ペドロ・デ・アルバラード

Pedro

de Alvarado, c.1485-1541

☆ペドロ・デ・アルバラード(Pedro de Alvarado;

c. 1485 – 4 July 1541)は、スペインの征服者であり、グアテマラの統治者であった 。

彼はキューバ征服、フアン・デ・グリハルバによるユカタン半島とメキシコ湾沿岸の探検、そしてエルナン・コルテスが率いたアステカ帝国征服に参加した。彼

はグアテマラ、ホンジュラス、エルサルバドルを含む中米の大半の征服者と考えられている。

生涯を通じて、アルバラドは強欲で残酷な人物として評判となり、先住民やスペイン人双方からさまざまな犯罪や虐待の容疑をかけられた。1541年、先住民

の反乱を鎮圧しようとしていたアルバラドは、誤って馬に踏みつぶされ、数日後に死亡した。

| Pedro de Alvarado

(Spanish pronunciation: [ˈpeðɾo ðe alβaˈɾaðo]; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541)

was a Spanish conquistador and governor of Guatemala.[1] He

participated in the conquest of Cuba, in Juan de Grijalva's exploration

of the coasts of the Yucatán Peninsula and the Gulf of Mexico, and in

the conquest of the Aztec Empire led by Hernán Cortés. He is considered

the conquistador of much of Central America, including Guatemala,

Honduras, and El Salvador. During his life, Alvarado developed a reputation for greed and cruelty, and was accused of various crimes and abuses by natives and Spaniards alike.[2] In 1541, while attempting to quell a native revolt, Alvarado was accidentally crushed by a horse, dying a few days later.[2] |

ペドロ・デ・アルバラード(スペイン語発音: [ˈpeðɾo ðe

alβaˈɾaðo]; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541)は、スペインの征服者であり、グアテマラの統治者であった [1]

彼はキューバ征服、フアン・デ・グリハルバによるユカタン半島とメキシコ湾沿岸の探検、そしてエルナン・コルテスが率いたアステカ帝国征服に参加した。彼

はグアテマラ、ホンジュラス、エルサルバドルを含む中米の大半の征服者と考えられている。 生涯を通じて、アルバラドは強欲で残酷な人物として評判となり、先住民やスペイン人双方からさまざまな犯罪や虐待の容疑をかけられた[2]。1541年、 先住民の反乱を鎮圧しようとしていたアルバラドは、誤って馬に踏みつぶされ、数日後に死亡した[2]。 |

| Character and appearance Pedro de Alvarado was flamboyant and charismatic,[3] and was both a brilliant military commander[4] and a cruel, hardened man.[5] He is described as having "good features and bearing", and when presented with a picture of him, the Aztecs referred to him as Tōnatiuh.[6][7] The Aztecs gave Alvarado this name because of his blond hair, and also his infamous temper.[8][9] He was handsome,[10] and presented an affable appearance, but was volatile and quick to anger.[11] He was ruthless in his dealings with the indigenous peoples he set out to conquer. Historians judge that his greed drove him to excessive cruelty,[5] and his Spanish contemporaries denounced his extreme brutality during his lifetime. He was a poor governor of territories he had conquered, and restlessly sought out new adventures.[12] His tactical brutality, such as the massacre in the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan, often undermined strategic considerations.[13] He was also accused of cruelty against fellow Spaniards.[14] Alvarado was little suited to govern; when he held governing positions, he did little to establish stable foundations for colonial rule. His letters show no interest in civil matters, and he only discussed exploration and war.[15] Alvarado stubbornly resisted attempts by the Spanish Crown to establish ordered taxation in Guatemala, and refused to acknowledge such attempts. As governor of Guatemala, Alvarado has been described by W. George Lovell et al. as "an insatiable despot who recognized no authority but his own and who regarded Guatemala as little more than his personal estate."[1] American historian William H. Prescott described Alvarado's character in the following terms: Alvarado was a cavalier of high family, gallant and chivalrous, and [Cortes'] warm personal friend. He had talents for action, was possessed of firmness and intrepidity, while his frank and dazzling manners made the Tonatiuh an especial favourite with the Mexicans. But, underneath this showy exterior, the future conqueror of Guatemala concealed a heart rash, rapacious, and cruel. He was altogether destitute of that moderation, which, in the delicate position he occupied, was a quality of more worth than all the rest. — William H. Prescott 1922, History of the Conquest of Mexico: Book 4, Chapter 8, p. 54. Spanish chronicler Antonio de Remesal commented that "Alvarado desired more to be feared than loved by his subjects, whether they were Indians or Spaniards."[16] In his easy recourse to violence, Alvarado was a product of his time, and Alvarado was not the only conquistador to have resorted to such actions. Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro carried out deeds of similar cruelty, but have not attracted as much criticism as Alvarado.[15] |

性格と外見 ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは華やかでカリスマ性があり、[3]優れた軍司令官[4]であると同時に、残酷で冷酷な人物でもあった[5]。彼は「容姿端麗で堂 々としている」と評され、アステカ人は彼の肖像を見せられると、彼をトナティウ(Tōnatiuh)と呼んだ[ 6][7] アステカ人は、彼の金髪と悪名高い気性の激しさを理由に、アルヴァラドにこの名前をつけた。 彼は征服を目指した先住民に対して冷酷な態度を取った。歴史家たちは、彼の強欲さが彼を過度の残虐性に走らせたと判断している[5]。また、スペインの同 時代人たちは、彼の生涯にわたる極端な残忍性を非難していた。彼は征服した領地の統治に失敗し、常に新たな冒険を追い求めていた[12]。 テノチティトランの大神殿での虐殺など、彼の戦略的な残虐性は、しばしば戦略的配慮を損なうものであった[13]。また、彼は同胞であるスペイン人に対す る残虐行為でも非難された[14]。アルヴァラドは統治には向いておらず、統治の地位に就いても、植民地支配の安定した基盤を築くことにはほとんど貢献し なかった。彼の手紙には、市民生活への関心はまったく見られず、探検と戦争についてのみ述べられている[15]。アルヴァラドは、グアテマラに秩序ある税 制を確立しようとするスペイン王室の試みに頑固に抵抗し、それを認めようとしなかった。グアテマラ総督として、アルバラドは W. ジョージ・ロベルらによって、「自分の権威以外認めず、グアテマラを自分の私有地としか考えていない、飽くことのない専制君主」[1] と評された。 アメリカの歴史家ウィリアム・H・プレスコットは、アルバラドの人格を次のように表現している。 アルバラドは、高貴な家柄の騎士であり、勇敢で騎士道精神に富み、コルテスの個人的な友人でもあった。彼は行動力があり、確固とした勇気と大胆さを持ち合 わせており、率直で目を見張るような物腰で、トナティウはメキシコ人から特に好かれていた。しかし、この派手な外見の下に、グアテマラの将来の征服者は、 軽率で貪欲、残酷な心を隠していた。彼は、自分が置かれた微妙な立場において、他のすべてよりも価値のある資質である節度をまったく持ち合わせていなかっ た。 — ウィリアム・H・プレスコット 1922年『メキシコ征服史』第4巻第8章54ページ スペインの歴史家アントニオ・デ・レメサルは、「アルバラードは、臣民から愛されるよりも恐れられることを望んでいた。その臣民がインディオであろうとス ペイン人であろうと、である」とコメントしている[16]。暴力に安易に頼ったアルバラードは、その時代の産物であった。このような行為に及んだ征服者 は、アルバラードだけではなかった。エルナン・コルテスやフランシスコ・ピサロも同様の残虐行為を行ったが、アルヴァラドほど批判を浴びてはいない [15]。 |

| Early life and family Pedro de Alvarado was born in 1485 in the town of Badajoz, Extremadura.[17] His father was Gómez de Alvarado,[18] and his mother was Leonor de Contreras, Gómez's second wife.[17] Pedro de Alvarado had a twin sister, Sarra, and four full-blood brothers, Jorge, Gonzalo, Gómez, and Juan.[19] Pedro had an illegitimate half brother, also named Juan, referred to in contemporary sources as Juan el Bastardo.[20] Very little is known of Pedro de Alvarado's early life before his arrival in the Americas. During the conquest of the Americas, tales of his youthful exploits in Spain became popular legends, but their veracity is doubtful.[21] An example is the tale then current that when he was a youth awaiting passage to the Americas, he climbed the church tower in Seville with some friends. A banner pole extended some 3.0 to 3.7 metres (10 to 12 ft) from an upper window. One of his companions walked out to the end of the pole after removing his cloak and sword, and returned to the tower backwards. Alvarado, afraid of being mocked, walked out onto the pole with both sword and cloak, and turned around at the end to return to the tower facing it.[22] Alvarado's paternal grandfather was Juan Alvarado "el Viejo" ("the elder"), who was comendador of Hornachos, and his paternal grandmother was Catalina Messía.[17] Pedro de Alvarado's uncle on his father's side was Diego de Alvarado y Messía,[18] who was the comendador of Lobón, Puebla, and Montijo, alcalde of Montánchez, and lord of Castellanos and of Cubillana. Diego was a veteran of the campaigns against the Moors.[17] |

生い立ちと家族 ペドロ・デ・アルバラードは1485年、スペインのエストレマドゥーラ州バダホスで生まれた[17]。父親はゴメス・デ・アルバラード[18]、母親はゴ メスの2番目の妻レオノール・デ・コントレラス[17]であった。ペドロ・デ・アルバラードには双子の姉サラ サラ、そして4人の実の兄弟、ホルヘ、ゴンサロ、ゴメス、フアンがいた[19]。ペドロには、同じくフアンという名の非嫡出の異母兄弟がおり、当時の資料 ではフアン・エル・バスティードと呼ばれていた[20]。 ペドロ・デ・アルバラドがアメリカ大陸に到着する前の生い立ちについてはほとんど知られていない。アメリカ大陸征服中、スペインでの彼の若き日の活躍の物 語は、人気のある伝説となったが、その真偽は疑わしい[21]。一例として、彼がまだ若く、アメリカ大陸への航海を待っている間、セビリアの教会の塔に何 人かの友人と登ったという当時の物語がある。旗竿は、上の窓から3.0~3.7メートル(10~12フィート)伸びていた。彼の仲間の一人がマントと剣を 外し、ポールの一番端まで歩いて行き、後ろ向きに塔に戻ってきた。嘲笑されるのを恐れたアルバラドは、剣とマントを手にポールの上まで歩き、ポールの先端 で向きを変えて塔に戻った[22]。 アルバラドの父方の祖父はフアン・アルバラド「エル・ビエホ」(「年長者」)で、ホルナチョスの司令官を務めていた。彼の父方の祖母はカタリナ・メシア だった[17]。ペドロ・デ・アルバラドの父方の叔父はディエゴ・デ・アルバラド・イ・メシア[18]で、ロボン、プエブラ、モンティホのコミエンダドー ル、モンタンチェスのアルカルデ、カステジャーノスとクビジャーナの領主だった。ディエゴは、ムーア人に対する戦いのベテランだった[17]。 |

