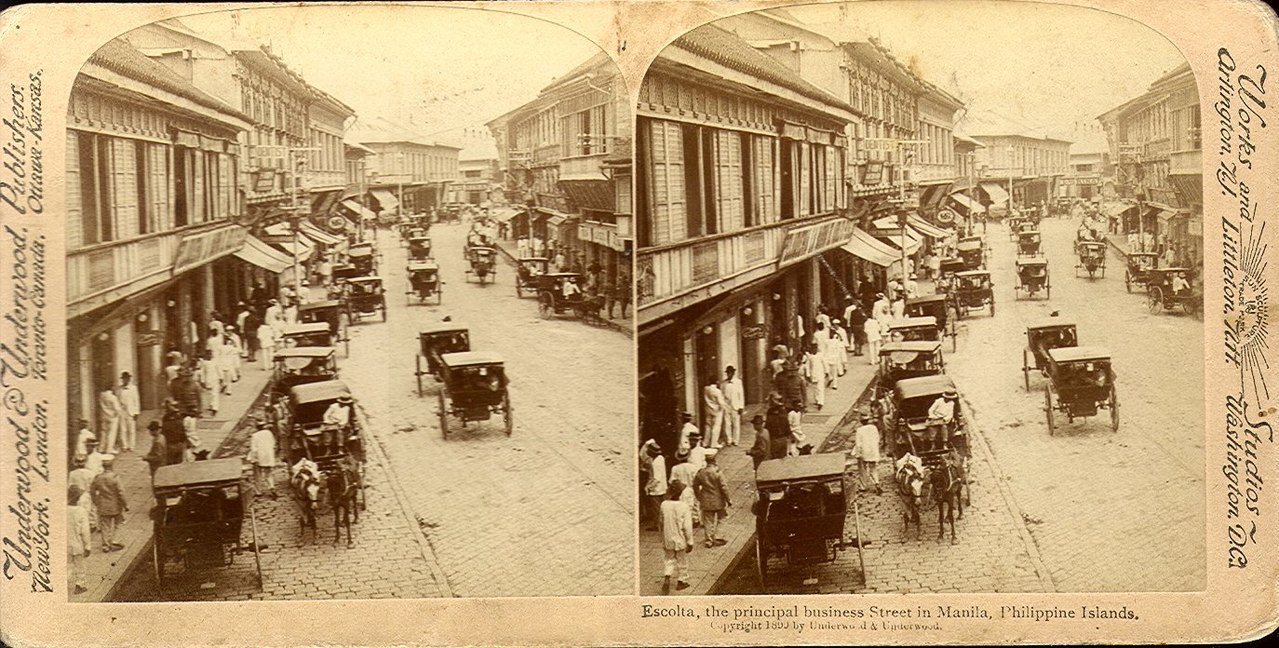

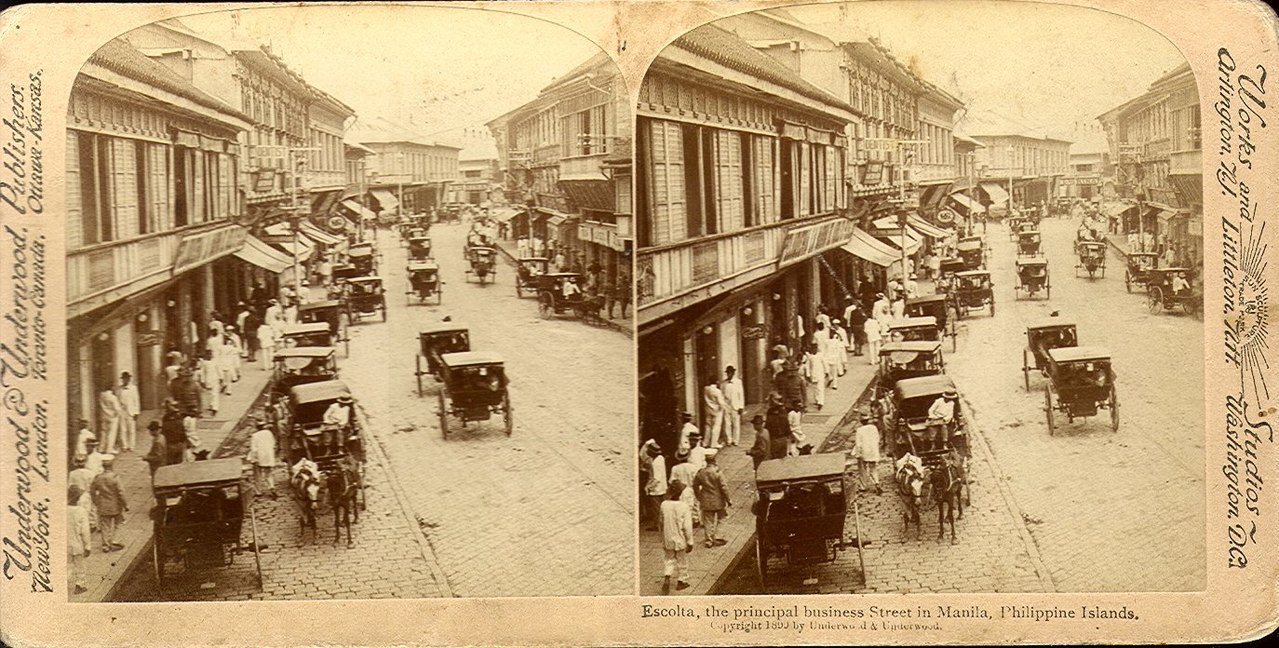

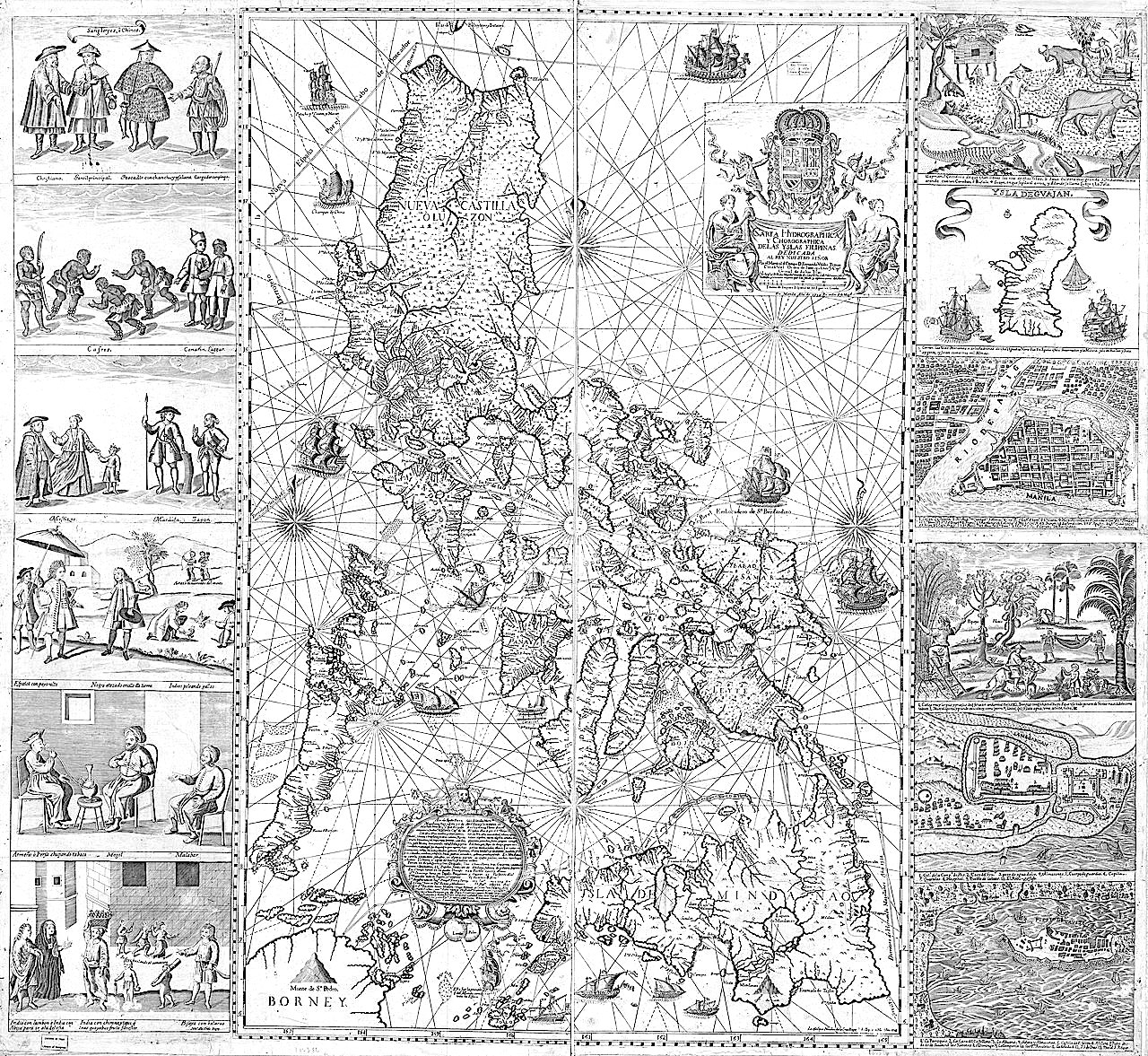

A hydrographical and chorographical chart of the Philippines, drawn by the Jesuit Father Pedro Murillo Velarde (1696-1753) and published in Manila in 1734/ Manila, capital of the Spanish East Indies, 1899.

フィリピンの歴史

(スペイン支配期)

History of the

Philippines under Spanish

settlement and rule (1565–1898)

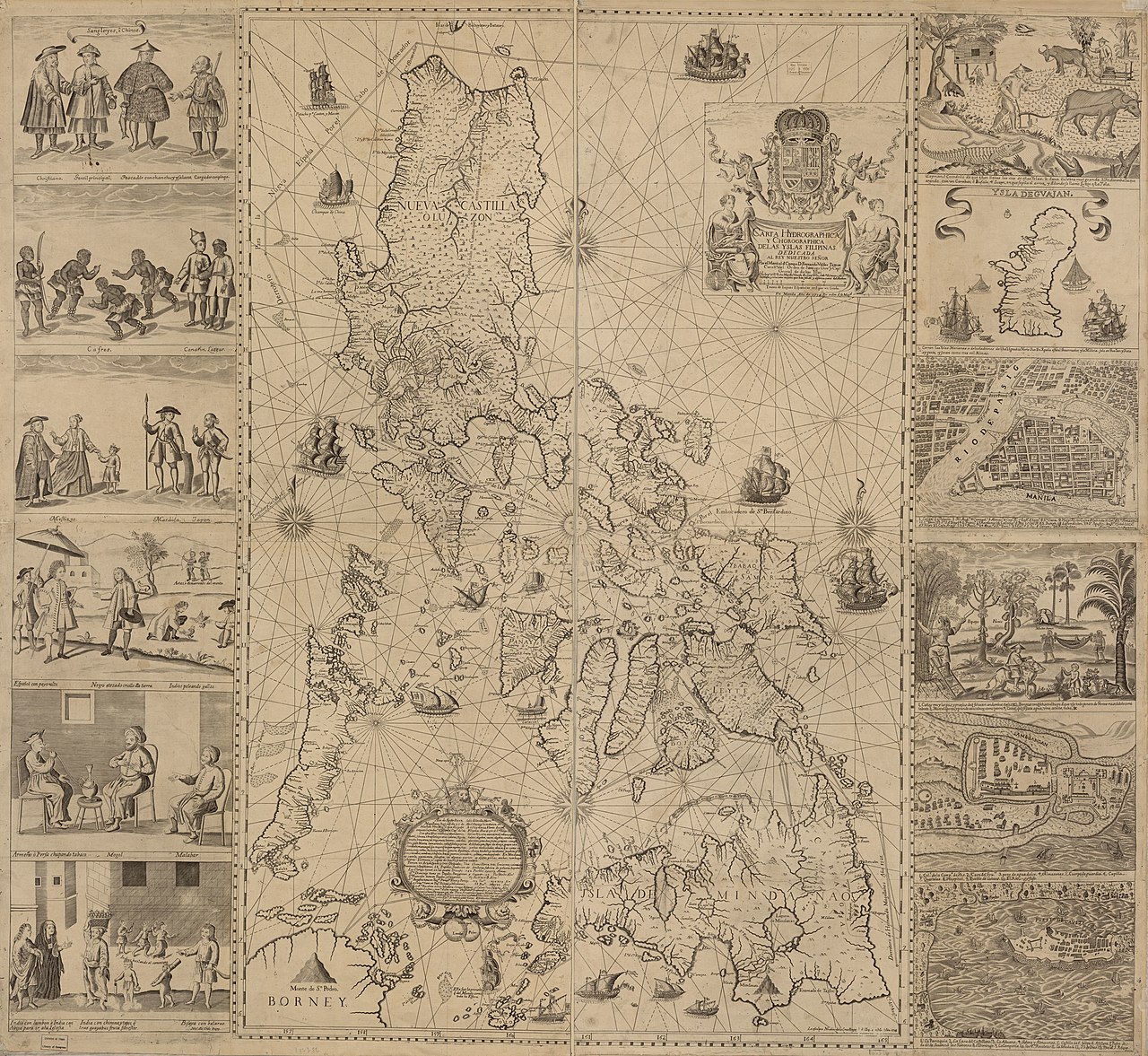

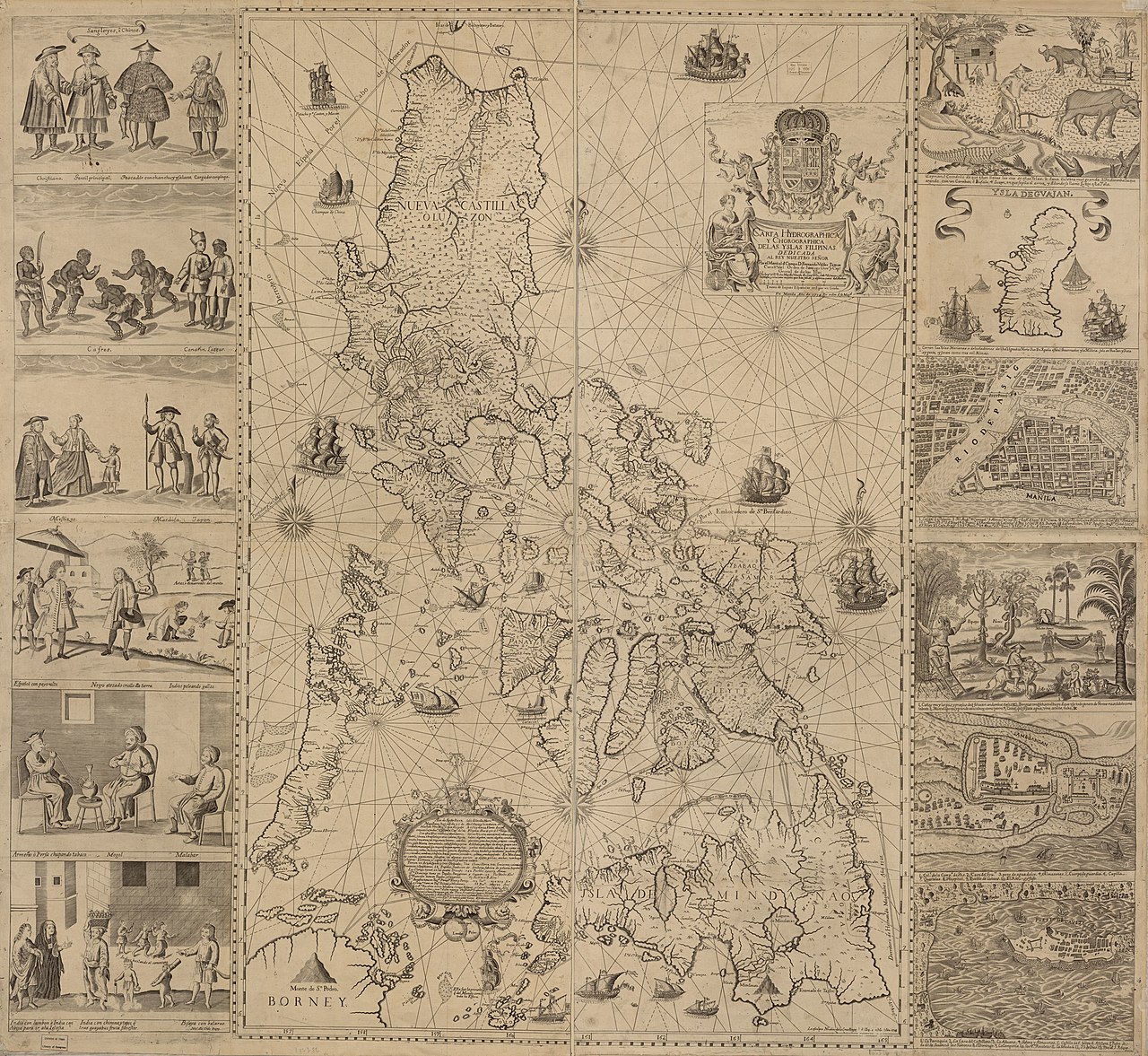

A hydrographical and chorographical chart

of the Philippines, drawn by

the Jesuit Father Pedro Murillo Velarde (1696-1753) and published in

Manila in 1734/ Manila, capital of the Spanish East Indies, 1899.

