グアラチャ

Guaracha

María

Teresa Vera & Rafael Zequeira [YouTube]

☆ グアラチャ(guaracha; ス ペイン語発音:[ɡwaʃa])は、キューバで生まれた音楽のジャンルで、テンポが速く、コミカルまたはピカレスクな歌詞が特徴である[1][2]。 グアラチャという言葉は、少なくとも18世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけて、この意味で使われてきた[3]。グアラチャは、ミュージカル劇場や労働者階級 のダンスサロンで演奏され、歌われた。19世紀半ばにはブフォ・コミック・シアターの不可欠な一部となった[4]。19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけ て、グアラチャはハバナの売春宿で好んで演奏された。

| The guaracha

(Spanish pronunciation: [ɡwaˈɾatʃa]) is a genre of music that

originated in Cuba, of rapid tempo and comic or picaresque

lyrics.[1][2] The word has been used in this sense at least since the

late 18th and early 19th century.[3] Guarachas were played and sung in

musical theatres and in working-class dance salons. They became an

integral part of bufo comic theatre in the mid-19th century.[4] During

the later 19th and the early 20th century the guaracha was a favourite

musical form in the brothels of Havana.[5][6] The guaracha survives

today in the repertoires of some trova musicians, conjuntos and

Cuban-style big bands. |

グ

アラチャ(スペイン語発音:[ɡwaʃa])は、キューバで生まれた音楽のジャンルで、テンポが速く、コミカルまたはピカレスクな歌詞が特徴である[1]

[2]。

グアラチャという言葉は、少なくとも18世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけて、この意味で使われてきた[3]。グアラチャは、ミュージカル劇場や労働者階級

のダンスサロンで演奏され、歌われた。19世紀半ばにはブフォ・コミック・シアターの不可欠な一部となった[4]。19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけ

て、グアラチャはハバナの売春宿で好んで演奏された。 |

| Early uses of the word Though the word may be historically of Spanish origin, its use in this context is of indigenous Cuban origin.[7] These are excerpts from reference sources, in date order: A Latin American carol "Convidando esta la noche" dates from at least the mid 17th century and both mentions and is a guaracha. It was composed or collected by Juan Garcia de Zespedes, 1620–1678, Puebla, Mexico. This is a Spanish guaracha, a musical style popular in Caribbean colonies. "Happily celebrating, some lovely shepherds sing the new style of juguetes for a guaracha. In this guaracha we celebrate while the baby boy is lost in dreams. Play and dance because we have fire in the ice and ice in the fire." The Gazeta de Barcelona has a number of advertisements for music that mention the guaracha.[8] The earliest mention in this source is #64, dated 11 August 1789, where there is an entry that reads "...otra del Sr. Brito, Portugues: el fandango, la guaracha y seis contradanzas, todo en cifra para guitarra...". A later entry #83, 15 October 1796, refers to a "...guaracha intitulada Tarántula...". "Báile de la gentualla casi desusado" (dance for the rabble, somewhat old-fashioned).[9] Leal comments on this: "The bailes de la gentualla are known on other occasions as bailes de cuna where people of different races mix. The guaracha employs the structure soloist–coro, that is to say, verses or passages vary between the chorus and the soloist, improvisation occurs, and references made to daily matters, peppered with crafty witticisms."[10] "Una canción popular que se canta a coro... Música u orquesta pobre, compuesta de acordeón o guitarra, güiro, maracas, etc". (a popular song, which is sung alternately (call & response?)... humble music and band &c).[11] "Cierto género musical" (a particular genre of music).[12] These references are all to music, but whether of the same type is not quite clear. The usage of guaracha is sometimes extended, then meaning, generally, to have a good time. A different sense of the word means jest or diversion. |

この語の初期の用法 この言葉は歴史的にはスペイン語起源かもしれないが、この文脈での使用はキューバ土着のものである[7]。以下は参考資料からの抜粋で、日付順である: ラテンアメリカのキャロル 「Convidando esta la noche 」は、少なくとも17世紀半ばのもので、グアラチャに言及し、またグアラチャである。フアン・ガルシア・デ・ゼスペデス(Juan Garcia de Zespedes, 1620-1678、メキシコ、プエブラ)によって作曲または収集された。これはスペインのグアラチャで、カリブ海の植民地で流行した音楽スタイルであ る。「幸せに祝って、何人かの愛らしい羊飼いたちが、グアラチャのための新しいスタイルのジュゲテスを歌う。このグアラチャでは、赤ん坊の男の子が夢の中 に迷い込んでいる間にお祝いする。氷の中に火があり、火の中に氷があるのだから、遊んで踊ろう」。 バルセロナのガゼータ紙には、グアラチャに言及した音楽の広告が多数掲載されている[8]。この資料で最も古い記述は、1789年8月11日付の64号 で、そこには「...otra del Sr. Brito, Portugues: el fandango, la guaracha y seis contradanzas, todo en cifra para guitarra...」という記述がある。1796年10月15日付の83番では、「...Tarántula...と題されたグアラチャ」について言 及している。 「Báile de la gentualla casi desusado"(庶民の踊り、やや古風)[9] レアルはこれについて次のようにコメントしている: 「バイレ・デ・ラ・ジェントゥアージャは、異なる人種が混ざり合うバイレ・デ・クーナとしても知られている。グアラチャはソリスト-コロという構造を採用 している。つまり、詩やパッセージはコーラスとソリストの間で変化し、即興が起こり、日常的な事柄に言及し、狡猾な皮肉をちりばめる」[10]。 「コーラスで歌うポピュラー・カンセー... アコルデオンやギター、グィロ、マラカスなどで構成される貧民のオルケスタの音楽」[10]。(交互に歌われるポピュラーソング(コール&レスポ ンス?)...地味な音楽とバンドなど)[11]。 「Cierto género musical"(特定のジャンルの音楽)[12]。 これらの言及はすべて音楽に関するものだが、同じ種類の音楽かどうかははっきりしない。グアラチャの用法は時に拡張され、一般的には「楽しい時間を過ご す」という意味になる。別の意味では、冗談や陽動という意味もある。 |

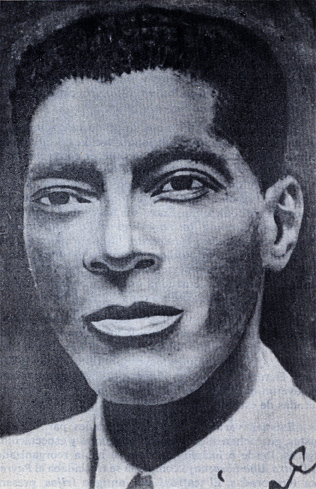

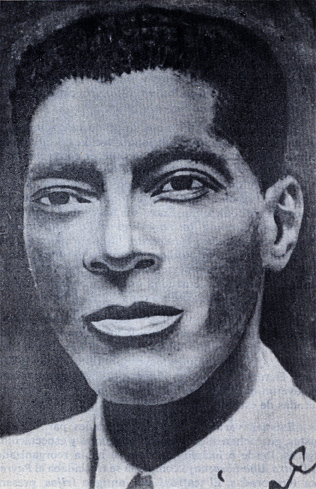

Emergence of the Guaracha María Teresa Vera & Rafael Zequeira On January 20, 1801, Buenaventura Pascual Ferrer published a note in a newspaper called "El Regañón de La Havana", in which he refers to certain chants that "run outside there through vulgar voices". Between them he mentioned a "guaracha" named "La Guabina", about which he says: "in the voice of those that sings it, tastes like any thing dirty, indecent or disgusting that you can think about…" At a later time, in an undetermined date, "La Guabina" appears published among the first musical scores printed in Havana at the beginning of the 19th century.[13] According to the commentaries published in "El Regañón de La Habana", we can conclude that those "guarachas" were very popular within the Havana population at that time, because in the same previously mentioned article the author says: "…but most importantly, what bothers me most is the liberty with which a number of chants are sung throughout the streets and town homes, where innocence is insulted and morals offended… by many individuals, not just of the lowest class, but also by some people that are supposed to be called well educated…". Therefore, we can say that those "guarachas" of a very audacious content, were apparently already sung within a wide social sector of the Havana population.[13] Buenaventura Pascual Ferrer mentions also that at the beginning of the 19th century up to fifty dance parties were held in Havana every day, where the famous "Guaracha" was sung and danced among other popular pieces.[14] |

