商品フェティシズム

Commodity fetishism

Commodity

fetishism: In the economics of the marketplace, producers and consumers

perceive each other by means of the money and goods that they exchange.

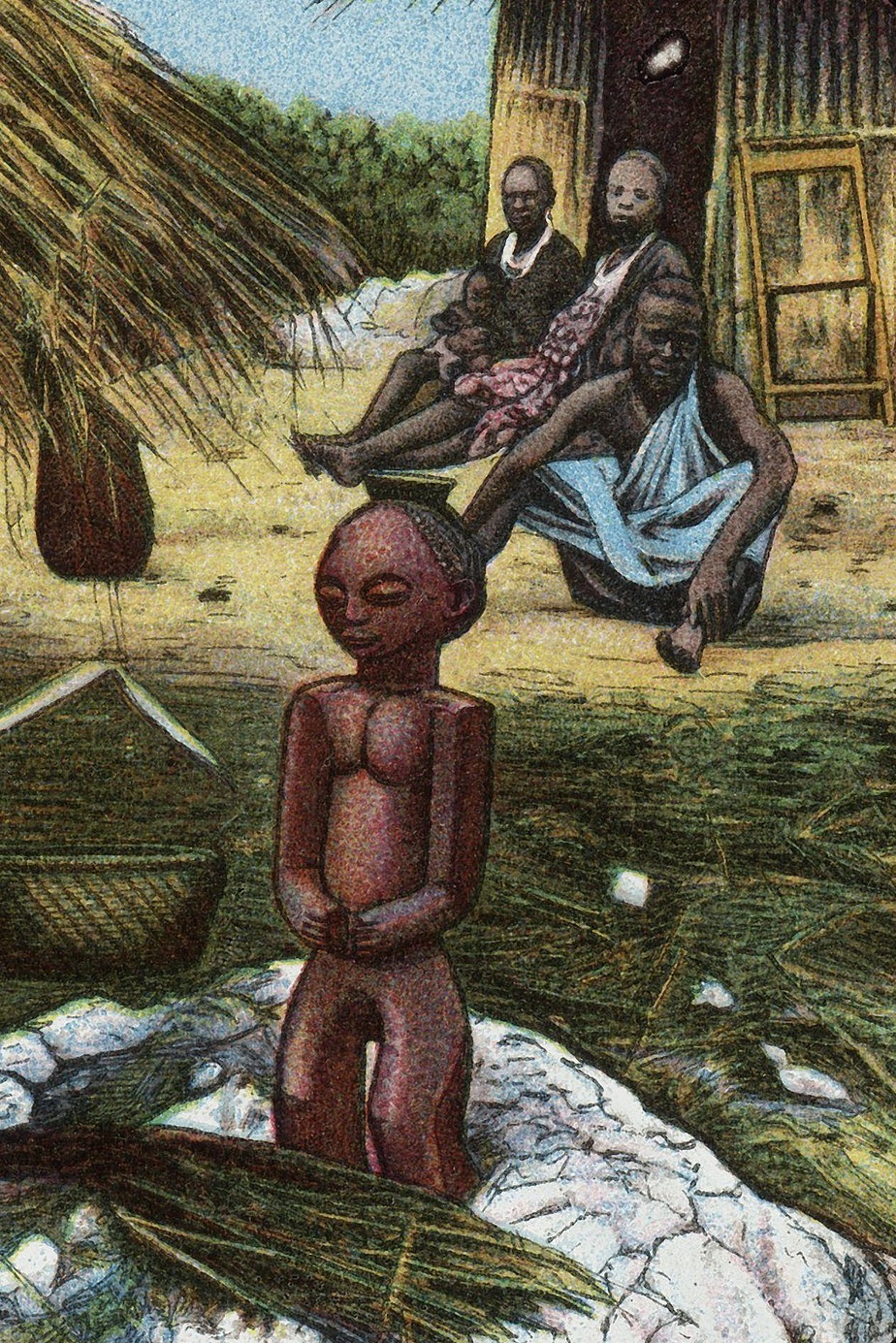

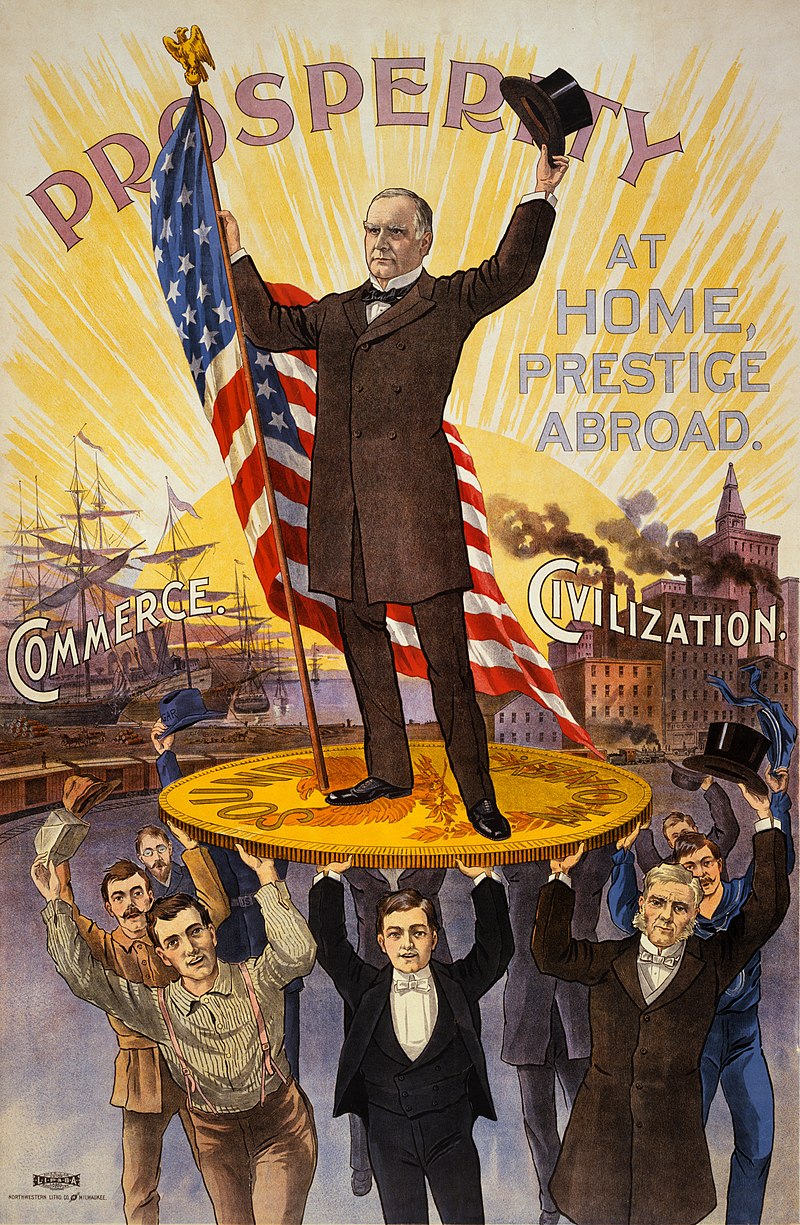

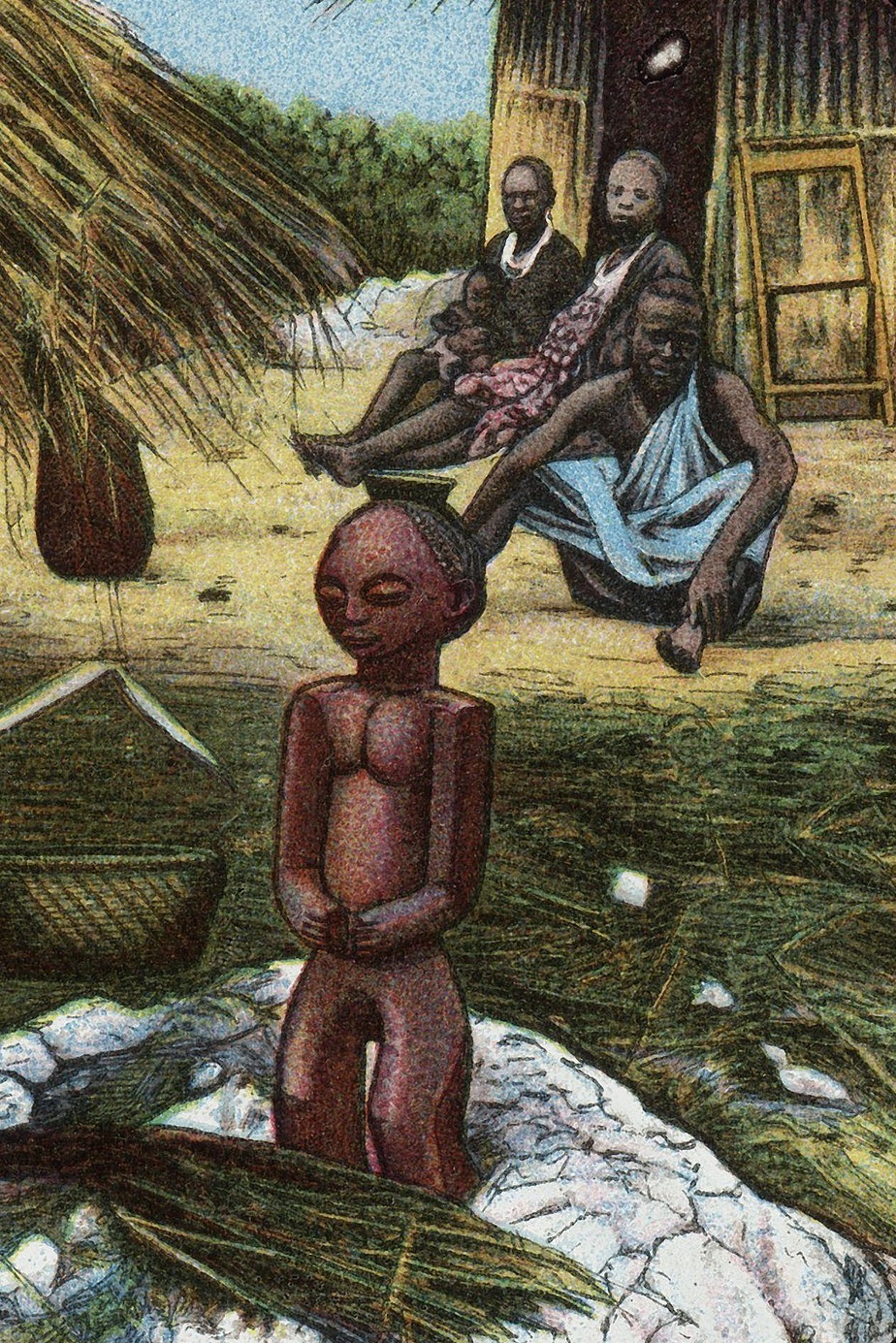

A South African fetish figurine whose supernatural powers protect the owner and kin in the natural world (c. 1900)

