グロリア・アンサルドゥア

Gloria Anzaldúa,

1942-2004

☆グロリア・エヴァンジェリーナ・アンサルドゥア(1942年9月26日 - 2004年5月15日)は、チカーナ・フェミニズム、

文化理論、クィア理論を研究したアメリカの学者である。彼女の最も有名な著作『国境地帯/ラ・フロンテラ:新たなメスティーサ』(1987年)は、メキシ

コとテキサスの国境地帯で育った自身の経験に大まかに基づいており、生涯にわたる社会的・文化的周縁化の体験を作品に取り込んだ。また、ネパントラ、コヨ

クサウルキの要請、新たな部族主義、精神的活動主義といった概念を含め、国境沿いで発展する周縁的・中間的・混血の文化に関する理論を展開した。[1]

[2] その他の主要著作には、チェリー・モラガとの共編著『この橋は私の背中と呼ばれる:急進的女性有色人種の著作集』(1981年)がある。

| Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa

(September 26, 1942 – May 15, 2004) was an American scholar of Chicana

feminism, cultural theory, and queer theory. She loosely based her

best-known book, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987), on

her life growing up on the Mexico–Texas border and incorporated her

lifelong experiences of social and cultural marginalization into her

work. She also developed theories about the marginal, in-between, and

mixed cultures that develop along borders, including on the concepts of

Nepantla, Coyoxaulqui imperative, new tribalism, and spiritual

activism.[1][2] Her other notable publications include This Bridge

Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981), co-edited

with Cherríe Moraga. |

グ

ロリア・エヴァンジェリーナ・アンサルドゥア(1942年9月26日 -

2004年5月15日)は、チカーナ・フェミニズム、文化理論、クィア理論を研究したアメリカの学者である。彼女の最も有名な著作『国境地帯/ラ・フロン

テラ:新たなメスティーサ』(1987年)は、メキシコとテキサスの国境地帯で育った自身の経験に大まかに基づいており、生涯にわたる社会的・文化的周縁

化の体験を作品に取り込んだ。また、ネパントラ、コヨクサウルキの要請、新たな部族主義、精神的活動主義といった概念を含め、国境沿いで発展する周縁的・

中間的・混血の文化に関する理論を展開した。[1][2]

その他の主要著作には、チェリー・モラガとの共編著『この橋は私の背中と呼ばれる:急進的女性有色人種の著作集』(1981年)がある。 |

| Early life and education Anzaldúa was born in the Rio Grande Valley of south Texas on September 26, 1942, the eldest of four children born to Urbano and Amalia (née García) Anzaldúa. Her great-grandfather, Urbano Sr., once a precinct judge in Hidalgo County, was the first owner of the Jesús María Ranch on which she was born. Her mother grew up on an adjoining ranch, Los Vergeles ("the gardens"), which was owned by her family, and she met and married Urbano Anzaldúa when both were very young. Anzaldúa was a descendant of Spanish settlers to come to the Americas in the 16th and 17th centuries. The surname Anzaldúa is of Basque origin. Her paternal grandmother was of Spanish and German ancestry, descending from some of the earliest settlers of the South Texas range country.[3] She has described her father's family as being "very poor aristocracy, but aristocracy anyway" and her mother as "very india, working class, with maybe some black blood which is always looked down on in the valley where I come from."[4] |

幼少期と教育 アンサルドゥアは1942年9月26日、テキサス州南部のリオグランデ・バレーで生まれた。ウルバノとアマリア(旧姓ガルシア)・アンサルドゥア夫妻の4 人の子供の長女である。彼女の曽祖父であるウルバノ・シニアはかつてヒダルゴ郡の地区判事を務め、彼女が生まれたヘスス・マリア牧場の初代所有者だった。 母親は隣接する牧場ロス・ベルヘレス(「庭園」の意)で育った。この牧場は彼女の家族が所有していた。彼女はウルバノ・アンサルドゥアと出会い、二人が非 常に若い頃に結婚した。アンサルドゥア家は16世紀から17世紀にかけてアメリカ大陸に渡ったスペイン人入植者の子孫である。アンサルドゥアという姓はバ スク語に由来する。父方の祖母はスペインとドイツの血を引いており、南テキサス牧畜地帯の初期入植者の子孫であった[3]。彼女は父方の家族を「非常に貧 しい貴族階級だが、それでも貴族階級だ」と表現し、母方を「非常にインディアン系の労働者階級で、おそらく黒人の血も混ざっている。私の出身地であるこの 谷間では、そういう血筋は常に軽蔑されるものだ」と述べている[4]。 |

| Anzaldúa

wrote that her family gradually lost their wealth and status over the

years, eventually being reduced to poverty and being forced into

migrant labor, something her family resented because "[t]o work in the

fields is the lowest job, and to be a migrant worker is even lower."

Her father was a tenant farmer and sharecropper who kept 60% of what he

earned, while 40% went to a white-owned corporation called Rio Farms,

Inc. Anzaldúa claimed that her family lost their land due to a

combination of both "taxes and dirty manipulation" from white people

who were buying up land in South Texas through "trickery" and from the

behavior of her "very irresponsible grandfather", who lost "a lot of

land and money through carelessness". Anzaldúa was left with an

inheritance of "a little piece" of 12 acres, which she deeded over to

her mother Amalia. Her maternal grandmother Ramona Dávila had amassed

land grants from the time Texas was part of Mexico, but the land was

lost due to "carelessness, through white peoples' greed, and my

grandmother not knowing English".[4] |

ア

ンサルドゥアは、家族が年月をかけて富と地位を失い、ついに貧困に陥り、出稼ぎ労働を強いられたと記している。家族はこれを恨んでいた。「畑仕事は最も卑

しい仕事であり、出稼ぎ労働者はさらに下だ」と。彼女の父親は小作農であり、収穫の60%を収入として得ていたが、残りの40%はリオ・ファームズ社とい

う白人所有の企業に支払われていた。アンサルドゥアは、家族が土地を失った原因として、南テキサスで「策略」を用いて土地を買い占める白人たちの「税金と

汚い操作」と、自身の「非常に無責任な祖父」の行動を挙げている。祖父は「不注意で多くの土地とお金を失った」のだ。アンサルドゥアが相続したのはわずか

12エーカーの「小さな土地」で、彼女はこれを母アマリアに譲渡した。母方の祖母ラモナ・ダビラはテキサスがメキシコ領だった時代から土地の権利を蓄積し

ていたが、「不注意、白人の貪欲さ、そして祖母が英語を理解していなかったこと」によって土地は失われたのである。[4] |

| Anzaldúa

wrote that she did not call herself an "india", but still claimed

Indigenous ancestry. In "Speaking across the Divide", from The Gloria

E. Anzaldúa Reader, she states that her white/mestiza grandmother

described her as "pura indita" due to dark spots on her buttocks.

Later, Anzaldúa wrote that she "recognized myself in the faces of the

braceros that worked for my father. Los braceros were mostly indios

from central Mexico who came to work the fields in south Texas. I

recognized the Indian aspect of mexicanos by the stories my

grandmothers told and by the foods we ate." Despite her family not

identifying as Mexican, Anzaldúa believed that "we were still Mexican

and that all Mexicans are part Indian." Although Anzaldúa has been

criticized by Indigenous scholars for allegedly appropriating

Indigenous identity, Anzaldúa claimed that her Indigenous critics had

"misread or ... not read enough of my work." Despite claiming to be

"three quarters Indian", she also wrote that she was afraid she was

"violating Indian cultural boundaries" and afraid that her theories

could "unwittingly contribute to the misappropriation of Native

cultures" and of "people who live in real Indian bodies." She wrote

that while worried that "mestizaje and a new tribalism" could

"detribalize" Indigenous peoples, she believed the dialogue was

imperative "no matter how risky." Writing about the "Color of Violence"

conference organized by Andrea Smith in Santa Cruz, Anzaldúa accused

Native American women of engaging in "a lot of finger pointing" because

they had argued that non-Indigenous Chicanas' use of Indigenous

identity is a "continuation of the abuse of native spirituality and the

Internet appropriation of Indian symbols, rituals, vision quests, and

spiritual healing practices like shamanism."[5][6] When she was 11 years old, Anzaldúa's family relocated to Hargill, Texas.[7] She graduated as valedictorian of Edinburg High School in 1962.[8] |

アンサルドゥア

は、自らを「インディア(女性先住民)」とは呼ばなかったが、それでも先住民の血筋を主張したと記している。『グロリア・E・アンサルドゥア・リーダー』

所収の「分断を越えて語る」において、彼女は白人/メスティーソの祖母が、自身の臀部の黒い斑点から「純粋なインディタ」と呼んだと述べている。後にアン

サルドゥアは「父のために働いたブラセロたちの顔に自分自身を見出した」と記した。ブラセロとは主にメキシコ中部出身のインディオで、テキサス州南部の畑

で働くために渡ってきた者たちである。祖母たちの語る物語や食卓の料理から、メキシコ人の中のインディアン的側面を認識した」と記している。家族がメキシ

コ人としての自覚を持たなかったにもかかわらず、アンサルドゥアは「我々は依然としてメキシコ人であり、全てのメキシコ人はインディアンである」と信じて

いた。先住民学者から先住民アイデンティティの盗用を批判されたアンサルドゥアは、批判者たちが「私の著作を誤解しているか、あるいは十分に読んでいな

い」と反論した。「四分の三はインディアン」と自認しながらも、彼女は「インディアンの文化的境界を侵害しているのではないか」と恐れ、自身の理論が「無

意識のうちに先住民文化の盗用」や「生きたインディアンの身体を持つ人々」への侵害に寄与する可能性を懸念したと記している。彼女は「混血化と新たな部族

主義」が先住民を「部族から切り離す」可能性を懸念しつつも、その対話が「どれほど危険であろうとも」不可欠だと信じていたと記している。サンタクルーズ

でアンドレア・スミスが主催した「暴力の色」会議について記したアンサルドゥアは、非先住民のチカーナが先住民のアイデンティティを利用することは「先住

民の精神性の虐待と、インターネット上でのインディアンの象徴・儀礼・ビジョンクエスト・シャーマニズムのような精神的癒しの実践の流用を継続するもの

だ」と主張した先住民女性たちを「多くの非難合戦」に陥っていると非難した。[5] [6] アンサルドゥアは11歳の時、家族と共にテキサス州ハーギルへ移住した。[7] 1962年にはエディンバーグ高校を首席で卒業した。[8] |

