主人と奴隷の関係

(テキスト)

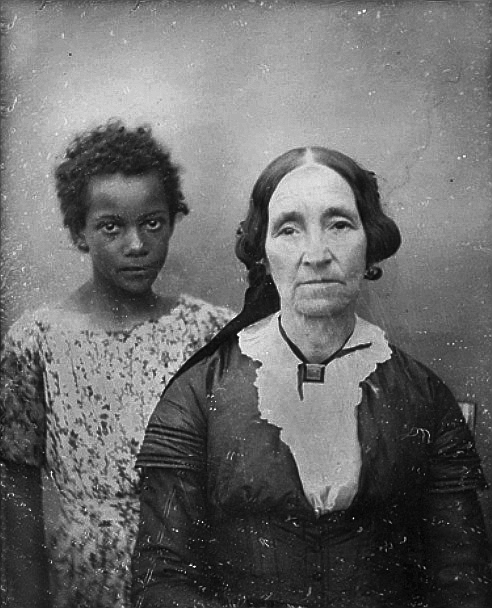

Hegel, Herrschaft und Knechtschaft

From Left to right; «Two women in a garden face each other. The one on the right is drinking from a long glass offered to her by a serving-woman in a blue smock. . . . Espalier trees against a red-brick wall provide the background». (Virginia Surtees, Dante Gabriel Rossetti 1828-1882, The Paintings and Drawings – A Catalogue Raisonneé, 1971, no. 112, 2 volumes, vol. I., p.68)/ Die Völker des Erdballs : nach ihrer Abstammung und Verwandtschaft, und ihren Eigenthümlichkeiten in Regierungsform, Religion, Sitte und Tracht by Heinrich Karl Wilhelm Berhaus, published 1845-1847./ Portrait of an older woman in New Orleans with her enslaved servant girl in the mid-19th century☆ 『精神現象学』の同名の章の第一部で、G.W.F.ヘーゲルは自己意識 の弁証法的運動を提示する。自己意識の両方の瞬間は、それぞれの他者を認識することによって、自己のうちに、また自己のために統一性を見出す。こうして自 己意識と主観性は、すでに純粋に間主観的なものとして展開される(→解説編はこちら「主人と奴隷の関係(解説編)」;アクチュアル な奴隷制は「奴隷の哲学」へリンクしてください)。

★ 以下は、『精神現象学』B.自己意識、IV.自己確信の真理、A.支配と隷属の当該ページとその翻訳です。

| Selbstständigkeit und Unselbstständigkeit des Selbstbewußtseins; Herrschaft und Knechtschaft | 自己意識の独立と非独立;支配と隷属 |

| Das Selbstbewußtsein ist an und

für sich, indem, und dadurch, daß es für ein Anderes an und für sich

ist; d.h. es ist nur als ein Anerkanntes. Der Begriff dieser seiner

Einheit in seiner Verdopplung, der sich im Selbstbewußtsein

realisierenden Unendlichkeit, ist eine vielseitige und vieldeutige

Verschränkung, so daß die Momente derselben teils genau

auseinandergehalten, teils in dieser Unterscheidung zugleich auch als

nicht unterschieden, oder immer in ihrer entgegengesetzten Bedeutung

genommen und erkannt werden müssen. Die Doppelsinnigkeit des

Unterschiedenen liegt in dem Wesen des Selbstbewußtseins, unendlich,

oder unmittelbar das Gegenteil der Bestimmtheit, in der es gesetzt ist,

zu sein. Die Auseinanderlegung des Begriffs dieser geistigen Einheit in

ihrer Verdopplung stellt uns die Bewegung des Anerkennens dar. |

自己意識は、それ自身の中にあり、それ自身のためにあるという事実を通

して、別のもののためにある。この単一性の二重の概念、すなわち自己意識においてそれ自身を実現する無限性の概念は、多面的であいまいなもつれであり、そ

れゆえ、その瞬間は部分的に正確に区別されなければならず、部分的にはこの区別においても、区別されないものとして、あるいは常に反対の意味においてとら

えられ、認識されなければならない。区別されたものの二重の意味は、自己意識が無限であるという性質、あるいは自己意識が設定されている決定性とは正反対

であるという性質にある。二重の意味を持つこの精神的統一の概念を解体することは、認識の動きを私たちに提示する。 |

| Es ist für das Selbstbewußtsein

ein anderes Selbstbewußtsein; es ist außer sich gekommen. Dies hat die

gedoppelte Bedeutung, erstlich, es hat sich selbst verloren, denn es

findet sich als ein anderes Wesen; zweitens, es hat damit das Andere

aufgehoben, denn es sieht auch nicht das Andere als Wesen, sondern sich

selbst im Andern. |

自己意識にとって、それはもうひとつの自己意識である。このことは二重の意味を持っている。第一に、自らを見失い、別の存在として自らを見出すからである。第二に、それによって他者を取り消すからである。他者を存在として見るのではなく、他者の中に自らを見るからである。 |