| First campaigns in the Americas Alvarado and his brothers crossed the Atlantic Ocean before 1511, possibly in 1510.[23] By 1511 a system of licenses had been established in Spain to control the flow of colonists to the New World. The only one of the Alvarado brothers that appears in the registers is Juan de Alvarado, in 1511, leading to the assumption that the rest were already in the Americas by the time the licensing system was established.[24] The Alvarado brothers stopped off at Hispaniola, but there are few mentions of their stay there in historical documents.[25] Soon after arriving in Santo Domingo, on Hispaniola, Pedro de Alvarado established a friendship with Hernán Cortés, who at the time was serving as public scribe. Alvarado joined Cortés to participate in the conquest of Cuba,[26] under the command of Diego de Velázquez. The conquest of Cuba was launched in 1511, and Pedro de Alvarado was accompanied by his brothers.[27] Soon after the invasion, Alvarado was managing a prosperous hacienda in the new colony.[26] It is around this time that Pedro de Alvarado emerges into the historical record as a prosperous and influential hacienda-owner, already well connected with Velázquez, who was now governor of Cuba.[27] Grijalva expedition, 1518 Main article: Spanish conquest of Yucatán § Juan de Grijalva, 1518  Juan de Grijalva  The coast of Cozumel was Alvarado's first sight of Yucatán. Diego Velázquez, the governor of Cuba, was enthused by Francisco Hernández de Córdoba's report of gold in the newly discovered Yucatán Peninsula.[28] He organised an expedition consisting of four ships and 260 men.[29] He placed his nephew Juan de Grijalva in overall command;[30] Pedro de Alvarado captained one of the ships.[31] The small fleet was stocked with crossbows, muskets, barter goods, salted pork and cassava bread.[32] The fleet left Cuba in April 1518,[33] and made its first landfall upon the island of Cozumel,[34] off the east coast of Yucatán.[33] The Maya inhabitants of Cozumel fled the Spanish; the fleet then sailed south from Cozumel, along the east coast of the peninsula.[35] The Spanish spotted three large Maya cities along the coast. On Ascension Thursday the fleet discovered a large bay, which the Spanish named Bahía de la Ascensión.[33] Grijalva did not land at any of these cities and turned back north to loop around the north of the Yucatán Peninsula and sail down the west coast.[35] At Campeche the Spanish opened fire against the city with small cannon; the inhabitants fled, allowing the Spanish to take the abandoned city. The Maya remained hidden in the forest, so the Spanish boarded their ships and continued along the coast.[34] At Champotón, the fleet was approached by a small number of large war canoes, but the ships' cannon soon put them to flight.[34] At the mouth of the Tabasco River the Spanish sighted massed warriors and canoes but the natives did not approach.[36] By means of interpreters, Grijalva indicated that he wished to trade and bartered wine and beads in exchange for food and other supplies. From the natives they received a few gold trinkets and news of the riches of the Aztec Empire to the west. The expedition continued far enough to confirm the reality of the gold-rich empire,[37] sailing as far north as Pánuco River.[33] At the Papaloapan River, Alvarado ordered his ship upriver, leaving the rest of the small fleet behind to wait for him at the river mouth. This action greatly angered Grijalva, who feared that a lone ship could be lost. After this, the Spanish referred to the river as the Río de Alvarado ("Alvarado's River").[38] A little further along the coast, the fleet encountered settlements under Aztec dominion, and was met by Aztec emissaries with gifts of gold and jewels sent by the Emperor Moctezuma II.[39] As punishment for entering the Papaloapan River without orders, Grijalva sent Alvarado with the ship San Sebastián to relay news of the discoveries back to Cuba. Alvarado made a triumphal entry to Santiago de Cuba, with a great display of the wealth that had been gained from the expedition. His early arrival in Cuba allowed him to ingratiate himself with the Governor Velázquez before Grijalva's return.[40] The rest of the fleet put into the port of Havana five months after it had left.[33] Grijalva was coldly received by the governor, who Alvarado had turned against him, claiming much of the glory of the expedition for himself.[41] |

アメリカ大陸での最初のキャンペーン アルヴァラドと彼の兄弟たちは、おそらく1510年、1511年以前に大西洋を渡った[23]。1511年までに、新世界への入植者の流れを管理するため のライセンス制度がスペインで確立されていた。登録簿に名前が残っているアルヴァラド兄弟はフアン・デ・アルヴァラドのみで、1511年の記録であること から、他の兄弟は許可制が導入される前にすでにアメリカ大陸に到着していたと推測される[24]。アルヴァラド兄弟は イスパニョーラ島に立ち寄ったが、彼らがそこに滞在していたという記述は歴史的資料にはほとんどない[25]。 イスパニョーラ島のサントドミンゴに到着後まもなく、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは当時公文書係を務めていたエルナン・コルテスと友人関係を築いた。アルヴァ ラドは、ディエゴ・デ・ベラスケスの指揮下、コルテスとともにキューバ征服に参加した[26]。キューバ征服は1511年に開始され、ペドロ・デ・アルバ ラドは兄弟たちとともに参加した[27]。侵略後まもなく、アルバラドは新植民地で繁栄する大農園を経営していた[26]。この頃から、ペドロ・デ・アル バラドは、すでにキューバ総督となっていたベラスケスと深い関わりを持ち、裕福で影響力のある大農園主として歴史の記録に登場するようになった[27]。 グリハルバ遠征、1518年 メイン記事: スペインによるユカタン半島征服 § フアン・デ・グリハルバ、1518年  フアン・デ・グリハルバ  コズメル島の海岸は、アルバラドがユカタン半島を初めて目にした場所である。 キューバ総督ディエゴ・ベラスケスは、新たに発見されたユカタン半島に金鉱があることをフランシスコ・エルナンデス・デ・コルドバから報告を受け、大いに 興奮した[28]。彼は4隻の船と260人の隊員からなる遠征隊を組織した[29]。彼は甥のフアン・デ・グリハルバを総指揮官に任命し[30]、ペド ロ・デ・アルバラドは船の1隻の船長を務めた[31]。この小さな船団には、クロスボウ、マスケット銃、物々交換用の品々が積み込まれていた。食料、塩漬 け豚肉、キャッサバパンなどである[32]。 船団は1518年4月にキューバを出航し[33]、ユカタン半島の東海岸沖にあるコスメル島に初めて上陸した[34]。コスメルのマヤ住民はスペイン人を 逃れ、船団はコスメルから半島東海岸沿いに南下した[35]。スペイン人は海岸沿いに3つの大きなマヤの都市を発見した。昇天祭の木曜日、船団は大きな湾 を発見し、スペイン人はそれをバヒア・デ・ラ・アセンシオンと名付けた[33]。 グリハルバはこれらのどの都市にも上陸せず、ユカタン半島の北側を周回して西海岸を下るために北に戻った[35]。カンペチェでは、スペイン人が小型の大 砲で町に対して砲撃を開始し、住民は逃げ出し、スペイン人は廃墟となった町を占領することができた。マヤ族は森の中に隠れたままであったため、スペイン人 は船に乗り込み、海岸沿いを進んだ[34]。 チャモトンでは、スペイン船団に大型のカヌーが数隻近づいてきたが、船の大砲ですぐに追い払われた[34]。タバスコ川河口でスペイン人は大勢の戦士とカ ヌーを目撃したが、先住民は近づいてこなかった[36]。通訳を介してグリハルバは、交易をしたいと伝え、食料やその他の物資と引き換えにワインとビーズ を交換した。先住民からは、いくつかの金の装身具と、西に広がるアステカ帝国の富についての情報を手に入れた。 遠征は、金の豊富な帝国の実在を確認できるほど遠くまで続けられ、パンウコ川まで北上した[33]。 パパロアパン川で、アルバラドは船を川を上流に航行させ、残りの小艦隊は河口で彼を待つように命じた。この行動はグリハルバを大いに怒らせた。グリハルバ は、単独の船が遭難するのではないかと懸念していたのだ。この後、スペイン人はこの川を「リオ・デ・アルバラード」(アルバラードの川)と呼ぶようになっ た[38]。海岸沿いを少し進むと、艦隊はアステカの支配下にある集落に遭遇し、モクテスマ2世皇帝からの金や宝石の贈り物を持ったアステカの使節に出迎 えられた[39]。モクテスマ2世皇帝からの金や宝石の贈り物だった[39]。 命令なしにパパロアパン川に入った罰として、グリハルバはアルヴァラドにサン・セバスチャン号を率いてキューバに発見の知らせを届けるよう命じた。アル ヴァラドは、遠征で得た富を誇示しながら、サンティアゴ・デ・クーバに凱旋した。キューバへの早期到着により、グリハルバが戻る前に、彼は総督ベラスケス に気に入られることができた[40]。残りの船団は、出発から5か月後にハバナ港に入港した[33]。グリハルバは、アルヴァラドが総督に敵対し、探検の 栄光をほとんど自分の手柄として主張したため、総督から冷たく迎えられた[41]。 |

| Expedition to Mexico, 1519 See also: Spanish conquest of Yucatán § Hernán Cortés, 1519  Old painting of a bearded young man facing slightly to the right. He is wearing a dark jacket with a high collar topped by a white ruff, with ornate buttons down the front. The painting is dark and set in an oval with the letters "HERNAN CORTES" in a rectangle underneath. Hernán Cortés led the expedition against the Aztecs. Grijalva's return aroused great interest in Cuba. A new expedition was organised, with a fleet of eleven ships carrying 500 men and some horses. Hernán Cortés was placed in command;[33] Pedro de Alvarado and his brothers Jorge, Gómez and Juan "El Bastardo" joined the expedition. Cortés charged Pedro de Alvarado with gathering recruits from the inland estates of Cuba.[41] The crew included officers that would become famous conquistadors, including Cristóbal de Olid, Gonzalo de Sandoval and Diego de Ordaz. Also aboard were Francisco de Montejo and Bernal Díaz del Castillo, veterans of the Grijalva expedition.[33] Alvarado once again commanded the San Sebastián, with 60 men under his orders.[42] The fleet made its first landfall at Cozumel, and remained there for several days. Maya temples were cast down and a Christian cross was put up on one of them.[33] From Cozumel, the fleet looped around the north of the Yucatán Peninsula and followed the coast to the Tabasco River.[43] In Tabasco, the fleet anchored at Potonchán,[44] a Chontal Maya town.[45] The Maya prepared for battle but the Spanish horses and firearms quickly decided the outcome.[44] From Potonchán, the fleet continued to San Juan de Ulua.[46] The crew stayed only a short time before relocating to a promontory near Quiahuiztlan[47] and Cempoala, a subject city of the Aztec Empire.[44] Some of the Spaniards stayed near the coast when Cortés journeyed inland but Alvarado accompanied Cortés on the inland march.[48] While marching toward Tenochtitlan, the expedition made a slight detour to travel through Tlaxcalteca lands. The Tlaxcalteca attacked the Spanish force numerous times but they were unable to rout the Spanish forces. After making an alliance with the Tlaxcalteca, the Spanish went on to conquer the Aztecs.[49]  The remains of the "Castillo de Alvarado", Chamela, Jalisco Alvarado commanded one of the eleven vessels in the fleet and also acted as Cortés' second in command during the expedition's first stay in the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlán. Relations between the Spaniards and their hosts were uneasy, especially given Cortés' repeated insistence that the Aztecs desist from idol worship and human sacrifice; in order to ensure their own safety, the Spaniards took the Aztec king Moctezuma hostage. When Cortés returned to the Gulf coast to deal with the newly arrived hostile expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez, Alvarado remained in Tenochtitlan as commander of the Spanish enclave, with strict orders to make sure that Moctezuma not be permitted to escape.[50][page needed] During Cortés' absence, relations between the Spaniards and their hosts went from bad to worse, and Alvarado perpetrated the Massacre in the Great Temple, killing Aztec nobles and priests observing a religious festival.[51]: 283–286 Alvarado claims he did so because he feared the Aztecs were plotting against him but there is no physical evidence to support this claim and the alleged warnings he received came from tortured captives that very likely would have said anything to make the torture stop.[52] When Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan, he found the Spanish force under siege. After Moctezuma was killed in the attempt to negotiate with his own people, the Spaniards determined to escape by fighting their way across one of the causeways that led from the city across the lake and to the mainland.[51]: 286, 294, 296 In a bloody nocturnal action of 10 July 1520, known as La Noche Triste, Alvarado led the rear-guard and was badly wounded.[51][53]: 296–300 According to satirical verses by Gonzalo Ocampo, in reference to Alvarado crossing a causeway gap during the escape, Alvarado's escape became known as Salto de Alvarado ("Alvarado's Leap").[51]: 296–300 Pedro then participated in the Siege of Tenochtitlan, commanding one of four forces under Cortés.[51]: 315, 319, 333, 351, 355–356, 358, 360, 363, 369–370, 372 Alvarado was wounded when Cuauhtemoc attacked all three Spanish camps on the feast day of St. John.[51]: 377–378, 381, 384–385, 388–389 Alvarado's company was the first to make it to the Tlateloco marketplace, setting fire to the Aztec shrines. Cortés' and Sandoval's companies joined him there after four more days of fighting.[51]: 396–308 |

