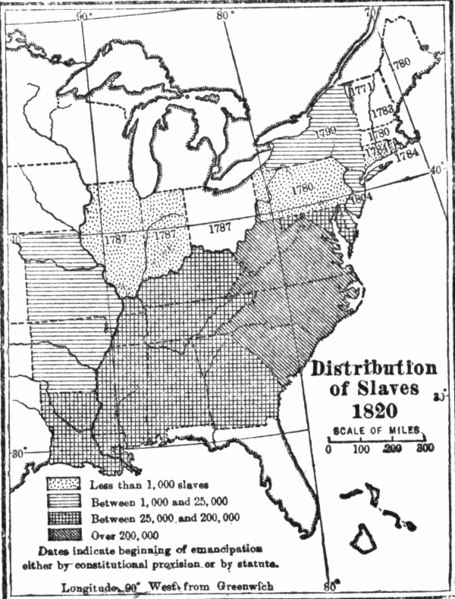

Source: Slavery and the Constitution.

奴隷の哲学

Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death. 1982 では……

「オーランド・ パターソンは『奴隷制と社会的死』で、奴 隷制がアフリカ系アメリカ人にけっして持たせようとしなかった制度の―つが、親族関係だという重要な指摘をおこなった。奴隷の主人が、つねに奴隷の家族を 所有して、奴隷の家の女をレイプし威圧し、男たちを女性化する家父長として機能していた。奴隷の家庭のなかでは、女は彼女たちの男によって保護されること はなく、男たちは女や子どもを守り治める役割を行使することはできなかった。パターソンがしばしば暗示しているのは、親族関係に対する一次的攻撃は、奴隷 の家庭のなかの女と子どもに対する父親の権利の剥奪だということだが、彼がわたしたちに提示した重要な概念は、奴隷を生きながらの死として取り扱うこの奴 隷制の局面を描写するために、彼が使った「社会的な死」という概念である」——ジュディス・バトラー『アンティゴネーの主 張』竹村和子訳、 p. 143 、青土社, 2002年(→下記の「奴隷制と社会的死」を参照のこと)

奴隷の定義は、(特定の)人間の人格権が認め られず、その人間が、物のように処分された り売買できる状態であると言うことができます。つまり奴隷制は、奴隷が主人によって「所有」されている、つまり私有財産として、可処分できるというのが、 その認識の基本的枠組みによって支えられていた制度でした。それゆえに、1982年に『奴隷制と社会的死』という全世界での奴隷制度につい てまとめた社会学者のオーランド・パターソンは、奴隷制を「支配関係の最も極端な形 態の一つであり、主人から見れば完全な権力の限界に近づき、奴隷から見れば完全な無力の限界に近づいている」社会制度だと喝破しています。

奴隷制は、身分制社会の特徴と言われてきました。「家畜のように奴隷化する」という表現 がありますが、歴史に存在した奴隷制度のすべてが、均質的なものではなく、奴隷にどのような権利を認めてきたのかについては、多様性があります。

(さまざまな奴隷反乱という先行例を除いて)奴隷制の撤廃を理論的に考えたのは、身分制 社会の撤廃を考えた啓蒙思想にあると言われています。啓蒙思想では、自由と平等という基本理念からは、奴隷制の考えが相容れないことを明確にしたからで す。

また、奴隷制を撤廃し続けるには、社会がそれを維持しなければならないことも見えてきま す(→社会契約論)。維持するためには、社会はなんらかの力(権力)をもつ必要があると考えて きた人たちがいることも、また見えてきます(→統治術に関するノート)。

このように、今日に我々にとって荒唐無稽と思われる「奴隷制」を考え、それを子どもたち に、わかるように説明するなかで、啓蒙の理性がどのようなものであったのかが、復習することができます。

「奴隷と主人」というテーマは、ヘーゲルの『精神現象学』の 中にも、これとはまったく違った 形で展開されます(さらに興味深い議論はフランツ・ファノンの著作にも登場します)。

奴隷は英語では、slave (スレイブ)と言いますが、これは古いフランス語の esclave 、ラテン語の Scclavus から由来し、捕まっている状態のことを指します。戦争行為の後に捕虜を処刑するのではなく、労働力として利用したのが、奴隷のはじまりだといわれていま す。しかし、奴隷の調達目的のために戦争をしかけるということも歴史的にはありましたので、奴隷制の起源を〈有用性の発見〉から説明するのには限界があり ます。

現在を生きる我々にとって、奴隷制を考える意味は次のとおりです。

近代社会の中に、奴隷制は法的に廃絶され、我々の道徳においても否定されているにもかか わらず、「奴隷に類する」制度がいくらでも残っているのはなぜか。

児童労働や、女性の(売春を目的とした)人身売買が、現在もなお続いているのはなぜか?

これらのことを明らかにするために、奴隷制は、すでに終わってしまった過去の蛮習ではな く、現在においても継続する「奴隷に類する制度」を明らかにし、それを廃絶するために、繰り返し思い起こし、記憶しなければならない社会制度なのです。

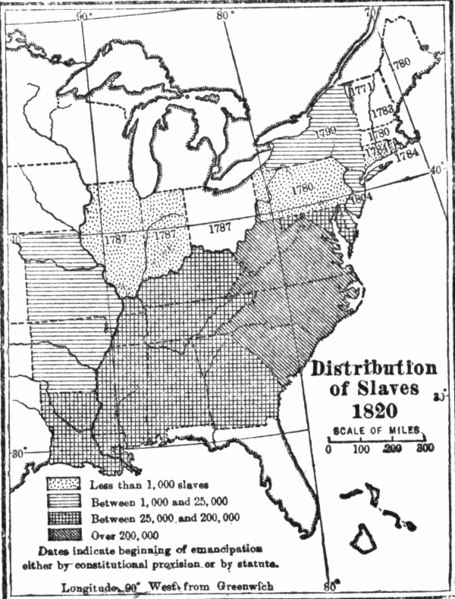

Photograph

of a slave boy in the Sultanate of Zanzibar. 'An Arab master's

punishment for a slight offence.' c. 1890.