| Es muß dies sein Anderssein

aufheben; dies ist das Aufheben des ersten Doppelsinnes, und darum

selbst ein zweiter Doppelsinn; erstlich, es muß darauf gehen, das

andere selbstständige Wesen aufzuheben, um dadurch seiner als des

Wesens gewiß zu werden; zweitens geht es hiemit darauf, sich selbst

aufzuheben, denn dies Andere ist es selbst. |

これは第一の二重感覚の廃止であり、したがってそれ自体が第二の二重感覚である。第一に、それによって存在者としての自分自身を認識するために、独立した他の存在を廃止しようと努めなければならない。 |

| Dies doppelsinnige Aufheben

seines doppelsinnigen Andersseins ist ebenso eine doppelsinnige

Rückkehr in sich selbst; denn erstlich erhält es durch das Aufheben

sich selbst zurück; denn es wird sich wieder gleich durch das Aufheben

seines Andersseins; zweitens aber gibt es das andere Selbstbewußtsein

ihm wieder ebenso zurück, denn es war sich im Andern, es hebt dies sein

Sein im Andern auf, entläßt also das andere wieder frei. |

この二重感覚的な他者性の二重感覚的なキャンセルは、同様に二重感覚的なそれ自身への回帰でもある。第一に、それはキャンセルを通して自分自身を取り戻す。なぜなら、それは他者性のキャンセルを通して再び自分自身のようになるからである。 |

| Diese Bewegung des

Selbstbewußtseins in der Beziehung auf ein anderes Selbstbewußtsein ist

aber auf diese Weise vorgestellt worden, als das Tun des Einen; aber

dieses Tun des Einen hat selbst die gedoppelte Bedeutung, ebensowohl

sein Tun als das Tun des Andern zu sein; denn das Andere ist ebenso

selbstständig, in sich beschlossen, und es ist nichts in ihm, was nicht

durch es selbst ist. Das erste hat den Gegenstand nicht vor sich, wie

er nur für die Begierde zunächst ist, sondern einen für sich seienden

selbstständigen, über welchen es darum nichts für sich vermag, wenn er

nicht an sich selbst dies tut, was es an ihm tut. Die Bewegung ist also

schlechthin die gedoppelte beider Selbstbewußtsein. Jedes sieht das

Andre dasselbe tun, was es tut; jedes tut Selbst, was es an das Andre

fodert; und tut darum, was es tut, auch nur insofern, als das Andre

dasselbe tut; das einseitige Tun wäre unnütz; weil, was geschehen soll,

nur durch beide zustande kommen kann. |

しかし、別の自己意識との関係におけるこの自己意識の運動は、このよう

にして、一方の作用として示されてきた。しかし、この一方の作用は、それ自体、その作用であると同時に、他方の作用でもあるという二重の意味をもってい

る。最初のものは、最初は欲望のためだけにあるように、その前に対象を持っているのではなく、それ自身のために存在する独立した対象を持っている。した

がって運動とは、両者の二重の自己意識なのである。それぞれが、自分がすることと同じことをしている他方を見る。それぞれが、他方に要求することを自分自

身にもする。 |

| Das Tun ist also nicht nur

insofern doppelsinnig, als es ein Tun ebensowohl gegen sich als gegen

das Andre, sondern auch insofern, als es ungetrennt ebensowohl das Tun

des Einen als des Andern ist. |

したがって、行為とは、それ自身に対する行為であると同時に、他者に対する行為でもあるという点で、曖昧であるだけでなく、分離することなく、一方の行為であると同時に他方の行為でもある。 |

