Your Mediun make yourself, you are media of your medium, a draft

メディアは我々自身を形づくる

Your Mediun make yourself, you are media of your medium, a draft

メディアは我々自身を形づくる

池田光穂

【メ ディアの定義】「ある所与の文化において、有意味なデータをアドレス指定して送り、記録保存し、処理することを可能ならしめる諸技術と諸制度のネットワー ク」キットラーのメディアの定義『書き取りシステム1800・1900』邦訳書解説(p.769)——メディアはメッセージである、より

| 高 度メディア社会の時空間 |

| 社 会意識の審級としてのメディア |

| 想 像の共同体と、複数形の再部族化 |

| 新しい器 |

| フ レキシブルでインフレキシブルなメディア理解に向けて |

| メディアは我々自身を形づくる(pdf) |

| 情 報メディアと倫理 |

| マーシャル・マクルー ハンの3つの病気 |

| 文化産業論 |

| 人 間=機械論・再訪 |

| ハイパーテキスト |

| スピノ ザの人生と作品 |

高度メディア社会 (sophisticated information society, or highly information-oriented society, both are bullshit buzz-terms by Japanese Information 'Ancient' Scientists, JIAS)における社会倫理を調査研究することは、私にとって人間の多様な可能態について考察することにほかならない。具体的な人 間生活への参加と観察を通して、人間存在がどのように社会的に構成されているのかについて、多大な関心を持ち続けてきた文化人類学の先達たちと同様、私も また人間存在の社会的構築の可能性と限界を見極めたい。そこで立てられる具体的な設問は、メディアに関する我々の常識が社会の中でどのように産み出される かということである。

まず用語の整理からおこなう。

高度メディア社会とは、どのような社会だろうか。私はまず、それを現代日本における日常生活から想像してみたい。マスメディアが発達して いるのは先進開発地域であり、日本を含めた欧米先進諸国の都市の富裕な人々が享受しているメディアの需要環境を、高度メディア社会のプロトタイプとみるこ とが可能だ。現に、マルチメディアに関する文化論・社会論に関する議論は、日本と、より進んだと考えられているアメリカ合衆国での事例が検討されることが 多い。だから我々の身の周りの環境を、さしあたり高度メディア社会としてみてみよう。だが、それはメディア環境が十全に発達していない部分(地域や空間あ るいは人間環境)を視座に入れてはじめてより一層明確になるだろう。だから「低度」メディア社会を想定したり、高度メディア社会にもメディアの度合いが低 度な局所場が存在することを念頭において議論する必要がある。

次に、社会倫理は、社会のさまざまな組織が個人に与える明示的あるいは暗示的な規範や慣習のこと、としてとらえたい。そのようなミニマム な定義にもとづけば、「人間が正しく生きるべき指針を与えるもの」あるいは「人間が根本的に安らぐことのできる場所」(船木1994:4)が倫理であると みなすことも肯けよう。倫理は、したがって、説明することよりも生きることが重要になる人間活動の領域なのである。

では、高度メディア社会の属性とは何であろうか? 我々の生きている日常の生活空間の中で、高度にメディア化されているものと、そうでな いものを弁別する具体的な指標とは何だろうか? つまり何を用いているときに高度メディア化した体験をし、何を用いているときにはそうではないのか? パ ソコン、インターネット、ワープロ、ゲームのような双方向のインタラクティブなメディア;テレビ、ビデオ、ラジオのような受容を主とする一方向メディア; 電話や電子メールのようなインタラクティブな人間の活動を電子的に補助するメディア、などメディアの種類は千差万別である。またメディア提示のされ方にも とづいて、個々のメディアの要素の多寡においても、マルチメディアのように、それらの機能が複合の度合いの程度からも、高度メディア社会の属性を析出する ことができる。これらのことは、ホット/クールというメディアという二項対立に基づいて分析したマクルーハンの手法を思い起こさせるが、いずれにせよ、高 度メディア社会を表象する現象を見いだし、その属性について多角的に考察することは、我々のメディア理解のための探究の基本形となる。

我々の研究には、新しいメディアを多角的に利用するということが、どのような感覚を広げるのかを自ら実験するというスタイルをもりこんで いる。私にとっての研究計画の初年度の最大の経験は、インターネット利用の幅が広がったということである。それは、旧年度までは電子メールの利用をのぞけ ば、インターネットの利用はブラウザーを使ってネットサーフィン、つまり次々と画面から画面へと興味に応じて閲覧を続けることだけしかおこなわなかった。 しかし、今年度からWWWサーバに自分のウェブページを立ち上げ、情報発信を始めた。ウェブページの運営とそれに対する閲覧者の反応は、私がそれまで論文 や講演という形でしか自己の主張を公開する手段がなかった可能性を広げるばかりでなく、WWWサーバーにおける情報発信についての自己とネットワーク社会 との関係について、改めて考えさせられる契機になった。この経験は、それまで持ったことのない異質な体験であると同時に、ある種の倫理的な場所に踏み込ん だような体験であった。また同時に自分自身の身体が分離し、あたかもの分身をもつような経験でもあった。このような事態は、我々の研究対象にした時代や社 会の人々も同じように体験してきたり、これから体験することなのであろう。この種の体験を分析する枠組みを、さまざまな形で仮説的に提示することも我々の 課題になるだろう。

我々が経験のレベルで異質の倫理の時空間に踏み込むことは、人類にとって新しい倫理の時空間に踏み込んだことになるのだろうか。メディア の歴史ならびに人類学的研究が明らかにしてきたことは、あるメディアが優位を占める局面から、別のメディアに置き換わるという移行を通して、旧来のメディ アと旧来の価値観をもつ社会の成員は、それを旧来の認知的枠組みから解釈し、自分たちに納得のいく形に馴化し、その別の新しい局面に自らを適合させようと する傾向がみられることである。馴化のプロセスは、数世代以上におよぶ長期的なものもあれば、同世代内で短期的に終了することもある。

近代は、このようなメディア受容の適応様式に加えて、自分たちが承認した肯定的価値──それはしばしば合理性と有用性の観点によって判断 される──を具現化するものを新規で良きものと位置づけ、それを進んで受容する解釈と実践の体系を造り上げてきたところに大きな特色がある。もちろん、そ れらの取捨選択には恣意的な要素も多く介在し、即時的な対応と事後的な解釈の混成体が、我々の目の前にあるわけだ。新規なものは進歩とともに、概ね肯定的 な価値が与えられてきた。

このような合理性判断にもとづく実践行為は、それ自体で文化的に価値づけられた社会現象であり、先のような馴化のプロセスと見なすること ができる。だが、近代における高度メディア社会の登場は、それまでの人間が経験してきた文化的衝撃の中でも最大級のものであるという主張──それは信仰や 神話に近い──も数多く存在する。「実は予想を裏切って僅かな影響しか与えていない」という対抗神話の言説もまた多く存在するが、このような対抗神話の流 通そのものは逆に社会的影響の大きさを物語っている(西垣 1994)。それぞれの主張の真偽はともかくとして、高度メディア社会の到来は、我々の社会意識のあり方に大いなる再考の機会を与えていることは確かだ。

●サイバーパンク︎▶︎サイバーパンクにおいて倫理は可能か?▶︎︎︎メディアはメッセージである▶︎▶︎︎▶

本稿は、以上のような問題意識に立って、高度メディア社会が「新しい意識」を形づくっている様態とは何なのか、メディアが社会意識を形成 するとすれば、それはどのような形態をとりうると考えられているのか、我々の社会意識が形成される際に、主要なシンボルや根本となるメタファーが見られる とすれば、それは果たしてどのようなものか、等について、私の研究関心に引きつけて、以下の節において考察してみたい。

伝統的なマルクス主義の視点に立てば、メディアを含めたもろもろの上部構造のあり方は、その社会の下部構造である経済によって規定され、 上部構造の一部たるメディアと下部構造の相互作用関係、つまり弁証法的な関係によって展開するという見方をとるだろう。実際に、マルクス主義からその批判 のためのアイディアをとる研究者は、1960年代のメディアの発達が人間の意識を変革するというA・トフラーやM・マクルーハンの立場を、プチブルジョア の発想と断定し、誰がメディアの支配権をもつかという観点から考察されていないと批判してきた。だが、メディアに関する唯物論的な批判には、貧困な図式の 虜になったものが多い。なぜだろう。上部構造の一部をなすメディアが下部構造に与えるフィードバックのスピードにマルクス主義者たちはついていけなかった のか。メディアそのものがもつ「下部構造」性──マーク・ポスターの言う情報様式──についての無理解に根ざす初歩的な誤りによるものなのか。それは19 世紀の機械のメタファー的想像力の限界でもあるように思える。

今日のメディア論を概観すれば、その多くはメディアが社会の構成員が持ちうる意識や知覚に大きな影響を与える、つまりメディアは社会意識 の審級であるという命題を前提にして議論されているものが多いことに気づくはずだ。教条的なマルクス主義者の感情を逆撫でするはずである。マクルーハンは 『メディアの理解』(1964)において、活字の登場と「電気」メディアの登場が人間の社会意識にどのような影響を与えるかを指摘しているが、彼はその命 題に忠実な論者の一人であった。

──活字による印刷は複雑な手工芸木版を最初に機械化したものであり、その後のいっさいの機械化の原型となった。‥‥活字印刷が 情報を蓄積する手段あるいは知識を迅速に回収する新しい手段に他ならないと見るならば、それによって時間と空間の両方において、心理的にも社会的にも、郷 党精神(parochialism)と部族精神(tribalism)とは終わりを遂げた。

