ヒポクラテスの誓い

Hippocratic Oath

☆ 「ヒポクラテスの誓い」 は、歴史的に医師が行ってきた倫理の誓いである。ギリシアの医学書で最も広く知られているもののひとつである。この誓いの原形は、新 米医師が多くの癒しの神々によって、特定の倫理基準を守ることを誓うものである。この誓いは、西洋世界における医療倫理の最も初期の表現であり、今日でも 最も重要な意味を持つ医療倫理のいくつかの原則を確立した。その中には、医療上の守秘義務やノンマレフィケンスの原則が含まれる。医療実践の指針となり、 情報を提供し続ける特定の原則を明確にしたものとして、この古文書は歴史的、象徴的な価値以上のものがある。様々な管轄区域の法律法規に明記されており、 宣誓に違反した場合には、宣誓の象徴的な性質を越えて、刑事責任やその他の責任を問われる可能性がある。この誓いの原文は、紀元前5世紀から3世紀の間に イオニア語ギリシア語で書かれたものである。伝統的にはギリシア人医師ヒポクラテスのものとされ、 通常『ヒポクラテス著作集』に収録されているが、現代の学者の中には、ヒポクラテス自身が書いたものではないと考える者もいる(→「ヒポクラテスの誓い批判」)。

The Hippocratic

Oath

is an oath of ethics historically taken by physicians. It is one of the

most widely known of Greek medical texts. In its original form, it

requires a new physician to swear, by a number of healing gods, to

uphold specific ethical standards. The oath is the earliest expression

of medical ethics in the Western world, establishing several principles

of medical ethics which remain of paramount significance today. These

include the principles of medical confidentiality and non-maleficence.

As the seminal articulation of certain principles that continue to

guide and inform medical practice, the ancient text is of more than

historic and symbolic value. It is enshrined in the legal statutes of

various jurisdictions, such that violations of the oath may carry

criminal or other liability beyond the oath's symbolic nature. The Hippocratic

Oath

is an oath of ethics historically taken by physicians. It is one of the

most widely known of Greek medical texts. In its original form, it

requires a new physician to swear, by a number of healing gods, to

uphold specific ethical standards. The oath is the earliest expression

of medical ethics in the Western world, establishing several principles

of medical ethics which remain of paramount significance today. These

include the principles of medical confidentiality and non-maleficence.

As the seminal articulation of certain principles that continue to

guide and inform medical practice, the ancient text is of more than

historic and symbolic value. It is enshrined in the legal statutes of

various jurisdictions, such that violations of the oath may carry

criminal or other liability beyond the oath's symbolic nature.The original oath was written in Ionic Greek, between the fifth and third centuries BC.[1] Although it is traditionally attributed to the Greek doctor Hippocrates and it is usually included in the Hippocratic Corpus, some modern scholars do not regard it as having been written by Hippocrates himself. |

「ヒ

ポクラテスの誓い」は、歴史的に医師が行ってきた倫理の誓いである。ギリシアの医学書で最も広く知られているもののひとつである。この誓いの原形は、新米

医師が多くの癒しの神々によって、特定の倫理基準を守ることを誓うものである。この誓いは、西洋世界における医療倫理の最も初期の表現であり、今日でも最

も重要な意味を持つ医療倫理のいくつかの原則を確立した。その中には、医療上の守秘義務やノンマレフィケンスの原則が含まれる。医療実践の指針となり、情

報を提供し続ける特定の原則を明確にしたものとして、この古文書は歴史的、象徴的な価値以上のものがある。様々な管轄区域の法律法規に明記されており、宣

誓に違反した場合には、宣誓の象徴的な性質を越えて、刑事責任やその他の責任を問われる可能性がある。 「ヒ

ポクラテスの誓い」は、歴史的に医師が行ってきた倫理の誓いである。ギリシアの医学書で最も広く知られているもののひとつである。この誓いの原形は、新米

医師が多くの癒しの神々によって、特定の倫理基準を守ることを誓うものである。この誓いは、西洋世界における医療倫理の最も初期の表現であり、今日でも最

も重要な意味を持つ医療倫理のいくつかの原則を確立した。その中には、医療上の守秘義務やノンマレフィケンスの原則が含まれる。医療実践の指針となり、情

報を提供し続ける特定の原則を明確にしたものとして、この古文書は歴史的、象徴的な価値以上のものがある。様々な管轄区域の法律法規に明記されており、宣

誓に違反した場合には、宣誓の象徴的な性質を越えて、刑事責任やその他の責任を問われる可能性がある。この誓いの原文は、紀元前5世紀から3世紀の間にイオニア語ギリシア語で書かれたものである[1]。伝統的にはギリシア人医師ヒポクラテスのものとされ、 通常『ヒポクラテス著作集』に収録されているが、現代の学者の中には、ヒポクラテス自身が書いたものではないと考える者もいる。 |

