ジェラルド・エーデルマンとニューラル・ダーウィニズム

Gerald Maurice Edelman, 1929-2014,

and his Neural Darwinism

ジェラルド・エーデルマンとニューラル・ダーウィニズム

Gerald Maurice Edelman, 1929-2014,

and his Neural Darwinism

★ジェラルド・モーリス・エデルマン(1929年7月1日 - 2014年5月17日)は、アメリカの生物学者で、ロドニー・ロバート・ポーターと共に免疫系に関する研究で1972年にノーベル生理学・医学賞を共同受 賞した[1]。 [1] エーデルマンのノーベル賞受賞研究は、抗体分子の構造の発見に関するものである[2]。 彼はインタビューで、免疫系の構成要素が個人の生涯にわたって進化する様子は、脳の構成要素が生涯にわたって進化する様子に類似していると述べている。こ のように、ノーベル賞を受賞した免疫系の研究と、その後の神経科学や心の哲学の研究とは、(それなりの)連続性がある。

| Gerald

Maurice Edelman (/ˈɛdəlmən/; July 1, 1929 – May 17, 2014) was an

American biologist who shared the 1972 Nobel Prize in Physiology or

Medicine for work with Rodney Robert Porter on the immune system.[1]

Edelman's Nobel Prize-winning research concerned discovery of the

structure of antibody molecules.[2] In interviews, he has said that the

way the components of the immune system evolve over the life of the

individual is analogous to the way the components of the brain evolve

in a lifetime. There is a continuity in this way between his work on

the immune system, for which he won the Nobel Prize, and his later work

in neuroscience and in philosophy of mind. |

ジェ

ラルド・モーリス・エデルマン(/ˈ,, 1929年7月1日 -

2014年5月17日)は、アメリカの生物学者で、ロドニー・ロバート・ポーターと共に免疫系に関する研究で1972年にノーベル生理学・医学賞を共同受

賞した[1]。 [1] エーデルマンのノーベル賞受賞研究は、抗体分子の構造の発見に関するものである[2]。

彼はインタビューで、免疫系の構成要素が個人の生涯にわたって進化する様子は、脳の構成要素が生涯にわたって進化する様子に類似していると述べている。こ

のように、ノーベル賞を受賞した免疫系の研究と、その後の神経科学や心の哲学の研究とは、(それなりの)連続性がある。 |

| Early life Gerald Edelman was born in 1929[3] in Ozone Park, Queens, New York, to Jewish parents, physician Edward Edelman, and Anna (née Freedman) Edelman, who worked in the insurance industry.[4] He studied violin for years, but eventually realized that he did not have the inner drive needed to pursue a career as a concert violinist, and decided to go into medical research instead.[5] He attended public schools in New York, graduating from John Adams High School,[6] and going on to college in Pennsylvania where he graduated magna cum laude with a B.S. from Ursinus College in 1950 and received an M.D. from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in 1954.[4] |

幼少期 ジェラルド・エデルマンは1929年[3]、ニューヨーク州クイーンズのオゾンパークで、ユダヤ人の両親、医師のエドワード・エデルマンと保険業界で働い ていたアナ(旧姓フリードマン)・エデルマンの間に生まれた[4]。 彼は何年もバイオリンを学んでいたが、やがてコンサートバイオリニストとしてのキャリアに必要な内なる意欲を持っていないと気づき、代わりに医学研究へ進 むことを決心した。 [5] ニューヨークのパブリックスクールに通い、ジョン・アダムズ高校を卒業[6]、ペンシルベニアの大学に進学し、1950年にアーサイナス大学から学士号を 優秀な成績で卒業、1954年にペンシルベニア大学医学部から医学博士号を取得した[4]。 |

| Career After a year at the Johnson Foundation for Medical Physics, Edelman became a resident at the Massachusetts General Hospital; he then practiced medicine in France while serving with US Army Medical Corps.[4] In 1957, Edelman joined the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research as a graduate fellow, working in the laboratory of Henry Kunkel and receiving a Ph.D. in 1960.[4] The institute made him the assistant (later associate) dean of graduate studies; he became a professor at the school in 1966.[4] In 1992, he moved to California and became a professor of neurobiology at The Scripps Research Institute.[7] After his Nobel prize award, Edelman began research into the regulation of primary cellular processes, particularly the control of cell growth and the development of multi-celled organisms, focusing on cell-to-cell interactions in early embryonic development and in the formation and function of the nervous system. These studies led to the discovery of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), which guide the fundamental processes that help an animal achieve its shape and form, and by which nervous systems are built. One of the most significant discoveries made in this research is that the precursor gene for the neural cell adhesion molecule gave rise in evolution to the entire molecular system of adaptive immunity.[8] For his efforts, Edelman was an elected member of both the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1968) and the American Philosophical Society (1977).[9][10] |

経歴 ジョンソン医学物理学財団で1年過ごした後、マサチューセッツ総合病院の研修医となり、その後、アメリカ陸軍医療部隊に所属しながらフランスで医療行為を 行った[4]。1957年にロックフェラー医学研究所に大学院生として加わり、ヘンリー・クンケル教授の研究室で働き、1960年に博士号を取得する [4]。 1992年にカリフォルニアに移り、スクリプス研究所の神経生物学教授に就任した[7]。 ノーベル賞受賞後、エーデルマンは、初期胚発生における細胞間相互作用や神経系の形成と機能に着目し、特に細胞増殖の制御や多細胞生物の発生など、細胞の 一次過程の制御に関する研究を開始した。これらの研究は、動物がその姿や形を獲得するための基本的なプロセスを導き、神経系を構築する細胞接着分子 (CAM)の発見へとつながった。この研究で得られた最も重要な発見の1つは、神経細胞接着分子の前駆体遺伝子が、進化の過程で適応免疫の分子システム全 体を生み出したことである[8]。 その功績により、エーデルマンはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミー(1968年)とアメリカ哲学協会(1977年)の両会員に選出された[9][10]。 |

| Nobel Prize While in Paris serving in the Army, Edelman read a book that sparked his interest in antibodies.[11] He decided that, since the book said so little about antibodies, he would investigate them further upon returning to the United States, which led him to study physical chemistry for his 1960 Ph.D.[11] Research by Edelman and his colleagues and Rodney Robert Porter in the early 1960s produced fundamental breakthroughs in the understanding of the antibody's chemical structure, opening a door for further study.[12] For this work, Edelman and Porter shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1972.[1] In its Nobel Prize press release in 1972, the Karolinska Institutet lauded Edelman and Porter's work as a major breakthrough: The impact of Edelman's and Porter's discoveries is explained by the fact that they provided a clear picture of the structure and mode of action of a group of biologically particularly important substances. By this they laid a firm foundation for truly rational research, something that was previously largely lacking in immunology. Their discoveries represent clearly a break-through that immediately incited a fervent research activity the whole world over, in all fields of immunological science, yielding results of practical value for clinical diagnostics and therapy.[13] |

ノーベル賞 エーデルマンは、陸軍士官としてパリに駐屯していたとき、ある本を読んで抗体への興味を持ちました[11]。 その本には抗体についてほとんど書かれていなかったため、米国に戻ったらもっと調べてみようと思い、1960年に物理化学を専攻して博士号を取得しました [11]。 [11] 1960年代初頭、エデルマンとその同僚、ロドニー・ロバート・ポーターによる研究は、抗体の化学構造の理解に基本的なブレークスルーをもたらし、さらな る研究の扉を開いた[12]。 この業績により、エデルマンとポーターは1972年にノーベル生理学・医学賞を共同受賞している[1]。 カロリンスカ研究所は、1972年のノーベル賞のプレスリリースで、エデルマンとポーターの研究を大きなブレークスルーとして賞賛している。 エデルマンとポーターの発見のインパクトは、生物学的に特に重要な物質群の構造と作用機序を明確に示したという事実によって説明される。これによって、そ れまで免疫学にほとんど欠けていた、真に合理的な研究の基礎が築かれたのである。彼らの発見は、明らかにブレークスルーであり、直ちに全世界の免疫学のあ らゆる分野における熱狂的な研究活動を引き起こし、臨床診断と治療に実用的価値のある結果をもたらした[13]。 |

| Disulfide bonds Edelman's early research on the structure of antibody proteins revealed that disulfide bonds link together the protein subunits.[2] The protein subunits of antibodies are of two types, the larger heavy chains and the smaller light chains. Two light and two heavy chains are linked together by disulfide bonds to form a functional antibody. Molecular models of antibody structure Using experimental data from his own research and the work of others, Edelman developed molecular models of antibody proteins.[14] A key feature of these models included the idea that the antigen binding domains of antibodies (Fab) include amino acids from both the light and heavy protein subunits. The inter-chain disulfide bonds help bring together the two parts of the antigen binding domain. Antibody sequencing Edelman and his colleagues used cyanogen bromide and proteases to fragment the antibody protein subunits into smaller pieces that could be analyzed for determination of their amino acid sequence.[15][16] At the time when the first complete antibody sequence was determined (1969)[17] it was the largest complete protein sequence that had ever been determined. The availability of amino acid sequences of antibody proteins allowed recognition of the fact that the body can produce many different antibody proteins with similar antibody constant regions and divergent antibody variable regions. Topobiology Topobiology is Edelman's theory which asserts that morphogenesis is driven by differential adhesive interactions among heterogeneous cell populations and it explains how a single cell can give rise to a complex multi-cellular organism. As proposed by Edelman in 1988, topobiology is the process that sculpts and maintains differentiated tissues and is acquired by the energetically favored segregation of cells through heterologous cellular interactions. |

ジスルフィド結合 エーデルマンは、抗体タンパク質の構造に関する初期の研究により、ジスルフィド結合がタンパク質サブユニット同士を結びつけていることを明らかにした [2]。抗体のタンパク質サブユニットには、大きな重鎖と小さな軽鎖の2種類が存在する。2本の軽鎖と2本の重鎖がジスルフィド結合によって結合し、機能 的な抗体を形成している。 抗体構造の分子モデル エーデルマンは、自身の研究および他の研究者の研究による実験データを用いて、抗体タンパク質の分子モデルを構築した[14]。 このモデルの大きな特徴は、抗体の抗原結合ドメイン(Fab)には、軽鎖および重鎖の両方のタンパク質サブユニットのアミノ酸が含まれているという考え方 であった。鎖間ジスルフィド結合は、抗原結合ドメインの2つの部分を結合させるのに役立っている。 抗体の配列決定 エーデルマンらは、臭化シアノゲンとプロテアーゼを用いて抗体タンパク質のサブユニットを断片化し、アミノ酸配列の解析に成功しました[15][16]。 抗体タンパク質のアミノ酸配列が明らかになったことで、抗体定数領域が類似し、抗体可変領域が分岐した、多種多様な抗体タンパク質が体内で作られるという 事実が認識されるようになりました[15]。 トポバイオロジー エーデルマンが提唱した理論で、形態形成は異種細胞集団の接着相互作用の差によって駆動されるとし、単一細胞が複雑な多細胞生物を生み出すことを説明する ものである。エーデルマンが1988年に提唱したトポバイオロジーは、分化した組織を彫刻し維持するプロセスであり、異種細胞間の相互作用によりエネル ギー的に有利な細胞の分離によって獲得される。 |

