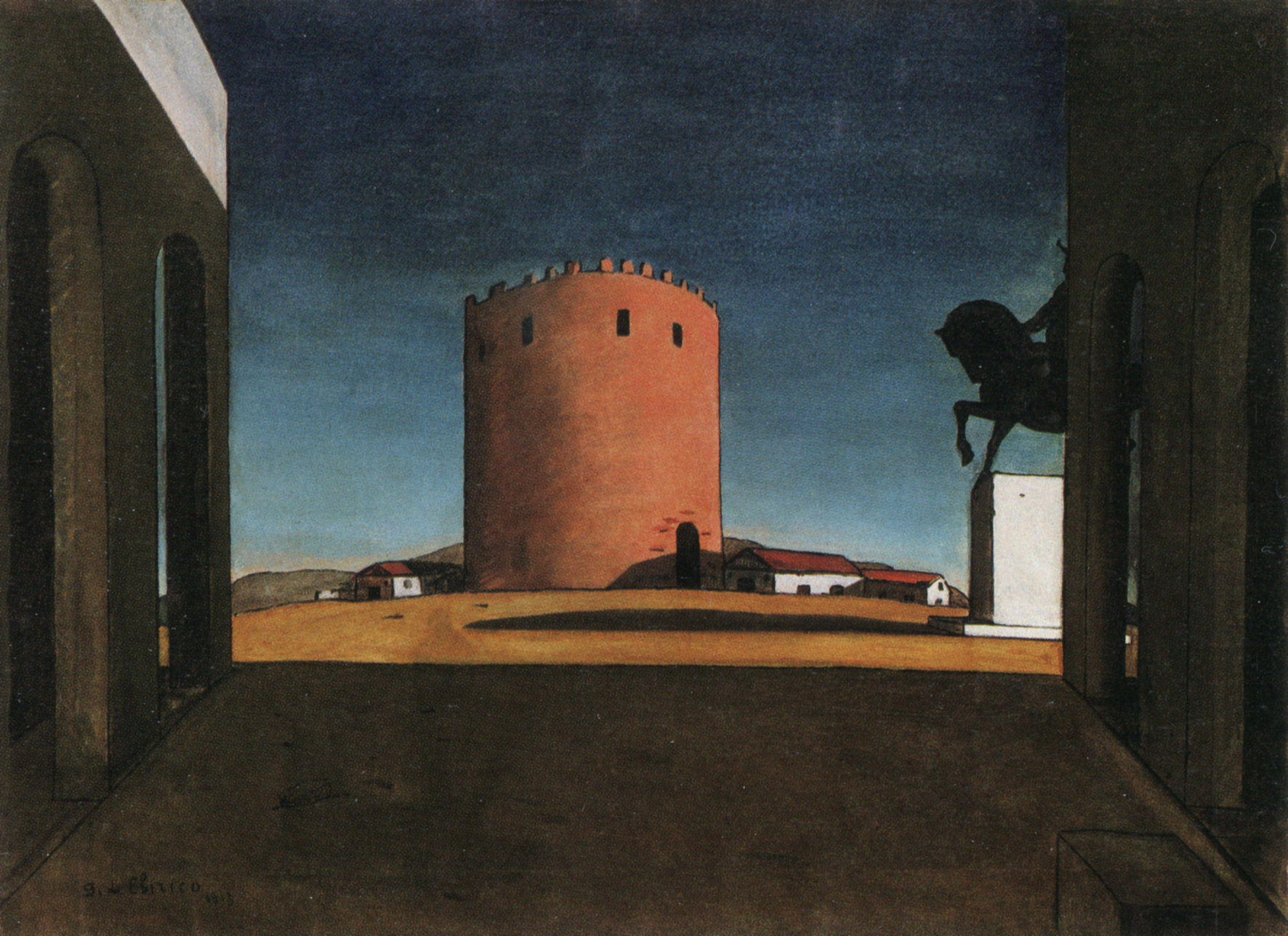

| Expansion This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (April 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Surrealism in the 20s" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)  Giacometti's Woman with Her Throat Cut, 1932 (cast 1949), Museum of Modern Art, New York City The movement in the mid-1920s was characterized by meetings in cafes where the Surrealists played collaborative drawing games, discussed the theories of Surrealism, and developed a variety of techniques such as automatic drawing. Breton initially doubted that visual arts could even be useful in the Surrealist movement since they appeared to be less malleable and open to chance and automatism. This caution was overcome by the discovery of such techniques as frottage, grattage[30] and decalcomania. Soon more visual artists became involved, including Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Francis Picabia, Yves Tanguy, Salvador Dalí, Luis Buñuel, Alberto Giacometti, Valentine Hugo, Méret Oppenheim, Toyen, Kansuke Yamamoto and later after the second war: Enrico Donati, Vinicius Pradella and Denis Fabbri. Though Breton admired Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp and courted them to join the movement, they remained peripheral.[31] More writers also joined, including former Dadaist Tristan Tzara, René Char, and Georges Sadoul.  André Masson. Automatic Drawing. 1924. Ink on paper, 23.5 × 20.6 cm. Museum of Modern Art, New York. In 1925 an autonomous Surrealist group formed in Brussels. The group included the musician, poet, and artist E. L. T. Mesens, painter and writer René Magritte, Paul Nougé, Marcel Lecomte, and André Souris. In 1927 they were joined by the writer Louis Scutenaire. They corresponded regularly with the Paris group, and in 1927 both Goemans and Magritte moved to Paris and frequented Breton's circle.[19] The artists, with their roots in Dada and Cubism, the abstraction of Wassily Kandinsky, Expressionism, and Post-Impressionism, also reached to older "bloodlines" or proto-surrealists such as Hieronymus Bosch, and the so-called primitive and naive arts. André Masson's automatic drawings of 1923 are often used as the point of the acceptance of visual arts and the break from Dada, since they reflect the influence of the idea of the unconscious mind. Another example is Giacometti's 1925 Torso, which marked his movement to simplified forms and inspiration from preclassical sculpture. However, a striking example of the line used to divide Dada and Surrealism among art experts is the pairing of 1925's Little Machine Constructed by Minimax Dadamax in Person (Von minimax dadamax selbst konstruiertes maschinchen)[32] with The Kiss (Le Baiser)[33] from 1927 by Max Ernst.[clarify] The first is generally held to have a distance, and erotic subtext, whereas the second presents an erotic act openly and directly.[improper synthesis?] In the second the influence of Miró and the drawing style of Picasso is visible with the use of fluid curving and intersecting lines and colour, whereas the first takes a directness that would later be influential in movements such as Pop art.  Giorgio de Chirico, The Red Tower (La Tour Rouge), 1913, Guggenheim Museum Giorgio de Chirico, and his previous development of metaphysical art, was one of the important joining figures between the philosophical and visual aspects of Surrealism. Between 1911 and 1917, he adopted an unornamented depictional style whose surface would be adopted by others later. The Red Tower (La tour rouge) from 1913 shows the stark colour contrasts and illustrative style later adopted by Surrealist painters. His 1914 The Nostalgia of the Poet (La Nostalgie du poète)[34] has the figure turned away from the viewer, and the juxtaposition of a bust with glasses and a fish as a relief defies conventional explanation. He was also a writer whose novel Hebdomeros presents a series of dreamscapes with an unusual use of punctuation, syntax, and grammar designed to create an atmosphere and frame its images. His images, including set designs for the Ballets Russes, would create a decorative form of Surrealism, and he would be an influence on the two artists who would be even more closely associated with Surrealism in the public mind: Dalí and Magritte. He would, however, leave the Surrealist group in 1928. In 1924, Miró and Masson applied Surrealism to painting. The first Surrealist exhibition, La Peinture Surrealiste, was held at Galerie Pierre in Paris in 1925. It displayed works by Masson, Man Ray, Paul Klee, Miró, and others. The show confirmed that Surrealism had a component in the visual arts (though it had been initially debated whether this was possible), and techniques from Dada, such as photomontage, were used. The following year, on March 26, 1926, Galerie Surréaliste opened with an exhibition by Man Ray. Breton published Surrealism and Painting in 1928 which summarized the movement to that point, though he continued to update the work until the 1960s. |