1519年のメキシコ遠征 関連項目:ユカタン半島征服 § エルナン・コルテス、1519年  少し右を向いた髭を生やした青年の古い絵画。彼は、白いラッフルが飾られた高い襟のついた暗い色のジャケットを着ており、前面に装飾的なボタンが付いている。絵画は暗く、楕円形に描かれており、その下には「HERNAN CORTES」という文字が四角く描かれている。 エルナン・コルテスはアステカに対する遠征を指揮した。 グリハルバの帰還により、キューバへの関心が高まった。11隻の船団に500人の兵士と数頭の馬を乗せた新たな遠征隊が編成された。エルナン・コルテスが 指揮官に任命され[33]、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドと彼の兄弟であるホルヘ、ゴメス、フアン「エル・バスティード」が遠征に参加した。コルテスは、ペド ロ・デ・アルバラドにキューバの内陸部の領地から兵士を集めるよう命じた[41]。乗組員には、クリストバル・デ・オリド、ゴンサロ・デ・サンドバル、 ディエゴ・デ・オルダスなど、後に有名な征服者となる将校が含まれていた。また、グリハルバ遠征のベテランであるフランシスコ・デ・モンテホとベルナル・ ディアス・デル・カスティージョも乗船していた[33]。 アルバラドは再びサン・セバスティアン号を指揮し、60人の部下を従えた[42]。船団は最初にコスメル島に上陸し、数日間そこに留まった。マヤの神殿は 破壊され、そのうちの1つにキリスト教の十字架が立てられた[33]。コズメルから、船団はユカタン半島の北を周回し、海岸沿いにタバスコ川まで進んだ [43]。タバスコでは、船団はチョルタル・マヤ族の町ポトンチャン[44]に停泊した [45] マヤ人は戦闘の準備をしたものの、スペイン人の馬と火器がすぐに戦況を決定した[44]。ポトンチャンから、船団はサン・ファン・デ・ウルアへと進んだ [46]。乗組員はキアウイストラン[47]とC アステカ帝国の属国であったエンポアラ[44]。スペイン人の一部は、コルテスが内陸部へ移動する際に海岸付近にとどまったが、アルバラドはコルテスの内 陸部への行軍に同行した[48]。テノチティトランへ向かう途中、遠征隊はトラスカルテカ族の土地を通るために少し回り道をした。トラスカルテカ族はスペ イン軍に何度も攻撃を仕掛けたが、スペイン軍を撃破することはできなかった。トラスカルテカ族と同盟を結んだスペイン軍は、アステカ族の征服に乗り出した [49]。  「アルヴァラド城」の遺跡、ハレラ、ハリスコ州 アルヴァラドは艦隊の11隻の船の1隻を指揮し、また、遠征隊がアステカの首都テノチティトランに初めて滞在した際には、コルテスの副官も務めた。スペイ ン人とアステカ人の関係は不安定で、特にコルテスがアステカ人に偶像崇拝と人身御供をやめるよう再三主張したため、スペイン人は自分たちの安全を確保する ためにアステカの王モクテスマを人質とした。コルテスがメキシコ湾岸に戻り、新たに到着したパンフィロ・デ・ナルバエス率いる敵対的な遠征隊に対処する 間、アルバラドはスペイン人居住区の司令官としてテノチティトランに残り、モクテスマが逃亡しないように厳重に監視するよう厳命された[50][ページ番 号が必要]。 コルテスの不在中、スペイン人と先住民の関係は悪化し、アルバラドは「大寺院」で虐殺を犯し、 アルヴァラドは、アステカ人が自分に反乱を企てているのではないかと恐れたためだと主張しているが、この主張を裏付ける物的証拠はなく、また、彼が受けた とされる警告は拷問を受けた捕虜によるもので、拷問を止めさせるために何でも言う可能性が高かった[52]。コルテスがテノチティトランに戻ると、スペイ ン軍は包囲されていた。モクテスマが自国民との交渉を試み、殺害された後、スペイン人は、都市から湖を渡り本土へと続く堤防の一つを戦いながら抜け、脱出 することを決意した[51]: 286, 294, 296 。1520年7月10日の血塗られた夜間の作戦は、「ラ・ノーチェ・トリステ(悲しみの 夜)」として知られている。アルヴァラードは殿軍を率い、重傷を負った[51][53]: 296–300 ゴンサロ・オカンポの風刺詩によると、アルヴァラードが脱出の際に陸橋の隙間を渡ったことから、アルヴァラードの脱出は「アルヴァラードの跳躍」として知 られるようになった[51]: 296–3 その後、ペドロはテノチティトラン包囲戦に参加し、コルテスの指揮下にある4つの部隊の1つを指揮した[51]: 315, 319, 333, 351, 355–356, 358, 360, 363, 369–370, 372 アルヴァラードは、聖ヨハネの祝日にクアウテモックがスペイン人の3つのキャンプをすべて攻撃した際に負傷した[51]: 377–378, 381, 384–385, 388–389 アルヴァラードの部隊は、最初にトラテロコ市場に到着し、アステカの神社に火を放った。コルテスとサンドバルの部隊は、さらに4日間の戦闘の末、そこに合 流した[51]: 396–308 |

| Conquest of Soconusco and Guatemala Main article: Spanish conquest of Guatemala ... we waited until they came close enough to shoot their arrows, and then we smashed into them; as they had never seen horses, they grew very fearful, and we made a good advance ... and many of them died. ---Pedro de Alvarado describing the approach to Quetzaltenango in his 3rd letter to Hernán Cortés[54] Cortés despatched Pedro de Alvarado to invade Guatemala with 180 cavalry, 300 infantry, crossbows, muskets, 4 cannons, large amounts of ammunition and gunpowder, and thousands of allied Mexican warriors.[55] Pedro de Alvarado passed through Soconusco with a sizeable force in 1523, en route to conquer Guatemala.[56] Alvarado's army included hardened veterans of the conquest of the Aztecs, and included cavalry and artillery;[57] there were also a great many indigenous allies from Cholula, Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, Tlaxcala, and Xochimilco.[58] Alvarado was received in peace in Soconusco, and the inhabitants swore allegiance to the Spanish Crown. They reported that neighbouring groups in Guatemala were attacking them because of their friendly outlook towards the Spanish. Alvarado's letter to Hernán Cortés describing his passage through Soconusco is lost, and knowledge of events there come from the account of Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who was not present, but related the report of Gonzalo de Alvarado.[59] By 1524, Soconusco had been completely pacified by Alvarado and his forces.[60]  A page from the Lienzo de Tlaxcala showing the conquest of Quetzaltenango Pedro de Alvarado and his army advanced along the Pacific coast unopposed until they reached the Samalá River in western Guatemala. This region formed a part of the K'iche' kingdom, and a K'iche' army tried unsuccessfully to prevent the Spanish from crossing the river. Once across, the conquistadors ransacked nearby settlements in an effort to terrorise the K'iche'.[61] On 8 February 1524 Alvarado's army fought a battle at Xetulul, called Zapotitlán by his Mexican allies (modern San Francisco Zapotitlán). Although suffering many injuries inflicted by defending K'iche' archers, the Spanish and their allies stormed the town and set up camp in the marketplace.[62] Alvarado then turned to head upriver into the Sierra Madre mountains towards the K'iche' heartlands, crossing the pass into the fertile valley of Quetzaltenango. On 12 February 1524 Alvarado's Mexican allies were ambushed in the pass and driven back by K'iche' warriors but the Spanish cavalry charge that followed was a shock for the K'iche', who had never before seen horses. The cavalry scattered the K'iche' and the army crossed to the city of Xelaju (modern Quetzaltenango) only to find it deserted.[63] Almost a week later, on 18 February 1524,[64] a K'iche' army confronted the Spanish army in the Quetzaltenango valley and were comprehensively defeated; many K'iche' nobles were among the dead.[65] This battle exhausted the K'iche' militarily and they asked for peace and offered tribute, inviting Pedro de Alvarado into their capital Q'umarkaj, which was known as Tecpan Utatlan to the Nahuatl-speaking allies of the Spanish. Alvarado was deeply suspicious of the K'iche' intentions but accepted the offer and marched to Q'umarkaj with his army.[66]  Grass- and scrub-covered ruins set against a backdrop of low pine forest. A crumbling squat square tower stands behind to the right, all that remains of the Temple of Tohil, with the remains of the walls of the ballcourt to the left in the foreground. Q'umarkaj was the capital of the K'iche' kingdom until it was burnt by Alvarado's forces. In March 1524 Pedro de Alvarado entered Q'umarkaj at the invitation of the remaining lords of the K'iche' after their catastrophic defeat,[67] fearing that he was entering a trap.[65] He encamped on the plain outside the city rather than accepting lodgings inside.[68] Fearing the great number of K'iche' warriors gathered outside the city and that his cavalry would not be able to manoeuvre in the narrow streets of Q'umarkaj, he invited the leading lords of the city, Oxib-Keh (the king) and Beleheb-Tzy (the king elect) to visit him in his camp.[69] As soon as they did so, he seized them and kept them as prisoners in his camp. The K'iche' warriors, seeing their lords taken prisoner, attacked the Spaniards' indigenous allies and managed to kill one of the Spanish soldiers.[70] At this point Alvarado decided to have the captured K'iche' lords burnt to death, and then proceeded to burn the entire city.[71] After the destruction of Q'umarkaj and the execution of its rulers, Pedro de Alvarado sent messages to Iximche, capital of the Kaqchikel, proposing an alliance against the remaining K'iche' resistance.[66] Kaqchikel alliance and conquest of the Tz'utujil On 14 April 1524, soon after the defeat of the K'iche', the Spanish were invited into Iximche and were well received by the lords Belehe Qat and Cahi Imox.[72][nb 1] The Kaqchikel kings provided native soldiers to assist the conquistadors against continuing K'iche' resistance and to help with the defeat of the neighbouring Tz'utuhil kingdom.[73] The Spanish only stayed briefly in Iximche before continuing through Atitlán, Escuintla and Cuscatlán. The Spanish returned to the Kaqchikel capital on 23 July 1524 and on 27 July, Pedro de Alvarado declared Iximche as the first capital of Guatemala, Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala ("St. James of the Knights of Guatemala").[74]  View across hills to a broad lake bathed in a light mist. The mountainous lake shore curves from the left foreground backwards and to the right, with several volcanoes rising from the far shore, framed by a clear blue sky above. The Tz'utujil kingdom had its capital on the shore of Lake Atitlán. The Kaqchikel appear to have entered into an alliance with the Spanish to defeat their enemies, the Tz'utujil, whose capital was Tecpan Atitlan.[66] Pedro de Alvarado sent two Kaqchikel messengers to Tecpan Atitlan at the request of the Kaqchikel lords, both of whom were killed by the Tz'utujil.[75] When news of the killing of the messengers reached the Spanish at Iximche, the conquistadors marched against the Tz'utujil with their Kaqchikel allies.[66] Pedro de Alvarado left Iximche just 5 days after he had arrived there, with 60 cavalry, 150 Spanish infantry and an unspecified number of Kaqchikel warriors. The Spanish and their allies arrived at the lakeshore after a day's hard march, without encountering any opposition. Seeing the lack of resistance, Alvarado rode ahead with 30 cavalry along the lake shore. Opposite a populated island the Spanish at last encountered hostile Tz'utujil warriors and charged among them, scattering and pursuing them to a narrow causeway across which the surviving Tz'utujil fled.[76] The rest of Alvarado's army soon reinforced his party and they successfully stormed the island. This battle took place on 18 April.[77] The following day the Spanish entered Tecpan Atitlan but found it deserted. Pedro de Alvarado camped in the centre of the city and sent out scouts to find the enemy. They managed to catch some locals and used them to send messages to the Tz'utujil lords, ordering them to submit to the king of Spain. The Tz'utujil leaders responded by surrendering to Pedro de Alvarado and swearing loyalty to Spain, at which point Alvarado considered them pacified and returned to Iximche.[77] Three days after Pedro de Alvarado returned to Iximche, the lords of the Tz'utujil arrived there to pledge their loyalty and offer tribute to the conquistadors.[78] A short time afterwards a number of lords arrived from the Pacific lowlands to swear allegiance to the king of Spain.[79] Kaqchikel rebellion Pedro de Alvarado rapidly began to demand gold in tribute from the Kaqchikels, souring the friendship between the two peoples.[80] He demanded that their kings deliver 1000 gold leaves, each worth 15 pesos.[81][nb 2] The Kaqchikel people abandoned their city and fled to the forests and hills on 28 August 1524. Ten days later the Spanish declared war on the Kaqchikel.[80] Two years later, on 9 February 1526, a group of sixteen Spanish deserters burnt the palace of the Ahpo Xahil, sacked the temples and kidnapped a priest, acts that the Kaqchikel blamed on Pedro de Alvarado.[82][nb 3] The Kaqchikel kept up resistance against the Spanish for a number of years. On 9 May 1530, exhausted by the warfare that had seen the deaths of their best warriors and the enforced abandonment of their crops,[83] the two kings of the most important clans returned from the wilds.[80] A day later they were joined by many nobles and their families and many more people; they then surrendered at the new Spanish capital at Ciudad Vieja.[80] Pacific lowlands of Guatemala  A page from the Lienzo de Tlaxcala depicting the conquest of Izcuintepeque On 8 May 1524, Pedro de Alvarado continued southwards to the Pacific coastal plain with an army numbering approximately 6000,[nb 4] where he defeated the Pipil of Panacal or Panacaltepeque near Izcuintepeque on 9 May.[84] Alvarado described the terrain approaching the town as very difficult, covered with dense vegetation and swampland that made the use of cavalry impossible; instead he sent men with crossbows ahead. The Pipil withdrew their scouts because of the heavy rain, believing that the Spanish and their allies would not be able to reach the town that day.[85] Pedro de Alvarado pressed ahead and when the Spanish entered the town the defenders were completely unprepared, with the Pipil warriors indoors sheltering from the torrential rain. In the battle that ensued, the Spanish and their indigenous allies suffered minor losses but the Pipil were able to flee into the forest, sheltered from Spanish pursuit by the weather and the vegetation. Pedro de Alvarado ordered the town to be burnt and sent messengers to the Pipil lords demanding their surrender, otherwise he would lay waste to their lands.[85] According to Alvarado's letter to Cortés, the Pipil came back to the town and submitted to him, accepting the king of Spain as their overlord.[86] The Spanish force camped in the captured town for eight days.[85] A few years later, in 1529, Pedro de Alvarado was accused of using excessive brutality in his conquest of Izcuintepeque, amongst other atrocities.[87]  The Pacific slope of Jutiapa was the scene of a number of battles with the Xinca. In Guazacapán, Pedro de Alvarado described his encounter with people who were neither Maya nor Pipil, speaking a different language altogether; these people were probably Xinca.[88] At this point Alvarado's force consisted of 250 Spanish infantry accompanied by 6,000 indigenous allies, mostly Kaqchikel and Cholutec.[89] Alvarado and his army defeated and occupied the most important Xinca city, named as Atiquipaque. The defending warriors were described by Alvarado as engaging in fierce hand-to-hand combat using spears, stakes and poisoned arrows. The battle took place on 26 May 1524 and resulted in a significant reduction of the Xinca population.[88] Alvarado's army continued eastwards from Atiquipaque, seizing several more Xinca cities. Because Alvarado and his allies could not understand the Xinca language, Alvarado took extra precautions on the march eastward by strengthening his vanguard and rearguard with ten cavalry apiece. In spite of these precautions the baggage train was ambushed by a Xinca army soon after leaving Taxisco. Many indigenous allies were killed and most of the baggage was lost, including all the crossbows and ironwork for the horses.[90] This was a serious setback and Alvarado camped his army in Nancintla for eight days, during which time he sent two expeditions against the attacking army.[91] Alvarado sent out Xinca messengers to make contact with the enemy but they failed to return. Messengers from the city of Pazaco, in the modern department of Jutiapa,[92] offered peace to the conquistadors but when Alvarado arrived there the next day the inhabitants were preparing for war. Alvarado's troops encountered a sizeable quantity of gathered warriors and quickly routed them through the city's streets. From Pazaco, Alvarado crossed the Río Paz and entered what is now El Salvador.[93] |

