The J.S. Mill's Harm Principle, harm priciple

危害原理・危害原則

The J.S. Mill's Harm Principle, harm priciple

危害原理・危害原則(Harm principle)とは、ある個人の行動の自由を制限する (=干渉する)際に、唯一可能なのは、その個人が他人に対して危害を加えることに抵抗することだけである、という原則のことをさす。

この抵抗の中には、広義の不服従や攻撃も含まれる が、この範囲にはさまざまな解釈が可能である。なお危害原理は、他人に危害を加えてはならないという道徳 を意味するものではない(ただし、危害原理からこの道徳を論理的に引き出す(=演繹)することは可能である)。また、危害をもたらす未来における危険性 (=リスク)を拡大解釈して、予防としてその個人の自由を制限する根拠を引き出すことは論理的にはできない。

この原理はジョン・スチュアート・ミルの自由論 (1860)の所論による。この原理を述べた当該箇所は次のように書かれてある。

" That principle is, that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others." (J.S. Mill, On Liberty, 1860)

「その原理とは、人類が、個人的にまたは集団的に、 だれかの行動の自由に正当に干渉しうる唯一の目的は、自己防衛だということである。すなわち、文明社会 の成員に対し、彼の意志に反して、正当に権力を行使しうる唯一の目的は、他者にたいする危害の防止である」早坂忠訳(ミル 1967: 224)。

「その原理とはこうだ。人間が個人としてではあれ、 集団としてであれ、誰の行動の自由に干渉するのが正当だといえるのは、自衛を目的とする場合だけであ る。文明社会で個人に対して力を行使するのが正当だといえるのはただひとつ、他人に危害が及ぶのを防ぐことを目的とする場合だけである」山岡洋一訳、(ミ ル 2011:26)。

ここからわかるように、ミルは"Harm Principle" という用語を自ら発案したわけでなく、この用語の中に、ミルの危害に関する原理・原則を提案したものを後の人たちが危害原理として採用したものなのであ る。

★文化人類学からみた「危害原則」

ちなみに、ミルはこれ は「判断が能力が成熟した」大 人にのみ原則が適用することができると、次のように言う。

「この原則は判断能力 が成熟した人だけに適用するこ とを意図している。子供や、法的に 成人に達していない若者は対象にならない。世話を必要としない年齢に達していないのであれば、本人の行動で起こりうる危害に対しても、外部からの危害に対 しても保護する必要がある。同じ理由で、社会が十分に発達していない遅れた民族も、対象から除外していいだろう」(ミル 2011:27)。

21世紀を生きる文化人類学者からみると若干悲しい 「遅れた民族」という概念を、あまり針小棒大化して、彼は植民地主義者だとか白人の帝国主義者の傲慢と 判断しても、我々の世界と時代道徳で、ミルを判定するという誹りを受けてしまうだろう。ミルの著作は、この時代を生きた英国の産業革命のまっただ中の市民 生活や、ビクトリア朝時代最盛期の大英帝国の植民者の人種主義や、当時の社会の「進歩や発展」思想をたっぷりと含んでいるにも関わらず、ミルの危害原則の 時代を我々もまた共有しているからである。

ミルのこの原理から、導きだせるものは以下のような 前提である。

(1)社会生活を営む成人は、他者に危害を加えなけ れば、基本的に何をしても自由である、あるいは、そのような権利を有する。

(2)社会は、ある個人が他者に対する危害をおこな おうとする時にのみ、ある個人がもつ行動の自由に制限をかけることができる。

(3)自由な個人と、それに干渉する社会との関係は 「他者に対する危害」を中心に考えることができる。

★【問題】みなさんは、このミルの危害原理・危害原則を用い て、医療の分野での議論でどのようなことができるのか考えてください。

| The harm principle

holds that the actions of individuals should be limited only to prevent

harm to other individuals. John Stuart Mill articulated the principle

in the 1859 essay On Liberty, where he argued that "The only purpose

for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a

civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to

others."[1] An equivalent was earlier stated in France's Declaration of

the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 as, "Liberty consists in

