ラ・メトリ『人間=機械論』ノート

L'homme machine revisited in post-modern era

ラ・メトリ『人間=機械論』ノート

L'homme machine revisited in post-modern era

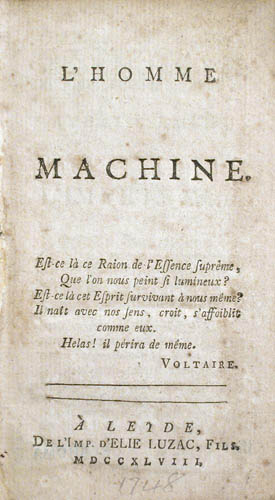

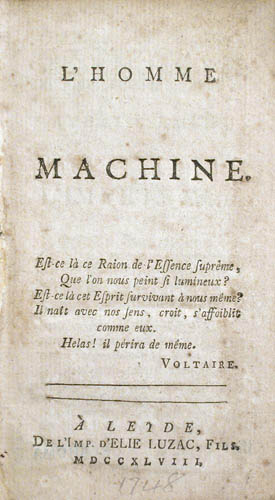

Page de titre de l'édition

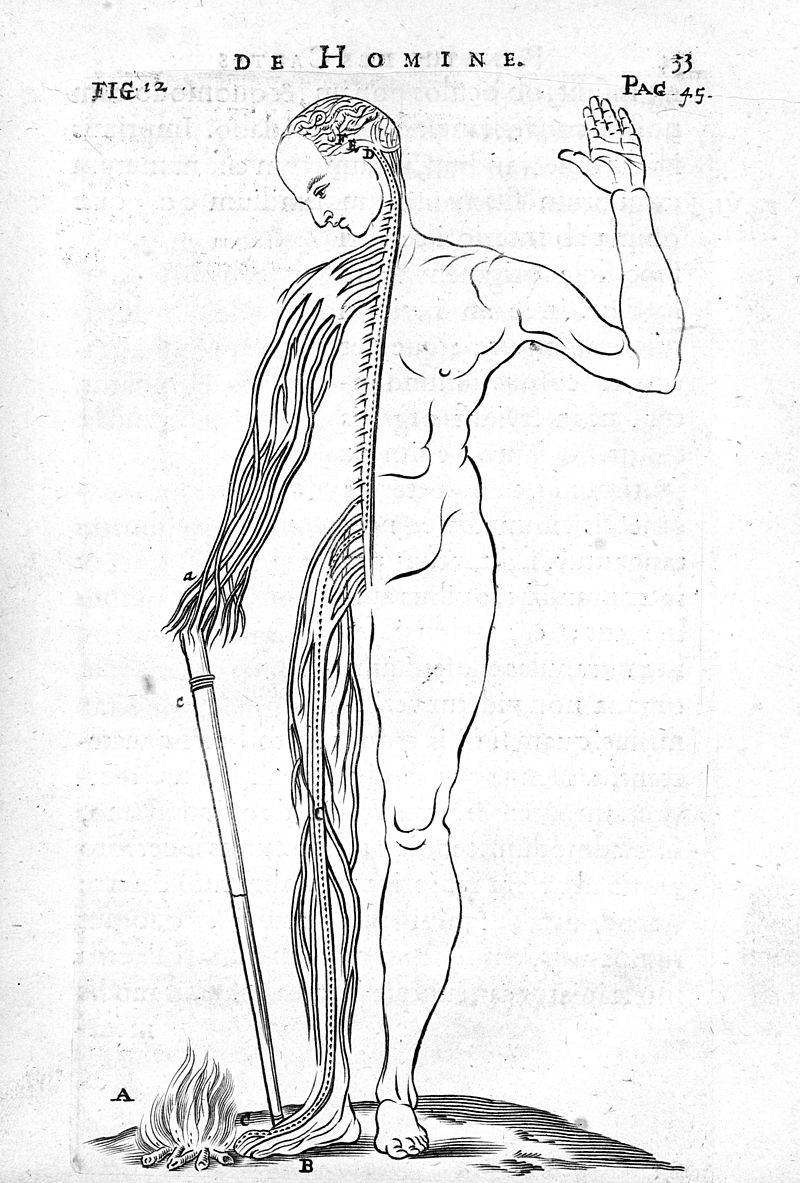

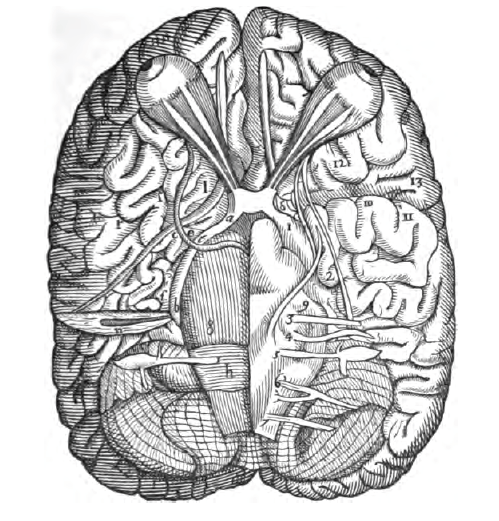

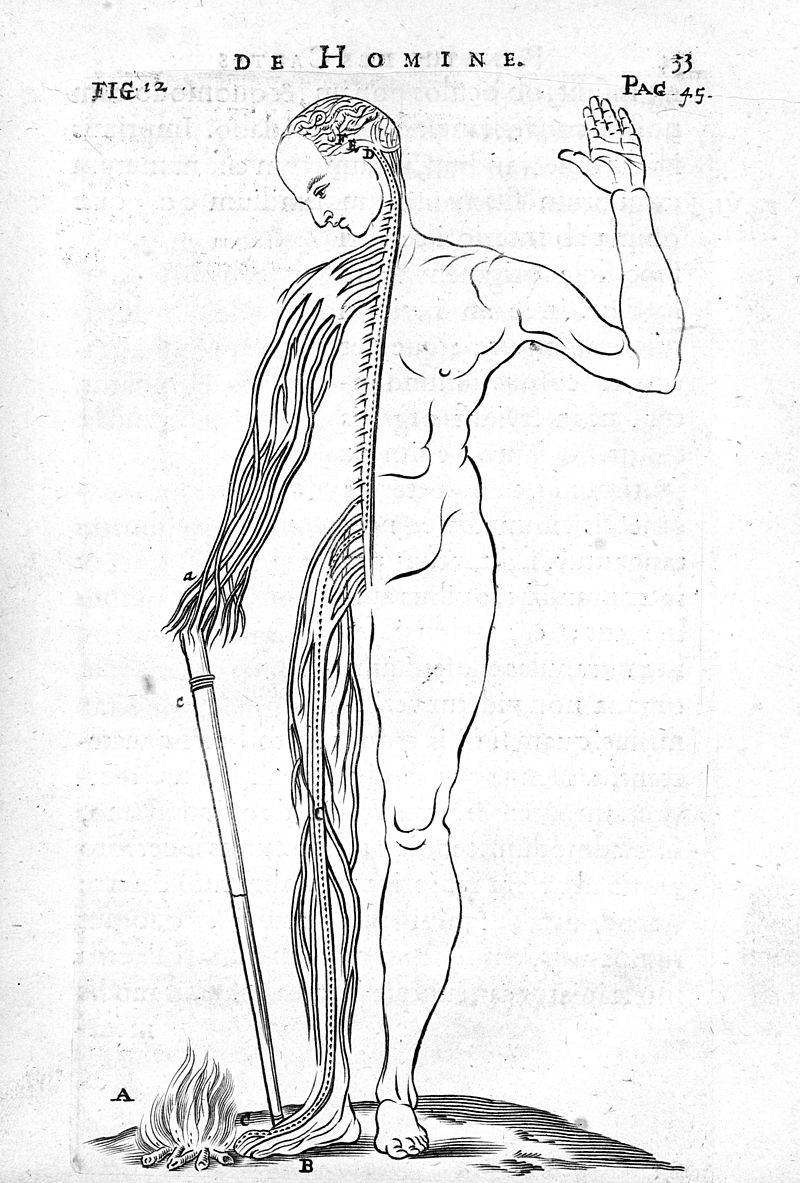

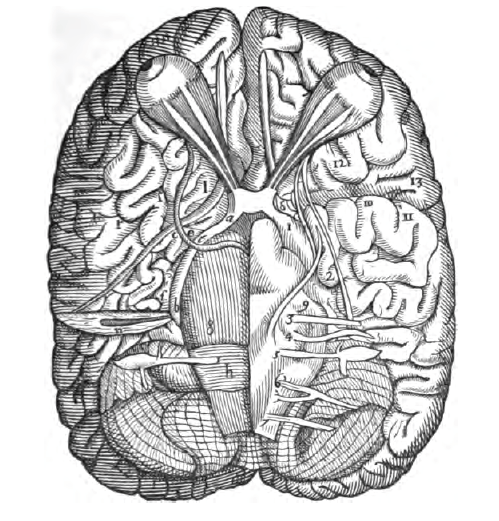

originale./La Mettrie/essin anatomique (1662) décrivant le système

nerveux./Dessin anatomique (1573) décrivant la morphologie du cerveau./

「人間は身体的感覚(sensibilité physique) によっていったん動き始めると,そのあらゆる行為を必然的に行っていく、ひとつの機械である」Claude Adrien Helvétius(1715-1771)

★英訳からの重訳テキストへのサイト内タグジャンプはこちら(オリジナルテキスト)L'homme machine (Man a Machine).(重訳『人間=機械論』)

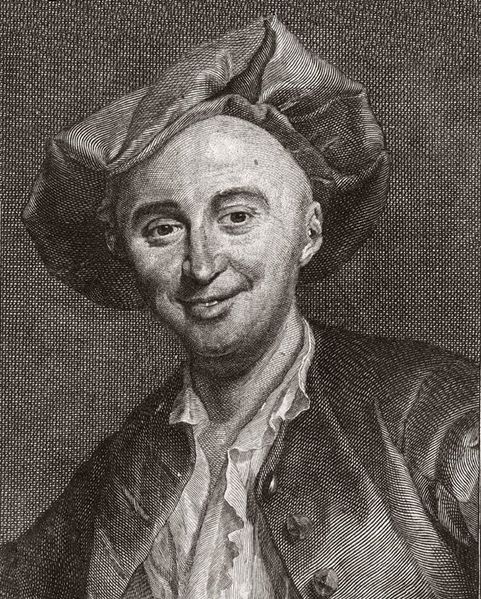

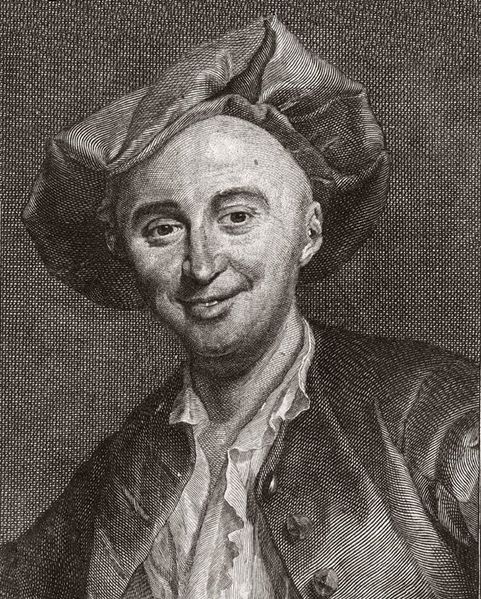

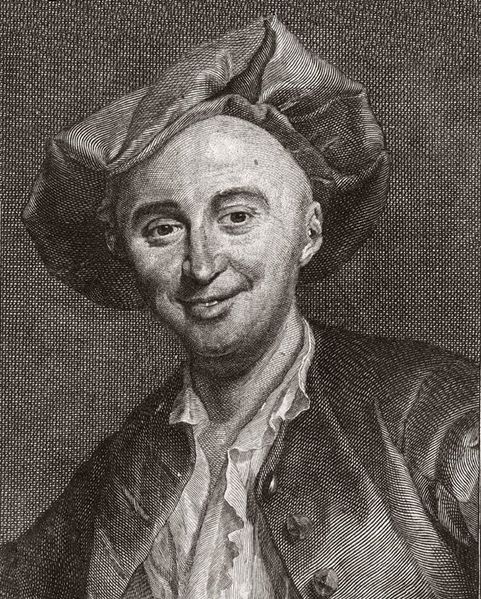

| Julien Offray de La

Mettrie (French: [ɔfʁɛ də la metʁi]; November 23, 1709[1] – November

11, 1751) was a French physician and philosopher, and one of the

earliest of the French materialists of the Enlightenment. He is best

known for his work L'homme machine (Man a Machine).[2] La Mettrie is most remembered for taking the position that humans are complex animals and no more have souls than other animals do. He considered that the mind is part of the body and that life should be lived so as to produce pleasure (hedonism). His views were so controversial that he had to flee France and settle in Berlin. |

