日本の高齢化

Hyper-Aged Society, Japan [超高齢化社会]

Population

pyramid of Japan from 2020 to projections up to 2100

☆日本は世界で最も高齢者の割合が高い国で ある。[1] 2014年の推計によると、日本の人口の約38%が60歳以上、25.9%が65歳以上であり、2022年には29.1%に増加すると予測されている。 2050年には、日本の人口の3分の1が65歳以上になると推定されている。[2] 日本における人口の高齢化は、韓国や中国など他の国々における同様の傾向に先んじて起こった。[3][4] 人口置換水準を下回る出生率と高い平均余命を特徴とする日本の高齢化は、今後も継続すると見込まれている。日本では、1947年から1949年にかけて戦 後のベビーブームが起こったが、その後は長期間にわたって出生率が低下した。[5] これらの傾向により、2008年10月に1億2810万人でピークに達した後、日本の人口は減少に転じた。[6] 2014年の日本の人口は1億2700万人と推定されている。この数値は、現在の人口動態の傾向が続いた場合、2040年までに1億700万人(16% 減)、2050年までに9700万人(24%減)にまで減少すると予測されている。 [7] 2020年の世界的な分析では、2100年までに総人口が50%以上減少する可能性がある23カ国のうちの1つとして日本が挙げられている。[8] これらの傾向により、一部の研究者は、日本が都市部と地方の両方で「超高齢化社会」へと変貌しつつあると主張している。[9] 日本国民は概ね、日本を快適で近代的な国と捉えており、「人口危機」という感覚は広まっていない。[6] 政府は、人口動態の変化が経済や社会サービスに与える影響への懸念に応えるため、出生率の回復と高齢者の社会参加を促す政策を実施している。

| Japan

has the highest proportion of elderly citizens of any country in the

world.[1] 2014 estimates showed that about 38% of the Japanese

population was above the age of 60, and 25.9% was above the age of 65,

a figure that increased to 29.1% by 2022. By 2050, an estimated

one-third of the population in Japan is expected to be 65 and older.[2]

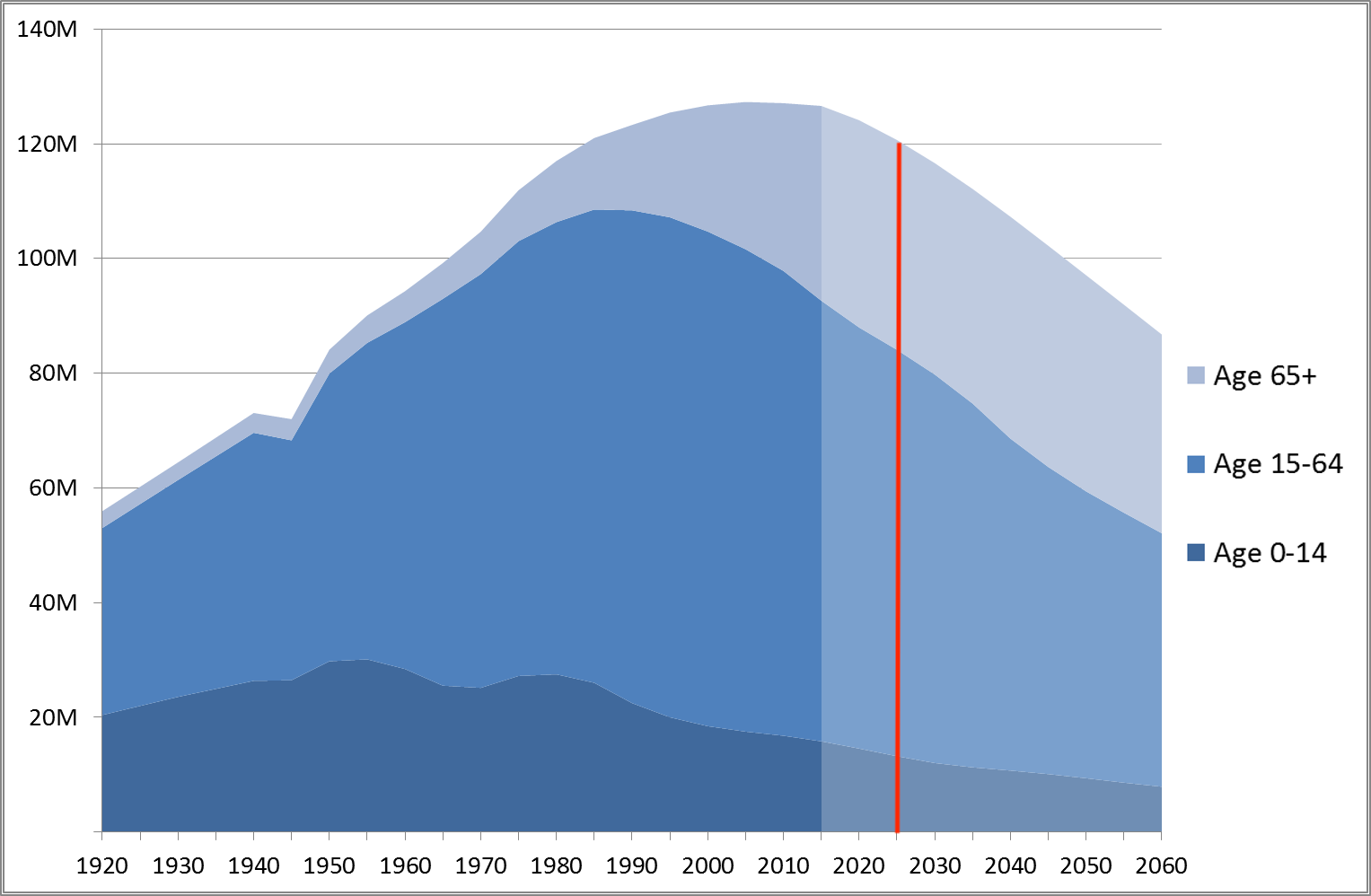

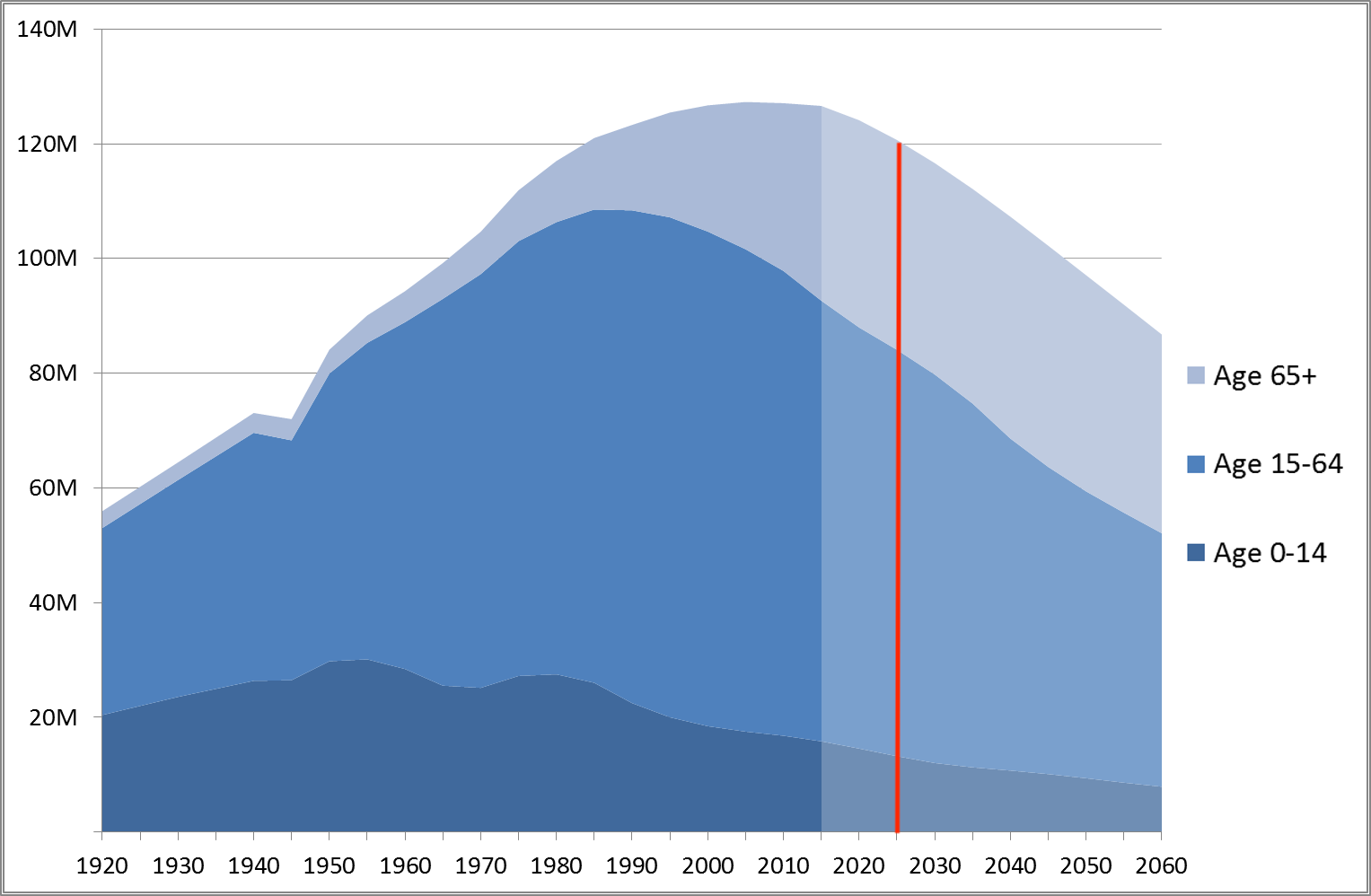

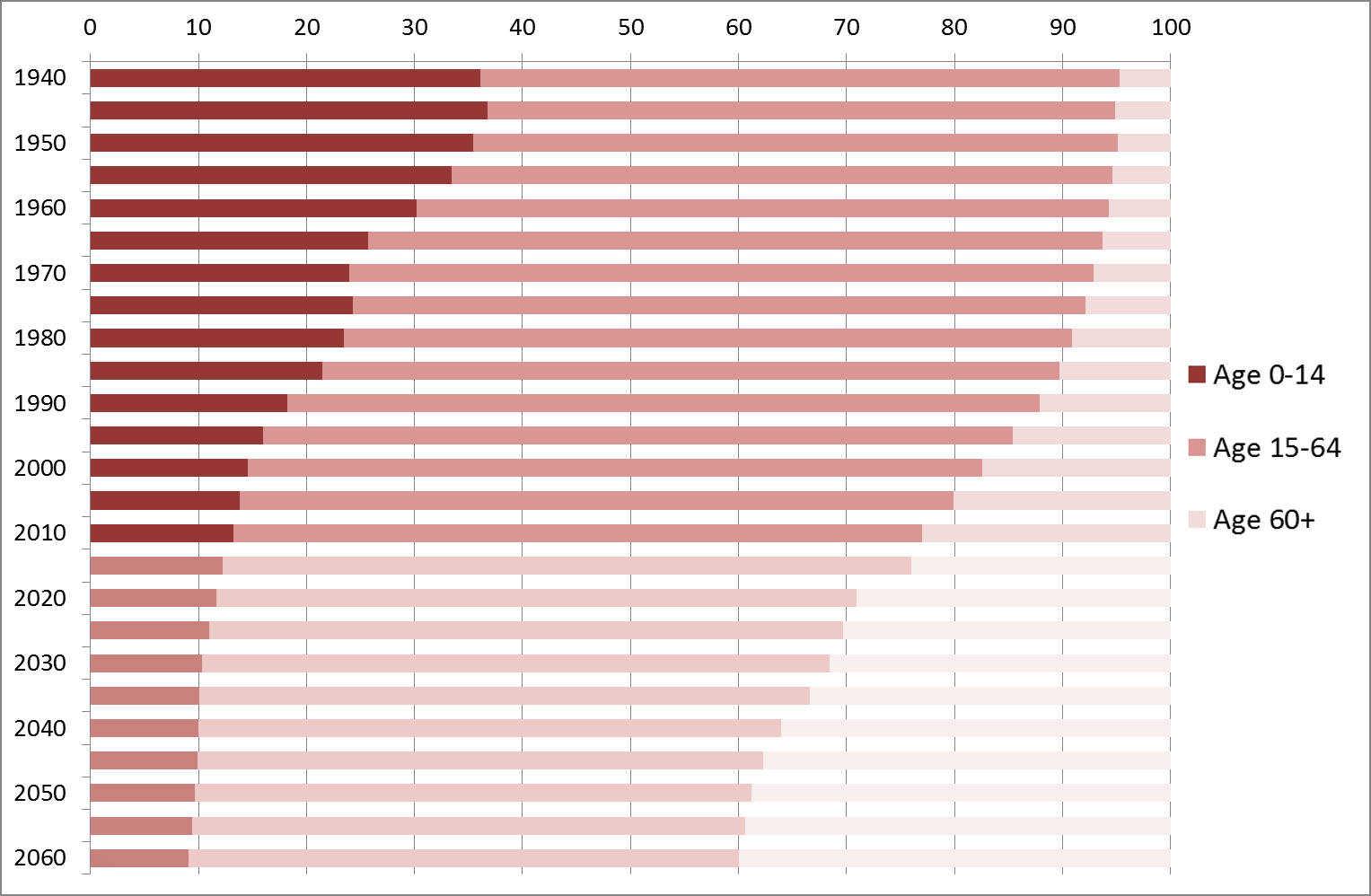

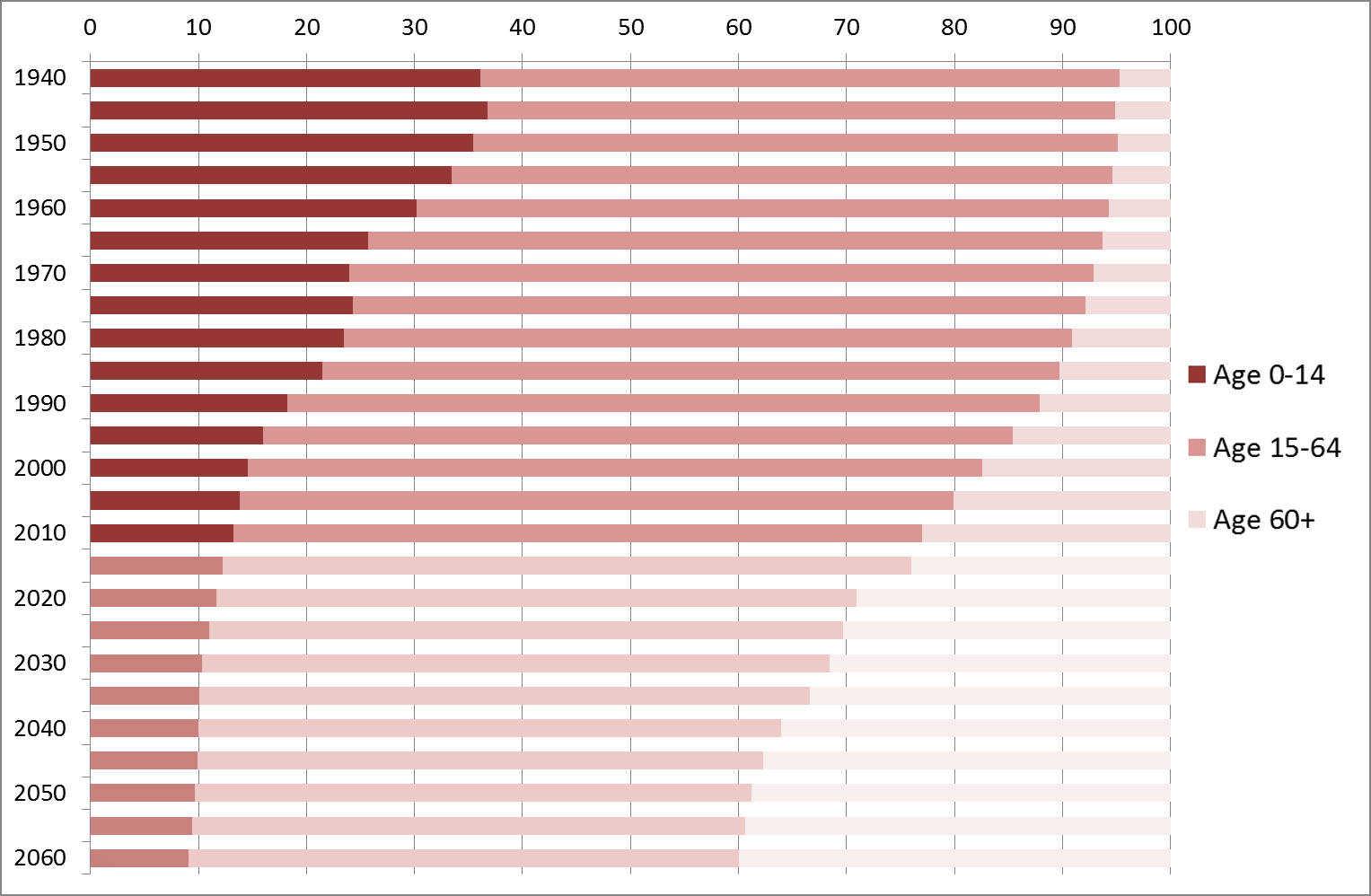

Population aging in Japan preceded similar trends in other countries,

such as South Korea and China.[3][4] The ageing of Japanese society, characterized by sub-replacement fertility rates and high life expectancy, is expected to continue. Japan had a post-war baby boom between 1947 and 1949, followed by a prolonged period of low fertility.[5] These trends resulted in the decline of Japan's population after reaching a peak of 128.1 million in October 2008.[6] In 2014, Japan's population was estimated to be 127 million. This figure is expected to shrink to 107 million (by 16%) by 2040 and to 97 million (by 24%) by 2050 if this current demographic trend continues.[7] A 2020 global analysis found that Japan was one of 23 countries that could see a total population decline of 50% or more by 2100.[8] These trends have led some researchers to claim that Japan is transforming into a "super-ageing" society in both rural and urban areas.[9] Japanese citizens largely view Japan as comfortable and modern, with no widespread sense of a "population crisis".[6] The Japanese government has responded to concerns about the stresses demographic changes place on the economy and social services with policies intended to restore the fertility rate as well as increase the activity of the elderly in society.[10] Japan's population in three demographic categories, from 1920 to 2010, with projections to 2060

|

日本は世界で最も高齢者の割合が高

い国である。[1]

