伝統の創造

The Invention of Tradition, or or fetishism for history, 伝統の創造あるいは歴史に対するフェティシズム

Evening at Balmoral Castle, 1854

伝統の創造

The Invention of Tradition, or or fetishism for history, 伝統の創造あるいは歴史に対するフェティシズム

Evening at Balmoral Castle, 1854

"The invention of tradition is a concept made prominent in the eponymous 1983 book edited by British Marxist intellectual E. J. Hobsbawm (1917-2012) and T. O. Ranger. In their Introduction the editors argue that many "traditions" which "appear or claim to be old are often quite recent in origin and sometimes invented." - Invented tradition.

「伝

統の発明は、イギリスのマルクス主義知識人E・J・ホブズボーム(1917-2012)とT・O・レンジャーが編集した1983年の同名の著書で顕著に

なった概念である。その「はじめに」の中で編者たちは、「古くからあるように見えたり、古くからあると主張したりする伝統」の多くは、その起源がごく最近

のものであることが多く、時には発明されたものであることもある、と論じている」。

"In the Introduction, Hobsbawm argues that many "traditions" which "appear or claim to be old are often quite recent in origin and sometimes invented."[2] They distinguish the "invention" of traditions in this sense from "starting" or "initiating" a tradition which does not then claim to be old. The phenomenon is particularly clear in the modern development of the nation and of nationalism, creating a national identity promoting national unity, and legitimising certain institutions or cultural practices." - Invented tradition.

「序

文でホブズボームは、「古い伝統のように見えたり、古いと主張したりする伝統」の多くは、その起源がごく最近のものであることが多く、時には発明されたも

のであることもある、と論じている。

彼らはこの意味での伝統の「発明」を、古いと主張しない伝統の「開始」や「開始」とは区別している。

この現象は、国家やナショナリズムの近代的発展において特に顕著であり、国民統合を促進する国民的アイデンティティを生み出し、特定の制度や文化的慣習を

正当化する。」

伝 統の創造とは、エリック・ホブスボームとテレンス・レンジャーの編著本(論集)『伝 統の創造』 という書名に由来することばで、近代社会において、伝統に根ざしていることが価値があり、権威であるという「信条」ないしは「信仰」が生まれ、それが意図 的に整備されるという社会現象のことをさす。たとえば、「古来」スコットランドの伝統とされる、祖先のアイデンティティを表象する、タータンチェックの文 様の多くは19世紀に発明されたもの、などである。

ド イツのナチ(国家社会主義ドイツ労働者党)は、デモクラシー的伝統とは異なった意味における「伝統の創造」を政治的プロパンガンダに多用した。

例 えば「ミュンヘン一揆の際、「アドルフ・ヒトラー衝撃隊」は、警官隊の銃撃で転倒したヒトラーを文字通り盾となってかばい、5名の隊員が代わりに警官の銃 撃を受けて死亡した[7]。ウルリヒ・グラーフもヒトラー衝撃隊の隊員としてヒトラーをかばい、重傷を負った人物である[4]。この時彼らの血で染まった 党旗が残されたが、ヒトラーは彼らの功績を忘れず、のちにニュルンベルク党大会で突撃隊や親衛隊の部隊にこの「血染めの党旗(Blutfahne)」に触れさせて忠誠を誓わせる儀式を行っている [7]。」出典:ウィキペディア「親衛隊 (ナチス)」)

こ の「血染 めの党旗(Blutfahne)」であるが、英語のウィキペディアの「聖なるナ チスのシンボル(Blutfahne as Sacred Nazi symbol)」に以下のように記載されている。

"After Hitler received the flag, he had it fitted to a new staff and finial; just below the finial was a silver dedication sleeve which bore the names of the 16 dead participants of the putsch.[3] Bauriedl was one of the 16 honorees. In addition, the flag was no longer attached to the staff by its original sewn-in sleeve, but by a red-white-black intertwined cord which ran through the sleeve instead./ In 1926, at the second Nazi Party congress at Weimar, Hitler ceremonially bestowed the flag on Joseph Berchtold, then head of the SS.[1] The flag was thereafter treated as a sacred object by the Nazi Party and carried by SS-Sturmbannführer Jakob Grimminger at various Nazi Party ceremonies. One of the most visible uses of the flag was when Hitler, at the Party's annual Nuremberg rallies, touched other Nazi banners with the Blutfahne, thereby "sanctifying" them.[4] This was done in a special ceremony called the "flag consecration" (Fahnenweihe).[1]/ When not in use, the Blutfahne was kept at the headquarters of the Nazi Party in Munich (the Brown House) with an SS guard of honour. The flag had a small tear in it, believed to have been caused during the Putsch, that went unrepaired for a number of years."

