エルナン・コルテス

Hernán Cortés, 1485-1527

☆ エルナン・コルテス・デ・モンロイ・イ・ピサロ・アルタミラノ、オアハカの谷の初代侯爵[a][b](1485年12月 - 1547年12月2日)は、スペインの征服者であり、16世紀初頭にアステカ帝国を滅ぼし、現在のメキシコ本土の大部分をカスティーリャ王の支配下に置い た遠征隊を率いた。コルテスは、スペインによるアメリカ大陸植民地化の第一段階を始めたスペイン人探検家および征服者の世代の一人であった。 スペインのメディナで、それほど高貴ではない家柄に生まれたコルテスは、新世界での冒険と富を追い求めることを選んだ。彼はイスパニョーラ島に行き、その 後キューバへ渡り、そこでエンコミエンダ(特定の被支配者の労働権)を得た。彼は、その島でスペイン人が建設した2番目の町で、短期間ではあるが、町長 (magistrate)を務めた。1519年、彼は自らも出資した第3回大陸遠征の隊長に選出された。キューバ総督のディエゴ・ベラスケス・デ・クエヤ ルとの確執により、遠征隊は直前になって呼び戻されることになったが、コルテスは命令を無視した。 大陸に到着したコルテスは、先住民のいくつかの部族と手を組むという戦略を成功させた。また、先住民の女性ドニャ・マリーナを通訳として起用した。彼女は 後にコルテスの長男を出産した。キューバ総督がコルテスを逮捕するために使者を送った際、コルテスは彼らと戦い、勝利した。そして、増援部隊を率いてい た。コルテスは、反逆罪で処罰される代わりに、自らの功績を認められるよう王に直訴する手紙を書いた。アステカ帝国を滅ぼしたのち、コルテスはオアハカ侯 爵の称号を授けられたが、より権威のある副王の称号は高位の貴族であるアントニオ・デ・メンドーサに与えられた。1541年、コルテスはスペインに戻り、 6年後に自然死した。

| Hernán Cortés de

Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca[a][b]

(December 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish conquistador who led

an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought

large portions of what is now mainland Mexico under the rule of the

King of Castile in the early 16th century. Cortés was part of the

generation of Spanish explorers and conquistadors who began the first

phase of the Spanish colonization of the Americas. Born in Medellín, Spain, to a family of lesser nobility, Cortés chose to pursue adventure and riches in the New World. He went to Hispaniola and later to Cuba, where he received an encomienda (the right to the labor of certain subjects). For a short time, he served as alcalde (magistrate) of the second Spanish town founded on the island. In 1519, he was elected captain of the third expedition to the mainland, which he partly funded. His enmity with the governor of Cuba, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, resulted in the recall of the expedition at the last moment, an order which Cortés ignored. Arriving on the continent, Cortés executed a successful strategy of allying with some indigenous people against others. He also used a native woman, Doña Marina, as an interpreter. She later gave birth to his first son. When the governor of Cuba sent emissaries to arrest Cortés, he fought them and won, using the extra troops as reinforcements.[1] Cortés wrote letters directly to the king asking to be acknowledged for his successes instead of being punished for mutiny. After he overthrew the Aztec Empire, Cortés was awarded the title of marqués del Valle de Oaxaca, while the more prestigious title of viceroy was given to a high-ranking nobleman, Antonio de Mendoza. In 1541 Cortés returned to Spain, where he died six years later of natural causes. |

エルナン・コルテス・デ・モンロイ・イ・ピサロ・アルタミラノ、オアハ

カの谷の初代侯爵[a][b](1485年12月 -

1547年12月2日)は、スペインの征服者であり、16世紀初頭にアステカ帝国を滅ぼし、現在のメキシコ本土の大部分をカスティーリャ王の支配下に置い

た遠征隊を率いた。コルテスは、スペインによるアメリカ大陸植民地化の第一段階を始めたスペイン人探検家および征服者の世代の一人であった。 スペインのメディナで、それほど高貴ではない家柄に生まれたコルテスは、新世界での冒険と富を追い求めることを選んだ。彼はイスパニョーラ島に行き、その 後キューバへ渡り、そこでエンコミエンダ(特定の被支配者の労働権)を得た。彼は、その島でスペイン人が建設した2番目の町で、短期間ではあるが、町長 (magistrate)を務めた。1519年、彼は自らも出資した第3回大陸遠征の隊長に選出された。キューバ総督のディエゴ・ベラスケス・デ・クエヤ ルとの確執により、遠征隊は直前になって呼び戻されることになったが、コルテスは命令を無視した。 大陸に到着したコルテスは、先住民のいくつかの部族と手を組むという戦略を成功させた。また、先住民の女性ドニャ・マリーナを通訳として起用した。彼女は 後にコルテスの長男を出産した。キューバ総督がコルテスを逮捕するために使者を送った際、コルテスは彼らと戦い、勝利した。そして、増援部隊を率いてい た。コルテスは、反逆罪で処罰される代わりに、自らの功績を認められるよう王に直訴する手紙を書いた。アステカ帝国を滅ぼしたのち、コルテスはオアハカ侯 爵の称号を授けられたが、より権威のある副王の称号は高位の貴族であるアントニオ・デ・メンドーサに与えられた。1541年、コルテスはスペインに戻り、 6年後に自然死した。 |

| Name See also: Spanish naming customs Cortés himself used the form "Hernando" or "Fernando" for his first name, as seen in the contemporary archive documents, his signature and the title of an early portrait.[2] William Hickling Prescott's Conquest of Mexico (1843) also refers to him as Hernando Cortés. At some point writers began using the shortened form of "Hernán" more generally.[when?] |

名前 参照:スペインの命名慣習 コルテス自身は、現代の記録文書や彼の署名、初期の肖像画のタイトルに見られるように、ファーストネームとして「ヘルナンド」または「フェルナンド」とい う形を使用していた。ウィリアム・ヒックリング・プレスコット著『メキシコ征服』(1843年)でも、彼はヘルナンド・コルテスとして言及されている。あ る時期から、作家たちはより一般的に「ヘルナン」という短縮形を使用するようになった。[いつ?] |