2014年の推計によると、日本の人口の約38%が60歳以上、25.9%が65歳以上であり、2022年には29.1%に増加すると予測されている。

2050年には、日本の人口の3分の1が65歳以上になると推定されている。[2]

日本における人口の高齢化は、韓国や中国など他の国々における同様の傾向に先んじて起こった。[3][4] 人口置換水準を下回る出生率と高い平均余命を特徴とする日本の高齢化は、今後も継続すると見込まれている。日本では、1947年から1949年にかけて戦 後のベビーブームが起こったが、その後は長期間にわたって出生率が低下した。[5] これらの傾向により、2008年10月に1億2810万人でピークに達した後、日本の人口は減少に転じた。[6] 2014年の日本の人口は1億2700万人と推定されている。この数値は、現在の人口動態の傾向が続いた場合、2040年までに1億700万人(16% 減)、2050年までに9700万人(24%減)にまで減少すると予測されている。 [7] 2020年の世界的な分析では、2100年までに総人口が50%以上減少する可能性がある23カ国のうちの1つとして日本が挙げられている。[8] これらの傾向により、一部の研究者は、日本が都市部と地方の両方で「超高齢化社会」へと変貌しつつあると主張している。[9] 日本国民は概ね、日本を快適で近代的な国と捉えており、「人口危機」という感覚は広まっていない。[6] 政府は、人口動態の変化が経済や社会サービスに与える影響への懸念に応えるため、出生率の回復と高齢者の社会参加を促す政策を実施している。[10] 1920 年から2010年までの日本の人口動態3区分、2060年までの予測値  |

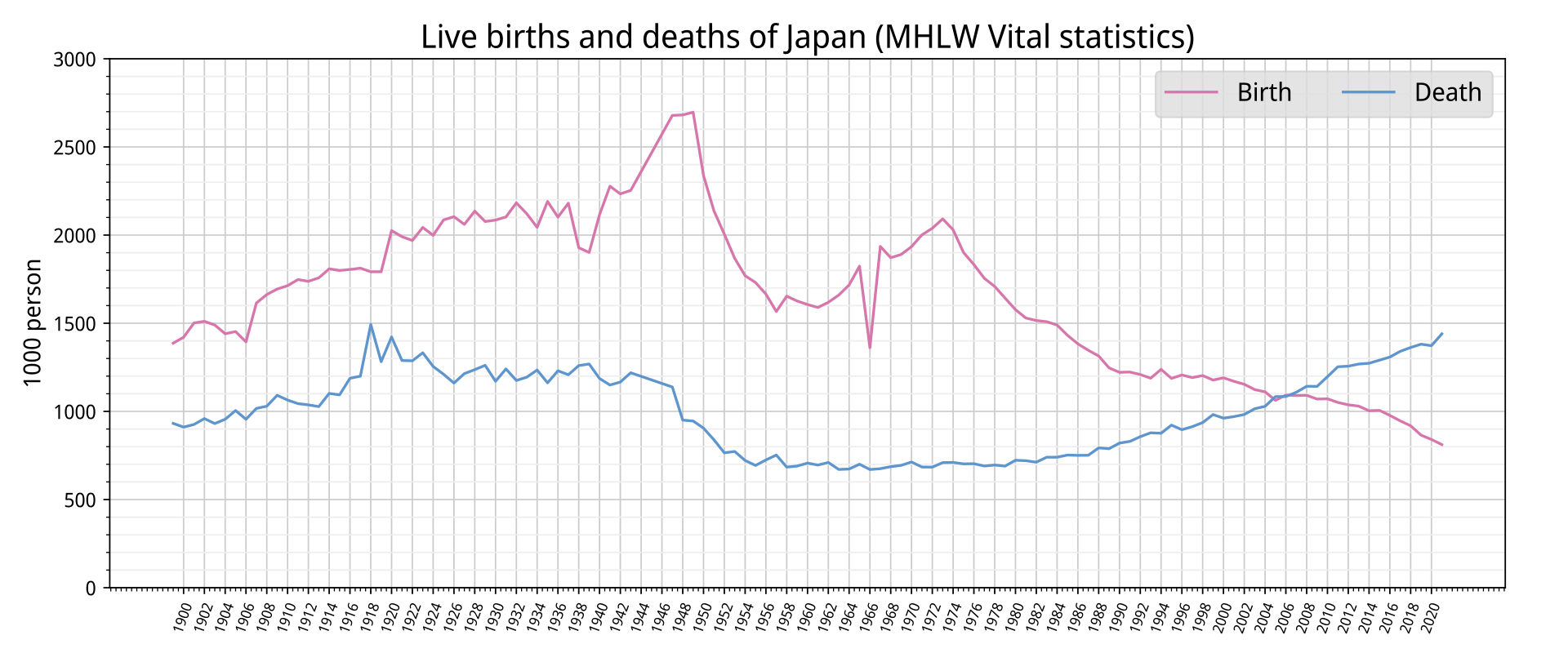

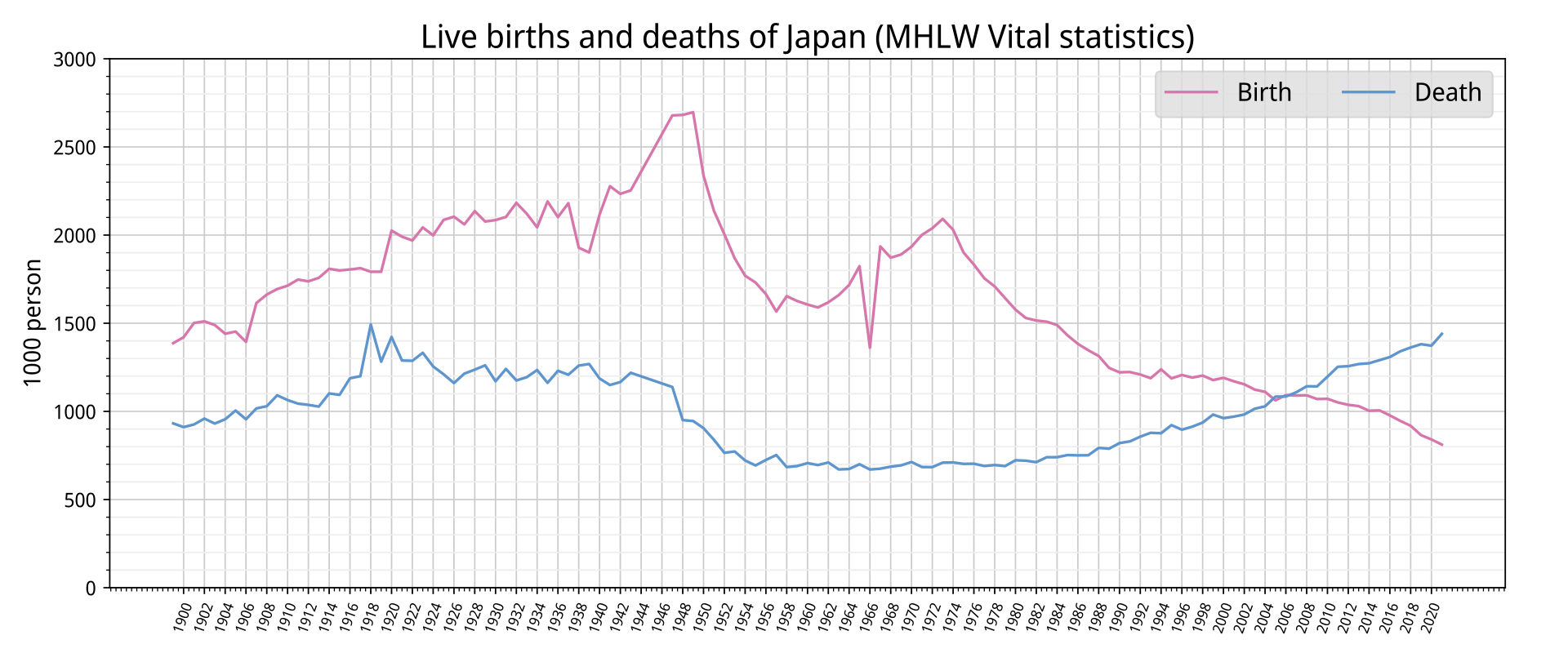

| Ageing dynamics Further information: Demographics of Japan  Japan's demographic transition 1888-2019 From 1974 to 2014, the number of Japanese people 65 years or older nearly quadrupled, accounting for 26% of Japan's population at 33 million individuals. In the same period, the proportion of children aged 14 and younger decreased from 24.3% in 1975 to 12.8% in 2014.[11] The number of elderly people surpassed the number of children in 1997. Sales of adult diapers surpassed diapers for babies in 2014.[12] This change in the demographic makeup of Japanese society, referred to as population ageing (kōreikashakai, 高齢化社会),[13] has taken place in a shorter period of time than in any other country. According to population projections based on the current fertility rate, individuals over the age of 65 will account for 40% of the population by 2060,[14][15] and the total population will fall by one-third from 128 million in 2010 to 87 million by 2060.[16] The proportion of old Japanese citizens will soon level off. However, due to stagnant birth rates, it is estimated that the proportion of young people (under the age of 19) in Japan will constitute only 13 percent in the year 2060, decreasing from 40 percent in 1960.[5] Economists at Tohoku University established a countdown to national extinction, which projects that Japan will have only one remaining child in 4205.[17] These predictions prompted a pledge by Prime Minister Shinzō Abe to set a threshold for population decline at 100 million.[10][12] |

高齢化の動態 さらに詳しい情報:日本の人口統計  日本の人口推移 1888年~2019年 1974年から2014年の間に、65歳以上の日本人の数はほぼ4倍となり、3,300万人で日本の人口の26%を占めるようになった。同じ期間に、14 歳以下の子供の割合は1975年の24.3%から2014年には12.8%に減少した。[11] 高齢者の数は1997年に子供の数を上回った。2014年には大人用おむつの売り上げが赤ちゃん用おむつの売り上げを上回った。[12] この日本社会の人口構成の変化は、高齢化社会(こうれいかしゃかい、高齢化社会)と呼ばれ、[13] 他のどの国よりも短期間で起こった。 現在の出生率に基づく人口予測によると、2060年には65歳以上の高齢者が人口の40%を占めるようになり[14][15]、総人口は2010年の1億 2800万人から2060年には8700万人へと3分の1減少する見通しである[16]。高齢者の割合は間もなく頭打ちになる。しかし、出生率の低迷によ り、日本の19歳以下の若者人口の割合は、1960年の40パーセントから2060年には13パーセントに減少すると推定されている。 東北大学の経済学者は、日本が4205年には子供が1人しかいなくなるという「国民消滅へのカウントダウン」を発表した。[17] これらの予測を受けて、安倍晋三首相は人口減少の閾値を1億人と設定する方針を打ち出した。[10][12] |

Causes Japan's birth and death rates, The drop in 1966 was due to it being a hinoe uma: a year which is viewed as ill-omened in the Japanese Zodiac.[18] Further information: Marriage in Japan High life expectancy Japan's life expectancy was 85.1 years in 2016:[19] 81.7 years for males and 88.5 years for females.[20] As Japan's overall population shrinks due to low fertility rates, the proportion of the elderly increases.[21] Life expectancy at birth increased rapidly from the end of World War II — when the average life expectancy was 54 years for women and 50 for men — and the percentage of the population aged 65 years and older has increased steadily since the 1950s. Japan is a well-known example, with close to 30 percent of its population aged 65 years or older.[22] The increase in life expectancy translated into a depressed mortality rate until the 1980s, but mortality has increased again to a historic high, since 1950, of 10.1 per 1000 people in 2013.[11] Factors such as improved nutrition, advanced medical and pharmacological technologies, and improved living conditions have all contributed to the longer-than-average life expectancy. Peace and prosperity following World War II were integral to the massive economic growth of post-war Japan, contributing further to the population's longevity.[21] The proportion of healthcare spending has also dramatically increased as Japan's older population spends more time in hospitals and visiting physicians. On any given day in 2011, 2.9% of people aged 75–79 were in a hospital, and 13.4% were visiting a physician.[23] |

原因 日本の出生率と死亡率、1966年の低下は、丙午(ひのえうま)であったためである。丙午は、日本の干支では不吉な年とされている。[18] さらに詳しい情報:日本の結婚 高い平均余命 2016年の日本の平均余命は85.1歳であり、男性は81.7歳、女性は88.5歳である。[20] 少子化により日本の総人口が減少するにつれ、高齢者の割合は増加している。[21] 平均寿命は、第二次世界大戦後、急速に伸びた。終戦時の平均寿命は、女性が54歳、男性が50歳であったが、1950年代以降、65歳以上の人口の割合は 着実に増加している。日本はよく知られた例であり、65歳以上の人口が全人口の30パーセント近くを占めている。[22] 平均余命の増加は、1980年代までは死亡率の低下につながったが、死亡率は再び上昇し、2013年には1000人あたり10.1人と、1950年以来の 過去最高を記録した。[11] 栄養状態の改善、医療および薬学技術の進歩、生活環境の改善といった要因がすべて、平均寿命を上回る長寿に寄与している。第二次世界大戦後の平和と繁栄 は、戦後の日本の大規模な経済成長に不可欠であり、さらに国民の長寿化に貢献した。[21] また、日本の高齢人口が病院で過ごす時間や医師の診察を受ける時間が長くなるにつれ、医療費の割合も劇的に増加している。2011年の任意の1日におい て、75歳から79歳までの人口の2.9%が病院に、13.4%が医師の診察を受けていた。[23] |

