唯 物 論

Materialism

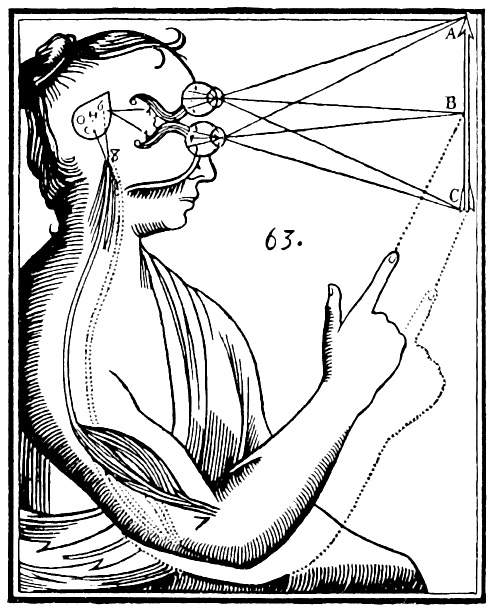

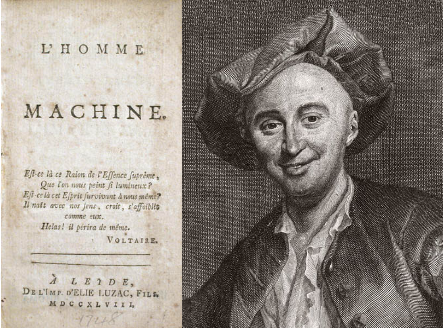

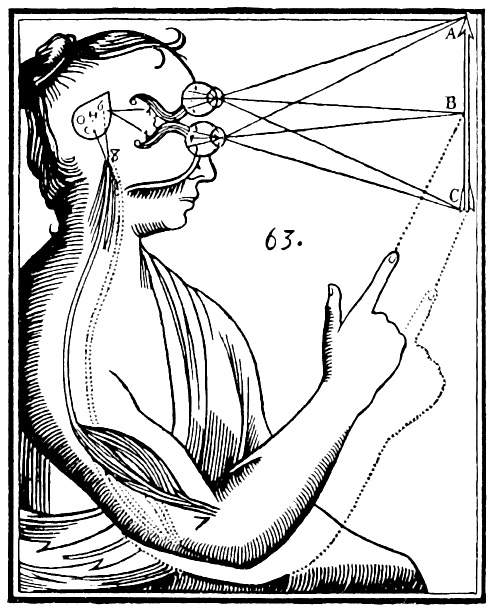

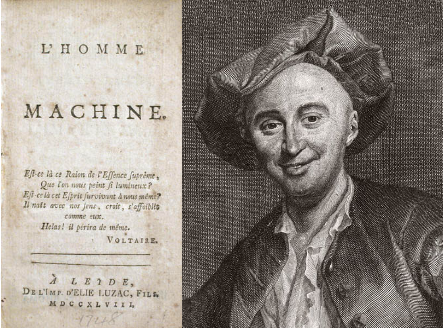

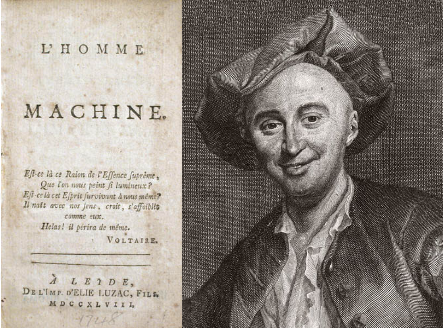

In 1748, French doctor and philosopher La Mettrie espouses a materialistic definition of the human soul in L'Homme Machine.

唯 物 論

Materialism

In 1748, French doctor and philosopher La Mettrie espouses a materialistic definition of the human soul in L'Homme Machine.

唯物論 (materialism):唯物論あるいは唯物主義の基盤は、観念や精 神、心などの根底には物質があると考え、そのような根拠性をもたない思考や観念は無効とする考え方である。唯物論者であることのパラドックス(逆説)は、 自分自身の思考の根拠性を、徹頭徹尾、観念論(idealism)あるいは唯心論(mentalism)の立場で考え抜くことである。唯物 論は、物理主義 (Physicalism) としても言い換えることができる。

物理主義と は、「すべては物理的である」というスローガンに似たテーゼ(命題) のことである。古代ギリシャの哲学者タレスが唱えた「すべては水である」というテーゼや、18世紀の哲学者バークレーの「すべては精神である」という観念 論と同様に、形而上学的なテーゼとして意図されているのが普通である。つまり、現実の世界(宇宙とそこにあるすべてのもの)の性質は、ある条件、つまり物 理的であるという条件に適合しているというのが一般的な考え方である。もちろん、物理主義者は、一見して物理的とは思えないような、生物学的、心理学的、 道徳的、社会的、数学的な性質を持つものが世界に数多く存在することを否定はしない。しかし、それでも彼らは、結局のところ、そうしたものは物理的なもの である、あるいは少なくとも物理的なものと重要な関係を持つものである、と主張する。

唯物論のより頑迷な立場は、排除的唯物論(Eliminative materialism)と呼ばれる。排除的唯物論(または唯物排除論)とは、私たちの通常の常識的な心の理解は深く間違っており、常識的に想定 される心の状態の一部または全部は実際には存在せず、心の科学の成熟に果たすべき役割はない、という過激な主張である。デカルトは、私たちが当たり前だと 思っていることの多くに異議を唱えたことで有名だが、彼は、ほとんどの場合、自分の心の内容については確信を持つことができると主張したのである。排除的 唯物論者はこの点で、デカルトよりもさらに進んで、デカルトが当然視していた様々な 心的状態の存在に異議を唱えているのである。

| Materialism is a

form of philosophical monism which holds that matter is the fundamental

substance in nature, and that all things, including mental states and

consciousness, are results of material interactions of material things.