グアラチャの出現 マリア・テレサ・ベラ&ラファエル・ゼケイラ 1801年1月20日、ブエナベントゥーラ・パスクアル・フェレールは、「El Regañón de La Havana 」と呼ばれる新聞に、「下品な声で外を流れる 」ある聖歌について言及した。その中で彼は、「ラ・グアビーナ 」という名の 「グアラチャ 」について触れている。「それを歌う人の声には、あなたが考えつくどんな汚いもの、卑猥なもの、嫌なもののような味がする... 」と彼は言う。その後、年代は定かではないが、19世紀初頭にハバナで印刷された最初の楽譜の中に「ラ・グアビーナ」が掲載されている[13]。 El Regañón de La Habana 「に掲載された解説によれば、これらの 」グアラチャ "は当時のハバナの人々の間で非常に人気があったと結論づけることができる: 「...しかし、最も重要なことは、無邪気さが侮辱され、モラルが損なわれている...多くの人々によって、最下層の人々だけでなく、教養があると言われ る人々によっても...」と述べている。したがって、非常に大胆な内容のこれらの「グアラチャス」は、ハバナの人々の幅広い社会的部門ですでに歌われてい たようだと言える[13]。 ブエナヴェントゥーラ・パスクアル・フェレールは、19世紀初頭にはハバナで毎日50ものダンス・パーティーが開かれており、そこで有名な「グアラチャ」 が他のポピュラー曲に混じって歌われ、踊られていたとも述べている[14]。 |

Guaracha as a dance Ballerine dancing « la Quarache » in act 1 of La muette de Portici at the Académie royale de musique (Salle Le Peletier, Paris) in 1828. There is little evidence as to what style of dance was originally performed to the guaracha in Cuba. Some engravings from the 19th century suggest that it was a dance of independent couples, that is, not a sequence dance such as the contradanza.[15] The prototype independent couples dance was the waltz (early 19th century Vals in Cuba). The first creole dance form in Cuba known for certain to be danced by independent couples was the danzón. If the guaracha is an earlier example, this would be interesting from a dance history point of view. Guarachas in bufo theatre During the 19th century, the bufo theatre, with its robust humour, its creolized characters and its guarachas, played a part in the movement for the emancipation of slaves and the independence of Cuba. They played a part in criticising authorities, lampooning public figures and supporting heroic revolutionaries.[16][17] Satire and humour are significant weapons for a subjugated people. In 1869 at the Teatro Villanueva in Havana an anti-Spanish bufo was playing, when suddenly some Spanish Voluntarios attacked the theatre, killing some ten or so patrons. The context was that the Ten Years' War had started the previous year, when Carlos Manuel de Céspedes had freed his slaves, and declared Cuban independence. Creole sentiments were running high, and the Colonial government and their rich Spanish traders were reacting. Not for the first or the last time, politics and music were closely intertwined, for musicians had been integrated since before 1800. Bufo theatres were shut down for some years after this tragic event. In bufos the guaracha would occur at places indicated by the author: guaracheros would enter in coloured shirts, white trousers and boots, handkerchiefs on their heads, the women in white coats, and the group would perform the guaracha. In general the guaracha would involve a dialogue between the tiple, the tenor and the chorus. The best period of the guaracha on stage was early in the 20th century in the Alhambra theatre in Havana, when such composers as Jorge Anckermann, José Marín Varona and Manuel Mauri wrote numbers for the top stage singer Adolfo Colombo.[18] Most of the leading trova musicians wrote guarachas: Pepe Sánchez, Sindo Garay, Manuel Corona, and later Ñico Saquito. |

ダンスとしてのグアラシャ 1828年、王立音楽アカデミー(パリのサル・ル・ペレティエ)で『ポルティチの娘』第1幕の「ラ・クアラチェ」を踊るバレリーヌ。 もともとキューバでどのようなスタイルのダンスがグアラチャに合わせて踊られていたのかについては、ほとんど証拠がない。19世紀の彫像の中には、コント ラダンザのようなシークエンスダンスではなく、独立したカップルのダンスであったことを示唆するものもある[15]。独立したカップルのダンスの原型はワ ルツ(19世紀初頭のキューバのバルス)であった。独立したカップルによって踊られたことが確実視されているキューバの最初のクレオール舞踊形式はダンソ ンである。グアラチャがそれ以前の例だとすれば、舞踊史の観点からも興味深い。 ブフォ劇場でのグアラチャ 19世紀、ブフォ劇場は、ユーモアにあふれ、クレオール化された登場人物とグアラチャで、奴隷解放運動とキューバ独立運動の一翼を担った。当局を批判し、 公人を揶揄し、英雄的な革命家を支援する役割を果たしたのである[16][17]。 1869年、ハバナのビジャヌエバ劇場で反スペイン的なブフォが上演されていたとき、突然スペイン人ヴォランタリオたちが劇場を襲撃し、10人ほどの観客 が殺された。その背景には、前年に10年戦争が始まり、カルロス・マヌエル・デ・セスペデスが奴隷を解放し、キューバ独立を宣言したことがあった。クレ オールの感情は高まり、植民地政府と裕福なスペイン人商人たちは反発していた。政治と音楽が密接に結びついたのは、これが最初でも最後でもなかった。この 悲劇的な出来事の後、ブフォの劇場は何年か閉鎖された。 グアラケージョは色つきのシャツに白いズボンとブーツ、頭にはハンカチ、女性は白いコートを着て入場し、グアラケージョを演奏する。一般的にグアラチャ は、ティプル、テノール、コーラスの掛け合いで進行する。舞台におけるグアラチャの最盛期は、20世紀初頭のハバナのアルハンブラ劇場で、ホルヘ・アンケ ルマン、ホセ・マリーン・ヴァローナ、マヌエル・マウリといった作曲家が、舞台のトップ歌手アドルフォ・コロンボのためにナンバーを書いた時であった [18]: ペペ・サンチェス、シンド・ガライ、マヌエル・コロナ、そして後にニーコ・サキートである。 |

| Lyrics The use of lyrics in theatre music is common, but their use in popular dance music was not common in the 18th and 19th centuries. Only the habanera had sung lyrics, and the guaracha definitely predates the habanera by some decades. Therefore, the guaracha is the first Cuban creole dance music which included singers. The Havana Diario de la Marina of 1868 says: "The bufo troupe, we think, has an extensive repertory of tasty guarachas, with which to keep its public happy, better than the Italian songs."[19] The lyrics were full of slang, and dwelt on events and people in the news. Rhythmically, guaracha exhibits a series of rhythm combinations, such as 6 8 with 2 4.[20][21] Alejo Carpentier quotes a number of guaracha verses that illustrate the style: Mi marido se murió, Dios en el cielo lo tiene y que lo tenga tan tenido que acá jamás nunca vuelva. (My husband died, God in heaven has him; May he keep him so well That he never comes back!) No hay mulata más hermosa. más pilla y más sandunguera, ni que tenga en la cadera más azúcar que mi Rosa. (There's no mulatta more gorgeous, more wicked and more spicy, nor one whose hips have got more sugar than my Rosa!) [22] |