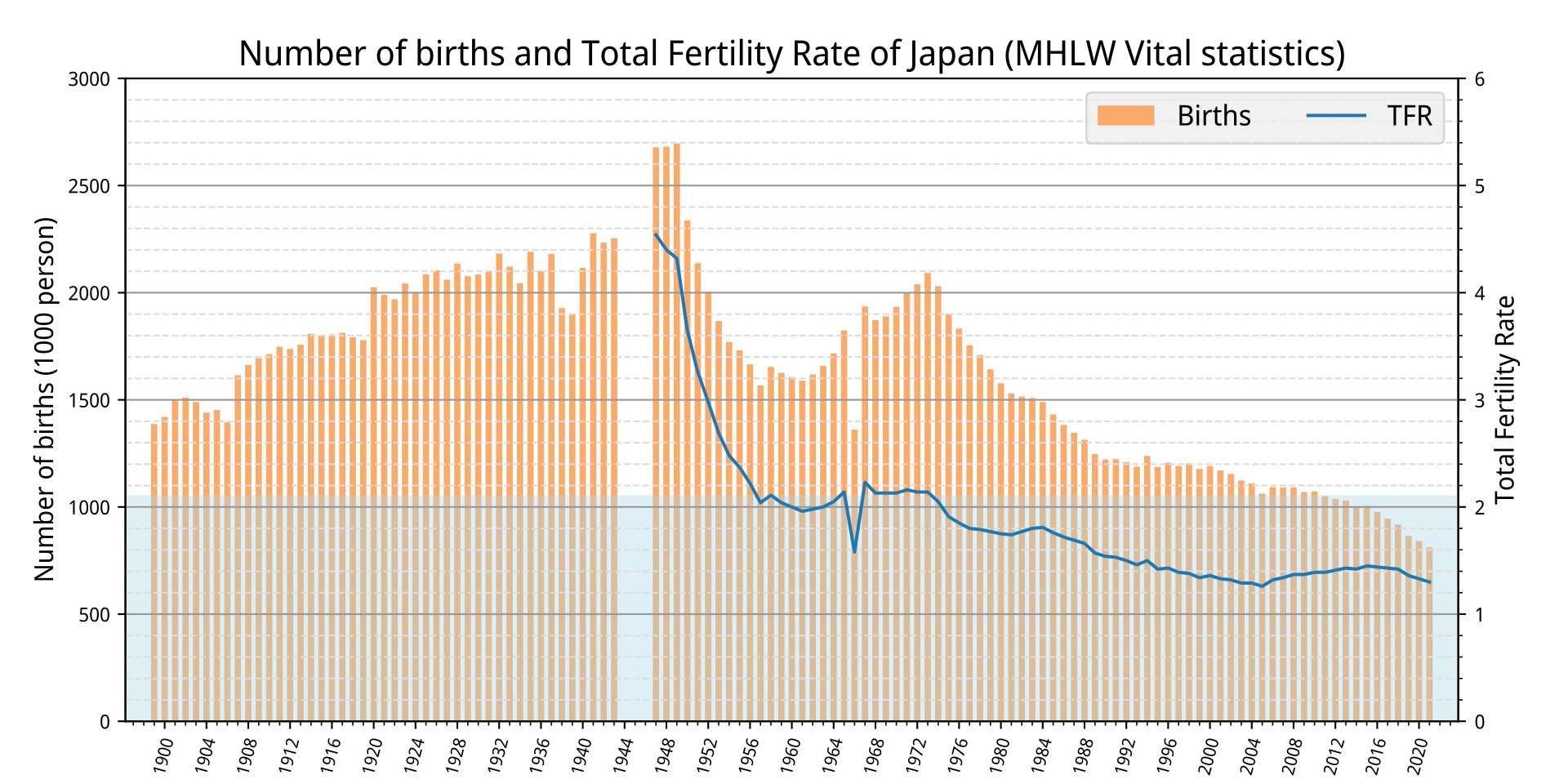

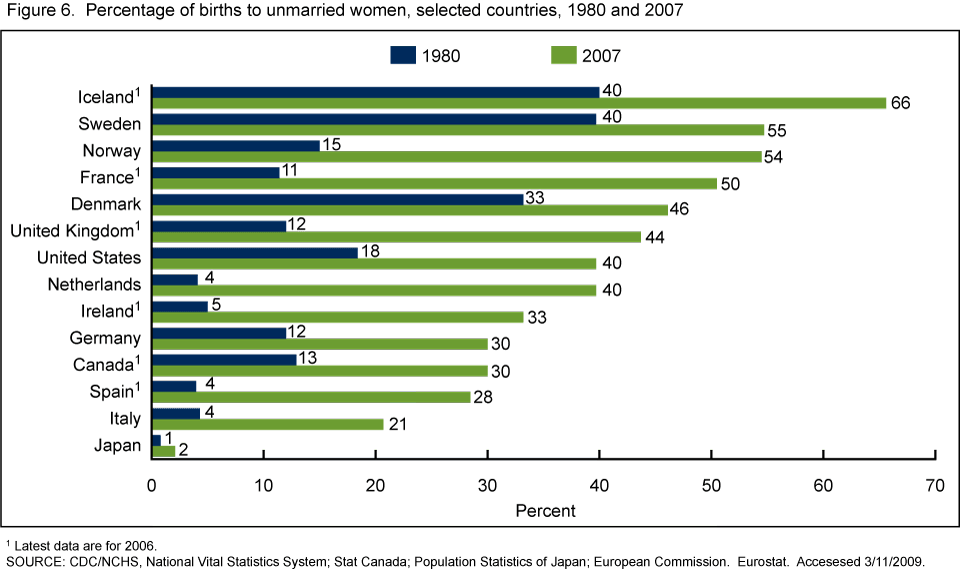

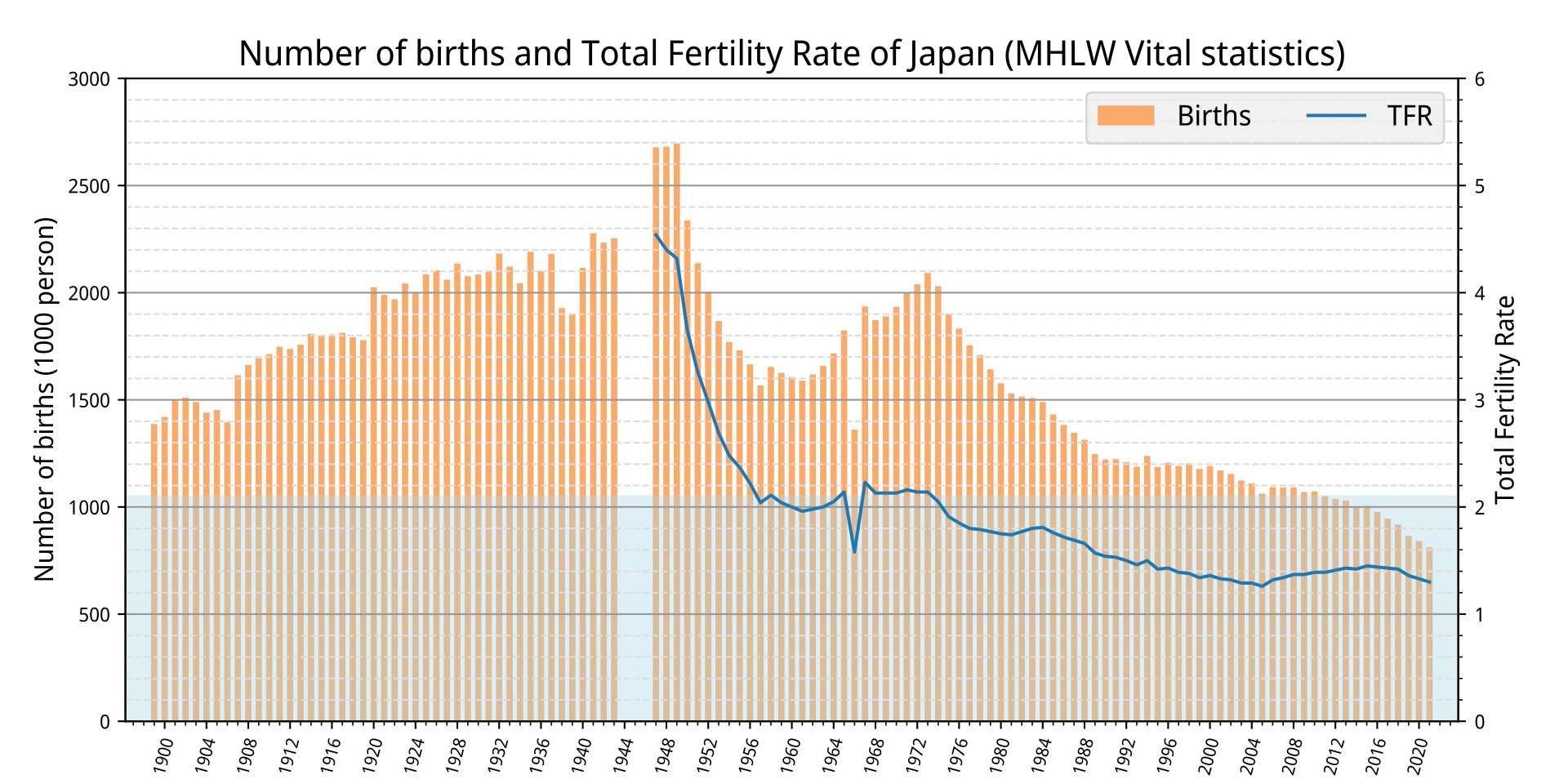

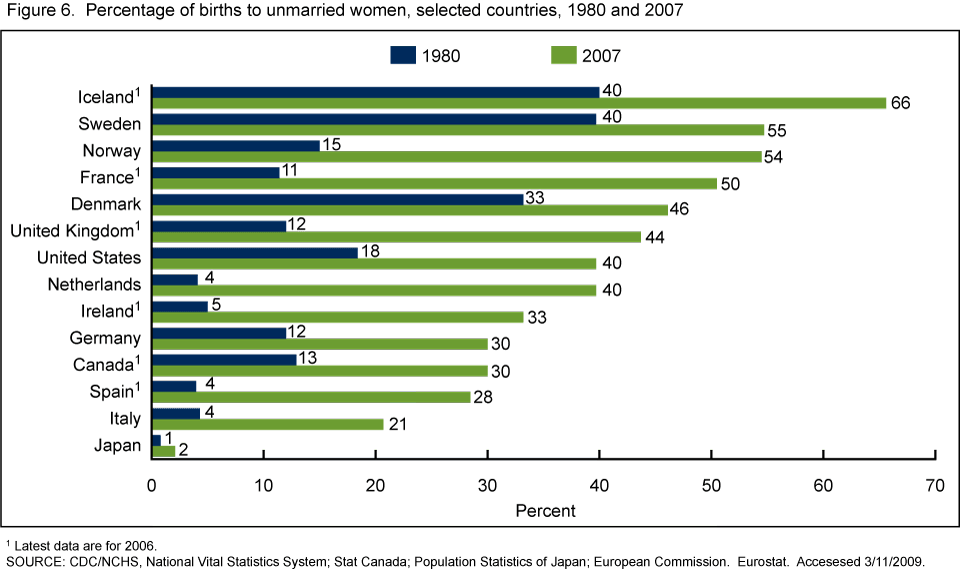

Low fertility rate Total fertility rate and births of Japan  The percentage of births to unmarried women in selected countries, 1980 and 2007.[24] As can be seen in the figure, Japan has not followed the trend of Western countries of children born outside of marriage to the same degree. Japan's total fertility rate, or TFR, the number of children born from each woman in her lifetime, has remained below the replacement threshold of 2.1 since 1974, and reached a historic low of 1.26 in 2005.[11] In 2016, the TFR was 1.41 children born per woman.[20] Experts believe that signs of a slight recovery reflect the expiration of a "tempo effect," arising from a shift in the timing of children being born rather than any positive change.[25] |

低い出生率 日本の合計特殊出生率と出生数  一部の国における未婚女性からの出生数の割合、1980年と2007年[24] 図からわかるように、日本は欧米諸国における婚外出産の傾向を同じ程度には追ってはいない。 日本の合計特殊出生率(TFR)は、1人の女性が生涯に産む子供の数を示すが、1974年以降、人口置換水準である2.1を下回り続け、2005年には 1.26という過去最低の水準に達した。 [11] 2016年には、TFRは女性1人あたり1.41人の子供が生まれた。[20] 専門家は、わずかな回復の兆しは、子供が生まれる時期の変化による「テンポ効果」の期限切れを反映していると信じており、それは何らかの前向きな変化によ るものではないと考えている。[25] |

| Economy and culture A range of economic and cultural factors contributed to the decline in childbirth during the late 20th century: later and fewer marriages, higher education, urbanization, increase in nuclear family households (rather than the extended family), poor work-life balance, increased participation of women in the workforce, a decline in wages and lifetime employment, small living spaces and the high cost of raising a child.[26][27][28][29] Many young people face economic insecurity due to a lack of regular employment. About 40% of Japan's labor force is non-regular, including part-time and temporary workers.[30] Non-regular employees earn about 53 percent less than regular ones on a comparable monthly basis, according to the Labor Ministry.[31] Young men in this group are less likely to consider marriage or to be married.[32][33] Many young Japanese people also report that fatigue from overwork hinders their motivation to pursue romantic relationships.[34][35] Although most married couples have two or more children,[36] a growing number of young people postpone or entirely reject marriage and parenthood. Conservative gender roles often mean that women are expected to stay home with the children rather than work.[37] Between 1980 and 2010, the percentage of the population who had never married increased from 22% to almost 30%, even as the population continued to age,[11] and by 2035 one in four men will not marry during their prime parenthood years.[38] The Japanese sociologist Masahiro Yamada coined the term parasite singles (パラサイトシングル, parasaito shinguru) for unmarried women in their late 20s and 30s who continue to live with their parents.[39] A government survey released in June 2022 said that among singles, 46.4% desired to get married, while around a quarter explicitly preferred to remain single (26.5% of men and 25.4% of women). Common reasons for forgoing marriage include the loss of freedom, financial burden, and housework. Hitherto unmarried women cited the burden of housework, childcare and nursing care as major reasons, with men citing financial and job instability. Some women also stated a desire not to change their surname.[40] |

経済と文化 20世紀後半における少子化には、さまざまな経済的・文化的要因が影響している。晩婚化・非婚化、高等教育の普及、都市化、核家族世帯の増加(拡大家族よ りも)、ワークライフバランスの悪化、女性の労働力参加の増加、賃金と終身雇用の低下、狭い居住空間、子育て費用の高騰などである。[26][27] [28][29] 多くの若者が、正規雇用に就けないことによる経済的不安に直面している。日本の労働人口の約40%が非正規雇用であり、パートタイムや派遣労働者などが含 まれる。[30] 労働省によると、非正規雇用者の賃金は、同等の月給ベースで正規雇用者の約53%である。 [31] このグループに属する若い男性は、結婚を考える可能性が低く、また結婚している可能性も低い。[32][33] また、多くの日本の若者は、過労による疲労が恋愛関係を築く意欲を妨げていると報告している。[34][35] ほとんどの夫婦には2人以上の子供がいるが、[36] 結婚や出産を先延ばしにしたり、完全に拒否する若者が増えている。保守的な性別役割分担により、女性は仕事よりも家庭で子供を育てることを期待されること が多い。[37] 1980年から2010年の間に、一度も結婚したことのない人口の割合は22%から30%近くに増加し、人口の高齢化が進む中、2035年には4人のうち 1人の男性が、子育ての盛りの時期に結婚しないことになる。 [38] 日本の社会学者、山田昌弘は、20代後半から30代の未婚女性で親と同居を続ける人々を指す「パラサイト・シングル」(パラサイトシングル、 parasaito shinguru)という造語を考案した。[39] 2022年6月に発表された政府調査によると、独身者のうち46.4%が結婚を希望しているが、約4分の1は独身のままでいることを明確に望んでいる(男 性の26.5%、女性の25.4%)。結婚を先延ばしにする理由として、自由を失うこと、経済的な負担、家事などが挙げられる。未婚の女性は、家事、育 児、介護の負担を主な理由として挙げ、男性は経済的な負担や仕事の不安定さを挙げている。また、一部の女性は、姓を変えたくないという希望も述べている。 [40] |

| Virginity and abstinence rates In 2015, 1 in 10 Japanese adults in their 30s reported having had no heterosexual sexual experiences. After accounting for people who may have had same-sex intercourse, researchers estimated that around 5 percent of people lack any sexual experience whatsoever.[41] The percentage of 18 to 39-year-old women without sexual experience was 24.6% in 2015, an increase from 21.7% in 1992. Likewise, the percentage of 18 to 39-year-old men without sexual experience was 25.8% in 2015, an increase from 20% in 1992. Men with stable jobs and a high income were found to be more likely to have sex, while low-income men were 10 to 20 times more likely to have had no sex experience. Conversely, women with lower income were more likely to have had intercourse.[42][a] Men who are unemployed are eight times more likely to be virgins, and men who are part-time or temporary employed had a four times higher virginity rate.[43] According to a 2010 survey, 61% of single Japanese men in their 20s, and 70% of single Japanese men in their 30s, call themselves "herbivore men" (sōshoku danshi), meaning that they are not interested in getting married or having a girlfriend.[44] A 2022 survey by the Japanese Cabinet Office found that around 40% of unmarried Japanese men in their 20s have never been on a date.[45] By comparison, 25% of young adult women said they never dated.[45] It is estimated that 5% of married men and women who have had zero dating partners have used konkatsu (short for kekkon katsudo, or marriage hunting, a series of strategies and events similar to finding employment) services to find a spouse.[45] |

処女性と禁欲率 2015年、30代の日本人成人の10人に1人が異性との性的経験がないと報告した。同性との性交渉の経験がある可能性がある人々を考慮した上で、研究者 らは、何らかの性的経験がない人の割合は約5%であると推定している。[41] 18歳から39歳までの女性の性的経験のない人の割合は、2015年には24.6%であり、1992年の21.7%から増加している。同様に、18歳から 39歳までの男性で性的経験のない人の割合は2015年には25.8%であり、1992年の20%から増加している。安定した仕事に就き、高収入の男性は 性交渉を持つ可能性が高いことが分かっているが、低収入の男性は性交渉の経験がない可能性が10倍から20倍高い。逆に、低収入の女性は性交渉の経験があ る可能性が高い。[42][a] 無職の男性は童貞である可能性が8倍高く、パートタイムまたは臨時雇用されている男性は童貞率が4倍高い。[43] 2010年の調査によると、20代の独身男性の61%、30代の独身男性の70%が、結婚や交際の意思がない「草食男子」であると自称している。 2022年の内閣府の調査では、20代の未婚男性の約40%がデートの経験がないことが分かった。[45] それと比較すると、若い大人の女性の25%がデートをしたことがないと答えた。 [45] 交際相手がゼロの既婚男女のうち、5%が結婚相手を見つけるために「コンカツ(婚活の略語)」サービスを利用していると推定されている。婚活とは、就職活 動に似た一連の戦略やイベントを指す。[45] |

Effects Japan's demographic age composition from 1940 to 2010, with projections out to 2060 Demographic trends are altering relations within and across generations, creating new government responsibilities and changing many aspects of Japanese social life. The aging and decline of the working-age population has triggered concerns about the future of the nation's workforce, potential economic growth, and the solvency of the national pension and healthcare services.[46] |

影響 1940年から2010年までの日本の人口動態構成、2060年までの予測 人口動態の変化は世代間の関係を変化させ、政府の新たな責任を生み出し、日本の社会生活の多くの側面を変えている。生産年齢人口の高齢化と減少は、労働力 人口の将来、潜在的な経済成長、国民年金や医療サービスの支払い能力に対する懸念を引き起こしている。[46] |

