悪魔との契約

pact with devil

「悪魔との契約(悪魔との交渉)」はマイケル・タウ シグ『悪魔と商品の物神性』(1980)においてよく知られる議論である。ラテンアメリカの鉱山労働者やプランテーション日雇い労働者の間で、突 然羽振り がよくなった仕事仲間は、突然死や失踪などその後の不幸な顚末を迎えるが、それは大切なものと引き換えに悪魔との契約をしたのだという一見すると「迷信」 のように思える人々の解釈である。しかし、タウシグはマルクス『資本論』における貨幣と資本の増殖性という「商品の物神性(フェティシズム)」を手掛かり にして、資本主義社会の外縁部でも悪魔(=資本家)との契約における羽振りが良くなる(=資本の増殖)という同型の現象がみられることを指摘している。我 々のみが信じている経済合理性を一般化することを「悪魔との契約」の理論は雄弁に語っている。「不法」移民労働を通してアメリカと接続する資本の流通は、 規模と速度において住民の解釈学を産ませるほどの規模なのかもしれない。

+++

「『南米の悪魔と商品崇拝』は、人類学に関する論争の書物であり、コロンビアとボリビアの農 村およ び都市の労働者たちが抱く、一見魔法のような一連の信念の分析でもある。タウッシグの論争は、人類学の主たる関心事は西洋(特に資本主義)文化を批判する ことである、というものである。さらに、世界資本主義経済の周辺部に暮らす人々は、資本主義に対して批判的な視点を持っているため、自分たちの文化的な表 現を用いて資本主義に対する批判を明確に述べると主張している。 したがって、人類学者は、自分たちの文化に対する批判的な洞察力を得る方法として、世界資本主義経済の周辺部に暮らす人々を研究すべきであると結論づけて いる。つまり、この論争は人類学者の研究対象を他文化から自文化へと移し、かつての人類学の研究対象(先住民など)を価値ある批判的思考家として再評価す るものである。」https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Taussig

「タウッシグは、このアプローチを2つの信念に適用している。1つは彼自身のフィールド調査 と人類学者ジュン・ナッシュの調査の両方に基づく信念、もう1つは彼自身の調査のみに基づく信念である。1つ目は、コロンビアの半プロレタリア化した農民 (ボリビアの錫鉱山労働者にも同様のケースがある)が抱く信念である。サトウキビ切りをプロレタリア化した労働者は、悪魔と契約を結び、多額の金を手に入 れることができるが、その金は軽薄な消費財にしか使えない。また、切り手は早死にして悲惨な最期を遂げる、というものだ。タウッシグは、以前の人類学者 は、この信念は資本主義以前の文化の名残である、あるいは平準化メカニズム(仲間の中で誰一人として著しく裕福になる者がいないようにすること)として機 能すると主張していたかもしれないと示唆している。しかしタウッシグは、悪魔を通して農民たちは、資本主義は資本が生産的であるという魔法のような信念に 基づいているという認識を表明していると主張している。実際には資本主義は貧困、病気、死を生み出している。2つ目の信念は、資本が生産的であるという資 本主義の主張に対する農民たちの理解を示すもう一つの例である。すなわち、ある人々が、洗礼を受けるのは赤ちゃんではなくペソであるというスイッチを操作 するという信念である。その結果、お金は生き物であり、どのように使われようとも、もとの持ち主に戻ってくる。そして、もとの持ち主のもとに、より多くの お金をもたらしてくれる」https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Taussig

☆悪魔との契約(Deal with the Devil)

