非決定論

Indeterminism

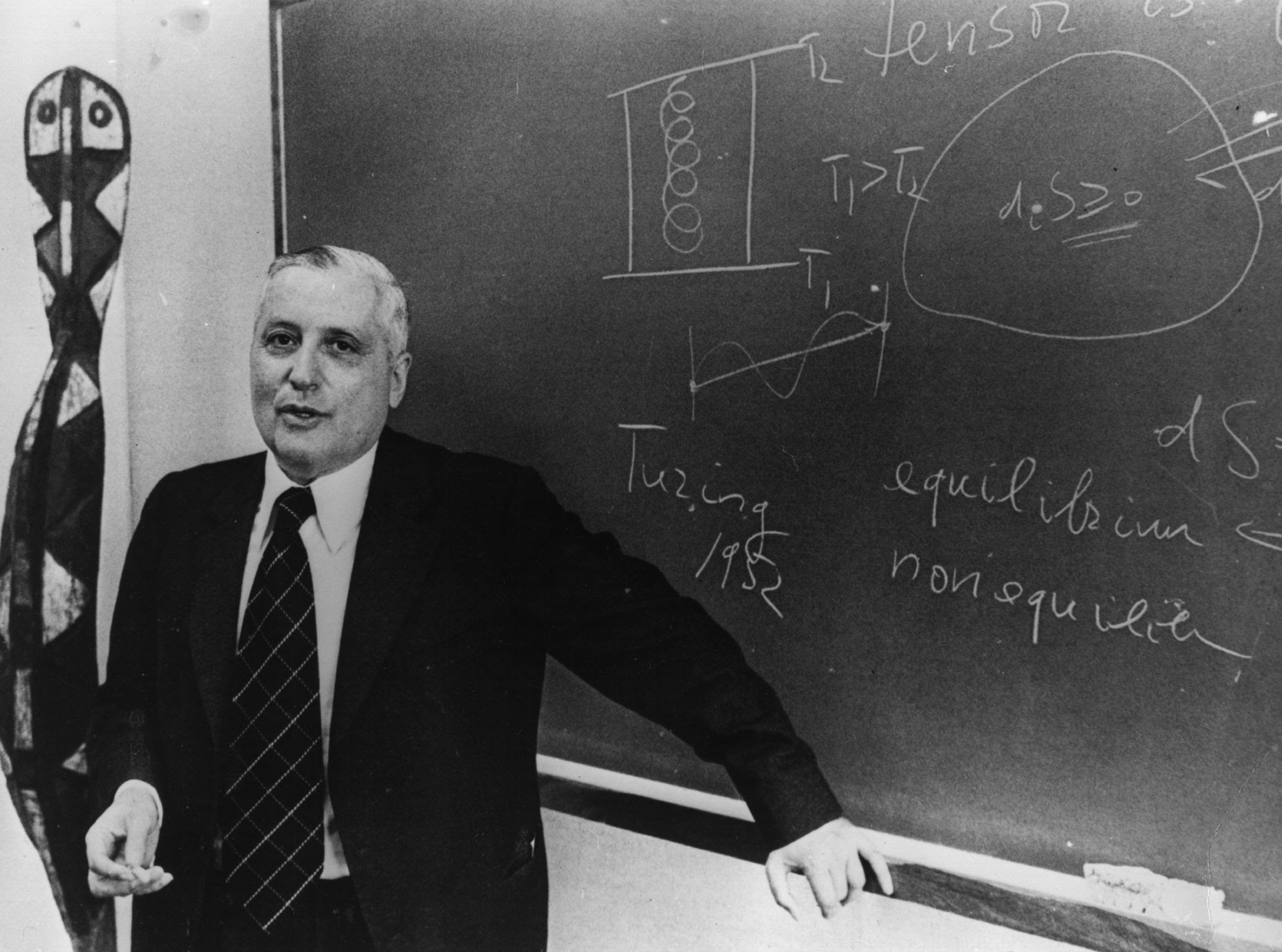

Ilya Prigogine, 1917-2003

☆ 不確定性とは、出来事(あるいは特定の出来事、あるいは特定の種類の出来事)は引き起こされない、あるいは決定論的には引き起こされないという考え方である。

| Indeterminism

is the idea that events (or certain events, or events of certain types)

are not caused, or are not caused deterministically. It is the opposite of determinism and related to chance. It is highly relevant to the philosophical problem of free will, particularly in the form of libertarianism. In science, most specifically quantum theory in physics, indeterminism is the belief that no event is certain and the entire outcome of anything is probabilistic. Heisenberg's uncertainty principle and the "Born rule", proposed by Max Born, are often starting points in support of the indeterministic nature of the universe.[1] Indeterminism is also asserted by Sir Arthur Eddington, and Murray Gell-Mann. Indeterminism has been promoted by the French biologist Jacques Monod's essay "Chance and Necessity". The physicist-chemist Ilya Prigogine argued for indeterminism in complex systems. |

