ハイチ革命

Haitian Revolution

Portrait of

Jean-Baptiste Belley by Anne-Louis Girodet de

Roussy-Trioson, 1797

☆

ハイチ革命(フランス語: Révolution haïtienne [ʁevɔlysjɔ̃ a.isján]またはGuerre de

l'indépendance、ハイチ・クレオール語: Lagè d

Lendependans)は、サン=ドマング(現在のハイチ)において、フランスの植民地支配に対して自力で解放された奴隷たちによって成功した反乱で

ある[2]。

この革命は、奴隷制から解放され(強制労働から解放されたわけではないが)[3]、非白人と元捕虜によって統治される国家の建国につながった、人類史上唯

一の奴隷の反乱として知られている[4]。

反乱は1791年8月22日に始まり[5]、1804年に旧植民地の独立によって終結した。この革命には、黒人、両人種、フランス人、スペイン人、イギリ

ス人、ポーランド人が参加し、元奴隷のトゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュールがハイチの最も著名な将軍として頭角を現した。革命の成功は大西洋世界の歴史におけ

る決定的な瞬間であり[6][7]、奴隷制度に対する革命の影響はアメリカ大陸全体に及んだ。フランスの支配が終わり、旧植民地における奴隷制度が廃止さ

れた後、旧奴隷が獲得した自由を守ることに成功し、すでに自由であった有色人種の協力のもと、白人ヨーロッパ人からの独立が実現した[8][9]

[10]。

この革命は、約1900年前にスパルタクスがローマ共和国に対して反乱を起こし失敗して以来、最大の奴隷蜂起であり[11]、黒人の劣等性や奴隷が自らの

自由を獲得し維持する能力について長年ヨーロッパで信じられてきた信念に挑戦した。反乱軍の組織力と圧力下での粘り強さは、半球の奴隷所有者に衝撃と恐怖

を与える物語を鼓舞した[12]。

歴史家のミシェル=ロルフ・トルイヨは、ハイチ革命の歴史学はフランス革命の歴史学に「沈黙させられている」と評している[13][14][15]。

| The Haitian

Revolution (French: Révolution haïtienne [ʁevɔlysjɔ̃ a.isjɛn] or Guerre

de l'indépendance; Haitian Creole: Lagè d Lendependans) was a

successful insurrection by self-liberated slaves against French

colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti.[2]

The revolution was the only known slave uprising in human history that

led to the founding of a state which was both free from slavery (though

not from forced labour)[3] and ruled by non-whites and former

captives.[4] The revolt began on 22 August 1791,[5] and ended in 1804 with the former colony's independence. It involved black, biracial, French, Spanish, British, and Polish participants—with the ex-slave Toussaint Louverture emerging as Haiti's most prominent general. The successful revolution was a defining moment in the history of the Atlantic World[6][7] and the revolution's effects on the institution of slavery were felt throughout the Americas. The end of French rule and the abolition of slavery in the former colony was followed by a successful defense of the freedoms the former slaves had won, and with the collaboration of already free people of color, of their independence from white Europeans.[8][9][10] The revolution was the largest slave uprising since Spartacus' unsuccessful revolt against the Roman Republic nearly 1,900 years earlier,[11] and challenged long-held European beliefs about alleged black inferiority and about slaves' ability to achieve and maintain their own freedom. The rebels' organizational capacity and tenacity under pressure inspired stories that shocked and frightened slave owners in the hemisphere.[12] Compared to other Atlantic revolutions, the events in Haiti have received comparatively little public attention in retrospect: historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot characterizes the historiography of the Haitian Revolution as being "silenced" by that of the French Revolution.[13][14][15] |

ハイチ革命(フランス語: Révolution

haïtienne [ʁevɔlysjɔ̃ a.isján]またはGuerre de l'indépendance、ハイチ・クレオール語:

Lagè d

Lendependans)は、サン=ドマング(現在のハイチ)において、フランスの植民地支配に対して自力で解放された奴隷たちによって成功した反乱で

ある[2]。

この革命は、奴隷制から解放され(強制労働から解放されたわけではないが)[3]、非白人と元捕虜によって統治される国家の建国につながった、人類史上唯

一の奴隷の反乱として知られている[4]。 反乱は1791年8月22日に始まり[5]、1804年に旧植民地の独立によって終結した。この革命には、黒人、両人種、フランス人、スペイン人、イギリ ス人、ポーランド人が参加し、元奴隷のトゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュールがハイチの最も著名な将軍として頭角を現した。革命の成功は大西洋世界の歴史におけ る決定的な瞬間であり[6][7]、奴隷制度に対する革命の影響はアメリカ大陸全体に及んだ。フランスの支配が終わり、旧植民地における奴隷制度が廃止さ れた後、旧奴隷が獲得した自由を守ることに成功し、すでに自由であった有色人種の協力のもと、白人ヨーロッパ人からの独立が実現した[8][9] [10]。 この革命は、約1900年前にスパルタクスがローマ共和国に対して反乱を起こし失敗して以来、最大の奴隷蜂起であり[11]、黒人の劣等性や奴隷が自らの 自由を獲得し維持する能力について長年ヨーロッパで信じられてきた信念に挑戦した。反乱軍の組織力と圧力下での粘り強さは、半球の奴隷所有者に衝撃と恐怖 を与える物語を鼓舞した[12]。 歴史家のミシェル=ロルフ・トルイヨは、ハイチ革命の歴史学はフランス革命の歴史学に「沈黙させられている」と評している[13][14][15]。 |

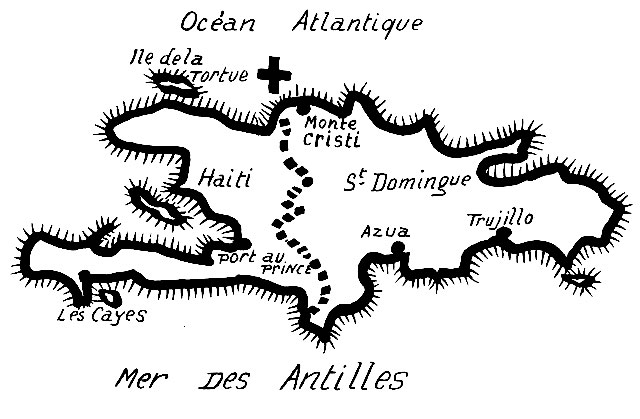

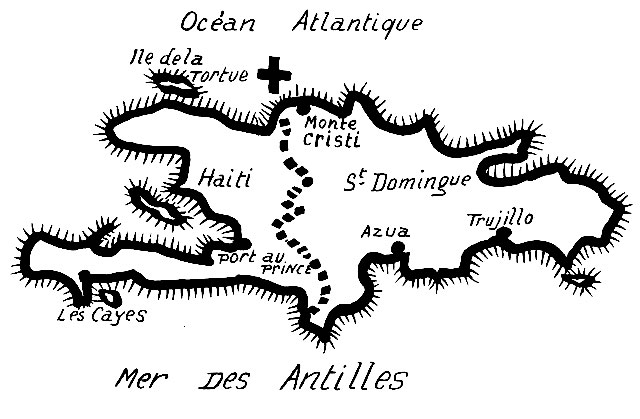

| Background Slave economy in Saint-Domingue Much of Caribbean economic development in the 18th century was contingent on Europeans' demand for sugar. Plantation owners produced sugar as a commodity crop from cultivation of sugarcane, which required extensive labor. The colony of Saint-Domingue also had extensive coffee, cocoa, and indigo plantations, but these were smaller and less profitable than the sugar plantations.[16] The commodity crops were traded for European goods. Starting in the 1730s, French engineers constructed complex irrigation systems to increase sugarcane production. By the 1740s, Saint-Domingue, together with the British colony of Jamaica, had become the main suppliers of the world's sugar. Production of sugar depended on extensive manual labor provided by enslaved Africans. An average of 600 ships engaged every year in shipping products from Saint-Domingue to Bordeaux, and the value of the colony's crops and goods was almost equal in value to all of the products shipped from the Thirteen Colonies to Great Britain.[17] The livelihood of 1 million of the approximately 25 million people who lived in France in 1789 depended directly upon the agricultural imports from Saint-Domingue, and several million indirectly depended upon trade from the colony to maintain their standard of living.[18] Saint-Domingue was the most profitable French colony in the world, indeed one of the most profitable of all the European colonies in the 18th century. Slavery sustained sugar production under harsh conditions; diseases such as malaria (brought from Africa) and yellow fever caused high mortality, thriving in the tropical Caribbean climate. In 1787 alone, approximately 20,000 slaves were transported from Africa to Saint-Domingue, in comparison to the roughly 38,000 slaves that were imported to the British West Indies.[17] The death rate from yellow fever was such that at least 50% of the slaves from Africa died within a year of arriving, so while the white planters preferred to work their slaves as hard as possible, providing them only the bare minimum of food and shelter, they calculated that it was better to get the most work out of their slaves with the lowest expense possible, since they were probably going to die of yellow fever anyway.[19] The death rate was so high that polyandry—one woman being married to several men at the same time—developed as a common form of marriage among the slaves.[19] As slaves had no legal rights, rape by planters, their unmarried sons, or overseers was a common occurrence on the plantations.[20]  Haitian-drawn map of the island of Ayiti / Quisqueya, 1937 |

背景 サン=ドマングにおける奴隷経済 18世紀のカリブ海の経済発展の多くは、ヨーロッパ人の砂糖需要に依存していた。プランテーションの所有者は、大規模な労働力を必要とするサトウキビの栽 培から、商品作物として砂糖を生産した。サン=ドマングー植民地には、コーヒー、カカオ、インディゴのプランテーションもあったが、これらは砂糖プラン テーションよりも小規模で収益性も低かった[16]。 1730年代から、フランスの技術者たちはサトウキビ生産を増やすために複雑な灌漑システムを建設した。1740年代までに、サン=ドマングーは、イギリ スの植民地ジャマイカとともに、世界の砂糖の主要供給国となった。砂糖の生産は、奴隷にされたアフリカ人による大規模な手作業に依存していた。サン=ドマ ングからボルドーへの製品出荷には、毎年平均600隻の船が従事しており、植民地の農作物と商品の価値は、13植民地からイギリスに出荷されるすべての製 品とほぼ同額であった[17]。[1789年にフランスに住んでいた約2500万人の人民のうち100万人がサン=ドマングからの農産物の輸入に直接依存 し、数百万人が間接的にサン=ドマングからの貿易に依存して生活水準を維持していた[18]。サン=ドマングは世界で最も収益性の高いフランスの植民地で あり、18世紀のヨーロッパの植民地の中でも最も収益性の高い植民地の一つであった。 マラリア(アフリカから持ち込まれた)や黄熱病などの病気は、カリブ海の熱帯気候の中で繁殖し、高い死亡率をもたらした。1787年だけでも、アフリカか らサン=ドマングーに運ばれた奴隷は約2万人で、イギリス領西インド諸島に輸入された奴隷が約3万8千人であったのと比較すると、その差は歴然である [17]。[17]黄熱病による死亡率は、アフリカからの奴隷の少なくとも50%が到着後1年以内に死亡するほどであった。そのため、白人の耕作者たちは 奴隷をできるだけ過酷に働かせ、最低限の食料と住居しか与えないことを好んだが、彼らは、奴隷はどうせ黄熱病で死ぬのだろうから、できるだけ低い費用で奴 隷から多くの労働を引き出した方がよいと計算した。[19]死亡率が非常に高かったため、一人の女性が複数の男性と同時に結婚する一夫多妻制が奴隷の間で 一般的な結婚形態として発展した[19]。 奴隷には法的権利がなかったため、プランテーションではプランターやその未婚の息子、監督によるレイプが日常茶飯事であった[20]。  Haitian-drawn map of the island of Ayiti / Quisqueya, 1937 |

| Demographics The largest sugar plantations and concentrations of slaves were in the north of the island, and whites lived in fear of slave rebellion.[21] Even by the standards of the Caribbean, French slave masters were extremely cruel in their treatment of slaves.[17] They used the threat and acts of physical violence to maintain control and suppress efforts at rebellion. When slaves left the plantations or disobeyed their masters, they were subject to whipping or to more extreme torture such as castration or burning, the punishment being both a personal lesson and a warning for other slaves. King Louis XIV of France passed the Code Noir in 1685 in an attempt to regulate such violence and the treatment of slaves in general in the colony, but masters openly and consistently broke the code. During the 18th century, local legislation reversed parts of it.[22][page needed] In 1758, the planters began passing legislation restricting the rights of other groups of people until a rigid caste system was defined. Most historians classify the people of the era into three groups: The first group were white colonists, or les blancs. This group was generally subdivided into the plantation owners and a lower class of whites who often served as overseers or day laborers, as well as artisans and shopkeepers. The second group were free people of color, or gens de couleur libres, who were usually mixed-race (sometimes referred to as mulattoes), being of both African and French descent. These gens de couleur tended to be educated and literate, and the men often served in the army or as administrators on plantations. Many were children of white planters and enslaved mothers, or free women of color. Others had purchased their freedom from their owners through the sale of their own produce or artistic works. They often received education or artisan training, and sometimes inherited freedom or property from their fathers. Some gens de couleur owned and operated their own plantations and became slave owners. The third group, outnumbering the others by a ratio of ten to one, was made up of mostly African-born slaves. A high rate of mortality among them meant that planters continually had to import new slaves. This kept their culture more African and separate from other people on the island. Many plantations had large concentrations of slaves from a particular region of Africa, and it was therefore somewhat easier for these groups to maintain elements of their culture, religion, and language. This also separated new slaves from Africa from creoles (slaves born in the colony), who already had kin networks and often had more prestigious roles on plantations and more opportunities for emancipation.[22] Most slaves spoke a patois of the French language known as Haitian Creole, which was also used by island-born mulattoes and whites for communication with the workers.[23] The majority of the slaves were Yoruba from what is now modern Nigeria, Fon from what is now Benin, and Kongo from the Kingdom of Kongo in what is now modern northern Angola and the western Congo.[24] The Kongolese at 40% were the largest of the African ethnic groups represented amongst the slaves.[19] The slaves developed their own religion, a syncretic mixture of Catholicism and West African religions known as Vodou, usually called "voodoo" in English. This belief system implicitly rejected the Africans' status as slaves.[25] |

