フーゴ・グローティウス

Hugo Grotius, 1583-1645

sasasa

☆ フーゴ・グロティウス(1583年4月10日 - 1645年8月28日)は、フーゴー・デ・グルート(Huig de Groot)としても知られる: [オランダの人文主義者、外交官、弁護士、神学者、法学者、政治家、詩人、劇作家。デルフトに生まれ、ライデン大学で学ぶ。オランダ共和国の宗教政策をめ ぐる論争に関与したため、レーヴェシュタイン城に投獄されたが、ゴリンケムに運ばれた書物の入った箱に隠されて脱出。グロティウスは亡命先のフランスで主 要著作のほとんどを執筆した。グロティウスは16世紀から17世紀にかけて、哲学、政治理論、法学の分野で重要な人物であった。フランシスコ・デ・ヴィ トーリアやアルベリコ・ジェン ティリの初期の著作とともに、彼の著作はプロテスタントの自然法に基づく国際法の基礎を築いた。彼の著作のうち2冊は、国際法の分野で永続的な影響を与え た: フランスのルイ13世に献呈された『戦争と平和の法』(De jure belli ac pacis)と、グロティウスが「国際法の父」と呼ばれる『自由海域』(Mare Liberum)である。グロティウス以前は、権利は何よりも物に付随するものとして認識されていたが、グロティウス以後は、権利は人に属するものであ り、行為能力の表現として、あるいは何かを実現するための手段として認識されるようになった。フランシスコ・デ・ヴィトーリアやアルベリコ・ジェンティリ の初期の著作とともに、彼の著作はプロテスタントの自然法に基づく国際法の基礎を築いた。彼の著作のうち2冊は、国際法の分野で永続的な影響を与えた。国 家の主権は単に神の意志によって支配者にあるのではなく、支配者にそのような権威を与えることに同意した国民に由来するという考えを支持していた。 また、グロティウスは国際社会の教義を最初に定式化した人物ではないと考えられているが、武力や戦争によってではなく、実際の法律とその法律を執行するた めの相互の合意によって統治される、国家からなる一つの社会という考えを明確に定義した最初の人物の一人であった。グロティウスが提唱した国際社会の理念 は、ウェストファリア講和の中で具体的に表現され、グロティウスはこの近代最初の一般的平和解決の知的父と考えられる」。さらに、アルミニウス主義ないしは神学(Arminianism) への貢献は、メソジスト教やペンテコステ派など、後のアルミニウス主義に基づく運動の種を提供するのに役立った。自由貿易を神学的に支えたことから、彼は 「経済神学者」とも考えられている。

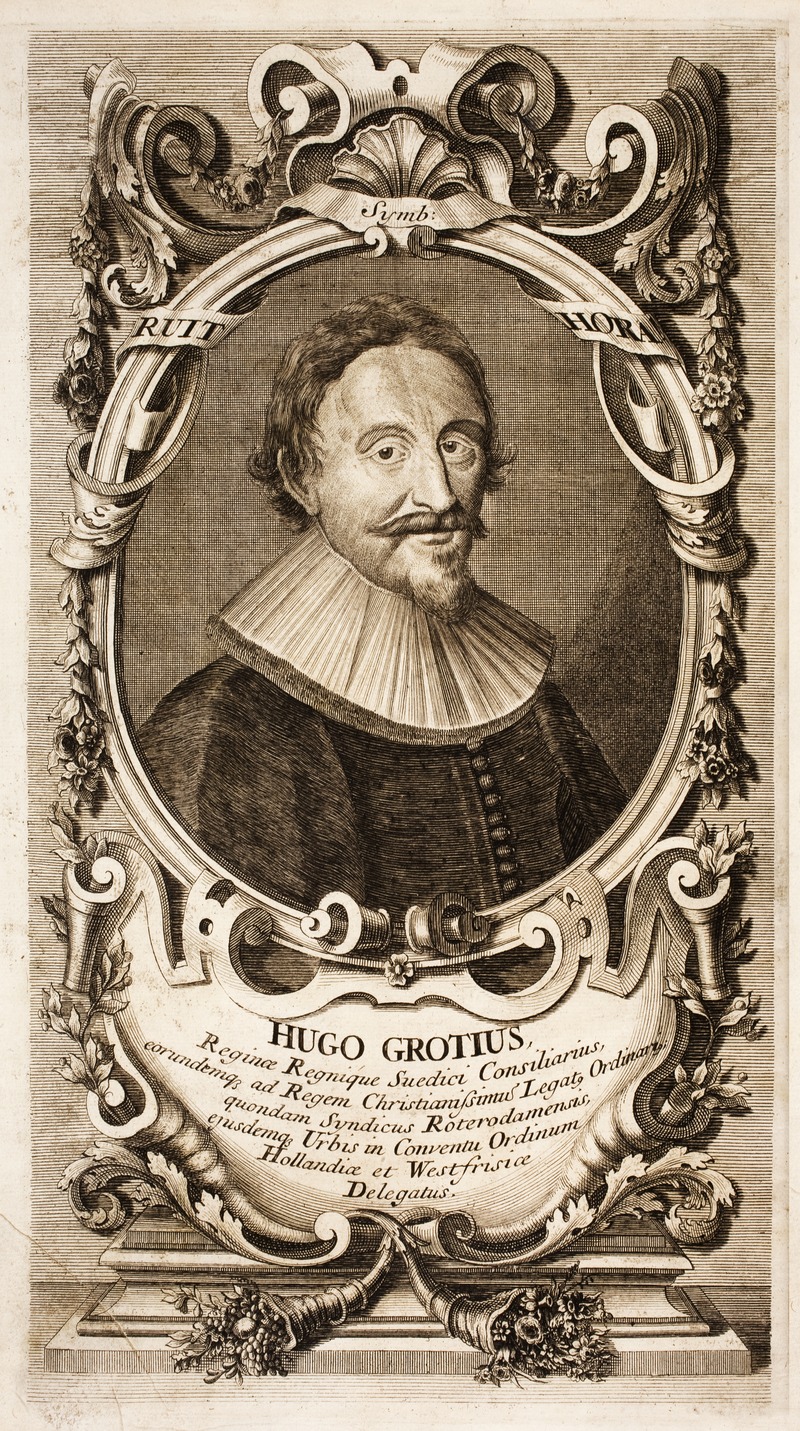

| Hugo Grotius

(/ˈɡroʊʃiəs/; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Huig de

Groot (Dutch: [ˈɦœyɣ də ˈɣroːt]) and Hugo de Groot (Dutch: [ˈɦyɣoː -]),

was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, statesman,

poet and playwright. A teenage prodigy, he was born in Delft and

studied at Leiden University. He was imprisoned in Loevestein Castle

for his involvement in the controversies over religious policy of the

Dutch Republic, but escaped hidden in a chest of books that was

transported to Gorinchem. Grotius wrote most of his major works in

exile in France. Grotius was a major figure in the fields of philosophy, political theory and law during the 16th and 17th centuries. Along with the earlier works of Francisco de Vitoria and Alberico Gentili, his writings laid the foundations for international law, based on natural law in its Protestant side. Two of his books have had a lasting impact in the field of international law: De jure belli ac pacis (On the Law of War and Peace) dedicated to Louis XIII of France and the Mare Liberum (The Free Seas) for which Grotius has been called the "father of international law".[4] Grotius has also contributed significantly to the evolution of the notion of rights. Before him, rights were above all perceived as attached to objects; after him, they are seen as belonging to persons, as the expression of an ability to act or as a means of realizing something. Peter Borschberg suggests that Grotius was significantly influenced by Francisco de Vitoria and the School of Salamanca in Spain, who supported the idea that the sovereignty of a nation does not lie simply in a ruler through God's will, but originates in its people, who agree to confer such authority upon a ruler.[5] It is also thought that Grotius was not the first to formulate the international society doctrine, but he was one of the first to define expressly the idea of one society of states, governed not by force or warfare but by actual laws and mutual agreement to enforce those laws. As Hedley Bull declared in 1990: "The idea of international society which Grotius propounded was given concrete expression in the Peace of Westphalia, and Grotius may be considered the intellectual father of this first general peace settlement of modern times."[6] Additionally, his contributions to Arminian theology helped provide the seeds for later Arminian-based movements, such as Methodism and Pentecostalism; Grotius is acknowledged as a significant figure in the Arminian-Calvinist debate. Because of his theological underpinning of free trade, he is also considered an "economic theologist".[7] After fading over time, the influence of Grotius's ideas revived in the 20th century following the First World War. |