──印刷もまたそれ以外の人間の拡張と同じであって、心理的ならびに社会的な影響を及ぼし、以前の文化の境界と模様を突然に変え てしまった。‥‥情報を移動するのに電気という手段を用いるようになって、われわれの活字文化はいま変わりつつある。それは、ちょうど、印刷術が発明され て、中世の写本やスコラの文化が変化を受けたのと同じである。

──アルファベット(およびその拡張である活字)が知識という力を拡張させることを可能にし、部族民の絆を壊滅させた。かくし て、部族民の紐帯を爆破させて、ばらばらの個人の集合としてしまった。電気による書字と速度は、瞬間的かつ持続的に、個人の上に他のすべての人に関心を注 ぐ。こうして、個人はふたたび部族民となる。人間の一族全体がもう一度、ひとつの部族となる。(邦訳pp.173-175を一部改訳、原著pp.170- 172)

しかし、もちろん事態はこのような単純なものでない。新しいメディアの普及が人々の意識を変容したということを、指摘することはたやすい が、論証することはきわめて困難である。また、それ以前に、そのような問題提起の前提つまり、新しいメディアの普及が人間の認知に影響を与え、それが総体 としての人間の意識を変化させたという設問が、なぜ学問上の問題になり、それが真面目に議論されるようになったかということが、時代や社会の文脈から理解 される必要があるようだ。

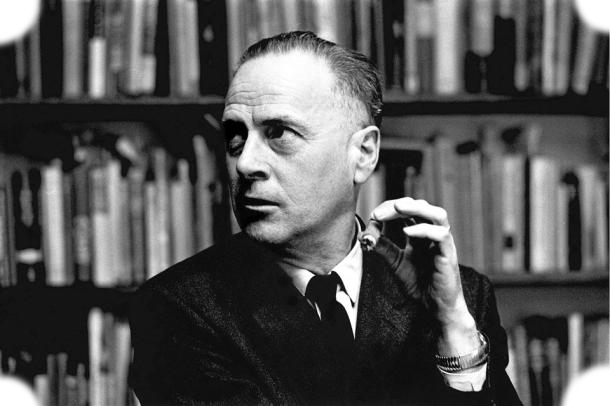

メディア研究史を繙けば、新しいメディアが人間の意識を変え、それが現代の我々の社会意識のあり方を知る上で重要な示唆を与えるという主 張は意外と新しいことに気づくはずである。W・ベンヤミンの「複製技術時代の芸術」(1935)はその嚆矢の一つであろうが、カナダのH・イニス (1951)、M・マクルーハン(1951,1962,1964)以降、議論は本格化し、現在の我々の議論により親和性をもつようになる。とくに北アメリ カにおける本格的なテレビ時代の到来によって、マクルーハンの議論は、きわめて大きな社会的影響力をもった。

メディアの普及とそれに影響を受ける人々というアイディアは、識字を中心とした歴史上の「民衆」(Illich and Sanders 1988)や「未開の心」(Goody 1977)への影響力、政治思想史(Anderson 1987)や文化研究(Tomlinson 1991)などの随所にみられる。

総じて、1960年代のメディア論の中心的な議論はテレビメディアに関するもので、この新興のメディアは人間の感覚や意識を変えつつある という主張であった。マクルーハンの『グーテンベルグの銀河系』(1962)は、それまで彼が蓄積してきたメディア論の総決算とも言えるものであり、そこ では、さまざまな時代や場所を超えて、新しいメディアの普及は旧来のメディアに慣れ親しんできた人間に衝撃を与えるだけでなく、メディアの理解に習熟する ことが、新しい世界観を得るということに深い関係をもつことを多面的に論じている。類似の議論も数多く見られた。このような現象は、今日の我々がコン ピュータやインターネットの普及に関する社会的影響力の過剰な期待や議論の沸騰という事態と似ていなくはない。

フランスを中心としておこった1970年代以降の文化や消費の記号論的な解釈(Baudrillard, Barthes)は、それまで論じられることが少なかったメディアの否定的側面に関する説明を通してメディア論に衝撃を与えた。例えばモードの体系は一種 の言語的な記号の体系である、高度資本主義の矛盾は生産の場から消費の場に移行する(記号の消費)、非現実の現実化(ハイパーリアル)の世の中に我々はい る、という指摘がなされた。これは疎外論を通して大衆社会を批判したい知識人にうってつけの言説を提供することになる。また一般には、メディアがもつ消費 活動、それもどちからというと幻影に振り回される現代生活というニュアンスをもって大衆に膾炙した。

ところが1980年代後半からのパーソナル・コンピュータの能力の向上と低価格化による爆発的な普及を背景に、インターネットやヴァー チャル・リアリティに関する議論がおもにアメリカ合衆国など先進諸国のコンピュータ技術者の間でさかんに議論されるようになってきた。この議論の背景に は、膨大な情報が取り扱えるコンピュータメディアの発達や成熟、カメラや録音機、今日ではビデオ撮影機等のパーソナル・メディアのコンピュータによる管理 や、自己実現としての情報発信技術などが、ごく当たり前のものとなるほど普及してきたことがあげられる。

メディアの歴史的変化とその環境を利用する人々の意識の変化という命題は、20世紀に起きた大衆向けの映画の普及(ベンヤミン)、テレビ の普及(マクルーハン)、そして今日のネットワークにつながれたパーソナルコンピュータの普及(現代の論客たち)という技術革新とその大衆化の時期を軌を 同じくして登場してきたことがわかる。メディアが我々の社会意識を変えつつあるという「自覚」は、新種のメディアが急速に普及する社会過程と同調的に、あ るいはやや遅延を伴って現れることが容易に推測されるだろう。少なくとも、人間にはメディアの影響力に脅威を感じたとき、従来維持してきた社会意識を再編 成させ、自分に合った形に鋳直す過程がそこには見られることを指摘しておきたい。

社会意識の審級としてメディアを考える際には、このあたりの見極めをもって議論を整理する必要がある。

| THE PRINTED WORD,

Architect of Nationalism |

||

| 1 |

You may perceive,

Madam," said Dr. Johnson with a pugilistic smile,

that I am well-bred to a degree of needless scrupulosity " Whatever

the degree of conformity the Doctor had achieved with the new

stress of his time on white-shirted tidiness, he was quite aware of the

growing social demand for visual presentability. |

「ご存じのとおり、私は不必要に細心の注意を払うほど礼儀正しい人間

だ」とジョンソン博士は、拳を握り締めたような微笑みを浮かべて言った。当時の新しい風潮である白いシャツの整頓さに、博士がどの程度順応していたかに関

わらず、彼は、外見の整頓さが社会的にますます重要視されていることをよく認識していた。 |

| 2 |

Printing from

movable types was the first mechanization of a

complex handicraft, and became the archetype of all subsequent

mechanization. From Rabelais and More to Mill and Morris, the

typographic explosion extended the minds and voices of men to

reconstitute the human dialogue on a world scale that has bridged

the ages. For if seen merely as a store of information, or as a new

means of speedy retrieval of knowledge, typography ended

parochialism and tribalism, psychically and socially, both m space

and in time. Indeed the first two centuries of printing from movable

types were motivated much more by the desire to see

ancient and medieval books than by the need to read and write new

ones. Until 1 700 much more than SO per cent of all printed books

were ancient or medieval. Not only antiquity but also the Middle

Ages were given to the first reading public of the printed word. And

the medieval texts were by far the most popular. |

活字による印刷は、複雑な手工業の最初の機械化であり、その後のすべて

の機械化の原型となった。ラブレからモア、ミル、モリスに至るまで、活字の爆発的な普及は、人々の思考と声を広げ、時代を超えた世界規模の人間の対話を再

構築した。もし活版印刷を単なる情報の貯蔵庫や、知識を迅速に検索する新たな手段と見なすなら、活版印刷は空間的にも時間的にも、心理的・社会的に地方主

義と部族主義を終わらせた。実際、活版印刷の最初の2世紀は、新しい本を読む必要よりも、古代や中世の本を見たいという願望によって動機付けられていた。

1700年まで、印刷された本の90%以上が古代や中世の書籍だった。古代だけでなく、中世のテキストも、印刷された言葉の最初の読者層に与えられた。そ

して、中世のテキストが圧倒的に最も人気があった。 |

| 3 |

Like

any other extension of man, typography had psychic and social

consequences that suddenly shifted previous boundaries and patterns of

culture. In bringing the ancient and medieval worlds into fusion --or,

as some would say, confusion -- the printed book created a third world,

the modern world, which now encounters a new electric technology or a

new extension of man. Electric means of moving of information are

altering our typographic culture as sharply as print modified medieval

manuscript and scholastic culture. Beatrice Warde has recently

described in Alphabet an electric display of letters painted by light.

