道徳あるいは道徳性

Morality

Allegory

with a portrait of a Venetian senator (Allegory of the morality of

earthly things), attributed to Tintoretto, 1585

☆ 道徳(どうとく、ラテン語のmoralitas「態度、性格、適切な行動」から)とは、意図、決定、行動を適切なもの、すなわち正しいものと、不適切なも の、すなわち間違っているものに分類することである[1]。道徳は、特定の哲学、宗教、文化に由来する行動規範に由来する基準や原則の体系である場合もあ れば、普遍的であると理解される基準に由来する場合もある[2]。 道徳哲学には、道徳存在論や道徳認識論といった抽象的な問題を研究するメタ倫理学と、脱ontological ethicsや帰結主義といった道徳的意思決定のより具体的な体系を研究する規範倫理学がある。規範的倫理哲学の例として、黄金律が挙げられる: 「人は、他人が自分を扱ってほしいと思うように他人を扱うべきである」[3][4]。 非道徳性とは、道徳に対する積極的な反対(すなわち、善または正しいものに対する反対)であり、一方、非道徳性とは、特定の一連の道徳的基準または原則に 対する無自覚、無関心、または不信として様々に定義される[5][6][7]。

☆「必然的に私的倫理の理論である道徳的哲学が到達しうる最高点は、因果律と自由のアンチノミーです」(アドルノ 2006:290)。

★道徳的世界観は思考を欠いた矛盾の大巣窟である(カント「純粋理性批判」B637)——ヘーゲル

★

道徳とは、カントによれば不可能なことを要求するものである。ただしカントはそれに飽き足らず、この不可能の次元が伝統的な倫理学のなかに包摂されていな

いことに気づき、リアルなもののまわりを堂々巡りする欲望(=ある種の余剰)の次元、を唯一可能で正当な倫理の領域として定めたのだ(→定言命法)

| Morality (from Latin

moralitas 'manner, character, proper behavior') is the categorization

of intentions, decisions and actions into those that are proper, or

right, and those that are improper, or wrong.[1] Morality can be a body

of standards or principles derived from a code of conduct from a

particular philosophy, religion or culture, or it can derive from a

standard that is understood to be universal.[2] Morality may also be

specifically synonymous with "goodness", "appropriateness" or

"rightness". Moral philosophy includes meta-ethics, which studies abstract issues such as moral ontology and moral epistemology, and normative ethics, which studies more concrete systems of moral decision-making such as deontological ethics and consequentialism. An example of normative ethical philosophy is the Golden Rule, which states: "One should treat others as one would like others to treat oneself."[3][4] Immorality is the active opposition to morality (i.e., opposition to that which is good or right), while amorality is variously defined as an unawareness of, indifference toward, or disbelief in any particular set of moral standards or principles.[5][6][7] |

道徳(どうとく、ラテン語のmoralitas「態度、性格、適切な行

動」から)とは、意図、決定、行動を適切なもの、すなわち正しいものと、不適切なもの、すなわち間違っているものに分類することである[1]。道徳は、特

定の哲学、宗教、文化に由来する行動規範に由来する基準や原則の体系である場合もあれば、普遍的であると理解される基準に由来する場合もある[2]。 道徳哲学には、道徳存在論や道徳認識論といった抽象的な問題を研究するメタ倫理学と、脱ontological ethicsや帰結主義といった道徳的意思決定のより具体的な体系を研究する規範倫理学がある。規範的倫理哲学の例として、黄金律が挙げられる: 「人は、他人が自分を扱ってほしいと思うように他人を扱うべきである」[3][4]。 非道徳性とは、道徳に対する積極的な反対(すなわち、善または正しいものに対する反対)であり、一方、非道徳性とは、特定の一連の道徳的基準または原則に 対する無自覚、無関心、または不信として様々に定義される[5][6][7]。 |

| Evolution of morality and History of ethics |

|

| Ethics Ethics (also known as moral philosophy) is the branch of philosophy which addresses questions of morality. The word "ethics" is "commonly used interchangeably with 'morality' ... and sometimes it is used more narrowly to mean the moral principles of a particular tradition, group, or individual."[8] Likewise, certain types of ethical theories, especially deontological ethics, sometimes distinguish between ethics and morality.  Immanuel Kant introduced the categorical imperative: "Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law." Philosopher Simon Blackburn writes that "Although the morality of people and their ethics amounts to the same thing, there is a usage that restricts morality to systems such as that of Immanuel Kant, based on notions such as duty, obligation, and principles of conduct, reserving ethics for the more Aristotelian approach to practical reasoning, based on the notion of a virtue, and generally avoiding the separation of 'moral' considerations from other practical considerations."[9] |

倫理学 倫理学(どうがく、英: Ethics)とは、道徳の問題を扱う哲学の一分野である。倫理学」という言葉は「一般的に『道徳』と互換的に使用され......特定の伝統、集団、ま たは個人の道徳原理を意味するためにより狭く使用されることもある」[8]。同様に、ある種の倫理理論、特に義務論的倫理学は、倫理と道徳を区別すること がある。  イマヌエル・カントは定言命法を導入した。「自分がその格律に従ってのみ行動し、それによって同時に、それが普遍的な法則となるように意志することができる」。 哲学者のサイモン・ブラックバーンは、「人々の道徳と倫理は同じものであるが、道徳を義務、義務、行動原理といった概念に基づくイマヌエル・カントのよう な体系に限定し、倫理を徳の概念に基づく実践的推論に対するよりアリストテレス的なアプローチに留保し、一般的に他の実践的考察から「道徳的」考察を分離 することを避ける用法がある」と書いている[9]。 |

| Descriptive and normative In its descriptive sense, "morality" refers to personal or cultural values, codes of conduct or social mores that are observed to be accepted by a significant number of individuals (not necessarily all) in a society. It does not connote objective claims of right or wrong, but only refers to claims of right and wrong that are seen to be made and to conflicts between different claims made. Descriptive ethics is the branch of philosophy which studies morality in this sense.[10] In its normative sense, "morality" refers to whatever (if anything) is actually right or wrong, which may be independent of the values or mores held by any particular peoples or cultures. Normative ethics is the branch of philosophy which studies morality in this sense.[10] |

記述的と規範的 記述的な意味での「道徳」とは、ある社会でかなりの数の個人(必ずしも全員ではない)に受け入れられていると観察される人格的または文化的価値観、行動規 範、社会的モラルを指す。善悪の客観的な主張を意味するのではなく、善悪の主張がなされているように見え、異なる主張の間で対立していることを意味する。 記述倫理学は、この意味での道徳を研究する哲学の一分野である[10]。 規範的な意味において「道徳」とは、実際に正しいか間違っているかは何であれ(もし何であれ)、特定の民族や文化が持つ価値観や風俗とは無関係なものを指す。規範倫理学は、この意味での道徳を研究する哲学の一分野である[10]。 |

| Realism and anti-realism Philosophical theories on the nature and origins of morality (that is, theories of meta-ethics) are broadly divided into two classes: Moral realism is the class of theories which hold that there are true moral statements that report objective moral facts. For example, while they might concede that forces of social conformity significantly shape individuals' "moral" decisions, they deny that those cultural norms and customs define morally right behavior. This may be the philosophical view propounded by ethical naturalists, but not all moral realists accept that position (e.g. ethical non-naturalists).[11] Moral anti-realism, on the other hand, holds that moral statements either fail or do not even attempt to report objective moral facts. Instead, they hold that moral sentences are either categorically false claims of objective moral facts (error theory); claims about subjective attitudes rather than objective facts (ethical subjectivism); or else do not attempt to describe the world at all but rather something else, like an expression of an emotion or the issuance of a command (non-cognitivism). Some forms of non-cognitivism and ethical subjectivism, while considered anti-realist in the robust sense used here, are considered realist in the sense synonymous with moral universalism. For example, universal prescriptivism is a universalist form of non-cognitivism which claims that morality is derived from reasoning about implied imperatives, and divine command theory and ideal observer theory are universalist forms of ethical subjectivism which claim that morality is derived from the edicts of a god or the hypothetical decrees of a perfectly rational being, respectively. |

