フェティシズム

フェティシズム(Fetishism)とは、性的嗜好のフェチと同様、事物 (物質)の中に精神性が宿っているようにみえる、信仰形態のことをさす。呪物(フェチ)を崇めるカルト(=崇拝集団)のようにもみえるので、フェティシズ ムは呪物崇拝(じゅぶつすうはい)とも呼ばれるが、あまり馴染みにくいので、私はフェティシズムと呼ぶ(→「商品フェティシズム」とは区分せよ)。

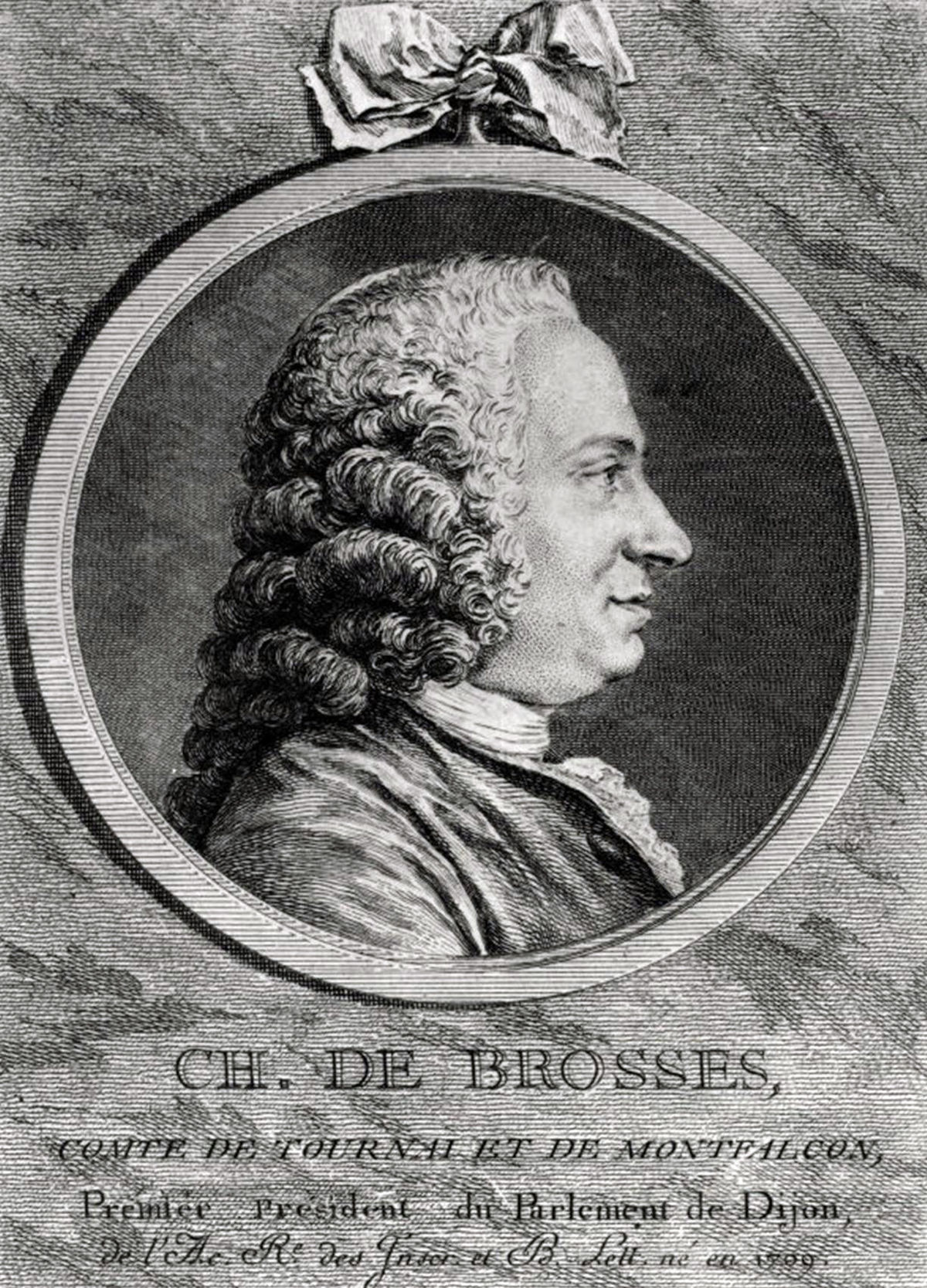

この用語は西アフリカの宗教と古代エジプトの宗教を比較研究していた、シャルル・ド・ブロス (Charles de Brosses, 1709-1777)によって1760年に『フェティシュ諸神の崇拝』(Du Culte des dieux fétiches)造語された。

ド・ブロスは feitiço(フェティソ)すなわち護符の意味を転じて、人類最古の信仰形態をフェティシズムと命名している。ウィキペディア日本語は次のように説明し ている:

「ビュフォンやルソーと同時代のド・ブロスは、18 世紀当時としては最新の研究方法であった比較宗教学の立場から、当時のアフリカ大陸やアメリカ大陸に残存する原初的信仰について研究した。そしてその土着 信仰をフェティシズムと命名し、およそつぎのように特徴づけた。これは本来の宗教以前のもので、本来の宗教の出発点である偶像崇拝(Idolatrie) が存在するよりも古い。