決定論

Determinism

☆ 決定論(determinism)とは、人間の意思決定や行動を含め、宇宙におけるすべての出来事は因果的に必然であるとする哲学的見解である。哲学の歴史を通じて、決定論は 多様な、時には重なり合う動機や考察から発展してきた。永遠主義と同様に、決定論は概念としての未来よりもむしろ特定の出来事に焦点を当てる。決定論の対 極にあるのが不確定論(非決定論;Indeterminism)であり、事象は決定論的に引き起こされるのではなく、むしろ偶然によって起こるという考え方である。決定論はしばしば自由意志と対比 されるが、この2つは両立すると主張する哲学者もいる。

★文化決定論▶︎自由意志▶︎︎唯物論▶環境決定論︎▶非決定論︎︎▶︎▶

| Determinism

is the philosophical view that all events in the universe, including

human decisions and actions, are causally inevitable.[1] Deterministic

theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from

diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and considerations. Like

eternalism, determinism focuses on particular events rather than the

future as a concept. The opposite of determinism is indeterminism, or

the view that events are not deterministically caused but rather occur

due to chance. Determinism is often contrasted with free will, although some philosophers claim that the two are compatible.[2][3] Historically, debates about determinism have involved many philosophical positions and given rise to multiple varieties or interpretations of determinism. One topic of debate concerns the scope of determined systems. Some philosophers have maintained that the entire universe is a single determinate system, while others identify more limited determinate systems. Another common debate topic is whether determinism and free will can coexist; compatibilism and incompatibilism represent the opposing sides of this debate. Determinism should not be confused with the self-determination of human actions by reasons, motives, and desires. Determinism is about interactions which affect cognitive processes in people's lives.[4] It is about the cause and the result of what people have done. Cause and result are always bound together in cognitive processes. It assumes that if an observer has sufficient information about an object or human being, that such an observer might be able to predict every consequent move of that object or human being. Determinism rarely requires that perfect prediction be practically possible. |

決

定論とは、人間の意思決定や行動を含め、宇宙におけるすべての出来事は因果的に必然であるとする哲学的見解である[1]。哲学の歴史を通じて、決定論は多

様な、時には重なり合う動機や考察から発展してきた。永遠主義と同様に、決定論は概念としての未来よりもむしろ特定の出来事に焦点を当てる。決定論の対極

にあるのが不確定論であり、事象は決定論的に引き起こされるのではなく、むしろ偶然によって起こるという考え方である。決定論はしばしば自由意志と対比されるが、この2つは両立すると主張する哲学者もいる[2][3]。 歴史的に、決定論に関する議論は多くの哲学的立場を巻き込み、決定論の複数の多様性や解釈を生み出してきた。議論のトピックの一つは、決定されたシステム の範囲に関するものである。宇宙全体が単一の決定論的システムであると主張する哲学者もいれば、より限定された決定論的システムを特定する哲学者もいる。 また、決定論と自由意志が共存できるかどうかということもよく議論されるテーマであり、両立主義と非両立主義がこの議論の対立点を表している。 決定論を、理由、動機、欲望による人間の行動の自己決定と混同してはならない。決定論とは、人々の生活における認知過程に影響を与える相互作用に関するも のであり、人々が行ったことの原因と結果に関するものである[4]。原因と結果は認知過程において常に結びついている。決定論は、観察者がある物体や人間 について十分な情報を持っていれば、そのような観察者はその物体や人間のすべての結果的な動きを予測できるかもしれないと仮定している。決定論では、完全 な予測が現実的に可能であることはほとんど要求されない。 |

| Varieties "Determinism" may commonly refer to any of the following viewpoints. Causal Causal determinism, sometimes synonymous with historical determinism (a sort of path dependence), is "the idea that every event is necessitated by antecedent events and conditions together with the laws of nature."[5] However, it is a broad enough term to consider that:[6] ...One's deliberations, choices, and actions will often be necessary links in the causal chain that brings something about. In other words, even though our deliberations, choices, and actions are themselves determined like everything else, it is still the case, according to causal determinism, that the occurrence or existence of yet other things depends upon our deliberating, choosing and acting in a certain way. Causal determinism proposes that there is an unbroken chain of prior occurrences stretching back to the origin of the universe. The relation between events and the origin of the universe may not be specified. Causal determinists believe that there is nothing in the universe that has no cause or is self-caused. Causal determinism has also been considered more generally as the idea that everything that happens or exists is caused by antecedent conditions.[7] In the case of nomological determinism, these conditions are considered events also, implying that the future is determined completely by preceding events—a combination of prior states of the universe and the laws of nature.[5] These conditions can also be considered metaphysical in origin (such as in the case of theological determinism).[6]  Many philosophical theories of determinism frame themselves with the idea that reality follows a sort of predetermined path. Nomological Nomological determinism is the most common form of causal determinism and is generally synonymous with physical determinism. This is the notion that the past and the present dictate the future entirely and necessarily by rigid natural laws and that every occurrence inevitably results from prior events. Nomological determinism is sometimes illustrated by the thought experiment of Laplace's demon.[8] Although sometimes called scientific determinism, the term is a misnomer for nomological determinism. Necessitarianism Necessitarianism is a metaphysical principle that denies all mere possibility and maintains that there is only one possible way for the world to exist. Leucippus claimed there are no uncaused events and that everything occurs for a reason and by necessity.[9] Predeterminism Predeterminism is the idea that all events are determined in advance.[10][11] The concept is often argued by invoking causal determinism, implying that there is an unbroken chain of prior occurrences stretching back to the origin of the universe. In the case of predeterminism, this chain of events has been pre-established, and human actions cannot interfere with the outcomes of this pre-established chain. Predeterminism can be categorized as a specific type of determinism when it is used to mean pre-established causal determinism.[10][12] It can also be used interchangeably with causal determinism—in the context of its capacity to determine future events.[10][13] However, predeterminism is often considered as independent of causal determinism.[14][15] Biological The term predeterminism is also frequently used in the context of biology and heredity, in which case it represents a form of biological determinism, sometimes called genetic determinism.[16] Biological determinism is the idea that all human behaviors, beliefs, and desires are fixed by human genetic nature. Friedrich Nietzsche explained that human beings are "determined" by their bodies and are subject to its passions, impulses, and instincts.[17] Fatalism Fatalism is normally distinguished from determinism,[18] as a form of teleological determinism. Fatalism is the idea that everything is fated to happen, resulting in humans having no control over their future. Fate has arbitrary power, and does not necessarily follow any causal or deterministic laws.[7] Types of fatalism include hard theological determinism and the idea of predestination, where there is a God who determines all that humans will do. This may be accomplished through either foreknowledge of their actions, achieved through omniscience[19] or by predetermining their actions.[20] Theological Theological determinism is a form of determinism that holds that all events that happen are either preordained (i.e., predestined) to happen by a monotheistic deity, or are destined to occur given its omniscience. Two forms of theological determinism exist, referred to as strong and weak theological determinism.[21] Strong theological determinism is based on the concept of a creator deity dictating all events in history: "everything that happens has been predestined to happen by an omniscient, omnipotent divinity."[22] Weak theological determinism is based on the concept of divine foreknowledge—"because God's omniscience is perfect, what God knows about the future will inevitably happen, which means, consequently, that the future is already fixed."[23] There exist slight variations on this categorization, however. Some claim either that theological determinism requires predestination of all events and outcomes by the divinity—i.e., they do not classify the weaker version as theological determinism unless libertarian free will is assumed to be denied as a consequence—or that the weaker version does not constitute theological determinism at all.[24] With respect to free will, "theological determinism is the thesis that God exists and has infallible knowledge of all true propositions including propositions about our future actions," more minimal criteria designed to encapsulate all forms of theological determinism.[25] Theological determinism can also be seen as a form of causal determinism, in which the antecedent conditions are the nature and will of God.[6] Some have asserted that Augustine of Hippo introduced theological determinism into Christianity in 412 CE, whereas all prior Christian authors supported free will against Stoic and Gnostic determinism.[26] However, there are many Biblical passages that seem to support the idea of some kind of theological determinism. Adequate Adequate determinism is the idea, because of quantum decoherence, that quantum indeterminacy can be ignored for most macroscopic events. Random quantum events "average out" in the limit of large numbers of particles (where the laws of quantum mechanics asymptotically approach the laws of classical mechanics).[27] Stephen Hawking explains a similar idea: he says that the microscopic world of quantum mechanics is one of determined probabilities. That is, quantum effects rarely alter the predictions of classical mechanics, which are quite accurate (albeit still not perfectly certain) at larger scales.[28] Something as large as an animal cell, then, would be "adequately determined" (even in light of quantum indeterminacy).[citation needed] Many-worlds The many-worlds interpretation accepts the linear causal sets of sequential events with adequate consistency yet also suggests constant forking of causal chains creating "multiple universes" to account for multiple outcomes from single events.[29] Meaning the causal set of events leading to the present are all valid yet appear as a singular linear time stream within a much broader unseen conic probability field of other outcomes that "split off" from the locally observed timeline. Under this model causal sets are still "consistent" yet not exclusive to singular iterated outcomes. The interpretation sidesteps the exclusive retrospective causal chain problem of "could not have done otherwise" by suggesting "the other outcome does exist" in a set of parallel universe time streams that split off when the action occurred. This theory is sometimes described with the example of agent based choices but more involved models argue that recursive causal splitting occurs with all wave functions at play.[30] This model is highly contested with multiple objections from the scientific community.[31][32] Philosophical varieties Nature/nurture controversy Although some of the above forms of determinism concern human behaviors and cognition, others frame themselves as an answer to the debate on nature and nurture. They will suggest that one factor will entirely determine behavior. As scientific understanding has grown, however, the strongest versions of these theories have been widely rejected as a single-cause fallacy.[33] In other words, the modern deterministic theories attempt to explain how the interaction of both nature and nurture is entirely predictable. The concept of heritability has been helpful in making this distinction. Biological determinism, sometimes called genetic determinism, is the idea that each of human behaviors, beliefs, and desires are fixed by human genetic nature. Behaviorism involves the idea that all behavior can be traced to specific causes—either environmental or reflexive. John B. Watson and B. F. Skinner developed this nurture-focused determinism. Cultural materialism, contends that the physical world impacts and sets constraints on human behavior. Cultural determinism, along with social determinism, is the nurture-focused theory that the culture in which we are raised determines who we are. Environmental determinism, also known as climatic or geographical determinism, proposes that the physical environment, rather than social conditions, determines culture. Supporters of environmental determinism often[quantify] also support behavioral determinism. Key proponents of this notion have included Ellen Churchill Semple, Ellsworth Huntington, Thomas Griffith Taylor and possibly Jared Diamond, although his status as an environmental determinist is debated.[34] Determinism and prediction Other "deterministic"[opinion] theories actually seek only to highlight the importance of a particular factor in predicting the future. These theories often use the factor as a sort of guide or constraint on the future. They need not suppose that complete knowledge of that one factor would allow the making of perfect predictions. Psychological determinism can mean that humans must act according to reason, but it can also be synonymous with some sort of psychological egoism. The latter is the view that humans will always act according to their perceived best interest. Linguistic determinism proposes that language determines (or at least limits) the things that humans can think and say and thus know. The Sapir–Whorf hypothesis argues that individuals experience the world based on the grammatical structures they habitually use. Economic determinism attributes primacy to economic structure over politics in the development of human history. It is associated with the dialectical materialism of Karl Marx. Technological determinism is the theory that a society's technology drives the development of its social structure and cultural values. |

