グレン・グールド

Glenn Gould, 1932-1982

☆ グレン・ハーバート・グールド(1932年9月25日 - 1982年10月4日)は、カナダのクラシック・ピアニスト。ヨハン・セバスティアン・バッハの鍵盤作品の解釈者として有名である。彼の演奏は、卓越した 技術的熟練とバッハの音楽の対位法的テクスチュアを明確に表現する能力によって際立っていた。グールドは、ショパン、リスト、ラフマニノフなどのロマン派のピアノ作品のほとんどを拒否し、バッハとベートーヴェンを中心に、後期ロマン派やモダニズム の作曲家の作品を好んだ。グールドはまた、モーツァルト、ハイドン、スクリャービン、ブラームス、ヤン・ピーテルスゾーン・スウェーリンク、ウィリアム・ バード、オーランド・ギボンズといったバロック以前の作曲家、パウル・ヒンデミット、アーノルド・シェーンベルク、リヒャルト・シュトラウスといった20 世紀の作曲家の作品も録音している。グールドは作家、放送作家でもあり、作曲や指揮にも手を染めていた。クラシック音楽に関するテレビ番組を制作し、その中でグールドは、台本に書かれた方法 で話し、演奏したり、インタビュアーと対話したりした。カナダの孤立した地域を題材にした3本のミュジーク・コンクレート・ラジオ・ドキュメンタリーを制 作。音楽雑誌への寄稿も多く、音楽理論について論じた。グールドは風変わりなことで知られ、鍵盤楽器での型破りな音楽解釈や物言いから、ライフスタイルや 行動様式に至るまで、多岐にわたった。人前で演奏することを嫌い、31歳でコンサートをやめてスタジオ録音とメディアに専念した。

| Glenn Herbert Gould[fn

1] (/ɡuːld/; né Gold;[fn 2] 25 September 1932 – 4 October 1982) was a

Canadian classical pianist. He was among the most famous and celebrated

pianists of the 20th century,[1] renowned as an interpreter of the

keyboard works of Johann Sebastian Bach. His playing was distinguished

by remarkable technical proficiency and a capacity to articulate the

contrapuntal texture of Bach's music. Gould rejected most of the Romantic piano literature by Chopin, Liszt, Rachmaninoff, and others, in favour of Bach and Beethoven mainly, along with some late-Romantic and modernist composers. Gould also recorded works by Mozart, Haydn, Scriabin, and Brahms; pre-Baroque composers such as Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, William Byrd, and Orlando Gibbons; and 20th-century composers including Paul Hindemith, Arnold Schoenberg, and Richard Strauss. Gould was also a writer and broadcaster, and dabbled in composing and conducting. He produced television programmes about classical music, in which he would speak and perform, or interact with an interviewer in a scripted manner. He made three musique concrète radio documentaries, collectively the Solitude Trilogy, about isolated areas of Canada. He was a prolific contributor to music journals, in which he discussed music theory. Gould was known for his eccentricities, ranging from his unorthodox musical interpretations and mannerisms at the keyboard to aspects of his lifestyle and behaviour. He disliked public performance, and stopped giving concerts at age 31 to concentrate on studio recording and media. |

グ

レン・ハーバート・グールド[fn 1](/ɡ Gold; [fn 2] 1932年9月25日 -

1982年10月4日)は、カナダのクラシック・ピアニスト。ヨハン・セバスティアン・バッハの鍵盤作品の解釈者として有名である。彼の演奏は、卓越した

技術的熟練とバッハの音楽の対位法的テクスチュアを明確に表現する能力によって際立っていた。 グールドは、ショパン、リスト、ラフマニノフなどのロマン派のピアノ作品のほとんどを拒否し、バッハとベートーヴェンを中心に、後期ロマン派やモダニズム の作曲家の作品を好んだ。グールドはまた、モーツァルト、ハイドン、スクリャービン、ブラームス、ヤン・ピーテルスゾーン・スウェーリンク、ウィリアム・ バード、オーランド・ギボンズといったバロック以前の作曲家、パウル・ヒンデミット、アーノルド・シェーンベルク、リヒャルト・シュトラウスといった20 世紀の作曲家の作品も録音している。 グールドは作家、放送作家でもあり、作曲や指揮にも手を染めていた。クラシック音楽に関するテレビ番組を制作し、その中でグールドは、台本に書かれた方法 で話し、演奏したり、インタビュアーと対話したりした。カナダの孤立した地域を題材にした3本のミュジーク・コンクレート・ラジオ・ドキュメンタリーを制 作。音楽雑誌への寄稿も多く、音楽理論について論じた。グールドは風変わりなことで知られ、鍵盤楽器での型破りな音楽解釈や物言いから、ライフスタイルや 行動様式に至るまで、多岐にわたった。人前で演奏することを嫌い、31歳でコンサートをやめてスタジオ録音とメディアに専念した。 |