フー

ゴ・グロティウス(/ˈʃiəs/; 1583年4月10日 - 1645年8月28日)は、フーゴー・デ・グルート(Huig de

Groot、オランダ語: [ˈ♣ dəroː])、フーゴー・デ・グルート(Hugo de Groot、オランダ語: [ˈɣ

dəroː])としても知られる:

[オランダの人文主義者、外交官、弁護士、神学者、法学者、政治家、詩人、劇作家。デルフトに生まれ、ライデン大学で学ぶ。オランダ共和国の宗教政策をめ

ぐる論争に関与したため、レーヴェシュタイン城に投獄されたが、ゴリンケムに運ばれた書物の入った箱に隠されて脱出。グロティウスは亡命先のフランスで主

要著作のほとんどを執筆した。 グロティウスは16世紀から17世紀にかけて、哲学、政治理論、法学の分野で重要な人物であった。フランシスコ・デ・ヴィトーリアやアルベリコ・ジェン ティリの初期の著作とともに、彼の著作はプロテスタントの自然法に基づく国際法の基礎を築いた。彼の著作のうち2冊は、国際法の分野で永続的な影響を与え た: フランスのルイ13世に献呈された『戦争と平和の法』(De jure belli ac pacis)と、グロティウスが「国際法の父」と呼ばれる『自由海域』(Mare Liberum)である。グロティウス以前は、権利は何よりも物に付随するものとして認識されていたが、グロティウス以後は、権利は人に属するものであ り、行為能力の表現として、あるいは何かを実現するための手段として認識されるようになった。 ピーター・ボルシュベルクによれば、グロティウスはフランシスコ・デ・ヴィトーリアとスペインのサラマンカ学派から大きな影響を受けており、彼らは国家の 主権は単に神の意志によって支配者にあるのではなく、支配者にそのような権威を与えることに同意した国民に由来するという考えを支持していた。 [5] また、グロティウスは国際社会の教義を最初に定式化した人物ではないと考えられているが、武力や戦争によってではなく、実際の法律とその法律を執行するた めの相互の合意によって統治される、国家からなる一つの社会という考えを明確に定義した最初の人物の一人であった。グロティウスが提唱した国際社会の理念 は、ウェストファリア講和の中で具体的に表現され、グロティウスはこの近代最初の一般的平和解決の知的父と考えられる」[6]。さらに、アルミニウス神学 への貢献は、メソジスト教やペンテコステ派など、後のアルミニウス主義に基づく運動の種を提供するのに役立った。自由貿易を神学的に支えたことから、彼は 「経済神学者」とも考えられている[7]。 グロティウスの思想は時間の経過とともに衰退していったが、第一次世界大戦後の20世紀にその影響力が復活した。 |

| Early life Grotius at age 16, by Jan Antonisz. van Ravesteyn, 1599 Born in Delft during the Dutch Revolt, Grotius was the first child of Jan Cornets de Groot and Alida van Overschie. His father was a man of learning, once having studied with the eminent Justus Lipsius at Leiden University,[8] as well as of political distinction. His family was considered Delft patrician as his ancestors played an important role in local government since the 13th century.[9] Jan de Groot was also translator of Archimedes and friend of Ludolph van Ceulen. He groomed his son from an early age in a traditional humanist and Aristotelian education.[10] A prodigious learner, Grotius entered Leiden University when he was just eleven years old.[9] There he studied with some of the most acclaimed intellectuals in northern Europe, including Franciscus Junius, Joseph Justus Scaliger, and Rudolph Snellius.[11] At age 16 (1599), he published his first book: a scholarly edition of the late antique author Martianus Capella's work on the seven liberal arts, Martiani Minei Felicis Capellæ Carthaginiensis viri proconsularis Satyricon. It remained a reference for several centuries.[12] In 1598, at the age of 15 years, he accompanied Johan van Oldenbarnevelt to a diplomatic mission in Paris. On this occasion, the King Henri IV of France would have presented Grotius to his court as "the miracle of Holland".[13] During his stay in France, he passed or bought a law degree from the University of Orleans.[14] In Holland, Grotius earned an appointment as advocate to The Hague in 1599[15] and then as official historiographer for the States of Holland in 1601. It was on this date that the States of Holland requested from Grotius an account of the United Provinces’ revolt against Spain;[4] Grotius is indeed contemporary with the Eighty Years' War between Spain and the Netherlands.[14] The resulting work, entitled Annales et Historiae de rebus Belgicis, describing the period from 1559 to 1609, was written in the style of the Roman historian Tacitus[16] and was first finished in 1612. The States however did not publish it, possibly because of the way the work resonated with the politico-religious tensions within the Dutch Republic (see below).[17] His first occasion to write systematically on issues of international justice came in 1604, when he became involved in the legal proceedings following the seizure by Dutch merchants of a Portuguese carrack and its cargo in the Singapore Strait.[citation needed] Throughout his life Grotius wrote a variety of philological, theological and politico-theological works. In 1608, he married Maria van Reigersberch; they had three daughters and four sons.[14] Jurist career Page written in Grotius' hand from the manuscript of De Indis (circa 1604/05) The Dutch were at war with Spain; although Portugal was closely allied with Spain, it was not yet at war with the Dutch. Near the start of the war, Grotius's cousin captain Jacob van Heemskerk captured a loaded Portuguese carrack merchant ship, Santa Catarina, off present-day Singapore in 1603.[18] Heemskerk was employed with the United Amsterdam Company (part of the Dutch East India Company), and though he did not have authorization from the company or the government to initiate the use of force, many shareholders were eager to accept the riches that he brought back to them.[19] Not only was the legality of keeping the prize questionable under Dutch statute, but a faction of shareholders (mostly Mennonite) in the Company also objected to the forceful seizure on moral grounds, and of course, the Portuguese demanded the return of their cargo. The scandal led to a public judicial hearing and a wider campaign to sway public (and international) opinion.[citation needed] It was in this wider context that representatives of the Company called upon Grotius to draft a polemical defence of the seizure.[19] Portrait of Grotius at age 25 (Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt, 1608) The result of Grotius' efforts in 1604/05 was a long, theory-laden treatise that he provisionally entitled De Indis (On the Indies). Grotius sought to ground his defense of the seizure in terms of the natural principles of justice. In this, he had cast a net much wider than the case at hand; his interest was in the source and ground of war's lawfulness in general. The treatise was never published in full during Grotius' lifetime, perhaps because the court ruling in favor of the Company preempted the need to garner public support.[citation needed] In The Free Sea (Mare Liberum, published 1609) Grotius formulated the new principle that the sea was international territory and all nations were free to use it for seafaring trade.[20] Grotius, by claiming 'free seas' (freedom of the seas), provided suitable ideological justification for the Dutch breaking up of various trade monopolies through its formidable naval power. England, competing fiercely with the Dutch for domination of world trade, opposed this idea and claimed in John Selden's Mare clausum (The Closed Sea), "That the Dominion of the British Sea, or That Which Incompasseth the Isle of Great Britain, is, and Ever Hath Been, a Part or Appendant of the Empire of that Island."[21] It is generally assumed that Grotius first propounded the principle of freedom of the seas, although all countries in the Indian Ocean and other Asian seas accepted the right of unobstructed navigation long before Grotius wrote his De Jure Praedae (On the Law of Spoils) in the year of 1604. Additionally, 16th century Spanish theologian Francisco de Vitoria had postulated the idea of freedom of the seas in a more rudimentary fashion under the principles of jus gentium.[22] Grotius's notion of the freedom of the seas would persist until the mid-20th century, and it continues to be applied even to this day for much of the high seas, though the application of the concept and the scope of its reach is changing. |

