ハーバート・スペンサー

Herbert Spencer, 1820-1903

☆ ハーバート・スペンサー(Herbert Spencer、1820年4月27日 - 1903年12月8日)は、哲学者、心理学者、生物学者、社会学者、人類学者として活躍したイギリスの博識家である。スペンサーは、チャールズ・ダーウィ ンの1859年の著書『種の起源』を読んだ後、1864年の著書『生物学原理』で「適者生存」という表現を初めて使用した。この用語は自然淘汰を強く示唆 しているが、スペンサーは進化論を社会学や倫理学の領域にも拡大して捉えていたため、ラマルク主義も支持していた。 スペンサーは、進化論を包括的な概念として発展させ、物理的世界、生物、人間の精神、そして人間の文化や社会の進歩的発展として捉えた。博識家として、倫 理、宗教、人類学、経済学、政治理論、哲学、文学、天文学、生物学、社会学、心理学など、幅広い分野に貢献した。彼は存命中、主に英語圏の学術界において 絶大な権威を誇っていた。スペンサーは「19世紀末における最も著名なヨーロッパの知識人」であったが、1900年以降は影響力が急激に低下した。 1937年にはタルコット・パーソンズが「今、スペンサーを読む者はいるだろうか?」と問いかけている。

| Herbert Spencer (27

April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a

philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist.

Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he

coined in Principles of Biology (1864) after reading Charles Darwin's

1859 book On the Origin of Species. The term strongly suggests natural

selection, yet Spencer saw evolution as extending into realms of

sociology and ethics, so he also supported Lamarckism.[1][2] Spencer developed an all-embracing conception of evolution as the progressive development of the physical world, biological organisms, the human mind, and human culture and societies. As a polymath, he contributed to a wide range of subjects, including ethics, religion, anthropology, economics, political theory, philosophy, literature, astronomy, biology, sociology, and psychology. During his lifetime he achieved tremendous authority, mainly in English-speaking academia. Spencer was "the single most famous European intellectual in the closing decades of the nineteenth century"[3][4] but his influence declined sharply after 1900: "Who now reads Spencer?" asked Talcott Parsons in 1937.[5] |

ハーバート・スペンサー(Herbert

Spencer、1820年4月27日 -

1903年12月8日)は、哲学者、心理学者、生物学者、社会学者、人類学者として活躍したイギリスの博識家である。スペンサーは、チャールズ・ダーウィ

ンの1859年の著書『種の起源』を読んだ後、1864年の著書『生物学原理』で「適者生存」という表現を初めて使用した。この用語は自然淘汰を強く示唆

しているが、スペンサーは進化論を社会学や倫理学の領域にも拡大して捉えていたため、ラマルク主義も支持していた。 スペンサーは、進化論を包括的な概念として発展させ、物理的世界、生物、人間の精神、そして人間の文化や社会の進歩的発展として捉えた。博識家として、倫 理、宗教、人類学、経済学、政治理論、哲学、文学、天文学、生物学、社会学、心理学など、幅広い分野に貢献した。彼は存命中、主に英語圏の学術界において 絶大な権威を誇っていた。スペンサーは「19世紀末における最も著名なヨーロッパの知識人」であったが[3][4]、1900年以降は影響力が急激に低下 した。1937年にはタルコット・パーソンズが「今、スペンサーを読む者はいるだろうか?」と問いかけている。[5] |

| Early life and education Spencer was born in Derby, England, on 27 April 1820, the son of William George Spencer (generally called George).[6] Spencer's father was a religious dissenter who drifted from Methodism to Quakerism, and who seems to have transmitted to his son an opposition to all forms of authority. He ran a school founded on the progressive teaching methods of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and also served as Secretary of the Derby Philosophical Society, a scientific society which had been founded in 1783 by Erasmus Darwin, the grandfather of Charles Darwin. Spencer was educated in empirical science by his father, while the members of the Derby Philosophical Society introduced him to pre-Darwinian concepts of biological evolution, particularly those of Erasmus Darwin and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. His uncle, the Reverend Thomas Spencer,[7] vicar of Hinton Charterhouse near Bath, completed Spencer's limited formal education by teaching him some mathematics and physics, and enough Latin to enable him to translate some easy texts. Thomas Spencer also imprinted on his nephew his own firm free-trade and anti-statist political views. Otherwise, Spencer was an autodidact who acquired most of his knowledge from narrowly focused readings and conversations with his friends and acquaintances.[8] |

幼少期と教育 スペンサーは1820年4月27日、イングランドのダービーで、ウィリアム・ジョージ・スペンサー(通称ジョージ)の息子として生まれた。[6] スペンサーの父親はメソジスト教会からクエーカー教に転向した宗教的反対派(religious dissenter) であり、あらゆる権威に反対する姿勢を息子に伝えたようだ。彼は、ヨハン・ハインリヒ・ペスタロッチの進歩的な教授法に基づく学校を運営し、また、チャー ルズ・ダーウィンの祖父にあたるエラスムス・ダーウィンが1783年に設立した科学団体「ダービー哲学協会」の書記も務めていた。 スペンサーは父親から経験科学を学んだが、ダービー哲学協会の会員たちは、特にエラスムス・ダーウィンとジャン=バティスト・ラマルクのダーウィン以前の 生物進化論の概念を彼に紹介した。彼の伯父にあたるトマス・スペンサー牧師(Thomas Spencer)は、バース近郊のヒントン・チャーターハウスの牧師であり、スペンサーの限られた正規の教育を補うために、彼に数学と物理学を教え、簡単 な文章を翻訳できる程度のラテン語を教えた。トマス・スペンサーはまた、甥であるスペンサーに、自由貿易と反国家主義の政治的見解を強く植え付けた。それ 以外では、スペンサーは独学で、狭い範囲に絞った読書や友人・知人との会話から、ほとんどの知識を習得した。 |

Career As a young man Both as an adolescent and as a young man, Spencer found it difficult to settle to any intellectual or professional discipline. He worked as a civil engineer during the railway boom of the late 1830s, while also devoting much of his time to writing for provincial journals that were nonconformist in their religion and radical in their politics. Writing Spencer published his first book, Social Statics (1851), whilst working as sub-editor on the free-trade journal The Economist from 1848 to 1853. He predicted that humanity would eventually become completely adapted to the requirements of living in society with the consequential withering away of the state. Its publisher, John Chapman, introduced Spencer to his salon which was attended by many of the leading radical and progressive thinkers of the capital, including John Stuart Mill, Harriet Martineau, George Henry Lewes and Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot), with whom he was briefly romantically linked. Spencer himself introduced the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, who would later win fame as 'Darwin's Bulldog' and who remained Spencer's lifelong friend. However, it was the friendship of Evans and Lewes that acquainted him with John Stuart Mill's A System of Logic and with Auguste Comte's positivism and which set him on the road to his life's work. He strongly disagreed with Comte.[9] Spencer's second book, Principles of Psychology, published in 1855, explored a physiological basis for psychology, and was the fruit of his friendship with Evans and Lewes. The book was founded on his fundamental assumption that the human mind is subject to natural laws and that these can be discovered within the framework of general biology. This permitted the adoption of a developmental perspective not merely in terms of the individual (as in traditional psychology), but also of the species and the race. Through this paradigm, Spencer aimed to reconcile the associationist psychology of Mill's Logic, the notion that the human mind is constructed from atomic sensations held together by the laws of the association of ideas, with the apparently more 'scientific' theory of phrenology, which locates specific mental functions in specific parts of the brain.[10] Spencer argued that both these theories are partial accounts of the truth: repeated associations of ideas are embodied in the formation of specific strands of brain tissue, and these can be passed from one generation to the next by means of the Lamarckian mechanism of use-inheritance. The Psychology, he believed, would do for the human mind what Isaac Newton had done for matter.[11] However, the book was not initially successful and the last of the 251 copies of its first edition were not sold until June 1861. Spencer's interest in psychology derived from a more fundamental concern which was to establish the universality of natural law.[12] In common with others of his generation, including the members of Chapman's salon, he was possessed with the idea of demonstrating that it is possible to show that everything in the universe – including human culture, language, and morality – could be explained by laws of universal validity. This was in contrast to the views of many theologians of the time who insisted that some parts of creation, in particular the human soul, are beyond the realm of scientific investigation. Comte's Système de Philosophie Positive had been written with the ambition of demonstrating the universality of natural law, and Spencer was to follow Comte in the scale of his ambition. However, Spencer differed from Comte in believing it is possible to discover a single law of universal application which he identified with progressive development and was to call the principle of evolution. In 1858, Spencer produced an outline of what was to become the System of Synthetic Philosophy. This immense undertaking, which has few parallels in the English language, aimed to demonstrate that the principle of evolution applies in biology, psychology, sociology (Spencer appropriated Comte's term for the new discipline) and morality. Spencer envisaged that this work of ten volumes would take twenty years to complete; in the end, it took him twice as long and consumed almost all the rest of his long life. Despite Spencer's early struggles to establish himself as a writer, by the 1870s he had become the most famous philosopher of the age.[13] His works were widely read during his lifetime, and by 1869 he was able to support himself solely on the profit of book sales and on income from his regular contributions to Victorian periodicals which were collected as three volumes of Essays. His works were translated into German, Italian, Spanish, French, Russian, Japanese and Chinese, and into many other languages and he was offered honours and awards all over Europe and North America. He also became a member of the Athenaeum, an exclusive Gentleman's Club in London open only to those distinguished in the arts and sciences, and the X Club, a dining club of nine founded by T.H. Huxley that met every month and included some of the most prominent thinkers of the Victorian age (three of whom would become presidents of the Royal Society). Members included physicist-philosopher John Tyndall and Darwin's cousin, the banker and biologist Sir John Lubbock. There were also some quite significant satellites such as liberal clergyman Arthur Stanley, the Dean of Westminster; and guests such as Charles Darwin and Hermann von Helmholtz were entertained from time to time. Through such associations, Spencer had a strong presence in the heart of the scientific community and was able to secure an influential audience for his views. Later life The last decades of Spencer's life were characterised by growing disillusionment and loneliness. He never married, and after 1855 was a life-long hypochondriac[14] who complained endlessly of pains and maladies that no physician could diagnose at that time.[15] His excitability and sensitivity to disagreement handicapped his social life: His nervous sensibility was extreme. A game of billiards was enough to deprive him of his night's rest. He had been looking forward with pleasure to a meeting with Huxley; but he gave it up because there was a difference on some scientific question between them, and this might have given rise to an argument, which Spencer's nerves could not bear.[16] By the 1890s his readership had begun to desert him while many of his closest friends died and he had come to doubt the confident faith in progress that he had made the centre-piece of his philosophical system. His later years were also ones in which his political views became increasingly conservative. Whereas Social Statics had been the work of a radical democrat who believed in votes for women (and even for children) and in the nationalisation of the land to break the power of the aristocracy, by the 1880s he had become a staunch opponent of female suffrage and made common cause with the landowners of the Liberty and Property Defence League against what they saw as the drift towards 'socialism' of elements (such as Sir William Harcourt) within the administration of William Ewart Gladstone – largely against the opinions of Gladstone himself. Spencer's political views from this period were expressed in what has become his most famous work, The Man Versus the State.  Tomb, Highgate Cemetery The exception to Spencer's growing conservatism was that he remained throughout his life an ardent opponent of imperialism and militarism. His critique of the Boer War was especially scathing, and it contributed to his declining popularity in Britain.[17] He was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society in 1883.[18] Invention of paper-clip Spencer also invented a precursor to the modern paper clip, though it looked more like a modern cotter pin. This "binding-pin" was distributed by Ackermann & Company. Spencer shows drawings of the pin in Appendix I (following Appendix H) of his autobiography along with published descriptions of its uses.[19] Death and legacy In 1902, shortly before his death, Spencer was nominated for the Nobel Prize for literature, which was assigned to the German Theodor Mommsen. He continued writing all his life, in later years often by dictation, until he succumbed to poor health at the age of 83. His ashes are interred in the eastern side of London's Highgate Cemetery facing Karl Marx's grave. At Spencer's funeral, the Indian nationalist leader Shyamji Krishna Varma announced a donation of £1,000 to establish a lectureship at Oxford University in tribute to Spencer and his work.[20] |