☆マルクス主義哲学において、商品フェティシズム(commodity fetishism)とは、生産と交換の経済関係を、人々ではなく物(貨幣や商品)間の関係として認識することである。物象化の 一形態である商品フェティシズムは、経済価値を労働力や、商品を生み出した人間関係、商品やサービスから生じるものではなく、商品に内在するものとして提 示する(→「フェティシズム」)。

| In

Marxist philosophy, commodity fetishism is the perception of the

economic relationships of production and exchange as relationships

among things (money and merchandise) rather than among people. As a

form of reification, commodity fetishism presents economic value as

inherent to the commodities, and not as arising from the workforce,

from the human relations that produced the commodity, the goods and the

services.[1][2] |

マ

ルクス主義哲学において、商品フェティシズムとは、生産と交換の経済関係を、人々ではなく物(貨幣や商品)間の関係として認識することである。物象化の一

形態である商品フェティシズムは、経済価値を労働力や、商品を生み出した人間関係、商品やサービスから生じるものではなく、商品に内在するものとして提示

する。[1][2] |

| Concept In the first chapter of Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (1867), commodity fetishism is used to explain how the social organization of labour manifests in the buying and selling of commodities (goods and services). In the marketplace, social relations among people—who makes what, who works for whom, the production-time for a commodity, etc.—are represented as social relations among objects.[3] In the process of commercial exchange, commodities appear in a depersonalized form, obscuring the social relations inherent to their production.[4] Marx explained the sociology of commodity fetishism: As against this, the commodity-form, and the value-relation of the products of labour, within which it appears, have absolutely no connection with the physical nature of the commodity and the material relations arising out of this. It is nothing but the definite social relation, between men, themselves, which assumes here, for them, the fantastic form of a relation between things. In order, therefore, to find an analogy, we must take flight into the misty realm of religion. There the products of the human brain appear as autonomous figures endowed with a life of their own, which enter into relations, both with each other and with the human race. So it is in the world of commodities with the products of men's hands. I call this the fetishism which attaches itself to the products of labour as soon as they are produced as commodities, and is, therefore, inseparable from the production of commodities.[5] According to Marx, the operation of commodity fetishism requires the owners of capital to actively ignore or maintain an indifference to the relational whole that produces a commodity.[6]: 132 |

概念 『資本論:政治経済批判』(1867年)の第1章では、商品フェティシズムが、労働の社会的組織が商品(物品やサービス)の売買にどのように現れるかを説 明するのに用いられている。市場では、人々の社会的関係(誰が何を生産するか、誰が誰のために働くか、商品の生産時間など)は、物と物との社会的関係とし て表される。 商業取引の過程では、商品が人間性を排除した形態で現れるため、その生産に内在する社会的関係が不明瞭になる。[4] マルクスは商品フェティシズムの社会学を次のように説明している。 これに対して、商品形態、およびその中に現れる労働生産物の価値関係は、商品の物理的性質や、そこから生じる物質的関係とはまったく関係がない。それは、 人間同士の明確な社会的関係が、ここでは物と物との関係という幻想的な形態を仮定しているにすぎない。したがって類似点を見つけるためには、宗教の霧に包 まれた領域に飛翔しなければならない。そこでは、人間の脳が生み出した産物が、独自の生命を持つ自律的な存在として現れ、互いに、そして人類と関係を持 つ。人間の労働の産物である商品についても同様である。私はこれを、商品として生産された途端に労働の産物に付着するフェティシズムと呼ぶ。したがって、 これは商品の生産と不可分である。[5] マルクスによれば、商品フェティシズムの作用により、資本の所有者は商品を生み出す関係全体を積極的に無視したり、無関心を維持したりすることが必要となる。[6]:132 |