It was a Norman McLaren movie advertisement of which she asks Do you

wonder that I was late for the theatre that night, when I tell you that

I saw two club-footed Egyptian A's . . . walking off arm-in-arm with

the unmistakable swagger of a music-hall comedy-team? I saw base-serifs

pulled together as if by ballet shoes, so that the letters tripped off

literally sur les pointes . . . after forty centuries of the

necessarily static Alphabet, I saw what its members could do in the

fourth dimension of Time, "flux," movement. You may well say that I was

electrified. Nothing could be farther from typographic culture with its

"place for everything and everything in its place." Mrs. Warde has

spent her life in the study of typography and she shows sure tact in

her startled response to letters that are not printed by types but

painted by light. It may be that the explosion that began with phonetic

letters (the "dragon's teeth" sowed by King Cadmus) will reverse into

"implosion" under the impulse of the instant speed of electricity. The

alphabet (and its extension into typography) made possible the spread

of the power that is knowledge, and shattered the bonds of tribal man,

thus exploding him into agglomeration of individuals. |

他のあらゆる人間の延長と同様に、タイポグラフィも、それ

までの文化の境界やパターンを一気に覆すような、精神的・社会的な影響をもたらしました。古代と中世の世界を融合(あるいは、混乱と表現する人もいるで

しょう)させた印刷本は、第三の世界、すなわち現代の世界を生み出し、その現代は、今、新しい電気技術、つまり人間の新たな延長と遭遇しています。情報を

伝達する電気的手段は、印刷が中世の写本や学問文化を変えたのと同じくらい、タイポグラフィ文化を大きく変えています。ベアトリス・ウォードは最近、光で

描かれた文字の電気ディスプレイ「アルファベット」について述べています。それはノーマン・マクラーレンの映画の広告で、彼女は次のように尋ねています。

その夜、私が映画館に遅れたことを不思議に思うでしょう。なぜなら、私は、2 人のクラブフットのエジプト人の A

が、ミュージックホールのコメディチームのような紛れもない威勢のいい歩き方で腕を組んで歩いていくのを見たからです。私は、バレエシューズで引き寄せら

れたようなベースセリフを見て、文字が文字通り「つま先立ち」で飛び出していくのを見た... 40

世紀にわたって必然的に静的であったアルファベットが、時間の 4

次元、「流動性」という動きの中で何ができるかを私は見たのだ。私は感電したと言ってもいいだろう。「すべてのものに所定の位置があり、すべてのものがそ

の位置にある」というタイポグラフィ文化から、これほどかけ離れたものはないだろう。ウォード夫人は生涯をタイポグラフィの研究に捧げてきた。彼女は、活

字で印刷されていない文字ではなく、光で描かれた文字に対する驚きの反応において、確かな感覚を示している。フォネティック文字(カドモス王が蒔いた「竜

の歯」)から始まった爆発は、電気の瞬時の速度の衝動の下で「内向爆発」に逆転するかもしれない。アルファベット(およびその拡張であるタイポグラフィ)

は、知識という力の拡散を可能にし、部族人間の絆を破壊し、個々の集まりへと爆発させた。 |

| 4 |

Electric

writing and speed pour upon him, instantaneously and continuously, the

concerns of all other men. He becomes tribal once more. The human

family becomes one tribe again. Any student of the social history of

the printed book is likely to be puzzled by the lack of understanding

of the psychic and social effects of printing. In five centuries

explicit comment and awareness of the effects of print on human

sensibility are very scarce. But the same observation can be made about

all the extensions of man, whether it be clothing or the computer. An

extension appears to be an amplification of an organ, a sense or a

function, that inspires the central nervous system to a self-protective

gesture of numbing of the extended area, at least so far as direct

inspection and awareness are concerned. Indirect comment on the effects

of the printed book is available in abundance in the work of Rabelais,

Cervantes, Montaigne, Swift, Pope, and Joyce. They used typography to

create new art forms. Psychically the printed book, an extension of the

visual faculty, intensified perspective and the fixed point of view.

Associated with the visual stress on point of view and the vanishing

point that provides the illusion of perspective there comes another

illusion that space is visual, uniform and continuous. |

電気的な文字と速度が、瞬時に、そ

して絶え間なく、他のすべての人間の懸念を彼に浴びせる。彼は再び部族の一員となる。人類の家族は再び一つの部族となる。印刷物の社会史を研究する者は、

印刷の心理的・社会的影響に対する理解の欠如に困惑するだろう。5世紀の間、印刷が人間の感性に与える影響に関する明確なコメントや認識は極めて稀だ。し

かし、同じ観察は、衣服やコンピュータを含む人間のあらゆる拡張形態にも当てはまる。拡張は、器官、感覚、または機能の増幅のように見え、中枢神経系に、

少なくとも直接的な観察と意識の範囲内では、拡張された領域の麻痺という自己保護的な反応を引き起こす。印刷物の効果に関する間接的なコメントは、ラブ

レ、セルバンテス、モンテーニュ、スウィフト、ポープ、ジョイスの作品に豊富に存在する。彼らは活版印刷を用いて新しい芸術形式を創造した。心理的に、印

刷された本は視覚の延長として、遠近法と固定された視点の強度を高めた。視点への視覚的ストレスと、遠近法の錯覚を提供する消失点と関連して、空間が視覚

的、均一、連続的であるという別の錯覚が生じる。 |

| 5 |

The

linearity precision and uniformity of the arrangement of movable types

are inseparable from these great cultural forms and innovations of

Renaissance experience. The new intensity of visual stress and private

point of view in the first century of printing were united to the means

of self-expression made possible by the typographic extension of man.

Socially, the typographic extension of man brought in nationalism,

industrialism, mass markets, and universal literacy and education. For

print presented an image of repeatable precision that inspired totally

new forms of extending social energies. Print released great psychic

and social energies in the Renaissance, as today in Japan or Russia, by

breaking the individual out of the traditional group while providing a

model of how to add individual to individual in massive agglomeration

of power. |

活字の直線

的な精度と配置の均一性は、ルネサンスの経験によるこれらの偉大な文化形態や革新と切り離せないものだ。印刷の最初の 1

世紀に見られた視覚的ストレスの新たな強さと個人的な視点は、活字による人間の表現手段の拡大によって可能になった。社会的には、活字による人間の表現手

段の拡大は、ナショナリズム、工業主義、大衆市場、そして普遍的な識字と教育をもたらした。印刷は、繰り返しの精度を持つイメージを提示し、社会的なエネ

ルギーを拡張する全く新しい形態を刺激した。印刷は、ルネサンス時代、そして現在の日本やロシアにおいて、伝統的な集団から個人を解放しつつ、巨大な権力

集積の中に個人を統合するモデルを提供することで、大きな心理的・社会的エネルギーを解放した。 |

| 6 |

The

same spirit of private enterprise that emboldened authors and artists

to cultivate self-expression led other men to create giant

corporations, both military and commercial. Perhaps the most

significant of the gifts of typography to man is that of detachment and

noninvolvement--the power to act without reacting. Science since the

Renaissance has exalted this gift which has become an embarrassment in

the electric age, in which all people are involved in all others at all

times. The very word "disinterested," expressing the loftiest

detachment and ethical integrity of typographic man, has in the past

decade been increasingly used to mean: "He couldn't care less." The

same integrity indicated by the term "disinterested" as a mark of the

scientific and scholarly temper of a literate and enlightened society

is now increasingly repudiated as "specialization" and fragmentation of

knowledge and sensibility. The fragmenting and analytic power of the

printed word in our psychic lives gave us that "dissociation of

sensibility" which in the arts and literature since Cezanne and since

Baudelaire has been a top priority for elimination in every program of

reform in taste and knowledge. In the "implosion" of the electric age

the separation of thought and feeling has come to seem as strange as

the departmentalization of knowledge in schools and universities. |

作

家や芸術家たちが自己表現を育むことを勇気づけたのと同じ民間企業の精神が、他の人々を軍事および商業の巨大企業を創設へと駆り立てた。おそらく、タイポ

グラフィが人類にもたらした最も重要な贈り物は、客観性と非関与、つまり反応せずに行動する力だろう。ルネサンス以来、科学はこの贈り物を称賛してきた

が、すべての人々が常にすべての人々と関わっている電気時代では、この贈り物は厄介なものとなっている。「無関心」という言葉は、タイポグラフィの人間の

最も高貴な客観性と倫理的整合性を表現するものだったが、過去10年間で「どうでもいい」という意味で increasingly

使われるようになった。同じ「無関心」という言葉が、文字を読み書きでき、啓蒙された社会の科学的・学問的な態度を示すものとして示していた整合性は、現

在では「専門化」と知識や感性の断片化として increasingly

否定されている。私たちの精神生活における印刷物の断片化と分析力は、セザンヌやボードレール以来、芸術や文学において、趣味や知識の改革プログラムにお

いて最優先の排除対象となってきた「感性の分離」をもたらした。電気時代の「内破」において、思考と感情の分離は、学校や大学における知識の部門化と同じ

くらい奇妙なものになってきている。 |

| 7 |

Yet

it was precisely the power to separate thought and feeling, to be able

to act without reacting, that split literate man out of the tribal

world of close family bonds in private and and social life. Typography

was no more an addition to the scribal art than the motorcar was an

addition to the horse. Printing had its "horse-less carriage" phase of

being misconceived and misapplied during its first decades, when it was

not uncommon for the purchaser of a printed book to take it to a scribe

to have it copied and illustrated. Even in the early eighteenth century

a "textbook" was still defined as a "Classick Author written very wide

by the Students, to give room for an Interpretation dictated by the

Master, &c, to be inserted in the Interlines" (O.E.D.). Before

printing, much of the time in school and college classrooms was spent

in making such texts. The classroom tended to be a scriptorium with a

commentary. The student was an editor-publisher. By the same token the

book market was a secondhand market of relatively scarce items.

Printing changed learning and marketing processes alike. The book was

the first teaching machine and also the first mass-produced commodity.