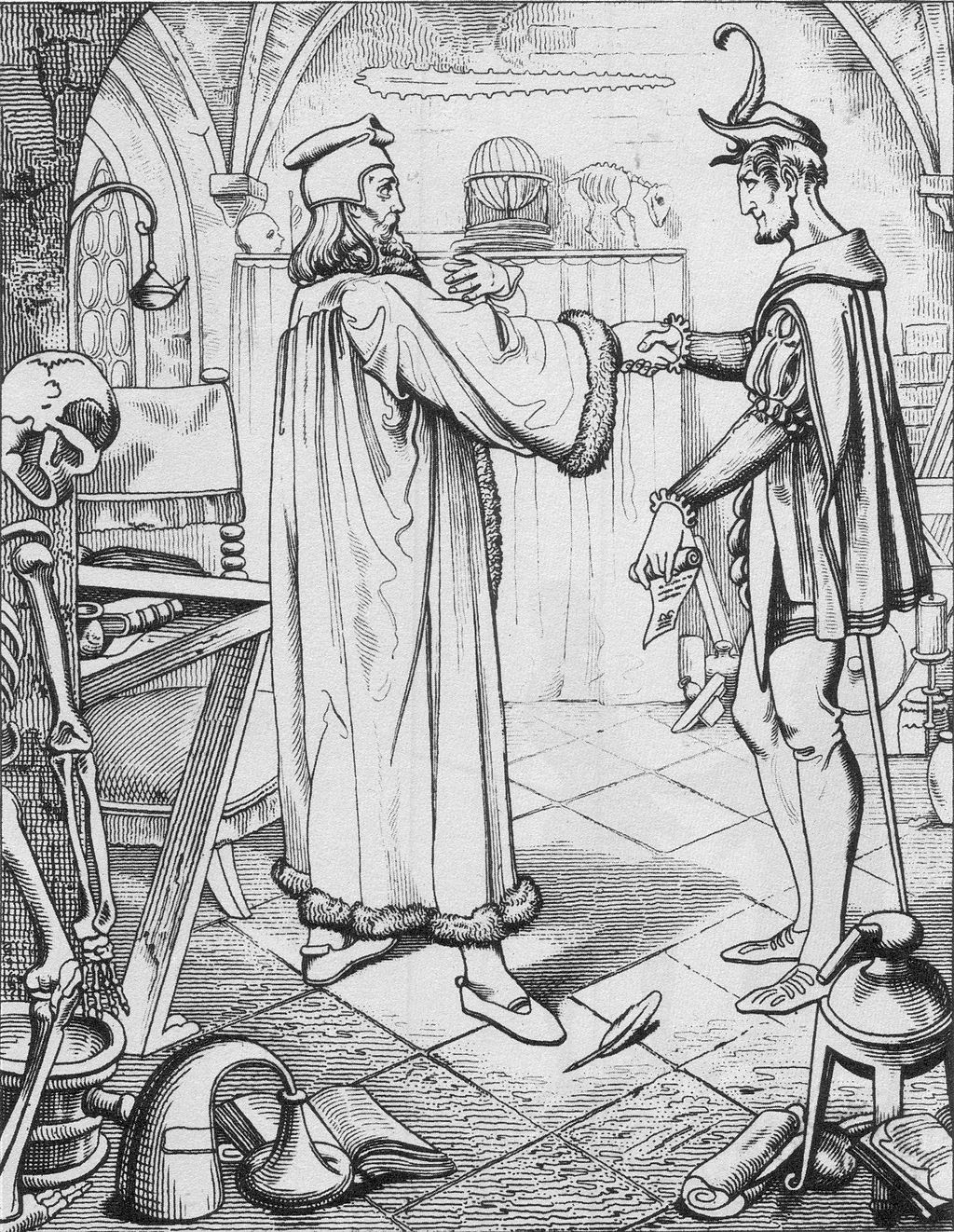

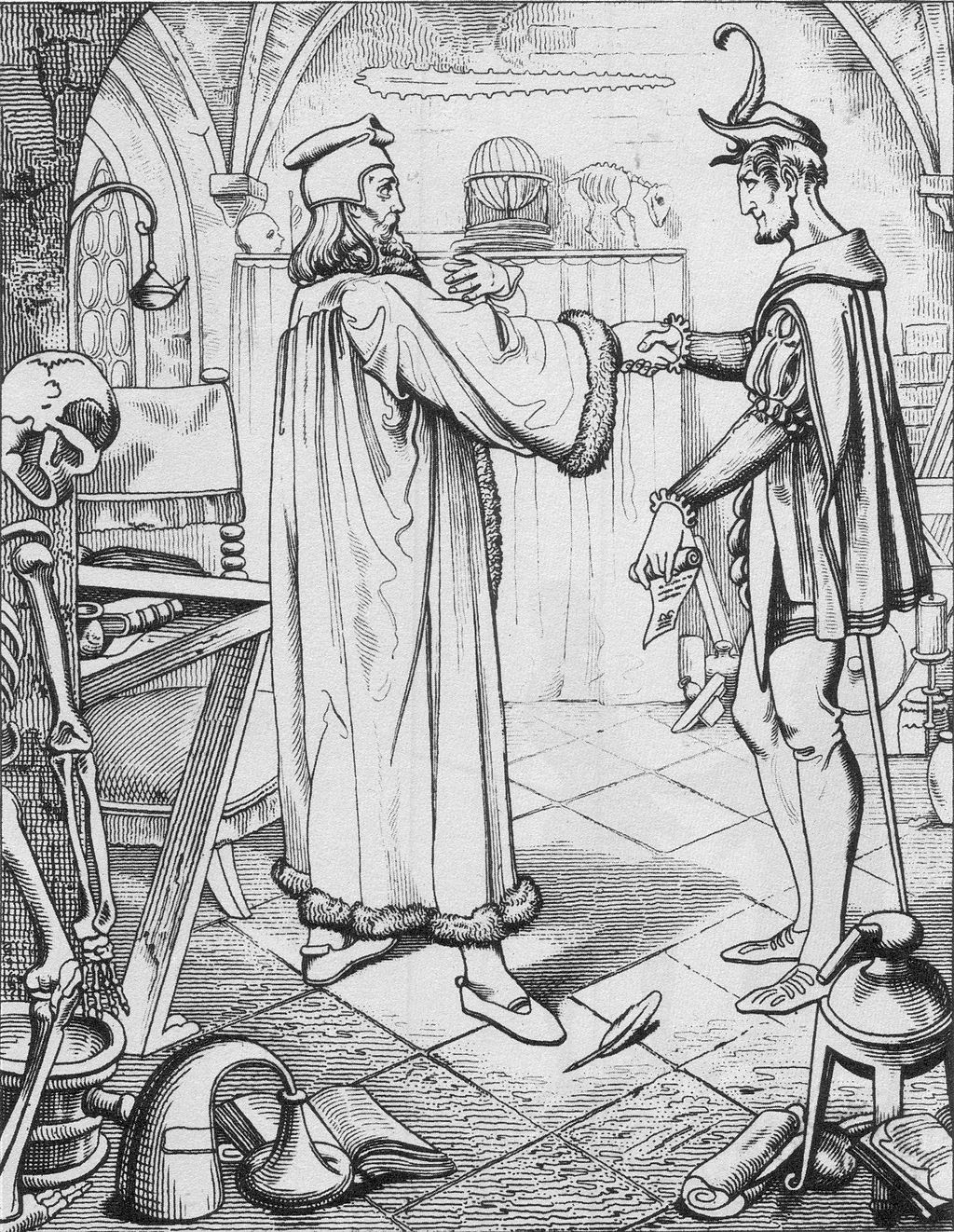

Engraving of Faust's pact with Mephisto, by Adolf Gnauth (circa 1840) A deal with the Devil or Faustian bargain[a] is a cultural motif exemplified by the legend of Faust and the figure of Mephistopheles, as well as being elemental to many Christian traditions. According to traditional Christian belief about witchcraft, the pact is between a person and the Devil or another demon, trading a soul for diabolical favours, which vary by the tale, but tend to include youth, knowledge, wealth, fame and power. It was also believed that some people made this type of pact just as a sign of recognising the minion as their master, in exchange for nothing. The bargain is a dangerous one, as the price of the fiend's service is the wagerer's soul. For most religions, the tale may have a bad end, with eternal damnation for the foolhardy venturer. Conversely, it may have a comic twist, in which a wily peasant outwits the devil, characteristically on a technical point. The person making the pact sometimes tries to outwit the devil, but loses in the end (e.g., man sells his soul for eternal life because he will