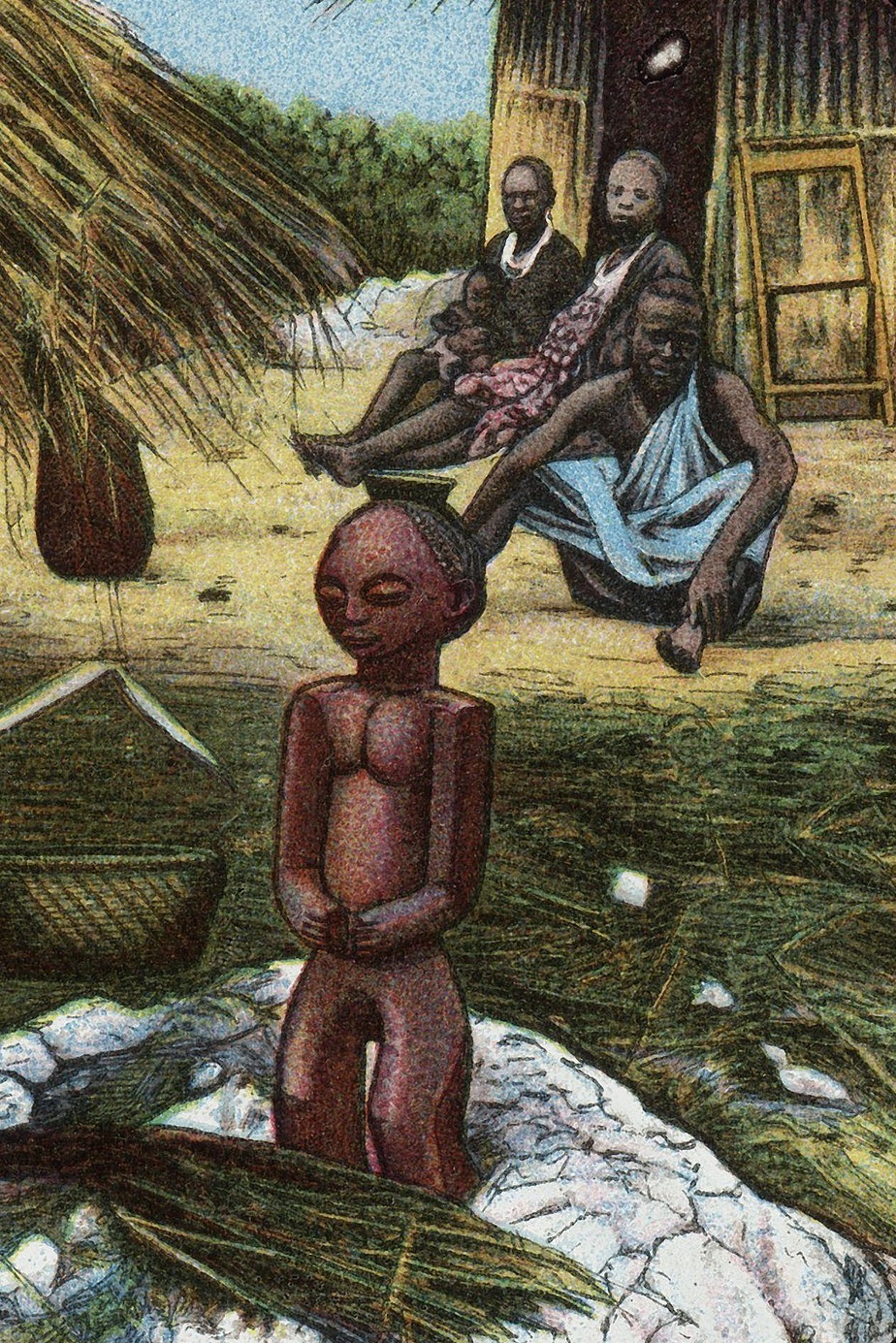

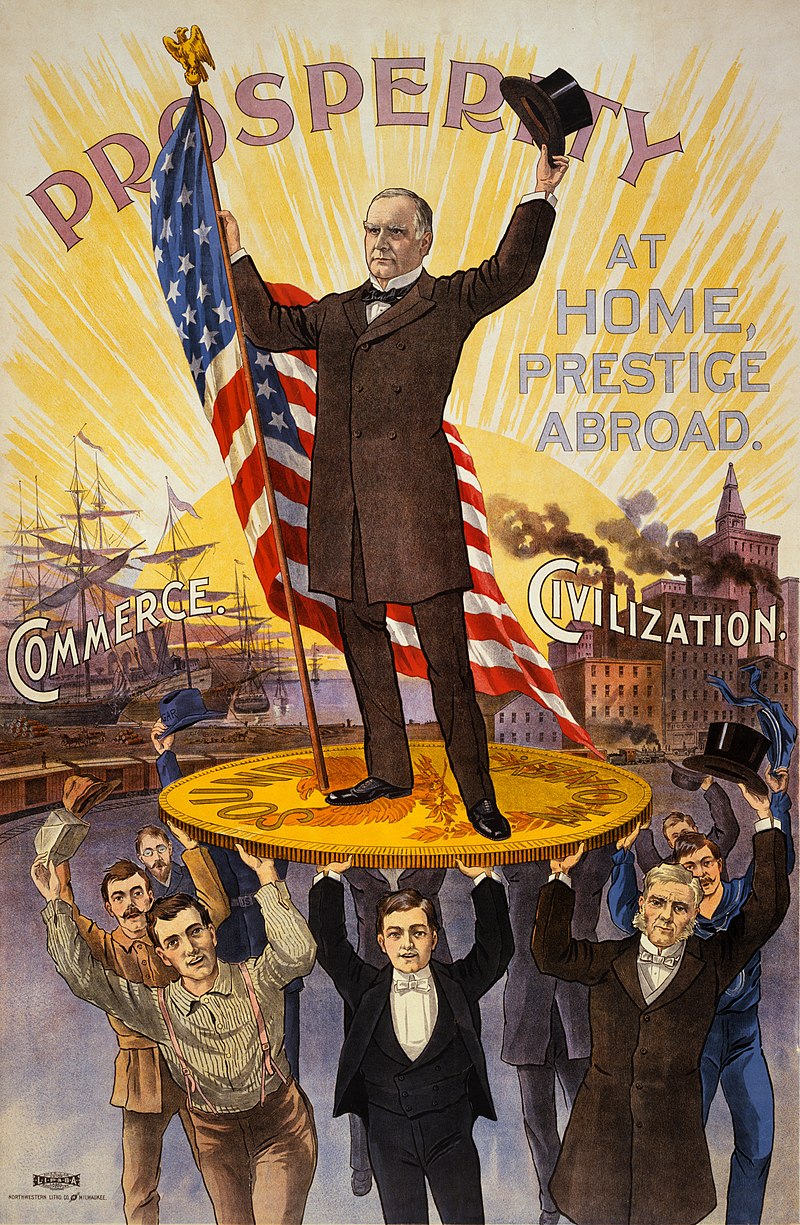

Development A South African fetish figurine whose supernatural powers protect the owner and kin in the natural world (c. 1900)  Presidential candidate William McKinley stands on an oversized gold coin carried by a merchant, a capitalist, a businessman, a craftsman and others, beneath the word "Prosperity" A political poster shows gold coin as the basis of prosperity (c. 1896). The theory of commodity fetishism (German: Warenfetischismus) originated from Karl Marx's references to fetishes and fetishism in his analyses of religious superstition, and in the criticism of the beliefs of political economists.[7] Marx borrowed the concept of "fetishism" from The Cult of Fetish Gods (1760) by Charles de Brosses, which proposed a materialist theory of the origin of religion.[8][9] Moreover, in the 1840s, the philosophic discussion of fetishism by Auguste Comte, and Ludwig Feuerbach's psychological interpretation of religion also influenced Marx's development of commodity fetishism.[10][11] Marx's first mention of fetishism appeared in 1842, in his response to a newspaper article by Karl Heinrich Hermes, which defended Germany on religious grounds.[12] Hermes agreed with the German philosopher Hegel in regarding fetishism as the crudest form of religion. Marx dismissed that argument and Hermes's definition of religion as that which elevates man "above sensuous appetites". Instead, Marx said that fetishism is "the religion of sensuous appetites", and that the fantasy of the appetites tricks the fetish worshipper into believing that an inanimate object will yield its natural character to gratify the desires of the worshipper. Therefore, the crude appetite of the fetish worshipper smashes the fetish when it ceases to be of service.[13][14][15] The next mention of fetishism was in the 1842 Rheinische Zeitung newspaper articles about the "Debates on the Law on Thefts of Wood", wherein Marx spoke of the Spanish fetishism of gold and the German fetishism of wood as commodities:[16] The savages of Cuba regarded gold as a fetish of the Spaniards. They celebrated a feast in its honour, sang in a circle around it, and then threw it into the sea. If the Cuban savages had been present at the sitting of the Rhine Province Assembly, would they not have regarded wood as the Rhinelanders' fetish? But a subsequent sitting would have taught them that the worship of animals is connected with this fetishism, and they would have thrown the hares into the sea in order to save the human beings. In the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, Marx spoke of the European fetish of precious-metal money: The nations which are still dazzled by the sensuous glitter of precious metals, and are, therefore, still fetish-worshippers of metal money, are not yet fully developed money-nations. [Note the] contrast of France and England. The extent to which the solution of theoretical riddles is the task of practice, and is effected through practice, the extent to which true practice is the condition of a real and positive theory, is shown, for example, in fetishism. The sensuous consciousness of the fetish-worshipper is different from that of the Greek, because his sensuous existence is different. The abstract enmity between sense and spirit is necessary so long as the human feeling for nature, the human sense of nature, and, therefore, also the natural sense of man, are not yet produced by man's own labour.[17] |

展開 超自然的な力によって持ち主とその家族を自然界から守る南アフリカのフェティッシュ・フィギュリン(1900年頃)  「繁栄」という文字の下に商人、資本家、実業家、職人などが運ぶ特大の金貨の上に立つ大統領候補のウィリアム・マッキンリー 政治ポスターでは、繁栄の基礎として金貨が描かれている(1896年頃)。 商品フェティシズム(ドイツ語:Warenfetischismus)の理論は、カール・マルクスが迷信の分析や政治経済学者の信念の批判においてフェ ティシズムやフェティシズムについて言及したことから始まった。[7] マルクスは、宗教の起源に関する唯物論的理論を提唱したシャルル・ド・ブロスの『フェティッシュ崇拝』(1760年)から「フェティシズム」という概念を 借用した。 [8][9] さらに、1840年代には、オーギュスト・コントによるフェティシズムの哲学的な議論や、ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハによる宗教の心理学的解釈も、マ ルクスの商品フェティシズムの展開に影響を与えた。 マルクスがフェティシズムについて初めて言及したのは1842年、カール・ハインリヒ・ヘルメスの新聞記事への反論においてであった。ヘルメスは、フェ ティシズムを宗教の最も粗野な形態であるとみなす点で、ドイツの哲学者ヘーゲルに同意していた。マルクスはその主張を退け、ヘルメスの「宗教とは人間を感 覚的欲求から解放するもの」という定義を否定した。その代わりに、フェティシズムは「感覚的欲望の宗教」であり、欲望の幻想がフェティシストを騙して、無 生物が自然の性質を放棄し、崇拝者の欲望を満たすように思わせるとマルクスは述べた。したがって、フェティシストの粗野な欲望は、フェティッシュが役目を 終えたときにそれを破壊する。 次にフェティシズムについて言及されたのは、1842年の新聞『ライン新聞』に掲載された「木材窃盗に関する法律についての討論」に関する記事で、マルクスはスペインの金に対するフェティシズムとドイツの木材に対するフェティシズムを商品として論じている。 キューバの未開人は金をスペイン人のフェティッシュとしていた。彼らは金に敬意を表して祝宴を開き、金の周りに輪になって歌い、そして金を海に投げ込ん だ。もしキューバの野蛮人がライン州議会の会議に出席していたら、彼らは木をライン地方の人々のフェティシズムの対象とみなしただろうか?しかし、その後 の会議で、動物崇拝がこのフェティシズムと結びついていることを彼らは学んだだろう。そして、彼らは人間を救うためにウサギを海に投げ込んだだろう。 1844年の経済・哲学草稿の中で、マルクスはヨーロッパの貴金属崇拝について次のように述べている。 貴金属の感覚的な輝きに今なお目を奪われ、したがって今なお金属貨幣を崇拝している国民は、まだ十分に発展した貨幣国家ではない。フランスとイギリスの対 照を考えてみよう。理論的な謎の解決が実践の課題であり、実践を通じて実現されるものである程度、真の実践が現実的かつ積極的な理論の条件である程度は、 例えばフェティシズムに示されている。フェティシストの感覚意識はギリシア人のそれとは異なる。なぜなら、彼らの感覚的存在は異なるからだ。感覚と精神の 間の抽象的な敵対関係は、人間が自然に対する感覚、自然に対する感覚、そしてそれゆえに人間に対する自然の感覚を、人間の労働によってまだ作り出していな い限り、必要である。[17] |

| Ethnology In the ethnological notebooks, he commented upon the archaeological reportage of The Origin of Civilization and the Primitive Condition of Man: Mental and Social conditions of Savages (1870), by John Lubbock.[18] In the Outlines of the Critique of Political Economy (Grundrisse, 1859), he criticized the liberal arguments of the French economist Frédéric Bastiat; and about fetishes and fetishism Marx said: In real history, wage labour arises out of the dissolution of slavery and serfdom—or of the decay of communal property, as with Oriental and Slavonic peoples—and, in its adequate, epoch-making form, the form which takes possession of the entire social being of labour, out of the decline and fall of the guild economy, of the system of Estates, of labour and income in kind, of industry carried on as rural subsidiary occupation, of small-scale feudal agriculture, etc. In all these real historic transitions, wage labour appears as the dissolution, the annihilation of relations in which labour was fixed on all sides, in its income, its content, its location, its scope, etc. Hence, as negation of the stability of labour and of its remuneration. The direct transition from the African's fetish to Voltaire's "Supreme Being", or from the hunting gear of a North American savage to the capital of the Bank of England, is not so absurdly contrary to history, as is the transition from Bastiat's fisherman to the wage labourer.[19] In A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859), Marx referred to A Discourse on the Rise, Progress, Peculiar Objects, and Importance of Political Economy (1825), by John Ramsay McCulloch, who said that "In its natural state, matter ... is always destitute of value", with which Marx concurred, saying that "this shows how high even a McCulloch stands above the fetishism of German 'thinkers' who assert that 'material', and half a dozen similar irrelevancies are elements of value". Furthermore, in the manuscript of "Results of the Immediate Process of Production" (c. 1864), an appendix to Capital: Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1 (1867), Marx said that: ... we find in the capitalist process of production [an] indissoluble fusion of use-values in which capital subsists [as] means of production and objects defined as capital, when what we are really faced with is a definite social relationship of production. In consequence, the product embedded in this mode of production is equated with the commodity, by those who have to deal with it. It is this that forms the foundation for the fetishism of the political economists.[20] Hence did Karl Marx apply the concepts of fetish and fetishism, derived from economic and ethnologic studies, to the development of the theory of commodity fetishism, wherein an economic abstraction (value) is psychologically transformed (reified) into an object, which people choose to believe has an intrinsic value, in and of itself.[21] |