歌詞 劇場音楽で歌詞が使われることはよくあるが、ポピュラーダンス音楽で歌詞が使われることは、18~19世紀には一般的ではなかった。歌詞が歌われたのはハ バネラだけで、グアラチャは間違いなくハバネラより何十年も前である。したがって、グアラチャは歌い手を含む最初のキューバ・クレオール舞踊音楽である。 1868年のHavana Diario de la Marinaによれば、「ブフォ一座は、イタリア歌曲よりも、大衆を満足させるような、おいしいグアラチャの幅広いレパートリーを持っていると思われる。 リズム的には、グアラチャは一連のリズムの組み合わせを示す。 8と2 4.[20][21] アレホ・カルペンティル(Alejo Carpentier)は、グアラチャのスタイルを示す多くの詩を引用している: 私の夫は死んだ、 天界の神がおられる 天上のディオスはそれを持っている 私の夫は死んだ。 (私の夫は死んだ、 天国の神が彼を連れている; 主人は死んだ。 彼が二度と戻ってこないように!) これほど美しい女性はいない。 MAS PILLA Y MAS SANDUNGUÉRA、 そして、その胸には MAS AZUCA QUE MI ROSA. (これほどゴージャスなムラッタはいない、 もっと邪悪で、もっとスパイシーだ、 私のロサほどゴージャスで、邪悪で、スパイシーなムラッタはいない。 (私のローザほどゴージャスで邪悪でスパイシーな混血はいない。) [22] |

| Guaracha in the 20th century In the mid-20th century the style was taken up by the conjuntos and big bands as a type of up-tempo music. Many of the early trovadores, such as Manuel Corona (who worked in a brothel area of Havana), composed and sung guarachas as a balance for the slower boleros and canciónes. Ñico Saquito was primarily a singer and composer of guarachas. The satirical lyric content also fitted well with the son, and many bands played both genres. Today it seems scarcely to exist as a distinct musical form, except in the hands of trova musicians; in larger groups it has been absorbed into the vast maw of salsa. Singers who could handle the fast lyrics and were good improvisors were called guaracheros or guaracheras. Celia Cruz was an example, though she, like Miguelito Valdés and Benny Moré, sung almost every type of Cuban lyric well. A better example is Cascarita (Orlando Guerra), who was distinctly less comfortable with boleros, but brilliant with fast numbers. In modern Cuban music so many threads are interwoven that one cannot easily distinguish these older roots. Perhaps in the lyrics of Los Van Van the topicality and sauciness of the old guarachas found new life, though the rhythm would have surprised the old-timers. Among other composers who have written guarachas is Morton Gould – the piece is found in the third movement of his Latin American Symphonette (Symphonette No. 4) (1940). Later in the 1980s Pedro Luis Ferrer and Virulo (Alejandro García Villalón) sought to renovate the guaracha, devising modern takes on the old themes. |

20世紀のグアラチャ 20世紀半ば、グアラチャはアップテンポの音楽としてコンフントやビッグバンドに取り入れられた。マヌエル・コロナ(Manuel Corona) (ハバナの売春宿街で働いていた)のような初期のトロバドールの多くは、ゆっくりとしたボレロやカンシオネスとのバランスをとるためにグアラチャを作曲 し、歌っていた。ニーコ・サキートは主にグアラチャを歌い、作曲した。風刺的な歌詞の内容は息子とも相性がよく、多くの楽団が両方のジャンルを演奏した。 現在では、トローバのミュージシャンの手によって演奏される以外は、独特の音楽形式として存在することはほとんどないようだ。 速い歌詞を操り、即興演奏に長けた歌手は、グアラチェロスまたはグアラチェーラと呼ばれた。ミゲリート・バルデスやベニー・モレのように、ほとんどすべて のタイプのキューバの歌詞を上手に歌ったセリア・クルスが その例だ。もっと良い例はカスカリータ(オルランド・ゲラ)で、彼女はボレロは苦手だったが、速いナンバーは素晴らしかった。現代のキューバ音楽では、多 くの糸が織り込まれているため、これらの古いルーツを簡単に見分けることはできない。おそらくロス・ヴァン・ヴァンの歌詞には、昔のグアラチャが持ってい た話題性や洒落っ気が新しい命を吹き込まれたのだろう。 グアラチャを作曲した作曲家にモートン・グールドがいるが、この曲は彼の『ラテン・アメリカン・シンフォネット(シンフォネット第4番)』(1940年) の第3楽章に収録されている。その後1980年代には、ペドロ・ルイス・フェレールとヴィルロ(アレハンドロ・ガルシア・ヴィラロン)がグアラチャの刷新 を図り、古いテーマを現代風にアレンジした。 |

| Guaracha in Puerto Rico During the 19th century, many Bufo Theater Companies arrived in Puerto Rico from Cuba, and they brought with them the guaracha. At a later time the guaracha was adopted in Puerto Rico and became part of the Puerto Rican musical tradition, such as the "Rosarios Cantaos", the Baquiné, the Christmas songs and the Children's songs. The guaracha is a style of song-dance which is also considered music for the Christmas "Parrandas" and concert popular music. Several modern genres, such as rumba and salsa, are considered to be influenced by the guaracha. The guaracha has been cultivated during the 20th century by Puerto Rican musicians such as Rafael Hernández, Pedro Flores, Bobby Capó, Tite Curet, Rafael Cortijo, Ismael Rivera, Francisco Alvarado, Luigi Teixidor and "El Gran Combo". Some famous guarachas are Hermoso Bouquet, Pueblo Latino, Borracho no vale, Compay póngase duro, Mujer trigueña, Marinerito and Piel Canela.[23] daniel santos -Toma jabón pa' que lave |

プエルトリコのグアラチャ 19世紀、多くのブフォ劇団がキューバからプエルトリコに到着し、グアラチャを持ち込んだ。その後、グアラチャはプエルトリコで採用され、「ロサリオス・ カンタオ」、バキネ、クリスマス・ソング、子供の歌など、プエルトリコ音楽の伝統の一部となった。 グアラチャは歌と踊りのスタイルで、クリスマスの「パランダ」やコンサートのポピュラー音楽の音楽ともなっている。ルンバやサルサなど、いくつかの現代的 なジャンルは、グアラチャの影響を受けていると考えられている。グアラチャは、ラファエル・エルナンデス、ペドロ・フローレス、ボビー・カポー、タイテ・ キュレット、ラファエル・コルティージョ、イスマエル・リベラ、フランシスコ・アルバラード、ルイジ・テイキシドール、「エル・グラン・コンボ」といった プエルトリコのミュージシャンたちによって20世紀に培われた。 有名なガラチャには、エルモソ・ブーケ、プエブロ・ラティーノ、ボラーチョ・ノー・ヴァレ、コンパイ・ポンガセ・ドゥーロ、ムヘール・トリゲーニャ、マリ ネリート、ピエル・カネラなどがある[23]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guaracha | |

