偶像崇拝

Idolatry

☆ 偶像崇拝(Idolatry)とは、偶像を神であるかのように崇拝することである。[1][2][3] アブラハムの宗教(すなわちユダヤ教、キリスト教、イスラム教)において、偶像崇拝とはアブラハムの神以外の何か、あるいは誰かを神であるかのように崇拝 することを意味する。[4][5] これらの一神教において、偶像崇拝は「偽りの神々の崇拝」と見なされ、十戒などの聖典によって禁じられている。[4] 他の一神教も同様の規則を適用する場合がある。[6] 例えば「偽りの神」という表現は、アブラハムの宗教において、非アブラハム的異教の宗教における偶像や神々、あるいは特定の重要性が付与された競合する存 在や対象を指す蔑称として用いられる。[7] 逆に、アニミズムや多神教の信者は、一神教の神々が持つとされる特性を、実在の神が備えているとは信じないため、様々な一神教の神々を「偽りの神」と見な すことがある。神を一切信じない無神論者は、無神論的観点では全ての神々が該当するにもかかわらず、通常「偽りの神」という用語を使用しない。この用語の 使用は、特定の神々を崇拝するが他の神々を崇拝しない有神論者に限定されるのが一般的である。[4]

※写真や画像の多くは省略している。詳しくはオリジナル情報(Idolatry)を参照されたい。

| Idolatry is the

worship of an idol as though it were a deity.[1][2][3] In Abrahamic

religions (namely Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) idolatry connotes

the worship of something or someone other than the Abrahamic God as if

it were God.[4][5] In these monotheistic religions, idolatry has been

considered as the "worship of false gods" and is forbidden by texts

such as the Ten Commandments.[4] Other monotheistic religions may apply

similar rules.[6] For instance, the phrase false god is a derogatory term used in Abrahamic religions to indicate cult images or deities of non-Abrahamic Pagan religions, as well as other competing entities or objects to which particular importance is attributed.[7] Conversely, followers of animistic and polytheistic religions may regard the gods of various monotheistic religions as "false gods" because they do not believe that any real deity possesses the properties ascribed by monotheists to their sole deity. Atheists, who do not believe in any deities, do not usually use the term false god even though that would encompass all deities from the atheist viewpoint. Usage of this term is generally limited to theists, who choose to worship some deity or deities, but not others.[4] In many Indian religions, which include Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, idols (murti) are considered as symbolism for the Absolute but are not the Absolute itself,[8] or icons of spiritual ideas,[8][9] or the embodiment of the divine.[10] It is a means to focus one's religious pursuits and worship (bhakti).[8][11][9] In the traditional religions of Ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, Africa, Asia, the Americas and elsewhere, the reverence of cult images or statues has been a common practice since antiquity, and idols have carried different meanings and significance in the history of religion.[7][1][12] Moreover, the material depiction of a deity or more deities has always played an eminent role in all cultures of the world.[7] The opposition to the use of any icon or image to represent ideas of reverence or worship is called aniconism.[13] The destruction of images as icons of veneration is called iconoclasm,[14] and this has long been accompanied with violence between religious groups that forbid idol worship and those who have accepted icons, images and statues for veneration.[15][16] The definition of idolatry has been a contested topic within Abrahamic religions, with many Muslims and most Protestant Christians condemning the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox practice of venerating the Virgin Mary in many churches as a form of idolatry.[17][18] The history of religions has been marked with accusations and denials of idolatry. These accusations have considered statues and images to be devoid of symbolism. Alternatively, the topic of idolatry has been a source of disagreements between many religions, or within denominations of various religions, with the presumption that icons of one's own religious practices have meaningful symbolism, while another person's different religious practices do not.[19][20] |

偶像崇拝とは、偶像を神であるかのように崇拝することである。[1]

[2][3]

アブラハムの宗教(すなわちユダヤ教、キリスト教、イスラム教)において、偶像崇拝とはアブラハムの神以外の何か、あるいは誰かを神であるかのように崇拝

することを意味する。[4][5]

これらの一神教において、偶像崇拝は「偽りの神々の崇拝」と見なされ、十戒などの聖典によって禁じられている。[4]

他の一神教も同様の規則を適用する場合がある。[6] 例えば「偽りの神」という表現は、アブラハムの宗教において、非アブラハム的異教の宗教における偶像や神々、あるいは特定の重要性が付与された競合する存 在や対象を指す蔑称として用いられる。[7] 逆に、アニミズムや多神教の信者は、一神教の神々が持つとされる特性を、実在の神が備えているとは信じないため、様々な一神教の神々を「偽りの神」と見な すことがある。神を一切信じない無神論者は、無神論的観点では全ての神々が該当するにもかかわらず、通常「偽りの神」という用語を使用しない。この用語の 使用は、特定の神々を崇拝するが他の神々を崇拝しない有神論者に限定されるのが一般的である。[4] ヒンドゥー教、仏教、ジャイナ教を含む多くのインド宗教では、偶像(ムルティ)は絶対者の象徴とみなされるが、絶対者そのものではない[8]、あるいは精 神的観念の象徴[8][9]、あるいは神性の具現化である[10]。これは宗教的追求と崇拝(バクティ)に集中するための手段である[8]。[11] [9] 古代エジプト、ギリシャ、ローマ、アフリカ、アジア、アメリカ大陸など世界各地の伝統宗教において、祭祀像や彫像への崇敬は古代より普遍的な慣行であり、 偶像は宗教史において異なる意味と意義を担ってきた。[7][1][12] さらに、神々を物質的に表現する行為は、世界のあらゆる文化において常に卓越した役割を果たしてきた。[7] 崇敬や礼拝の概念を表すためのいかなる図像や像の使用にも反対する姿勢は、偶像否定主義と呼ばれる。[13] 崇敬の対象としての像を破壊する行為は偶像破壊運動と呼ばれ、[14] これは偶像礼拝を禁じる宗教集団と、崇敬のために像や図像、彫像を受け入れる集団との間で、長い間暴力的な対立を伴ってきた。偶像崇拝の定義はアブラハム の宗教内で論争の的となっており、多くのイスラム教徒や大半のプロテスタント系キリスト教徒は、カトリックや東方正教会が多くの教会で聖母マリアを崇拝す る慣行を偶像崇拝の一形態として非難している。 宗教の歴史は偶像崇拝の非難と否定に彩られてきた。こうした非難は、像や画像に象徴性が欠けていると見なしてきた。一方で、偶像崇拝の問題は多くの宗教 間、あるいは様々な宗教の宗派内で意見の相違を生んできた。自らの宗教的実践における聖像には意味ある象徴性がある一方、他者の異なる宗教的実践にはそれ がないという前提が背景にあるのだ[19][20]。 |

| Etymology and nomenclature The term idolatry comes from the Ancient Greek word eidololatria (εἰδωλολατρία), which itself is a compound of two words: eidolon (εἴδωλον "image/idol") and latreia (λατρεία "worship", related to λάτρις).[21] The word eidololatria thus means "worship of idols", which in Latin appears first as idololatria, then in Vulgar Latin as idolatria, therefrom it appears in 12th century Old French as idolatrie, which for the first time in mid 13th century English appears as "idolatry".[22][23] Although the Greek appears to be a loan translation of the Hebrew phrase avodat elilim, (עבודת אלילים) which is attested in rabbinic literature (e.g., bChul., 13b, Bar.), the Greek term itself is not found in the Septuagint, Philo, Josephus, or in other Hellenistic Jewish writings.[citation needed] The original term used in early rabbinic writings is oved avodah zarah (AAZ, worship in strange service, or "pagan"), while avodat kochavim umazalot (AKUM, worship of planets and constellations) is not found in its early manuscripts.[24] The later Jews used the term עֲבוֹדָה זָרָה, avodah zarah, meaning "foreign worship".[25] Idolatry has also been called idolism,[26] iconolatry[27] or idolodulia in historic literature.[28] |

語源と命名法 偶像崇拝という用語は、古代ギリシャ語のeidololatria(εἰδωλολατρία)に由来する。この語自体は二つの単語の複合語である: eidolon(εἴδωλον「像/偶像」)とlatreia(λατρεία「崇拝」、λάτριςに関連)。[21] したがってeidololatriaは「偶像の崇拝」を意味し、ラテン語では最初にidololatriaとして現れ、俗ラテン語ではidolatria となり、そこから12世紀古フランス語でidolatrieとして現れ、13世紀中頃の英語で初めて「idolatry」として登場する。[22] [23] ギリシャ語はヘブライ語のavodat elilim(עבודת אלילים)の借訳と思われるが、この語自体はセプトゥアギンタ、フィロン、ヨセフス、その他のヘレニズム期ユダヤ文献には見られない。[出典必要] 初期ラビ文献で使用された原語は「オヴェド・アヴォダ・ザラ」(AAZ、異教の奉仕、すなわち「異教徒」)であり、「アヴォダト・コハヴィム・ウマザロッ ト」(AKUM、惑星や星座の崇拝)は初期写本には見られない。[24] 後代のユダヤ人は「異教の礼拝」を意味する「アヴォダ・ザラ(עֲבוֹדָה זָרָה)」という用語を用いた。[25] 偶像崇拝は歴史的文献において偶像主義[26]、偶像礼拝[27]、あるいは偶像崇拝(idolodulia)とも呼ばれてきた。[28] |

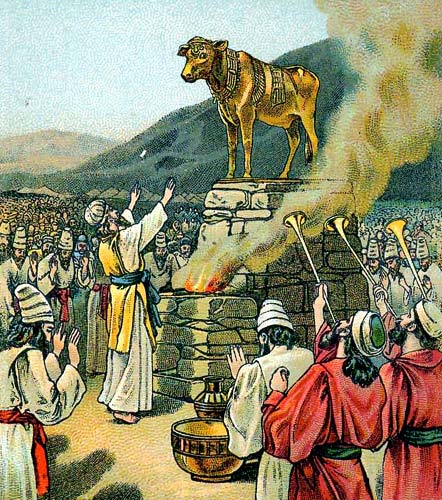

| Prehistoric and ancient civilizations The earliest so-called Venus figurines have been dated to the prehistoric Upper Paleolithic era (35–40 ka onwards).[29] Archaeological evidence from the islands of the Aegean Sea have yielded Neolithic era Cycladic figures from 4th and 3rd millennium BC, idols in namaste [which?] posture from Indus Valley civilization sites from the 3rd millennium BC, and much older petroglyphs around the world show humans began producing sophisticated images.[30][31] However, because of a lack of historic texts describing these, it is unclear what, if any connection with religious beliefs, these figures had,[32] or whether they had other meaning and uses, even as toys.[33][34][35] The earliest historic records confirming idols are from the ancient Egyptian civilization, thereafter related to the Greek civilization.[36] By the 2nd millennium BC two broad forms of cult image appear, in one images are zoomorphic (god in the image of animal or animal-human fusion) and in another anthropomorphic (god in the image of man).[32] The former is more commonly found in ancient Egypt influenced beliefs, while the anthropomorphic images are more commonly found in Indo-European cultures.[36][37] Symbols of nature, useful animals or feared animals may also be included by both. The stelae from 4,000 to 2,500 BC period discovered in France, Ireland through Ukraine, and in Central Asia through South Asia, suggest that the ancient anthropomorphic figures included zoomorphic motifs.[37] In Nordic and Indian subcontinent, bovine (cow, ox, -*gwdus, -*g'ou) motifs or statues, for example, were common.[38][39] In Ireland, iconic images included pigs.[40] The Ancient Egyptian religion was polytheistic, with large idols that were either animals or included animal parts. Ancient Greek civilization preferred human forms, with idealized proportions, for divine representation.[36] The Canaanites of West Asia incorporated a golden calf into their pantheon.[41] The ancient philosophy and practices of the Greeks, thereafter Romans, were imbued with polytheistic idolatry.[42][43] They debate what is an image and if the use of image is appropriate. To Plato, images can be a remedy or poison to the human experience.[44] To Aristotle, states Paul Kugler, an image is an appropriate mental intermediary that "bridges between the inner world of the mind and the outer world of material reality", the image is a vehicle between sensation and reason. Idols are useful psychological catalysts, they reflect sense data and pre-existing inner feelings. They are neither the origins nor the destinations of thought but the intermediary in the human inner journey.[44][45] Fervid opposition to the idolatry of the Greeks and Romans was of Early Christianity and later Islam, as evidenced by the widespread desecration and defacement of ancient Greek and Roman sculptures that have survived into the modern era.[46][47][48] |