多様性 「決定論」とは、一般的に以下のいずれかの視点を指すことがある。 因果的決定論 因果決定論は、歴史的決定論(一種の経路依存性)と同義語であることもあるが、「すべての出来事は、自然の法則とともに、先行する出来事や条件によって必然化されるという考え方」である[5]。 ......自分の熟慮、選択、行動は、何かをもたらす因果の連鎖において必要なリンクとなることが多い。言い換えれば、私たちの熟慮、選択、行動自体が 他のすべてのものと同様に決定されているとしても、因果決定論によれば、さらに他のものの発生や存在は、私たちがある方法で熟慮し、選択し、行動すること に依存しているのである。 因果決定論は、宇宙の起源にまでさかのぼる、事前の出来事の切れ目のない連鎖があると提唱する。出来事と宇宙の起源の関係は特定できないかもしれない。因 果決定論者は、宇宙には原因がないもの、あるいは自己原因によるものは存在しないと考える。因果的決定論はまた、より一般的には、起こることや存在するこ とはすべて先行する条件によって引き起こされるという考えとして考えられている[7]。名論的決定論の場合、これらの条件は事象ともみなされ、未来が先行 する事象-宇宙の先行状態と自然の法則の組み合わせ-によって完全に決定されることを示唆している[5]。  決定論の多くの哲学的理論は、現実はある種のあらかじめ決められた道筋をたどるという考えに基づいている。 名目的決定論 名目的決定論は因果的決定論の最も一般的な形態であり、一般的に物理的決定論と同義である。これは、過去と現在が厳密な自然法則によって完全かつ必然的に 未来を決定し、すべての出来事は必然的に以前の出来事から生じるという考え方である。名目的決定論は、ラプラスの悪魔の思考実験によって説明されることも ある[8]。科学的決定論と呼ばれることもあるが、この用語は名目的決定論の誤用である。 必要主義 必要主義(Necessitarianism)は形而上学的な原理であり、単なる可能性をすべて否定し、世界が存在する可能性は一つしかないと主張する。ロイキッポスは、原因のない出来事は存在せず、すべては理由があって必然的に起こると主張した[9]。 前決定論 この概念はしばしば因果的決定論を持ち出すことによって主張され、宇宙の起源にまで遡る事前の出来事の連鎖があることを暗示している。事前決定論の場合、この出来事の連鎖は事前に確立されており、人間の行動はこの事前に確立された連鎖の結果に干渉することはできない。 また、将来の事象を決定する能力という意味で、因果的決定論と互換的に使用されることもある[10][13]。 生物学的 生物学的決定論という用語は生物学や遺伝の文脈でもよく使われ、その場合は生物学的決定論の一形態を表し、遺伝的決定論と呼ばれることもある[16]。 フリードリヒ・ニーチェは、人間は肉体によって「決定」され、その情熱、衝動、本能に従うと説明した[17]。 運命論 宿命論は通常、決定論とは区別され、目的論的決定論の一形態である[18]。運命論とは、すべてのことは起こるべくして起こり、その結果、人間は自分の未 来をコントロールすることができないという考え方である。運命には恣意的な力があり、必ずしも因果律や決定論的な法則に従うとは限らない[7]。運命論の 種類には、ハード神学的決定論や宿命論があり、そこでは人間が行うことをすべて決定する神が存在する。これは全知全能によって達成される人間の行動の予知 [19]、または人間の行動をあらかじめ決定することによって達成される[20]。 神学的決定論 神学的決定論は決定論の一形態であり、起こるすべての出来事は一神教の神によって起こるようにあらかじめ定められている(すなわち、宿命づけられている) か、あるいは全知全能の神によって起こるように運命づけられているかのどちらかであるとする。神学的決定論には、強い神学的決定論と弱い神学的決定論の2 つの形式が存在する[21]。 強い神学的決定論は、創造主である神が歴史上のすべての出来事を指示しているという概念に基づいている: 「起こることはすべて、全知全能の神性によって起こるように定められている」[22]。 弱い神学的決定論は、神の予知の概念に基づいている-「神の全知は完全であるため、神が未来について知っていることは必然的に起こる。神学的決定論は、神 によるすべての出来事と結果の定めを必要とする-すなわち、結果として自由意志が否定されると仮定されない限り、弱いバージョンを神学的決定論として分類 しない-と主張する者もいれば、弱いバージョンは神学的決定論を全く構成しないと主張する者もいる[24]。 自由意志に関しては、「神学的決定論とは、神が存在し、私たちの将来の行動に関する命題を含むすべての真の命題について無謬の知識を持っているというテーゼであり、神学的決定論のすべての形態を包含するように設計された、より最小限の基準である」[25]。 神学的決定論はまた、因果的決定論の一形態と見ることもでき、その場合、先行条件は神の性質と意志である[6]。ヒッポのアウグスティヌスが紀元412年 に神学的決定論をキリスト教に導入したと主張する者もいるが、それ以前のキリスト教の著者はすべて、ストア派やグノーシス派の決定論に対して自由意志を支 持していた[26]。しかし、ある種の神学的決定論の考えを支持していると思われる聖書の箇所が数多くある。 適切な決定論 適切な決定論とは、量子デコヒーレンスにより、ほとんどの巨視的事象において量子の不確定性は無視できるという考え方である。量子力学の法則が古典力学の 法則に漸近的に近づく)粒子の数が多い限界では、ランダムな量子事象は「平均化」される。つまり、量子の効果は古典力学の予測をほとんど変えないが、より 大きなスケールでは(まだ完全には確実ではないものの)かなり正確である[28]。 多世界解釈 多世界解釈は、十分な一貫性をもって連続する事象の線形因果集合を受け入れる一方で、単一の事象から生じる複数の結果を説明するために「複数の宇宙」を生 み出す因果連鎖の絶え間ない分岐を示唆している[29]。つまり、現在に至る事象の因果集合はすべて有効であるが、局所的に観察される時間軸から「分岐」 する他の結果について、より広範な目に見えない円錐形の確率場の中で、特異な線形時間の流れとして現れる。このモデルのもとでは、因果セットは依然として 「一貫」しているが、単数の反復結果に限定されるものではない。 この解釈は、行動が起こったときに分かれた平行宇宙の時間の流れの集合の中に「他の結果が存在する」ことを示唆することによって、「そうでなければできな かった」という排他的な遡及的因果連鎖の問題を回避する。この理論はエージェントに基づく選択の例で説明されることもあるが、より複雑なモデルでは、すべ ての波動関数が作用して再帰的因果分裂が起こると主張している[30]。 哲学的多様性 自然/育ち論争 上記の決定論の形態のいくつかは、人間の行動や認知に関するものであるが、他のものは、自然と育ちに関する論争への回答として自らを組み立てている。彼ら は、一つの要因が行動を完全に決定することを示唆する。しかし、科学的理解が深まるにつれて、これらの理論の最も強力なバージョンは、単一原因の誤謬とし て広く否定されている[33]。言い換えれば、現代の決定論的理論は、自然と養育の両方の相互作用が完全に予測可能であることを説明しようとしている。遺 伝率の概念は、この区別をつけるのに役立っている。 生物学的決定論は、遺伝的決定論と呼ばれることもあるが、人間の行動、信念、欲望のそれぞれは、人間の遺伝的性質によって固定されているという考え方である。 行動主義とは、すべての行動は特定の原因(環境的なもの、反射的なもの)にたどることができるという考え方である。ジョン・B・ワトソンとB・F・スキナーは、この育ちに焦点を当てた決定論を展開した。 文化的唯物論は、物理的世界が人間の行動に影響を与え、制約を与えると主張する。 文化的決定論は、社会的決定論とともに、私たちが育った文化が私たちのあり方を決定するという、育ち重視の理論である。 気候的決定論や地理的決定論としても知られる環境決定論は、社会的条件よりもむしろ物理的環境が文化を決定すると提唱している。環境決定論の支持者は行動 決定論も支持することが多い。この概念の主要な支持者にはエレン・チャーチル・センプル、エルズワース・ハンチントン、トーマス・グリフィス・テイラー、 そしておそらくジャレド・ダイアモンドがいるが、彼の環境決定論者としての地位については議論がある[34]。 決定論と予測 他の「決定論的な」[意見]理論は、実際には未来を予測する上での特定の要因の重要性を強調しようとするだけである。これらの理論では、しばしばその要因 を未来に対する一種の指針や制約として用いる。その1つの要因を完全に知れば、完璧な予測が可能になると考える必要はない。 心理学的決定論は、人間は理性に従って行動しなければならないという意味もあるが、ある種の心理的エゴイズムと同義であることもある。後者は、人間は常に自分の認識する最善の利益に従って行動するという考え方である。 言語決定論は、人間が考えたり言ったりできること、ひいては知ることができることは言語によって決定される(あるいは少なくとも制限される)と提唱する。サピア=ウォーフ仮説は、個人は習慣的に使用する文法構造に基づいて世界を経験すると主張する。 経済決定論は、人類の歴史の発展において、政治よりも経済構造が優先するとする。カール・マルクスの弁証法的唯物論と関連している。 技術決定論は、社会の技術がその社会構造と文化的価値観の発展を促すという理論である。 |