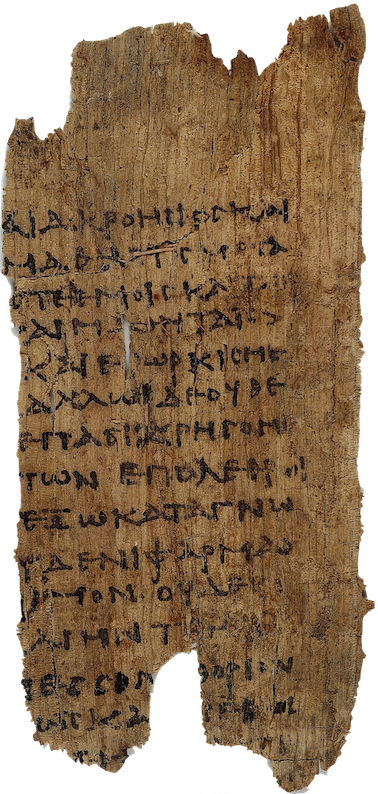

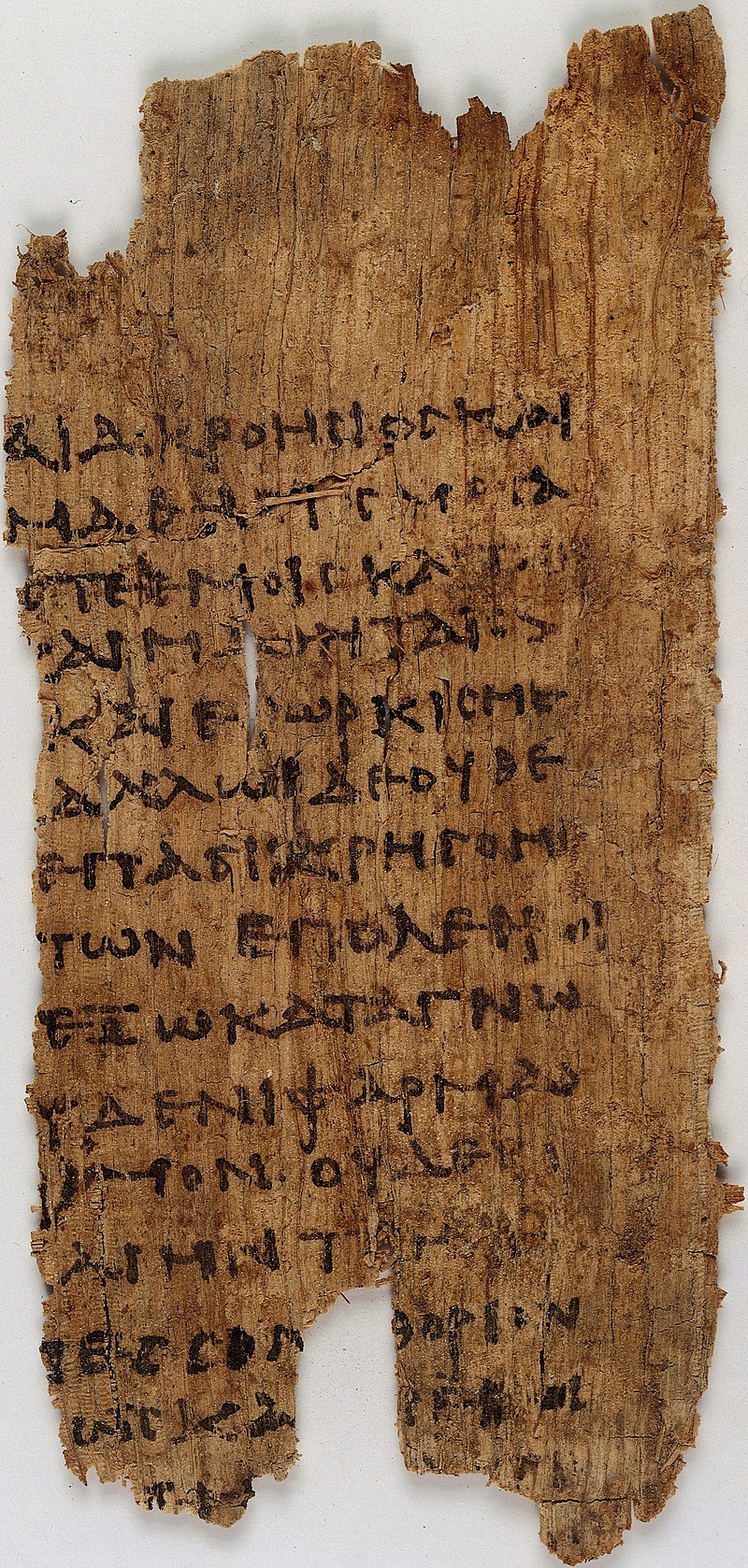

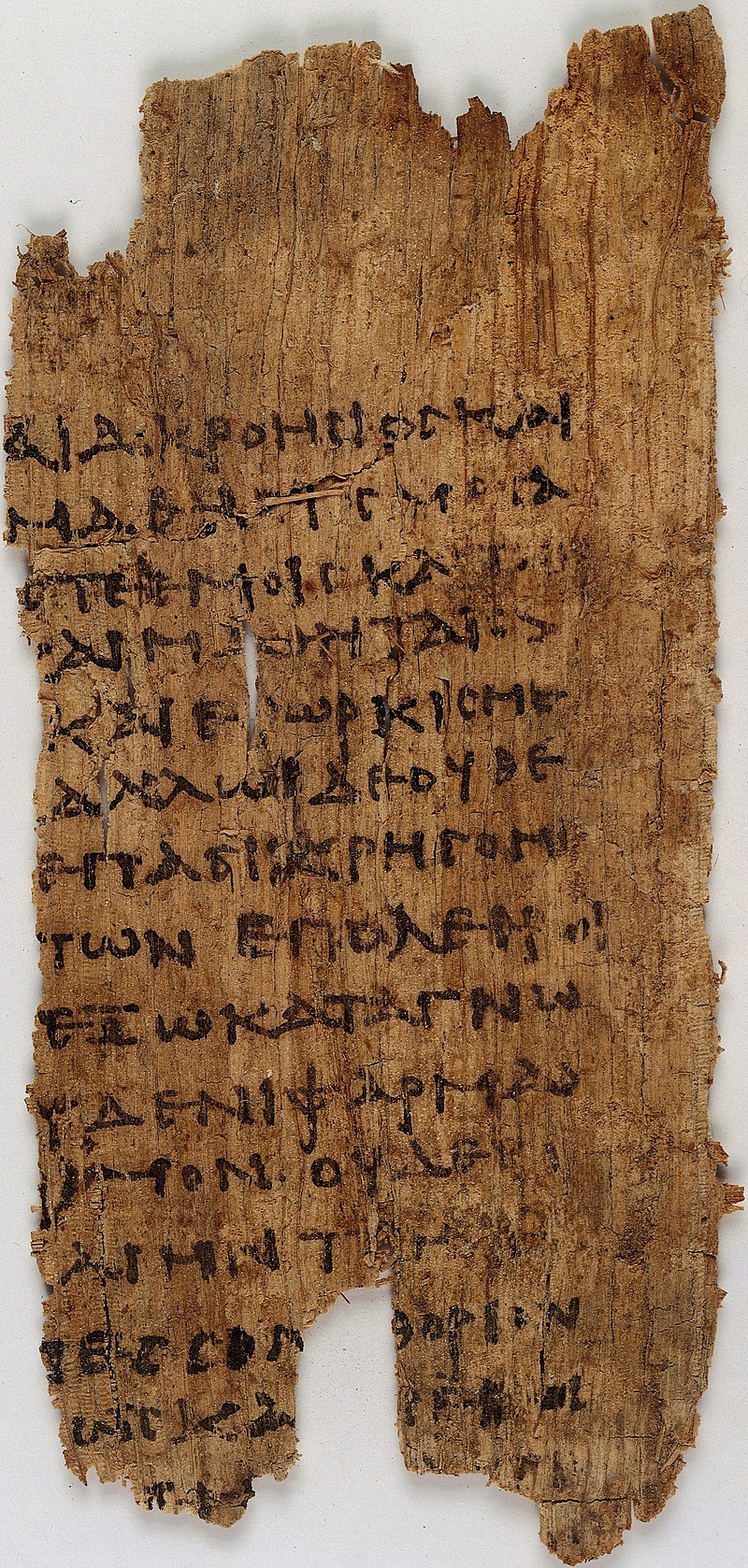

| Text of the oath Earliest surviving copy  A fragment of the oath on the 3rd-century Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 2547. The oldest partial fragments of the oath date to circa AD 275. The oldest extant version dates to roughly the 10th–11th century, held in the Vatican Library.[2] A commonly cited version, dated to 1595, appears in Koine Greek with a Latin translation.[3][4] In this translation, the author translates "πεσσὸν" to the Latin "fœtum." Below is the Hippocratic Oath, in Greek, from the 1923 Loeb edition, followed by the English translation: |

