音楽の歴史

History of music

☆ 【音楽の歴史:History of music】 音楽の定義は世界中で大きく異なるが、すべての既知の文化が音楽に関わっているため、音楽は文化の普遍的な要素とみなされている。音楽の起源については、 依然として議論が分かれている。評論家たちは、音楽を言語の起源と関連付け、音楽が言語よりも前に、後に、あるいは同時に生まれたかについて、さまざまな 意見が飛び交っている。さまざまな分野の研究者によって多くの説が提唱されているが、広く認められているものはまだない。ほとんどの文化には、音楽の発明 に関する独自の神話的な起源があり、それぞれが属する神話、宗教、または哲学的な信念に根ざしている。 先史時代の音楽は、骨の笛の証拠から、上旧石器時代(約4万年前)に初めて明確に年代が特定されているが、実際の起源がより古い中期旧石器時代(30万年 から5万年前)にあるかどうかは不明である。先史時代の音楽についてはほとんど知られておらず、その痕跡は主にいくつかの単純なフルートや打楽器に限られ ている。しかし、こうした証拠は、夏王朝やインダス文明などの先史社会にも、ある程度音楽が存在していたことを示している。文字が発達すると、文字を持つ 文明の音楽、すなわち古代音楽が、中国、エジプト、ギリシャ、インド、ペルシャ、メソポタミア、中東の主要な社会で登場した。古代音楽全体について多くの 一般化を行うことは困難ですが、既知の資料から判断すると、単旋律と即興性が特徴的だったと考えられる。古代の歌の形式では、歌詞と音楽が密接に結びつい ていた。最も古い現存する音楽記譜法はこの時代から残っているが、リグ・ヴェーダや詩経のような多くのテキストは、伴奏音楽なしの形で残っている。シルク ロードの出現と文化間の接触の増加は、音楽のアイデア、実践、楽器の伝播と交換を促した。このような相互作用により、唐朝の音楽は中央アジアの伝統に大き く影響を受け、唐朝の音楽、日本の雅楽、韓国の宮廷音楽は互いに影響し合った。 歴史的に、宗教はしばしば音楽の触媒となってきた。ヒンドゥー教のヴェーダは、インドの古典音楽に大きな影響を与え、儒教の五経は、その後の中国音楽の基 礎を築いてきた。7 世紀にイスラム教が急速に広まった後、イスラム音楽はペルシャとアラブ世界を支配し、イスラムの黄金時代には、数多くの重要な音楽理論家が活躍した。初期 キリスト教教会によって作曲され、演奏された音楽は、西洋古典音楽の伝統を正式に確立した[1]。この伝統は中世音楽へと続き、ポリフォニー、五線譜、現 代の多くの楽器の初期形態が発展した。宗教の有無に加え、社会の音楽は、社会経済組織や経験、気候、技術へのアクセスなど、その文化のあらゆる側面から影 響を受ける。多くの文化は、音楽を他の芸術形式と組み合わせている。例えば、中国の四芸や中世の四学問(quadrivium)などが挙げられる。音楽が 表現する感情や思想、音楽が演奏され聴かれる状況、音楽家や作曲家に対する態度などは、地域や時代によって異なる。多くの文化は、芸術音楽(または「クラ シック音楽」)、民謡、ポピュラー音楽を区別している。

| Although definitions

of music vary wildly throughout the world, every known culture partakes

in it, and it is thus considered a cultural universal. The origins of

music remain highly contentious; commentators often relate it to the

origin of language, with much disagreement surrounding whether music

arose before, after or simultaneously with language. Many theories have

been proposed by scholars from a wide range of disciplines, though none

has achieved broad approval. Most cultures have their own mythical

origins concerning the invention of music, generally rooted in their

respective mythological, religious or philosophical beliefs. The music of prehistoric cultures is first firmly dated to c. 40,000 BP of the Upper Paleolithic by evidence of bone flutes, though it remains unclear whether or not the actual origins lie in the earlier Middle Paleolithic period (300,000 to 50,000 BP). There is little known about prehistoric music, with traces mainly limited to some simple flutes and percussion instruments. However, such evidence indicates that music existed to some extent in prehistoric societies such as the Xia dynasty and the Indus Valley civilisation. Upon the development of writing, the music of literate civilizations—ancient music—was present in the major Chinese, Egyptian, Greek, Indian, Persian, Mesopotamian, and Middle Eastern societies. It is difficult to make many generalizations about ancient music as a whole, but from what is known it was often characterized by monophony and improvisation. In ancient song forms, the texts were closely aligned with music, and though the oldest extant musical notation survives from this period, many texts survive without their accompanying music, such as the Rigveda and the Shijing Classic of Poetry. The eventual emergence of the Silk Road and increasing contact between cultures led to the transmission and exchange of musical ideas, practices, and instruments. Such interaction led to the Tang dynasty's music being heavily influenced by Central Asian traditions, while the Tang dynasty's music, the Japanese gagaku and Korean court music each influenced each other. Historically, religions have often been catalysts for music. The Vedas of Hinduism immensely influenced Indian classical music, and the Five Classics of Confucianism laid the basis for subsequent Chinese music. Following the rapid spread of Islam in the 7th century, Islamic music dominated Persia and the Arab world, and the Islamic Golden Age saw the presence of numerous important music theorists. Music written for and by the early Christian Church properly inaugurates the Western classical music tradition,[1] which continues into medieval music where polyphony, staff notation and nascent forms of many modern instruments developed. In addition to religion or the lack thereof, a society's music is influenced by all other aspects of its culture, including social and economic organization and experience, climate, and access to technology. Many cultures have coupled music with other art forms, such as the Chinese four arts and the medieval quadrivium. The emotions and ideas that music expresses, the situations in which music is played and listened to, and the attitudes toward musicians and composers all vary between regions and periods. Many cultures have or continue to distinguish between art music (or 'classical music'), folk music, and popular music. |

音楽の定義は世界中で大きく異なるが、すべての既知の文化が音楽に関

わっているため、音楽は文化の普遍的な要素とみなされている。音楽の起源については、依然として議論が分かれている。評論家たちは、音楽を言語の起源と関

連付け、音楽が言語よりも前に、後に、あるいは同時に生まれたかについて、さまざまな意見が飛び交っている。さまざまな分野の研究者によって多くの説が提

唱されているが、広く認められているものはまだない。ほとんどの文化には、音楽の発明に関する独自の神話的な起源があり、それぞれが属する神話、宗教、ま

たは哲学的な信念に根ざしている。 先史時代の音楽は、骨の笛の証拠から、上旧石器時代(約4万年前)に初めて明確に年代が特定されているが、実際の起源がより古い中期旧石器時代(30万 年から5万年前)にあるかどうかは不明である。先史時代の音楽についてはほとんど知られておらず、その痕跡は主にいくつかの単純なフルートや打楽器に限ら れ ている。しかし、こうした証拠は、夏王朝やインダス文明などの先史社会にも、ある程度音楽が存在していたことを示している。文字が発達すると、文字を持つ 文明の音楽、すなわち古代音楽が、中国、エジプト、ギリシャ、インド、ペルシャ、メソポタミア、中東の主要な社会で登場した。古代音楽全体について多くの 一般化を行うことは困難ですが、既知の資料から判断すると、単旋律と即興性が特徴的だったと考えられる。古代の歌の形式では、歌詞と音楽が密接に結びつ いていた。最も古い現存する音楽記譜法はこの時代から残っているが、リグ・ヴェーダや詩経のような多くのテキストは、伴奏音楽なしの形で残っている。シル クロードの出現と文化間の接触の増加は、音楽のアイデア、実践、楽器の伝播と交換を促した。このような相互作用により、唐朝の音楽は中央アジアの 伝統に大きく影響を受け、唐朝の音楽、日本の雅楽、韓国の宮廷音楽は互いに影響し合った。 歴史的に、宗教はしばしば音楽の触媒となってきた。ヒンドゥー教のヴェーダは、インドの古典音楽に大きな影響を与え、儒教の五経は、その後の中国音楽 の基礎を築いてきた。7 世紀にイスラム教が急速に広まった後、イスラム音楽はペルシャとアラブ世界を支配し、イスラムの黄金時代には、数多くの重要な音楽理論家が活躍した。 初期キリスト教教会によって作曲され、演奏された音楽は、西洋古典音楽の伝統を正式に確立した[1]。この伝統は中世音楽へと続き、ポリフォニー、五線 譜、現代の多くの楽器の初期形態が発展した。宗教の有無に加え、社会の音楽は、社会経済組織や経験、気候、技術へのアクセスなど、その文化のあらゆる側面 から影響を受ける。多くの文化は、音楽を他の芸術形式と組み合わせている。例えば、中国の四芸や中世の四学問(quadrivium)などが挙げられる。 音楽が表現する感情や思想、音楽が演奏され聴かれる状況、音楽家や作曲家に対する態度などは、地域や時代によって異なる。多くの文化は、芸術音楽(または 「クラシック音楽」)、民謡、ポピュラー音楽を区別している。 |

|

|

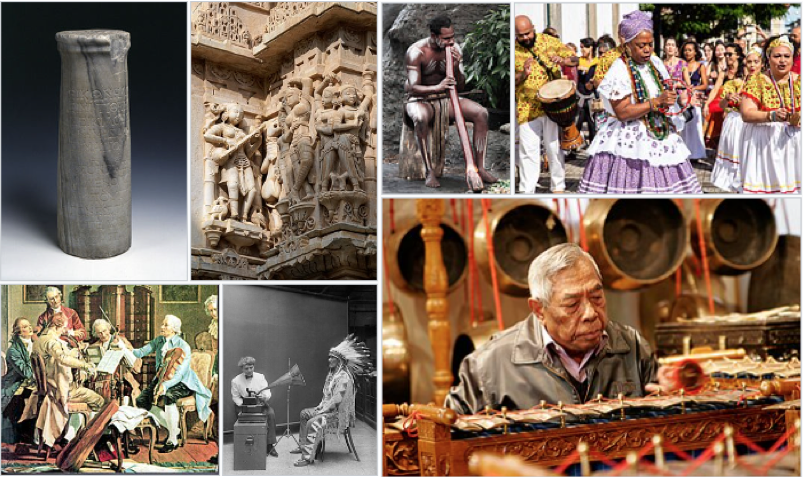

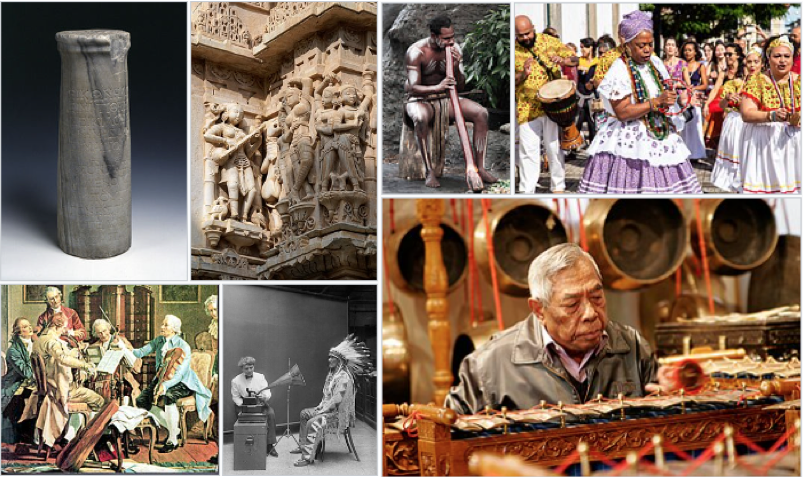

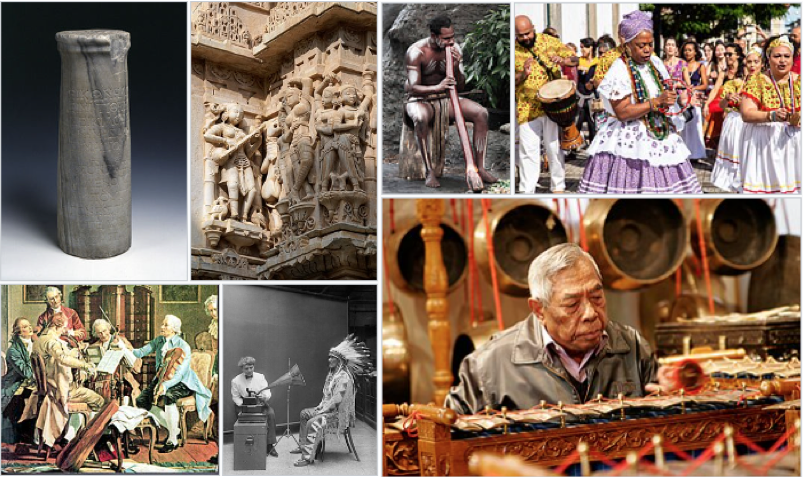

| Sculptures on the Jagdish

Temple, Udaipur of musicians, one of which plays an instrument similar

to the Rudra veena Blackfoot chief Mountain Chief listening to a recording by Frances Densmore in 1916 Performers in the Samba de Roda festival, a music and dance celebration in the Bahia region of Brazil A man playing the gendèr outside of the Embassy of Indonesia, Canberra A man playing the didgeridoo, an indigenous instrument of Australia Joseph Haydn playing in a string quartet, in a painting from before 1790 |

