わたしはゾンビと歩いた

I Walked with a Zombie

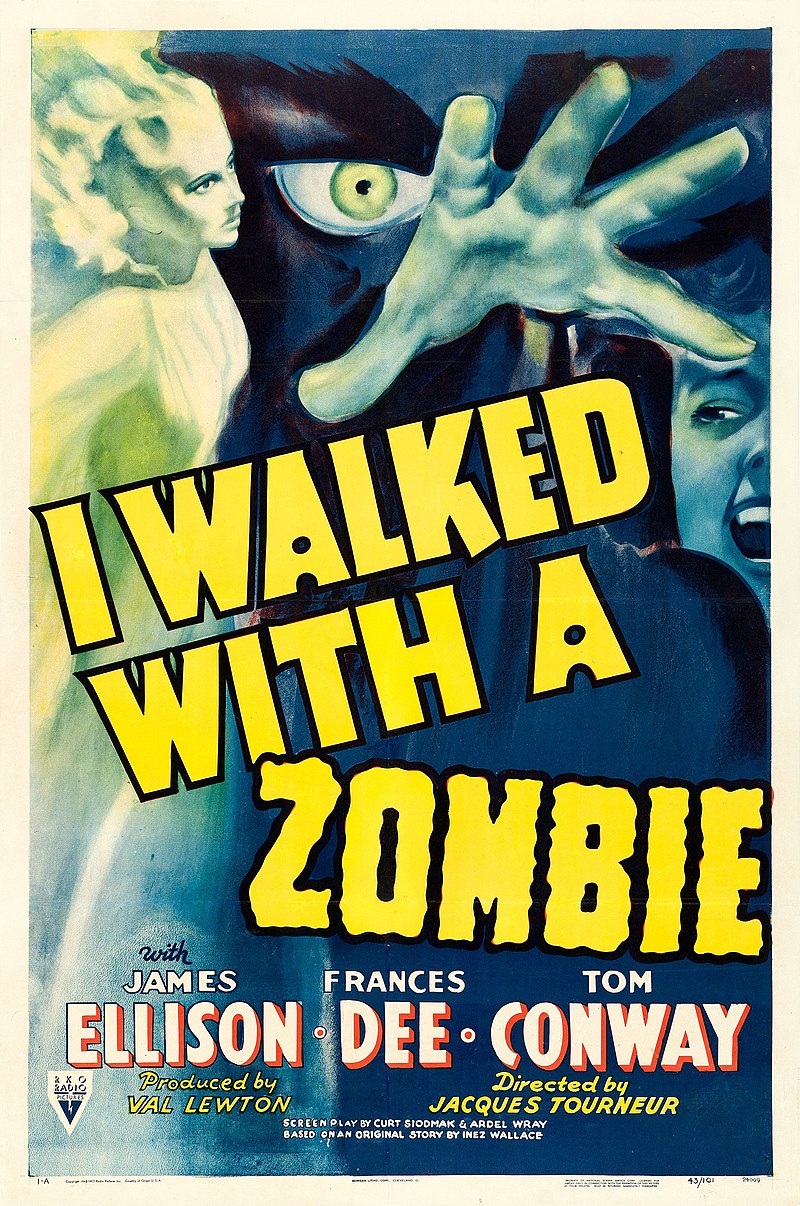

Theatrical release poster by William Rose

☆ I Walked with a Zombie は、 ジャック・トゥルヌール監督、ヴァル・リュートン製作、RKOピクチャーズの1943年のアメリカン・ホラー映画である。主演はジェームズ・エリソン、フ ランシス・ディー、トム・コンウェイで、カリブ海の砂糖農園主の病弱な妻を看護するために旅したカナダ人看護師が、ヴードゥーの儀式を目撃し、ウォーキン グデッドに遭遇する。カート・シオドマクとアーデル・レイが脚本を担当し、イネス・ウォレスによる同タイトルの論文に基づいているほか、シャーロット・ブ ロンテによる1847年の小説『ジェーン・エア』の物語を部分的に再解釈している[1][2]。 この映画は1943年4月21日にニューヨークで初公開され、同月末に広く劇場公開された。奴隷制度と人種主義をテーマとし、アフリカのディアスポラ宗 教、特にハイチのヴードゥー教に関連する信仰を描いていることから分析されている。公開当時は賛否両論の評価を受けたが、回顧的な評価は肯定的なものが多 い。

| I Walked with a

Zombie is a 1943 American horror film directed by Jacques Tourneur and

produced by Val Lewton for RKO Pictures. It stars James Ellison,

Frances Dee, and Tom Conway, and follows a Canadian nurse who travels

to care for the ailing wife of a sugar plantation owner in the

Caribbean, where she witnesses Vodou rituals and possibly encounters

the walking dead. The screenplay, written by Curt Siodmak and Ardel

Wray, is based on an article of the same title by Inez Wallace, and

also partly reinterprets the narrative of the 1847 novel Jane Eyre by

Charlotte Brontë.[1][2] The film premiered in New York City on April 21, 1943, before receiving a wider theatrical release later that month. It has been analyzed for its themes of slavery and racism, and for its depiction of beliefs associated with African diaspora religions, particularly Haitian Vodou. Though it received mixed reviews upon its release, retrospective assessments of the film have been more positive. |