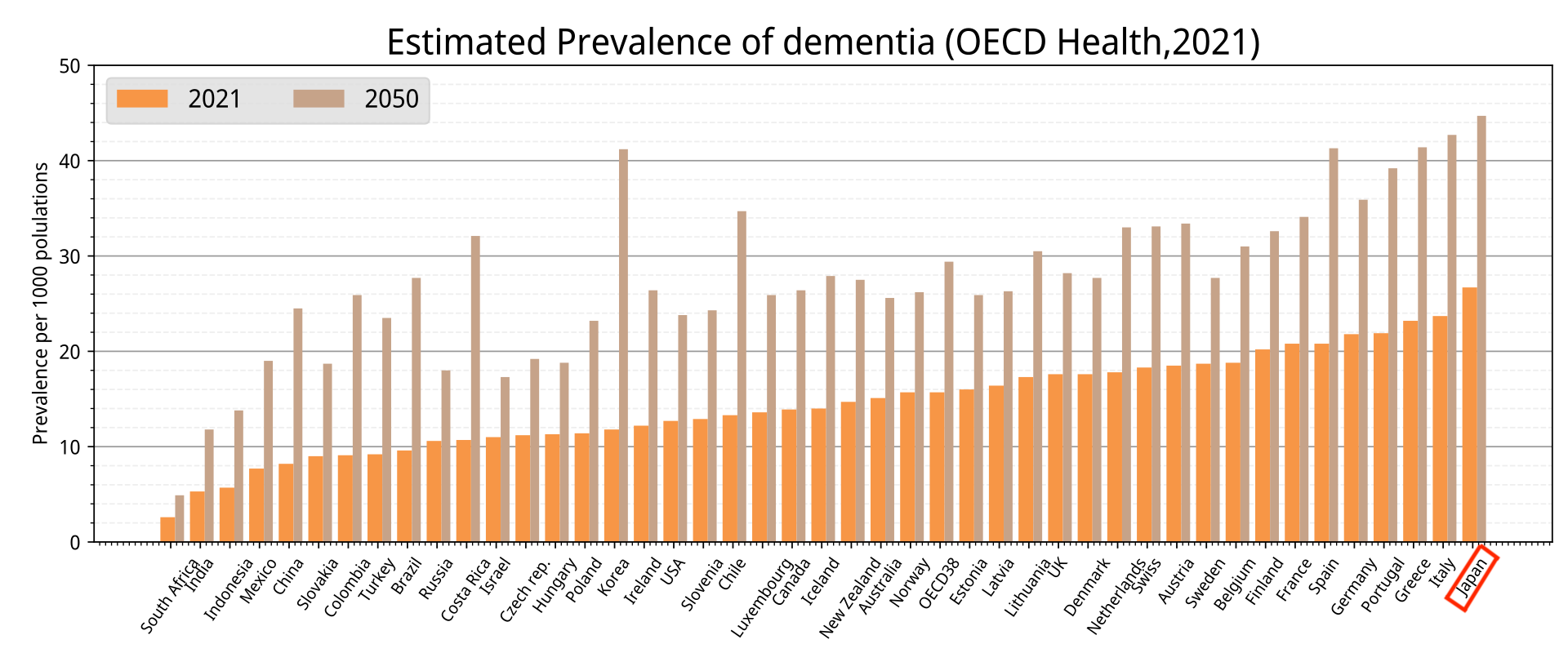

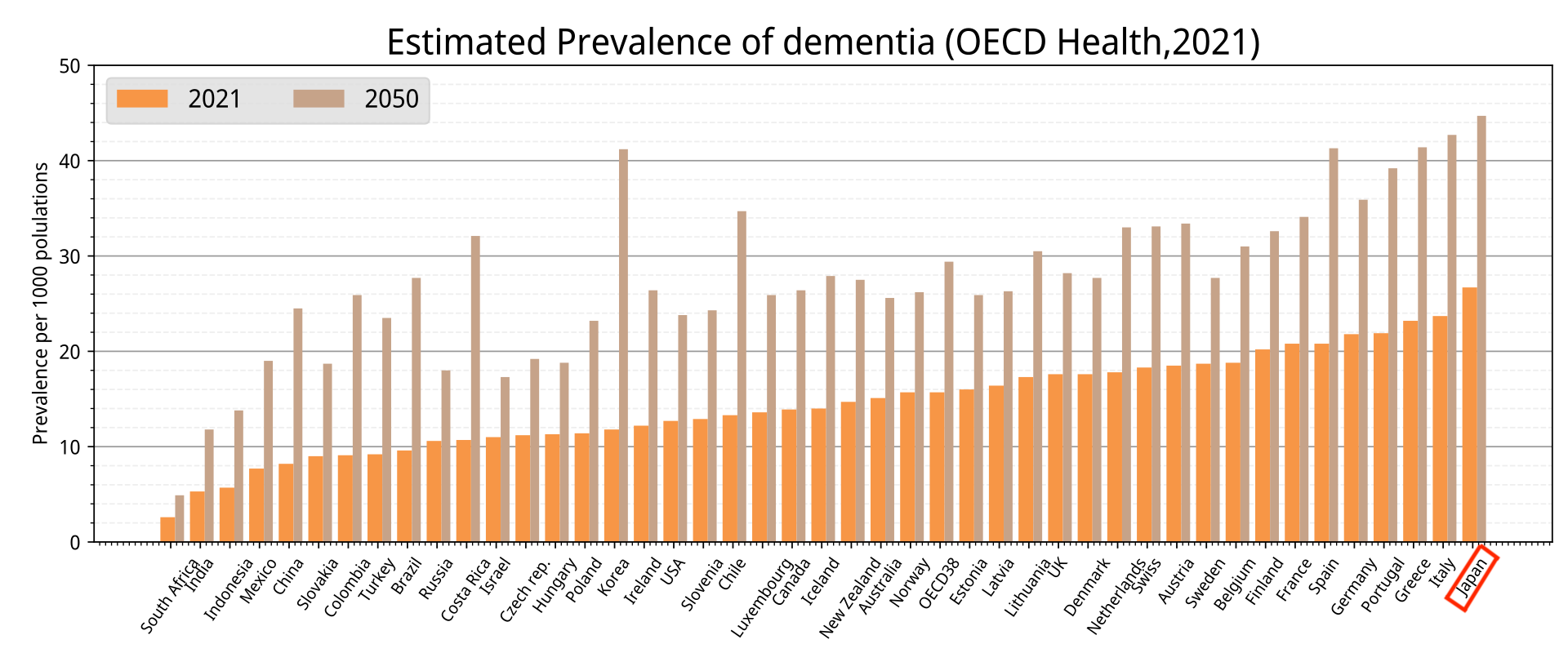

| Social A smaller population could make the country's crowded metropolitan areas more livable, and the stagnation of economic output might still benefit a shrinking workforce. However, low birth rates and high life expectancy have also inverted the standard population pyramid, forcing a narrowing base of young people to provide and care for a bulging older cohort, even as they try to form families of their own.[47] In 2014, the age dependency ratio (the ratio of people over 65 to those aged 15–65, indicating the ratio of the dependent elderly population to those of working age) was 40%.[11] This is expected to increase to 60% by 2036 and to nearly 80% by 2060.[48]  The prevalence of dementia in OECD countries, per 1,000 population, 2021 Elderly Japanese have traditionally entrusted themselves with the care of their adult children, and government policies still encourage the creation of sansedai kazoku (三世代家族, "three-generation households"), where a married couple cares for both children and parents. In 2015, 177,600 people between the ages of 15 and 29 were caring directly for an older family member.[49] However, the migration of young people into Japan's major cities, the entrance of women into the workforce, and the increasing cost of care for both young and old dependents have required new solutions, including nursing homes, adult daycare centers, and home health programs.[50] Every year, Japan closes 400 primary and secondary schools, converting some of them to care centers for the elderly.[51] In 2008, it was recorded that there were approximately 6,000 special nursing homes available that cared for 420,000 Japanese elders.[52] With many nursing homes in Japan, the demand for more caregivers is high. Nonetheless, family caregivers are preferred in Japan as the main caregiver, and it is predicted that Japanese elderly people can perform activities of daily living (ADLs) with fewer assistance and live longer if their main caregiver is related to them.[52] Many elderly people live alone and isolated. Every year, thousands of deaths go unnoticed for days or even weeks, a modern phenomenon known as kodoku-shi (孤独死, "solitary death").[53] During the first half of 2024, the National Police Agency reported that 37,227 individuals living alone were found dead at home, with 70% of these being aged 65 and above, and nearly 4,000 bodies discovered more than a month after death, including 130 that remained unnoticed for at least a year.[54] The disposable income in Japan's older population has increased business in biomedical technologies research in cosmetics and regenerative medicine.[5] |

社会 人口が減少すれば、都市部の過密状態が緩和され、生活しやすくなる可能性がある。また、経済生産の停滞は、労働人口の減少という恩恵をもたらすかもしれな い。しかし、出生率の低下と平均余命の伸長により、標準的な人口ピラミッドが逆転し、若い世代が自分たちの家族を形成しようとする一方で、膨れ上がった高 齢者層を支え、介護しなければならないという状況に追い込まれている。 [47] 2014年には、年齢依存率(65歳以上の人口を15歳から65歳の人口で割った比率で、生産年齢人口に対する依存的な高齢者人口の比率を示す)は40% であった。[11] これが2036年には60%、2060年には80%近くにまで増加すると予測されている。[48]  OECD諸国における人口1,000人当たりの認知症有病率、2021年 日本の高齢者は伝統的に、成人した子供たちに介護を任せてきたが、政府の政策は今でも、結婚した夫婦が子供と親の両方を介護する三世代家族(三世代世帯) の形成を奨励している。2015年には、15歳から29歳までの17万7600人が高齢の家族の直接介護をしていた。[49] しかし、若者の大都市への移住、女性の労働力参加、そして若者や高齢者の扶養家族の介護費用の増加により、老人ホーム、成人向けデイケアセンター、在宅医 療プログラムなど、新たな解決策が必要となっている。 [50] 日本では毎年、400校の小中学校が閉鎖され、その一部が老人介護施設に転用されている。[51] 2008年の記録によると、約6,000の特別養護老人ホームがあり、42万人の高齢者が入所している。[52] 日本には多くの老人介護施設があるため、介護士の需要は高い。それでもなお、日本では家族介護者が主な介護者として好まれており、主な介護者が親族である 場合、日本の高齢者はより少ない介助で日常生活動作(ADL)を行うことができ、より長生きできると予測されている。 多くの高齢者は一人暮らしで孤立している。毎年、数千人の死亡が数日間、あるいは数週間も発見されないという孤独死と呼ばれる現代的な現象が起きている。 [53] 2024年の前半、警察庁は、一人暮らしの37,227人が自宅で死亡しているのが発見され、その70%が65歳以上であり、4,000体近くの死体が死 亡から1か月以上経過して発見され、その中には少なくとも1年間発見されなかった130体も含まれていたと報告した。 日本の高齢者層の可処分所得の増加により、化粧品や再生医療のバイオメディカルテクノロジー研究のビジネスが活況を呈している。[5] |

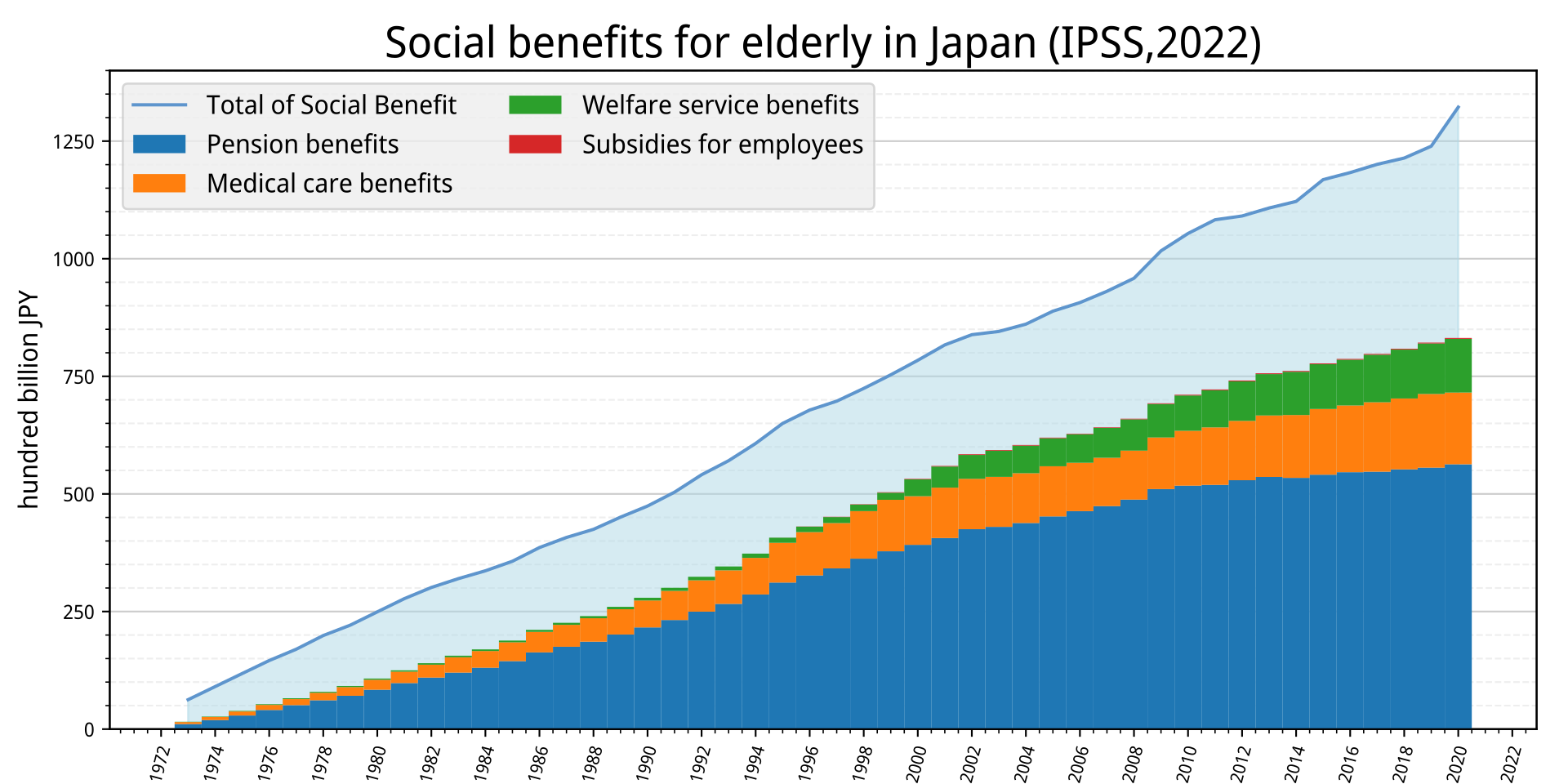

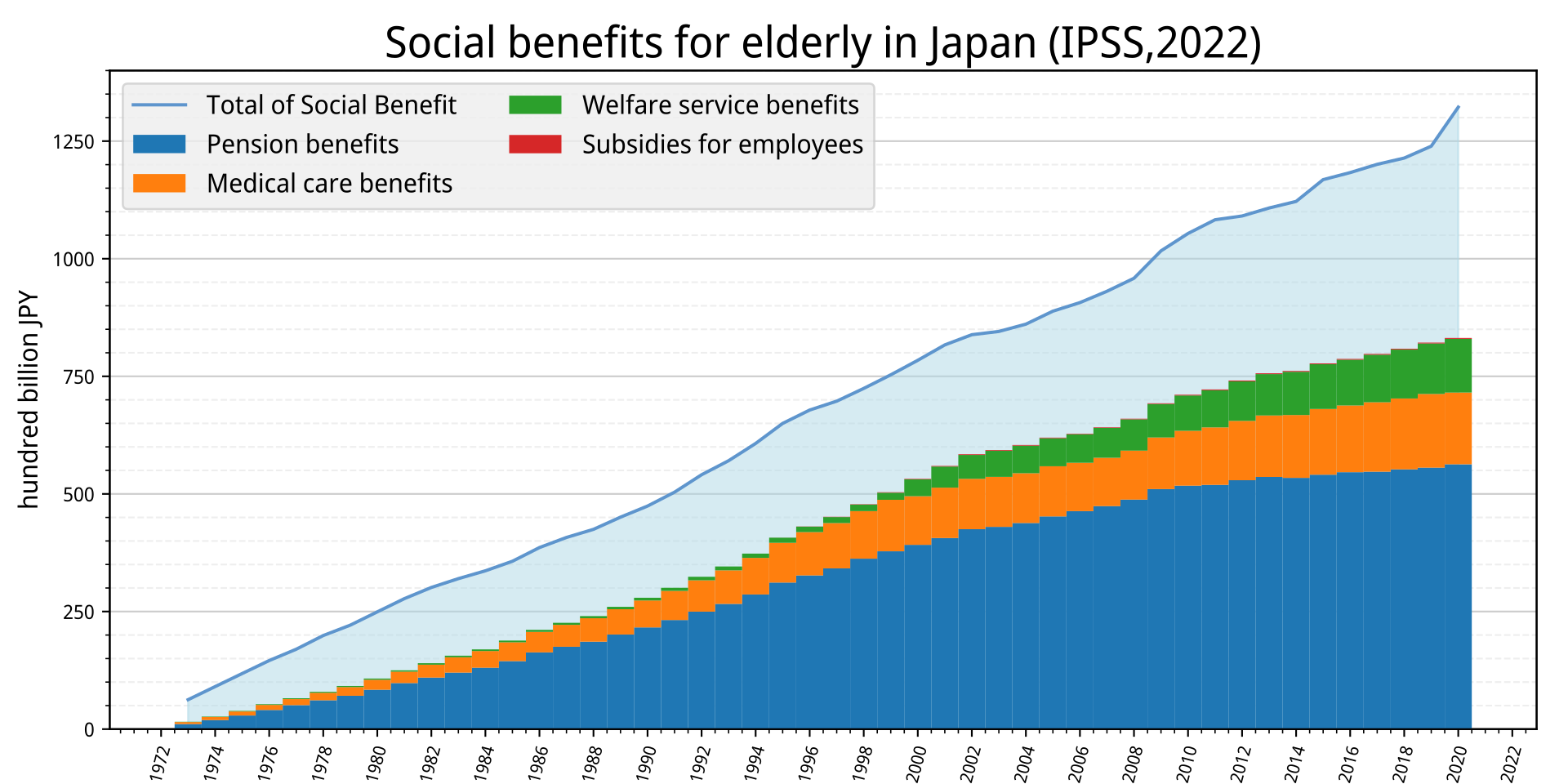

| Political The Greater Tokyo Area is virtually the only locality in Japan to see population growth, mostly due to internal migration from other parts of the country. Between 2005 and 2010, the population of 36 of Japan's 47 prefectures shrank by as much as 5%.[11] Many rural and suburban areas are struggling with an epidemic of abandoned homes, 8 million across Japan in 2015.[55][56] Masuda Hiroya, a former Minister for Internal Affairs and Communications who heads the private think tank Japan Policy Council, estimated that about half the municipalities in Japan could disappear between now and 2040 due to the migration of young people, especially young women, from rural areas into Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya, where around half of Japan's population is currently concentrated.[57] The government is establishing a regional revitalization task force and focusing on developing regional hub cities, especially Sapporo, Sendai, Hiroshima and Fukuoka.[58]  An abandoned home in Yubari district, Hokkaido, an area which has seen population decline Internal migration and population decline have created a severe regional imbalance in electoral power, where the weight of a single vote depends on where it was cast. Some depopulated districts send three times as many representatives per voter to the National Diet as their growing urban counterparts. In 2014, the Supreme Court of Japan declared that the disparities in voting power violates the Constitution, but the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, which relies on rural and older voters, has been slow to make the necessary realignment.[47][59][60]  Social benefits for the elderly in Japan, 2022 The increasing proportion of elderly people has a major impact on government spending and policies. As recently as the early 1970s, the cost of public pensions, healthcare, and welfare services for the aged amounted to only about 6% of Japan's national income. In 1992, that figure increased to 18%, and it is expected to increase to 28% in 2025.[61] Healthcare and pension systems are also expected to come under severe strain. In the mid-1980s, the government began to re-evaluate the relative burdens of government and the private sector in health care and pensions, and it established policies to control government costs in these programs. The large share of elderly, inflation-averse voters may hinder the political attractiveness of higher inflation, consistent with empirical evidence that aging leads to lower inflation.[62] Japan's aging is a major factor in the nation bearing one of the highest public debts in the world at 246.14% of its GDP.[63][64] The aging and shrinking population has also created serious recruitment challenges for the Japan Self-Defense Forces.[65] |

政治 東京首都圏は、日本国内で人口が増加している唯一の地域であり、その主な理由は、他の地域からの国内移住である。2005年から2010年の間に、日本の 47都道府県のうち36都道府県で人口が5%減少した。[11] 多くの地方や郊外地域では、2015年には日本全国で800万戸に達する空き家の急増に悩まされている。 [55][56] 民間シンクタンク「日本政策研究センター」代表で元総務大臣の増田寛也氏は、特に若い女性を中心に地方から東京、大阪、名古屋への若者の移住が続き、 2040年までに日本の自治体の約半数が消滅する可能性があると推定している。 [57] 政府は地域活性化対策本部を設置し、特に札幌、仙台、広島、福岡といった地域の中核都市の開発に重点的に取り組んでいる。[58]  人口減少が進む北海道夕張市の廃屋 国内の人口移動と人口減少により、選挙権の地域格差が深刻化している。選挙権は、その行使の場所によって重みが異なる。過疎化が進む一部の地区では、成長 を続ける都市部の地区と比較して、有権者1人当たりの国会議員数が3倍となっている。2014年、日本の最高裁判所は、投票権の格差は憲法違反であると宣 言したが、地方や高齢者の有権者に依存する与党の自由民主党は、必要な再編を遅らせている。[47][59][60]  日本の高齢者向け社会保障給付、2022年 高齢者の割合の増加は、政府の支出と政策に大きな影響を与える。1970年代初頭には、高齢者向けの公的年金、医療、福祉サービスの費用は日本の国民所得 のわずか約6%であった。1992年にはその割合は18%に増加し、2025年には28%に増加すると予想されている。[61] 医療および年金制度もまた、深刻な負担に直面することが予想される。1980年代半ばに、政府は医療および年金における政府と民間の負担割合を再評価し始 め、これらの制度における政府負担を抑制する政策を打ち出した。 高齢者層の多くを占めるインフレを嫌う有権者層は、インフレ率上昇の政治的な魅力を妨げる可能性がある。高齢化がインフレ率の低下につながるという実証的 証拠と一致している。[62] 日本の高齢化は、GDPの246.14%という世界でも最高水準の公的債務を国民が抱える主な要因となっている。[63][64] 高齢化と人口減少は、自衛隊の深刻な採用難も引き起こしている。 [65] |

