日本のヘルスケアシステム

Health care system in Japan

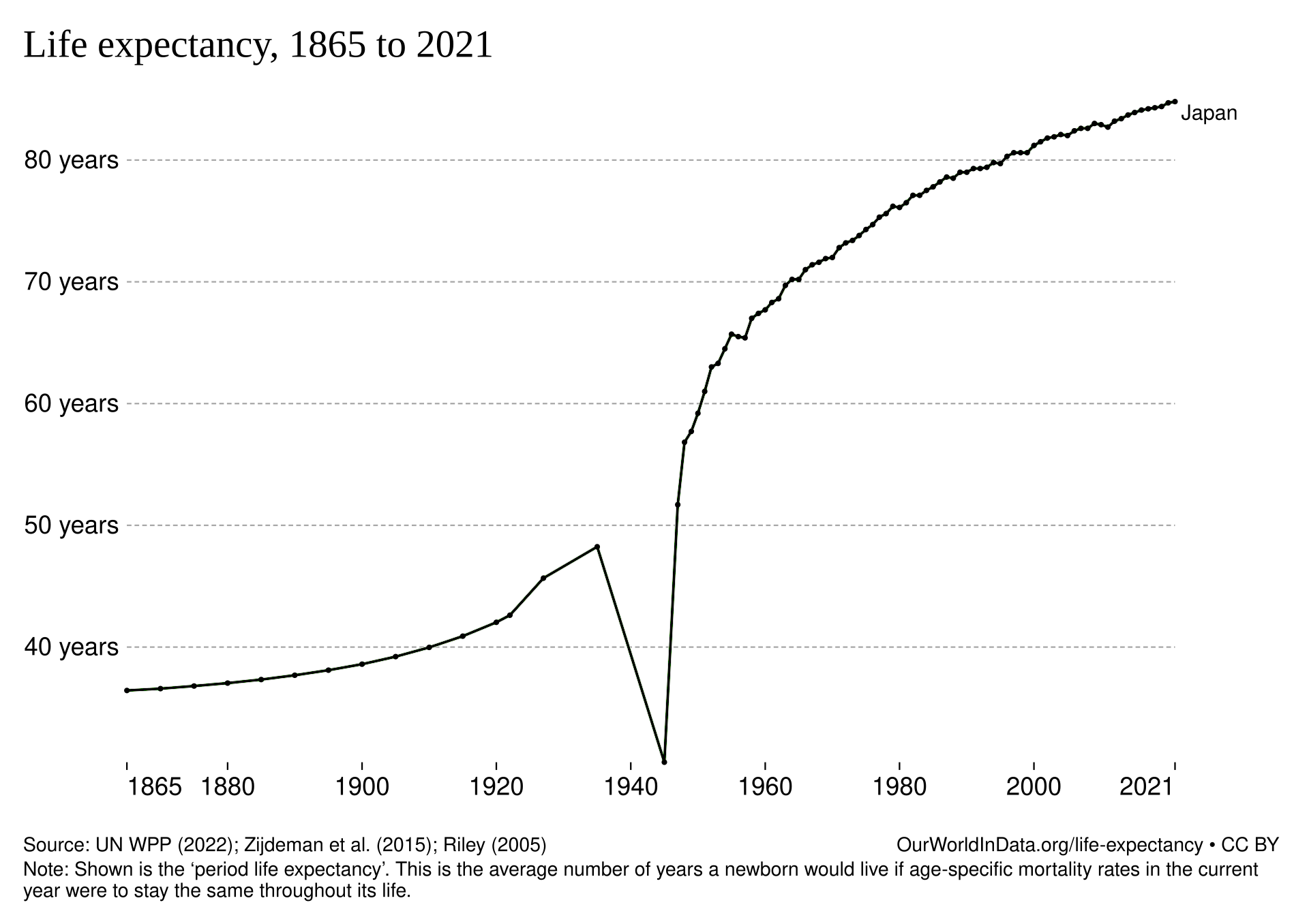

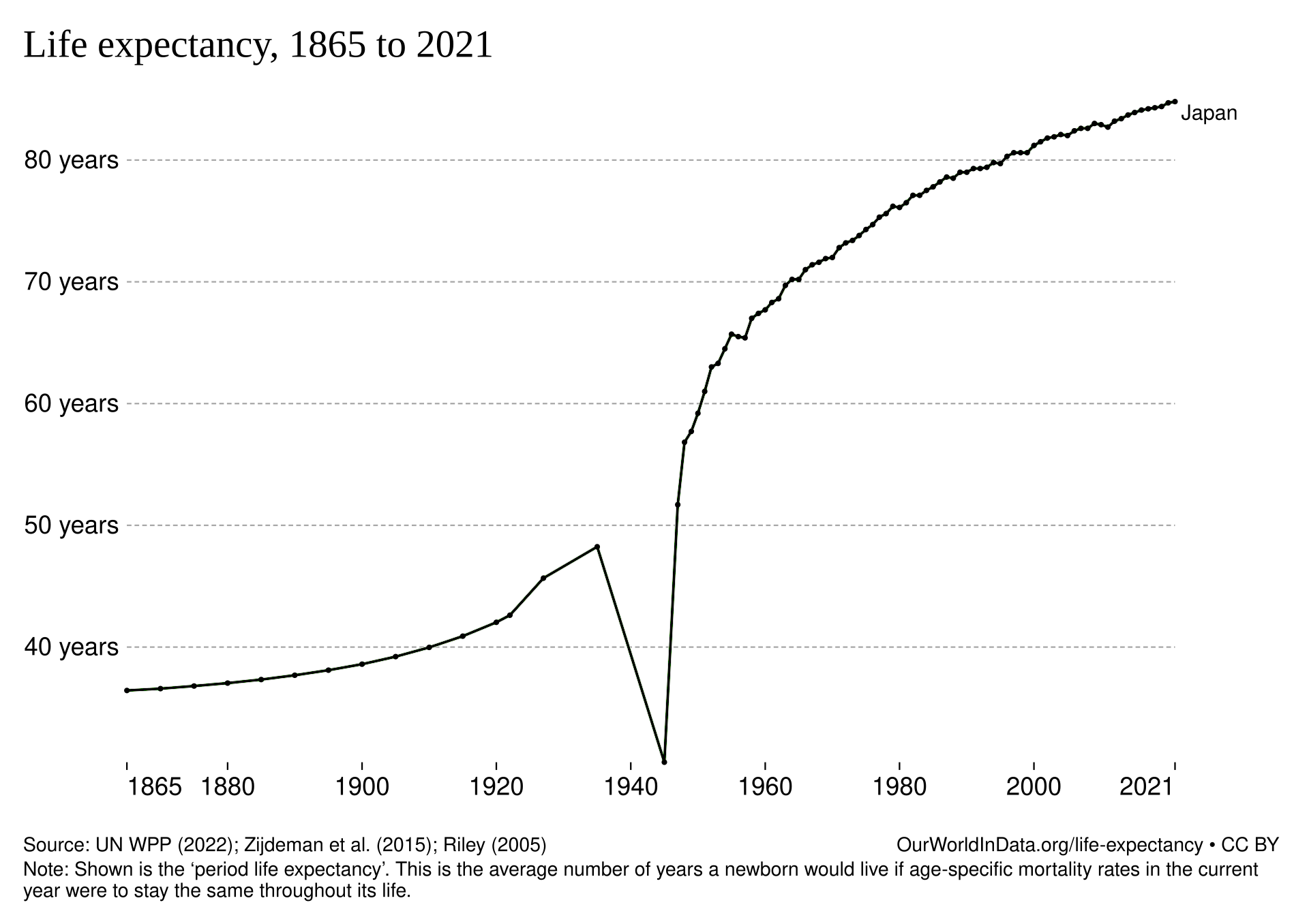

Development

of life expectancy in Japan

☆ 日本の医療制度は、健康診断、出産前ケア、感染症対策など、さまざまなサービスを提供しており、その費用の 30% は患者が負担し、残りの 70% は政府が負担している。医療サービスの個人負担分は、政府委員会が定めた料金に基づき、比較的平等にアクセスできる国民皆保険制度によって支払われる。日 本の住民は、法律により健康保険に加入することが義務付けられている。雇用主による健康保険に加入していない人民は、地方自治体が運営する国民健康保険に 加入することができる。患者は、自由に医師や医療機関を選択することができ、保険適用を拒否されることはない。病院は、法律により非営利団体として運営さ れ、医師によって管理されなければならない。 医療費は、政府によって厳格に規制され、手頃な水準に維持されている。被保険者の収入と年齢に応じて、患者は医療費の10%、20%、または30%を負担 し、残額は政府が負担する。[1] また、世帯ごとに収入と年齢に応じて月額の上限が設定されており、上限を超える医療費は免除または政府が補填する。 保険未加入の患者は医療費の100%を自己負担するが、政府の補助金を受けている低所得世帯は医療費が免除される(→「超高齢化社会・日本」)。

| The health care

system in Japan provides different types of services, including

screening examinations, prenatal care and infectious disease control,

with the patient accepting responsibility for 30% of these costs while

the government pays the remaining 70%. Payment for personal medical

services is offered by a universal health care insurance system that

provides relative equality of access, with fees set by a government

committee. All residents of Japan are required by the law to have

health insurance coverage. People without insurance from employers can

participate in a national health insurance program, administered by

local governments. Patients are free to select physicians or facilities

of their choice and cannot be denied coverage. Hospitals, by law, must

be run as non-profits and be managed by physicians. Medical fees are strictly regulated by the government to keep them affordable. Depending on the family's income and the age of the insured, patients are responsible for paying 10%, 20%, or 30% of medical fees, with the government paying the remaining fee.[1] Also, monthly thresholds are set for each household, again depending on income and age, and medical fees exceeding the threshold are waived or reimbursed by the government. Uninsured patients are responsible for paying 100% of their medical fees, but fees are waived for low-income households receiving a government subsidy. |

日本の医療制度は、健康診断、出産前ケア、感染症対策など、さまざまな

サービスを提供しており、その費用の 30% は患者が負担し、残りの 70%

は政府が負担している。医療サービスの個人負担分は、政府委員会が定めた料金に基づき、比較的平等にアクセスできる国民皆保険制度によって支払われる。日

本の住民は、法律により健康保険に加入することが義務付けられている。雇用主による健康保険に加入していない人民は、地方自治体が運営する国民健康保険に

加入することができる。患者は、自由に医師や医療機関を選択することができ、保険適用を拒否されることはない。病院は、法律により非営利団体として運営さ

れ、医師によって管理されなければならない。 医療費は、政府によって厳格に規制され、手頃な水準に維持されている。被保険者の収入と年齢に応じて、患者は医療費の10%、20%、または30%を負担 し、残額は政府が負担する。[1] また、世帯ごとに収入と年齢に応じて月額の上限が設定されており、上限を超える医療費は免除または政府が補填する。 保険未加入の患者は医療費の100%を自己負担するが、政府の補助金を受けている低所得世帯は医療費が免除される。 |

History National Cancer Center Hospital in the Tsukiji district of Tokyo The modern Japanese health care system started to develop just after the Meiji Restoration with the introduction of Western medicine. Statutory insurance, however, was not established until 1927 when the first employee health insurance plan was created.[2] In 1961, Japan achieved universal health insurance coverage, and almost everyone became insured. However, the copayment rates differed greatly. While those who enrolled in employees' health insurance needed to pay only a nominal amount at the first physician visit, their dependents and those who enrolled in National Health Insurance had to pay 50% of the fee schedule price for all services and medications. From 1961 to 1982, the copayment rate was gradually lowered to 30%.[3] Since 1983, all elderly persons have been covered by government-sponsored insurance.[4] In the late 1980s, government and professional circles were considering changing the system so that primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of care would be clearly distinguished within each geographical region. Further, facilities would be designated by level of care and referrals would be required to obtain more complex care. Policymakers and administrators also recognized the need to unify the various insurance systems and control costs. By the early 1990s, there were more than 1,000 mental hospitals, 8,700 general hospitals, and 1,000 comprehensive hospitals with a total capacity of 1.5 million beds. Hospitals provide both out-patient and in-patient care. In addition, 79,000 clinics offered primarily out-patient services, and there were 48,000 dental clinics. Most physicians and hospitals sold medication directly to patients, but there were 36,000 pharmacies where patients could purchase synthetic or herbal medication. Around the same time, there were nearly 191,400 physicians, 66,800 dentists, and 333,000 nurses, plus more than 200,000 people licensed to practice massage, acupuncture, moxibustion, and other East Asian therapeutic methods. |