人口動態 最大の砂糖プランテーションと奴隷の集中地は島の北部であり、白人は奴隷の反乱を恐れて生活していた[21]。 カリブ海の基準から見ても、フランスの奴隷主人たちは奴隷に対して非常に残酷な扱いをしていた[17]。彼らは支配を維持し、反乱の努力を抑制するため に、脅しや肉体的な暴力行為を用いた。奴隷が農園を去ったり、主人に逆らったりすると、鞭打ちや、去勢や火あぶりなどのより極端な拷問が行われた。フラン ス国王ルイ14世は、植民地におけるこのような暴力と奴隷の扱い全般を規制するため、1685年にノワール法典を制定したが、主人たちは公然と一貫してこ の法典を破っていた。18世紀には、地方法によってその一部が覆された[22][要出典]。 1758年、プランターたちは、厳格なカースト制度が定義されるまで、他のグループの人民の権利を制限する法律を通過させ始めた。ほとんどの歴史家は当時の人民を3つのグループに分類している: 第一のグループは、白人の入植者(les blancs)である。このグループは一般に、プランテーションの所有者と、監督や日雇い労働者、職人や店主を務めることの多い下層階級の白人に細分化された。 第二のグループは有色人種(gens de couleur libres)の自由民で、通常アフリカ系とフランス系の混血の人種であった。これらの有色人種は教育を受け、識字率が高い傾向があり、男性はしばしば軍 隊やプランテーションの管理者として働いた。多くは、白人プランターと奴隷にされた母親、あるいは有色人種の自由な女性との間の子どもであった。また、自 分の農産物や芸術作品の販売を通じて、所有者から自由を買い取った者もいた。彼らはしばしば教育や職人の訓練を受け、父親から自由や財産を相続することも あった。自分の農園を経営し、奴隷所有者となった有色人種もいた。 第3のグループは、他のグループを10対1の割合で上回り、ほとんどがアフリカ生まれの奴隷で構成されていた。彼らの死亡率は高く、プランターは絶えず新 しい奴隷を輸入しなければならなかった。そのため、彼らの文化はよりアフリカ的で、島の他の人民から切り離されていた。多くのプランテーションでは、アフ リカの個別主義地域出身の奴隷が集中していたため、これらのグループにとっては、彼らの文化、宗教、言語の要素を維持することがいくらか容易であった。こ のことはまた、アフリカからの新しい奴隷と、すでに親族ネットワークを持っていたクレオール(植民地で生まれた奴隷)とを分け、しばしばプランテーション でより名誉ある役割を持ち、奴隷解放の機会も多かった[22]。ほとんどの奴隷はハイチ・クレオールとして知られるフランス語のパトワを話し、島生まれの 混血や白人も労働者とのコミュニケーションに使用していた[23]。 奴隷の大多数は、現在のナイジェリア出身のヨルバ人、現在のベナン出身のフォン人、現在のアンゴラ北部とコンゴ西部のコンゴ王国出身のコンゴ人であった[24]。この信仰体系は、アフリカ人が奴隷であることを暗に否定していた[25]。 |

| Social conflict Saint-Domingue was a society seething with hatred, with white colonists and black slaves frequently coming into violent conflict. The French historian Paul Fregosi wrote: "Whites, mulattos and blacks loathed each other. The poor whites couldn't stand the rich whites, the rich whites despised the poor whites, the middle-class whites were jealous of the aristocratic whites, the whites born in France looked down upon the locally born whites, mulattoes envied the whites, despised the blacks and were despised by the whites; free Negroes brutalized those who were still slaves, Haitian born blacks regarded those from Africa as savages. Everyone—quite rightly—lived in terror of everyone else. Haiti was hell, but Haiti was rich."[26] — The French historian Paul Fregosi Many of these conflicts involved slaves who had escaped the plantations. Many runaway slaves—called maroons—hid on the margins of large plantations, living off the land and what they could steal from their former masters. Others fled to towns, to blend in with urban slaves and freed blacks who often migrated to those areas for work. If caught, these runaway slaves would be severely and violently punished. However, some masters tolerated petit marronages, or short-term absences from plantations, knowing these allowed release of tensions.[22] The larger groups of runaway slaves who lived in the hillside woods away from white control often conducted violent raids on the island's sugar and coffee plantations. Although the numbers in these bands grew large (sometimes into the thousands), they generally lacked the leadership and strategy to accomplish large-scale objectives. The first effective maroon leader to emerge was the charismatic Haitian Vodou priest François Mackandal, who inspired his people by drawing on African traditions and religions. He united the maroon bands and established a network of secret organizations among plantation slaves, leading a rebellion from 1751 through 1757. Although Mackandal was captured by the French and burned at the stake in 1758, large armed maroon bands persisted in raids and harassment after his death.[21][27] |

社会紛争 サン=ドマングーは憎しみが渦巻く社会であり、白人入植者と黒人奴隷はしばしば激しく対立した。フランスの歴史家ポール・フレゴシはこう書いている: 「白人、混血、黒人は互いに憎み合っていた。貧乏な白人は金持ちの白人に我慢できず、金持ちの白人は貧乏な白人を軽蔑し、中流階級の白人は貴族の白人に嫉 妬し、フランス生まれの白人は地元生まれの白人を見下し、混血は白人を妬み、黒人を軽蔑し、白人に軽蔑された。自由ニグロはまだ奴隷だった人々を残虐に扱 い、ハイチ生まれの黒人はアフリカから来た人々を野蛮人と見なした。誰もが-まったく当然のことだが-他人を恐れて生きていた。ハイチは地獄だったが、ハ イチは豊かだった」[26]。 - フランスの歴史家ポール・フレゴシ こうした紛争の多くは、プランテーションから逃亡した奴隷が関わっていた。逃亡奴隷の多くはマルーンと呼ばれ、大規模プランテーションの境界に潜み、土地 と元の主人から盗めるものだけで生活していた。また、都市部の奴隷や自由の身となった黒人たちに紛れ込むために、町に逃げ込む者もいた。これらの逃亡奴隷 は、捕まれば厳しく、暴力的に罰せられた。しかし、一部の主人たちは、プチ・マロナージュ(短期間の農園からの不在)を容認し、それが緊張の緩和を可能に することを知っていた[22]。 白人の支配から離れた山腹の森に住んでいた逃亡奴隷の大きな集団は、しばしば島の砂糖やコーヒーのプランテーションに暴力的な襲撃を加えた。これらの集団 の人数は大きくなったが(時には数千人規模)、一般的に大規模な目的を達成するためのリーダーシップと戦略を欠いていた。最初に現れた効果的なマルーン指 導者は、ハイチのカリスマ的ヴードゥー司祭フランソワ・マッカンダルで、彼はアフリカの伝統と宗教を利用して人民を鼓舞した。彼はマルーン人のバンドを団 結させ、農園奴隷の間に秘密組織のネットワークを築き、1751年から1757年まで反乱を指導した。マッカンダルは1758年にフランス軍に捕らえられ 火あぶりにされたが、彼の死後も大規模な武装したマルーンの一団が襲撃や嫌がらせを続けた[21][27]。 |

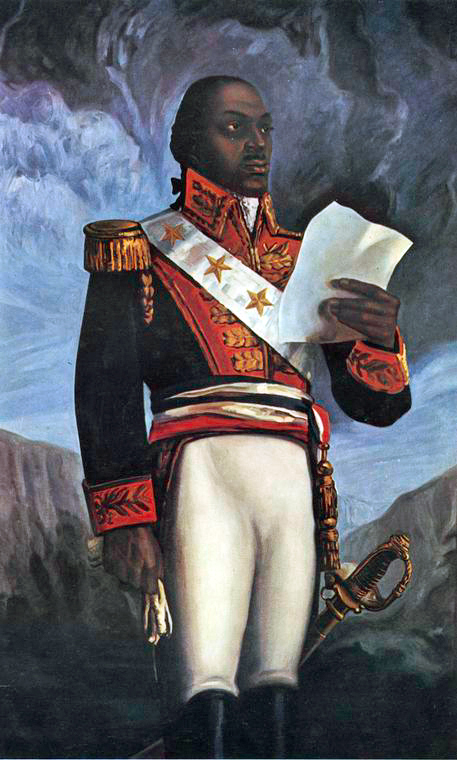

| Slavery in Enlightenment thought French writer Guillaume Raynal attacked slavery in his history of European colonization. He warned, "the Africans only want a chief, sufficiently courageous, to lead them on to vengeance and slaughter."[28] Raynal's Enlightenment philosophy went deeper than a prediction and reflected many similar philosophies, including those of Rousseau and Diderot. Raynal's admonition was written thirteen years before the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which highlighted freedom and liberty but did not abolish slavery.  Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Belley by Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, 1797 In addition to Raynal's influence, Toussaint Louverture, a free black who was familiar with Enlightenment ideas within the context of European colonialism, would become a key "enlightened actor" in the Haitian Revolution. Enlightened thought divided the world into "enlightened leaders" and "ignorant masses."[29] Louverture sought to bridge this divide between the popular masses and the enlightened few by striking a balance between Western Enlightened thought as a necessary means of winning liberation, and not propagating the notion that it was morally superior to the experiences and knowledge of people of color on Saint-Domingue.[30][31] Louverture wrote a constitution for a new society in Saint-Domingue that abolished slavery. The existence of slavery in Enlightened society was an incongruity that had been left unaddressed by European scholars prior to the French Revolution. Louverture took on this inconsistency directly in his constitution. In addition, he exhibited a connection to Enlightenment scholars through the style, language,and accent of this text.[clarification needed][32][page needed] Like Louverture, Jean-Baptiste Belley was an active participant in the insurrection. The portrait of Belley by Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson depicts a man who encompasses the French view of its colonies, creating a stark dichotomy between the refinement of Enlightenment thought and the reality of the situation in Saint-Domingue, through the bust of Raynal and the figure of Belley, respectively. While distinguished, the portrait still portrays a man trapped by the confines of race. Girodet's portrayal of the former National Convention deputy is telling of the French opinion of colonial citizens by emphasizing the subject's sexuality and including an earring. Both of these racially charged symbols reveal the desire to undermine the colony's attempts at independent legitimacy, as citizens of the colonies were not able to access the elite class of French Revolutionaries because of their race.[33] |

啓蒙思想における奴隷制度 フランスの作家ギヨーム・レイナルはヨーロッパの植民地化の歴史の中で奴隷制を攻撃した。彼は、「アフリカ人は、復讐と殺戮へと彼らを導く、十分に勇気の ある酋長だけが欲しいのだ」と警告した[28]。レイナルの啓蒙思想は、予言以上に深く、ルソーやディドロを含む多くの類似した哲学を反映していた。レイ ナルの勧告は、自由と解放を強調しながら奴隷制を廃止しなかった「人間と市民の権利宣言」の13年前に書かれた。  ジャン=バティスト・ベレーの肖像 アンヌ=ルイ・ジロデ・ド・ルーシー=トリオソン作 1797年 レイナルの影響に加え、ヨーロッパの植民地主義の文脈の中で啓蒙思想に親しんでいた自由黒人トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュールは、ハイチ革命における重要な 「啓蒙主義者」となる。啓蒙思想は世界を「啓蒙された指導者」と「無知な大衆」に分けていた[29]。ルーヴェルチュールは、解放を勝ち取るために必要な 手段としての西洋の啓蒙思想と、それがサン=ドマングーに住む有色人種の経験や知識よりも道徳的に優れているという考え方を広めないこととのバランスをと ることで、大衆と少数の啓蒙主義者との間のこの溝を埋めようとした[30][31]。啓蒙社会における奴隷制の存在は、フランス革命以前のヨーロッパの学 者たちによって放置されてきた矛盾であった。ルーヴェルチュールは自らの憲法の中で、この矛盾を直視した。さらに、彼はこの文章の文体、言葉遣い、アクセ ントを通して啓蒙主義の学者たちとのつながりを示した[clarification needed][32][page needed]。 ルーヴェルチュールと同様、ジャン=バティスト・ベレーも反乱に積極的に参加した。アンヌ=ルイ・ジロデ・ド・ルーシー=トリオソンによるベレーの肖像画 は、フランスの植民地観を包括する人物を描いており、レイナルの胸像とベレーの姿を通して、それぞれ啓蒙思想の洗練とサン=ドマングの現実との間に厳しい 二項対立を生み出している。肖像画は際立ったものではあるが、人種という枠に囚われた人間を描いていることに変わりはない。ジロデが描いた元国民大会副議 長の肖像は、被写体のセクシュアリティを強調し、耳飾りをつけることで、植民地市民に対するフランスの見方を物語っている。植民地の市民は、人種を理由に フランス革命家のエリート階級に近づくことができなかったからである[33]。 |

| Situation in 1789 Social stratification In 1789, Saint-Domingue produced 60% of the world's coffee and 40% of the sugar imported by France and Britain. The colony was not only the most profitable possession of the French colonial empire, but it was the wealthiest and most prosperous colony in the Caribbean.[17] The colony's white population numbered 40,000; mulattoes and free blacks, 28,000; and black slaves, an estimated 452,000.[34] This was almost half the total slave population in the Caribbean, estimated at one million that year.[35] Enslaved blacks, regarded as the lowest class of colonial society, outnumbered whites and free people of color by a margin of almost eight to one.[36] Two-thirds of the slaves were African born, and they tended to be less submissive than those born in the Americas and raised in slave societies.[37] The death rate in the Caribbean exceeded the birth rate, so imports of enslaved Africans were necessary to maintain the numbers required to work the plantations. The slave population declined at an annual rate of two to five percent, due to overwork, inadequate food and shelter, insufficient clothing and medical care, and an imbalance between the sexes, with more men than women.[38] Some slaves were of a creole elite class of urban slaves and domestics, who worked as cooks, personal servants and artisans around the plantation house. This relatively privileged class was chiefly born in the Americas, while the under-class born in Africa labored hard, and often under abusive and brutal conditions. Among Saint-Domingue's 40,000 white colonists, European-born Frenchmen monopolized administrative posts. The sugar planters, or grands blancs (literally, "big whites"), were chiefly minor aristocrats. Most returned to France as soon as possible, hoping to avoid the dreaded yellow fever, which regularly swept the colony.[39] The lower-class whites, petits blancs (literally "small whites"), included artisans, shopkeepers, slave dealers, overseers, and day laborers. Saint-Domingue's free people of color, or gens de couleur libres, numbered more than 28,000. Around that time, colonial legislations, concerned with this growing and strengthening population, passed discriminatory laws that required these freedmen to wear distinctive clothing and limited where they could live. These laws also barred them from occupying many public offices.[16] Many freedmen were also artisans and overseers, or domestic servants in the plantation houses.[40] Le Cap Français (Le Cap), a northern port, had a large population of free people of color, including freed slaves. These men would become important leaders in the slave rebellion and later revolution.[22] |