ソコヌスコとグアテマラの征服 メイン記事:スペインによるグアテマラ征服... 彼らが矢を射るのに十分な距離まで近づいてくるのを待ち、それから彼らに突撃した。彼らは馬を見たことがなかったので非常に怯え、我々は大きく前進し...彼らの多くは死んだ。 ----ペドロ・デ・アルバラドが、エルナン・コルテスへの3通目の手紙の中で、ケツァルテナンゴへの進軍について述べている[54]。 コルテスはペドロ・デ・アルバラドをグアテマラ侵攻に派遣し、180人の騎兵、300人の歩兵、クロスボウ、マスケット銃、4門の大砲、大量の 大量の弾薬と火薬、そして数千人の同盟メキシコ戦士を従えていた[55]。ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは、1523年にグアテマラ征服の途上でソコヌスコをか なりの兵力とともに通過した[56]。アルバラドの軍には、アステカ征服のベテラン兵士が含まれており、 騎兵と砲兵もいた[57]。また、チョルーラ、テノチティトラン、テスココ、トラスカラ、ソチミルコからも多くの先住民が同盟軍に加わっていた[58]。 アルヴァラドはソコヌスコで平和的に迎えられ、住民たちはスペイン王室への忠誠を誓った。彼らは、スペインに友好的な姿勢を示しているために、グアテマラ の近隣集団から攻撃を受けていることを報告した。ソコヌスコを通過した際の様子を説明するアルヴァラドからエルナン・コルテス宛ての書簡は紛失しており、 現地での出来事の知識は、その場にいなかったがゴンサロ・デ・アルヴァラドの報告を伝えたベルナル・ディアス・デル・カスティージョの記述によるものであ る[59]。1524年までに、ソコヌスコは ソコンスコは、アルバラドとその軍隊によって完全に平定された[60]。  ケツァルテナンゴの征服を描いた「トラスカラ図」の一ページ ペドロ・デ・アルバラドとその軍隊は、グアテマラ西部のサマラ川に到着するまで、太平洋沿岸を何の抵抗もなく進軍した。この地域はキチェ王国の領土の一部 であり、キチェ軍はスペイン軍が川を渡るのを阻止しようとしたが、失敗に終わった。征服者たちは川を渡ると、キチェ族を威嚇しようと近くの集落を略奪した [61]。1524年2月8日、アルヴァラドの軍は、彼のメキシコ人同盟軍がザポティトラン(現在のサンフランシスコ・ザポティトラン)と呼んでいたケツ トゥルルで戦闘を行った。キチェ族の弓兵の攻撃により多くの負傷者を出したが、スペイン軍とその同盟軍は町を急襲し、市場に野営地を張った[62]。 その後、アルヴァラドはキチェ族の本拠地であるシエラマドレ山脈を目指して川を上り、峠を越えてケツァルテナンゴの肥沃な谷へと向かった。1524年2月 12日、アルヴァラドのメキシコ人同盟軍は峠で待ち伏せ攻撃を受け、キチェ族の戦士たちに追い返された。しかし、それに続くスペイン騎兵隊の突撃は、それ まで馬を見たことがなかったキチェ族にとって衝撃的だった。騎兵隊はキチェ族を散らし、軍隊はケツァルテナンゴ(現在のケツァルテナンゴ)の町へ渡った が、そこはすでに無人だった[63]。 ほぼ1週間後の1524年2月18日[64]、ケツァルテナンゴ渓谷でキチェ族軍がスペイン軍と対峙し、 大敗を喫し、キチェ族の貴族の多くが戦死した[65]。この戦いでキチェ族は軍事的に疲弊し、和平を求め、貢納を申し出た。そして、スペイン人のナワトル 語を話す同盟者たちにはテクパン・ウタトランとして知られていた首都クマルカハにペドロ・デ・アルバラードを招いた。アルヴァラドはキチェ族の意図を深く 疑っていたが、申し出を受け入れ、軍とともにクマルカハへと進軍した[66]。  背後に広がる松林を背景に、草や低木に覆われた遺跡。右奥には、崩れかけた四角い塔がそびえ立つ。これがトヒル神殿の遺跡で、手前の左側にはボールコートの城壁の跡が残っている。 クマルカは、アルヴァラドの軍勢によって焼失するまで、キチェ王国の首都であった。 1524年3月、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドはキチェの残存領主たちの招きに応じてクマルカに入城した。彼らは壊滅的な敗北を喫した後、罠に嵌まるのではない かと恐れていた[65]。彼は宿舎に入る代わりに、市外にある平原に野営地を張った[68]。街の外に集まったキチェ族の戦士たちの多さと、クマルカジュ の狭い路地で騎馬隊が機動できないことを恐れた彼は、街の有力者であったオキブ・ケ(王)とベレヘブ・ツィ(次期王)を自分の陣営に招待した[69]。 彼らがやってくるとすぐに、彼は彼らを捕らえて自分の陣営で囚人として監禁した。キチェ族の戦士たちは、自分たちの領主が捕虜になったのを見て、スペイン 人の先住民同盟軍を攻撃し、スペイン兵1人を殺すことに成功した[70]。この時点で、アルバラドは捕虜となったキチェ族の領主たちを火あぶりにして殺す ことを決意し、その後、街全体を焼き払った[71]。クマルカージの破壊と支配者の処刑の後、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは アルヴァラドは、カクチケル族の首都イシムチェにメッセージを送って、残存するキチェ族の抵抗勢力に対する同盟を提案した[66]。 カクチケル族の同盟とツツヒル族の征服 1524年4月14日、キチェ族の敗北直後、スペイン人はイシムチェに招待され、ベレヘ・カットとカヒ・イモックスの両王から歓待を受けた[72][注釈 1]。 ベレ・カトとカヒ・イモックスである[72][注釈 1]。カクチケル族の王たちは、征服者たちを援助し、抵抗を続けるキチェ族を制圧し、近隣のツトゥヒル王国の滅亡を助けるために、先住民兵士を提供した [73]。スペイン人は、アティトラン、エスクイントラ、クスカトランを経て進む前に、イシムチェに短期間滞在しただけだった。スペイン人は1524年7 月23日にカクチケル王国の首都に戻った。そして7月27日、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドはグアテマラの最初の首都としてイシムチェを宣言し、サンティアゴ・ デ・ロス・カバリェロス・デ・グアテマラ(グアテマラ騎士団の聖ヤコブ)と名付けた。  丘陵地帯から、薄い霧に包まれた広大な湖を眺める。山がちな湖岸は、手前の左側から奥に向かって右にカーブし、向こう岸にはいくつもの火山がそびえ立ち、その背景には澄み切った青空が広がっている。 ツトゥヒル王国は、アティトラン湖の湖畔に首都を置いていた。 カクチケル族は、敵であるツトゥヒル族(首都はテクパン・アティトラン)を倒すためにスペイン人と同盟を結んだようである[66]。ペドロ・デ・アルバラ ドは、カクチケル族の領主の要請により、2人のカクチケル族の使者をテクパン・アティトランに派遣したが、2人ともツツジル族に殺された[75]。 ] 使者の殺害の知らせがイシムチェのスペイン人に届いたとき、コンキスタドールたちはカクチケル族の同盟軍とともにツトゥヒル族に戦いを挑んだ[66]。 ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは、到着からわずか5日後にイシムチェを去った。60人の騎兵、150人のスペイン人歩兵、そして不明数のカクチケル族戦士を率い て。スペイン人とその同盟軍は、1日かけての苦難の行軍の後、何の抵抗もなく湖畔に到着した。抵抗がないことを見て、アルバラドは30人の騎兵とともに湖 畔を先導した。人口の多い島の対岸で、スペイン軍はついに敵対的なツツジルの戦士たちと遭遇し、彼らの中に突撃した。生き残ったツツジル族は狭い通路に逃 げ込んだが、スペイン軍は彼らを追い散らし、追跡した[76]。アルヴァラドの軍隊の残りがすぐに彼の部隊を補強し、彼らは島を成功裏に攻略した。この戦 闘は4月18日に行われた[77]。 翌日、スペイン軍はテクパン・アティトランに入ったが、そこは無人だった。ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは町の中心部に野営し、敵を見つけるために斥候を派遣し た。彼らは何人かの地元民を捕らえることに成功し、ツツジルの首長にスペイン国王に服従するよう命じるメッセージを伝えるために彼らを利用した。ツツジル 族の首長は、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドに降伏し、スペインへの忠誠を誓うことでこれに答えた。アルバラドはこれでツツジル族を平定したと考え、イシムチェに 戻った[77]。ペドロ・デ・アルバラドがイシムチェに戻ってから3日後、ツツジル族の首長が 征服者たちに忠誠を誓い、貢物を捧げるためにそこへ到着した。[78] その後まもなく、太平洋低地からスペイン王への忠誠を誓うために多くの領主たちが到着した。[79] カクチケル族の反乱 ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは、カクチケル族から貢物として金を要求し始めた。両民族間の友好関係は悪化した[80]。彼は、彼らの王が1枚15ペソの金貨 1000枚を納めるよう要求した[81][nb 2]。カクチケル族は1524年8月28日、自分たちの都市を捨てて森や丘へと逃げた。その10日後、スペインはカクチケルに宣戦布告した[80]。 2年後、1526年2月9日、16人のスペイン人脱走兵がアポ・シャヒルの宮殿を焼き、寺院を略奪し、司祭を誘拐した。カクチケルはこれらの行為をペド ロ・デ・アルバラドのせいだとした[82][nb 3]。カクチケルはスペインに対して何年も抵抗を続けた。1530年5月9日、最も優秀な戦士たちの死と作物の放棄を強いられた戦争に疲れ果てた2人の有 力氏族の王が、荒野から戻ってきた[80]。翌日、多くの貴族とその家族、さらに多くの人々が彼らに加わり、彼らは スペインの新しい首都シウダー・ビエハで降伏した[80]。 グアテマラの太平洋低地  イスクインテペケの征服を描いた「トラスカラ図」のページ 1524年5月8日、ペドロ・デ・アルバラードは、約6000人の軍隊を率いてさらに南下し、太平洋沿岸平野へと進軍した[nb 4] そこで彼は5月9日、イスクインテペケ近郊のパナカルまたはパナカルテペケのピピル族を撃破した[84]。アルヴァラドは、町に近づく地形が非常に険し く、密集した植生と湿地帯に覆われて騎兵隊の進軍が不可能であると説明し、代わりにクロスボウを持った兵士を先陣に送った。ピピル族は激しい雨のために斥 候を撤退させ、スペイン人とその同盟軍は当日中に町に到着できないだろうと考えた[85]。 ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは前進を続け、スペイン軍が町に入ったとき、守備隊はまったく準備ができておらず、ピピル族の戦士たちは豪雨から逃れるために屋内 に避難していた。戦闘の結果、スペイン人と先住民同盟軍は軽微な損失を被ったが、ピピル族は天候と植生に守られ、スペイン軍の追撃をかわして森に逃げ込む ことができた。ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは町を焼き払うよう命じ、ピピルの領主たちに降伏を要求する使者を送った。さもなければ領地が荒廃すると脅した [85]。 アルバラドがコルテスに送った手紙によると、ピピル族は町に戻り、スペイン国王を彼らの支配者として受け入れ、彼に服従した[86]。スペイン軍は、占領 した町に8日間野営した[85]。その数年後の1529年、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは、イズクインテペケ征服において残虐行為を行ったとして、その他の残 虐行為とともに告発された[87]。  フティアパの太平洋側の斜面は、シンカ族との数々の戦いの舞台となった。 グアサカパンで、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは、マヤ族でもピピル族でもない、まったく異なる言語を話す人々との出会いについて述べている。これらの人々はお そらくシンカ族だった[88]。この時点で、アルバラドの軍勢は 250人のスペイン人歩兵と、主にカクチケル族とチョルテカ族からなる6,000人の先住民同盟軍で構成されていた[89]。アルヴァラドとその軍は、最 も重要なシンカ族の都市であるアティキパケを制圧し占領した。アルヴァラドは、守備隊が槍や杭、毒矢を使った激しい白兵戦を展開したと記している。この戦 闘は1524年5月26日に起こり、シンカ族の人口を大幅に減少させた[88]。 アルヴァラドの軍隊はアティキパケから東に進軍し、さらにいくつかのシンカ族の都市を占領した。アルヴァラドと彼の同盟軍はシンカ族の言語を理解できな かったため、アルヴァラドは東進するにあたり、前衛と後衛にそれぞれ10人の騎兵を配置するなど、特別な注意を払った。これらの注意にもかかわらず、タク シスコを出発して間もなく、荷物運搬隊はシンカ族の軍隊に待ち伏せ攻撃された。多くの先住民同盟軍が殺され、荷馬車のほとんどと、クロスボウや馬具の鉄製 品がすべて失われた[90]。 これは大きな挫折であり、アルヴァラドはナンシントラに8日間軍を駐留させ、その間、攻撃軍に対して2つの遠征隊を送った[91]。アルヴァラドは敵と接 触するためにシンカ族の使者を派遣したが、彼らは戻ってくることはなかった。ユティアパ県パサコ市からの使者はコンキスタドールに和平を申し出たが、翌日 アルヴァラドが到着すると、住民たちはすでに戦争の準備を始めていた。アルヴァラドの部隊は、集結した多数の戦士と遭遇し、市街地の通りで彼らを素早く撃 破した。パサコから、アルヴァラドはリオ・パス川を渡り、現在のエルサルバドルに入った[93]。 |

