ヒラリー・パットナム

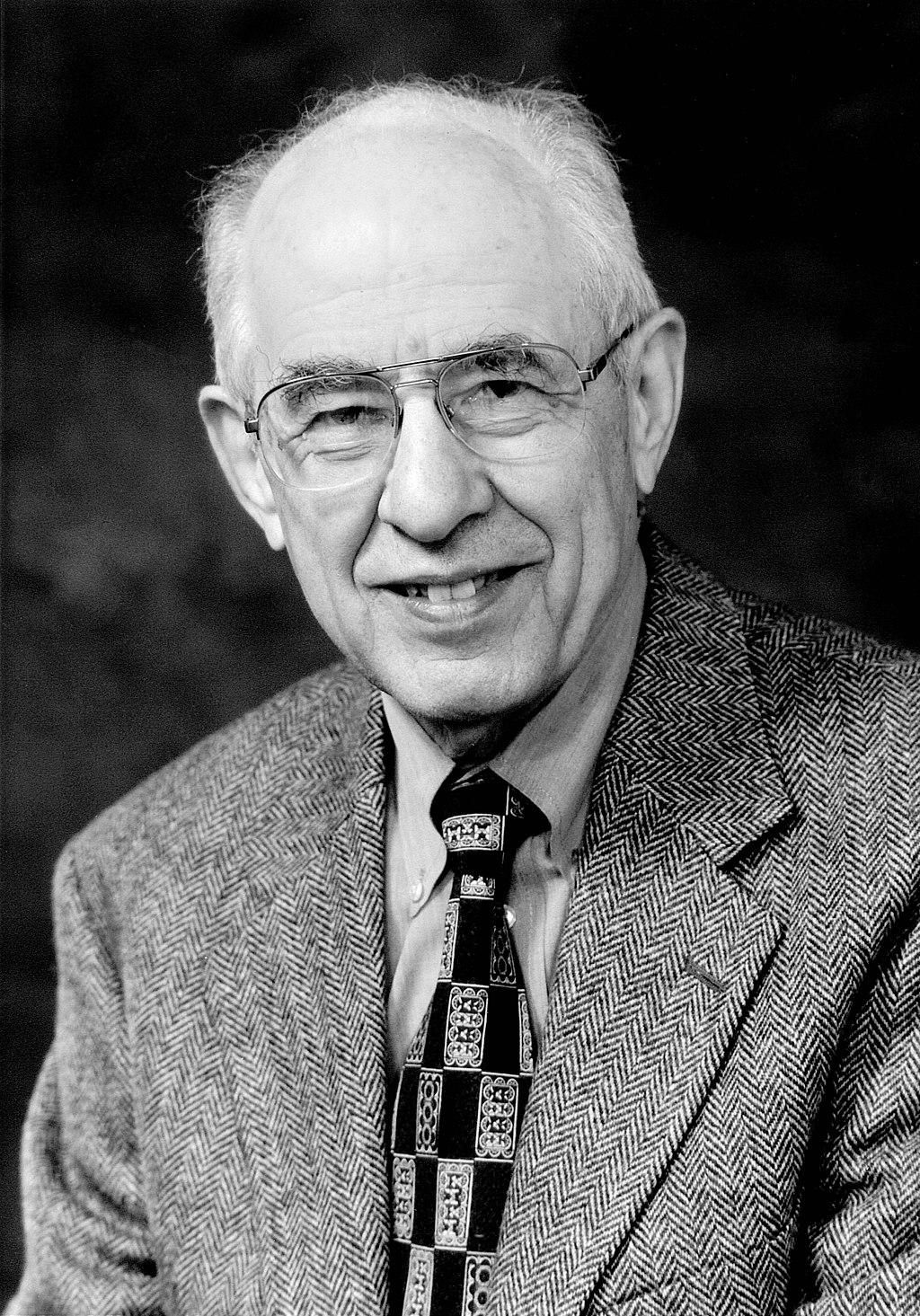

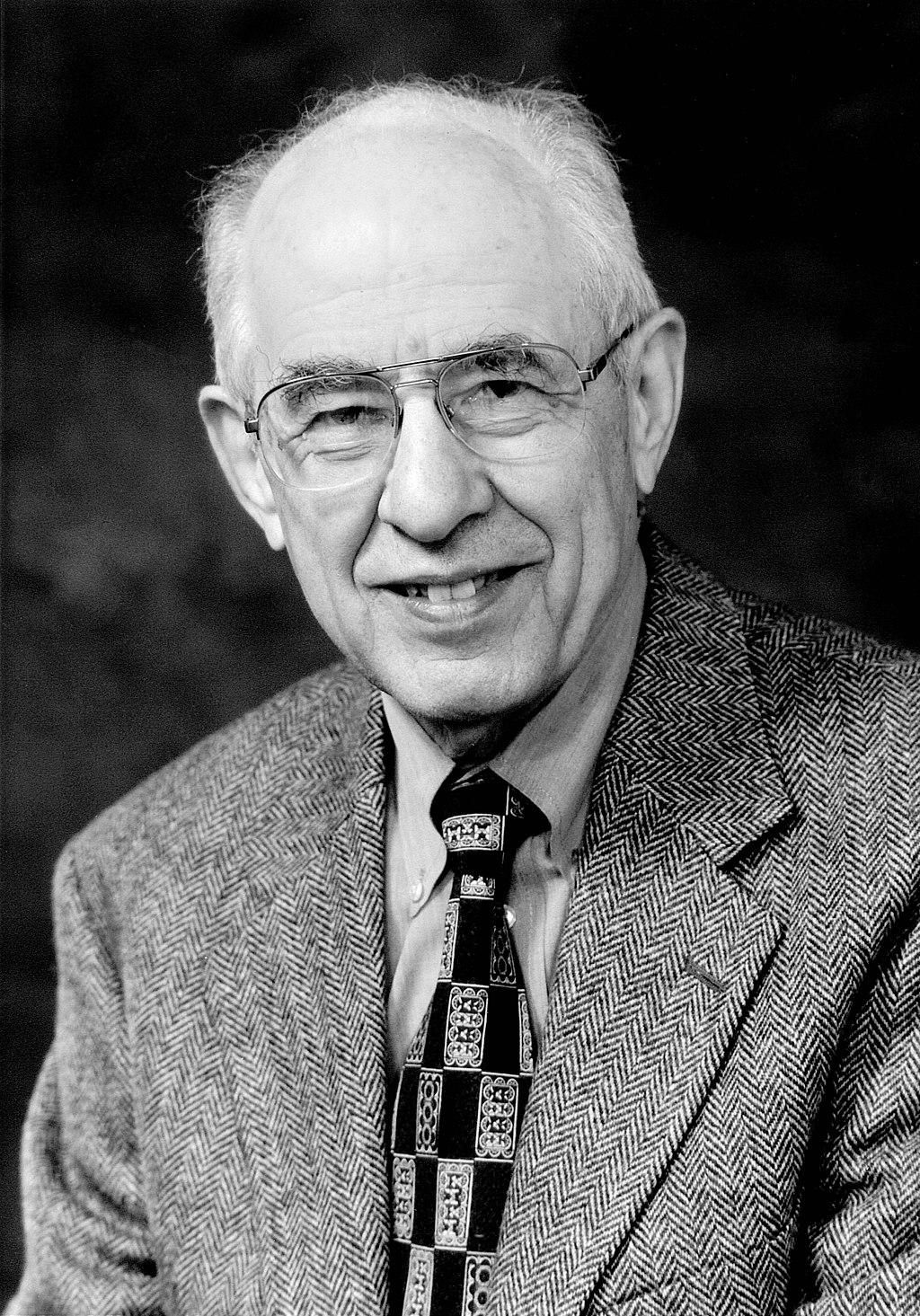

Hilary Whitehall Putnam, 1926-2016

☆ヒラリー・ホワイトホール・パトナム(Hilary Whitehall Putnam、1926 年7月31日 - 2016年3月13日)は、20世紀後半の分析哲学におけるアメリカの哲学者、数学者、計算機科学者である。彼は、心の哲学、言語哲学、数学哲学、科学哲 学の研究に貢献した。哲学以外の分野では、パトナムは数学とコンピュータ科学に貢献した。マーティン・デイヴィスとともに、ブール代数満足度問題のデービ ス・パトナムアルゴリズムを開発し、ヒルベルトの第10問題の解決不能性を証明するのに貢献した。パトナムは、自身の哲学上の立場についても、他者のそれ と同様に厳密な精査を適用し、それぞれの立場を厳密に分析し、その欠陥を明らかにするまで続けた。その結果、自身の立場を頻繁に変更するとの評判を得るこ ととなった 。心の哲学において、パトナムは心の複数の実現可能性という自身の仮説に基づき、心的状態と物理的状態の同一性を否定し、心身問題に関する有力な理論であ る機能主義の概念を支持した。言語哲学では、ソール・クリプキらとともに、参照の因果理論を展開し、 意味の外部性という概念を導入し、ツイン・アースと呼ばれる思考実験に基づいて、意味の独自の理論を構築した。 数学哲学では、パトナムとクワインは、数学的実体の実在性を主張するクワイン=パトナムの不可欠性論を展開し、後に数学は純粋に論理的ではなく、「準経験 的」であるという見解を支持した。 認識論では、パトナムは「脳は容器の中にある」という思考実験を批判した。この思考実験は、認識論的懐疑論に強力な論拠を提供しているように見えるが、パ トナムはその首尾一貫性を疑うことでこれを批判したのである。形而上学では、パトナムは当初は形而上学的実在論という立場を支持していたが、最終的にはそ の最も著名な批判者の一人となり、まず「内的実在論」という見解を採用したが、後にこれを放棄した。こうした見解の変化にもかかわらず、パトナムは科学実 在論に終始こだわり続けた。科学実在論とは、成熟した科学理論は、物事のあり方をほぼ正確に記述しているという見解である。晩年の研究では、パトナムはア メリカの実用主義、ユダヤ哲学、倫理学にますます関心を抱くようになり、より幅広い哲学の伝統に関わるようになった。また、メタ哲学にも関心を示し、彼が 狭量で誇張された関心事とみなしたものから「哲学を刷新」しようとした。彼は時に政治的に物議を醸す人物であり、特に1960年代後半から1970年代初 頭にかけて進歩的労働党に関与していたことで知られている。