| Theory of consciousness (Secondary consciousness) In his later career, Edelman was noted for his theory of consciousness, documented in a trilogy of technical books and in several subsequent books written for a general audience, including Bright Air, Brilliant Fire (1992),[18][19] A Universe of Consciousness (2001, with Giulio Tononi), Wider than the Sky (2004) and Second Nature: Brain Science and Human Knowledge (2007). In Second Nature Edelman defines human consciousness as: "... what you lose on entering a dreamless deep sleep ... deep anesthesia or coma ... what you regain after emerging from these states. [The] experience of a unitary scene composed variably of sensory responses ... memories ... situatedness ..." The first of Edelman's technical books, The Mindful Brain (1978),[20] develops his theory of Neural Darwinism, which is built around the idea of plasticity in the neural network in response to the environment. The second book, Topobiology (1988),[21] proposes a theory of how the original neuronal network of a newborn's brain is established during development of the embryo. The Remembered Present (1990)[22] contains an extended exposition of his theory of consciousness. In his books, Edelman proposed a biological theory of consciousness, based on his studies of the immune system. He explicitly roots his theory within Charles Darwin's Theory of Natural Selection, citing the key tenets of Darwin's population theory, which postulates that individual variation within species provides the basis for the natural selection that eventually leads to the evolution of new species.[23] He explicitly rejected dualism and also dismissed newer hypotheses such as the so-called 'computational' model of consciousness, which liken the brain's functions to the operations of a computer. Edelman argued that mind and consciousness are purely biological phenomena, arising from complex cellular processes within the brain, and that the development of consciousness and intelligence can be explained by Darwinian theory. Edelman's theory seeks to explain consciousness in terms of the morphology of the brain. A brain comprises a massive population of neurons (approx. 100 billion cells) each with an enormous number of synaptic connections to other neurons. During development, the subset of connections that survive the initial phases of growth and development will make approximately 100 trillion connections with each other. A sample of brain tissue the size of a match head contains about a billion connections, and if we consider how these neuronal connections might be variously combined, the number of possible permutations becomes hyper-astronomical – in the order of ten followed by millions of zeros.[24] The young brain contains many more neural connections than will ultimately survive to maturity, and Edelman argued that this redundant capacity is needed because neurons are the only cells in the body that cannot be renewed and because only those networks best adapted to their ultimate purpose will be selected as they organize into neuronal groups. |

意識に関する理論 後年、エーデルマンは意識に関する理論で知られるようになり、専門書の三部作や、その後一般読者向けに書かれたいくつかの本、すなわちBright Air, Brilliant Fire (1992), [18][19] A Universe of Consciousness (2001, Giulio Tononiと共同), Wider than the Sky (2004) and Second Natureで記録されている。Second Nature: Brain Science and Human Knowledge (2007)がある。 エーデルマンは『セカンドネイチャー』の中で、人間の意識を次のように定義している。 「夢のない深い眠り、深い麻酔、昏睡に入るときに失うもの、そして、これらの状態から脱した後に取り戻すもの。[感覚反応...記憶...位置関係...から多様に構成される一元的な情景の経験 "である。 エーデルマンの最初の専門書である『マインドフルな脳』(1978年)[20]は、環境に応じた神経ネットワークの可塑性という考えを軸にした神経ダー ウィニズムの理論を展開している。2冊目の『トポバイオロジー』(1988年)[21]は、胚の発生過程で新生児の脳の本来の神経回路網が確立されるとい う説を提唱している。また、『想起される現在』(1990年)[22]は、彼の意識に関する理論を拡大解釈したものである。 エーデルマンは、著書の中で、免疫系の研究に基づいて、意識に関する生物学的理論を提唱した。彼は、自分の理論をチャールズ・ダーウィンの自然淘汰理論の 中に明確に根付かせ、ダーウィンの集団論の主要な教義を引用して、種内の個々の変異が、最終的に新しい種の進化につながる自然選択の基礎を提供すると仮定 している[23]。 彼は二元論を明確に否定し、脳の機能をコンピューターの操作 にたとえた、意識のいわゆる「計算」モデルなどの新しい仮説をも否定している。エーデルマンは、心と意識は、脳内の複雑な細胞プロセスから生じる純粋な生 物学的現象であり、意識と知能の発達はダーウィン理論で説明できると主張した。 エーデルマンの説は、意識を脳の形態から説明しようとするものである。脳は、膨大な数のニューロン(約1000億個)の集団からなり、それぞれが他の ニューロンとの間に膨大な数のシナプス結合を持っている。脳が発達する過程で、成長・発達の初期段階を乗り越えた神経細胞は、約100兆個の神経細胞間の 結合を形成する。若い脳には、最終的に成熟するまで生き残るであろう数よりも多くの神経接続が含まれており、エーデルマンは、ニューロンが体内で更新されない唯一の細胞であり、ニューロン群に編成される際に最終目的に最も適合したネットワークのみが選択されるため、この冗長能力が必要であると主張した[24]。 |

| Neural Darwinism Edelman's theory of neuronal group selection, also known as 'Neural Darwinism', has three basic tenets—Developmental Selection, Experiential Selection and Reentry. 1. Developmental selection -- the formation of the gross anatomy of the brain is controlled by genetic factors, but in any individual the connectivity between neurons at the synaptic level and their organisation into functional neuronal groups is determined by somatic selection during growth and development. This process generates tremendous variability in the neural circuitry—like the fingerprint or the iris, no two people will have precisely the same synaptic structures in any comparable area of brain tissue. Their high degree of functional plasticity and the extraordinary density of their interconnections enables neuronal groups to self-organise into many complex and adaptable "modules." These are made up of many different types of neurons which are typically more closely and densely connected to each other than they are to neurons in other groups. 2. Experiential selection -- Overlapping the initial growth and development of the brain, and extending throughout an individual's life, a continuous process of synaptic selection occurs within the diverse repertoires of neuronal groups. This process may strengthen or weaken the connections between groups of neurons and it is constrained by value signals that arise from the activity of the ascending systems of the brain, which are continually modified by successful output. Experiential selection generates dynamic systems that can 'map' complex spatio-temporal events from the sensory organs, body systems and other neuronal groups in the brain onto other selected neuronal groups. Edelman argues that this dynamic selective process is directly analogous to the processes of selection that act on populations of individuals in species, and he also points out that this functional plasticity is imperative, since not even the vast coding capability of entire human genome is sufficient to explicitly specify the astronomically complex synaptic structures of the developing brain.[25] 3. Reentry(neural circuitry) —the concept of reentrant signalling between neuronal groups. He defines reentry as the ongoing recursive dynamic interchange of signals that occurs in parallel between brain maps, and which continuously interrelates these maps to each other in time and space (film clip: Edelman demonstrates spontaneous group formation among neurons with re-entrant connections[26]). Reentry depends for its operations on the intricate networks of massively parallel reciprocal connections within and between neuronal groups, which arise through the processes of developmental and experiential selection outlined above. Edelman describes reentry as "a form of ongoing higher-order selection ... that appears to be unique to animal brains" and that "there is no other object in the known universe so completely distinguished by reentrant circuitry as the human brain." |

神経ダーウィニズム エーデルマンの神経細胞群選択説は、「神経ダーウィニズム」とも呼ばれ、「発達的選択」「経験的選択」「再入可能性」の3つの基本的な考え方を持っている。 1. しかし、どの個体においても、シナプスレベルでのニューロン間の結合と、機能的なニューロングループへの編成は、成長・発達中の体細胞淘汰によって決定さ れる。この過程は、指紋や虹彩のように、神経回路に非常に大きな変異をもたらす。神経細胞は、その高い機能的可塑性と相互接続の密度により、複雑で適応性 の高い多くの「モジュール」に自己組織化することができる。これらは多くの異なるタイプのニューロンで構成され、通常、他のグループのニューロンよりも緊 密かつ高密度に互いに接続されている。 2. 経験的選択 -- 脳の初期成長と発達に重なり、個人の生涯を通じて、神経細胞群の多様なレパートリーの中でシナプスの選択の連続的な過程が起こる。このプロセスは、神経細 胞群間の結合を強めたり弱めたりするもので、脳の上行系の活動から生じる価値信号によって制約され、成功した出力によって継続的に修正される。経験的選択 は、感覚器官、身体システム、脳内の他のニューロン群からの複雑な時空間事象を、選択された他のニューロン群に「写像」できる動的システムを生み出すので ある。エーデルマンは、この動的な選択過程は、種における個体群に作用する選択過程に直接類似していると主張し、また、ヒトゲノム全体の膨大なコーディン グ能力でさえ、発達中の脳の天文学的に複雑なシナプス構造を明示的に特定するには十分ではないので、この機能的可塑性は必須であると指摘している [25]。 3. リエントリー(神経回路) -神経細胞群間の再入力信号の概念。彼はリエントリーを、脳の地図間で並行して起こる継続的な再帰的な動的信号の交換であり、これらの地図を時間的・空間 的に相互に連続的に関連付けるものと定義する(映像。エーデルマンは、リエントリ接続を持つニューロン間で自発的なグループ形成を実演している [26])。リエントリーは、ニューロングループ内およびニューロングループ間の大規模な並列相互接続の複雑なネットワークにその動作を依存しており、そ れは上記の発達的および経験的選択のプロセスを通じて生じる。エーデルマンは、リエントリーを「動物の脳に特有の...継続的な高次の選択の一形態」であ り、「既知の宇宙において、人間の脳ほどリエントラント回路によって完全に区別される対象はない」と述べている。 |

| Evolution theory Edelman and Gally were the first to point out the pervasiveness of degeneracy in biological systems and the fundamental role that degeneracy plays in facilitating evolution.[27] Later career Edelman founded and directed The Neurosciences Institute, a nonprofit research center in San Diego that between 1993 and 2012 studied the biological bases of higher brain function in humans. He served on the scientific board of the World Knowledge Dialogue project.[28] Edelman was a member of the USA Science and Engineering Festival's Advisory Board.[29] Personal Edelman married Maxine M. Morrison in 1950.[4] They have two sons, Eric, a visual artist in New York City, and David, an adjunct professor of neuroscience at University of San Diego. Their daughter, Judith Edelman, is a bluegrass musician,[30] recording artist, and writer. Some observers[who?] have noted that a character in Richard Powers' The Echo Maker may be a nod at Edelman. Health and death Later in his life, he had prostate cancer and Parkinson's disease.[31] Edelman died on May 17, 2014, in La Jolla, California, aged 84.[3][32][33] |

進化論 エデルマンとガリィは、生物系に縮退が広く存在し、縮退が進化を促進する上で基本的な役割を担っていることを初めて指摘した[27]。 その後のキャリア エデルマンは、1993年から2012年にかけて、サンディエゴにヒトの高次脳機能の生物学的基盤を研究する非営利の研究センター、ニューロサイエンス研 究所を設立し、その所長となった。また、World Knowledge Dialogueプロジェクトの科学委員会のメンバーでもあった[28]。 エデルマンはUSA Science and Engineering Festivalの諮問委員会のメンバーであった[29]。 個人 エーデルマンは1950年にマキシン・M・モリソンと結婚した[4]。二人の息子、エリックはニューヨークで視覚芸術家、デヴィッドはサンディエゴ大学で 神経科学の助教授である。娘のジュディス・エーデルマンは、ブルーグラス・ミュージシャン[30]、レコーディング・アーティスト、作家として活躍してい る。リチャード・パワーズの『エコー・メーカー』の登場人物がエーデルマンを意識しているのではないかと指摘する人もいる[who?]。 健康と死 後年、前立腺癌とパーキンソン病を患った[31] エデルマンは2014年5月17日、カリフォルニア州ラ・ホーヤで84歳で死去した[3][32][33]。 |

| Neural Darwinism: The Theory of Neuronal Group Selection (Basic Books, New York 1987). ISBN 0-19-286089-5 Topobiology: An Introduction to Molecular Embryology (Basic Books, 1988, Reissue edition 1993) ISBN 0-465-08653-5 The Remembered Present: A Biological Theory of Consciousness (Basic Books, New York 1990). ISBN 0-465-06910-X Bright Air, Brilliant Fire: On the Matter of the Mind (Basic Books, 1992, Reprint edition 1993). ISBN 0-465-00764-3 The Brain, Edelman and Jean-Pierre Changeux, editors, (Transaction Publishers, 2000). ISBN 0-7658-0717-3 A Universe of Consciousness: How Matter Becomes Imagination, Edelman and Giulio Tononi, coauthors, (Basic Books, 2000, Reprint edition 2001). ISBN 0-465-01377-5 Wider than the Sky: The Phenomenal Gift of Consciousness (Yale Univ. Press 2004) ISBN 0-300-10229-1 Second Nature: Brain Science and Human Knowledge (Yale University Press 2006) ISBN 0-300-12039-7 |

|

| Biologically inspired computing Embodied philosophy Embodied cognition Reentry (neural circuitry) List of Nobel laureates |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerald_Edelman |

|

| Secondary consciousness

is an individual's accessibility to their history and plans. The

ability allows its possessors to go beyond the limits of the remembered

present of primary consciousness.[1] Primary consciousness can be

defined as simple awareness that includes perception and emotion. As

such, it is ascribed to most animals. By contrast, secondary

consciousness depends on and includes such features as self-reflective

awareness, abstract thinking, volition and metacognition.[1][2] The

term was coined by Gerald Edelman.

