ヘーゲル『精神現象学』1807年

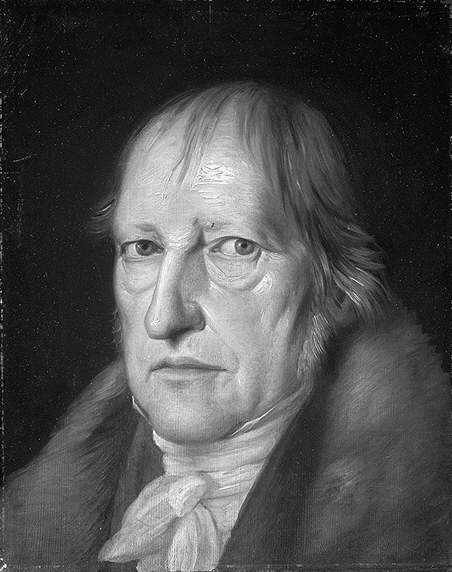

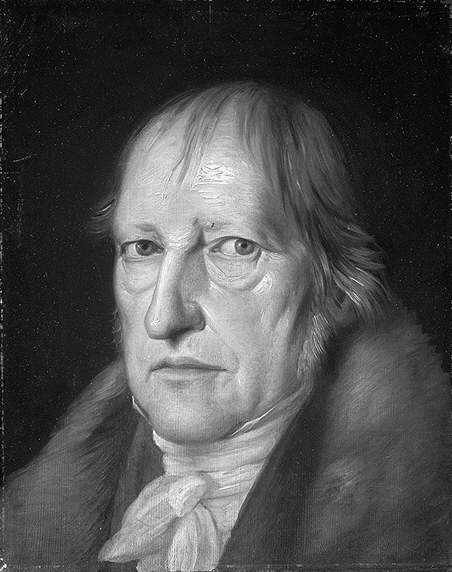

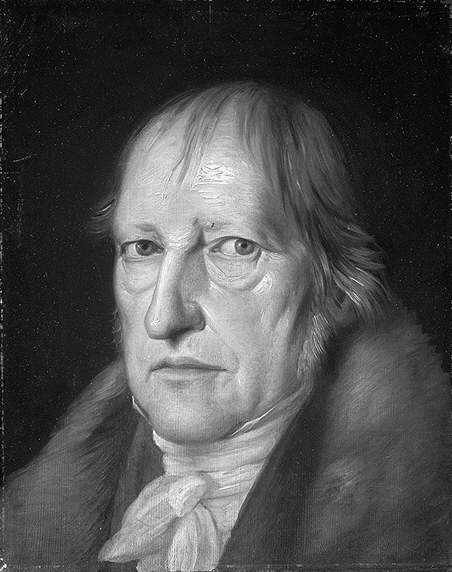

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, 1770-1831,

Phänomenologie

des Geistes, 1808

1802 『信仰と知』において「純粋理性批判」の演繹論の超越論的統覚を主観/客観の統一を表現するものとして評価(→「ヘーゲルからみたカント評価」)

1803 アダム・スミス『諸国民の富(国富論)』 を読みインパクトをうける(→イェーナ期の著作に影響し「陶冶(Bildung)と しての労働」の概念を見いだす)

1805 ゲーテの推挙でイエーナ大学の 員外教授(助教授)となる

1806-1807 「精神現象学」の原稿の完成(クリスティアーナ・ブルクハルトとの情事/ナポレオンの中に世界精神をみる)

1807(37歳) G.W.F. Hegel[ヘーゲル], Phänomenologie des Geistes, (1807)[ドイツ語電子テキストポータル]Marxist.org(→「長谷川宏訳を中心とした『精神現象学入門』」)

1807

イエーナ大学閉鎖。『バンベルク・ツァイトゥンク』の編集者となる。『精神現象学(Phänomenologie des Geistes)The Phenomenology of Spirit』あるいは"Phenomenology of Mind"を刊行[ドイツ語テキスト]1807 年には、蓄えと『現象学』からの支払いが底 をつき、非嫡出子ルートヴィヒを養うためにも金銭が必要となった ため、バンベルクに移住せざるを得なかった。 そこで彼は、ニーダマーの助力により、地元紙『バンベルガー・ツァイトゥング』の編集者となった。ルートヴィヒ・フィッシャーと彼の母親はイエナ に残った。

1809-1815 ニュルンベルクのギムナジウム[9年制の中高一貫校]の校長兼哲学教授。在任中に、教育の理念と教養をめぐる5件の講演が残っている。

●精神現象学と論理の学の異動(→テキストの英訳「精神現象学」)

"A glance at the table of contents of Science of Logic reveals the same triadic structuring among the categories or thought determinations discussed that has been noted among the shapes of consciousness in the Phenomenology. At the highest level of its branching structure there are the three books devoted to the doctrines of being, essence, and concept, while in turn, each book has three sections, each section containing three chapters, and so on. In general, each of these individual nodes deals with some particular category. In fact, Hegel’s categorial triads appear to repeat Kant’s own triadic way of articulating the categories in the Table of Categories (Critique of Pure Reason A80/B106) in which the third term in the triad in some way integrates the first two. (In Hegel’s terminology, he would say that the first two were [aufgehoben] in the third—while the first two are negated by the third, they continue to work within the context defined by it.) Hegel’s later treatment of the syllogism found in Book 3, in which he follows Aristotle’s own three-termed schematism of the syllogistic structure, repeats this triadic structure as does his ultimate analysis of its component concepts as the moments of universality, particularity, and singularity."- all the citations from "Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, of The Stanford Encyclopedia of Pilosophy"

『論理学の科学』の目次を見ると、『現象学』におけ

る意識の形と同じように、論じられるカテゴリーや思考の決定の間に三項対立の構造があることがわかる。その枝分かれ構造の最上位には、存在、本質、概念の

教義に充てられた3冊の本があり、順に各本には3つのセクションがあり、各セクションには3つの章がある、といった具合に。一般に、これらの個々の結節

は、それぞれ、ある特定のカテゴリーを扱っている。実際、ヘーゲルのカテゴリー三段論法は、カントが『カテゴリー表』(『純粋理性批判』

A80/B106)において、三段論法の第三項が何らかの形で最初の二項を統合する形でカテゴリーを明示する方法を繰り返すように見える(ヘーゲルの用語

では、三段論法の三項が三項を統合する)。(ヘーゲルの用語法では、最初の二つは第三項において止揚=[aufgehoben]され、最初の二つは第三項

によって否定されるが、第三項によって定義される文脈の中で働き続ける、と言うだろう)。第3巻に見られるヘーゲルの三段論法は、アリストテレスの三段論

法に倣っているが、普遍性、特殊性、特異性の瞬間としての構成概念を究極的に分析するのと同様に、この三段論法を繰り返しているのである。

"Reading into the first chapter of Book 1, Being, it is quickly seen that the transitions of the Logic broadly repeat those of the first chapters of the Phenomenology, now, however, as between the categories themselves rather than between conceptions of the respective objects of conscious experience. Thus, being is the thought determination with which the work commences because it at first seems to be the most immediate, fundamental determination that characterises any possible thought content at all. (In contrast, being in the Phenomenology’s Sense-certainty chapter was described as the known truth of the purported immediate sensory given—the category that it was discovered to instantiate.) Whatever thought is about, that topic must in some sense exist. Like those purported simple sensory givens with which the Phenomenology starts, the category being looks to have no internal structure or constituents, but again in a parallel to the Phenomenology, it is the effort of thought to make this category explicit that both undermines it and brings about new ones. Being seems to be both immediate and simple, but it will show itself to be, in fact, only something in opposition to something else, nothing. The point seems to be that while the categories being and nothing seem both absolutely distinct and opposed, on reflection (and following Leibniz’s principle of the identity of indiscernibles) they appear identical as no criterion can be invoked which differentiates them. The only way out of this paradox is to posit a third category within which they can coexist as negated (Aufgehoben) moments. This category is becoming, which saves thinking from paralysis because it accommodates both concepts. Becoming contains being and nothing in the sense that when something becomes it passes, as it were, from nothingness to being. But these contents cannot be understood apart from their contributions to the overarching category: this is what it is to be negated (aufgehoben) within the new category."- all the citations from "Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, of The Stanford Encyclopedia of Pilosophy"

第1巻の第1章「存在」を読み進めると、論理学の推

移が現象学の第1章の推移とほぼ同じであることがすぐにわかるが、今度は、意識経験のそれぞれの対象についての観念の間ではなく、カテゴリーそれ自体の間

である。このように、「存在」がこの作品の冒頭を飾る思考決定であるのは、それが最初、あらゆる可能な思考内容を特徴づける最も直接的で根本的な決定であ

るように思われるからである。(これに対して、『現象学』の「感覚的確信」の章における「存在」は、即時的な感覚的与件、つまりそれがインスタンス化する

ことが発見されたカテゴリーの既知の真理として説明されている)。思考が何についてであれ、そのトピックはある意味で存在しなければならない。現象学の出

発点となった単純な感覚的与件のように、存在というカテゴリーには内部構造や構成要素がないように見えるが、やはり現象学と並行して、このカテゴリーを明

示しようとする思考の努力が、それを弱め、新しいカテゴリーをもたらすのである。存在とは、即物的で単純であるように見えるが、実は、他の何か、つまり無

に対立する何かでしかないことを示すことになる。要は、存在と無というカテゴリーは絶対的に区別され、対立しているように見えるが、(ライプニッツの無分

別の同一性の原則に従って)内省すると、両者を区別するいかなる基準も持ち出せないので同一に見えるということであろう。このパラドックスから抜け出す唯

一の方法は、否定=止揚された(Aufgehoben)瞬間として共存できる第三のカテゴリーを措定することである。このカテゴリーとは、両概念を受け入

れることができるため、思考を麻痺から救う「なりゆき」である。何かが「なる」とき、それはいわば無から有へと移行するという意味で、「なる」ことは有と

無を含んでいる。しかし、これらの内容は、包括的なカテゴリーへの貢献から切り離して理解することはできない。これこそ、新しいカテゴリーの中で否定=止

揚される(Aufgehoben)ことである。

★章立て(長谷川宏版 1998)——画面クリックで拡大します

★この図版のdoc ファイルはこちら[Phaenomenologie_Geistes_hase_jap.doc ]→この図版のpdfファイルはこちら[Phaenomenologie_Geistes_hase_jap.pdf]

☆精神現象学リンク集

●ハイデガー「ヘーゲルの「経驗」概念 」Erläuterungen der "Einleitung" zu Hegels "Phänomenologie des Geistes," 1943

「ヘーゲルが1807年に精神の現象学を公表したときに、この著作の巻頭に掲げた表題は、「意識の経験の学」と書かれている」(ハイデッガー 1954:79)【→【目次】0/16 ヘーゲル「精神現象学」1807:はじめに】

★ドイツ語ウィキペディアからの記事

Die

Phänomenologie des Geistes ist

das 1807 veröffentlichte erste Hauptwerk des Philosophen Georg Wilhelm

Friedrich Hegel. Es stellt den Ersten Theil seines Systems der

Wissenschaft dar. Der „Phänomenologie“ sollte sich die Darstellung der

„Realen Wissenschaften“ anschließen – die „Philosophie der Natur“ und

die des „Geistes“. Titelblatt, 1807 Hegel entwickelt in dieser Wissenschaft von den Erscheinungsweisen des Geistes das Emporsteigen des Geistes von der einfachen, naiven Wahrnehmung über das Bewusstsein, das Selbstbewusstsein, die Vernunft, Geist und Geschichte, die Offenbarung bis hin zum absoluten Wissen des Weltgeistes. Dabei untersucht er das Werden der Wissenschaft als Einheit von Inhalt und Methode sowie die Erscheinungen des Geistes als Verwirklichung unseres Selbst, als Einheit von Sein und Nichts ebenso wie als absolute Ganzheit. Ort der Wahrheit ist dabei der Begriff im wissenschaftlichen System und nicht die Anschauung. Die Erkenntnis der Wahrheit liegt in der Einsicht, dass die Gegensätzlichkeit von Subjekt und Objekt dialektisch auf einem höheren Niveau aufgehoben wird, da das eine nicht ohne das andere existiert, beide also eine Einheit bilden. Das Werk setzt sich sowohl mit erkenntnistheoretischen als auch ethischen und geschichtsphilosophischen Grundfragen auseinander. Von besonderer Bedeutung ist die Rezeption des Kapitels über das Selbstbewusstsein, das die dialektische Betrachtung von Herrschaft und Knechtschaft enthält und ein wesentlicher Ausgangspunkt für Marx’ Beschäftigung mit der Analyse der Klassenverhältnisse in der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft war. Die Phänomenologie des Geistes gilt als das erste typische Werk Hegels, auf das er später auch immer wieder Bezug nimmt. Hegel versucht hier, alle wichtigen Themen, die ihn zuvor beschäftigten, systematisch auszuarbeiten. Er setzt sich darin mit den Positionen auseinander, die den damaligen philosophischen Diskurs beherrschten: Immanuel Kants Dualismus, das Unmittelbarkeitsdenken Jacobis und die Identitätsphilosophie Schellings. Das Werk wurde von Hegel zunächst als eine systematische Einführung in sein philosophisches System konzipiert. Die ersten drei Teile (Bewusstsein, Selbstbewusstsein, Vernunft) wurden von ihm später in abgekürzter Form, als das zweite Moment des subjektiven Geistes, in das System der Enzyklopädie (1817) aufgenommen. 1812 veröffentlichte Hegel die Wissenschaft der Logik, die sich in der Vorrede auf die Phänomenologie bezieht. In der Enzyklopädie der philosophischen Wissenschaften (zuerst 1817 erschienen) arbeitete er viele ihrer Fragestellungen in die „Wissenschaft des Geistes“ ein. |

1807年に出版された『精神現象学』は、哲学者ゲオルク・ヴィルヘル

ム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルの最初の主要著作である。これは彼の科学体系の最初の部分を表している。「現象学」は、「実在科学」である「自然哲学」と「精