不確定性とは、出来事(あるいは特定の出来事、あるいは特定の種類の出来事)は引き起こされない、あるいは決定論的には引き起こされないという考え方である。 決定論の反対であり、偶然性と関連している。自由意志の哲学的問題、特にリバタリアニズムと深く関係している。科学、特に物理学の量子論では、不確定性と は、どんな出来事も確実ではなく、すべての結果は確率的であるという信念である。ハイゼンベルクの不確定性原理やマックス・ボルンによって提唱された「ボ ルン則」は、しばしば宇宙の不確定性を支持する出発点となっている[1]。アーサー・エディントン卿やマレー・ゲルマンも不確定性を主張している。非決定 論はフランスの生物学者ジャック・モノのエッセイ「偶然と必然」によって提唱された。物理学者で化学者のイリヤ・プリゴジンは、複雑系における不確定性を 主張した。 |

| Necessary but insufficient causation Further information: Necessary and sufficient conditions Indeterminists do not have to deny that causes exist. Instead, they can maintain that the only causes that exist are of a type that do not constrain the future to a single course; for instance, they can maintain that only necessary and not sufficient causes exist. The necessary/sufficient distinction works as follows: If x is a necessary cause of y; then the presence of y implies that x definitely preceded it. The presence of x, however, does not imply that y will occur. If x is a sufficient cause of y, then the presence of y implies that x may have preceded it. (However, another cause z may alternatively cause y. Thus the presence of y does not imply the presence of x, or z, or any other suspect.) It is possible for everything to have a necessary cause, even while indeterminism holds and the future is open, because a necessary condition does not lead to a single inevitable effect. Indeterministic (or probabilistic) causation is a proposed possibility, such that "everything has a cause" is not a clear statement of indeterminism. |

必要だが不十分な因果関係 さらなる情報 必要条件と十分条件 不確定論者は、原因が存在することを否定する必要はない。その代わりに、存在する唯一の原因は、未来を一つの方向に拘束しないタイプのものであると主張す ることができる。例えば、必要な原因だけが存在し、十分な原因は存在しないと主張することができる。必要/十分の区別は次のように機能する: xがyの必然的原因である場合、yの存在はxが確実にそれに先行することを意味する。しかし、xの存在はyの発生を意味しない。 xがyの十分原因である場合、yの存在は、xがそれに先行したかもしれないことを意味する。(したがって、yの存在はxやz、あるいは他の容疑者の存在を意味しない)。 非決定論が成立し、未来が開かれていても、すべてのものに必要な原因があることは可能である。不確定論的(あるいは確率論的)因果関係は、提案された可能性であり、「すべてのものには原因がある」というのは不確定論の明確な表明ではない。 |

| Probabilistic causation Main article: Probabilistic causation Interpreting causation as a deterministic relation means that if A causes B, then A must always be followed by B. In this sense, war does not cause deaths, nor does smoking cause cancer. As a result, many turn to a notion of probabilistic causation. Informally, A probabilistically causes B if A's occurrence increases the probability of B. This is sometimes interpreted to reflect the imperfect knowledge of a deterministic system but other times interpreted to mean that the causal system under study has an inherently indeterministic nature. (Propensity probability is an analogous idea, according to which probabilities have an objective existence and are not just limitations in a subject's knowledge).[2] It can be proved that realizations of any probability distribution other than the uniform one are mathematically equal to applying a (deterministic) function (namely, an inverse distribution function) on a random variable following the latter (i.e. an "absolutely random" one[3]); the probabilities are contained in the deterministic element. A simple form of demonstrating it would be shooting randomly within a square and then (deterministically) interpreting a relatively large subsquare as the more probable outcome. |

確率的因果関係 主な記事 確率的因果関係 因果関係を決定論的な関係として解釈すると、AがBを引き起こすのであれば、Aは必ずBを引き起こすということになる。その結果、多くの人が確率的因果関 係という概念に目を向ける。これは決定論的システムの不完全な知識を反映していると解釈されることもあるが、研究対象の因果システムが本質的に決定論的で ないことを意味していると解釈されることもある。(傾向確率は類似の考え方であり、それによれば確率は客観的な存在であり、対象の知識における単なる制限 ではない)[2]。 一様分布以外の確率分布の実現は、後者(すなわち「絶対ランダム」なもの[3])に従う確率変数に(決定論的な)関数(すなわち逆分布関数)を適用するこ とと数学的に等しいことが証明できる。確率は決定論的要素に含まれている。これを示す簡単な形は、正方形内で無作為に射撃を行い、(決定論的に)比較的大 きな部分正方形をより確率の高い結果と解釈することである。 |

| Intrinsic indeterminism versus unpredictability A distinction is generally made between indeterminism and the mere inability to measure the variables (limits of precision). This is especially the case for physical indeterminism (as proposed by various interpretations of quantum mechanics). Yet some philosophers have argued that indeterminism and unpredictability are synonymous.[4] |

本質的な不確定性と予測不可能性 一般的に、不確定性と変数を測定できないこと(精度の限界)は区別される。これは特に物理的な不確定性(量子力学の様々な解釈によって提唱されている)の場合である。しかし、不確定性と予測不可能性は同義であると主張する哲学者もいる[4]。 |