|

二次意識とは、個人が自分の歴史や計画にアクセスできることである。一

次意識は、知覚と感情を含む単純な意識と定義できる。そのため、ほとんどの動物が持っている。これに対し、二次意識は自己反省的な意識、抽象的な思考、意

志、メタ認知などの機能に依存し、それを含む[1][2]。この言葉はジェラルド・エデルマンによって作られた。

|

| Brief history and overview Since Descartes's proposal of dualism, it became a general consensus that the mind had become a matter of philosophy and that science was not able to penetrate the issue of consciousness- that consciousness was outside of space and time. However, over the last 20 years, many scholars have begun to move toward a science of consciousness. Such notable neuroscientists that have led the move to neural correlates of the self and of consciousness are Antonio Damasio and Gerald Edelman. Damasio has demonstrated that emotions and their biological foundation play a critical role in high level cognition,[3][4] and Edelman has created a framework for analyzing consciousness through a scientific outlook. The current problem consciousness researchers face involves explaining how and why consciousness arises from neural computation.[5][6] In his research on this problem, Edelman has developed a theory of consciousness, in which he has coined the terms primary consciousness and secondary consciousness.[1] The author puts forward the belief that consciousness is a particular kind of brain process; linked and integrated, yet complex and differentiated.[7] |

簡単な歴史と概要 デカルトが二元論を提唱して以来、心は哲学の問題であり、意識の問題-意識は空間と時間の外にある-は科学では突き止められないというのが一般的な見解と なった。しかし、この20年ほどの間に、多くの学者が意識を科学する方向に向かい始めた。自己と意識の神経的相関関係への動きを先導してきた著名な神経科 学者は、アントニオ・ダマシオとジェラルド・エーデルマンである。ダマシオは情動とその生物学的基盤が高度な認知に重要な役割を果たすことを示し[3] [4]、エーデルマンは意識を科学的に分析する枠組みを構築した。意識研究者が現在直面している問題は、意識が神経計算からどのように、そしてなぜ生じる のかを説明することである。 この問題に対する研究の中で、エーデルマンは一次意識と二次意識という用語を用いて意識理論を構築した[1]。著者は、意識とは脳のプロセスの一種で、リ ンクし統合されているが複雑で分化しているという考えを提唱している[7]。 |

| Evolution towards secondary consciousness Edelman argues that the evolutionary emergence of consciousness depended on the natural selection of neural systems that gave rise to consciousness, but not on selection for consciousness itself. He is noted for his theory of neuronal group selection, also known as Neural Darwinism, which posits that consciousness is the product of natural selection. He believes consciousness is not something separate from the real world, thus the attempt to eliminate Descartes’ "dualism" as a possible consideration. He also rejects theories based on the notion that the brain is a computer or an instructional system. Instead, he suggests that the brain is a selectional system, one in which large numbers of variant circuits are generated epigenetically. He claims the potential connectivity in the neural net "far exceeds the number of elementary particles in the universe"[1][8] |

二次意識への進化 エーデルマンは、意識の進化的な出現は、意識を生み出す神経システムの自然淘汰に依存しており、意識そのものの淘汰には依存していないと主張する。彼は、 意識が自然淘汰の産物であるとする、神経ダーウィニズムとも呼ばれる神経細胞群淘汰の理論で有名である。意識は現実世界と切り離されたものではないと考 え、デカルトの「二元論」を排除しようとするものである。また、脳はコンピュータや命令系統であるという説を否定している。その代わりに、脳は選択システ ムであり、エピジェネティックに多数の可変回路が生成されるシステムであることを示唆している。神経網の潜在的な結合力は「宇宙の素粒子の数をはるかに超 えている」と主張している[1][8]。 |

| Dynamic core hypothesis and re-entry Dynamic core hypothesis Edelman elaborates on the dynamic core hypothesis (DCH), which describes the thalamocortical region- the region believed to be the integration center of consciousness. The DCH reflects the use and disuse of interconnected neuronal networks during stimulation of this region. It has been shown through computer models that neuronal groups existing in the cerebral cortex and thalamus interact in the form of synchronous oscillation.[9] The interaction between distinct neuronal groups forms the "dynamic core" and may help explain the nature of conscious experience. Re-entry Edelman integrates the DCH hypothesis into Neural Darwinism, in which metastable interactions in the thalamocortical region cause a process of selectionism through re-entry, a host of internal feedback loops. "Re-entry", as Edelman states, "provides the critical means by which the activities of distributed multiple brain areas are linked, bound, and then dynamically altered in time during perceptual categorization. Both diversity and re-entry are necessary to account for the fundamental properties of conscious experience." These re-entrant signals are reinforced by areas Edelman calls "degenerate". Degeneracy doesn't imply deterioration, but instead redundancy as many areas in the brain handle the same or similar tasks. With this brain structure emerging in early humans, selection could favor certain brains and pass their patterns down the generations. Habits once erratic and highly individual ultimately became the social norm.[1][8] Exhibiting secondary consciousness in the animal kingdom While animals with primary consciousness have long-term memory, they lack explicit narrative, and, at best, can only deal with the immediate scene in the remembered present. While they still have an advantage over animals lacking such ability, evolution has brought forth a growing complexity in consciousness, particularly in mammals. Animals with this complexity are said to have secondary consciousness. Secondary consciousness is seen in animals with semantic capabilities, such as the four great apes. It is present in its richest form in the human species, which is unique in possessing complex language made up of syntax and semantics. In considering how the neural mechanisms underlying primary consciousness arose and were maintained during evolution, it is proposed that at some time around the divergence of reptiles into mammals and then into birds, the embryological development of large numbers of new reciprocal connections allowed rich re-entrant activity to take place between the more posterior brain systems carrying out perceptual categorization and the more frontally located systems responsible for value-category memory.[1] The ability of an animal to relate a present complex scene to its own previous history of learning conferred an adaptive evolutionary advantage. At much later evolutionary epochs, further re-entrant circuits appeared that linked semantic and linguistic performance to categorical and conceptual memory systems. This development enabled the emergence of secondary consciousness.[8][10] Self-recognition For the advocates of the idea of a secondary consciousness, self-recognition serves as a critical component and a key defining measure.[citation needed] What is most interesting then, is the evolutionary appeal that arises with the concept of self-recognition. In non-human species and in children, the "mirror test" has been used as an indicator of self-awareness. In these experiments, subjects are placed in front of a mirror and provided with a mark that cannot be seen directly but is visible in the mirror.[11][12] There have been numerous findings in the past 30 years which display fairly clear evidence of possessors of self-recognition including the following animals: Chimpanzees, orangutans and gorillas.[13][14][15] Dolphins and elephants. Findings suggestive of self-recognition in mammals other than apes have been reported.[16][17] Magpies.[12] It should be mentioned that even in the chimpanzee, the species most studied and with the most convincing findings, clear-cut evidence of self-recognition is not obtained in all individuals tested. Occurrence is about 75% in young adults and considerably less in young and old individuals.[18] For Monkeys, non-primate mammals, and in a number of bird species, exploration of the mirror and social displays were observed. However, hints at mirror-induced self-directed behavior have been obtained.[19] Self-recognition study in the magpie It was recently thought that self-recognition was restricted to mammals with large brains and highly evolved social cognition but absent from animals without a neocortex. However, in a recent study, an investigation of self-recognition in corvids was carried out, and significant result quantified the ability of self-recognition in the magpie. Mammals and birds inherited the same brain components from their last common ancestor nearly 300 million years ago, and have since independently evolved and formed significantly different brain types. The results of the mirror and mark tests showed that neocortex-less magpies are capable of understanding that a mirror image belongs to their own body. The findings show that magpies respond in the mirror and mark test in a manner similar to apes, dolphins and elephants. This is a remarkable capability that, although not fully concrete in its determination of self-recognition, is at least a prerequisite of self-recognition. This is not only of interest regarding the convergent evolution of social intelligence; it is also valuable for an understanding of the general principles that govern cognitive evolution and their underlying neural mechanisms. The magpies were chosen to study based on their empathy/ lifestyle, a possible precursor for their ability of self-awareness.[12] Research on animal consciousness Many researchers of consciousness have looked upon such types of research in animals as significant and interesting approaches. Ursula Voss of the Universität Bonn believes that the theory of protoconsciousness may serve as adequate explanation for self-recognition found in this bird species, as they would develop secondary consciousness during REM sleep. She added that many types of birds have very sophisticated language systems.[citation needed] Don Kuiken of the University of Alberta finds such research interesting as well as if we continue to study consciousness with animal models (with differing types of consciousness), we would be able to separate the different forms of reflectiveness found in today's world.[citation needed] |