| In dieser Bewegung sehen wir

sich den Prozeß wiederholen, der sich als Spiel der Kräfte darstellte,

aber im Bewußtsein. Was in jenem für uns war, ist hier für die Extreme

selbst. Die Mitte ist das Selbstbewußtsein, welches sich in die Extreme

zersetzt, und jedes Extrem ist diese Austauschung seiner Bestimmtheit,

und absoluter Übergang in das entgegengesetzte. Als Bewußtsein aber

kommt es wohl außer sich, jedoch ist es in seinem Außer-sich-sein

zugleich in sich zurückgehalten, für sich, und sein Außer-sich ist für

es. Es ist für es, daß es unmittelbar anderes Bewußtsein ist, und nicht

ist; und ebenso, daß dies Andere nur für sich ist, indem es sich als

für sich Seiendes aufhebt, und nur im Für-sich-sein des Andern für sich

ist. Jedes ist dem andern die Mitte, durch welche jedes sich mit sich

selbst vermittelt und zusammenschließt, und jedes sich und dem Andern

unmittelbares für sich seiendes Wesen, welches zugleich nur durch diese

Vermittlung so für sich ist. Sie anerkennen sich als gegenseitig sich

anerkennend. |

この動きには、力の拮抗として現れたプロセスの繰り返しが、意識におい

て見られる。その過程では私たちのためにあったものが、ここでは極端なもの自身のためにある。中心は自己意識であり、自己意識は両極端に分解し、それぞれ

の極端は決定権の交換であり、その反対への絶対的な移行である。しかし、意識として、それは確かにそれ自身の外側にあるが、それ自身の外側にあることで、

それは同時に、それ自身のために、それ自身の内側に引き留められ、その外側はそれ自身のためにある。そして同様に、この他者は自分自身のためにしか存在せ

ず、自分自身のために存在することを打ち消し、他者が自分自身のために存在することにおいてのみ、自分自身のために存在するのである。それぞれが他者に

とっての中心であり、その中心を通してそれぞれが自分自身と媒介し一体化する。互いが互いを認識することによって、互いが互いを認識するのである。 |

| Dieser reine Begriff des

Anerkennens, der Verdopplung des Selbstbewußtseins in seiner Einheit,

ist nun zu betrachten, wie sein Prozeß für das Selbstbewußtsein

erscheint. Er wird zuerst die Seite der Ungleichheit beider darstellen,

oder das Heraustreten der Mitte in die Extreme, welche als Extreme sich

entgegengesetzt, und das eine nur Anerkanntes, der andre nur

Anerkennendes ist. |

この純粋な「認識」の概念、すなわち自己意識がその統一性において倍増

することについては、その過程が自己意識に現れるものとして、今考えなければならない。それはまず、両者の不平等の側面、つまり両極端への中心の出現を表

すだろう。両極端は互いに対立し、一方は認識されるものでしかなく、他方は認識されるものでしかない。 |

| Das Selbstbewußtsein ist

zunächst einfaches Für-sich-sein, sichselbstgleich durch das

Ausschließen alles andern aus sich; sein Wesen und absoluter Gegenstand

ist ihm Ich; und es ist in dieser Unmittelbarkeit, oder in diesem Sein

seines Für-sich-seins, Einzelnes. Was Anderes für es ist, ist als

unwesentlicher, mit dem Charakter des Negativen bezeichneter

Gegenstand. Aber das Andre ist auch ein Selbstbewußtsein; es tritt ein

Individuum einem Individuum gegenüber auf. So unmittelbar auftretend

sind sie füreinander in der Weise gemeiner Gegenstände; selbstständige

Gestalten, in das Sein des Lebens – denn als Leben hat sich hier der

seiende Gegenstand bestimmt – versenkte Bewußtsein, welche füreinander

die Bewegung der absoluten Abstraktion, alles unmittelbare Sein zu

vertilgen, und nur das rein negative Sein des sichselbstgleichen

Bewußtseins zu sein, noch nicht vollbracht, oder sich einander noch

nicht als reines Für-sich-sein, das heißt als Selbstbewußtsein

dargestellt haben. Jedes ist wohl seiner selbst gewiß, aber nicht des

Andern, und darum hat seine eigne Gewißheit von sich noch keine

Wahrheit; denn seine Wahrheit wäre nur, daß sein eignes Für-sich-sein

sich ihm als selbstständiger Gegenstand, oder, was dasselbe ist, der

Gegenstand sich als diese reine Gewißheit seiner selbst dargestellt

hätte. Dies aber ist nach dem Begriffe des Anerkennens nicht möglich,

als daß wie der Andere für ihn, so er für den Andern, jeder an sich

selbst durch sein eigenes Tun, und wieder durch das Tun des andern,

diese reine Abstraktion des Für-sich-seins vollbringt. |

その本質であり絶対的な対象は「私」であり、この即時性において、ある

いは「私」であるという存在において、「私」は個である。アンドレにとって他者とは、否定によって特徴づけられる実体のない対象である。しかし、アンドレ