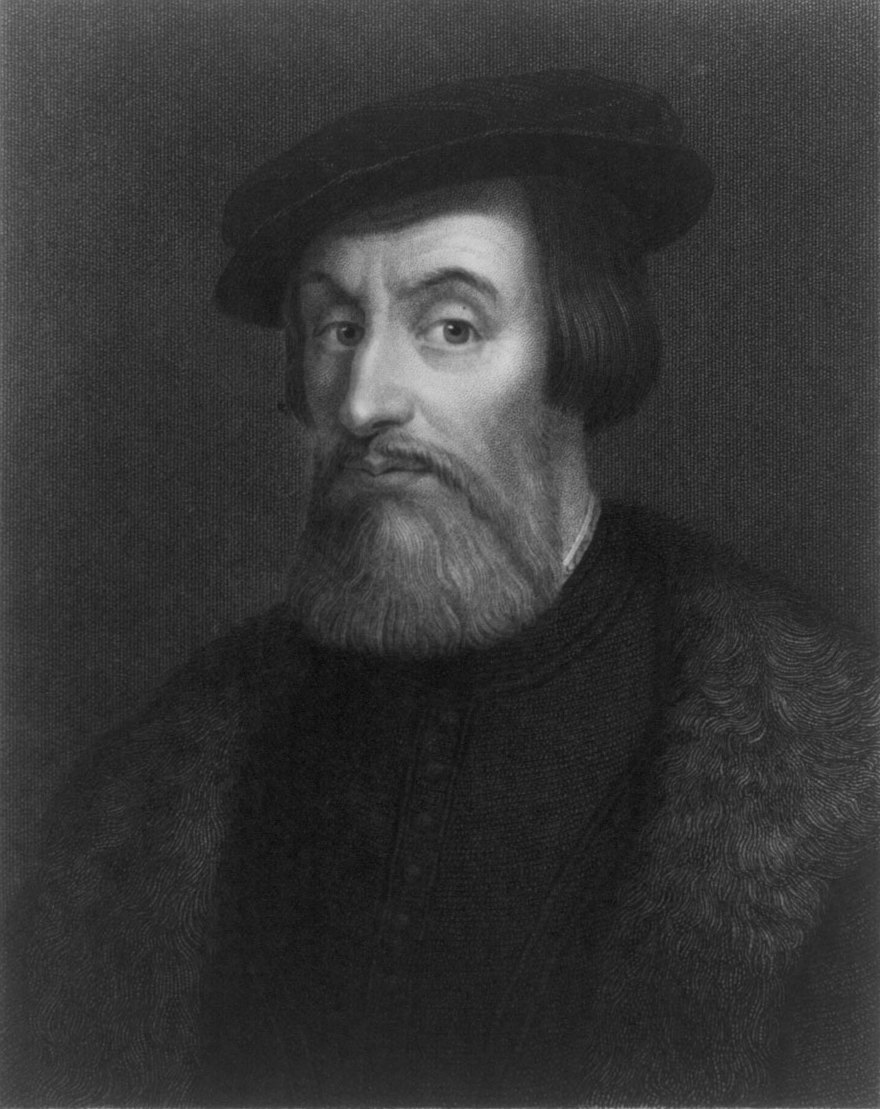

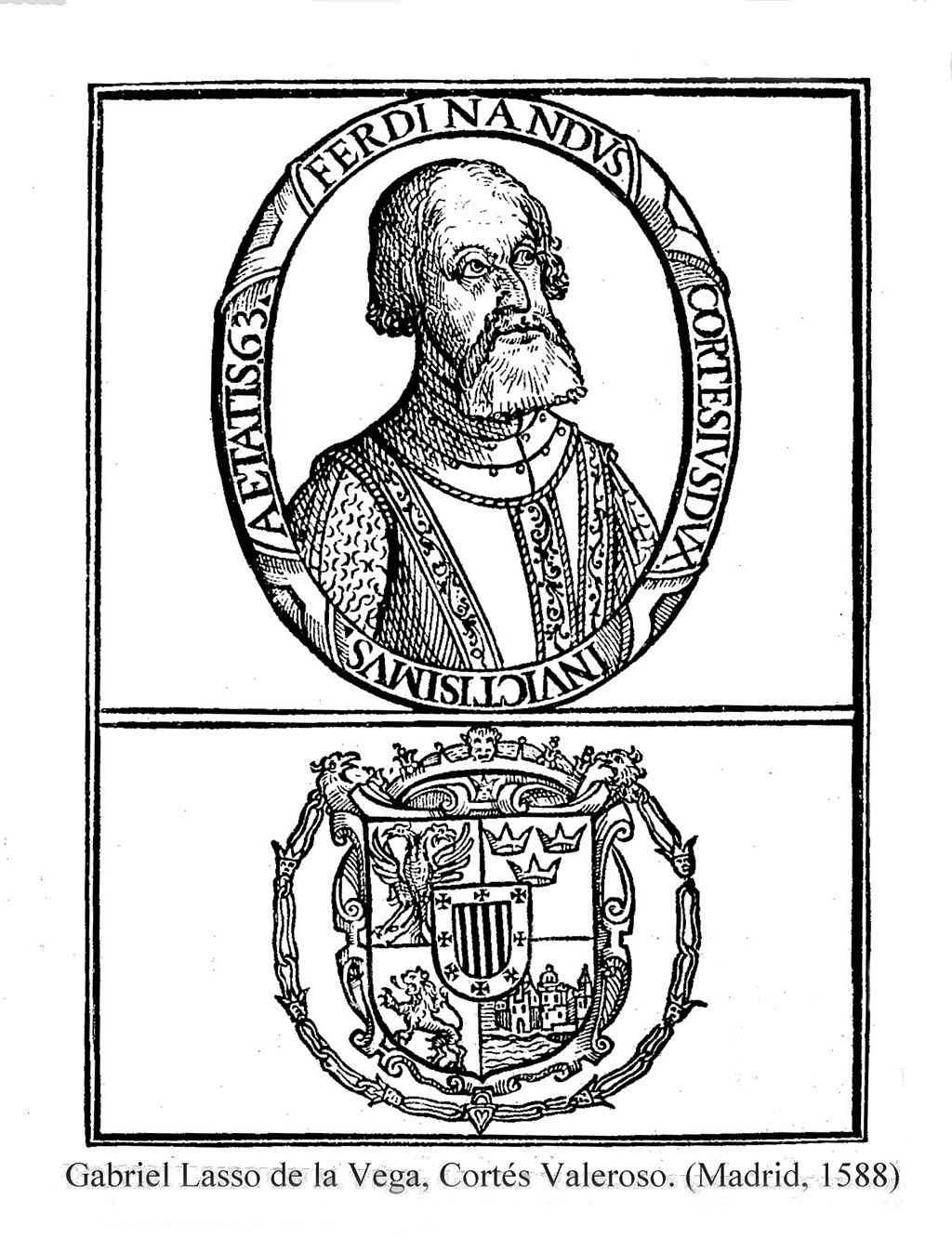

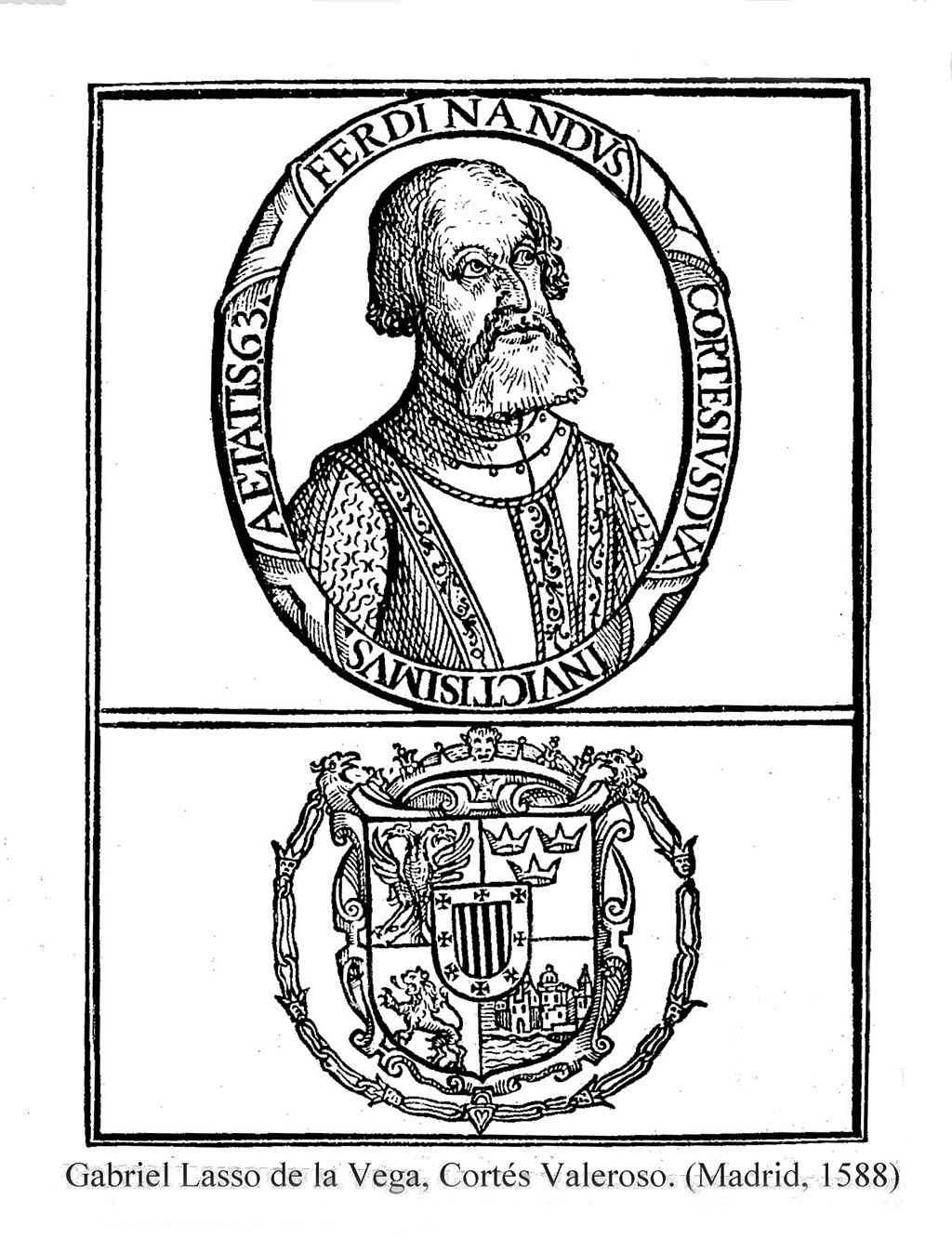

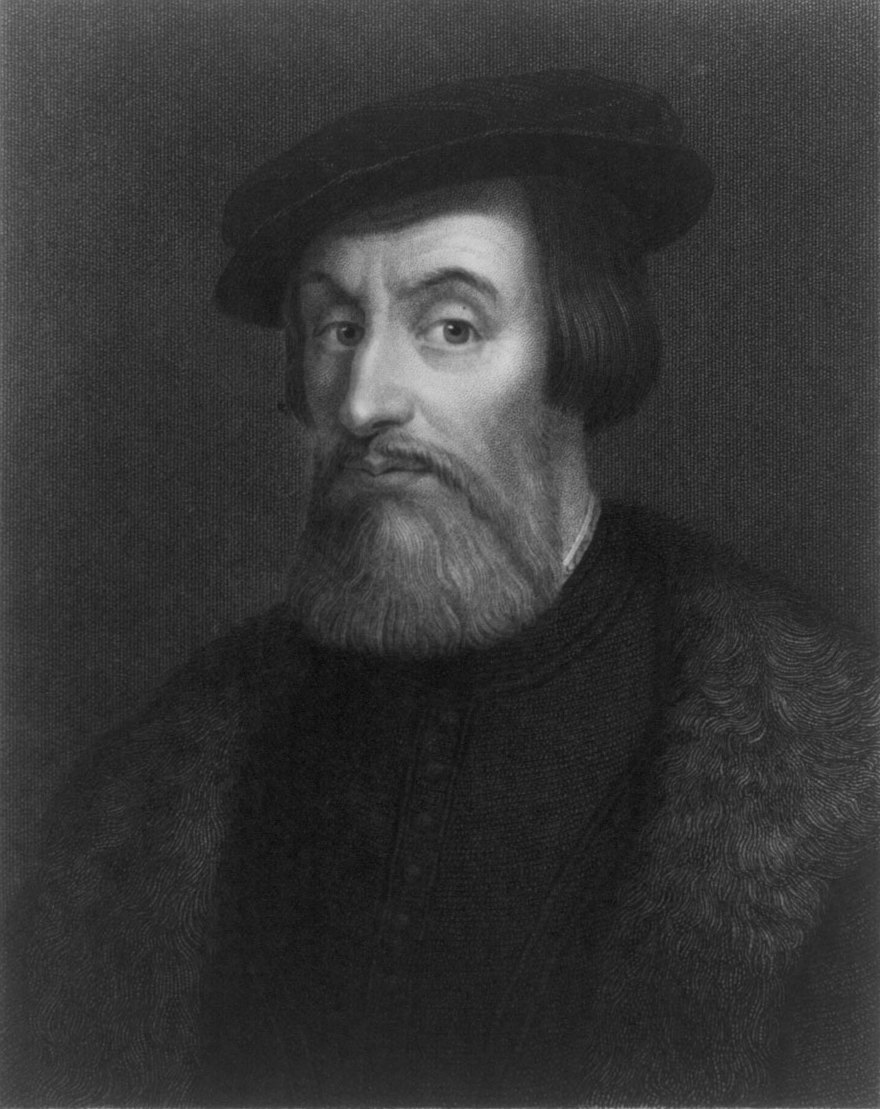

| Physical appearance In addition to the illustration by the German artist Christoph Weiditz in his Trachtenbuch, there are three known portraits of Hernán Cortés which were likely made during his lifetime, though only copies of them have survived. All of these portraits show Cortés in the later years of his life.[3] The account of the conquest of the Aztec Empire written by Bernal Díaz del Castillo, gives a detailed description of Hernán Cortés's physical appearance: He was of good stature and body, well proportioned and stocky, the color of his face was somewhat grey, not very cheerful, and a longer face would have suited him more. His eyes seemed at times loving and at times grave and serious. His beard was black and sparse, as was his hair, which at the time he sported in the same way as his beard. He had a high chest, a well shaped back and was lean with little belly.[4] — Bernal Díaz del Castillo |

外見 ドイツ人画家クリストフ・ヴァイディッツによる『民族衣装図鑑』の挿絵に加え、現存するのは複製のみであるが、エルナン・コルテスの存命中に描かれたと見 られる肖像画が3点知られている。 これらの肖像画はいずれも晩年のコルテスを描いている。[3] ベルナル・ディアス・デル・カスティージョが著したアステカ帝国征服記には、エルナン・コルテスの外見について次のように詳細に記されている。 彼は長身で均整のとれたがっちりとした体格で、顔色はやや青白く、あまり陽気なタイプではなく、もっと面長な顔立ちが似合っていた。彼の目は時に愛らし く、時に厳粛で真剣な印象を与えた。彼の髭は黒く、まばらに生えており、髪も同様に、当時、髭と同じように伸ばしていた。彼は胸板が厚く、背筋が伸び、お 腹はあまり出ていなかった。 — バーナル・ディアス・デル・カスティーリョ |

Early life Weiditz's depiction of Cortés in 1529  Copy of a portrait of Cortés dated to the year 1525 Cortés was born in 1485 in the town of Medellín, then a village in the Kingdom of Castile, now a municipality of the modern-day province of Badajoz in Extremadura, Spain. His father, Martín Cortés de Monroy, born in 1449 to Rodrigo or Ruy Fernández de Monroy and his wife María Cortés, was an infantry captain of distinguished ancestry but slender means. Hernán's mother was Catalína Pizarro Altamirano.[5] Through his mother, Hernán was second cousin once removed of Francisco Pizarro, who later conquered the Inca Empire of modern-day Peru (and not to be confused with another Francisco Pizarro, who joined Cortés to conquer the Aztecs). Cortés' maternal grandmother, Leonor Sánchez Pizarro Altamirano, was first cousin of Pizarro's father Gonzalo Pizarro y Rodriguez.[5] Through his father, Hernán was related to Nicolás de Ovando, the third governor of Hispaniola. His paternal great-grandfather was Rodrigo de Monroy y Almaraz, 5th Lord of Monroy. According to his biographer and chaplain, Francisco López de Gómara, Cortés was pale and sickly as a child. At the age of 14, he was sent to study Latin under an uncle in Salamanca. Later historians have misconstrued this personal tutoring as time enrolled at the University of Salamanca.[6] After two years, Cortés returned home to Medellín, much to the irritation of his parents, who had hoped to see him equipped for a profitable legal career. However, those two years in Salamanca, plus his long period of training and experience as a notary, first in Valladolid and later in Hispaniola, gave him knowledge of the legal codes of Castile that he applied to help justify his unauthorized conquest of Mexico.[7] At this point in his life, Cortés was described by Gómara as ruthless, haughty, and mischievous.[8] The 16-year-old youth had returned home to feel constrained by life in his small provincial town. By this time, news of the exciting discoveries of Christopher Columbus in the New World was streaming back to Spain. |

幼少期 1529年のコルテスの描写(ヴァイディッツ作)  1525年とされるコルテスの肖像画の複製 コルテスは1485年、カスティーリャ王国の村であったメディナ(現在のスペイン、エストレマドゥラ州バダホス県の自治体)で生まれた。父親のマルティ ン・コルテス・デ・モンロイは、1449年にロドリーゴまたはルイ・フェルナンデス・デ・モンロイとその妻マリア・コルテスの間に生まれ、由緒ある家柄で はあったが、貧しい歩兵隊長であった。 エルナン・コルテスの母親はカタリナ・ピサロ・アルタミラノであった。 母方の従兄弟にあたるフランシスコ・ピサロは、後に現在のペルーのインカ帝国を征服した(アステカ征服にコルテスとともに出陣したフランシスコ・ピサロと は別人である)。コルテスの母方の祖母レオノール・サンチェス・ピサロ・アルタミラノは、ピサロの父ゴンサロ・ピサロ・イ・ロドリゲスの従姉妹であった。 父方の祖父ニコラス・デ・オバンドは、イスパニオラ島の第3代総督であった。父方の曾祖父はロドリーゴ・デ・モンロイ・イ・アルマラスで、モンロイの第5 代領主であった。 伝記作家であり、コルテスのチャプレンでもあったフランシスコ・ロペス・デ・ゴマラによると、コルテスは子供の頃は青白く病弱だったという。14歳のと き、サラマンカに住む叔父のもとでラテン語を学ぶために送られた。後の歴史家たちは、この個人指導をサラマンカ大学在学中と誤解しているが、実際にはそう ではなかった。 2年後、コルテスは両親の期待を裏切り、メデジンに帰郷した。両親は息子が法律家として成功することを望んでいたのだ。しかし、サラマンカでの2年間と、 バジャドリッド、そして後にイスパニョーラ島で公証人として長期間にわたって経験を積んだことで、カスティーリャの法律に関する知識を得た。この知識は、 メキシコ征服の正当性を主張する際に役立てられた。 この時点でのコルテスは、ゴマラによって冷酷で尊大、そして悪戯好きと評されていた。[8] 16歳の青年は、故郷に戻ったものの、小さな地方都市での生活に窮屈さを感じていた。この頃、クリストファー・コロンブスによる新大陸での刺激的な発見の ニュースがスペインに次々と届いていた。 |

| Plans

were made for Cortés to sail to the Americas with a family acquaintance

and distant relative, Nicolás de Ovando, the newly appointed Governor

of Hispaniola. (This island is now divided between Haiti and the

Dominican Republic). Cortés suffered an injury and was prevented from

traveling. He spent the next year wandering the country, probably

spending most of his time in Spain's southern ports of Cadiz, Palos,

Sanlucar, and Seville. He finally left for Hispaniola in 1504 and

became a colonist.[9] Arrival Cortés reached Hispaniola in a ship commanded by Alonso Quintero, who tried to deceive his superiors and reach the New World before them in order to secure personal advantages. Quintero's mutinous conduct may have served as a model for Cortés in his subsequent career. Upon his arrival in 1504 in Santo Domingo, the capital of Hispaniola, the 18-year-old Cortés registered as a citizen; this entitled him to a building plot and land to farm. Soon afterward, Governor Nicolás de Ovando granted him an encomienda and appointed him as a notary of the town of Azua de Compostela. His next five years seemed to help establish him in the colony; in 1506, Cortés took part in the conquests of Hispaniola and Cuba. The expedition leader awarded him a large estate of land and Taíno slaves for his efforts.[10] Cuba (1511–1519) In 1511, Cortés accompanied Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, an aide of the Governor of Hispaniola, in his expedition to conquer Cuba. Afterwards Velázquez was appointed Governor of Cuba. At the age of 26, Cortés was made clerk to the treasurer with the responsibility of ensuring that the Crown received the quinto, or customary one fifth of the profits from the expedition. Velázquez was so impressed with Cortés that he secured a high political position for him in the colony. He became secretary for Governor Velázquez. Cortés was twice appointed municipal magistrate (alcalde) of Santiago. In Cuba, Cortés became a man of substance with an encomienda to provide Indian labor for his mines and cattle. This new position of power also made him the new source of leadership, which opposing forces in the colony could then turn to. In 1514, Cortés led a group which demanded that more Indians be assigned to the settlers. As time went on, relations between Cortés and Governor Velázquez became strained.[11] Cortés found time to become romantically involved with Catalina Xuárez (or Juárez), the sister-in-law of Governor Velázquez. Part of Velázquez's displeasure seems to have been based on a belief that Cortés was trifling with Catalina's affections. Cortés was temporarily distracted by one of Catalina's sisters but finally married Catalina, reluctantly, under pressure from Governor Velázquez. However, by doing so, he hoped to secure the good will of both her family and that of Velázquez.[12] It was not until he had been almost 15 years in the Indies that Cortés began to look beyond his substantial status as mayor of the capital of Cuba and as a man of affairs in the thriving colony. He missed the first two expeditions, under the orders of Francisco Hernández de Córdoba and then Juan de Grijalva, sent by Diego Velázquez to Mexico in 1518. News reached Velázquez that Juan de Grijalva had established a colony on the mainland where there was a bonanza of silver and gold, and Velázquez decided to send him help. Cortés was appointed captain-general of this new expedition in October 1518, but was advised to move fast before Velázquez changed his mind.[11] With Cortés's experience as an administrator, knowledge gained from many failed expeditions, and his impeccable rhetoric he was able to gather six ships and 300 men, within a month. Velázquez's jealousy exploded and he decided to put the expedition in other hands. However, Cortés quickly gathered more men and ships in other Cuban ports. |

コ

ルテスは、家族の知り合いで遠縁の親戚であるニコラス・デ・オバンド(新しくイスパニオラの総督に任命された)とともにアメリカ大陸へ航海する計画を立て

た。(この島は現在、ハイチとドミニカ共和国に分割されている。)コルテスは負傷し、旅に出ることができなかった。彼はその後1年間を放浪し、おそらくス

ペインの南部の港であるカディス、パロス、サンルーカル、セビリアでほとんどの時間を過ごした。1504年にようやくイスパニョーラ島へ向けて出発し、入

植者となった。[9] 到着 コルテスは、上官たちを欺き、個人的な利益を確保するために彼らより先に新世界に到着しようとした、アロンソ・キンテーロが指揮する船でイスパニョーラ島に到着した。キンテーロの反乱的な行動は、その後のコルテスのキャリアの模範となったかもしれない。 1504年にイスパニオラ島の首都サント・ドミンゴに到着した18歳のコルテスは、市民として登録した。これにより、コルテスは農地として使用する土地と 建物を所有する権利を得た。その後まもなく、総督ニコラス・デ・オバンドは彼にエンコミエンダを与え、アスア・デ・コンポステーラの公証人に任命した。そ の後5年間で、彼は植民地での地位を確立したようだった。1506年、コルテスはイスパニョーラ島とキューバの征服に参加した。遠征隊のリーダーは、彼の 功績を称え、広大な土地とタイノ族の奴隷を与えた。[10] キューバ(1511年~1519年) 1511年、コルテスはイスパニョーラ総督の補佐官であったディエゴ・ベラスケス・デ・クエヤルのキューバ征服遠征に同行した。その後、ベラスケスは キューバ総督に任命された。26歳のコルテスは、遠征による利益の5分の1を王が確実に受け取れるようにする責任を負う財務官補佐となった。 ベラスケスは、コルテスに感銘を受け、植民地における高い政治的地位を彼に確保した。コルテスはベラスケス総督の秘書となった。コルテスは2度、サンティ アゴの地方裁判所判事(alcalde)に任命された。キューバでは、コルテスは鉱山や家畜の労働力としてインディアンを供給するエンコミエンダを所有す る実力者となった。この新たな権力により、コルテスは植民地内の反対勢力が頼れる新たな指導者となった。1514年、コルテスは入植者に割り当てるイン ディアンを増やすよう要求するグループを率いた。 時が経つにつれ、コルテスとベラスケス総督の関係は緊張したものになっていった。[11] コルテスはベラスケス総督の義理の妹カタリナ・スアレス(またはフアレス)と恋愛関係になる時間を見つけた。ベラスケスが不快感を示した理由の一部は、コ ルテスがカタリナの愛情を弄んでいるという考えに基づいているようである。コルテスは一時的にカタリナの姉妹の1人に心を奪われたが、最終的にはベラスケ ス総督の圧力により、不本意ながらカタリナと結婚した。しかし、そうすることで、カタリナの家族とベラスケス総督の両方の好意を確保できることを期待して いた。 コルテスが、キューバの首都の市長や、繁栄する植民地の事業家としての地位を越えた視野を持つようになったのは、インドに15年近く滞在してからだった。 彼は、1518年にディエゴ・ベラスケスがメキシコに派遣したフランシスコ・エルナンデス・デ・コルドバとフアン・デ・グリハルバの最初の2回の遠征に参 加できなかった。フアン・デ・グリハルバが銀や金の鉱脈がある大陸に植民地を築いたという知らせがベラスケスのもとに届き、ベラスケスは彼を助けに派遣す ることを決めた。1518年10月、コルテスは新探検隊の隊長に任命されたが、ベラスケスが考えを変える前に素早く行動するよう助言された。 コルテスの行政官としての経験、多くの失敗に終わった遠征から得た知識、そして非の打ちどころのない弁舌により、彼は1か月以内に6隻の船と300人の兵 士を集めることができた。 ベラスケスの嫉妬は爆発し、彼は遠征隊を他の手に委ねることを決めた。 しかし、コルテスはすぐに他のキューバの港でさらに多くの兵士と船を集めた。 |