民族学 民族学のノートでは、ジョン・ラブ ロック著『文明の起源と人間の原始状態:野蛮人の精神的・社会的状態』(1870年)の考古学的ルポルタージュについてコメントしている。[18] 『経済学批判要綱』(1859年)では、フランスの経済学者フレデリック・バシアの自由主義的議論を批判し、フェティシズムとフェティシズムについて、マ ルクスは次のように述べている。 現実の歴史において、賃労働は奴隷制や農奴制の解消、すなわち東洋民族やスラブ民族に見られる共同所有財産の衰退から生じた。また、ギルド経済、身分制 度、現物支給による労働と収入、農村の副業として行われる産業、 小規模な封建的農業など。こうした現実の歴史的変遷のすべてにおいて、賃金労働は、労働がその収入、内容、場所、範囲など、あらゆる面で固定されていた関 係の解消、消滅として現れる。したがって、労働とその報酬の安定性の否定として現れる。アフリカ人のフェティシズムからヴォルテールの「至高者」への直接 的な移行、あるいは北米の野蛮人の狩猟道具からイングランド銀行の資本への直接的な移行は、バスティアの漁師から賃金労働者への移行ほど、歴史に反するも のではない。[19] 『経済学批判への寄与』(1859年)の中で、マルクスはジョン・ラムゼイ・マッカローの『政治経済学の勃興、進歩、特異性、重要性に関する講話』 (1825年)に言及し、マッカローが「自然状態では、物質は... 常に価値を欠いている」と述べ、これにマルクスも同意し、「これは、『物質』やその他半ダースの同様の無関係なものが価値の要素であると主張するドイツの 『思想家』たちのフェティシズムがいかに低俗であるかを示している」と述べた。 さらに、『資本論』第1巻(1867年)の付録である『生産の即時過程の結果』(1864年頃)の草稿の中で、マルクスは次のように述べている。 ... 資本主義的生産過程において、使用価値が不可分の形で融合し、資本が生産手段として存続し、資本として定義された対象が存在する。しかし、私たちが実際に 直面しているのは、明確な社会的生産関係である。その結果、この生産様式に埋め込まれた生産物は、それを取り扱う人々によって商品と同一視される。これ が、政治経済学者のフェティシズムの基礎となっているのである。[20] したがって、カール・マルクスは、経済学や民族学の研究から導き出されたフェティシズムとフェティシズムの概念を、経済的抽象物(価値)が心理的に物体へ と変容(物象化)し、人々がその物体自体に本質的な価値があると信じるようになるという商品フェティシズム理論の展開に適用した。[21] |

| Critique In the critique of political economy Main article: Critique of political economy Marx proposed that in a society where independent, private producers trade their products with each other, of their own volition and initiative, and without much coordination of market exchange, the volumes of production and commercial activities are adjusted in accordance with the fluctuating values of the products (goods and services) as they are bought and sold, and in accordance with the fluctuations of supply and demand. Because their social coexistence, and its meaning, is expressed through market exchange (trade and transaction), people have no other relations with each other. Therefore, social relations are continually mediated and expressed with objects (commodities and money). How the traded commodities relate will depend upon the costs of production, which are reducible to quantities of human labour, although the worker has no control over what happens to the commodities that they produce. (See: Entfremdung, Marx's theory of alienation) |

批判 政治経済学の批判において 詳細は「政治経済学の批判」を参照 マルクスは、独立した私的な生産者が、市場取引の調整をほとんど行わずに、自らの意思と主導権に基づいて互いの生産物を取引する社会では、生産量と商業活 動は、商品(物品およびサービス)が売買される際に変動する価値と、需要と供給の変動に応じて調整されると提案した。彼らの社会的共存とその意味は市場取 引(売買や取引)によって表現されるため、人々は互いにそれ以外の関係を持たない。したがって、社会関係は絶えず物(商品や貨幣)によって媒介され、表現 される。取引される商品がどのように関係し合うかは、生産コストに依存する。生産コストは人間の労働量に還元できるが、労働者は自分が生産した商品がどう なるかについては制御できない。(参照:疎外、マルクスの疎外理論) |

| Domination of things The concept of the intrinsic value of commodities (goods and services) determines and dominates the economic (business) relationships among people, to the extent that buyers and sellers continually adjust their beliefs (financial expectations) about the value of things—either consciously or unconsciously—to the proportionate price changes (market value) of the commodities over which buyers and sellers believe they have no true control. That psychologic perception transforms the trading-value of a commodity into an independent entity (an object), to the degree that the social value of the goods and services appears to be a natural property of the commodity itself. Thence objectified, the market appears as if self-regulated (by fluctuating supply and demand) because, in pursuit of profit, the consumers of the products ceased to perceive the human co-operation among capitalists that is the true engine of the market where commodities are bought and sold; such is the domination of things in the market. |

モノの支配 商品(物品およびサービス)の本質的価値の概念は、人々の経済的(ビジネス)関係を決定し、支配する。買い手と売り手は、自分たちが真の支配力を持たない と考えている商品の価格変動(市場価値)に比例して、モノの価値に関する信念(財務上の期待)を絶えず調整する。その心理的知覚により、商品やサービスの 社会的価値が商品の自然な特性であるかのように見える程度まで、商品の取引価値が独立した存在(対象)へと変化する。このように客体化された市場は、あた かも(需要と供給の変動によって)自己規制されているかのように見える。なぜなら、利益追求のために、商品の購入者である消費者は、商品が売買される市場 の真の原動力である資本家間の人間的協力関係を認識しなくなるからである。市場では、モノが支配的な地位を占めている。 |

| Objectified value The value of a commodity originates from the human being's intellectual and perceptual capacity to consciously (subjectively) ascribe a relative value (importance) to a commodity, the goods and services manufactured by the labour of a worker. Therefore, in the course of the economic transactions (buying and selling) that constitute market exchange, people ascribe subjective values to the commodities, which the buyers and the sellers then perceive as objective values, the market-exchange prices that people will pay for the commodities. |

客観化された価値 商品の価値は、労働者の労働によって製造された商品やサービスに、意識的に(主観的に)相対的な価値(重要性)を付与する人間の知的・知覚的能力に由来す る。したがって、市場取引を構成する経済取引(売買)の過程において、人々は商品に主観的な価値を付与し、買い手と売り手はそれを客観的な価値、つまり人 々が商品に対して支払う市場取引価格として認識する。 |

| Naturalization of market behaviour In a capitalist society, the human perception that "the market" is an independent, sentient entity, is how buyers, sellers, and producers naturalize market exchange (the human choices and decisions that constitute commerce) as a series of "natural phenomena ... that ... happen of their own accord". Such were the political-economy arguments of the economists whom Karl Marx criticized when they spoke of the "natural equilibria" of markets, as if the price (value) of a commodity were independent of the volition and initiative of the capitalist producers, buyers, and sellers of commodities. In the 18th century, the Scottish social philosopher and political economist Adam Smith, in The Wealth of Nations (1776) proposed that the "truck, barter, and exchange" activities of the market were corresponding economic representations of human nature, that is, the buying and selling of commodities were activities intrinsic to the market, and thus are the "natural behaviour" of the market. Hence, Smith proposed that a market economy was a self-regulating entity that "naturally" tended towards economic equilibrium, wherein the relative prices (the value) of a commodity ensured that the buyers and sellers obtained what they wanted for and from their goods and services.[22] In the 19th century, Karl Marx contradicted the artifice of Adam Smith's "naturalisation of the market's behaviour" as a politico-ideologic apology—by and for the capitalists—which allowed human economic choices and decisions to be misrepresented as fixed "facts of life", rather than as the human actions that resulted from the will of the producers, the buyers, and the sellers of the commodities traded at market. Such "immutable economic laws" are what Capital: Critique of Political Economy (1867) revealed about the functioning of the capitalist mode of production, how goods and services (commodities) are circulated among a society; and thus explain the psychological phenomenon of commodity fetishism, which ascribes an independent, objective value and reality to a thing that has no inherent value—other than the value given to it by the producer, the seller, and the buyer of the commodity. |

市場行動の自然化 資本主義社会において、「市場」が独立した意思を持つ存在であるという人間の認識が、買い手、売り手、生産者が市場取引(商業を構成する人間の選択や決 定)を「自然現象」として自然化するものである。カール・マルクスが批判した経済学者たちの政治経済学上の主張は、あたかも商品の価格(価値)が、その商 品の生産者、購入者、販売者である資本家の意志やイニシアティブとは無関係であるかのように、市場の「自然な均衡」について語っていた。 18世紀、スコットランドの社会哲学者であり政治経済学者のアダム・スミスは著書『諸国民の富』(1776年)の中で、市場における「トラック、バー ター、交換」の活動は人間の本質を反映した経済活動であると提唱した。つまり、商品の売買は市場の本質的な活動であり、市場の「自然な行動」である。した がって、スミスは市場経済は「自然に」経済的均衡に向かう自己調整的な存在であると提唱し、商品の相対価格(価値)が、売り手と買い手が商品やサービスに 対して望むものを確実に手に入れることを保証すると主張した。[22] 19世紀、カール・マルクスは、アダム・スミスの「市場の行動の自然化」という策略を、政治的・イデオロギー的な弁明として、資本家による資本家のための ものと矛盾した。それは、市場で取引される商品を生み出す生産者、購入者、販売者の意思の結果として生じる人間の行動ではなく、人間の経済的な選択や決定 が、固定された「生活の事実」として誤って表現されることを許容するものだった。このような「不変の経済法則」は、資本論(1867年)が資本主義的生産 様式の機能について明らかにしたものであり、商品やサービス(商品)が社会の中でどのように流通するかを示している。また、商品フェティシズムという心理 現象を説明している。商品フェティシズムとは、商品に内在する価値(生産者、販売者、購入者によって付与された価値以外の価値)を、独立した客観的な価値 や現実としてみなす現象である。 |

| Masking In a capitalist economy, a character mask (Charaktermaske) is the functional role with which a person relates and is related to in a society composed of stratified social classes, especially in relationships and market-exchange transactions; thus, in the course of buying and selling, the commodities (goods and services) usually appear other than they are, because they are masked (obscured) by the role-playing of the buyer and the seller. Moreover, because the capitalist economy of a class society is an intrinsically contradictory system, the masking of the true socio-economic character of the transaction is an integral feature of its function and operation as market exchange. In the course of business competition among themselves, buyers, sellers, and producers cannot do business (compete) without obscurity—confidentiality and secrecy—thus the necessity of the character masks that obscure true economic motive. Central to the Marxist critique of political economy is the obscurantism of the juridical labour contract, between the worker and the capitalist, that masks the true, exploitive nature of their economic relationship—that the worker does not sell his and her labour, but that the worker sells individual labour power, the human capacity to perform work and manufacture commodities (goods and services) that yield a profit to the producer. The work contract is the mask that obscures the economic exploitation of the difference between the wages paid for the labour of the worker, and the new value created by the labour of the worker. Marx thus established that in a capitalist society the creation of wealth is based upon "the paid and unpaid portions of labour [that] are inseparably mixed up with each other, and the nature of the whole transaction is completely masked by the intervention of a contract, and the pay received at the end of the week"; and that:[23][24][25] Vulgar economics actually does nothing more than to interpret, to systematize and turn into apologetics—in a doctrinaire way—the ideas of the agents who are trapped within bourgeois relations of production. So it should not surprise us that, precisely within the estranged form of appearance of economic relations in which these prima facie absurd and complete contradictions occur—and all science would be superfluous if the form of appearance of things directly coincided with their essence—that precisely here vulgar economics feels completely at home, and that these relationships appear all the more self-evident to it, the more their inner interconnection remains hidden to it, even though these relationships are comprehensible to the popular mind. — Capital, Volume III.[26] |