宗教でないフェティシズムと宗教の一形態である偶像崇拝との相違は決定的で、例えば前者においては崇拝者が自らの手で可視の神体す なわちフェティシュを自然物の中から選びとるが、後者においては神は不可視のものとして偶像の背後に潜む。つまり前者ではフェティシュそれ自体が端的に神 であるのに対し、後者においてフェティシュはいわば神の代理か偶像かである。その背後か天上にはなにかいっそう高級な神霊が存在する。また、フェティシズ ムにおいてフェティシュは、信徒の要求に応えられなければ虐待されるか打ち棄てられるかするが、偶像崇拝において神霊は信徒に対し絶対者なのである。こう してド・ブロスは、フェティシズムを宗教と明確に区別したのである」フェティシュ諸 神の崇拝)

しかしながら、「ハーバート・スペンサーなどの哲学 者たちは、呪物崇拝が「原初宗教」であったとするド・ブロスの理論を否定した。同じ世紀において、E・B・タイラーやJ・F・マクレナンなどの人類学者や 比較宗教学者たちが、呪物崇拝を説明するため、アニミズムやトーテミズムの理論を発展させた。/タイラーとマクレナンは、呪物崇拝の概念を通じて宗教歴史 学者たちは、人間と神のあいだの関係から人間と物品のあいだの関係へと、関心を切り替えることが可能になったと考えた。彼らはまた、この概念によって、彼 ら自身が歴史と社会学における中心問題として「誤謬」だと見なしていた、自然の出来事に関する因果的説明のモデルが確立されたとも考えた」ウィキ=呪物崇拝)