Manuel

Corona Raimundo

(17 June 1880, in Caibarién – 9 January 1950 in Marianao, Havana) was a

Cuban trova musician, and a long-term professional rival of Sindo Garay. Manuel Corona one of the four greats of the trova [1] He came to Havana when the Cuban War of Independence broke out, and worked as a bootblack and a cigar-roller. His supervisor at the cigar factory taught him the guitar, and in 1905 he set up in a café in the red-light district of San Isidro. The district was controlled by the chulo (pimp) Alberto Yarini (1882–1910), who became famous for introducing French prostitutes (putas francesas) willing to perform more salacious acts than even the Cubans were used to.[2] The francesas cut heavily into the profits of the Cuban putas, and the result was a gang war in which Yarini was killed. Corona was present through all this, playing and singing to the punters, whores and pimps. He and one of the girls developed a love affair, and soon enough her pimp was on his trail. In a line that might have come from "Frankie and Johnny", Corona said later "She was a whore, and she had her man, but I liked her." The pimp came after him with a knife, and a cut to his hand prevented him playing the guitar again. From then on he lived from his compositions.[3] He wrote hundreds of compositions, some of them amongst the finest examples of Cuban sentiment, such as Mercedes, Longina, Santa Cecilia and Aurora. Guarachas such as El servicio obligatorio (National Service) and Acelera, Ñico, acelera were topical comments. La habanera was a deliberate reply to Garay's La bayamesa. Corona died in poverty.[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manuel_Corona_(musician) |

マヌエル・コロナ・ライムンド(1880年6月17日、カイバレン生ま

れ - 1950年1月9日、ハバナ、マリアナオ出身)は、キューバのトロバ音楽家で、シンド・ガライの長年のライバルだった。 マヌエル・コロナ トロバの四大巨頭の一人[1]。 キューバ独立戦争勃発と同時にハバナに渡り、靴磨きと葉巻職人として働いた。葉巻工場の上司からギターを教わり、1905年にサン・イシドロの歓楽街のカ フェに入った。この地区はチュロ(ポン引き)のアルベルト・ヤリーニ(1882年-1910年)が支配していたが、彼はキューバ人でさえ慣れていないよう な淫らな行為をしてくれるフランス人娼婦(プータ・フランセーサ)を連れてきたことで有名になった[2]。フランセーサはキューバ人プータたちの利益を大 きく削り、その結果、ヤリーニが殺されたギャングの抗争が起こった。 コローナはそのすべてに立ち会い、客、売春婦、ポン引きたちに演奏し、歌った。コロナと一人の女は恋に落ち、やがて彼女のポン引きがコロナを追うように なった。『フランキーとジョニー』に出てきそうなセリフだが、コロナは後にこう語っている。ポン引きはナイフを持って彼を追いかけ、手に切り傷を負った彼 は二度とギターを弾けなくなった。それ以来、彼は作曲で生活するようになった[3]。 彼は何百もの曲を書いたが、そのうちのいくつかは、メルセデス、ロンギナ、サンタ・セシリア、オーロラなど、キューバ情緒の最高傑作に数えられている。 El servicio obligatorio(国民服務義務)やAcelera, Ñico, aceleraなどのグアラチャは、時事的なコメントだった。La habanera(ラ・ハバネラ)は、ガライのLa bayamesa(ラ・バヤメサ)に対する意図的な返答であった。コローナは貧困の中で亡くなった[4]。 |

Trova

[ˈtɾoβa] is a style of Cuban popular music originating in the 19th

century. Trova was created by itinerant musicians known as trovadores

who travelled around Cuba's Oriente province, especially Santiago de

Cuba, and earned their living by singing and playing the guitar.[1]