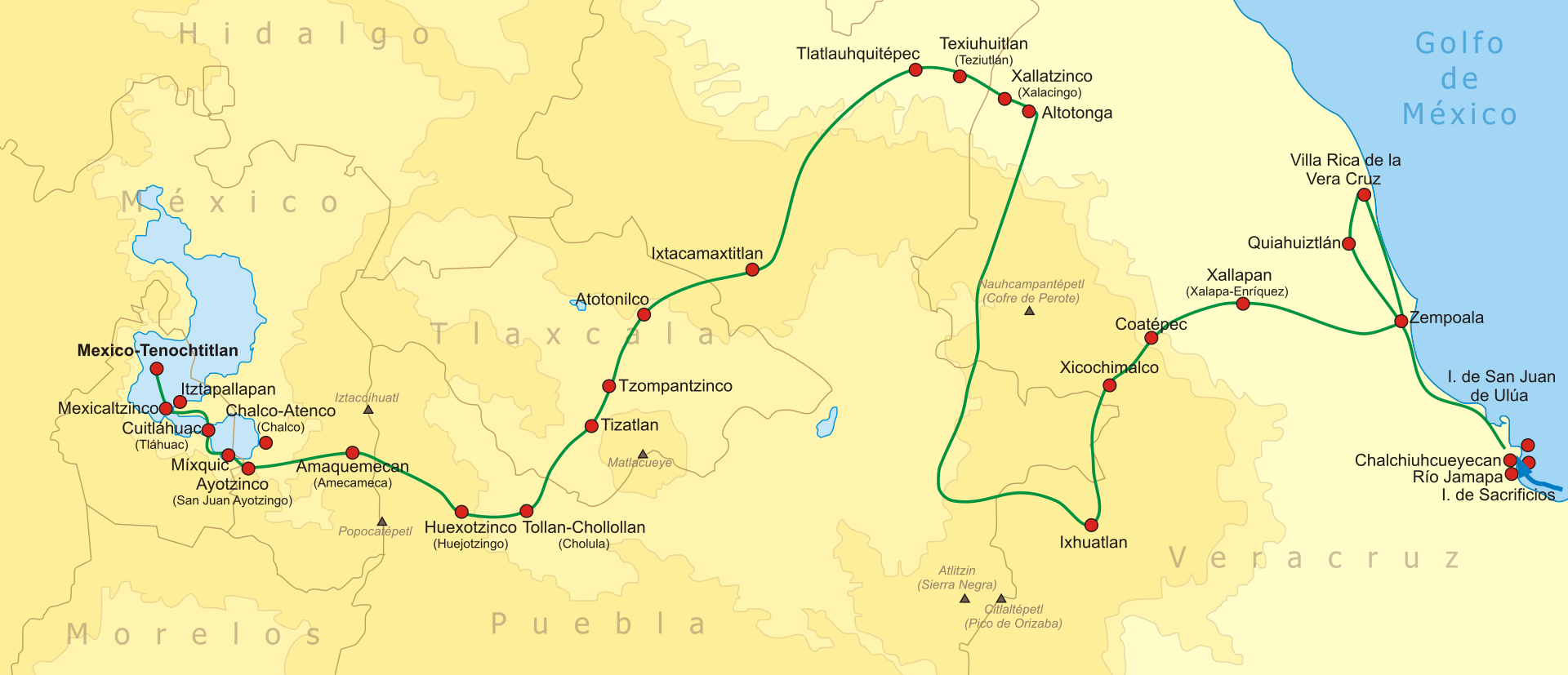

| Conquest of Mexico (1519–1521) Main article: Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire  A map depicting Cortés's invasion route from the coast to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan In 1518, Velázquez put Cortés in command of an expedition to explore and secure the interior of Mexico for colonization. At the last minute, due to the old argument between the two, Velázquez changed his mind and revoked Cortés's charter. Cortés ignored the orders and, in an act of open mutiny, went anyway in February 1519. He stopped in Trinidad, Cuba, to hire more soldiers and obtain more horses. Accompanied by about 11 ships, 500 men (including seasoned slaves[13]), 13 horses, and a small number of cannon, Cortés landed on the Yucatán Peninsula in Maya territory.[14] There he encountered Geronimo de Aguilar, a Spanish Franciscan priest who had survived a shipwreck followed by a period in captivity with the Maya, before escaping.[14] Aguilar had learned the Chontal Maya language and was able to translate for Cortés.[15]  Hernando Cortes landing in Mexico in 1519, met by natives; with foliate borders and a portrait of Cortes in a medallion. (Miniature : 15,55 x 10,80 cm; Feuillet : 15,24 x 24,8 cm, Langue Latin; British Library : Add. MS 37177) Cortés's military experience was almost nonexistent, but he proved to be an effective leader of his small army and won early victories over the coastal Indians.[16] In March 1519, Cortés formally claimed the land for the Spanish crown. Then he proceeded to Tabasco, where he met with resistance and won a battle against the natives. He received twenty young indigenous women from the vanquished natives, and he converted them all to Christianity.[15] Among these women was La Malinche, his future mistress and mother of his son Martín.[1] Malinche knew both the Nahuatl language and Chontal Maya, thus enabling Cortés to communicate with the Aztecs through Aguilar.[17]: 82, 86–87 At San Juan de Ulúa on Easter Sunday 1519, Cortés met with Moctezuma II's Aztec Empire governors Tendile and Pitalpitoque.[17]: 89  Cortés scuttling his own fleet off the coast of Veracruz in order to eliminate the possibility of retreat In July 1519, his men took over Veracruz. By this act, Cortés dismissed the authority of the governor of Cuba to place himself directly under the orders of King Charles.[14] To eliminate any ideas of retreat, Cortés scuttled his ships.[18] |

メキシコ征服(1519年-1521年) 詳細は「スペインによるアステカ帝国征服」を参照  コルテスの海岸からアステカの首都テノチティトランへの侵略ルートを描いた地図 1518年、ベラスケスは、コルテスにメキシコ内陸部の探検と植民地化を命じた。 直前になって、2人の間の古い確執により、ベラスケスは考えを変え、コルテスの勅許を取り消した。 コルテスは命令を無視し、公然と反乱を起こし、1519年2月に進軍した。 彼はキューバのトリニダッドに立ち寄り、兵士と馬をさらに調達した。約11隻の船、500人の兵士(熟練した奴隷を含む[13])、13頭の馬、そして少 数の大砲を伴ったコルテスは、マヤ族の領土であるユカタン半島に上陸した。[14] そこで彼は、スペイン人フランシスコ会の神父で、難破後にマヤ族に捕らえられ、その後脱出したジェロニモ・デ・アギラールと遭遇した。アギラールは、ショ ントゥル・マヤ語を習得しており、 コルテスの通訳を務めた。  エルナン・コルテスが1519年にメキシコに上陸し、先住民と出会う場面。葉模様の縁取りと、メダリオンに収められたコルテスの肖像画がある。(Miniature : 15,55 x 10,80 cm; Feuillet : 15,24 x 24,8 cm, Langue Latin; British Library : Add. MS 37177) コルテスの軍事的経験はほとんどなかったが、彼は小規模な軍隊の有能な指揮官となり、沿岸インディアンに対して早期に勝利を収めた。1519年3月、コル テスはスペイン王のためにその土地を正式に領有権を主張した。その後、彼はタバスコに進軍し、そこで抵抗に遭い、先住民との戦いに勝利した。彼は、打ち負 かした先住民から20人の若い先住民女性を受け取り、全員をキリスト教に改宗させた。 この女性の中には、後にコルテスの愛人となり、息子のマルティンの母親となるラ・マルインチェがいた。[1] マルインチェはナワトル語とショントラ・マヤ語の両方を話せたため、コルテスはアギラールを通じてアステカ人と意思疎通することができた。[17]: 82, 86–87 1519年の復活祭の日曜日、サン・ファン・デ・ウルーアで、コルテスはモクテスマ2世のアステカ帝国の総督テンディレとピタルプ・イトケと会見した。 。[17]: 89  撤退の可能性を排除するために、コルテスはベラクルス沖で自らの艦隊を沈没させた 1519年7月、彼の部下たちはベラクルスを占領した。この行為により、コルテスはキューバ総督の権限を排除し、自らを国王カルロスの直接の命令下に置いた。[14] 撤退の可能性を排除するために、コルテスは艦隊を沈没させた。[18] |

| March on Tenochtitlán In Veracruz, he met some of the tributaries of the Aztecs and asked them to arrange a meeting with Moctezuma II, the tlatoani (ruler) of the Aztec Empire.[18] Moctezuma repeatedly turned down the meeting, but Cortés was determined. Leaving a hundred men in Veracruz, Cortés marched on Tenochtitlán in mid-August 1519, along with 600 soldiers, 15 horsemen, 15 cannons, and hundreds of indigenous carriers and warriors.[14] On the way to Tenochtitlán, Cortés made alliances with indigenous peoples such as the Totonacs of Cempoala and the Nahuas of Tlaxcala. The Otomis initially, and then the Tlaxcalans clashed with the Spanish in a series of three battles from 2 to 5 September 1519, and at one point, Diaz remarked, "they surrounded us on every side". After Cortés continued to release prisoners with messages of peace, and realizing the Spanish were enemies of Moctezuma, Xicotencatl the Elder and Maxixcatzin persuaded the Tlaxcalan warleader, Xicotencatl the Younger, that it would be better to ally with the newcomers than to kill them.[17]: 143–155, 171 In October 1519, Cortés and his men, accompanied by about 1,000 Tlaxcalteca,[17]: 188 marched to Cholula, the second-largest city in central Mexico. Cortés, either in a pre-meditated effort to instill fear upon the Aztecs waiting for him at Tenochtitlan or (as he later claimed, when he was being investigated) wishing to make an example when he feared native treachery, massacred thousands of unarmed members of the nobility gathered at the central plaza, then partially burned the city.[17]: 199–200 |

テノチティトランへの進軍 ベラクルスで、彼はアステカの支族の何人かと出会い、アステカ帝国の君主(tlatoani)であるモクテスマ2世との面会を申し入れた。[18] モクテスマは何度も面会を断ったが、コルテスは決意を固めていた。100人の兵士をベラクルスに残し、コルテスは600人の兵士、15人の騎兵、15門の 大砲、そして数百人の先住民の運搬人や戦士たちとともに、1519年8月中旬にテノチティトランへと進軍した。 テノチティトランへの道中、コルテスは、クエンポアラのトトナック族やトラスカラのナワ族といった先住民と同盟を結んだ。オトミ族とトラスカラン族は、 1519年9月2日から5日にかけて3度にわたってスペイン軍と衝突し、一時は「彼らに四方八方から囲まれた」とディアスが述べた。その後、コルテスは和 平のメッセージを携えて捕虜を解放し続け、スペイン人がモクテスマの敵であることを知った。シコテンカトル・エル・アンヘルとマキシシンカティンは、トラ ンカスカンの軍司令官であるシコテンカトル・エル・ヤングに、彼らを殺すよりも新参者と手を組む方が得策であると説得した。[17]: 143–155, 171 1519年10月、コルテスと彼の部下は、約1,000人のトラスカテカ族を従えて[17]:188、メキシコ中央部で2番目に大きな都市であるショルー ラへと進軍した。コルテスは、テノチティトランで待ち構えていたアステカ人に恐怖を与えるために事前に計画していたのか、あるいは(後に調査を受けた際に 主張したように)先住民の裏切りを恐れて見せしめにしたかったのか、いずれにせよ、中央広場に集まっていた数千人の非武装の貴族階級の人々を虐殺し、その 後、都市の一部を焼き払った。[17]:199-200 |

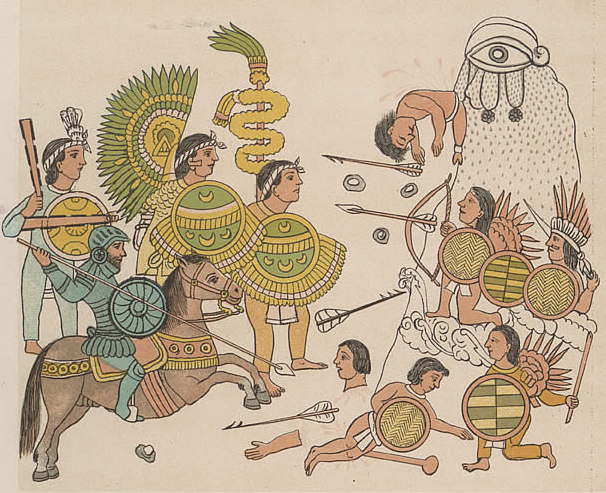

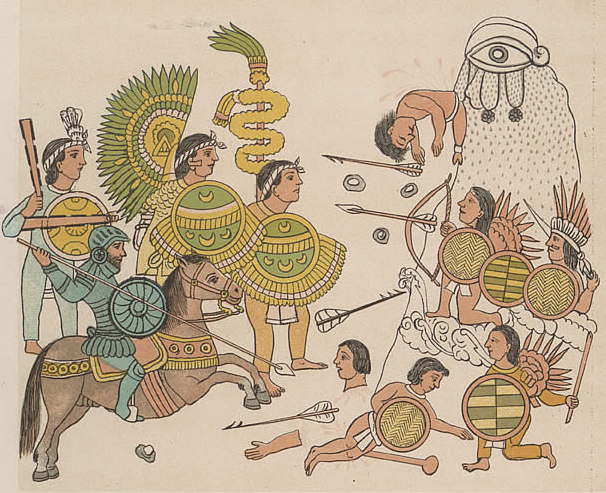

Cortés and La Malinche meet Moctezuma in Tenochtitlán, November 8, 1519. By the time he arrived in Tenochtitlán, the Spaniards had a large army. On November 8, 1519, they were peacefully received by Moctezuma II.[19] Moctezuma deliberately let Cortés enter the Aztec capital, the island city of Tenochtitlán, hoping to get to know their weaknesses better and to crush them later.[14] Moctezuma gave lavish gifts of gold to the Spaniards which, rather than placating them, excited their ambitions for plunder. In his letters to King Charles, Cortés claimed to have learned at this point that he was considered by the Aztecs to be either an emissary of the feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl or Quetzalcoatl himself—a belief which has been contested by a few modern historians.[20][21] But quickly Cortés learned that several Spaniards on the coast had been killed by Aztecs while supporting the Totonacs, and decided to take Moctezuma as a hostage in his palace, indirectly ruling Tenochtitlán through him.[22]  Cristóbal de Olid leads Spanish soldiers with Tlaxcalan allies in the conquests of Jalisco, 1522. Meanwhile, Velázquez sent another expedition, led by Pánfilo de Narváez, to oppose Cortés, arriving in Mexico in April 1520 with 1,100 men.[14] Cortés left 200 men in Tenochtitlán and took the rest to confront Narváez. He overcame Narváez, despite his numerical inferiority, and convinced the rest of Narváez's men to join him.[14] In Mexico, one of Cortés's lieutenants Pedro de Alvarado, committed the massacre in the Great Temple, triggering a local rebellion.[23] Cortés speedily returned to Tenochtitlán. On July 1, 1520, Moctezuma was killed (he was stoned to death by his own people, as reported in Spanish accounts; although some claim he was murdered by the Spaniards once they realized his inability to placate the locals). Faced with a hostile population, Cortés decided to flee for Tlaxcala. During the Noche Triste (June 30 – July 1, 1520), the Spaniards managed a narrow escape from Tenochtitlán across the Tlacopan causeway, while their rearguard was being massacred. Much of the treasure looted by Cortés was lost (as well as his artillery) during this panicked escape from Tenochtitlán.[14] |