経歴 青年期 青年期および青年時代を通じて、スペンサーは知的または専門的な規律に落ち着くことが困難であった。1830年代後半の鉄道ブームの時期には土木技師として働きながら、宗教的には非国教派、政治的には急進派の地方誌に多くの時間を割いて執筆活動を行っていた。 執筆 スペンサーは、1848年から1853年まで自由貿易誌『エコノミスト』の副編集者を務める傍ら、最初の著書『社会静力学』(1851年)を出版した。彼 は、人類は最終的に社会生活の要求に完全に適応し、国家は必然的に衰退すると予言した。その出版社のジョン・チャップマンは、スペンサーをサロンに紹介し た。そこには、ジョン・スチュアート・ミル、ハリエット・マーティノー、ジョージ・ヘンリー・ルイスのような、首都の急進的で進歩的な思想家の多くが参加 していた。スペンサー自身は、後に「ダーウィンのブルドッグ」として名声を博し、スペンサーの生涯の友人となった生物学者トマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーを 紹介した。しかし、エヴァンスとルイスの友情によって、ジョン・スチュアート・ミルの『論理学体系』とオーギュスト・コントの実証主義を知り、それが生涯 の研究テーマへの道筋となった。 彼はコントに強く反対していた。[9] スペンサーの2冊目の著書『心理学原理』は1855年に出版され、心理学の生理学的基礎を探究したもので、エヴァンズとルイスの友人関係の賜物であった。 この本は、人間の心は自然法則に従うものであり、それらは一般的な生物学の枠組みの中で発見できるという彼の根本的な仮定に基づいていた。これにより、単 に個人(従来の心理学のように)という観点だけでなく、種や人種という観点からも、発達的視点の採用が可能となった。このパラダイムを通じて、スペンサー はミルの『論理』における連想説心理学、すなわち人間の心は原子感覚から構成され、観念の連想の法則によって結びつけられているという考え方を、一見より 「科学的」な骨相学の理論、すなわち特定の精神機能を脳の特定の部位に位置づける理論と調和させることを目指した。 スペンサーは、これらの理論はどちらも真実の一部を説明しているに過ぎないと主張した。すなわち、思考の繰り返しは脳組織の特定の繊維の形成に具現化さ れ、これらはラマルクの用遺伝のメカニズムによって世代から世代へと受け継がれる。彼は、心理学はアイザック・ニュートンが物質に対して行ったことと同じ ことを人間の心に対して行うだろうと考えていた。[11] しかし、この本は当初は成功せず、初版の251部が完売したのは1861年6月になってからだった。 スペンサーの心理学への関心は、自然法則の普遍性を確立するというより根本的な関心から生じたものである。[12] チャップマンのサロンに集う人々を含む同世代の人々と同様に、彼は、宇宙のすべて、すなわち人間の文化、言語、道徳などを普遍的な法則によって説明できる ことを示すことが可能であるという考えに取り付かれていた。これは、当時の多くの神学者たちが主張していた、創造物の一部、特に人間の魂は科学的調査の領 域を超えているという見解とは対照的であった。コントの『哲学体系』は、自然法則の普遍性を証明するという野望を持って書かれたものであり、スペンサーは コントの野望の規模をさらに拡大して引き継いだ。しかし、スペンサーは、普遍的に適用できる単一の法則を発見することが可能であると信じており、これを進 歩的発展と同一視し、進化の原理と呼んだ点で、コントとは異なっていた。 1858年、スペンサーは『総合哲学体系』の概要をまとめた。この膨大な事業は、英語圏では類を見ないもので、進化の原理が生物学、心理学、社会学(スペ ンサーは、この新しい学問分野にコントの用語を流用した)、そして道徳に適用できることを証明することを目的としていた。スペンサーは、10巻からなるこ の作品を完成させるには20年を要すると考えていたが、実際にはその2倍の年月がかかり、彼の長い人生のほとんどを費やすこととなった。 作家としての地位を確立するのに初期には苦労したものの、1870年代にはスペンサーは同時代で最も著名な哲学者となっていた。[13] 彼の作品は生前から広く読まれており、1869年には本の販売による利益とヴィクトリア朝の定期刊行物への定期的な寄稿による収入だけで生計を立てること ができていた。彼の作品はドイツ語、イタリア語、スペイン語、フランス語、ロシア語、日本語、中国語など、多くの言語に翻訳され、ヨーロッパと北米各地で 名誉や賞を授与された。また、芸術や科学の分野で優れた業績を残した人物のみが入会を許されるロンドンの会員制クラブ「アテナウム」や、T.H. ハクスリーが創設した9人制の会食クラブ「Xクラブ」の会員にもなった。Xクラブは毎月開催され、ヴィクトリア朝時代を代表する思想家の何人か(うち3人 は王立協会の会長に就任)が参加していた。 会員には物理学者にして哲学者のジョン・ティンダルや、ダーウィンの従兄弟で銀行家であり生物学者のジョン・ラブロック卿などがいた。また、ウェストミン スター寺院の首席司祭で自由主義的な聖職者であったアーサー・スタンリーのような著名人もおり、チャールズ・ダーウィンやヘルマン・フォン・ヘルムホルツ のようなゲストも時折招かれていた。こうしたつながりを通じて、スペンサーは科学界の中心で強い存在感を示し、自身の考えに影響力を持つ聴衆を確保するこ とができた。 晩年 スペンサーの晩年は、幻滅と孤独感の増大によって特徴づけられる。彼は結婚せず、1855年以降は生涯にわたって心気症を患い[14]、当時医師が診断できない痛みや病気を延々と訴え続けた[15]。彼の興奮性と意見の相違に対する感受性は、彼の社交生活を妨げた。 神経の感受性は極端に強かった。ビリヤードのゲームをすると、一晩の休息が台無しになるほどだった。彼はハクスリーとの会合を楽しみにしていたが、科学的 な問題で意見が食い違い、口論になる可能性があったため、会合を断念した。スペンサーの神経は、それを耐えることができなかった。 1890年代には、彼の読者層が離れ始め、親しい友人の多くが亡くなったことで、彼は自身の哲学体系の中心に据えていた進歩に対する自信に疑いを抱くよう になった。晩年には政治的見解も保守化していった。『社会静力学』では、女性(さらには子供)の参政権や貴族の権力を打破するための土地の国有化を信条と する急進的な民主主義者であったが、1880年代には女性参政権の強硬な反対派となり 女性参政権の強硬な反対派となり、自由と財産防衛連盟の地主たちと手を組み、ウィリアム・グラッドストーン政権内の一部(例えばサー・ウィリアム・ハー コート)が「社会主義」に傾倒していると見なした。これは主にグラッドストーン自身の意見に反するものであった。スペンサーのこの時期の政治的見解は、彼 の最も有名な著作『人間対国家』に表現されている。  墓、ハイゲート墓地 スペンサーの保守主義が強まる中で、例外的に生涯を通じて帝国主義と軍国主義の熱烈な反対者であり続けた。 特に辛らつな批判を展開したボーア戦争への批判は、英国での彼の人気低下の一因となった。[17] 1883年にはアメリカ哲学協会の会員に選出された。[18] ペーパークリップの発明 スペンサーは、現代のペーパークリップの先駆けとなるものを発明したが、それは現代の割りピンに似ていた。この「結束ピン」は、アッカーマン・アンド・カ ンパニーによって販売された。スペンサーは、自伝の付録I(付録Hに続く)にこのピンの図面を掲載し、その用途についての説明も掲載している。 死と遺産 1902年、死の直前にスペンサーはノーベル文学賞にノミネートされたが、受賞したのはドイツのテオドール・モムゼンであった。 彼は生涯を通じて執筆を続け、晩年は口述筆記も行い、83歳で体調不良により死去するまで書き続けた。彼の遺灰は、ロンドンにあるハイゲート墓地の東側、 カール・マルクスの墓に面した場所に埋葬されている。スペンサーの葬儀では、インドのナショナリストの指導者であるシャムジー・クリシュナ・ヴァルマが、 スペンサーと彼の業績を称え、オックスフォード大学に講師職を設立するために1,000ポンドを寄付すると発表した。[20] |

| Synthetic philosophy The basis for Spencer's appeal to many of his generation was that he appeared to offer a ready-made system of belief which could substitute for conventional religious faith at a time when orthodox creeds were crumbling under the advances of modern science.[21] Spencer's philosophical system seemed to demonstrate that it is possible to believe in the ultimate perfection of humanity on the basis of advanced scientific conceptions such as the first law of thermodynamics and biological evolution. In essence, Spencer's philosophical vision was formed by a combination of deism and positivism. On the one hand, he had imbibed something of eighteenth-century deism from his father and other members of the Derby Philosophical Society and from books like George Combe's immensely popular The Constitution of Man (1828). This treated the world as a cosmos of benevolent design, and the laws of nature as the decrees of a 'Being transcendentally kind.' Natural laws are thus the statutes of a well-governed universe that have been decreed by the Creator with the intention of promoting human happiness. Although Spencer lost his Christian faith as a teenager and later rejected any 'anthropomorphic' conception of the Deity, he nonetheless held fast to this conception at an almost subconscious level. At the same time, however, he owed far more than he would ever acknowledge to positivism, in particular in its conception of a philosophical system as the unification of the various branches of scientific knowledge. He also followed positivism in his insistence that it is only possible to have genuine knowledge of phenomena and hence that it is idle to speculate about the nature of the ultimate reality. The tension between positivism and his residual deism ran through the entire System of Synthetic Philosophy. Spencer followed Comte in aiming for the unification of scientific truth; it was in this sense that his philosophy aimed to be 'synthetic.' Like Comte, he was committed to the universality of natural law, the idea that the laws of nature apply without exception, to the organic realm as much as to the inorganic, and to the human mind as much as to the rest of creation. The first objective of Synthetic Philosophy was thus to demonstrate that there are no exceptions to being able to discover scientific explanations, in the form of natural laws, of all the phenomena of the universe. Spencer's volumes on biology, psychology, and sociology were all intended to demonstrate the existence of natural laws in these specific disciplines. Even in his writings on ethics, he held that it is possible to discover 'laws' of morality that have the status of laws of nature while still having normative content, a conception which can be traced to George Combe's Constitution of Man. The second objective of the Synthetic Philosophy was to show that these same laws lead inexorably to progress. In contrast to Comte, who stressed only the unity of the scientific method, Spencer sought the unification of scientific knowledge in the form of the reduction of all natural laws to one fundamental law, the law of evolution. In this respect, he followed the model laid down by the Edinburgh publisher Robert Chambers in his anonymous Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844). Although often dismissed as a lightweight forerunner of Charles Darwin's The Origin of Species, Chambers' book was, in reality, a programme for the unification of science which aimed to show that Laplace's nebular hypothesis for the origin of the solar system and Lamarck's theory of species transformation are both instances of 'one magnificent generalisation of progressive development' (Lewes' phrase). Chambers was associated with Chapman's salon and his work served as the unacknowledged template for the Synthetic Philosophy.[22] |

総合哲学 スペンサーが同世代の多くの人々を惹きつけた理由は、正統派の信条が近代科学の進歩によって揺らいでいた時代に、従来の宗教的信仰に代わる既製の信念体系 を提示したように見えたからである。[21] スペンサーの哲学体系は、熱力学の第一法則や生物の進化といった高度な科学的概念に基づいて、人類の究極的な完全性を信じることは可能であることを示して いるように思われた。 要するに、スペンサーの哲学的なビジョンは、自然神学と実証主義の組み合わせによって形成された。一方では、彼は父親やダービー哲学協会の他のメンバー、 そしてジョージ・コーム著の『人間の憲法』(1828年)のような非常に人気のあった書籍から、18世紀の自然神学の考え方を吸収していた。この本では、 世界は慈悲深い設計による宇宙として扱われ、自然法則は「超越的に慈悲深い存在」の命令として説明されている。自然法則は、人間の幸福を促進する目的で創 造主が定めた、統治された宇宙の掟である。スペンサーは10代の頃にキリスト教の信仰を失い、その後、神を擬人化する考え方を一切否定したが、それでもこ の考え方はほぼ無意識のレベルで彼の中に根強く残っていた。しかし同時に、彼は実証主義、特に科学的知識の諸分野の統一としての哲学体系という考え方に、 自ら認める以上に多くを負っていた。また、現象についてのみ真の知識が得られると主張し、究極の現実の本質について推測するのは無意味であるという点で も、彼は実証主義に従っていた。実証主義と彼に残っていた神智論との間の緊張関係は、総合哲学体系全体にわたって存在していた。 スペンサーは、科学的真理の統一を目指したコントの考えを継承した。この意味において、彼の哲学は「総合的」であることを目指した。コンテと同様に、彼は 自然法則の普遍性に専心し、自然法則は無機物にも有機体にも、そして人間の精神にも創造物の残りの部分にも例外なく適用されるという考え方を支持した。総 合哲学の第一の目的は、宇宙のあらゆる現象について、自然法則という形で科学的な説明を発見できることに例外はないことを証明することだった。スペンサー の生物学、心理学、社会学に関する著作はすべて、これらの特定の分野における自然法則の存在を実証することを目的としていた。倫理に関する著作において も、規範的内容を持ちながらも自然法則と同等の地位を持つ道徳の「法則」を発見することが可能であると主張しており、この考え方はジョージ・コームの『人 間憲章』に遡ることができる。 総合哲学の第二の目的は、これらの法則が必然的に進歩につながることを示すことだった。科学的方法の統一のみを強調したコンテとは対照的に、スペンサー は、すべての自然法則を1つの基本法則である進化の法則に還元する形で、科学的知識の統一を求めた。この点において、彼はエディンバラの出版業者ロバー ト・チェンバースが匿名で発表した『創造の自然史の痕跡』(1844年)で示したモデルに従った。チャールズ・ダーウィンの『種の起源』の先駆けとなる軽 薄な著作としてしばしば見くびられてきたが、実際には、科学の統一プログラムであり、ラプラスによる太陽系の起源に関する星雲説とラマルクによる種の変異 説は、どちらも「進歩的発展の壮大な一般化」の一例であることを示すことを目的としていた(ルイスの表現)。チェンバースはチャップマンのサロンと関係が あり、彼の作品は総合哲学の知られざる雛形となった。[22] |