神」の哲学に続くものとなる。 タイトルページ、1807年 この『精神の現れ方の科学』において、ヘーゲルは精神の単純な素朴な知覚から意識、自己意識、理性、精神、歴史、啓示、そして最終的には世界精神の絶対的 な知識に至るまでの精神の昇華を展開している。 その際、彼は科学の発展を内容と方法の統一体として、また精神の現象を自己実現として、存在と無の統一体として、そして絶対的な全体として考察している。 真理の場所は、科学的体系における概念であり、見解ではない。真理の知識は、主観と客観の間の対立が弁証法的により高いレベルで保留されるという洞察にあ る。なぜなら、一方は他方なしには存在しないため、2つが1つの統一体を形成するからである。 この著作は、根本的な認識論的、倫理的、歴史哲学的な問題を扱っている。自己意識の章の受容は、支配と隷属の弁証法的考察を含み、ブルジョワ社会における 階級関係のマルクスの分析にとって重要な出発点となった。 『精神現象学』はヘーゲルによる最初の典型的な著作と考えられており、後にヘーゲルは繰り返しこの著作に言及している。この著作において、ヘーゲルはそれ まで自身を悩ませていた重要なテーマを体系的に詳細に説明しようと試みている。その際、ヘーゲルは当時の哲学論を支配していた立場、すなわち イマヌエル・カントの二元論、ヤコビの即自性哲学、シェリングの同一哲学などである。この著作は当初、ヘーゲル自身の哲学体系の体系的な入門書として構想 された。最初の3部(意識、自己意識、理性)は後に、主観的精神の第二の局面として、百科全書(1817年)の体系に簡略化された形で盛り込まれた。 1812年、ヘーゲルは『論理学の科学』を出版し、その序文で現象学について言及した。『哲学科学の百科事典』(1817年初版)では、その多くの問題を 「精神の科学」に取り入れた。 |

| Inhaltlicher Überblick Einen Überblick bietet das Inhaltsverzeichnis. Bereits die erste Auflage hatte zwei Inhaltsgliederungen, ursprünglich I-VII sowie später von Hegel hinzugefügt A-C, DD. Vorrede Das Programm der Phänomenologie wird dargestellt. Einleitung Was heißt Erkennen? I. Die sinnliche Gewissheit; oder das Diese und das Meinen / (A.) Bewusstsein II. Die Wahrnehmung; oder das Ding, und die Täuschung / (A.) Bewusstsein III. Kraft und Verstand, Erscheinung und übersinnliche Welt / (A.) Bewusstsein Bewusstsein: Seine Stufen sind sinnliche Gewissheit, Wahrnehmung und Verstand. IV. Die Wahrheit der Gewissheit seiner selbst / (B.) Selbstbewusstsein Das Selbstbewusstsein macht die Erfahrung von Selbständigkeit und Unselbständigkeit, trägt den Konflikt von Herr und Knecht aus und erlangt ein erstes Gefühl von Freiheit. Das unglückliche Bewusstsein der römischen Kaiserzeit, das in das Christentum mündet, ist die Vorstufe der Vernunft. V. Gewissheit und Wahrheit der Vernunft / (C.) (AA.) Vernunft Über die Naturbeobachtung gelangt sie zu ersten Formen der Selbsterkenntnis, verwirklicht ihr Selbstbewusstsein und bildet Individualität heraus. VI. Der Geist / (BB.) Der Geist Die Sittlichkeit bildet die wahre Substanz des Geistes. Als Recht ist der Geist in seiner objektiven Form. In seiner entfremdeten Form erscheint er als Bildung und Aufklärung. Die Moralität ist die reflektierte Einheit von Recht und Sittlichkeit. In ihr erscheint das Bewusstsein, dass der Geist die einzige Substanz ist, als reines Wissen. VII. Die Religion / (CC.) Die Religion Im Christentum, der geoffenbarten Religion, tritt das Bewusstsein in Form der Vorstellung auf, dass Gott im Grunde Geist ist. VIII. Das absolute Wissen / (DD.) Das absolute Wissen Der absolute Geist ist im Grunde nur in Form des Wissen von sich selbst und nicht von etwas ihm Äußerlichen. Der Geist ist so Subjekt und Objekt zugleich. Indem ihm dies zu Bewusstsein kommt, wird sein Wissen um sich selbst zum absoluten Wissen. |

内容の概要 目次は概要を提供する。初版にはすでに2つの目次があり、当初はI-VII、後にヘーゲルによってA-C、DDが追加された。 序文 現象学のプログラムが提示される。 序論 認識するとは何を意味するのか? I. 感覚的確実性、またはこれと意見 / (A.) 意識 II. 知覚、または物事と幻想 / (A.) 意識 III. 力と理解、外観と超感覚的世界 / (A.) 意識 意識:その段階は感覚的確実性、知覚、理解である。 IV. それ自体の確実性の真理 / (B.) 自意識 自意識は、独立と依存を経験し、主人と召使の間の葛藤を解決し、自由の 最初の感覚を獲得する。キリスト教へとつながったローマ帝国時代の不幸な意識は、理性の先駆けである。 V. 理性の確実性と真理 / (C.) (AA.) 理性 自然の観察を通じて、自己認識の最初の形に到達し、自己認識を自覚し、 個性を発達させる。 VI. 精神 / (BB.) 精神 道徳は精神の真の物質を形作る。 権利として、精神は客観的な形態にある。 疎外された形態では、それは教育や啓蒙として現れる。 道徳は、権利と道徳の反映された統一である。 精神が唯一の物質であるという意識は、純粋な知識として現れる。 VII. 宗教 / (CC.) 宗教 啓示宗教であるキリスト教において、意識は「神は本質的に精神である」 という考えの形を取る。 VIII. 絶対的知識 / (DD.) 絶対的知識 絶対的精神は本質的に、それ自身を知るという形のみであり、それ自身以 外の何かではない。したがって、精神は同時に主観と客観である。それがこのことに気づくと、それ自身についての知識は絶対的知識となる。 |

| Werbetext Anzeige im Intelligenzblatt der Jenaer Allgemeinen Literatur-Zeitung vom 28. Oktober 1807:[1] „Dieser Band stellt das werdende Wissen dar. Die Phänomenologie des Geistes soll an die Stelle der psychologischen Erklärungen oder auch der abstrakten Erörterungen über die Begründung des Wissens treten. Sie betrachtet die Vorbereitung zur Wissenschaft aus einem Gesichtspunkte, wodurch sie eine neue, interessante, und die erste Wissenschaft der Philosophie ist. Sie faßt die verschiedenen Gestalten des Geistes als Stationen des Weges in sich, durch welchen er reines Wissen oder absoluter Geist wird. Es wird daher in den Hauptabteilungen dieser Wissenschaft, die wieder in mehrere zerfallen, das Bewußtsein, das Selbstbewußtsein, die beobachtende und handelnde Vernunft, der Geist selbst, als sittlicher, gebildeter und moralischer Geist, und endlich als religiöser in seinen unterschiedlichen Formen betrachtet. Der dem ersten Blick sich als Chaos darbietende Reichtum der Erscheinungen des Geistes ist in eine wissenschaftliche Ordnung gebracht, welche sich nach ihrer Notwendigkeit darstellt, in der die unvollkommenen sich auflösen und in höhere übergehen, welche ihre nächste Wahrheit sind. Die letzte Wahrheit finden sie zunächst in der Religion und dann in der Wissenschaft, also dem Resultate des Ganzen. In der Vorrede erklärt sich der Verfasser über das, was ihm Bedürfnis der Philosophie auf ihrem jetzigen Standpunkte zu sein scheint; ferner über die Anmaßung und den Unfug der philosophischen Formeln, der gegenwärtig die Philosophie herabwürdigt, und über das, worauf es überhaupt bei ihr und ihrem Studium ankommt. Der zweite Band wird das System der Logik als spekulativer Philosophie und der zwei übrigen Teile der Philosophie, die Wissenschaften der Natur und des Geistes enthalten.“ |

広告文 1807年10月28日付の『イエナ・アルゲマイネ・リテラチュール・ツァイトゥング』紙の『インテリゲンツブラット』への広告:[1] 「本書は、初期の知識を提示するものである。『精神現象学』は、心理学的な説明や、知識の基礎に関する抽象的な議論に取って代わることを目的としている。 科学の準備を、新しい、興味深い、哲学における最初の科学とする視点から考察する。それは、純粋な知識や絶対精神へと至る道のりの段階として、精神のさま ざまな形態を包括している。この科学の主なセクションは、さらにいくつかのセクションに分かれており、意識、自己意識、観念と実践の理性、道徳的、教養の ある倫理的な精神としての精神そのもの、そして最終的には宗教的な精神としての精神のさまざまな形態を考察している。一見混沌として見える心の現象の豊か さは、科学的秩序にまとめられ、その必要性に従って提示されている。不完全なものはより高次のものへと溶解し、融合し、それらが最も近い真実となる。彼ら はまず宗教において、そして科学において究極の真実を見出す。それは全体の結果である。 序文で著者は、現在の哲学の発展状況において哲学が必要とされる理由について説明している。さらに、現在哲学を衰退させている哲学上の公式の気取りやナン センスさについて論じ、哲学とその研究において何が重要であるかを論じている。 第2巻には、思弁哲学としての論理学の体系と、哲学の残りの2つの部分である自然と精神の科学が含まれる。 |

| Vorrede und Einleitung Vorrede Die Vorrede zur Phänomenologie des Geistes ist nicht nur von großem Umfang, sondern auch inhaltlich vielschichtig. Daher sollen hier nur zentrale Gedanken dargestellt werden. Die Vorrede beginnt mit Hegels manchen Leser sicher überraschenden Enttäuschung der üblichen Erwartung an eine Vorrede, dass sie nämlich Absichten und Ergebnisse der Forschungsarbeit des Autors skizziere und sich von allen früheren falschen Darstellungen anderer abgrenze und distanziere. Seine darüber hinausgehende Vorstellung von philosophischer Wissenschaft macht Hegel zunächst bildlich durch den Vergleich mit dem Wachstum einer Pflanze deutlich und lässt damit zugleich erfahren, was er in seiner Vorrede beabsichtigt, nämlich die schrittweise Hinführung des Lesers zu seiner ungewohnten dialektischen Denkweise, ohne die seine Wissenschaft nicht verstanden werden kann: „Die Knospe verschwindet in dem Hervorbrechen der Blüte, und man könnte sagen, daß jene von dieser widerlegt wird, ebenso wird durch die Frucht die Blüte für ein falsches Dasein der Pflanze erklärt, und als ihre Wahrheit tritt jene an die Stelle von dieser. Diese Formen unterscheiden sich nicht nur, sondern verdrängen sich auch als unverträglich miteinander. Aber ihre flüssige Natur macht sie zugleich zu Momenten der organischen Einheit, worin sie sich nicht nur nicht widerstreiten, sondern eins so notwendig als das andere ist, und diese gleiche Notwendigkeit macht erst das Leben des Ganzen aus.“ Das Ganze der Wahrheit ist ohne die widersprüchlich erscheinende und sich von einem inneren Ziel her weitertreibende Entwicklung der „Teile“ auseinander nicht sinnvoll zu verstehen, ebenso ist die Wahrheit der Philosophie nur als sich entwickelnde Ganzheit scheinbar widersprüchlicher Denkweisen entwickelbar und darstellbar. Daher kann die Vorrede keine „Ergebnisse“ skizzieren und sich nicht von früheren falschen Meinungen distanzieren, sondern muss die Bewegung des Denkens selbst in seiner lebendigen Entwicklung darstellen, auch wenn die Darstellung von Meinungen, Zielen und Absichten als Voraussetzung und Anfang der Wissenschaft ihren Wert behält. Hegel sieht sich an einem Wendepunkt des Denkens stehen, in dem ein qualitativer Sprung eintritt, nachdem die bisherigen Denkweisen sich gegenseitig erschöpft haben. Ergebnis dieses Sprungs ist jedoch noch nicht das ausentwickelte neue System der Wissenschaft, sondern zunächst ihr einfacher Begriff, der unverständlich und esoterisch wirken kann. Die gegensätzlichen philosophischen Strömungen seiner Zeit, der Kantianismus, Fichte und die Romantik, vor allem Schelling, weisen daher das Neue zunächst noch zurück: „Der eine Teil pocht auf den Reichtum des Materials und die Verständlichkeit, der andre verschmäht wenigstens diese und pocht auf die unmittelbare Vernünftigkeit und Göttlichkeit.“ Das Neue im Wissenschaftsverständnis Hegels gegen die formalistisch aufgefasste Substanz (A=A) oder die gefühlte Substanz ist der besondere Subjektcharakter des Absoluten. „Es kömmt nach meiner Einsicht, welche sich durch die Darstellung des Systems selbst rechtfertigen muß, alles darauf an, das Wahre nicht als Substanz, sondern ebensosehr als Subjekt aufzufassen und auszudrücken.“ Besonders versucht Hegel den kantischen Dualismus, der damals in Deutschland vorherrschte, zu überwinden. Alle bisherigen Philosophien findet Hegel ungenügend, weil sie in gegensätzlichen Standpunkten verharren. Sie fallen in widersprüchliche Positionen auseinander und begreifen den zwischen ihnen auftretenden Widerspruch nicht als ein wesentliches Moment der Wahrheit. Sein Programm ist es, die Philosophie als Wissenschaft zu begründen. Dieser wissenschaftliche Standpunkt muss aber, so lautet Hegels Diagnose, erst gewonnen werden.[2] So versteht er sie als eine Hinführung zur Wissenschaft oder als Wissenschaft, die sich noch in ihrem Werden befindet. „Dies Werden der Wissenschaft überhaupt, oder des Wissens, ist es, was diese Phänomenologie des Geistes darstellt.“[3] Er untersucht das Bewusstsein, wie es sich unmittelbar vorfindet, um von ihm aus zum wahren oder absoluten Wissen vorzudringen. Um dies zu erreichen, muss der Geist einsehen, was das Wissen selbst ist.[4] Das Bewusstsein, so wie es sich unmittelbar vorfindet, ist für Hegel der erscheinende Geist. Er ist der Gegenstand der Phänomenologie. Sein Grundsatz ist: „Das Wahre ist das Ganze. Das Ganze aber ist nur das durch seine Entwicklung sich vollendende Wesen. Es ist von dem Absoluten zu sagen, dass es wesentlich Resultat, dass es erst am Ende das ist, was es in Wahrheit ist; und hierin eben besteht seine Natur, Wirkliches, Subjekt oder Sichselbstwerden zu sein.“[5] Hegel spielt hier auf Kants transzendentale Dialektik in dessen Kritik der reinen Vernunft an, in der die Vernunft auf die Totalität der Bedingungen des Erkennens und damit einhergehend auf das bedingte Unbedingte zielt. Seiner Prognose nach bringt es Kant nur zu einer subjektiven Reflexionsphilosophie, weil bei ihm das Unbedingte kein Gegenstand objektiv gültigen Wissens sein kann und sie dadurch, wie Hegel sagt, in einem unendlichen Gegensatz zum Absoluten bleibt. Für Hegel ist die Totalität nicht nur Gegenstand der Vernunft, kein nur übergeordnetes Prinzip, sondern die „Bewegung der Vernunft selbst in ihrer Selbsterfassung, die zugleich die Erfassung ihrer Bedingung ist.“[6] Er sagt also, dass Wahrheit nicht im Festhalten eines starren Ergebnisses besteht, sondern erst das Zusammenspiel des Resultats und der Entwicklung des Ganzen die Wahrheit konstituiert. Das Wahre ist für ihn nur als System wirklich und es muss allein das Geistige als das Wirkliche aussprechen. Im Wissen des Geistes um sich scheint für Hegel das Wissen seinen absoluten Standpunkt gewonnen zu haben. Nur der Geist bleibt, indem er aus sich herausgeht, zugleich in sich selbst.[7] Um dieses Insichgehen des Geistes gewährleisten zu können und nicht in der empirischen Anschauung zu verweilen oder diese kritiklos zu übernehmen, muss Philosophie die Anstrengung des Begriffes auf sich nehmen. Die Methode dieser Wissenschaft muss in der Lage sein, die Bewegung der Sache selbst darzustellen. Einleitung Gegenstand der Einleitung zur Phänomenologie des Geistes ist zuerst eine Kritik an Kants Unterscheidung zwischen den Dingen an sich und den Dingen für uns. Hegel meint, dass diese Unterscheidung uns den Weg zur Erkenntnis des Absoluten versperrt und dass sie sinnlos sei. Hegel bevorzugt einen völlig anderen Weg und zwar einen solchen, den er „Weg der Verzweiflung“ nennt. Damit meine er, dass der Philosoph den Gang des sogenannten natürlichen Selbstbewusstseins nur zu beschreiben hat, ohne sich einzumischen. Das Bewusstsein muss dabei unterschiedliche Gestalten annehmen, deren Unzulänglichkeiten es einzusehen hat und dadurch zu einer anderen Gestalt gelangen kann. Ziel dieser Bewegung sei laut Hegel der absolute Geist, wo das Bewusstsein sich endlich als Ende und Anfang seiner eigenen Bewegung begreift. |