the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the

exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those

which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the

same rights. These limits can only be determined by law." It finds

earlier expression in Thomas Jefferson's 1785 "Notes on the State of

Virginia," Query 17 (Religion) in which he writes, "The legitimate

powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to

others."[2] |

危害原則とは、個人の行動は他の個人への危害を防ぐためにのみ制限され

るべきだという考え方である。ジョン・スチュアート・ミルは、1859年に発表した「自由について」というエッセイの中で、この原則を明確にし、「文明共

同体の構成員に対して、その意思に反して権力を正当に行使できる唯一の目的は、他者への危害を防止することである」と主張した。

それ以前にも、1789年にフランスで発表された『人間と市民の権利宣言』において、「自由は、他の誰にも害を与えないことをすべて行う自由からなる。し

たがって、各人の自然権の行使は、社会の他の構成員に同じ権利の享有を保証するもの以外には、何の制限もない。この限界は、法律によってのみ決定され

る」。これは、トーマス・ジェファーソンが1785年に発表した「バージニア州についてのノート」第17問(宗教)の中で、「政府の正当な権限は、他人を

傷つけるような行為にのみ及ぶ」と書いている[2]。 |

| Definition The belief "that no one should be forcibly prevented from acting in any way he chooses provided his acts are not invasive of the free acts of others" has become one of the basic principles of libertarian politics.[3] In R v Malmo-Levine, the Supreme Court of Canada claimed that there was no such thing as the harm principle even though it had been found to be a principle of fundamental justice in the courts below and had been found in all the key documents in the formulation of the concept of justice in Western society, including but not limited to the English and French Constitutions, John Stuart Mill's On Liberty, and modern case law. The Harm Principle is found in article 5 of the first English-language constitution from 1647: "An Agreement of the People for a firme and present Peace, upon grounds of common right and freedome....", presented to the Army Council, E. 412, 21. October 28, 1647: That the laws ought to be equal, so they must be good and not evidently destructive to the safety and well-being of the people. The Harm Principle is found in Articles 4 and 5 of the first French constitution (and first nationally adopted constitution) from 1789: Declaration of Human and Civic Rights of 26 August 1789: Liberty consists in being able to do anything that does not harm others: thus, the exercise of the natural rights of every man has no bounds other than those that ensure to the other members of society the enjoyment of these same rights. These bounds must be determined only by Law. The Law has the right to forbid only those actions that are injurious to society. Nothing that is not forbidden by Law may be hindered, and no one may be compelled to do what the Law does not ordain. The harm principle was first fully articulated by the English philosopher John Stuart Mill [JSM] (1806–1873) in the first chapter of On Liberty (1859),[1] where he argued that: The object of this Essay is to assert one very simple principle, as entitled to govern absolutely the dealings of society with the individual in the way of compulsion and control, whether the means used be physical force in the form of legal penalties, or the moral coercion of public opinion. That principle is, that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant. He cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinion of others, to do so would be wise, or even right... The only part of the conduct of anyone, for which he is amenable to society, is that which concerns others. In the part which merely concerns himself, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign. — John Stuart Mill[4] Mill also put the harm principle within his list of rights that sprung from liberty. It was found within his list of political rights (political activities that did not involve harm to others) - but also within his non-political liberty rights - his "tastes and pursuits" - activities which did not involve politics and did not involve harm to others: This, then, is the appropriate region of human liberty. It comprises, first, the inward domain of consciousness; demanding liberty of conscience, in the most comprehensive sense; liberty of thought and felling; absolute freedom of opinion and sentiment on all subjects; practical or speculative, scientific, moral, or theological. The principle of expressing and publishing opinions may seem to fall under a different principle, since it belongs to that part of the conduct of an individual which concerns other people; but, being almost of as much importance as the liberty of thought itself, and resting in great part on the same reasons, is practically inseparable from it. Secondly, the principle requires liberty of tastes and pursuits; of framing the plan of our life to suit our own character; of doing as we like, subject to such consequences as may follow; without impediment from our fellow-creatures, so long as what we do does not harm them even though they should think our conduct foolish, perverse, or wrong. One might rightly argue that the "pursuit of Happiness" mentioned in the 1776 US Declaration of Independence was one of the "tastes and pursuits" that Mill had in mind: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness . . . The Harm Principle is also found in recent US case law - in the case of the People v Alvarez, from the Supreme Court of California, in May, 2002: In every criminal trial, the prosecution must prove the corpus delicti, or the body of the crime itself - i.e., the fact of injury, loss, or harm, and the existence of a criminal agency as its cause. The Harm Principle even found its way into the drug laws of Columbia, in 1994, and again in 2009: In July 2009, the Columbian Supreme Court of Justice reconfirmed the 1994 ruling of the Constitutional Court by determining that the possession of drugs for personal use 'cannot be the object of any punishments,' when the incident occurred 'in the exercise of his personal and private rights, [and] the accused did not harm others. In their decision in R v Malmo-Levine, the Supreme Court did not explain how the Harm Principle was both 1) not a principle of fundamental justice, and 2) found in all these sources of fundamental justice. Even if a self-regarding action results in harm to oneself, it is still beyond the sphere of justifiable state coercion. Harm itself is not a non-moral concept. The infliction of harm upon another person is what makes an action wrong.[5] Harm can also result from a failure to meet an obligation. Morality generates obligations. Duty may be exacted from a person in the same way as a debt, and it is part of the notion of duty that a person may be rightfully compelled to fulfill it.[4][5] |