ウダイプールのジャグディッシュ寺院にある、楽器を演奏する音楽家たち

の彫刻。そのうちの 1 人は、ルドラ・ヴィーナに似た楽器を演奏している。 1916 年、フランシス・デンスモアによる録音に耳を傾けるブラックフット族の首長、マウンテン・チーフ。 ブラジルのバイア地方で開催される音楽と踊りの祭典、サンバ・デ・ロダ祭りの出演者たち。 キャンベラのインドネシア大使館前でジェンデルを演奏する男性。 オーストラリアの伝統楽器ディジュリドゥを演奏する男性 1790年以前に描かれた絵画で、弦楽四重奏を演奏するヨゼフ・ハイドン |

| "But

that music is a language by whose means messages are elaborated, that

such messages can be understood by the many but sent out only by the

few, and that it alone among all language unites the contradictory

character of being at once intelligible and untranslatable—these facts

make the creator of music a being like the gods and make music itself

the supreme mystery of human knowledge."----Claude Lévi-Strauss, The

Raw and the Cooked[2] |

「し

かし、その音楽はメッセージが精巧に表現される言語であり、そのようなメッセージは多くの人々に理解されるものの、ごく少数の者によってのみ発信されるも

のであり、また、すべての言語の中で唯一、理解可能でありながら翻訳不可能なという矛盾した性質を併せ持つものである。これらの事実により、音楽の創造者

は神のような存在となり、音楽そのものは人間の知識の至高の謎となるのだ。」——クロード・レヴィ=ストロース、『生の食物と調理された食物』[2] |

| Origins Further information: Evolutionary musicology § The origins of music See also: Music archaeology, Definition of music, and Timeline of musical events Music is regarded as a cultural universal,[3][4] though definitions of it vary depending on culture and throughout history.[5] As with many aspects of human cognition, it remains debated as to what extent the origins of music will ever be understood, with scholars often taking polarizing positions.[6][7] The origin of music is often discussed alongside the origin of language, with the nature of their connection being the subject of much debate.[8] However, before the mid-late 20th century, both topics were seldom given substantial attention by academics.[9][10][n 1] Since the topic's resurgence, the principal source of contention is divided into three perspectives: whether music began as a kind of proto-language (a result of adaptation) that led to language; if music is a spandrel (a phenotypic by-product of evolution) that was the result of language; or if music and language both derived from a common antecedent.[12][13][n 2][n 3] There is little consensus on any particular theory for the origin of music, which have included contributions from archaeologists, cognitive scientists, ethnomusicologists, evolutionary biologists, linguists, neuroscientists, paleoanthropologists, philosophers, and psychologists (developmental and social).[22][n 4] Some of the most prominent theories are as follows: Music arose as an elaborate form of sexual selection, perhaps arising in mating calls.[24] This theory, perhaps the first significant one on music's origins,[25] is generally credited to Charles Darwin.[26] It first appeared in Darwin's 1871 book The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex,[9][27] and has since been criticized as there is no evidence that either human sex is "more musical" thus no evidence of sexual dimorphism; there are currently no other examples of sexual selection that do not include considerable sexual dimorphism.[28] Recent commentators, citing music's use in other animals's mating systems, have nonetheless propagated and developed Darwin's theory; such scholars include Peter J.B. Slater, Katy Payne, Björn Merker, Geoffrey Miller and Peter Todd.[29] Music arose alongside language, both of which supposedly descend from a "shared precursor".[30][31][29] The biologist Herbert Spencer was an important early proponent of this theory, as was the composer Richard Wagner,[26] who termed the music and language's shared ancestor as "speech-music".[12] Since the 21st-century, a number of scholars have supported this theory, particularly the archeologist Steven Mithen.[26] Music arose to fulfill a practical need. Propositions include: To assist in organizing cohesive labor, first proposed by the economist Karl Bücher.[26] To improve the ease and range of long-distance communication, first proposed by the musicologist Carl Stumpf.[26] To enhance communication with the divine or otherwise supernatural, first proposed by the anthropologist Siegfried Nadel.[26][32] To assist in "coordination, cohesion and cooperation", particularly in the context of families or communities.[26][29] To be a means for frightening off predators or enemies of some kind.[26] Music had two origins, "from speech (logogenic) and from emotional expression (pathogenic)", first proposed by the musicologist Curt Sachs. Reflecting on the diversity of music around the world, Sachs noted that some music confines to either a communicative or expressionistic form, suggesting that these aspects developed separately.[26] Music presents sounds that are based on two primary origins: 1) the sounds heard by the fetus in the womb and 2) emotionally generated vocalizations, according to the theory of the emotional origins of music first proposed by David Teie.[33] This theory accounts for musical elements found in all cultures, including pulse, meter, discreet single-frequency segments (notes), continuousness, and instruments that create resonance-enhanced periodic sounds. Many cultures have their own mythical origins on the creation of music.[34][35] Specific figures are sometimes credited with inventing music, such as Jubal in Christian mythology,[26] the legendary Shah Jamshid in Persian/Iranian mythology,[36] the goddess Saraswati in Hinduism,[37] and the muses in Ancient Greek mythology.[35] Some cultures credit multiple originators of music; ancient Egyptian mythology associates it with numerous deities, including Amun, Hathor, Isis and Osiris, but especially Ihy.[38] There are many stories relating to music's origins in Chinese mythology,[39][n 5] but the most prominent is that of the musician Ling Lun, who—on the orders of the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi)—invented bamboo flute by imitating the song of the mythical fenghuang birds.[40] |

起源 詳細情報:進化音楽学 § 音楽の起源 関連項目:音楽考古学、音楽の定義、音楽の歴史 音楽は文化の普遍的現象とみなされている[3][4]が、その定義は文化や時代によって異なる。[5] 人間の認知の多くの側面と同様に、音楽の起源がどこまで理解できるかは依然として議論の的となっており、学者たちはしばしば対立する立場を取っている。 [6][7] 音楽の起源は、言語の起源と並んでよく議論され、その関連性の本質は多くの議論の対象となっている。[8] しかし、20 世紀半ばから後半にかけては、どちらのトピックも学者たちからほとんど注目されていなかった。[9][10][n 1] このテーマの再興以来、主な論争は3つの視点に分けられる:音楽が言語への適応の結果として生まれた「原始言語」のようなものだったのか、言語の結果とし て生まれた「スパンドレル」(進化の副産物)なのか、または音楽と言語が共通の祖先から派生したのか、という問いだ。[12][13][n 2][n 3] 音楽起源に関する特定の理論については、考古学者、認知科学者、民族音楽学者、進化生物学者、言語学者、神経科学者、古人類学者、哲学者、心理学者(発達 および社会)などの貢献があるものの、ほとんどコンセンサスは得られていない。[22][n 4] 最も著名な理論の一部を以下に示す。 音楽は、おそらく交尾の鳴き声から生まれた、精巧な性的選択の形態として出現した。[24] この理論は、おそらく音楽起源に関する最初の重要な理論であり[25]、一般にチャールズ・ダーウィンによるものとされている。[26] これはダーウィンの1871年の著書『人間の由来と性選択』[9][27] に初めて登場し、以来、人間において「より音楽的」な性がないため、性差の証拠がないとして批判されてきた。現在、性差を伴わない性選択の他の例は存在し ない。[28] 最近の研究者は、他の動物の交尾システムにおける音楽の役割を指摘しつつも、ダーウィンの理論を継承し発展させてきた。このような研究者には、ピーター・ J・B・スレーター、ケイティ・ペイン、ビョルン・メルカー、ジェフリー・ミラー、ピーター・トッドなどが含まれる。[29] 音楽は言語と共に発生し、両者は「共通の祖先」から派生したとされる。[30][31][29] 生物学者ハーバート・スペンサーは、この理論の重要な初期支持者であり、作曲家リヒャルト・ワーグナーも同様で、音楽と言語の共通の祖先を「音声音楽」と 呼んだ。[12] 21 世紀以降、多くの学者がこの理論を支持しており、特に考古学者のスティーブン・ミズンが有名だ。[26] 音楽は、実用的な必要から生まれた。その提案には、次のようなものがある。 経済学者カール・ビュッヒャーが最初に提案した、結束力のある労働の組織化を支援するため。 音楽学者カール・シュトゥンプフが最初に提案した、長距離のコミュニケーションの容易さと範囲を改善するため。 人類学者ジークフリート・ナデルが最初に提案した、神や超自然的な存在とのコミュニケーションを強化するため。 特に家族やコミュニティにおいて、「調整、結束、協力」を支援するため。[26][29] ある種の捕食者や敵を威嚇する手段となること。[26] 音楽には、「言語(ロゴジェニック)と感情表現(パトジェニック)の 2 つの起源がある」と、音楽学者カート・サックスが最初に提唱した。サックスは、世界中の音楽の多様性を考察し、一部の音楽はコミュニケーションや表現のい ずれかの形式に限定されており、これらの側面は別々に発展してきたことを示唆した。[26] 音楽は、デビッド・テイが最初に提唱した音楽の感情的起源説によると、1)胎児が子宮内で聞く音、2)感情から生じる発声、という 2 つの主な起源に基づく音で構成されている。この説は、パルス、拍子、個別の単一周波数の音(音符)、連続性、共鳴によって周期的な音を生み出す楽器など、 あらゆる文化に見られる音楽的要素を説明している。 多くの文化には、音楽の創造に関する独自の神話的な起源がある。[34][35] 特定のキャラクターが音楽の発明者として称えられる場合もあり、例えばキリスト教神話におけるジュバル[26]、ペルシャ/イラン神話における伝説の シャー・ジャムシード[36]、ヒンドゥー教における女神サラスヴァティ[37]、古代ギリシャ神話におけるムーサなどがある。[35] いくつかの文化では、音楽の起源を複数の創始者に帰属させています。古代エジプトの神話では、音楽はアムン、ハトホル、イシス、オシリスを含む多くの神々 と関連付けられていますが、特にイヒが重視されています。[38] 中国神話には音楽の起源に関する多くの物語がある[39][n 5]が、最も著名なのは、黄帝(ホアンディ)の命により、伝説の鳳凰の歌を模倣して竹笛を発明した音楽家リン・ルンの物語だ[40]。 |

| Prehistory Main article: Prehistoric music  Top left, the purported Divje Babe Flute from Divje Babe, Slovenia;[41] top right a Aurignacian bone flute from Geissenklösterle, Germany;[42] bottom a gudi bone flute in the modern-day Jiahu, Wuyang, Henan Province. In the broadest sense, prehistoric music—more commonly termed primitive music in the past[43][44][n 6]—encompasses all music produced in preliterate cultures (prehistory), beginning at least 6 million years ago when humans and chimpanzees last had a common ancestor.[45] Music first arose in the Paleolithic period,[46] though it remains unclear as to whether this was the Middle (300,000 to 50,000 BP) or Upper Paleolithic (50,000 to 12,000 BP).[47] The vast majority of Paleolithic instruments have been found in Europe and date to the Upper Paleolithic.[48] It is certainly possible that singing emerged far before this time, though this is essentially impossible to confirm.[49] The potentially oldest instrument is the Divje Babe Flute from the Divje Babe cave in Slovenia, dated to 43,000 and 82,000 and made from a young cave bear femur.[50] Purportedly used by Neanderthals, the Divje Babe Flute has received extensive scholarly attention, and whether it is truly a musical instrument or an object formed by animals is the subject of intense debate.[41] If the former, it would be the oldest known musical instrument and evidence of a musical culture in the Middle Paleolithic.[51] Other than the Divje Babe Flute and three other doubtful flutes,[n 7] there is virtually no surviving Middle Paleolithic musical evidence of any certainty, similar to the situation in regards to visual art.[46] The earliest objects whose designations as musical instruments are widely accepted are bone flutes from the Swabian Jura, Germany, namely from the Geissenklösterle, Hohle Fels and Vogelherd caves.[52] Dated to the Aurignacian (of the Upper Paleolithic) and used by Early European modern humans, from all three caves there are eight examples, four made from the wing bones of birds and four from mammoth ivory; three of these are near complete.[52] Three flutes from the Geissenklösterle are dated as the oldest, c. 43,150–39,370 BP.[53][n 8] Considering the relative complexity of flutes, it is likely earlier instruments existed, akin to objects that are common in later hunter and gatherer societies, such as rattles, shakers, and drums.[49] The absence of other instruments from and before this time may be due to their use of weaker—and thus more biodegradable—materials,[46] such as reeds, gourds, skins, and bark.[54] A painting in the Cave of the Trois-Frères dating to c. 15,000 BCE is thought to depict a shaman playing a musical bow.[55] Prehistoric cultures are thought to have had a wide variety of uses for music, with little unification between different societies.[56] Music was likely of particular value when food and other basic needs were scarce.[56] It is also probable that prehistoric cultures viewed music as intrinsically connected with nature, and may have believed its use influenced the natural world directly.[56] The earliest instruments found in prehistoric China are 12 gudi bone flutes in the modern-day Jiahu, Wuyang, Henan Province from c. 6000 BCE.[57][58][n 9][n 10] The only instruments dated to the prehistoric Xia dynasty (c. 2070–1600) are two qing, two small bells (one earthenware, one bronze), and a xun.[60] Due to this extreme scarcity of surviving instruments and the general uncertainty surrounding most of the Xia, creating a musical narrative of the period is impractical.[60] In the Indian subcontinent, the prehistoric Indus Valley civilisation (from c. 2500–2000 BCE in its mature state) has archeological evidence that indicates simple rattles and vessel flutes were used, while iconographical evidence suggests early harps and drums also existed.[61] An ideogram in the later IVC contains the earliest known depiction of an arched harp, dated sometime before 1800 BCE.[62] |

先史時代 主な記事:先史時代の音楽  左上、スロベニアのディヴィエ・バベで発見されたとされるディヴィエ・バベのフルート[41]、右上、ドイツのガイセンクロスターレで発見されたオーリ ニャック文化の骨製フルート[42]、下、河南省武陽の現代の贾湖で発見されたグディの骨製フルート。 最も広い意味での先史時代の音楽(過去には「原始音楽」とよく呼ばれていた[43][44][n 6])は、文字を持たない文化(先史時代)で生産されたすべての音楽を包含し、少なくとも600万年前、人類とチンパンジーが最後に共通の祖先を持ってい た時期から始まります。[45] 音楽は旧石器時代に初めて出現した[46]が、これが中期(30万~5万年前)か後期(5万~1万2千年前)かは不明だ[47]。旧石器時代の楽器のほと んどはヨーロッパで発見されており、後期旧石器時代に遡る。[48] 歌がこれよりはるかに前に出現した可能性は十分にあるが、これを確認することは本質的に不可能だ。[49] 最古の楽器とされるのは、スロベニアのディヴジェ・バベ洞窟から発見されたディヴジェ・バベ・フルートで、4万3000年から8万2000年前に遡り、若 い洞窟熊の太腿骨から作られている。[50] ネアンデルタール人が使用したとされるディヴィエ・バベのフルートは、学者の間で大きな注目を集めており、それが本当に楽器なのか、あるいは動物によって 作られた物なのかについては、激しい議論が繰り広げられている。[41] 前者の場合、これは最古の楽器であり、中旧石器時代の音楽文化の証拠となる。[51] ディヴジェ・バベの笛と3つの疑わしい笛[n 7]を除けば、中期旧石器時代の確実な音楽的証拠はほとんど存在せず、視覚芸術の状況と類似している。[46] 楽器としての指定が広く受け入れられている最古の遺物は、ドイツのスワビアン・ジュラ山地から出土した骨笛で、ゲッセンクローステルレ、ホーレ・フェル ス、ヴォーゲルヘルドの洞窟から発見されたものがある。[52] 上旧石器時代のオーリニャック文化に属し、早期ヨーロッパ現代人類によって使用されたこれらの笛は、3つの洞窟から合計8例が発見されており、そのうち4 つは鳥の翼骨から、4つはマンモスの象牙から作られている。そのうち3つはほぼ完全な状態である。[52] ガイセンクロスターレの3つのフルートは、最も古いもので、約43,150~39,370年前と推定されている。[53][n 8] フルートの相対的な複雑さを考慮すると、後期の狩猟採集社会で一般的な、ガラガラ、シェーカー、ドラムなどの楽器に似た、より古い楽器が存在していた可能 性が高い。[49] この時代以前からの他の楽器の欠如は、葦、瓢箪、皮、樹皮など、より脆弱で分解しやすい材料の使用に起因する可能性がある。[46][54] トロワ・フレール洞窟の約15,000 BCEに遡る絵画には、シャーマンが音楽用弓を演奏する様子が描かれていると考えられている。[55] 先史時代の文化では、音楽はさまざまな用途に用いられていたと考えられていますが、異なる社会間で統一性はほとんどありませんでした[56]。音楽は、食 料やその他の基本的なニーズが乏しい時代に特に重要な役割を果たしていたと考えられます[56]。また、先史時代の文化では、音楽は本質的に自然とは密接 に関連しているものと見なされ、その使用が自然界に直接影響を与えると信じられていた可能性もあります。[56] 先史時代の中国で発見された最古の楽器は、紀元前6000年頃の河南省武陽県嘉湖で発見された12本の骨笛「古笛」です。[57][58][n 9][n 10] 先史時代の夏王朝(紀元前2070年~1600年頃)に遡る楽器は、2つのチン、2つの小さなベル(1つは陶器製、もう1つは青銅製)、および1つのシュ ンだけです。[60] 残存する楽器の極端な希少性と、夏王朝に関する多くの点での不確実性のため、この時代の音楽的叙述を構築することは現実的ではありません。[60] インド亜大陸では、先史時代のインダス文明(成熟期:紀元前 2500 年頃~2000 年頃)の遺跡から、単純なガラガラや容器を楽器として使っていたことを示す考古学的証拠が見つかっている。また、図像的な証拠からは、初期のハープや太鼓 も存在していたことが示唆されている。[61] 後期のインダス文明のイデオグラムには、紀元前1800年以前に遡る最古のアーチ型ハープの描写が含まれている。[62] |