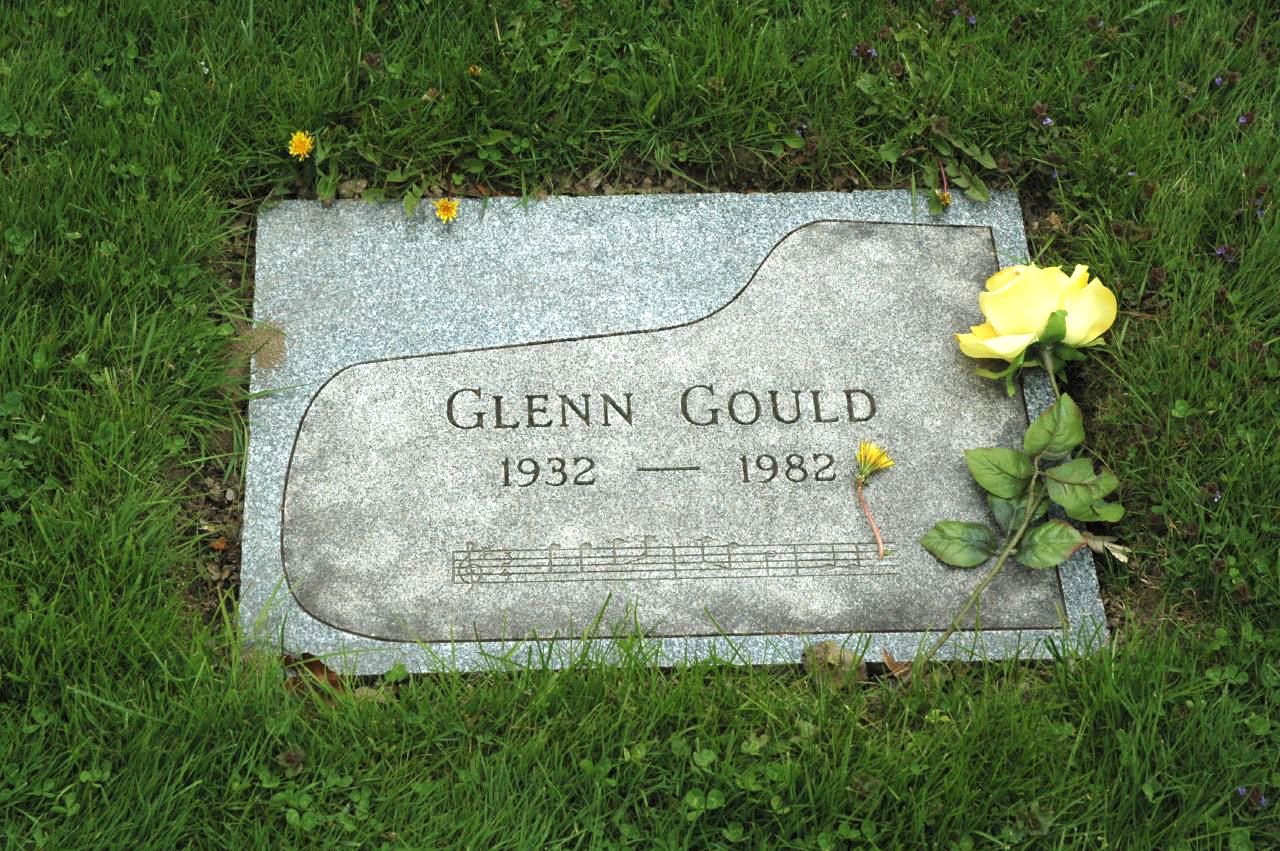

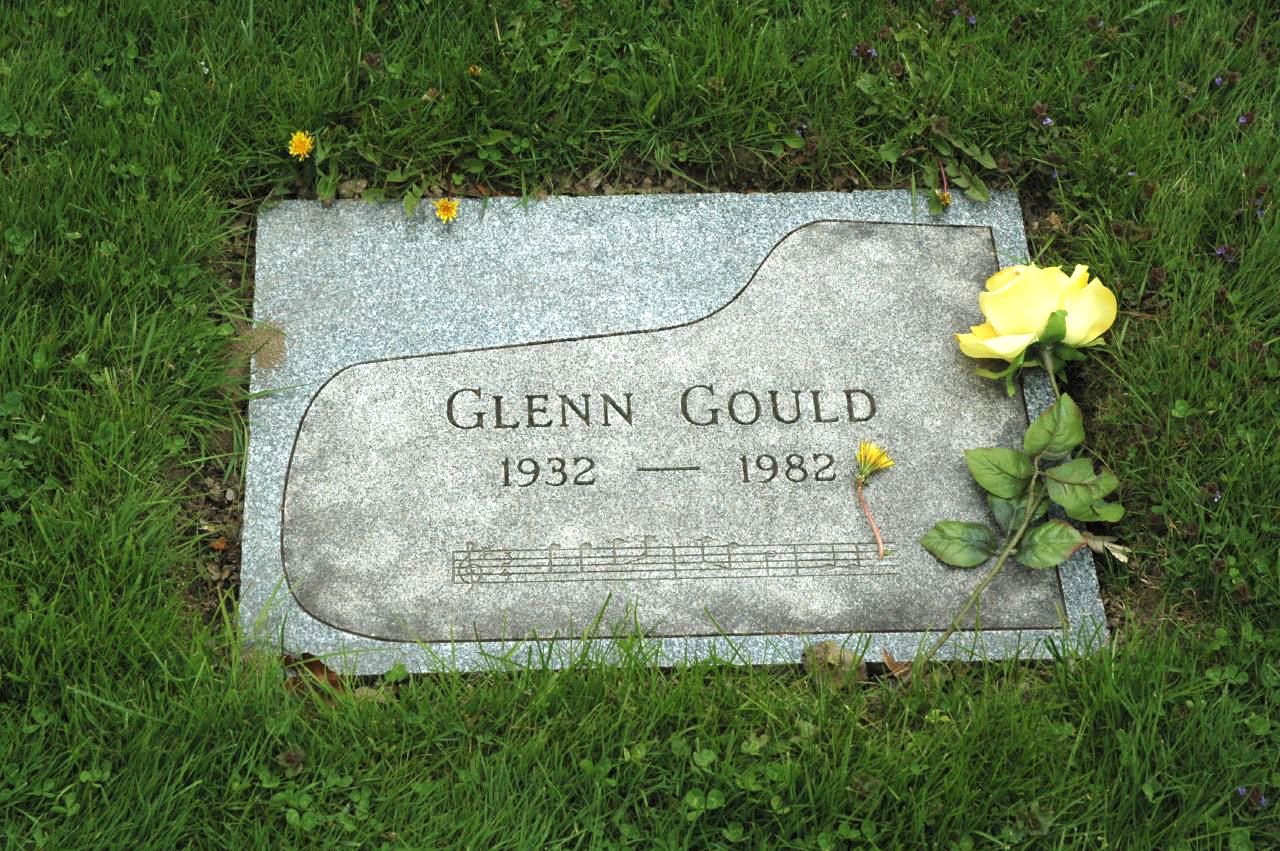

| Life Early life  Gould in February 1946 with his dog and his parakeet, Mozart[2][3] Glenn Gould was born at home in Toronto, on 25 September 1932, the only child of Russell Herbert Gold (1901–1996) and Florence Emma Gold (née Greig; 1891–1975),[4] Presbyterians of Scottish, English, and Norwegian ancestry.[5] The family's surname was informally changed to Gould around 1939 to avoid being mistaken for Jewish, given the prevailing anti-Semitism of pre-war Toronto.[fn 3] Gould had no Jewish ancestry,[fn 4] though he sometimes joked about the subject, such as "When people ask me if I'm Jewish, I always tell them that I was Jewish during the war."[6] His childhood home has been named a historic site.[7] His interest in music and his talent as a pianist were evident very early. Both parents were musical; his mother, especially, encouraged his musical development from infancy. Hoping he would become a successful musician, she exposed him to music during her pregnancy.[8] She taught him the piano and as a baby, he reportedly hummed instead of crying, and wiggled his fingers as if playing a keyboard instrument, leading his doctor to predict that he would "be either a physician or a pianist".[9] He learned to read music before he could read words,[10][11][12] and it was observed that he had perfect pitch at age three. When presented with a piano, the young Gould was reported to strike single notes and listen to their long decay, a practice his father Bert noted was different from typical children.[11] Gould's interest in the piano was concomitant with an interest in composition. He played his pieces for family, friends, and sometimes large gatherings—including, in 1938, a performance at the Emmanuel Presbyterian Church (a few blocks from the Gould family home) of one of his compositions.[13] Gould first heard a live musical performance by a celebrated soloist at age six. This profoundly affected him. He later described the experience: It was Hofmann. It was, I think, his last performance in Toronto, and it was a staggering impression. The only thing I can really remember is that, when I was being brought home in a car, I was in that wonderful state of half-awakeness in which you hear all sorts of incredible sounds going through your mind. They were all orchestral sounds, but I was playing them all, and suddenly I was Hofmann. I was enchanted.[10][14]  Gould with his teacher, Alberto Guerrero, at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, in 1945. Guerrero demonstrated his technical idea that Gould should "pull down" at the keys instead of striking them from above. At age 10, he began attending the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto (known until 1947 as the Toronto Conservatory of Music). He studied music theory with Leo Smith, organ with Frederick C. Silvester, and piano with Alberto Guerrero.[15] Around the same time, he injured his back as a result of a fall from a boat ramp on the shore of Lake Simcoe.[fn 5] This incident is apocryphally related to the adjustable-height chair his father made shortly thereafter. Gould's mother would urge the young Gould to sit up straight at the keyboard.[16] He used this chair for the rest of his life, taking it with him almost everywhere.[10] The chair was designed so that Gould could sit very low and allowed him to pull down on the keys rather than striking them from above, a central technical idea of Guerrero's.[17] Gould developed a technique that enabled him to choose a very fast tempo while retaining the "separateness" and clarity of each note. His extremely low position at the instrument permitted him more control over the keyboard. Gould showed considerable technical skill in performing and recording a wide repertoire including virtuosic and romantic works, such as his own arrangement of Ravel's La valse and Liszt's transcriptions of Beethoven's Fifth and Sixth Symphonies. Gould worked from a young age with Guerrero on a technique known as finger-tapping: a method of training the fingers to act more independently from the arm.[18] Gould passed his final Conservatory examination in piano at age 12, achieving the highest marks of any candidate, and thus attaining professional standing as a pianist.[19] One year later he passed the written theory exams, qualifying for an Associate of the Toronto Conservatory of Music (ATCM) diploma.[fn 6][19] Piano Gould was a child prodigy[20] and was described in adulthood as a musical phenomenon.[fn 7] He claimed to have almost never practiced on the piano itself, preferring to study repertoire by reading,[fn 8] another technique he had learned from Guerrero. He may have spoken ironically about his practising, though, as there is evidence that, on occasion, he did practise quite hard, sometimes using his own drills and techniques.[fn 9] He seemed able to practise mentally, once preparing for a recording of Brahms's piano works without playing them until a few weeks before the sessions.[21] Gould could play a vast repertoire of piano music, as well as a wide range of orchestral and operatic transcriptions, from memory.[22] He could "memorize at sight" and once challenged a friend to name any piece of music that he could not "instantly play from memory".[23] The piano, Gould said, "is not an instrument for which I have any great love as such ... [but] I have played it all my life, and it is the best vehicle I have to express my ideas." In the case of Bach, Gould noted, "[I] fixed the action in some of the instruments I play on—and the piano I use for all recordings is now so fixed—so that it is a shallower and more responsive action than the standard. It tends to have a mechanism which is rather like an automobile without power steering: you are in control and not it; it doesn't drive you, you drive it. This is the secret of doing Bach on the piano at all. You must have that immediacy of response, that control over fine definitions of things."[24] As a teenager, Gould was significantly influenced by Artur Schnabel[fn 10][25] and Rosalyn Tureck's recordings of Bach[26] (which he called "upright, with a sense of repose and positiveness"), and the conductor Leopold Stokowski.[27] Gould was known for his vivid imagination. Listeners regarded his interpretations as ranging from brilliantly creative to outright eccentric. His pianism had great clarity and erudition, particularly in contrapuntal passages, and extraordinary control. Gould believed the piano to be "a contrapuntal instrument" and his whole approach to music was centered in the Baroque. Much of the homophony that followed he felt belongs to a less serious and less spiritual period of art. Gould had a pronounced aversion to what he termed "hedonistic" approaches to piano repertoire, performance, and music generally. For him, "hedonism" in this sense denoted a superficial theatricality, something to which he felt Mozart, for example, became increasingly susceptible later in his career.[28] He associated this drift toward hedonism with the emergence of a cult of showmanship and gratuitous virtuosity on the concert platform in the 19th century and later. The institution of the public concert, he felt, degenerated into the "blood sport" with which he struggled, and which he ultimately rejected.[29] Performances On 5 June 1938, at age five, Gould played in public for the first time, joining his family on stage to play piano at a church service at the Business Men's Bible Class in Uxbridge, Ontario, in front of a congregation of about 2,000.[30][31] In 1945, at 13, he made his first appearance with an orchestra in a performance of the first movement of Beethoven's 4th Piano Concerto with the Toronto Symphony.[32] His first solo recital followed in 1947,[33] and his first recital on radio was with the CBC in 1950.[34] This was the beginning of Gould's long association with radio and recording. He founded the Festival Trio chamber group in 1953 with cellist Isaac Mamott and violinist Albert Pratz.[citation needed] External images image icon Glenn Gould performing at the piano in Toronto, Canada, in 1956 image icon Glenn Gould, c. 1960s, with Leonard Bernstein and Igor Stravinsky in rehearsal with the New York Philharmonic Gould made his American debut on 2 January 1955, in Washington, D.C. at The Phillips Collection. The music critic Paul Hume wrote in the Washington Post, "January 2 is early for predictions, but it is unlikely that the year 1955 will bring us a finer piano recital than that played yesterday afternoon in the Phillips Gallery. We shall be lucky if it brings us others of equal beauty and significance."[35] A performance at The Town Hall in New York City followed on 11 January. Gould's reputation quickly grew. In 1957, he undertook a tour of the Soviet Union, becoming the first North American to play there since World War II.[36] His concerts featured Bach, Beethoven, and the serial music of Schoenberg and Berg, which had been suppressed in the Soviet Union during the era of Socialist Realism. Gould debuted in Boston in 1958, playing for the Peabody Mason Concert Series.[37] On 31 January 1960, Gould first appeared on American television on CBS's Ford Presents series, performing Bach's Keyboard Concerto No. 1 in D minor (BWV 1052) with Leonard Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic.[38] Gould believed that the institution of the public concert was an anachronism and a "force of evil", leading to his early retirement from concert performance. He argued that public performance devolved into a sort of competition, with a non-empathetic audience mostly attendant to the possibility of the performer erring or failing critical expectation; and that such performances produced unexceptional interpretations because of the limitations of live music. He set forth this doctrine, half in jest, in "GPAADAK", the Gould Plan for the Abolition of Applause and Demonstrations of All Kinds.[39] On 10 April 1964, he gave his last public performance, at Los Angeles's Wilshire Ebell Theater.[40] Among the pieces he performed were Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 30, selections from Bach's The Art of Fugue, and Hindemith's Piano Sonata No. 3.[fn 11] Gould performed fewer than 200 concerts, of which fewer than 40 were outside Canada. For a pianist such as Van Cliburn, 200 concerts would have amounted to about two years' touring.[41] One of Gould's reasons for abandoning live performance was his aesthetic preference for the recording studio, where, in his words, he developed a "love affair with the microphone".[fn 12] There, he could control every aspect of the final musical product by selecting parts of various takes. He felt that he could realize a musical score more fully this way. Gould felt strongly that there was little point in re-recording centuries-old pieces if the performer had no new perspective to bring. For the rest of his life, he eschewed live performance, focusing instead on recording, writing, and broadcasting. Eccentricities Replica of Gould's piano chair Gould was widely known for his unusual habits. He often hummed or sang while he played, and his audio engineers were not always able to exclude his voice from recordings. Gould claimed that his singing was unconscious and increased in proportion to his inability to produce his intended interpretation on a given piano. It is likely that the habit originated in his having been taught by his mother to "sing everything that he played", as his biographer Kevin Bazzana wrote. This became "an unbreakable (and notorious) habit".[42] Some of Gould's recordings were severely criticised because of this background "vocalising". For example, a reviewer of his 1981 rerecording of the Goldberg Variations wrote that many listeners would "find the groans and croons intolerable".[43] Gould was known for his peculiar, even theatrical, gesticulations while playing. Another oddity was his insistence on absolute control over every aspect of his environment. The temperature of the recording studio had to be precisely regulated; he invariably insisted that it be extremely warm. According to another of Gould's biographers, Otto Friedrich, the air-conditioning engineer had to work just as hard as the recording engineers.[44] The piano had to be set at a certain height and would be raised on wooden blocks if necessary.[45] A rug would sometimes be required for his feet.[46] He had to sit exactly 14 inches (360 mm) above the floor, and would play concerts only with the chair his father had made. He used this chair even when the seat was completely worn.[47] His chair is so closely identified with him that it is shown in a place of honour in a glass case at Library and Archives Canada. Conductors had mixed responses to Gould and his playing habits. George Szell, who led Gould in 1957 with the Cleveland Orchestra, remarked to his assistant, "That nut's a genius."[48] Bernstein said, "There is nobody quite like him, and I just love playing with him."[48] Bernstein created a stir at the concert of April 6, 1962, when, just before the New York Philharmonic was to perform the Brahms Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor with Gould, he informed the audience that he was assuming no responsibility for what they were about to hear. He asked the audience: "In a concerto, who is the boss – the soloist or the conductor?", to which the audience laughed. "The answer is, of course, sometimes the one and sometimes the other, depending on the people involved."[49] Specifically, Bernstein was referring to their rehearsals, with Gould's insistence that the entire first movement be played at half the indicated tempo. The speech was interpreted by Harold C. Schonberg, music critic for The New York Times, as an abdication of responsibility and an attack on Gould.[50] Plans for a studio recording of the performance came to nothing. The live radio broadcast was subsequently released on CD, Bernstein's disclaimer included. Gould was averse to cold and wore heavy clothing (including gloves) even in warm places. He was once arrested, possibly being mistaken for a vagrant, while sitting on a park bench in Sarasota, Florida, dressed in his standard all-climate attire of coat, hat and mittens.[51] He also disliked social functions. He hated being touched, and in later life limited personal contact, relying on the telephone and letters for communication. On a visit to Steinway Hall in New York City in 1959, the chief piano technician at the time, William Hupfer, greeted Gould with a slap on the back. Gould was shocked by this, and complained of aching, lack of coordination, and fatigue because of it. He went on to explore the possibility of litigation against Steinway & Sons if his apparent injuries were permanent.[52] He was known for cancelling performances at the last minute, which is why Bernstein's aforementioned public disclaimer opened with, "Don't be frightened, Mr. Gould is here ... [he] will appear in a moment." In his liner notes and broadcasts, Gould created more than two dozen alter egos for satirical, humorous, and didactic purposes, permitting him to write hostile reviews or incomprehensible commentaries on his own performances. Probably the best-known are the German musicologist Karlheinz Klopweisser, the English conductor Sir Nigel Twitt-Thornwaite, and the American critic Theodore Slutz.[53] These facets of Gould, whether interpreted as neurosis or "play",[54] have provided ample material for psychobiography. Gould was a teetotaller and did not smoke.[55] He did not cook; instead he often ate at restaurants and relied on room service. He ate one meal a day, supplemented by arrowroot biscuits and coffee.[55] In his later years he claimed to be vegetarian, though this is not certain.[fn 13] Personal life External audio audio icon Gould performing J. S. Bach's Italian Concerto in F major, BWV 971 and various Bach Preludes and Fugues audio icon Gould performing J. S. Bach's The Art of Fugue, BWV 1080, on organ and piano Gould lived a private life. The documentary filmmaker Bruno Monsaingeon said of him: "No supreme pianist has ever given of his heart and mind so overwhelmingly while showing himself so sparingly."[56] He never married, and biographers have spent considerable time on his sexuality. Bazzana writes that "it is tempting to assume that Gould was asexual, an image that certainly fits his aesthetic and the persona he sought to convey, and one can read the whole Gould literature and be convinced that he died a virgin"—but he also mentions that evidence points to "a number of relationships with women that may or may not have been platonic and ultimately became complicated and were ended".[57] One piece of evidence arrived in 2007. When Gould was in Los Angeles in 1956, he met Cornelia Foss, an art instructor, and her husband Lukas, a conductor. After several years, she and Gould became lovers.[58] In 1967, she left her husband for Gould, taking her two children with her to Toronto. She purchased a house near Gould's apartment. In 2007, Foss confirmed that she and Gould had had a love affair for several years. According to her, "There were a lot of misconceptions about Glenn, and it was partly because he was so very private. But I assure you, he was an extremely heterosexual man. Our relationship was, among other things, quite sexual." Their affair lasted until 1972, when she returned to her husband. As early as two weeks after leaving her husband, Foss noticed disturbing signs in Gould, alluding to unusual behaviour that was more than "just neurotic".[58] Specifically, he believed that "someone was spying on him", according to Foss's son.[59] Health and death Though an admitted hypochondriac,[60][fn 14] Gould had many pains and ailments, but his autopsy revealed few underlying problems in areas that often troubled him.[fn 15] He worried about everything from high blood pressure (which in his later years he recorded in diary form) to the safety of his hands. (Gould rarely shook people's hands, and habitually wore gloves.)[fn 16][fn 17] The spine injury he experienced as a child led physicians to prescribe, usually independently, an assortment of analgesics, anxiolytics, and other drugs. Bazzana has speculated that Gould's increasing use of a variety of prescription medications over his career may have had a deleterious effect on his health. It had reached the stage, Bazzana writes, that "he was taking pills to counteract the side effects of other pills, creating a cycle of dependency".[61] In 1956, Gould told photojournalist Jock Carroll about "my hysteria about eating. It's getting worse all the time."[62] In his biography, psychiatrist Peter F. Ostwald noted Gould's increasing neurosis about food in the mid-1950s, something Gould had spoken to him about. Ostwald later discussed the possibility that Gould had developed a "psychogenic eating disorder" around this time.[63] In 1956, Gould was also taking Thorazine, an anti-psychotic medication, and reserpine, another anti-psychotic, which can also be used to lower blood pressure.[64] Cornelia Foss has said that Gould took many antidepressants, which she blamed for his deteriorating mental state.[65] Whether Gould's behaviour fell within the autism spectrum has been debated.[7] The diagnosis was first suggested by psychiatrist Peter Ostwald, a friend of Gould's, in the 1997 book Glenn Gould: The Ecstasy and Tragedy of Genius.[63] There has also been speculation that he may have had bipolar disorder, because he sometimes went several days without sleep, had extreme increases in energy, drove recklessly, and in later life endured severe depressive episodes.[66]  Gould's grave marker, with incipit of Bach's Goldberg Variations On 27 September 1982, two days after his 50th birthday, after experiencing a severe headache, Gould had a stroke that paralyzed the left side of his body. He was admitted to Toronto General Hospital and his condition rapidly deteriorated. By 4 October, there was evidence of brain damage, and Gould's father decided that his son should be taken off life support.[67] Gould's public funeral was held in St. Paul's Anglican Church on 15 October with singing by Lois Marshall and Maureen Forrester. The service was attended by over 3,000 people and was broadcast on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. He is buried next to his parents in Toronto's Mount Pleasant Cemetery (section 38, lot 1050).[68] The first few bars of the Goldberg Variations are carved on his grave marker.[69] An animal lover, Gould left half his estate to the Toronto Humane Society; the other half went to the Salvation Army.[70] In 2000, a movement disorder neurologist suggested in a paper that Gould had dystonia, "a problem little understood in his time."[71] |