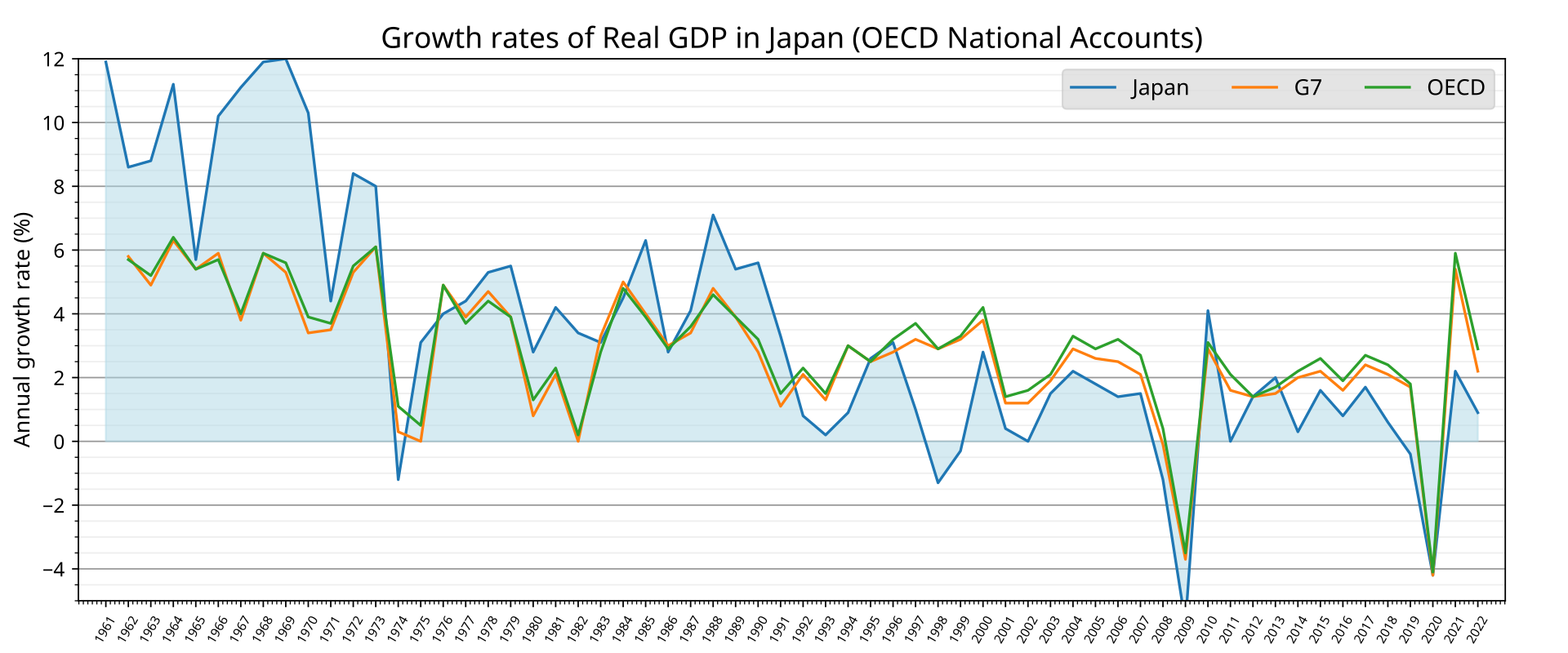

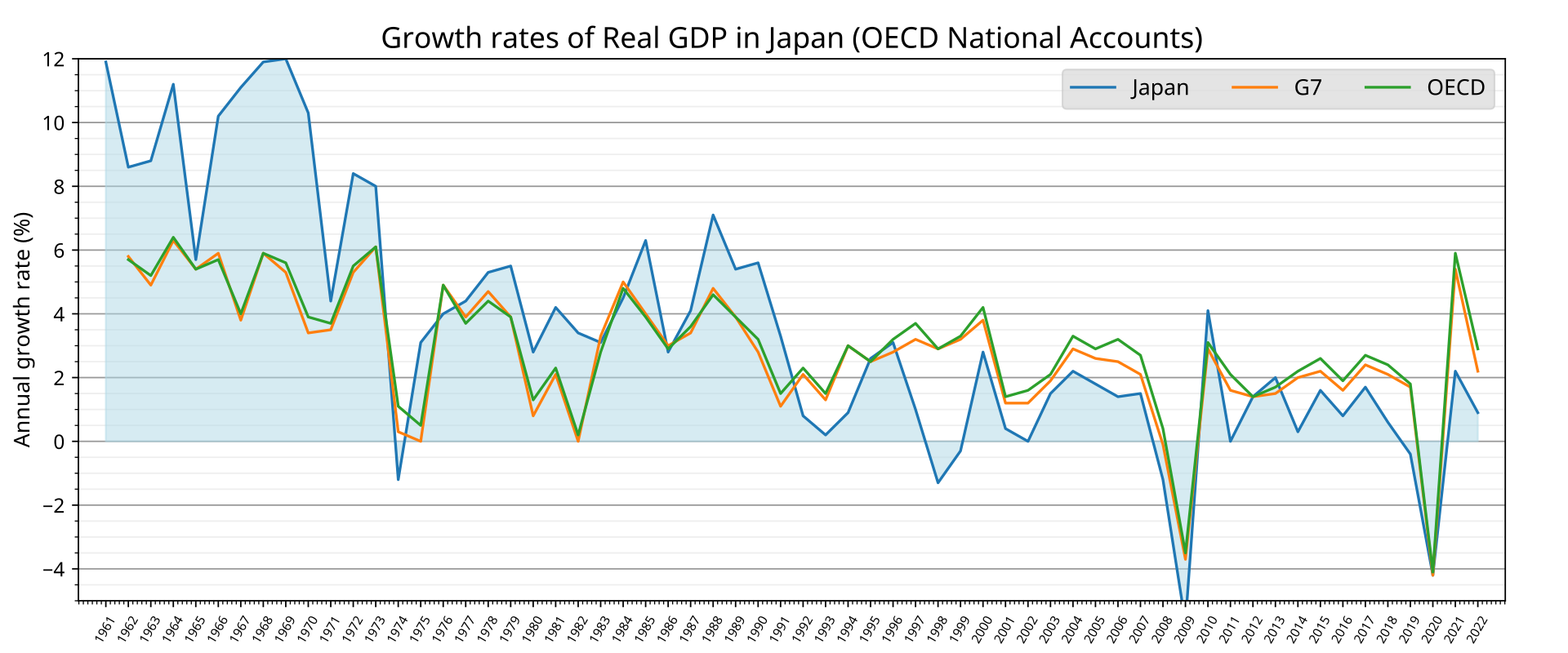

| Economic Main article: Economy of Japan  The real GDP growth rate in Japan, 1961 to 2022 From the 1980s onwards, there has been an increase in older-age workers and a shortage of young workers in Japan's workforce, owing to factors such as Japanese employment practices and the professional participation of women. The U.S. Census Bureau estimated in 2002 that Japan would experience an 18% decrease of young workers in its workforce and an 8% decrease in its consumer population by 2030. The Japanese labor market is currently under pressure to meet demands for workers, with 125 jobs for every 100 job seekers at the end of 2015, as older generations retire and younger professionals become fewer.[66] Japan made a radical change to its healthcare system by introducing long-term-care insurance in 2000.[5] The government has also invested in medical technologies such as regenerative medicines and cell therapy to recruit and retain more of the older population into the workforce.[5] A range of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have also pioneered new practices for retaining workers beyond mandatory retirement ages, such as through workplace improvements as well as job tasks specifically created for older workers.[67] Japanese companies increased the mandatory retirement age from 55 to as high as 65 during the 1980s and 1990s, with many firms allowing employees to work beyond the retirement age.[68] The government has gradually increased the age at which pension benefits begin from 60 to 65.[69] Shortfalls in the pension system have driven many people of retirement age to remain in the workforce, with some elderly individuals being driven into poverty.[70] The retirement age may go even higher in the future if the proportion of the elderly increases. A study by the UN Population Division in 2000 found that Japan would need to raise its retirement age to 77 (or allow net immigration of 17 million by 2050) to maintain its worker-to-retiree ratio.[71][72] Consistent immigration into Japan may prevent further population decline, and many academics have argued for Japan to develop policies to support large influxes of young immigrants.[73][6] Less desirable industries, such as agriculture and construction, face the most severe threats. The average farmer in Japan is 70 years old;[74] while about a third of construction workers are 55 or older, including many expected to retire in the next ten years, only one in ten is younger than 30.[75][76] The decline in the working population has also caused the nation's military to shrink.[5] The decline in working-aged cohorts may lead to a shrinking economy if productivity does not increase faster than the rate of Japan's decreasing workforce.[77] The OECD estimates that similar labor shortages in Austria, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, and Sweden will depress the European Union's economic growth by 0.4 percentage points annually from 2000 to 2025, after which shortages will cost the EU 0.9 percentage points in growth. In Japan, labor shortages will lower growth by 0.7% annually until 2025, after which Japan will experience an annual 0.9% loss in growth.[78] |

経済 詳細は「日本の経済」を参照  日本の実質GDP成長率、1961年から2022年 1980年代以降、日本の労働力人口では高齢労働者の増加と若年労働者の不足が起こっている。これは、日本の雇用慣行や女性の職業参加などの要因によるも のである。米国勢調査局は2002年、2030年までに日本の労働人口における若年労働者の割合が18%減少し、消費者人口が8%減少すると推定した。高 齢世代の退職と若手専門家の減少により、日本の労働市場は現在、労働力需要を満たすために圧力を受けている。2015年末には求職者100人に対して求人 数は125人であった。 日本は2000年に介護保険を導入し、医療制度に抜本的な改革を行った。[5] 政府はまた、高齢者の労働人口への参加と定着を促すため、再生医療や細胞治療などの医療技術にも投資している。 [5] また、職場環境の改善や高齢者向けに特別に考案された職務内容など、定年退職年齢を超えて労働者を雇用し続けるための新しい慣行を先駆的に取り入れた中小 企業も数多くある。[67] 日本企業は1980年代と1990年代に定年退職年齢を55歳から65歳まで引き上げ、多くの企業が定年退職年齢を超えて従業員が働くことを許可してい る。 [68] 政府は年金給付開始年齢を60歳から65歳へと徐々に引き上げている。[69] 年金制度の不足により、定年退職年齢に達した多くの人々が労働市場にとどまることを余儀なくされ、一部の高齢者は貧困に追い込まれている。 高齢者の割合が増加すれば、定年退職年齢は今後さらに引き上げられる可能性がある。2000年の国連人口部の調査では、労働者と退職者の比率を維持するに は、定年を77歳まで引き上げるか(または2050年までに1700万人の純移民を受け入れるか)が必要であると結論づけている。[71][72] 日本への継続的な移民は、さらなる人口減少を防ぐ可能性があり、多くの学者が、日本への若い移民の大量流入を支援する政策を展開すべきだと主張している。 [73][6] 農業や建設業などの望ましくない産業は、最も深刻な脅威に直面している。日本の平均的な農家は70歳であり[74]、建設業では労働者の約3分の1が55 歳以上であり、その中には今後10年以内に退職する予定の労働者も多く含まれているが、30歳未満の労働者は全体のわずか1割である[75][76]。労 働人口の減少は、国民の軍縮にもつながっている[5]。 生産性が日本の労働人口減少率よりも速く上昇しなければ、生産年齢人口の減少は経済の縮小につながる可能性がある。[77] OECDは、オーストリア、ドイツ、ギリシャ、イタリア、スペイン、スウェーデンにおける同様の労働力不足が、2000年から2025年にかけて毎年 0.4パーセントポイント、EUの経済成長を押し下げるだろうと推定している。その後、労働力不足はEUの成長を0.9パーセントポイント押し下げるだろ う。日本では、労働力不足により2025年まで毎年0.7%の成長率低下が見込まれ、その後は毎年0.9%の成長率低下が予想される。[78] |

| Places with high birthrates Nagareyama The city Nagareyama in Chiba Prefecture is 30 kilometers from Tokyo.[79] In the early 2000s, Nagareyama experienced an exodus of young people, due to lack of childcare facilities.[79] In 2003, then-mayor Yoshiharu Izaki made investments in childcare centers a primary focus of the city's spending, developing infrastructure such as a transit service at Nagareyama-centralpark Station where parents can drop off their children on their way to work, following which children are shuttled to day-care centers by buses, driven by local seniors, and a summer camp for children while their parents work during holidays.[79] These initiatives have lured young working parents from Tokyo to Nagareyama. The city's population grew over 20% between 2006 and 2019, with many parents listing childcare as one of the main reasons of the move.[79] 85% of families in the city have more than one child, and young children are expected to outnumber the elderly in the near future.[79][80] Matsudo and Akashi Matsudo city in Chiba has had a population increase of 3.1% since 2015. The increase is said to arise from day-care centers near or inside train stations, which are without waiting lists, and co-working spaces that include childcare rooms.[80] The population of Akashi in Hyōgo grew 3.6%. This is attributed to a childcare facility with a large indoor playground near the local JR train station built in 2017. A subscription service in the region also includes free deliveries of infant necessities, such as diapers.[80] |

出生率の高い地域 流山 千葉県流山市は東京から30キロメートル離れている。[79] 2000年代初頭、流山市では保育施設の不足により若者の流出が起こった。 2003年、当時の市長であった井崎義治氏は、保育所への投資を市の支出の最優先事項とし、親が通勤時に子どもを流山セントラルパーク駅で降ろし、その 後、地元の高齢者が運転するバスで保育所に送迎するサービスや、親が働いている間の子ども向けのサマーキャンプなどのインフラを整備した。 [79] こうした取り組みにより、東京から若い共働き世代の親たちが流山に惹きつけられている。2006年から2019年の間に、この市の人口は20%以上増加 し、多くの親が移住の主な理由の一つとして子育てを挙げている。[79] この市の家庭の85%は子供が1人以上おり、近い将来、幼児が年配者を上回ると予想されている。[79][80] 松戸市と明石市 千葉県松戸市の人口は2015年以降、3.1%増加している。増加の要因として、駅周辺や駅構内に待機児童のない保育所や、託児所付きのコワーキングス ペースが挙げられている。 兵庫県明石市の人口は3.6%増加した。これは2017年に地元のJR駅近くに大型室内遊具を備えた保育施設が建設されたことによる。この地域の定期購入 サービスでは、おむつなどの乳児用品の無料配送も行われている。[80] |

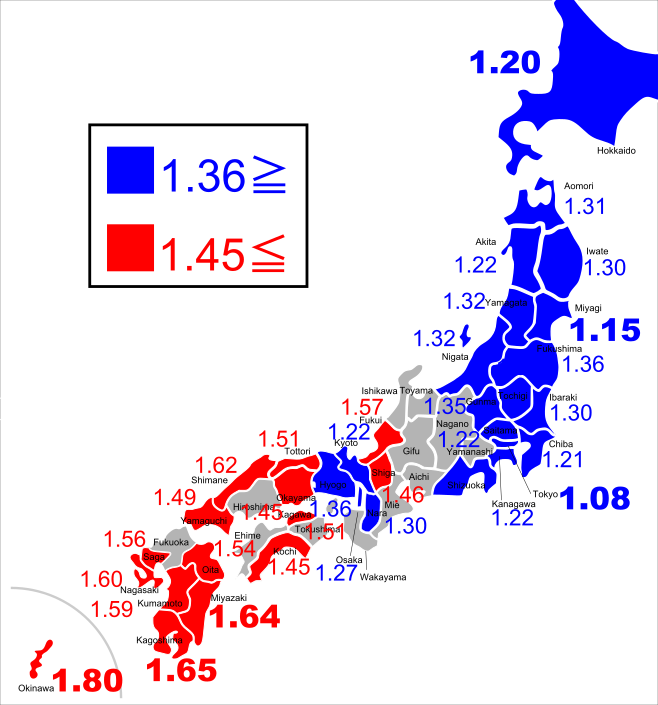

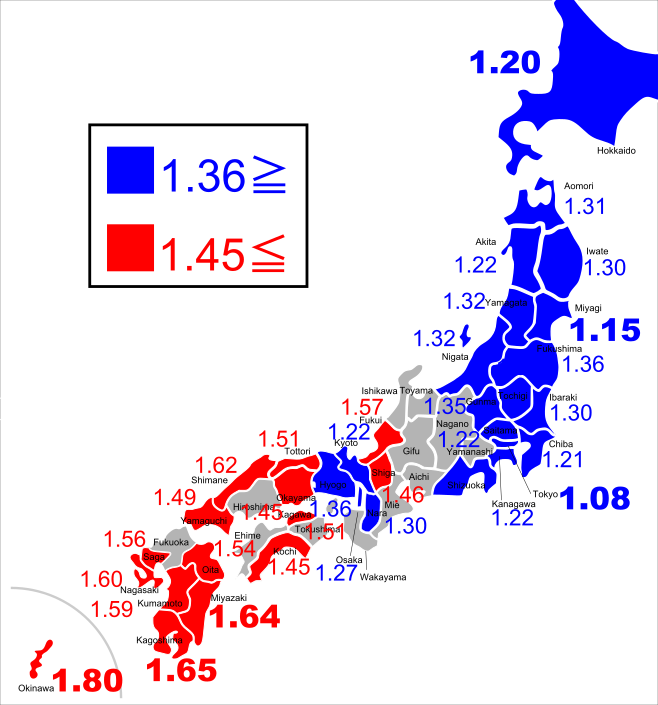

West Japan Japanese prefectures by total fertility rate (TFR), 2021 Western Japan (Kyushu, Chūgoku region, and Shikoku) has a higher birth rate than Central and Eastern Japan.[81] 13 of the 15 prefectures with a TFR of 1.45 or higher are all located in the Kyushu, Chugoku regions or Shikoku, with the other two prefectures being Fukui and Saga.[82] Prefectures with a low TFR are concentrated in eastern or northern Japan.[82] Okinawa Prefecture Okinawa prefecture has had the highest birth rate in Japan for over 40 years since recording began in 1899. In 2018, the prefecture was the only one with a natural population increase, with 15,732 births and 12,157 deaths. While the national average fertility rate that year was 1.42, with Tokyo having the lowest rate of 1.20, Okinawa had a rate of 1.89.[83] The average age of marriage is lower in Okinawa, at 30 years for men and 28.8 years for women; the national average is 31.1 years for men and 29.4 years for women.[84] Reasons for families tending to have more than two children include Okinawan social norms, cheaper costs of living, as well as lower stress, and competition education levels, despite Okinawa having less welfare for children compared to other regions in Japan. The Okinawan culture also emphasises a form of mutual aid called yuimaru, with relatives living close together to help family members with childrearing. Okinawa also has increasing numbers of ikumen; fathers who are actively involved in parenting.[84] |