ダイナミックコア仮説と再突入 ダイナミックコア仮説 エーデルマンは、意識の統合中枢と考えられている視床皮質領域について、ダイナミックコア仮説(DCH)を詳しく説明している。DCHは、この領域に刺激 を与えると、相互接続されたニューロンネットワークが使われたり使われなかったりすることを反映している。大脳皮質と視床に存在する神経細胞群が同期振動 の形で相互作用することがコンピュータモデルによって示されている[9]。異なる神経細胞群間の相互作用が「ダイナミックコア」を形成し、意識経験の本質 を説明するのに役立つと考えられる。 再入力 エーデルマンはDCH仮説をNeural Darwinismに統合しており、視床皮質領域における準安定な相互作用が、内部フィードバックループのホストである再突入を通じて選択主義のプロセス を引き起こすと述べている[10]。「エーデルマンは、「リエントリーとは、知覚のカテゴリー化において、分散した複数の脳領域の活動がリンクし、結合 し、そして時間的に動的に変化するための重要な手段である」と述べている。意識経験の基本的な特性を説明するためには、多様性とリエントリーの両方が必要 である」。これらのリエントラント信号は、エーデルマンが「退化」と呼ぶ領域によって補強されている。縮退は劣化を意味するのではなく、脳内の多くの領域 が同じあるいは類似のタスクを処理するため、冗長性を意味する。このような脳構造が初期の人類に出現したことで、淘汰は特定の脳を優遇し、そのパターンを 世代を超えて受け継ぐことができるようになった。かつては不規則で非常に個人的だった習慣が、最終的には社会的な規範となったのである[1][8]。 動物界における二次意識の発現 一次意識を持つ動物は長期記憶を持つが、明示的な物語性を欠き、せいぜい記憶された現在の目の前の光景にしか対処することができない。このように、一次意 識を持つ動物は、一次意識を持たない動物よりも有利な立場にあるが、進化により、特に哺乳類において意識の複雑さが増している。このような複雑さを持つ動 物は、二次意識を持つと言われている。二次意識は、四大猿のような意味能力を持つ動物に見られる。また、構文と意味論からなる複雑な言語を持つヒトという 種に、最も豊かな形で存在する。進化の過程で一次意識の基盤となる神経機構がどのように生まれ、維持されたかを考える上で、爬虫類が哺乳類に、そして鳥類 に分岐した頃のある時期に、胚的に新しい相互結合が大量に発達し、知覚的分類を行うより後方の脳システムと価値カテゴリー記憶を行うより前方のシステム間 で豊かな再入力活動が行われるようになったと提案された[1]。さらに進化の後期には、意味的・言語的パフォーマンスをカテゴリー記憶や概念的記憶システ ムに結びつける、さらなる再入可能な回路が出現した。この発展が二次意識の出現を可能にしたのである[8][10]。 自己認識 二次意識の考えを支持する者にとって、自己認識は重要な構成要素であり、重要な定義づけの指標となる[citation needed]。人間以外の種や子供では、自己認識の指標として「鏡テスト」が使われてきた。この実験では、被験者を鏡の前に置き、直接は見えないが鏡に 映る印を与える[11][12]。 過去30年間に、以下の動物を含む自己認識の保有者についてかなり明確な証拠を示す多くの発見があった。 チンパンジー、オランウータン、ゴリラ[13][14][15]。 イルカ、ゾウ 類人猿以外の哺乳類でも自己認知を示唆する所見が報告されている[16][17]。 カササギ[12]。 最も研究され、最も説得力のある所見を得た種であるチンパンジーにおいてさえ、テストされたすべての個体で自己認識の明確な証拠が得られるわけではないこ とに言及すべきです。サルや霊長類以外の哺乳類、多くの鳥類では鏡の探索や社会的なディスプレイが観察された[18]。しかし、鏡に誘導された自己指示行 動のヒントは得られている[19]。 カササギの自己認識研究 近年、自己認識は大脳が大きく社会的認知が高度に発達した哺乳類に限られ、大脳新皮質を持たない動物にはないと考えられていた。しかし、最近の研究で、カ ササギの自己認知の調査が行われ、カササギの自己認知能力を数値化したことが大きな成果であった。哺乳類と鳥類は、約3億年前に最後の共通祖先から同じ脳 成分を受け継ぎ、その後独自に進化して大きく異なる脳型を形成してきた。鏡像テストとマークテストの結果、新皮質がないカササギは、鏡像が自分の体のもの であることを理解することができることがわかった。今回の発見は、カササギが鏡やマークテストで、類人猿、イルカ、ゾウと同様の反応を示すことを示してい る。これは、自己認識の判断が完全に具体化されていないものの、少なくとも自己認識の前提条件となる驚くべき能力である。これは、社会的知性の収斂進化に 関する興味だけでなく、認知進化を支配する一般原理とその根底にある神経機構を理解する上でも貴重である。カササギは、自己認識の能力の前兆となりうる共 感性/生活様式に基づき、研究対象として選ばれた[12]。 動物の意識に関する研究 意識の研究者の多くは、このような動物による研究を重要かつ興味深いアプローチとしてとらえている。ボン大学のウルスラ・ヴォスは、レム睡眠中に二次意識 を発達させることから、原意識説はこの鳥類に見られる自己認識の適切な説明となりうると考えている。彼女は、多くの種類の鳥が非常に洗練された言語システ ムを持っていることも付け加えた[citation needed] アルバータ大学のドン・カイケンも、(意識のタイプが異なる)動物モデルを使って意識の研究を続ければ、今日の世界で見られるさまざまな形態の反射性を分 離できるようになるだろうとして、こうした研究を興味深いものと考えている[citation needed]。 |

| Lucid vs. non-lucid dreaming as a model In the last couple of decades, dream research has begun to focus on the field of consciousness. Through lucid dreaming, NREM sleep, REM sleep, and waking states, many dream researchers are attempting to scientifically explore consciousness. When exploring consciousness through the concept of dreams, many researchers believe the general characteristics that constitute primary and secondary consciousness remain intact: "Primary consciousness is a state in which you have no future or past, a state of just being…. no executive ego control in your dreams, no planning, things just happen to you, you just are in a dream. Yet, everything feels real…Secondary is based on language, has to do with self-reflection, it has to do with forming abstractions, and that is dependent of language. Only animals with language have secondary consciousness".[citation needed] Circuitry/anatomy There have been studies used to determine what parts of the brain are associated with lucid dreaming, NREM sleep, REM sleep and waking states. The goal of these studies is often to seek physiological correlates of dreaming and apply them in the hopes of understanding relations to consciousness. Prefrontal cortex Some notable, albeit criticized findings include the functions of the prefrontal cortex that are most relevant to the self-conscious awareness that is lost in sleep, commonly termed as 'executive' functions. These include self-observation, planning, prioritizing and decision-making abilities, which are, in turn, based upon more basic cognitive abilities such as attention, working memory, temporal memory and behavioral inhibition[20][21] Some experimental data which display differences between the self-awareness experienced in waking and its diminution in dreaming can be explained by deactivation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during REM sleep. It has been proposed that deactivation results from a direct inhibition of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortical neurons by acetylcholine, the release of which is enhanced during REM sleep.[22] Research Experiments and studies have been taken out to test neural correlations of lucid dreams with consciousness in dream research. Although there are many difficulties in conducting lucid dreaming research (e.g. number of lucid subjects, 'type' of lucidity achieved, etc.), there have been studies with significant results. In one study, researchers sought physiological correlates of lucid dreaming. They showed that the unusual combination of hallucinatory dream activity and wake-like reflective awareness and agentive control experienced in lucid dreams is paralleled by significant changes in electrophysiology. Participants were recorded using 19-channel Electroencephalography (EEG), and 3 achieved lucidity in the experiment. Differences between REM sleep and lucid dreaming were most prominent in the 40-Hz frequency band. The increase in 40-Hz power was especially strong at frontolateral and frontal sites. Their findings include the indication that 40-Hz activity holds a functional role in the modulation of conscious awareness across different conscious states. Furthermore, they termed lucid dreaming as a hybrid state, or that lucidity occurs in a state with features of both REM sleep and waking. In order to move from non-lucid REM sleep dreaming to lucid REM sleep dreaming, there must be a shift in brain activity in the direction of waking.[23] Other well-known contributing scholars involved with lucid dream research and consciousness, yet primarily based in fields such as psychology and philosophy include: Stephen LaBerge- most known for his lucid dreaming education and facilitation. His technique of signaling to a collaborator monitoring his EEG with agreed-upon eye movements during REM sleep became the first published, scientifically-verified signal from a dreamer's mind to the outside world.[24][25] Thomas Metzinger- known for his correlate of neuroscience and philosophy in understanding consciousness. He is praised for his ability to probe and link fundamental issues between these fields.[26][27] Paul Tholey- most known for his research on rare, non-ordinary ego experiences and OBEs that arise with lucid dreaming. He has also studied the cognitive abilities of dream characters in lucid dreams through various experiments.[28] Protoconsciousness The theory of protoconsciousness, developed by Allan Hobson, a creator of the Activation-synthesis hypothesis, has been developed through dream research and involves the idea of a secondary consciousness. Hobson suggests that brain states underlying waking and dreaming cooperate and that their functional interplay is crucial to the optimal functioning of both. Ultimately, he proposes the idea that REM sleep provides opportunities to the brain to prepare itself for its main integrative functions, including secondary consciousness, which would explain the developmental and evolutionary considerations to be taken with birds.[citation needed] This functional interplay which occurs during REM sleep constitutes a 'proto-conscious' state which preludes consciousness and can develop and maintain higher order consciousness.[29] AIM model As the activation-synthesis hypothesis has evolved, it has metamorphosed into the three-dimensional framework known as the AIM model. The AIM model describes a method of mapping conscious states onto an underlying physiological state space. The AIM model relates not just to wake/sleep states of consciousness, but to all states of consciousness. By choosing activation, input source, and mode of neuromodulation as the three dimensions, the proposers believe to have selected "how much information is being processed by the brain (A), what information is being processed (I), and how it is being processed (M).[30] Hobson, Schott, and Stickgold propose three aspects of the AIM model: Conscious states are in large part determined by three interdependent processes, the level of brain activation ("A"), the origin of inputs ("I") to the activated areas, and the relative levels of activation of aminergic (noradrenergic and serotonergic) and cholinergic neuromodulators ("M").[30] The AIM Model proposes that all of the universes' possible brain-mind states can be exemplified with a three-dimensional state space, with axes A, I, and M (activation, input, and mode), and that the state of the brain-mind at any given instant of time can be described as a point in this space. Since the AIM model represents brain-mind state as a sequence of points, Hobson adds that time is a fourth dimension of the model.[30] The AIM model proposes that all three parameters defining the state space are continuous variables, and any point in the state space can in theory be occupied.[30] |