never die to pay his end of the bargain. Immune to the death penalty, he commits murder, but is sentenced to life in prison). A number of famous works refer to pacts with the devil, from the numerous European Devil's Bridges to the violin virtuosity of Giuseppe Tartini and Niccolò Paganini to the "crossroad" myth associated with Robert Johnson. In Stith Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, "Bargain with the devil" constitutes motif number M210 and "Man sells soul to devil" motif number M211.[1] |

ファウストとメフィストの契約のエングレーヴィング、アドルフ・グノート作(1840年頃) 悪魔との契約、あるいはファウスト的契約[a]は、ファウスト伝説やメフィスト像に代表される文化的モチーフであり、また多くのキリスト教の伝統にとって 重要な要素でもある。妖術に関する伝統的なキリスト教の信仰によれば、この契約は人格と悪魔または別の悪魔との間で結ばれ、極悪非道な恩恵と魂を交換する もので、その内容は物語によって異なるが、若さ、知識、富、名声、権力などが含まれる傾向がある。 また、人民の中には、手下を自分の主人として認める証として、この種の契約を結ぶ者もいると信じられている。この契約は危険なもので、悪魔の奉仕の対価は 賃借人の魂だからだ。ほとんどの宗教にとって、この物語はバッドエンドで、無鉄砲な冒険者には永遠の天罰が下るかもしれない。逆に、狡猾な農民が悪魔を出 し抜くというコミカルな展開になることもある。契約を結ぶ人格は悪魔を出し抜こうとすることもあるが、結局は負ける(例えば、男は永遠の命と引き換えに魂 を売る。死刑を免れた彼は殺人を犯すが、終身刑を言い渡される)。 ヨーロッパに数多く存在する悪魔の橋から、ジュゼッペ・タルティーニやニコロ・パガニーニのヴァイオリンの妙技、ロバート・ジョンソンにまつわる「十字 路」神話に至るまで、悪魔との契約に言及した有名な作品は数多い。 スティス・トンプソンの『民俗文学のモチーフ索引』では、「悪魔との取引」はモチーフ番号M210、「悪魔に魂を売る男」はモチーフ番号M211を構成し ている[1]。 |