| Structural Structural determinism is the philosophical view that actions, events, and processes are predicated on and determined by structural factors.[35] Given any particular structure or set of estimable components, it is a concept that emphasizes rational and predictable outcomes. Chilean biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela popularized the notion, writing that a living system's general order is maintained via a circular process of ongoing self-referral, and thus its organization and structure defines the changes it undergoes.[36] According to the authors, a system can undergo changes of state (alteration of structure without loss of identity) or disintegrations (alteration of structure with loss of identity). Such changes or disintegrations are not ascertained by the elements of the disturbing agent, as each disturbance will only trigger responses in the respective system, which in turn, are determined by each system's own structure. On an individualistic level, what this means is that human beings as free and independent entities are triggered to react by external stimuli or change in circumstance. However, their own internal state and existing physical and mental capacities determine their responses to those triggers. On a much broader societal level, structural determinists believe that larger issues in the society—especially those pertaining to minorities and subjugated communities—are predominantly assessed through existing structural conditions, making change of prevailing conditions difficult, and sometimes outright impossible. For example, the concept has been applied to the politics of race in the United States of America and other Western countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia, with structural determinists lamenting structural factors for the prevalence of racism in these countries.[37] Additionally, Marxists have conceptualized the writings of Karl Marx within the context of structural determinism as well. For example, Louis Althusser, a structural Marxist, argues that the state, in its political, economic, and legal structures, reproduces the discourse of capitalism, in turn, allowing for the burgeoning of capitalistic structures. Proponents of the notion highlight the usefulness of structural determinism to study complicated issues related to race and gender, as it highlights often gilded structural conditions that block meaningful change.[38] Critics call it too rigid, reductionist and inflexible. Additionally, they also criticize the notion for overemphasizing deterministic forces such as structure over the role of human agency and the ability of the people to act. These critics argue that politicians, academics, and social activists have the capability to bring about significant change despite stringent structural conditions. With free will Main article: Free will Philosophers have debated both the truth of determinism, and the truth of free will. This creates the four possible positions in the figure. Compatibilism refers to the view that free will is, in some sense, compatible with determinism. The three incompatibilist positions deny this possibility. The hard incompatibilists hold that free will is incompatible with both determinism and indeterminism, the libertarians that determinism does not hold, and free will might exist, and the hard determinists that determinism does hold and free will does not exist. The Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza was a determinist thinker, and argued that human freedom can be achieved through knowledge of the causes that determine desire and affections. He defined human servitude as the state of bondage of anyone who is aware of their own desires, but ignorant of the causes that determined them. However, the free or virtuous person becomes capable, through reason and knowledge, to be genuinely free, even as they are being "determined". For the Dutch philosopher, acting out of one's own internal necessity is genuine freedom while being driven by exterior determinations is akin to bondage. Spinoza's thoughts on human servitude and liberty are respectively detailed in the fourth[39] and fifth[40] volumes of his work Ethics. The standard argument against free will, according to philosopher J. J. C. Smart, focuses on the implications of determinism for free will.[41] He suggests free will is denied whether determinism is true or not. He says that if determinism is true, all actions are predicted and no one is assumed to be free; however, if determinism is false, all actions are presumed to be random and as such no one seems free because they have no part in controlling what happens. With the soul Some determinists argue that materialism does not present a complete understanding of the universe, because while it can describe determinate interactions among material things, it ignores the minds or souls of conscious beings. A number of positions can be delineated: Immaterial souls are all that exist (idealism). Immaterial souls exist and exert a non-deterministic causal influence on bodies (traditional free-will, interactionist dualism).[42][43] Immaterial souls exist but are part of a deterministic framework. Immaterial souls exist, but exert no causal influence, free or determined (epiphenomenalism, occasionalism) Immaterial souls do not exist – there is no mind–body dichotomy, and there is a materialistic explanation for intuitions to the contrary. With ethics and morality Another topic of debate is the implication that determinism has on morality. Philosopher and incompatibilist Peter van Inwagen introduced this thesis, when arguments that free will is required for moral judgments, as such:[44] The moral judgment that X should not have been done implies that something else should have been done instead. That something else should have been done instead implies that there was something else to do. That there was something else to do, implies that something else could have been done. That something else could have been done implies that there is free will. If there is no free will to have done other than X we cannot make the moral judgment that X should not have been done. |

構造的 構造決定論とは、行動、事象、プロセスは構造的要因に基づき、構造的要因によって決定されるという哲学的見解である[35]。任意の特定の構造または推定 可能な構成要素の集合が与えられた場合、合理的で予測可能な結果を強調する概念である。チリの生物学者ウンベルト・マトゥラナとフランシスコ・バレラはこ の概念を普及させ、生命システムの一般的な秩序は継続的な自己言及の循環プロセスによって維持され、したがってその組織と構造はそれが受ける変化を定義す る、と書いている。このような変化や崩壊は、攪乱を引き起こす要因によって把握されることはない。なぜなら、それぞれの攪乱はそれぞれのシステムにおける 反応を引き起こすだけであり、その反応はそれぞれのシステム自身の構造によって決定されるからである。 個人主義的なレベルで言えば、自由で独立した存在である人間は、外部からの刺激や状況の変化によって反応を引き起こすということだ。しかし、その引き金に 対する反応を決定するのは、彼ら自身の内的状態や既存の肉体的・精神的能力である。より広い社会レベルでは、構造決定論者は、社会におけるより大きな問 題、特にマイノリティや被支配コミュニティに関わる問題は、既存の構造的条件によって主に評価され、現状を変えることは困難であり、時にはまったく不可能 であると考える。例えば、この概念はアメリカ合衆国やイギリス、オーストラリアなどの西洋諸国における人種政治に適用されており、構造決定論者はこれらの 国々における人種差別の蔓延の構造的要因を嘆いている[37]。さらに、マルクス主義者はカール・マルクスの著作を構造決定論の文脈で概念化している。例 えば、構造的マルクス主義者であるルイ・アルチュセールは、国家はその政治的、経済的、法的構造において資本主義の言説を再生産し、ひいては資本主義的構 造の急成長を可能にしていると主張している。 この概念の支持者は、構造決定論が人種やジェンダーに関連する複雑な問題を研究するのに有用であることを強調している。さらに、彼らはまた、人間の主体性 の役割や人々の行動能力よりも、構造のような決定論的な力を強調しすぎていると批判する。これらの批判者は、政治家、学者、社会活動家は、厳しい構造的条 件にもかかわらず、大きな変化をもたらす能力を持っていると主張する。 自由意志とともに 主な記事 自由意志 哲学者たちは決定論の真理と自由意志の真理の両方について議論してきた。その結果、図のような4つの立場が生まれる。両立主義とは、自由意志はある意味で 決定論と両立するという見解のことである。つの非適合論者はこの可能性を否定する。自由意志は決定論と不確定論の両方と両立しないとするハード非両立論 者、決定論は成立せず、自由意志は存在するかもしれないとするリバタリアン、決定論は成立し、自由意志は存在しないとするハード決定論者である。オランダ の哲学者バルーク・スピノザは決定論者であり、人間の自由は欲望や情念を決定する原因を知ることによって達成できると主張した。彼は人間の隷属を、自分の 欲望は知っているが、それを決定する原因を知らない人の束縛状態と定義した。しかし、自由な人、あるいは徳のある人は、理性と知識によって、「決定」され ているにもかかわらず、純粋に自由であることができるようになる。オランダの哲学者にとっては、自分の内的な必要性から行動することが真の自由であり、外 的な決定によって動かされることは束縛に似ている。人間の隷属と自由に関するスピノザの考えは、彼の著作『倫理学』の第4巻[39]と第5巻[40]にそ れぞれ詳述されている。 哲学者J・J・C・スマートによれば、自由意志に対する標準的な議論は、自由意志に対する決定論の含意に焦点を当てている[41]。決定論が真であれば、 全ての行動は予測され、誰も自由であるとは仮定されないが、決定論が偽であれば、全ての行動はランダムであると仮定され、何が起こるかをコントロールする ことに関与していないため、誰も自由であるとは思えないと彼は言う。 魂とともに 決定論者の中には、唯物論は宇宙の完全な理解を示していないと主張する者もいる。なぜなら、唯物論は物質的なものの間の確定的な相互作用を記述することはできるが、意識のある存在の心や魂を無視しているからである。 いくつかの立場がある: 非物質的な魂が存在するすべてである(観念論)。 非物質的な魂は存在し、身体に非決定論的な因果的影響を及ぼす(伝統的な自由意志、相互作用論的二元論)[42][43]。 非物質的な魂は存在するが、決定論的な枠組みの一部である。 非物質的な魂は存在するが、自由であれ決定論的であれ、因果的な影響力を及ぼさない(エピフェノメナリズム、機会主義) 非物質的な魂は存在しない - 心と体の二分法は存在せず、それに反する直観には唯物論的な説明がある。 倫理と道徳 決定論が道徳に及ぼす影響についても議論がある。 哲学者であり非両立論者であるピーター・ヴァン・インワーゲンは、道徳的判断には自由意志が必要であるという議論の際に、このテーゼを次のように紹介している[44]。 Xがなされるべきではなかったという道徳的判断は、何か他のことが代わりになされるべきであったことを意味する。 代わりに何か他のことをすべきだったということは、何か他にすべきことがあったということを意味する。 他になすべきことがあったということは、他になすべきことがあったかもしれないということを意味する。 何か他のことができたということは、自由意志があることを意味する。 もしX以外のことをする自由意志がなければ、Xをすべきでなかったという道徳的判断を下すことはできない。 |