「ヒ

トラーは旗を受け取った後、新しい杖とフィニアルに取り付けさせた。フィニアルのすぐ下には銀の献辞袖があり、そこにはプシュで死んだ16人の参加者の名

前が記されていた。

バウリエドルはその16人の一人であった。さらに、国旗は元のように縫い付けられた袖ではなく、袖を通る赤白黒の紐で旗に取り付けられていた。

1926年、ワイマールで開催された第2回ナチ党大会で、ヒトラーはこの旗を当時の親衛隊長ヨーゼフ・ベルヒトルトに儀式的に授与した[1]。その後、旗

はナチ党の神聖なものとして扱われ、ナチ党のさまざまな式典で親衛隊親衛隊長のヤコブ・グリミンガーが携行した。

この旗の最も目に見える使い方のひとつは、党の年次ニュルンベルク集会でヒトラーが他のナチスの旗をブルートファーネで触れ、それによって「神聖化」した

ことである。 これは「旗の聖別」(Fahnenweihe)と呼ばれる特別な儀式で行われた。

使用されていないとき、ルートファーネはミュンヘンのナチ党本部(ブラウン・ハウス)に保管され、親衛隊の儀仗兵が待機した。旗には一揆の際に生じたと思

われる小さな裂け目があり、何年もの間、修復されることはなかった。」

Adolf

Hitler reviewing SA members in 1935. He is accompanied by the Blutfahne

and its bearer SS-Sturmbannführer Jakob Grimminger(1892-1969).

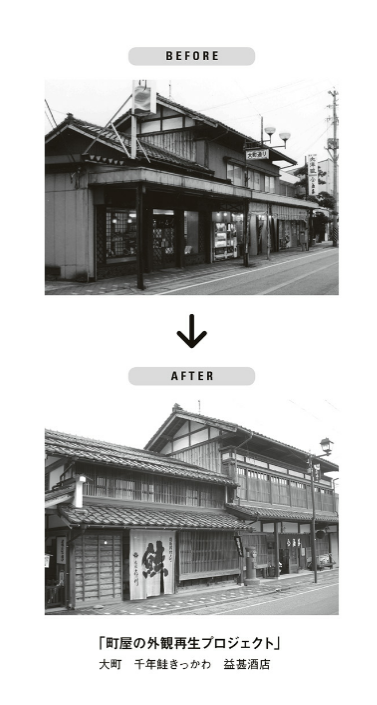

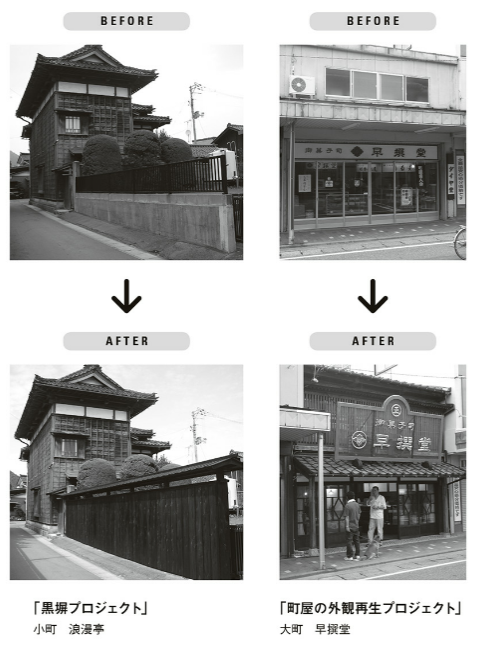

21 世紀以降に、日本の地方都市での行政や地元が先導した「民家再生」や「昔の街並み再現」は、その伝統の創造を(ホブスボームらの研究の意図などとは無自覚 に)《伝統的なるものは本物だ》という民衆的感覚のもとに彼らが意図的におこなったものである。