先史時代と古代文明 最も古いいわゆるヴィーナス像は、先史時代の上部旧石器時代(3万5千~4万年前以降)に遡る。[29] エーゲ海諸島の考古学的証拠からは、新石器時代のキクラデス像(紀元前4千年紀~3千年紀)、インダス文明遺跡の合掌姿勢の偶像(紀元前3千年紀)、そし て世界中のさらに古い岩刻画が発見されており、人類が精巧な造形物を制作し始めたことを示している。[30][31] しかし、これらを記述した歴史的文献が不足しているため、これらの像が宗教的信念と何らかの関連を持っていたのか、あるいは玩具としての用途を含む他の意 味や用途があったのかは不明である。[32][33][34][35] 偶像の存在を裏付ける最古の歴史的記録は古代エジプト文明に由来し、その後ギリシャ文明に関連付けられる。紀元前2千年紀までに、二つの主要な偶像形態が 現れる。一つは動物形態(動物または人獣融合の姿を帯びた神)、もう一つは人間形態(人間の姿を帯びた神)である。前者は古代エジプトの影響を受けた信仰 でより一般的であり、後者はインド・ヨーロッパ文化圏でより広く見られる。[36][37] 自然の象徴、有用な動物、あるいは恐れられる動物も、両者によって取り入れられることがある。フランス、アイルランドからウクライナ、中央アジアから南ア ジアにかけて発見された紀元前4000年から2500年の石碑は、古代の人型像が動物的モチーフを含んでいたことを示唆している。[37] 北欧やインド亜大陸では、例えば牛(雌牛、雄牛、-*gwdus、-*g'ou)のモチーフや像が一般的であった。[38][39] アイルランドでは、象徴的な像に豚が含まれていた。[40] 古代エジプトの宗教は多神教であり、動物そのもの、あるいは動物の部位を含む巨大な偶像が用いられた。古代ギリシャ文明は神々の表現に、理想化された比例を持つ人間形を好んだ。[36] 西アジアのカナン人は黄金の子牛を神々の体系に取り込んだ。[41] ギリシャ人、そして後にローマ人の古代哲学と実践は、多神教的な偶像崇拝に染まっていた。[42][43] 彼らは像とは何か、像の使用が適切かどうかを論じた。プラトンにとって、像は人間の経験にとって薬にも毒にもなり得る[44]。アリストテレスは、像を 「心の内なる世界と物質的現実の外なる世界をつなぐ」適切な精神的仲介者、感覚と理性の間の媒介物と位置づけたとポール・クグラーは述べる。偶像は有用な 心理的触媒であり、感覚データと既存の内面感情を反映する。それらは思考の起点でも終点でもなく、人間の内なる旅路における媒介物である。[44] [45] ギリシャ・ローマの偶像崇拝に対する激しい反対は、初期キリスト教や後のイスラム教に見られ、現代まで残存する古代ギリシャ・ローマ彫刻の広範な冒涜や損 傷がその証左である。[46][47][48] |

| Abrahamic religions Judaism Main articles: Idolatry in Judaism and Aniconism in Judaism This is an image of a copy of the 1675 Ten Commandments, at the Amsterdam Esnoga synagogue, produced on parchment in 1768 by Jekuthiel Sofer, a prolific Jewish scribe in Amsterdam. It has Hebrew language writing in two columns separated between, and surrounded by, ornate flowery patterns. A 1768 synagogue parchment with the Ten Commandments by Jekuthiel Sofer. Among other things, it prohibits idolatry.[49] Moses Indignant at the Golden Calf, painting by William Blake, 1799–1800 Judaism prohibits any form of idolatry[50] even if they are used to worship the one God of Judaism as occurred during the sin of the golden calf. According to the second word of the decalogue, Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image. The worship of foreign gods in any form or through icons is not allowed.[50][51] Many Jewish scholars such as Rabbi Saadia Gaon, Rabbi Bahya ibn Paquda, and Rabbi Yehuda Halevi have elaborated on the issues of idolatry. One of the oft-cited discussions is the commentary of Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon (Maimonides) on idolatry.[51] According to the Maimonidean interpretation, idolatry in itself is not a fundamental sin, but the grave sin is the denial of God's omnipresence that occurs with the belief that God can be corporeal. In the Jewish belief, the only image of God is man, one who lives and thinks; God has no visible shape, and it is absurd to make or worship images; instead man must worship the invisible God alone.[51][52] The commandments in the Hebrew Bible against idolatry forbade the practices and gods of ancient Akkad, Mesopotamia, and Egypt.[53][54] The Hebrew Bible states that God has no shape or form, is utterly incomparable, is everywhere and cannot be represented in a physical form of an idol.[55] Biblical scholars have historically focused on the textual evidence to construct the history of idolatry in Judaism, a scholarship that post-modern scholars have increasingly begun deconstructing.[19] This biblical polemics, states Naomi Janowitz, a professor of Religious Studies, has distorted the reality of Israelite religious practices and the historic use of images in Judaism. The direct material evidence is more reliable, such as that from the archaeological sites, and this suggests that the Jewish religious practices have been far more complex than what biblical polemics suggest. Judaism included images and cultic statues in the First Temple period, the Second Temple period, Late Antiquity (2nd to 8th century CE), and thereafter.[19][56] Nonetheless, these sorts of evidence may be simply descriptive of Ancient Israelite practices in some—possibly deviant—circles, but cannot tell us anything about the mainstream religion of the Bible which proscribes idolatry.[57] The history of Jewish religious practice has included idols and figurines made of ivory, terracotta, faience and seals.[19][58] As more material evidence emerged, one proposal has been that Judaism oscillated between idolatry and iconoclasm. However, the dating of the objects and texts suggest that the two theologies and liturgical practices existed simultaneously. The claimed rejection of idolatry because of monotheism found in Jewish literature and therefrom in biblical Christian literature, states Janowitz, has been unreal abstraction and flawed construction of the actual history.[19] The material evidence of images, statues and figurines taken together with the textual description of cherub and "wine standing for blood", for example, suggests that symbolism, making religious images, icon and index has been integral part of Judaism.[19][59][60] Every religion has some objects that represent the divine and stand for something in the mind of the faithful, and Judaism too has had its holy objects and symbols such as Torah scrolls and holy books, Tefillin, the Menorah, mezuzah and many more.[19] |

アブラハムの宗教 ユダヤ教 主な記事: ユダヤ教における偶像崇拝とユダヤ教における無像崇拝 これは1675年の十戒の写本である。アムステルダムのエスノガ会堂に所蔵され、1768年にアムステルダムの多作なユダヤ人筆写者イェクティエル・ソファーによって羊皮紙に制作された。ヘブライ語の文字が二列に記され、その間と周囲を華やかな花模様が囲んでいる。 1768年、イェクティエル・ソフェルによる十戒を記したシナゴーグの羊皮紙。とりわけ偶像崇拝を禁じている[49]。 『黄金の子牛に憤るモーセ』ウィリアム・ブレイク作、1799–1800年 ユダヤ教は偶像崇拝のあらゆる形態を禁じている。たとえユダヤ教の唯一神を崇拝するために用いられる場合でも、黄金の子牛の罪で起きたように禁じられる。 十戒の第二戒「刻んだ像を作ってはならない」に則り、異教の神々をいかなる形態であれ、あるいは偶像を通じて崇拝することは許されない。 ラビ・サアディア・ガオン、ラビ・バヒヤ・イブン・パクダ、ラビ・イェフダ・ハレヴィなど多くのユダヤ教学者たちが偶像崇拝の問題について論じている。よ く引用される議論の一つは、ラビ・モーシェ・ベン・マイモン(マイモニデス)による偶像崇拝に関する注釈である[51]。マイモニデスの解釈によれば、偶 像崇拝そのものは根本的な罪ではない。重大な罪は、神が物質的実体を持つという信念に伴う、神の遍在性の否定である。ユダヤ教の信仰において、神の唯一の 像は人間、すなわち生き、思考する存在である。神には目に見える形はなく、像を作り崇拝することは荒唐無稽である。代わりに人間は、目に見えない神のみを 崇拝すべきだ。[51][52] ヘブライ聖書における偶像崇拝禁止の戒律は、古代アッカド、メソポタミア、エジプトの慣習や神々を禁じたものである。[53][54] ヘブライ聖書は、神には形も姿もなく、全く比類がなく、遍在し、偶像という物理的な形態で表現することはできないと述べている。[55] 聖書学者たちは歴史的に、ユダヤ教における偶像崇拝の歴史を構築するためにテキスト的証拠に焦点を当ててきたが、この学問はポストモダン学者たちによって 次第に解体され始めている。[19] 宗教学教授ナオミ・ジャノウィッツは、この聖書論争がイスラエル人の宗教的実践とユダヤ教における歴史的な像の使用の実態を歪めてきたと述べている。考古 学遺跡などからの直接的な物質的証拠の方が信頼性が高く、ユダヤ教の宗教的実践は聖書論争が示唆するよりもはるかに複雑であったことを示唆している。ユダ ヤ教は第一神殿期、第二神殿期、古代末期(紀元2~8世紀)、そしてその後も、画像や祭祀用彫像を含んでいた。[19][56] とはいえ、こうした証拠は古代イスラエルの特定の(おそらくは逸脱した)集団の慣行を単に記述しているに過ぎず、偶像崇拝を禁じる聖書の主流宗教について は何も語っていない。[57] ユダヤ教の宗教的実践の歴史には、象牙、テラコッタ、ファイアンス、印章で作られた偶像や小像が含まれている。[19][58] より多くの物的証拠が明らかになるにつれ、ユダヤ教は偶像崇拝と偶像破壊の間で揺れ動いていたという説が提唱されてきた。しかし、遺物や文書の年代測定 は、この二つの神学と礼拝的実践が同時に存在していたことを示唆している。ユダヤ教文献、ひいては聖書に基づくキリスト教文献に見られる一神教ゆえの偶像 崇拝拒絶は、ジャノウィッツによれば、非現実的な抽象概念であり、実際の歴史を歪めて構築したものである[19]。像や彫像、人形といった物質的証拠と、 例えばケルビムや「血を象徴するワイン」といった文書の記述を総合すると、象徴主義、すなわち宗教的イメージや偶像、指標の制作がユダヤ教の不可欠な要素 であったことが示唆される。[19][59][60] あらゆる宗教には、神聖なものを表し、信者の心の中で何かを象徴する対象が存在する。ユダヤ教にもまた、トーラーの巻物や聖典、テフィリン、メノラー、メ ズーザーなど、数多くの聖なる対象や象徴が存在してきたのである。[19] |

| Christianity Main articles: Religious images in Christian theology and Aniconism in Christianity  St. Benedict destroying a pagan idol, by Juan Rizi (1600–1681) Ideas on idolatry in Christianity are based on the first of Ten Commandments. You shall have no other gods before me.[61] This is expressed in the Bible in Exodus 20:3, Matthew 4:10, Luke 4:8 and elsewhere, e.g.:[61] Ye shall make you no idols nor graven image, neither rear you up a standing image, neither shall ye set up any image of stone in your land, to bow down unto it: for I am the Lord your God. Ye shall keep my sabbaths, and reverence my sanctuary. — Leviticus 26:1–2, King James Bible[62] The Christian view of idolatry may generally be divided into two general categories: the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox view which accepts the use of religious images,[63] and the views of many Protestant churches that considerably restrict their use. However, many Protestants have used the image of the cross as a symbol.[64][65] Catholicism The veneration of Mary, Jesus Christ, and the Black Madonna are common practices in the Catholic Church. The Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church have traditionally defended the use of icons. The debate on what images signify and whether reverence with the help of icons in church is equivalent to idolatry has lasted for many centuries, particularly from the 7th century until the Reformation in the 16th century.[66] These debates have supported the inclusion of icons of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the Apostles, the iconography expressed in stained glass, regional saints and other symbols of Christian faith. It has also supported the practices such as the Catholic mass, burning of candles before pictures, Christmas decorations and celebrations, and festive or memorial processions with statues of religious significance to Christianity.[66][67][68] St. John of Damascus, in his "On the Divine Image", defended the use of icons and images, in direct response to the Byzantine iconoclasm that began widespread destruction of religious images in the 8th century, with support from emperor Leo III and continued by his successor Constantine V during a period of religious war with the invading Umayyads.[69] John of Damascus wrote, "I venture to draw an image of the invisible God, not as invisible, but as having become visible for our sakes through flesh and blood", adding that images are expressions "for remembrance either of wonder, or an honor, or dishonor, or good, or evil" and that a book is also a written image in another form.[70][71] He defended the religious use of images based on the Christian doctrine of Jesus as an incarnation.[72] St. John the Evangelist cited John 1:14, stating that "the Word became flesh" indicates that the invisible God became visible, that God's glory manifested in God's one and only Son as Jesus Christ, and therefore God chose to make the invisible into a visible form, the spiritual incarnated into the material form.[73][74]  Pope Pius V praying with a crucifix, painting by August Kraus The early defense of images included exegesis of Old and New Testament. Evidence for the use of religious images is found in Early Christian art and documentary records. For example, the veneration of the tombs and statues of martyrs was common among early Christian communities. In 397 St. Augustine of Hippo, in his Confessions 6.2.2, tells the story of his mother making offerings for the tombs of martyrs and the oratories built in the memory of the saints.[75] Images function as the Bible for the illiterate, and incite people to piety and virtue. — Pope Gregory I, 7th century[76] The Catholic defense mentions textual evidence of external acts of honor towards icons, arguing that there are a difference between adoration and veneration and that the veneration shown to icons differs entirely from the adoration of God. Citing the Old Testament, these arguments present examples of forms of "veneration" such as in Genesis 33:3, with the argument that "adoration is one thing, and that which is offered in order to venerate something of great excellence is another". These arguments assert, "the honor given to the image is transferred to its prototype", and that venerating an image of Christ does not terminate at the image itself – the material of the image is not the object of worship – rather it goes beyond the image, to the prototype.[77][76][78] According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church: The Christian veneration of images is not contrary to the first commandment which proscribes idols. Indeed, "the honor rendered to an image passes to its prototype," and "whoever venerates an image venerates the person portrayed in it." The honor paid to sacred images is a "respectful veneration," not the adoration due to God alone: Religious worship is not directed to images in themselves, considered as mere things, but under their distinctive aspect as images leading us on to God incarnate. The movement toward the image does not terminate in it as image, but tends toward that whose image it is.[79] It also points out the following: Idolatry not only refers to false pagan worship. It remains a constant temptation to faith. Idolatry consists in divinizing what is not God. Man commits idolatry whenever he honors and reveres a creature in place of God, whether this be gods or demons (for example, satanism), power, pleasure, race, ancestors, the state, money, etc.[80] The manufacture of images of Jesus, the Virgin Mary and Christian saints, along with prayers directed to these has been widespread among the Catholic faithful.[81] |