☆ ヨーロッパ人による最初の記録に残る訪問は、1521年3月17日に、現在の東サマール州グイアン市に属するホモンホン島に上陸したフェルディナンド・マ ゼランの遠征隊である。彼らはマクタン島の酋長ラプラプの軍隊との戦いに敗れ、マゼランは戦死した。[19][20][21] スペイン領フィリピンは、ヌエバ・エスパーニャの太平洋進出と、1565年2月13日にメキシコからミゲル・ロペス・デ・レガスピの遠征隊が到着したこと から始まった。彼はセブに最初の恒久的な入植地を築いた。[22] フィリピン諸島の大部分がスペインの支配下に入り、フィリピンとして知られる最初の統一された政治体制が誕生した。スペインの植民地支配により、キリスト 教、法体系、アジア最古の近代的な大学が導入された。フィリピンはメキシコを拠点とするヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王領の統治下に置かれた。その後、メキシコ の独立に伴い、植民地はスペインに直接統治されるようになった。 スペインによる統治は、米西戦争におけるスペインの敗北により、1898年に終了した。その後、フィリピンはアメリカの領土となった。アメリカ軍はエミリ オ・アギナルドが率いる革命を鎮圧した。アメリカはフィリピンを統治するために、島嶼政府を樹立した。1907年、フィリピン議会が選挙により選出され た。米国はジョーンズ法で独立を約束した。[23] 1935年、完全な独立までの10年間の暫定措置としてフィリピン自治領が樹立された。しかし、1942年の第二次世界大戦中、日本はフィリピンを占領し た。1945年、米軍が日本軍を撃破した。1946年のマニラ条約により、フィリピン共和国が独立した。

★︎先スペイン期のフィリピンの歴史▶フィリピンの歴史(スペイン支配期:1565–1898)︎▶フィリピン共和国の歴史(1899〜現在)︎︎▶︎

| History of the

Philippines before Spanish conquest |

先スペイン期のフィリピンの歴史 |

| Spanish

settlement and rule (1565–1898) Main articles: History of the Philippines (1565–1898), Captaincy General of the Philippines, and Spanish East Indies. |

スペインによる植民地化と統治(1565年~1898年) 主な記事:フィリピンの歴史(1565年~1898年)、フィリピン総督、スペイン領東インド |

| Early Spanish expeditions and

conquests Main articles: Ruy López de Villalobos and Spanish–Moro conflict A Spanish expedition around the world led by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan sighted Samar Island but anchored off Suluan Island on March 16, 1521. They landed the next day on Homonhon Island, now part of Guiuan, Eastern Samar. Magellan claimed the islands he saw for Spain and named them Islas de San Lázaro. He established friendly relations with some of the local leaders especially with Rajah Humabon and converted some of them to Roman Catholicism. In the Philippines, they explored many islands including the island of Mactan. However, Magellan was killed during the Battle of Mactan against the local datu, Lapulapu.[20][184][185] Over the next several decades, other Spanish expeditions were dispatched to the islands. Ruy López de Villalobos led an expedition that visited Leyte and Samar in 1543 and named them Las Islas Filipinas in honor of Philip of Asturias, the Prince of Asturias at the time.[186] Philip became Philip II of Spain on January 16, 1556, when his father, Charles I of Spain (who also reigned as Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor), abdicated the Spanish throne. The name was then extended to the entire archipelago later on in the Spanish era.  1734 Spanish Chart of the Philippine Islands European colonialization began in earnest when Spanish explorer Miguel López de Legazpi arrived from Mexico in 1565 and formed the first European settlements in Cebu. Beginning with just five ships and five hundred men accompanied by Augustinian monks, and further strengthened in 1567 by two hundred soldiers, he was able to repel the Portuguese and create the foundations for the unification and colonialization of the Archipelago.[187] In 1571, the Spanish, their Latin-American recruits and their Filipino (Visayan) allies, commanded by able conquistadors such as Mexico-born Juan de Salcedo (who was in love with Tondo's princess, Kandarapa, a romance his Spanish grandfather Miguel Lopez de Legaspi, disapproved of) attacked Maynila, a vassal-state of the Brunei Sultanate and liberated plus incorporated the kingdom of Tondo as well as establishing Manila as the capital of the Spanish East Indies.[188][189][190] During the early part of the Spanish colonialization of the Philippines, the Spanish Augustinian friar Gaspar de San Agustín, O.S.A., describes Iloilo and Panay as one of the most populated islands in the archipelago and the most fertile of all the islands of the Philippines. He also talks about Iloilo, particularly the ancient settlement of Halaur, as site of a progressive trading post and a court of illustrious nobilities.[191] Legazpi built a fort in Maynila and made overtures of friendship to Lakan Dula, Lakan of Tondo, who accepted. However, Maynila's former ruler, the Muslim rajah, Rajah Sulayman, who was a vassal to the Sultan of Brunei, refused to submit to Legazpi, but failed to get the support of Lakan Dula or of the Pampangan and Pangasinan settlements to the north. When Tarik Sulayman and a force of Kapampangan and Tagalog Muslim warriors attacked the Spaniards in the battle of Bangkusay, he was finally defeated and killed, the Spanish also destroyed the walled Kapampangan city-state of Cainta. |

初期のスペインの探検と征服 主な記事:ルイ・ロペス・デ・ビジャロボスとスペイン・モロ紛争 ポルトガル人探検家フェルディナンド・マゼラン率いるスペインの探検隊が世界周航中にサマール島を発見したが、1521年3月16日にスールアン島沖に停 泊した。彼らは翌日、現在では東サマール州ギウアンに属するホモンホン島に上陸した。マゼランは、目にした島々をスペイン領として領有権を主張し、サン・ ラザロ諸島と名付けた。彼は、特にラジャ・フマボンをはじめとする地元の指導者たちと友好関係を築き、彼らの一部をローマ・カトリックに改宗させた。フィ リピンでは、マクタン島をはじめとする多くの島々を探検した。しかし、マゼランは、地元のダトゥであるラプラプとのマクタン島の戦いで命を落とした。 [20][184][185] その後数十年にわたって、スペインの他の探検隊が島々へ派遣された。ルイ・ロペス・デ・ビジャロボスは1543年にレイテ島とサマール島を訪れた探検隊を 率い、当時のアストゥリアス公フェリペに敬意を表して、それらの島々を「ラス・イスラス・フィリピンナス(Las Islas Filipinas)」と名付けた。[186] フェリペは、父であるスペイン王カルロス1世(神聖ローマ皇帝カール5世としても君臨)が1556年1月16日にスペイン王位を退いたことにより、スペイ ン王フェリペ2世となった。その後、スペイン統治時代を通じて、この名称はフィリピン諸島全体に広がった。  1734年スペインのフィリピン諸島地図 ヨーロッパによるフィリピン植民地化は、1565年にスペインの探検家ミゲル・ロペス・デ・レガスピがメキシコからセブ島に到着し、最初のヨーロッパ人入 植地を築いたときに本格化した。わずか5隻の船と500人の男たち、そして同行したアウグスティノ修道会の修道士たちとともに始まった彼の活動は、 1567年に200人の兵士によってさらに強化され、ポルトガル人を撃退し、列島の統一と植民地化の基礎を築くことができた。[187] 1571年、スペイン人、ラテンアメリカから徴集された兵士たち、そしてフィリピン人(ビサヤ人)の同盟者たちは、メキシコ生まれのフアン・デ・サルセー ド(彼は トンド王女カンダラパと恋仲であったが、スペイン人の祖父ミゲル・ロペス・デ・レガスピはこれを認めなかった)は、ブルネイ・スルタン国の属国であったマ ニラを攻撃し、トンド王国を解放するとともに併合し、マニラをスペイン領東インドの首都とした。[188][189][190] スペインによるフィリピン植民地化の初期、スペインの アウグスティノ会の修道士ガスパル・デ・サン・アウグスティン(O.S.A.)は、イロイロとパナイをフィリピン諸島で最も人口の多い島々であり、フィリ ピン諸島の中でも最も肥沃な島々であると記述している。また、彼はイロイロ、特に古代の集落ハラウールについて、先進的な貿易拠点であり、著名な貴族の宮 廷であったと述べている。 レガスピはマニラに砦を築き、トンドのラカン・ドゥラに友好の申し入れを行い、ラカン・ドゥラはこれを受け入れた。しかし、マニラの元支配者で、ブルネイ のスルタンの家臣であったイスラム教徒のラジャ、ラジャ・スレイマンはレガスピに従うことを拒否し、ラカン・ドゥラやパンパンガンの北にあるパンガシナン 入植地の支持を得ることもできなかった。タリク・スレイマンとカパンパンガン人とタガログ人のイスラム教徒の戦士たちがバンクサイの戦いでスペイン軍を攻 撃した際、ついに彼は敗北し、殺された。スペイン軍は、城壁に囲まれたカパンパンガン人の都市国家、カインタも破壊した。 |

A late 17th-century manuscript by Gaspar de San Agustin from the Archive of the Indies, depicting López de Legazpi's conquest of the Philippines (Source) In 1578, the Castilian War erupted between the Christian Spaniards and Muslim Bruneians over control of the Philippine archipelago. On one side, the newly Christianized non-Muslim Visayans of Panay and Cebu, as well as Butuan (which were from northern Mindanao), as well as the remnants of Bo-ol (Dapitan) had previously waged war against the Sultanate of Sulu, Sultanate of Maguindanao and Kingdom of Maynila, then joined the Spanish in the war against the Bruneian Empire and its allies, the Bruneian puppet-state of Maynila, Sulu which had dynastic links with Brunei as well as Maguindanao which was an ally of Sulu. The Spanish and its Visayan allies assaulted Brunei and seized its capital, Kota Batu. This was achieved as a result in part of the assistance rendered to them by two noblemen, Pengiran Seri Lela and Pengiran Seri Ratna. The former had traveled to Manila to offer Brunei as a tributary of Spain for help to recover the throne usurped by his brother, Saiful Rijal.[192] The Spanish agreed that if they succeeded in conquering Brunei, Pengiran Seri Lela would indeed become the sultan, while Pengiran Seri Ratna would be the new Bendahara. In March 1578, the Spanish fleet, led by De Sande himself, acting as Capitán General, started their journey towards Brunei. The expedition consisted of 400 Spaniards and Mexicans, 1,500 Filipino natives and 300 Borneans.[193] The campaign was one of many, which also included action in Mindanao and Sulu.[194][195] The Spanish succeeded in invading the capital on April 16, 1578, with the help of Pengiran Seri Lela and Pengiran Seri Ratna. Sultan Saiful Rijal and Paduka Seri Begawan Sultan Abdul Kahar were forced to flee to Meragang then to Jerudong. In Jerudong, they made plans to chase the conquering army away from Brunei. The Spanish suffered heavy losses due to a cholera or dysentery outbreak.[196][197] They were so weakened by the illness that they decided to abandon Brunei to return to Manila on June 26, 1578, after just 72 days. Before doing so, they burned the mosque, a high structure with a five-tier roof.[198] Pengiran Seri Lela died in August–September 1578, probably from the same illness that had afflicted his Spanish allies, although there was suspicion, he could have been poisoned by the ruling sultan. Seri Lela's daughter, the Bruneian princess, left with the Spanish and went on to marry a Christian Tagalog, named Agustín de Legazpi of Tondo and had children in the Philippines.[199] |

インドの文書館に保管されている、17世紀後半のガスパール・デ・サン・アグスティンによる写本。ロペス・デ・レガスピによるフィリピン征服を描いたもの (Source) 1578年、フィリピン諸島の支配権を巡り、キリスト教徒のスペイン人とイスラム教徒のブルネイ人との間でカスティーリャ戦争が勃発した。一方の側には、 新たにキリスト教に改宗した非イスラム教徒のビサヤ人(パナイ島とセブ島)やブトゥアン(ミンダナオ島北部)の住民、そしてボオル(ダピタン)の残党がお り、これらは以前にスールー王国、マギンダナオ王国、マニラ王国と戦い、その後、スペイン軍とともにブルネイ帝国とその同盟国であるブルネイの傀儡国家マ ニラ、 ブルネイの朝貢国であったマニラ、ブルネイと同盟関係にあったスールーの同盟国であるスールー、そしてマギンダナオと王朝的なつながりがあったスールー。 スペインとビサヤ同盟軍はブルネイを攻撃し、首都コタ・バトゥを占領した。これは、2人の貴族、ペルギリ・セリ・レラとペルギリ・セリ・ラトナの助力が あったからこそ達成できた。前者はマニラに赴き、弟のサイフル・リジャルが奪取した王位の回復を支援してもらうため、ブルネイをスペインの属国として提供 することを申し出ていた。[192] スペイン側は、ブルネイ征服に成功すれば、ペンギラン・セリ・レラが実際にスルタンとなり、ペンギラン・セリ・ラトナが新たなベダハラとなることに同意し た。1578年3月、デ・サンデ自身が総指揮官として率いるスペイン艦隊がブルネイに向けて出発した。この遠征隊はスペイン人およびメキシコ人400名、 フィリピン先住民1,500名、ボルネオ人300名で構成されていた。[193] この遠征は数ある遠征の1つであり、ミンダナオ島やスールー諸島での作戦行動も含まれていた。[194][195] スペインは1578年4月16日、ペンギラン・スリ・レラとペンギラン・スリ・ラトナの助力を得て首都への侵攻に成功した。スルタン・サイフル・リジャル とパドゥカ・スリ・ベガワン・スルタン・アブドゥル・カハルはメラガン、そしてジェルドンへと逃亡を余儀なくされた。ジェルドンで彼らはブルネイからスペ インの征服軍を追い払う計画を立てた。スペイン軍はコレラや赤痢の流行により大きな損害を被った。[196][197] 彼らは病により弱体化したため、1578年6月26日にブルネイを放棄してマニラへ戻ることを決めた。わずか72日間の滞在であった。その前に、彼らは5 層の屋根を持つ高い建造物であるモスクを焼き払った。[198] ペリンガン・セリ・レラは1578年8月から9月にかけて死去した。おそらくは、スペイン人の同盟者たちを苦しめたのと同じ病気によるものだったが、統治 するスルタンに毒殺されたのではないかという疑いもあった。セリ・レラの娘であるブルネイ王女はスペイン人とともに去り、キリスト教徒のタガログ人、トン ドのアグスティン・デ・レガスピと結婚し、フィリピンで子供をもうけた。[199] |