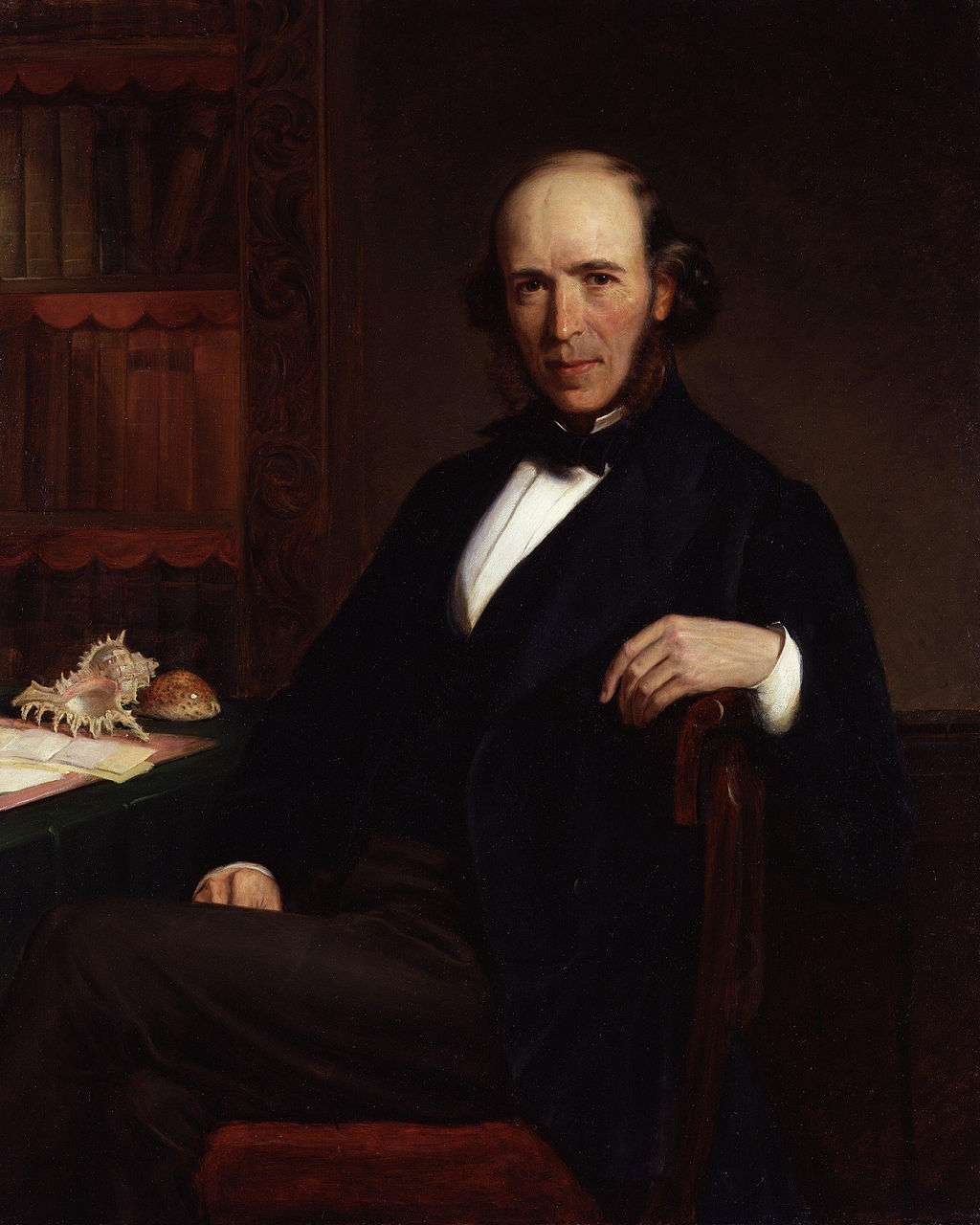

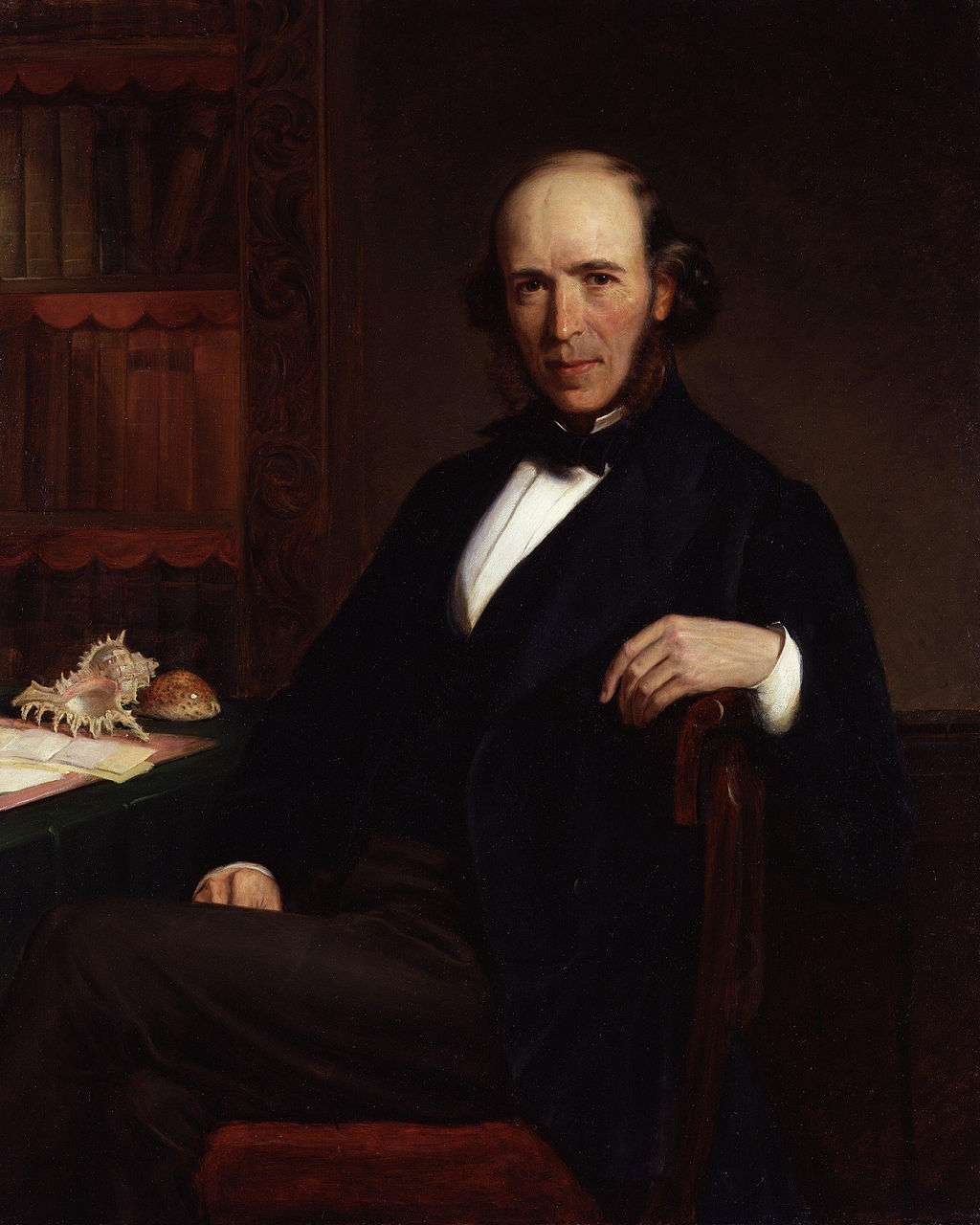

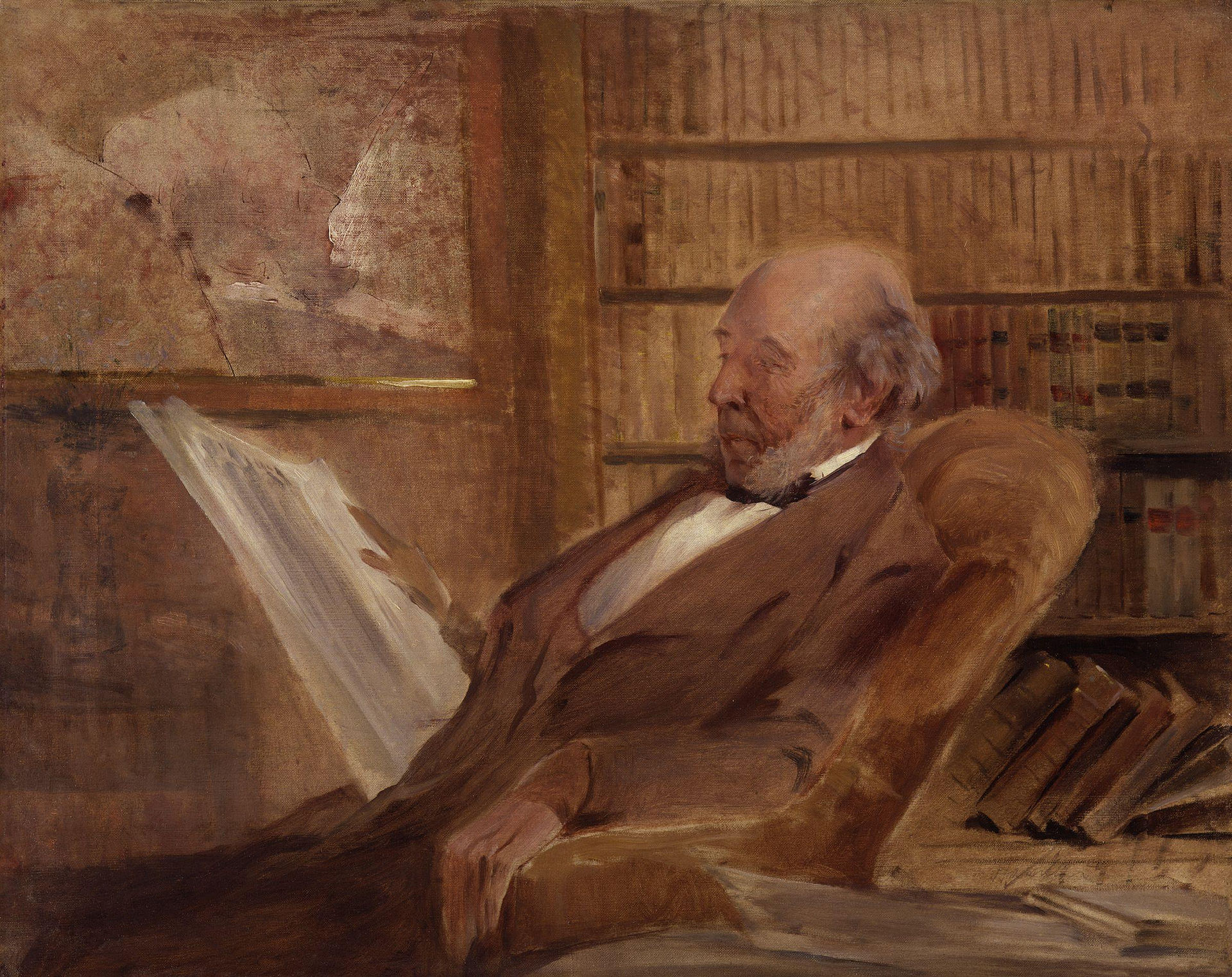

Evolution Portrait of Spencer by John Bagnold Burgess, 1871–72 Spencer first articulated his evolutionary perspective in his essay, 'Progress: Its Law and Cause', published in Chapman's Westminster Review in 1857, and which later formed the basis of the First Principles of a New System of Philosophy (1862). In it he expounded a theory of evolution which combines insights from Samuel Taylor Coleridge's essay 'The Theory of Life' – itself derivative from Friedrich von Schelling's Naturphilosophie – with a generalisation of von Baer's law of embryological development. Spencer posited that all structures in the universe develop from a simple, undifferentiated, homogeneity to a complex, differentiated, heterogeneity while undergoing increasing integration of the differentiated parts. This evolutionary process can be observed, Spencer believed, throughout the cosmos. It is a universal law, applying to the stars and galaxies and to biological organisms, and to human social organisation and to the human mind. It differed from other scientific laws only in its greater generality, and the laws of the special sciences can be shown to be illustrations of this principle. The principles described by Herbert Spencer received a variety of interpretations. Bertrand Russell stated in a letter to Beatrice Webb in 1923: 'I don't know whether [Spencer] was ever made to realize the implications of the second law of thermodynamics; if so, he may well be upset. The law says that everything tends to uniformity and a dead level, diminishing (not increasing) heterogeneity'.[23] Spencer's attempt to explain the evolution of complexity was radically different from that of Darwin's Origin of Species which was published two years later. Spencer is often, quite erroneously, believed to have merely appropriated and generalised Darwin's work on natural selection. But although after reading Darwin's work he coined the phrase 'survival of the fittest' as his own term for Darwin's concept,[1] and is often misrepresented as a thinker who merely applied the Darwinian theory to society, he only grudgingly incorporated natural selection into his preexisting overall system. The primary mechanism of species transformation that he recognised was Lamarckian use-inheritance which posited that organs are developed or are diminished by use or disuse and that the resulting changes may be transmitted to future generations. Spencer believed that this evolutionary mechanism is also necessary to explain 'higher' evolution, especially the social development of humanity. Moreover, in contrast to Darwin, he held that evolution has a direction and an end-point, the attainment of a final state of equilibrium. He tried to apply the theory of biological evolution to sociology. He proposed that society is the product of change from lower to higher forms, just as in the theory of biological evolution, the lowest forms of life are said to be evolving into higher forms. Spencer claimed that man's mind has evolved in the same way from the simple automatic responses of lower animals to the process of reasoning in the thinking man. Spencer believed in two kinds of knowledge: knowledge gained by the individual and knowledge gained by the race. According to his thinking intuition, or knowledge learned unconsciously, is the inherited experience of the race. Spencer in his book Principles of Biology (1864), proposed a pangenesis theory that involves "physiological units" assumed to be related to specific body parts and responsible for the transmission of characteristics to offspring. These hypothetical hereditary units are similar to Darwin's gemmules.[24] |