キリスト教 主な記事:キリスト教神学における宗教的イメージとキリスト教における偶像崇拝禁止  異教の偶像を破壊する聖ベネディクト、フアン・リジ作(1600–1681)[オリジナル画像] キリスト教における偶像崇拝に関する考え方は、十戒の最初の戒めに基づいている。 「わたしのほかに、わたしの神となるものを拝んではならない」[61] これは聖書の出エジプト記20:3、マタイによる福音書4:10、ルカによる福音書4:8などに記されている。例えば: [61] 汝らは偶像や彫像を作ってはならない。また、立像を立てたり、石像を立ててそれにひれ伏したりしてはならない。私は汝らの神、主である。汝らは私の安息日を守り、私の聖所を尊ばねばならない。 — レビ記26:1–2、欽定訳聖書[62] キリスト教における偶像崇拝の観点は、大きく二つの類型に分けられる。宗教的画像の使用を認めるカトリック・東方正教会の見解[63]と、その使用を大幅 に制限する多くのプロテスタント教会の見解である。ただし、多くのプロテスタントは十字架の画像を象徴として用いてきた[64][65]。 カトリック カトリック教会では、聖母マリア、イエス・キリスト、黒マリア像への崇敬が一般的な慣行である。 カトリック教会と正教会は伝統的にイコンの使用を擁護してきた。像が何を象徴するのか、また教会におけるイコンを用いた崇敬が偶像崇拝に等しいかどうかに ついての議論は、特に7世紀から16世紀の宗教改革まで、何世紀にもわたって続いた。[66] これらの論争は、イエス・キリスト、聖母マリア、使徒たちのイコン、ステンドグラスに表現された図像、地域の聖人、その他のキリスト教信仰の象徴の包含を 支持してきた。また、カトリックのミサ、絵画の前でのろうそくの燃焼、クリスマスの装飾と祝祭、キリスト教にとって宗教的に重要な像を用いた祝祭的または 追悼的な行列といった慣習も支持してきた。[66][67] [68] ダマスコの聖ヨハネは『神像論』において、8世紀に皇帝レオ3世の支持を得て始まり、後継者コンスタンティノス5世がウマイヤ朝との宗教戦争期に継続した ビザンツの聖像破壊運動に直接応答し、聖像や画像の使用を擁護した。[69] ダマスコのヨハネはこう記している。「私は見えない神の姿を描くことを敢えてする。それは見えない神そのものではなく、肉と血を通して私たちのために見え るものとなった神の姿である」と述べ、像は「驚嘆、敬意、侮辱、善、悪のいずれかを記憶するための表現」であり、書物もまた別の形態の書かれた像であると 付け加えた。[70][71] 彼はキリスト教のイエス・キリストの受肉という教義に基づいて、像の宗教的利用を擁護した。[72] 福音書記者ヨハネはヨハネによる福音書1章14節を引用し、「言葉は肉となった」とは見えない神が見えるものとなり、神の栄光が唯一の子イエス・キリスト に現れたことを示すと述べた。したがって神は、見えないものを見える形に、霊的なものを物質的な形に受肉させることを選んだのである。[73] [74]  十字架像を前に祈る教皇ピウス5世、アウグスト・クラウス作 初期の聖像擁護論には旧約聖書と新約聖書の解釈が含まれていた。宗教的画像の使用は初期キリスト教美術や文献記録に証拠が残る。例えば殉教者の墓や像への 崇敬は初期キリスト教共同体で一般的であった。397年、ヒッポのアウグスティヌスは『告白録』6.2.2において、母が殉教者の墓や聖人を記念して建て られた礼拝堂に供物を捧げた話を記している。[75] 画像は聖書と同様の機能を果たす 文盲者にとって、そして 人々を敬虔と徳へと駆り立てる。 — 教皇グレゴリウス1世、7世紀[76] カトリック側の弁明は、聖像に対する外的な敬意の行為に関する聖書的根拠を挙げ、崇拝と尊崇には違いがあり、聖像への尊崇は神への崇拝とは全く異なるもの であると主張する。旧約聖書を引用し、創世記33:3などの「尊崇」の形態を例示しながら、「崇拝は一つのことであり、卓越したものを尊崇するために捧げ られるものは別物である」と論じる。これらの議論は「像に捧げられた敬意はその原型に移される」と主張し、キリストの像を崇敬することは像そのもので終わ らない——像の物質が崇拝の対象ではない——むしろ像を超えて原型へと至るとする。[77][76] [78] カトリック教会のカテキズムによれば: キリスト教における像への崇敬は、偶像を禁じる第一戒律に反するものではない。実際、「像に捧げられる栄誉はその原型に移る」のであり、「像を崇敬する者 は、そこに描かれた人格を崇敬する」のである。聖なる像への敬意は「畏敬の念」であって、神のみに捧げるべき崇拝ではない: 宗教的崇拝は、単なる物として扱われる像そのものに向けられるのではなく、受肉した神へと導く像という独特の側面において向けられる。像への動きは像そのものの中で終わるのではなく、像が表す対象へと向かう。[79] また、以下の点を指摘している: 偶像崇拝は、偽りの異教的礼拝だけを指すのではない。それは信仰に対する絶え間ない誘惑であり続ける。偶像崇拝とは、神ではないものを神格化することであ る。人間は、神に代わって被造物を崇め敬うとき、それが神々や悪魔(例えばサタニズム)、権力、快楽、人種、祖先、国家、金銭などであろうと、常に偶像崇 拝を犯すのである。[80] イエス、聖母マリア、キリスト教聖人の像の制作と、それらに向けた祈りは、カトリック信徒の間で広く行われてきた。[81] |

| Orthodox Church The Eastern Orthodox Church has differentiated between latria and dulia. A latria is the worship due God, and latria to anyone or anything other than God is doctrinally forbidden by the Orthodox Church; however dulia has been defined as veneration of religious images, statues or icons which is not only allowed but obligatory.[82] This distinction was discussed by Thomas Aquinas in section 3.25 of Summa Theologiae.[83]  The veneration of images of Mary is called Marian devotion (above: Lithuania), a practice questioned in the majority of Protestant Christianity.[84][85] In Orthodox apologetic literature, the proper and improper use of images is extensively discussed. Exegetical Orthodox literature points to icons and the manufacture by Moses (under God's commandment) of the Bronze Snake in Numbers 21:9, which had the grace and power of God to heal those bitten by real snakes. Similarly, the Ark of the Covenant was cited as evidence of the ritual object above which Yahweh was present.[86][87] Veneration of icons through proskynesis was codified in 787 AD by the Seventh Ecumenical Council.[88][89] This was triggered by the Byzantine Iconoclasm controversy that followed raging Christian-Muslim wars and a period of iconoclasm in West Asia.[88][90] The defense of images and the role of the Syrian scholar John of Damascus was pivotal during this period. The Eastern Orthodox Church has ever since celebrated the use of icons and images. Eastern Rite Catholics also accepts icons in their Divine Liturgy.[91] |

正教会 東方正教会はラトリアとデュリアを区別している。ラトリアとは神に捧げる崇拝であり、神以外の誰かや何かにラトリアを捧げることは正教会の教義上禁じられ ている。しかしデュリアは宗教的な像や彫像、イコンへの崇敬と定義され、単に許されるだけでなく義務とされている。[82] この区別はトマス・アクィナスが『神学大全』第3部第25章で論じている。[83]  マリア像への崇敬はマリア崇敬(上図:リトアニア)と呼ばれ、プロテスタントキリスト教の大多数では疑問視されている慣行である。[84][85] 正教会の弁証文献では、像の適切な使用と不適切な使用が広く論じられている。聖書解釈に基づく正教文献は、民数記21章9節に記されたモーセ(神の命令に より)が製作した青銅の蛇を例に挙げる。この蛇は神の恵みと力を帯び、本物の蛇に噛まれた者を癒した。同様に、契約の箱はヤハウェが臨在する儀礼用器物の 証拠として引用されている。[86][87] プロスキネシスによるイコン崇敬は、787年に開催された第7回公会議で正式に認められた。[88][89] これは、キリスト教徒とイスラム教徒の激しい戦争と西アジアにおける偶像破壊運動の後に起きたビザンツ帝国の偶像破壊論争がきっかけとなった。[88] [90] この時期、像の擁護とシリアの学者ヨハネス・ダマスコスの役割が極めて重要であった。東方正教会はその後もイコンや画像の使用を称賛してきた。東方典礼カ トリック教会もまた、聖体礼儀においてイコンを受け入れている。[91] |

| Protestantism The idolatry debate has been one of the defining differences between papal Catholicism and anti-papal Protestantism.[92] The anti-papal writers have prominently questioned the worship practices and images supported by Catholics, with many Protestant scholars listing it as the "one religious error larger than all others". The sub-list of erring practices have included among other things the veneration of Virgin Mary, the Catholic mass, the invocation of saints, and the reverence expected for and expressed to pope himself.[92] The charges of supposed idolatry against the Roman Catholics were leveled by a diverse group of Protestants, from Anglicans to Calvinists in Geneva.[92][93] Altar with Christian Bible and crucifix on it, in a Lutheran Protestant church Protestants did not abandon all icons and symbols of Christianity. They typically avoid the use of images, except the cross, in any context suggestive of veneration. The cross remained their central icon.[64][65] Technically both major branches of Christianity have had their icons, states Carlos Eire, a professor of religious studies and history, but its meaning has been different to each and "one man's devotion was another man's idolatry".[94] This was particularly true not only in the intra-Christian debate, states Eire, but also when soldiers of Catholic kings replaced "horrible Aztec idols" in the American colonies with "beautiful crosses and images of Mary and the saints".[94] Protestants often accuse Catholics of idolatry, iconolatry, and even paganism; in the Protestant Reformation such language was common to all Protestants. In some cases, such as the Puritan groups denounced all forms of religious objects, regardless of whether it was a statue or sculpture, or image, including the Christian cross.[95] The Waldensians were accused of idolatry by inquisitors.[96] The body of Christ on the cross is an ancient symbol used within the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, and Lutheran Churches, in contrast with some Protestant groups, which use only a simple cross. In Judaism, the reverence to the icon of Christ in the form of cross has been seen as idolatry.[97] However, some Jewish scholars disagree and consider Christianity to be based on Jewish belief and not truly idolatrous.[98] |

プロテスタント 偶像崇拝論争は、ローマ・カトリックと反教皇主義のプロテスタントを分かつ決定的な差異の一つであった[92]。反教皇主義の著述家たちは、カトリックが 支持する礼拝慣行や聖像を顕著に疑問視し、多くのプロテスタント学者たちはこれを「他のあらゆる誤りを凌駕する唯一の宗教的誤り」と列挙している。誤った 慣行のサブリストには、とりわけ聖母マリアへの崇敬、カトリックのミサ、聖人への祈願、そして教皇自身に対する敬意の要求と表現が含まれていた。[92] ローマ・カトリックに対する偶像崇拝の嫌疑は、英国国教会からジュネーブのカルヴァン派に至るまで、多様なプロテスタント集団によって提起された。 [92] [93] ルーテル派プロテスタント教会にある、キリスト教聖書と十字架が置かれた祭壇 プロテスタントはキリスト教のあらゆる聖像や象徴を放棄したわけではない。彼らは通常、崇拝を連想させる文脈では十字架以外の画像の使用を避ける。十字架 は彼らの中心的な聖像であり続けた。[64][65] 宗教学・歴史学教授カルロス・アイレによれば、技術的にはキリスト教の二大宗派とも聖像を有してきたが、その意味はそれぞれ異なり、「ある者の信仰は別の 者にとって偶像崇拝であった」のである。[94] アイレによれば、これはキリスト教内部の論争においてのみならず、カトリック王の兵士たちがアメリカ植民地で「恐ろしいアステカの偶像」を「美しい十字架 や聖母マリア、聖人の像」に置き換えた際にも特に顕著であった。[94] プロテスタントはしばしばカトリックを偶像崇拝、聖像崇拝、さらには異教主義と非難する。宗教改革期にはこうした表現が全プロテスタントに共通していた。 ピューリタン派など一部のグループは、キリスト教の十字架を含むあらゆる宗教的対象物を、それが彫像であれ彫刻であれ画像であれ、一切非難した。[95] ヴァルド派は異端審問官から偶像崇拝の罪で告発された。[96] 十字架上のキリストの体は、カトリック、東方正教会、英国国教会、ルーテル教会で用いられる古代の象徴である。これに対し、単純な十字架のみを用いるプロ テスタント派もある。ユダヤ教では、十字架の形をしたキリストの像への崇敬は偶像崇拝と見なされてきた。[97] しかし、一部のユダヤ人学者はこれに異議を唱え、キリスト教はユダヤ教の信仰に基づくものであり、真の意味での偶像崇拝ではないと考える。[98] |