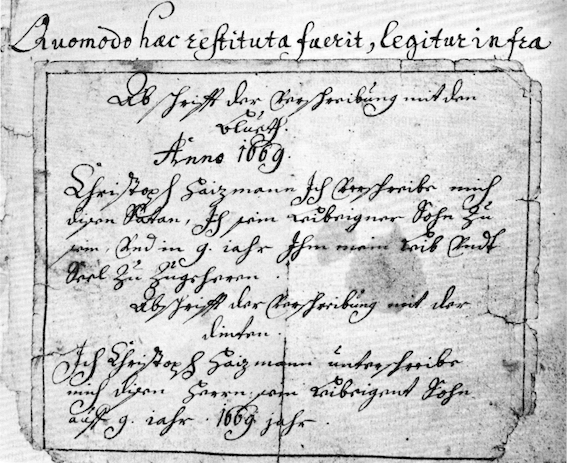

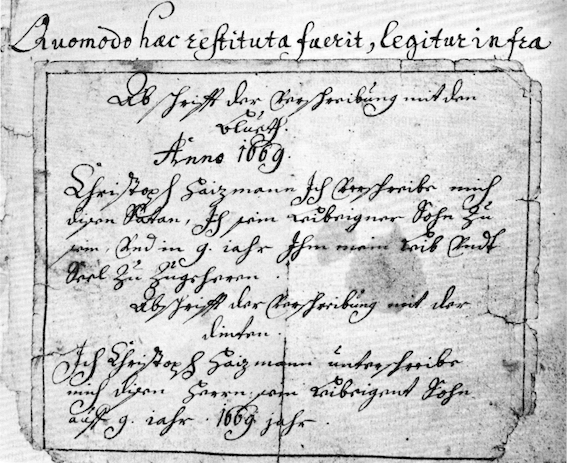

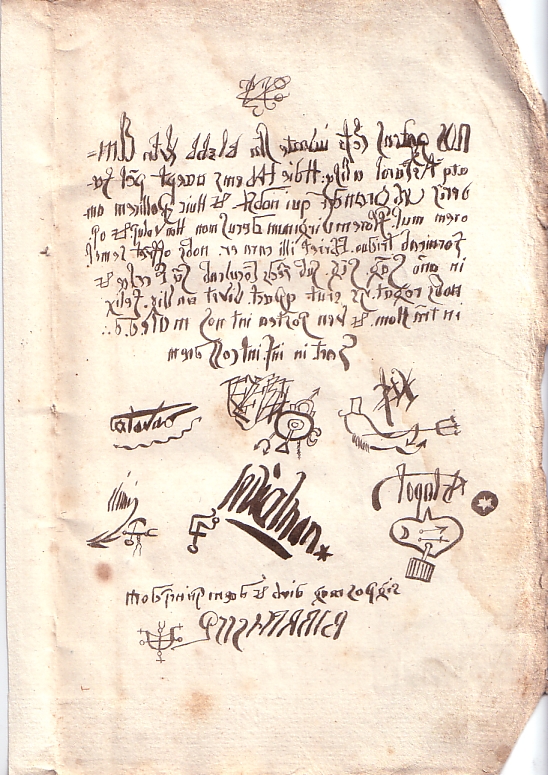

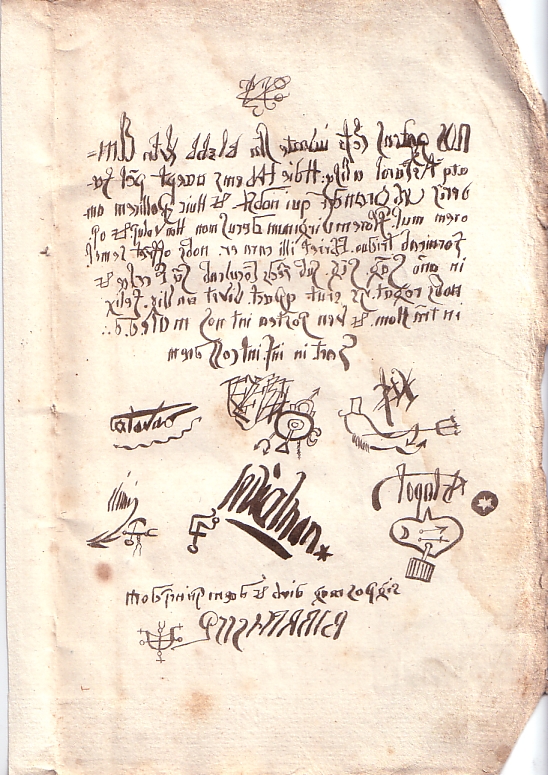

Synopsis Copy of a written deal by Christoph Haizmann from 1669. It is usually thought that individuals who make a pact also promise to demons that they will kill children or consecrate them to the devil at the moment of birth (many midwives were accused of this, due to the number of children who died at birth in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance), take part in Witches' Sabbaths, have sexual relations with demons, and sometimes engender children from a succubus, or an incubus in the case of women.[citation needed] The pact can be either oral or written.[2] An oral pact may be made by means of invocations, conjurations, or rituals to attract the demon; once the conjurer thinks the demon is present, they ask for the wanted favour and offer their soul in exchange, and no evidence is left of the pact. But according to some witch trials, an oral pact left evidence in the form of the Witches' mark, an indelible mark where the marked person had been touched by the devil to seal the pact. The mark could be used as a proof to determine that the pact was made. It was also believed that on the spot where the mark was left, the marked person could feel no pain. A written pact consists in the same forms of attracting the demon, but includes a written act, usually signed with the conjurer's blood (although sometimes it was also alleged that the whole act had to be written with blood; meanwhile some demonologists defended the idea of using red ink instead of blood and others suggested the use of animal blood instead of human blood).[3] These acts present themselves as diabolical pacts, though there is not always certainty of an actor's authentic sanity. Usually the acts included strange characters that were said to be the signature of a demon, and each one had his own sigil. Books like The Lesser Key of Solomon (also known as Lemegeton Clavicula Salomonis) give a detailed list of these signs, known as diabolical signatures. The Malleus Maleficarum discusses several alleged instances of pacts with the Devil, especially concerning women. It was considered that all witches and warlocks had made a pact with one of the demons, usually Satan. According to demonology, there is a specific month, day of the week, and hour to call each demon, so the invocation for a pact has to be done at the right time. Also, as each demon has a specific function, a certain demon is invoked depending on what the conjurer is going to ask. In the narrative of the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus is offered a series of bargains by the devil, in which he is promised worldly riches and glory in exchange for serving the devil rather than God. Upon rejecting the devil's overtures, he embarks on his travels as the Messiah.[4] |

あらすじ 1669年に書かれたクリストフ・ハイツマンの契約書の写し。 通常、盟約を結ぶ者は、悪魔に対して、子供を殺すこと、あるいは生まれた瞬間に悪魔に捧げること(中世とルネサンス期には出産時に死亡する子供が多かった ため、多くの助産婦がこのことで非難された)、妖術師の安息日に参加すること、悪魔と性的関係を持つこと、時にはサキュバス(女性の場合はインキュバス) から子供を生むことも約束すると考えられている[要出典]。 盟約は口伝でも書面でも可能である[2]。口伝の盟約は、悪魔を引き寄せるための呼びかけ、呪文、儀礼によって行われることがあり、呪術師が悪魔がいると 思えば、望みの頼みごとをし、それと引き換えに魂を差し出す。しかし、いくつかの妖術師裁判によれば、口約束は妖術師の印という形で証拠を残し、印を押さ れた人格が悪魔に触れて盟約を封印した消えない印となる。この印は、盟約が結ばれたことを証明する証拠として使われた。また、印が残された場所では、印を 押された人格は痛みを感じないと信じられていた。書面による盟約は、悪魔を引き寄せるという点では同じであるが、書面による行為を含み、通常は呪術師の血 で署名される(ただし、行為全体を血で書かなければならないと主張されることもあった。 これらの演技は極悪非道な契約であるが、演技者が正気であるかどうかは必ずしも確かではない。通常、行為には悪魔のサインと言われる奇妙な文字が含まれ、 それぞれが自分の紋章を持っていた。ソロモン小鍵』(Lemegeton Clavicula Salomonisとしても知られる)のような本には、極悪非道のサインとして知られるこれらのサインの詳細なリストが載っている。 マレウス・マレフィカルム』には、悪魔との契約、特に女性に関する疑惑の事例がいくつか論じられている。妖術師や魔法使いは皆、悪魔の一人、たいていはサタンと契約していると考えられていた。 悪魔学によれば、それぞれの悪魔を呼び出す月、曜日、時間が決まっているため、盟約の呼びかけは適切な時間に行わなければならない。また、それぞれの悪魔には特定の働きがあるため、呪術師が何を求めるかによって特定の悪魔を呼び出す。 共観福音書の物語では、イエスは悪魔から一連の取引を持ちかけられ、神ではなく悪魔に仕える代わりにこの世の富と栄光を約束される。悪魔の誘いを断ると、イエスはメシアとして旅に出る[4]。 |