出典:吉川美貴『まちづ

くりの非常識な教科書』主婦の友社、2018年より

●ホブズボームからの引用

"Nothing appears more ancient, and linked to an immemorial past, than the pageantry which surrounds British monarchy in its public ceremonial manifestations. Yet, as a chapter in this book establishes, in its modern form it is the product of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. 'Traditions' which appear or claim to be old are often quite recent in origin and sometimes invented. Anyone familiar with the colleges of ancient British universities will be able to think of the institution of such 'traditions' on a local scale, though some -like the annual Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols in the chapel of King's College, Cambridge on Christmas Eve~ may become generalized through the modern mass medium of radio. This observation formed the starting-point of a conference organized by the historical journal Past & Present, which in turn forms the basis of the present book. " (Hobsbawm 1983:1)

「英国王室の公式儀式にまつわる壮麗な行事 ほど、太古の昔から連綿と続いているように見えるものはない。しかし、この本の章で明らかにされているように、その現代的な形は19世紀後半から20世紀 にかけての産物である。古くから伝わるように見える「伝統」は、その起源がごく最近であることも多く、時にはでっちあげられたものもある。古代の英国大学 に詳しい人なら、地域レベルでこのような「伝統」の制度を思い浮かべることができるだろう。しかし、中には、ケンブリッジ大学キングスカレッジのチャペル でクリスマスイブに毎年行われる「ナイン・レッスンズ・アンド・キャロル」のように、現代のマスメディアであるラジオを通じて一般化されるものもある。こ の観察が、歴史雑誌『Past & Present』が主催した会議の出発点となり、それが本書の基礎となった」 (Hobsbawm 1983:1)。

| Invented traditions

are cultural practices that are presented or perceived as traditional,

arising from the people starting in the distant past, but which in fact

are relatively recent and often even consciously invented by

identifiable historical actors. The concept was highlighted in the 1983

book The Invention of Tradition, edited by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence

Ranger.[1] Hobsbawm's introduction argues that many "traditions" which

"appear or claim to be old are often quite recent in origin and

sometimes invented."[2] This "invention" is distinguished from

"starting" or "initiating" a tradition that does not then claim to be

old. The phenomenon is particularly clear in the modern development of

the nation and of nationalism, creating a national identity promoting

national unity, and legitimising certain institutions or cultural

practices.[3] |

伝統の発明(Invention of

Tradition)とは、遠い過去に始まった人々によって伝統的なものとし

て提示されたり認識されたりする文化的慣習のことであるが、実際には比較的最近のものであ

り、多くの場合、特定可能な歴史的行為者によって意識的に発明されたものである。この概念は、エリック・ホブズボーム(Eric

Hobsbawm)とテレンス・レンジャー(Terence Ranger)が編集した1983年の著書『The Invention of

Tradition』(伝統の発明)[1]の中で強調されている。ホブズボームの序文では、「古い伝統のように見えたり、古い伝統であると主張したりす

る」多くの「伝統」は、その起源が極めて新しく、時には発明されたものであることが多いと論じている[2]。この現象は、国家とナショナリズムの近代的発

展において特に顕著であり、国民統合を促進する国民的アイデンティティを生み出し、特定の制度や文化的慣習を正当化する[3]。 |

| Application of the term and

paradox The concept has been applied to cultural phenomena such as the "Highland myth" in Scotland,[4][5] the traditions of major religions,[6][7] some Korean martial arts such as Taekwondo,[8] and some Japanese martial arts, such as Judo.[9] It has influenced related concepts such as Benedict Anderson's imagined communities and the pizza effect.[10] Indeed, the sharp distinction between "tradition" and "modernity" is often itself invented. The concept is "highly relevant to that comparatively recent historical innovation, the 'nation', with its associated phenomena: nationalism, the nation-state, national symbols, histories, and the rest." Hobsbawm and Ranger remark on the "curious but understandable paradox: modern nations and all their impedimenta generally claim to be the opposite of novel, namely rooted in remotest antiquity, and the opposite of constructed, namely human communities so 'natural' as to require no definition other than self-assertion."[11] The concept of authenticity is also often questionable. |