1789年の状況 社会階層 1789年、サン=ドマングーは世界のコーヒーの60%、フランスとイギリスが輸入する砂糖の40%を生産していた。同植民地はフランス植民地帝国で最も収益性の高い領地であっただけでなく、カリブ海で最も裕福で繁栄した植民地であった[17]。 植民地の白人人口は40,000人、混血と自由黒人は28,000人、黒人奴隷は452,000人と推定された[34]。 これは、その年に100万人と推定されたカリブ海の奴隷総人口のほぼ半分であった[35]。植民地社会の最下層階級とみなされた奴隷化された黒人は、白人 と自由有色人種をほぼ8対1の境界で上回っていた[36]。 奴隷の3分の2はアフリカ生まれであり、アメリカ大陸で生まれ奴隷社会で育った奴隷よりも従順でない傾向があった[37]。カリブ海では死亡率が出生率を 上回っていたため、プランテーションで働くために必要な数を維持するためには奴隷となったアフリカ人の輸入が必要であった。奴隷の人口は、過労、不十分な 食料と住居、不十分な衣服と医療、女性よりも男性の方が多いという男女間の不均衡[38]のために、年間2~5パーセントの割合で減少した。一部の奴隷 は、プランテーションの家の周りで料理人、人格奉仕者、職人として働く都市奴隷と家政婦のクレオール・エリート階級であった。この比較的特権的な階級は主 にアメリカ大陸で生まれたが、アフリカで生まれた下層階級は過酷な労働を強いられ、しばしば虐待的で残忍な条件の下で働いた。 サン=ドマングの4万人の白人入植者のうち、ヨーロッパ生まれのフランス人が行政のポストを独占していた。砂糖のプランター、つまりグラン・ブラン(文字 通り「大きな白人」)は、主に小貴族だった。下層階級の白人、プティ・ブラン(小白人)には、職人、商店主、奴隷商人、監督、日雇い労働者などがいた。 サン=ドマングの自由有色人(gens de couleur libres)は28,000人以上であった。その頃、植民地の立法府は、増加し強化されるこの人口を懸念し、これらの自由民に特徴的な衣服の着用を義務 付け、居住地を制限する差別的な法律を制定した。これらの法律はまた、多くの公職に就くことを禁じていた[16]。多くの自由民はまた、職人や監督、ある いはプランテーションの家事使用人でもあった[40]。北部の港であるル・キャップ・フランセ(ル・キャップ)には、解放奴隷を含む有色人種の自由民が多 く住んでいた。これらの人々は奴隷の反乱や後の革命において重要な指導者となる[22]。 |

| Regional conflicts Saint-Domingue's Northern province was the center of shipping and trading, and had the largest population of grands blancs.[41] The Plaine-du-Nord on the northern shore of Saint-Domingue was the most fertile area, having the largest sugar plantations and therefore the most slaves. It was the area of greatest economic importance, especially as most of the colony's trade went through these ports. The largest and busiest port was Le Cap, the former capital of Saint-Domingue.[22] Enslaved Africans in this region lived in large groups of workers in relative isolation, separated from the rest of the colony by the high mountain range known as the Massif du Nord. The Western province, however, grew significantly after the colonial capital was moved to Port-au-Prince in 1751, becoming increasingly wealthy in the second half of the 18th century. The Southern province lagged in population and wealth because it was geographically separated from the rest of the colony. However, this isolation allowed freed slaves to find profit in trade with Jamaica, and they gained power and wealth here.[22] In addition to these interregional tensions, there were conflicts between proponents of independence, those loyal to France, and allies of Britain and Spain—who coveted control of the valuable colony. |

地域紛争 サン=ドマング北部の県は海運と交易の中心地であり、グラン・ブランの人口が最も多かった[41]。サン=ドマング北岸のプレイン=デュ=ノールは最も肥 沃な地域であり、最大の砂糖プランテーションがあったため、奴隷が最も多かった。特に植民地の貿易のほとんどがこれらの港を経由していたため、経済的に最 も重要な地域であった。この地域の奴隷となったアフリカ人は、マシフ・デュ・ノールとして知られる高い山脈によって植民地の他の地域から隔てられ、相対的 に孤立した状態で大規模な労働者集団として暮らしていた[22]。 しかし、西部州は1751年に植民地首都がポルトープランスに移された後に大きく発展し、18世紀後半にはますます裕福になった。南部州は地理的に植民地 の他の地域から切り離されていたため、人口と富の面で遅れをとった。このような地域間の緊張に加え、独立支持者、フランスに忠誠を誓う者、貴重な植民地の 支配権を狙うイギリスやスペインの同盟国との対立があった。 |

| Effects of the French Revolution Further information: French Revolution After the establishment of the French First Republic, the National Assembly made radical changes to French laws and, on 26 August 1789, published the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, declaring all men free and equal. The Declaration was ambiguous as to whether this equality applied to women, slaves, or citizens of the colonies, and thus influenced the desire for freedom and equality in Saint-Domingue. White planters saw it as an opportunity to gain independence from France, which would allow them to take control of the island and create trade regulations that would further their own wealth and power.[16] However, the Haitian Revolution quickly became a test of the new French republic, as it radicalized the slavery question and forced French leaders to recognize the full meaning of their stated ideology.[42] The African population on the island began to hear of the agitation for independence by the planters, who had resented France's limitations on the island's foreign trade. The Africans mostly allied with the royalists and the British, as they understood that if Saint-Domingue's independence were to be led by white slave masters, it would probably mean even harsher treatment and increased injustice for the African population. The planters would be free to operate slavery as they pleased without the existing minimal accountability to their French peers.[41] Saint-Domingue's free people of color, most notably Julien Raimond, had been actively appealing to France for full civil equality with whites since the 1780s. Raimond used the French Revolution to make this the major colonial issue before the National Assembly. In October 1790, another wealthy free man of color, Vincent Ogé, demanded the right to vote under the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. When the colonial governor refused, Ogé led a brief 300-man insurgency in the area around Le Cap, fighting to end racial discrimination in the area.[43] He was captured in early 1791, and brutally executed by being "broken on the wheel" before being beheaded.[44] While Ogé was not fighting against slavery, his treatment was cited by later slave rebels as one of the factors in their decision to rise up in August 1791 and resist treaties with the colonists. The conflict up to this point was between factions of whites, and between whites and free blacks. Enslaved blacks watched from the sidelines.[21] Leading 18th-century French writer Count Mirabeau had once said the Saint-Domingue whites "slept at the foot of Vesuvius",[45] suggesting the grave threat they faced should the majority of slaves launch a sustained major uprising. |

フランス革命の影響 さらに詳しい情報 フランス革命 フランス第一共和制の成立後、国民議会はフランスの法律を抜本的に改正し、1789年8月26日に「人間と市民の権利宣言」を発表し、すべての人間が自由 で平等であることを宣言した。この宣言は、この平等が女性、奴隷、植民地の市民に適用されるのか曖昧であったため、サン=ドマングにおける自由と平等への 願望に影響を与えた。白人のプランターたちは、これをフランスから独立する好機と捉え、島を支配し、自分たちの富と権力をさらに高めるような貿易規制を作 ることを可能にした[16]。しかし、ハイチ革命はすぐに新しいフランス共和国の試練となり、奴隷制問題を急進化させ、フランスの指導者たちは自分たちが 表明したイデオロギーの完全な意味を認識することを余儀なくされた[42]。 島のアフリカ系住民は、島の外国貿易に対するフランスの制限に憤慨していたプランターによる独立運動を耳にするようになった。アフリカ人たちは、サン=ド マングの独立が白人の奴隷所有者によって主導されることになれば、おそらくアフリカ系住民にとってさらに過酷な待遇と不正の拡大を意味することを理解して いたため、ほとんどが王党派とイギリスに味方した。耕作者たちは、フランスの同業者に対する既存の最低限の説明責任を負うことなく、好きなように奴隷制度 を運営する自由を得ることになる[41]。 サン=ドマングの自由人民、とりわけジュリアン・ライモンは、1780年代から白人との完全な市民的平等をフランスに積極的に訴えていた。ライモンはフラ ンス革命を利用して、この問題を国民議会における植民地問題の主要課題とした。1790年10月、もう一人の裕福な有色人種の自由人、ヴァンサン・オジェ は、人間と市民の権利宣言に基づく選挙権を要求した。植民地総督がこれを拒否すると、オジェはル・キャップ周辺地域で300人規模の反乱を短期間起こし、 この地域の人種差別をなくすために戦った[43]。 彼は1791年初めに捕らえられ、斬首される前に「轆轤で壊される」という残酷な処刑を受けた[44]。 オジェは奴隷制度に反対して戦っていたわけではなかったが、彼の扱いは後の奴隷反乱軍が1791年8月に蜂起し、植民地との条約に抵抗する決意をした要因 の一つとして挙げられている。この時点までの対立は、白人の派閥間、および白人と自由黒人との間のものだった。奴隷にされた黒人たちは傍観していた [21]。 18世紀のフランスを代表する作家であるミラボー伯爵は、かつてサン=ドマングーの白人は「ヴェスヴィオ火山のふもとで眠っていた」と述べており[45]、大多数の奴隷が持続的に大規模な反乱を起こした場合に、彼らが直面する重大な脅威を示唆していた。 |

| 1791 slave rebellion Main article: 1791 slave rebellion Further information: Slavery in Haiti |