In amplifying and extending the written word, typography revealed and

greatly extended the structure of writing. Today, with the cinema and

the electric speed-up of information movement, the formal structure of

the printed word, as of mechanism in general, stands forth like a

branch washed up on the beach. |

し

かし、まさに思考と感情を分離し、反応せずに行動できる力が、文字を扱う人間を、私生活や社会生活において密接な家族関係に縛られた部族社会から切り離し

た。活版印刷は、馬車に対する自動車のような、書記術への追加的な発明ではなかった。印刷は、最初の数十年間、誤解され誤用される「馬のない馬車」の段階

を経た。その頃、印刷された本を購読した人が、それを書記に持ち込んで写し取りや挿絵を依頼することは珍しくなかった。18世紀初頭でも、「教科書」は

「学生が教師の指示に従って解釈を挿入するための余白を広く残して書かれた古典作家」と定義されていた(O.E.D.)。印刷以前、学校や大学の教室での

時間の多くは、このようなテキストの作成に費やされていた。教室は、解説付きの写本室のような場所だった。学生は編集者兼出版者だった。同様に、書籍市場

は比較的希少な品物の古本市場だった。印刷は学習とマーケティングのプロセスを同時に変えた。本は最初の教育機械であり、最初の大量生産品でもあった。文

字を拡大し拡張する過程で、活字は文字の構造を明らかにし、大きく拡張した。今日、映画と情報の電気的な高速化により、印刷された文字の形式的な構造は、

一般の機械の構造と同様に、浜辺に打ち上げられた枝のように浮き彫りになっている。 |

| 8 |

A

new medium is never an addition to an old one, nor does it leave the

old one in peace. It never ceases to oppress the older media until it

finds new shapes and positions for them. Manuscript culture had

sustained an oral procedure in education that was called

"scholasticism" at its higher levels; but by putting the same text in

front of any given number of students or readers print ended the

scholastic regime of oral disputation very quickly. Print provided a

vast new memory for past writings that made a personal memory

inadequate. Margaret Mead has reported that when she brought several

copies of the same book to a Pacific island there was great excitement.

The natives had seen books, but only one copy of each, which they had

assumed to be unique. Their astonishment at the identical character of

several books was a natural response to what is after all the most

magical and potent aspect of print and mass production. It involves a

principle of extension by homogenization that is the key to

understanding Western power. The open society is open by virtue of a

uniform typographic educational processing that permits indefinite

expansion of any group by additive means. |

新

しいメディアは、決して古いメディアに追加されるものではなく、古いメディアを放置するものでもない。それは、古いメディアに新しい形や位置を見つけるま

で、その抑圧を絶えず続ける。手書き文化は、教育において「スコラ哲学」と呼ばれる口頭での手続きを維持してきたが、印刷技術は、同じテキストを任意の数

の学生や読者の前に提示することで、口頭での論争によるスコラ哲学の体制を非常に迅速に終焉させた。印刷は、個人の記憶では不十分な、過去の著作の膨大な

新しい記憶を提供した。マーガレット・ミードは、太平洋の島に同じ本を何冊か持っていくと、大きな興奮が起こったと報告している。先住民たちは、本を見た

ことはあったが、それは 1

冊しかなく、それが唯一のものだと思っていたのだ。複数の本がまったく同じであることに彼らが驚愕したのは、結局のところ、印刷と大量生産の最も呪術的で

強力な側面に対する当然の反応だった。これには、均質化による拡張の原理が関わっており、これは西洋の力を理解する上で重要な鍵となる。開かれた社会は、

あらゆる集団を無制限に拡大できる、均質な活字による教育プロセスによって開かれている。 |

| 9 |

The

printed book based on typographic uniformity and repeatability in the

visual order was the first teaching machine, just as typography was the

first mechanization of a handicraft. Yet in spite of the extreme

fragmentation or specialization of human action necessary to achieve

the printed word, the printed book represents a rich composite of

previous cultural inventions. The total effort embodied in the

illustrated book in print offers a striking example of the variety of

separate acts of invention that are requisite to bring about a new

technological result. The psychic and social consequences of print

included an extension of its fissile and uniform character to the

gradual homogenization of diverse regions with the resulting

amplification of power, energy, and aggression that we associate with

new nationalisms. Psychically, the visual extension and amplification

of the individual by print had many effects. Perhaps as striking as any

other is the one mentioned by Mr. E. M. Forster, who, when discussing

some Renaissance types, suggested that "the printing press, then only a

century old, had been mistaken for an engine of immortality, and men

had hastened to commit to it deeds and passions for the benefit of

future ages." People began to act as though immortality were inherent

in the magic repeatability and extensions of print. |

活字の統一性と視覚的な順序の反復

性に基づいて作成された印刷本は、活字が手工業の最初の機械化であったように、最初の教育機械でした。しかし、印刷文字を実現するために必要な人間の行動

の極端な分業や専門化にもかかわらず、印刷本は過去の文化的発明の豊かな複合体です。印刷された図鑑に具現化された全努力は、新しい技術的成果をもたらす

ために必要な、さまざまな個別の発明行為の多様性を示す顕著な例だ。印刷の精神的および社会的影響としては、その分裂性および均一性が、さまざまな地域の

漸進的な均質化に拡大し、その結果、新しいナショナリズムに伴う権力、エネルギー、攻撃性の増幅をもたらしたことが挙げられる。精神的には、印刷による個

人の視覚的拡大および増幅は、多くの影響をもたらした。おそらく最も印象的なのは、E. M.

フォースター氏が、ルネサンスのいくつかのタイプについて論じながら、「当時、まだ 1

世紀しか経っていなかった印刷は、不滅のエンジンと間違えられ、人々は、将来世代のために、その印刷に自分の行為や情熱を刻むことを急いだ」と述べたこと

だろう。人々は、印刷の呪術的な再現性と拡張性に不滅の性質があるかのように振る舞い始めたのだ。 |

| 10 |

Another

significant aspect of the uniformity and repeatability of the printed

page was the pressure it exerted toward "correct" spelling, syntax, and

pronunciation. Even more notable were the effects of print in

separating poetry from song, and prose from oratory, and popular from

educated speech. In the matter of poetry it turned out that, as poetry

could be read without being heard, musical instruments could also be

played without accompanying any verses. Music veered from the spoken

word, to converge again with Bartok and Schoenberg. With typography the

process of separation (or explosion) of functions went on swiftly at

all levels and in all spheres; nowhere was this matter observed and

commented on with more bitterness than in the plays of Shakespeare.

Especially in King Lear, Shakespeare provided an image or model of the

process of quantification and fragmentation as it entered the world of

politics and of family life. Lear at the very opening of the play

presents "our darker purpose" as a plan of delegation of powers and

duties: Only we shall retain The name, and all th' addition to a King;