| Slavery

and Social Death Contents Introduction: The Constituent Elements of Slavery I The Internal Relations of Slavery 1 The Idiom of Power 2 Authority, Alienation and Social Death 3 Honor and Degradation II Slavery as an Institutional Process 4 Enslavement of "Free" Persons 5 Enslavement by Birth 6 The Acquisition of Slaves 7 The Condition of Slavery 8 Manumission: Its Meaning and Modes 9 The Status of Freed Persons 10 Patterns of Manumission III The Dialectics of Slavery 11 The Ultimate Slave 12 Slavery as Human Farasitism 334 Appendix A: Note on Statistical Methods 345 Appendix B: Slaveholding Societies in the Murdock World Sample Appendix C: The Large-Scale Slave Systems Notes Index +++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Slavery and Social Death +++++++++++++++++++++++++++ The chief proponent of the relationship between social death and slavery is Orlando Patterson, who states his findings in his 1982 book, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study. Patterson first defines slavery as "one of the most extreme forms of the relation of domination, approaching the limits of total power from the viewpoint of the master, and of total powerlessness from the viewpoint of the slave."[9, p. 3.] Social death had both internal and external effects on enslaved people, changing their views of themselves and the way they were regarded by society. Slavery and social death can be linked in all civilizations where slavery existed, including China, Rome, Africa, Byzantium, Greece, Europe, and the Americas.[10] "Slavery is one of the most extreme forms of the relation of domination, approaching the limits of total power from the viewpoint of the master, and of total powerlessness from the viewpoint of the slave. Yet it differs from other forms of extreme domination in very special ways. If we are to understand how slavery is distinctive, we must first clarify the concept of power."(1982: 1) The beginning of social death comes from the initial enslavement process, which would most likely come from capture during a battle. A captive would be spared from death and created a slave, although this was a conditional commutation since death was only suspended as long as the slave submitted to his powerlessness. This pardon from death was replaced with social death, which would manifest both physically and psychologically.[11] Externally, slaves would undergo the loss of their identities through such practices as replacing their names, being branded to indicate their social condition, given a specific dress code that further established them as slaves to the public, castration, and having their heads shaved.[12] Each of these acts alienated the slaves from their previous identities and symbolized their loss of freedom and power and their total dependency on their master’s will. The psychological process of social death included the effect of rejection as a member of society and becoming genealogically isolated through the loss of heritage and the right to pass on their ancestry to their children.[13] In fact, all social bonds were seen as illegitimate unless they were validated by the master. Enslaved people were denied an independent social structure and were not even deemed fully human, as they were only seen as a representation of their master and had no honor or power of their own.[14] The degree to which these practices took place was based on the two modes of social death, intrusive and extrusive. In the intrusive mode, rituals were developed for the incorporation of an external enemy into the culture as a slave. In the extrusive mode, traditions evolved for including those who have "fallen into slavery" from within society into the slave status.[15] Both of these modes provided a process for the institutionalization of socially dead individuals. Power played an essential role in the relationship between a slave and master, and violence was often deemed a necessary component of slavery. A slave was seen to have no worth. They had no name of their own and no honor. Instead, their worth and honor was transferred to the master and gave him an elevated social status among his peers.[16] Violence within the relationship was considered essential because of the low motivation of the enslaved people, and it was also a factor in creating social death and exercising power over the slaves. Whipping was not only a method of punishment but also a consciously chosen symbolic device to remind slaves of their status.[17] This physical violence had other psychological effects as well, gradually creating an attitude of self-blame and an acknowledgement of the complete control that a master had. Interviews with former American slaves included statements such as "slaves get the masters they deserve" and "I was so bad I needed the whipping", demonstrating the justification that slaves had no right to expect kindness or compassion because of their status in society and the devastating mental effects from social death.[18] These effects demonstrated the expectations of the behavior of a slave who had experienced social death. The individuals viewed as the ultimate slaves, the palace eunuchs from Byzantium and China, were essentially a paradox. These slaves were trusted by emperors and could be extremely influential. They were expected to be loyal, brave, and obedient, yet they were still considered low and debased and were shunned by society.[19] While Orlando Patterson gives the most extensive study on slavery and social death, he has several critics of his analysis. Those who reviewed the book disliked his refusal to define slaves as property because other groups could fit this definition as well, including women and children.[20] Patterson also does not compare the treatment of slaves to other socially marginalized groups, such as prostitutes, criminals, and indentured servants.[21] The third critique given about Patterson’s book is the lack of primary sources. Commentators noted that the argument in Slavery and Social Death would have been much stronger had Patterson utilized testimony from enslaved people of their views and meanings of honor, domination, and community.[22] |

目次 はじめに 奴隷制の構成要素 I 奴隷制の内部関係 1 権力のイディオム 2 権威、疎外、社会的死 3 名誉と劣化 II 制度的過程としての奴隷制 4 「自由人」の奴隷化 5 出生による奴隷化 6 奴隷の獲得 7 奴隷の条件 8 解雇: その意味と形態 9 解放された者の地位 10 解放のパターン III 奴隷制の弁証法 11 究極の奴隷 12 人間の極端性としての奴隷 334 付録A 統計的方法に関するメモ 345 付録B マードック世界サンプルにおける奴隷保有社会 付録C: 大規模奴隷制度 注 索引 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 奴隷制と社会的死 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 社会的死と奴隷制の関係についての主な提唱者はオーランド・パターソンであり、彼は1982年の著書『奴隷制と社会的死』の中でその所見を述べている: 比較研究)で述べている。パターソンはまず、奴隷制を「支配関係の最も極端な形態の 一つであり、主人から見れば完全な権力の限界に近づき、奴隷から見れば完全な無力の限界に近づいている」と定義している[9]。社会的死は 奴隷にされた人々に内的・外的な影響を及ぼし、彼らの自分自身に対する見方や社会からの見られ方を変えた。奴隷制と社会的死は、中国、ローマ、アフリカ、 ビザンチウム、ギリシャ、ヨーロッパ、アメリカ大陸など、奴隷制が存在したすべての文明において結びつけることができる[10]。 「奴隷制は支配関係の最も極端な形態の一つであり、主人から見れば完全な権力の限界に近づき、奴隷から見れば完全な無力の限界に近づく。しかし、他の極端 な支配形態とは非常に特殊な点で異なっている。奴隷制がどのように特徴的であるかを理解するには、まず権力の概念を明確にしなければならない。」 社会的死の始まりは、最初の奴隷化プロセスからであり、それはおそらく 戦闘中の捕虜からであろう。捕虜は死を免れ、奴隷となるが、これは奴隷が無力に服従している限り死が停止されるだけであったため、条件付きの減刑であっ た。この死からの恩赦は社会的な死に取って代わられ、それは肉体的にも心理的にも現れるものであった[11]。 外見的には、奴隷は名前を付け替えられたり、社会的条件を示すために焼 き印を押されたり、世間に対して奴隷であることをさらに確立させる特定の服装規定を 与えられたり、去勢されたり、頭を剃られたりするなどの行為を通じて、アイデンティティの喪失を経験することになる[12]。これらの行為 のそれぞれは、 奴隷をそれまでのアイデンティティから疎外し、自由と権力の喪失と主人の意志への完全な依存を象徴するものであった。社会的死の心理的過程には、社会の一 員としての拒絶の影響や、遺産や先祖の血筋を子供たちに伝える権利の喪失によって系譜的に孤立することも含まれていた[13]。事実、すべての社会的絆 は、主人によって承認されない限り、非合法なものとみなされた。奴隷にされた人々は独立した社会構造を否定され、完全な人間であるとさえみなされなかっ た。侵入的モードでは、外敵を奴隷として文化に組み込むための儀式が発達した。侵入的モードでは、社会の内部から「奴隷に転落した」人々を奴隷の地位に組 み込むための伝統が発展した。 権力は奴隷と主人の関係において本質的な役割を果たし、暴力はしばしば 奴隷制に必要な要素であるとみなされた。奴隷には何の価値もないとみなされた。彼ら には名前も名誉もない。その代わり、彼らの価値と名誉は主人に移され、主人は仲間内で高い社会的地位を与えられていた[16]。奴隷にされ た人々のモチ ベーションが低いため、関係の中での暴力は不可欠であると考えられており、また社会的死を生み出し、奴隷に対する権力を行使する要因でもあった。鞭打ちは 罰の方法であっただけでなく、奴隷に自分たちの身分を思い起こさせるために意識的に選ばれた象徴的な装置でもあった[17]。この肉体的暴力は他の心理的 な影響も及ぼし、徐々に自己を責める態度を生み出し、主人が完全に支配していることを認めるようになった。アメリカの元奴隷のインタビューには、「奴隷は それにふさわしい主人を得る」、「私はとても悪かったので鞭打ちが必要だった」といった記述があり、奴隷は社会における地位のために親切や思いやりを期待 する権利がないという正当化と、社会的な死による壊滅的な精神的影響を示していた[18]。 これらの効果は、社会的死を経験した奴隷の行動に対する期待を示していた。究極の奴隷と見なされていたビザンティウムと中国の宮廷宦官は、本質的にパラ ドックスであった。これらの奴隷は皇帝に信頼され、極めて大きな影響力を持つことができた。彼らは忠実で勇敢で従順であることが期待されていたが、それで もなお卑しく堕落しているとみなされ、社会から敬遠されていた[19]。 オーランド・パターソンは奴隷制度と社会的死について最も広範な研究を 行ったが、彼の分析にはいくつかの批判がある。パターソンはまた、奴隷の扱いを、売 春婦、犯罪者、年季奉公人など、社会的に疎外された他の集団と比較していない。解説者たちは、パターソンが名誉、支配、共同体についての彼らの見解や意味 について奴隷にされた人々の証言を利用していれば、『奴隷制と社会的死』の議論はもっと強力なものになっていただろうと指摘している[22]。 22- Michael Craton. Review of Slavery and Social Death by Orlando Patterson. Journal of American History, p 862. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_death |

|

| The

power relation has three facets. The first is social and involves the

use or threat of violence in the control of one person by another. The

second

is the psychological facet of influence, the capacity to persuade

another person to change the way he perceives his interests and his

circumstances. And

third is the cultural facet of authority, "the means of transforming

force into

right, and obedience into duty" which, according to Jean Jacques

Rousseau,

the powerful find necessary "to ensure them continual mastership."

Rousseau

felt that the source of "legitimate powers" lay in those "conventions"

which today we would call culture. But he did not specify the area of

this

vast human domain in which the source of authority was to be found.