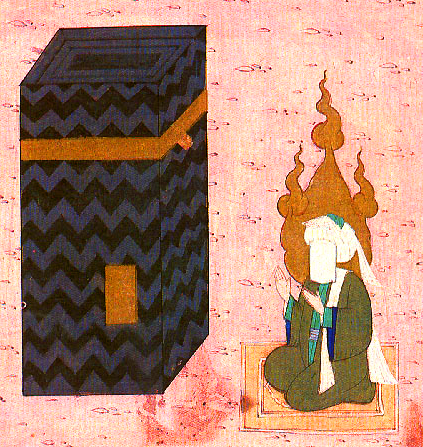

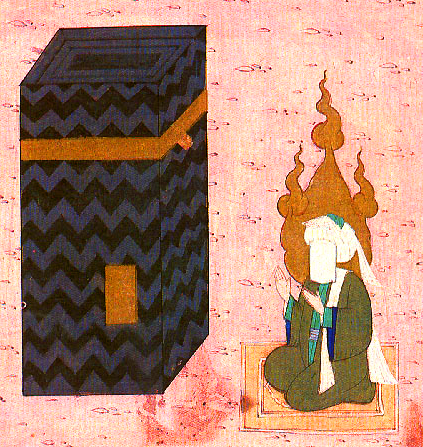

| Islam Main articles: Shirk (Islam) and Taghut See also: Aniconism in Islam and Blasphemy and Islam In Islamic sources, the concept of shirk (triliteral root: sh-r-k) can refer to "idolatry", though it is most widely used to denote "association of partners with God".[99] The concept of Kufr (k-f-r) can also include idolatry (among other forms of disbelief).[100][101] The one who practices shirk is called mushrik (plural mushrikun) in the Islamic scriptures.[102] The Quran forbids idolatry.[102] Over 500 mentions of kufr and shirk are found in the Quran,[100][103] and both concepts are strongly forbidden.[99] The Islamic concept of idolatry extends beyond polytheism, and includes some Christians and Jews as muširkūn (idolaters) and kafirun (infidels).[104][105] For example: Those who say, “Allah is the Messiah, son of Mary,” have certainly fallen into disbelief. The Messiah ˹himself˺ said, “O Children of Israel! Worship Allah—my Lord and your Lord.” Whoever associates others with Allah ˹in worship˺ will surely be forbidden Paradise by Allah. Their home will be the Fire. And the wrongdoers will have no helpers. — Surah Al-Ma'idah 5:72 Shia classical theology differs in the concept of Shirk. According to Twelver theologians, the attributes and names of God have no independent and hypostatic existence apart from the being and essence of God. Any suggestion of these attributes and names being conceived of as separate is thought to entail polytheism. It would be even incorrect to say God knows by his knowledge which is in his essence but God knows by his knowledge which is his essence. Also God has no physical form and he is insensible.[106] The border between theoretical Tawhid and Shirk is to know that every reality and being in its essence, attributes and action are from him (from Him-ness), it is Tawhid. Every supernatural action of the prophets is by God's permission as Quran points to it. The border between the Tawhid and Shirk in practice is to assume something as an end in itself, independent from God, not as a road to God (to Him-ness).[107] Ismailis go deeper into the definition of Shirk, declaring they don't recognize any sort of ground of being by the esoteric potential to have intuitive knowledge of the human being. Hence, most Shias have no problem with religious symbols and artworks, and with reverence for Walis, Rasūls and Imams. Islam strongly prohibits all form of idolatry, which is part of the sin of shirk (Arabic: شرك); širk comes from the Arabic root Š-R-K (ش ر ك), with the general meaning of "to share". In the context of the Qur'an, the particular sense of "sharing as an equal partner" is usually understood as "attributing a partner to Allah". Shirk is often translated as idolatry and polytheism.[99] In the Qur'an, shirk and the related word (plural Stem IV active participle) mušrikūn (مشركون) "those who commit shirk" refers to the enemies of Islam (as in verse 9.1–15).  "Muhammad at the Ka'ba" from the Siyer-i Nebi. Muhammad is shown with veiled face, c. 1595. Within Islam, shirk is sin that can only be forgiven if the person who commits it asks God for forgiveness; if the person who committed it dies without repenting God may forgive any sin except for committing shirk. [citation needed] In practice, especially among strict conservative interpretations of Islam, the term has been greatly extended and means deification of anyone or anything other than the singular God. [citation needed] In Salafi-Wahhabi interpretation, it may be used very widely to describe behaviour that does not literally constitute worship, including use of images of sentient beings, building a structure over a grave, associating partners with God, giving his characteristics to others beside him, or not believing in his characteristics.[citation needed] 19th century Wahhabis regarded idolatry punishable with the death penalty, a practice that was "hitherto unknown" in Islam.[108][109] However, Classical Orthodox Sunni thought used to be rich in Relics and Saint veneration, as well as pilgrimage to their shrines. Ibn Taymiyya, a medieval theologian that influenced modern days Salafists, was put in prison for his negation of veneration of relics and Saints, as well as pilgrimage to Shrines, which was considered unorthodox by his contemporary theologians. According to Islamic tradition, over the millennia after Ishmael's death, his progeny and the local tribes who settled around the oasis of Zam-Zam gradually turned to polytheism and idolatry. Several idols were placed within the Kaaba representing deities of different aspects of nature and different tribes. Several heretical rituals were adopted in the Pilgrimage (Hajj) including doing naked circumambulation.[110] In her book, Islam: A Short History, Karen Armstrong asserts that the Kaaba was officially dedicated to Hubal, a Nabatean deity, and contained 360 idols that probably represented the days of the year.[111] But by Muhammad's day, it seems that the Kaaba was venerated as the shrine of Allah, the High God. Allah was never represented by an idol.[112] Once a year, tribes from all around the Arabian peninsula, whether Christian or pagan, would converge on Mecca to perform the Hajj, marking the widespread conviction that Allah was the same deity worshipped by monotheists.[111] Guillaume in his translation of Ibn Ishaq, an early biographer of Muhammad, says the Ka'aba might have been itself addressed using a feminine grammatical form by the Quraysh.[113] Circumambulation was often performed naked by men and almost naked by women.[110] It is disputed whether al-Lat and Hubal were the same deity or different. Per a hypothesis by Uri Rubin and Christian Robin, Hubal was only venerated by Quraysh and the Kaaba was first dedicated to al-Lat, a supreme god of individuals belonging to different tribes, while the pantheon of the gods of Quraysh was installed in Kaaba after they conquered Mecca a century before Muhammad's time.[114] |

イスラム教 主な記事:シャイフク(イスラム教)とタグート 関連項目:イスラム教における偶像崇拝禁止と冒涜とイスラム教 イスラム教の文献において、シャイフク(三文字語根:sh-r-k)の概念は「偶像崇拝」を指すこともあるが、最も広く使われるのは「神に他の存在を並べ る行為」を意味する。[99] クフル(k-f-r)の概念もまた、偶像崇拝(その他の不信仰形態を含む)を含むことがある。[100][101] イスラム聖典において、シャイールクを実践する者はムシュリク(複数形ムシュリクーン)と呼ばれる。[102] クランは偶像崇拝を禁じている。[102] クランにはクフルとシャイールクが500回以上言及されており、[100][103] 両概念は強く禁じられている。[99] イスラムにおける偶像崇拝の概念は多神教を超え、一部のキリスト教徒やユダヤ教徒をもムシュリクーン(偶像崇拝者)やカフィルーン(不信仰者)に含める。[104][105] 例えば: 「アッラーはマリアの子メシアである」と言う者たちは、確かに不信仰に陥った。メシア自身は言った。「イスラエルの子孫よ!アッラーを崇拝せよ。彼はわが 主であり、汝らの主である。」アッラーに他を併せ祀る者は、必ずアッラーによって楽園を禁じられる。彼らの住まいは火獄である。そして悪を行う者には、助 け手はない。 — スーラ・アル=マーイダ 5:72 シーア派古典神学は、シルク(多神教)の概念において異なる。十二イマーム派の神学者によれば、神の属性と名は、神の存在と本質から独立した実体的な存在 を持たない。これらの属性や名が別個に存在すると考えることは、多神教を意味するとされる。神が本質に内在する知識によって知る、と言うことさえ誤りであ り、神は本質そのものである知識によって知るのである。また神には物理的な形はなく、感覚を持たない。[106] 理論上のタウヒードとシルクとの境界は、あらゆる実在と存在が、その本質、属性、行為において神(神性)から来ていると知ることである。それがタウヒード である。預言者たちの超自然的な行為は全て、クルアーンが示すように神の許可によるものである。実践におけるタウヒードとシルクとの境界は、何かを神(神 性)への道ではなく、神から独立した目的そのものとして想定することである。[107] イスマーイール派はシャイークの定義をさらに深く掘り下げ、人間が直観的知識を持つ秘教的潜在性による存在の根拠を一切認めないと宣言する。ゆえに、大多 数のシーア派は宗教的象徴や芸術作品、ワリー(聖者)、ラスール(使徒)、イマームへの敬意に何ら問題を抱かない。 イスラム教はあらゆる形態の偶像崇拝を強く禁じており、これはシャイーク(アラビア語: شرك)の罪の一部である。シャイークはアラビア語の語根Š-R-K(ش ر ك)に由来し、一般的な意味は「共有する」である。クルアーンの文脈では、「対等なパートナーとして共有する」という特定の意味は、通常「アッラーにパー トナーを帰属させること」と理解される。シャイークはしばしば偶像崇拝や多神教と訳される[99]。クルアーンにおいて、シャイークおよび関連語(複数 形・第4語幹・能動態分詞)ムシュリクーン(مشركون)「シャイークを犯す者たち」は、イスラムの敵を指す(9章1-15節など)。  『シーヤール・イ・ネビー』所収「カアバのムハンマド」。顔にベールをまとったムハンマドの描写、約1595年。 イスラム教において、シルクは犯した人格が神に赦しを請わなければ赦されない罪である。犯した人格が悔い改めずに死んだ場合、神はシルク以外のあらゆる罪 を赦すことがある。[出典必要] 実際には、特に厳格な保守的解釈のイスラム教徒の間では、この用語の意味が大きく拡大され、唯一の神以外の誰かや何かを神格化することを指すようになっ た。[出典必要] サラフィー・ワッハーブ派の解釈では、文字通り崇拝を構成しない行為を広く指す場合がある。これには、知覚ある存在の像の使用、墓の上に建造物を建てる行 為、神に同等の存在を結びつける行為、神の特性を神以外の者に与える行為、あるいは神の特性を信じない行為などが含まれる。[出典必要] 19世紀のワッハーブ派は偶像崇拝を死刑に値する罪と見なし、これはイスラムにおいて「これまで知られていなかった」慣行であった。[108][109] しかし古典的な正統スンニ派思想は、聖遺物や聖人崇敬、聖堂巡礼に富んでいた。現代のサラフィストに影響を与えた中世神学者イブン・タイミーヤは、聖遺物 や聖人崇敬、聖堂巡礼を否定したため投獄された。当時の神学者たちはこれを異端と見なしたのである。 イスラムの伝統によれば、イシュマエルの死後、数千年の間に、彼の子孫とザムザムのオアシス周辺に定住した地元の部族は、徐々に多神教と偶像崇拝へと転じ ていった。カアバには、自然の異なる側面や異なる部族の神々を表すいくつかの偶像が置かれた。巡礼(ハッジ)では、裸で巡礼を行うなど、いくつかの異端的 な儀礼が採用された。[110] カレン・アームストロングは著書『イスラム教:その短い歴史』の中で、カアバはナバテアの神フバルに正式に捧げられており、おそらく1年の日数を表す 360体の偶像が安置されていたと主張している[111]。しかし、ムハンマドの時代には、カアバは最高神アッラーの聖堂として崇拝されていたようだ。 アッラーは偶像で表現されることは決してなかった。[112] 年に一度、アラビア半島中の部族が、キリスト教徒であれ異教徒であれ、メッカに集まり、ハッジを行った。これは、アッラーが一神教徒が崇拝する神と同じ神 であるという広範な信念を物語っている。[111] ムハンマドの初期伝記作家イブン・イシャークの翻訳者ギヨームによれば、クライシュ族はカアバ自体を女性形の文法形態で呼んでいた可能性がある [113]。巡礼の周回は男性は裸で、女性はほぼ裸で行われることが多かった[110]。アル=ラートとフバルが同一の神か異なる神かは議論の余地があ る。ウリ・ルービンとクリスチャン・ロビンの仮説によれば、フバルはクライシュ族のみが崇拝し、カアバは当初、異なる部族に属する個人たちの最高神である アル・ラートに捧げられていた。クライシュ族の神々の神殿は、ムハンマドの時代より一世紀前に彼らがメッカを征服した後、カアバに設置されたのである。 [114] |