現実主義と反現実主義 道徳の本質と起源に関する哲学的理論(つまりメタ倫理学の理論)は、大きく2つのクラスに分けられる: 道徳的実在論は、客観的な道徳的事実を報告する真の道徳的声明が存在するとする理論である。例えば、社会適合の力が個人の「道徳的」決定を大きく形作るこ とは認めるかもしれないが、そうした文化的規範や慣習が道徳的に正しい行動を規定することは否定する。これは倫理的自然主義者が提唱する哲学的見解である かもしれないが、全ての道徳的現実主義者がその立場を受け入れているわけではない(例えば倫理的非自然主義者)[11]。 一方、道徳的反実在論は、道徳的言明は客観的な道徳的事実を報告しないか、報告しようとさえしないとする。その代わりに、道徳的文章は客観的な道徳的事実 についての断定的に誤った主張であるか(誤り理論)、客観的事実ではなく主観的態度についての主張であるか(倫理的主観主義)、あるいは世界を全く記述し ようとせず、むしろ感情の表現や命令の発動のような何か別のものであるとする(非認知主義)。 非認知主義や倫理的主観主義の中には、ここで使われる強固な意味での反実在主義でありながら、道徳的普遍主義と同義の意味での実在主義と見なされるものも ある。例えば、普遍的規定主義は非認知主義の普遍主義的形態であり、道徳は暗黙の命令についての推論から導かれると主張する。また、神的命令論や理想的観 察者論は倫理的主観主義の普遍主義的形態であり、道徳はそれぞれ神の勅令や完全に理性的な存在の仮定の命令から導かれると主張する。 |

| Anthropology Morality with practical reasoning Practical reason is necessary for the moral agency but it is not a sufficient condition for moral agency.[12] Real life issues that need solutions do need both rationality and emotion to be sufficiently moral. One uses rationality as a pathway to the ultimate decision, but the environment and emotions towards the environment at the moment must be a factor for the result to be truly moral, as morality is subject to culture. Something can only be morally acceptable if the culture as a whole has accepted this to be true. Both practical reason and relevant emotional factors are acknowledged as significant in determining the morality of a decision.[13][neutrality is disputed] |

人間学 実践的理性による道徳 実践的理性は道徳的行為に必要だが、道徳的行為の十分条件ではない[12]。解決策を必要とする現実の問題は、十分に道徳的であるために合理性と感情の両 方を必要とする。人は最終的な決定への道筋として合理性を用いるが、道徳は文化に左右されるものであるため、その結果が真に道徳的であるためには、その時 々の環境や環境に対する感情も要因とならなければならない。道徳は文化に左右されるものであるため、文化全体がそれを受け入れている場合にのみ、何かが道 徳的に受け入れられるのである。現実的な理由と関連する感情的な要因の両方が、意思決定の道徳性を決定する上で重要であると認められている[13][中立 性が争われている]。 |

| Tribal and territorial Celia Green made a distinction between tribal and territorial morality.[14] She characterizes the latter as predominantly negative and proscriptive: it defines a person's territory, including his or her property and dependents, which is not to be damaged or interfered with. Apart from these proscriptions, territorial morality is permissive, allowing the individual whatever behaviour does not interfere with the territory of another. By contrast, tribal morality is prescriptive, imposing the norms of the collective on the individual. These norms will be arbitrary, culturally dependent and 'flexible', whereas territorial morality aims at rules which are universal and absolute, such as Kant's 'categorical imperative' and Geisler's graded absolutism. Green relates the development of territorial morality to the rise of the concept of private property, and the ascendancy of contract over status. |

部族道徳と領土道徳 セリア・グリーンは、部族的道徳と領土的道徳を区別した[14] 。このような禁止事項を除けば、縄張り道徳は寛容であり、他人の縄張りを侵害しない範囲であれば、どんな行動も許される。対照的に、部族道徳は規定的であ り、集団の規範を個人に押し付ける。これらの規範は恣意的で文化に依存し、「柔軟」であるのに対し、縄張り道徳はカントの「定言命法」やガイスラーの「段 階的絶対主義」のような普遍的で絶対的なルールを目指す。グリーンは、縄張り道徳の発展と私有財産の概念の台頭、身分よりも契約の優位性を関連付けてい る。 |

| In-group and out-group Main article: In-group and out-group Some observers hold that individuals apply distinct sets of moral rules to people depending on their membership of an "in-group" (the individual and those they believe to be of the same group) or an "out-group" (people not entitled to be treated according to the same rules). Some biologists, anthropologists and evolutionary psychologists believe this in-group/out-group discrimination has evolved because it enhances group survival. This belief has been confirmed by simple computational models of evolution.[15] In simulations this discrimination can result in both unexpected cooperation towards the in-group and irrational hostility towards the out-group.[16] Gary R. Johnson and V.S. Falger have argued that nationalism and patriotism are forms of this in-group/out-group boundary. Jonathan Haidt has noted[17] that experimental observation indicating an in-group criterion provides one moral foundation substantially used by conservatives, but far less so by liberals. In-group preference is also helpful at the individual level for the passing on of one's genes. For example, a mother who favors her own children more highly than the children of other people will give greater resources to her children than she will to strangers', thus heightening her children's chances of survival and her own gene's chances of being perpetuated. Due to this, within a population, there is substantial selection pressure exerted toward this kind of self-interest, such that eventually, all parents wind up favoring their own children (the in-group) over other children (the out-group). |

内集団と外集団 主な記事 内集団と外集団 一部の観察者は、「内集団」(個人と同じ集団に属すると考える人々)か「外集団」(同じ規則に従って扱われる資格のない人々)に属するかによって、個人は 人々に異なる道徳的規則を適用すると考えている。生物学者、人類学者、進化心理学者の中には、このような内集団/外集団の差別は、集団の生存を高めるため に進化してきたと考える者もいる。この信念は、進化に関する単純な計算モデルによって確認されている[15]。シミュレーションでは、この差別は、内集団 に対する予期せぬ協力と、外集団に対する非合理的な敵意の両方をもたらす可能性がある[16]。ゲイリー・R・ジョンソンとV.S.ファルガーは、ナショ ナリズムと愛国心は、この内集団/外集団境界の一形態であると主張している。ジョナサン・ヘイトは、内集団基準を示す実験的観察が、保守派には実質的に使 用される道徳的基盤の1つを提供するが、リベラル派にははるかに少ないことを指摘している[17]。 内集団選好は個人レベルでも遺伝子の継承に役立つ。例えば、他人の子供よりも自分の子供をより好む母親は、他人の子供よりも自分の子供に大きな資源を与え る。このため、集団内では、このような利己的な選択圧が大きく働き、最終的にはすべての親が他の子ども(外集団)よりも自分の子ども(内集団)を好むよう になる。 |

| Comparing cultures Peterson and Seligman[18] approach the anthropological view looking across cultures, geo-cultural areas and across millennia. They conclude that certain virtues have prevailed in all cultures they examined. The major virtues they identified include wisdom / knowledge; courage; humanity; justice; temperance; and transcendence. Each of these include several divisions. For instance humanity includes love, kindness, and social intelligence. Still, others theorize that morality is not always absolute, contending that moral issues often differ along cultural lines. A 2014 PEW research study among several nations illuminates significant cultural differences among issues commonly related to morality, including divorce, extramarital affairs, homosexuality, gambling, abortion, alcohol use, contraceptive use, and premarital sex. Each of the 40 countries in this study has a range of percentages according to what percentage of each country believes the common moral issues are acceptable, unacceptable, or not moral issues at all. Each percentage regarding the significance of the moral issue varies greatly on the culture in which the moral issue is presented.[19] Advocates of a theory known as moral relativism subscribe to the notion that moral virtues are right or wrong only within the context of a certain standpoint (e.g., cultural community). In other words, what is morally acceptable in one culture may be taboo in another. They further contend that no moral virtue can objectively be proven right or wrong[20] Critics of moral relativism point to historical atrocities such as infanticide, slavery, or genocide as counter arguments, noting the difficulty in accepting these actions simply through cultural lenses. Fons Trompenaars, author of Did the Pedestrian Die?, tested members of different cultures with various moral dilemmas. One of these was whether the driver of a car would have his friend, a passenger riding in the car, lie in order to protect the driver from the consequences of driving too fast and hitting a pedestrian. Trompenaars found that different cultures had quite different expectations, from none to definite.[21] Anthropologists from Oxford's Institute of Cognitive & Evolutionary Anthropology (part of the School of Anthropology & Museum Ethnography) analysed ethnographic accounts of ethics from 60 societies, comprising over 600,000 words from over 600 sources and discovered what they believe to be seven universal moral rules: help your family, help your group, return favours, be brave, defer to superiors, divide resources fairly, and respect others' property.[22][23] |