| Antiquity Main article: Ancient music  Drawing of the tablet with the Hymn to Nikkal (c. 1400 BCE), the oldest of the Hurrian songs Following the advent of writing, literate civilizations are termed part of the ancient world, the first of which is Sumerian literature of Abu Salabikh (now Southern Iraq) of c. 2600 BCE.[63] Though the music of Ancient societies was extremely diverse, some fundamental concepts arise prominently in virtually all of them, namely monophony, improvisation and the dominance of text in musical settings.[64] Varying song forms were present in Ancient cultures, including China, Egypt, Greece, India, Mesopotamia, Rome, and the Middle East.[65] The text, rhythm, and melodies of these songs were closely aligned, as was music in general, with magic, science, and religion.[65] Complex song forms developed in later ancient societies, particularly the national festivals of China, Greece, and India.[65] Later Ancient societies also saw increased trade and transmission of musical ideas and instruments, often shepherded by the Silk Road.[66][67] For example, a tuning key for a qin-zither from 4th–5th centuries BCE China includes considerable Persian iconography.[68] In general, not enough information exists to make many other generalizations about ancient music between cultures.[65] The few actual examples of ancient music notation that survive usually exist on papyrus or clay tablets.[65] Information on musical practices, genres, and thought is mainly available through literature, visual depictions, and increasingly as the period progresses, instruments.[65] The oldest surviving written music is the Hurrian songs from Ugarit, Syria. Of these, the oldest is the Hymn to Nikkal (hymn no. 6; h. 6), which is somewhat complete and dated to c. 1400 BCE.[69] However, the Seikilos epitaph is the earliest entirely complete noted musical composition. Dated to the 2nd Century CE or later, it is an epitaph, perhaps for the wife of the unknown Seikilos.[70] |

古代 主な記事:古代音楽  ニッカールへの賛歌(紀元前1400年頃)が刻まれた石碑の図。ヒッタイトの歌の中で最も古いもの。 文字の出現後、文字を持つ文明は古代世界の一部と呼ばれ、その最初のものは紀元前2600年頃のシュメール文学(現在のイラク南部)である。[63] 古代社会の音楽は極めて多様だったが、ほぼすべての社会でいくつかの基本的な概念が顕著に現れている。すなわち、単旋律、即興、および音楽におけるテキス トの優位性である。[64] 古代文化には、中国、エジプト、ギリシャ、インド、メソポタミア、ローマ、中東など、多様な歌の形式が存在した。[65] これらの歌の歌詞、リズム、メロディーは、音楽全般と同様に、呪術、科学、宗教と密接に関連していた。[65] 複雑な歌の形式は、後の古代社会、特に中国、ギリシャ、インドの国民的祭典で発展した。[65] 後の古代社会では、シルクロードを媒介として、音楽的なアイデアや楽器の交流が活発になった。[66][67] 例えば、紀元前4~5世紀の中国の琴の調律鍵には、ペルシャのアイコングラフィーが数多く含まれている。[68] 一般的に、文化間の古代音楽について多くの一般的な結論を導き出すには、十分な情報が不足している。[65] 現存する古代の楽譜の実際の例はごくわずかであり、通常はパピルスや粘土板に記されている。[65] 音楽の実践、ジャンル、思想に関する情報は、主に文学、視覚的表現、そして時代が進むにつれて楽器からも入手可能になってきている。[65] 最も古い現存する楽譜は、シリアのウガリットで発見されたフルリ人の歌だ。そのうち最も古いものは、ニッカールへの賛歌(賛歌第6番;h. 6)で、ある程度完全な形で残っており、紀元前1400年頃と推定されている。[69] しかし、最も古い完全な楽譜は、2世紀CE以降に作成されたセイキロスの碑文である。これは、未知のセイキロスの妻のための碑文である可能性が高い。 [70] |

| China Shang and Zhou They strike the bells, kin, kin, They play the se-zither, play the qin-zither, The mouth organ and chime stones sound together; They sing the Ya and Nan Odes, And perform flawlessly upon their flutes. Shijing, Ode 208, Gu Zhong[71] Translated by John S. Major[72] By the mid-13th century BCE, the Late Shang dynasty had developed writing, which mostly exists as divinatory inscriptions on the ritualistic oracle bones but also as bronze inscriptions.[73][74] As many as 11 oracle script characters may refer to music to some extent, some of which could be iconographical representations of instruments themselves.[75] The stone bells qing appears to have been particularly popular with the Shang ruling class,[n 11] and while no surviving flutes have been dated to the Shang,[77] oracle script evidence suggests they used ocarinas (xun), transverse flute (xiao and dizi), douple pipes, the mouthorgan (sheng), and maybe the pan flute (paixiao).[78][n 12] Due to the advent of the bronze in 2000 BCE,[80] the Shang used the material for bells—the ling [zh] (鈴), nao [zh] (鐃) and zhong (鐘)[59]—that can be differentiated in two ways: those with or without a clapper and those struck on the inside or outside.[81] Drums, which are not found from before the Shang,[82] sometimes used bronze, though they were more often wooden (bangu).[83][59][n 13] The aforementioned wind instruments certainly existed by the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE), as did the first Chinese string instruments: the qin (or guqin) and se zithers.[59][n 14] The Zhou saw the emergence of major court ensembles and the well known Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (after 433 BCE) contains a variety of complex and decorated instruments.[59] Of the tomb, the by-far most notable instrument is the monumental set of 65 tuned bianzhong bells, which range five octaves requiring at least five players; they are still playable and include rare inscriptions on music.[86]  The monumental Bianzhong of Marquis Yi of Zeng, c. 5th century BCE, from Hubei Ancient Chinese instruments served both practical and ceremonial means. People used them to appeal to supernatural forces for survival needs,[87] while pan flutes may have been used to attract birds while hunting,[88] and drums were common in sacrifices and military ceremonies.[82] Chinese music has always been closely associated with dance, literature and fine arts;[89] many early Chinese thinkers also equated music with proper morality and governance of society.[90][n 15] Throughout the Shang and Zhou music was a symbol of power for the Imperial court,[93] being used in religious services as well as the celebration of ancestors and heroes.[87][94] Confucius (c. 551–479) formally designated the music concerned with ritual and ideal morality as the superior yayue (雅樂; "proper music"), in opposition to suyue (俗樂; "vernacular/popular music"),[87][95] which included virtually all non-ceremonial music, but particularly any that was considered excessive or lascivious.[95] During the Warring States Period when of Confucius's lifetime, officials often ignored this distinction, preferring more lively suyue music and using the older yayue traditional solely for political means.[96] Confucius and disciples such as Mencius considered this preference virtueless and saw ill of the leaders' ignorance of ganying,[97] a theory that held music was intrinsically connected to the universe.[98][99][n 16] Thus, many aspects of Ancient Chinese music were aligned with cosmology: the 12 pitch shí-èr-lǜ system corresponded equally with certain weights and measurements; the pentatonic scale with the five wuxing;[99] and the eight tone classification of Chinese instruments of bayin with the eight symbols of bagua.[100] No actual music or texts on the performance practices of Ancient Chinese musicians survive.[101] The Five Classics of the Zhou dynasty include musical commentary; the I Ching and Chunqiu Spring and Autumn Annals make references, while the Liji Book of Rites contains a substantial discussion (see the chapter Yue Ji Record of Music).[40] While the Yue Jing Classic of Music is lost,[80] the Shijing Classic of Poetry contains 160 texts to now lost songs from the Western Zhou period (1045–771).[102] |

中国 殷と周 彼らは鐘を鳴らし、キン、キン、 彼らはセツ、チンツを弾き、 口琴と石琴が一緒に鳴り響く。 彼らはヤとナンオードを歌い、 フルートを完璧に演奏する。 詩経、オード 208、Gu Zhong[71] 翻訳:ジョン・S・メジャー[72] 紀元前13世紀半ばまでに、商王朝後期には文字が発達し、主に儀式用の占骨に占いの文字として残っているが、青銅器の文字としても残っている。[73] [74] 占骨文字の11文字は、音楽に何らかの形で関連していると考えられ、そのうちの一部は楽器そのものの図像的表現である可能性もある。[75] 石製の鈴「青」は、殷の支配層の間で特に人気があったようだが[n 11]、殷の時代に作られたと推定されるフルートは現存していないが[77]、甲骨文字の証拠から、オカリナ(xun)、横笛(xiao および dizi)、二重管楽器、口琴(sheng)、そしておそらくパンフルート(paixiao)も使用されていたことが示唆されている[78]。[n 12] 紀元前2000年ごろの青銅の登場により[80]、商朝は青銅を鐘(ling [zh]、nao [zh]、zhong)の材料として使用した。これらは2つの方法で区別できる:打槌の有無と、内側または外側を打つもの。[81] 太鼓は商朝以前には存在しなかったが[82]、青銅製のものもあったが、木製(バンゴ)が一般的だった[83][59][n 13]。上述の管楽器は周朝(紀元前1046年~紀元前256年)までに確実に存在し、最初の中国弦楽器である琴(グチン)とセ・ジターも存在した [59]。[n 14] 周朝には主要な宮廷楽団が成立し、曾侯乙の墓(紀元前433年以降)には複雑で装飾された多様な楽器が収められている。[59] 墓の中で最も注目すべき楽器は、5オクターブをカバーし、少なくとも5人の演奏者を要する65個の調律されたビアンジョン鐘の巨大なセットで、現在も演奏 可能で、音楽の文字が刻まれた珍しい例を含む。[86]  紀元前 5 世紀頃、湖北省で発見された曾侯乙の巨大な鉦。 古代中国の楽器は、実用と儀式の両方の目的で使用されていました。人々は、生存のために超自然的な力を呼び起こすために楽器を使用していました[87]、 パンフルートは狩猟の際に鳥を引き寄せるために使用されていた可能性があります[88]、太鼓は犠牲の儀式や軍事儀式でよく使用されていました。[82] 中国の音楽は常に舞踊、文学、美術と密接に関連してきた。[89] 多くの古代中国の思想家は、音楽を適切な道徳と社会の統治と同一視した。[90][n 15] 商朝と周朝を通じて、音楽は帝室の権力の象徴であり、宗教儀式や先祖や英雄の祝典にも使用された。[87][94] 孔子(紀元前 551 年頃~479 年)は、儀礼や理想的な道徳に関する音楽を「雅楽(ややく)」と正式に指定し、それとは対照的に、儀式以外のほぼすべての音楽、特に過度または淫らである とみなされた音楽を「俗楽(すやく)」と指定した[87][95]。[95] 孔子の生涯における戦国時代には、官僚たちはこの区別を無視し、より活気のある俗楽を好み、古い雅楽の伝統を政治的目的のみに利用した。[96] 孔子や孟子などの弟子たちは、この好みを徳のないものと見なし、指導者の「雅楽」の無知を非難した。[97] 「雅楽」は、音楽が宇宙と本質的に結びついているという理論に基づいていた。[98][99][n 16] したがって、古代中国の音楽の多くの側面は宇宙論と一致していた:12音階の「しじゅうる」システムは特定の重量と測定単位と対応し、五音階は五行と対応 し[99]、中国の楽器の八音分類「ばいにん」は八卦の八つの象徴と対応していた。[100] 古代中国の音楽家の演奏方法に関する実際の音楽や文献は現存していない。[101] 周王朝の五経には音楽に関する解説が含まれており、易経と春秋には言及があり、礼記には詳細な議論が記載されている(章「楽記」を参照)。[40] 『楽経』は失われていますが、[80] 『詩経』には、西周時代(1045–771)の失われた歌160篇が収録されています。[102] |

Qin and Han Two musicians of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 CE), Shanghai Museum The Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE), established by Qin Shi Huang, lasted for only 15 years, but the purported burning of books resulted in a substantial loss of previous musical literature.[67] The Qin saw the guzheng become a particularly popular instrument; as a more portable and louder zither, it meet the needs of an emerging popular music scene.[103][n 17] During the Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), there were attempts to reconstruct the music of the Shang and Zhou, as it was now "idealized as perfect".[100][67] A Music Bureau, the Yuefu, was founded or at its height by at least 120 BCE under Emperor Wu of Han,[104][n 18] and was responsible for collecting folksongs. The purpose of this was twofold; it allowed the Imperial Court to properly understand the thoughts of the common people,[89] and it was also an opportunity for the Imperial Court to adapt and manipulate the songs to suit propaganda and political purposes.[100][67][n 19] Employing ceremonial, entertainment-oriented and military musicians,[106] the Bureau also performed at a variety of venues, wrote new music, and set music to commissioned poetry by noted figures such as Sima Xiangru.[107] The Han dynasty had officially adopted Confucianism as the state philosophy,[67] and the ganying theories became a dominant philosophy.[108] In practice, however, many officials ignored or downplayed Confucius's high regard for yayue over suyue music, preferring to engage in the more lively and informal later.[109] By 7 BCE the Bureau employed 829 musicians; that year Emperor Ai either disbanded or downsized the department,[67][107] due to financial limitations,[67] and the Bureau's increasingly prominent suyue music which conflicted with Confucianism.[106] The Han dynasty saw a preponderance of foreign musical influences from the Middle East and Central Asia: the emerging Silk Road led to the exchange of musical instruments,[66] and allowed travelers such as Zhang Qian to relay with new musical genres and techniques.[67] Instruments from said cultural transmission include metal trumpets and instruments similar to the modern oboe and oud lute, the latter which became the pipa.[66] Other preexisting instruments greatly increased in popularity, such as the qing,[88] panpipes,[110] and particularly the qin-zither (or guqin), which was from then on the most revered instrument, associated with good character and morality.[85] |