I Walked with a

Zombie』は、ジャック・トゥルヌール監督、ヴァル・リュートン製作、RKOピクチャーズの1943年のアメリカン・ホラー映画である。主演はジェー

ムズ・エリソン、フランシス・ディー、トム・コンウェイで、カリブ海の砂糖農園主の病弱な妻を看護するために旅したカナダ人看護師が、ヴードゥーの儀式を

目撃し、ウォーキングデッドに遭遇する。カート・シオドマクとアーデル・レイが脚本を担当し、イネス・ウォレスによる同タイトルの論文に基づいているほ

か、シャーロット・ブロンテによる1847年の小説『ジェーン・エア』の物語を部分的に再解釈している[1][2]。 この映画は1943年4月21日にニューヨークで初公開され、同月末に広く劇場公開された。奴隷制度と人種主義をテーマとし、アフリカのディアスポラ宗 教、特にハイチのヴードゥー教に関連する信仰を描いていることから分析されている。公開当時は賛否両論の評価を受けたが、回顧的な評価は肯定的なものが多 い。 |

Plot Darby Jones as the zombie-like Carrefour On a snowy Ottawa day, young nurse Betsy Connell is interviewed to care for the wife of Paul Holland, a sugar plantation owner on Saint Sebastian, a Caribbean island. Although she is told little about the patient, Betsy looks forward to the warmer climate and accepts the job, laughing it off when asked if she believes in witchcraft. The coachman who takes Betsy to Paul's house, Fort Holland, tells her Saint Sebastian's Afro-Caribbean population is descended from slaves brought by Paul's ancestors. At her first dinner, Betsy meets Paul's younger half-brother and employee, Wesley Rand, who, though good-humored, clearly resents Paul. She encounters Jessica, her patient, wandering the grounds that night, and is initially frightened by the nonverbal, affectless woman, who, as Dr. Maxwell later informs Betsy, was left without the willpower to speak or act by herself after a tropical fever irreparably damaged her spinal cord. Betsy learns from a calypso musician's song that Paul kept Jessica from running away with Wesley right before she became sick. The issues surrounding Jessica have driven Wesley to drink, and the simmering tension between him and Paul frequently threatens to boil over. Paul apologizes to Betsy for bringing her to Saint Sebastian and admits he feels responsible for Jessica's condition. Betsy, who has fallen in love with Paul, becomes determined to make him happy by curing Jessica and gets him to agree to a risky insulin shock treatment. When that fails, Alma, Paul's maid, convinces Betsy to take Jessica to be healed by the houngan (Vodou priest) at the houmfort (Vodou temple). After a man dressed in black performs a ritual dance using a small sword, Betsy gets in line at the houmfort to ask the spirit Damballa to heal Jessica. Instead, she is pulled inside a hut and is shocked to see Mrs. Rand, Paul and Wesley's mother, who works with Maxwell. Mrs. Rand reveals that, with the houngan's knowledge, she has been telling the islanders that Vodou spirits speak through her so they will comply with her medical and sanitary recommendations. Meanwhile, Jessica attracts the attention of the man in black, who stabs her in the arm. She does not bleed, causing murmurs of "zombie" among the onlookers, and Mrs. Rand tells Betsy to take Jessica home. An upset Paul greets them, but he softens when he learns Betsy was trying to help him, and lets her know he no longer loves his wife. The Voudou congregation demands Jessica be delivered to them for further ritualistic tests, so Maxwell and local authorities want her sent to an asylum on a different island. Paul resists because Wesley wants Jessica to stay, and he tells Betsy to return to Canada before he makes her as unhappy as he made Jessica before her illness. At night, Carrefour, a zombie who guards a crossroads, is sent to retrieve Jessica, approaching Betsy instead after she puts on Jessica's robe, but Mrs. Rand orders him to leave. Maxwell visits to report there will be an official investigation to determine Jessica's fate. Faced with scandal, and with her sons at each other's throats, Mrs. Rand says Jessica is not sick or insane, but dead, as she went to the houmfort the night Jessica tried to run away with Wesley and, possessed, asked the houngan to make Jessica a zombie. Only Wesley believes the story, and he later asks Betsy to euthanize Jessica, though Betsy refuses. Using a small effigy of Jessica, the man in black and the houngan attempt to draw her to the houmfort. Paul and Betsy stop her the first time, but Wesley helps her the second, following with an arrow removed from a garden statue depicting Saint Sebastian, "Ti-Misery", that was once the figurehead of a Holland-family slave ship. The man in black stabs the doll with a pin to mirror Wesley stabbing Jessica with the arrow, who is pursued slowly by Carrefour as he carries her body into the sea. Jessica and Wesley are discovered floating in the surf; their bodies are brought back to Fort Holland. A voice-over condemns Jessica as an evil woman who led Paul astray, but asks God's forgiveness for the dead, Ti-Misery looming in the background. Betsy and Paul console each other. |