1791年の奴隷反乱 主な記事 1791年奴隷の反乱 さらに詳しい情報 ハイチの奴隷制度 |

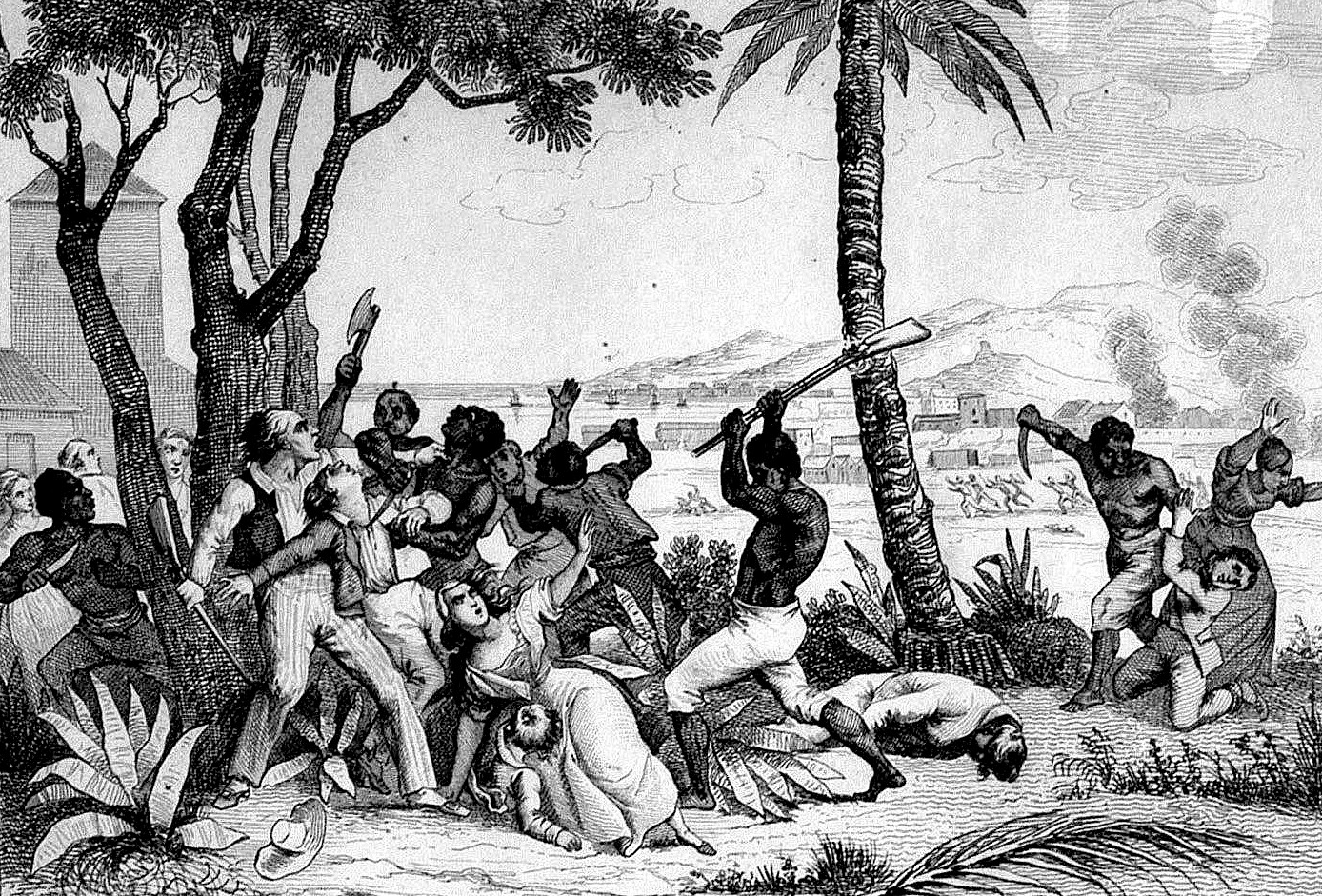

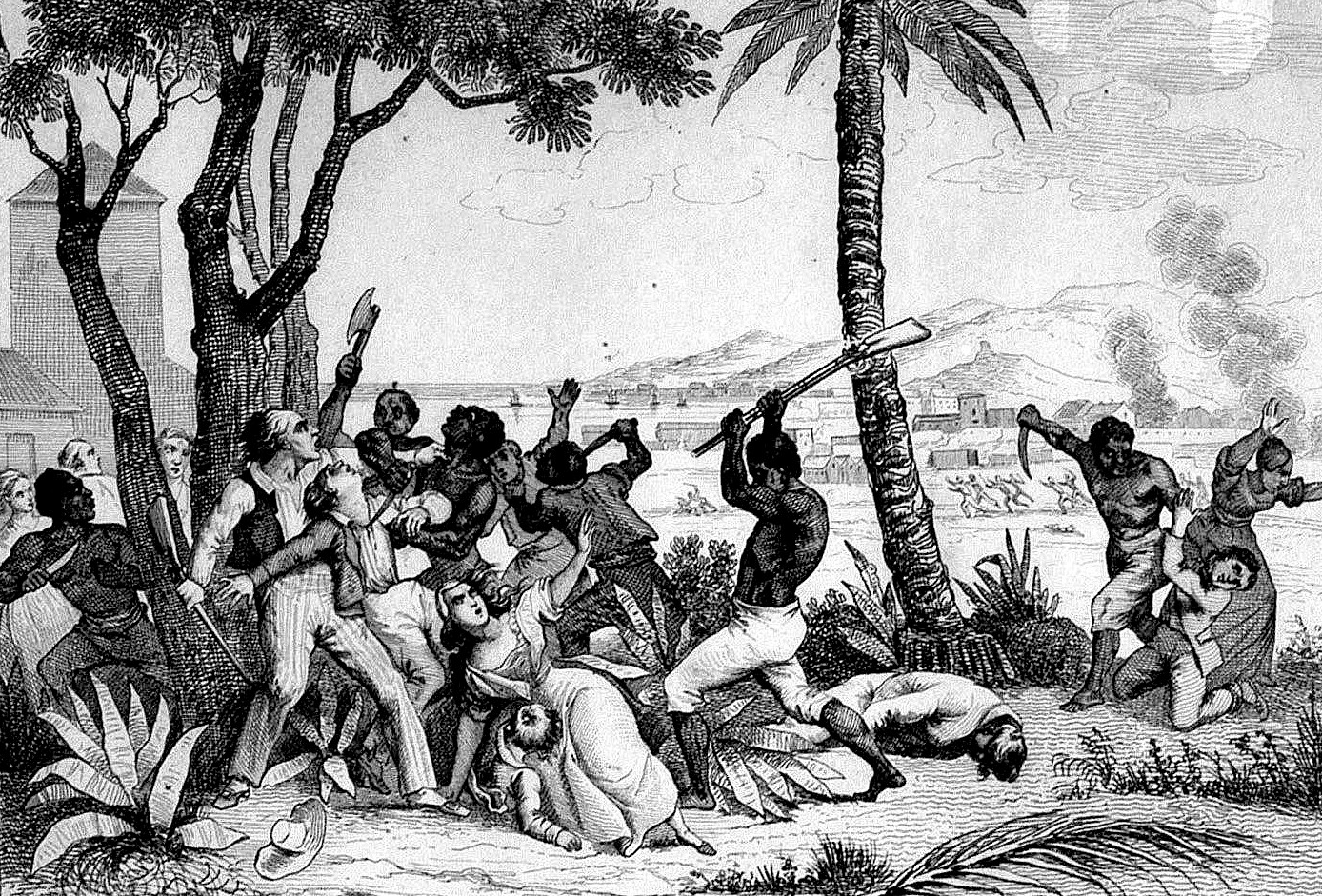

| Onset of the revolution Guillaume Raynal attacked slavery in the 1780 edition of his history of European colonization. He also predicted a general slave revolt in the colonies, saying that there were signs of "the impending storm".[46] One such sign was the action of the French revolutionary government to grant citizenship to wealthy free people of color in May 1791. Since white planters refused to comply with this decision, within two months isolated fighting broke out between the former slaves and the whites. This added to the tense climate between slaves and grands blancs.[47] Raynal's prediction came true on the night of 21 August 1791, when the slaves of Saint-Domingue rose in revolt; thousands of slaves attended a secret vodou ceremony as a tropical storm came in — the lightning and the thunder were taken as auspicious omens — and later that night, the slaves began to kill their masters and plunged the colony into civil war.[48] The signal to begin the revolt had been given by Dutty Boukman, a high priest of vodou and leader of the Maroon slaves, and Cecile Fatiman during a religious ceremony at Bois Caïman on the night of 14 August.[49] Within the next ten days, slaves had taken control of the entire Northern Province in an unprecedented slave revolt. Whites kept control of only a few isolated, fortified camps. The slaves sought revenge on their masters through "pillage, rape, torture, mutilation, and death".[50] The long years of oppression by the planters had left many blacks with a hatred of all whites, and the revolt was marked by extreme violence from the very start. The masters and mistresses were dragged from their beds to be killed, and the heads of French children were placed on pikes that were carried at the front of the rebel columns.[48] In the south, beginning in September, thirteen thousand slaves and rebels led by Romaine-la-Prophétesse, based in Trou Coffy, took supplies from and burned plantations, freed slaves, and occupied (and burned) the area's two major cities, Léogâne and Jacmel.[51][52][53][54] The planters had long feared such a revolt, and were well armed with some defensive preparations. But within weeks, the number of slaves who joined the revolt in the north reached 100,000. Within the next two months, as the violence escalated, the slaves killed 4,000 whites and burned or destroyed 180 sugar plantations and hundreds of coffee and indigo plantations.[50] At least 900 coffee plantations were destroyed, and the total damage inflicted over the next two weeks amounted to 2 million francs.[55] In September 1791, the surviving whites organized into militias and struck back, killing about 15,000 blacks.[55] Though demanding freedom from slavery, the rebels did not demand independence from France at this point. Most of the rebel leaders professed to be fighting for the king of France, who they believed had issued a decree freeing the slaves, which had been suppressed by the colonial governor. As such, they were demanding their rights as Frenchmen which had been granted by the king.[56] |

革命の勃発 ギョーム・レイナルは、1780年版のヨーロッパ植民地化史の中で奴隷制を攻撃した。彼はまた、植民地における一般的な奴隷反乱を予測し、「差し迫った 嵐」の兆候があると述べた[46]。そのような兆候のひとつは、1791年5月にフランス革命政府が裕福な自由有色人種に市民権を与えるという行動をとっ たことであった。白人のプランターがこの決定に従うことを拒否したため、2ヵ月以内に元奴隷と白人の間で孤立した戦闘が勃発した。これは奴隷とグラン・ブ ランとの間の緊張した情勢に拍車をかけた[47]。 レイナルの予言は1791年8月21日の夜に的中し、サン=ドマングの奴隷たちは反乱を起こした。何千人もの奴隷たちが、熱帯性暴風雨がやってくる中、秘 密のヴォドゥーの儀式に参加した。[48]反乱開始の合図は、8月14日の夜、ボワ・カイマンで行われた宗教儀式において、ヴードゥーの高僧でありマルー ン人奴隷の指導者であったダッティ・ブークマンとセシル・ファティマンによって出された[49]。それから10日以内に、奴隷たちは前代未聞の奴隷反乱で 北部州全体を掌握した。白人は少数の孤立した要塞化されたキャンプだけを支配下に置いた。奴隷たちは「略奪、強姦、拷問、切断、死」[50]によって主人 たちに復讐しようとした。長年にわたるプランターによる抑圧によって、多くの黒人はすべての白人を憎むようになり、反乱は最初から極端な暴力によって特徴 づけられた。主人や女主人は寝床から引きずり出されて殺され、フランス人の子供たちの首は反乱軍の隊列の先頭に担がれる矛の上に置かれた[48]。南部で は9月から、ロメーヌ=ラ=プロフェテス率いる1万3,000人の奴隷と反乱軍がトゥルー・コフィを拠点に、プランテーションから物資を奪って焼き払い、 奴隷を解放し、この地域の2つの主要都市であるレオガンヌとジャクメルを占領した(そして焼き払った)[51][52][53][54]。 耕作者たちは長い間このような反乱を恐れており、ある程度の防衛準備で武装していた。しかし、数週間のうちに北部で反乱に参加した奴隷の数は10万人に達 した。その後2ヶ月の間に暴力がエスカレートし、奴隷たちは4,000人の白人を殺害し、180の砂糖プランテーションと数百のコーヒーと藍のプランテー ションを焼き払った[50]。 奴隷制からの解放を要求していたが、反乱軍はこの時点ではフランスからの独立を要求していなかった。反乱軍の指導者たちのほとんどは、フランス国王のため に戦っていると公言しており、フランス国王は、植民地総督によって弾圧された奴隷解放令を出したと考えていた。そのため、彼らは国王によって与えられてい たフランス人としての権利を要求していた[56]。 |

Slave rebellion of 1791 By 1792, slave rebels controlled a third of Saint-Domingue.[57] The success of the rebellion caused the National Assembly to realize it was facing an ominous situation. The Assembly granted civil and political rights to free men of color in the colonies in March 1792.[50] Countries throughout Europe, as well as the United States, were shocked by the decision, but the Assembly was determined to stop the revolt. Apart from granting rights to free people of color, the Assembly dispatched 6,000 French soldiers to the island.[58] A new governor sent by Paris, Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, abolished slavery in the Northern Province and had hostile relations with the planters, whom he saw as royalists.[59] The same month, a coalition of whites and conservative free blacks and forces under French commissaire nationale Edmond de Saint-Léger put down the Trou Coffy uprising in the south,[53][60][61] after André Rigaud, then based near Port-au-Prince, declined to ally with them.[62] |

1791年の奴隷反乱 1792年までに、奴隷の反乱軍はサン・ドマングの3分の1を支配していた[57] 。反乱の成功により、国民議会は不吉な状況に直面していることを認識した。国民議会は1792年3月、植民地の有色人種自由人に市民的・政治的権利を付与 した[50]。ヨーロッパ諸国やアメリカはこの決定に衝撃を受けたが、国民議会は反乱を阻止する決意を固めた。パリから派遣された新しい総督レジェ=フェ リシテ・ソントナックスは北部州の奴隷制を廃止し、王党派とみなした耕作者と敵対的な関係を持った。[59]同じ月、白人と保守的な自由黒人の連合軍とフ ランスの国家委員エドモン・ド・サン=レジェ率いる軍が南部でトゥルー・コフィの反乱を鎮圧したが[53][60][61]、当時ポルトープランス近郊に 拠点を置いていたアンドレ・リゴーが彼らとの同盟を断念した後であった[62]。 |

| Britain and Spain enter the conflict Meanwhile, in 1793, France declared war on Great Britain. The grands blancs in Saint-Domingue, unhappy with Sonthonax, pleaded with British authorities in Jamaica for assistance against the Republican commissioners.[59] The first Pitt ministry of Great Britain, in particular Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger and Secretary of State for War Henry Dundas, made plans to invade Saint-Domingue. Both men recognised the financial value of the colony and its status as a useful bargaining chip in possible peace negotiations with France. Furthermore, they were concerned the ongoing slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue could lead to similar unrest in the British West Indies.[63] Dundas instructed Sir Adam Williamson, the lieutenant-governor of Jamaica, to sign an agreement with representatives of counterrevolutionary French colonists in the colony which promised to restore the ancien régime, discrimination against free people of color and protect slavery, a move that drew criticism from British abolitionists William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson.[64][65] The troops who came to Saint-Domingue from Britain had an extremely low survival rate, often dying to diseases such as yellow fever. The British government would send less trained adolescents to maintain strong regiments. The incompetence of the new soldiers, combined with the ravaging of disease upon the army, led to a very unsuccessful campaign in Saint-Domingue.[65] The American journalist James Perry notes that the great irony of the British campaign in Saint-Domingue was that it ended as a complete debacle, costing the British treasury millions of pounds and the British military thousands upon thousands of dead, all for nothing.[66] Spain, which controlled the rest of the island of Hispaniola (Santo Domingo), also joined the conflict and fought with Britain against France. The proportion of slaves was not as high in the Spanish portion of the island. Spanish forces invaded Saint-Domingue and were joined by the rebels. For most of the conflict, the British and Spanish supplied the rebels with food, ammunition, arms, medicine, naval support, and military advisors. By August 1793, there were only 3,500 French soldiers on the island. On 20 September 1793, about 600 British soldiers from Jamaica landed at Jérémie to be greeted with shouts of, "Vivent les Anglais!" from the French population.[67] On 22 September 1793, Mole St. Nicolas, the main French naval base in Saint-Domingue, surrendered to the Royal Navy peacefully.[68] |