マスク 資本主義経済において、人格マスク(Charaktermaske)とは、階級社会で構成される社会において、特に人間関係や市場取引において、人格が関 わり、関わられる機能的役割である。したがって、売買の過程では、商品(物品やサービス)は通常、本来の姿とは異なる形で現れる。なぜなら、買い手と売り 手の役割演技によってマスク(隠蔽)されるからである。さらに、階級社会の資本主義経済は本質的に矛盾したシステムであるため、取引の真の社会経済的特徴 を覆い隠すことは、市場取引としての機能と運営の不可欠な特徴である。買い手、売り手、生産者間の企業間競争においては、機密性と秘密性という不明瞭性な しには取引(競争)を行うことができないため、真の経済的動機を不明瞭にする仮面の必要性がある。 マルクス主義の政治経済批判の中心となるのは、労働者と資本家間の法的な労働契約におけるオキュルティズムであり、それは彼らの経済関係の真の搾取的本質 を覆い隠している。すなわち、労働者は自分の労働力を売っているのではなく、個々の労働力、すなわち生産者に利益をもたらす商品(物品やサービス)を製造 する人間の能力を売っているのだ。労働契約は、労働者の労働に対して支払われる賃金と、労働者の労働によって新たに生み出される価値との間の経済的搾取を 覆い隠す仮面である。 マルクスは、資本主義社会では富の創出が「賃金労働と非賃金労働の不可分に混ざり合ったもの」であり、「取引全体の性質は契約の介入によって完全に覆い隠され、賃金は週の終わりに支払われる」と主張した。そして、[23][24][25] 低俗な経済学は、ブルジョワ的生産関係に縛り付けられたエージェントたちの考え方を、教条主義的に解釈し、体系化し、弁証法に変えること以上のことは実際 には何もしない。したがって、 まさに、一見したところ不合理で完全な矛盾が起こる経済関係の疎外された外見のなかで、つまり、事物の外見の形がその本質と直接的に一致するのであれば、 科学はすべて不要であるが、まさにこの場所で通俗経済学は完全に居心地が良く、これらの関係が大衆の心には理解できるにもかかわらず、その内的な相互関係 が隠されたままであるほど、これらの関係がより一層自明なものに見える。 —『資本論』第3巻[26]。 |

| Opacity of economic relations The primary valuation of the trading-value of goods and services (commodities) is expressed as money-prices. The buyers and the sellers determine and establish the economic and financial relationships; and afterwards compare the prices in and the price trends of the market. Moreover, because of the masking of true economic motive, neither the buyer, nor the seller, nor the producer perceive and understand every human labour-activity required to deliver the commodities (goods and services), nor do they perceive the workers whose labour facilitated the purchase of commodities. The economic results of such collective human labour are expressed as the values and the prices of the commodities; the value-relations between the amount of human labour and the value of the supplied commodity. |

経済関係の不透明性 商品やサービス(商品)の取引価値の主な評価は、貨幣価格として表現される。買い手と売り手が経済的・財政的関係を決定し、確立し、その後、市場の価格と 価格動向を比較する。さらに、真の経済的動機が覆い隠されているため、買い手も売り手も生産者も、商品(物品やサービス)を提供するために必要なあらゆる 人的労働活動を認識することも理解することもなく、また、商品の購入を容易にした労働者も認識しない。このような集団的労働の経済的結果は、商品の価値と 価格として表現される。すなわち、供給された商品の価値と、提供された労働量との価値関係である。 |

| Capitalism as religion Main article: Capitalism as Religion In the essay "Capitalism as Religion" (1921), Walter Benjamin said that whether or not people treat capitalism as a religion was a moot subject, because "One can behold in capitalism a religion, that is to say, capitalism essentially serves to satisfy the same worries, anguish, and disquiet formerly answered by so-called religion." That the religion of capitalism is manifest in four tenets: "Capitalism is a purely cultic religion, perhaps the most extreme that ever existed" "The permanence of the cult" "Capitalism is probably the first instance of a cult that creates guilt, not atonement" "God must be hidden from it, and may be addressed only when guilt is at its zenith".[27][28] |

宗教としての資本主義を 詳細は「資本主義を宗教として」を参照 1921年の論文「資本主義を宗教として」において、ウォルター・ベンヤミンは、人々が資本主義を宗教として扱うかどうかは議論の余地があるとした。なぜ なら、「資本主義には宗教を見ることができる。つまり、資本主義は本質的に、かつていわゆる宗教が応えていたのと同じ不安や苦悩、動揺を満たすために役立 つ」からである。資本主義の宗教は、次の4つの教義に明示されている。 「資本主義は純粋なカルト宗教であり、おそらくこれまで存在した中で最も極端なものである」 「カルトの永続性」 「資本主義は、おそらく罪悪感を生み出すカルトの最初の事例であり、償いは生み出さない」 「神はそこから隠されねばならず、罪悪感が頂点に達したときにのみ、神に語りかけることができるかもしれない」[27][28] |

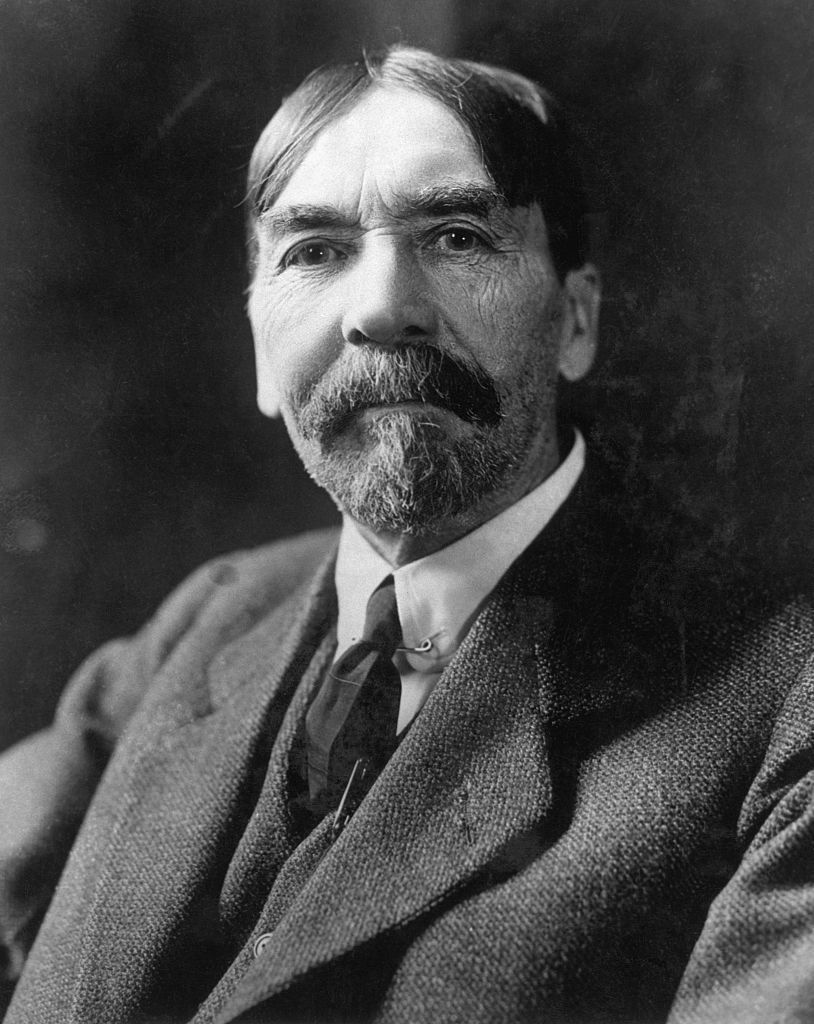

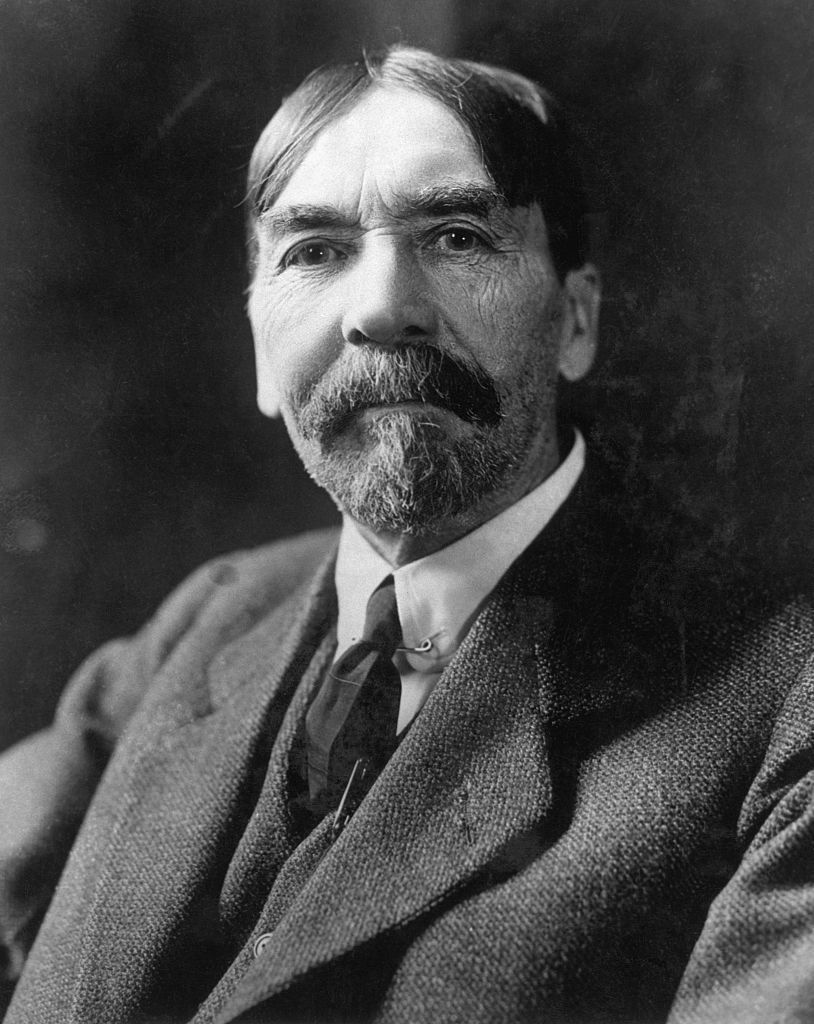

| Applications Cultural theory  The Hungarian philosopher György Lukács developed Karl Marx's theory of commodity fetishism to develop reification theory.  Thorstein Veblen proposed the conspicuous consumption of commodities as the pursuit of social prestige. Since the 19th century, when Karl Marx presented the theory of commodity fetishism, in Section 4, "The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret thereof", of the first chapter of Capital: Critique of Political Economy (1867), the constituent concepts of the theory, and their sociologic and economic explanations, have proved intellectually fertile propositions that permit the application of the theory (interpretation, development, adaptation) to the study, examination, and analysis of other cultural aspects of the political economy of capitalism, such as: |