用語の適用とパラドックス この概念は、スコットランドの「ハイランド神話」[4][5]、主要な宗教の伝統[6][7]、テコンドーなどの韓国武術の一部[8]、柔道などの日本武 術の一部[9]などの文化現象に適用されている。ベネディクト・アンダーソンの想像上の共同体やピザ効果[10]などの関連概念にも影響を与えている。 実際、「伝統」と「現代性」を峻別すること自体がしばしば発明されている。この概念は「ナショナリズム、国民国家、国のシンボル、歴史、その他といった関 連する現象とともに、比較的最近の歴史的革新である "国家 "と大いに関連している」。ホブズボームとレンジャーは、「不思議だが理解できるパラドックス:近代国家とその障害物は一般的に、最も遠い古代に根ざした 斬新さとは正反対のものであり、構築されたものとは正反対のもの、すなわち自己主張以外の定義を必要としないほど「自然な」人間共同体であると主張する」 と述べている[11]。 |

| Pseudo-folklore Pseudo-folklore or fakelore is inauthentic, manufactured folklore presented as if it were genuinely traditional. The term can refer to new stories or songs made up, or to folklore that is reworked and modified for modern tastes. The element of misrepresentation is central; artists who draw on traditional stories in their work are not producing fakelore unless they claim that their creations are real folklore.[12] Over the last several decades the term has generally fallen out of favor in folklore studies because it places an emphasis on origin instead of ongoing practice to determine authenticity. The term fakelore was coined in 1950 by American folklorist Richard M. Dorson[12] in his article "Folklore and Fake Lore" published in The American Mercury. Dorson's examples included the fictional cowboy Pecos Bill, who was presented as a folk hero of the American West but was actually invented by the writer Edward S. O'Reilly in 1923. Dorson also regarded Paul Bunyan as fakelore. Although Bunyan originated as a character in traditional tales told by loggers in the Great Lakes region of North America, William B. Laughead (1882–1958), an ad writer working for the Red River Lumber Company, invented many of the stories about him that are known today. According to Dorson, advertisers and popularizers turned Bunyan into a "pseudo folk hero of twentieth-century mass culture" who bore little resemblance to the original.[13] Folklorismus also refers to the invention or adaptation of folklore. Unlike fakelore, however, folklorismus is not necessarily misleading; it includes any use of a tradition outside the cultural context in which it was created. The term was first used in the early 1960s by German scholars, who were primarily interested in the use of folklore by the tourism industry. However, professional art based on folklore, TV commercials with fairy tale characters, and even academic studies of folklore are all forms of folklorism.[14][15] |

疑似フォークロア 擬似フォークロア(fseudo-folklore)またはフェイクロア(fakelore)とは、あたかも本物の伝統であるかのように見せかけた、本物 でない作り物のフォークロアのことである。この用語は、新しく作られた物語や歌、あるいは現代の嗜好に合わせて作り直され改変されたフォークロアを指すこ ともある。作品に伝統的な物語を取り入れた芸術家は、その創作物が本物のフォークロアであると主張しない限り、フェイクローレを生み出していることにはな らない[12]。ここ数十年の間、この用語は一般にフォークロア研究において好まれなくなったが、それは真正性を決定するために継続的な実践ではなく起源 に重きを置いているからである。 フェイクローレという用語は、1950年にアメリカの民俗学者リチャード・M・ドーソン[12]が『アメリカン・マーキュリー』誌に発表した論文「フォー クロアとフェイク伝承」の中で用いた造語である。ドーソンの例には、アメリカ西部の民俗的英雄として登場するが、実際には1923年に作家のエドワード・ S・オライリーによって創作された架空のカウボーイ、ペコス・ビルが含まれていた。ドーソンはまた、ポール・バニヤンもフェイクだと考えていた。バニヤン の起源は北米五大湖地方の樵たちが語る伝統的な物語の登場人物であったが、レッド・リバー木材会社で働く広告ライター、ウィリアム・B・ローグヘッド (1882~1958年)が、今日知られている彼にまつわる物語の多くを創作した。ドーソンによれば、広告主や大衆化した人々はバニヤンを「20世紀の大 衆文化の擬似的な民俗英雄」に仕立て上げ、オリジナルとはほとんど似ても似つかないものにした[13]。 フォークロリスムス(Folklorismus)とは、フォークロアの発明や翻案も指す。しかし、フェイクローレとは異なり、フォークロリスムスは必ずし も誤解を招くものではない。この用語が初めて使われたのは1960年代初頭のことで、ドイツの学者たちは主に観光産業によるフォークロアの利用に関心を寄 せていた。しかし、フォークロアに基づくプロの芸術、おとぎ話の登場人物を使ったテレビコマーシャル、さらにはフォークロアの学術的研究さえも、すべて フォークロリズムの一形態である[14][15]。 |