歴史 東京・築地にある国立がん研究センター 日本の現代的な保健医療制度は、西洋医学の導入とともに明治維新直後に発展し始めた。しかし、法定保険は1927年に最初の従業員健康保険制度が創設されるまで確立されなかった[2]。 1961年、日本は国民皆保険を実現し、ほぼ全員が保険に加入することになった。しかし、自己負担の割合は大きく異なっていた。被保険者は初診時にわずか な自己負担で済むが、被扶養者や国民健康保険に加入している人は、診療や薬代について、診療報酬の 50% を自己負担しなければならなかった。1961 年から 1982 年にかけて、自己負担率は 30% まで徐々に引き下げられた[3]。 1983年以降、すべての高齢者は政府が支援する保険の対象となっている[4]。 1980年代後半、政府および専門家界では、各地域内で一次、二次、三次医療を明確に区分する制度への変更が検討されていた。さらに、医療施設は医療のレ ベルに応じて指定され、より複雑な医療を受けるには紹介状が必要となる予定だった。政策立案者や行政担当者も、多様な保険制度の統一とコスト管理の必要性 を認識していた。 1990年代初頭には、精神病院が1,000施設以上、一般病院が8,700施設、総合病院が1,000施設あり、総病床数は150万床に達していた。病 院は外来診療と入院診療の両方を提供している。さらに、主に外来診療を提供する79,000のクリニックと、48,000の歯科クリニックが存在した。ほ とんどの医師と病院は患者に直接医薬品を販売していたが、合成薬やハーブ薬を購入できる36,000の薬局が存在した。同時期には、医師が約 191,400 人、歯科医師が 66,800 人、看護師が 333,000 人、さらにマッサージ、鍼、灸、その他の東アジアの治療法を実践する免許を持つ人民が 20 万人以上いた。 |