ジュリアン・オフレイ・ド・ラ・メトリ(フランス語:[ɔfʁɛ,

1709[1] 11月23日 -

1751年11月11日)は、フランスの医師、哲学者で、啓蒙主義におけるフランスの最も早い唯物論者の一人であった。著書『機械としての人間』

(L'homme machine)が最もよく知られている[2]。 ラ・メトリは、人間は複雑な動物であり、他の動物と同様に魂を持っていないとする立場をとったことで最もよく知られている。彼は、心は身体の一部であり、 人生は快楽を生み出すように生きるべきであると考えた(快楽主義)。そのため、彼はフランスを脱出し、ベルリンに移住した。 |

| La Mettrie was born at

Saint-Malo in Brittany on November 23, 1709, and was the son of a

prosperous textile merchant. His initial schooling took place in the

colleges of Coutances and Caen. After attending the Collège du Plessis

in Paris, he seemed to have acquired a vocational interest in becoming

a clergyman, but after studying theology in the Jansenist schools for

some years, his interests turned away from the Church. In 1725, La

Mettrie entered the College d'Harcourt to study philosophy and natural

science, probably graduating around 1728. At this time, D'Harcourt was

pioneering the teaching of Cartesianism in France.[3] In 1734, he went

on to study under Hermann Boerhaave, a renowned physician who,

similarly, had originally intended on becoming a clergyman. It was

under Boerhaave that La Mettrie was influenced to try to bring changes

to medical education in France.[4] |

ラ・メトリは、1709年11月23日、ブルターニュのサン・マロで、

繊維商として栄えた息子のもとに生まれた。初めはクタンスとカーンのカレッジで教育を受けた。パリのコレージュ・デュ・プレシに入学し、聖職者になること

を志したようだが、数年間ヤンセニスト派の学校で神学を学んだ後、その関心は教会から遠のいた。1725年、ラ・メトリはダルクール大学に入学し、哲学と

自然科学を学び、おそらく1728年頃に卒業した。1734年、高名な医師であったヘルマン・ボエルハーヴェに師事するが、彼もまた元々は聖職者になるつ

もりであった。ボエルハーヴェのもとで、ラ・メトリはフランスの医学教育に変化をもたらそうとする影響を受けた[4]。 |

| Medical career After his studies at D'Harcourt, La Mettrie decided to take up the profession of medicine. A friend of the La Mettrie family, François-Joseph Hunauld, who was about to take the chair of anatomy at the Jardin du Roi, seems to have influenced him in this decision. For five years, La Mettrie studied at faculty of medicine in Paris, and enjoyed the mentorship of Hunauld.[3] In 1733, however, he departed for Leiden to study under the famous Herman Boerhaave. His stay in Holland proved to be short but influential. In the following years, La Mettrie settled down to professional medical practice in his home region of Saint-Malo, disseminating the works and theories of Boerhaave through the publication and translation of several works. He married in 1739 but the marriage, which produced two children, proved an unhappy one. In 1742 La Mettrie left his family and travelled to Paris, where he obtained the appointment of surgeon to the Gardes Françaises regiment, taking part in several battles during the War of the Austrian Succession. This experience would instill in him a deep aversion to violence which is evident in his philosophical writings. Much of his time, however, was spent in Paris, and it is likely that during this time he made the acquaintance of Maupertuis and the Marquise de Châtelet.[3] |

医学の道へ ダルクールで学んだ後、ラ・メトリは医学の道に進むことを決意する。この決断は、ラ・メトリ家の友人で、ジャルダン・デュ・ロワの解剖学教授に就任しよう としていたフランソワ=ジョゼフ・ユノーの影響によるものであったようだ。ラ・メトリは5年間、パリの医学部で学び、ユノルドの指導を受けることになる [3]。 しかし、1733年、有名なヘルマン・ボアハーヴェに師事するため、ライデンに向けて出発した。オランダでの滞在は短期間であったが、大きな影響を与え た。その後、ラ・メトリは故郷のサン・マロで開業し、いくつかの著作の出版や翻訳を通じて、ボエルハーヴェの著作や理論を広めた。1739年に結婚した が、2人の子供をもうけ、不幸な結婚生活となった。1742年、ラ・メトリは家族を残してパリに渡り、ガール・フランセーズ連隊の外科医に任命され、オー ストリア継承戦争でいくつかの戦いに参加した。この経験は、彼に暴力に対する深い嫌悪感を植え付け、彼の哲学的な著作の中にも表れている。しかし、多くの 時間はパリで過ごし、その間にモーペルテュイやシャトレ侯爵夫人と知り合ったようである[3]。 |

| It was in these years, during an

attack of fever, that he made observations on himself with reference to

the action of quickened blood circulation upon thought, which led him

to the conclusion that mental processes were to be accounted for as the

effects of organic changes in the brain and nervous system. This

conclusion he worked out in his earliest philosophical work, the

Histoire naturelle de l'âme (1745). So great was the outcry caused by

its publication that La Mettrie was forced to quit his position with

the French Guards, taking refuge in Leiden. There he developed his

doctrines still more boldly and completely in L'Homme machine, a

hastily written treatise based upon consistently materialistic and

quasi-atheistic principles.[3] La Mettrie's materialism was in many

ways the product of his medical concerns, drawing on the work of

17th-century predecessors such as the Epicurean physician Guillaume

Lamy.[5] The ethical implications of these principles would later be worked out in his Discours sur le bonheur; La Mettrie considered it his magnum opus.[6] Here he developed his theory of remorse, i.e. his view about the inauspicious effects of the feelings of guilt acquired at early age during the process of enculturation. This was the idea which brought him the enmity of virtually all thinkers of the French Enlightenment, and a damnatio memoriae[7] which was lifted only a century later by Friedrich Albert Lange in his Geschichte des Materialismus. |

この頃、熱病にかかった彼は、血液循環の促進が思考に及ぼす影響につい

て自分自身を観察し、その結果、精神のプロセスは脳と神経系における有機的変化の影響として説明されるべきであるという結論に至ったのである。この結論

は、彼の最も初期の哲学的著作である「Histoire naturelle de

l'âme」(1745)に結実した。この著作が出版されると大きな反響を呼び、ラ・メトリはフランス衛兵の職を辞してライデンに避難することを余儀なく

された。ラ・メトリの唯物論は、エピキュリアン派の医師ギヨーム・ラミーなどの17世紀の先達の仕事を参考にして、多くの点で彼の医学的関心から生まれた

ものであった[5]。 これらの原則の倫理的な意味合いは後に『Discours sur le bonheur』としてまとめられ、ラ・メトリはこれを自分の最高傑作と考えた[6]。ここで彼は反省の理論、つまり幼い頃に文化的な過程で身につけた罪 悪感の不吉な効果に関する彼の見解を展開した。これは、フランス啓蒙主義のほぼすべての思想家から敵視され、1世紀後にフリードリヒ・アルベルト・ランゲ が『唯物論の歴史』で持ち上げたdamnatio memoriae[7]となった思想である。 |

| Philosophy Julien de La Mettrie is considered one of the most influential determinists of the eighteenth century. He believed that mental processes were caused by the body. He expressed these thoughts in his most important work Man a Machine. There he also expressed his belief that humans worked like a machine. This theory can be considered to build off the work of Descartes and his approach to the human body working as a machine.[8] La Mettrie believed that man, body and mind, worked like a machine. Although he helped further Descartes' view of mechanization in explaining human bodily behavior, he argued against Descartes' dualistic view on the mind. His opinions were so strong that he stated that Descartes was actually a materialist in regards to the mind.[9] The philosopher David Skrbina considers La Mettrie an adherent of "vitalistic materialism": [10] To him, mind was a very real entity, and clearly it was embedded in a material cosmos. An obvious solution, therefore, was to see matter itself as inherently dynamic, capable of feeling, even intelligent. Motion and mind derive from some inherent powers of life or sentience that dwell in matter itself or in the organizational properties of matter. That view, sometimes called vitalistic materialism, is the one that LaMettrie—and later Diderot—adopted. Commentators often portray LaMettrie as a mechanist because it is assumed that anyone who denies the spiritual realm must see all things, and in particular all living things, as products of dead matter. It is quite common, even today, to equate materialism with mechanism. But, as has been noted, the two are logically independent. ...Though he obviously adopted the term ‘machine’ in his L’Homme Machine, it was in a specifically vitalistic sense. |

哲学 ジュリアン・ド・ラ・メトリは、18世紀において最も影響力のある決定論者の一人と考えられている。彼は、精神的なプロセスは身体によって引き起こされる と考えた。彼はこの考えを彼の最も重要な作品『機械としての人間』で表現した。そこでは、人間は機械のように働くという信念も表明している。この理論はデ カルトの仕事と、人間の体が機械のように働くという彼のアプローチを土台にしていると考えることができます[8]。ラ・メトリは人間、身体と精神が機械の ように働くと信じていたのです。彼は人間の身体的行動を説明する上でデカルトの機械化という見方をさらに後押ししたが、心についてはデカルトの二元論的な 見方に反論していた。彼の意見は非常に強く、デカルトは心に関して実は唯物論者であると述べている[9]。 哲学者のデヴィッド・スクルビナはラ・メトリを「生命論的唯物論」の信奉者とみなしている[10]。[10] 彼にとって、心は非常に現実的な存在であり、明らかに物質的な宇宙の中に埋め込まれているものであった。従って、明白な解決策は、物質そのものを本質的に 動的であり、感情を持ち、知性を持つことができると見なすことであった。運動と心は、物質そのもの、あるいは物質の組織的性質に宿る、生命や感覚を持つ固 有の力 に由来する。このような考え方は、活力的唯物論と呼ばれることもあり、ラメットリや後にディドロが採用した考え方である。ラメットリーを機械論者と呼ぶ論 者が多いのは、霊的領域を否定する者は、万物、特に生物を死んだ物質の産物と見なすに違いないと思われているからである。今日でも、唯物論と機械論を同一 視することはよくあることである。しかし、すでに述べたように、この2つは論理的に独立したものである。...彼は『人間機械』の中で明らかに「機械」と いう言葉を採用したが、それは特に生命論的な意味においてであった。 |

| Man and the animal Prior to Man a Machine he published The Natural History of the Soul in 1745. He argued that humans were just complex animals.[9] A great deal of controversy emerged due to his belief that "from animals to man there is no abrupt transition".[11] He later built on that idea: he claimed that humans and animals were composed of organized matter. He believed that humans and animals were only different in regards to the complexity that matter was organized. He compared the differences between man and animal to those of high quality pendulum clocks and watches stating: "[Man] is to the ape, and to the most intelligent animals, as the planetary pendulum of Huygens is to a watch of Julien Le Roy".[11] The idea that essentially no real difference between humans and animals existed was based on his findings that sensory feelings were present in animals and plants.[12] While he did recognize that only humans spoke a language, he thought that animals were capable of learning a language. He used apes as an example, stating that if they were trained they would be "perfect [men]".[8] He further expressed his ideas that man was not very different from animals by suggesting that we learn through imitation as do animals. His beliefs about humans and animals were based on two types of continuity. The first being weak continuity, suggesting that humans and animals are made of the same things but are organized differently. His main emphasis however was on strong continuity, the idea that the psychology and behavior between humans and animals was not all that different. |

人間と動物 人間という機械』に先立ち、彼は1745年に『魂の博物誌』を出版した。彼は人間は複雑な動物に過ぎないと主張した[9]。「動物から人間への急激な移行 はない」という彼の信念のために多くの論争が生まれた[11]。彼は後にその考えを基に、人間と動物が組織的な物質で構成されていると主張した。彼は人間 と動物が異なるのは、物質が組織化されている複雑さに関してだけであると考えた。彼は人間と動物の違いを高級な振り子時計や腕時計に例えて、次のように述 べた。人間と動物の違いを高級な振り子時計や腕時計に例えて、「人間は猿にとって、そして最も知的な動物にとって、ホイヘンスの惑星の振り子がジュリア ン・ル・ロワの時計にとってそうであるように」[11]と述べている。人間と動物の間に本質的に本当の違いは存在しないという考えは、動物や植物に感覚的 感情が存在しているという彼の発見に基づいている[12]。彼は人間だけが言語を話すことを認識していたが、動物は言語を学習する能力があると考えたので あった。彼は猿を例にして、もし彼らが訓練されれば「完璧な(人間)」になると述べている[8]。さらに彼は、人間が動物と同じように模倣によって学ぶこ とを示唆して、人間が動物とあまり違わないという彼の考えを表現している。 人間と動物に関する彼の信念は2種類の連続性に基づいていた。一つは弱い連続性で、人間と動物は同じものからできているが、異なる組織であることを示唆し ている。しかし、彼が最も重視したのは強い連続性で、人間と動物の間の心理や行動はそれほど違わないという考えであった。 |

| Man a machine La Mettrie believed that man worked like a machine due to mental thoughts depending on bodily actions. He then argued that the organization of matter at a high and complex level resulted in human thought. He did not believe in the existence of God. He rather chose to argue that the organization of humans was done to provide the best use of complex matter as possible.[9] La Mettrie arrived at this belief after finding that his bodily and mental illnesses were associated with each other. After gathering enough evidence, in medical and psychological fields, he published the book.[13] Some of the evidence La Mettrie presented was disregarded due to the nature of it. He argued that events such as a beheaded chicken running around, or a recently removed heart of an animal still working, proved the connection between the brain and the body. While theories did build off La Mettrie's, his works were not necessarily scientific. Rather, his writings were controversial and defiant.[14] |