| Connection to folklore The term fakelore is often used by those who seek to expose or debunk modern reworkings of folklore, including Dorson himself, who spoke of a "battle against fakelore".[16] Dorson complained that popularizers had sentimentalized folklore, stereotyping the people who created it as quaint and whimsical[12] – whereas the real thing was often "repetitive, clumsy, meaningless and obscene".[17] He contrasted the genuine Paul Bunyan tales, which had been so full of technical logging terms that outsiders would find parts of them difficult to understand, with the commercialized versions, which sounded more like children's books. The original Paul Bunyan had been shrewd and sometimes ignoble; one story told how he cheated his men out of their pay. Mass culture provided a sanitized Bunyan with a "spirit of gargantuan whimsy [that] reflects no actual mood of lumberjacks".[13] Daniel G. Hoffman said that Bunyan, a folk hero, had been turned into a mouthpiece for capitalists: "This is an example of the way in which a traditional symbol has been used to manipulate the minds of people who had nothing to do with its creation."[18] Others have argued that professionally created art and folklore are constantly influencing each other and that this mutual influence should be studied rather than condemned.[19] For example, Jon Olson, a professor of anthropology, reported that while growing up he heard Paul Bunyan stories that had originated as lumber company advertising.[20] Dorson had seen the effect of print sources on orally transmitted Paul Bunyan stories as a form of cross-contamination that "hopelessly muddied the lore".[13] For Olson, however, "the point is that I personally was exposed to Paul Bunyan in the genre of a living oral tradition, not of lumberjacks (of which there are precious few remaining), but of the present people of the area."[20] What was fakelore had become folklore again. Responding to his opponents' argument that the writers have the same claim as the original folk storytellers, Dorson writes that the difference amounts to the difference between traditional culture and mass culture.[12] |

フォークロアとのつながり ドーソン自身もその一人であり、彼は「フェイクロアとの戦い」について語った[16]。ドーソンは、民衆化した人々がフォークロアを感傷的にし、フォーク ロアを創作した人々を古風で気まぐれなものとしてステレオタイプ化し[12]、その一方で本物はしばしば「反復的で、不器用で、無意味で、卑猥」であると 訴えた。 [17]彼は、専門的な伐採用語が多用され、部外者には理解しにくい部分があった本物のポール・バニヤンの物語と、児童書のように聞こえる商業化された バージョンとを対比させた。本来のポール・バニヤンは抜け目がなく、時には無神経で、ある物語では部下から給料をだまし取ったという。大衆文化は、「木こ りの実際の気分を反映しない、巨大な気まぐれの精神」[13]を持つ、衛生化されたバニヤンを提供した。ダニエル・G・ホフマンは、民衆の英雄であるバニ ヤンが資本家の口車に乗せられてしまったと述べている: 「これは、伝統的なシンボルが、その創作とは何の関係もない人々の心を操るために利用された一例である」[18]。 また、専門的に創作された芸術と民間伝承は常に互いに影響を与え合っており、この相互の影響は非難されるよりもむしろ研究されるべきであると主張する者も いる[19]。例えば、人類学の教授であるジョン・オルソンは、幼少期に製材会社の広告として生まれたポール・バニヤンの物語を聞いたと報告している [20]。 [20]ドーソンは、ポール・バニヤンの物語が印刷された情報源によって口承で伝えられるようになることを、「伝承を絶望的に泥沼化させる」二次汚染の一 形態と見なしていた[13]。しかしオルソンにとっては、「重要なのは、私が個人的にポール・バニヤンに接したのは、木こり(現存しているのはごく少数で ある)ではなく、その地域の現存する人々の生きた口承伝承というジャンルであったということである。 作家たちはオリジナルの民話の語り手と同じ主張を持っているという反対派の主張に対して、ドーソンは、その違いは伝統文化と大衆文化の違いに等しいと書い ている[12]。 |