1519年11月8日、コルテスとラ・マルインチェはテノチティトランでモクテスマと対面した。 テノチティトランに到着したときには、スペイン軍は大軍勢となっていた。1519年11月8日、彼らはモクテスマ2世に平和的に迎え入れられた。[19] モクテスマは意図的にコルテスをアステカの首都、テノチティトランの島都に入らせ、彼らの弱点をよりよく知り、後にそれを叩くことを期待していた。 [14] モクテスマはスペイン人たちに大量の黄金を贈ったが、それは彼らをなだめるというよりも、むしろ彼らの略奪への野心をかき立てるものだった。コルテスは、 スペイン王カルロス1世宛ての手紙の中で、この時点で、アステカ人から自分は羽毛の生えた蛇の神ケツァルコアトルの使者か、あるいはケツァルコアトルその 人であると考えられていることを知ったと主張している。この考えについては、現代の歴史家の一部から異論が出されている。[20][21]しかし、コルテ スはすぐに、トトナック族を支援している間に、海岸にいたスペイン人数名がアステカ人に殺害されたことを知り、 モクテスマを人質として宮殿に収監し、彼を通じて間接的にテノチティトランを支配することを決めた。  1522年、クリストバル・デ・オリドは、トラスカラ同盟軍とともにスペイン兵を率いてハリスコ州を征服した。 一方、ベラスケスは、コルテスに対抗するためにパンフィロ・デ・ナルバエスを司令官とする別の遠征隊を派遣し、1520年4月に1,100人の兵士ととも にメキシコに到着した。[14] コルテスは200人の兵士をテノチティトランに残し、残りの兵士を率いてナルバエスと対峙した。彼は、数で劣勢であったにもかかわらずナルバエスを打ち負 かし、ナルバエスの残りの兵士たちを説得して味方につけた。[14] メキシコでは、コルテスの副官の一人ペドロ・デ・アルバラードが大寺院で虐殺を行い、地元の反乱を引き起こした。 コルテスは急いでテノチティトランに戻った。1520年7月1日、モクテスマは殺害された(スペイン人の記録によると、モクテスマは自国民によって石打ち の刑に処されたとされているが、モクテスマが地元民をなだめることができなかったことを知ったスペイン人によって殺害されたという説もある)。敵意に満ち た住民を前にしたコルテスは、トラスカラに逃亡することを決めた。ノチェ・トリステ(1520年6月30日~7月1日)の間、スペイン軍はテノチティトラ ンからトラコパン水路を渡り、後衛が虐殺される中、辛うじて脱出に成功した。コルテスが略奪した財宝の多くは、テノチティトランからのこのパニックに陥っ た脱出の際に失われた(大砲も同様である)[14]。 |

| Destruction of Tenochtitlán After a battle in Otumba, they managed to reach Tlaxcala, having lost 870 men.[14] With the assistance of their allies, Cortés's men finally prevailed with reinforcements arriving from Cuba. Cortés began a policy of attrition towards Tenochtitlán, cutting off supplies and subduing the Aztecs' allied cities. During the siege he would construct brigantines in the lake and slowly destroy blocks of the city to avoid fighting in an urban setting. The Mexicas would fall back to Tlatelolco and even succeed in ambushing the pursuing Spanish forces, inflicting heavy losses, but would ultimately be the last portion of the island that resisted the conquistadores. The siege of Tenochtitlan ended with Spanish victory and the destruction of the city.[1][24] In January 1521, Cortés countered a conspiracy against him, headed by Antonio de Villafana, who was hanged for the offense.[14] Finally, with the capture of Cuauhtémoc, the tlatoani (ruler) of Tenochtitlán, on August 13, 1521, the Aztec Empire was captured, and Cortés was able to claim it for Spain, thus renaming the city Mexico City. From 1521 to 1524, Cortés personally governed Mexico.[14] |

テノチティトランの破壊 オトンバでの戦いの後、彼らは870人の兵士を失いながらも、なんとかトラスカラにたどり着いた。[14] 同盟国の支援を受け、コルテスの軍勢はキューバからの援軍も到着し、ついに優勢となった。コルテスはテノチティトランに対する消耗戦政策を開始し、補給を 断ち、アステカと同盟関係にある都市を制圧した。包囲の間、彼は湖でブリガンティン船を建造し、市街地での戦闘を避けるために、都市のブロックを徐々に破 壊していった。メシカ族はトラテロルコに退却し、スペイン軍の追撃部隊を待ち伏せることに成功し、大きな損害を与えたが、最終的には征服者たちに抵抗した 最後の部分となった。テノチティトラン包囲戦はスペインの勝利と都市の破壊によって幕を閉じた。[1][24] 1521年1月、コルテスは、アントニオ・デ・ビジャファナが主導した彼に対する陰謀に対抗し、ビジャファナは罪状により絞首刑となった。[14] ついに、1521年8月13日にテノチティトランの君主クアウテモックが捕らえられ、アステカ帝国は征服され、コルテスはこれをスペインの領土と主張し、 都市名をメキシコシティと改称した 。1521年から1524年にかけて、コルテスは自らメキシコを統治した。[14] |

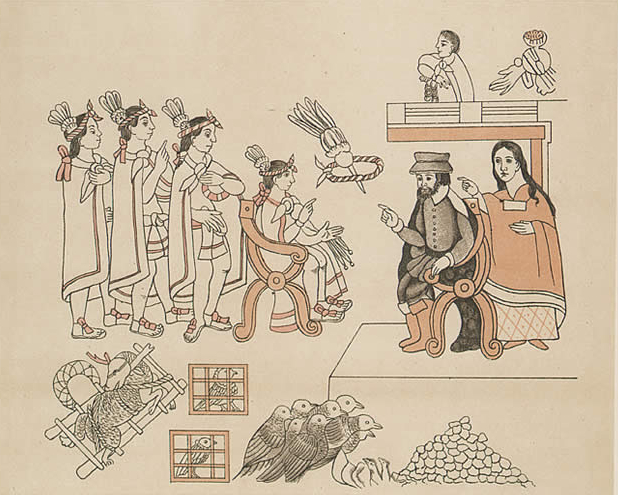

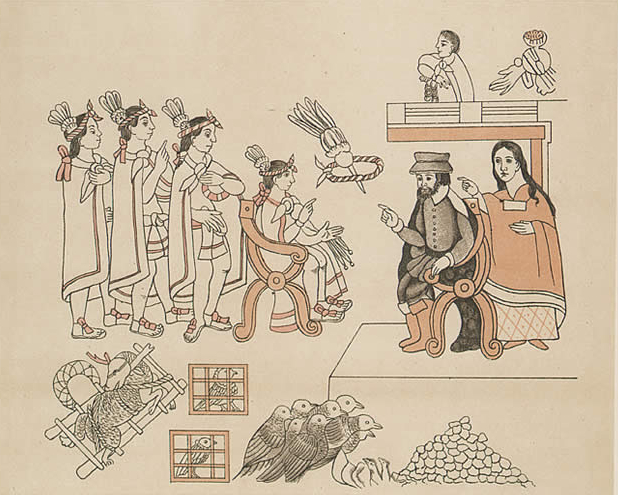

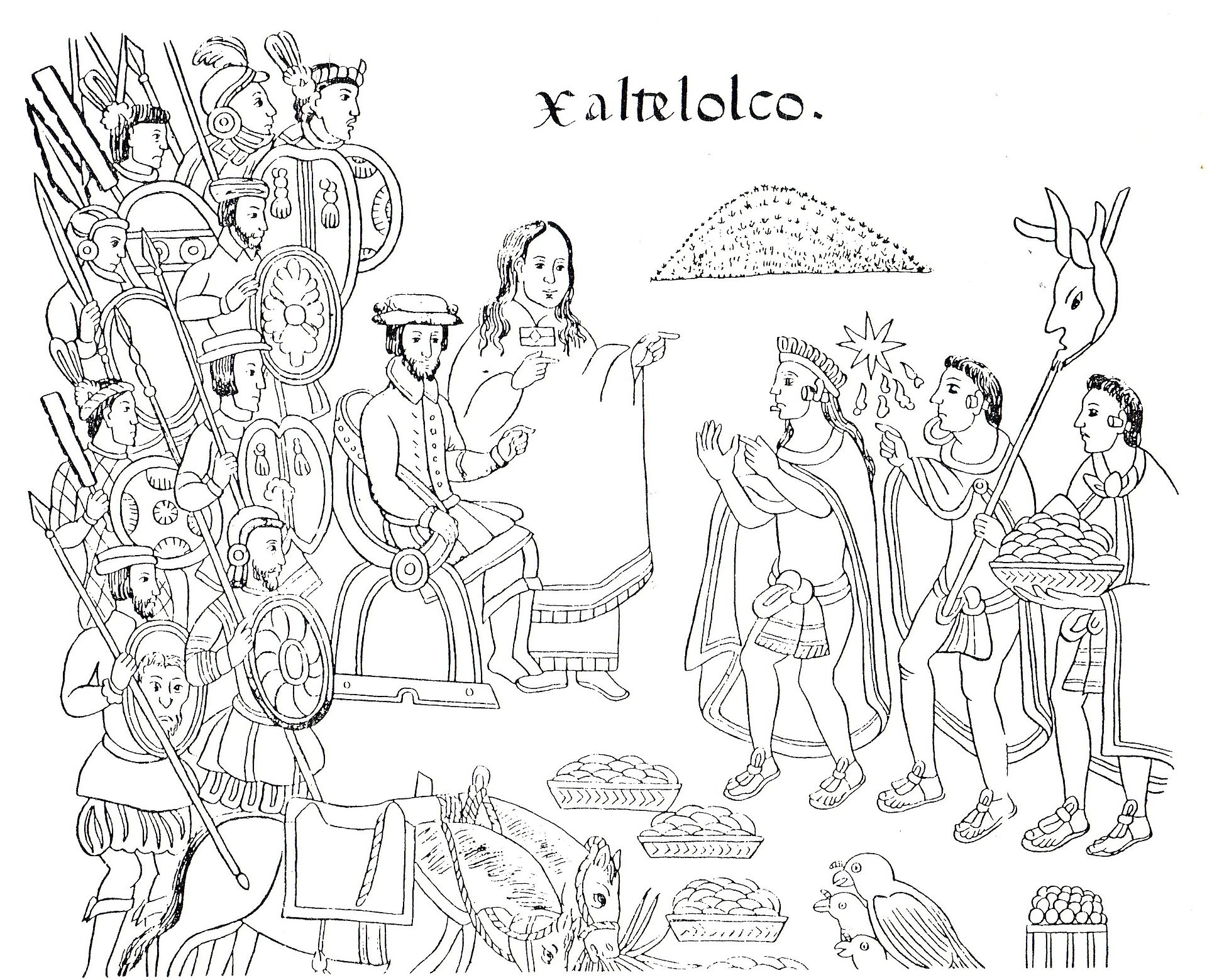

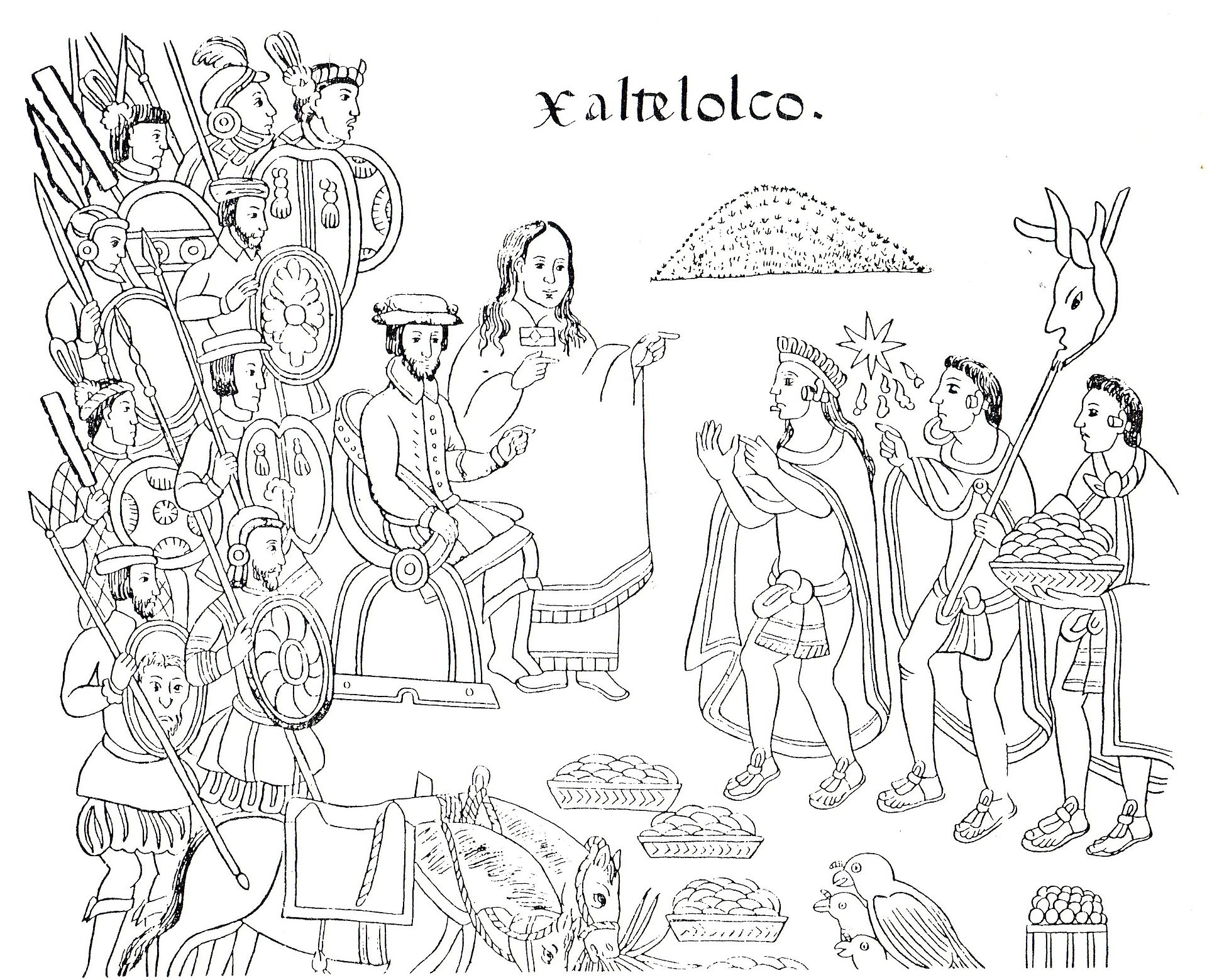

Appointment to governorship of Mexico and internal dissensions A painting from Diego Muñoz Camargo's History of Tlaxcala (Lienzo Tlaxcala), c. 1585, showing La Malinche and Hernán Cortés Many historical sources have conveyed an impression that Cortés was unjustly treated by the Spanish Crown, and that he received nothing but ingratitude for his role in establishing New Spain. This picture is the one Cortés presents in his letters and in the later biography written by Francisco López de Gómara. However, there may be more to the picture than this. Cortés's own sense of accomplishment, entitlement, and vanity may have played a part in his deteriorating position with the king: Cortés personally was not ungenerously rewarded, but he speedily complained of insufficient compensation to himself and his comrades. Thinking himself beyond reach of restraint, he disobeyed many of the orders of the Crown, and, what was more imprudent, said so in a letter to the emperor, dated October 15, 1524 (Ycazbalceta, "Documentos para la Historia de México", Mexico, 1858, I). In this letter Cortés, besides recalling in a rather abrupt manner that the conquest of Mexico was due to him alone, deliberately acknowledges his disobedience in terms which could not fail to create a most unfavourable impression.[25] King Charles appointed Cortés as governor, captain general and chief justice of the newly conquered territory, dubbed "New Spain of the Ocean Sea". But also, much to the dismay of Cortés, four royal officials were appointed at the same time to assist him in his governing—in effect, submitting him to close observation and administration. Cortés initiated the construction of Mexico City, destroying Aztec temples and buildings and then rebuilding on the Aztec ruins what soon became the most important European city in the Americas.[14] Cortés managed the founding of new cities and appointed men to extend Spanish rule to all of New Spain, imposing the encomienda system in 1524.[14] He reserved many encomiendas for himself and for his retinue, which they considered just rewards for their accomplishment in conquering central Mexico. However, later arrivals and members of factions antipathetic to Cortés complained of the favoritism that excluded them.[26] In 1523, the Crown (possibly influenced by Cortés's enemy, Bishop Fonseca),[27] sent a military force under the command of Francisco de Garay to conquer and settle the northern part of Mexico, the region of Pánuco. This was another setback for Cortés who mentioned this in his fourth letter to the King in which he describes himself as the victim of a conspiracy by his archenemies Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, Diego Columbus and Bishop Fonseca as well as Francisco Garay. The influence of Garay was effectively stopped by this appeal to the King who sent out a decree forbidding Garay to interfere in the politics of New Spain, causing him to give up without a fight. |