文化を比較する ピーターソンとセリグマン[18]は、文化、地理的文化圏、そして千年単位で人類学的な視点にアプローチしている。彼らは、調査したすべての文化において 特定の美徳が優勢であったと結論付けている。彼らが特定した主要な徳には、知恵・知識、勇気、人間性、正義、節制、超越が含まれる。これらにはそれぞれい くつかの区分がある。例えば、人間性には愛、優しさ、社会的知性などが含まれる。 それでもなお、道徳は常に絶対的なものではないという理論もあり、道徳的な問題は文化的な境界線に沿って異なることが多いと主張している。2014年に行 われたPEWの調査によると、離婚、婚外恋愛、同性愛、ギャンブル、中絶、アルコール使用、避妊具の使用、婚前交渉など、一般的に道徳に関連する問題には 文化的に大きな違いがあることが明らかになった。この調査の対象となった40カ国は、それぞれの国の何パーセントが、一般的な道徳的問題を容認できるか、 容認できないか、あるいはまったく道徳的問題ではないと考えているかによって、パーセンテージの幅がある。道徳的問題の重要性に関する各割合は、道徳的問 題が提示される文化によって大きく異なる[19]。 道徳的相対主義として知られる理論の支持者は、道徳的美徳は特定の立場(例えば、文化的共同体)の文脈内でのみ正しいか間違っているかであるという考え方 を支持している。言い換えれば、ある文化圏では道徳的に容認されることでも、別の文化圏ではタブーとされることがあるということだ。さらに、道徳的美徳の 正誤を客観的に証明することはできないと主張する[20]。道徳的相対主義の批判者は、反論として幼児虐殺、奴隷制度、大量虐殺などの歴史的残虐行為を挙 げ、これらの行為を単に文化的なレンズを通して受け入れることの難しさを指摘する。 歩行者は死んだのか』の著者であるフォンス・トロンペナーズは、異なる文化圏の人々に様々な道徳的ジレンマを課す実験を行った。そのひとつが、スピードの 出しすぎで歩行者をはねた結果から運転手を守るために、車の運転手が同乗している友人に嘘をつかせるかどうかというものだった。トロンペナーズは、文化が 異なれば、期待するものは全くないものから明確なものまで、かなり異なるものであることを発見した[21]。 オックスフォード大学認知進化人類学研究所(人類学・博物館民族誌学部の一部)の人類学者は、60の社会から600以上の情報源から60万語以上の倫理に関する民族誌の記述を分析し、7つの普遍的な道徳的ルールと考えられるものを発見した。 |

| Evolution See also: Altruism § Evolutionary explanations, Evolution of morality, and Evolutionary ethics The development of modern morality is a process closely tied to sociocultural evolution. Some evolutionary biologists, particularly sociobiologists, believe that morality is a product of evolutionary forces acting at an individual level and also at the group level through group selection (although to what degree this actually occurs is a controversial topic in evolutionary theory). Some sociobiologists contend that the set of behaviors that constitute morality evolved largely because they provided possible survival or reproductive benefits (i.e. increased evolutionary success). Humans consequently evolved "pro-social" emotions, such as feelings of empathy or guilt, in response to these moral behaviors. On this understanding, moralities are sets of self-perpetuating and biologically driven behaviors which encourage human cooperation. Biologists contend that all social animals, from ants to elephants, have modified their behaviors, by restraining immediate selfishness in order to improve their evolutionary fitness. Human morality, although sophisticated and complex relative to the moralities of other animals, is essentially a natural phenomenon that evolved to restrict excessive individualism that could undermine a group's cohesion and thereby reducing the individuals' fitness.[24] On this view, moral codes are ultimately founded on emotional instincts and intuitions that were selected for in the past because they aided survival and reproduction (inclusive fitness). Examples: the maternal bond is selected for because it improves the survival of offspring; the Westermarck effect, where close proximity during early years reduces mutual sexual attraction, underpins taboos against incest because it decreases the likelihood of genetically risky behaviour such as inbreeding. The phenomenon of reciprocity in nature is seen by evolutionary biologists as one way to begin to understand human morality. Its function is typically to ensure a reliable supply of essential resources, especially for animals living in a habitat where food quantity or quality fluctuates unpredictably. For example, some vampire bats fail to feed on prey some nights while others manage to consume a surplus. Bats that did eat will then regurgitate part of their blood meal to save a conspecific from starvation. Since these animals live in close-knit groups over many years, an individual can count on other group members to return the favor on nights when it goes hungry (Wilkinson, 1984) Marc Bekoff and Jessica Pierce (2009) have argued that morality is a suite of behavioral capacities likely shared by all mammals living in complex social groups (e.g., wolves, coyotes, elephants, dolphins, rats, chimpanzees). They define morality as "a suite of interrelated other-regarding behaviors that cultivate and regulate complex interactions within social groups." This suite of behaviors includes empathy, reciprocity, altruism, cooperation, and a sense of fairness.[25] In related work, it has been convincingly demonstrated that chimpanzees show empathy for each other in a wide variety of contexts.[26] They also possess the ability to engage in deception, and a level of social politics[27] prototypical of our own tendencies for gossip and reputation management. Christopher Boehm (1982)[28] has hypothesized that the incremental development of moral complexity throughout hominid evolution was due to the increasing need to avoid disputes and injuries in moving to open savanna and developing stone weapons. Other theories are that increasing complexity was simply a correlate of increasing group size and brain size, and in particular the development of theory of mind abilities. |

進化 も参照のこと: 利他主義§進化論的説明、道徳の進化、進化倫理学 現代の道徳の発展は、社会文化的進化と密接に結びついた過程である。進化生物学者、特に社会生物学者の中には、道徳は個人レベルで、また集団淘汰を通じて 集団レベルでも働く進化の力の産物だと考える者もいる(ただし、実際にどの程度そうなっているかは、進化論において議論の分かれるところである)。社会生 物学者の中には、道徳を構成する一連の行動が進化したのは、それらが生存や繁殖に利益をもたらす可能性があった(つまり、進化的成功が高まった)からだと 主張する者もいる。その結果、人間はこれらの道徳的行動に対応して、共感や罪悪感といった「親社会的」感情を進化させた。 このような理解からすると、道徳性とは、人間の協力を促す、自己永続的で生物学的に駆動された行動の集合である。生物学者は、アリからゾウに至るまですべ ての社会的動物は、進化的適性を向上させるために、目先の利己主義を抑えて行動を修正してきたと主張する。人間の道徳は、他の動物の道徳と比較すると洗練 され複雑ではあるが、本質的には、集団の結束を弱め、それによって個人のフィットネスを低下させる可能性のある過剰な個人主義を制限するために進化した自 然現象である[24]。 この見解によれば、道徳規範は究極的には感情的な本能や直感に基づくものであり、それらは生存と生殖(包括的適合性)を助けるために過去に選択されたもの である。例:母性的な絆は子孫の生存を向上させるため選択される。幼少期に接近することで相互の性的魅力が低下するヴェスターマルク効果は、近親交配など 遺伝的にリスクの高い行動をとる可能性を低下させるため、近親相姦に対するタブーを支えている。 進化生物学者たちは、自然界における互恵性という現象を、人間の道徳性を理解するためのひとつの方法と見なしている。その機能は通常、特に餌の量や質が予 測不可能に変動する生息域に住む動物にとって、必要不可欠な資源の確実な供給を保証することである。例えば、吸血コウモリの中には獲物を食べられない夜が ある一方で、余剰分を消費できるコウモリもいる。食べたコウモリは、飢餓から救うために血液の一部を吐き出す。これらの動物は長年にわたって緊密な集団で 生活しているため、空腹になった夜に他の集団のメンバーが恩返しをしてくれることを期待できる(Wilkinson, 1984)。 Marc BekoffとJessica Pierce (2009)は、道徳性とは複雑な社会集団で生活するすべての哺乳類(オオカミ、コヨーテ、ゾウ、イルカ、ネズミ、チンパンジーなど)に共有されていると 思われる一連の行動能力であると主張している。彼らは道徳を「社会集団内の複雑な相互作用を培い、制御する、相互に関連する他者への配慮行動群」と定義し ている。この一連の行動には、共感、互恵性、利他性、協調性、公平感などが含まれる[25]。関連する研究において、チンパンジーが様々な文脈で互いに共 感を示すことが説得力を持って証明されている[26]。 クリストファー・ベーム(1982)[28]は、ヒト科動物の進化の過程で道徳的な複雑さが段階的に発達したのは、開けたサバンナへの移動と石器の開発に おいて、紛争や傷害を避ける必要性が高まったためであるという仮説を立てている。他の説では、複雑さの増大は単に集団の大きさと脳の大きさの増大の相関で あり、特に心の理論の能力の発達によるものだという。 |