定義 自分の行為が他人の自由な行為を侵害するものでない限り、何人も自分の選んだ方法で行動することを強制的に妨げられるべきではない」という信念は、リバタ リアン政治の基本原則の一つとなっている[3]。 R v. Malmo-Levine事件において、カナダ最高裁判所は、害悪原則は下級審において基本的正義の原則であると認定され、イギリス憲法やフランス憲法、 ジョン・スチュアート・ミルの『自由について』、近代判例法などを含むがこれらに限定されない、西洋社会における正義の概念の定式化におけるすべての重要 な文書に記載されているにもかかわらず、害悪原則というものは存在しないと主張した。 害悪原則は、1647年に制定された最初の英文憲法の第5条「共通の権利と自由を根拠とする、堅固かつ現在の平和のための人民の合意」(E. 412, 21. 1647年10月28日 法律は平等であるべきであり、国民の安全と幸福を明らかに破壊するものであってはならない。 害悪原則は、1789年に制定された最初のフランス憲法(そして全国的に採択された最初の憲法)の第4条と第5条に見られる: 1789年8月26日の「人権および市民権宣言」である: 自由とは、他人に害を与えないことを何でもできることである。したがって、すべての人間の自然権の行使は、社会の他の構成員にこれらの同じ権利の享有を保 障するもの以外の境界を有しない。これらの境界は、法によってのみ決定されなければならない。法は、社会を害する行為のみを禁止する権利を有する。法に よって禁じられていないことは妨げられてはならず、法が命じていないことを何人も強制されてはならない。 害悪の原則は、イギリスの哲学者ジョン・スチュアート・ミル[JSM](1806-1873)が『自由について』(1859)の第1章[1]で初めて明確 に主張した: このエッセイの目的は、使用される手段が法的罰則という物理的な力であろうと、世論という道徳的強制であろうと、強制と統制の方法における社会と個人との 取引を絶対的に支配する権利があるとして、一つの非常に単純な原則を主張することである。その原則とは、人類が、個人としてであれ集団としてであれ、集団 の誰かの行動の自由に干渉することが正当化される唯一の目的は、自己防衛であるということである。文明社会の一員に対して、その意思に反して権力を正当に 行使できる唯一の目的は、他者への危害を防ぐことである。肉体的であれ道徳的であれ、彼自身の利益は十分な理由にはならない。そうすることが本人のために なるから、そうすることが本人の幸福につながるから、他人の意見ではそうすることが賢明だから、あるいは正しいから......という理由で、本人が正当 な手段で強制されたり、我慢させられたりすることはありえない。誰であれ、社会に対して従順であるべき行為は、他者に関わる部分だけである。単に自分自身 に関わる部分においては、彼の独立性は当然ながら絶対である。自分自身について、自分の身体と心について、個人は主権者である。 - ジョン・スチュアート・ミル[4] ミルはまた、自由から生まれた権利のリストの中に危害原則を入れた。それは、政治的権利(他者への危害を伴わない政治的活動)だけでなく、非政治的自由権 (政治に関与せず、他者への危害を伴わない活動)である「嗜好と追求」にも含まれていた: これが人間の自由の適切な領域である。最も包括的な意味での良心の自由、思想と感情の自由、実践的か思索的か、科学的か道徳的か神学的か、あらゆる主題に 関する意見と感情の絶対的自由が要求される。意見の表明と公表の原則は、個人の行動のうち他人に関わる部分に属するため、別の原則に該当するように思われ るかもしれないが、思想の自由そのものとほとんど同じくらい重要であり、同じ理由に大きく依存しているため、実質的には切っても切り離せないものである。 第二に、この原則は、嗜好や追求の自由を要求する。自分の性格に合うように人生設計を立てること、自分の好きなように行動すること、その結果生じる可能性 のあることを前提とすること、たとえ同胞が私たちの行動を愚劣、陋劣、あるいは間違っていると考えたとしても、私たちの行動が同胞に害を与えない限り、同 胞に妨げられることがないことを要求する。 1776年の米国独立宣言で言及された「幸福の追求」は、ミルが念頭に置いていた「嗜好と追求」の一つであると、ある人は正しく主張するかもしれない: われらは、これらの真理を自明のものとする。すなわち、すべての人は平等に造られ、創造主によって一定の譲ることのできない権利を与えられており、これら の権利の中には生命、自由および幸福の追求がある。 害悪原則は、2002年5月にカリフォルニア州最高裁で下されたPeople v. Alvarezの判例にも見られる: すべての刑事裁判において、検察側は犯罪の本体、すなわち傷害、損失、被害の事実と、その原因としての犯罪機関の存在を証明しなければならない。 危害原則は、1994年と2009年にコロンビアの麻薬取締法にも導入された: 2009年7月、コロンビアの最高裁判所は、「個人的かつ私的な権利の行使であり、被告人が他者に危害を加えていない」場合、個人的な使用のための薬物所 持は「処罰の対象とはなり得ない」と判断し、1994年の憲法裁判所の判決を再確認した。 R v Malmo-Levine事件の判決において、最高裁は、「危害の原則」が、1)基本的正義の原則ではないこと、2)基本的正義のすべての源泉に見出され ること、について説明しなかった。 たとえ自己中心的な行動が自分自身に害をもたらすとしても、それは国家による強制が正当化される範囲を超えている。 危害そのものは非道徳的な概念ではない。他者に危害を加えることこそが、ある行為を間違ったものにしているのである[5]。 危害はまた、義務を果たさなかったことから生じることもある。道徳は義務を生み出す。義務は債務と同じように人から要求されることがあり、人がそれを履行 することを正当に強制されることがあるというのは義務の概念の一部である[4][5]。 |