メキシコ総督への任命と内部の不和 ディエゴ・ムニョス・カマルゴ作『トラスカラの歴史』(Lienzo Tlaxcala)より、ラ・マルインチェとエルナン・コルテスを描いた1585年頃の絵画 多くの歴史資料は、コルテスがスペイン王から不当に扱われたという印象を与えている。また、彼は新スペインの建国に貢献したにもかかわらず、その見返りと して受け取ったのは感謝の言葉だけだったという印象も与えている。この絵は、コルテスが手紙や、後にフランシスコ・ロペス・デ・ゴマラが書いた伝記の中で 描いているものである。しかし、この絵には他にも何か意味があるのかもしれない。コルテス自身の達成感、権利意識、虚栄心が、国王との関係悪化の一因と なった可能性がある。 コルテス個人としては決して不誠実な報酬を受けていたわけではないが、自分と仲間たちへの報酬が十分でないとすぐに不満を漏らした。自制の及ばない存在で あると考えた彼は、王の命令の多くに背き、さらに軽率なことに、1524年10月15日付けの皇帝宛ての手紙でそのことを述べた (Ycazbalceta, 「Documentos para la Historia de México」, Mexico, 1858, I)。この手紙の中で、コルテスは、メキシコ征服が自分ひとりの功績であるとかなり唐突に思い起こしただけでなく、最も好ましくない印象を与えるに違いな い表現で、自分の不服従を故意に認めた。[25] カルロス国王は、コルテスを「海洋のスペイン」とあだ名された新征服地の総督、総司令官、最高裁判事に任命した。しかし、コルテスを落胆させることに、同 時に4人の王室高官が任命され、コルテスの統治を補佐することになった。事実上、コルテスは厳しい監視と管理下に置かれることになった。コルテスはメキシ コシティの建設を開始し、アステカの神殿や建造物を破壊し、アステカの遺跡の上に再建した。この都市は、すぐにアメリカ大陸で最も重要なヨーロッパの都市 となった。 コルテスは新都市の建設を指揮し、1524年にエンコミエンダ制度を導入して、スペインの支配をヌエバ・エスパーニャ全土に拡大するよう人々を任命した。 [14] 彼は、自分自身と随行員のために多くのエンコミエンダを確保した。これは、中央メキシコ征服の功績に対する正当な報酬だと考えられていた。しかし、後に到 着した者やコルテスに反感を持つ派閥のメンバーは、自分たちを排除するような優遇措置に不満を訴えた。[26] 1523年、王冠(おそらくコルテスの敵であるフォンセカ司教の影響を受けて)は、フランシスコ・デ・ガライの指揮下にある軍隊をメキシコ北部のパンコ地 域征服と入植のために派遣した。これはコルテスにとってまたもやの挫折であり、彼はこのことを国王宛ての4通目の手紙の中で触れ、自身が宿敵であるディエ ゴ・ベラスケス・デ・クエヤル、ディエゴ・コロンブス、フォンセカ司教、そしてフランシスコ・ガライによる陰謀の犠牲者であると述べている。ガライの影響 力は、国王へのこの訴えによって事実上阻止され、国王はガライにヌエバ・エスパーニャの政治に干渉することを禁じる勅令を発し、ガライは戦うことなく降参 した。 |

Royal grant of arms (1525) The coat of arms awarded to Cortés, by King Carlos I of Spain Although Cortés had flouted the authority of Diego Velázquez in sailing to the mainland and then leading an expedition of conquest, Cortés's spectacular success was rewarded by the crown with a coat of arms, a mark of high honor, following the conqueror's request. The document granting the coat of arms summarizes Cortés's accomplishments in the conquest of Mexico. The proclamation of the king says in part: We, respecting the many labors, dangers, and adventures which you underwent as stated above, and so that there might remain a perpetual memorial of you and your services and that you and your descendants might be more fully honored ... it is our will that besides your coat of arms of your lineage, which you have, you may have and bear as your coat of arms, known and recognized, a shield ...[28]: 43 The grant specifies the iconography of the coat of arms, the central portion divided into quadrants. In the upper portion, there is a "black eagle with two heads on a white field, which are the arms of the empire".[28]: 43 Below that is a "golden lion on a red field, in memory of the fact that you, the said Hernando Cortés, by your industry and effort brought matters to the state described above" (i.e., the conquest).[28]: 43 The specificity of the other two quadrants is linked directly to Mexico, with one quadrant showing three crowns representing the three Aztec emperors of the conquest era, Moctezuma, Cuitlahuac, and Cuauhtemoc[28]: 43 and the other showing the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan.[28]: 43 Encircling the central shield are symbols of the seven city-states around the lake and their lords that Cortés defeated, with the lords "to be shown as prisoners bound with a chain which shall be closed with a lock beneath the shield".[28]: 44–45 |

1525年、王室から授与された紋章 スペイン王カルロス1世からコルテスに授与された紋章 コルテスは、ディエゴ・ベラスケスの権威を無視して本土へ向かい、征服遠征を指揮したにもかかわらず、コルテスの目覚ましい成功は、征服者の要請を受け て、王冠から高貴の証である紋章を与えられるという形で報われた。紋章を授与する文書は、コルテスのメキシコ征服における功績を要約している。国王の宣言 には次のように述べられている。 我々は、あなたが上述の通り経験した数々の労苦、危険、冒険を尊重し、あなたとあなたの功績を永遠に記念し、あなたとあなたの子孫がより一層称えられるよ うに... あなたには、あなたが持つ家系の紋章に加えて、盾を紋章として持つことを許可し、これを認知する。[28]:43 この勅許状では、紋章の図像が指定されており、中央部分は4つの象限に分割されている。上段には「白地に2つの頭を持つ黒い鷲」があり、これは「帝国の紋 章」である。[28]: 43 下段には「赤地に金色のライオン」があり、これは「あなたが、すなわちエルナンド・コルテスが、その才覚と努力によって、上述の状況に至ったことを記念す る」ものである(すなわち、征服)。[28]: 43 残りの2つの象限の特異性は メキシコに直接関連するもので、征服時代の3人のアステカ皇帝、モクテスマ、クイトラワク、クアウテモックを表す3つの王冠が描かれた象限と、アステカの 首都テノチティトランが描かれた象限がある。[28]: 43 中央の盾の周囲には、コルテスが打ち負かした湖周辺の7つの都市国家とその領主のシンボルが描かれており、 「鎖でつながれた捕虜として描かれ、盾の下で錠が閉じられる」[28]: 44-45。 |

Death of his first wife and remarriage Sculpture of Juana de Zúñiga, second wife of Cortés, for her tomb Cortés's wife Catalina Súarez arrived in New Spain around summer 1522, along with her sister and brother.[29] His marriage to Catalina was at this point extremely awkward, since she was a kinswoman of the governor of Cuba, Diego Velázquez, whose authority Cortés had thrown off and who was therefore now his enemy. Catalina lacked the noble title of doña, so at this point his marriage with her no longer raised his status. Their marriage had been childless. Since Cortés had sired children with a variety of indigenous women, including a son around 1522 by his cultural translator, Doña Marina, Cortés knew he was capable of fathering children. Cortés's only male heir at this point was illegitimate, but nonetheless named after Cortés's father, Martín Cortés. This son Martín Cortés was also popularly called "El Mestizo".[30][31] Catalina Suárez died under mysterious circumstances the night of November 1–2, 1522. There were accusations at the time that Cortés had murdered his wife.[1] There was an investigation into her death, interviewing a variety of household residents and others.[32] The documentation of the investigation was published in the nineteenth century in Mexico and these archival documents were uncovered in the twentieth century.[33][34] The death of Catalina Suárez produced a scandal and investigation, but Cortés was now free to marry someone of high status more appropriate to his wealth and power. In 1526, he built an imposing residence for himself, the Palace of Cortés in Cuernavaca, in a region close to the capital where he had extensive encomienda holdings. In 1529 he had been accorded the noble designation of don, but more importantly was given the noble title of Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca and married the Spanish noblewoman Doña Juana de Zúñiga. The marriage produced three children, including another son, who was also named Martín. As the first-born legitimate son, Don Martín Cortés y Zúñiga was now Cortés's heir and succeeded him as holder of the title and estate of the Marquessate of the Valley of Oaxaca.[35] Cortés's legitimate daughters were Doña Maria, Doña Catalina, and Doña Juana.[36] |

最初の妻の死と再婚 コルテスの2番目の妻フアナ・デ・スニガの墓のための彫刻 コルテスの妻カタリナ・スアレスは、姉と弟とともに、1522年夏頃にヌエバ・エスパーニャに到着した。[29] コルテスが権力を奪い、敵対する立場となったキューバ総督ディエゴ・ベラスケスの親族であったため、カタリナとの結婚は非常に気まずいものとなった。カタ リナには貴族の称号である「ドニャ」がなかったため、この時点で彼女との結婚はもはや彼の地位向上にはつながらなかった。彼らの結婚には子供がいなかっ た。コルテスは、1522年頃に文化の翻訳者ドニャ・マリーナとの間に息子をもうけるなど、さまざまな先住民女性との間に子供をもうけていたため、自分が 子供をもうける能力があることを知っていた。この時点でコルテスの唯一の男子相続人は非嫡出子であったが、それでもコルテスの父親であるマルティン・コル テスにちなんで名付けられた。このマルティン・コルテスという息子は一般に「エル・メスティソ」と呼ばれていた。[30][31] カタリナ・スアレスは1522年11月1日から2日にかけての夜、不可解な状況下で死亡した。当時、コルテスが妻を殺害したという非難があった。[1] 彼女の死について調査が行われ、屋敷の住人やその他の人々への聞き取りが行われた。[32] 調査の記録は19世紀にメキシコで出版され、これらの公文書は20世紀になって発見された。[33][34] カタリナ・スアレスの死はスキャンダルと調査を引き起こしたが、コルテスは今や、自身の富と権力にふさわしい地位の高い女性と結婚することが許された。 1526年、彼は首都にほど近い広大なエンコミエンダ領地を所有するクエルナバカに、堂々とした邸宅を建設した。1529年には「ドン」の称号を授けられ たが、それ以上に重要なのはオアハカ渓谷の侯爵の称号を授けられ、スペイン貴族の女性ドニャ・フアナ・デ・スニガと結婚したことである。この結婚により3 人の子供が生まれ、その中には同じくマルティンと名付けられた息子がいた。長男として、ドン・マルティン・コルテス・イ・スニガは、コルテスの後継者とな り、オアハカ渓谷の侯爵の称号と財産を受け継いだ。[35] コルテスの正妻との間の娘は、ドニャ・マリア、ドニャ・カタリナ、ドニャ・フアナであった。[36] |

| Cortés and the "Spiritual Conquest" of Mexico Since the conversion to Christianity of indigenous peoples was an essential and integral part of the extension of Spanish power, making formal provisions for that conversion once the military conquest was completed was an important task for Cortés. During the Age of Discovery, the Catholic Church had seen early attempts at conversion in the Caribbean islands by Spanish friars, particularly the mendicant orders. Cortés made a request to the Spanish monarch to send Franciscan and Dominican friars to Mexico to convert the vast indigenous populations to Christianity. In his fourth letter to the king, Cortés pleaded for friars rather than diocesan or secular priests because those clerics were in his view a serious danger to the Indians' conversion. If these people [Indians] were now to see the affairs of the Church and the service of God in the hands of canons or other dignitaries, and saw them indulge in the vices and profanities now common in Spain, knowing that such men were the ministers of God, it would bring our Faith into much harm that I believe any further preaching would be of no avail.[37] He wished the mendicants to be the main evangelists. Mendicant friars did not usually have full priestly powers to perform all the sacraments needed for conversion of the Indians and growth of the neophytes in the Christian faith, so Cortés laid out a solution to this to the king. Your Majesty should likewise beseech His Holiness [the pope] to grant these powers to the two principal persons in the religious orders that are to come here, and that they should be his delegates, one from the Order of St. Francis and the other from the Order of St. Dominic. They should bring the most extensive powers Your Majesty is able to obtain, for, because these lands are so far from the Church of Rome, and we, the Christians who now reside here and shall do so in the future, are so far from the proper remedies of our consciences and, as we are human, so subject to sin, it is essential that His Holiness should be generous with us and grant to these persons most extensive powers, to be handed down to persons actually in residence here whether it be given to the general of each order or to his provincials.[38] The Franciscans arrived in May 1524, a symbolically powerful group of twelve known as the Twelve Apostles of Mexico, led by Fray Martín de Valencia. Franciscan Geronimo de Mendieta claimed that Cortés's most important deed was the way he met this first group of Franciscans. The conqueror himself was said to have met the friars as they approached the capital, kneeling at the feet of the friars who had walked from the coast. This story was told by Franciscans to demonstrate Cortés piety and humility and was a powerful message to all, including the Indians, that Cortés's earthly power was subordinate to the spiritual power of the friars. However, one of the first twelve Franciscans, Fray Toribio de Benavente Motolinia does not mention it in his history.[39] Cortés and the Franciscans had a particularly strong alliance in Mexico, with Franciscans seeing him as "the new Moses" for conquering Mexico and opening it to Christian evangelization. In Motolinia's 1555 response to Dominican Bartolomé de Las Casas, he praises Cortés. And as to those who murmur against the Marqués del Valle [Cortés], God rest him, and who try to blacken and obscure his deeds, I believe that before God their deeds are not as acceptable as those of the Marqués. Although as a human he was a sinner, he had faith and works of a good Christian, and a great desire to employ his life and property in widening and augmenting the fair of Jesus Christ, and dying for the conversion of these gentiles ... Who has loved and defended the Indians of this new world like Cortés? ... Through this captain, God opened the door for us to preach his holy gospel and it was he who caused the Indians to revere the holy sacraments and respect the ministers of the church.[40] In Fray Bernardino de Sahagún's 1585 revision of the conquest narrative first codified as Book XII of the Florentine Codex, there are laudatory references to Cortés that do not appear in the earlier text from the indigenous perspective. Whereas Book XII of the Florentine Codex concludes with an account of Spaniards' search for gold, in Sahagún's 1585 revised account, he ends with praise of Cortés for requesting the Franciscans be sent to Mexico to convert the Indians.[41] |

コルテスとメキシコの「精神征服」 先住民のキリスト教への改宗はスペインの勢力拡大に不可欠かつ不可分の要素であったため、軍事的征服が完了した時点でその改宗を正式に規定することは、コ ルテスにとって重要な任務であった。大航海時代、カトリック教会はスペイン修道士、特に托鉢修道会によるカリブ海諸島での初期の改宗の試みを見ていた。コ ルテスはスペイン国王に、フランシスコ会とドミニコ会の修道士をメキシコに派遣し、広大な先住民の人口をキリスト教に改宗させるよう要請した。国王への4 通目の手紙で、コルテスは教区司祭や世俗の司祭ではなく修道士を要請した。なぜなら、それらの聖職者はインディアンの改宗にとって深刻な脅威であるとコル テスは考えていたからだ。 もしこれらの人々(インディアン)が今、教会の運営や神への奉仕が参事会員やその他の高官の手に委ねられているのを目にし、彼らがスペインで今や一般的に なっている悪徳や冒涜にふけっているのを目にし、そのような人々が神の使徒であることを知れば、それは我々の信仰に大きな害をもたらすだろう。私は、これ 以上の布教は無駄になるだろうと信じている。[37] 彼は托鉢僧たちを主な布教者として望んでいた。托鉢修道会士は通常、インディアンの改宗やキリスト教信仰における新入信者の成長に必要なすべての秘跡を行うための司祭としての完全な権限を持っていなかったため、コルテスは国王にこの問題の解決策を提示した。 陛下はローマ教皇に、この地に来る予定の修道会の主要人物2人にこれらの権限を付与し、彼らを教皇の代理とすべきであると懇願すべきである。そのうちの1 人は聖フランシスコ修道会、もう1人は聖ドミニコ修道会から選ぶべきである。彼らは、ローマ教会から遠く離れたこの地に居住するキリスト教徒である我々に とって、最も広範な権限を獲得すべきである。なぜなら、我々は良心の適切な救済から遠く離れており、人間であるがゆえに罪に陥りやすいからだ。そのため、 法王は我々に対して寛大であるべきであり、これらの人物に最も広範な権限を付与し、実際にこの地に居住する人物に引き継がれるべきである。各修道会の総長 に与えられるにせよ、その管区長に与えられるにせよ、である。[38] フランシスコ会は1524年5月に到着した。彼らは象徴的な意味で強力な12人のグループであり、マルティン・デ・バレンシア修道士が率いる「メキシコの 十二使徒」として知られていた。フランシスコ会のヘロニモ・デ・メンドーサは、コルテスの最も重要な功績は、この最初のフランシスコ会グループとの出会い 方であったと主張した。征服者自身が、修道士たちが首都に近づく際に彼らと出会い、海岸から歩いてきた修道士たちの足元にひざまずいたと言われている。こ の話は、フランシスコ会修道士たちがコルテスの信心深さと謙虚さを示すために語ったものであり、コルテスの世俗的な権力は修道士たちの精神的な権力に従属 しているという、インディアンを含むすべての人々への強力なメッセージであった。しかし、最初の12人のフランシスコ会の修道士の一人であるトリービオ・ デ・ベナベンテ・モトリーニアは、その歴史の中でこの逸話を言及していない。[39] コルテスとフランシスコ会はメキシコにおいて特に強力な同盟関係にあり、フランシスコ会はメキシコを征服し、キリスト教の布教に開放したコルテスを「新し いモーセ」とみなしていた。モトリーニアは1555年にドミニコ会のバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスに宛てた返答の中で、コルテスを賞賛している。 そして、マルケス・デル・バジェ(コルテス)に対して悪口を言う者たち、神のご加護があらんことを、そして、彼の功績を中傷し、隠そうとする者たちについ て、私は、神の前では彼らの行為はマルケスのそれほど受け入れられるものではないと信じている。人間としては罪人であったが、彼は善良なキリスト教徒とし ての信仰と行いを持ち、人生と財産をイエス・キリストの教えを広め、増大させるために捧げ、異教徒の改宗のために命を捧げることを強く望んでいた。コルテ スほどこの新世界インディアンを愛し、守った人物がいただろうか?この隊長を通して、神は我々に神聖な福音を説く扉を開いてくださった。そして、インディ アンに神聖な秘跡を尊び、教会の聖職者を尊敬するようにさせたのは彼であった。[40] 1585年に修道士ベルナルディノ・デ・サアグンが征服物語を改訂した際、フィレンツェ・コーデックスの第12巻として初めて体系化されたが、先住民の視 点から書かれたそれ以前のテキストには見られないコルテスへの賞賛の言及がある。フィレンツェ写本第12巻がスペイン人の黄金探索の記述で締めくくられて いるのに対し、サアグンの1585年の改訂版では、コルテスがインディアン改宗のためにフランシスコ会士をメキシコに派遣するよう要請したことを称賛して 終わっている。[41] |