はまた自己意識でもある。このように直接的に現れることで、両者は互いに共通の対象である。独立した形体であり、生命の存在に浸された意識であり、ここで

は現存する対象が自らを生命として決定しているのだが、両者は互いに、すべての直接的な存在を消滅させ、自己と同じ意識の純粋に否定的な存在となる、とい

う絶対的抽象化の運動をまだ成し遂げていない。なぜなら、その真実は、自分自身の存在-自我-が独立した対象として自分に提示されたこと、あるいは、同じ

ことであるが、その対象が自分自身のこの純粋な確信として自分に提示されたことにほかならないからである。他者が自分のためにするように、自分も他者のた

めにするのであり、それぞれが自分自身の行為を通して、また他者の行為を通して、自分自身のための存在という純粋な抽象化を達成するのである。 |

| Die Darstellung seiner aber als

der reinen Abstraktion des Selbstbewußtseins besteht darin, sich als

reine Negation seiner gegenständlichen Weise zu zeigen, oder es zu

zeigen, an kein bestimmtes Dasein geknüpft, an die allgemeine

Einzelnheit des Daseins überhaupt nicht, nicht an das Leben geknüpft zu

sein. Diese Darstellung ist das gedoppelte Tun; Tun des Andern, und Tun

durch sich selbst. Insofern es Tun des Andern ist, geht also jeder auf

den Tod des Andern. Darin aber ist auch das zweite, das Tun durch sich

selbst, vorhanden; denn jenes schließt das Daransetzen des eignen

Lebens in sich. Das Verhältnis beider Selbstbewußtsein ist also so

bestimmt, daß sie sich selbst und einander durch den Kampf auf Leben

und Tod bewähren. – Sie müssen in diesen Kampf gehen, denn sie müssen

die Gewißheit ihrer selbst, für sich zu sein, zur Wahrheit an dem

Andern und an ihnen selbst erheben. Und es ist allein das Daransetzen

des Lebens, wodurch die Freiheit, wodurch es bewährt wird, daß dem

Selbstbewußtsein nicht das Sein, nicht die unmittelbare Weise, wie es

auftritt, nicht sein Versenktsein in die Ausbreitung des Lebens – das

Wesen, sondern daß an ihm nichts vorhanden, was für es nicht

verschwindendes Moment wäre, daß es nur reines Für-sich-sein ist. Das

Individuum, welches das Leben nicht gewagt hat, kann wohl als Person

anerkannt werden; aber es hat die Wahrheit dieses Anerkanntseins als

eines selbstständigen Selbstbewußtseins nicht erreicht. Ebenso muß

jedes auf den Tod des andern gehen, wie es sein Leben daransetzt; denn

das Andre gilt ihm nicht mehr als es selbst; sein Wesen stellt sich ihm

als ein Andres dar, es ist außer sich; es muß sein Außersichsein

aufheben; das Andre ist mannigfaltig befangenes und seiendes

Bewußtsein; es muß sein Anderssein als reines Für-sich-sein oder als

absolute Negation anschauen. |

しかし、自己意識の純粋な抽象としての表象は、自らをその客観的態様の純

粋な否定として示すこと、あるいは、いかなる特定の存在にも束縛されないこと、存在の一般的特異性にまったく束縛されないこと、生命に束縛されないことを

示すことで成り立っている。この表象は二重の行為であり、他者の行為であり、それ自身を通しての行為である。他者の行為である限り、それぞれが他者の死に

向かう。しかし、この中には、第二の、自分自身を通して行うことも存在する。二つの自己意識の関係は、このように、生死を賭けた闘いによって、自分自身と

互いを証明するように決定される。-

二人はこの闘争に入らなければならない。なぜなら、二人は自分自身の確かさ、自分自身のための存在であることを、相手と自分自身の中の真実にまで高めなけ

ればならないからである。そして、自由が証明されるのは、生命を身にまとうことによってのみであり、それによって、自己意識が存在することではなく、それ

が現れる直接的な方法でもなく、生命の膨張の中に没入することでもなく、本質であることが証明されるのである。生きる勇気のない個人は、確かに人として認

識されうるが、独立した自己意識として認識される真理には到達していない。なぜなら、他者はもはや自分自身として自分に当てはまらないからである。自分の

存在は他者として自分に提示され、それは自分自身の外にある。 |

| Diese Bewährung aber durch den

Tod hebt ebenso die Wahrheit, welche daraus hervorgehen sollte, als

damit auch die Gewißheit seiner selbst überhaupt auf; denn wie das

Leben die natürliche Position des Bewußtseins, die Selbstständigkeit

ohne die absolute Negativität, ist, so ist er die natürliche Negation

desselben, die Negation ohne die Selbstständigkeit, welche also ohne

die geforderte Bedeutung des Anerkennens bleibt. Durch den Tod ist zwar

die Gewißheit geworden, daß beide ihr Leben wagten, und es an ihnen und

an dem Andern verachteten; aber nicht für die, welche diesen Kampf

bestanden. Sie heben ihr in dieser fremden Wesenheit, welches das

natürliche Dasein ist, gesetztes Bewußtsein, oder sie heben sich, und

werden als die für sich sein wollenden Extreme aufgehoben. Es

verschwindet aber damit aus dem Spiele des Wechsels das wesentliche

Moment, sich in Extreme entgegengesetzter Bestimmtheiten zu zersetzen;