序文と序説 序文 『精神現象学』の序文は、非常に長いだけでなく、内容も複雑である。そのため、ここでは中心的な考え方のみを紹介する。 序文は、ヘーゲルが序文に通常期待されること、すなわち、著者の研究活動の意図と成果の概略を述べ、それ以前の他者による誤った表現から距離を置くこと、 に失望したことから始まる。ヘーゲルはまず、哲学科学のより広範な概念を、植物の成長と比較することで説明することから始める。これはまた、序文における 彼の意図を伝えるものでもある。すなわち、読者を段階的に導き、彼の独特な弁証法的思考法へと導くこと、すなわち、その思考法を理解しなければ彼の科学は 理解できないということである。 「蕾は花の開花によって消え去り、花によって蕾が論破されたと言える。同様に、果実は花を植物の偽りの存在として説明し、花は果実によって真実として置き 換えられる。これらの形態は異なるだけでなく、互いに相容れないものとして置き換えられる。しかし、その流動的な性質は、それらが有機的に統一された瞬間 を作り出す。その瞬間においては、それらは互いに矛盾するのではなく、一方が他方と同じくらい必要であり、この同じ必要性が全体の生命を構成しているの だ。 全体としての真理は、内的な目標によって推進される「部分」の、一見矛盾する展開なしには意味のある形で理解することはできない。同様に、哲学の真理は、 一見矛盾する思考方法の展開する全体性としてのみ展開され、提示することができる。したがって、序文では「成果」を概説することはできず、また過去の誤っ た意見から距離を置くこともできない。しかし、意見、目標、意図を科学の前提条件および始まりとして提示することには依然として価値があるとしても、思考 の動きそのものを生き生きとした発展として提示しなければならない。ヘーゲルは、思考の転換期に自らを位置づけている。そこでは、それまでの思考方法が互 いに消耗し尽くした後に質的な飛躍が起こる。しかし、この飛躍の結果は、まだ完全に発展した新しい科学体系ではなく、当初は単純な概念であり、理解不能で 難解に思える可能性もある。そのため、同時代の哲学潮流であるカント主義、フィヒテ、ロマン主義、特にシェリングは、当初は新しいものを拒絶した。 「一方は、物質の豊かさと理解可能性を主張し、他方は少なくともこれらを拒絶し、直接的な妥当性と神性を主張する」 形式主義的に考えられた実体(A=A)や感覚的な実体に対するヘーゲルの科学観における新しいものは、絶対の特殊な主観的性格である。 「私の考えでは、それは体系自体の提示によって正当化されなければならないが、すべては、実体としてではなく、同様に主題として真実を理解し表現すること に依存している。」 特にヘーゲルは、当時ドイツで広く浸透していたカントの二元論を克服しようとした。ヘーゲルは、それまでの哲学はすべて、立場を対立させることに固執して いるため不十分であると考えた。それらは矛盾する立場に分裂し、その間の矛盾を本質的な真理の瞬間として把握していない。彼の計画は、哲学を科学として確 立することである。しかし、ヘーゲルの診断によると、この科学的視点はまず達成されなければならない。2] したがって、彼はそれを科学への指針、あるいはまだ発展途上にある科学として理解している。 「科学一般、あるいは知識のこの発展は、この『精神現象学』が表現しているものである。」3] 彼は、意識を即座に見出されるものとして検証し、そこから真の知識や絶対的な知識へと到達しようとする。これを達成するには、心は知識そのものが何である かを理解しなければならない。ヘーゲルにとって、即座に見出される意識とは、現れる心である。それは現象学の対象である。彼の原則は次のとおりである。 「真なるものは全体である。しかし、全体とは、発展を通じて自己を完成させる本質にほかならない。絶対とは、本質的には結果であり、真の姿となるのは最終 的な段階においてのみである。そして、これがまさに、現実となること、主体となること、あるいはそれ自身となること、という絶対の本質である」[5] ヘーゲルはここで、カントの『純粋理性批判』における超越論的弁証法を暗示している。理性は知識の条件の全体性を目指し、そうすることで条件付きの絶対を 目指している。ヘーゲルの予言によると、カントは主観的な反省哲学を達成したにすぎない。なぜなら、カントにとって絶対は客観的に有効な知識の対象とはな り得ず、したがってヘーゲルの言うように、絶対とは無限の対照をなすものとして残るからである。ヘーゲルにとって、全体性とは理性の対象であるだけでな く、より高次の原理であるだけでなく、「自己理解における理性の運動であり、同時にその状態の理解でもある」[6] ものである。したがって、ヘーゲルは、真理とは硬直した結果に固執することではなく、結果と全体の発展の相互作用のみが真理を構成すると述べている。彼に とって、真実は体系としてのみ現実であり、真実を表現できるのは精神だけである。精神が自己について知ることで、ヘーゲルにとって知識は絶対的な視点を得 たように思われる。精神だけが残る。それは自己から離れ、同時に自己の中に存在する。7] 精神の内側への転回を保証し、経験的な観察に留まったり、批判することなく受け入れたりしないためには、哲学は概念の努力をしなければならない。この科学 の方法は、物事そのものの運動を提示できなければならない。 序論 『精神現象学』の序論の主題は、まず第一に、物自体と物自体のためのものとの区別に関するカントの批判である。ヘーゲルは、この区別が絶対者に関する知識 への道を閉ざし、無意味であると論じている。ヘーゲルは、まったく異なる道、彼が「絶望の道」と呼ぶものを好む。つまり、哲学者は干渉することなく、いわ ゆる自然な自己意識の過程を描写するだけでよいという意味である。意識はさまざまな形態を取らねばならず、その不十分さを認識しなければならない。そうす ることで、異なる形態に到達することができる。ヘーゲルによれば、この運動の目標は絶対精神であり、そこで意識は最終的に、自身の運動の終わりであり始ま りでもある自己を理解する。 |

| Bewusstsein Ausgangspunkt der Phänomenologie des Geistes ist die Transzendentalphilosophie Kants, in der die Bedingungen der Möglichkeit von Erkenntnis im Zusammenwirken von Anschauung, Verstand und Selbstbewusstsein (Synthetische Einheit der Apperzeption) untersucht werden. Hegel will nunmehr das Selbstbewusstsein nicht als von Kant lediglich Vorgegebenes betrachtet sehen, sondern seinen geschichtlichen Prozess des Werdens nachvollziehen, um hierbei den Nachweis zu führen, wie Bewusstsein zum Bewusstsein seiner selbst voranschreitet, um sich in dieser rückbezüglichen Selbstüberschreitung als Geist zu realisieren. Der Mensch offenbart in seinem Denken nicht nur die Logik des Seins, sondern auch sein Ichsein. Das elementarste Bewusstsein der Daseinserkenntnis ist die „sinnliche Gewissheit“. Im Laufe des gleichnamigen Kapitels versucht Hegel zu zeigen, dass, „was sie [die sinnliche Gewissheit] weiß, nur dies [...ist]: es ist; [...]“[8]. Ausgehend von der wahrgenommenen Existenz seines reinen noch bestimmunglosen Ichs („Dieser“) und der noch bestimmunglosen Gegenstände („Dieses“), sowie deren beiden Gestaltformen des Hier und Jetzt, erkennt die sinnliche Gewissheit die Allgemeinheiten dieser an. Egal, was wir sinnlich auffassen, bleibt das Hier und Jetzt erhalten. Und „[e]in solches Einfaches, das durch Negation ist, weder dieses noch jenes, ein Nichtdieses, und ebenso gleichgültig, auch dieses wie jenes zu sein, nennen wir ein Allgemeines.[9]“ Nachfolgend erkennt die sinnliche Gewissheit die Allgemeinheiten des Ich[10]., sowie die Vermittlung dieser drei Allgemeinheiten[11]. Durch die „Begierde“ erscheinen dem Subjekt die Dinge als äußere von ihm abgespaltene Wirklichkeit. Als aktiv tätiges Selbst negiert der Mensch durch sein Handeln das Dasein, und mit der Verwandlung des Daseins verändert er sich selbst. Mit diesem Nichts, der Negation in sich, ist er ein Werdender in Zeit und Geschichte. Mit der animalischen Begierde entwickelt er lediglich ein körperliches Selbstgefühl, erst insoweit sich seine Begierde nicht bloß auf einen vorgegeben konsumierbaren Gegenstand, sondern auf ein Nichtseiendes bezieht, transzendiert sein Dasein zum Selbstbewusstsein, das sich von der Befangenheit im Dasein befreien kann und zu Autonomie und Freiheit gelangt. |

認識(Bewusstsein) 精神現象学の出発点はカントの超越論哲学であり、そこでは直観、理解、自己意識(統覚)の相互作用において、認識の可能性の条件が検討されている。ヘーゲ ルは、自己意識を単にカントが与えたものとしてではなく、その歴史的なプロセスを理解することによって、意識が自己意識へとどのように進歩していくかを証 明し、この自己超越的な自己実現において、自己が精神として実現されることを理解しようとした。 彼の思考において、人間は存在の論理だけでなく、自己性をも明らかにする。 存在の知識に関する最も初歩的な意識は「感覚的確実性」である。ヘーゲルは同名の章の中で、「感覚的確信が知るものは、ただこれだけである。それは存在す る。」[8]と示そうとしている。純粋で未だ決定されていない自己(「これ」)と未だ決定されていない対象(「これ」)の存在、そして「ここ」と「今」と いう2つの形態を認識した感覚的確信は、これらの一般性を認識する。感覚で何を感じようとも、今ここは不変である。そして、「これでもあれでもない、非こ れである、これであることもあれであることも等しく無関心である、このような単純なものを、我々は一般と呼ぶ」[9]。その後、感覚的確信は、我[10] の一般性を認識し、さらにこれら3つの一般性の媒介[11]をも認識する。「欲望」を通じて、物事は主体にとって、自分から切り離された外部の現実として 現れる。能動的に関わる自己として、人間は行動を通じて存在を否定し、存在の変容とともに、自らも変化する。この無、すなわち自己内の否定によって、人間 は時間と歴史の中で「なるもの」となる。動物的な欲望によって、彼は単に肉体的な自己意識を発達させるだけである。彼の欲望が、単にあらかじめ定められた 消費可能な対象ではなく、非在へと向かう場合にのみ、彼の存在は自己意識へと超越し、存在の束縛から解放され、自律性と自由を獲得することができる。 |

| Selbstbewusstsein Herrschaft und Knechtschaft → Hauptartikel: Die Dialektik von Herr und Knecht In der Vielzahl der Begierden, die sich gegenseitig ausschließen können, kommt der Mensch in Konflikt mit seinen Mitmenschen. Im Kampf um Anerkennung gerät der Unterlegene gegenüber dem Sieger in ein Abhängigkeitsverhältnis, das ihn in die Knechtschaft führt. Durch die Arbeit des Knechts gewinnt der Herr die Freiheit über die Natur. Doch die Arbeit des Knechts bringt eine Steigerung des Denkens, Technik, Wissenschaft und Kunst hervor und einen Fortschritt hin zu einer Idee der Freiheit, die den Knecht auf revolutionäre Art von der Abhängigkeit von seinem Gebieter befreien kann. Die Geschichte ist ein Prozess der Arbeit und des Kampfes um Anerkennung, eine Geschichte der Dialektik von Herrschaft und Knechtschaft, die in eine Synthese von Herrschaft und Knechtschaft mündet. |