| Expedition to Honduras and aftermath (1524–1541) See also: Spanish conquest of Yucatán § Hernán Cortés in the Maya lowlands, 1524–25; Spanish conquest of Honduras; Spanish conquest of Guatemala § Cortés in Petén; and Spanish conquest of Petén § Cortés in Petén Expedition to Honduras (1524–1526) From 1524 to 1526, Cortés headed an expedition to Honduras where he defeated Cristóbal de Olid, who had claimed Honduras as his own under the influence of the Governor of Cuba Diego Velázquez. Fearing that Cuauhtémoc might head an insurrection in Mexico, he brought him with him to Honduras. In a controversial move, Cuauhtémoc was executed during the journey. Raging over Olid's treason, Cortés issued a decree to arrest Velázquez, whom he was sure was behind Olid's treason. This, however, only served to further estrange the Crown of Castile and the Council of Indies, both of which were already beginning to feel anxious about Cortés's rising power.[42] Cortés's fifth letter to King Charles attempts to justify his conduct, concludes with a bitter attack on "various and powerful rivals and enemies" who have "obscured the eyes of your Majesty".[43] Charles, who was also Holy Roman Emperor, had little time for distant colonies (much of Charles's reign was taken up with wars with France, the German Protestants and the expanding Ottoman Empire),[44] except insofar as they contributed to finance his wars. In 1521, year of the Conquest, Charles was attending to matters in his German domains and Bishop Adrian of Utrecht functioned as regent in Spain. Velázquez and Fonseca persuaded the regent to appoint a commissioner (a Juez de residencia, Luis Ponce de León) with powers to investigate Cortés's conduct and even arrest him. Cortés was once quoted as saying that it was "more difficult to contend against [his] own countrymen than against the Aztecs."[45] Governor Diego Velázquez continued to be a thorn in his side, teaming up with Bishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, chief of the Spanish colonial department, to undermine him in the Council of the Indies. A few days after Cortés's return from his expedition, Ponce de León suspended Cortés from his office of governor of New Spain. The Licentiate then fell ill and died shortly after his arrival, appointing Marcos de Aguilar as alcalde mayor. The aged Aguilar also became sick and appointed Alonso de Estrada governor, who was confirmed in his functions by a royal decree in August 1527. Cortés, suspected of poisoning them, refrained from taking over the government. Estrada sent Diego de Figueroa to the south. De Figueroa raided graveyards and extorted contributions, meeting his end when the ship carrying these treasures sank. Albornoz persuaded Alonso de Estrada to release Gonzalo de Salazar and Chirinos. When Cortés complained angrily after one of his adherents' hands was cut off, Estrada ordered him exiled. Cortés sailed for Spain in 1528 to appeal to King Charles. |

ホンジュラス遠征とその余波(1524年~1541年) 参照:ユカタン半島征服の項、1524年~1525年、マヤ低地におけるエルナン・コルテス、ホンジュラス征服、グアテマラ征服の項、ペテンにおけるコルテス、ペテン征服の項、ペテンにおけるコルテス ホンジュラス遠征(1524年~1526年) 1524年から1526年にかけて、コルテスはホンジュラス遠征を指揮し、キューバ総督ディエゴ・ベラスケスの影響下でホンジュラスを自らの領土と主張し ていたクリストバル・デ・オリドを打ち負かした。コルテスは、クアウテモックがメキシコで反乱を起こすのではないかと恐れ、彼をホンジュラスに同行させ た。物議を醸した動きの中で、クアウテモックは旅の途中で処刑された。オリドの反逆を激しく非難したコルテスは、オリドの反逆の黒幕であると確信していた ベラスケスを逮捕する命令を発した。しかし、これはカスティーリャ王とインド審議会との関係をさらに悪化させるだけであり、両者ともすでにコルテスの台頭 する権力に不安を感じ始めていた。 コルテスがカルロス1世に宛てた5通目の手紙は、自らの行動を正当化しようとするもので、結論では「様々な強力なライバルや敵」が「陛下の目を曇らせてい る」と痛烈に非難している。[43] また神聖ローマ皇帝でもあったカルロスは、遠く離れた植民地にあまり関心がなく(カルロスの治世の大半はフランス、ドイツのプロテスタント、そして拡大す るオスマン帝国との戦争に費やされた)、[44] ただし、それらが戦争の資金調達に貢献する場合を除いては、である。。1521年、征服の年、シャルルはドイツ領内の問題に対処しており、ユトレヒトの司 教エイドリアンがスペインの摂政を務めていた。 ベラスケスとフォンセカは摂政に説得し、コルテスの行動を調査し、場合によっては逮捕する権限を持つ委員(フエス・デ・レジデンシア、ルイス・ポンセ・ デ・レオン)を任命させた。コルテスはかつて「アステカ人と争うよりも、自国の同胞と争う方が難しい」と語ったことがあると伝えられている。[45] 総督ディエゴ・ベラスケスは、スペイン植民地部門の責任者であるフアン・ロドリゲス・デ・フォンセカ司教と手を組み、インド審議会でコルテスを貶めようと した。 コルテスが遠征から戻った数日後、ポンセ・デ・レオンは、コルテスをヌエバ・エスパーニャ総督の職から解任した。その後、コルテスは到着後まもなく病に倒 れ、マルコス・デ・アギラールをアルカルデ・メイヨに任命した。高齢のアギラールも病に倒れ、アロンソ・デ・エストラーダを総督に任命した。1527年8 月の王令により、デ・エストラーダは総督の職務を継続することが承認された。コルテスは彼らを毒殺した容疑で、政権の掌握を控えた。 エストラーダはディエゴ・デ・フィゲロアを南へ派遣した。フィゲロアは墓地を荒らし、貢献を強要したが、財宝を積んだ船が沈没した際に命を落とした。アル ボルノスはアロンソ・デ・エストラーダにゴンサロ・デ・サラザールとチリノスを解放するよう説得した。コルテスが支持者の一人の手を切られたことに怒って 訴えたため、エストラーダはコルテスに追放を命じた。コルテスは1528年にスペインに向けて出帆し、カルロス国王に訴えた。 |

First return to Spain (1528) and Marquessate of the Valley of Oaxaca Emperor Charles V with Hound (1532), a painting by the 16th-century artist Jakob Seisenegger In 1528, Cortés returned to Spain to appeal to the justice of his master, Charles V. Juan Altamirano and Alonso Valiente stayed in Mexico and acted as Cortés's representatives during his absence. Cortés presented himself with great splendor before Charles V's court. By this time Charles had returned and Cortés forthrightly responded to his enemy's charges. Denying he had held back on gold due the crown, he showed that he had contributed more than the quinto (one-fifth) required. Indeed, he had spent lavishly to build the new capital of Mexico City on the ruins of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, leveled during the siege that brought down the Aztec empire. He was received by Charles with every distinction, and decorated with the order of Santiago. In return for his efforts in expanding the still young Spanish Empire, Cortés was rewarded in 1529 by being accorded the noble title of don but more importantly named the "Marqués del Valle de Oaxaca" (Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca) and married the Spanish noblewoman Doña Juana Zúñiga, after the 1522 death of his much less distinguished first wife, Catalina Suárez. The noble title and senorial estate of the Marquesado was passed down to his descendants until 1811. The Oaxaca Valley was one of the wealthiest regions of New Spain, and Cortés had 23,000 vassals in 23 named encomiendas in perpetuity.[14][46] Although confirmed in his land holdings and vassals, he was not reinstated as governor and was never again given any important office in the administration of New Spain. During his travel to Spain, his property was mismanaged by abusive colonial administrators. He sided with local natives in a lawsuit. The natives documented the abuses in the Huexotzinco Codex. The entailed estate and title passed to his legitimate son Don Martín Cortés upon Cortés's death in 1547, who became the Second Marquess. Don Martín's association with the so-called Encomenderos' Conspiracy endangered the entailed holdings, but they were restored and remained the continuing reward for Hernán Cortés's family through the generations. |

1528年にスペインに初めて帰国し、オアハカ渓谷の侯爵領を獲得 16世紀の芸術家ヤコブ・ゼイゼネッガーによる絵画『猟犬を連れた皇帝カルロス5世』(1532年) 1528年、コルテスはスペインに戻り、主君であるカール5世の正義に訴えた。フアン・アルタミラノとアロンソ・バジェンテはメキシコに残り、コルテス不 在中の代理を務めた。コルテスはカール5世の宮廷で、非常に堂々とした態度で現れた。この時までにカールは戻ってきており、コルテスは敵の告発に率直に答 えた。彼は、王冠のために金を保留していたことを否定し、要求された5分の1以上の貢献をしたことを示した。実際、彼はアステカ帝国を滅ぼした包囲戦の間 に破壊されたアステカの首都テノチティトランの跡地に、新しい首都メキシコシティを建設するために贅沢に資金を費やしていた。 彼はシャルルから最高の敬意をもって迎えられ、サンティアゴ勲章を授与された。スペイン帝国の拡大に貢献した功績により、1529年には「ドン」の称号が 与えられ、さらに重要な「オアハカの谷の侯爵(Marqués del Valle de Oaxaca)」の称号を授けられ、1522年に最初の妻カタリナ・スアレスが亡くなった後、スペイン貴族の女性ドニャ・フアナ・スニガと結婚した。侯爵 の称号と領地は、1811年まで子孫に受け継がれた。オアハカ渓谷はヌエバ・エスパーニャで最も裕福な地域のひとつであり、コルテスは23のエンコミエン ダに2万3000人の家臣を永世的に抱えていた。 領地と家臣団の保有は認められたものの、総督職には復帰せず、その後もヌエバ・エスパーニャの行政において重要な役職に就くことはなかった。スペインへの 帰路、彼の財産は横暴な植民地行政官によって不当に扱われた。彼は訴訟において地元の先住民の側に立った。先住民たちは、フエソツィンコ・コーデックスに その横暴を記録した。 1547年にコルテスが死去すると、正当な息子であるドン・マルティン・コルテスが遺産と称号を継承し、第2代侯爵となった。ドン・マルティンがエンコミ エンダ派陰謀事件に関与したことで、遺産は危機に瀕したが、その後回復し、何世代にもわたってヘルナン・コルテスの家族に継続的に受け継がれた。 |

| Return to Mexico (1530) and appointment of a viceroy (1535) This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this article by introducing citations to additional sources at this section. (November 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message)   Two copies of the same portrait, the original was likely made during his lifetime. The left copy is dated to the 17th century and the right copy was made by José Salomé Pina, c. 1879. This portrait is characterized by having a different armor than other portraits.[3] Cortés returned to Mexico in 1530 with new titles and honors. Although Cortés still retained military authority and permission to continue his conquests, Don Antonio de Mendoza was appointed in 1535 as a viceroy to administer New Spain's civil affairs. This division of power led to continual dissension, and caused the failure of several enterprises in which Cortés was engaged. On returning to Mexico, Cortés found the country in a state of anarchy. There was a strong suspicion in court circles of an intended rebellion by Cortés. After reasserting his position and reestablishing some sort of order, Cortés retired to his estates at Cuernavaca, about 30 miles (48 km) south of Mexico City. There he concentrated on the building of his palace and on Pacific exploration. Remaining in Mexico between 1530 and 1541, Cortés quarreled with Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán and disputed the right to explore the territory that is today California with Antonio de Mendoza, the first viceroy. Cortés acquired several silver mines in Zumpango del Rio in 1534. By the early 1540s, he owned 20 silver mines in Sultepec, 12 in Taxco, and 3 in Zacualpan. Earlier, Cortés had claimed the silver in the Tamazula area.[47] In 1536, Cortés explored the northwestern part of Mexico and discovered the Baja California peninsula. Cortés also spent time exploring the Pacific coast of Mexico. The Gulf of California was originally named the Sea of Cortés by its discoverer Francisco de Ulloa in 1539. This was the last major expedition by Cortés. |

メキシコへの帰還(1530年)と副王の任命(1535年) この節は主に、または完全に単一の出典に依拠している。関連する議論は、トークページで見つけることができる。この記事を改善するために、この節に追加の 出典を導入することで、この記事の改善にご協力ください。 (2015年11月) (このメッセージの削除方法とタイミングについてはこちらをご覧ください)   同じ肖像画の2つの複製があり、オリジナルは彼の存命中に描かれた可能性が高い。左の複製は17世紀のものとされ、右の複製はホセ・サロメ・ピナによって1879年頃に描かれた。この肖像画は、他の肖像画とは異なる鎧を身に着けていることで特徴づけられる。 コルテスは1530年に新たな称号と栄誉を携えてメキシコに戻った。コルテスは依然として軍事権限と征服を継続する許可を保持していたが、1535年にド ン・アントニオ・デ・メンドーサがヌエバ・エスパーニャの民政を管理する総督に任命された。この権力の分割は継続的な不和を招き、コルテスが関与したいく つかの事業の失敗の原因となった。メキシコに戻ったコルテスは、国が無政府状態にあることを知った。宮廷ではコルテスによる反乱の企てを強く疑っていた。 地位を再主張し、ある程度の秩序を回復した後、コルテスはメキシコシティの南約30マイル(48キロ)にあるクエルナバカの領地に隠居した。そこで彼は宮 殿の建設と太平洋探検に専念した。1530年から1541年の間メキシコに留まったコルテスは、ヌニョ・ベルトラン・デ・グスマンと口論し、初代副王のア ントニオ・デ・メンドーサとカリフォルニア(当時はスペイン領)の領有権をめぐって争った。 1534年、コルテスはスンパンゴ・デル・リオの銀鉱山をいくつか獲得した。1540年代初頭までに、彼はサルテペックに20、タスコに12、サクアルパンに3の銀鉱山を所有していた。それ以前に、コルテスはタマズラ地域の銀を所有していたと主張していた。 1536年、コルテスはメキシコ北西部を探検し、バハ・カリフォルニア半島を発見した。コルテスはメキシコの太平洋岸の探検にも時間を費やした。カリフォ ルニア湾は、1539年に発見者のフランシスコ・デ・ウロアによって、当初はコルテス海と名付けられた。これがコルテスによる最後の主要な遠征となった。 |

| Later life and death Second return to Spain After his exploration of Baja California, Cortés returned to Spain in 1541, hoping to confound his angry civilians, who had brought many lawsuits against him (for debts, abuse of power, etc.).[14] On his return he went through a crowd to speak to the emperor, who demanded of him who he was. "I am a man," replied Cortés, "who has given you more provinces than your ancestors left you cities."[48][49] Expedition against Algiers Main article: Algiers expedition (1541)  An engraving of a middle-aged Cortés by 19th-century artist William Holl The emperor finally permitted Cortés to join him and his fleet commanded by Andrea Doria at the great expedition against Algiers in the Barbary Coast in 1541, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire. During this campaign, Cortés was almost drowned in a storm that hit his fleet while he was pursuing the Pasha of Algiers.[50] Last years, death, and remains Having spent a great deal of his own money to finance expeditions, he was now heavily in debt. In February 1544 he made a claim on the royal treasury, but was ignored for the next three years. Disgusted, he decided to return to Mexico in 1547. When he reached Seville, he was stricken with dysentery. He died in Castilleja de la Cuesta, Seville province, on December 2, 1547, from a case of pleurisy at the age of 62. He left his many mestizo and white children well cared for in his will, along with every one of their mothers. He requested in his will that his remains eventually be buried in Mexico. Before he died he had the Pope remove the "natural" status of four of his children (legitimizing them in the eyes of the church), including Martín, the son he had with Doña Marina (also known as La Malinche), said to be his favourite.[citation needed] His daughter, Doña Catalina, however, died shortly after her father's death. |