| Hilary Whitehall

Putnam (/ˈpʌtnəm/; July 31, 1926 – March 13, 2016) was an American

philosopher, mathematician, computer scientist, and figure in analytic

philosophy in the second half of the 20th century. He contributed to

the studies of philosophy of mind, philosophy of language, philosophy

of mathematics, and philosophy of science.[5] Outside philosophy,

Putnam contributed to mathematics and computer science. Together with

Martin Davis he developed the Davis–Putnam algorithm for the Boolean

satisfiability problem[6] and he helped demonstrate the unsolvability

of Hilbert's tenth problem.[7] Putnam applied equal scrutiny to his own philosophical positions as to those of others, subjecting each position to rigorous analysis until he exposed its flaws.[8] As a result, he acquired a reputation for frequently changing his positions.[9] In philosophy of mind, Putnam argued against the type-identity of mental and physical states based on his hypothesis of the multiple realizability of the mental, and for the concept of functionalism, an influential theory regarding the mind–body problem.[5][10] In philosophy of language, along with Saul Kripke and others, he developed the causal theory of reference, and formulated an original theory of meaning, introducing the notion of semantic externalism based on a thought experiment called Twin Earth.[11] In philosophy of mathematics, Putnam and W. V. O. Quine developed the Quine–Putnam indispensability argument, an argument for the reality of mathematical entities,[12] later espousing the view that mathematics is not purely logical, but "quasi-empirical".[13] In epistemology, Putnam criticized the "brain in a vat" thought experiment, which appears to provide a powerful argument for epistemological skepticism, by challenging its coherence.[14] In metaphysics, he originally espoused a position called metaphysical realism, but eventually became one of its most outspoken critics, first adopting a view he called "internal realism",[15] which he later abandoned. Despite these changes of view, throughout his career Putnam remained committed to scientific realism, roughly the view that mature scientific theories are approximately true descriptions of ways things are.[16] In his later work, Putnam became increasingly interested in American pragmatism, Jewish philosophy, and ethics, engaging with a wider array of philosophical traditions. He also displayed an interest in metaphilosophy, seeking to "renew philosophy" from what he identified as narrow and inflated concerns.[17] He was at times a politically controversial figure, especially for his involvement with the Progressive Labor Party in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[18] |

ヒラリー・ホワイトホール・パトナム(/ˈpʌtnəm/、1926年

7月31日 -

2016年3月13日)は、20世紀後半の分析哲学におけるアメリカの哲学者、数学者、計算機科学者である。彼は、心の哲学、言語哲学、数学哲学、科学哲

学の研究に貢献した。[5]

哲学以外の分野では、パトナムは数学とコンピュータ科学に貢献した。マーティン・デイヴィスとともに、ブール代数満足度問題のデービス・パトナムアルゴリ

ズムを開発し[6]、ヒルベルトの第10問題の解決不能性を証明するのに貢献した。[7] パトナムは、自身の哲学上の立場についても、他者のそれと同様に厳密な精査を適用し、それぞれの立場を厳密に分析し、その欠陥を明らかにするまで続けた。 [8] その結果、自身の立場を頻繁に変更するとの評判を得ることとなった 。心の哲学において、パトナムは心の複数の実現可能性という自身の仮説に基づき、心的状態と物理的状態の同一性を否定し、心身問題に関する有力な理論であ る機能主義の概念を支持した。言語哲学では、ソール・クリプケらとともに、参照の因果理論を展開し、 意味の外部性という概念を導入し、ツイン・アースと呼ばれる思考実験に基づいて、意味の独自の理論を構築した。 数学哲学では、パトナムとクワインは、数学的実体の実在性を主張するクワイン=パトナムの不可欠性論を展開し、後に数学は純粋に論理的ではなく、「準経験 的」であるという見解を支持した。 認識論では、パトナムは「脳は容器の中にある」という思考実験を批判した。この思考実験は、認識論的懐疑論に強力な論拠を提供しているように見えるが、パ トナムはその首尾一貫性を疑うことでこれを批判したのである。[14] 形而上学では、パトナムは当初は形而上学的実在論という立場を支持していたが、最終的にはその最も著名な批判者の一人となり、まず「内的実在論」という見 解を採用したが、後にこれを放棄した。こうした見解の変化にもかかわらず、パトナムは科学実在論に終始こだわり続けた。科学実在論とは、成熟した科学理論 は、物事のあり方をほぼ正確に記述しているという見解である。[16] 晩年の研究では、パトナムはアメリカの実用主義、ユダヤ哲学、倫理学にますます関心を抱くようになり、より幅広い哲学の伝統に関わるようになった。また、 メタ哲学にも関心を示し、彼が狭量で誇張された関心事とみなしたものから「哲学を刷新」しようとした。[17] 彼は時に政治的に物議を醸す人物であり、特に1960年代後半から1970年代初頭にかけて進歩的労働党に関与していたことで知られている。[18] |

| Life Hilary Whitehall Putnam was born on July 31, 1926, in Chicago, Illinois.[19] His father, Samuel Putnam, was a scholar of Romance languages, columnist, and translator who wrote for the Daily Worker, a publication of the American Communist Party, from 1936 to 1946.[20] Because of his father's commitment to communism, Putnam had a secular upbringing, although his mother, Riva, was Jewish.[8] In early 1927, six months after Hilary's birth, the family moved to France, where Samuel was under contract to translate the surviving works of François Rabelais.[17][19] In a 2015 autobiographical essay, Putnam said that his first childhood memories were from his life in France, and his first language was French.[17] Putnam completed the first two years of his primary education in France before he and his parents returned to the U.S. in 1933, settling in Philadelphia.[19] There, he attended Central High School, where he met Noam Chomsky, who was a year behind him.[17]: 8 The two remained friends—and often intellectual opponents—for the rest of Putnam's life.[21] Putnam studied philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, receiving his B.A. degree and becoming a member of the Philomathean Society, the country's oldest continually existing collegiate literary society.[8][22] He did graduate work in philosophy at Harvard University[8] and later at UCLA's philosophy department, where he received his Ph.D. in 1951 for his dissertation, The Meaning of the Concept of Probability in Application to Finite Sequences.[2][23] Putnam's dissertation supervisor Hans Reichenbach was a leading figure in logical positivism, the dominant school of philosophy of the day; one of Putnam's most consistent positions was his rejection of logical positivism as self-defeating.[22] Over the course of his life, Putnam was his own philosophical adversary, changing his positions on philosophical questions and critiquing his previous views.[11] After obtaining his PhD, Putnam taught at Northwestern University (1951–52), Princeton University (1953–61), and MIT (1961–65). For the rest of his career, Putnam taught at Harvard's philosophy department, becoming Cogan University Professor. In 1962, he married fellow philosopher Ruth Anna Putnam (born Ruth Anna Jacobs), who took a teaching position in philosophy at Wellesley College.[22][24][25] Rebelling against the antisemitism they experienced during their youth, the Putnams decided to establish a traditional Jewish home for their children.[26] Since they had no experience with the rituals of Judaism, they sought out invitations to other Jewish homes for Seder. They began to study Jewish rituals and Hebrew, became more interested in Judaism, self-identified as Jews, and actively practiced Judaism. In 1994, Hilary celebrated a belated bar mitzvah service; Ruth Anna's bat mitzvah was celebrated four years later.[26] In the 1960s and early 1970s, Putnam was an active supporter of the American Civil Rights Movement and he was also an active opponent of the Vietnam War.[18] In 1963, he organized one of MIT's first faculty and student anti-war committees.[22][24] After moving to Harvard in 1965, he organized campus protests and began teaching courses on Marxism. Putnam became an official faculty advisor to the Students for a Democratic Society and in 1968 a member of the Progressive Labor Party (PLP).[22][24] He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1965.[27] After 1968, his political activities centered on the PLP.[18] The Harvard administration considered these activities disruptive and attempted to censure Putnam.[28][29] Putnam permanently severed his relationship with the PLP in 1972.[30] In 1997, at a meeting of former draft resistance activists at Boston's Arlington Street Church, he called his involvement with the PLP a mistake. He said he had been impressed at first with the PLP's commitment to alliance-building and its willingness to attempt to organize from within the armed forces.[18] In 1976, Putnam was elected president of the American Philosophical Association. The next year, he was selected as Walter Beverly Pearson Professor of Mathematical Logic in recognition of his contributions to the philosophy of logic and mathematics. While breaking with his radical past, Putnam never abandoned his belief that academics have a particular social and ethical responsibility toward society. He continued to be forthright and progressive in his political views, as expressed in the articles "How Not to Solve Ethical Problems" (1983) and "Education for Democracy" (1993).[22] Putnam was a Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1999.[31] He retired from teaching in June 2000, becoming Cogan University Professor Emeritus, but as of 2009 continued to give a seminar almost yearly at Tel Aviv University. He also held the Spinoza Chair of Philosophy at the University of Amsterdam in 2001.[32] His corpus includes five volumes of collected works, seven books, and more than 200 articles. Putnam's renewed interest in Judaism inspired him to publish several books and essays on the topic.[33] With his wife, he co-authored several essays and a book on the late-19th-century American pragmatist movement.[22] For his contributions in philosophy and logic, Putnam was awarded the Rolf Schock Prize in 2011[34] and the Nicholas Rescher Prize for Systematic Philosophy in 2015.[35] Putnam died at his home in Arlington, Massachusetts, on March 13, 2016.[36] At the time of his death, Putnam was Cogan University Professor Emeritus at Harvard University. |