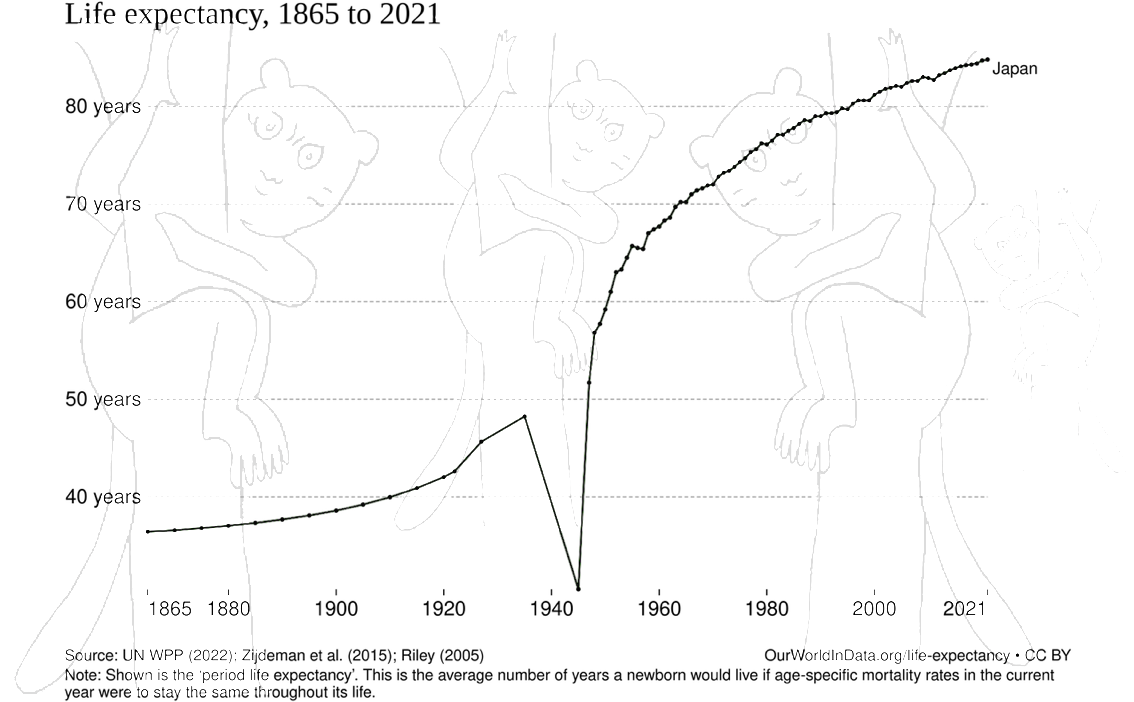

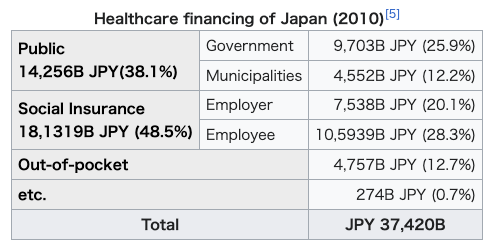

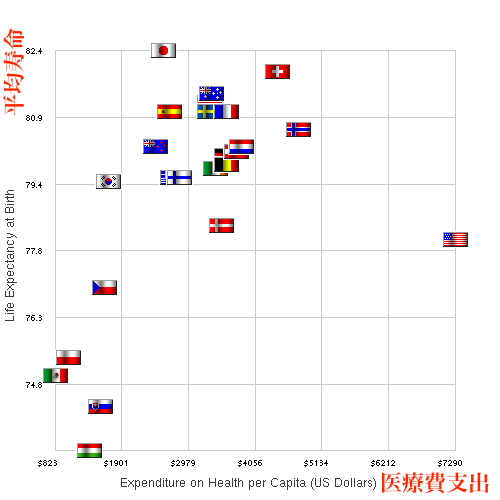

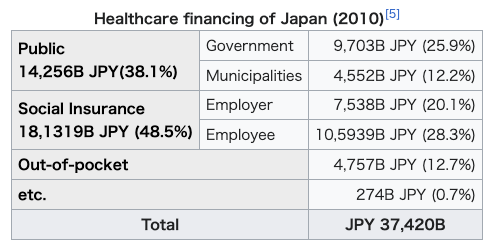

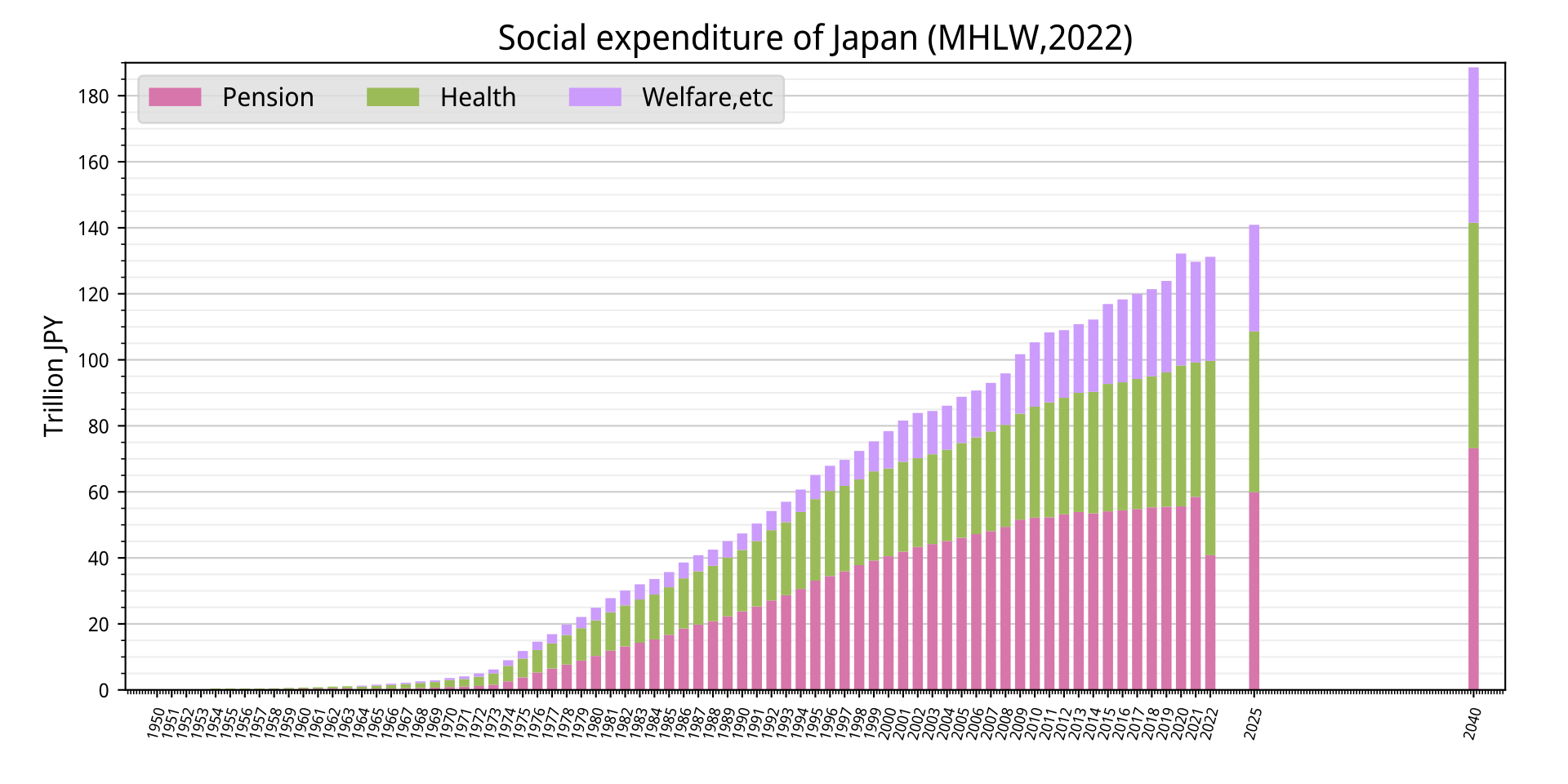

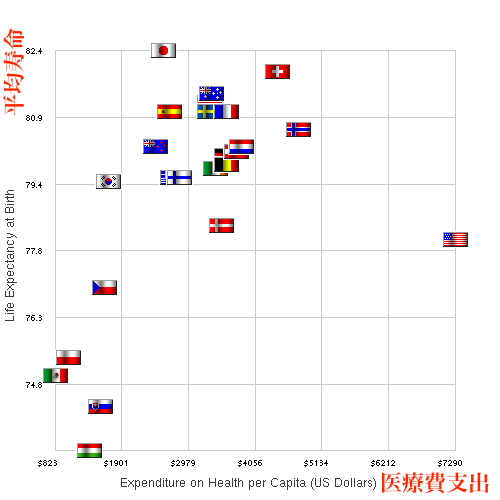

| Cost Healthcare financing of Japan (2010)[5] Public  14,256B JPY(38.1%) Government 9,703B JPY (25.9%) Municipalities 4,552B JPY (12.2%) Social Insurance 18,1319B JPY (48.5%) Employer 7,538B JPY (20.1%) Employee 10,5939B JPY (28.3%) Out-of-pocket 4,757B JPY (12.7%) etc. 274B JPY (0.7%) Total JPY 37,420B  Social expenditure of Japan  Comparison of healthcare spending and life expectancy for some countries in 2007 In 2008, Japan spent about 8.2% of the nation's gross domestic product (GDP), or US$2,859.7 or 405,737.84 Yen per capita, on health, ranking 20th among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. The share of gross domestic product was the same as the average of OECD states in 2008.[6] According to 2018 data, share of gross domestic products rose to 10.9% of GDP, overtaking the OECD average of 8.8%.[6] The government has controlled costs over decades using the national uniform fee schedule for reimbursement. The government is also able to reduce fees when the economy stagnates.[7] In the 1980s, health care spending was rapidly increasing as was the case with many industrialized nations. While some countries like the U.S. allowed costs to rise, Japan tightly regulated the health industry to rein in costs.[8] Fees for all health care services are set every two years by negotiations between the health ministry and physicians. The negotiations determine the fee for every medical procedure and medication, and fees are identical across the country. If physicians attempt to game the system by ordering more procedures to generate income, the government may lower the fees for those procedures at the next round of fee setting.