| Philosophy Ancient Greek philosophy Leucippus The oldest mention of the concept of chance is by the earliest philosopher of atomism, Leucippus, who said: "The cosmos, then, became like a spherical form in this way: the atoms being submitted to a casual and unpredictable movement, quickly and incessantly".[5] Aristotle Main article: Four causes Aristotle described four possible causes (material, efficient, formal, and final). Aristotle's word for these causes was αἰτίαι (aitiai, as in aetiology), which translates as causes in the sense of the multiple factors responsible for an event. Aristotle did not subscribe to the simplistic "every event has a (single) cause" idea that was to come later. In his Physics and Metaphysics, Aristotle said there were accidents (συμβεβηκός, sumbebekos) caused by nothing but chance (τύχη, tukhe). He noted that he and the early physicists found no place for chance among their causes. We have seen how far Aristotle distances himself from any view which makes chance a crucial factor in the general explanation of things. And he does so on conceptual grounds: chance events are, he thinks, by definition unusual and lacking certain explanatory features: as such they form the complement class to those things which can be given full natural explanations.[6] — R.J. Hankinson, "Causes" in Blackwell Companion to Aristotle Aristotle opposed his accidental chance to necessity: Nor is there any definite cause for an accident, but only chance (τυχόν), namely an indefinite (ἀόριστον) cause.[7] It is obvious that there are principles and causes which are generable and destructible apart from the actual processes of generation and destruction; for if this is not true, everything will be of necessity: that is, if there must necessarily be some cause, other than accidental, of that which is generated and destroyed. Will this be, or not? Yes, if this happens; otherwise not.[8] Pyrrhonism The philosopher Sextus Empiricus described the Pyrrhonist position on causes as follows: ...we show the existence of causes are plausible, and if those, too, are plausible which prove that it is incorrect to assert the existence of a cause, and if there is no way to give preference to any of these over others – since we have no agreed-upon sign, criterion, or proof, as has been pointed out earlier – then, if we go by the statements of the Dogmatists, it is necessary to suspend judgment about the existence of causes, too, saying that they are no more existent than non-existent[9] Epicureanism Epicurus argued that as atoms moved through the void, there were occasions when they would "swerve" (clinamen) from their otherwise determined paths, thus initiating new causal chains. Epicurus argued that these swerves would allow us to be more responsible for our actions, something impossible if every action was deterministically caused. For Epicureanism, the occasional interventions of arbitrary gods would be preferable to strict determinism. Early modern philosophy In 1729 theTestament of Jean Meslier states: "The matter, by virtue of its own active force, moves and acts in blind manner".[10] Soon after Julien Offroy de la Mettrie in his L'Homme Machine. (1748, anon.) wrote: "Perhaps, the cause of man's existence is just in existence itself? Perhaps he is by chance thrown in some point of this terrestrial surface without any how and why". In his Anti-Sénèque [Traité de la vie heureuse, par Sénèque, avec un Discours du traducteur sur le même sujet, 1750] we read: "Then, the chance has thrown us in life".[11] In the 19th century the French Philosopher Antoine-Augustin Cournot theorized chance in a new way, as series of not-linear causes. He wrote in Essai sur les fondements de nos connaissances (1851): "It is not because of rarity that the chance is actual. On the contrary, it is because of chance they produce many possible others."[12] Modern philosophy Charles Peirce Tychism (Greek: τύχη "chance") is a thesis proposed by the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce in the 1890s.[13] It holds that absolute chance, also called spontaneity, is a real factor operative in the universe. It may be considered both the direct opposite of Albert Einstein's oft quoted dictum that: "God does not play dice with the universe" and an early philosophical anticipation of Werner Heisenberg's uncertainty principle. Peirce does not, of course, assert that there is no law in the universe. On the contrary, he maintains that an absolutely chance world would be a contradiction and thus impossible. Complete lack of order is itself a sort of order. The position he advocates is rather that there are in the universe both regularities and irregularities. Karl Popper comments[14] that Peirce's theory received little contemporary attention, and that other philosophers did not adopt indeterminism until the rise of quantum mechanics. Arthur Holly Compton In 1931, Arthur Holly Compton championed the idea of human freedom based on quantum indeterminacy and invented the notion of amplification of microscopic quantum events to bring chance into the macroscopic world. In his somewhat bizarre mechanism, he imagined sticks of dynamite attached to his amplifier, anticipating the Schrödinger's cat paradox.[15] Reacting to criticisms that his ideas made chance the direct cause of our actions, Compton clarified the two-stage nature of his idea in an Atlantic Monthly article in 1955. First there is a range of random possible events, then one adds a determining factor in the act of choice. A set of known physical conditions is not adequate to specify precisely what a forthcoming event will be. These conditions, insofar as they can be known, define instead a range of possible events from among which some particular event will occur. When one exercises freedom, by his act of choice he is himself adding a factor not supplied by the physical conditions and is thus himself determining what will occur. That he does so is known only to the person himself. From the outside one can see in his act only the working of physical law. It is the inner knowledge that he is in fact doing what he intends to do that tells the actor himself that he is free.[16] Compton welcomed the rise of indeterminism in 20th century science, writing: In my own thinking on this vital subject I am in a much more satisfied state of mind than I could have been at any earlier stage of science. If the statements of the laws of physics were assumed correct, one would have had to suppose (as did most philosophers) that the feeling of freedom is illusory, or if [free] choice were considered effective, that the laws of physics ... [were] unreliable. The dilemma has been an uncomfortable one.[17] Together with Arthur Eddington in Britain, Compton was one of those rare distinguished physicists in the English speaking world of the late 1920s and throughout the 1930s arguing for the “liberation of free will” with the help of Heisenberg’s indeterminacy principle, but their efforts had been met not only with physical and philosophical criticism but most primarily with fierce political and ideological campaigns.[18] Karl Popper In his essay Of Clouds and Clocks, included in his book Objective Knowledge, Popper contrasted "clouds", his metaphor for indeterministic systems, with "clocks", meaning deterministic ones. He sided with indeterminism, writing I believe Peirce was right in holding that all clocks are clouds to some considerable degree — even the most precise of clocks. This, I think, is the most important inversion of the mistaken determinist view that all clouds are clocks[19] Popper was also a promoter of propensity probability. Robert Kane Kane is one of the leading contemporary philosophers on free will.[20][21] Advocating what is termed within philosophical circles "libertarian freedom", Kane argues that "(1) the existence of alternative possibilities (or the agent's power to do otherwise) is a necessary condition for acting freely, and (2) determinism is not compatible with alternative possibilities (it precludes the power to do otherwise)".[22] It is important to note that the crux of Kane's position is grounded not in a defense of alternative possibilities (AP) but in the notion of what Kane refers to as ultimate responsibility (UR). Thus, AP is a necessary but insufficient criterion for free will. It is necessary that there be (metaphysically) real alternatives for our actions, but that is not enough; our actions could be random without being in our control. The control is found in "ultimate responsibility". What allows for ultimate responsibility of creation in Kane's picture are what he refers to as "self-forming actions" or SFAs — those moments of indecision during which people experience conflicting wills. These SFAs are the undetermined, regress-stopping voluntary actions or refrainings in the life histories of agents that are required for UR. UR does not require that every act done of our own free will be undetermined and thus that, for every act or choice, we could have done otherwise; it requires only that certain of our choices and actions be undetermined (and thus that we could have done otherwise), namely SFAs. These form our character or nature; they inform our future choices, reasons and motivations in action. If a person has had the opportunity to make a character-forming decision (SFA), he is responsible for the actions that are a result of his character. Mark Balaguer Mark Balaguer, in his book Free Will as an Open Scientific Problem[23] argues similarly to Kane. He believes that, conceptually, free will requires indeterminism, and the question of whether the brain behaves indeterministically is open to further empirical research. He has also written on this matter "A Scientifically Reputable Version of Indeterministic Libertarian Free Will".[24] |