| She

managed to pursue a university education, despite the racism, sexism

and other forms of oppression she experienced as a seventh-generation

Tejana and Chicana. In 1968, she received a B.A. degree in English,

Art, and Secondary Education from University of Texas–Pan American, and

an M.A. in English and Education from the University of Texas at

Austin. While in Austin, she joined politically active cultural poets

and radical dramatists such as Ricardo Sanchez, and Hedwig Gorski. |

彼

女は第七世代のテハノ系・チカーノ系として経験した人種主義、性差別、その他の抑圧にもかかわらず、大学教育を受けることに成功した。1968年、テキサ

ス大学パンアメリカン校で英語・美術・中等教育の学士号を取得し、テキサス大学オースティン校で英語と教育学の修士号を取得した。オースティン在学中、リ

カルド・サンチェスやヘドウィグ・ゴルスキといった政治的に活動的な文化詩人や急進的な劇作家たちと交流した。 |

| Career and major works After obtaining a Bachelor of Arts in English from the Pan American University (now University of Texas Rio Grande Valley), Anzaldúa worked as a preschool and special education teacher. In 1977, she moved to California, where she supported herself through her writing, lectures, and occasional teaching stints about feminism, Chicano studies, and creative writing at San Francisco State University, the University of California, Santa Cruz, Florida Atlantic University, and other universities. She is perhaps best known for co-editing This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981) with Cherríe Moraga, editing Making Face, Making Soul/Haciendo Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Women of Color (1990), and co-editing This Bridge We Call Home: Radical Visions for Transformation (2002). Anzaldúa also wrote the semi-autobiographical Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987). At the time of her death, she was close to completing the book manuscript, Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality, which she also planned to submit as her dissertation. It has now been published posthumously by Duke University Press (2015). Her children's books include Prietita Has a Friend (1991), Friends from the Other Side – Amigos del Otro Lado (1993), and Prietita y La Llorona (1996). She also authored many fictional and poetic works. She made contributions to fields of feminism, cultural theory/Chicana, and queer theory.[9] Her essays are considered foundational texts in the burgeoning field of Latinx philosophy.[10][11][12] Anzaldúa wrote a speech called "Speaking in Tongues: A Letter to Third World Women Writers", focusing on the shift towards an equal and just gender representation in literature but away from racial and cultural issues because of the rise of female writers and theorists. She also stressed in her essay the power of writing to create a world that would compensate for what the real world does not offer.[13] |

経歴と主な作品 パンアメリカン大学(現テキサス大学リオグランデバレー校)で英文学の学士号を取得後、アンサルドゥアは幼稚園教諭および特別支援教育の教師として働い た。1977年にカリフォルニア州へ移住し、サンフランシスコ州立大学、カリフォルニア大学サンタクルス校、フロリダ・アトランティック大学などでフェミ ニズム、チカーノ研究、創作執筆に関する執筆活動、講演、臨時講師として生計を立てた。 彼女はチェリー・モラガとの共編著『この橋は私の背中と呼ぶ:急進的女性有色人種の著作集』(1981年)、編著『顔を作り、魂を作る/ハシエンディオ・ カラス:女性有色人種の創造的・批判的視点』(1990年)、共編著『この橋は我らが家と呼ぶ:変革のための急進的ビジョン』(2002年)で最もよく知 られている。アンサルドゥアはまた、半自伝的作品『国境地帯/ラ・フロンテラ:新たなメスティーサ』(1987年)を執筆した。死の直前には、博士論文と して提出する予定だった『闇の中の光/ルス・エン・ロ・オスキュロ:アイデンティティ、スピリチュアリティ、現実の再構築』の原稿をほぼ完成させていた。 これは現在、デューク大学出版局より遺作として刊行されている(2015年)。児童書には『プリエティータに友達ができた』(1991年)、『向こう側の 友達』(1993年)、『プリエティータと泣く女』(1996年)がある。また多くの小説や詩作品も執筆した。 フェミニズム、文化理論/チカーナ研究、クィア理論の分野に貢献した[9]。彼女のエッセイは、発展途上のラティンクス哲学分野における基礎的文献と見なされている[10][11]。[12] アンサルドゥアは「異言で語る:第三世界の女性作家たちへの手紙」と題した演説を執筆した。そこでは、女性作家や理論家の台頭により、文学における平等で 公正なジェンダー表現への移行が焦点とされ、人種や文化の問題からは距離を置いた。また彼女はエッセイの中で、現実世界が提供しないものを補う世界を創り 出すための、書くことの力を強調した。[13] |

| This Bridge Called My Back Anzaldúa's essay '"La Prieta" deals with her manifestation of thoughts and horrors that have constituted her life in Texas. Anzaldúa identifies herself as an entity without a figurative home and/or peoples to completely relate to. To supplement this deficiency, Anzaldúa created her own sanctuary, Mundo Zurdo, whereby her personality transcends the norm-based lines of relating to a certain group. Instead, in her Mundo Zurdo, she is like a "Shiva, a many-armed and legged body with one foot on brown soil, one on white, one in straight society, one in the gay world, the man's world, the women's, one limb in the literary world, another in the working class, the socialist, and the occult worlds".[14] The passage describes the identity battles which the author had to engage in throughout her life. Since early childhood, Anzaldúa has had to deal with the challenge of being a woman of color. From the beginnings she was exposed to her own people, to her own family's racism and "fear of women and sexuality".[15] Her family's internalized racism immediately cast her as the "other" because of their bias that being white and fair-skinned means prestige and royalty, when color subjects one to being almost the scum of society (just as her mother had complained about her prieta dating a mojado from Peru). The household she grew up in was one in which the male figure was the authoritarian head, while the female, the mother, was stuck in all the biases of this paradigm. Although this is the difficult position in which white, patriarchal society has cast women of color, gays and lesbians, she does not make them out to be the archenemy, because she believes that "casting stones is not the solution"[16] and that racism and sexism do not come from only whites but also people of color. Throughout her life, the inner racism and sexism from her childhood would haunt her, as she often was asked to choose her loyalties, whether it be to women, to people of color, or to gays/lesbians. Her analogy to Shiva is well-fitted, as she decides to go against these conventions and enter her own world: Mundo Zurdo, which allows the self to go deeper, to transcend the lines of convention and, at the same time, to recreate the self and the society. This is for Anzaldúa a form of religion, one that allows the self to deal with the injustices that society throws at it and to come out a better person, a more reasonable person. An entry in the book, titled "Speaking In Tongues: A Letter To Third World Women Writers", spotlights the dangers Anzaldúa considers women writers of color deal with, dangers that are rooted in a lack of privileges. She talks about the transformation of writing styles and how we are taught not to air our truths. Folks are outcast as a result of speaking and writing with their native tongues. Anzaldúa wants more women writers of color to be visible and be well represented in text. Her essay compels us to write with compassion and with love. For writing is a form of gaining power by speaking our truths, and it is seen as a way to decolonize, to resist, and to unite women of color collectively within the feminist movement. |

この橋は私の背中と呼ばれる アンサルドゥアのエッセイ「ラ・プリエタ」は、テキサスでの彼女の人生を形作ってきた思考と恐怖の表出を扱っている。アンサルドゥアは、比喩的な故郷や完 全に帰属できる民族を持たない存在として自らを位置づける。この欠如を補うため、アンサルドゥアは自らの聖域「ムンド・ズルド」を創り出した。そこでは彼 女の人格は、特定の集団への帰属という規範に基づく境界線を超越する。代わりに、彼女の世界「ムンド・スルド」において、彼女は「シヴァ神のような存在」 である。それは「多くの腕と脚を持つ身体」であり、「一つの足は褐色の土の上に、もう一つは白人の土の上に、一つはストレート社会に、一つはゲイの世界 に、男の世界に、女の世界に、一つの肢は文学の世界に、別の肢は労働者階級、社会主義、そしてオカルトの世界に」あるのだ。[14] この一節は、著者が生涯にわたって戦わねばならなかったアイデンティティの葛藤を描いている。幼少期から、アンサルドゥアは有色人種の女性であることの課 題と向き合わねばならなかった。幼少期から彼女は自らの民族、家族の差別主義、そして「女性と性への恐怖」に晒されてきた[15]。家族の内部化された人 種主義は、白人で色白であることが威信と高貴さを意味する一方、有色人種は社会の屑同然扱いされるという偏見ゆえ、彼女を即座に「他者」として位置づけた (母親がプリエタ(黒人)である娘がペルーのモハド(不法移民)と交際することを嘆いたように)。彼女が育った家庭では、男性が権威主義的な家長であり、 女性である母親はこのパラダイムのあらゆる偏見に縛られていた。これは白人中心の父権社会が有色人種の女性やゲイ・レズビアンを置いた困難な立場だが、彼 女は彼らを大敵とは見なさない。「石を投げることは解決にならない」[16]と信じ、人種主義や性差別は白人だけでなく有色人種からも生まれると考えるか らだ。彼女の人生を通じて、幼少期からの内面化した人種主義や性差別は彼女を苦しめ続けた。女性、有色人種、ゲイやレズビアンのいずれに忠誠を誓うか、常 に選択を迫られたのだ。シヴァ神への彼女の比喩は極めて適切だ。彼女はこうした慣習に抗い、自らを深く掘り下げ、慣習の境界を超越し、同時に自己と社会を 再創造する世界「ムンド・ズルド(左利きの世界)」へ踏み込むことを決意する。これはアンサルドゥアにとって一種の宗教であり、社会が投げかける不正と向 き合い、より良き人格、より理性的人格へと成長するための手段なのである。 本書の「異言で語る:第三世界の女性作家たちへの手紙」と題された一節は、アンサルドゥアが有色人種の女性作家が直面すると考える危険性に焦点を当てる。 その危険性は特権の欠如に根ざしている。彼女は文体の変容について語り、我々が真実を口外しないよう教え込まれてきたことを述べる。母語で語り、書くこと で人々は追放される。アンサルドゥアはより多くの有色人種の女性作家が可視化され、テキストで適切に表現されることを望む。彼女のエッセイは、思いやりと 愛をもって書くよう私たちに迫る。なぜなら書くことは真実を語ることで力を得る手段であり、脱植民地化、抵抗、フェミニズム運動内での有色人種女性たちの 団結をもたらす方法と見なされるからだ。 |