拡大 このセクションにはオリジナルの研究が含まれている可能性があります。 主張を検証し、インライン引用を追加することで改善してください。独自研究のみからなる記述は削除してください。(2021年4月)(このテンプレート メッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)このセクションには検証のための追加引用が必要です。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加する ことで、この記事の改善にご協力ください。ソースのないものは、異議申し立てがなされ、削除されることがあります。出典を探す 「20年代のシュルレアリスム」 - ニュース - 新聞 - 本 - 学術 - JSTOR (April 2021) (このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)  ジャコメッティの《喉を切られた女》1932年(1949年鋳造)、ニューヨーク近代美術館蔵 1920年代半ばの運動は、シュルレアリストたちが共同でドローイングゲームをしたり、シュルレアリスムの理論について議論したり、自動ドローイングなど さまざまな技法を開発したりするカフェでの会合が特徴的だった。ブルトンは当初、視覚芸術がシュルレアリスム運動に役立つのかどうかさえ疑っていた。この 警戒心は、フロッタージュ、グラッタージュ[30]、デカルコマニアといった技法の発見によって克服された。 第二次世界大戦後は、エンリコ・ドナーティ、ヴィニシウス・プラデッラ、ドゥニ・ファブリらがいる。ブルトンはパブロ・ピカソやマルセル・デュシャンを敬 愛し、運動への参加を呼びかけたが、彼らは周辺にとどまった[31]。  アンドレ・マッソン 自動ドローイング。1924. 紙にインク、23.5×20.6cm。ニューヨーク近代美術館蔵。 1925年、ブリュッセルでシュルレアリスムの自主グループが結成された。このグループには、音楽家、詩人、芸術家のE・L・T・メサンス、画家で作家の ルネ・マグリット、ポール・ヌジェ、マルセル・ルコント、アンドレ・スーリらがいた。1927年には作家のルイ・スクテネールが加わった。ダダやキュビス ム、ワシリー・カンディンスキーの抽象主義、表現主義、ポスト印象派にルーツを持つ芸術家たちは、ヒエロニムス・ボスのような古い「血統」やシュルレアリ スムの原型、いわゆるプリミティブ・アートや素朴芸術にも手を伸ばした。 アンドレ・マッソンが1923年に発表した自動ドローイングは、視覚芸術の受容とダダからの脱却のきっかけとしてよく使われる。もうひとつの例は、ジャコメッティの1925年の「トルソ」で、単純化された形態への移行と古典以前の彫刻からの着想を示している。 しかし、美術の専門家の間でダダとシュルレアリスムを分けるために使われる線引きの顕著な例は、1925年の『ミニマックス・ダダマックスが個人的に構築 した小さな機械』(Von minimax dadamax selbst konstruiertes maschinchen)[32]とマックス・エルンストの1927年の『接吻』(Le Baiser)[33]の対である。 [明確]1つ目は一般的に距離があり、エロティックなサブテキストを持っていると考えられているのに対し、2つ目はオープンで直接的にエロティックな行為 を提示している[不適切な合成?]2つ目では、流動的な曲線と交差する線と色の使用により、ミロとピカソのドローイングのスタイルの影響が見られるのに対 し、1つ目は後にポップ・アートのような動きに影響を与えることになる直接性を取っている。  ジョルジョ・デ・キリコ《赤い塔(ラ・トゥール・ルージュ)》1913年、グッゲンハイム美術館蔵 ジョルジョ・デ・キリコと、彼のそれまでの形而上学的芸術の展開は、シュルレアリスムの哲学的側面と視覚的側面の重要な接点のひとつであった。1911年 から1917年にかけて、デ・キリコは装飾のない描写スタイルを採用した。1913年の『赤い塔』(La tour rouge)には、後にシュルレアリスムの画家たちが採用することになる、峻烈な色彩のコントラストと挿絵的なスタイルが表れている。1914年の『詩人 の郷愁』(La Nostalgie du poète)[34]は、人物が鑑賞者から背を向けており、眼鏡をかけた胸像とレリーフとしての魚の並置は、従来の説明を覆す。彼はまた作家でもあり、小 説『ヘブドメロス』では、句読点、構文、文法を独特に用いて一連の夢物語を表現し、雰囲気を作り出し、イメージを枠にはめることを意図している。バレエ・ リュスのセットデザインを含む彼のイメージは、シュルレアリスムの装飾的な形式を生み出すことになり、世間一般にシュルレアリスムとさらに密接に結びつく ことになる2人の芸術家に影響を与えることになる: ダリとマグリットである。しかし、彼は1928年にシュルレアリスムのグループから離脱する。 1924年、ミロとマッソンはシュルレアリスムを絵画に応用。1925年、最初のシュルレアリスム展「La Peinture Surrealiste」がパリのギャルリーピエールで開催された。マッソン、マン・レイ、パウル・クレー、ミロらの作品が展示された。この展覧会では、 シュルレアリスムが視覚芸術の要素を持っていることが確認され(当初はそれが可能かどうか議論されていたが)、フォトモンタージュなどダダの技法が用いら れた。翌1926年3月26日、ギャルリー・シュルレアリストはマン・レイの展覧会でオープンした。ブルトンは1928年に『シュルレアリスムと絵画』を 出版し、それまでの運動を総括したが、1960年代まで更新を続けた。 |

| Surrealist literature See also: List of Surrealist poets The first Surrealist work, according to leader Brêton, was Les Chants de Maldoror;[35] and the first work written and published by his group of Surréalistes was Les Champs Magnétiques (May–June 1919).[36] Littérature contained automatist works and accounts of dreams. The magazine and the portfolio both showed their disdain for literal meanings given to objects and focused rather on the undertones; the poetic undercurrents present. Not only did they give emphasis to the poetic undercurrents, but also to the connotations and the overtones which "exist in ambiguous relationships to the visual images."[37] Because Surrealist writers seldom, if ever, appear to organize their thoughts and the images they present, some people find much of their work difficult to parse. This notion however is a superficial comprehension, prompted no doubt by Breton's initial emphasis on automatic writing as the main route toward a higher reality. But—as in Breton's case—much of what is presented as purely automatic is actually edited and very "thought out". Breton himself later admitted that automatic writing's centrality had been overstated, and other elements were introduced, especially as the growing involvement of visual artists in the movement forced the issue, since automatic painting required a rather more strenuous set of approaches. Thus, such elements as collage were introduced, arising partly from an ideal of startling juxtapositions as revealed in Pierre Reverdy's poetry. And—as in Magritte's case (where there is no obvious recourse to either automatic techniques or collage)—the very notion of convulsive joining became a tool for revelation in and of itself. Surrealism was meant to be always in flux—to be more modern than modern—and so it was natural there should be a rapid shuffling of the philosophy as new challenges arose. Artists such as Max Ernst and his surrealist collages demonstrate this shift to a more modern art form that also comments on society.[38] Surrealists revived interest in Isidore Ducasse, known by his pseudonym Comte de Lautréamont, and for the line "beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella", and Arthur Rimbaud, two late 19th-century writers believed to be the precursors of Surrealism. Examples of Surrealist literature are Artaud's Le Pèse-Nerfs (1926), Aragon's Irene's Cunt (1927), Péret's Death to the Pigs (1929), Crevel's Mr. Knife Miss Fork (1931), Sadegh Hedayat's the Blind Owl (1937), and Breton's Sur la route de San Romano (1948). La Révolution surréaliste continued publication into 1929 with most pages densely packed with columns of text, but which also included reproductions of art, among them works by de Chirico, Ernst, Masson, and Man Ray. Other works included books, poems, pamphlets, automatic texts and theoretical tracts. Surrealist films Main article: Surrealist cinema Early films by Surrealists include: Entr'acte by René Clair (1924) The Seashell and the Clergyman (French: La Coquille et le clergyman) by Germaine Dulac, scenario by Antonin Artaud (1928) L'Étoile de mer by Man Ray (1928) Un Chien Andalou by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí (1929) L'Âge d'Or by Buñuel and Dalí (1930) The Blood of a Poet (French: Le sang d'un poète) by Jean Cocteau (1930) Surrealist photography Famous Surrealist photographers are the American Man Ray, the French/Hungarian Brassaï, French Claude Cahun and the Dutch Emiel van Moerkerken.[39][40] Surrealist theatre The word surrealist was first used by Apollinaire to describe his 1917 play Les Mamelles de Tirésias ("The Breasts of Tiresias"), which was later adapted into an opera by Francis Poulenc.[citation needed] Roger Vitrac's The Mysteries of Love (1927) and Victor, or The Children Take Over (1928) are often considered the best examples of Surrealist theatre, despite his expulsion from the movement in 1926.[41][42][43] The plays were staged at the Theatre Alfred Jarry, the theatre Vitrac co-founded with Antonin Artaud, another early Surrealist who was expelled from the movement.[44] Following his collaboration with Vitrac, Artaud would extend Surrealist thought through his theory of the Theatre of Cruelty. Artaud rejected the majority of Western theatre as a perversion of its original intent, which he felt should be a mystical, metaphysical experience.[45] Instead, he envisioned a theatre that would be immediate and direct, linking the unconscious minds of performers and spectators in a sort of ritual event, Artaud created in which emotions, feelings, and the metaphysical were expressed not through language but physically, creating a mythological, archetypal, allegorical vision, closely related to the world of dreams.[46][47] The Spanish playwright and director Federico García Lorca, also experimented with surrealism, particularly in his plays The Public (1930), When Five Years Pass (1931), and Play Without a Title (1935). Other surrealist plays include Aragon's Backs to the Wall (1925).[48] Gertrude Stein's opera Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights (1938) has also been described as "American Surrealism", though it is also related to a theatrical form of cubism.[49] Surrealist music Main article: Surrealist music In the 1920s several composers were influenced by Surrealism, or by individuals in the Surrealist movement. Among them were Bohuslav Martinů, André Souris, Erik Satie,[50] Francis Poulenc,[51][52] and Edgard Varèse, who stated that his work Arcana was drawn from a dream sequence.[53] Souris in particular was associated with the movement: he had a long relationship with Magritte, and worked on Paul Nougé's publication Adieu Marie. Music by composers from across the twentieth century have been associated with surrealist principles, including Pierre Boulez,[54] György Ligeti,[55] Mauricio Kagel, Olivier Messiaen,[56] and Thomas Adès.[57][58] Germaine Tailleferre of the French group Les Six wrote several works which could be considered to be inspired by Surrealism[citation needed], including the 1948 ballet Paris-Magie (scenario by Lise Deharme), the operas La Petite Sirène (book by Philippe Soupault) and Le Maître (book by Eugène Ionesco).[59] Tailleferre also wrote popular songs to texts by Claude Marci, the wife of Henri Jeanson, whose portrait had been painted by Magritte in the 1930s. Even though Breton by 1946 responded rather negatively to the subject of music with his essay Silence is Golden, later Surrealists, such as Paul Garon, have been interested in—and found parallels to—Surrealism in the improvisation of jazz and the blues. Jazz and blues musicians have occasionally reciprocated this interest. For example, the 1976 World Surrealist Exhibition included performances by David "Honeyboy" Edwards. |