生涯 ヒラリー・ホワイトホール・パトナムは1926年7月31日、イリノイ州シカゴで生まれた。[19] 父親のサミュエル・パトナムはロマンス諸語学者であり、コラムニスト、翻訳家でもあり、1936年から1946年までアメリカ共産党の機関紙『デイリー・ ワーカー』に寄稿していた。[20] 父親が共産主義に傾倒していたため、パトナムは世俗的な環境で育ったが、母親のリヴァは ユダヤ人であった。[8] 1927年初頭、ヒラリーが生まれてから6か月後、一家はフランスに移住した。サミュエルはフランソワ・ラブレーの遺作の翻訳契約を結んでいた。[17] [19] 2015年の自伝的エッセイで、パトナムは最初の幼少期の記憶はフランスでの生活からであり、最初の言語はフランス語だったと述べている。[17] パトナムはフランスで初等教育の最初の2年間を終えた後、両親とともに 1933年に両親とともにアメリカに戻り、フィラデルフィアに定住した。[19] そこで彼はセントラル高校に通い、1学年下のノーム・チョムスキーと出会った。[17]:8 2人はその後も友人であり、しばしば知的な論争相手でもあった。[21] パトナムはペンシルベニア大学で哲学を学び、学士号を取得し、 同国で最も古い歴史を持つカレッジ制の文芸協会である。[8][22] ハーバード大学で哲学の大学院課程を修了し[8]、その後カリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校(UCLA)の哲学部で研究を続け、1951年に「有限シーケ ンスへの応用における確率概念の意味」という論文で博士号を取得した。[2][23] パトナムの論文指導教官であったハンス・ライヘンバッハは、当時の哲学界を支配していた論理実証主義の第一人者であった。。パトナムの最も一貫した立場 は、論理実証主義を自己矛盾的として拒絶したことである。[22]生涯を通じて、パトナムは自身の哲学上の敵対者であり、哲学上の疑問に対する立場を変 え、それまでの見解を批判した。[11] 博士号取得後、パトナムはノースウェスタン大学(1951年から1952年)、プリンストン大学(1953年から1961年)、マサチューセッツ工科大学 (1961年から1965年)で教鞭をとった。その後はハーバード大学の哲学部の教授となり、コーガン大学特別教授となった。1962年、彼は同じく哲学 者のルース・アンナ・パトナム(旧姓ルース・アンナ・ジェイコブス)と結婚した。彼女はウェルズリー大学の哲学の教職に就いた。[22][24][25] 若い頃に経験した反ユダヤ主義に反発したパトナム夫妻は、子供たちのために伝統的なユダヤ人の家庭を築くことを決意した。[26] ユダヤ教の儀式の経験がなかったため、彼らはセダー(過ぎ越しの祭)のために他のユダヤ人の家庭への招待状を探した。彼らはユダヤ教の儀式やヘブライ語の 学習を始め、ユダヤ教への関心を深め、自らをユダヤ人と認識し、ユダヤ教を積極的に実践するようになった。1994年、ヒラリーは遅ればせながらバル・ミ ツヴァの儀式を行い、ルース・アンナのバット・ミツヴァはそれから4年後に執り行われた。 1960年代から1970年代初頭にかけて、パトナムはアメリカ公民権運動の積極的な支援者であり、 また、ベトナム戦争の反対派としても積極的に活動していた。[18] 1963年には、MIT初の教員と学生による反戦委員会を組織した。[22][24] 1965年にハーバード大学に移ってからは、キャンパスでの抗議活動を行い、マルクス主義のコースを教え始めた。パトナムは、民主的社会を求める学生の公 式な学内アドバイザーとなり、1968年には進歩労働党(PLP)の党員となった。[22][24] 1965年には、アメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された。[27] 1968年以降、彼の政治活動はPLPに集中した。 ハーバード大学当局はこれらの活動を混乱を招くものと考え、パットナムを非難しようとした。[28][29] パットナムは1972年にPLPとの関係を完全に断った。[30] 1997年、ボストンのアーリントン・ストリート教会での元徴兵忌避活動家の会合で、彼はPLPとの関わりを「間違いだった」と述べた。彼は、当初は PLPの同盟構築への献身と軍内部からの組織化を試みる意欲に感銘を受けていたと述べた。 1976年、パトナムはアメリカ哲学協会の会長に選出された。翌年、彼は論理学と数学への貢献が認められ、数学論理学のウォルター・ビバリー・ピアソン教 授に選出された。急進的な過去を断ち切った後も、パトナムは学問には社会に対する特別な社会的・倫理的責任があるという信念を捨てなかった。彼は政治的見 解において率直かつ進歩的な姿勢を貫き、そのことは「倫理的問題の解決法」(1983年)や「民主主義のための教育」(1993年)などの論文にも表れて いる。[22] パトナムは英国学士院の通信会員であった。1999年にはアメリカ哲学協会の会員に選出された。[31] 2000年6月に教職を退き、コーガン大学名誉教授となったが、2009年現在もテルアビブ大学でほぼ毎年セミナーを行っている。また、2001年にはア ムステルダム大学でスピノザ哲学講座の教授も務めた。[32] 彼の著作には、5巻の論文集、7冊の著書、200以上の論文がある。ユダヤ教への関心を再び抱いたことで、このテーマに関するいくつかの著書や論文を発表 するようになった。[33] 妻と共同で、19世紀後半のアメリカのプラグマティズム運動に関するいくつかの論文と著書を執筆した。[22] 哲学と論理学への貢献により、パトナムは2011年にロルフ・ショック賞[34]、2015年にニコラス・レシャー体系哲学賞[35]を受賞した。パトナ ムは2016年3月13日、マサチューセッツ州アーリントンの自宅で死去した。[36] 死去時、パトナムはハーバード大学のコーガン大学名誉教授であった。 |

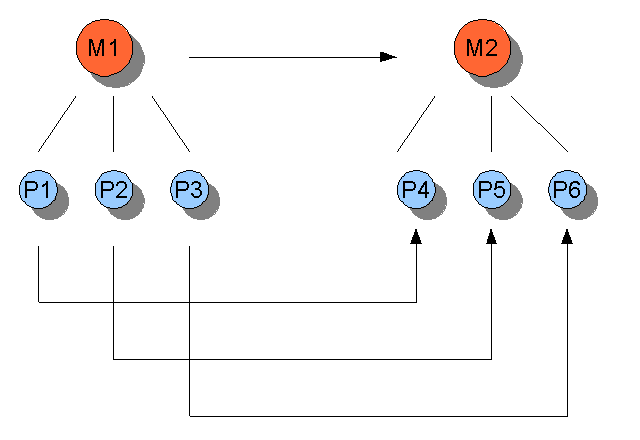

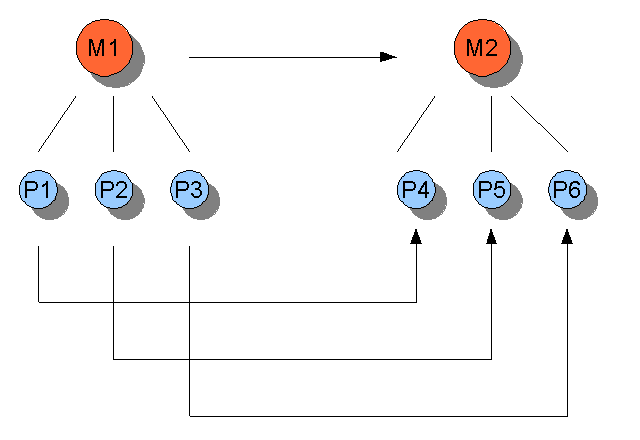

| Philosophy of mind Multiple realizability  An illustration of multiple realizability. M stands for mental and P stands for physical. It can be seen that more than one P can instantiate one M, but not vice versa. Causal relations between states are represented by the arrows (M1 goes to M2, etc.). Putnam's best-known work concerns philosophy of mind. His most noted original contributions to that field came in several key papers published in the late 1960s that set out the hypothesis of multiple realizability.[37] In these papers, Putnam argues that, contrary to the famous claim of the type-identity theory, pain may correspond to utterly different physical states of the nervous system in different organisms even if they all experience the same mental state of "being in pain".[37] Putnam cited examples from the animal kingdom to illustrate his thesis. He asked whether it was likely that the brain structures of diverse types of animals realize pain, or other mental states, the same way. If they do not share the same brain structures, they cannot share the same mental states and properties, in which case mental states must be realized by different physical states in different species. Putnam then took his argument a step further, asking about such things as the nervous systems of alien beings, artificially intelligent robots and other silicon-based life forms. These hypothetical entities, he contended, should not be considered incapable of experiencing pain just because they lack human neurochemistry. Putnam concluded that type-identity theorists had been making an "ambitious" and "highly implausible" conjecture that could be disproved by one example of multiple realizability. This is sometimes called the "likelihood argument", as it focuses on the claim that multiple realizability is more likely than type-identity theory.[38][39]: 640 Putnam also formulated an a priori argument in favor of multiple realizability based on what he called "functional isomorphism". He defined the concept in these terms: "Two systems are functionally isomorphic if 'there is a correspondence between the states of one and the states of the other that preserves functional relations'." In the case of computers, two machines are functionally isomorphic if and only if the sequential relations among states in the first exactly mirror the sequential relations among states in the other. Therefore, a computer made of silicon chips and one made of cogs and wheels can be functionally isomorphic but constitutionally diverse. Functional isomorphism implies multiple realizability.[38][39]: 637 Putnam, Jerry Fodor, and others argued that along with being an effective argument against type-identity theories, multiple realizability implies that any low-level explanation of higher-level mental phenomena is insufficiently abstract and general. Functionalism, which identifies mental kinds with functional kinds that are characterized exclusively in terms of causes and effects, abstracts from the level of microphysics, and therefore seemed to be a better explanation of the relation between mind and body. In fact, there are many functional kinds, including mousetraps and eyes, that are multiply realized at the physical level.[38][40][39]: 648–649 [41]: 6 Multiple realizability has been criticized on the grounds that, if it were true, research and experimentation in the neurosciences would be impossible.[42] According to William Bechtel and Jennifer Mundale, to be able to conduct such research in the neurosciences, universal consistencies must either exist or be assumed to exist in brain structures. It is the similarity (or homology) of brain structures that allows us to generalize across species.[42] If multiple realizability were an empirical fact, results from experiments conducted on one species of animal (or one organism) would not be meaningful when generalized to explain the behavior of another species (or organism of the same species).[43] Jaegwon Kim, David Lewis, Robert Richardson and Patricia Churchland have also criticized metaphysical realism.[44][45][46][47] Machine state functionalism Putnam himself put forth the first formulation of such a functionalist theory. This formulation, now called "machine-state functionalism", was inspired by analogies Putnam and others made between the mind and Turing machines.[48] The point for functionalism is the nature of the states of the Turing machine. Each state can be defined in terms of its relations to the other states and to the inputs and outputs, and the details of how it accomplishes what it accomplishes and of its material constitution are completely irrelevant. According to machine-state functionalism, the nature of a mental state is just like the nature of a Turing machine state. Just as "state one" simply is the state in which, given a particular input, such-and-such happens, so being in pain is the state which disposes one to cry "ouch", become distracted, wonder what the cause is, and so forth.[49] Rejection of functionalism Ian Hacking called Representation and Reality (1988) a book that "will mostly be read as Putnam’s denunciation of his former philosophical psychology, to which he gave the name 'functionalism'."[50] Writing in Noûs, Barbara Hannon described "the inventor of functionalism" as arguing "against his own former computationalist views".[51] Putnam's change of mind was primarily due to the difficulties computational theories have in explaining certain intuitions with respect to the externalism of mental content.[52] This is illustrated by his Twin Earth thought experiment.[non-primary source needed] In 1988 Putnam also developed a separate argument against functionalism based on Fodor's generalized version of multiple realizability. Asserting that functionalism is really a watered-down identity theory in which mental kinds are identified with functional kinds, he argued that mental kinds may be multiply realizable over functional kinds. The argument for functionalism is that the same mental state could be implemented by the different states of a universal Turing machine.[53][non-primary source needed] Despite Putnam's rejection of functionalism, it has continued to flourish and been developed into numerous versions by Fodor, David Marr, Daniel Dennett, and David Lewis, among others.[54] Functionalism helped lay the foundations for modern cognitive science[54] and is the dominant theory of mind in philosophy today.[55] By 2012 Putnam accepted a modification of functionalism called "liberal functionalism". The view holds that "what matters for consciousness and for mental properties generally is the right sort of functional capacities and not the particular matter that subserves those capacities".[56] The specification of these capacities may refer to what goes on outside the organism's "brain", may include intentional idioms, and need not describe a capacity to compute something or other.[56] Putnam himself formulated one of the main arguments against functionalism, the Twin Earth thought experiment, though there have been additional criticisms. John Searle's Chinese room argument (1980) is a direct attack on the claim that thought can be represented as a set of functions. It is designed to show that it is possible to mimic intelligent action with a purely functional system, without any interpretation or understanding. Searle describes a situation in which a person who speaks only English is locked in a room with Chinese symbols in baskets and a rule book in English for moving the symbols around. People outside the room instruct the person inside to follow the rule book for sending certain symbols out of the room when given certain symbols. The people outside the room speak Chinese and are communicating with the person inside via the Chinese symbols. According to Searle, it would be absurd to claim that the English speaker inside "knows" Chinese based on these syntactic processes alone. This argument attempts to show that systems that operate merely on syntactic processes cannot realize any semantics (meaning) or intentionality (aboutness). Searle thus attacks the idea that thought can be equated with following a set of syntactic rules and concludes that functionalism is an inadequate theory of the mind.[57] Ned Block has advanced several other arguments against functionalism.[58] |