プロット ゾンビのようなカルフール役のダービー・ジョーンズ 雪の降るオタワのある日、若い看護師ベッツィ・コーネルは、カリブ海の島、セイント・セバスチャンの砂糖農園主ポール・ホランドの妻の看護をするよう面接 を受ける。患者のことはほとんど知らされていなかったが、ベッツィは温暖な気候を楽しみにし、魔術を信じているかと聞かれても笑い飛ばしながら、この仕事 を引き受ける。 ポールの家、フォート・ホランドまでベッツィーを連れて行った馬車男は、セイント・セバスティアンのアフロ・カリビアン人口は、ポールの先祖が連れてきた 奴隷の子孫であると彼女に告げる。最初の夕食で、ベッツィーはポールの腹違いの弟で従業員のウェスリー・ランドに出会うが、彼はユーモアはあるものの、明 らかにポールを恨んでいる。マクスウェル博士が後にベッツィーに伝えるところによると、彼女は熱帯熱で脊髄を回復不能なまでに損傷した後、自分で話したり 行動したりする意志を失ってしまったのだという。 ベッツィーはカリプソ・ミュージシャンの歌から、ジェシカが病気になる直前、ポールがウェズリーと逃げ出さないように引き留めたことを知る。ジェシカをめ ぐる問題がウェスリーを酒に溺れさせ、彼とポールの間に煮えたぎる緊張がたびたび沸騰しそうになる。ポールはベッツィをセイント・セバスチャンに連れてき たことを謝り、ジェシカの病状に責任を感じていることを認める。ポールと恋に落ちたベッツィーは、ジェシカを治して彼を幸せにしようと決意し、危険なイン スリン・ショック療法に同意させる。それが失敗すると、ポールのメイドであるアルマはベッツィを説得し、フーンガン(ヴードゥー教の司祭)にジェシカを癒 してもらうためにフーンフォート(ヴードゥー教の寺院)に連れて行く。 黒装束の男が小刀を使って儀式的な踊りを披露した後、ベッツィは精霊ダンバラにジェシカを癒してもらおうとフームフォートの列に並ぶ。代わりに小屋の中に 引っ張り込まれた彼女は、マクスウェルと一緒に働いているポールとウェスリーの母親、ランド夫人を見てショックを受ける。ランド夫人は、フーンガンの知識 を得て、島民にヴードゥーの霊が自分を通して話すと伝え、島民が自分の医療や衛生に関する勧告に従うようにしていることを明かす。一方、ジェシカは黒服の 男に目をつけられ、腕を刺される。彼女は出血しなかったため、見物人からは「ゾンビだ」という声が上がり、ランド夫人はベッツィにジェシカを家に連れて帰 るように言う。動揺したポールは二人を出迎えるが、ベッツィが自分を助けようとしてくれたことを知ると軟化し、もはや妻を愛していないことを彼女に告げ る。 ヴードゥーの信徒たちは、儀式的なテストのためにジェシカを引き渡すよう要求するため、マクスウェルと地元当局は彼女を別の島の精神病院へ送ることを望 む。ポールは、ウェズリーがジェシカに残ってほしいからと抵抗し、病気になる前のジェシカのように彼女を不幸にする前にカナダに帰るようベッツィに言う。 夜、十字路を警備するゾンビ、カルフールがジェシカの奪還に向かわされ、ジェシカのローブを着たベッツィに近づくが、ランド夫人に立ち去るよう命じられ る。 マクスウェルは、ジェシカの運命を決める公式調査が行われることを報告しに訪れる。ジェシカがウェスリーと逃げようとした夜、フーンガンにジェシカをゾン ビにするよう頼んだ。その話を信じたのはウェスリーだけで、彼は後にジェシカを安楽死させるようベッツィに頼むが、ベッツィは拒否する。 ジェシカの小さな人形を使い、黒衣の男とフーガンはジェシカをフーンフォートに引き寄せようとする。一度目はポールとベッツィーが止めるが、二度目はウェ スリーが彼女を助け、かつてホーランド家の奴隷船の船首であった聖セバスチャンを描いた庭の彫像「ティ・ミゼリー」から取り出した矢で追いかける。黒衣の 男は、ジェシカを矢で刺すウェスリーを映すように、人形をピンで刺し、ジェシカの遺体を海に運ぶカルフールにゆっくりと追われる。ジェシカとウェスリーは 波間に浮かんでいるところを発見され、2人の遺体はフォート・ホランドに持ち帰られる。ナレーションはジェシカをポールを迷わせた悪女として非難するが、 死者のために神の許しを請う。ベッツィとポールは慰め合う。 |

