骨相学・頭蓋骨学・頭蓋論

phrenology

このページは、骨相学(フレノロジー)にはじまる、科学的フェティシ ズムの歴史について考えるものである。骨相学は、精神的特徴を予測するために頭蓋骨の凸凹を測定することを含む疑似科学である[1][2]。 それは、脳が心の器官であり、特定の脳領域が局所的、特定の機能またはモジュールを持っているという概念に基づいている[3] それらのアイデアは両方とも現実に根拠を持っていますが、骨相学は科学から逸脱した方法で経験的知識を超えて外挿されたものである。 [1796年にドイツの医師フランツ・ヨーゼフ・ガルによって開発され[6]、この学問は19世 紀、特に1810年頃から1840年まで影響力を持った。イギリスの骨相学の中心はエジンバラで、1820年にエジンバラ骨相学協会が設立された。

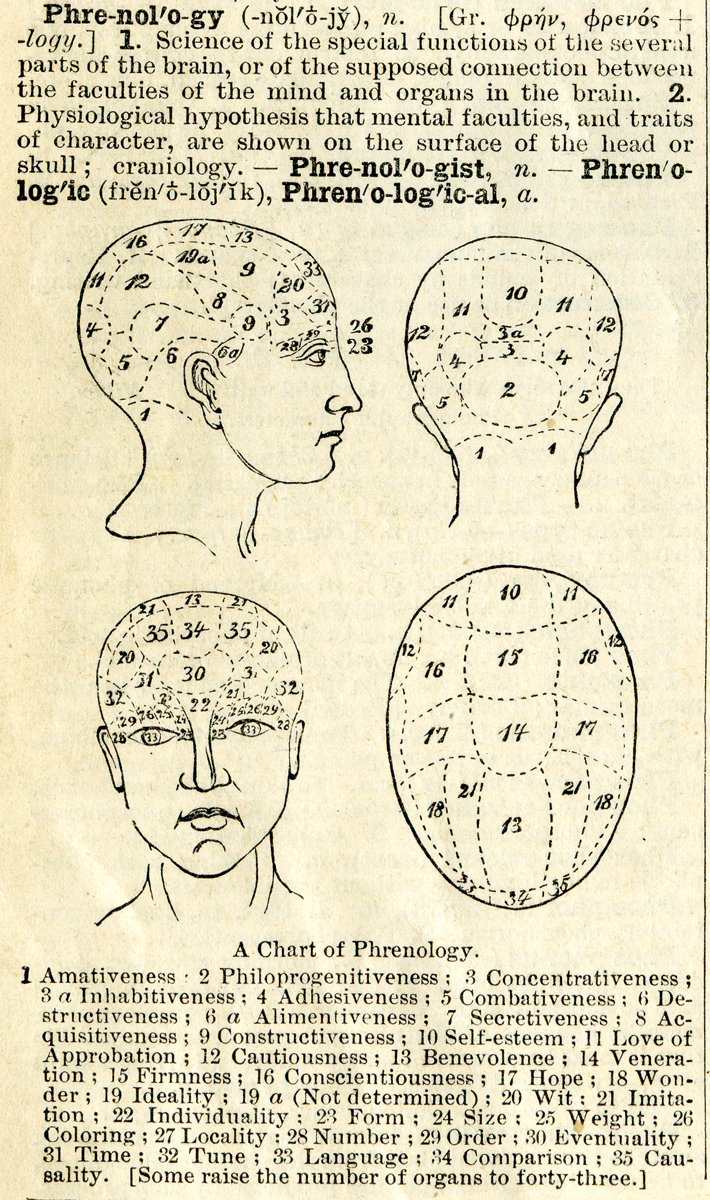

Phrenology is "a pseudoscience which involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.[1][2] It is based on the concept that the brain is the organ of the mind, and that certain brain areas have localized, specific functions or modules.[3] Although both of those ideas have a basis in reality, phrenology extrapolated beyond empirical knowledge in a way that departed from science.[1][4] The central phrenological notion that measuring the contour of the skull can predict personality traits is discredited by empirical research.[5] Developed by German physician Franz Joseph Gall in 1796,[6] the discipline was influential in the 19th century, especially from about 1810 until 1840. The principal British centre for phrenology was Edinburgh, where the Edinburgh Phrenological Society was established in 1820." - Phrenology.

骨相学(こっそ うがく、Phrenology: Phrenologie)とは、頭蓋測定学とも呼ばれ、 脳は精神活動に対応する複数の器官の集合体であり、その器官・機能の差が頭蓋の大きさ・形状に現れると主張する学説である。19世紀に隆盛を誇り、後に大 脳生理学が機能主義的な骨相学となり学問的ヘゲモニーが移動した。もちろん、20世紀以降では古典骨相学は流行しなくなったが、その後には、自然人類学の 計測研究や、ゲノム分析以降の人類『起源』研究など、現代の骨相学は、以前隆盛をたもっている。

The Phrenologist, a sketch by A.S.

Hartrick, 1895

古典骨相学の復習(ウィキペディア「骨相学」の記述による)

| Phrenology Phrenology is "a pseudoscience which involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.[1][2] It is based on the concept that the brain is the organ of the mind, and that certain brain areas have localized, specific functions or modules.[3] Although both of those ideas have a basis in reality, phrenology extrapolated beyond empirical knowledge in a way that departed from science.[1][4] The central phrenological notion that measuring the contour of the skull can predict personality traits is discredited by empirical research.[5] Developed by German physician Franz Joseph Gall in 1796,[6] the discipline was influential in the 19th century, especially from about 1810 until 1840. The principal British centre for phrenology was Edinburgh, where the Edinburgh Phrenological Society was established in 1820." - Phrenology.  Phrenological skull, European, 19th century. Wellcome Collection, London Etymology The term phrenology, from Ancient Greek φρήν (phrēn) 'mind' and λόγος (logos) 'knowledge', was used in the early 19th century to refer to what would now be considered psychology: a broader study of the mind and human mental faculties. This meaning has been eclipsed by the more specific study of the skull shape to infer psychological traits. Other terms historically used to discuss this specific relationship between the skull and the mind, and especially Gall's study of them include craniology, cranioscopy, zoonomy, organology, bumpology and functionalism.[13] Craniology and cranioscopy became detached from the specific sense of phrenology, and were later used to refer merely to the study of the skull, as in anthropology.[14] Many of the other words had or have meanings in other sciences, and their use to refer to the study of phrenology is now archaic. |

骨相学 骨相学は、精神的特徴を予測するために頭蓋骨の凸凹を測定することを含 む疑似科学である[1][2]。 それは、脳が心の器官であり、特定の脳領域が局所的、特定の機能またはモジュールを持っているという概念に基づいている[3] それらのアイデアは両方とも現実に根拠を持っていますが、骨相学は科学から逸脱した方法で経験的知識を超えて外挿されたものである。 [1796年にドイツの医師フランツ・ヨーゼフ・ガルによって開発され[6]、この学問は19世 紀、特に1810年頃から1840年まで影響力を持った。イギリスの骨相学の中心はエジンバラで、1820年にエジンバラ骨相学協会が設立された。  頭蓋骨の骨相学標本、ヨーロッパ、19世紀。ウェルカム・コレクション、ロンドン 語源 頭蓋学(フレンロジー)という用語は、古代ギリシャ語のφρήν(フレン)「心」とλόγος(ロゴス)「知識」に由来する。19世紀初頭には、現代でい う心理学、すなわち心と人間の精神的能力に関する広範な研究を指す言葉として用いられた。しかしこの意味は、頭蓋骨の形状から心理的特性を推測するという より専門的な研究に取って代わられた。 頭蓋骨と精神のこの特定の関係を論じるために歴史的に用いられた他の用語、特にガルによる研究に関連するものは、頭蓋学(craniology)、頭蓋鏡 検査(cranioscopy)、動物学(zoonomy)、器官学(organology)、隆起学(bumpology)、機能主義 (functionalism)などである。[13] 頭蓋学と頭蓋鏡検査は、頭蓋骨学の特定の意味から切り離され、後に人類学におけるように、単に頭蓋骨の研究を指すために用いられるようになった。[14] 他の多くの用語は、他の科学分野で意味を持っていたか、現在も持っている。それらの用語が頭蓋骨学の研究を指すために用いられることは、今では古風であ る。 |

| Phrenology is today recognized

as pseudoscience.[1][2][7][8][9][10] The methodological rigor of

phrenology was doubtful even for the standards of its time, since many

authors already regarded phrenology as pseudoscience in the 19th

century.[11][12][13][14] There have been various studies conducted that

discredited phrenology, most of which were done with ablation

techniques. Marie-Jean-Pierre Flourens demonstrated through ablation

that the cerebrum and cerebellum accomplish different functions. He

found that the impacted areas never carried out the functions that were

proposed through the pseudoscience, phrenology. However, Paul Broca was

the one who demolished the idea that phrenology was a science when he

discovered and named the "Broca's area". The patient's ability to

produce language was lost while their ability to understand language

remained intact. Through an autopsy examining their brains, he found

that there was damage to the left frontal lobe. He concluded that this

area of the brain was responsible for language production. Between

Flourens and Broca, the claims to support phrenology were dismantled.

Phrenological thinking was influential in the psychiatry and psychology

of the 19th century. Gall's assumption that character, thoughts, and

emotions are located in specific areas of the brain is considered an

important historical advance toward neuropsychology.[15][16] He

contributed to the idea that the brain is spatially organized, but not

in the way he proposed. There is a clear division of labor in the brain

but none of which even remotely correlates to the size of the head or

the structure of the skull. While it contributed to the advancement in

understanding the brain and its functions, remaining skeptical is

something that was learnt overtime. Phrenology was argued to be a

science, when in fact it is a pseudoscience. While phrenology itself has long been discredited, the study of the inner surface of the skulls of archaic human species allows modern researchers to obtain information about the development of various areas of the brains of those species, and thereby infer something about their cognitive and communicative abilities,[17] and possibly even something about their social life.[18] Due to its limitations, this technique is sometimes criticized as "paleo-phrenology".[18] |

骨相学は今日では疑似科学と認識されている[1][2][7][8]

[9][10]が、19世紀にはすでに多くの著者が骨相学を疑似科学としており、当時の水準から見てもその方法論の厳密さは疑問であった。

11][12][13][14]

骨相学を否定する研究はさまざま行われたが、多くは剥離技術によってなされたものであった。マリー=ジャン=ピエール・フルーランスは、大脳と小脳が異な

る機能を果たすことを切除によって証明した。その結果、大脳と小脳は、疑似科学である骨相学で提唱されたような機能を果たしていないことがわかったので

す。しかし、骨相学が科学であるという考えを打ち破ったのは、ポール・ブローカが「ブローカ野」を発見し命名したときであった。この患者さんは、言葉を発

する能力は失われていたが、言葉を理解する能力は残っていた。検死で彼らの脳を調べたところ、左前頭葉に損傷があることがわかった。彼は、この脳の領域が

言語生成を担っていると結論づけた。フローレンスとブローカの間で、骨相学を支持する主張は解体された。骨相学的な考え方は、19世紀の精神医学や心理学

に影響を及ぼした。性格、思考、感情が脳の特定の領域にあるというガルの仮定は、神経心理学に向けた重要な歴史的進歩であると考えられている[15]

[16]。

彼は脳が空間的に組織化されているという考えに貢献したが、彼が提案したような形では無かった。脳には明確な分業があるが、そのどれもが頭の大きさや頭蓋

骨の構造とは微塵も相関していないのである。脳とその機能の解明には貢献したが、懐疑的であり続けることは、長い時間をかけて学んできたことである。骨相

学は科学であると主張されたが、実際は疑似科学である。 骨相学自体は長い間信用されていないが、古代の人類の頭蓋骨の内側を研究することによって、現代の研究者はそれらの種の脳の様々な領域の発達に関する情報 を得ることができ、それによって彼らの認知能力やコミュニケーション能力に関する何か、そしておそらく彼らの社会生活に関する何かさえ推測することができ る[17]。 その限界から、この手法は「古骨相学」として批判されることもある[18]。 |