応用 文化論  ハンガリーの哲学者、ジェルジ・ルカーチは、カール・マルクスの商品フェティシズム論を発展させ、物象化論を展開した。  トールステイン・ヴェブレンは、商品の誇示的消費を社会的威信の追求として提唱した。 カール・マルクスが『資本論』第1章第4節「商品の拝物神崇拝とその秘密」で拝物神説を提示した19世紀以降、 その理論の構成概念と社会学的および経済学的説明は、資本主義の政治経済学の他の文化的側面に関する研究、調査、分析に理論を適用(解釈、展開、適応)す ることを可能にする知的豊饒な命題であることが証明されている。 |

| Social prestige In the 19th century, Thorstein Veblen (The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions, 1899) developed the social status (prestige) relationship between the producer of consumer goods and the aspirations to prestige of the consumer. To avoid the status anxiety of not being of or belonging to "the right social class", the consumer establishes a personal identity (social, economic, cultural) that is defined and expressed by the commodities (goods and services) that they buy, own, and use; the domination of things that communicate the "correct signals" of social prestige, of belonging. (See: Conspicuous consumption.) |

社会的威信 19世紀、トールステイン・ヴェブレン(『有閑階級論:制度に関する経済学的考察』1899年)は、消費財の生産者と消費者の威信へのあこがれとの間の社 会的地位(威信)の関係を明らかにした。「正しい社会階級」に属していないという地位不安を回避するために、消費者は、購入、所有、使用する商品(物品や サービス)によって定義され表現される人格(社会的、経済的、文化的)を確立する。社会的な威信や帰属意識を伝える「正しいシグナル」を発するものを支配 するのだ。(参照:誇示的消費) |

| Reification In History and Class Consciousness (1923), György Lukács started from the theory of commodity fetishism for his development of reification (the psychological transformation of an abstraction into a concrete object) as the principal obstacle to class consciousness. About which Lukács said: "Just as the capitalist system continuously produces and reproduces itself economically on higher levels, the structure of reification progressively sinks more deeply, more fatefully, and more definitively into the consciousness of Man"—hence, commodification pervaded every conscious human activity, as the growth of capitalism commodified every sphere of human activity into a product that can be bought and sold in the market.[29] (See: Verdinglichung, Marx's theory of reification.) |

物象化 『歴史と階級意識』(1923年)において、ゲオルク・ルカーチは、物象化(抽象概念が具体的な対象物へと心理的に変化すること)を階級意識の主要な障害 として発展させるために、商品のフェティシズム論から出発した。ルカーチは次のように述べている。「資本主義システムが経済的により高いレベルで絶えず自 己生産と自己再生産を行うのと同様に、物象化の構造は、人間の意識にますます深く、より運命的に、より決定的に浸透していく」――したがって、商品化は、 資本主義の成長に伴い、人間のあらゆる活動領域が市場で売買可能な商品へと商品化されるように、あらゆる意識的な人間の活動に浸透した。[29](参照: 物神化、マルクスの物象化論を参照。 |

| Industrialized culture Commodity fetishism is theoretically central to the Frankfurt School philosophy, especially in the work of the sociologist Theodor W. Adorno, which describes how the forms of commerce invade the human psyche; how commerce casts a person into a role not of his or her making; and how commercial forces affect the development of the psyche. In the book Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944), Adorno and Max Horkheimer presented the Theory of the Culture Industry to describe how the human imagination (artistic, spiritual, intellectual activity) becomes commodified when subordinated to the "natural commercial laws" of the market. To the consumer, the cultural goods and services sold in the market appear to offer the promise of a richly developed and creative individuality, yet the inherent commodification severely restricts and stunts the human psyche, so that the man and the woman consumer has little "time for myself", because of the continual personification of cultural roles over which he and she exercise little control. In personifying such cultural identities, the person is a passive consumer, not the active creator, of his or her life; the promised life of individualistic creativity is incompatible with the collectivist, commercial norms of bourgeois culture. In Capital, Volume 1, Marx remarked that "In bourgeois society the legal fiction prevails that each person, as a buyer, has an encyclopedic knowledge of commodities".[30] From 2017 onward, however, the world's consumers can use the Google Lens app on their mobile phone, to scan any object in order to find out information and prices for that object (or a very similar object). According to a survey by financial services firm Empower, Americans nowadays spend 2.5 hours a day, or 873 hours per year, on "dreamscrolling" (i.e digital window shopping and gazing at dream purchases).[31] |

産業化された文化 商品崇拝は、フランクフルト学派の理論の中心であり、特に社会学者テオドール・W・アドルノの著作では、商業の形態が人間の精神にどのように侵入するか、 商業が人格をその人の意図しない役割に押し込めるか、商業的な力が精神の発達にどのように影響するかについて説明している。アドルノとマックス・ホルクハ イマーは著書『啓蒙の弁証法』(1944年)の中で、人間の想像力(芸術的、精神的、知的活動)が市場の「自然な商業法則」に従属することで商品化される 様子を説明する「文化産業論」を提示した。 消費者にとって、市場で販売されている文化的な商品やサービスは、豊かに発達した創造的な個性を約束するもののように見えるが、本質的な商品化は人間の精 神を厳しく制限し、抑制する。そのため、男性も女性も「自分のための時間」をほとんど持てない。なぜなら、彼らがほとんどコントロールできない文化的な役 割が絶えず擬人化されるからだ。このような文化的アイデンティティを人格化する中で、その人格は、自らの人生の能動的な創造者ではなく、受動的な消費者と なる。個人主義的な創造性による約束された人生は、ブルジョワ文化の集団主義的、商業的な規範とは相容れない。 『資本論』第1巻で、マルクスは「ブルジョワ社会では、各個人が購入者として商品の百科事典的な知識を持っているという法的な想定が支配的である」と述べ ている。[30] しかし、2017年以降、世界の消費者は、携帯電話のGoogle Lensアプリを使用して、あらゆる物体をスキャンし、その物体(または非常に類似した物体)に関する情報や価格を調べることができる。金融サービス会社 エンパワーの調査によると、アメリカ人は現在、1日あたり2.5時間、つまり年間873時間を「夢見るスクロール(デジタルウィンドウショッピングや夢の 買い物に目を向けること)」に費やしているという。[31] |

| Commodity narcissism In the study From Commodity Fetishism to Commodity Narcissism (2012) the investigators applied the Marxist theory of commodity fetishism to psychologically analyse the economic behaviour (buying and selling) of the contemporary consumer. With the concept of commodity narcissism, the psychologists Stephen Dunne and Robert Cluley proposed that consumers who claim to be ethically concerned about the manufacturing origin of commodities, nonetheless behaved as if ignorant of the exploitative labour conditions under which the workers produced the goods and services, bought by the "concerned consumer"; that, within the culture of consumerism, narcissistic men and women have established shopping (economic consumption) as a socially acceptable way to express aggression.[32] Researchers find no evidence that a greater manufacturing base can spur economic growth, while improving government effectiveness and regulation quality are more promising for facilitating economic growth.[33] |

商品ナルシシズム 研究論文『商品フェティシズムから商品ナルシシズムへ』(2012年)において、研究者はマルクス主義の「商品フェティシズム」理論を応用し、現代の消費 者の経済行動(購買と販売)を心理学的観点から分析した。商品ナルシシズムという概念を提唱した心理学者のスティーブン・ダンとロバート・クルーリーは、 商品の製造元について倫理的な懸念を表明する消費者は、その商品やサービスを生産する労働者が搾取的な労働条件のもとで働いていることをまるで知らないか のように振る舞っていると主張した。消費主義文化の中で、ナルシスト的な男性と女性は、攻撃性を表現する社会的に容認された方法として買い物(経済消費) を確立したのである。 [32] 研究者たちは、製造基盤の拡大が経済成長を促進するという証拠は見出していない。一方で、政府の効率性と規制の質を改善することが、経済成長を促進する上 でより有望である。[33] |

| Ethical consumption Environmentally "conscious" consumers want their purchased products to be environmentally ethical. According to James G. Carrier,[34] on a personal level their purchases can make them feel more positively moral and second they can help put pressure on firms in a competitive market to change the way they do things. Marx's 1867 notion of commodity fetishism which concerns the idea that ethical consumption is going beyond the two reasons first noted by Carrier.[according to whom?] Certain commodities are perceived in a particular way that the consumer ignores or denies the labor time entailed in the process of production or for that matter any detailed background people and process that is viable in creating an ethical product. Capitalists have the intention of selling to an audience with commercial gain - the use of nature as a strategy is vital in urging people to buy their product. Ethical consumption is mostly concerned with the social, political and environmental context of objects - and consumers want a product that meets their moral criteria, something non-exploitative. These baseline concepts need to be visible and eye-catching with recognizable verifications. This is very common in ecotourism who produce eco-friendliness as a reason to buy and visit. Advertising protection and conservation attracts visitors and media attention. These capitalists make no point to vary in their images and photographs or captions - the repetition of nature is always colorful and vibrant, gentle and reserved. They are "fetishizing" nature as a marketing technique. Portraying themselves as a business that protects nature satisfies their clientele so that the consumer cannot see the objects and mechanisms used to actually produce it. Carrier describes how the environment itself is fetishized as a consumable product through parks and other areas of land being used as bodies or images attached to promises of natural experiences or protection efforts in return for money. Carrier also offers the example of fair-trade coffee as a way that commodity fetishism is seen in ethical consumption. If fair-trade coffee promises that it is direct, cooperative supply chain between growers and consumers through images of coffee growers and messaging on the bag of coffee, this becomes more relevant to consumer decision making than the reality that many other "middle-men" were needing in the roasting, packaging, marketing, and transportation of that commodity.[35] Ethical consumption is believed by advocates of the theory to allow people to lead more moral lives as well as affect the world by placing economic pressure on firms to change their production processes and products to become more ethical to remain competitive within the greater market. The fetishization of nature and natural resources often leads through its commodification as a product to be advertised. Conceptual categories need to be "legible, be visible and recognizable"[36] in order to be effective as ethical standards. The advertising on items listed and named as fair trade often misrepresents the actual production process, especially in products requiring extensive and hard labor to produce, such as coffee. It also often becomes exploitative as it uses the images of ethnic small holders rather than the ethnic migrants and wage laborers who do the majority of the work. The use of images not only fetishizes the product, but defines ethicality as a whole.[37] A common narrative now is whether or not ethical consumption is at all possible in a globalized world of highly interconnected capitalism and trade. It relies on ideas of greenwashing in which producers use environmentalism and fair trade ideals to advertise their products without living up to the ideals. The false image of environmentalism disguises the unsustainable practices being utilized. Another critique is the overall effectiveness of individual consumer choices without large-scale systemic change through government regulation. Accessibility is another issue, as ethical products are often more expensive and less accessible to low-income activists. |