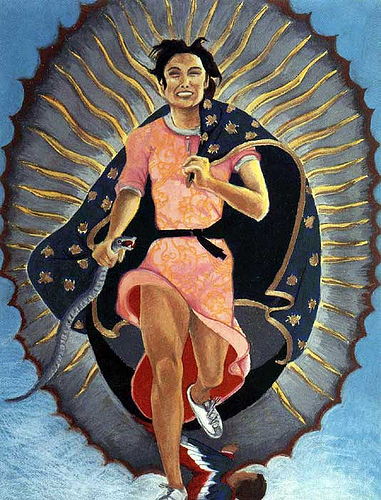

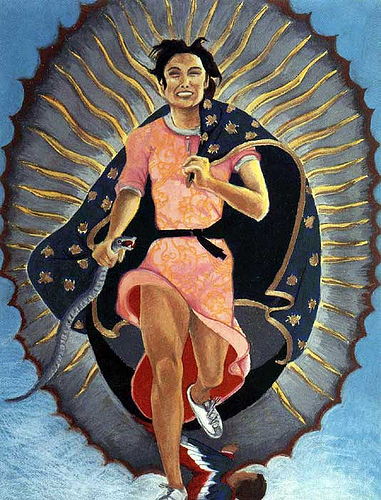

| Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza She is highly known for this autotheoretical book, which discusses her life growing up on the Mexico–Texas border. It was selected as one of the 38 best books of 1987 by Library Journal. Borderlands examines the condition of women in Chicano and Latino culture. Anzaldúa discusses several critical issues related to Chicana experiences: heteronormativity, colonialism, and male dominance. She gives a very personal account of the oppression of Chicana lesbians and talks about the gendered expectations of behavior that normalizes women's deference to male authority in her community. She develops the idea of the "new mestiza" as a "new higher consciousness" that will break down barriers and fight against the male/female dualistic norms of gender. The first half of the book is about isolation and loneliness in the borderlands between cultures. The latter half of the book is poetry. In the book, Anzaldúa uses two variations of English and six variations of Spanish. By doing this, she deliberately makes it difficult for non-bilinguals to read. Language was one of the barriers Anzaldúa dealt with as a child, and she wanted readers to understand how frustrating things are when there are language barriers. The book was written as an outlet for her anger and encourages one to be proud of one's heritage and culture.[17] In chapter 3 of the book, titled "Entering Into the Serpent", Anzaldúa discusses three key women in Mexican culture – La Llorona, La Malinche, and Our Lady of Guadalupe – known as the "Three Mothers" (Spanish: Las Tres Madres), and explores their relationship to Mexican culture.[18]  Yolanda Lopez's 1978 rendition of La Virgen de Guadalupe, titled 'Portrait of the Artist as the Virgen of Guadalupe.' |

ボーダーランズ/ラ・フロンテラ:新たなメスティーサ 彼女はメキシコとテキサスの国境地帯で育った自身の生涯を論じたこの自己理論的著作で広く知られる。同書はライブラリー・ジャーナル誌により1987年の ベスト38冊に選出された。『ボーダーランズ』はチカーノおよびラティーノ文化における女性の状況を検証する。アンサルドゥアはチカーナ体験に関連するい くつかの重要な問題、すなわちヘテロノーマティビティ、植民地主義、男性優位について論じている。彼女はチカーナ・レズビアンへの抑圧について非常にパー ソナルな記述を行い、コミュニティ内で女性の男性権威への従順さを正常化する、性別に基づく行動への期待について語っている。彼女は「新たなメスティサ」 という概念を「新たな高次の意識」として展開し、それが障壁を打ち破り、男性/女性の二元的規範と戦うと論じる。本書の前半は文化の境界地帯における孤立 と孤独について、後半は詩で構成されている。本書でアンサルドゥアは、英語の二つの変種とスペイン語の六つの変種を用いている。これにより、意図的に非バ イリンガルが読むのを困難にしている。言語はアンサルドゥアが子供時代に直面した障壁の一つであり、読者に言語障壁がある時の苛立ちを理解させたかったの だ。本書は彼女の怒りの発露として書かれ、自らの遺産と文化を誇りに持つよう促している。[17] 本書第3章「蛇の中へ入る」では、アンサルドゥアはメキシコ文化における三人の重要な女性——ラ・ジョローナ、ラ・マリンチェ、グアダルーペの聖母——を 「三人の母たち」(スペイン語: Las Tres Madres)として論じ、彼女たちがメキシコ文化とどう関わっているかを探っている。[18]  ヨランダ・ロペスが1978年に描いた『グアダルーペの聖母』の肖像画。題名は『芸術家としての自画像:グアダルーペの聖母として』。 |

| Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality Anzaldúa wrote Light in the Dark during the last decade of her life. Drawn from her unfinished dissertation for her PhD in Literature from University of California, Santa Cruz, the book is carefully organized from The Gloria Anzaldúa Papers, 1942–2004 by AnaLouise Keating, Anzaldúa's literary trustee. The book represents her most developed philosophy.[19] Throughout Light in the Dark, Anzaldúa weaves personal narratives into deeply engaging theoretical readings to comment on numerous contemporary issues – including the September 11 attacks, neocolonial practices in the art world, and coalitional politics. She valorizes subaltern forms and methods of knowing, being, and creating that have been marginalized by Western thought, and theorizes her writing process as a fully embodied artistic, spiritual, and political practice. Light in the Dark contains multiple transformative theories including include the nepantleras, the Coyolxauhqui imperative (named for the Aztec goddess Coyolxāuhqui), spiritual activism, and others. |

闇の中の光/ルス・エン・ロ・オスキュロ:アイデンティティ、スピリチュアリティ、現実の再構築 アンサルドゥアは『闇の中の光』を人生の最後の10年間に執筆した。カリフォルニア大学クルス校の文学博士号取得に向けた未完の博士論文を基にしており、 アンサルドゥアの文学的遺産の管理人であるアナ・ルイーズ・キーティングが編纂した『グロリア・アンサルドゥア文書集 1942-2004』から慎重に構成されている。本書は彼女の最も成熟した哲学を表している。[19] 『闇の中の光』全体を通して、アンサルドゥアは人格の物語を深く魅力的な理論的読解に織り込み、9.11同時多発テロ事件、美術界における新植民地主義的 実践、連合政治など、数多くの現代的課題について論評している。彼女は西洋思想によって境界化されてきた、サバルタンの知覚・存在・創造の形態と方法を評 価し、自らの執筆過程を、身体全体で実践される芸術的・精神的・政治的実践として理論化している。『闇の中の光』には、ネパンテレス、コヨルサウキの命題 (アステカの女神コヨルサウキに因む)、精神的活動主義など、複数の変革的理論が含まれている。 |

| Themes in writing Nepantilism Anzaldúa drew on Nepantla, a Nahuatl word that means "in the middle", to conceptualize her experience as a Chicana woman. She coined the term "Nepantlera". "Nepantleras are threshold people; they move within and among multiple, often conflicting, worlds and refuse to align themselves exclusively with any single individual, group, or belief system."[20] |

執筆におけるテーマ ネパンティリズム アンサルドゥアは、ナワトル語で「中間」を意味する「ネパントラ」という語を用いて、チカーナ女性としての自身の経験を概念化した。彼女は「ネパンテラ」 という用語を造語した。「ネパンテラは境界の人民である。彼らは複数の、しばしば対立する世界の中や間で移動し、いかなる個人、集団、信念体系にも排他的 に同調することを拒む。」 [20] |

| Spirituality See also: Spiritual activism and Chicano § Spirituality Anzaldúa described herself as a very spiritual person and stated that she experienced four out-of-body experiences during her lifetime. In many of her works, she referred to her devotion to la Virgen de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe), Nahuatl/Toltec divinities, and to the Yoruba orishás Yemayá and Oshún.[21] In 1993, she expressed regret that scholars had largely ignored the "unsafe" spiritual aspects of Borderlands and bemoaned the resistance to such an important part of her work.[22] In her later writings, she developed the concepts of spiritual activism and nepantleras to describe the ways contemporary social actors can combine spirituality with politics to enact revolutionary change. Anzaldúa has written about the influence of hallucinogenic drugs on her creativity, particularly psilocybin mushrooms. During one 1975 psilocybin mushroom trip when she was "stoned out of my head", she coined the term "the multiple Glorias" or the "Gloria Multiplex" to describe her feeling of multiplicity, an insight that influenced her later writings.[23] |