心の哲学 多重実現可能性  多重実現可能性の説明。Mはmental(心的)、Pはphysical(物理的)を表す。1つのMを複数のPが実現できるが、その逆はありえないことがわかる。状態間の因果関係は矢印で表される(M1がM2になる、など)。 パトナムの最も有名な業績は、心の哲学に関するものである。この分野における彼の最も著名な独自の貢献は、1960年代後半に発表された複数の主要論文 で、多重実現可能性の仮説を提示したものである。[37]これらの論文において、パトナムは、 同一性理論の有名な主張とは逆に、たとえ「痛い」という同じ精神状態を経験していたとしても、異なる生物では神経系のまったく異なる物理的状態が痛みに相 当している可能性がある、とパットナムは主張している。[37] パットナムは自身の論文を説明するために、動物界の例を挙げた。彼は、多様な種類の動物が、痛みやその他の精神状態を同じ方法で認識している可能性がある かどうかを問うた。もし脳の構造が同じでないのであれば、同じ精神状態や性質を共有することはできない。その場合、精神状態は異なる種において異なる物理 的状態によって認識される必要がある。その後、パトナムは議論をさらに一歩進め、宇宙人の神経系、人工知能ロボット、その他のシリコンベースの生命体など について問うた。仮説上のこれらの存在は、人間の神経化学が欠如しているからといって、痛みを経験できないと考えるべきではないと彼は主張した。プルイッ トは、タイプ同一説の論者は「野心的」で「非常にありそうにない」仮説を立てており、それは複数の実現可能性の例によって反証できると結論づけた。これは 「可能性の論証」と呼ばれることもある。なぜなら、複数の実現可能性はタイプ同一性理論よりも可能性が高いという主張に焦点を当てているからである。 [38][39]: 640 また、パトナムは「機能的等価性」と呼ぶものに基づいて、複数の実現可能性を支持する先験的論証を展開した。彼はその概念を次のように定義した。「2つの システムは、機能的同型である。すなわち、一方の状態と他方の状態の間に機能的関係を維持する対応関係がある場合」である。コンピュータの場合、2つのマ シンは、一方の状態のシーケンシャルな関係が他方の状態のシーケンシャルな関係と完全に一致する場合にのみ、機能的同型である。したがって、シリコンチッ プで構成されたコンピュータと歯車や車輪で構成されたコンピュータは、機能的には同型であるが、構造的には異なる可能性がある。機能的等価性は、複数の実 現可能性を意味する。[38][39]: 637 パトナム、ジェリー・フォダー、およびその他の人々は、型同一性理論に対する有効な反論であるとともに、複数の実現可能性は、高次精神現象の低次レベルで の説明は抽象的かつ一般的には不十分であることを意味すると主張した。心的種類を、原因と結果によってのみ特徴づけられる機能的種類と同一視する機能主義 は、ミクロ物理学のレベルから抽象化しているため、心と身体の関係をよりよく説明しているように思われた。実際、マウストラップや目など、多くの機能的種 類が物理的レベルで多重的に実現されている。[38][40][39]: 648–649 [41]: 6 多重的な実現可能性は、 もしそれが真実であれば、神経科学における研究や実験は不可能になるという理由からである。[42] ウィリアム・ベッテルとジェニファー・マンデールによると、神経科学においてそのような研究を行うためには、脳の構造に普遍的な一貫性が存在するか、ある いは存在すると仮定しなければならない。脳構造の類似性(または相同性)によって、種を超えた一般化が可能になるのである。[42] もし複数の実現可能性が経験的事実であるならば、ある種の動物(またはある生物)に対して行われた実験の結果は、別の種の行動(または 。[43] キム、デビッド・ルイス、ロバート・リチャードソン、パトリシア・チャーチランドもまた形而上学的実在論を批判している。[44][45][46] [47] 機械状態機能主義 パトナム自身が、このような機能主義理論の最初の定式化を提示した。この理論は現在「機械状態機能主義」と呼ばれているが、パトナムや他の人々が心と チューリング機械を比較したことに着想を得たものである。機能主義の要点はチューリング機械の状態の性質である。各状態は他の状態や入力・出力との関係に よって定義することができ、それが何をどのように達成するか、またその物質的構成の詳細は全く関係がない。機械状態機能主義によると、心的状態の本質は チューリング機械の状態の本質とまったく同じである。「状態1」が単に特定の入力が与えられた場合に「~が起こる」という状態であるように、痛みを感じる ことは「痛い」と叫んだり、気が散ったり、原因が何なのか考えたりする状態である。 機能主義の拒絶 イアン・ハッキングは『表象と現実』(1988年)を「ほとんどがパトナムによる『機能主義』という名を与えられたかつての哲学心理学への非難として読ま れるだろう」本であると評した。[50] ノウス誌に寄稿したバーバラ・ハノンは、「機能主義の発明者」が「自身のかつての計算論的見解に反対する」と論じていると述べた。 [51] パトナムの考えの変化は、計算理論が心的内容の外部性に関するある直観を説明することの難しさに主として起因する。[52] これは彼の「双子の地球」思考実験によって示されている。[非一次資料が必要] 1988年、パトナムはまた、フォダーの一般化された多重実現可能性のバージョンを基に、機能主義に対する別の論点を展開した。機能主義は、心の種類が機 能の種類と同一視される、実質的には弱められた同一説であると主張し、心の種類は機能の種類に重複して実現される可能性があると論じた。機能主義の論拠 は、同じ心的状態は、ユニバーサル・チューリング・マシンの異なる状態によって実装できるというものである。[53][非一次資料が必要] パトナムが機能主義を否定したにもかかわらず、機能主義はその後も盛んに研究され、フォダー、デビッド・マール、 ダニエル・デネット、デイヴィッド・ルイスなどによって、多数のバージョンが開発されている。[54] 機能主義は、現代の認知科学の基礎を築くのに役立ち[54]、今日の哲学における心の支配的な理論である。[55] 2012年までに、パトナムは「リベラル機能主義」と呼ばれる機能主義の修正を受け入れた。この見解では、「意識や精神的な性質にとって重要なのは、適切 な機能的能力であり、その能力を支える特定の物質ではない」とされている。[56] これらの能力の仕様は、生物の「脳」の外側で起こることを指す場合も 意図的なイディオムを含み、何かを計算する能力を説明する必要はない。[56] パトナム自身も、機能主義に対する主な反論のひとつである「双子の地球」思考実験を考案したが、さらに追加の批判も存在する。ジョン・サールの「中国語の 部屋」論(1980年)は、思考が関数の集合として表現できるという主張に対する直接的な攻撃である。これは、解釈や理解を一切必要とせずに、純粋な関数 システムで知的な行動を模倣できることを示すことを目的としている。サールは、英語しか話さない人物が、バスケットに入った中国語の記号と、その記号を移 動させるための英語のルールブックがある部屋に閉じ込められている状況を説明する。部屋の外にいる人々は、特定の記号が与えられたら、その記号を部屋の外 に送るというルールブックに従うよう、部屋の中にいる人に指示する。部屋の外にいる人々は中国語を話し、部屋の中の人物と中国語の記号を使ってコミュニ ケーションを取る。 ジョン・サールによれば、このような構文処理プロセスだけに基づいて、英語話者が中国語を「知っている」と主張するのは馬鹿げている。この議論は、単に統 語論的なプロセスだけで機能するシステムでは、意味論(意味)や志向性(aboutness)を認識することはできないことを示そうとしている。 したがって、Searleは思考が統語論的なルールに従うことと同一視できるという考え方を攻撃し、機能主義は心の理論として不十分であると結論づけてい る。[57] Ned Blockは機能主義に対して、他にもいくつかの反論を展開している。[58] |