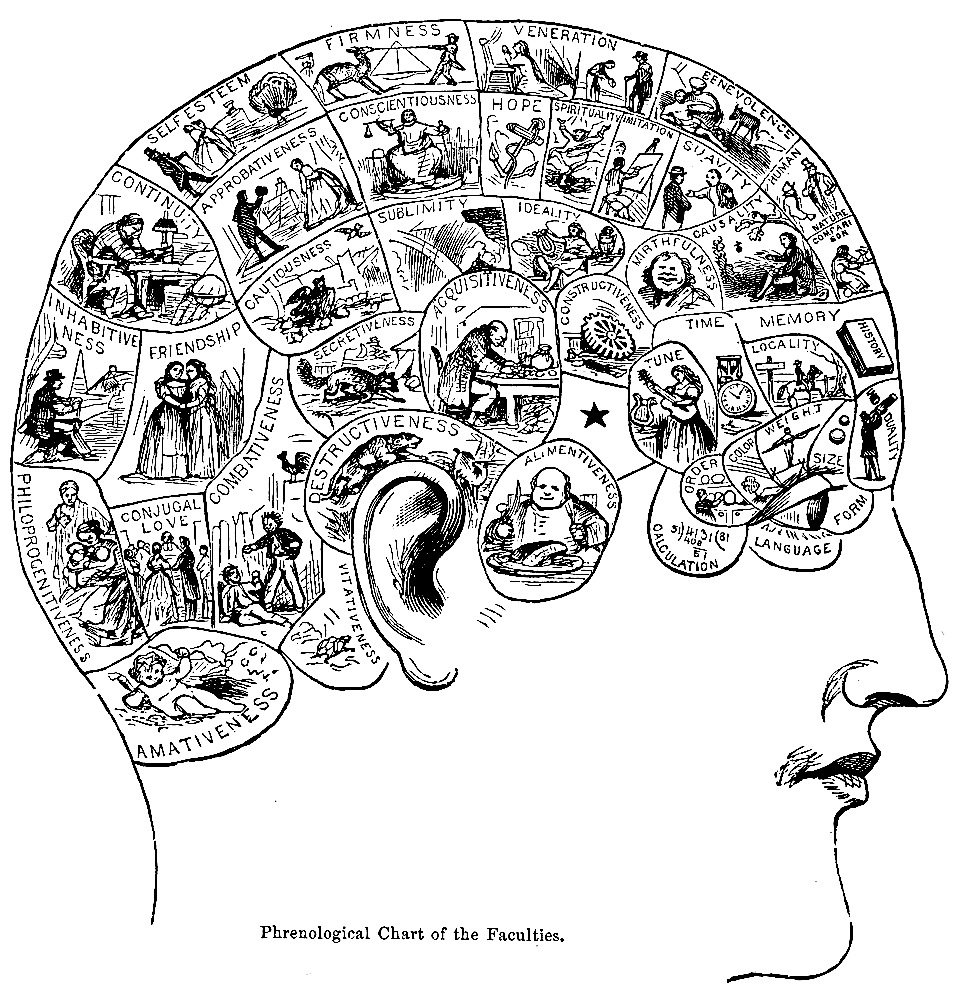

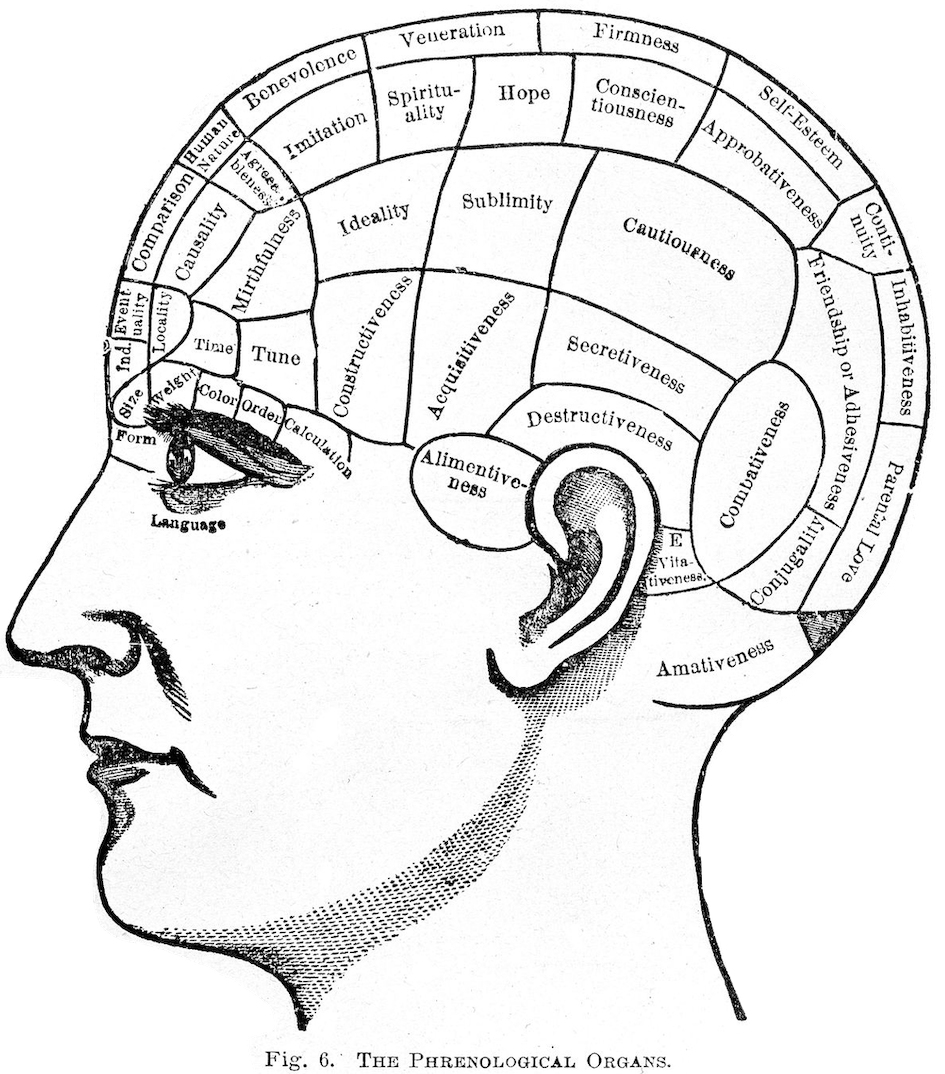

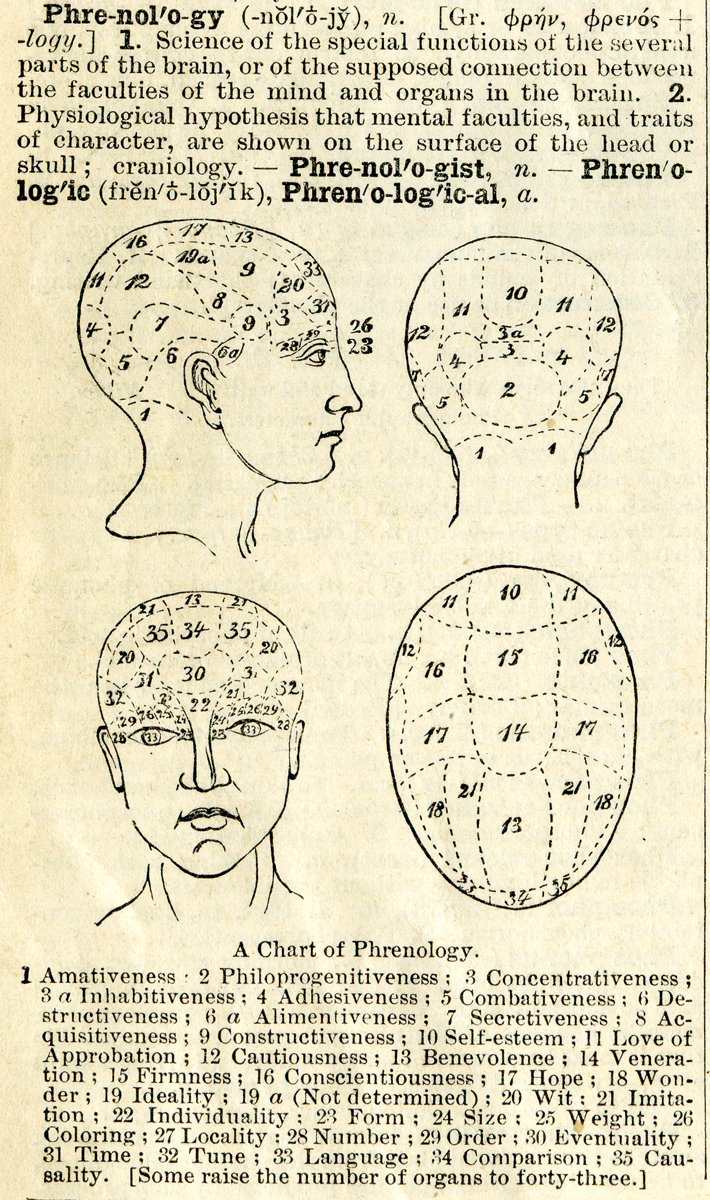

| Mental faculties Phrenologists believe that the human mind has a set of various mental faculties, each one represented in a different area of the brain. For example, the faculty of "philoprogenitiveness", from the Greek for "love of offspring", was located centrally at the back of the head (see illustration of the chart from Webster's Academic Dictionary). These areas were said to be proportional to a person's propensities. The importance of an organ was derived from relative size compared to other organs. It was believed that the cranial skull—like a glove on the hand—accommodates to the different sizes of these areas of the brain, so that a person's capacity for a given personality trait could be determined simply by measuring the area of the skull that overlies the corresponding area of the brain. Phrenology, which focuses on personality and character, is distinct from craniometry, which is the study of skull size, weight and shape, and physiognomy, the study of facial features. |

精神能力 骨相学者は、人間の心には様々な精神能力があり、それぞれが脳の異なる部位に代表することができると考えている。例えば、ギリシャ語で「子孫を愛する」と いう意味の「philoprogenitiveness」という能力は、後頭部の中央に位置していた(ウェブスター学術辞典の図表を参照)。 これらの部位は、その人の性向に比例すると言われていた。臓器の重要性は、他の臓器との相対的な大きさから導き出された。頭蓋骨は手のひらにはめる手袋の ようなもので、脳の各領域の大きさに対応できると考えられていた。そのため、ある性格特性に対するその人の能力は、対応する脳の領域に重なる頭蓋骨の面積 を測定するだけで判断できると考えられていた。 頭蓋骨の大きさ、重さ、形状を調べるクラニオメトリーや、顔の特徴を調べる人相学とは異なり、性格や個性に着目するのが骨相学である。 |