イギリスとスペインが参戦 一方、1793年、フランスはイギリスに宣戦布告した。ソントナックスに不満を抱いていたサン=ドマングのグラン・ブランは、ジャマイカのイギリス当局に 共和国委員会に対する援助を嘆願した[59]。イギリスの第一ピット省、特にウィリアム・ピット青年首相とヘンリー・ダンダス陸軍国務長官は、サン=ドマ ング侵攻を計画した。両者は植民地の経済的価値とフランスとの和平交渉の切り札としての地位を認めていた。ダンダスはジャマイカの副知事アダム・ウィリア ムソン卿に、アンシャン・レジームの復活、有色人種自由人に対する差別、奴隷制の保護を約束した協定に、植民地の反革命的なフランス人入植者の代表と署名 するよう指示した。[64][65] イギリスからサン=ドマングに派遣された部隊の生存率は極めて低く、黄熱病などの病気で死亡することも多かった。イギリス政府は、強力な連隊を維持するた めに、あまり訓練されていない青年を送ることになった。アメリカのジャーナリスト、ジェームズ・ペリーは、サン=ドマングにおけるイギリスの作戦の大きな 皮肉は、それが大失敗に終わったことであり、イギリス国庫は数百万ポンドを失い、イギリス軍は何千何万という死者を出したが、すべては無駄であったと述べ ている[66]。 残りのイスパニョーラ島(サント・ドミンゴ)を支配していたスペインもこの紛争に参加し、イギリスとともにフランスと戦った。島のスペイン領では奴隷の割 合はそれほど高くなかった。スペイン軍はサン・ドミンゴに侵攻し、反乱軍と合流した。紛争のほとんどの期間、イギリスとスペインは反乱軍に食糧、弾薬、武 器、医薬品、海軍支援、軍事顧問を供給した。1793年8月までに島にいたフランス兵はわずか3,500人だった。1793年9月20日、ジャマイカから 約600人のイギリス兵がジェレミーに上陸し、フランス人住民から「アングレを生き返らせろ!」という叫び声で迎えられた[67]。1793年9月22 日、サン=ドマングにおけるフランス海軍の主要拠点であったモール・サン=ニコラはイギリス海軍に平和的に降伏した[68]。 |

| French declare slavery abolished To prevent military disaster, and secure the colony for republican France as opposed to Britain, Spain, and French royalists, separately or in combination, the French commissioners Sonthonax and Étienne Polverel offered freedom to the slaves who would agree to fight alongside them. Then, under pressure, they gradually emancipated all the slaves of the colony. On 29 August 1793, Sonthonax proclaimed the abolition of slavery in the northern province. On 31 October, Étienne Polverel did the same in the other two western and southern provinces.[69] Sonthonax sent three of his deputies, namely the colonist Louis Duffay, the free black army officer Jean-Baptiste Belley and a free man of color, Jean-Baptiste Mills, to seek the National Convention's endorsement for the emancipation of slaves near the end of January 1794.[70] On 4 February, Dufay gave a speech to the convention arguing that abolishing slavery was the only way to keep the colony in control of the French, and that former slaves would willingly work to restore the colony.[70] The convention deputies agreed and made the dramatic decree that "slavery of the blacks is abolished in all the colonies; consequently, it decrees that all men living in the colonies, without distinction of color, are French citizens and enjoy all the rights guaranteed by the constitution".[70][71] The National Convention abolished slavery by law in France and all its colonies, and granted civil and political rights to all black men in the colonies. The French constitutions of 1793 and 1795 both included the abolition of slavery. The constitution of 1793 never went into effect, but that of 1795 did; it lasted until it was replaced by the consular and imperial constitutions under Napoleon Bonaparte. Despite racial tensions in Saint-Domingue, the French revolutionary government at the time welcomed abolition with a show of idealism and optimism. The emancipation of slaves was viewed as an example of liberty for other countries, much as the American Revolution was meant to serve as the first of many liberation movements. Georges Danton, one of the Frenchmen present at the meeting of the National Convention, expressed this sentiment: Representatives of the French people, until now our decrees of liberty have been selfish, and only for ourselves. But today we proclaim it to the universe, and generations to come will glory in this decree; we are proclaiming universal liberty ... We are working for future generations; let us launch liberty into the colonies; the English are dead, today.[72] In nationalistic terms, the abolition of slavery also served as a moral triumph of France over England, as seen in the latter half of the above quote. Yet Toussaint Louverture did not stop working with the Spanish Army until sometime later, as he was suspicious of the French. The British force that landed in Saint-Domingue in 1793 was too small to conquer the colony, being capable only of holding only few coastal enclaves. The French planters were disappointed as they had hoped to regain power; Sonthonax was relieved, as he had twice refused ultimatums from Commodore John Ford to surrender Port-au-Prince.[68] In the meantime, a Spanish force under Captain-General Joaquín García y Moreno had marched into the Northern Province.[59] Louverture, the ablest of the Haitian generals, had joined the Spanish, accepting an officer's commission in the Spanish Army and being made a knight in the Order of St. Isabella.[73] The main British force for the conquest of Saint-Domingue under General Charles Grey, nicknamed "No-flint Grey", and Admiral Sir John Jervis set sail from Portsmouth on 26 November 1793, which was in defiance of the well-known rule that the only time that one could campaign in the West Indies was from September to November, when the mosquitoes that carried malaria and yellow fever were scarce.[74] After arriving in the West Indies in February 1794, Grey chose to conquer Martinique, Saint Lucia, and Guadeloupe. Troops under the command of John Whyte did not arrive in Saint-Domingue until 19 May 1794.[75] Rather than attacking the main French bases at Le Cap and Port-de-Paix, Whyte chose to march towards Port-au-Prince, whose harbour was reported to have forty-five ships loaded with sugar.[76] Whyte took Port-au-Prince, but Sonthonax and the French forces were allowed to leave in exchange for not burning the sugar-loaded ships.[77] By May 1794, the French forces were severed in two by Toussaint, with Sonthonax commanding in the north and André Rigaud leading in the south.[73] As slavery continued to exist in areas of Saint-Domingue under British occupation, the colony's Black residents were motivated to fight against them on the side of the French.[78] |

フランスが奴隷制度の廃止を宣言 軍事的災難を防ぎ、イギリス、スペイン、フランス王党派に対抗して共和国フランスの植民地を確保するため、フランス軍総監ソントナックスとエティエンヌ・ ポルヴェレルは、彼らとともに戦うことに同意する奴隷に自由を与えた。その後、圧力のもと、彼らは植民地のすべての奴隷を徐々に解放していった。1793 年8月29日、ソントナックスは北部地方における奴隷制度の廃止を宣言した。10月31日には、エティエンヌ・ポルヴェレルが他の西部と南部の2県でも同 じことを行った[69]。 ソントナックスは1794年1月末近くに奴隷解放のために3人の代議員、すなわち植民地主義者のルイ・デュフェイ、自由黒人陸軍将校のジャン=バティス ト・ベレー、自由有色人種のジャン=バティスト・ミルズを国民大会の承認を求めるために派遣した[70]。2月4日、デュフェイは奴隷制廃止が植民地をフ ランス人の支配下に保つ唯一の方法であり、元奴隷は植民地復興のために進んで働くだろうと主張する演説を大会で行った。[70]大会代議員はこれに同意 し、「黒人の奴隷制はすべての植民地で廃止される。その結果、植民地に住むすべての者は、肌の色の区別なくフランス国民であり、憲法が保障するすべての権 利を享受する」という劇的な命令を下した[70][71]。 ナショナリズムは、フランスとそのすべての植民地における奴隷制を法律で廃止し、植民地に住むすべての黒人に市民権と政治的権利を与えた。1793年と 1795年のフランス憲法はいずれも奴隷制の廃止を含んでいた。1793年の憲法は発効しなかったが、1795年の憲法は発効し、ナポレオン・ボナパルト の領事憲法と帝国憲法に取って代わられるまで存続した。サン=ドマングでは人種間の緊張があったにもかかわらず、当時のフランス革命政府は理想主義と楽観 主義を示して奴隷解放を歓迎した。奴隷解放は、アメリカ革命が多くの解放運動の最初の例となることを意図していたように、他国にとっての自由の模範と見な されたのである。ナショナリズム国民大会に出席したフランス人の一人、ジョルジュ・ダントンはこのような感想を述べている: フランス人民の代表者たちよ、これまでわれわれの自由宣言は利己的なものであり、われわれ自身のためだけのものであった。私たちは普遍的な自由を宣言しているのだ。我々は未来の世代のために働いている。植民地に自由を打ち出そう。イギリス人は今日、死んだのだ」[72]。 ナショナリスト的には、上記の引用の後半に見られるように、奴隷制廃止はイギリスに対するフランスの道徳的勝利でもあった。しかし、トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュールがスペイン軍と行動を共にするのをやめたのは、フランス軍を疑っていたからである。 1793年にサン・ドマングに上陸したイギリス軍は、植民地を征服するには規模が小さすぎた。ソントナックスは、ジョン・フォード提督からのポルトープラ ンス降伏の最終通告を2度にわたって拒否していたため、安堵した[68]。その間に、ホアキン・ガルシア・イ・モレノ大将率いるスペイン軍が北部州に進軍 していた。[ハイチの将軍の中で最も有能であったルーヴェルチュールはスペイン軍に加わり、スペイン軍の将校を引き受け、聖イザベラ騎士団の騎士となった [73]。 ノー・フリント・グレイ」というニックネームを持つチャールズ・グレイ将軍とサー・ジョン・ジャーヴィス提督率いるサン・ドマング征服のためのイギリス主 力部隊は、1793年11月26日にポーツマスから出航したが、これは西インド諸島で作戦を行えるのはマラリアや黄熱病を媒介する蚊が少ない9月から11 月だけというよく知られた規則に反したものであった[74]。ジョン・ホワイティ指揮下の部隊がサン・ドマングに到着したのは1794年5月19日のこと であった[75]。ホワイティはル・キャップとポート=ド=ペにあるフランス軍の主要拠点を攻撃するよりも、砂糖を積んだ45隻の船が停泊していると報告 されていたポルトープランスに向かって進軍することを選んだ[76]。ホワイティはポルトープランスを占領したが、ソントナックスとフランス軍は砂糖を積 んだ船を焼却しないことと引き換えに退去を許された。[1794年5月までにフランス軍はトゥーサンによって2つに分断され、ソントナックスが北部を、ア ンドレ・リゴーが南部を指揮することになった[73]。イギリスの占領下にあったサン=ドマングの地域では奴隷制が続いていたため、植民地の黒人住民はフ ランス側について奴隷制と戦う気になった[78]。 |

| Spanish depart Saint Domingue In May 1794, Toussaint suddenly joined the French and turned against the Spanish, ambushing his allies as they emerged from attending mass in a church at San Raphael on 6 May 1794.[73] The Haitians soon expelled the Spanish from Saint-Domingue.[73] Toussaint proved to be forgiving of the whites, insisting that he was fighting to assert the rights of the slaves as black French people to be free. He said he did not seek independence from France, and urged the surviving whites, including the former slave masters, to stay and work with him in rebuilding Saint-Domingue.[79] Rigaud had checked the British in the south, taking the town of Léogâne by storm and driving the British back to Port-au-Prince.[73] During the course of 1794, most of the British forces were killed by yellow fever, the dreaded "black vomit" as the British called it. Within two months of arriving in Saint-Domingue, the British lost 40 officers and 600 men to yellow fever.[66] Of Grey's 7,000 men, about 5,000 died of yellow fever while the Royal Navy reported losing "forty-six masters and eleven hundred men dead, chiefly of yellow fever".[66] The British historian Sir John Fortescue wrote, "It is probably beneath the mark to say that twelve thousand Englishmen were buried in the West Indies in 1794".[66] Rigaud failed in attempt to retake Port-au-Prince, but on Christmas Day 1794, he stormed and retook Tiburon in a surprise attack.[73] The British lost about 300 men, and Rigaud's forces took no prisoners, summarily executing any soldier or sailor they captured.[80] |

スペイン、サン・サンドマングを去る 1794年5月、トゥーサンは突如フランス軍に加わり、スペイン軍に反旗を翻し、1794年5月6日にサン・ラファエル教会でミサに出席していた味方を待 ち伏せした[73]。ハイチ人はすぐにスペイン軍をサン=ドミンゲから追放した[73]。トゥーサンは白人に寛容であることを証明し、自分はフランス黒人 として奴隷が自由になる権利を主張するために戦っているのだと主張した。彼はフランスからの独立は求めていないと述べ、かつての奴隷主人たちを含む生き 残った白人たちに、サン=ドマングー再建のために残って共に働くよう促した[79]。 リゴーは南部でイギリス軍を牽制し、レオガン(Léogâne)の町を襲撃してイギリス軍をポルトープランスに追い返した[73]。1794年の間にイギ リス軍のほとんどは黄熱病、イギリス人が「黒いゲロ」と呼ぶ恐ろしい黄熱病によって死亡した。グレイの7,000人の部下のうち約5,000人が黄熱病で 死亡し、イギリス海軍は「主に黄熱病で46人の船長と1,100人が死亡した」と報告している[66]。[イギリスの歴史家サー・ジョン・フォーテス キューは「1794年に西インド諸島で1万2,000人のイギリス人が埋葬されたというのは、おそらく的外れであろう」と記している[66] リゴーはポルトープランスの奪還に失敗したが、1794年のクリスマスの日に奇襲攻撃でティブロンを襲撃し奪還した[73]。 イギリス軍は約300人の兵士を失い、リゴー軍は捕虜を取らず、捕らえた兵士や船員を即刻処刑した[80]。 |