| Criticism One reviewer (Peter Burke) noted that the "'invention of tradition' is a splendidly subversive phrase", but it "hides serious ambiguities". Hobsbawm "contrasts invented traditions with what he calls 'the strength and adaptability of genuine traditions'. But where does his 'adaptability', or his colleague Ranger's 'flexibility' end, and invention begin? Given that all traditions change, is it possible or useful to attempt to discriminate the 'genuine' antiques from the fakes?"[21] Another also praised the high quality of the articles but had qualifications. "Such distinctions" (between invented and authentic traditions) "resolve themselves ultimately into one between the genuine and the spurious, a distinction that may be untenable because all traditions (like all symbolic phenomena) are humanly created ('spurious') rather than naturally given ('genuine')."[22] Pointing out that "invention entails assemblage, supplementation, and rearrangement of cultural practices so that in effect traditions can be preserved, invented, and reconstructed", Guy Beiner proposed that a more accurate term would be "reinvention of tradition", signifying "a creative process involving renewal, reinterpretation and revision".[23] |

批判 ある評者(Peter Burke)は、「『伝統の発明』は見事に破壊的なフレーズである」としながらも、「深刻な曖昧さを隠している」と指摘している。ホブズボームは「彼が 『本物の伝統の強さと適応性』と呼ぶものと、発明された伝統とを対比している。しかし、彼の言う『適応性』、あるいは同僚のレンジャーの言う『柔軟性』は どこで終わり、どこからが発明なのだろうか?すべての伝統が変化することを考えれば、"本物の "アンティークと偽物を見分けようとすることは可能なのだろうか、有用なのだろうか。「このような区別は、結局のところ、本物と偽物の区別に帰着してしま う。 「22] 「発明は文化的実践の集合化、補足、再配置を伴うので、実質的に伝統は保存され、発明され、再構築されうる」と指摘するガイ・バイナーは、より正確な用語 は「伝統の再発明」であり、「更新、再解釈、改訂を伴う創造的プロセス」を意味すると提唱している[23]。 |

| Examples of American fakelore In addition to Paul Bunyan and Pecos Bill, Dorson identified the American folk hero Joe Magarac as fakelore.[13] Magarac, a fictional steelworker, first appeared in 1931 in a Scribner's Magazine story by the writer Owen Francis. He was a literal man of steel who made rails from molten metal with his bare hands; he refused an opportunity to marry to devote himself to working 24 hours a day, worked so hard that the mill had to shut down, and finally, in despair at enforced idleness, melted himself down in the mill's furnace to improve the quality of the steel. Francis said he heard this story from Croatian immigrant steelworkers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; he reported that they told him the word magarac was a compliment, then laughed and talked to each other in their own language, which he did not speak. The word actually means "donkey" in Croatian, and is an insult. Since no trace of the existence of Joe Magarac stories prior to 1931 has been discovered, Francis's informants may have made the character up as a joke on him. In 1998, Gilley and Burnett reported "only tentative signs that the Magarac story has truly made a substantive transformation from 'fake-' into 'folklore'", but noted his importance as a local cultural icon.[24] Other American folk heroes that have been called fakelore include Old Stormalong, Febold Feboldson,[13] Big Mose, Tony Beaver, Bowleg Bill, Whiskey Jack, Annie Christmas, Cordwood Pete, Antonine Barada, and Kemp Morgan.[25] Marshall Fishwick describes these largely literary figures as imitations of Paul Bunyan.[26] Additionally, scholar Michael I. Niman describes the Legend of the Rainbow Warriors – a belief that a "new tribe" will inherit the ways of the Native Americans and save the planet – as an example of fakelore.[27] |