秦と漢 東漢時代(25年~220年)の2人の音楽家、上海博物館 秦の始皇帝によって設立された秦王朝(221年~206年)は、わずか15年の短命に終わったが、書籍の焼却により、それまでの音楽文献の多くが失われた とされている[67]。秦では、古筝が特に人気のある楽器となりました。持ち運びが簡単で音量の大きいこの楽器は、新興のポピュラー音楽シーンでのニーズ にぴったりだったのです。[103][n 17] 漢王朝(紀元前202年~220年)には、商と周の音楽が「完璧な理想」とみなされ、その再現が試みられました。[100][67] 音楽局である楽府は、漢の武帝の治世下、少なくとも紀元前 120 年までに設立され、最盛期を迎えました[104][n 18]、民謡の収集を担当していました。その目的は 2 つありました。1 つは、宮廷が庶民の考えを正しく理解すること[89]、もう 1 つは、宮廷が宣伝や政治的な目的に合わせて歌を改変し、操作する機会とすることでした。[100][67][n 19] 儀式、娯楽、軍事向けの音楽家を採用していた[106] この局は、さまざまな会場で演奏を行い、新しい楽曲を作曲し、司馬相如などの著名人の詩に楽曲を付けました[107]。漢王朝は儒教を国教として正式に採 用しており[67]、甘音説が支配的な哲学となりました。[108] しかし実際には、多くの官僚は孔子が雅楽を雅楽よりも重視した点を無視したり軽視したりし、より活気があり非公式な雅楽を好んだ。[109] 紀元前7年、局は829人の音楽家を雇用していたが、その年、皇帝は財政難のため、局を解散または縮小した。[67][107] 財政的制約のため[67]、および局内でますます影響力を増した「随楽」音楽が儒教と矛盾したため[106]。漢王朝時代には、中東と中央アジアからの外 国の音楽的影響が優勢となった:シルクロードの台頭により音楽楽器の交流が促進され[66]、張騫のような旅行者が新たな音楽ジャンルや技術を持ち帰った [67]。こうした文化の伝播によって伝わった楽器には、金属製のトランペットや、現代のオーボエやウード・リュートに似た楽器があり、後者は琵琶となっ た[66]。また、青[88]、パンパイプ[110]、そして特に琴(または古琴)など、以前から存在していた楽器の人気も大幅に高まり、それ以降、琴 は、良き人格や道徳と関連付けられ、最も尊敬される楽器となった[85]。 |

| Greece Main article: Music of ancient Greece Greek written history extends far back into Ancient Greece, and was a major part of ancient Greek theatre. In ancient Greece, mixed-gender choruses performed for entertainment, celebration and spiritual reasons.[citation needed] Instruments included the most important wind instrument, the double-reed aulos,[111] as well as the plucked string instrument, the lyre,[112] especially the special kind called a kithara. |

ギリシャ 主な記事:古代ギリシャの音楽 ギリシャの文字による歴史は古代ギリシャにまでさかのぼり、古代ギリシャの演劇の重要な部分を占めていた。古代ギリシャでは、娯楽、祝祭、精神的な目的の ために、男女混血の合唱団が演奏を行っていた。楽器としては、最も重要な管楽器である双簧管のアウロス[111]、弦楽器の竪琴[112]、特にキタラと 呼ばれる特殊なものが挙げられる。 |

| India Main article: Music in ancient India The principal sources on the music of ancient India are textual and iconographical; specifically, some theoretical treatises in Sanskrit survive, there are brief mentions in general literature and many sculptures of Ancient Indian musicians and their instruments exist.[113] Ancient Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit literature frequently contains musical references, from the Vedas to the works of Kalidasa and the Ilango Adigal's epic Silappatikaram.[114] Despite this, little is known on the actual musical practices of ancient India and the information available forces a somewhat homogeneous perspective on the music of the time, even though evidence indicates that in reality, it was far more diverse.[113] The monumental arts treatise Natya Shastra is among the earliest and chief sources for Ancient Indian music; the music portions alone are likely from the Gupta period (4th century to 6th century CE).[115] |

インド 主な記事:古代インドの音楽 古代インドの音楽に関する主な情報源は、文献や図像です。具体的には、サンスクリット語で書かれた理論に関する論文がいくつか残っており、一般文学にも簡 単に言及があり、古代インドの音楽家や楽器の彫刻も数多く残っています。[113] 古代サンスクリット語、パーリ語、プラークリット語の文学には、ヴェーダからカリダーサの著作、イランゴ・アディガルの大叙事詩『シラッパティカラム』ま で、音楽に関する言及が頻繁にみられる。[114] しかし、古代インドの実際の音楽実践についてはほとんど知られておらず、入手可能な情報は当時の音楽にやや均一な視点をもたらす。しかし、証拠は実際には はるかに多様であったことを示している。[113] 記念碑的な芸術論文『ナティヤ・シャストラ』は、古代インドの音楽に関する最も古く、最も重要な情報源のひとつだ。音楽に関する部分だけでも、グプタ時代 (4 世紀から 6 世紀)のものである可能性が高い。[115] |

| Persia and Mesopotamia Further information: Music of Mesopotamia and Achaemenid music Up to the Achaemenid period  The Bull Headed Lyre of Ur, found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, is the best known of the ancient Lyres of Ur In general, it is impossible to create a thorough outline of the earliest music in Persia due to a paucity of surviving records.[116] Evidenced by c. 3300–3100 BCE Elam depictions, arched harps are the first affirmation of Persian music, though it is probable that they existed well before their artistic depictions.[117] Elamite bull lyres from c. 2450 have been found in Susa, while more than 40 small Oxus trumpets have been found in Bactria and Margiana, dated to the c. 2200–1750 Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex.[118][n 20] The oxus trumpets seem to have had a close association with both religion and animals; a Zoroastrian myth in which Jamshid attract animals with the trumpet suggests that the Elamites used them for hunting.[119] In many ways the earliest known musical cultures of Iran are strongly connected with those of Mesopotamia. Ancient arched harps (c. 3000) also exist in the latter and the scarcity of instruments makes it unclear as to which culture the harp originated.[117] Far more bull lyres survive in Ur of Mesopotamia, notably the Bull Headed Lyre of Ur, though they are nearly identical to their contemporary Elamite counterparts.[120] From the evidence in terracotta plaques, by the 2nd-century BCE the arched harp was displaced by the angular harps, which existed in 20-string vertical and nine-string horizontal variants.[121] Lutes were purportedly used in Mesopotamia by at least 2300 BCE, but not until c. 1300 BCE do they appear in Iran, where they became the dominant string instruments of Western Iran, though the available evidence suggests its popularity was outside of the elite.[122] The rock reliefs of Kul-e Farah show that sophisticated Persian court ensembles emerged in the 1st-century BCE, in the which the central instrument was the arched harp.[123] The prominence of musicians in these certain rock reliefs suggests they were essential in religious ceremonies.[124] Like earlier periods, extremely little contemporary information on the music of the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE) exists.[68][125] Most knowledge on the Achaemenid musical culture comes from Greek historians.[125] In his Histories, Herodotus noted that Achaemenid priests did not use aulos music in their ceremonies, while Xenophon reflected on his visit to Persia in the Cyropaedia, mentioning the presence of many female singers at court.[68] Athenaeus also mentions female singers when noting that 329 of them had been taken from the King of Kings Darius III by Macedonian general Parmenion.[68] Later Persian texts assert that gōsān poet-musician minstrels were prominent and of considerable status in court.[126] |

ペルシャとメソポタミア 詳細情報:メソポタミアの音楽とアケメネス朝の音楽 アケメネス朝時代まで  ウル王家の墓地で発見された「ウル牛頭形リュート」は、ウルで発見された古代のリュートの中で最も有名なものです。 ペルシャの最も古い音楽について、残存する記録が極めて少ないため、詳細な概要をまとめることは不可能だ。[116] 紀元前3300年~3100年頃のエラムの描画から、アーチ型のハープがペルシャ音楽の最初の証拠とされるが、これよりはるかに前から存在していた可能性 が高い。[117] 紀元前2450年頃のエラムの雄牛形リュールはスサで発見されており、バクトリアとマルギアナでは、紀元前2200~1750年のバクトリア・マルギアナ 考古学複合体(BMAC)に属する40点を超える小型のオクサス・トランペットが発見されている。[118][n 20] オクサス・トランペットは、宗教と動物の両方と密接な関係があったようだ。ゾロアスター教の神話で、ジャムシードがトランペットで動物を引き寄せるエピ ソードは、エラム人がそれらを狩猟に用いていたことを示唆している。[119] イランで最も古い音楽文化は、多くの点でメソポタミアの文化と強く結びついている。古代のアーチ型ハープ(約3000年)も後者に見られ、楽器の希少性か ら、ハープがどの文化で起源したかは不明だ。[117] メソポタミアのウルでは、特にウル牛頭リュートを含む多くの牛形リュートが保存されていますが、これらは同時期のエラムのリュートとほぼ同一です。 [120] テラコッタの板の証拠から、紀元前2世紀までにアーチ型ハープは角型ハープに置き換えられ、20弦の垂直型と9弦の水平型のバリエーションが存在していま した。[121] ルートはメソポタミアで紀元前2300年頃には使用されていたとされていますが、イランに現れるのは紀元前1300年頃で、その後西イランの主要な弦楽器 となりました。ただし、既存の証拠からは、その人気はエリート層以外で広まったことが示唆されています。[122] クル・エ・ファラの岩壁 relief は、紀元前1世紀に高度なペルシャの宮廷楽団が成立したことを示しており、その中心楽器はアーチ型ハープだった。[123] これらの特定の岩壁 relief における音楽家の目立った存在は、彼らが宗教儀式において不可欠な役割を果たしていたことを示唆している。[124] 以前の時代と同様、アケメネス朝(紀元前550年~紀元前330年)の音楽に関する同時代の情報はほとんど残っていない。[68][125] アケメネス朝の音楽文化に関する知識のほとんどは、ギリシャの歴史家によるものだよ。[125] ヘロドトスは『歴史』の中で、アケメネス朝の僧侶たちは儀式でアウルス音楽を使用しなかったと記している一方、クセノフォンは『キュロパエディア』の中 で、ペルシャ訪問の感想を述べ、宮廷に多くの女性歌手たちがいたことを述べている。[68] アテナイオスも、マケドニアの将軍パルメニオンが王の王ダレイオス3世から329人の女性歌手を奪ったと記す際に、女性歌手を言及している。[68] 後代のペルシアのテキストでは、ゴサン詩人・音楽家・吟遊詩人が宮廷で顕著な地位を占めていたと主張されている。[126] |

| Parthian and Sasanian periods Further information: Parthian music and Sasanian music  Terracotta statue of a Parthian lute player The Parthian Empire (247 BCE to 224 CE) saw an increase in textual and iconographical depictions of musical activity and instruments. 2nd century BCE Parthian rhuta (drinking horns) found in the ancient capital of Nisa include some of the most vivid depictions of musicians from the time. Pictorial evidence such as terracotta plaques show female harpists, while plaques from Babylon show panpipes, as well as string (harps, lutes and lyres) and percussion instruments (tambourines and clappers). Bronze statues from Dura-Europos depict larger panpipes and double aulos. Music was evidently used in ceremonies and celebrations; a Parthian-era stone frieze in Hatra shows a wedding where musicians are included, playing trumpets, tambourines, and a variety of flutes. Other textual and iconographical evidence indicates the continued prominence of gōsān minstrels. However, like the Achaemenid period, Greek writers continue to be a major source for information on Parthian music. Strabo recorded that the gōsān learned songs telling tales of gods and noblemen, while Plutarch similarly records the gōsān lauding Parthian heroes and mocking Roman ones. Plutarch also records, much to his bafflement, that rhoptra (large drums) were used by the Parthian army to prepare for war.[127]  c. 379 CE Bas relief of Sassanid women playing the chang in Taq-e Bostan, Iran The Sasanian period (226–651 CE), however, has left ample evidence of music. This influx of Sasanian records suggests a prominent musical culture in the Empire,[36] especially in the areas dominated by Zoroastrianism.[128] Many Sassanian Shahanshahs were ardent supporters of music, including the founder of the empire Ardashir I and Bahram V.[128] Khosrow II (r. 590–628) was the most outstanding patron, his reign being regarded as a golden age of Persian music.[128] Musicians in Khosrow's service include Āzādvar-e Changi (or Āzād),[125] Bamshad, the harpist Nagisa (Nakisa), Ramtin, Sarkash and Barbad,[116] who was the most famous.[129] These musicians were usually active as minstrels, which were performers who worked as both court poets and musicians;[130] in the Sassanian Empire there was little distinction between poetry and music.[131] |

パルティア時代とササン朝時代 詳細情報:パルティア音楽とササン朝音楽  パルティアのリュート奏者のテラコッタ像 パルティア帝国(紀元前247年から224年)では、音楽活動や楽器に関する記述や図像表現が増加した。紀元前2世紀のパルティアのルータ(飲酒用角杯) は、古代の首都ニサで発見され、当時の音楽家の最も鮮明な描写の一部を含む。テラコッタの板絵には女性ハープ奏者が描かれており、バビロンの板絵にはパン パイプ、弦楽器(ハープ、リュート、リール)および打楽器(タンバリン、クラッパー)が描かれている。デュラ・エウロポスの青銅像には、より大きなパンパ イプとダブル・アウルスが表現されている。音楽は明らかに儀式や祝祭で使用されていた。ハトラのパルティア時代石彫浮彫には、トランペット、タンバリン、 さまざまなフルートを演奏する音楽家が参加する結婚式の場面が描かれている。他のテキストや図像資料は、ゴサン吟遊詩人の継続的な重要性を示している。し かし、アケメネス朝時代と同様に、パルティアの音楽に関する情報は主にギリシャの作家から得られている。ストラボンは、ゴサンが神々や貴族の物語を歌う歌 を学んだと記録しており、プルタルコスも同様に、ゴサンがパルティアの英雄を称賛し、ローマの英雄を嘲笑したと記録している。プルタルコスは、パルティア 軍が戦争の準備にロプトラ(大きな太鼓)を使用していたことを、非常に困惑しながら記録している[127]。  379年頃、イランのタク・エ・ボスタンにある、チャンを演奏するササン朝女性の浅浮き彫り しかし、ササン朝時代(226–651 CE)には、音楽に関する豊富な記録が残されている。このササン朝の記録の流入は、帝国に音楽文化が盛んだったことを示唆している[36]、特にゾロアス ター教が支配的な地域で[128]。多くのササン朝シャハーンシャハは音楽の熱心な支援者であり、帝国の創始者アルダシール1世とバフラム5世もその例に 漏れない。[128] ホスロー2世(在位590–628)は最も傑出したパトロンであり、その治世はペルシャ音楽の黄金時代とされている。[128] ホスローの侍臣には、アザドヴァル・エ・チャンギ(またはアザド)、[125] バムシャド、ハープ奏者のナギサ(ナキサ)、ラムティン、サルカシュ、そして最も有名なバルバド[116] などがいた[129]。これらの音楽家は通常、宮廷の詩人であり音楽家でもある吟遊詩人として活動していた[130]。ササン朝では、詩と音楽の区別はほ とんどなかった[131]。 |

| Other Arab and African cultures The Western African Nok culture (modern-day Nigeria) existed from c. 500–200 BCE and left a considerable amount of sculptures.[132] Among these are depictions of music, such as a man who shakes two objects thought to be maracas. Another sculpture includes a man with his mouth opening (possibly singing) while there is also a sculpture of a man playing a drum.[133] |