進化 スペンサーの肖像画、ジョン・バニョールド・バージェス画、1871年~1872年 スペンサーは、1857年にチャップマンズ・ウェストミンスター・レビュー誌に掲載された論文「進歩:その法則と原因」で初めて進化論的見解を明確に示 し、後に『新哲学体系の第一原理』(1862年)の基礎となった。そこでは、フリードリヒ・フォン・シェリングの自然哲学から派生したサミュエル・テイ ラー・コールリッジの論文『生命の理論』の洞察と、フォン・ベールの発生学上の発達法則の一般化とを組み合わせた進化論を展開している。スペンサーは、宇 宙のすべての構造は、単純で未分化な均質性から、分化した複雑な異質性へと発展し、分化した部分の統合が進むと仮定した。この進化の過程は、宇宙全体で観 察できるとスペンサーは考えた。それは普遍的な法則であり、星や銀河、生物、人間の社会組織や精神にも当てはまる。他の科学法則と異なるのは、その一般性 のみであり、特殊科学の法則はこの原則の例証であることが示される。 ハーバート・スペンサーが述べた原理は、さまざまな解釈がなされている。バートランド・ラッセルは1923年にベアトリス・ウェッブに宛てた手紙の中で、 「スペンサーが熱力学第二法則の意味するところを理解していたかどうかはわからない。もし理解していたのであれば、彼は動揺したかもしれない。この法則 は、あらゆるものは均一性と平坦に向かっており、不均一性は減少する(増加しない)と述べている」と述べている。[23] スペンサーが複雑性の進化を説明しようとした試みは、2年後に出版されたダーウィンの『種の起源』のそれとは根本的に異なっていた。スペンサーはしばし ば、かなり誤って、ダーウィンの自然淘汰に関する研究を単に借用し一般化しただけであると信じられている。しかし、ダーウィンの著作を読んだ後、ダーウィ ンの概念を表現する独自の用語として「適者生存」という言葉を造語した[1]にもかかわらず、しばしばダーウィン理論を社会に適用しただけの思想家として 誤って表現されるが、彼は不本意ながら自然淘汰を既存の全体的なシステムに組み込んだだけである。彼が認識した種変異の主なメカニズムは、ラマルクの用遺 伝説であり、器官は使用または不使用によって発達または退化し、その結果生じた変化は将来の世代に伝達される可能性があるというものである。スペンサー は、この進化メカニズムは「より高度な」進化、特に人類の社会的発展を説明するためにも必要であると考えた。さらに、ダーウィンとは対照的に、進化には方 向性と終着点、すなわち最終的な平衡状態の達成があるという見解を持っていた。彼は生物進化論を社会学に応用しようとした。彼は、社会は生物進化論におけ るように、より低い形態からより高い形態への変化の産物であると提唱した。生物進化論では、生命の最も低い形態がより高い形態へと進化しているとされる。 スペンサーは、人間の精神も同様に、下等動物の単純な自動反応から、思考する人間の推論のプロセスへと進化していると主張した。スペンサーは、個人が得る 知識と人類が得る知識という2種類の知識を信じていた。彼の考えでは、直観、つまり無意識に学んだ知識は、人類が受け継いできた経験である。 スペンサーは著書『生物学原理』(1864年)の中で、「生理学的単位」という、特定の身体部位に関連し、子孫への形質の伝達を担うと想定される単位を含む「パンゲネシス理論」を提唱した。この仮説上の遺伝単位は、ダーウィンの「ゲムル」に類似している。[24] |

Sociology In his 70s Spencer read with excitement the original positivist sociology of Auguste Comte. A philosopher of science, Comte had proposed a theory of sociocultural evolution that society progresses by a general law of three stages. Writing after various developments in biology, however, Spencer rejected what he regarded as the ideological aspects of Comte's positivism, attempting to reformulate social science in terms of his principle of evolution, which he applied to the biological, psychological and sociological aspects of the universe. Spencer is also generally credited as the first to use the term 'social structure.' Given the primacy which Spencer placed on evolution, his sociology might be described as social Darwinism mixed with Lamarckism. However, despite its popularity, this view of Spencer's sociology is mistaken. While his political and ethical writings have themes consistent with social Darwinism, such themes are absent in Spencer's sociological works, which focus on how processes of societal growth and differentiation lead to changing degrees of complexity in social organization[25] The evolutionary progression from simple, undifferentiated homogeneity to complex, differentiated heterogeneity is exemplified, Spencer argued, by the development of society. He developed a theory of two types of society, the militant and the industrial, which corresponded to this evolutionary progression. Militant society, structured around relationships of hierarchy and obedience, is simple and undifferentiated; industrial society, based on voluntary, contractually assumed social obligations, is complex and differentiated. Society, which Spencer conceptualised as a 'social organism' evolved from the simpler state to the more complex according to the universal law of evolution. Moreover, industrial society is the direct descendant of the ideal society developed in Social Statics, although Spencer now equivocated over whether the evolution of society would result in anarchism (as he had first believed) or whether it points to a continued role for the state, albeit one reduced to the minimal functions of the enforcement of contracts and external defence. Though Spencer made some valuable contributions to early sociology, not least in his influence on structural functionalism, his attempt to introduce Lamarckian or Darwinian ideas into the realm of sociology was unsuccessful. It was considered by many, furthermore, to be actively dangerous. Hermeneuticians of the period, such as Wilhelm Dilthey, would pioneer the distinction between the natural sciences (Naturwissenschaften) and human sciences (Geisteswissenschaften). In the United States, the sociologist Lester Frank Ward, who would be elected as the first president of the American Sociological Association, launched a relentless attack on Spencer's theories of laissez-faire and political ethics. Although Ward admired much of Spencer's work he believed that Spencer's prior political biases had distorted his thought and had led him astray.[26] In the 1890s, Émile Durkheim established formal academic sociology with a firm emphasis on practical social research. By the turn of the 20th century the first generation of German sociologists, most notably Max Weber, had presented methodological antipositivism. However, Spencer's theories of laissez-faire, survival-of-the-fittest and minimal human interference in the processes of natural law had an enduring and even increasing appeal in the social science fields of economics and political science, and one writer has recently made the case for Spencer's importance for a sociology that must learn to take energy in society seriously.[27] |

社会学 70代で スペンサーは、オーギュスト・コントの原初的実証主義社会学に興奮しながら目を通した。科学哲学者であるコントは、社会は3段階の一般的な法則によって進 歩するという社会文化進化論を提唱していた。しかし、生物学のさまざまな進展を経て執筆されたスペンサーの著書では、彼はコントのポジティヴィズムの観念 的側面とみなしたものを否定し、宇宙の生物学的、心理学的、社会学的な側面に応用した自身の進化論の原則に基づいて社会科学を再定義しようとした。スペン サーはまた、「社会構造」という用語を初めて使用した人物としても一般的に認められている。 スペンサーが進化論を重視したことを踏まえると、彼の社会学は社会ダーウィニズムとラマルク主義の混合と表現できるかもしれない。しかし、その人気にもか かわらず、スペンサーの社会学に対するこの見方は誤りである。彼の政治的・倫理的な著作には社会ダーウィニズムと一致するテーマがあるが、スペンサーの社 会学的な著作にはそのようなテーマは見られず、社会の成長と分化のプロセスが社会組織の複雑性の度合いの変化にどのようにつながるかに焦点を当てている [25] 単純で未分化な均質性から複雑で分化した異質性への進化の過程は、社会の発展によって例証されるとスペンサーは論じた。彼は、この進化の過程に対応する2 つのタイプの社会、すなわち軍事的および産業的社会の理論を展開した。軍事的社会は、階層と服従の関係を基盤とする単純で未分化な社会であり、産業的社会 は、契約上の社会的義務を自発的に負うことを基盤とする複雑で分化した社会である。スペンサーが「社会有機体」として概念化した社会は、進化の普遍的な法 則に従って、より単純な状態からより複雑な状態へと進化していった。さらに、産業社会は『社会静力学』で描かれた理想社会の直系の子孫であるが、スペン サーは社会の進化が(当初考えていたように)無政府主義につながるのか、あるいは国家の役割が継続するのか(ただし、国家の役割は契約の執行や国防といっ た最低限の機能に縮小される)については、後に意見を変えている。 スペンサーは初期の社会学に貴重な貢献をしたが、特に構造機能主義に与えた影響は大きかった。しかし、ラマルク説やダーウィン説を社会学の領域に導入しよ うとした試みは成功しなかった。さらに、それは多くの人々から積極的に危険視されていた。当時の解釈学者、例えばヴィルヘルム・ディルタイなどは、自然科 学(Naturwissenschaften)と人文科学(Geisteswissenschaften)の区別を先駆けて提唱した。米国では、後に米国 社会学会の初代会長に選出される社会学者レスター・フランク・ウォードが、スペンサーの自由放任主義と政治倫理に関する理論に容赦ない攻撃を仕掛けた。ス ペンサーの業績の多くを称賛していたウォードであったが、スペンサーの政治的偏見が彼の思想を歪め、誤った方向に導いたと信じていた。[26] 1890年代には、エミール・デュルケムが実用的な社会調査を重視した正式な学術社会学を確立した。20世紀の変わり目には、ドイツの社会学者第一世代、 特にマックス・ウェーバーが方法論的反実証主義を提示していた。しかし、スペンサーの自由放任主義、適者生存、自然法のプロセスにおける最小限の人間の干 渉に関する理論は、経済学や政治学といった社会科学分野において、今なお、あるいはますます大きな影響力を持ち続けている。最近では、社会におけるエネル ギーを真剣に受け止めることを学ばなければならない社会学にとって、スペンサーの重要性について論じた著述もある。[27] |

| Ethics Spencer predicted in his first book that the endpoint of the evolutionary process will be the creation of 'the perfect man in the perfect society' with human beings becoming completely adapted to social life. The chief difference between Spencer's earlier and later conceptions of this process is the evolutionary timescale involved. The psychological – and hence also the moral – constitution which has been bequeathed to the present generation by our ancestors, and which we in turn will hand on to future generations, is in the process of gradual adaptation to the requirements of living in society. For example, aggression is a survival instinct which was necessary in the primitive conditions of life, but is maladaptive in advanced societies. Because human instincts have a specific location in strands of brain tissue, they are subject to the Lamarckian mechanism of use-inheritance so that gradual modifications could be transmitted to future generations. Over the course of many generations, the evolutionary process will ensure that human beings will become less aggressive and increasingly altruistic, leading eventually to a perfect society in which no one would cause another person pain. However, Spencer held, for evolution to produce the perfect individual it is necessary for present and future generations to experience the 'natural' consequences of their conduct. Only in this way will individuals have the incentives required to work on self-improvement and thus to hand an improved moral constitution to their descendants. Hence anything that interferes with the 'natural' relationship of conduct and consequence was to be resisted and this included the use of the coercive power of the state to relieve poverty, to provide public education, or to require compulsory vaccination. Although charitable giving is to be encouraged even it has to be limited by the consideration that suffering is frequently the result of individuals receiving the consequences of their actions. Hence too much individual benevolence directed to the 'undeserving poor' would break the link between conduct and consequence that Spencer considered fundamental to ensuring that humanity continues to evolve to a higher level of development. Spencer adopted a utilitarian standard of ultimate value – the greatest happiness of the greatest number – and the culmination of the evolutionary process will be the maximization of utility. In the perfect society, individuals would not only derive pleasure from the exercise of altruism ('positive beneficence') but would aim to avoid inflicting pain on others ('negative beneficence'). They would also instinctively respect the rights of others, leading to the universal observance of the principle of justice – each person had the right to a maximum amount of liberty that was compatible with a like liberty in others. 'Liberty' is interpreted to mean the absence of coercion, and is closely connected to the right to private property. Spencer termed this code of conduct 'Absolute Ethics' which provided a scientifically grounded moral system that could substitute for the supernaturally-based ethical systems of the past. However, he recognized that our inherited moral constitution does not currently permit us to behave in full compliance with the code of Absolute Ethics, and for this reason, we need a code of 'Relative Ethics' which takes into account the distorting factors of our present imperfections. Spencer's distinctive view of musicology was also related to his ethics. Spencer thought that the origin of music is to be found in impassioned oratory. Speakers have persuasive effect not only by the reasoning of their words, but by their cadence and tone – the musical qualities of their voice serve as "the commentary of the emotions upon the propositions of the intellect," as Spencer put it. Music, conceived as the heightened development of this characteristic of speech, makes a contribution to the ethical education and progress of the species. "The strange capacity which we have for being affected by melody and harmony, may be taken to imply both that it is within the possibilities of our nature to realize those intenser delights they dimly suggest, and that they are in some way concerned in the realization of them. If so the power and the meaning of music become comprehensible; but otherwise they are a mystery."[28] Spencer's last years were characterized by a collapse of his initial optimism, replaced instead by a pessimism regarding the future of mankind. Nevertheless, he devoted much of his efforts to reinforcing his arguments and preventing the misinterpretation of his monumental theory of non-interference. |