The sway, revenue, execution of the rest, Beloved sons, be yours: which

to confirm, This coronet part between you. This act of fragmentation

and delegation blasts Lear, his kingdom, and his family. |

印

刷物の均一性と再現性のもう一つの重要な側面は、それが「正しい」綴り、文法、発音に対して与えた圧力だった。さらに注目すべきは、印刷物が詩と歌、散文

と演説、大衆的な言葉と教養ある言葉とを分離した効果だった。詩に関しては、詩は聞かなくても読むことができるため、楽器も詩を伴わずに演奏することがで

きることがわかった。音楽は言葉から離れ、バルトークやシェーンベルクを通じて再び言葉と融合した。活版印刷により、機能の分離(または爆発)のプロセス

は、あらゆるレベルと分野で急速に進んだ。この現象が最も苦々しく観察され、指摘されたのは、シェイクスピアの戯曲だった。特に『キング・ラー』では、

シェイクスピアは、政治と家族生活の世界に浸透する量化と分断のプロセスを、イメージやモデルとして提示した。リアは劇の冒頭で、「私たちの暗い目的」を

権限と義務の委譲計画として提示する:「我々だけが王の名と王の付随する一切を保持する。統治権、収入、その他の権限は、愛する息子たちよ、あなたたちの

ものとする。これを確認するため、この冠をあなたたちで分けよ」。この断片化と委譲の行為は、リア、彼の王国、そして彼の家族を破壊する。 |

| 11 |

Yet

to divide and rule was the dominant new idea of the organization of

power in the Renaissance. "Our darker purpose" refers to Machiavelli

himself, who had developed an individualist and quantitative idea of

power that struck more fear in that time than Marx in ours. Print,

then, challenged the corporate patterns of medieval organization as

much as electricity now challenges our fragmented individualism. The

uniformity and repeatability of print permeated the Renaissance with

the idea of time and space as continuous measurable quantities. The

immediate effect of this idea was to desacralize the world of nature

and the world of power alike. The new technique of control of physical

processes by segmentation and fragmentation separated God and Nature as

much as Man and Nature, or man and man. Shock at this departure from

traditional vision and inclusive awareness was often directed toward

the figure of Machiavelli, who had merely spelled out the new

quantitative and neutral or scientific ideas of force as applied to the

manipulation of kingdoms. Shakespeare's entire work is taken up with

the themes of the new delimitations of power, both kingly and private. |

し

かし、分断して支配するという考えは、ルネサンス時代の権力組織における支配的な新しい思想だった。「私たちの暗い目的」とは、その時代においてマルクス

が私たちの時代にもたらしたよりも大きな恐怖を与えた、個人主義的で定量的な権力観を提唱したマキャヴェッリ自身を指している。印刷は、中世の組織形態の

企業的パターンに、現在電気の断片化した個人主義が挑戦するように、挑戦した。印刷の均一性と再現性は、時間と空間を連続的で測定可能な量としてルネサン

スに浸透させた。この思想の直後の効果は、自然の世界と権力の世界の両方を神聖化から解き放つことだった。物理的プロセスを分割と断片化によって制御する

新たな技術は、神と自然を、人間と自然、または人間と人間を同様に分離した。この伝統的なビジョンと包括的な意識からの離反に対する衝撃は、しばしばマ

キャベリの人物に向けられた。彼は、王国操作に適用される新たな量的で中立的または科学的力概念を単に明示したに過ぎなかった。シェイクスピアの全作品

は、王権と私権の両方の新たな権力境界のテーマに満ちている。 |

| 12 |

No

greater horror could be imagined in his time than the spectacle of

Richard II, the sacral king, undergoing the indignities of imprisonment

and denudation of his sacred prerogatives. It is in Troilus and

Cressida, however, that the new cults of fissile, irresponsible power,

public and private, are paraded as a cynical charade of atomistic

competition: Take the instant way; For honour travels in a strait so

narrow Where one but goes abreast: keep, then, the path; For emulation

hath a thousand sons That one by one pursue: if you give way, Or hedge

aside from the direct forthright, Like to an enter'd tide they all rush

by And leave you hindmost. . . The image of society as segmented into a

homogeneous mass of quantified appetites shadows Shakespeare's vision

in the later plays. Of the many unforeseen consequences of typography,

the emergence of nationalism is, perhaps, the most familiar. |

彼の時代において、神聖な王である

リチャード2世が投獄され、神聖な特権を剥奪されるという光景ほど恐ろしいものは想像できなかった。しかし、『トロイラスとクレシダ』では、分裂的で責任

を問われない公的・私的な新たな権力崇拝が、原子的な競争の皮肉な茶番劇として披露されている: 即座に行け; 栄誉は狭き道を行くものだから、

並んで進むことはできない: だから道を守れ; 競争心は千の息子を産むから、 彼らは一人ずつ追いかけてくる: もし道を譲ったり、

直接の道から外れたりすれば、 押し寄せる潮のように皆が押し寄せ、 あなたを後方に置き去りにするだろう。 .

.社会が同質的な欲望の塊に分割されたイメージは、シェイクスピアの後の作品におけるビジョンを影のように覆っている。活版印刷の多くの予期せぬ結果のう

ち、ナショナリズムの台頭は、おそらく最もよく知られているだろう。 |

| 13 |

Political

unification of populations by means of vernacular and language

groupings was unthinkable before printing turned each vernacular into

an extensive mass medium. The tribe, an extended form of a family of

blood relatives, is exploded by print, and is replaced by an

association of men homogeneously trained to be individuals. Nationalism

itself came as an intense new visual image of group destiny and status,

and depended on a speed of information movement unknown before

printing. Today nationalism as an image still depends on the press but

has all the electric media against it. In business, as in politics, the

effect of even jet-plane speeds is to render the older national

groupings of social organization quite unworkable. In the Renaissance

it was the speed of print and the ensuing market and commercial

developments that made nationalism (which is continuity and competition

in homogeneous space) as natural as it was new. By the same token, the

heterogeneities and noncompetitive discontinuities of medieval guilds

and family organization had become a great nuisance as speed-up of

information by print called for more fragmentation and uniformity of

function. The Benvenuto Cellinis, the

goldsmith-cum-painter-cum-sculptor-cum-writer-cum-condottiere, became

obsolete. Once a new technology comes into a social milieu it cannot

cease to permeate that milieu until every institution is saturated. |

印刷が各地方言語を大規模なマスメ

ディアに変える以前、方言や言語集団による人口の政治的統一は考えられなかった。血縁関係にある家族の拡張形態である部族は、印刷によって崩壊し、個々人

として均質に訓練された人々の連合体に置き換えられた。ナショナリズム自体は、集団の運命と地位を象徴する強烈で新しい視覚的イメージとして登場し、印刷

技術以前には知られていなかった情報の移動速度に依存していた。今日、イメージとしてのナショナリズムは依然として報道機関に依存しているが、あらゆる電

気メディアがそれに反対している。ビジネスにおいても、政治と同様に、ジェット機の速度でさえ、従来の国家による社会組織を機能不全に陥らせる影響力を

持っている。ルネサンス時代、ナショナリズム(均質な空間における継続性と競争)を当然のものとしたのは、印刷の速度と、それに伴う市場と商業の発展だっ

た。同様に、印刷による情報の高速化によって機能の細分化と均一化が求められるようになったため、中世のギルドや家族組織のような不均一で非競争的な不連

続性は大きな障害となった。金細工師兼画家兼彫刻家兼作家兼傭兵隊長であるベンヴェヌート・チェッリーニのような人物は、時代遅れになった。新しい技術が

社会環境に導入されると、その技術は、すべての機関が飽和状態になるまで、その環境から消えることはない。 |

| 14 |

Typography

has permeated every phase of the arts and sciences in the past five

hundred years. It would be easy to document the processes by which the

principles of continuity, uniformity, and repeatability have become the

basis of calculus and of marketing, as of industrial production,

entertainment, and science. It will be enough to point out that

repeatability conferred on the printed book the strangely novel

character of a uniformly priced commodity opening the door to price

systems. The printed book had in addition the quality of portability

and accessibility that had been lacking in the manuscript. Directly

associated with these expansive qualities was the revolution in

expression. Under manuscript conditions the role of being an author was

a vague and uncertain one, like that of a minstrel. Hence,

self-expression was of little interest. Typography, however, created a

medium in which it was possible to speak out loud and bold to the world

itself, just as it was possible to circumnavigate the world of books

previously locked up in a pluralistic world of monastic cells. Boldness

of type created boldness of expression. Uniformity reached also into

areas of speech and writing, leading to a single tone and attitude to

reader and subject spread throughout an entire composition. |

タイポグラフィは、過去500年

間、芸術と科学のあらゆる分野に浸透してきました。連続性、統一性、反復可能性の原則が、微積分やマーケティング、工業生産、娯楽、科学の基盤となったプ

ロセスを文書化することは容易です。印刷物に反復可能性がもたらした、均一価格の商品としての不思議な新奇性が、価格体系の扉を開いたことを指摘するだけ

で十分でしょう。印刷された本は、手稿には欠けていた携帯性とアクセス性の質も持っていた。これらの拡張的な性質と直接関連していたのが、表現の革命だっ

た。手稿の時代には、作者の役割は吟遊詩人のような曖昧で不確かなものだった。したがって、自己表現はほとんど興味の対象ではなかった。しかし、タイポグ

ラフィは、世界に対して大声で大胆に発言できるメディアを生み出した。これは、以前、修道院の細胞のような多元的な世界に閉じ込められていた書籍の世界を

周回するのと同様だった。文字の boldness は表現の boldness

を生み出した。均一性は言語と文章の領域にも及んだ。これにより、読者や対象に対する単一のトーンと態度が、作品全体に広がった。 |

| 15 |

The

"man of letters" was born. Extended to the spoken word, this literate

equitone enabled literate people to maintain a single "high tone" in

discourse that was quite devastating, and enabled nineteenth-century

prose writers to assume moral qualities that few would now care to

simulate. Permeation of the colloquial language with literate uniform

qualities has flattened out educated speech till it is a very

reasonable acoustic facsimile of the uniform and continuous visual

effects of typography. From this technological effect follows the

further fact that the humor, slang, and dramatic vigor of

American-English speech are monopolies of the semi-literate. These

typographical matters for many people are charged with controversial

values. Yet in any approach to understanding print it is necessary to

stand aside from the form in question if its typical pressure and life

are to be observed. Those who panic now about the threat of the newer

media and about the revolution we are forging, vaster in scope than

that of Gutenberg, are obviously lacking in cool visual detachment and

gratitude for that most potent gift bestowed on Western man by literacy

and typography: his power to act without reaction or involvement. It is

this kind of specialization by dissociation that has created Western

power and efficiency. Without this dissociation of action from feeling

and emotion people are hampered and hesitant. Print taught men to say,

"Damn the torpedoes. Full steam ahead!" |

「文人」が誕生した。この識字能力

は話し言葉にも広がり、識字能力のある人々は、会話において単一の「高調」を維持することが可能となり、19

世紀の散文作家たちは、現在ではほとんど誰も真似しようとはしないような道徳的資質を身につけた。口語に、識字者特有の均質な性質が浸透した結果、教育を

受けた人々の話し方は平坦になり、活字の均質で連続的な視覚的効果と非常によく似た、非常に合理的な音響的複製となった。この技術的効果から、アメリカ英

語のユーモア、スラング、劇的な力強さは、半識字者だけのものとなっているという事実も生じている。多くの人々にとって、こうした活字に関する問題は、物

議を醸す価値のある問題だ。しかし、印刷物を理解するいかなるアプローチにおいても、その典型的な圧力と生命力を観察するためには、その形式から距離を置

く必要がある。現在、新しいメディアの脅威や、グーテンベルクのそれよりも規模の大きな革命についてパニックに陥っている人々は、明らかに冷静な視覚的距

離感と、文字と活版印刷が西洋人に与えた最も強力な贈り物——反応や関与なしに行動する力——への感謝に欠けている。この分離による専門化こそが、西洋の

力と効率を生み出したのだ。行動と感情や感情を分離しなければ、人民は行動に支障をきたし、躊躇してしまう。印刷は、人々に「魚雷なんてくそくらえ。全速

力で前進せよ!」と教えることを教えたのだ。 |

| 16 |

||

| 17 |

||

| 18 |

||

| 19 |

政治学者ベネディクト・アンダーソンの著作『想像の共同体』(1983,1991)の議論に慣れ親しんだ者は、次のようなマクルーハンの 文章に出会ったとき、驚きを隠すことができない。