生い立ち 16歳のグロティウス、ヤン・アントニシュ・ファン・レーヴェスタイン作、1599年 オランダ動乱の時代にデルフトで生まれたグロティウスは、ヤン・コルネッツ・デ・グルートとアリダ・ファン・オヴェルシーの第一子であった。父親は学問の 人であり、ライデン大学では高名なユストゥス・リプシウスに師事し[8]、政治的にも優れた人物であった。彼の先祖は13世紀以来地方政府で重要な役割を 果たしていたため、彼の家系はデルフトの貴族とみなされていた[9]。 ヤン・デ・グルートはアルキメデスの翻訳者でもあり、ルドルフ・ファン・セウレンの友人でもあった。グロティウスは幼い頃から伝統的な人文主義、アリスト テレス主義の教育を受けさせ、11歳でライデン大学に入学。 [11]16歳のとき(1599年)、彼は最初の本を出版した。それは、後期アンティークの作家マルティアヌス・カペラの7つの教養に関する著作 『Martiani Minei Felicis Capellæ Carthaginiensis viri proconsularis Satyricon』の学術的な版であった。これは数世紀にわたって参考文献であり続けた[12]。 1598年、15歳のとき、ヨハン・ファン・オルデンバルネヴェルトのパリでの外交使節団に同行。この時、フランス国王アンリ4世はグロティウスを「オラ ンダの奇跡」として宮廷に献上した[13]。 オランダでは、1599年にハーグの弁護人に任命され[15]、1601年にはオランダ国の公式歴史学者となった。スペインとオランダの間で起こった80 年戦争とグロティウスはまさに同時代人である[14]。その結果、1559年から1609年までを記述した『Annales et Historiae de rebus Belgicis』と題された著作は、ローマの歴史家タキトゥスのスタイルで書かれ[16]、1612年に完成した。しかし、オランダ共和国内の政治的・ 宗教的緊張(下記参照)と共鳴する作品であったためか、州はこの作品を出版しなかった[17]。 1604年、グロティウスはシンガポール海峡でオランダ商人がポルトガルのカラックとその積荷を差し押さえた事件の法的手続きに関与するようになり、国際正義の問題について初めて体系的に執筆した[citation needed]。 1608年にマリア・ファン・ライガースベルクと結婚し、3人の娘と4人の息子をもうけた[14]。 法学者としてのキャリア グロティウスの手による『De Indis』(1604/05年頃)の写本。 オランダはスペインと戦争中であり、ポルトガルはスペインと密接な同盟関係にあったが、オランダとはまだ戦争中ではなかった。開戦間近の1603年、グロ ティウスの従兄弟である船長のヤコブ・ファン・ヘームスケルクは、現在のシンガポール沖でポルトガルのカラック商船サンタ・カタリーナ号を拿捕した [18]。ヘームスケルクはユナイテッド・アムステルダム会社(オランダ東インド会社の一部)に雇われており、武力行使を開始する許可を会社や政府から得 ていなかったが、多くの株主は彼が持ち帰った富を喜んで受け入れた[19]。 オランダの法令上、賞品を保持することの合法性が疑問視されただけでなく、会社の株主(主にメノナイト)の一派も道徳的な理由から強引な押収に反対し、も ちろんポルトガル人は積荷の返還を要求した。このスキャンダルは、公開の司法審問につながり、世論(そして国際世論)を動かすための広範なキャンペーンへ と発展した[citation needed]。このような広範な状況の中で、会社の代表者がグロティウスに呼びかけ、差し押さえに対する極論的な弁明書を起草させた[19]。 グロティウス25歳の時の肖像画(Michiel Jansz.) 1604年から2005年にかけてのグロティウスの努力の結果は、仮に『インドについて』と題した、理論に満ちた長い論文であった。グロティウスは、正義 の自然原則の観点から接収を擁護しようとした。グロティウスの関心は戦争全般の合法性の源泉と根拠であった。グロティウスが存命中にこの論考の全文が出版 されることはなかったが、それはおそらく、会社側に有利な判決が下されたことで、世論の支持を集める必要性が先取りされたからであろう[要出典]。 グロティウスは『自由な海』(Mare Liberum、1609年刊)の中で、海は国際的な領土であり、すべての国が海上貿易のために海を自由に利用できるという新しい原則を打ち出した [20]。世界貿易の支配をめぐってオランダと激しく競争していたイングランドは、この考え方に反対し、ジョン・セルデンの『閉ざされた海』(Mare clausum)の中で、「イギリス海の支配権、すなわちグレートブリテン島を包含するものは、その島の帝国の一部または付属物であり、これまでもそうで あった」と主張した[21]。 一般的には、グロティウスが最初に海洋の自由の原則を提唱したと考えられているが、インド洋やその他のアジア海域のすべての国々は、グロティウスが 1604年に『De Jure Praedae(略奪の法について)』を著すずっと前に、妨げのない航行の権利を認めていた。さらに、16世紀のスペインの神学者フランシスコ・デ・ヴィ トーリアは、ユス・ジェンティウムの原則の下で、より初歩的な形で海洋の自由という概念を提唱していた[22]。グロティウスの海洋の自由という概念は 20世紀半ばまで存続し、今日に至るまで公海の大部分に適用され続けているが、その概念の適用と適用範囲は変化している。 |