According to philosophical materialism, mind and consciousness are

by-products or epiphenomena of material processes (such as the

biochemistry of the human brain and nervous system), without which they

cannot exist. Materialism directly contrasts with idealism, according

to which consciousness is the fundamental substance of nature. Materialism is closely related to physicalism—the view that all that exists is ultimately physical. Philosophical physicalism has evolved from materialism with the theories of the physical sciences to incorporate more sophisticated notions of physicality than mere ordinary matter (e.g. spacetime, physical energies and forces, and dark matter). Thus, some prefer the term physicalism to materialism, while others use the terms as if they were synonymous. Philosophies traditionally opposed or largely historically unreconciled to the scientific theories of materialism or physicalism include idealism, pluralism, dualism, panpsychism, and other forms of monism. Epicureanism is a philosophy of materialism from classical antiquity that was a major forerunner of modern science. Though ostensibly a deist, Epicurus affirmed the literal existence of the Greek gods in either some type of celestial "heaven" cognate from which they ruled the Universe (if not on a literal Mount Olympus), and his philosophy promulgated atomism, while Platonism taught roughly the opposite, despite Plato's teaching of Zeus as God. |

唯物論とは哲学的一元論の一形態であり、物質が自然界における基本的な

物質であり、精神状態や意識を含む万物は物質同士の相互作用の結果であるとする。哲学的唯物論によれば、心や意識は物質的過程(人間の脳や神経系の生化学

など)の副産物や副次的現象であり、それなしでは存在しえない。唯物論は、意識が自然の基本的な物質であるとする観念論とは正反対である。 唯物論は物理主義(存在するものはすべて究極的には物理的なものであるという考え方)と密接な関係がある。哲学的物理主義は、物理科学の理論とともに唯物 論から発展し、単なる通常の物質(時空、物理的エネルギーや力、ダークマターなど)よりも洗練された物理性の概念を取り入れている。そのため、唯物論より も物理主義という言葉を好む人もいれば、同義語であるかのように使う人もいる。 唯物論や物理主義の科学的理論に伝統的に反対してきた、あるいは歴史的にほとんど調和してこなかった哲学には、観念論、多元主義、二元論、汎心論、その他 の形の一元論などがある。エピクロス主義は、古典古代に生まれた唯物論の哲学であり、近代科学の主要な先駆けであった。表向きは神学者だが、エピクロスは ギリシア神話の神々が(文字通りのオリンポス山ではないにせよ)宇宙を支配する天の「天」のようなものの中に文字通りに存在することを肯定し、彼の哲学が 原子論を広めたのに対し、プラトン主義はゼウスを神とするプラトンの教えにもかかわらず、ほぼ正反対のことを説いた。 |