und die Mitte fällt in eine tote Einheit zusammen, welche in tote, bloß

seiende, nicht entgegengesetzte Extreme zersetzt ist; und die beiden

geben und empfangen sich nicht gegenseitig voneinander durch das

Bewußtsein zurück, sondern lassen einander nur gleichgültig, als Dinge,

frei. Ihre Tat ist die abstrakte Negation, nicht die Negation des

Bewußtseins, welches so aufhebt, daß es das Aufgehobene aufbewahrt und

erhält, und hiemit sein Aufgehobenwerden überlebt. |

生が意識の自然な立場であり、絶対的な否定を伴わない独立であるよう

に、死はその自然な否定であり、独立を伴わない否定であり、それゆえ認識という必要な意味を持たないままである。死によって、両者がその生を敢行し、両者

と他者を軽蔑したことは確かになった。彼らは、自然な存在であるこの異質な存在に設定された意識を高めるか、自分自身を高め、自分自身のためになりたい極

端な存在として取り消される。しかし、正反対の決定である両極端への分解の本質的な瞬間は、こうして変化の戯れから消え去り、中心は死んだ統一体へと崩壊

し、それは死んだ、ただ存在する、正反対でない両極端へと分解される。両者は意識を通して互いに与え合うことも、受け取り合うこともせず、ただ物自体とし

て、無関心に、自由に互いを離れるだけである。両者の行為は抽象的な否定であって、意識の否定ではない。意識は、廃絶されたものを保存し維持するような方

法で廃絶し、それによって廃絶されたものを存続させるのである。 |

| In dieser Erfahrung wird es dem

Selbstbewußtsein, daß ihm das Leben so wesentlich als das reine

Selbstbewußtsein ist. Im unmittelbaren Selbstbewußtsein ist das

einfache Ich der absolute Gegenstand, welcher aber für uns oder an sich

die absolute Vermittlung ist, und die bestehende Selbstständigkeit zum

wesentlichen Momente hat. Die Auflösung jener einfachen Einheit ist das

Resultat der ersten Erfahrung; es ist durch sie ein reines

Selbstbewußtsein, und ein Bewußtsein gesetzt, welches nicht rein für

sich, sondern für ein Anderes, das heißt, als seiendes Bewußtsein oder

Bewußtsein in der Gestalt der Dingheit ist. Beide Momente sind

wesentlich; – da sie zunächst ungleich und entgegengesetzt sind, und

ihre Reflexion in die Einheit sich noch nicht ergeben hat, so sind sie

als zwei entgegengesetzte Gestalten des Bewußtseins; die eine das

selbstständige, welchem das Für-sich-sein, die andere das

unselbstständige, dem das Leben oder das Sein für ein Anderes das Wesen

ist; jenes ist der Herr, dies der Knecht. |

この経験において、生命が純粋な自己意識と同様に自己意識にとって不可

欠であることが明らかになる。直接的な自己意識においては、単純な「私」が絶対的な対象であり、それはしかし、私たちのため、あるいはそれ自身のための絶

対的な媒介であり、その本質的な瞬間として現存する独立性を持っている。その単純な単一性の解消は、最初の経験の結果である。それを通して、純粋な自己意

識が確立され、純粋に自分のためではなく、別のもののため、つまり、存在意識として、あるいは事物の形の意識としての意識が確立される。両者の瞬間は本質

的なものである。最初は不平等で対立しており、統一への反映がまだ生じていないため、両者は対立する2つの意識形態のようなものである。一方は独立的なも

のであり、自分自身のための存在こそが本質であり、他方は従属的なものであり、生命や他者のための存在こそが本質である。 |

| Der Herr ist das für sich

seiende Bewußtsein, aber nicht mehr nur der Begriff desselben, sondern

für sich seiendes Bewußtsein, welches durch ein anderes Bewußtsein mit

sich vermittelt ist, nämlich durch ein solches, zu dessen Wesen es

gehört, daß es mit selbstständigem Sein oder der Dingheit überhaupt

synthesiert ist. Der Herr bezieht sich auf diese beiden Momente, auf

ein Ding, als solches, den Gegenstand der Begierde, und auf das

Bewußtsein, dem die Dingheit das Wesentliche ist; und, indem er a) als

Begriff des Selbstbewußtseins unmittelbare Beziehung des Für-sich-seins

ist, aber b) nunmehr zugleich als Vermittlung, oder als ein

Für-sich-sein, welches nur durch ein Anderes für sich ist, so bezieht

er sich a) unmittelbar auf beide, und b) mittelbar auf jedes durch das

andere. Der Herr bezieht sich auf den Knecht mittelbar durch das

selbstständige Sein; denn eben hieran ist der Knecht gehalten; es ist

seine Kette, von der er im Kampfe nicht abstrahieren konnte, und darum

sich als unselbstständig, seine Selbstständigkeit in der Dingheit zu

haben, erwies. Der Herr aber ist die Macht über dies Sein, denn er

erwies im Kampfe, daß es ihm nur als ein Negatives gilt; indem er die

Macht darüber, dies Sein aber die Macht über den Andern ist, so hat er

in diesem Schlusse diesen andern unter sich. Ebenso bezieht sich der

Herr mittelbar durch den Knecht auf das Ding; der Knecht bezieht sich,

als Selbstbewußtsein überhaupt, auf das Ding auch negativ und hebt es

auf; aber es ist zugleich selbstständig für ihn, und er kann darum

durch sein Negieren nicht bis zur Vernichtung mit ihm fertig werden,

oder er bearbeitet es nur. Dem Herrn dagegen wird durch diese

Vermittlung die unmittelbare Beziehung als die reine Negation

desselben, oder der Genuß; was der Begierde nicht gelang, gelingt ihm,

damit fertig zu werden, und im Genusse sich zu befriedigen. Der