| Arminian controversy, arrest and exile Further information: History of Calvinist–Arminian debate Further information: Ordinum Hollandiae ac Westfrisiae pietas Aided by his continued association with Van Oldenbarnevelt, Grotius made considerable advances in his political career, being retained as Oldenbarnevelt's resident advisor in 1605, Advocate General of the Fisc of Holland, Zeeland and Friesland in 1607, and then as Pensionary of Rotterdam (the equivalent of a mayoral office) in 1613.[23] Also in 1613, following the capture of two Dutch ships by the British, he was sent on a mission to London,[24] a mission tailored to a man who wrote Mare liberum [The Free Seas] in 1609. However, it was opposed by the English by reason of force and he didn't obtain the return of the boats.[24] In these years a great theological controversy broke out between the chair of theology at Leiden Jacobus Arminius and his followers (who are called Arminians or Remonstrants) and the strongly Calvinist theologian, Franciscus Gomarus, whose supporters are termed Gomarists or Counter-Remonstrants.[citation needed] Leiden University "was under the authority of the States of Holland – they were responsible, among other things, for the policy concerning appointments at this institution, which was governed in their name by a board of Curators – and, in the final instance, the States were responsible for dealing with any cases of heterodoxy among the professors."[25] The domestic dissension resulting over Arminius' professorship was overshadowed by the continuing war with Spain, and the professor died in 1609 on the eve of the Twelve Years' Truce. The new peace would move the people's focus to the controversy and Arminius' followers.[citation needed] Grotius played a decisive part in this politico-religious conflict between the Remonstrants, supporters of religious tolerance, and the orthodox Calvinists or Counter-Remonstrants.[24] Controversy within Dutch Protestantism The controversy expanded when the Remonstrant theologian Conrad Vorstius was appointed to replace Jacobus Arminius as the theology chair at Leiden. Vorstius was soon seen by Counter-Remonstrants as moving beyond the teachings of Arminius into Socinianism and he was accused of teaching irreligion. Leading the call for Vorstius' removal was theology professor Sibrandus Lubbertus. On the other side Johannes Wtenbogaert (a Remonstrant leader) and Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, Grand Pensionary of Holland, had strongly promoted the appointment of Vorstius and began to defend their actions. Gomarus resigned his professorship at Leyden, in protest that Vorstius was not removed.[citation needed] The Counter-Remonstrants were also supported in their opposition by King James I of England "who thundered loudly against the Leyden nomination and gaudily depicted Vorstius as a horrid heretic. He ordered his books to be publicly burnt in London, Cambridge, and Oxford, and he exerted continual pressure through his ambassador in the Hague, Ralph Winwood, to get the appointment cancelled."[26] James began to shift his confidence from Oldenbarnevelt towards Maurice. Grotius joined the controversy by defending the civil authorities' power to appoint (independently of the wishes of religious authorities) whomever they wished to a university's faculty. He did this by writing Ordinum Pietas, "a pamphlet...directed against an opponent, the Calvinist Franeker professor Lubbertus; it was ordered by Grotius' masters the States of Holland, and thus written for the occasion – though Grotius may already have had plans for such a book."[27] The work is twenty-seven pages long, is "polemical and acrimonious" and only two-thirds of it speaks directly about ecclesiastical politics (mainly of synods and offices).[27] The work met with a violent reaction from the Counter-Remonstrants, and "It might be said that all Grotius' next works until his arrest in 1618 form a vain attempt to repair the damage done by this book."[27] Grotius would later write De Satisfactione aiming "at proving that the Arminians are far from being Socinians".[27] Edict of toleration Led by Oldenbarnevelt, the States of Holland took an official position of religious toleration towards Remonstrants and Counter-Remonstrants. Grotius, (who acted during the controversy first as Attorney General of Holland, and later as a member of the Committee of Counsellors) was eventually asked to draft an edict to express the policy of toleration.[28] This edict, Decretum pro pace ecclesiarum was completed in late 1613 or early 1614. The edict put into practice a view that Grotius had been developing in his writings on church and state (see Erastianism): that only the basic tenets necessary for undergirding civil order (e.g., the existence of God and His providence) ought to be enforced while differences on obscure theological doctrines should be left to private conscience.[29] Statue of Grotius in Delft, the Netherlands The edict "imposing moderation and toleration on the ministry", was backed up by Grotius with "thirty-one pages of quotations, mainly dealing with the Five Remonstrant Articles."[27] In response to Grotius' Ordinum Pietas, Professor Lubbertus published Responsio Ad Pietatem Hugonis Grotii in 1614. Later that year Grotius anonymously published Bona Fides Sibrandi Lubberti in response to Lubbertus.[27] Jacobus Trigland joined Lubberdus in expressing the view that tolerance in matters of doctrine was inadmissible, and in his 1615 works Den Recht-gematigden Christen: Ofte vande waere Moderatie and Advys Over een Concept van moderatie[30] Trigland denounced Grotius' stance. In late 1615, when Middelburg professor Antonius Walaeus published Het Ampt der Kerckendienaren (a response to Johannes Wtenbogaert's 1610 Tractaet van 't Ampt ende authoriteit eener hoogher Christelijcke overheid in kerckelijkcke zaken) he sent Grotius a copy out of friendship. This was a work "on the relationship between ecclesiastical and secular government" from the moderate counter-remonstrant viewpoint.[27] In early 1616 Grotius also received the 36 page letter championing a remonstrant view Dissertatio epistolica de Iure magistratus in rebus ecclesiasticis from his friend Gerardus Vossius.[27] The letter was "a general introduction on (in)tolerance, mainly on the subject of predestination and the sacrament...[and] an extensive, detailed and generally unfavourable review of Walaeus' Ampt, stuffed with references to ancient and modern authorities."[27] When Grotius wrote asking for some notes "he received a treasure-house of ecclesiastical history. ...offering ammunition to Grotius, who gratefully accepted it".[27] Around this time (April 1616) Grotius went to Amsterdam as part of his official duties, trying to persuade the civil authorities there to join Holland's majority view about church politics. In early 1617 Grotius debated the question of giving counter-remonstrants the chance to preach in the Kloosterkerk in The Hague which had been closed. During this time lawsuits were brought against the States of Holland by counter-remonstrant ministers and riots over the controversy broke out in Amsterdam. Arrest and exile Loevestein Castle at the time of Grotius' imprisonment in 1618–21 Main article: Trial of Oldenbarnevelt, Grotius and Hogerbeets As the conflict between civil and religious authorities escalated, in order to maintain civil order Oldenbarnevelt eventually proposed that local authorities be given the power to raise troops (the Sharp Resolution of August 4, 1617). Such a measure undermined the unity of the Republic's military force, the very same reason Spain had managed to retake so much lost territory in the 1580s, something the Captain-General of the republic, Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange could not allow with the treaty nearing its end.[citation needed] Maurice seized the opportunity to solidify the preeminence of the Gomarists, whom he had supported, and to eliminate the nuisance he perceived in Oldenbarnevelt (the latter had previously brokered the Twelve Years' Truce with Spain in 1609 against Maurice's wishes). During this time Grotius made another attempt to address ecclesiastical politics by completing De Imperio Summarum Potestatum circa Sacra, on "the relations between the religious and secular authorities...Grotius had even cherished hopes that publication of this book would turn the tide and bring back peace to church and state".[27]  Grotius' escape from Loevestein Castle in 1621 The conflict between Maurice and the States of Holland, led by Oldenbarnevelt and Grotius, about the Sharp Resolution and Holland's refusal to allow a National Synod, came to a head in July 1619 when a majority in the States General authorized Maurice to disband the auxiliary troops in Utrecht. Grotius went on a mission to the States of Utrecht to stiffen their resistance against this move, but Maurice prevailed. The States General then authorized him to arrest Oldenbarnevelt, Grotius and Rombout Hogerbeets on 29 August 1618. They were tried by a court of delegated judges from the States General. Van Oldenbarnevelt was sentenced to death and was beheaded in 1619. Grotius was sentenced to life imprisonment and transferred to Loevestein Castle.[31] From his imprisonment in Loevestein, Grotius made a written justification of his position "as to my views on the power of the Christian [civil] authorities in ecclesiastical matters, I refer to my...booklet De Pietate Ordinum Hollandiae and especially to an unpublished book De Imperio summarum potestatum circa sacra, where I have treated the matter in more detail...I may summarize my feelings thus: that the [civil] authorities should scrutinize God's Word so thoroughly as to be certain to impose nothing which is against it; if they act in this way, they shall in good conscience have control of the public churches and public worship – but without persecuting those who err from the right way."[27] Because this stripped Church officials of any power some of their members (such as Johannes Althusius in a letter to Lubbertus) declared Grotius' ideas diabolical.[27]  A book chest exhibited at Loevestein, presumed to be that in which Grotius escaped in 1621 In 1621, with the help of his wife and his maidservant, Elsje van Houwening, Grotius managed to escape the castle in a book chest and fled to Paris. In the Netherlands today, he is mainly famous for this daring escape. Both the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the museum Het Prinsenhof in Delft claim to have the original book chest in their collection.[32] |