宣誓文 現存する最古の写し  3世紀のパピルスOxyrhynchus 2547に記された宣誓文の断片。 最古の誓いの断片はAD275年頃のもの。現存する最古のものは、バチカン図書館に所蔵されているおよそ10~11世紀のものである[2]。一般的に引用 されているのは、1595年のコイネ・ギリシア語とラテン語訳である[3][4]。 以下は、1923年のLoeb版によるギリシャ語の「ヒポクラテスの誓い」とその英訳である: |

| ὄμνυμι

Ἀπόλλωνα ἰητρὸν καὶ Ἀσκληπιὸν καὶ Ὑγείαν καὶ Πανάκειαν καὶ θεοὺς πάντας

τε καὶ πάσας, ἵστορας ποιεύμενος, ἐπιτελέα ποιήσειν κατὰ δύναμιν καὶ

κρίσιν ἐμὴν ὅρκον τόνδε καὶ συγγραφὴν τήνδε: ἡγήσεσθαι μὲν τὸν διδάξαντά με τὴν τέχνην ταύτην ἴσα γενέτῃσιν ἐμοῖς, καὶ βίου κοινώσεσθαι, καὶ χρεῶν χρηΐζοντι μετάδοσιν ποιήσεσθαι, καὶ γένος τὸ ἐξ αὐτοῦ ἀδελφοῖς ἴσον ἐπικρινεῖν ἄρρεσι, καὶ διδάξειν τὴν τέχνην ταύτην, ἢν χρηΐζωσι μανθάνειν, ἄνευ μισθοῦ καὶ συγγραφῆς, παραγγελίης τε καὶ ἀκροήσιος καὶ τῆς λοίπης ἁπάσης μαθήσιος μετάδοσιν ποιήσεσθαι υἱοῖς τε ἐμοῖς καὶ τοῖς τοῦ ἐμὲ διδάξαντος, καὶ μαθητῇσι συγγεγραμμένοις τε καὶ ὡρκισμένοις νόμῳ ἰητρικῷ, ἄλλῳ δὲ οὐδενί. διαιτήμασί τε χρήσομαι ἐπ᾽ ὠφελείῃ καμνόντων κατὰ δύναμιν καὶ κρίσιν ἐμήν, ἐπὶ δηλήσει δὲ καὶ ἀδικίῃ εἴρξειν. οὐ δώσω δὲ οὐδὲ φάρμακον οὐδενὶ αἰτηθεὶς θανάσιμον, οὐδὲ ὑφηγήσομαι συμβουλίην τοιήνδε: ὁμοίως δὲ οὐδὲ γυναικὶ πεσσὸν φθόριον δώσω. ἁγνῶς δὲ καὶ ὁσίως διατηρήσω βίον τὸν ἐμὸν καὶ τέχνην τὴν ἐμήν. οὐ τεμέω δὲ οὐδὲ μὴν λιθιῶντας, ἐκχωρήσω δὲ ἐργάτῃσιν ἀνδράσι πρήξιος τῆσδε. ἐς οἰκίας δὲ ὁκόσας ἂν ἐσίω, ἐσελεύσομαι ἐπ᾽ ὠφελείῃ καμνόντων, ἐκτὸς ἐὼν πάσης ἀδικίης ἑκουσίης καὶ φθορίης, τῆς τε ἄλλης καὶ ἀφροδισίων ἔργων ἐπί τε γυναικείων σωμάτων καὶ ἀνδρῴων, ἐλευθέρων τε καὶ δούλων. ἃ δ᾽ ἂν ἐνθεραπείῃ ἴδω ἢ ἀκούσω, ἢ καὶ ἄνευ θεραπείης κατὰ βίον ἀνθρώπων, ἃ μὴ χρή ποτε ἐκλαλεῖσθαι ἔξω, σιγήσομαι, ἄρρητα ἡγεύμενος εἶναι τὰ τοιαῦτα. ὅρκον μὲν οὖν μοι τόνδε ἐπιτελέα ποιέοντι, καὶ μὴ συγχέοντι, εἴη ἐπαύρασθαι καὶ βίου καὶ τέχνης δοξαζομένῳ παρὰ πᾶσιν ἀνθρώποις ἐς τὸν αἰεὶ χρόνον: παραβαίνοντι δὲ καὶ ἐπιορκέοντι, τἀναντία τούτων.[5] |

私はアポロン・ヒーラーに、アスクレピオスに、ヒギイアに、パナセア

に、そしてすべての神々と女神に誓い、彼らを私の証人とし、私の能力と判断に従って、この誓いとこの契約を実行する。 この術の師を私の両親と同等とし、私の生計のパートナーとし、師が金銭を必要とする時は私のものを師と共有し、師の家族を私の兄弟とみなし、彼らがこの術 を学びたければ、手数料も年季奉公もなしに教える。 私は、私の最大の能力と判断にしたがって、患者のためになるような食事療法を行い、患者に害を与えたり、不公平を与えたりすることはない[6]。同様に、 中絶させるためのペッサリーを女性に与えることもしません。しかし、私は自分の人生と芸術の両方を純粋で神聖なものに保つ。私はナイフを使わず、たとえ石 で苦しんでいる人にさえも使わない。 どのような家に入ろうとも、私は病人を助けるために入る。また、私は意図的な悪事や害をなすことを一切慎み、特に、男女を問わず、奴隷であろうと自由であ ろうと、その肉体を乱用することを慎む。また、職業上見聞きしたこと、また職業外の人との交わりにおいて見聞きしたこと、それが海外に公表されるべきでは ないことであったとしても、私はそのようなことを聖なる秘密として、決して漏らしません。 もし私がこの誓いを実行し、それを破らないならば、私の人生と私の芸術のために、すべての人の間で永遠に名声を得ることができるであろうが、もし私がこの 誓いを破り、自分自身を誓うならば、その逆のことが私に起こるであろう。 |