| Dharmic religions Provenance The first attested date in peer-reviewed academic literature for the worship of murti (Sanskrit) or vigraha (Sanskrit) in India is not clear, as different sources have different opinions and interpretations. However, the Indus Valley Civilization (circa 2500 - 1500 BCE) may have produced some of the earliest murtis or vigrahas in India, as evidenced by various terracotta and bronze figurines found in the archaeological sites. Some of these figurines have been interpreted as representations of deities, such as the so-called Pashupati seal, which depicts a horned figure surrounded by animals and possibly identified with Shiva. Another example is the bronze statuette of a Dancing Girl, which some scholars have associated with Parvati or Shakti. However, these interpretations are not universally accepted, and some scholars have argued that the Indus Valley Civilization did not practice murti or vigraha worship, but rather used symbols and signs to express their religious beliefs.[115] The Vedic period (circa 1500 - 500 BCE) is traditionally considered as the origin of Hinduism proper, but it also did not emphasize murti or vigraha worship, as the Vedic religion was mainly focused on fire sacrifices and hymns to various gods and goddesses. However, some Vedic texts do mention the use of clay or wooden images for ritual purposes, such as the Shatapatha Brahmana (circa 8th - 6th century BCE), which describes how a clay image of Prajapati (the creator god) was made and consecrated for the agnicayana ritual. Another example is the Aitareya Brahmana (circa 8th - 6th century BCE), which mentions how a wooden image of Varuna (the god of water and law) was installed in a temple and worshipped by the king. These examples suggest that murti or vigraha worship was not unknown in the Vedic period, but it was not widespread nor dominant.[115] The post-Vedic period (circa 500 BCE - 300 CE) witnessed the emergence and development of various religious movements and schools, such as Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Shaktism, Buddhism, Jainism and others. This period also saw the rise of murti or vigraha worship as a prominent feature of Hinduism, as evidenced by various literary and archaeological sources. For instance, the Ramayana (circa 5th - 4th century BCE) and the Mahabharata (circa 4th - 3rd century BCE) contain several references to murti or vigraha worship, such as Rama worshipping a Shiva linga at Rameshwaram, or Krishna installing an image of Vishnu at Dwarka. Another example is the Buddhist text Lalitavistara Sutra (circa 3rd century BCE - 3rd century CE), which mentions how Buddha's mother Maya dreamt of a white elephant entering her womb, and how King Suddhodana made an image of this elephant and worshipped it. Moreover, many stone and metal sculptures of various deities and saints have been found from this period onwards, such as the famous Pancha Rathas at Mahabalipuram (circa 7th century CE), which depict five chariots dedicated to different gods and goddesses.[115] General The oldest forms of the ancient religions of India apparently made no use of idols. While the Vedic literature leading up to Hinduism is extensive, in the form of Samhitas, Brahmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads, and has been dated to have been composed over a period of centuries (1200 BC to 200 BC),[116] historical Vedic religion appears not to have used idols up to around 500 BC at least. The early Buddhist and Jain (pre-200 BC) traditions suggest no evidence of idolatry. The Vedic literature mentions many gods and goddesses, as well as the use of Homa (votive ritual using fire), but it does not mention images or their worship.[116][117] The ancient Buddhist, Hindu and Jaina texts discuss the nature of existence, whether there is or is not a creator deity such as in the Nasadiya Sukta of the Rigveda, they describe meditation, they recommend the pursuit of simple monastic life and self-knowledge, they debate the nature of absolute reality as Brahman or Śūnyatā, yet the ancient Indian texts mention no use of images. Indologists such as the Max Muller, Jan Gonda, Pandurang Vaman Kane, Ramchandra Narayan Dandekar, Horace Hayman Wilson, Stephanie Jamison and other scholars state that "there is no evidence for icons or images representing god(s)" in the ancient religions of India. Use of idols developed among the Indian religions later,[116][118] perhaps first in Buddhism, where large images of the Buddha appear by the 1st century AD. According to John Grimes, a professor of Indian philosophy, Indian thought denied even dogmatic idolatry of its scriptures. Everything has been left to challenge, arguments and enquiry, with the medieval Indian scholar Vācaspati Miśra stating that not all scripture is authoritative, only scripture which "reveals the identity of the individual self and the supreme self as the non-dual Absolute".[119] |

ダルマ宗教 起源 インドにおけるムルティ(サンスクリット語)またはヴィグラハ(サンスクリット語)の崇拝が学術文献で初めて確認された時期は、資料によって見解や解釈が 異なるため、明確ではない。しかし、インダス文明(紀元前2500年~1500年頃)は、考古学遺跡で発見された様々なテラコッタや青銅の置物から、イン ドにおける最も初期のムルティやヴィグラハを生み出した可能性がある。これらの像の中には、いわゆるパシュパティ印章のように、動物に囲まれた角のある姿 を描いたものなど、神々の表現と解釈されるものもある。これはおそらくシヴァ神と同一視されている。別の例として、踊る少女の青銅像がある。一部の学者は これをパールヴァティーまたはシャクティに関連づけている。しかし、これらの解釈は普遍的に受け入れられているわけではなく、インダス文明はムルティや ヴィグラハの崇拝を行わず、むしろ象徴や記号を用いて宗教的信念を表現していたと主張する学者もいる。[115] ヴェーダ時代(紀元前1500年~500年頃)は伝統的にヒンドゥー教の起源とされるが、この時代もムルティやヴィグラハ崇拝を重視しなかった。ヴェーダ 宗教は主に火の犠牲と諸神への賛歌に焦点を当てていたからである。ただし、一部のヴェーダ文献では儀礼用の粘土像や木像の使用に言及している。例えば 『シャタパタ・ブラフマナ』(紀元前8~6世紀頃)は、創造神プラジャパティの粘土像がアグニチャヤナ儀礼のために如何に作られ、聖別されたかを記述して いる。別の例として、アイテーリヤ・ブラフマナ(紀元前8~6世紀頃)には、ヴァルナ(水と法の神)の木像が寺院に安置され、王によって礼拝されたことが 記されている。これらの事例は、ヴェーダ時代においてムルティやヴィグラハの礼拝が全く知られていなかったわけではないが、広く普及していたわけでも支配 的でもなかったことを示唆している。[115] ヴェーダ後期(紀元前500年頃~紀元300年頃)には、ヴァイシュナヴァ派、シャイヴァ派、シャクティ派、仏教、ジャイナ教など様々な宗教運動や学派が 出現し発展した。この時期には、様々な文献や考古学的資料が示すように、ムルティ(ヴィグラハ)崇拝がヒンドゥー教の顕著な特徴として台頭した。例えば 『ラーマーヤナ』(紀元前5~4世紀頃)や『マハーバーラタ』(紀元前4~3世紀頃)には、ラーマがラーメシュワラムでシヴァ・リンガを礼拝した話や、ク リシュナがドワルカにヴィシュヌ像を安置した話など、ムルティ(ヴィグラハ)崇拝に関する記述が複数見られる。別の例として、仏教経典『ラリタヴィシュタ ラ経』(紀元前3世紀~紀元後3世紀頃)には、仏陀の母マヤが白い象が胎内に入る夢を見たこと、そして父スッドダナ王がこの象の像を作り礼拝したことが記 されている。さらに、この時代以降、様々な神々や聖者を描いた石像や金属像が数多く発見されている。例えばマハーバリプラムにある有名なパンチャ・ラータ ス(7世紀頃)は、五つの戦車を表現したもので、それぞれ異なる神々や女神に捧げられている。[115] 一般論 インドの古代宗教の最も古い形態は、明らかに偶像を使用していなかった。ヒンドゥー教へと至るヴェーダ文献は、サムヒター、ブラフマナ、アーラニャカ、ウ パニシャッドといった形で膨大であり、その成立は数世紀(紀元前1200年から紀元前200年)にわたるとされている[116]。しかし歴史的なヴェーダ 宗教は、少なくとも紀元前500年頃までは偶像を使用していなかったようだ。初期仏教とジャイナ教(紀元前200年以前)の伝統には偶像崇拝の証拠は見ら れない。ヴェーダ文献は多くの神々や女神、火を用いた奉納儀礼(ホーマー)について言及しているが、像やその崇拝については触れていない。[116] [117] 古代の仏教、ヒンドゥー教、ジャイナ教の経典は、存在の本質、リグ・ヴェーダのナサディヤ・スクタのような創造神の存在の有無について論じ、瞑想について 述べ、質素な修道生活と自己認識の追求を勧め、ブラフマンやシュンヤタとしての絶対的現実の本質について論じているが、古代インドの経典は像の使用につい て一切言及していない。マックス・ミュラー、ヤン・ゴンダ、パンドゥラン・ヴァマン・ケイン、ラムチャンドラ・ナラヤン・ダンデカル、ホラティウス・ヘイ マン・ウィルソン、ステファニー・ジャミソンなどのインド学者たちは、インドの古代宗教には「神々を表す偶像や像の存在を示す証拠はない」と述べている。 偶像の使用は、後にインドの宗教の中で発展した[116][118]、おそらくは仏教で最初であり、1世紀までに大きな仏像が登場している。 インド哲学の教授であるジョン・グライムズによれば、インドの思想は、その聖典に対する教条的な偶像崇拝さえも否定していた。すべては、挑戦、議論、探究 に委ねられており、中世インドの学者ヴァーカスパティ・ミシュラは、すべての聖典が権威あるものではなく、「個々の自己と至高の自己を非二元的な絶対者と して明らかにする」聖典だけが権威あるものであると述べている。 |