スピリチュアリティ 関連項目: スピリチュアル・アクティビズム、チカーノ § スピリチュアリティ アンサルドゥアは自らを非常にスピリチュアルな人格と表現し、生涯で四度の体外離脱体験をしたと述べている。多くの著作で、彼女はグアダルーペの聖母 (ラ・ビジェン・デ・グアダルーペ)、ナワトル/トルテカの神々、ヨルバの神々イェマヤとオシュンへの信仰について言及している。[21] 1993年には、研究者たちが国境地帯の「危険な」精神的側面をほとんど無視していることを後悔し、自身の作品の重要な部分に対する抵抗を嘆いた。 [22] 後期の著作では、現代の社会活動家が精神性と政治を結びつけて革命的変化を実現する方法を説明するため、スピリチュアル・アクティビズムとネパンテラスの 概念を発展させた。 アンサルドゥアは、幻覚剤、特にサイロシビンを含むキノコが自身の創造性に与えた影響について記している。1975年のあるサイロシビンキノコ体験中、彼 女が「完全にハイになっていた」時に、自身の多重性を表現する「複数のグロリア」あるいは「グロリア・マルチプレックス」という用語を考案した。この洞察 は彼女の後の著作に影響を与えた。[23] |

| Language and "linguistic terrorism" Anzaldua's works weave English and Spanish together as one language, an idea stemming from her theory of "borderlands" identity. Her autobiographical essay "La Prieta" was published in (mostly) English in This Bridge Called My Back, and in (mostly) Spanish in Esta puente, mi espalda: Voces de mujeres tercermundistas en los Estados Unidos. In her writing, Anzaldúa uses a unique blend of eight dialects, two variations of English and six of Spanish. In many ways, by writing in a mix of languages, Anzaldúa creates a daunting task for the non-bilingual reader to decipher the full meaning of the text. Language, clearly one of the borders Anzaldúa addressed, is an essential feature to her writing. Her book is dedicated to being proud of one's heritage and to recognizing the many dimensions of her culture.[7] Anzaldúa emphasized in her writing the connection between language and identity. She expressed dismay with people who gave up their native language in order to conform to the society they were in. Anzaldúa was often scolded for her improper Spanish accent and believed it was a strong aspect to her heritage; therefore, she labels the qualitative labeling of language "linguistic terrorism."[24] She spent a lot of time promoting acceptance of all languages and accents.[25] In an effort to expose her stance on linguistics and labels, Anzaldúa explained, "While I advocate putting Chicana, tejana, working-class, dyke-feminist poet, writer theorist in front of my name, I do so for reasons different than those of the dominant culture... so that the Chicana and lesbian and all the other persons in me don't get erased, omitted, or killed."[26] Despite the connection between language and identity, Anzaldúa also highlighted that language is a bridge that linked mainstream communities and marginalized communities.[27] She claimed language is a tool that identifies marginalized communities, represents their heritage and cultural backgrounds. The connection which language created is two-way, it not only encourage marginalized communities to express themselves, but also calls on mainstream communities to engage with the language and culture of marginalized communities. |

言語と「言語テロリズム」 アンサルドゥアの著作は英語とスペイン語をひとつの言語として織り交ぜている。これは彼女の「ボーダーランド」アイデンティティ理論に由来する考え方だ。 自伝的エッセイ『ラ・プリエタ』は『この橋は私の背中』では(主に)英語で、『Esta puente, mi espalda: Voces de mujeres tercermundistas en los Estados Unidos』では(主に)スペイン語で発表された。アンサルドゥアの文章では、8つの方言、すなわち英語の2つの変種とスペイン語の6つの変種が独特の 混合で使用されている。言語を混ぜて書くことで、アンサルドゥアは多くの点で、非バイリンガルの読者にテキストの完全な意味を解読するという困難な課題を 突きつけている。言語は、アンサルドゥアが扱った境界の一つであり、彼女の著作において不可欠な要素だ。彼女の著作は、自らのルーツを誇りに思うこと、そ して自身の文化の多様な側面を認識することに捧げられている。[7] アンサルドゥアは著作の中で、言語とアイデンティティの結びつきを強調した。彼女は、周囲の社会に順応するために母国語を放棄する人々に対して失望を表明 した。アンサルドゥアは不適切なスペイン語アクセントを非難されることが多かったが、それを自らのルーツの強みと捉え、言語に対する質的レッテル貼りを 「言語テロリズム」と呼んだ[24]。彼女はあらゆる言語とアクセントの受容を推進するために多くの時間を費やした[25]。言語学とレッテルに対する自 身の立場を明らかにするため、アンサルドゥアはこう説明した。「私は自分の名前に『チカーナ、テハーナ、労働者階級、レズビアン・フェミニスト詩人、作家 理論家』と付けることを提唱しているが、その理由は支配的文化のそれとは異なる…そうすることで、私の中のチカーナでありレズビアンであり、その他すべて の人格が消去されず、省略されず、殺されないためだ」[26] 言語とアイデンティティの関連性にもかかわらず、アンサルドゥアは言語が主流コミュニティと周縁化されたコミュニティを結ぶ架け橋でもあると強調した [27]。言語は周縁化されたコミュニティを特定し、その遺産や文化的背景を表現する道具だと主張した。言語が生み出す繋がりは双方向であり、周縁化され たコミュニティが自己表現することを促すだけでなく、主流コミュニティに対し、周縁化されたコミュニティの言語や文化と関わるよう呼びかけるものである。 |

| Health, body, and trauma Anzaldúa experienced at a young age, symptoms of the endocrine condition that caused her to stop growing physically at the age of twelve.[28] As a child, she would wear special girdles fashioned for her by her mother in order to disguise her condition. Her mother would also ensure that a cloth was placed in Anzaldúa's underwear as a child in case of bleeding. Anzaldúa remembers, "I'd take [the bloody cloths] out into this shed, wash them out, and hang them really low on a cactus so nobody would see them.... My genitals... [were] always a smelly place that dripped blood and had to be hidden." She eventually underwent a hysterectomy in 1980 when she was 38 years old to deal with uterine, cervical, and ovarian abnormalities.[22] Anzaldúa's poem "Nightvoice" alludes to a history of child sexual abuse, as she writes: "blurting out everything how my cousins/took turns at night when I was five eight ten."[29] |

健康、身体、そしてトラウマ アンサルドゥアは幼い頃から内分泌疾患の症状を経験し、12歳で身体の成長が止まった[28]。子供の頃、彼女は母親が特注で作ったコルセットを着用し、 その状態を隠していた。母親はまた、出血に備えてアンサルドゥアの下着に布を敷くよう常に気を配っていた。アンサルドゥアはこう回想する。「血のついた布 を小屋に持ち込み、洗い、サボテンの低い枝に干した。誰にも見られないようにね……私の性器は……いつも血が滴り、臭う場所だった。隠さねばならなかっ た」 子宮、子宮頸部、卵巣の異常に対処するため、彼女は1980年、38歳の時に子宮摘出手術を受けた。[22] アンサルドゥアの詩「ナイトヴォイス」は、子供の頃の性的虐待の歴史をほのめかしている。彼女はこう書いている。「全てをぶちまける 従兄弟たちが/夜に順番に襲ったこと 私が五歳 八歳 十歳の時に」[29] |

| Mestiza / border culture One of Anzaldúa's major contributions was her introduction to United States academic audiences of the term mestizaje, meaning a state of being beyond binary ("either-or") conception, into academic writing and discussion. In her theoretical works, Anzaldúa called for a "new mestiza," which she described as an individual aware of her conflicting and meshing identities and uses these "new angles of vision" to challenge binary thinking in the Western world. The "borderlands" that she refers to in her writing are geographical as well as a reference to mixed races, heritages, religions, sexualities, and languages. Anzaldúa is primarily interested in the contradictions and juxtapositions of conflicting and intersecting identities. She points out that having to identify as a certain, labelled, sex can be detrimental to one's creativity as well as how seriously people take you as a producer of consumable goods.[30] The "new mestiza" way of thinking is illustrated in postcolonial feminism.[31] In education, Anzaldúa's practice of border challenges the traditionally structured binary understanding of gender.[32] It recognizes gender identity is not fixed or singular concept but rather a complex terrain. Encouraged educators to provide a safe and open platform for students to learn, recognize, and identify themselves comfortably. Anzaldúa called for people of different races to confront their fears to move forward into a world that is less hateful and more useful. In "La Conciencia de la Mestiza: Towards a New Consciousness," a text often used in women's studies courses, Anzaldúa insisted that separatism invoked by Chicanos/Chicanas is not furthering the cause but instead keeping the same racial division in place. Many of Anzaldúa's works challenge the status quo of the movements in which she was involved. She challenged these movements in an effort to make real change happen to the world rather than to specific groups. Scholar Ivy Schweitzer writes, "her theorizing of a new borderlands or mestiza consciousness helped jump start fresh investigations in several fields – feminist, Americanist [and] postcolonial."[33] |