Filipinos during the Spanish era. (Tipos del País) Concurrently, northern Luzon became a center of the "Bahan Trade" (comercio de bafan), found in Luís Fróis' Historia de Japam, mainly refers to the robberies, raids, and pillages conducted by the Japanese pirates of Kyūshūa as they assaulted the China seas. The Sengoku period (1477–1603) or the warring states period of Japan had spread the wakō's 倭寇 (Japanese Pirates) activities in the China Seas, some groups of these raiders relocated to the Philippines and established their settlements in Luzon. Because of the proximity to China's beaches, the Philippines were favorable a location to launch raids on the provinces of Guangdong and Fujian, and for shipping with Indochina and the Ryūkyū Islands.[200] These were the halcyon days of the Philippine branch of the Bahan trade. Thus, the Spanish sought to fight off these Japanese Pirates, prominent among whom was warlord Tayfusa,[201] whom the Spaniards expelled after he set up the beginnings of a city-state of Japanese pirates in Northern Luzon.[202] The Spanish repelled them in the fabled 1582 Cagayan battles.[203] Due to the 1549 Ming ban on trade leveled against the Ashikaga shogunate as a consequence of the Wokou pirate raids, this resulted in the ban for all the Japanese to enter China, and for Chinese ships to sail to Japan. Thus, Manila became the only place where the Japanese and Chinese can openly trade, often also trading Japanese silver for Chinese silk.[204] In 1587, Magat Salamat, one of the children of Lakandula, along with Lakandula's nephew and lords of the neighboring areas of Tondo, Pandacan, Marikina, Candaba, Navotas and Bulacan, were executed when the Tondo Conspiracy of 1587–1588 failed[205] in which a planned grand alliance with the Japanese Christian-captain, Gayo, (Gayo himself was a Woku who once pirated in Cagayan) and Brunei's sultan, would have restored the old aristocracy. Its failure resulted in the hanging of Agustín de Legaspi and the execution of Magat Salamat (the crown-prince of Tondo).[206] Thereafter, some of the conspirators were exiled to Guam or Guerrero, Mexico. Spanish power was further consolidated after Miguel López de Legazpi's complete assimilation of Madja-as, his subjugation of Rajah Tupas, the Rajah of Cebu and Juan de Salcedo's conquest of the provinces of Zambales, La Union, Ilocos, the coast of Cagayan, and the ransacking of the Chinese warlord Limahong's pirate kingdom in Pangasinan.[207][208] The Spanish also invaded Northern Taiwan and Ternate in Indonesia, using Filipino warriors, before they were driven out by the Dutch.[209] The Sultanate of Ternate reverted to independence and afterwards led a coalition of sultanates against Spain.[210][211] While Taiwan became the stronghold of the Ming-loyalist and pirate state of the Kingdom of Tungning. The Spanish and the Moros of the sultanates of Maguindanao, Lanao and Sulu also waged many wars over hundreds of years in the Spanish–Moro conflict, they were supported by the Papuan language speaking Sultanate of Ternate in Indonesia which regained independence from Spain,[212] as well as the Sultanate of Brunei, not until the 19th century did Spain succeed in defeating the Sulu Sultanate and taking Mindanao under nominal suzerainty. The Spanish considered their war with the Muslims in Southeast Asia an extension of the Reconquista, a centuries-long campaign to retake and rechristianize the Spanish homeland which was invaded by the Muslims of the Umayyad Caliphate. The Spanish expeditions into the Philippines were also part of a larger Ibero-Islamic world conflict[213] that included a war against the Ottoman Caliphate which had just invaded former Christian lands in the Eastern Mediterranean and which had a center of operations in Southeast Asia at its nearby vassal, the Sultanate of Aceh.[214] Thus the Philippines became a theatre of the ongoing world-wide-ranging Ottoman–Habsburg wars. In time, Spanish fortifications were also set up in Taiwan and the Maluku islands. These were abandoned and the Spanish soldiers, along with the newly Christianized natives of the Moluccas, withdrew back to the Philippines in order to re-concentrate their military forces because of a threatened invasion by the Japan-born Ming-dynasty loyalist, Koxinga, ruler of the Kingdom of Tungning.[215] However, the planned invasion was aborted. Meanwhile, settlers were sent to the Pacific islands of Palau and the Marianas.[216] |

スペイン統治時代のフィリピン人。 同時に、ルソン島北部は「バハン貿易」(comercio de bafan)の中心地となった。これは、ルイス・フロイスの『日本史』に見られるもので、主に、九州の倭寇が中国海賊を襲撃した際の強盗、襲撃、略奪行為 を指す。戦国時代(1477年~1603年)または日本の戦国時代は、中国海における倭寇(和寇)の活動を広めた。これらの海賊の一部はフィリピンに移住 し、ルソン島に定住地を築いた。中国の海岸に近いという地理的条件から、フィリピンは広東省や福建省への襲撃を仕掛けるのに好都合な場所であり、インドシ ナや琉球諸島との貿易にも適していた。[200] これが、バハン貿易のフィリピン支店にとっての黄金時代であった。そのため、スペインはこれらの日本人海賊を撃退しようとした。中でも著名なのは武将のタ イフサで、彼はルソン島北部に日本人海賊の都市国家の始まりを築いた後、スペイン人によって追放された。[202] スペイン人は、伝説的な1582年のカガヤンでの戦いで彼らを撃退した。[203] 1549年の明による貿易禁止令は、 倭寇の襲撃の結果として、1549年に明が足利幕府に対して貿易禁止令を発令したため、これにより、全ての日本人の中国への入国と、中国船の日本への航行 が禁止された。そのため、マニラは唯一、日本人と中国人が公然と貿易を行うことのできる場所となり、しばしば、日本の銀と中国の絹を交換する場ともなっ た。 1587年、ラカンダラの子供たちの一人であるマガット・サラマットは、ラカンダラの甥や、トンド、パンダカン、マリキナ、カンダバ、ナボタス、ブラカン といった近隣地域の領主たちとともに、1587年から1588年にかけてのトンド陰謀事件(Tondo Conspiracy of 1587–1588)が失敗した際に処刑された。この陰謀事件は、キリシタンである日本人船長ガヨ(Gayo)との同盟を計画したものであった( 自身はかつてカガヤンで海賊行為を行っていたウォク族であった)とブルネイのスルタンとの同盟により、旧貴族階級が復活するはずであった。この計画の失敗 により、アグスティン・デ・レガスピが絞首刑となり、マガット・サラマット(トンドの王太子)が処刑された。[206] その後、一部の共謀者はグアム島やメキシコのゲレロに追放された。 ミゲル・ロペス・デ・レガスピによるマジャス族の完全同化、セブ王ラジャ・トゥパスの服従、フアン・デ・サルセードによるパンガシナン州の中国軍閥リマホ ン海賊王国の略奪、ザンバレス州、ラ・ウニオン州、イロコス州、カガヤン州沿岸の征服により、スペインの権力はさらに強化された。 スペインはフィリピンの戦士たちを従えて、オランダに駆逐される前に台湾北部とインドネシアのテルナテ島にも侵攻した。[209] テルナテ・スルタン国は独立を取り戻し、その後はスルタン国の連合軍を率いてスペインと戦った。[210][211] 一方、台湾は明朝に忠誠を誓う海賊国家である東寧王国の本拠地となった。スペインとマギンダナオ、ラナオ、スールーのモロ人のスルタン国も、スペイン・モ ロ紛争で何百年にもわたって多くの戦争を繰り広げたが、彼らはスペインから独立を回復したインドネシアのテルナテのスルタン国(パプア諸語話者)やブルネ イのスルタン国から支援を受けていた。スペインがスールーのスルタン国を打ち負かし、 ミンダナオ島を名目上の宗主権下に置くことに成功した。 スペイン人は、東南アジアのイスラム教徒との戦争をレコンキスタの延長線上にあるものと考えた。レコンキスタとは、ウマイヤ朝のイスラム教徒に侵略された スペイン本土を奪還し、キリスト教化する数世紀にわたるキャンペーンである。スペインによるフィリピン遠征は、より大きなイベロ・イスラム世界間の紛争の 一部でもあった。この紛争には、東地中海のキリスト教国を侵略したばかりで、東南アジアを拠点とするオスマン帝国カリフ制との戦争も含まれていた。 やがて、スペイン軍も台湾とマルク諸島に要塞を建設した。これらは放棄され、スペイン兵士たちは、新たにキリスト教に改宗したマルク諸島の原住民ととも に、日本生まれで明朝の忠臣である鄭成功(東寧王)による侵略の脅威に備え、軍事力を再結集するためにフィリピンへと撤退した。[215] しかし、計画されていた侵略は中止された。その間、入植者はパラオとマリアナ諸島に送られた。[216] |

The sketch of the Plaza de Roma Manila by Fernando Brambila, a member of the Malaspina Expedition during their stop in Manila in 1792. In 1593, a diplomatic entourage addressed to the "King of Luzon" from the King of Cambodia which bore an elephant as a tribute[217] arrived in Manila. The King of Cambodia which witnessed the military activity of precolonial Luzones people who were mercenaries across Southeast Asia including at Burma and Siam,[218] now implored the new rulers of Luzon, the Spaniards, to aid him in a war to retake his kingdom from an invasion by the Siamese.[219] That had caused the ill-fated Spanish expedition to Cambodia that although ended in failure had set the foundations of the future restoration of Cambodia from Thai rule under French Cochinchina which tapped Spanish allies. |

1792年にマニラに立ち寄ったマラスピーナ遠征隊のメンバーであるフェルナンド・ブランビラによるマニラのプラザ・デ・ローマのスケッチ。 1593年には、カンボジア王から「ルソン王」宛てに、貢ぎ物として象を伴った外交使節団がマニラに到着した。ビルマやシャム(タイ)を含む東南アジア全 域で傭兵として活動していた先コロニアル期のルソン人たちの軍事活動を目の当たりにしたカンボジア王は、[218] 現在では、シャム(タイ)による侵略から王国を取り戻すための戦争で支援してくれるよう、ルソン島の新たな支配者であるスペイン人に懇願した。[219] これが、失敗に終わったものの、スペインがカンボジアに遠征した不幸な出来事の原因となり、 タイの支配下からスペインの同盟国フランス領コーチシナの支援を受けてカンボジアの将来の復興の基礎を築いた。 |

| Incorporation to the

Mexico-based Viceroyalty of New Spain The founding of Manila by uniting the dominions of Sulayman III and Rajah Ache Matanda of Maynila who was a vassal to the Sultan of Brunei, and Lakandula of Tondo who paid tribute to Ming dynasty China – caused the creation of Manila on February 6, 1579, through the Papal bull Illius Fulti Præsidio by Pope Gregory XIII, encompassing all Spanish colonies in Asia as a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Mexico.[220] Aside from Manila the capital, the Spanish and Latino populations were first concentrated in the 5 newly founded Spanish Royal Cities of Cebu, Arevalo, Nueva Segovia, Nueva Caceres, and Vigan.[221] Aside from these cities, they were also scattered across the Presidios of Cavite, Calamianes, Caraga, and Zamboanga.[222] For much of the Spanish period, the Philippines was part of the Mexico-based Viceroyalty of New Spain. Of the Spaniards and Latinos sent to the Philippines, almost half of the individuals levied to Manila were reported in judicial files as españoles (Spanish born in the colonies), and about a third, as mestizos. Castizos amounted to a total of 15 percent, while peninsulares (Spaniards born in Spain) were around 5 percent of those punished with deportation to Manila.[223] |

メキシコを拠点とするヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王領への編入 スレイマン3世の領地と、ブルネイのスルタンに服従していたマニラのラジャ・アチェ・マトゥンダ、および明王朝中国に貢納していたトンドのラカンダラを統 合してマニラが創設されたことにより、1579年2月6日、教皇グレゴリウス13世の教皇勅書「イルス・フルティ・プレシディオ」によって、アジアのすべ てのスペイン植民地をメキシコ大司教区の教区として包含するマニラが誕生した マニラ首都圏を除いて、スペイン人とラテン系住民は、新たにスペインの王立都市として建設されたセブ、アレバロ、ヌエバ・セゴビア、ヌエバ・カセレス、ビ ガンの5都市に最初に集中した。スペイン統治時代のほとんどの間、フィリピンはメキシコを拠点とするヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王領の一部であった。フィリピ ンに送られたスペイン人およびラテンアメリカ人のうち、マニラに徴収された個人のほぼ半数が、司法ファイルにespañoles(植民地生まれのスペイン 人)として記録されており、約3分の1がメスチゾとして記録されていた。カスティソは合計15パーセントに達し、一方、ペニンスラレス(スペイン生まれの スペイン人)はマニラへの追放刑に処せられた者の5パーセントほどであった。[223] |

Spanish settlement during the

16th and 17th centuries Spanish era Manila canal The "Memoria de las Encomiendas en las Islas" of 1591, just twenty years after the conquest of Luzon, reveals a remarkable progress in the work of colonialization and the spread of Christianity.[224] A cathedral was built in the city of Manila with an episcopal palace, Augustinian, Dominican and Franciscan monasteries and a Jesuit house. The king maintained a hospital for the Spanish settlers and there was another hospital for the natives run by the Franciscans. In order to defend the settlements the Spaniards established in the Philippines, a network of military fortresses called "Presidios" were constructed and officered by the Spaniards, and sentried by Latin-Americans and Filipinos, across the archipelago, to protect it from foreign nations such as the Portuguese, British and Dutch as well as raiding Muslims and Wokou.[225] The Manila garrison was composed of roughly four hundred Spanish soldiers and the area of Intramuros as well as its surroundings, were initially settled by 1200 Spanish families.[226] In Cebu City, at the Visayas, the settlement received a total of 2,100 soldier-settlers from New Spain.[227] At the immediate south of Manila, Mexicans were present at Ermita[228] and at Cavite[229][230][231] where they were stationed as sentries. In addition, men conscripted from Peru, were also sent to settle Zamboanga City in Mindanao, to wage war upon Muslim pirates.[232] These Peruvian soldiers who settled in Zamboanga were led by Don Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera who was governor of Panama.[233] He also used Panamanians, including even some Genoese from Panama Viejo descended from colonists at the Republic of Genoa, a nation once active in the Crusades.[234] There were also communities of Spanish-Mestizos that developed in Iloilo,[235] Negros[236] and Vigan.[237] |

16世紀から17世紀にかけてのスペイン人入植地 スペイン統治時代 マニラ運河 1591年の「Memoria de las Encomiendas en las Islas(諸島におけるエンコミエンダの記録)」は、ルソン島征服からわずか20年後の記録であり、植民地化の進展とキリスト教の普及が著しいことを示 している。[224] マニラ市には大聖堂が建てられ、司教の宮殿、アウグスティノ会、ドミニコ会、フランシスコ会の修道院、イエズス会の施設が置かれた。国王はスペイン人入植 者のための病院を維持し、フランシスコ会が運営する先住民のための別の病院もあった。スペイン人がフィリピンに築いた入植地を守るため、「プレシディオ」 と呼ばれる軍事要塞のネットワークが建設され、スペイン人が指揮を執り、ラテンアメリカ人とフィリピン人が見張り役を務めた。この要塞は、ポルトガル、イ ギリス、オランダなどの外国勢力や、イスラム教徒や倭寇の襲撃から列島を守るために建てられた。 マニラの駐屯地にはおよそ400人のスペイン兵が配備され、イントラムロスとその周辺には当初、1200人のスペイン人家族が定住した。[226] ビサヤ地方のセブ市では、ヌエバ・エスパーニャから合計2100人の兵士入植者がやってきた。[227] マニラのすぐ南には、メキシコ人がエルミタに[228]、カヴィテにも [229][230][231] 彼らは見張りとして駐留していた。さらに、ペルーから徴集された兵士たちも、ミンダナオ島のザンボアンガ市に送られ、イスラム教徒の海賊と戦うことになっ た。[232] ザンボアンガ市に定住したペルー人兵士たちは、パナマ総督であったドン・セバスティアン・ウルタード・デ・コルクエラに率いられていた。[233] 彼はパナマ人たちも利用し、その中にはパナマ・ビエホのジェノヴァ人(かつて十字軍で活躍したジェノヴァ共和国からの入植者の子孫)も含まれていた。。ま た、イロイロ、ニグロス、ビガンにはスペイン系メスチゾのコミュニティも発展していた。[235][236][237] |

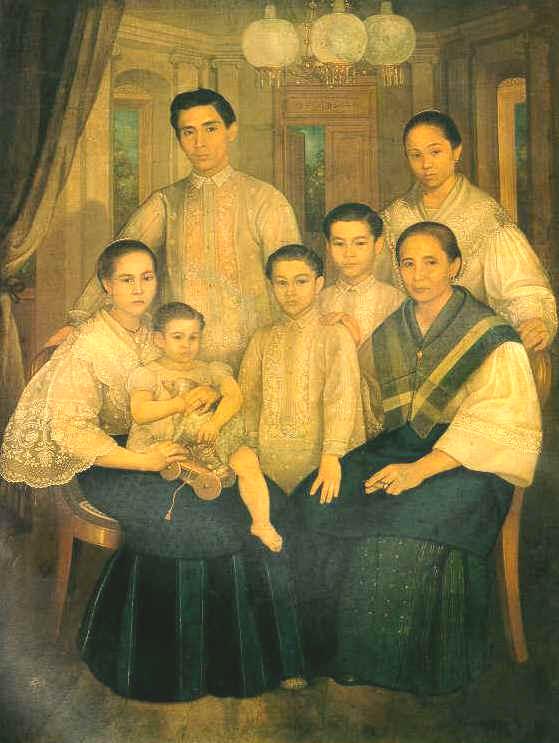

Principalía family by Simón Flores y de la Rosa, uncle of painter Fabián de la Rosa Interactions between native Filipinos[239] and immigrant Spaniards plus the Latin-Americans and their Spanish-Mestizo descendants eventually caused the formation of a new language, Chavacano, a creole of Mexican Spanish.[240] Meanwhile, in the suburb of Tondo, there was a convent run by Franciscan friars and another by the Dominicans that offered Christian education to the Chinese converted to Christianity. The same report reveals that in and around Manila were collected 9,410 tributes, indicating a population of about 30,640 who were under the instruction of thirteen missionaries (ministers of doctrine), apart from the monks in monasteries. In the former province of Pampanga the population estimate was 74,700 and 28 missionaries. In Pangasinan 2,400 people with eight missionaries. In Cagayan and islands Babuyanes 96,000 people but no missionaries. In La Laguna 48,400 people with 27 missionaries. In Bicol and Camarines Catanduanes islands 86,640 people with fifteen missionaries. Based on the tribute counts, the total founding population of Spanish-Philippines was 667,612 people,[241] of which: 20,000 were Chinese migrant traders,[242] 15,600 were Latino soldier-colonists sent from Peru and Mexico (In the 1600s),[243] Immigrants included 3,000 Japanese residents,[244] and 600 pure Spaniards from Europe.[245] Of the 600 Spaniards from Europe, two hundred and thirty-six of them were given encomiendas and were ennobled, as they scattered across the many provinces of the Philippines to serve as administrators.[246] There was also a large but unknown number of Indian Filipinos as majority of the slaves imported into the archipelago were from Bengal or Southern India,[247] adding Dravidian speaking South Indians and Indo-European speaking Bangladeshis into the ethnic mix, and the rest were Malays and Negritos. They were under the care of 140 missionaries, of which 79 were Augustinians, nine Dominicans and 42 Franciscans.[248] Adding during the Spanish evacuation of Ternate, Indonesia, the 200 families of mixed Mexican-Filipino-Spanish and Moluccan-Portuguese descent who had ruled over the briefly Christianized Sultanate of Ternate (They later reverted to Islam) were relocated to Ternate, Cavite and Ermita, Manila.[249] and they were presaged by their previous ruler, Sultan Said Din Burkat who was enslaved but eventually converted to Christianity and was freed after being deported to Manila.[250] |