| British "great push" At this point, Pitt decided to launch what he called "the great push" to conquer Saint-Domingue and the rest of the French West Indies, sending out the largest expedition Britain had yet mounted in its history, a force of about 30,000 men to be carried in 200 ships.[73] Fortescue wrote that the aim of the British in the first expedition had been to destroy "the power of France in these pestilent islands ... only to discover when it was too late, that they practically destroyed the British army".[66] By this point, it was well known that service in the West Indies was virtually a death sentence. In Dublin and Cork, soldiers from the 104th, 105th, 111th, and 112th regiments rioted when they learned that they were being sent to Saint-Domingue.[81] The fleet for the "great push" left Portsmouth on 16 November 1795 and was wrecked by a storm, before sending out again on 9 December.[82] The overall forces in St Domingue was at that time under the command of the lieutenant-governor of Jamaica, Sir Adam Williamson.[83] He was optimistically given the title "Governor of St Domingue", and among his British forces were Jamaican "Black Shot" militias.[84] General Ralph Abercromby, the commander of the forces committed to the "great push", hesitated over which island to attack when he arrived in Barbados on 17 March 1796. He dispatched a force under Major General Gordon Forbes to Port-au-Prince.[82] Forbes's attempt to take the French-held city of Léogâne ended in disaster. The French had built a deep defensive ditch with palisades and Forbes had neglected to bring along heavy artillery.[85] The French commander, mulatto general Alexandre Pétion, proved to be an excellent artilleryman, who used the guns of his fort to disable two of the three ships of the line under Admiral Hyde Parker in the harbour, before turning his guns to a nearby British field battery; a French sortie led to a rout of Forbes' troops, who retreated back to Port-au-Prince.[85] As more ships arrived with British troops, more soldiers died of yellow fever.[85] By 1 June 1796, of the 1,000 from the 66th Regiment, only 198 had not been infected with yellow fever; and of the 1,000 men of the 69th Regiment, only 515 were not infected with yellow fever.[85] Abercromby predicted that at the current rate of yellow fever infection, all of the men from the two regiments were dead by November.[85] Ultimately, 10,000 British soldiers arrived in Saint Domingue by June, but aside from some skirmishing near Bombarde, the British remained in Port-au-Prince and other coastal enclaves, while yellow fever continued to ravage them.[85] The government attracted criticism in the House of Commons about the mounting costs of the expedition to Saint-Domingue. In February 1797, General John Graves Simcoe arrived to replace Forbes with orders to pull back British forces to Port-au-Prince.[86] As the human and financial costs of the expedition mounted, the British public demanded a withdrawal from Saint-Domingue, which was devouring money and soldiers, while failing to produce the expected profits.[87] On 11 April 1797, Colonel Thomas Maitland of the 62nd Regiment of Foot landed in Port-au-Prince, and wrote in a letter to his brother that British forces in Saint-Domingue had been "annihilated" by yellow fever.[86] Service in Saint-Domingue was extremely unpopular in the British Army owing to the terrible death toll caused by yellow fever. One British officer wrote of his horror of seeing his friends "drowned in their own blood" while "some died raving Mad".[87] Simcoe used the new British troops to push back French troops, but in a counter-offensive, Toussaint and Rigaud stopped the offensive. Toussaint retook the fortress at Mirebalais.[86] On 7 June 1797, Toussaint attacked Fort Churchill in an assault that was as noted for its professionalism as for its ferocity.[86] Under a storm of artillery, his troops placed ladders on the walls and were driven back four times, with heavy losses.[86] Even though Toussaint had been repulsed, the British were astonished that he had turned a group of former slaves with no military experience into troops whose skills were the equal of a European army.[86][88] |

イギリスの 「大プッシュ」 この時点でピットは、サン=ドマングとその他のフランス領西インド諸島を征服するために、彼が「偉大なる一押し」と呼ぶ遠征を開始することを決定し、イギ リス史上最大規模の遠征軍、約30,000人の兵力を200隻の船で運ぶ遠征軍を派遣した[73]。[フォーテスキューは、最初の遠征におけるイギリスの 目的は「これらの疫病が蔓延する島々におけるフランスの力」を破壊することであったと記している。ダブリンとコークでは、第104連隊、第105連隊、第 111連隊、第112連隊の兵士たちがサン=ドマングに送られることを知って暴動を起こした[81]。[彼は「セント・ドミンゴ総督」という楽観的な称号 を与えられ、イギリス軍の中にはジャマイカの「ブラック・ショット」民兵も含まれていた[84]。 1796年3月17日にバルバドスに到着したラルフ・アバクロンビー将軍は、「大攻勢」をかける部隊の指揮官として、どの島を攻撃すべきか逡巡していた。 彼はゴードン・フォーブス少将率いる部隊をポルトープランスに派遣した[82]。フォーブスのフランス領レオガン市攻略の試みは失敗に終わった。フランス 軍は柵で深い防御溝を築いており、フォーブスは重砲を持参するのを怠っていた。[フランス軍司令官アレクサンドル・ペシオン(Alexandre Pétion)は優れた砲兵であることが証明され、砦の大砲を使って港にいたハイド・パーカー提督率いる3隻の戦列艦のうち2隻を無力化し、その砲を近く のイギリス軍の野戦砲台に向けた。[1796年6月1日までに、第66連隊の1,000人のうち黄熱病に感染していなかったのは198人だけであり、第 69連隊の1,000人のうち黄熱病に感染していなかったのは515人だけであった[85]。 アバクロンビーは、現在の黄熱病の感染率では、11月までに2連隊の兵士全員が死亡すると予測した。[最終的に、6月までに1万人のイギリス兵がサン・ド ミンゲに到着したが、ボンバルド付近での小競り合いを除けば、イギリス兵はポルトープランスやその他の沿岸の飛び地に留まり、黄熱病が彼らを襲い続けた [85]。 政府は、サン・ドミンゲ遠征の費用がかさむことについて下院で批判を浴びた。1797年2月、ジョン・グレイヴス・シムコー将軍がフォーブスの後任として 到着し、イギリス軍をポルトープランスに引き揚げるよう命じた[86]。遠征の人的・財政的コストがかさむにつれて、イギリス国民は、期待された利益を生 み出せないまま、資金と兵士を食い潰していたサン・ドマングからの撤退を要求した[87]。 1797年4月11日、フット第62連隊のトーマス・メイトランド大佐はポルトープランスに上陸し、サン=ドマングーにいたイギリス軍は黄熱病によって 「全滅」したと弟に宛てた手紙に記している[86]。 黄熱病による死者の数がすさまじかったため、サン=ドマングーでの兵役はイギリス軍で非常に不評であった。あるイギリス軍将校は、友人たちが「自分の血で 溺れ死ぬ」のを見た恐怖を綴る一方、「狂い狂って死んだ者もいた」と記している[87]。シムコーは新しいイギリス軍を使ってフランス軍を押し返したが、 反攻に出たトゥーサンとリゴーは攻勢を止めた。トゥーサンはミレバレーの要塞を奪還した[86]。1797年6月7日、トゥーサンはチャーチル砦を攻撃し たが、その攻撃はその獰猛さと同様にプロフェッショナリズムの高さでも注目された[86]。大砲の嵐の中、彼の部隊は城壁に梯子をかけ、4度にわたって追 い返され、大きな損害を被った。[86]トゥーサンが撃退されたにもかかわらず、イギリスは彼が軍事経験のない元奴隷の集団をヨーロッパ軍と同等の技術を 持つ軍隊に変えたことに驚愕した[86][88]。 |

| British withdrawal In July 1797, Simcoe and Maitland sailed to London to advise a total withdrawal from Saint-Domingue. In March 1798 Maitland returned with a mandate to withdraw, at least from Port-au-Prince.[86] On 10 May 1798, Maitland met with Toussaint to agree to an armistice, and on 18 May the British left Port-au-Prince.[89] The British forces were reduced to only holding the western peninsular towns of Mole St Nicholas in the north and Jeremie in the south. The new governor of Jamaica, Alexander Lindsay, 6th Earl of Balcarres, urged Maitland not to withdraw from Mole St Nicholas. However, Toussaint sent a message to Balcarres, warning him that if he persisted, to remember that Jamaica was not far from St Domingue, and could be invaded.[90] Maitland knew that his forces could not defeat Toussaint, and that he had to take action to protect Jamaica from invasion.[91] British morale had collapsed with the news that Toussaint had taken Port-au-Prince, and Maitland decided to abandon all of Saint-Domingue, writing that the expedition had become such a complete disaster that withdrawal was the only sensible thing to do, even though he did not have the authority to do so.[89] On 31 August, Maitland and Toussaint signed an agreement whereby in exchange for the British pulling out of all of Saint-Domingue, Toussaint promised not to "meddle in the affairs of Jamaica".[89] Rigaud took control of Jeremie without any cost to his forces, as Maitland withdrew his southern forces to Jamaica. In the end of 1798, Maitland withdrew the last of his forces from Mole St Nicholas, as Toussaint took command of the fortress.[92] Maitland disbanded his "Black Shot" troops and left them in Saint-Domingue, fearing they might return to Jamaica and cause further unrest. Many of them subsequently joined Toussaint's army.[93] |

イギリスの撤退 1797年7月、シムコーとメイトランドはロンドンに出航し、サン=ドマングからの全面撤退を勧告した。1798年3月、メイトランドは少なくともポル トープランスからの撤退を命じられて帰還した[86]。1798年5月10日、メイトランドはトゥーサンと会談し、休戦協定に合意し、5月18日、イギリ ス軍はポルトープランスを離れた[89]。ジャマイカの新総督アレクサンダー・リンゼイ(第6代バルカレス伯爵)は、モール・セント・ニコラスから撤退し ないようメイトランドに求めた。しかし、トゥーサンはバルカレスにメッセージを送り、もし彼が固執するならば、ジャマイカはサン・ドミンゲからそう遠くな いところにあり、侵略される可能性があることを忘れるなと警告した[90]。 トゥーサンがポルトープランスを占領したというニュースでイギリスの士気は崩壊し、メイトランドはサン=ドミンゲ全域を放棄することを決定した。[8月 31日、メイトランドとトゥーサンは、イギリスがサン=ドマング全域から撤退する代わりに、トゥーサンが「ジャマイカの問題に干渉しない」ことを約束する 協定に調印した[89]。メイトランドが南軍をジャマイカに撤退させたため、リゴーは自軍に損害を与えることなくジェレミーを制圧した。1798年末、 トゥーサンが要塞の指揮権を握ったため、メイトランドは最後の部隊をモーレ・セント・ニコラスから撤退させた[92]。メイトランドは「ブラック・ショッ ト」部隊を解散させ、彼らがジャマイカに戻ってさらなる不安を引き起こすことを恐れて、彼らをサン=ドマングに残した。彼らの多くはその後トゥーサンの軍 隊に加わった[93]。 |

| Toussaint consolidates control After the departure of the British, Toussaint turned his attention to Rigaud, who was conspiring against him in the south of Saint Domingue.[94] In June 1799, Rigaud initiated the War of the South against Toussaint's rule, sending a brutal offensive at Petit-Goâve and Grand-Goâve. Taking no prisoners, Rigaud's predominantly mulatto forces put blacks and whites to the sword. Though the United States was hostile towards Toussaint, the U.S. Navy agreed to support Toussaint's forces with the frigate USS General Greene, commanded by Captain Christopher Perry, providing fire support to the blacks as Toussaint laid siege to the city of Jacmel, held by mulatto forces under the command of Rigaud.[95] To the United States, Rigaud's ties to France represented a threat to American commerce. On 11 March 1800, Toussaint took Jacmel and Rigaud fled on the French schooner La Diana.[95] Though Toussaint maintained he was still loyal to France, to all intents and purposes, he ruled Saint Domingue as its dictator.[96] |

トゥーサン、支配を固める 1799年6月、リゴーはトゥーサンの支配に対する南部戦争を開始し、プチゴーヴとグランゴーヴに残忍な攻勢をかけた。リゴーが率いる混血部隊は捕虜を取 らず、黒人と白人を刀で打ち殺した。アメリカはトゥーサンに敵対的であったが、アメリカ海軍はトゥーサン軍を支援することに同意し、クリストファー・ペ リー大尉が指揮するフリゲートUSSジェネラル・グリーンは、トゥーサンがリゴーの指揮する混血部隊の保持するジャクメル市を包囲する際、黒人たちに火力 支援を提供した[95]。アメリカにとって、リゴーのフランスとの結びつきはアメリカの通商に対する脅威であった。1800年3月11日、トゥーサンは ジャクメルを占領し、リゴーはフランスのスクーナー船ラ・ディアナ号で逃亡した[95]。トゥーサンはまだフランスに忠誠を誓っていたが、意図主義を貫 き、独裁者としてサン・ドミンギューを統治した[96]。 |

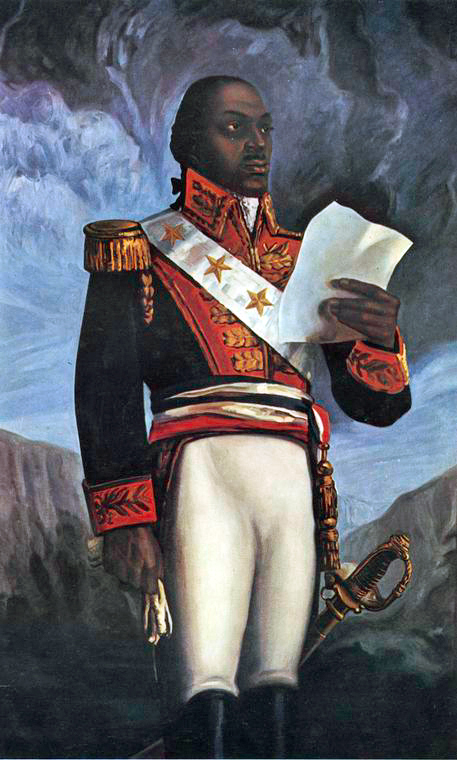

Leadership of Louverture General Toussaint Louverture Toussaint Louverture Toussaint Louverture, although a self-educated former domestic slave, was one of the most successful black commanders. Like Jean François and Biassou, he initially fought for the Spanish crown. After the British had invaded Saint-Domingue, Louverture decided to fight for the French if they would agree to free all the slaves. Sonthonax had proclaimed an end to slavery on 29 August 1792. Louverture worked with a French general, Étienne Laveaux, to ensure that all slaves would be freed. Louverture abandoned the Spanish Army in the east and brought his forces over to the French side on 6 May 1794 after the Spanish refused to take steps to end slavery.[97] Under the military leadership of Toussaint, the former slaves succeeded in winning concessions from the British and expelled the Spanish forces. In the end, Toussaint essentially restored control of Saint-Domingue to France. Having made himself master of the island, however, Toussaint did not wish to surrender too much power to France. He began to rule the country as an effectively autonomous entity. Louverture overcame a succession of local rivals, including: the Commissioner Sonthonax, a French white man who gained support from many Haitians, angering Louverture; André Rigaud, a free man of color who fought to keep control of the South in the War of the South ; and Comte d'Hédouville, who forced a fatal wedge between Rigaud and Louverture before escaping to France. Louverture led an invasion of neighboring Santo Domingo (December 1800), and freed the slaves there on 3 January 1801. In 1801, Louverture issued a constitution for Saint-Domingue that decreed he would be governor-for-life and called for black autonomy and a sovereign black state. In response, Napoleon Bonaparte dispatched a large expeditionary force of French soldiers and warships to the island, led by Bonaparte's brother-in-law Charles Leclerc, to restore French rule.[96] They were under secret instructions to restore slavery, at least in the formerly Spanish-held part of the island. Bonaparte ordered that Toussaint was to be treated with respect until the French forces were established; once that was done, Toussaint was to be summoned to Le Cap and arrested; if he failed to show, Leclerc was to wage "a war to the death" with no mercy and all of Toussaint's followers to be shot when captured.[98] Once that was completed, slavery would be ultimately restored.[96] The numerous French soldiers were accompanied by mulatto troops led by Alexandre Pétion and André Rigaud, mulatto leaders who had been defeated by Toussaint three years earlier. |