哲学 古代ギリシャ哲学 レウキッポス 偶然性の概念に関する最古の記述は、最古の原子論哲学者レウシッポスによるものである: 「宇宙は、このようにして球形のようになった。原子は、気まぐれで予測不可能な運動に、素早く絶え間なくさらされている」[5]。 アリストテレス 主な記事 四つの原因 アリストテレスは4つの原因(物質的原因、効率的原因、形式的原因、最終的原因)を説明した。アリストテレスはこれらの原因をαἰτίαι (aitiai, aetiologyの意)と言い、事象を引き起こす複数の要因という意味で原因と訳した。アリストテレスは、後に登場する「すべての事象には(単一の)原 因がある」という単純化された考え方には賛同しなかった。 アリストテレスは『物理学』と『形而上学』の中で、偶然(τύχη、tukhe)以外の何ものによっても引き起こされない事故(συμβεβηκός、 sumbebekos)が存在すると述べている。アリストテレスは、自分たちや初期の物理学者たちは、その原因の中に偶然を見出すことはできなかったと述 べている。 我々はアリストテレスが、偶然を物事の一般的説明における重要な要因とする考え方から、どれほど距離を置いているかを見てきた。そしてアリストテレスは概 念的な理由からそうしているのである。偶然の事象は定義上非日常的であり、ある種の説明的特徴を欠いていると彼は考えている。 - R.J. Hankinson, "Causes" in Blackwell Companion to Aristotle アリストテレスは偶然の偶然を必然に対立させた: 偶然にはいかなる明確な原因も存在せず、偶然(τυχόν)、すなわち不確定(Āόριστον)な原因のみが存在する。 生成と破壊の実際の過程とは別に、生成可能であり破壊可能である原理と原因が存在することは明らかである。もしこれが真実でなければ、すべては必然的なものとなる。そうなるのか、ならないのか。そうであればそうであり、そうでなければそうではない。 ピュロン主義 哲学者セクストゥス・エンピリクスは、原因に関するピュロン主義の立場を次のように述べている: ......我々は原因の存在がもっともらしいことを示し、原因の存在を主張することが正しくないことを証明するそれらもまたもっともらしいとするなら ば、そして、これらのいずれかを他のものよりも優先させる方法がないとするならば--先に指摘されたように、我々は合意された標識、基準、証明を持ってい ないので--、教条主義者の言明に従うならば、原因の存在についても判断を保留する必要があり、それらは存在しないよりも存在しないと言う[9]。 エピクロス主義 エピクロスは、原子が空虚の中を移動するとき、原子が決定された経路から「それる」(clinamen)ことがあり、それによって新たな因果の連鎖が始ま ると主張した。もしすべての行動が決定論的に引き起こされているとしたら、それは不可能なことである。エピクロスにとっては、厳密な決定論よりも、恣意的 な神々の時々の介入の方が望ましいのである。 近世哲学 1729年、ジャン・メスリエの遺言はこう述べている: 「物質は、それ自身の活動的な力によって、盲目的に動き、行動する」[10]。 その直後、ジュリアン・オフロワ・ド・ラ・メトリは『人間機械』(L'Homme Machine. (1748年、不明)はこう書いている: 「おそらく、人間の存在の原因は存在そのものにあるのだろう。おそらく彼は、この地上のどこかの地点に、何の方法も理由もなく、偶然に投げ出されたのだろう」。 反セネック』(Traité de la vie heureuse, par Sénèque, avec un Discours du traducteur sur le même sujet, 1750)にはこうある: 「そして、偶然が私たちを人生に投げ込んだ」[11]。 19世紀、フランスの哲学者アントワーヌ=オーギュスタン・クルノは、偶然を直線的ではない一連の原因として新しい方法で理論化した。彼はEssai sur les fondements de nos connaissances (1851)でこう書いている: 「偶然が実際にあるのは、希少性のためではない。それどころか、偶然が他の多くの可能性を生み出すのである」[12]。 現代哲学 チャールズ・パース タイキズム(ギリシャ語: τύχη "chance")は、1890年代にアメリカの哲学者チャールズ・サンダース・パイアースによって提唱されたテーゼである[13]。これは、よく引用さ れるアルバート・アインシュタインの独断の正反対とも考えられる: 「神は宇宙とサイコロを振らない」というアルベルト・アインシュタインの口癖の真逆であり、ヴェルナー・ハイゼンベルクの不確定性原理を哲学的に先取りし たものでもある。 もちろん、ペアーズは宇宙に法則が存在しないと主張しているわけではない。それどころか、絶対的に偶然な世界は矛盾であり、不可能であると主張している。 秩序の完全な欠如は、それ自体が一種の秩序なのである。彼が提唱する立場は、むしろ宇宙には規則性と不規則性の両方が存在するというものである。 カール・ポパーは、ペイスの理論は現代ではほとんど注目されておらず、他の哲学者は量子力学が台頭するまで不確定論を採用しなかったとコメントしている[14]。 