シモン・フロールス・イ・デ・ラ・ローサによるプリンシピア家、画家ファビアン・デ・ラ・ローサの叔父 フィリピン人[239]とスペインからの移民、およびラテンアメリカからの移民とそのスペイン系混血の子孫との交流により、最終的にメキシコ・スペイン語 のクレオールであるチャバカノ語という新たな言語が形成された。[240] 一方、トンドの郊外には、キリスト教に改宗した中国人にキリスト教教育を行うフランシスコ会の修道院とドミニコ会の修道院があった。同じ報告書によると、 マニラとその周辺では9,410人の貢納者が集められ、修道院の僧侶を除いて、13人の宣教師(教義の伝道師)の指導下にあった人口は約30,640人で あったことが明らかになっている。パンパンガ州の旧州では、人口は74,700人、宣教師は28人であった。パンガシナン州では、人口は2,400人、宣 教師は8人であった。カガヤンとバブヤネス諸島には96,000人の住民がいるが宣教師はいない。ラグナには48,400人の住民と27人の宣教師がい る。ビコールとカマリネス・カタンドゥアネス諸島には86,640人の住民と15人の宣教師がいる。貢納者数から推定すると、スペイン領フィリピンの建国 時の総人口は667,612人であり、その内訳は以下の通りである。20,000人は中国からの移住商人[242]、15,600人はペルーとメキシコか ら送られたラテン系の兵士入植者(1600年代)[243]、移民には3,000人の日本人居住者[244]、ヨーロッパからの純粋なスペイン人600人 [245]が含まれていた。ヨーロッパからの600人のスペイン人のうち、236人は エンコミエンダを与えられ、貴族の称号を得た。彼らはフィリピンの多くの州に散らばり、行政官として働いた。[246] また、ベンガルや南インドから連れてこられた奴隷が大半を占めていたため、多数のフィリピン系インディアンがいたが、その数は不明である。[247] ドラヴィダ語を話す南インド人とインド・ヨーロッパ語を話すバングラデシュ人が民族の混合に加わり、残りはマレー人とネグリトであった。彼らは140人の 宣教師の保護下に置かれており、そのうち79人がアウグスティノ会、9人がドミニコ会、42人がフランシスコ会であった。[248] スペインがインドネシアのテルナテ島から撤退する際に、メキシコ、フィリピン、スペインとモルッカ諸島、ポルトガルの混血で、短期間キリスト教化されたテ ルナテのスルタン国を統治していた200家族(後にイスラム教に改宗)がテルナテ島、カヴィテ、マニラのエルミタに移住した。 。彼らは、以前の支配者であったスルタン・サイード・ディン・ブルカットに先立たれ、奴隷として売られたが、最終的にはキリスト教に改宗し、マニラに追放 された後に解放された。[250] |

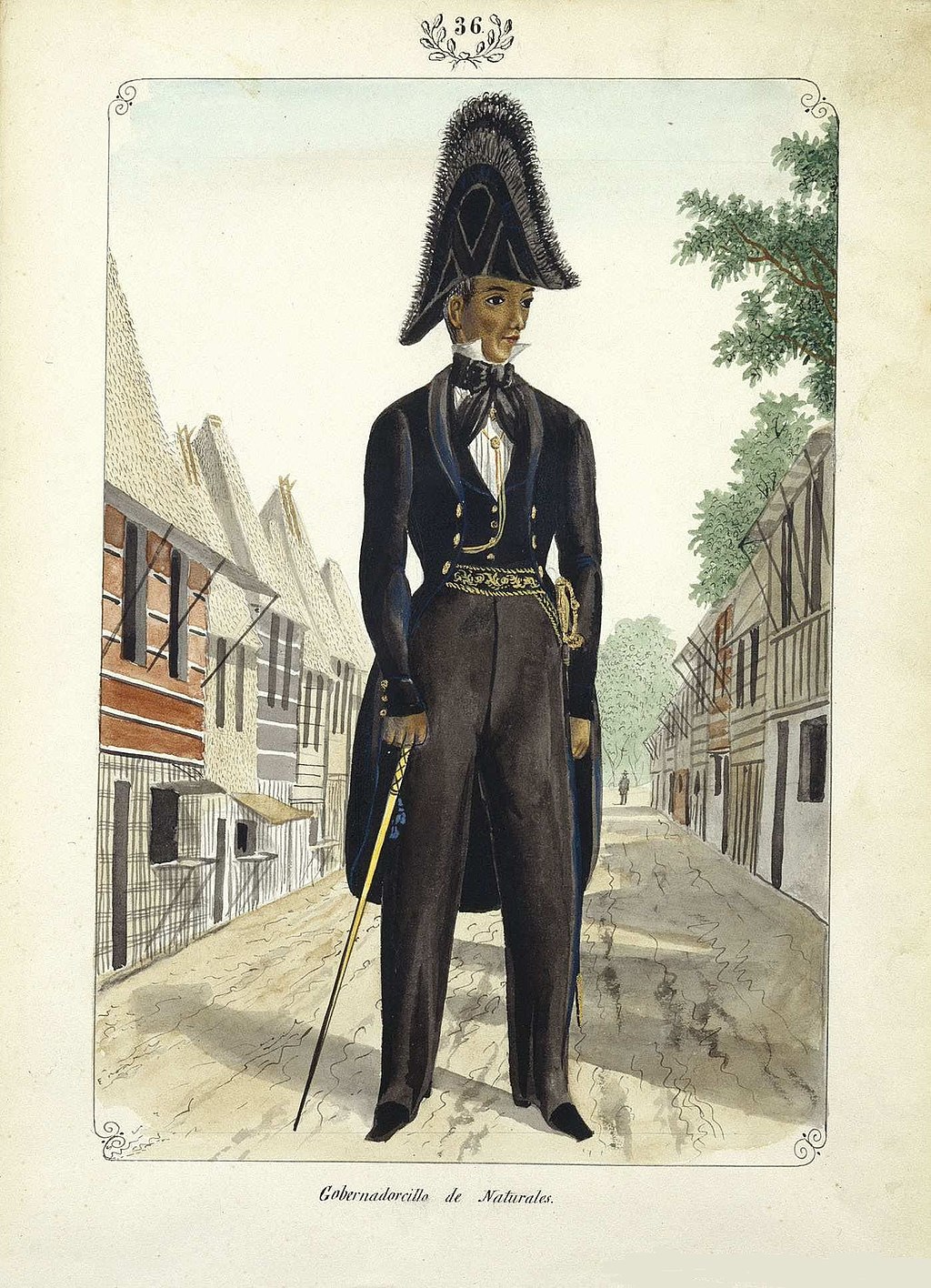

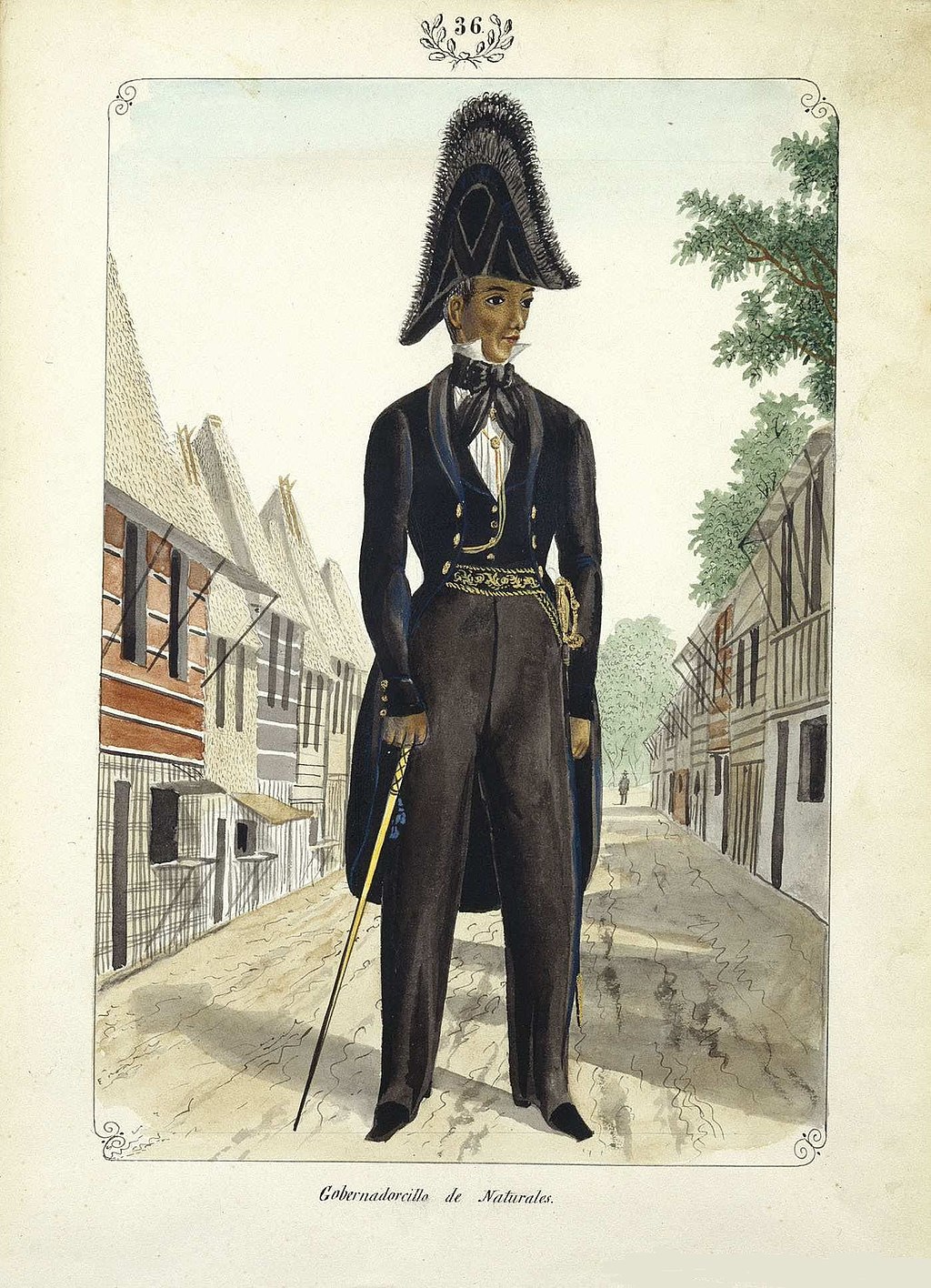

A Gobernadorcillo de Naturales comparable to a modern-day mayor. Mostly of Indio descent. The islands were fragmented and sparsely populated[251] due to constant inter-kingdom wars[252] and natural disasters (as the country is on the Typhoon belt and Pacific Ring of Fire),[183] which made it easy for Spanish invasion. The Spanish then brought political unification to most of the Philippine archipelago via the conquest of the various small maritime states although they were unable to fully incorporate parts of the sultanates of Mindanao and the areas where the ethnic groups and highland plutocracy of the animist Ifugao of Northern Luzon were established. The Spanish introduced elements of western civilization such as the code of law, western printing and the Gregorian calendar alongside new food resources such as maize, pineapple and chocolate from Latin America.[253] Education played a major role in the socio-economic transformation of the archipelago. The oldest universities, colleges, and vocational schools and the first modern public education system in Asia were all created during the Spanish colonial period, and by the time Spain was replaced by the United States as the colonial power, Filipinos were among the most educated subjects in all of Asia.[254] The Jesuits founded the Colegio de Manila in 1590, which later became the Universidad de San Ignacio, a royal and pontifical university. They also founded the Colegio de San Ildefonso on August 1, 1595. After the expulsion of the Society of Jesus in 1768, the management of the Jesuit schools passed to other parties. On April 28, 1611, through the initiative of Bishop Miguel de Benavides, the University of Santo Tomas was founded in Manila. The Jesuits also founded the Colegio de San José (1601) and took over the Escuela Municipal, later to be called the Ateneo de Manila University (1859). All institutions offered courses included not only religious topics but also Science subjects such as physics, chemistry, natural history and mathematics. The University of Santo Tomás, for example, started by teaching theology, philosophy and humanities and the Faculty of Jurisprudence and Canonical Law, together with the schools of medicine and pharmacy were opened during the 18th century. |

現代の市長に相当するGobernadorcillo de Naturales。主にインディオの血筋。 島々は分裂し、人口もまばらであった[251]。これは、絶え間ない王国間の戦争[252]や自然災害(フィリピンは台風ベルトおよび環太平洋火山帯に位 置しているため)[183]が原因であり、スペインによる侵略を容易にした。スペイン人は、フィリピン諸島のほとんどの地域を、さまざまな海洋小国家の征 服を通じて政治的に統一したが、ミンダナオのスルタン国や、北ルソン島に住むアニミズムのイフガオ族の高地寡頭制が確立された地域を完全に併合することは できなかった。スペイン人は、ラテンアメリカからトウモロコシ、パイナップル、チョコレートなどの新たな食糧資源とともに、法典、西洋式印刷、グレゴリオ 暦などの西洋文明の要素を導入した。 教育は、この列島の社会経済の変革において大きな役割を果たした。最古の大学、カレッジ、専門学校、そしてアジアで最初の近代的な公的教育制度はすべてス ペインの植民地時代に創設され、スペインが米国に植民地支配の地位を奪われたときには、フィリピン人はアジアで最も教育を受けた国民の一人となっていた。 [254] イエズス会は1590年にコレヒオ・デ・マニラを創設し、後にコレヒオ・デ・サン・イグナシオは王立・教皇庁立大学となった。また、1595年8月1日に はコレヒオ・デ・サン・イルデフォンソも設立した。1768年のイエズス会の追放後、イエズス会が運営していた学校は他の団体に引き継がれた。1611年 4月28日、ミゲル・デ・ベナビデス司教の主導により、サント・トーマス大学がマニラに設立された。イエズス会はコレヒオ・デ・サン・ホセ(1601年) も設立し、後にアテネオ・デ・マニラ大学(1859年)となるエスクエラ・ムニシパルも引き継いだ。これらの教育機関では、宗教に関する科目だけでなく、 物理学、化学、自然史、数学などの科学科目も教えられていた。例えば、サント・トーマス大学は、神学、哲学、人文科学の教育から始まり、法学部と教会法が 18世紀に開設され、医学部と薬学部も開設された。 |

Bahay na bato, a typical Filipino urban house during the colonial era Outside the tertiary institutions, the efforts of missionaries were in no way limited to religious instruction but also geared towards promoting social and economic advancement of the islands. They cultivated into the natives their taste for music and taught Spanish language to children.[255] They also introduced advances in rice agriculture, brought from America maize and cocoa and developed the farming of indigo, coffee and sugar cane. The only commercial plant introduced by a government agency was the plant of tobacco. Church and state were inseparably linked in Spanish policy, with the state assuming responsibility for religious establishments.[256] One of Spain's objectives in colonialization of the Philippines was the conversion of the local population to Roman Catholicism. The work of conversion was facilitated by the disunity and insignificance of other organized religions, except for Islam, which was still predominant in the southwest.[256] The pageantry of the church had a wide appeal, reinforced by the incorporation of indigenous social customs into religious observances. The eventual outcome was a new Roman Catholic majority, from which the Muslims of western Mindanao and the upland tribal and animistic peoples of Luzon remained detached and alienated (Ethnic groups such as the Ifugaos of the Cordillera region and the Mangyans of Mindoro). |