シュルレアリスム文学 こちらも参照: シュルレアリスムの詩人一覧 リーダーのブレトンによれば、最初のシュルレアリスム作品は『マルドロールの聖歌』(Les Chants de Maldoror)であり[35]、シュルレアリスムのグループによって書かれ出版された最初の作品は『シャン・マグネティック』(Les Champs Magnétiques、1919年5月~6月)であった[36]。雑誌もポートフォリオも、モノに与えられた文字通りの意味を軽んじ、むしろそこにある 詩的な底流に焦点を当てた。詩的な底流だけでなく、「視覚的イメージとのあいまいな関係の中に存在する」含蓄や倍音にも重点を置いていた[37]。 シュルレアリスムの作家たちは、自分の思考や提示するイメージを整理しているように見えることはほとんどないため、彼らの作品の多くを解析するのが難しい と感じる人もいる。しかし、この考え方は表面的な理解であり、ブルトンが当初、高次の現実に向かう主要な経路として自動書記を強調していたことに促された ものであることは間違いない。しかし、ブルトンの場合と同様に、純粋な自動書記として提示されるものの多くは、実際には編集され、非常に「考え抜かれた」 ものである。ブルトン自身は後に、自動筆記の中心性が誇張されすぎていたことを認め、他の要素が導入された。特に、運動への視覚芸術家の関与が強まるにつ れて、自動絵画はより厳しい一連のアプローチを必要とするため、その問題を余儀なくされた。ピエール・ルヴェルディの詩に見られるような、驚くような並置 の理想から、コラージュのような要素が導入されたのである。そして、マグリットの場合と同様に(自動的な技法やコラージュに頼ることは明らかではない が)、痙攣的な接合という概念そのものが、啓示のための道具となった。シュルレアリスムは常に流動的であり、モダンよりもモダンであることを意図していた ため、新たな挑戦が生まれれば、哲学が急速に変化するのは当然のことだった。マックス・エルンストや彼のシュルレアリスム的なコラージュのような芸術家た ちは、社会に対するコメントも兼ねた、より現代的な芸術形態への移行を実証している[38]。 シュルレアリストたちは、「ミシンと傘が解剖台で偶然出会うように美しい」というセリフで知られるロートレアモン伯爵のペンネームで知られるイシドール・ デュカスや、アルチュール・ランボーというシュルレアリスムの先駆者とされる19世紀末の2人の作家への関心を復活させた。 シュルレアリスム文学の例としては、アルトーの『Le Pèse-Nerfs』(1926年)、アラゴンの『Irene's Cunt』(1927年)、ペレの『Death to the Pigs』(1929年)、クレヴェルの『Mr. Knife Miss Fork』(1931年)、サデグ・ヘダヤットの『The Blind Owl』(1937年)、ブルトンの『Sur la route de San Romano』(1948年)などがある。 La Révolution surréaliste』は1929年まで刊行され、ほとんどのページがテキストでびっしりと埋め尽くされていたが、デ・キリコ、エルンスト、マッソン、 マン・レイなどの作品の複製も掲載されていた。その他の作品には、書籍、詩、パンフレット、自動テキスト、理論書などがあった。 シュルレアリスム映画 主な記事 シュルレアリスム映画 シュルレアリストによる初期の映画には以下のものがある: ルネ・クレールの『Entr'acte』(1924年) ジェルメーヌ・デュラックの『貝殻と聖職者』(仏:La Coquille et le clergyman)、アントナン・アルトーのシナリオ(1928年) マン・レイ作『L'Étoile de mer』(1928年) ルイス・ブニュエルとサルバドール・ダリによる『Un Chien Andalou』(1929年) ブニュエルとダリによる『L'Âge d'Or』(1930年) 詩人の血(仏:Le sang d'un poète) by ジャン・コクトー(1930年) シュルレアリスムの写真 シュルレアリスムの写真家として有名なのは、アメリカのマン・レイ、フランス/ハンガリーのブラッサイ、フランスのクロード・カウン、オランダのエミール・ヴァン・モアケルケン[39][40]。 シュルレアリスム演劇 シュルレアリスムという言葉は、アポリネールが1917年に発表した戯曲『ティレジアスの乳房』(Les Mamelles de Tireésias)を表現するために使われたのが最初であり、後にフランシス・プーランクによってオペラ化された[要出典]。 ロジェ・ヴィトラックの『愛の神秘』(1927年)と『ヴィクトール、あるいは子供たちが乗っ取る』(1928年)は、1926年に運動から追放されたにもかかわらず、しばしばシュルレアリスム演劇の最良の例と考えられている[41][42][43]。 ヴィトラックとの共同作業の後、アルトーは「残酷劇場」の理論を通してシュルレアリスムの思想を拡張することになる。アルトーは、西洋演劇の大半を、神秘 的で形而上学的な体験であるべきだと感じていたその本来の意図の倒錯として否定した[45]。その代わりに、彼は即物的で直接的な演劇を構想し、一種の儀 式的な出来事において演者と観客の無意識の心を結びつける。アルトーは、感情、感情、形而上学的なものが言語を通してではなく身体的に表現され、夢の世界 と密接に関連した神話的、原型的、寓話的なヴィジョンを創造した[46][47]。 スペインの劇作家であり演出家であったフェデリコ・ガルシア・ロルカもまた、シュルレアリスムの実験を行っており、特に彼の戯曲『The Public』(1930年)、『When Five Years Pass』(1931年)、『Play Without a Title』(1935年)において顕著である。他のシュルレアリスム劇にはアラゴンの『壁に背を向けて』(1925年)などがある[48]。ガートルー ド・スタインのオペラ『ファウストゥス博士、灯をともす』(1938年)も「アメリカのシュルレアリスム」と評されているが、キュビスムの演劇形態とも関 連している[49]。 シュルレアリスムの音楽 主な記事 シュルレアリスム音楽 1920年代、何人かの作曲家がシュルレアリスムの影響を受けた。その中には、ボフスラフ・マルティヌー、アンドレ・スーリ、エリック・サティ、[50] フランシス・プーランク、[51][52] エドガール・ヴァレーズなどがおり、彼は自身の作品『アルカナ』が夢のシークエンスから描かれたと述べている[53]。 特にスーリはこの運動と関係が深く、マグリットと長い付き合いがあり、ポール・ヌジェの出版物『アデュー・マリー』に携わった。ピエール・ブーレーズ [54]、ギョルジー・リゲティ[55]、マウリシオ・カジェル、オリヴィエ・メシアン[56]、トーマス・アデス[57][58]など、20世紀の作曲 家の音楽はシュルレアリスムの原理と関連している。 フランスのグループ「レ・シックス」のジェルメーヌ・タイユフェールは、1948年のバレエ『パリ・マギー』(シナリオ:リゼ・ドゥアルム)、オペラ 『ラ・プティット・シレーヌ』(原作:フィリップ・スポー)、『ル・メートル』(原作:ウジェーヌ・イヨネスコ)など、シュルレアリスムに触発されたと考 えられる作品をいくつか書いている。 1946年までのブルトンは、『沈黙は黄金である』というエッセイで音楽の主題に否定的な反応を示していたが、ポール・ガロンなど後のシュルレアリストた ちは、ジャズやブルースの即興演奏に興味を持ち、シュルレアリスムとの類似性を見出している。ジャズやブルースのミュージシャンたちは、時折この関心に応 えてきた。例えば、1976年の世界シュルレアリスム展では、デヴィッド・"ハニーボーイ"・エドワーズが演奏した。 |

| Surrealism and international politics Surrealism as a political force developed unevenly around the world: in some places more emphasis was on artistic practices, in other places on political practices, and in other places still, Surrealist praxis looked to supersede both the arts and politics. During the 1930s, the Surrealist idea spread from Europe to North America, South America (founding of the Mandrágora group in Chile in 1938), Central America, the Caribbean, and throughout Asia, as both an artistic idea and as an ideology of political change.[60][61] Politically, Surrealism was Trotskyist, communist, or anarchist.[60] The split from Dada has been characterised as a split between anarchists and communists, with the Surrealists as communist. Breton and his comrades supported Leon Trotsky and his International Left Opposition for a while, though there was an openness to anarchism that manifested more fully after World War II. Some Surrealists, such as Benjamin Péret, Mary Low, and Juan Breá, aligned with forms of left communism. When the Dutch surrealist photographer Emiel van Moerkerken came to Breton, he did not want to sign the manifesto because he was not a Trotskyist. For Breton being a communist was not enough. Breton denied Van Moerkerken's pictures for a publication afterwards.[39] This caused a split in surrealism. Others fought for complete liberty from political ideologies, like Wolfgang Paalen, who, after Trotsky's assassination in Mexico, prepared a schism between art and politics through his counter-surrealist art-magazine DYN and so prepared the ground for the abstract expressionists. Dalí supported capitalism and the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco but cannot be said to represent a trend in Surrealism in this respect; in fact, he was considered, by Breton and his associates, to have betrayed and left Surrealism. Benjamin Péret, Mary Low, Juan Breá, and Spanish-native Eugenio Fernández Granell joined the POUM during the Spanish Civil War.[60][61] Breton's followers, along with the Communist Party, were working for the "liberation of man". However, Breton's group refused to prioritize the proletarian struggle over radical creation such that their struggles with the Party made the late 1920s a turbulent time for both. Many individuals closely associated with Breton, notably Aragon, left his group to work more closely with the Communists.[60][61] Surrealists have often sought to link their efforts with political ideals and activities. In the Declaration of January 27, 1925,[62] for example, members of the Paris-based Bureau of Surrealist Research (including Breton, Aragon and Artaud, as well as some two dozen others) declared their affinity for revolutionary politics. While this was initially a somewhat vague formulation, by the 1930s many Surrealists had strongly identified themselves with communism. The foremost document of this tendency within Surrealism is the Manifesto for a Free Revolutionary Art,[63] published under the names of Breton and Diego Rivera, but actually co-authored by Breton and Leon Trotsky.[64] However, in 1933 the Surrealists' assertion that a "proletarian literature" within a capitalist society was impossible led to their break with the Association des Ecrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires, and the expulsion of Breton, Éluard and Crevel from the Communist Party.[19] In 1925, the Paris Surrealist group and the extreme left of the French Communist Party came together to support Abd-el-Krim, leader of the Rif uprising against French colonialism in Morocco. In an open letter to writer and French ambassador to Japan, Paul Claudel, the Paris group announced: We Surrealists pronounced ourselves in favour of changing the imperialist war, in its chronic and colonial form, into a civil war. Thus we placed our energies at the disposal of the revolution, of the proletariat and its struggles, and defined our attitude towards the colonial problem, and hence towards the colour question. The anticolonial revolutionary and proletarian politics of "Murderous Humanitarianism" (1932) which was drafted mainly by Crevel, signed by Breton, Éluard, Péret, Tanguy, and the Martiniquan Surrealists Pierre Yoyotte and J.M. Monnerot perhaps makes it the original document of what is later called "black Surrealism",[65] although it is the contact between Aimé Césaire and Breton in the 1940s in Martinique that really lead to the communication of what is known as "black Surrealism". Anticolonial revolutionary writers in the Négritude movement of Martinique, a French colony at the time, took up Surrealism as a revolutionary method – a critique of European culture and a radical subjective. This linked with other Surrealists and was very important for the subsequent development of Surrealism as a revolutionary praxis. The journal Tropiques, featuring the work of Césaire along with Suzanne Césaire, René Ménil, Lucie Thésée, Aristide Maugée and others, was first published in 1941.[66] In 1938 André Breton traveled with his wife, the painter Jacqueline Lamba, to Mexico to meet Trotsky (staying as the guest of Diego Rivera's former wife Guadalupe Marin), and there he met Frida Kahlo and saw her paintings for the first time. Breton declared Kahlo to be an "innate" Surrealist painter.[67] Internal politics In 1929 the satellite group associated with the journal Le Grand Jeu, including Roger Gilbert-Lecomte, Maurice Henry and the Czech painter Josef Sima, was ostracized. Also in February, Breton asked Surrealists to assess their "degree of moral competence", and theoretical refinements included in the second manifeste du surréalisme excluded anyone reluctant to commit to collective action, a list which included Leiris, Limbour, Morise, Baron, Queneau, Prévert, Desnos, Masson and Boiffard. Excluded members launched a counterattack, sharply criticizing Breton in the pamphlet Un Cadavre, which featured a picture of Breton wearing a crown of thorns. The pamphlet drew upon an earlier act of subversion by likening Breton to Anatole France, whose unquestioned value Breton had challenged in 1924. The disunion of 1929–30 and the effects of Un Cadavre had very little negative impact upon Surrealism as Breton saw it, since core figures such as Aragon, Crevel, Dalí and Buñuel remained true to the idea of group action, at least for the time being. The success (or the controversy) of Dalí and Buñuel's film L'Age d'Or in December 1930 had a regenerative effect, drawing a number of new recruits, and encouraging countless new artistic works the following year and throughout the 1930s. Disgruntled surrealists moved to the periodical Documents, edited by Georges Bataille, whose anti-idealist materialism formed a hybrid Surrealism intending to expose the base instincts of humans.[19][68] To the dismay of many, Documents fizzled out in 1931, just as Surrealism seemed to be gathering more steam. There were a number of reconciliations after this period of disunion, such as between Breton and Bataille, while Aragon left the group after committing himself to the French Communist Party in 1932. More members were ousted over the years for a variety of infractions, both political and personal, while others left in pursuit of their own style. By the end of World War II, the surrealist group led by André Breton decided to explicitly embrace anarchism. In 1952 Breton wrote "It was in the black mirror of anarchism that surrealism first recognised itself."[69] Breton was consistent in his support for the francophone Anarchist Federation and he continued to offer his solidarity after the Platformists supporting Fontenis transformed the FA into the Fédération Communiste Libertaire. He was one of the few intellectuals who continued to offer his support to the FCL during the Algerian war when the FCL suffered severe repression and was forced underground. He sheltered Fontenis whilst he was in hiding. He refused to take sides on the splits in the French anarchist movement and both he and Peret expressed solidarity as well with the new Fédération anarchiste set up by the synthesist anarchists and worked in the Antifascist Committees of the 60s alongside the FA.[69] |