アルミニウス論争、逮捕、追放 さらなる情報 カルヴァン派とアーミン派の論争の歴史 さらなる情報 オルディヌム・オランダイア・アク・ウェストフリジア・ピエタス(Ordinum Hollandiae ac Westfrisiae pietas 1605年にはオルデンバルネヴェルトの専属顧問に、1607年にはオランダ、ゼーラント、フリースラント州の財務長官に、1613年にはロッテルダムの 年金官(市長に相当)に任命された。 [23]また1613年、2隻のオランダ船がイギリスに拿捕されたことを受け、1609年に『自由の海』(Mare liberum)を著した人物に合わせた使節団をロンドンに派遣された[24]。しかし、武力を理由にイギリス側に反対され、船の返還を得ることはできな かった[24]。 この年、ライデンの神学教授ヤコブス・アルミニウスとその支持者たち(アルミニウス派またはレモンスラント派と呼ばれる)と、カルヴァン派の神学者フラン シスカス・ゴマルス(ゴマルス派または反レモンスラント派と呼ばれる)との間で神学論争が勃発した。アルミニウスの教授職をめぐって生じた国内の不和は、 スペインとの戦争が続く中で影を潜め、教授は1609年、12年休戦の前夜に死去した。グロティウスは、宗教的寛容を支持するルモンスト派と、正統派のカ ルヴァン派または反ルモンスト派との間のこの政治的・宗教的対立において決定的な役割を果たした[24]。 オランダプロテスタント内の論争 論争が拡大したのは、ヤコブス・アルミニウスの後任として、再定立派の神学者コンラッド・フォルスティウスがライデンの神学教授に任命されたときであっ た。ヴォルスティウスはすぐに反レモンストロント派から、アルミニウスの教えを越えてソシニア主義に移行していると見なされ、無宗教を教えていると非難さ れた。ヴォルスティウスの罷免を求めたのは、神学教授のシブランドゥス・ルッベルトゥスであった。他方、ヨハネス・ヴェンテンボガート(錬金術師の指導 者)とヨハン・ファン・オルデンバルネヴェルト(オランダ大年金受給者)は、ヴォルスティウスの任命を強く推し進め、彼らの行動を擁護し始めた。ゴマルス は、ヴォルスティウスが罷免されなかったことに抗議して、ライデンの教授職を辞した[citation needed]。反レモンストラーントは、イングランド王ジェームズ1世からも反対を支持され、「彼はライデンの指名に大声で反対し、ヴォルスティウスを 恐ろしい異端者として派手に描いた。ジェームズ1世は彼の著書をロンドン、ケンブリッジ、オックスフォードで公に焼却するよう命じ、ハーグの大使ラルフ・ ウィンウッドを通じて、この指名を取り消すよう圧力をかけ続けた」[26]。 グロティウスは、(宗教的権威の意向とは無関係に)大学の教授に誰を任命してもよいという文教当局の権限を擁護することで、論争に加わった。これは、「反 対者であるカルヴァン派のフランケール人教授ルッベルトゥスに対する小冊子であり、グロティウスの主人であるオランダ州から命じられ、そのために書かれた ものであるが、グロティウスはすでにそのような本の構想を持っていたのかもしれない」[27]。 この著作は27ページで、「極論的で険悪」であり、その3分の2だけが教会政治(主に会堂と役職)について直接語っている。 [27]この著作は反レモンストロント派の激しい反発を受け、「1618年に逮捕されるまでのグロティウスの次の著作はすべて、この本が与えた損害を修復 しようとするむなしい試みであったと言えるかもしれない」[27]。グロティウスは後に『De Satisfactione』を執筆し、「アルミニウス派がソサイノス派とはほど遠いことを証明する」ことを目指した[27]。 寛容の勅令 オルデンバルネヴェルトに率いられたオランダ諸国は、レモンスタン派と反レモンスタン派に対して宗教的寛容を公式に表明した。グロティウス(この論争の 間、最初はオランダ検事総長として、後に参事会メンバーとして活動)は、最終的に寛容の方針を表明する勅令の起草を依頼された[28]。この勅令 『Decretum pro pace ecclesiarum』は1613年末から1614年初めに完成した。この勅令は、グロティウスが教会と国家に関する著作(エラスティアニズムを参照) の中で展開していた、市民秩序を支えるために必要な基本的信条(例えば、神の存在と神の摂理)のみが強制されるべきであり、不明瞭な神学的教義に関する相 違は個人の良心に委ねられるべきであるという見解を実践するものであった[29]。 オランダ、デルフトのグロティウス像 この「聖職者に節度と寛容を課す」勅令は、グロティウスによって「主にリモンストラント5箇条を扱った31ページの引用」で裏付けられた[27]。グロ ティウスの『Ordinum Pietas』に対する反論として、ルベルトゥス教授は1614年に『Responsio Ad Pietatem Hugonis Grotii』を出版した。その年の暮れ、グロティウスはルッベルトゥスへの応答として匿名で『Bona Fides Sibrandi Lubberti』を出版した[27]。 ヤーコプス・トリグランドはルベルトゥスとともに、教義の問題において寛容であることは許されないという見解を表明し、1615年の著作『Den Recht-gematigden Christen: Ofte vande were Moderatie and Advys Over een Concept van Moderatie[30]』でグロティウスの姿勢を非難している。 1615年後半、ミッデルブルクのアントニウス・ワラエウスが『ケルケンディエナレンの法則(Het Ampt der Kerckendienaren)』(ヨハネス・ウェンボガートの『ケルケンディエナレンの法則』(1610年)への反論)を出版すると、彼はグロティウ スに友情からコピーを送った。これは穏健な反立憲派の視点からの「教会政治と世俗政治の関係についての」著作であった[27]。1616年初頭、グロティ ウスは友人であったゲラルドゥス・ヴォシウスからも、反立憲派の見解を支持する36ページの書簡Dissertatio epistolica de Iure magistratus in rebus ecclesiasticisを受け取った[27]。 この書簡は、「(中略)寛容に関する一般的な紹介であり、主に宿命と聖餐に関するものであった。この頃(1616年4月)、グロティウスは公務の一環とし てアムステルダムに赴き、教会政治についてオランダの多数派の意見に加わるよう、アムステルダムの民政当局を説得しようとした。 1617年初頭、グロティウスは、閉鎖されていたハーグのクローステルケルク(Kloosterkerk)で、反教会の人々に説教の機会を与える問題につ いて議論した。この間、反教会の牧師たちがオランダ州を相手取って訴訟を起こし、アムステルダムではこの論争をめぐる暴動が起こった。 逮捕と亡命 1618年から21年にかけてグロティウスが投獄されたローヴェシュタイン城 主な記事 オルデンバルネヴェルト、グロティウス、ホーガービーツの裁判 民政当局と宗教当局の対立が激化する中、オルデンバルネヴェルトは民政秩序を維持するため、最終的に地方当局に軍隊を起こす権限を与えることを提案した (1617年8月4日のシャープ決議)。このような措置は共和国軍の団結を弱めるものであり、スペインが1580年代に多くの領土を奪還したのと同じ理由 であった。 [要出典] モーリスは、自分が支持していたゴマール派の優位を固め、オルデンバルネヴェルトという厄介者を排除する好機をつかんだ(オルデンバルネヴェルトは 1609年にモーリスの意に反してスペインとの12年休戦を仲介していた)。この時期、グロティウスは、「宗教的権威と世俗的権威の関係」についての 『De Imperio Summarum Potestatum circa Sacra』を完成させ、教会政治に取り組もうと試みていた[27]。  1621年、ローヴェシュタイン城からのグロティウスの脱出 1619年7月、オルデンバルネヴェルトとグロティウスを中心とするモーリスとオランダ諸州との間で、シャープ決議とオランダの全国シノドス拒否をめぐる 対立が勃発。グロティウスはユトレヒト州へ使節団を派遣し、この動きに反対する州側の抵抗を強めたが、モーリスはこれを押し切った。そして州総長は、 1618年8月29日にオルデンバルネヴェルト、グロティウス、ロンブート・ホーガービーツを逮捕する権限を与えた。彼らは州総督から委任された裁判官で 構成される法廷によって裁かれた。オルデンバルネヴェルトは死刑を宣告され、1619年に斬首された。グロティウスは終身刑を宣告され、ローヴェシュタイ ン城に移された[31]。 ローベスタインでの投獄生活から、グロティウスは「教会的な問題におけるキリスト教(民)当局の権力に関する私の見解については、私の...小冊子『De Pietate Ordinum Hollandiae』、特に未刊の『De Imperio summarum potestatum circa sacra』を参照し、そこで私はこの問題をより詳細に扱った...」と自分の立場を正当化する文書を作成した。 もし彼らがこのように行動するならば、彼らは良心の呵責のもとに公の教会と公の礼拝を管理することができるであろうが、正しい道から外れた人々を迫害する ことはないであろう。  1621年にグロティウスが逃亡した際のものと推定される、ローベスタインに展示された書櫃 1621年、グロティウスは、妻と女中のエルシエ・ファン・ホウヴェニングの助けを借りて、書櫃で城を脱出し、パリに逃亡した。今日のオランダでは、グロ ティウスは主にこの大胆な逃亡劇で有名である。アムステルダムのRijksmuseumとデルフトのHet Prinsenhof美術館は、オリジナルの本箱を所蔵していると主張している[32]。 |