バハイ・ナ・バト(Bahay na bato)、植民地時代の典型的なフィリピン都市住宅 高等教育機関の外では、宣教師たちの努力は宗教指導に留まらず、島の社会・経済発展の促進にも向けられた。彼らは音楽の趣味を現地人に教え、子供たちにス ペイン語を教えた。[255] また、アメリカから持ち込まれたトウモロコシやカカオを導入し、藍、コーヒー、サトウキビの農業を発展させた。政府機関によって導入された唯一の商業用植 物は、タバコであった。 スペインの政策では、宗教と国家は不可分の関係にあり、国家が宗教施設の責任を担っていた。[256] スペインがフィリピンを植民地化する目的のひとつは、現地住民をローマ・カトリックに改宗させることだった。改宗活動は、イスラム教を除いては、他の組織 化された宗教が分裂しており、また重要視されていなかったため、容易に進められた。イスラム教は南西部では依然として優勢であった。[256] 教会の壮麗な祭事は広く人々を惹きつけ、土着の社会慣習が宗教的儀式に取り入れられたことで、その魅力はさらに強まった。最終的な結果は、新たなローマ・ カトリック教徒の多数派であった。そこから、ミンダナオ島西部のイスラム教徒やルソン島高地の部族や精霊信仰の民(コルディリェラ地方のイフガオ族やミン ドロ島のマンギャン族などの民族)は疎外されたままであった。 |

Villa Fernandina de Vigan founded by the Mexican conquistador Juan de Salcedo. At the lower levels of administration, the Spanish built on traditional village organization by co-opting local leaders. This system of indirect rule helped create an indigenous upper class, called the principalía, who had local wealth, high status, and other privileges. This perpetuated an oligarchic system of local control. Among the most significant changes under Spanish rule was that the indigenous idea of communal use and ownership of land was replaced with the concept of private ownership and the conferring of titles on members of the principalía.[256] Around 1608 William Adams, an English navigator, contacted the interim governor of the Philippines, Rodrigo de Vivero y Velasco, on behalf of Tokugawa Ieyasu, who wished to establish direct trade contacts with New Spain. Friendly letters were exchanged, officially starting relations between Japan and New Spain. From 1565 to 1821, the Philippines was governed as a territory of the Viceroyalty of New Spain from Mexico, via the Royal Audiencia of Manila, and administered directly from Spain from 1821 after the Mexican revolution,[257] until 1898. The Manila galleons, were constructed in Bicol and Cavite.[258] The Manila galleons were accompanied with a large naval escort as it traveled to and from Manila and Acapulco.[259] The galleons sailed once or twice a year, between the 16th and 19th centuries.[260] The Manila Galleons brought with them goods,[261] settlers[230] and military reinforcements[262] destined for the Philippines, from Latin America.[263] The reverse voyage also brought Asian commercial products[264] and immigrants[265] to the western side of the Americas.[266] Legally, the Manila Galleons were only allowed to trade between Mexico and the Philippines; however, illegal trade, commerce, and inter-migration, were happening in secret between the Philippines and other would-be nations in the Spanish Americas due to the tremendous demand and profitability of Asian products in Latin America and this clandestine defiance of Spanish colonial decrees forbidding trade, continued all throughout the term of the Manila Galleons.[267] |

メキシコの征服者ファン・デ・サルセードが建設したビガン・フェルナンディナ邸。 スペイン人は、行政の下層部では、地元の指導者を採用することで、伝統的な村落組織を基盤とした統治を行った。この間接統治のシステムは、地元の富や高い 地位、その他の特権を持つ、プリンシピアと呼ばれる先住民の上流階級を生み出すのに役立った。これにより、地元を支配する寡頭制が永続することとなった。 スペイン統治下で最も重要な変化のひとつは、土地の共同利用と共同所有という先住民の考え方が、私有の概念とプリンシピアのメンバーへの称号授与という考 え方に置き換えられたことである。 1608年頃、イギリス人航海士ウィリアム・アダムスが、スペイン領フィリピン総督ロドリゴ・デ・ビベロ・イ・ベラスコに、スペイン領ニュー・スペインと の直接貿易関係を望む徳川家康の代理として接触した。親善的な書簡が交換され、日本とヌエバ・エスパーニャの公式な関係が開始された。1565年から 1821年にかけて、フィリピンはメキシコのヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王領の領土として統治され、マニラ王立聴罪院を経由して、メキシコ革命後の1821年 から1898年まではスペインから直接統治された。 マニラ・ガレオン船はビコールとカヴィテで建造された。[258] マニラ・ガレオン船はマニラとアカプルコの間を航行する際には、多数の護衛艦を伴っていた。[259] ガレオン船は16世紀から19世紀にかけて、年に1度か2度航海した。[260] マニラ・ガレオン船は、ラテンアメリカからフィリピンへ向かう物資[261]、入植者[230]、軍事増援部隊[ ラテンアメリカからフィリピンへ運ばれた。[263] 逆の航海では、アジアの商業製品[264] や移民[265] がアメリカ大陸の西側にもたらされた。[266] 法的には、マニラ・ガレオン船はメキシコとフィリピン間の貿易のみが許可されていたが、フィリピンとスペイン領アメリカ内の他の国々との間では、アジア製 品の需要と収益性の高さに後押しされ、違法な貿易、商業、移民が秘密裏に行われていた ラテンアメリカにおけるアジア製品の需要と収益性の高さに後押しされ、スペインの植民地支配下における貿易禁止令に公然と背くかたちで、マニラ・ガレオン 船の時代を通じて密かに続けられた。[267] |

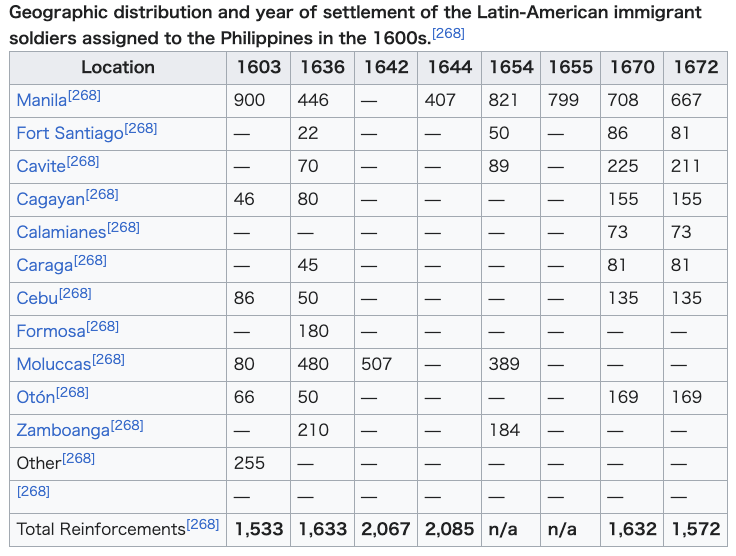

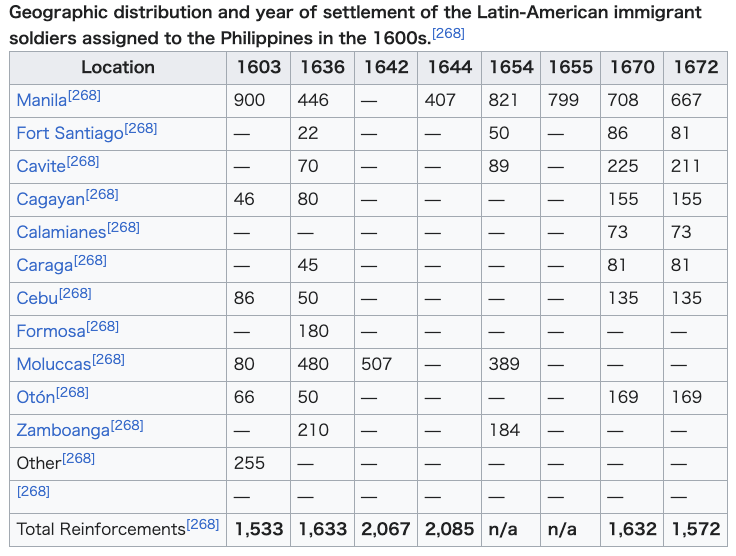

Geographic distribution and year

of settlement of the Latin-American immigrant soldiers assigned to the

Philippines in the 1600s.[268] The Spanish military fought off various indigenous revolts and several external challenges, especially from the British, Dutch, and Portuguese and Chinese pirates. Roman Catholic missionaries converted most of the lowland inhabitants to Christianity and founded schools, universities, and hospitals. In 1863 a Spanish decree introduced education, establishing public schooling in Spanish.[269] In 1646, a series of five naval actions known as the Battles of La Naval de Manila was fought between the forces of Spain and the Dutch Republic, as part of the Eighty Years' War. Although the Spanish forces consisted of just two Manila galleons and a galley with crews composed mainly of Filipino volunteers, against three separate Dutch squadrons, totaling eighteen ships, the Dutch squadrons were severely defeated in all fronts by the Spanish-Filipino forces, forcing the Dutch to abandon their plans for an invasion of the Philippines. In 1687, Isaac Newton included an explicit reference to the Philippines in his classic Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica by mentioning Leuconia, the ancient Ptolemaic name for the Philippines.[71] |

1600年代にフィリピンに配属されたラテンアメリカ系移民兵士の地理

的分布と配属年。[268] スペイン軍は、先住民によるさまざまな反乱や、特にイギリス、オランダ、ポルトガル、中国の海賊によるいくつかの外部からの挑戦を撃退した。ローマ・カト リックの宣教師たちは、低地に住む住民のほとんどをキリスト教に改宗させ、学校、大学、病院を設立した。1863年、スペインの法令により教育が導入さ れ、スペイン語による公立学校が設立された。 1646年には、80年戦争の一部として、スペインとオランダ共和国の軍勢の間で、マニラ海戦として知られる5つの海戦が繰り広げられた。スペイン軍はマ ニラ・ガレオン船2隻とフィリピン人志願兵が中心の乗組員を乗せたガレー船1隻のみであったが、オランダの3つの艦隊、合計18隻の船団に対して、スペイ ン・フィリピン軍は全面的にオランダ艦隊を打ち破り、オランダはフィリピン侵略計画を断念せざるを得なかった。 1687年、アイザック・ニュートンは、古典的名著『自然哲学の原理』の中で、フィリピンを明確に参照し、フィリピンを古代のプトレマイオス朝の名称であ る「ルオコニア」と呼んだ。[71] |

Spanish rule during the 18th

century Coat of arms of Manila were at the corners of the Cross of Burgundy in the Spanish-Filipino battle standard. Colonial income derived mainly from entrepôt trade: The Manila Galleons sailing from the port of Manila to the port of Acapulco on the west coast of Mexico brought shipments of silver bullion, and minted coin that were exchanged for return cargoes of Asian, and Pacific products. A total of 110 Manila galleons set sail in the 250 years of the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade (1565 to 1815). There was no direct trade with Spain until 1766.[256]  Plaza Santo Tomas in Intramuros, Manila; where the Santo Domingo Church, Colegio de Santa Rosa and the original University of Santo Tomas were built during the Spanish era. The Philippines was never profitable as a colony during Spanish rule, and the long war against the Dutch from the West, in the 17th century together with the intermittent conflict with the Muslims in the South and combating Japanese Wokou piracy from the North nearly bankrupted the colonial treasury.[256] Furthermore, the state of near constant war caused a high death and desertion rate among the Mestizo and Indio (Native American) soldiers[263] sent from Mexico and Peru that were stationed in the Philippines.[270] The high death and desertion rate also applied to the native Filipino[239] warriors conscripted by Spain, to fight in battles all across the archipelago. The repeated wars, lack of wages and near starvation were so intense, almost half of the soldiers sent from Latin America either died or fled to the countryside to live as vagabonds among the rebellious natives or escaped enslaved Indians (from India)[271] where they race-mixed through rape or prostitution, further blurring the racial caste system Spain tried hard to maintain.[272] Mixed Spanish-Filipino descent may be more common than expected as many Spaniards often had Filipino concubines and mistresses and they frequently produced children out of wedlock.[273] These circumstances contributed to the increasing difficulty of governing the Philippines. The Royal Fiscal of Manila wrote a letter to King Charles III of Spain in which he advises to abandon the colony, but the religious orders opposed this since they considered the Philippines a launching pad for the conversion of the Far East.[citation needed] The Philippines survived on an annual subsidy paid by the Spanish Crown and often procured from taxes and profits accrued by the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico), and the 200-year-old fortifications at Manila had not been improved much since first built by the Spanish.[274] This was one of the circumstances that made possible the brief British occupation of Manila between 1762 and 1764. |

18世紀のスペイン統治 スペインとフィリピンの戦いの旗印には、マニラの紋章がブルゴーニュ十字の四隅に描かれていた。 植民地収入は主に中継貿易から得られた。マニラのガレオン船はマニラ港からメキシコ西海岸のアカプルコ港まで航海し、銀塊や鋳造貨幣をアジアや太平洋地域 の産物と交換して持ち帰った。マニラ・アカプルコ間ガレオン貿易(1565年から1815年)の250年間で、合計110隻のマニラ・ガレオン船が出航し た。1766年まではスペインとの直接貿易は存在しなかった。  イントラムロス(マニラ)のサント・トーマス広場。スペイン統治時代には、サント・ドミンゴ教会、コレヒオ・デ・サンタ・ロサ、サント・トーマス大学が建 てられた。 スペインの支配下ではフィリピンは植民地として利益をもたらすことはなく、17世紀には西からのオランダとの長期にわたる戦争、南からのイスラム教徒との 断続的な紛争、北からの倭寇の海賊行為により、植民地政府の財政は破綻寸前まで追い込まれた。[256] さらに、絶え間なく続く戦争状態により、 メキシコとペルーからフィリピンに派遣された混血や先住民の兵士の間でも、高い死亡率と離隊率が記録されている。[270] 高い死亡率と離隊率は、スペインが徴兵したフィリピン人戦士にも当てはまり、彼らはフィリピン諸島全域で戦った。繰り返される戦争、賃金の欠如、飢餓寸前 の状況は苛烈を極め、ラテンアメリカから派遣された兵士のほぼ半数が死亡するか、田舎に逃亡して反乱中の先住民のなかで浮浪者として暮らすか、奴隷となっ たインディアン(インド出身)のなかに紛れ込んで[271]、レイプや売春によって人種混合を行い、スペインが維持しようと努めていた人種的カースト制度 をさらに曖昧なものにした。スペイン人とフィリピン人の混血は、予想以上に多い可能性がある。なぜなら、多くのスペイン人が 多くのスペイン人がフィリピン人の妾や愛人を持ち、婚姻外で子供をもうけることが多かったためである。[273] このような状況は、フィリピン統治の難しさを増すことにつながった。マニラ王立財務局はスペイン王カルロス3世に植民地を放棄するよう助言する書簡を送っ たが、フィリピンを極東の改宗の足がかりとみなしていたため、修道会はこれに反対した。[要出典] フィリピンはスペイン王室から支払われる年賦で生き延びており、その多くはヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王領(メキシコ)から徴収された税金や利益から調達され ていた。また、マニラの築200年の要塞は、スペイン人によって最初に建設されて以来、ほとんど改善されていなかった。[274] これが、1762年から1764年にかけての短期間ではあったが、イギリスによるマニラ占領を可能にした状況のひとつであった。 |

| British occupation (1762–1764) Main article: British occupation of Manila Britain declared war against Spain on January 4, 1762, and on September 24, 1762, a force of British Army regulars and British East India Company soldiers, supported by the ships and men of the East Indies Squadron of the British Royal Navy, sailed into Manila Bay from Madras, India.[275] Manila was besieged and fell to the British on October 4, 1762. Outside of Manila, the Spanish leader Simón de Anda y Salazar organized a militia of 10,000 mostly from Pampanga to resist British attempts to extend their conquest outside Manila. Anda y Salazar established his headquarters first in Bulacan, then in Bacolor.[276] After a number of skirmishes and failed attempts to support Filipino uprisings, the British command admitted to the War Secretary in London that the Spanish were "in full possession of the country".[277] The occupation of Manila ended in April 1764 as agreed to in the peace negotiations for the Seven Years' War in Europe. The Spanish then persecuted the Binondo Chinese community for its role in aiding the British.[278] An unknown number of Indian soldiers known as sepoys, who came with the British, deserted and settled in nearby Cainta, Rizal, which explains the uniquely Indian features of generations of Cainta residents.[279] |