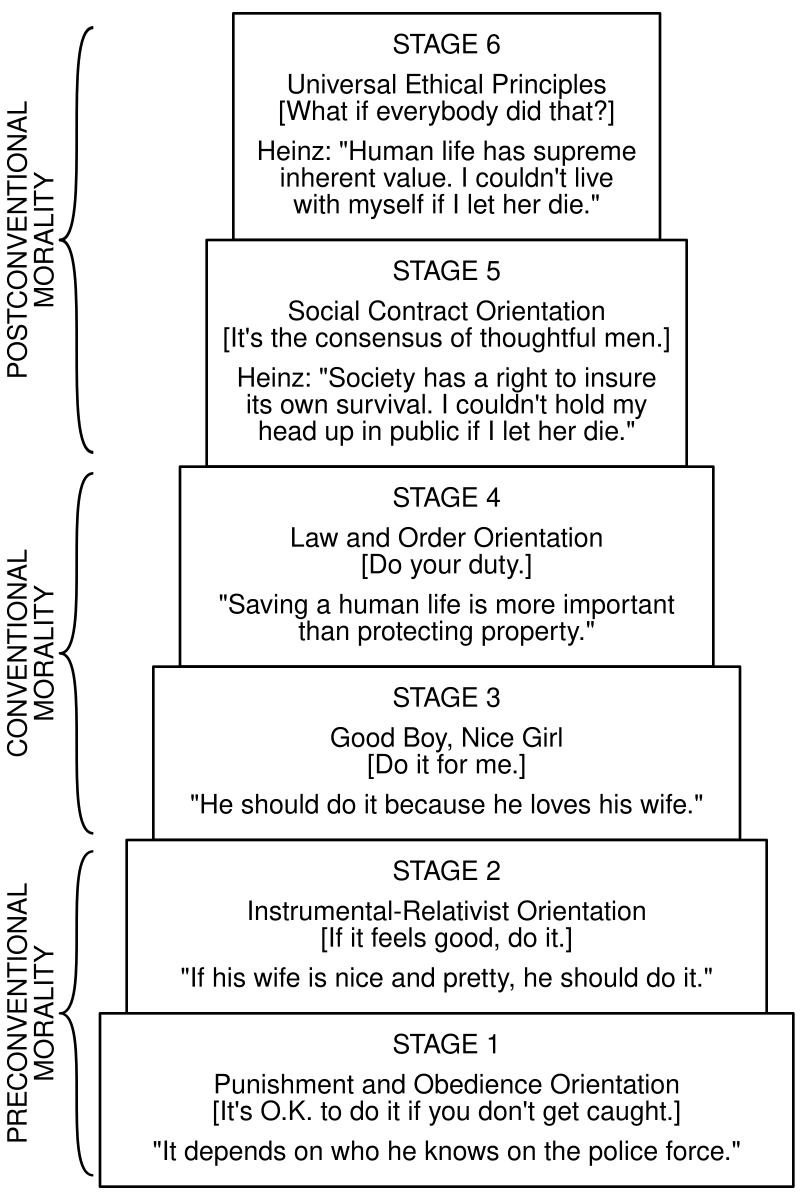

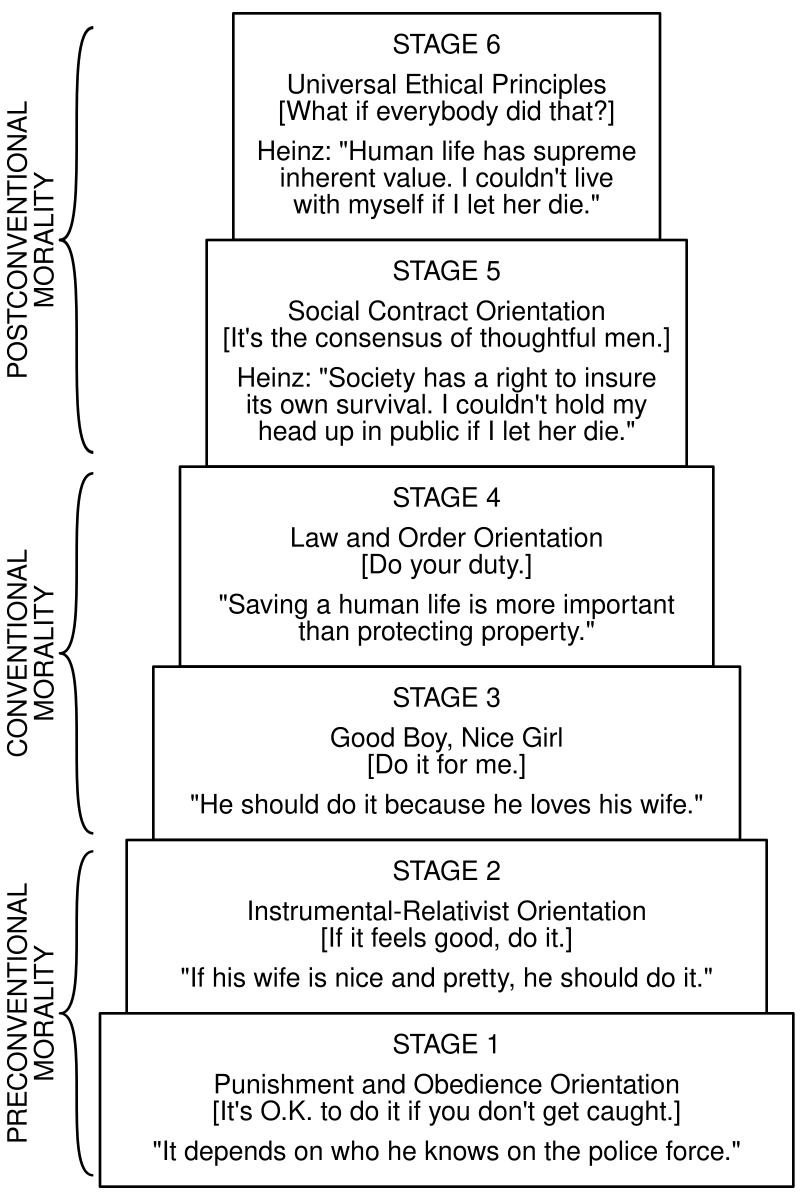

| Psychology Main article: Moral psychology See also: Kohlberg's stages of moral development and Jean Piaget § Education and development of morality  Kohlberg's model of moral development In modern moral psychology, morality is sometimes considered to change through personal development. Several psychologists have produced theories on the development of morals, usually going through stages of different morals. Lawrence Kohlberg, Jean Piaget, and Elliot Turiel have cognitive-developmental approaches to moral development; to these theorists morality forms in a series of constructive stages or domains. In the Ethics of care approach established by Carol Gilligan, moral development occurs in the context of caring, mutually responsive relationships which are based on interdependence, particularly in parenting but also in social relationships generally.[29] Social psychologists such as Martin Hoffman and Jonathan Haidt emphasize social and emotional development based on biology, such as empathy. Moral identity theorists, such as William Damon and Mordechai Nisan, see moral commitment as arising from the development of a self-identity that is defined by moral purposes: this moral self-identity leads to a sense of responsibility to pursue such purposes. Of historical interest in psychology are the theories of psychoanalysts such as Sigmund Freud, who believe that moral development is the product of aspects of the super-ego as guilt-shame avoidance. Theories of moral development therefore tend to regard it as positive moral development: the higher stages are morally higher, though this, naturally, involves a circular argument. The higher stages are better because they are higher, but the better higher because they are better. As an alternative to viewing morality as an individual trait, some sociologists as well as social- and discursive psychologists have taken upon themselves to study the in-vivo aspects of morality by examining how persons conduct themselves in social interaction.[30][31][32][33] A new study analyses the common perception of a decline in morality in societies worldwide and throughout history. Adam M. Mastroianni and Daniel T. Gilbert present a series of studies indicating that the perception of moral decline is an illusion and easily produced, with implications for misallocation of resources, underuse of social support, and social influence. To begin with, the authors demonstrate that people in no less than 60 nations hold the belief that morality is deteriorating continuously, and this conviction has been present for the last 70 years. Subsequently, they indicate that people ascribe this decay to the declining morality of individuals as they age and the succeeding generations. Thirdly, the authors demonstrate that people's evaluations of the morality of their peers have not decreased over time, indicating that the belief in moral decline is an illusion. Lastly, the authors explain a basic psychological mechanism that uses two well-established phenomena (distorted exposure to information and distorted memory of information) to cause the illusion of moral decline. The authors present studies that validate some of the predictions about the circumstances in which the perception of moral decline is attenuated, eliminated, or reversed (e.g., when participants are asked about the morality of people closest to them or people who lived before they were born).[34] |