倫理 スペンサーは最初の著書で、進化の最終段階は「完璧な社会における完璧な人間」の創造であり、人間は社会生活に完全に適応するだろうと予測した。スペン サーがこのプロセスについて初期に抱いていた考えと、後に抱くようになった考えとの主な違いは、進化にかかる時間軸である。私たちの祖先が現在の世代に受 け継ぎ、そして私たちがまた次の世代に受け継ぐ心理的、そして道徳的体質は、社会生活の要求に徐々に適応していく過程にある。例えば、攻撃性は生存本能で あり、原始的な生活環境では必要不可欠であったが、高度な社会では不適応である。人間の衝動は脳組織の特定の部位に存在するため、ラマルクの用遺伝の法則 に従い、徐々に変化したものが次世代に受け継がれる。何世代にもわたる進化の過程で、人間はより攻撃性が少なく利他的になっていき、最終的には誰も他人に 苦痛を与えることのない完璧な社会が実現するだろう。 しかしスペンサーは、進化が完璧な個人を生み出すためには、現在および将来の世代が自らの行動の「自然な」結果を経験することが必要であると主張した。そ うして初めて、個人が自己改善に努めるための動機付けが生まれ、その結果、より道徳的な体質を子孫に引き継ぐことができる。したがって、行動と結果の「自 然な」関係を妨げるものはすべて抵抗されるべきであり、これには、貧困救済、公教育の提供、あるいは強制予防接種を目的とした国家の強制力の行使も含まれ ていた。慈善活動は奨励されるべきであるが、苦しみはしばしば個人が自らの行動の結果として受けるものであるという事実を考慮して、その範囲は限定されな ければならない。したがって、「救うに値しない貧困層」に個人が行き過ぎた善意を示すことは、スペンサーが人類がより高いレベルへと進化し続けるために不 可欠であると考えた「行動と結果のつながり」を断ち切ることになる。 スペンサーは、最大多数の最大幸福という功利主義的な究極の価値基準を採用し、進化の過程の集大成は効用の最大化であるとした。完全な社会では、個人は利 他主義(「積極的博愛」)の実践から喜びを得るだけでなく、他者に苦痛を与えることを避ける(「消極的博愛」)ことを目指す。また、本能的に他者の権利を 尊重し、普遍的な正義の原則の遵守につながる。すなわち、各人は他者の同様の自由と両立する最大限の自由を享受する権利がある、というものである。「自 由」とは強制の不在を意味すると解釈され、私有財産の権利と密接に関連している。スペンサーは、この行動規範を「絶対的倫理」と呼び、過去の超自然的倫理 体系に代わる科学的根拠に基づく道徳体系を提供した。しかし、彼は、私たちが受け継いできた道徳的体質では、現状では「絶対的倫理」の規範に完全に準拠し た行動を取ることはできないと認識していた。そのため、私たちは、現在の不完全さゆえの歪み要因を考慮した「相対的倫理」の規範を必要としている。 スペンサーの音楽学に関する独特な見解は、彼の倫理観とも関連している。スペンサーは、音楽の起源は情熱的な演説にあると考えた。演説者は、言葉の論理だ けでなく、抑揚やトーンによって説得力を持つ。声の音楽的な性質は、「知性の命題に対する感情の解説」として機能する。音楽は、この言語の特性をさらに発 展させたものと捉えることができ、倫理教育や人類の進歩に貢献する。「メロディやハーモニーに影響を受けるという我々のもつ不思議な能力は、それらがぼん やりと示唆する、より深い喜びを我々の本質が実現できる可能性があること、そしてそれらがその実現に何らかの形で関わっていることを暗示していると解釈で きるかもしれない。もしそうであれば、音楽の力と意味は理解できる。しかし、そうでなければ、それは謎である。」[28] スペンサーの晩年は、当初の楽観主義が崩れ、代わりに人類の未来に対する悲観主義に取って代わられたことで特徴づけられる。それでもなお、彼は自身の主張を強化し、彼の「不干渉」という画期的な理論の誤った解釈を防ぐことに多くの労力を費やした。 |

| Agnosticism Spencer's reputation among the Victorians owed a great deal to his agnosticism. He rejected theology as representing the 'impiety of the pious.' He was to gain much notoriety from his repudiation of traditional religion, and was frequently condemned by religious thinkers for allegedly advocating atheism and materialism. Nonetheless, unlike Thomas Henry Huxley, whose agnosticism was a militant creed directed at 'the unpardonable sin of faith' (in Adrian Desmond's phrase), Spencer insisted that he was not concerned with undermining religion in the name of science, but to bring about a reconciliation of the two. The following argument is a summary of Part 1 of his First Principles (2nd ed. 1867). Starting either from religious belief or from science, Spencer argued, we are ultimately driven to accept certain indispensable but literally inconceivable notions. Whether we are concerned with a Creator or the substratum which underlies our experience of phenomena, we can frame no conception of it. Therefore, Spencer concluded, that religion and science agree in the supreme truth that human understanding is only capable of 'relative' knowledge. This is the case since, owing to the inherent limitations of the human mind, it is only possible to obtain knowledge of phenomena, not of the reality ('the absolute') underlying phenomena. Hence both science and religion must come to recognise as the 'most certain of all facts that the Power which the Universe manifests to us is utterly inscrutable.' He called this awareness of 'the Unknowable' and he presented worship of the Unknowable as capable of being a positive faith which could substitute for conventional religion. Indeed, he thought that the Unknowable represents the ultimate stage in the evolution of religion, the final elimination of its last anthropomorphic vestiges. |

不可知論 ヴィクトリア朝の人々におけるスペンサーの名声は、彼の不可知論によるところが大きい。彼は、神学は「敬虔な者の不敬」を体現しているとしてこれを否定し た。彼は伝統的な宗教を否定したことで悪評を買い、無神論と唯物論を擁護しているとして宗教思想家たちからたびたび非難された。しかし、トマス・ヘン リー・ハックスリーの不可知論が「許しがたい信仰の罪」(エイドリアン・デズモンドの表現)を標的とした好戦的な信条であったのに対し、スペンサーは、科 学の名のもとに宗教を弱体化させることを目的としているのではなく、むしろ両者の和解をもたらすことを目的としていると主張した。以下は、彼の著書 『First Principles』(第2版、1867年)の第1部の要約である。 宗教的信念から出発しても、科学から出発しても、スペンサーは、私たちは最終的に、不可欠ではあるが文字通りには想像できない概念を受け入れるよう迫られ ると論じた。創造主についてであれ、現象の経験の根底にある基盤についてであれ、私たちはそれを概念化することはできない。したがって、スペンサーは結論 づけた。宗教と科学は、人間の理解力が「相対的な」知識しか得られないという至高の真理において一致している、と。これは、人間の心には本来的な限界があ るため、現象の知識は得られても、現象の背後にある現実(「絶対的なもの」)の知識は得られないからである。したがって、科学と宗教の両者は、いずれも 「宇宙が私たちに示している力はまったく不可解である」という「すべての事実の中で最も確かなもの」を認識しなければならない。彼はこの「不可知」の認識 を「不可知」と呼び、不可知への崇拝は、従来の宗教に代わる積極的な信仰となり得るものだと提示した。実際、彼は不可知が宗教の進化における究極の段階で あり、その最後の擬人観の痕跡を完全に排除したものだと考えていた。 |

| Political views Spencerian views in 21st-century circulation derive from his political theories and memorable attacks on the reform movements of the late 19th century. He has been claimed as a precursor by right-libertarians and anarcho-capitalists. Austrian School economist Murray Rothbard called Social Statics "the greatest single work of libertarian political philosophy ever written."[29] Spencer argued that the state is not an "essential" institution and that it will "decay" as a voluntary market organisation comes to replace the coercive aspects of the state.[30] He also argued that the individual has a "right to ignore the state."[31] As a result of this perspective, Spencer was harshly critical of patriotism. In response to being told that British troops were in danger during the Second Afghan War (1878–1880) he replied: "When men hire themselves out to shoot other men to order, asking nothing about the justice of their cause, I don't care if they are shot themselves."[32] Politics in late Victorian Britain moved in directions that Spencer disliked, and his arguments provided so much ammunition for conservatives and individualists in Europe and America that they are still in use in the 21st century. The expression "There is no alternative" (TINA), made famous by prime minister Margaret Thatcher, may be traced to its emphatic use by Spencer.[33] By the 1880s, he was denouncing "the new Toryism", that is, the "social reformist wing" of the Liberal Party, the wing to some extent hostile to prime minister William Ewart Gladstone, this faction of the Liberal Party Spencer compared to the interventionist "Toryism" of such people as the former Conservative Party prime minister Benjamin Disraeli. In The Man Versus the State (1884), he attacked Gladstone and the Liberal Party for losing its proper mission (they should be defending personal liberty, he said) and instead promoting paternalist social legislation (what Gladstone himself called "Construction", an element in the modern Liberal party that he opposed). Spencer denounced Irish land reform, compulsory education, laws to regulate safety at work, prohibition and temperance laws, tax-funded libraries, and welfare reforms. His main objections were threefold: the use of the coercive powers of the government, the discouragement given to voluntary self-improvement, and the disregard of the "laws of life". The reforms, he said, were tantamount to "socialism", which he said was about the same as "slavery" in terms of limiting human freedom. Spencer vehemently attacked the widespread enthusiasm for the annexation of colonies and imperial expansion, which subverted all he had predicted about evolutionary progress from 'militant' to 'industrial' societies and states.[34] Spencer anticipated many of the analytical standpoints of later right-libertarian theorists such as Friedrich Hayek, especially in his "law of equal liberty", his insistence on the limits to predictive knowledge, his model of spontaneous social order, and his warnings about the "unintended consequences" of collectivist social reforms.[35] While often caricatured as ultra-conservative, Spencer had been more radical, or left-libertarian,[36] earlier in his career, opposing private property in land and claiming that each person has a latent claim to participate in the use of the earth (views that influenced Georgism),[37] calling himself "a radical feminist" and advocating the organisation of trade unions as a bulwark against "exploitation by bosses", and favoured an economy organised primarily in free worker co-operatives as a replacement for wage-labor.[38] Although he retained support for unions, his views on the other issues had changed by the 1880s. He came to predict that social welfare programmes would eventually lead to the socialisation of the means of production, saying "all socialism is slavery." Spencer defined a slave as a person who "labours under coercion to satisfy another's desires" and believed that under socialism or communism the individual would be enslaved to the whole community rather than to a particular master, and "it means not whether his master is a single person or society."[39] Social Darwinism For many, the name of Herbert Spencer is virtually synonymous with Social Darwinism, a social theory that applies the law of the survival of the fittest to society and is integrally related to the nineteenth-century rise in scientific racism. In his famed work Social Statics (1850), he argued that imperialism had served civilization by clearing the inferior races off the earth: "The forces which are working out the great scheme of perfect happiness, taking no account of incidental suffering, exterminate such sections of mankind as stand in their way. … Be he human or be he brute – the hindrance must be got rid of."[40] Yet, in the same work, Spencer goes on to say that the incidental evolutionary benefits derived from such barbarous practices do not serve as justifications for them going forward.[41] Spencer's association with social Darwinism might have its origin in a specific interpretation of his support for competition. Whereas in biology the competition of various organisms can result in the death of a species or organism, the kind of competition Spencer advocated is closer to the one used by economists, where competing individuals or firms improve the well-being of the rest of society. Spencer viewed private charity positively, encouraging both voluntary association and informal care to aid those in need, rather than relying on government bureaucracy or force. He further recommended that private charitable efforts would be wise to avoid encouraging the formation of new dependent families by those unable to support themselves without charity.[42] Focusing on the form as well as the content of Spencer's "Synthetic Philosophy", one writer has identified it as the paradigmatic case of "social Darwinism", understood as a politically motivated metaphysic very different in both form and motivation from Darwinist science.[43] In a letter to the Japanese government regarding intermarriage with Westerners, Spencer stated that "if you mix the constitution of two widely divergent varieties which have severally become adapted to widely divergent modes of life, you get a constitution which is adapted to the mode of life of neither – a constitution which will not work properly." He goes on to say that America has failed to limit the immigration of Chinese and restrict their contact, especially sexual, with the presumed European stock. He states "if they mix they must form a bad hybrid" regarding the issue of Chinese and (ethnically European) Americans. Spencer ends his letter with the following blanket statement against all immigration: "In either case, supposing the immigration to be large, immense social mischief must arise, and eventually social disorganization. The same thing will happen if there should be any considerable mixture of European or American races with the Japanese."[44] |