イギリス占領(1762年~1764年) 詳細は「マニラ占領」を参照 1762年1月4日、イギリスはスペインに宣戦布告し、1762年9月24日、イギリス陸軍正規兵とイギリス東インド会社の兵士からなる部隊が、イギリス 海軍東インド艦隊の船と乗組員の支援を受け、インドのマドラスからマニラ湾に入港した。[275] マニラは包囲され、1762年10月4日にイギリスに降伏した。 マニラ郊外では、スペインの指導者シモン・デ・アンダ・イ・サラサールが、マニラ郊外へのイギリスの征服拡大を阻止するために、パンパンガ州を中心に1万 人の民兵を組織した。アンダ・イ・サラサールはまずブラカンに、次にバコロルに司令部を設置した。[276] いくつかの小競り合いとフィリピン人蜂起への支援の失敗の後、イギリス軍司令部はロンドンの陸軍大臣に、スペインが「完全にこの国を支配している」ことを 認めた。[277] マニラ占領は、ヨーロッパでの七年戦争の和平交渉で合意されたとおり、1764年4月に終了した。その後、スペインは英国を支援したとしてビノンドの中国 人コミュニティを迫害した。[278] セポイとして知られるインド人兵士の数は不明だが、英国軍に従軍していた彼らの多くが脱走し、リサール州の近郊にあるカインタに定住した。これが、カイン タ住民の世代にわたってインド独特の特徴が受け継がれている理由である。[279] |

| Spanish rule in the second part

of the 18th century In 1766 direct communication was established with Spain and trade with Europe through a national ship based on Spain. In 1774, colonial officers from Bulacan, Tondo, Laguna de Bay, and other areas surrounding Manila reported with consternation that discharged soldiers and deserters (from Mexico, Spain and Peru) during the British occupation were providing the indios military training for the weapons that had been disseminated all over the territory during the war.[280] Expeditions from Spain were administered since 1785 by the Real Compañía de Filipinas, which was granted a monopoly of trade between Spain and the islands that lasted until 1834, when the company was terminated by the Spanish crown due to poor management and financial losses.[281] About this time, Governor-General Anda complained that the Latin-American and Spanish soldiers sent to the Philippines had dispersed "all over the islands, even the most distant, looking for subsistence".[282] In 1781, Governor-General José Basco y Vargas established the Economic Society of the Friends of the Country.[283] The Philippines was administered from the Viceroyalty of New Spain until the independence to Mexico in 1821 necessitated the direct rule from Spain of the Philippines from that year. In the late 1700s to early 1800s, Joaquín Martínez de Zúñiga, an Agustinian Friar, in his Two Volume Book: "Estadismo de las islas Filipinas"[284][285] compiled a census of the Spanish-Philippines based on the tribute counts (Which represented an average family of seven to ten children[286] and two parents, per tribute)[287] and came upon the following statistics: |

18世紀後半のスペイン支配 1766年、スペインとの直接通信が確立し、スペインを拠点とする国民船によるヨーロッパとの貿易が開始された。1774年、ブラカン、トンド、ラグナ・ デ・バイ、およびマニラ周辺のその他の地域から派遣された植民地役人は、イギリス占領下で退役した兵士や脱走兵(メキシコ、スペイン、ペルー出身)が、戦 争中に領土全体に広まった武器の使用方法をインディオに軍事訓練していると驚愕して報告した。[280] スペインからの遠征は、1785年よりレアル・コンパニア・デ・フィリピンが管理し、 1834年まで続き、経営不振と財政赤字によりスペイン王室によって廃止された。[281] この頃、アンダ総督は、フィリピンに送られたラテンアメリカとスペインの兵士たちが「島々を離れ、最も遠い場所まで食料を求めて散らばってしまった」と不 満を述べた。[282] 1781年、総督ホセ・バスコ・イ・バルガスは「祖国の友経済協会」を設立した。[283] フィリピンは、1821年にメキシコが独立するまでヌエバ・エスパーニャ副王領から統治されていたが、その年以降はスペインによるフィリピン直接統治が必 要となった。 1700年代後半から1800年代初頭にかけて、アグスティノ会の修道士ホアキン・マルティネス・デ・スニガは、2巻からなる著書『 「Estadismo de las islas Filipinas」[284][285]という2巻本で、貢納の数に基づいてスペイン領フィリピンの国勢調査をまとめた(貢納1件につき、両親2人と子 供7~10人の平均的な家族を代表するもの[286][287])。そして、次の統計にたどり着いた。 |

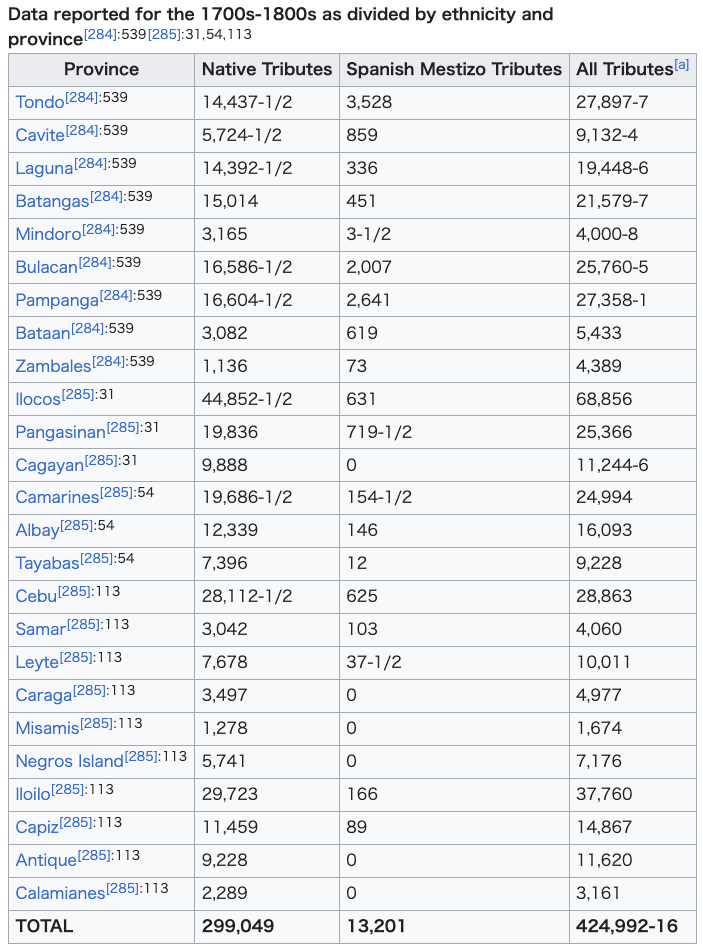

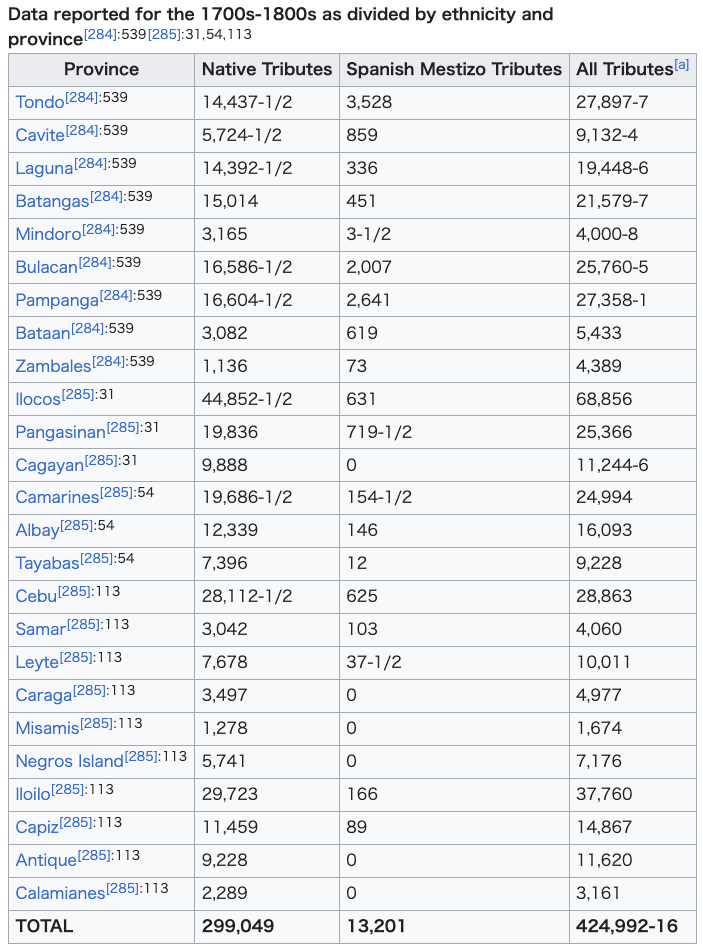

Data reported for the

1700s-1800s as divided by ethnicity and

province[284]: 539 [285]: 31, 54, 113  The Spanish-Filipino population as a proportion of the provinces widely varied; with as high as 19% of the population of Tondo province [284]: 539 (The most populous province and former name of Manila), to Pampanga 13.7%,[284]: 539 Cavite at 13%,[284]: 539 Laguna 2.28%,[284]: 539 Batangas 3%,[284]: 539 Bulacan 10.79%,[284]: 539 Bataan 16.72%,[284]: 539 Ilocos 1.38%,[285]: 31 Pangasinan 3.49%,[285]: 31 Albay 1.16%,[285]: 54 Cebu 2.17%,[285]: 113 Samar 3.27%,[285]: 113 Iloilo 1%,[285]: 113 Capiz 1%,[285]: 113 Bicol 20%,[288] and Zamboanga 40%.[288] According to the data, in the Archdiocese of Manila which administers much of Luzon under it, about 10% of the population was Spanish-Filipino.[284]: 539 Summing up all the provinces including those with no Spanish Filipinos, all in all, in the total population of the Philippines, Spanish Filipinos and mixed Spanish-Filipinos composed 5% of the population.[284]: 539 [285]: 31, 54, 113 The book, "Intercolonial Intimacies Relinking Latin/o America to the Philippines, 1898–1964 By Paula C. Park" citing "Forzados y reclutas: los criollos novohispanos en Asia (1756-1808)" gave a higher number of later Mexican soldier-immigrants to the Philippines, pegging the number at 35,000 immigrants in the 1700s,[289] in a Philippine population which was only around 1.5 Million,[290] thus forming 2.33% of the population.[291] Meanwhile, government records show that 20% of the Philippines' total population were either pure Chinese or Mixed Chinese-Filipinos[292][293] |

1700年代から1800年代のデータを民族と州別に分類した報告書

[284]: 539[285]: 31, 54, 113 スペイン系フィリピン人の人口は、州によって大きく異なっていた。最も人口の多い州であり、かつてのマニラの名称であるトンド州では人口の19%を占めて いた[284]:539(人口の最も多い州であり、かつてのマニラの名称)から、パンパンガ州では13.7%[284]:539、カヴィテ州では13% [284]:539、ラグナ州では2.28%[28 4]: 539 バタンガス 3%,[284]: 539 ブラカン 10.79%,[284]: 539 バターン 16.72%,[284]: 539 イロコス 1.38%,[285]: 31 パンガシナン 3.49%,[285]: 31 アルバイ 1.16%、[285]: 54 セブ 2.17%、[285]: 113 サマール 3.27%、[285]: 113 イロイロ 1%、[285]: 113 カピス 1%、[285]: 113 ビコール 20%、[288] および ザンボアンガ 40%。[ 288] データによると、マニラ大司教区はルソン島の大部分を管轄しており、人口の約10%がスペイン系フィリピン人であった。[284]:539 スペイン系フィリピン人がいない地域も含めたすべての州を合計すると、フィリピンの総人口のうち、スペイン系フィリピン人とスペイン系フィリピン人の混血 は5%を占めていた。[284]:5 39 [285]: 31, 54, 113 「植民地間の親密さ:ラテンアメリカとフィリピンを再び結びつける、1898年から1964年」という本の中で、ポーラ・C・パークは「Forzados y reclutas: los criollos novohispanos en Asia (1756-1808)」を引用し、メキシコからフィリピンへの後年の兵士移民の数を3万5000人と推定している。 フィリピン人口は150万人ほどであったため、人口の2.33%を占めることになる。 一方、政府の記録によると、フィリピン総人口の20%は純粋な中国人か、中国人とフィリピン人の混血であったとされる。 |

Spanish rule during the 19th

century The landing of the Spanish expedition to Sulu by Antonio Brugada. The Philippines was included in the vast territory of the Kingdom of Spain, in the first constitution of Spain promulgated in Cadiz in 1812. It was never a colony as modern-day historical literature would say, but an overseas region in Asia (Spanish Constitution 1812). The Spanish Constitution of 1870 provides for the first autonomous community for "Archipelago Filipino" where all provinces in the Philippine Islands will be given the semi-independent home rule program.  Filipina mestiza women During the 19th century Spain invested heavily in education and infrastructure. Through the Education Decree of December 20, 1863, Queen Isabella II of Spain decreed the establishment of a free public school system that used Spanish as the language of instruction, leading to increasing numbers of educated Filipinos.[294] Additionally, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 cut travel time to Spain, which facilitated the rise of the ilustrados, an enlightened class of Spanish-Filipinos that had been able to enroll in Spanish and European universities. A great number of infrastructure projects were undertaken during the 19th century that put the Philippine economy and standard of living ahead of most of its Asian neighbors and even many European countries at that time. Among them were a railway system for Luzon, a tramcar network for Manila, and Asia's first steel suspension bridge Puente Claveria, later called Puente Colgante. [295] |

19世紀のスペイン統治 アントニオ・ブルガダによるスールーへのスペイン遠征隊の着陸。 フィリピンは、1812年にスペインのカディスで公布されたスペイン最初の憲法において、スペイン王国の広大な領土に含まれていた。それは、現代の歴史文 献が言うような植民地ではなく、アジアの海外地域であった(1812年スペイン憲法)。1870年のスペイン憲法は、フィリピン諸島のすべての州に準独立 の自治制度を設ける「フィリピン諸島」という初の自治共同体を規定した。  フィリピン人混血女性(1899) 19世紀の間、スペインは教育とインフラに多額の投資を行った。1863年12月20日の教育令により、スペインのイサベル2世女王は、スペイン語を教授 言語とする無料の公立学校制度の設立を命じ、これにより、教育を受けたフィリピン人が増加した。[294] さらに、1869年のスエズ運河の開通によりスペインへの渡航時間が短縮され、これにより、スペイン語やヨーロッパの大学に入学できるようになったスペイ ン系フィリピン人の知識階級であるイルストラドスの台頭が促された。スペインやヨーロッパの大学に入学できるようになった。 19世紀には、フィリピン経済と生活水準をアジアのほとんどの国々や当時のヨーロッパの多くの国々よりも先進的なものにする数多くのインフラプロジェクト が実施された。その中には、ルソン島を走る鉄道システム、マニラの路面電車網、アジア初の鋼鉄製吊り橋プエンテ・クラベリア(後にプエンテ・コルガンテと 呼ばれる)などがあった。 [295] |