心理学 主な記事 道徳心理学 も参照のこと: コールバーグの道徳的発達段階とジャン・ピアジェ§道徳の教育と発達  コールバーグの道徳性発達モデル 現代の道徳心理学では、道徳性は人格の発達によって変化すると考えられている。異なる心理学者が道徳の発達に関する理論を生み出しており、通常は段階を経 て道徳が変化していく。ローレンス・コールバーグ(Lawrence Kohlberg)、ジャン・ピアジェ(Jean Piaget)、エリオット・トゥリエル(Elliot Turiel)は、道徳性の発達に対する認知発達的アプローチを持っている。これらの理論家にとって道徳性は、一連の構成的段階または領域において形成さ れる。キャロル・ギリガンによって確立されたケアの倫理(Ethics of care)のアプローチでは、道徳性の発達は、特に子育てにおいてであるが、社会的関係全般においても、相互依存に基づく思いやりのある、相互に反応し合 う関係性の中で生じる[29]。マーティン・ホフマンやジョナサン・ヘイトなどの社会心理学者は、共感などの生物学に基づく社会的・感情的発達を重視して いる。ウィリアム・デーモンやモルデカイ・ニサンなどの道徳的アイデンティティ理論家は、道徳的コミットメントは、道徳的目的によって定義される自己アイ デンティティの発達から生じると考えている。心理学において歴史的に興味深いのは、ジークムント・フロイトのような精神分析学者の理論である。彼らは、道 徳的発達は罪悪感-恥辱回避という超自我の側面の産物であると考えている。道徳的発達の理論では、道徳的発達を肯定的なものとみなす傾向がある。より高い 段階はより高いからより良いが、より良い段階はより良いからより良いのである。 道徳を個人の特質とみなす代わりに、社会科学者や社会心理学者、言説心理学者の中には、人格が社会的相互作用の中でどのように行動するかを調べることによって、道徳の生体内における側面を研究することに取り組んでいる者もいる[30][31][32][33]。 新しい研究は、世界的な、そして歴史を通しての社会における道徳の低下という共通の認識を分析している。アダム・M・マストロヤンニとダニエル・T・ギル バートは、モラルの低下という認識は錯覚であり、容易に生み出されるものであることを示す一連の研究を発表し、資源の配分の誤り、社会的支援の利用不足、 社会的影響力への影響を示唆している。まず著者らは、60カ国以上の国民が、モラルは継続的に低下しているという信念を抱いており、この信念は過去70年 間存在し続けていることを示している。続いて、人々はこの衰退を、年齢を重ねるにつれて低下する個人のモラルと、それを引き継ぐ世代のモラルのせいだと考 えていることを示す。第三に、著者らは、同世代の人々のモラルに対する人々の評価が時間の経過とともに低下していないことを示し、モラルの低下という信念 が幻想であることを示している。最後に著者らは、モラル低下の錯覚を引き起こす2つの確立された現象(情報への歪んだ暴露と情報の歪んだ記憶)を利用した 基本的な心理学的メカニズムを説明する。著者らは、道徳的低下の認知が減弱、消失、逆転する状況(例えば、参加者が最も身近な人や自分が生まれる前に生き ていた人の道徳性について質問された場合)について、いくつかの予測を検証する研究を紹介している[34]。 |

| Moral cognition Moral cognition refers to cognitive processes implicated in moral judgment and decision making, and moral action. It consists of several domain-general cognitive processes, ranging from perception of a morally salient stimulus to reasoning when faced with a moral dilemma. While it is important to mention that there is not a single cognitive faculty dedicated exclusively to moral cognition,[35][36] characterizing the contributions of domain-general processes to moral behavior is a critical scientific endeavor to understand how morality works and how it can be improved.[37] Cognitive psychologists and neuroscientists investigate the inputs to these cognitive processes and their interactions, as well as how these contribute to moral behavior by running controlled experiments.[38] In these experiments putatively moral versus nonmoral stimuli are compared to each other, while controlling for other variables such as content or working memory load. Often, the differential neural response to specifically moral statements or scenes, are examined using functional neuroimaging experiments. Critically, the specific cognitive processes that are involved depend on the prototypical situation that a person encounters.[39] For instance, while situations that require an active decision on a moral dilemma may require active reasoning, an immediate reaction to a shocking moral violation may involve quick, affect-laden processes. Nonetheless, certain cognitive skills such as being able to attribute mental states—beliefs, intents, desires, emotions to oneself, and others is a common feature of a broad range of prototypical situations. In line with this, a meta-analysis found overlapping activity between moral emotion and moral reasoning tasks, suggesting a shared neural network for both tasks.[40] The results of this meta-analysis, however, also demonstrated that the processing of moral input is affected by task demands. Regarding the issues of morality in video games, some scholars believe that because players appear in video games as actors, they maintain a distance between their sense of self and the role of the game in terms of imagination. Therefore, the decision-making and moral behavior of players in the game are not representing player's Moral dogma.[41] It has been recently found that moral judgment consists in concurrent evaluations of three different components that align with precepts from three dominant moral theories (virtue ethics, deontology, and consequentialism): the character of a person (Agent-component, A); their actions (Deed-component, D); and the consequences brought about in the situation (Consequences-component, C).[42] This, implies that various inputs of the situation a person encounters affect moral cognition. Jonathan Haidt distinguishes between two types of moral cognition: moral intuition and moral reasoning. Moral intuition involves the fast, automatic, and affective processes that result in an evaluative feeling of good-bad or like-dislike, without awareness of going through any steps. Conversely, moral reasoning does involve conscious mental activity to reach a moral judgment. Moral reasoning is controlled and less affective than moral intuition. When making moral judgments, humans perform moral reasoning to support their initial intuitive feeling. However, there are three ways humans can override their immediate intuitive response. The first way is conscious verbal reasoning (for example, examining costs and benefits). The second way is reframing a situation to see a new perspective or consequence, which triggers a different intuition. Finally, one can talk to other people which illuminates new arguments. In fact, interacting with other people is the cause of most moral change.[43] |

道徳的認知 道徳的認知とは、道徳的判断や意思決定、道徳的行動に関与する認知過程を指す。道徳的認知は、道徳的に重要な刺激の認知から、道徳的ジレンマに直面したと きの推論に至るまで、いくつかの領域全般にわたる認知過程から構成される。道徳的認知に特化した単一の認知学部が存在しないことに言及することは重要であ るが[35][36]、道徳的行動に対する領域全般的過程の寄与を特徴付けることは、道徳性がどのように機能し、どのように改善できるかを理解するために 重要な科学的努力である[37]。 認知心理学者や神経科学者は、これらの認知過程へのインプットとそれらの相互作用、さらにそれらが道徳的行動にどのように寄与しているかを、統制された実 験を行うことによって調査している[38]。これらの実験では、内容やワーキングメモリ負荷などの他の変数を統制しながら、仮に道徳的な刺激と非道徳的な 刺激が互いに比較される。多くの場合、特に道徳的な発言や場面に対する差異的な神経反応は、機能的神経画像実験を用いて調べられる。 例えば、道徳的ジレンマに対して能動的な意思決定が必 要な状況では能動的な推論が必要かもしれないが、衝撃的な 道徳的違反に対する即時的な反応では、情動を伴う迅速な 処理が必要かもしれない。それにもかかわらず、心的状態-信念、意図主義、欲求、感情-を自分自身や他者に帰属させることができるといった特定の認知技能 は、広範な原型的状況に共通する特徴である。これと同様に、あるメタ分析では、道徳的感情と道徳的推論タスクの間に重複した活動が認められ、両タスクの神 経ネットワークが共有されていることが示唆されている[40]。ただし、このメタ分析の結果は、道徳的入力の処理がタスクの要求によって影響を受けること も示している。 ビデオゲームにおけるモラルの問題について、一部の学者は、プレイ ヤーはビデオゲームに俳優として登場するため、想像力という点 で自己の感覚とゲームの役割の間に距離を保つと考える。したがって、ゲームにおけるプレイヤーの意思決定や道徳的行動は、プレイヤーのモラルのドグマを表 しているわけではない[41]。 道徳的判断は、3つの支配的な道徳理論(徳倫理、義務論、帰結主義)の教訓に沿った3つの異なる構成要素の同時評価で構成されることが最近判明した:人物 の人格(Agent-構成要素、A)、彼らの行動(Deed-構成要素、D)、および状況でもたらされる結果(Consequences-構成要素、C) [42]。 ジョナサン・ヘイトは2種類の道徳的認知を区別している:道徳的直観と道徳的推論である。道徳的直観は、善悪や好き嫌いの評価的感覚をもたらす、高速で自 動的で感情的なプロセスを含む。逆に、道徳的推理は道徳的判断に達するための意識的な精神活動を伴う。道徳的推論は道徳的直観に比べ、統制がとれており、 感情的でない。道徳的判断を下すとき、人間は最初の直感を裏付けるために道徳的推論を行う。しかし、人間が直感的な反応を上書きする方法は3つある。第一 の方法は、意識的な言語的推論である(例えば、費用と便益を検討する)。第二の方法は、状況をリフレーミングして新しい視点や結果を見ることで、異なる直 感を引き起こす。最後に、他の人と話すことで、新たな論点が見えてくる。実際、他の人々との交流は、ほとんどの道徳的変化の原因である[43]。 |