メスティーサ/境界文化 アンサルドゥアの主要な貢献の一つは、二項対立(「どちらか一方」)を超えた存在状態を意味する「メスティサージュ」という概念を、米国の学術界に導入し たことだ。彼女は理論的著作において「新たなメスティサ」を提唱した。これは自身の矛盾し絡み合うアイデンティティを自覚し、こうした「新たな視点」を用 いて西洋世界の二項思考に挑戦する個人を指す。彼女の著作で言及される「ボーダーランド」は地理的領域であると同時に、混血の、遺産、宗教、セクシュアリ ティ、言語の混合を指す。アンサルドゥアが主に注目するのは、対立し交差するアイデンティティの矛盾と並置である。特定のラベル化された性別として自己を 定義せざるを得ない状況は、個人の創造性を損なうだけでなく、消費財の生産者として人民があなたをどれほど真剣に受け止めるかにも影響すると彼女は指摘す る。[30] この「新たなメスティーサ的思考」はポストコロニアル・フェミニズムにおいて具体化される。[31] 教育分野では、アンサルドゥアの境界実践が伝統的な二元論的性別理解に挑戦する。[32] それは性別アイデンティティが固定的・単一的な概念ではなく、複雑な領域であることを認める。教育者に対し、学生が安心して学び、自己を認識・特定できる 安全で開放的な場を提供するよう促した。 アンサルドゥアは、異なる人種の人民が自らの恐怖と向き合い、憎しみが少なく有用な世界へと前進するよう求めた。女性学の授業で頻繁に用いられるテキスト 『メスティサの意識:新たな意識へ』において、彼女はチカーノ/チカーナが唱える分離主義が運動を前進させるどころか、同じ人種的分断を固定化していると 主張した。アンサルドゥアの著作の多くは、彼女が関わった運動の現状に挑戦している。特定の集団ではなく世界に真の変化をもたらすため、彼女はこれらの運 動に異議を唱えたのだ。学者アイビー・シュワイツァーはこう記している。「彼女の新たな国境地帯やメスティーサ意識に関する理論化は、フェミニズム、アメ リカ研究、ポストコロニアル研究など複数の分野で新たな探求を加速させる助けとなった」[33] |

| Sexuality In the same way that Anzaldúa often wrote that she felt that she could not be classified as only part of one race or the other, she felt that she possessed a multi-sexuality. When growing up, Anzaldúa expressed that she felt an "intense sexuality" towards her own father, children, animals, and even trees. AnaLouise Keating considered omitting Anzaldúa's sexual fantasies involving incest and bestiality for being "rather shocking" and "pretty radical", but Anzaldúa insisted that they remain because "to me, nothing is private." Anzaldúa claimed she had "sexual fantasies about father-daughter, sister-brother, woman-dog, woman-wolf, woman-jaguar, woman-tiger, or woman-panther. It was usually a cat- or dog-type animal." Anzaldúa also specified that she may have "mistaken this connection, this spiritual connection, for sexuality." She was attracted to and later had relationships with both men and women. Although she identified herself as a lesbian in most of her writing and had always experienced attraction to women, she also wrote that lesbian was "not an adequate term" to describe herself. She stated that she "consciously chose women" and consciously changed her sexual preference by changing her fantasies, arguing that "You can change your sexual preference. It's real easy." She stated that she "became a lesbian in my head first, the ideology, the politics, the aesthetics" and that the "touching, kissing, hugging, and all came later".[22] Anzaldúa wrote extensively about her queer identity and the marginalization of queer people, particularly in communities of color.[34] |

セクシュアリティ アンサルドゥアが、自分が単一の人種に分類できないと感じていたのと同じように、彼女は自分が複数のセクシュアリティを持っていると感じていた。成長期、 アンサルドゥアは実の父親や子供、動物、さらには木々に対しても「強烈な性的衝動」を抱いていたと語っている。アナ・ルイーズ・キーティングは近親相姦や 獣姦を題材にしたアンサルドゥアの性的幻想を「かなり衝撃的」で「かなり過激」であるとして削除を検討したが、アンサルドゥアは「私にとって、何もプライ ベートなものはない」と主張し、その記述を残すよう固執した。アンサルドゥアは「父と娘、兄と妹、女性と犬、女性と狼、女性とジャガー、女性と虎、あるい は女性とパンサーとの性的幻想を抱いた。大抵は猫や犬のような動物だった」と主張した。また「この繋がり、この精神的な繋がりを、性的なものと誤解してい たのかもしれない」とも述べている。彼女は男性にも女性にも惹かれ、後に両者と関係を持った。ほとんどの著作で自らをレズビアンと認識し、常に女性への魅 力を感じてきたが、レズビアンは自分を表す「適切な用語ではない」とも記している。彼女は「意識的に女性を選んだ」と述べ、幻想を変えることで性的嗜好を 意図的に変えたと主張し、「性的嗜好は変えられる。それは実に簡単だ」と主張した。彼女は「まず頭の中でレズビアンになった。イデオロギー、政治、美学に おいて」と述べ、「触れ合い、キス、抱擁などは全て後から来た」と記している。[22] アンサルドゥアは自身のクィアなアイデンティティと、特に有色人種コミュニティにおけるクィアな人々の周縁化について広く執筆した。[34] |

| Feminism Anzaldúa self-identifies in her writing as a feminist, and her major works are often associated with Chicana feminism and postcolonial feminism. Anzaldúa writes of the oppression she experiences specifically as a woman of color, as well as the restrictive gender roles that exist within the Chicano community. In Borderlands, she also addresses topics such as sexual violence perpetrated against women of color.[35] Her theoretical work on border culture is considered a precursor to Latinx Philosophy.[36] |

フェミニズム アンサルドゥアは自身の著作においてフェミニストと自認しており、その主要な著作はしばしばチカーナ・フェミニズムやポストコロニアル・フェミニズムと関 連づけられる。アンサルドゥアは、有色人種の女性として特に経験する抑圧について、またチカーノ共同体内に存在する制限的な性別役割について書いている。 『ボーダーランズ』では、有色人種の女性に対する性的暴力といったテーマにも言及している[35]。彼女の境界文化に関する理論的著作は、ラティンクス哲 学の先駆者と見なされている[36]。 |

| Criticism Anzaldúa has been criticized for neglecting and erasing Afro-Latino and Afro-Mexican history, as well as for drawing inspiration from José Vasconcelos' La raza cósmica without critiquing the racism, anti-blackness, and eugenics within the work of Vasconcelos.[37] Josefina Saldaña-Portillo's 2001 essay "Who's the Indian in Aztlán?" criticizes the "indigenous erasure" in the work of Anzaldúa as well as Anzaldúa's "appropriation of state sponsored Mexican indigenismo."[38] Juliet Hooker in "Hybrid subjectivities, Latin American mestizaje, and Latino political thought on race" also describes some of Anzaldúa's work as, "deploy[ing] an overly romanticized portrayal of indigenous peoples that looks onto the past rather than contemporary indigenous movements".[39] |

批判 アンサルドゥアは、アフリカ系ラテン系およびアフリカ系メキシコ人の歴史を軽視し抹消したこと、またホセ・バスコンセロスの『宇宙人種論』から着想を得ながら、バスコンセロスの著作に内在する人種主義、反黒人主義、優生学を批判しなかったことで非難されている。[37] ホセフィーナ・サルダーニャ=ポルティージョの2001年の論文「アストランのインディアンとは誰か?」は、アンサルドゥアの著作における「先住民の抹 消」と、アンサルドゥアによる「国家が支援するメキシコの先住民主義の流用」を批判している。[38] ジュリエット・フッカーは「ハイブリッドな主観性、ラテンアメリカのメスティサージュ、そして人種に関するラティーノ政治思想」において、アンサルドゥア の著作の一部を「現代の先住民運動ではなく過去を顧みる、過度にロマンチック化された先住民像を展開している」と評している。[39] |

| Awards Before Columbus Foundation American Book Award (1986) – This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color[40] Lambda Lesbian Small Book Press Award (1991)[41] Lesbian Rights Award (1991)[42] Sappho Award of Distinction (1992)[42] National Endowment for the Arts Fiction Award (1991)[43] American Studies Association Lifetime Achievement Award (Bode-Pearson Prize – 2001).[44] Additionally, her work Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza was recognized as one of the 38 best books of 1987 by Library Journal and 100 Best Books of the Century by both Hungry Mind Review and Utne Reader. In 2012, she was named by Equality Forum as one of their 31 Icons of the LGBT History Month.[45] |

受賞歴 コロンブス以前財団アメリカン・ブック賞(1986年) – 『この橋は私の背中と呼ばれた:急進的な有色人種女性たちの著作』[40] ラムダ・レズビアン・スモール・ブック・プレス賞(1991年)[41] レズビアン権利賞(1991年)[42] サッフォー優秀賞(1992年) [42] 全米芸術基金 フィクション賞(1991年)[43] アメリカ研究協会 生涯功労賞(ボーデ=ピアソン賞 – 2001年)。[44] さらに、彼女の著作『国境地帯/ラ・フロンテラ:新たなメスティーサ』は、ライブラリー・ジャーナル誌による1987年ベスト38冊、ハングリー・マインド・レビュー誌とウトネ・リーダー誌による「世紀のベスト100冊」に選ばれた。 2012年には、イコールティ・フォーラムにより「LGBT歴史月間31人のアイコン」の一人に選出された。[45] |

| Death and legacy Anzaldúa died on May 15, 2004, at her home in Santa Cruz, California, from complications of diabetes. At the time of her death, she was working toward the completion of her dissertation to receive her doctorate in Literature from the University of California, Santa Cruz.[46] It was awarded posthumously in 2005. The Chicana/o Latina/o Research Center (CLRC) at University of California, Santa Cruz offers the annual Gloria E. Anzaldúa Distinguished Lecture Award and The Gloria E. Anzaldúa Award for Independent Scholars and Contingent Faculty is offered annually by the American Studies Association. The latter "...honors Anzaldúa's outstanding career as an independent scholar and her labor as contingent faculty, along with her groundbreaking contributions to scholarship on women of color and to queer theory. The award includes a lifetime membership in the ASA, a lifetime electronic subscription to American Quarterly, five years access to the electronic library resources at the University of Texas at Austin, and $500".[47] In 2007, three years after Anzaldúa's death, the Society for the Study of Gloria Anzaldúa (SSGA) was established to gather scholars and community members who continue to engage Anzaldúa's work. The SSGA co-sponsors a conference – El Mundo Zurdo – every 18 months.[48] The Gloria E. Anzaldúa Poetry Prize is awarded annually, in conjunction with the Anzaldúa Literary Trust, to a poet whose work explores how place shapes identity, imagination, and understanding. Special attention is given to poems that exhibit multiple vectors of thinking: artistic, theoretical, and social, which is to say, political. First place is publication by Newfound, including 25 contributor copies, and a $500 prize.[49] The National Women's Studies Association honors Anzaldúa, a valued and long-active member of the organization, with the annual Gloria E. Anzaldúa Book Prize, which is designated for groundbreaking monographs in women's studies that makes significant multicultural feminist contributions to women of color/transnational scholarship.[50] To commemorate what would have been Anzaldúa's 75th birthday, on September 26, 2017 Aunt Lute Books published the anthology Imaniman: Poets Writing in the Anzaldúan Borderlands edited by ire'ne lara silva and Dan Vera with an introduction by United States Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera[51] and featuring the work of 52 contemporary poets on the subject of Anzaldúa's continuing impact on contemporary thought and culture.[52] On the same day, Google commemorated Anzaldúa's achievements and legacy through a Doodle in the United States.[53][54] |