| Theophilus of Adana The predecessor of The Faustus in the Christian religion is Theophilus ("Friend of God" or "Beloved of God") the unhappy and despairing cleric, disappointed in his worldly career by his bishop, who sells his soul to the devil but is redeemed by the Virgin Mary.[5] His story appears in a Greek version of the 6th century written by a "Eutychianus" who claims to have been a member of the household in question. A 9th-century Miraculum Sancte Marie de Theophilo penitente inserts a Virgin as intermediary with diabolus, his "patron", providing the prototype of a closely linked series in the Latin literature of the West.[6] In the 10th century, the poet nun Hroswitha of Gandersheim adapted the text of Paulus Diaconus for a narrative poem that elaborates Theophilus' essential goodness and internalizes the seduction of good and evil, in which the devil is magus, a necromancer. As in her model, Theophilus receives back his contract from the devil, displays it to the congregation, and soon dies. A long poem on the subject by Gautier de Coincy (1177/8–1236), entitled Le miracle de Théophile: ou comment Théophile vint à la pénitence provided material for a 13th-century play by Rutebeuf, Le Miracle de Théophile, where Theophilus is the central pivot in a frieze of five characters, the Virgin and the bishop flanking him on the side of good, the Jew and the devil on the side of evil. |

アダナのテオフィロス キリスト教におけるファウストゥスの前身は、テオフィロス(「神の友」または「神に愛された者」)である。テオフィロスは、司教に世俗的なキャリアを失望させられ、悪魔に魂を売るが、聖母マリアによって救済される。 9世紀のMiraculum Sancte Marie de Theophilo penitenteは、彼の「守護者」であるディアボルスとの仲介役として聖母を挿入しており、西洋のラテン文学における密接に結びついたシリーズの原型となっている[6]。 10世紀、ガンダースハイムの詩人修道女フロスウィーダは、パウルス・ディアコヌスのテキストを、テオフィロスの本質的な善性を精緻化し、善と悪の誘惑を 内面化した物語詩に翻案した。彼女のモデルと同じように、テオフィロスは悪魔から契約書を取り戻し、それを信徒に見せ、やがて死ぬ。 ゴーティエ・ド・コワンシー(1177/8-1236)のこの主題に関する長編詩『テオフィルの奇跡:テオフィルがペニテンスになった理由』は、ルトブーフによる13世紀の戯曲『テオフィルの奇跡』の素材となった。 |