| Neuroscience See also: Science of morality and Neuromorality The brain areas that are consistently involved when humans reason about moral issues have been investigated by multiple quantitative large-scale meta-analyses of the brain activity changes reported in the moral neuroscience literature.[44][40][45][46] The neural network underlying moral decisions overlaps with the network pertaining to representing others' intentions (i.e., theory of mind) and the network pertaining to representing others' (vicariously experienced) emotional states (i.e., empathy). This supports the notion that moral reasoning is related to both seeing things from other persons' points of view and to grasping others' feelings. These results provide evidence that the neural network underlying moral decisions is probably domain-global (i.e., there might be no such things as a "moral module" in the human brain) and might be dissociable into cognitive and affective sub-systems.[44] Cognitive neuroscientist Jean Decety thinks that the ability to recognize and vicariously experience what another individual is undergoing was a key step forward in the evolution of social behavior, and ultimately, morality.[47] The inability to feel empathy is one of the defining characteristics of psychopathy, and this would appear to lend support to Decety's view.[48][49] Recently, drawing on empirical research in evolutionary theory, developmental psychology, social neuroscience, and psychopathy, Jean Decety argued that empathy and morality are neither systematically opposed to one another, nor inevitably complementary.[50][51] |

ニューロサイエンス こちらも参照のこと: 道徳の科学と神経道徳 人間が道徳的問題について推論する際に一貫して関与する脳領域は、道徳的神経科学の文献で報告されている脳活動の変化に関する複数の定量的大規模メタアナ リシスによって調査されている[44][40][45][46]。道徳的判断の根底にある神経回路網は、他者の意図の表出に関わる回路網(すなわち、心の 理論)および他者の(身をもって経験した)感情状態の表出に関わる回路網(すなわち、共感)と重なっている。このことは、道徳的推論が、他人の視点から物事を見ることと、他人の感情を把握することの両方に関係しているという考え方を支持している。これらの結果は、道徳的判断の根底にある神経回路網はおそらく領域グローバルであり(すなわち、人間の脳には「道徳モジュール」などというものは存在しないのかもしれない)、認知と情動のサブシステムに解離可能である可能性を示す証拠となる[44]。 認知神経科学者のジャン・デセティは、他の個人が経験していることを認識し、身をもって経験する能力は、社会的行動、ひいては道徳の進化において重要な一 歩であったと考えている。 [48][49]最近、進化論、発達心理学、社会神経科学、サイコパスにおける経験的研究をもとに、ジャン・ディセティは共感と道徳は体系的に対立するも のでも、必然的に補完し合うものでもないと主張した[50][51]。 |

| Brain areas An essential, shared component of moral judgment involves the capacity to detect morally salient content within a given social context. Recent research implicated the salience network in this initial detection of moral content.[52] The salience network responds to behaviorally salient events[53] and may be critical to modulate downstream default and frontal control network interactions in the service of complex moral reasoning and decision-making processes. The explicit making of moral right and wrong judgments coincides with activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPC), a region involved in valuation, while intuitive reactions to situations containing implicit moral issues activates the temporoparietal junction area, a region that plays a key role in understanding intentions and beliefs.[54][52] Stimulation of the VMPC by transcranial magnetic stimulation, or neurological lesion, has been shown to inhibit the ability of human subjects to take into account intent when forming a moral judgment. According to such investigations, TMS did not disrupt participants' ability to make any moral judgment. On the contrary, moral judgments of intentional harms and non-harms were unaffected by TMS to either the RTPJ or the control site; presumably, however, people typically make moral judgments of intentional harms by considering not only the action's harmful outcome but the agent's intentions and beliefs. So why were moral judgments of intentional harms not affected by TMS to the RTPJ? One possibility is that moral judgments typically reflect a weighted function of any morally relevant information that is available at the time. Based on this view, when information concerning the agent's belief is unavailable or degraded, the resulting moral judgment simply reflects a higher weighting of other morally relevant factors (e.g., outcome). Alternatively, following TMS to the RTPJ, moral judgments might be made via an abnormal processing route that does not take belief into account. On either account, when belief information is degraded or unavailable, moral judgments are shifted toward other morally relevant factors (e.g., outcome). For intentional harms and non-harms, however, the outcome suggests the same moral judgment as to the intention. Thus, the researchers suggest that TMS to the RTPJ disrupted the processing of negative beliefs for both intentional harms and attempted harms, but the current design allowed the investigators to detect this effect only in the case of attempted harms, in which the neutral outcomes did not afford harsh moral judgments on their own.[55] Similarly, individuals with a lesion of the VMPC judge an action purely on its outcome and are unable to take into account the intent of that action.[56] |

脳領域 道徳的判断に不可欠で共有される要素には、与えられた社会的文脈の中で道徳的に顕著な内容を検出する能力が含まれる。最近の研究では、この道徳的内容の最 初の検出にはサリエンスネットワークが関与していることが示唆されている[52]。サリエンスネットワークは、行動的に顕著な事象に反応し[53]、複雑 な道徳的推論と意思決定過程における下流のデフォルトネットワークと前頭前野制御ネットワークの相互作用を調節するのに重要であると考えられる。 道徳的な善悪の判断を明示的に行うことは、評価に関与する領域である前頭前皮質(VMPC)の活性化と一致し、一方、暗黙的な道徳的問題を含む状況に対す る意図主義的反応は、意図と信念の理解に重要な役割を果たす領域である側頭頭頂接合部(Temporoparietal Junction Area)を活性化する[54][52]。 経頭蓋磁気刺激、つまり神経学的病変によるVMPCへの刺激は、道徳的判断を形成する際に意図主義を考慮するヒト被験者の能力を抑制することが示されてい る。このような研究によれば、TMSは被験者の道徳的判断能力を阻害しなかった。それどころか、意図的な危害とそうでないものに対する道徳的判断は、 RTPJまたは対照部位のいずれにTMSを用いても影響を受けなかった。しかしおそらく、人は通常、行為の有害な結果だけでなく、行為者の意図や信念を考 慮することによって、意図的な危害に対する道徳的判断を下すのであろう。では、なぜ意図的危害に対する道徳的判断はRTPJへのTMSの影響を受けなかっ たのだろうか?一つの可能性として、道徳的判断は通常、その時点で入手可能なあらゆる道徳的に関連する情報の重み付けされた関数を反映していることが考え られる。この考え方に基づけば、エージェントの信念に関する情報が利用できないか、劣化している場合、結果として生じる道徳的判断は、単に他の道徳的に関 連する要素(例えば結果)の重み付けを高く反映したものになる。あるいは、RTPJへのTMS後、信念を考慮しない異常な処理経路を介して道徳的判断がな されるかもしれない。いずれにせよ、信念の情報が低下したり利用できなくなったりすると、道徳的判断は他の道徳的関連要素(例えば結果)の方にシフトす る。しかし、意図主義的な危害とそうでない危害では、結果は意図と同じ道徳的判断を示唆する。したがって、研究者らは、RTPJへのTMSが意図的加害と 未遂加害の両方に対する否定的信念の処理を妨害することを示唆しているが、今回のデザインによって、研究者らは、中立的な結果がそれ自体で厳しい道徳的判 断を与えなかった未遂加害の場合にのみ、この効果を検出することができた[55]。 同様に、VMPCに病変のある人は、ある行為を純粋にその結果だけで判断し、その行為の意図を考慮することができない[56]。 |

| Genetics [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2022) Moral intuitions may have genetic bases. A 2022 study conducted by scholars Michael Zakharin and Timothy C. Bates, and published by the European Journal of Personality, found that moral foundations have significant genetic bases.[57] Another study, conducted by Smith and Hatemi, similarly found significant evidence in support of moral heritability by looking at and comparing the answers of moral dilemmas between twins.[58] Genetics play a role in influencing prosocial behaviors and moral decision-making. Genetics contribute to the development and expression of certain traits and behaviors, including those related to morality. However, it is important to note that while genetics play a role in shaping certain aspects of moral behavior, morality itself is a multifaceted concept that encompasses cultural, societal, and personal influences as well. |