死と遺産 アンサルドゥアは2004年5月15日、カリフォルニア州サンタクルーズの自宅で糖尿病の合併症により死去した。死の直前まで、カリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校で文学博士号取得に向け、博士論文の完成に取り組んでいた[46]。博士号は2005年に追贈された。 カリフォルニア大学サンタクルス校のチカーナ/ラティーナ研究センター(CLRC)は毎年「グロリア・E・アンサルドゥア記念講演賞」を授与している。ま たアメリカ研究協会(ASA)は毎年「グロリア・E・アンサルドゥア独立研究者・非常勤教員賞」を授与している。後者の賞は「...アンサルドゥアが独立 研究者として示した卓越した業績、非正規教員としての労苦、そして有色人種女性研究とクィア理論への画期的な貢献を称えるものである。受賞者にはアメリカ 研究協会(ASA)の終身会員資格、『アメリカン・クォータリー』の電子版終身購読権、テキサス大学オースティン校電子図書館リソースの5年間アクセス 権、および500ドルが授与される」[47]。 アンサルドゥアの死後3年を経た2007年、彼女の業績を引き継ぐ学者やコミュニティメンバーを結集するためグロリア・アンサルドゥア研究協会(SSGA)が設立された。SSGAは18ヶ月ごとに「エル・ムンド・ズルド」会議を共催している。[48] グロリア・E・アンサルドゥア詩賞は、アンサルドゥア文学信託と共同で毎年授与される。受賞対象は、場所がアイデンティティ、想像力、理解をいかに形成す るかを探求する詩作を手がける詩人である。特に重視されるのは、芸術的、理論的、社会的(すなわち政治的)という複数の思考ベクトルを示す詩作だ。最優秀 賞にはニューファウンド社による出版権(寄稿者用書籍25冊含む)と500ドルの賞金が与えられる。[49] 全米女性学協会は、長年にわたり同組織の貴重なメンバーとして活動したアンサルドゥアを称え、毎年「グロリア・E・アンサルドゥア書籍賞」を授与してい る。この賞は、女性学における画期的な単行本を対象とし、有色人種の女性/越境的な学術研究に重要な多文化フェミニスト的貢献をもたらした作品に贈られ る。[50] アンサルドゥアの生誕75周年を記念し、2017年9月26日にアント・ルート・ブックスよりアンソロジー『イマニマン:アンサルドゥアの国境地帯で詩を 書く詩人たち』が刊行された。アンザルドゥアの境界地帯で書く詩人たち』を刊行した。編集はイレネ・ララ・シルバとダン・ベラが担当し、米国桂冠詩人フア ン・フェリペ・エレラが序文を寄せた[51]。本書には52人の現代詩人が寄稿し、アンザルドゥアが現代思想と文化に与え続ける影響を主題としている。 [52] 同日、グーグルは米国でドゥードルを通じてアンサルドゥアの功績と遺産を称えた。[53][54] |

| Archives Housed at the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas at Austin, the Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa Papers, 1942–2004 contains more than 125 feet of published and unpublished materials including manuscripts, poetry, drawings, recorded lectures, and other archival resources.[55] AnaLouise Keating is one of the Anzaldúa Trust's trustees. Anzaldúa maintained a collection of figurines, masks, rattles, candles, and other ephemera used as altar (altares) objects at her home in Santa Cruz, California. These altares were an integral part of her spiritual life and creative process as a writer.[56] The altar collection is presently housed by the Special Collections department of the University Library at the University of California, Santa Cruz. |

アーカイブ テキサス大学オースティン校のネティ・リー・ベンソン・ラテンアメリカコレクションに所蔵されているグロリア・エヴァンジェリーナ・アンサルドゥア文書 (1942年~2004年)は、原稿、詩、絵画、録音講義、その他のアーカイブ資料を含む、125フィート(約38メートル)以上の出版済みおよび未出版 の資料を収めている。[55] アナ・ルイーズ・キーティングはアンサルドゥア信託の理事の一人である。アンサルドゥアはカリフォルニア州サンタクルーズの自宅において、祭壇(アルタレ ス)の供物として用いられた置物、仮面、ガラガラ、蝋燭、その他の一時的な物品のコレクションを保持していた。これらのアルタレスは、彼女の精神生活と作 家としての創造的プロセスに不可欠な要素であった。[56] この祭壇コレクションは現在、カリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校大学図書館の特別コレクション部門に所蔵されている。 |

| Works Main article: List of works by Gloria E. Anzaldúa This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981), co-edited with Cherríe Moraga, 4th ed., Duke University Press, 2015. ISBN 0-943219-22-1. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987), 4th ed., Aunt Lute Books, 2012. ISBN 1-879960-12-5. Making Face, Making Soul/Haciendo Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Feminists of Color, Aunt Lute Books, 1990. ISBN 1-879960-10-9. Interviews/Entrevistas, edited by AnaLouise Keating, Routledge, 2000. ISBN 0-415-92503-7. This Bridge We Call Home: Radical Visions for Transformation, co-edited with AnaLouise Keating, Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0-415-93682-9. The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader, edited by AnaLouise Keating. Duke University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-8223-4564-0. Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality, edited by AnaLouise Keating, Duke University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-8223-6009-4. Children's books Prietita Has a Friend (1991) Friends from the Other Side/Amigos del Otro Lado (1995) Prietita y La Llorona (1996) |

作品 主な記事: グロリア・E・アンサルドゥアの作品一覧 『この橋は私の背中と呼ばれる: 急進的な有色人種の女性たちによる著作集』(1981年)、シェリー・モラガとの共編、第4版、デューク大学出版局、2015年。ISBN 0-943219-22-1。 『ボーダーランズ/ラ・フロンテラ:新たなメスティーサ』(1987年)、第4版、オント・ルート・ブックス、2012年。ISBN 1-879960-12-5。 『顔を作り、魂を作る/ハシエンディオ・カラス:有色人種フェミニストによる創造的・批判的視点』(1990年、オント・ルート・ブックス刊)。ISBN 1-879960-10-9。 『インタビュー/エントレビスタス』(アナ・ルイーズ・キーティング編、2000年、ラウトリッジ刊)。ISBN 0-415-92503-7。 『我らが故郷と呼ぶこの橋:変革のための急進的ビジョン』アナ・ルイーズ・キーティングとの共編、ラウトリッジ、2002年。ISBN 0-415-93682-9。 『グロリア・アンサルドゥア・リーダー』アナ・ルイーズ・キーティング編、デューク大学出版局、2009年。ISBN 978-0-8223-4564-0。 『闇の中の光/ルス・エン・ロ・オスキュロ:アイデンティティ、スピリチュアリティ、現実の再構築』アナ・ルイーズ・キーティング編、デューク大学出版局、2015年。ISBN 978-0-8223-6009-4。 児童書 『プリエティタに友達ができた』(1991年) 『向こう側からの友達』(1995年) 『プリエティタと泣く女』(1996年) |

| Feminism in Latin America Latino literature Latinx philosophy Latino poetry Chicana literature |