[9] This was the case when the fee for an MRI was lowered by 35% in 2002 by the government.[9] Thus, as of 2009, in the U.S. an MRI of the neck region could cost $1,500, but in Japan, it cost US$98.[10] Once a patient's monthly copayment reaches a cap, no further copayment is required.[11] The threshold for the monthly copayment amount is tiered into three levels according to income and age.[7][12] To cut costs, Japan uses generic drugs. As of 2010, Japan had a goal of adding more drugs to the nation's National Health Insurance listing. Age-related conditions remain one of the biggest concerns. Pharmaceutical companies focus on marketing and research toward that part of the population.[13] |

費用 日本の医療財政(2010年)[5] 公的  14兆2,560億円(38.1%) 政府 9兆7,030億円(25.9%) 地方自治体 4兆5,520億円(12.2%) 社会保険 18,1319億円(48.5%) 雇用主 7,538億円(20.1%) 被雇用者 10,5939億円(28.3%) 自己負担 4,757億円(12.7%) その他 274億円(0.7%) 合計 37兆4,200億円  日本の社会支出  2007年のいくつかの国の医療支出と平均寿命の比較 2008年、日本は国民総生産(GDP)の約8.2%、1人当たり2,859.7米ドル(405,737.84円)を保健に費やし、経済協力開発機構 (OECD)加盟国中20位だった。国内総生産に占める割合は、2008年のOECD諸国の平均と同じだった[6]。2018年のデータによると、国内総 生産に占める割合は10.9%に上昇し、OECD平均の8.8%を上回った[6]。 政府は、全国統一の診療報酬体系を用いて、数十年にわたり医療費を抑制してきた。また、経済が低迷した場合は、料金を引き下げることもできる[7]。 1980年代、多くの先進国と同様に、日本の医療費も急速に増加していた。米国など一部の国では医療費の増加を容認したが、日本は医療業界を厳しく規制し て医療費を抑制した[8]。すべての医療サービスの料金は、2年ごとに厚生労働省と医師が交渉して決定される。交渉で医療行為や薬品の料金が決定され、全 国で一律となっている。医師が収入を増やすために医療行為を過剰に指示する「診療報酬の濫用」が発生した場合、政府は次回の料金設定時にその医療行為の料 金を引き下げる可能性がある。[9] 2002年にMRIの料金が35%引き下げられた事例がこれに該当する。 [9] したがって、2009年時点で、米国では首のMRI検査が$1,500かかるのに対し、日本ではUS$98で受けられる。[10] 患者の月間自己負担額が上限に達すると、それ以上の自己負担は不要となる。 [11] 自己負担額の上限は、収入と年齢に応じて 3 段階に分けられている。[7][12] コスト削減のため、日本はジェネリック医薬品を使用している。2010 年、日本は国民健康保険の対象医薬品リストにさらに医薬品を追加するという目標を掲げた。加齢に伴う疾患は依然として最大の課題のひとつである。製薬会社 は、この層に向けたマーケティングと研究に注力している。[13] |