政治的見解 21世紀に流通しているスペンサーの政治的見解は、彼の政治理論と19世紀後半の改革運動に対する印象的な攻撃に由来する。彼は右派リバタリアンやアナル コ・キャピタリストから先駆者であると主張されている。オーストリア学派の経済学者であるマレー・ロスバードは、『社会静力学』を「リバタリアン政治哲学 の最も偉大な著作」と呼んだ。[29] スペンサーは、国家は「本質的な」制度ではなく、国家の強制的な側面が自発的な市場組織に取って代わられることで「腐敗」すると主張した。[30] また、個人は「国家を無視する権利」を有しているとも主張した。[31] この見解の結果、スペンサーは愛国主義を厳しく批判した。第二次アフガン戦争(1878年~1880年)において英国軍が危険にさらされているという指摘 に対して、彼は「人々が、その大義の正義について何も問うことなく、命令に従って他の人間を撃つために身を売るのであれば、彼らが撃たれても私は気にしな い」と答えた。 ヴィクトリア朝後期の英国の政治はスペンサーが好まない方向に進み、彼の主張はヨーロッパやアメリカの保守主義者や個人主義者たちに多くの武器を提供し、 それらは21世紀の今日でも使用されている。マーガレット・サッチャー首相によって有名になった「他に選択肢はない(There is no alternative)」(TINA)という表現は、スペンサーが強調して使用したことに由来する可能性がある。[33] 1880年代までに、彼は「新しいトーリー主義」、すなわち すなわち、自由党の「社会改革派」、つまりウィリアム・グラッドストーン首相に敵対する一部の派閥を指し、スペンサーはこれを保守党の元首相ベンジャミ ン・ディズレーリの介入主義的な「トーリー主義」と比較した。著書『人間対国家』(1884年)の中で、彼はグラッドストーンと自由党が本来の使命を見失 い(本来は個人の自由を守るべきであると彼は主張した)、その代わりに父権主義的な社会立法を推進している(グラッドストーン自身はこれを「建設」と呼 び、彼はこれに反対した)と攻撃した。スペンサーは、アイルランドの土地改革、義務教育、労働安全衛生法、禁酒法、節酒法、税金による図書館、福祉改革な どを非難した。彼の主な反対理由は3つあった。政府による強制力の行使、自発的な自己改善の阻害、そして「人生の法則」の無視である。彼は、これらの改革 は「社会主義」に等しいと述べた。社会主義は人間の自由を制限するという点において「奴隷制」とほぼ同様であると彼は述べた。スペンサーは、植民地の併合 や帝国の拡大に対する広範な熱狂を激しく攻撃した。それは、彼が「好戦的な」社会から「産業的な」社会や国家への進化の進歩について予測したすべてを覆す ものだった。[34] スペンサーは、フリードリヒ・ハイエクなどの後年の右派リバタリアン理論家の分析的観点の多くを予想していた。特に、「平等な自由の法則」、予測的知識の 限界に関する主張、自発的社会秩序のモデル、集団主義的社会改革の「予期せぬ結果」に関する警告などである。しばしば極端な保守主義者として戯画化される スペンサーであったが、キャリアの初期にはより急進的、あるいは左派リバタリアンであった。土地の私有に反対し、地球の利用に参加する潜在的な権利を各人 が有していると主張していた(この見解はジョージズムに影響を与えた)[37]。急進的フェミニスト」と称し、「上司による搾取」に対する防波堤として労 働組合の結成を提唱し、賃金労働に代わるものとして、自由労働者協同組合を主体とした経済を支持していた。[38] 彼は労働組合への支持を維持していたが、その他の問題に関する見解は1880年代までに変化していた。彼は、社会福祉プログラムが最終的には生産手段の社 会化につながるだろうと予言するようになり、「社会主義はすべて奴隷制である」と述べた。スペンサーは奴隷を「他者の欲求を満たすために強制的に労働する 人」と定義し、社会主義や共産主義の下では個人は特定の主人ではなく社会全体に隷属することになり、「主人は1人の人間か社会かということではない」と信 じていた。 社会ダーウィニズム 多くの人々にとって、ハーバート・スペンサーの名は事実上、社会ダーウィニズムと同義である。社会ダーウィニズムとは、社会に適者生存の法則を適用する社 会理論であり、19世紀に台頭した科学的な人種差別主義と密接に関連している。彼の有名な著書『社会静力学』(1850年)では、帝国主義は劣った人種を 地球上から排除することで文明に貢献してきたと主張している。「完全な幸福という壮大な計画を実現するために、付随する苦痛を考慮することなく、その計画 の障害となる人類の一部を絶滅させる。人間であろうと獣であろうと、障害となるものは排除しなければならない」[40] しかし、同じ著作の中でスペンサーは、そのような野蛮な行為から派生する進化上の付随的な利益は、それらの行為を今後も継続する正当な理由にはならないと 述べている。[41] スペンサーの社会ダーウィニズムとの関連性は、競争を支持する彼の考え方を特定の解釈から来ているのかもしれない。生物学では、さまざまな生物の競争は種 の死につながる可能性があるが、スペンサーが提唱した競争は、経済学者が用いる競争に近いもので、競争する個人や企業が社会の他の部分の幸福を向上させる というものである。スペンサーは、民間の慈善活動を肯定的に捉え、政府の官僚や武力に頼るのではなく、自発的な団体や非公式なケアを奨励し、困っている人 々を支援した。さらに、慈善活動によって自活できない人々が新たに扶養家族を形成することを助長することは賢明ではないと、私的な慈善活動の取り組みを推 奨した。[42] スペンサーの『総合哲学』の内容だけでなく形式にも注目したある著者は、この著作を「社会ダーウィニズム」の典型的な事例であると指摘している。「社会 ダーウィニズム」とは、ダーウィンの科学とは形式も動機も大きく異なる政治的な動機に基づく形而上学として理解されている。[43] 西洋人との混血に関する日本政府宛ての手紙の中で、スペンサーは「それぞれに大きく異なる生活様式に適応してきた、大きく異なる2つの品種の体質を混ぜ合 わせると、どちらの生活様式にも適応していない体質、つまり正常に機能しない体質が生まれる」と述べている。さらに、アメリカは中国人の移民を制限し、彼 らがヨーロッパ系と想定される人々との接触、特に性的接触を制限することに失敗したと述べている。彼は、中国人と(民族的にはヨーロッパ系の)アメリカ人 との問題について、「もし彼らが混ざり合うのであれば、悪い雑種が生まれるに違いない」と述べている。スペンサーは、すべての移民に対する次のような包括 的な主張で手紙を締めくくっている。「いずれにしても、移民が大量に流入すれば、甚大な社会的な弊害が生じ、最終的には社会の崩壊を招くことになるだろ う。ヨーロッパ人やアメリカ人と日本人が相当程度混ざり合うことになれば、同じことが起こるだろう」[44]。 |