晩年と死 二度目のスペイン帰還 コルテスは、バハ・カリフォルニアの探検を終えると、1541年にスペインに帰還した。彼に対して多くの訴訟を起こしていた(負債、権力の乱用など)怒れ る市民たちを困惑させることを期待してのことだった。[14] 帰国後、彼は群衆の間を通り抜け皇帝に面会し、皇帝は彼が誰なのかを尋ねた。「私は、あなたの先祖が都市を残した以上に多くの州をあなたに与えた男です」 とコルテスは答えた。[48][49] アルジェ遠征 詳細は「アルジェ遠征 (1541年)」を参照  19世紀の芸術家ウィリアム・ホルの描いた中年期のコルテスの版画 皇帝はついにコルテスに、1541年にオスマン帝国領であった北アフリカのバルバリー海岸のアルジェリアに対する大遠征に、アンドレア・ドーリアが指揮す る艦隊に加わることを許可した。この遠征中、コルテスはアルジェリアのパシャを追跡中に襲った嵐で、艦隊とともに溺れそうになった。 晩年、死、そして遺骸 探検の資金調達に私財を投じたため、彼は多額の負債を抱えることとなった。1544年2月、彼は王室の財政に要求を申し立てたが、その後3年間無視され続 けた。失望した彼は、1547年にメキシコに戻ることを決意した。セビリアに到着したとき、彼は赤痢にかかっていた。1547年12月2日、62歳で胸膜 炎によりセビリア県のカスティーリャ・デ・ラ・クエスタで死去した。 彼は、混血や白人の多くの子供たちと、その母親たち一人一人を遺言でしっかりと面倒を見るように残した。遺言で、遺骸は最終的にメキシコに埋葬されるよう 要請した。死の床で、彼は教皇に、ドニャ・マリーナ(ラ・マリンチェとも呼ばれる)との間の息子マルティンを含む4人の子供の「自然な」地位を剥奪させた (教会の目から見て彼らの存在を合法化した)。マルティンは彼のお気に入りであったと言われている。[要出典] しかし、彼の娘であるドニャ・カタリナは、父の死後まもなくして亡くなった。 |

Bust Hernán Cortés in the General Archive of the Indies in Seville After his death, his body was moved more than eight times for several reasons. On December 4, 1547, he was buried in the mausoleum of the Duke of Medina in the church of San Isidoro del Campo, Sevilla. Three years later (1550) due to the space being required by the duke, his body was moved to the altar of Santa Catarina in the same church. In his testament, Cortés asked for his body to be buried in the monastery he had ordered to be built in Coyoacan in México, ten years after his death, but the monastery was never built. So in 1566, his body was sent to New Spain and buried in the church of San Francisco de Texcoco, where his mother and one of his sisters were buried.  Tomb of Cortés in the Hospital de Jesús Nazareno, which he founded in Mexico City In 1629, Cortes's last male descendant Don Pedro Cortés, fourth Marquez del Valle, died. The viceroy decided to move the bones of Cortés along with those of his descendant to the Franciscan church in México. This was delayed for nine years, while his body stayed in the main room of the palace of the viceroy. Eventually it was moved to the Sagrario of Franciscan church, where it stayed for 87 years. In 1716, it was moved to another place in the same church. In 1794, his bones were moved to the "Hospital de Jesus" (founded by Cortés), where a statue by Tolsá and a mausoleum were made. There was a public ceremony and all the churches in the city rang their bells.[citation needed] In 1823, after the independence of México, it seemed imminent that his body would be desecrated, so the mausoleum was removed, the statue and the coat of arms were sent to Palermo, Sicily, to be protected by the Duke of Terranova. The bones were hidden, and everyone thought that they had been sent out of México. In 1836, his bones were moved to another place in the same building.[clarification needed] It was not until November 24, 1946, that they were rediscovered,[51]: 467 thanks to the discovery of a secret document by Lucas Alamán. His bones were put in the charge of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH). The remains were authenticated by INAH.[51]: 468 They were then restored to the same place, this time with a bronze inscription and his coat of arms.[52] When the bones were first rediscovered, the supporters of the Hispanic tradition in Mexico were excited, but one supporter of an indigenist vision of Mexico "proposed that the remains be publicly burned in front of the statue of Cuauhtemoc, and the ashes flung into the air".[51]: 468 Following the discovery and authentication of Cortés's remains, there was a discovery of what were described as the bones of Cuauhtémoc, resulting in a "battle of the bones".[51]: 468 On December 16, 1560, the lawsuits related to vassals of the Cortes estate were resolved by a royal order issued by Philip II.[53] |

セビリアのインディアス総合古文書館に埋葬されたエルナン・コルテス 彼の死後、さまざまな理由により、遺体は8回以上も移転された。1547年12月4日、遺体はセビリアのサン・イシドロ・デル・カンポ教会にあるメディナ 公爵の霊廟に埋葬された。3年後(1550年)、公爵のスペース確保のため、遺体は同じ教会のサンタ・カタリナ祭壇に移された。コルテスは遺言で、死後 10年後にメキシコのテスココに建設を命じていた修道院に埋葬するよう指示したが、修道院は建設されなかった。そのため、1566年に遺体はヌエバ・エス パーニャに送られ、母親と姉妹の一人が埋葬されていたサン・フランシスコ・デ・テスココ教会に埋葬された。  コルテスがメキシコシティに創設したイエス・ナサレノ病院にあるコルテスの墓 1629年、コルテスの最後の男子子孫である第4代マルケス・デル・バジェのドン・ペドロ・コルテスが死去した。副王は、コルテスの遺骨を子孫の遺骨とと もにメキシコのフランシスコ会教会に移すことを決めた。副王の宮殿のメインルームに安置されていたコルテスの遺体は、この決定が実行されるまで9年間その ままにされていた。最終的に遺体はフランシスコ会教会のサグラリオに移され、87年間そこに安置された。1716年には同じ教会内の別の場所に移された。 1794年には遺体は「ホスピタル・デ・ヘスス」(コルテスが創設)に移され、トルサによる像と霊廟が作られた。公開式典が開催され、市内のすべての教会 の鐘が鳴らされた。 1823年、メキシコの独立後、彼の遺体が冒涜されることが差し迫っているように思われたため、霊廟は撤去され、像と紋章はシチリア島のパレルモに送ら れ、テラノヴァ公爵によって保護されることになった。遺骨は隠され、誰もが遺骨はメキシコ国外に送られたと思っていた。1836年、彼の遺骨は同じ建物内 の別の場所に移された。[要出典] 再発見されたのは1946年11月24日になってからだった。[51]:467 これは、ルーカス・アラマンによる秘密文書の発見のおかげである。彼の遺骨は、国立人類学歴史研究所(INAH)に引き渡された。遺骨はINAHによって 真正であると認証された。[51]: 468 遺骨はその後、同じ場所に復元された。今回は青銅製の碑文と彼の紋章が付けられた。[52] 遺骨が最初に再発見されたとき、メキシコにおけるヒスパニックの伝統を支持する人々は興奮したが、メキシコの土着主義的なビジョンを支持する人々は「遺骨 をクアウテモックの像の前で公に燃やし、灰を空中に撒くことを提案した」という。[51]: 468 コルテスの遺骨の発見と認証に続いて、クアウテモックの遺骨とされるものが発見され、「骨の戦い」が起こった。」と提案した。[51]:468 コルテスの遺骨の発見と認証に続いて、クアウテモクの骨とされるものが発見され、「骨の争奪戦」が起こった。[51]:468 1560年12月16日、コルテス家の家臣たちに関する訴訟は、フェリペ2世の勅令によって解決した。[53] |

| Taxa named after Cortés Cortés is commemorated in the scientific name of a subspecies of Mexican lizard, Phrynosoma orbiculare cortezii.[54] |

コルテスにちなんで名付けられた分類群 コルテスは、メキシコに生息するトカゲの一亜種、Phrynosoma orbiculare corteziiの学名にその名を残している。[54] |

| Disputed interpretation of his life There are relatively few sources to the early life of Cortés; his fame arose from his participation in the conquest of Mexico and it was only after this that people became interested in reading and writing about him. Probably the best source is his letters to the king which he wrote during the campaign in Mexico, but they are written with the specific purpose of putting his efforts in a favourable light and so must be read critically. Another main source is the biography written by Cortés's private chaplain Lopez de Gómara, which was written in Spain several years after the conquest. Gómara never set foot in the Americas and knew only what Cortés had told him, and he had an affinity for knightly romantic stories which he incorporated richly in the biography. The third major source is written as a reaction to what its author calls "the lies of Gomara", the eyewitness account written by the Conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo which does not paint Cortés as a romantic hero, but rather tries to emphasize that Cortés's men should also be remembered as important participants in the undertakings in Mexico.  1,000-Spanish-peseta note issued in 1992 In the years following the conquest more critical accounts of the Spanish arrival in Mexico were written. The Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas wrote his A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies which raises strong accusations of brutality and heinous violence towards the Indians; accusations against both the conquistadors in general and Cortés in particular.[55] The accounts of the conquest given in the Florentine Codex by the Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún and his native informants are also less than flattering towards Cortés. The scarcity of these sources has led to a sharp division in the description of Cortés's personality and a tendency to describe him as either a vicious and ruthless person or a noble and honorable cavalier. |

彼の生涯に関する解釈の相違 コルテスの初期の生涯に関する資料は比較的少ない。彼の名声はメキシコ征服への参加によって高まり、人々が彼について読み書きすることに興味を持つようになったのは、征服の後になってからである。 おそらく最良の資料は、メキシコ遠征中に彼が王に宛てて書いた手紙であろう。しかし、それらの手紙は、自らの功績を好意的に見せるという特定の目的を持っ て書かれたものであり、批判的に読む必要がある。もう一つの主な資料は、征服から数年後にスペインで書かれた、コルテスの私設司祭ロペス・デ・ゴマラによ る伝記である。ゴマラはアメリカ大陸に足を踏み入れたことはなく、コルテスから聞いた話だけを基にしており、騎士道物語に親しみを持っていたため、伝記に もその要素がふんだんに取り入れられている。3つ目の主要な情報源は、著者が「ゴマラの嘘」と呼ぶものへの反応として書かれたもので、征服者ベルナル・ ディアス・デル・カスティージョによる目撃証言は、ロマンチックな英雄としてコルテスを描くものではなく、むしろコルテスの部下たちもメキシコでの事業に おける重要な参加者として記憶されるべきであることを強調しようとしている。  1992年に発行された1,000スペイン・ペセタ紙幣 征服後の数年間で、スペイン人のメキシコ到着に関するより批判的な記述が書かれるようになった。ドミニコ会の修道士バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは著書 『インディアスの破壊についての簡潔な記録』で、インディアンに対する残忍で凶悪な暴力行為について強い非難を展開し、征服者一般、特にコルテスに対する 非難を述べた。[55] フランシスコ会のベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグンと彼の出生地の協力者たちが『フィレンツェ写本』で述べた征服の記述も、コルテスに対して好意的ではな い。こうした資料の不足により、コルテスの人格に関する記述は大きく分かれ、彼を悪辣で冷酷な人物と見るか、高潔で名誉ある騎士と見るかの傾向が生まれて いる。 |

Representations in Mexico Monument in Mexico City commemorating the encounter of Cortés and Moctezuma at the Hospital de Jesús Nazareno In México there are few representations of Cortés. However, many landmarks still bear his name, from the castle Palacio de Cortés in the city of Cuernavaca to some street names throughout the republic. The pass between the volcanoes Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatépetl where Cortés took his soldiers on their march to Mexico City. It is known as the Paso de Cortés. The muralist Diego Rivera painted several representation of him but the most famous, depicts him as a powerful and ominous figure along with Malinche in a mural in the National Palace in Mexico City.  Monument in Mexico City known as "Monumento al Mestizaje" In 1981, President Lopez Portillo tried to bring Cortés to public recognition. First, he made public a copy of the bust of Cortés made by Manuel Tolsá in the Hospital de Jesús Nazareno with an official ceremony, but soon a nationalist group tried to destroy it, so it had to be taken out of the public.[56] Today the copy of the bust is in the "Hospital de Jesús Nazareno"[57] while the original is in Naples, Italy, in the Villa Pignatelli. Later, another monument, known as "Monumento al Mestizaje" by Julián Martínez y M. Maldonado (1982) was commissioned by Mexican president José López Portillo to be put in the "Zócalo" (Main square) of Coyoacan, near the place of his country house, but it had to be removed to a little known park, the Jardín Xicoténcatl, Barrio de San Diego Churubusco, to quell protests. The statue depicts Cortés, Malinche and their son Martín.[58] There is another statue by Sebastián Aparicio, in Cuernavaca, was in a hotel "El casino de la selva". Cortés is barely recognizable, so it sparked little interest. The hotel was closed to make a commercial center, and the statue was put out of public display by Costco the builder of the commercial center.[56] |

メキシコにおける表現 メキシコシティにある、コルテスとモクテスマの出会いを記念するモニュメント(Hospital de Jesús Nazareno メキシコでは、コルテスを表現したものはほとんどない。しかし、クエルナバカのパラシオ・デ・コルテス城から、共和国中のいくつかの通りの名前に至るまで、多くの名所が今でも彼の名を冠している。 コルテスが兵士たちを率いてメキシコシティへ向かった火山、イスタシワトル山とポポカテペトル山の間の峠。これは「コルテスの峠」として知られている。 壁画画家のディエゴ・リベラは、彼を題材にした作品をいくつか描いているが、最も有名なのは、メキシコシティの国立宮殿の壁画に描かれた、マリンチェとともに描かれた、強力で不吉な人物としての姿である。  メキシコシティにある「モニュメント・アル・メスティサヘ(人種の融合記念碑)」と呼ばれるモニュメント 1981年、ロペス・ポルティージョ大統領は、コルテスを公に認知させようとした。まず、ホスピタル・デ・ヘスス・ナサレノでマヌエル・トルサが制作した コルテスの胸像の複製を公式の式典で公開したが、すぐに民族主義グループがそれを破壊しようとしたため、公開は中止された。[56] 現在、胸像の複製は「ホスピタル・デ・ヘスス・ナサレノ」に展示されているが、[57] オリジナルはイタリアのナポリにあるヴィラ・ピニャテッリに展示されている。 その後、メキシコ大統領ホセ・ロペス・ポルティージョの命により、フリアン・マルティネス・イ・M・マルドナード(1982年)による「モニュメント・ア ル・メスティソ(混血の記念碑)」が、コヨアカンにある「ソカロ(メイン広場)」の、彼の別荘の近くに設置されることになったが、抗議を鎮めるために、あ まり知られていない公園、サンディエゴ・チュルブスコ地区のキシコテンカトル庭園に移設された 抗議を鎮めるために、この像は撤去された。この像は、コルテス、マルインチェ、そして彼らの息子マルティンを描いている。 クエルナバカには、セバスティアン・アパリシオによる別の像が存在していた。この像はホテル「エル・カジノ・デ・ラ・セルバ」に置かれていた。コルテスは ほとんど認識できないほどで、ほとんど関心を呼ばなかった。ホテルは商業施設に建て替えるために閉鎖され、像は建設業者であるコストコによって一般公開か ら外された。 |