生涯 生い立ち  1946年2月、愛犬とインコのモーツァルトと[2][3]。 グレン・グールドは1932年9月25日、トロントの自宅でラッセル・ハーバート・ゴールド(1901-1996)とフローレンス・エマ・ゴールド(旧姓 グレイグ、1891-1975)の一人子として生まれた[4]。 [グールドはユダヤ人の先祖を持たないが[fn 4]、「ユダヤ人かと聞かれたら、いつも戦争中にユダヤ人だったと答える」[6]などと冗談を言うこともあった[7]。 彼の音楽への関心とピアニストとしての才能は、幼い頃から明らかだった。両親はともに音楽家であり、特に母親は幼児期から彼の音楽的成長を促した。母親 は、彼が音楽家として成功することを願い、妊娠中に彼を音楽に触れさせた[8]。 赤ちゃんの頃、彼は泣く代わりに鼻歌を歌い、鍵盤楽器を弾くように指をくねらせたと伝えられ、主治医に「医者かピアニストになるだろう」と予言された [9]。ピアノを手渡されると、幼いグールドは単音を打ち、その長い減衰を聴いたと言われている。1938年にはエマニュエル長老教会(グールド家の数ブ ロック先)で彼の作曲した曲を演奏するなど、家族や友人、時には大きな集まりのために作品を演奏した[13]。 グールドが初めて著名なソリストの生演奏を聴いたのは6歳のとき。これは彼に大きな影響を与えた。後に彼はその体験をこう語っている: ホフマンだった。それはホフマンで、トロントでの最後の演奏だったと思う。ただひとつ本当に覚えているのは、車で家まで送ってもらうとき、いろいろな信じ られないような音が頭の中を駆け巡る、あの素晴らしい半覚醒状態にあったということだ。それらはすべてオーケストラの音だったけれど、私はそれらをすべて 演奏していて、突然私はホフマンになった。私は魅了された[10][14]。  1945年、トロントの王立音楽院にて、師であるアルベルト・ゲレロとグールド。ゲレロは、グールドが鍵盤を上から叩くのではなく「下に引く」べきだという技術的なアイデアを示した。 10歳でトロントの王立音楽院(1947年までトロント音楽院として知られる)に通い始める。音楽理論をレオ・スミスに、オルガンをフレデリック・C・シ ルヴェスターに、ピアノをアルベルト・ゲレーロに学んだ[15]。グールドの母親は、幼いグールドにキーボードの前に背筋を伸ばして座るよう促していた [16]。グールドは生涯この椅子を使い続け、ほとんどどこへでも持って行った[10]。この椅子は、グールドが非常に低い位置に座れるように設計されて おり、ゲレロの中心的な技術的アイデアである、上から叩くのではなく、鍵盤を引き下げることができるようになっていた[17]。 グールドは、それぞれの音の「分離」と明瞭さを保ちながら、非常に速いテンポを選択することを可能にするテクニックを開発した。楽器の位置が極めて低かっ たため、鍵盤をより自由にコントロールすることができた。ラヴェルの「ラ・ヴァルス」の自作編曲や、ベートーヴェンの交響曲第5番と第6番のリストによる トランスクリプションなど、ヴィルトゥオーゾ的でロマンティックな作品を含む幅広いレパートリーの演奏と録音において、グールドはかなりの技術力を発揮し た。グールドは若い頃からゲレロのもとでフィンガータッピングとして知られるテクニックに取り組んでいた。 グールドは12歳で音楽院のピアノ科の最終試験に合格し、受験者の中で最高の成績を収め、ピアニストとしてプロとしての地位を獲得した[19]。その1年 後、彼は理論の筆記試験に合格し、トロント音楽院准教授(ATCM)のディプロマを取得する資格を得た[fn 6][19] 。 ピアノ グールドは神童であり[20]、大人になってからは音楽的現象と評された[fn 7]。彼はピアノそのもので練習したことはほとんどないと主張し、ゲレロから学んだもうひとつの技法である[fn 8]読譜によってレパートリーを学ぶことを好んだ。グールドは精神的に練習することができたようで、ブラームスのピアノ作品のレコーディングのために、 セッションの数週間前まで弾かずに準備していたこともあった[21]。 [21] グールドはピアノ曲の膨大なレパートリーを弾くことができたし、オーケストラやオペラの幅広いトランスクリプションも記憶から弾くことができた[22]。 彼は「一目で記憶する」ことができ、「記憶から即座に弾く」ことができない曲を挙げるよう友人に挑んだこともあった[23]。 グールドは、「ピアノは、それほど好きな楽器ではない......。[しかし、私は生涯ピアノを弾き続けてきたし、自分の考えを表現するための最良の手段 なのだ。バッハの場合、グールドは「私が演奏する楽器のいくつかはアクションを固定し、現在すべてのレコーディングに使用しているピアノも固定されてい る。それはむしろパワーステアリングのない自動車のようなメカニズムになりがちだ。バッハをピアノで演奏する秘訣はここにある。即座に反応し、物事の細か い定義をコントロールしなければならない」[24]。 10代の頃、グールドはアルトゥール・シュナーベル[fn 10][25]とロザリン・トゥレックのバッハの録音[26](彼はこれを「直立した、安息と積極性の感覚を持つ」と呼んだ)や指揮者のレオポルド・スト コフスキー[27]に大きな影響を受けた。聴衆は、グールドの解釈は素晴らしく独創的なものから奇抜なものまで様々であると評価した。彼のピアニズムは、 特に対位法的なパッセージにおいて、非常に明晰で博識であり、並外れたコントロール能力を持っていた。グールドはピアノを「対位法的な楽器」だと信じてお り、彼の音楽に対するアプローチの中心はバロックにあった。それに続くホモフォニーの多くは、あまり深刻でなく、精神的な芸術の時代に属するものだと彼は 感じていた。 グールドは、ピアノのレパートリーや演奏、音楽全般に対する、彼が「快楽主義」と呼ぶアプローチに強い嫌悪感を抱いていた。彼にとって、この意味での「快 楽主義」とは、表面的な芝居がかったものを意味し、例えばモーツァルトは、そのキャリアの後半になると、ますますその影響を受けやすくなっていったと彼は 感じていた[28]。公的なコンサートという制度は、彼が苦闘し、最終的に拒否した「血のスポーツ」へと堕落したと彼は感じていた[29]。 公演 1938年6月5日、グールドは5歳にして初めて人前で演奏し、オンタリオ州アクスブリッジにあるビジネス・メンズ・バイブル・クラス(Business Men's Bible Class)の教会礼拝で、約2,000人の会衆を前に、家族と一緒にステージに上がってピアノを弾いた。 [1945年、13歳のときにトロント交響楽団とベートーヴェンのピアノ協奏曲第4番第1楽章を演奏し、オーケストラと初共演を果たした[32]。 1947年には初のソロ・リサイタルが行われ[33]、1950年にはCBCのラジオで初のリサイタルを行った[34]。1953年にはチェリストのアイ ザック・マモット、ヴァイオリニストのアルバート・プラッツとともに室内楽グループ「フェスティバル・トリオ」を結成した[要出典]。 外部画像 image icon 1956年、カナダのトロントでピアノを演奏するグレン・グールド。 1960年代頃、ニューヨーク・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団のリハーサルでレナード・バーンスタイン、イーゴリ・ストラヴィンスキーと。 グールドは1955年1月2日、ワシントンD.C.のフィリップス・コレクションでアメリカ・デビューを果たした。音楽評論家のポール・ヒュームはワシン トン・ポスト紙にこう書いている。「1月2日は予想には早いが、1955年にフィリップス・ギャラリーで昨日の午後に演奏された以上の素晴らしいピアノ・ リサイタルが実現するとは思えない。1月11日にはニューヨークのタウン・ホールで演奏が行われた。グールドの名声は急速に高まった。彼のコンサートで は、バッハ、ベートーヴェン、そして社会主義リアリズムの時代にソ連で弾圧されていたシェーンベルクやベルクの連弾曲が演奏された[36]。1958年、 グールドはピーボディ・メイソン・コンサート・シリーズで演奏し、ボストンでデビューした[37]。1960年1月31日、グールドはCBSのフォード・ プレゼンツ・シリーズで初めてアメリカのテレビに出演し、レナード・バーンスタイン指揮ニューヨーク・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団とバッハのキーボード協奏 曲第1番ニ短調(BWV 1052)を演奏した[38]。 グールドは、パブリック・コンサートという制度は時代錯誤であり、「悪の力」であると考え、コンサート活動から早期に引退した。グールドは、公開演奏は一 種の競争であり、無感情な聴衆は演奏家が誤ったり、批評家の期待を裏切ったりする可能性にほとんど付き合わされるものであり、そのような演奏は生演奏の限 界のために例外的でない解釈を生み出すものだと主張した。1964年4月10日、彼はロサンゼルスのウィルシャー・エベル劇場で最後の公演を行った。 [40] 演奏曲目は、ベートーヴェンのピアノ・ソナタ第30番、バッハの『フーガの技法』からの抜粋、ヒンデミットのピアノ・ソナタ第3番など。ヴァン・クライ バーンのようなピアニストにとって、200回のコンサートは約2年間のツアーに相当する[41]。 グールドが生演奏を放棄した理由のひとつは、レコーディング・スタジオに対する彼の美的嗜好であった。グールドは、この方法で楽譜をより完全に実現できる と感じていた。グールドは、何世紀も前の曲を再録音しても、演奏者に新しい視点がなければ意味がないと強く感じていた。グールドは生涯、生演奏を避け、録 音、執筆、放送に専念した。 奇抜さ グールドのピアノ椅子のレプリカ グールドはその変わった癖で広く知られていた。彼はしばしば演奏中に鼻歌を歌い、オーディオ・エンジニアは録音から彼の声を除外することができなかった。 グールドは、彼の歌は無意識のものであり、あるピアノで意図した解釈を生み出せないことに比例して増加すると主張していた。その習慣は、伝記作家のケヴィ ン・バッツァーナが書いているように、彼が母親から「弾くものはすべて歌いなさい」と教えられていたことに由来しているようだ。グールドのレコーディング の中には、この「ボーカリゼーション」のせいで酷評されたものもある。例えば、1981年に彼が再録音したゴールドベルク変奏曲の批評家は、多くの聴き手 は「うめき声やうなり声に耐えられない」と書いている[43]。もうひとつの奇妙な点は、彼の環境のあらゆる面に対する絶対的なコントロールへのこだわり だった。レコーディング・スタジオの温度は正確に調節されなければならず、彼は常に極端に暖かくするよう主張していた。グールドの伝記作家の一人である オットー・フリードリッヒによれば、空調エンジニアはレコーディング・エンジニアと同じくらい働かなければならなかったという[44]。 ピアノは一定の高さに置かなければならず、必要であれば木製のブロックの上に上げなければならなかった[45]。 足元には敷物が必要なこともあった[46]。彼の椅子は、カナダ図書館公文書館のガラスケースに展示されているほど、彼との関係が深い。 指揮者たちは、グールドと彼の演奏習慣に対して様々な反応を示した。1957年にクリーヴランド管弦楽団でグールドを指揮したジョージ・セルは、アシスタ ントに「あのナッツは天才だ」と言った[48]。 バーンスタインは「彼のような人は誰もいないし、私は彼と演奏するのが大好きだ」と言った[48]。 バーンスタインは1962年4月6日のコンサートで、ニューヨーク・フィルハーモニックがグールドとブラームスのピアノ協奏曲第1番ニ短調を演奏する直前 に、聴衆に「これから聴かれる演奏に何の責任も負わない」と告げ、波紋を呼んだ。彼は聴衆に尋ねた: 「協奏曲では、ソリストと指揮者、どちらがボスですか?「具体的には、バーンスタインは、グールドが第1楽章の全曲を指示されたテンポの半分で演奏するこ とにこだわった彼らのリハーサルについて言及していた。このスピーチは、『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙の音楽評論家ハロルド・C・ションバーグによって、 責任放棄とグールドへの攻撃と解釈された[50]。その後、ラジオの生放送はバーンスタインの免責条項付きでCD化された。 グールドは寒さを嫌い、暖かい場所でも手袋などの厚着をした。フロリダ州サラソタの公園のベンチに座っていたとき、コート、帽子、ミトンという全天候型の 標準的な服装で、浮浪者と間違われて逮捕されたこともある[51]。触られることを嫌い、晩年は個人的な接触を制限し、電話や手紙でのコミュニケーション に頼っていた。1959年にニューヨークのスタインウェイ・ホールを訪れた際、当時の主任ピアノ技師であったウィリアム・ヒュプファーがグールドの背中を 叩いて挨拶した。グールドはこれにショックを受け、そのせいで痛みや協調性の欠如、疲労を訴えた。グールドは直前になって公演をキャンセルすることで知ら れており、バーンスタインが前述した公の場で「怖がらないでください、グールドさんはここにいます。[グールド氏はここにいます。 グールドはライナーノートや放送の中で、風刺的、ユーモラス、教訓的な目的で20人以上の分身を作り、自分の演奏について敵対的な批評や理解しがたい解説 を書くことを許した。おそらく最もよく知られているのは、ドイツの音楽学者カールハインツ・クロプヴァイサー、イギリスの指揮者サー・ナイジェル・トゥ イット=ソーンウェイト、アメリカの批評家セオドア・スラッツであろう[53]。グールドのこうした一面は、神経症として解釈されるにせよ、「遊び」とし て解釈されるにせよ[54]、心理伝記に十分な材料を提供した。 グールドは禁酒家で、タバコも吸わなかった[55]。料理はせず、レストランで食事をしたり、ルームサービスに頼ることが多かった。晩年はベジタリアンであると主張していたが、定かではない。 私生活 外部オーディオ オーディオ・アイコン J. S. バッハのイタリア協奏曲 ヘ長調 BWV 971とバッハの前奏曲とフーガを演奏するグールド。 オーディオ・アイコン J. S. バッハの『フーガの技法』BWV 1080をオルガンとピアノで演奏するグールド。 グールドはプライベートな生活を送っていた。ドキュメンタリー映画監督のブルーノ・モンサンジョンは、彼についてこう語っている: 「グールドは一度も結婚しておらず、伝記作家たちは彼のセクシュアリティについてかなりの時間を費やしている。バッツァーナは、「グールドが無性愛者で あったと仮定したくなるが、それは彼の美学と彼が伝えようとした人物像に確かに合致するイメージであり、グールドの文献をすべて読めば、彼が童貞のまま死 んだと確信できる」と書いているが、彼はまた、「プラトニックな関係であったかもしれないし、そうでなかったかもしれないが、最終的には複雑な関係にな り、終止符を打たれた女性との数多くの関係」を示す証拠があることにも言及している[57]。 証拠のひとつは2007年に届いた。グールドが1956年にロサンゼルスに滞在していたとき、彼は美術講師のコーネリア・フォスと彼女の夫で指揮者のルー カスに出会った。数年後、彼女とグールドは恋人になった[58]。1967年、彼女は夫のもとを去り、2人の子供を連れてトロントに向かった。彼女はグー ルドのアパートの近くに家を購入した。2007年、フォスは彼女とグールドが数年間愛し合っていたことを認めた。彼女によれば、「グレンについては多くの 誤解があったし、それは彼がとてもプライベートな人だったせいでもある。でも断言するわ、彼は極めて異性愛者だった。私たちの関係は、とりわけかなり性的 なものだった" ふたりの関係は1972年まで続き、彼女は夫のもとに戻った。フォスは夫と別れて2週間後には早くもグールドの不穏な兆候に気づいており、「単なる神経 症」以上の異常な行動を示唆していた[58]。特に、フォスの息子によれば、彼は「誰かが自分をスパイしている」と考えていた[59]。 健康と死 自他共に認める心気症[60][fn 14]であったグールドは、多くの痛みや病気を抱えていたが、彼の検死では、しばしば彼を悩ませていた分野における根本的な問題はほとんど発見されなかっ た[fn 15]。 彼は高血圧(晩年は日記の形で記録していた)から手の安全まで、あらゆることを心配していた。(グールドはめったに人と握手することはなく、習慣的に手袋 をしていた)[fn 16][fn 17] 幼少期に経験した脊椎の損傷により、医師は鎮痛剤、抗不安剤、その他の薬物を、通常は単独で処方するようになった。バッツァーナは、グールドがそのキャリ アを通じてさまざまな処方薬を使用するようになったことが、彼の健康に悪影響を及ぼしたのではないかと推測している。バッツァーナは、「彼は他の薬の副作 用を打ち消すために薬を服用し、依存のサイクルを作り出していた」と書いている[61]。1956年、グールドはフォトジャーナリストのジョック・キャロ ルに「食べることについてのヒステリー。精神科医のピーター・F・オストワルドはその伝記の中で、1950年代半ばにグールドが食に関するノイローゼを強 めていたことを指摘している。オストワルドは後に、グールドがこの頃に「心因性摂食障害」を発症した可能性について論じている[63]。 1956年、グールドは抗精神病薬のソラジンと、同じく抗精神病薬で血圧を下げる効果のあるレセルピンを服用していた[64]。 コーネリア・フォスは、グールドが多くの抗うつ薬を服用しており、それが彼の精神状態の悪化の原因であると述べている[65]。 グールドの行動が自閉症スペクトラムに当てはまるかどうかは議論されてきた[7]。 この診断は、グールドの友人である精神科医ピーター・オストワルドが1997年に出版した『グレン・グールド: また、グールドが双極性障害を患っていたのではないかという憶測もある[63]。グールドは数日間眠らずに過ごすことがあり、極端にエネルギーが増大し、 無謀な運転をし、晩年には激しい抑うつエピソードに耐えていたからである[66]。  バッハのゴルトベルク変奏曲が刻まれたグールドの墓標。 1982年9月27日、50歳の誕生日を迎えた2日後、激しい頭痛に襲われたグールドは脳卒中で左半身が麻痺した。グールドはトロント総合病院に入院し、 病状は急速に悪化した。10月4日までに脳に損傷が見られたため、グールドの父親は息子の生命維持装置を外すべきだと決断した[67]。グールドの一般葬 は10月15日にセント・ポール英国国教会で行われ、ロイス・マーシャルとモーリーン・フォレスターが歌った。葬儀には3,000人以上が参列し、その模 様はカナダ放送協会で放送された。グールドはトロントのマウント・プレザント墓地(セクション38、ロット1050)に両親の隣に埋葬された[68]。 墓標にはゴールドベルク変奏曲の最初の数小節が刻まれている[69]。動物愛好家であったグールドは、財産の半分をトロント動物愛護協会に、残りの半分を 救世軍に寄付した[70]。 2000年、運動障害の神経学者は、グールドが「彼の時代にはほとんど理解されていなかった問題」であるジストニアであることを論文で示唆した[71]。 |