According to nueva trova musician Noel Nicola, Cuban trovadors sang

original songs or songs written by contemporaries, accompanied

themselves on guitar, and aimed to feature music that had a poetic

sensibility.[2] This definition fits best the singers of boleros, and

less well the Afrocubans singing funky sones (El Guayabero) or even

guaguancós and abakuá (Chicho Ibáñez). It rules out, perhaps unfairly,

singers who accompanied themselves on the piano.[3] Casa de la Trova, Santiago de Cuba Trova musicians have played an important part in the evolution of Cuban popular music. Collectively, they have been prolific as composers, and have provided a start for many later musicians whose career lay in larger groupings. Socially, they reached every community in the country, and have helped to spread Cuban music throughout the world.[4] The founders Pepe Sánchez, born José Sánchez (Santiago de Cuba, 19 March 1856 – 3 January 1918), is known as the father of the trova style and the creator of the Cuban bolero.[5] He had some experience in bufo, but had no formal training in music. With remarkable natural talent, he composed numbers in his head and never wrote them down. As a result, most of these numbers are now lost forever, though some two dozen or so survive because friends and disciples wrote them down. His first bolero, Tristezas, is still remembered today. He also created advertisement jingles before the radio.[6] He was the model and teacher for the great trovadores who followed him.[7] The first, and one of the longest-lived, was Sindo Garay, born Antonio Gumersindo Garay Garcia (Santiago de Cuba, 12 April 1867 – Havana, 17 July 1968). He was the most outstanding composer of trova songs, and his best have been sung and recorded many times. Perla marina, Adiós a La Habana, Mujer bayamesa, El huracán y la palma, Guarina and many others are now part of Cuba's heritage. Garay was also musically illiterate – in fact, he only taught himself the alphabet at 16 – but in his case not only were scores recorded by others, but there are recordings as well. In the 1890s Garay got involved in the Cuban War of Independence, and decided a stay in Hispaniola (Haiti and Dominican Republic) would be a good idea. It was, and he came back with a wife. Garay settled in Havana in 1906, and in 1926 joined Rita Montaner and others to visit Paris, spending three months there singing his songs. He broadcast on radio, made recordings and survived into modern times. He used to say "Not many men have shaken hands with both José Martí and Fidel Castro!" Carlos Puebla, whose life spanned the old and the new trova, told a good joke about him: "Sindo celebrated his 100th birthday several times – in fact, whenever he was short of money!"[8][9]  The four greats of the trova from left: Rosendo Ruiz, Manuel Corona Sindo Garay, Alberto Villalón José 'Chicho' Ibáñez (Corral Falso,[10] 22 November 1875 – Havana, 18 May 1981)[11] was the first trovador (that we know of) to specialize in the son and also on guaguancós and afrocuban rhythms from the abakuá. He played the tres rather than the Spanish guitar, and developed his own technique for this Cuban guitar. During his extremely long career, Chicho sang and played the son in streets, plazas, cafés, nightclubs and other venues throughout Cuba. In the 1920s, when the sextetos became popular, he was forced to sell his compositions to these larger groups and their composers in order to survive. His compositions include Toma, mamá, que te manda tía, Evaristo, No te metas Caridad, Ojalá (sones); Yo era dichoso, Al fin mujer (bolero-sones); Qué más me pides, La saya de Oyá (guaguancós). He worked throughout Cuba, and latterly a short film was made of him ('See also' below). The composer Rosendo Ruiz (Santiago de Cuba, 1 March 1885 – Havana, 1 January 1983) was a trovador almost as long-lived as Ibáñez and Garay. He wrote the criolla Mares y Arenas in 1911, the workers' anthem Redención in 1917, the bolero Confesión, the guajira Junto al cañaveral and the pregón-son Se va el dulcerito. He was the author of a well-known guitar manual. Manuel Corona (Caibarién, 17 June 1880 – Havana 9 January 1950) started his career in a red-light district of Havana. Originally a singer-guitarist, he became a prolific composer after his hand was damaged by a pimp's knife. It was a case of "She was a whore, and she had her man, but I loved her". Alberto Villalón (Santiago de Cuba, 7 June 1882 – Havana 16 07 1955) advanced the trova guitar technique and had a hand in the birth of the son septetos. Garay, Ruiz, Villalón and Corona were known as the four greats of the trova, but Ibáñez and the following trovadores should be regarded as of equally high stature. The 20th century Patricio Ballagas (Camagüey, 17 March 1879 – Havana, 15 February 1920); Eusebio Delfín (Palmira, 1 April 1893 – Havana, 28 April 1965); María Teresa Vera (Guanajay, 6 February 1895 – Havana, 17 December 1965); Lorenzo Hierrezuelo (El Caney, 5 September 1907 – Havana, 16 November 1993); Joseíto Fernández (September 5, 1908 – October 11, 1979); Ñico Saquito (Antonio Fernandez: Santiago de Cuba, 1901 – Havana, 4 August 1982); Carlos Puebla (Manzanillo, 11 September 1917 – Havana, 12 July 1989) and Compay Segundo (Máximo Francisco Repilado Muñoz: Siboney, 18 November 1907 – Havana, 13 July 2003) were all great trova musicians. And let's not forget the Trío Matamoros, who worked together for most of their lives. Matamoros was one of the greats.[12] Most trovadors were creolized, drawing from both Spanish and African traditions and styles even-handedly. There were exceptions. Guillermo Portabales (Cienfuegos, 6 April 1911 – San Juan, Puerto Rico 25 October 1970) and Carlos Puebla were mostly in the guajiro (peasant) tradition, whilst El Guayabero – Faustino Oramas – (Holguín, 4 June 1911 – Holguín, 28 March 2007) was black and funky in style and content. He was the last of the old trova, the oldest working musician in Cuba, at 95, when he died. His double entendres were a joy.  Compay Segundo at the Hotel Nacional de Cuba Trova musicians often worked in pairs and trios, some of them exclusively solo (Compay Segundo). As the sextetos / septetos / conjuntos grew in popularity many trovadores joined in the larger groups. The technique of guitar-playing gradually improved; the early trovadors, being self-taught, had rather limited techniques. Later, some tapped into classical guitar techniques to revive the accompaniment of the trova. Guyún (Vincente Gonzalez Rubiera, Santiago de Cuba, 27 October 1908–Havana, 1987) studied under Severino López, and developed a modern concept of harmony, and a way to apply classical technique to popular Cuban music. He became more adventurous, yet still in Cuban vein, and in 1938 stopped performing to devote himself to teaching the guitar. This bore fruit, and two generations of Cuban guitarists bear witness to his influence. Perhaps the greatest guitarist amongst modern Cuban trovadors is Eliades Ochoa (b. Songo – La Maya, Santiago de Cuba, 22 June 1946), the leader of Cuarteto Patria. Ochoa learnt both Spanish guitar and the Cuban trés; Cuban composer and classical guitarist Leo Brouwer told him that he did not need to learn more about musical technique as he already knew too much! Ochoa plays now with an eight-stringed guitar (a self-designed hybrid of an acoustic six-string and the Cuban trés). Cuerteto Patría includes his brother Humberto Ochoa on guitar, son Eglis Ochoa on maracas, William Calderón on bass, Aníbal Ávila on claves and trumpet, and Roberto Torres on congas. Offshoots of the trova The trova movement has given rise to offshoots which have grown in the fertile musical earth of Cuba and other Latin-American countries. The following are elements in the trova's great influence: 1. The huge number of lyric compositions which have been used in all areas of Latin-American popular music. 