アーサー・ホリー・コンプトン 1931年、アーサー・ホリー・コンプトンは、量子の不確定性に基づく人間の自由という考えを支持し、巨視的な世界に偶然性をもたらすために、微視的な量 子事象の増幅という概念を発明した。彼の少々奇妙なメカニズムでは、シュレーディンガーの猫のパラドックスを先取りして、増幅器にダイナマイトの棒を取り 付けることを想像していた[15]。 コンプトンは、1955年のAtlantic Monthly誌の記事で、彼の考えが偶然を我々の行動の直接的な原因にしているという批判に反応し、彼の考えの2段階の性質を明らかにした。まずランダ ムな可能性のある事象の範囲があり、次に選択行為における決定因子が加わる。 一連の既知の物理的条件は、これから起こる出来事を正確に特定するには不十分である。これらの条件は、知ることができる限りにおいて、その代わりに、起こ りうる出来事の範囲を定義し、その中からある特定の出来事が起こることになる。人が自由を行使するとき、その選択行為によって、物理的条件によって供給さ れるのではない要素を自ら加え、何が起こるかを自ら決定しているのである。そうすることは、その人自身にしかわからない。外から見れば、彼の行為には物理 的法則が働いているようにしか見えない。自分が自由であることを行為者自身に告げるのは、自分が意図したことを実際に行っているという内的知識なのである [16]。 コンプトンは20世紀の科学における不確定論の台頭を歓迎し、こう書いている: この重要なテーマに関する私自身の思考において、私は科学のどの初期の段階よりもはるかに満足した状態にある。もし物理法則の記述が正しいと仮定するなら ば、(ほとんどの哲学者がそうであったように)自由という感覚は幻想的なものであると考えなければならなかったであろうし、もし[自由な]選択が有効であ ると考えるならば、物理法則は......信頼できないものであると考えなければならなかったであろう。[物理法則は信頼できない このジレンマは不快なものであった。 イギリスのアーサー・エディントンとともに、コンプトンはハイゼンベルクの不確定性原理の助けを借りて「自由意志の解放」を主張する、1920年代後半か ら1930年代にかけての英語圏における稀に見る著名な物理学者の一人であったが、彼らの努力は物理学的・哲学的批判にさらされただけでなく、最も主要な ものとしては熾烈な政治的・イデオロギー的キャンペーンにさらされたのであった[18]。 カール・ポパー ポパーは、著書『客観的知識』に収録されたエッセイ『雲と時計』の中で、不確定性システムの比喩である「雲」と決定論的システムを意味する「時計」を対比させた。彼は決定論に味方し、次のように書いた。 最も正確な時計でさえも、すべての時計はかなりの程度雲である、という点で、私はペイスが正しかったと信じている。これは、すべての雲は時計であるという誤った決定論者の見解の最も重要な逆転であると私は思う[19]。 ポパーは傾向確率の推進者でもあった。 ロバート・ケイン ケインは自由意志に関する現代を代表する哲学者の一人である[20][21]。哲学界で「リバタリアン的自由」と呼ばれているものを提唱するケインは、 「(1)代替可能性の存在(あるいはそうでないことをする代理人の力)は自由に行動するための必要条件であり、(2)決定論は代替可能性と両立しない(そ うでないことをする力を排除する)」と主張している。 [22] ケインの立場の核心は、代替可能性(AP)の擁護ではなく、ケインが究極的責任(UR)と呼ぶ概念に根ざしていることに注意することが重要である。した がって、APは自由意志にとって必要だが不十分な基準である。私たちの行動に(形而上学的に)現実的な代替可能性があることは必要だが、それだけでは十分 ではない。そのコントロールは「究極的責任」にある。 ケインの描く創造に対する究極の責任を可能にするのは、彼が「自己形成行為」あるいはSFAと呼ぶものであり、人々が相反する意志を経験する優柔不断な瞬 間である。これらのSFAは、URに必要とされるエージェントのライフヒストリーにおける、未決定の、逆行を阻止する自発的な行為や遠慮である。URは、 私たち自身の自由意志によって行われるすべての行為が未決定であること、したがって、すべての行為や選択について、そうでなければできなかったであろうこ とを要求しているのではなく、私たちの選択や行為のうちの特定のものが未決定であること(したがって、そうでなければできたであろうこと)、すなわち SFAを要求しているにすぎない。これらは私たちの性格や性質を形成するものであり、私たちの将来の選択、理由、行動における動機に影響を与える。もし人 が人格形成的な決定(SFA)をする機会があったなら、その人はその人格の結果である行動に責任がある。 マーク・バラガー マーク・バラガーはその著書『未解決の科学的問題としての自由意志』[23]において、ケインと同様の主張を行っている。彼は概念的に、自由意志には不確 定性が必要であり、脳が不確定的に振る舞うかどうかという問題はさらなる実証的研究の余地があると考えている。彼はこの問題について「不確定論的自由意志 の科学的に評判の良いバージョン」[24]も書いている。 |