Nor,

for that matter, did Weber, the leading modern student of the subject.4

In

Chapter 2 I show that authority rests on the control of those private

and

public symbols and ritual processes that induce (and se~uce) people to

obey

because they feel satisfied and dutiful when they do so. (Parterson

1982:1-2) |

権

力関係には3つの側面がある。第一は社会的なもので、ある人を他の人が支配する際に暴力を使ったり脅したりすることである。第二は影響力という心

理的な側

面であり、他人を説得して自分の利益や状況の捉え方を変えさせる能力である。ジャン・ジャック・ルソーによれば、権力者は

"継続的な支配を保証するために

"必要であると考える。ルソーは、「正当な権力」の源泉は、今日でいうところの「文化」である「慣習」にあると考えた。しかし、ルソーは、この広大な人間

の領域の中で、権威の源泉がどこにあるのかを特定しなかった。第2章では、権威は私的・公的なシンボルや儀礼的プロセスのコントロールにあり、そのプロセ

スによって人々は満足し、従順であると感じるので、従うように誘導される(誘導される)ことを示す。 |

| Social death is the condition of

people not accepted as fully human by wider society. It refers to when

someone is treated as if they are dead or non-existent.[1] It is used

by sociologists such as Orlando Patterson and Zygmunt Bauman, and

historians of slavery and the Holocaust to describe the part played by

governmental and social segregation in that process.[2][3] Examples of

social death are: Racial and gender exclusion, persecution, slavery, and apartheid.[4][5][6] Governments can exclude individuals or groups from society. Examples: Protestant minority groups in early modern Europe; ostracism in Ancient Athens; Dalits in India; criminals; prostitutes, outlaws[7][8] Institutionalization and segregation of those labeled with a mental illness. Change in the identity of an individual. This was a major theme during the Renaissance. It could be said that the degeneration theory and theories similar to this theory are the most extreme examples of social death. The idea of degeneration has been popular in both right-wing and left-wing politics. Both left-wing and right-wing politics have used the word decadence to describe social groups whose social, moral, religious, aesthetic, or political commitments tend towards the inhibition of any or all forms of progress (as used by some critics on the left to describe their opponents on the right) or towards the undermining of fundamental forms of order (as used by some critics on the right to describe their opponents on the left). In either political optic, the forces of decadence may be internal or external. Internally, the members of political opposition may represent those who have allowed essential ideals to lapse from their view of the world. Externally, members of another society may be considered as cherishing ideals which introduce forces of collapse into the worlds wherein they are immigrants. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_death ●本文より +++++++++++++++++++++++++++ The Contradictions of Slavery(pp.32-33) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++ The coercive problem of slavery occasioning the Roman fictive legal "solution" that was to influence all subsequent Western conceptions of slavery and the continental law of property was part of a wider, more fundamental set of problems posed by this relation in all kinds of social orders, and to these I now return. Earlier, I observed that in its coercive aspect slavery was less problematic in societies where the personalistic idiom was dominant. It would be a mistake, however, to claim that slavery was never problematic in such societies. The main advantage of having slaves in these, as in all other kinds of societies, was their inherent flexibility. Because slaves were natally alienated, they could be used in ways not possible with even the most, dominated of nonslave subordinates with natal claims. Whatever the prevailing idiom, slaves could always be used either as direct objects of domination or as an indirect means of dominating others. In many primitive societies where there was little differentiation in the possession of wealth, slaves were usually the major (sometimes the only) form of wealth that made such differentiation possible. Claude Meillassoux and others have shown how in many parts of pre-European West Africa masters used slaves not only as direct objects of domination, but as a primary means of reproducing and accumulating wealth both in persons (more slaves) and in goods. This was done by exploiting the female slaves' reproductive and farming capacity, and the farming and military capacity of the male slaves. In many of these societies the primary objective was not to increase the consumption of goods but to convert wealth into power over nonslaves. As Igor Kopytoff and Suzanne Miers neatly expressed it with respect to the less centralized parts of Africa, there was not a mass consumption society with ever-increasing demand for commodities, but a society with a mass demand for persons as retainers in the escalating demand for power. Power over slaves, then, was both the direct exercise and enjoyment of power and an investment in the means of reproducing and accumulating power over others. In being so used, slavery was clearly problematic for the prevailing personalistic idiom with its humanized fictive kinship expression. Since the slave obviously did not belong, to define him as a junior fictive kinsman undermined the authenticity of fictive kin assimilation with respect to nonslave retainers. The relation gave the master an advantage in the competition for status and power, but it was an advantage that broke the rules of the game and threatened to undermine the ideological expression of the prevailing idiom. |

社会的死(しゃかいてきし)とは、より広い社会から完全な人間として受

け入れられていない人々の状態のことである。オーランド・パターソンやジグムント・バウマンなどの社会学者や、奴隷制度やホロコーストの歴史家によって、

社会的死のプロセスにおいて政府や社会的隔離が果たした役割を説明するために使われる: 人種的・ジェンダー的排除、迫害、奴隷制、アパルトヘイトなどである[4][5][6]。 政府は個人や集団を社会から排除することができる。例として 近世ヨーロッパにおけるプロテスタントの少数集団、古代アテネにおける追放、インドにおけるダリット、犯罪者、売春婦、無法者[7][8]。 精神病のレッテルを貼られた人々の施設化や隔離。 個人のアイデンティティの変化。これはルネサンス期の大きなテーマであった。 退廃論やこの理論に類似した理論は、社会的死の最も極端な例であると言える。退化という考え方は、右翼政治でも左翼政治でも人気がある。左翼政治も右翼政 治も、社会的、道徳的、宗教的、美学的、あるいは政治的コミットメントが、あらゆる形態の進歩を阻害する傾向(左翼の一部の批評家が右翼の敵対者を表現す る際に用いる)、あるいは基本的な秩序形態を損なう傾向(右翼の一部の批評家が左翼の敵対者を表現する際に用いる)にある社会集団を表現するために、退廃 という言葉を使ってきた。いずれの政治的視角においても、退廃の勢力は内的なものである場合もあれば、外的なものである場合もある。内部的には、政治的反 対勢力のメンバーは、本質的な理想を世界観から逸脱させた人々を表しているのかもしれない。外部的には、別の社会の成員は、彼らが移民している世界に崩壊 の力を持ち込む理想を大切にしていると考えられるかもしれない。 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_death ●本文より +++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 奴隷制の矛盾 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 奴隷制の強制的な問題は、その後の西洋の奴隷制と大陸の財産法に関するすべての概念に影響を与えることになった、ローマ帝国による架空の法的「解決策」で あり、あらゆる種類の社会秩序においてこの関係がもたらす、より広範で根本的な問題の一部であった。 先に私は、個人主義的なイディオムが支配的な社会では、奴隷制度はその強制的な側面において問題が少なかったと述べた。しかし、そのような社会では奴隷制 が決して問題にならなかったと主張するのは間違いである。このような社会で奴隷を持つことの主な利点は、他のあらゆる種類の社会と同様に、その固有の柔軟 性であった。奴隷は生得的に疎外されていたため、生得的な権利を主張する非奴隷の部下であっても、最も支配的な部下では不可能な方法で利用することができ た。 どのような言い方が一般的であれ、奴隷は常に直接的な支配の対象として、あるいは他者を支配する間接的な手段として使われた。富の所有にほとんど差別がな かった多くの原始社会では、奴隷は通常、そのような差別化を可能にする主要な(時には唯一の)富の形態であった。Claude Meillassouxらは、ヨーロッパ以前の西アフリカの多くの地域で、主人たちが奴隷を直接的な支配の対象としてだけでなく、人(より多くの奴隷)と 財の両方の富を再生産し蓄積する主要な手段として利用していたことを明らかにしている。これは、女性奴隷の生殖能力と農業能力、男性奴隷の農業能力と軍事 能力を利用することによって行われた。これらの社会の多くでは、財の消費を増やすことではなく、富を非奴隷に対する権力に変えることが第一の目的だった。 イゴール・コピトフとスザンヌ・ミアーズがアフリカのあまり中央集権的でない地域について端的に表現したように、そこには、商品に対する需要が増え続ける 大量消費社会ではなく、権力に対する需要が高まる中で家来となる人に対する大量需要がある社会があったのである。奴隷に対する権力は、権力の直接的な行使 と享受であると同時に、他者に対する権力を再生産し蓄積する手段への投資でもあった。このように利用されることで、奴隷制度は、人間化された架空の親族関 係を表現する一般的な個人主義的イディオムにとって明らかに問題となった。奴隷は明らかに所属していないのだから、彼を下級の架空血族として定義すること は、奴隷以外の家来に対する架空血族同化の信憑性を損なうことになる。この関係は、地位と権力をめぐる競争において主人に優位性を与えたが、それはゲーム のルールを破る優位性であり、一般的な慣用句のイデオロギー的表現を損なう恐れがあった。 |