2. Unforgettable musical compositions which became latin standards. 3. The bolero, the musical form most closely associated with the trova, and its relative the canción. 4. The development of guitar technique in popular music. 5. Themes and initiatives related to politico-social events, such as Afrocubanismo, Filín (feeling), and Nueva trova. Filin Main article: Filin The word is derived from feeling; it was a US–influenced popular musical fashion of the late 40s and the 50s. It describes a style of post-microphone jazz-influenced romantic song (crooning).[13] Its Cuban roots were in the bolero and the canción. Some Cuban quartets, such as Cuarteto d'Aida and Los Zafiros, modelled themselves on U.S. close-harmony groups. Others were singers who had heard Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan and Nat King Cole. Filín singers included César Portillo de la Luz, José Antonio Méndez, who spent a decade in Mexico from 1949 to 1959, Frank Domínguez, the blind pianist Frank Emilio Flynn, and the great singers of boleros Elena Burke and the still-performing Omara Portuondo, who both came from the Cuarteto d'Aida. The filín movement, which originally had a place every afternoon on Radio Mil Diez, survived the first few years of the revolution quite well, but somehow did not suit the new circumstances and gradually withered, leaving its roots in jazz, romantic song and the bolero perfectly healthy. Some of its most prominent singers, such as Pablo Milanés, took up the banner of the nueva trova. Nueva trova Main article: Nueva trova The Cuban Nueva trova dates from the 1967/68, after the Cuban Revolution of 1959, and the consequent political and social changes. It differed from the traditional trova, not because the musicians were younger, but because the content was, in the widest sense, political. Nueva trova is defined, not only by its connection with Castro's revolution, but also by its lyrics. The lyrics attempt to escape the banalities of life (e.g. love) by concentrating on socialism, injustice, sexism, colonialism, racism and similar 'serious' issues.[14] Silvio Rodríguez and Pablo Milanés became the most important exponents of this style. Carlos Puebla and Joseíto Fernández were long-time trova singers who added their weight to the new regime, but of the two only Puebla wrote special pro-revolution songs.[15] The regime gave plenty of support to musicians willing to write and sing anti-U.S. or pro-revolution songs; this was quite a bonus in an era when many of the traditional musicians were finding it difficult or impossible to earn a living. In 1967 the Casa de las Américas in Havana held a Festival de la canción de protesta (protest songs). Much of the effort was spent applauding causes that would annoy the U.S. government. Tania Castellanos, a filín singer and author, wrote ¡Por Angela! in support of Angela Davis. César Portillo de la Luz wrote Oh, valeroso Viet Nam.[16] These were hot topics of the 1970s, but their topicality declined as time passed. Nueva Trova, initially so popular, was dealt a blow by the fall of the Soviet Union, though it was already fading. It suffered inside Cuba, perhaps from a growing disenchantment with one-party rule, and externally, from the vivid contrast with the Buena Vista Social Club film and recordings. Audiences round the world have had their eyes opened to the extraordinary charm and musical quality of the older forms of Cuban music. By contrast, topical themes that seemed so relevant in the 1960s and 70s now seem dry and passé; once a theme is no longer topical, the piece rests solely on its musical quality. Those pieces of high musical and lyrical quality, amongst which Puebla's Hasta siempre stands out, will probably last as long as Cuba lasts.[17][18] Other notables The musicians featured here are a few notables amongst hundreds of excellent musicians living the same kind of life. No complete list exists, though the musicians listed below have been mentioned in at least one source.[19] After the name, one or two of their best compositions are noted: Salvador Adams ("Me causa celos") Ángel Almenares ("Por qué me engañaste?") José (Pepe) Banderas ("Boca roja") Emiliano Blez Garbey ("Besada por el mar") Julio Brito ("Flor de ausencia") Miguel Companioni ("Mujer perjura") Juan de Dios Hechavarria ("Mujer indigna", "Tiene Bayamo", "Laura") José (Pepe) Figarola Salazar ("Un beso en le alma") Graciano Gómez Vargas ("En falso", "Yo sé de esa mujer") Rafael Gómez (aka Teofilito) ("Pensamiento") Oscar Hernández Falcón ("Ella y yo", "La Rosa roja") Ramón Ivonet ("Levanta") Eulalio Limonta Manuel Luna Salgado ("La cleptómana") Nené Manfugás Rafael Saroza Valdés ("Guitarra mía") Duos, trios, groups During a career, a musician may work in many different line-ups. Because of the limited sonority of the guitar, trova musicians preferred small groups, or solo performances. Boleros tend to benefit from two voices, primo and segundo, giving to melodic phrases a richness in contrast with the basic rhythm of the cinquillo.[20] Duos Guaronex y Sindo: Sindo Garay and his son. Floro y Miguel: Floro Zorilla and Miguel Zaballa. Outstanding in their day. Floro y Cruz: Floro Zorilla and Juan Cruz. Cruz was a terrific baritone. Pancho Majagua y Tata Villegas: Francisco Salvo and Carlos Villegas. María Teresa y Zequieira: María Teresa Vera and Rafael Zequeira. Dúo Ana María y María Teresa: two female voices, Ana María García and Ma. Teresa Vera. Justa García also sang duo with each of these two women. Lorenzo Hierrezuelo and María Teresa Vera. José 'Galleguito' Parapar y Higinio Rodríguez. Juan de la Cruz y Bienvenido León. Manuel Luna y José Castillo. Dúo Hermanos Enriso: Enrique 'Chungo' and Rafael 'Nené' Enriso. Dúo Luna–Armiñan: Pablo Armiñan (primo) and Manuel Luna (segundo and guitar) Dúo Pablito–Castillo: Pablo Armiñan (primo) and Augusto Castillo (segundo). Dúo Pablito y Limonta: Pablo Armiñan (voz primo and guitar accompanist) and Juan Limonta (segunda, guitar and author). Extremely popular in Santiago de Cuba in the 1920s. Dúo Juanito Valdés y Rafael Enriso. Dúo Carbo–Quevedo: Pablo Quevedo (primo) and Panchito Carbó (segundo and guitar). Dúo Hermanas Martí: Amelia and Bertha. Dúo Sirique y Miguel: Alfredo 'Sirique' González and Miguel Doyble. Los Compadres: Lorenzo Hierrezuelo, first with Compay Segundo, then with Rey Caney. Trios Trio Palabras: Vania Martinez, Liane Pérez, Nubia González. See also 1977 Del hondo del corazón. 20min film, Dir. Constante Diego. Figures of the traditional trova talk and sing. 1974 Chicho Ibáñez. 11min film, Dir. Juan Carlos Tabío. Short film on the trovador José 'Chicho' Ibáñez (1875–1981), who talks and sings at the age of 99. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trova |