| Mathematics In probability theory, a stochastic process, or sometimes random process, is the counterpart to a deterministic process (or deterministic system). Instead of dealing with only one possible reality of how the process might evolve over time (as is the case, for example, for solutions of an ordinary differential equation), in a stochastic or random process there is some indeterminacy in its future evolution described by probability distributions. This means that even if the initial condition (or starting point) is known, there are many possibilities the process might go to, but some paths may be more probable and others less so. Classical and relativistic physics The idea that Newtonian physics proved causal determinism was highly influential in the early modern period. "Thus physical determinism [..] became the ruling faith among enlightened men; and everybody who did not embrace this new faith was held to be an obscurantist and a reactionary".[25] However: "Newton himself may be counted among the few dissenters, for he regarded the solar system as imperfect, and consequently as likely to perish".[26] Classical chaos is not usually considered an example of indeterminism, as it can occur in deterministic systems such as the three-body problem. John Earman has argued that most physical theories are indeterministic.[27][28] For instance, Newtonian physics admits solutions where particles accelerate continuously, heading out towards infinity. By the time reversibility of the laws in question, particles could also head inwards, unprompted by any pre-existing state. He calls such hypothetical particles "space invaders". John D. Norton has suggested another indeterministic scenario, known as Norton's Dome, where a particle is initially situated on the exact apex of a dome.[29] Branching space-time is a theory uniting indeterminism and the special theory of relativity. The idea was originated by Nuel Belnap.[30] The equations of general relativity admit of both indeterministic and deterministic solutions. Boltzmann Ludwig Boltzmann, was one of the founders of statistical mechanics and the modern atomic theory of matter. He is remembered for his discovery that the second law of thermodynamics is a statistical law stemming from disorder. He also speculated that the ordered universe we see is only a small bubble in much larger sea of chaos. The Boltzmann brain is a similar idea. Evolution and biology Darwinian evolution has an enhanced reliance on the chance element of random mutation compared to the earlier evolutionary theory of Herbert Spencer. However, the question of whether evolution requires genuine ontological indeterminism is open to debate[31] In the essay Chance and Necessity (1970) Jacques Monod rejected the role of final causation in biology, instead arguing that a mixture of efficient causation and "pure chance" lead to teleonomy, or merely apparent purposefulness. The Japanese theoretical population geneticist Motoo Kimura emphasises the role of indeterminism in evolution. According to neutral theory of molecular evolution: "at the molecular level most evolutionary change is caused by random drift of gene mutants that are equivalent in the face of selection.[32] Prigogine In his 1997 book, The End of Certainty, Prigogine contends that determinism is no longer a viable scientific belief. "The more we know about our universe, the more difficult it becomes to believe in determinism." This is a major departure from the approach of Newton, Einstein and Schrödinger, all of whom expressed their theories in terms of deterministic equations. According to Prigogine, determinism loses its explanatory power in the face of irreversibility and instability.[33] Prigogine traces the dispute over determinism back to Darwin, whose attempt to explain individual variability according to evolving populations inspired Ludwig Boltzmann to explain the behavior of gases in terms of populations of particles rather than individual particles.[34] This led to the field of statistical mechanics and the realization that gases undergo irreversible processes. In deterministic physics, all processes are time-reversible, meaning that they can proceed backward as well as forward through time. As Prigogine explains, determinism is fundamentally a denial of the arrow of time. With no arrow of time, there is no longer a privileged moment known as the "present," which follows a determined "past" and precedes an undetermined "future." All of time is simply given, with the future as determined or undetermined as the past. With irreversibility, the arrow of time is reintroduced to physics. Prigogine notes numerous examples of irreversibility, including diffusion, radioactive decay, solar radiation, weather and the emergence and evolution of life. Like weather systems, organisms are unstable systems existing far from thermodynamic equilibrium. Instability resists standard deterministic explanation. Instead, due to sensitivity to initial conditions, unstable systems can only be explained statistically, that is, in terms of probability. Prigogine asserts that Newtonian physics has now been "extended" three times, first with the use of the wave function in quantum mechanics, then with the introduction of spacetime in general relativity and finally with the recognition of indeterminism in the study of unstable systems. Quantum mechanics Main article: Quantum indeterminacy At one time, it was assumed in the physical sciences that if the behavior observed in a system cannot be predicted, the problem is due to lack of fine-grained information, so that a sufficiently detailed investigation would eventually result in a deterministic theory ("If you knew exactly all the forces acting on the dice, you would be able to predict which number comes up"). However, the advent of quantum mechanics removed the underpinning from that approach, with the claim that (at least according to the Copenhagen interpretation) the most basic constituents of matter at times behave indeterministically. This comes from the collapse of the wave function, in which the state of a system upon measurement cannot in general be predicted. Quantum mechanics only predicts the probabilities of possible outcomes, which are given by the Born rule. Non-deterministic behavior in wave function collapse is not only a feature of the Copenhagen interpretation, with its observer-dependence, but also of objective collapse and other theories. Opponents of quantum indeterminism suggested that determinism could be restored by formulating a new theory in which additional information, so-called hidden variables,[35] would allow definite outcomes to be determined. For instance, in 1935, Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen wrote a paper titled "Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete?" arguing that such a theory was in fact necessary to preserve the principle of locality. In 1964, John S. Bell was able to define a theoretical test for these local hidden variable theories, which was reformulated as a workable experimental test through the work of Clauser, Horne, Shimony and Holt. The negative result of the 1980s tests by Alain Aspect ruled such theories out, provided certain assumptions about the experiment hold. Thus any interpretation of quantum mechanics, including deterministic reformulations, must either reject locality or reject counterfactual definiteness altogether. David Bohm's theory is the main example of a non-local deterministic quantum theory. The many-worlds interpretation is said to be deterministic, but experimental results still cannot be predicted: experimenters do not know which 'world' they will end up in. Technically, counterfactual definiteness is lacking. A notable consequence of quantum indeterminism is the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which prevents the simultaneous accurate measurement of all a particle's properties. Cosmology Primordial fluctuations are density variations in the early universe which are considered the seeds of all structure in the universe. Currently, the most widely accepted explanation for their origin is in the context of cosmic inflation. According to the inflationary paradigm, the exponential growth of the scale factor during inflation caused quantum fluctuations of the inflaton field to be stretched to macroscopic scales, and, upon leaving the horizon, to "freeze in". At the later stages of radiation- and matter-domination, these fluctuations re-entered the horizon, and thus set the initial conditions for structure formation. Neuroscience Neuroscientists such as Björn Brembs and Christof Koch believe thermodynamically stochastic processes in the brain are the basis of free will, and that even very simple organisms such as flies have a form of free will.[36] Similar ideas are put forward by some philosophers such as Robert Kane. Despite recognizing indeterminism to be a very low-level, necessary prerequisite, Björn Brembs says that it's not even close to being sufficient for addressing things like morality and responsibility.[36] Other views Against Einstein and others who advocated determinism, indeterminism—as championed by the English astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington—says that a physical object has an ontologically undetermined component that is not due to the epistemological limitations of physicists' understanding. The uncertainty principle, then, would not necessarily be due to hidden variables but to an indeterminism in nature itself.[37] Determinism and indeterminism are examined in Causality and Chance in Modern Physics by David Bohm. He speculates that, since determinism can emerge from underlying indeterminism (via the law of large numbers),[38] and that indeterminism can emerge from determinism (for instance, from classical chaos), the universe could be conceived of as having alternating layers of causality and chaos.[39] |