モデルとしての明晰夢と非明晰夢の比較 ここ数十年の間に、夢の研究は意識の分野に焦点を当てるようになった。明晰夢、NREM睡眠、REM睡眠、覚醒状態を通じて、多くの夢研究者が意識を科学 的に探求しようとしている。夢の概念を通して意識を探るとき、多くの研究者は一次意識と二次意識の一般的な特徴がそのまま残っていると考えている。「一次 意識とは、未来も過去もない、ただ存在しているだけの状態...夢の中では実行的な自我のコントロールもなく、計画性もなく、ただ物事が起こる、ただ夢の 中にいるだけの状態です。しかし、すべてが現実のように感じられます。二次意識は言語に基づいており、自己反省に関係し、抽象概念を形成することに関係 し、それは言語に依存しています。言語を持つ動物だけが二次意識を持つ」[citation needed]. 回路・解剖学 脳のどの部分が明晰夢、NREM睡眠、REM睡眠と覚醒状態に関連しているかを決定するために使われる研究がある。これらの研究の目的は、しばしば夢想の生理学的相関を求め、意識との関係を理解することを期待してそれらを適用することである。 前頭前野 批判されてはいるが、注目すべき発見として、睡眠中に失われる自己意識に最も関連する前頭前野の機能、一般に「実行」機能と呼ばれるものがある。これらの 機能には、自己観察、計画、優先順位付け、意思決定能力が含まれ、これらは順に、注意、ワーキングメモリ、一時記憶、行動抑制といったより基本的な認知能 力に基づく[20][21]。覚醒時に経験する自己認識と夢見る時のその低下との間の差異を示すいくつかの実験データは、レム睡眠中の背外側前頭前野の不 活性化によって説明することが可能である。レム睡眠中に放出が促進されるアセチルコリンによって背外側前頭前野のニューロンが直接抑制されることによって 不活性化が生じることが提案されている[22]。 研究内容 夢の研究において、明晰夢と意識の神経的な相関を検証する実験や研究が行われている。明晰夢の研究を行うには多くの困難(明晰になる被験者の数、達成された明晰度の「タイプ」など)があるが、重要な結果をもたらす研究がある。 ある研究では、研究者は明晰夢の生理学的な相関を探った。その結果、明晰夢で経験される幻覚的な夢と、覚醒時のような反射的な意識と行動的な制御の珍しい 組み合わせは、電気生理の著しい変化と並行していることが示された。参加者は19チャンネルの脳波計で記録され、実験では3人が明晰夢を達成した。レム睡 眠と明晰夢の違いは、40Hzの周波数帯域で最も顕著であった。40Hzのパワー増加は、特に前頭葉外側と前頭部で強かった。この結果は、40Hzの活動 が、異なる意識状態間の意識調節に機能的な役割を担っていることを示唆するものであった。さらに、彼らは明晰夢をハイブリッド状態、つまりレム睡眠と覚醒 の両方の特徴を持つ状態で明晰夢が起こる、と呼んでいる。明晰でないレム睡眠の夢から明晰なレム睡眠の夢に移行するためには、脳の活動が覚醒の方向にシフ トする必要がある[23] その他、明晰夢研究や意識に関わる著名な貢献者であるが、主に心理学や哲学などの分野をベースとしている研究者がいる。 スティーブン・ラバージ-明晰夢の教育および促進で最もよく知られている。レム睡眠中に脳波をモニターしている協力者に合意した目の動きで合図する彼の技術は、夢を見ている人の心から外界への科学的に検証された最初の信号として発表された[24][25]。 トーマス・メッツィンガー-意識の理解における神経科学と哲学の相関関係で知られる。これらの分野の間の基本的な問題を探り、結びつける能力で賞賛されている[26][27]。 ポール・トーリー-明晰夢で生じる稀な非日常的自我体験とOBEに関する研究で最もよく知られている。彼はまた様々な実験を通して明晰夢における夢の登場人物の認知能力を研究している[28]。 原始意識 アクティベーション-シンセシス仮説の創造者であるアラン・ホブソンによって開発された原意識論は、夢の研究を通じて発展したもので、二次意識の考えを含 んでいる。ホブソンは、覚醒と夢の基礎となる脳状態が協力し合い、その機能的相互作用が両者の最適な機能発揮に不可欠であることを示唆している。最終的 に、彼はレム睡眠が二次意識を含む主要な統合的機能のために脳を準備する機会を提供するという考えを提唱しており、これは鳥と一緒に取るべき発達的・進化 的考察を説明するだろう[citation needed] レム睡眠中に発生するこの機能相互作用は、意識を先取りする「原意識」状態を構成し、高次意識を発達・維持できる。[29]レム睡眠中に発生する機能相互 作用は、意識を先取りする「原意識状態」を構成している。 AIMモデル 活性化合成仮説が発展するにつれて、AIMモデルとして知られる3次元の枠組みへと変容してきた。AIMモデルは、意識状態を基礎となる生理学的状態空間 にマッピングする方法を説明するものである。AIMモデルは、意識の覚醒/睡眠状態だけでなく、すべての意識状態に関係する。活性化、入力源、神経調節の モードの3次元を選ぶことによって、提案者は「どれだけの情報が脳によって処理されているか(A)、どんな情報が処理されているか(I)、そしてどのよう に処理されているか(M)」を選択したと考えている[30]。 ホブソン、ショット、スティックゴールドはAIMモデルの3つの側面を提案している。 意識的な状態は3つの相互依存的なプロセス、脳の活性化のレベル(「A」)、活性化された領域への入力(「I」)の起源、およびアミン作動性(ノルアドレ ナリン作動性およびセロトニン作動性)およびコリン作動性神経調節因子(「M」)の活性化の相対レベルによって大部分が決定される[30]。 AIMモデルは、宇宙で起こりうるすべての脳-心の状態は、A、I、M(活性化、入力、モード)を軸とする3次元の状態空間で例示でき、任意の瞬間の脳- 心の状態はこの空間における点として記述できると提唱している[30]。AIMモデルは脳-心の状態を点の列として表現するので、ホブソンは時間がこのモ デルの4番目の次元であると付け加えている[30]。 AIMモデルは、状態空間を定義する3つのパラメータはすべて連続変数であり、理論的には状態空間内の任意の点を占めることができることを提案している[30]。 |

| Criticism of lucid dreaming model Secondary consciousness, as it remains a controversial topic, has received often contrasting findings and beliefs regarding lucid dreaming as a model, which entails the true difficulty in understanding consciousness. The most common of recent criticisms include: - The analyzed circuitry involved in lucid dreaming, REM sleep, NREM sleep, and waking states used to determine reflective ability. If, as many scholars have come to suggest, typical non-lucid REM dreaming reflects primary consciousness, the belief that typical non-lucid dreaming is accompanied by de-activation of the DL-PFC becomes significant. Although the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DL-PFC) is believed to be the site of "executive ego control", it has never been tested. - The idea of "executive ego control" and its articulation. Kuiken has stated that typical non-lucid REM dreaming may involve another form of self-regulative activity that is not related to activation of the DL-PFC. There is evidence that the subtle self-regulation characteristic of musical improvisation is similar in pattern to the activations and de-activations (including de-activation of the DL-PFC) that characterize REM sleep. It is probable that the loss of one conscious form of self-regulation during non-lucid dreaming creates the possibility for the adoption of an unconscious, but "fluid" form of self-regulation that resembles that of musical improvisation. It is possible, he believes, that non-lucid dreaming entails self-regulated but fluid openness to 'what comes,’ rather than the direct self-monitoring and inhibition that enable 'rational' planning and decision making.[31] In a recent study, it has been proven that unconscious task-relevant signals can actively trigger and initiate an inhibition to respond, thereby breaking the alleged close correlation between consciousness and inhibitory control.[32] This proves that self-regulative activities (a characteristic of secondary consciousness for many scholars) can occur independently of consciousness of consciousness. - Using lucid dreaming as a model of secondary consciousness. Some scholars believe lucid dreaming does not constitute a single type of reflectiveness. It is already argued that there may be different kinds of reflectiveness that might define secondary consciousness, so the difficulty in using lucid dreaming as a model is greatly increased. For example, there may be a realization in a dream that will often go without gaining control. There are different amounts of 'executive functions' taken between lucid dreams, thus displaying how there are many different types of reflectiveness involved in 'lucid' dreaming.[citation needed] |

明晰夢モデルへの批判 二次意識は、依然として論争の的となっているように、モデルとしての明晰夢に関しては、しばしば対照的な発見や信念が寄せられており、それは意識の理解の真の難しさを内包している。 最近の批判で最も多いのは、以下のようなものである。 - 明晰夢、レム睡眠、NREM睡眠、覚醒状態に関わる分析回路が反射能力の判断に使われること。多くの学者が示唆するように、典型的な非明晰夢であるレム睡 眠が一次意識を反映しているとすれば、典型的な非明晰夢がDL-PFCの脱活性化を伴っているという考え方は重要な意味を持つようになる。背外側前頭前皮 質(DL-PFC)は「実行的自我制御」の部位であると考えられているが、これまで検証されたことはない。 - 実行的自我制御」という考え方とその明瞭化。Kuikenは、典型的な非明晰レム睡眠には、DL-PFCの活性化とは関係のない別の形の自己調節活動が含 まれている可能性があると述べている。音楽の即興演奏に特徴的な微妙な自己調節は、レム睡眠を特徴づける活性化と脱活性化(DL-PFCの脱活性化を含 む)とパターンが似ているという証拠がある。非明晰夢の中で意識的な自己調節が失われると、無意識的だが「流動的」な、即興演奏に似た自己調節が採用され る可能性があるのだろう。彼は、非明晰夢は「合理的」な計画や意思決定を可能にする直接的な自己監視や抑制ではなく、「来るもの」に対する自己制御的だが 流動的な開放性を伴う可能性があると考えている[31]。 最近の研究において、無意識のタスク関連信号が積極的にトリガーして応答する抑制を開始することが証明されていて、それによって意識と抑制制御との密接な 相関関係が疑われているが、それは破られた[32] これは自己調整活動(多くの学者にとっての第二意識の特徴)が意識とは独立して起こりうることを証明するものである。 - 明晰夢を二次意識のモデルとして使われる。明晰夢は単一のタイプの反射性を構成するものではないと考える学者もいる。二次意識を定義しうる反射性にはさま ざまな種類があるかもしれないと既に論じられているので、明晰夢をモデルとして使うことの難しさが大きくなっている。例えば、夢の中で、しばしば制御を得 ることなく進んでしまうような気づきがあるかもしれない。明晰夢の間で取られる「実行機能」の量が異なるため、「明晰」な夢に関わる反射性の種類がいかに 多いかを示している[要出典]。 |

| Consciousness Lucid dream Primary consciousness Neural Darwinism |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Secondary_consciousness |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

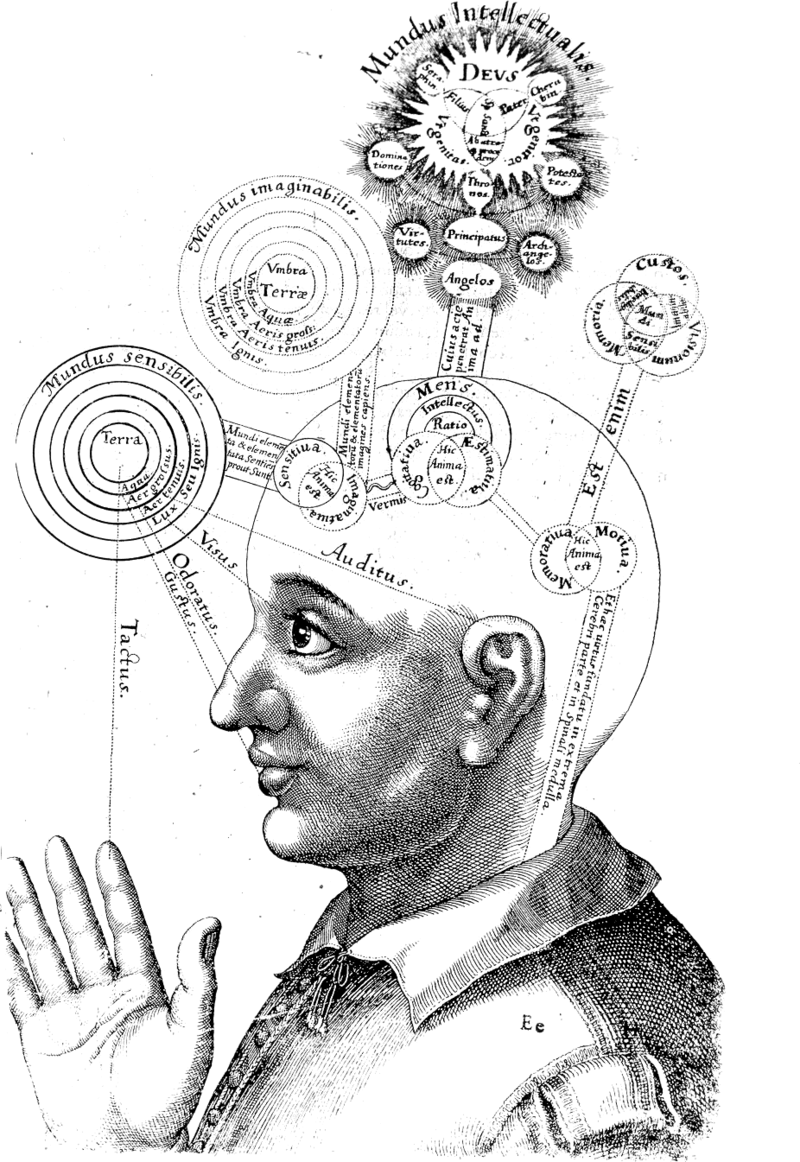

Representation of consciousness from the seventeenth century.obert Fludd - Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris […] historia, tomus II (1619), tractatus I, sectio I, liber X, De triplici animae in corpore visione