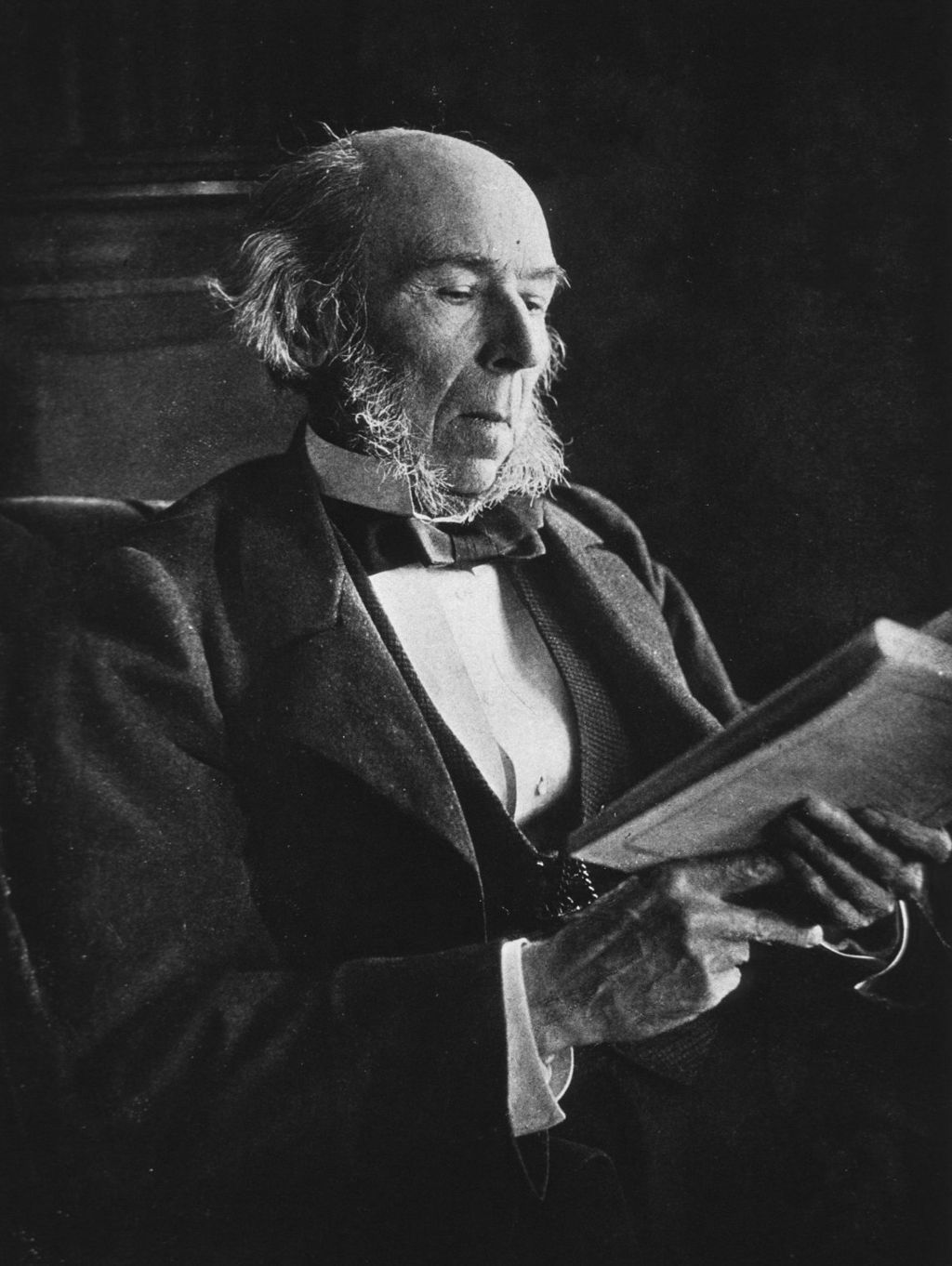

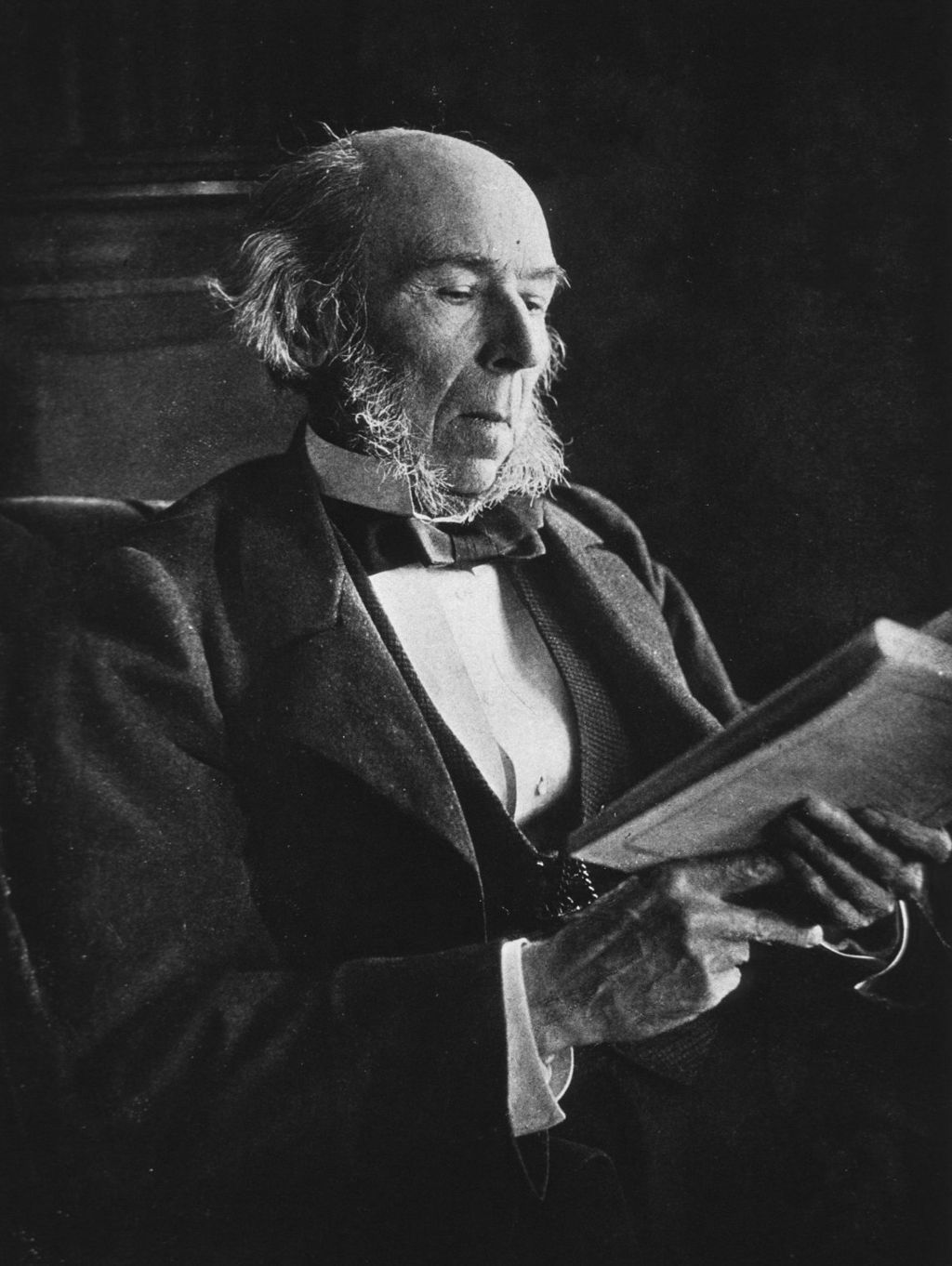

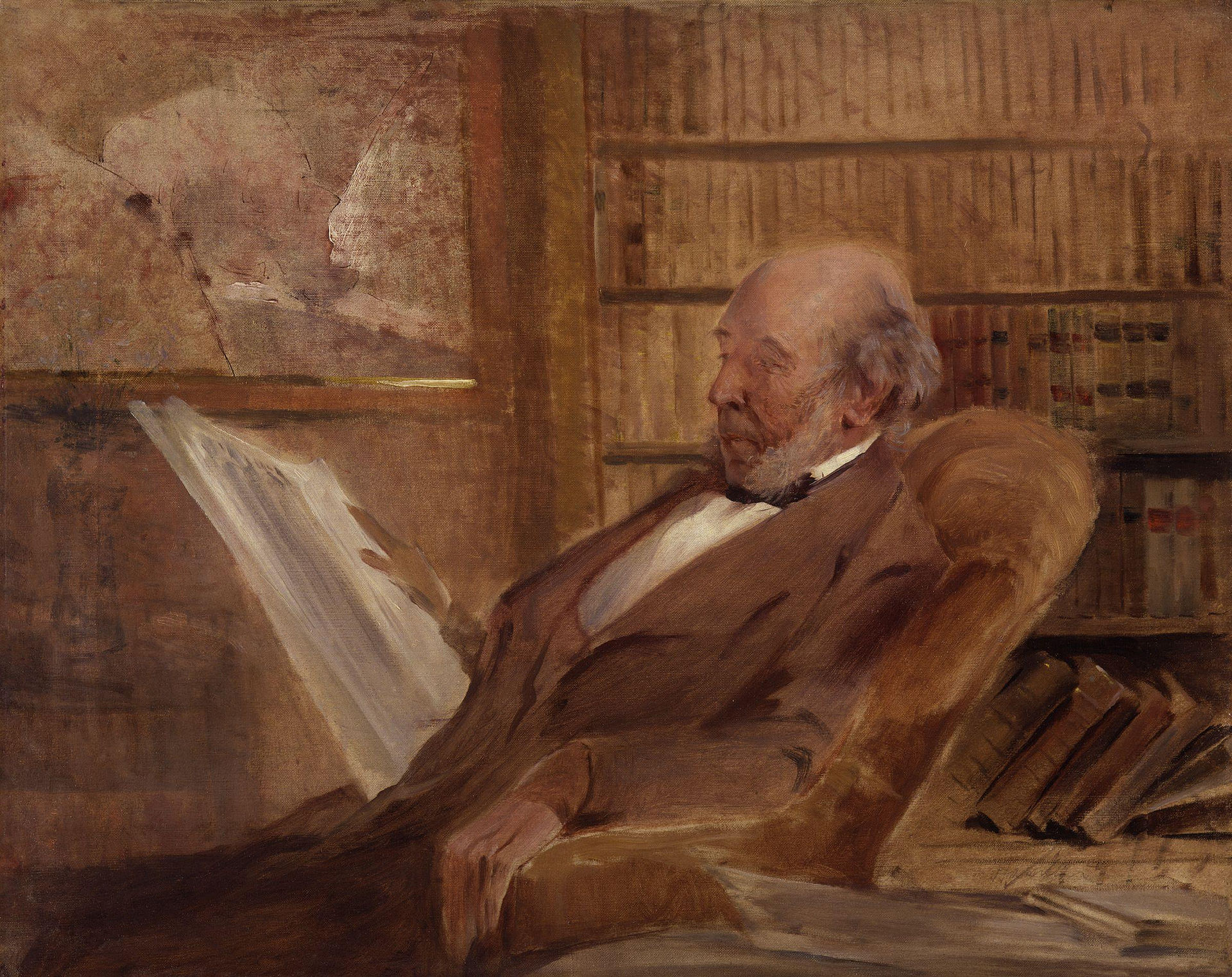

| General influence While most philosophers fail to achieve much of a following outside the academy of their professional peers, by the 1870s and 1880s Spencer had achieved an unparalleled popularity, as the sheer volume of his sales indicate. He was perhaps the only philosopher in history to sell over a million copies of his works during his own lifetime.[45] In the United States, where pirated editions were still commonplace, his authorised publisher, Appleton, sold 368,755 copies between 1860 and 1903. This figure did not differ much from his sales in his native Britain, and once editions in the rest of the world are added in the figure of a million copies seems like a conservative estimate. As William James remarked, Spencer "enlarged the imagination, and set free the speculative mind of countless doctors, engineers, and lawyers, of many physicists and chemists, and of thoughtful laymen generally."[46] The aspect of his thought that emphasised individual self-improvement found a ready audience in the skilled working class. Spencer's influence among leaders of thought was also immense, though it was most often expressed in terms of their reaction to, and repudiation of, his ideas. As his American follower John Fiske observed, Spencer's ideas were to be found "running like the weft through all the warp" of Victorian thought.[47] Such varied thinkers as Henry Sidgwick, T.H. Green, G.E. Moore, William James, Henri Bergson, and Émile Durkheim defined their ideas in relation to his. Durkheim's Division of Labour in Society is to a very large extent an extended debate with Spencer, from whose sociology, many commentators now agree, Durkheim borrowed extensively.[48]  Portrait of Spencer by John McLure Hamilton, c. 1895 In post-1863-Uprising Poland, many of Spencer's ideas became integral to the dominant fin-de-siècle ideology, "Polish Positivism". The leading Polish writer of the period, Bolesław Prus, hailed Spencer as "the Aristotle of the nineteenth century" and adopted Spencer's metaphor of society-as-organism, giving it a striking poetic presentation in his 1884 micro-story, "Mold of the Earth", and highlighting the concept in the introduction to his most universal novel, Pharaoh (1895). The early 20th century was hostile to Spencer. Soon after his death, his philosophical reputation went into a sharp decline. Half a century after his death, his work was dismissed as a "parody of philosophy",[49] and the historian Richard Hofstadter called him "the metaphysician of the homemade intellectual, and the prophet of the cracker-barrel agnostic."[50] Nonetheless, Spencer's thought had penetrated so deeply into the Victorian age that his influence did not disappear entirely. In recent years, much more positive estimates have appeared,[51] as well as a still highly negative estimate.[52] Political influence Despite his reputation as a social Darwinist, Spencer's political thought has been open to multiple interpretations. His political philosophy could both provide inspiration to those who believed that individuals were masters of their fate, who should brook no interference from a meddling state, and those who believed that social development required a strong central authority. In Lochner v. New York, conservative justices of the United States Supreme Court could find inspiration in Spencer's writings for striking down a New York law limiting the number of hours a baker could work during the week, on the ground that this law restricted liberty of contract. Arguing against the majority's holding that a "right to free contract" is implicit in the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote: "The Fourteenth Amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer's Social Statics." Spencer has also been described as a quasi-anarchist, as well as an outright anarchist. Marxist theorist Georgi Plekhanov, in his 1909 book Anarchism and Socialism, labelled Spencer a "conservative Anarchist".[53] Spencer's work has frequently been seen as a model for later libertarian thinkers, such as Robert Nozick, and he continues to be read–and is often invoked–by libertarians on issues concerning the function of government and the fundamental character of individual rights.[54] Spencer's ideas also became very influential in China and Japan largely because he appealed to the reformers' desire to establish a strong nation-state with which to compete with the Western powers. His thought was introduced by the Chinese scholar Yen Fu, who saw his writings as a prescription for the reform of the Qing state.[55] Spencerism was so influential in China that it was synthesized into the Chinese translation of the Origin of Species, in which Darwin's branching view of evolution was converted into a linear-progressive one.[56] Spencer also influenced the Japanese Westernizer Tokutomi Soho, who believed that Japan was on the verge of transitioning from a "militant society" to an "industrial society", and needed to quickly jettison all things Japanese and take up Western ethics and learning.[57] He also corresponded with Kaneko Kentaro, warning him of the dangers of imperialism.[58] Savarkar writes in his Inside the Enemy Camp, about reading all of Spencer's works, of his great interest in them, of their translation into Marathi, and their influence on the likes of Tilak and Agarkar, and the affectionate sobriquet given to him in Maharashtra – Harbhat Pendse.[59] Influence on literature Spencer greatly influenced literature and rhetoric. His 1852 essay, "The Philosophy of Style", explored a growing trend of formalist approaches to writing. Highly focused on the proper placement and ordering of the parts of an English sentence, he created a guide for effective composition. Spencer aimed to free prose writing from as much "friction and inertia" as possible, so that the reader would not be slowed by strenuous deliberations concerning the proper context and meaning of a sentence. Spencer argued that writers should aim "To so present ideas that they may be apprehended with the least possible mental effort" by the reader. He argued that by making the meaning as readily accessible as possible, the writer would achieve the greatest possible communicative efficiency. This was accomplished, according to Spencer, by placing all the subordinate clauses, objects and phrases before the subject of a sentence so that, when readers reached the subject, they had all the information they needed to completely perceive its significance. While the overall influence that "The Philosophy of Style" had on the field of rhetoric was not as far-reaching as his contribution to other fields, Spencer's voice lent authoritative support to formalist views of rhetoric. Spencer influenced literature inasmuch as many novelists and short story authors came to address his ideas in their work. Spencer was referenced by George Eliot, Leo Tolstoy, Machado de Assis, Thomas Hardy, Bolesław Prus, George Bernard Shaw, Abraham Cahan, Richard Austin Freeman, D. H. Lawrence, and Jorge Luis Borges. Arnold Bennett greatly praised First Principles, and the influence it had on Bennett may be seen in his many novels. Jack London went so far as to create a character, Martin Eden, a staunch Spencerian. It has also been suggested[by whom?] that the character of Vershinin in Anton Chekhov's play The Three Sisters is a dedicated Spencerian. H. G. Wells used Spencer's ideas as a theme in his novella, The Time Machine, employing them to explain the evolution of man into two species. It is perhaps the best testimony to the influence of Spencer's beliefs and writings that his reach was so diverse. He influenced not only the administrators who shaped their societies' inner workings, but also the artists who helped shape those societies' ideals and beliefs. In Rudyard Kipling's novel Kim, the Anglophile Bengali spy Hurree Babu admires Herbert Spencer and quotes him to comic effect: "They are, of course, dematerialised phenomena. Spencer says." "I am good enough Herbert Spencerian, I trust, to meet little thing like death, which is all in my fate, you know." "He thanked all the Gods of Hindustan, and Herbert Spencer, that there remained some valuables to steal." Upton Sinclair, in One Clear Call, 1948, quips that "Huxley said that Herbert Spencer's idea of a tragedy was a generalization killed by a fact; ..."[60] |