西日本 合計特殊出生率(TFR)による日本の都道府県別ランキング、2021年 西日本(九州、中国地方、四国)は、中部および東日本よりも出生率が高い。[81] TFRが1.45以上の15都道府県のうち13県はすべて九州、中国地方、四国にあり、残りの2県は福井県と佐賀県である。 合計特殊出生率が低い都道府県は、東日本または北日本に集中している。 沖縄県 沖縄県は、1899年の統計開始以来、40年以上にわたって出生率が日本一である。2018年には、出生数15,732人、死亡数12,157人となり、 自然増減数が全国で唯一プラスとなった。その年の全国平均の出生率は1.42で、東京は1.20と最も低かったが、沖縄は1.89であった。[83] 沖縄の平均結婚年齢は男性30歳、女性28.8歳と低く、全国平均は男性31.1歳、女性29.4歳である。[84] 沖縄の社会規範、生活費の安さ、ストレスの少なさ、教育レベルの競争意識の高さなどが、2人以上の子供を持つ傾向にある理由として挙げられる。沖縄は、日 本国内の他の地域と比較すると子供向けの福祉が少ないにもかかわらずである。また、沖縄文化では、ゆいまーると呼ばれる相互扶助の精神が重視されており、 親戚が近くに住んで子育てを手助けする。また、育児に積極的に参加する父親、いわゆるイクメンも増えている。[84] |

| Government policies Main article: Family policy in Japan The Japanese government has developed policies to encourage fertility and retain more of its population, especially women and the elderly, in the workforce.[85] Incentives for family formation include expanded childcare avenues, new benefits for those who have children, and a state-sponsored dating service.[86][87] Policies focused on engaging more women in the workplace include longer maternity leave and legal protections against pregnancy discrimination, known in Japan as matahara (マタハラ, maternity harassment).[85][88] However, "Womenomics", the set of policies intended to bring more women into the workplace as part of Prime Minister Shinzō Abe's economic recovery plan, has struggled to overcome cultural barriers and entrenched stereotypes.[89] These policies could prove useful for bringing women back into the workforce after having children, but academics have noted that they can also merely encourage productivity among women who opt not to have children. The Japanese government has introduced other policies to address the growing elderly population as well, especially in rural areas, where the government has tried to improve welfare services such as long-term care facilities and other services that can help families at homes, such as daycare or in-home nursing assistance. The Gold Plan was introduced in 1990 to improve these services and has attempted to reduce the burden of care placed on families; long-term care insurance was introduced in 2000.[90] On June 13, 2023, Kishida's cabinet determined the implementation of the "Strategic Policy for Children's Future" at a meeting in order to implement countermeasures against the declining birthrate under a different angle. Kishida's government intends to establish the "All Children's Daycare System (tentative name), to be carried out through 2024. This system will allow fathers to flexibly take vacational leaves that can be used flexibly on hourly bases, regardless of working conditions. The aim is to have this system in full-scale implementation in 2025. In addition, child allowances will be raised: The allowance for the first and second children will be 15,000 yen per month for those between the ages of 0 and 3, and 10,000 yen per month for those between the ages of 3 and high school age. For the third and subsequent children, the monthly amount will be 30,000 yen for all children from age 0 to high school age.[91] |

政府の政策 詳細は「日本の家族政策」を参照 日本政府は、出生率を上げ、特に女性と高齢者の労働人口を維持するための政策を展開している。[85] 家族形成へのインセンティブとしては、保育施設の拡充、子供を持つ人への新たな給付金、国営の結婚相談所などがある。 [86][87] 職場への女性の参加を促す政策には、より長い産休や、日本ではマタハラ(マタニティ・ハラスメント)として知られる妊娠差別に対する法的保護が含まれてい る。[85][88] しかし、安倍晋三首相の経済再生計画の一環として、職場への女性の参加を促す一連の政策「ウーマノミクス」は、文化的障壁や根強い固定観念を克服するのに 苦戦している。[89] これらの政策は、出産後に女性を労働力として職場に戻すのに役立つ可能性があるが、学者たちは、子供を持たないことを選んだ女性たちの生産性を高めるだけ になる可能性もあると指摘している。日本政府は、特に地方部で高齢者人口の増加に対処するための他の政策も導入しており、介護施設などの福祉サービスや、 保育や在宅看護支援など家庭を支援するサービスの改善に取り組んでいる。ゴールドプランは、これらのサービスを改善するために1990年に導入され、家族 にかかる介護負担の軽減が試みられた。2000年には介護保険が導入された。[90] 2023年6月13日、岸田内閣は少子化対策を異なる角度から実施するため、「子ども未来戦略」の実施を閣議決定した。岸田内閣は「全子ども保育制度(仮 称)」を2024年までに実施する方針である。この制度では、労働条件に関係なく、父親が柔軟に取得できる時間単位の休暇を認める。2025年の本格実施 を目指す。また、子ども手当の増額も行う。第1子および第2子については、0歳から3歳までは月額1万5000円、3歳から高校生までは月額1万円とな る。第3子以降については、0歳から高校生まで、すべて月額3万円となる。[91] |

| Immigration Main article: Immigration to Japan A net decline in population due to a historically low birth rate has raised the issue of immigration as a way to compensate for labor shortages.[92][93] Professor Noriko Tsuya, of Keio University, states that it is not realistic to combat Japan's low birthrate with the increase of immigration. The government should keep working to further help women and couples balance their work and family roles in order to boost fertility.[94] While public opinion polls tend to show low support for immigration, most people support an expansion in working-age migrants on a temporary basis to maintain Japan's economic status.[95][96] Comparative reviews show that Japanese attitudes are broadly neutral and place Japanese acceptance of migrants in the middle of developed countries.[97][98] Japan's government is also trying to increase tourism rates, which helps their economy. The government has also expanded options available for international students, allowing them to begin work and potentially stay in Japan to help the economy. Existing initiatives such as the JET Program encourage English-speaking people from across the world to work in Japan as English language teachers. Japan is strict when accepting refugees into their country. Only 27 out of 7,500 refugee applicants were accepted into Japan in 2015. However, Japan provides high levels of foreign and humanitarian aid.[99] In 2016, there was a 44% increase in asylum seekers to Japan from Indonesia, Nepal, and the Philippines. Since Japan does not generally permit low-skilled workers to enter, many people went through the asylum route instead. This allowed immigrants to apply for asylum and begin work six months after the application. However, it did not allow foreigners without valid visas to apply for work.[92] |

移民 詳細は「日本の移民」を参照 歴史的な低出生率による人口の純減により、労働力不足を補う方法として移民受け入れの問題が浮上している。慶應義塾大学の津谷喜一郎教授は、移民の受け入 れによって日本の少子化に対処することは現実的ではないと述べている。政府は、出生率を上げるために、女性や夫婦が仕事と家庭を両立できるよう、さらに支 援していくべきである。世論調査では移民受け入れへの支持は低い傾向にあるが、ほとんどの人は、日本の経済的地位を維持するために、労働年齢にある移民を 一時的に受け入れることには賛成している。 日本政府はまた、経済を活性化させるために観光率の増加も図っている。政府はまた、留学生が就職し、経済を活性化させるために日本に滞在できる可能性を広 げている。JETプログラムなどの既存の取り組みは、世界中の英語話者に英語教師として日本で働くことを奨励している。 日本は難民の受け入れには厳しい国である。2015年には、7,500人の難民申請者のうち、わずか27人しか受け入れなかった。しかし、日本は外国およ び人道支援を高いレベルで提供している。[99] 2016年には、インドネシア、ネパール、フィリピンからの日本への亡命希望者が44%増加した。日本では一般的に低技能労働者の入国は許可されないた め、多くの人が代わりに亡命ルートを利用した。これにより、移民は亡命を申請し、申請から6か月後に就労を開始することが可能となった。しかし、有効なビ ザを持たない外国人が就労を申請することは認められなかった。[92] |

| Work-life balance Further information: Japanese work environment and Salaryman Japan has expanded its policies on work-life balance with the goal of improving the conditions for increasing birth rate, with the passing of the Child Care and Family Care Leave Law, which took effect in June 2010.[100] The law provides parents the opportunity to take up to one year of leave after the birth of a child, with the possibility to extend the leave for another six months if the child is not accepted to a nursery school. It also allows employees with preschool-age children the following allowances: up to five days of leave in the event of a child's injury or sickness; limits on the amount of overtime in excess of 24 hours per month based on an employee's request; limits on working late at night based on an employee's request; and opportunities for shorter working hours and flex time for employees.[101] The laws stated aims were to, in the following decade, increase the female employment rate from 65% to 72%, decrease the percentage of employees working 60 hours or more per week from 11% to 6%, increase the rate of use of annual paid leave from 47% to 100%, increase the rate of child care leave from 72% to 80% for females and .6% to 10% for men, and increase the hours spent by men on childcare and housework in households with a child under six years of age from 1 hour to 2.5 hours a day.[100] |

ワークライフバランス 詳細情報:日本の労働環境とサラリーマン 日本は、出生率向上を目的としたワークライフバランス政策を拡大し、2010年6月に施行された育児・介護休業法を制定した。[100] この法律は、子供が生まれた後、最大1年間の休暇を取得できる機会を両親に提供しており、子供が保育園に入れない場合は、さらに6ヶ月間休暇を延長できる 可能性もある。また、就学前の子供を持つ従業員には、子供の怪我や病気の場合に最大5日間の休暇を取得できること、従業員の申請に基づき、月24時間を超 える時間外労働の上限を設定すること、従業員の申請に基づき深夜労働の上限を設定すること、従業員の申請に基づき時短勤務やフレックスタイム制を適用する ことなどが認められている。[101] この法律は、次の10年間で、女性の就業率を65%から72%に、週60時間以上働く従業員の割合を11%から6%に、年次有給休暇の取得率を47%から 100%に、育児休業取得率を女性で72%から80%、男性で6%から10%に、 6%から10%に引き上げ、6歳未満の子供がいる家庭では、男性の育児・家事の時間を1日1時間から2.5時間に増やす。[100] |

| Comparisons with other countries Japan's population is aging faster than any other country on the planet.[102] The population of those 65 years or older roughly doubled in 24 years, from 7.1% of the population in 1970 to 14.1% in 1994. The same increase took 61 years in Italy, 85 years in Sweden, and 115 years in France.[103] Life expectancy for women in Japan is 87 years, five years more than that of the U.S.[104] Men in Japan have a life expectancy of 81 years, four years more than that of the U.S.[104] Japan has more centenarians than any other country, 58,820 in 2014, or 42.76% per 100,000 people. Almost one in five of the world's centenarians live in Japan, and 87% of them are women.[105] In contrast to Japan, a more open immigration policy has allowed Australia, Canada, and the United States to grow their workforce despite low fertility rates.[78] An expansion of immigration is often rejected as a solution to population decline by Japan's political leaders and people for reasons including the fear of foreign crime and a desire to preserve cultural traditions.[106]  Japan's elderly percentage, in comparison with the U.S., 1990 to 2008 As recently developed nations continue to experience improved health care and lower fertility rates, the growth of the elderly population will continue to rise. In 1970–1975, only 19 countries had a fertility rate that can be considered below-replacement fertility, and there were no countries with exceedingly low fertility (<1.3 children). However, between 2000 and 2005, there were 65 countries with below-replacement fertility, and 17 with exceedingly low fertility.[107] Historically, European countries have had the largest elderly populations by proportion as they became developed nations earlier, experiencing subsequent drops in fertility rates. However, many Asian and Latin American countries, incl. Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico, are quickly catching up to this trend. As of 2015, 22 of the 25 oldest countries are located in Europe, but parts of Asia such as South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan are expected to be in the list by 2050.[108] In South Korea, where the fertility rate is the world's lowest (0.81 as of 2022), the population is expected to peak in 2030.[109] The smaller states of Singapore and Taiwan are also struggling to boost fertility rates from record lows and manage aging populations. China's fertility rate is lower than Japan's and is aging faster than almost every other country in modern history.[110] More than a third of the world's elderly (65 and older) live in East Asia and the Pacific, and many of the economic concerns raised first in Japan can be projected to the rest of the region.[111][112] India's population is aging similarly to that of Japan, but with a 50-year lag. A study of the populations of India and Japan for the years 1950 to 2015 combined with median variant population estimates for the years 2016 to 2100 shows that India is 50 years behind Japan on the aging process.[113] One of the distinguishing features of Japan's elderly population, in particular, is that it is both fast-growing and having one of the highest life expectancies. According to the World Health Organization, Japanese people are able to live 75 years fully healthy and without any disabilities. Demographic data shows that Japan is an older and more quickly aging society than the United States.[114] |

他国との比較 日本の高齢化は世界で最も急速に進んでいる。[102] 65歳以上の人口は、1970年の人口の7.1%から1994年の14.1%へと、24年間でほぼ2倍になった。同じ増加率は、イタリアでは61年、ス ウェーデンでは85年、フランスでは115年を要した。[103] 日本の女性の平均余命は87歳で、米国より5年長い。[104] 日本の男性の平均余命は81歳で、米国より4年長い。 [104] 日本は2014年には10万人あたり42.76%にあたる58,820人の百寿者を数え、百寿者の数では世界一である。世界の百寿者の5人に1人近くが日 本に住んでおり、その87%は女性である。 日本とは対照的に、より開放的な移民政策により、オーストラリア、カナダ、アメリカでは出生率が低いにもかかわらず労働人口を増やすことに成功している。 [78] 移民の拡大は、外国人の犯罪を恐れる気持ちや文化的な伝統を守りたいという理由から、日本の政治指導者や国民によって人口減少の解決策としてはしばしば拒 否されている。[106]  日本の高齢化率の推移(米国との比較)1990年~2008年 最近になって先進国では、医療の改善と出生率の低下が継続しているため、高齢者人口の増加は今後も続くと考えられる。1970年から1975年には、人口 置換水準を下回ると考えられる合計特殊出生率を記録した国は19カ国のみであり、出生率が極端に低い国(1.3人未満)は存在しなかった。しかし、 2000年から2005年の間には、人口置換水準を下回る出生率の国が65カ国、極端に低い出生率の国が17カ国あった。[107] 歴史的に見ると、ヨーロッパ諸国は先進国として発展する時期が早く、出生率の低下を経験したため、高齢者人口の割合が最も高くなっている。しかし、アルゼ ンチン、ブラジル、チリ、メキシコなど、アジアやラテンアメリカの多くの国々が急速にこの傾向に追いつきつつある。2015年現在、高齢化が進んでいる上 位25カ国のうち22カ国がヨーロッパに位置しているが、2050年までには韓国、香港、台湾などのアジアの一部もそのリストに加わると予想されている。 [108] 出生率が世界最低(2022年時点で0.81)の韓国では、人口が2030年にピークに達すると予想されている。 [109] シンガポールや台湾といった小規模国家も、過去最低の出生率を押し上げ、高齢化に対処することに苦慮している。中国の出生率は日本よりも低く、近代史上ほ とんどの国よりも急速に高齢化が進んでいる。[110] 世界の高齢者(65歳以上)の3分の1以上が東アジアおよび太平洋地域に住んでおり、日本において最初に提起された経済的懸念の多くは、この地域の他の国 々にも当てはまる。[111][112] インドの人口の高齢化は、日本とほぼ同様であるが、50年遅れている。1950年から2015年までのインドと日本の人口調査と、2016年から2100 年までの中央値推定人口を組み合わせた調査によると、インドは高齢化プロセスにおいて日本より50年遅れていることが分かった。 日本の高齢者人口の特徴として特に際立っているのは、その人口が急速に増加していることと、平均余命が世界でも最高水準にあることである。世界保健機関 (WHO)によると、日本人は75歳まで完全に健康で障害のない生活を送ることができる。人口統計データによると、日本は米国よりも高齢化が進んでおり、 高齢化のスピードも速い。[114] |

| See also Children's Day (Japan) Demographics of Japan Elderly people in Japan Marriage in Japan Respect for the Aged Day Retired husband syndrome General: List of countries and dependencies by population List of countries and dependencies by population density Generational accounting Sub-replacement fertility International: Aging of South Korea Aging of China Aging of Europe Aging of the United States Russian Cross |