| I

swear by Apollo Healer, by Asclepius, by Hygieia, by Panacea, and by

all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will carry

out, according to my ability and judgment, this oath and this indenture. To hold my teacher in this art equal to my own parents; to make him partner in my livelihood; when he is in need of money to share mine with him; to consider his family as my own brothers, and to teach them this art, if they want to learn it, without fee or indenture; to impart precept, oral instruction, and all other instruction to my own sons, the sons of my teacher, and to indentured pupils who have taken the Healer's oath, but to nobody else. I will use those dietary regimens which will benefit my patients according to my greatest ability and judgment, and I will do no harm or injustice to them.[6] Neither will I administer a poison to anybody when asked to do so, nor will I suggest such a course. Similarly I will not give to a woman a pessary to cause abortion. But I will keep pure and holy both my life and my art. I will not use the knife, not even, verily, on sufferers from stone, but I will give place to such as are craftsmen therein. Into whatsoever houses I enter, I will enter to help the sick, and I will abstain from all intentional wrong-doing and harm, especially from abusing the bodies of man or woman, bond or free. And whatsoever I shall see or hear in the course of my profession, as well as outside my profession in my intercourse with men, if it be what should not be published abroad, I will never divulge, holding such things to be holy secrets. Now if I carry out this oath, and break it not, may I gain for ever reputation among all men for my life and for my art; but if I break it and forswear myself, may the opposite befall me.[5] – Translation by W.H.S. Jones. |

私はアポロン・ヒーラーに、アスクレピオスに、ヒギイアに、パナセア

に、そしてすべての神々と女神に誓い、彼らを私の証人とし、私の能力と判断に従って、この誓いとこの契約を実行する。 この術の師を私の両親と同等とし、私の生計のパートナーとし、師が金銭を必要とする時は私のものを師と共有し、師の家族を私の兄弟とみなし、 彼らがこの術を学びたければ、手数料も年季奉公もなしに教える。 私は、私の最大の能力と判断にしたがって、患者のためになるような食事療法を行い、患者に害を与えたり、不公平を与えたりしない。毒薬を投与 するよう求められても、私は毒薬を投与しないし、そのような方法を勧めることもない。同様に、中絶させるためのペッサリーを女性に与えることもしません。 しかし、私は自分の人生と芸術の両方を純粋で神聖なものに保つ。 いかなる家に入っても、病人を助けるために入り、あらゆる意図的な悪事や危害を避け、特に男であれ女であれ、奴隷であれ自由であれ、その肉体を乱用しな い。 もし私がこの誓いを実行し、それを破らないならば、私の人生と私の芸術のために、すべての人の間で永遠に名声を得ることができるであろう。 |

| "First do no harm" Main article: Primum non nocere It is often said that the exact phrase "First do no harm" (Latin: Primum non nocere) is a part of the original Hippocratic oath. Although the phrase does not appear in the AD 245 version of the oath, similar intentions are vowed by, "I will abstain from all intentional wrong-doing and harm". The phrase primum non nocere is believed to date from the 17th century. Another equivalent phrase is found in Epidemics, Book I, of the Hippocratic school: "Practice two things in your dealings with disease: either help or do not harm the patient".[7] The exact phrase is believed to have originated with the 19th-century English surgeon Thomas Inman.[8] |

"まず危害を加えない" 主な記事 プリマム・ノン・ノセア まず「害をなすなかれ」(ラテン語:Primum non nocere)という言葉は、ヒポクラテスの誓いの原文の一部であるとよく言われる。AD245年版の誓いにはこのフレーズは登場しないが、「私は意図的 な不正行為や危害を一切行わない」と同様の意思を誓っている。このprumum non nocereというフレーズは17世紀に作られたと考えられている(→「危害原則」)。 ヒポクラテス学派の『疫学』第1巻にも、これに相当する言葉がある: 「病気に対処する際には、患者を助けるか、害を与えないかの2つのことを実践せよ」[7]。この正確な言い回しは、19世紀のイギリスの外科医トーマス・ インマンに由来すると考えられている[8]。 |