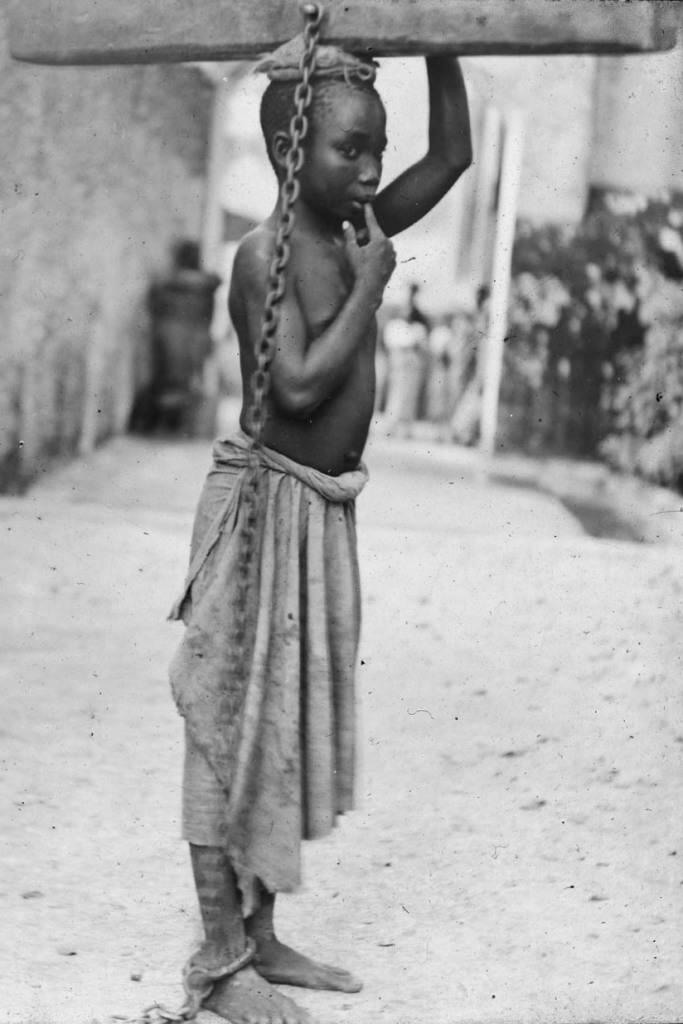

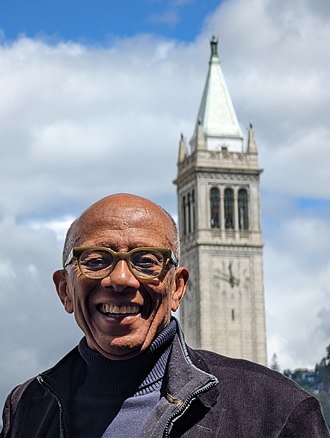

| Horace Orlando Patterson, b. 1940 |

オーランド・パターソン教授について |

Horace

Orlando Patterson OM (born 5 June 1940) is a Jamaican-American

historian and sociologist known for his work on the history of race and

slavery in the United States and Jamaica, as well as the sociology of

development. He is currently the John Cowles Professor of Sociology at

Harvard University.[1] Patterson's 1991 book Freedom in the Making of

Western Culture won the U.S. National Book Award for Nonfiction.[2] Horace

Orlando Patterson OM (born 5 June 1940) is a Jamaican-American

historian and sociologist known for his work on the history of race and

slavery in the United States and Jamaica, as well as the sociology of

development. He is currently the John Cowles Professor of Sociology at

Harvard University.[1] Patterson's 1991 book Freedom in the Making of

Western Culture won the U.S. National Book Award for Nonfiction.[2]Early life and education Horace Orlando Patterson was born on 5 June 1940 in Westmoreland Parish, Jamaica,[3][4] to Almina Morris and Charles A. Patterson.[5] His parents were strong supporters of Jamaica’s People National Party, the political party he grew up to serve a few decades later. His father was a local detective while his mother became a seamstress. He had six half-siblings on his father's side but was his mother’s only child.[6] He grew up in Clarendon Parish in the small town of May Pen.[7] He attended primary school there, then moved to Kingston to attend Kingston College. While attending Kingston College, Patterson won a Jamaica Government Exhibition scholarship in 1958. Before matriculating in 1959, he taught for a year at the Excelsior High School in Jamaica.[6] He went on to earn a BSc in Economics with a concentration in Sociology from the University of the West Indies, Mona, in 1962.[8] He served as president of the Economics Society, president of the Literary Society and editor of the student magazine 'the Pelican'.[6] Patterson earned his PhD in sociology at the London School of Economics in 1965, where he wrote his PhD thesis, the Sociology of Slavery.[9][6] His dissertation adviser was David Glass.[10] He also wrote for the recently founded New Left Review, his first work being "The Essays of James Baldwin" in 1964.[11] While in London he was associated with the Caribbean Artists Movement, whose second meeting, in January 1967, was held at the Pattersons' North London flat.[12] Career Orlando Patterson, before speaking at the University of California, Berkeley on 2 May 2023 Earlier in his career, Patterson was concerned with the economic and political development of his home country, Jamaica. He served as special advisor to Michael Manley, Prime Minister of Jamaica, from 1972 to 1979 while serving as a tenured professor at Harvard University. Committed to working both jobs, Patterson split his time between Jamaica and the United States. He often flew to Jamaica the day after his last lecture.[6] Patterson is best known for his work on the relationship between slavery and social death, which he has worked on extensively and written several books about. Other contributions include historical sociology and fictional writing with themes of post-colonialism. Patterson has also spent time analyzing social science's scholarship and ethical considerations.[13] Patterson currently holds the John Cowles Chair in sociology at Harvard University. In October 2015 he received the Gold Musgrave Medal in recognition of his contribution to literature.[14] In 2020 he was appointed a member of the Order of Merit, Jamaica's third-highest national honour.[15] Professional associations Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences Ernest W. Burgess Fellow, American Academy of Political and Social Science[16] Member, American Sociological Association https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orlando_Patterson |