ト

ロバ[ˈtɾoβa]は、19世紀に生まれたキューバのポピュラー音楽のスタイルである。トロバは、キューバのオリエンテ州、特にサンティアゴ・デ・クー

バを旅し、歌とギターの演奏で生計を立てていたトロバドールと呼ばれる旅人音楽家たちによって創始された。 [1]

ヌエバ・トロバ・ミュージシャンのノエル・ニコラによれば、キューバのトロバドールはオリジナル曲や同時代のミュージシャンが書いた曲を歌い、ギターで伴

奏をつけ、詩的な感性を持った音楽を特徴とすることを目指した[2]。この定義は、ボレロスを歌うシンガーに最もよく当てはまり、ファンキーなソン(エ

ル・グアヤベーロ)やグアガンコスやアバクア(チチョ・イバニェス)を歌うアフロキューバ人にはあまり当てはまらない。おそらく不公平なことに、ピアノ伴

奏をする歌手は除外されている[3]。 カサ・デ・ラ・トロバ、サンティアゴ・デ・クーバ トロバの音楽家たちは、キューバのポピュラー音楽の発展において重要な役割を果たしてきた。集団として、彼らは作曲家として多作であり、より大きなグルー プでキャリアを積んだ多くの後進の音楽家に出発点を提供した。社会的にも、彼らはキューバのあらゆるコミュニティに働きかけ、キューバ音楽を世界中に広め ることに貢献した[4]。 創設者たち ホセ・サンチェス(José Sánchez、サンティアゴ・デ・クーバ、1856年3月19日~1918年1月3日)生まれのペペ・サンチェスは、トロバ・スタイルの父、キューバの ボレロの創始者として知られている[5]。驚くべき天賦の才能を持つ彼は、頭の中でナンバーを作曲し、それを書き留めることはなかった。その結果、これら のナンバーのほとんどは永久に失われてしまったが、20数曲は友人や弟子たちが書き留めたために残っている。彼の最初のボレロ『トリステーザス』は、今日 でも記憶に残っている。彼はまた、ラジオ以前の広告ジングルも創作した[6]。彼は、彼に続く偉大なトロヴァドールたちの手本であり、師であった[7]。 最初の、そして最も長生きした一人は、アントニオ・グメルシンド・ガルシア(Antonio Gumersindo Garay Garcia、サンティアゴ・デ・クーバ、1867年4月12日 - ハバナ、1968年7月17日)生まれのシンド・ガライ(Sindo Garay)である。彼はトロバの歌の最も優れた作曲家であり、彼の最高傑作は何度も歌われ、録音されている。Perla marina、Adiós a La Habana、Mujer bayamesa、El huracán y la palma、Guarina、その他多くの曲は、今やキューバの遺産の一部となっている。ガレイは音楽的な文盲でもあった。実際、彼は16歳の時にアル ファベットを独学で学んだだけだったが、彼の場合、楽譜が他の人によって録音されただけでなく、レコーディングも存在する。 1890年代、ガレイはキューバ独立戦争に巻き込まれ、イスパニョーラ(ハイチとドミニカ共和国)に滞在することを決めた。そうして彼は妻を連れて帰国し た。ガレイは1906年にハバナに定住し、1926年にはリタ・モンタネールらとパリを訪れ、そこで3ヶ月間自分の歌を歌った。彼はラジオで放送し、レ コーディングを行い、現代まで生き残った。彼はよく 「ホセ・マルティとフィデル・カストロの両方と握手した男はそうそういない!」と言っていた。カルロス・プエブラは、新旧のトロバにまたがる人生を送った が、彼についてジョークを言った: 「シンドは何度も100歳の誕生日を祝った。実際、お金がないときはいつでも!」[8][9]。  トロヴァの4人の偉人 左から ロセンド・ルイス、マヌエル・コロナ シンド・ガライ、アルベルト・ビジャロン ホセ・'チチョ'・イバニェス(コラル・ファルソ、1875年11月22日-ハバナ、1981年5月18日)[11]は、ソンを専門とし、グアガンコーや アバクアのアフロキューバのリズムも演奏した最初のトロバドールである。彼はスパニッシュ・ギターではなくトレスを弾き、このキューバ産ギターのために独 自のテクニックを開発した。非常に長いキャリアの間、チチョはキューバ中の路上、広場、カフェ、ナイトクラブなどで歌い、演奏した。1920年代、六重奏 団が人気を博すようになると、彼は生き残るために、自分の作曲した曲をこのような大きなグループやその作曲家たちに売り込むことを余儀なくされた。彼の作 曲した曲には、Toma, mamá, que te manda tía, Evaristo, No te metas Caridad, Ojalá(歌)、Yo era dichoso, Al fin mujer(ボレロ歌)、Qué más me pides, La saya de Oyá(グアガン歌)などがある。キューバ全土で活動し、後に短編映画も制作された(下記参照)。 作曲家ロセンド・ルイス(サンティアゴ・デ・クーバ、1885年3月1日-ハバナ、1983年1月1日)は、イバニェスやガライと同じくらい長命なトロバ ドールである。1911年にクリオラの「Mares y Arenas」、1917年に労働者賛歌「Redención」、ボレロの「Confesión」、グアヒーラの「Junto al cañaveral」、プレゴンの「Se va el dulcerito」を作曲した。有名なギター教則本の著者でもある。 マヌエル・コロナ(1880年6月17日カイバリェン - 1950年1月9日ハバナ)は、ハバナの歓楽街でキャリアをスタートさせた。元々はシンガー・ギタリストだったが、ポン引きのナイフで手を傷つけられた 後、多作な作曲家となった。彼女は売春婦で男もいたが、私は彼女を愛していた」というケースだった。アルベルト・ビジャロン(サンティアゴ・デ・クーバ、 1882年6月7日 - ハバナ、1955年7月16日)は、トロバ・ギターのテクニックを発展させ、息子セプテットの誕生に貢献した。 ガレイ、ルイス、ビジャロン、コロナがトロバの4大巨頭として知られているが、イバニェスやそれに続くトロバドールも同様に高い評価を受けるべきだろう。 20世紀 パトリシオ・バラガス(カマグエイ、1879年3月17日~ハバナ、1920年2月15日)、エウセビオ・デルフィン(パルミラ、1893年4月1日~ハ バナ、1965年4月28日)、マリア・テレサ・ベラ(グアナハイ、1895年2月6日~ハバナ、1965年12月17日)、ロレンソ・ヒエレスエロ(エ ル・カネイ、1907年9月5日~ハバナ、1993年11月16日)、ホセイト・フェルナンデス(1908年9月5日~1979年10月11日)、ニコ・ サキート(アントニオ・フェルナンデス: カルロス・プエブラ(マンサニージョ、1917年9月11日-ハバナ、1989年7月12日)、コンパイ・セグンド(マキシモ・フランシスコ・レピラー ド・ムニョス:シボニー、1907年11月18日-ハバナ、2003年7月13日)は、いずれも偉大なトロバ・ミュージシャンだった。そして、生涯の大半 を共にしたトリオ・マタモロスも忘れてはならない。マタモロスは偉大な人物の一人だった[12]。 ほとんどのトロバドールはクレオール化しており、スペインとアフリカの両方の伝統とスタイルを均等に取り入れていた。例外もあった。ギジェルモ・ポルタバ レス(Guillermo Portabales, Cienfuegos, 6 April 1911 - San Juan, Puerto Rico, 25 October 1970)とカルロス・プエブラ(Carlos Puebla)はグアヒーロ(農民)の伝統を受け継ぎ、エル・グアヤベーロ(El Guayabero - Faustino Oramas, Holguín, 4 June 1911 - Holguín, 28 March 2007)はスタイルも内容もブラックでファンキーだった。95歳で亡くなった彼は、キューバで最も高齢の現役ミュージシャン、オールド・トロバの最後の 一人だった。彼の二枚舌は楽しいものだった。  コンパイ・セグンド ホテル・ナシオナル・デ・クーバにて トロバの音楽家たちは、しばしば2人1組や3人組で活動したが、中にはもっぱらソロで活動する者もいた(コンパイ・セグンド)。六重奏/七重奏/コンフン トの人気が高まるにつれ、多くのトロヴァドールが大きなグループに加わった。 ギター演奏のテクニックは徐々に向上していったが、初期のトロヴァドールは独学だったため、テクニックはかなり限られていた。その後、クラシック・ギター のテクニックを取り入れて、トロヴァの伴奏を復活させた者もいる。グユン(Vincente Gonzalez Rubiera、サンティアゴ・デ・クーバ、1908年10月27日-ハバナ、1987年)は、セヴェリーノ・ロペスに師事し、和声の現代的な概念と、ポ ピュラーなキューバ音楽にクラシックのテクニックを応用する方法を開発した。1938年、ギターの指導に専念するため、演奏活動を休止した。これが実を結 び、2世代のキューバ人ギタリストが彼の影響を証明している。 現代のキューバ人ギタリストの中で最も偉大なのは、クアルテート・パトリアのリーダー、エリアデス・オチョア(1946年6月22日、サンティアゴ・デ・ クーバ、ソンゴ・ラ・マヤ生まれ)だろう。オチョアはスパニッシュ・ギターとキューバン・トレの両方を学んだ。