アメリカのフェイクロアの例 ポール・バニヤンやペコス・ビルに加えて、ドーソンはアメリカの民間ヒーロー、ジョー・マガラックをフェイクロアの一人とした[13]。マガラックは架空 の鉄鋼労働者で、1931年に作家オーウェン・フランシスによるスクリブナーズ誌の物語で初めて登場した。彼は、溶けた金属から素手でレールを作る、文字 通りの鋼鉄の男であった。彼は、1日24時間働くことに専念するために結婚の機会を拒み、工場が操業停止に追い込まれるほど働き、最後には、強制された怠 惰に絶望し、鋼鉄の品質を向上させるために工場の炉で自らを溶かした。フランシスは、この話をペンシルベニア州ピッツバーグのクロアチア系移民の鉄鋼労働 者から聞いたという。彼らはマガラックという言葉は褒め言葉だと言い、それから笑いながら、彼が話せない母国語で互いに語り合ったと報告した。この言葉は クロアチア語で「ロバ」を意味し、侮辱である。1931年以前にジョーマガラックの物語が存在した痕跡は発見されていないため、フランシスの情報提供者 は、彼へのジョークとしてこのキャラクターをでっち上げたのかもしれない。1998年、ギリーとバーネットは「マガラックの物語が本当に『フェイク-』か ら『フォークロア』へと実質的な変貌を遂げたという暫定的な兆候しかない」と報告したが、地元の文化的象徴としての重要性には言及している[24]。 フェイクロアと呼ばれる他のアメリカのフォークヒーローには、オールド・ストーメロン、フェボルド・フェボルドソン、[13]ビッグ・モーズ、トニー・ ビーバー、ボウレッグ・ビル、ウィスキー・ジャック、アニー・クリスマス、コードウッド・ピート、アントニン・バラダ、ケンプ・モーガンなどがいる [25]。マーシャル・フィッシュウィックは、これらの主に文学的な人物をポール・バニヤンの模倣であると述べている。 [26]さらに、学者のマイケル・I・ニマンは、「虹の戦士伝説」-「新しい部族」がネイティブ・アメリカンのやり方を継承し、地球を救うという信仰-を フェイクロアの一例として説明している[27]。 |

| False etymology Folklorismus Hoax Imagined community Mythopoeia Old wives' tale Pseudo-mythology Snopes.com Urban legend |

誤った語源 フォークロリズム デマ 想像上の共同体 神話創作 迷信 疑似神話 スノープス・ドットコム 都市伝説 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Invented_tradition |

●The

invention of tradition / edited by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger,

Cambridge : Cambridge University Press , 1992, c1983 .

"Many of the traditions which we think of as very ancient in their origins were not in fact sanctioned by long usage over the centuries, but were invented comparatively recently. This book explores examples of this process of invention - the creation of Welsh and Scottish 'national culture'; the elaboration of British royal rituals in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; the origins of imperial rituals in British India and Africa; and the attempts by radical movements to develop counter-traditions of their own. It addresses the complex interaction of past and present, bringing together historians and anthropologists in a fascinating study of ritual and symbolism which poses new questions for the understanding of our history." - Nielsen BookData.

1. Introduction: inventing traditions Eric Hobsbawm

2. The invention of tradition: the Highland tradition of Scotland Hugh Trevor Roper

3. From a death to a view: the hunt for the Welsh past in the Romantic period Prys Morgan

4. The context, performance and meaning of ritual: the British Monarchy and the Invention of Tradition, c. 1820-1977 David Cannadine

5. Representing authority of tradition in Victorian India Bernard S. Cohen

6. The invention of tradition in Colonial Africa Terence Roger

7. Mass-producing traditions: Europe, 1870-1914 Eric Hobsbawm.

リ ンク(サイト内)

リ ンク

文 献

そ

の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099