| Perspectives Writings External audio audio icon Glenn Gould performs Bach's: Prelude & Fugue No. 1–24, BWV 846–869; Prelude & Fugue No. 1–24, BWV 870–893; English Suite No. 1–6, BWV 806–811; French Suite No. 1–6, BWV 812–817; Goldberg Variations No. 1–30, BWV 988; Partita No. 1–6, BWV 825–830; and various Inventions, Sinfonias & Contrapunctus audio icon Glenn Gould and the Columbia Symphony Orchestra with Vladimir Golschmann circa 1967 in Bach's Keyboard Concertos: No. 3 in D major, BWV 1054; No. 5 in F minor, BWV 1056; No. 7 in G minor, BWV 1058 Gould periodically told interviewers he would have been a writer if he had not been a pianist.[72] He expounded his criticism and philosophy of music and art in lectures, convocation speeches, periodicals, and CBC radio and television documentaries. Gould participated in many interviews, and had a predilection for scripting them to the extent that they may be seen to be as written work as much as off-the-cuff discussions. Gould's writing style was highly articulate, but sometimes florid, indulgent, and rhetorical. This is especially evident in his (frequent) attempts at humour and irony.[fn 18] Bazzana writes that although some of Gould's "conversational dazzle" found its way into his prolific written output, his writing was "at best uneven [and] at worst awful".[73] While offering "brilliant insights" and "provocative theses", Gould's writing is often marred by "long, tortuous sentences" and a "false formality", Bazzana writes.[74] In his writing, Gould praised certain composers and rejected what he deemed banal in music composition and its consumption by the public, and also gave analyses of the music of Richard Strauss, Alban Berg and Anton Webern. Despite a certain affection for Dixieland jazz, Gould was mostly averse to popular music. He enjoyed a jazz concert with his friends as a youth, mentioned jazz in his writings, and once criticized the Beatles for "bad voice leading"[fn 19]—while praising Petula Clark and Barbra Streisand. Gould and jazz pianist Bill Evans were mutual admirers, and Evans made his record Conversations with Myself using Gould's Steinway model CD 318[75] piano. On art Gould's perspective on art is often summed up by this 1962 quotation: "The justification of art is the internal combustion it ignites in the hearts of men and not its shallow, externalized, public manifestations. The purpose of art is not the release of a momentary ejection of adrenaline but is, rather, the gradual, lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity."[76] Gould repeatedly called himself "the last puritan", a reference to the philosopher George Santayana's 1935 novel of the same name.[77] But he was progressive in many ways, promulgating the atonal composers of the early 20th century, and anticipating, through his deep involvement in the recording process, the vast changes technology had on the production and distribution of music. Mark Kingwell summarizes the paradox, never resolved by Gould nor his biographers, this way: He was progressive and anti-progressive at once, and likewise at once both a critic of the Zeitgeist and its most interesting expression. He was, in effect, stranded on a beachhead of his own thinking between past and future. That he was not able, by himself, to fashion a bridge between them is neither surprising, nor, in the end, disappointing. We should see this failure, rather, as an aspect of his genius. He both was and was not a man of his time.[78] Technology The issue of "authenticity" in relation to an approach like Gould's has been greatly debated (although less so by the end of the 20th century): is a recording less authentic or "direct" for having been highly refined by technical means in the studio? Gould likened his process to that of a film director[79]—one knows that a two-hour film was not made in two hours—and implicitly asked why the recording of music should be different. He went so far as to conduct an experiment with musicians, sound engineers, and laypeople in which they were to listen to a recording and determine where the splices occurred. Each group chose different points, but none was wholly successful. While the test was hardly scientific, Gould remarked, "The tape does lie, and nearly always gets away with it".[80] In the lecture and essay "Forgery and Imitation in the Creative Process", one of his most significant texts,[81] Gould makes explicit his views on authenticity and creativity. He asks why the epoch in which a work is received influences its reception as "art", postulating a sonata of his own composition that sounds so like one of Haydn's that it is received as such. If, instead, the sonata had been attributed to an earlier or later composer, it becomes more or less interesting as a piece of music. Yet it is not the work that has changed but its relation within the accepted narrative of music history. Similarly, Gould notes the "pathetic duplicity" in the reception of high-quality forgeries by Han van Meegeren of new paintings attributed to the Dutch master Johannes Vermeer, before and after the forgery was known. Gould preferred an ahistorical, or at least pre-Renaissance, view of art, minimizing the identity of the artist and the attendant historical context in evaluating the artwork: "What gives us the right to assume that in the work of art we must receive a direct communication with the historical attitudes of another period? ... moreover, what makes us assume that the situation of the man who wrote it accurately or faithfully reflects the situation of his time? ... What if the composer, as historian, is faulty?"[82] Recordings Further information: Glenn Gould discography External audio audio icon Gould performing Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 4, with Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic in 1961 audio icon Gould performing Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 2 audio icon Gould performing music by Orlando Gibbons and William Byrd in 1993 Studio In creating music, Gould much preferred the control and intimacy provided by the recording studio. He disliked the concert hall, which he compared to a competitive sporting arena. He gave his final public performance in 1964, and thereafter devoted his career to the studio, recording albums and several radio documentaries. He was attracted to the technical aspects of recording, and considered the manipulation of tape to be another part of the creative process. Although Gould's recording studio producers have testified that "he needed splicing less than most performers",[83] Gould used the process to give himself total artistic control over the recording process. He recounted his recording of the A minor fugue from Book I of The Well-Tempered Clavier and how it was spliced together from two takes, with the fugue's expositions from one take and its episodes from another.[84] Gould's first commercial recording (of Berg's Piano sonata, Op. 1) came in 1953 on the short-lived Canadian Hallmark label. He soon signed with Columbia Records' classical music division and, in 1955, recorded Bach: The Goldberg Variations, his breakthrough work. Although there was some controversy at Columbia about the appropriateness of this "debut" piece, the record received extraordinary praise and was among the best-selling classical music albums of its era.[85] Gould became closely associated with the piece, playing it in full or in part at many recitals. A new recording of the Goldberg Variations, in 1981, was among his last albums; the piece was one of a few he recorded twice in the studio. The 1981 release was one of CBS Masterworks' first digital recordings. The 1955 interpretation is highly energetic and often frenetic; the later is slower and more deliberate[86][87]—Gould wanted to treat the aria and its 30 variations as a cohesive whole.[fn 20] Gould said Bach was "first and last an architect, a constructor of sound, and what makes him so inestimably valuable to us is that he was beyond a doubt the greatest architect of sound who ever lived".[88] He recorded most of Bach's other keyboard works, including both books of The Well-Tempered Clavier and the partitas, French Suites, English Suites, inventions and sinfonias, keyboard concertos, and a number of toccatas (which interested him least, being less polyphonic). For his only recording at the organ, he recorded some of The Art of Fugue, which was also released posthumously on piano. As for Beethoven, Gould preferred the composer's early and late periods. He recorded all five of the piano concertos, 23 of the piano sonatas,[89] and numerous bagatelles and variations. Gould was the first pianist to record any of Liszt's piano transcriptions of Beethoven's symphonies (beginning with the Fifth Symphony, in 1967, with the Sixth released in 1969). Gould also recorded works by Brahms, Mozart, and many other prominent piano composers, though he was outspoken in his criticism of the Romantic era as a whole. He was extremely critical of Chopin. When asked whether he found himself wanting to play Chopin, he replied: "No, I don't. I play it in a weak moment—maybe once a year or twice a year for myself. But it doesn't convince me."[90] But in 1970, he played Chopin's B minor sonata for the CBC and said he liked some of the miniatures and "sort of liked the first movement of the B minor". Although he recorded all of Mozart's sonatas and admitted enjoying the "actual playing" of them,[91] Gould said he disliked Mozart's later works.[92] He was fond of a number of lesser-known composers such as Orlando Gibbons, whose Anthems he had heard as a teenager,[93] and whose music he felt a "spiritual attachment" to.[94] He recorded a number of Gibbons's keyboard works, and called him his favourite composer,[95][96] despite his better-known admiration for Bach.[fn 21] He made recordings of piano music by Jean Sibelius (the Sonatines and Kyllikki), Georges Bizet (the Variations Chromatiques de Concert and the Premier nocturne), Richard Strauss (the Piano Sonata, the Five Pieces, and Enoch Arden with Claude Rains), and Hindemith (the three piano sonatas and the sonatas for brass and piano). He also made recordings of Schoenberg's complete piano works. In early September 1982, Gould made his final recording: Strauss's Piano Sonata in B minor.[97] Collaborations External videos video icon Glenn Gould performing on YouTube Bach's Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 on a "harpsipiano" with Julius Baker and Oscar Shumsky for CBC Television in 1962 video icon Glenn Gould performing Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 17, Op. 31, No. 2 ("Tempest") in 1960 video icon Glenn Gould performing Beethoven's Variations and Fugue for Piano in E-flat major, Op. 35 (Eroica Variations) in 1960 The success of Gould's collaborations was to a degree dependent upon his collaborators' receptiveness to his sometimes unconventional readings of the music. The musicologist Michael Stegemann considered Gould's television collaboration with American violinist Yehudi Menuhin in 1965, in which they played works by Bach, Beethoven and Schoenberg, a success because "Menuhin was ready to embrace the new perspectives opened up by an unorthodox view".[98] But Stegemann deemed the 1966 collaboration with soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, recording Strauss's Ophelia Lieder, an "outright fiasco".[98] Schwarzkopf believed in "total fidelity" to the score, and objected to the temperature: The studio was incredibly overheated, which may be good for a pianist but not for a singer: a dry throat is the end as far as singing is concerned. But we persevered nonetheless. It wasn't easy for me. Gould began by improvising something Straussian—we thought he was simply warming up, but no, he continued to play like that throughout the actual recordings, as though Strauss's notes were just a pretext that allowed him to improvise freely.[99] Gould recorded Schoenberg, Hindemith, and Ernst Krenek with numerous vocalists, including Donald Gramm and Ellen Faull. He also recorded Bach's six sonatas for violin and harpsichord (BWV 1014–1019) with Jaime Laredo, and the three sonatas for viola da gamba and keyboard with Leonard Rose. Claude Rains narrated their recording of Strauss's melodrama Enoch Arden. Gould also collaborated with members of the New York Philharmonic, the flutist Julius Baker and the violinist Rafael Druian, in a recording of Bach's Brandenburg Concerto No. 4,[100] and with Leopold Stokowski and the American Symphony Orchestra in a performance of Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 5 in 1966.[101] Gould collaborated extensively with Vladimir Golschmann and the Columbia Symphony Orchestra for the Columbia Masterworks label in his recording of Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 1 in 1958[102] and several works by Bach in the 1960s, including the Keyboard Concerto No. 3 (BWV 1054), the Keyboard Concerto No. 5 (BWV 1056) and the Keyboard Concerto No. 7 (BWV 1058) in 1967[103] and the Keyboard Concerto No. 2 in E major (BWV 1053) and the Keyboard Concerto No. 4 in A major (BWV 1055) in 1969.[104] Documentaries Gould made numerous television and radio programs for CBC Television and CBC Radio. Notable productions include his musique concrète Solitude Trilogy, which consists of The Idea of North, a meditation on Northern Canada and its people; The Latecomers, about Newfoundland; and The Quiet in the Land, about Mennonites in Manitoba. All three use a radiophonic electronic-music technique that Gould called "contrapuntal radio", in which several people are heard speaking at once—much like the voices in a fugue—manipulated through overdubbing and editing. His experience of driving across northern Ontario while listening to Top 40 radio in 1967 inspired one of his most unusual radio pieces, The Search for Petula Clark, a witty and eloquent dissertation on Clark's recordings.[105] Also among Gould's CBC programs was an educational lecture on the music of Bach, "Glenn Gould On Bach", which featured a collaborative performance with Julius Baker and Oscar Shumsky of the Brandenburg Concerto No. 5.[106][107] |