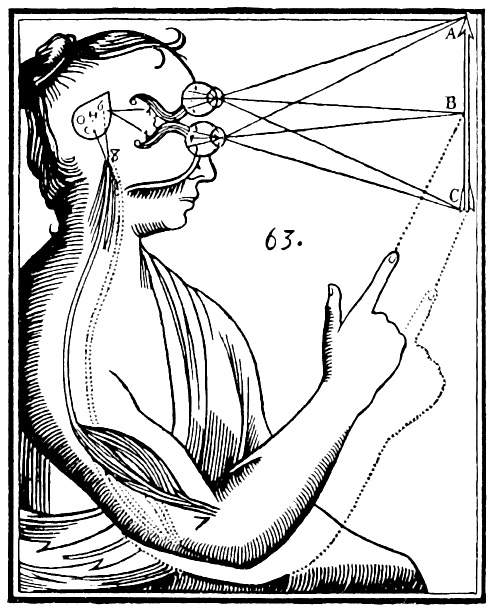

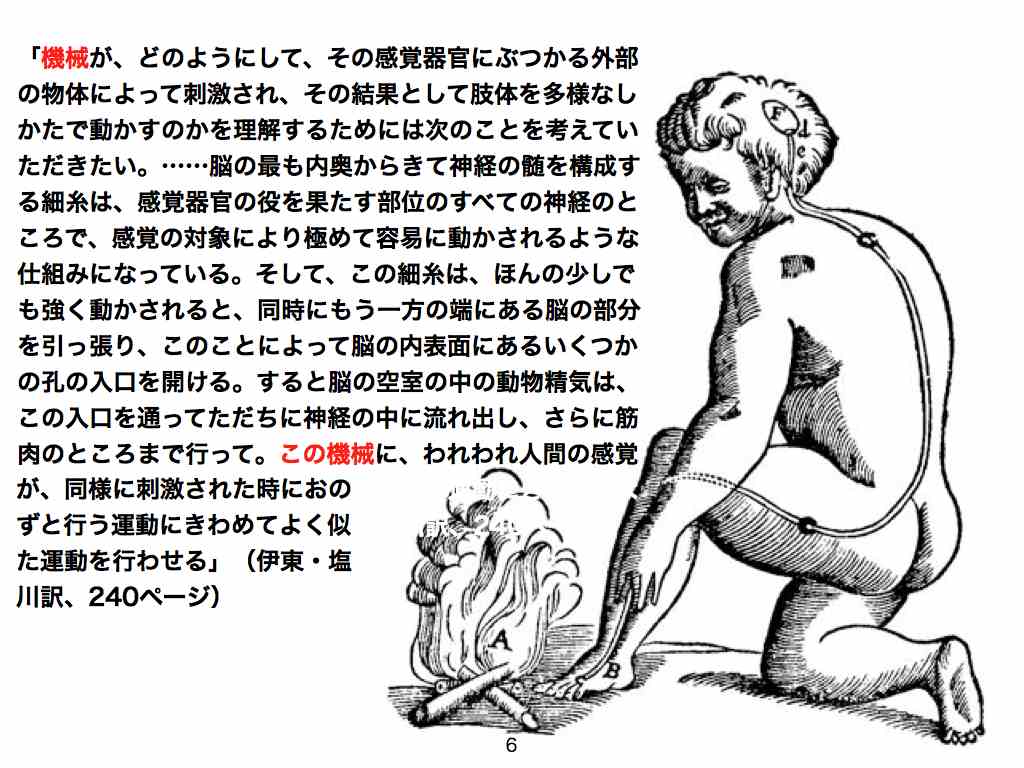

Overview In 1748, French doctor and

philosopher La Mettrie espouses a materialistic definition of the human

soul in L'Homme Machine. In 1748, French doctor and

philosopher La Mettrie espouses a materialistic definition of the human

soul in L'Homme Machine.Materialism belongs to the class of monist ontology, and is thus different from ontological theories based on dualism or pluralism. For singular explanations of the phenomenal reality, materialism is in contrast to idealism, neutral monism, and spiritualism. It can also contrast with phenomenalism, vitalism, and dual-aspect monism. Its materiality can, in some ways, be linked to the concept of determinism, as espoused by Enlightenment thinkers.[citation needed] Despite the large number of philosophical schools and their nuances,[1][2][3] all philosophies are said to fall into one of two primary categories, defined in contrast to each other: idealism and materialism.[a] The basic proposition of these two categories pertains to the nature of reality: the primary difference between them is how they answer two fundamental questions—what reality consists of, and how it originated. To idealists, spirit or mind or the objects of mind (ideas) are primary, and matter secondary. To materialists, matter is primary, and mind or spirit or ideas are secondary—the product of matter acting upon matter.[3] The materialist view is perhaps best understood in its opposition to the doctrines of immaterial substance applied to the mind historically by René Descartes; by itself, materialism says nothing about how material substance should be characterized. In practice, it is frequently assimilated to one variety of physicalism or another. Modern philosophical materialists extend the definition of other scientifically observable entities such as energy, forces, and the spacetime continuum; some philosophers, such as Mary Midgley, suggest that the concept of "matter" is elusive and poorly defined.[4] During the 19th century, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels extended the concept of materialism to elaborate a materialist conception of history centered on the roughly empirical world of human activity (practice, including labor) and the institutions created, reproduced or destroyed by that activity. They also developed dialectical materialism, by taking Hegelian dialectics, stripping them of their idealist aspects, and fusing them with materialism (see Modern philosophy).[5] Non-reductive materialism Materialism is often associated with reductionism, according to which the objects or phenomena individuated at one level of description, if they are genuine, must be explicable in terms of the objects or phenomena at some other level of description—typically, at a more reduced level. Non-reductive materialism explicitly rejects this notion, taking the material constitution of all particulars to be consistent with the existence of real objects, properties or phenomena not explicable in the terms canonically used for the basic material constituents. Jerry Fodor held this view, according to which empirical laws and explanations in "special sciences" like psychology or geology are invisible from the perspective of basic physics.[6] |

概要 1748年、フランスの医師であり哲学者であったラ・メトリは、『人間

機械』(L'Homme Machine)の中で、人間の魂の唯物論的定義を唱えた。 1748年、フランスの医師であり哲学者であったラ・メトリは、『人間

機械』(L'Homme Machine)の中で、人間の魂の唯物論的定義を唱えた。唯物論は一元論的存在論に属し、二元論や多元論に基づく存在論とは異なる。現象的現実の特異な説明については、唯物論は観念論、中立的一元論、精神論と対 照的である。また、現象論、生命論、二面的一元論とも対照的である。その唯物性は、ある意味では、啓蒙思想家が信奉する決定論の概念と結びつけることがで きる[要出典]。 この2つのカテゴリーの基本的な命題は現実の性質に関するものであり、両者の主な違いは、現実が何から構成されているのか、そして現実はどのように発生し たのかという2つの基本的な問いにどのように答えるかということである。観念論者にとっては、精神や心、あるいは心の対象(観念)が第一義的なものであ り、物質は第二義的なものである。唯物論者にとっては、物質が一次的なものであり、心や精神やイデアは二次的なもの、つまり物質が物質に作用した産物であ る[3]。 唯物論者の見解は、ルネ・デカルトによって歴史的に心に適用された非物質的物質の教義との対立においておそらく最もよく理解される。実際、唯物論は物理主 義の一種か別のものに同化されることが多い。 現代の哲学的唯物論者は、エネルギー、力、時空連続体など、科学的に観測可能な他の実体の定義を拡張している。メアリー・ミッドグリーのような哲学者の中 には、「物質」の概念はとらえどころがなく、定義が不十分であると指摘する者もいる[4]。 19世紀には、カール・マルクスとフリードリヒ・エンゲルスが唯物論の概念を拡張し、人間の活動(労働を含む実践)とその活動によって創造、再生産、破壊 される制度というおおよそ経験的な世界を中心とした歴史の唯物論的概念を精緻化した。彼らはまた、ヘーゲル弁証法から観念論的な側面を取り除き、唯物論と 融合させることによって弁証法的唯物論を発展させた(近代哲学を参照)[5]。 非還元的唯物論 唯物論はしばしば還元主義と結びついており、ある記述のレベルで個別化された対象や現象が本物であるならば、他の記述のレベル-典型的には、より縮小され たレベル-の対象や現象の観点から説明可能でなければならないというものである。 非還元的唯物論はこの考え方を明確に否定し、すべての特殊の物質的構成は、基本的な物質構成要素に正統的に使われている用語では説明できない実在の物体、 性質、現象の存在と矛盾しないと考える。ジェリー・フォドーは、心理学や地質学のような「特殊な科学」における経験的法則や説明は、基本的な物理学の観点 からは不可視であるとし、このような見解を持っていた[6]。 |