●哲学では、意図性とは、心や精神状態が、物事、性質、状態について存在し、表象し、あるいはそれを代弁する力をいう。個人の心的状態について意図性があると言うことは、それが心的表現である、あるいは内容を持つと いうことである。さらに、話し手が自分の心的状態の内容を他者に伝える目的で、何らかの自然言語から言葉を発し、あるいは形式言語から絵や記号を描く限 り、話し手によって使われるこれらの人工物も内容や意図性を持つのである。意図性」は哲学者の言葉である。19世紀の最後の四半世紀にフランツ・ブレンターノが哲学に導入して以来、表現のパズルを指す言葉として使われ、これらはすべて心の哲学と言語哲学の接点にある。

| https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/intentionality/ In philosophy, intentionality is the power of minds and mental states to be about, to represent, or to stand for, things, properties and states of affairs. To say of an individual’s mental states that they have intentionality is to say that they are mental representations or that they have contents. Furthermore, to the extent that a speaker utters words from some natural language or draws pictures or symbols from a formal language for the purpose of conveying to others the contents of her mental states, these artifacts used by a speaker too have contents or intentionality. ‘Intentionality’ is a philosopher’s word: ever since it was introduced into philosophy by Franz Brentano in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, it has been used to refer to the puzzles of representation, all of which lie at the interface between the philosophy of mind and the philosophy of language. A picture of a dog, a proper name (e.g., ‘Fido’), the common noun ‘dog’ or the concept expressed by the word can mean, represent, or stand for, one or several hairy barking creatures. A complete thought, a full sentence or a picture can stand for or describe a state of affairs. How could some of the represented things (e.g., dinosaurs) be arbitrarily remote in space and time from the representation (e.g., a human thought or utterance about dinosaurs tokened in 2018), while others (e.g., numbers) may not even be in space and time at all? How could some representations (e.g., direct quotations such as ‘dinosaur’) even stand for themselves? How does a complex representation (e.g., a complete thought or a full sentence) inherit its meaning or content from the meanings or contents of its constituents? How should one construe the relationship between the iconic content of pictorial representations and the conceptual content of proposition-like representations (thoughts and utterances)? How should one understand the relation between the content of an individual’s mental state and the meanings of external symbols used by the individual to express her internal mental states? Are representations of the world part of the world they represent? Do all of an individual’s mental states have intentionality or only some of them? |

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/intentionality/ 哲学では、意図性とは、心や精神状態が、物事、性質、状態について存在し、表象し、あるいはそれを代弁する力をいう。個人の心的状態について意図性があると言うことは、それが心的表現である、あるいは内容を持つと いうことである。さらに、話し手が自分の心的状態の内容を他者に伝える目的で、何らかの自然言語から言葉を発し、あるいは形式言語から絵や記号を描く限 り、話し手によって使われるこれらの人工物も内容や意図性を持つのである。意図性」は哲学者の言葉である。19世紀の最後の四半世紀にフランツ・ブレンターノが哲学に導入し て以来、表現のパズルを指す言葉として使われ、これらはすべて心の哲学と言語哲学の接点にある。犬の絵、固有名詞(例:「ファイドー」)、普通名詞 「犬」、あるいはその言葉によって表される概念は、毛むくじゃらの吠える生き物を一つあるいは複数意味したり、表したり、表したりすることができる。完全 な思考、完全な文、または絵は、ある状態を表したり記述したりすることができます。表現されたもの(例えば恐竜)の中には、表現(例えば2018年に「話 をする恐竜」に関する人間の思考や発話)から空間的にも時間的にも任意に離れたものがある一方で、他のもの(例えば数字)は空間と時間に全く存在しないこ とさえあり得るのはどうしてだろうか。ある表現(例えば、「恐竜」のような直接的な引用)は、どのようにしてそれ自体で成り立っているのだろうか?複雑な 表現(例えば、完全な思考や完全な文)は、その構成要素の意味や内容から、どのように意味や内容を継承するのだろうか。絵画的表現の象徴的内容と命題的表 現(思考や発話)の概念的内容との関係をどのように解釈すべきか?個人の心的状態の内容と、その個人が内的心的状態を表現するために使われる外部記号の意 味との関係をどのように理解したらよいのだろうか。世界の表象は、それが表象する世界の一部なのか?個人の心的状態のすべてが意図性を持つのか、それとも その一部だけが意図性を持つのか? |

| 1. Why is intentionality so-called? Contemporary discussions of the nature of intentionality are an integral part of discussions of the nature of minds: what are minds and what is it to have a mind? They arise in the context of ontological and metaphysical questions about the fundamental nature of mental states: states such as perceiving, remembering, believing, desiring, hoping, knowing, intending, feeling, experiencing, and so on. What is it to have such mental states? How does the mental relate to the physical, i.e., how are mental states related to an individual’s body, to states of his or her brain, to his or her behavior and to states of affairs in the world? Why is intentionality so-called? For reasons soon to be explained, in its philosophical usage, the meaning of the word ‘intentionality’ should not be confused with the ordinary meaning of the word ‘intention.’ As indicated by the meaning of the Latin word tendere, which is the etymology of ‘intentionality,’ the relevant idea behind intentionality is that of mental directedness towards (or attending to) objects, as if the mind were construed as a mental bow whose arrows could be properly aimed at different targets. In medieval logic and philosophy, the Latin word intentio was used for what contemporary philosophers and logicians nowadays call a ‘concept’ or an ‘intension’: something that can be both true of non-mental things and properties—things and properties lying outside the mind—and present to the mind. On the assumption that a concept is itself something mental, an intentio may also be true of mental things. For example, the concept of a dog, which is a first-level intentio, applies to individual dogs or to the property of being a dog. It also falls under various higher-level concepts that apply to it, such as being a concept, being mental, etc. If so, then while the first-level concept is true of non-mental things, the higher-level concepts may be true of something mental. Notice that on this way of thinking, concepts that are true of mental things are presumably logically more complex than concepts that are true of non-mental things. Although the meaning of the word ‘intentionality’ in contemporary philosophy is related to the meanings of such words as ‘intension’ (or ‘intensionality’ with an s) and ‘intention,’ nonetheless it ought not to be confused with either of them. On the one hand, in contemporary English, ‘intensional’ and ‘intensionality’ mean ‘non-extensional’ and ‘non-extensionality,’ where both extensionality and intensionality are logical features of words and sentences. For example, ‘creature with a heart’ and ‘creature with a kidney’ have the same extension because they are true of the same individuals: all the creatures with a kidney are creatures with a heart. But the two expressions have different intensions because the word ‘heart’ does not have the same extension, let alone the same meaning, as the word ‘kidney.’ On the other hand, intention and intending are specific states of mind that, unlike beliefs, judgments, hopes, desires or fears, play a distinctive role in the etiology of actions. By contrast, intentionality is a pervasive feature of many different mental states: beliefs, hopes, judgments, intentions, love and hatred all exhibit intentionality. In fact, Brentano held that intentionality is the hallmark of the mental: much of twentieth century philosophy of mind has been shaped by what, in this entry, will be referred to as “Brentano’s third thesis.” Furthermore, it is worthwhile to distinguish between levels of intentionality. Many of an individual’s psychological states with intentionality (e.g., beliefs) are about (or represent) non-mental things, properties and states of affairs. Many are also about another’s psychological states (e.g., another’s beliefs). Beliefs about others’ beliefs display what is known as ‘higher-order intentionality.’ Since the seminal (1978) paper by primatologists David Premack and Guy Woodruff entitled “Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind?”, under the heading ‘theory of mind,’ much empirical research of the past thirty years has been devoted to the psychological questions whether non-human primates can ascribe psychological states with intentionality to others and how human children develop their capacity to ascribe to others psychological states with intentionality (cf. the comments by philosophers Jonathan Bennett, Daniel Dennett and Gilbert Harman to Premack and Woodruff’s paper and the SEP entry folk psychology: as a theory). The concept of intentionality has played a central role both in the tradition of analytic philosophy and in the phenomenological tradition. As we shall see, some philosophers go so far as claiming that intentionality is characteristic of all mental states. Brentano’s characterization of intentionality is quite complex. At the heart of it is Brentano’s notion of the ‘intentional inexistence of an object,’ which is analyzed in the next section. |

1. 意図性とはなぜそう呼ばれるのか? 意図性の本質に関する現代の議論は、「心とは何か」「心を持つとはどういうことか」という心の本質に関する議論に不可欠なものである。このような議論は、 精神状態(知覚、記憶、信念、願望、希望、知識、意図、感情、経験など)の基本的な性質に関する存在論的、形而上学的な疑問との関連で生じている。このよ うな精神状態を持つことは何なのか?つまり、精神状態は、個人の身体、脳の状態、行動、世界の情勢とどのように関係しているのだろうか? なぜ意図性はいわゆる?まもなく説明される理由から、その哲学的な用法において、「意図性」という言葉の意味は、「意図」という言葉の通常の意味と混同さ れるべきではないのです。意図性」の語源であるラテン語のtendereの意味が示すように、意図性の背後にある関連する考え方は、あたかも心を心の弓と 解釈してその矢を異なる目標に適切に向けることができるように、対象に向かって(または対象に注目して)心の指向性を持つというものである。中世の論理学 や哲学では、ラテン語の intentio は、現代の哲学者や論理学者が今日「概念」あるいは「内 容」と呼んでいるものに使われていた。概念とはそれ自体心的なものであるという前提に立てば、「意図」もまた心的なものに対して真である可能性がある。例 えば、第一レベルの意図である犬という概念は、個々の犬や犬であるという性質に適用される。また、概念である、心的であるなど、様々な上位概念に該当す る。そうであれば、第一水準の概念が非心理的なものに対して真であるのに対して、上位の概念は心的なものに対して真である可能性があることになる。このよ うな考え方では、心的なものに対して成り立つ概念は、非心的なものに対して成り立つ概念よりも論理的に複雑であると推定されることに注意してください。 現代哲学における「意図性」という言葉の意味は、「intension」(sを付けて「intentionionality」)や「intention」 などの言葉の意味と関連しているが、それにもかかわらず、これらの言葉のいずれとも混同されるべきではないだろう。一方、現代英語では、 「intentionional」「intentionionality」は「非延長性」「非延長性」を意味し、拡張性と集中性はともに単語や文の論理的 特徴である。例えば、「心臓を持つ生き物」と「腎臓を持つ生き物」は、「腎臓を持つ生き物はすべて心臓を持つ生き物である」という同じ個体について真であ るため、同じ拡張性を持っている。しかし、「心臓」という単語は「腎臓」という単語と同じ意味どころか、同じ延長を持たないので、この二つの表現は異なる 意図を持っている。一方、意図と意図は、信念、判断、希望、欲望、恐怖とは異なり、行為の病因において特徴的な役割を果たす具体的な心の状態である。対照 的に、意図性は多くの異なる心的状態に広く見られる特徴であり、信念、希望、判断、意図、愛、憎悪はすべて意図性を示す。実際、ブレンターノは意図性が心 の特徴であるとした。20世紀の心の哲学の多くは、このエントリで「ブレンターノの第三のテーゼ」と呼ばれるものによって形成されてきた。 さらに、意図性のレベルを区別することも意義がある。意図性を持つ個人の心理状態(例えば信念)の多くは、非心理的なもの、性質、状態 についてである(あるいは表す)。また、多くは他人の心理的状態(例えば、他人の信念)についてのものである。他人の信念に関する信念は、「高次の意図 性」と呼ばれるものを示す。霊長類学者のデイヴィッド・プレマックとガイ・ウッドラフによる「チンパンジーには心の理論があるのか」と題する精選論文 (1978年)以来、「心の理論」という見出しで、過去30年間の多くの実証研究が、人間以外の霊長類が意図性をもって心理状態を他者に帰属させられるの か、人間の子供は意図性をもって心理状態を他人に帰属させる能力をどのようにして身につけるのかという心理学的問題に注がれている(cf. 哲学者のジョナサン・ベネット、ダニエル・デネット、ギルバート・ハーマンがプレマックとウッドラフの論文に寄せたコメントや、SEPの「フォーク心理 学:理論として」の項を参照)。 意図性の概念は、分析哲学の伝統と現象学の伝統の双方において中心的な役割を果た してきた。後述するように、哲学者の中には、意図性がすべての心的状態に特徴的であるとまで主張する者もいる。ブレンタノの意図性の特徴づけは非常に複雑 である。その中心は、次節で分析するブレンターノの「対象の意図的な非存在」概念である。 |