自己認識(Selbstbewusstsein) 支配と隷属(→主人と奴隷の関係) → 詳細は主従の弁証法を参照 相互に排他的になりうる多数の欲望において、人間は同類の人間と対立する。承認をめぐる闘争において敗者は勝者への依存関係に陥り、隷属へと導かれる。使 用人の労働を通じて、主人は自然に対する自由を得る。しかし、使用人の労働は、思想、技術、科学、芸術の深化をもたらし、使用人を革命的な方法で主人への 依存から解放する自由という概念への進歩をもたらす。 歴史とは、労働と承認の闘争のプロセスであり、支配と隷属の弁証法の歴史であり、支配と隷属の総合へと至るものである。 |

| Absolutes Wissen Das „absolute Wissen“ wird am Ende des Werkes dargestellt. Dies ist nicht etwa allumfassendes oder perfektes Wissen, in dem Sinne, dass nun nichts weiter gewusst werden kann. Das Denken ist am Ende nach Hans Friedrich Fulda eher „ein ‚Tätigkeitswissen' oder ein Wissen in der Bewegung der Reflexion, weil es nur an seinem Anderen, d. h. an Bestimmungen des Gegenstandes zum Ausdruck kommt.“[12] Im absoluten Wissen fallen Subjekt und Objekt zusammen. Nicht so, dass es keinen Unterschied mehr zwischen dem Bewusstsein und dem Gegenstand des Bewusstseins gäbe; sondern so, dass die Bewegung der Selbstvermittlung vollständig zu Bewusstsein tritt und sich der Geist dadurch als die Substanz oder der Grund ebendieser Vermittlung erkennt. Die Formen des absoluten Wissens bestehen als geoffenbarte Religion und Philosophie. Erst in der geoffenbarten Religion entsteht das Bewusstsein, dass Gott in Wahrheit Geist ist. „Der Inhalt des Vorstellens ist der absolute Geist“.[13] „Die Wissenschaft enthält sich in ihr selbst diese Notwendigkeit, der Form des reinen Begriffes sich zu entäußern, und den Übergang des Begriffs ins Bewusstsein. Denn der sich selbst wissende Geist, eben darum, dass er seinen Begriff erfasst, ist er die unmittelbare Gleichheit mit sich selbst, welche in ihrem Unterschiede die Gewißheit vom Unmittelbaren ist, oder das sinnliche Bewußtsein,– der Anfang von dem wir ausgegangen; dieses Entlassen seiner aus der Form seines Selbsts ist die höchste Freiheit und Sicherheit seines Wissens von sich.“[14] Der absolute Geist wird in der geoffenbarten Religion als das vorgestellt, was dem historischen Prozess zugrunde liegt. Es zeigt sich, dass es möglich ist, die Wirklichkeit als Substanz zu fassen. So geht die Religion in das absolute Wissen über. „Es stellt sich deshalb heraus, dass die als Substanz gedachte Wirklichkeit als Subjekt verstanden werden muss.“[15] |

絶対的な知識(Absolutes Wissen) 「絶対的な知識」は作品の最後に提示される。これは、これ以上何も知ることができないという意味で、包括的でも完璧な知識でもない。ハンス・フリードリ ヒ・フルダによると、終結における思考はむしろ「『活動の知識』または反射の運動における知識である。なぜなら、それは他者においてのみ、つまり対象の決 定においてのみ表現されるからだ」[12]。絶対的知識においては、主観と客観は一致する。意識と意識の対象との間に差異がなくなるわけではない。しか し、自己媒介の運動が完全に意識化され、それによって精神は、この媒介の物質または基盤として自己を認識する。絶対的知識の形態は、啓示宗教と哲学として 存在する。神が真に精神であるという認識が生じるのは、啓示宗教においてのみである。「提示される内容は、絶対精神である」[13]。 「科学は、純粋概念の形式と概念の意識への推移を表現する必要性を、その内に含んでいる。自己を認識する精神にとって、概念を把握することは、差異におけ る直接性、すなわち感覚的意識の確実性であり、それ自身との直接的な等価性である。この等価性は、我々がスタート地点とした、自己からの解放であり、自己 の知識における最高の自由と確実性である。」[14] 啓示宗教においては、絶対精神は歴史的過程の根底にあるものとして提示される。それは、現実を実体として把握することが可能であることを示している。した がって、宗教は絶対的な知識へと融合する。「したがって、実体として考えられる現実とは、主体として理解されなければならないことが明らかになる。」 [15] |

| Standpunkt des Idealismus Hegels Phänomenologie des Geistes ist vom Standpunkt des Idealismus vorgezeichnet, wie er in Fichtes Denken zum Ausdruck kommt, der alles Wissen auf die spontane Selbstgewissheit des absolut gesetzten Ichs (dem Selbstbewusstsein) zurückführt. Nach Fichte ist sie die erste Ursache und der absolute Grund der Welt. Allerdings bleibt von Fichtes Philosophie bei Hegel nur der Ausgangspunkt übrig: die Subjektivität. Das Absolute kann Fichte zufolge nicht erkannt, nur geglaubt werden. Auch von Schelling, für den alles außerhalb des Ich Natur ist, die wir nur anschauen, nicht aber begreifen können, setzt sich Hegel implizit ab. Der Maßstab für die Prüfung der Wahrheit des Wissens, für die Erkenntnis des Absoluten, liegt für ihn im Bewusstsein selbst – insofern ist seine Position als idealistisch zu bezeichnen. Hegel will also das ungebildete natürliche Bewusstsein auf die Höhe der Wissenschaft heben. Wahrnehmung und Empfindung seien in ein sprachlich formuliertes Allgemeines, also auf allgemeine Begriffe zu bringen. Nur insoweit ist ihre Erfassung möglich, und hier erfahren sie ihre dialektische Bewegung. In dem von Hegel im gleichnamigen Oberkapitel als „Vernunft“ Bezeichneten wird das Denken mit dem Sein identifiziert. „Die Vernunft ist die Gewissheit des Bewusstseins, alle Realität zu sein: so spricht der Idealismus ihren Begriff aus.“ (G.W.F. Hegel: Phänomenologie des Geistes, S. 179) Der Verstand gerät in seiner Entwicklung immer wieder notwendig in Widersprüche, und der Vernunft gelingt es, dies aufzugreifen und neue Begriffe zu entfalten. Als „Geist“ wird die „absolute Identität“ zum moralischen Selbstbewusstsein. In der christlichen Religion schließlich wird auch die „Menschwerdung des göttlichen Wesens“ in ein Allgemeines gedeutet: als Offenbarung der Einheit des menschlichen Selbstbewusstseins mit dem Göttlichen. Kritiker der Hegelschen Dialektik wie etwa Bernhard Lakebrink[16] verweisen u. a. darauf, dass Hegel dem Nichts zu unrecht eine Wirkmacht zuspricht. Damit wäre das Nichts jedoch nicht das Nichts, sondern eine Form des Seins. Wollte man wirklich das Sein mit dem Nicht-Sein gleichsetzen, wäre letztlich jede Aussage und ihr Gegenteil wahr und die (Hegelsche) Wissenschaft damit am Ende. |

観念論的な立場(Standpunkt des Idealismus) ヘーゲルの『精神現象学』は、フィヒテの考え方に示されているように、観念論の立場から出発している。フィヒテは、すべての知識は、絶対的に確立された自 我(自己意識)の自発的な自己確信にまで遡ることができると主張した。フィヒテによれば、それは世界の第一原因であり、絶対的な根拠である。しかし、ヘー ゲルの著作では、フィヒテの哲学の出発点である主観性のみが残っている。フィヒテによれば、絶対的なものは知ることはできず、信じるのみである。ヘーゲル はまた、自我の外にあるものはすべて自然であり、それは見ることはできても理解することはできないとするシェリングとも暗に距離を置いている。彼にとっ て、知識の真偽を試す基準、絶対的なものの知識は、意識そのものにある。この点において、彼の立場は観念論的であると表現することができる。 ヘーゲルは、無学な自然意識を科学のレベルにまで高めようとしている。知覚と感覚は、言語的に定式化された一般、つまり一般的な用語で表現することができ る。この範囲内でのみ、それらの理解が可能であり、この範囲内でそれらは弁証法的な運動を経験する。ヘーゲルが「理性」と呼ぶものについては、同名の章 で、思考は存在と同一視される。「理性とは、あらゆる現実が存在しているという意識の確信である。これが観念論がその概念を表現する方法である。」 (G.W.F.ヘーゲル著『精神現象学』179ページ)その発展において、理解は繰り返し、必然的に矛盾に陥るが、理性はこれをうまく取り入れ、新たな概 念を展開することに成功する。 「絶対同一性」は「精神」として、道徳的自覚となる。キリスト教では、最終的に「神の化身」も一般的な言葉で解釈される。すなわち、人間の自意識と神の一 体性の啓示としてである。 ベルンハルト・ラケブリンク(Bernhard Lakebrink)などのヘーゲルの弁証法の批判者は、ヘーゲルが虚無に力を与えていると指摘している。しかし、これは虚無を虚無ではなく、存在の一形 態とするものである。もし存在と非存在を同一視したいのであれば、究極的にはあらゆる主張とその反対が真実となり、(ヘーゲル的な)科学は終わりを迎える ことになる。 |

| Ausgaben (1807): Erstausgabe. Bamberg/Würzburg: Verlag Joseph Anton Goebhardt (System der Wissenschaft. Erster Theil, die Phänomenologie des Geistes), Digitalisat und Volltext im Deutschen Textarchiv (1832, 2. Auflage 1841): Werke, Bd. 2. Hg. vom Verein der Freunde des Verewigten (1907, 2. Auflage 1921, 3. 1928, 4. 1937, 5. 1949, 6. 1952): Philosophische Bibliothek, Bd. 114., hg. von G. Lasson, ab 4. Auflage hg. von J. Hoffmeister, Leipzig, ab 6. Auflage Hamburg: Felix Meiner (1970): Theorie Werkausgabe, Bd. 3. Hg. von E. Moldenhauer und K.M. Michel, Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp (heute als stw603), ISBN 3-518-28203-4) (1970, 2. Auflage 1973): Mit einem Nachwort von Georg Lukács sowie ausgewählte Texte und Kommentar zur Rezeptionsgeschichte v. Gerhard Göhler, Frankfurt/M.: Ullstein Nr. 35505. ISBN 3-548-35055-0. (1980): Gesammelte Werke (historisch-kritische Ausgabe), Bd. 9., hg. von der Rheinisch-Westfälischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wolfgang Bonsiepen und Reinhard Heede, Hbg.: Meiner. (1988): Philosophische Bibliothek, Bd. 414, beruhend auf dem Text der kritischen Edition (GW 9, 1980), neu hrsg. von Hans-Friedrich Wessels und Heinrich Clairmont, ISBN 978-3-7873-0769-2. |

エディション (1807):初版。バンベルク/ヴュルツブルク:Verlag Joseph Anton Goebhardt(科学体系。第1部、精神現象学)、デジタル化版およびドイツ語テキストアーカイブの全文 (1832、第2版1841):作品、第2巻。故人を偲ぶ会編 (1907年、第2版1921年、第3版1928年、第4版1937年、第5版1949年、第6版1952年):『哲学文庫』第114巻、G.ラッソン 編、第4版よりJ.ホフマイスター編、ライプツィヒ、第6版よりハンブルク:フェリックス・マイナー (1970):理論、作品版、第3巻。E. MoldenhauerとK.M. Michel編、フランクフルト・アム・マイン:Suhrkamp(現在ではstw603として知られている)、ISBN 3-518-28203-4) (1970年、第2版1973年):ゲオルク・ルカーチのエピローグ、およびゲルハルト・ゲーラーによる抜粋テキストと受容の歴史に関する論評付き。フラ ンクフルト・アム・マイン:Ullstein No. 35505。ISBN 3-548-35055-0。 (1980): Gesammelte Werke (historisch-kritische Ausgabe), 第9巻、ライン・ヴェストファーレン科学アカデミー編、ヴォルフガング・ボンシペンおよびラインハルト・ヘーデ、ハンブルク:マイナー。 (1988): 哲学的ライブラリー、第414巻、批判版(GW 9、1980年)のテキストに基づく、ハンス・フリードリヒ・ヴェッセルスとハインリヒ・クレアモントによる新編集、ISBN 978-3-7873-0769-2。 |

| Literatur Andreas Arndt (Hrsg.): Phänomenologie des Geistes. XXIII. Internationaler Hegel-Kongress 2000 in Zagreb. 2 Bände. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003613-3, ISBN 3-05-003712-1. Georg W. Bertram: Hegels Phänomenologie des Geistes. Ein systematischer Kommentar. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-15-961252-2. Robert Brandom: A Spirit of Trust: A Reading of Hegel’s Phenomenology. Harvard University Press, 2019. Deutsche Ausgabe: Im Geiste des Vertrauens. Eine Lektüre der »Phänomenologie des Geistes«. Aus dem Amerikanischen übersetzt von Sebastian Koth und Aaron Shoichet. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2021, ISBN 978-3-518-58769-0 Eugen Fink: Hegel. Phänomenologische Interpretation der „Phänomenologie des Geistes“. Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1977; 2. Auflage ebenda 2007, ISBN 3-465-01282-8, ISBN 3-465-03519-4, ISBN 978-3-465-03519-0. Hans Friedrich Fulda, Dieter Henrich (Hrsg.): Materialien zu Hegels „Phänomenologie des Geistes“. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-518-27609-3. Frank-Peter Hansen: G.W.F. Hegel: Phänomenologie des Geistes. Ein einführender Kommentar. Paderborn 1994, ISBN 3-8252-1826-0. Henry S. Harris: Hegel’s Ladder. 2 Bände. Hackett, Indianapolis 1997. Thomas Sören Hoffmann (Hrsg.): Hegel als Schlüsseldenker der modernen Welt. Beiträge zur Deutung der „Phänomenologie des Geistes“ aus Anlaß ihres 200-Jahr-Jubiläums, Meiner, Hamburg 2009. (online einsehbar bei Google Books) Klaus Erich Kaehler / Werner Marx: Die Vernunft in Hegels Phänomenologie des Geistes, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 978-3-465-02537-5. Alexandre Kojève: Hegel. Eine Vergegenwärtigung seines Denkens. Kommentar zur Phänomenologie des Geistes. Mit einem Anhang: Hegel, Marx und das Christentum (hrsg. von Iring Fetscher), Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp 1975, erweiterte Neuausgabe 2005. Ralf Ludwig: Hegel für Anfänger – Phänomenologie des Geistes. Eine Lese-Einführung. 4. Aufl. Dtv, München 2003, ISBN 3-423-30125-2. Werner Marx: Hegels Phänomenologie des Geistes. Die Bestimmung ihrer Idee in „Vorrede“ und „Einleitung“, Frankfurt am Main 2006 (3), ISBN 978-3-465-03494-0. John O’Donohue: Person als Vermittlung. Die Dialektik von Individualität und Allgemeinheit in Hegels "Phänomenologie des Geistes" ; eine philosophisch-theologische Interpretation (= Tübinger Studien zur Theologie und Philosophie, Bd. 4). Grünewald, Mainz 1993, ISBN 3-7867-1625-0. Tom Rockmore: Cognition: An Introduction to Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit, University of California Press, Berkeley 1997. Josef Schmidt: „Geist“, „Religion“ und „absolutes Wissen“. Ein Kommentar zu den drei gleichnamigen Kapiteln aus Hegels „Phänomenologie des Geistes“. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart/Berlin/Köln 1997. Ludwig Siep: Der Weg der Phänomenologie des Geistes, Suhrkamp Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 978-3-518-29075-0. Pirmin Stekeler-Weithofer: Hegels Phänomenologie des Geistes. Ein dialogischer Kommentar. 2 Bände. Meiner, Hamburg 2014. Klaus Vieweg / Wolfgang Welsch (Hrsg.): Hegels Phänomenologie des Geistes. Ein kooperativer Kommentar zu einem Schlüsselwerk der Moderne, Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Wissenschaft 1876, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-518-29476-5. Yirmiyahu Yovel: Hegel's Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit, Princeton 2005, ISBN 0-691-12052-8 (Übersetzung der Vorrede ins Englische bei paralleler Kommentierung fast jeden Satzes) |