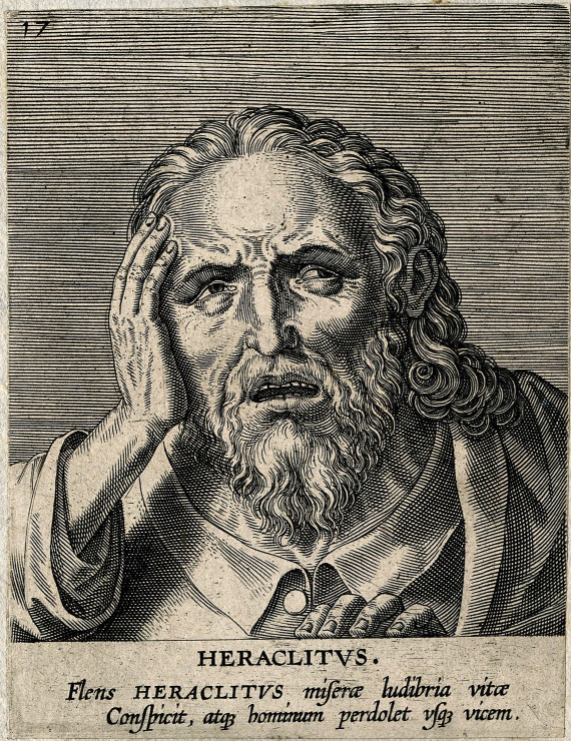

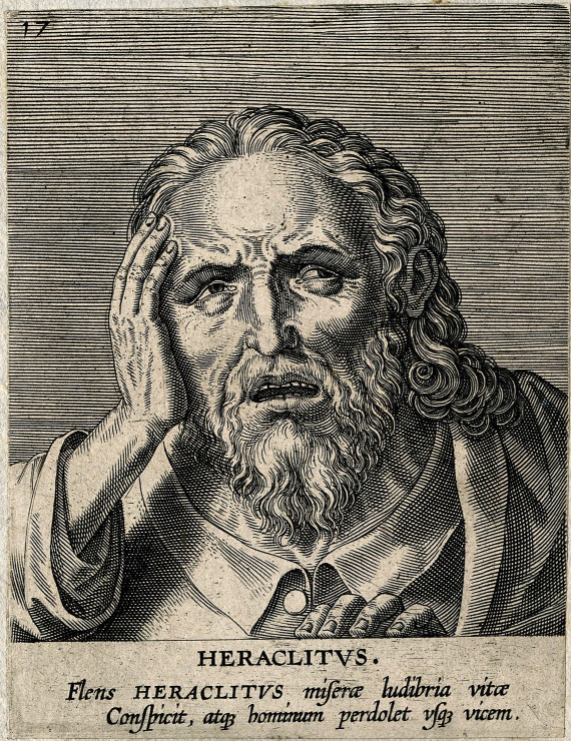

| History Determinism was developed by the Greek philosophers during the 7th and 6th centuries BCE by the Pre-socratic philosophers Heraclitus and Leucippus, later Aristotle, and mainly by the Stoics. Some of the main philosophers who have dealt with this issue are Marcus Aurelius, Omar Khayyam, Thomas Hobbes, Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Leibniz, David Hume, Baron d'Holbach (Paul Heinrich Dietrich), Pierre-Simon Laplace, Arthur Schopenhauer, William James, Friedrich Nietzsche, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Ralph Waldo Emerson and, more recently, John Searle, Ted Honderich, and Daniel Dennett. Mecca Chiesa notes that the probabilistic or selectionistic determinism of B. F. Skinner comprised a wholly separate conception of determinism that was not mechanistic at all. Mechanistic determinism assumes that every event has an unbroken chain of prior occurrences, but a selectionistic or probabilistic model does not.[45][46] Western Tradition In the West, some elements of determinism have been expressed in Greece from the 6th century BCE by the Presocratics Heraclitus[47] and Leucippus.[48] The first notions of determinism appears to originate with the Stoics, as part of their theory of universal causal determinism.[49] The resulting philosophical debates, which involved the confluence of elements of Aristotelian Ethics with Stoic psychology, led in the 1st–3rd centuries CE in the works of Alexander of Aphrodisias to the first recorded Western debate over determinism and freedom,[50] an issue that is known in theology as the paradox of free will. The writings of Epictetus as well as middle Platonist and early Christian thought were instrumental in this development.[51] Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides said of the deterministic implications of an omniscient god:[52] "Does God know or does He not know that a certain individual will be good or bad? If thou sayest 'He knows', then it necessarily follows that [that] man is compelled to act as God knew beforehand he would act, otherwise God's knowledge would be imperfect."[53] Newtonian mechanics This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. See Wikipedia's guide to writing better articles for suggestions. (April 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Determinism in the West is often associated with Newtonian mechanics/physics, which depicts the physical matter of the universe as operating according to a set of fixed laws. The "billiard ball" hypothesis, a product of Newtonian physics, argues that once the initial conditions of the universe have been established, the rest of the history of the universe follows inevitably. If it were actually possible to have complete knowledge of physical matter and all of the laws governing that matter at any one time, then it would be theoretically possible to compute the time and place of every event that will ever occur (Laplace's demon). In this sense, the basic particles of the universe operate in the same fashion as the rolling balls on a billiard table, moving and striking each other in predictable ways to produce predictable results. Whether or not it is all-encompassing in so doing, Newtonian mechanics deals only with caused events; for example, if an object begins in a known position and is hit dead on by an object with some known velocity, then it will be pushed straight toward another predictable point. If it goes somewhere else, the Newtonians argue, one must question one's measurements of the original position of the object, the exact direction of the striking object, gravitational or other fields that were inadvertently ignored, etc. Then, they maintain, repeated experiments and improvements in accuracy will always bring one's observations closer to the theoretically predicted results. When dealing with situations on an ordinary human scale, Newtonian physics has been successful. But it fails as velocities become some substantial fraction of the speed of light and when interactions at the atomic scale are studied. Before the discovery of quantum effects and other challenges to Newtonian physics, "uncertainty" was always a term that applied to the accuracy of human knowledge about causes and effects, and not to the causes and effects themselves. Newtonian mechanics, as well as any following physical theories, are results of observations and experiments, and so they describe "how it all works" within a tolerance. However, old western scientists believed if there are any logical connections found between an observed cause and effect, there must be also some absolute natural laws behind. Belief in perfect natural laws driving everything, instead of just describing what we should expect, led to searching for a set of universal simple laws that rule the world. This movement significantly encouraged deterministic views in Western philosophy,[54] as well as the related theological views of classical pantheism. Eastern tradition This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (December 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) The idea that the entire universe is a deterministic system has been articulated in both Eastern and non-Eastern religions, philosophy, and literature. The ancient Arabs that inhabited the Arabian Peninsula before the advent of Islam used to profess a widespread belief in fatalism (ḳadar) alongside a fearful consideration for the sky and the stars as divine beings, which they held to be ultimately responsible for every phenomena that occurs on Earth and for the destiny of humankind.[55] Accordingly, they shaped their entire lives in accordance with their interpretations of astral configurations and phenomena.[55] In the I Ching and philosophical Taoism, the ebb and flow of favorable and unfavorable conditions suggests the path of least resistance is effortless (see: Wu wei). In the philosophical schools of the Indian Subcontinent, the concept of karma deals with similar philosophical issues to the Western concept of determinism. Karma is understood as a spiritual mechanism which causes the eternal cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (saṃsāra).[56] Karma, either positive or negative, accumulates according to an individual's actions throughout their life, and at their death determines the nature of their next life in the cycle of Saṃsāra.[56] Most major religions originating in India hold this belief to some degree, most notably Hinduism,[56] Jainism, Sikhism, and Buddhism. The views on the interaction of karma and free will are numerous, and diverge from each other. For example, in Sikhism, god's grace, gained through worship, can erase one's karmic debts, a belief which reconciles the principle of karma with a monotheistic god one must freely choose to worship.[57] Jainists believe in compatibilism, in which the cycle of Saṃsara is a completely mechanistic process, occurring without any divine intervention. The Jains hold an atomic view of reality, in which particles of karma form the fundamental microscopic building material of the universe. Ājīvika In ancient India, the Ājīvika school of philosophy founded by Makkhali Gosāla (around 500 BCE), otherwise referred to as "Ājīvikism" in Western scholarship,[58] upheld the Niyati ("Fate") doctrine of absolute fatalism or determinism,[58][59][60] which negates the existence of free will and karma, and is therefore considered one of the nāstika or "heterodox" schools of Indian philosophy.[58][59][60] The oldest descriptions of the Ājīvika fatalists and their founder Gosāla can be found both in the Buddhist and Jaina scriptures of ancient India.[58][60] The predetermined fate of living beings and the impossibility to achieve liberation (moksha) from the eternal cycle of birth, death, and rebirth was the major distinctive philosophical and metaphysical doctrine of this heterodox school of Indian philosophy,[58][59][60] annoverated among the other Śramaṇa movements that emerged in India during the Second urbanization (600–200 BCE).[58] Buddhist philosophy contains several concepts which some scholars[by whom?] describe as deterministic to various levels. One concept which is argued[by whom?] to support a hard determinism is the idea of dependent origination, which claims that all phenomena (dharma) are necessarily caused by some other phenomenon, which it can be said to be dependent on, like links in a massive chain. In traditional Buddhist philosophy, this concept is used to explain the functioning of the cycle of saṃsāra; all actions exert a karmic force, which will manifest results in future lives. In other words, righteous or unrighteous actions in one life will necessarily cause good or bad responses in another.[61] Another Buddhist concept which many scholars perceive to be deterministic is the idea of non-self, or anattã.[62] In Buddhism, attaining enlightenment involves one realizing that in humans there is no fundamental core of being which can be called the "soul", and that humans are instead made of several constantly changing factors which bind them to the cycle of Saṃsāra.[62] Some scholars argue that the concept of non-self necessarily disproves the ideas of free will and moral culpability. If there is no autonomous self, in this view, and all events are necessarily and unchangeably caused by others, then no type of autonomy can be said to exist, moral or otherwise. However, other scholars disagree, claiming that the Buddhist conception of the universe allows for a form of compatibilism. Buddhism perceives reality occurring on two different levels, the ultimate reality which can only be truly understood by the enlightened, and the illusory and false material reality. Therefore, Buddhism perceives free will as a notion belonging to material reality, while concepts like non-self and dependent origination belong to the ultimate reality; the transition between the two can be truly understood, Buddhists claim, by one who has attained enlightenment.[63] |