Alleged historical examples Urbain Grandier's bogus diabolical pact  Pope Sylvester II and the devil in an illustration of c. 1460. An extensive legend of a supposed devilish pact was focused on the character of Pope Sylvester II (946–1003), a prominent and skilled scholar and scientist in his lifetime, who had studied mathematics and astrology in the then-Muslim cities of Córdoba and Seville. According to the legend, spread by William of Malmesbury and Cardinal Beno, Sylvester II had also learned sorcery, using a book of spells stolen from an Arab philosopher.[7] He had a pact with a female demon called Meridiana, who appeared after he had been rejected by his earthly love, and with whose help he managed to ascend to the papal throne (another legend tells that he won the papacy by playing dice with the devil).[8] The Icelandic priest and scholar Sæmundur Sigfússon (1056–1133) was credited in Icelandic folklore with having made pacts with the devil and managing by various tricks to get the better of the deal. For example, in one famous story, Sæmundur made a pact with the devil that the devil should bring him home to Iceland from Europe on the back of a seal. Sæmundur escaped a diabolical end when, on arrival, he hit the seal on the head with the Bible, killing it, and stepping safely ashore.[9] (see Sæmundr fróði). According to a medieval legend associated with the Codex Gigas, the scribe was a monk who broke his monastic vows and was sentenced to be walled up alive. In order to avoid this harsh penalty he promised to create in one night a book to glorify the monastery forever, including all human knowledge. Near midnight, he became sure that he could not complete this task alone so he made a special prayer, not addressed to God but to the fallen angel Lucifer, asking him to help him finish the book in exchange for his soul. The devil completed the manuscript and the monk added the devil's picture out of gratitude for his aid.[10] Notable supposed deals with the devil were struck between the 15th and 18th centuries. The motif lives on among musicians until the 20th century: Johann Georg Faust (1466/80–1541), whose life was the origin of the Faust legend.[11] John Fian (executed on 27 January 1591), A doctor and school teacher who was declared as a notorious sorcerer. He confessed to have a compact with Satan during the North Berwick witch trials in Scotland which he confessed to King James as the trial proceedings were taking place but later promised that he would renounce his compact with Satan and vow to lead the life of a Christian. The next morning, he confessed that the devil came to him in his cell dressed all in black and holding a white wand, demanding Fian continue his faithful service, according to his first oath and promise that he made. Fian testified that he renounced Satan to his face saying "Get thee behind me, thou Satan, and start pushing, for I have listened too much to thee, and by the same thou hast undone me, in respect whereof I will utterly undo you." He confessed that the devil then answered "That once ere thou die thou shall be mine." The devil afterwards broke the white wand, and immediately vanished from his sight. He then was given a chance to lead the life he promised but the same night he stole a key to his cell and escaped. He was eventually captured and tortured until his execution.[12] Urbain Grandier (1590–1634), a 17th-century French priest, who was tried and burned at the stake for witchcraft. One of the documents presented at his trial was a diabolical pact he supposedly signed, which also bears what are supposed to be the seals of several demons, including that of Satan himself. Christoph Haizmann (1651/2–1700), a 17th-century painter from Bavaria, allegedly signed two pacts to be a "bounden son" to the devil in 1668.[13] Bernard Fokke, a 17th-century captain for the Dutch East India Company, renowned for his uncanny speed from the Dutch Republic to Java, which led to legends that he was in league with the devil. He is also alleged to be the model for the ghostly captain of the Flying Dutchman.[14] Jonathan Moulton (1726–1787), an 18th-century brigadier general of the New Hampshire Militia, alleged to have sold his soul to the devil to have his boots filled with gold coins when hung by the fireplace every month. Giuseppe Tartini (8 April 1692–26 February 1770), Venetian violinist and composer, who believed that his Devil's Trill Sonata was inspired by the devil's appearance before him in a dream.[15] Niccolò Paganini (27 October 1782–27 May 1840), an Italian violinist who may not have started the rumor but played along with it.[16] Philippe Musard (1793–1859), French composer and, more importantly, orchestra leader, whose wild conducting and sensuous concerts generated the rumor while a celebrity in Paris in the 1830s.[17] Tommy Johnson (1896–1 November 1956), blues musician.[18] Robert Johnson (8 May 1911–6 August 1938), blues musician, who legend claims met Satan at a crossroads and signed over his soul to play the blues and gain mastery of the guitar.[18] Infernus (born on 18 June 1972), black metal musician; unlike the claims above, it is Infernus himself who directly claims he sold his soul to the Devil. According to the official website for Infernus' band Gorgoroth, Infernus founded the band "[a]fter making a pact with the Devil in 1992".[19] Infernus is also on record (including in Newsweek magazine) publicly stating that he worships Satan.[20][21] The Charlie Daniels song "The Devil Went Down to Georgia" recounts a Faustian bargain where the protagonist fiddle player Johnny is challenged by the Devil to a fiddle-playing competition, and eventually wins. His prize is a golden fiddle. |