| History Early history See also: History of metaphysical naturalism Before Common Era Materialism developed, possibly independently, in several geographically separated regions of Eurasia during what Karl Jaspers termed the Axial Age (c. 800–200 BC). In ancient Indian philosophy, materialism developed around 600 BC with the works of Ajita Kesakambali, Payasi, Kanada and the proponents of the Cārvāka school of philosophy. Kanada became one of the early proponents of atomism. The Nyaya–Vaisesika school (c. 600–100 BC) developed one of the earliest forms of atomism (although their proofs of God and their positing that consciousness was not material precludes labelling them as materialists). Buddhist atomism and the Jaina school continued the atomic tradition.[citation needed] Ancient Greek atomists like Leucippus, Democritus and Epicurus prefigure later materialists. The Latin poem De Rerum Natura by Lucretius (99 – c. 55 BC) reflects the mechanistic philosophy of Democritus and Epicurus. According to this view, all that exists is matter and void, and all phenomena result from different motions and conglomerations of base material particles called atoms (literally "indivisibles"). De Rerum Natura provides mechanistic explanations for phenomena such as erosion, evaporation, wind, and sound. Famous principles like "nothing can touch body but body" first appeared in Lucretius's work. Democritus and Epicurus did not espouse a monist ontology, instead espousing the ontological separation of matter and space (i.e. that space is "another kind" of being).[citation needed] Early Common Era Wang Chong (27 – c. 100 AD) was a Chinese thinker of the early Common Era said to be a materialist.[7] Later Indian materialist Jayaraashi Bhatta (6th century) in his work Tattvopaplavasimha (The Upsetting of All Principles) refuted the Nyāya Sūtra epistemology. The materialistic Cārvāka philosophy appears to have died out some time after 1400; when Madhavacharya compiled Sarva-darśana-samgraha (A Digest of All Philosophies) in the 14th century, he had no Cārvāka (or Lokāyata) text to quote from or refer to.[8] In early 12th-century al-Andalus, Arabian philosopher Ibn Tufail (a.k.a. Abubacer) discussed materialism in his philosophical novel, Hayy ibn Yaqdhan (Philosophus Autodidactus), while vaguely foreshadowing historical materialism.[9] Modern philosophy Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679)[10] and Pierre Gassendi (1592–1665)[11] represented the materialist tradition in opposition to the attempts of René Descartes (1596–1650) to provide the natural sciences with dualist foundations. There followed the materialist and atheist abbé Jean Meslier (1664–1729), along with the French materialists: Julien Offray de La Mettrie, German-French Baron d'Holbach (1723–1789), Denis Diderot (1713–1784), and other French Enlightenment thinkers. In England, John "Walking" Stewart (1747–1822) believed matter has a moral dimension, which had a major impact on the philosophical poetry of William Wordsworth (1770–1850). In late modern philosophy, German atheist anthropologist Ludwig Feuerbach signaled a new turn in materialism in his 1841 book The Essence of Christianity, which presented a humanist account of religion as the outward projection of man's inward nature. Feuerbach introduced anthropological materialism, a version of materialism that views materialist anthropology as the universal science.[12] Feuerbach's variety of materialism heavily influenced Karl Marx,[13] who in the late 19th century elaborated the concept of historical materialism—the basis for what Marx and Friedrich Engels outlined as scientific socialism: The materialist conception of history starts from the proposition that the production of the means to support human life and, next to production, the exchange of things produced, is the basis of all social structure; that in every society that has appeared in history, the manner in which wealth is distributed and society divided into classes or orders is dependent upon what is produced, how it is produced, and how the products are exchanged. From this point of view, the final causes of all social changes and political revolutions are to be sought, not in men's brains, not in men's better insights into eternal truth and justice, but in changes in the modes of production and exchange. They are to be sought, not in the philosophy, but in the economics of each particular epoch. — Friedrich Engels, Socialism: Scientific and Utopian (1880) Through his Dialectics of Nature (1883), Engels later developed a "materialist dialectic" philosophy of nature, a worldview that Georgi Plekhanov, the father of Russian Marxism, called dialectical materialism.[14] In early 20th-century Russian philosophy, Vladimir Lenin further developed dialectical materialism in his 1909 book Materialism and Empirio-criticism, which connects his opponents' political conceptions to their anti-materialist philosophies. A more naturalist-oriented materialist school of thought that developed in the mid-19th century was German materialism, which included Ludwig Büchner (1824–1899), the Dutch-born Jacob Moleschott (1822–1893), and Carl Vogt (1817–1895),[15][16] even though they had different views on core issues such as the evolution and the origins of life.[17] Contemporary history See also: Contemporary philosophy Analytic philosophy See also: Physicalism and Scientific materialism Contemporary analytic philosophers (e.g. Daniel Dennett, Willard Van Orman Quine, Donald Davidson, and Jerry Fodor) operate within a broadly physicalist or scientific materialist framework, producing rival accounts of how best to accommodate the mind, including functionalism, anomalous monism, and identity theory.[18] Scientific materialism is often synonymous with, and has typically been described as, a reductive materialism. In the early 21st century, Paul and Patricia Churchland[19][20] advocated a radically contrasting position (at least in regard to certain hypotheses): eliminative materialism. Eliminative materialism holds that some mental phenomena simply do not exist at all, and that talk of such phenomena reflects a spurious "folk psychology" and introspection illusion. A materialist of this variety might believe that a concept like "belief" has no basis in fact (e.g. the way folk science speaks of demon-caused illnesses). With reductive materialism at one end of a continuum (our theories will reduce to facts) and eliminative materialism at the other (certain theories will need to be eliminated in light of new facts), revisionary materialism is somewhere in the middle.[18] Continental philosophy See also: Speculative materialism and Transcendental materialism Contemporary continental philosopher Gilles Deleuze has attempted to rework and strengthen classical materialist ideas.[21] Contemporary theorists such as Manuel DeLanda, working with this reinvigorated materialism, have come to be classified as new materialists.[22] New materialism has become its own subfield, with courses on it at major universities, as well as numerous conferences, edited collections and monographs devoted to it. Jane Bennett's 2010 book Vibrant Matter has been particularly instrumental in bringing theories of monist ontology and vitalism back into a critical theoretical fold dominated by poststructuralist theories of language and discourse.[23] Scholars such as Mel Y. Chen and Zakiyyah Iman Jackson have critiqued this body of new materialist literature for neglecting to consider the materiality of race and gender in particular.[24][25] Métis scholar Zoe Todd, as well as Mohawk (Bear Clan, Six Nations) and Anishinaabe scholar Vanessa Watts,[26] query the colonial orientation of the race for a "new" materialism.[27] Watts in particular describes the tendency to regard matter as a subject of feminist or philosophical care as a tendency too invested in the reanimation of a Eurocentric tradition of inquiry at the expense of an Indigenous ethic of responsibility.[28] Other scholars, such as Helene Vosters, echo their concerns and have questioned whether there is anything particularly "new" about "new materialism", as Indigenous and other animist ontologies have attested to what might be called the "vibrancy of matter" for centuries.[29] Others, such as Thomas Nail, have critiqued "vitalist" versions of new materialism for depoliticizing "flat ontology" and being ahistorical.[30][31] Quentin Meillassoux proposed speculative materialism, a post-Kantian return to David Hume also based on materialist ideas.[32] Defining "matter" The nature and definition of matter—like other key concepts in science and philosophy—have occasioned much debate:[33] Is there a single kind of matter (hyle) that everything is made of, or are there multiple kinds? Is matter a continuous substance capable of expressing multiple forms (hylomorphism)[34] or a number of discrete, unchanging constituents (atomism)?