一般的な影響 ほとんどの哲学者が、専門分野の同業者以外にはあまり支持者を獲得できないなか、スペンサーは1870年代から1880年代にかけて、彼の著作の販売部数 の多さが示すように、他に類を見ないほどの人気を博した。おそらく、彼は生涯に100万部を超える著作を売り上げた史上唯一の哲学者である。海賊版がまだ 一般的であった米国では、彼の正規の出版社であるアプルトン社が1860年から1903年の間に368,755部を販売した。この数字は、彼の母国である イギリスでの売り上げとそれほど変わらず、その他の国での版を加えると、100万部という数字は控えめな推定であると思われる。ウィリアム・ジェームズが 述べたように、スペンサーは「想像力を拡大し、数えきれないほどの医師、エンジニア、弁護士、多くの物理学者や化学者、そして一般の思慮深い素人の思索的 な心を解き放った」[46]。個人の自己改善を強調する彼の思想は、熟練した労働者階級に多くの支持者を獲得した。 思想家たちに与えたスペンサーの影響もまた甚大であったが、それはほとんどの場合、彼らのスペンサーの思想に対する反応や拒絶という形で表れた。彼のアメ リカの信奉者ジョン・フィスクが観察したように、スペンサーの思想はヴィクトリア朝の思想の「縦糸すべてに横糸のように走っている」ものであった。 [47] ヘンリー・サイドウィック、T.H.グリーン、G.E.ムーア、ウィリアム・ジェームズ、アンリ・ベルクソン、エミール・デュルケームといった多様な思想 家たちは、スペンサーの思想との関連で自らの思想を定義した。デュルケムの『社会における分業』は、非常に多くの部分でスペンサーとの議論を拡張したもの であり、多くの論者は、デュルケムがスペンサーの社会学から多くを借用したことに同意している。[48]  ジョン・マクルア・ハミルトンによるスペンサーの肖像画、1895年頃 1863年の蜂起後のポーランドでは、スペンサーの多くの考えが、世紀末の支配的なイデオロギーである「ポーランド・ポジティヴィズム」の不可欠な要素と なった。ポーランドの代表的な作家であるボレスワフ・プルスは、スペンサーを「19世紀のアリストテレス」と称賛し、スペンサーの「社会は有機体である」 という比喩を採用した。1884年の短編小説『大地の雛形』では、この比喩を印象的な詩的な表現で提示し、最も普遍的な小説『ファラオ』(1895年)の 序文では、この概念を強調した。 20世紀初頭はスペンサーにとって厳しい時代であった。彼の死後まもなく、彼の哲学的な評価は急激に下落した。彼の死後半世紀が経つと、彼の作品は「哲学 のパロディ」と見なされるようになり[49]、歴史家のリチャード・ホフスタッターは彼を「自家製知識人の形而上学者、そして、ありふれた不可知論の預言 者」と呼んだ[50]。しかし、スペンサーの思想はヴィクトリア朝時代に深く浸透していたため、彼の影響力が完全に消滅することはなかった。 近年では、より肯定的な評価も登場しているが[51]、依然として非常に否定的な評価もある[52]。 政治的影響 社会ダーウィニストとしての彼の評判にもかかわらず、スペンサーの政治思想は多様な解釈が可能である。彼の政治哲学は、個人が自らの運命の主であり、干渉 的な国家からの干渉を一切受け入れないべきであると考える人々、また、社会の発展には強力な中央権威が必要であると考える人々、双方にインスピレーション を与えるものであった。Lochner v. New York(ニューヨーク対ロクナー)において、米国最高裁判所の保守派判事は、この法律が契約の自由を制限しているという理由で、パン職人が週に働くこと のできる時間数を制限するニューヨーク州法を破棄するにあたり、スペンサーの著作からインスピレーションを得た可能性がある。「契約の自由」は合衆国憲法 修正第14条の適正手続き条項に暗黙のうちに含まれているという多数派の見解に反対して、オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ・ジュニアは次のように書いた。 「合衆国憲法修正第14条はハーバート・スペンサー氏の『社会静力学』を制定したものではない。スペンサーは、純粋なアナーキストであると同時に、準ア ナーキストとも評されている。マルクス主義の理論家ゲオルギー・プレハーノフは、1909年の著書『アナーキズムと社会主義』でスペンサーを「保守派のア ナーキスト」と評した。[53] スペンサーの著作は、ロバート・ノージックなどの後のリバタリアン思想家の模範と見なされることが多く、政府の機能や個人の権利の基本的性格に関する問題について、リバタリアンによって今でも読まれ、しばしば引用されている。[54] スペンサーの思想は、西洋列強と競争できる強力な国民国家を樹立したいという改革派の願望に訴えたことが主な理由で、中国や日本でも大きな影響力を持ち始 めた。彼の思想は、清国の改革の処方箋としてスペンサーの著作を捉えた中国人学者イエン・フー(Yen Fu)によって紹介された。[55] スペンサー主義は中国で大きな影響力を持ち、ダーウィンの進化論の分岐説を直線的進歩説に変えた『種の起源』の中国語訳に統合された。[56] スペンサーはまた、 日本の西洋化論者である徳富蘇峰にも影響を与えた。蘇峰は、日本は「戦闘的社会」から「産業社会」へと移行する瀬戸際にあり、日本のあらゆるものを速やか に放棄し、西洋の倫理と学問を取り入れる必要があると信じていた。[57] また、金子堅太郎とも文通し、帝国主義の危険性を警告していた。[ 58] サバルカールは著書『敵陣の内部』の中で、スペンサーの著作をすべて読み、非常に興味を持ったこと、マラーティー語に翻訳されたこと、ティラクやアガルカ ルらに影響を与えたこと、マハラシュトラ州で彼につけられた愛称「ハーバート・ペンドセ」について書いている。 文学への影響 スペンサーは文学と修辞学に多大な影響を与えた。1852年の論文「文体論」では、文章を書く際の形式主義的アプローチの傾向が強まっていることを探求し た。英語の文章の各部分の適切な配置と順序付けに重点的に取り組み、効果的な文章の書き方を指南した。スペンサーは、散文をできる限り「摩擦と慣性」から 解放し、読者が文の適切な文脈や意味について熟考することによって文章の理解が遅れることがないようにすることを目指した。スペンサーは、作家は「読者が 最小限の精神的な努力で理解できるような方法でアイデアを提示する」ことを目指すべきだと主張した。 彼は、意味をできる限り容易に理解できるようにすることで、作家は最大限のコミュニケーション効率を達成できると主張した。スペンサーによれば、これは従 属節、目的語、句をすべて文の主語の前に配置することで達成され、読者が主語に到達したときには、その意味を完全に理解するために必要なすべての情報を得 ていることになる。『The Philosophy of Style』が修辞学の分野に与えた全体的な影響は、他の分野への貢献ほど広範囲に及ぶものではなかったが、スペンサーの主張は修辞学の形式主義的な見解 に権威ある裏付けを与えた。 スペンサーは、多くの小説家や短編小説の作家たちが作品の中で彼の考えを取り上げるようになったという点で、文学にも影響を与えた。スペンサーは、ジョー ジ・エリオット、レフ・トルストイ、マシャード・デ・アシス、トマス・ハーディ、ボレスワフ・プルス、ジョージ・バーナード・ショー、エイブラハム・カハ ン、リチャード・オースティン・フリーマン、D.H. ローレンス、ホルヘ・ルイス・ボルヘスらに引用された。アーノルド・ベネットは『第一原理』を大いに賞賛し、ベネットに与えた影響は、彼の多くの小説に見 ることができる。ジャック・ロンドンは、スペンサーの熱心な信奉者であるマーティン・エデンというキャラクターを創作したほどである。また、アントン・ チェーホフの戯曲『三人姉妹』のヴェルシーニンというキャラクターは、熱心なスペンサー信奉者であるという説もある。H.G.ウェルズは、スペンサーの思 想をテーマとして、人間が2つの種に分かれて進化する過程を説明するのに用いた。スペンサーの信念と著作の影響力がどれほど広範囲に及んでいたかを示す最 良の証拠と言えるだろう。 彼は、社会の内部構造を形成する行政官だけでなく、社会の理想や信念を形成する芸術家にも影響を与えた。 ラドヤード・キップリングの小説『キム』では、英国びいきのベンガル人スパイ、フーリー・バブがハーバート・スペンサーを賞賛し、次のように引用して笑い を誘っている。「もちろん、それは非物質化現象だ。スペンサーが言っている。」 「私はハーバート・スペンサーの信奉者として十分な知識を持っているので、死のような小さな出来事にも対処できると信じている。死はすべて私の運命なのだ から。」 「彼は、盗むべき貴重品が残っていることに感謝して、ヒンドゥスターニーの神々やハーバート・スペンサーに感謝した。」 1948年の『One Clear Call』の中で、アプトン・シンクレアは「ハックスレーは、ハーバート・スペンサーの悲劇の概念は、事実によって殺された一般論であると述べた。」と皮 肉を言っている。[60] |

| Primary sources Papers of Herbert Spencer in Senate House Library, University of London Education (1861) System of Synthetic Philosophy, in ten volumes First Principles ISBN 0-89875-795-9 (1862) Principles of Biology (1864, 1867; revised and enlarged: 1898), in two volumes Volume I – Part I: The Data of Biology; Part II: The Inductions of Biology; Part III: The Evolution of Life; Appendices Volume II – Part IV: Morphological Development; Part V: Physiological Development; Part VI: Laws of Multiplication; Appendices Principles of Psychology (1870, 1880), in two volumes Volume I – Part I: The Data of Psychology; Part II: The Inductions of Psychology; Part III: General Synthesis; Part IV: Special Synthesis; Part V: Physical Synthesis; Appendix Volume II – Part VI: Special Analysis; Part VII: General Analysis; Part VIII: Congruities; Part IX: Corollaries Principles of Sociology, in three volumes Volume I (1874–75; enlarged 1876, 1885) – Part I: Data of Sociology; Part II: Inductions of Sociology; Part III: Domestic Institutions Volume II – Part IV: Ceremonial Institutions (1879); Part V: Political Institutions (1882); Part VI [published here in some editions]: Ecclesiastical Institutions (1885) Volume III – Part VI [published here in some editions]: Ecclesiastical Institutions (1885); Part VII: Professional Institutions (1896); Part VIII: Industrial Institutions (1896); References Principles of Ethics, in two volumes Volume I – Part I: The Data of Ethics Archived 7 May 2005 at the Wayback Machine (1879); Part II: The Inductions of Ethics (1892); Part III: The Ethics of Individual Life (1892); References Volume II – Part IV: The Ethics of Social Life: Justice (1891); Part V: The Ethics of Social Life: Negative Beneficence (1892); Part VI: The Ethics of Social Life: Positive Beneficence (1892); Appendices The Study of Sociology (1873, 1896) Archived 15 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine An Autobiography Archived 27 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine (1904), in two volumes See also Spencer, Herbert (1904). An Autobiography. D. Appleton and Company. v1 Life and Letters of Herbert Spencer by David Duncan Archived 16 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine (1908) v2 Life and Letters of Herbert Spencer by David Duncan Archived 17 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine (1908) Descriptive Sociology; or Groups of Sociological Facts, parts 1–8, classified and arranged by Spencer, compiled and abstracted by David Duncan, Richard Schepping, and James Collier (London, Williams & Norgate, 1873–1881). Essay Collections: Illustrations of Universal Progress: A Series of Discussions (1864, 1883) The Man Versus the State (1884) Essays: Scientific, Political, and Speculative (1891), in three volumes: Volume I (includes "The Development Hypothesis", "Progress: Its Law and Cause", "The Factors of Organic Evolution" and others) Volume II (includes "The Classification of the Sciences", The Philosophy of Style (1852), The Origin and Function of Music", "The Physiology of Laughter", and others) Volume III (includes "The Ethics of Kant", "State Tamperings With Money and Banks", "Specialized Administration", "From Freedom to Bondage", "The Americans", and others) Various Fragments (1897, enlarged 1900) Facts and Comments (1902) Great Political Thinkers (1960) |

一次資料 ロンドン大学、上院図書館所蔵のハーバート・スペンサーの論文 教育(1861年 総合哲学体系、全10巻 第一原理 ISBN 0-89875-795-9(1862年 生物学の原理(1864年、1867年、改訂版および増補版:1898年)、全2巻 第1巻 - 第1部:生物学のデータ、第2部:生物学の帰納法、第3部:生命の進化、付録 第2巻 - 第4部:形態学的発展、第5部:生理学的発展、第6部:増殖の法則、付録 『心理学原理』(1870年、1880年)全2巻 第1巻 - 第1部:心理学のデータ、第2部:心理学の帰納法、第3部:一般総合、第4部:特殊総合、第5部:物理総合、付録 第2巻 第VI部:特殊分析 第VII部:一般分析 第VIII部:一致 第IX部:補論 社会学原理、全3巻 第1巻(1874年~75年、1876年、1885年に増補) 第I部:社会学のデータ 第II部:社会学の帰納法 第III部:家庭制度 第2巻 - 第4部:儀礼制度(1879年)、第5部:政治制度(1882年)、第6部 [一部の版ではここに掲載]:教会制度(1885年 第3巻 - 第6部 [一部の版ではここに掲載]:教会制度(1885年)、第7部:職業制度(1896年)、第8部:産業制度(1896年)、参考文献 倫理の原則、2巻 第1巻 - 第1部:倫理のデータ 2005年5月7日アーカイブ分 (1879年); 第2部:倫理の誘導 (1892年); 第3部:個人の生活の倫理 (1892年); 参考文献 第2巻 - 第4部:社会生活の倫理:正義(1891年);第5部:社会生活の倫理:消極的恩恵(1892年);第6部:社会生活の倫理:積極的恩恵(1892年);付録 社会学の研究(1873年、1896年) 2012年5月15日アーカイブ分 自伝 2011年2月27日アーカイブ分 (1904年)、2巻 スペンサー、ハーバート(1904年)『自伝』D.アプルトン・アンド・カンパニー v1 デイヴィッド・ダンカン著『ハーバート・スペンサーの生涯と書簡』2011年3月16日アーカイブ分 (1908年) v2 デイヴィッド・ダンカン著『ハーバート・スペンサーの生涯と書簡』 アーカイブ 2011年8月17日 - ウェイバックマシン (1908) 『記述社会学、または社会学的事実のグループ』第1巻から第8巻、スペンサーによる分類と編纂、デイヴィッド・ダンカン、リチャード・シェッピング、ジェイムズ・コリアーによる編集と要約(ロンドン、ウィリアムズ・アンド・ノーゲート、1873年~1881年)。 エッセイ集: 『普遍的進歩の図解:一連の議論』(1864年、1883年) 『人間対国家』(1884年) 『エッセイ:科学的、政治的、思索的』(1891年)全3巻: 第1巻(「発展の仮説」、「進歩:その法則と原因」、「有機的進化の要因」などを含む) 第2巻(「科学の分類」、「スタイルの哲学(1852年)」、「音楽の起源と機能」、「笑いの生理学」などを含む) 第3巻(「カントの倫理学」、「国家による貨幣と銀行への干渉」、「専門行政」、「自由から束縛へ」、「アメリカ人」など さまざまな断片(1897年、1900年に増補版 事実とコメント(1902年 偉大な政治思想家たち(1960年 |

| Philosophers' critiques Herbert Spencer: An Estimate and Review (1904) by Josiah Royce. Lectures on the Ethics of T.H. Green, Mr. Herbert Spencer, and J. Martineau Archived 17 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine (1902) by Henry Sidgwick. Spencer-smashing at Washington (1894) by Lester F. Ward. A Perplexed Philosopher (1892) by Henry George. Remarks on Spencer's Definition of Mind as Correspondence (1878) by William James. |

哲学者の評論 ハーバート・スペンサー:評価とレビュー(1904年)ジョサイア・ロイス著 T.H.グリーン、ハーバート・スペンサー、J.マーティノーの倫理に関する講義(1902年)ヘンリー・シジウィック著 ワシントンでのスペンサー叩き(1894年)レスター・F・ウォード著 困惑する哲学者(1892年)ヘンリー・ジョージ著 スペンサーの「心」の定義に関する考察(1878年)ウィリアム・ジェームズ著 |

| Walter Bagehot Geolibertarianism Organicism |

ウォルター・ベイゴット 自由放任主義 有機体 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Spencer |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