Begierde gelang dies nicht wegen der Selbstständigkeit des Dinges; der

Herr aber, der den Knecht zwischen es und sich eingeschoben, schließt

sich dadurch nur mit der Unselbstständigkeit des Dinges zusammen, und

genießt es rein; die Seite der Selbstständigkeit aber überläßt er dem

Knechte, der es bearbeitet. |

主人(der

Herr)とは、それ自身のために存在する意識であるが、もはや単にその概念ではなく、それ自身のために存在する意識であり、それは別の意識、すなわち、

独立した存在や一般的な事物性と合成されることを本質とする意識によって、それ自身と媒介される。主人はこの二つの瞬間、欲望の対象である物自体、および物

性が本質である意識に言及し、a)自己意識の概念として、それは自己のために存在することの直接的な関係であるが、b)媒介として、あるいは別のものに

よってのみ自己のために存在する自己のために存在するものとして、同時に、a)両者に直接言及し、b)他者を通してそれぞれに間接的に言及する。主人は、

独立した存在を通して間接的にしもべに関係する。なぜなら、しもべが捕らえられているのはまさにこれであり、それは彼の鎖であり、彼はそこから闘争の中で

捨象することができず、それゆえ、依存的であることが証明され、その事において独立性を持つことができなかったからである。しかし、主人はこの存在を支配す

る力であり、それは主人にとって否定的なものにすぎないことを闘争の中で証明したからである。主人はこの存在を支配する力であるが、この存在は他者を支配する

力であるという点で、主人はこの結論において、この他者を自分の下に置いている。同じように、主人は使用人を通して間接的に物自体と関係する。使用人もま

た、一般的な自己意識として、物自体と否定的に関係し、それを打ち消す。しかし同時に、それは彼にとって独立したものであり、それゆえ、彼はそれを否定す

ることによって消滅するところまで折り合いをつけることができない、あるいは、彼はそれに働きかけるだけである。一方、主人は、この媒介を通して、それの

純粋な否定、すなわち享受としての直接的な関係となる。欲望が成功しなかったことを、主人は享受において処理し、満足させることに成功する。欲望がこれに

成功しなかったのは、物自体の独立性のためである。しかし、物自体と自分との間に召使を介在させた主人は、それによって自分自身を物自体の非独立性とのみ

一体化させ、純粋にそれを享受する。 |

| In diesen beiden Momenten wird

für den Herrn sein Anerkanntsein durch ein anderes Bewußtsein; denn

dieses setzt sich in ihnen als Unwesentliches, einmal in der

Bearbeitung des Dings, das anderemal in der Abhängigkeit von einem

bestimmten Dasein; in beiden kann es nicht über das Sein Meister werden

und zur absoluten Negation gelangen. Es ist also hierin dies Moment des

Anerkennens vorhanden, daß das andere Bewußtsein sich als Für-sich-sein

aufhebt, und hiemit selbst das tut, was das erste gegen es tut. Ebenso

das andere Moment, daß dies Tun des zweiten das eigne Tun des ersten

ist; denn, was der Knecht tut, ist eigentlich Tun des Herrn; diesem ist

nur das Für-sich-sein, das Wesen; er ist die reine negative Macht, der

das Ding nichts ist, und also das reine wesentliche Tun in diesem

Verhältnisse; der Knecht aber ein nicht reines, sondern unwesentliches

Tun. Aber zum eigentlichen Anerkennen fehlt das Moment, daß, was der

Herr gegen den Andern tut, er auch gegen sich selbst, und was der

Knecht gegen sich, er auch gegen den Andern tue. Es ist dadurch ein

einseitiges und ungleiches Anerkennen entstanden. |

この二つの瞬間において、主人にとって、認識された自分の存在は、別の

意識に取って代わられる。後者はその二つの瞬間において、一方では物自体の働きにおいて、他方ではある存在への依存において、本質的でないものとして自己

を確立する。つまり、他方の意識は、それ自身にとっての存在としてそれ自身を消し去り、それによって、最初の意識がそれ自身に対して行うことを、それ自身

のために行うのである。同様に、もう一つの瞬間は、第二のこの行為は第一の行為そのものである、というものである。しかし、主人が他者に対して行うこと

は、自分自身に対しても行うことであり、従者が自分自身に対して行うことは、他者に対しても行うことである、ということを実際に認識する瞬間が欠けてい

る。その結果は、一方的で不平等な認識である。 |

| Das unwesentliche Bewußtsein ist

hierin für den Herrn der Gegenstand, welcher die Wahrheit der Gewißheit

seiner selbst ausmacht. Aber es erhellt, daß dieser Gegenstand seinem

Begriffe nicht entspricht, sondern daß darin, worin der Herr sich

vollbracht hat, ihm vielmehr ganz etwas anderes geworden als ein

selbstständiges Bewußtsein. Nicht ein solches ist für ihn, sondern

vielmehr ein unselbstständiges; er also nicht des Für-sich-seins, als

der Wahrheit gewiß, sondern seine Wahrheit ist vielmehr das

unwesentliche Bewußtsein, und das unwesentliche Tun desselben. |

実体のない意識は、主人にとって、自分自身の確かさの真理を構成する対象

である。しかし、この対象が彼の概念に対応しているのではなく、主人が自分自身を達成したその中で、彼は独立した意識とはまったく異なるものになっているこ

とは明らかである。したがって、彼は真理として自分自身のために存在することを確信しているのではなく、むしろ彼の真理は非本質的な意識であり、それを非

本質的に行うことなのである。 |

| Die Wahrheit des selbstständigen

Bewußtseins ist demnach das knechtische Bewußtsein. Dieses erscheint

zwar zunächst außer sich und nicht als die Wahrheit des

Selbstbewußtsein. Aber wie die Herrschaft zeigte, daß ihr Wesen das

Verkehrte dessen ist, was sie sein will, so wird auch wohl die

Knechtschaft vielmehr in ihrer Vollbringung zum Gegenteile dessen

werden, was sie unmittelbar ist; sie wird als in sich zurückgedrängtes

Bewußtsein in sich gehen, und zur wahren Selbstständigkeit sich

umkehren. |

したがって、独立した意識の真理とは、奉仕者の意識である。最初は、こ

れは自己意識の真理ではなく、自己意識の外側にあるように見える。しかし、支配がその本質がなりたいものの逆であることを示したように、隷属もまた、その

成就において、それが直接あるものの逆となり、自分自身に押し戻された意識として自分自身の中に入り込み、真の独立へと立ち返るだろう。 |

| Wir

sahen nur, was die Knechtschaft im Verhältnisse der Herrschaft ist.