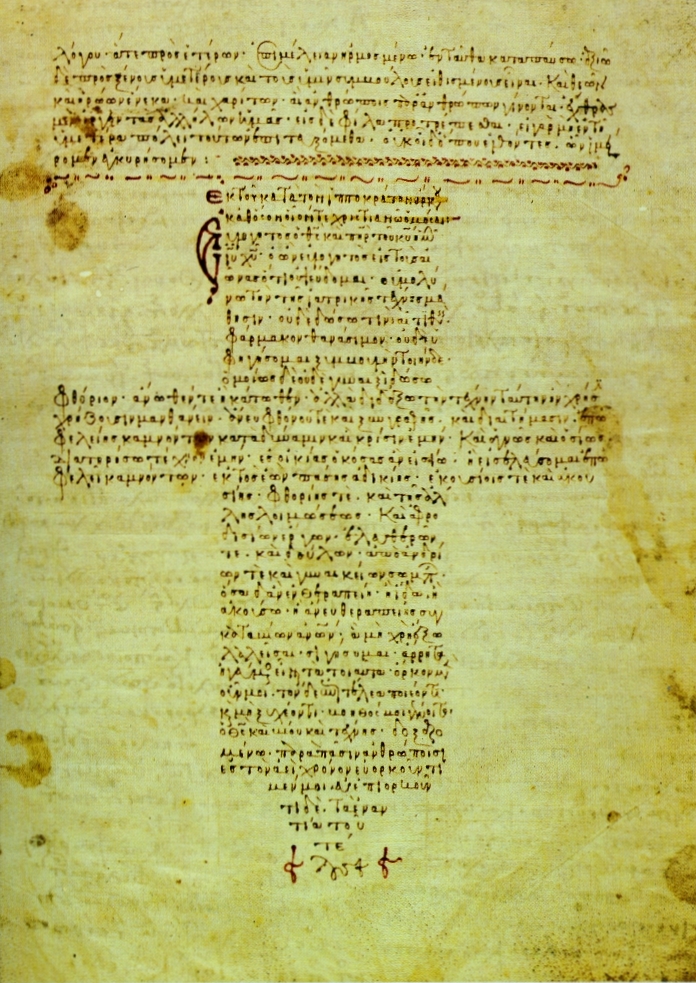

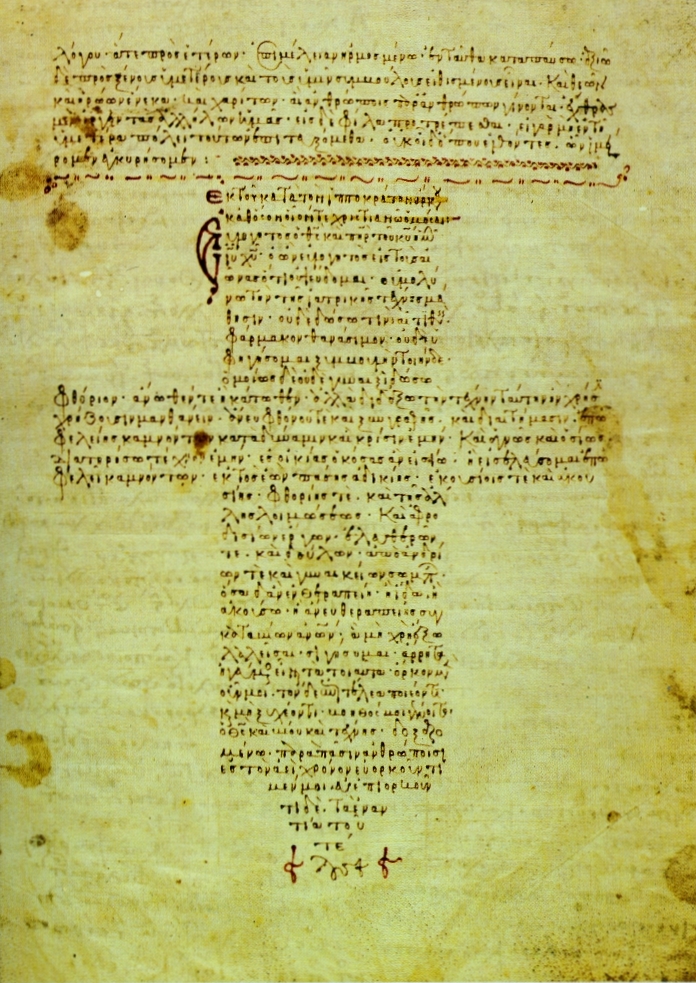

Context and interpretation A 12th-century Greek manuscript of the oath The oath is arguably the best known text of the Hippocratic Corpus, although most modern scholars do not attribute it to Hippocrates himself, estimating it to have been written in the fourth or fifth century BC.[9] Alternatively, classical scholar Ludwig Edelstein proposed that the oath was written by the Pythagoreans, an idea that others questioned for lack of evidence for a school of Pythagorean medicine.[10] While Pythagorean philosophy displays a correlation to the Oath's values, the proposal of a direct relationship has been mostly discredited in more recent studies. [11] Its general ethical principles are also found in other works of the Corpus: the Physician mentions the obligation to keep the 'holy things' of medicine within the medical community (i.e. not to divulge secrets); it also mentions the special position of the doctor with regard to his patients, especially women and girls.[12] However, several aspects of the oath contradict patterns of practice established elsewhere in the Corpus. Most notable is its ban on the use of the knife, even for small procedures such as lithotomy, even though other works in the Corpus provide guidance on performing surgical procedures.[13] Providing poisonous drugs would certainly have been viewed as immoral by contemporary physicians if it resulted in murder. However, the absolute ban described in the oath also forbids euthanasia. Several accounts of ancient physicians willingly assisting suicides have survived.[14] Multiple explanations for the prohibition of euthanasia in the oath have been proposed: it is possible that not all physicians swore the oath, or that the oath was seeking to prevent widely held concerns that physicians could be employed as political assassins.[15] The interpreted AD 275 fragment of the oath contains a prohibition of abortion that is in contradiction to original Hippocratic text On the Nature of the Child, which contains a description of an abortion, without any implication that it was morally wrong,[16] and descriptions of abortifacient medications are numerous in the ancient medical literature.[17] The oath's stance on abortion was unclear even in the ancient world where physicians debated whether the specification of pessaries was a ban on simply pessaries, or a blanket ban on all abortion methods.[18] Scribonius Largus was adamant in AD 43 (the earliest surviving reference to the oath) that it precluded abortion.[19] In the 1st or 2nd century AD work Gynaecology, Soranus of Ephesus wrote that one party of medical practitioners followed the Oath and banished all abortifacients, while the other party—to which he belonged—was willing to prescribe abortions, but only for the sake of the mother's health.[19][20] William Henry Samuel Jones states that "abortion... though doctors are forbidden to cause it, was possibly not condemned in all cases". He believed that the oath prohibited abortions, though not under all circumstances.[18] John M. Riddle argues that because Hippocrates specified pessaries, he only meant pessaries and therefore it was acceptable for a Hippocratic doctor to perform abortions using oral drugs, violent means, a disruption of daily routine or eating habits, and more. Other scholars, most notably Ludwig Edelstein, believe that the author intended to prohibit any and all abortions.[18] Olivia De Brabandere writes that regardless of the author's original intention, the vague and polyvalent nature of the relevant line has allowed both professionals and non-professionals to interpret and use the oath in several ways.[18] While many Christian versions of the Hippocratic Oath, particularly from the Middle Ages, explicitly prohibited abortion, the prohibition is often omitted from many oaths taken in US medical schools today, though it remains controversial.[21] The oath stands out among comparable ancient texts on medical ethics and professionalism through its heavily religious tone, a factor which makes attributing its authorship to Hippocrates particularly difficult. Phrases such as 'but I will keep pure and holy both my life and my art' suggest a deep, almost monastic devotion to the art of medicine. He who keeps to the oath is promised 'reputation among all men for my life and for my art'. This contrasts heavily with Galenic writings on professional ethics, which employ a far more pragmatic approach, where good practice is defined as effective practice, without reference to deities.[22] The oath's importance among the medical community is nonetheless attested by its appearance on the tombstones of physicians, and by the fourth century AD it had come to stand for the medical profession.[23] The oath continued to be in use in the Byzantine Christian world with its references to pagan deities replaced by a Christian preamble, as in the 12th-century manuscript pictured in the shape of a cross.[24] |