[35] Does matter have intrinsic properties (substance theory)[36] or lack them (prima materia)? One challenge to the conventional concept of matter as tangible "stuff" came with the rise of field physics in the 19th century. Relativity shows that matter and energy (including the spatially distributed energy of fields) are interchangeable. This enables the ontological view that energy is prima materia and matter is one of its forms. In contrast, the Standard Model of particle physics uses quantum field theory to describe all interactions. On this view it could be said that fields are prima materia and the energy is a property of the field.[citation needed] According to the dominant cosmological model, the Lambda-CDM model, less than 5% of the universe's energy density is made up of the "matter" the Standard Model describes, and most of the universe is composed of dark matter and dark energy, with little agreement among scientists about what these are made of.[37] With the advent of quantum physics, some scientists believed the concept of matter had merely changed, while others believed the conventional position could no longer be maintained. Werner Heisenberg said: "The ontology of materialism rested upon the illusion that the kind of existence, the direct 'actuality' of the world around us, can be extrapolated into the atomic range. This extrapolation, however, is impossible...atoms are not things."[38] The concept of matter has changed in response to new scientific discoveries. Thus materialism has no definite content independent of the particular theory of matter on which it is based. According to Noam Chomsky, any property can be considered material, if one defines matter such that it has that property.[39] The philosophical materialist Gustavo Bueno uses a more precise term than matter, the stroma.[40] Physicalism Main article: Physicalism George Stack distinguishes between materialism and physicalism: In the twentieth century, physicalism has emerged out of positivism. Physicalism restricts meaningful statements to physical bodies or processes that are verifiable or in principle verifiable. It is an empirical hypothesis that is subject to revision and, hence, lacks the dogmatic stance of classical materialism. Herbert Feigl defended physicalism in the United States and consistently held that mental states are brain states and that mental terms have the same referent as physical terms. The twentieth century has witnessed many materialist theories of the mental, and much debate surrounding them.[41] But not all conceptions of physicalism are tied to verificationist theories of meaning or direct realist accounts of perception. Rather, physicalists believe that no "element of reality" is missing from the mathematical formalism of our best description of the world. "Materialist" physicalists also believe that the formalism describes fields of insentience. In other words, the intrinsic nature of the physical is non-experiential.[citation needed] Religious and spiritual views Christianity Main article: Materialism and Christianity Hinduism and Transcendental Club See also: Vaisheshika [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2022) Most Hindus and transcendentalists regard all matter as an illusion, or maya, blinding humans from the truth. Transcendental experiences like the perception of Brahman are considered to destroy the illusion.[42] Criticism and alternatives From contemporary physicists Rudolf Peierls, a physicist who played a major role in the Manhattan Project, rejected materialism: "The premise that you can describe in terms of physics the whole function of a human being ... including knowledge and consciousness, is untenable. There is still something missing."[43] Erwin Schrödinger said, "Consciousness cannot be accounted for in physical terms. For consciousness is absolutely fundamental. It cannot be accounted for in terms of anything else."[44] Werner Heisenberg wrote: "The ontology of materialism rested upon the illusion that the kind of existence, the direct 'actuality' of the world around us, can be extrapolated into the atomic range. This extrapolation, however, is impossible ... Atoms are not things."[45] Quantum mechanics Some 20th-century physicists (e.g., Eugene Wigner[46] and Henry Stapp),[47] and some modern physicists and science writers (e.g., Stephen Barr,[48] Paul Davies, and John Gribbin) have argued that materialism is flawed due to certain recent findings in physics, such as quantum mechanics and chaos theory. According to Gribbin and Davies (1991): Then came our Quantum theory, which totally transformed our image of matter. The old assumption that the microscopic world of atoms was simply a scaled-down version of the everyday world had to be abandoned. Newton's deterministic machine was replaced by a shadowy and paradoxical conjunction of waves and particles, governed by the laws of chance, rather than the rigid rules of causality. An extension of the quantum theory goes beyond even this; it paints a picture in which solid matter dissolves away, to be replaced by weird excitations and vibrations of invisible field energy. Quantum physics undermines materialism because it reveals that matter has far less "substance" than we might believe. But another development goes even further by demolishing Newton's image of matter as inert lumps. This development is the theory of chaos, which has recently gained widespread attention. — Paul Davies and John Gribbin, The Matter Myth, Chapter 1: "The Death of Materialism" Digital physics The objections of Davies and Gribbin are shared by proponents of digital physics, who view information rather than matter as fundamental. The physicist and proponent of digital physics John Archibald Wheeler wrote, "all matter and all things physical are information-theoretic in origin and this is a participatory universe."[49] Some founders of quantum theory, such as Max Planck, shared their objections. He wrote: As a man who has devoted his whole life to the most clear headed science, to the study of matter, I can tell you as a result of my research about atoms this much: There is no matter as such. All matter originates and exists only by virtue of a force which brings the particle of an atom to vibration and holds this most minute solar system of the atom together. We must assume behind this force the existence of a conscious and intelligent Mind. This Mind is the matrix of all matter. — Max Planck, Das Wesen der Materie (1944) James Jeans concurred with Planck, saying, "The Universe begins to look more like a great thought than like a great machine. Mind no longer appears to be an accidental intruder into the realm of matter."[50] Philosophical objections In the Critique of Pure Reason, Immanuel Kant argued against materialism in defending his transcendental idealism (as well as offering arguments against subjective idealism and mind–body dualism).[51][52] But Kant argues that change and time require an enduring substrate.[53][54] Postmodern/poststructuralist thinkers also express skepticism about any all-encompassing metaphysical scheme. Philosopher Mary Midgley[55] argues that materialism is a self-refuting idea, at least in its eliminative materialist form.[56][57][58][59] Varieties of idealism Arguments for idealism, such as those of Hegel and Berkeley, often take the form of an argument against materialism; indeed, Berkeley's idealism was called immaterialism. Now, matter can be argued to be redundant, as in bundle theory, and mind-independent properties can, in turn, be reduced to subjective percepts. Berkeley gives an example of the latter by pointing out that it is impossible to gather direct evidence of matter, as there is no direct experience of matter; all that is experienced is perception, whether internal or external. As such, matter's existence can only be inferred from the apparent (perceived) stability of perceptions; it finds absolutely no evidence in direct experience.[60] If matter and energy are seen as necessary to explain the physical world, but incapable of explaining mind, dualism results. Emergence, holism and process philosophy seek to ameliorate the perceived shortcomings of traditional (especially mechanistic) materialism without abandoning materialism entirely.[citation needed] Materialism as methodology Some critics object to materialism as part of an overly skeptical, narrow or reductivist approach to theorizing, rather than to the ontological claim that matter is the only substance. Particle physicist and Anglican theologian John Polkinghorne objects to what he calls promissory materialism—claims that materialistic science will eventually succeed in explaining phenomena it has not so far been able to explain.[61] Polkinghorne prefers "dual-aspect monism" to materialism.[62] Some scientific materialists have been criticized for failing to provide clear definitions of matter, leaving the term materialism without any definite meaning. Noam Chomsky states that since the concept of matter may be affected by new scientific discoveries, as has happened in the past, scientific materialists are being dogmatic in assuming the opposite.[39] |