関連項目 こどもの日(日本) 日本の人口統計 日本の高齢者 日本の結婚 敬老の日 退職した夫の症候群 一般: 人口による国と属領の一覧 人口密度による国と属領の一覧 世代会計 少子化対策 国際: 韓国の高齢化 中国の人口高齢化 ヨーロッパの高齢化 米国の高齢化 ロシア十字 |

| The data on sexual

experience is only for heterosexual intercourse; the study did not

collect data on homosexual experience. "Elderly citizens accounted for record 28.4% of Japan's population in 2018, data show". The Japan Times. 15 September 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2020. "Aging in Japan|ILC-Japan". www.ilcjapan.org. Retrieved 2017-03-21. Lipscy, Phillip Y. (2023). "Japan: the harbinger state". Japanese Journal of Political Science. 24 (1): 80–97. doi:10.1017/S1468109922000329. ISSN 1468-1099. "An ageing country shows others how to manage". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2024-05-31. Marlow, Iain (13 November 2015). "Bold steps: Japan's remedy for a rapidly aging society". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2017-04-05. Armstrong, Shiro (May 16, 2016). "Japan's Greatest Challenge (And It's Not China): Massive Population Decline". The National Interest. Archived from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved June 22, 2020. Johnston, Eric (16 May 2015). "Is Japan becoming extinct?". The Japan Times Online. Retrieved 13 September 2018. Vollset, Stein Emil; Goren, Emily; Yuan, Chun-Wei; Cao, Jackie; Smith, Amanda E; Hsiao, Thomas; Bisignano, Catherine; Azhar, Gulrez S; Castro, Emma; Chalek, Julian; Dolgert, Andrew J; Frank, Tahvi; Fukutaki, Kai; Hay, Simon I; Lozano, Rafael (2020). "Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study". The Lancet. 396 (10258): 1285–1306. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30677-2. PMC 7561721. PMID 32679112. Muramatsu, Naoko; Akiyama, Hiroko (1 August 2011). "Japan: Super-Aging Society Preparing for the Future". The Gerontologist. 51 (4): 425–432. doi:10.1093/geront/gnr067. PMID 21804114. Yoshida, Reiji (29 October 2015). "Abe convenes panel to tackle low birthrate, aging population". The Japan Times. Retrieved 21 February 2016. Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication, Statistics Bureau. "Japan Statistical Yearbook, Chapter 2: Population and Households". Retrieved 13 January 2016. "Fighting Population Decline, Japan Aims to Stay at 100 Million". Nippon.com. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2016. Traphagan, John W. (2003). Demographic Change and the Family in Japan's Aging Society. Suny Series in Japan in Transition, SUNY Series in Aging and Culture, Suny Series in Japan in Transition and Suny Series in Aging and Culture. SUNY Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0791456491. "Japan population to shrink by a third by 2060". The Guardian. 30 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2016. International Futures. "Population of Japan, Aged 65 and older". Retrieved 2012-12-05. Population Projections for Japan (January 2012): 2011 to 2060, table 1-1 (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, retrieved 13 January 2016). Yoshida, Hiroshi; Ishigaki, Masahiro. "Web Clock of Child Population in Japan". Mail Research Group, Graduate School of Economics and Management, Tohoku University. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2017. Clyde Haberman (1987-01-15). "Japan's Zodiac: '66 was a very odd year". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-05-14. "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Archived from the original on 2015-11-16. Retrieved 2017-04-06. "East Asia/Southeast Asia :: Japan — the World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". 22 September 2022. "Population Aging and Aged Society: Population Aging and Life Expectancy" (PDF). International Longevity Center Japan. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017. "What do demographic changes mean for labor supply?". World Bank Blogs. Retrieved 2024-04-21. "Health Status: Utilization of Health Care" (PDF). International Longevity Center Japan. Retrieved March 21, 2017. "Changing Patterns of Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States". CDC/National Center for Health Statistics. May 13, 2009. Retrieved September 24, 2011. Harding, Robin (4 February 2016). "Japan birth rate recovery questioned". Financial Times. Retrieved 21 February 2016. Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan. "Chapter 5". Statistical Handbook of Japan 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2016. Yamada, Masahiro (3 August 2012). "Japan's Deepening Social Divides: Last Days for the "Parasite Singles"". Nippon.com. Retrieved 14 January 2016. "Why the Japanese are having so few babies". The Economist. 23 July 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2016. Kato, Akihiko. "The Japanese Family System: Change, Continuity, and Regionality over the Twentieth century" (PDF). Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-09-28. "1 in 4 men, 1 in 7 women in Japan still unmarried at age 50: Report". The Japan Times Online. 2017-04-05. Nohara, Yoshiaki (1 May 2017). "Japan Labor Shortage Prompts Shift to Hiring Permanent Workers". Bloomberg. Retrieved 12 January 2018. IPSS, "Attitudes toward Marriage and Family among Japanese Singles" (2011), p. 4. Hoenig, Henry; Obe, Mitsuru (8 April 2016). "Why Japan's Economy Is Laboring". Wall Street Journal. Ishimura, Sawako (October 24, 2017). "お疲れ女子の6割は恋愛したくない!?「疲労の原因」2位は仕事内容、1位は?(60% of tired women do not want to love!? "Cause of fatigue" second place work content, first place?)". Cocoloni Inc. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2019. Shoji, Kaori (December 2, 2017). "Women in Japan too tired to care about dating or searching for a partner". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2019. National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (IPSS). "Marriage Process and Fertility of Japanese Married Couples." (2011). pp. 9–14. Soble, Jonathan (January 1, 2015). "The New York Times". Retrieved March 20, 2017. Yoshida, Reiji (31 December 2015). "Japan's population dilemma, in a single-occupancy nutshell". The Japan Times. Retrieved 14 January 2016. Wiseman, Paul (2 June 2004). "No sex please we're Japanese". USA Today. Retrieved May 10, 2012. "1 in 4 singles aged in 30s in Japan unwilling to marry: gov't survey". Mainichi. June 14, 2022. Archived from the original on June 16, 2022. Cyrus Ghaznavi, Haruka Sakamoto, Daisuke Yoneoka, Shuhei Nomura, Kenji Shibuya, Peter Ueda. 2019. Trends in heterosexual inexperience among young adults in Japan: analysis of national surveys, 1987-2015. BMC Public Health. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-019-6677-5 Shibuya, Kenji (8 April 2019). "First national estimates of virginity rates in Japan". The University of Tokyo. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved April 20, 2019. Shibuya, Kenji (8 April 2019). "Let's Talk About (No) Sex: A Closer Look at Japan's 'Virginity Crisis'". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2019. Harney, Alexandra (15 June 2009). "Japan panics about the rise of "herbivores"—young men who shun sex, don't spend money, and like taking walks. - Slate Magazine". Slate.com. Retrieved 20 August 2012. "Roughly 40 percent of single Japanese men in their 20s have never been on a date, survey says". June 15, 2022. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Hashimoto, Ryutaro (attributed). General Principles Concerning Measures for the Aging Society. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved 2011-3-5. Soble, Jonathan (26 February 2016). "Japan Lost Nearly a Million People in 5 Years, Census Says". New York Times. Retrieved 27 February 2016. Population Projections for Japan (January 2012): 2011 to 2060, table 1-4 (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, retrieved 13 January 2016). Oi, Mariko (16 March 2015). "Who will look after Japan's elderly?". BBC. Retrieved 23 February 2016. Kelly, William (1993). "Finding a Place in Metropolitan Japan: Transpositions of Everyday Life". In Gordon, Andrew (ed.). Postwar Japan as History. University of California Press. pp. 189–238. ISBN 978-0-520-07475-0. McNeill, David (2 December 2015). "Falling Japanese population puts focus on low birth rate". The Irish Times. Retrieved 24 February 2016. Olivares-Tirado, Pedro (2014). Trends and Factors in Japan's Long-term Care Insurance System: Japan's 10-year Experience. Springer. pp. 80–130. ISBN 978-94-007-7874-0. Bremner, Matthew (26 June 2015). "The Lonely End". Slate. Retrieved 21 February 2016. Khalil, Hafsa (30 August 2024). "Japan: Nearly 4,000 people found more than month after dying alone, report says". BBC. Retrieved 31 August 2024. Otake, Tomoko (7 January 2014). "Abandoned homes a growing menace". The Japan Times. Retrieved 27 February 2016. Soble, Jonathan (23 August 2015). "A Sprawl of Ghost Homes in Aging Tokyo Suburbs". New York Times. Retrieved 27 February 2016. Tadashi, Hitora (25 August 2014). "Slowing the Population Drain From Japan's Regions". Nippon.com. Retrieved 24 February 2016. "Abe to target revitalization at regional level". The Japan Times. Jiji. 21 July 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2016. Masunaga, Hidetoshi (12 December 2013). "The Quest for Voting Equality in Japan". Nippon.com. Retrieved 27 February 2016. Takenaka, Harukata (30 July 2015). "Weighing Vote Disparity in Japan's Upper House". Nippon.com. Retrieved 27 February 2016. Faiola, Anthony (28 July 2006). "The Face of Poverty Ages In Rapidly Graying Japan". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 February 2016. Yamada, Kyohei; Park, Gene (2022). "Aging and the politics of monetary policy in Japan". Japanese Journal of Political Science. 23 (4): 333–349. doi:10.1017/S1468109922000226. ISSN 1468-1099. "Japan's population set to plummet by 40 million in a generation". The Independent. 2017-04-11. Archived from the original on 2017-04-13. Retrieved 2018-03-13. "The 20 countries with the greatest public debt". World Economic Forum. 16 July 2015. Retrieved 2018-04-04. Le, Tom Phuong (2021). Japan's Aging Peace: Pacifism and Militarism in the Twenty-First Century. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-55328-5. Warnock, Eleanor (24 December 2015). "Japan consumer prices up, but spending sluggish". Market Watch. Retrieved 21 February 2016. Martine, Julien; Jaussaud, Jacques (2018). "Prolonging working life in Japan: Issues and practices for elderly employment in an aging society". Contemporary Japan. 30 (2): 227–242. doi:10.1080/18692729.2018.1504530. S2CID 169746160. Nomura, Kyoko; and Koizumi, Akio. "Strategy against aging society with declining birthrate in Japan", Industrial Health, December 7, 2016. Accessed January 18, 2024. "Mounting labor shortages in the 1980 s and 90s led many Japanese companies to increase the mandatory retirement age from 55 to 60 or 65, and today, many allow their employees to continue working after official retirement." Rajnes, David. "The Evolution of Japanese Employer-Sponsored Retirement Plans", Social Security Bulletin, November 3, 2007. Accessed January 18, 2024. "The current eligible age for full EPI benefits will rise from age 60 to age 65 in the coming decades. For men, the earliest age to receive retirement benefits will increase by 1 year every 3 years from 2013 until it reaches age 65 in 2025; for women, the earliest age to receive benefits will rise by 1 year every 3 years starting in 2018 until it reaches age 65 in 2030 (Kabe 2006)." Siripala, Thisanka. "Surviving Old Age Is Getting Harder in Japan; Seniors living in poverty or working to supplement their income are on the rise as Japan's public pension system cracks under a super aging society.", The Diplomat, January 19, 2023. Accessed January 18, 2024. "Japan's poverty line survey conducted in 2019 determined that a minimum annual income of approximately $10,000 is needed to purchase daily essentials. However, seniors over 65 receive an annual basic pension of roughly $6,000 or $460 each month, which is not enough to cover daily expenses. Women are disproportionately vulnerable to poverty in old age compared to their male counterparts." "Aging Populations in Europe, Japan, Korea, Require Action". India Times. 2000. Archived from the original on 2007-12-01. Retrieved 2007-12-15. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-06-23. Retrieved 2017-06-28. Schlesinger, Jacob M. (2015). "Aging Gracefully: entrepreneurs and exploring robotics and other innovations to unleash the potential of the elderly". WSJ: 1–15. Harding, Robin (21 February 2016). "Japan seeks to bank on global appetite for sushi and wagyu beef". Financial Times. Retrieved 23 February 2016. "Builders face lack of young workers". The Japan Times. Kyodo. 23 October 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2016. Takami, Kosuke; Wamoto, Takako; Itsuki, Kotaro (22 February 2014). "Young laborer shortage growing dire on Japan's construction sites". "Into the unknown". The Economist. Vol. 397, no. 8709. 20 Nov 2010. pp. SS3 – SS4. ProQuest 807974249. Paul S. Hewitt (2002). "Depopulation and Ageing in Europe and Japan: The Hazardous Transition to a Labor Shortage Economy". International Politics and Society. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-15. "Japan Baby Boom: City's policies turn around population decline". TRT World. 2019-09-14. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 2019-12-28. "Not all Japanese towns are shrinking: 300 show how it's done". Nikkei. June 26, 2021. Archived from the original on June 26, 2021. 出生率 九州5県で上昇 昨年 「西高東低」傾向鮮明に 令和2年(2020)人口動態統計月報年計(概数)の概況 Number of newborns in Japan fell to record low while population dropped faster than ever in 2018 Elizabeth Lee (2019-12-21). "Fertility secrets of Okinawa give birth to hope in sexless, ageing Japan". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 2019-12-29. "Urgent Policies to Realize a Society in Which All Citizens are Dynamically Engaged" (PDF). Kantei (Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet). Retrieved 24 February 2016. "Young Japanese 'decline to fall in love'". BBC News. 2012-01-11. Ghosh, Palash (21 March 2014). "Japan Encourages Young People To Date And Mate To Reverse Birth Rate Plunge, But It May Be Too Late". International Business Times. Retrieved 24 February 2016. Rodionova, Zlata (16 November 2015). "Half of Japanese women workers fall victim to 'maternity harassment' after pregnancy". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 24 February 2016. Chen, Emily S. (6 October 2015). "When Womenomics Meets Reality". The Diplomat. Retrieved 21 February 2016. Tanaka, Kimiko; Iwasawa, Miho (30 September 2010). "Aging in Rural Japan—Limitations in the Current Social Care Policy". Journal of Aging & Social Policy. 22 (4): 394–406. doi:10.1080/08959420.2010.507651. PMC 2951623. PMID 20924894. "児童手当の拡充は24年10月から...岸田首相が会見、出産費用の保険適用は26年度導入". 読売新聞オンライン (in Japanese). 2023-06-13. Retrieved 2023-09-18. Jozuka, Emiko; Ogura, Junko. "Can Japan survive without immigrants?". CNN. Retrieved 2023-06-10. Brasor, Philip (27 October 2018). "Proposed reform to Japan's immigration law causes concern". Japan Times. Retrieved 24 November 2018. Tsuya, Noriko (2022-10-26). "Will Japan's population shrink or swim?". {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) "51% of Japanese support immigration, double from 2010 survey - AJW by The Asahi Shimbun". Ajw.asahi.com. Retrieved 2015-09-06. Facchini, Giovanni; Margalit, Yotam; Nakata, Hiroyuki (December 2016). "Countering Public Opposition to Immigration: The Impact of Information Campaigns". IZA Institute of Labor Economics. Simon, Rita J.; Lynch, James P. (June 1999). "A Comparative Assessment of Public Opinion toward Immigrants and Immigration Policies". International Migration Review. 33 (2): 455–467. doi:10.1177/019791839903300207. JSTOR 2547704. PMID 12319739. S2CID 13523118. "New Index Shows Least, Most Accepting Countries for Migrants". 23 August 2017. Retrieved 2018-10-25. Green, David (2017-03-27). "As Its Population Ages, Japan Quietly Turns to Immigration". migrationpolicy.org. Retrieved 2018-03-13. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, "Introduction to the Revised Child Care and Family Care Leave Law," http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/index.html, accessed May 22, 2011. Japanese government's Employment Service Center "雇用継続給付" https://www.hellowork.go.jp/insurance/insurance_continue.html Archived 2020-11-12 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved April 24, 2017 "Japan's demography: The incredible shrinking country". The Economist. 25 March 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2016. "Statistical Handbook of Japan". Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication. 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2016. Martin, Jacob M. Schlesinger and Alexander (29 November 2015). "Graying Japan Tries to Embrace the Golden Years". Wall Street Journal. "Centenarians in Japan: 50,000-Plus and Growing". Nippon.com. 1 June 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2016. Burgess, Chris (18 June 2014). "Japan's 'no immigration principle' looking as solid as ever". The Japan Times. Retrieved 21 February 2016. Naohiro Ogawa; Rikiya Matsukura (2007). "Ageing in Japan: The health and wealth of older persons" (PDF). un.org. Retrieved 28 February 2018. He, Wan; Goodkind, Daniel; Kowal, Paul (March 2016). "An Aging World : 2015". International Population Reports. 16: 1–30. Kamiya, Takeshi (24 February 2022). "South Korea's birthrate drops to new low amid economic anxiety". The Asahi Shinbun. Retrieved 11 April 2022. Toshiya, Tsugami (16 September 2021). "Why Society Will be the Real Loser from China's Low Birth Rate". Nippon.com. Retrieved 11 April 2022. "Rapid Aging in East Asia and Pacific Will Shrink Workforce and Increase Public Spending". World Bank. 9 December 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2016. "The Future of Population in Asia: Asia's Aging Population" (PDF). East West Center. Honolulu: East-West Center. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016. "Is India Aging Like Japan? Visualizing Population Pyramids". SocialCops Blog. 2016-06-22. Retrieved 2016-07-04. Karasawa, Mayumi; Curhan, Katherine B.; Markus, Hazel Rose; Kitayama, Shinobu S.; Love, Gayle Dienberg; Radler, Barry T.; Ryff, Carol D. (July 2011). "Cultural Perspectives on Aging and Well-Being: A Comparison of Japan and the United States". The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 73 (1): 73–98. doi:10.2190/AG.73.1.d. PMC 3183740. PMID 21922800. |