ホ

レス・オーランド・パターソンOM(1940年6月5日生まれ)はジャマイカ系アメリカ人の歴史家、社会学者で、米国とジャマイカにおける人種と奴隷制の

歴史、開発社会学の研究で知られる。1991年に出版された『Freedom in the Making of Western

Culture』は全米図書賞ノンフィクション部門を受賞[2]。 ホ

レス・オーランド・パターソンOM(1940年6月5日生まれ)はジャマイカ系アメリカ人の歴史家、社会学者で、米国とジャマイカにおける人種と奴隷制の

歴史、開発社会学の研究で知られる。1991年に出版された『Freedom in the Making of Western

Culture』は全米図書賞ノンフィクション部門を受賞[2]。生い立ちと教育 1940年6月5日、ホレス・オーランド・パターソンはジャマイカのウェストモーランド・パリッシュでアルミナ・モリスとチャールズ・A・パターソンの間 に生まれた[3][4]。父親は地元の刑事で、母親は裁縫師になった。父方には6人の異母兄妹がいたが、母方は一人っ子であった[6]。彼はクラレンド ン・パリッシュのメイペンという小さな町で育った[7]。キングストン・カレッジ在学中の1958年、パターソンはジャマイカ政府展示会の奨学金を獲得。 1959年に入学する前に、ジャマイカのエクセルシオール・ハイスクールで1年間教鞭をとった[6]。1962年に西インド諸島大学モナ校で社会学を専攻 し、経済学の学士号を取得した[8]。 [6]パターソンは1965年にロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスで社会学の博士号を取得し、博士論文『奴隷制の社会学』を執筆した[9][6]。 経歴 2023年5月2日、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校での講演前のオーランド・パターソン。 そのキャリアの初期、パターソンは母国ジャマイカの経済的・政治的発展に取り組んでいた。1972年から1979年まで、ジャマイカ首相マイケル・マン リーの特別顧問を務めるかたわら、ハーバード大学の終身教授を務めた。両方の仕事をこなすため、パターソンはジャマイカとアメリカの間を行き来した。最後 の講義の翌日にジャマイカに飛ぶことも多かった[6]。 パターソンは、奴隷制と社会的死の関係についての研究で最もよく知られている。その他、歴史社会学やポストコロニアリズムをテーマとしたフィクションの執 筆などにも貢献している。パターソンはまた、社会科学の学問と倫理的考察の分析にも時間を費やしている[13]。 パターソンは現在、ハーバード大学で社会学のジョン・カウルズ・チェアを務めている。 2015年10月、文学への貢献が認められ、ゴールド・マスグレイブ・メダルを受賞[14]。2020年には、ジャマイカで3番目に高い国家栄誉である功 労勲章のメンバーに任命された[15]。 専門家協会 アメリカ芸術科学アカデミー、フェロー アーネスト・W・バージェスフェロー、アメリカ政治社会科学アカデミー[16]。 アメリカ社会学会会員 |

| James Madison's Montpelier,

located in Orange County, Virginia, was the plantation house of the

Madison family, including Founding Father and fourth president of the

United States James Madison and his wife, Dolley. The 2,650-acre (10.7

km2) property is open seven days a week with the mission of engaging

the public with the enduring legacy of Madison's most powerful idea:

government by the people. Montpelier was declared a National Historic Landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. It was included in the Madison-Barbour Rural Historic District in 1991. In 1983, the last private owner of Montpelier, Marion duPont Scott, bequeathed the estate to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The National Trust for Historic Preservation (NTHP) has owned and operated the estate since 1984. In 2000, The Montpelier Foundation formed with the goal of transforming James Madison's historic estate into a dynamic cultural institution. From 2003 to 2008 the NTHP carried out a major restoration, in part to return the mansion to its original size of 22 rooms as it was during the years when it was occupied by James and Dolley Madison. Extensive interior and exterior work was done during the restoration. Archeological investigations in the 21st century revealed new information about African-American life at the plantation, and a gift from philanthropist David Rubenstein enabled the National Trust to restore the slave quarters in the South Yard and open a slavery exhibition, The Mere Distinction of Colour, in 2017. In June 2021, the Montpelier Foundation approved bylaws to share in governance of the estate with the Montpelier Descendants Committee, composed of descendants of those enslaved at the estate.[4][5] After some controversy,[6] the Montpelier Descendants Committee achieved parity within the Foundation,[7] holding 14 of 25 seats on the board as of May 2022,[8] including the chair.[9] |

バージニア州オレンジ郡にあるジェームズ・マディソンのモントペリア

は、アメリカ建国の父であり第4代大統領ジェームズ・マディソンとその妻ドリーを含むマディソン家のプランテーションハウスであった。エーカー(10.7

キロ平方メートル)の敷地は、マディソンの最も強力な思想である「人民による政治」の不朽の遺産を一般の人々に知ってもらうことを使命として、週7日開館

している。 モンペリエは国定歴史建造物に指定され、1966年に国家歴史登録財に登録された。1991年にはマディソン・バーバー田園歴史地区に含まれた。1983 年、モンペリエの最後の個人所有者であったマリオン・デュポン・スコットが、この地所を歴史保存ナショナル・トラストに遺贈した。 1984年以来、ナショナル・トラスト・フォー・ヒストリック・プリザベーション(NTHP)がこの邸宅を所有・運営している。2000年、ジェームズ・ マディソンの歴史的邸宅をダイナミックな文化施設に変えることを目的に、モンペリエ財団が設立された。2003年から2008年にかけて、NTHPはこの 邸宅をジェームズ・マディソンとドリー・マディソンが住んでいた当時の22室という広さに戻すことを目的に、大規模な修復を行った。修復にあたっては、内 外装の大規模な工事が行われた。 21世紀に行われた考古学的調査により、プランテーションでのアフリカ系アメリカ人の生活に関する新たな情報が明らかになり、慈善家デイヴィッド・ルーベ ンスタインからの寄付により、ナショナルトラストはサウスヤードの奴隷宿舎を修復し、2017年に奴隷制度に関する展示会『The Mere Distinction of Colour』をオープンすることができた。2021年6月、モンペリエ財団は、同農園で奴隷にされた人々の子孫で構成されるモンペリエ子孫委員会と、同 農園の統治を分担する細則を承認した[4][5]。いくつかの論争の後[6]、モンペリエ子孫委員会は財団内で平等を達成し[7]、2022年5月現在、 理事会の25議席のうち14議席を占め[8]、議長も務めている[9]。 |