歴史 初期の歴史 こちらも参照: 形而上学的自然主義の歴史 共通時代以前 唯物論は、カール・ヤスパースが軸時代(紀元前800年頃~紀元前200年頃)と呼んだ時代に、ユーラシア大陸の地理的に離れたいくつかの地域で、おそら く独立して発展した。 古代インド哲学では、紀元前600年頃、アジタ・ケサカンバリ、パヤシ、カナダ、カーヴァーカ学派の哲学者たちの著作によって唯物論が発展した。カナダは 原子論の初期の提唱者の一人となった。ナーヤ・ヴァイセーシカ学派(紀元前600~100年頃)は、原子論の最も初期の形態のひとつを発展させた(ただ し、彼らの神についての証明と、意識が物質的なものではないという仮定は、彼らが唯物論者であるというレッテルを貼ることを排除している)。仏教の原子論 とジャイナ派は原子論の伝統を引き継いだ[要出典]。 レウシッポス、デモクリトス、エピクロスといった古代ギリシャの原子論者は、後の唯物論者を予見していた。ルクレティウス(紀元前99年~紀元前55年 頃)のラテン語詩『De Rerum Natura』は、デモクリトスとエピクロスの機械論的哲学を反映している。この考え方によれば、存在するものはすべて物質と空虚であり、すべての現象は 原子(文字通り「不可分なもの」)と呼ばれる基本的な物質粒子のさまざまな運動と凝集から生じる。De Rerum Natura』では、浸食、蒸発、風、音などの現象を機械論的に説明している。身体以外に身体に触れるものはない」といった有名な原理は、ルクレティウス の著作で初めて登場する。デモクリトスとエピクロスは一元論的存在論を支持せず、物質と空間の存在論的分離(すなわち空間は存在の「別の種類」である)を 支持した[要出典]。 共通時代初期 後のインドの唯物論者ジャヤラシ・バッタ(6世紀)は、その著作『タットヴォーパプラヴァーシムハ』(諸原理の動揺)の中で、ニャーヤ・スートラの認識論 に反論している。唯物論的なカーヴァーカ哲学は1400年以降に消滅したようであり、14世紀にマダヴァチャーリヤが『サルヴァ・ダルシャナ・サムグラ ハ』(Sarva-darśana-samgraha)を編纂した際には、カーヴァーカ(またはローカーヤタ)のテキストを引用したり参照したりすること はなかった[8]。 12世紀初頭のアル=アンダルスでは、アラビアの哲学者イブン・トゥファイル(別名アブバセル)が哲学小説『Hayy ibn Yaqdhan(Philosophus Autodidactus)』の中で唯物論を論じており、同時に歴史的唯物論を漠然と予見していた[9]。 近代哲学 トマス・ホッブズ(1588-1679)[10]とピエール・ガッサンディ(1592-1665)[11]は、自然科学に二元論的な基礎を与えようとした ルネ・デカルト(1596-1650)の試みに対抗する唯物論の伝統を代表する人物であった。その後、唯物論者であり無神論者であったジャン・メスリエ修 道院長(1664-1729)が、フランスの唯物論者たちとともに続いた: ジュリアン・オフレイ・ド・ラ・メトリ(Julien Offray de La Mettrie)、ドイツ系フランス人のドルバック男爵(Baron d'Holbach)(1723-1789)、ドゥニ・ディドロ(Denis Diderot)(1713-1784)、その他のフランス啓蒙思想家たちである。イギリスでは、ジョン・"ウォーキング"・スチュワート(1747- 1822)が物質には道徳的側面があると考え、ウィリアム・ワーズワース(1770-1850)の哲学詩に大きな影響を与えた。 近世後期の哲学では、ドイツの無神論的人間学者ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハが1841年に著した『キリスト教の本質』で唯物論に新たな転回を示した。 フォイエルバッハは、唯物論的人間学を普遍的な科学とみなす唯物論のバージョンである人間学的唯物論を導入した[12]。 フォイエルバッハの様々な唯物論はカール・マルクスに大きな影響を与え[13]、カール・マルクスは19世紀後半に、マルクスとフリードリヒ・エンゲルス が科学的社会主義として概説したものの基礎となる史的唯物論の概念を精緻化した: 歴史の唯物論的概念は、人間の生活を支える手段の生産と、生産に次いで生産されたものの交換が、すべての社会構造の基礎であるという命題から出発する。歴 史に現れたすべての社会において、富が分配され、社会が階級や秩序に分けられる方法は、何が生産され、それがどのように生産され、生産物がどのように交換 されるかに依存している。この観点からすれば、すべての社会的変化と政治革命の最終的な原因は、人間の頭脳にではなく、永遠の真理と正義に対する人間のよ り良い洞察にではなく、生産と交換の様式の変化に求められるべきである。それは哲学にではなく、それぞれの時代の経済学に求められるのである。 - フリードリヒ・エンゲルス『社会主義 科学的でユートピア的な社会主義 (1880) 自然弁証法』(1883年)を通じて、エンゲルスは後に「唯物弁証法的」な自然哲学を発展させ、ロシア・マルクス主義の父であるゲオルギー・プレハーノフ が弁証法的唯物論と呼んだ世界観を確立した[14]。20世紀初頭のロシア哲学において、ウラジーミル・レーニンは1909年の著書『唯物論と経験批判』 において弁証法的唯物論をさらに発展させ、対立する人々の政治的観念を彼らの反唯物論的哲学に結びつけた。 19世紀半ばに発展した、より自然主義志向の唯物論学派は、ルートヴィヒ・ビュヒナー(1824年-1899年)、オランダ生まれのヤコブ・モレショット (1822年-1893年)、カール・フォクト(1817年-1895年)を含むドイツの唯物論であった[15][16]。 現代史 以下も参照: 現代哲学 分析哲学 以下も参照: 物理主義、科学的唯物論 現代の分析哲学者(ダニエル・デネット、ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワイン、ドナルド・デイヴィッドソン、ジェリー・フォドーなど)は、広義の物理 主義または科学的唯物論の枠組みの中で活動しており、機能主義、異常一元論、同一性理論など、心をどのように収容するのが最善であるかについての対立する 説明を生み出している[18]。 科学的唯物論はしばしば還元的唯物論と同義であり、典型的には還元的唯物論として説明されてきた。21世紀初頭、ポールとパトリシア・チャーチランド [19][20]は、(少なくとも特定の仮説に関しては)根本的に対照的な立場である排除的唯物論を提唱した。消去的唯物論は、いくつかの心的現象は単に まったく存在せず、そのような現象の話は偽りの「民間心理学」や内観の錯覚を反映しているとする。この種の唯物論者は、「信念」のような概念には何の根拠 もないと考えるかもしれない(例えば、悪魔が原因の病気について民間科学が語るように)。 還元的唯物論(我々の理論は事実に還元される)と消去的唯物論(新たな事実に照らして、ある種の理論は消去される必要がある)の連続体の一方の端にあり、 修正的唯物論はその中間にある[18]。 大陸哲学 以下も参照: 思弁的唯物論と超越論的唯物論 現代の大陸哲学者であるジル・ドゥルーズは、古典的な唯物論の考え方を再構築し、強化することを試みている[21]。 マニュエル・デランダのような現代の理論家は、このように再活性化された唯物論に取り組んでおり、新唯物論者として分類されるようになっている[22]。 新唯物論は独自のサブフィールドとなっており、主要な大学ではそれに関する講座が開かれているほか、数多くの会議、編集されたコレクション、モノグラフが それに捧げられている。 ジェーン・ベネットの2010年の著書『Vibrant Matter』は、一元論的存在論と生命論の理論を、言語と言説のポスト構造主義的理論が支配する批判的な理論的枠組みに戻すことに特に貢献した [23]。メル・Y・チェンやザキヤ・イマン・ジャクソンといった学者たちは、このような新物質論的文献群を、特に人種とジェンダーの物質性を考慮するこ とを怠っていると批判している[24][25]。 メティスの学者であるゾーイ・トッドやモホーク族(ベア・クラン、シックス・ネーションズ)、アニシナベ族の学者であるヴァネッサ・ワッツ[26]は、 「新しい」唯物論のための人種の植民地的な方向性を問うている。 [28] Helene Vostersのような他の学者たちは彼らの懸念に共鳴し、先住民や他のアニミズム的存在論が何世紀にもわたって「物質の活力」とでも呼ぶべきものを証明 してきたように、「新物質論」について特に「新しい」ものがあるかどうか疑問視している[29]。 またThomas Nailのような他の学者たちは、「フラットな存在論」を非政治化し、非歴史的であるとして新物質論の「活力主義的」バージョンを批判している[30] [31]。 Quentin Meillassouxは、唯物論的な考えに基づいたデイヴィッド・ヒュームへのポスト・カント派の回帰である思弁的唯物論を提唱していた[32]。 物質 "の定義 科学や哲学における他の重要な概念と同様に、物質の性質と定義は多くの議論を引き起こしてきた。 