遺伝学 [アイコン] このセクションは拡張が必要だ。追加することで手助けができる。(2022年5月) 道徳的直観には遺伝的基盤があるかもしれない。学者マイケル・ザカリンとティモシー・C・ベイツが2022年に実施し、『European Journal of Personality』誌で発表した研究によると、道徳的直観には重要な遺伝的基盤があることが判明した[57]。スミスとハテミが実施した別の研究で も同様に、双生児間の道徳的ジレンマの回答を調べ、比較することで、道徳的遺伝性を支持する有意な証拠を発見した[58]。 遺伝は向社会的行動や道徳的意思決定に影響を与える役割を果たす。遺伝は、道徳に関連するものも含め、特定の形質や行動の発達や発現に寄与している。しか し、遺伝が道徳的行動のある側面を形成する役割を果たす一方で、道徳そのものは文化的、社会的、人格的な影響も包含する多面的な概念であることに注意する ことが重要である。 |

| Politics If morality is the answer to the question 'how ought we to live' at the individual level, politics can be seen as addressing the same question at the social level, though the political sphere raises additional problems and challenges.[59] It is therefore unsurprising that evidence has been found of a relationship between attitudes in morality and politics. Moral foundations theory, authored by Jonathan Haidt and colleagues,[60][61] has been used to study the differences between liberals and conservatives, in this regard.[17][62] Haidt found that Americans who identified as liberals tended to value care and fairness higher than loyalty, respect and purity. Self-identified conservative Americans valued care and fairness less and the remaining three values more. Both groups gave care the highest over-all weighting, but conservatives valued fairness the lowest, whereas liberals valued purity the lowest. Haidt also hypothesizes that the origin of this division in the United States can be traced to geo-historical factors, with conservatism strongest in closely knit, ethnically homogeneous communities, in contrast to port-cities, where the cultural mix is greater, thus requiring more liberalism. Group morality develops from shared concepts and beliefs and is often codified to regulate behavior within a culture or community. Various defined actions come to be called moral or immoral. Individuals who choose moral action are popularly held to possess "moral fiber", whereas those who indulge in immoral behavior may be labeled as socially degenerate. The continued existence of a group may depend on widespread conformity to codes of morality; an inability to adjust moral codes in response to new challenges is sometimes credited with the demise of a community (a positive example would be the function of Cistercian reform in reviving monasticism; a negative example would be the role of the Dowager Empress in the subjugation of China to European interests). Within nationalist movements, there has been some tendency to feel that a nation will not survive or prosper without acknowledging one common morality, regardless of its content. Political morality is also relevant to the behavior internationally of national governments, and to the support they receive from their host population. The Sentience Institute, co-founded by Jacy Reese Anthis, analyzes the trajectory of moral progress in society via the framework of an expanding moral circle.[63] Noam Chomsky states that ... if we adopt the principle of universality: if an action is right (or wrong) for others, it is right (or wrong) for us. Those who do not rise to the minimal moral level of applying to themselves the standards they apply to others—more stringent ones, in fact—plainly cannot be taken seriously when they speak of appropriateness of response; or of right and wrong, good and evil. In fact, one of them, maybe the most, elementary of moral principles is that of universality, that is, If something's right for me, it's right for you; if it's wrong for you, it's wrong for me. Any moral code that is even worth looking at has that at its core somehow.[64] |

政治 道徳が個人レベルにおける「いかに生きるべきか」という問いに対する答えであるとすれば、政治は社会レベルにおける同じ問いに取り組んでいるとみなすこと ができる。ジョナサン・ハイドらが著した道徳的基盤理論[60][61]は、この点に関してリベラル派と保守派の違いを研究するために用いられている [17][62]。保守派を自認するアメリカ人は、配慮と公正さをより低く評価し、残りの3つの価値をより高く評価した。どちらのグループも、気遣いを最 も高く評価したが、保守派は公正さを最も低く評価し、リベラル派は純粋さを最も低く評価した。ハイドはまた、アメリカにおけるこの分断の起源は、地理的歴 史的要因に帰結すると仮定している。 集団道徳は、共有された概念や信念から発展し、文化やコミュニティ内での行動を規制するために成文化されることが多い。様々に定義された行動は、道徳的ま たは非道徳的と呼ばれるようになる。道徳的な行動を選択する個人は一般的に「道徳的な繊維」を持っているとされ、一方、不道徳な行動にふける人は社会的に 退廃しているというレッテルを貼られることがある。集団の存続は、道徳規範に広く適合しているかどうかにかかっている。新たな課題に対応して道徳規範を調 整できないことが、ある共同体の終焉につながることもある(肯定的な例としては、修道会を復活させたシトー会の改革が挙げられるが、否定的な例としては、 中国をヨーロッパの利益に服従させた皇太后の役割が挙げられる)。ナショナリズム運動の中には、その内容にかかわらず、一つの共通の道徳を認めなければ国 民は存続も繁栄もできないと考える傾向がある。 政治的道徳は、国民政府の国際的な行動や、国民からの支持にも関係する。ジェーシー・リース・アンシスが共同設立した感覚研究所は、拡大する道徳の輪とい う枠組みを通じて、社会における道徳の進歩の軌跡を分析している[63]。 ノーム・チョムスキーは次のように述べている。 ある行為が他者にとって正しい(あるいは間違っている)ならば、それは我々にとっても正しい(あるいは間違っている)。他人に適用する基準を自分にも適用 するという最低限の道徳的水準に達しない者は、実際にはもっと厳しいものであるが、彼らが対応の適切さ、あるいは善悪や善悪について語るとき、まともに相 手にされることはない。実際、道徳的原則の中で最も初歩的なもののひとつは、普遍性である。見る価値のある道徳規範には、その核心がある。 |

| Religion Main articles: Ethics in religion and Morality and religion See also: Divine command theory, Divine law, Religious law, Secular ethics, and Secular morality Religion and morality are not synonymous. Morality does not depend upon religion although for some this is "an almost automatic assumption".[65] According to The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Ethics, religion and morality "are to be defined differently and have no definitional connections with each other. Conceptually and in principle, morality and a religious value system are two distinct kinds of value systems or action guides."[66] |

宗教 主な記事 宗教における倫理、道徳と宗教 も参照のこと: 神聖命令説、神聖法、宗教法、世俗倫理、世俗道徳も参照のこと。 宗教と道徳は同義ではない。ウェストミンスターキリスト教倫理辞典』によれば、宗教と道徳は「異なる定義がなされるべきであり、互いに定義上の関連はな い」とされている。概念的にも原理的にも、道徳と宗教的価値体系は2つの異なる種類の価値体系あるいは行動指針である」[66]。 |

| Empirical analyses Several studies have been conducted on the empirics of morality in various countries, and the overall relationship between faith and crime is unclear.[b] A 2001 review of studies on this topic found "The existing evidence surrounding the effect of religion on crime is varied, contested, and inconclusive, and currently, no persuasive answer exists as to the empirical relationship between religion and crime."[78] Phil Zuckerman's 2008 book, Society without God, based on studies conducted during 14 months in Scandinavia in 2005–2006, notes that Denmark and Sweden, "which are probably the least religious countries in the world, and possibly in the history of the world", enjoy "among the lowest violent crime rates in the world [and] the lowest levels of corruption in the world".[79][c] Dozens of studies have been conducted on this topic since the twentieth century. A 2005 study by Gregory S. Paul published in the Journal of Religion and Society stated that, "In general, higher rates of belief in and worship of a creator correlate with higher rates of homicide, juvenile and early adult mortality, STD infection rates, teen pregnancy, and abortion in the prosperous democracies," and "In all secular developing democracies a centuries long-term trend has seen homicide rates drop to historical lows" with the exceptions being the United States (with a high religiosity level) and "theistic" Portugal.[80][d] In a response, Gary Jensen builds on and refines Paul's study.[81] he concludes that a "complex relationship" exists between religiosity and homicide "with some dimensions of religiosity encouraging homicide and other dimensions discouraging it". In April 2012, the results of a study which tested their subjects' pro-social sentiments were published in the Social Psychological and Personality Science journal in which non-religious people had higher scores showing that they were more motivated by their own compassion to perform pro-social behaviors. Religious people were found to be less motivated by compassion to be charitable than by an inner sense of moral obligation.[82][83] |