その他のアラブおよびアフリカの文化 西アフリカのノク文化(現在のナイジェリア)は、紀元前500年から200年頃まで存在し、数多くの彫刻を残した[132]。その中には、マラカスと思わ れる2つの物を振る男性などの音楽を描いたものもある。また、口を開けた(おそらく歌っている)男性や、太鼓を叩く男性を描いた彫刻もある。[133] |

| Post-classical era Further information: Central Asian and Chinese music Japanese gagaku music Main article: Gagaku The imperial court of Japan developed gagaku ((雅楽); lit. 'elegant music') music, originating from the Gagakuryō imperial music academy established in 701 CE during the Asuka period.[134] Though the word gagaku derives from the Chinese yayue music, the latter originally referred to Confucian ritual music, while gagaku extends to many genres, styles and instruments.[134][135][n 21] In the tradition's early history, the three main genres were wagaku (native Japanese music), sankangaku (music from the Three Kingdoms of Korea) and tōgaku (music from China's Tang dynasty), as well as more minor genres such as toragaku, gigaku, and rin’yūgaku. Uniquely among Asian music of this time, there are numerous extant scores of gagaku music from the 8th to 11th centuries.[135] A major shift in gagaku music occurred in the 9th century, namely the development of a distinction between tōgaku and komagaku music. Tōgaku was a Chinese-influenced style, which combined with the rin’yūgaku tradition, referred to as "Music of the Left" (sahō). Komagaku was then referred to as "Music of the Right" (uhō), encompassing music influenced by both Korea (sankangaku) and Balhae (bokkaigaku). Though this division was prominent, it was not strict and the tōgaku and komagaku styles nonetheless interlaced and influenced each other.[135] The long Heian period (794–1185) saw much patronage of gagaku music from the court, as it accompanied many festivals and celebrations. Numerous new genres emerged at this time, such as the saibara and rōei song forms.[135][136] Gagaku ensembles consist of a wide variety of instruments and are the largest such formations in traditional Japanese music.[137] |

後古典時代 詳細情報:中央アジアと中国の音楽 日本の雅楽 主な記事:雅楽 日本の宮廷では、701年に飛鳥時代に設立された雅楽庁(がかくちょう)で、雅楽(がかく)という音楽が発展した[134]。雅楽という言葉は、中国の雅 楽(やげき)に由来するが、後者はもともと儒教の儀礼音楽を指していたのに対し、雅楽は多くのジャンル、様式、楽器に及んでいる。[134][135] [n 21] 伝統の初期の歴史において、主要な3つのジャンルは和楽(日本の伝統音楽)、三邦楽(朝鮮半島三国時代の音楽)、唐楽(中国唐朝の音楽)であり、さらに小 規模なジャンルとして虎楽、儀楽、林陰楽などが存在した。この時代のアジア音楽において唯一、8世紀から11世紀にかけてのガガク音楽の楽譜が数多く現存 している。[135] 9 世紀には、雅楽音楽に大きな変化が起こり、東楽と小雅楽の区別が生まれた。東楽は中国の影響を受けた様式で、林陰楽の伝統と融合し、「左道」と呼ばれた。 小雅楽は「右の音楽」(右法)と呼ばれ、朝鮮(三間雅楽)と渤海(北雅楽)の影響を受けた音楽を含む。この区分は顕著だったが、厳格なものではなく、東雅 楽と小雅楽の様式は相互に交わり、影響し合った。[135] 長い平安時代(794–1185)には、宮廷から雅楽への支援が盛んになり、多くの祭礼や祝典で演奏された。この時代には、サイバラやロエイなどの新たな ジャンルが数多く生まれた。[135][136] 雅楽の楽団は多様な楽器から構成され、伝統的な日本音楽において最も大規模な編成となっている。[137] |

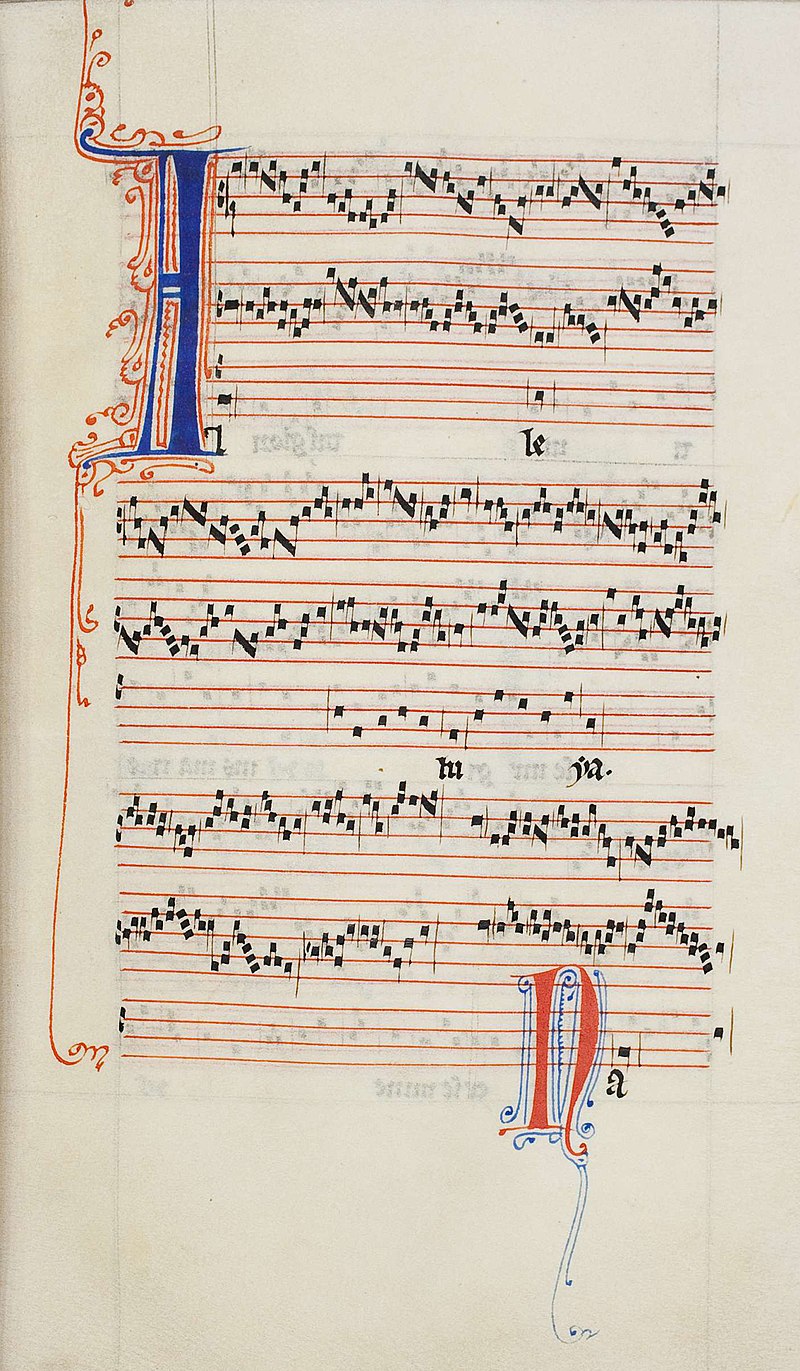

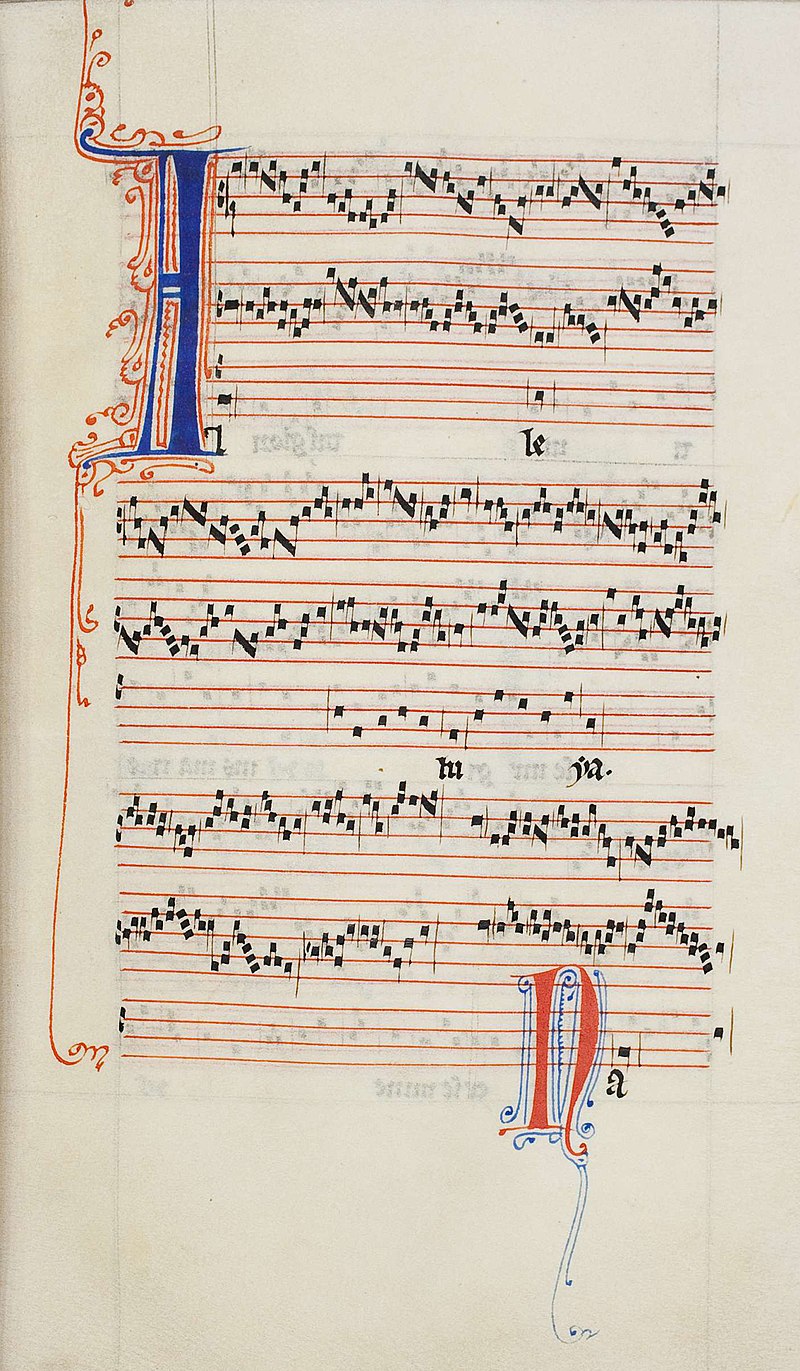

| Medieval Europe Main article: Medieval music See also: List of medieval composers, List of medieval music theorists, and List of medieval musical instruments  Alleluia nativitas by Perotin from the Codex Guelf.1099 Modern scholars generally define 'Medieval music' as the music of Western Europe during the Middle Ages,[138] from approximately the 6th to 15th centuries. Music was certainly prominent in the Early Middle Ages, as attested by artistic depictions of instruments, writings about music, and other records; however, the only repertory of music which has survived from before 800 to the present day is the plainsong liturgical music of the Roman Catholic Church, the largest part of which is called Gregorian chant. Pope Gregory I, who gave his name to the musical repertory and may himself have been a composer, is usually claimed to be the originator of the musical portion of the liturgy in its present form, though the sources giving details on his contribution date from more than a hundred years after his death. Many scholars believe that his reputation has been exaggerated by legend. Most of the chant repertory was composed anonymously in the centuries between the time of Gregory and Charlemagne. During the 9th century, several important developments took place. First, there was a major effort by the Church to unify the many chant traditions and suppress many of them in favor of the Gregorian liturgy. Second, the earliest polyphonic music was sung, a form of parallel singing known as organum. Third, and of the greatest significance for music history, notation was reinvented after a lapse of about five hundred years, though it would be several more centuries before a system of pitch and rhythm notation evolved having the precision and flexibility that modern musicians take for granted. Several schools of polyphony flourished in the period after 1100: the St. Martial school of organum, the music of which was often characterized by a swiftly moving part over a single sustained line; the Notre Dame school of polyphony, which included the composers Léonin and Pérotin, and which produced the first music for more than two parts around 1200; the musical melting-pot of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, a pilgrimage destination and site where musicians from many traditions came together in the late Middle Ages, the music of whom survives in the Codex Calixtinus; and the English school, the music of which survives in the Worcester Fragments and the Old Hall Manuscript. Alongside these schools of sacred music a vibrant tradition of the secular song developed, as exemplified in the music of the troubadours, trouvères, and Minnesänger. Much of the later secular music of the early Renaissance evolved from the forms, ideas, and the musical aesthetic of the troubadours, courtly poets, and itinerant musicians, whose culture was largely exterminated during the Albigensian Crusade in the early 13th century. Forms of sacred music which developed during the late 13th century included the motet, conductus, discant, and clausulae. One unusual development was the Geisslerlieder, the music of wandering bands of flagellants during two periods: the middle of the 13th century (until they were suppressed by the Church); and the period during and immediately following the Black Death, around 1350, when their activities were vividly recorded and well-documented with notated music. Their music mixed folk song styles with penitential or apocalyptic texts. The 14th century in European music history is dominated by the style of the ars nova, which by convention is grouped with the medieval era in music, even though it had much in common with early Renaissance ideals and aesthetics. Much of the surviving music of the time is secular, and tends to use the formes fixes: the ballade, the virelai, the lai, the rondeau, which correspond to poetic forms of the same names. Most pieces in these forms are for one to three voices, likely with instrumental accompaniment: famous composers include Guillaume de Machaut and Francesco Landini. |