機械としての人間 ラ・メトリは、人間は精神的思考が身体的行為に依存するため、機械のように働くと考えた。そして、物質が高度で複雑なレベルで組織化された結果、人間の思 考が生まれたと主張した。彼は、神の存在を信じていなかった。むしろ彼は、人間の組織は複雑な物質をできるだけ有効に利用するために行われたと主張するこ とを選んだのである[9]。 ラ・メトリは自分の身体的な病気と精神的な病気が互いに関連していることを発見した後に、この信念に至った。医学と心理学の分野で十分な証拠を集めた後、 彼はこの本を出版した[13]。 ラ・メトリが提示した証拠の中には、その性質上、無視されるものもあった。彼は、首を切られた鶏が走り回ったり、最近摘出された動物の心臓がまだ動いてい たりするような出来事は、脳と身体の間のつながりを証明するものであると主張した。ラ・メトリーの理論が発展したとはいえ、彼の著作は必ずしも科学的とは いえない。むしろ、彼の著作は論争的であり、反抗的であった[14]。 |

| Human nature He further expressed his radical beliefs by asserting himself as a determinist, dismissing the use of judges.[8] He disagreed with Christian beliefs and emphasized the importance of going after sensual pleasure, a hedonistic approach to human behavior.[12] He further looked at human behavior by questioning the belief that humans have a higher sense of morality than animals. He noted that animals rarely tortured each other and argued that some animals were capable of some level of morality. He believed that as machines, humans would follow the law of nature and ignore their own interests for those of others.[9] |

人間性 彼はさらに、決定論者であることを主張し、裁判官の使用を否定することで、彼の過激な信念を表現した[8]。 彼はキリスト教の信念に同意せず、人間の行動に対する快楽主義的アプローチである、感覚的快楽を求めることの重要性を強調した[12]。 彼はさらに、人間が動物よりも道徳心が高いという信念に疑問を呈することで人間の行動に目を向けていた。彼は動物がお互いに拷問することはほとんどないこ とに注目し、一部の動物はある程度の道徳を持つことができると主張した。彼は機械として人間は自然の法則に従い、他人のために自分の利益を無視すると信じ ていた[9]。 |

| Influence La Mettrie most directly influenced Pierre Jean Georges Cabanis, a prominent French physician. He worked off La Mettrie's materialistic views but modified them in order to be not as extreme. La Mettrie's extreme beliefs were rejected strongly, but his work did help influence psychology, specifically behaviorism. His influence is seen in the reductionist approach of behavioral psychologists.[12] However, the backlash he received was so strong that many behaviorists knew very little to nothing about La Mettrie and rather built off other materialists with similar arguments.[9] |

影響力 ラ・メトリが最も直接的に影響を受けたのは、フランスの著名な医師であるピエール・ジャン・ジョルジュ・カバニスである。彼はラ・メトリーの唯物論的見解 を参考にしながらも、極端でないように修正した。ラ・メトリの極端な信念は強く否定されたが、彼の仕事は心理学、特に行動主義に影響を与えるのに役立っ た。しかし、彼が受けた反発は非常に強く、多くの行動主義者はラ・メトリについてほとんど何も知らず、むしろ同様の主張を持つ他の唯物論者から構築してい た[9]。 |

| Journey to Prussia La Mettrie's hedonistic and materialistic principles caused outrage even in the relatively tolerant Netherlands. So strong was the feeling against him that in 1748 he was compelled to leave for Berlin, where, thanks in part to the offices of Maupertuis, the Prussian king Frederick the Great not only allowed him to practice as a physician, but appointed him court reader. There La Mettrie wrote the Discours sur le bonheur (1748), which appalled leading Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire, Diderot and D'Holbach due to its explicitly hedonistic sensualist principles which prioritised the unbridled pursuit of pleasure above all other things.[5] |

プロイセンへの旅 ラ・メトリの快楽主義、唯物論は、比較的寛容なオランダでさえも激怒させた。プロイセン王フリードリヒ大王は、マウペルトゥイの働きかけもあって、ラ・メ トリの医師としての活動を許可しただけでなく、宮廷読書人に任命したのである。そこでラ・メトリは『享楽についての論考』(1748年)を書いたが、この 論考は、他のすべてのものよりも快楽の無制限な追求を優先するという、明らかに快楽主義的な官能主義によって、ヴォルテール、ディドロ、ドルバックといっ た啓蒙主義の主要思想家を愕然とさせた[5]。 |

| Death La Mettrie's celebration of sensual pleasure was said to have resulted in his early death. The French ambassador to Prussia, Tyrconnel, grateful to La Mettrie for curing him of an illness, held a feast in his honour. It was claimed that La Mettrie wanted to show either his power of gluttony or his strong constitution by devouring a large quantity of pâté de faisan aux truffes. As a result, he developed a gastric illness of some sort. Soon after he began suffering from a severe fever and eventually died.[3][8] Frederick the Great gave the funeral oration, which remains the major biographical source on La Mettrie's life. He declared: "La Mettrie died in the house of Milord Tirconnel, the French plenipotentiary, whom he had restored to life. It seems that the disease, knowing with whom it had to deal, was cunning enough to attack him first by the brain, in order to destroy him the more surely. A violent fever with fierce delirium came on. The invalid was obliged to have recourse to the science of his colleagues, but he failed to find the succor that his own skill had so often afforded as well to himself as to the public".[1]" Frederick further described him as a good devil and medic but a very bad author.[15] He was survived by his wife and a 5-year-old daughter. La Mettrie's collected Œuvres philosophiques appeared after his death in several editions, published in London, Berlin and Amsterdam. |

死 ラ・メトリは、官能的な快楽を謳歌した結果、早世したと言われている。プロイセン駐在のフランス大使ティルコネルは、ラ・メトリの病気が治ったことに感謝 し、彼のために祝宴を催した。その際、ラ・メトリは自分の大食漢ぶりと強靭な体質を示すために、大量のパテ・ド・ファイザン・オ・トリュフを食べたと言わ れている。その結果、彼は胃の病気のようなものを患ってしまった。間もなく激しい発熱に見舞われ、やがて死亡した[3][8]。 フリードリヒ大王は、ラ・メトリの生涯に関する主要な伝記資料である葬儀の演説を行った。彼はこう宣言した。「ラ・メトリは、彼が生き返らせたフランス全 権大使のティルコネル卿の家で死んだ。病気は相手をよく知っていて、より確実に彼を破壊するために、まず脳を攻撃するほど狡猾であったようだ。そして、激 しい発熱と譫妄(せんもう)が起こった。病人は同僚の科学に頼らざるを得なかったが、自分の腕前が一般人と同様に自分にもたらしてくれた救いを見つけるこ とができなかった」[1]。フレデリックはさらに、彼を「良い悪魔であり医者であったが、非常に悪い作家であった」と評している[15]。 彼は妻と5歳の娘に先立たれた。 ラ・メトリの『哲学的作品集』は、彼の死後、ロンドン、ベルリン、アムステルダムで出版され、いくつかの版が出ている。 |

| This article incorporates text

from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed.

(1911). "Lamettrie, Julien Offray de". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16

(11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–130. |

|

| Selected works Histoire Naturelle de l'Âme. 1745 (anon.) École de la Volupté. 1746, 1747 (anon.) Politique du Médecin de Machiavel. 1746 (anon.) L'Homme Machine. 1748 (anon.) L'Homme Plante. 1748 (anon.) Ouvrage de Pénélope ou Machiavel en Médecine. 1748 (pseudonym: Aletheius Demetrius) Discours sur le bonheur ou Anti-Sénèque [Traité de la vie heureuse, par Sénèque, avec un Discours du traducteur sur le même sujet]. 1748 (anon.) L'Homme plus que Machine. 1748 (anon.) Système d'Épicure. 1750 (anon.) L'Art de Jouir. 1751 (anon.) |

|

| Collected works Œuvres philosophiques, 2 vols., Paris: Fayard 1984, 1987 ISBN 2-213-01839-1; ISBN 978-2-213-01983-3 [vol. 3] Ouvrage de Pénélope ou Machiavel en Médecine, Paris: Fayard 2002 ISBN 2-213-61448-2 Œuvres philosophiques, 1 vol., Paris: Coda 2004 ISBN 2-84967-002-2 |

|

| Critical editions of his major

works Aram Vartanian (ed.): La Mettrie's L'homme machine. A Study in the Origins of an Idea, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1960) John F. Falvey (ed.): La Mettrie. Discours sur le bonheur in Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century, vol. cxxxiv (Banbury, Oxfordshire: The Voltaire Foundation, 1975) Ann Thomson (ed.): La Mettrie's Discours préliminaire. in Materialism and Society in the Mid-Eighteenth Century (Genève: Librairie Droz, 1981) Théo Verbeek (Ed.): Le Traité de l'Ame de La Mettrie, 2 vols. (Utrecht: OMI-Grafisch Bedrijf, 1988) |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julien_Offray_de_La_Mettrie |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

★『人間=機械論』は、自由主義の医師兼哲学者Julien Offray de La Mettrie(1709-1751)が1748年にライデンで出版した作品である

| L'Homme Machine est

un ouvrage du médecin-philosophe libertin Julien Offray de La Mettrie

(1709-1751) paru en 1748 à Leyde1. Inspiré par le concept d'"animal-machine" formulé un siècle plus tôt par René Descartes dans son Discours de la Méthode, La Mettrie s'inscrit ici dans le mécanisme, courant philosophique qui aborde l'ensemble des phénomènes physiques suivant le modèle des liens de cause à effet (déterminisme) et plus largement une éthique radicalement matérialiste2. C'est par ce livre qu'il s'est fait connaître dans l’histoire de la philosophie, ne serait-ce que par son titre évocateur. |

『人間=機械論』は、自由主義の医師兼哲学者Julien

Offray de La Mettrie(1709-1751)が1748年にライデンで出版した作品である1。 ルネ・デカルトが1世紀前に『方法論序説』で打ち立てた「動物-機械」の概念に触発されたラ・メトリの作品は、あらゆる物理現象を原因と結果のモデル(決 定論)に従ってアプローチする哲学的傾向、より広くは根本的に物質主義の倫理観を持つメカニズムの一部である2。 彼が哲学史に名を残すことになったのは、この本を通じてであり、その刺激的なタイトルからしても、である。 |

| Un scientifique plus qu'un

philosophe Des recherches constituent pour La Mettrie un matériau plus précieux que les écrits de n'importe quel philosophe, Descartes compris, qui sont trop spéculatifs à ses yeux3. |

哲学者というより科学者 ラ・メトリーにとって、研究は、デカルトを含むどの哲学者の著作よりも貴重な材料であり、彼の目にはあまりにも思弁的に映るのである3。 |

| Positionnement philosophique Partant de ses connaissances en physiologie, que ne possèdent pas les philosophes, La Mettrie considère que, comme par le passé, les philosophes se trompent quand ils dissertent sur l’Homme. Les spéculations théoriques sont à ses yeux sans intérêt, seule en revanche la méthode empirique lui paraît légitime. Bien qu'inspiré par Descartes en tant qu'initiateur du mécanisme, et dès 1745, La Mettrie rejette « cet absurde système (...) que les bêtes sont de pures machines4. ». La Mettrie rejette vigoureusement toute forme de dualisme au profit du monisme. En d'autres termes, il rejette toute idée de Dieu, même celle des panthéistes, qui voient Dieu dans la nature, comme encore Voltaire, des années plus tard, y recherchera « le grand horloger ». Ses positions sont sans ambiguïté matérialistes : |

哲学的な立場 ラ・メトリは、哲学者が持っていない生理学の知識に基づいて、過去にそうであったように、哲学者が人間を論じるとき、間違っていると考えるのである。理論 的な思索には興味がなく、経験的な方法のみが正当であると考えたのだ。 メカニズムの創始者であるデカルトに触発され、1745年の時点で、ラ・メトリは「獣は純粋な機械であるというこの不条理なシステム(...)」を否定し ている4 。 4 ラ・メトリは、あらゆる二元論を徹底的に否定し、一元論を支持した。つまり、ヴォルテールが数年後に「偉大なる時計職人」を探すように、自然の中に神を見 出す汎神論者の考えさえも否定しているのである。 彼の立場は紛れもなく唯物論者である。 |

| « Qui sait si la raison de

l'existence de l'homme ne serait pas dans son existence même ?