Aber sie ist Selbstbewußtsein, und was sie hienach an und für sich

selbst ist, ist nun zu betrachten. Zunächst ist für die

Knechtschaft der Herr das Wesen; also das selbstständige für sich

seiende Bewußtsein ist ihr die Wahrheit, die jedoch für sie noch nicht

an ihr ist. Allein sie hat diese Wahrheit der reinen Negativität und

des Für-sich-seins in der Tat an ihr selbst; denn sie hat dieses Wesen

an ihr erfahren. Dies Bewußtsein hat nämlich nicht um dieses oder

jenes, noch für diesen oder jenen Augenblick Angst gehabt, sondern um

sein ganzes Wesen; denn es hat die Furcht des Todes, des absoluten

Herrn, empfunden. Es ist darin innerlich aufgelöst worden, hat durchaus

in sich selbst erzittert, und alles Fixe hat in ihm gebebt. Diese reine

allgemeine Bewegung, das absolute Flüssigwerden alles Bestehens ist

aber das einfache Wesen des Selbstbewußtseins, die absolute

Negativität, das reine Für-sich-sein, das hiemit an diesem Bewußtsein

ist. Dies Moment des reinen Für-sich-sein ist auch für es, denn im

Herrn ist es ihm sein Gegenstand. Es ist ferner nicht nur diese

allgemeine Auflösung überhaupt, sondern im Dienen vollbringt es sie

wirklich; es hebt darin in allen einzelnen Momenten seine

Anhänglichkeit an natürliches Dasein auf, und arbeitet dasselbe hinweg. |

私たちは、支配との関係において隷属とは何かを見てきたに過ぎない。しかし、それは自己意識であり、それ自体において、またそれ自体のために、それが何であるかが、今、考察されるべきものである。ま