文脈と解釈 誓いの言葉を記した12世紀のギリシャ写本 誓いの言葉は、ヒポクラテス語録の中で最もよく知られたテキストであることは間違いないが、現代の学者の多くはヒポクラテス自身によるものだとは考えてお らず、紀元前4~5世紀に書かれたと推定している[9]。 [9] あるいは、古典学者のルートヴィヒ・エーデルシュタインが、この誓いはピタゴラス人によって書かれたと提唱したが、ピタゴラス学派の医学を示す証拠がない として、他の学者たちはこの考えに疑問を呈した[10]。[11] その一般的な倫理原則は、『コーパス』の他の作品にも見られる。『医師』は、医学の「聖なるもの」を医学界に留めておく義務(すなわち、秘密を漏らさない こと)に言及しており、また、患者、特に女性や少女に対する医師の特別な立場にも言及している[12]。しかし、この誓いのいくつかの側面は、『コーパ ス』の他の箇所で確立された実践パターンと矛盾している。最も顕著なのは、『コーパス』の他の著作では外科的処置を行う際の指針が示されているにもかかわ らず、結石除去のような小さな処置であってもナイフの使用を禁止していることである[13]。 毒薬の提供は、それが殺人につながるのであれば、現代の医師にとっては確かに不道徳とみなされたであろう。しかし、宣誓書に記されている絶対的な禁止は、 安楽死も禁じている。古代の医師が進んで自殺を幇助したという証言がいくつか残っている[14]。誓いの中で安楽死が禁止されていることについては、複数 の説明が提唱されている。すべての医師が誓いを立てたわけではない可能性や、医師が政治的な暗殺者として雇われるのではないかという広く抱かれている懸念 を防ぐために誓いを立てた可能性などがある[15]。 解釈されたAD275年の誓いの断片には中絶の禁止が含まれているが、これはヒポクラテスの原典『子供の性質について』と矛盾するものであり、中絶が道徳 的に間違っているという含意はなく、中絶に関する記述が含まれている[16]。 [17]中絶に対する誓いのスタンスは、ペッサリーの指定が単にペッサリーの禁止なのか、それともすべての中絶方法の包括的禁止なのかについて医師たちが 議論していた古代世界でも不明確でした。 [18]スクリボニウス・ラルガスは、AD43年(誓いに関する現存する最古の文献)において、誓いが中絶を除外していると固く主張していました [19]。AD1世紀か2世紀に書かれた『婦人科学』の中で、エフェソスのソラヌスは、開業医の一派は誓いに従い、すべての中絶薬を追放し、もう一派は中 絶を処方することを厭わなかったが、母親の健康のためにのみ処方したと書いています。 [19][20]ウィリアム・ヘンリー・サミュエル・ジョーンズは、「中絶は......医師がそれを引き起こすことは禁じられているが、おそらくすべて の場合において非難されたわけではない」と述べている。ジョン・M・リドルは、ヒポクラテスがペッサリーを指定したのはペッサリーだけを意味していたた め、ヒポクラテスの医師が経口薬や暴力的な手段、日常生活や食習慣の乱れなどを用いて中絶を行うことは容認されていたと主張しています。オリヴィア・デ・ ブラバンデーレは、作者の当初の意図にかかわらず、関連する行が曖昧で多義的であるため、専門家もそうでない人も、この誓いをいくつかの方法で解釈し、使 用することができる、と書いている。 [18] 特に中世のヒポクラテスの誓いの多くのキリスト教版では、中絶を明確に禁止していたが、今日、米国の医学部で行われる多くの誓いでは、この禁止はしばしば 省略されているが、依然として論争の的となっている[21]。 この誓いは、宗教的な色彩が濃く、ヒポクラテスの作者であると断定することを難しくしている。しかし、私は、私の人生と私の芸術の両方を純粋かつ聖なるも のに保ちます」というようなフレーズは、医学の芸術に対する深い、ほとんど修道僧のような献身を示唆している。この誓いを守る者は、「私の人生と私の技術 について、万人の間での名声」を約束される。これは、職業倫理に関するガレノスの著作が、神々に言及することなく、効果的な実践として優れた実践を定義す る、はるかに実際的なアプローチを採用しているのとは大きく対照的である[22]。 それにもかかわらず、医学界における誓いの重要性は、医師の墓碑にその誓いが刻まれていることで証明されており、紀元4世紀には、この誓いは医療専門職を 象徴するものとなっていた[23]。 この誓いは、十字架の形で描かれた12世紀の写本のように、異教の神々への言及をキリスト教の前文に置き換えて、ビザンチン・キリスト教世界で使用され続 けた[24]。 |

Modern versions and relevance An engraving of Hippocrates by Peter Paul Rubens, 1638 The Hippocratic Oath has been eclipsed as a document of professional ethics by more extensive, regularly updated ethical codes issued by national medical associations, such as the AMA Code of Medical Ethics (first adopted in 1847), and the British General Medical Council's Good Medical Practice. These documents provide a comprehensive overview of the obligations and professional behaviour of a doctor to their patients and wider society. Doctors who violate these codes may be subjected to disciplinary proceedings, including the loss of their license to practice medicine. Nonetheless, the length of these documents has made their distillations into shorter oaths an attractive proposition. In light of this fact, several updates to the oath have been offered in modern times,[25][26] some facetious.[27] The oath has been modified numerous times. In the United States, the majority of osteopathic medical schools use the Osteopathic Oath in place of or in addition to the Hippocratic Oath. The Osteopathic Oath was first used in 1938, and the current version has been in use since 1954.[28] One of the most significant revisions was first drafted in 1948 by the World Medical Association (WMA), called the Declaration of Geneva. "During the post World War II and immediately after its foundation, the WMA showed concern over the state of medical ethics in general and over the world. The WMA took up the responsibility for setting ethical guidelines for the world's physicians. It noted that in those years the custom of medical schools to administer an oath to its doctors upon graduation or receiving a license to practice medicine had fallen into disuse or become a mere formality".[29] In Nazi Germany, medical students did not take the Hippocratic Oath, although they knew the ethic of "nil nocere"—do no harm.[30][failed verification] In the 1960s, the Hippocratic Oath was changed to require "utmost respect for human life from its beginning", making it a more secular obligation, not to be taken in the presence of any gods, but before only other people. When the oath was rewritten in 1964 by Louis Lasagna, Academic Dean of the School of Medicine at Tufts University, the prayer was omitted, and that version has been widely accepted and is still in use today by many US medical schools:[31] I swear to fulfill, to the best of my ability and judgment, this covenant: I will respect the hard-won scientific gains of those physicians in whose steps I walk, and gladly share such knowledge as is mine with those who are to follow. I will apply, for the benefit of the sick, all measures [that] are required, avoiding those twin traps of overtreatment and therapeutic nihilism. I will remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon's knife or the chemist's drug. I will not be ashamed to say "I know not", nor will I fail to call in my colleagues when the skills of another are needed for a patient's recovery. I will respect the privacy of my patients, for their problems are not disclosed to me that the world may know. Most especially must I tread with care in matters of life and death. If it is given me to save a life, all thanks. But it may also be within my power to take a life; this awesome responsibility must be faced with great humbleness and awareness of my own frailty. Above all, I must not play at God. I will remember that I do not treat a fever chart, a cancerous growth, but a sick human being, whose illness may affect the person's family and economic stability. My responsibility includes these related problems, if I am to care adequately for the sick. I will prevent disease whenever I can, for prevention is preferable to cure. I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings, those sound of mind and body as well as the infirm. If I do not violate this oath, may I enjoy life and art, respected while I live and remembered with affection thereafter. May I always act so as to preserve the finest traditions of my calling and may I long experience the joy of healing those who seek my help. In a 1989 survey of 126 US medical schools, only three of them reported use of the original oath, while thirty-three used the Declaration of Geneva, sixty-seven used a modified Hippocratic Oath, four used the Oath of Maimonides, one used a covenant, eight used another oath, one used an unknown oath, and two did not use any kind of oath. Seven medical schools did not reply to the survey.[32] As of 1993, only 14% of medical oaths prohibited euthanasia, and only 8% prohibited abortion.[33] In a 2000 survey of US medical schools, all of the then extant medical schools administered some type of profession oath. Among schools of modern medicine, sixty-two of 122 used the Hippocratic Oath, or a modified version of it. The other sixty schools used the original or modified Declaration of Geneva, Oath of Maimonides, or an oath authored by students and or faculty. All nineteen osteopathic schools used the Osteopathic Oath.[34] In France, it is common for new medical graduates to sign a written oath.[35][36] In 1995, Sir Joseph Rotblat, in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize, suggested a Hippocratic Oath for Scientists.[37] In 2007 US citizen Rafiq Abdus Sabir was convicted for making a pledge to Al Qaeda thus agreeing to provide medical aid to wounded terrorists.[38] As of 2018 all US medical school graduates made some form of public oath but none used the original Hippocratic Oath. A modified form or an oath unique to that school is often used. A review of 18 of these oaths was criticized for their wide variability: "Consistency would help society see that physicians are members of a profession that's committed to a shared set of essential ethical values."[39] |