展望 著作 外部オーディオ audio icon グレン・グールドによるバッハの演奏: 前奏曲とフーガ第1-24番(BWV 846-869)、前奏曲とフーガ第1-24番(BWV 870-893)、イギリス組曲第1-6番(BWV 806-811)、フランス組曲第1-6番(BWV 812-817)、ゴールドベルク変奏曲第1-30番(BWV 988)、パルティータ第1-6番(BWV 825-830)、インヴェンション、シンフォニア、コントラプンクトゥスなど。 バッハの鍵盤協奏曲第3番ニ長調BWV1054、第5番ヘ短調BWV1056、第7番ト短調BWV1058。 グールドは定期的にインタビュアーに、ピアニストでなかったら作家になっていただろうと語っている[72]。講演、招集演説、定期刊行物、CBCのラジオ やテレビのドキュメンタリー番組で、音楽と芸術に対する批評と哲学を展開した。グールドは多くのインタヴューに参加し、その場しのぎの議論と同じように、 書かれた仕事と見なすことができるほど、インタヴューを台本化することを好んだ。グールドの文体は非常に明瞭であったが、時に華美で耽美的、修辞的であっ た。これは特にユーモアと皮肉を(頻繁に)試みたことに顕著である[fn 18] バザーナは、グールドの「会話のまばゆさ」の一部は彼の多作な著作に見られるものの、彼の文章は「よく言えばむらだらけ、悪く言えばひどい」ものであった と書いている[73]。 また、リヒャルト・シュトラウス、アルバン・ベルク、アントン・ヴェーベルンの音楽についても分析を行っている。ディキシーランド・ジャズにはある種の愛 着を抱いていたものの、グールドはポピュラー音楽をほとんど嫌っていた。少年時代に友人たちとジャズ・コンサートを楽しんだり、著作の中でジャズに触れた り、ビートルズを「声の通りが悪い」[fn 19]と批判する一方で、ペトゥラ・クラークやバーブラ・ストライサンドを賞賛したこともあった。グールドとジャズ・ピアニストのビル・エヴァンスは共通 のファンであり、エヴァンスはグールドのスタインウェイ・モデルCD318[75]のピアノを使ってレコード『Conversations with Myself』を制作した。 芸術について グールドの芸術観は、しばしば1962年のこの引用に集約されている: 「芸術の正当性は、それが人の心に点火する内発的な燃焼であり、浅薄で外在化された公的な表現ではない。芸術の目的は、アドレナリンを瞬間的に放出するこ とではなく、むしろ、驚きと平穏の状態を徐々に、生涯にわたって構築することである」[76]。 グールドは自らを「最後の清教徒」と繰り返し呼んだが、これは哲学者ジョージ・サンタヤーナが1935年に発表した同名の小説にちなんだものである [77]。しかし彼は多くの点で進歩的であり、20世紀初頭の無調音楽の作曲家たちを広めるとともに、レコーディング・プロセスへの深い関わりを通して、 テクノロジーが音楽の生産と流通にもたらした大きな変化を先取りしていた。マーク・キングウェルは、グールドも彼の伝記作家たちも決して解決しなかったパ ラドックスをこう要約している: 彼は進歩的であると同時に反進歩的であり、同様に時代精神の批判者であると同時にその最も興味深い表現者でもあった。彼は事実上、過去と未来の間にある自 分の思考の海辺に取り残されていた。彼が自分自身の力で両者の間に橋を架けることができなかったのは、驚くべきことでもなければ、結局は残念なことでもな い。この失敗は、むしろ彼の天才の一面と見るべきだろう。彼は時代の人であると同時に、時代の人ではなかったのだ[78]。 技術 グールドのようなアプローチに関する「真正性」の問題は、(20世紀末にはそれほどではなくなったが)大いに議論されてきた。グールドは自分のプロセスを 映画監督のそれになぞらえ[79]、2時間の映画が2時間で作られたわけではないことを知っている。彼は、音楽家、サウンド・エンジニア、そして一般人を 対象に、録音を聴いてどこで継ぎ接ぎが起きているかを判断するという実験を行った。各グループは異なるポイントを選んだが、完全に成功したものはなかっ た。このテストは科学的とは言い難かったが、グールドは「テープは嘘をつくもので、ほとんどいつもその嘘から逃れられる」と述べた[80]。 グールドの最も重要なテクストのひとつである講義とエッセイ「創造的プロセスにおける偽造と模倣」[81]において、グールドは真正性と創造性についての 見解を明らかにしている。彼は、作品が受容された時代が、なぜ「芸術」としての受容に影響を及ぼすのかを問い、ハイドンのソナタにそっくりな自作のソナタ を仮定して、それがそのように受容されていることを示す。その代わりに、そのソナタがもっと前、あるいはもっと後の作曲家の作品であったなら、音楽として の面白さは多少なりとも増すだろう。しかし、変わったのは作品ではなく、受け入れられている音楽史の物語の中での関係なのである。同様にグールドは、オラ ンダの巨匠ヨハネス・フェルメールの作品とされるハン・ファン・ミーゲレンによる高品質な贋作が、贋作が知られる前と後でどのように受け止められたかにつ いて、「哀れな二重性」を指摘している。 グールドは非歴史的な、少なくともルネサンス以前の芸術観を好み、作品を評価する際に画家の身元やそれに付随する歴史的背景を最小限にした: 「芸術作品の中に、別の時代の歴史的態度との直接的なコミュニケーションを受けなければならないと仮定する権利が、どうして我々にあるのだろうか。歴史家 としての作曲家が間違っていたらどうするのか? 録音 さらなる情報 グレン・グールドのディスコグラフィ 外部オーディオ オーディオ・アイコン 1961年、レナード・バーンスタイン指揮ニューヨーク・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団とベートーヴェンのピアノ協奏曲第4番を演奏するグールド。 オーディオ・アイコン ベートーヴェンのピアノ協奏曲第2番を演奏するグールド オーディオ・アイコン オーランド・ギボンズとウィリアム・バードの曲を演奏するグールド(1993年 スタジオ グールドは音楽を創作する上で、レコーディング・スタジオによるコントロールと親密さを好んだ。彼はコンサートホールをスポーツの競技場に例えて嫌ってい た。彼は1964年に最後の公開演奏を行い、その後はスタジオでの活動に専念し、アルバムやいくつかのラジオ・ドキュメンタリーを録音した。彼はレコー ディングの技術的な側面に惹かれ、テープを操作することも創造的なプロセスの一部と考えていた。グールドのレコーディング・スタジオのプロデューサーは 「彼は他の演奏家よりもスプライシングを必要としなかった」と証言しているが[83]、グールドはレコーディング・プロセスを完全に芸術的にコントロール するためにこのプロセスを利用した。彼は『平均律クラヴィーア曲集』第1巻のイ短調フーガを録音した際、2つのテイクをスプライシングし、1つのテイクで はフーガのエクスポジションを、もう1つのテイクではそのエピソードを録音したと語っている[84]。 グールドの最初の商業録音(ベルクのピアノ・ソナタ作品1)は、1953年に短命に終わったカナダのホールマーク・レーベルからリリースされた。すぐにコ ロンビア・レコードのクラシック部門と契約し、1955年にバッハの『ゴールドベルク変奏曲』を録音。この "デビュー "曲の適切さについてコロンビアでは賛否両論があったが、このレコードは並外れた賞賛を受け、当時のクラシック音楽で最も売れたアルバムのひとつとなった [85]。グールドはこの曲と密接な関係を持つようになり、多くのリサイタルで全曲または一部を演奏した。1981年のゴールドベルク変奏曲の新録音は、 彼の最後のアルバムのひとつであり、この曲は彼がスタジオで2度録音した数少ない作品のひとつであった。1981年のリリースは、CBSマスターワークス 初のデジタル録音のひとつである。1955年の解釈は非常にエネルギッシュで、しばしば熱狂的であるが、後の解釈はよりゆっくりと、より慎重である [86][87]-グールドはアリアとその30の変奏曲をまとまりのある全体として扱いたかったのである[fn 20]。 グールドは、バッハは「最初で最後の建築家であり、音の構築者であり、彼が私たちにとって計り知れないほど貴重な存在であるのは、彼が間違いなく、かつて 生きた中で最も偉大な音の建築家であったからである」と述べている[88]。オルガンでの唯一のレコーディングでは、『フーガの技法』の一部を録音した。 ベートーヴェンに関しては、グールドはこの作曲家の初期と後期を好んだ。ピアノ協奏曲全5曲、ピアノ・ソナタ全23曲[89]、バガテルと変奏曲を数多く 録音している。リストのベートーヴェンの交響曲のピアノ・トランスクリプションを録音した最初のピアニストでもある(1967年の交響曲第5番から始ま り、第6番は1969年にリリースされた)。 グールドはブラームス、モーツァルト、その他多くの著名なピアノ作曲家の作品も録音しているが、ロマン派時代全体に対する批判は露骨だった。ショパンに対 しては極めて批判的だった。ショパンを弾きたいと思うことがあるかと尋ねられると、彼はこう答えた: 「いいえ。年に1度か2度、自分のために弾くことはある。しかし、1970年、彼はCBCのためにショパンのロ短調ソナタを演奏し、いくつかのミニチュア が好きで、「ロ短調の第1楽章がなんとなく好きだ」と語った。 彼はモーツァルトのソナタをすべて録音し、その「実際の演奏」を楽しんでいることを認めたが[91]、グールドはモーツァルトの後期の作品は嫌いだと言っ た[92]。彼はオーランド・ギボンズのようなあまり知られていない多くの作曲家が好きで、そのアンセムは10代の頃に聴いたことがあり[93]、その音 楽には「精神的な愛着」を感じていた。 [94]彼はギボンズの鍵盤作品を数多く録音し、バッハへの賞賛がよく知られているにもかかわらず、彼をお気に入りの作曲家と呼んだ[95][96]。 [ジャン・シベリウス(ソナチネとキルリッキ)、ジョルジュ・ビゼー(演奏会用色彩変奏曲とノクターン第1番)、リヒャルト・シュトラウス(ピアノ・ソナ タ、5つの小品、クロード・レインズとのエノク・アーデン)、ヒンデミット(3つのピアノ・ソナタと金管楽器とピアノのためのソナタ)のピアノ曲を録 音。) また、シェーンベルクのピアノ作品全集の録音も行っている。1982年9月初旬、グールドは最後の録音を行った: シュトラウスのピアノ・ソナタ ロ短調である[97]。 コラボレーション 外部ビデオ 1962年、グレン・グールドがCBCテレビのためにジュリアス・ベイカー、オスカー・シュムスキーとともにバッハのブランデンブルク協奏曲第5番をハープシピアノで演奏。 1960年、グレン・グールドがベートーヴェンのピアノ・ソナタ第17番、作品31、第2番(「テンペスト」)を演奏している様子。 1960年、ベートーヴェンの「ピアノのための変奏曲とフーガ 変ホ長調 作品35(エロイカ変奏曲)」を演奏するグレン・グールド。 グールドの共同作業の成功は、時に型破りな彼の音楽解釈に対する共同作業者の受容性にある程度依存していた。音楽学者のミヒャエル・シュテゲマンは、 1965年にグールドがアメリカのヴァイオリニスト、ユーディ・メニューインとテレビ番組で共演し、バッハ、ベートーヴェン、シェーンベルクの作品を演奏 したことを「メニューインが異端的な見方によって切り開かれた新しい視点を受け入れる準備ができていた」ために成功したとみなしている[98]。しかし シュテゲマンは、1966年にソプラノ歌手のエリザベート・シュヴァルツコップフとのコラボレーションでシュトラウスの『オフィーリア歌曲集』を録音した ことを「まったくの大失敗」とみなしている[98]: スタジオは信じられないほど暖房が効きすぎていて、ピアニストにはいいかもしれないが、歌手には向かない。しかし、それでも我慢した。私にとっては簡単な ことではなかった。グールドは、まずシュトラウス風の即興演奏から始めた。私たちは、彼が単にウォーミングアップをしているのだと思ったが、そうではな く、実際のレコーディングではずっとそのような演奏を続けていた。 グールドは、シェーンベルク、ヒンデミット、エルンスト・クレネックを、ドナルド・グラムやエレン・フォールを含む多くの声楽家と録音した。また、バッハ のヴァイオリンとチェンバロのための6つのソナタ(BWV 1014-1019)をハイメ・ラレードと、ヴィオラ・ダ・ガンバとキーボードのための3つのソナタをレナード・ローズと録音した。シュトラウスのメロド ラマ『エノク・アーデン』の録音では、クロード・レインズがナレーションを務めた。また、グールドはニューヨーク・フィルハーモニックのメンバー、フルー ト奏者のジュリアス・ベイカーとヴァイオリニストのラファエル・ドルイアンとバッハのブランデンブルク協奏曲第4番の録音で共演し[100]、1966年 にはレオポルド・ストコフスキーとアメリカ交響楽団とベートーヴェンのピアノ協奏曲第5番を演奏した[101]。 1958年にはベートーヴェンのピアノ協奏曲第1番[102]を、1960年代には鍵盤協奏曲第3番(BWV1054)を含むバッハのいくつかの作品をコ ロンビア・マスターワークス・レーベルでウラディーミル・ゴルシュマン指揮コロンビア交響楽団と録音している[101]。1967年にはキーボード協奏曲 第3番(BWV 1054)、キーボード協奏曲第5番(BWV 1056)、キーボード協奏曲第7番(BWV 1058)[103]、1969年にはキーボード協奏曲第2番ホ長調(BWV 1053)、キーボード協奏曲第4番イ長調(BWV 1055)など。 ドキュメンタリー グールドは、CBCテレビとCBCラジオで数多くのテレビ番組やラジオ番組を制作した。代表的な作品には、カナダ北部とその人々についての瞑想作品 『The Idea of North』、ニューファンドランド島についての『The Latecomers』、マニトバ州のメノナイトについての『The Quiet in the Land』からなる、ムジーク・コンクレートによる『Solitude』3部作がある。この3作とも、グールドが「コントラプンタル・ラジオ」と呼ぶラジ オフォニックな電子音楽技法が用いられており、複数の人物が一度に話す声が、オーバーダビングと編集によって操作されたフーガの声のように聴こえる。 1967年にトップ40のラジオを聴きながらオンタリオ州北部をドライブした経験から、彼の最も珍しいラジオ作品のひとつである『The Search for Petula Clark(ペトゥラ・クラークを探せ)』は、クラークのレコーディングに関するウィットに富んだ雄弁な論文である[105]。 また、グールドのCBCの番組には、バッハの音楽についての教育的レクチャー「Glenn Gould On Bach」があり、ジュリアス・ベイカーとオスカー・シュムスキーとのブランデンブルク協奏曲第5番の共演が紹介された[106][107]。 |