| History Madison family In 1723, James Madison's grandfather, Ambrose Madison, and his brother-in-law, Thomas Chew, received a patent for 4,675 acres (18.92 km2) of land in the Piedmont of Virginia. Ambrose, his wife Frances Madison, and their three children moved to the plantation in 1732, naming it Mount Pleasant. (Archaeologists have located this first site near the Madison Family Cemetery.) Ambrose died six months later; according to court records, he was poisoned by three enslaved Africans. At the time, Ambrose Madison held 29 slaves and close to 4,000 acres (16 km2).[10] After his death, Frances managed the estate with the help of their son, Colonel James Madison Sr. Madison Sr. expanded the plantation to include building services and blacksmithing in the 1740s, and bought additional slaves to cultivate tobacco and other crops. He married Nelly Conway Madison (1731–1829) and had 12 children. James Madison Sr.'s first-born son, also named James, was born on March 16, 1751, at Belle Grove, his mother's family estate in Port Conway, where she had returned for his birth. James Madison spent his early years at Mount Pleasant. In the early 1760s, Madison Sr. built a new house half a mile away, which structure forms the heart of the main house at Montpelier today. Built around 1764, it has two stories of brick laid in a Flemish bond pattern, and a low, hipped roof with chimney stacks at both ends. His son James Madison later stated that he remembered helping move furniture to the new home. The building of Montpelier represents Phase 1 (1764–1797) of the construction. Upon completion, the Madisons owned one of the largest brick dwellings in Orange County.[11] Phase 2 (1797–1800) of construction began in 1797, after son James returned to Montpelier with his new wife Dolley Madison. He was then 39 and she was a young widow with a child. At this time Madison added a thirty-foot extension and a Tuscan portico to the house. Madison's widowed mother, Nelly, still resided in the house following the death of her husband, James Sr., in 1801.[12] In the last period of construction, Phase 3 (1809–1812), Madison had a large drawing room added, as well as one-story wings at each end of the house and he directed construction of single-story flat-roofed extensions at either end of the house; these provided space for the separate household of the newlyweds James and Dolley Madison. After his second term as president, in 1817 Madison retired there full-time with his wife Dolley.[11] James Madison died in 1836 and is buried in the family cemetery at Montpelier. His widow Dolley Madison moved back to Washington, D.C., in 1837 after his death. In 1844 she sold the plantation to Henry W. Moncure. After Dolley Madison died in 1849, she was buried in Washington, D.C., and later re-interred at Montpelier near her husband James. After Dolley Madison sold the estate to Henry W. Moncure in 1844, the property was held by six successive owners before the du Ponts bought Montpelier in 1901. The various owners and the dates associated with the site include: Benjamin Thornton (1848–1854), William H. Macfarland (1854–1855), Alfred V. Scott (1855–1857), Thomas J. Carson and Frank Carson (1857–1881), Louis F. Detrick and William L. Bradley (1881–1900) and Charles King Lennig (1900).[13] The name Montpelier The origins of the name Montpelier are uncertain, but the first recorded use of the name comes from a 1781 James Madison letter. Madison personally liked the French spelling of the name Montpellier. The city of Montpellier, France, was a famous resort. Clues from letters and visitor descriptions suggest these origins of the plantation's name.[14] Slavery at Montpelier The work of Montpelier was done primarily by its about 100 enslaved African people during James Madison's tenure as owner. Slaves served in a variety of roles: field workers, domestic servants in charge of cleaning, cooking, and care of clothing; and as artisans for the mill, forge, wheelwright, and other carpentry and woodworking. During the time that the Madisons owned the estate, "five, six, and possibly seven generations of African Americans were born into slavery at Montpelier."[10] The most well-known slave from Montpelier was Paul Jennings (1799-1874), Madison's body servant from 1817 to 1835. When Jennings went to the White House at age 10, he served at table and did other work. Senator Daniel Webster purchased Jennings from the widowed Dolley Madison in 1845, and gave him his freedom. Jennings continued to live in Washington, DC, where he worked as a laborer at the federal Pension Bureau and became a homeowner.[15] In 1848, Jennings helped plan the largest slave escape in United States history, as 77 slaves from the Washington, DC area took to The Pearl, a schooner, intending to sail up the Chesapeake Bay to a free state.[16][17] They were captured and most were sold to the Deep South. Jennings was noted for his reminiscences of Madison, A Colored Man's Reminiscences of James Madison (1865), which is considered the first White House memoir.[18] Archaeological research and documentary analysis has revealed much about the life of Montpelier-born slave, Catherine Taylor (ca. 1820 – after 1889). Catherine married Ralph Taylor, a house slave, and had four children with him. When Dolley Madison moved to Washington, D.C. in the years after James Madison's death, Ralph was chosen to accompany her to serve her in the capital. Dolley kept Catherine at Montpelier for several months after she brought Ralph to D.C., and then brought Catherine to D.C. later Dolley Madison transferred (or deeded), most of the enslaved people to her son, John Payne Todd. He stipulated in his will that upon his death, the slaves would be manumitted. However, due to legal and financial complications after Todd's death, the slaves were not manumitted. The Taylors petitioned James C. Maguire, the administrator of the estate, for their freedom. After being officially freed in 1853, they chose to live in Washington, which had a large free black community and opportunities for varied work.[19] The Montpelier staff continues to research the enslaved community by a variety of methods: studying historical documents such as court records and autobiographies, conducting archaeological excavations, contacting current descendants, and document the contributions and sacrifices of the enslaved community.[20] The duPont family After some renovations in the later 19th century (c. 1855 and c. 1880), the house was acquired in 1901 by William and Annie Rogers duPont, of the duPont family. A horse enthusiast, William duPont built barns, stables, and other buildings for equestrian use. The duPonts were among several wealthy families in the Upper South who were influential in the development of Thoroughbred horse racing in the United States. The duPont family also added a Hodgson House to the property. These were known as "America's First Organized Prefabricated House Manufacturer before Aladdin, Sears, and Montgomery Ward", emphasizing that the homes could technically be built in a day. Still located on Montpelier's property, it is now known as the "Bassett House."[21] William and Annie had a daughter, Marion duPont, and a son William duPont Jr. Upon William duPont Sr.'s death in 1928, William duPont Jr. inherited the family's Bellevue estate in Delaware, whereupon he had the estate's mansion converted into a replica of Montpelier (now preserved as a state park),[22] and Marion inherited the Montpelier estate. Marion preserved much of the core of the Madison home, gardens, and grounds as a legacy for all Americans. After her father's death, Marion made only one change to the house; she remodeled her parents' music room in the latest Art Deco style, using modern and innovative materials such as laminated plywood, chrome, glass block, and plate glass mirrors. A weather vane was installed on the ceiling, which allowed wind direction to direct the hounds for fox hunting. An exact replica of the Art Deco room can be seen in the DuPont Gallery, in the Visitors' Center at Montpelier. Prior to her parents moving into the property, they enlarged the house considerably, adding wings that more than doubled the number of rooms to 55. Her parents also had the brick covered with a stucco exterior for a lighter look. Hunt Races In 1934, Marion and her brother William founded the Montpelier Hunt Races, to be held on the grounds. Natural hedges were used as jumps for the steeplechase. The races continue to be held annually, the first Saturday each November. Marion duPont Scott died in 1983 and bequeathed the property to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, with $10 million (~$23.2 million in 2021) as an endowment to buy and maintain it. Her father's will had stated that if she died childless, the property would go to her brother William duPont Jr. and his children. As he had died in 1965, his five children legally inherited the property. In 1984, the heirs of Marion duPont Scott, in accordance with her wishes, transferred ownership of Montpelier to the National Trust for Historic Preservation.[23] National Trust Property Since the National Trust for Historic Preservation took ownership in 1984, the organization has worked to restore Montpelier to the Madison era. It has paid tribute to Marion duPont Scott's influence by retaining one of her favorite rooms in the newly renovated and expanded Visitor's Center, along with the annual Montpelier Hunt Races.[24] In 2000, the National Trust established Montpelier as a co-stewardship property, administered by The Montpelier Foundation. The Robert H. Smith Center for the Constitution provided an Education Center for students and teachers. It sponsors the "We the People" program to promote the understanding of civics for upper elementary and secondary students, along with national and state programs for teachers, such as the National Advanced Content Seminars, which focuses on historical content and teaching methods.[24] In conjunction with the James Madison University Field School, Montpelier has been the site of annual, seasonal archeological excavations from April to November. Under a four-year collaborative research grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, four quarters have been excavated related to the lives of enslaved African Americans: including the Stable Quarter (2009), South and Kitchen Yards (2011), Tobacco Barn Quarter (2012), and Field Quarter (2013).[25] The excavations have revealed early structures in those areas, including possible slave quarters, as well as a variety of artifacts dating to the Madison residency and their slaves. The artifacts are helping researchers form a much broader and deeper picture of the lives of the slaves at Montpelier. "The four residential locations provide a unique opportunity to compare and contrast the conditions of chattel slavery of the period. Differences and similarities between these locations – particularly architectural styles and household goods such as ceramics, glassware, and clothing items – reflect the relationship of individual households to each other, the community to which they belong, their relationship to the overarching plantation complex, and regional patterns of both market access and cultural traditions. From 2003 to 2008 the National Trust carried out a $25 million restoration to return the mansion to its 1820 state; it is again less than half the size of the expanded residence created by the DuPont family. The National Trust is conducting a search for furnishings either original to the property or of its era. Restoration View of the Blue Ridge Mountains from the second floor of the front of James Madison's Montpelier, Orange County, VA. A $25 million restoration project launched in October 2003 was completed on Constitution Day, September 17, 2008. A Restoration Celebration was held with major funding by National Trust Community Investment Corporation.[26] The restoration returned Montpelier to its 1820 appearance: it demolished additions made to the house by the duPont family, removed the stucco exterior to reveal the original brick, restored the original brick exterior, and reconstructed the house's interior as it appeared during Madison's tenure as owner. Authentic materials were used in the restoration, including horsehair plaster, and paint containing linseed oil and chalk. The Collections staff and archaeologists are working to understand the decorations of each room and recreate room settings as closely as possible to what the Madisons knew.[27] A wing in the visitors' center has been dedicated to the duPont family. It includes a restored art deco Red Room from the Marion duPont Scott era, moved from the mansion and permanently installed here.[27] Entrance to the gardens at Montpelier Restored Montpelier train depot is now a civil rights museum The Mere Distinction of Colour In 2017, Montpelier added to its existing interpretations of slavery – including the Gilmore Cabin and the Jim Crow–era Train Station, both of which are permanent installations – with the opening of the exhibition, The Mere Distinction of Colour.[28] This exhibition, funded by a donation from philanthropist David Rubenstein, explores the history and legacies of American slavery both at Montpelier and nationwide. The Mere Distinction of Colour spans the cellars of the Madison house, the south cellar exploring the Montpelier slavery story, and the north cellar analyzing the economics and legacies of slavery. The exhibition is the culmination of decades of archaeological and documentary research conducted by Montpelier staff and advisors. One of the unique features of this exhibition is that it was guided by living descendants of the slaves who once inhabited Montpelier and the surrounding area. Montpelier has an active descendant community, some of whom have genealogical proof of their ancestry, and others who are connected through oral histories that have been passed down through generations. The South Cellar details the Montpelier story of slavery, complete with the voices of descendants and the names of everyone known to be enslaved on the property throughout the Madison ownership. The North Cellar analyses the national slave narrative, talking about how slavery become institutionalized in American society and how profitable the slave trade was for all of the colonies, not exclusively the south. The unguided Mere Distinction of Colour installation is free with the purchase of any tour ticket,[29] and is open to the public Thursday to Monday. Today Montpelier is open to visitors Thursday to Monday except Thanksgiving and Christmas, with the following hours: January – March: 9:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m, April – October: 9:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m., November – December: 9:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. Montpelier includes the a Hands-on-Restoration-Tent open from April–October; Hands-on-Archaeology Lab and Kid-Sized Archaeology open daily; Hands-on-Cooking offered April–October; Civil War and Gilmore Farm Trail open daily; and, the Archaeology Dig open April–October. Visitors can also walk around the James Madison Landmark Forest, a 200-acre (0.81 km2) stand of old growth forest.[30] |