現代版と関連性 ピーター・パウル・ルーベンスによるヒポクラテスのエングレーヴィング 1638年 ヒポクラテスの誓いは、AMAの医療倫理綱領(1847年初採択)や英国医師会の適正医療規範など、各国の医師会が発行する、より広範で定期的に更新され る倫理綱領によって、職業倫理の文書としては駆逐されてしまった。これらの文書は、医師が患者や広く社会に対して果たすべき義務や専門家としての行動につ いて、包括的な概要を示している。これらの規範に違反した医師は、医師免許の剥奪を含む懲戒手続きを受ける可能性がある。それにもかかわらず、これらの文 書は長いため、より短い宣誓書にまとめることが魅力的な提案となっている。この事実を踏まえて、現代では宣誓書のいくつかの更新が提案されている[25] [26]。 宣誓は何度も修正されてきた。 米国では、オステオパシー医科大学の大半が、ヒポクラテスの誓いの代わりに、あるいはヒポクラテスの誓いに加えて、オステオパシーの誓いを使用している。 オステオパシーの誓いは1938年に初めて使用され、現在のバージョンは1954年から使用されている[28]。 最も重要な改訂の一つは、世界医師会(WMA)によって1948年に最初に起草されたもので、ジュネーブ宣言と呼ばれている。「第二次世界大戦後、設立直 後から、WMAは一般的な、そして世界的な医療倫理のあり方に懸念を示していた。WMAは、世界の医師のための倫理ガイドラインを設定する責任を負った。 WMAは、当時の医学部では、卒業時や医師免許取得時に医師宣誓を行う習慣が廃れていたり、単なる形式的なものになっていたことを指摘した。 1960年代、ヒポクラテスの誓いは「人間の生命をその始まりから最大限に尊重する」ことを求めるものに変更され、より世俗的な義務となった。1964年 にタフツ大学医学部の学部長であったルイス・ラザーニャによって宣誓文が書き直された際、祈りは省略され、そのバージョンは広く受け入れられ、現在でも多 くの米国の医学部で使用されている[31]。 私は、私の能力と判断力の限りを尽くして、この誓いを果たすことを誓います: 私は、その歩みを共にする医師たちが苦労の末に得た科学的成果を尊重し、私の知識を、後に続く者たちと喜んで分かち合います。 私は病人のために、過剰治療と治療的虚無主義という双子の罠を避けつつ、必要なあらゆる手段を適用する。 私は、医学には科学と同様に芸術があり、温かさ、共感、理解が外科医のナイフや化学者の薬に勝ることがあることを忘れない。 患者の回復のために他の医師の技術が必要とされるとき、私は恥ずかしげもなく「知らない」と言い、同僚を呼ぶことを怠らない。 私は患者のプライバシーを尊重する。患者の問題は、世間に知られるような形で私に公表されるものではない。特に、生と死にかかわる問題には慎重に対処しな ければならない。命を救うことが私に与えられたのなら、感謝に堪えない。しかし、命を絶つこともまた私の力の及ぶところかもしれない。この重大な責任に は、大きな謙虚さと自らの弱さを自覚して立ち向かわなければならない。何よりも、私は神をもてあそんではならない。 私が治療するのは、熱のグラフや癌の増殖ではなく、病気の人間であり、その病気はその人の家庭や経済的安定に影響を及ぼすかもしれないということを忘れて はならない。病人に十分なケアをするのであれば、私の責任にはこれらの関連問題も含まれる。 私は、できる限り病気を予防する。 私は社会の一員であることを忘れず、心身の健全な人々や病弱な人々など、すべての同胞に対して特別な義務を負います。 もしこの誓いに背くことがなければ、私は人生と芸術を楽しみ、生きている間は尊敬され、その後も親愛の情をもって記憶されますように。そして、私の助けを 求める人々を癒す喜びを長く味わうことができますように。 1989年にアメリカの医学部126校を対象に行われた調査では、オリジナルの誓いを使用していると回答したのはわずか3校で、33校がジュネーブ宣言、 67校が修正ヒポクラテスの誓い、4校がマイモニデスの誓い、1校が誓約書、8校が別の誓い、1校が不明な誓い、2校がいかなる誓いも使用していなかっ た。調査に回答しなかった医学部は7校であった[32]。 1993年の時点で、安楽死を禁止している医学宣誓はわずか14%であり、中絶を禁止しているのはわずか8%であった[33]。 2000年に行われたアメリカの医学部の調査では、当時存在していたすべての医学部が何らかの職業宣誓を行っていた。近代医学部のうち、122校のうち 62校がヒポクラテスの誓い、またはそれを修正したものを使用していた。残りの60校は、ジュネーブ宣言、マイモニデスの誓い、または学生や教授陣が作成 した誓いを、オリジナルまたは修正して使用していた。19のオステオパシー学校はすべてオステオパシーの誓いを使用していた[34]。 フランスでは、新卒の医学生が宣誓書に署名することが一般的である[35][36]。 1995年、ジョセフ・ロットブラット卿はノーベル平和賞の受賞スピーチで、科学者のためのヒポクラテスの誓いを提案した[37]。 2007年、米国市民のラフィク・アブドゥス・サビールは、アルカイダに誓約書を作成し、負傷したテロリストに医療援助を提供することに同意したとして有 罪判決を受けた[38]。 2018年現在、米国のすべての医学部卒業生は何らかの形で公の誓いを立てているが、オリジナルのヒポクラテスの誓いを用いた者はいない。修正された形式 やその学校独自の宣誓が用いられることが多い。これらの誓いのうち18の誓いを検証したところ、そのばらつきの大きさが批判された: 「一貫性があれば、医師は本質的な倫理的価値を共有する専門職の一員であることを社会に示すことができる」[39]。 |