シュルレアリスムと国際政治 ある場所では芸術的実践が重視され、別の場所では政治的実践が重視され、さらに別の場所では、シュルレアリスムの実践が芸術と政治の両方に取って代わろう とした。1930年代、シュルレアリスムの思想はヨーロッパから北アメリカ、南アメリカ(1938年にチリでマンドラゴラ・グループを設立)、中央アメリ カ、カリブ海諸国、そしてアジア全域へと、芸術的思想として、また政治的変革のイデオロギーとして広がっていった[60][61]。 政治的には、シュルレアリスムはトロツキスト、共産主義者、無政府主義者であった[60]。ダダからの分裂は無政府主義者と共産主義者の分裂として特徴づ けられ、シュルレアリストは共産主義者であった。ブルトンと彼の同志たちは、しばらくの間、レオン・トロツキーと彼の国際左翼反対同盟を支持していたが、 第二次世界大戦後、無政府主義に対する開放的な姿勢がより顕著になった。ベンジャミン・ペレ、メアリー・ロー、ファン・ブレアといったシュルレアリストの 中には、左翼共産主義に賛同する者もいた。オランダのシュルレアリスム写真家エミール・ヴァン・モアカーケンがブルトンのもとを訪れたとき、彼はトロツキ ストではなかったため、マニフェストへの署名を望まなかった。ブルトンにとって、共産主義者であるだけでは十分ではなかったのだ。このことがシュルレアリ スムの分裂を引き起こした。また、メキシコでトロツキーが暗殺された後、反シュルレアリスムの美術雑誌『DYN』を通して芸術と政治の分裂を準備し、抽象 表現主義者たちの地ならしをしたヴォルフガング・パーレンのように、政治的イデオロギーからの完全な自由を求めて戦った者もいた。ダリは資本主義とフラン シスコ・フランコのファシスト独裁を支持したが、この点ではシュルレアリスムの潮流を代表しているとは言えない。ベンジャミン・ペレ、メアリー・ロウ、フ アン・ブレア、そしてスペイン出身のエウヘニオ・フェルナンデス・グラネルはスペイン内戦中にPOUMに参加した[60][61]。 ブルトンの信奉者たちは共産党とともに「人間の解放」のために活動していた。しかし、ブルトンのグループは、急進的な創造よりもプロレタリア闘争を優先す ることを拒否したため、党との闘争によって1920年代後半は両者にとって激動の時代となった。ブルトンと密接な関係にあった多くの人物、特にアラゴン は、共産主義者とより密接に活動するために彼のグループを去った[60][61]。シュルレアリストたちは、しばしば自分たちの活動を政治的な理想や活動 と結びつけようとしてきた。例えば、1925年1月27日の宣言[62]では、パリを拠点とするシュルレアリスム研究局(ブルトン、アラゴン、アルトー、 その他20数名)のメンバーは、革命政治への親和性を宣言している。これは当初はやや曖昧な表現だったが、1930年代までには多くのシュルレアリストが 共産主義を強く意識するようになった。シュルレアリスムにおけるこの傾向の最たる文書が、ブルトンとディエゴ・リベラの名義で発表された『自由革命芸術宣 言』[63]であるが、実際にはブルトンとレオン・トロツキーの共著である[64]。 しかし1933年、資本主義社会における「プロレタリア文学」は不可能であるというシュルレアリストたちの主張によって、彼らはエクリヴァン・エ・アーティスト革命家協会と決別し、ブルトン、エルアール、クレヴェルは共産党から追放された[19]。 1925年、パリのシュルレアリスト・グループとフランス共産党の極左は、モロッコにおけるフランスの植民地主義に反対するリフ蜂起の指導者アブド=エル =クリムを支援するために一緒になった。作家で駐日フランス大使のポール・クローデルに宛てた公開書簡の中で、パリのグループはこう発表した:私たちシュ ルレアリストは、慢性的で植民地的な帝国主義戦争を内戦に変えることを支持します。こうしてわれわれは、革命とプロレタリアートとその闘争のために力を尽 くし、植民地問題、ひいては色彩問題に対するわれわれの態度を明確にした。 反植民地革命的でプロレタリア的な政治である『殺人的人道主義』(1932年)は、主にクレヴェルによって起草され、ブルトン、エルアール、ペレ、タン ギー、そしてマルティニカのシュルレアリストであるピエール・ヨヨットとJ.M.が署名した。モネロによって、後に「黒いシュルレアリスム」と呼ばれるも のの原型となった文書である[65]。 当時フランスの植民地であったマルティニークのネグリチュード運動に参加していた反植民地的な革命作家たちは、革命的な方法としてシュルレアリスムを取り 上げた。これは他のシュルレアリストたちと結びつき、革命的実践としてのシュルレアリスムのその後の発展にとって非常に重要だった。シュザンヌ・セゼー ル、ルネ・メニル、リュシー・テゼ、アリスティド・モージェらとともにセゼールの作品を特集した雑誌『Tropiques』は1941年に創刊された [66]。 1938年、アンドレ・ブルトンは妻で画家のジャクリーヌ・ランバとともにトロツキーに会うためにメキシコを訪れ(ディエゴ・リベラの前妻グアダルーペ・ マリンの客として滞在)、そこでフリーダ・カーロに出会い、初めて彼女の絵を見た。ブルトンはカーロを「生来の」シュルレアリスムの画家であると宣言した [67]。 内部政治 1929年、ロジェ・ジルベール=ルコント、モーリス・アンリ、チェコの画家ジョゼフ・シマら、雑誌『ル・グラン・ジュー』に関連した衛星グループは追放 された。また2月には、ブルトンがシュルレアリストたちに「道徳的能力の度合い」を評価するよう求め、第2次シュルレアリスム宣言に盛り込まれた理論的洗 練により、集団行動に消極的な者は排除された。排除されたメンバーは反撃を開始し、茨の冠をかぶったブルトンの写真を掲載したパンフレット『Un Cadavre』でブルトンを痛烈に批判した。この小冊子は、ブルトンを1924年にブルトンが疑問を呈していたアナトール・フランスになぞらえるとい う、以前の破壊的行為に基づくものであった。 アラゴン、クレヴェル、ダリ、ブニュエルといった中心人物は、少なくとも当分の間は、集団行動の理念に忠実であり続けたからである。1930年12月のダ リとブニュエルの映画『L'Age d'Or』の成功(あるいは論争)は再生効果をもたらし、多くの新人を引き寄せ、翌年から1930年代にかけて無数の新しい芸術作品を促した。 不満を抱いたシュルレアリストたちは、ジョルジュ・バタイユが編集する定期刊行物『ドキュメント』誌に移った。彼の反理想主義的唯物論は、人間の根源的な本能を暴露することを意図したハイブリッドなシュルレアリスムを形成していた。 1932年にフランス共産党に入党したアラゴンはグループを脱退した。さらに多くのメンバーが、政治的、個人的なさまざまな違反行為によって追放された。 第二次世界大戦が終わる頃には、アンドレ・ブルトン率いるシュルレアリスト・グループは、明確にアナーキズムを受け入れることを決めた。1952年、ブル トンは「シュルレアリスムが初めて自分自身を認識したのは、アナーキズムという黒い鏡の中だった」と書いている[69]。ブルトンはフランス語圏のアナー キスト連盟を一貫して支持し、フォンテニを支持する綱領主義者たちがFAをリベルタール共産主義連盟に変えた後も連帯を表明し続けた。アルジェリア戦争 中、FCLが激しい弾圧を受け、地下に潜らざるを得なくなった際にも、FCLを支援し続けた数少ない知識人の一人である。彼は、フォンテニが潜伏している 間、匿った。彼はフランスのアナキスト運動における分裂についてどちらかの側につくことを拒否し、彼とペレは共に、統合主義アナキストによって設立された 新しいアナキスト連盟(Fédération anarchiste)との連帯を表明し、FAと共に60年代の反ファシスト委員会で活動した[69]。 |