Peut-être a-t-il été jeté au hasard sur la surface de la Terre [...]

semblable à ces champignons qui paraissent d'un jour à l'autre, ou à

ces fleurs qui bordent les fossés et couvrent les murailles.5 » |

【引用】「人間の存在理由は、その存在そのものにあるのではないのか

"と、誰にわかるだろう。おそらく、彼は地球の表面に無造作に投げ出されたのだろう[...]。ある日突然現れるキノコや、溝に沿って壁を覆う花のよう

に」5。 |

| Selon lui, c'est à tort que «

nous imaginons ou plutôt nous supposons une cause supérieure ». |

彼によると、「より高い原因を想像するというか、想定する」ことが間違

いなのだそうだ。 |

| « Concluons donc hardiment que

l'homme est une machine et qu'il n'y a dans tout l'Univers qu'une seule

substance. Ce n'est point ici une hypothèse [...], l'ouvrage de préjugé

ou de ma raison seule. [...] mais [...] le raisonnement le plus

vigoureux [...] à la suite d'une multitude d'observations physiques

qu'aucun savant ne contestera6. » |

"したがって、人間は機械であり、全宇宙にたった一つの物質しか存在し

ないと大胆に結論づけよう。これは仮説[...]でも、偏見や私の理性だけの仕事でもない。[しかし、[...]最も精力的な推論は、[...]どの科学

者も異議を唱えない多数の物理的観察に従ったものである6。 |

| Postérité Dès le xixe siècle, dans son Histoire du matérialisme, l'historien allemand Friedrich-Albert Lange compare La Mettrie à Copernic et Galilée : de même que ces derniers ont autrefois développé une image du cosmos dégagée de toute emprise religieuse, La Mettrie a traité la question de la conscience en dehors de toute considération métaphysique7. Les théories de La Mettrie anticipent les recherches en sciences cognitives et en neurobiologie, à la fin du xxe siècle8. De fait, en 1983, dans leurs livres respectifs, Le Cerveau Machine et L'Homme neuronal, le médecin Marc Jeannerod et le neurobiologiste Jean-Pierre Changeux font état de leur dette intellectuelle à l'égard de La Mettrie 9 Et en 2013, le philosophe Yves Charles Zarka estime que le livre préfigure non seulement les techniques d'interactions homme-machine, qui se mettent en place à la fin du xxe siècle, mais la théorie de l'homme augmenté du transhumanisme10. |

後世の人々 19世紀には、ドイツの歴史家ランゲが『唯物論史』のなかで、ラ・メトリをコペルニクスやガリレオと比較している。後者がかつて宗教の影響を排除した宇宙 像を構築したように、ラ・メトリは形而上学的考察なしに意識の問題を扱った7。 ラ・メトリの理論は、20世紀末の認知科学や神経生物学の研究を先取りしたものである8。 実際、1983年、医師のマルク・ジャンヌローと神経生物学者のジャン・ピエール・シャングーは、それぞれの著書『神経機械』と『神経人間』の中で、ラ・ メトリーへの知的負託を表明している9。 そして2013年、哲学者のイヴ・シャルル・ザルカは、本書が20世紀末に整備されつつあるマンマシンインタラクションの技術だけでなく、トランスヒュー マニズムのオーグメント・マン理論をも予見していると考えている10。 |

| https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%27Homme_Machine. |

|

| Yves Charles Zarka, né le 14

mars 1950, est philosophe, professeur émérite à l'université de Paris

(Sorbonne). Il est global professor à l'université de Pékin et enseigne

à l'université Ca' Foscari de Venise, à l'université La Sapienza de

Rome. Il est fondateur et directeur de la revue Cités (PUF). Il a été directeur de recherche au CNRS, où il dirigeait le Centre d’histoire de la philosophie moderne et le Centre Thomas-Hobbes. Il a dirigé le centre PHILéPOL (philosophie, épistémologie et politique) de l'université Paris au sein duquel les recherches s'organisent sur le concept de « monde émergent ». Ses recherches portent sur la démocratie, les nouveaux enjeux environnementaux, la nouvelle configuration du pouvoir au niveau mondial, le cosmopolitisme et la tolérance. |

イヴ・シャルル・ザルカは1950年3月14日生まれ。哲学者、パリ大

学(ソルボンヌ大学)名誉教授。北京大学グローバル教授、ベネチアのカ・フォスカリ大学、ローマのラ・サピエンツァ大学で教鞭をとる。雑誌『Cités』

(PUF)の創刊者であり、ディレクター。 CNRSでは、近代哲学史研究センターとトーマス・ホッブズ研究センターの研究部長を務めた。パリ大学のPHILéPOLセンター(哲学、認識論、政治 学)を指揮し、「新興世界」の概念を中心に研究を組織している。研究テーマは、民主主義、新しい環境問題、グローバルレベルでの新しい権力構成、コスモポ リタニズム、寛容性など。 |

| Yves Charles Zarka est, de 1974

à 1988, professeur de philosophie dans le secondaire, puis il est

docteur en philosophie1, habilité à diriger des recherches. Il est directeur du Centre d'histoire de la philosophie moderne du CNRS (1996-2004) et du Centre Thomas-Hobbes du CNRS (1990-2002). Au CNED, il est nommé responsable de l'enseignement du CAPES et de l’agrégation externe et interne de philosophie (1997-2004). Yves Charles Zarka dirige à l'université Paris-Descartes l’équipe PHILéPOL (Centre de philosophie, d’épistémologie et de politique)2. Il assure la responsabilité d’un programme ANR intitulé DEMOENV « La démocratie face aux enjeux environnementaux » (2011-2015) auquel collabore PHILéPOL, l'IRSTEA et l'ICD-CREIDD (université de technologie de Troyes) et d'un autre programme sur « Territoires, population et citoyenneté en Europe ». Il dirige également un programme de l'IDEX de Sorbonne Paris Cité sur "La démocratie et les mutations de l'espace public en Europe" en collaboration avec le Centre de recherches politiques de Sciences Po (CEVIPOF) et Paris III (ICEE). Ces dernières années il a dirigé un autre programme ANR-Université de Paris Descartes (2006-2010) intitulé LEGICONTEST « Concurrences de légitimité, types de contestation et réforme de l’État ». |

1974年から1988年まで、イヴ・シャルル・ザルカは中学校で哲学

の教師をした後、哲学の博士号1 を取得し、研究の指導権を得た。 CNRS現代哲学史センター所長(1996-2004年)、CNRSトーマス・ホッブスセンター所長(1990-2002年)。CNEDでは、CAPES と哲学の外部・内部アグレガシオン(1997-2004)の教育責任者に任命される。イヴ・シャルル・ザルカは、パリ・デカルト大学のPHILéPOL チーム(哲学・認識論・政治学のためのセンター)2 のディレクターを務めている。また、PHILéPOL、IRSTEA、ICD-CREIDD(トロワ工科大学)が協力するDEMOENV「環境問題に直面 する民主主義」(2011-2015)というANRプログラムのほか、「欧州における領土、人口、市民権」というプログラムの責任者でもある。また、ソル ボンヌ・パリ・シテ校のIDEXで、パリ政治学院(CEVIPOF)およびパリ第3大学(ICEE)と共同で、「ヨーロッパにおける民主主義と公共空間の 変容」に関するプログラムを指導しています。近年は、LEGICONTEST "Competitions of legitimacy, types of contestation and state reform "と題したANR-University of Paris Descartesプログラム(2006-2010)を指導している。 |

| Professeur à l'université de

Paris, où il est titulaire de la chaire de philosophie politique3, Yves

Charles Zarka est également global professor à l'université de Pékin.

Il est visiting professor à l'université Ca' Foscari de Venise et à

l'université "La Sapienza" de Rome. Il donne également des

enseignements à l'université de New York, à l'université de Barcelone

ou encore à l'université de Porto Alegre (Brésil), etc. Outre un grand nombre d’ouvrages d’histoire de la philosophie politique (en particulier sur Hobbes, Machiavel, Foucault et autres)4 tous traduits en plusieurs langues, ses recherches se situent au carrefour de la philosophie contemporaine, de l’épistémologie des sciences sociales, et des sciences politiques. C’est dans ce cadre qu’il étudie les transformations de la démocratie, les nouvelles problématiques environnementales, l’idée cosmopolitique, etc. Aux PUF, il dirige trois collections : « Fondements de la politique », « Intervention philosophique », « Débats philosophiques » ; chez Armand Colin, « Émergences » ; chez Vrin, l'édition des Œuvres de Hobbes et la collection « Hobbes Supplementa »; chez Mimésis, la collection "Philosophie et société". Directeur de la revue Cités aux PUF (80 numéros parus)5. Il est également membre du comité de rédaction de la revue Archives de philosophie (de 1988 à 2017), du comité scientifique de la revue Droits (PUF), du British Journal for the History of Philosophy (Francis & Taylor, Londres), de la revue Science et Esprit (éditions Bellarmin, Ottawa)6, la revue Derechos y Libertades (Dykinson, Madrid). Le 28 mai 2015, Yves-Charles Zarka intervient avec Michel Field en tant que « Grand témoin » dans les Rencontres maçonniques La Fayette entre le Grand Orient de France et la Grande Loge Nationale de France7. |

パリ大学教授で政治哲学の講座を持ち3、イヴ・シャルル・ザルカは北京

大学のグローバル教授でもある。ヴェネチアのカ・フォスカリ大学およびローマのラ・サピエンツァ大学の客員教授を務める。また、ニューヨーク大学、バルセ

ロナ大学、ポルト・アレグレ大学(ブラジル)等でも教鞭をとっている。 政治哲学史に関する多くの著作(特にホッブズ、マキャベリ、フーコーなど)4 があり、そのすべてが数カ国語に翻訳されているほか、現代哲学、社会科学の認識論、政治学が交差する場所に位置している。この枠組みの中で、民主主義の変 容、新たな環境問題、コスモポリタン思想などを研究しているのである。 PUFでは、"Fondements de la politique", "Intervention philosophique", "Débats philosophiques", Armand Colinでは、"Émergences", Vrinでは、ホッブズの作品集と "Hobbes Supplementa", Mimésisでは "Philosophie et Societyété" を指導しています。PUFのジャーナル「シテス」ディレクター(80号発行)5. また、雑誌Archives de philosophieの編集委員(1988年から2017年まで)、雑誌Droits(PUF)の科学委員会、英国哲学史ジャーナル(Francis & Taylor、ロンドン)、雑誌Science et Esprit(éditions Bellarmin、オタワ)6 、雑誌Derechos y Libertades(Dykinson、マドリード)にも所属している。 2015年5月28日、イヴ=シャルル・ザルカは、ミシェル・フィールドとともに、グラン・オリエント・ド・フランスとグラン・ロジェ・ナショナル・ド・ フランスの間のRencontres maçonniques La Fayetteに「グラン・テモアン」として介入した7。 |

| https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yves_Charles_Zarka |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