歴史 決定論は、紀元前7世紀から6世紀にかけてギリシャの哲学者たちによって、ソクラテス以前の哲学者ヘラクレイトスとレウシッポス、後のアリストテレス、そ して主にストア派によって発展させられた。この問題を扱った主な哲学者には、マルクス・アウレリウス、オマル・ハイヤーム、トマス・ホッブズ、バルーク・ スピノザ、ゴットフリート・ライプニッツ、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、ドルバック男爵(パウル・ハインリッヒ・ディートリッヒ)、ピエール=シモン・ラプラ ス、アルトゥール・ショーペンハウアー、ウィリアム・ジェームズ、フリードリヒ・ニーチェ、アルベルト・アインシュタイン、ニールス・ボーア、ラルフ・ワ ルド・エマーソン、そして最近ではジョン・サール、テッド・ホンデリッチ、ダニエル・デネットがいる。 メッカ・キエサは、B.F.スキナーの確率論的決定論や選択論的決定論は、決定論とはまったく別の概念であり、機械論的なものではなかったと指摘する。機 械論的決定論は、すべての事象が事前に発生した切れ目のない連鎖を持っていると仮定しているが、選択論的あるいは確率論的モデルはそうではない[45] [46]。 西洋の伝統 西洋では、決定論のいくつかの要素は紀元前6世紀にギリシャでヘラクレイトス[47]とレウシッポスによって表現されていた[48]。 [その結果、アリストテレス倫理学とストア派の心理学の要素が融合した哲学的論争が起こり、紀元後1世紀から3世紀にかけてアフロディジアスのアレクサン ダーの著作において、決定論と自由をめぐる西洋で初めて記録された論争に至った[50]。エピクテトスの著作や中世プラトン主義、初期キリスト教の思想が この発展に役立った[51]。 ユダヤの哲学者モーゼ・マイモニデスは全知全能の神の決定論的な意味合いについて次のように述べている[52]。もし汝が『神は知っている』と言うなら ば、必然的に人間は神があらかじめ知っていたとおりに行動せざるを得ないことになる。 ニュートン力学 このセクションの口調や文体は、ウィキペディアで使われている百科事典的な口調を反映していないかもしれません。よりよい記事の書き方については、ウィキ ペディアのガイドをご覧ください。(2022年4月) (このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 西洋における決定論は、しばしばニュートン力学・物理学と関連しており、宇宙の物理的物質が一組の固定された法則に従って動作するように描かれている。 ニュートン物理学の産物である「ビリヤード・ボール」仮説は、宇宙の初期条件が一度確立されれば、宇宙の残りの歴史は必然的に従うと主張する。物理的な物 質と、その物質を支配するすべての法則を、ある時点で完全に把握することが実際に可能であれば、これから起こるであろうすべての出来事の時間と場所を計算 することが理論的に可能になる(ラプラスの悪魔)。この意味で、宇宙の基本粒子は、ビリヤード台の上で転がる玉と同じように、予測可能な方法で動き、互い にぶつかり合って予測可能な結果を生み出す。 例えば、ある物体が既知の位置から始まり、既知の速度の物体に真正面からぶつかると、その物体は別の予測可能な点に向かってまっすぐに押し出される。例え ば、物体が既知の位置から出発し、既知の速度の物体に正面から衝突された場合、物体は予測可能な別の地点に向かってまっすぐに押し出される。もし物体が別 の地点に向かった場合、物体の元の位置、衝突した物体の正確な方向、うっかり無視してしまった重力場などの測定値を疑わなければならないとニュートン派は 主張する。そして、実験を繰り返し、精度を向上させれば、観測結果は常に理論的に予測された結果に近づくと主張する。通常の人間スケールの状況を扱う場 合、ニュートン物理学は成功してきた。しかし、速度が光速の何分の一かになり、原子スケールの相互作用が研究されるようになると、ニュートン物理学は失敗 する。量子効果の発見やその他のニュートン物理学への挑戦が始まる以前は、「不確定性」は常に原因と結果に関する人間の知識の精度に適用される用語であ り、原因と結果そのものに適用される用語ではなかった。 ニュートン力学も、それに続くあらゆる物理理論も、観察と実験の結果であり、許容範囲内で「それがどのように機能するか」を記述している。しかし、古い西 洋の科学者たちは、観察された原因と結果の間に論理的なつながりが見出されるなら、その背後にも絶対的な自然法則があるはずだと信じていた。すべてを動か しているのは完全な自然法則であり、私たちが期待すべきことを記述しているに過ぎないと信じることで、世界を支配する普遍的な単純法則のセットを探し求め るようになった。この動きは、古典的な汎神論の関連する神学的見解と同様に、西洋哲学における決定論的見解を大きく後押しした[54]。 東洋の伝統 このセクションには独自の研究が含まれている可能性があります。主張を検証し、インライン引用を追加することによって、それを改善してください。独自の研 究のみからなる記述は削除してください。(2010年12月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 宇宙全体が決定論的なシステムであるという考え方は、東洋と非東洋の宗教、哲学、文学の両方で明言されてきた。 イスラム教が出現する以前にアラビア半島に居住していた古代アラブ人は、運命論(ḳadar)に対する広範な信仰を公言しており、それと同時に神的存在としての空と星に対する恐るべき配慮を公言していた。 易経』や哲学的な道教では、有利な条件と不利な条件の浮き沈みは、最も抵抗の少ない道が楽であることを示唆している(参照:Wu wei)。インド亜大陸の哲学的流派では、カルマの概念は西洋の決定論の概念と同様の哲学的問題を扱っている。カルマは、生・死・再生の永遠のサイクルを 引き起こす精神的なメカニズムとして理解されている[56]。カルマは、肯定的なものであれ否定的なものであれ、個人の生涯を通じての行為に応じて蓄積さ れ、その死によって、サーラのサイクルにおける次の人生の性質が決定される[56]。インド発祥の主要な宗教のほとんどは、ヒンドゥー教[56]、ジャイ ナ教[56]、シーク教、仏教を筆頭に、この信仰をある程度保持している。 カルマと自由意志の相互作用に関する見解は多数あり、互いに異なっている。例えば、シーク教では、崇拝によって得られる神の恩寵によってカルマの負債を帳 消しにすることができるとし、カルマの原理と、崇拝することを自由に選択しなければならない一神教の神とを調和させる信念を持つ[57]。ジャイナ教で は、サワラのサイクルは完全に機械論的なプロセスであり、神の介入なしに起こるという相利共生主義を信じる。ジャイナ教徒は原子的な現実観を持っており、 カルマの粒子が宇宙の基本的な微視的構成要素を形成している。 不動明王 古代インドにおいて、マッカリー・ゴサーラ(紀元前500年頃)によって創始された不動明王学派は、西洋の学問では「不動明王主義」と呼ばれ[58]、自 由意志とカルマの存在を否定する絶対運命論または決定論のニヤティ(「運命」)教義を支持し[58][59][60]、それゆえインド哲学のナースティカ または「異端」学派のひとつと見なされている。 [58][59][60]不動明王運命論者とその創始者ゴサーラに関する最古の記述は、古代インドの仏教とジャイナの経典の両方に見出すことができる。 [58][60]生きとし生けるものの定められた運命と、生・死・再生の永遠のサイクルからの解脱(モークシャ)を達成することの不可能性は、このインド 哲学の異端学派の主要な特徴的な哲学的・形而上学的教義であり、第二次都市化(前600年~前200年)の間にインドで発生した他のシュラーマーナ運動の 中で発見された[58][59][60]。 仏教哲学には、ある学者は[誰が?]様々なレベルで決定論的であると説明するいくつかの概念が含まれている。 その一つは従属起源の考え方であり、すべての現象(ダルマ)は、巨大な鎖のリンクのように、他の現象によって必然的に引き起こされると主張する。伝統的な 仏教哲学では、この概念はササーラのサイクルの機能を説明するために使用されます。言い換えれば、ある人生における正しい行為や正しくない行為は、必然的 に別の人生において良い反応や悪い反応を引き起こすということである[61]。 多くの学者が決定論的であると認識しているもう一つの仏教の概念は、無我(anattã)という考え方である[62]。仏教において悟りを得るということ は、人間には「魂」と呼べるような存在の根本的な核が存在せず、その代わりに、人間はササーラのサイクルに縛られるいくつかの絶えず変化する要素でできて いるということを悟るということである[62]。 非自己という概念は、自由意志や道徳的責任という考え方を必然的に否定すると主張する学者もいる。この見解によれば、自律的な自己が存在せず、すべての出 来事が必然的かつ不変的に他者によって引き起こされるのであれば、道徳的であろうとなかろうと、いかなる種類の自律性も存在しないと言える。しかし、仏教 の宇宙観は相利共生を可能にすると主張する学者もいる。仏教は、悟りを開いた者だけが真に理解できる究極の現実と、幻想的で偽りの物質的現実という、2つ の異なるレベルで現実が起きていると認識している。したがって、仏教は自由意志を物質的現実に属する概念として認識し、一方、無我や依他起のような概念は 究極的現実に属するものであり、両者の間の移行は悟りを開いた者だけが真に理解できると仏教徒は主張する[63]。 |