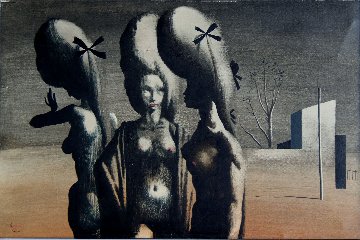

| Golden age Throughout the 1930s, Surrealism continued to become more visible to the public at large. A Surrealist group developed in London and, according to Breton, their 1936 London International Surrealist Exhibition was a high-water mark of the period and became the model for international exhibitions. Another English Surrealist group developed in Birmingham, meanwhile, and was distinguished by its opposition to the London surrealists and preferences for surrealism's French heartland. The two groups would reconcile later in the decade. Dalí and Magritte created the most widely recognized images of the movement. Dalí joined the group in 1929 and participated in the rapid establishment of the visual style between 1930 and 1935. Surrealism as a visual movement had found a method: to expose psychological truth; stripping ordinary objects of their normal significance, to create a compelling image that was beyond ordinary formal organization, in order to evoke empathy from the viewer. 1931 was a year when several Surrealist painters produced works which marked turning points in their stylistic evolution: Magritte's Voice of Space (La Voix des airs)[70] is an example of this process, where three large spheres representing bells hang above a landscape. Another Surrealist landscape from this same year is Yves Tanguy's Promontory Palace (Palais promontoire), with its molten forms and liquid shapes. Liquid shapes became the trademark of Dalí, particularly in his The Persistence of Memory, which features the image of watches that sag as if they were melting. The characteristics of this style—a combination of the depictive, the abstract, and the psychological—came to stand for the alienation which many people felt in the modern period, combined with the sense of reaching more deeply into the psyche, to be "made whole with one's individuality". Between 1930 and 1933, the Surrealist Group in Paris issued the periodical Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution as the successor of La Révolution surréaliste. From 1936 through 1938 Wolfgang Paalen, Gordon Onslow Ford, and Roberto Matta joined the group. Paalen contributed Fumage and Onslow Ford Coulage as new pictorial automatic techniques. Long after personal, political and professional tensions fragmented the Surrealist group, Magritte and Dalí continued to define a visual program in the arts. This program reached beyond painting, to encompass photography as well, as can be seen from a Man Ray self-portrait, whose use of assemblage influenced Robert Rauschenberg's collage boxes.  Max Ernst, L'Ange du Foyer ou le Triomphe du Surréalisme (1937), private collection During the 1930s Peggy Guggenheim, an important American art collector, married Max Ernst and began promoting work by other Surrealists such as Yves Tanguy and the British artist John Tunnard. Major exhibitions in the 1930s 1936 – London International Surrealist Exhibition is organised in London by the art historian Herbert Read, with an introduction by André Breton. 1936 – Museum of Modern Art in New York shows the exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism. 1938 – A new Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme was held at the Beaux-arts Gallery, Paris, with more than 60 artists from different countries, and showed around 300 paintings, objects, collages, photographs and installations. The Surrealists wanted to create an exhibition which in itself would be a creative act and called on Marcel Duchamp, Wolfgang Paalen, Man Ray and others to do so. At the exhibition's entrance Salvador Dalí placed his Rainy Taxi (an old taxi rigged to produce a steady drizzle of water down the inside of the windows, and a shark-headed creature in the driver's seat and a blond mannequin crawling with live snails in the back) greeted the patrons who were in full evening dress. Surrealist Street filled one side of the lobby with mannequins dressed by various Surrealists. Paalen and Duchamp designed the main hall to seem like cave with 1,200 coal bags suspended from the ceiling over a coal brazier with a single light bulb which provided the only lighting, as well as the floor covered with humid leaves and mud.[71] The patrons were given flashlights with which to view the art. On the floor Wolfgang Paalen created a small lake with grasses and the aroma of roasting coffee filled the air. Much to the Surrealists' satisfaction the exhibition scandalized the viewers.[31] |

黄金時代 1930年代を通じて、シュルレアリスムは一般大衆の目に触れる機会が増え続けた。シュルレアリスムのグループはロンドンで発展し、ブルトンによれば、彼 らの1936年のロンドン国際シュルレアリスム展は、この時代の最高潮であり、国際的な展覧会のモデルとなった。一方、バーミンガムでは、ロンドンのシュ ルレアリストたちと対立し、シュルレアリスムの中心地であるフランスを好む、もうひとつのイギリスのシュルレアリスト・グループが発展した。この2つのグ ループは10年後に和解する。 ダリとマグリットは、この運動で最も広く知られたイメージを創り出した。ダリは1929年にグループに参加し、1930年から1935年にかけての視覚的スタイルの急速な確立に参加した。 視覚運動としてのシュルレアリスムは、心理的真実を暴くという方法を発見した。普通の物から通常の意味を取り除き、見る者の共感を呼び起こすために、通常の形式的な構成を超えた説得力のあるイメージを作り出した。 1931年は、何人かのシュルレアリスムの画家が、彼らの様式的進化の転機となる作品を発表した年だった: マグリットの『空間の声』(La Voix des airs)[70]はこのプロセスの一例で、鐘を表す3つの大きな球体が風景の上にぶら下がっている。同じ年に制作されたもうひとつのシュルレアリスムの 風景画は、イヴ・タンギの『プロモントワール宮殿』(Palais promontoire)である。液体状の形はダリのトレードマークとなり、特に『記憶の固執』では、溶けるようにたるむ時計のイメージが特徴的である。 このスタイルの特徴である描写的、抽象的、心理的なものの組み合わせは、近代において多くの人々が感じていた疎外感を象徴するようになり、「自分の個性を完全にする」ために、精神により深く入り込もうという感覚と結びついた。 1930年から1933年にかけて、パリのシュルレアリスム・グループは、『シュルレアリスムの革命』の後継として、定期刊行物『Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution』を発行した。 1936年から1938年にかけて、ヴォルフガング・パーレン、ゴードン・オンスロー・フォード、ロベルト・マッタがグループに参加。パアレンはフマージュ、オンスロー・フォードはクーラージュを新しい絵画的自動技法として貢献した。 個人的、政治的、職業的な緊張がシュルレアリスト・グループを分断した後も、マグリットとダリは芸術における視覚的なプログラムを定義し続けた。ロバー ト・ラウシェンバーグのコラージュボックスに影響を与えたアッサンブラージュを用いたマン・レイの自画像からもわかるように、このプログラムは絵画にとど まらず、写真にも及んでいる。  マックス・エルンスト《ロワイヤーの憤怒、あるいはシュールレアリスムの凱旋》(1937年)、個人蔵 1930年代、アメリカの重要な美術コレクターであったペギー・グッゲンハイムは、マックス・エルンストと結婚し、イヴ・タンギーやイギリスの画家ジョン・タンナードなど、他のシュルレアリスムの作品を奨励し始めた。 1930年代の主な展覧会 1936年 - ロンドンで、美術史家ハーバート・リードが企画し、アンドレ・ブルトンが紹介するロンドン国際シュルレアリスム展が開催される。 1936年 - ニューヨーク近代美術館で「ファンタスティック・アート、ダダ、シュルレアリスム」展が開催される。 1938年 - パリのボザール・ギャラリーで国際シュルレアリスム展が開催され、各国から60人以上のアーティストが参加し、約300点の絵画、オブジェ、コラージュ、 写真、インスタレーションが展示される。シュルレアリスムたちは、それ自体が創造的行為となるような展覧会を作りたいと考え、マルセル・デュシャン、ヴォ ルフガング・パーレン、マン・レイらに呼びかけた。展覧会の入り口には、サルバドール・ダリの雨のタクシー(窓の内側から水滴が降り注ぎ、運転席にはサメ の頭をした生き物、後部座席には生きたカタツムリがうようよしている金髪のマネキンが乗っている)が置かれ、イブニングドレスに身を包んだ観客を出迎え た。シュルレアリスト・ストリートは、様々なシュルレアリストの服を着たマネキンでロビーの片側を埋め尽くしていた。パーレンとデュシャンは、メインホー ルを洞窟のように設計し、天井から吊るされた1,200個の石炭袋と、唯一の照明となる電球1個の石炭火鉢、そして湿気の多い葉と泥で覆われた床を設けた [71]。床にはヴォルフガング・パーレンが草で小さな湖を作り、コーヒーの焙煎の香りが充満していた。シュルレアリストたちは大満足で、この展覧会は観 客をスキャンダラスにさせた[31]。 |

World War II and the Post War period Yves Tanguy Indefinite Divisibility, 1942, Albright Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York World War II created havoc not only for the general population of Europe but especially for the European artists and writers that opposed Fascism and Nazism. Many important artists fled to North America and relative safety in the United States. The art community in New York City in particular was already grappling with Surrealist ideas and several artists like Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock, and Robert Motherwell converged closely with the surrealist artists themselves, albeit with some suspicion and reservations. Ideas concerning the unconscious and dream imagery were quickly embraced. By the Second World War, the taste of the American avant-garde in New York swung decisively towards Abstract Expressionism with the support of key taste makers, including Peggy Guggenheim, Leo Steinberg and Clement Greenberg. However, it should not be easily forgotten that Abstract Expressionism itself grew directly out of the meeting of American (particularly New York) artists with European Surrealists self-exiled during World War II. In particular, Gorky and Paalen influenced the development of this American art form, which, as Surrealism did, celebrated the instantaneous human act as the well-spring of creativity. The early work of many Abstract Expressionists reveals a tight bond between the more superficial aspects of both movements, and the emergence (at a later date) of aspects of Dadaistic humor in such artists as Rauschenberg sheds an even starker light upon the connection. Up until the emergence of Pop Art, Surrealism can be seen to have been the single most important influence on the sudden growth in American arts, and even in Pop, some of the humor manifested in Surrealism can be found, often turned to a cultural criticism. The Second World War overshadowed, for a time, almost all intellectual and artistic production. In 1939 Wolfgang Paalen was the first to leave Paris for the New World as exile. After a long trip through the forests of British Columbia, he settled in Mexico and founded his influential art-magazine Dyn. In 1940 Yves Tanguy married American Surrealist painter Kay Sage. In 1941, Breton went to the United States, where he co-founded the short-lived magazine VVV with Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, and the American artist David Hare. However, it was the American poet, Charles Henri Ford, and his magazine View which offered Breton a channel for promoting Surrealism in the United States. The View special issue on Duchamp was crucial for the public understanding of Surrealism in America. It stressed his connections to Surrealist methods, offered interpretations of his work by Breton, as well as Breton's view that Duchamp represented the bridge between early modern movements, such as Futurism and Cubism, to Surrealism. Wolfgang Paalen left the group in 1942 due to political/philosophical differences with Breton.  The Conspirators by Colin Middleton (1942), the Irish Surrealist's response to the Belfast Blitz Though the war proved disruptive for Surrealism, the works continued. Many Surrealist artists continued to explore their vocabularies, including Magritte. Many members of the Surrealist movement continued to correspond and meet. While Dalí may have been excommunicated by Breton, he neither abandoned his themes from the 1930s, including references to the "persistence of time" in a later painting, nor did he become a depictive pompier. His classic period did not represent so sharp a break with the past as some descriptions of his work might portray, and some, such as André Thirion, argued that there were works of his after this period that continued to have some relevance for the movement. When the war reached Ireland with the Belfast Blitz in May 1941, Colin Middleton, who had experimented with surrealist themes in the 1930s, responded with a series of dark works reflecting the shocked state of the people of the city. These were exhibited at the Belfast Municipal Gallery and Museum after its restoration in 1943, following near destruction in the blitz.[72] During the 1940s Surrealism's influence was also felt in England, America and the Netherlands where Gertrude Pape and her husband Theo van Baaren helped to popularize it in their publication The Clean Handkerchief.[73] Mark Rothko took an interest in biomorphic figures, and in England Henry Moore, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon and Paul Nash used or experimented with Surrealist techniques. However, Conroy Maddox, one of the first British Surrealists whose work in this genre dated from 1935, remained within the movement, and organized an exhibition of current Surrealist work in 1978 in response to an earlier show which infuriated him because it did not properly represent Surrealism. Maddox's exhibition, titled Surrealism Unlimited, was held in Paris and attracted international attention. He held his last one-man show in 2002, and died three years later. Magritte's work became more realistic in its depiction of actual objects, while maintaining the element of juxtaposition, such as in 1951's Personal Values (Les Valeurs Personnelles)[74] and 1954's Empire of Light (L’Empire des lumières).[75] Magritte continued to produce works which have entered artistic vocabulary, such as Castle in the Pyrenees (Le Château des Pyrénées),[76] which refers back to Voix from 1931, in its suspension over a landscape. Other figures from the Surrealist movement were expelled. Several of these artists, like Roberto Matta (by his own description) "remained close to Surrealism".[31] Frida Kahlo should be mentioned. She had a New York solo exhibition in 1938 with 25 paintings, encouraged by Breton himself. After the crushing of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Endre Rozsda returned to Paris to continue creating his own word that had been transcended the surrealism. The preface to his first exhibition in the Furstenberg Gallery (1957) was written by Breton yet.[77] Many new artists explicitly took up the Surrealist banner. Dorothea Tanning and Louise Bourgeois continued to work, for example, with Tanning's Rainy Day Canape from 1970. Duchamp continued to produce sculpture in secret including an installation with the realistic depiction of a woman viewable only through a peephole. Breton continued to write and espouse the importance of liberating the human mind, as with the publication The Tower of Light in 1952. Breton's return to France after the War, began a new phase of Surrealist activity in Paris, and his critiques of rationalism and dualism found a new audience. Breton insisted that Surrealism was an ongoing revolt against the reduction of humanity to market relationships, religious gestures and misery and to espouse the importance of liberating the human mind. Major exhibitions of the 1940s, '50s and '60s 1942 – First Papers of Surrealism – New York – The Surrealists again called on Duchamp to design an exhibition. This time he wove a 3-dimensional web of string throughout the rooms of the space, in some cases making it almost impossible to see the works.[78] He made a secret arrangement with an associate's son to bring his friends to the opening of the show, so that when the finely dressed patrons arrived, they found a dozen children in athletic clothes kicking and passing balls and skipping rope. His design for the show's catalog included "found", rather than posed, photographs of the artists.[31] 1947 – International Surrealist Exhibition – Galerie Maeght, Paris[79] 1959 – International Surrealist Exhibition – Paris 1960 – Surrealist Intrusion in the Enchanters' Domain – New York |