| 2. Intentional inexistence Contemporary discussions of the nature of intentionality were launched and many of them were anticipated by Franz Brentano (1874, 88–89) in his book, Psychology From an Empirical Standpoint, from which I quote two famous paragraphs: Every mental phenomenon is characterized by what the Scholastics of the Middle Ages called the intentional (or mental) inexistence of an object, and what we might call, though not wholly unambiguously, reference to a content, direction toward an object (which is not to be understood here as meaning a thing), or immanent objectivity. Every mental phenomenon includes something as object within itself, although they do not do so in the same way. In presentation, something is presented, in judgment something is affirmed or denied, in love loved, in hate hated, in desire desired and so on. This intentional inexistence is characteristic exclusively of mental phenomena. No physical phenomenon exhibits anything like it. We can, therefore, define mental phenomena by saying that they are those phenomena which contain an object intentionally within themselves. As one reads these lines, numerous questions arise: what does Brentano mean when he says that the object towards which the mind directs itself ‘is not to be understood as meaning a thing’? What can it be for a phenomenon (mental or otherwise) to exhibit ‘the intentional inexistence of an object’? What is it for a phenomenon to ‘include something as object within itself’? Do ‘reference to a content’ and ‘direction toward an object’ express two distinct ideas? Or are they two distinct ways of expressing one and the same idea? If intentionality can relate a mind to something that either does not exist or exists wholly within the mind, what sort of relation can it be? Replete as they are with complex, abstract and controversial ideas, these two short paragraphs have set the agenda for all subsequent philosophical discussions of intentionality in the late nineteenth and the twentieth century. There has been some discussion over the meaning of Brentano’s expression ‘intentional inexistence.’ Did Brentano mean that the objects onto which the mind is directed are internal to the mind itself (in-exist in the mind)? Or did he mean that the mind can be directed onto non-existent objects? Or did he mean both? (See Crane, 1998 for further discussion.) Some of the leading ideas of the phenomenological tradition can be traced back to this issue. Following the lead of Edmund Husserl (1900, 1913), who was both the founder of phenomenology and a student of Brentano’s, the point of the phenomenological analysis has been to show that the essential property of intentionality of being directed onto something is not contingent upon whether some real physical target exists independently of the intentional act itself. To achieve this goal, two concepts have been central to Husserl’s internalist interpretation of intentionality: the concept of a noema (plural noemata) and the concept of epoche (i.e., bracketing) or phenomenological reduction. By the word ‘noema,’ Husserl refers to the internal structure of mental acts. The phenomenological reduction is meant to help get at the essence of mental acts by suspending all naive presuppositions about the difference between real and fictitious entities (on these complex phenomenological concepts, see the papers by Føllesdal and others conveniently gathered in Dreyfus (1982). For further discussion, see Bell (1990) and Dummett (1993). In the two paragraphs quoted above, Brentano sketches an entire research programme based on three distinct theses. According to the first thesis, it is constitutive of the phenomenon of intentionality, as it is exhibited by mental states such as loving, hating, desiring, believing, judging, perceiving, hoping and many others, that these mental states are directed towards things different from themselves. According to the second thesis, it is characteristic of the objects towards which the mind is directed by virtue of intentionality that they have the property which Brentano calls intentional inexistence. According to the third thesis, intentionality is the mark of the mental: all and only mental states exhibit intentionality. Unlike Brentano’s third thesis, Brentano’s first two theses can hardly be divorced from each other. The first thesis can easily be recast so as to be unacceptable unless the second thesis is accepted. Suppose that it is constitutive of the nature of intentionality that one could not exemplify such mental states as loving, hating, desiring, believing, judging, perceiving, hoping, and so on, unless there was something to be loved, hated, desired, believed, judged, perceived, hoped, and so on. If so, then it follows from the very nature of intentionality (as described by the first thesis) that nothing could exhibit intentionality unless there were objects—intentional objects—that satisfied the property Brentano called intentional inexistence. Now, the full acceptance of Brentano’s first two theses raises a fundamental ontological question in philosophical logic. The question is: are there such intentional objects? Does due recognition of intentionality force us to postulate the ontological category of intentional objects? This question has given rise to a major division within analytic philosophy. The prevailing (or orthodox) response has been a resounding ‘No.’ But an important minority of philosophers, whom I shall call ‘the intentional-object’ theorists, have argued for a positive response to the question. Since intentional objects need not exist, according to intentional-object theorists, there are things that do not exist. According to their critics, there are no such things. We shall directly examine the intentional-object theorists approach in section 7. Before doing so, in section 3, we shall examine the way singular thoughts about concrete particulars in space and time can be and have been construed as paradigms of genuine intentional relations. On this relational construal, an individual’s ordinary singular thought about a concrete physical particular involves a genuine relation between the individual’s mind and the concrete physical particular. In sections 4–5, we shall examine two puzzles that further arise on the orthodox paradigm. First, we shall deal with the puzzle of how a rational person can believe of an object referred to by one singular term that it instantiates a property and simultaneously disbelieve of the same object referred to by a distinct singular term that it instantiates the same property. Section 4 is devoted to Frege’s solution to this puzzle. In section 5, we shall scrutinize Russell’s solution to the puzzle of true negative existential statements. In section 6, we shall see how the theory of direct reference emerged within the orthodox paradigm out of a critique of both Frege’s notion of sense and Russell’s assumption that most proper names in natural languages are disguised definite descriptions. |

2. 意図の非存在 意図性の本質に関する現代的な議論は、フランツ・ブレンターノ(1874、88-89)の著書『経験的立場からの心理学』によって開始され、その多くが先取りされている: あらゆる心的現象は、中世のスコラ学徒たちが「意図的(あるいは心的)非対象性」と呼んだもの、そして、完全には一義的ではないが、「内容への言及」、 「対象への方向性(ここではモノを意味するものと理解してはならない)」、「内在的対象性」と呼ぶべきものによって特徴づけられる。すべての心的現象は、 同じようにはいかないが、それ自体の中に対象として何かを含んでいる。提示においては何かが提示され、判断においては何かが肯定されたり否定されたりし、 愛においては愛され、憎しみにおいては憎まれ、欲望においては欲望される、といった具合である。 この意図的な非存在は、もっぱら精神現象に特徴的である。物理現象にはこのようなものはない。したがって、心的現象とは、それ自身の中に意図的に対象を含む現象である、と定義することができる。 この一節を読むと、さまざまな疑問が湧いてくる。ブレンターノが、心が自らを向ける対象は「あるものを意味するものとして理解されるべきではない」と言っ たのはどういう意味なのか。ある現象(精神的なものであれ、そうでないものであれ)が「対象の意図的な非存在」を示すとはどういうことなのか。ある現象が 「それ自身の中に対象として何かを含む」とは何なのか。ある内容への言及」と「ある対象への方向づけ」は、2つの異なる考えを表しているのか?それとも、 同じ考えを表現する2つの異なる方法なのか?もし意図性が心を、存在しないもの、あるいは完全に心の中に存在するものに関係づけることができるとしたら、 それはどのような関係なのだろうか。 複雑で、抽象的で、論争の的となるようなアイデアが満載されたこの2つの短いパラグラフは、19世紀後半から20世紀にかけて、意図性についてのその後の すべての哲学的議論のアジェンダとなった。ブレンターノの「意図的非存在」という表現の意味をめぐっては、いくつかの議論がある。ブレンターノは、心が向 けられる対象は心自身の内部にある(心の中に存在する)という意味だったのか。それとも、心は存在しない対象にも向けられるという意味だったのか。それと もその両方を意味していたのだろうか?(さらなる議論はCrane, 1998を参照)。 現象学の伝統を代表する思想のいくつかは、この問題にまで遡ることができる。現象学の創始者であり、ブレンターノの弟子でもあったエドムント・フッサール (1900年、1913年)のリードに従い、現象学的分析の要点は、意図性が何かに向けられるという本質的な性質が、意図行為自体とは無関係に実在する物 理的対象が存在するかどうかに左右されないことを示すことであった。この目的を達成するために、フッサールの内発主義的な意図性解釈では、ノエマ(複数形 のノエマータ)という概念と、エポシュ(=括弧付け)あるいは現象学的還元という2つの概念が中心となってきた。ノエマ」という言葉によって、フッサール は心的行為の内的構造を指している。現象学的還元は、実在と架空の実体の違いに関する素朴な前提をすべて停止することで、心的行為の本質に迫るためのもの である(これらの複雑な現象学的概念については、Dreyfus (1982)に都合よくまとめられているFøllesdalらの論文を参照されたい)。さらなる議論は、Bell (1990)とDummett (1993)を参照。 上に引用した2つのパラグラフの中で、ブレンターノは3つの異なるテーゼに基づく研究プログラム全体をスケッチしている。第一のテーゼによれば、愛するこ と、憎むこと、欲望すること、信じること、判断すること、知覚すること、希望すること、その他多くの心的状態によって示されるように、これらの心的状態が 自分自身とは異なるものに向けられていることは、意図性という現象の構成要素である。第二のテーゼによれば、意図性によって心が向けられる対象には、ブレ ンターノが意図的非存在と呼ぶ性質があるという特徴がある。第三のテーゼによれば、意図性は心的なものの印であり、すべての、そして唯一の心的状態が意図 性を示す。 ブレンターノの第3のテーゼとは異なり、ブレンターノの最初の2つのテーゼは互いに切り離すことができない。第一のテーゼは、第二のテーゼが受け入れられ なければ受け入れられないように、容易に再構成することができる。愛するもの、憎むもの、欲望するもの、信じるもの、判断するもの、知覚するもの、希望す るもの、などといった心的状態は、愛するもの、憎むもの、欲望するもの、信じるもの、判断するもの、知覚するもの、希望するもの、などといったものが存在 しない限り例示できないということが、意図性の本質を構成しているとしよう。もしそうであれば、(第一テーゼによって説明される)意図性の本質から、ブレ ンターノが意図的不存在と呼ぶ性質を満たす対象(意図的対象)が存在しない限り、何ものも意図性を示すことはできないということになる。 さて、ブレンターノの最初の2つのテーゼを全面的に受け入れると、哲学的論理学において根本的な存在論的疑問が生じる。それは、そのような意図的対象は存 在するのか、という問題である。意図性の認識によって、意図的対象という存在論的カテゴリーを仮定せざるを得ないのだろうか。この問いは、分析哲学に大き な分裂をもたらした。一般的な(あるいはオーソドックスな)回答は「ノー」である。しかし、私が「意図的対象論者」と呼ぶ重要な少数派の哲学者たちは、こ の問いに対する肯定的な回答を主張してきた。意図的対象は存在する必要がないので、意図的対象論者によれば、存在しないものが存在することになる。彼らの 批判によれば、そのようなものは存在しない。 第7節では、意図的対象論者のアプローチを直接検証することにしよう。その前に第3節では、空間と時間における具体的な特定物についての特異な思考が、真 正な意図的関係のパラダイムとして解釈されうるか、また解釈されてきたかを検証する。この関係的解釈では、具体的な物理的特定物に関する個人の通常の特異 的思考は、個人の心と具体的な物理的特定物との間の真正な関係を含んでいる。第4節から第5節では、オーソドックスなパラダイムでさらに生じる2つのパズ ルを検討する。第一に、理性的な人間が、ある単数項によって参照される対象について、それがある性質をインスタンス化していると信じ、同時に、別の単数項 によって参照される同じ対象について、それが同じ性質をインスタンス化していると信じないことができるのか、というパズルを扱う。第4節では、このパズル に対するフレーゲの解答を紹介する。第5節では、真に否定的な実存的言明のパズルに対するラッセルの解答を精査する。第6節では、フレーゲのセンス概念 と、自然言語における固有名詞の大半は定言記述に偽装されたものであるというラッセルの仮定に対する批判から、正統的なパラダイムにおいて直接参照の理論 がどのように生まれたかを紹介する。 |