すべてのものが単一種類の物質(hyle)でできているのか、それとも複数の種類があるのか。 物質は複数の形態を表現することができる連続的な物質(hylomorphism)[34]なのか、それとも多数の離散的で不変の構成要素 (atomism)[35]なのか。 物質には本質的な性質があるのか(物質論)[36]、あるいはないのか(プリマ・マテリア)。 有形の「もの」としての物質という従来の概念に対する一つの挑戦は、19世紀における場の物理学の台頭によってもたらされた。相対性理論は、物質とエネル ギー(場の空間的に分布したエネルギーを含む)が交換可能であることを示している。これにより、エネルギーは原始物質であり、物質はその形態のひとつであ るという存在論的な見方が可能になった。対照的に、素粒子物理学の標準モデルは、場の量子論を使ってすべての相互作用を記述している。この見解では、場は 原始物質であり、エネルギーは場の性質であると言える[要出典]。 支配的な宇宙論モデルであるラムダ-CDMモデルによれば、宇宙のエネルギー密度のうち、標準モデルが記述する「物質」で構成されているのは5%未満であ り、宇宙の大部分は暗黒物質と暗黒エネルギーで構成されているが、これらが何でできているかについては科学者の間でほとんど合意が得られていない [37]。 量子物理学の出現により、物質の概念が変わっただけだと考える科学者もいれば、従来の立場はもはや維持できないと考える科学者もいた。ヴェルナー・ハイゼ ンベルクは言った: 唯物論の存在論は、存在の種類、つまり私たちを取り巻く世界の直接的な『実在性』が、原子の範囲にまで外挿できるという幻想の上に成り立っていた。しか し、この外挿は不可能である...原子はモノではない」[38]。 物質の概念は、新たな科学的発見に応じて変化してきた。従って唯物論は、それが基づいている特定の物質理論とは無関係に、明確な内容を持たない。ノーム・ チョムスキーによれば、物質がその性質を持つように定義すれば、どのような性質も物質とみなすことができる[39]。 哲学的唯物論者のグスタボ・ブエノは物質よりも正確な用語である間質(stroma)を使用している[40]。 物理主義 主な記事 物理主義 ジョージ・スタックは唯物論と物理主義を区別している: 20世紀には、実証主義から物理主義が生まれた。物理主義は、意味のある記述を検証可能な、あるいは原理的に検証可能な物理的な身体や過程に限定する。そ れは、修正可能な経験的仮説であり、それゆえ古典的唯物論の独断的なスタンスを欠いている。ハーバート・ファイグルは米国で物理主義を擁護し、精神状態は 脳の状態であり、精神用語は物理用語と同じ参照語を持っていると一貫して主張した。20世紀には多くの唯物論的な精神論が登場し、それらを取り巻く多くの 議論があった[41]。 しかし、物理主義のすべての概念が意味の検証主義的理論や知覚の直接的実在論的説明と結びついているわけではない。むしろ、物理主義者は、世界の最善の記 述の数学的形式論から「現実の要素」が欠落することはないと信じている。「唯物論的」物理主義者はまた、形式論が無感覚の領域を記述していると信じてい る。言い換えれば、物理の本質的な性質は非経験的である。 宗教的・精神的見解 キリスト教 主な記事 唯物論とキリスト教 ヒンドゥー教と超越クラブ も参照: ヴァイシェシカ [アイコン]. このセクションは拡張が必要です。追加することで手助けができます。(2022年11月) ほとんどのヒンズー教徒や超越論者は、すべての物質は幻想、すなわちマーヤであり、人間を真実から見えなくしていると見なしている。ブラフマンの知覚のよ うな超越的な経験は、幻想を破壊すると考えられている[42]。 批判と代替案 現代の物理学者から マンハッタン計画で主要な役割を果たした物理学者ルドルフ・パイエルスは、唯物論を否定した。「知識や意識を含む人間の全機能を物理学的に記述できるとい う前提は成り立たない。まだ何かが欠けている」[43]。 エルヴィン・シュレーディンガーは「意識は物理学の用語では説明できない。意識は絶対的に根源的なものだからだ。意識は他の何ものかの観点から説明するこ とはできない」[44]。 ヴェルナー・ハイゼンベルクは、「唯物論の存在論は、存在の種類、つまり私たちを取り巻く世界の直接的な『実在性』が、原子の範囲にまで外挿できるという 幻想の上に成り立っていた。しかし、この外挿は不可能である。原子はモノではない」[45]。 量子力学 20世紀の物理学者(ユージン・ウィグナー[46]やヘンリー・スタップなど)や[47]、現代の物理学者や科学作家(スティーヴン・バー、[48]ポー ル・デイヴィス、ジョン・グリビンなど)は、量子力学やカオス理論といった物理学における最近のある発見によって、唯物論には欠陥があると主張している。 グリビンとデイヴィス(1991)によれば、次のようになる: その後、量子論が登場し、物質に対するイメージが一変した。原子の微視的な世界は、単に日常的な世界の縮小版であるという古い思い込みは捨て去られなけれ ばならなかった。ニュートンの決定論的な機械は、波動と粒子の影を帯びた逆説的な結合に取って代わられた。量子論の拡張はこれさえも超えている。固体の物 質が溶け出し、目に見えない場のエネルギーの奇妙な励起や振動に取って代わられるという絵を描いているのだ。量子物理学は唯物論を根底から覆すものであ り、それは物質が私たちが信じているよりもはるかに少ない「実体」しか持たないことを明らかにするからである。しかし、ニュートンの「物質は不活性な塊で ある」というイメージを打ち壊すことで、さらに別の展開がある。それが、最近広く注目されているカオス理論である。 - ポール・デイヴィスとジョン・グリビン『物質神話』第1章:"物質主義の死" デジタル物理学 デイヴィスとグリビンの異論は、物質ではなく情報を基本的なものとみなすデジタル物理学の支持者にも共通する。物理学者でデジタル物理学の提唱者である ジョン・アーチボルド・ウィーラーは、「すべての物質と物理的なすべてのものは情報理論的な起源であり、これは参加型の宇宙である」と書いている。彼はこ う書いている: 最も明晰な頭脳を持つ科学、つまり物質の研究に生涯を捧げてきた者として、原子に関する研究の結果として、私はこれだけは言える: 物質というものは存在しない。すべての物質は、原子の粒子を振動させ、原子という最も微細な太陽系をつなぎとめる力によってのみ発生し、存在する。この力 の背後には、意識的で知的なマインドが存在すると考えなければならない。このマインドこそが、すべての物質の母体なのである。 - マックス・プランク, Das Wesen der Materie (1944) ジェームス・ジーンズもプランクに同意し、「宇宙は偉大な機械というよりも、偉大な思考のように見え始める。心はもはや、物質の領域への偶然の侵入者には 見えない」[50]。 哲学的反論 イマヌエル・カントは『純粋理性批判』において、超越論的観念論を擁護するために唯物論に反論している(主観的観念論や心身二元論に対する反論も提供して いる)[51][52]が、カントは変化と時間には永続的な基体が必要だと主張している[53][54]。 ポストモダン/ポスト構造主義の思想家たちもまたあらゆる包括的な形而上学的スキームに対する懐疑を表明している。哲学者のメアリー・ミッドグリー [55]は、唯物論は少なくともその消去的な唯物論の形態においては、自己反駁的な思想であると主張している[56][57][58][59]。 観念論の多様性 ヘーゲルやバークレーのような観念論の主張は、しばしば唯物論に対する反論の形をとる。さて、物質は束理論におけるように冗長であると主張することがで き、心に依存しない性質は主観的知覚に還元することができる。バークレーは後者の例として、物質に関する直接的な証拠を集めることは不可能であることを指 摘している。なぜなら、物質に関する直接的な経験は存在しないからである。そのため、物質の存在は知覚の見かけ上の(知覚された)安定性から推測されるだ けであり、直接的な経験にはまったく証拠がない[60]。 物質とエネルギーが物理的世界を説明するためには必要であるが、心を説明することはできないと見なされれば、二元論が生じる。創発、ホリズム、プロセス哲 学は、唯物論を完全に放棄することなく、伝統的な(特に機械論的な)唯物論の欠点を改善しようとしている[要出典]。 方法論としての唯物論 物質が唯一の物質であるという存在論的な主張よりも、理論化に対する過度に懐疑的で狭い、あるいは還元主義的なアプローチの一部として唯物論に異議を唱え る批評家もいる。素粒子物理学者であり聖公会の神学者であるジョン・ポルキンホーンは、彼が約束的唯物論と呼ぶものに異議を唱えている-唯物論的科学は、 今のところ説明できていない現象を説明することにいずれ成功するだろうという主張である[61]。 科学的唯物論者の中には、物質の明確な定義を提供することができず、唯物論という用語が明確な意味を持たないままになっているという批判を受けている者も いる。ノーム・チョムスキーは、物質の概念は過去に起こったように新たな科学的発見によって影響を受ける可能性があるため、科学的唯物論者はその反対を仮 定することは独断的であると述べている[39]。 |