| Transcriptions, compositions, and conducting Further information: List of compositions by Glenn Gould External audio audio icon Glenn Gould collaborating with Vladimir Golschmann and the Columbia Symphony Orchestra in Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15 in 1958 audio icon Glenn Gould and Vladimir Golschmann with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra in J. S. Bach's: Keyboard Concerto No. 2 in E major, BWV 1053 and Keyboard Concerto No. 4 in A major, BWV 1055 in 1969 audio icon Glenn Gould's String Quartet in F minor, Op. 1, performed by the Symphonia Quartet in 1960 Gould was also a prolific transcriber of orchestral repertoire for piano. He transcribed his own Wagner and Ravel recordings, as well as Strauss's operas and Schubert's and Bruckner's symphonies,[10] which he played privately for pleasure.[fn 22] Gould dabbled in composition, with few finished works. As a teenager, he wrote chamber music and piano works in the style of the Second Viennese School. Significant works include a string quartet, which he finished in his 20s (published 1956, recorded 1960), and his cadenzas to Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 1. Later works include the Lieberson Madrigal (soprano, alto, tenor, bass [SATB] and piano),[108] and So You Want to Write a Fugue? (SATB with piano or string-quartet accompaniment). His String Quartet (Op. 1) received a mixed reaction: The Christian Science Monitor and Saturday Review were quite laudatory, the Montreal Star less so.[109] There is little critical commentary on Gould's compositions because there are few of them; he never succeeded beyond Opus 1, and left a number of works unfinished.[110] He attributed his failure as a composer to his lack of a "personal voice".[111] Most of his work is published by Schott Music. The recording Glenn Gould: The Composer contains his original works. Towards the end of his life, Gould began conducting. He had earlier directed Bach's Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 and the cantata Widerstehe doch der Sünde from the harpsipiano (a piano with metal hammers to simulate a harpsichord's sound), and Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 2 (the Urlicht section) in the 1960s. His first known public appearance conducting occurred in 1939 when he was six, while appearing as a pianist in a concert for the Business Men's Bible Class in Uxbridge.[112] By 1957 he emerged as the conductor for the CBC Television program Chrysler Festival, in which he collaborated with Maureen Forrester.[112] In the same year he also joined forces with the CBC Vancouver Orchestra as a conductor in a radio broadcast of Mozart's Symphony No. 1 and Schubert's Symphony No. 4 ("Tragic").[112] In 1958, Gould wrote to Golschmann of his "temporary retirement" from conducting, apparently as a result of the unanticipated muscular strain it created.[112] Gould found himself "practically crippled" after his conducting appearances and unable to perform properly at the piano.[112] Yet even at the age of 26, Gould continued to contemplate retiring as a piano soloist and devoting himself entirely to conducting.[112] Immediately before his death, he was finalizing plans to appear as a conductor of Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 2 in 1982 and in recordings of Mendelssohn's Hebrides Overture and Beethoven's Coriolan Overture in 1983.[113] His last recording as a conductor was of Wagner's Siegfried Idyll in its original chamber-music scoring. He intended to spend his later years conducting, writing about music, and composing while pursuing an idlyllic "neoThoreauvian way of life" in the countryside.[114][113] |