第二次世界大戦と戦後 イヴ・タンギー《不定形の分割性》1942年、オルブライト・ノックス美術館、バッファロー、ニューヨーク州 第二次世界大戦は、ヨーロッパの一般市民だけでなく、特にファシズムやナチズムに反対したヨーロッパの芸術家や作家たちに大混乱をもたらした。多くの重要 な芸術家たちが北米に逃れ、比較的安全なアメリカにたどり着いた。アルシール・ゴーリキー、ジャクソン・ポロック、ロバート・マザーウェルといった芸術家 たちは、シュルレアリスムの芸術家たち自身と、多少の疑念や留保を抱きながらも、密接に交流していた。無意識や夢のイメージに関するアイデアはすぐに受け 入れられた。第二次世界大戦までには、ニューヨークのアメリカン・アヴァンギャルドの嗜好は、ペギー・グッゲンハイム、レオ・スタインバーグ、クレメン ト・グリーンバーグといった主要な嗜好メーカーの支持を得て、抽象表現主義へと決定的に傾いた。しかし、抽象表現主義そのものが、第二次世界大戦中に亡命 したヨーロッパのシュルレアリストとアメリカ(特にニューヨーク)の芸術家たちが出会ったことから直接発展したことを簡単に忘れてはならない。特にゴーリ キーとパーレンは、シュルレアリスムがそうであったように、人間の瞬間的な行為を創造性の源泉として讃えるこのアメリカ芸術の発展に影響を与えた。多くの 抽象表現主義者の初期の作品は、両者の運動のより表面的な側面の間の緊密な結びつきを明らかにし、ラウシェンバーグのようなアーティストにダダイスティッ クなユーモアの側面が(後日)出現したことで、その結びつきにさらに鮮明な光を当てている。ポップ・アートが出現するまでは、シュルレアリスムがアメリカ 芸術の急激な成長に最も重要な影響を与えたと見ることができ、ポップの中にもシュルレアリスムのユーモアの一部が見られ、しばしば文化批判に転化されてい る。 第二次世界大戦は、一時期、ほとんどすべての知的・芸術的生産に影を落とした。1939年、ヴォルフガング・パーレンは亡命者としてパリから新大陸に向 かった。ブリティッシュコロンビアの森を巡る長い旅の後、メキシコに定住し、影響力のあるアート雑誌『Dyn』を創刊した。1940年、イヴ・タンギーは アメリカのシュルレアリスムの画家ケイ・セイジと結婚。1941年、ブルトンはアメリカに渡り、マックス・エルンスト、マルセル・デュシャン、アメリカの 芸術家デイヴィッド・ヘアらと短命の雑誌『VVV』を共同創刊。しかし、ブルトンにアメリカでシュルレアリスムを広めるチャンネルを提供したのは、アメリ カの詩人シャルル・アンリ・フォードと彼の雑誌『View』だった。ビュー』誌のデュシャン特集は、アメリカにおけるシュルレアリスムの一般的な理解に とって極めて重要なものだった。この特集は、デュシャンとシュルレアリスムの手法とのつながりを強調し、ブルトンによる彼の作品の解釈を提供し、デュシャ ンが未来派やキュビスムといった近世初期の運動とシュルレアリスムとの架け橋となるというブルトンの見解も紹介した。ヴォルフガング・パーレンは、ブルト ンとの政治的/哲学的な相違により、1942年にグループを脱退した。  コリン・ミドルトン作『共謀者たち』(1942年)、アイルランドのシュルレアリストによるベルファスト電撃戦への反応 戦争はシュルレアリスムにとって破壊的であったが、作品は継続された。マグリットをはじめ、多くのシュルレアリスムの芸術家たちが、自らのボキャブラリー を探求し続けた。シュルレアリスム運動のメンバーの多くは、文通や会合を続けていた。ダリはブルトンから破門されたかもしれないが、後の絵画で「時間の持 続」に言及するなど、1930年代からのテーマを放棄したわけでもなく、描写的なポンピエになったわけでもない。また、アンドレ・ティリオンのように、こ の時期以降の彼の作品には、運動と何らかの関連性を持ち続けるものがあると主張する者もいた。1941年5月、ベルファストの電撃戦によってアイルランド に戦火が及ぶと、1930年代にシュルレアリスムのテーマで実験的な試みを行っていたコリン・ミドルトンは、街の人々の衝撃的な状況を反映した一連の暗い 作品で応戦した。これらは、電撃戦でほぼ破壊された後、1943年に修復された後、ベルファスト市立ギャラリーと博物館で展示された[72]。 1940年代、シュルレアリスムの影響はイギリス、アメリカ、オランダでも感じられ、ガートルード・ペイプと彼女の夫テオ・ファン・バーレンは、出版物 『The Clean Handkerchief』においてシュルレアリスムの普及に貢献した[73]。マーク・ロスコは生物形態学的な人物像に関心を持ち、イギリスではヘン リー・ムーア、ルシアン・フロイト、フランシス・ベーコン、ポール・ナッシュがシュルレアリスムの技法を用いたり、実験したりした。しかし、1935年に このジャンルの作品を発表した最初のイギリス人シュルレアリストの一人であるコンロイ・マドックスは、シュルレアリスムにとどまり、1978年には、シュ ルレアリスムを正しく表現していないという理由で彼を激怒させた以前の展覧会に対抗して、現在のシュルレアリスムの作品を集めた展覧会を開催した。マドッ クスの展覧会は「シュルレアリスム・アンリミテッド」と題され、パリで開催され、国際的な注目を集めた。彼は2002年に最後の個展を開催し、その3年後 に亡くなった。マグリットの作品は、1951年の『個人的価値』(Les Valeurs Personnelles)[74]や1954年の『光の帝国』(L'Empire des lumières)のように、並置の要素を維持しながらも、実際の物体の描写においてより現実的になっていった[75]。 シュルレアリスム運動の他の人物は追放された。ロベルト・マッタのように「シュルレアリスムに近い存在であり続けた」アーティストもいた[31]。彼女は1938年にニューヨークで25点の個展を開催し、ブルトン自身によって奨励された。 1956年のハンガリー革命の鎮圧後、エンドレ・ロズダはパリに戻り、シュルレアリスムを超越した独自の言葉を創作し続けた。フルステンバーグ画廊での彼の最初の展覧会(1957年)の序文は、まだブルトンによって書かれていた[77]。 多くの新しい芸術家たちがシュルレアリスムの旗印を明確に掲げた。ドロテア・タニングとルイーズ・ブルジョワは、例えば1970年のタニングの《雨の日の カナッペ》のような作品を制作し続けた。デュシャンは、のぞき穴からしか見ることのできないリアルな女性の姿を描いたインスタレーションなど、秘密裏に彫 刻を制作し続けた。 ブルトンは、1952年に出版した『光の塔』のように、人間の心を解放することの重要性を説き、執筆活動を続けた。戦後、フランスに戻ったブルトンは、パ リでシュルレアリスム活動の新たな局面を迎え、合理主義と二元論に対する彼の批評は新たな読者を獲得した。ブルトンは、シュルレアリスムとは、人間性を市 場関係や宗教的ジェスチャーや悲惨さに還元することへの継続的な反乱であり、人間の心を解放することの重要性を主張した。 1940年代、50年代、60年代の主な展覧会 1942年 - 第1回シュルレアリスム展 - ニューヨーク - シュルレアリストたちはデュシャンに再び展覧会のデザインを依頼。このとき彼は、空間の部屋全体に3次元的な紐の網を張り巡らせ、場合によっては作品をほ とんど見ることができないようにした[78]。彼は、展覧会のオープニングに彼の友人たちを連れてくるよう、同僚の息子と密かに取り決めをし、精巧に着 飾った観客たちが到着すると、運動着を着た12人の子供たちがボールを蹴ったり、パスしたり、縄跳びをしたりしていた。展覧会のカタログのデザインには、 ポーズをとった写真ではなく、「拾った」アーティストの写真が使われた[31]。 1947年 - 国際シュルレアリスム展 - ギャルリ・メグ、パリ[79]。 1959年 - 国際シュルレアリスム展(パリ 1960年 - シュルレアリスムによる魔法使いの領地への侵入(ニューヨーク |