歴史 マディソン家 1723年、ジェームズ・マディソンの祖父アンブローズ・マディソンと義弟トマス・チューは、バージニア州ピードモントに4,675エーカー (18.92km2)の土地の特許を取得。アンブローズと妻のフランシス・マディソン、そして3人の子供たちは、1732年にこの農園に移り住み、マウン ト・プレザントと名付けた。(考古学者たちは、この最初の場所をマディソン家の墓地の近くに発見した)。裁判記録によると、アンブローズは3人の奴隷アフ リカ人に毒殺されたという。当時、アンブローズ・マディソンは29人の奴隷と4,000エーカー(16km2)近い土地を所有していた[10]。彼の死 後、フランシスは息子のジェームズ・マディソン・シニア大佐の助けを借りて農園を管理した。 マディソン・シニアは、1740年代にプランテーションを拡大し、建築サービスや鍛冶を行うようになり、タバコやその他の作物を栽培するために奴隷を買い 足した。彼はネリー・コンウェイ・マディソン(1731-1829)と結婚し、12人の子供をもうけた。 ジェームズ・マディソン・シニアの長男もジェームズと名付けられ、1751年3月16日にポート・コンウェイにある母親の実家の地所ベル・グローブで生ま れた。ジェームズ・マディソンは幼少期をマウント・プレザントで過ごした。 1760年代初頭、マディソン・シニアは半マイル離れた場所に新しい家を建て、その構造が今日のモントピリアのメインハウスの中心をなしている。1764 年頃に建てられたこの邸宅は、フレミッシュ・ボンド様式の煉瓦造りの2階建てで、低い寄棟屋根の両端に煙突がある。息子のジェームズ・マディソンは、新居 への家具の移動を手伝ったことを覚えていると後に語っている。モンペリエの建設は、その第1期(1764年~1797年)にあたる。完成時、マディソン家 はオレンジ郡で最大級のレンガ造りの住居を所有していた[11]。 第2段階(1797年~1800年)の建設は、息子のジェームズが新妻のドリー・マディソンと共にモンペリエに戻った後の1797年に始まった。彼は当時 39歳で、彼女は子持ちの若い未亡人だった。この時、マディソンは家に30フィートの増築とトスカーナ風のポーティコを加えた。マディソンの未亡人の母ネ リーは、1801年に夫のジェームズ・シニアが亡くなった後もこの家に住んでいた[12]。 最後の建設期間である第3期(1809年~1812年)には、マディソンは大きな応接間を増築させ、家の両端に1階建ての棟を設け、家の両端に平屋建ての 平屋根の増築を指示した。大統領として2期目の任期を終えたマディソンは、1817年に妻のドリーとともにフルタイムでそこに隠居した[11]。 ジェームズ・マディソンは1836年に死去し、モンペリエの家族墓地に埋葬された。未亡人のドリー・マディソンは彼の死後、1837年にワシントン D.C.に戻った。1844年、彼女は農園をヘンリー・W・モンキュアに売却。1849年にドリー・マディソンが死去した後、彼女はワシントンD.C.に 埋葬されたが、後に夫ジェームズの近くのモンペリエに再び埋葬された。 1844年にドルリー・マディソンがヘンリー・W・モンキュアに不動産を売却した後、1901年にデュポン夫妻がモンペリエを購入するまで、この土地は6 人の所有者によって所有された。さまざまな所有者と、この土地にまつわる日付は以下の通り: ベンジャミン・ソーントン(1848年~1854年)、ウィリアム・H・マクファーランド(1854年~1855年)、アルフレッド・V・スコット (1855年~1857年)、トーマス・J・カーソンとフランク・カーソン(1857年~1881年)、ルイス・F・デトリックとウィリアム・L・ブラッ ドリー(1881年~1900年)、チャールズ・キング・レニグ(1900年)[13]。 モンペリエの名称 モンペリエの名前の起源は定かではないが、記録に残る最初の使用は1781年のジェームズ・マディソンの手紙に由来する。マディソンは個人的にモンペリエ という名前のフランス語表記を気に入っていた。フランスのモンペリエは有名なリゾート地だった。手紙や訪問者の記述から、農園名の由来がこのようなもので あることが示唆されている[14]。 モンペリエの奴隷制度 モンペリエの仕事は、ジェームズ・マディソンが所有者として在任中、主に約100人のアフリカ人奴隷によって行われた。奴隷たちは、畑仕事人、掃除、料 理、衣服の手入れを担当する家事使用人、製粉所、鍛冶場、轆轤工、その他の大工や木工の職人など、さまざまな役割を果たした。マディソン家が領地を所有し ていた間、「5世代、6世代、おそらく7世代のアフリカ系アメリカ人がモンペリエで奴隷として生まれた」[10]。 モンペリエ出身の最も有名な奴隷は、1817年から1835年までマディソンの身体使用人だったポール・ジェニングス(1799-1874)である。ジェ ニングスは10歳でホワイトハウスに赴任すると、食卓で給仕やその他の仕事をした。ダニエル・ウェブスター上院議員は1845年、未亡人となったドリー・ マディソンからジェニングスを買い取り、自由を与えた。ジェニングスはワシントンDCに住み続け、連邦年金局で労働者として働き、家の所有者となった [15]。 1848年、ジェニングスはワシントンDC周辺から77人の奴隷がチェサピーク湾を航海して自由州を目指すスクーナー船「パール号」に乗り込み、アメリカ 史上最大の奴隷逃亡を計画する手助けをした[16][17]。ジェニングスはマディソンを回想した『A Colored Man's Reminiscences of James Madison』(1865年)で知られ、これは最初のホワイトハウス回想録とされている[18]。 考古学的研究と文書分析により、モンペリエ生まれの奴隷キャサリン・テイラー(1820年頃~1889年以降)の生涯について多くのことが明らかになっ た。キャサリンは家内奴隷のラルフ・テイラーと結婚し、彼との間に4人の子供をもうけた。ジェームズ・マディソンの死後、ドルリー・マディソンがワシント ンD.C.に移ったとき、ラルフは首都で彼女に仕えるために同行することになった。ドルリーはラルフをD.C.に連れて行った後、数ヶ月間キャサリンをモ ンペリエに留め、その後キャサリンをD.C.に連れて行った。 ドルリー・マディソンは、奴隷にされていた人々のほとんどを、息子のジョン・ペイン・トッドに譲渡(または権利譲渡)した。彼は遺言の中で、自分の死後、 奴隷を解放すると定めていた。しかし、トッドの死後、法的および財政的な複雑さが生じたため、奴隷は召還されませんでした。テイラー夫妻は、遺産管理人で あるジェームズ・C・マグワイアに、奴隷の自由を請願した。1853年に正式に解放された後、彼らは大規模な自由黒人コミュニティがあり、様々な仕事をす る機会があったワシントンに住むことを選んだ[19]。 モンペリエのスタッフは、裁判記録や自伝などの歴史文書の研究、考古学的発掘調査、現在の子孫との接触、奴隷社会の貢献と犠牲の記録など、さまざまな方法 で奴隷社会の研究を続けている[20]。 デュポン家 19世紀後半(1855年頃と1880年頃)に何度か改築された後、1901年にデュポン家のウィリアムとアニー・ロジャースのデュポン夫妻がこの家を取 得した。馬の愛好家であったウィリアム・デュポンは、馬術用の納屋や厩舎、その他の建物を建てた。デュポン夫妻は、アメリカにおけるサラブレッド競馬の発 展に影響を与えたアッパー・サウスの裕福な一族である。デュポン家は敷地内にホジソン・ハウスも増築した。これらは「アラジン、シアーズ、モンゴメリー ウォード以前のアメリカ初の組織化されたプレハブ住宅メーカー」として知られ、技術的には1日で家を建てられることを強調していた。現在もモンペリエの敷 地内にあり、「バセット・ハウス」として知られている[21]。 ウィリアムとアニーには娘のマリオン・デュポンと息子のウィリアム・デュポン・ジュニアがいた。1928年にウィリアム・デュポン・シニアが亡くなると、 ウィリアム・デュポン・ジュニアはデラウェア州にある一族のベルビュー邸を相続し、同邸の邸宅をモンペリエのレプリカ(現在は州立公園として保存)に改築 させ[22]、マリオンがモンペリエ邸を相続した。