| Cast Frances Dee as Betsy Connell Tom Conway as Paul Holland James Ellison as Wesley Rand Edith Barrett as Mrs. Rand James Bell as Dr. Maxwell Christine Gordon as Jessica Holland Theresa Harris as Alma Sir Lancelot as Calypso Singer Darby Jones as Carrefour[a] Jeni Le Gon as Dancer[5] Rita Christiani as a friend of Melise (uncredited)[5] Jieno Moxzer as the sabreur (uncredited)[5] |

キャスト フランシス・ディー(ベッツィー・コネル役 トム・コンウェイ(ポール・ホランド役 ジェームズ・エリソン(ウェスリー・ランド役 イーディス・バレット(ランド夫人役 ジェームズ・ベル(マクスウェル博士役 クリスティン・ゴードン(ジェシカ・ホランド役 テレサ・ハリス(アルマ役 ランスロット卿(カリプソ歌手役 カルフール役ダービー・ジョーンズ[a] ダンサー[5]役のジェニ・ル・ゴン メリーゼの友人役リタ・クリスチャニ(クレジットなし)[5] ジエノ・モクザー as the sabreur(クレジットなし)[5] |

| Production Development RKO executives, rather than producer Val Lewton, chose the film's title,[6] which was taken from an article of the same name written by Inez Wallace for American Weekly Magazine.[7] Whereas the article detailed Wallace's experience meeting "zombies", by which she meant, not the literal living dead, but rather people she encountered working on a plantation in Haiti whose vocal cords and cognitive abilities had been impaired by drug use, rendering them obedient servants who understood and followed simple orders,[8] Lewton asked screenwriters Curt Siodmak and Ardel Wray to research the practices of Haitian Vodou and use Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre as a model for the narrative structure,[9] purportedly proclaiming that he wanted to make a "West Indian version of Jane Eyre."[10] Siodmak's initial draft, which was revised significantly by Wray and Lewton, revolved around the wife of a plantation owner who is made into a zombie to prevent her from leaving him and moving to Paris.[11] Casting Anna Lee was originally slated for the role ultimately played by Frances Dee, but had to bow out due to another commitment.[12] Dee received $6,000 for her performance in the film,[13] and Darby Jones was paid, based on his weekly contract salary of $450, $75 a day, totaling $225 for his three days of work.[13] Filming Principal photography for the film, which Wray described it as being shot on a "shoestring budget",[11] began October 26, 1942,[11] and wrapped less than a month later, on November 19.[14] |

生産 製作 この映画のタイトルは、プロデューサーのヴァル・リュートンではなく、RKOの幹部が選んだもので、イネス・ウォレスが『アメリカン・ウィークリー』誌に 書いた同名の記事から取られた[6]。 [その記事は、ウォレスが 「ゾンビ 」に出会った経験を詳述したものであったが、その 「ゾンビ 」とは、文字どおりの生ける屍ではなく、ハイチの農園で働く人民のことであり、薬物の使用によって声帯や認知能力が損なわれ、簡単な命令を理解し従う従順 な召使いになってしまったという意味であった、 [ルートンは脚本家のカート・シオドマクとアーデル・レイに、ハイチのヴードゥーの慣習を研究し、シャーロット・ブロンテの『ジェーン・エア』を物語構成 のモデルとして使うよう依頼した[9]。 「10]シオドマクの最初の草稿は、レイとルートンによって大幅に修正されたが、農園主の妻が自分から離れてパリに移住するのを阻止するためにゾンビにさ れるという内容だった[11]。 キャスティング アンナ・リーは当初、最終的にフランシス・ディーが演じる予定であったが、別の仕事が入ったため降板した[12]。 撮影 レイが「わずかな予算」で撮影されたと表現したこの映画の主要撮影は、1942年10月26日に開始され[11]、1ヵ月も経たない11月19日に終了した[14]。 |