ルーヴェルチュールのリーダーシップ トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュール将軍 トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュール トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュールは、独学で学んだ元家事奴隷であったが、最も成功した黒人指揮官の一人であった。ジャン・フランソワやビアスーと同様、彼 は当初スペイン王家のために戦った。イギリスがサン=ドマングに侵攻した後、ルーヴェルチュールはフランスがすべての奴隷の解放に同意するならば、フラン スのために戦うことを決意した。ソントナックスは1792年8月29日に奴隷制度の廃止を宣言していた。ルーヴェルチュールはフランスの将軍エティエン ヌ・ラヴォーと協力し、すべての奴隷が解放されるようにした。ルーヴェルチュールは、スペインが奴隷制度廃止の措置を取ることを拒否したため、1794年 5月6日に東部のスペイン軍を放棄し、フランス側に軍を引き入れた[97]。 トゥーサンの軍事的指導の下、元奴隷たちはイギリスから譲歩を勝ち取ることに成功し、スペイン軍を追放した。最終的にトゥーサンはサン=ドマング島の支配 権を実質的にフランスに回復した。しかし、島の主となったトゥーサンは、フランスに大きな権力を明け渡すことを望まなかった。彼はこの国を事実上の自治体 として統治し始めた。ルーヴェルチュールは、多くのハイチ人の支持を得てルーヴェルチュールを怒らせたフランス系白人のソントナックス長官、南部戦争で南 部の支配権を維持するために戦った有色人種の自由人アンドレ・リゴー、フランスに逃れる前にリゴーとルーヴェルチュールの間に致命的なくさびを打ち込んだ ヘドゥヴィルコントなど、地元のライバルを次々と克服した。ルーヴェルチュールは隣国サント・ドミンゴへの侵攻(1800年12月)を指揮し、1801年 1月3日には同地の奴隷を解放した。 1801年、ルーヴェルチュールはサン=ドミンゴの憲法を発布し、終身知事となることを宣言し、黒人の自治と主権国家を求めた。これに対してナポレオン・ ボナパルトは、ボナパルトの義弟シャルル・ルクレールに率いられたフランスの兵士と軍艦からなる大規模な遠征軍をこの島に派遣し、フランスの統治を回復さ せた[96]。ボナパルトは、フランス軍が確立するまではトゥーサンを丁重に扱うこと、それが完了したら、トゥーサンをル・キャップに呼び出して逮捕する こと、もしトゥーサンが姿を見せなければ、ルクレールは容赦なく「死の戦争」を行い、トゥーサンの従者たちは捕らえられたら全員射殺することを命じた [98]。[それが完了すれば、最終的に奴隷制が復活する[96]。多数のフランス兵は、3年前にトゥーサンに敗れた混血の指導者であるアレクサンドル・ ペシオンとアンドレ・リゴーが率いる混血部隊を伴っていた。 |

| Napoleon invades Haiti The French arrived on 2 February 1802 at Le Cap with the Haitian commander Henri Christophe being ordered by Leclerc to turn over the city to the French.[99] When Christophe refused, the French assaulted Le Cap and the Haitians set the city afire rather than surrender it.[99] Leclerc sent Toussaint letters promising him: "Have no worries about your personal fortune. It will be safeguarded for you, since it has been only too well earned by your own efforts. Do not worry about the liberty of your fellow citizens".[100] When Toussaint still failed to appear at Le Cap, Leclerc issued a proclamation on 17 February 1802: "General Toussaint and General Christophe are outlawed; all citizens are ordered to hunt them down, and treat them as rebels against the French Republic".[101] Captain Marcus Rainsford, a British Army officer who visited Saint-Domingue observed the training of the Haitian Army, writing: "At a whistle, a whole brigade ran three or four hundred yards, and then, separating, threw themselves flat on the ground, changing to their backs and sides, and all the time keeping up a strong fire until recalled...This movement is executed with such facility and precision as totally to prevent cavalry from charging them in bushy and hilly country".[101] |

ナポレオン、ハイチに侵攻 フランス軍は1802年2月2日にル・キャップに到着し、ハイチ軍司令官アンリ・クリストフはルクレールから街をフランス軍に明け渡すよう命じられた [99]。クリストフが拒否すると、フランス軍はル・キャップを襲撃し、ハイチ軍は街を明け渡す代わりに火を放った[99]。ルクレールはトゥーサンに約 束の手紙を送った: 「人格の心配はいらない。君の個人的な財産については心配するな。それは君自身の努力によって勝ち得たものだから、必ず守ってくれる。同胞の自由について も心配するな」[100]。それでもトゥーサンがル・キャップに現れなかったため、ルクレールは1802年2月17日に布告を出した: 「トゥーサン将軍とクリストフ将軍は無法者であり、全市民は彼らを追い詰め、フランス共和国に対する反逆者として扱うよう命ずる」[101] サン=ドマングを訪れたイギリス陸軍将校マーカス・レインズフォード大尉はハイチ軍の訓練を観察し、こう記している: 「汽笛が鳴ると、旅団全体が3、400ヤード走り、離れて地面に平伏し、背中と横を変え、呼び戻されるまでずっと強い砲火を放ち続ける......この動 きは、雑木林や丘陵地帯で騎兵隊が突撃するのを完全に防ぐほどの設備と正確さで実行される」[101]。 |

| Haitian resistance and scorched-earth tactics In a letter to Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Toussaint outlined his plans for defeating the French using scorched-earth: "Do not forget, while waiting for the rainy reason which will rid us of our foes, that we have no other resource than destruction and fire. Bear in mind that the soil bathed with our sweat must not furnish our enemies with the smallest sustenance. Tear up the roads with shot; throw corpses and horses into all the foundations, burn and annihilate everything in order that those who have come to reduce us to slavery may have before their eyes the image of the hell which they deserve".[101] Dessalines never received the letter as he had already taken to the field, evaded a French column sent to capture him and stormed Léogâne.[101] The Haitians burned down Léogâne and killed all of the French with the Trinidadian historian C. L. R. James writing of Dessalines's actions at Léogâne: "Men, women and children, indeed all the whites who came into his hands, he massacred. And forbidding burial, he left stacks of corpses rotting in the sun to strike terror into the French detachments as they toiled behind his flying columns".[101] The French had been expecting the Haitians to happily go back to being their slaves, as they believed it was natural for blacks to be the slaves of whites, and were stunned to learn how much the Haitians hated them for wanting to reduce them back to a life in chains.[101] A visibly shocked General Pamphile de Lacroix after seeing the ruins of Léogâne wrote: "They heaped up bodies" which "still had their attitudes; they were bent over, their hands outstretched and beseeching; the ice of death had not effaced the look on their faces".[101] Leclerc ordered four French columns to march on Gonaives, which was the main Haitian base.[102] One of the French columns was commanded by General Donatien de Rochambeau, a proud white supremacist and a supporter of slavery who detested the Haitians for wanting to be free. Toussaint tried to stop Rochambeau at Ravine-à-Couleuvre, a very narrow gully up in the mountains that the Haitians had filled with chopped down trees.[102] In the ensuring Battle of Ravine-à-Couleuvres, after six hours of fierce hand-to-hand fighting with no quarter given on either side, the French finally broke through, albeit with heavy losses.[102] During the battle, Toussaint personally took part in the fighting to lead his men in charges against the French.[102] After losing 800 men, Toussaint ordered a retreat.[102] |

ハイチの抵抗と焦土戦術 ジャン=ジャック・デサリンヌに宛てた手紙の中で、トゥーサンは焦土戦術を用いたフランス軍打倒計画の概略を述べている。われわれの汗を浴びた土が、敵に わずかな糧も与えてはならないことを肝に銘じよ。道路を銃で破り、死体や馬をすべての土台に投げ込み、すべてを燃やして消滅させ、われわれを奴隷にしよう とやってきた者たちが、自分たちにふさわしい地獄の姿を目の前にすることができるようにするのだ」。[101]デサリーヌはすでに戦場に出ており、彼を捕 らえるために派遣されたフランス軍の隊列を避け、レオガン(Léogâne)を襲撃したため、その手紙を受け取ることはなかった[101]: 「男も女も子供も、彼の手に渡ったすべての白人を虐殺した。そして、埋葬することを禁じ、日なたで腐敗した死体の山を放置し、フランス軍の分遣隊が隊列の 後ろで労苦するのを恐怖に陥れた」[101]。フランス軍は、黒人は白人の奴隷であるのが当然だと考えていたため、ハイチ人が喜んで自分たちの奴隷に戻る ことを期待していたが、自分たちを鎖につながれた生活に戻そうとするハイチ人がどれほど自分たちを嫌っているかを知り、唖然とした。[101]目に見えて 衝撃を受けたパンフィル・ド・ラクロワ将軍は、レオガンヌの廃墟を見た後、「彼らは遺体を積み上げていた。 ルクレールはフランス軍4隊にハイチの主要拠点であったゴナイヴへの進軍を命じた[102]。フランス軍の1隊はドナティアン・ド・ロシャンボー将軍が指 揮していたが、彼は誇り高き白人至上主義者であり、自由を望むハイチ人を嫌悪する奴隷制支持者であった。トゥーサンはラヴィン・ア・クルーヴルでロシャン ボーを阻止しようとしたが、ラヴィン・ア・クルーヴルはハイチ人が切り倒した木々で埋めた山の上の非常に狭い谷間であった[102]。ラヴィン・ア・ク ルーヴルの戦いでは、6時間に及ぶ激しい手と手の戦いの後、フランス軍は大きな犠牲を出しながらもついに突破した。[戦闘中、トゥーサンは自ら戦闘に参加 し、人格を率いてフランス軍に突撃した[102]。800人の兵士を失ったトゥーサンは撤退を命じた[102]。 |

| Crête-à-Pierrot fortress The Haitians next tried to stop the French at a British-built fort up in the mountains called Crête-à-Pierrot, a battle that is remembered as a national epic in Haiti.[102] While Toussaint took to the field, he left Dessalines in command of Crête-à-Pierrot, who from his fastness could see three French columns converging on the fort.[102] Dessalines appeared before his men standing atop of a barrel of gunpowder, holding a lit torch, saying: "We are going to be attacked, and if the French put their feet in here, I shall blow everything up", leading his men to reply "We shall die for liberty!".[102] The first of the French columns to appear before the fort was commanded by General Jean Boudet, whose men were harassed by skirmishers until they reached a deep ditch the Haitians had dug.[102] As the French tried to cross the ditch, Dessalines ordered his men who were hiding to come out and open fire, hitting the French with a tremendous volley of artillery and musket fire, inflicting heavy losses on the attackers.[102] General Boudet himself was wounded and as the French dead and wounded started to pile up in the ditch, the French retreated.[102] The next French commander who tried to assault the ditch was General Charles Dugua, joined shortly afterwards by the column commanded by Leclerc.[102] All of the French assaults ended in total failure, and after the failure of their last attack, the Haitians charged the French, cutting down any Frenchmen.[102] General Dugua was killed, Leclerc was wounded and the French lost about 800 dead.[103] The final French column to arrive was the one commanded by Rochambeau, who brought along heavy artillery that knocked out the Haitian artillery, though his attempt to storm the ditch also ended in failure with about 300 of his men killed.[103] Over the following days, the French kept on bombarding and assaulting the fort, only to be repulsed every time while the Haitians defiantly sang songs of the French Revolution, celebrating the right of all men to be equal and free.[103] The Haitian psychological warfare was successful with many French soldiers asking why they were fighting to enslave the Haitians, who were only asserting the rights promised by the Revolution to make all men free.[103] Despite Bonaparte's attempt to keep his intention to restore slavery a secret, it was widely believed by both sides that was why the French had returned to Haiti, as a sugar plantation could only be profitable with slave labour.[citation needed] Finally after twenty days of siege with food and ammunition running out, Dessalines ordered his men to abandon the fort on the night of 24 March 1802 and the Haitians slipped out of the fort to fight another day.[103] Even Rochambeau, who hated all blacks was forced to admit in a report: "Their retreat—this miraculous retreat from our trap—was an incredible feat of arms".[103] The French had won, but they had lost 2,000 dead against an opponent whom they held in contempt on racial grounds, believing all blacks to be stupid and cowardly, and furthermore, that it was shortages of food and ammunition that forced the Haitians to retreat, not because of any feats of arms by the French army.[103] After the Battle of Crête-à-Pierrot, the Haitians abandoned conventional warfare and reverted to guerrilla tactics, making the French hold over much of the countryside from Le Cap down to the Artibonite valley very tenuous.[103] With March, the rainy season came to Saint-Domingue, and as stagnant water collected, the mosquitoes began to breed, leading to yet another outbreak of yellow fever.[103] By the end of March, 5,000 French soldiers had died of yellow fever and another 5,000 were hospitalized with yellow fever, leading to a worried Leclerc to write in his diary: "The rainy season has arrived. My troops are exhausted with fatigue and sickness".[103] |