──印刷が及ぼす心理的および社会的帰結には、我々が新しいナショナリズムと関連させているような事態、つまり、印 刷の分裂的かつ画一的な性格を拡張して、さまざまの地域を次第に均質化させ、結果的に権力、エネルギー、侵略を増殖をさせる事態が含まれる。

──印刷されたページの画一性と反復性には、もう一つの重要な局面があった、それが正しい綴り字、文法、発音という ものに向けて圧力をかけ始めたということだ。

──印刷本の上に、画一の定価をつけられた商品という奇妙に新鮮な性格を付与したのが反復性であり、その結果、価格 システムへの道を開いた。‥‥加えて、印刷された書物には、携帯の便利さ、入手のしやすさという性格があった。‥‥こうした拡張的性格と直接の関係にある のが、表現の革命であった。‥‥活字印刷によって世界そのものに向かって。大声かつ大胆に訴えかけることのできるメディアが生み出された。

──活字印刷の影響が数多くあるなかで、たぶん、ナショナリズムの出現がもっともよく知られたものであろう。方言お よび言語の集団によって人間を政治的に統一するというのは、個々の方言が印刷によって広大なマス・メディアに変ずる以前には考えられないことであっ た。‥‥ナショナリズムそれ自体は、集団の運命と地位を強烈に示す新しい視覚的なイメージとして到来したもので、印刷以前には知られていなかったような迅 速な情報移動に依存していた。

──こんにち、一つのイメージとしてのナショナリズムは、あいかわらず印刷に依存しているけれども、それはすべて電 気メディアの挑戦を受けている。政治においてもビジネスにおいても、平等のジェット機のスピードの影響で、古い国家集団という社会組織はまったく役に立た なくなっている。ルネサンス期に、(均質の空間における連続と競合である)ナショナリズムが新しいものであったばかりか、自然なものでありえたのは、印刷 の迅速さと、その結果として生ずる市場と商業の発展のせいであった(邦訳pp.171-181を一部改訳、原著pp.175-177)。

我々が驚く理由は、アンダーソンがナショナリズムを醸成するものとしての出版資本主義(print capitalism)を定式化した際の諸特性が、すでにここで素描的に集約されてあるからだ。アンダーソンの著作のねらいは、ナショナリズムに先行する 同じ規模の文化システムである宗教共同体と王国との比較とのなかで、ナショナリズムを大規模に人々を動員する文化システムとしてとらえたことにある。その 中で地方新聞を代表とする出版資本主義の発達は、人々を「イメージとして心に描かれた想像の政治共同体」として、歴史上まったく新しい範疇であり集団に属 する個人のアイデンティティの一部たる「国民」を形成することに貢献したとみる。マクルーハンの不定形で思いつき的な発想を、アンダーソンはより洗練され た形で整理し論証しようとしているからである。

マクルーハンは、ルネサンス以前の部族社会(性)、ルネサンス以降のナショナリズム、「電気」時代のナショナリズムと、メディアが形成す る社会意識の彼独自の時間的発達に沿って時代を区分するのに対して、アンダーソンは、政治学者らしく、宗教共同体、王国との政治形態の比較区分の中で国民 国家を出版資本主義との関連の中で分析する。

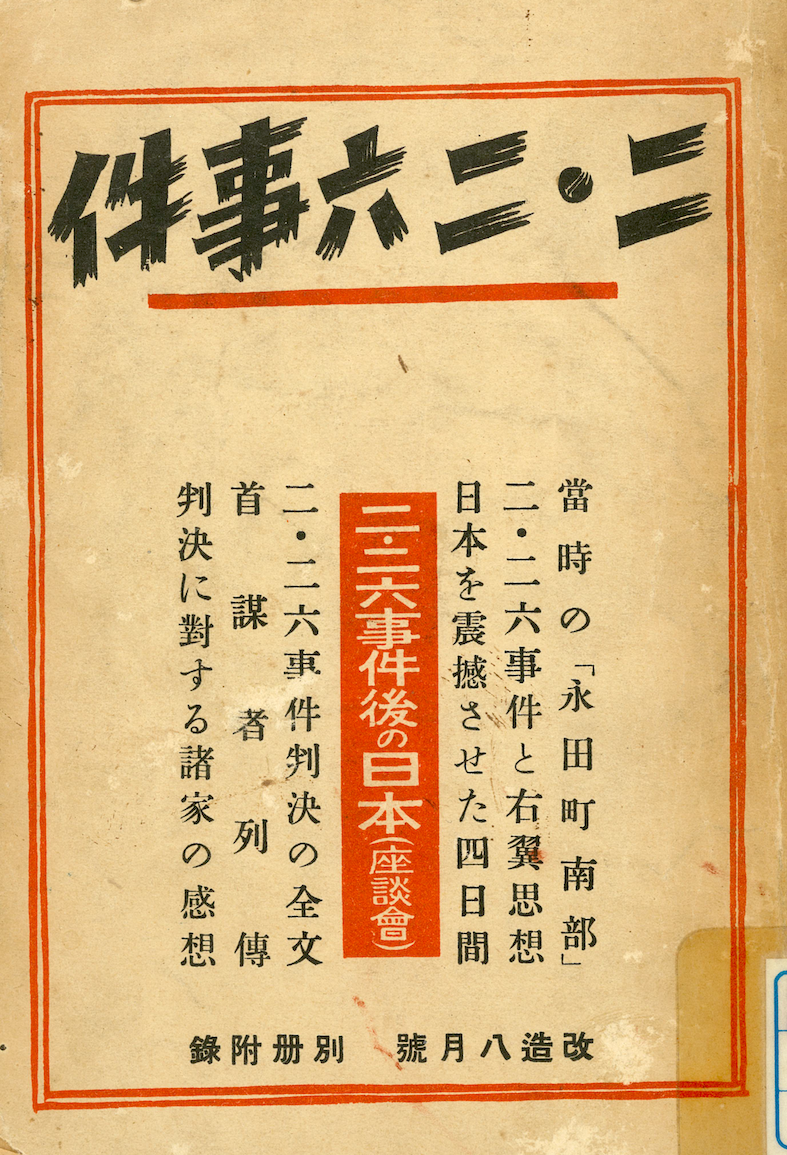

印刷言語は、それまでの写本の秘儀的な知識を、大量複製による「印刷知識」として再編成することに成功する。この印刷知識は、マクルーハ ンによると「最初の二世紀は、新しいものを読んだり書いたりしなければならない必要よりは、古代および中世の書物をみたいという欲望のほうにむしろ動機」 (p.173)がおかれていた。

フェーブルとマルタン『書物の登場』によると、17世紀の初頭には世界で2億冊の書籍が出版されていたが、これは商業資本主義の発達の賜 物であり、この事態はラテン語で書かれた書物を排除しながら、俗語で書かれた大量の本が席巻した結果である。アンダーソンは、俗語化の推進を第一に資本主 義の発達に求めているが、それを加速したのはラテン語の脱神秘化、宗教改革、中央集権化の道具としての俗語の使用があったとする。これらはメディア論以前 の古典的な歴史学者のあげる諸要因である。だが、それは彼に言わせれば、不可欠の要素ではない。

──新しい想像の国民共同体は、この要因のいずれか、いやそれどころか、すべての要因が欠落していたとしても、なお出現したであ ろうとすら考えられる。積極的な意味で、この新しい共同体の想像を可能にしたのは、生産システムと生産関係(資本主義)、コミュニケーション技術(印刷・ 出版)、そして人間の言語的多様性という宿命性のあいだの、なかば偶然の、しかし、爆発的な相互作用であった(p.79 強調は引用者)。

アンダーソンはさらに、この文章の脚注において、先のフェーブルとマルタンの所論を引き、ヨーロッパ社会における紙が歴史的に登場する以 前にブルジョアジーが先行して存在し、紙質の改善もまた紙の登場から75年後のことであった、と指摘する。つまり、資本主義において紙が利用され、それが 出版資本主義を成立を可能にしたこと、それ自体が偶然であったことを示唆している。彼によると、ナショナリズムの発達に出版資本主義は不可欠であったが、 その出版資本主義の成立は歴史における偶然だと言うのである。

ナショナリズムの成立と出版資本主義の関係について、もう少し考えてみたい。彼はナショナリズムを3つの類型としてとらえる。18世紀後 半から19世紀初頭の新大陸アメリカで生まれた最初のナショナリズム、19世紀ヨーロッパの民衆的ナショナリズム、そして19世紀後半から20世紀にかけ て周辺国ではじまる公定ナショナリズムである。新大陸における世界で初めてのナショナリズムが、出版資本主義との関連で論じられる。

新大陸生まれのヨーロッパ人であるクレオールの共同体が、なぜヨーロッパより歴史的に早く「我々国民という観念」を発展させたか、という 問題をアンダーソンは立てる。この種の問題には、先行研究によってすでに解答は与えられていた。従来の説は(1)18世紀後半におけるマドリードの支配強 化、と(2)自由主義的解放思想の普及、という観点から説明するものである。しかし、彼はそれを不十分なものとして退ける。