ラテンアメリカにおけるフェミニズム ラティーノ文学 ラティーノ哲学 ラティーノ詩 チカーナ文学 |

| General and cited references Adams, Kate. "Northamerican Silences: History, Identity, and Witness in the Poetry of Gloria Anzaldúa, Cherríe Moraga, and Leslie Marmon Silko". Elaine Hedges and Shelley Fisher Fishkin (eds), Listening to Silences: New Essays in Feminist Criticism. NY: Oxford University Press, 1994. 130–145. Print. Alarcón, Norma. "Anzaldúa's Frontera: Inscribing Gynetics". Smadar Lavie and Ted Swedenburg (eds). Displacement, Diaspora, and Geographies of Identity. Durham: Duke University Press, 1996. 41–52. Print. Alcoff, Linda Martín. "The Unassimilated Theorist". PMLA 121.1 (2006): 255–259 Almeida, Sandra Regina Goulart. "Bodily Encounters: Gloria Anzaldúa's Borderlands / La Frontera". Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of Language and Literature 39 (2000): 113–123. Web. August 21, 2012. Anzaldúa, Gloria E., 2003. "La Conciencia de la Mestiza: Towards a New Consciousness", pp. 179–187, in Carole R. McCann and Seung-Kyung Kim (eds), Feminist Theory Reader: Local and Global Perspectives, New York: Routledge. Bacchetta, Paola. "Transnational Borderlands. Gloria Anzaldúa's Epistemologies of Resistance and Lesbians 'of Color' in Paris". In Norma Cantu, Christina L. Gutierrez, Norma Alarcón and Rita E. Urquijo-Ruiz (eds), El Mundo Zurdo: Selected Works from the Society for the Study of Gloria Anzaldúa 2007 to 2009, 109–128. San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 2010. Barnard, Ian. "Gloria Anzaldúa's Queer Mestizaje". MELUS 22.1 (1997): 35–53. Blend, Benay. "'Because I Am in All Cultures at the Same Time': Intersections of Gloria Anzaldúa's Concept of Mestizaje in the Writings of Latin-American Jewish Women". Postcolonial Text 2.3 (2006): 1–13. Web. August 21, 2012. Keating, AnaLouise, and Gloria Gonzalez-Lopez (eds), Bridging: How Gloria Anzaldua's Life and Work Transformed Our Own (University of Texas Press; 2011), 276 pp. Bornstein-Gómez, Miriam. "Gloria Anzaldúa: Borders of Knowledge and (re)Signification." Confluencia 26.1 (2010): 46–55 EBSCO Host. Web. August 21, 2012. Capetillo-Ponce, Jorge. "Exploring Gloria Anzaldúa's Methodology in Borderlands/La Frontera—The New Mestiza". Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 4.3 (2006): 87–94. Scholarworks UMB. Web. August 21, 2012. Castillo, Debra A. "Anzaldúa and Transnational American Studies". PMLA 121.1 (2006): 260–265. David, Temperance K. "Killing to Create: Gloria Anzaldúa's Artistic Solution to 'Cervicide'". Intersections Online 10.1 (2009): 330–340. WAU Libraries. Web. July 9, 2012. Donadey, Anne. "Overlapping and Interlocking Frames for Humanities Literary Studies: Assia Djebar, Tsitsi Dangarembga, Gloria Anzaldúa". College Literature 34.4 (2007): 22–42. Enslen, Joshua Alma. "Feminist prophecy: a Hypothetical Look into Gloria Anzaldúa's 'La Conciencia de la Mestiza: Towards a new Consciousness' and Sara Ruddick's 'Maternal Thinking'". LL Journal 1.1 (2006): 53–61 OJS. Web. August 21, 2012. Fishkin, Shelley Fisher. "Crossroads of Cultures: The Transnational Turn in American Studies – Presidential Address to the American Studies Association, November 12, 2004". American Quarterly 57.1 (2005): 17–57. Project Muse. Web. February 10, 2010. Friedman, Susan Stanford. Mappings: Feminism and the Cultural Geographies of Encounter. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1998. Print. Hartley, George. "'Matriz Sin Tumba': The Trash Goddess and the Healing Matrix of Gloria Anzaldúa's Reclaimed Womb". MELUS 35.3 (2010): 41–61. Project Muse. Web. August 21, 2012. Hedges, Elaine and Shelley Fisher Fishkin (eds), Listening to Silences: New Essays in Feminist Criticism. NY: Oxford UP, 1994. Print. Hedley, Jane. "Nepantilist Poetics: Narrative and Cultural Identity in the Mixed-Language Writings of Irena Klepfisz and Gloria Anzaldúa". Narrative 4.1 (1996): 36–54 Herrera-Sobek, María. "Gloria Anzaldúa: Place, Race, Language, and Sexuality in the Magic Valley". PMLA 121.1 (2006): 266–271. Hilton, Liam. "Peripherealities: Porous Bodies; Porous Borders: The 'Crisis' of the Transient in a Borderland of Lost Ghosts". Graduate Journal of Social Science 8.2 (2011): 97–113. Web. August 21, 2012. Keating, AnaLouise, ed. EntreMundos/AmongWorlds: New Perspectives on Gloria Anzaldúa. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005. Keating, AnaLouise. Women Reading, Women Writing: Self-Invention in Paula Gunn Allen, Gloria Anzaldúa and Audre Lorde. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996. Lavie, Smadar and Ted Swedenburg (eds), Displacement, Diaspora, and Geographies of Identity. Durham: Duke University Press, 1996. Print. Lavie, Smadar. "Staying Put: Crossing the Israel–Palestine Border with Gloria Anzaldúa", Anthropology and Humanism Quarterly, June 2011, Vol. 36, Issue 1. This article won the American Studies Association's 2009 Gloria E. Anzaldúa Award for Independent Scholars. Mack-Canty, Colleen. "Third-Wave Feminism and the Need to Reweave the Nature/Culture Duality", pp. 154–179, in NWSA Journal, Fall 2004, Vol. 16, Issue 3. Lioi, Anthony. "The Best-Loved Bones: Spirit and History in Anzaldúa's 'Entering into the Serpent.'" Feminist Studies 34.1/2 (2008): 73–98. Lugones, María. "On Borderlands / La Frontera: An Interpretive Essay". Hypatia 7.4 (1992): 31–37 Martinez, Teresa A.. "Making Oppositional Culture, Making Standpoint: A Journey into Gloria Anzaldúa's Borderlands". Sociological Spectrum 25 (2005): 539–570 Tayor & Francis. Web. August 21, 2012. Negrón-Muntaner, Frances. "Bridging Islands: Gloria Anzaldúa and the Caribbean". PMLA 121,1 (2006): 272–278 MLA. Web. August 21, 2012. Pérez, Emma. "Gloria Anzaldúa: La Gran Nueva Mestiza Theorist, Writer, Activist-Scholar". pp. 1–10, in NWSA Journal; Summer 2005, Vol. 17, Issue 2. Ramlow, Todd R.. "Bodies in the Borderlands: Gloria Anzaldúa and David Wojnarowicz's Mobility Machines". MELUS 31.3 (2006): 169–187. Rebolledo, Tey Diana. "Prietita y el Otro Lado: Gloria Anzaldúa's Literature for Children". PMLA 121.1 (2006): 279–784. Reuman, Ann E. "Coming Into Play: An Interview with Gloria Anzaldua" p. 3, in MELUS; Summer 2000, Vol. 25, Issue 2. Saldívar-Hull, Sonia. "Feminism on the Border: From Gender Politics to Geopolitics". Criticism in the Borderlands: Studies in Chicano Literature, Culture, and Ideology. Héctor Calderón and José´David Saldívar (eds). Durham: Duke University Press, 1991. 203–220. Print. Schweitzer, Ivy. "For Gloria Anzaldúa: Collecting America, Performing Friendship". PMLA 121.1 (2006): 285–291 Smith, Sidonie. Subjectivity, Identity, and the Body: Women's Autobiographical Practices in the Twentieth Century. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1993. Print. Solis Ybarra, Priscilla. "Borderlands as Bioregion: Jovita González, Gloria Anzaldúa, and the Twentieth-Century Ecological Revolution in the Rio Grande Valley". MELUS 34.2 (2009): 175–189. Spitta, Silvia. Between Two Waters: Narratives of Transculturation in Latin America (Rice UP 1995; Texas A&M 2006) Stone, Martha E. "Gloria Anzaldúa" pp. 1, 9, in Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide; January/February 2005, Vol. 12, Issue 1. Vargas-Monroy, Liliana. "Knowledge from the Borderlands: Revisiting the Paradigmatic Mestiza of Gloria Anzaldúa". Feminism and Psychology 22.2 (2011): 261–270. Vivancos Perez, Ricardo F. doi:10.1057/9781137343581 Radical Chicana Poetics. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. Ward, Thomas. "Gloria Anzaldúa y la lucha fronteriza", in Resistencia cultural: La nación en el ensayo de las Américas, Lima, 2004, pp. 336–342. Yarbro-Bejarano, Yvonne. "Gloria Anzaldúa's Borderlands / La Frontera: Cultural Studies, 'Difference' and the Non-Unitary Subject". Cultural Critique 28 (1994): 5–28. |