| Buddhism See also: Aniconism in Buddhism Buddhists praying before a statue in Tibet (left) and Vietnam According to Eric Reinders, icons and idolatry have been an integral part of Buddhism throughout its later history.[120] Buddhists, from Korea to Vietnam, Thailand to Tibet, Central Asia to South Asia, have long produced temples and idols, altars and malas, relics to amulets, images to ritual implements.[120][121][122] The images or relics of Buddha are found in all Buddhist traditions, but they also feature gods and goddesses such as those in Tibetan Buddhism.[120][123] Bhakti (called Bhatti in Pali) has been a common practice in Theravada Buddhism, where offerings and group prayers are made to Cetiya and particularly images of Buddha.[124][125] Karel Werner notes that Bhakti has been a significant practice in Theravada Buddhism, and states, "there can be no doubt that deep devotion or bhakti / bhatti does exist in Buddhism and that it had its beginnings in the earliest days".[126] According to Peter Harvey – a professor of Buddhist Studies, Buddha idols and idolatry spread into northwest Indian subcontinent (now Pakistan and Afghanistan) and into Central Asia with Buddhist Silk Road merchants.[127] The Hindu rulers of different Indian dynasties patronized both Buddhism and Hinduism from 4th to 9th century, building Buddhist icons and cave temples such as the Ajanta Caves and Ellora Caves which featured Buddha idols.[128][129][130] From the 10th century, states Harvey, the raids into northwestern parts of South Asia by Muslim Turks destroyed Buddhist idols, given their religious dislike for idolatry. The iconoclasm was so linked to Buddhism, that the Islamic texts of this era in India called all idols as Budd.[127] The desecration of idols in cave temples continued through the 17th century, states Geri Malandra, from the offense of "the graphic, anthropomorphic imagery of Hindu and Buddhist shrines".[130][131] In East Asia and Southeast Asia, worship in Buddhist temples with the aid of icons and sacred objects has been historic.[132] In Japanese Buddhism, for example, Butsugu (sacred objects) have been integral to the worship of the Buddha (kuyo), and such idolatry considered a part of the process of realizing one's Buddha nature. This process is more than meditation, it has traditionally included devotional rituals (butsudo) aided by the Buddhist clergy.[132] These practices are also found in Korea and China.[122][132] Hinduism Main article: Murti Ganesha statue during a contemporary festival (left), and Bhakti saint Meera singing before an image of Krishna In Hinduism, an icon, image or statue is called murti or pratima.[8][133] Major Hindu traditions such as Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Shaktism, and Smartism favor the use of a murti (idol). These traditions suggest that it is easier to dedicate time and focus on spirituality through anthropomorphic or non-anthropomorphic icons. The Bhagavad Gita – a Hindu scripture, in verse 12.5, states that only a few have the time and mind to ponder and fix on the unmanifested Absolute (abstract formless Brahman), and it is much easier to focus on qualities, virtues, aspects of a manifested representation of god, through one's senses, emotions and heart, because the way human beings naturally are.[134][135] A murti in Hinduism, states Jeaneane Fowler – a professor of Religious Studies specializing on Indian Religions, is itself not god, it is an "image of god" and thus a symbol and representation.[8] A murti is a form and manifestation, states Fowler, of the formless Absolute.[8] Thus a literal translation of murti as idol is incorrect, when idol is understood as superstitious end in itself. Just like the photograph of a person is not the real person, a murti is an image in Hinduism but not the real thing, but in both cases the image reminds of something of emotional and real value to the viewer.[8] When a person worships a murti, it is assumed to be a manifestation of the essence or spirit of the deity, the worshipper's spiritual ideas and needs are meditated through it, yet the idea of ultimate reality – called Brahman in Hinduism – is not confined in it.[8] Devotional (bhakti movement) practices centered on cultivating a deep and personal bond of love with God, often expressed and facilitated with one or more murti, and includes individual or community hymns, japa or singing (bhajan, kirtana, or arati). Acts of devotion, in major temples particularly, are structured on treating the murti as the manifestation of a revered guest,[11] and the daily routine can include awakening the murti in the morning and making sure that it "is washed, dressed, and garlanded."[136][137][Note 1] In Vaishnavism, the building of a temple for the murti is considered an act of devotion, but non-murti symbolism is also common wherein the aromatic tulasi plant or shaligrama is an aniconic reminder of the spiritualism in Vishnu.[136] In the Shaivism tradition of Hinduism, Shiva may be represented as a masculine idol, or half-man half woman Ardhanarishvara form, in an anicon linga-yoni form. The worship rituals associated with the murti, correspond to ancient cultural practices for a beloved guest, and the murti is welcomed, taken care of, and then requested to retire.[138][139] Christopher John Fuller states that an image in Hinduism cannot be equated with a deity and the object of worship is the divine whose power is inside the image, and the image is not the object of worship itself, Hindus believe everything is worthy of worship as it contains divine energy.[140] The idols are neither random nor intended as superstitious objects, rather they are designed with embedded symbolism and iconographic rules which sets the style, proportions, the colors, the nature of items the images carry, their mudra and the legends associated with the deity.[140][141][142] The Vāstusūtra Upaniṣad states that the aim of the murti art is to inspire a devotee towards contemplating the Ultimate Supreme Principle (Brahman).[142] This text adds (abridged): From the contemplation of images grows delight, from delight faith, from faith steadfast devotion, through such devotion arises that higher understanding (parāvidyā) that is the royal road to moksha. Without the guidance of images, the mind of the devotee may go ashtray and form wrong imaginations. Images dispel false imaginations. (... ) It is in the mind of Rishis (sages), who see and have the power of discerning the essence of all created things of manifested forms. They see their different characters, the divine and the demoniac, the creative and the destructive forces, in their eternal interplay. It is this vision of Rishis, of gigantic drama of cosmic powers in eternal conflict, which the Sthapakas (Silpins, murti and temple artists) drew the subject-matter for their work. — Pippalada, Vāstusūtra Upaniṣad, Introduction by Alice Boner et al.[143] Some Hindu movements founded during the colonial era, such as the Arya Samaj and Satya Mahima Dharma reject idolatry.[144][145][146] Jainism Gomateshwara Bahubali statue in Jainism Devotional idolatry has been a prevalent ancient practice in various Jaina sects, wherein learned Tirthankara (Jina) and human gurus have been venerated with offerings, songs and Āratī prayers.[147] Like other major Indian religions, Jainism has premised its spiritual practices on the belief that "all knowledge is inevitably mediated by images" and human beings discover, learn and know what is to be known through "names, images and representations". Thus, idolatry has been a part of the major sects of Jainism such as Digambara and Shvetambara.[148] The earliest archaeological evidence of the idols and images in Jainism is from Mathura, and has been dated to be from the first half of the 1st millennium AD.[149] The creation of idols, their consecration, the inclusion of Jaina layperson in idols and temples of Jainism by the Jaina monks has been a historic practice.[148] However, during the iconoclastic era of Islamic rule, between the 15th and 17th century, a Lonka sect of Jainism emerged that continued pursuing their traditional spirituality but without the Jaina arts, images and idols.[150] Sikhism Main article: Idolatry in Sikhism Sikhism is a monotheistic Indian religion, and Sikh temples are devoid of idols and icons for God.[151][152] Yet, Sikhism strongly encourages devotion to God.[153][154] Some scholars call Sikhism a Bhakti sect of Indian traditions.[155][156] In Sikhism, "Nirguni Bhakti" is emphasised – devotion to a divine without Gunas (qualities or form),[156][157][158] but its scripture also accepts representations of God with formless (nirguni) and with form (saguni), as stated in Adi Granth 287.[159][160] Sikhism condemns worshipping images or statues as if it were God,[161] but have historically challenged the iconoclastic policies and Hindu temple destruction activities of Islamic rulers in India.[162] Sikhs house their scripture and revere the Guru Granth Sahib as the final Guru of Sikhism.[163] It is installed in Sikh Gurdwara (temple), many Sikhs bow or prostrate before it on entering the gurdwara.[Note 1] Guru Granth Sahib is ritually installed every morning, and put to bed at night in many Gurdwaras.[170][171][172] In the Dasam Bani, Guru Gobind Singh wrote "I am idol-breaker" on line 95 of his Zafarnamah.[173] |

仏教 関連項目: 仏教における偶像崇拝の否定 チベット(左)とベトナムで仏像の前で祈る仏教徒 エリック・ラインダースによれば、仏教の後の歴史を通じて、偶像と偶像崇拝は仏教の不可欠な部分であった[120]。韓国からベトナム、タイからチベッ ト、中央アジアから南アジアに至る仏教徒は、長い間、寺院や偶像、祭壇や数珠、遺物から護符、像から儀礼用具までを作り出してきた[120][121]。 [122] 仏像や仏舎利は全ての仏教伝統に見られるが、チベット仏教のように神々や女神も特徴的である。[120][123] バクティ(パーリ語でバッティ)は上座部仏教において一般的な実践であり、チェーティヤ(仏塔)や特に仏像への供養と集団礼拝が行われる。[124] [125] カレル・ヴェルナーは、バクティが上座部仏教において重要な実践であったと指摘し、「深い信仰心、すなわちバクティ/バッティが仏教に確かに存在し、その 起源が最も初期の時代に遡ることは疑いようがない」と述べている。[126] 仏教学教授ピーター・ハーヴェイによれば、仏像と偶像崇拝は仏教シルクロード商人によってインド亜大陸北西部(現在のパキスタン・アフガニスタン)及び中 央アジアへ伝播した[127]。4世紀から9世紀にかけて、異なるインド各王朝のヒンドゥー教支配者たちは仏教とヒンドゥー教の両方を庇護し、アジャンタ 石窟やエローラ石窟など仏像を祀る仏教の偶像や石窟寺院を建立した。[128][129][130] ハーヴェイによれば、10世紀以降、イスラム教徒のトルコ人による南アジア北西部への襲撃が仏教の偶像を破壊した。彼らは偶像崇拝を宗教的に忌避したから だ。この偶像破壊運動は仏教と深く結びついていたため、当時のインドにおけるイスラム教の文献では、あらゆる偶像を「ブッダ」と呼んでいた[127]。洞 窟寺院における偶像の冒涜は17世紀まで続いたとゲリ・マランドラは述べており、その理由は「ヒンドゥー教と仏教の聖堂における、具体的かつ擬人化された 造像」に対する冒涜行為であった[130][131]。 東アジアと東南アジアでは、仏教寺院における偶像や聖具を用いた礼拝は歴史的に行われてきた[132]。例えば日本仏教では、仏具(聖具)は仏礼拝(供 養)に不可欠であり、こうした偶像崇拝は自らの仏性を悟る過程の一部と見なされてきた。この過程は単なる瞑想を超え、伝統的に僧侶による儀礼(仏道)を 伴ってきた。[132] こうした実践は韓国や中国でも見られる。[122][132] ヒンドゥー教 詳細記事: ムルティ 現代の祭典におけるガネーシャ像(左)、クリシュナ像の前で歌うバクティ聖者ミーラ ヒンドゥー教において、偶像や像はムルティ(murti)またはプラティマ(pratima)と呼ばれる[8][133]。ヴァイシュナヴァ派、シャイ ヴァ派、シャクティ派、スマルタ派といった主要なヒンドゥー教派はムルティ(偶像)の使用を好む。これらの教派は、擬人化された像や非擬人化された像を通 じて、時間を捧げ精神性に集中することが容易であると示唆している。ヒンドゥー教の聖典『バガヴァッド・ギーター』12.5節は、顕現しない絶対者(抽象 的で形のないブラフマン)を思索し心に留める時間と精神を持つ者はごく少数だと述べている。人間の自然なあり方ゆえに、感覚や感情、心を通じて神の顕現し た姿の性質や徳、側面へ集中する方がはるかに容易だとするのだ[134]。[135] ヒンドゥー教におけるムルティについて、インド宗教を専門とする宗教学教授ジーン・ファウラーは、それ自体が神ではなく「神の像」であり、したがって象徴 であり表現であると述べている。[8] フォーラーによれば、ムルティは無形の絶対者の形と顕現である[8]。したがって、偶像を迷信的な目的そのものとして理解する場合、ムルティを文字通り 「偶像」と訳すのは誤りだ。人の写真が人格ではないのと同様に、ヒンドゥー教におけるムルティは実体ではなく像であるが、いずれの場合もその像は観る者に とって感情的・現実的な価値を持つ何かを思い起こさせる。[8] 人格がムルティを崇拝する際、それは神の本質や霊の顕現と見なされる。崇拝者の精神的観念や欲求はそれを通じて瞑想されるが、究極の現実(ヒンドゥー教で はブラフマンと呼ばれる)の観念はそれに閉じ込められてはいない。[8] バクティ(献身)運動の修行は、神との深く個人的な愛の絆を育むことに焦点を当てている。これはしばしば一つ以上のムルティを用いて表現・促進され、個人 または共同体の賛歌、ジャパ(数珠つなぎの唱和)、歌唱(バジャン、キルタナ、またはアーラティ)を含む。特に主要な寺院における奉仕行為は、ムルティを 尊ばれる客人の現れとして扱うことに基づいている[11]。日常の儀式には、朝にムルティを起こし、「洗われ、着せられ、花輪をかけられる」ことを確認す ることが含まれる[136][137][注1]。 ヴァイシュナヴァ派では、ムルティのための寺院を建てることも信仰行為と見なされるが、ムルティ以外の象徴も一般的である。例えば、芳香のあるトゥラシ (聖なるバジリカ)やシャリグラマ(聖なる石)は、ヴィシュヌの霊性を無像的に想起させるものである。[136] ヒンドゥー教のシャイヴィズム伝統では、シヴァは男性像、半男半女のアルダナーリシュヴァラ像、あるいは無像のリンガ・ヨニ像として表される。ムルティに 関連する儀礼は、古来の文化における賓客をもてなす慣習に対応し、ムルティは歓迎され、世話され、そして退去を求められる。[138][139] クリストファー・ジョン・フラーは、ヒンドゥー教における像は神そのものと同一視できず、崇拝の対象は像内に宿る神聖な力であり、像自体が崇拝の対象では ないと述べる。ヒンドゥー教徒は、あらゆるものに神聖なエネルギーが宿るため、全てが崇拝に値すると信じている。[140] 偶像は恣意的に作られたものでも、迷信的な対象として意図されたものでもない。むしろ、様式、比例、色彩、像が携える物品の性質、その印(ムドラ)、そし て神に関連する伝説を定める、埋め込まれた象徴性と図像学的規則に基づいて設計されている。[140][141][142] 『ヴァストゥー・スートラ・ウパニシャッド』は、ムルティ芸術の目的は、信者を究極の至高原理(ブラフマン)の観想へと導くことにあると述べる。 [142] この経典は次のように補足する(要約): 像の観想から喜びが生まれ、喜びから信仰が生まれ、信仰から揺るぎない献身が生まれる。そのような献身を通じて、解脱への王道たる高次の理解(パラヴィ ディヤ)が生じる。像の導きなくして、信者の心は誤った道(アシュトラ)へ迷い、誤った想像を形成するかもしれない。像は誤った想像を払拭する。 (...) それはリシ(聖者)の心の中にある。彼らは顕現した形を持つ全ての創造物の本質を見抜き、識別する力を持つ。彼らはそれらの異なる性質、神聖なるものと悪 魔的なもの、創造的な力と破壊的な力を、永遠の相互作用の中で見るのだ。このリシたちの視座、すなわち永遠の葛藤を続ける宇宙の力による巨大なドラマこそ が、シュタパカ(彫刻家、ムルティ(神像)や寺院の芸術家)たちが作品の主題として描いたものである。 — ピッパラダ、『ヴァストゥー・スートラ・ウパニシャッド』、アリス・ボナー他による序文 [143] 植民地時代に創設されたアーリヤ・サマージやサティヤ・マヒマ・ダルマといった一部のヒンドゥー運動は偶像崇拝を拒否している。[144][145] [146] ジャイナ教 ジャイナ教におけるゴマテーシュワラ・バフバリ像 様々なジャイナ教派において、信仰に基づく偶像崇拝は古代から広く行われてきた。そこでは、学識あるティルタンカラ(ジーナ)や人間のグルが、供物や歌、 アーラティーの祈りによって崇敬されてきた。[147] 他の主要なインド宗教と同様に、ジャイナ教も「あらゆる知識は必然的にイメージを介して伝達される」という信念を精神的実践の前提としている。人間は「名 称、イメージ、表現」を通じて知られうるものを発見し、学び、認識するのだ。したがって、偶像崇拝はディガンバラ派やシュヴェータンバラ派といったジャイ ナ教の主要宗派の一部であった。[148] ジャイナ教における偶像や像の最も古い考古学的証拠はマトゥラーから発見され、紀元後1千年紀前半のものと年代測定されている。[149] 偶像の制作、その奉献、そしてジャイナ教徒の僧侶によるジャイナ教徒の一般信徒を偶像や寺院に包含する行為は、歴史的な慣行であった。[148] しかし、15世紀から17世紀にかけてのイスラム支配下の偶像破壊運動の時代には、ジャイナ教のロンカ派が台頭し、彼らは伝統的な精神性を追求し続けた が、ジャイナ教の芸術、像、偶像は用いなかった。[150] シク教 詳細記事: シク教における偶像崇拝 シク教は一神教のインド宗教であり、シク教寺院には神を象徴する偶像や像は存在しない。[151][152] しかしながら、シク教は神への献身を強く推奨している。[153][154] 一部の学者はシク教をインド伝統におけるバクティ(献身)宗派と呼ぶ。[155] [156] シク教では「ニルグニ・バクティ」が強調される。これはグナ(属性や形)を持たない神への信仰を指す。[156][157][158] しかしその聖典は、アディ・グラント287に記されているように、形を持たない(ニルグニ)神と形を持つ(サグニ)神の表現も認めている。[159] [160] シク教は像や彫像を神そのものとして崇拝することを非難する[161]が、歴史的にインドにおけるイスラム支配者たちの偶像破壊政策やヒンドゥー寺院破壊 活動に異議を唱えてきた[162]。シク教徒は聖典を安置し、グル・グラント・サーヒブをシク教の最終的なグルとして崇敬する。[163] グルドワラ(寺院)に安置されており、多くのシク教徒はグルドワラに入る際、これに向かって頭を下げたり、ひれ伏したりする。[注1] 多くのグルドワラでは、グル・グラント・サーヒブは毎朝儀礼的に安置され、夜には寝かせられる。[170][171] [172] ダサム・バニにおいて、グル・ゴビンド・シンはザファルナーマの第95行に「私は偶像破壊者である」と記した。[173] |