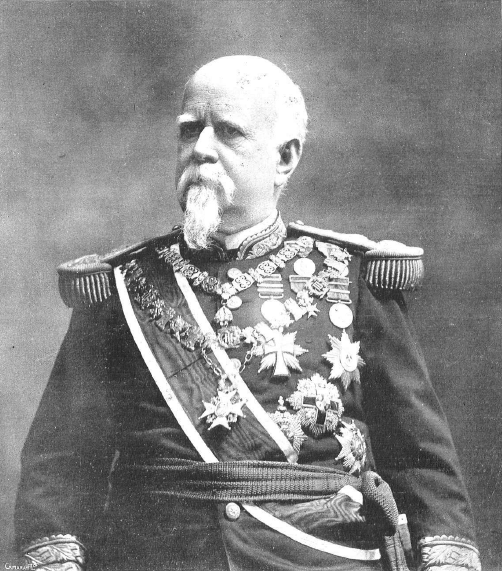

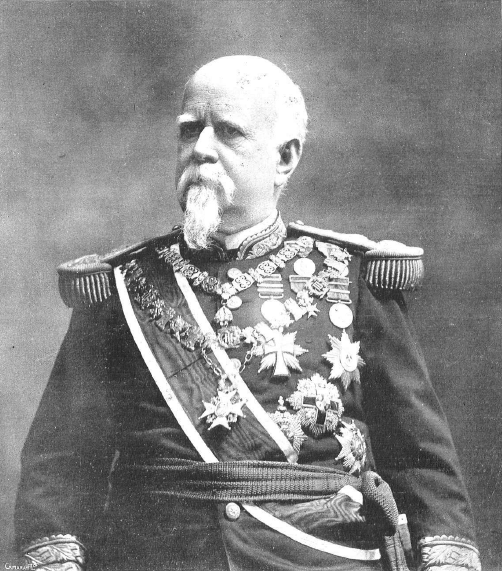

Ilustrados in Madrid, c. 1890 On August 1, 1851, the Banco Español-Filipino de Isabel II was established to attend the needs of the rapid economic boom, that had greatly increased its pace since the 1800s as a result of a new economy based on a rational exploitation of the agricultural resources of the islands. The increase in textile fiber crops such as abacá, oil products derived from the coconut, indigo, that was growing in demand, etc., generated an increase in money supply that led to the creation of the bank. Banco Español-Filipino was also granted the power to print a Philippine-specific currency (the Philippine peso) for the first time (before 1851, many currencies were used, mostly the pieces of eight).  Filipino Marcelo Azcárraga Palmero born in Manila to a Vizcayan Spaniard who was a peninsulares general in the Philippines José de Azcárraga and a Filipina mestiza María Palmero. He became the Prime minister of Spain. Spanish Manila was seen in the 19th century as a model of colonial governance that effectively put the interests of the original inhabitants of the islands before those of the colonial power. As John Crawfurd put it in its History of the Indian Archipelago, in all of Asia the "Philippines alone did improve in civilization, wealth, and populousness under the colonial rule" of a foreign power.[296] John Bowring, Governor General of British Hong Kong from 1856 to 1860, wrote after his trip to Manila: Credit is certainly due to Spain for having bettered the condition of a people who, though comparatively highly civilized, yet being continually distracted by petty wars, had sunk into a disordered and uncultivated state. The inhabitants of these beautiful Islands upon the whole, may well be considered to have lived as comfortably during the last hundred years, protected from all external enemies and governed by mild laws vis-a-vis those from any other tropical country under native or European sway, owing in some measure, to the frequently discussed peculiar (Spanish) circumstances which protect the interests of the natives.[297] In The Inhabitants of the Philippines, Frederick Henry Sawyer wrote: Until an inept bureaucracy was substituted for the old paternal rule, and the revenue quadrupled by increased taxation, the Filipinos were as happy a community as could be found in any colony. The population greatly multiplied; they lived in competence, if not in affluence; cultivation was extended, and the exports steadily increased. [...] Let us be just; what British, French, or Dutch colony, populated by natives can compare with the Philippines as they were until 1895?.[298] The first official census in the Philippines was carried out in 1878. The colony's population as of December 31, 1877, was recorded at 5,567,685 persons.[299] This was followed by the 1887 census that yielded a count of 6,984,727,[300] while that of 1898 yielded 7,832,719 inhabitants.[301] |

マドリードのイルストラードス(=啓蒙主義者たち)、1890年頃 1851年8月1日、スペイン・フィリピン銀行(Banco Español-Filipino de Isabel II)が設立された。これは、1800年代以降、島の農業資源の合理的な開発を基盤とする新たな経済により、急速な経済成長がもたらされ、そのペースが大 幅に加速したことを受けたものであった。アバカなどの繊維作物、ココナッツから採れる石油製品、需要の高まりつつあった藍などの生産量の増加により、通貨 供給量が増加し、銀行の設立につながった。スペイン・フィリピン銀行は、フィリピン独自の通貨(フィリピン・ペソ)を初めて印刷する権限も与えられた (1851年以前は、多くの通貨が使用されていたが、主に8分の1ドルが使用されていた)。  フィリピン人マルセロ・アスカルガ・パルメロは、ビスカヤ出身でフィリピン総督であったスペイン人ホセ・デ・アスカルガとフィリピン人混血のメスティーサ であるマリア・パルメロの間にマニラで生まれた。彼はスペインの首相となった。 19世紀には、スペイン領マニラは、植民地支配のモデルとして、植民地権力よりも島の先住民の利益を優先する効果的な統治を行っていたと見なされていた。 ジョン・クロフォードは著書『インディアン諸島史』の中で、アジア全体において「外国の植民地支配下にあって文明、富、人口が発展したのはフィリピンだけ だった」と述べている。[296] 1856年から1860年まで香港総督を務めたジョン・ボウリングは、マニラを訪れた後に次のように記している。 スペインは、比較的高い文明化を達成していたにもかかわらず、小競り合いの絶えない戦争によって無秩序で未開な状態に陥っていた人々の状況を改善した。こ れらの美しい島々の住民は、概して、この100年間、外部からの侵略から守られ、温和な法律のもとで統治されてきた。これは、熱帯の国々の中で、先住民ま たはヨーロッパ人の支配下にある国々の中でも、とりわけ、先住民の利益を守るために度々議論される独特な(スペインの)事情によるものである。 フィリピン住民』の中で、フレデリック・ヘンリー・ソーヤーは次のように書いている。 無能な官僚が旧来の父権的な統治に取って代わるまで、そして増税によって歳入が4倍になるまでは、フィリピン人はどの植民地でも見られるような幸福な共同 体であった。人口は大幅に増加し、彼らは豊かではないにしても、それなりに生活していた。耕作地は拡大し、輸出は着実に増加した。[...] 公平に見てみよう。1895年以前のフィリピンと肩を並べられるような、英国、フランス、オランダの植民地が存在しただろうか?[298] フィリピンで最初の公式な国勢調査は1878年に実施された。1877年12月31日時点での植民地の人口は5,567,685人と記録された。 [299] これに続いて1887年の国勢調査では6,984,727人、[300] 1898年の調査では7,832,719人が記録された。[301] |

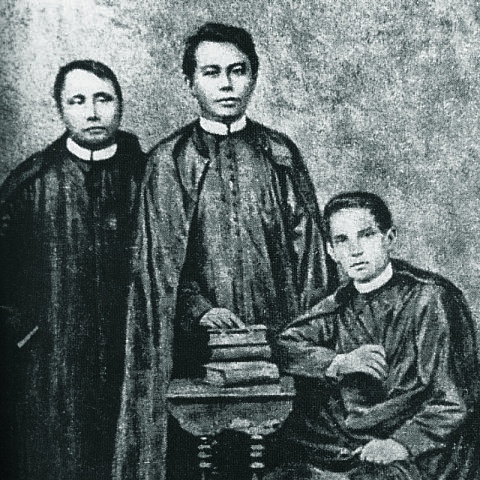

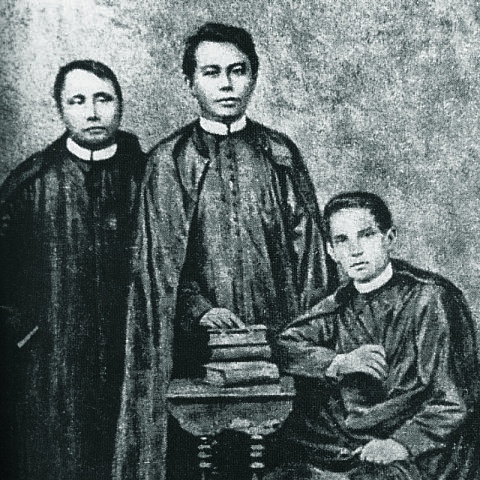

| Latin-American revolutions and

direct Spanish rule Main article: Philippine Military Activities in the Americas  Filipino Mestizo priests Mariano Gomez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora collectively known as the Gomburza was wrongly executed after 1872 Cavite mutiny. It sparked the movements that would later bring about the revolution that would end Spain's control of the archipelago. In the Americas; overseas Filipinos were involved in several anti-colonial movements, Filomeno V. Aguilar Jr. in his paper: "Manilamen and seafaring: engaging the maritime world beyond the Spanish realm", stated therein that Filipinos who were internationally called Manilamen were active in the navies and armies of the world even after the era of the Manila Galleons such as the case of the Argentine war of independence wherein an Argentinian of French descent, Hypolite Bouchard, laid siege to Monterey California as a privateer for the Argentine army. His second ship, the Santa Rosa, which was captained by the American Peter Corney, had a multi-ethnic crew which included Filipinos.[302] It has been proposed that those Filipinos were recruited in San Blas, an alternative port to Acapulco Mexico where several Filipinos had settled during the Manila-Acapulco Galleon trade era.[303] Argentinian-Philippine relations can be traced even earlier since the Philippines already received immigrants from South America, like the soldier Juan Fermín de San Martín, who was the brother of the leader of the Argentinian Revolution Jose de San Martin. Likewise, in Mexico, about 200 Filipinos were recruited by Miguel Hidalgo in his revolution against Spain, the most prominent of which was the Manila-born Ramon Fabié[304][305] afterwards when the revolution was continued by President Guerrero, General Isidoro Montes de Oca, another Filipino-Mexican, had participated in the Mexican Revolutionary war against Spain too.[306] The recent participation of overseas Filipinos in Anti-Imperial wars in the Americas started even earlier when Filipinos in the settlement of Saint Malo, Louisiana assisted the United States in the defense of New Orleans during the War of 1812.[307] Upon Mexican independence, the Filipinos had such an effect on Mexico that there were plans among the newly independent Mexicans, to help the Filipinos revolt against Spain too, there was even a secret memorandum from the Mexican government which read: Now that we Mexicans have fortunately obtained our independence by revolution against Spanish rule, it is our solemn duty to help the less fortunate countries especially the Philippines, with whom our country has had the most intimate relations during the last two centuries and a half. We should send secret agents with a message to their inhabitants to rise in revolution against Spain and that we shall give them financial and military assistance to win their freedom. Should the Philippines succeed in gaining her independence from Spain, we must felicitate her warmly and from an alliance of amity and commerce with her as a sister nation. Moreover, we must resume the intimate Mexico-Philippine relations, as they were during the halcyon days of the Acapulco-Manila galleon trade.[308] Likewise, in this period, overseas Filipinos were also active in the Asia-Pacific especially in China and Indochina. During the Taiping rebellion, Frederick Townsend Ward had a militia employing foreigners to quell the rebellion for the Qing government, at first he hired American and European adventurers but they proved unruly, while recruiting for better troops, he met his aide-de-camp, Vincente (Vicente?) Macanaya, who was twenty three years old in 1860 and was part of the large Filipino population then living in Shanghai, who "were handy on board ships and more than a little troublesome on land", as Caleb Carr journalistically put it.[309] Smith, another writer about China also notes in his book: "Mercenaries and Mandarins" that Manilamen were "Reputed to be brave and fierce fighters" and "were plentiful in Shanghai and always eager for action". During this Taiping rebellion, by July 1860, Townsend Ward's force of Manilamen ranging from one to two hundred mercenaries successfully assaulted Sung-Chiang Prefecture.[310] Thus, while the Philippines was slowly engendered with revolutionary fervour being suppressed by Spain, overseas Filipinos have had an active role in the military and naval engagements of various nations in the Americas and Asia-Pacific.[311] Soldiers from the Philippines were recruited by France, which was allied to Spain, to initially protect Indo-Chinese converts to Roman Catholicism who were persecuted by their native governments, and later for an actual conquest of Vietnam and Laos as well as the establishment of the Protectorate of Cambodia which was liberated from Thai invasions and re-established as a vassal-state of France with the combined Franco-Spanish-Filipino forces creating French Cochinchina which was governed from the former Cambodian and now Vietnamese city of Saigon.[312] |

ラテンアメリカの革命とスペインの直接統治 詳細は「フィリピン軍のアメリカ大陸での活動」を参照  フィリピン人のメスティーソ司祭、マリアノ・ゴメス、ホセ・ブルゴス、ヒサント・サモラは、総称してゴンブルサと呼ばれ、1872年のカヴィテの反乱後に 誤って処刑された。この事件は、後にスペインによるフィリピン諸島支配を終わらせる革命を引き起こす運動のきっかけとなった。 アメリカ大陸では、海外在住のフィリピン人がいくつかの反植民地運動に関与していた。フィリメノ・V・アギラー・ジュニアは論文「 「マニラ人および船乗り:スペイン領を越えた海洋世界との関わり」という論文で、マニラガレオン船の時代以降も、国際的にマニラ人と呼ばれるフィリピン人 は世界の海軍や陸軍で活躍していたと述べている。例えば、アルゼンチンの独立戦争では、フランス系アルゼンチン人のイポリット・ブシャールが、アルゼンチ ン軍の私掠船としてカリフォルニア州モントレーを包囲した。彼の2隻目の船、サンタ・ローザ号はアメリカ人のピーター・コーニーが船長を務め、フィリピン 人を含む多民族の乗組員が乗っていた。[302] それらのフィリピン人は、アカプルコ・メキシコの代替港であるサンブラスで採用されたと提案されている。アカプルコ・マニラ・ガレオン貿易時代には、フィ リピン人の一部がサンブラスに定住していた。[303] アルゼンチンとフィリピンの関係は、フィリピンがすでに南アメリカからの移民を受け入れていたことから、さらにさかのぼることができる。アルゼンチン革命 の指導者ホセ・デ・サン・マルティンの兄弟である兵士フアン・フェルミン・デ・サン・マルティンなど、南米からの移民を受け入れていた。同様に、メキシコ では、スペインに対するミゲル・イダルゴの革命において、約200人のフィリピン人が参加した。その中でも最も著名なのは、マニラ生まれのラモン・ファビ エである。[304][305] その後、ゲレロ大統領が革命を継続した際には、同じくフィリピン系メキシコ人のイシドロ・モンテス・デ・オカ将軍もスペインに対するメキシコ革命戦争に参 加した。[306] 海外在住フィリピン人がアメリカ大陸における反帝国戦争に参加したのは、 1812年の米英戦争中、ルイジアナ州セント・マロの入植地にいたフィリピン人が、ニューオーリンズ防衛のためにアメリカ合衆国を支援したときには、すで に始まっていた。 メキシコ独立の際には、フィリピン人がメキシコに与えた影響は大きく、新たに独立したメキシコ人たちの間では、フィリピン人のスペインに対する反乱を支援 する計画もあった。メキシコ政府による秘密覚書には次のように書かれていた。 スペインの支配に対する革命によって幸運にも独立を勝ち得た我々メキシコ人にとって、特に過去2世紀半の間、我が国と最も親密な関係を築いてきたフィリピ ンという恵まれない国を支援することは、厳粛な義務である。我々は秘密諜報員を送り込み、スペインに対する革命を起こすよう住民たちにメッセージを伝える べきである。そして、彼らの自由獲得のために財政的・軍事的支援を行うべきである。フィリピンがスペインからの独立に成功した場合、私たちはフィリピンを 心から祝福し、姉妹国民として友好と通商の同盟を結ばなければならない。さらに、アカプルコとマニラを結ぶガレオン船貿易の黄金時代のように、親密なメキ シコ・フィリピン関係を再開しなければならない。 同様に、この時代には、海外在住のフィリピン人もアジア太平洋地域、特に中国やインドシナで活躍していた。太平天国の乱の最中、フレデリック・タウンゼン ト・ウォードは清国政府のために反乱を鎮圧する外国人を雇った民兵を組織した。当初はアメリカ人とヨーロッパ人の冒険家を雇ったが、彼らは手に負えないこ とが判明した。より優秀な兵士を募集しているときに、ウォードは副官のヴィンセンテ・マカナヤ(1860年当時23歳)と出会った。マカナヤは当時上海に 住んでいた大勢のフィリピン人の一人であり、ジャーナリストのケイレブ・カーは「船の上では役に立つが、陸では少々厄介な存在」と表現している。陸では少 々厄介な存在でもあった」とジャーナリストのケイレブ・カーは述べている。[309] 中国に関する別の著作もあるスミスも著書『傭兵とマンダリン』の中で、マニラ人は「勇敢で獰猛な戦士として知られていた」と記している。「上海にはマニラ 人が多く、常に戦いを求めていた」とも述べている。この太平天国の乱の最中、1860年7月までに、タウンゼント・ウォードの指揮下にあった100人から 200人のフィリピン人傭兵部隊は、広東省の襲撃に成功した。[310] このように、スペインによる抑圧によりフィリピン国内で徐々に革命熱が高まっていた一方で、海外在住のフィリピン人は、南北アメリカおよびアジア太平洋地 域のさまざまな国民の軍事および海軍活動において積極的な役割を果たしていた。[311] フィリピン人兵士は スペインと同盟関係にあったフランスによって徴兵されたフィリピン人兵士は、当初は、自国政府から迫害されていたインドシナ半島のローマ・カトリック改宗 者を保護するために、後にベトナムとラオスの実際の征服、およびタイの侵略から解放され、フランス・スペイン・フィリピン連合軍によってフランス属国とし て再建され、かつてのカンボジアの都市で現在はベトナムの都市であるサイゴンから統治されたフランス領コーチシナの確立のために、カンボジア保護領の確立 のために派遣された。ベトナムの都市サイゴンから統治されていた。[312] |