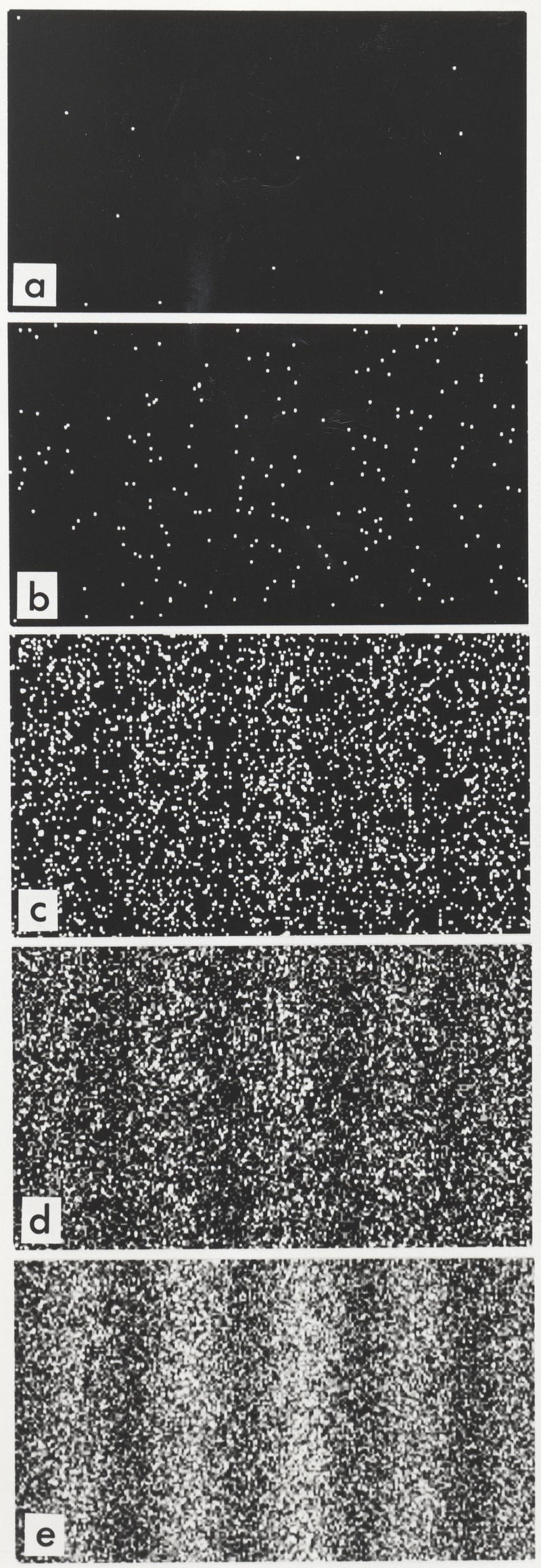

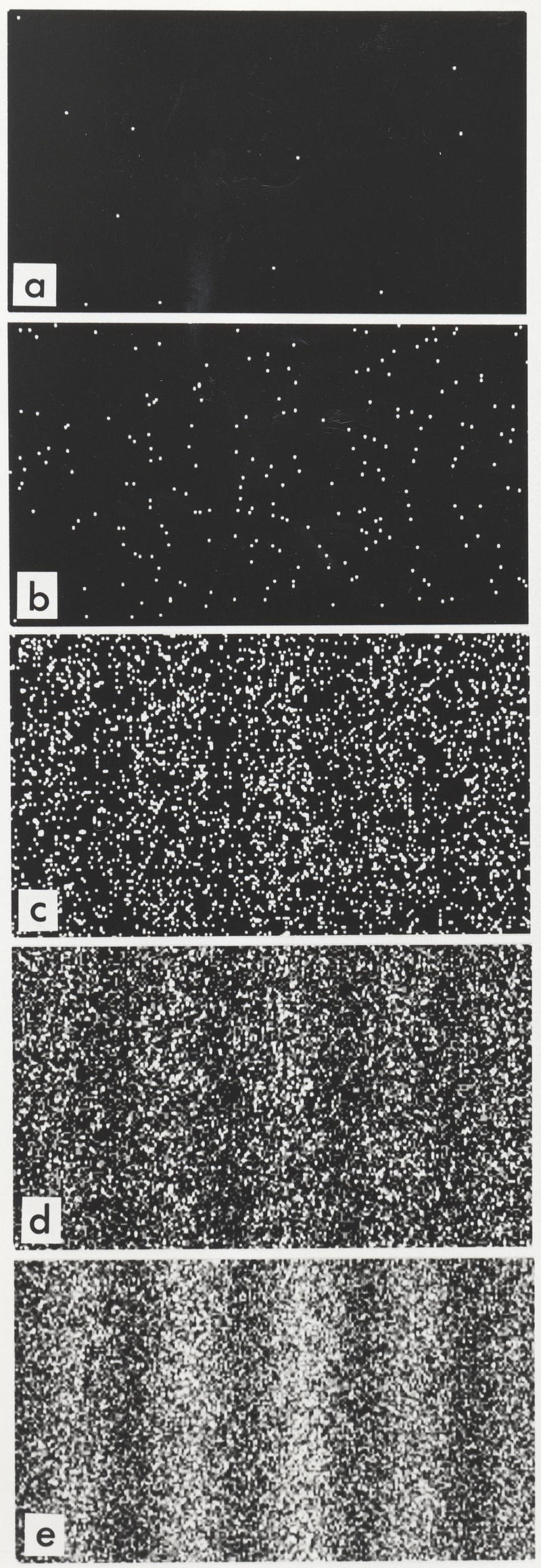

| Modern scientific perspective Generative processes Main article: Emergence Although it was once thought by scientists that any indeterminism in quantum mechanics occurred at too small a scale to influence biological or neurological systems, there is indication that nervous systems are influenced by quantum indeterminism due to chaos theory.[64] It is unclear what implications this has for the problem of free will given various possible reactions to the problem in the first place.[65] Many biologists do not grant determinism: Christof Koch, for instance, argues against it, and in favour of libertarian free will, by making arguments based on generative processes (emergence).[66] Other proponents of emergentist or generative philosophy, cognitive sciences, and evolutionary psychology, argue that a certain form of determinism (not necessarily causal) is true.[67][68][69][70] They suggest instead that an illusion of free will is experienced due to the generation of infinite behaviour from the interaction of finite-deterministic set of rules and parameters. Thus the unpredictability of the emerging behaviour from deterministic processes leads to a perception of free will, even though free will as an ontological entity does not exist.[67][68][69][70]  In Conway's Game of Life, the interaction of just four simple rules creates patterns that seem somehow "alive". As an illustration, the strategy board-games chess and Go have rigorous rules in which no information (such as cards' face-values) is hidden from either player and no random events (such as dice-rolling) happen within the game. Yet, chess and especially Go with its extremely simple deterministic rules, can still have an extremely large number of unpredictable moves. When chess is simplified to 7 or fewer pieces, however, endgame tables are available that dictate which moves to play to achieve a perfect game. This implies that, given a less complex environment (with the original 32 pieces reduced to 7 or fewer pieces), a perfectly predictable game of chess is possible. In this scenario, the winning player can announce that a checkmate will happen within a given number of moves, assuming a perfect defense by the losing player, or fewer moves if the defending player chooses sub-optimal moves as the game progresses into its inevitable, predicted conclusion. By this analogy, it is suggested, the experience of free will emerges from the interaction of finite rules and deterministic parameters that generate nearly infinite and practically unpredictable behavioural responses. In theory, if all these events could be accounted for, and there were a known way to evaluate these events, the seemingly unpredictable behaviour would become predictable.[67][68][69][70] Another hands-on example of generative processes is John Horton Conway's playable Game of Life.[71] Nassim Taleb is wary of such models, and coined the term "ludic fallacy." Compatibility with the existence of science Certain philosophers of science argue that, while causal determinism (in which everything including the brain/mind is subject to the laws of causality) is compatible with minds capable of science, fatalism and predestination is not. These philosophers make the distinction that causal determinism means that each step is determined by the step before and therefore allows sensory input from observational data to determine what conclusions the brain reaches, while fatalism in which the steps between do not connect an initial cause to the results would make it impossible for observational data to correct false hypotheses. This is often combined with the argument that if the brain had fixed views and the arguments were mere after-constructs with no causal effect on the conclusions, science would have been impossible and the use of arguments would have been a meaningless waste of energy with no persuasive effect on brains with fixed views.[72] Mathematical models Many mathematical models of physical systems are deterministic. This is true of most models involving differential equations (notably, those measuring rate of change over time). Mathematical models that are not deterministic because they involve randomness are called stochastic. Because of sensitive dependence on initial conditions, some deterministic models may appear to behave non-deterministically; in such cases, a deterministic interpretation of the model may not be useful due to numerical instability and a finite amount of precision in measurement. Such considerations can motivate the consideration of a stochastic model even though the underlying system is governed by deterministic equations.[73][74][75] Quantum and classical mechanics Day-to-day physics Further information: Macroscopic quantum phenomena Since the beginning of the 20th century, quantum mechanics—the physics of the extremely small—has revealed previously concealed aspects of events. Before that, Newtonian physics—the physics of everyday life—dominated. Taken in isolation (rather than as an approximation to quantum mechanics), Newtonian physics depicts a universe in which objects move in perfectly determined ways. At the scale where humans exist and interact with the universe, Newtonian mechanics remain useful, and make relatively accurate predictions (e.g. calculating the trajectory of a bullet). But whereas in theory, absolute knowledge of the forces accelerating a bullet would produce an absolutely accurate prediction of its path, modern quantum mechanics casts reasonable doubt on this main thesis of determinism. Quantum realm Quantum physics works differently in many ways from Newtonian physics. Physicist Aaron D. O'Connell explains that understanding the universe, at such small scales as atoms, requires a different logic than day-to-day life does. O'Connell does not deny that it is all interconnected: the scale of human existence ultimately does emerge from the quantum scale. O'Connell argues that we must simply use different models and constructs when dealing with the quantum world.