クレタ・ピエロ要塞 この戦いはハイチの国民的叙事詩として記憶されている[102]。 トゥーサンが戦地に赴く一方で、彼はデッサリネスをクレタ=ピエロの指揮官に任せた。デッサリネスはその砦から、フランス軍の3つの隊列が砦に集結するの を見ることができた: 「我々は攻撃されようとしている。もしフランス軍がここに足を踏み入れたら、私はすべてを吹き飛ばすだろう」と言い、部下たちは「自由のために死のう!」 と答えた[102]。砦の前に最初に現れたフランス軍の隊列はジャン・ブーデ将軍が指揮しており、その隊列はハイチ軍が掘った深い溝に到達するまで小競り 合いに苦しめられた。[フランス軍が溝を横切ろうとすると、デサリネスは隠れていた部下たちに出てきて銃撃を開始するよう命じ、大砲とマスケット銃の凄ま じい一斉射撃でフランス軍を攻撃し、攻撃隊に大きな損害を与えた。[ブーデ将軍自身も負傷し、フランス軍の死傷者が溝に積み重なり始めたため、フランス軍 は退却した。[フランス軍の攻撃はすべて失敗に終わり、最後の攻撃が失敗した後、ハイチ軍はフランス軍に突撃し、フランス軍兵士を皆殺しにした。最後に到 着したフランス軍の隊列はロシャンボー(Rochambeau)が指揮するもので、ロシャンボーはハイチの大砲隊を打ちのめす大砲を携えていたが、溝を襲 撃しようとした彼の試みも失敗に終わり、彼の部下約300人が死亡した[103]。[その後の数日間、フランス軍は砲撃と砦への襲撃を続けたが、ハイチ人 が反抗的にフランス革命の歌を歌い、すべての人が平等で自由である権利を謳歌する中、そのたびに撃退された[103]。ハイチ人の心理戦は成功し、多くの フランス兵が、すべての人を自由にするという革命によって約束された権利を主張しているだけのハイチ人を、なぜ奴隷にするために戦うのかと問いかけた。 [ボナパルトは奴隷制を復活させる意図主義を秘密にしておこうとしたにもかかわらず、フランス軍がハイチに戻ってきたのはそのためだと両陣営に広く信じら れていた。[食料も弾薬も底をつき、20日間にわたる包囲戦の末、デサリネスは1802年3月24日の夜に部下に砦を放棄するよう命じ、ハイチ人は別の日 に戦うために砦を抜け出した[103]。すべての黒人を嫌っていたロシャンボーでさえ、報告書の中で認めざるを得なかった: 「フランス軍は勝利したが、人種的な理由で軽蔑し、すべての黒人は愚かで臆病であると信じていた相手に対して2,000人の戦死者を出し、さらにハイチ人 を撤退させたのは食料と弾薬の不足であり、フランス軍の武力によるものではなかった[103]。 クレタ・ピエロの戦いの後、ハイチ軍は通常戦を放棄し、ゲリラ戦術に回帰したため、ル・キャップからアルティボニット渓谷に至る地方の大部分に対するフラ ンス軍の支配力は非常に弱くなった。[3月、サン=ドマングに雨季が訪れ、淀んだ水が溜まると蚊が繁殖し始め、黄熱病が再び流行した[103]。3月末ま でに、5,000人のフランス兵が黄熱病で死亡し、さらに5,000人が黄熱病で入院し、心配したルクレールは日記にこう書いた: 「雨季がやってきた。我が軍は疲労と病気で疲れきっている」[103]。 |

| Capture of Toussaint On 25 April 1802, the situation suddenly changed when Christophe defected, along with much of the Haitian Army, to the French.[103] Louverture was promised his freedom if he agreed to integrate his remaining troops into the French army. Louverture agreed to this on 6 May 1802.[103] Just what motivated Toussaint to give up the fight has been the subject of much debate with most probable explanation being that he was just tired after 11 years of war.[104] Under the terms of surrender, Leclerc gave his solemn word that slavery would not be restored in Saint-Domingue, that blacks could be officers in the French Army, and that the Haitian Army would be allowed to integrate into the French Army. Leclerc also gave Toussaint a plantation at Ennery.[103] Toussaint was later deceived, seized by the French and shipped to France. He died months later in prison at Fort-de-Joux in the Jura Mountains.[27] Shortly afterwards, the ferocious Dessalines rode into Le Cap to submit to France and was rewarded by being made the governor of Saint-Marc, a place that Dessalines ruled with his customary cruelty.[104] However, the surrender of Christophe, Toussaint, and Dessalines did not mean the end of Haitian resistance. Throughout the countryside, guerrilla warfare continued and the French staged mass executions via firing squads, hanging, and drowning Haitians in bags.[104] Rochambeau invented a new means of mass execution, which he called "fumigational-sulphurous baths": killing hundreds of Haitians in the holds of ships by burning sulphur to make sulphur dioxide to gas them.[104] |

トゥーサンの捕縛 1802年4月25日、クリストフがハイチ軍の大部分とともにフランス軍に離反すると、状況は急変した[103]。ルーヴェルチュールは、残存兵力をフラ ンス軍に統合することに同意すれば、自由を約束された。ルーヴェルチュールは1802年5月6日にこれに同意した[103]。トゥーサンが戦いを放棄した 動機については多くの議論があるが、11年間の戦争で疲弊していたという説が有力である[104]。 降伏の条件として、ルクレールはサン=ドマングに奴隷制を復活させないこと、黒人がフランス軍の将校になれること、ハイチ軍のフランス軍への統合を認める ことを厳粛に約束した。ルクレールはトゥーサンにエネリーの農園も与えた[103]。トゥーサンは後に騙され、フランス軍に捕らえられ、フランスに送られ た。その直後、凶暴なデッサリーヌがフランスに服従するためにル・キャップに乗り込み、その報いとしてデッサリーヌはサン・マルクの総督となった。ロシャ ンボーは「燻蒸・硫黄浴」と呼ばれる新しい大量処刑の方法を考案した。硫黄を燃やして二酸化硫黄を作り、ガスにして船の船倉で数百人のハイチ人を殺すとい うものであった[104]。 |

War of independence Battle at "Snake Gully" in 1802 Rebellion against reimposition of slavery See also: Polish Legions (Napoleonic period) § The Haitian campaign For a few months, the island was quiet under Napoleonic rule. But when it became apparent that the French intended to re-establish slavery (because they had nearly done so on Guadeloupe), black cultivators revolted in the summer of 1802. Yellow fever had decimated the French; by the middle of July 1802, the French lost about 10,000 dead to yellow fever.[105] By September, Leclerc wrote in his diary that he had only 8,000 fit men left as yellow fever had killed the others.[104] In 1802, Napoleon added a Polish legion of around 5,200 to the forces sent to Saint-Domingue to fight off the slave rebellion. However, the Poles were told that there was a revolt of prisoners in Saint-Domingue. Upon arrival and the first fights, the Polish soldiers soon discovered that what was actually taking place in the colony was a rebellion of slaves fighting off their French masters for their freedom.[106] During this time, there was a familiar situation going on back in their homeland as these Polish soldiers were fighting for their liberty from the occupying forces of Russia, Prussia, and Austria that began in 1772. Many Poles believed that if they fought for France, Bonaparte would reward them by restoring Polish independence, which had been ended with the Third Partition of Poland in 1795.[105] As hopeful as the Haitians, many Poles were seeking union amongst themselves to win back their freedom and independence by organizing an uprising. As a result, many Polish soldiers admired their opponents, to eventually turn on the French army and join the Haitian slaves. Polish soldiers participated in the Haitian revolution of 1804, contributing to the establishment of the world's first free black republic and the first independent Caribbean state.[106] Haiti's first head of state Jean-Jacques Dessalines called Polish people "the White Negroes of Europe", which was then regarded a great honor, as it meant brotherhood between Poles and Haitians. Many years later François Duvalier, the president of Haiti who was known for his black nationalist and Pan-African views, used the same concept of "European white negroes" while referring to Polish people and glorifying their patriotism.[107][108][109] After Haiti gained its independence, the Poles acquired Haitian citizenship for their loyalty and support in overthrowing the French colonialists, and were called "black" by the Haitian constitution.[110] |

独立戦争 1802年「スネーク・ガリー」での戦い 奴隷制復活に反対する反乱 以下も参照のこと: ポーランド軍団(ナポレオン時代) § ハイチの戦い 数ヶ月の間、島はナポレオンの支配下で静かだった。しかし、フランスがグアドループ島で奴隷制を復活させようとしていたことが明らかになると、1802年 夏、黒人の耕作者たちが反乱を起こした。黄熱病はフランス軍を壊滅させた。1802年7月中旬までに、フランス軍は黄熱病で約10,000人の死者を出し た[105]。 9月までに、ルクレールは黄熱病で他の兵士が死亡したため、8,000人の兵士しか残っていないと日記に記している[104]。 1802年、ナポレオンは奴隷の反乱を撃退するため、約5,200人のポーランド軍団をサン・ドマングに派遣した。しかし、ポーランド軍はサン=ドマング で囚人の反乱が起きていることを知らされた。到着して最初の戦闘が始まると、ポーランド兵たちはすぐに、植民地で実際に起こっていたのは、奴隷たちが自由 のためにフランス人主人を撃退する反乱であったことを知った[106]。この時期、ポーランド兵たちは1772年に始まったロシア、プロイセン、オースト リアの占領軍から自分たちの自由を守るために戦っており、祖国ではおなじみの状況が進行していた。多くのポーランド人は、フランスのために戦えば、ボナパ ルトが1795年の第三次ポーランド分割によって消滅したポーランドの独立を回復して報いてくれると信じていた。その結果、多くのポーランド兵が敵対勢力 を賞賛し、最終的にはフランス軍に反旗を翻してハイチ奴隷に加わった。ポーランド兵は1804年のハイチ革命に参加し、世界初の自由な黒人共和国とカリブ 海初の独立国家の樹立に貢献した[106]。 ハイチの初代国家元首ジャン=ジャック・デサリネスはポーランド人を「ヨーロッパの白いニグロ」と呼び、ポーランド人とハイチ人の間の兄弟愛を意味し、当 時は大変名誉なこととされていた。何年も後、黒人ナショナリストと汎アフリカ主義で知られたハイチ大統領のフランソワ・デュヴァリエは、ポーランド人を指 して「ヨーロッパの白人ニグロ」という同じ概念を使い、彼らの愛国心を称えた[107][108][109]。 ハイチが独立した後、ポーランド人はフランスの植民地主義者を打倒するための忠誠と支持のためにハイチ国籍を取得し、ハイチの憲法で「黒人」と呼ばれるよ うになった[110]。 |

| Dessalines and Pétion join Haitian forces Dessalines and Pétion remained allied with France until they switched sides again, in October 1802, and fought against the French. As Leclerc lay dying of yellow fever and heard that Christophe and Dessalines had joined the rebels, he reacted by ordering all of the blacks living in Le Cap to be killed by drowning in the harbour.[111] In November, Leclerc died of yellow fever, like much of his army.[27][112] His successor, the Vicomte de Rochambeau, fought an even more brutal campaign. Rochambeau waged a near-genocidal campaign against the Haitians, killing everyone who was black.[111] Rochambeau imported about 15,000 attack dogs from Jamaica, who had been trained to savage blacks and mulattoes.[111] (Other sources suggest the dogs may have been dogo cubanos sourced in their hundreds from Cuba rather than Jamaica.)[113] At the Bay of Le Cap, Rochambeau had blacks drowned. No one would eat fish from the bay for months afterward, as no one wished to eat the fish that had eaten human flesh.[111] Bonaparte, hearing that most of his army in Saint-Domingue had died of yellow fever and the French held only Port-au-Prince, Le Cap, and Les Cayes, sent about 20,000 reinforcements to Rochambeau.[111]  France's Leclerc Expedition to Haiti in 1804 Dessalines matched Rochambeau in his vicious cruelty. At Le Cap, when Rochambeau hanged 500 blacks, Dessalines replied by killing 500 whites and sticking their heads on spikes all around Le Cap, so that the French could see what he was planning on doing to them.[111] Rochambeau's atrocities helped rally many former French loyalists to the rebel cause. Many on both sides had come to see the war as a race war where no mercy was to be given. The Haitians burned French prisoners alive, cut them up with axes, or tied them to a board and sawed them into two.[104] |

デサリーヌとペシオンがハイチ軍に加わる デサリーヌとペシオンは、1802年10月に再びフランス側に寝返り、フランス軍と戦うまで、フランスとの同盟関係を維持した。ルクレールは黄熱病で瀕死 の状態にあり、クリストフとデサリネスが反乱軍に加わったと聞くと、ル・キャップに住む黒人全員を港で溺れさせて殺すよう命じた[111]。 11月、ルクレールは軍の多くと同様に黄熱病で死亡した[27][112]。 彼の後継者であるロシャンボー宰相はさらに残忍な作戦を行った。ロシャンボーはハイチ人に対してジェノサイドに近いキャンペーンを展開し、黒人を皆殺しに した[111]。 ロシャンボーはジャマイカから約15,000頭の攻撃犬を輸入し、黒人や混血を残虐に扱うように訓練していた[111](他の資料によれば、犬はジャマイ カではなくキューバから数百頭調達したドゴ・キューバノであった可能性がある)[113]。 ル・キャップ湾でロシャンボーは黒人を溺死させた。ボナパルトは、サン=ドマングにいた自軍のほとんどが黄熱病で死亡し、フランス軍はポルトープランス、 ル・キャップ、レ・ケーズしか保持していないことを知り、ロシャンボーに約2万の援軍を送った[111]。  1804年、フランスのルクレールによるハイチ遠征 デサリネスはロシャンボーに匹敵する凶悪な残虐行為を行った。ル・キャップにおいて、ロシャンボーが500人の黒人を絞首刑に処したとき、デッサリーヌは 500人の白人を殺害し、その首をル・キャップの周囲にトゲで刺した。両陣営の多くは、この戦争を情け容赦のない人種戦争とみなすようになっていた。ハイ チ人たちはフランス人捕虜を生きたまま焼いたり、斧で切り刻んだり、板に縛り付けてのこぎりで2つに切断したりした[104]。 |