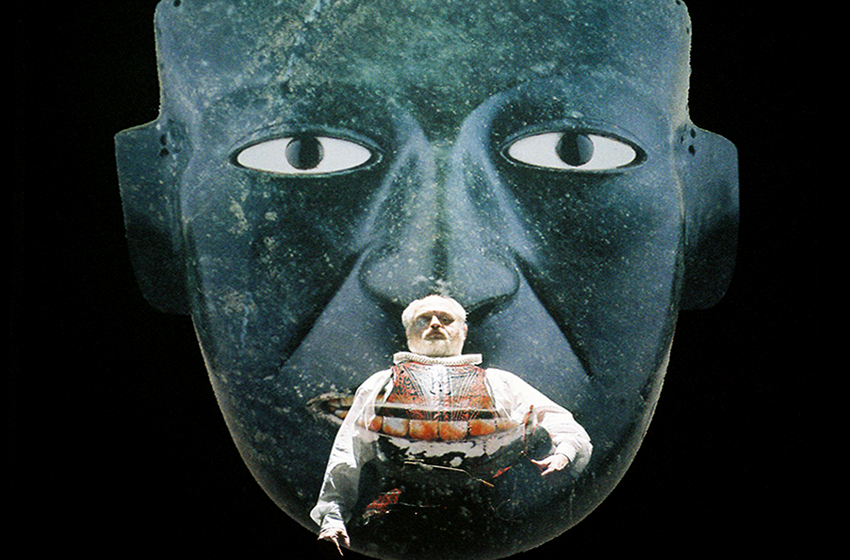

Cultural depictions Scene from the opera La Conquista, 2005 Hernán Cortés is a character in the opera La Conquista (2005) by Italian composer Lorenzo Ferrero, which depicts the major episodes of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521. Writings: the Cartas de Relación Cortés's personal account of the conquest of Mexico is narrated in his five letters addressed to Charles V. These five letters, the cartas de relación [es], are Cortés's only surviving writings. See "Letters and Dispatches of Cortés", translated by George Folsom (New York, 1843); Prescott's "Conquest of Mexico" (Boston, 1843); and Sir Arthur Helps's "Life of Hernando Cortes" (London, 1871).[48] His first letter was considered lost, and the one from the municipality of Veracruz has to take its place. It was published for the first time in volume IV of "Documentos para la Historia de España", and subsequently reprinted. The Segunda Carta de Relacion, bearing the date of October 30, 1520, appeared in print at Seville in 1522. The third letter, dated May 15, 1522, appeared at Seville in 1523. The fourth, October 20, 1524, was printed at Toledo in 1525. The fifth, on the Honduras expedition, is contained in volume IV of the Documentos para la Historia de España.[59][60] |

文化的な描写 オペラ『ラ・コンキスタ』の1場面、2005年 エルナン・コルテスは、イタリアの作曲家ロレンツォ・フェレーロによるオペラ『ラ・コンキスタ』(2005年)の登場人物である。このオペラは、1521年のスペインによるアステカ帝国征服の主なエピソードを描いたものである。 著作:Cartas de Relación コルテスによるメキシコ征服の個人的な記録は、カルロス5世宛てに書かれた5通の手紙に語られている。この5通の手紙、cartas de relación [es]は、コルテスが残した唯一の著作である。「コルテスの書簡と報告書」(ジョージ・フォルソム訳、ニューヨーク、1843年)、「メキシコ征服」 (プレスコット著、ボストン、1843年)、「ヘルナンド・コルテスの生涯」(サー・アーサー・ヘルプス著、ロンドン、1871年)を参照。[48] 彼の最初の書簡は紛失したと考えられており、代わりにベラクルス自治体の書簡が残されている。この書簡は『スペイン史資料』第4巻で初めて出版され、その後再版された。 1520年10月30日付けの「セグンダ・カルタ・デ・レラシオネス」は、1522年にセビリアで印刷された。1522年5月15日付の第3通は、 1523年にセビリアで出版された。第4通は1524年10月20日付で、1525年にトレドで印刷された。第5通はホンジュラス遠征に関するもので、ス ペイン史資料集の第4巻に収録されている。[59][60] |

| Children Natural children of Don Hernán Cortés doña Catalina Pizarro, born between 1514 and 1515 in Santiago de Cuba or maybe later in Nueva España, daughter of an indigenous woman in Cuba, Leonor Pizarro.[citation needed] Doña Catalina married Juan de Salcedo, a conqueror and encomendero, with whom she had a son, Pedro.[61] don Martín Cortés, born in Coyoacán in 1522, son of doña Marina (La Malinche), called the First Mestizo; about him was written The New World of Martín Cortés; married doña Bernaldina de Porras and had two children: doña Ana Cortés don Fernando Cortés, Principal Judge of Veracruz. Descendants of this line are alive today in Mexico.[62] don Luis Cortés, born in 1525, son of doña Antonia or Elvira Hermosillo, a native of Trujillo (Cáceres)[63] doña Leonor Cortés Moctezuma, born in 1527 or 1528 in Ciudad de Mexico, daughter of Aztec princess Tecuichpotzin (baptized Isabel), born in Tenochtitlan on July 11, 1510, and died on July 9, 1550, the eldest legitimate daughter of Moctezuma II Xocoyotzin and wife doña María Miahuaxuchitl; married to Juan de Tolosa, a Basque merchant and miner.[64] doña María Cortés de Moctezuma, daughter of an Aztec princess; nothing more is known about her except that she probably was born with some deformity.[citation needed] He married twice: firstly in Cuba to Catalina Suárez Marcaida, who died at Coyoacán in 1522 without issue, and secondly in 1529 to doña Juana Ramírez de Arellano de Zúñiga, daughter of don Carlos Ramírez de Arellano, 2nd Count of Aguilar and wife the Countess doña Juana de Zúñiga, and had: don Luis Cortés y Ramírez de Arellano, born in Texcoco in 1530 and died shortly after his birth. doña Catalina Cortés de Zúñiga, born in Cuernavaca in 1531 and died shortly after her birth. don Martín Cortés y Ramírez de Arellano, 2nd Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca, born in Cuernavaca in 1532, married at Nalda on February 24, 1548, his twice cousin once removed doña Ana Ramírez de Arellano y Ramírez de Arellano and had issue, currently extinct in male line doña María Cortés de Zúñiga, born in Cuernavaca between 1533 and 1536, married to don Luis de Quiñones y Pimentel, 5th Count of Luna doña Catalina Cortés de Zúñiga, born in Cuernavaca between 1533 and 1536, died unmarried in Sevilla after the funeral of her father doña Juana Cortés de Zúñiga, born in Cuernavaca between 1533 and 1536, married Don Fernando Enríquez de Ribera y Portocarrero, 2nd Duke of Alcalá de los Gazules, 3rd Marquess of Tarifa and 6th Count of Los Molares, and had issue |

子供 ドン・エルナン・コルテスの実子 ドニャ・カタリナ・ピサロは、1514年から1515年の間にサンティアゴ・デ・クーバで、あるいはそれ以降にヌエバ・エスパーニャで生まれた。キューバ の先住民女性レオノール・ピサロの娘である。[要出典] ドニャ・カタリナは征服者でありエンコムエンデロであったフアン・デ・サルセードと結婚し、彼との間にペドロという息子がいた。[61] ドン・マルティン・コルテスは1522年にコヨアカンで生まれ、ドニャ・マリーナ(ラ・マリンチェ)の息子で、最初の混血人と呼ばれた。彼については『マ ルティン・コルテスの新世界』という本が書かれている。ドニャ・ベルナルディナ・デ・ポラスと結婚し、2人の子供をもうけた。 ドニャ・アナ・コルテス ドニャ・フェルナンド・コルテス、ベラクルス州の首席判事。この系統の子孫は現在もメキシコに生存している。[62] ドニャ・アントニアまたはエルビラ・エルモシージョの息子、1525年生まれのドニャ・ルイス・コルテス、トルヒージョ(カセレス)出身[63] 1527年または1528年にメキシコシティで生まれたドニャ・レオノール・コルテス・モクテスマは、アステカ王テクイチョトシン(洗礼名イサベル)の娘 であり、1510年7月11日にテノチティトランで生まれ、1550年7月9日に亡くなった。モクテスマ2世ショコヨティンの長女であり、妻ドニャ・マリ ア・ミアウァシュティトの バスク人の商人で鉱山労働者であったフアン・デ・トロサと結婚した。 アステカ王女の娘であるドニャ・マリア・コルテス・デ・モクテスマについては、おそらく何らかの奇形で生まれたという以外には、ほとんど知られていない。 彼は2度結婚した。最初は1522年にコヨアカンで死去したカタリナ・スアレス・マルカイダ(キューバで結婚)との間に子供はいなかった。2度目は 1529年にドン・カルロス・ラミレス・デ・アレドノ(アギラール伯)の娘で、アレドノ伯爵夫人ドンナ・フアナ・デ・スニガとの間に生まれたドンナ・フア ナ・ラミレス・デ・アレドノ(1530年にテスココで誕生し、誕生後まもなく死去)との間には、 ドン・ルイス・コルテス・イ・ラミレス・デ・アレドノは1530年にテスココで生まれ、出生直後に死亡した。 ドンナ・カタリナ・コルテス・デ・スニガは1531年にクエルナバカで生まれ、出生直後に死亡した。 オアハカの谷の第2代侯爵、ドン・マルティン・コルテス・イ・ラミレス・デ・アレドノ、1532年クエルナバカ生まれ、1548年2月24日ナルダで、従 兄弟の姪にあたるドンナ・アナ・ラミレス・デ・アレドノ・イ・ラミレス・デ・アレドノと結婚し、子供をもうけるが、現在では男系が途絶えている ドニャ・マリア・コルテス・デ・スニガは、1533年から1536年の間にクエルナバカで生まれ、ルナ伯爵の5代目であるドン・ルイス・デ・キニョネス・イ・ピメンテルと結婚した ドニャ・カタリナ・コルテス・デ・スニガは、1533年から1536年の間にクエルナバカで生まれ、父の葬儀の後、セビリアで未婚のまま死去した ドニャ・フアナ・コルテス・デ・スニガは、1533年から1536年の間にクエルナバカで生まれ、アルカラ・デ・ロス・ガズルス公爵、タリファ侯爵、ロス・モラレス伯爵の第2代ドン・フェルナンド・エンリケス・デ・リベラ・イ・ポルトカレロと結婚し、子供をもうけた。 |

| In popular culture Hernán Cortés (called by the Italian form of his name, "Fernando") is the hero of Antonio Vivaldi's 1733 opera Motezuma.[65] Cortés features as an antagonist in the 1980 novel Aztec by Gary Jennings.[66] Cortés was portrayed (as "Hernando Cortez") by actor Cesar Romero in the 1947 historical adventure film Captain from Castile.[67] "Cortez the Killer", a 1975 song by Neil Young.[68] |

大衆文化において、 エルナン・コルテス(イタリア式の名前「フェルナンド」で呼ばれる)は、アントニオ・ヴィヴァルディの1733年のオペラ『モテュサ』の主人公である。 [65] コルテスは、1980年の小説『アステカ』の悪役として登場する。 1947年の歴史冒険映画『キャプテン・フロム・カスティーリャ』では、俳優のシーザー・ロメロが「エルナンド・コルテス」としてコルテスを演じた。 1975年のニール・ヤングの楽曲『コルテス・ザ・キラー』。 |

| History of Mexico History of Mexico City New Spain Palace of Cortés, Cuernavaca Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire Spanish Empire |

メキシコの歴史 メキシコシティの歴史 ヌエバ・エスパーニャ コルテス宮殿、クエルナバカ アステカ帝国のスペインによる征服 スペイン帝国 |

| Further reading Primary sources Cortés, Hernán. Letters – available as Letters from Mexico translated by Anthony Pagden. Yale University Press, 1986. ISBN 0-300-09094-3. Available online in Spanish from an 1866 edition. Cortés, Hernán. Escritos sueltos de Hernán Cortés. Biblioteca Histórica de la Iberia. vol 12. Mexico 1871. Díaz del Castillo, Bernal. The Conquest of New Spain – available as The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico: 1517–1521 ISBN 0-306-81319-X Díaz del Castillo, Bernal, Carrasco, David, Rolena. Adorno, Sandra Messinger Cypess, and Karen Vieira Powers. The History of the Conquest of New Spain. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008 León-Portilla, Miguel (Ed.) (1992) [1959]. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Ángel María Garibay K. (Nahuatl-Spanish trans.), Lysander Kemp (Spanish-English trans.), Alberto Beltran (illus.) (Expanded and updated ed.). Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-5501-4. (textbook anthology of indigenous primary sources) López de Gómara, Francisco, Cortés: The Life of the Conqueror by His Secretary, Ed. and trans. Lesley Byrd Simpson. Berkeley: University of California Press 1964. López de Gómara, Francisco. Hispania Victrix; First and Second Parts of the General History of the Indies, with the whole discovery and notable things that have happened since they were acquired until the year 1551, with the conquest of Mexico and New Spain University of California Press, 1966 Prescott, William H. History of the Conquest of Mexico, with a Preliminary View of Ancient Mexican Civilization, and the Life of the Conqueror, Hernando Cortes Last Will and Testament of Hernán Cortés Letter From Hernán Cortés to Charles the V Hernán Cortés Power of Attorney, 1526 From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress Praeclara Ferdinandi Cortesii de noua maris oceani Hyspania narratio sacratissimo... 1524. From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress Secondary sources Boruchoff, David A. "Hernán Cortés." International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2nd. ed. (2008), vol. 2, pp. 146–149. Brooks, Francis J. "Motecuzoma Xocoyotl, Hernán Cortés, and Bernal Díaz del Castillo: The Construction of an Arrest." Hispanic American Historical Review (1995): 149–183. Chamberlain, Robert S. "Two unpublished documents of Hernán Cortés and New Spain, 1519 and 1524." Hispanic American Historical Review 19 (1939) 120–137. Chamberlain, Robert S. "La controversia entre Cortés y Velázquez sobre la gobernación de Nueva España, 1519–1522" in Anales de la Sociedad de Geografía e Historia de Guatemala, vol XIX 1943. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cortes, Hernan" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 205–207. Cline, Howard F. "Hernando Cortés and the Aztec indians in Spain." The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress. Vol. 26. No. 2. Library of Congress, 1969. Denhardt. Robert Moorman. "The equine strategy of Cortés." Hispanic American Historical Review 18 (1938) 550–555. Elliott, J.H., "The mental world of Hernán Cortés." In Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. Fifth Series (1967) 41–58. Frankl, Victor. "Hernán Cortés y la tradición de las Siete Partidas." Revista de Historia de América 53–54 (1962) 9–74. Himmerich y Valencia, Robert. The Encomenderos of New Spain, 1521–1555, Austin: University of Texas Press 1991 Jacobs, W.J. Hernando Cortés. New York: Franklin Watts, Inc. 1974. Keen, Benjamin, The Aztecs Image in Western Thought, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press 1971. Konetzke, Richard. "Hernán Cortés como poblador de la Nueva España." Estudios Cortesianos, pp. 341–381. Madrid 1948. Levy, Buddy. Conquistador: Hernán Cortés, King Montezuma, and the Last Stand of the Aztecs. 2008 ISBN 978-0-553-80538-3 Lorenzana, Francisco Antonio. Viaje de Hernán Cortés a la Peninsula de Californias. Mexico 1963 MacNutt, F.A. Fernando Cortés and the Conquest of Mexico, 1485–1547. New York and London 1909. Madariaga, Salvador de. Hernán Cortés, Conqueror of Mexico. Mexico 1942. Marks, Richard Lee. Cortés: The Great Adventurer and the Fate of Aztec Mexico. Alfred A. Knopf, 1993. Mathes, W. Michael, ed. The Conquistador in California: 1535. The Voyage of Fernando Cortés to Baja California in Chronicles and Documents. Vol. 31. Dawson's Book Shop, 1973. Maura, Juan Francisco."Cobardía, falsedad y opportunismo español: algunas consideraciones sobre la "verdadera" historia de la conquista de la Nueva España" Lemir (Revista de literatura medieval y del Renacimiento) 7 (2003): 1–29. Medina, José Toribio. Ensayo Bio–bibliográfico sobre Hernán Cortés. Introducción de Guillermo Feliú Cruz. Santiago de Chile 1952. Miller, Robert Ryal. "Cortés and the first attempt to colonize California." Calif Hist QJ Calif Hist Soc 53.1 (1974): 4–16. Petrov, Lisa. For an Audience of Men: Masculinity, Violence and Memory in Hernán Cortés's Las Cartas de Relación and Carlos Fuentes's Fictional Cortés. University of Wisconsin–Madison, 2004. Phelan, John Leddy The Millennial Kingdom of the Franciscans in the New World, chapter 3, "Hernán Cortés, the Moses of the New World", Berkeley: University of California Press, 2nd ed., revised, 1971, pp. 33–34. William H. Prescott (1898). Mexico and the Life of the Conqueror Fernando Cortes. Vol. 2. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier. Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest Oxford University Press (2003) ISBN 0-19-516077-0 Silva, José Valerio. El legalismo de Hernán Cortés como instrumento de su conquista. Mexico 1965. Stein, R.C. The World's Greatest Explorers: Hernando Cortés. Illinois: Chicago Press Inc. 1991. Thomas, Hugh (1993). Conquest: Cortés, Montezuma, and the Fall of Old Mexico ISBN 0-671-51104-1 Todorov, TzvetanThe Conquest of America (1996) ISBN 0-06-132095-1 Toro, Alfonso. Un crimen de Hernán Cortés. La muerte de Doña Catalina Xuárez Marcaida, estudio histórico y medico legal. Mexico 1922 Wagner, H.R. "The lost first letter of Cortés." Hispanic American Historical Review. 21 (1941) 669–672. White, Jon Manchip. (1971) Cortés and the Downfall of the Aztec Empire ISBN 0-7867-0271-0 |