[76] Quantum mechanics is the product of a careful application of the scientific method, logic and empiricism. The Heisenberg uncertainty principle is frequently confused with the observer effect. The uncertainty principle actually describes how precisely we may measure the position and momentum of a particle at the same time—if we increase the accuracy in measuring one quantity, we are forced to lose accuracy in measuring the other. "These uncertainty relations give us that measure of freedom from the limitations of classical concepts which is necessary for a consistent description of atomic processes."[77]  Although it is not possible to predict the arrival position or time for any particle, probabilities of arrival predict the final pattern of events. This is where statistical mechanics come into play, and where physicists begin to require rather unintuitive mental models: A particle's path simply cannot be exactly specified in its full quantum description. "Path" is a classical, practical attribute in everyday life, but one that quantum particles do not meaningfully possess. The probabilities discovered in quantum mechanics do nevertheless arise from measurement (of the perceived path of the particle). As Stephen Hawking explains, the result is not traditional determinism, but rather determined probabilities.[78] In some cases, a quantum particle may indeed trace an exact path, and the probability of finding the particles in that path is one (certain to be true). In fact, as far as prediction goes, the quantum development is at least as predictable as the classical motion, but the key is that it describes wave functions that cannot be easily expressed in ordinary language. As far as the thesis of determinism is concerned, these probabilities, at least, are quite determined. These findings from quantum mechanics have found many applications, and allow people to build transistors and lasers. Put another way: personal computers, Blu-ray players and the Internet all work because humankind discovered the determined probabilities of the quantum world.[79] On the topic of predictable probabilities, the double-slit experiments are a popular example. Photons are fired one-by-one through a double-slit apparatus at a distant screen. They do not arrive at any single point, nor even the two points lined up with the slits (the way it might be expected of bullets fired by a fixed gun at a distant target). Instead, the light arrives in varying concentrations at widely separated points, and the distribution of its collisions with the target can be calculated reliably. In that sense the behavior of light in this apparatus is predictable, but there is no way to predict where in the resulting interference pattern any individual photon will make its contribution (although, there may be ways to use weak measurement to acquire more information without violating the uncertainty principle). Some (including Albert Einstein) have argued that the inability to predict any more than probabilities is simply due to ignorance.[80] The idea is that, beyond the conditions and laws can be observed or deduced, there are also hidden factors or "hidden variables" that determine absolutely in which order photons reach the detector screen. They argue that the course of the universe is absolutely determined, but that humans are screened from knowledge of the determinative factors. So, they say, it only appears that things proceed in a merely probabilistically determinative way. In actuality, they proceed in an absolutely deterministic way. John S. Bell criticized Einstein's work in his famous Bell's theorem, which, under a strict set of assumptions, demonstrates that quantum mechanics can make statistical predictions that would be violated if local hidden variables really existed. A number of experiments have tried to verify such predictions, and so far they do not appear to be violated. Current experiments continue to verify the result, including the 2015 "Loophole Free Test" that plugged all known sources of error and the 2017 "Cosmic Bell Test" experiment that used cosmic data streaming from different directions toward the Earth, precluding the possibility the sources of data could have had prior interactions. Bell's theorem has been criticized from the perspective of its strict set of assumptions. A foundational assumption to quantum mechanics is the Principle of locality. To abandon this assumption would require the construction of a non-local hidden variable theory. Therefore, it is possible to augment quantum mechanics with non-local hidden variables to achieve a deterministic theory that is in agreement with experiment.[81] An example is the Bohm interpretation of quantum mechanics. Bohm's Interpretation, though, violates special relativity and it is highly controversial whether or not it can be reconciled without giving up on determinism. Another foundational assumption to quantum mechanics is that of free will,[82] which has been argued[83] to be foundational to the scientific method as a whole. Bell acknowledged that abandoning this assumption would both allow for the maintenance of determinism as well as locality.[84] This perspective is known as superdeterminism, and is defended by some physicists such as Sabine Hossenfelder and Tim Palmer.[85] More advanced variations on these arguments include quantum contextuality, by Bell, Simon B. Kochen and Ernst Specker, which argues that hidden variable theories cannot be "sensible", meaning that the values of the hidden variables inherently depend on the devices used to measure them. This debate is relevant because there are possibly specific situations in which the arrival of an electron at a screen at a certain point and time would trigger one event, whereas its arrival at another point would trigger an entirely different event (e.g. see Schrödinger's cat—a thought experiment used as part of a deeper debate). In his 1939 address "The Relation between Mathematics and Physics" [86] Paul Dirac points out that purely deterministic classical mechanics cannot explain the cosmological origins of the universe; today the early universe is modeled quantum mechanically.[87] Thus, quantum physics casts reasonable doubt on the traditional determinism of classical, Newtonian physics in so far as reality does not seem to be absolutely determined. This was the subject of the famous Bohr–Einstein debates between Einstein and Niels Bohr and there is still no consensus.[88][89] Adequate determinism (see Varieties, above) is the reason that Stephen Hawking called libertarian free will "just an illusion".[78] |