| Release Theatrical distribution  A theater in Montreal that showed I Walked with a Zombie in 1943 I Walked with a Zombie had its theatrical premiere on April 8, 1943, in Cleveland, Ohio, which was the hometown of Inez Wallace, the author of the film's source material.[15] It opened in New York City on April 21, before expanding wide on April 30,[16] and continued to screen in North American theaters until as late as December 19, when it was at the Rialto in Casper, Wyoming.[17] The film was re-released in the United States by RKO in 1956, opening in Los Angeles in July[18] and screening nationwide throughout the fall and into late December.[19][20] Home media The film was released on DVD by Warner Home Video in 2005 as part of "The Val Lewton Horror Collection", a 9-film box set, on the same disc as The Body Snatcher (1945).[21] In 2024, The Criterion Collection announced a 4K/Blu-ray release of the film as part of the double feature set, I Walked with a Zombie / The Seventh Victim: Produced by Val Lewton.[22] |

リリース 劇場配給  1943年、『I Walked with a Zombie』を上映したモントリオールの劇場 I Walked with a Zombie』は1943年4月8日、オハイオ州クリーブランドで劇場公開された[15]。 この映画は1956年にRKOによってアメリカで再公開され、7月にロサンゼルスで公開され[18]、秋から12月下旬まで全国で上映された[19][20]。 ホームメディア この作品は2005年にワーナー・ホーム・ビデオからDVD化され、『ボディ・スナッチャー』(1945年)と同じディスクに収録された9作品のボックスセット『ヴァル・リュートン・ホラー・コレクション』の一部としてリリースされた[21]。 2024年、クライテリオン・コレクションは2本立てセット『I Walked with a Zombie / The Seventh Victim』の一部として本作の4K/Blu-rayリリースを発表した: ヴァル・リュートン製作[22]。 |

| Reception Contemporaneous reviews Initial reception for the film was mixed. While The New York Times was critical, calling it "a dull, disgusting exaggeration of an unhealthy, abnormal concept of life",[23] Wanda Hale of the New York Daily News awarded it two-and-a-half out of three stars and praised it as a "spine-chilling horror film".[24] Whereas The Boston Globe felt the film "gets nowhere in the telling and finishes its overdone melodramatics with a most unconvincing climax",[25] a reviewer in Albany, New York, said it "rigs up a great atmosphere for the haunt and holler audience and, compared with Cat People, the movie with which it is mentioned most often in publicity, it is a success."[26] Retrospective assessments On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 85% based on 41 reviews, with an average score of 8.1/10; the site's "critics consensus" reads: "Evocative direction by Jacques Tourneur collides with the low-rent production values of exploitateer Val Lewton in I Walked with a Zombie, a sultry sleeper that's simultaneously smarmy, eloquent and fascinating."[27] Author and film critic Leonard Maltin gave the film three-and-a-half out of four stars, praising its atmosphere and story and calling it an "Exceptional Val Lewton chiller".[28] Dennis Schwartz awarded the film an "A" grade, praising the atmosphere, the story, and Tourneur's direction.[29] TV Guide awarded the film their highest rating of five out of five stars, calling it "an unqualified horror masterpiece".[30] Alan Jones of Radio Times gave the film four out of five stars, writing: "Jacques Tourneur's direction creates palpable fear and tension in a typically low-key nightmare from the Lewton fright factory. The lighting, shadows, exotic setting and music all contribute to the immensely disturbing atmosphere, making this stunning piece of poetic horror a classic of the genre."[31] In 2007, Stylus Magazine named I Walked with a Zombie the fifth best zombie film of all time.[32] In 2021, Apichatpong Weerasethakul gave the name of Jessica Holland to the main heroine of Memoria, in tribute to I Walked with a Zombie.[33] |