実証的(経験的)分析 このトピックに関する研究の2001年のレビューでは、「宗教が犯罪に及ぼす影響をめぐる既存の証拠は多様であり、論争が多く、結論が出ていない。 フィル・ザッカーマンの2008年の著書『Society without God(神なき社会)』は、2005年から2006年にかけての14ヶ月間に北欧で実施された調査に基づいており、デンマークとスウェーデンは「おそらく 世界で最も宗教色の薄い国であり、おそらく世界の歴史上でも最も宗教色の薄い国」でありながら、「世界で最も暴力犯罪率が低く、世界で最も汚職のレベルが 低い国」であると指摘している[79][c]。 このテーマについては、20世紀以来、何十もの研究が行われてきた。2005年に『ジャーナル・オブ・レリジョン・アンド・ソサエティ』誌に掲載されたグ レゴリー・S・ポールによる研究では、「一般的に、創造主に対する信仰と崇拝の割合が高いことは、繁栄した民主主義国家において、殺人、少年期および成人 初期の死亡率、性病感染率、10代の妊娠、中絶の割合が高いことと相関している」、「すべての世俗的な発展途上民主主義国家において、何世紀にもわたる長 期的な傾向として、殺人率は歴史的な低水準まで低下している」と述べられており、例外は(宗教性の高い)米国と「有神論」のポルトガルである。 [80][d]これに対して、ゲーリー・ジェンセンはポールの研究を基に改良を加えている。[81]彼は宗教性と殺人の間には「複雑な関係」が存在し、 「宗教性のある次元では殺人を助長し、別の次元では殺人を抑制する」と結論付けている。2012年4月、被験者の親社会的感情をテストした研究結果が Social Psychological and Personality Science誌に発表された。宗教的な人々は、道徳的義務感よりも同情心によって慈善的な行動をとる動機付けが弱いことがわかった[82][83]。 |

| Ethics Integrity Applied ethics Appeal to tradition Buddhist ethics Christian ethics De(徳) Emotional intelligence Ethical dilemma Good and evil Ideology Index of ethics articles Islamic ethics Jewish ethics Moral agency Moral character Moral conviction Moral intelligence Moral outsourcing Moral panic Moral skepticism Outline of ethics Value theory Worldview |

倫理 誠実さ 応用倫理 伝統に訴える 仏教倫理 キリスト教倫理 徳 感情的知性 倫理的ジレンマ 善と悪 イデオロギー 倫理に関する記事の索引 イスラム倫理 ユダヤ倫理 道徳的主体性 道徳的性格 道徳的確信 道徳的知性 道徳的アウトソーシング 道徳パニック 道徳的懐疑主義 倫理学の概要 価値論 世界観 |

| Churchland, Patricia Smith

(2011). Braintrust : What Neuroscience Tells Us about Morality.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13703-2.

(Reviewed in The Montreal Review) Richard Dawkins, "The roots of morality: why are we good?", in The God Delusion, Black Swan, 2007 (ISBN 978-0-552-77429-1). Harris, Sam (2010). The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4391-7121-9. Lunn, Arnold, and Garth Lean (1964). The New Morality. London: Blandford Press. John Newton, Complete Conduct Principles for the 21st Century, 2000. ISBN 0967370574. Prinz, Jesse (Jan–Feb 2013). "Morality is a Culturally Conditioned Response". Philosophy Now. Slater S.J., Thomas (1925). "Book I: Morality" . A manual of moral theology for English-speaking countries. Burns Oates & Washbourne Ltd. Stace, Walter Terence (1937). The Concept of Morals. New York: The MacMillan Company; Reprinted 1975 by permission of Macmillan Publishing Co. Inc., and also reprinted by Peter Smith Publisher Inc, January 1990. ISBN 978-0-8446-2990-2. Trompenaars, Fons (2003). Did the Pedestrian Die?: Insights from the World's Greatest Culture Guru. Oxford: Capstone. ISBN 978-1-84112-436-0. Yandell, Keith E. (1973). God, man, and religion: readings in the philosophy of religion. McGraw-Hill. containing articles by Paterson Brown: "Religious Morality", (from Mind, 1963). "Religious Morality: a Reply to Flew and Campbell", (from Mind, 1964). "God and the Good", (from Religious Studies, 1967). Ashley Welch, "Virtuous behaviors sanction later sins: people are quick to treat themselves after a good deed or healthy act" March 4, 2012. Roberto Andorno, "Do our moral judgements need to be guided by principles?" Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 2012, 21(4), 457–65. |

Churchland, Patricia Smith

(2011). Braintrust: What Neuroscience Tells Us about Morality.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13703-2.

(モントリオール・レビューで書評)→脳がつくる倫理 : 科学と哲学から道徳の起源にせまる / パトリシア・S・チャーチランド著 ; 信原幸弘, 樫則章, 植原亮訳, 京都 : 化学同人 , 2013.8 リチャード・ドーキンス、「道徳の根源:人はなぜ善良なのか」、『神の妄想』、ブラック・スワン、2007年(ISBN 978-0-552-77429-1). Harris, Sam (2010). The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values. ニューヨーク: Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4391-7121-9. Lunn, Arnold, and Garth Lean (1964). The New Morality. London: Blandford Press. ジョン・ニュートン『21世紀の完全行動原則』2000年。ISBN 0967370574. Prinz, Jesse (Jan-Feb 2013). 「道徳は文化的に条件付けられた反応である」. Philosophy Now. Slater S.J., Thomas (1925). "Book I: 道徳」. A manual of moral theology for English-speaking countries. バーンズ・オーツ&ウォッシュボーン社。 Stace, Walter Terence (1937). 道徳の概念. ニューヨーク: The MacMillan Company; Reprinted 1975 by permission of Macmillan Publishing Co. また、Peter Smith Publisher Inc. ISBN 978-0-8446-2990-2. Trompenaars, Fons (2003). 歩行者は死んだのか?Did the Pedestrian Die?: Insights from the World's Greatest Culture Guru. オックスフォード: Capstone. ISBN 978-1-84112-436-0. Yandell, Keith E. (1973). God, man, and religion: readings in the philosophy of religion. マクグローヒル。パターソン・ブラウンの論文を含む: 宗教的道徳」(『マインド』1963年より)。 宗教的道徳:フリューとキャンベルへの返答」(『マインド』1964年)。 神と善」(『宗教学』1967年)。 アシュレー・ウェルチ「高潔な行動は後の罪を制裁する:人は善行や健全な行為の後、すぐに自分をいたわる」2012年3月4日。 Roberto Andorno, 「Do our moral judgements need to be guided by principles?」. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 2012, 21(4), 457-65. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morality |

****

| Probleme

der Moralphilosophie (1963) / Theodor W. Adorno ; herausgegeben von

Thomas Schröder, Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp , 2010. - (Suhrkamp

Taschenbuch Wissenschaft ; 1983) |

道徳哲学講義 / T.W.アドルノ著 ; 船戸満之訳, 東京 : 作品社 , 2006.9 |

| 著者の「道徳哲学の諸問題」というタイトルで行った講義 (フランクフルト大学, 1963年) をテープから採録した速記録に基づいたもの 原著 (Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp, c1996) の翻訳 アドルノ邦訳著作リスト: p303 |

内容説明 実践理性の優位を説きつつ徳の追求と幸福の追求の背反定立(アンチノミー)に逢着するカントの「道徳哲学」に対し、自由意志と深い洞察に基づく無限の限定否定を提起する『否定弁証法』「自由の章」への前哨。 目次 第1回講議(一九六三年五月七日) 第二回講義(一九六三年五月九日) 第三回講義(一九六三年五月十四日) 第四回講義(一九六三年五月十六日) 第五回講義(一九六三年五月二十八日) 第六回講義(一九六三年五月三十日) 第七回講義(一九六三年六月十八日) 第八回講義(一九六三年六月二十日) 第九回講義(一九六三年六月二十七日) 第十回講義(一九六三年七月二日) 第十一回講義(一九六三年七月四日) 第十二回講義(一九六三年七月九日) 第十三回講義(一九六三年七月十一日) 第十四回講義(一九六三年七月十六日) 第十五回講義(一九六三年七月十八日) 第十六回講義(一九六三年七月二十三日) 第十七回講義(一九六三年七月二十五日) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