| Post-Breton Surrealism In the 1960s, the artists and writers associated with the Situationist International were closely associated with Surrealism. While Guy Debord was critical of and distanced himself from Surrealism, others, such as Asger Jorn, were explicitly using Surrealist techniques and methods. The events of May 1968 in France included a number of Surrealist ideas, and among the slogans the students spray-painted on the walls of the Sorbonne were familiar Surrealist ones. Joan Miró would commemorate this in a painting titled May 1968. There were also groups who associated with both currents and were more attached to Surrealism, such as the Revolutionary Surrealist Group. During the 1980s, behind the Iron Curtain, Surrealism again entered into politics with an underground artistic opposition movement known as the Orange Alternative. The Orange Alternative was created in 1981 by Waldemar Fydrych (alias 'Major'), a graduate of history and art history at the University of Wrocław. They used Surrealist symbolism and terminology in their large-scale happenings organized in the major Polish cities during the Jaruzelski regime and painted Surrealist graffiti on spots covering up anti-regime slogans. Major himself was the author of a "Manifesto of Socialist Surrealism". In this manifesto, he stated that the socialist (communist) system had become so Surrealistic that it could be seen as an expression of art itself. Surrealistic art also remains popular with museum patrons. The Guggenheim Museum in New York City held an exhibit, Two Private Eyes, in 1999, and in 2001 Tate Modern held an exhibition of Surrealist art that attracted over 170,000 visitors. In 2002 the Met in New York City held a show, Desire Unbound, and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris a show called La Révolution surréaliste. Surrealist groups and literary publications have continued to be active up to the present day, with groups such as the Chicago Surrealist Group, the Leeds Surrealist Group, and the Surrealist Group of Stockholm. Jan Švankmajer of the Czech-Slovak Surrealists continues to make films and experiment with objects. Impact and influences While Surrealism is typically associated with the arts, it has impacted many other fields. In this sense, Surrealism does not specifically refer only to self-identified "Surrealists", or those sanctioned by Breton, rather, it refers to a range of creative acts of revolt and efforts to liberate imagination.[80] In addition to Surrealist theory being grounded in the ideas of Hegel, Marx and Freud, to its advocates its inherent dynamic is dialectical thought.[81] Surrealist artists have also cited the alchemists, Dante, Hieronymus Bosch,[82][83] the Marquis de Sade,[82] Charles Fourier, Comte de Lautréamont and Arthur Rimbaud as influences.[84][85] May 68 Surrealists believe that non-Western cultures also provide a continued source of inspiration for Surrealist activity because some may induce a better balance between instrumental reason and imagination in flight than Western culture.[86][87] Surrealism has had an identifiable impact on radical and revolutionary politics, both directly — as in some Surrealists joining or allying themselves with radical political groups, movements and parties — and indirectly — through the way in which Surrealists emphasize the intimate link between freeing imagination and the mind, and liberation from repressive and archaic social structures. This was especially visible in the New Left of the 1960s and 1970s and the French revolt of May 1968, whose slogan "All power to the imagination" quoted by The Situationists and Enragés[88] from the originally Marxist "Rêvé-lutionary" theory and praxis of Breton's French Surrealist group.[89] Postmodernism and popular culture Many significant literary movements in the later half of the 20th century were directly or indirectly influenced by Surrealism. This period is known as the Postmodern era; though there is no widely agreed upon central definition of Postmodernism, many themes and techniques commonly identified as Postmodern are nearly identical to Surrealism. First Papers of Surrealism presented the fathers of surrealism in an exhibition that represented the leading monumental step of the avant-gardes towards installation art.[90] Many writers from and associated with the Beat Generation were influenced greatly by Surrealists. Philip Lamantia[91] and Ted Joans[92] are often categorized as both Beat and Surrealist writers. Many other Beat writers show significant evidence of Surrealist influence. A few examples include Bob Kaufman,[93][94] Gregory Corso,[95] Allen Ginsberg,[96] and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.[97] Artaud in particular was very influential to many of the Beats, but especially Ginsberg and Carl Solomon.[98] Ginsberg cites Artaud's "Van Gogh – The Man Suicided by Society" as a direct influence on "Howl",[99] along with Apollinaire's "Zone",[100] García Lorca's "Ode to Walt Whitman",[101] and Schwitters' "Priimiititiii".[102] The structure of Breton's "Free Union" had a significant influence on Ginsberg's "Kaddish".[103] In Paris, Ginsberg and Corso met their heroes Tristan Tzara, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Benjamin Péret, and to show their admiration Ginsberg kissed Duchamp's feet and Corso cut off Duchamp's tie.[104] William S. Burroughs, a core member of the Beat Generation and a postmodern novelist, developed the cut-up technique with former surrealist Brion Gysin—in which chance is used to dictate the composition of a text from words cut out of other sources—referring to it as the "Surrealist Lark" and recognizing its debt to the techniques of Tristan Tzara.[105] Postmodern novelist Thomas Pynchon, who was also influenced by Beat fiction, experimented since the 1960s with the surrealist idea of startling juxtapositions; commenting on the "necessity of managing this procedure with some degree of care and skill", he added that "any old combination of details will not do. Spike Jones Jr., whose father's orchestral recordings had a deep and indelible effect on me as a child, said once in an interview, 'One of the things that people don't realize about Dad's kind of music is, when you replace a C-sharp with a gunshot, it has to be a C-sharp gunshot or it sounds awful.'"[21] Many other postmodern fiction writers have been directly influenced by Surrealism. Paul Auster, for example, has translated Surrealist poetry and said the Surrealists were "a real discovery" for him.[106] Salman Rushdie, when called a Magical Realist, said he saw his work instead "allied to surrealism".[107][108] David Lynch regarded as a surrealist filmmaker being quoted, "David Lynch has once again risen to the spotlight as a champion of surrealism,"[109] in regard to his show Twin Peaks. For the work of other postmodernists, such as Donald Barthelme[110] and Robert Coover,[111] a broad comparison to Surrealism is common. Magic realism, a popular technique among novelists of the latter half of the 20th century especially among Latin American writers, has some obvious similarities to Surrealism with its juxtaposition of the normal and the dream-like, as in the work of Gabriel García Márquez.[112] Carlos Fuentes was inspired by the revolutionary voice in Surrealist poetry and points to inspiration Breton and Artaud found in Fuentes' homeland, Mexico.[113] Though Surrealism was a direct influence on Magic Realism in its early stages, many Magic Realist writers and critics, such as Amaryll Chanady[114] and S. P. Ganguly,[115] while acknowledging the similarities, cite the many differences obscured by the direct comparison of Magic Realism and Surrealism such as an interest in psychology and the artefacts of European culture they claim is not present in Magic Realism. A prominent example of a Magic Realist writer who points to Surrealism as an early influence is Alejo Carpentier who also later criticized Surrealism's delineation between real and unreal as not representing the true South American experience.[116][117] Surrealist groups See also: Category:Surrealist groups Surrealist individuals and groups have carried on with Surrealism after the death of André Breton in 1966. The original Paris Surrealist Group was disbanded by member Jean Schuster in 1969, but another Parisian surrealist group was later formed. The current Surrealist Group of Paris has recently published the first issue of their new journal, Alcheringa. The Group of Czech-Slovak Surrealists never disbanded, and continue to publish their journal Analogon, which now spans almost 100 volumes. Surrealism and the theatre Surrealist theatre and Artaud's "Theatre of Cruelty" were inspirational to many within the group of playwrights that the critic Martin Esslin called the "Theatre of the Absurd" (in his 1963 book of the same name). Though not an organized movement, Esslin grouped these playwrights together based on some similarities of theme and technique; Esslin argues that these similarities may be traced to an influence from the Surrealists. Eugène Ionesco in particular was fond of Surrealism, claiming at one point that Breton was one of the most important thinkers in history.[118][119] Samuel Beckett was also fond of Surrealists, even translating much of the poetry into English.[120][121] Other notable playwrights whom Esslin groups under the term, for example Arthur Adamov and Fernando Arrabal, were at some point members of the Surrealist group.[122][123][124] Alice Farley is an American-born artist who became active during the 1970s in San Francisco after training in dance at the California Institute of the Arts.[125] Farley uses vivid and elaborate costuming that she describes as "the vehicles of transformation capable of making a character's thoughts visible".[125] Often collaborating with musicians such as Henry Threadgill, Farley explores the role of improvisation in dance, bringing in an automatic aspect to the productions.[126] Farley has performed in a number of surrealist collaborations including the World Surrealist Exhibition in Chicago in 1976.[125] Alleged precursors in older art Various much older artists are sometimes claimed as precursors of Surrealism. Foremost among these are Hieronymus Bosch,[127] and Giuseppe Arcimboldo, whom Dalí called the "father of Surrealism."[128] Apart from their followers, other artists who may be mentioned in this context include Joos de Momper, for some anthropomorphic landscapes. Many critics feel these works belong to fantastic art rather than having a significant connection with Surrealism.[129] |