Man—Machine,

Julien Offray de La Mettrie; The moral advantages of La Mettrie’s view

of man

| A start on

thinking about materialism |

唯物論について考えることからはじめよう |

|

| Divine revelation |

||

| Some empirical

facts |

||

| Food |

||

| Other influences |

||

| Physical

constitution |

||

| The ability to

learn |

||

| Language |

||

| Imagination |

||

| Humanity’s assets |

||

| Attention |

||

| Man and the other

animals |

||

| Innocent criminals |

||

| The law of nature |

||

| The existence of

God |

||

| The law of nature |

||

| Self-moving body

parts |

||

| The ‘springs’ of

the human machine |

||

| More about the

organisation of the human body |

||

| Feeling and thought |

||

| Solving two

‘riddles’ |

||

| From sperm to man |

||

| Reconciling

ourselves to our ignorance . . |

(英語からの重訳)Man-Machine,

Julien Offray de La Mettrie; The moral advantages of La Mettrie’s view

of man, http://bactra.org/LaMettrie/Machine/

| Man a Machine Julien Offray de La Mettrie 1748 |

『人間機械論』 ジュリアン・オフレイ・デ・ラ・メトリ 1748年 |

| It

is not enough for a wise man to study nature and truth; he should dare

state truth for the benefit of the few who are willing and able to

think. As for the rest, who are voluntarily slaves of prejudice, they

can no more attain truth, than frogs can fly. I reduce to two the systems of philosophy which deal with man's soul. The first and older system is materialism; the second is spiritualism. The metaphysicians who have hinted that matter may well be endowed with the faculty of thought have perhaps not reasoned ill. For there is in this case a certain advantage in their inadequate way of expressing their meaning. In truth, to ask whether matter can think, without considering it otherwise than in itself, is like asking whether matter can tell time. It may be foreseen that we shall avoid this reef upon which Locke had the bad luck to shipwreck. The Leibnizians with their monads have set up an unintelligible hypothesis. They have rather spiritualized matter than materialized the soul. How can we define a being whose nature is absolutely unknown to us? Descartes and all the Cartesians, among whom the followers of Malebranche have long been numbered, have made the same mistake. They have taken for granted two distinct substances in man, as if they had seen them, and positively counted them. The wisest men have declared that the soul can not know itself save by the light of faith. However, as reasonable beings they have thought that they could reserve for themselves the right of examining what the Bible means by the word ``spirit,'' which it uses in speaking of the human soul. And if in their investigation, they do not agree with the theologians on this point, are the theologians more in agreement among themselves on all other points? Here is the result in a few words of all their reflections. If there is a God, he is the Author of nature was well as of revelation. He has given us the one to explain the other, and reason to make them agree. To distrust the knowledge that can be drawn from the study of animated bodies, is to regard nature and revelation as two contraries which destroy each other, and consequently to dare uphold the absurd doctrine, that God contradicts Himself in His various works and deceives us. If there is a revelation, it can not then contradict nature. By nature only can we understand the meaning of the words of the Gospel, of which experience is the only truly interpreter. In fact, the commentators before our time have only obscured the truth. We can judged of this by the author of the Spectacle of Nature. ``It is astonishing,'' he says concerning Locke, ``that a man who degrades our soul far enough to consider it a soul of clay should dare set up reason as judge and sovereign arbiter of the mysteries of faith, for,'' he adds, ``what an astonishing idea of Christianity one would have, if one were to follow reason.'' Not only do these reflections fail to elucidate faith, but they also constitute such frivolous objections to the method of those who undertake to interpret the Scripture, that I am almost ashamed to waste time in refuting them. The excellence of reason does not depend on a big word devoid of meaning (immateriality), but on the force, extent, and perspicuity of reason itself. Thus a ``soul of clay'' which should discover, at one glance, as it were, the relations and the consequences of an infinite number of ideas hard to understand, would evidently be preferable to a foolish and stupid soul, though that were composed of the most precious elements. A man is not a philosopher because, with Pliny, he blushes over the wretchedness of our origin. What seems vile is here the most precious of things, and seems to be the object of nature's highest art and most elaborate care. But as man, even though he should come from an apparently still more lowly source, would yet be the most perfect of all beings, so whatever the origin of his soul, if it is pure, noble, and lofty, it is a beautiful soul which dignifies the man endowed with it. Pluche's second way of reasoning seems vicious to me, even in his system, which smacks a little of fanaticism; for [on his view] if we have an idea of faith as being contrary to the clearest principles, to the most incontestable truths, we must yet conclude, out of respect for revelation and its author, that this conception is false, and that we do not yet understand the meaning of the words of the Gospel. Of the two alternatives, only one is possible: either everything is illusion, nature as well as revelation, or experience alone can explain faith. But what can be more ridiculous than the position of our author! Can one imagine hearing a Peripatetic say, ``We ought not to accept the experiments of Torricelli, for if we should accept them, if we should rid ourselves of the horror of the void, what an astonishing philosophy we should have!'' I have shown how vicious the reasoning of Pluche is in order to prove, in the first place, that if there is a revelation, it is not sufficiently demonstrated by the mere authority of the Church, and without any appeal to reason, as all those who fear reason claim: and in the second place, to protect against all assault the method of those who would wish to follow the path that I open to them, of interpreting supernatural things, incomprehensible in themselves, in the light of those ideas with which nature has endowed us. Experience and observation should therefore be our only guides here. Both are to be found throughout the records of the physicians who were philosophers, and not in the works of the philosophers who were not physicians. The former have traveled through and illuminated the labyrinth of man; they alone have laid bare those springs [of life] hidden under the external integument which conceals so many wonders from our eyes. They alone, tranquilly contemplating our soul, have surprised it, a thousand times, both in its wretchedness and in its glory, and they have no more despised it in the first estate, than they have admired it in the second. Thus, to repeat, only the physicians have a right to speak on this subject. What could the others, especially the theologians, have to say? Is it not ridiculous to hear them shamelessly coming to conclusions about a subject concerning which they have had no means of knowing anything, and from which on the contrary they have been completely turned aside by obscure studies that have led them to a thousand prejudiced opinions, - in a word, to fanaticism, which adds yet more to their ignorance of the mechanism of the body? |

賢者は自然や真理を研究するだけでは十分ではない。思考する意思と能力を持つ少数の人々のために、あえて真理を述べるべきなのだ。自ら進んで偏見の奴隷となっている残りの者たちは、カエルが飛ぶことができるのと同じように、真理に到達することはできない。 人間の魂を扱う哲学の体系を2つに分類する。第一の古い体系は唯物論であり、第二の体系は精神論である。 物質にも思考能力が備わっている可能性を示唆した形而上学者は、おそらく間違った推論をしてはいない。というのも、この場合、その意味を表現する方法が不 適切であることに、ある種の利点があるからである。実のところ、物質が考えることができるかどうかを問うのは、それ自体について考えるのでなければ、物質 が時間を知ることができるかどうかを問うようなものである。ロックが不運にも難破してしまったこの岩礁を避けることは、予見できるかもしれない。 ライプニッツ派のモナドは、理解しがたい仮説を立てた。彼らは魂を物質化したというよりも、むしろ物質を精神化したのである。本性がまったくわからない存在を、どうやって定義できるだろうか。 デカルトをはじめとするデカルト派も、マールブランシュの信奉者たちも、同じ過ちを犯している。彼らは、あたかも人間の中に2つの異なる物質があることを当然視し、あたかもそれを見たかのように数え上げた。 最も賢明な人々は、魂は信仰の光によらなければ自分自身を知ることはできないと宣言してきた。しかし、理性的な存在である彼らは、聖書が人間の魂について 語るときに使っている「霊」という言葉が何を意味するのかを調べる権利を自分たちに留保できると考えた。そして、もしこの点について神学者たちと意見が一 致しないのであれば、他のすべての点について神学者たちの意見は一致しているのだろうか? ここに、彼らのすべての考察の結果がいくつかの言葉で示されている。神が存在するとすれば、神は自然の創造者であると同時に啓示の創造者でもある。神は私たちに、一方を説明するために他方を与え、両者を一致させるために理性を与えた。 生体の研究から引き出される知識に不信感を抱くことは、自然と啓示を互いに破壊し合う相反するものとみなすことであり、その結果、神はそのさまざまな御業においてご自身と矛盾し、私たちを欺くという不合理な教義をあえて支持することになる。 啓示があるとすれば、それが自然と矛盾することはありえない。自然によってのみ、私たちは福音の言葉の意味を理解することができる。実際、私たちの時代以 前の注解者たちは、真理をあいまいにしてきたにすぎない。このことは、『自然の光景』の著者によって判断できる。私たちの魂を粘土の魂と見なすほど堕落さ せた人間が、信仰の神秘の裁判官として、また主権者として、あえて理性を立てるとは驚くべきことである。 このような考察は、信仰を解明できないばかりか、聖書を解釈しようとする人々の方法に対する軽薄な反論である。 理性の卓越性は、意味のない大きな言葉(非物質性)に左右されるのではなく、理性そのものの力、広がり、明瞭さに左右されるのである。したがって、理解し がたい無限の観念の関係や帰結を、いわば一目で発見する「粘土の魂」は、それが最も貴重な要素で構成されていたとしても、愚かで愚かな魂よりも好ましいこ とは明らかである。プリニウスと同じように、私たちの出自の惨めさに赤面するからといって、人は哲学者ではない。下劣に見えるものが、ここでは最も貴重な ものであり、自然の最高の芸術と最も精巧な配慮の対象であるように見える。しかし、たとえ人間がもっと卑しい源から生まれたとしても、あらゆる存在の中で 最も完全な存在であるように、魂の起源が何であれ、それが純粋で気高く、高尚であれば、それは美しい魂であり、それを与えられた人間を威厳づけるものであ る。 プルーシュの第二の推論の仕方は、狂信的な臭いが少しする彼の体系においても、私には悪意に満ちているように思われる。[彼の見解では]もし私たちが、最 も明確な原理や、最も疑いようのない真理に反するような信仰観念を持っているとしても、啓示とその作者への敬意から、この観念は誤りであり、私たちは福音 の言葉の意味をまだ理解していないと結論づけなければならない。 つまり、自然も啓示もすべてが幻想であるか、経験だけが信仰を説明できるか、である。しかし、著者の立場ほど滑稽なものがあるだろうか!トリチェッリの実 験を受け入れるべきではない。もし受け入れるとしたら、もし虚空の恐怖を取り除くとしたら、なんと驚くべき哲学を手に入れることになることか。 私がプルーシュの推論がいかに悪質であるかを示したのは、第一に、啓示があるとすれば、それは教会の権威だけでは十分に証明されず、理性を恐れるすべての 人々が主張するように、理性に訴えることなく証明されることを証明するためであり、第二に、それ自体では理解できない超自然的な事柄を、自然が我々に授け た観念の光の中で解釈するという、私が彼らに開いた道を歩もうとする人々の方法を、あらゆる攻撃から守るためである。したがって、ここでは経験と観察が唯 一の指針となる。この二つは、哲学者であった医師たちの記録の至るところに見られるが、医師でなかった哲学者たちの著作には見られない。前者は人間の迷宮 を旅して照らし出し、彼らだけが、私たちの目から多くの不思議を隠している外皮の下に隠されている[生命の]泉を裸にした。彼らはただ一人、私たちの魂を 静かに観察し、その惨めさにも栄光にも何千回となく驚かせ、第一の状態では軽蔑することもなく、第二の状態では賞賛することもなかった。繰り返すが、この テーマについて語る権利があるのは医師だけである。他の人たち、特に神学者たちが何を言うことができようか。彼らが恥ずかしげもなく、何一つ知るすべもな く、それどころか、曖昧な研究によって完全に脇に追いやられ、千差万別の偏見に満ちた意見、一言で言えば、身体のメカニズムに対する無知にさらに拍車をか ける狂信主義に導かれたテーマについて、結論を下すのを聞くのは滑稽ではないだろうか。 |

| But even though we have chosen the best guides, we shall still find many thorns and stumbling blocks in the way. Man is so complicated a machine that it is impossible to get a clear idea of the machine beforehand, and hence impossible to define it. For this reason, all the investigations have been vain, which the greatest philosophers have made à priori, that is to to say, in so far as they use, as it were, the wings of the spirit. Thus it is only à posteriori or by trying to disentangle the soul from the organs of the body, so to speak, that one can reach the highest probability concerning man's own nature, even though one can not discover with certainty what his nature is. Let us then take in our hands the staff of experience, paying no heed to the accounts of all the idle theories of the philosophers. TO be blind and to think one can do without this staff if the worst kind of blindness. How truly a contemporary writer says that the only vanity fails to gather from secondary causes the same lessons as from primary causes! One can and one even ought to admire all these fine geniuses in their most useless works, such men as Descartes, Malebranche, Leibnitz, Wolff and the rest, but what profit, I ask, has any one gained from their profound meditations, and from all their works? Let us start out then to discover not what has been thought, but what must be thought for the sake of repose in life. There are as many different minds, different characters, and different customs, as there are different temperaments. Even Galen knew this truth which Descartes carried so far as to claim that medicine alone can change minds and morals, along with bodies. (By the write of L'historie de l'âme, this teaching is incorrectly attributed to Hippocrates.) It is true that melancholy, bile, phlegm, blood etc., - according to the nature, the abundance, and the different combination of these humors - make each man different from another. In disease the soul is sometimes hidden, showing no sign of life; sometimes it is so inflamed by fury that it seems to be doubled; sometimes, imbecility vanishes and the convalescence of an idiot produces a wise man. Sometimes, again, the greatest genius becomes imbecile and looses the sense of self. Adieu then to all that fine knowledge, acquired at so high a price, and with so much trouble! Here is a paralytic who asks is his leg is in bed with him; there is a soldier who thinks that he still has the arm which has been cut off. The memory of his old sensations, and of the place to which they were referred by his soul, is the cause of this illusion, and of this kind of delirium. The mere mention of the member which he has lost is enough to recall it to his mind, and to make him feel all its motions; and this causes him an indefinable and inexpressible kind of imaginary suffering. This man cries like a child at death's approach, while this other jests. What was needed to change the bravery of Caius Julius, Seneca, or Petronius into cowardice or faintheartedness? Merely an obstruction in the spleen, in the liver, an impediment in the portal vein. Why? Because the imagination is obstructed along with the viscera, and this gives rise to all the singular phenomena of hysteria and hypochondria. What can I add to the stories already told of those who imagine themselves transformed into wolf-men, cocks or vampires, or of those who think that the dead feed upon them? Why should I stop to speak of the man who imagines that his nose or some other member is of glass? The way to help this man to regain his faculties and his own flesh-and-blood nose is to advise him to sleep on hay, lest he beak the fragile organ, and then to set fire to the hay that he may be afraid of being burned - a far which has sometimes cured paralysis. But I must touch lightly on facts which everybody knows. Neither shall I dwell long on the details of the effects of sleep. Here a tired soldier snores in a trench, in the middle of the thunder of hundreds of cannon. His soul hears nothing; his sleep is as deep as apoplexy. A bomb is on the point of crushing him. He will feel this less perhaps than he feels an insect which is under his foot. On the other hand, this man who is devoured by jealousy, hatred, avarice, or ambition, can never find any rest. The most peaceful spot, the freshest and most calming drinks are alike useless to one who has not freed his heart from the torment of passion. The soul and the body fall asleep together. As the motion of the blood is calmed, a sweet feeling of peace and quiet spreads through the whole mechanism. The soul feels itself little by little growing heavy as the eyelids droop, and loses its tenseness, as the fibres of the brain relax; thus little by little it becomes as if paralyzed and with it all the muscles of the body. These can no longer sustain the weight of the head, and the soul can no longer bear the burden of thought; it is in sleep as if it were not. Is the circulation too quick? the soul cannot sleep. Is the soul too much excited? the blood cannot be quieted: it gallops through the veins with an audible murmur/ Such are the two opposite causes of insomnia. A single fright in the midst of our dreams makes the heart beat at double speed and snatches us from needed and delicious repose, as a real grief or an urgent need would do. Lastly as the mere cessation of the functions of the soul produces sleep, there are, even when we are awake (or at least when we are half awake), kinds of very frequent short naps of the mind, vergers' dreams, which show that the soul does not always wait for the body to sleep. For if the soul is not fast asleep, it surely is not far from sleep, since it cannot point out a single object to which it has attended, among the uncounted number of confused ideas which, so to speak, fill the atmosphere of our brains like clouds. Opium is too closely related to the sleep it produces, to be left out of consideration here. This drug intoxicates, like wine, coffee, etc., each in its own measure and according to the dose. It makes a man happy in a state which would seemingly be the tomb of feeling, as it is the image of death. How sweet is this lethargy! The soul would long never to emerge from it. For the soul has been a prey to the most intense sorrow, but now feels only the joy of suffering past, and of sweetest peace. Opium alters even the will, forcing the soul which wished to wake and to enjoy life, to sleep in spite of itself. I shall omit any reference to the effect of poisons. Coffee, the well-known antidote for wine, by scourging the imagination, cures our headaches and scatters our cares without laying up for us, as wine does, other headaches for the morrow. But let us contemplate the soul in its other needs. The human body is a machine which winds its own springs. It is the living image of perpetual movement. Nourishment keeps up the movement which fever excites. Without food, the soul pines away, goes mad, and dies exhausted. The soul is a taper whose light flares up the moment before it goes out. But nourish the body, pour into its veins life-giving juices and strong liquors, and then the soul grows strong like them, as if arming itself with a proud courage, and the soldier whom water would have made to flee, grows bold and runs joyously to death to the sound of drums. Thus a hot drink sets into stormy movement the blood which a cold drink would have calmed. What power there is in a meal! Joy revives in a sad heart, and infects the souls of comrades, who express their delight in the friendly songs in which the Frenchman excels. The melancholy man alone is dejected, and the studious man is equally out of place [in such company]. |