キューバの作曲家でクラシック・ギタリスト のレオ・ブローウェルは彼に、音楽的テクニックについてはすでに知りすぎているので、これ以上学ぶ必要はないと言った!オチョアは現在、8弦ギター(ア コースティック6弦とキューバン・トレのハイブリッド)を使って演奏している。クエルテート・パトリアには、兄のウンベルト・オチョアがギター、息子のエ グリス・オチョアがマラカス、ウィリアム・カルデロンがベース、アニバル・アビラがクラベス、トランペット、ロベルト・トーレスがコンガで参加している。 トローバの分派 トローバ・ムーブメントは、キューバをはじめとするラテンアメリカ諸国の肥沃な音楽の大地で育った分派を生み出した。以下は、トローバが大きな影響力を持 つ要素である: 1. 1.ラテンアメリカのポピュラー音楽のあらゆる分野で使用されてきた膨大な数の抒情的楽曲。 2. ラテン・スタンダードとなった忘れがたい楽曲。 3. 3.ボレロは、トローバと最も密接に結びついた音楽形式であり、カンシオンはその親戚である。 4. ポピュラー音楽におけるギター奏法の発展 5. アフロキューバニスモ、フィリン(フィーリング)、ヌエバ・トロバなど、政治的・社会的出来事に関連したテーマと取り組み。 フィリン 主な記事 フィリン フィーリングから派生した言葉で、40年代後半から50年代にかけて米国の影響を受けたポピュラー音楽の流行である。マイクロフォン後のジャズの影響を受 けたロマンティックな歌(クルーニング)のスタイルを表す[13]。キューバのルーツはボレロとカンシオンである。クアルテート・ダイーダやロス・ザフィ ロスといったキューバのカルテットは、アメリカのクローズ・ハーモニー・グループを手本にしていた。また、エラ・フィッツジェラルドやサラ・ヴォーン、 ナット・キング・コールを聴いたことのある歌手もいた。フィリンの歌手には、セザール・ポルティージョ・デ・ラ・ルス、1949年から1959年までの 10年間をメキシコで過ごしたホセ・アントニオ・メンデス、フランク・ドミンゲス、盲目のピアニスト、フランク・エミリオ・フリン、ボレロスの大歌手エレ ナ・バークと現在も演奏活動を続けるオマーラ・ポルトゥオンドがいた。 もともとラジオ・ミル・ディエスで毎日午後に放送されていたフィリン・ムーブメントは、革命の最初の数年間はよく生き延びたが、どういうわけか新しい状況 には合わず、ジャズ、ロマンティック・ソング、ボレロのルーツは完全に健全なまま、次第に枯れていった。パブロ・ミラネスのような最も著名な歌手の何人か は、ヌエバ・トロバの旗を掲げた。 ヌエバ・トロバ 主な記事 ヌエバ・トロバ キューバのヌエバ・トロバは、1959年のキューバ革命とそれに伴う政治的・社会的変化の後、1967年から68年にかけて生まれた。伝統的なトローバと 異なるのは、音楽家が若かったからではなく、その内容が広い意味で政治的だったからである。ヌエバ・トロバは、カストロ革命との関連だけでなく、その歌詞 によっても定義される。歌詞は、社会主義、不正義、性差別、植民地主義、人種差別、そして同様の「深刻な」問題に集中することで、人生の平凡さ(例えば恋 愛)から逃れようとする。カルロス・プエブラとホセイト・フェルナンデスは、新体制に重きを置いた長年のトローバ歌手だったが、2人のうちプエブラだけが 特別に親革命的な曲を書いた[15]。 多くの伝統的な音楽家が生計を立てることが困難か不可能であった時代には、これは非常に喜ばしいことであった。1967年、ハバナのカサ・デ・ラス・アメ リカスは、プロテスト・ソング・フェスティバルを開催した。その努力の多くは、アメリカ政府を困らせるような大義名分に拍手を送ることに費やされた。フィ リピン人歌手であり作家でもあるタニア・カステジャーノスは、アンジェラ・デイヴィスを支持して『アンジェラのために!』を書いた。セサル・ポルティー ジョ・デ・ラ・ルスは『ああ、ヴェトナム』を書いた[16]。これらは1970年代のホットなトピックだったが、時が経つにつれて話題性は薄れていった。 ヌエバ・トローバは、当初は非常に人気があったが、ソビエト連邦の崩壊によって打撃を受けた。キューバ国内では、おそらく一党支配への幻滅の高まりから、 また対外的には、ブエナ・ビスタ・ソシアル・クラブの映画やレコーディングとの鮮やかなコントラストから、苦境に立たされた。世界中の聴衆は、キューバ音 楽の古い形式が持つ並外れた魅力と音楽的な質に目を見開かされた。それとは対照的に、1960年代や70年代にはとても適切だと思われた話題性のあるテー マは、今では乾いて古臭く感じられる。プエブラの「Hasta siempre」が傑出しているように、高い音楽性と叙情性を備えた作品は、おそらくキューバが存続する限り続くだろう[17][18]。 その他の著名人 ここで取り上げたミュージシャンは、同じような生活を送っている何百人もの優れたミュージシャンの中の数少ない著名人である。完全なリストは存在しない が、以下に挙げる音楽家は少なくとも1つの情報源で言及されている[19]。 名前の後に、彼らの最も優れた作曲の1つか2つが記されている: サルバドール・アダムス(「Me causa celos) アンヘル・アルメナーレス(「Por qué me engañaste?) ホセ(ペペ)・バンデラス(「Boca roja」) エミリアーノ・ブレス・ガルベイ("Besada por el mar) フリオ・ブリトー(「オーセンシアの花) ミゲル・コンパニオニ("Mujer perjura) フアン・デ・ディオス・ヘチャバリア(「Mujer indigna」、「Tiene Bayamo」、「Laura」) ホセ(ペペ)・フィガロラ・サラサール(「Un beso en le alma」) グラシアーノ・ゴメス・バルガス(「En falso」、「Yo sé de esa mujer」) ラファエル・ゴメス(別名テオフィリート)("ペンサミエント) オスカル・エルナンデス・ファルコン(「Ella y yo」、「La Rosa roja) ラモン・イボネット(『レバンタ) エウラリオ・リモンタ マヌエル・ルナ・サルガド(「ラ・クレプトマナ) ネネ・マンフガス ラファエル・サロサ・バルデス(「Guitarra mía) デュオ、トリオ、グループ ミュージシャンはキャリアの中で、さまざまな編成で活動することがある。ギターの音域は限られているため、トローバの音楽家は小編成のグループやソロ演奏 を好んだ。ボレロは、プリモとセグンドの2声部がメロディックなフレーズに豊かさを与え、チンキージョの基本的なリズムとは対照的である[20]。 デュオ グアロネックスとシンド シンド・ガライとその息子。 フロロ・イ・ミゲル:フロロ・ゾリージャとミゲル・サバラ。当時は傑出した存在だった。 フロロ・イ・クルス フロロ・ゾリージャとフアン・クルス。クルスは素晴らしいバリトンだった。 パンチョ・マジャグアとタタ・ビジェガス: フランシスコ・サルボとカルロス・ビジェガス。 マリア・テレサ・イ・ゼケイラ:マリア・テレサ・ベラとラファエル・ゼケイラ。 ドゥオ・アナ・マリア・イ・マリア・テレサ:2人の女声、アナ・マリア・ガルシアとMa. Teresa Veraである。フスタ・ガルシアもこの2人の女性とデュオを組んだ。 ロレンソ・ヒエレスエロとマリア・テレサ・ベラ。 ホセ'ガレギート'パラパルとヒギニオ・ロドリゲス。 フアン・デ・ラ・クルスとビエンベニド・レオン。 マヌエル・ルナとホセ・カスティーリョ ドゥオ・エルマノス・エンリソ エンリケ'チュンゴ'とラファエル'ネネ'エンリソ。 ドゥオ・ルナ・アルミニャン パブロ・アルミニャン(プリモ)とマヌエル・ルナ(セグンドとギター) ドゥオ・パブリート=カスティーリョ:パブロ・アルミーニャン(プリモ)とアウグスト・カスティーリョ(セグンド) ドゥオ・パブリート・イ・リモンタ パブロ・アルミーニャン(プリモ、ギター伴奏)とフアン・リモンタ(セグンダ、ギター、作家)。1920年代にサンティアゴ・デ・クーバで絶大な人気を 誇った。 ドゥオ・フアニト・バルデスとラファエル・エンリソ。 ドゥオ・カルボ=ケベド:パブロ・ケベド(プリモ)とパンチート・カルボ(セグンド、ギター)。 ドゥオ・エルマナス・マルティ アメリアとベルサ。 ドゥオ・シリケ・イ・ミゲル:アルフレド'シリケ'ゴンサレスとミゲル・ドイブル。 ロス・コンパドレス ロレンソ・ヒエレスエロ、最初はコンパイ・セグンドと、その後レイ・カネイと。 トリオ トリオ・パラブラス: バニア・マルティネス、リアン・ペレス、ヌビア・ゴンサレス。 以下も参照のこと。 1977年 心臓の鼓動。20分映画、監督:コンスタンテ・ディエゴ。コンスタンテ・ディエゴ監督。伝統的なトローバの人々が語り、歌う。 1974年 チチョ・イバニェス。11分の映画、監督:フアン・カルロス・タビオ。フアン・カルロス・タビオ監督。99歳にして語り、歌うトロバドール、ホセ・'チ チョ'・イバニェス(1875-1981)の短編映画。 |

SON DE LA LOMA - Trío Matamoros(キューバのグアラチャ)

daniel santos -Toma jabón pa' que lave(プエルトリコのグアラチャ)

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