ポスト・ブルトン・シュルレアリスム 1960年代、シチュアシオニスト・インターナショナルのアーティストや作家たちは、シュルレアリスムと密接な関係にあった。ギー・ドゥボールはシュルレ アリスムに批判的で距離を置いていたが、アスガー・ヨルンのように、シュルレアリスムの技法や手法を明確に用いていた者もいた。1968年5月にフランス で起こった事件には、シュルレアリスムの思想が数多く含まれており、学生たちがソルボンヌ大学の壁にスプレーで描いたスローガンの中には、おなじみのシュ ルレアリスムのものもあった。ジョアン・ミロは『1968年5月』というタイトルの絵画でこれを記念している。また、革命的シュルレアリスト・グループの ように、両方の潮流と結びつき、よりシュルレアリスムに傾倒したグループもあった。 1980年代、鉄のカーテンの向こう側で、シュルレアリスムは、オレンジ・オルタナティヴとして知られる地下の芸術的反対運動によって、再び政治に参入し た。オレンジ・オルタナティブは1981年、ヴロツワフ大学で歴史と美術史を専攻したワルデマル・フィドリッヒ(通称「メジャー」)によって創設された。 彼らは、ヤルゼルスキ政権時代にポーランドの主要都市で開催された大規模なハプニングにシュルレアリスムの象徴や用語を用い、反政権のスローガンを覆い隠 すようにシュルレアリスムの落書きをした。マジョール自身、「社会主義シュルレアリスム宣言」の著者であった。このマニフェストの中で彼は、社会主義(共 産主義)体制は、芸術の表現そのものと見なせるほどシュルレアリスムになったと述べている。 シュルレアリスム芸術はまた、美術館の常連客にも依然として人気がある。ニューヨークのグッゲンハイム美術館は1999年に「二人のプライベート・アイ ズ」展を開催し、2001年にはテート・モダンがシュルレアリスム美術の展覧会を開催し、17万人以上を動員した。2002年にはニューヨークのメトロポ リタン美術館で「欲望を解き放つ」展が、パリのポンピドゥー・センターでは「シュルレアリスムの革命」展が開催された。 シュルレアリスムのグループや文芸誌は現在も活動を続けており、シカゴ・シュルレアリスム・グループ、リーズ・シュルレアリスム・グループ、ストックホル ムのシュルレアリスム・グループなどがある。チェコ・スロバキア・シュルレアリスムのヤン・シュヴァンクマイエルは、映画制作やオブジェの実験を続けてい る。 影響と影響 シュルレアリスムは一般的に芸術と結びついているが、他の多くの分野にも影響を与えている。この意味で、シュルレアリスムは特に自称「シュルレアリスト」 やブルトンによって公認された者だけを指すのではなく、むしろ想像力を解放するための反乱と努力の創造的行為の範囲を指す。 [80]シュルレアリスムの理論がヘーゲル、マルクス、フロイトの思想に根ざしていることに加え、その提唱者たちにとってその固有のダイナミズムは弁証法 的思考である[81]。 シュルレアリスムのアーティストたちはまた、影響を受けたものとして、錬金術師、ダンテ、ヒエロニムス・ボス、[82][83]サド侯爵、[82]シャル ル・フーリエ、ロートレアモン伯爵、アルチュール・ランボーを挙げている[84][85]。 1968年5月 シュルレアリストたちは、非西洋文化もまたシュルレアリスムの活動にとって継続的なインスピレーションの源になると信じている。シュルレアリス ムは急進的で革命的な政治に明白な影響を及ぼしたが、それは一部のシュルレアリストたちが急進的な政治グループ、運動、政党に参加したり、同盟を結んだり するという直接的な意味でも、またシュルレアリストたちが自由な想像力や精神と抑圧的で古臭い社会構造からの解放との間の密接なつながりを強調するという 間接的な意味でも同様である。これは特に1960年代と1970年代の新左翼と1968年5月のフランスの反乱において顕著であり、そのスローガンである 「想像力にすべての力を」は、ブルトンのフランスのシュルレアリスト・グループのもともとマルクス主義的な「レーヴェ=ルシオン」の理論と実践からシチュ アシオニストとエンラジェによって引用された[88]。 ポストモダニズムと大衆文化 20世紀後半における多くの重要な文学運動は、シュルレアリスムの影響を直接的または間接的に受けている。この時代はポストモダンの時代として知られてい る。ポストモダニズムの中心的な定義として広く合意されているものはないが、一般的にポストモダンとして認識されている多くのテーマや技法はシュルレアリ スムとほぼ同じである。 ファースト・ペイパーズ・オブ・シュルレアリスム』は、シュルレアリスムの父たちを紹介する展覧会で、インスタレーション・アートに向かう前衛芸術の代表 的な記念碑的な一歩となった[90]。フィリップ・ラマンティア[91]とテッド・ジョーンズ[92]は、ビートとシュルレアリスムの両方の作家に分類さ れることが多い。他の多くのビート作家は、シュルレアリスムの影響を顕著に示している。特にアルトーは多くのビート、特にギンズバーグとカール・ソロモン に大きな影響を与えた。 [98]ギンズバーグは「ハウル」に直接影響を与えたものとしてアルトーの「ゴッホ-社会に自殺させられた男」を挙げており[99]、アポリネールの 「ゾーン」、[100]ガルシア・ロルカの「ウォルト・ホイットマンへの頌歌」、[101]シュヴィッタースの「プリティミティイ」を挙げている。 [パリでは、ギンズバーグとコルソは彼らのヒーローであるトリスタン・ツァラ、マルセル・デュシャン、マン・レイ、ベンジャミン・ペレに会い、賞賛を示す ためにギンズバーグはデュシャンの足にキスをし、コルソはデュシャンのネクタイを切り落とした[104]。 ビート・ジェネレーションの中心メンバーであり、ポストモダンの小説家であるウィリアム・S・バロウズは、元シュルレアリストのブリオン・ガイシンと共 に、他の資料から切り取られた言葉からテキストの構成を指示するために偶然を利用するカット・アップ技法を開発し、それを「シュルレアリスムのヒバリ」と 呼び、トリスタン・ツァラの技法への負債を認識していた[105]。 ポストモダンの小説家であるトマス・ピンチョンもまたビート・フィクションの影響を受けており、1960年代からシュルレアリスム的な発想である驚愕の並 置を試みている。スパイク・ジョーンズJr.は、父親のオーケストラのレコーディングが、子供のころの私に深く忘れがたい影響を与えたが、あるインタ ビューでこう語っている。『パパのような音楽について人々が気づいていないことのひとつは、Cシャープを銃声に置き換えたとき、Cシャープの銃声でなけれ ばひどい音になってしまうということだ』」[21]。 他の多くのポストモダン小説家も、シュルレアリスムの影響を直接受けている。例えば、ポール・オースターはシュルレアリスムの詩を翻訳し、シュルレアリス ムは彼にとって「本当の発見」であったと述べている[106]。サルマン・ラシュディは、魔術的リアリストと呼ばれたとき、代わりに自分の作品は「シュル レアリスムと結びついている」と述べた[107][108]。 デヴィッド・リンチは、彼の番組『ツイン・ピークス』に関して、「デヴィッド・リンチはシュルレアリスムのチャンピオンとして再びスポットライトを浴びる ようになった」と引用されている[109]。ドナルド・バートヘルム[110]やロバート・クーヴァー[111]のような他のポストモダニストの作品につ いては、シュルレアリスムとの幅広い比較が一般的である。 マジック・リアリズムは20世紀後半の小説家、特にラテンアメリカの作家の間で人気のある手法であり、ガブリエル・ガルシア・マルケスの作品に見られるよ うな、通常のものと夢のようなものの並置というシュルレアリスムとの明らかな類似点がある[112]。カルロス・フエンテスはシュルレアリスムの詩におけ る革命的な声に触発され、ブルトンやアルトーがフエンテスの故郷であるメキシコで見出したインスピレーションを指摘している。 [シュルレアリスムは初期の段階ではマジック・リアリズムに直接的な影響を与えたが、アマリル・チャナディ[114]やS・P・ガングリー[115]のよ うなマジック・リアリズムの作家や批評家の多くは、類似点を認めつつも、マジック・リアリズムには存在しないと主張する心理学やヨーロッパ文化の工芸品へ の関心など、マジック・リアリズムとシュルレアリスムを直接比較することで不明瞭になる多くの相違点を挙げている。シュルレアリスムが初期に影響を受けた と指摘するマジック・リアリズムの作家の顕著な例はアレホ・カルペンティエルであり、彼はまた後にシュルレアリスムの現実と非現実の間の境界線が真の南米 の経験を表していないと批判している[116][117]。 シュルレアリスムのグループ シュルレアリスムのグループ: カテゴリー:シュルレアリスムのグループ 1966年にアンドレ・ブルトンが亡くなった後も、シュルレアリスムの個人やグループはシュルレアリスムを継承している。オリジナルのパリ・シュルレアリ スト・グループは1969年にメンバーのジャン・シュスターによって解散させられたが、その後、別のパリ・シュルレアリスト・グループが結成された。現在 のパリのシュルレアリスト・グループは、最近、新しい雑誌『アルチェリンガ』の創刊号を発行した。チェコ・スロバキアのシュルレアリスト・グループは解散 することなく、現在100巻近くに及ぶ機関誌『アナロゴン』を発行し続けている。 シュルレアリスムと演劇 シュルレアリスム演劇とアルトーの「残酷の劇場」は、批評家マルティン・エスリン(1963年の同名の著書で)が「不条理の劇場」 と呼んだ劇作家グループの多くにインスピレーションを与えた。組織化された運動ではなかったが、エスリン氏はテーマや手法の類似性に基づいてこれらの劇作 家をグループ分けした。エスリン氏は、これらの類似性はシュルレアリスムからの影響によるものだと主張している。特にウジェーヌ・イヨネスコはシュルレア リスムを好んでおり、ある時点ではブルトンは歴史上最も重要な思想家の一人であると主張していた[118][119]。サミュエル・ベケットもシュルレア リストを好んでおり、その詩の多くを英語に翻訳していたほどである[120][121]。エスリンがこの用語でグループ化している他の著名な劇作家、例え ばアルトゥール・アダモフやフェルナンド・アラバルは、ある時点ではシュルレアリスト・グループのメンバーであった[122][123][124]。 アリス・ファーレイはアメリカ生まれのアーティストであり、カリフォルニア芸術大学でダンスの訓練を受けた後、1970年代にサンフランシスコで活動する ようになった[125]。ファーレイは鮮やかで精巧な衣装を用いており、彼女はそれを「キャラクターの思考を可視化することができる変容の乗り物」と表現 している。 [1976年にシカゴで開催された世界シュルレアリスム展をはじめ、多くのシュルレアリスムとのコラボレーションに出演している[125]。 古い芸術における前駆者 シュルレアリスムの先駆けとして、かなり古い時代の様々な芸術家が主張されることがある。その最たるものがヒエロニムス・ボッシュであり[127]、ダリ が「シュルレアリスムの父」と呼んだジュゼッペ・アルチンボルドである[128]。彼らの信奉者たちとは別に、この文脈で言及される可能性のある他の芸術 家には、擬人化された風景画を描いたヨース・デ・モンペールがいる。多くの批評家は、これらの作品はシュルレアリスムとの重要なつながりがあるというより も、むしろファンタスティック・アートに属するものだと感じている[129]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surrealism |

|

| Surrealist artists Bizarre Object List of films influenced by the Surrealist movement Surrealist cinema Women surrealists Exquisite corpse Neo-Fauvism – Poetic style of painting Organic Surrealism Outsider art – Art created outside the boundaries of official culture by those untrained in the arts Psychedelic art – Visual art inspired by psychedelic experiences Salón de Mayo (Cuba) |

シュルレアリスム芸術家 奇妙なオブジェ シュルレアリスム運動に影響を受けた映画のリスト シュルレアリスム映画 女性シュルレアリスト エクスキューズド・コープス ネオ・フォーヴィズム – 詩的な絵画スタイル 有機的シュルレアリスム アウトサイダー・アート – 芸術の訓練を受けていない人々が、公式文化の枠組み外で制作した芸術 サイケデリック・アート – サイケデリック体験からインスパイアされた視覚芸術 サロンド・マヨ(キューバ) |