| Restrictions In On Liberty, J. S. Mill writes that his principle does not apply to persons judged as mentally ill, "barbarians" (which he assimilated to minors) and minors[6] while the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen did not concern women, slaves, foreigners and minors, as they were not citizens. Modern interpretation of the principle often does not make distinction of race or sex. Broader definitions of harm In the same essay, Mill further explains the principle as a function of two maxims: The maxims are, first, that the individual is not accountable to society for his actions, in so far as these concern the interests of no person but himself. Advice, instruction, persuasion, and avoidance by other people, if thought necessary by them for their own good, are the only measures by which society can justifiably express its dislike or disapprobation of his conduct. Secondly, that for such actions as are prejudicial to the interests of others, the individual is accountable, and may be subjected either to social or to legal punishments, if society is of opinion that the one or the other is requisite for its protection. (LV2) The second of these maxims has become known as the social authority principle.[7] However, the second maxim also opens the question of broader definitions of harm, up to and including harm to the society. The concept of harm is not limited to harm to another individual but can be harm to individuals plurally, without specific definition of those individuals. This is an important principle for the purpose of determining harm that only manifests gradually over time—such that the resulting harm can be anticipated, but does not yet exist at the time that the action causing harm was taken. It also applies to other issues—which range from the right of an entity to discharge broadly polluting waste on private property, to broad questions of licensing, and to the right of sedition. |