ず第一に、主人は隷属の本質である。したがって、それ自身のために存在する独立した意識はその真理であり、しかしそれはまだそれ自身の中にはない。しか

し、この純粋な否定性と、自分のために存在するという真理を、この意識は確かに自分の中に持っている。この意識は、あれもこれも、この瞬間も瞬間も恐れて

いるのではなく、その全存在を恐れているのである。この意識は、絶対的な主人である死の恐怖を感じてきたのだ。この意識は、内的にその中に溶け込み、自分の

中で震え、固定されたものすべてがその中で震えてきた。しかし、この純粋な一般的な動き、すべての存在の絶対的な液化は、自己意識の単純な本質であり、絶

対的な否定性であり、この意識の中にある純粋な「存在のための存在」である。この純粋な存在の瞬間は、この意識のためでもある。さらに、この一般的な解消

だけでなく、奉仕することにおいても、それは本当に達成される。 |

| Das Gefühl der absoluten Macht

aber überhaupt, und im einzelnen des Dienstes ist nur die Auflösung an

sich, und obzwar die Furcht des Herrn der Anfang der Weisheit ist, so

ist das Bewußtsein darin für es selbst, nicht das Für-sich-sein. Durch

die Arbeit kömmt es aber zu sich selbst. In dem Momente, welches der

Begierde im Bewußtsein des Herrn entspricht, schien dem dienenden

Bewußtsein zwar die Seite der unwesentlichen Beziehung auf das Ding

zugefallen zu sein, indem das Ding darin seine Selbstständigkeit

behält. Die Begierde hat sich das reine Negieren des Gegenstandes, und

dadurch das unvermischte Selbstgefühl vorbehalten. Diese Befriedigung

ist aber deswegen selbst nur ein Verschwinden, denn es fehlt ihr die

gegenständliche Seite oder das Bestehen. Die Arbeit hingegen ist

gehemmte Begierde, aufgehaltenes Verschwinden, oder sie bildet. Die

negative Beziehung auf den Gegenstand wird zur Form desselben, und zu

einem bleibenden; weil eben dem arbeitenden der Gegenstand

Selbstständigkeit hat. Diese negative Mitte oder das formierende Tun

ist zugleich die Einzelnheit oder das reine Für-sich-sein des

Bewußtseins, welches nun in der Arbeit außer es in das Element des

Bleibens tritt; das arbeitende Bewußtsein kommt also hiedurch zur

Anschauung des selbstständigen Seins, als seiner selbst. |

主人を畏れることは知恵の始まりではあるが、そこにある意識はそれ自身の

ためのものであり、それ自身のためにあるのではない。しかし、労働を通じて、それはそれ自身に到達する。主人の意識における欲望に対応する瞬間、物自体に対

する本質的でない関係の側は、物自体がその中で独立性を保っているという点で、奉仕する意識に落ちたように見える。欲望は、対象の純粋な否定、つまり混じ

りけのない自己の感覚を自分のためにとっておいたのである。しかしこの満足は、客観的な側面や存在を欠いているため、それ自体消失にすぎない。他方、労働

は、抑制された欲望であり、阻止された消失であり、あるいはそれが形成されたものである。対象に対する否定的な関係は、同じものの形態となり、永続的なも

のとなる。この否定的な中心あるいは形成作用は、同時に意識の特異性あるいは純粋な存在-自己のための存在であり、それは今、その外側の仕事の中に留まる

要素に入り込んでいる。 |

| Das Formieren hat aber nicht nur

diese positive Bedeutung, daß das dienende Bewußtsein sich darin als

reines Für-sich-sein zum Seienden wird; sondern auch die negative,

gegen sein erstes Moment, die Furcht. Denn in dem Bilden des Dinges

wird ihm die eigne Negativität, sein Für-sich-sein, nur dadurch zum

Gegenstande, daß es die entgegengesetzte seiende Form aufhebt. Aber

dies gegenständliche Negative ist gerade das fremde Wesen, vor welchem

es gezittert hat. Nun aber zerstört es dies fremde Negative, setzt sich

als ein solches in das Element des Bleibens; und wird hiedurch für sich

selbst, ein für sich Seiendes. Im Herrn ist ihm das Für-sich-sein ein

Anderes oder nur für es; in der Furcht ist das Für-sich-sein an ihm

selbst; in dem Bilden wird das Für-sich-sein als sein eignes für es,

und es kömmt zum Bewußtsein, daß es selbst an und für sich ist. Die

Form wird dadurch, daß sie hinausgesetzt wird, ihm nicht ein Anderes

als es; denn eben sie ist sein reines Für-sich-sein, das ihm darin zur

Wahrheit wird. Es wird also durch dies Wiederfinden seiner durch sich

selbst eigner Sinn, gerade in der Arbeit, worin es nur fremder Sinn zu

sein schien. – Es sind zu dieser Reflexion die beiden Momente der

Furcht und des Dienstes überhaupt, sowie des Bildens notwendig, und

zugleich beide auf eine allgemeine Weise. Ohne die Zucht des Dienstes

und Gehorsams bleibt die Furcht beim Formellen stehen, und verbreitet

sich nicht über die bewußte Wirklichkeit des Daseins. Ohne das Bilden

bleibt die Furcht innerlich und stumm, und das Bewußtsein wird nicht

für es selbst. Formiert das Bewußtsein ohne die erste absolute Furcht,

so ist es nur ein eitler eigner Sinn; denn seine Form oder Negativität

ist nicht die Negativität an sich; und sein Formieren kann ihm daher

nicht das Bewußtsein seiner als des Wesens geben. Hat es nicht die

absolute Furcht, sondern nur einige Angst ausgestanden, so ist das

negative Wesen ihm ein äußerliches geblieben, seine Substanz ist von

ihm nicht durch und durch angesteckt. Indem nicht alle Erfüllungen

seines natürlichen Bewußtseins wankend geworden, gehört es an sich noch

bestimmtem Sein an; der eigne Sinn ist Eigensinn, eine Freiheit, welche

noch innerhalb der Knechtschaft stehenbleibt. So wenig ihm die reine

Form zum Wesen werden kann, so wenig ist sie, als Ausbreitung über das

Einzelne betrachtet, allgemeines Bilden, absoluter Begriff, sondern

eine Geschicklichkeit, welche nur über einiges, nicht über die

allgemeine Macht und das ganze gegenständliche Wesen mächtig ist. |

しかし、形づくるということは、その中で奉仕する意識が純粋な存在とし

ての存在になるという肯定的な意味だけでなく、その最初の瞬間である恐怖に対する否定的な意味も持っている。というのも、物自体の形成において、それ自身

の否定性、つまり、存在することそれ自体としての存在は、存在することの正反対の形式を打ち消すという点においてのみ、その対象となるからである。しか

し、この客観的な否定性こそ、まさにそれが震え上がった異質な存在なのである。しかし、今、それはこの異質な否定を破壊し、そのような存在としての自分自

身を安住の要素の中に置き、それによって自分自身のための存在となる。主人においては、それ自身はそれ自身にとって他者であり、それ自身にとってのみ存在す

る。恐怖においては、それ自身はそれ自身の中に存在する。形は、それが外に出されることで、それ自身以外のものになるのではない。なぜなら、その純粋な

「存在-自我」こそが、その中でそれ自身のための真理となるからである。こうして形は、自分自身を再発見することによって、自分自身の感覚となるのであ

る。- 恐怖の瞬間と奉仕の瞬間の二つは、形成の瞬間と同様に、この反省のために必

要であり、同時に、一般的な意味で必要である。奉仕と服従の規律がなければ、恐れは形式的なものにとどまり、

存在の意識的現実を超えて広がることはない。形成がなければ、恐れは内向的で無言のままであり、意識はそれ自身のためになることはない。もし意識が最初の

絶対的な恐れに耐えることなく形成されるなら、それは自分自身の虚しい感覚に過ぎない。もしそれが絶対的な恐怖に耐えたのではなく、何らかの恐怖に耐えた

に過ぎないのであれば、否定的な本質はそれにとって外的なもののままであり、その実体はそれに完全に感染しているわけではない。その自然な意識のすべての

成就が不安定になったわけではないので、それ自体はまだ明確な存在に属している。純粋な形がそれにとって本質となりうるのと同じように、個を超えた拡張、

一般的な形成、絶対的な概念とみなされることもほとんどなく、一般的な力と客観的存在全体に対してではなく、一部に対してのみ強力である巧みさである。 |

| https://www.projekt-gutenberg.org/hegel/phaenom/pha4a002.html |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099