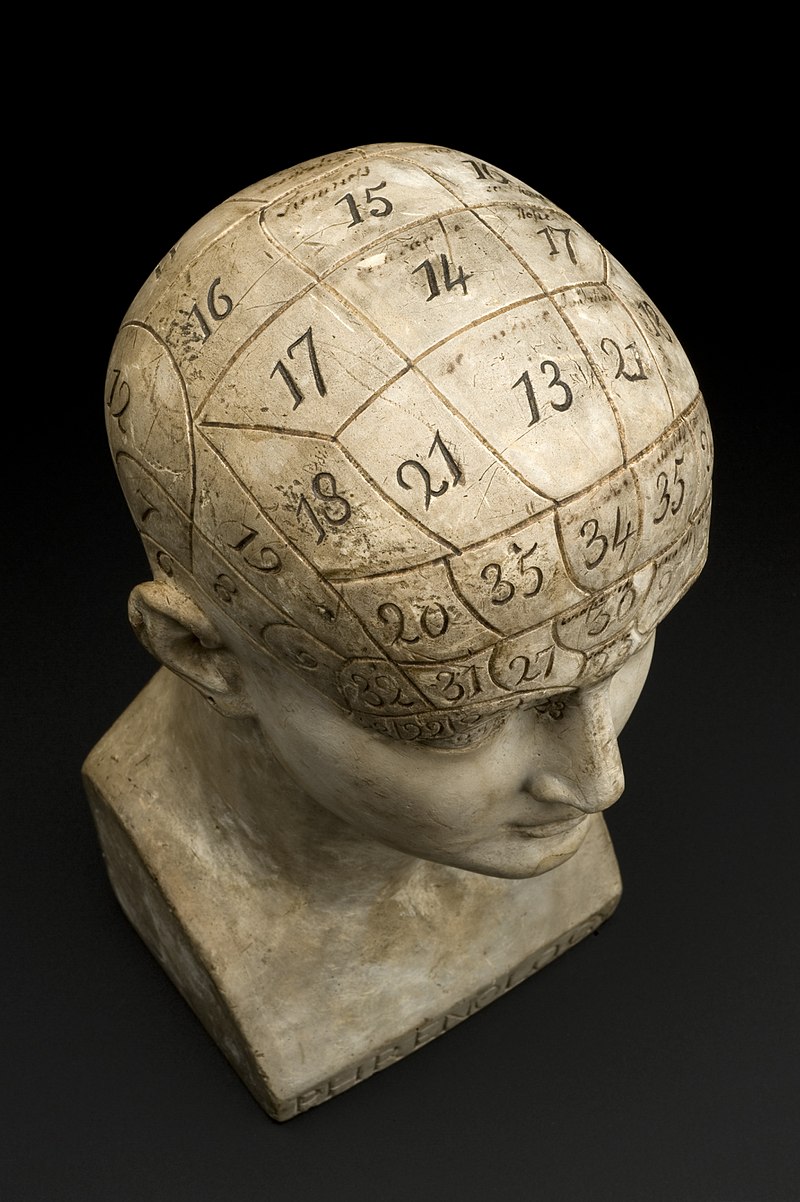

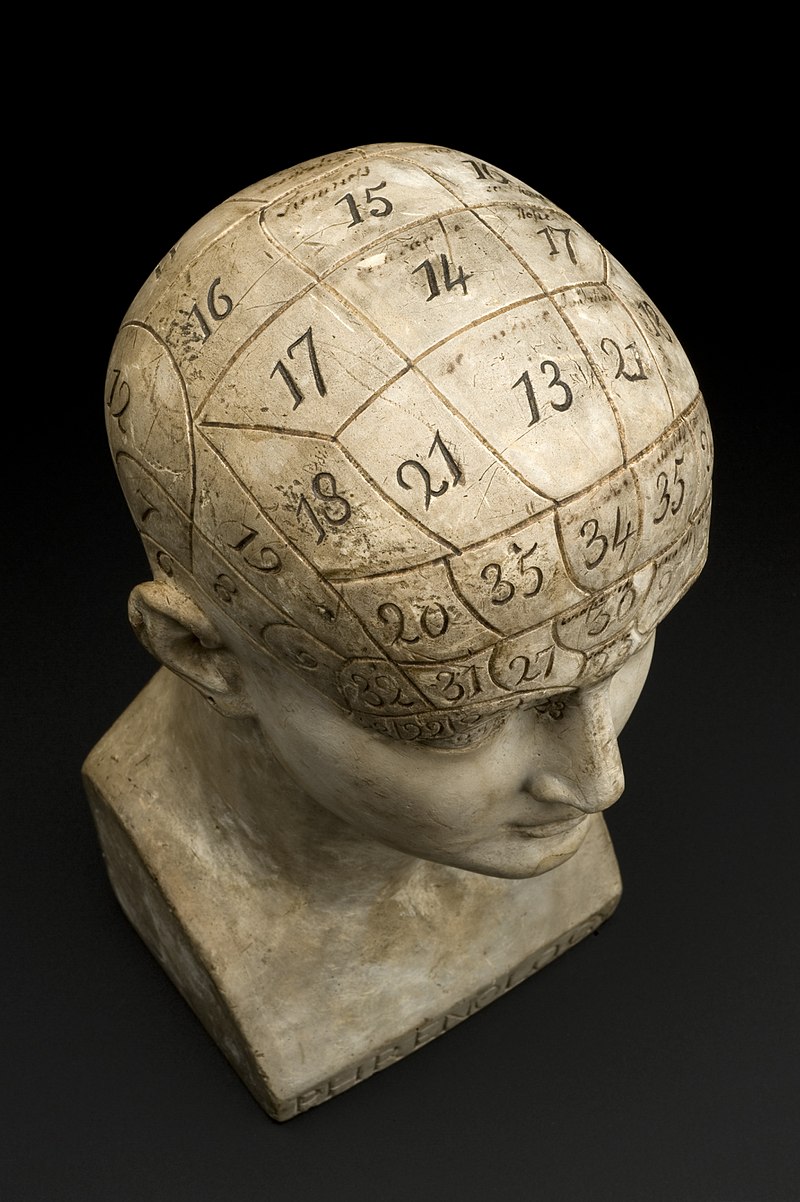

Method Numbered phrenological bust Phrenology is a process that involves observing and/or feeling the skull to determine an individual's psychological attributes. Franz Joseph Gall believed that the brain was made up of 27 individual organs that determined personality, the first 19 of these 'organs' he believed to exist in other animal species. Phrenologists would run their fingertips and palms over the skulls of their patients to feel for enlargements or indentations.[19] The phrenologist would often take measurements with a tape measure of the overall head size and more rarely employ a craniometer, a special version of a caliper. In general, instruments to measure sizes of cranium continued to be used after the mainstream phrenology had ended. The phrenologists put emphasis on using drawings of individuals with particular traits, to determine the character of the person and thus many phrenology books show pictures of subjects. From absolute and relative sizes of the skull the phrenologist would assess the character and temperament of the patient. Gall's list of the "brain organs" was specific. An enlarged organ meant that the patient used that particular "organ" extensively. The number—and more detailed meanings—of organs were added later by other phrenologists. The 27 areas varied in function, from sense of color, to religiosity, to being combative or destructive. Each of the 27 "brain organs" was located under a specific area of the skull. As a phrenologist felt the skull, he would use his knowledge of the shapes of heads and organ positions to determine the overall natural strengths and weaknesses of an individual. Phrenologists believed the head revealed natural tendencies but not absolute limitations or strengths of character. The first phrenological chart gave the names of the organs described by Gall; it was a single sheet, and sold for a cent. Later charts were more expansive.[20] |

方法 番号がふられた骨相学胸像 骨相学とは、頭蓋骨を観察したり、触ったりして、個人の心理的特性を判断する方法である。フランツ・ヨーゼフ・ガルは、脳は人格を決定する27の器官から 構成されていると考え、このうち最初の19の器官は他の動物種にも存在すると考えていました。骨相学者は、患者の頭蓋骨を指先や手のひらでなぞり、肥大や へこみを感じ取る[19]。骨相学者は、しばしば巻尺で頭全体のサイズを測り、より稀にノギスの特別バージョンであるクラニオメータを使用する。一般に、 頭蓋の大きさを測る器具は、骨相学の主流が終わった後も使用され続けた。また、骨相学者は、特定の特徴を持つ人物の絵を用いて、その人物の性格を判断する ことに重きを置いていたため、多くの骨相学の本には被験者の写真が掲載されている。骨相学者は、頭蓋骨の絶対的、相対的な大きさから、患者の性格や気質を 判断した。 ガルは「脳の器官」を具体的にリストアップした。臓器が肥大しているということは、その患者がその "臓器 "を多用することを意味する。その後、他の骨相学者によって、器官の数やより詳細な意味が追加された。27の部位は、色彩感覚、宗教性、闘争性、破壊性な ど、さまざまな機能をもっていた。27の「脳の器官」は、それぞれ頭蓋骨の特定の部位に位置していた。骨相学者が頭蓋骨を触ると、頭の形や臓器の位置に関 する知識を駆使して、その人の生まれ持った長所と短所を判断することができる。骨相学者は、頭部を見れば生まれつきの傾向はわかるが、絶対的な限界や性格 の強さはわからないと考えた。最初の骨相表は、ガルが説明した器官の名称を示したもので、1枚で1セントで売られていた。後のチャートでは、より拡大され た[20]。 |

A definition of phrenology with chart from Webster's Academic Dictionary, c. 1895 Among the first to identify the brain as the major controlling center for the body were Hippocrates and his followers, inaugurating a major change in thinking from Egyptian, biblical and early Greek views, which based bodily primacy of control on the heart.[21] This belief was supported by the Greek physician Galen, who concluded that mental activity occurred in the brain rather than the heart, contending that the brain, a cold, moist organ formed of sperm, was the seat of the animal soul—one of three "souls" found in the body, each associated with a principal organ.[22] The Swiss pastor Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741–1801) introduced the idea that physiognomy related to the specific character traits of individuals, rather than general types, in his Physiognomische Fragmente, published between 1775 and 1778.[23] His work was translated into English and published in 1832 as The Pocket Lavater, or, The Science of Physiognomy.[24] He believed that thoughts of the mind and passions of the soul were connected with an individual's external frame. Of the forehead, When the forehead is perfectly perpendicular, from the hair to the eyebrows, it denotes an utter deficiency of understanding. (p. 24) In 1796 the German physician Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828) began lecturing on organology: the isolation of mental faculties[25] and later cranioscopy which involved reading the skull's shape as it pertained to the individual. It was Gall's collaborator Johann Gaspar Spurzheim who would popularize the term "phrenology".[25][26] In 1809 Gall began writing his principal[27] work, The Anatomy and Physiology of the Nervous System in General, and of the Brain in Particular, with Observations upon the possibility of ascertaining the several Intellectual and Moral Dispositions of Man and Animal, by the configuration of their Heads. It was not published until 1819. In the introduction to this main work, Gall makes the following statement in regard to his doctrinal principles, which comprise the intellectual basis of phrenology:[28] The Brain is the organ of the mind The brain is not a homogenous unity, but an aggregate of mental organs with specific functions The cerebral organs are topographically localized Other things being equal, the relative size of any particular mental organ is indicative of the power or strength of that organ Since the skull ossifies over the brain during infant development, external craniological means could be used to diagnose the internal states of the mental characters |

頭蓋骨相学の定義と図表(『ウェブスター学術辞典』より、1895年頃) ヒポクラテスとその信奉者たちは、脳が身体の主要な制御中枢であること を初めて明らかにし、身体の制御の優位性を心臓に置いていたエジプト、聖書、初期のギリシャの見解に大きな変化をもたらした[21]。 [この信念はギリシャの医師ガレンによって支持され、精神活動は心臓よりも脳で起こると結論付けられ、精子で形成された冷たく湿った器官である脳が、それ ぞれ主要な器官と関連付けられた体内にある3つの「魂」のうちの1つである動物の魂の場所であると主張した[22]。 スイスの牧師であるヨハン・カスパー・ラバター(1741-1801)は、1775年から1778年にかけて出版された『人相学断片』において、人相学が 一般的なタイプではなく、個人の特定の性格特性に関連するという考えを導入した[23]。 彼の作品は英語に翻訳されて、1832年に『ポケットラバター、または人相学の科学』として出版された[24]。 彼は心の思考と魂の情熱が個人の外見的骨格と関連していると信じていた。 額について、額が髪の毛から眉毛まで完全に垂直であるとき、それは理解力が全く欠如していることを示す。(p. 24) 1796年、ドイツの医師フランツ・ヨーゼフ・ガル(1758-1828)は、器官学(精神能力の分離)[25]の講義を始め、後に頭蓋鏡検査(個人に関 係する頭蓋骨の形を読み取ること)を行うようになった。骨相学」という言葉を広めたのは、ガールの共同研究者であるヨハン・ガスパール・シュプルツハイム であった[25][26]。 1809年にガルは彼の主要な[27]作品、一般的に神経系、特に脳の解剖学と生理学、およびそれらの頭の形状によって、人間と動物のいくつかの知的およ び道徳的な処分を確認する可能性に関する観測を書き始めました。この本が出版されたのは1819年である。この主著の序文で、ガルは骨相学の知的基盤を構 成する彼の教義的原則に関して次のように述べている[28]。 脳は心の器官である 脳は均質な統一体ではなく、特定の機能を持つ精神器官の集合体である。 大脳器官は地形的に局在している。 他の条件が同じであれば、特定の精神器官の相対的な大きさは、その器官の力や強さを示している 幼児の発育過程で頭蓋骨が脳の上に骨化するので、頭蓋学的な外的手段で精神的な性格の内部状態を診断することができる。 |