| A fetish is an

object believed to have supernatural powers, or in particular, a

human-made object that has power over others. Essentially, fetishism is

the attribution of inherent non-material value, or powers, to an

object. Talismans and amulets are related. Fetishes are often used in

spiritual or religious context. |

フェティッシュとは、超自然的な力があると信じられている物体、特に、

他者に対して力を及ぼす人間が作った物体を指す。本質的には、フェティシズムとは物体に本質的な非物質的な価値や力を付与することである。お守りや魔除け

もこれに関連する。フェティッシュは、精神世界や宗教的な文脈でよく用いられる。 |

| Historiography The word fetish derives from the French fétiche, which comes from the Portuguese feitiço ("spell"), which in turn derives from the Latin facticius ("artificial") and facere ("to make").[1] The term fetish has evolved from an idiom used to describe a type of object created in the interaction between European travelers and Native West Africans in the early modern period to an analytical term that played a central role in the perception and study of non-Western art in general and African art in particular. William Pietz, who, in 1994, conducted an extensive ethno-historical study[2] of the fetish, argues that the term originated in the coast of West Africa during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Pietz distinguishes between, on the one hand, actual African objects that may be called fetishes in Europe, together with the indigenous theories of them, and on the other hand, "fetish", an idea, and an idea of a kind of object, to which the term above applies.[3] According to Pietz, the post-colonial concept of "fetish" emerged from the encounter between Europeans and Africans in a very specific historical context and in response to African material culture. He begins his thesis with an introduction to the complex history of the word: My argument, then, is that the fetish could originate only in conjunction with the emergent articulation of the ideology of the commodity form that defined itself within and against the social values and religious ideologies of two radically different types of noncapitalist society, as they encountered each other in an ongoing cross-cultural situation. This process is indicated in the history of the word itself as it developed from the late medieval Portuguese feitiço, to the sixteenth-century pidgin Fetisso on the African coast, to various northern European versions of the word via the 1602 text of the Dutchman Pieter de Marees... The fetish, then, not only originated from, but remains specific to, the problem of the social value of material objects as revealed in situations formed by the encounter of radically heterogeneous social systems, and a study of the history of the idea of the fetish may be guided by identifying those themes that persist throughout the various discourses and disciplines that have appropriated the term.[4] Stallybrass concludes that "Pietz shows that the fetish as a concept was elaborated to demonize the supposedly arbitrary attachment of West Africans to material objects. The European subject was constituted in opposition to a demonized fetishism, through the disavowal of the object."[5] |

歴史学/歴史記述 フェティシズムという語は、フランス語のフェティッシュ(fétiche)に由来し、これはポルトガル語のフェイチス(feitiço)(「呪文」)に由 来し、さらにラテン語のファクティキウス(facticius)(「人工の」)とファチェレ(facere)(「作る」)に由来する。 [1] フェティシズムという用語は、近現代初期にヨーロッパの旅行者と西アフリカの原住民との交流のなかで生み出されたある種の物体を表現する慣用句から、非西 洋美術一般、特にアフリカ美術の認識と研究において中心的な役割を果たす分析用語へと発展した。 ウィリアム・ピーツは、1994年にフェティッシュに関する広範な民族史的研究[2]を実施し、この用語は16世紀から17世紀にかけて西アフリカの海岸 で生まれたと主張している。ピーツは、ヨーロッパで「フェティッシュ」と呼ばれる可能性のある実際のアフリカの物品と、それらに対する土着の理論を一方 に、そして「フェティッシュ」という概念、そしてある種の物品の概念をもう一方に区別している。 ピーツによると、「フェティシズム」というポストコロニアルの概念は、ヨーロッパ人とアフリカ人の出会いという非常に特殊な歴史的文脈において、アフリカ の物質文化への反応として生まれた。 彼は論文の冒頭で、この言葉の複雑な歴史について紹介している。 そして、私の主張は、フェティシズムは、非資本主義社会の2つの根本的に異なるタイプの社会が、継続中の異文化交流の状況で遭遇した際に、それらの社会の 社会的価値や宗教的イデオロギーに対して、またそれらを定義する商品形態のイデオロギーの新たな明確化と結びついてのみ発生し得た、というものである。こ のプロセスは、中世後期のポルトガル語のfeitiçoという語が、16世紀のアフリカ沿岸部でピジン語となったフェティッソを経て、1602年のオラン ダ人ピーテル・デ・マリースによるテキストを通じて、さまざまな北ヨーロッパのバージョンへと発展したという、その語の歴史自体に示されている。フェティ シズムは、その起源となっただけでなく、根本的に異質な社会システムの遭遇によって形成された状況に示されるような、物質的な物体の社会的価値の問題に特 有なものであり続けている。フェティシズムの概念の歴史を研究する際には、この用語を借用したさまざまな言説や学問分野全体を通じて一貫して存在するテー マを特定することが指針となるだろう。 スタリーブラスは、「ピーツは、フェティシズムという概念が、西アフリカ人が物質的な物体に恣意的に執着しているとされることを悪魔化するために作り出さ れたことを示している。ヨーロッパの主体は、悪魔化されたフェティシズムに対する対立概念として、対象の否認を通じて形成された」と結論づけている。 [5] |