数学 確率論では、確率過程、あるいはランダム過程は、決定論的過程(あるいは決定論的システム)と対をなすものである。例えば常微分方程式の解の場合のよう に)過程が時間とともにどのように発展するかという1つの可能な現実だけを扱うのではなく、確率過程またはランダム過程では、確率分布によって記述される 将来の発展には不確定性がある。つまり、初期条件(あるいは出発点)がわかっていても、プロセスが進む可能性はたくさんあるが、確率の高い道もあれば、そ うでない道もあるということである。 古典物理学と相対論的物理学 ニュートン物理学が因果的決定論を証明したという考えは、近世に大きな影響を与えた。「こうして物理学的決定論は啓蒙された人々の間で支配的な信仰とな り、この新しい信仰を受け入れない者は皆、蒙昧主義者であり反動主義者であるとされた」[25]。しかし、「ニュートン自身は太陽系を不完全なものとみな し、その結果滅びる可能性があるとみなしたので、数少ない反対者の一人に数えられるかもしれない」[26]。 古典的なカオスは、3体問題のような決定論的なシステムでも起こりうるため、通常は不確定性の例とは考えられていない。 例えば、ニュートン物理学では、粒子が連続的に加速し、無限大に向かう解を認めている。問題となっている法則の時間的可逆性によって、粒子は既存の状態に促されることなく、内側に向かうこともできる。彼はこのような仮想粒子を「スペース・インベーダー」と呼んでいる。 ジョン・D・ノートンはノートンのドームとして知られる別の不確定性シナリオを提案しており、そこでは粒子は最初ドームの正確な頂点に位置している[29]。 分岐時空は、不確定性と特殊相対性理論を統合する理論である。一般相対性理論の方程式は、非決定論的な解と決定論的な解の両方を認めている[30]。 ボルツマン ルートヴィヒ・ボルツマンは統計力学と現代原子論の創始者の一人である。熱力学第二法則が無秩序に由来する統計法則であることを発見したことで知られる。 彼はまた、私たちが見ている秩序ある宇宙は、もっと大きなカオスの海の中の小さな泡に過ぎないと推測した。ボルツマン脳も同様の考えである。 進化と生物学 ダーウィン進化論は、それ以前のハーバート・スペンサーの進化論に比べ、ランダムな突然変異という偶然の要素への依存を高めている。しかし、進化が真正の存在論的不確定性を必要とするかどうかについては議論の余地がある[31]。 ジャック・モノは『偶然と必然』(1970年)というエッセイの中で、生物学における最終的な因果関係の役割を否定し、その代わりに効率的な因果関係と「純粋な偶然」の混合がテレオノミー、つまり単に見かけ上の目的性をもたらすと主張した。 日本の理論的集団遺伝学者の木村元男は、進化における不確定性の役割を強調している。中立的な分子進化論によれば 分子レベルでは、ほとんどの進化的変化は、淘汰に直面しても等価である遺伝子変異体のランダムなドリフトによって引き起こされる」[32]。 プリゴジン 1997年に出版された著書『確実性の終焉』の中で、プリゴジンは決定論はもはや科学的信念としては成り立たないと主張している。「宇宙について知れば知 るほど、決定論を信じることは難しくなる」。これは、ニュートン、アインシュタイン、シュレーディンガーのアプローチとは大きく異なる。プリゴジンによれ ば、決定論は不可逆性と不安定性の前で説明力を失う。 プリゴジンは、決定論をめぐる論争をダーウィンにまで遡る。ダーウィンは、進化する集団に従って個体差を説明しようとしたため、ルートヴィヒ・ボルツマン が気体の挙動を個々の粒子ではなく粒子の集団という観点から説明するようになった。決定論的物理学では、すべての過程は時間可逆的である。プリゴジンが説 明するように、決定論は基本的に時間の矢を否定するものである。時間の矢がなければ、"現在 "という特権的な瞬間はもはや存在せず、それは決定された "過去 "に続き、決定されていない "未来 "に先行する。すべての時間は単純に与えられ、未来は過去と同じように決定され、あるいは決定されない。不可逆性によって、時間の矢は物理学に再び導入さ れる。プリゴジンは、拡散、放射性崩壊、太陽放射、気象、生命の出現と進化など、不可逆性の例を数多く挙げている。気象システムと同様、生物も熱力学的平 衡から遠く離れた不安定なシステムである。不安定性は標準的な決定論的説明を拒む。その代わりに、初期条件に敏感なため、不安定系は統計的に、つまり確率 論的にしか説明できない。 量子力学における波動関数の使用、一般相対性理論における時空の導入、そして不安定系の研究における不確定性の認識である。 量子力学 主な記事 量子の不確定性 一時期、物理科学では、ある系で観察される振る舞いが予測できない場合、その問題は微細な情報の欠如によるものであり、十分に詳細な調査を行えば、最終的 には決定論的な理論が得られると考えられていた(「サイコロに作用するすべての力を正確に知っていれば、どの数字が出るか予測できるだろう」)。 