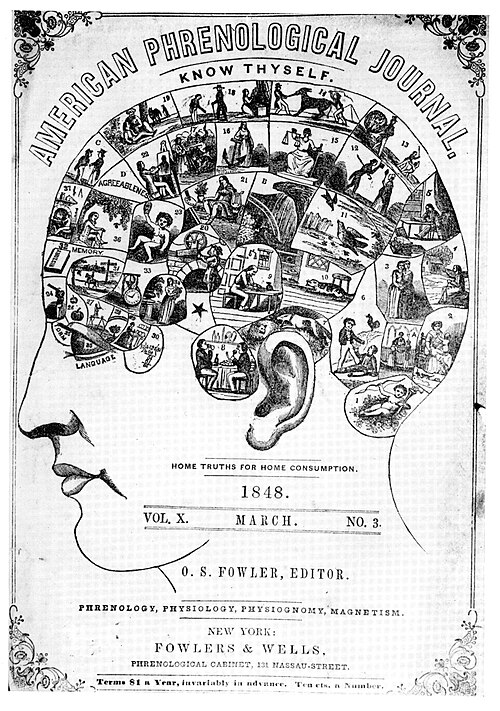

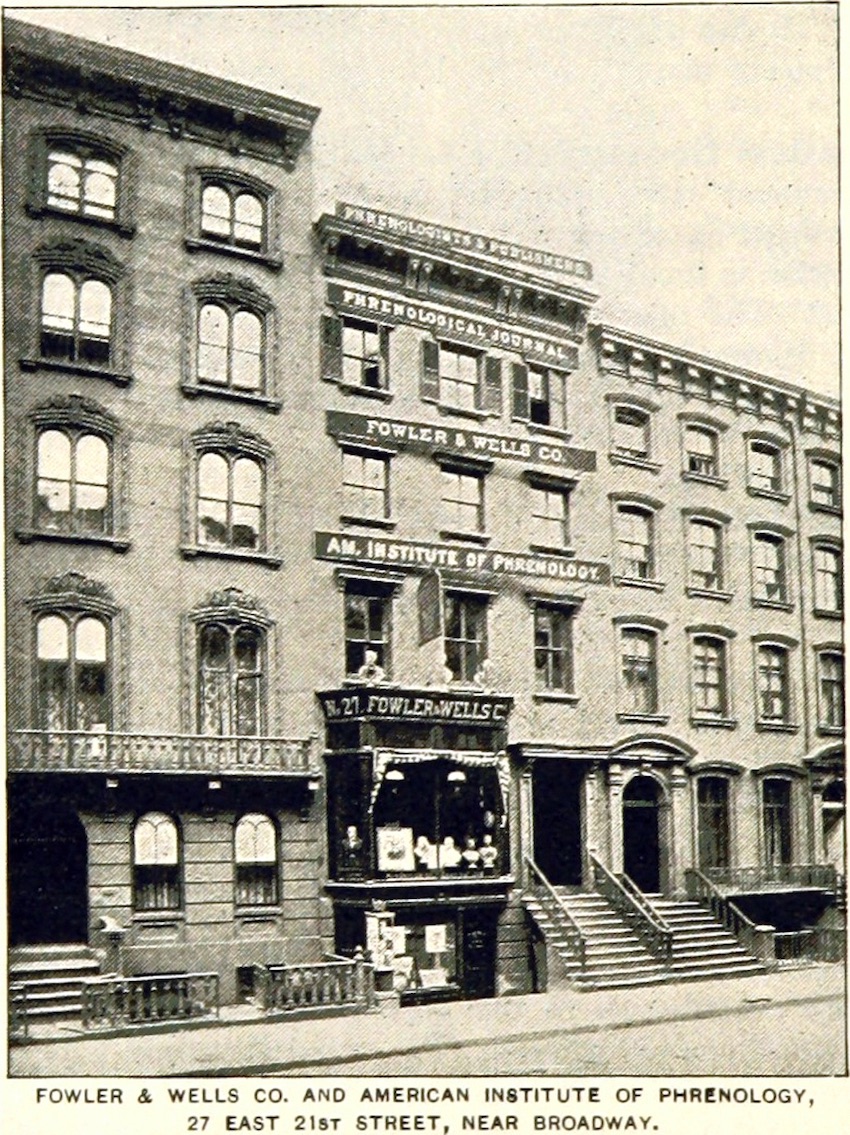

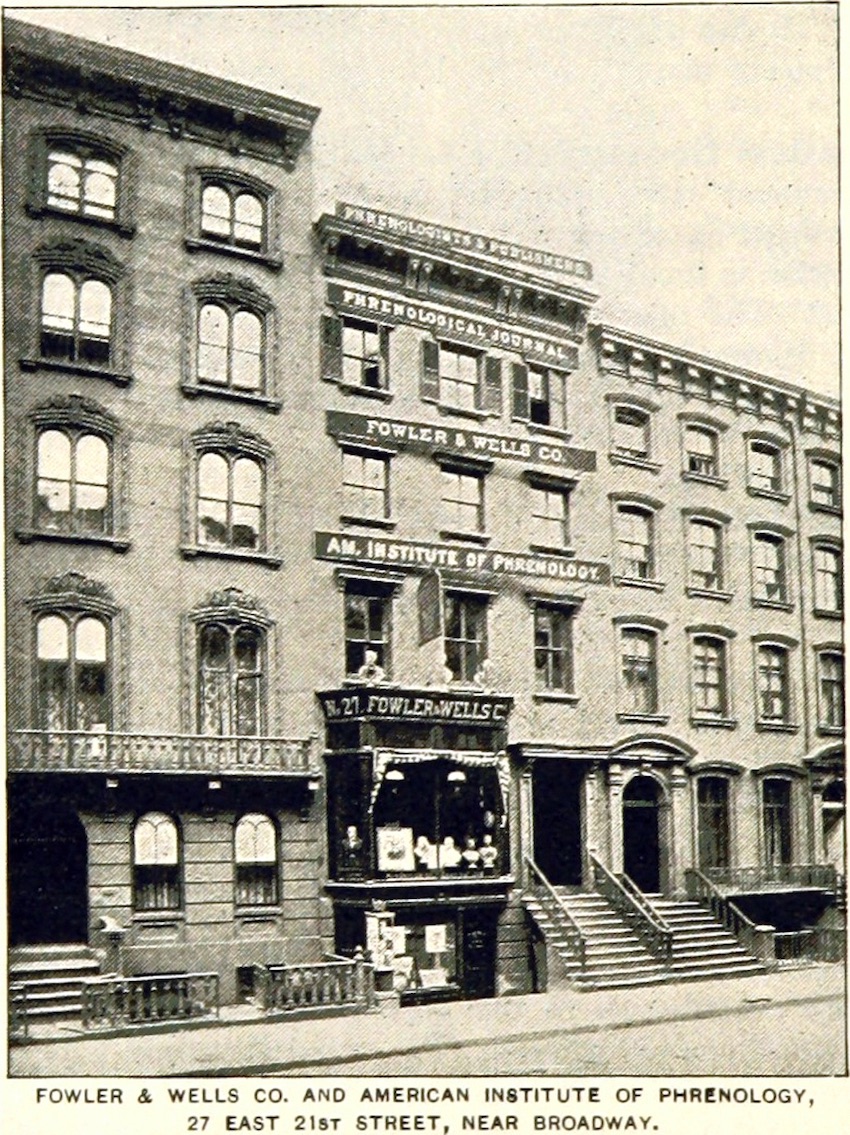

| Through careful observation and

extensive experimentation, Gall believed he had established a

relationship between aspects of character, called faculties, with

precise organs in the brain. Johann Spurzheim was Gall's most important collaborator. He worked as Gall's anatomist until 1813 when for unknown reasons they had a permanent falling out.[25] Publishing under his own name Spurzheim successfully disseminated phrenology throughout the United Kingdom during his lecture tours through 1814 and 1815[29] and the United States in 1832 where he would eventually die.[30]  Gall was more concerned with creating a physical science, so it was through Spurzheim that phrenology was first spread throughout Europe and America.[25] Phrenology, while not universally accepted, was hardly a fringe phenomenon of the era. George Combe would become the chief promoter of phrenology throughout the English-speaking world after he viewed a brain dissection by Spurzheim, convincing him of phrenology's merits. The popularization of phrenology in the middle and working classes was due in part to the idea that scientific knowledge was important and an indication of sophistication and modernity.[31] Cheap and plentiful pamphlets, as well as the growing popularity of scientific lectures as entertainment, also helped spread phrenology to the masses. Combe created a system of philosophy of the human mind[32] that became popular with the masses because of its simplified principles and wide range of social applications that were in harmony with the liberal Victorian world view.[29] George Combe's book On the Constitution of Man and its Relationship to External Objects sold over 200,000 copies through nine editions.[33] Combe also devoted a large portion of his book to reconciling religion and phrenology, which had long been a sticking point. Another reason for its popularity was that phrenology balanced between free will and determinism.[34] A person's inherent faculties were clear, and no faculty was viewed as evil, though the abuse of a faculty was. Phrenology allowed for self-improvement and upward mobility, while providing fodder for attacks on aristocratic privilege.[34][35] Phrenology also had wide appeal because of its being a reformist philosophy not a radical one.[36] Phrenology was not limited to the common people, and both Queen Victoria and Prince Albert invited George Combe to read the heads of their children.[37]  1848 edition of American Phrenological Journal published by Fowlers & Wells, New York The American brothers Lorenzo Niles Fowler (1811–1896) and Orson Squire Fowler (1809–1887) were leading phrenologists of their time. Orson, together with associates Samuel Robert Wells and Nelson Sizer, ran the phrenological business and publishing house Fowlers & Wells in New York City. Meanwhile, Lorenzo spent much of his life in England, where he initiated the famous phrenological publishing house L. N. Fowler & Co. and gained considerable fame with his phrenology head (a china head showing the phrenological faculties), which has become a symbol of the discipline.[38] Orson Fowler was known for his octagonal house. |

ガルは、注意深い観察と膨大な実験によって、能力

(faculties)と呼ばれる人格の側面と、脳の中の正確な器官との関係を確立したと考えた。 ガールの最も重要な協力者はヨハン・スプルツハイムであった。彼は1813年までガルの解剖学者として働いていたが、理由は不明だが、永久に仲違いしてい た[25]。スパーツハイムは自分の名前で出版し、1814年と1815年の講演旅行でイギリス中に骨相学を広めることに成功し[29]、1832年には アメリカで死亡することになる[30]。  ガルは物理的な科学を作ることにもっと関心を持っていたので、骨相学が最初にヨーロッパとアメリカに広まったのはスパーツハイムを通してであった [25] 骨相学は普遍的に受け入れられていなかったが、その時代の周辺現象とは言い難いものであった。ジョージ・コムは、スパーツハイムの脳の解剖を見た後、英語 圏で骨相学の主要な推進者になり、骨相学の利点について彼を納得させることになる。 中産階級や労働者階級に骨相学が普及したのは、科学的知識が重要であり、洗練された近代性を示しているという考えによるものであった[31]。安くて豊富 なパンフレットや、娯楽としての科学講演の人気の高まりも、大衆に骨相学を広めることに貢献した。コンブは人間の心の哲学の体系を作り上げ[32]、その 単純化された原理と自由主義のヴィクトリア朝の世界観と調和する幅広い社会的応用のために大衆の人気を得た[29] ジョージ・コンブの著書『人間の構造と外部の物体との関係について』は9つの版を通して20万部以上売れた[33] またコンブの本の大部分は、長い間難航していた宗教と骨相学を調和することに割かれた。人気のもう一つの理由は、骨相学が自由意志と決定論の間でバランス をとっていたことである[34]。人の固有の能力は明確であり、能力の乱用はあっても、どの能力も悪とはみなされなかった。骨相学は自己改善と上昇志向を 可能にする一方で、貴族の特権に対する攻撃の材料を提供した[34][35]。 骨相学はまた、過激なものではなく、改革派の哲学であることから広くアピールしていた[36]。 骨相学は庶民に限定されておらず、ヴィクトリア女王とアルバート王子はジョージ・コンブを招いて彼らの子供の頭を占った[37]。  1848年版『アメリカ頭蓋骨学雑誌』ニューヨークのファウラーズ&ウェルズ社刊 アメリカのロレンゾ・ナイルズ・ファウラー(1811-1896)とオーソン・スクワイア・ファウラー(1809-1887)の兄弟は、当時を代表する骨 相学者であった。オーソンは、同僚のサミュエル・ロバート・ウェルズとネルソン・サイザーとともに、ニューヨークで骨相学のビジネスと出版社ファウラーズ &ウェルズを経営していました。一方、ロレンソは人生の大半をイギリスで過ごし、有名な骨相学の出版社L. N. Fowler & Co.を起こし、学問のシンボルとなった骨相学ヘッド(骨相学の能力を示す陶製の頭部)でかなりの名声を得た[38]。 オーソン・ファウラーは八角形の家で知られていた。 |

| Phrenology came about at a time

when scientific procedures and standards for acceptable evidence were

still being codified.[39] In the context of Victorian society,

phrenology was a respectable scientific theory. The Phrenological

Society of Edinburgh founded by George and Andrew Combe was an example

of the credibility of phrenology at the time, and included a number of

extremely influential social reformers and intellectuals, including the

publisher Robert Chambers, the astronomer John Pringle Nichol, the

evolutionary environmentalist Hewett Cottrell Watson, and asylum

reformer William A. F. Browne. In 1826, out of the 120 members of the

Edinburgh society an estimated one third were from a medical

background.[40] By the 1840s there were more than 28 phrenological

societies in London with over 1,000 members.[33] Another important

scholar was Luigi Ferrarese, the leading Italian phrenologist.[41] He

advocated that governments should embrace phrenology as a scientific

means of conquering many social ills, and his Memorie Riguardanti La

Dottrina Frenologica (1836), is considered "one of the fundamental

19th-century works in the field".[41] Traditionally the mind had been studied through introspection. Phrenology provided an attractive, biological alternative that attempted to unite all mental phenomena using consistent biological terminology.[42] Gall's approach prepared the way for studying the mind that would lead to the downfall of his own theories.[43] Phrenology contributed to development of physical anthropology, forensic medicine, knowledge of the nervous system and brain anatomy as well as contributing to applied psychology.[44] John Elliotson was a brilliant but erratic heart specialist who became a phrenologist in the 1840s. He was also a mesmerist and combined the two into something he called phrenomesmerism or phrenomagnatism.[40] Changing behaviour through mesmerism eventually won out in Elliotson's hospital, putting phrenology in a subordinate role.[39] Others amalgamated phrenology and mesmerism as well, such as the practical phrenologists Collyer and Joseph R. Buchanan. The benefits of combining mesmerism and phrenology was that the trance the patient was placed in was supposed to allow for the manipulation of his/her penchants and qualities.[40] For example, if the organ of self-esteem was touched, the subject would take on a haughty expression.[45] Phrenology was mostly discredited as a scientific theory by the 1840s. This was due only in part to a growing amount of evidence against phrenology.[40] Phrenologists had never been able to agree on the most basic mental organ numbers, going from 27 to over 40,[47][48] and had difficulty locating the mental organs. Phrenologists relied on cranioscopic readings of the skull to find organ locations.[49] Jean Pierre Flourens' experiments on the brains of pigeons indicated that the loss of parts of the brain either caused no loss of function, or the loss of a completely different function than what had been attributed to it by phrenology. Flourens' experiment, while not perfect, seemed to indicate that Gall's supposed organs were imaginary.[43][50] Scientists had also become disillusioned with phrenology since its exploitation with the middle and working classes by entrepreneurs. The popularization had resulted in the simplification of phrenology and mixing in it of principles of physiognomy, which had from the start been rejected by Gall as an indicator of personality.[51] Phrenology from its inception was tainted by accusations of promoting materialism and atheism, and being destructive of morality. These were all factors which led to the downfall of phrenology.[49][52] Recent studies, using modern day technology like Magnetic Resonance Imaging have further disproven phrenology claims.[53] |