| History Initially, the Portuguese developed the concept of the fetish to refer to the objects used in religious practices by West African natives.[4] The contemporary Portuguese feitiço may refer to more neutral terms such as charm, enchantment, or abracadabra, or more potentially offensive terms such as juju, witchcraft, witchery, conjuration or bewitchment. The medieval Lollards issued polemics that anticipated fetishism.[6] The concept was popularized in Europe circa 1757, when Charles de Brosses used it in comparing West African religion to the magical aspects of ancient Egyptian religion. Later, Auguste Comte employed the concept in his theory of the evolution of religion, wherein he posited fetishism as the earliest (most primitive) stage, followed by polytheism and monotheism. However, ethnography and anthropology would classify some artifacts of polytheistic and monotheistic religions as fetishes. The eighteenth-century intellectuals who articulated the theory of fetishism encountered this notion in descriptions of "Guinea" contained in such popular voyage collections as Ramusio's Viaggio e Navigazioni (1550), de Bry's India Orientalis (1597), Purchas's Hakluytus Posthumus (1625), Churchill's Collection of Voyages and Travels (1732), Astley's A New General Collection of Voyages and Travels (1746), and Prevost's Histoire generale des voyages (1748).[7] The theory of fetishism was articulated at the end of the eighteenth century by G. W. F. Hegel in Lectures on the Philosophy of History. According to Hegel, Africans were incapable of abstract thought, their ideas and actions were governed by impulse, and therefore a fetish object could be anything that then was arbitrarily imbued with "imaginary powers".[8] |

歴史 当初、ポルトガル人は、西アフリカの原住民の宗教的儀式で使用される物品を指すために「フェティシズム」という概念を開発した。[4] 現代のポルトガル語のfeitiçoは、魅力、魅惑、またはアブラカダブラのようなより中立的な用語、あるいは、ジュジュ、ウィッチクラフト、ウィッチ チェリー、コンジュレーション、またはビウィッチメントのようなより攻撃的な可能性のある用語を指す場合がある。中世のロラード派は、フェティシズムを予 見する論争を展開した。[6] この概念は1757年頃にヨーロッパで広まった。シャルル・ド・ブロスが西アフリカの宗教を古代エジプトの呪術的側面と比較する際に用いたのが最初であ る。その後、オーギュスト・コントが自身の宗教進化論の中でこの概念を採用し、フェティシズムを最も初期(最も原始的)な段階とし、多神教、一神教と続く と仮定した。しかし、民族誌学や人類学では、多神教や一神教の宗教のいくつかの人工物をフェティシズムとして分類している。 18世紀のフェティシズム理論を明確にした知識人たちは、ラミュシオ著『航海旅行記』(1550年)、デ・ブリ著『東インド』(1597年)、 プルチャスの『ハクルートゥス・ポススムス』(1625年)、チャーチルの『航海と旅行のコレクション』(1732年)、アスリーの『航海と旅行の新しい 一般コレクション』(1746年)、プレヴォの『航海の歴史』(1748年)などである。[7] フェティシズムの理論は、18世紀末にG. W. F. ヘーゲルが著書『歴史哲学講義』で明確に述べた。ヘーゲルによれば、アフリカ人は抽象的な思考ができず、彼らの考えや行動は衝動によって支配されているた め、フェティッシュな対象は「想像上の力」を恣意的に吹き込まれたものであれば何でもあり得るという。[8] |

Practice A voodoo fetish market in Lomé, Togo, 2008 The use of the concept in the study of religion derives from studies of traditional West African religious beliefs, as well as from Vodun, which in turn derives from those beliefs. Fetishes were commonly used in some Native American religions and practices.[9] For example, the bear represented the shaman, the buffalo was the provider, the mountain lion was the warrior, and the wolf was the pathfinder, the cause of the war.[9] |