──しかし、マドリードの攻勢と自由主義の精神は、なるほどスペイン領アメリカにおける抵抗の衝動を理解する上で重要であって も、それ自体としては、チリ、ベネズエラ、メキシコのような実体が、なぜ、感情的に受け入れられ、また政治的にうまくおくことになったのかを、説明するも のではない。あるいはまた、なぜ、サン・マルティンが、特定の原住民を「ペルー人」なる新語によって定義すべしと布告せねばならなかったのか、そしてま た、結局のところ、なぜあのようなほんものの犠牲が払われたのかを説明するものでもない(p.95)。

新たな解答の手がかりは、南アメリカの新生共和国が植民地時代における行政単位と合致しており、それは植民地時代をとおして地域として実 体化されていったこととに注目すべきであるという。

また、行政組織がどのようにして「意味」としての祖国を創造するのかを考える必要がある。彼は、絶対主義王制下における人間と文書の互換 性に注目する。そして、人的な互換性を補完する文書の互換性は、標準化した国家語の発達によって促進されることになるという。

このような国家体制のもとで、はじめてクレオールはヨーロッパの人間──狭義にはイベリア半島居住および半島出身の新大陸人ペニンスラー ル──との類的な一致と制度上における処遇の不一致を知ることになる。それを、想像の共同性という観念を強化したものは、17世紀末から始まる新聞等のプ リントメディアである。

──新聞という概念それ自体がすでに、「世界的事件」すら地方語読者の特定の創造の世界には屈折して入ってゆくということを意味 しており、そして、想像の共同体にとって、時間軸に沿った着実で揺るぎない同時性の観念は、決定的に重要な観念であった。

─[18世紀後半初期のアメリカ大陸の地方新聞──引用者]は、基本的、市場の添え物として始まった。‥‥本国についてのニュー スの他に、商業ニュース──船の到着出帆予定、港での商品価格の動向──そしてされに植民地における政治的任命、金持ちの家族の結婚などが掲載されてい た。別の言い方をすれば、同一紙面に、この結婚とあの船、この価格とあの司教をまとめたのは、まさに植民地行政と市場システムの構造それ自体であった。こ うして、カラカスの新聞は、まったく自然に、また非政治的に、その特定の読者同胞の集団に、これらの船、花嫁、司教、価格の属する想像の共同体を創造した (pp.108-109; p.107)。

このようなアンダーソンの想像の共同体としての「国民」の議論は、メディアの発達がそれにふさわしい想像の共同体をつくることを示唆す る。この議論はマクルーハンが、荒削りの主張したまま放棄しておいた、地球の人間の一族(human family)が「もう一度、一つの部族になる」ことを思い起こさずにはおれない。これをマクルーハンの「単数の再部族化論」として名付け、さらに検討し てみよう。なお、「部族」は社会が個々の部族からなりたつことを前提に創出された分類範疇であるため、単数の部族化という表現は撞着語法であることを予め 理解しておこう。

電子メディアによって我々の五官は本来の感覚を取り戻し、世界はどんどん小さくなる、つまり我々は地球村の住民となる。そして我々は失わ れた神話的世界の中に再び生きるようになる。これが再部族化に関するマクルーハンの青写真である。彼の部族概念は、未開社会に関する幅の広い文献の渉猟か ら導かれ、その部族民のイメージは、アルカイックな世界に住む住民のことであり、彼らの思考法もまた近代人とは根本的に異なる人間と考えていた。その意味 でマクルーハンは部族民を今日では人種主義的な発想の源泉と見なされることが多い、本質主義的的なものとしてとらえている。もちろんこの見方は決して特異 なものではなく、次節に述べるように、西洋近代が培ってきた未開人イメージの基本形にほかならない。さて、この単数の部族民は地球村とセットで考えられ、 彼/彼女らはあたかも、認識と価値を共有する単一性の中に収斂してゆくと考えられている。マクルーハンの部族は、西洋文明の波に曝されて滅びゆく神話的世 界に住む人たちという見解を踏まえたものであり、後述するルース・ベネディクトの未開人観にも通底するのは当然で、北アメリカのヒューマニスティックな人 類学者が印刷メディアを通して生産してきたものなのである。植民地時代に培われた部族概念にみられるように特定の人間集団に当てはめられた本質主義──そ れを生産したのは印刷メディアだ──が、電気メディアによって結果的に克服(救済?)されるというのは、まったく皮肉である。彼は、電気メディアの発達に よって印刷言語が押しつける世界観から解放されるユートピアの人間像のなかに、かつての部族民──もちろん西洋によって想像として構築された部族民──を 見ている。換言するならば、それはルソーの高貴なる野蛮人の電子版、あるいはマルチメディア時代のピグマリオンにほかならない。

しかし、印刷メディアを通して「国民」という主体が人々によって想像=創造されてきたわけであるし、植民地時代に成立した西欧宗主国の民 族学や歴史学が「部族」や「カースト」という分類範疇の創出に少なからず貢献してきた、より正確に言い換えるなら、それらの分類範疇が実体化してきたとい う事実は、アンダーソンのみらならず多方面から指摘されている。それだけではない。世界各地の民族紛争の原因となっている、「民族」の本質主義的な対立 は、植民地時代における民族や部族の分類の確定に起源をもつことが多数ある。マスメディアを通して、民族の対立や差異が調和不可能な根本的であるかのよう な言説が現在横行している。不幸にも、民族学者の一部が、このような本質主義的な文化のイメージの再生産に荷担しているケースも見うけられる。このような 事態は、新たなる「国民」の再編成、つまり分離独立を要求したり、隣接内の「同胞」の保護を名目とする武力介入等をさらに引き起こす直接および間接的な原 因となっている。部族や民族の境界は、新たに細分化されたり再編成されることがあっても、単一化する見込みは現段階では、とうてい考えられない。

マクルーハンのメディアによる地球の再部族化の予言は当たっていたと言える。しかし、それは彼の言うような地球村の「単数の再部族化」で はなかった。距離の遠近を問わない部族の細分化であり、メディアの発達は差異の微分化、つまり複数の再部族化のみならず新部族化産出に拍車をかけていると 言っても過言ではない。このような西洋が自分で作り出した苦境に西洋はどのように立ち向かおうとしているのか。また我々はどう立ち向かうのだろうか.

── はじめに、神はみんなに器を与えた。粘土でできた器だ。この器で彼らは自分たちのいのちを飲んだ。‥‥彼らはみんなそれで水をすくったが、彼らの器はそれ ぞれ別々だ。我々の器は今では壊れてしまった。もう終わってしまったのだ(Benedict 1959:21-22)。

これはルース・ベネディクトが書きとめたディガー・インディアンの首長ラモンの語りである。ラモンの言う器は、彼らの伝統的な儀礼体系に みられる独特の概念であるのか、それとも彼自身の思いつきであったのかは、彼女自身も分からないという。彼女は白人によって滅ぼされてゆく彼らの文化体系 ──彼女は価値基準と信条の構造(fabric)と表現する──の崩壊の象徴として「我々の器は壊れてしまった」という表現をとりあげた。ベネディクト は、ラモンたちが水を掬っていた器が失われて、もはや取り返しがつかないと述べるが、かと言って彼らが完全に絶望的な状況の中に生きているというわけでは ないとも言う。白人との交渉の中で生きるという、別の生き方の器は残されているからである。つまり、苦悩の宿命を担ってはいるが、彼らは2つの文化の中で 生きているからだ。他方、ベネディクトによると北アメリカの「単一のコスモポリタンな文化」における社会科学、心理学、そして神学でさえも、ラモンの表現 する「真理」を拒絶してきたし、そのような語りに耳を傾けてこなかった。

はたして自分たちの器を失い、別の器しか残されていないラモンにとって、新たな器をもちうることが可能だろうか。また彼らの器についての み議論すれば、我々はそれで事足りるだろうか。ラモンの器は、ラモン個人が生み出したメタファーであるのと同時に、ディガーの人びとが共有できるメタ ファーであり、また人類学者ベネディクトとの対話の中で生まれた共感のメタファーでもある。ラモンの器は、一種の象徴表現のひとつであるが、器それ自体 は、我々の用語法に従うならば媒体(メディア)のことに他ならない。

ベネディクトの例を引くまでもなく、従来の人類学が他の人文社会科学の諸分野に対して独自性を強調するとき、駆使される修辞はおもに、 (1)伝統社会と近代社会の二分法を立てて、近代社会の内容を特段に吟味することなく伝統社会の「独自性」を強調すること、(2)そのように強調される伝 統社会が、多種多様性をもち、社会の全体性からの解釈をもってはじめて理解しうるものであること、である。これらの2つの修辞のうち、前者は人類学外部の 研究領域に、後者は類似の研究をおこなう隣接研究領域ならびに人類学の領域の内部にむけて利用されてきた。ここでは、それらのうち前者の修辞は、社会意識 の産出にかんする議論にはもはや効力をもたないことを説明し、伝統と近代という二分法的な思考に代わる代替的方法について考察する。