骨相学は、科学的な手順や許容できる証拠の基準がまだ成文化されていた

時期に生まれた[39]。ヴィクトリア社会の文脈では、骨相学は尊敬に値する科学理論であった。ジョージとアンドリュー・コムによって設立されたエディン

バラの骨相学協会は、当時の骨相学の信頼性の一例であり、出版社のロバート・チェンバース、天文学者のジョン・プリングル・ニコル、進化的環境論者の

ヒューエット・コットレル・ワトソン、亡命者改革者のウィリアム・A・F・ブラウンなど、非常に影響力のある社会改革者と知識人が含まれていました。

1826年、エディンバラ協会の120人のメンバーのうち、3分の1は医学的背景を持っていたと推定される[40]。

1840年代までに、ロンドンには28以上の骨相学協会があり、1000人以上のメンバーがいた[33]。

[彼は、政府が多くの社会的悪を征服するための科学的手段として骨相学を受け入れるべきだと提唱し、彼のMemorie Riguardanti La

Dottrina Frenologica(1836)、「この分野における19世紀の基本作品の一つ」と見なされている[41]。 伝統的に、心は内観を通して研究されていた。骨相学は、一貫した生物学的用語を使用してすべての精神的な現象を統一しようとする魅力的で生物学的な代替案 を提供しました[42]。 ガルのアプローチは、彼自身の理論の崩壊につながる心の研究のための道を準備しました[43] 骨相学は、応用心理学に貢献すると同時に、人類学の発展、法医学、神経系と脳解剖学の知識として寄与しました[44]。 ジョン・エリオットソンは、1840年代に骨相学者になった、優秀だが不安定な心臓の専門家であった。彼は、メスメリストでもあり、2つを組み合わせてフ レノメスメリズムまたはフレノマグナティズムと呼んでいた[40]。メスメリズムによる行動の変化は、結局エリオットソンの病院では勝っており、骨相学を 従属的な役割に置いていた[39] 他にも実践骨相学者のコリアやジョセフRブキャナンなど骨相学とメスメリズムを融合させる者もいた。メスメリズムと骨相学を組み合わせることの利点は、患 者をトランス状態にすることで、患者の性癖や資質を操作することができるとされていた[40]。例えば、自尊心の器官に触れられた場合、被験者は高慢な表 情をするようになる[45]。 骨相学は1840年代までに科学的理論としてほとんど信用されなくなった。40]骨相学者は27から40以上の最も基本的な精神器官の数に同意することが できず、精神器官を見つけることが困難であった[47][48]。骨相学者は器官の位置を見つけるために頭蓋骨の頭蓋鏡の読み取りに頼っていた[49]。 ジャン・ピエール・フローレンスのハトの脳に関する実験は、脳の一部を失っても機能が失われないか、骨相学によってそれに起因していたものとは全く異なる 機能の喪失を引き起こすことを示唆していた。フルーレンズの実験は完璧ではなかったが、ガルの想定していた器官が架空のものであることを示しているように 思われた[43][50]。科学者たちも、企業家によって中産階級や労働者階級に利用されて以来、骨相学に幻滅するようになっていた。大衆化は骨相学を単 純化し、人相学の原理と混合する結果となったが、これらは当初から人格の指標としてギャルによって拒否されていた[51]。これらは骨相学の没落につな がったすべての要因であった[49][52]。磁気共鳴画像法のような現代の技術を使用した最近の研究は、骨相学の主張をさらに反証している[53]。 |

| During the early 20th century, a

revival of interest in phrenology occurred, partly because of studies

of evolution, criminology and anthropology (as pursued by Cesare

Lombroso). The most famous British phrenologist of the 20th century was

the London psychiatrist Bernard Hollander (1864–1934). His main works,

The Mental Function of the Brain (1901) and Scientific Phrenology

(1902), are an appraisal of Gall's teachings. Hollander introduced a

quantitative approach to the phrenological diagnosis, defining a method

for measuring the skull, and comparing the measurements with

statistical averages.[54] In Belgium, Paul Bouts (1900–1999) began studying phrenology from a pedagogical background, using the phrenological analysis to define an individual pedagogy. Combining phrenology with typology and graphology, he coined a global approach known as psychognomy. Bouts, a Roman Catholic priest, became the main promoter of renewed 20th-century interest in phrenology and psychognomy in Belgium. He was also active in Brazil and Canada, where he founded institutes for characterology. His works Psychognomie and Les Grandioses Destinées individuelle et humaine dans la lumière de la Caractérologie et de l'Evolution cérébro-cranienne are considered standard works in the field. In the latter work, which examines the subject of paleoanthropology, Bouts developed a teleological and orthogenetical view on a perfecting evolution, from the paleo-encephalical skull shapes of prehistoric man, which he considered still prevalent in criminals and savages, towards a higher form of mankind, thus perpetuating phrenology's problematic racializing of the human frame. Bouts died on March 7, 1999. His work has been continued by the Dutch foundation PPP (Per Pulchritudinem in Pulchritudine), operated by Anette Müller, one of Bouts' students. During the 1930s, Belgian colonial authorities in Rwanda used phrenology to explain the so-called superiority of Tutsis over Hutus.[55] |

20世紀初頭、ロンブローゾの進化論、犯罪学、人類学などの研究によ

り、骨相学は再び注目されるようになった。20世紀のイギリスの骨相学者として最も有名なのは、ロンドンの精神科医バーナード・ホランダー(1864-

1934)である。彼の主著『脳の精神機能』(1901年)、『科学的骨相学』(1902年)は、ガルの教えを評価したものである。ホランダーは骨相学的

診断に定量的なアプローチを導入し、頭蓋骨を測定する方法を定義し、測定値を統計的平均値と比較した[54]。 ベルギーでは、ポール・ブーツ(Paul Bouts, 1900-1999)が教育学の背景から骨相学を研究し始め、骨相学的分析を用いて個々の教育学を定義した。骨相学を類型学やグラフ学と組み合わせること で、彼は心理認識学として知られるグローバルなアプローチを作り上げた。ローマ・カトリックの司祭であったボウトは、ベルギーにおいて、20世紀における 骨相学と人相学の新たな関心を呼び起こす主要な推進者となった。また、ブラジルやカナダでも活動し、人物学の研究所を設立した。彼の著作『心理学』や『個 と人間との大いなる運命(Les Grandioses Destinées individuelle et humaine dans la lumière de la Caractérologie et de l'Evolution cérébro-cranienne)』はこの分野の代表作とみなされている。古人類学を主題とする後者では、犯罪者や未開人に多く見られる先史時代の古 脳型頭蓋骨から、より高度な人類への完璧な進化を目指すという、望遠的かつ正統的な考え方を展開し、骨相学の問題である人間の骨格の人種化を永続させるこ とに成功する。バウツは1999年3月7日に死去した。彼の研究は、ボウトの弟子の一人であるアネット・ミュラーが運営するオランダの財団PPP(Per Pulchritudinem in Pulchritudine)によって継続されている。 1930年代、ルワンダのベルギー植民地当局は、いわゆるツチ族のフツ族に対する優越性を説明するために骨相学を用いていた[55]。 |

| Racism Some scientists believed phrenology affirmed European superiority over other races. By comparing skulls of different ethnic groups it was thought to allow for ranking of races from least to most evolved. Broussais, a disciple of Gall, proclaimed that the Caucasians were the most beautiful while peoples like the Australian Aboriginal and Māori would never become civilized since "they had no cerebral organ for producing great artists."[56] Few phrenologists argued against the emancipation of the slaves, while many used it to advocate for slavery.[57] Instead they argued that through education and interbreeding the "lesser peoples" could improve.[58] Another argument was that the natural inequality of people could be used to situate them in the most appropriate place in society.[57] |

人種差別 科学者の中には、骨相学はヨーロッパ人が他の人種より優れていることを証明するものだと信じている人がいた。異なる民族の頭蓋骨を比較することで、最も進 化していない民族から最も進化している民族へとランク付けすることができると考えられたのだ。ガルの弟子であるブルセは、コーカサス人が最も美しく、一方 でオーストラリアのアボリジニやマオリのような民族は「偉大な芸術家を生み出すための大脳を持たない」ため、決して文明的になることはないと宣言していた [56]。 [57]その代わりに彼らは教育と交配を通じて「劣等民族」が向上することができると主張した[58]。もう一つの主張は、人々の自然の不平等が社会の中 で最も適切な場所に彼らを位置づけるために利用することができるというものであった[57]。 |

| Gender stereotyping Gender stereotyping was also common with phrenology. Women whose heads were generally larger in the back with lower foreheads were thought to have underdeveloped organs necessary for success in the arts and sciences while having larger mental organs relating to the care of children and religion.[59] While phrenologists did not contest the existence of talented women, this minority did not provide justification for citizenship or participation in politics.[60] |

ジェンダー・ステレオタイピング ジェンダー・ステレオタイピングもまた、骨相学ではよく見られることである。頭が一般的に背中で大きく、額が低い女性は、芸術や科学で成功するために必要 な器官が未発達である一方で、子供の世話や宗教に関連する大きな精神器官を持っていると考えられていた[59]。 骨相学者は才能ある女性の存在に異議を唱えなかったが、この少数派は市民権や政治への参加に正当性を与えることはなかった[60]。 |

| Education One of the considered practical applications of phrenology was education. Due to the nature of phrenology people were naturally considered unequal, as very few people would have a naturally perfect balance between organs. Thus education would play an important role in creating a balance through rigorous exercise of beneficial organs while repressing baser ones. One of the best examples of this is Félix Voisin, who, for approximately ten years, ran a reform school in Issy for the express purpose of correction of the mind of children who had suffered some hardship. Voisin focused on four categories of children for his reform school:[61] Slow learners Spoiled, neglected, or harshly treated children Willful, disorderly children Children at high risk of inheriting mental disorders |

教育 骨相学の実用的な応用として考えられていたのが、教育である。骨相学の性質上、人々は当然不平等であると考えられており、器官間のバランスが自然に完璧な 状 態にある人はほとんどいない。そこで、有益な器官を厳しく鍛え、卑しい器官を抑制することで、バランスを整える教育が重要な役割を果たすことになる。その 代表的な例がフェリックス・ヴォワザンである。彼は、苦難に満ちた子供たちの心の矯正を明確な目的として、約10年間にわたりイッシーで少年院を経営し た。ヴォワザンは、次の4つのカテゴリーに分類される子どもたちに着目して学校を運営した[61]。 学習能力の低い子供 甘やかされ、放置され、過酷な扱いを受けている子どもたち 意思の強い、乱暴な子供 精神障害を受け継ぐ危険性の高い子どもたち |

| Criminology Phrenology was one of the first[clarification needed] to bring about the idea of rehabilitation of criminals instead of vindictive punishments that would not stop criminals, only with the reorganizing a disorganized brain would bring about change.[62] Voisin believed along with others the accuracy of phrenology in diagnosing criminal tendencies. Diagnosis could point to the type of offender, the insane, an idiot or brute, and by knowing this an appropriate course of action could be taken.[61] A strict system of reward and punishment, hard work and religious instruction, was thought to be able to correct those who had been abandoned and neglected with little education and moral ground works. Those who were considered intellectually disabled could be put to work and housed collectively while only criminals of intellect and vicious intent needed to be confined and isolated.[63] Phrenology also advocated variable prison sentences, the idea being that those who were only defective in education and lacking in morals would soon be released while those who were "mentally deficient" could be watched and the truly abhorrent criminals would never be released.[36][64][65] For other patients phrenology could help redirect impulses, one homicidal individual became a butcher to control his impulses, while another became a military chaplain so he could witness killings.[66] Phrenology also provided reformist arguments for the lunatic asylums of the Victorian era. John Conolly, a physician interested in psychological aspects of disease, used phrenology on his patients in an attempt to use it as a diagnostic tool. While the success of this approach is debatable, Conolly, through phrenology, introduced a more humane way of dealing with the mentally ill.[39] The first phrenological testimony in a court of law was solicited by American lawyer John Neal in Portland, Maine, in 1834.[67] Neal argued unsuccessfully that the jury should take leniency on his client because the part of his brain associated with violent behavior was inflamed.[68] |

犯罪学 骨相学は、犯罪者を止めない執念深い罰の代わりに、犯罪者の更生という考えをもたらした最初の[clarification needed]ものの1つであり、無秩序な脳を再編成することによってのみ変化をもたらすことができる。ヴォワザンも他の人とともに、犯罪傾向を診断する 際の骨相学の正確さを信じていた[62]。診断によって犯罪者のタイプ、精神異常者、馬鹿者、獣などを指摘することができ、それを知ることによって適切な 行動方針を取ることができた[61] 厳しい報酬と罰のシステム、勤勉、宗教的指導によって、教育や道徳的基盤がほとんどなく見捨てられ放置されていた人々を矯正することができると考えられて いた。知的に障害があると考えられる人々は、知性と悪意のある犯罪者だけが閉じ込められ隔離される必要がある一方で、働かせたり集団で収容することができ た[63]。 また骨相学は可変的な懲役刑を提唱し、教育に欠陥があり道徳に欠けているだけの人々はすぐに釈放され、「精神的欠陥」のある人々は監視され本当に忌まわし い犯罪者は決して出られないだろうという考えであった。 [他の患者にとって骨相学は衝動を方向付けるのに役立ち、ある殺人者は衝動を制御するために肉屋になり、別の者は殺人を目撃できるように軍のチャプレンに なった[66]。 骨相学はヴィクトリア時代の精神病院のための改革派の議論も提供するものであった。病気の心理的な側面に興味を持つ医師であるジョン・コノリーは、診断 ツールとして使用するために、患者に骨相学を使用することを試みていた。このアプローチの成功は議論の余地があるが、コノリーは骨相学を通じて、精神病患 者を扱うより人道的な方法を導入した[39]。 法廷での最初の骨相学的証言は、1834年にメイン州ポートランドでアメリカの弁護士ジョン・ニールによって求められた[67]。 ニールは、彼のクライアントに暴力的な行動と関連する脳の部分が炎症を起こしているので陪審は寛容でなければならないと主張して失敗してしまった [68]。 |

| Psychiatry In psychiatry, phrenology was proposed as a viable model in order to the disciplinary field. The South Italian psychiatrist Biagio Miraglia proposed a new classification of mental illness based on brain functions as they were described by Gall. In Miraglia's view, madness is consequent to dysfunctions of the cerebral organs: "The organs of the brain that may become ill in isolation or in complex get their activities infected through energy, or depression, or inertia or deficiency. So the madness can take the appearance of these three characteristic forms; i.e. for enhanced activity, or for depressed activity, or for inertia or deficiency of brain activities".[69] |