しかし、たとえ最良のガイドを選んだとしても、その道には多くのいばらやつまずきがある。 人間は非常に複雑な機械であるため、事前に機械の明確な考えを得ることは不可能であり、したがって機械を定義することも不可能である。このため、偉大な哲 学者たちがアプリオリに、つまり、いわば精神の翼を使う限りにおいて行ってきた研究は、すべてむなしいものであった。いわば、魂を肉体の器官から切り離そ うとすることによってのみ、人間の本質が何であるかを確実に発見することはできなくても、人間自身の本質に関する最高の蓋然性に到達することができるので ある。 それでは、哲学者たちの戯言に耳を貸さず、経験の杖を手に取ろう。盲目でありながら、この杖なしでもやっていけると考えるのは、最悪の盲目である。二次的 な原因から、一次的な原因と同じ教訓を得ることができないのは、唯一の虚栄心である!デカルト、マレブランシュ、ライプニッツ、ヴォルフなど、最も役立た ずの作品に登場する優れた天才たちを賞賛することはできるし、賞賛すべきであるとさえ思う。それでは、これまで考えられてきたことではなく、人生の安息の ために考えなければならないことを発見することから始めよう。 さまざまな気質があるように、さまざまな心、さまざまな性格、さまざまな習慣がある。ガレノスでさえ知っていたこの真理を、デカルトは医学だけが肉体とと もに心や道徳を変えることができると主張するまでになった。(L'historie de l'âme』の記述によれば、この教えはヒポクラテスの誤りである)。憂鬱、胆汁、痰、血液など、これらの体液の性質、量、組み合わせの違いによって、人 間がそれぞれ異なるのは事実である。 病気のとき、魂は時には隠れていて、生きている気配を見せない。またある時は、最大の天才が無能になり、自己の感覚を失うこともある。高価な代償を払い、 苦労の末に手に入れた素晴らしい知識とはおさらばだ!自分の脚はベッドの中にあるのだろうかと尋ねる麻痺患者がいる。このような錯覚や錯乱の原因は、昔の 感覚と、それが魂によって指し示された場所の記憶にある。失った部位を思い出すには、その部位を口にするだけで十分であり、その部位のすべての動きを感じ させる。この男は死が近づくと子供のように泣き、この男は冗談を言う。カイアス・ユリウスやセネカやペトロニウスの勇敢さを、臆病さや気弱さに変えるため に何が必要だったのか。脾臓や肝臓、門脈に障害があるだけだ。なぜか?想像力が臓器とともに障害され、ヒステリーや心気症のような奇妙な現象を引き起こす からだ。 オオカミ男やコックや吸血鬼に変身した自分を想像する人たちや、死者が自分を食べていると考える人たちの話はすでに語られている。自分の鼻や他の部位がガ ラスだと想像する人の話を、なぜ私が止めなければならないのか。この男が自分の能力と生身の鼻を取り戻すのを助ける方法は、壊れやすい器官をくちばしにし ないように干し草の上で寝るように助言することである。しかし、私は誰もが知っている事実に軽く触れなければならない。 睡眠がもたらす影響の詳細についても、長くは触れない。疲れた兵士が塹壕の中でいびきをかいている。彼の魂は何も聞いていない。彼の眠りは脳溢血のように 深い。爆弾が彼を押しつぶそうとしている。爆弾が彼を押しつぶそうとしているのを、彼はおそらく、足の下にいる虫を感じるほどには感じないだろう。 一方、嫉妬、憎しみ、欲望、野心にむしばまれた人間は、決して安息を得ることができない。情熱の苦しみから心を解放していない者にとっては、最も安らげる場所も、最も新鮮で心を落ち着かせる飲み物も、同じように役に立たない。 魂と肉体は一緒に眠りに落ちる。血液の動きが落ち着くと、平和で静かな甘い感覚がメカニズム全体に広がる。魂は、まぶたが垂れ下がるにつれて少しずつ重く なり、脳の線維が弛緩するにつれて緊張を失っていくのを感じる。これらの筋肉はもはや頭の重さを支えることができず、魂はもはや思考の重荷に耐えることが できない。 血行が速すぎると、魂は眠ることができない。魂が興奮しすぎているのか、血液は静まることができない。夢を見ている最中に一度でも恐怖を感じると、心臓の 鼓動は倍速になり、本当の悲しみや緊急の必要性がそうさせるように、必要で美味しい安息から私たちを奪ってしまう。最後に、魂の機能が停止するだけでも睡 眠が生じるが、私たちが目覚めているときでさえ(あるいは少なくとも半分目覚めているときでさえ)、非常に頻繁に短時間の仮眠をとる種類の心、つまり ヴァージャーの夢があり、これは魂が常に肉体の眠りを待っているわけではないことを示している。いわば雲のように脳の大気を満たしている数え切れないほど の混乱した観念の中で、魂が注意を向けている対象をひとつも指摘できないのだから。 アヘンは、それがもたらす睡眠とあまりに密接な関係があるため、ここで考察の対象から外すことはできない。この薬物は、ワインやコーヒーなどと同じよう に、それぞれの量に応じた酔い方をする。一見、死のイメージのように、感情の墓場であるような状態でも、人を幸福にする。この無気力はなんと甘美なことだ ろう!魂はこの無気力から決して抜け出したくないと願うだろう。魂は最も激しい悲しみの餌食となったが、今は過去の苦しみと最も甘い平和の喜びだけを感じ るからだ。アヘンは意志さえも変質させ、目を覚まして人生を楽しみたいと願った魂を、自分自身にもかかわらず眠らせるのだ。毒物の影響については、ここで は言及を省略する。 ワインの解毒剤として知られるコーヒーは、想像力を奮い立たせることで、頭痛を治し、心配事を分散させる。しかし、魂が必要とする他のものについても考えてみよう。 人間の身体は、自分でゼンマイを巻く機械である。それは、絶え間ない運動の生きた姿である。栄養は、熱が興奮させる運動を維持する。食べ物がなければ、魂 は衰え、狂い、疲れ果てて死ぬ。魂は、火が消える瞬間に燃え上がるテーパーである。しかし、肉体に栄養を与え、生命を与えるジュースや強い酒を血管に注ぎ 込めば、魂はそれらのように強くなり、まるで誇り高き勇気で武装するかのようになる。このように、熱い飲み物は、冷たい飲み物なら静まるはずの血液を、嵐 のように躍動させる。 食事にはどんな力があるのだろう!悲しい心に喜びがよみがえり、仲間たちの魂に伝染し、フランス人が得意とする親しみやすい歌で喜びを表現する。憂鬱な男は一人で意気消沈し、勉強熱心な男も同じように[このような仲間には]ふさわしくない。 |

| Raw

meat makes animals fierce, and it would have the same effect on man.

This is so true that the English who eat meat red and bloody, and not

as well done as ours, seem to share more or less in the savagery due to

this kind of food, and to other causes which can be rendered

ineffective by education only. This savagery creates in the soul,

pride, hatred, scorn of other nations, indocility and other sentiments

which degrade the character, just as heavy food makes a dull and heavy

mind whose usual traits are laziness and indolence. Pope understood well the full power of greediness when he said: Catius is ever moral, ever grave Thinks who endures a knave is next a knave, Save just at dinner - then prefers no doubt A rogue with ven'son to a saint without. Elsewhere he says: See the same man in vigor, in the gout, Alone, in company, in place or out, Early at business and at hazard late, Mad at a fox chase, wise at a debate, Drunk at a borough, civil at a ball, Friendly at Hackney, faithless at White Hall. In Switzerland we had a bailiff by the name of M. Steigner de Wittghofen. When he fasted he was a most upright and even a most indulgent judge, but woe to the unfortunate man whom he found on the culprit's bench after he had had a large dinner! He was capable of sending the innocent like the guilty to the gallows. We think we are, and in fact we are, good men, only as we are gay or brave; everything depends on the way our machine is running. One is sometimes inclined to say that the soul is situated in the stomach, and that Van Helmont, who said that the seat of the soul was in the pylorus, made only the mistake of taking the part for the whole. To what excesses cruel hunger can bring us! We no longer regard even our own parents and children. We tear them to pieces eagerly and make horrible banquets of them; and in the fury with which we are carried away, the weakest is always the prey of the strongest. La grossesse, cette émule désirée des pâles couleurs, ne se contente pas d'amener le plus souvent à sa suites le goûts dépravés qui accompagnent ces deux états: elle a quelquefois fait exécuter à l'âme les plus affreux complots; effets d'une maine subite, qui étouffe jusqu'à la loi naturelle. Ce'st ainsi que le cerveau, cette matrice de l'esprit, se pervertit à sa manière, avec celle du corps. Quelle autre fureur d'homme ou de femme, dans ceux que la continence et la santé poursuivent! C'est peu pour cette fille timide et modeste d'avoir perdu toute honte et toute pudeur; elle ne regarde plus l'inceste, que comme une femme galante regarde l'adultère. Si ses besoins ne trouvent pas de prompts soulagements, ils ne se borneront point aux simples accidents d'une passion utérine, à la manie, etc.; cette malheureuse mourra d'un mal, dont il y a tant de médecins. One needs only eyes to see the necessary influence of old age on reason. The soul follows the progress of the body, as it does the progress of education. In the weaker sex, the soul accords also with delicacy of temperament, and from this delicacy follow tenderness, affection, quick feelings due more to passion than to reason, prejudices, and superstitions, whose strong impress can hardly be effaced. Man, on the other hand, whose brain and nerves partake of the firmness of all solids, has not only stronger features but also a more vigorous mind. Education, which women lack, strengthens his mind still more. Thus with such help of nature and art, why should not a man be more grateful, more generous, more constant in friendship, stronger in adversity? But, to follow almost exactly the thought of the author of the Lettres sur la Physiognomie, the sex which unites the charms of the mind and of the body with almost all the tenderest and most delicate feelings of the heart, should not envy us the two capacities which seem to have been given to man, the one merely to enable him better to fathom the allurements of beauty, and the other merely to enable him to minister better to its pleasure. It is no more necessary to be just as great a physiognomist as this author, in order to guess the quality of the mind from the countenance or the shape of the features, provided these are sufficiently marked, than it is necessary to be a great doctor to recognize a disease accompanied by all it marked symptoms. Look at the portraits of Locke, of Steele, of Boerhaave, of Maupertuis, and the rest, and you will not be surprised to find strong faces and eagle eyes. Look over a multitude of others, and you can always distinguish the man of talent from the man of genius, and often even an honest man from a scoundrel. For example it has been noticed that a celebrated poet combines (in his portrait) the look of a pickpocket with the fire of Prometheus. History provides us with a noteworthy example of the power of temperature. The famous Duke of Guise was so strongly convinced that Henry the Third, in whose power he had so often been, would never dare assassinate him, that he went to Blois. When the Chancellor Chiverny learned of the duke's departure, he cried, ``He is lost.'' After this fatal prediction had been fulfilled by the event, Chiverny was asked why he made it. ``I have known the king for twenty years,'' said he; ``he is naturally kind and even weakly indulgent, but I have noticed that when it is cold, it takes nothing at all to provoke him and send him into a passion.'' One nation is of heavy and stupid wit, and another quick, light and penetrating. Whence comes this difference, if not in part from the difference in foods, and difference in inheritance, and in part from the mixture of the diverse elements which float around in the immensity of the void? The mind, like the body, has its contagious diseases and its scurvy. Such is the influence of climate, that a man who goes from one climate to another, feels the change, in spite of himself. He is a walking plant which has transplanted itself; if the climate is not the same, it will surely either degenerate or improve. Furthermore, we catch everything from those with whom we come in contact; their gestures, their accent, etc.; just as the eyelid is instinctively lowered when a blow is foreseen, or (as for the same reason) the body of the spectator mechanically imitates, in spite of himself, all the motions of a good mimic. From what I have just said, it follows that a brilliant man is his own best company, unless he can find others of the same sort. In the society of the unintelligent, the mind grows rusty for lack of exercise, as at tennis a ball that is served badly is badly returned. I should prefer an intelligent man without an education, if he were still young enough, to a man badly educated. A badly trained mind is like an actor whom the provinces have spoiled. Thus, the diverse states of the soul are always correlative with those of the body. But the better to show this dependence, in its completeness and its causes, let us here make use of comparative anatomy; let us lay bare the organs of man and of animals. How can human nature be known, if we may not derive any light from an exact comparison of the structure of man and of animals? In general, the form and the structure of the brains of quadrupeds are almost the same as those of the brain of man; the same shape, the same arrangement everywhere, with this essential difference, that of all the animals man is the one whose brain is largest, and, in proportion to its mass, more convoluted than the brain of any other animal; then come the monkey, the beaver, the elephant, the dog, the fox, the cat. These animals are most like man, for among them, too, one notes the same progressive analogy in relation to the corpus callosum in which Lancisi - anticipating the late M. de la Peyronie - established the seat of the soul. The latter, however, illustrated the theory by innumerable experiments. Next after all the quadrupeds, birds have the largest brains. Fish have large heads, but these are void of sense, like the heads of many men. Fish have no corpus callosum, and very little brain, while insects entirely lack brain. I shall not launch out into any more detail about the varieties of nature, nor into conjectures concerning them, for there is an infinite number of both, as any one can see by reading no further than the treatises of Willis De Cerebro and De Anima Brutorum. |