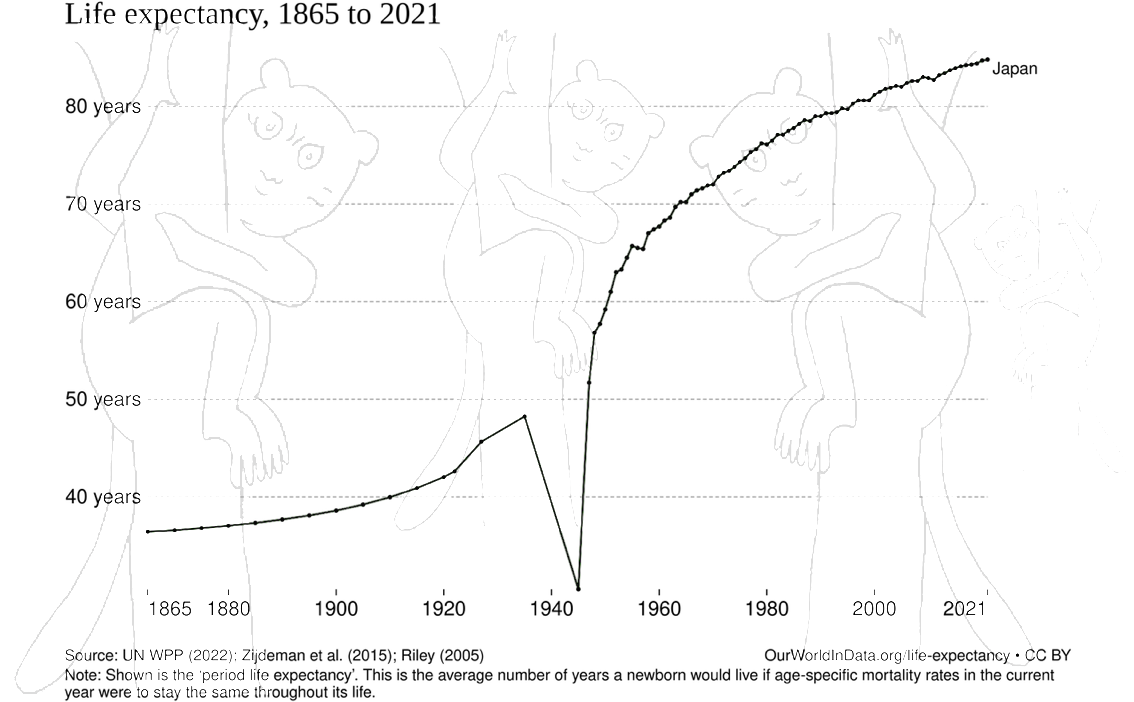

| Provision Development of life expectancy in Japan  Practising physicians per capita from 1960 to 2008 People in Japan have the longest life expectancy at birth of those in any country in the world. Life expectancy at birth was 83 years in 2009 (male 79.6 years, female 86.4 years).[6] This was achieved in a fairly short time through a rapid reduction in mortality rates secondary to communicable diseases from the 1950s to the early 1960s, followed by a large reduction in stroke mortality rates after the mid-60s.[14] In 2008 the number of acute care beds per 1000 total population was 8.1, which was higher than in other OECD countries such as the U.S. (2.7).[6] Comparisons based on this number may be difficult to make, however, since 34% of patients were admitted to hospitals for longer than 30 days even in beds that were classified as acute care.[15] Staffing per bed is very low. There are four times more MRI scanners per head, and six times the number of CT scanners, compared with the average European provision. The average patient visits a doctor 13 times a year - more than double the average for OECD countries.[16] In 2008 per 1000 population, the number of practising physicians was 2.2, which was almost the same as that in the U.S. (2.4). The number of practising nurses was 9.5, which was a little lower than that in U.S. (10.8), and almost the same as that in UK (9.5) or in Canada (9.2).[6] Physicians and nurses are licensed for life with no requirement for license renewal, continuing medical or nursing education, and no peer or utilization review.[17] OECD data lists specialists and generalists together for Japan[6] because these two are not officially differentiated. Traditionally, physicians have been trained to become subspecialists,[18] but once they have completed their training, only a few have continued to practice as subspecialists. The rest have left the large hospitals to practice in small community hospitals or open their clinics without any formal retraining as general practitioners.[7] Unlike many countries, there is no system of general practitioners in Japan, instead, patients go straight to specialists, often working in clinics. |

規定 日本の平均寿命の推移 1960年から2008年までの1人あたりの開業医数 日本の国民は、世界でも最も平均寿命が長い国民です。2009年の出生時平均寿命は83歳(男性79.6歳、女性86.4歳)だった。[6] これは、1950年代から1960年代初頭にかけて伝染病による死亡率が急速に低下し、その後1960年代半ば以降、脳卒中による死亡率が大幅に減少した ことにより、比較的短期間で達成された。[14] 2008年の急性期病床数は、総人口1,000人あたり8.1床で、米国などの他のOECD諸国よりも高かった。(2.7)よりも高かった。[6] ただし、この数値に基づく比較は困難である可能性がある。なぜなら、急性期病床に分類された病床でも、患者の34%が30日以上入院していたからである。 [15] 病床当たりの職員数は非常に低い。MRIスキャナーの台数は欧州平均の4倍、CTスキャナーの台数は6倍となっている。患者は年間平均13回医師を受診し ており、OECD諸国の平均の2倍以上となっている。[16] 2008年の人口1,000人当たりの医師数は2.2人で、米国(2.4人)とほぼ同じだった。看護師数は9.5人で、米国(10.8人)よりやや低かっ た。(10.8)とほぼ同じで、イギリス(9.5)やカナダ(9.2)とほぼ同じ水準だった。[6] 医師と看護師は生涯にわたる免許を取得し、免許の更新や継続的な医療・看護教育の義務はなく、同業者による審査や利用状況の審査もない。[17] OECDのデータでは、日本については専門医と一般医が一緒に分類されている[6]。これは、両者が公式には区別されていないためだ。伝統的に、医師はサ ブスペシャリストになるための訓練を受けていますが[18]、訓練を修了した後、サブスペシャリストとして働き続けるのはごく一部です。残りは大規模病院 を離れて、小規模な地域病院で働くか、正式な再訓練を受けずに一般開業医としてクリニックを開業しています[7]。多くの国と異なり、日本には一般開業医 の制度はなく、患者は直接専門医(多くの場合クリニックで働く)を受診します。 |