中世ヨーロッパ 主な記事:中世音楽 関連項目:中世作曲家一覧、中世音楽理論家一覧、中世楽器一覧  ペロティン作曲「アレリア・ナティヴィタス」『ゲルフ写本』1099年 現代の学者たちは、一般的に「中世音楽」を、中世、つまり6世紀から15世紀頃までの西ヨーロッパの音楽と定義している[138]。音楽は、楽器の芸術的 表現、音楽に関する著作、その他の記録から明らかなように、初期中世において確かに重要な役割を果たしていた。しかし、800年以前に作成され、現在まで 残っている唯一の音楽レパートリーは、ローマ・カトリック教会の平唱式典礼音楽であり、その大部分はグレゴリオ聖歌と呼ばれている。グレゴリオ聖歌の名称 の由来となった教皇グレゴリウス1世は、自身も作曲家であった可能性があり、現在の礼拝音楽の起源とされるが、彼の貢献に関する詳細な記録は、彼の死後 100年以上経ってから残されたものばかりだ。多くの研究者は、彼の評判が伝説によって過大評価されていると考える。グレゴリウスとカール大帝の間の数世 紀に、聖歌のレパートリーのほとんどが匿名で作曲された。 9世紀には、いくつかの重要な進展があった。まず、教会は多くの聖歌の伝統を統一し、グレゴリオ聖歌を優先して多くの伝統を抑制する大規模な努力を行っ た。第二に、ポリフォニー音楽の最初期の形態であるオルガヌムと呼ばれる並行歌唱が歌われた。第三に、音楽史において最も重要なのは、約500年の空白を 経て記譜法が再発明されたことだ。ただし、現代の音楽家が当然視する音高とリズムの記譜システムが確立されるまでには、さらに数世紀を要した。 1100年以降の時期には、複数のポリフォニーの流派が繁栄した:オルガヌムのサン・マルシャル派は、単一の持続音の上に迅速に動くパートが特徴的だっ た;ノートルダム派のポリフォニーは、レオーニンとペロティンを含む作曲家たちを含み、1200年ごろに2声以上のための最初の音楽を生み出した; ガリシアのサンティアゴ・デ・コンポステーラは、中世後期に多くの伝統を持つ音楽家が集まる巡礼地であり、音楽の融合の場となった。その音楽は『カリク ティヌス写本』に伝わる。また、イングランド派の音楽は『ウォルター・フラグメント』と『オールド・ホール写本』に伝わる。これらの聖歌の流派と並行し て、世俗歌の活気ある伝統が発展し、トゥルバドゥール、トロヴェール、ミンネゼンガーの音楽がその例だ。初期ルネサンスの後の世俗音楽の多くは、トゥルバ ドゥール、宮廷詩人、放浪音楽家の形式、思想、音楽的美学から発展した。彼らの文化は、13世紀初頭のアルビジョア十字軍によってほぼ絶滅した。 13世紀後半に発展した聖歌の形式には、モテット、コンダクトゥス、ディスカント、クラウズラなどが含まれる。珍しい発展としては、13 世紀半ば(教会によって抑圧されるまで)と、1350 年頃のペストの流行中および直後の 2 つの時期に、鞭打ちの巡礼者たちによる音楽「ガイスラーリーダー」がある。彼らの活動は、楽譜とともに生き生きと記録され、よく文書化されている。彼らの 音楽は、民謡のスタイルと、悔恨や終末論的な歌詞が混血の音楽だった。ヨーロッパの音楽史における14世紀は、ars nova(アルス・ノヴァ)のスタイルが支配的だった。このスタイルは慣習的に中世音楽の時代と分類されるが、初期ルネサンスの理想や美学と多くの共通点 を持っていた。当時の残存する音楽の多くは世俗的で、formes fixes(固定形式)を多用している。具体的には、ballade(バラード)、virelai(ヴィレライ)、lai(ライ)、rondeau(ロン デウ)など、同じ名前の詩形に対応する形式だ。これらの形式の作品のほとんどは、1から3声で、おそらく楽器伴奏付きだ。有名な作曲家には、ギヨーム・ ド・マショーやフランチェスコ・ランディーニがいる。 |

| Byzantine Main article: Byzantine music See also: List of Byzantine composers Prominent and diverse musical practices were present in the Byzantine Empire, which existed by 395 to 1453.[139] Both sacred and secular music were commonplace, with sacred music frequently used in church services and secular music in many events including, ceremonies dramas, ballets, banquets, festivals and sports games.[140][141] However, despite its popularity, secular Byzantine music was harshly criticized by the Church Fathers, particularly Jerome.[141] Composers of sacred music, especially hymns and chants, are generally well documented throughout the history of Byzantine music. However, those before the reign of Justinian I are virtually unknown; the monks Anthimos, Auxentios and Timokles are said to have written troparia, but only the text to a single one by Auxentios survives.[142] The first major form was the kontakion, of which Romanos the Melodist was the foremost composer.[143] In the late 7th century the kanōn overtook the kontakion in popularity; Andrew of Crete became its first significant composer, and is traditionally credited as the genre's originator,[144] though modern scholars now doubt this attribution.[145] The kañon reached its peak with the music of John of Damascus and Cosmas of Maiuma and later Theodore of Stoudios and Theophanes the Branded in the 8th and 9th centuries respectively.[140] Composers of secular music are considerably less documented. Not until late in the empire's history are composers known by name, with Joannes Koukouzeles, Xenos Korones and Joannes Glykys as the leading figures.[146] Like their Western counterparts of the same period, Byzantine composers were primarily men.[147] Kassia is a major exception to this; she was a prolific and important composer of sticheron hymns and the only woman whose works entered the Byzantine liturgy.[148] A few other women are known to have been composers, Thekla, Theodosia, Martha and the daughter of John Kladas (her given name is unrecorded).[149][150] Only the latter has any surviving work, a single antiphon.[151] Some Byzantine emperors are known to have been composers, such as Leo VI the Wise and Constantine VII.[152][153] |

ビザンチン 主な記事:ビザンチン音楽 関連項目:ビザンチンの作曲家一覧 395年から1453年まで存在したビザンチン帝国では、多様で著名な音楽活動が行われていた[139]。宗教音楽と世俗音楽の両方が広く普及しており、 宗教音楽は教会の礼拝で頻繁に使用され、世俗音楽は儀式、演劇、バレエ、宴会、祭り、スポーツの試合など、さまざまなイベントで使用されていた。 [140][141] しかし、その人気にもかかわらず、世俗的なビザンチン音楽は、教父たち、特にジェロームによって厳しく批判された。[141] 聖歌、特に賛美歌や聖歌の作曲家は、ビザンチン音楽の歴史を通じて、一般的によく記録されている。しかし、ユスティニアヌス 1 世以前の作曲家は、ほとんど知られていない。修道士アンティモス、アウクセンティオス、ティモクレスがトロパリヤを作曲したと言われているが、現存してい るのはアウクセンティオスの 1 曲の歌詞だけだ。[142] 最初の主要な形式はコンタクイオンで、メロディストのロマノスが最も著名な作曲家だった。[143] 7 世紀後半、カノンがコントアクイオンの人気を凌ぐようになり、クレタのアンドルーが最初の重要な作曲家となり、このジャンルの創始者として伝統的に認めら れている[144] が、現代の学者たちはこの帰属に疑問を抱いている。[145] カノンは、8 世紀と 9 世紀に、それぞれダマスコのヨハネス、マイウマのコスマス、そして後にストゥディオスのテオドレオスとテオファネス・ブランドによって、その頂点を迎え た。世俗音楽の作曲家については、記録がかなり少ない。帝国の歴史の後半になって初めて、ヨハネス・ククゼレス、クセノス・コロネス、ヨハネス・グリキス といった作曲家が名前で知られるようになった[146]。 同時代の西洋の作曲家と同様、ビザンチンの作曲家も主に男性だった。[147] カシアはこれに対する主要な例外で、スティケロン聖歌の多作で重要な作曲家であり、ビザンチン礼拝に作品が採用された唯一の女性だ。[148] 他の女性作曲家として、テクラ、テオドシア、マルタ、ジョン・クラダスの娘(名前は記録されていない)が知られている。[149][150] 現存する作品は、後者のアンティフォン1曲のみだ。[151] レオ6世「賢王」やコンスタンティノス7世など、作曲家として知られるビザンチン皇帝も存在する。[152][153] |

| Early modern and modern periods Globe icon. The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this section, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new section, as appropriate. (July 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Indian classical music Main article: Indian classical music Further information: Hindustani classical music and Carnatic classical music See also: List of Carnatic composers During the ancient and medieval periods, the classical music of the Indian subcontinent was a largely unified practice. By the 14th century, socio-political turmoil inaugurated by the Delhi Sultanate began to isolate Northern and Southern India, and independent traditions in each region began emerging. By the 16th-century two distinct styles had formed: the Hindustani classical music of the North and the Carnatic classical music of the South.[154] One of the major differences between them is that the Northern Hindustani vein was considerably influenced by the Persian and Arab musical practices of the time.[155] Carnatic music is largely devotional; the majority of the songs are addressed to the Hindu deities. Indian classical music (marga) is monophonic and based on a single melody line or raga rhythmically organized through talas. |

近世および近代 地球のアイコン。 このセクションの例や見解は、このテーマに関する世界的な見解を必ずしも反映しているわけではない。このセクションを改善したり、トークページで議論した り、必要に応じて新しいセクションを作成したりすることができる。(2021年7月) (このメッセージの削除方法と時期についてはこちらをご覧ください) インドのクラシック音楽 主な記事:インドのクラシック音楽 詳細情報:ヒンドゥスターニー古典音楽およびカルナティック古典音楽 関連項目:カルナティック作曲家一覧 古代および中世、インド亜大陸のクラシック音楽は、ほぼ統一された慣習でした。14 世紀になると、デリー・スルタン朝によって引き起こされた社会政治的混乱により、インド北部と南部が分離し始め、各地域で独立した伝統が生まれてきまし た。16 世紀までに、北部のヒンドゥスターニー古典音楽と南部のカルナティック古典音楽という 2 つの異なるスタイルが形成された。[154] 両者の大きな違いの 1 つは、北部のヒンドゥスターニー音楽は、当時のペルシャやアラビアの音楽の影響を強く受けていることだ。[155] カルナティック音楽は、その大部分が宗教的な音楽であり、歌の大部分はヒンドゥー教の神々に向けられている。 インドの古典音楽(マルガ)は、単旋律で、単一の旋律線またはタラスによってリズミカルに編成されたラーガに基づいています。 |

| Western classical music Main article: Western classical music Renaissance Main article: Renaissance music See also: List of Renaissance composers  Guillaume Du Fay (left), with Gilles Binchois (right) in a c. 1440 Illuminated manuscript copy of Martin le Franc's Le champion des dames The beginning of the Renaissance in music is not as clearly marked as the beginning of the Renaissance in the other arts, and unlike in the other arts, it did not begin in Italy, but in northern Europe, specifically in the area currently comprising central and northern France, the Netherlands, and Belgium. The style of the Burgundian composers, as the first generation of the Franco-Flemish school is known, was at first a reaction against the excessive complexity and mannered style of the late 14th century ars subtilior, and contained clear, singable melody and balanced polyphony in all voices. The most famous composers of the Burgundian school in the mid-15th century are Guillaume Dufay, Gilles Binchois, and Antoine Busnois. By the middle of the 15th century, composers and singers from the Low Countries and adjacent areas began to spread across Europe, especially into Italy, where they were employed by the papal chapel and the aristocratic patrons of the arts (such as the Medici, the Este, and the Sforza families). They carried their style with them: smooth polyphony which could be adapted for sacred or secular use as appropriate. Principal forms of sacred musical composition at the time were the mass, the motet, and the laude; secular forms included the chanson, the frottola, and later the madrigal. The invention of printing had an immense influence on the dissemination of musical styles, and along with the movement of the Franco-Flemish musicians, contributed to the establishment of the first truly international style in European music since the unification of Gregorian chant under Charlemagne.[citation needed] Composers of the middle generation of the Franco-Flemish school included Johannes Ockeghem, who wrote music in a contrapuntally complex style, with varied texture and an elaborate use of canonical devices; Jacob Obrecht, one of the most famous composers of masses in the last decades of the 15th century; and Josquin des Prez, probably the most famous composer in Europe before Palestrina, and who during the 16th century was renowned as one of the greatest artists in any form. Music in the generation after Josquin explored increasing complexity of counterpoint; possibly the most extreme expression is in the music of Nicolas Gombert, whose contrapuntal complexities influenced early instrumental music, such as the canzona and the ricercar, ultimately culminating in Baroque fugal forms. By the middle of the 16th century, the international style began to break down, and several highly diverse stylistic trends became evident: a trend towards simplicity in sacred music, as directed by the Counter-Reformation Council of Trent, exemplified in the music of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina; a trend towards complexity and chromaticism in the madrigal, which reached its extreme expression in the avant-garde style of the Ferrara School of Luzzaschi and the late century madrigalist Carlo Gesualdo; and the grandiose, sonorous music of the Venetian school, which used the architecture of the Basilica San Marco di Venezia to create antiphonal contrasts. The music of the Venetian school included the development of orchestration, ornamented instrumental parts, and continuo bass parts, all of which occurred within a span of several decades around 1600. Famous composers in Venice included the Gabrielis, Andrea and Giovanni, as well as Claudio Monteverdi, one of the most significant innovators at the end of the era. |

西洋クラシック音楽 主な記事:西洋クラシック音楽 ルネサンス 主な記事:ルネサンス音楽 参照:ルネサンスの作曲家一覧  ギヨーム・デュ・ファイ(左)とジル・ビンチョワ(右)、1440年頃のマルタン・ル・フランの『Le champion des dames』の写本 音楽におけるルネサンスの始まりは、他の芸術分野のように明確に定まってはおらず、他の芸術分野とは異なり、イタリアではなく、北ヨーロッパ、具体的には 現在のフランス中部および北部、オランダ、ベルギーの地域から始まった。フランコ・フランドル派の第一世代として知られるブルゴーニュの作曲家のスタイル は、14 世紀後半のアルス・スブティリオールの過度の複雑さと作法的なスタイルに対する反動として生まれ、明瞭で歌やすいメロディーと、すべての声部のバランスの とれたポリフォニーを特徴としていました。15世紀中頃のブルゴーニュ派の最も著名な作曲家は、ギヨーム・デュファイ、ジル・ビンチョワ、アントワーヌ・ ブズノワだ。 15世紀半ばまでに、低地諸国と隣接地域出身の作曲家と歌手がヨーロッパ全土に広がり、特にイタリアで教皇の礼拝堂や芸術のパトロンである貴族(メディチ 家、エステ家、スフォルツァ家など)に雇われた。彼らは自身のスタイルを持ち込んだ:神聖な用途にも世俗的な用途にも適応可能な滑らかなポリフォニー。当 時の宗教音楽の主な形式は、ミサ、モテット、ラウデであり、世俗音楽にはシャンソン、フロットラ、そして後にマドリガルがあった。 印刷の発明は音楽スタイルの普及に多大な影響を与え、フランコ・フランドル音楽家の移動と相まって、カール大帝によるグレゴリオ聖歌の統一以来、ヨーロッ パ音楽における最初の真に国際的なスタイル確立に貢献した。[出典が必要] フランコ・フランドル派の中間世代の作曲家には、対位法的に複雑なスタイルで、多様なテクスチャーと精巧なカノン技法を用いた音楽を作曲したヨハネス・ オッケゲム; 15世紀後半のミサ曲の最も著名な作曲家の一人であるヤコブ・オブレヒト;そして、パレストリーナ以前にヨーロッパで最も著名な作曲家であり、16世紀に はあらゆる分野で最も偉大な芸術家の一人として称賛されたジョスquin des Prez。ジョスquinの後の世代の音楽は、対位法の複雑さをさらに追求した。その最も極端な表現は、ニコラス・ゴムベルトの音楽に見られ、その対位法 の複雑さは、カンツォーナやリチェルカーレなどの初期の器楽音楽に影響を与え、最終的にバロックのフーガ形式に結実した。 16世紀半ばまでに、国際的なスタイルは崩壊し始め、いくつかの多様なスタイルの傾向が顕著になった:トリエント公会議の反宗教改革の指針に従った聖歌の 簡素化傾向、ジョヴァンニ・ピエルルイージ・ダ・パレストリーナの音楽に代表される; マドリガルにおける複雑さと半音階主義の傾向は、ルッツァスキ派のフェラーラ派や16世紀末のマドリガル作曲家カルロ・ジェズアルドの先駆的なスタイルで 極限に達した;そして、ヴェネツィア派の壮大で響き渡る音楽は、サン・マルコ大聖堂の建築構造を利用して対位法的な対比を生み出した。ヴェネツィア派の音 楽には、1600年ごろの数十年間に発展した管弦楽法、装飾的な器楽パート、通奏低音パートが含まれていました。ヴェネツィアの著名な作曲家には、ガブリ エリの父子(アンドレアとジョヴァンニ)や、時代の終焉期に最も重要な革新者の一人であるクラウディオ・モンテヴェルディがいます。 |