しかし、量子力学の登場により、(少なくともコペンハーゲン解釈によれば)物質の最も基本的な構成要素は、時として決定論的でない振る舞いをするという主 張がなされ、このアプローチの下支えがなくなった。これは波動関数の崩壊に由来するもので、測定時の系の状態は一般に予測できない。量子力学が予測するの は、ボルン則によって与えられる可能性のある結果の確率だけである。波動関数の崩壊における非決定論的振る舞いは、観測者依存性を持つコペンハーゲン解釈 の特徴であるだけでなく、客観的崩壊や他の理論の特徴でもある。 量子不確定性論に反対する人々は、追加的な情報、いわゆる隠れた変数[35]によって明確な結果を決定することができる新しい理論を定式化することによっ て決定論を回復することができると提案した。例えば、1935年にアインシュタイン、ポドルスキー、ローゼンは "Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete? "と題する論文を書き、そのような理論は局所性の原理を維持するために必要であると主張した。1964年、ジョン・S・ベルは、これらの局所的隠れ変数理 論に対する理論的テストを定義することができ、それはクラウザー、ホーン、シモニー、ホルトの研究によって実行可能な実験的テストとして再構成された。ア ラン・アスペクトによる1980年代の実験の否定的な結果は、実験に関するある仮定が成り立つ限り、このような理論を否定するものであった。したがって、 決定論的な再定式化を含む量子力学の解釈は、局所性を否定するか、反事実的な確定性を完全に否定しなければならない。デビッド・ボームの理論は、非局所的 な決定論的量子論の主な例である。 多世界解釈は決定論的であると言われているが、実験結果を予測することはできない。技術的には、反事実的確定性が欠けているのである。 量子不確定性の顕著な帰結として、ハイゼンベルクの不確定性原理がある。これは、粒子のすべての性質を同時に正確に測定することを妨げるものである。 宇宙論 原初のゆらぎとは、宇宙初期の密度変化のことで、宇宙のあらゆる構造の種と考えられている。現在、その起源について最も広く受け入れられている説明は、宇 宙のインフレーションである。インフレーションのパラダイムによれば、インフレーションの間にスケールファクターが指数関数的に増大したため、インフラト ンの量子揺らぎが巨視的スケールにまで引き伸ばされ、地平線を離れると「フリーズ・イン」した。その後、輻射と物質が同化する段階で、これらの揺らぎが再 び地平線の中に入り込み、構造形成の初期条件を整えた。 神経科学 ビョルン・ブレムスやクリストフ・コッホのような神経科学者は、脳における熱力学的に確率的な過程が自由意志の基礎であり、ハエのような非常に単純な生物でさえも自由意志の一形態を持っていると考えている。 ビョルン・ブレムスは、不確定性は非常に低レベルで必要な前提条件であると認識しているにもかかわらず、道徳や責任といったものを扱うには十分であるとまでは言えないと述べている[36]。 その他の見解 決定論を提唱したアインシュタインや他の人々に対して、イギリスの天文学者アーサー・エディントン卿によって提唱された不確定性主義は、物理学者が理解す ることの認識論的限界によるものではない、存在論的に決定されない要素を物理的物体が持っていると言っている。したがって、不確定性原理は、必ずしも隠れ た変数によるものではなく、自然そのものの不確定性によるものである[37]。 決定論と不確定論は、デイヴィッド・ボームによる『現代物理学における因果性と偶然性』の中で検討されている。彼は、決定論は(大数の法則によって)根底 にある不確定性から生まれることがあり[38]、不確定性は(例えば古典的なカオスから)決定論から生まれることがあるため、宇宙は因果性とカオスの交互 の層を持っていると考えることができると推測している[39]。 |

| Catastrophism Chance (disambiguation) Interpretations of quantum mechanics: Comparisons chart Free will Incompatibilism Luck Nondeterminism (disambiguation) Randomness Uncertainty |

破局論(カタストロフィ論) チャンス(曖昧さ回避) 量子力学の解釈 比較表 自由意志 非両立論 運 非決定論(曖昧さ回避) ランダム性 不確実性 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indeterminism |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