疑惑の歴史的事例 ウルバン・グランディエの偽の悪魔の契約  1460年頃のイラストに描かれた教皇シルヴェスター2世と悪魔。 悪魔の盟約とされる広範な伝説は、教皇シルヴェスター2世(946-1003)の人物に焦点を当てたものである。シルヴェスター2世は生前、著名で熟練し た学者・科学者であり、当時のイスラム教の都市コルドバとセビリアで数学と占星術を学んでいた。マルムズベリーのウィリアムやベノ枢機卿によって広められ た伝説によれば、シルヴェスター2世はアラブの哲学者から盗んだ呪術書を使って邪術も学んでいた[7]。 彼は地上の恋に落ちた後に現れたメリディアーナと呼ばれる女性の悪魔と契約し、その助けを借りて法王の座に就くことに成功した(別の伝説では、悪魔とサイ コロを振って法王の座を勝ち取ったとされている)[8]。 アイスランドの司祭であり学者であったセームンドゥル・シグフソン(1056-1133)は、アイスランドの民間伝承の中で、悪魔と契約し、様々な策略に よって契約を有利に進めたと信じられている。例えば、ある有名な話では、セームンドゥルは悪魔と契約を交わし、悪魔がアザラシの背中に乗ってヨーロッパか らアイスランドに彼を連れ帰るという約束をした。セームンドゥルは到着後、聖書でアザラシの頭を殴って殺し、無事に上陸して極悪非道な結末を免れた[9] (Sæmundr fróðiを参照)。 ギガス写本にまつわる中世の伝説によれば、この書記は修道士であったが、修道誓願を破り、生きたまま牢獄に入れられることを宣告された。この過酷な刑罰を 免れるため、彼は一晩で修道院を永遠に讃える書物を創作すると約束した。真夜中近くになって、彼は自分一人ではこの仕事を成し遂げられないと確信し、神で はなく堕天使ルシファーに特別な祈りを捧げ、自分の魂と引き換えに本を完成させるのを手伝ってくれるよう頼んだ。悪魔は原稿を完成させ、修道士は彼の援助 に感謝して悪魔の絵を書き加えた[10]。 15世紀から18世紀にかけて、悪魔との注目すべき取引が行われた。このモチーフは20世紀まで音楽家の間で生き続けている: ヨハン・ゲオルク・ファウスト(1466/80-1541)の生涯はファウスト伝説の起源となった[11]。 ジョン・フィアン(1591年1月27日に処刑)、悪名高い邪術師として公表された医師で学校教師。スコットランドのノース・バーウィックでの妖術師裁判 でサタンと契約していたことを告白し、裁判が行われている最中にジェームズ王に告白したが、後にサタンとの契約を破棄し、クリスチャンの生活を送ると約束 した。翌朝、悪魔が黒い服を着て白い杖を持って独房に現れ、フィアンが最初にした誓いと約束に従って忠実な奉仕を続けるよう要求してきたと告白した。フィ アンはサタンに面と向かってこう言ったと証言した。「サタンよ、私の後ろへ行け、そして押しのけろ。悪魔はこう答えたと告白した。悪魔はその後、白い杖を 折り、すぐに彼の視界から消えた。その後、彼は約束通りの生活を送るチャンスを与えられたが、その夜、独房の鍵を盗んで逃亡した。結局彼は捕らえられ、処 刑されるまで拷問を受けた[12]。 ウルバン・グランディエ(1590-1634)は17世紀のフランスの司祭で、妖術の罪で裁判にかけられ火あぶりにされた。彼の裁判で提出された文書のひ とつに、彼が署名したとされる極悪非道な契約書があり、そこにはサタン自身を含む複数の悪魔の印鑑とされるものも押されていた。 バイエルン出身の17世紀の画家クリストフ・ハイツマン(1651/2-1700)は、1668年に悪魔の「縛られた息子」となる2つの盟約に署名したとされる[13]。 ベルナール・フォッケ(Bernard Fokke)は17世紀のオランダ東インド会社の船長で、オランダ共和国からジャワ島までの驚異的なスピードで有名であり、悪魔と結託していたという伝説 を生んだ。彼はまた、『空飛ぶオランダ人』の幽霊船長のモデルであるとも言われている[14]。 ジョナサン・モールトン(1726-1787)は18世紀のニューハンプシャー州民兵准将で、毎月暖炉のそばに吊るすとブーツが金貨で満たされるという悪魔に魂を売ったとされる。 ジュゼッペ・タルティーニ(1692年4月8日-1770年2月26日)、ヴェネツィアのヴァイオリニスト、作曲家。彼は悪魔のトリル・ソナタが夢の中で悪魔が彼の前に現れたことに触発されたと信じていた[15]。 ニコロ・パガニーニ(1782年10月27日-1840年5月27日)はイタリアのヴァイオリニストで、この噂を流したわけではないが、一緒に演奏した可能性がある[16]。 フィリップ・ミュサール(1793年-1859年)、フランスの作曲家、さらに重要なのはオーケストラの指導者で、1830年代にパリで有名人であったときに、そのワイルドな指揮と官能的なコンサートがこの噂を生んだ[17]。 トミー・ジョンソン(1896年-1956年11月)、ブルース・ミュージシャン[18]。 ロバート・ジョンソン(1911年5月8日-1938年8月6日)、ブルース・ミュージシャン。伝説によれば、彼は十字路でサタンと出会い、ブルースを演奏しギターをマスターするために魂を譲渡したと言われている[18]。 インフェルヌス(1972年6月18日生まれ)、ブラック・メタル・ミュージシャン。上記の主張とは異なり、悪魔に魂を売ったと直接主張しているのはイン フェルヌス自身である。InfernusのバンドGorgorothの公式ウェブサイトによると、Infernusは「1992年に悪魔と契約を交わした 後」バンドを結成した[19]。Infernusはまた、(Newsweek誌を含む)公的にサタンを崇拝していると公言している。 チャーリー・ダニエルズの曲「The Devil Went Down to Georgia」は、主人公のフィドル奏者ジョニーが悪魔からフィドル演奏の勝負を挑まれ、最終的に勝利するというファウスト的な取引を描いている。彼の賞品は黄金のフィドルである。 |

| Metaphor The term "a deal with the Devil" (or "Faustian bargain") is also used metaphorically to condemn a person or persons perceived as having cooperated with an evil person or organization. An example of this is the Nazi-Jewish negotiations during The Holocaust, both positively[citation needed] and negatively.[22] Under Jewish law, the principle of pikuach nefesh ("saving life") is an obligation to compromise one's principles in order to preserve human life. Rudolf Kastner was accused of negotiating with the Nazis to save a select few at the expense of the many. The term has been mis-used in reference to Kastner's act.[22] |

隠喩 悪魔との取引」(または「ファウスト的取引」)という用語は、悪人や悪組織に協力したとみなされる人格や人物を非難する隠喩としても使われる。その例とし て、ホロコーストにおけるナチスとユダヤ人の交渉が挙げられる。ユダヤ法では、ピクアハ・ネフェシュ(「命を救う」)の原則は、人命を守るために自分の原 則を妥協する義務である。ルドルフ・カストナーは、多くの人々を犠牲にして選ばれた少数の人々を救うためにナチスと交渉したと非難された。この言葉は、カ ストナーの行為に関して誤用されている[22]。 |

| Deals with the Devil in popular culture Daniel Salthenius Demonic possession Devil in popular culture Devil's Bridge Fall of man Freischütz Oh, God! film trilogy Osculum infame Pact ink Pan Twardowski The Smith and the Devil Works based on Faust Mephistopheles in the arts and popular culture Drak (mythology) |

ポピュラー・カルチャーにおける悪魔との取引 ダニエル・サルテニウス 悪魔憑き ポピュラー・カルチャーにおける悪魔 悪魔の橋 人間の堕落 フライシュッツ オー・ゴッド!映画三部作 オスカー・インファム 盟約インク パン・トワドフスキ スミスと悪魔 ファウストを題材にした作品 芸術とポピュラー・カルチャーにおけるメフィストフェレス ドラク(神話) |