一般文献と引用文献 アダムズ、ケイト。「北米の沈黙:グロリア・アンサルドゥア、チェリー・モラガ、レスリー・マーモン・シルコの詩における歴史、アイデンティティ、そして 証言」。エレイン・ヘッジズとシェリー・フィッシャー・フィシュキン(編)、『沈黙に耳を傾けて:フェミニスト批評の新論集』。ニューヨーク:オックス フォード大学出版局、1994年。130–145頁。印刷物。 アラルコン、ノルマ。「アンサルドゥアのフロンテラ:女性性の刻印」スマダル・ラヴィ、テッド・スウェーデンバーグ(編)『移住、ディアスポラ、そしてアイデンティティの地理学』ダーラム:デューク大学出版、1996年。41–52頁。印刷物。 アルコフ、リンダ・マルティン。「同化されない理論家」 PMLA 121.1 (2006): 255–259 アルメイダ、サンドラ・レジーナ・ゴウラート。「身体的遭遇:グロリア・アンサルドゥアの『国境地帯/ラ・フロンテラ』」。『イルハ・ド・デステロ:言語と文学のジャーナル』39 (2000): 113–123. ウェブ。2012年8月21日。 アンサルドゥア、グロリア・E.、2003年。「混血の女性としての自覚:新たな意識へ向けて」、pp. 179–187、キャロル・R・マッキャンとスンギョン・キム(編)、『フェミニスト理論読本:ローカルとグローバルの視点』、ニューヨーク:ラウトリッジ。 バッケッタ、パオラ。「トランスナショナル・ボーダーランズ。グロリア・アンサルドゥアの抵抗の認識論とパリの『有色人種』レズビアンたち」。ノルマ・カ ントゥ、クリスティーナ・L・グティエレス、ノルマ・アラルコン、リタ・E・ウルキホ=ルイス編『エル・ムンド・ズルド:グロリア・アンサルドゥア研究協 会2007-2009年選集』所収、109-128頁。サンフランシスコ:オント・ルート、2010年。 バーナード、イアン。「グロリア・アンサルドゥアのクィアなメスティサージュ」。『MELUS』22.1 (1997): 35–53。 ブレンド、ベネイ。「『なぜなら私はあらゆる文化の中に同時に存在するから』:ラテンアメリカ系ユダヤ人女性たちの著作におけるグロリア・アンサルドゥア のメスティサージュ概念の交差」。ポストコロニアル・テキスト 2.3 (2006): 1–13. Web. 2012年8月21日. キーティング、アナルイーズ、グロリア・ゴンザレス=ロペス(編)、『架け橋:グロリア・アンサルドゥアの人生と作品が私たちを変えた方法』(テキサス大学出版局; 2011年)、276頁。 ボーンシュタイン=ゴメス、ミリアム。「グロリア・アンサルドゥア:知識と(再)意味付けの境界」。『コンフルエンシア』26.1号(2010年):46–55頁。EBSCO Host。ウェブ。2012年8月21日。 カペティージョ=ポンセ、ホルヘ。「『国境地帯/ラ・フロンテラ―新たなメスティーサ』におけるグロリア・アンサルドゥアの方法論を探る」。『ヒューマ ン・アーキテクチャー:自己認識社会学ジャーナル』4巻3号(2006年):87–94頁。Scholarworks UMB。ウェブ。2012年8月21日。 カスティージョ、デブラ・A。「アンサルドゥアとトランスナショナル・アメリカン・スタディーズ」。『PMLA』121巻1号(2006年):260–265頁。 デイヴィッド、テンペランス・K。「創造のための殺戮:グロリア・アンサルドゥアの『セルヴィサイド』に対する芸術的解決策」。『Intersections Online』10巻1号(2009年): 330–340. WAU図書館. ウェブ. 2012年7月9日. ドナデイ, アン. 「人文文学研究のための重なり合い、絡み合う枠組み: アッシア・ジェバル、ツィツィ・ダンガレンバ、グロリア・アンサルドゥア」. College Literature 34.4 (2007): 22–42. エンスレン、ジョシュア・アルマ。「フェミニスト的予言:グロリア・アンサルドゥア『混血の意識:新たな意識へ』とサラ・ラディック『母性思考』への仮説的考察」。『LLジャーナル』1巻1号(2006年):53–61 OJS。ウェブ。2012年8月21日。 フィッシュキン、シェリー・フィッシャー。「文化の交差点:アメリカ研究におけるトランスナショナル・ターン ― アメリカ研究協会会長演説、2004年11月12日」。『アメリカン・クォーターリー』57.1 (2005): 17–57. Project Muse. Web. 2010年2月10日。 フリードマン、スーザン・スタンフォード。『マッピング:フェミニズムと遭遇の文化的地理学』プリンストン大学出版局、1998年。印刷物。 ハートリー、ジョージ。「『墓なき母胎』:グロリア・アンサルドゥアの再生された子宮におけるゴミの女神と癒しの母胎」『MELUS』35巻3号(2010年):41–61頁。Project Muse。ウェブ。2012年8月21日。 ヘッジズ、エレインとシェリー・フィッシャー・フィシュキン(編)、『沈黙に耳を傾ける:フェミニスト批評の新論集』。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局、1994年。印刷物。 ヘドリー、ジェーン。「非パンティリスト詩学:イレーナ・クレプフィシュとグロリア・アンサルドゥアのミヘ言語作品における物語と文化的アイデンティティ」。ナラティブ 4.1 (1996): 36–54 エレラ=ソベック、マリア。「グロリア・アンサルドゥア:『魔法の谷』における場所、人種、言語、そしてセクシュアリティ」。PMLA 121.1 (2006): 266–271。 ヒルトン、リアム。「周辺性:多孔性の身体、多孔性の境界:失われた亡霊たちの辺境における『危機』」。『社会科学大学院ジャーナル』8巻2号(2011年):97–113頁。ウェブ。2012年8月21日。 キーティング、アナルイーズ編。『エントレムンドス/アモンワールドズ:グロリア・アンサルドゥアに関する新たな視点』。ニューヨーク:パルグレイブ・マクミラン、2005年。 キーティング、アナルイーズ。『読む女性、書く女性:ポーラ・ガン・アレン、グロリア・アンサルドゥア、オードリー・ロードにおける自己の発明』。フィラデルフィア:テンプル大学出版局、1996年。 ラヴィ、スマダルとテッド・スウェーデンバーグ(編)。『追放、ディアスポラ、そしてアイデンティティの地理学』。ダーラム:デューク大学出版局、1996年。印刷物。 ラヴィ、スマダル。「留まること:グロリア・アンサルドゥアと共にイスラエル・パレスチナ国境を越えて」。『人類学とヒューマニズム季刊』2011年6月、第36巻第1号。本論文はアメリカ研究協会より2009年度グロリア・E・アンサルドゥア独立研究者賞を受賞した。 マック・キャンティ、コリーン。「第三波フェミニズムと自然と文化の二元性を再構築する必要性」、『NWSAジャーナル』2004年秋号、第16巻第3号、pp.154-179。 リオイ、アンソニー。「最も愛された骨:アンサルドゥアの『蛇の中へ』における精神と歴史」フェミニスト研究 34.1/2 (2008): 73–98. ルゴネス、マリア。「国境地帯について / La Frontera:解釈的エッセイ」ヒュパティア 7.4 (1992): 31–37 マルティネス、テレサ A. 「対立する文化の創造、視点の創造:グロリア・アンサルドゥアの『国境地帯』への旅」。Sociological Spectrum 25 (2005): 539–570 Tayor & Francis. Web. 2012年8月21日。 ネグロン・ムンタネール、フランシス。「島々をつなぐ:グロリア・アンサルドゥアとカリブ海」。PMLA 121,1 (2006): 272–278 MLA. Web. 2012年8月21日。 Pérez, Emma. 「グロリア・アンサルドゥア:偉大なる新メスティゾ理論家、作家、活動家・学者」. pp. 1–10, in NWSA Journal; Summer 2005, Vol. 17, Issue 2. ラムロー、トッド・R. 「国境地帯の身体:グロリア・アンサルドゥアとデイヴィッド・ウォイナロウィッツのモビリティ・マシーン」. MELUS 31.3 (2006): 169–187. レボジェド、テイ・ダイアナ. 「プリエティータと向こう側:グロリア・アンサルドゥアの児童文学」。PMLA 121.1 (2006): 279–784. ルーマン、アン・E. 「遊びの中へ:グロリア・アンサルドゥアとの対話」。p. 3, MELUS; 2000年夏号, 第25巻第2号. サルディバル=ハル、ソニア。「国境のフェミニズム:ジェンダー政治から地政学へ」。『国境地帯の批評:チカーノ文学・文化・イデオロギー研究』。ヘク ター・カルデロン、ホセ・ダビッド・サルディバル編。ダーラム:デューク大学出版局、1991年。203–220頁。印刷物。 シュワイツァー、アイヴィー。「グロリア・アンサルドゥアのために:アメリカを収集し、友情を実践する」。『PMLA』121巻1号(2006年):285–291頁 スミス、シドニー。『主体性、アイデンティティ、そして身体:20世紀における女性の自伝的実践』。ブルーミントン、インディアナ州:インディアナ大学出版局、1993年。印刷物。 ソリス・イバラ、プリシラ。「境界地帯としてのバイオリージョン:ホビタ・ゴンザレス、グロリア・アンサルドゥア、そしてリオ・グランデ・バレーにおける二十世紀の生態学的革命」。『MELUS』34巻2号(2009年):175–189頁。 スピッタ、シルビア。『二つの水の間:ラテンアメリカにおける文化交差の物語』(ライス大学出版 1995年;テキサスA&M大学出版 2006年) ストーン、マーサ・E. 「グロリア・アンサルドゥア」pp. 1, 9, 『ゲイ&レズビアン・レビュー・ワールドワイド』2005年1月/2月号、第12巻第1号。 バルガス=モンロイ、リリアナ。「境界地帯からの知:グロリア・アンサルドゥアのパラダイム的メスティーサを再考する」。『フェミニズムと心理学』22巻2号(2011年):261–270頁。 ビバンコス・ペレス、リカルド・F. doi:10.1057/9781137343581 『ラディカル・チカーナ詩学』。ロンドン・ニューヨーク:パルグレイブ・マクミラン、2013年。 ウォード、トーマス。「グロリア・アンサルドゥアと国境地帯の闘い」、『文化的抵抗:アメリカ大陸における国家の試み』所収、リマ、2004年、336–342頁。 ヤーブロ=ベハラーノ、イヴォンヌ。「グロリア・アンサルドゥアの『国境地帯/ラ・フロンテラ』:文化研究、『差異』、そして非単一的主体」『文化批評』28号(1994年):5–28頁。 |

| Broe, Mary Lynn; Ingram, Angela

(1989). Women's writing in exile. Chapel Hill: University of North

Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4251-5. Castillo, Debra A. (2005). Redreaming America: Toward a Bilingual American Culture. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 1-4237-4364-4. OCLC 62750478. González, Christopher (2017). Permissible Narratives: The Promise of Latino/a Literature. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8142-1350-6. OCLC 975447664. Zaytoun, Kelli D. (2022). Shapeshifting Subjects: Gloria Anzaldúa's Naguala and Border Arte. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. doi:10.5622/illinois/9780252044434.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-252-04443-4. Martín-Rodríguez, Manuel M., "Gloria E. Anzaldúa" Perez, Rolando (2020). "The Bilingualisms of Latino-a Literatures". In Stavans, Ilan (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Latino Studies. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-069120-2. OCLC 1121419672. |

ブロエ、メアリー・リン;イングラム、アンジェラ(1989年)。『亡命における女性の執筆』チャペルヒル:ノースカロライナ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8078-4251-5。 カスティージョ、デブラ・A.(2005年)。『アメリカを再夢見る:二言語アメリカ文化へ向けて』オールバニ:ニューヨーク州立大学出版局。ISBN 1-4237-4364-4。OCLC 62750478。 ゴンザレス、クリストファー(2017)。『許容される物語:ラティーノ/ラティーナ文学の約束』。コロンバス:オハイオ州立大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8142-1350-6。OCLC 975447664。 ザイトゥーン、ケリー・D.(2022)。『変容する主体:グロリア・アンサルドゥアのナグアラとボーダー・アルテ』。シャンペーン:イリノイ大学出版 局。doi:10.5622/illinois/9780252044434.001.0001。ISBN 978-0-252-04443-4。 マルティン=ロドリゲス、マヌエル・M.、「グロリア・E・アンサルドゥア」 ペレス、ロランド(2020)。「ラティーノ文学のバイリンガリズム」。スタヴァンズ、イラン(編)。『オックスフォード・ハンドブック・オブ・ラティー ノ研究』。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-069120-2。OCLC 1121419672。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gloria_Anzald%C3%BAa |

Gloria Anzaldúa. Oakland, Ca. 1988, queer Chicana poet author of Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987).

グロリア・アンサルドゥア。カリフォルニア州オークランド。1988年。クィア・チカーナ詩人。『ボーダーランズ/ラ・フロンテラ:新たなメスティーサ』(1987年)の著者。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099