文献 アンドレアス・アーント(編):『精神現象学』。第23回ヘーゲル国際会議2000(ザグレブ)。2巻。Akademie-Verlag、ベルリン 2002年、ISBN 3-05-003613-3、ISBN 3-05-003712-1。 ゲオルク・W・バートラム著『ヘーゲルの『精神現象学』。体系的な注釈』。レクラム社、シュトゥットガルト 2017年、ISBN 978-3-15-961252-2。 ロバート・ブランドン著『信頼の精神:ヘーゲルの『精神現象学』の解釈』。ハーバード大学出版局、2019年。 ドイツ語版:『信頼の精神。「精神現象学」の読解』。セバスチャン・コットとアーロン・ショワシェによる英訳。シュルカンプ、ベルリン 2021年、ISBN 978-3-518-58769-0 オイゲン・フィンク著『ヘーゲル。「精神現象学」の現象学的解釈』ヴィットリオ・クロスターマン、フランクフルト・アム・マイン 1977年、第2版 同上 2007年、ISBN 3-465-01282-8、ISBN 3-465-03519-4、ISBN 978-3-465-03519-0。 ハンス・フリードリヒ・フルダ、ディーター・ヘンリッヒ(編):ヘーゲル著『精神現象学』資料集。Suhrkamp、フランクフルト・アム・マイン 1998年、ISBN 3-518-27609-3。 フランク=ペーター・ハンゼン著『G.W.F.ヘーゲル:精神現象学。入門解説』パーダーボルン 1994年、ISBN 3-8252-1826-0。 ヘンリー・S・ハリス著『ヘーゲルの梯子』全2巻。ハケット、インディアナポリス 1997年。 トーマス・ソレン・ホフマン(編):『ヘーゲル、現代世界における鍵となる思想家。「精神現象学」の解釈への貢献、その200周年記念を機に』、マイネ ル、ハンブルク、2009年。(Googleブックスでオンライン閲覧可能) クラウス・エーリッヒ・ケーラー/ヴェルナー・マルクス著『ヘーゲルの「精神現象学」における理性』フランクフルト・アム・マイン、1992年、ISBN 978-3-465-02537-5。 アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ著『ヘーゲル。その思想の視覚化。精神現象学の注釈。付録:ヘーゲル、マルクス、キリスト教』(イリング・フェトシェール 編)、フランクフルト・アム・マイン:スールカンプ社、1975年、2005年増補新版。 ラルフ・ルートヴィヒ著『ヘーゲル入門―精神現象学。読み物形式の入門書。第4版。Dtv、ミュンヘン2003年、ISBN 3-423-30125-2。 ヴェルナー・マルクス著『ヘーゲルの精神現象学。「序文」と「序説」におけるその理念の規定』、フランクフルト・アム・マイン2006年(3)、ISBN 978-3-465-03494-0。 ジョン・オドノフー:媒介としての人間。ヘーゲルの『精神現象学』における個別性と一般性の弁証法;哲学的・神学的解釈(『神学と哲学のテュービンゲン研 究』第4巻)。グリューネヴァルト、マインツ1993年、ISBN 3-7867-1625-0。 トム・ロックモア著『認識:ヘーゲルの『精神現象学』入門』カリフォルニア大学出版局、バークレー、1997年。 ヨゼフ・シュミット著『「精神」、「宗教」、そして「絶対的知識」』ヘーゲル著『精神現象学』の同名の3章についての論評。コッホマー社、シュトゥットガ ルト/ベルリン/ケルン、1997年。 ルートヴィヒ・ジープ著『精神現象学の道』、Suhrkamp Paperback、フランクフルト・アム・マイン 2000年、ISBN 978-3-518-29075-0。 ピルミン・シュテッケラー=ヴァイトホーファー著『ヘーゲル『精神現象学』。対話形式の注釈。全2巻』、マイネル、ハンブルク 2014年。 クラウス・ヴィーゲ / ヴォルフガング・ヴェルシュ(編):『ヘーゲルの精神現象学。近代の主要著作に対する協調的注釈』、Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Wissenschaft 1876、フランクフルト・アム・マイン 2008年、ISBN 978-3-518-29476-5。 Yirmiyahu Yovel: Hegel's Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit, Princeton 2005, ISBN 0-691-12052-8 (ヘーゲルの『精神現象学』序文の英訳。ほぼすべての文章に注釈が付いている) |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ph%C3%A4nomenologie_des_Geistes |

| Vorrede |

(序文と呼ばれているもの)※精神現象学が書かれた後に、作成されたもの ※以下は熊野純彦訳(2018)が伏したインデックスとページである(上巻) ・哲学書に序文は必要か(10) ・哲学的体系どうしの関係について(12) ・教養のはじまり、実体的な生からの離脱にある(15) ・真理は学的な体系としてのみ実現される ・直接知の立場が、このことに反対している(17) ・精神の現況はどのようなものであり、哲学になにが要求されているのか(18) ・哲学に対するそのような要求の背後にあるもの(20) ・私たちの時代は誕生の時代である(24) ・登場してきたばかりの学には、避けがたく欠陥がある(25) ・学の内容と形式をめぐるあらそい(29) ・形式主義の批判——すべての牛が黒くなる夜(30) ・真なるものは主体として把握され、表現されなければならない(33) ・実在と、それをとらえる形式は不可分である(35) ・真なるものとは、自己展開してゆく全体である(37) ・アリストテレスの「不動の動者」にことよせて(41) ・主語=述語という命題形式の不十分さについて(42) ・知はただ体系としてのみ現実的なものである(43) ・真なるものは体系として現実的となるが、それは絶対的なものが精神だからである(45) ・絶対的に他であるもののうちで純粋に自己を認識すること(47) ・精神の現象学は、学一般あるいは知の生成を叙述する(50) ・精神現象学の課題——特殊な個人から普遍的な個人への道程(51) ・精神現象学が叙述するのは、世界精神が遍歴してきた形態のすべてである(54) ・熟知されていることがらは、認識されたことがらではない(56) ・表象の分析——精神の生は死に直面して、死を超える(58) ・古代における予備学のありかたは、近代のそれとは異なっている(61) ・論理学と精神現象学との関係——後者が明らかにするのは意識の世界性である(63) ・学の体系・第一部としての精神現象学の課題(64) ・意識の経験の学から思弁的哲学としての論理学へ(65) ・精神の現象学はたんに否定的な道程であるか(67) ・真理と非真理との関係について(68) ・歴史記述上の真理について(71) ・数学的な真理と哲学的な真理(72) ・数学的な認識の欠陥について(74) ・数学の目的と素材——量と空間(76) ・純粋数学と応用数学——あるいは時間について(79) ・数学的認識と対照されるかぎりでの哲学的認識について(80) ・哲学では、数学的方法はすでに時代遅れである(82) ・再び形式主義について——その自然哲学を中心に(85) ・形式主義的な「構成」の例——医学理論とその他の場合(87) ・カント的な悟性の立場と学の立場との差異(91) ・存在と思考が一致することの意味(94) ・ヌース、イデア、エイドス(97) ・存在するものはそれ自身において概念であり、形式である(99) ・序文における断言が、べつの断言によって反駁されることはない(100) ・哲学研究にさいして要求されることはなにか(101) ・詭弁的な思考の二つの側面(1)(103) ・詭弁的な思考の二つの側面(2)(105) ・命題形式・思考(108) ・哲学的テキストが難解であるとされる理由(110) ・弁証法的な運動とその叙述(112) ・命題的形式と弁証法的方式(114) ・哲学もまた修得されるべきいっこの仕事である(116) ・いわゆる健全な悟性と詩的な哲学(117) ・健全な人間悟性とその欺瞞(119) ・学問に王道はないということ(121) ・プラトン、アリストテレスの受容史にことよせて(122) ・普遍性の時代と個人の役割(125) |

| Einleitung | (序論と呼ばれているもの)※精神現象学が書かれる前に、作成されたもの |

| I. Die sinnliche Gewißheit; oder das Diese und das Meinen |

|

| II. Die Wahrnehmung; oder das Ding, und die Täuschung |

|

| III. Kraft und Verstand, Erscheinung und übersinnliche Welt |

|

| IV. Die Wahrheit der Gewißheit seiner selbst A. Selbstständigkeit und Unselbstständigkeit des Selbstbewußtseins; Herrschaft und Knechtschaft B. Freiheit des Selbstbewußtseins; Stoizismus, Skeptizismus und das unglückliche Bewußtsein |

|

| V. Gewißheit und Wahrheit der Vernunft A. Beobachtende Vernunft a. Beobachtung der Natur b. Die Beobachtung des Selbstbewußtseins in seiner Reinheit und seiner Beziehung auf äußre Wirklichkeit; logische und psychologische Gesetze c. Beobachtung der Beziehung des Selbstbewußtseins auf seine unmittelbare Wirklichkeit; Physiognomik und Schädellehre |

|

| B. Die Verwirklichung des vernünftigen Selbstbewußtseins durch sich selbst a. Die Lust und die Notwendigkeit b. Das Gesetz des Herzens und der Wahnsinn des Eigendünkels c. Die Tugend und der Weltlauf |

|

| C. Die Individualität, welche sich an und für sich selbst reell ist a. Das geistige Tierreich und der Betrug, oder die Sache selbst b. Die gesetzgebende Vernunft c. Gesetzprüfende Vernunft |

|

| VI. Der Geist A. Der wahre Geist, die Sittlichkeit a. Die sittliche Welt, das menschliche und göttliche Gesetz, der Mann und das Weib b. Die sittliche Handlung, das menschliche und göttliche Wissen, die Schuld und das Schicksal c. Rechtszustand |

|

| B. Der sich entfremdete Geist; die Bildung I. Die Welt des sich entfremdeten Geistes a. Die Bildung und ihr Reich der Wirklichkeit b. Der Glauben und die reine Einsicht II. Die Aufklärung a. Der Kampf der Aufklärung mit dem Aberglauben b. Die Wahrheit der Aufklärung III. Die absolute Freiheit und der Schrecken |

|

| C. Der seiner selbst gewisse Geist. Die Moralität a. Die moralische Weltanschauung b. Die Verstellung c. Das Gewissen, die schöne Seele, das Böse und seine Verzeihung |

|

| VII. Die Religion A. Natürliche Religion a. Das Lichtwesen b. Die Pflanze und das Tier c. Der Werkmeister |

|

| B. Die Kunst-Religion a. Das abstrakte Kunstwerk b. Das lebendige Kunstwerk c. Das geistige Kunstwerk C. Die offenbare Religion |

|

| VIII. Das absolute Wissen | |

| https://www.marxists.org/deutsch/philosophie/hegel/phaenom/ |

★英語ウィキペディアからの記事

| The

Phenomenology of

Spirit (German: Phänomenologie

des Geistes) is the most

widely-discussed philosophical work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel;

its German title can be translated as either The Phenomenology of

Spirit or The Phenomenology of Mind. Hegel described the work,

published in 1807, as an "exposition of the coming to be of

knowledge".[1] This is explicated through a necessary self-origination

and dissolution of "the various shapes of spirit as stations on the way

through which spirit becomes pure knowledge".[1] The book marked a significant development in German idealism after Immanuel Kant. Focusing on topics in metaphysics, epistemology, ontology, ethics, history, religion, perception, consciousness, existence, logic, and political philosophy, it is where Hegel develops his concepts of dialectic (including the lord-bondsman dialectic), absolute idealism, ethical life, and Aufhebung. It had a profound effect in Western philosophy, and "has been praised and blamed for the development of existentialism, communism, fascism, death of God theology, and historicist nihilism".[2] |

『精神現象学』(せいしんげんしょうがく、ドイツ語:

Phänomenologie des

Geistes)は、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルの最も広く議論されている哲学書である。ヘーゲルは1807年に出版されたこの著作

を「知の到来についての説明」[1]と説明しており、これは「精神が純粋な知となる途中の駅としての精神の様々な形」の必要な自己発生と分解を通して説明

されている[1]。 本書は、イマヌエル・カント以降のドイツ観念論における重要な発展を示した。形而上学、認識論、存在論、倫理学、歴史、宗教、知覚、意識、存在、論理学、 政治哲学のトピックに焦点を当て、ヘーゲルが弁証法(主従弁証法を含む)、絶対的観念論、倫理的生活、アウフヘーヴングの概念を発展させた。ヘーゲルは西 洋哲学に多大な影響を与え、「実存主義、共産主義、ファシズム、神の死神学、歴史主義的ニヒリズムの発展のために称賛されたり非難されたりしてきた」 [2]。 |