| Quality Japanese outcomes for high-level medical treatment of physical health are generally competitive with those of the US. A comparison of two reports in the New England Journal of Medicine by MacDonald et al. (2001) [19] and Sakuramoto et al.(2007) [20] suggest that outcomes for gastro-esophageal cancer is better in Japan than the US in both patients treated with surgery alone and surgery followed by chemotherapy. Japan excels in the five-year survival rates of colon cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer and liver cancer based on the comparison of a report by the American Association of Oncology and another report by the Japan Foundation for the Promotion of Cancer Research.[21] The same comparison shows that the US excels in the five-year survival of rectal cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer and malignant lymphoma. Surgical outcomes tend to be better in Japan for most cancers while overall survival tends to be longer in the US due to the more aggressive use of chemotherapy in late-stage cancers. A comparison of the data from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) 2009 and Japan Renology Society 2009 shows that the annual mortality of patients undergoing dialysis in Japan is 13% compared to 22.4% in the US. Five-year survival of patients under dialysis is 59.9% in Japan and 38% in the US. In an article titled "Does Japanese Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Qualify as a Global Leader?"[22] Masami Ochi of Nippon Medical School points out that Japanese coronary bypass surgeries surpass those of other countries in multiple criteria. According to the International Association of Heart and Lung Transplantation, the five-year survival of heart transplant recipients around the world who had their heart transplants between 1992 and 2009 was 71.9% (ISHLT 2011.6) while the five-year survival of Japanese heart transplant recipients is 96.2% according to a report by Osaka University.[23] However, only 120 heart transplants have been performed domestically by 2011 due to a lack of donors. In contrast to physical health care, the quality of mental health care in Japan is relatively low compared to most other developed countries. Despite reforms, Japan's psychiatric hospitals continue to largely rely on outdated methods of patient control, with their rates of compulsory medication, isolation (solitary confinement) and physical restraints (tying patients to beds) much higher than in other countries.[24] High levels of deep vein thrombosis have been found in restrained patients in Japan, which can lead to disability and death.[25] Rather than decreasing the use of restraints as has been done in many other countries,[26] the incidence of use of medical restraints in Japanese hospitals doubled in the nearly ten years from 2003 (5,109 restrained patients) through 2014 (10,682).[27] The 47 local government prefectures have some responsibility for overseeing the quality of health care, but there is no systematic collection of treatment or outcome data. They oversee annual hospital inspections. The Japan Council for Quality Health Care accredits about 25% of hospitals.[28] One problem with the quality of Japanese medical care is the lack of transparency when medical errors occur. In 2015 Japan introduced a law to require hospitals to conduct reviews of patient care for any unexpected deaths and to provide the reports to the next of kin and a third party organization. However, it is up to the hospital to decide whether the death was unexpected. Neither patients nor the patients' families are allowed to request reviews, which makes the system ineffective.[29][30] Meanwhile, Japanese healthcare providers are reluctant to provide open information because Japanese medical journalists tend to embellish, sensationalize, and in some cases fabricate anti-medical criticisms with little recourse for medical providers to correct the false claims once they have been made.[31] However, the increased number of hospital visits per capita compared to other nations and the generally good overall outcome suggests the rate of adverse medical events are not higher than in other countries. Around 92% of hospitals in Japan have an insufficient number of doctors while having sufficient nurses, while only 10% of hospitals have a sufficient number of doctors and an insufficient number of nurses.[32] Another problem has been an uneven distribution of health personnel, with rural areas favoured over cities.[33] A no-fault approach to cases of children born with cerebral palsy was introduced in 2009. This led to reduced litigation and 25% fewer children born with the condition.[34] |

質 身体の健康に関する高度医療の成果は、概ね米国と競合するレベルにある。New England Journal of Medicine に掲載された MacDonald ら(2001)[19] と Sakuraimoto ら(2007)[20] の 2 つの報告を比較すると、胃食道がんの治療成績は、手術単独、手術と化学療法の併用いずれの場合も、米国よりも日本の方が優れていることが示唆される。アメ リカ腫瘍学会(American Association of Oncology)の報告と日本がん研究促進財団(Japan Foundation for the Promotion of Cancer Research)の報告の比較によると、大腸がん、肺がん、膵がん、肝がんの5年生存率は日本が優れています[21]。同じ比較では、直腸がん、乳が ん、前立腺がん、悪性リンパ腫の5年生存率は米国が優れています。手術成績はほとんどの癌で日本の方が良好ですが、進行期癌における化学療法の積極的な使 用により、全体的な生存期間は米国の方が長くなっています。米国腎臓データシステム(USRDS)2009年と日本腎臓学会2009年のデータ比較による と、透析を受けている患者の年間死亡率は、日本では13%に対し、米国では22.4%です。透析を受けている患者の5年生存率は、日本では59.9%、米 国では38%です。 「日本の冠動脈バイパス手術は世界トップレベルか?」[22]という記事で、日本医科大学の大地正美氏は、日本の冠動脈バイパス手術は複数の基準で他国を 上回っていると指摘しています。国際心臓肺移植学会の報告によると、1992年から2009年に心臓移植を受けた世界中の患者の5年生存率は71.9% (ISHLT 2011.6)であるのに対し、大阪大学の報告によると、日本の心臓移植患者の5年生存率は96.2%だ。 [23] しかし、ドナーの不足により、2011年までに国内で実施された心臓移植は120件にとどまっている。 身体的保健とは対照的に、日本の精神保健の質は、他の先進国に比べて比較的低い。改革にもかかわらず、日本の精神科病院は依然として患者管理に古い方法に 依存しており、強制投薬、隔離(単独拘禁)、身体拘束(患者をベッドに縛る)の割合は他の国よりもはるかに高い。[24] 日本の拘束患者では深部静脈血栓症の発生率が高く、これは障害や死亡を引き起こす可能性がある。 [25] 他の多くの国で拘束の使用を減らす措置が取られているのに対し、[26] 日本の病院における医療用拘束の使用率は、2003年(5,109人)から2014年(10,682人)までの約10年間で2倍に増加した。[27] 47 の都道府県は、医療の質の監督に一定の責任を負っているが、治療や治療結果に関するデータを体系的に収集しているわけではない。都道府県は、毎年、病院の 検査を監督している。日本医療品質協会は、約 25% の病院を認定している[28]。日本の医療の質に関する問題の一つは、医療過誤が発生した場合の透明性の欠如である。2015年、日本は病院に対し、予期 せぬ死亡事例について患者ケアのレビューを実施し、その報告書を遺族と第三者機関に提出することを義務付ける法律を導入した。しかし、死亡が予期せぬもの かどうかを判断するのは病院の裁量に委ねられている。患者やその家族はレビューを請求する権利がないため、このシステムは効果的ではない。 [29][30] 一方、日本の医療ジャーナリストは、事実を美化し、センセーショナルに報じる傾向があり、場合によっては医療批判をでっち上げることもあるため、日本の医 療従事者は情報を公開することに消極的だ。しかし、他の国に比べて一人当たりの病院受診回数が多いことや、全体的な治療成績が良好であることを考えると、 医療事故の発生率は他の国よりも高くはないと考えられる。 日本の病院の約 92% は、看護師は十分だが医師が不足しており、医師は十分だが看護師が不足している病院は 10% に留まっています[32]。もう一つの問題は、都市部よりも地方に医療従事者が集中している、医療従事者の偏在です[33]。 2009年に、脳性麻痺で生まれた子供に対する過失責任を問わないアプローチが導入された。これにより、訴訟件数が減少するとともに、脳性麻痺で生まれる子供の数が25%減少した。[34] |