トランスクリプション、作曲、指揮 さらに詳しい情報 グレン・グールド作曲リスト 外部オーディオ 音声アイコン ベートーヴェンのピアノ協奏曲第1番ハ長調作品15でウラディーミル・ゴルシュマン指揮コロンビア交響楽団と共演するグレン・グールド(1958年 オーディオ・アイコン J. S. バッハの「鍵盤協奏曲第2番ハ長調作品15」をコロンビア交響楽団と共演するグレン・グールドとウラディーミル・ゴルシュマン: キーボード協奏曲第2番ホ長調BWV1053、キーボード協奏曲第4番イ長調BWV1055(1969年 1960年、シンフォニア・カルテットによるグレン・グールドの弦楽四重奏曲ヘ短調作品1。 グールドはまた、オーケストラのレパートリーをピアノ用に多作にトランスクライブした。自身のワーグナーやラヴェルの録音、シュトラウスのオペラ、シューベルトやブルックナーの交響曲[10]を書き写し、趣味で個人的に演奏していた[fn 22]。 作曲にも手を出したが、完成した作品はほとんどなかった。10代の頃は、第二ウィーン楽派のスタイルで室内楽やピアノ作品を書いた。代表作には、20代で 完成させた弦楽四重奏曲(1956年出版、1960年録音)や、ベートーヴェンのピアノ協奏曲第1番のカデンツァなどがある。その後の作品には、リーバー ソン・マドリガル(ソプラノ、アルト、テノール、バス[SATB]とピアノ)[108]、So You Want to Write a Fugue? (SATB、ピアノまたは弦楽四重奏伴奏)。弦楽四重奏曲(作品1)は様々な反響を呼んだ: クリスチャン・サイエンス・モニター』紙と『サタデー・レビュー』紙はかなり称賛していたが、『モントリオール・スター』紙はそれほどでもなかった [109]。グールドの作曲に関する批評はほとんどない。録音はグレン・グールド: The Composer』には彼のオリジナル作品が収録されている。 晩年、グールドは指揮を始めた。1960年代には、バッハのブランデンブルク協奏曲第5番とカンタータ「Widerstehe doch der Sünde」をハープシピアノ(金属ハンマーでチェンバロの音を模したピアノ)で、グスタフ・マーラーの交響曲第2番(ウルリッヒトの部分)を指揮した。 1957年には、CBCテレビの番組『クライスラー・フェスティバル』の指揮者として登場し、モーリーン・フォレスターと共演した[112]。 同年には、CBCバンクーバー管弦楽団の指揮者として、モーツァルトの交響曲第1番とシューベルトの交響曲第4番(『悲劇的』)のラジオ放送に参加した [112]。 1958年、グールドはゴルシュマンに指揮からの「一時的な引退」を書き送っているが、これはどうやら指揮による予期せぬ筋肉への負担の結果であったよう だ[112]。 グールドは、指揮者として出演した後、自分自身が「事実上不自由」であり、ピアノでまともな演奏ができないことに気づいた[112]。 [亡くなる直前には、1982年にベートーヴェンのピアノ協奏曲第2番を、1983年にはメンデルスゾーンのヘブリディーズ序曲とベートーヴェンのコリオ ラン序曲を指揮者として録音する計画を詰めていた[113]。晩年は、田舎でのんびりと「ネオ・ソロー的な生き方」を追求しながら、指揮をしたり、音楽に ついて書いたり、作曲したりして過ごすつもりだった[114][113]。 |