精神医学 精神医学では、骨相学が学問分野の秩序を保つために有効なモデルとして提案された。南イタリアの精神科医ビアッジョ・ミラグリアは、ガルが述べた脳機能に 基づく精神疾患の新しい分類を提案した。ミラリアの考えでは、狂気は大脳器官の機能障害に起因するものである。「脳の器官は、単独であるいは複合的に病気 になる可能性があるが、その活動は、エネルギー、鬱、惰性、欠乏によって感染する。だから、狂気はこれらの3つの特徴的な形態の外観をとることができる; すなわち、脳活動の強化のため、または抑圧された活動のため、または慣性または欠乏のため」[69]。 |

| Psychology In the Victorian era, phrenology as a psychology was taken seriously and permeated the literature and novels of the day. Many prominent public figures. such as the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher (a college classmate and initial partner of Orson Fowler) promoted phrenology actively as a source of psychological insight and self-knowledge.[70] In Europe and the United States, many people visited phrenologists to have their heads analysed. After such an examination, clients received a written delineation of their character or a standardized chart with their score, combined with advice on how to improve themselves.[71] People also consulted phrenologists for advice in matters such as hiring personnel or finding suitable marriage partners.[72][73] As such, phrenology as a brain science waned but developed into the popular psychology of the 19th century. |

心理学 ヴィクトリア時代には、心理学としての骨相学が真剣にとらえられ、当時の文学や小説に浸透していた。多くの著名な公人、例えば、牧師であるHenry Ward Beecher(大学のクラスメートであり、Orson Fowlerの最初のパートナー)は、心理的洞察と自己認識の源として骨相学を積極的に推進した[70]。ヨーロッパとアメリカでは、多くの人々が自分の 頭を分析させるために骨相学者を訪問した。このような検査の後、顧客は彼らの性格の描写を書いたものや、彼らのスコアを記した標準化されたチャートを受け 取り、どのように自分自身を改善するかについてのアドバイスと組み合わせた[71]。 また、人々は人事採用や適切な結婚相手を見つけるといった問題でアドバイスを得るために骨相学者に相談した[72][73]。 そのため脳科学としての骨相学は衰退し、19世紀の大衆心理学として発展することとなる。 |

| Britain Phrenology was introduced at a time when the old theological and philosophical understanding of the mind was being questioned and no longer seemed adequate in a society that was experiencing rapid social and demographic changes.[74] Phrenology became one of the most popular movements of the Victorian Era. In part phrenology's success was due to George Combe tailoring phrenology for the middle class. Combe's book On the Constitution of Man and its Relationship to External Objects was one of the most popular of the time, selling over two hundred thousand copies in a ten-year period. Phrenology's success was also partly because it was introduced at a time when scientific lectures were becoming a form of middle-class entertainment, exposing a large demographic of people to phrenological ideas who would not have heard them otherwise.[75] As a result of the changing times, new avenues of exposure and its multifaceted appeal, phrenology flourished in popular culture[76] although it was discredited as scientific theory by 1840. |

イギリス 骨相学は、古い神学的、哲学的な心の理解が疑問視され、急速な社会的、人口的変化を経験していた社会ではもはや適切ではないと思われた時に導入された [74]。骨相学はヴィクトリア時代の最も人気のある運動の1つになった。骨相学の成功は、ジョージ・コムが中流階級のために骨相学を仕立てたことに起因 しているところがある。コームの著書『On the Constitution of Man and its Relationship to External Objects』は、当時最も人気のある本の一つで、10年間で20万部以上売れた。骨相学の成功は、科学講演が中流階級の娯楽の一形態になりつつあった 時期に紹介されたこともあり、そうでなければ聞くことのなかった多くの層の人々に骨相学の考えを知らしめた[75]。時代の変化、新しい露出の手段、その 多面的な魅力により、1840年までに科学理論として信用されなかったものの、骨相学は大衆文化で栄えた[76]。 |

| France While still not a fringe movement, there was not popular widespread support of phrenology in France. This was not only due to strong opposition to phrenology by French scholars but also once again accusations of promoting atheism, materialism and radical religious views. Politics in France also played a role in preventing rapid spread of phrenology.[77] In Britain phrenology had provided another tool to be used for situating demographic changes; the difference was there was less fear of revolutionary upheaval in Britain compared with France. Given that most French supporters of phrenology were liberal, left-wing or socialist, it was an objective of the social elite of France, who held a restrained vision of social change, that phrenology remain on the fringes. Another objection was that phrenology seemed to provide a built in excuse for criminal behaviour, since in its original form it was essentially deterministic in nature.[77] |

フランス フランスでは、フリンジ運動とまではいかないものの、骨相学を広く支持する人はいませんでした。これは、フランスの学者による骨相学への強い反対だけでな く、無神論、唯物論、急進的な宗教観を促進するという非難が再び起こったためであった。イギリスでは骨相学は人口動態の変化を位置づけるために使用される 別のツールを提供していたが、フランスと比較してイギリスでは革命的な動乱に対する恐怖が少なかったという違いがあった[77]。フランスの骨相学の支持 者のほとんどがリベラル、左翼、社会主義者であったことを考えると、骨相学が縁の下の力持ちであり続けることは、社会的変化に対して抑制的なビジョンを 持っているフランスの社会エリートの目標であった。もう1つの反対意見は、骨相学はその本来の形では本質的に決定論的であるため、犯罪行為に対して組み込 まれた言い訳を提供しているように見えるということであった[77]。 |

| Ireland Phrenology arrived in Ireland in 1815, through Spurzheim.[78] While Ireland largely mirrored British trends, with scientific lectures and demonstrations becoming a popular pastime of the age, by 1815 phrenology had already been ridiculed in some circles priming the audiences to its skeptical claims.[79] Because of this the general public valued it more for its comic relief than anything else; however, it did find an audience in the rational dissenters who found it an attractive alternative to explain human motivations without the attached superstitions of religion.[80] The supporters of phrenology in Ireland were relegated to scientific subcultures because the Irish scholars neglected marginal movements like phrenology, denying it scientific support in Ireland.[31] In 1830 George Combe came to Ireland, his self-promotion barely winning out against his lack of medical expertise, still only drawing lukewarm crowds. This was due to not only the Vatican's decree that phrenology was subversive of religion and morality but also that, based on phrenology, the "Irish Catholics were sui generis a flawed and degenerate breed".[81] Because of the lack of scientific support, along with religious and prejudicial reasons, phrenology never found a wide audience in Ireland. |

アイルランド アイルランドは、科学的な講義やデモンストレーションが時代の人気娯楽となり、イギリスの傾向を大きく反映していたが、1815年までに骨相学はすでに一 部の界隈で嘲笑され、その懐疑的な主張に対する聴衆の前兆となっていた[79]。 このため、一般大衆は他の何よりもそのコミックリリーフとしてそれを評価していた。しかしながら、宗教の付随する迷信なしに人間の動機を説明するための魅 力ある代替物とする合理的な反対派に聴衆がいたことは確かであった[80]。 [アイルランドにおける骨相学の支持者は、アイルランドの学者が骨相学のような限界的な運動を軽視し、アイルランドにおける科学的なサポートを否定したた め、科学的なサブカルチャーに追いやられた[31] 1830年にジョージ・コムがアイルランドに来たが、彼の自己宣伝は医学的専門知識の欠如に対して辛うじて勝ち、それでも生ぬるい群集を集めるのみであっ た。これは、骨相学が宗教と道徳を破壊するものであるというバチカンの命令だけでなく、骨相学に基づいて、「アイルランドのカトリックは欠陥があり退化し た品種である」というものであった[81] 宗教と偏見の理由とともに、科学的支援の欠如のために、骨相学はアイルランドで幅広い聴衆を見つけることはなかった。 |

| United States The first publication in the United States in support of phrenology was published by Dr. John Bell, who reissued Combe's essays with an introductory discourse, in 1822.[82] The following year, Dr. John G. Wells of Bowdoin College "commenced an annual exposition, and recommendation of its doctrines, to his class".[82] In 1834, Dr. John D. Godman, professor of anatomy at Rutgers Medical College, emphatically defended phrenology when he wrote:[83] It is, however, allowable to take as a principle, that there will be a relation betwixt vigour of intellect and perfection of form; and that, therefore, history will direct us to the original and chief family of mankind. We therefore ask, which are the nations that have excelled and figured in history, not only as conquerors, but as forwarding, by their improvements in arts and sciences, the progress of human knowledge? Phrenological teachings had become a widespread popular movement by 1834, when Combe came to lecture in the United States.[84] Sensing commercial possibilities men like the Fowlers became phrenologists and sought additional ways to bring phrenology to the masses.[85] Though a popular movement, the intellectual elite of the United States found phrenology attractive because it provided a biological explanation of mental processes based on observation, yet it was not accepted uncritically. Some intellectuals accepted organology while questioning cranioscopy.[86] Gradually the popular success of phrenology undermined its scientific merits in the United States and elsewhere, along with its materialistic underpinnings, fostering radical religious views. There was increasing evidence to refute phrenological claims, and by the 1840s it had largely lost its credibility.[72] In the United States, especially in the South, phrenology faced an additional obstacle in the antislavery movement. While phrenologists usually claimed the superiority of the European race, they were often sympathetic to liberal causes including the antislavery movement; this sowed skepticism about phrenology among those who were pro-slavery.[87] The rise and surge in popularity in mesmerism, phrenomesmerism, also had a hand in the loss of interest in phrenology among intellectuals and the general public.[45][88]  American Institute of Phrenology (New York, 1893) |

アメリカ 米国で骨相学を支持する最初の出版物は、1822年にジョン・ベル博士によって出版された。翌年、ボウディン大学のジョン・G・ウェルズ博士は「彼のクラ スに対して、その教義の年次説明と推奨を始めた」[82]。 1834年に、ラトガー医学大学解剖学の教授であるジョン・D・ゴッドマン博士は、彼が書いた時に骨相学を力強く擁護した[83]。 しかし、知性の活力と形の完成度の間に関係があることを原則とすることは可能であり、それゆえ、歴史は人類の原初的かつ主要な家族へと我々を導くだろう。 そこでわれわれは、歴史上、征服者としてだけでなく、芸術や科学の改良によって人類の知識の進歩を促し、傑出していた国はどこであったかと問いたい。 84] 商業的な可能性を感じていたファウラー家のような人々は骨相学者になり、大衆に骨相学をもたらすためのさらなる方法を模索していた。 85] 大衆運動ではあったが、アメリカの知的エリートたちは、観察に基づいて精神のプロセスを生物学的に説明している骨相学を魅力的だと感じていたが、しかしそ れは無批判に受け入れられたわけではなかった。一部の知識人は器官学を受け入れながら、頭蓋鏡に疑問を呈していた[86]。次第に、骨相学の大衆的な成功 は、アメリカ合衆国やその他の地域において、その科学的利点やその物質主義的基盤が損なわれ、過激な宗教観が助長された。骨相学の主張を否定する証拠が増 え、1840年代には、その信頼性をほとんど失っていた[72]。アメリカ、特に南部では、骨相学は反奴隷運動においてさらなる障害に直面していた。骨相 学者は通常ヨーロッパ人種の優位性を主張する一方で、反奴隷運動を含む自由主義的な運動に共感することが多く、これは奴隷制を支持する人々の間で骨相学に 対する懐疑心を植え付けた[87]。 メスメリズム(骨相学)の台頭と人気の急上昇も知識人や一般人の間で骨相学に対する興味を失わせることに関与していた[45][88]。  アメリカ骨相学研究所(ニューヨーク, 1893) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phrenology |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| South Africa Upon arrival in South Africa, phrenology clashed with the liberalist Cape residents, among whom were missionaries, merchants, and middle class, that held staunch beliefs in the equality of the human race in al varieties.[87] They were advocates for theories of environmental racial differences rather than the phrenological held belief in innate differences of the mind between Africans and Europeans. Nonetheless, South Africa became the place where a lot of phrenologists, particularly in Britain, were receiving subjects to study the heads of Africans. Thomas Pringle was a friend of Combe and Mackenzie who was sending the skulls of Xhosa and Bushman indigenous tribes-people back to a friend in London, John Epps while doing field research in the Cape.[87] Pringle was just one of many medical and military men on the frontier of the South Africa territory that were taking sample of local Africans and sending them back to Britain as patrons of phrenology. Liberals of South Africa would continue to remain skeptical of the validity of phrenology as it pertained to the pre-determining of ones character based on organs in their brain. Editor A.J. Ardine for the periodical A Catechism of Phrenology would add that he "remained unconvinced by the new science".[87] While residents of the Western coastal urban regions of South Africa were skeptical of the ideological beliefs behind phrenology, those on the inland frontier were very receptive to the ideas of "biological determinism".[87] Andrew Smith, better known as the founder of zoology, as well as Robert Knox were among these frontiersmen who were supportive and adherent to the ethnological implications of phrenology. Many phrenologists who came to South Africa, or took example from the native people there, would use findings to fuel more racist implications of the pseudoscience. Bushmen and other African people that had the misfortune of living on the frontier were subject to being remarked as similar "to that of the monkey" in facial structure.[87] They had effectively become targets for European imperialist that sought to prove the superiority of their civilization through one sided field work. The inherit issue with their world view was that they conceived these ideas in Europe before coming to Africa on a mission to seek confirmation bias for their rhetoric. |