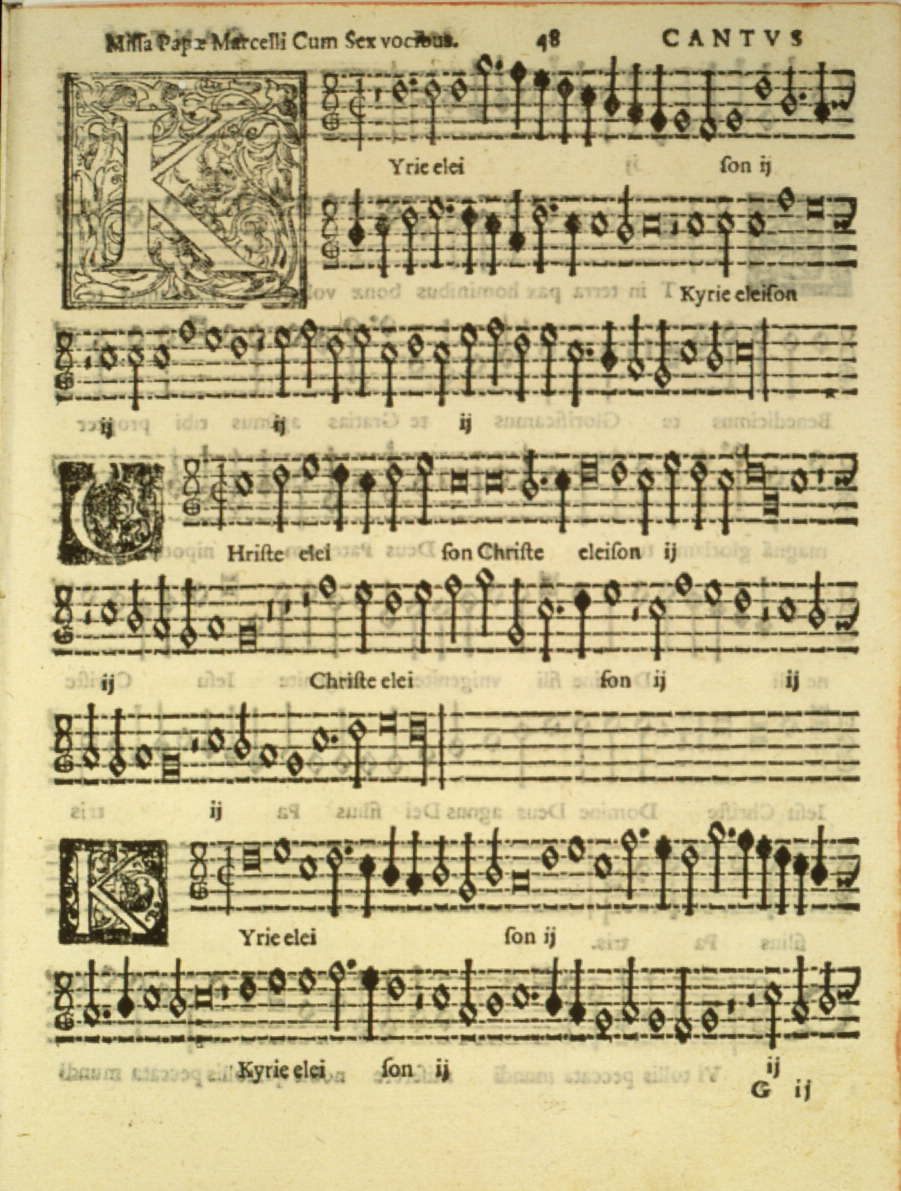

Sheet music for part of the Missa Papae Marcelli by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Most parts of Europe had active and well-differentiated musical traditions by late in the century. In England, composers such as Thomas Tallis and William Byrd wrote sacred music in a style similar to that written on the continent, while an active group of home-grown madrigalists adapted the Italian form for English tastes: famous composers included Thomas Morley, John Wilbye and Thomas Weelkes. Spain developed instrumental and vocal styles of its own, with Tomás Luis de Victoria writing refined music similar to that of Palestrina, and numerous other composers writing for the new guitar. Germany cultivated polyphonic forms built on the Protestant chorales, which replaced the Roman Catholic Gregorian Chant as a basis for sacred music, and imported the style of the Venetian school (the appearance of which defined the start of the Baroque era there). In addition, Dutch and German composers, particularly Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, wrote enormous amounts of organ music, establishing the basis for the later Baroque organ style which culminated in the work of J.S. Bach. France developed a unique style of musical diction known as musique mesurée, used in secular chansons, with composers such as Guillaume Costeley and Claude Le Jeune prominent in the movement. One of the most revolutionary movements in the era took place in Florence in the 1570s and 1580s, with the work of the Florentine Camerata, who ironically had a reactionary intent: dissatisfied with what they saw as contemporary musical depravities, their goal was to restore the music of the ancient Greeks. Chief among them were Vincenzo Galilei, the father of the astronomer, and Giulio Caccini. The fruits of their labors was a declamatory melodic singing style known as monody, and a corresponding staged dramatic form: a form known today as opera. The first operas, written around 1600, also define the end of the Renaissance and the beginning of the Baroque eras. Music prior to 1600 was modal rather than tonal. Several theoretical developments late in the 16th century, such as the writings on scales on modes by Gioseffo Zarlino and Franchinus Gaffurius, led directly to the development of common practice tonality. The major and minor scales began to predominate over the old church modes, a feature which was at first most obvious at cadential points in compositions, but gradually became pervasive. Music after 1600, beginning with the tonal music of the Baroque era, is often referred to as belonging to the common practice period. |

ジョヴァンニ・ピエルルイージ・ダ・パレストリーナの「ミサ・パパエ・マルチェッリ」の一部楽譜 16世紀後半には、ヨーロッパの大部分で活発で多様性に富んだ音楽伝統が確立されていた。イギリスでは、トマス・タリスやウィリアム・バードのような作曲 家が、大陸で書かれた音楽と似たスタイルの宗教音楽を作曲した一方、国内で育ったマドリガル作曲家の活発なグループが、イタリアの形式をイギリス人の好み に合わせて適応させた。著名な作曲家にはトマス・モリー、ジョン・ウィルビー、トマス・ウィールクスなどがいる。スペインは独自の器楽と声楽のスタイルを 発展させ、トマス・ルイス・デ・ビクトリアはパレストリーナに似た洗練された音楽を創作し、多くの作曲家が新しいギターのための作品を書いた。ドイツで は、プロテスタントのコラールを基盤としたポリフォニー形式が育成され、ローマ・カトリックのグレゴリオ聖歌に代わって聖歌の基盤となった。また、ヴェネ ツィア派のスタイルが輸入され(その出現はバロック時代の始まりを定義した)。さらに、オランダとドイツの作曲家、特にヤン・ピエテルスゾーン・スウェリ ンクは、膨大な量のオルガン音楽を作曲し、J.S.バッハの作品で最高潮に達した後のバロックオルガンスタイルの基礎を築いた。フランスでは、世俗的な シャンソンで使用される、ムジーク・メズール(musique mesurée)として知られる独特の音楽的発音法が開発され、ギヨーム・コステリーやクロード・ル・ジュヌなどの作曲家がこの運動の第一人者となった。 この時代で最も革命的な運動のひとつは、1570年代から1580年代にかけてフィレンツェで起こった、フィレンツェ・カメラータの活動だった。皮肉なこ とに、この運動は反動的な意図を持っていた。彼らは、当時の音楽が堕落していることに不満を抱き、古代ギリシャの音楽を復活させることを目標としていた。 その中心人物は、天文学者の父であるヴィンチェンツォ・ガリレイとジュリオ・カッチーニだった。彼らの努力の成果は、独唱形式のメロディックな歌唱スタイ ルである「モノディ」と、それに伴う舞台劇形式である「オペラ」だった。1600年ごろに書かれた最初のオペラは、ルネサンスの終わりとバロック時代の始 まりを定義する作品でもある。 1600年以前の音楽は、調性ではなくモードに基づいていた。16世紀後半の理論的発展、例えばジョゼッフォ・ザルリーノとフランキヌス・ガフルリウスに よるモードに関するスケールに関する著作は、共通実践調性の発展に直接つながった。長調と短調のスケールが古い教会モードに代わって主流となり、この特徴 は当初は作曲の終止点で最も顕著だったが、徐々に普遍化していった。1600年以降の音楽は、バロック時代の調性音楽から始まり、しばしば共通実践期に属 するものとされる。 |

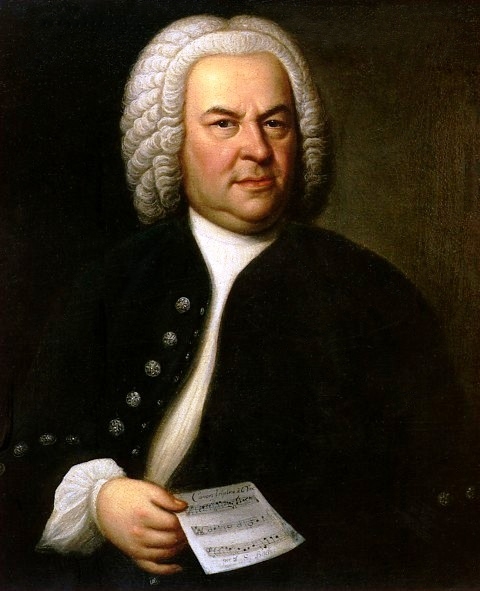

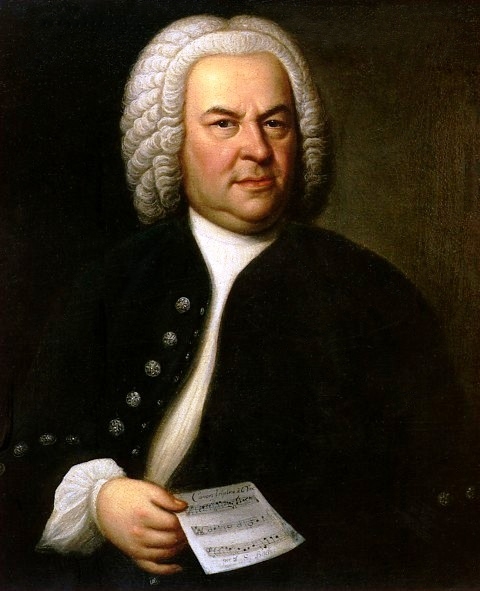

| Baroque Main article: Baroque music See also: List of Baroque composers  J. S. Bach The Baroque era took place from 1600 to 1750, as the Baroque artistic style flourished across Europe and, during this time, music expanded in its range and complexity. Baroque music began when the first operas (dramatic solo vocal music accompanied by orchestra) were written. During the Baroque era, polyphonic contrapuntal music, in which multiple, simultaneous independent melody lines were used, remained important (counterpoint was important in the vocal music of the medieval era).[clarification needed] German, Italian, French, Dutch, Polish, Spanish, Portuguese, and English Baroque composers wrote for small ensembles including strings, brass, and woodwinds, as well as for choirs and keyboard instruments such as pipe organ, harpsichord, and clavichord. During this period several major music forms were defined that lasted into later periods when they were expanded and evolved further, including the fugue, the invention, the sonata, and the concerto.[156] The late Baroque style was polyphonically complex and richly ornamented. Important composers from the Baroque era include Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, Johann Sebastian Bach, Arcangelo Corelli, François Couperin, Girolamo Frescobaldi, George Frideric Handel, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Claudio Monteverdi, Georg Philipp Telemann, Domenico Scarlatti and Antonio Vivaldi. |

バロック 主な記事:バロック音楽 関連項目:バロック作曲家一覧  J. S. バッハ バロック時代は 1600 年から 1750 年にかけて、バロック芸術様式がヨーロッパ全土で隆盛を極めた時期で、この間に音楽は範囲と複雑さを拡大した。バロック音楽は、最初のオペラ(オーケスト ラ伴奏による劇的な独唱音楽)が作曲されたときに始まった。バロック時代には、複数の独立したメロディラインが同時に使用されるポリフォニックな対位法音 楽が重要視された(対位法は中世の声楽音楽でも重要だった)。[説明が必要] ドイツ、イタリア、フランス、オランダ、ポーランド、スペイン、ポルトガル、イギリスのバロック作曲家は、弦楽器、金管楽器、木管楽器を含む小規模なアン サンブル、合唱団、パイプオルガン、ハープシコード、クラヴィコードなどの鍵盤楽器のための作品を書いた。この期間に、後世に発展し進化を遂げた主要な音 楽形式が定義された。これにはフーガ、インヴェンション、ソナタ、コンチェルトが含まれる。[156] 後期バロック様式は多声的に複雑で、豊かに装飾されていた。バロック時代の重要な作曲家には、ヤン・ピエテルスゾーン・スヴェリント、ヨハン・セバスティ アン・バッハ、アルカンジェロ・コレッリ、フランソワ・クープラン、ジロラモ・フレスコバルディ、ゲオルク・フリードリヒ・ヘンデル、ジャン=バティス ト・リュリ、ジャン=フィリップ・ラモー、クラウディオ・モンテヴェルディ、ゲオルク・フィリップ・テレマン、ドメニコ・スカルラッティ、アントニオ・ ヴィヴァルディなどがいる。 |

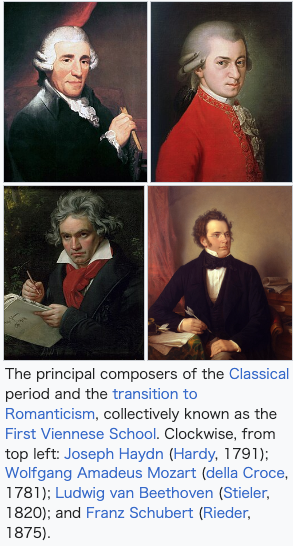

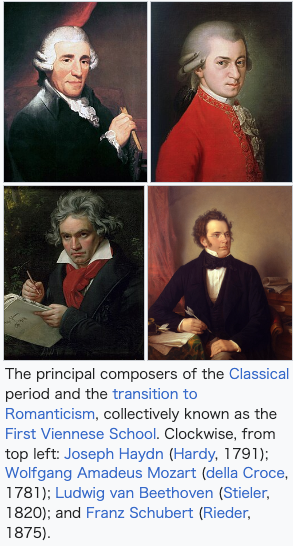

| Classical Main article: Classical period (music) See also: List of Classical-era composers  The principal composers of the Classical period and the transition to Romanticism, collectively known as the First Viennese School. Clockwise, from top left: Joseph Haydn (Hardy, 1791); Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (della Croce, 1781); Ludwig van Beethoven (Stieler, 1820); and Franz Schubert (Rieder, 1875). The music of the Classical period is characterized by homophonic texture, or an obvious melody with accompaniment. These new melodies tended to be almost voice-like and singable, allowing composers to actually replace singers as the focus of the music. Instrumental music therefore quickly replaced opera and other sung forms (such as oratorio) as the favorite of the musical audience and the epitome of great composition. However, opera did not disappear: during the classical period, several composers began producing operas for the general public in their native languages (previous operas were generally in Italian). Along with the gradual displacement of the voice in favor of stronger, clearer melodies, counterpoint also typically became a decorative flourish, often used near the end of a work or for a single movement. In its stead, simple patterns, such as arpeggios and, in piano music, Alberti bass (an accompaniment with a repeated pattern typically in the left hand), were used to liven the movement of the piece without creating a confusing additional voice. The now-popular instrumental music was dominated by several well-defined forms: the sonata, the symphony, and the concerto, though none of these were specifically defined or taught at the time as they are now in music theory. All three derive from sonata form, which is both the overlying form of an entire work and the structure of a single movement. Sonata form matured during the Classical era to become the primary form of instrumental compositions throughout the 19th century. The early Classical period was ushered in by the Mannheim School, which included such composers as Johann Stamitz, Franz Xaver Richter, Carl Stamitz, and Christian Cannabich. It exerted a profound influence on Joseph Haydn and, through him, on all subsequent European music. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was the central figure of the Classical period, and his phenomenal and varied output in all genres defines our perception of the period. Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert were transitional composers, leading into the Romantic period, with their expansion of existing genres, forms, and even functions of music. |