| 1. Stith Thompson, Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, 2nd ed. (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1955–58), vol. 5, pp. 39-40. 2. "Dealing with the Devil: Professor Explores Contracts with the Prince of Darkness in Popular Culture". University of Virginia School of Law. 25 July 2012. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2023. 3. William Godwin (1876). "Lives of the Necromancers". p. 16. 4. Matthew 4:1-11; Mark 1:12-13; Luke 4:1-13 5. Palmer, Phillip Mason; More, Robert Pattison (1936). The Sources of the Faust Tradition: From Simon Magus to Lessing. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 3444206. 6. Representative examples of the Latin tradition were analysed by Moshe Lazar, "Theophilus: Servant of Two Masters. The Pre-Faustian Theme of Despair and Revolt" in Modern Language Notes 87.6, (Nathan Edelman Memorial Issue November 1972) pp. 31–50. 7. Brian A. Catlos, Infidel Kings and Unholy Warriors (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus And Giroux, 2014), 83. 8. Butler, E. M. (1948). The Myth of the Magus. Cambridge University Press. p. 157. 9. Gísli Sigurðsson, 'Icelandic National Identity: From Romanticism to Tourism', in Making Europe in Nordic Contexts, ed. by Pertti J. Anttonen, NIF Publications, 35 (Turku: Nordic Institute of Folklore, University of Turku, 1996), pp. 41–76 (p. 52). 10. Rajandran, Sezin (12 September 2007). "Satanic inspiration". The Prague Post. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013. 11. Ruickbie, Leo (2009). Faustus: The Life and Times of a Renaissance Magician. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-5090-9. 12. King James (14 May 2016). Daemonologie. A Critical Edition. In Modern English. 2016. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 112–115. ISBN 978-1-5329-6891-4. 13. Vandendriessche, Gaston (1965). The Parapraxis in the Haizmann Case of Sigmund Freud. Louvain: Publications Universitaires. 14. Eyers, Jonathan (2011), Don't Shoot the Albatross! Nautical Myths and Superstitions, A&C Black, ISBN 978-1-4081-3131-2 15. Richter, Simon (18 July 2008). "Did Giuseppe Tartini Sell His Soul to the Devil?". University of Pennsylvania. 16. Schonberg, Harold C. (1997). The Lives of the Great Composers (3rd ed.). Norton. ISBN 0-393-03857-2. OCLC 34356892. 17. Hemmings, F. W. J. (1987). Culture and Society in France 1789 - 1848. London: Bloomsbury Reader. p. 394. ISBN 978-1-4482-0507-3. 18. Weissman, Dick (2005). Blues: The Basics. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-97067-9. OCLC 56194839. 19. "Gorgoroth.info - Biography". Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2023. 20. "Gorgoroth Interview 2009". 21. "gorgoroth Resources and Information". ww16.gorgoroth.org. Archived from the original on 5 October 2006. 22. Adam LeBor (23 August 2000). "Eichmann's List: a pact with the devil". The Independent. Retrieved 13 November 2009. |

1. Stith Thompson, Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, 2nd ed. (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1955-58), vol. 5, pp. 39-40. 2. 「悪魔との取引: 教授がポピュラー・カルチャーにおける闇の王子との契約を探る」。バージニア大学ロースクール。25 July 2012. 2019年5月11日に原文からアーカイブされた。2023年3月10日取得。 3. William Godwin (1876). 「Lives of the Necromancers」. p. 16. 4. マタイ4:1-11; マルコ1:12-13; ルカ4:1-13 5. Palmer, Phillip Mason; More, Robert Pattison (1936). The Sources of the Faust Tradition: From Simon Magus to Lessing. ニューヨーク: Oxford University Press. OCLC 3444206. 6. ラテン語の伝統の代表例は、Moshe Lazar, "Theophilus: Theophilus: Servant of Two Masters. The Pre-Faustian Theme of Despair and Revolt" in Modern Language Notes 87.6, (Nathan Edelman Memorial Issue November 1972) pp. 31-50. 7. Brian A. Catlos, Infidel Kings and Unholy Warriors (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus And Giroux, 2014), 83. 8. バトラー、E. M. (1948). The Myth of the Magus. Cambridge University Press. p. 157. 9. Gísli Sigurðsson, 'Icelandic National Identity: From Romanticism to Tourism', in Making Europe in Nordic Contexts, ed. by Pertti J. Anttonen, NIF Publications, 35 (Turku: Nordic Institute of Folklore, University of Turku, 1996), pp. 10. Rajandran, Sezin (12 September 2007). 「悪魔の霊感". The Prague Post. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. 2013年12月10日取得。 11. Ruickbie, Leo (2009). ファウストゥス: The Life and Times of a Renaissance Magician. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-5090-9. 12. King James (14 May 2016). Daemonologie. 批評版。現代英語で。2016. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-5329-6891-4. 13. Vandendriessche, Gaston (1965). ジークムント・フロイトのハイズマン事件におけるパララクシス。Louvain: Publications Universitaires. 14. Eyers, Jonathan (2011), Don't Shoot the Albatross!Nautical Myths and Superstitions, A&C Black, ISBN 978-1-4081-3131-2. 15. Richter, Simon (18 July 2008). 「Did Giuseppe Tartini Sell His Soul to the Devil?」. University of Pennsylvania. 16. Schonberg, Harold C. (1997). The Lives of the Great Composers (3rd ed.). ノートン。ISBN 0-393-03857-2. OCLC 34356892. 17. Hemmings, F. W. J. (1987). フランスにおける文化と社会 1789 - 1848. London: Bloomsbury Reader. ISBN 978-1-4482-0507-3. 18. Weissman, Dick (2005). ブルース: The Basics. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-97067-9. OCLC 56194839. 19. 「Gorgoroth.info - バイオグラフィー」. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. 2023年2月5日取得。 20. 「Gorgoroth Interview 2009」. 21. 「gorgoroth Resources and Information」. ww16.gorgoroth.org. 2006年10月5日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。 22. Adam LeBor (23 August 2000). 「アイヒマンのリスト:悪魔との契約」. The Independent. 2009年11月13日閲覧。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deal_with_the_Devil |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099