性的経験に関するデータは異性間での性交渉のみであり、この調査では同

性愛の経験に関するデータは収集されていない。 「2018年の日本の高齢者人口は過去最高の28.4%を占めたことがデータで示された。」The Japan Times. 2019年9月15日。2020年6月7日取得。 「日本の高齢化|ILC-Japan」www.ilcjapan.org。2017年3月21日取得。 Lipscy, Phillip Y. (2023). 「Japan: the harbinger state」. Japanese Journal of Political Science. 24 (1): 80–97. doi:10.1017/S1468109922000329. ISSN 1468-1099. 「高齢化社会の国が他国に示した管理方法」エコノミスト。ISSN 0013-0613。2024年5月31日取得。 マロー、イアン(2015年11月13日)。「大胆な一歩:急速な高齢化社会に対する日本の対策」グローブ・アンド・メール。2017年4月5日取得。 アームストロング、シロ(2016年5月16日)。「日本最大の課題(そしてそれは中国ではない):人口の大幅減少」。ナショナル・インタレスト。 2017年3月21日のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年6月22日取得。 ジョンストン、エリック(2015年5月16日)。「日本は絶滅しつつあるのか?」ジャパンタイムズオンライン。2018年9月13日取得。 Vollset, Stein Emil; Goren, Emily; Yuan, Chun-Wei; Cao, Jackie; Smith, Amanda E; Hsiao, Thomas; Bisignano, Catherine; Azhar, Gulrez S; Castro, Emma; Chalek, Julian; Dolgert, Andrew J; Frank, Tahvi; Fukutaki, Kai; Hay, Simon I; Lozano, Rafael (2020). 「2017年から2100年までの195の国と地域における出生率、死亡率、人口移動、人口シナリオ:Global Burden of Disease Studyの予測分析」。The Lancet. 396 (10258): 1285–1306. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30677-2. PMC 7561721. PMID 32679112. 村松奈緒子、秋山弘子(2011年8月1日)。「日本:超高齢社会が未来に備える」。The Gerontologist。51(4):425-432。doi:10.1093/geront/gnr067。PMID 21804114。 吉田玲司 (2015年10月29日). 「安倍首相、少子高齢化対策会議を招集」. ジャパンタイムズ. 2016年2月21日閲覧。 総務省統計局. 「日本の統計年鑑、第2章:人口と世帯」. 2016年1月13日閲覧。 「人口減少と戦う日本、1億人維持を目指す」. Nippon.com. 2014年8月26日. 2016年2月21日閲覧。 Traphagan, John W. (2003). Demographic Change and the Family in Japan's Aging Society. サンヨー・シリーズ・イン・ジャパン・イン・トランジション、サンヨー・シリーズ・イン・エイジング・アンド・カルチャー、サンヨー・シリーズ・イン・ ジャパン・イン・トランジション、サンヨー・シリーズ・イン・エイジング・アンド・カルチャー。SUNYプレス。p.16。ISBN 978-0791456491。 「日本の人口は2060年までに3分の1減少する」『ガーディアン』。2014年1月30日。2016年1月14日取得。 国際未来予測。「65歳以上の日本の人口」。2012年12月5日取得。 日本の将来推計人口(平成24年1月推計):2011年~2060年、表1-1(国立社会保障・人口問題研究所、2016年1月13日取得)。 吉田, 洋; 石垣, 雅大. 「日本の子供の人口のウェブ時計」. 東北大学大学院経済学研究科・経済学部メール研究グループ. 2018年7月18日オリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年3月14日閲覧。 クライド・ハバーマン (1987年1月15日). 「日本の干支:66年は非常に奇妙な年だった」. ニューヨーク・タイムズ. 2018年5月14日閲覧。 「The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency」. 2015年11月16日オリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年4月6日閲覧。 「East Asia/Southeast Asia :: Japan — the World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency「. 2022年9月22日. 「Population Aging and Aged Society: Population Aging and Life Expectancy」 (PDF). International Longevity Center Japan. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017. 「人口動態の変化は労働供給にどのような影響を与えるのか?」世界銀行ブログ。2024年4月21日取得。 「健康状態:医療の利用」(PDF)国際長寿センター日本。2017年3月21日取得。 「米国における非婚出産の変化パターン」. CDC/国立保健統計センター. 2009年5月13日. 2011年9月24日取得。 ハーディング、ロビン(2016年2月4日)。「日本の出生率回復に疑問符」. フィナンシャル・タイムズ. 2016年2月21日取得。 総務省統計局「第5章」。『統計でみる日本の統計2014』。2016年1月18日取得。 山田昌弘(2012年8月3日)。「深まる日本の社会格差:パラサイト・シングルも終焉か」。『Nippon.com』。2016年1月14日取得。 「なぜ日本人はこんなに子供を産まなくなったのか」エコノミスト、2014年7月23日。2016年1月14日閲覧。 加藤彰彦「日本家族システム:20世紀における変化、継続性、地域性」(PDF)マックス・プランク人口学研究所。オリジナルのPDFよりアーカイブ (2022年9月28日) 「50歳になっても未婚の男性は4人に1人、女性は7人に1人:報告書」. ジャパンタイムズオンライン. 2017年4月5日. 野原義明 (2017年5月1日). 「労働力不足が正社員雇用へのシフトを促す」. ブルームバーグ. 2018年1月12日取得. IPSS, 「Attitudes toward Marriage and Family among Japanese Singles」 (2011), p. 4. Hoenig, Henry; Obe, Mitsuru (2016年4月8日). 「Why Japan's Economy Is Laboring」. Wall Street Journal. 石村佐和子 (2017年10月24日). 「お疲れ女子の6割は恋愛したくない!?「疲労の原因」2位は仕事内容、1位は?」. Cocoloni Inc. 2018年1月7日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年4月21日閲覧。 庄司かおり (2017年12月2日). 「日本女性は疲れすぎて、デートやパートナー探しに興味なし」. ジャパンタイムズ. 2019年1月7日アーカイブのオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年4月21日閲覧。 国立社会保障・人口問題研究所 (IPSS). 「結婚プロセスと日本人夫婦の出生率」. (2011). pp. 9–14. ソブル, ジョナサン (2015年1月1日). 「ニューヨーク・タイムズ」. 2017年3月20日閲覧。 吉田玲司 (2015年12月31日). 「日本人口のジレンマ、一人用ナッツで一言」. ジャパンタイムズ. 2016年1月14日閲覧。 ワイズマン、ポール(2004年6月2日)。「セックスはごめんだ、俺たちは日本人だ」。USAトゥデイ。2012年5月10日取得。 「30代の独身者の4人に1人が結婚する意思がない:政府調査」。毎日。2022年6月14日。2022年6月16日のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。 サイラス・ガズナヴィ、坂本遥、米岡大輔、野村周平、澁谷健司、ピーター・ウエダ。2019年。日本の若年成人における異性経験の傾向:1987年から 2015年の全国調査の分析。BMC公衆衛生。DOI: 10.1186/s12889-019-6677-5 渋谷健司 (2019年4月8日). 「日本における童貞率の初の全国推計」. 東京大学. 2019年4月8日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年4月20日閲覧。 渋谷健司 (2019年4月8日). 「Let's Talk About (No) Sex: A Closer Look at Japan's 『Virginity Crisis』」. The Diplomat. 2019年4月19日アーカイブ。2019年4月21日閲覧。 ハーニー、アレクサンドラ(2009年6月15日)。「草食系男子の増加に日本がパニック - セックスを避け、お金を使わず、散歩を好む若い男性たち。 - Slate Magazine」。 Slate.com。2012年8月20日取得。 「20代の独身男性の約4割がデート未経験、調査で明らかに」2022年6月15日。2022年6月15日、オリジナルよりアーカイブ。 橋本龍太郎(帰属)。高齢社会対策大綱。外務省。2011年3月5日取得。 Soble, Jonathan (2016年2月26日). 「Japan Lost Nearly a Million People in 5 Years, Census Says」. New York Times. 2016年2月27日閲覧。 日本の将来推計人口(平成24年1月推計)平成23年1月推計:2011年から2060年、表1-4(国立社会保障・人口問題研究所、2016年1月13 日取得)。 大井真理子 (2015年3月16日). 「日本の高齢者は誰が面倒を見るのか?」. BBC. 2016年2月23日閲覧。 ケリー, ウィリアム (1993年). 「Finding a Place in Metropolitan Japan: Transpositions of Everyday Life」. In Gordon, Andrew (ed.). Postwar Japan as History. カリフォルニア大学出版局. pp. 189–238. ISBN 978-0-520-07475-0. マクニール, デイヴィッド (2015年12月2日). 「Falling Japanese population puts focus on low birth rate」. The Irish Times. 2016年2月24日閲覧。 オリヴァレス=ティラド, ペドロ (2014). 日本の介護保険制度における傾向と要因:日本の10年間の経験。Springer。80-130ページ。ISBN 978-94-007-7874-0。 Bremner, Matthew (2015年6月26日). 「The Lonely End」. Slate. 2016年2月21日閲覧。 ハリル、ハフサ(2024年8月30日)。「日本:孤独死で亡くなってから1か月以上経ってから発見された人が4,000人近くに上るという報告書」。 BBC。2024年8月31日取得。 大竹智子(2014年1月7日)。「放置された家屋が深刻な問題に」。ジャパンタイムズ。2016年2月27日取得。 Soble, Jonathan (2015年8月23日). 「A Sprawl of Ghost Homes in Aging Tokyo Suburbs」. New York Times. 2016年2月27日閲覧。 Tadashi, Hitora (2014年8月25日). 「Slowing the Population Drain From Japan's Regions」. Nippon.com. 2016年2月24日閲覧。 「安倍首相、地方活性化を狙う」『ジャパンタイムズ』時事通信社、2014年7月21日。2016年2月24日閲覧。 増永英俊「日本における投票の平等の追求」『ニッポンドットコム』2013年12月12日。2016年2月27日閲覧。 竹中治堅 (2015年7月30日). 「日本の参議院選挙における一票の格差を考える」. Nippon.com. 2016年2月27日閲覧。 Faiola, Anthony (2006年7月28日). 「The Face of Poverty Ages In Rapidly Graying Japan」. The Washington Post. 2016年2月21日閲覧。 山田恭平、パーク・ジーン (2022年). 「高齢化と日本の金融政策の政治学」. Japanese Journal of Political Science. 23 (4): 333–349. doi:10.1017/S1468109922000226. ISSN 1468-1099. 「日本の人口は1世代で4000万人減少する見通し」『インデペンデント』2017年4月11日。2017年4月13日オリジナルよりアーカイブ。 2018年3月13日閲覧。 「公的債務が最も大きい20カ国」『世界経済フォーラム』2015年7月16日。2018年4月4日取得。 Le, Tom Phuong (2021). Japan's Aging Peace: Pacifism and Militarism in the Twenty-First Century. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-55328-5. ウォーノック、エレノア(2015年12月24日)。「日本の消費者物価は上昇するが、消費は低迷」。Market Watch。2016年2月21日取得。 マルタン、ジュリアン、ジャック・ジョサウド(2018年)。「日本の労働期間延長:高齢化社会における高齢者雇用に関する問題と実務」。 Contemporary Japan. 30 (2): 227–242. doi:10.1080/18692729.2018.1504530. S2CID 169746160. 野村恭子、小泉彰夫。「日本の少子高齢化対策」、産業保健、2016年12月7日。2024年1月18日アクセス。「1980年代と90年代に深刻化した 労働力不足により、多くの日本企業は定年退職年齢を55歳から60歳または65歳に引き上げた。そして今日では、多くの企業が定年退職後も従業員に継続し て働いてもらっている。」 Rajnes, David. 「The Evolution of Japanese Employer-Sponsored Retirement Plans」, Social Security Bulletin, November 3, 2007. Accessed January 18, 2024. "今後数十年のうちに、EPIの給付金受給資格年齢は60歳から65歳に引き上げられる。男性の場合、退職給付の受給開始年齢は2013年から3年ごとに 1歳ずつ引き上げられ、2025年に65歳に達する。女性の場合、給付の受給開始年齢は2018年から3年ごとに1歳ずつ引き上げられ、2030年に65 歳に達する(Kabe 2006)」。 シリパラ、ティンカ著。「高齢期を生き延びることが日本では難しくなっている。高齢者の貧困や、収入を補うために働く高齢者が増加している。超高齢化社会 により、日本の公的年金制度がひっ迫しているためだ。」『ザ・ディプロマット』2023年1月19日。2024年1月18日アクセス。「2019年に実施 された日本の貧困線調査では、生活必需品を購入するには最低でも年間約1万ドルの収入が必要であると判断された。しかし、65歳以上の高齢者は年間約 6,000ドル、つまり毎月460ドルの基本年金を受け取っているが、これは日々の出費を賄うには十分ではない。女性は男性に比べて老後の貧困に不釣り合 いに脆弱である。」 「ヨーロッパ、日本、韓国の高齢化は対策を必要としている。」 インド・タイムズ。2000年。2007年12月1日アーカイブ。2007年12月15日取得。 「アーカイブコピー」(PDF)。2017年6月23日アーカイブ。2017年6月28日取得。 シュレジンジャー、ジェイコブ・M. (2015年). 「老いてなお美しく:起業家とロボット工学やその他のイノベーションの探求による高齢者の潜在能力の開放」. WSJ: 1–15. ハーディング、ロビン (2016年2月21日). 「日本、寿司と和牛への世界的な需要に期待」. フィナンシャル・タイムズ. 2016年2月23日閲覧。 「建設業は若年労働者の不足に直面している」。ジャパンタイムズ。共同通信。2013年10月23日。2016年2月23日取得。 高見康介、和元貴子、五木匡太郎(2014年2月22日)。「日本の建設現場では若年労働者の不足が深刻化している」。 「未知の世界へ」。エコノミスト。第397巻、第8709号。2010年11月20日。SS3~SS4ページ。ProQuest 807974249。 ポール・S・ヒューイット(2002年)。「ヨーロッパと日本の人口減少と高齢化:労働力不足経済への危険な移行」。国際政治と社会。2007年12月 27日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2007年12月15日取得。 「日本のベビーブーム:都市の政策が人口減少に歯止めをかける」TRTワールド。2019年9月14日。2019年9月25日時点のオリジナルよりアーカ イブ。2019年12月28日取得。 「すべての日本の町が縮小しているわけではない:300の町がその方法を示している」『日経』2021年6月26日。2021年6月26日アーカイブ。 出生率 九州5県で上昇 昨年 「西高東低」傾向鮮明に 令和2年(2020)人口動態統計月報年計(概数)の概況 2018年の日本の新生児数は過去最低を記録し、人口減少はかつてないほど加速した エリザベス・リー(2019年12月21日)。「沖縄の出生率の秘密が、性別のない高齢化社会の日本に希望をもたらす」。サウスチャイナ・モーニング・ポ スト。2019年12月25日のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年12月29日取得。 「すべての国民が生き生きと活躍できる社会を実現するための緊急対策」(PDF)。内閣(内閣総理大臣及び内閣)。2016年2月24日取得。 「日本の若者は『恋に落ちることを拒否』」。BBCニュース。2012年1月11日。 Ghosh, Palash (2014年3月21日). 「Japan Encourages Young People To Date And Mate To Reverse Birth Rate Plunge, But It May Be Too Late」. International Business Times. 2016年2月24日閲覧。 Rodionova, Zlata (2015年11月16日). 「Half of Japanese women workers fall victim to 『maternity harassment』 after pregnancy」. The Independent. 2015年11月17日のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年2月24日取得。 Chen, Emily S. (2015年10月6日). 「ウーマノミクスが現実と直面するとき」。The Diplomat. 2016年2月21日取得。 田中きみ子、岩澤美帆 (2010年9月30日). 「地方における高齢化 - 現行の社会福祉政策の限界」. エイジング・アンド・ソーシャル・ポリシージャーナル. 22 (4): 394–406. doi:10.1080/08959420.2010.507651. PMC 2951623. PMID 20924894. 「児童手当の拡充は24年10月から...岸田首相が会見、出産費用の保険適用は26年度導入」. 読売新聞オンライン (日本語). 2023年6月13日. 2023年9月18日閲覧。 Jozuka, Emiko; Ogura, Junko. 「移民なしで日本は生き残れるか?」. CNN. 2023年6月10日閲覧。 Brasor, Philip (2018年10月27日). 「Proposed reform to Japan's immigration law causes concern」. Japan Times. 2018年11月24日閲覧。 津谷典子 (2022年10月26日). 「日本の人口は減るか増えるか?」. {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) 「日本人の51%が移民受け入れに賛成、2010年の調査から倍増 - AJW by The Asahi Shimbun」. Ajw.asahi.com. 2015年9月6日閲覧。 ファッチーニ、ジョヴァンニ、ヨタム・マルガリット、中田裕之(2016年12月)。「移民に対する国民の反対意見に対抗する:情報キャンペーンの影 響」。IZA労働経済研究所。 Simon, Rita J.; Lynch, James P. (1999年6月). 「A Comparative Assessment of Public Opinion toward Immigrants and Immigration Policies」. International Migration Review. 33 (2): 455–467. doi:10.1177/019791839903300207. JSTOR 2547704. PMID 12319739. S2CID 13523118. 「New Index Shows Least, Most Accepting Countries for Migrants」. 2017年8月23日. 2018年10月25日閲覧。 グリーン、デビッド(2017年3月27日)。「高齢化が進む中、日本はひっそりと移民に頼るようになった」。migrationpolicy.org。 2018年3月13日取得。 厚生労働省「改正育児・介護休業法のあらまし」http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/index.html、2011年5月22 日アクセス。 日本政府の雇用サービスセンター「雇用継続給付」https: //www.hellowork.go.jp/insurance/insurance_continue.html 2020年11月12日アーカイブ分 2017年4月24日取得 「日本の人口動態:信じられないほど人口が減少している国」『エコノミスト』2014年3月25日。2016年1月14日取得 「日本の統計要覧」総務省。2015年。2016年1月14日取得。 マーティン、ジェイコブ・M・シュレジンジャー、アレクサンダー(2015年11月29日)。「高齢化する日本、黄金の時代を迎え入れようとしている」。 ウォール・ストリート・ジャーナル。 「日本の百寿者:5万人以上で増加中」. Nippon.com. 2015年6月1日. 2016年2月21日閲覧。 Burgess, Chris (2014年6月18日). 「日本の『移民受け入れ反対』の原則は依然として揺るぎない」. The Japan Times. 2016年2月21日閲覧。 小川直宏、松倉立弥 (2007年). 「日本の高齢化:高齢者の保健と福祉」 (PDF). un.org. 2018年2月28日閲覧。 He, Wan; Goodkind, Daniel; Kowal, Paul (2016年3月). 「An Aging World : 2015」. International Population Reports. 16: 1–30. 神谷武史 (2022年2月24日). 「韓国、出生率が過去最低に 経済不安背景に」. 朝日新聞. 2022年4月11日閲覧。 津上俊哉 (2021年9月16日). 「中国「低出生率」の本当の敗者は社会だ」. Nippon.com. 2022年4月11日閲覧。 「東アジア・太平洋地域における急速な高齢化は労働力を減少させ、公共支出を増やす」世界銀行。2015年12月9日。2016年2月27日取得。 「アジアの人口の未来:アジアの高齢化人口」(PDF)イースト・ウェスト・センター。ホノルル:イースト・ウェスト・センター。2002年。オリジナル (PDF)よりアーカイブ。2016年3月12日。2016年2月27日取得。 「インドは日本のように高齢化しているのか?人口ピラミッドの可視化」SocialCops Blog. 2016年6月22日。2016年7月4日取得。 唐沢眞由美、Curhan, Katherine B.、Markus, Hazel Rose、北山忍、Love, Gayle Dienberg、Radler, Barry T.、Ryff, Carol D. (2011年7月). 「高齢化と幸福に関する文化的視点:日本と米国の比較」。The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 73 (1): 73–98. doi:10.2190/AG.73.1.d. PMC 3183740. PMID 21922800. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aging_of_Japan |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