| Chinese and Sinosphere Traditions [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2022) Japan In Japan, there are images of some kami (i.e. deities) such as those of Fūjin and Raijin at the Buddhist temple Sanjūsangen-dō. North Korean Juche Main article: Juche Kim Il Sung instituted worship of himself amongst the citizens of North Korea, and this act is considered the only instance of a modern country deifying its ruler.[174][175][176] As many citizens frequently bow before statues and portraits of him, scholars have considered the Juche state religion to be a form of idolatry.[177][178][179] |

中国と中華圏の伝統 [icon] この節は拡充が必要である。追加して貢献できる。(2022年8月) 日本 日本では、仏教寺院の三十三間堂に風神や雷神などの神々の像がある。 北朝鮮の主体思想 主な記事:主体思想 金日成は北朝鮮の市民の間で自身への崇拝を確立し、この行為は現代国家が統治者を神格化した唯一の事例と見なされている。[174][175][176] 多くの市民が頻繁に彼の像や肖像画に頭を垂れることから、学者らは主体思想国家宗教を偶像崇拝の一形態と見なしている。[177][178][179] |

| Traditional religions Africa See also: Traditional African religions An Orisha deity (left) and an artwork depicting a kneeling female worshipper with child, by Yoruba people Africa has numerous ethnic groups, and their diverse religious idea have been grouped as African Traditional Religions, sometimes abbreviated to ATR. These religions typically believe in a Supreme Being which goes by different regional names, as well as spirit world often linked to ancestors, and mystical magical powers through divination.[180] Idols and their worship have been associated with all three components in the African Traditional Religions.[181] According to J.O. Awolalu, proselytizing Christians and Muslims have mislabelled idol to mean false god, when in the reality of most traditions of Africa, the object may be a piece of wood or iron or stone, yet it is "symbolic, an emblem and implies the spiritual idea which is worshipped".[182] The material objects may decay or get destroyed, the emblem may crumble or substituted, but the spiritual idea that it represents to the heart and mind of an African traditionalist remains unchanged.[182] Sylvester Johnson – a professor of African American and Religious Studies, concurs with Awolalu, and states that the colonial era missionaries who arrived in Africa, neither understood the regional languages nor the African theology, and interpreted the images and ritualism as "epitome of idolatry", projecting the iconoclastic controversies in Europe they grew up with, onto Africa.[183] First with the arrival of Islam in Africa, then during the Christian colonial efforts, the religiously justified wars, the colonial portrayal of idolatry as proof of savagery, the destruction of idols and the seizure of idolaters as slaves marked a long period of religious intolerance, which supported religious violence and demeaning caricature of the African Traditional Religionists.[184][185][186] The violence against idolaters and idolatry of Traditional Religion practicers of Africa started in the medieval era and continued into the modern era.[187][188][189] The charge of idolatry by proselytizers, state Michael Wayne Cole and Rebecca Zorach, served to demonize and dehumanize local African populations, and justify their enslavement and abuse locally or far off plantations, settlements or for forced domestic labor.[190][191] Americas Inti Raymi, a winter solstice festival of the Inca people, reveres Inti – the sun deity. Offerings include round bread and maize beer.[192] Statues, images and temples have been a part of the Traditional Religions of the indigenous people of the Americas.[193][194][195] The Incan, Mayan and Aztec civilizations developed sophisticated religious practices that incorporated idols and religious arts.[195] The Inca culture, for example, has believed in Viracocha (also called Pachacutec) as the creator deity and nature deities such as Inti (sun deity), and Mama Cocha the goddess of the sea, lakes, rivers and waters.[196][197][198] The Aztec Tula Atlantean statues (above) have been called as symbols of idolatry, but may have just been stone images of warriors.[199] In Mayan culture, Kukulkan has been the supreme creator deity, also revered as the god of reincarnation, water, fertility and wind.[200] The Mayan people built step pyramid temples to honor Kukulkan, aligning them to the Sun's position on the spring equinox.[201] Other deities found at Mayan archaeological sites include Xib Chac – the benevolent male rain deity, and Ixchel – the benevolent female earth, weaving and pregnancy goddess.[201] A deity with aspects similar to Kulkulkan in the Aztec culture has been called Quetzalcoatl.[200] Missionaries came to the Americas with the start of Spanish colonial era, and the Catholic Church did not tolerate any form of native idolatry, preferring that the icons and images of Jesus and Mary replace the native idols.[94][202][193] Aztec, for example, had a written history which included those about their Traditional Religion, but the Spanish colonialists destroyed this written history in their zeal to end what they considered as idolatry, and to convert the Aztecs to Catholicism. The Aztec Indians, however, preserved their religion and religious practices by burying their idols under the crosses, and then continuing their idol worship rituals and practices, aided by the syncretic composite of atrial crosses and their idols as before.[203] During and after the imposition of Catholic Christianity during Spanish colonialism, the Incan people retained their original beliefs in deities through syncretism, where they overlay the Christian God and teachings over their original beliefs and practices.[204][205][206] The male deity Inti became accepted as the Christian God, but the Andean rituals centered around idolatry of Incan deities have been retained and continued thereafter into the modern era by the Incan people.[206][207] Philippines Igorot hipag depicting war deities (c. 1900) Anito in modern Filipino context can mean idolatry or an idol of heathen deity[208][209][210] Anito worship in ancient Philippines involves venerating carved images often made from wood that represent ancestral spirits and ancestral deities. These wooden figures, known as anito or sometimes bulul among certain groups like the Ifugao, were believed to embody the presence or power of the spirits they represent. Indigenous Filipinos offered prayers, food, and rituals to these images, treating them not merely as symbols but as actual vessels or manifestations of the supernatural. This act of directing devotion and reverence toward physical objects, as though the spirit resided within or could be influenced through them, classifies the practice as idolatry in many theological frameworks, particularly those that distinguish between worship of a supreme being and veneration of material representations.[211][212][213][214][215][216] Polynesia The Polynesian people have had a range of polytheistic theologies found across the Pacific Ocean. The Polynesian people produced idols from wood, and congregated around these idols for worship.[217][218] The Christian missionaries, particularly from the London Missionary Society such as John Williams, and others such as the Methodist Missionary Society, characterized these as idolatry, in the sense of islanders worshipping false gods. They sent back reports which primarily focussed on "overthrow of pagan idolatry" as evidence of their Christian sects triumph, with fewer mentions of actual converts and baptism.[219][220] Religious tolerance and intolerance The term false god is often used throughout the Abrahamic scriptures (Torah, Tanakh, Bible, and Quran) to single out Yahweh[221] (interpreted by Jews, Samaritans, and Christians) or Elohim/Allah[222] (interpreted by Muslims) as the only true God.[4] Nevertheless, the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament itself recognizes and reports that originally the Israelites were not monotheists but actively engaged in idolatry and worshipped many foreign, non-Jewish Gods besides Yahweh and/or instead of him,[223] such as Baal, Astarte, Asherah, Chemosh, Dagon, Moloch, Tammuz, and more, and continued to do so until their return from the Babylonian exile[221] (see Ancient Hebrew religion). Judaism, the oldest Abrahamic religion, eventually shifted into a strict, exclusive monotheism,[5] based on the sole veneration of Yahweh,[224][225][226] the predecessor to the Abrahamic conception of God.[Note 2] The vast majority of religions in history have been and/or are still polytheistic, worshipping many diverse deities.[230] Moreover, the material depiction of a deity or more deities has always played an eminent role in all cultures of the world.[7] The claim to worship the "one and only true God" came to most of the world with the arrival of Abrahamic religions and is the distinguishing characteristic of their monotheistic worldview,[5][230][231][232] whereas virtually all the other religions in the world have been and/or are still animistic and polytheistic.[230] Some Neopagan religions such as Wicca utilize statues of deities within their worship experience.[233] The accusations and presumption that all idols and images are devoid of symbolism, or that icons of one's own religion are "true, healthy, uplifting, beautiful symbolism, mark of devotion, divine", while of other person's religion are "false, an illness, superstitious, grotesque madness, evil addiction, satanic, and cause of all incivility" is more a matter of subjective personal interpretation, rather than objective impersonal truth.[19] Regina Schwartz and some other contemporary scholars state allegations that idols only represent false gods, followed by iconoclastic destruction is only little more than religious intolerance.[234][235] The Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume wrote in his essay Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779) that the worship of different gods and idols in Pagan religions is premised on religious pluralism, tolerance, and acceptance of diverse representations of the divine. In contrast, Abrahamic monotheistic religions are intolerant, have attempted to destroy freedom of expression and have violently forced others to accept and worship their conception of God.[20 |