| Aleatory materialism Antimaterialism beliefs: Gnosticism Idealism Immaterialism Maya (religion) Mind–body dualism Platonic realism Supernaturalism Transcendentalism Cārvāka Christian materialism Critical realism Cultural materialism Dialectical materialism Economic materialism Existence French materialism Grotesque body Historical materialism Hyle Incorporeality Madhyamaka, a philosophy of Middle Way Marxist philosophy of nature Materialist feminism Metaphysical naturalism Model-dependent realism Naturalism (philosophy) Philosophical materialism Philosophy of mind Physicalism Postmaterialism Quantum energy Rational egoism Reality in Buddhism Scientistic materialism Substance theory Transcendence (religion) |

偶発的唯物論 反物質主義の信念 グノーシス主義 観念論 非物質主義 マヤ(宗教) 心身二元論 プラトン的実在論 超自然主義 超越論 カーヴァーカ キリスト教唯物論 批判的リアリズム 文化的唯物論 弁証法的唯物論 経済的唯物論 実存 フランス唯物論 グロテスクな身体 歴史的唯物論 ハイレ インコーポラリティ マディヤマカ、中道の哲学 マルクス主義の自然哲学 唯物論的フェミニズム 形而上学的自然主義 モデル依存実在論 自然主義(哲学) 哲学的唯物論 心の哲学 物理主義 ポスト唯物論 量子エネルギー 合理的エゴイズム 仏教における現実 科学的唯物論 物質理論 超越(宗教) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Materialism |

|

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