Access Japanese Super Ambulance, Tokyo Fire Department In Japan, services are provided either through regional/national public hospitals or through private hospitals/clinics, and patients have universal access to any facility, though hospitals tend to charge more to those patients without a referral. As mentioned above, costs in Japan tend to be quite low compared to those in other developed countries, but utilization rates are much higher. Most one-doctor clinics do not require reservations and same-day appointments are the rule rather than the exception. Japanese patients favour medical technology such as CT scans and MRIs, and they receive MRIs at a per capita rate 8 times higher than the British and twice as high as Americans.[9] In most cases, CT scans, MRIs and many other tests do not require waiting periods. Japan has about three times as many hospitals per capita as the US[35] and, on average, Japanese people visit the hospital more than four times as often as the average American.[35] Access to medical facilities is sometimes abused. Some patients with mild illnesses tend to go straight to the hospital emergency departments rather than accessing more appropriate primary care services. This causes a delay in helping people who have more urgent and severe conditions who need to be treated in the hospital environment. There is also a problem with misuse of ambulance services, with many people taking ambulances to hospitals with minor issues not requiring an ambulance. In turn, this causes delays for ambulances arriving for serious emergencies. Nearly 50% of the ambulance rides in 2014 were minor conditions where citizens could have taken a taxi instead of an ambulance to get treated.[36] Due to the issue of large numbers of people visiting hospitals for relatively minor problems, a shortage of medical resources can be an issue in some regions. The problem has become a wide concern in Japan, particularly in Tokyo. A report has shown that more than 14,000 emergency patients were rejected at least three times by hospitals in Japan before getting treatment. A government survey for 2007, which got a lot of attention when it was released in 2009, cited several such incidents in the Tokyo area, including the case of an elderly man who was turned away by 14 hospitals before dying 90 minutes after being finally admitted,[37] and that of a pregnant woman complaining of a severe headache being refused admission to seven Tokyo hospitals and later dying of an undiagnosed brain hemorrhage after giving birth.[38] The so-called "tarai mawashi" (ambulances being rejected by multiple hospitals before an emergency patient is admitted) has been attributed to several factors such as medical reimbursements set so low that hospitals need to maintain very high occupancy rates to stay solvent, hospital stays being cheaper for the patient than low-cost hotels, the shortage of specialist doctors and low-risk patients with minimal need for treatment flooding the system. |

アクセス 東京消防庁のスーパー救急車 日本では、医療サービスは地域・国の公立病院、または私立病院・診療所によって提供されており、患者はどの施設も利用することができるが、紹介状のない患 者は病院がより高い治療費を請求する傾向がある。前述のように、日本の医療費は他の先進国に比べてかなり低い傾向があるが、利用率ははるかに高い。ほとん どの1人診療クリニックは予約不要で、当日予約が一般的です。日本の患者はCTスキャンやMRIなどの医療技術を好んで利用し、MRIの受診率はイギリス 人の8倍、アメリカ人の2倍です[9]。CTスキャン、MRIを含む多くの検査は、通常、待ち時間なしで受けられます。日本は、1 人当たりの病院数が米国の約 3 倍[35] であり、日本人は平均して、米国人の 4 倍以上も病院を訪れている[35]。 医療施設の利用が乱用される場合もある。軽度の病気の患者の中には、より適切な一次医療サービスを利用せずに、直接病院の救急外来を受診する傾向がある。 これにより、病院での治療が必要な、より緊急かつ重篤な症状の患者の治療が遅れることになる。また、救急車を誤用する問題もあり、救急車を必要としない軽 度の症状で救急車を利用して病院に行く人が多くいる。その結果、重篤な救急患者が救急車による搬送を待つ時間が長くなる。2014 年の救急車の出動の 50% 近くは、市民が救急車ではなくタクシーで治療を受けることができた軽度の症例だった[36]。 比較的軽度の症状で病院を訪れる人が多いため、一部の地域では医療資源の不足が問題となっている。この問題は、東京を中心に、日本全国で広く懸念されてい る。ある報告書によると、日本国内の病院で治療を受ける前に少なくとも3回以上拒否された緊急患者が1万4,000人を超えていることが示されている。 2007年に実施され、2009年に公表されて注目を集めた政府調査では、東京地域で複数の同様の事例が報告されており、 その中には、14の病院から断られ、最終的に入院してから90分後に死亡した高齢男性のケース[37]や、激しい頭痛を訴えた妊娠中の女性が東京の7つの 病院から入院を拒否され、出産後に診断されなかった脳出血で死亡したケースが含まれていました。 [38] いわゆる「たらい回し」(救急患者が複数の病院で受け入れを拒否される状態)は、医療費の報酬が極めて低く、病院が経営を維持するために高い入院率を維持 する必要があること、患者にとって病院での入院が低コストホテルよりも安価であること、専門医の不足、治療の必要性が低い低リスク患者がシステムを過負荷 にしていることなど、複数の要因に起因しているとされている。 |