生肉は動物を凶暴化させる。

赤くて血なまぐさい、しかも私たちほど上手くはない肉を食べるイギリス人は、多かれ少なかれ、この種の食べ物による野蛮さと、教育によってのみ効果がなく

なるその他の原因による野蛮さを共有しているようだ。この野蛮さは、プライド、憎しみ、他国への軽蔑、無教養など、人格を低下させる感情を魂に生み出す。 ローマ教皇は、貪欲の持つ力をよく理解していた: カティウスは常に道徳的であり、常に重大である。 カティウスは常に道徳的であり、常に厳格である、 晩餐の時だけは別だ。 ヴェンソンのいる悪党は、ヴェンソンのいない聖人よりも好きだ。 また、彼は言う: 元気な時も、痛風の時も、同じ男を見よ、 一人でも、仲間でも、場所でも、外でも、 仕事には早く、危険には遅く、 キツネ追いには狂い、議論には賢い、 自治区では酔い、舞踏会では礼儀正しい、 ハックニーでは友好的、ホワイトホールでは不誠実。 スイスにはヴィットホーフェンのシュタイグナーという廷吏がいた。断食しているときは、彼は非常に高潔で、寛容な裁判官であった。しかし、夕食をたらふく 食べた後、彼が罪人の席にいるのを見つけた不幸な男は悲惨であった!彼は罪のない人を、罪のある人と同じように絞首台に送ることができたのだ。 私たちは、自分がガイ(たくましい男)であるか勇敢であるかによって、自分が善人であると思うし、実際に善人であると思う。魂は胃の中にあり、魂の座は幽門にあると言ったヴァン・ヘルモントは、部分と全体を取り違えただけだと言いたくなることがある。 残酷な飢えは、私たちにどんな過剰なものをもたらすのだろう!私たちはもはや、自分の親や子供さえも顧みない。そして、その怒りに流され、弱い者は常に強い者の餌食となる。 そして、私たちが流される怒りの中で、最も弱い者は常に最も強い者の餌食となるのである。そのため、精神の母体である神経が、肉体と同じように変質してしまうのだ。 不摂生と健康が促進されるのは、男性であれ女性であれ、他にどんな苦しみがあるからだろう!この臆病で慎ましやかな少女は、すべての名誉と美貌を失ったか らと言って、それ以上侮辱を気にすることはない。その欲望は、心躍らせるようなものでなく、情熱的で、男らしく、などという単純な偶発的なものでしかな い。 老いが理性に及ぼす必要な影響を見るには、ただ目を凝らすだけでよい。魂は、教育の進歩がそうであるように、肉体の進歩に従う。弱い性別では、魂は気質の 繊細さとも一致し、この繊細さから、優しさ、愛情、理性よりも情熱に起因する素早い感情、偏見、迷信が生じ、その強い印象はなかなか消えない。一方、人間 は、脳と神経があらゆる固体の固さを帯びているため、顔立ちがしっかりしているだけでなく、精神も旺盛である。女性に欠けている教育は、彼の心をさらに強 くする。このように、自然と芸術の助けがあれば、男はより感謝し、より寛大になり、友情に厚く、逆境に強くなるはずではないか。しかし、『人相学への手 紙』の著者の考えにほぼ忠実に従えば、心と身体の魅力と、ほとんどすべての最も優しくて繊細な心の感情とを結びつける性は、人間に与えられたと思われる二 つの能力、すなわち、一方は美の魅力をよりよく理解できるようにするため、もう一方は美の喜びをよりよく味わえるようにするためだけの能力を、私たちにう らやましがらせてはならない。 この著者のように、人相学の大家でなくても、表情や顔立ちから心の質を推し量ることはできる。ロック、スティール、ボアハーヴェ、モウペルテュイなどの肖 像画を見れば、強い顔と鷲のような目を発見しても驚かないだろう。他の多くの人たちを見渡せば、才能のある人と天才的な人、そしてしばしば正直な人と悪党 を見分けることができる。たとえば、ある有名な詩人の肖像画には、スリのような風貌とプロメテウスの炎が組み合わされている。 歴史は、気温の力を示す特筆すべき例を教えてくれる。かの有名なギーズ公爵は、かつて権力を握っていたアンリ3世が自分を暗殺することなどあり得ないと強 く確信し、ブロワに向かった。シヴェルニー宰相は公爵の出発を知ると、「彼は失われた」と叫んだ。この致命的な予言が見事に的中した後、シヴェルニーはな ぜ予言をしたのかと尋ねられた。国王とは20年来の付き合いです」と彼は言った。「彼は生来親切で、弱々しくさえ甘やかされていますが、寒いときには、彼 を刺激して激情に走らせることなどまったく必要ないことに気づきました」。 ある国民は重く愚かな機知に富み、別の国民は素早く、軽く、鋭い。この違いはいったいどこから来るのだろう。その理由のひとつが、食物の違いや遺伝の違い によるものでなければ、また、その理由のひとつが、虚空の広大さを漂う多様な要素の混合によるものでなければ、これはいったい何なのだろう。身体と同じよ うに、心にも伝染病や壊血病がある。 気候の影響は大きく、ある気候から別の気候へと移っていく人間は、自分とは無関係にその変化を感じる。気候が同じでなければ、必ず退化するか改善するかのどちらかである。 同じ理由で)観客の身体は、自分にもかかわらず、優れたモノマネの動作をすべて機械的に真似るのである。 今述べたことから、聡明な人間は、同じようなタイプの人間を見つけられなければ、自分自身が最高の仲間であるということになる。テニスでサーブされたボー ルがうまく返せないように、知性のない人たちと一緒にいると、運動不足のために心が錆びついてしまう。私は、もし彼がまだ十分に若ければ、教育を受けてい ない知的な人間の方が、教育を受けていない人間よりも好きである。ひどく訓練された精神は、地方が台無しにした俳優のようなものだ。 このように、魂のさまざまな状態は、常に肉体の状態と相関関係にある。しかし、この依存関係を、その完全性と原因においてよりよく示すために、ここで比較 解剖学を利用しよう。人間と動物の構造を正確に比較することから何の光も得られないとしたら、どうして人間の本性を知ることができようか。 一般に、四足動物の脳の形と構造は、人間の脳の形とほとんど同じである。同じ形、同じ配置がいたるところにあるが、本質的な違いは、すべての動物の中で人 間の脳が最も大きく、その質量に比例して、他のどの動物の脳よりも入り組んでいることである。これらの動物は人間に最もよく似ている。なぜなら、これらの 動物の間でも、ランシジが(故ラ・ペイロニー氏に先駆けて)魂の座を確立した脳梁に関連して、同じような漸進的な類似が見られるからである。しかし後者 は、無数の実験によってこの理論を説明した。四足動物の次に脳が大きいのは鳥類である。魚類は頭が大きいが、これは多くの人間の頭のように感覚がない。魚 には脳梁がなく、脳はほとんどない。 なぜなら、ウィリスの『脳』(De Cerebro)と『脳』(De Anima Brutorum)を読めば誰でもわかるように、どちらも無限に存在するからである。 |

| I

shall draw the conclusions which follow clearly from these

incontestable observations: 1st, that the fiercer animals are, the less

brain they have; 2d, that this organ seems to increase in size in

proportion to the gentleness of the animal; 3d, that nature seems here

eternally to impose a singular condition, that the more one gains in

intelligence the more one loses in instinct. Does this bring gain or

loss? Do not think, however, that I wish to infer by that, that the size alone of the brain, is enough to indicate the degree of tameness in animals: the quality must correspond to the quantity, and the solids and liquids must be in that due equilibrium which constitutes health. If, as is ordinarily observed, the imbecile does not lack brain, his brain will be deficient in its consistency - for instance, in being too soft. The same thing is true of the insane, and the defects of their brains do not always escape our investigation. But if the causes of imbecility, insanity, etc., are not obvious, where shall we look for the causes of the diversity of all minds? They would escape the eyes of a lynx and of an argus. A mere nothing, a tiny fiber, something that could never be found by the most delicate anatomy, would have made of Erasmus and Fontenelle two idiots, and Fontenelle himself speaks of this very fact in one of his best dialogues. Willis has noticed in addition to the softness of the brain-substance in children, puppies and birds, that the corpora striata are obliterated and discolored in all these animals, and that the striations are as imperfectly formed as in paralytics. Il ajoute, ce qui est vrai, que l'homme a la protubérance annulaire fort grosse; et ensuite toujours diminutivement par dégrés, le singe et les autres animaux nommés ci-devant, tandis que le veau, le boeuf, le loup, la brebis, le cochon, etc. qui ont cette partie d'un tès petit volume, ont les nattes et testes fort gros. However cautious and reserved one may be about the consequences that can be deduced from these observations, and from many others concerning the kind of variation in the organs, nerves, etc., [one must admit that] so many different varieties cannot be the gratuitous play of nature. They prove at least the necessity for a good and vigorous physical organization, since throughout the animal kingdom the soul gains force with the body and acquires keenness, as the body gains strength. Let us pause to contemplate the varying capacities of animals to learn. Doubtless the analogy best framed leads the mind to think that the causes we have mentioned produce all the difference that is found between animals and men, although we must confess that our weak understanding, limited to the coarsest observations, cannot see the bonds that exist between cause and effect. This is a kind of harmony that philosophers will never know. Among animals, some learn to speak and sing; they remember tunes, and strike the notes as exactly as a musician. Others, for instance the ape, show more intelligence, and yet cannot learn music. What is the reason for this, except some defect in the organs of speech? But is this defect so essential to the structure that it could never be remedied? In a word, would it be absolutely impossible to teach the ape a language? I do not think so. I should choose a large ape in preference to any other, until by some good fortune another kind should be discovered, more like us, for nothing prevents there being such a one in regions unknown to us. The ape resembles us so strongly that naturalists have called it ``wild man'' or ``man of the woods.'' I should take it in the condition of the pupils of Amman, that is to say, I should not want it to be too young or too old; for apes that are brought to Europe are usually too old. I would choose the one with the most intelligent face, and the one which, in a thousand little ways, best lived up to its look of intelligence. Finally not considering myself worthy to be his master, I should put him in the school of that excellent teacher whom I have just named, or with another teacher equally skillful, if there is one. You know by Amman's work, and by all those who have interpreted his method, all the wonders he has been able to accomplish for those born deaf. In their eyes he discovered ears, as he himself explained, and in how short a time! In short he taught them to hear, speak, read, and write. I grant that a deaf person's eyes see more clearly and are keener than if he were not deaf, for the loss of one member or sense can increase the strength or acuteness of another, but apes see and hear, they understand what they hear and see, and grasp so perfectly the signs that are made to them, that I doubt not that they would surpass the pupils of Amman in any other game or exercise. Why then should the education of monkeys be impossible? Why might not the monkey, by dint of great pains, at last imitate after the manner of deaf mutes, the motions necessary for pronunciation. I do not dare decide whether the monkey's organs of speech, however trained, would be incapable of articulation. But, because of the great analogy between ape and man and because there is no known animal whose external and internal organs so strikingly resemble man's, it would surprise me if speech were absolutely impossible to the ape. Locke, who was certainly never suspected of credulity, found no difficulty in believing the story told by Sir William Temple in his memoirs, about a parrot which could answer rationally, and which had learned to carry on a kind of connected conversation, as we do. I know that people have ridiculed this great metaphysician; but suppose some one should have announced that reproduction sometimes take place without eggs or a female, would he have found many partisans? Yet M. Trembley has found cases where reproduction takes place without copulation and by fission. Would not Amman too have passed for mad if he had boasted that he could instruct scholars like his in so short a time, before he had happily accomplished the feat? His successes, have, however, astonished the world; and he, like the author of The History of the Polyps, has risen to immortality at one bound. Whoever owes the miracles that he works to his own genius surpasses, in my opinion, the man who owes his to chance. He who has discovered the art of adorning the most beautiful of kingdoms [of nature], and of giving it perfections that it did not have, should be ranked above an idle creator of frivolous systems, or a painstaking author of sterile discoveries. Amman's discoveries are certainly of a much greater value; he has freed men from the instinct to which they seemed to be condemned, and has given them ideas, intelligence, or in a word, a soul which they would never have had. What greater power than this! Let us not limit the resources of nature; they are infinite, especially when reinforced by great art. Could not the device which opens the Eustachian canal of the deaf, open that of apes? Might not a happy desire to imitate the master's pronunciation, liberate the organs of speech in animals that imitate so many other signs with such skill and intelligence? Not only do I defy any one to name any really conclusive experiment which proves my view impossible and absurd; but such is the likeness of the structure and functions of the ape to ours that I have very little doubt that if this animal were properly trained he might at last be taught to pronounce, and consequently to know, a language. Then he would no longer be a wild man, nor a defective man, but he would be a perfect man, a little gentleman, with as much matter or muscle as we have, for thinking and profiting by his education. The transition from animals to man is not violent, as true philosophers will admit. What was man before the invention of words and the knowledge of language? An animal of his own species with much less instinct than the others. In those days, he did not consider himself king over the other animals, nor was he distinguished from the ape, and from the rest, except as the ape itself differs from the other animals, i.e., by a more intelligent face. Reduced to the bare intuitive knowledge of the Leibnizians he saw only shapes and colors, without being able to distinguish between them: the same, old as young, child at all ages, he lisped out his sensations and his needs, as a god that is hungry or tired of sleeping, asks for something to eat, or for a walk. Words, languages, laws, sciences, and the fine arts have come, and by them finally the rough diamond of our mind has been polished. Man has been trained in the same way as animals. He has become an author, as they have become beasts of burden. A geometrician has learned to perform the most difficult demonstrations and calculations, as a monkey has learned to take his little hat off and on, and to mount his tame dog. All has been accomplished through signs, every species has learned what it could understand, and in this way men have acquired symbolic knowledge, still so called by our German philosophers. Nothing, as any one can see, is so simple as the mechanism of our education. Everything may be reduced to sounds or words that pass from the mouth of one through the ears of another into his brain. At the same moment, he perceives through his eyes the shape of the bodies of which these words are the arbitrary signs. But who was the first to speak? Who was the first teacher of the human race? Who invented the means of utilizing the plasticity of our organism? I cannot answer: the names of these first splendid geniuses have been lost in the night of time. But art is the child of nature, so nature must have long preceded it. We must think that the men who were the most highly organized, those on whom nature has lavished her richest gifts, taught the others. They could not have heard a new sound for instance, nor experienced new sensations, nor been struck by all the varied and beautiful objects that compose the ravishing spectacle of nature without finding themselves in the state of mind of the deaf man of Chartres, whose experience was first related by the great Fontenelle, when, at forty years, he heard for the first time, the astonishing sound of bells. Would it be absurd to conclude from this that the first mortals tried after the manner of this deaf man, or like animals and like mutes (another kind of animals), to express their new feeling by motions depending on the nature of their imagination, and therefore afterwards by spontaneous sounds, distinctive of each animal, as the natural expression of their surprise, their joy, their ecstasies and their needs? For doubtless those whom nature endowed with finer feeling had also greater facility in expression. |