マリオンは、マディソンの邸宅の中心部、庭園、敷地の大部分を、すべてのアメリカ人のための遺産として 保存した。父親の死後、マリオンがこの邸宅に加えた変更はただひとつ。両親の音楽室を最新のアール・デコ様式に改装し、積層合板、クロームメッキ、ガラス ブロック、板ガラスの鏡など、モダンで革新的な素材を使用した。天井には風見鶏が設置され、キツネ狩りの猟犬に風向きを指示できるようにした。アール・デ コの部屋の正確なレプリカは、モントピリアのビジターセンターにあるデュポン・ギャラリーで見ることができる。彼女の両親がこの土地に移り住む前に、邸宅 を大幅に増築し、部屋数を2倍以上の55に増やした。また、両親はレンガをスタッコで覆い、明るい外観にした。 ハント・レース 1934年、マリオンと弟のウィリアムは、敷地内で開催されるモンペリエ・ハント・レースを創設した。天然の生垣が障害飛越競技のジャンプ台として使用さ れた。レースは毎年11月の第1土曜日に開催されている。 マリオン・デュポン・スコットは1983年に死去し、この土地を購入し維持するための基金として1,000万ドル(2021年には2,320万ドル)を歴 史保存ナショナル・トラストに遺贈した。彼女の父の遺言書には、もし彼女に子供がいなければ、この土地は彼女の兄ウィリアム・デュポン・ジュニアとその子 供たちに贈られると記されていた。彼は1965年に亡くなっていたので、彼の5人の子供たちが合法的に財産を相続した。1984年、マリオン・デュポン・ スコットの相続人は、彼女の遺志に従い、モンペリエの所有権を歴史保存ナショナル・トラストに譲渡した[23]。 ナショナル・トラストの財産 1984年に歴史保存ナショナル・トラストが所有権を取得して以来、同組織はモンペリエをマディソン時代に復元することに取り組んできた。マリオン・デュ ポン・スコットの影響力に敬意を表し、毎年開催されるモンペリエ・ハント・レースとともに、新しく改修・拡張されたビジターセンターに彼女のお気に入りの 部屋を残している[24]。 2000年、ナショナル・トラストはモンペリエを共同管理財産として設立し、モンペリエ財団が管理している。 ロバート・H・スミス憲法センターは、学生や教師のための教育センターを提供。同センターは、小学校高学年および中学生を対象に公民の理解を促進する 「We the People」プログラムを主催しているほか、歴史的内容や教授法に焦点を当てた「National Advanced Content Seminars」など、教師のための国や州のプログラムも実施している[24]。 ジェームズ・マディソン大学フィールド・スクールと連携して、モンペリエは毎年4月から11月までの季節的な考古学的発掘調査の場所となっている。全米人 文科学基金(National Endowment for the Humanities)からの4年間の共同研究助成金により、奴隷にされたアフリカ系アメリカ人の生活に関連する4つのクォーターが発掘された:ステーブ ル・クォーター(2009年)、サウス・ヤードとキッチン・ヤード(2011年)、タバコ・バーン・クォーター(2012年)、フィールド・クォーター (2013年)[25] 発掘により、奴隷宿舎の可能性を含むこれらの地域の初期の建造物や、マディソン居住者とその奴隷にまつわる様々な遺物が発見された。これらの遺物は、モン ペリエの奴隷たちの生活について、研究者たちがより広く深いイメージを形成するのに役立っている。"4つの居住地は、当時の動産奴隷の状況を比較対照する またとない機会を提供してくれる。特に建築様式や、陶磁器、ガラス製品、衣料品などの家財道具の違いや共通点は、個々の家同士の関係や、彼らが属するコ ミュニティ、包括的な農園団地との関係、市場へのアクセスや文化的伝統の地域的なパターンを反映している。 2003年から2008年にかけて、ナショナル・トラストはこの邸宅を1820年の状態に戻すために2500万ドルの修復工事を行った。ナショナル・トラ ストは、この邸宅のオリジナルか、その時代の調度品を探している。 修復 ジェームズ・マディソンのモントペリエ(バージニア州オレンジ郡)の正面2階からブルーリッジ山脈を望む。 2003年10月に開始された2500万ドルの修復プロジェクトは、2008年9月17日の憲法記念日に完了した。修復祝賀会は、ナショナル・トラスト・ コミュニティ・インベストメント・コーポレーションが主な資金を提供し、開催された[26]。この修復により、モンペリエは1820年当時の姿に戻され た。デュポン家によって増築された建物は取り壊され、漆喰の外壁が取り除かれ、オリジナルのレンガ造りの外壁が現れ、オリジナルのレンガ造りの外壁が復元 された。修復には、馬毛の漆喰、亜麻仁油とチョークを含む塗料など、本物の材料が使われた。コレクションのスタッフと考古学者は、各部屋の装飾を理解し、 マディソン夫妻が知っていたものにできるだけ近い部屋のセッティングを再現することに取り組んでいる[27]。 ビジターセンターの一棟は、デュポン家に捧げられている。ここには、マリオン・デュポン・スコット時代のアールデコ調のレッドルームが復元され、邸宅から 移築されて常設されている[27]。 モンペリエの庭園入口 復元されたモンペリエの車両基地は、現在は公民権博物館となっている。 単なる色の区別 2017年、モンペリエは、ギルモア・キャビンやジム・クロウ時代の車両基地など、既存の奴隷制の解釈に加え、「The Mere Distinction of Colour」展を常設展示としてオープンした[28]。この展示は、慈善家デイヴィッド・ルーベンスタインの寄付によって賄われ、モンペリエと全米の奴 隷制の歴史と遺産を探求している。The Mere Distinction of Colour」はマディソン邸の地下室にまたがっており、南側の地下室ではモンペリエの奴隷制の物語を、北側の地下室では奴隷制の経済と遺産を分析してい る。この展示は、モンペリエのスタッフとアドバイザーが数十年にわたって行った考古学的・文書学的調査の集大成である。 この展示のユニークな特徴のひとつは、かつてモンペリエとその周辺地域に居住していた奴隷の子孫がガイドを務めたことだ。モンペリエには活発な子孫コミュ ニティがあり、その中には先祖の系図的証拠を持つ者もいれば、代々受け継がれてきた口承史でつながっている者もいる。 サウスセラーでは、子孫の声や、マディソン所有時代を通じてこの土地で奴隷として扱われていたことが判明している全員の名前とともに、モンペリエの奴隷制 度に関する物語を詳しく紹介している。北側の地下室では、奴隷制度がアメリカ社会でどのように制度化されたのか、奴隷貿易が南部だけでなく植民地全体に とっていかに有益であったかを語り、全国的な奴隷の物語を分析する。 ガイドなしの「Mere Distinction of Colour(単なる色の違い)」インスタレーションは、ツアーチケットの購入で無料となり[29]、木曜日から月曜日まで一般公開されている。 今日 モンペリエは、感謝祭とクリスマスを除く木曜日から月曜日まで開館しており、開館時間は以下の通り: 1月~3月 1月~3月:午前9時~午後3時、4月~10月:午前9時~午後3時: 1月~3月:午前9時~午後3時、4月~10月:午前9時~午後3時、11月~12月:午前9時~午後3時。 モンペリエには、4月~10月にオープンするハンズオン・レストレーション・テント、毎日オープンするハンズオン・考古学ラボとキッズ・サイズ考古学、4 月~10月にオープンするハンズオン・クッキング、毎日オープンする南北戦争とギルモア・ファーム・トレイル、4月~10月にオープンする考古学ディグが ある。また、200エーカー(0.81km2)の原生林であるジェームズ・マディソン・ランドマーク・フォレストを散策することもできる[30]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montpelier_(Orange,_Virginia) |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099