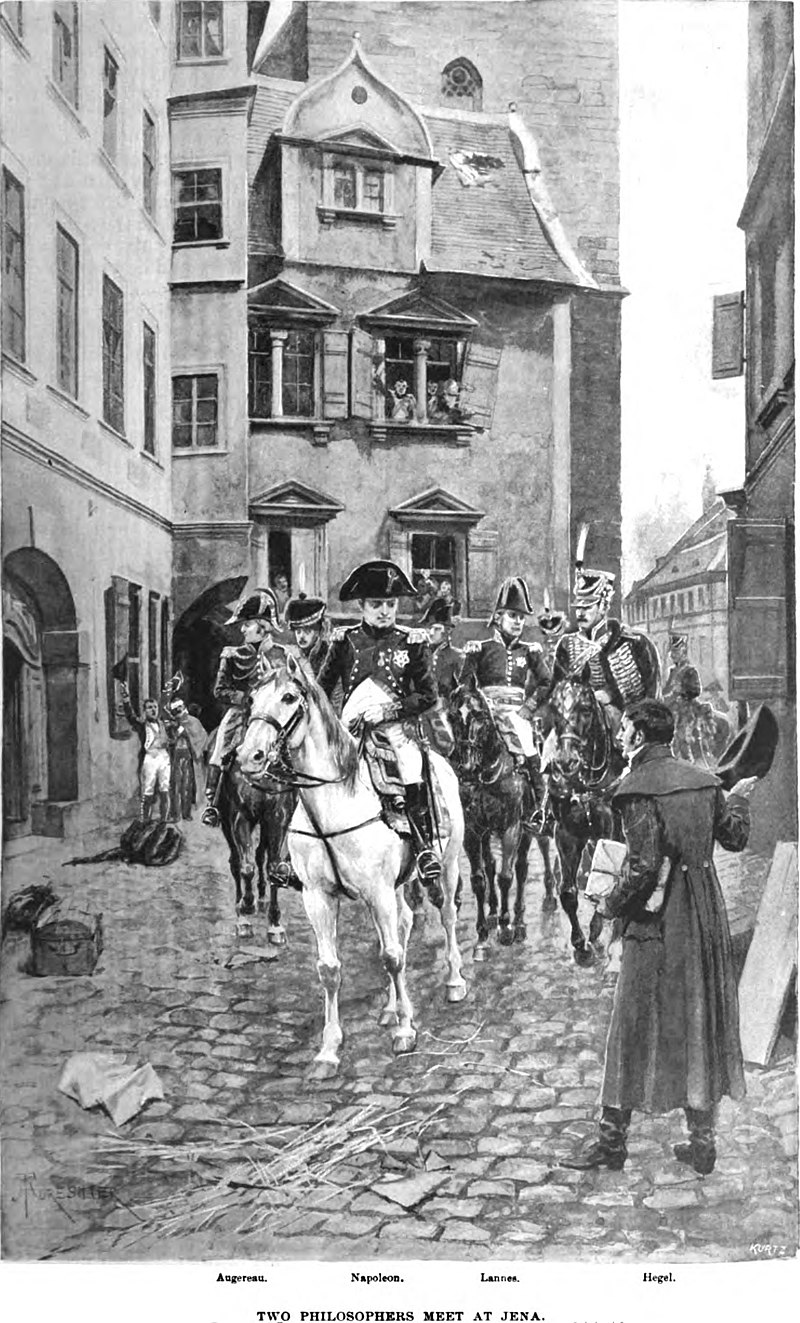

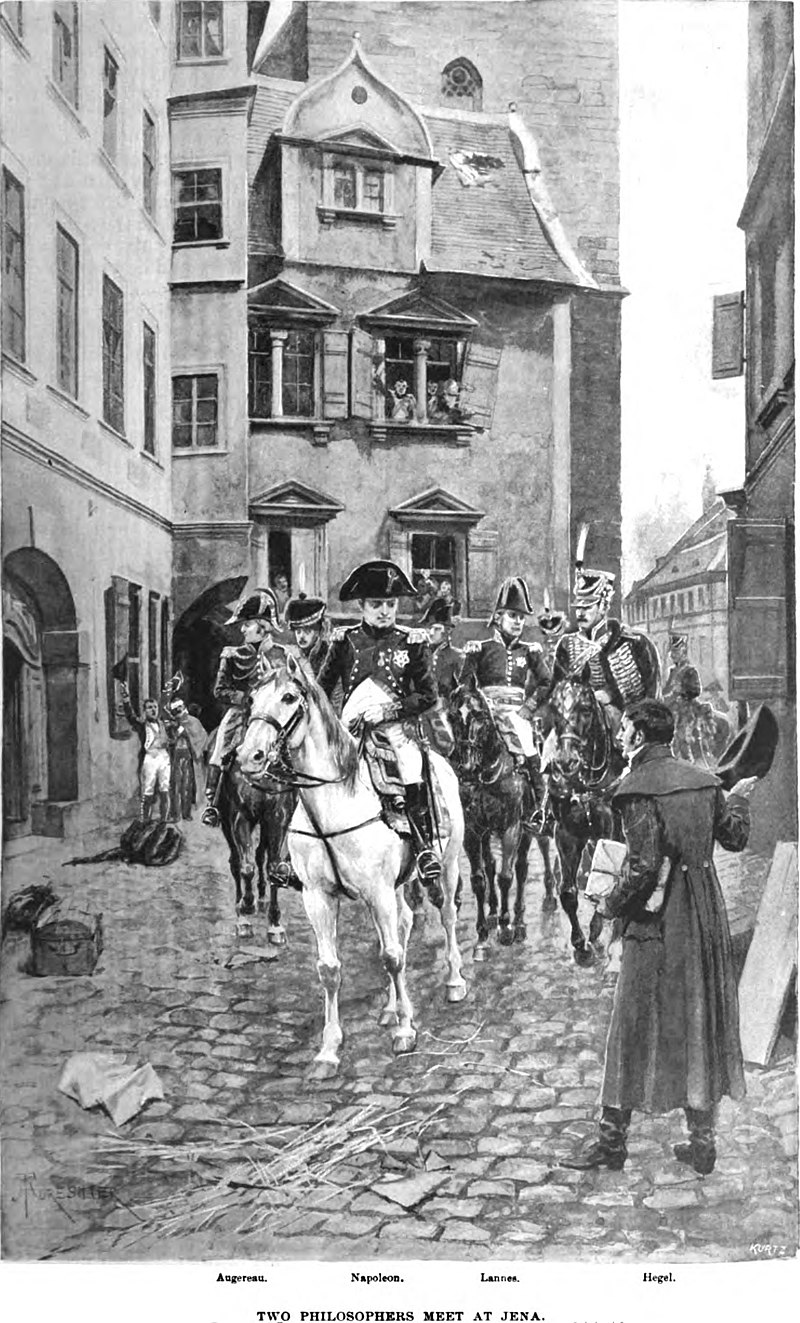

| Historical context "Hegel and Napoleon in Jena" (illustration from Harper's Magazine, 1895) Hegel was putting the finishing touches to this book as Napoleon engaged Prussian troops on October 14, 1806, in the Battle of Jena on a plateau outside the city. On the day before the battle, Napoleon entered the city of Jena. Later that same day, Hegel wrote a letter to his friend, the theologian Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer: I saw the Emperor – this world-soul – riding out of the city on reconnaissance. It is indeed a wonderful sensation to see such an individual, who, concentrated here at a single point, astride a horse, reaches out over the world and masters it ... this extraordinary man, whom it is impossible not to admire.[3] In 2000, Terry Pinkard notes that Hegel's comment to Niethammer "is all the more striking since at that point he had already composed the crucial section of the Phenomenology in which he remarked that the Revolution had now officially passed to another land (Germany) that would complete 'in thought' what the Revolution had only partially accomplished in practice."[4] |

歴史的背景 イエナにおけるヘーゲルとナポレオン」(1895年『ハーパーズ・マガジン』からの挿絵) ナポレオンが1806年10月14日、イエナ郊外の台地でプロイセン軍とイエナの戦いで交戦したとき、ヘーゲルはこの本の仕上げをしていた。戦いの前日、 ナポレオンはイエナ市内に入った。その日のうちに、ヘーゲルは友人である神学者フリードリヒ・イマヌエル・ニーテンマーに手紙を書いた: 私は皇帝が、この世界魂が、偵察のために街を走り出すのを見た。このような個人を見るのは実に素晴らしい感覚である。馬にまたがり、この一点に集中し、世 界に手を伸ばし、世界を支配する......この非凡な人物を賞賛しないことは不可能である」[3]。 2000年、テリー・ピンカードは、ニーチェンマーに対するヘーゲルのコメントについて、「その時点で彼はすでに『現象学』の重要な部分を構成しており、 その中で、革命が実践において部分的にしか達成できなかったことを『思想において』完成させるであろう別の土地(ドイツ)に、革命は公式に移ったのだと述 べていたのだから、なおさら印象的である」と指摘している[4]。 |

| Publication history The Phenomenology of Spirit was published with the title “System of Science: First Part: The Phenomenology of Spirit”.[5] Some copies contained either "Science of the Experience of Consciousness", or "Science of the Phenomenology of Spirit" as a subtitle between the "Preface" and the "Introduction".[5] On its initial publication, the work was identified as Part One of a projected "System of Science", which would have contained the Science of Logic "and both the two real sciences of philosophy, the Philosophy of Nature and the Philosophy of Spirit”[6] as its second part. The Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences, in its third section (Philosophy of Spirit), contains a second subsection (The Encyclopedia Phenomenology) that recounts in briefer and somewhat altered form the major themes of the original Phenomenology. |

出版の経緯 『精神の現象学』は「科学の体系」というタイトルで出版された: 第一部: また、「序文」と「序論」の間に副題として「意識の経験の科学」または「精神の現象学の科学」が含まれているものもあった[5]。最初の出版時、この著作 は、論理学の科学と哲学の2つの真の科学である「自然の哲学」と「精神の哲学」[6]をその第2部として含む「科学の体系」の第1部として特定された。哲 学諸科学百科事典』は、その第3部(精神の哲学)に第2部(現象学百科事典)を含み、オリジナルの現象学の主要なテーマをより簡潔かついくぶん変更した形 で詳述している。 |

| The book consists of a Preface

(written after the rest was completed), an Introduction, and six major

divisions (of greatly varying size).[a] (A) Consciousness is divided into three chapters: (I) Sensuous-Certainty, (II) Perceiving, and (III) Force and the Understanding. (B) Self-Consciousness contains one chapter: (IV) The Truth of Self-Certainty which contains a preliminary discussion of Life and Desire, followed by two subsections: (A) Self-Sufficiency and Non-Self-Sufficiency of Self-Consciousness; Mastery and Servitude and (B) Freedom of Self-Consciousness: Stoicism, Skepticism, and the Unhappy Consciousness. Notable is the presence of the discussion of the dialectic of the lord and bondsman.[to whom?] (C), (AA) Reason contains one chapter: (V) The Certainty and Truth of Reason which is divided into three chapters: (A) Observing Reason, (B) The Actualization of Rational Self-Consciousness Through Itself, and (C) Individuality, Which, to Itself, is Real in and for Itself. (BB) Spirit contains one chapter: (VI) Spirit or Geist which is again divided into three chapters: (A) True Spirit, Ethical Life, (B) Spirit Alienated from Itself: Cultural Formation, and (C) Spirit Certain of Itself: Morality. (CC) Religion contains one chapter: (VII) Religion, which is divided into three chapters: (A) Natural Religion, (B) The Art-Religion, and (C) Revealed Religion. (DD) Absolute Knowing contains one chapter: (VIII) Absolute Knowing.[b] Due to its obscure nature and the many works by Hegel that followed its publication, even the structure or core theme of the book itself remains contested. First, Hegel wrote the book under close time constraints with little chance for revision (individual chapters were sent to the publisher before others were written). Furthermore, according to some readers, Hegel may have changed his conception of the project over the course of the writing. Secondly, the book abounds with both highly technical argument in philosophical language, and concrete examples, either imaginary or historical, of developments by people through different states of consciousness. The relationship between these is disputed: whether Hegel meant to prove claims about the development of world history, or simply used it for illustration; whether or not the more conventionally philosophical passages are meant to address specific historical and philosophical positions; and so forth. Jean Hyppolite famously interpreted the work as a Bildungsroman that follows the progression of its protagonist, Spirit, through the history of consciousness,[9] a characterization that remains prevalent among literary theorists. However, others contest this literary interpretation and instead read the work as a "self-conscious reflective account"[10] that a society must give of itself in order to understand itself and therefore become reflective. Martin Heidegger saw it as the foundation of a larger "System of Science" that Hegel sought to develop,[11] while Alexandre Kojève saw it as akin to a "Platonic Dialogue ... between the great Systems of history."[12] It has also been called "a philosophical roller coaster ... with no more rhyme or reason for any particular transition than that it struck Hegel that such a transition might be fun or illuminating."[13] |

本書は、序文(残りの部分が完成した後に書かれた)、序論、および6つ

の主要な部門(大きさは大きく異なる)で構成されている[a]。 (A)意識は3つの章に分かれている: (I)感覚的確信、 (II) 知覚、そして (III)力と理解。 (B)自己意識は1章からなる: (IV)自己意識の真理は、生命と欲望についての予備的議論を含み、(A)自己意識の自己充足と非自己充足、支配と隷属、(B)自己意識の自由という2つ のサブセクションが続く: ストイシズム、懐疑主義、不幸な意識。特筆すべきは、主君と束縛者の弁証法についての議論があることである。 (C)、(AA)理性は1章を含む: (A)理性を観察すること、(B)理性的自己意識のそれ自身による実現、(C)個性、それはそれ自身にとって、それ自身において、またそれ自身のために実 在する。 (BB)精神には1つの章がある: (A)真の精神、倫理的生命、(B)それ自身から疎外された精神: A)真の精神、倫理的生活、(B)それ自身から疎外された精神、文化的形成、(C)それ自身を確信する精神: 道徳。 (CC)宗教には1つの章がある: (A)自然宗教、(B)芸術宗教、(C)啓示宗教。 (DD)絶対的知には1つの章がある: (VIII)絶対知[b]。 その曖昧な性質と、出版後に出版されたヘーゲルによる多くの著作のために、この本自体の構造や核となるテーマさえも論争されたままである。第一に、ヘーゲ ルは時間的制約の中で本書を執筆し、改訂の機会はほとんどなかった(個々の章は、他の章が執筆される前に出版社に送られた)。さらに、一部の読者によれ ば、ヘーゲルは執筆の過程でプロジェクトの構想を変更した可能性があるという。第二に、この本には、哲学的な言葉による高度に専門的な議論と、さまざまな 意識状態を通じて人々が発展していく具体的な例(想像的なものであれ歴史的なものであれ)の両方があふれている。ヘーゲルが世界史の発展についての主張を 証明するつもりだったのか、それとも単に説明のために使ったのか、より慣習的な哲学的文章が特定の歴史的・哲学的立場を取り上げるためのものなのか、など など。 ジャン・イポリットはこの作品を、意識の歴史を通して主人公スピリットの成長を描くビルドゥングスロマンと解釈したことで有名であり[9]、この解釈は文 学理論家の間で今でも広く浸透している。しかし、この文学的解釈に異議を唱え、その代わりにこの作品を、社会が自らを理解し、それゆえに反省的になるため に自らに与えなければならない「自意識的反省的説明」[10]として読む者もいる。マルティン・ハイデガーはこの作品を、ヘーゲルが発展させようとしたよ り大きな「科学の体系」の基礎であるとみなし[11]、アレクサンドル・コジェーヴはこの作品を「歴史の偉大な体系間の......プラトニックな対話」 のようなものであるとみなしている[12]。 |

| Preface The Preface to the text is a preamble to the scientific system and cognition in general. Paraphrased “on scientific cognition" in the table of contents, its intent is to offer a rough idea on scientific cognition, while at the same time aiming "to rid ourselves of a few forms which are only impediments to philosophical cognition".[14] As Hegel’s own announcement noted, it was to explain "what seems to him the need of philosophy in its present state; also about the presumption and mischief of the philosophical formulas that are currently degrading philosophy, and about what is altogether crucial in it and its study".[15] It can thus be seen as a heuristic attempt at creating the need of philosophy (in the present state) and of what philosophy itself in its present state needs. This involves an exposition on the content and standpoint of philosophy, i.e, the true shape of truth and the element of its existence, that is interspersed with polemics aimed at the presumption and mischief of philosophical formulas and what distinguishes it from that of any previous philosophy, especially that of his German Idealist predecessors (Kant, Fichte, and Schelling).[16] The Hegelian method consists of actually examining consciousness' experience of both itself and of its objects and eliciting the contradictions and dynamic movement that come to light in looking at this experience. Hegel uses the phrase "pure looking at" (reines Zusehen) to describe this method. If consciousness just pays attention to what is actually present in itself and its relation to its objects, it will see that what looks like stable and fixed forms dissolve into a dialectical movement. Thus, philosophy, according to Hegel, cannot just set out arguments based on a flow of deductive reasoning. Rather, it must look at actual consciousness, as it really exists. Hegel also argues strongly against the epistemological emphasis of modern philosophy from Descartes through Kant, which he describes as having to first establish the nature and criteria of knowledge prior to actually knowing anything, because this would imply an infinite regress, a foundationalism that Hegel maintains is self-contradictory and impossible. Rather, he maintains, we must examine actual knowing as it occurs in real knowledge processes. This is why Hegel uses the term "phenomenology". "Phenomenology" comes from the Greek word for "to appear", and the phenomenology of mind is thus the study of how consciousness or mind appears to itself. In Hegel's dynamic system, it is the study of the successive appearances of the mind to itself, because on examination each one dissolves into a later, more comprehensive and integrated form or structure of mind. |