| Violation There is no direct punishment for breaking the Hippocratic Oath, although an arguable equivalent in modern times is medical malpractice, which carries a wide range of punishments, from legal action to civil penalties.[40] In the United States, several major judicial decisions have made reference to the classical Hippocratic Oath, either upholding or dismissing its bounds for medical ethics: Roe v. Wade, Washington v. Harper, Compassion in Dying v. State of Washington (1996), and Thorburn v. Department of Corrections (1998).[41] In antiquity, the punishment for breaking the Hippocratic oath could range from a penalty to losing the right to practice medicine.[42] In 2022, a college in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu saw a batch of medical students undertaking the Charaka shapath, a Sanskrit Oath by the name of ancient sage physician Maharishi Charak instead of the Hippocratic oath. The state government subsequently dismissed the Dean of the Madurai medical college for this act.[43][44][45] |

違反 ヒポクラテスの誓いを破った場合の直接的な処罰はないが、現代においてこれに相当するものとして、法的措置から民事罰まで幅広い処罰を伴う医療過誤がある ことは論を待たない[40]。米国では、いくつかの主要な司法判断が古典的なヒポクラテスの誓いに言及しており、医療倫理に関するその境界線を支持または 否定している: ロー対ウェイド事件、ワシントン対ハーパー事件、Compassion in Dying対ワシントン州事件(1996年)、Thorburn対矯正局事件(1998年)[41]。古代では、ヒポクラテスの誓いを破った場合の罰則 は、刑罰から医療行為を行う権利を失うことまで様々であった[42]。 2022年、インドのタミル・ナードゥ州にある大学では、医学生の一団がヒポクラテスの誓いの代わりに、古代の賢人医師マハリシ・チャラクの名前によるサ ンスクリット語の誓いであるチャラカ・シャパスを引き受けた。州政府はその後、この行為を理由にマドゥライ医科大学の学部長を解任した[43][44] [45]。 |

| Hospital Corpsman Pledge Medical ethics Participation of medical professionals in American executions Patient safety Peelian principles Primum non nocere Sushruta § Followers Sun Simiao White Coat Ceremony Ethical codes of conduct for physicians Charaka shapath Declaration of Geneva Nightingale Pledge Oath of Asaph Seventeen Rules of Enjuin Vejjavatapada Ethical principles for human experimentation Declaration of Helsinki Human experimentation in the United States Nuremberg code Ethical practices for engineers Iron Ring Order of the Engineer Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer Science Hippocratic Oath for Scientists |

病院隊員の誓い 医療倫理 アメリカの死刑執行への医療関係者の参加 患者の安全 ピールの原則 プリマム・ノン・ノセア スシュルタ § フォロワー 孫思悼 白衣の儀式 医師の倫理的行動規範 チャラカ・シャパス ジュネーブ宣言 ナイチンゲールの誓い アサフの誓い エンジュイン十七則 ベジャヴァタパダ 人体実験の倫理原則 ヘルシンキ宣言 米国における人体実験 ニュルンベルク綱領 技術者の倫理慣行 鉄の指輪 技術者勲章 技術者召集の儀式 科学 科学者のためのヒポクラテスの誓い |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hippocratic_Oath |

★ ヒポクラテスの誓いを現代的な倫理学的概念から論駁する(→「ヒポクラテスの誓い批判」)

| 私はアポローンに、アスクレピオスに、ヒュギ

エイアに、パナケイア

に、そしてすべての神々と女神に誓い、彼らを私の証人とし、私の能力と判断に従って、この誓いとこの契約を実行する。 |

1)アメリカ大統領の就任で新任者は聖書に手を置くが、これは(不可知

論を含む)無神論あるいは合理主義的精神に照らして、非合理つまり迷信的呪術的行為である。ただし、理神論的な立場に譲歩すれば、(理性的でかつ倫理的

に)神聖なものに誓うという立場は容認されるだろう。だから、このような神の名を連ねる必要はない。 |

| この術の師を私の両親と同等とし、私の生計のパートナーとし、師が金銭

を必要とする時は私のものを師と共有し、師の家族を私の兄弟とみなし、彼らがこの術を学びたければ、手数料も年季奉公もなしに教える。 |

2)好意的にパラフレイズすれば、職業倫理に奉じるという趣旨であれ

ば、容認可能である。医術は現代社会では学校教育制度のなかで授業料で賄われるので、このような主張はナンセンスである。ただし必ずしも授業料を徴収しな

くても成績優秀者には、奨学金や学費の免除の制度があり、そのことを内包しているのであれば、首肯できる。ただし、このような文言をあげる必要はない。 |

| 私は、私の最大の能力と判断にしたがって、患者のためになるような食事

療法を行い、患者に害を与えたり、不公平を与えたりしない。毒薬を投与するよう求められても、私は毒薬を投与しないし、そのような方法を勧めることもな

い。同様に、中絶させるためのペッサリーを女性に与えることもしません。しかし、私は自分の人生と醫術(アート)の両方を純粋で神聖なものに保つ。 |

3)現在の医療倫理のなかで唯一有効な主張は、無害原則(Primum non nocere)である。ただし、これは他の医療倫理上の誓約があれば、包括的に主張すべきもので、無害原則は、医療者が守るべきマ クシムのひとつにすぎない。堕胎中絶は、現今では女性のリプロダクティブヘルスや選択の権利などで規定されるので、ここでの普遍原則としての主張は採用さ れない。 |

| いかなる家に入っても、病人を助けるために入り、あらゆる意図的な悪事

や危害を避け、特に男であれ女であれ、奴隷であれ自由であれ、その肉体を乱用しない。 |

4)無害原則にくわえ、患者の同意なしに、実験的な医療をおこなわない ことを含意するものと考えられる。これはヘルシンキ宣言などで代替可能である。 |

| もし私がこの誓いを実行し、それを破らないならば、私の人生と私の醫術

(アート)のために、すべての人の間で永遠に名声を得ることができるであろう。 |

5)希望的観測や予言にあたる文章で、現代的には何の意味ももたない。 以上のことを勘案すれば、他の医療者のより高度で洗練された医療倫理原則をもって、この誓詞を代替することができるので、ヒポクラテスの誓いは、現代の医 療倫理を遵守する上では、宗教的あるいは儀式的以上の意味をもたない。 |

★ ヒポクラテスの誓いについて詳しく学ぼう(→「ヒポクラテスの誓い」)

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