| Cuzcatlan (El Salvador) See also: Spanish conquest of El Salvador Alvarado led the first effort by Spanish forces to extend their dominion to the nation of Cuzcatlan (in modern El Salvador), in June 1524. These efforts established many towns such as San José Acatempa in 1525 and Esquipulas in 1560. Spanish efforts were firmly resisted by the indigenous people known as the Pipil and their Mayan speaking neighbors. Despite Alvarado's initial success in the Battle of Acajutla, the indigenous people of Cuzcatlán, who according to tradition were led by a warlord called Atlácatl, defeated the Spaniards and their auxiliaries, and forced them to withdraw to Guatemala. Alvarado was wounded on his left thigh, remaining handicapped for the rest of his life. He abandoned the war and appointed his brother, Gonzalo de Alvarado, to continue the task. Two subsequent expeditions were required (the first in 1525, followed by a smaller group in 1528) to bring the Pipil under Spanish control. In 1528 the conquest of Cuzcatlán was completed and the city of San Salvador was established. |

クスカトラン(エルサルバドル) 関連項目:スペインによるエルサルバドルの征服 1524年6月、アルヴァラドはスペイン軍によるクスカトラン(現在のエルサルバドル)への支配拡大の最初の試みを行った。これらの試みは、1525年の サン・ホセ・アカテンパや1560年のエスキプラスなど、多くの町を建設した。スペインの試みは、ピピル族と呼ばれる先住民とマヤ語を話す近隣住民によっ て断固として抵抗された。 アカフトラの戦いでアルヴァラドが最初に勝利を収めたにもかかわらず、アトラカトルと呼ばれる軍閥に率いられたという言い伝えのあるクスカトランの先住民 がスペイン人とその援軍を破り、グアテマラへの撤退を余儀なくさせた。 アルバラドは左太ももを負傷し、生涯にわたって障害を負った。彼は戦争を放棄し、弟のゴンサロ・デ・アルバラドに任務を引き継がせた。ピピル族をスペイン の支配下に置くために、2回の遠征が必要となった(1525年の最初の遠征に続き、1528年には小規模な遠征が行われた)。1528年、クスカトラン征 服が完了し、サンサルバドル市が建設された。 |

| Titles and first marriage On 18 December 1527, the king of Spain named Alvarado as governor of Guatemala; two days later he granted him the coveted military title of Adelantado. Alvarado's close friendship with Cortés was broken in the same year; Alvarado had promised Cortés that he would marry Cecilia Vázquez, Cortes' cousin. Alvarado broke his promise and instead married Francisca de la Cueva.[94] Technically, this was not his first marriage as he married an indigenous woman, daughter to Xicotencatl the Elder, who was referred to as Dona Luisa by Spanish speakers and Tlecuiluatzin by Nahuatl speakers. Francisca de la Cueva was well connected at the royal court, being the niece of Francisco de los Cobos, the king's secretary, and a member of the powerful noble house of Albuquerque. This marriage gave Alvarado extra leverage at court and was far more useful to his long term interests; Alvarado thereafter maintained a friendship with Francisco de los Cobos that allowed him access to the king's favour. In 1528, by coincidence both Alvarado and Cortés were in Seville at the same time, but Cortés ignored him.[94] Francisca de la Cueva died shortly after their arrival in America. Alvarado remained governor of Guatemala until his death. He was made Knight of Santiago in 1527. |

称号と最初の結婚 1527年12月18日、スペイン国王はアルバラードをグアテマラ総督に任命し、その2日後には彼に憧れの軍事称号である「先駆者」を与えた。アルバラー ドとコルテスの親交は同年、破たんした。アルバラードはコルテスの従姉妹であるセシリア・バスケスと結婚するとコルテスに約束していた。アルヴァラドは約 束を破り、フランシスカ・デ・ラ・クエバと結婚した[94]。厳密に言えば、これは彼の最初の結婚ではなかった。というのも、彼は先住民の女性と結婚した のである。その女性は、スペイン語話者からはドナ・ルイーサ、ナワトル語話者からはトルクイルアツィンと呼ばれていたシコテンカトル・エルダーの娘だっ た。 フランシスカ・デ・ラ・クエバは、王の秘書であるフランシスコ・デ・ロス・コボス(Francisco de los Cobos)の姪であり、有力貴族アルバカーキ家の出身であったため、王宮で有力なコネクションを持っていた。この結婚により、アルヴァラドは王宮でより 大きな影響力を持ち、長期的な利益を得る上で大いに役立った。アルヴァラドはその後、フランシスコ・デ・ロス・コボスと友好関係を保ち、王の寵愛を得るこ とを許された。1528年、偶然にもアルヴァラドとコルテスが同時にセビリアに滞在していたが、コルテスはアルヴァラドを無視した[94]。 フランシスカ・デ・ラ・クエバは、彼らがアメリカに到着して間もなく亡くなった。アルヴァラドはグアテマラ総督の地位を死ぬまで維持した。1527年にはサンティアゴ騎士団の一員となった。 |

| Peru By 1532, Alvarado's friendship with Hernán Cortés had soured, and he no longer trusted him. At this time Alvarado requested permission from the king for an expedition south along the Pacific coast, to conquer any lands there that had not already been claimed for the Crown, and specifically rejected that Cortés should accompany him.[95] In 1534, Alvarado heard tales of the riches of Peru, headed south to the Andes and attempted to bring the province of Quito under his rule. When he arrived, he found the land already held by Francisco Pizarro's lieutenant Sebastián de Belalcázar. The two forces of Conquistadors almost came to battle; however, Alvarado bartered to Pizarro's group most of his ships, horses, and ammunition, plus most of his men, for a comparatively modest sum of money, and returned to Guatemala.[50][page needed] |

ペルー 1532年までに、アルバラドとエルナン・コルテスの友情は悪化し、彼はもはや彼を信頼しなくなっていた。この時に、アルヴァラドは国王に、太平洋沿岸を 南下し、まだ王室の領土となっていない土地を征服する遠征の許可を求めた。そして、コルテスが同行することを特に拒否した[95]。1534年、アルヴァ ラドはペルーの富についての噂を聞き、アンデス山脈を目指して南下し、キト州を支配下に収めようとした。到着してみると、その地はすでにフランシスコ・ピ サロの副官セバスティアン・デ・ベラルカサルが支配していた。2つのコンキスタドール軍は戦闘寸前までいったが、アルヴァラドはピサロのグループに、船、 馬、弾薬のほとんどと、部下たちのほとんどを比較的少額の金と交換し、グアテマラに戻った[50][ページ番号が必要] |

| Governor of Honduras See also: Spanish conquest of Honduras In 1532, Alvarado received a Royal Cedula naming him Governor of the Province of Honduras. At that time, Honduras consisted of a single settlement of Spaniards in Trujillo, but he declined to act on it. In 1533 or 1534 he began to send his own work gangs of enslaved Africans and Native Americans into the parts of Honduras adjacent to Guatemala to work the placer gold deposits. In 1536, ostensibly in response to a letter asking for aid from Andrés de Cereceda, then acting Governor of the Province of Honduras, Alvarado and his army of Indian allies arrived in Honduras, just as the Spanish colonists were preparing to abandon the country and go look for gold in Peru. In June, 1536, Alvarado engaged the indigenous resistance led by Cicumba in the lower Ulua river valley, and won. He divided up the Indian labor in repartimiento grants to his soldiers and some of the colonists, and returned to Guatemala. During a visit to Spain, in 1537, Alvarado had the governorship of Honduras reconfirmed in addition to that of Guatemala for the next seven years. His governorship of Honduras was not uncontested. Francisco de Montejo had a rival claim, and was installed by the Spanish king as Governor of Honduras in 1540. Ten years after being widowed, Alvarado married one of his first wife's sisters, Beatriz de la Cueva, who outlived him. After the death of Alvarado, de la Cueva maneuvered her own election and succeeded him as governor of Guatemala, becoming the only woman to govern a major political division of the Americas in Spanish colonial times. She drowned a few days after taking office in the destruction of the capital city Ciudad Vieja by a sudden mudflow from the Volcán de Agua in 1541. |

ホンジュラス総督 関連項目:スペインによるホンジュラスの征服 1532年、アルバラドはホンジュラス総督に任命される王令を受けた。当時、ホンジュラスはトルヒーヨにスペイン人が住む集落が1つあるだけだったが、彼 はこれを辞退した。1533年または1534年、彼は奴隷となったアフリカ人とネイティブアメリカンからなる労働者をホンジュラスとグアテマラの国境付近 に送り込み、砂金採掘に従事させた。 1536年、ホンジュラス州知事代理のアンドレス・デ・セレセダからの支援要請に応えるため、アルヴァラドと彼の率いるインディオ同盟軍は、スペイン人入 植者がホンジュラスを放棄し、ペルーで金を探しに行こうとしていたまさにその頃、ホンジュラスに到着した。1536年6月、アルヴァラドは、ウルア川下流 域でシクンバが率いる先住民の抵抗勢力と交戦し、勝利を収めた。彼はインディオの労働力を兵士や一部の入植者に分配し、グアテマラに戻った。 1537年にスペインを訪問した際、アルバラドはグアテマラに加えてホンジュラスの総督職を7年間再確認させた。 彼のホンジュラス総督職は異論を唱える者もいた。フランシスコ・デ・モンテホは対抗馬であり、1540年にスペイン王によってホンジュラス総督に任命され た。妻に先立たれてから10年後、アルバラドは最初の妻の姉妹の一人、ベアトリス・デ・ラ・クエバと結婚した。 アルバラドの死後、デ・ラ・クエバは知事選に立候補し、グアテマラ知事の座を継承した。スペイン植民地時代のアメリカ大陸で、主要な政治単位を統治した唯 一の女性となった。彼女は1541年、火山アグアからの突然の土石流による首都シウダービエハの破壊から数日後に溺死した。 |