序文 序文は、科学的体系と認識一般についての前置きである。目次に「科学的認識について」とあるように、この序文の意図は、科学的認識についての大まかな考え 方を提示すると同時に、「哲学的認識にとって障害でしかないいくつかの形式を取り除くこと」を目指すことにある。 [14] ヘーゲル自身の発表が述べているように、それは「現在の状態における哲学の必要性と思われるもの、また現在哲学を劣化させている哲学的公式の僭越と誤謬に ついて、そして哲学とその研究において全く重要なものは何か」について説明することであった。これには、哲学の内容と立場、すなわち真理の真の姿とその存 在の要素についての説明が含まれ、哲学的公式の僭称と悪意、そして哲学をそれまでの哲学、特に彼のドイツ観念論的先達(カント、フィヒテ、シェリング)の 哲学と区別するものを目的とした極論が散りばめられている[16]。 ヘーゲルの方法は、意識が自分自身とその対象の両方について経験することを実際に検証し、この経験を見ることで浮かび上がってくる矛盾と動的な動きを引き 出すことからなる。ヘーゲルはこの方法を説明するのに、「純粋に見る」(reines Zusehen)という言葉を用いている。もし意識が、自分自身の中に実際に存在するもの、そしてその対象との関係に注意を払うだけなら、安定した固定し た形に見えるものが弁証法的な運動へと溶けていくのがわかるだろう。このように、ヘーゲルによれば、哲学は演繹的な推論の流れに基づいて議論を展開するだ けではだめなのである。むしろ、実際に存在する意識を見なければならない。 ヘーゲルはまた、デカルトからカントに至る近代哲学の認識論的強調に強く反対している。カントは、実際に何かを知る前に、まず知識の性質と基準を確立しな ければならないと述べているが、これは無限の逆行を意味するからであり、ヘーゲルが自己矛盾であり不可能だと主張する基礎論である。なぜなら、それは無限 後退を意味するからであり、ヘーゲルが主張する基礎主義は自己矛盾であり不可能だからである。これが、ヘーゲルが「現象学」という言葉を使う理由である。 「現象学」は「現れる」という意味のギリシャ語に由来しており、心の現象学とは、意識や心がそれ自体にどのように現れるかを研究することである。ヘーゲル の力動的体系では、心のそれ自身に対する連続的な出現の研究である。なぜなら、吟味の結果、それぞれの出現は、後の、より包括的で統合された心の形態や構 造に溶解するからである。 |

| Introduction Whereas the Preface was written after Hegel completed the Phenomenology, the Introduction was written beforehand. In the Introduction, Hegel addresses the seeming paradox that we cannot evaluate our faculty of knowledge in terms of its ability to know the Absolute without first having a criterion for what the Absolute is, one that is superior to our knowledge of the Absolute. Yet, we could only have such a criterion if we already had the improved knowledge that we seek. To resolve this paradox, Hegel adopts a method whereby the knowing that is characteristic of a particular stage of consciousness is evaluated using the criterion presupposed by consciousness itself. At each stage, consciousness knows something, and at the same time distinguishes the object of that knowledge as different from what it knows. Hegel and his readers will simply "look on" while consciousness compares its actual knowledge of the object—what the object is "for consciousness"—with its criterion for what the object must be "in itself". One would expect that, when consciousness finds that its knowledge does not agree with its object, consciousness would adjust its knowledge to conform to its object. However, in a characteristic reversal, Hegel explains that under his method, the opposite occurs. As just noted, consciousness' criterion for what the object should be is not supplied externally but rather by consciousness itself. Therefore, like its knowledge, the "object" that consciousness distinguishes from its knowledge is really just the object "for consciousness"—it is the object as envisioned by that stage of consciousness. Thus, in attempting to resolve the discord between knowledge and object, consciousness inevitably alters the object as well. In fact, the new "object" for consciousness is developed from consciousness' inadequate knowledge of the previous "object". Thus, what consciousness really does is to modify its "object" to conform to its knowledge. Then the cycle begins anew as consciousness attempts to examine what it knows about this new "object". The reason for this reversal is that, for Hegel, the separation between consciousness and its object is no more real than consciousness' inadequate knowledge of that object. The knowledge is inadequate only because of that separation. At the end of the process, when the object has been fully "spiritualized" by successive cycles of consciousness' experience, consciousness will fully know the object and at the same time fully recognize that the object is none other than itself. At each stage of development, Hegel, adds, "we" (Hegel and his readers) see this development of the new object out of the knowledge of the previous one, but the consciousness that we are observing does not. As far as it is concerned, it experiences the dissolution of its knowledge in a mass of contradictions, and the emergence of a new object for knowledge, without understanding how that new object has been born. |

序論 『序文』がヘーゲルの『現象学』完成後に書かれたのに対し、『序論』はその前に書かれた。 序論においてヘーゲルは、絶対者とは何かという基準、すなわち絶対者についてのわれわれの知識よりも優れた基準をまず持たなければ、絶対者を知る能力とい う観点からわれわれの知識能力を評価することはできないという、一見パラドックスに見える問題を取り上げている。しかし、私たちがそのような基準を持つこ とができるのは、私たちが求める改善された知識をすでに持っている場合だけである。 このパラドックスを解決するために、ヘーゲルは、意識の特定の段階に特徴的な「知ること」を、意識そのものが前提とする基準を用いて評価するという方法を 採用する。各段階において、意識は何かを知っていると同時に、その知識の対象を、自分が知っているものとは異なるものとして区別する。ヘーゲルとその読者 は、意識が対象についての実際の知識-対象が「意識にとって」何であるか-を、対象が「それ自体において」何でなければならないかという基準と比較する 間、ただ「見守る」ことになる。意識は、自分の知識がその対象と一致しないことがわかると、自分の知識をその対象に適合させるように調整するだろう、と予 想するだろう。しかし、ヘーゲルは特徴的な逆転の発想で、彼の方法のもとではその逆のことが起こると説明する。 先にも述べたように、対象がどうあるべきかという意識の基準は、外部から供給されるのではなく、むしろ意識自身によって供給される。したがって、その知識 と同様に、意識がその知識から区別する「対象」は、実際には「意識にとっての」対象にすぎない--それは、意識のその段階が思い描く対象なのである。した がって、知識と対象との間の不和を解消しようとすると、意識は必然的に対象も変えてしまう。実際、意識にとっての新しい「対象」は、以前の「対象」に対す る意識の不十分な知識から発展したものである。したがって、意識が実際に行っていることは、その「対象」を自分の知識に適合するように修正することであ る。そして、意識がこの新しい「対象」について知っていることを調べようとするので、サイクルが新たに始まる。 この逆転の理由は、ヘーゲルにとって、意識とその対象との間の分離は、意識がその対象について不十分な知識を持っていること以上に現実的なものではないか らである。知識が不十分なのは、その分離があるからにほかならない。過程の最後には、対象が意識の経験の連続的なサイクルによって完全に「精神化」された とき、意識は対象を完全に知り、同時に対象が自分自身にほかならないことを完全に認識する。 それぞれの発展段階において、「われわれ」(ヘーゲルとその読者)は、前の対象についての知識から新しい対象が発展していくのを見るが、われわれが観察し ている意識はそうではない。ヘーゲルに関する限り、ヘーゲルはその知識が矛盾の塊の中に溶解し、知識のための新たな対象が出現するのを経験するが、その新 たな対象がどのようにして誕生したのかは理解できないのである。 |

| Important concepts Hegelian dialectic See also: Georg_Wilhelm_Friedrich_Hegel § Dialectics,_speculation,_idealism The famous dialectical process of thesis–antithesis–synthesis has been controversially attributed to Hegel. Whoever looks for the stereotype of the allegedly Hegelian dialectic in Hegel's Phenomenology will not find it. What one does find on looking at the table of contents is a very decided preference for triadic arrangements. ... But these many triads are not presented or deduced by Hegel as so many theses, antitheses, and syntheses. It is not by means of any dialectic of that sort that his thought moves up the ladder to absolute knowledge. — Walter Kaufmann (1965). Hegel. Reinterpretation, Texts, and Commentary. p. 168. Regardless of (ongoing) academic controversy regarding the significance of a unique dialectical method in Hegel's writings, it is true, as Professor Howard Kainz (1996) affirms, that there are "thousands of triads" in Hegel's writings. Importantly, instead of using the famous terminology that originated with Kant and was elaborated by J. G. Fichte, Hegel used an entirely different and more accurate terminology for dialectical (or as Hegel called them, "speculative") triads. Hegel used two different sets of terms for his triads, namely, "abstract–negative–concrete" (especially in his Phenomenology of 1807), as well as "immediate–mediate–concrete" (especially in his Science of Logic of 1812), depending on the scope of his argumentation. When one looks for these terms in his writings, one finds so many occurrences that it may become clear that Hegel employed the Kantian using a different terminology. Hegel explained his change of terminology. The triad terms "abstract–negative–concrete" contain an implicit explanation for the flaws in Kant's terms. The first term, "thesis", deserves its anti-thesis simply because it is too abstract. The third term, "synthesis", has completed the triad, making it concrete and no longer abstract by absorbing the negative. Sometimes Hegel used the terms "immediate–mediate–concrete, to describe his triads. The most abstract concepts are those that present themselves to our consciousness immediately. For example, the notion of Pure Being for Hegel was the most abstract concept of all. The negative of this infinite abstraction would require an entire Encyclopedia, building category by category, dialectically, until it culminated in the category of Absolute Mind or Spirit (since the German word Geist can mean either 'mind' or 'spirit'). Unfolding of species Further information: Spiritual evolution Hegel describes a sequential progression from inanimate objects to animate creatures to human beings. This is frequently compared to Charles Darwin's evolutionary theory.[citation needed] However, unlike Darwin, Hegel thought that organisms had agency in choosing to develop along this progression by collaborating with other organisms.[17][18] Hegel understood this to be a linear process of natural development with a predetermined end. He viewed this end teleologically as its ultimate purpose and destiny.[17][19][20] |

重要な概念 ヘーゲル弁証法 も参照: ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル§弁証法、_思弁、_理想主義 テーゼ-アンチテーゼ-シンセシスという有名な弁証法的過程は、ヘーゲルによるものと論争されてきた。 ヘーゲルの『現象学』のなかに、ヘーゲル弁証法とされるものの固定観念を探す人は、それを見つけることはできないだろう。目次を見るとわかるのは、三項対 立的な配置を非常に好んでいることである。... しかし、これらの多くの三項対立は、ヘーゲルによって多くのテーゼ、アンチテーゼ、シンセシスとして提示されたり、推論されたりしているわけではない。 ヘーゲルの思想が絶対知への階段を上るのは、その種の弁証法によるのではない。 - ヴァルター・カウフマン (1965). ヘーゲル。再解釈、テクスト、注釈』168頁。 ヘーゲルの著作における独自の弁証法的方法の意義に関する(現在進行中の)学術的論争にかかわらず、ハワード・カインツ教授(1996)が断言するよう に、ヘーゲルの著作には「何千もの三段論法」が存在するのは事実である。重要なのは、カントに端を発し、J.G.フィヒテによって精緻化された有名な用語 を用いる代わりに、ヘーゲルは弁証法的(あるいはヘーゲルが「思弁的」と呼ぶ)三項対立に対して、まったく異なる、より正確な用語を用いたことである。 すなわち、「抽象-否定-具体」(特に1807年の『現象学』において)と「即時-中間-具体」(特に1812年の『論理学』において)である。 ヘーゲルの著作の中でこれらの用語を探すと、非常に多くの用語が出てくるので、ヘーゲルが異なる用語を使ってカント派を採用していたことが明らかになるか もしれない。 ヘーゲルは用語の変更をこう説明している。抽象-否定-具体」という三項対立の用語には、カントの用語の欠陥に対する暗黙の説明が含まれている。最初の用 語である「テーゼ」は、抽象的すぎるという理由だけで、反テーゼに値する。第三の用語である「総合」は、否定を吸収することによって三項対立を具体化し、 抽象的でなくした。 ヘーゲルは三項対立を「即時-中間-具体」という言葉で表現することがある。最も抽象的な概念とは、私たちの意識に即座に現れる概念である。例えば、ヘー ゲルにとっての純粋存在の概念は、最も抽象的な概念であった。この無限に抽象化された概念を否定するには、『百科全書』全体が必要であり、範疇をひとつひ とつ弁証法的に構築し、絶対的な心または精神(ドイツ語のGeistは「心」または「精神」のいずれかを意味する)の範疇に達するまでである。 種の展開 さらなる情報 霊的進化 ヘーゲルは、無生物から有生物、そして人間へと順次進化していくと述べている。これはチャールズ・ダーウィンの進化論とよく比較される[要出典]。しか し、ダーウィンとは異なり、ヘーゲルは、生物は他の生物と協力することによって、この進行に沿って発展することを選択する主体性を持っていると考えた [17][18]。彼はこの終末を究極的な目的であり運命であると遠隔論的に捉えていた[17][19][20]。 |