南アフリカ(→「南アフリカと英国の頭蓋骨相学ネットワーク」) 南アフリカに到着すると、骨相学は自由主義的なケープの住民たちと衝突した。その中には宣教師、商人、中産階級が含まれており、彼らはあらゆる人種におけ る人類の平等を固く信じていた。[87] 彼らは、アフリカ人とヨーロッパ人の間に精神の先天的な差異があるという骨相学の主張ではなく、環境による人種的差異の理論を支持していた。しかしなが ら、南アフリカは多くの頭蓋骨学者、特に英国人学者たちがアフリカ人の頭部を研究対象として受け取る場所となった。トーマス・プリングルはコンブやマッケ ンジーの友人であり、ケープでの現地調査中にコサ族やブッシュマン族といった先住民の頭蓋骨をロンドンの友人ジョン・エップスに送り返していた。[87] プリングルは、南アフリカ辺境地帯で現地アフリカ人を標本として採取し、頭蓋骨学の支持者として英国へ送り返していた多くの医療関係者や軍人の一人に過ぎ なかった。南アフリカの自由主義者たちは、脳の器官に基づいて性格を予め決定するという頭蓋骨学の有効性については、引き続き懐疑的であり続けた。定期刊 行物『頭蓋骨学要綱』の編集者A.J.アーディンは、自身が「この新科学に納得していなかった」と付け加えている。[87] 南アフリカ西海岸の都市部住民が頭蓋骨学の思想的背景に懐疑的だった一方、内陸フロンティアの住民は「生物学的決定論」の思想に非常に好意的であった。 [87] 動物学の創始者として知られるアンドリュー・スミスやロバート・ノックスらも、辺境の開拓者たちの中に含まれ、頭蓋骨相学が持つ民族学的含意を支持し固守 した。南アフリカに渡った多くの頭蓋骨相学者、あるいは現地の先住民を研究対象とした者たちは、その知見を偽科学のより人種差別的な含意を煽るために利用 した。フロンティアに暮らす不幸に見舞われたブッシュマンや他のアフリカの人民は、顔の構造が「猿に似ている」と評される対象となった。[87] 彼らは事実上、一方的な現地調査を通じて自らの文明の優越性を証明しようとするヨーロッパ帝国主義者たちの標的となっていた。彼らの世界観に内在する問題 は、アフリカに赴く前からヨーロッパでこうした思想を構築し、自らのレトリックを裏付けるための確認バイアスを探し求める使命を帯びていた点にある。 |

| Specific phrenological modules From Combe:[88] Propensities An 1887 phrenology chart Propensities do not form ideas; they solely produce propensities common to animals and man. Adhesiveness Alimentiveness Amativeness Acquisitiveness Causality Cautiousness Combativeness Concentrativeness Constructiveness Destructiveness Ideality Love of life Philoprogenitiveness Secretiveness Sentiments Lower sentiments These are common to man and animal. Cautiousness Love of approbation Self-esteem Truthfulness Superior sentiments These produce emotion or feeling lacking in animals. Benevolence Conscientiousness Firmness Hope Ideality Imitation Veneration Wit or Mirthfulness Wonder Intellectual faculties These are to know the external world and physical qualities Coloring Eventuality Form Hearing Individuality Language Locality Number Order Sight Size Smell Taste Time Touch Tune Weight Reflecting faculties These produce ideas of relation or reflect. They minister to the direction and gratification of all the other powers: Causality Comparison |

特定の骨相学モジュール コムブより:[88] 傾向性 1887年の骨相学図表 傾向性は観念を形成しない。動物と人間に共通する傾向性のみを生む。 粘着性 摂食性 愛欲性 獲得欲 因果性 慎重性 闘争性 集中力 建設性 破壊性 理想性 生命愛 子孫愛 秘密性 感情 低次感情 これらは人間と動物に共通する。 慎重性 称賛への愛 自尊心 真実性 高次の感情 これらは動物に欠ける感情や感覚を生み出す。 慈愛 良心 堅固さ 希望 理想性 模倣 崇敬 機知または陽気さ 驚嘆 知的能力 これらは外界と物理的性質を認識する 色彩 可能性 形態 聴覚 個性 言語 場所 数 秩序 視覚 大きさ 嗅覚 味覚 時間 触覚 調和 重量 反射能力 これらは関係の概念を生み出す。他の全ての能力の方向付けと満足に寄与する: 因果性 比較 |

| Phrenology as popular science Part of phrenology's rise in popularity was the availability of ideas from scholars that were shared throughout the nineteenth century. Various societies all over Europe and in the United States kept the middle class well informed on the developments in the pseudoscientific field of research by way of regularly publishing journals. One of the earliest publications of phrenology was George Combe's Phrenological Journal which sat among other books, pamphlets, and articles he published in order to popularize the pseudoscience.[89] As mentioned previously, phrenology had a wide reach and a multi-faceted appeal from nobility to working class, and this would be his breakthrough publication in Great Britain. The most compelling argument Combe would make for the superiority of European nations and people over that of the rest of the world would be in an article he published titled "On the Cerebral Development of Nations". In this publication he determined that the reason Africa, Asian, and American Indians had never had a superior civilization due to "their inherent mental deficiencies".[89] The Edinburgh Phrenological Society had their own scholarly journal called the Phrenological Journal and Miscellany which ran from 1823 to 1847.[89] This was highly influential and the most highly sought after publication to read on phrenology in the British provinces in the early nineteenth century. |

頭蓋骨学としての大衆科学 頭蓋骨学が人気を博した一因は、19世紀を通じて共有された学者の思想が広く入手可能だったことにある。ヨーロッパ各地やアメリカ合衆国の様々な団体が、 定期的に刊行する雑誌を通じて、中産階級に疑似科学的な研究分野の進展を十分に知らせていた。 頭蓋骨学の初期出版物の一つがジョージ・コムの『頭蓋骨学ジャーナル』だ。これは彼が偽科学を普及させるために刊行した他の書籍、パンフレット、記事の中 に位置づけられる。[89] 前述の通り、頭蓋骨学は貴族から労働者階級まで幅広い層に多面的な魅力を持ち、この出版物が英国における彼の躍進のきっかけとなった。コムが欧州国民と民 族の優越性を世界に主張する最も説得力ある論拠は、『諸国民の脳発達について』と題した論文に示された。この出版物で彼は、アフリカ・アジア・アメリカイ ンドの人が優れた文明を築けなかった理由を「彼らに内在する精神的な欠陥」に帰したのである。[89] エディンバラ骨相学協会は『骨相学雑誌と雑録』という学術誌を1823年から1847年まで発行していた[89]。これは非常に影響力があり、19世紀初 頭の英国地方において骨相学に関する最も入手困難な出版物であった。 |

| Influences on popular culture Several literary critics have noted the influence of phrenology[90] (and physiognomy) in Edgar Allan Poe's fiction.[91] Phrenology (2002) by the Roots was named so after group member Black Thought saw an article in a scientific journal and the group "appropriated the term, not only for its political irony ..."[92] Phrenology, as well as physiognomy appears in a number of popular Victorian-era media and journal publications such as Dracula and The Picture of Dorian Gray.[93] In both of these works, the villains are shown to have the face of evil and it is heavily implied that the facial structure of characters can lead to some sort of conclusion as to the nature of their character. Works such as these gave the pseudoscience validation, and shows how far spread and influential its implications about the way people act being connected to their head structure truly were. |

大衆文化への影響 複数の文学評論家が、エドガー・アラン・ポーの小説における頭蓋骨学[90](および人相学)の影響を指摘している。[91] ルーツの楽曲『Phrenology』(2002年)は、メンバーのブラック・ソートが科学雑誌の記事を見て名付けたもので、グループは「その政治的皮肉 だけでなく、この用語を流用した」[92]。 頭蓋骨相学や人相学は、ドラキュラやドリアン・グレイの肖像など、ヴィクトリア朝時代の数多くの大衆メディアや雑誌出版物に登場する。[93] これらの作品では、悪役は悪の顔をしていると描かれ、登場人物の顔の構造からその性格の本質を推測できることが強く示唆されている。こうした作品群が疑似 科学に正当性を与え、人間の行動が頭部の構造と結びついているというその示唆が、いかに広く浸透し影響力を持っていたかを示している。 |

| Phrenology's decline in

popularity A popular contemporary argument for the decline of phrenology was an inherit problem with its wider reach to groups of people that construed it for their own agenda.[94] Each new iteration that it went through, as it was constantly being picked up and interpreted, it strayed farther from scientific structure. As early as the 1840's, phrenology had its fair share of critics from other scientists and philosophical thinkers of the time. Clergymen in particular protested against the human mind being reduced to a secular, materialistic thing that could be understood without the notion of a soul.[94] |

頭蓋骨相学の衰退 頭蓋骨相学が衰退した現代的な理由として、その理論を自らの思惑に都合よく解釈する人民に広まったことが根本的な問題だったと言われる[94]。理論が繰 り返し解釈され、新たな解釈が加えられるたびに、科学的な構造から遠ざかっていったのだ。 早くも1840年代には、当時の他の科学者や哲学思想家たちから頭蓋骨学に対する批判が相次いでいた。特に聖職者たちは、人間の精神が魂という概念なしに 理解できる世俗的で物質的なものに還元されることに強く抗議したのである。[94] |

| Anthropometry – Measurement of

the human individual Boston Phrenological Society Brodmann's areas – 52 distinct regions of the brain's cerebral cortex Characterology – The study of character Localization of brain function – Theory that regions of the brain are specialized for functions Metoposcopy Moral insanity – Obsolete term for type of mental disorder Neuroepistemology Neuro-imaging – Set of techniques to measure and visualize aspects of the nervous system Onychomancy – Form of divination using fingernails Palmistry – Foretelling the future through the study of the palm Pathognomy – Study of expressed emotions Phreno-magnetism – Pseudo-scientific phenomenon discovered by Robert Hanham Collyer in 1839 Psychograph – Phrenology machine Racial policy of Nazi Germany – Set of laws implemented in Nazi Germany The Zoist – Academic journal devoted to pseudoscientific concepts |

人体計測学 – 人間の個体を測定する学問 ボストン頭蓋骨相学会 ブロドマン領域 – 大脳皮質の52の特定領域 性格学 – 性格を研究する学問 脳機能局在説 – 脳の各領域が特定の機能に特化しているとする理論 額相学 道徳的狂気 – 精神障害の一種を指す廃れた用語 神経認識論 神経画像診断 – 神経系の側面を測定・可視化する技術群 爪相学 – 爪を用いた占いの形態 手相学 – 手相の研究による未来予測 病態表情学 – 表出された感情の研究 頭蓋磁気学 – 1839年にロバート・ハンハム・コリアーが発見した疑似科学的現象 サイコグラフ – 頭蓋骨測定器 ナチス・ドイツの人種政策 – ナチス・ドイツで施行された一連の法律 ザ・ゾイスト – 疑似科学的概念を専門とする学術誌 |

| Bibliography Anonymous (1860). "Sir William Hamilton on Phrenology". American Journal of Psychiatry. 16 (3): 249–260. doi:10.1176/ajp.16.3.249. Bunge, M. (1985). Treatise on Basic Philosophy. Vol. 7 (Part 2). Dordrecht: Reidel Publishing Company. Christison-Lagay, K. L.; Cohen, Y. E. (2013). "The Neural Representation of Vocalisation Perception". Animal Communication Theory: Information and Influence. New York: State University of New York Press. Combe, George (1851). A System of Phrenology. Boston: Benjamin B. Mussey and Company. Archived from the original on 2023-02-05. Retrieved 2012-06-10. Cooter, R. (1990). "The Conservatism of 'Pseudoscience'". Philosophy of Science and the Occult. New York: State University of New York Press. Flourens, P. (1844). Elementary Treatise on Human Physiology. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 150. Leaney, Enda (2006). "Phrenology in Nineteenth-Century Ireland". New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua. 10 (3): 24–42. doi:10.1353/nhr.2006.0058. JSTOR 20558078. S2CID 144035028. Lyons, Sherrie L. (2009). Species, Serpents, Spirits, and Skulls: Science at the Margins in the Victorian Age. Vol. 53. Albany: New York Press. pp. 141–143. doi:10.2979/victorianstudies.53.1.141. ISBN 978-1438427973. JSTOR 10.2979/victorianstudies.53.1.141. S2CID 141992807. {{cite book}}: |journal= ignored (help) McCandless, Peter (1992). "Mesmerism and Phrenology in Antebellum Charleston: 'Enough of the Marvellous'". The Journal of Southern History. 58 (2): 199–230. doi:10.2307/2210860. JSTOR 2210860. McGrew, Roderick E. (1985). Encyclopedia of Medical History. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. ISBN 978-0070450875. Parssinen, T. M. (Autumn 1974). "Popular Science and Society: The Phrenology Movement in Early Victorian Britain". Journal of Social History. 8 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1353/jsh/8.1.1. JSTOR 3786523. PMID 11632363. Robinson Storer, H. (1866). "Report on Insanity in Women". Transactions of the American Medical Association. 16: 134. Staum, Martin S. (2003). Labeling People: French Scholars on Society, Race and Empire, 1815–1848. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0773525801. Archived from the original on 2023-02-05. Retrieved 2016-01-27. Stiles, Anne (2012). Popular Fiction and Brain Science in the Late Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Thompson, Courtney E. (2021). An Organ of Murder: Crime, Violence, and Phrenology in Nineteenth-Century America. Rutgers University Press. Archived from the original on 2021-06-04. Retrieved 2021-06-25. Winn, J. M. (1879). "Mind and Living Particles". Journal of Psychological Medicine and Mental Pathology. 5 (1): 18–29. PMC 5122056. PMID 28906933. |