レセプション 同時代の批評 この映画の最初の評判は賛否両論だった。ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙は「不健康で異常な人生の概念を誇張した、退屈でうんざりするような作品」と酷評した が[23]、『ニューヨーク・デイリー・ニュース』紙のワンダ・ヘイルは3つ星のうち2つ半をつけ、「背筋が凍るようなホラー映画」と称賛した[24]。 [24]ボストン・グローブ紙が、この映画は「話がどこにも進まず、行き過ぎたメロドラマを最も説得力のないクライマックスで終わらせた」と感じたのに対 し[25]、ニューヨーク州オルバニーの批評家は、この映画は「お化け屋敷やホラーの観客のために素晴らしい雰囲気を作り上げており、宣伝で最もよく言及 される映画である『キャット・ピープル』と比較すると、成功している」と述べた[26]。 回顧的評価 レビューアグリゲーターサイトRotten Tomatoesでは、41のレビューに基づく支持率は85%、平均スコアは8.1/10である: ジャック・トゥルヌールによる刺激的な演出が、搾取者ヴァル・リュートンの低俗な演出と衝突する『ゾンビと歩けば』は、同時に不機嫌で、雄弁で、魅惑的な 寝物語である」[27]。 作家で映画評論家のレナード・マルティンは、この映画に4つ星中3つ半の評価を与え、その雰囲気とストーリーを賞賛し、「ヴァル・ルートンの例外的なチ ラー」と呼んだ[28]。 デニス・シュワルツは、この映画に「A」の評価を与え、雰囲気、ストーリー、そしてトゥルヌールの演出を賞賛した[29]。 TVガイドは、この映画に5つ星中5つの最高評価を与え、「文句なしのホラーの傑作」と呼んだ[30]: 「ジャック・トゥルヌールの演出は、ルートン恐怖工場の典型的な控えめな悪夢の中に、手に取るような恐怖と緊張感を生み出している。照明、影、エキゾチッ クな舞台設定、音楽はすべて、非常に不穏な雰囲気に貢献しており、この詩的なホラーの見事な作品は、このジャンルの古典となっている」[31]。 2007年、スタイラス・マガジンは『I Walked with a Zombie』を史上最高のゾンビ映画第5位に選出した[32]。 2021年、アピチャッポン・ウィーラセタクンは『I Walked with a Zombie』へのオマージュとして、『Memoria』のメインヒロインにジェシカ・ホランドという名前を与えた[33]。 |

| Themes and interpretations Slavery and racism "Carre-Four must have confronted audiences that summer as an especially charged figure, even if his exact significance requires after-the-fact interpretation. An iconography of racial violence haunts his scenes even amid the erasure of rope-and-gun specifics. Alone, dead, beautifully and self-consciously staged, facing the audience directly and meant for its inspection alone in a story explicitly about a people's long memories of slavery, he is disquietingly insisted upon." – Alexander Nemerov on the character of Carrefour[34] Historian and author Alexander Nemerov asserted that I Walked with a Zombie uses stillness as a metaphor for slavery "in ways that center on Carre-Four",[35] who, like Ti-Misery, "the slave ship's figurehead, is a static and insentient figure". He wrote that the character personifies a link between slavery and the concept of zombies, citing anthropologist Wade Davis, who said: "Zombis do not speak, cannot fend for themselves, do not even know their names. Their fate is enslavement."[36] Numerov added that Carrefour "suggests the violent subjugation and the emergent power of blacks" during World War II, calling the character "a simultaneous portrayal of strength and victimization",[34] and characterized Darby Jones' portrayal as a "monumental [...] dominant screen presence"[37] that, in the context of the war and the American Double V campaign, "equaled the performances of far more famous black actors in the depiction of a charged conceit: the black man standing alone."[13] Numerov stated that both Carrefour and Ti-Misery "conjure the lynching of a black man",[36] pointing to the film's final shot, which is of Ti-Misery, as particularly establishing the figurehead as an image reminiscent of lynching.[36] Of the narration in the final scene, which is the only narration in the film not spoken by Betsy, he wrote that the line "pity those who are dead, and wish peace and happiness to the living" is "meant to encompass the white characters [...] But the decision to end with the sculpture of Ti Misery and the voice of the black man directs these sentiments back to 'the misery and pain of slavery.'"[38] As the film was released during World War II, Nemerov said "the film's final words and image implied a Willkie-style acknowledgement of injustice at home."[38] Writer Lee Mandelo characterized Ti-Misery as a symbolic representation of "brutality and intense suffering".[39] He lamented that the film's initial thematic arc, which he wrote made "a few grasps for a more sensitive commentary", was "flipped around to discuss the 'enslavement' of the beautiful white woman, Jessica, who has been either made a zombie or is an up-and-moving catatonic", saying it was "flinch-inducing, as it takes the suffering of the black population of the island and gives it over to a white woman".[39] Both Nemerov and Mandelo discussed the references in the film to the residents of Saint Sebastian, due to the island's history of slavery, still crying at the births of children and laughing at funerals. Mandelo called this "a cultural tradition that comes from a life without freedom".[35][39] Writer Jim Vorel asserted that "Although the setting of the film is a post-slavery island of Saint Sebastian, the film's constant visual motifs of bondage and servitude never allow the viewer to forget the horrors of their not-so-distant past."[40] Regarding Carrefour, writer Vikram Murthi asserted that "It's not his visage that unsettles, but rather the history beneath his face. It's no wonder that neither the Hollands nor Betsy can hardly bear to stare at him; he reflects the corrosion of their collective soul."[4] |