Death in the Mixtón War, 1541 Alvarado's death, depicted in the indigenous Codex Telleriano-Remensis. The glyph to the right of his head represents his Nahuatl name, Tonatiuh ("Sun").  Modern memorial stone in the ruins of Antigua cathedral, marking Pedro de Alvarado's tomb Alvarado developed a plan to outfit an armada that would sail from the western coast of Mexico to China and the Spice Islands. At great cost, he assembled and equipped 13 ships and approximately 550 soldiers for the expedition. The fleet was about to set sail in 1541 when Alvarado received a letter from Cristóbal de Oñate, pleading for help against hostile Indians who were besieging him at Nochistlán.[51]: Ch.203 The siege was part of a major revolt by the Mixtón natives of the Nueva Galicia region of Mexico. Alvarado gathered his troops and went to help Oñate. In a freak accident, he was crushed by a horse that was spooked and ran amok.[51]: Ch.203 Alvarado lay in agony before eventually dying a few days later, on July 4, 1541, and was buried in the church at Tiripetío, a village between Pátzcuaro and Morelia (in present-day Michoacán). Four decades after Alvarado's death, his mestiza daughter Leonor de Alvarado Xicoténcatl paid to transport his remains to Guatemala for reburial in the cathedral of the city of Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala, now Antigua Guatemala. |

1541年のミクストゥン戦争での死 先住民による『テジェリアーノ・レメンシス写本』に描かれたアルバラドの死。彼の頭部の右側にある記号は、彼のナワトル語名「トナティウ」(「太陽」)を表している。  ペドロ・デ・アルバラドの墓を示す、アンティグア大聖堂跡の近代的な記念碑(1960) アルバラドは、メキシコ西海岸から中国と香料諸島まで航行する艦隊を編成する計画を立てた。多大な費用をかけて、彼は13隻の船と約550人の兵士を集 め、遠征の準備を整えた。1541年、船団が出航しようとしていたとき、アルヴァラドはクリストバル・デ・オニャテから手紙を受け取った。手紙には、ノチ ストランで彼を包囲している敵対的なインディアンに対する支援を求める内容が書かれていた[51]: Ch.203 包囲は、メキシコのヌエバ・ガリシア地方に住むミストンの先住民による大規模な反乱の一部であった。アルヴァラドは軍隊を集め、オニャテを助けに向かっ た。不運な事故で、彼は馬に驚いて暴れ出した馬に踏みつけられてしまった[51]: Ch.203 。アルヴァラドは苦しみながら数日後、1541年7月 4日に息を引き取り、パツクアロとモレリア(現在のミチョアカン州)の間の村、ティリペティオの教会に埋葬された。 アルヴァラドの死から40年後、彼のメスティーサ(混血)の娘レオノール・デ・アルヴァラド・キシコテンカトルが、グアテマラのサンティアゴ・デ・ロス・ カバリェロス・デ・グアテマラ(現在のアンティグア・グアテマラ)の大聖堂に再埋葬するため、遺体の輸送費用を支払った。 |

| Family After the death of her husband, Beatriz de la Cueva maneuvered her own election and succeeded him as governor of Guatemala, becoming the only woman to govern a major political division of the Americas in Spanish colonial times.[96] Alvarado had no children from either of his legal marriages. His life companion was his concubine Luisa de Tlaxcala (also called Xicoténcatl or Tecubalsi, her original names after Catholic baptism). She was a Nahua noblewoman, daughter of the Tlaxcallan King Xicotencatl the Elder. Luisa was given by her father in 1519 to Hernán Cortés as a proof of respect and friendship. In turn Cortés gave her in guard to Pedro de Alvarado,[51]: 178 who quickly and unremarkably became her lover. Luisa followed Alvarado in his pursuit of conquests beyond central Mexico. Despite never being his legitimate wife, Luisa de Tlaxcala had numerous possessions and was respected as a Doña, both for her relationship with Alvarado and for her noble origin. She died in 1535 and was buried at the Guatemala Cathedral. With Luisa de Tlaxcala Pedro de Alvarado had three children: Leonor de Alvarado y Xicotenga Tecubalsi, born in the newly founded Spanish city of Santiago de los Caballeros, who married Pedro de Portocarrero, a conqueror trusted by his father-in-law, whom he accompanied during the conquests of Mexico and Guatemala. Portocarrero participated in numerous battles against the Indians. Leonor married a second time,[97] to Francisco de la Cueva y Guzman.[51]: 178–179 The Alvarado fortune remained with their descendants for generations to come, in the family of Villacreces de la Cueva y Guzmán, governors of this part of Guatemala. Pedro de Alvarado, named for his father,[51]: 178 who disappeared at sea when traveling to Spain Diego de Alvarardo, El Mestizo, who died in 1554 in the civil wars of Peru. By other women, in more casual relationships, he had two other children: Gómez de Alvarado, without further notice Ana (Anita) de Alvarado |

家族 夫の死後、ベアトリス・デ・ラ・クエバは自ら選挙に打って出て、グアテマラ総督の後任となり、スペイン植民地時代のアメリカ大陸の主要政治単位を統治した唯一の女性となった[96]。 アルバラドは、2度の合法的な結婚のいずれからも子供はいなかった。 彼の生涯の伴侶は、愛妾ルイーサ・デ・トラスカラ(カトリックの洗礼を受けた後の彼女の旧名、キシコテンカトルまたはテクバルシとも呼ばれる)であった。 彼女はナワ族の貴族で、トラスカラン王のキシコテンカトル・エルデ(Xicotencatl the Elder)の娘であった。 ルイサは1519年に、敬意と友情の証として、父親からエルナン・コルテスに贈られた。コルテスは彼女をペドロ・デ・アルバラドに預けたが、[51]: 178 彼はすぐに、そして目立たず、彼女の恋人となった。ルイサは、メキシコ中央部以遠の征服を目指すアルバラドに従った。ルイーサ・デ・トラスカラは彼の正妻 ではなかったが、多くの財産を所有し、アルヴァラドとの関係と高貴な出自の両方により、ドニャ(貴婦人)として尊敬されていた。彼女は1535年に死去 し、グアテマラ大聖堂に埋葬された。 ルイーサ・デ・トラスカラとの間に、ペドロ・デ・アルヴァラドは3人の子供を設けた。 レオン・デ・アルバラド・イ・キシコテンガ・テクバルシは、スペイン人が新たに建設したサンティアゴ・デ・ロス・カバリェロスで生まれ、義父から信頼され ていた征服者ペドロ・デ・ポルトカレロと結婚した。ポルトカレロはメキシコとグアテマラの征服に同行した。ポルトカレロはインディアンとの戦いに数多く参 加した。 レオノールは2度目の結婚をし、フランシスコ・デ・ラ・クエバ・イ・グスマンと結婚した[51]: 178–179。アルヴァラド家の財産は、グアテマラのこの地域の知事であったビジャクレセス・デ・ラ・クエバ・イ・グスマン家の子孫に何世代にもわたって受け継がれた。 スペインへの航海中に海上で消息を絶った父にちなんで名付けられたペドロ・デ・アルバラード[51]: 178 1554年にペルーの内戦で亡くなったディエゴ・デ・アルバラルド、通称「メスティーソ 他にも、よりカジュアルな関係だった女性との間に、2人の子供がいた。 それ以上の情報は不明な ゴメス・デ・アルバラード アナ(アニタ)・デ・アルバラード |

| References in modern culture Alvarado is portrayed in Lew Wallace's novel The Fair God. One of Montezuma's daughters falls in love with him in a dream before she had ever seen him, when they do meet he returns her love and gives her an iron cross necklace so she can convert to Christianity. She is killed during the battle of La Noche Triste. This is a rare positive depiction of Pedro de Alvarado.[citation needed] Pedro de Alvarado is identified as the torturer of Tzinacán, the narrator in Jorge Luis Borges's story The Writing of the God, first published in 1949.[98] Pedro de Alvarado is a character in the historical novel The Serpent and the Eagle by Edward Rickford. The multiple-protagonist novel recounts the first few months of the Spanish-Mexica war and features a number of chapters from Pedro's point of view.[citation needed]  Page 58 of the Lienzo de Tlaxcala (ca C.E.1552), Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza with his Allies Tlaxcaltek meets the Caxcanes and Zacatecos in Xochipillâ, in a battle. The place is shown on a mountain at the top right of the picture, with a child. It holds a flower branch (Xochitl) in its hand. The battle was fought during the Mixtón War in C.E.1541. |

現代文化における言及 アルバラドは、ルイス・ウォレスの小説『The Fair God』で描かれている。モンテスマの娘の一人が、彼と会ったこともないうちに夢の中で彼に恋をする。実際に会ったとき、彼は彼女の愛に応え、彼女がキリ スト教に改宗できるよう鉄十字架のネックレスを彼女に与える。彼女はラ・ノチェ・トリステの戦いで命を落とす。これは、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドについて描 かれた数少ない肯定的な描写である[出典が必要]。 ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは、ホルヘ・ルイス・ボルヘスの短編小説『神々の書』(1949 年初版)の語り手であるツィナカン(Tzinacán)の拷問者であるとされている[98]。 ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは、エドワード・リックフォードの歴史小説『蛇と鷲』の登場人物である。複数の主人公が登場するこの小説は、スペイン・メキシコ戦争の最初の数か月間を語り、ペドロの視点から書かれた章が数多く登場する。  「トラスカラ図」(1552年頃)の58ページには、副王アントニオ・デ・メンドーサとその同盟者トラスカルテケ族が、ソチピッリでカシュカン族とザカテ コ族と戦っている様子が描かれている。 場所は、右上の山の上に描かれており、子供が描かれている。 その子は手に花枝(ソチトル)を持っている。この戦いは、西暦1541年のミシュトン戦争中に起こった。 |

| Black legend (Spain) La Noche Triste Mixtón War Spanish Conquest Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire Tecún Umán |

黒い伝説(スペイン) 悲しみの夜 ミシュトン戦争 スペインによる征服 アステカ帝国に対するスペインの征服 テクン・ウマン |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedro_de_Alvarado |

|

| Adelantado

(UK: /ˌædəlænˈtɑːdoʊ/,[1][2] US: /-lɑːnˈ-/,[2][3] Spanish:

[aðelanˈtaðo]; meaning "advanced") was a title held by some Spanish

nobles in service of their respective kings during the Middle Ages. It

was later used as a military title held by some Spanish conquistadores

of the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. Adelantados were granted directly by the monarch the right to become governors and justices of a specific region, which they were charged with conquering, in exchange for funding and organizing the initial explorations, settlements and pacification of the target area on behalf of the Crown of Castile. These areas were usually outside the jurisdiction of an existing audiencia or viceroy, and adelantados were authorized to communicate directly with the Council of the Indies.[4] The reconquista The term has its origins in the reconquista and comes from the phrase por adelantado (Spanish: 'in advance', although translations stating 'one who goes before' and 'the forward man' are also found). According to the Siete Partidas the office of adelantado was the equivalent of the Roman praefectus urbi (transl. urban prefect). The earliest definitively known adelantado was appointed by Alfonso X in 1253 in the recently conquered territory of La Frontera (Andalusia). However the office had precedents in the duties and rights held by some officers of the Navarrese dynasty of Castile and León, and Álvar Fáñez or Fortún Sánchez in the Ebro valley performed similar services in detached territories beyond the frontier. It was during this time that the Siete Partidas, commissioned by Alfonso X, more precisely defined the powers of the office. That law code created the position of an adelantado mayor, who was at the same time an intermediary appellate judge, located in the judicial hierarchy between local justices and the king's court, and an executive officer, who as a direct representative of the king was charged with implementing royal orders in his assigned area. Most appointees were from the upper nobility or the royal family. After its success in Andalusia, the institution was introduced in the northern areas of the peninsula, merging with and becoming indistinguishable from an older judicial office, the Royal Merinos. Overseas Beyond the peninsula, the term adelantado was granted to Alonso Fernández de Lugo in the conquest of the Canary Islands and was confirmed to members of his family. The term became modified over time. During the colonization of the Americas and the Spanish East Indies (Asia), each charter specified different powers to each adelantado, sometimes in a vague manner, which often led to confusion as in the case between Juan de Oñate and the Viceroy of New Spain.[5] The title was granted both as an inheritable title and one that lasted for the grantee's life only. With the publication of the Ordinances Concerning Discoveries (Ordenanzas de descubrimientos, nueva población y pacificación de las Indias) in 1573, the attributes of adelantados became regularized, although the title was granted much less often after this date, especially since the institutions of audiencias, governors and viceroys had been developed.[6] Nevertheless, the Ordinances are useful because they illustrate the powers adelantados often had. The Ordinances established that adelantados, in their capacity as governors and justices of the new territories, had the right to hear civil and criminal cases in appeal, to name the regidores and employees of the cabildos of any towns founded, to name interim treasury officials, to issue ordinances on the use of land and mines, to establish districts, and to organize militias and name their captains.  The adelantado grants of Charles V prior to the establishment of the Viceroyalty of Peru The first use of the title adelantado in the Americas was by Bartholomew Columbus, brother of Christopher Columbus, who governed Hispaniola under this title during his brother's absence from 1494 to 1498. It was later inherited by Diego Colón after much litigation. Other conquistadors who were granted the title include: 1512: Juan Ponce de León for Florida and Biminí, renewed in 1524 for his son, Luis 15??: Rodrigo de Bastidas for the Isthmus of Panama and Santa Marta 1514: Vasco Núñez de Balboa for the South Sea 1518: Ferdinand Magellan for the Spice Islands 1518: Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar for Yucatán[7] 1527: Pánfilo de Narváez for Florida 1527: Pedro de Alvarado for Guatemala[8] 1529: Francisco Pizarro for Peru,[9] and Pedro de Mendoza for Argentina 1535: Pedro Fernández de Lugo for Santa Marta (as son of Alonso Fernández de Lugo, Adelantado of Tenerife and La Palma, he was a second-generation adelantado) 1537: Hernando de Soto for Florida 1538: Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada for the New Kingdom of Granada 1540: Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca for Río de la Plata 1549: Pedro de Valdivia for Chile 1565: Juan Vásquez de Coronado for Costa Rica 1565: Pedro Menéndez de Avilés for Florida 1571: Miguel López de Legazpi for the Philippines 1595: Alvaro de Mendaña, and after his death his wife Isabel Barreto, for the Solomon Islands, and Juan de Oñate for the Kingdom of New Mexico [8]García Añoveros, Jesús María. Don Pedro de Alvarado: las fuentes históricas, documentación, crónicas y biblografía existente, Mesoamérica, vol. 13 (June 1987), pp. 243–282. CIRMA: Antigua Guatemala, Guatemala ISSN 0252-9963, OCLC 7141215, p. 247. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedro_de_Alvarado |