倫理的消費 環境に「配慮する」消費者は、購入する製品が環境的に倫理的であることを望む。ジェームズ・G・キャリアーによると、[34] 個人のレベルでは、購入することで道徳的により前向きな気持ちになることができ、次に、競争市場において企業がやり方を変えるよう圧力をかけることができ る。1867年にマルクスが提唱した商品フェティシズムの概念は、倫理的消費が、キャリアが最初に指摘した2つの理由を超えているという考え方に関係して いる。特定の商品が、生産過程で必要とされる労働時間を消費者が無視または否定するような形で認識されている。また、倫理的な製品を製造する上で重要な、 人々やプロセスに関する詳細な背景も無視または否定されている。資本主義者は、営利目的で聴衆に販売しようとする。自然を戦略として利用することは、人々 に製品を買わせるために不可欠である。倫理的な消費は、主に、対象物の社会的、政治的、環境的な背景に関係している。消費者は、道徳的な基準を満たし、搾 取的でない製品を求めている。これらの基本的な概念は、目に見える形で、わかりやすく検証する必要がある。これは、購入や訪問の理由として環境への配慮を アピールするエコツーリズムではよく見られる。 自然保護や保全を宣伝することは、訪問者やメディアの注目を集める。 こうした資本主義者は、イメージや写真、キャプションを変えるつもりはない。自然の繰り返しは常にカラフルで活気があり、穏やかで控えめである。彼らは マーケティング手法として自然を「フェティッシュ化」している。自然保護を謳うことで顧客を満足させ、消費者は自然保護の対象となる物や仕組みを目にする ことはない。キャリアは、環境そのものが公園やその他の土地が自然体験や保護活動の代償としてのお金と引き換えに提供される自然体験や保護活動の約束に付 随する身体やイメージとして、消費可能な製品としてフェティッシュ化されていることを説明している。また、キャリアは、倫理的消費における商品フェティシ ズムの例として、フェアトレードコーヒーを挙げている。フェアトレードコーヒーが、コーヒー生産者の画像やコーヒー袋に印刷されたメッセージを通じて、生 産者と消費者の直接的な協力関係に基づくサプライチェーンを約束している場合、その商品が焙煎、包装、マーケティング、輸送の過程で多くの「仲介業者」を 必要としているという現実よりも、消費者の意思決定により関連性が高くなる。 倫理的な消費は、人々がより道徳的な生活を送れるようになるだけでなく、企業に対して生産工程や製品をより倫理的なものに変えるよう経済的な圧力をかける ことで、より大きな市場で競争力を維持できるようになるという理論の支持者たちによって信じられている。自然や天然資源の神格化は、しばしば商品化され、 広告される製品としてつながっている。倫理基準として効果的であるためには、概念カテゴリーは「読みやすく、目に見え、認識できる」ものでなければならな い[36]。フェアトレードとしてリストアップされ、名付けられた商品に関する広告は、実際の生産工程を誤って伝えることが多く、特にコーヒーのように生 産に広範で重労働を必要とする製品ではその傾向が強い。また、その広告は、大半の作業を行う民族移民や賃金労働者ではなく、小規模な農家の民族のイメージ を使用しているため、搾取的であることが多い。イメージの使用は、製品を神聖視するだけでなく、倫理観全体を定義づける。[37] 現在、よく語られるのは、高度に相互接続された資本主義と貿易の世界において、倫理的な消費が果たして可能なのかどうかという点である。 それは、生産者が環境保護やフェアトレードの理念を掲げながら、その理念を実践することなく自社製品を宣伝するというグリーンウォッシングの考え方に依存 している。 環境保護の偽りのイメージは、利用されている持続不可能な慣行を覆い隠している。また、政府による規制による大規模なシステム変更を伴わない、個々の消費 者の選択の全体的な有効性に対する批判もある。倫理的な製品は価格が高く、低所得層の活動家には手が届きにくい場合が多いというアクセスの問題もある。 |

| Social Alienation In The Society of the Spectacle (1967), Guy Debord presented the theory of "le spectacle"—the systematic conflation of advanced capitalism, the mass communications media, and a government amenable to exploiting those factors. The spectacle transforms human relations into objectified relations among images, and vice versa; the exemplar spectacle is television, the communications medium wherein people passively allow (cultural) representations of themselves to become the active agents of their beliefs. The spectacle is the form that society assumes when the Arts, the instruments of cultural production, have been commodified as commercial activities that render an aesthetic value into a commercial value (a commodity). Whereby artistic expression then is shaped by the person's ability to sell it as a commodity, that is, as artistic goods and services. Capitalism reorganizes personal consumption to conform to the commercial principles of market exchange; commodity fetishism transforms a cultural commodity into a product with an economic "life of its own" that is independent of the volition and initiative of the artist, the producer of the commodity. What Karl Marx critically anticipated in the 19th century, with "The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret thereof", Guy Debord interpreted and developed for the 20th century—that in modern society, the psychologic intimacies of intersubjectivity and personal self-relation are commodified into discrete "experiences" that can be bought and sold. The Society of the Spectacle is the ultimate form of social alienation that occurs when a person views his or her being (self) as a commodity that can be bought and sold, because they regard every human relation as a (potential) business transaction. (See: Entfremdung, Marx's theory of alienation) |

社会的疎外 『スペクタクルの社会』(1967年)において、ギー・ドゥボールは「スペクタクル」の理論を提示した。スペクタクルとは、高度資本主義、マスメディア、 そしてそれらを搾取する政府の組織的な結合である。スペクタクルは、人間関係をイメージ間の客体化された関係に変え、またその逆も起こる。典型的なスペク タクルはテレビであり、人々は受動的に自分自身の(文化的)表現を信念の積極的な担い手とさせるコミュニケーション媒体である。スペクタクルとは、芸術と いう文化生産の手段が、美的価値を商業的価値(商品)に転換する商業活動として商品化されたときに、社会がとる形態である。芸術表現は、それを商品として 販売する人格の能力、つまり芸術品や芸術サービスとして販売する能力によって形作られる。 資本主義は、市場取引の商業的原則に適合するように個人的消費を再編成する。商品フェティシズムは、文化商品を、その商品の生産者である芸術家の意志やイ ニシアティブから独立した、経済的な「独自の生命」を持つ製品へと変質させる。カール・マルクスが19世紀に『商品崇拝論』で批判的に予見したことを、 ギ・ドゥボールは20世紀のために解釈し、発展させた。すなわち、現代社会では、主観性と個人的な自己関係の心理的な親密さが、個別的な「経験」として商 品化され、売買されるようになったということである。『スペクタクルの社会』は、人格(自己)を売買可能な商品として見なすことによって生じる究極の社会 的疎外の形である。なぜなら、あらゆる人間関係を(潜在的な)商取引と見なすからである。(参照:『疎外論』、マルクスの疎外理論) |

| Semiotic sign Jean Baudrillard applied commodity fetishism to explain the subjective feelings of men and women towards consumer goods in the "realm of circulation"; that is, the cultural mystique (mystification) that advertising ascribed to the commodities (goods and services) in order to encourage the buyer to purchase the goods and services as aids to the construction of his and her cultural identity. In the book For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign (1972), Baudrillard developed the semiotic theory of "the Sign" (sign value) as a development of Marx's theory of commodity fetishism and of the exchange value vs. use value dichotomy of capitalism. |

記号論的記号 ジャン・ボードリヤールは、商品フェティシズムを「流通の領域」における消費財に対する男女の主観的な感情を説明するものとして適用した。つまり、広告が 商品(物品やサービス)に付与する文化的神秘性(ミスティフィケーション)であり、購入者が商品やサービスを購入し、自身の文化的アイデンティティを構築 する手助けとなるよう促すものである。ボードリヤールは著書『記号の政治経済学批判のために』(1972年)において、マルクスの商品崇拝論と資本主義に おける交換価値と使用価値の二分法を発展させたものとして、「記号」(記号価値)の記号論を展開した。 |

| Intellectual property In the 21st century, the political economy of capitalism reified the abstract objects that are information and knowledge into the tangible commodities of intellectual property, which are produced by and derived from the labours of the intellectual and the white collar workers. Philosophic base The economist Michael Perelman critically examined the belief systems from which arose intellectual property rights, the field of law that commodified knowledge and information. Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis critically reviewed the belief systems of the theory of human capital.[38] Knowledge, as the philosophic means to a better life, is contrasted with capitalist knowledge (as commodity and capital), produced to generate income and profit. Such commodification detaches knowledge and information from the (user) person, because, as intellectual property, they are independent, economic entities. Knowledge: authentic and counterfeit In Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991), the Marxist theorist Fredric Jameson linked the reification of information and knowledge to the post-modern distinction between authentic knowledge (experience) and counterfeit knowledge (vicarious experience), which usually is acquired through the mass communications media. In Critique of Commodity Aesthetics: Appearance, Sexuality and Advertising in Capitalist Society (1986), the philosopher Wolfgang Fritz Haug presents a "critique of commodity aesthetics" that examines how human needs and desires are manipulated and reshaped for commercial gain.[39] Financial risk management The sociologists Frank Furedi and Ulrich Beck studied the development of commodified types of knowledge in the business culture of "risk prevention" in the management of money. The Post–World War II economic expansion (c. 1945–1973) created very much money (capital and savings), while the dominant bourgeois ideology of money favoured the risk-management philosophy of the managers of investment funds and financial assets. From such administration of investment money, manipulated to create new capital, arose the preoccupation with risk calculations, which subsequently was followed by the "economic science" of risk prevention management.[40][41] In light of which, the commodification of money as "financial investment funds" allows an ordinary person to pose as a rich person, as an economic risk-taker able to risk losing money invested to the market. Hence, the fetishization of financial risk as "a sum of money" is a reification that distorts the social perception of the true nature of financial risk, as experienced by ordinary people.[42] Moreover, the valuation of financial risk is susceptible to ideological bias; that contemporary fortunes are achieved from the insight of experts in financial management, who study the relationship between "known" and "unknown" economic factors, by which human fears about money can be manipulated and exploited. Commodified art The cultural critics Georg Simmel and Walter Benjamin examined and described the fetishes and fetishism of art, by means of which "artistic" commodities are produced for sale in the market, and how commodification determines and establishes the value of the artistic commodities (goods and services) derived from legitimate Art; for example, the selling of an artist's personal effects as "artistic fetishes". Legal traducement In the field of law, the scholar Evgeny Pashukanis (The General Theory of Law and Marxism, 1924), the Austrian politician Karl Renner, the German political scientist Franz Leopold Neumann, the British socialist writer China Miéville, the labour-law attorney Marc Linder, and the American legal philosopher Duncan Kennedy (The Role of Law in Economic Theory: Essays on the Fetishism of Commodities, 1985) have respectively explored the applications of commodity fetishism in their contemporary legal systems, and reported that the reification of legal forms misrepresents social relations.[43][44] |