テーマと解釈 奴隷制度と人種主義 「カレ・フォアは、その正確な意義は事後的な解釈を必要とするとしても、その夏、特に荷担した人物として観客に立ちはだかったに違いない。人種的暴力の図 像は、ロープと銃の具体的な描写が消されても、彼のシーンにつきまとう。ひとりぼっちで、死んでいて、美しく、自意識的に演出され、観客に直接向かい合っ ていて、人民の奴隷制の長い記憶を明確に描いた物語の中で、観客だけが見ることができるように、彼は不穏に主張されている」。 - アレクサンドル・ネメロフ、カルフールのキャラクターについて[34]。 歴史家であり作家でもあるアレクサンダー・ネメロフは、『私はゾンビと歩いた』は奴隷制の隠喩として「カレフールを中心とした方法で」静止を使用している と主張する[35]。彼は、このキャラクターが奴隷制度とゾンビの概念のつながりを擬人化していると書き、人類学者ウェイド・デイヴィスの言葉を引用し た: 「ゾンビは言葉を話さず、自活できず、自分の名前さえ知らない。彼らの運命は奴隷化である」[36]。ヌメロフは、カルフールは第二次世界大戦中の「黒人 の暴力的な服従と出現した力を示唆している」と付け加え、このキャラクターを「強さと犠牲の同時描写」と呼び[34]、ダービー・ジョーンズの描写を「記 念碑的な(......)支配的なスクリーン・プレゼンス」[34]と評した。 ......)圧倒的なスクリーン上の存在感」[37]であり、戦争とアメリカのダブルV作戦という文脈の中で、「黒人が一人で立っているという有料の観 念の描写において、はるかに有名な黒人俳優のパフォーマティビティに匹敵した」[13]と評している。 ヌメロフは、カルフールもティ=ミザリーも「黒人のリンチを想起させる」と述べており[36]、特にティ=ミザリーを撮った映画の最後のショットが、リン チを想起させるイメージとして図頭を定着させたと指摘している[36]。 ベッツィが語らない唯一のナレーションであるラストシーンのナレーションについて、彼は「死んだ者を憐れみ、生きている者に平和と幸福を願う」という台詞 が「白人の登場人物を包含することを意図している[...]」と書いている。 中略)しかし、ティ・ミザリーの彫刻と黒人の声で終わるという決定は、これらの感情を『奴隷制の悲惨さと痛み』に戻すものである」[38]。この映画が第 二次世界大戦中に公開されたため、ネメロフは「映画の最後の言葉と映像は、ウィルキー流の自国の不正義を認めることを暗示していた」と述べている [38]。 作家のリー・マンデロは、『ティ・ミゼリ』を「残忍さと強烈な苦しみ」を象徴的に表現した作品だと評している[39]。 [39]彼は、「より繊細な論評のためにいくつかの工夫がなされている」と書いたこの映画の最初の主題の弧が、「ゾンビにされたか、起き上がりこぼしの緊 張状態にある美しい白人女性ジェシカの『奴隷化』を論じるために反転させられている」と嘆き、「島の黒人住民の苦しみを白人女性に譲り渡すような、たじろ ぐようなものだ」と述べた[39]。 ネメロフもマンデロも、この映画の中で、セント・セバスチャンの住民が、島の奴隷制の歴史ゆえに、いまだに子どもの誕生で泣き、葬式で笑っていることについて言及した。マンデロはこれを「自由のない生活から生まれた文化的伝統」と呼んだ[35][39]。 作家のジム・ヴォレルは、「この映画の舞台は奴隷制度後のセント・セバスチャン島だが、この映画の束縛と隷属の絶え間ない視覚的モチーフは、そう遠くない 過去の恐怖を観る者に決して忘れさせることはない」と主張した[40]。 カルフールについて、作家のヴィクラム・ムルティは、「不安にさせるのは彼の容貌ではなく、むしろ彼の顔の下にある歴史だ」と主張した。オランダ人もベッ ツィーも彼を見つめることに耐えられないのも無理はない。彼は彼らの集団的な魂の腐食を反映しているのだ」[4]。 |