| Legacy and honours Park bench sculpture of Gould located outside the Canadian Broadcasting Centre Gould's star on Canada's Walk of Fame Gould is one of the most acclaimed musicians of the 20th century. His unique pianistic method, insight into the architecture of compositions, and relatively free interpretation of scores created performances and recordings that were revelatory to many listeners and highly objectionable to others. Philosopher Mark Kingwell wrote, "his influence is made inescapable. No performer after him can avoid the example he sets ... Now, everyone must perform through him: he can be emulated or rejected, but he cannot be ignored."[115] Among the pianists who acknowledged Gould's influence are András Schiff, Zoltán Kocsis, Ivo Pogorelić, and Peter Serkin.[116] Artists influenced by Gould include painter George Condo.[117] One of Gould's performances of the Prelude and Fugue in C major from Book II of The Well-Tempered Clavier was chosen for inclusion on the NASA Voyager Golden Record by a committee headed by Carl Sagan. The record was placed on the spacecraft Voyager 1. On 25 August 2012, the spacecraft became the first to cross the heliopause and enter the interstellar medium.[118] Gould is a popular subject of biography and critical analysis. Philosophers such as Kingwell and Giorgio Agamben have interpreted his life and ideas.[119] References to Gould and his work are plentiful in poetry, fiction, and the visual arts.[120] François Girard's Genie Award-winning 1993 film Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould includes interviews with people who knew him, dramatizations of scenes from his life, and fanciful segments including an animation set to music. Thomas Bernhard's 1983 novel The Loser purports to be an extended first-person essay about Gould and his lifelong friendship with two fellow students from the Mozarteum school in Salzburg, both of whom have abandoned their careers as concert pianists due to the intimidating example of Gould's genius. Gould left an extensive body of work beyond the keyboard. After retiring from concertising, he was increasingly interested in other media, including audio and film documentary and writing, through which he mused on aesthetics, composition, music history, and the effect of the electronic age on media consumption. (Gould grew up in Toronto at the same time that Canadian theorists Marshall McLuhan, Northrop Frye, and Harold Innis were making their mark on communications studies.)[121][122] Anthologies of Gould's writing and letters have been published, and Library and Archives Canada holds a significant portion of his papers. In 1983, Gould was posthumously inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame.[123] He was inducted into Canada's Walk of Fame in Toronto in 1998, and designated a National Historic Person in 2012.[124][125] A federal plaque reflecting the designation was erected next to a sculpture of him in downtown Toronto.[126] The Glenn Gould Studio at the Canadian Broadcasting Centre in Toronto was named after him. To commemorate what would have been Gould's 75th birthday, the Canadian Museum of Civilization held an exhibition, Glenn Gould: The Sounds of Genius, in 2007. The multimedia exhibit was held in conjunction with Library and Archives Canada.[127] |

遺産と栄誉 カナダ放送センターの外にあるグールドの公園のベンチの彫刻 カナダのウォーク・オブ・フェイムにあるグールドの星 グールドは20世紀で最も高く評価された音楽家のひとりである。彼のユニークなピアニスティック・メソッド、作曲の構造に対する洞察力、楽譜の比較的自由 な解釈は、多くの聴き手にとって啓示的であり、他の聴き手にとっては非常に不愉快な演奏や録音を生み出した。哲学者のマーク・キングウェルは「彼の影響は 避けられない。彼以降の演奏家は、彼が示す模範を避けることはできない......。グールドの影響を認めたピアニストには、アンドラーシュ・シフ、ゾル タン・コチシュ、イヴォ・ポゴレリッチ、ピーター・サーキンがいる[116]。 グールドの影響を受けたアーティストには、画家のジョージ・コンドがいる[117]。 グールドが演奏した『平均律クラヴィーア曲集』第2巻の「前奏曲とフーガ ハ長調」は、カール・セーガンを委員長とする委員会によってNASAボイジャー・ゴールデン・レコードに収録されることが決まった。このレコードは宇宙船 ボイジャー1号に搭載された。2012年8月25日、探査機ボイジャー1号は初めてヘリオポーズを越え、星間物質に突入した[118]。 グールドは伝記や批評分析の対象として人気がある。キングウェルやジョルジョ・アガンベンなどの哲学者が彼の人生と思想を解釈している[119]。 グールドと彼の作品への言及は、詩、小説、視覚芸術の中に数多く存在する[120]。 フランソワ・ジラールが1993年にジニー賞を受賞した映画『Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould』には、彼を知る人々へのインタビュー、彼の人生のシーンのドラマ化、音楽に合わせたアニメーションを含む空想的な部分が含まれている。トーマ ス・ベルンハルトの1983年の小説『The Loser』は、グールドと、ザルツブルクのモーツァルテウム音楽院に在籍していた2人の学生との生涯にわたる友情についての一人称エッセイである。 グールドは、鍵盤楽器以外にも幅広い作品を残した。コンサート活動から引退した後は、オーディオや映画のドキュメンタリー、執筆活動など、他のメディアへ の関心を高めていき、それらを通して美学、作曲、音楽史、電子時代がメディア消費に与える影響などについて考察した。(グールドは、カナダの理論家である マーシャル・マクルーハン、ノースロップ・フライ、ハロルド・イニスがコミュニケーション学に大きな足跡を残した同時期にトロントで育った。 1983年、グールドは死後、カナダ音楽の殿堂入りを果たした[123]。1998年にはトロントのWalk of Fameに選出され、2012年にはNational Historic Personに指定された[124][125]。トロントのダウンタウンにある彼の彫刻の隣には、この指定を反映した連邦政府のプレートが建てられた [126]。グールドの75歳の誕生日を記念して、カナダ文明博物館は2007年にグレン・グールド展を開催した: The Sounds of Genius)」を2007年に開催した。このマルチメディア展示はカナダ図書館公文書館と共同で開催された[127]。 |

| Glenn Gould Foundation Main article: Glenn Gould Foundation The Glenn Gould Foundation was established in Toronto in 1983 to honour Gould and keep alive his memory and life's work. The foundation's mission "is to extend awareness of the legacy of Glenn Gould as an extraordinary musician, communicator, and Canadian, and to advance his visionary and innovative ideas into the future", and its prime activity is the triennial awarding of the Glenn Gould Prize to "an individual who has earned international recognition as the result of a highly exceptional contribution to music and its communication, through the use of any communications technologies."[128] The prize consists of CA$100,000 and the responsibility of awarding the CA$15,000 Glenn Gould Protégé Prize to a young musician of the winner's choice. Glenn Gould School Main article: The Glenn Gould School The Royal Conservatory of Music Professional School in Toronto adopted the name The Glenn Gould School in 1997 after its most famous alumnus.[129] |

グレン・グールド財団 主な記事 グレン・グールド財団 グレン・グールド財団は1983年、グールドを称え、彼の記憶と生涯の仕事を継承するためにトロントに設立された。同財団の使命は、「非凡な音楽家、コ ミュニケーター、カナダ人としてのグレン・グールドの遺産を広く認知させ、彼の先見的で革新的なアイデアを未来へと発展させること」であり、その主な活動 は、「あらゆる通信技術を駆使して、音楽とそのコミュニケーションに極めて優れた貢献をした結果、国際的な評価を得た個人」にグレン・グールド賞を授与す ることである。 「賞金は10万カナダドル[128]で、グレン・グールド・プロトジェ賞(15,000カナダドル)は、受賞者が選んだ若い音楽家に贈られる。 グレン・グールド・スクール 主な記事 グレン・グールド・スクール トロントの王立音楽院プロフェッショナル・スクールは、最も有名な卒業生にちなんで、1997年にグレン・グールド・スクールという名称を採用した[129]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glenn_Gould |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