そもそも伝統と近代、あるいは未開と文明の二分法が生まれてくる前提条件とは何だったのか。

それを一言でいうと、近代社会の省察のための参照点として、伝統社会が対比的関係の中で持ち込まれることになったということである。19 世紀における伝統社会に関する研究は、当時の宣教師や商人からの通信を通して断片的に集積がはじまった「未開社会」や西欧の周辺社会の習俗の記述をもと に、慣習法、親族組織、宗教等の比較研究からはじまった。このような研究に拍車をかけたのは、フーコーの言う古典主義時代に分類表(タブロー)に配列され ていた事物が、19世紀以降には時系列のなかでの変化として捉えられるようになったという人文学の知的枠組みにおける変更にも関係しているように思われ る。時系列的な発想のもっとも強力なものは、発展というモデルであり、進化主義はその時代を代表する思潮である。ところが、この進化主義が提示する、時系 列における先行する古代と、周辺の空間にある「未開社会」の配置を、進化や発展という因果法則に関連づける方法には、それに先行する分類表的発想により親 和性が見られるように思える。より大胆に言えば、進化主義には伝統と近代の二分法というものは、存在しない。この断絶を象徴するものが伝統と近代を理念的 な二分法として考えるM・ウェーバーの見解であり、彼は歴史における因果法則に関しては大いなる疑問を抱き、特に進化論的な進歩の概念を退けている。

伝統と近代の二分法は、19世紀も終わりになってデュルケーム『社会分業論』(1893)によって明確な形を与えられた。この社会学にお ける社会観の単純化と、その傍証に関する議論の洗練化は、それまでの進化主義とは完全に発想や理解を画するものである。ただし彼の議論は、伝統(未開)社 会は近代社会にくらべて個人の自由度が少ない──つまり新しい器を持ち得ない──というものではない。デュルケームの社会観には個人の自由度などというも のは存在しない、あるいはあっても微々たるものにすぎない。個人が自由や閉塞を感じることすらも、彼らの属する社会によって規定されていることを、彼の方 法論とそれに基づく一連の著作は示している。初期の機能主義人類学の古典は、このデュルケーム的な思考を、具体的な「未開社会」に徹底化して集積に血道を あげた結果であると言っても過言ではない。

G・ジンメルを含めて近代社会学の創設に多大なる影響を与えた上のような人たちは、近代人が主体性をもち、合理的に行動するための自由が 与えているということなどは、ゆめ考えてはいなかった。フィールドワークの方法論も確立し、近代社会科学として認知されつつあった機能主義人類学は、デュ ルケーム的命題を守り、個々の具体的な「未開社会」の固有の実体を明らかにすることに邁進した。しかしながら、この努力の結果は、「未開人」の意識に関す る社会拘束性に関する過度の期待を煽ったことになる。しばしば人類学が文化を本質主義化したという批判の論拠はここに求められる。あたかも新しい器をもつ ことができる主体という西洋近代のアイデンティティの神話のネガ像を、未開社会の機能主義人類学は提供したのである。そこでは、近代社会においても人々の 主体的選択もまた社会的に構成されたものであるという視点と、伝統社会における人々の主体的選択の様態そのものに関する視点は、共に捨象されたのである。 したがって未開社会の文化の本質主義化は、人類学の政治性──例えば、人類学は植民地科学の一つであるという批判──だけに還元される問題ではなく、西洋 近代社会の自己と他者の認識におけるある種の帰結であった。

文化を本質主義的に捉えてきたという批判が本格化する以前は、伝統社会に住む人々が、その社会組織の構成原理に則って経験を形成するとい う理解が──新植民地主義批判という稀な例を除けば──比較的長い間受け入れられてきた。それは、西洋近代に対するアンチテーゼであり、また認識論的な反 省材料にもなったからである。

この時代における人類学の役回りは、その文化の本質主義的な「理論」を、より高度に洗練させてゆくことにほかならなかった。ラモンの器の 例で言うならば、「古い器」に関するさまざまな情報が蓄積され、それについての議論が雪だるま式に増殖していった過程である。何事も文化に収斂させる人類 学理論が発展してゆくわけであるが、その営為は近代批判という弁明のもとで正当化された。その極限形態の例としてレヴィ=ストロースの構造主義があげられ る。レヴィ=ストロースは音韻論の構造からの構造主義アイディアを発展させたことはよく知られているが、社会理論に関しては、彼はデュルケームとモースの 知的遺産をたっぷりと受け継いだ。だから構造主義において主体性をもった個人というものは存在しないのは、当然の帰結なのである。五月革命の頃、構造主義 の外側からはアンチ・ヒューマニズムのラベルを貼られ、自己弁明としてはヒューマニズムを主張したことは、構造主義の社会観のアンビバレントな面をよく表 している。システムに支配された社会観をとる点では構造主義はアンチ・ヒューマニスティックであるが、ここの社会の固有性にあくまでもこだわる点では極め てヒューマニスティックなのである。構造主義には、新しい器について建設的な意見を表明するための認識論的な枠組みがそもそも欠けているし、そのような関 心は無益なのである。

ポスト構造主義における、文化の本質主義による隘路の乗り越えのひとつと考えられるのが、ギアーツによる人類学における解釈学的な転回で あり、またさらに、ある意味で文化の本質主義をさらに推進させたことにある。しかし、文化の本質を決定するのは解釈の妥当性や「厚い記述」であるので、文 化の本質的な解釈自体もまた反省の材料になりうる。解釈人類学が、自己に向けられる文化の本質主義批判から逃れる潜在的な可能性をもつのも、実はこの営為 にある。だが解釈人類学は、ラモンの言う器の形態、材質、文様などについて、より洗練された議論を重ねることに成功はしたかもしれないが、壊れた器を、は たして取り戻すことが可能なのか、あるいは新しい器を自ら作り出すことができるのかについては、解答を留保したままなのである。もちろん、その可能性はな いとは言えない(Geertz 1988:146-149)。

もちろん、重要なことは解釈人類学のみならず、メディアを社会意識の審級とする議論にとって重要なことは、新しい器を人類がどのような形 で持ち得るのか、そして、そうであるならその器はどのようなものなのかを明らかにすることである。

エミリー・マーチンは『フレキシビリティ──ポリオの日々からエイズの時代までのアメリカ文化における免疫性の役割』(1994)という 興味深い民族誌において、1950年代以降のアメリカ合衆国における免疫概念が、どのような大衆化を遂げたかについて専門家ならびに非専門家へのインター ビュー調査、科学的読み物の分析等を駆使して明らかにしている。

マーチンの著作のタイトルにあるように、フレキシブル=柔軟な身体は、現代の北アメリカにおける身体のあり方を表象するものである。それ は、外部から要請された身体のあり方についての隠喩的表現であると同時に、人々が受容しつつある身体の表象でもある。例えば、免疫学における身体の防御機 構の説明のように、身体はさまざな外部から個々の侵襲を守るために柔軟に対応することを要求される。それは身体の外部へも伸展してゆくメタファーである。 ちょうど会社組織が雇用者調整を柔軟にして、不確実な経済環境を生き残ったり、解雇された労働者がフレキシブルに次の雇用機会を生かしていけるように。フ レキシブルな身体=世界観は、我々に可能性を付与するが、同時に我々をかえって弱い存在に陥れる可能性も持つ。そして、フレキシブルな身体のあり方は、別 の局面では古典的でインフレキシブルな疾病観や健康観への挑戦となる。文化の本質主義に代表されるようなインフレキシブルな他者表象への挑戦でもあるから だ。

高度メディア社会においてフレキシブルというメタファーはどのような局面において流通しているだろうか。メディア利用のスタイルにフレキ シビリティは暗黙のうちに要求されており、メディアの利用は、我々のフレキシビリティを高めるという表現も、コンピュータをはじめとするビジネス機器の広 告の中で発見することは困難ではない。フレキシビリティは我々の生活のあり方をも表象する。

フレキシブルな身体意識がなぜ今日の人々のあいだで受容されるのだろうか。フレキシブルな身体意識は、主体性の確立という、近代の身体の 成り立ちの古めかしい図式と、どのような関係をもつのだろうか。そして、フレキシブルという外部から与えらたメタファーを、はたして我々自身が操作可能な メタファーとして新たに組み直して使うことが可能なのだろうか。

このようなフレキシブルな身体についての問いは、高度メディアの状況についても同じように発することができる。なぜ高度なメディアを利用 することが良しとされて、さしたる抵抗もなく受容されつつあるのだろうか。高度メディアの発達によって、我々のアイデンティティの形成の様式は変わりうる のだろうか。そして、我々は高度なメディアを、自分たちに与えられた以上に可能性のあるものとして利用しているのだろうか。

高度メディア社会における人類学的な調査研究の活動が、その独自性を発揮できるのはメディアとしての身体と、ちょうどマクルーハンが言っ たような身体の延長としてのメディアの相互作用(弁証法)を明らかにすることにある。ともに我々の考え方の基本にある隠喩的想像力に関わる事象であり、今 日における権力と暴力について考えるための重要な尺度となっているからである。

クレジット:池田光穂「メディアは我々自 身を形づくる──社会意識の産出に関する予備的考察」『高度メディア社会における社会倫理の実証的研究 (I)』[文部省科学研究費補助金・基盤研究(B)高度メディア社会における社会倫理の実証的研究・課題番号09410015・平成9 年度研究成果報告書]、船木亨編、pp.19-30、熊本大学文学部、1998

文献

最後までお読み(あるいはスクロールしていただきありがとうございます)この論文の

pdf版をつくっています;御利用ください(パスワードなし):Media_make-us_ourselves.pdf

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Q.E.D.

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