| 3. The relational nature of singular thoughts Many non-intentional relations hold of concrete particulars in space and time. If and when they do, their relata cannot fail to exist. If Cleopatra kisses Caesar, then both Cleopatra and Caesar must exist. Not so with intentional relations. If Cleopatra loves Caesar, then presumably there is some concrete particular in space and time whom Cleopatra loves. But one may also love Anna Karenina (not a concrete particular in space and time, but a fictitious character). Similarly, the relata of the admiration relation (another intentional relation) are not limited to concrete particulars in space and time. One may admire not only Albert Einstein but also Sherlock Holmes (a fictitious character). As the following passage from the Appendix to the 1911 edition of his 1874 book testifies, this asymmetry between non-intentional and intentional relations puzzled Brentano: What is characteristic of every mental activity is, as I believe I have shown, the reference to something as an object. In this respect, every mental activity seems to be something relational. […] In other relations both terms—both the fundament and the terminus—are real, but here only the first term—the fundament is real. […] If I take something relative […] something larger or smaller for example, then, if the larger thing exists, the smaller one exists too. […] Something like what is true of relations of similarity and difference holds true for relations of cause and effect. For there to be such a relation, both the thing that causes and the thing that is caused must exist. […] It is entirely different with mental reference. If someone thinks of something, the one who is thinking must certainly exist, but the object of his thinking need not exist at all. In fact, if he is denying something, the existence of the object is precisely what is excluded whenever his denial is correct. So the only thing which is required by mental reference is the person thinking. The terminus of the so-called relation does not need to exist in reality at all. For this reason, one could doubt whether we really are dealing with something relational here, and not, rather, with something somewhat similar to something relational in a certain respect, which might, therefore, better be called “quasi-relational.” While the orthodox paradigm is clearly consistent with the possibility that general thoughts may involve abstract objects (e.g., numbers) and abstract properties and relations, none of which are in space and time, special problems arise with respect to singular thoughts construed as intentional relations to non-existent or fictitious objects. Two related assumptions lie at the core of the orthodox paradigm. One is the assumption that the mystery of the intentional relation should be elucidated against the background of non-intentional relations. The other is the assumption that intentional relations which seem to involve non-existent (e.g., fictitious) entities should be clarified by reference to intentional relations involving particulars existing in space and time. The paradigm of the intentional relation that satisfies the orthodox picture is the intentionality of what can be called singular thoughts, namely those true thoughts that are directed towards concrete individuals or particulars that exist in space and time. A singular thought is such that it would not be available—it could not be entertained—unless the concrete individual that is the target of the thought existed. Unlike the propositional contents of general thoughts that involve only abstract universals such as properties and/or relations, the propositional content of a singular thought may involve in addition a relation to a concrete individual or particular. The contrast between ‘singular’ and ‘general’ propositions has been much emphasized by Kaplan (1978, 1989). In a slightly different perspective, Tyler Burge (1977) has characterized singular thoughts as incompletely conceptualized or de re thoughts whose relation to the objects they are about is supplied by the context. On some views, the object of the singular thought is even part of it. On the orthodox view, part of the importance of true singular thoughts for a clarification of intentionality lies in the fact that some true singular thoughts are about concrete perceptible objects. Singular thoughts about concrete perceptible objects may seem simpler and more primitive than either general ones or thoughts about abstract entities. Consider, for example, what must be the case for belief-ascription (1) to be true: Ava believes that Lionel Jospin is a Socialist. Intuitively, the belief ascribed to Ava by (1) has intentionality in the sense that it is of or about Lionel Jospin and the property of being a Socialist. Besides being a belief (i.e., a special attitude different from a wish, a desire, a fear or an intention), the identity of Ava’s belief depends on its propositional content. What Ava believes is identified by the embedded ‘that’-clause that can stand all by itself as in (2): Lionel Jospin is a Socialist. On the face of it, an utterance of (2) is true if and only if a given concrete individual does exemplify the property of being a Socialist. Arguably, it is essential to the proposition that Ava believes—the proposition expressed by an utterance of (2)—that it is about Jospin and the property of being a Socialist. Just by virtue of having such a true belief, Ava must therefore stand in relation—the belief relation—to Jospin and the property of being a Socialist. Notice that Ava can have a belief about Jospin and the property of being a Socialist even though she has never seen Jospin in person. From within the orthodox paradigm, one central piece of the mystery of intentionality can be brought out by reflection on the conditions in which simple singular thoughts about concrete individuals are true. This is the problem of the relational nature of the contents of true singular beliefs. In order to generate this problem, it is not necessary to ascend to false or abstract beliefs about fictional entities. It is enough to consider how a true thought about a concrete individual that exists in space and time can arise. On the one hand, Ava’s belief seems to be a singular belief about a concrete individual. It seems essential to Ava’s belief that it has the propositional content that it has. And it seems essential to the propositional content of Ava’s belief that Ava must stand in relation to somebody else who can be very remote from her in either space or time. On the other hand, Ava’s belief is a state internal to Ava. As John Perry (1994, 187) puts it, beliefs and other so-called ‘propositional attitudes’ seem to be “local mental phenomena.” How can it be essential to an internal state of Ava’s that Ava stands in relation to someone else? How can one reconcile the local and the relational characters of propositional attitudes? |

3. 特異な思考の関係性 多くの非意図的な関係は、空間と時間における具体的な特殊性を保持する。もしそうであるなら、そしてそうであるとき、その関係性が存在しないことはありえ ない。クレオパトラがシーザーにキスをすれば、クレオパトラもシーザーも存在しなければならない。意図的関係はそうではない。クレオパトラがカエサルを愛 しているなら、おそらくクレオパトラが愛している具体的な特定の人物が時空間に存在する。しかし、アンナ・カレーニナ(時空間における具体的な特定の人物 ではなく、架空の人物)を愛することもできる。同様に、感嘆関係(もうひとつの意図的関係)の関係者は、時空間における具体的な特定者に限定されない。人 はアルバート・アインシュタインだけでなく、シャーロック・ホームズ(架空の人物)にも憧れるかもしれない。1874年の著作の1911年版の付録の次の 一節が物語るように、非意図的関係と意図的関係の間のこの非対称性がブレンターノを困惑させた: すべての精神活動に特徴的なのは、私が示したと思うように、何かを対象として参照することである。この点で、あらゆる精神活動は関係的なものであるように 思われる。[...)他の関係においては、基点と終点の両方の項が実在するが、ここでは第一項(基点)のみが実在する。[...]相対的なものを [...]、たとえば大きいもの、小さいものとするならば、大きいものが存在するならば、小さいものも存在する。[類似と相違の関係に当てはまることが、 原因と結果の関係にも当てはまる。このような関係が存在するためには、原因となるものと原因とされるものの両方が存在しなければならない。[中略)心的参 照ではまったく異なる。もし誰かが何かを考えるなら、考えている本人は確かに存在しなければならないが、考えている対象はまったく存在する必要はない。実 際、もしその人が何かを否定しているのであれば、その否定が正しいときにはいつでも、その対象の存在こそが排除されるのである。つまり、心的参照に必要な のは、考えている本人だけなのである。いわゆる関係の終端は、現実に存在する必要はまったくない。このような理由から、私たちがここで扱っているのは本当 に関係的な何かではなく、むしろある点では関係的な何かといくらか似ていて、それゆえ "準関係的な何か "と呼んだ方がいいような何かではないか、と疑いたくなる。 オーソドックスなパラダイムは、一般的な思考が抽象的な対象(例えば数)や抽象的な性質や関係を含む可能性とは明らかに矛盾しないが、存在しないか架空の 対象に対する意図的な関係として解釈される特異な思考に関しては特別な問題が生じる。オーソドックスなパラダイムの中核には、関連する2つの前提が横た わっている。ひとつは、意図的関係の謎は非意図的関係を背景として解明されるべきだという仮定である。もうひとつは、存在しない(たとえば架空の)実体を 含むように見える意図的関係は、空間と時間に存在する特殊な実体を含む意図的関係を参照することによって解明されるべきだという仮定である。 オーソドックスな図式を満足させる意図的関係のパラダイムは、単数思考と呼 ばれるものの意図性、すなわち、空間と時間の中に存在する具体的な個体や特 殊な存在に向けられた真の思考である。特異な思考とは、その思考の対象である具体的な個人が存在しなければ、その思考を利用することができない、つまり、 その思考を受け入れることができないような思考である。性質や関係といった抽象的な普遍性のみを含む一般的な思考の命題内容とは異なり、単数 の思考の命題内容には、具体的な個人や特定との関係が含まれることがある。カプラン(1978, 1989)は、「単数」と「一般」の命題の対比を強調している。これとは少し異なる観点から、Tyler Burge (1977)は、単数思考を不完全に概念化された思考、ま たは概念化されていない思考として特徴づけている。ある見方では、特異思考の対象はその一部でさえある。オーソドックスな考え方では、意図性の解明におけ る真の単数思考の重要性の一 部は、真の単数思考が具体的な知覚可能な対象に関するものであることにある。具体的な知覚可能な対象についての単数思考は、一般的な思考や抽象的な実 体についての思考よりも単純で原始的なものに見えるかもしれない。 例えば、信念記述(1)が真であるためには何が必要かを考えてみよう: アバはリオネル・ジョスパンが社会主義者だと信じている。 直観的には、(1)によってアバに与えられた信念は、ライオネル・ヨス パンと社会主義者という性質についてのものであるという意味で、意図性を持つ。信念(すなわち、願望、欲望、恐怖、意図とは異なる特別な態度)であること に加えて、エヴァの信念の同一性は、その命題的内容に依存する。アバが何を信じているかは、(2)のようにそれ自体で成り立つ「that」節が埋め込まれ ることによって特定される: リオネル・ジョスパンは社会主義者だ。 一見したところ、(2)の発話は、与えられた具体的な個人が社会主義者であるという性質を例証している場合にのみ真である。おそらく、アバが信じる命題- (2)の発話によって表現される命題-にとって、それがジョスパンや社会主義者であるという性質に関するものであることは不可欠である。そのような真の信 念を持つという事実だけで、アヴァはジョスパンおよび社会主義者であるという性質との関係-信念関係-に立たなければならない。アバはジョス パンを実際に見たことがなくても、ジョスパンや社会主義者であるという性質につい ての信念を持つことができる。 オーソドックスなパラダイムの中から、具体的な個人についての単純な単一的思考が真である条件について考察することによって、意図性の謎の中心的な部分が 浮かび上がってくる。これは、真の単一的信念の内容の関係性の問題である。この問題を生み出すために、架空の存在についての偽の信念や抽象的な信念にまで 踏み込む必要はない。空間と時間の中に存在する具体的な個人についての真の思考がどのように生 じるかを考えれば十分である。一方では、エヴァの信念は具体的な個人についての特異な信念のように見える。エヴァの信念がそのような命題的な内容を持つこ とは、エヴァの信念にとって 不可欠なことのように思われる。そして、エヴァの信念の命題的な内容にとって、エヴァが、空間的にも時間的にもエヴァから非常に離れている可能性のある他 の誰かとの関係の中に立っていなければならないということは、不可欠なことのように思われる。他方、エヴァの信念はエヴァの内部にある状態である。ジョ ン・ペリー(1994, 187)が言うように、信念やその他のいわゆる「命題的態度」は "局所的な心的現象 "であるようだ。エヴァの内的状態にとって、エヴァが他の誰かとの関係の中に立っているということが、どうして本質的なことなのだろうか。命題的態度の局 所的性格と関係的性格をどのように調和させることができるのだろうか。 |

| 4. How can distinct beliefs be about one and the same object? |

|

| 5. True negative existential beliefs |

|

| 6. Direct reference |

|

| 7. Are there intentional objects? |

|

| 8. Is intensionality a criterion of intentionality? |

|

| 9. Can intentionality be naturalized? |

|