実践 トーゴのロメにおけるヴードゥー教のフェティシズム市場、2008年 宗教研究におけるこの概念の使用は、西アフリカの伝統的宗教的信念の研究に由来する。また、ヴードゥー教も、それらの信念に由来するものである。 フェティシズムは、一部のネイティブアメリカンの宗教や慣習でも一般的に用いられていた。例えば、熊はシャーマン、バッファローは食料提供者、マウンテンライオンは戦士、そしてオオカミは先導者であり、戦争の原因であった。 |

| Japan Katō Genchi [ja] (1873–1965), a Shinto priest and scholar of comparative religion, applied the term "fetish" to the historical study of traditional Japanese religion. He cited jewelry, swords, mirrors, and scarves as examples of fetishism in Shinto.[10] In rural areas of Japan, he said he could find many traces of animism, totemism, fetishism, and phallicism.[11] He also maintained that the Ten Sacred Treasures [ja] were fetishes and the Imperial Regalia of Japan retained the same traits, and pointed out the similarities with the Pusaka heirlooms of the natives of the East Indies and the sacred Tjurunga of the Central Australians.[12] He noted that the divine sword Kusanagi no Tsurugi, which was believed to provide supernatural protection ('blessings'), was deified and enshrined (at what is now the Atsuta Shrine).[12] Akaruhime no Kami, the female deity of Hiyurikuso Shrine [ja], was said to have originally been a red ball before transforming into a beautiful woman.[12] The jewel around Izanagi-no-Mikoto's neck was deified and called Mikuratana-no-kami.[12] The Anglo-Irish diplomat and scholar William George Aston (1841–1911) also maintained that Kusanagi no Tsurugi could be seen as an example of fetishism. Originally an offering, the enshrined sword became a mitamashiro (lit. 'spirit representative', 'spirit-token'), more commonly known as the shintai (lit. 'god-body'; a sacred object containing the kami or 'spirit').[13] Aston observed that people tended to think of the mitama ('spirit') of a deity first as the seat of his or her real presence, and secondly as the deity itself. In practice, the distinction between mitama and shintai was fluid, and shintai even came to be identified as the god's body.[13] For example, the cooking furnace (kamado) itself was worshiped as a deity.[13] Given the vagueness of such distinctions – further accentuated by the restricted usage of images (e.g., in painting or sculpture) – there was a tendency to ascribe special virtues to certain physical objects in place of the deity.[13] In modern times, the American linguist Roy Andrew Miller (1924–2014) observed that the pamphlet of the nationalistic Kokutai no Hongi proclamation (1937) and the Imperial Rescript on Education (1890) were also often worshipped as "fetishes", and were respectfully placed and kept in household altars (kamidana).[14][n 1] |

日本 加藤玄智(1873年-1965年)は、神道家であり比較宗教学者でもあった。彼は「フェティシズム」という用語を日本の伝統宗教の歴史研究に適用した。 彼は、神道におけるフェティシズムの例として、装飾品、刀剣、鏡、スカーフなどを挙げた。 [10] 日本の農村部では、アニミズム、トーテミズム、フェティシズム、ファリシズムの痕跡を数多く見つけることができると彼は述べた。[11] また、十種の神宝[ja]はフェティッシュであり、日本の三種の神器も同様の特徴を保持していると主張し、東インド諸島の先住民のプサカ家宝や中央オース トラリアの聖なるトゥジュンガとの類似性を指摘した。 [12] また、超自然的な保護(「祝福」)をもたらすと考えられていた神剣クサナギノツルギが神格化され、熱田神宮(現存)に祀られたと指摘している。[12] 日ユリクソウ神社(日ユリクソウ神社)の女神であるアカルヒメノカミは、もともと赤い玉だったものが美しい女性に変身したと伝えられている。 [12] イザナギノミコトの首にかけられていた玉は神格化され、ミクラタナノカミと呼ばれた。 アングロ・アイルランド人の外交官であり学者でもあったウィリアム・ジョージ・アストン(1841年 - 1911年)も、草薙剣はフェティシズムの一例であると主張した。もともとは奉納された剣が祀られるようになり、それはミタマシロ(文字通り「精神の代理 人」、「精神の証」)となり、より一般的に「シンタイ」(文字通り「神の身体」、すなわち「精神」を含む神聖な物体)として知られるようになった。 [13] アストンは、人々は神の「ミタマ(霊魂)」を、まず神の現実の存在の座として、次に神そのものとして考える傾向があると観察した。実際には、ミタマとシタ イの区別は流動的であり、シタイは神の身体として認識されるようになった。[13] たとえば、調理用の炉(かまど)そのものが神として崇拝された。 [13] こうした区別のあいまいさ(絵画や彫刻などにおける画像の使用制限によってさらに強調された)を踏まえると、神の代わりに特定の物体に特別な徳を帰属させ る傾向があった。[13] 近代では、アメリカの言語学者ロイ・アンドリュー・ミラー(1924年 - 2014年)が、国粋主義的な『国体本義』(1937年)のパンフレットや教育勅語(1890年)も「フェティッシュ」として崇拝されることが多く、神棚 に敬意を払って置かれ、保管されていることを観察している。[14][n 1] |