現代科学の視点 生成過程 主な記事 創発 かつて科学者たちは、量子力学における不確定性は生物学的システムや神経学的システムに影響を与えるにはあまりにも小さなスケールで起こっていると考えて いたが、カオス理論によって神経系が量子の不確定性の影響を受けていることが示唆されている[64]: 例えばクリストフ・コッホは、生成過程(創発)に基 づいた議論をすることで、決定論に反対し、自由意志を支持してい る[66]。創発主義や生成哲学の他の支持者、認知科学、進化心理学は、 ある種の決定論(必ずしも因果的ではない)が真実であると主張してい る[67][68][69][70]。彼らは代わりに、有限決定論的な規則とパラメー タの相互作用から無限の行動が生成されることによって、自由意志の錯 覚が経験されることを示唆している。従って、存在論的実体としての自由意志は存在しないにもかかわら ず、決定論的プロセスから出現する振る舞いの予測不可能性が自由意志の知覚 をもたらすのである[67][68][69][70]。  コンウェイの「ライフ・ゲーム」では、たった4つの単純なルールの相互作用が、何らかの形で「生きている」ように見えるパターンを生み出す。 例証として、戦略ボードゲームであるチェスと囲碁は、どちらのプレイヤーからも情報(カードの表 の値など)が隠されておらず、ゲーム内でランダムな出来事(サイコロを振るなど)が起こらない厳密なルール を持っている。しかし、チェスや、特に極めて単純な決定論的ルールを持つ囲碁は、それでもなお、予測不可能な手を極めて多く持つことができる。しかし、 チェスを7個以下の駒に単純化した場合、どの手を打てば完璧なゲームになるかを示す終盤表が利用できる。このことは、(元の32個の駒を7個以下に減らし て)それほど複雑でない環境が与えられれば、完全に予測可能なチェスのゲームが可能であることを意味している。このシナリオでは、勝利したプレイヤーは、 負けたプレイヤーが完璧な防御をしたと仮定した場合、与えられた手数以内にチェックメイトが起こると発表することができる。この類推によれば、自由意志の 経験は、ほぼ無限で実質的に予測不可能な行動反応を生み出す有限のルールと決定論的パラメーターの相互作用から生まれることが示唆される。理論的には、も しこれらの事象がすべて説明でき、これらの事象を評 価する既知の方法があれば、一見予測不可能に見える行動も予測可能になる だろう[67][68][69][70]。生成過程のもう一つの実践的な例として、ジョン・ホート ン・コンウェイのプレイ可能なゲーム・オブ・ライフがある[71]。 科学の存在との適合性 ある種の科学哲学者は、因果決定論(脳/心を含むすべてのものが因果律の法則に従う)は科学が可能な心と両立するが、運命論や宿命論は両立しないと主張し ている。これらの哲学者は、因果決定論とは、各ステップが前のステップによって決定されることを意味し、したがって観察データからの感覚的入力によって脳 がどのような結論に達するかを決定することができるのに対し、その間のステップが最初の原因と結果を結びつけない運命論は、観察データによって誤った仮説 を修正することが不可能になるという区別をしている。これはしばしば、もし脳が固定的な見解を持っていて、議論が結論に対して何の因果関係も持たない単な る後付けのものであったなら、科学は不可能であり、議論の使用は固定的な見解を持つ脳に対して何の説得効果も持たない無意味なエネルギーの浪費であったで あろうという議論と組み合わされる[72]。 数学モデル 物理システムの多くの数学モデルは決定論的である。これは微分方程式を含むほとんどのモデルに当てはまる(特に経時変化率を測定するもの)。ランダム性を 含むため決定論的でない数学モデルは確率論的と呼ばれる。初期条件に敏感に依存するため、決定論的モデルの中には非決定論的に振る舞うように見えるものも ある。このような場合、数値的不安定性や測定精度の有限性から、モデルの決定論的解釈は有用ではないかもしれない。このような考察は、基礎となるシステム が決定論的方程式によって支配されているにもかかわらず、確率モデルの考察を動機付けることがある[73][74][75]。 量子力学と古典力学 日常物理学 更なる情報 巨視的量子現象 20世紀に入ってから、量子力学(極めて小さいものの物理学)は、これまで隠されていた事象の側面を明らかにした。それ以前は、日常生活の物理学である ニュートン物理学が主流だった。量子力学の近似としてではなく)ニュートン物理学は、物体が完全に決定された方法で動く宇宙を描いている。人間が存在し、 宇宙と相互作用するスケールでは、ニュートン力学は依然として有用であり、比較的正確な予測(例えば弾丸の軌道計算)を行う。しかし、理論的には、弾丸を 加速させる力の絶対的な知識があれば、弾丸の進路を絶対的に正確に予測することができるが、現代の量子力学は、この決定論の主要なテーゼに妥当な疑問を投 げかけている。 量子領域 量子物理学はニュートン物理学とは多くの点で異なる。物理学者アーロン・D・オコネルは、原子という小さなスケールで宇宙を理解するには、日常生活とは異 なる論理が必要だと説明する。オコネルは、すべてが相互に関連していることを否定はしない。人間存在のスケールは、究極的には量子スケールから生まれるの だ。量子力学は、科学的方法、論理学、経験論を注意深く応用した産物である。ハイゼンベルクの不確定性原理は、しばしばオブザーバー効果と混同される。不 確定性原理は実際には、粒子の位置と運動量を同時にどれだけ正確に測定できるかを説明するもので、一方の量を測定する精度を上げれば、もう一方の量を測定 する精度は失わざるを得ない。「これらの不確定性関係は、原子過程の一貫した記述に必要な、古典的概念の制限からの自由度を与えてくれる」[77]。  どの粒子についても到着位置や時間を予測することは不可能であるが、到着の確率は事象の最終的なパターンを予測する。 これが統計力学の出番であり、物理学者がかなり直感的でないメンタルモデルを要求し始めるところである: 粒子の経路は、量子論的な記述では正確に特定できない。「経路」は日常生活における古典的で実用的な属性であるが、量子粒子には意味のある属性ではない。 それでも、量子力学で発見された確率は、(粒子の知覚された経路の)測定から生じる。スティーブン・ホーキング博士が説明するように、その結果は伝統的な 決定論ではなく、むしろ決定された確率である。実際、予測に関しては、量子の発展は少なくとも古典的な運動と同じくらい予測可能であるが、重要なのは、通 常の言語では簡単に表現できない波動関数を記述することである。決定論のテーゼに関する限り、これらの確率は、少なくとも、かなり決定されている。量子力 学のこれらの発見は、多くの応用を見出し、トランジスタやレーザーを作ることを可能にしている。別の言い方をすれば、パーソナルコンピュータ、ブルーレイ プレーヤー、インターネットはすべて、人類が量子世界の決定された確率を発見したからこそ機能するのである[79]。 予測可能な確率という話題では、二重スリット実験がよく知られた例である。光子は二重スリット装置を通して遠くのスクリーンに向けて一個ずつ発射される。 光子はどの一点にも到達せず、スリットに並んだ2点にも到達しない(遠くの標的に向けて固定銃で発射された弾丸に期待されるような)。その代わり、光は大 きく離れた地点にさまざまな濃度で到達し、標的との衝突の分布を確実に計算することができる。その意味で、この装置における光の振る舞いは予測可能である が、結果として生じる干渉パターンのどこで個々の光子が寄与するかを予測する方法はない(ただし、不確定性原理に違反することなく、より多くの情報を得る ために弱い測定を利用する方法はあるかもしれない)。 アルベルト・アインシュタインを含む)何人かは、確率以上のことを予測できないのは単に無知によるものだと主張している[80]。この考え方は、条件や法 則が観測されたり推論されたりする以上に、光子がどのような順序で検出器のスクリーンに到達するかを決定する隠れた要因や「隠れた変数」が存在するという ものである。彼らは、宇宙の行方は絶対的に決定されているが、人間はその決定要因を知ることができない、と主張する。つまり、物事は単に確率論的に決定的 に進んでいるように見えるだけなのだという。実際には、絶対的に決定論的な方法で物事は進むのである。 ジョン・S・ベルは、有名なベルの定理でアインシュタインの研究を批判した。この定理は、厳密な仮定の下で、量子力学が局所的な隠れた変数が本当に存在す るならば破られるであろう統計的予測を行うことができることを証明するものである。多くの実験がこのような予測を検証しようと試みられてきたが、今のとこ ろ予測は破れていないようである。現在の実験では、既知のエラー源をすべて塞いだ2015年の「抜け穴のないテスト」や、異なる方向から地球に向かって流 れてくる宇宙データを使い、データ源が事前に相互作用していた可能性を排除した2017年の「宇宙ベルテスト」など、結果を検証し続けている。 ベルの定理は、その厳密な仮定セットの観点から批判されてきた。量子力学の基礎となる仮定は「局所性の原理」である。この仮定を放棄するには、非局所的な 隠れ変数理論を構築する必要がある。したがって、実験と一致する決定論的理論を実現するために、量子力学を非局所的な隠れた変数で補強することは可能であ る[81]。しかし、ボームの解釈は特殊相対性理論に違反しており、決定論をあきらめることなく和解できるかどうかは非常に議論の的となっている。 量子力学のもう一つの基礎となる仮定は、自由意志の仮定であり[82]、これは科学的方法全体にとって基礎となるものであると主張されている[83]。ベ ルはこの仮定を放棄することで局所性とともに決定論の維持が可能になることを認めている[84]。この視点は超決定論として知られており、サビーネ・ホッ センフェルダーやティム・パーマーなどの一部の物理学者によって擁護されている[85]。 これらの議論のより高度なバリエーションとして、ベル、サイモン・B・コーヘン、エルンスト・スペッカーによる量子文脈論があり、これは隠れ変数理論が「感覚的」であることはあり得ないと主張している。 この議論が重要なのは、ある時点と時刻に電子がスクリーンに到着するとある事象が発生するが、別の時点に到着すると全く別の事象が発生するという特定の状況があり得るからである(例えば、より深い議論の一環として使われる思考実験「シュレーディンガーの猫」を参照)。 ポール・ディラックは1939年の講演「数学と物理学の関係」の中で[86]、純粋に決定論的な古典力学では宇宙の起源を説明できないと指摘している。 このように、量子物理学は、現実が絶対的に決定されていないように見える限りにおいて、古典的なニュートン物理学の伝統的な決定論に妥当な疑念を投げかけ ている。これはアインシュタインとニールス・ボーアの間で有名なボーア=アインシュタイン論争のテーマとなり、未だにコンセンサスは得られていない [88][89]。 スティーヴン・ホーキングがリバタリアン的自由意志を「幻想に過ぎない」と呼んだ理由は、適切な決定論(上記の「多様性」を参照)である[78]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Determinism |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