知的財産 21世紀の資本主義の政治経済は、情報や知識という抽象的な対象を、知的労働者やホワイトカラーの労働によって生産され、そこから派生する知的財産という有形の商品へと物象化する。 哲学的な基盤 経済学者のマイケル・ペレルマンは、知的財産権という概念が生じた信念体系を批判的に検証した。知的財産権とは、知識や情報を商品化する法律分野である。 サミュエル・ボウルズとハーバート・ギンティスは、人的資本理論の信念体系を批判的に検証した。[38] 知識は、より良い生活を実現するための哲学的手段であるが、収入や利益を生み出すために生産される資本主義的な知識(商品や資本)とは対照的である。 このような商品化は、知的財産として独立した経済的実体である知識や情報を人格から切り離す。 知識:本物と偽物 ポストモダニズム、あるいは後期資本主義の文化論(1991年)の中で、マルクス主義理論家のフレドリック・ジェイムスンは、情報と知識の物象化を、本物 の知識(経験)と偽物の知識(代理経験)というポストモダンの区別と関連付けた。後者は通常、マスメディアを通じて得られるものである。哲学者ヴォルフガ ング・フリッツ・ハウグは著書『商品美学批判:資本主義社会における外観、セクシュアリティ、広告』(1986年)で、「商品美学批判」を提示し、人間の ニーズや欲求が商業的利益のためにいかに操作され、形作られるかを検証している。[39] 金融リスク管理 社会学者のフランク・フレディとウルリッヒ・ベックは、マネーの管理における「リスク予防」というビジネス文化の中で、商品化された知識のタイプがどのよ うに発展してきたかを研究した。第二次世界大戦後の経済拡大(1945年頃~1973年)は、資本(資本と貯蓄)を大量に生み出したが、支配的なブルジョ ワのイデオロギーは、投資資金や金融資産の管理者のリスク管理の哲学を好んだ。このような投資資金の運用から、新たな資本を生み出すために操作されたリス ク計算への過剰な関心が生まれ、その後、リスク予防管理の「経済学」が続いた。[40][41] これを踏まえると、「金融投資資金」として商品化されたお金によって、一般の人々が富裕層を装い、市場に投資した資金を失うリスクを負う経済的なリスク テーカーとなることができる。したがって、「金銭の総額」としての金融リスクの神聖視は、一般の人々が経験する金融リスクの本質に対する社会的な認識を歪 める物象化である。[42] さらに、金融リスクの評価はイデオロギー的な偏見の影響を受けやすい。現代の富は、経済的な「既知」と「未知」の要因の関係を研究する金融管理の専門家の 洞察力によって達成される。それによって、人々のお金に対する不安が操作され、利用される可能性がある。 商品化された芸術 文化批評家のゲオルク・ジンメルとヴァルター・ベンヤミンは、芸術作品が市場で販売されるために「芸術的」商品が生産される方法、および商品化が正統な芸 術から派生した芸術的商品(物品およびサービス)の価値を決定し、確立する方法について、芸術作品とフェティシズムを調査し、記述した。例えば、芸術家の 私物を「芸術的フェティシズム」として販売するなどである。 法的誹謗中傷 法学の分野では、学者のエフゲニー・パシュカニス(『法とマルクス主義の一般理論』1924年)、オーストリアの政治家カール・レンナー、ドイツの政治学 者フランツ・レオポルト・ノイマン、イギリスの社会派作家チャイナ・ミエヴィル、労働法弁護士マーク・リンダー、アメリカの法哲学者ダンカン・ケネディ (『経済理論における法の役割: 1985年)は、それぞれ現代の法制度における商品フェティシズムの応用を研究し、法的形式の物象化が社会関係を誤って表現していると報告している。 [43][44] |

Criticism The Tribuna of the Uffizi (1772–1778) by Johann Zoffany depicts the commodity-fetishism metamorphosis of oil paintings into culture-industry products. In Portrait of a Marxist as a Young Nun (1988), Professor Helena Sheehan said that the analogy between religious faith and commodity fetishism is a mistaken interpretation, because people do not worship commodities (money and merchandise) by attributing supernatural powers to inanimate objects, to a fetish. That the belief that value-relationships inherent to a commodity described is not religious belief, because value-relations do not possess the psychological characteristics of spiritual beliefs. That interpretation is proved by the possibility of a person's possessing religious faith, whilst being aware of the psychology of commodity fetishism, and thus being critical of the fetishization of money and merchandise, thus, a person's disbelief in the golden calf is integral to the person's iconoclasm against the idolatry of money.[45] |

批判 ヨハン・ゾファンニーによる『ウフィツィ美術館のトリブナー』(1772年~1778年)は、油絵が文化産業製品へと変貌する商品フェティシズムを描いている。 『若い修道女のマルクス主義者』(1988年)の中で、ヘレナ・シーハン教授は、宗教的信仰と商品崇拝の類似性は誤った解釈であると述べている。なぜな ら、人々は無生物である商品(貨幣や商品)に超自然的力を付与して崇拝しているわけではないからだ。商品に内在する価値関係は、精神的な信念の心理的特性 を持たないため、宗教的信念ではない。その解釈は、商品フェティシズムの心理を理解しながらもなお宗教的信仰を持つ人格の存在によって証明される。した がって、貨幣や商品の偶像化を批判する人格は、偶像崇拝である金への信仰を持たない。[45] |

| Pre-Marxist theories Simple living Marxist theories pertinent to the theory of commodity fetishism Character mask Commodity (Marxism) Critique of political economy Exchange value False consciousness Fetishism Labor theory of value Law of value Real prices and ideal prices Reification (Marxism) Relations of production Use value Value-form Post-Marxist theories derived from the theory of commodity fetishism Essays of Marx's Theory of Value by Isaak Illich Rubin History and Class Consciousness, "Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat" (theories of class consciousness and of reification) by Geörg Lukács The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord (full text) The System of Objects by Jean Baudrillard Neomaterialism by Joshua Simon Time, Labor and Social Domination by Moishe Postone Value criticism (in German Wertkritik) |

マルクス主義以前の理論 質素な生活 商品フェティシズム論に関連するマルクス主義理論 性格の仮面 商品(マルクス主義 政治経済批判 交換価値 偽りの意識 フェティシズム 価値の労働理論 価値法則 現実の価格と理想の価格 物象化(マルクス主義 生産関係 使用価値 価値形態 商品フェティシズム論から派生したポスト・マルクス主義理論 イサク・イリイチ・ルービン著『マルクスの価値論試論 ゲオルク・ルカーチ著『歴史と階級意識』所収の論文「物象化とプロレタリアートの意識」(階級意識論、物象化論 ギー・ドゥボール著『スペクタクルの社会』(全文 ジャン・ボードリヤール著『物の体系 ジョシュア・サイモン著『ネオ・マテリアリズム モイシェ・ポストーン著『時間・労働・社会的支配 価値批判(ドイツ語ではヴェルトクリティック) |

| Sandel, Michael (2012). What

money can't buy : the moral limits of markets. New York: Farrar, Straus

and Giroux. ISBN 9780374203030. Bottomore, Tom (1991). A Dictionary of Marxist thought. Oxford, UK Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell Reference. ISBN 9780631180821. Debord, Guy (2009). The Society of the Spectacle. Eastbourne: Soul Bay Press. ISBN 9780955955334. Fine, Ben (2010). Marx's Capital. London & New York: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0745330167. Harvey, David (2010). A companion to Marx's Capital. London New York: Verso. ISBN 978-1844673599. Lukács, György (1971). History and Class Consciousness : studies in Marxist dialectics. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262620208. Marx, Karl (1981). Capital :Volume 1: A critique of political economy. London New York, N.Y: Penguin Books in association with New Left Review. ISBN 9780140445688. Douglas, Mary (1996). The world of goods : towards an anthropology of consumption : with a new introduction. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415130479. |

Sandel, Michael (2012). What

money can't buy : the moral limits of markets. New York: Farrar, Straus

and Giroux. ISBN 9780374203030. Bottomore, Tom (1991). A Dictionary of Marxist thought. Oxford, UK Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell Reference. ISBN 9780631180821. デボード、ガイ(2009年)。『スペクタクルの社会』。イーストボーン:ソウルベイプレス。ISBN 9780955955334。 ファイン、ベン(2010年)。『マルクスの資本論』。ロンドン&ニューヨーク:プルートプレス。ISBN 978-0745330167。 ハーヴェイ、デイヴィッド(2010年)。『資本論』入門。ロンドン、ニューヨーク:ヴァーソ。ISBN 978-1844673599。 ルカーチ、ジェルジ(1971年)。『歴史と階級意識:マルクス主義弁証法研究』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MITプレス。ISBN 9780262620208。 マルクス、カール(1981年)。資本論:第1巻:政治経済批判。ロンドン、ニューヨーク:ペンギンブックス、ニューレフトレビューとの提携。ISBN 9780140445688。 ダグラス、メアリー(1996年)。『モノの世界:消費人類学への試み:新序文付』。ロンドン、ニューヨーク:ルードリッジ。ISBN 9780415130479。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commodity_fetishism |

|

| Capital, Chapter 1, Section 4 – The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret Thereof All of Chapter One – Marx's logical presentation Isaac Rubin's commentary on Marx "The Reality behind Commodity Fetishism" David Harvey, Reading Marx's Capital, Reading Marx's Capital – Class 2, Chapters 1–2, The Commodity (video lecture) Biene Baumeister,Die Marxsche Kritik des Fetischismus (outline in German) Understanding Capitalism Part IV: Capitalism, Culture and Society |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