| Philippines In the pre-colonial Philippine context, Anito fetishes were central to the animistic beliefs of the early Filipinos. These objects, often human-made, served as physical representations of spiritual entities or ancestral spirits. Their role in rituals, worship, and daily life illustrates the rich spiritual tradition of the early Austronesian peoples who inhabited the Philippine archipelago. Anito fetishes refer to objects imbued with spiritual significance, often crafted to house or represent spirits collectively known as Anito. These were usually Ancestor Spirits also called Anito The souls of deceased relatives who provided guidance, protection, or blessings to their descendants. Anito fetishes were typically carved from wood, stone, or bone, and they served as both a focus of worship and a conduit for spiritual energy. Anito fetishes were placed in shrines or sacred areas where offerings such as food, drinks, or animal sacrifices were made. These offerings were meant to appease or gain favours from the ancestor spirits and spirits of the dead and deities and celestial beings called Diwata. The term Anito is deeply rooted in Austronesian linguistic heritage, with similar terms found across related culture Proto-Malayo-Polynesian: qanitu (spirit of the dead) Proto-Austronesian: qaNiCu (ancestor spirit) Indonesian and Malaysian: Hantu or Antu (spirit or ghost) Polynesian: Atua or Aitu (ancestral ghost or spirit)[16][17][18][19] Anito—widely understood today by Filipinos in the Philippines in contemporary as referring to ancestor spirits or spirits of the dead, evil spirits and the wooden idols and fetish that represent them.[20][21][22][23]Anito In Philippine mythology, refers to ancestor spirits, spirits of the dead, evil spirits and the wooden idols that represent or house them. In contrast, within the context of folk religion[24][25][26] |

フィリピン 植民地化以前のフィリピンでは、アニト信仰は初期のフィリピン人の精霊信仰の中心であった。 これらの物品は、多くの場合、人間の手によって作られたもので、精神的存在や祖先の霊を象徴する物理的な存在であった。 儀式や崇拝、日常生活におけるこれらの役割は、フィリピン列島に居住していた初期のオーストロネシア民族の豊かな精神伝統を物語っている。アニトの偶像崇 拝とは、精神的な意義を持つ物体を指し、アニトとして総称される霊を宿らせたり象徴したりするために作られることが多い。これらは通常、アニトとも呼ばれ る祖先の霊である。子孫に導きや保護、祝福を与える亡くなった親族の魂である。アニトの偶像は通常、木、石、骨から彫り出され、崇拝の対象であると同時 に、霊的なエネルギーの媒介としても機能した。アニトの偶像は、食物、飲み物、動物などの生け贄が捧げられる神殿や聖域に置かれた。これらの生け贄は、祖 先の霊や死者の霊、ディワタと呼ばれる神々や天上の存在を鎮めたり、その恩恵を得ることを目的としていた。アニトという用語は、オーストロネシア語族の言 語遺産に深く根付いており、関連する文化圏では以下のような同様の用語が見られる。 マレー・ポリネシア祖語:qanitu(死者の霊) オーストロネシア祖語:qaNiCu(祖先の霊) インドネシア語およびマレー語:HantuまたはAntu(霊または幽霊) ポリネシア語: アトゥアまたはアイトゥ(先祖の幽霊または霊)[16][17][18][19] アニト—現代のフィリピンでは、フィリピン人によって広く、先祖の霊や死者の霊、悪霊、それらを象徴する木製の偶像や呪物などを指す言葉として理解されて いる。 [20][21][22][23]アニト フィリピン神話では、先祖の霊、死者の霊、悪霊、それらを表すか宿る木製の偶像を指す。これに対し、民間信仰の文脈では[24][25][26] |