| Criticism Walter Kaufmann, on the question of organisation, argued that Hegel's arrangement, "over half a century before Darwin published his Origin of Species and impressed the idea of evolution on almost everybody's mind, was developmental."[21] The idea is supremely suggestive but, in the end, untenable according to Kaufmann: "The idea of arranging all significant points of view in such a single sequence, on a ladder that reaches from the crudest to the most mature, is as dazzling to contemplate as it is mad to try seriously to implement it".[22] While Kaufmann viewed Hegel as right in seeing that the way a view is reached is not necessarily external to the view itself, since, on the contrary, a knowledge of the development, including the prior positions through which a human being passed before adopting a position may make all the difference when it comes to comprehending his or her position, some aspects of the conception are still somewhat absurd and some of the details bizarre.[23] Kaufmann also remarks that the very table of contents of the Phenomenology may be said to "mirror confusion" and that "faults are so easy to find in it that it is not worth while to adduce heaps of them."[citation needed] However, he excuses Hegel since he understands that the author of the Phenomenology "finished the book under an immense strain".[24] The feminist philosopher Kelly Oliver argues that Hegel’s discussion of women in The Phenomenology of Spirit undermines the entirety of the text. Oliver points out that for Hegel, every element of consciousness must be conceptualizable, but that in Hegel’s discussion of the family, woman is established as in principle unconceptualizable. Oliver writes that “unlike the master or slave, the feminine or woman does not contain the dormant seed of its opposite.” This means that Hegel’s feminine is nothing other than the negation of the masculine and as such it must be excluded from the story of masculine consciousness. Thus, Oliver argues, the Phenomenology of Spirit is a phenomenology of masculine consciousness; the universalist pretensions of the text are not achieved, as it leaves out the phenomenology of feminine consciousness.[25] Referencing The work is usually abbreviated as PdG (Phänomenologie des Geistes), followed by the pagination or paragraph number of the German original edition. It is also abbreviated as PS (The Phenomenology of Spirit) or as PM (The Phenomenology of Mind), followed by the pagination or paragraph number of the English translation used by each author. |

批判 ダーウィンが『種の起源』を出版し、ほとんどすべての人の心に進化の考えを印象づける半世紀以上も前に、ヘーゲルの配置は発展的なものであった」 [21]。 [22]カウフマンは、ある見解に到達する方法は必ずしもその見解自体の外部にあるわけではない、それどころか、ある立場を採用する前に人間が通過した先 行する立場を含む発展についての知識は、その立場を理解する上ですべての違いをもたらすかもしれない、というヘーゲルの見方は正しいとしながらも、その観 念のいくつかの側面は依然としていくぶん不合理であり、いくつかの細部は奇妙である。 [23]カウフマンはまた、『現象学』の目次そのものが「混乱を映し出す鏡」であり、「欠点を見つけるのは非常に簡単であり、それを山ほど挙げるのは割に 合わない」[citation needed]と述べているが、彼は『現象学』の著者が「膨大な緊張の下でこの本を書き上げた」ことを理解しているので、ヘーゲルを弁解している [24]。 フェミニストの哲学者であるケリー・オリバーは、『精神現象学』におけるヘーゲルの女性論は、このテクスト全体を根底から覆すものであると論じている。オ リヴァーは、ヘーゲルにとって意識のあらゆる要素は概念化可能でなければならないが、ヘーゲルの家族に関する議論では、女性は原理的に概念化不可能なもの として確立されていると指摘する。オリヴァーは、「主人や奴隷とは異なり、女性や女には、その正反対のものの眠っている種が含まれていない」と書いてい る。つまり、ヘーゲルのいう女性性とは、男性性の否定以外の何ものでもなく、そのようなものとして、男性性の意識の物語から排除されなければならないとい うことである。このようにオリヴァーは、『精神の現象学』は男性的意識の現象学であり、女性的意識の現象学が省かれているため、このテクストの普遍主義的 な気取りは達成されていないと主張する[25]。 参照 この著作は通常PdG(Phänomenologie des Geistes)と略され、その後にドイツ語原版のページ番号または段落番号が続く。また、PS (The Phenomenology of Spirit)またはPM (The Phenomenology of Mind)と略されることもある。 |

| English translations G. W. F. Hegel: The Phenomenology of Spirit, translated by Peter Fuss and John Dobbins (University of Notre Dame Press, 2019) Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: The Phenomenology of Spirit (Cambridge Hegel Translations), translated by Terry Pinkard (Cambridge University Press, 2018) ISBN 0-52185579-9 Hegel: The Phenomenology of Spirit: Translated with introduction and commentary, translated by Michael Inwood (Oxford University Press, 2018) ISBN 0-19879062-7 Phenomenology of Spirit, translated by A. V. Miller with analysis of the text and foreword by J. N. Findlay (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977) ISBN 0-19824597-1 Phenomenology of Mind, translated by J. B. Baillie (London: Harper & Row, 1967) Hegel's Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit, translated with introduction, running commentary and notes by Yirmiyahu Yovel (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004) ISBN 0-69112052-8. Texts and Commentary: Hegel's Preface to His System in a New Translation With Commentary on Facing Pages, and "Who Thinks Abstractly?", translated by Walter Kaufmann (South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press, 1977) ISBN 0-26801069-2. "Introduction", "The Phenomenology of Spirit", translated by Kenley R. Dove, in Martin Heidegger, "Hegel's Concept of Experience" (New York: Harper & Row, 1970) "Sense-Certainty", Chapter I, "The Phenomenology of Spirit", translated by Kenley R. Dove, "The Philosophical Forum", Vol. 32, No 4 "Stoicism", Chapter IV, B, "The Phenomenology of Spirit", translated by Kenley R. Dove, "The Philosophical Forum", Vol. 37, No 3 "Absolute Knowing", Chapter VIII, "The Phenomenology of Spirit", translated by Kenley R. Dove, "The Philosophical Forum", Vol. 32, No 4 Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit: Selections Translated and Annotated by Howard P. Kainz. The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-27101076-2 Phenomenology of Spirit selections translated by Andrea Tschemplik and James H. Stam, in Steven M. Cahn, ed., Classics of Western Philosophy (Hackett, 2007) Hegel's Phenomenology of Self-consciousness: text and commentary [A translation of Chapter IV of the Phenomenology, with accompanying essays and a translation of "Hegel's summary of self-consciousness from 'The Phenomenology of Spirit' in the Philosophical Propaedeutic"], by Leo Rauch and David Sherman. State University of New York Press, 1999. |

http://www.waste.org/~roadrunner/Hegel/PhenSpirit/index.html Preface Vorrede Introduction Einleitung A. Consciousness I. Sense-Certainty, This, & Meaning Die sinnliche Gewißheit; oder das Diese und das Meinen II. Perception, Thing, & Deceptiveness II. Die Wahrnehmung; oder das Ding, und die Täuschung III. Force & Understanding III. Kraft und Verstand, Erscheinung und übersinnliche Welt B. Self-Consciousness IV. True Nature of Self-Certainty IV. Die Wahrheit der Gewißheit seiner selbst A. Lordship & Bondage A. Selbstständigkeit und Unselbstständigkeit des Selbstbewußtseins;Herrschaft und Knechtschaft B. Unhappy Consciousness B. Freiheit des Selbstbewußtseins; Stoizismus, Skeptizismus und das unglückliche Bewußtsein Reason's Certainty and Reason's Truth Gewissdheit und Wahrheit der Vernu Physiognomik und SchNft> Observation as a Process of Reason A Beobachtende Vernunft Free Concrete Mind Freeheit und Wahrheit der Vernunft Reason Beobachtende Vernunft Physiognomy and Phrenology Physiognomik und Schädellehre Realization of Rational Self-Consciousness B Die Verwirklichung des vernünftigen Selbstbewußtseins durch sich selbst Pleasure and Necessity a Die Lust und die Notwendigkeit The Law of the Heart b Das Gesetz des Herzens und der Wahnsinn des Eigendünkels Virtue and the Course of the World” c Die Tugend und der Weltlauf Individuality C Die Individualität Self-Contained Individuals a Das geistige Tierreich und der Betrug, oder die Sache selbst Reason as Lawgiver Die gesetzgebende Vernunft Reason as Testing Law c Gesetzprüfende Vernunft Spirit VI Der Geist Objective Spirit: The Ethical Order A Der wahre Geist , die Sittlichkeit The Ethical World a Die sittliche Welt, Guilt and Destiny die Schuld und das Schicksal Legal Status c Rechtszustand Status The Spirit in Self-Estrangement Der sich entfremdete Geist; The World of Spirit in Self-Estrangement Die Welt des sich entfremdeten Geistes Culture and its Realm of Actuality Die Bildung und ihr Reich der Wirklichkeit Belief and Pure Insight Der Glauben und die reine Einsicht Enlightenment Die Aufklärung The Struggle of Enlightenment and Superstition Der Kampf der Aufklärung mit dem Aberglauben The Truth of Enlightenment Die Wahrheit der Aufklärung Absolute Freedom and Terror Die absolute Freiheit und der Schrecken Morality Die Moralität The Moral View of the World a Die moralische Weltanschauung Dissemblance Die Verstellung Conscience Das Gewissen, die schöne Seele, das Böse und seine Verzeihung Religion Die Religion Natural Religion Natürliche Religion Religion in the Form of Art Die Kunst-Religion The Abstract Work of Art Das abstrakte Kunstwerk The Living Work of Art Das lebendige Kuntswerk Religion in the Form of Art : Das geistige Kunstwerk Revealed Religion Die offenbare Religion Absolute Knowledge Absolute Wissen |

| Process theology Sittlichkeit The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology Weltgeist De divisione naturae |

プロセス神学 シトリヒカイト ヨーロッパ科学の危機と超越論的現象学 世界主義 自然分割論 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Phenomenology_of_Spirit |

★目次(→「G.W.F.ヘーゲル『精神現象学』1807年への入門」で詳述)

1812-1816 大論理学 (Wissenschaft der Logik、1812-16年)

| Phänomenologie

des Geistes |

Hegel’s

Phenomenology of Mind |

| Eine Erklärung,

wie sie einer Schrift in einer Vorrede nach der Gewohnheit

vorausgeschickt wird -- über den Zweck, den der Verfasser sich in ihr

vorgesetzt, sowie über die Veranlassungen und das Verhältnis, worin er

sie zu andern frühern oder gleichzeitigen Behandlungen desselben

Gegenstandes zu stehen glaubt -- scheint bei einer philosophischen

Schrift nicht nur überflüssig, sondern um der Natur der Sache willen

sogar unpassend und zweckwidrig zu sein. Denn wie und was von

Philosophie in einer Vorrede zu sagen schicklich wäre -- etwa eine

historische Angabe der Tendenz und des Standpunkts, des allgemeinen

Inhalts und der Resultate, eine Verbindung von hin und her sprechenden

Behauptungen und Versicherungen über das Wahre --, kann nicht für die

Art und Weise gelten, in der die philosophische Wahrheit darzustellen

sei. -- |

§ 1. In the case

of a philosophical work it seems not only superfluous, but, in view of

the nature of philosophy, even inappropriate and misleading to begin,

as writers usually do in a preface, by explaining the end the author

had in mind, the circumstances which gave rise to the work, and the

relation in which the writer takes it to stand to other treatises on

the same subject, written by his predecessors or his contemporaries.

For whatever it might be suitable to state about philosophy in a

preface -- say, an historical sketch of the main drift and point of

view, the general content and results, a string of desultory assertions

and assurances about the truth -- this cannot be accepted as the form

and manner in which to expound philosophical truth. |

●加藤尚武・プロジェクト

序章 『精神現象学』の成立をめぐる謎

第1章 『精神現象学』の基本概念―「序文」と「緒 論」

第2章 知と対象の関係構造―意識

第3章 他者との関係のなかで思索し、生きる自覚的 な存在―自己意識

第4章 世界を自己とみなす自己意識(1)―観察す る理性

第5章 世界を自己とみなす自己意識(2)―行為す る理性

第6章 和解に至る「精神」の歴史

第7章 精神の自己認識の完成―宗教

第8章 精神の旅の終着駅―絶対知

★(再掲):目次(→「G.W.F.ヘーゲル『精神現象学』1807年への入門」で詳述)

| Hegel's

Phenomenology of Mind(英独対照表示) |

Phänomenologie des Geistes(英独対照表示) |

|

| 1 |

精神現象学はひとつのプランのもとに書か

れているか? |

序章 『精神現象学』の成立をめぐる謎 |

| 2 |

精神現象学は体系においてどういう位置づ

けをもつか? |

|

| 3 |

自著広告(の妙味) |

|

| 4 |

哲学体系の自己完結性とそれへの導入 |

第1章 『精神現象学』の基本概念―「序 文」と「緒 論」 |

| 5 |

実体=主体論 |

|

| 6 |

反省哲学とその克服|「緒論」の意識 |

|

| 7 |

感覚的確信の弁証法 |

第2章 知と対象の関係構造―意識 |

| 8 |

知覚と物の矛盾構造 |

|

| 9 |

悟性と力 |

|

| 10 |

意識論を克服する経験が「生」への自覚と

なる |

第3章 他者との関係のなかで思索し、生 きる自覚的 な存在―自己意識 |

| 11 |

世界のうちで関係が拓かれるとき——承認

をめぐる闘い |

|

| 12 |

自由への覚醒——ストア主義の内面への逃

亡と懐疑主義の否定する自由 |

|

| 13 |

神に近づくことが神に背くことになる不幸

な意識 |

|

| 14 |

世界のなかに「自己」を見出す観念論 |

第4章 世界を自己とみなす自己意識 (1)―観察す る理性 |

| 15 |

自然の観察 |

|

| 16 |

人間の観察 |

|

| 17 |

行為する理性の社会的なかかわり——理性

的な自己意識の自分自身による実現 |

第5章 世界を自己とみなす自己意識 (2)―行為す る理性 |

| 18 |

世間という大きな書物 |

|

| 19 |