制限 J.S.ミルは『自由について』の中で、精神障害者、「野蛮人」(彼はこれを未成年者と同化している)、未成年者と判断された者には彼の原則は適用されな いと書いている[6]。一方、「人間と市民の権利に関する宣言」では、女性、奴隷、外国人、未成年者は市民ではないので関係なかった。 この原則の現代的な解釈では、人種や性別を区別しないことが多い。 危害の広範な定義 同じエッセイの中で、ミルはさらに2つの極意の機能として原則を説明している: その原則とは、第一に、個人はその行為について社会に対して責任を負わないというものである。助言、指導、説得、他の人々による回避は、もし他の人々が自 分たちの利益のために必要だと考えるなら、社会が彼の行為に対する嫌悪や不賛成を正当に表明できる唯一の手段である。第二に、他人の利益を害するような行 為については、個人は説明責任を負い、社会がその保護のために必要であると考える場合には、社会的処罰または法的処罰のいずれかを受けることができる。 (LV2)。 この第二の格言は、社会的権威の原理として知られるようになった[7]。 しかしながら、第二の格言はまた、社会に対する危害を含む、より広範な危害の定義の問題をも提起している。危害の概念は、他の個人に対する危害に限定され るものではなく、それらの個人を具体的に定義することなく、全体として個人に対する危害となりうる。 これは、時間の経過とともに徐々に顕在化する危害、つまり結果として生じる危害を予測することはできるが、危害の原因となる行為が行われた時点ではまだ存 在しない危害を判断するための重要な原則である。この原則はまた、私有地に広く汚染廃棄物を排出する事業者の権利から、許認可に関する広範な問題、扇動権 に至るまで、他の問題にも適用される。 |

| Critique of Harm Principle Scholars[who?] have argued that the harm principle does not provide a narrow scope of which actions count as harmful towards oneself or the population and it cannot be used to determine whether people can be punished for their actions by the state. A state can determine whether an action is punishable by determining what harm the action causes. If a morally unjust action occurs but leaves no indisputable form of harm, there is no justification for the state to act and punish the perpetrators for their actions.[9] The harm principle has an ambiguous definition of what harm specifically is and what justifies a state to intervene.[9] Scholars[who?] have also said that the harm principle does not specify on whether the state is justified with intervention tactics. This ambiguity can lead a state to define what counts as a harmful self-regarding action at its own discretion. This freedom might allow for an individual's own liberty and rights to be in danger. It would not be plausible for a state to intervene with an action that will negatively affect the population more than an individual.[10] The harm principle scope of usage has been described as too wide to directly follow and implement possible punishment by a state.[10] |

危害原則への批判 学者[誰?]は、危害原則は、どの行為が自分自身や集団にとって危害であるかという狭い範囲を規定するものではなく、人々がその行為によって国家から罰せ られるかどうかを決定するために用いることはできないと主張している。国家は、ある行為が罰せられるかどうかを、その行為がどのような害をもたらすかを判 断することによって決定することができる。道徳的に不当な行為が発生しても、議論の余地のない形の危害が残らないのであれば、国家が行動して加害者を処罰 する正当性はない[9]。危害原則は、具体的にどのような危害があり、国家が介入する正当性があるのかについて曖昧な定義をしている[9]。 学者[誰?]はまた、危害原則は国家が介入戦術をとることが正当化されるかどうかについて明示していないと述べている。この曖昧さは、国家が自らの裁量で 何を有害な自己決定行為とみなすかを定義することにつながりかねない。この自由は、個人の自由や権利が危険にさらされることを許すかもしれない。国家が、 個人よりも集団に悪影響を与える行為で介入することは妥当ではないだろう[10]。危害原則の使用範囲は、国家による処罰の可能性を直接追認し実行するに は広すぎると説明されている[10]。 |

| Ahimsa Classical liberalism Primum non nocere - "first, to do no harm" Do no significant harm principle (DNSH) Law of equal liberty Libertarianism Non-aggression principle Wiccan Rede |

アヒンサー 古典的自由主義 プリムム・ノン・ノケレ - 「まず、害をなさないこと 著しい損害を与えない原則(DNSH) 平等な自由の法則 リバタリアニズム 非侵略の原則 ウィッカの教え |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harm_principle |

リンク

文献

その他の情報(→「医療人類学辞

典にもどる」)

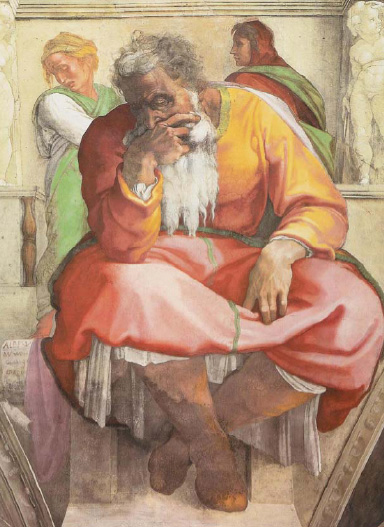

預言者ジェレマイヤー

Do not paste, but [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!