| Insurance Health insurance is, in principle, mandatory for residents of Japan, but there is no penalty for the 10% of individuals who choose not to comply, making it optional in practice.[39][40] Apart from conventional Western medicine and healthcare, Japanese insurance also covers traditional health therapies like acupuncture and health massages, etc., from licensed therapists.[41] There is a total of eight health insurance systems in Japan,[42] with around 3,500 health insurers. According to Mark Britnell, it is widely recognised that there are too many small insurers.[43] They can be divided into two categories, Employees' Health Insurance (健康保険, Kenkō-Hoken) and National Health Insurance (国民健康保険, Kokumin-Kenkō-Hoken). Employees’ Health Insurance is broken down into the following systems:[42] Union Managed Health Insurance Government Managed Health Insurance Seaman's Insurance National Public Workers Mutual Aid Association Insurance Local Public Workers Mutual Aid Association Insurance Private School Teachers’ and Employees’ Mutual Aid Association Insurance National Health Insurance is generally reserved for self-employed people and students, and social insurance is normally for corporate employees. National Health Insurance has two categories:[42] National Health Insurance for each city, town or village National Health Insurance Union Public health insurance covers most citizens/residents and the system pays 70% or more of medical and prescription drug costs with the remainder being covered by the patient (upper limits apply).[44] The monthly insurance premium is paid per household and scaled to annual income. Supplementary private health insurance is available only to cover the co-payments or non-covered costs and has a fixed payment per day in hospital or per surgery performed, rather than per actual expenditure.[45][46] There is a separate system of insurance - Kaigo-Hoken (介護保険) - for long-term care, run by the municipal governments. People over 40 have contributions of around 2% of their income.[43] Insurance for individuals is paid for by both employees and employers. This ends up accounting for 95% of the coverage for individuals.[47] Patients in Japan must pay 30% of medical costs. If there is a need to pay a much higher cost, they get reimbursed up to 80-90%. Seniors who are covered by SHSS (senior insurance) only pay 10% out of pocket.[48] As of 2016, healthcare providers spend billions on inpatient care and outpatient care. 152 billion is spent on inpatient care while 147 billion is spent on outpatient care. As far as the long term goes, 41 billion is spent.[49] Today, Japan has the severe problem of paying for rising medical costs, benefits that are not equal from one person to another and even burdens on each of the nation's health insurance programs.[50] One of the ways Japan has improved its healthcare more recently is by passing the Industrial Competitiveness Enhancement Action Plan. The goal is to help prevent diseases so people live longer. If preventable diseases are prevented, Japan will not have to spend as much on other costs. The action plan also provides a higher quality of medical and health care.[51] |

保険 健康保険は、原則として日本の居住者は加入が義務付けられているが、加入を拒否する 10% の個人には罰則は設けられておらず、実際には任意となっている[39][40]。日本の保険は、従来の西洋医学や医療だけでなく、鍼灸や健康マッサージな どの伝統的な健康療法も、認可を受けた施術者によるものについては保険の対象となっている。 [41] 日本には合計 8 つの健康保険制度があり[42]、約 3,500 の健康保険者が存在している。マーク・ブリトネル氏によると、小規模な保険者が多すぎることは広く認識されている[43]。これらは、従業員健康保険(健 康保険、Kenkō-Hoken)と国民健康保険(国民健康保険、Kokumin-Kenkō-Hoken)の 2 つに分類できる。健康保険は、以下の制度に分かれている[42]。 組合健康保険 政府健康保険 船員保険 国家公務員共済組合保険 地方公務員共済組合保険 私立学校教職員共済組合保険 国民健康保険は、一般的に自営業者や学生のために用意されており、社会保険は通常、企業従業員を対象としている。国民健康保険には 2 つのカテゴリーがある[42]。 各市町村の国民健康保険 国民健康保険組合 公的健康保険は、ほとんどの国民/住民をカバーしており、医療費および処方薬代の 70% 以上を保険が負担し、残りは患者が負担する(上限あり)。[44] 月額保険料は世帯ごとに、年収に応じて算定される。補足的な民間健康保険は、自己負担分や保険適用外の費用のみを対象とし、実際の支出額ではなく、入院日 数や手術回数に応じて 1 日あたりの定額で支払われる。[45][46] 介護については、地方自治体が運営する別の保険制度(介護保険)がある。40 歳以上は、収入の約 2% を保険料として納めている。[43] 個人の保険は、従業員と雇用主の両方が負担する。これにより、個人の保険の95%が賄われている。[47] 日本の患者は医療費の30%を自己負担する。高額な費用が発生した場合、80~90%が償還される。SHSS(高齢者保険)に加入している高齢者は、自己 負担が10%のみだ。[48]2016年現在、医療提供者は入院医療と外来医療に数十億ドルを費やしている。入院医療には152億ドル、外来医療には 147億ドルが支出されている。長期的な観点では、41億ドルが支出されている。[49] 今日、日本は、医療費の増加、個人間の給付の格差、さらには各国民健康保険制度の負担増という深刻な問題を抱えている[50]。日本が最近、医療を改善し た方法のひとつは、「産業競争力強化行動計画」を可決したことだ。その目標は、病気の予防により、人民の寿命を延ばすことだ。予防可能な病気が予防されれ ば、日本は他の費用にそれほど支出する必要がなくなる。この行動計画は、医療と保健の質の向上も目指している[51]。 |

| Health in Japan Aging of Japan Birth in Japan Hikikomori Suicide in Japan Erwin Bälz—a foreign government advisor and cofounder of modern medicine in Japan Health care compared—tabular comparisons with the U.S., Canada, and other countries not shown above List of hospitals in Japan Public health centres in Japan Social welfare in Japan |

日本の保健 日本の高齢化 日本の出産 ひきこもり 日本の自殺 エルヴィン・ベルツ - 外国政府顧問、日本における近代医学の創始者の一人 医療の比較 - 米国、カナダ、および上記以外の国々との表による比較 日本の病院一覧 日本の保健所 日本の社会福祉 |

| Sources 講談社インターナショナル (2003). Bairingaru Nihon jiten (in Japanese) (2003 ed.). 講談社インターナショナル. ISBN 4-7700-2720-6. - Total pages: 798 "employees' health insurance". Japan: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Tokyo: Kodansha Ltd. 1993. ISBN 4069310983. OCLC 27812414. (set), (volume 1). - Total pages: 1924 Rapoport, John; Jacobs, Philip; Jonsson, Egon (13 July 2009). Cost Containment and Efficiency in National Health Systems: A Global Comparison Health Care and Disease Management (2009 ed.). Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-32110-0. - Total pages: 247 |

出典 講談社インターナショナル (2003). Bairingaru Nihon jiten (日本語) (2003年版). 講談社インターナショナル. ISBN 4-7700-2720-6. - 総ページ数: 798 「従業員の健康保険」。日本図鑑。東京:講談社。1993年。ISBN 4069310983。OCLC 27812414。(セット)、(第 1 巻)。- 総ページ数:1924 Rapoport, John; Jacobs, Philip; Jonsson, Egon (2009年7月13日). Cost Containment and Efficiency in National Health Systems: A Global Comparison Health Care and Disease Management (2009年版). Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-32110-0. - 総ページ数:247 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_care_system_in_Japan |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