アデランタード、Adelantado(英国:

/ˌædəlænˈtɑːdoʊ/、[1][2] 米国:/-lɑːnˈ-/、[2][3]

スペイン語:[aðelanˈtaðo]、意味は「先進的」)は、中世においてそれぞれの王に仕えるスペイン貴族の一部が保持していた称号である。その

後、15世紀から17世紀にかけて活躍したスペインの征服者たちにも、軍事称号として用いられた。 アドランタドは、カスティーリャ王国のために資金調達や初期探検、入植、対象地域の平定を指揮する代わりに、征服を任された特定の地域の総督や判事になる 権利を君主から直接与えられた。これらの地域は通常、既存のオーディエンシアや副王の管轄外であり、adelantadosはインド評議会と直接連絡を取 る権限を持っていた[4]。 レコンキスタ この用語はレコンキスタに由来し、por adelantado(スペイン語で「前もって」の意味。ただし、「先に行く者」「先手」と訳される場合もある)という言葉に由来する。シエテ・パルティ ダスによると、adelantado の役職は、ローマの都市長官(praefectus urbi)に相当する。 最も古い記録に残る adelantado は、1253年にアルフォンソ10世によって、新たに征服されたラ・フロンテーラ(アンダルシア)に任命された。しかし、この役職は、カスティーリャ・レ オン王国のナバラ王朝の役人が持つ職務と権利に先行例があり、エブロ川流域のアルバル・ファネスやフォルトゥン・サンチェスは、国境を越えた離れた領土で 同様の職務を行っていた。アルフォンソ10世が委嘱した「シエテ・パルティダス」により、この役職の権限がより明確に定義されたのは、この時期のことであ る。 この法典により、地方裁判官と国王の法廷の中間に位置する上訴裁判官であり、同時に仲介役でもある「アバンタド・マヨール」という役職が創設された。ま た、国王の直接の代理人として、任命された地域において王の命令を執行する執行官も創設された。任命者のほとんどは、上流貴族または王族出身であった。ア ンダルシアでの成功後、この制度は半島北部にも導入され、それまでの司法機関である王室メリノスと統合され、区別がつかなくなった。 海外 半島以外では、アロンソ・フェルナンデス・デ・ルゴがカナリア諸島の征服でアランテドの称号を与えられ、彼の家族にもその称号が与えられた。この称号は時 代とともに変化していった。アメリカ大陸とスペイン領東インド(アジア)の植民地化時代、各特権状には、各アドランタドに異なる権限が規定されていた。時 には曖昧な表現が使われており、フアン・デ・オニャテとヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王のケースのように、しばしば混乱を招いた[5]。 この称号は、世襲可能な称号として、また授与者の生涯のみ有効な称号として与えられた。1573年に「新大陸の発見、新植民地、インドの平定に関する法 令」(Ordenanzas de descubrimientos, nueva población y pacificación de las Indias)が公布され、アドランタドの権限が規定された。 しかし、この法令は、アドランタドがしばしば有していた権限を明らかにしているため、有用である。この法令により、アドランタドは、新領地の知事および判 事として、民事および刑事事件の控訴審を審理する権利、新たに設立された町の評議会(カビルド)のレヒドール(評議員)および職員を任命する権利、臨時の 財務官を任命する権利、土地および鉱山の使用に関する法令を公布する権利、地区を設置する権利、民兵を組織し、その隊長を任命する権利を有することが定め られた。  ペルー副王領の設立に先立つ、カルロス5世のアドランタド特権 アメリカ大陸で初めて「アドランタド」の称号を使用した人物は、クリストファー・コロンブスの弟であるバルトロメオ・コロンブスである。彼は1494年か ら1498年にかけて、兄の不在中にイスパニョーラ島をこの称号で統治した。その後、ディエゴ・コロンスが多くの訴訟を経てこの称号を継承した。この称号 を授与されたその他の征服者としては、以下の者がいる。 1512年:フロリダとビミニの領有権を授与されたフアン・ポンセ・デ・レオン。1524年に息子のルイスに更新 15??年:パナマ地峡とサンタマルタの領有権を授与されたロドリゴ・デ・バスティダス 1514年: バスコ・ヌニェス・デ・バルボアが南太平洋を担当 1518年:フェルディナンド・マゼランが香料諸島を担当 1518年:ディエゴ・ベラスケス・デ・クエヤールがユカタン半島を担当[7] 1527年:パンフィロ・デ・ナルバエスがフロリダを担当 1527年:ペドロ・デ・アルバラドがグアテマラを担当[8] 1529年:フランシスコ・ピサロがペルーを担当[ 9]、アルゼンチンではペドロ・デ・メンドーサ 1535年:ペドロ・フェルナンデス・デ・ルゴ、サンタマルタ(テネリフェ島とラ・パルマ島のアドランタードであったアルフォンソ・フェルナンデス・デ・ルゴの息子として、彼は2代目アドランタードであった) 1537年:フロリダ、エルナンド・デ・ソト 1538年:グラナダ新王国、ゴンサロ・ヒメネス・デ・ケサダ 1540年: アルヴァル・ヌニェス・カベサ・デ・バカがリオ・デ・ラ・プラタに 1549年:ペドロ・デ・バルディビアがチリに 1565年:フアン・バスケス・デ・コロナドがコスタリカに 1565年:ペドロ・メネンデス・デ・アビレスがフロリダに 1571年:ミゲル・ロペス・デ・レガスピがフィリピンに 1595年: ソロモン諸島は、アルヴァロ・デ・メンダーニャ、そして彼の死後、妻イサベル・バレトが、ニューメキシコ王国はフアン・デ・オニャテが領有した。 |