伝統宗教 アフリカ 関連項目: アフリカの伝統宗教 ヨルバ族によるオリシャ神(左)と、子供を抱えた跪く女性信者を描いた美術作品 アフリカには数多くの民族グループが存在し、その多様な宗教観念は「アフリカの伝統宗教」としてまとめられる。略してATRとも呼ばれる。これらの宗教は 通常、地域によって異なる名称で呼ばれる至高の存在を信じるとともに、祖先と結びつくことが多い霊界、そして占いを介した神秘的な呪術的な力を信奉する。 [180] 偶像とその崇拝は、アフリカの伝統宗教におけるこれら三つの要素すべてに関連付けられてきた。[181] J.O. アウォラルによると、布教活動を行うキリスト教徒やイスラム教徒は偶像を誤って「偽りの神」と定義してきた。しかし実際には、アフリカの多くの伝統におい て、その対象は木や鉄や石の塊であっても、「象徴であり、エンブレムであり、崇拝される霊的な概念を暗示するもの」なのである。[182] 物質的な対象は朽ちたり破壊されたりし、象徴は崩れたり置き換えられたりするかもしれない。しかし、アフリカの伝統主義者の心と精神においてそれが表す霊 的な理念は、決して変わらない。[182] アフリカ系アメリカ人研究・宗教学教授シルベスター・ジョンソンはアウォラルーの見解に同意し、アフリカに到来した植民地時代の宣教師たちは地域言語もア フリカ神学も理解せず、像や儀礼を「偶像崇拝の典型」と解釈したと述べる。彼らは自らが育ったヨーロッパの偶像破壊論争をアフリカに投影したのだ。 [183] まずイスラム教がアフリカに伝来し、続いてキリスト教による植民地化が進む中で、宗教的正当化を伴う戦争、偶像崇拝を野蛮の証拠とする植民地側の描写、偶 像の破壊、偶像崇拝者の奴隷化といった行為が、長きにわたる宗教的不寛容の時代を画した。これは宗教的暴力と、アフリカの伝統宗教信者に対する侮蔑的な風 刺画を助長したのである。[184][185][186] アフリカの伝統宗教実践者に対する偶像崇拝者への暴力は中世に始まり、近代まで続いた。[187][188][189] 改宗者たちによる偶像崇拝の告発は、現地のアフリカ人を悪魔化し非人間化する役割を果たし、奴隷化や虐待を正当化した。その対象は現地でも遠方のプラン テーションや入植地でも、あるいは強制的な家事労働でもあった。[190][191] アメリカ大陸 インカの冬至祭「インティ・ライミ」は太陽神インティを崇拝する。供物には丸いパンとトウモロコシのビールが含まれる。[192] 像や画像、寺院はアメリカ先住民の伝統宗教の一部であった。[193][194][195] インカ、マヤ、アステカの文明は、偶像や宗教芸術を取り入れた洗練された宗教的実践を発展させた。[195] 例えばインカ文化では、創造神としてビラコチャ(パチャクテクとも呼ばれる)を信じ、インティ(太陽神)や海・湖・川・水の女神ママ・コチャなどの自然神 を崇拝した。[196][197] [198] アステカのトゥーラ・アトランティス像(上図)は偶像崇拝の象徴と呼ばれてきたが、単に石造りの戦士像であった可能性もある。[199] マヤ文化においてククルカンは至高の創造神であり、転生の神、水の神、豊穣の神、風の神としても崇められてきた。[200] マヤ人はククルカンを称えるため階段ピラミッド寺院を建造し、春分点の太陽の位置に合わせて配置した。[201] マヤ遺跡で見つかる他の神々には、慈悲深い雨の神シブ・チャク、そして慈悲深い大地・織物・妊娠の女神イクシェルがいる。[201] アステカ文化においてククルカンと類似した側面を持つ神はケツァルコアトルと呼ばれた。[200] スペイン植民地時代の始まりと共に宣教師がアメリカ大陸に到来し、カトリック教会は先住民の偶像崇拝を一切容認せず、先住民の偶像をイエスとマリアの像や 画像で置き換えることを望んだ。[94] [202][193] 例えばアステカには、彼らの伝統宗教に関する記述を含む文字による歴史があったが、スペインの植民者たちは、偶像崇拝と見なしたものを終わらせ、アステカ 人をカトリックに改宗させる熱意から、この文字による歴史を破壊した。しかしアステカ族は、偶像を十字架の下に埋めて保存し、その後も偶像崇拝の儀礼や慣 習を継続した。彼らは、キリスト教の十字架と自らが崇拝する偶像を融合させたシンクレティズム(混合信仰)によって、以前と同様に信仰を保ち続けたのであ る。[203] スペイン植民地時代におけるカトリックキリスト教の強制期間中およびその後も、インカの人々は、自らの信仰と慣習の上にキリスト教の神と教えを重ね合わせ るシンクレティズムを通じて、神々への本来の信仰を維持した。[204][205] [206] 男性神インティはキリスト教の神として受け入れられたが、インカ神々の偶像崇拝を中心としたアンデスの儀礼はその後も維持され、現代に至るまでインカ民族 によって継承されている。[206][207] フィリピン 戦争の神々を描いたイゴロット族のヒパグ(約1900年) 現代フィリピン語におけるアニトは、偶像崇拝や異教の神々の偶像を意味する場合がある[208][209][210] 古代フィリピンにおけるアニト崇拝は、祖先の霊や祖先の神々を表す、しばしば木で彫られた像を崇拝することを含む。これらの木像はアニト、あるいはイフガ オ族などの特定の集団ではブルルとも呼ばれ、それらが表す霊の存在や力を体現していると信じられていた。先住フィリピン人はこれらの像に祈りや食物を捧 げ、儀礼を行った。彼らは像を単なる象徴ではなく、超自然的な存在の器あるいは現れそのものとして扱った。霊が像の中に宿っているか、像を通じて影響を与 えられうるかのように、物理的な対象物に献身と畏敬を向けるこの行為は、多くの神学的枠組み、特に至高の存在への崇拝と物質的表現への崇敬を区別する枠組 みにおいて、偶像崇拝として分類される。[211][212][213][214][215][216] ポリネシア ポリネシアの人々は太平洋全域に見られる多様な多神教の神学を持っていた。彼らは木から偶像を作り、その周りに集まって礼拝した。[217][218] キリスト教宣教師、特にロンドン宣教協会(ジョン・ウィリアムズら)やメソジスト宣教協会などは、島民が偽りの神を崇拝しているという意味で、これらを偶 像崇拝と特徴づけた。彼らは主に「異教の偶像崇拝の打倒」をキリスト教派の勝利の証拠として報告し、実際の改宗者や洗礼についてはあまり言及しなかった。 [219] [220] 宗教的寛容と不寛容 「偽りの神」という用語は、アブラハムの宗教の聖典(トーラー、タナハ、聖書、クルアーン)全体で頻繁に使用され、ヤハウェ[221](ユダヤ教徒、サマ リア人、キリスト教徒によって解釈される)またはエロヒム/アッラー[222](イスラム教徒によって解釈される)を唯一の真の神として特定するために用 いられる。[4] しかしながら、ヘブライ聖書/旧約聖書自体が認めているように、元来イスラエル人は一神教徒ではなく、ヤハウェに加えて、あるいはヤハウェの代わりに、バ アル、アスタルテ、アシェラ、ケモシュ、 ダゴン、モロク、タムズなどである。この状態はバビロン捕囚からの帰還[221]まで続いた(古代ヘブライ宗教参照)。アブラハムの宗教の中で最も古いユ ダヤ教は、最終的に厳格で排他的な一神教へと移行した[5]。これはヤハウェ[224][225][226]への唯一の崇拝に基づくもので、アブラハムの 神観念の前身である。[注2] 歴史上、大多数の宗教は多神教であり、今もなお多様な神々を崇拝している[230]。さらに、神々を物質的に表現することは、世界のあらゆる文化において 常に重要な役割を果たしてきた。[7] 「唯一真の神」を崇拝するという主張は、アブラハムの宗教の到来と共に世界のほとんどに広まり、その一神教的世界観の特徴となった[5][230] [231][232]。一方、世界の他の宗教のほぼ全ては、今も昔もアニミズム的かつ多神教的である。[230] ウィッカなどの新異教主義宗教では、礼拝体験において神々の像を利用する。[233] あらゆる偶像や像が象徴性を欠いているという非難や思い込み、あるいは自宗教の聖像は「真実で健全、高揚感を与え美しい象徴であり、信仰の証、神聖なも の」である一方、他人格の聖像は「偽りであり、 病、迷信、グロテスクな狂気、邪悪な中毒、悪魔的、あらゆる非礼の原因」とする非難や前提は、客観的な普遍的真理というより、主観的な個人的解釈の問題で ある。[19] レジーナ・シュワルツら現代の学者たちは、偶像は偽りの神々のみを表し、それに続く偶像破壊は宗教的不寛容に過ぎないと主張している。[234] [235] スコットランド啓蒙思想家のデイヴィッド・ヒュームは、著書『自然宗教に関する対話』(1779年)において、異教の宗教における異なる神々や偶像の崇拝 は、宗教的多元主義、寛容、そして神性の多様な表現の受容を前提としていると記している。これに対し、アブラハムの一神教は不寛容であり、表現の自由を破 壊しようとし、自らの神観念を受け入れ崇拝するよう他者に暴力的に強制してきたのである。[20] |

| Buddhist devotion – prayer ritual in Buddhism Dambana Kemetism Deity El Tío Fetishism Jezebel Perceptions of religious imagery in natural phenomena Puja (Hinduism) – prayer ritual in Hinduism |

仏教の信仰 – 仏教における祈りの儀礼 ダンバナ ケメティズム 神 エル・ティオ フェティシズム イゼベル 自然現象における宗教的イメージの認識 プージャ(ヒンドゥー教) – ヒンドゥー教における祈りの儀礼 |

| Notes 1. Such idol caring practices are found in other religions. For example, the Infant Jesus of Prague is venerated in many countries of the Catholic world. In the Prague Church it is housed, it is ritually cared for, cleaned and dressed by the sisters of the Carmelites Church, changing the Infant Jesus' clothing to one of the approximately hundred costumes donated by the faithfuls as gift of devotion.[164][165] The idol is worshipped with the faithful believing that it renders favors to those who pray to it.[165][166][167] Such ritualistic caring of the image of baby Jesus is found in other churches and homes in Central Europe and Portugal / Spain influenced Christian communities with different names, such as Menino Deus.[166][168][169] 2. Although the Semitic god El is indeed the most ancient predecessor to the Abrahamic god,[223][224][227][228] this specifically refers to the ancient ideas Yahweh once encompassed in the Ancient Hebrew religion, such as being a storm- and war-god, living on mountains, or controlling the weather.[223][224][227][228][229] Thus, in this page's context, "Yahweh" is used to refer to God as conceived in the Ancient Hebrew religion, and should not be referenced when describing his later worship in today's Abrahamic religions. |

注記 1. このような偶像への世話の慣習は他の宗教にも見られる。例えば、プラハの幼子イエスはカトリック世界の多くの国で崇敬されている。プラハの教会では、カル メル会修道女たちによって儀礼的に世話をされ、清められ、着せ替えられる。幼子イエスの衣装は、信者たちが信仰の証として寄進した約百着の衣装の中から選 ばれる。[164] [165] 信者たちは、この偶像が祈りを捧げる者に恩恵を与えると信じて崇拝している。[165][166][167] このような幼子イエスの像に対する儀式的世話は、中央ヨーロッパやポルトガル/スペインの影響を受けたキリスト教共同体内の他の教会や家庭でも見られ、メ ニーノ・デウスなど異なる名称で呼ばれている。[166][168] [169] 2. 確かにセム系の神エルはアブラハムの神々の最も古い先駆者である[223][224][227][228]が、ここでは特に古代ヘブライ宗教においてヤハ ウェが包含していた概念、すなわち嵐や戦争の神、山に住む神、天候を支配する神といった側面を指す。[223][224][227][228][229] したがって、本項の文脈において「ヤハウェ」は古代ヘブライ宗教における神の概念を指すものであり、現代のアブラハム宗教における後世の崇拝形態を記述す る際には使用すべきではない。 |

| References |

|

| Further reading Juan Sebastián Hernández Valencia (2023). Hombres ciegos, ídolos huecos: fetichismo y alteridad en la crítica de la idolatría del Apocalipsis de Abrahán (Medellín: Fondo Editorial Universidad Católica Luis Amigó) ISBN 978-958-8943-91-6 Swagato Ganguly (2017). Idolatry and The Colonial Idea of India: Visions of Horror, Allegories of Enlightenment. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138106161 Reuven Chaim Klein (2018). God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry. Mosaica Press. ISBN 978-1946351463. Yechezkel Kaufmann (1960). The Religion of Israel: From its Beginnings to the Babylonin Exile. Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0805203646. Faur, José; Faur, Jose (1978), "The Biblical Idea of Idolatry", The Jewish Quarterly Review, 69 (1): 1–15, doi:10.2307/1453972, JSTOR 1453972 Brichto, Herbert Chanan (1983), "The Worship of the Golden Calf: A Literary Analysis of a Fable on Idolatry", Hebrew Union College Annual, 54: 1–44, JSTOR 23507659 Pfeiffer, Robert H. (1924), "The Polemic against Idolatry in the Old Testament", Journal of Biblical Literature, 43 (3/4): 229–240, doi:10.2307/3259257, JSTOR 3259257 Bakan, David (1961), "Idolatry in Religion and Science", The Christian Scholar, 44 (3): 223–230, JSTOR 41177237 Siebert, Donald T. (1984), "Hume on Idolatry and Incarnation", Journal of the History of Ideas, 45 (3): 379–396, doi:10.2307/2709231, JSTOR 2709231 Orellana, Sandra L. (1981), "Idols and Idolatry in Highland Guatemala", Ethnohistory, 28 (2): 157–177, doi:10.2307/481116, JSTOR 481116 |

さらに読む フアン・セバスティアン・エルナンデス・バレンシア(2023)。『盲目の男たち、空虚な偶像:アブラハムの黙示録における偶像崇拝批判におけるフェティシズムと他者性』(メデジン:カトリック大学ルイス・アミゴ出版)ISBN 978-958-8943-91-6 スワガト・ガンギー(2017)。『偶像崇拝とインディアスの植民地主義思想:恐怖のビジョン、啓蒙の寓話』。ラウトレッジ。ISBN 978-1138106161 ルーベン・ハイム・クライン(2018)。『神対神々:偶像崇拝の時代におけるユダヤ教』。モザイカ・プレス。ISBN 978-1946351463。 イェヘズケル・カウフマン(1960)。『イスラエルの宗教:その始まりからバビロン捕囚まで』。シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0805203646。 フォール、ホセ;フォール、ホセ(1978)、「偶像崇拝に関する聖書の考え方」、The Jewish Quarterly Review、69 (1): 1–15、doi:10.2307/1453972、JSTOR 1453972 ブリクト、ハーバート・チャナン(1983)、『黄金の子牛の崇拝:偶像崇拝に関する寓話の文学的分析』、ヘブライ・ユニオン・カレッジ・アニュアル、54: 1–44、JSTOR 23507659 Pfeiffer, Robert H. (1924), 「旧約聖書における偶像崇拝に対する論争」, Journal of Biblical Literature, 43 (3/4): 229–240, doi:10.2307/3259257, JSTOR 3259257 バカン、デイヴィッド(1961)、『宗教と科学における偶像崇拝』、The Christian Scholar、44 (3): 223–230、JSTOR 41177237 シーバート、ドナルド・T. (1984)、「偶像崇拝と受肉に関するヒューム」、『思想史ジャーナル』、45 (3): 379–396、doi:10.2307/2709231、JSTOR 2709231 オレリャーナ、サンドラ・L. (1981)、「グアテマラ高地の偶像と偶像崇拝」、Ethnohistory、28 (2): 157–177、doi:10.2307/481116、JSTOR 481116 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Idolatry |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099