これらの疑いようのない観察

から、私は明らかに導かれる結論を導き出そう:

第1に、獰猛な動物ほど脳が少ないこと、第2に、この器官は動物の優しさに比例して大きくなるようであること、第3に、自然は、知性を得れば得るほど本能

を失うという特異な条件を永遠に課しているように思われることである。これは得をもたらすのか、それとも損をもたらすのか。 質は量に対応し、固体と液体は健康を構成する適切な平衡状態になければならない。 通常観察されるように、無能力者に脳が欠けていないとすれば、その脳はその一貫性に欠けることになる。同じことが心神喪失者にも当てはまり、彼らの脳の欠 陥は常に我々の調査を免れない。しかし、無能や狂気などの原因が明らかでないとすれば、すべての心の多様性の原因をどこに求めればいいのだろうか。それら はオオヤマネコやアーガスの目から逃れられるだろう。エラスムスとフォントネルを二人の馬鹿にしたのは、最も繊細な解剖学では決して見つけることのできな い、単なる無、小さな繊維であった。 ウィリスは、子供、子犬、鳥類の脳実質が軟らかいことに加えて、これらの動物すべてにおいて線条体が抹消され変色していること、筋が麻痺患者と同様に不完 全に形成されていることに気づいた。さらに、これは事実であるが、人間は非常に大きな環状突起を持ち、次にサルや上に挙げた他の動物は、常に少しずつ減少 していくが、子牛、牛、狼、羊、豚などは、この部分の容積は非常に小さいが、非常に大きな辮髪と精巣を持つ、と付け加えている。 これらの観察から、また器官や神経などの変異の種類に関する他の多くの観察から推測される結果について、いかに慎重で控えめであろうとも、[人は]これほ ど多くの異なる種類が自然の無償の遊びであるはずがないことを認めなければならない。動物界全体を通じて、魂は肉体とともに力を増し、肉体が力を増すにつ れて鋭敏さを獲得するのだから。 動物の学習能力の違いについて考えてみよう。間違いなく、最もうまく組み立てられた類推は、これまで述べてきた原因が、動物と人間の間に見られるすべての違いを生み出していると思わせる。これは、哲学者には決してわからない種類の調和である。 動物のなかには、話したり歌ったりすることを学ぶものがいる。彼らは曲を覚え、音楽家のように正確に音を奏でる。一方、例えば猿のように、より知能が高い にもかかわらず、音楽を学ぶことができないものもいる。その理由は何だろう。発声器官に何らかの欠陥があるからではないだろうか。しかしこの欠陥は、決し て改善できないほど本質的な構造なのだろうか?つまり、猿に言葉を教えることは絶対に不可能なのだろうか?私はそうは思わない。 幸運にも、私たちにより似た別の種が発見されるまでは、私は他のどの類人猿よりも大型の類人猿を選ぶだろう。類人猿は私たちに非常によく似ているため、博 物学者はそれを「野生人」あるいは「森の人」と呼んでいる。つまり、若すぎても老けすぎてもいけない。ヨーロッパに持ち込まれる類人猿はたいてい老けすぎ ているからだ。私は、最も知的な顔立ちのもの、そして千差万別の小さな方法で、その知的な顔立ちに最もふさわしいものを選ぶだろう。最終的には、自分がそ の子の師匠になるにはふさわしくないと考え、先ほど名前を挙げた優秀な先生の学校に入れるか、同じように腕の立つ先生がいれば、その先生のところに入れる だろう。 アンマンの仕事ぶりや、彼の方法を解釈したすべての人たちによって、彼が生まれつき耳の聞こえない人たちに成し遂げた奇跡の数々を、あなたは知っているは ずだ。彼自身が説明したように、彼は彼らの目に耳を発見した!要するに、彼は彼らに聞き、話し、読み、書くことを教えたのだ。聾唖者の目が、聾唖者でない 場合よりも明瞭に見え、鋭敏であることは認める。しかし、類人猿は見たり聞いたりし、聞いたり見たりしたことを理解し、彼らに示された手話を完璧に理解す る。では、なぜサルの教育が不可能なのだろうか?猿が大変な苦労をして、ついには耳の不自由な唖のように、発音に必要な動作を真似るようにならないわけが ない。サルの発声器官がいかに訓練されたものであっても、発音ができないかどうかは、あえて判断しない。しかし、類人猿と人間との間には大きな類似性があ り、また、外的および内的器官が人間にこれほど酷似している動物は知られていないのだから、もし猿に発声が絶対に不可能だとしたら、それは驚きである。 ウィリアム・テンプル卿が回想録の中で語った、理性的な受け答えができ、私たちと同じように一種のつながりのある会話をするようになったオウムの話を、信 憑性を疑われたことのないロックが信じることに何の困難も感じなかった。人々がこの偉大な形而上学者を嘲笑したことは知っているが、もし誰かが、卵や雌が いなくても生殖が行われることがあると発表したとしたら、その人は多くの支持者を得ただろうか?しかし、M.トレンブリーは、交尾がなくても分裂によって 生殖が行われるケースを発見した。アンマンも、もし彼がその偉業をめでたく成し遂げる前に、彼のような学者を短期間で指導できると自慢していたら、気違い 扱いされたのではないだろうか?しかし、彼の成功は世界を驚嘆させた。彼は『ポリープの歴史』の著者と同じように、一気に不死身にのし上がったのである。 私の考えでは、奇跡を自分の才能に帰する者は、偶然に帰する者を凌駕する。最も美しい王国(自然)に装飾を施し、その王国になかった完全性を与える術を発 見した者は、軽薄なシステムを創造する無為な創造者や、不毛な発見をする苦心の作者よりも上位にランクされるべきである。アンマンの発見は、確かにもっと 大きな価値がある。彼は人間を、彼らが非難されているように思われる本能から解放し、彼らにアイデアや知性、一言で言えば、彼らが決して持つことのなかっ た魂を与えたのだ。これ以上の力があるだろうか! 自然の力を制限してはならない。自然の力は無限であり、特に偉大な芸術によって補強されたときには無限である。 耳の聞こえない人の耳管を開く装置が、猿の耳管を開くことはできないだろうか。師匠の発音を真似したいという幸福な願望が、他の多くのサインを巧みに、そ して知的に真似る動物の言語器官を解放することはできないだろうか?私の見解が不可能で不合理であることを証明するような、本当に決定的な実験を挙げる者 はいないどころか、類人猿の構造と機能が我々と似ていることから、この動物が適切に訓練されれば、ついに発音を教えられ、その結果、言語を知るようになる かもしれないと、私はほとんど疑わない。そうなれば、もはや野生の人間でも、欠陥のある人間でもなく、完全な人間、小さな紳士になる。 真の哲学者が認めるように、動物から人間への移行は暴力的なものではない。言葉が発明され、言葉を知る以前の人間とは何だったのか。同じ種の動物でありな がら、他の動物よりもはるかに本能が乏しかった。当時、人間は自分が他の動物の上に立つ王だとは思っていなかったし、類人猿やその他の動物から区別されて もいなかった。ライプニッツ派のような素朴な直観的知識に還元された彼は、形と色しか見ず、それらを区別することはできなかった。同じように、老いも若き も、子供も、あらゆる年齢で、彼は自分の感覚と欲求を口にした。 言葉、言語、法律、科学、そして芸術が生まれ、それらによってついに私たちの心のダイヤモンドの原石が磨かれた。人間は動物と同じように訓練されてきた。 動物が重荷を負わされる獣になったように、人間も作者になったのだ。幾何学者は、猿が小さな帽子を脱いだりかぶったりすることや、飼いならされた犬に馬乗 りになることを学んだように、最も難しい実演や計算を行うことを学んだ。あらゆる種が理解できることを学び、このようにして人間は象徴的知識を獲得してき た。 私たちの教育の仕組みほど単純なものはない。すべては、ある人の口から別の人の耳を通って、その人の脳に入る音や言葉に還元することができる。同時に、彼は目を通して、これらの言葉が恣意的な記号である身体の形を知覚する。 しかし、最初に言葉を発したのは誰か。人類最初の教師は誰か?私たちの器官の可塑性を利用する手段を発明したのは誰か?私は答えることができない。これらの最初の素晴らしい天才たちの名前は、時の夜の中で失われてしまった。しかし、芸術は自然の産物である。 最も高度に組織化された人たち、自然が最も豊かな恩恵を与えた人たちが、他の人たちに教えたと考えなければならない。例えば、新しい音を聞いたり、新しい 感覚を体験したり、自然の驚異的な光景を構成する多様で美しい対象すべてに心を打たれたりすることは、シャルトルの聾唖者が40歳のときに初めて鐘の驚く べき音を聞いたときのような心境に陥ることなしにはありえなかった。 このことから、最初の人間が、この聾唖者のように、あるいは動物や唖者(別の種類の動物)のように、想像力の性質に依存した運動によって新しい感覚を表現 しようとし、その結果、驚き、喜び、恍惚感、欲求の自然な表現として、それぞれの動物に特徴的な自発的な音によって表現しようとしたと結論づけるのは不合 理だろうか。間違いなく、自然がより繊細な感覚を授けた動物は、表現する能力もより高かったのだ。 |

| That

is the way in which, I think, men have used their feeling and their

instinct to gain intelligence and then have employed their intelligence

to gain knowledge. Those are the ways, so far as I can understand them,

in which men have filled the brain with the ideas, for the reception of

which nature made it. Nature and man have helped each other; and the

smallest beginnings have, little by little, increased, until everything