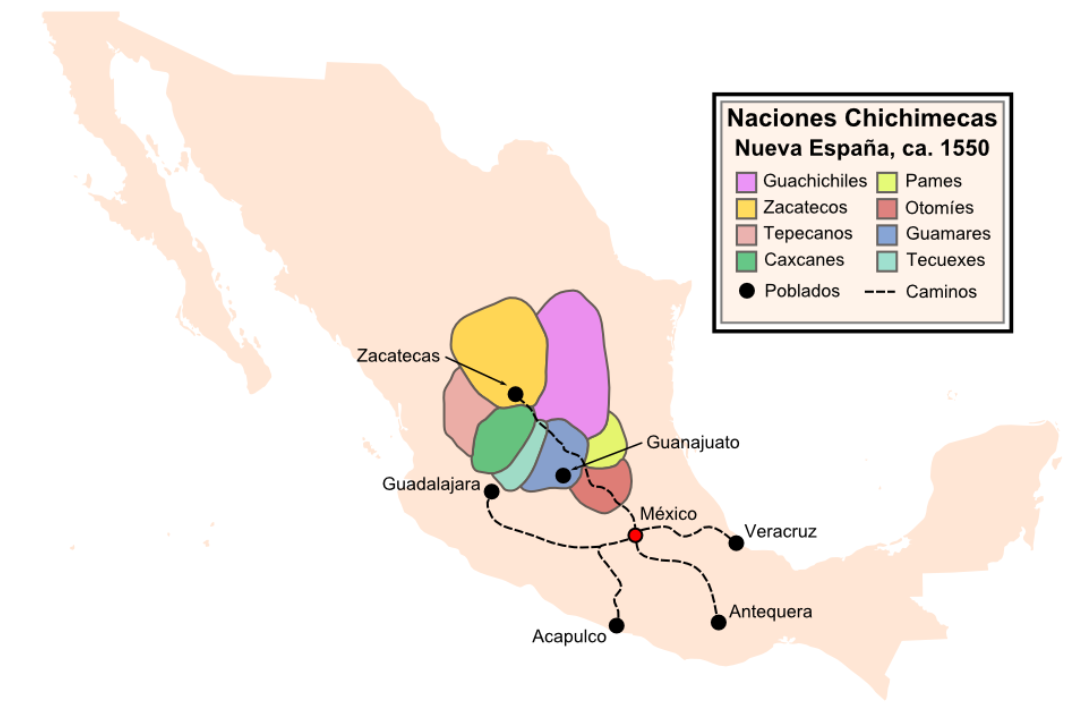

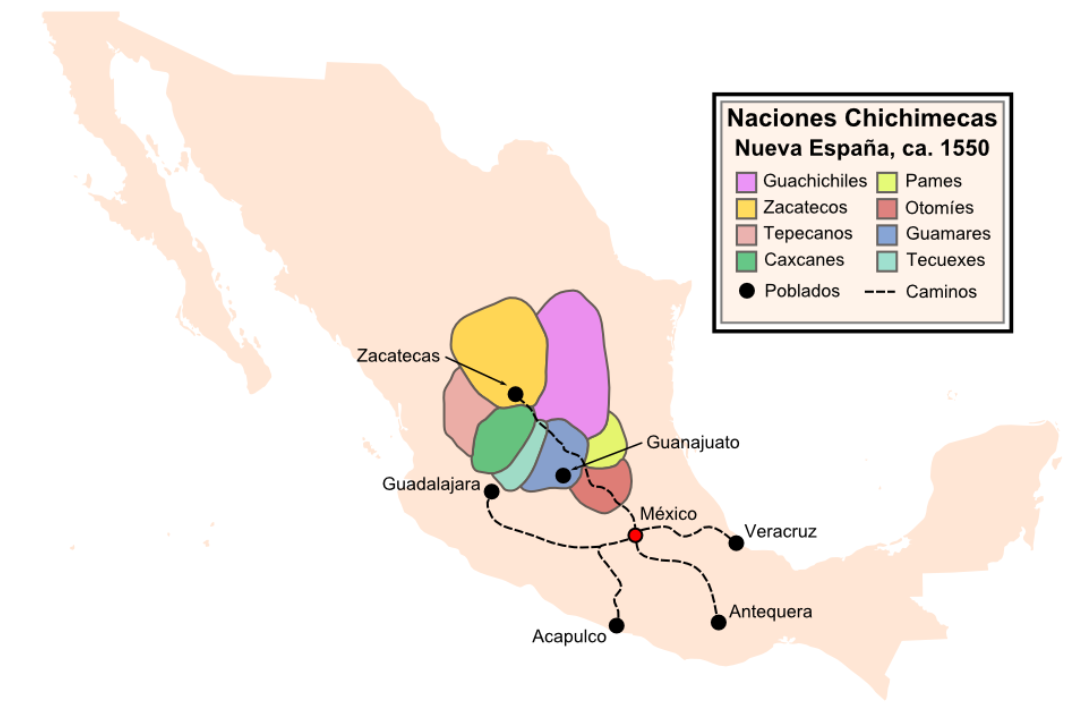

| The Mixtón War

(1540–1542) was a rebellion by the Caxcan people of northwestern Mexico

against the Spanish conquerors. The war was named after Mixtón, a hill

in Zacatecas which served as an Indigenous stronghold. The Caxcanes  The location of the native peoples in the area in which the Mixton War was fought Although other indigenous groups also fought against the Spanish in the Mixtón War, the Caxcanes were the "heart and soul" of the resistance.[1] The Caxcanes lived in the northern part of the present-day Mexican state of Jalisco, in southern Zacatecas, and Aguascalientes. They are often considered part of the Chichimeca, a generic term used by the Spaniards and Aztecs for all the nomadic and semi-nomadic Native Americans living in the deserts of northern Mexico. However, the Caxcanes seem to have been sedentary, depending upon agriculture for their livelihood and living in permanent towns and settlements. They were, perhaps, the most northerly of the agricultural, town-and-city dwelling peoples of interior Mexico.[2] The Caxcanes are believed to have spoken a Uto-Aztecan language. Other Native Americans participating in the revolt were the Zacatecos from the state of the same name. Background The first contact of the Caxcanes and other indigenous peoples of the northwestern Mexico with the Spanish, was in 1529 when Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán set forth from Mexico City with 300-400 Spaniards and 5,000 to 8,000 Aztec and Tlaxcalan allies on a march through Nayarit, Jalisco, Durango, Sinaloa, and Zacatecas.[3] Over a six-year period Guzmán, who was brutal even by the standards of the day, killed, tortured, and enslaved thousands of natives. Guzmán’s policy was to "terrorize the natives with often unprovoked killing, torture, and enslavement".[4] Guzmán and his lieutenants founded towns and Spanish settlements in the region, called Nueva Galicia, including Guadalajara in or near the homeland of the Caxcanes. But the Spaniards encountered increased resistance as they moved further from the complex hierarchical societies of Central Mexico and attempted to force natives into servitude through the encomienda system. The War  Francisco Tenamaztle, indigenous leader in the Mixtón War, statue on the main square of Nochistlán de Mejía, Zacatecas In spring 1540, the Caxcanes and their allies struck back, emboldened perhaps by the fact that Governor Francisco Vásquez de Coronado had taken more than 1,600 Spaniards and indigenous allies from the region northward with him on his expedition to what would become the American southwest.[5] The province was thus bereft of many of its most competent soldiers. The spark that set off the war was apparently the arrest of eighteen rebellious indigenous leaders and the hanging of nine of them in mid-1540. Later in the same year the natives rose up to kill, roast, and eat the encomendero Juan de Arze.[6] Spanish authorities also became aware that the natives were participating in "devilish" dances. After killing two Catholic priests, many natives fled the encomiendas and took refuge in the mountains, especially in the hill fortress of Mixtón. Acting Governor Cristóbal de Oñate led a Spanish and native force to quell the rebellion. The Caxcanes killed a delegation of one priest and ten Spanish soldiers. Oñate attempted to storm Mixtón, but the natives on the summit repelled his attack.[7] Oñate then requested reinforcements from the capital, Mexico City.[8] The command structure of the Caxcanes is unknown but the most prominent leader who emerged among them was Tenamaztle of Nochistlán, Zacatecas. The death of Pedro de Alvarado is pictured at the top left. The indigenous leader Francisco Tenamaztle faces Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza at the bottom left. Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza called upon the experienced conquistador Pedro de Alvarado to assist in putting down the revolt. Alvarado declined to await reinforcements and attacked Mixtón in June 1541 with 400 Spaniards and an unknown number of indigenous allies.[9] He was met there by an estimated 15,000 natives under Tenamaztle and Don Diego, a Zacateco. The first attack of the Spanish was repulsed with 10 Spaniards and many indigenous allies killed. Subsequent attacks by Alvarado were also unsuccessful and on June 24 Alvarado was injured when a horse fell on him. He died on July 4.[10] Emboldened, the natives attacked the city of Guadalajara in September but were repulsed.[11] The indigenous army retired to Nochistlán and other strongpoints. The Spanish authorities were now thoroughly alarmed and feared that the revolt would spread. They assembled a force of 450 Spaniards and 30,000-60,000 Aztec, Tlaxcalan, and other natives, and under Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza invaded the land of the Caxcanes.[12] With his overwhelming force, Mendoza reduced the indigenous strongholds one-by-one in a war of no quarter. On November 9, 1541, he captured the city of Nochistlán and Tenamaztle, but the indigenous leader later escaped.[13] Tenamaztle would remain at large as a guerilla until 1550. In early 1542 the stronghold of Mixtón fell to the Spaniards and the rebellion was over. In the aftermath of the natives' defeat, "thousands were dragged off in chains to the mines, and many of the survivors (mostly women and children) were transported from their homelands to work on Spanish farms and haciendas.".[14] By the viceroy's order, many of those captured after the fall of Mixtón were executed, some by cannon fire, some torn apart by dogs, and others stabbed. The reports of the excessive violence caused the Council of the Indies to undertake a secret investigation into the conduct of the viceroy.[15] Aftermath As one authority said, the success of Cortés in defeating the Aztecs in only two years "created an illusion of European superiority over the Indian as a warrior." However, the Spanish victories over the Aztecs and other complex societies "proved to be but a prelude to a far longer military struggle against the peculiar and terrifying prowess of Indian America’s more primitive warriors."[16] Victory in the Mixtón War enabled the Spanish to control the region in which Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico’s second largest city, was located. It also opened up Spanish access to the deserts of the north in which Spanish explorers would search for and find rich silver deposits.[17] After their defeat the Caxcanes were absorbed into Spanish society and lost their identity as a distinct people. They would later serve as auxiliaries to Spanish soldiers in their continued advance northward.[18] Spanish expansion after the Mixtón War would lead to the longer and even more bloody Chichimeca War (1550–1590). The Spanish were forced to change their policy from one of forcibly subjugating the native population to accommodation and gradual absorption, a process taking centuries. The Caxcanes possibly survive into the 21st century, at least in folk festivals, as the Tastuane people. Annual fiestas of the Tastuanes in towns such as Moyahua de Estrada, and Apozol, Zacatecas, commemorate the Mixtón War.[citation needed] |

ミシュトン戦争(1540年~1542年)は、スペインの征服者に対するメキシコ北西部のカシュカン族による反乱であった。この戦争は、先住民の拠点となっていたサカテカス州の丘、ミシュトンにちなんで名付けられた。 カシュカン族  ミシュトン戦争が戦われた地域における先住民族の位置 ミシュトン戦争では、他の先住民族もスペイン軍と戦ったが、カシュカン族は抵抗運動の「中心」であった[1]。カシュカン族は、現在のメキシコのハリスコ 州北部、サカテカス州南部、アグアスカリエンテス州に住んでいた。彼らはチチメカ族の一部と見なされることが多い。チチメカ族とは、スペイン人とアステカ 人が、メキシコ北部の砂漠地帯に住む遊牧民および半遊牧民のアメリカ先住民すべてを指す総称として用いた言葉である。しかし、カシュカン族は定住生活を 送っていたようで、農業を生活の糧とし、恒久的な町や集落に住んでいた。彼らはおそらく、メキシコ内陸部の農業を営み、町や都市に住む人々の中で最も北部 に住んでいた人々だった[2]。カシュカン族はウト・アステカ語族の言語を話していたと考えられている。この反乱に参加した他の先住民には、同名の州出身 のサカテコス族がいた。 背景 カシュカン族やメキシコ北西部の先住民とスペイン人の最初の接触は、1529年にヌニョ・ベルトラン・デ・グスマンが300~400人のスペイン人と 5,000~8,000人のアステカ人とトラスカラン人の同盟軍を率いてメキシコシティを出発し、 3] 6年間にわたり、当時の基準でも残忍なグスマンは、何千人もの先住民を殺害、拷問、奴隷にした。グスマンの方針は、「先住民を、理由もなく殺戮、拷問、奴 隷化によって恐怖に陥れる」ことだった[4]。グスマンとその部下たちは、この地域一帯にヌエバ・ガリシアと呼ばれる町やスペイン人入植地を建設した。そ の中には、カシュカネス族の本国またはその周辺地域であるグアダラハラも含まれていた。しかし、スペイン人は、複雑な階層社会を持つメキシコ中央部から遠 ざかるにつれ、抵抗に遭うようになった。また、エンコミエンダ制度を通じて先住民を強制労働に服従させようとしたが、これも失敗に終わった。 戦争  ミシュトン戦争の土着民指導者フランシスコ・テナマズトル、サカテカス州ノチストラン・デ・メヒアの中心広場の銅像 1540年春、カシュカン族とその同盟軍は反撃に出た。おそらく、総督フランシスコ・バスケス・デ・コロナドが フランシスコ・バスケス・デ・コロナド総督が、後にアメリカ南西部となる地域への遠征に、1,600人以上のスペイン人と先住民同盟軍を連れて北へ向かっ たという事実が彼らを勇気づけたのかもしれない[5]。こうして、この地方は有能な兵士の大半を失うことになった。戦争のきっかけとなったのは、1540 年半ばに18人の反乱を起こした先住民指導者が逮捕され、そのうち9人が絞首刑に処されたことだった。同年後半、先住民たちはエンコメンドーロ(土地所有 権を持つスペイン人)のフアン・デ・アルゼを殺し、焼き、食べるために蜂起した[6]。スペイン当局は、先住民たちが「悪魔的な」踊りに参加していること に気づいた。2人のカトリック司祭を殺害した後、多くの先住民はエンコミエンダから逃れ、特にミクストンの丘の要塞のような山中に避難した。代理知事クリ ストバル・デ・オニャテはスペイン人と先住民の部隊を率いて反乱を鎮圧した。 カシュカン族は、司祭1人とスペイン兵10人の代表団を殺害した。オニャテはミクストンの急襲を試みたが、山頂にいた先住民たちが攻撃を撃退した[7]。 オニャテはその後、首都メキシコシティに増援を要請した[8]。 カシュカンの指揮系統は不明だが、その中で最も著名な指導者は、サカテカス州ノチストランのテナマズトルであった。 左上にペドロ・デ・アルバラドの死が描かれている。左下には、先住民指導者フランシスコ・テナマズトルが副王アントニオ・デ・メンドーサと対峙している。 副王アントニオ・デ・メンドーサは、経験豊富な征服者ペドロ・デ・アルバラドに、反乱の鎮圧を支援するよう要請した。アルヴァラドは援軍を待つことを拒否 し、1541年6月に400人のスペイン人と不明数の先住民同盟軍を率いてミクストンを攻撃した[9]。彼はそこで、テナマズトルとザカテコ人のドン・ ディエゴが率いる推定1万5000人の先住民と遭遇した。スペイン軍の最初の攻撃は撃退され、10人のスペイン人と多くの先住民同盟軍が命を落とした。ア ルヴァラドによるその後の攻撃も成功せず、6月24日、アルヴァラドは馬にひかれて負傷した。 7月4日に死亡した[10]。 勢いに乗った先住民たちは9月にグアダラハラを攻撃したが、撃退された[11]。 先住民軍はノチストランや他の要塞に撤退した。スペイン当局は完全に警戒態勢に入り、反乱が拡大することを恐れた。彼らは450人のスペイン人と3万~6 万人のアステカ人、トラスカラ人、その他の先住民からなる軍勢を編成し、副王アントニオ・デ・メンドーサの指揮の下、カシュカンの土地に侵攻した [12]。圧倒的な戦力で、メンドーサは容赦のない戦争で先住民の拠点の一つ一つを制圧していった。1541年11月9日、彼はノチストランとテナマズト ルを攻略したが、先住民の指導者は後に脱走した[13]。テナマズトルは1550年までゲリラとして逃走を続けた。1542年初頭、ミクストンの拠点がス ペイン軍に制圧され、反乱は終結した。先住民の敗北の後、「何千人もの人々が鎖につながれ鉱山に連行され、生き残った多くの人々(ほとんどが女性と子供) は故郷からスペイン人の農場や大農園に連れて行かれて働かされた」[14]。総督の命令により、ミクストンの陥落後に捕らえられた多くの人々が処刑され た。その中には大砲で撃たれた者、犬に食い殺された者、刺殺された者もいた。この残虐行為の報告を受け、スペイン領インド会議は総督の行為について秘密裏 に調査することになった[15]。 その後 ある権威者が述べたように、コルテスがわずか2年でアステカ人を破った成功は、「ヨーロッパ人が戦士としてインディアンよりも優れているという幻想を生み 出した」。しかし、スペインがアステカやその他の複合社会を制圧したことは、「インディアンアメリカのもっと原始的な戦士たちの独特で恐ろしい戦力に対す る、はるかに長い軍事闘争の前触れにすぎなかった」[16]。 ミシュトン戦争の勝利により、スペインはメキシコ第2の都市であるハリスコ州グアダラハラがある地域を支配することが可能になった。また、スペイン人探検家が豊富な銀鉱脈を発見することになる北部の砂漠へのスペイン人の進出も実現した[17]。 カシュカンの人々は敗北後、スペイン社会に取り込まれ、独自の民族としてのアイデンティティを失った。彼らはその後、スペイン兵の補助部隊として、スペイ ン軍の北進に協力することになる[18]。ミクストゥン戦争後のスペインの拡張政策は、さらに長期化し、より血なまぐさいチチメカ戦争(1550年 ~1590年)へとつながった。スペインは、先住民を強制的に征服するという政策から、融和と段階的な吸収という政策へと転換せざるを得なくなり、そのプ ロセスには数世紀を要した。 カシュカ人は、少なくとも民俗祭においては、21世紀にも存続している可能性がある。タストゥアネ族としてである。モヤフア・デ・エストラーダやアポソル(サカテカス州)などの町で行われるタストゥアネ族の年間祭りは、ミシュトン戦争を記念するものである。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mixt%C3%B3n_War | |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099