Voodoo A scene taking place in a houmfort, or Haitian Vodou temple Vorel argued that the film approaches the beliefs associated with African diaspora religions, particularly Haitian Vodou, in a more thoughtful manner than earlier films like White Zombie (1932).[40] He wrote that I Walked with a Zombie "not only depict[s] them with surprising accuracy and dignity, but consider[s] how those beliefs could be co-opted by the white man as one more element of control over the lives of the island inhabitants."[40] Nemerov compared the setting of the houmfort, with its black attendees and musical performances, to a Harlem nightclub[41] and noted the film's depiction of a performance of the Haitian Vodou song "O Legba", provided to the film by folklorist Leroy Antoine, as evidence of the research conducted by the filmmakers.[5] Additionally, he wrote that when Alma instructs Betsy on how to reach the houmfort, "her description of Carre-Four as a 'god' sounds almost like 'guard,' and the two words combine not only to define his voodoo role, guardian of the crossroads, but also to assert the importance of his triviality: like the doorman at an actual club, he is a guard who holds godlike power."[42] Haitian Vodou researcher Laënnec Hurbon felt the "director displayed Haitian voodoo as a series of bizarre practices, chief among them the sorcerers' ability to kill people and then reanimate them in a state of living death. The idea flourished."[43] |

ヴードゥー ハイチのヴードゥー教寺院で起こるシーン ヴォレルは、この映画は『ホワイト・ゾンビ』(1932年)のような以前の映画よりも思慮深い方法で、アフリカン・ディアスポラの宗教、特にハイチのヴォドゥーに関連する信仰にアプローチしていると主張した。 ネメロフは、黒人の参加者と音楽演奏があるフームフォートの舞台をハーレムのナイトクラブと比較し[41]、映画製作者が行った調査の証拠として、民俗学 者のルロイ・アントワーヌが映画に提供したハイチ・ヴォドゥの歌「オ・レグバ」の演奏の描写を挙げた。 [さらに彼は、アルマがベッツィにフームフォートへの行き方を指示するとき、「彼女の言う 「神 」としてのカレ=フォーは、ほとんど 「番人 」のように聞こえ、この2つの言葉が組み合わさることで、ヴードゥーの役割である十字路の守護者を定義するだけでなく、彼の些細なことの重要性も主張す る:実際のクラブのドアマンのように、彼は神のような力を持つ番人なのだ」と書いている[42]。 ハイチ・ヴードゥー研究者のラエンネック・ハーボンは、「監督はハイチのヴードゥーを一連の奇妙な慣習として見せており、中でも魔術師が人民を殺し、生ける屍のような状態で生き返らせる能力を持っている」と感じた。このアイデアは成功した」[43]。 |

| List of cult films |

カルト映画のリスト |

| Bibliography Bansak, Edmund G. (2003). Fearing the Dark: The Val Lewton Career. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1709-4. Fujiwara, Chris (2015) [2001]. Jacques Tourneur: The Cinema of Nightfall. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6561-9. Hanson, Patricia K.; Dunkleberger, Amy (1999). AFI: American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States : Feature Films 1941-1950 Indexes. Vol. 2. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0520215214. Hurbon, Laënnec (1995). Voodoo: Truth and Fantasy. 'New Horizons' series. Translated by Frankel, Lory. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-30049-7. Nemerov, Alexander (2005). Icons of Grief: Val Lewton's Home Front Pictures. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520241008. Wallace, Inez (1986). "I Walked with a Zombie". In Haining, Peter (ed.). Zombie! Stories of the Walking Dead. London: W.H. Allen. ISBN 978-0-426-20161-8. |

書誌 Bansak, Edmund G. (2003). ヴァル・リュートンのキャリア。Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1709-4. Fujiwara, Chris (2015) [2001]. ジャック・トゥルヌール: ザ・シネマ・オブ・ナイトフォール. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6561-9. Hanson, Patricia K.; Dunkleberger, Amy (1999). AFI: アメリカン・フィルム・インスティテュート(AFI)米国製作映画カタログ: 長編映画 1941-1950 索引。カリフォルニア州ロサンゼルス: カリフォルニア大学出版局。ISBN 0520215214. Hurbon, Laënnec (1995). ヴードゥー: Truth and Fantasy. 'New Horizons' シリーズ。フランケル、ローリー訳。ロンドン: テムズ&ハドソン. ISBN 978-0-500-30049-7. Nemerov, Alexander (2005). Icons of Grief: Val Lewton's Home Front Pictures. カリフォルニア大学出版局。ISBN 978-0520241008. Wallace, Inez (1986). 「I Walked with a Zombie」. In Haining, Peter (ed.). Zombie!Stories of the Walking Dead. London: W.H. Allen. ISBN 978-0-426-20161-8. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Walked_with_a_Zombie |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