| Philosophy of language Semantic externalism One of Putnam's contributions to philosophy of language is his semantic externalism, the claim that terms' meanings are determined by factors outside the mind, encapsulated in his slogan that "meaning just ain't in the head". His views on meaning, first laid out in Meaning and Reference (1973), then in The Meaning of "Meaning" (1975), use his "Twin Earth" thought experiment to defend this thesis.[59][60] Twin Earth shows this, according to Putnam, since on Twin Earth everything is identical to Earth, except that its lakes, rivers and oceans are filled with XYZ rather than H2O. Consequently, when an earthling, Fredrick, uses the Earth-English word "water", it has a different meaning from the Twin Earth-English word "water" when used by his physically identical twin, Frodrick, on Twin Earth. Since Fredrick and Frodrick are physically indistinguishable when they utter their respective words, and since their words have different meanings, meaning cannot be determined solely by what is in their heads.[61] This led Putnam to adopt a version of semantic externalism with regard to meaning and mental content.[14][38] The philosopher of mind and language Donald Davidson, despite his many differences of opinion with Putnam, wrote that semantic externalism constituted an "anti-subjectivist revolution" in philosophers' way of seeing the world. Since Descartes's time, philosophers had been concerned with proving knowledge from the basis of subjective experience. Thanks to Putnam, Saul Kripke, Tyler Burge and others, Davidson said, philosophy could now take the objective realm for granted and start questioning the alleged "truths" of subjective experience.[62] Theory of meaning Along with Kripke, Keith Donnellan, and others, Putnam contributed to what is known as the causal theory of reference.[5] In particular, he maintained in The Meaning of "Meaning" that the objects referred to by natural kind terms—such as "tiger", "water", and "tree"—are the principal elements of the meaning of such terms. There is a linguistic division of labor, analogous to Adam Smith's economic division of labor, according to which such terms have their references fixed by the "experts" in the particular field of science to which the terms belong. So, for example, the reference of the term "lion" is fixed by the community of zoologists, the reference of the term "elm tree" is fixed by the community of botanists, and chemists fix the reference of the term "table salt" as sodium chloride. These referents are considered rigid designators in the Kripkean sense and are disseminated outward to the linguistic community.[38][63]: 33 Putnam specifies a finite sequence of elements (a vector) for the description of the meaning of every term in the language. Such a vector consists of four components: the object to which the term refers, e.g., the object individuated by the chemical formula H2O; a set of typical descriptions of the term, referred to as "the stereotype", e.g., "transparent", "colorless", and "hydrating"; the semantic indicators that place the object into a general category, e.g., "natural kind" and "liquid"; the syntactic indicators, e.g., "concrete noun" and "mass noun". Such a "meaning-vector" provides a description of the reference and use of an expression within a particular linguistic community. It provides the conditions for its correct usage and makes it possible to judge whether a single speaker attributes the appropriate meaning to it or whether its use has changed enough to cause a difference in its meaning. According to Putnam, it is legitimate to speak of a change in the meaning of an expression only if the reference of the term, and not its stereotype, has changed.[17]: 339–340 But since no possible algorithm can determine which aspect—the stereotype or the reference—has changed in a particular case, it is necessary to consider the usage of other expressions of the language.[38][non-primary source needed] Since there is no limit to the number of such expressions to be considered, Putnam embraced a form of semantic holism.[64] Despite the many changes in his other positions, Putnam consistently adhered to semantic holism. Michael Dummett, Jerry Fodor, Ernest Lepore, and others have identified problems with this position. In the first place, they suggest that, if semantic holism is true, it is impossible to understand how a speaker of a language can learn the meaning of an expression in the language. Given the limits of our cognitive abilities, we will never be able to master the whole of the English (or any other) language, even based on the (false) assumption that languages are static and immutable entities. Thus, if one must understand all of a natural language to understand a single word or expression, language learning is simply impossible. Semantic holism also fails to explain how two speakers can mean the same thing when using the same expression, and therefore how any communication is possible between them. Given a sentence P, since Fred and Mary have each mastered different parts of the English language and P is related in different ways to the sentences in each part, P means one thing to Fred and something else to Mary. Moreover, if P derives its meaning from its relations with all the sentences of a language, as soon as the vocabulary of an individual changes by the addition or elimination of a sentence, the totality of relations changes, and therefore also the meaning of P. As this is a common phenomenon, the result is that P has two different meanings in two different moments in the life of the same person. Consequently, if one accepts the truth of a sentence and then rejects it later on, the meaning of what one rejected and what one accepted are completely different and therefore one cannot change opinions with regard to the same sentences.[65][page needed][66][page needed][67][page needed] |

言語哲学 意味外部主義 パトナムが言語哲学に貢献したもののひとつに、用語の意味は心以外の要因によって決定されるという主張である意味外部主義がある。これは「意味は頭の中に はない」という彼のスローガンに集約されている。意味に関する彼の見解は、まず『意味と参照』(1973年)で、次に『「意味」の意味』(1975年)で 提示され、この論文を擁護するために「ツイン・アース」思考実験が用いられている。[59][60] ツイン・アースでは、湖や川、海がH2OではなくXYZで満たされていることを除いて、すべてが地球と同一である。したがって、地球人のフレデリックが 「水」という地球英語の単語を使用した場合、その物理的に同一の双子のフロドリックがツイン・アースで「水」というツイン・アース英語の単語を使用した場 合とは異なる意味になる。フレドリックとフロドリックは、それぞれの言葉を口にする際には外見上は区別がつかないし、彼らの言葉の意味が異なるため、頭の 中身だけでは意味を決定できない。[61] これにより、パトナムは意味と心的内容に関して、意味外部論のバージョンを採用することになった 。心の哲学と言語学の専門家であるドナルド・デヴィッドソンは、パトナムとの意見の相違は多々あるものの、意味外部論は哲学者の世界の見方に「反主観主義 的革命」をもたらしたと述べている。デカルト以来、哲学者たちは主観的経験を基礎とした知識の証明に重点を置いていた。パトナム、ソール・クリプケ、タイ ラー・バージェス、その他の人々のおかげで、デビッドソンは、哲学は今や客観的領域を当然視し、主観的経験の主張される「真実」を問い直すことができるよ うになったと述べた。 意味の理論 クリプケ、キース・ドネラン、その他の人々とともに、パトナムは 参照の因果理論として知られるものに貢献した。[5] 特に、著書『「意味」の意味』において、自然種概念(「虎」、「水」、「木」など)によって参照される対象は、そのような用語の意味の主要な要素であると 主張した。アダム・スミスの経済学における分業に類似した言語学上の分業があり、それによれば、そのような用語は、その用語が属する特定の科学分野におけ る「専門家」によって参照が固定される。例えば、「ライオン」という用語の参照先は動物学者のコミュニティによって固定され、「ニレの木」という用語の参 照先は植物学者のコミュニティによって固定され、「食塩」という用語の参照先は化学者によって塩化ナトリウムとして固定される。これらの参照先は、クリプ ケ流の厳格な指定子とみなされ、言語コミュニティに広められる。[38][63]: 33 パトナムは、言語の各用語の意味を記述するために、有限の要素のシーケンス(ベクトル)を特定している。このようなベクトルは4つの要素で構成される。 すなわち、用語が指し示す対象、例えば化学式H2Oで特定される物体、 「ステレオタイプ」と呼ばれる用語の典型的な記述のセット、例えば「透明 透明」、「無色」、および「水和」など、 その対象を一般的なカテゴリーに位置づける意味上の指標、例えば「自然種」や「液体」など、 構文上の指標、例えば「具象名詞」や「集合名詞」などである。 このような「意味ベクトル」は、特定の言語コミュニティ内での表現の参照と使用の記述を提供する。また、その正しい使用法の条件を提供し、単一の話者がそ の表現に適切な意味を付与しているか、あるいはその使用法が変化して意味に違いが生じているかを判断することを可能にする。パトナムによれば、表現の意味 の変化について語ることは、その用語の参照先が変化した場合のみ正当である。ただし、ステレオタイプではなく参照先が変化した場合に限る。[17]: 339–340 しかし、特定のケースにおいてステレオタイプと参照先のどちらが変化したかを決定できるアルゴリズムは存在しないため、 、その言語の他の表現の用法を考慮する必要がある。[38][非プライマリソースが必要] 考慮すべき表現の数に制限はないため、パトナムは意味論的全体論の一形態を受け入れた。[64] 他の立場では多くの変更があったにもかかわらず、パトナムは一貫して意味論的全体論に固執した。マイケル・ダメット、ジェリー・フォドー、アーネスト・レ ポー、その他の人々は、この立場に問題があることを指摘している。まず第一に、意味 holism が真であるならば、言語話者がその言語における表現の意味をどのようにして学習できるのか理解できない、と彼らは指摘する。認知能力に限界がある以上、言 語は静的で不変な存在であるという(誤った)前提に立ったとしても、英語(またはその他の言語)のすべてを習得することは決してできない。したがって、自 然言語をすべて理解しなければ、単語や表現を理解できないのであれば、言語学習は不可能である。また、意味論的全体論では、2人の話し手が同じ表現を使用 しているときに、どのようにして同じことを意味し、それゆえにどのようにしてコミュニケーションが可能になるのかを説明できない。文Pを例にとると、フ レッドとメアリーはそれぞれ異なる部分の英語を習得しており、Pはそれぞれの部分の文と異なる形で関連しているため、Pはフレッドにとっては1つの意味を 持ち、メアリーにとっては別の意味を持つ。さらに、Pが言語のすべての文章との関係から意味を導くものである場合、個人の語彙が文章の追加や削除によって 変化すると、関係の全体が変化し、したがってPの意味も変化する。これはよくある現象であるため、結果として、同じ人物の人生における2つの異なる時点に おいて、Pは2つの異なる意味を持つことになる。したがって、ある文章の真実性を一旦受け入れ、その後それを否定した場合、否定したものと受け入れたもの との意味は全く異なるため、同じ文章に関して意見を変えることはできない。[65][要ページ番号][66][要ページ番号][67][要ページ番号] |

| Philosophy of mathematics In the philosophy of mathematics, Putnam has utilized indispensability arguments to argue for a realist interpretation of mathematics. In his 1971 book Philosophy of Logic, he presented what has since been called the locus classicus of the Quine–Putnam indispensability argument.[12] The argument, which he attributed to Willard Van Orman Quine, is presented in the book as "quantification over mathematical entities is indispensable for science, both formal and physical; therefore we should accept such quantification; but this commits us to accepting the existence of the mathematical entities in question."[68] According to Charles Parsons, Putnam "very likely" endorsed this version of the argument in his early work, but later came to deny some of the views present in it.[69]: 128 In 1975, Putnam formulated his own indispensability argument based on the no miracles argument in the philosophy of science, saying, "I believe that the positive argument for realism [in science] has an analogue in the case of mathematical realism. Here too, I believe, realism is the only philosophy that doesn't make the success of the science a miracle".[70] According to Putnam, Quine's version of the argument was an argument for the existence of abstract mathematical objects, while Putnam's own argument was simply for a realist interpretation of mathematics, which he believed could be provided by a "mathematics as modal logic" interpretation that need not imply the existence of abstract objects.[69]: 61–62  The Quine–Putnam indispensability argument has been extremely influential in the philosophy of mathematics, inspiring continued debate and development of the argument in contemporary philosophy of mathematics. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, many in the field consider it the best argument for mathematical realism.[12] Prominent counterarguments come from Hartry Field, who argues that mathematics is not indispensable to science, and Penelope Maddy and Elliott Sober, who dispute whether we are committed to mathematical realism even if it is indispensable to science.[12] |