| Life in Paris Grotius then fled to Paris, where the authorities granted him an annual royal pension.[33] Grotius lived in France almost continuously from 1621 to 1644. His stay coincides with the period (1624-1642) during which the Cardinal Richelieu led France under the authority of Louis XIII. In France in 1625 Grotius published his most famous book, De jure belli ac pacis [On the Law of War and Peace] dedicated to Louis XIII of France. While in Paris, Grotius set about rendering into Latin prose a work which he had originally written as Dutch verse in prison, providing rudimentary yet systematic arguments for the truth of Christianity. The Dutch poem, Bewijs van den waren Godsdienst, was published in 1622, the Latin treatise in 1627, under the title De veritate religionis Christianae. In 1631 he tried to return to Holland, but the authorities remained hostile to him. He moved to Hamburg in 1632. But as early as 1634, the Swedes - a European superpower - sent him to Paris as ambassador. He remained ten years in this position where he had the mission to negotiate for Sweden the end of the Thirty Years War. During this period, he had been interested in the unity of Christians and published many texts that will be grouped under the title of Opera Omnia Theologica. Governmental theory of atonement Grotius also developed a particular view of the atonement of Christ known as the "Governmental theory of atonement". He theorized that Jesus' sacrificial death occurred in order for the Father to forgive while still maintaining his just rule over the universe. This idea, further developed by theologians such as John Miley, became one of the prominent views of the atonement in Methodist Arminianism.[34] |

パリでの生活 その後、グロティウスはパリに逃れ、当局から毎年王室年金が支給されるようになった[33]。グロティウスがフランスに滞在したのは、リシュリュー枢機卿 がルイ13世の権威の下でフランスを率いていた時代(1624年~1642年)と重なる。1625年、グロティウスはフランスで最も有名な著書『戦争と平 和の法(De jure belli ac pacis)』を出版し、フランスのルイ13世に献呈した。 パリ滞在中、グロティウスは、もともと獄中でオランダ語の詩として書いていたものをラテン語の散文に直し、キリスト教の真理について初歩的だが体系的な議 論を展開した。オランダ語の詩『Bewijs van den waren Godsdienst』は1622年に、ラテン語の論文は『De veritate religionis Christianae』というタイトルで1627年に出版された。 1631年、彼はオランダに戻ろうとしたが、当局は依然として彼を敵視していた。1632年にハンブルクに移った。しかし、1634年には早くもヨーロッ パの大国スウェーデンから大使としてパリに派遣された。スウェーデンのために三十年戦争の終結を交渉する使命を負った。この間、彼はキリスト教の統一に関 心を持ち、『オペラ・オムニア・テオロジカ』のタイトルでまとめられた多くのテキストを出版した。政府による贖罪論グロティウスはまた、「贖罪の政府説」 として知られるキリストの贖罪についての特別な見解も展開した。 彼は、イエスの犠牲的な死は、御父が宇宙に対する公正な支配を維持しつつ赦すために起こったと理論化した。この考えは、ジョン・マイリーのような神学者たちによってさらに発展し、メソジスト・アルミニスト主義における贖罪の有力な見解の一つとなった[34]。 |

| De Jure Belli ac Pacis Main article: De jure belli ac pacis  Title page from the second edition (Amsterdam 1631) of De jure belli ac pacis Living in the times of the Eighty Years' War between Spain and the Netherlands and the Thirty Years' War between Catholic and Protestant European nations (Catholic France being in the otherwise Protestant camp), it is not surprising that Grotius was deeply concerned with matters of conflicts between nations and religions. His most lasting work, begun in prison and published during his exile in Paris, was a monumental effort to restrain such conflicts on the basis of a broad moral consensus. Grotius wrote: Fully convinced...that there is a common law among nations, which is valid alike for war and in war, I have had many and weighty reasons for undertaking to write upon the subject. Throughout the Christian world I observed a lack of restraint in relation to war, such as even barbarous races should be ashamed of; I observed that men rush to arms for slight causes, or no cause at all, and that when arms have once been taken up there is no longer any respect for law, divine or human; it is as if, in accordance with a general decree, frenzy had openly been let loose for the committing of all crimes.[35] De jure belli ac pacis libri tres (On the Law of War and Peace: Three books) was first published in 1625, dedicated to Grotius' current patron, Louis XIII. The treatise advances a system of principles of natural law, which are held to be binding on all people and nations regardless of local custom. The work is divided into three books: Book I advances his conception of war and of natural justice, arguing that there are some circumstances in which war is justifiable. Book II identifies three 'just causes' for war: self-defense, reparation of injury, and punishment; Grotius considers a wide variety of circumstances under which these rights of war attach and when they do not. Book III takes up the question of what rules govern the conduct of war once it has begun; influentially, Grotius argued that all parties to war are bound by such rules, whether their cause is just or not. Further information: Temperamenta belli Natural law  Engraved portrait of Grotius Grotius' concept of natural law had a strong impact on the philosophical and theological debates and political developments of the 17th and 18th centuries. Among those he influenced were Samuel Pufendorf and John Locke, and by way of these philosophers his thinking became part of the cultural background of the Glorious Revolution in England and the American Revolution.[36] In Grotius' understanding, nature was not an entity in itself, but God's creation. Therefore, his concept of natural law had a theological foundation.[37] The Old Testament contained moral precepts (e.g. the Decalogue), which Christ confirmed and therefore were still valid. They were useful in interpreting the content of natural law. Both Biblical revelation and natural law originated in God and could therefore not contradict each other.[38] Later years Many exiled Remonstrants began to return to the Netherlands after the death of Prince Maurice in 1625 when toleration was granted to them. In 1630 they were allowed complete freedom to build and run churches and schools and to live anywhere in Holland. The Remonstrants guided by Johannes Wtenbogaert set up a presbyterial organization. They established a theological seminary at Amsterdam where Grotius came to teach alongside Episcopius, van Limborch, de Courcelles, and Leclerc. In 1634 Grotius was given the opportunity to serve as Sweden's ambassador to France. Axel Oxenstierna, regent of the successor of the recently deceased Swedish king, Gustavus Adolphus, was keen to have Grotius in his employ. Grotius accepted the offer and took up diplomatic residence in Paris, which remained his home until he was released from his post in 1645.[citation needed] In 1644, the queen Christine of Sweden, who had become an adult, began to perform her duties and brought him back to Stockholm. During the winter of 1644–1645 he went to Sweden in difficult conditions, which he decided to leave in the summer of 1645. While departing from his last visit to Sweden, Grotius was shipwrecked on the voyage. He washed up on the shore of Rostock, ill and weather-beaten, and on August 28, 1645, he died; his body at last returned to the country of his youth, being laid to rest in the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft.[39][40] |