参考文献 匿名 (1860). 「ウィリアム・ハミルトン卿の頭蓋骨相学論」. アメリカ精神医学雑誌. 16 (3): 249–260. doi:10.1176/ajp.16.3.249. Bunge, M. (1985). 『基礎哲学論』第7巻(第2部). ドルドレヒト: Reidel Publishing Company. Christison-Lagay, K. L.; Cohen, Y. E. (2013). 「発声知覚の神経表現」. 『動物コミュニケーション理論:情報と影響』. ニューヨーク: ニューヨーク州立大学出版局. コンブ、ジョージ (1851). 『骨相学体系』. ボストン: ベンジャミン・B・マッシー社. 2023年2月5日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2012年6月10日に取得. クーター、R. (1990). 「『疑似科学』の保守性」. 『科学哲学とオカルト』. ニューヨーク: ニューヨーク州立大学出版局. フルーラン、P. (1844). 『人間生理学初級講義』. ニューヨーク: ハーパー・アンド・ブラザーズ. p. 150. リーニー、エンダ (2006). 「19世紀アイルランドにおける頭蓋骨学」『ニュー・ハイバーニア・レビュー/アイリス・エイリアナック・ヌア』10巻3号、24-42頁。doi: 10.1353/nhr.2006.0058。JSTOR 20558078。S2CID 144035028。 ライアンズ、シェリー・L.(2009)。『種、蛇、精霊、そして頭蓋骨:ヴィクトリア朝時代の境界における科学』。第53巻。オールバニ:ニューヨー ク・プレス。141–143頁。doi:10.2979/victorianstudies.53.1.141。ISBN 978-1438427973。JSTOR 10.2979/victorianstudies.53.1.141。S2CID 141992807。{{cite book}}: |journal= 無視 (help) マッキャンドレス、ピーター (1992). 「南北戦争前のチャールストンにおける催眠術と骨相学:『驚異はもう十分だ』」. 『南部史ジャーナル』. 58 (2): 199–230. doi:10.2307/2210860. JSTOR 2210860. McGrew, Roderick E. (1985). 『医学史事典』. ニューヨーク: McGraw-Hill Book Company. ISBN 978-0070450875. Parssinen, T. M. (1974年秋). 「大衆科学と社会:ヴィクトリア朝初期英国における骨相学運動」. 『社会史ジャーナル』. 8 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1353/jsh/8.1.1. JSTOR 3786523. PMID 11632363. ロビンソン・ストーラー, H. (1866). 「女性における精神異常に関する報告」. アメリカ医師会誌. 16: 134. スタウム、マーティン・S.(2003)。『人民へのレッテル貼り:1815-1848年のフランス学者による社会、人種、帝国論』。モントリオール:マ ギル・クイーンズ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0773525801。2023年2月5日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2016年1月27日に取得。 スタイルズ、アン(2012)。『19世紀後半の大衆小説と脳科学』。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 トンプソン、コートニー・E.(2021)。『殺人の器官:19世紀アメリカにおける犯罪、暴力、頭蓋骨学』。ラトガース大学出版局。2021年6月4日 にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2021年6月25日に閲覧。 ウィン、J. M. (1879). 「心と生きた粒子」. 心理医学・精神病理学雑誌. 5 (1): 18–29. PMC 5122056. PMID 28906933. |

| "Phrenology",

North American Review, 1833 p. 59 Manual of Phrenology. Open Content Alliance eBook Collection, Manual of phrenology: being an analytical summary of the system of Doctor Gall, on the faculties of man and the functions of the brain : translated from the 4th French ed New illustrated self-instructor in phrenology and physiology. Open Content Alliance eBook Collection, Fowler, O. S. (Orson Squire) (1809–1887); Fowler, L. N. (Lorenzo Niles) (1811–1896) The History of Phrenology on the Web by John van Wyhe, PhD. Phrenology: an Overview includes The History of Phrenology by John van Wyhe, PhD. Examples of phrenological tools can be seen in The Museum of Questionable Medical Devices in Minneapolis, Minnesota Historical Anatomies on the Web: Joseph Vimont: Traité de phrénologie humaine et comparée. (Paris, 1832–1835). Selected pages scanned from the original work. US National Library of Medicine. Jean-Claude Vimont: Phrénologie à Rouen, les moulages du musée Flaubert d'histoire de la médecine Phrenology: History of a Classic Pseudoscience – by Steven Novella MD The Skeptic's Dictionary by Robert Todd Carroll |

「頭蓋骨学」、『北米評論』、1833年、59ページ 頭蓋骨学手引書。オープン・コンテンツ・アライアンス電子書籍コレクション、『頭蓋骨学手引書:人間の能力と脳の機能に関するガル博士の体系の分析的要 約:第4版フランス語版からの翻訳』 新図解頭蓋骨学・生理学自習書。オープン・コンテンツ・アライアンス電子書籍コレクション、ファウラー、O. S.(オーソン・スクワイア)(1809–1887);ファウラー、L. N.(ロレンゾ・ナイルズ)(1811–1896) ウェブ上の頭蓋骨学の歴史 ジョン・ヴァン・ワイ博士著 頭蓋骨学:概説 ジョン・ヴァン・ワイ博士著『頭蓋骨学の歴史』を含む 頭蓋骨測定の器具の例は、ミネソタ州ミネアポリスにある「怪しげな医療器具博物館」で見られる。 ウェブ上の歴史的解剖学資料:ジョゼフ・ヴィモン『比較人間頭蓋骨測定論』(パリ、1832–1835年)。原著から選んだページをスキャンしたもの。米 国国立医学図書館所蔵。 ジャン=クロード・ヴィモン:ルーアンの頭蓋骨学、医学史フラウベール博物館の鋳型 頭蓋骨学:古典的疑似科学の歴史 ― スティーブン・ノベラ医学博士著 懐疑主義者の辞典 ― ロバート・トッド・キャロル著 |

|

|

|

|

|

Franz Joseph

Gall, 1758-1828

「ウィーン大学卒業後、ウィーンで開 業していたドイツ人医師フランツ・ヨーゼフ・ガル(1758-1828)は、脳の解剖学と神経の生理学の研究につとめ、脳髄が繊維のシステムであること、 錐体路系とその交差の存在、そして動眼・三叉・外旋神経など各神経の起始点を突き止めるなど、大脳生理学上の多くの発見を行うなど、神経解剖学に大きな功 績を残した人物であった。/ガルはまたイタリアの解剖学者モルガーニ(英語版)の著書『疾病の所在と原因について』(1761年)を参考にして、幼児や成 人の正常脳、各種の病気の人の脳、天才人の脳、動物の脳などを比較研究することで、独自の〈器官学Organologie〉を編み上げていき、1796年 から私的な講義を開き、これを講義した。/ガルの「器官学」によれば、脳は「色、 音、言語、名誉、友情、芸術、哲学、盗み、殺人、謙虚、高慢、社交」などといった精神活動に対応した27 個の「器官」の集まりとされ、各器官の働きの個人差が頭蓋の大きさや形状に現れるのだとされた。これはもっとも初期の脳機能局在論であり、また近代骨相学 のはじまりである。/ガルの主張によれば、たとえば「破壊官」や「粘着官」といった器官が大きいものは、執拗で残忍な傾向が強い。……/1802年、ガル の学説はあまりに唯物論的であるとされ、さらにキリスト教に反するとされて、ガルはオーストリア帝国によってウィーンから追放される。しかしガルはヨー ロッパ各地で講演を続けた。/1807年にはパリに移り、ここで解剖学者ヨハン・シュプルツハイム(Johann Spurzheim, 1776-1832)と連名で『神経系、とくに脳の解剖学と生理学』全4巻 (1810年 - 1819年刊行) 、『脳とその部位の機能』全6巻(1822年 - 1825年刊行)を発表する」

Johann Spurzheim,

1776-1832;Thomas

Ignatius Maria Forster (1789-1860, British) from The Royal Society.

「ガルは自分の学説を「脳蓋観察論」 (cranioscopie)と呼んでいた。骨相学(phrenology)という名称は、トーマス・フォースター(Thomas Ignatius Maria Forster, 1789-1860) が1815年にガルの学説をイギリスへ紹介する際に名づけたもので、1818年にシュプルツハイムがこの名称を取り入れて定着した。/これはギリシア語の φρήν(「心」を意味する)に由来する phrēn と、同じくギリシア語の λόγος(「知識」を意味する)に由来 する logos(ロゴス)からなる語である。/骨相学は、19世紀前半の欧米で大いに流行する。大衆的な人気を博した理由は、精神と頭蓋骨の対応という考え方 が直感的に理解しやすかったことに加えて、頭蓋骨の形という容易に計測できるものから個人の気質がわかるという主張により、専門家でなくても骨相学的性格 判断を行うことができたためである。当時の名士たちはこぞって肖像画の額を広く描かせて、思慮深さをアピールする風潮も生まれたという。/1822年、フ ランス政府はシュプルツハイムの講義を禁止した。/1832

年、パリに骨相学会が設立された。頭 蓋骨の収集と脳の計量が流行し、巷に骨相図が氾濫した。欧 米のあちらこちらの町で骨相学会が誕生し、多くの有名な学者が、骨相学という学問研究の発展のために、自分の頭蓋骨を死後に提供した。/またスヴェーデン ボリ、ハイドンら有

名人の頭蓋骨が、熱心な骨相学者に

よって墓から持ち去られる事件が起こった。……学問的にも、フーフェラント、フルーラン、フィリッ

プ・ピネルらにより否定され、大脳中枢の解剖学的知見が蓄積され、その「地図」が明確に決定されてゆくにつれて、ガルの器官説自体が否定されていく。/ガ

ルが当初から関心を持っていた犯罪への応用において、犯人の頭蓋骨を計るという初期の骨相学的な犯罪の計測学から、犯罪者の様々なプロフィールを蓄積する

実証的犯罪研究へとつながっていく(たとえばチェーザレ・ロンブローゾを祖とする犯罪生物学など)。……また「気質」を判定するという骨相学の志向は、ロ

ンブローゾの生来的犯罪人説のような犯罪の素質論(犯罪を犯すか否かは当人の素質に左右される)から、優生学や人間改良思想へと展開していく。これは断種

論(特定の人種を断つことを目指す)の背景にもつながる危険を持っていた。/骨相学の「頭蓋骨の形から個人の性格がわかる」という単純な主張は否定された

が、精神的機能が特定の神経構造に基盤を持つという現代的な見方は脳機能局在論となった。また言語獲得、友情、道徳性、直観的な物理能力、心の理論などが

一般的知能として混在するのではなく、独立して存在し、遺伝的であり、個別に独立して機能するというアイディアは「心のモジュール説」と呼ばれ、認知科学

や心の哲学で議論されている。/また古人類学では、化石人類や化石霊長類の頭骨形状から、一般的な知能や特定の脳機能(特に言語能力)を推測する」骨相学)

1895年のウェブスター教養辞典に掲載された骨相

学による脳の地図。 ガルによれば、脳は、色、 音、言語、名誉、友情、芸術、哲学、盗み、殺人、謙虚、高慢、社交などといった精神活動に対応した27

個の〈器官〉の集まりであるとされた。A definition of phrenology with chart from Webster's

Academic Dictionary, circa 1895

*****

"We know the role that anthropology has played in the erasure of Indigenous peoples in the Americas through its salvage/savage ethnography project and its continued use of human remains for “research” purposes. Anthropology has consistently erased Indigenous peoples, just as it has consistently dehumanized Black people. Anthropology is founded on the savage slot, and this is a systemic and structural condition that spans beyond our intentions." - An Interview with the Editor of American Anthropologist about the March 2020 Cover Controversy, by AAA

「人類学が、サルベージ/野蛮民族誌プロジェクトや、研究目的での人骨の使用を通じて、アメ

リカ大陸の先住民を消し去る上で果たしてきた役割は周知の事実である。人類学は、黒人を一貫して非人間化してきたのと同様に、一貫して先住民を消し去って

きた。人類学は野蛮な立場に立脚しており、これは私たちの意図を超えた、体系的で構造的な状況である。」

●現代の骨相学:ゲノムサイエンス(→現代の骨相学とゲノムサイエンス)

東京大学の医科学研究所のヒトゲノム解析センター (Human Genome Center)は次のように その学問の目的がかかれてある(2021年3月19日採集)。

"The purpose of human genome research is to contribute to our human society through the diagnosis, prevention, and development of treatment methods for cancer, infectious diseases and other difficult diseases. The mission of the center is to promote this human genome research, greatly develop genomic medicine, and establish a new genomic medicine in the Society 5.0 era, and simultaneously build their foundations. To that end, we promote genomic medical science, medical informatics, artificial intelligence research for clinical translation of genomic information, and research on ethical, legal, and social issues. In addition, we operate a supercomputer system SHIROKANE for all researchers in life science regardless of academic or non-academic institutions/companies, and at the same time, provide seminars such as technical guidance course for users. We also accept researchers aiming at genomic research from all over the world and provide intensive courses for training." https://www.ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp/imsut/en/lab/hgclink/index.html

「ヒトゲノム研究の目的は、がんや感染症などの難治

性疾患の診断、予防、治療法の開発を通じて、人類社会に貢献することである。当センターの使命は、このヒトゲノム研究を推進し、ゲノム医療を飛躍的に発展

させ、Society

5.0時代の新しいゲノム医療を確立することであり、同時にその基盤を構築することである。そのため、ゲノム医療科学、医療情報学、ゲノム情報の臨床応用

に向けた人工知能研究、倫理・法・社会問題研究を推進している。また、学術・非学術機関・企業を問わず、生命科学の研究者向けにスーパーコンピュータシス

テム「SHIROKANE」を運用し、同時に利用者向け技術講習会などのセミナーも実施している。また、ゲノム研究を目指す世界中の研究者を受け入れ、集

中的なトレーニングコースを提供している」

★DNA Myth

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099