数学哲学 数学哲学において、パトナムは数学の現実主義的解釈を主張するために必要不可欠性論法を利用した。1971年の著書『論理学の哲学』において、彼はクワイ ン=パトナムの不可欠性論証の典型例と呼ばれるものを提示した。[12] ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインに帰するこの論証は、同著において「数学的対象に対する数量化は、形式科学であれ物理科学であれ、科学にとって不 可欠である。したがって、このような数量化を受け入れるべきである。しかし、これは問題となっている数学的対象の存在を受け入れることを意味する」と提示 されている。 チャールズ・パーソンズによると、パトナムは初期の著作において「おそらく」このバージョンの議論を支持していたが、後にその一部の見解を否定するように なったという。[69]:128 1975年、パトナムは科学哲学における「奇跡は起こらない」という議論に基づいて、独自の「不可欠性」の議論を展開した。「私は、科学における実在論の 肯定的な議論には、数学的実在論の場合に類似したものがあると考えている。ここでも、科学の成功を奇跡とはしない唯一の哲学は、現実主義であると私は信じ ている」と述べている。[70] パトナムによれば、クワインの主張は抽象的な数学的対象の存在を主張するものであり、 一方、パトナム自身の主張は、数学の現実主義的解釈を求めるものであり、彼は「様相論理としての数学」という解釈によって、抽象的な対象の存在を暗示する ことなく、その解釈が可能であると考えていた。[69]: 61–62  クワイン=パトナムの不可欠性論は数学哲学に多大な影響を与え、現代の数学哲学における議論と発展を促した。スタンフォード哲学事典によると、この議論は 数学的実在論の最良の論拠であると考える専門家は多い。[12] 著名な反論は、数学は科学にとって不可欠ではないと主張するハートリー・フィールド、および、数学が科学にとって不可欠であるとしても、我々が数学的実在 論に固執しているかどうかは疑問であると論じるペネロペ・マディとエリオット・ソーバーによるものである。[12] |

| Mathematics and computer science Putnam has contributed to scientific fields not directly related to his work in philosophy.[5] As a mathematician, he contributed to the resolution of Hilbert's tenth problem in mathematics. This problem (now known as Matiyasevich's theorem or the MRDP theorem) was settled by Yuri Matiyasevich in 1970, with a proof that relied heavily on previous research by Putnam, Julia Robinson and Martin Davis.[73]  In computer science, Putnam is known for the Davis–Putnam algorithm for the Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT), developed with Martin Davis in 1960.[5] The algorithm finds whether there is a set of true or false values that satisfies a given Boolean expression so that the entire expression becomes true. In 1962, they further refined the algorithm with the help of George Logemann and Donald W. Loveland. It became known as the DPLL algorithm. It is efficient and still forms the basis of most complete SAT solvers.[6] |

数学と計算機科学 パトナムは、哲学の仕事とは直接関係のない科学分野にも貢献している。[5] 数学者として、彼は数学におけるヒルベルトの第10問題の解決に貢献した。この問題(現在ではマティアセビッチの定理またはMRDP定理として知られてい る)は、パトナム、ジュリア・ロビンソン、マーティン・デイヴィスによる過去の研究に大きく依存した証明によって、1970年にユーリ・マティアセビッチ によって解決された。[73]  コンピュータサイエンスにおいて、パトナムはマーティン・デイビスとともに1960年に開発したブール代数満足度問題(SAT)のデービス・パトナムアル ゴリズムで知られている。[5] このアルゴリズムは、与えられたブール式を満たす真または偽の値の集合があるかどうかを判断し、式全体が真になるようにする。1962年には、ジョージ・ ローゲマンとドナルド・W・ラブランドの協力を得て、さらに改良を加えた。このアルゴリズムはDPLLアルゴリズムとして知られるようになった。これは効 率的であり、現在でも最も完全なSATソルバーの基礎となっている。[6] |

Epistemology A "brain in a vat"—Putnam uses this thought experiment to argue that skeptical scenarios are impossible. In epistemology, Putnam is known for his argument against skeptical scenarios based on the "brain in a vat" thought experiment (a modernized version of Descartes's evil demon hypothesis). The argument is that one cannot coherently suspect that one is a disembodied "brain in a vat" placed there by some "mad scientist".[14][77] This follows from the causal theory of reference. Words always refer to the kinds of things they were coined to refer to, the kinds of things their user, or the user's ancestors, experienced. So, if some person, Mary, is a "brain in a vat", whose every experience is received through wiring and other gadgetry created by the mad scientist, then Mary's idea of a brain does not refer to a real brain, since she and her linguistic community have never encountered such a thing. To her a brain is actually an image fed to her through the wiring. Nor does her idea of a vat refer to a real vat. So if, as a brain in a vat, she says, "I'm a brain in a vat", she is actually saying, "I'm a brain-image in a vat-image", which is incoherent. On the other hand, if she is not a brain in a vat, then saying that she is a brain in a vat is still incoherent, because she actually means the opposite. This is a form of epistemological externalism: knowledge or justification depends on factors outside the mind and is not solely determined internally.[14][77] Putnam has clarified that his real target in this argument was never skepticism, but metaphysical realism, which he thought implied such skeptical scenarios were possible.[78][79] Since realism of this kind assumes the existence of a gap between how one conceives the world and the way the world really is, skeptical scenarios such as this one (or Descartes's evil demon) present a formidable challenge. By arguing that such a scenario is impossible, Putnam attempts to show that this notion of a gap between one's concept of the world and the way it is is absurd. One cannot have a "God's-eye" view of reality. One is limited to one's conceptual schemes, and metaphysical realism is therefore false.[80][81] Putnam's brain in a vat argument has been criticized.[82] Crispin Wright argues that Putnam's formulation of the brain-in-a-vat scenario is too narrow to refute global skepticism. The possibility that one is a recently disembodied brain in a vat is not undermined by semantic externalism. If a person has lived her entire life outside the vat—speaking the English language and interacting normally with the outside world—prior to her "envatment" by a mad scientist, when she wakes up inside the vat, her words and thoughts (e.g., "tree" and "grass") will still refer to the objects or events in the external world that they referred to before her envatment.[79] |

認識論 「脳の入った桶」—パトナムは、この思考実験を用いて、懐疑的なシナリオは不可能であると論じている。 認識論において、パトナムは「桶の中の脳」思考実験(デカルトの悪魔仮説の現代版)に基づく懐疑論シナリオに対する反論で知られている。その主張は、自分 が「狂気の科学者」によって置かれた「桶の中の脳」であると首尾一貫して疑うことはできないというものである。[14][77] これは、参照の因果理論から導かれる。言葉は常に、その言葉が指し示すように作られたもの、その言葉を使う人、あるいはその人の先祖が経験したもの、を指 し示す。 したがって、ある人物メアリーが「バットの中の脳」であり、その人物のあらゆる経験が狂気の科学者が作り出した配線やその他の装置を通じて受け取られてい るとすると、メアリーが抱く「脳」の概念は現実の脳を指し示すものではない。なぜなら、メアリーとその言語共同体は、そのようなものに出会ったことがない からだ。彼女にとって脳とは、実際には配線を通して彼女に送られるイメージである。また、彼女の考える「容器」も、現実の容器を指しているわけではない。 したがって、容器の中の脳である彼女が「私は容器の中の脳だ」と言う場合、実際には「私は容器の中の脳のイメージだ」と言っていることになり、これは支離 滅裂である。一方、もし彼女が「脳の入った容器」の中の人ではない場合、「脳の入った容器」の中の人であると言うことは、やはり支離滅裂である。なぜな ら、彼女が実際に意味しているのはその反対だからだ。これは認識論的外部性の形態である。知識や正当性は心以外の要因に依存し、心の中でのみ決定されるも のではない。[14][77] パトナムは、この議論における彼の真の標的は決して懐疑論ではなく、形而上学的実在論であったと明確にしている。彼は、そのような懐疑的なシナリオが起こ りうることを示唆していると考えていた。。この種の現実主義は、人が世界をどう捉えているかということと、世界が実際どうであるかということとの間に ギャップが存在することを前提としているため、このような懐疑的なシナリオ(あるいはデカルトの悪魔)は、非常に困難な課題を提示する。このようなシナリ オはありえないと主張することで、パトナムは、世界に対する概念と現実の世界との間にギャップがあるという考え方が不合理であることを示そうとしている。 人は現実に対して「神の目」のような見方を持つことはできない。人は自分の概念体系に制限されるため、形而上学的実在論は誤りである。[80][81] パトナムの脳漕内脳の議論は批判されている。[82] クリスピン・ライトは、パトナムの脳漕内脳シナリオの定式化は、グローバルな懐疑論を反証するには狭すぎると主張している。人が最近脳漕内の脳になった可 能性は、意味論的外部主義によって損なわれるものではない。もし、その人物が狂気の科学者によって「脳内」に閉じ込められる前に、英語を話し、外部世界と 通常通りに交流しながら、生涯を「脳内」以外の場所で過ごしていた場合、その人物が「脳内」で目覚めたとき、その人物の言葉や思考(例えば、「木」や 「草」)は、依然として「脳内」に閉じ込められる前に言及していた外部世界の物体や事象を指し示すだろう。[79] |