平和条約 主な記事平和への道  De jure belli ac pacis』第2版(アムステルダム1631年)のタイトルページ スペインとオランダの間で起こった80年戦争と、ヨーロッパのカトリックとプロテスタントの間で起こった30年戦争(カトリックのフランスはプロテスタン ト陣営に属していた)の時代に生きていたグロティウスが、国家間や宗教間の対立に深い関心を抱いていたことは驚くべきことではない。獄中で書き始められ、 パリでの亡命中に出版された彼の最も永続的な著作は、広範な道徳的コンセンサスに基づいてこのような対立を抑制するための記念碑的な努力であった。グロ ティウスはこう書いている: 戦争にも戦争中にも有効な、国家間の共通法が存在することを......私は完全に確信している。キリスト教世界全体を通じて、私は、野蛮な民族でさえ恥 ずべき戦争に関する自制心の欠如を観察した。私は、人々がわずかな理由、あるいはまったく理由もなく武器に殺到すること、そして、ひとたび武器を手にする と、神的であれ人間的であれ、もはや法を尊重することはないことを観察した。 De jure belli ac pacis libri tres(戦争と平和の法について:3冊の本)』は1625年に出版され、グロティウスの現在のパトロンであるルイ13世に献呈された。この論文は、自然 法の原則の体系を提唱したもので、地域の慣習に関係なく、すべての人々と国家を拘束するとされている。著作は3巻に分かれている: 第I巻は、戦争と自然正義の概念を提唱し、戦争が正当化される状況もあると主張する。 グロティウスは、戦争が正当化される状況として、自衛、損害賠償、懲罰の3つを挙げている。 第三巻では、戦争が始まった後、どのような規則が戦争の遂行を支配するかという問題を取り上げている。グロティウスは、その大義が正当であるか否かにかかわらず、戦争当事者はすべてこのような規則に拘束されると主張し、大きな影響を与えた。 さらに詳しく 自然法 自然法 グロティウスの肖像画 グロティウスの自然法の概念は、17世紀から18世紀にかけての哲学・神学論争や政治的展開に強い影響を与えた。グロティウスが影響を受けた哲学者の中に は、サミュエル・プーフェンドルフやジョン・ロックがおり、これらの哲学者を通じて、グロティウスの考え方はイギリスの栄光革命やアメリカ独立革命の文化 的背景の一部となった[36]。したがって、彼の自然法の概念は神学的な基盤を持っていた[37]。旧約聖書には、キリストが確認した道徳的戒律(デカロ グなど)が含まれており、したがってそれは現在でも有効であった。それらは自然法の内容を解釈する上で有用であった。聖書の啓示と自然法はともに神に由来 するものであり、したがって互いに矛盾することはなかった[38]。 後年 1625年にモーリス公が死去し、寛容が認められると、追放されていた多くの諌言派がオランダに戻り始めた。1630年には、教会や学校を建て、運営し、 オランダのどこにでも住むことが許された。ヨハネス・ヴェンテンボガートに導かれた改革派は、長老組織を設立した。彼らはアムステルダムに神学校を設立 し、グロティウスはエピスコピウス、ファン・リンボルク、ド・クールセル、ルクレールらとともに教鞭をとるようになった。 1634年、グロティウスはスウェーデンの駐仏大使を務める機会を与えられた。亡くなったばかりのスウェーデン国王グスタフス・アドルフスの後継者の摂政 であったアクセル・オクセンシュティールナは、グロティウスを自分の雇い主にすることを熱望していた。グロティウスはこの申し出を受け入れ、パリに外交官 としての住居を構えた。 1644年、成人したスウェーデン王妃クリスティーヌが職務を遂行するようになり、グロティウスはストックホルムに連れ戻された。1644年から1645年にかけての冬、彼は困難な状況の中でスウェーデンに赴き、1645年の夏にそこを離れることを決めた。 最後のスウェーデン訪問から出発する途中、グロティウスは航海中に難破した。そして1645年8月28日、病と天候に打ちのめされながらロストックの海岸 に漂着し、亡くなった。彼の遺体はついに若き日の祖国に戻り、デルフトのニーウェ・ケルクに安置された[39][40]。 |

Personal life Syntagma Arateorum Grotius' personal motto was Ruit hora ("Time is running away"); his last words were purportedly, "By understanding many things, I have accomplished nothing" (Door veel te begrijpen, heb ik niets bereikt).[41] Significant friends and acquaintances of his included the theologian Franciscus Junius, the poet Daniel Heinsius, the philologist Gerhard Johann Vossius, the historian Johannes Meursius, the engineer Simon Stevin, the historian Jacques Auguste de Thou, the Orientalist and Arabic scholar Erpinius, and the French ambassador in the Dutch Republic, Benjamin Aubery du Maurier, who allowed him to use the French diplomatic mail in the first years of his exile. He was also friends with the Brabantian Jesuit Andreas Schottus.[42] Grotius was the father of regent and diplomat Pieter de Groot. Influence of Grotius Grotius designed his theory to apply not only to states but also to rulers and subjects of law in general. Grotius's masterpiece De Jure Belli ac Pacis thus proved useful in the later development of theories of both private and criminal law.[43] From his time to the end of the 17th century The king of Sweden, Gustavus Adolphus, was said to have always carried a copy of De jure belli ac pacis in his saddle when leading his troops.[44] In contrast, King James VI and I of Great Britain reacted very negatively to Grotius' presentation of the book during a diplomatic mission.[44] Some philosophers, notably Protestants such as Pierre Bayle, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and the main representatives of the Scottish Enlightenment Francis Hutcheson, Adam Smith, David Hume, Thomas Reid held him in high esteem.[44] The French Enlightenment, on the other hand, was much more critical. Voltaire called it boring and Rousseau developed an alternative conception of human nature. Pufendorf, another theoretician of the natural law concept, was also skeptical.[44] Commentaries of the 18th century Andrew Dickson White wrote: Into the very midst of all this welter of evil, at a point in time to all appearance hopeless, at a point in space apparently defenseless, in a nation of which every man, woman, and child was under sentence of death from its sovereign, was born a man who wrought as no other has ever done for a redemption of civilization from the main cause of all that misery; who thought out for Europe the precepts of right reason in international law; who made them heard; who gave a noble change to the course of human affairs; whose thoughts, reasonings, suggestions, and appeals produced an environment in which came an evolution of humanity that still continues.[45] In contrast, Robert A. Heinlein satirized the Grotian governmental approach to theology in Methuselah's Children: "There is an old, old story about a theologian who was asked to reconcile the doctrine of Divine Mercy with the doctrine of infant damnation. 'The Almighty,' he explained, 'finds it necessary to do things in His official and public capacity which in His private and personal capacity He deplores.'"[46] Regain of interest in the 20th century The influence of Grotius declined following the rise of positivism in the field of international law and the decline of the natural law in philosophy.[47] The Carnegie Foundation has nevertheless re-issued and re-translated On the Law of War and Peace after the World War I.[48] At the end of the 20th century, his work aroused renewed interest as a controversy over the originality of his ethical work developed. For Irwing, Grotius would only repeat the contributions of Thomas Aquinas and Francisco Suárez.[49] On the contrary, Schneewind argues that Grotius introduced the idea that "the conflict can not be eradicated and could not be dismissed, even in principle, by the most comprehensive metaphysical knowledge possible of how the world is made up".[50][44] As far as politics is concerned, Grotius is most often considered not so much as having brought new ideas, but rather as one who has introduced a new way of approaching political problems. For Kingsbury and Roberts, "the most important direct contribution of ["On the Law of War and Peace"] lies in the way it systematically brings together practices and authorities on the traditional but fundamental subject of jus belli, which he organizes for the first time from a body of principles rooted in the law of nature".[51][52] |