| Minkisi Made and used by the BaKongo of western DRC, a nkisi (plural minkisi) is a sculptural object that provides a local habitation for a spiritual personality. Though some minkisi have always been anthropomorphic, they were probably much less "naturalistic" or "realistic" before the arrival of the Europeans in the nineteenth century; Kongo figures are more naturalistic in the coastal areas than inland.[3] As Christians tend to think of spirits as objects of worship, idols become the objects of idolatry when worship was addressed to false gods. In this way, European Christian colonialists regarded minkisi as idols on the basis of religious bias. The foreign Christians often called nkisi "fetishes" and sometimes "idols" because they are sometimes rendered in human form or semi-human form. Modern anthropology has generally referred to these objects either as "power objects" or as "charms". In addressing the question of whether a nkisi is a fetish, William McGaffey writes that the Kongo ritual system as a whole, bears a relationship similar to that which Marx supposed that "political economy" bore to capitalism as its "religion", but not for the reasons advanced by Bosman, the Enlightenment thinkers, and Hegel. The irrationally "animate" character of the ritual system's symbolic apparatus, including minkisi, divination devices, and witch-testing ordeals, obliquely expressed real relations of power among the participants in ritual. "Fetishism" is about relations among people, rather than the objects that mediate and disguise those relations.[3] Therefore, McGaffey concludes, to call a nkisi a fetish is to translate "certain Kongo realities into the categories developed in the emergent social sciences of nineteenth century, post-enlightenment Europe."[3] |

ミンキシ コンゴ民主共和国西部のバコンゴ族によって作られ、使用されるンキシ(複数形はミンキシ)は、精神的人格の住処となる彫刻である。ミンキシの中には、常に 擬人化されたものもあるが、19世紀にヨーロッパ人が到来する以前は、おそらくはるかに「写実的」または「現実的」ではなかったであろう。コンゴの偶像 は、内陸部よりも沿岸部の方がより写実的である。[3] キリスト教徒は霊を崇拝の対象と考える傾向にあるため、偶像は偽りの神々への崇拝が向けられたときに偶像崇拝の対象となる。このように、ヨーロッパのキリ スト教徒の植民地主義者たちは、宗教的偏見に基づいてミンキシを偶像とみなした。 外国人のキリスト教徒たちは、ンキシを「フェティッシュ」と呼ぶことが多く、また、それが人間や半人間の形をしていることもあるため、「偶像」と呼ぶこともあった。現代の人類学では、これらの物体は一般的に「パワー・オブジェクト」または「お守り」と呼ばれている。 ンキシがフェティッシュであるかどうかという問題について、ウィリアム・マクガフィーは、コンゴの儀式体系全体は、 マルクスが「政治経済」と資本主義の関係を「宗教」とみなしたのと似た関係にあると主張している。ただし、ボスマン、啓蒙思想家、ヘーゲルが主張した理由 によるものではない。ミンキシ、占い道具、呪術師の試練など、儀式システムの象徴体系が持つ非合理的な「生命」の性質は、儀式の参加者たちの間の実際の権 力関係を間接的に表現している。「フェティシズム」は、それらの関係を媒介し、偽装する物ではなく、人々の間の関係についてのものである。[3] したがって、マクガフィーは、ンキシをフェティッシュと呼ぶことは、「19世紀の啓蒙後のヨーロッパで発展した新興社会科学のカテゴリーに、特定のコンゴの現実を翻訳する」ことであると結論づけている。[3] |

| Boli Commodity fetishism |

ボリ 商品フェティシズム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fetishism |

文献

その他の情報

Do not paste, but [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099