古典 主な記事:古典派 (音楽) 関連項目:古典派作曲家一覧  古典派およびロマン主義への移行期の主要な作曲家たち。総称して「第一ウィーン楽派」として知られる。左上から時計回りに、ヨゼフ・ハイドン(ハーディ、 1791年)、ヴォルフガング・アマデウス・モーツァルト(デッラ・クローチェ、1781年)、ルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェン(スティラー、 1820年)、フランツ・シューベルト(リーダー、1875年)。 古典派の音楽は、ホモフォニックなテクスチャー、つまり伴奏のある明確なメロディーが特徴です。これらの新しいメロディーは、ほとんど声のような、歌える ものになり、作曲家は実際に歌手ではなく、音楽の中心として作曲に専念できるようになりました。そのため、器楽曲は、オペラやその他の歌形式(オラトリオ など)に代わって、音楽愛好家の人気を博し、優れた作曲の代表例となりました。しかし、オペラが消えたわけではありません。古典派時代、いくつかの作曲家 が、一般大衆向けに、自国語によるオペラを制作し始めました(それまでのオペラは、一般的にイタリア語でした)。 声楽がより力強く明確なメロディに置き換えられるにつれ、対位法も装飾的な装飾として用いられるようになり、作品の終わりや単一の楽章でよく使われるよう になった。その代わりに、アルペジオや、ピアノ音楽におけるアルベリッティ・バス(左手で繰り返されるパターンによる伴奏)のようなシンプルなパターン が、混乱を招く追加の声を創出せずに作品の動きを活気づけるために用いられた。現在人気の高い器楽音楽は、ソナタ、交響曲、協奏曲といういくつかの明確な 形式に支配されていたが、これらの形式は当時、現在の音楽理論のように具体的に定義されたり教えられるものではなかった。この3つはすべてソナタ形式から 派生しており、ソナタ形式は作品全体の形式であり、単一の楽章の構造でもある。ソナタ形式は、古典派時代に成熟し、19 世紀を通じて器楽曲の主要な形式となった。 古典派初期は、ヨハン・スタミッツ、フランツ・クサーヴァー・リヒター、カール・スタミッツ、クリスティアン・カンナビッチなどの作曲家たちによるマンハ イム派によって幕を開けた。この派は、ヨゼフ・ハイドンに多大な影響を与え、ハイドンを通じてその後のヨーロッパの音楽全体に大きな影響を与えた。ヴォル フガング・アマデウス・モーツァルトは古典派の中心的人物であり、あらゆるジャンルにおける驚異的な多作さが、この時代の認識を形作っている。ルートヴィ ヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェンとフランツ・シューベルトは、既存のジャンル、形式、さらには音楽の機能そのものを拡大し、ロマン派への過渡期を導いた作曲家 たちだ。 |

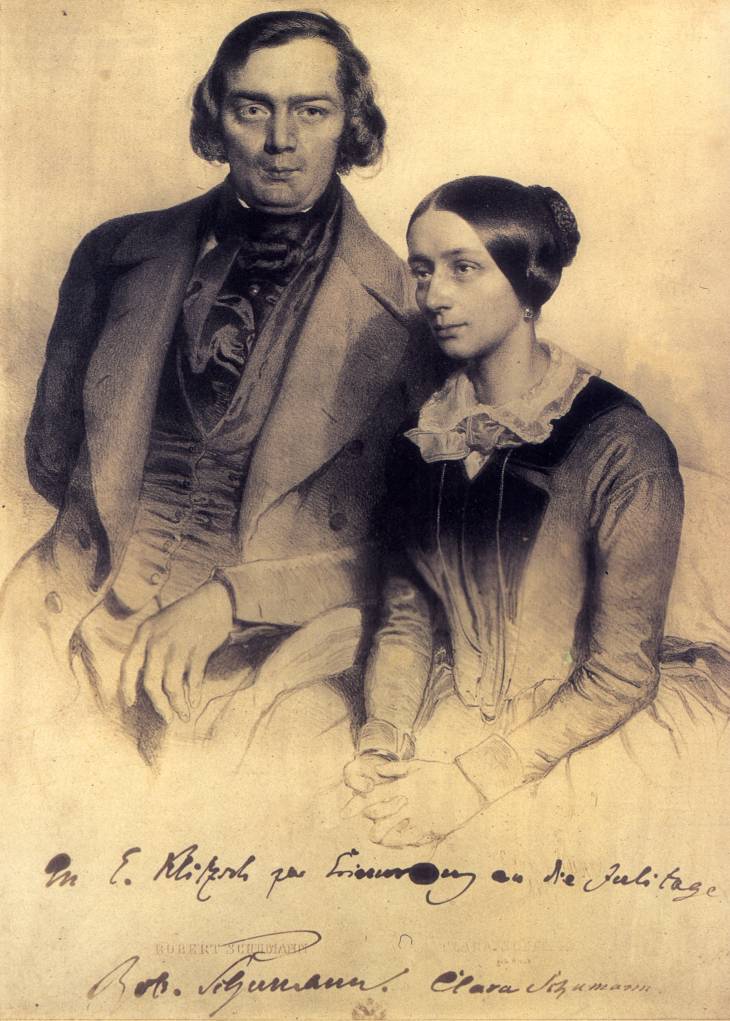

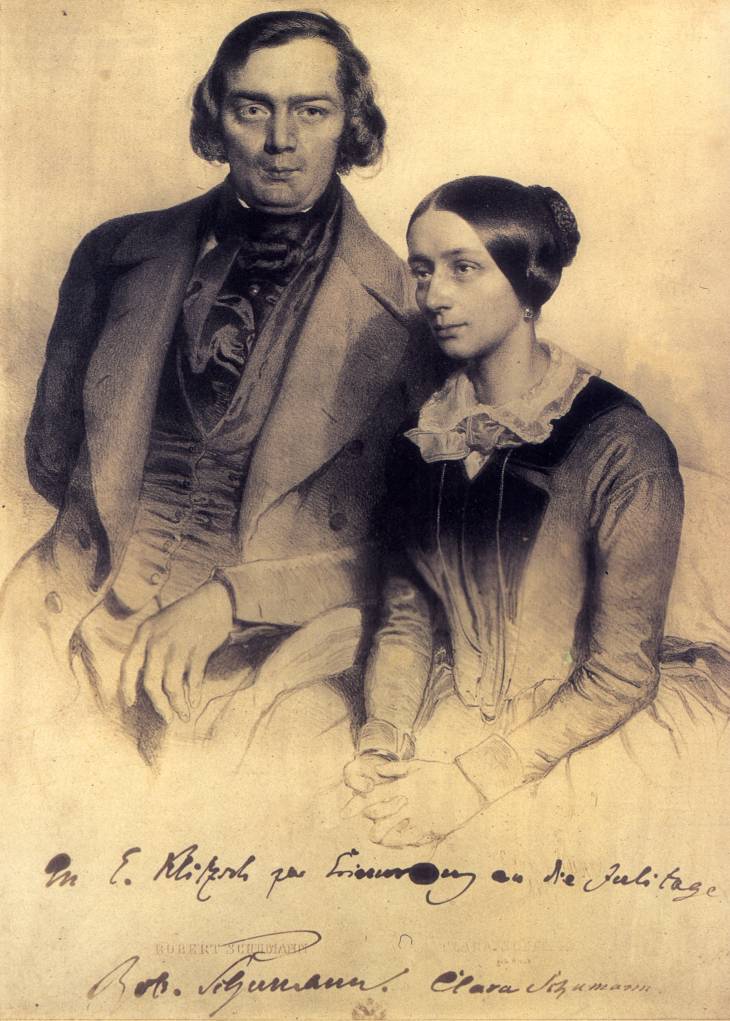

| Romantic Main article: Romantic music See also: List of Romantic composers  Clara and Robert Schumann In the Romantic period, music became more expressive and emotional, expanding to encompass literature, art, and philosophy. Famous early Romantic composers include Schumann, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Bellini, Donizetti, and Berlioz. The late 19th century saw a dramatic expansion in the size of the orchestra, and in the role of concerts as part of urban society. Famous composers from the second half of the century include Johann Strauss II, Brahms, Liszt, Tchaikovsky, Verdi, and Wagner. Between 1890 and 1910, a third wave of composers including Grieg, Dvořák, Mahler, Richard Strauss, Puccini, and Sibelius built on the work of middle Romantic composers to create even more complex – and often much longer – musical works. A prominent mark of late 19th-century music is its nationalistic fervor, as exemplified by such figures as Dvořák, Sibelius, and Grieg. Other prominent late-century figures include Saint-Saëns, Fauré, Rachmaninoff, Franck, Debussy and Rimsky-Korsakov. |

ロマン派 主な記事:ロマン派音楽 関連項目:ロマン派作曲家一覧  クララとロベルト・シューマン ロマン派時代、音楽はより表現力豊かで感情的になり、文学、芸術、哲学にも広がった。初期の有名なロマン派作曲家には、シューマン、ショパン、メンデルス ゾーン、ベッリーニ、ドニゼッティ、ベルリオーズなどがいる。19 世紀後半には、オーケストラの規模が飛躍的に拡大し、都市社会の一部としてコンサートの役割も拡大した。19 世紀後半の有名な作曲家としては、ヨハン・シュトラウス II 世、ブラームス、リスト、チャイコフスキー、ヴェルディ、ワーグナーなどが挙げられる。1890 年から 1910 年にかけて、グリーグ、ドヴォルザーク、マーラー、リヒャルト・シュトラウス、プッチーニ、シベリウスなどの作曲家たちによる第 3 の波が、中期のロマン派作曲家の作品の上に、さらに複雑で、多くの場合、より長い楽曲を生み出した。19 世紀後半の音楽の特徴は、ドヴォルザーク、シベリウス、グリーグなどの人物に代表されるナショナリスト的な熱狂だ。この時代の他の著名な人物としては、サ ン=サーンス、フォーレ、ラフマニノフ、フランク、ドビュッシー、リムスキー=コルサコフなどが挙げられる。 |

| 20th and 21st century Main article: 20th-century music Further information: 20th-century classical music, Modernism (music), Contemporary classical music, and Popular music See also: List of modernist composers, List of postmodernist composers, List of 20th-century classical composers, and List of 21st-century classical composers The 20th century saw a revolution in music listening as the radio gained popularity worldwide and new media and technologies were developed to record, edit and distribute music. Music performances became increasingly visual with the broadcast and recording of performances.[157] 20th-century music brought new freedom and wide experimentation with new musical styles and forms that challenged the accepted rules of music of earlier periods.[citation needed] The invention of musical amplification and electronic instruments, especially the synthesizer, in the mid-20th century revolutionized classical and popular music, and accelerated the development of new forms of music.[158] As for classical music, two fundamental schools determined the course of the century: that of Arnold Schoenberg and that of Igor Stravinsky.[159] However, other composers also had a notable influence. For example: Béla Bartók, Anton Webern, Dmitri Shostakovich, Olivier Messiaen, John Cage, Benjamin Britten, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Sofia Gubaidulina, Krzysztof Penderecki, Brian Ferneyhough, Kaija Saariaho.[160] The 20th century saw the unprecedented dissemination of popular music, that is, music with a wide appeal.[n 22] The term has its roots in the music of the American Tin Pan Alley, a group of prominent musicians and publishers who began to emerge during the 1880s in New York City. Although popular music is sometimes known as "pop music", the terms are not always interchangeable.[162] Popular music refers to a variety of music genres that appeal to the tastes of a large segment of the population,[163] whereas pop music usually refers to a specific genre within popular music.[164] Popular music songs and pieces typically have easily singable melodies. The song structure of popular music commonly involves repetition of sections, with the verse and chorus or refrain repeating throughout the song and the bridge providing a contrasting and transitional section within a piece.[165] |

20世紀および21世紀 主な記事:20世紀の音楽 詳細情報:20世紀のクラシック音楽、モダニズム(音楽)、現代クラシック音楽、ポピュラー音楽 関連項目:モダニズム作曲家の一覧、ポストモダニズム作曲家の一覧、20世紀のクラシック作曲家の一覧、21世紀のクラシック作曲家の一覧 20 世紀は、ラジオが世界中で普及し、音楽を録音、編集、配信するための新しいメディアや技術が開発され、音楽鑑賞に革命が起こった時代だった。演奏の放送や 録音により、音楽パフォーマンスはますます視覚的なものになっていった。[157] 20 世紀の音楽は、それまでの音楽の定説に挑む新しい音楽スタイルや形式の登場により、新たな自由と幅広い実験をもたらした。[要出典] 20世紀半ばに発明された音楽の増幅装置と電子楽器、特にシンセサイザーは、クラシック音楽とポピュラー音楽を革命的に変革し、新たな音楽形式の発展を加 速させた。[158] クラシック音楽においては、アーノルド・シェーンベルクとイゴール・ストラヴィンスキーの2つの根本的な流派が、20世紀の音楽の方向性を決定付けた。 [159] しかし、他の作曲家も顕著な影響を与えた。例えば:ベラ・バルトーク、アントン・ウェーベルン、ドミトリー・ショスタコーヴィチ、オリヴィエ・メシアン、 ジョン・ケージ、ベンジャミン・ブリテン、カールハインツ・シュトックハウゼン、ソフィア・グバイドゥリナ、クリストフ・ペンデレツキ、ブライアン・フェ ルニーホウ、カイヤ・サアリアホ。[160] 20世紀は、大衆音楽、つまり幅広い層に人気のある音楽が前例のないほど広まった時代だった。[n 22] この用語は、1880年代にニューヨークで台頭し始めた著名な音楽家や出版社のグループであるアメリカのティン・パン・アレーの音楽に由来する。大衆音楽 は「ポップ・ミュージック」とも呼ばれることがあるが、この2つの用語は必ずしも同義ではない。[162] ポピュラー音楽は、人口の大部分の好みに合う多様な音楽ジャンルを指す[163]のに対し、ポップ音楽は通常、ポピュラー音楽内の特定のジャンルを指す [164]。ポピュラー音楽の曲や楽曲は、一般的に歌いやすいメロディを持つ。ポピュラー音楽の曲の構造は、通常、セクションの反復を特徴とし、 verses(節)と chorus(コーラス)または refrain(リフレイン)が曲全体で繰り返し、 bridge(ブリッジ)が曲内の対照的で移行的なセクションを提供する[165]。 |