| Metaphilosophy and ontology In the late 1970s and the 1980s, stimulated by results from mathematical logic and by some of Quine's ideas, Putnam abandoned his long-standing defense of metaphysical realism—the view that the categories and structures of the external world are both causally and ontologically independent of the conceptualizations of the human mind—and adopted a rather different view, which he called "internal realism" or "pragmatic realism".[83]: 404 [84][85] Internal realism is the view that, although the world may be causally independent of the human mind, the world's structure—its division into kinds, individuals and categories—is a function of the human mind, and hence the world is not ontologically independent. The general idea is influenced by Immanuel Kant's idea of the dependence of our knowledge of the world on the categories of thought.[86] According to Putnam, the problem with metaphysical realism is that it fails to explain the possibility of reference and truth.[87] According to the metaphysical realist, our concepts and categories refer because they match up in some mysterious manner with the categories, kinds and individuals inherent in the external world. But how is it possible that the world "carves up" into certain structures and categories, the mind carves up the world into its own categories and structures, and the two carvings perfectly coincide? The answer must be that the world does not come pre-structured but that the human mind and its conceptual schemes impose structure on it.[81] In Reason, Truth, and History, Putnam identified truth with what he termed "idealized rational acceptability." The theory is that a belief is true if it would be accepted by anyone under ideal epistemic conditions.[15][83]: §7.1 Nelson Goodman formulated a similar notion in Fact, Fiction and Forecast (1956). "We have come to think of the actual as one among many possible worlds. We need to repaint that picture. All possible worlds lie within the actual one", Goodman wrote.[88] Putnam rejected this form of social constructivism, but retained the idea that there can be many correct descriptions of reality. None of these descriptions can be scientifically proven to be the "one, true" description of the world. He thus accepted "conceptual relativity"—the view that it may be a matter of choice or convention, e.g., whether mereological sums exist, or whether spacetime points are individuals or mere limits.[89][non-primary source needed] Curtis Brown has criticized Putnam's internal realism as a disguised form of subjective idealism, in which case it is subject to the traditional arguments against that position. In particular, it falls into the trap of solipsism. That is, if existence depends on experience, as subjective idealism maintains, and if one's consciousness ceased to exist, then the rest of the universe would also cease to exist.[86] In his reply to Simon Blackburn in the volume Reading Putnam, Putnam renounced internal realism[11] because it assumed a "cognitive interface" model of the relation between the mind and the world. Under the increasing influence of William James and the pragmatists, he adopted a direct realist view of this relation.[90][91][92]: 23–24 Although he abandoned internal realism, Putnam still resisted the idea that any given thing or system of things can be described in exactly one complete and correct way. He came to accept metaphysical realism in a broader sense, rejecting all forms of verificationism and all talk of our "making" the world.[93] In the philosophy of perception, Putnam came to endorse direct realism, according to which perceptual experiences directly present one with the external world. He once further held that there are no mental representations, sense data, or other intermediaries between the mind and the world.[52] By 2012, however, he rejected this commitment in favor of "transactionalism", a view that accepts both that perceptual experiences are world-involving transactions, and that these transactions are functionally describable (provided that worldly items and intentional states may be referred to in the specification of the function). Such transactions can further involve qualia.[56][94] |

形而上学と存在論 1970年代後半から1980年代にかけて、数学的論理学の成果やクワインのいくつかの考えに触発され、パトナムは長年擁護してきた形而上学的実在論(す なわち、外部世界のカテゴリーと構造は、人間の概念化から因果的にも存在論的にも独立しているという見解)を放棄し、 彼はそれを「内的実在論」または「実利主義的実在論」と呼んだ。[83]:404[84][85] 内的実在論は、世界は人間の心とは因果的に独立しているかもしれないが、世界の構造、すなわち種類、個体、カテゴリーへの分割は人間の心の機能であり、し たがって世界は存在論的には独立していないという見解である。この一般的な考え方は、イマニュエル・カントの「世界に対する我々の知識は思考の範疇に依存 する」という考え方に影響を受けている。[86] パトナムによれば、形而上学的実在論の問題点は、参照と真理の可能性を説明できないことである。[87] 形而上学的実在論者によれば、我々の概念と範疇は、外部世界に内在する範疇、種類、個体と、ある不可解な方法で一致しているため、参照される。しかし、世 界が特定の構造やカテゴリーに「区分」され、心は世界を独自のカテゴリーや構造に区分し、その2つの区分が完全に一致することは、どのようにして可能なの であろうか。その答えは、世界はあらかじめ構造化されているのではなく、人間の心とその概念体系が世界に構造を押し付けているということである。パトナム は著書『理性、真理、歴史』において、真理を「理想化された合理的な受容性」と定義した。その理論は、理想的な認識論的条件のもとで誰でもが受け入れるの であれば、その信念は真実であるというものである。[15][83]: §7.1 ネルソン・グッドマンは『事実、虚構、予測』(1956年)で同様の概念を提示した。「私たちは、現実を多くの可能な世界の1つとして考えるようになっ た。私たちはその絵を塗り替える必要がある。すべての可能な世界は、現実の世界の中に存在している」とグッドマンは書いた。[88] パトナムは、この種の社会構成主義を否定したが、現実の正しい記述は多数存在しうるという考えは維持した。 これらの記述のいずれも、科学的に「唯一の真の」世界の記述であると証明することはできない。したがって、彼は「概念相対性」を受け入れた。すなわち、例 えば、モレオロジー和が存在するかどうか、時空間の点が個体であるか単なる限界であるかといったことは、選択や慣習の問題であるという見解である。 [89][非一次資料が必要] カーティス・ブラウンは、パトナムの内的実在論を主観的観念論の偽装された形態として批判している。その場合、その立場に対する伝統的な議論の対象とな る。特に、それは唯我論の罠に陥る。つまり、主観的観念論が主張するように、存在が経験に依存しており、もし個人の意識が存在しなくなれば、宇宙の残りの 部分も存在しなくなるということである。[86] サイモン・ブラックバーンへの返答の中で、パトナムは『パトナムを読む』の中で、内的実在論を放棄した。[11] なぜなら、内的実在論は心と世界の関係における「認知インターフェース」モデルを前提としているからである。ウィリアム・ジェームズやプラグマティストの 影響が強まる中、彼はこの関係について直接実在論的な見解を採用した。[90][91][92]:23-24 内部実在論を放棄したとはいえ、パトナムは、あらゆる事物や事物の体系が、完全に正確な唯一の方法で記述できるという考えには依然として抵抗を示した。彼 はより広義の形而上学的実在論を受け入れるようになり、あらゆる検証主義の形や、世界を「作り出す」という考えをすべて否定した。 知覚の哲学において、パトナムは直接実在論を支持するようになった。直接実在論によれば、知覚経験は直接的に外部世界を提示する。また、かつては心的表 象、感覚データ、あるいは心と世界との間の他の仲介物はないと主張していたこともある[52]。しかし、2012年までに、彼はこの主張を退け、「トラン ザクショナリズム」という見解を支持するようになった。トランザクショナリズムは、知覚経験は世界を巻き込んだトランザクションであり、これらのトランザ クションは機能的に記述可能である(機能の仕様において、世界的な項目や意図的な状態を参照できる場合)という両方の見解を受け入れるものである。このよ うなトランザクションには、クオリアが関与している可能性もある。[56][94] |

| Quantum mechanics During his career, Putnam espoused various positions on the interpretation of quantum mechanics.[95] In the 1960s and 1970s, he contributed to the quantum logic tradition, holding that the way to resolve quantum theory's apparent paradoxes is to modify the logical rules by which propositions' truth values are deduced.[96][97] Putnam's first foray into this topic was "A Philosopher Looks at Quantum Mechanics" in 1965, followed by his 1969 essay "Is Logic Empirical?". He advanced different versions of quantum logic over the years,[98] and eventually turned away from it in the 1990s, due to critiques by Nancy Cartwright, Michael Redhead, and others.[11]: 265–280 In 2005, he wrote that he rejected the many-worlds interpretation because he could see no way for it to yield meaningful probabilities.[99] He found both de Broglie–Bohm theory and the spontaneous collapse theory of Ghirardi, Rimini, and Weber to be promising, yet also dissatisfying, since it was not clear that either could be made fully consistent with special relativity's symmetry requirements.[95] |

量子力学 パトナムは、そのキャリアの中で、量子力学の解釈についてさまざまな立場を支持してきた。[95] 1960年代と1970年代には、量子論の伝統に貢献し、量子論の明らかな矛盾を解決する方法は、 命題の真偽値が導かれる論理規則を修正することであると主張した。[96][97] このテーマに関するパトナムの最初の試みは、1965年の「哲学者が量子力学を見る」であり、1969年のエッセイ「論理は経験的か?」が続いた。彼は長 年にわたって量子論理の異なるバージョンを推し進めていたが[98]、最終的にはナンシー・カートライトやマイケル・レッドヘッドなどの批判により、 1990年代にはその考えを改めることとなった[11]:265–280。2005年には、彼は多世界解釈を否定した理由について、 有意義な確率を導く方法が見出せなかったためであると述べている。[99] ド・ブロイ=ボーム理論とギラルディ、リミニ、ウェーバーの自発的崩壊理論の両方を有望であるとしながらも、いずれも特殊相対性理論の対称性の要件と完全 に一致させることが可能であるかどうかは明らかではないため、満足のいくものではないと述べている。[95] |

| Neopragmatism and Wittgenstein In the mid-1970s, Putnam became increasingly disillusioned with what he perceived as modern analytic philosophy's "scientism" and focus on metaphysics over ethics and everyday concerns.[100]: 186–190 He also became convinced by his readings of James and John Dewey that there is no fact–value dichotomy; that is, normative (e.g., ethical and aesthetic) judgments often have a factual basis, while scientific judgments have a normative element.[89][11]: 240 For a time, under Ludwig Wittgenstein's influence, Putnam adopted a pluralist view of philosophy itself and came to view most philosophical problems as no more than conceptual or linguistic confusions philosophers created by using ordinary language out of context.[89][non-primary source needed] A book of articles on pragmatism by Ruth Anna Putnam and Hilary Putnam, Pragmatism as a Way of Life: The Lasting Legacy of William James and John Dewey, edited by David Macarthur, was published in 2017.[101] Many of Putnam's last works addressed the concerns of ordinary people, particularly social problems.[102] For example, he wrote about the nature of democracy, social justice and religion. He also discussed Jürgen Habermas's ideas, and wrote articles influenced by continental philosophy.[22] |