Santa Lucia Gate, Intramuros, Manila overlooking San Agustin, San Ignacio Church belltowers and Ateneo de Manila where Jose Rizal once studied. The Criollo and Latino dissatisfaction against the Peninsulares (Spaniards direct from Spain) spurred by their love of the land and their suffering people had a justified hatred against the exploitative Peninsulares who were only appointed to high positions due to their race and unflinching loyalty to the homeland. This resulted in the uprising of Andres Novales a Philippine born soldier who earned great fame in richer Spain but chose to return to serve in poorer Philippines. He was supported by local soldiers as well as former officers in the Spanish army of the Philippines who were primarily from the now sovereign Mexico[313] as well as the freshly independent nations of Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Chile, Argentina and Costa Rica.[314] The uprising was brutally suppressed but it foreshadowed the 1872 Cavite Mutiny that was a precursor to the Philippine Revolution.[315][316][317] However, Hispanic-Philippines reached its zenith when the Philippine-born Marcelo Azcárraga Palmero became a hero as he restored the Bourbon dynasty of Spain to the throne during his stint as Lieutenant-General (Three Star General) after the Bourbons have been deposed by revolutionaries. He eventually became Prime Minister of the Spanish Empire and was awarded membership in the Order of the Golden Fleece, which is considered the most exclusive and prestigious order of chivalry in the world.[318] In the aftermath of Chilean soldiers' participation in the Andres Novales uprising against Spain, the Irish-Chilean founder of Chile, Bernardo O'Higgins, caught wind of anti-Spanish sentiment among Filipinos and planned to send a fleet to liberate the Philippines from Spain, under the command of Scottish-Chilean admiral, Lord Thomas Cochrane. The fleet would have been sent to the Philippines had it not been for Bernardo O'Higgins' untimely exile.[319] |

イントラムロス、サンタ・ルシア門、マニラからサン・アグスチン、サン・イグナチオ教会の鐘楼、ホセ・リサールが学んだアテネオ・デ・マニラを望む。 土地への愛着と苦しむ人々への思いから、スペイン本国から派遣されたスペイン人(ペニンスラレス)に対するクリオージョとラテン系住民の不満は、人種と祖 国への揺るぎない忠誠心によって高い地位に任命された搾取的なペニンスラレスに対する正当な憎悪へと駆り立てられた。その結果、スペイン本国で名を馳せた ものの、より貧しいフィリピンで奉仕することを選んだフィリピン生まれの兵士、アンドレス・ノヴァレスの反乱が起こった。彼は現地の兵士や、主に現在のメ キシコ[313]、そしてコロンビア、ベネズエラ、ペルー、チリ、アルゼンチン、コスタリカといった独立したばかりの国民から成るフィリピン軍の元士官た ちから支持された。[314] この反乱は残忍に鎮圧されたが、1872年のカヴィテの反乱を予兆し、それはフィリピン革命の先駆けとなった。[315][316][317] しかしながら、 フィリピン生まれのマルセロ・アスカルガ・パルメロが英雄となったとき、すなわち、革命家たちによってブルボン朝が廃位された後に、中将(三つ星将官)と してブルボン朝を王位に復帰させたとき、フィリピン系スペイン人は絶頂期を迎えた。最終的にスペイン帝国の首相となり、世界で最も排他的で権威のある騎士 団とされる金羊毛騎士団の会員に任命された。[318]チリ軍がスペインに対するアンドレス・ノバレスの反乱に参加した結果、チリの創設者であるアイルラ ンド系チリ人のベルナルド・オヒギンズは、フィリピン人の反スペイン感情を察知し、 スコットランド系チリ人のトマス・コクラン提督の指揮下に置く予定であった。 ベルナルド・オヒギンズの早すぎる亡命がなければ、艦隊はフィリピンに送られたであろう。[319] |

| Philippine Revolution Main article: Philippine Revolution  Andrés Bonifacio, father of the Philippine Revolution. Revolutionary sentiments arose in 1872 after three Filipino priests, Mariano Gomez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, known as Gomburza, were accused of sedition by colonial authorities and executed by garotte. This would inspire the Propaganda Movement in Spain, organized by Marcelo H. del Pilar, José Rizal, Graciano López Jaena, and Mariano Ponce, that clamored for adequate representation to the Spanish Cortes and later for independence. José Rizal, the most celebrated intellectual and radical ilustrado of the era, wrote the novels "Noli Me Tángere", and "El filibusterismo", which greatly inspired the movement for independence.[320] The Katipunan, a secret society whose primary purpose was that of overthrowing Spanish rule in the Philippines, was founded by Andrés Bonifacio who became its Supremo (leader). In the 1860s to 1890s, in the urban areas of the Philippines, especially at Manila, according to burial statistics, as much as 3.3% of the population were pure European Spaniards and the pure Chinese were as high as 9.9%. The Spanish-Filipino and Chinese-Filipino Mestizo populations also fluctuated. Eventually, everybody belonging to these non-native categories diminished because they were assimilated into and chose to self-identify as pure Filipinos[321] since during the Philippine Revolution, the term "Filipino" included anybody born in the Philippines coming from any race.[322][323] That would explain the abrupt drop of otherwise high Chinese, Spanish and mestizo, percentages across the country by the time of the first American census in 1903.[324] The Philippine Revolution began in 1896. Rizal was wrongly implicated in the outbreak of the revolution and executed for treason in 1896. The Katipunan in Cavite split into two groups, Magdiwang, led by Mariano Álvarez (a relative of Bonifacio's by marriage), and Magdalo, led by Baldomero Aguinaldo cousin of Emilio Aguinaldo. Tension between the factions led to the Tejeros Convention in 1897, at which an election chose Emilio Aguinaldo as president over Bonifacio and Trias. Subsequent leadership conflicts with Bonifacio culminated in his execution by Aguinaldo's soldiers. Aguinaldo agreed to a truce with the Pact of Biak-na-Bato and Aguinaldo and his fellow revolutionaries were exiled to Hong Kong. Not all the revolutionary generals complied with the agreement. One, General Francisco Macabulos, established a Central Executive Committee to serve as the interim government until a more suitable one was created. Armed conflicts resumed, this time coming from almost every province in Spanish-governed Philippines. |

フィリピン革命 詳細は「フィリピン革命」を参照  フィリピン革命の父、アンドレス・ボニファシオ。 1872年、マリアノ・ゴメス、ホセ・ブルゴス、ハシント・サモラ(通称ゴンブルサ)の3人のフィリピン人司祭が植民地当局によって反逆罪で告発され、絞 首刑にされたことをきっかけに、革命的な感情が高まった。この事件は、スペインの国会に適切な代表を送ることを要求し、後に独立を要求した、マルセロ・ H・デル・ピラール、ホセ・リサール、グラシアーノ・ロペス・ハエナ、マリアノ・ポンセらによるスペインでの宣伝運動に影響を与えた。この時代で最も著名 な知識人であり急進的なイルストラドであったホセ・リサールは、小説『ノリ・メ・タンヘレ』と『エル・フィリブステリスモ』を執筆し、独立運動に多大な影 響を与えた。[320] フィリピンにおけるスペインの支配を打倒することを主な目的とした秘密結社カティプナンは、アンドレス・ボニファシオによって創設され、彼はそのスプルモ (指導者)となった。 1860年代から1890年代にかけて、フィリピンの都市部、特にマニラでは、埋葬統計によると、人口の3.3%が純粋なヨーロッパ系スペイン人で、純粋 な中国人は9.9%にも上った。スペイン系フィリピン人と中国系フィリピン人の混血人口も変動した。結局、これらの非ネイティブカテゴリーに属する人々は すべて減少した。なぜなら、彼らは同化されたり、純粋なフィリピン人として自己認識することを選んだりしたからである。フィリピン革命の間、「フィリピン 人」という用語は、フィリピンで生まれた人であれば、どの民族出身であっても含んでいたからである。[322][323] これが、1903年の最初の米国国勢調査の時点で、全国的に中国系、スペイン系、混血の割合が急激に減少した理由である。 324] フィリピン革命は1896年に始まった。リサールは革命勃発への関与を誤認され、1896年に反逆罪で処刑された。カヴィテのカティプナンは、マリアノ・ アルバレス(ボニファシオの義兄弟)が率いるマグディワングと、エミリオ・アギナルドの従兄弟であるバルドメロ・アギナルドが率いるマグダロの2つのグ ループに分裂した。各派閥間の緊張は1897年のテヘロス会議へとつながり、そこで選挙により、ボニファシオとトリアスを抑えてエミリオ・アギナルドが大 統領に選出された。その後、ボニファシオとの指導権争いはエスカレートし、アギナルドの兵士たちによってボニファシオは処刑された。アギナルドはビアッ ク・ナ・バト協定による休戦に同意し、アギナルドと革命派の仲間たちは香港に追放された。すべての革命軍司令官がこの合意に従ったわけではなかった。フラ ンシスコ・マカブロス将軍は、より適切な政府が樹立されるまでの間、暫定政府として中央執行委員会を設立した。今度はスペイン統治下のフィリピンのほぼす べての州から武力衝突が再開された。 |

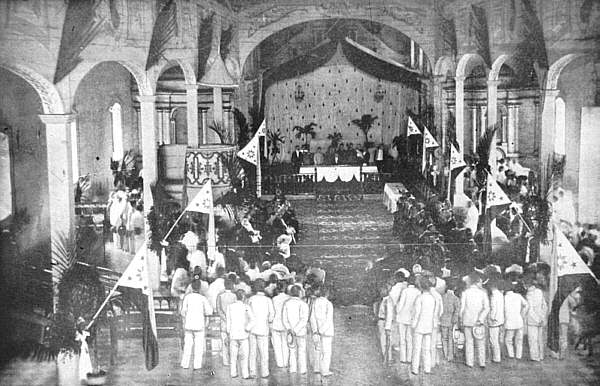

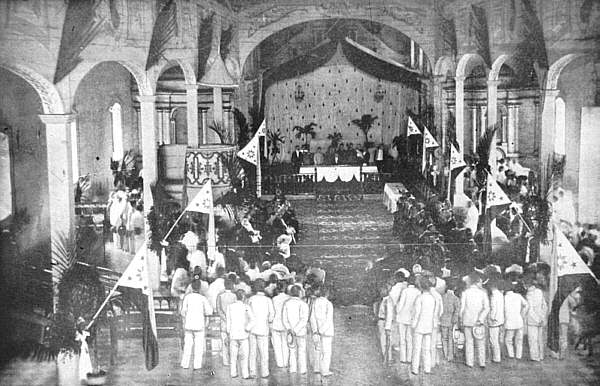

Revolutionaries gather during the Malolos Congress of the Revolutionary Government of the Philippines. In 1898, as conflicts continued in the Philippines, the USS Maine, having been sent to Cuba because of U.S. concerns for the safety of its citizens during an ongoing Cuban revolution, exploded and sank in Havana harbor. This event precipitated the Spanish–American War.[325] After Commodore George Dewey defeated the Spanish squadron at Manila, a German squadron arrived in Manila and engaged in maneuvers which Dewey, seeing this as obstruction of his blockade, offered war—after which the Germans backed down.[326] The German Emperor expected an American defeat, with Spain left in a sufficiently weak position for the revolutionaries to capture Manila—leaving the Philippines ripe for German picking.[327] The U.S. invited Aguinaldo to return to the Philippines in the hope he would rally Filipinos against the Spanish colonial government. Aguinaldo arrived on May 19, 1898, via transport provided by Dewey. On June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo declared the independence of the Philippines in Kawit, Cavite. Aguinaldo proclaimed a Revolutionary Government of the Philippines on June 23. By the time U.S. land forces arrived, the Filipinos had taken control of the entire island of Luzon except for the Spanish capitol in the walled city of Intramuros. In the Battle of Manila, on August 13, 1898, the United States captured the city from the Spanish. This battle marked an end of Filipino-American collaboration, as Filipino forces were prevented from entering the captured city of Manila, an action deeply resented by the Filipinos.[328] |

革命家たちがフィリピン革命政府のマロロス会議に集まる。 1898年、フィリピンでの紛争が続く中、キューバ革命のさなか、米国市民の安全を懸念してキューバに派遣されていたUSSメインがハバナ港で爆発・沈没 した。この事件がきっかけとなり、米西戦争が勃発した。[325] ジョージ・デューイ提督がマニラでスペイン艦隊を撃破した後、ドイツ艦隊がマニラに到着し、演習を行った。これを封鎖の妨害と見たデューイは宣戦布告し、 ドイツは撤退した。[326] ドイツ皇帝は、スペインが革命勢力にマニラを奪取できるほど十分に弱体化し、フィリピンがドイツの収穫に適した状態になることを期待していた。 27] 米国は、スペイン植民地政府に対してフィリピン人を結集させることを期待して、アギナルドにフィリピンへの帰国を呼びかけた。アギナルドは1898年5月 19日、ドゥエイが用意した輸送船で到着した。1898年6月12日、アギナルドはカヴィテ州カウィットでフィリピンの独立を宣言した。アギナルドは6月 23日、フィリピン革命政府の樹立を宣言した。米国陸軍が到着したときには、フィリピン人はイントラムロスという城壁都市にあるスペインの首都を除いてル ソン島全土を掌握していた。1898年8月13日のマニラの戦いにおいて、米国はスペインからマニラ市を奪取した。この戦いは、フィリピン軍がマニラ市へ の進入を妨げられたことで、フィリピンと米国の協力関係に終止符を打つこととなった。この措置はフィリピン国民の強い反発を招いた。[328] |

| The First Philippine Republic

(1899–1901) Emilio Aguinaldo, President of the First Philippine Republic On January 23, 1899, the First Philippine Republic was proclaimed under Asia's first democratic constitution, with Aguinaldo as its president.[320] Under Aguinaldo, The Philippine Revolutionary Army was also renowned to be racially tolerant and progressive as it had a multi-ethnic composition that included various other races and nationalities asides from the native Filipino,[239] being its officers. Juan Cailles an Indian and French Mestizo served as a Major General,[329] the Chinese Filipino José Ignacio Paua was a Brigadier General,[330] and Vicente Catalan who was appointed supreme Admiral of the Philippine Revolutionary Navy was a Cuban of Criollo descent.[331] There were even Japanese, French and Italian soldiers in the Revolution and Republic, such as the Japanese officer Captain Chizuno Iwamoto, French soldier Estaquio Castellor, and Italian revolutionary Captain Camillo Ricchiardi. And, even among the defeated Spanish Army and American invaders, there are those who defected to the side of the Philippine Republic. The most famous of which was African-American Captain David Fagen who joined the Filipinos due to his disgust of American racism against both African-Americans and Filipinos. Various nations, mostly Latin American, also influenced the new Republic, the Sun in the Philippine flag was taken from the Sun of May of Peru, Argentina, and Uruguay which symbolized Inti who was the Incan Sun God, while the stars in the flag were inspired by the stars in the flags of the nations of Texas, Cuba, and Puerto Rico.[332] The Constitution of the First Philippine Republic was also influenced by the Constitutions of Cuba, Belgium, Mexico, Brazil, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Guatemala, in addition to using the French Constitution of 1793.[333] |

フィリピン第一共和国(1899年~1901年) フィリピン第一共和国大統領エミリオ・アギナルド 1899年1月23日、アジア初の民主的憲法のもと、アギナルドを大統領とするフィリピン第一共和国が宣言された。[320] アギナルドのもと、フィリピン革命軍は、フィリピン人以外のさまざまな人種や国籍の者を含む多民族構成であったため、人種的に寛容で進歩的であったことで 知られていた。インド系フランス人の混血であるフアン・カイレスは少将を務め[329]、中国系フィリピン人のホセ・イグナシオ・パウアは准将 [330]、フィリピン革命海軍の最高司令官に任命されたビセンテ・カタランはキューバ系クリオーリョであった[331]。 革命と共和国には日本人、フランス人、イタリア人の兵士もおり、日本人将校の岩本千津乃大尉、フランス人兵士のエスタキオ・カステリョール、イタリア人 革命家カミッロ・リッカルディ大尉などがいた。 また、敗北したスペイン軍やアメリカ軍の侵略者の中にも、フィリピン共和国側に寝返った者もいた。 最も有名なのは、アフリカ系アメリカ人のデビッド・フェイゲン大尉で、アフリカ系アメリカ人とフィリピン人に対するアメリカの差別主義に嫌気がさし、フィ リピン人側に加わった。また、主にラテンアメリカ諸国の国民も、この新しい共和国に影響を与えた。フィリピン国旗の太陽は、インカ帝国の太陽神であるイン ティを象徴するペルー、アルゼンチン、ウルグアイの太陽から取られた。一方、国旗に描かれた星は、テキサス、キューバ、プエルトリコの国旗に描かれた星か ら着想を得たものである。[332] フィリピン第一共和国の憲法は、キューバ、ベルギー、メキシコ、ブラジル、ニカラグア 、コスタリカ、グアテマラの憲法の影響を受けているほか、1793年のフランス憲法も使用されている。[333] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Philippines |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