私生活 シンタグマ・アラテオルム グロティウスの座右の銘は「時の流れに身をまかせ」(Ruit hora)であり、最期の言葉は「多くのことを理解しても、私は何も成し遂げていない」(Door veel te begrijpen, heb ik niets bereikt)であったと言われている。 [41]彼の重要な友人や知人には、神学者フランシスクス・ユニウス、詩人ダニエル・ハインシウス、言語学者ゲルハルト・ヨハン・ヴォシウス、歴史学者ヨ ハネス・ムルシウス、技師シモン・ステヴァン、歴史学者ジャック・オーギュスト・ド・トゥー、東洋学者でアラビア語学者エルピニウス、そしてオランダ共和 国のフランス大使ベンジャミン・オーベリ・デュ・モーリエがいた。また、ブラバンシアのイエズス会士アンドレアス・ショットゥスとも親交があった [42]。 グロティウスは摂政で外交官のピーテル・デ・グルートの父であった。 グロティウスの影響 グロティウスはその理論を国家だけでなく、支配者や法の臣民一般にも適用できるように設計した。こうしてグロティウスの代表作『De Jure Belli ac Pacis』は、後の私法と刑法の理論の発展において有用であることが証明された[43]。 グロティウスの時代から17世紀末まで スウェーデン国王グスタフス・アドルフスは、軍隊を率いる際、鞍の中に常に『De jure belli ac pacis』を携帯していたと言われている[44]。 対照的に、イギリス国王ジェームズ6世と1世は、外交使節団の際にグロティウスがこの本を紹介したことに非常に否定的な反応を示した[44]。 一部の哲学者、特にプロテスタントのピエール・バイエル、ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツ、スコットランド啓蒙主義の主要な代表者であるフラ ンシス・ハッチェソン、アダム・スミス、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、トーマス・リードはグロティウスを高く評価していた[44]。ヴォルテールは啓蒙主義を 退屈なものと呼び、ルソーはそれに代わる人間性の概念を打ち立てた。自然法概念のもう一人の理論家であるプーフェンドルフも懐疑的であった[44]。 18世紀の注釈書 アンドリュー・ディクソン・ホワイトはこう書いている: このような悪の氾濫の真っただ中に、時間的には絶望的な地点に、空間的には無防備な地点に、男も女も子供も主権者から死の宣告を受けているような国家に、 このような不幸の主因から文明を救済するために、他の誰よりも尽力した人物が生まれた; 国際法における正しい理性の戒律をヨーロッパのために考え出し、それを世に知らしめ、人類の運命に崇高な変化をもたらした。 [45] 対照的に、ロバート・A・ハインラインは『メトシェラの子供たち』の中で、神学に対するグロート政府のアプローチを風刺している: 「神の慈悲の教義と幼児天罰の教義を調和させるよう求められた神学者の古い古い話がある。全能の神は、私的で個人的な立場では忌み嫌われることを、公的で 公的な立場では行う必要があるとお考えになる』と彼は説明した」[46]。 20世紀における関心の回復 国際法の分野における実証主義の台頭と哲学における自然法の衰退に伴い、グロティウスの影響力は低下した[47]。それにもかかわらず、カーネギー財団は 第一次世界大戦後に『戦争と平和の法について』を再発行し、再翻訳した[48]。アーウィングにとって、グロティウスはトマス・アクィナスやフランシス コ・スアレスの貢献を繰り返すだけであった[49]。それに対してシュネーウィンドは、グロティウスは「世界がどのように構成されているかについての可能 な限り包括的な形而上学的知識によって、対立を根絶することはできず、原理的にさえ退けることはできない」という考えを導入したと主張している[50] [44]。 政治に関する限り、グロティウスは新しい思想をもたらしたというよりも、むしろ政治的問題にアプローチする新しい方法を導入した人物として考えられること がほとんどである。キングスベリーとロバーツにとって、「[『戦争と平和の法について』]の最も重要な直接的貢献は、伝統的ではあるが基本的な主題である ユス・ベリに関する実践と権威を体系的にまとめ、自然法に根ざした原則の体系から初めて整理した点にある」[51][52]。 |

| Bibliography (selection) Marble bas-relief of Grotius among 23 reliefs of great historical lawgivers in the chamber of the U.S. House of Representatives in the United States Capitol  Annotationes ad Vetus Testamentum (1732) The Peace Palace Library in The Hague holds the Grotius Collection, which has a large number of books by and about Grotius. The collection was based on a donation from Martinus Nijhoff of 55 editions of De jure belli ac pacis libri tres. Works are listed in order of publication, with the exception of works published posthumously or after long delay (estimated composition dates are given).[53][54] Where an English translation is available, the most recently published translation is listed beneath the title. Martiani Minei Felicis Capellæ Carthaginiensis viri proconsularis Satyricon, in quo De nuptiis Philologiæ & Mercurij libri duo, & De septem artibus liberalibus libri singulares. Omnes, & emendati, & Notis, siue Februis Hug. Grotii illustrati [The Satyricon by Martianus Minneus Felix Capella, a man from Carthage, which includes the two books of 'On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury', and the book named 'On the Seven Liberal Arts'. Everything, including corrections, annotations as well as deletions and illustrations by Hug. Grotius] - 1599 Adamus exul (The Exile of Adam; tragedy) – The Hague, 1601 De republica emendanda (To Improve the Dutch Republic; manuscript 1601) – pub. The Hague, 1984 Parallelon rerumpublicarum (Comparison of Constitutions; manuscript 1601–02) – pub. Haarlem 1801–03 De Indis (On the Indies; manuscript 1604–05) – pub. 1868 as De Jure Praedae Christus patiens (The Passion of Christ; tragedy) – Leiden, 1608 Mare Liberum (The Free Seas; from chapter 12 of De Indis) – Leiden, 1609 De antiquitate reipublicae Batavicae (On the Antiquity of the Batavian Republic) – Leiden, 1610 (An extension of François Vranck's Deduction of 1587[55]) The Antiquity of the Batavian Republic, ed. Jan Waszink and others (van Gorcum, 2000). Meletius (manuscript 1611) – pub. Leiden, 1988 Meletius, ed. G.H.M. Posthumus Meyjes (Brill, 1988). Annales et Historiae de rebus Belgicis (Annals and History of the Low Countries' War; manuscript 1612-13) – pub. Amsterdam, 1657 The Annals and History of the Low-Countrey-warrs, ed. Thomas Manley (London, 1665): - Modern English translation of the Annales only in: Hugo Grotius, Annals of the War in the Low Countries, ed. with introduction by J. Waszink (Latin/English edition), Leuven UP 2023. Bibliotheca Latinitatis Novae, ISBN 978 94 6270 351 3 / eISBN 978 94 6166 485 3, doi:10.11116/9789461664853. - Modern Dutch translation of the Annales only in: Hugo de Groot, "Kroniek van de Nederlandse Oorlog. De Opstand 1559-1588", ed. Jan Waszink (Nijmegen, Vantilt 2014), with introduction, index, plates. Ordinum Hollandiae ac Westfrisiae pietas (The Piety of the States of Holland and Westfriesland) – Leiden, 1613 Ordinum Hollandiae ac Westfrisiae pietas, ed. Edwin Rabbie (Brill, 1995). De imperio summarum potestatum circa sacra (On the power of sovereigns concerning religious affairs; manuscript 1614–17) – pub. Paris, 1647 De imperio summarum potestatum circa sacra, ed. Harm-Jan van Dam (Brill, 2001). De satisfactione Christi adversus Faustum Socinum (On the satisfaction of Christ against [the doctrines of] Faustus Socinus) – Leiden, 1617 Defensio fidei catholicae de satisfactione Christi, ed. Edwin Rabbie (van Gorcum, 1990). Grotius, Hugo (1889). A defence of the Catholic faith concerning the satisfaction of Christ against Faustus Socinus (PDF). Andover, MA: W. F. Draper. Inleydinge tot de Hollantsche rechtsgeleertheit (Introduction to Dutch Jurisprudence; written in Loevenstein) – pub. The Hague, 1631 The Jurisprudence of Holland, ed. R.W. Lee (Oxford, 1926). Bewijs van den waaren godsdienst (Proof of the True Religion; didactic poem) – Rotterdam, 1622 Apologeticus (Defense of the actions which led to his arrest (This was for a long time the only source for what transpired during Grotius' trial in 1619, because the trial record was not published at the time. However, Robert Fruin edited this trial record in[56]) – Paris, 1922 De jure belli ac pacis (On the Law of War and Peace) – Paris, 1625 (2nd ed. Amsterdam 1631) Hugo Grotius: On the Law of War and Peace. Student edn. Ed. Stephen C. Neff (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012) De veritate religionis Christianae (On the Truth of the Christian religion) – Paris, 1627 The Truth of the Christian Religion, ed. John Clarke (Edinburgh, 1819). Sophompaneas (Joseph; tragedy) – Amsterdam, 1635 De origine gentium Americanarum dissertatio (Dissertation of the origin of the American peoples) – Paris 1642 Via ad pacem ecclesiasticam (The way to religious peace) – Paris, 1642 Annotationes in Vetus Testamentum (Commentaries on the Old Testament) – Amsterdam, 1644 Annotationes in Novum Testamentum (Commentaries on the New Testament) – Amsterdam and Paris, 1641–50 De fato (On Destiny) – Paris, 1648 |

ハーグの平和宮図書館はグロティウス・コレクションを所蔵している。このコレクションは、マルティヌス・ナイホフからの寄贈に基づくもので、『De jure belli ac pacis libri tres』の55版が所蔵されている。 作品は、死後または長い年月を経て出版された作品を除き、出版順にリストアップされている(推定作成日が記載されている)[53][54]。英語訳が入手可能な場合は、タイトルの下に最近出版された翻訳が記載されている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugo_Grotius |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099