新プラグマティズムとウィトゲンシュタイン 1970年代半ば、パットナムは、近代分析哲学の「科学主義」と、倫理や日常的な関心事よりも形而上学に重点を置く傾向に幻滅を深めていった。 [100]:186–190 また、 ジェイムズとジョン・デューイの研究から、事実と価値の二分法は存在しないという確信を得た。つまり、規範的な(例えば、倫理的、美的な)判断にはしばし ば事実上の根拠があるが、科学的判断には規範的な要素があるということである。[89][11]: 240 一時期、ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの影響を受け、 哲学そのものに対する多元論的な見解を採用し、ほとんどの哲学上の問題は、哲学者が文脈を無視して日常言語を使用することによって生み出された概念上また は言語上の混乱にすぎないという見解に至った。[89][一次資料以外の出典が必要] ルース・アンナ・パトナムとヒラリー・パトナムによるプラグマティズムに関する論文集『プラグマティズムという生き方: ウィリアム・ジェームズとジョン・デューイの永続する遺産』が2017年に出版された。[101] パトナムの最後の作品の多くは、特に社会問題など、一般の人々の懸念に対処したものだった。[102]例えば、彼は民主主義、社会正義、宗教の本質について書いた。また、ユルゲン・ハーバーマスの考えについても論じ、大陸哲学の影響を受けた論文も書いた。[22] |

| Works Books authored Putnam, H. (1971). Philosophy of Logic. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-04-160009-6. Putnam, H. (1975). Mathematics, Matter and Method. Philosophical Papers, vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20665-5. OCLC 59168146. 2nd. ed., 1985 paperback: ISBN 0-521-29550-5 Putnam, H. (1975). Mind, Language and Reality. Philosophical Papers, vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 88-459-0257-9. 2003 paperback: ISBN 0-521-29551-3 Putnam, H. (1978). Meaning and the Moral Sciences. Routledge and Kegan Paul. pp. 123–140. ISBN 978-0-710-08754-6. OCLC 318417931. Putnam, H. (1981). Reason, Truth, and History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23035-3. OCLC 442822274. 2004 paperback: ISBN 0-521-29776-1 Putnam, H. (1983). Realism and Reason. Philosophical Papers, vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24672-9. OCLC 490070776. 2002 paperback: ISBN 0-521-31394-5 Putnam, H. (1987). The Many Faces of Realism. La Salle, Ill.: Open Court. ISBN 0-8126-9043-5. Putnam, H. (1988). Representation and Reality. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-66074-7. OCLC 951364040. Putnam, H. (1990). Conant, J. F. (ed.). Realism with a Human Face. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-74945-0. OCLC 1014989000. Putnam, H. (1992). Renewing Philosophy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-76094-8. Putnam, H.; Cohen, Ted; Guyer, Paul, eds. (1993). Pursuits of Reason: Essays in Honor of Stanley Cavell. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 0-89672-266-X. Putnam, H. (1994). Conant, J. F. (ed.). Words and Life. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-95607-9. Putnam, H. (1995). Pragmatism: An Open Question. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19343-X. Based on the Gifford Lectures that Putnam delivered at the University of St Andrews in 1990 and 1991.[103] Putnam, H. (1999). The Threefold Cord: Mind, Body, and World. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10286-5. OCLC 868429895. Putnam, H. (2001). Enlightenment and Pragmatism. Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum. ISBN 978-9-023-23739-6. OCLC 248668591. Putnam, H. (2002). The Collapse of the Fact/Value Dichotomy and Other Essays. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01380-8. Putnam, H. (2002). Ethics Without Ontology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01851-6. Putnam, H. (2008). Jewish Philosophy as a Guide to Life: Rosenzweig, Buber, Levinas, Wittgenstein. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35133-3. OCLC 819172227. Putnam, H. (2012). De Caro, M.; Macarthur, D. (eds.). Philosophy in an Age of Science. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05013-6. OCLC 913024858. Putnam, H. (2016). De Caro, Mario (ed.). Naturalism, Realism, and Normativity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-65969-8. Putnam, H.; Putnam, R. A. (2017). Macarthur, David (ed.). Pragmatism as a Way of Life: The Lasting Legacy of William James and John Dewey. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-96750-2. Books edited Putnam, H. (1964). Benacerraf, Paul (ed.). Philosophy of Mathematics: Selected Readings. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. OCLC 1277244158. 2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-521-29648-X Hempel, Carl G.; Putnam, H.; Essler, Wilhelm K., eds. (1983). Methodology, Epistemology, and Philosophy of Science: Essays in Honour of Wolfgang Stegmüller. Dordrecht: D. Reidel. ISBN 978-9-027-71646-0. OCLC 299388752. Essler, Wilhelm K.; Putnam, H.; Stegmüller, Wolfgang, eds. (1985). Epistemology, Methodology, and Philosophy of Science: Essays in Honour of Carl G. Hempel. Dordrecht: D. Reidel. OCLC 793401994. Select papers, book chapters and essays .Putnam, H. (March 1967). "The 'Innateness Hypothesis' and Explanatory Models in Linguistics". Synthese. 17 (1): 12–22. doi:10.1007/BF00485014. JSTOR 20114532. S2CID 17124615. An exhaustive bibliography of Putnam's writings, compiled by John R. Shook, can be found in The Philosophy Of Hilary Putnam (2015).[104][105] |

作品 著書 パトナム、H. (1971年). 論理学の哲学. ニューヨーク: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-04-160009-6. パトナム、H. (1975年). 数学、物質、方法. 哲学論文集、第1巻. ケンブリッジ: ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-521-20665-5. OCLC 59168146. 第2版、1985年、ペーパーバック:ISBN 0-521-29550-5 Putnam, H. (1975). Mind, Language and Reality. Philosophical Papers, vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 88-459-0257-9. 2003年、ペーパーバック: ISBN 0-521-29551-3 パットナム、H. (1978年). 『意味と道徳科学』. ルートレッジ・アンド・ケーガン・ポール. pp. 123–140. ISBN 978-0-710-08754-6. OCLC 318417931. パットナム、H. (1981年). Reason, Truth, and History. ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-521-23035-3. OCLC 442822274. 2004年ペーパーバック: ISBN 0-521-29776-1 Putnam, H. (1983). Realism and Reason. Philosophical Papers, vol. 3. ケンブリッジ: ISBN 978-0-521-24672-9. OCLC 490070776. 2002年ペーパーバック:ISBN 0-521-31394-5 Putnam, H. (1987). The Many Faces of Realism. La Salle, Ill.: Open Court. ISBN 0-8126-9043-5. プットナム、H. (1988). 『表象と現実』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-66074-7. OCLC 951364040. プットナム、H. (1990). 『人間味のあるリアリズム』。コンアント、J. F. (編)。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-674-74945-0. OCLC 1014989000. Putnam, H. (1992). Renewing Philosophy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-76094-8. Putnam, H.; Cohen, Ted; Guyer, Paul, eds. (1993). Pursuits of Reason: スタンリー・キャヴェルへのオマージュ論文集。 ラボック:テキサス工科大学出版局。 ISBN 0-89672-266-X. パットナム、H. (1994). コナント、J. F. (編). 言葉と生命。 マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。 ISBN 0-674-95607-9. パットナム、H. (1995). プラグマティズム:未解決の問題。オックスフォード: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19343-X. 1990年と1991年にセント・アンドルーズ大学で行ったギフォード・レクチャーに基づく。[103] Putnam, H. (1999). The Threefold Cord: Mind, Body, and World. ニューヨーク: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10286-5. OCLC 868429895. Putnam, H. (2001). Enlightenment and Pragmatism. Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum. ISBN 978-9-023-23739-6. OCLC 248668591. プットナム、H. (2002). 『事実/価値二分法の崩壊とその他の論文』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 0-674-01380-8. プットナム、H. (2002). 『存在論なき倫理』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 0-674-01851-6. プットナム、H. (2008). 『ユダヤ哲学を人生の指針として:ローゼンツヴァイク、ブーバー、レヴィナス、ウィトゲンシュタイン』ブルーミントン:インディアナ大学出版。ISBN 978-0-253-35133-3。OCLC 819172227。 『科学の時代における哲学』デ・カロ、マッカーサー(編)。ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ:ハーバード大学出版。ISBN 978-0-674-05013-6. OCLC 913024858. Putnam, H. (2016). De Caro, Mario (ed.). Naturalism, Realism, and Normativity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-65969-8. Putnam, H.; Putnam, R. A. (2017). Macarthur, David (ed.). Pragmatism as a Way of Life: The Lasting Legacy of William James and John Dewey. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-96750-2. 編集書籍 Putnam, H. (1964). Benacerraf, Paul (ed.). Philosophy of Mathematics: Selected Readings. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. OCLC 1277244158. 2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-521-29648-X Hempel, Carl G.; Putnam, H.; Essler, Wilhelm K., eds. (1983). Methodology, Epistemology, and Philosophy of Science: ヴォルフガング・シュテグミュラーへのオマージュ論文集。 ドルドレヒト:D. Reidel. ISBN 978-9-027-71646-0. OCLC 299388752. エスラー、ヴィルヘルム・K.、パトナム、H.、シュテグミュラー、ヴォルフガング編。 (1985). 認識論、方法論、科学哲学:カール・G・ヘンペルへのオマージュ論文集。 ドルドレヒト: D. Reidel. OCLC 793401994. 論文、書籍の章、エッセイの抜粋。 Putnam, H. (1967年3月). 「The 『Innateness Hypothesis』 and Explanatory Models in Linguistics」. Synthese. 17 (1): 12–22. doi:10.1007/BF00485014. JSTOR 20114532. S2CID 17124615. ジョン・R・シュックが編集したパトナムの著作の包括的な書誌は、『ヒラリー・パトナムの哲学』(2015年)に掲載されている。[104][105] |

| American philosophy List of American philosophers |

アメリカ哲学 アメリカ人哲学者の一覧 |

| Conant, James; Chakraborty, Sanjit, eds. (2022). Engaging Putnam. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-110-76916-6. OCLC 1302581520. Ben-Menahem, Y., ed. (2005). Hilary Putnam. Contemporary Philosophy in Focus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81311-2. OCLC 912352048. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hilary_Putnam |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